DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-024-00501-1

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-20

تعزيز تقييم الأقران باستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي

k.j.topping@dundee.ac.uk

الملخص

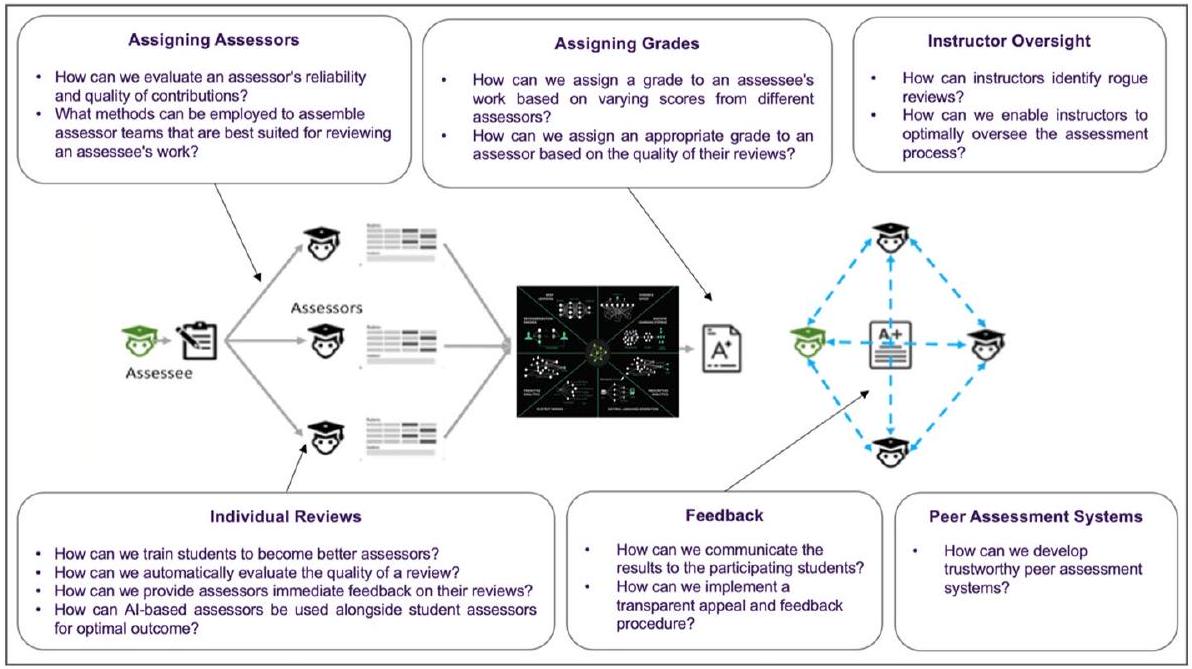

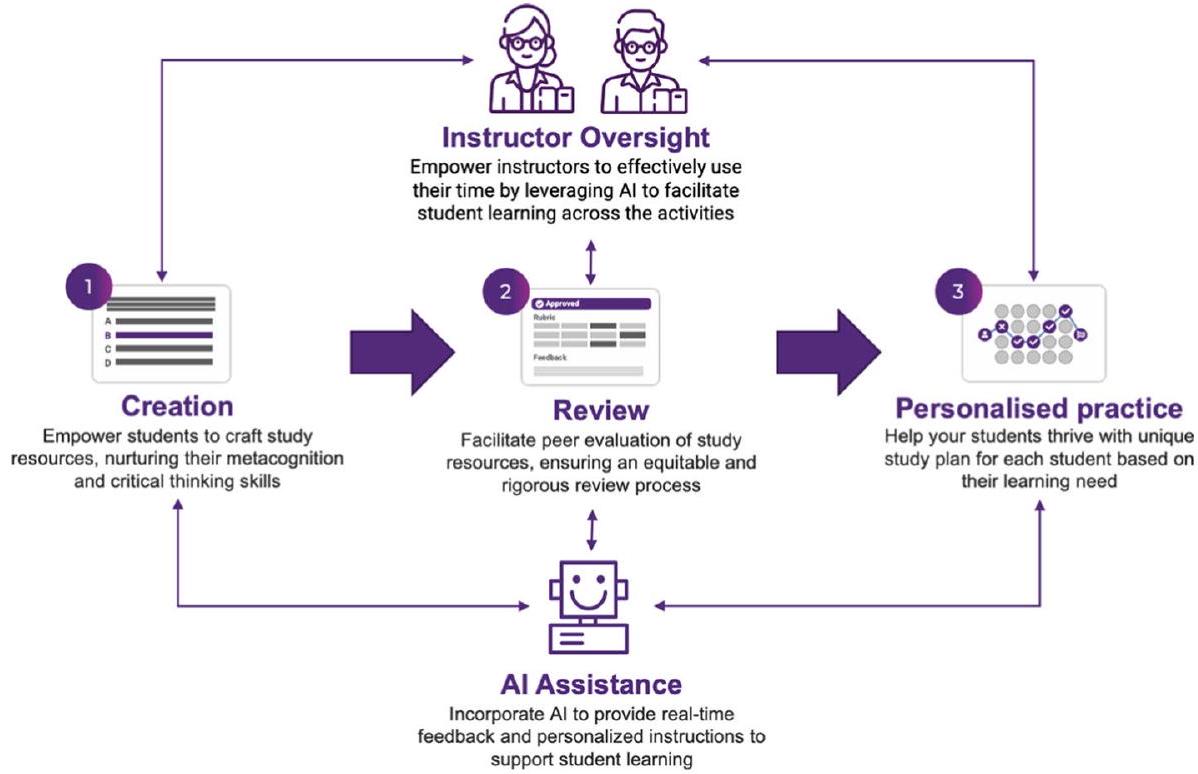

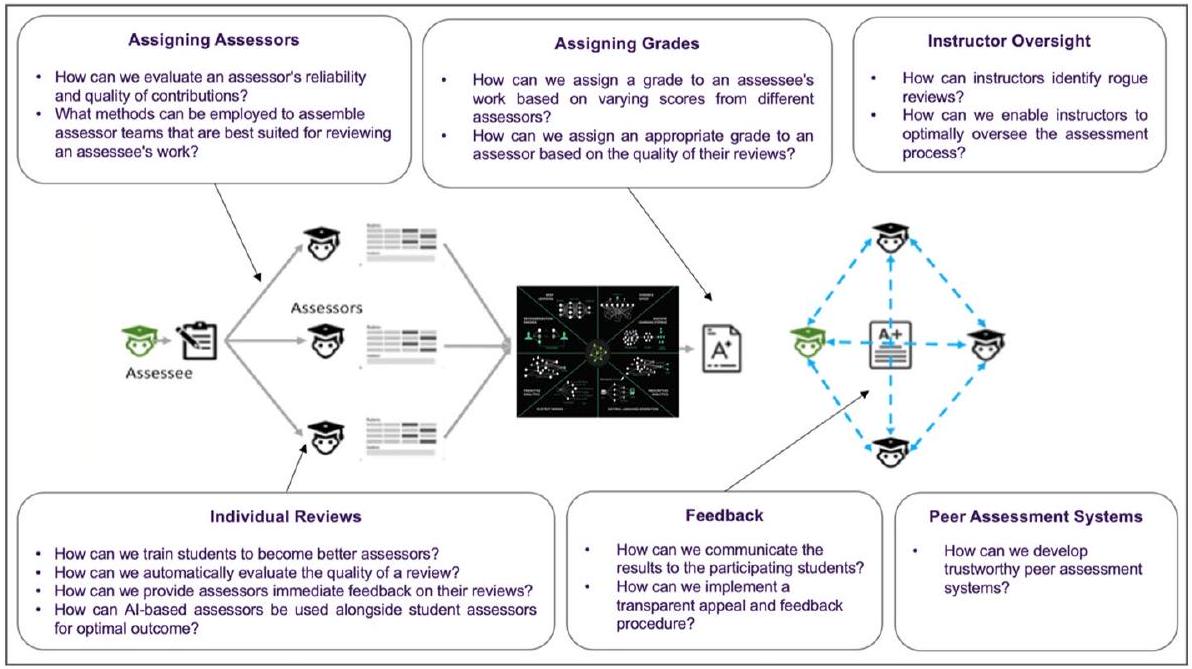

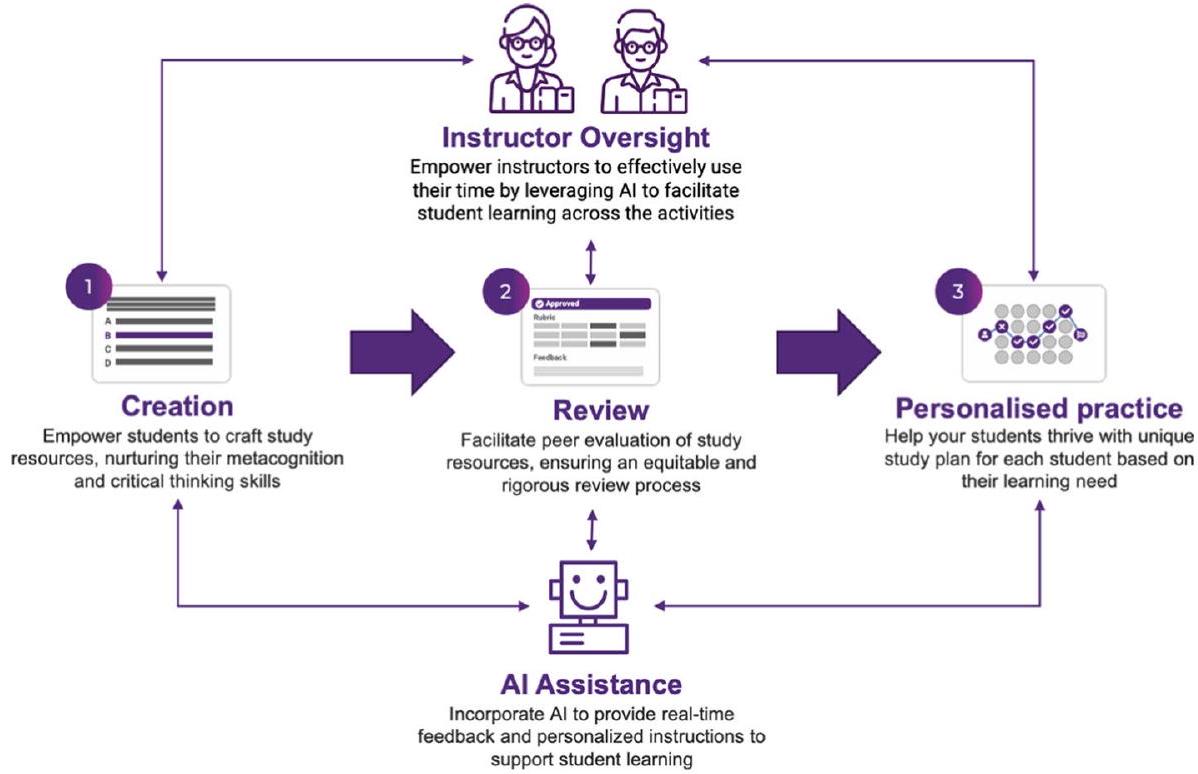

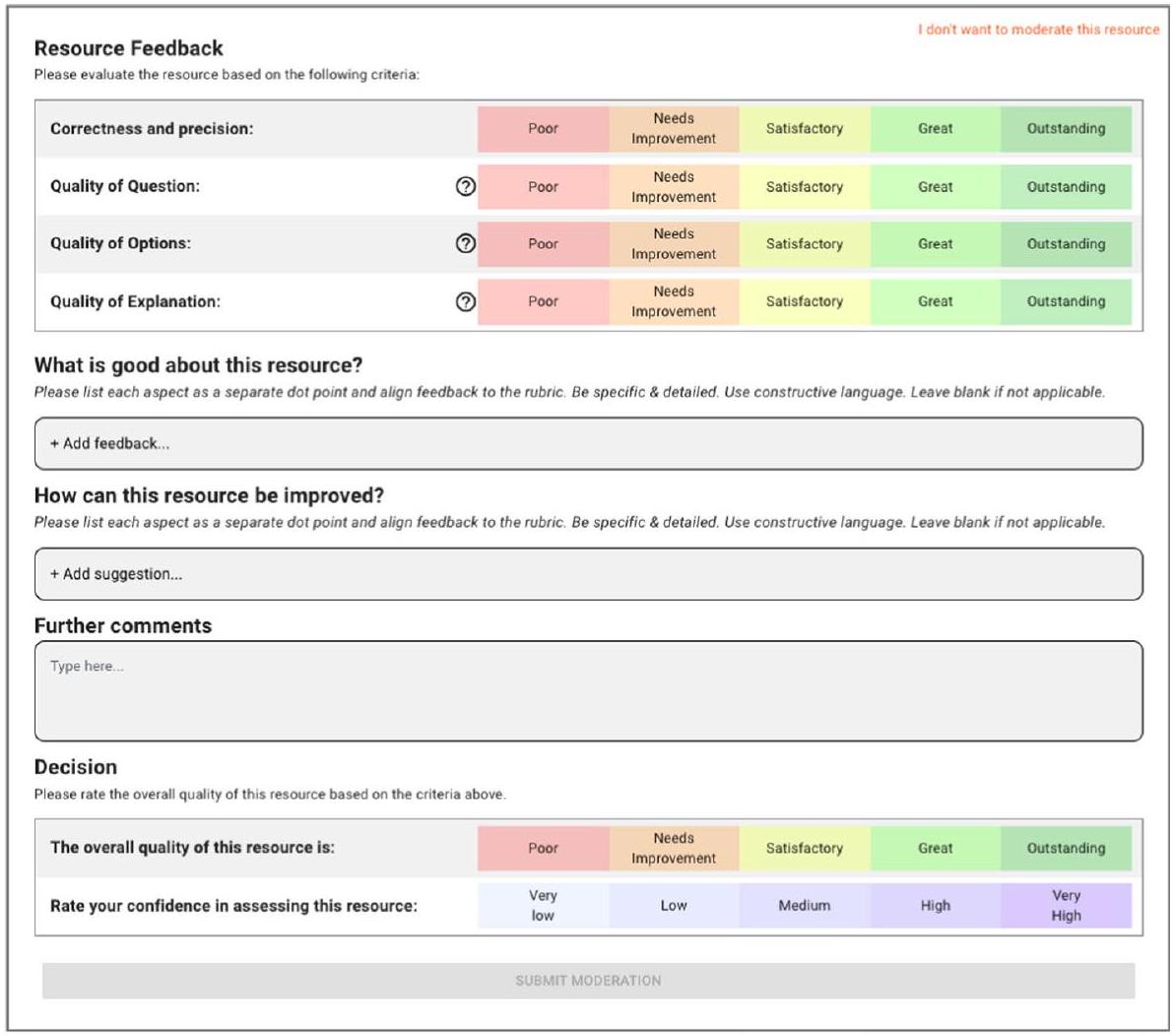

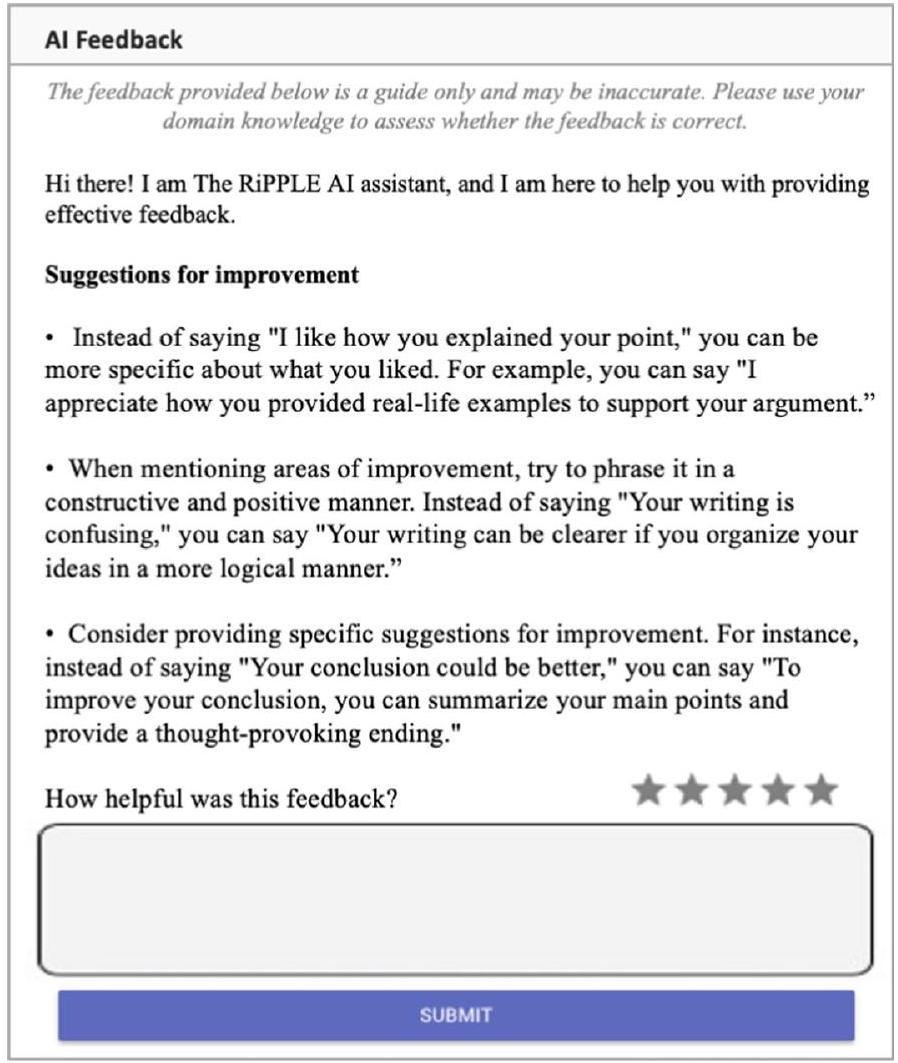

تستعرض هذه الورقة البحثية الأبحاث والممارسات المتعلقة بتعزيز تقييم الأقران باستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي. أهدافها هي تقديم هيكل الإطار النظري الذي يدعم الدراسة، تلخيص مراجعة شاملة للأدبيات التي توضح هذا الهيكل، وتقديم دراسة حالة توضح هذا الهيكل بشكل أكبر. يحتوي الإطار النظري على ستة مجالات: (i) تعيين مقيمي الأقران، (ii) تعزيز المراجعات الفردية، (iii) اشتقاق درجات/تعليقات الأقران، (iv) تحليل تعليقات الطلاب، (v) تسهيل إشراف المعلم و (vi) أنظمة تقييم الأقران. وجدت الغالبية العظمى من 79 ورقة في المراجعة أن الذكاء الاصطناعي حسّن تقييم الأقران. ومع ذلك، كان تركيز العديد من الأوراق على التنوع في الدرجات والتعليقات، والمنطق الضبابي وتحليل التعليقات بهدف تحقيق توازن في جودتها. كانت هناك أوراق قليلة نسبياً تركز على التعيين الآلي، والتقييم الآلي، والمعايرة، وفعالية العمل الجماعي والتعليقات الآلية، وهذه تستحق مزيدًا من البحث. تشير هذه الصورة إلى أن الذكاء الاصطناعي يحقق تقدمًا في تقييم الأقران، ولكن لا يزال هناك طريق طويل لنقطعه، خاصة في المجالات التي لم يتم البحث فيها بشكل كافٍ. تتضمن الورقة دراسة حالة لأداة تقييم الأقران RIPPLE، التي تستفيد من حكمة الطلاب، ورؤى من علوم التعلم والذكاء الاصطناعي لتمكين المعلمين الذين يعانون من ضيق الوقت من غمر طلابهم في تجارب تعلم عميقة وشخصية تعدهم بشكل فعال للعمل كمقيمين. بمجرد تدريبهم، يستخدمون مقياسًا شاملاً لتقييم موارد التعلم المقدمة من طلاب آخرين. وبالتالي، يخلقون مجموعات من موارد التعلم عالية الجودة التي يمكن استخدامها لتوصية محتوى مخصص للطلاب. تشرك RIPPLE الطلاب في ثلاث أنشطة متداخلة: الإنشاء، المراجعة والممارسة الشخصية، مما يولد العديد من أنواع الموارد. يتم تقديم تعليقات فورية مدفوعة بالذكاء الاصطناعي، ولكن يتم نصح الطلاب بتقييم ما إذا كانت دقيقة. تم تحديد الفرص والتحديات للباحثين والممارسين.

المقدمة

تحليلات التعلم في تحسين تقييم الأقران من قبل Misiejuk وWasson (2023)، الذين حددوا ثلاثة أدوار رئيسية: تعزيز أدوات البرمجيات، وتوليد تعليقات آلية وتصويرات. تم رسم أربعة مجالات تطبيق رئيسية: تفاعل الطلاب، وخصائص التعليقات، والمقارنة والتصميم. تتجاوز المراجعة السريعة في هذه الدراسة ذلك من خلال تناول جميع جوانب الذكاء الاصطناعي في تقييم الأقران والإشارة إلى التدخلات بدلاً من مجرد رسم خريطة للمجال.

إطار نظري لفرص الذكاء الاصطناعي في تقييم الأقران

تعيين مقيمي الأقران

تعزيز المراجعات الفردية

اشتقاق درجات/تعليقات الأقران

تحليل ملاحظات الطلاب

تسهيل إشراف المدرب

أنظمة تقييم الأقران

نماذج التقييم. يمكن أن تأخذ هذه النماذج في الاعتبار مجموعة أوسع من العوامل مقارنةً بالطرق التقليدية.

مراجعة سريعة للنطاق

المنهجية

النتائج

تعيين المقيمين الأقران

نهج قائم على نظرية استجابة العناصر وبرمجة الأعداد الصحيحة لتعيين المقيمين الأقران، لكنه لم يكن أكثر فعالية من التخصيص العشوائي وأوصى باستخدام مقيمين إضافيين من خارج المجموعة. تم تجربة نظام للكشف عن التواطؤ بعد الحدث من قبل وانغ وآخرون (2019أ). نظرت ورقتان فقط في نظام شامل للتعيين الذكي للمقيمين. كان لدى أنايا وآخرون (2019) نظام لتعيين المقيمين الأقران وفقًا للشبكات الاجتماعية، والذي كان أكثر فعالية من التخصيص العشوائي. بعد تقسيم الطلاب إلى أربع مجموعات حسب القدرة، وجد زونغ وشون (2023) أن المطابقة حسب القدرة المماثلة كانت الأكثر فعالية وأكثر فعالية من التخصيص العشوائي، باستثناء الطلاب ذوي القدرة المنخفضة.

تعزيز المراجعات الفردية

اشتقاق درجات/تعليقات الأقران

التقييم الآلي كان موضوع التقييم الآلي يحتوي على أربع أوراق (

ومع ذلك، كانت عرضة للغاية للتقارير الاستراتيجية (أي، المراجعة بأهداف غير التقييم في الاعتبار أو التلاعب بالنظام لتحسين درجة الفرد على حساب زملائه).

التقديمات وتقدير درجاتها المطلقة. أظهرت النتائج التجريبية أداءً أفضل مقارنةً بتقنيات تقييم الأقران الأخرى. تم اقتراح نهج قائم على الضبابية يهدف إلى تعزيز الصلاحية والموثوقية من قبل العلوي وآخرين (2018). قدم المؤلفون أمثلة توضيحية. تم تقديم تطبيق استبيان قائم على الأعداد الضبابية من قبل جوناس وآخرين (2018) من أجل تعزيز موثوقية التقييمات من الأقران. كانت دالة العضوية للعدد الضبابي تتكون من دالة عضوية سيغمويدية متزايدة ومتناقصة مرتبطة بمشغل تقاطع دومبي. سمح ذلك للمراجعين من الأقران بالتعبير عن عدم يقينهم وتباين أداء الشخص الذي تم مراجعته بطريقة كمية. تم تقديم دراسة حالة.

الدورات التعليمية المفتوحة عبر الإنترنت (MOOCs) كانت هناك أربع أوراق (

