المجلة: Scientific Reports، المجلد: 14، العدد: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50383-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38167926

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-02

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50383-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38167926

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-02

التغيرات في تعبيرات الوجه لدى الخيول خلال شدة الألم العظمي المختلفة

ترتبط عدد من تعبيرات الوجه بالألم في الخيول، ومع ذلك، لم يتم بعد وصف العرض الكامل للأنشطة الوجهية خلال الألم العظمي. كان الهدف من الدراسة الحالية هو رسم خريطة شاملة للتغيرات في الأنشطة الوجهية في ثمانية خيول مستريحة خلال تقدمها من حالة سليمة إلى درجات خفيفة ومتوسطة من الألم العظمي، الناتج عن حقن الليببوليسكاريد (LPS) في المفصل الكاحلي. تم قياس تقدم وتراجع العرج من خلال تحليل الحركة الموضوعي أثناء الحركة، وتم وصف الأنشطة الوجهية بواسطة EquiFACS في تسلسلات الفيديو.

الحصان (Equus caballus) هو حيوان مفضل للرفقة والرياضة، ولكن في الآونة الأخيرة، أُثيرت مخاوف بشأن رفاهية الخيول.

يتم تقييم الألم العظمي الخفيف في الخيول عادةً أثناء الحركة من خلال تقييم عدم التماثل في الحركة / العرج بشكل ذاتي أو قياس عدم التماثل في الحركة بشكل موضوعي. ومع ذلك، بين، على سبيل المثال، الخيول المستخدمة في الركوب وخيول التروت التي يُنظر إليها على أنها سليمة من قبل مالكيها، يصل إلى

يمكن أن يؤدي تضمين الأنشطة الوجهية/التجاعيد غير المدرجة في مقاييس الألم إلى تحسين دقة تقييم الألم العظمي الخفيف. كما قد يساعد فهم كيفية تزامن الأنشطة الوجهية خلال شدة الألم المختلفة. وبالتالي، فإن الوصف الشامل، بطريقة موحدة، لجميع الأنشطة الوجهية المعروضة مفقود وقد يساهم في أداة تقييم أكثر موثوقية لتحديد الألم العظمي المبكر.

نظام ترميز الحركة الوجهية (FACS)

كان هدف هذه الدراسة استكشاف التغيرات في مجموعة تعابير الوجه في الخيول المستريحة مع درجات مختلفة من الألم العظمي الحاد المستحث. تم استخدام عدم التماثل في الحركة كبديل للألم ولتحديد مستوى الشدة. قمنا باختبار الأداء التنبؤي لوحدات حركة الوجه (AUs) ووصف الحركة (ADs) لتحديد تلك المهمة في كشف الألم، وأجرينا اختيارًا مدفوعًا بالبيانات لوحدات الحركة المتزامنة ووصف الحركة تحت درجات مختلفة من الألم. كانت الفرضية التي تم اختبارها هي أن وحدات الحركة/وصف الحركة الموصوفة سابقًا (غلق نصف، دوار الأذن، موسع المنخر، رافع الذقن، المضغ) يمكن أن تتنبأ بالألم وتحدث معًا بشكل متكرر أكثر في الخيول التي تعاني من الألم العظمي مقارنة بتلك التي لا تعاني. كما افترضنا أن وحدات الحركة/وصف الحركة تحدث معًا بشكل أقل تكرارًا خلال الألم الخفيف مقارنة بالألم المعتدل.

النتائج

تم تحفيز الألم العظمي بنجاح من خلال الإدارة داخل المفصل للليبوبوليسكاريد (LPS) في مفصل الكاحل في جميع الخيول الثمانية. وتم تأكيد العرج في الأطراف الخلفية وزيادة عدم التماثل في الحركة من خلال تحليل المشي الموضوعي أثناء الجري. تم نشر تفاصيل حول التغيرات في درجات العرج التي تم تقييمها بشكل ذاتي وفي عدم التماثل في الحركة الذي تم قياسه بشكل موضوعي في مكان آخر.

