DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-023-04711-z

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38166490

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-03

تعزيز تحمل الملوحة في الخيار من خلال التخصيب الحيوي بالسيلينيوم والتطعيم

الملخص

خلفية يعتبر إجهاد الملوحة عاملاً محددًا رئيسيًا لنمو النباتات، خاصة في البيئات الجافة وشبه الجافة. للتخفيف من الآثار الضارة لإجهاد الملوحة على إنتاج الخضروات، ظهرت تقنيات تعزيز السيلينيوم (Se) وزراعة النباتات على أصول جذرية متحملة كطرق زراعة فعالة ومستدامة. هدفت هذه الدراسة إلى التحقيق في التأثيرات المشتركة لتعزيز السيلينيوم وزراعة النباتات على أصول جذرية متحملة على إنتاج الخيار المزروع تحت ظروف الدفيئة مع إجهاد الملوحة. اتبعت التجربة تصميمًا عشوائيًا بالكامل مع ثلاثة عوامل: مستوى الملوحة (0، 50، و100 مللي مول من NaCl)، تطبيق السيلينيوم الورقي (0، 5، و

الخلفية

تحمل الطعم للضغوط البيئية [17]. في النباتات المطعمة، يمكن أن يُعزى تحمل الإجهاد الناتج عن الملوحة إلى تراكم البرولين والسكريات القابلة للذوبان الكلية [18]، وزيادة القدرة المضادة للأكسدة [19]، وتقليل تراكم الصوديوم والكلور في الطعم [20].

المواد والأساليب

المواد النباتية والعلاجات التجريبية

تمت العملية باستخدام ملح سيلينات الصوديوم وتم تطبيقها في نفس الوقت مع تحفيز إجهاد الملوحة وتم رش السيلينيوم على الأوراق مرة واحدة. تم شراء سيلينات الصوديوم من شركة سيغما.

المعلمات المورفومترية

المعلمات الفسيولوجية أصباغ التمثيل الضوئي

كأس العالم للرغبي

تسرب الإلكتروليت (EL)

البروتينات والكربوهيدرات القابلة للذوبان

لتحديد كمية البرولين، تم تخفيف 1 مل من المستخلص الكحولي المذكور أعلاه مع 10 مل من الماء المقطر، وتم إضافة 5 مل من كاشف نينهيدرين.

لها. كانت تركيبة كاشف النينهدين لكل عينة تتضمن 0.125 جرام من النينهدين + 2 مل من حمض الفوسفوريك 6 م و 3 مل من حمض الأسيتيك الجليدي. بعد إضافة كاشف النينهدين، تم إضافة 5 مل من الحمض الجليدي، وتم وضع المزيج الناتج في حمام مائي مغلي عند

محتوى الفينولات الكلي والفلافونويدات

إجمالي محتوى البروتين

أنشطة إنزيمات مضادات الأكسدة

تركيز الصوديوم والبوتاسيوم

التحليلات الإحصائية

النتائج

المعلمات المورفومترية

وزن الجذر الجاف. وفقًا للنتائج التي تم الحصول عليها، فقد حسّن السيلينيوم تأثيرات الملوحة في النباتات المزروعة بحيث زادت خصائص النمو والعائد من الخيار بشكل ملحوظ مع زيادة السيلينيوم في جميع مستويات إجهاد الملوحة الثلاثة.

الخصائص الفسيولوجية الصفات الفسيولوجية

برولين

الكربوهيدرات القابلة للذوبان

إجمالي البروتين

إجمالي الفينولات والفلافونويدات

| الجدول 1 مقارنة متوسط تأثير مستويات مختلفة من إجهاد الملح، والسيلينيوم، والتطعيم على بعض الخصائص الشكلية لنبات الخيار. المتوسطات

|

||||||||||

| إجهاد الملح (مليمول) | سيلينات الصوديوم

|

الطعيم | ارتفاع النبات (سم) | وزن النبات الطازج (غ) | وزن الجذر الطازج (غ) | عدد العقد (-) | عدد الفواكه (-) | وزن الفاكهة الطازجة (غ) | محصول النبات (غرام لكل نبات

|

العائد الإجمالي (

|

| غير التطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 0 | الطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| غير التطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 0 | ٥ | الطعْم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| غير التطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 10 | الطعوم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| غير التطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 0 | الطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 50 | غير التطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ٥ | الطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| غير التطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 10 | الطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| غير التطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 0 | الطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| غير التطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 100 | ٥ | الطعْم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| غير التطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 10 | الطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| إجهاد الملح (مليمول) | سيلينات الصوديوم (ملغ)

|

الكلوروفيل أ

|

الكلوروفيل ب

|

إجمالي الكلوروفيل (ملغ)

|

كاروتينويد

|

| 0 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

| ٥ |

|

|

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 50 | ٥ |

|

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 100 | ٥ |

|

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

|

إنزيمات مضادة للأكسدة

كأس العالم للرغبي

إل

تركيز الصوديوم والبوتاسيوم

معالجة 0 مللي مولار من NaCl بـ

نقاش

| الجدول 3 مقارنة متوسط تأثير مستويات مختلفة من إجهاد الملح، والسيلينيوم، والتطعيم على بعض الخصائص الفسيولوجية لورقة الخيار. المتوسطات

|

|||||||||

| إجهاد الملح (مليمول) | سيلينات الصوديوم (ملغ)

|

الطعيم | برولين

|

السكريات القابلة للذوبان

|

إجمالي البروتين (

|

إجمالي الفينول (ملغ)

|

الفلافونويد (ملغ)

|

كاتالاز (وحدة

|

البيروكسيداز (وحدة

|

| 0 | غير مزروع |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| الطعْم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| غير التطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 0 | ٥ | الطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| غير التطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 10 | الطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| غير التطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 0 | الطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 50 | غير التطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ٥ | الطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| غير التطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 10 | الطعْم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| غير التطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 0 | الطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| غير مزروع |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 100 | ٥ | الطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| غير التطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 10 | الطعيم |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| إجهاد الملح (مليمول) | سيلينات الصوديوم (ملغ)

|

البوتاسيوم في الورقة

|

بوتاسيوم الجذر (

|

صوديوم الورقة

|

صوديوم الجذر (

|

| 0 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

| ٥ |

|

|

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 50 | ٥ |

|

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 100 | ٥ |

|

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

|

تقليل امتصاص الصوديوم ونقله تحت ظروف الإجهاد الملحي. استخدمت بعض الدراسات تطبيق السيلينيوم الورقي والتطعيم لزيادة نمو ثمار الطماطم، والمحصول، والجودة. وفقًا للنتائج، فإن التطعيم مع 2 و

يخلق ظروف امتصاص الماء والمغذيات. في الوقت نفسه، يحفز البرولين نسخ بروتينات مقاومة إجهاد الملوحة بحيث تتحمل النبات ظروف إجهاد الملوحة. قد يساعد رفع مستوى البرولين مع تطبيق السيلينيوم الورقي النباتات على مقاومة إجهاد الملوحة من خلال تعزيز نظام الدفاع المضاد للأكسدة. تحت ظروف إجهاد الملوحة، يؤدي السيلينيوم إلى زيادة تراكم بعض الأسموليتات المتوافقة، بما في ذلك البرولين والسكريات القابلة للذوبان الكلية. وفقًا لنتائجنا، زاد السيلينيوم من كمية الكلوروفيل.

مؤشرات جيدة لقياس كمية الضرر التأكسدي للغشاء. نظرًا لضعف الغشاء السيتوبلازمي، تتسرب محتويات الخلية، وتحدد كمية هذا الضرر من خلال قياس تسرب الإلكتروليت [92].

الاستنتاجات

و تحسين جودة وإنتاجية تطعيم نباتات الخيار.

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

موافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تاريخ الاستلام: 19 سبتمبر 2023 / تاريخ القبول: 27 ديسمبر 2023

نُشر على الإنترنت: 03 يناير 2024

References

- Feng D, Gao Q, Liu J, Tang J, Hua Z, Sun X. Categories of exogenous substances and their effect on alleviation of plant salt stress. Eur J Agron. 2023;142:126656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2022.126656.

- Hassani A, Azapagic A, Shokr N. Global predictions of primary soil salinization under changing climate in the 21 st century. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):6663. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26907-3.

- Okur B, Örçen N. Soil salinization and climate change. In: Prasad MNV, Pietrzykowski M, editors. Climate Change and Soil interactions. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2020. pp. 331-50.