على بيانات حقيقية مع 63,199 درجة تقييم متبادل. ربطوا تحيزات المقيّمين وموثوقياتهم بعوامل طلابية أخرى مثل انخراط الطلاب وأدائهم بالإضافة إلى أسلوب التعليق. تم تنفيذ نظام ذكاء اصطناعي لدورة MOOC معتمدة لمعالجة كل من النطاق والتأييد من قبل جوينر (2018). حقق الطلاب في الدورة عبر الإنترنت نتائج تعلم قابلة للمقارنة، وأبلغوا عن تجربة طلابية أكثر إيجابية وحددوا مشاكل البرمجة المجهزة بالذكاء الاصطناعي كأهم مساهم في تجاربهم. قدم سياروني وتيمبريني (2020) نظامًا قائمًا على الويب يحاكي فصل MOOC. سمح ذلك للمعلمين بتجربة استراتيجيات بيداغوجية مختلفة بناءً على التقييم المتبادل. كان بإمكان المعلم مراقبة ديناميات MOOC المحاكي، بناءً على نسخة معدلة من خوارزمية K-NN. أنتجت التجربة الأولى للنظام نتائج واعدة.

تحليل ملاحظات الطلاب

تحليل الملاحظات أبلغت أربع عشرة ورقة (18%) عن تحليل ملاحظات الطلاب. ركز أربعة منها على دقة المراجعة. ناقش ناكاياما وآخرون (2020) أفضل عدد من الأقران لتقديم تقييمات لبعضهم البعض، مرتبطًا بكفاءة الطالب وقدرته على التقييم. تم التحكم في عدد الأقران المعينين لنفس وظيفة التقييم من ثلاثة إلى 50 في ست خطوات باستخدام مقياس من 10 نقاط. انخفضت جميع معلمات النماذج تدريجيًا مع عدد الأقران. تم تطوير خوارزمية متعددة الأبعاد لمراقبة الجودة للتقييمات المتبادلة ومعلومات النص من قبل لي وآخرون (2020ب). تم دمج سلوك المستخدم، ومعلومات نص التعليق وعناصر أخرى معًا. كانت الإطار نموذجًا خطيًا لوغاريتميًا يؤدي إلى خوارزمية انحدار تدرجي. عند مقارنتها بالخوارزميات التقليدية، كان أداء النموذج أفضل. وصف باديا وبوبسكو (2020) LearnEval وطبقوه على سيناريوهات التعلم القائم على المشاريع. تم نمذجة كل طالب بناءً على الكفاءة والانخراط وقدرات التقييم. تم دمج وحدة درجات

تتضمن التصور. ومع ذلك، كان التقييم فقط من خلال تصورات الطلاب. استخدم هوانغ وآخرون (2023) ثلاثة أنظمة مختلفة لتحليل تعليقات الأقران، مصنفة تعليقات الأقران من حيث المحتوى المعرفي والحالة العاطفية. كان لنموذج تمثيلات المحولات ثنائية الاتجاه (BERT) أفضل النتائج وحسن التغذية الراجعة مع تقليل كبير في إرهاق الطلاب. عانى الأفراد الذين تلقوا ملاحظات أكثر اقتراحًا من انخفاض أكبر في الإرهاق العاطفي. على العكس من ذلك، عند تلقي ملاحظات أكثر سلبية و/أو تعزيز دون توجيه، كان المتعلمون يميلون إلى تجربة تجربة عاطفية أسوأ وأظهروا سلوك تعلم ذاتي أسوأ.

زادت من احتمال تنفيذ الطلاب (الثناء العام والموقع)، بينما قللت عدة ميزات من ذلك (الثناء المخفف، الحلول والتعليقات ذات النثر العالي). ثم تمت مقارنة ثلاثة شروط من قبل باتشان وآخرون (2017): فقط مسؤولية التقييم، فقط مسؤولية التعليقات، أو كل من مسؤولية التقييم والتعليقات. تم ترميز تقييمات الأقران وتعليقات الأقران. كان بناء تعليقات مفيدة له تأثير واسع على تقييم الأقران وكانت التقييمات المتسقة مستندة إلى هذا التعليق. يجب ملاحظة أن هناك خطًا رفيعًا بين تحليل التعليقات (في هذا القسم) وتعزيز المراجعات الفردية. إذا كان تحليل التعليقات فوريًا، وكان المراجعون يمكنهم رؤيته قبل تقديم مراجعة، فإنه يمكن أن يساعد المراجعين في تحسين مراجعاتهم. قد يعتبر هذا استخدامًا “تكوينيًا” لتحليل التعليقات. إذا تم تقديمه بدلاً من ذلك للمدرس كوسيلة لتقييم فعالية المراجع، فإنه يتم استخدامه “تراكميًا” لتحليل التعليقات.

الحكم المقارن التكيفي (ACJ) كان هناك ورقتان في هذه الفئة الفرعية

تسهيل إشراف المعلم

قدمت اختبار الأقران المباشر ومراجعة كود الأقران المباشرة. يمكن أن يحسن اختبار الأقران المباشر من قوة كود الطلاب من خلال السماح لهم بإنشاء ومشاركة اختبارات خفيفة الوزن مع الأقران. يمكن أن تحسن مراجعة كود الأقران المباشرة من فهم الكود من خلال تجميع الطلاب بذكاء لتعظيم مراجعات الكود ذات المعنى. ومع ذلك، كانت التقييمات قصيرة جدًا. وصف خسروي وآخرون (2021) مصادر المتعلمين، عبر نظام تكيفي يسمى RiPPLE، الذي تم استخدامه في أكثر من 50 دورة مع أكثر من 12000 طالب. قدمت الورقة تأملات مستندة إلى البيانات والدروس المستفادة. ركز دهل وآخرون (2022) على إيجاد تعيين للمقيمين إلى التقديمات التي تعظم خبرة المقيمين مع مراعاة قيود عدم الاستراتيجية. تم تطوير عدة خوارزميات زمنية متعددة الحدود لتعيين غير استراتيجي مع ضمانات جودة التعيين وتم تجربتها بنجاح.

أنظمة تقييم الأقران

الأداء، الدافع للتعلم، الكفاءة الذاتية، جودة مراجعة الأقران، صحة تقييم الأقران وسلوكيات التعلم عبر الإنترنت. تم إجراء تجربة لمدة 12 أسبوعًا مقارنة بين مقاطع الفيديو مع تعليقات الأقران، ومقاطع الفيديو مع تقييمات الأقران ومقاطع الفيديو مع تقييمات الأقران بالإضافة إلى تعليقات الأقران. قدمت المجموعة الأخيرة تعليقات أفضل وكانت الأكثر توافقًا مع درجات المعلم. في النظام المقترح من قبل ثاميزكانال وكومار (2020)، تم إجراء المعالجة المسبقة وإزالة الضوضاء بمساعدة التصفية، والتطبيع والضغط. ثم تم نشر التقسيم الداخلي والخارجي. تم تحديد حرف في ورقة الإجابة بواسطة الشبكات العصبية التلافيفية. تم تقييم الإجابات بواسطة شبكة عصبية بسيطة. كانت تجربة مقارنة أنواع الاختبارات لصالح النظام الجديد.