تحديد وحدات التقييم (AUs) والبيانات المرتبطة (ADs) المرتبطة بألم العظام

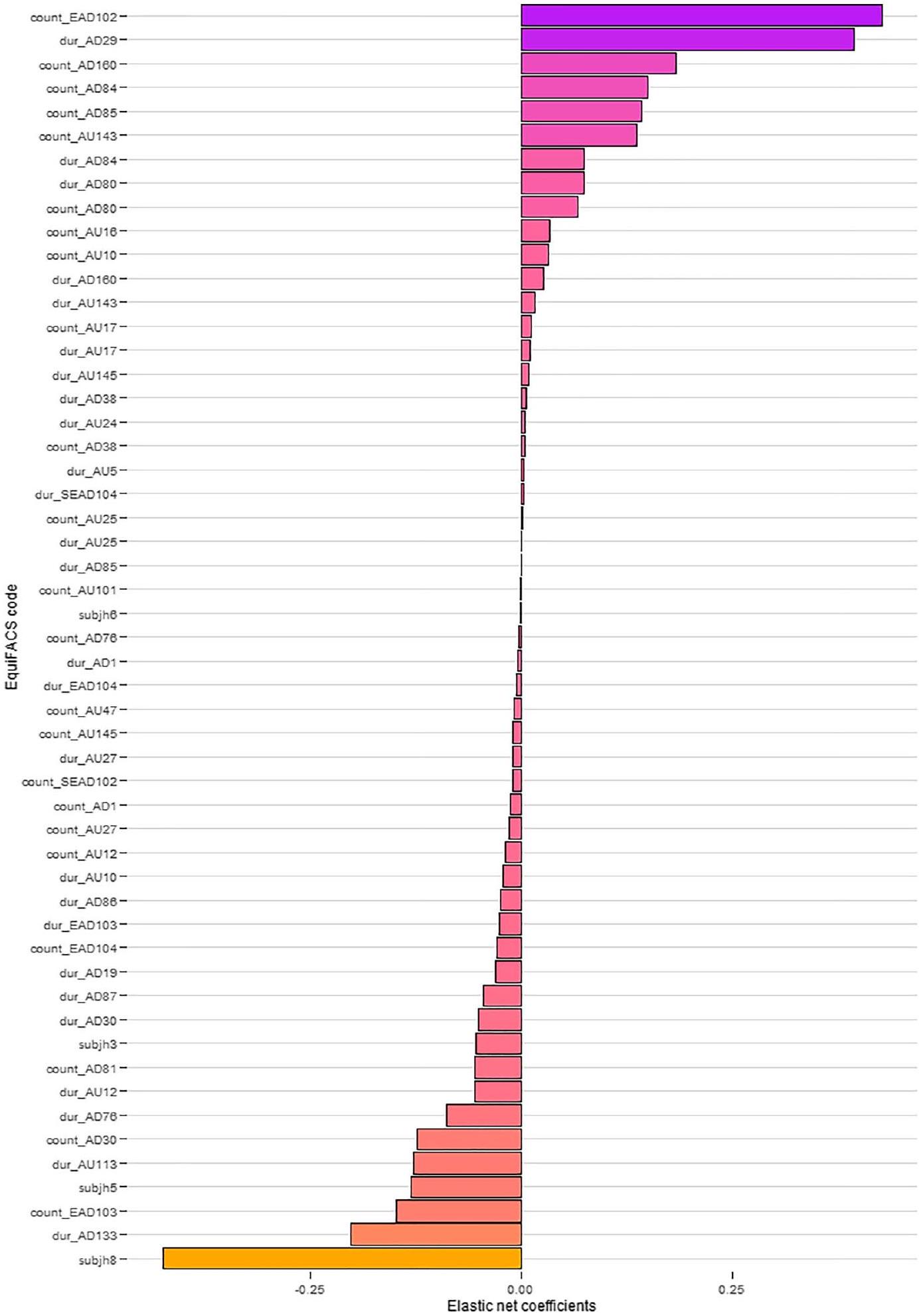

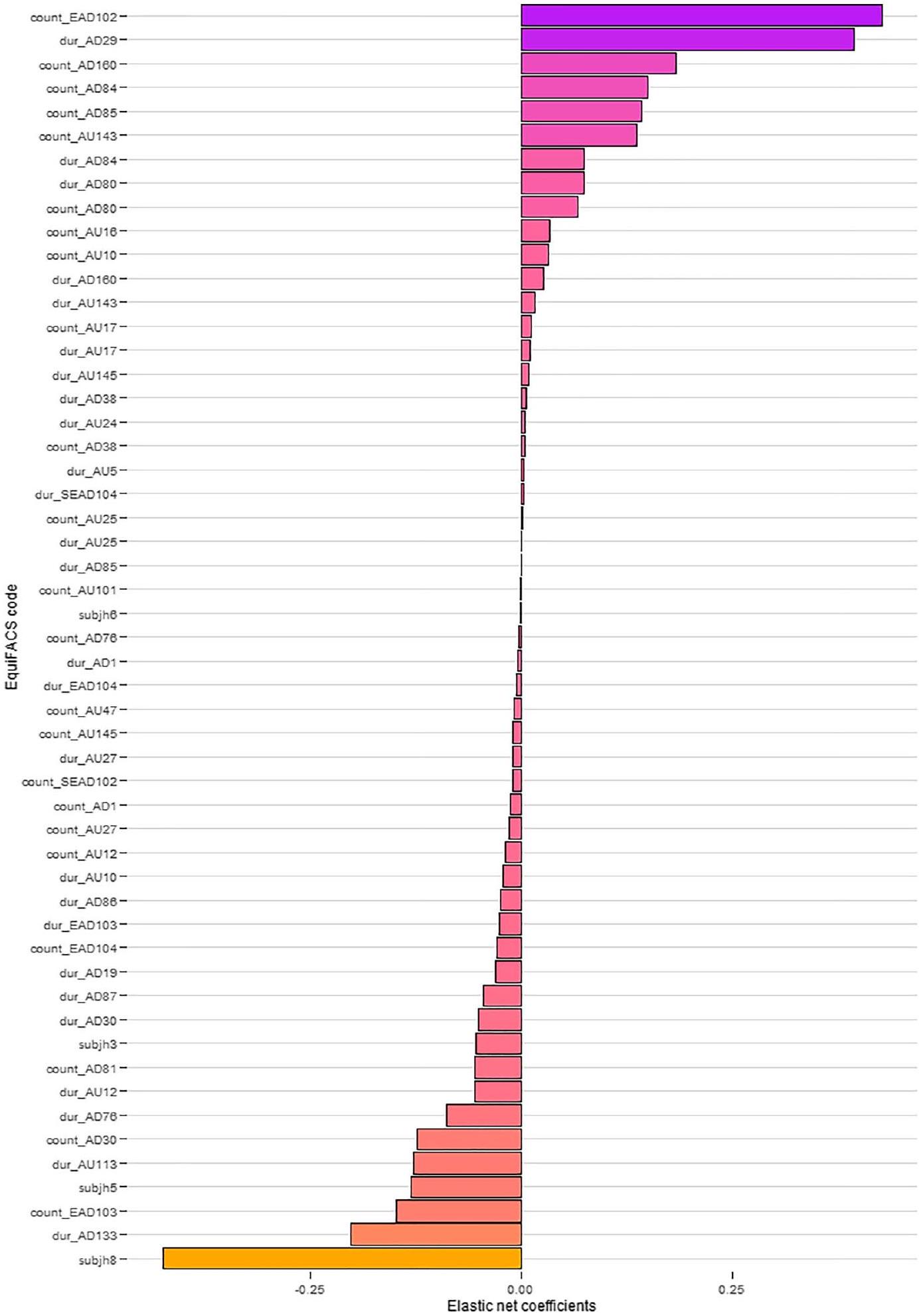

تم اختبار ما إذا كانت رموز EquiFACS يمكن أن تتنبأ بوجود ‘ألم’ أو بوجود ‘عدم ألم’ باستخدام الانحدار الشبكي المرن. تم تقديم معاملات النموذج في الملف S1 ورسمها في الشكل 1. تم اعتبار تلك التي لديها معامل يساوي 0 غير قادرة على التنبؤ بالألم. كان أفضل متنبئ للألم الذي اختاره النموذج هو تكرار تقارب كلا الأذنين (EAD102)، وكانت مدة دوران أذن واحدة (SEAD104) متنبئًا ضعيفًا للألم. لم تكن معظم الرموز الأخرى المتعلقة بالأذن قادرة على التنبؤ بالألم. كان تكرار ومدة تسطح كلا الأذنين (EAD103) والدوران (EAD104)، وتكرار تقارب أذن واحدة (SEAD102) مرتبطين بعدم وجود ألم. من بين الرموز التي تنتمي إلى الوجه العلوي، تم تصنيف تكرار ومدة إغلاق العين (AU143)، ومدة الومضة (AU145) ورافع الجفن العلوي (AU5) كمتنبئين بالألم. كان اثنا عشر من أصل 23 متنبئًا مرتبطًا بالألم.

| الإحصاءات الوصفية | الوسيط (الربع الأول والربع الثالث) | |