- Zhao S, Zhang Q, Liu M, Zhou H, Ma C, Wang P. Regulation of plant responses to salt stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:1-16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijms22094609.

- Abdelaal Kh. Cucumber grafting onto pumpkin can represent an interesting tool to minimize salinity stress. Physiological and anatomical studies. Middle East J Agric Res. 2017;6:953-75. https://www.researchgate.net/ publication/323883911.

- Savvas D, Papastavrou D, Ntatsi G, Ropokis A, Olympios C, Hartmann H, Schwarz D. Interactive effects of Grafting and Manganese Supply on Growth, Yield, and nutrient uptake by Tomato. HortScience Horts. 2009;44(7):1978-82. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.44.7.1978.

- Ntatsi G, Savvas D, Ntatsi G, Kläring H, Schwarz D. Growth, yield, and metabolic responses of temperature-stressed Tomato to Grafting onto rootstocks differing in Cold Tolerance. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2014;139(2):230-43. https:// doi.org/10.21273/JASHS.139.2.230.

- Ntatsi G, Savvas D, Papasotiropoulos V, Katsileros A, Zrenner RM, Hincha DK, Zuther E, Schwarz D. Rootstock Sub-optimal Temperature Tolerance determines transcriptomic responses after Long-Term Root cooling in Rootstocks and scions of grafted tomato plants. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:911. https://doi. org/10.3389/fpls.2017.00911.

- Savvas D, Öztekin GB, Tepecik M, Ropokis A, Tüzel Y, Ntatsi G, Schwarz D. Impact of grafting and rootstock on nutrient-to-water uptake ratios during the first month after planting of hydroponically grown tomato. J Hortic Sci

10. Fu X, Feng YQ, Zhang XW, Zhang YY, Bi HG, Ai XZ. Salicylic acid is involved in rootstock-Scion communication in improving the Chilling Tolerance of Grafted Cucumber. Front. Plant Sci. 2021;12:1-16. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fpls.2021.693344.

11. Jang Y, Moon JH, Kim SG, Kim T, Lee OJ, Lee HJ, Wi SH. Effect of low-temperature tolerant rootstocks on the growth and Fruit Quality of Watermelon in Semi-forcing and Retarding Culture. Agronomy. 2023;13:1-17. https://doi. org/10.3390/agronomy13010067.

12. Yetisir H, Uygur V. Responses of grafted watermelon onto different gourd species to salinity stress. J Plant Nutr. 2010;33:315-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. hpj.2018.08.003.

13. Huang Y, Bie Z, He S, Hua B, Zhen A, Liu Z. Improving cucumber tolerance to major nutrients induced salinity by grafting onto Cucurbita ficifolia. Environ Ex Bot. 2011;69:32-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2010.02.002.

14. Rouphael Y, Edelstein M, Savvas D, Colla G, Ntatsi G, Kumar P, Schwarz D. Grafting as a Tool for Tolerance of Abiotic stress. Vegetable Grafting: Principles and Practices. 2017;171-215. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781780648972.0171.

15. Ropokis A, Ntatsi G, Kittas C, Katsoulas N, Savvas D. Impact of Cultivar and Grafting on Nutrient and Water Uptake by Sweet Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) grown hydroponically under Mediterranean climatic conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:1244. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.01244.

16. Consentino BB, Rouphael Y, Ntatsi G, Pasquale CD, lapichino G, D’Anna F, Bella SL, Sabatino L. Agronomic performance and fruit quality in greenhouse grown eggplant are interactively modulated by iodine dosage and grafting. Sci Hortic. 2022;295:110891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2022.110891.

17. Parthasarathi TE, Ephrath J, Lazarovitch N. Grafting of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) onto potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) to improve salinity tolerance. Sci Hortic. 2021;282:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2021.110050.

18. Lu K, Sun J, Li Q, Li X, Jin S. Effect of cold stress on growth, physiological characteristics, and Calvin-Cycle-related gene expression of grafted Watermelon seedlings of different Gourd rootstocks. Horticulturae. 2021;7:1-13. https:// doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7100391.

19. López-Gómez E, San Juan MA, Diaz-Vivancos P, Mataix beneyto J, GarciaLegaz MF, Hernández JA. Effect of rootstocks grafting and boron on the antioxidant system and salinity tolerance on loqut plants (Eriobotyra Japonica Lidl). Environ Exp Bot. 2007;60:151-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. envexpbot.2006.10.007.

20. Zhu J, Bie Z, Huang Y, Han X. Effect of grafting on the growth and ion concentrations of cucumber seedlings under NaCl stress. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2008;54:895-902. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-0765.2008. 00306.x.

21. Etehadnia M, Waterer D, De Jong H, Tanino KK. Scion and Rootstock effects on ABA-mediated plant growth regulation and salt tolerance of acclimated and unacclimated potato genotypes. J Plant Growth Regul. 2008;27:125-40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-008-9039-6.

22. Shaterian J, Georges F, Hussain A, Tanin KK. Root to shoot communication and abscisic acid in calreticulin (CR) gene expression and salt stress tolerance in grafted diploid potato (Slanum sp.) clones. Environ Ex Bot. 2005;53:323-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2004.04.008.

23. Ulas F, Alim Aydın AU, Halit Y. Grafting for sustainable growth performance of melon (Cucumis melo) under salt stressed hydroponic condition. EJSD. 2019;8:201-210. https://doi.org/10.14207/ejsd.2019.v8n1p201.

24. Singh H, Kumar P, Kumar A, Kyriacou MC, Colla G, Rouphael Y. Grafting tomato as a tool to improve salt tolerance. Agronomy. 2020;10:1-22. https://doi. org/10.3390/agronomy10020263.

25. Yanyan Y, Shuoshuo W, Min W, Biao G, Qinghua SHI. Effect of different rootstocks on the salt stress tolerance in watermelon seedlings. Hortic Plant J. 2018;4:239-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpj.2018.08.003.

26. Colla G, Rouphae Y, Reac E, Cardarelli M. Grafting cucumber plants enhance tolerance to sodium chloride and sulfate salinization. Sci Hortic. 2012;135:177-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2011.11.023.

27. Elsheery NI, Helaly MN, Omar SO, John SVS, Zabochnicka-Swiątek M, Kalaji HM, Rastogi A. Physiological and molecular mechanisms of salinity tolerance in grafted cucumber. S Afr J Bot. 2020;130:90-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. sajb.2019.12.014.

28. Santa-Cruz A, Martinez-Rodriguez MM, Perez-Alfocea F, Romero-Aranda R, Bolarin MC. The rootstock effect on the tomato salinity response depends on the shoot genotype. Plant Sci. 2002;162:825-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0168-9452(02)00030-4.

29. Bayoumi Y, Abd-Alkarim E, El-Ramady H, El-Aidy F, Hamed ES, Taha N, Prohens J, Rakha M. Grafting improves Fruit Yield of Cucumber plants grown under

combined heat and soil salinity stresses. Horticulturae. 2021;7:1-14. https:// doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7030061.

30. Huang Y, Tang R, Cao Q, Bie Z. Improving the fruit yield and quality of cucumber by grafting onto the salt tolerant rootstock under NaCl stress. Sci Hortic. 2009;122:26-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2009.04.004.

31. Guo Z, Qin Y, Lv J, Wang X, Dong H, Dong X, Zhang T, Du N, Piao F. Luffa rootstock enhances salt tolerance and improves yield and quality of grafted cucumber plants by reducing sodium transport to the shoot. Environ Pollut. 2023;316:1-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120521.

32. Khademi Astaneh R, Bolandnazar S, Zaare Nahandi F, Oustan S. Effects of selenium on enzymatic changes and productivity of garlic under salinity stress.

33. Motesharezadeh B, Ghorbani S, Alikhani HA, Fatemi R, Ma Q. Investigation of different selenium sources and supplying methods for Selenium Enrichment of Basil vegetable (a Case Study under Calcareous and Non-calcareous Soil systems). Recent Pat Food Nutr Agric. 2020;12:73-82. https://doi.org/10.2174/ 2212798411666200611101032.

34. Genchi G, Lauria G, Catalano A, Sinicropi MS, Carocci A. Biological Activity of Selenium and its impact on Human Health. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(3):1-19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24032633.

35. Saleem MF, Kamal MA, Shahid M, Saleem A, Shakeel A, Anjum Sh. A. Exogenous Selenium-Instigated Physiochemical transformations Impart Terminal Heat Tolerance in BT Cotton. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2020;20:274-83. https://doi. org/10.1007/s42729-019-00139-3.