دراسة حالة

الإنشاء

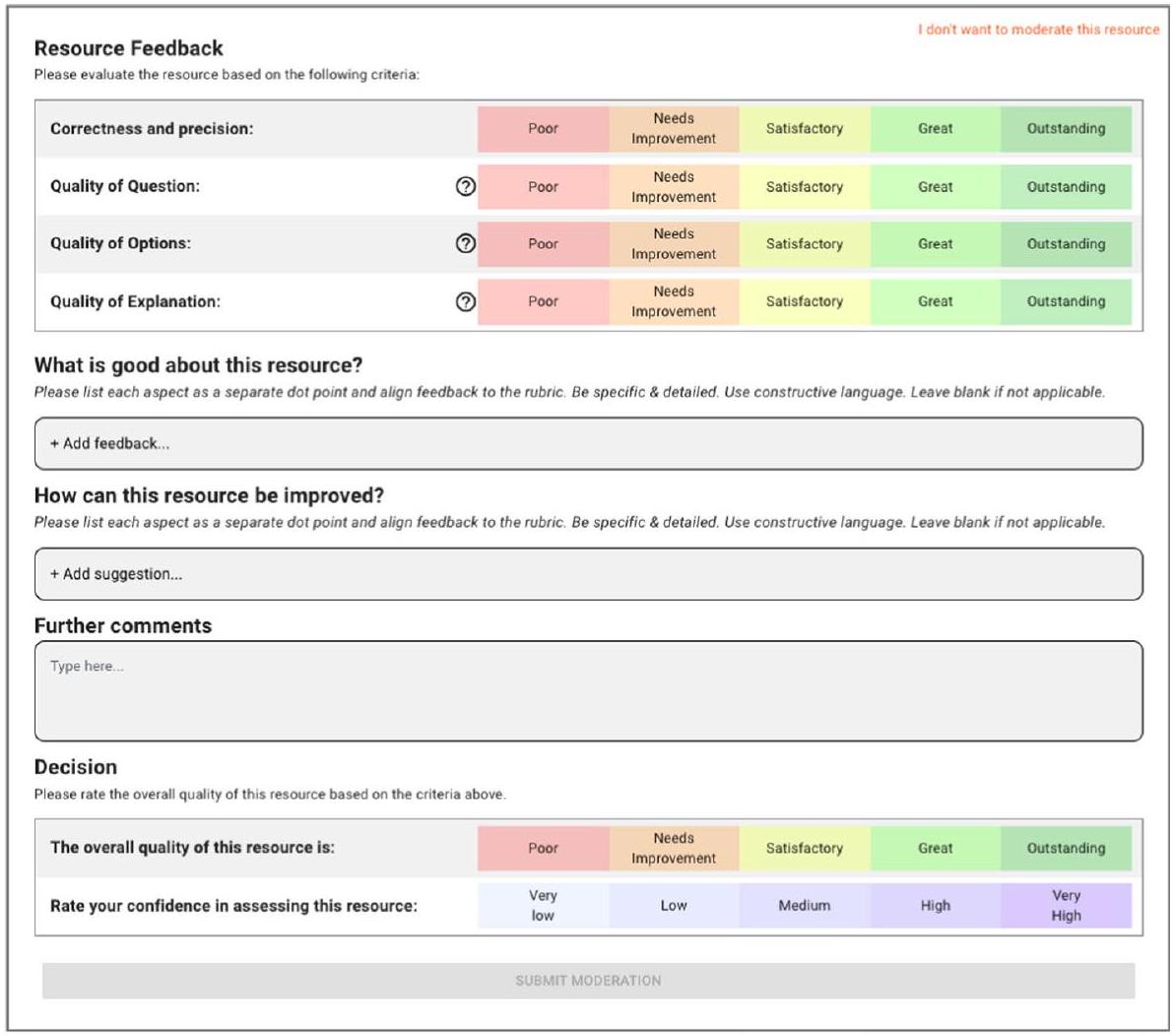

المراجعة

من خلال الموارد التي يقدمها الطلاب، تخضع هذه المواد لآلية مراجعة من قبل الأقران حيث يقوم الأقران بتقييم جودة المحتوى وملاءمته. تعزز عملية تقييم الأقران بيئة تعليمية تعاونية، حيث يتعلم الطلاب تطبيق المعايير الأكاديمية في سياق عملي، مما يعزز تعلمهم لمحتوى الدورة.