| لا ألم | ألم | |

| عدد التعليقات التوضيحية لكل فيديو | ١٠٢.٥ (٦٥.٨، ١٥١.٣) | 84.0 (61.0-129.0) |

| عدد التعليقات لكل حصان | 2314.0 (1822.0, 3267.25) | 1997.5 (1259.0, 2308.0) |

| مدة التعليقات (ث) | 0.466 (0.340, 0.700) | 0.491 (0.350, 0.750) |

الجدول 1. الإحصائيات الوصفية لمجموعة بيانات التعليقات. تمثل كل تعليق نشاطًا وجهًا محددًا. الوسيط، والربع الأول والربع الثالث لعدد التعليقات لكل تسلسل فيديو، وعدد التعليقات لكل حصان، ومدة كل تعليق بالثواني، في تسلسلات الفيديو الم labeled as ‘no pain’ و ‘pain’.

الشكل 1. معاملات الانحدار في اختبار أداء التنبؤ لوحدات العمل (AUs) ووصف العمل (ADs) باستخدام الانحدار الشبكي المرن. يتم عرض التردد (‘العدد’) والمدة (‘المدة’) لكل رمز من رموز EquiFACS. تشير قيم المعاملات الإيجابية إلى وجود ارتباط مع وجود الألم.

هز الجانب إلى الجانب (AD84)، إيماءة الرأس لأعلى ولأسفل بشكل متكرر (AD85)، وتكرار ومدة البلع (AD80) كانت مؤشرات قوية نسبيًا للألم. كانت وحدات العمل/وصف العمل المرتبطة بعدم وجود ألم في الغالب أوصافًا حركية: مدة الضربة (AD133)، هز الأذن (AD87)، إظهار اللسان (AD19)، العناية الشخصية (AD86)، إيماءة الرأس لأعلى.