36. Wu C, Dun Y, Zhang Z, Li M, Wu G. Foliar application of selenium and zinc to alleviate wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cadmium toxicity and uptake from cadmium-contaminated soil. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020;190:110091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.110091.

37. Golob A, Novak T, Marsic NK, Sircelj H, Stibij V, Jersa A, Kroflic A, Germ M. Biofortification with selenium and iodine changes morphological properties of Brassica oleracea L. var. Gongylodes and increases their contents in tubers. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2020;150:234-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. plaphy.2020.02.044.

38. Ali J, Jan IU, Ullah H. Selenium supplementation affects vegetative and yield attributes to escalate drought tolerance in okra. Sarhad J Agric. 2020;36:1209. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2020/36.1.120.129.

39. Elkelisha AA, Soliman MH, Alhaithlould HA, El-Esawie MA. Selenium protects wheat seedlings against salt stress-mediated oxidative damage by upregulating antioxidants and osmolytes metabolism. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2019;137:144-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.02.004.

40. Lan CY, Lin KH, Huang WD, Chen CC. Protective effects of selenium on wheat seedlings under salt stress. Agronomy. 2019;9:1-14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ agronomy9060272.

41. Desoky E-SM, Merwad A-RMA, Abo El-Maati MF, Mansour E, Arnaout SMAI, Awad MF, Ramadan MF, Ibrahim SA. Physiological and biochemical mechanisms of exogenously Applied Selenium for Alleviating Destructive impacts Induced by salinity stress in Bread Wheat. Agronomy. 2021;11:1-18. https:// doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11050926.

42. Rasool A, Shah WH, Mushtaq NU, Saleem S, Hakeem KR, ul Rehman R. Amelioration of salinity induced damage in plants by selenium application: a review. S Afr J Bot. 2022;147:98-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2021.12.029.

43. Regni L, Palmerini CA, Del Pino AM, Businelli D, D’Amato R, Mairech H, Marmottini F, Micheli M, Pacheco PH, Proietti P. Effects of selenium supplementation on olive under salt stress conditions. Sci Hortic. 2021;278:109866. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109866.

44. Farag HAS, Ibrahim MFM, El-Yazied AA, El-Beltagi HS, El-Gawad HGA, Alqurashi M, Shalaby TA, Mansour AT, Alkhateeb AA, Farag R. Applied Selenium as a powerful antioxidant to mitigate the Harmful effects of salinity stress in snap Bean seedlings. Agronomy. 2022;12:1-19. https://doi. org/10.3390/agronomy12123215.

45. Wu H, Fan S, Gong H, Guo J. Roles of salicylic acid in selenium-enhanced salt tolerance in tomato plants. Plant Soil. 2022;484:569-88. https://doi. org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1857198/v1.

46. Lichtenthaler HK. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Methods Enzymol. 1987;148:350-82. https://doi. org/10.1016/0076-6879(87)48036-1.

47. Schonfeld MA, Johnson RC, Carver BF, Mornhinweg DW. Water relations in winter wheat as drought resistance indicators. Crop Sci. 1988;28(3):526-31. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci1988.0011183X002800030021x.

48. Ben Hamed K, Castagna A, Salem EA, Ranieri A, Abdelly C. Sea fennel (Crithmum Maritimum L.) under salinity conditions: a comparison of leaf and

root antioxidant responses. Plant Growth Regul. 2007;53:185-94. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10725-007-9217-8.

49. Irigoyen JJ, Einerich DW, Sanchez-Diaz M. Water stress induced changes in concentrations of proline and total soluble sugars in nodulated alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) plants. Physiol Plant. 1992;84:55-60. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.1992.tb08764.x.

50. Paquin

51. Singleton VL, Rossi JA. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdicphosphotungstic acid reagents. Am J Enol Vitic. 1965;16:144-53. https://doi. org/10.5344/ajev.1965.16.3.144.

52. Bor JY, Chen HY, Yen G. Ch. Evaluation of antioxidant activity and inhibitory effect on nitric oxide production of some common vegetables. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:1680-6. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf0527448.

53. Bradford MM. Rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3.

54. Bergmeyer HU. Methods of enzymatic analysis. Berlin, Germany: Akademie Verlag; 1970. pp. 636-47.

55. Herzog V, Fahimi HD. A new sensitive colorimetric assay for peroxidase using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as hydrogen donor. Anal Biochem. 1973;55:554-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(73)90144-9.

56. AOAC. Official method of analysis. Association of official analytical. Chemists, washington, DC: USA; 1990.

57. Hasanuzzaman M, Anwar Hossain M, Fujita M. Selenium in higher plants: physiological role, antioxidant metabolism and abiotic stress tolerance. J. Plant Sci. 2010;5:354-75. https://doi.org/10.3923/jps.2010.354.375.

58. Paris P, Matteo GD, Tarchi M, Tosi L, Spaccino L, Lauteri M. Precision subsurface drip irrigation increases yield while sustaining water use efficiency in Mediterranean poplar bioenergy plantations. For Ecol Manag. 2018;409:749-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2017.12.013.

59. Yaldiz G, Camlica M. Selenium and salt interactions in sage (Salvia officinalis L.): growth and yield, chemical content, ion uptake. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;171:113855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113855.

60. Alinejadian Bidabadi A, Hasani M, Maleki A. The effect of amount and salinity of water on soil salinity and growth and nutrients concentration of spinach in a pot experiment. Iran J Soil Water Res. 2018;49:641-51. https://doi. org/10.22059/ijswr.2017.236843.667714.

61. Semida WM, Abd El-Mageed TA, Abdelkhalik A, Hemida KA, Abdurrahman HA, Howladar SM, Leilah AAA, Rady MOA. Selenium modulates antioxidant activity, osmoprotectants, and photosynthetic efficiency of onion under saline soil conditions. Agronomy. 2021;11:1-18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ agronomy11050855.

62. Karaca C, Aslan GE, Buyuktas D, Kurunc A, Bastug R, Navarro A. Effects of salinity stress on drip-irrigated tomatoes grown under Mediterranean-Type Greenhouse conditions. Agronomy. 2023;13:1-18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ agronomy13010036.

63. Shalaby TA, Abd-Alkarim E, El-Aidy F, Hamed ES, Sharaf-Eldin M, Taha N, El-Ramady H, Bayoumi Y, Dos Reis AR. Nano-selenium, silicon and

64. Admasie MA, Kurunc A, Cengiz MF. Effects of exogenous selenium application for enhancing salinity stress tolerance in dry bean. Sci Hortic. 2023;320:112238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112238.

65. Gou T, Yang L, Hu W, Chen X, Zhu Y, Guo J, Gong H. Silicon improves the growth of cucumber under excess nitrate stress by enhancing nitrogen assimilation and chlorophyll synthesis. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2020;152:5361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.04.031.

66. Farajimanesh A, Haghighi M, Mobli M. The Effect of different endemic cucurbita rootstocks on water relation and physiological changes of grafted cucumber under salinity stress. Int J Hortic Sci Technol. 2016;17:351-68. http://journal-irshs.ir/article-1-210-en.html.

67. Kacjan Maršić N, Štolfa P, Vodnik D, Košmelj K, Mikulič-Petkovšek M, Kump B, Vidrih R, Kokalj D, Piskernik S, Ferjančič B, Dragutinović M, Veberič R, Hudina M, Šircelj H. Physiological and biochemical responses of ungrafted and Grafted Bell Pepper Plants (Capsicum annuum L. var. Grossum (L.) Sendtn.) Grown under moderate salt stress. Plants. 2021;10(2):314. https://doi. org/10.3390/plants10020314.

68. Penella C, Nebauer SG, Quinones A, San Bautista A, Lopez-Galarza S, Calatayud A. Some rootstocks improve pepper tolerance to mild salinity

through ionic regulation. Plant Sci. 2015;230:12-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. plantsci.2014.10.007.

69. Ulas F. Effects of grafting on growth, root morphology and leaf physiology of pepino (Solanum muricatum Ait.) As affected by salt stress under hydroponic conditions. int J Agric Environs food sci. 2021;5:203-12. https://doi. org/10.31015/jaefs.2021.2.10.