ممارسة مخصصة

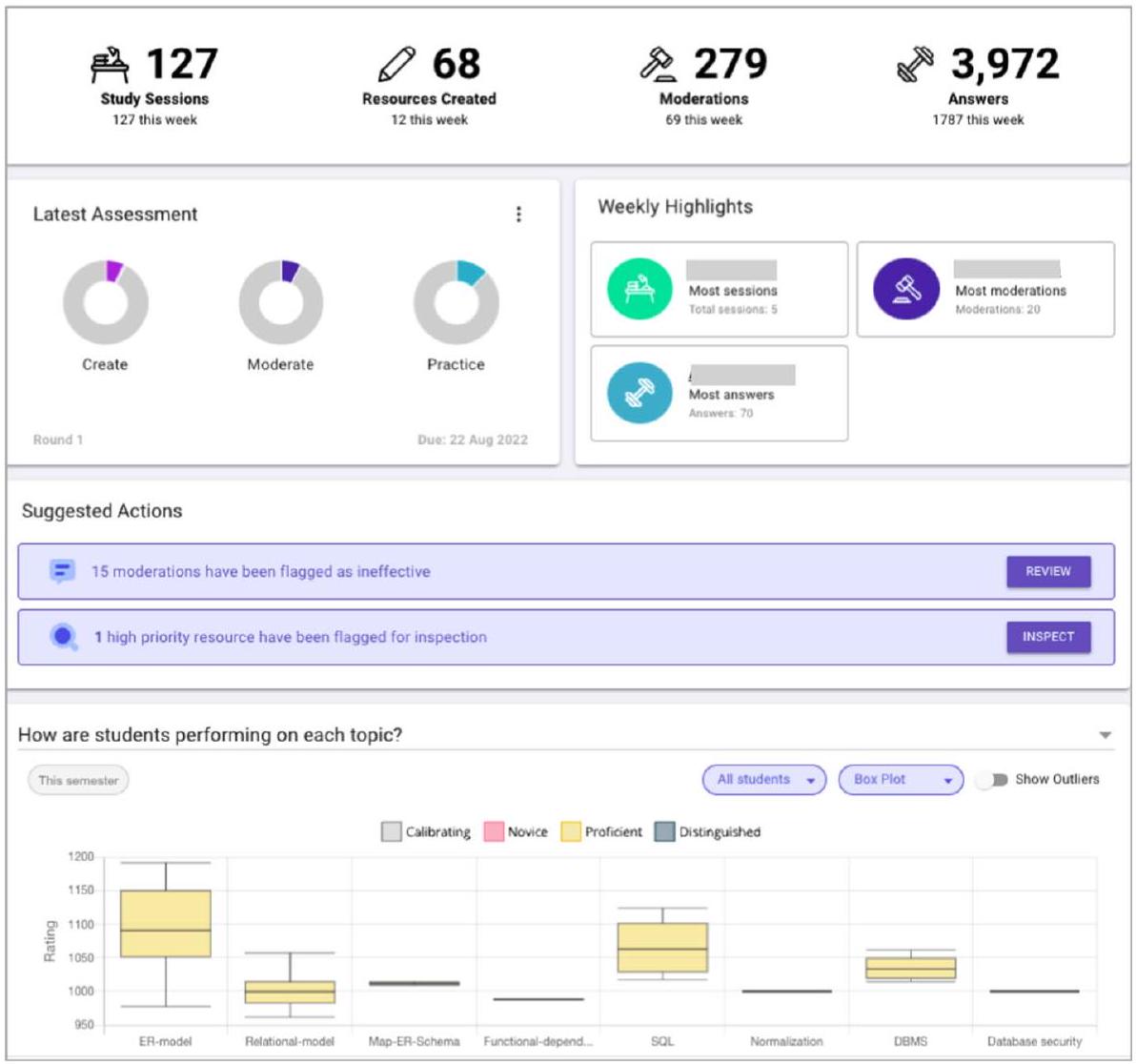

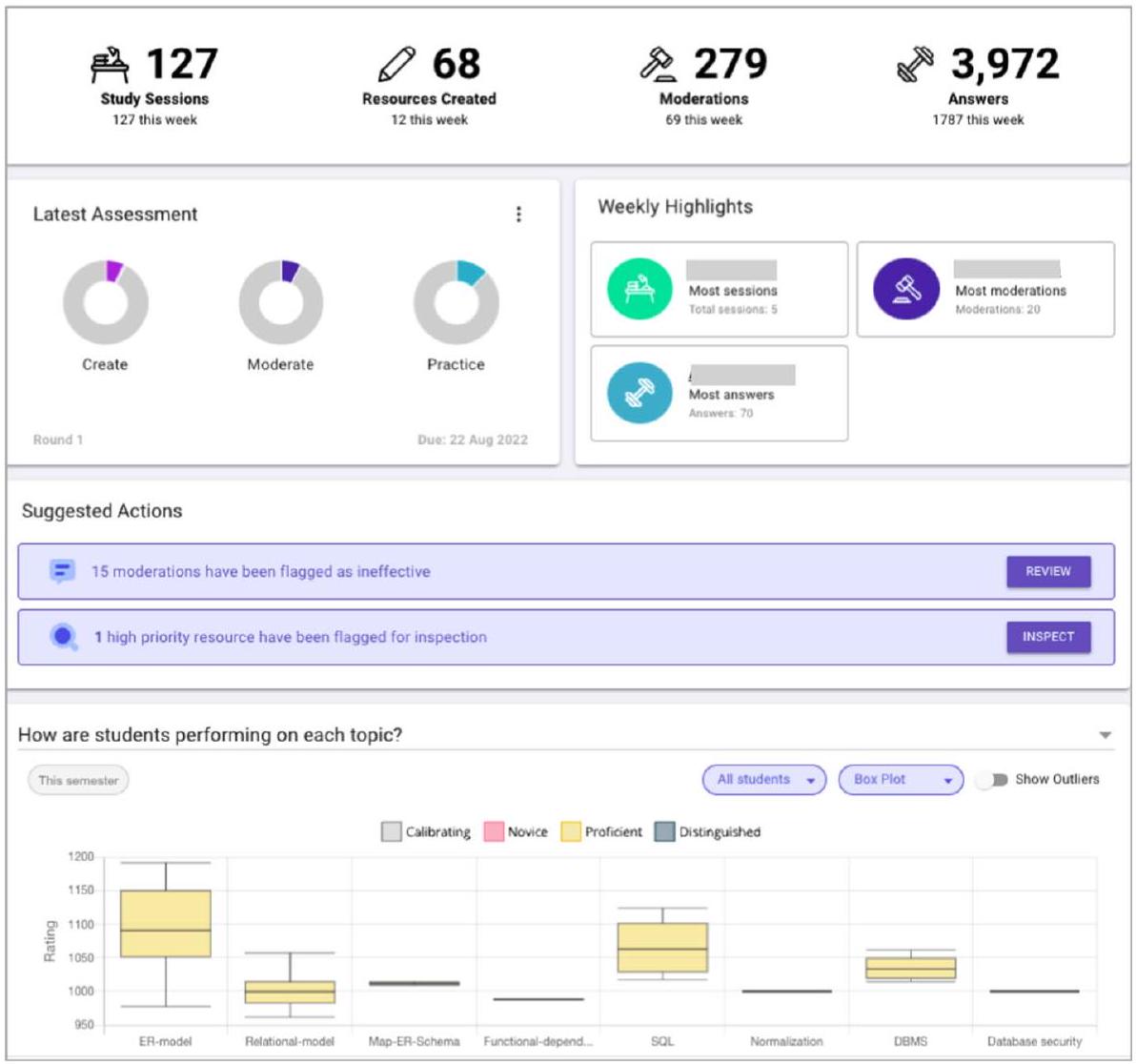

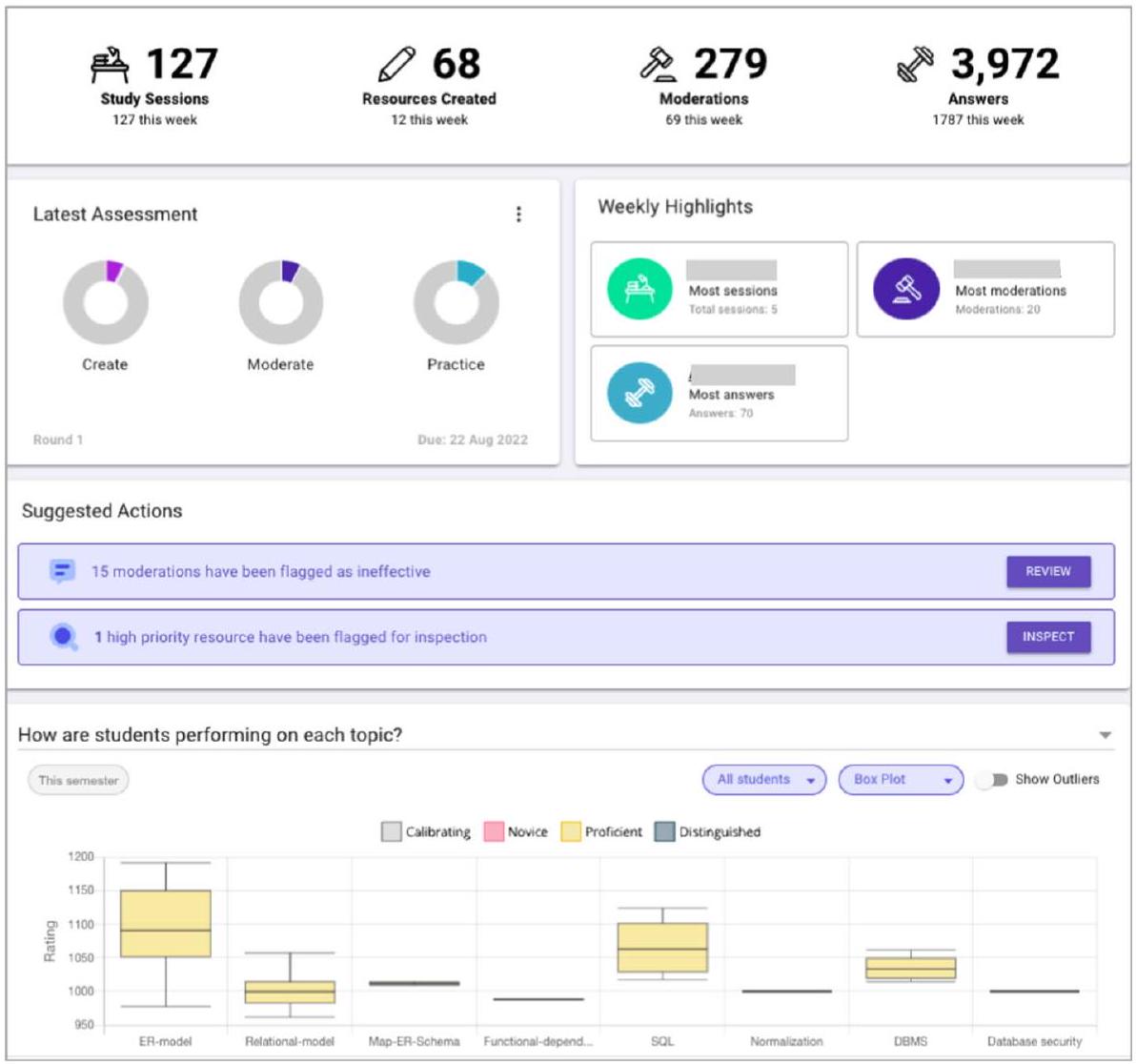

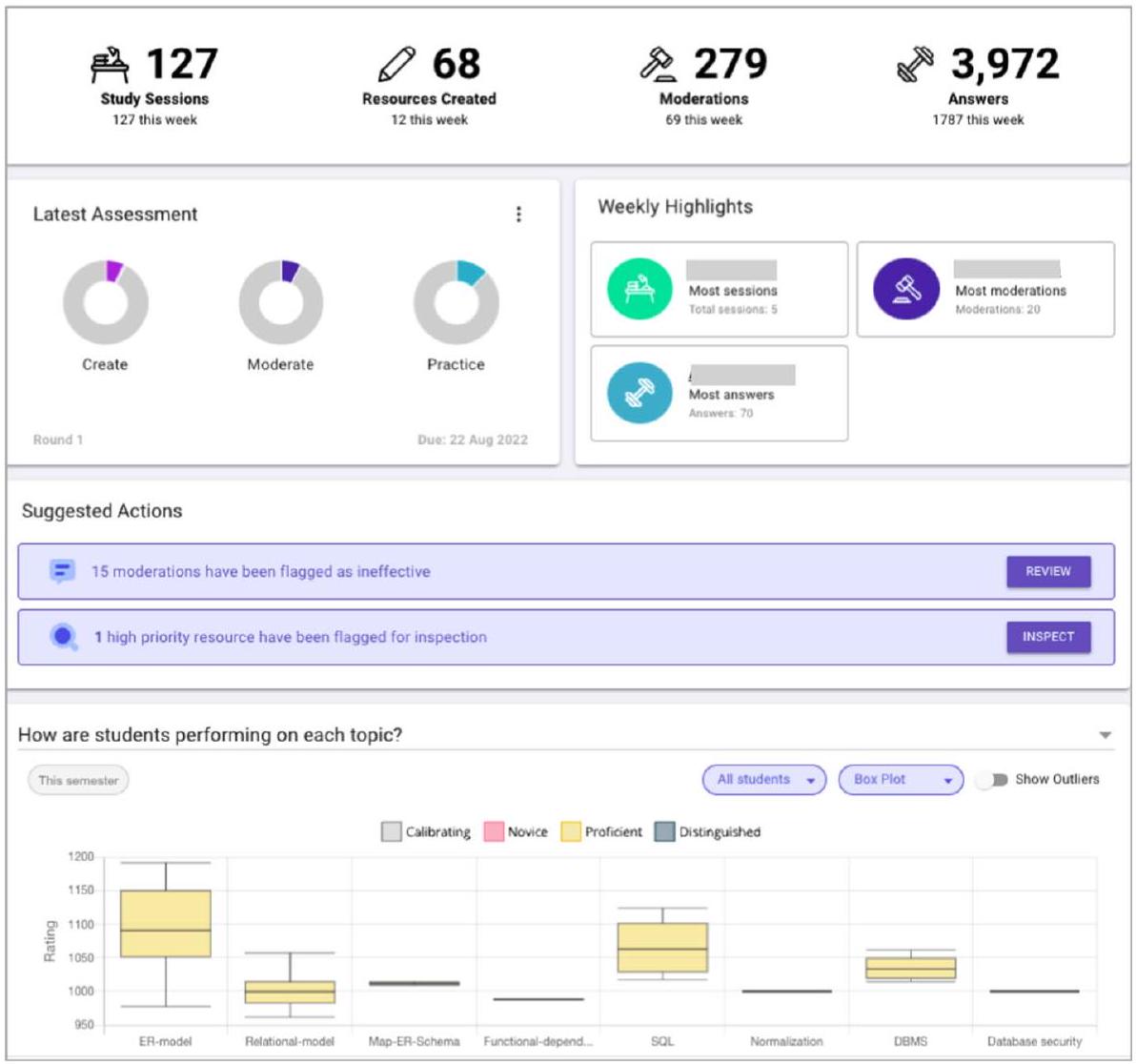

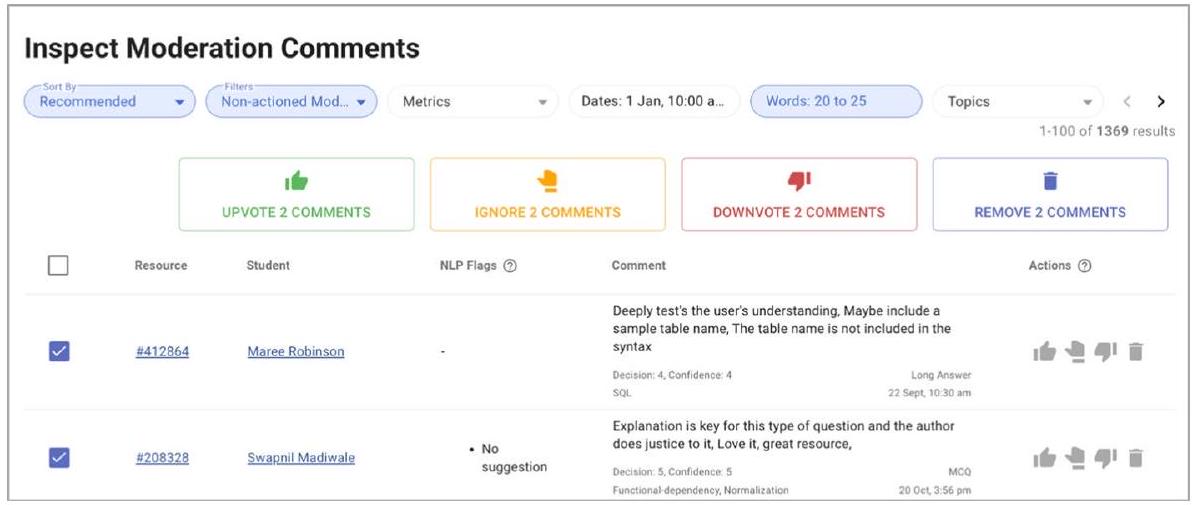

مراقبة المعلم

ملخص

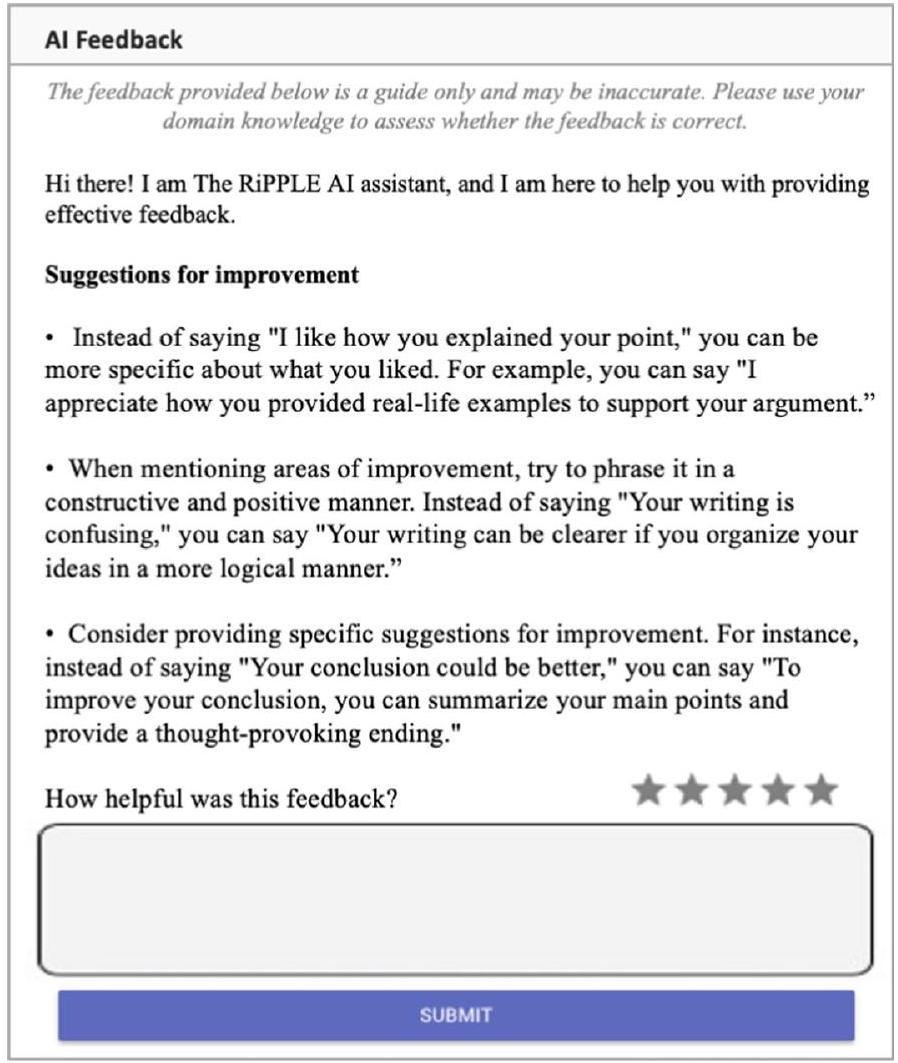

المساعدة أثناء مرحلة الإنشاء، يتم دمج الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي بسلاسة في المنصة لتقديم تعليقات فورية على الموارد المقدمة من الطلاب. تتضمن آلية التعليقات المدفوعة بالذكاء الاصطناعي ملخصًا شاملاً يفسر الهدف الرئيسي من المورد، مما يضمن توافق المحتوى مع النتائج التعليمية المقصودة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تسلط التعليقات الضوء على نقاط القوة في المورد، معترفًا بالعناصر المنفذة بشكل جيد التي تساهم في التعلم الفعال بالإضافة إلى اقتراحات لمجالات محددة للتحسين، مقدمة توصيات قابلة للتنفيذ يمكن أن تعزز فعالية المحتوى ووضوحه بشكل عام. في مرحلة المراجعة، يتم استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي مرة أخرى لتقديم تعليقات بناءة في الوقت الحقيقي، مصممة لتحديد المجالات المحتملة التي يمكن تعزيز المراجعة فيها، مثل تقديم تحليل أكثر تفصيلًا، أو تقديم تبريرات أوضح، أو اقتراح وجهات نظر بديلة. بالنسبة للممارسة المخصصة، تقوم خوارزميات الذكاء الاصطناعي في RiPPLE بتقييم قدرات الطلاب في كل موضوع دورة، موصية بالموارد الأكثر ملاءمة لمستوى معرفتهم الحالي.

تم اعتماد RiPPLE في أكثر من 250 عرضًا دراسيًا عبر مجموعة من التخصصات بما في ذلك الطب، والصيدلة، وعلم النفس، والتعليم، والأعمال، وتكنولوجيا المعلومات، والعلوم الحيوية. أنشأ أكثر من 50,000 طالب أكثر من 175,000 مورد تعليمي وأكثر من 680,000 تقييم من الأقران لتقييم جودة هذه الموارد. تم استخدام محرك RiPPLE التكيفي لتوصية بأكثر من ثلاثة ملايين مورد مخصص للطلاب. في الأقسام أدناه، نناقش كيف تستفيد RiPPLE من خمسة من المجالات الستة الموضحة في إطار العمل المقترح لدينا (حيث إنها نفسها نظام تقييم الأقران).