وأسفل (AD85)، ومضغ (AD81)، وتكرار ومدة حركة الفك الجانبية (AD30)، والتثاؤب (AD76)، وزيادة بياض العين (AD1). مدة سحب الشفاه الحاد (AU113)، وسحب زاوية الشفاه (AU12) ورفع الشفاه العليا (AU10)، وتكرار ومدة تمدد الفم (AU27)، ورفع الحاجب الداخلي المتكرر (AU101)، والغمزة الجزئية (AU47) والغمزة (AU145) كانت مرتبطة أيضًا بعدم وجود ألم. علاوة على ذلك، تم تحديد الحصان 3 و5 و6 و8 كمتنبئين سلبيين للألم في النموذج.

وأسفل (AD85)، ومضغ (AD81)، وتكرار ومدة حركة الفك الجانبية (AD30)، والتثاؤب (AD76)، وزيادة بياض العين (AD1). مدة سحب الشفاه الحاد (AU113)، وسحب زاوية الشفاه (AU12) ورفع الشفاه العليا (AU10)، وتكرار ومدة تمدد الفم (AU27)، ورفع الحاجب الداخلي المتكرر (AU101)، والغمزة الجزئية (AU47) والغمزة (AU145) كانت مرتبطة أيضًا بعدم وجود ألم. علاوة على ذلك، تم تحديد الحصان 3 و5 و6 و8 كمتنبئين سلبيين للألم في النموذج.