70. Sanwal SK, Man A, Kumar A, Kesh H, Kaur G, Rai AK, Kumar R, Sharma PC, Kumar A, Bahadur A, Singh B, Kumar P. Salt Tolerant Eggplant rootstocks modulate sodium partitioning in Tomato Scion and improve performance under saline conditions. Agriculture. 2022;12:1-15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ agriculture12020183.

71. Sabatino L, La Bella S, Ntatsi G, lapichino G, D’Anna F, De Pasquale C, Consentino BB, Rouphael Y. Selenium biofortification and grafting modulate plant performance and functional features of cherry tomato grown in a soilless system. Sci Hortic. 2021;285:110095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. scienta.2021.110095.

72. Hawrylak-Nowak B. Beneficial effects of Exogenous Selenium in Cucumber seedlings subjected to salt stress. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2009;132:259-69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-009-8402-1.

73. Afkari A, Farajpour P. Evaluation of the effect of vermicompost and salinity stress on the pigments content and some biochemical characteristics of borage (Borago Officinalis L.). JPEP. 2019;14(54):90. https://ecophysiologi.gorgan. iau.ir/article_668078.html?lang=en.

74. Shah SH, Houborg R, McCabe MF. Response of chlorophyll, carotenoid and SPAD-502 measurement to salinity and nutrient stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L). Agronomy. 2017;7:1-20. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy7030061.

75. Hawrylak-Nowak B. Selenite is more efficient than selenate in alleviation of salt stress in lettuce plants. Acta Biol Crac Ser Bot. 2015;57:49-54. https://doi. org/10.1515/abcsb-2015-0023.

76. Labanowska M, Filek M, Kurdziel M, Bidzińska E, Miszalski Z, Hartikainen H. EPR spectroscopy as a tool for investigation of differences in radical status in wheat plants of various tolerances to osmotic stress induced by NaCl and PEGtreatment. J. Plant Physiol. 2013;170:136-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jplph.2012.09.013.

77. de Oliveira Sousa VF, Dias TJ, Henschel JM, Júnior SDOM, Batista DS, Linné JA, Targino VA, da Silva RF. Castor bean cake increases osmoprotection and oil production in basil (Ocimum basilicum) under saline stress. Sci Hortic. 2023;309:111687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2022.111687.

78. Koleška I, Hasanagǐ c D, Oljǎ ca R, Murtí c S, Bosan cí c B. Todoroví c V. influence of grafting on the copper concentration in tomato fruits under elevated soil salinity. АГРОЗНАЊE. 2019;20:37-44. https://doi.org/10.7251/ AGREN1901037K.

79. Karimi R, Ebrahimi M, Amerian M. Abscisic acid mitigates NaCl toxicity in grapevine by influencing phytochemical compounds and mineral nutrients in leaves. Sci Hortic. 2021;288:1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. scienta.2021.110336.

80. Khedr AHA, Abbas MA, Wahid AAA, Quick WP, Abogadallah GM. Proline induces the expression of salt-stress-responsive proteins and may improve the adaptation of Pancratium maritimum L. to salt stress. J Exp Bot. 2003;54:2553-62. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erg277.

81. Sattar A, Cheema MA, Abbas T, Sher A, Ijaz Wasaya A, Yasir TA, Abbas T, Hussain M. Foliar applied silicon improves water relations, stay green and enzymatic antioxidants activity in late sown wheat. Silicon. 2020;12:223-30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-019-00115-7.

82. Nowak J, Kaklewski K, Ligocki M. Influence of selenium on oxidoreductive enzymes activity in soil and in plants. Soil Biol Biochem. 2004;36:1553-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2004.07.002.

83. Pietrak A, Salachna P, Łopusiewicz Ł. Changes in growth, ionic status, metabolites content and antioxidant activity of two FernsExposed to Shade, full sunlight, andSalinity. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:1-15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijms24010296.

84. Shekari F, Abbasi A, Mustafavi SH. Effect of silicon and selenium on enzymatic changes and productivity of dill in saline condition. J Saudi Soc Agric Sci. 2017;16:367-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssas.2015.11.006.

85. Walaa AE, Shatlah MA, Atteia MH, Sror HAM. Selenium induces antioxidant defensive enzymes and promotes tolerance against salinity stress in cucumber seedlings (Cucumis sativus). Arab Univ J Agric Sci. 2010;18:65-76. https:// doi.org/10.21608/ajs.2010.14917.

86. Sheikhalipour M, Esmaielpour B, Gohari G, Haghighi M, Jafari H, Farhadi H, Kulak M, Kalisz A. Salt stress mitigation via the Foliar application of ChitosanFunctionalized Selenium and Anatase Titanium Dioxide nanoparticles in

87. Sharifi P, Amirnia R, Torkian M, Shirani Bidabadi S. Protective role of exogenous selenium on salinity-stressed Stachys byzantine plants. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2021;21:2660-72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-021-00554-5.

88. Xu S, Zhao N, Qin D, Liu S, Jiang S, Xu L, Sun Z, Yan D, Hu A. The synergistic effects of silicon and selenium on enhancing salt tolerance of maize plants. Environ Exp Bot. 2021;187:104482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. envexpbot.2021.104482.

89. Rahman M, Rahman K, Sathi KS, Alam MM, Nahar K, Fujita M, Hasanuzzaman M. Supplemental Selenium and Boron Mitigate Salt-Induced oxidative damages in Glycine Max L. Plants. 2021;10:1-16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ plants10102224.

90. Levent Tuna A, Kaya C, Dikilitas M, Yokas IB, Burun B, Altunlu H. Comparative effects of various salicylic acid derivatives on key growth parameters and some enzyme activities in salinity stressed maize (Zea mays L.) plants. Pak. J. Bot. 2007;39:787-798. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12809/5077.

91. Khademi Astaneh R, Bolandnazar S, Zaare Nahandi F, Oustan S. Effects of selenium on enzymatic changes and productivity of garlic under salinity stress.

92. Liu H, Xiao C, Qiu T, Deng J, Cheng H, Cong X, Cheng S, Rao S, Zhang Y. Selenium regulates antioxidant, photosynthesis, and cell permeability in plants under various Abiotic stresses: a review. Plants. 2023;12:1-17. https:// doi.org/10.3390/plants12010044.

93. Jouyban Z. The effect of salt stress on plant growth. J Eng Appl Sci. 2012;2:710. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:39278033.

ملاحظة الناشر

- *المراسلات:

مسمومه أميريان

masoomehamerian@yahoo.com

قسم علوم وهندسة البستنة، كلية

العلوم الزراعية والهندسة، حرم الزراعة والطبيعة

الموارد، جامعة رازي، كرمانشاه، إيران

قسم علوم البستنة، كلية الزراعة، جامعة مراغه، مراغه، إيران

قسم علوم المحاصيل، مختبر المحاصيل الخضراء، الجامعة الزراعية في أثينا، أثينا، اليونان - تعني القيم المشار إليها بحروف مشابهة في الأعمدة أنها لا تختلف بشكل كبير عند

مستوى

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-023-04711-z

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38166490

Publication Date: 2024-01-03

Enhancing salinity tolerance in cucumber through Selenium biofortification and grafting

Abstract

Background Salinity stress is a major limiting factor for plant growth, particularly in arid and semi-arid environments. To mitigate the detrimental effects of salinity stress on vegetable production, selenium (Se) biofortification and grafting onto tolerant rootstocks have emerged as effective and sustainable cultivation practices. This study aimed to investigate the combined effects of Se biofortification and grafting onto tolerant rootstock on the yield of cucumber grown under salinity stress greenhouse conditions. The experiment followed a completely randomized factorial design with three factors: salinity level ( 0,50 , and 100 mM of NaCl ), foliar Se application ( 0,5 , and

Background

scion’s tolerance to environmental stresses [17]. In grafted plants, tolerance to salinity stress can be attributed to the accumulation of proline and total soluble sugars [18], enhanced antioxidant capacity [19], and reduced of sodium and chlorine accumulation in the scion [20].