تعيين مقيمي الأقران

مراجعات فردية

اشتقاق درجات/تعليقات الأقران

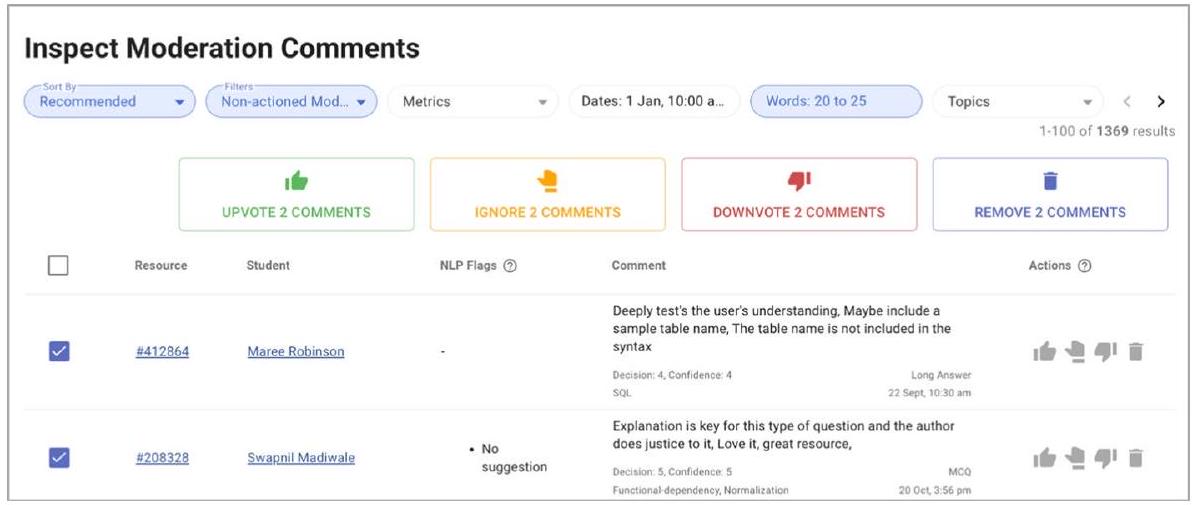

إشراف المدرب

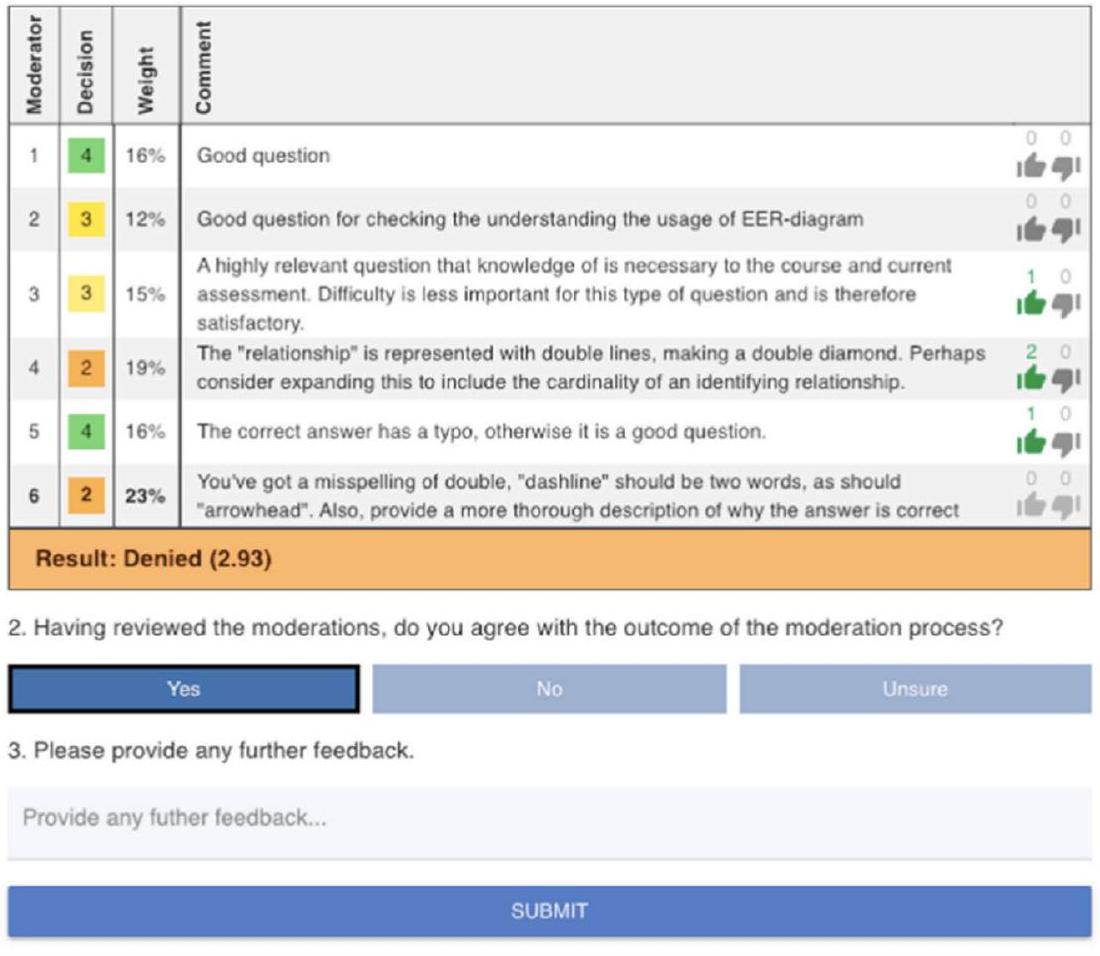

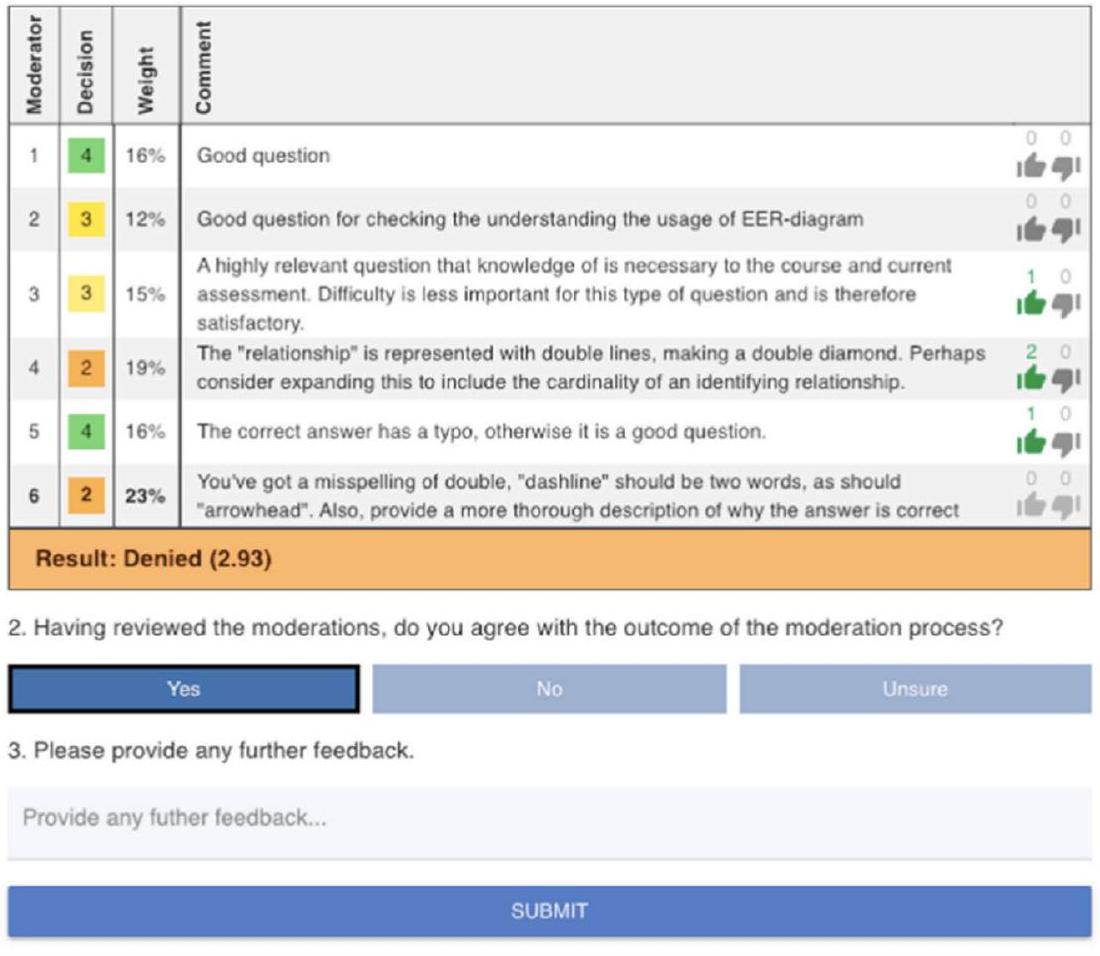

- يرجى التصويت على فائدة كل تعديل

تمت مراجعتها، مما يظهر خوارزمية التحقق العشوائي

ملخص دراسة الحالة

| منطقة الإطار | أمثلة من RiPPLE |

| تعيين المقيمين الأقران | تقييم موثوقية المقيمين باستخدام التعلم الآلي المتقدم، بما في ذلك انتشار الثقة القائم على الرسوم البيانية، يعزز مصداقية ودقة عملية المراجعة من قبل الأقران. |

| تعزيز المراجعات الفردية | تدمج RiPPLE الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي لتعزيز التغذية الراجعة من الأقران، حيث تقدم اقتراحات فورية وبناءة للتحسين. يقدم وكيل التغذية الراجعة بالذكاء الاصطناعي نفسه، ويقترح تحسينات، وينبه الطلاب بشأن الأخطاء المحتملة، ويمنح الطلاب القدرة على تقديم ملاحظات حول مدى فائدة ذلك. |

| اشتقاق درجات/تعليقات الأقران | يتطلب RiPPLE توافقًا بين عدة مشرفين لإنهاء تقييمات الموارد. حاليًا، يستخدم RiPPLE نهج انتشار الثقة القائم على الرسوم البيانية (Darvishi et al.، 2021) الذي يستنتج موثوقية كل مشرف. يتم اشتقاق القرار النهائي من متوسط مرجح للتقييمات المقدمة من المقيمين الأقران. |

| تسهيل إشراف المدربين | قسم “الإجراءات المقترحة” يقدم توصيات للمدرسين لفحص الموارد المميزة، ومراجعة التقييمات غير الفعالة، وتحديد الطلاب ذوي الأداء الضعيف، وتذكير الطلاب بالمهام غير المكتملة. واجهة استكشاف تعليقات الأقران تتيح تحليلًا مفصلًا للتعليقات، وتقدم أدوات للتصويت على التقييمات الجيدة، والتصويت ضد أو إزالة التعليقات غير الفعالة، وتصنيف التقييمات من أجل الكفاءة، مع مشاركة كبيرة من المدرسين في إدارة جودة تعليقات الأقران. |

| منطقة | عدد الأوراق | فئة فرعية | عدد أوراق الفئة الفرعية |

| تعيين المقيمين الأقران | ٤ | ||

| تعزيز المراجعات الفردية | ٧ | ||

| اشتقاق درجات/تعليقات الأقران | ٣٥ | التقييم الآلي | ٤ |

| تنوع الدرجات والتعليقات | ٧ | ||

| معايرة | ٥ | ||

| المنطق الضبابي واتخاذ القرار | ٨ | ||

| فعالية العمل الجماعي | ٤ | ||

| الدورات التعليمية المفتوحة عبر الإنترنت | ٤ | ||

| التقارير الاستراتيجية والخارجة عن السيطرة | ٣ | ||

| تحليل ملاحظات الطلاب | 19 | تحليل التعليقات | 14 |

| التعليقات الآلية | ٣ | ||

| الحكم المقارن التكيفي | 2 | ||

| تسهيل إشراف المدربين | ٤ | ||

| أنظمة تقييم الأقران | 10 | ||

| إجمالي | 79 |

مناقشة وتفسير ملخص الورقة بالكامل

وجدت نتائج الذكاء الاصطناعي إما جيدة مثل أو أسوأ من نتائج غير الذكاء الاصطناعي. بالطبع، قد يكون هذا متوقعًا نظرًا لتحيز النشر ولا يعكس بالضرورة ما سيختبره الممارسون عند التنفيذ في فصولهم الدراسية.

نقاط القوة والقيود

تحتاج الدراسات الأكبر شبه التجريبية إلى أن تكون أكثر توضيحًا. كانت العينات في الغالب من قبيل التيسير.

الفرص والتحديات للباحثين والممارسين للباحثين

تم استخدامه للكشف عن اتساق النصوص وتقييم الدرجات بشكل آلي، وتم تصميمه باستخدام نموذج BERT-RCNN. ومن المهم أيضًا أن نتذكر أن الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي له مخاطره. على سبيل المثال، قام أوفييدو-تريسبالاسيوس وآخرون (2023) بتحليل النصائح المتعلقة بالسلامة من ChatGPT وأثاروا مخاوف من سوء الاستخدام. بدا أن ChatGPT لا يفضل المحتويات بناءً على دقتها أو موثوقيتها. كانت الفئات ذات مستوى القراءة والكتابة والتعليم المنخفض في خطر أكبر من استهلاك محتوى غير موثوق.

للممارسين

الخاتمة

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمة المؤلف

التمويل

توفر البيانات والمواد

الإعلانات

المصالح المتنافسة

تاريخ الاستلام: 2 يناير 2024 تاريخ القبول: 10 أكتوبر 2024

تاريخ النشر على الإنترنت: 21 يناير 2025

References

References in the scoping review asterisked *

Abdi, S., Khosravi, H., Sadiq, S., & Gasevic, D. (2020). Complementing educational recommender systems with open learner models. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Learning Analytics & Knowledge (pp. 360-365). https://doi.org/10.1145/3375462.3375520

*Ahuja, R., Khan, D., Symonette, D., Pan, S., Stacey, S., & Engel, D. (2020a). Towards the automatic assessment of student teamwork. In Companion Proceedings of the 2020 ACM International Conference on Supporting Group Work (pp. 143-146). https://doi.org/10.1145/3323994.3369894

*Ahuja, R., Khan, D., Tahir, S., Wang, M., Symonette, D., Pan, S., & Engel, D. (2020b). Machine learning and student performance in teams. In: Bittencourt, I., Cukurova, M., Muldner, K., Luckin, R., Millán, E. (Eds.) Artificial Intelligence in Education. AIED 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 12164. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52240-7_55

*Anaya, A. R., Luque, M., Letón, E., & Hernández-del-Olmo, F. (2019). Automatic assignment of reviewers in an online peer assessment task based on social interactions. Expert Systems, 36, e12405. https://doi.org/10.1111/exsy. 12405

*Babik, D., Stevens, S. P., Waters, A., & Tinapple, D. (2020). The effects of dispersion and reciprocity on assessment fidelity in peer-review systems: A simulation study. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 13(3), 580-592. https://doi. org/10.1109/TLT.2020.2971495

*Babo, R., Rocha, J., Fitas, R., Suhonen, J., & Tukiainen, M. (2021). Self and peer e-assessment: A study on software usability. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education (IJICTE), 17(3), 68-85. https://doi.org/ 10.4018/IJICTE.20210701.oa5

*Badea, G., & Popescu, E. (2020). Supporting students by integrating an open learner model in a peer assessment platform. In: Kumar, V., & Troussas, C. (Eds.) Intelligent Tutoring Systems. ITS 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 12149. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49663-0_14

*Badea, G., & Popescu, E. (2022). A hybrid approach for mitigating learners’ rogue review behavior in peer assessment. In: Crossley, S., & Popescu, E. (Eds.) Intelligent Tutoring Systems. ITS 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 13284. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-09680-8_3

*Bawabe, S., Wilson, L., Zhou, T., Marks, E., & Huang, J. (2021). The UX factor: Using comparative peer review to evaluate designs through user preferences. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5 (CSCW2), Article No: 476, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1145/3479863

*Burrell, N., & Schoenebeck, G. (2021). Measurement integrity in peer prediction: A peer assessment case study. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM Conference on Economics and Computation 369-389. https://doi.org/10.1145/3580507. 3597744

*Campos, D. G., et al. (2024). Screening smarter, not harder: A comparative analysis of machine learning screening algorithms and heuristic stopping criteria for systematic reviews in educational research. Educational Psychology Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-024-09862-5

*Capuano, N., Loia, V., & Orciuoli, F. (2017). A fuzzy group decision making model for ordinal peer assessment. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 10(2), 247-259. https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2016.2565476

*Castro, M. S. O., Mello, R. F., Fiorentino, G., Viberg, O., Spikol, D., Baars, M., & Gašević, D. (2023). Understanding peer feedback contributions using natural language processing. In:Viberg, O., Jivet, I., Muñoz-Merino, P., Perifanou, M.,

*Chai, K. C., & Tay, K. M. (2014). A perceptual computing-based approach for peer assessment. In 9th International Conference on System of Systems Engineering (SOSE), Glenelg, SA, Australia, 60-165. https://doi.org/10.1109/SYSOSE.2014. 6892481.

*Chai, K. C., Tay, K. M., & Lim, C. P. (2015). A new fuzzy peer assessment methodology for cooperative learning of students. Applied Soft Computing, 32, 468-480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2015.03.056

*Chiu, M. M., Woo, C. K., Shiu, A., Liu, Y., & Luo, B. X. (2020). Reducing costly free-rider effects via OASIS. International Journal of Comparative Education and Development, 22(1), 30-48. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCED-07-2019-0041

*Cho, K., & Schunn, C. D. (2007). Scaffolded writing and rewriting in the discipline: A web-based reciprocal peer review system. Computers & Education, 48(3), 409-426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2005.02.004

Craig, C. D., & Kay, R. (2021). Examining peer assessment in online learning for higher education – A systematic review of the literature. Proceedings of ICERI2021 Conference, 8th-9th November 2021.

Darvishi, A., Khosravi, H., Rahimi, A., Sadiq, S., & Gašević, D. (2022a). Assessing the quality of student-generated content at scale: A comparative analysis of peer-review models. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 16(1), 106-120. https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2022.3229022

Darvishi, A., Khosravi, H., & Sadiq, S. (2021). Employing peer review to evaluate the quality of student generated content at scale: A trust propagation approach. In Proceedings of the Eighth ACM Conference on Learning@ Scale (pp. 139-150). https://doi.org/10.1145/3491140.3528286

*Darvishi, A., Khosravi, H., Sadiq, S., & Gašević, D. (2022b). Incorporating AI and learning analytics to build trustworthy peer assessment systems. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53(4), 844-875. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet. 13233

*Demonacos, C., Ellis, S., & Barber, J. (2019). Student peer assessment using Adaptive Comparative Judgment: Grading accuracy versus quality of feedback. Practitioner Research in Higher Education, 12(1), 50-59.

*Dhull, K., Jecmen, S., Kothari, P., & Shah, N. B. (2022). Strategyproofing peer assessment via partitioning: The price in terms of evaluators’ expertise. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Human Computation and Crowdsourcing, 10(1), 53-63. https://doi.org/10.1609/hcomp.v10i1.21987

*Djelil, F., Brisson, L., Charbey, R., Bothorel, C., Gilliot, J. M., & Ruffieux, P. (2021). Analysing peer assessment interactions and their temporal dynamics using a graphlet-based method. In: De Laet, T., Klemke, R., Alario-Hoyos, C., Hilliger, I., & Ortega-Arranz, A. (Eds.), Technology-Enhanced Learning for a Free, Safe, and Sustainable World. EC-TEL 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 12884. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86436-1_7

*EI Alaoui, M., El Yassini, K., & Ben-Azza, H. (2018). Enhancing MOOCs peer reviews validity and reliability by a fuzzy coherence measure. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Smart City Applications, 2018, Article No.: 57, 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1145/3286606.3286834

*Ellison, C. (2023). Effects of adaptive comparative judgement on student engagement with peer formative feedback. Practitioner Research in Higher Education, 15(1), 24-35.

*Fu, Q. K., Lin, C. J., & Hwang, G. J. (2019). Research trends and applications of technology-supported peer assessment: A review of selected journal publications from 2007 to 2016. Journal of Computers in Education, 6, 191-213. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s40692-019-00131-x

*Garcia-Souto, M. P. (2019). Making assessment of group work fairer and more insightful for students and time-efficient for staff with the new IPAC software. In INTED2019 Proceedings (pp. 8636-8641), IATED, Valencia, Spain. https://doi. org/10.21125/inted.2019.2154

*Hamer, J., Kell, C., & Spence, F. (2005). Peer assessment using Aropä. Ninth Australasian Computing Education Conference (ACE2007), Ballarat, Victoria, Australia, February 2007. https://www.academia.edu/2878638/Peer_assessment_ using_arop%C3%A4?auto=download&email_work_card=download

*He, Y., Hu, X., & Sun, G. (2019). A cognitive diagnosis framework based on peer assessment. In Proceedings of the ACM Turing Celebration Conference-China, Article No: 78, 1-6. New York, NY. Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3321408.3322850

Helden, G. V., Van Der Werf, V., Saunders-Smits, G. N., & Specht, M. M. (2023). The use of digital peer assessment in higher education – An umbrella review of literature. IEEE Access, 11, 22948-22960. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023. 3252914

*Hernández-González, J., & Herrera, P. J. (2023). On the supervision of peer assessment tasks: An efficient instructor guidance technique. in IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2023.3319733.