Materials and methods

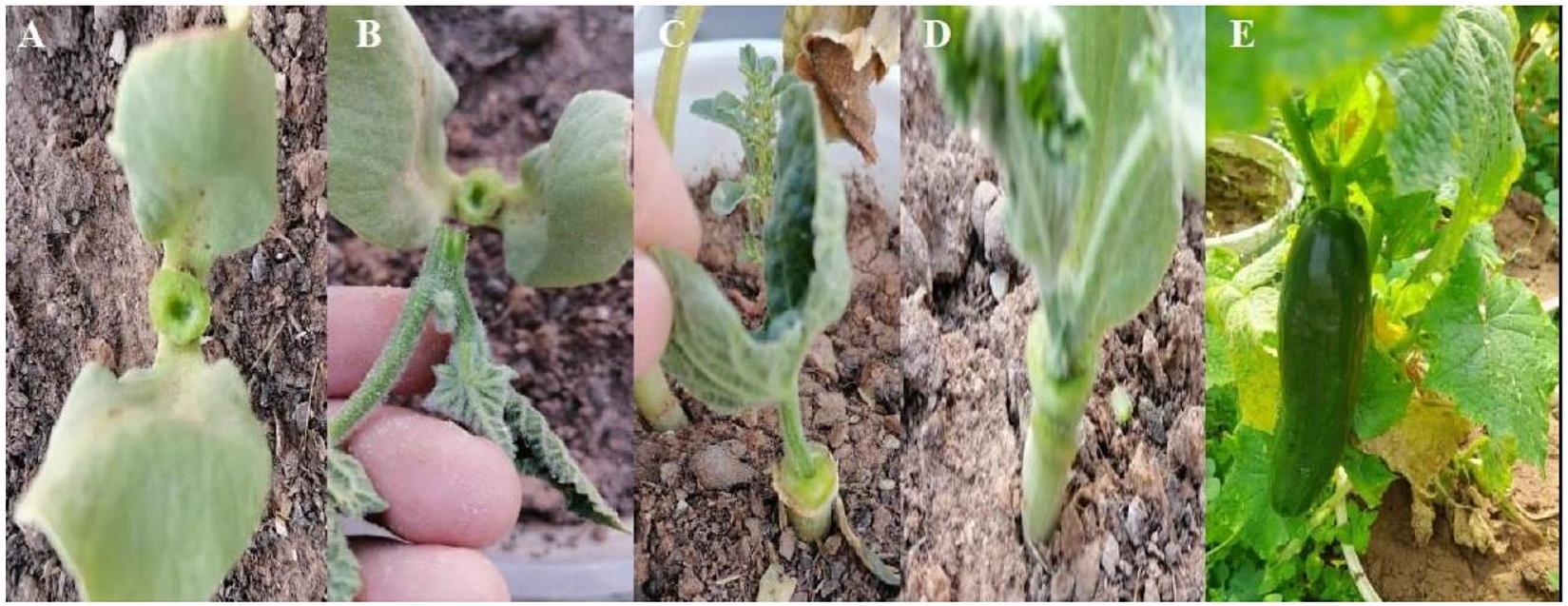

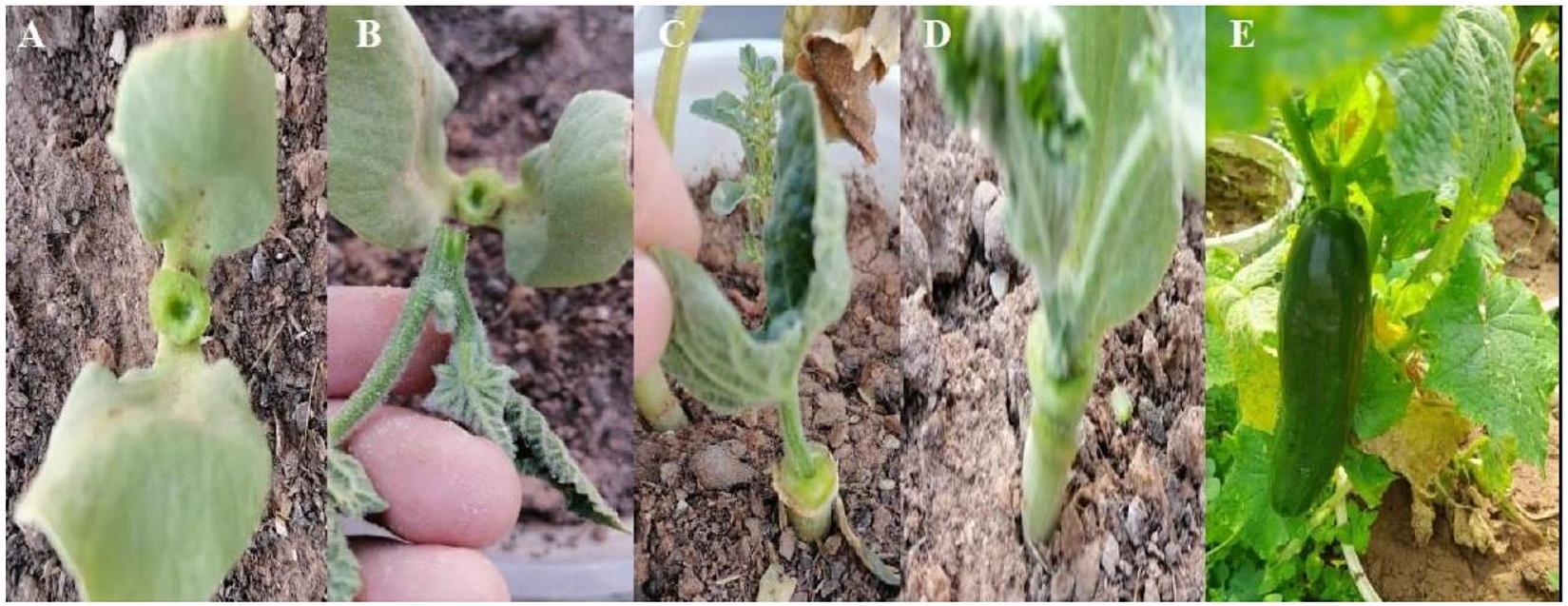

Plant materials and experimental treatments

performed using sodium selenate salt and was applied simultaneously with the induction of salinity stress and Se foliar spraying was done once. Sodium selenate was purchased from Sigma Company.

Morphometric parameters

Physiologic parameters Photosynthetic pigments

RWC

Electrolyte leakage (EL)

Proline and soluble carbohydrates

To determine the amount of proline, 1 ml of the abovementioned alcoholic extract was diluted with 10 ml of distilled water, and 5 ml of Ninhydrin reagent was added

to it. The composition of the Ninhydrin reagent for each sample included 0.125 g of Ninhydrin +2 ml of 6 M Phosphoric acid and 3 ml of Glacial acetic acid. After adding the Ninhydrin reagent, 5 ml of Glacial acid was added, and the resulting mixture was placed in a boiling water bath at

Total phenol and flavonoid content

Total protein content

Antioxidant enzyme activities

Sodium and potassium concentration

Statistical analyses

Results

Morphometric parameters

root dry weight. According to the obtained results, Se has improved the effects of salinity in transplanted plants so that in all three levels of salinity stress, the growth characteristics and yield of cucumber increased significantly with the increase of Se .

Physiological characteristics Physiological traits

Proline

Soluble carbohydrates

Total protein

Total phenol and flavonoid

| Table 1 Mean comparison of effect different levels of salt stress, Se and grafting on some morphological characteristics cucumber plant. Means

|

||||||||||

| Salt stress (mM) | Sodium selenate (

|

Grafting | Plant height (cm) | Fresh plant weight (g) | Fresh root weight (g) | Number of nodes (-) | Number of fruits (-) | Fresh fruit weight (g) | Plant yield (g plant

|

Total yield (

|

| Non-Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 0 | Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 0 | 5 | Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 10 | Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 0 | Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 50 | Non-Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 5 | Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 10 | Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 0 | Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 100 | 5 | Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 10 | Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Salt stress (mM) | Sodium selenate (mg

|

Chlorophyll a (

|

Chlorophyll b (

|

Total chlorophyll (mg

|

Carotenoid (

|

| 0 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

| 5 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 50 | 5 |

|

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 100 | 5 |

|

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

|

Antioxidant enzymes

RWC

EL

Sodium and potassium concentration

treating 0 mM NaCl with

Discussion

| Table 3 Mean comparison of effect different levels of salt stress, Se and grafting on some physiological characteristics cucumber leaf. Means

|

|||||||||

| Salt stress (mM) | Sodium selenate (mg

|

Grafting | Proline (

|

Soluble sugars (

|

Total Protein (

|

Total phenol (mg

|

Flavonoid (mg

|

Catalase (unit

|

Peroxidase (unit

|

| 0 | Non-Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Non-Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 0 | 5 | Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 10 | Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 0 | Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 50 | Non-Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 5 | Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 10 | Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 0 | Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 100 | 5 | Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 10 | Grafting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Salt stress (mM) | Sodium selenate (mg

|

Leaf potassium (

|

Root potassium (

|

Leaf sodium (

|

Root sodium (

|

| 0 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

| 5 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 50 | 5 |

|

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 100 | 5 |

|

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

|

reduction of sodium absorption and transport under salinity stress conditions. Some studies employed foliar Se application and grafting to increase tomato fruit growth, yield, and quality. According to the results, grafting with 2 and

creates water and nutrient absorption conditions. At the same time, proline induces the transcription of salinity stress-resistant proteins so that the plant tolerates salinity stress conditions [79]. Raising the proline level with foliar Se application may help plants resist salinity stress by enhancing the antioxidant defense system. Under salinity stress conditions, Se leads to increased accumulation of some compatible osmolytes, including proline and total soluble sugars [80]. According to our results, Se increased the amount of chlorophyll

good indicators for measuring the amount of oxidative damage to the membrane. Due to the cytoplasmic membrane’s vulnerability, the cell’s contents leak out, and the amount of this damage is determined by measuring electrolyte leakage [92].