*Hoang, L. P., Le, H. T., Van Tran, H., Phan, T. C., Vo, D. M., Le, P. A., & Pong-Inwong, C. (2022). Does evaluating peer assessment accuracy and taking it into account in calculating assessor’s final score enhance online peer assessment quality? Education and Information Technologies, 27, 4007-4035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10763-1

*Hsia, L. H., Huang, I., & Hwang, G. J. (2016). Effects of different online peer-feedback approaches on students’ performance skills, motivation and self-efficacy in a dance course. Computers & Education, 96, 55-71. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.compedu.2016.02.004

Hua, X., Nikolov, M., Badugu, N., & Wang, L. (2019). Argument mining for understanding peer reviews. arXiv:1903.10104. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1903.10104

*Huang, C., Tu, Y., Han, Z., Jiang, F., Wu, F., & Jiang, Y. (2023). Examining the relationship between peer feedback classified by deep learning and online learning burnout. Computers & Education, 207, 104910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. compedu.2023.104910

Hwang, G. J., Xie, H., Wah, B. W., & Gašević, D. (2020). Vision, challenges, roles and research issues of Artificial Intelligence in Education. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 1, 100001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2020. 100001

*Jónás, T., Tóth, Z. E., & Árva, G. (2018). Applying a fuzzy questionnaire in a peer review process. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 29(9-10), 1228-1245. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2018.1487616

*Joyner, D. (2018). Intelligent evaluation and feedback in support of a credit-bearing MOOC. In Artificial Intelligence in Education: 19th International Conference, AIED 2018, London, UK, June 27-30, 2018, Proceedings, Part II 19 (166-170). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93846-2_30

*Kalella, T., Lehtonen, T., Luostarinen, P., Riitahuhta, A., & Lanz, M. (2009). Introduction and evaluation of the peer evaluation tool. New Pedagogy, 287-292

Khosravi, H., Kitto, K., & Williams, J. J. (2019). RiPPLE: A crowdsourced adaptive platform for recommendation of learning activities. Journal of Learning Analytics, 6(3), 91-105. https://doi.org/10.18608/jla.2019.63.12

Khosravi, H., Demartini, G., Sadiq, S., & Gasevic, D. (2021). Charting the design and analytics agenda of learnersourcing systems. In LAK21: 11th International Learning Analytics and Knowledge Conference, 32-42. https://doi.org/10. 1145/3448139.3448143

Khosravi, H., Denny, P., Moore, S., & Stamper, J. (2023). Learnersourcing in the age of AI: Student, educator and machine partnerships for content creation. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 5, 100151. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100151

Kim, S. M., Pantel, P., Chklovski, T., & Pennacchiotti, M. (2006). Automatically assessing review helpfulness. In Proceedings of the 2006 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (pp. 423-430).

*Knight, S., Leigh, A., Davila, Y. C., Martin, L. J., & Krix, D. W. (2019). Calibrating assessment literacy through benchmarking tasks. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(8), 1121-1132. http://hdl.handle.net/10453/ 130201

*Kulkarni, C., Wei, K. P., Le, H., Chia, D., Papadopoulos, K., Cheng, J., Koller, D., & Klemmer, S. R. (2013). Peer and self assessment in massive online classes. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction., 20(6), 331-31. https:// doi.org/10.1145/2505057

*Kumar, K., Sharma, B., Khan, G. J., Nusair, S., & Raghuwaiya, K. (2020). An exploration on effectiveness of anonymous peer assessment strategy in online formative assessments. In 2020 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), Uppsala, Sweden. 1-5. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/FIE44824.2020.9274162.

*Lauw, H. W., Lim, E. P., & Wang, K. (2007). Summarizing review scores of “unequal” reviewers. In Proceedings of the 2007 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining (pp. 539-544). Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. https://doi.org/10.1137/1.9781611972771.58

Li, H. L., Xiong, Y., Hunter, C. V., Xiuyan Guo, X. Y., & Tywoniw, R. (2020a). Does peer assessment promote student learning? A meta-analysis. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(2), 193-211. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 02602938.2019.1620679

*Li, P., Yin, Z., & Li, F. (2020). Quality control method for peer assessment system based on multi-dimensional information. In: Wang, G., Lin, X., Hendler, J., Song, W., Xu, Z., & Liu, G. (Eds.), Web Information Systems and Applications. WISA 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 12432. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60029-7_17

Lin, P. (2022). Developing an intelligent tool for computer-assisted formulaic language learning from YouTube videos. ReCALL, 34(2), 185-200. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344021000252

Lin, Z., Yan, H. B., & Zhao, L. (2024). Exploring an effective automated grading model with reliability detection for largescale online peer assessment. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal. 12970

*Liu, C., Doshi, D., Bhargava, M., Shang, R., Cui, J., Xu, D., & Gehringer, E. (2023). Labels are not necessary: Assessing peerreview helpfulness using domain adaptation based on self-training. In Proceedings of the 18th Workshop on Innovative Use of NLP for Building Educational Applications (BEA 2023) 173-183. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2023.bea-1.15

*Madan, M., & Madan, P. (2015). Fuzzy viva assessment process through perceptual computing. In 2015 Annual IEEE India Conference (INDICON), New Delhi, India, 1-6. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/INDICON.2015.7443831.

*Masaki , U., Nguyen, D. T., & Ueno, M. (2019). Maximizing accuracy of group peer assessment using item response theory and integer programming. The Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence, 33. https://doi.org/10.11517/pjsai.JSAI2 019.0_4H2E503

Misiejuk, K., & Wasson, B. (2023). Learning analytics for peer assessment: A scoping review. In: Noroozi, O., & De Wever, B. (Eds.), The Power of Peer Learning. Springer, Champaign, IL. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29411-2_2

*Nakayama, M., Sciarrone, F., Uto, M., &Temperini, M. (2020). Impact of the number of peers on a mutual assessment as learner’s performance in a simulated MOOC environment using the IRT model. 2020 24th International Conference Information Visualisation (IV). Melbourne, Australia, 2020, 486-490. https://doi.org/10.1109/IV51561.2020.00084

*Ngu, A. H., Shepherd, J., & Magin, D. (1995). Engineering the “Peers” system: The development of a computer-assisted approach to peer assessment. Research and Development in Higher Education, 18, 582-587.

*Nguyen, H., Xiong, W., & Litman, D. (2016). Instant feedback for increasing the presence of solutions in peer reviews. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Demonstrations, San Diego, California. 6-10.

*Nguyen, H., Xiong, W., & Litman, D. (2017). Iterative design and classroom evaluation of automated formative feedback for improving peer feedback localization. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 27, 582-622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-016-0136-6

Ocampo, J. C. G., & Panadero, E. (2023). Web-based peer assessment platforms: What educational features influence learning, feedback and social interaction? In: O. Noroozi and B. de Wever (Eds.), The Power of Peer Learning. Champaign, IL: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29411-2_8

Oviedo-Trespalacios, O., Peden, A. E., Cole-Hunter, T., Costantini, A., Haghani, M., Rod, J. E., Kelly, S., Torkamaan, H., Tariq, A., Newton, J. D. A., Gallagher, T., Steinert, S., Filtness, A. J., & Reniers, G. (2023). The risks of using ChatGPT to obtain common safety-related information and advice. Safety Science, 167, 106244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2023. 106244

*Patchan, M. M., Schunn, C. D., & Clark, R. J. (2017). Accountability in peer assessment: Examining the effects of reviewing grades on peer ratings and peer feedback. Studies in Higher Education, 43(12), 2263-2278. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 03075079.2017.1320374

*Patchan, M. M., Schunn, C. D., & Correnti, R. J. (2016). The nature of feedback: How peer feedback features affect students’ implementation rate and quality of revisions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(8), 1098. https://doi.org/10. 1037/edu0000103

*Petkovic, D., Okada, K., Sosnick, M., Iyer, A., Zhu, S., Todtenhoefer, R., & Huang, S. (2012). A machine learning approach for assessment and prediction of teamwork effectiveness in software engineering education. In 2012 Frontiers in Education Conference Proceedings, Seattle, WA. 1-3. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/FIE.2012.6462205.

*Piech, C., Huang, J., Chen, Z., Do, C., Ng, A., & Koller, D. (2013). Tuned models of peer assessment in MOOCs. arXiv preprint arXiv:1307.2579. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1307.2579

Purchase, H., & Hamer, J. (2018). Peer-review in practice: Eight years of Aropä. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(7), 1146-1165. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1435776

*Ramachandran, L., Gehringer, E. F., & Yadav, R. K. (2017). Automated assessment of the quality of peer reviews using natural language processing techniques. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 27, 534-581. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s40593-016-0132-x

*Rao, D. H., Mangalwede, S. R., & Deshmukh, V. B. (2017). Student performance evaluation model based on scoring rubric tool for network analysis subject using fuzzy logic. In 2017 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computer, and Optimization Techniques (ICEECCOT), Mysuru, India (pp. 1-5). IEEE. https://doi.org/10. 1109/ICEECCOT.2017.8284623.

*Rashid, M. P., Gehringer, E. F., Young, M., Doshi, D., Jia, Q., & Xiao, Y. (2021). Peer assessment rubric analyzer: An NLP approach to analyzing rubric items for better peer-review. 2021 19th International Conference on Information Technology Based Higher Education and Training (ITHET), Sydney, Australia, 2021, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1109/ITHET 50392.2021.9759679.

*Rashid, M. P., Xiao, Y., & Gehringer, E. F. (2022). Going beyond” Good Job”: Analyzing helpful feedback from the student’s perspective. Paper presented at the International Conference on Educational Data Mining (EDM) (15th, Durham, United Kingdom, Jul 24-27, 2022). ERIC Number: ED624053.

*Ravikiran, M. (2020). Systematic review of approaches to improve peer assessment at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001. 10617. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2001.10617

*Rico-Juan, J. R., Gallego, A. J., & Calvo-Zaragoza, J. (2019). Automatic detection of inconsistencies between numerical scores and textual feedback in peer-assessment processes with machine learning. Computers & Education, 140, 103609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103609

*Russell, A. R. (2013). The evolution of Calibrated Peer Review. Trajectories of Chemistry Education Innovation and Reform, Chapter 9, pp 129-143. American Chemical Society Symposium Series, Vol. 1145. https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-20131145.ch009

*Saarinen, S., Krishnamurthi, S., Fisler, K., & Tunnell Wilson, P. (2019). Harnessing the wisdom of the classes: Classsourcing and machine learning for assessment instrument generation. In Proceedings of the 50th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education, 606-612. https://doi.org/10.1145/3287324.3287504

*Saccardi, I., Veth, D., & Masthoff, J. (2023). Identifying students’ group work problems: Design and field studies of a supportive peer assessment. Interacting with Computers. https://doi.org/10.1093/iwc/iwad044

*Sciarrone, F., & Temperini, M. (2020). A web-based system to support teaching analytics in a MOOC’s simulation environment. In 2020 24th International Conference Information Visualisation (IV), Melbourne, Australia (491-495). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/IV51561.2020.00085.

*Selmi, M., Hage, H., & Aïmeur, E. (2014). Opinion Mining for predicting peer affective feedback helpfulness. In International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing, 2, 419-425. SCITEPRESS. https://doi.org/10. 5220/0005158704190425

*Sharma, D., & Potey, M. (2018). Effective learning through peer assessment using Peergrade tool. In 2018 IEEE Tenth International Conference on Technology for Education (T4E), Chennai, India, 114-117. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ T4E.2018.00031.

*Shishavan, H. B., & Jalili, M. (2020). Responding to student feedback: Individualising teamwork scores based on peer assessment. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 1, 100019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2020. 100019

*Siemens, G., Marmolejo-Ramos, F., Gabriel, F., Medeiros, K., Marrone, R., Joksimovic, S., & de Laat, M. (2022). Human and artificial cognition. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 3, 100107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2022. 100107

*Stelmakh, I., Shah, N. B., & Singh, A. (2021). Catch me if I can: Detecting strategic behaviour in peer assessment. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 35(6), 4794-4802. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v35i6.16611

*Thamizhkkanal, M. R., & Ambeth Kumar, V. D. (2020). A neural based approach to evaluate an answer script. In: Hemanth, D., Kumar, V., Malathi, S., Castillo, O., & Patrut, B. (Eds.) Emerging Trends in Computing and Expert Technology. COMET 2019. Lecture Notes on Data Engineering and Communications Technologies, vol 35. Springer, Cham. https://doi. org/10.1007/978-3-030-32150-5_122

*Tiew, H. B., Chua, F. F., & Chan, G. Y. (2021). G-PAT: A group peer assessment tool to support group projects. In 2021 7th International Conference on Research and Innovation in Information Systems (ICRIIS), Johor Bahru, Malaysia, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRIIS53035.2021.9617037.

Topping, K. J. (2024). Improving thinking about thinking in the classroom: What works for enhancing metacognition. Routledge.

*Wang, A. Y., Chen, Y., Chung, J. J. Y., Brooks, C., & Oney, S. (2021). PuzzleMe: Leveraging peer assessment for in-class programming exercises. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5, Issue CSCW2, Article No: 415, 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1145/3479559

*Wang, Y., Li, H., Feng, Y., Jiang, Y., & Liu, Y. (2012). Assessment of programming language learning based on peer code review model: Implementation and experience report. Computers & Education, 59(2), 412-422. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.compedu.2012.01.007

*Wang, Y. Q., Liu, B. Y., Zhang, K., Jiang, Y. S., & Sun, F. Q. (2019a). Reviewer assignment strategy of peer assessment: Towards managing collusion in self-assignment. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Social Science, Public Health and Education (SSPHE 2018). https://doi.org/10.2991/ssphe-18.2019.75

*Wang, R., Wei, S., Ohland, M. W., & Ferguson, D. M. (2019b). Natural language processing system for self-reflection and peer-evaluation. In the Fourth North American International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Toronto, Canada, October 23-25, 2019 (pp. 229-238).

*Wei, S., Wang, R., Ohland, M. W., & Nanda, G. (2020). Automating anonymous processing of peer evaluation comments. In 2020 ASEE Virtual Annual Conference Content Access. https://doi.org/10.18260/1-2–35615

*Wu, C., Chanda, E., & Willison, J. (2010). SPARKPlus for self-and peer assessment on group-based honours’ research projects. The Education Research Group of Adelaide (ERGA) conference 2010: The Changing Face of Education, 24-25 September, 2010. https://hdl.handle.net/2440/61612

*Xiao, Y., Y., Gao, Y., Yue, C. H., & Gehringer, E. (2022). Estimating student grades through peer assessment as a crowdsourcing calibration problem. 20th International Conference on Information Technology Based Higher Education and Training (ITHET), Antalya, Turkey, 2022, pp. 1-9, https://doi.org/10.1109/ITHET56107.2022.10031993.

*Xiao, Y., Zingle, G., Jia, Q., Akbar, S., Song, Y., Dong, M., & Gehringer, E. (2020a). Problem detection in peer assessments between subjects by effective transfer learning and active learning. The International Conference on Educational Data Mining (EDM) (13th, Online, Jul 10-13, 2020). ERIC Number: ED608055

*Xiao, Y., Zingle, G., Jia, Q., Shah, H. R., Zhang, Y., Li, T., & Gehringer, E. F. (2020b). Detecting problem statements in peer assessments. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.04532. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2006.04532

Xiong, W., & Litman, D. (2010). Identifying problem localization in peer-review feedback. In V. Aleven, J. Kay, & J. Mostow (Eds.), Intelligent tutoring systems. ITS 2010. Lecture notes in computer science, 6095. Berlin: Springer. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/978-3-642-13437-1_93

*Xiong, W., & Litman, D. (2011). Automatically predicting peer-review helpfulness. In Proceedings of the 49th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Portland, Oregon, 502-507.

*Xiong, W., Litman, D., & Schunn, C. (2012). Natural language processing techniques for researching and improving peer feedback. Journal of Writing Research, 4(2), 155-176. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2012.04.02.3

*Xiong, Y., Schunn, C. D., & Wu, Y. (2023). What predicts variation in reliability and validity of online peer assessment? A large-scale cross-context study. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 39(6), 2004-2024. https://doi.org/10.1111/ jcal. 12861

Zheng, L. Q., Zhang, X., & Cui, P. P. (2020). The role of technology-facilitated peer assessment and supporting strategies: A meta-analysis. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(3), 372-386. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019. 1644603

*Zingle, G., Radhakrishnan, B., Xiao, Y., Gehringer, E., Xiao, Z., Pramudianto, F., Arnav, A. (2019). Detecting suggestions in peer assessments. International Conference on Educational Data Mining (EDM) (12th, Montreal, Canada, Jul 2-5, 2019). ERIC Number: ED599201.