Conclusions

and improve the quality and yield of grafting cucumber plants.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Received: 19 September 2023 / Accepted: 27 December 2023

Published online: 03 January 2024

References

- Feng D, Gao Q, Liu J, Tang J, Hua Z, Sun X. Categories of exogenous substances and their effect on alleviation of plant salt stress. Eur J Agron. 2023;142:126656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2022.126656.

- Hassani A, Azapagic A, Shokr N. Global predictions of primary soil salinization under changing climate in the 21 st century. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):6663. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26907-3.

- Okur B, Örçen N. Soil salinization and climate change. In: Prasad MNV, Pietrzykowski M, editors. Climate Change and Soil interactions. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2020. pp. 331-50.

- Zhao S, Zhang Q, Liu M, Zhou H, Ma C, Wang P. Regulation of plant responses to salt stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:1-16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijms22094609.

- Abdelaal Kh. Cucumber grafting onto pumpkin can represent an interesting tool to minimize salinity stress. Physiological and anatomical studies. Middle East J Agric Res. 2017;6:953-75. https://www.researchgate.net/ publication/323883911.

- Savvas D, Papastavrou D, Ntatsi G, Ropokis A, Olympios C, Hartmann H, Schwarz D. Interactive effects of Grafting and Manganese Supply on Growth, Yield, and nutrient uptake by Tomato. HortScience Horts. 2009;44(7):1978-82. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.44.7.1978.

- Ntatsi G, Savvas D, Ntatsi G, Kläring H, Schwarz D. Growth, yield, and metabolic responses of temperature-stressed Tomato to Grafting onto rootstocks differing in Cold Tolerance. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2014;139(2):230-43. https:// doi.org/10.21273/JASHS.139.2.230.

- Ntatsi G, Savvas D, Papasotiropoulos V, Katsileros A, Zrenner RM, Hincha DK, Zuther E, Schwarz D. Rootstock Sub-optimal Temperature Tolerance determines transcriptomic responses after Long-Term Root cooling in Rootstocks and scions of grafted tomato plants. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:911. https://doi. org/10.3389/fpls.2017.00911.

- Savvas D, Öztekin GB, Tepecik M, Ropokis A, Tüzel Y, Ntatsi G, Schwarz D. Impact of grafting and rootstock on nutrient-to-water uptake ratios during the first month after planting of hydroponically grown tomato. J Hortic Sci

10. Fu X, Feng YQ, Zhang XW, Zhang YY, Bi HG, Ai XZ. Salicylic acid is involved in rootstock-Scion communication in improving the Chilling Tolerance of Grafted Cucumber. Front. Plant Sci. 2021;12:1-16. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fpls.2021.693344.

11. Jang Y, Moon JH, Kim SG, Kim T, Lee OJ, Lee HJ, Wi SH. Effect of low-temperature tolerant rootstocks on the growth and Fruit Quality of Watermelon in Semi-forcing and Retarding Culture. Agronomy. 2023;13:1-17. https://doi. org/10.3390/agronomy13010067.

12. Yetisir H, Uygur V. Responses of grafted watermelon onto different gourd species to salinity stress. J Plant Nutr. 2010;33:315-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. hpj.2018.08.003.

13. Huang Y, Bie Z, He S, Hua B, Zhen A, Liu Z. Improving cucumber tolerance to major nutrients induced salinity by grafting onto Cucurbita ficifolia. Environ Ex Bot. 2011;69:32-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2010.02.002.

14. Rouphael Y, Edelstein M, Savvas D, Colla G, Ntatsi G, Kumar P, Schwarz D. Grafting as a Tool for Tolerance of Abiotic stress. Vegetable Grafting: Principles and Practices. 2017;171-215. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781780648972.0171.

15. Ropokis A, Ntatsi G, Kittas C, Katsoulas N, Savvas D. Impact of Cultivar and Grafting on Nutrient and Water Uptake by Sweet Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) grown hydroponically under Mediterranean climatic conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:1244. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.01244.

16. Consentino BB, Rouphael Y, Ntatsi G, Pasquale CD, lapichino G, D’Anna F, Bella SL, Sabatino L. Agronomic performance and fruit quality in greenhouse grown eggplant are interactively modulated by iodine dosage and grafting. Sci Hortic. 2022;295:110891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2022.110891.

17. Parthasarathi TE, Ephrath J, Lazarovitch N. Grafting of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) onto potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) to improve salinity tolerance. Sci Hortic. 2021;282:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2021.110050.

18. Lu K, Sun J, Li Q, Li X, Jin S. Effect of cold stress on growth, physiological characteristics, and Calvin-Cycle-related gene expression of grafted Watermelon seedlings of different Gourd rootstocks. Horticulturae. 2021;7:1-13. https:// doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7100391.

19. López-Gómez E, San Juan MA, Diaz-Vivancos P, Mataix beneyto J, GarciaLegaz MF, Hernández JA. Effect of rootstocks grafting and boron on the antioxidant system and salinity tolerance on loqut plants (Eriobotyra Japonica Lidl). Environ Exp Bot. 2007;60:151-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. envexpbot.2006.10.007.

20. Zhu J, Bie Z, Huang Y, Han X. Effect of grafting on the growth and ion concentrations of cucumber seedlings under NaCl stress. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2008;54:895-902. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-0765.2008. 00306.x.

21. Etehadnia M, Waterer D, De Jong H, Tanino KK. Scion and Rootstock effects on ABA-mediated plant growth regulation and salt tolerance of acclimated and unacclimated potato genotypes. J Plant Growth Regul. 2008;27:125-40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-008-9039-6.

22. Shaterian J, Georges F, Hussain A, Tanin KK. Root to shoot communication and abscisic acid in calreticulin (CR) gene expression and salt stress tolerance in grafted diploid potato (Slanum sp.) clones. Environ Ex Bot. 2005;53:323-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2004.04.008.

23. Ulas F, Alim Aydın AU, Halit Y. Grafting for sustainable growth performance of melon (Cucumis melo) under salt stressed hydroponic condition. EJSD. 2019;8:201-210. https://doi.org/10.14207/ejsd.2019.v8n1p201.

24. Singh H, Kumar P, Kumar A, Kyriacou MC, Colla G, Rouphael Y. Grafting tomato as a tool to improve salt tolerance. Agronomy. 2020;10:1-22. https://doi. org/10.3390/agronomy10020263.

25. Yanyan Y, Shuoshuo W, Min W, Biao G, Qinghua SHI. Effect of different rootstocks on the salt stress tolerance in watermelon seedlings. Hortic Plant J. 2018;4:239-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpj.2018.08.003.

26. Colla G, Rouphae Y, Reac E, Cardarelli M. Grafting cucumber plants enhance tolerance to sodium chloride and sulfate salinization. Sci Hortic. 2012;135:177-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2011.11.023.

27. Elsheery NI, Helaly MN, Omar SO, John SVS, Zabochnicka-Swiątek M, Kalaji HM, Rastogi A. Physiological and molecular mechanisms of salinity tolerance in grafted cucumber. S Afr J Bot. 2020;130:90-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. sajb.2019.12.014.

28. Santa-Cruz A, Martinez-Rodriguez MM, Perez-Alfocea F, Romero-Aranda R, Bolarin MC. The rootstock effect on the tomato salinity response depends on the shoot genotype. Plant Sci. 2002;162:825-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0168-9452(02)00030-4.