*Zong, Z., & Schunn, C. D. (2023). Does matching peers at finer-grained levels of prior performance enhance gains in task performance from peer review? International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 18, 425-456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-023-09401-4

ملاحظة الناشر

- ©المؤلفون 2025. الوصول المفتوح. هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام والمشاركة والتكيف والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج في أي وسيلة أو صيغة، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح ما إذا كانت هناك تغييرات قد تم إجراؤها. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر ائتمان للمادة. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة وكان استخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، ستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارة http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-024-00501-1

Publication Date: 2025-01-20

Enhancing peer assessment with artificial intelligence

k.j.topping@dundee.ac.uk

Abstract

This paper surveys research and practice on enhancing peer assessment with artificial intelligence. Its objectives are to give the structure of the theoretical framework underpinning the study, synopsize a scoping review of the literature that illustrates this structure, and provide a case study which further illustrates this structure. The theoretical framework has six areas: (i) Assigning Peer Assessors, (ii) Enhancing Individual Reviews, (iii) Deriving Peer Grades/Feedback, (iv) Analyzing Student Feedback, (v) Facilitating Instructor Oversight and (vi) Peer Assessment Systems. The vast majority of the 79 papers in the review found that artificial intelligence improved peer assessment. However, the focus of many papers was on diversity in grades and feedback, fuzzy logic and the analysis of feedback with a view to equalizing its quality. Relatively few papers focused on automated assignment, automated assessment, calibration, teamwork effectiveness and automated feedback and these merit further research. This picture suggests AI is making inroads into peer assessment, but there is still a considerable way to go, particularly in the under-researched areas. The paper incorporates a case study of the RIPPLE peer-assessment tool, which harnesses student wisdom, insights from the learning sciences and AI to enable time-constrained educators to immerse their students in deep and personalized learning experiences that effectively prepare them to serve as assessors. Once trained, they use a comprehensive rubric to vet learning resources submitted by other students. They thereby create pools of highquality learning resources which can be used to recommend personalized content to students. RIPPLE engages students in a trio of intertwined activities: creation, review and personalized practice, generating many resource types. AI-driven real-time feedback is given but students are counseled to assess whether it is accurate. Affordances and challenges for researchers and practitioners were identified.

Introduction

of learning analytics in improving peer assessment was offered by Misiejuk and Wasson (2023), who identified three main roles: enhancing software tools, generating automated feedback and visualizations. Four main application areas were mapped: student interaction, feedback characteristics, comparison and design. The rapid scoping review in this study goes beyond this in broadly addressing all of AI in peer assessment and noting interventions rather than merely mapping the field.

A theoretical framework for Al affordances in peer assessment

Assigning peer assessors

Enhancing individual reviews

Deriving peer grades/feedback

Analyzing student feedback

Facilitating instructor oversight

Peer assessment systems

assessment models. These models can take into account a wider range of factors than traditional methods.

Rapid scoping review

Methodology

Results

Assigning peer assessors

approach based on item response theory and integer programming for assigning peer assessors, but found it no more effective than random allocation and recommended the use of additional assessors from outside the group. A system of post hoc collusion detection was trialed by Wang et al. (2019a). Only two papers looked at a comprehensive system of intelligent assignment of assessors to assesses. Anaya et al. (2019) had a system of assigning peer assessors according to social networks, which was more effective than random assignment. Having divided students into four ability groups, Zong and Schunn (2023) found matching by similar ability the most effective and more effective than random allocation, except for low-ability students.

Enhancing individual reviews

Deriving peer grades/feedback

Automated Assessment The topic of Automated Assessment had four papers (

were however highly susceptible to strategic reporting (i.e., reviewing with aims other than assessment in mind or gaming the system to improve one’s grade at the expense of classmates).

the submissions and estimate their absolute grades. Experimental results showed better performance compared with other peer assessment techniques. A fuzzy-based approach that aimed to enhance validity and reliability was proposed by El Alaoui et al. (2018). The authors gave illustrative examples. The application of a fuzzy-number-based questionnaire was introduced by Jónás et al. (2018) in order to enhance the reliability of peer evaluations. The membership function of the fuzzy number was composed of an increasing and decreasing sigmoid membership function associated with Dombi’s intersection operator. This allowed peer reviewers to express their uncertainty and the variability of the reviewed person’s performance in a quantitative way. A case study was offered.

MOOCs Four papers (

accuracy on real data with 63,199 peer grades. They related grader biases and reliabilities to other student factors such as student engagement and performance as well as commenting style. An AI system for a MOOC-for-credit course to address both scale and endorsement was implemented by Joyner (2018). Students in the online course achieved comparable learning outcomes, reported a more positive student experience and identified AI-equipped programming problems as the primary contributor to their experiences. Sciarrone and Temperini (2020) presented a web-based system that simulated a MOOC class. This allowed teachers to experiment with different pedagogic strategies based on peer assessment. The teacher could observe the dynamics of the simulated MOOC, based on a modified version of the K-NN algorithm. A first trial of the system produced promising results.

Analyzing student feedback

Analysis of Feedback Fourteen papers (18%) reported on the analysis of student feedback. Four focused on review accuracy. Nakayama et al. (2020) discussed the best number of peers to give evaluations to each other, related to the student’s proficiency and assessment capability. The number of peers assigned to the same evaluation job was controlled from three to 50 in six steps using a 10-point scale. All parameters of the models gradually decreased with the number of peers. A multi-dimensional quality control algorithm for peer assessments and text information was developed by Li et al. (2020b). The user’s behavior, comment text information and other elements were combined together. The frame was a log-linear model leading to a gradient descent algorithm. When compared with traditional algorithms, the model performed better. Badea and Popescu (2020) described LearnEval and applied it to project-based learning scenarios. Each student was modeled on competence, involvement and assessment abilities. A scores

module involving visualization was incorporated. However, evaluation was only through student perceptions. Three different systems for analyzing peer comments were used by Huang et al. (2023), classifying peer comments in terms of cognitive content and affective state. The Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) model had the best results and improved feedback with significantly reduced student burnout. Individuals who received more suggestive feedback experienced a greater reduction in emotional exhaustion. By contrast, when receiving more negative feedback and/or reinforcement without guidance, learners tended to have a worse emotional experience and demonstrated poorer self-learning behavior.

features increased students’ likelihood of implementation (overall praise and localization), while several reduced it (mitigating praise, solutions and high-prose comments). Three conditions were then compared by Patchan et al. (2017): only rating accountability, only feedback accountability, or both rating and feedback accountability. Peer ratings and peer feedback were coded. Constructing helpful comments had a broad influence on peer assessment and consistent ratings were grounded in this commenting. It should be noted that there is a fine line between feedback analysis (in this section) and Enhancing Individual Reviews. If feedback analysis is instant, and reviewers can see it before submitting a review, it can help reviewers to improve their reviews. This might be considered a “formative” use of feedback analysis. If it is instead presented to the instructor as a way of assessing reviewer effectiveness, then it is being used “summatively” to analyze the feedback.

Adaptive Comparative Judgment (ACJ) There were two papers in this sub-category

Facilitating instructor oversight

delivered live peer testing and live peer code review. Live peer testing could improve students’ code robustness by allowing them to create and share lightweight tests with peers. Live peer code review could improve code understanding by intelligently grouping students to maximize meaningful code reviews. However, the evaluation was very brief. Khosravi et al. (2021) described learner sourcing, via an adaptive system called RiPPLE, which had been used in more than 50 courses with over 12,000 students. The paper offered data-driven reflections and lessons learned. Dhull et al. (2022) focused on finding an assignment of evaluators to submissions that maximized evaluators’ expertise subject to the constraint of strategy-proofness. Several polynomial-time algorithms for strategyproof assignment along with assignment-quality guarantees were developed and successfully trialed.

Peer assessment systems

performance, learning motivation, self-efficacy, peer review quality, peer assessment correctness and online learning behaviors. A 12-week experiment was conducted comparing videos with peer comments, videos with peer ratings and videos with peer ratings plus peer comments. The latter group provided better feedback and were most aligned with teacher scores. In the system proposed by Thamizhkanal and Kumar (2020), preprocessing and noise removal was done with the help of filtering, normalization and compression. Then internal and external segmentation was deployed. Identification of a letter in the answer script was done by convolutional neural networks. Evaluation of answers was done by a simple neural network. An experiment comparing test types was in favor of the new system.

Case study

Creation

Review

of resources by students, these materials are subjected to a peer review mechanism whereby peers evaluate the content’s quality and relevance. The peer assessment process fosters a collaborative learning environment, where students learn to apply academic standards in a practical context, further reinforcing their learning of the course content.

Personalized practice

Instructor monitoring

Abstract

Al assistance During the creation phase, generative AI is seamlessly integrated into the platform to provide immediate feedback on the resources submitted by students. This AIdriven feedback mechanism includes a comprehensive summary that interprets the primary objective of the resource, ensuring that the content aligns with the intended learning outcomes. Additionally, the feedback highlights the resource’s strengths, acknowledging well-executed elements that contribute to effective learning as well as suggestions for specific areas for improvement, offering actionable recommendations that can elevate the content’s overall effectiveness and clarity. In the review phase, generative AI is once again employed to deliver real time constructive feedback, designed to identify potential areas where the review could be strengthened, such as offering more detailed analysis, providing clearer justifications, or suggesting alternative perspectives. For personalized practice, RiPPLE’s AI algorithms assess students’ abilities in each course topic, recommending resources that are most suitable for their current knowledge level.

RiPPLE has been adopted in over 250 subject offerings across a range of disciplines including Medicine, Pharmacy, Psychology, Education, Business, IT and Biosciences. Over 50,000 students have created over 175,000 learning resources and over 680,000 peer evaluations rating the quality of these resources. The adaptive engine of RiPPLE has been used to recommend over three million personalized resources to students. In the sections below, we discuss how RiPPLE leverages five of the six areas outlined in our proposed framework (as it is itself a Peer Assessment System).

Assigning peer assessors

Individual reviews

Deriving peer grades/feedback

Instructor oversight

- Please vote on the helpfulness of each moderation

revised, demonstrating the spot-checking algorithm’s

Case study summary

| Framework area | Examples from RiPPLE |

| Assigning Peer Assessors | Advanced machine learning, including graph-based trust propagation, assesses assessor reliability. This enhances the credibility and accuracy of the peer review process |

| Enhancing Individual Reviews | RiPPLE integrates generative AI to enhance peer feedback, providing immediate, constructive suggestions for improvement. The AI feedback agent introduces itself, proposes enhancements, warns students of potential inaccuracies, and provides students the ability to provide feedback on its helpfulness |

| Deriving Peer Grades/Feedback | RiPPLE requires consensus among multiple moderators to finalize resource evaluations. Currently, RiPPLE uses a graph-based trust propagation approach (Darvishi et al., 2021) that infers the reliability of each moderator. The final decision is derived from a weighted average of the ratings given by peer evaluators |

| Facilitating Instructor Oversight | “Suggested Actions” section offers recommendations for instructors to inspect flagged resources, review ineffective evaluations, identify underperforming students, and remind students of incomplete tasks. The peer feedback exploration interface allows for detailed feedback analysis, offering tools to up-vote quality reviews, down-vote or remove ineffective feedback, and filter reviews for efficiency, with significant instructor engagement in managing peer feedback quality |

| Area | Number of papers | Sub-category | Number of Subcategory papers |

| Assigning Peer Assessors | 4 | ||

| Enhancing Individual Reviews | 7 | ||

| Deriving Peer Grades/Feedback | 35 | Automated Assessment | 4 |

| Diversity of Grades and Feedback | 7 | ||

| Calibration | 5 | ||

| Fuzzy Logic and Decision-Making | 8 | ||

| Teamwork Effectiveness | 4 | ||

| MOOCs | 4 | ||

| Strategic and Rogue Reporting | 3 | ||

| Analyzing Student Feedback | 19 | Analysis of Feedback | 14 |

| Automated Feedback | 3 | ||

| Adaptive Comparative Judgment | 2 | ||

| Facilitating Instructor Oversight | 4 | ||

| Peer Assessment Systems | 10 | ||

| Total | 79 |

Discussion and interpretation of the whole paper Summary

found AI outcomes only as good as or worse than non-AI outcomes. Of course, this might have been expected given publication bias and does not necessarily reflect what practitioners will experience when implementing in their own classrooms.

Strengths and limitations

illuminative, larger quasi-experimental studies are also needed. Samples were mostly of convenience.

Opportunities and challenges for researchers and practitioners For researchers

used to detect grade-text consistency and automated grading was designed with the BERT-RCNN model. It is also worth remembering that generative AI has its dangers. For example, Oviedo-Trespalacios et al. (2023) analyzed ChatGPT’s safety-related advice and raised misuse concerns. ChatGPT appeared not to favor contents based on their factuality or reliability. Populations with lower literacy and education were at higher risk of consuming unreliable content.

For practitioners

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Author contribution

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Declarations

Competing interests

Received: 2 January 2024 Accepted: 10 October 2024

Published online: 21 January 2025

References

References in the scoping review asterisked *

Abdi, S., Khosravi, H., Sadiq, S., & Gasevic, D. (2020). Complementing educational recommender systems with open learner models. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Learning Analytics & Knowledge (pp. 360-365). https://doi.org/10.1145/3375462.3375520

*Ahuja, R., Khan, D., Symonette, D., Pan, S., Stacey, S., & Engel, D. (2020a). Towards the automatic assessment of student teamwork. In Companion Proceedings of the 2020 ACM International Conference on Supporting Group Work (pp. 143-146). https://doi.org/10.1145/3323994.3369894

*Ahuja, R., Khan, D., Tahir, S., Wang, M., Symonette, D., Pan, S., & Engel, D. (2020b). Machine learning and student performance in teams. In: Bittencourt, I., Cukurova, M., Muldner, K., Luckin, R., Millán, E. (Eds.) Artificial Intelligence in Education. AIED 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 12164. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52240-7_55

*Anaya, A. R., Luque, M., Letón, E., & Hernández-del-Olmo, F. (2019). Automatic assignment of reviewers in an online peer assessment task based on social interactions. Expert Systems, 36, e12405. https://doi.org/10.1111/exsy. 12405

*Babik, D., Stevens, S. P., Waters, A., & Tinapple, D. (2020). The effects of dispersion and reciprocity on assessment fidelity in peer-review systems: A simulation study. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 13(3), 580-592. https://doi. org/10.1109/TLT.2020.2971495

*Babo, R., Rocha, J., Fitas, R., Suhonen, J., & Tukiainen, M. (2021). Self and peer e-assessment: A study on software usability. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education (IJICTE), 17(3), 68-85. https://doi.org/ 10.4018/IJICTE.20210701.oa5

*Badea, G., & Popescu, E. (2020). Supporting students by integrating an open learner model in a peer assessment platform. In: Kumar, V., & Troussas, C. (Eds.) Intelligent Tutoring Systems. ITS 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 12149. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49663-0_14

*Badea, G., & Popescu, E. (2022). A hybrid approach for mitigating learners’ rogue review behavior in peer assessment. In: Crossley, S., & Popescu, E. (Eds.) Intelligent Tutoring Systems. ITS 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 13284. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-09680-8_3

*Bawabe, S., Wilson, L., Zhou, T., Marks, E., & Huang, J. (2021). The UX factor: Using comparative peer review to evaluate designs through user preferences. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5 (CSCW2), Article No: 476, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1145/3479863

*Burrell, N., & Schoenebeck, G. (2021). Measurement integrity in peer prediction: A peer assessment case study. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM Conference on Economics and Computation 369-389. https://doi.org/10.1145/3580507. 3597744

*Campos, D. G., et al. (2024). Screening smarter, not harder: A comparative analysis of machine learning screening algorithms and heuristic stopping criteria for systematic reviews in educational research. Educational Psychology Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-024-09862-5

*Capuano, N., Loia, V., & Orciuoli, F. (2017). A fuzzy group decision making model for ordinal peer assessment. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 10(2), 247-259. https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2016.2565476

*Castro, M. S. O., Mello, R. F., Fiorentino, G., Viberg, O., Spikol, D., Baars, M., & Gašević, D. (2023). Understanding peer feedback contributions using natural language processing. In:Viberg, O., Jivet, I., Muñoz-Merino, P., Perifanou, M.,

*Chai, K. C., & Tay, K. M. (2014). A perceptual computing-based approach for peer assessment. In 9th International Conference on System of Systems Engineering (SOSE), Glenelg, SA, Australia, 60-165. https://doi.org/10.1109/SYSOSE.2014. 6892481.