29. Bayoumi Y, Abd-Alkarim E, El-Ramady H, El-Aidy F, Hamed ES, Taha N, Prohens J, Rakha M. Grafting improves Fruit Yield of Cucumber plants grown under

combined heat and soil salinity stresses. Horticulturae. 2021;7:1-14. https:// doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7030061.

30. Huang Y, Tang R, Cao Q, Bie Z. Improving the fruit yield and quality of cucumber by grafting onto the salt tolerant rootstock under NaCl stress. Sci Hortic. 2009;122:26-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2009.04.004.

31. Guo Z, Qin Y, Lv J, Wang X, Dong H, Dong X, Zhang T, Du N, Piao F. Luffa rootstock enhances salt tolerance and improves yield and quality of grafted cucumber plants by reducing sodium transport to the shoot. Environ Pollut. 2023;316:1-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120521.

32. Khademi Astaneh R, Bolandnazar S, Zaare Nahandi F, Oustan S. Effects of selenium on enzymatic changes and productivity of garlic under salinity stress.

33. Motesharezadeh B, Ghorbani S, Alikhani HA, Fatemi R, Ma Q. Investigation of different selenium sources and supplying methods for Selenium Enrichment of Basil vegetable (a Case Study under Calcareous and Non-calcareous Soil systems). Recent Pat Food Nutr Agric. 2020;12:73-82. https://doi.org/10.2174/ 2212798411666200611101032.

34. Genchi G, Lauria G, Catalano A, Sinicropi MS, Carocci A. Biological Activity of Selenium and its impact on Human Health. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(3):1-19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24032633.

35. Saleem MF, Kamal MA, Shahid M, Saleem A, Shakeel A, Anjum Sh. A. Exogenous Selenium-Instigated Physiochemical transformations Impart Terminal Heat Tolerance in BT Cotton. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2020;20:274-83. https://doi. org/10.1007/s42729-019-00139-3.

36. Wu C, Dun Y, Zhang Z, Li M, Wu G. Foliar application of selenium and zinc to alleviate wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cadmium toxicity and uptake from cadmium-contaminated soil. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020;190:110091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.110091.

37. Golob A, Novak T, Marsic NK, Sircelj H, Stibij V, Jersa A, Kroflic A, Germ M. Biofortification with selenium and iodine changes morphological properties of Brassica oleracea L. var. Gongylodes and increases their contents in tubers. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2020;150:234-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. plaphy.2020.02.044.

38. Ali J, Jan IU, Ullah H. Selenium supplementation affects vegetative and yield attributes to escalate drought tolerance in okra. Sarhad J Agric. 2020;36:1209. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2020/36.1.120.129.

39. Elkelisha AA, Soliman MH, Alhaithlould HA, El-Esawie MA. Selenium protects wheat seedlings against salt stress-mediated oxidative damage by upregulating antioxidants and osmolytes metabolism. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2019;137:144-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.02.004.

40. Lan CY, Lin KH, Huang WD, Chen CC. Protective effects of selenium on wheat seedlings under salt stress. Agronomy. 2019;9:1-14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ agronomy9060272.

41. Desoky E-SM, Merwad A-RMA, Abo El-Maati MF, Mansour E, Arnaout SMAI, Awad MF, Ramadan MF, Ibrahim SA. Physiological and biochemical mechanisms of exogenously Applied Selenium for Alleviating Destructive impacts Induced by salinity stress in Bread Wheat. Agronomy. 2021;11:1-18. https:// doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11050926.

42. Rasool A, Shah WH, Mushtaq NU, Saleem S, Hakeem KR, ul Rehman R. Amelioration of salinity induced damage in plants by selenium application: a review. S Afr J Bot. 2022;147:98-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2021.12.029.

43. Regni L, Palmerini CA, Del Pino AM, Businelli D, D’Amato R, Mairech H, Marmottini F, Micheli M, Pacheco PH, Proietti P. Effects of selenium supplementation on olive under salt stress conditions. Sci Hortic. 2021;278:109866. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109866.

44. Farag HAS, Ibrahim MFM, El-Yazied AA, El-Beltagi HS, El-Gawad HGA, Alqurashi M, Shalaby TA, Mansour AT, Alkhateeb AA, Farag R. Applied Selenium as a powerful antioxidant to mitigate the Harmful effects of salinity stress in snap Bean seedlings. Agronomy. 2022;12:1-19. https://doi. org/10.3390/agronomy12123215.

45. Wu H, Fan S, Gong H, Guo J. Roles of salicylic acid in selenium-enhanced salt tolerance in tomato plants. Plant Soil. 2022;484:569-88. https://doi. org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1857198/v1.

46. Lichtenthaler HK. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Methods Enzymol. 1987;148:350-82. https://doi. org/10.1016/0076-6879(87)48036-1.

47. Schonfeld MA, Johnson RC, Carver BF, Mornhinweg DW. Water relations in winter wheat as drought resistance indicators. Crop Sci. 1988;28(3):526-31. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci1988.0011183X002800030021x.

48. Ben Hamed K, Castagna A, Salem EA, Ranieri A, Abdelly C. Sea fennel (Crithmum Maritimum L.) under salinity conditions: a comparison of leaf and

root antioxidant responses. Plant Growth Regul. 2007;53:185-94. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10725-007-9217-8.

49. Irigoyen JJ, Einerich DW, Sanchez-Diaz M. Water stress induced changes in concentrations of proline and total soluble sugars in nodulated alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) plants. Physiol Plant. 1992;84:55-60. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.1992.tb08764.x.

50. Paquin

51. Singleton VL, Rossi JA. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdicphosphotungstic acid reagents. Am J Enol Vitic. 1965;16:144-53. https://doi. org/10.5344/ajev.1965.16.3.144.

52. Bor JY, Chen HY, Yen G. Ch. Evaluation of antioxidant activity and inhibitory effect on nitric oxide production of some common vegetables. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:1680-6. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf0527448.

53. Bradford MM. Rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3.

54. Bergmeyer HU. Methods of enzymatic analysis. Berlin, Germany: Akademie Verlag; 1970. pp. 636-47.

55. Herzog V, Fahimi HD. A new sensitive colorimetric assay for peroxidase using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as hydrogen donor. Anal Biochem. 1973;55:554-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(73)90144-9.

56. AOAC. Official method of analysis. Association of official analytical. Chemists, washington, DC: USA; 1990.

57. Hasanuzzaman M, Anwar Hossain M, Fujita M. Selenium in higher plants: physiological role, antioxidant metabolism and abiotic stress tolerance. J. Plant Sci. 2010;5:354-75. https://doi.org/10.3923/jps.2010.354.375.

58. Paris P, Matteo GD, Tarchi M, Tosi L, Spaccino L, Lauteri M. Precision subsurface drip irrigation increases yield while sustaining water use efficiency in Mediterranean poplar bioenergy plantations. For Ecol Manag. 2018;409:749-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2017.12.013.

59. Yaldiz G, Camlica M. Selenium and salt interactions in sage (Salvia officinalis L.): growth and yield, chemical content, ion uptake. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;171:113855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113855.

60. Alinejadian Bidabadi A, Hasani M, Maleki A. The effect of amount and salinity of water on soil salinity and growth and nutrients concentration of spinach in a pot experiment. Iran J Soil Water Res. 2018;49:641-51. https://doi. org/10.22059/ijswr.2017.236843.667714.

61. Semida WM, Abd El-Mageed TA, Abdelkhalik A, Hemida KA, Abdurrahman HA, Howladar SM, Leilah AAA, Rady MOA. Selenium modulates antioxidant activity, osmoprotectants, and photosynthetic efficiency of onion under saline soil conditions. Agronomy. 2021;11:1-18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ agronomy11050855.

62. Karaca C, Aslan GE, Buyuktas D, Kurunc A, Bastug R, Navarro A. Effects of salinity stress on drip-irrigated tomatoes grown under Mediterranean-Type Greenhouse conditions. Agronomy. 2023;13:1-18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ agronomy13010036.

63. Shalaby TA, Abd-Alkarim E, El-Aidy F, Hamed ES, Sharaf-Eldin M, Taha N, El-Ramady H, Bayoumi Y, Dos Reis AR. Nano-selenium, silicon and

64. Admasie MA, Kurunc A, Cengiz MF. Effects of exogenous selenium application for enhancing salinity stress tolerance in dry bean. Sci Hortic. 2023;320:112238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112238.