*Chai, K. C., Tay, K. M., & Lim, C. P. (2015). A new fuzzy peer assessment methodology for cooperative learning of students. Applied Soft Computing, 32, 468-480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2015.03.056

*Chiu, M. M., Woo, C. K., Shiu, A., Liu, Y., & Luo, B. X. (2020). Reducing costly free-rider effects via OASIS. International Journal of Comparative Education and Development, 22(1), 30-48. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCED-07-2019-0041

*Cho, K., & Schunn, C. D. (2007). Scaffolded writing and rewriting in the discipline: A web-based reciprocal peer review system. Computers & Education, 48(3), 409-426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2005.02.004

Craig, C. D., & Kay, R. (2021). Examining peer assessment in online learning for higher education – A systematic review of the literature. Proceedings of ICERI2021 Conference, 8th-9th November 2021.

Darvishi, A., Khosravi, H., Rahimi, A., Sadiq, S., & Gašević, D. (2022a). Assessing the quality of student-generated content at scale: A comparative analysis of peer-review models. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 16(1), 106-120. https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2022.3229022

Darvishi, A., Khosravi, H., & Sadiq, S. (2021). Employing peer review to evaluate the quality of student generated content at scale: A trust propagation approach. In Proceedings of the Eighth ACM Conference on Learning@ Scale (pp. 139-150). https://doi.org/10.1145/3491140.3528286

*Darvishi, A., Khosravi, H., Sadiq, S., & Gašević, D. (2022b). Incorporating AI and learning analytics to build trustworthy peer assessment systems. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53(4), 844-875. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet. 13233

*Demonacos, C., Ellis, S., & Barber, J. (2019). Student peer assessment using Adaptive Comparative Judgment: Grading accuracy versus quality of feedback. Practitioner Research in Higher Education, 12(1), 50-59.

*Dhull, K., Jecmen, S., Kothari, P., & Shah, N. B. (2022). Strategyproofing peer assessment via partitioning: The price in terms of evaluators’ expertise. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Human Computation and Crowdsourcing, 10(1), 53-63. https://doi.org/10.1609/hcomp.v10i1.21987

*Djelil, F., Brisson, L., Charbey, R., Bothorel, C., Gilliot, J. M., & Ruffieux, P. (2021). Analysing peer assessment interactions and their temporal dynamics using a graphlet-based method. In: De Laet, T., Klemke, R., Alario-Hoyos, C., Hilliger, I., & Ortega-Arranz, A. (Eds.), Technology-Enhanced Learning for a Free, Safe, and Sustainable World. EC-TEL 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 12884. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86436-1_7

*EI Alaoui, M., El Yassini, K., & Ben-Azza, H. (2018). Enhancing MOOCs peer reviews validity and reliability by a fuzzy coherence measure. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Smart City Applications, 2018, Article No.: 57, 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1145/3286606.3286834

*Ellison, C. (2023). Effects of adaptive comparative judgement on student engagement with peer formative feedback. Practitioner Research in Higher Education, 15(1), 24-35.

*Fu, Q. K., Lin, C. J., & Hwang, G. J. (2019). Research trends and applications of technology-supported peer assessment: A review of selected journal publications from 2007 to 2016. Journal of Computers in Education, 6, 191-213. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s40692-019-00131-x

*Garcia-Souto, M. P. (2019). Making assessment of group work fairer and more insightful for students and time-efficient for staff with the new IPAC software. In INTED2019 Proceedings (pp. 8636-8641), IATED, Valencia, Spain. https://doi. org/10.21125/inted.2019.2154

*Hamer, J., Kell, C., & Spence, F. (2005). Peer assessment using Aropä. Ninth Australasian Computing Education Conference (ACE2007), Ballarat, Victoria, Australia, February 2007. https://www.academia.edu/2878638/Peer_assessment_ using_arop%C3%A4?auto=download&email_work_card=download

*He, Y., Hu, X., & Sun, G. (2019). A cognitive diagnosis framework based on peer assessment. In Proceedings of the ACM Turing Celebration Conference-China, Article No: 78, 1-6. New York, NY. Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3321408.3322850

Helden, G. V., Van Der Werf, V., Saunders-Smits, G. N., & Specht, M. M. (2023). The use of digital peer assessment in higher education – An umbrella review of literature. IEEE Access, 11, 22948-22960. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023. 3252914

*Hernández-González, J., & Herrera, P. J. (2023). On the supervision of peer assessment tasks: An efficient instructor guidance technique. in IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2023.3319733.

*Hoang, L. P., Le, H. T., Van Tran, H., Phan, T. C., Vo, D. M., Le, P. A., & Pong-Inwong, C. (2022). Does evaluating peer assessment accuracy and taking it into account in calculating assessor’s final score enhance online peer assessment quality? Education and Information Technologies, 27, 4007-4035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10763-1

*Hsia, L. H., Huang, I., & Hwang, G. J. (2016). Effects of different online peer-feedback approaches on students’ performance skills, motivation and self-efficacy in a dance course. Computers & Education, 96, 55-71. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.compedu.2016.02.004

Hua, X., Nikolov, M., Badugu, N., & Wang, L. (2019). Argument mining for understanding peer reviews. arXiv:1903.10104. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1903.10104

*Huang, C., Tu, Y., Han, Z., Jiang, F., Wu, F., & Jiang, Y. (2023). Examining the relationship between peer feedback classified by deep learning and online learning burnout. Computers & Education, 207, 104910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. compedu.2023.104910

Hwang, G. J., Xie, H., Wah, B. W., & Gašević, D. (2020). Vision, challenges, roles and research issues of Artificial Intelligence in Education. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 1, 100001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2020. 100001

*Jónás, T., Tóth, Z. E., & Árva, G. (2018). Applying a fuzzy questionnaire in a peer review process. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 29(9-10), 1228-1245. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2018.1487616

*Joyner, D. (2018). Intelligent evaluation and feedback in support of a credit-bearing MOOC. In Artificial Intelligence in Education: 19th International Conference, AIED 2018, London, UK, June 27-30, 2018, Proceedings, Part II 19 (166-170). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93846-2_30

*Kalella, T., Lehtonen, T., Luostarinen, P., Riitahuhta, A., & Lanz, M. (2009). Introduction and evaluation of the peer evaluation tool. New Pedagogy, 287-292

Khosravi, H., Kitto, K., & Williams, J. J. (2019). RiPPLE: A crowdsourced adaptive platform for recommendation of learning activities. Journal of Learning Analytics, 6(3), 91-105. https://doi.org/10.18608/jla.2019.63.12

Khosravi, H., Demartini, G., Sadiq, S., & Gasevic, D. (2021). Charting the design and analytics agenda of learnersourcing systems. In LAK21: 11th International Learning Analytics and Knowledge Conference, 32-42. https://doi.org/10. 1145/3448139.3448143

Khosravi, H., Denny, P., Moore, S., & Stamper, J. (2023). Learnersourcing in the age of AI: Student, educator and machine partnerships for content creation. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 5, 100151. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100151

Kim, S. M., Pantel, P., Chklovski, T., & Pennacchiotti, M. (2006). Automatically assessing review helpfulness. In Proceedings of the 2006 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (pp. 423-430).

*Knight, S., Leigh, A., Davila, Y. C., Martin, L. J., & Krix, D. W. (2019). Calibrating assessment literacy through benchmarking tasks. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(8), 1121-1132. http://hdl.handle.net/10453/ 130201

*Kulkarni, C., Wei, K. P., Le, H., Chia, D., Papadopoulos, K., Cheng, J., Koller, D., & Klemmer, S. R. (2013). Peer and self assessment in massive online classes. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction., 20(6), 331-31. https:// doi.org/10.1145/2505057

*Kumar, K., Sharma, B., Khan, G. J., Nusair, S., & Raghuwaiya, K. (2020). An exploration on effectiveness of anonymous peer assessment strategy in online formative assessments. In 2020 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), Uppsala, Sweden. 1-5. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/FIE44824.2020.9274162.

*Lauw, H. W., Lim, E. P., & Wang, K. (2007). Summarizing review scores of “unequal” reviewers. In Proceedings of the 2007 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining (pp. 539-544). Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. https://doi.org/10.1137/1.9781611972771.58

Li, H. L., Xiong, Y., Hunter, C. V., Xiuyan Guo, X. Y., & Tywoniw, R. (2020a). Does peer assessment promote student learning? A meta-analysis. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(2), 193-211. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 02602938.2019.1620679

*Li, P., Yin, Z., & Li, F. (2020). Quality control method for peer assessment system based on multi-dimensional information. In: Wang, G., Lin, X., Hendler, J., Song, W., Xu, Z., & Liu, G. (Eds.), Web Information Systems and Applications. WISA 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 12432. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60029-7_17

Lin, P. (2022). Developing an intelligent tool for computer-assisted formulaic language learning from YouTube videos. ReCALL, 34(2), 185-200. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344021000252

Lin, Z., Yan, H. B., & Zhao, L. (2024). Exploring an effective automated grading model with reliability detection for largescale online peer assessment. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal. 12970

*Liu, C., Doshi, D., Bhargava, M., Shang, R., Cui, J., Xu, D., & Gehringer, E. (2023). Labels are not necessary: Assessing peerreview helpfulness using domain adaptation based on self-training. In Proceedings of the 18th Workshop on Innovative Use of NLP for Building Educational Applications (BEA 2023) 173-183. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2023.bea-1.15

*Madan, M., & Madan, P. (2015). Fuzzy viva assessment process through perceptual computing. In 2015 Annual IEEE India Conference (INDICON), New Delhi, India, 1-6. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/INDICON.2015.7443831.

*Masaki , U., Nguyen, D. T., & Ueno, M. (2019). Maximizing accuracy of group peer assessment using item response theory and integer programming. The Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence, 33. https://doi.org/10.11517/pjsai.JSAI2 019.0_4H2E503

Misiejuk, K., & Wasson, B. (2023). Learning analytics for peer assessment: A scoping review. In: Noroozi, O., & De Wever, B. (Eds.), The Power of Peer Learning. Springer, Champaign, IL. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29411-2_2

*Nakayama, M., Sciarrone, F., Uto, M., &Temperini, M. (2020). Impact of the number of peers on a mutual assessment as learner’s performance in a simulated MOOC environment using the IRT model. 2020 24th International Conference Information Visualisation (IV). Melbourne, Australia, 2020, 486-490. https://doi.org/10.1109/IV51561.2020.00084

*Ngu, A. H., Shepherd, J., & Magin, D. (1995). Engineering the “Peers” system: The development of a computer-assisted approach to peer assessment. Research and Development in Higher Education, 18, 582-587.

*Nguyen, H., Xiong, W., & Litman, D. (2016). Instant feedback for increasing the presence of solutions in peer reviews. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Demonstrations, San Diego, California. 6-10.

*Nguyen, H., Xiong, W., & Litman, D. (2017). Iterative design and classroom evaluation of automated formative feedback for improving peer feedback localization. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 27, 582-622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-016-0136-6

Ocampo, J. C. G., & Panadero, E. (2023). Web-based peer assessment platforms: What educational features influence learning, feedback and social interaction? In: O. Noroozi and B. de Wever (Eds.), The Power of Peer Learning. Champaign, IL: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29411-2_8

Oviedo-Trespalacios, O., Peden, A. E., Cole-Hunter, T., Costantini, A., Haghani, M., Rod, J. E., Kelly, S., Torkamaan, H., Tariq, A., Newton, J. D. A., Gallagher, T., Steinert, S., Filtness, A. J., & Reniers, G. (2023). The risks of using ChatGPT to obtain common safety-related information and advice. Safety Science, 167, 106244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2023. 106244

*Patchan, M. M., Schunn, C. D., & Clark, R. J. (2017). Accountability in peer assessment: Examining the effects of reviewing grades on peer ratings and peer feedback. Studies in Higher Education, 43(12), 2263-2278. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 03075079.2017.1320374

*Patchan, M. M., Schunn, C. D., & Correnti, R. J. (2016). The nature of feedback: How peer feedback features affect students’ implementation rate and quality of revisions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(8), 1098. https://doi.org/10. 1037/edu0000103

*Petkovic, D., Okada, K., Sosnick, M., Iyer, A., Zhu, S., Todtenhoefer, R., & Huang, S. (2012). A machine learning approach for assessment and prediction of teamwork effectiveness in software engineering education. In 2012 Frontiers in Education Conference Proceedings, Seattle, WA. 1-3. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/FIE.2012.6462205.

*Piech, C., Huang, J., Chen, Z., Do, C., Ng, A., & Koller, D. (2013). Tuned models of peer assessment in MOOCs. arXiv preprint arXiv:1307.2579. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1307.2579

Purchase, H., & Hamer, J. (2018). Peer-review in practice: Eight years of Aropä. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(7), 1146-1165. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1435776

*Ramachandran, L., Gehringer, E. F., & Yadav, R. K. (2017). Automated assessment of the quality of peer reviews using natural language processing techniques. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 27, 534-581. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s40593-016-0132-x

*Rao, D. H., Mangalwede, S. R., & Deshmukh, V. B. (2017). Student performance evaluation model based on scoring rubric tool for network analysis subject using fuzzy logic. In 2017 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computer, and Optimization Techniques (ICEECCOT), Mysuru, India (pp. 1-5). IEEE. https://doi.org/10. 1109/ICEECCOT.2017.8284623.

*Rashid, M. P., Gehringer, E. F., Young, M., Doshi, D., Jia, Q., & Xiao, Y. (2021). Peer assessment rubric analyzer: An NLP approach to analyzing rubric items for better peer-review. 2021 19th International Conference on Information Technology Based Higher Education and Training (ITHET), Sydney, Australia, 2021, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1109/ITHET 50392.2021.9759679.

*Rashid, M. P., Xiao, Y., & Gehringer, E. F. (2022). Going beyond” Good Job”: Analyzing helpful feedback from the student’s perspective. Paper presented at the International Conference on Educational Data Mining (EDM) (15th, Durham, United Kingdom, Jul 24-27, 2022). ERIC Number: ED624053.

*Ravikiran, M. (2020). Systematic review of approaches to improve peer assessment at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001. 10617. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2001.10617

*Rico-Juan, J. R., Gallego, A. J., & Calvo-Zaragoza, J. (2019). Automatic detection of inconsistencies between numerical scores and textual feedback in peer-assessment processes with machine learning. Computers & Education, 140, 103609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103609

*Russell, A. R. (2013). The evolution of Calibrated Peer Review. Trajectories of Chemistry Education Innovation and Reform, Chapter 9, pp 129-143. American Chemical Society Symposium Series, Vol. 1145. https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-20131145.ch009

*Saarinen, S., Krishnamurthi, S., Fisler, K., & Tunnell Wilson, P. (2019). Harnessing the wisdom of the classes: Classsourcing and machine learning for assessment instrument generation. In Proceedings of the 50th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education, 606-612. https://doi.org/10.1145/3287324.3287504

*Saccardi, I., Veth, D., & Masthoff, J. (2023). Identifying students’ group work problems: Design and field studies of a supportive peer assessment. Interacting with Computers. https://doi.org/10.1093/iwc/iwad044

*Sciarrone, F., & Temperini, M. (2020). A web-based system to support teaching analytics in a MOOC’s simulation environment. In 2020 24th International Conference Information Visualisation (IV), Melbourne, Australia (491-495). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/IV51561.2020.00085.

*Selmi, M., Hage, H., & Aïmeur, E. (2014). Opinion Mining for predicting peer affective feedback helpfulness. In International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing, 2, 419-425. SCITEPRESS. https://doi.org/10. 5220/0005158704190425

*Sharma, D., & Potey, M. (2018). Effective learning through peer assessment using Peergrade tool. In 2018 IEEE Tenth International Conference on Technology for Education (T4E), Chennai, India, 114-117. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ T4E.2018.00031.

*Shishavan, H. B., & Jalili, M. (2020). Responding to student feedback: Individualising teamwork scores based on peer assessment. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 1, 100019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2020. 100019