65. Gou T, Yang L, Hu W, Chen X, Zhu Y, Guo J, Gong H. Silicon improves the growth of cucumber under excess nitrate stress by enhancing nitrogen assimilation and chlorophyll synthesis. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2020;152:5361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.04.031.

66. Farajimanesh A, Haghighi M, Mobli M. The Effect of different endemic cucurbita rootstocks on water relation and physiological changes of grafted cucumber under salinity stress. Int J Hortic Sci Technol. 2016;17:351-68. http://journal-irshs.ir/article-1-210-en.html.

67. Kacjan Maršić N, Štolfa P, Vodnik D, Košmelj K, Mikulič-Petkovšek M, Kump B, Vidrih R, Kokalj D, Piskernik S, Ferjančič B, Dragutinović M, Veberič R, Hudina M, Šircelj H. Physiological and biochemical responses of ungrafted and Grafted Bell Pepper Plants (Capsicum annuum L. var. Grossum (L.) Sendtn.) Grown under moderate salt stress. Plants. 2021;10(2):314. https://doi. org/10.3390/plants10020314.

68. Penella C, Nebauer SG, Quinones A, San Bautista A, Lopez-Galarza S, Calatayud A. Some rootstocks improve pepper tolerance to mild salinity

through ionic regulation. Plant Sci. 2015;230:12-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. plantsci.2014.10.007.

69. Ulas F. Effects of grafting on growth, root morphology and leaf physiology of pepino (Solanum muricatum Ait.) As affected by salt stress under hydroponic conditions. int J Agric Environs food sci. 2021;5:203-12. https://doi. org/10.31015/jaefs.2021.2.10.

70. Sanwal SK, Man A, Kumar A, Kesh H, Kaur G, Rai AK, Kumar R, Sharma PC, Kumar A, Bahadur A, Singh B, Kumar P. Salt Tolerant Eggplant rootstocks modulate sodium partitioning in Tomato Scion and improve performance under saline conditions. Agriculture. 2022;12:1-15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ agriculture12020183.

71. Sabatino L, La Bella S, Ntatsi G, lapichino G, D’Anna F, De Pasquale C, Consentino BB, Rouphael Y. Selenium biofortification and grafting modulate plant performance and functional features of cherry tomato grown in a soilless system. Sci Hortic. 2021;285:110095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. scienta.2021.110095.

72. Hawrylak-Nowak B. Beneficial effects of Exogenous Selenium in Cucumber seedlings subjected to salt stress. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2009;132:259-69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-009-8402-1.

73. Afkari A, Farajpour P. Evaluation of the effect of vermicompost and salinity stress on the pigments content and some biochemical characteristics of borage (Borago Officinalis L.). JPEP. 2019;14(54):90. https://ecophysiologi.gorgan. iau.ir/article_668078.html?lang=en.

74. Shah SH, Houborg R, McCabe MF. Response of chlorophyll, carotenoid and SPAD-502 measurement to salinity and nutrient stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L). Agronomy. 2017;7:1-20. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy7030061.

75. Hawrylak-Nowak B. Selenite is more efficient than selenate in alleviation of salt stress in lettuce plants. Acta Biol Crac Ser Bot. 2015;57:49-54. https://doi. org/10.1515/abcsb-2015-0023.

76. Labanowska M, Filek M, Kurdziel M, Bidzińska E, Miszalski Z, Hartikainen H. EPR spectroscopy as a tool for investigation of differences in radical status in wheat plants of various tolerances to osmotic stress induced by NaCl and PEGtreatment. J. Plant Physiol. 2013;170:136-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jplph.2012.09.013.

77. de Oliveira Sousa VF, Dias TJ, Henschel JM, Júnior SDOM, Batista DS, Linné JA, Targino VA, da Silva RF. Castor bean cake increases osmoprotection and oil production in basil (Ocimum basilicum) under saline stress. Sci Hortic. 2023;309:111687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2022.111687.

78. Koleška I, Hasanagǐ c D, Oljǎ ca R, Murtí c S, Bosan cí c B. Todoroví c V. influence of grafting on the copper concentration in tomato fruits under elevated soil salinity. АГРОЗНАЊE. 2019;20:37-44. https://doi.org/10.7251/ AGREN1901037K.

79. Karimi R, Ebrahimi M, Amerian M. Abscisic acid mitigates NaCl toxicity in grapevine by influencing phytochemical compounds and mineral nutrients in leaves. Sci Hortic. 2021;288:1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. scienta.2021.110336.

80. Khedr AHA, Abbas MA, Wahid AAA, Quick WP, Abogadallah GM. Proline induces the expression of salt-stress-responsive proteins and may improve the adaptation of Pancratium maritimum L. to salt stress. J Exp Bot. 2003;54:2553-62. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erg277.

81. Sattar A, Cheema MA, Abbas T, Sher A, Ijaz Wasaya A, Yasir TA, Abbas T, Hussain M. Foliar applied silicon improves water relations, stay green and enzymatic antioxidants activity in late sown wheat. Silicon. 2020;12:223-30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-019-00115-7.

82. Nowak J, Kaklewski K, Ligocki M. Influence of selenium on oxidoreductive enzymes activity in soil and in plants. Soil Biol Biochem. 2004;36:1553-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2004.07.002.

83. Pietrak A, Salachna P, Łopusiewicz Ł. Changes in growth, ionic status, metabolites content and antioxidant activity of two FernsExposed to Shade, full sunlight, andSalinity. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:1-15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijms24010296.

84. Shekari F, Abbasi A, Mustafavi SH. Effect of silicon and selenium on enzymatic changes and productivity of dill in saline condition. J Saudi Soc Agric Sci. 2017;16:367-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssas.2015.11.006.

85. Walaa AE, Shatlah MA, Atteia MH, Sror HAM. Selenium induces antioxidant defensive enzymes and promotes tolerance against salinity stress in cucumber seedlings (Cucumis sativus). Arab Univ J Agric Sci. 2010;18:65-76. https:// doi.org/10.21608/ajs.2010.14917.

86. Sheikhalipour M, Esmaielpour B, Gohari G, Haghighi M, Jafari H, Farhadi H, Kulak M, Kalisz A. Salt stress mitigation via the Foliar application of ChitosanFunctionalized Selenium and Anatase Titanium Dioxide nanoparticles in

87. Sharifi P, Amirnia R, Torkian M, Shirani Bidabadi S. Protective role of exogenous selenium on salinity-stressed Stachys byzantine plants. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2021;21:2660-72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-021-00554-5.

88. Xu S, Zhao N, Qin D, Liu S, Jiang S, Xu L, Sun Z, Yan D, Hu A. The synergistic effects of silicon and selenium on enhancing salt tolerance of maize plants. Environ Exp Bot. 2021;187:104482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. envexpbot.2021.104482.

89. Rahman M, Rahman K, Sathi KS, Alam MM, Nahar K, Fujita M, Hasanuzzaman M. Supplemental Selenium and Boron Mitigate Salt-Induced oxidative damages in Glycine Max L. Plants. 2021;10:1-16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ plants10102224.

90. Levent Tuna A, Kaya C, Dikilitas M, Yokas IB, Burun B, Altunlu H. Comparative effects of various salicylic acid derivatives on key growth parameters and some enzyme activities in salinity stressed maize (Zea mays L.) plants. Pak. J. Bot. 2007;39:787-798. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12809/5077.

91. Khademi Astaneh R, Bolandnazar S, Zaare Nahandi F, Oustan S. Effects of selenium on enzymatic changes and productivity of garlic under salinity stress.

92. Liu H, Xiao C, Qiu T, Deng J, Cheng H, Cong X, Cheng S, Rao S, Zhang Y. Selenium regulates antioxidant, photosynthesis, and cell permeability in plants under various Abiotic stresses: a review. Plants. 2023;12:1-17. https:// doi.org/10.3390/plants12010044.

93. Jouyban Z. The effect of salt stress on plant growth. J Eng Appl Sci. 2012;2:710. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:39278033.

Publisher’s Note

- *Correspondence:

Masoomeh Amerian

masoomehamerian@yahoo.com

Department of Horticultural Sciences and Engineering, Faculty of

Agricultural Sciences and Engineering, Campus of Agriculture and Natural

Resources, Razi University, Kermanshah, Iran

Department of Horticultural Sciecne, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Maragheh, Maragheh, Iran

Department of Crop Science, Laboratory of Vegetable Crops, Agricultural University of Athens, Athens, Greece - Means indicated with similar letters in columns do not differ significantly at the

level