التزامن بين وحدات التعبير (AUs) والاضطرابات العاطفية (ADs) خلال مستويات مختلفة من شدة الألم

عند مقارنة تسلسلات الفيديو ‘بدون ألم’ مع تسلسلات ‘ألم’، حددت طريقة التزامن AUs وADs التالية كمتصلة: خافض الشفة السفلية (AU16)، فتح الشفاه (AU25)، غمزة نصفية (AU47)، أذن واحدة للأمام (SEAD101)، ودوران أذن واحدة (EAD104) (الشكل 2). AUs وADs التي اختارتها طريقة التزامن لمستويات مختلفة من شدة الألم (المحددة من خلال عدم التماثل في الحركة) موضحة في الجدول 2.

نقاش

تظهر الخيول المستريحة التي تعاني من ألم تقويمي مجموعة ديناميكية من تعبيرات الوجه تتكون من آذان غير متماثلة، وتغيرات في نشاط الوجه في منطقة العين والوجه السفلي. حسب علمنا، هذه هي الدراسة الأولى التي تستخدم نظام EquiFACS وعدم التماثل في الحركة كمعايير لقياس الألم في الخيول. تعتبر هاتان الطريقتان من الطرق الموضوعية للغاية، مقارنةً بالتقييم البصري للعَرَج والألم. باستخدام هذه

الشكل 2. رموز EquiFACS المختارة بواسطة طريقة التزامن والتي تتواجد بشكل ملحوظ أكثر في مقاطع الفيديو ‘الألم’ مقارنة بمقاطع الفيديو ‘عدم الألم’.

| رمز إيكوي فاك | مستوى شدة الألم | ||||||||

| 0-1 (

|

0-2 (

|

1-2 (

|

|||||||

| آذان | |||||||||

| أذن واحدة للأمام (SEAD101) |

|

||||||||

| دوار أذن مفرد (SEAD104) |

|

|

|||||||

| الوجه العلوي | |||||||||

| بلك (AU145) |

|

||||||||

| وميض نصف (AU47) |

|

|

|

||||||

| الوجه السفلي | |||||||||

| رافع الشفة العليا (AU10) |

|

||||||||

| مخفض الشفة السفلية (AU16) |

|

||||||||

| شفاه مفتوحة (AU25) |

|

||||||||

الجدول 2. وحدات العمل (AUs) ووصف إجراءات الأذن (EADs) المختارة بواسطة طريقة التزامن. تم تعريف مستويات شدة الألم بناءً على عدم تماثل الحركة. لم تعاني جميع الخيول من كلا مستويي شدة الألم، لذلك تم ذكر عدد الخيول (n) التي تعاني من كل مستوى من مستويات الشدة بين قوسين. تم مقارنة تكرار وحدات العمل المتزامنة ووصف إجراءات الأذن في مقاطع الفيديو ‘بدون ألم’ بتكرارها في مقاطع ‘شدة ألم خفيفة’.

من خلال الأساليب الموضوعية، كان من الممكن تأكيد بعض النتائج السابقة حول تعبيرات الوجه أثناء الألم في الخيول، مثل وجود آذان غير متماثلة أثناء الألم وأهمية الرمش النصفي في اكتشاف الألم. كما حددنا بمزيد من التفصيل ميزات أخرى مثل الأنشطة الديناميكية للوجه السفلي أثناء الألم، مقارنة بالدراسات السابقة التي أظهرت وجهًا سفليًا أكثر صمودًا. أظهرت الدراسة الحالية أن النمذجة التنبؤية يمكن أن تحدد وحدات التعبير (AUs) وأنماط الحركة (ADs) المرتبطة بالألم العظمي، حيث تم تحديد عدة وحدات تعبير وأنماط حركة تتعلق بالآذان والوجه السفلي والعينين، عند ذروة شدة الألم. من وجهة نظر إحصائية، عندما تحدث هذه الوحدات/الأنماط بشكل متكرر ولمدة طويلة مقارنةً بفترة الأساس، يمكن أن تشير إلى الألم. ومع ذلك، عند تقييم الألم في الإعدادات السريرية، نادرًا ما يعرف الجراح البيطري حالة الأساس للمريض الخيلي، لذا قد يكون من الصعب استنتاج هذه التنبؤات في تقييمات الألم السريرية. لذلك، أضفنا طريقة التزامن.

لزيادة احتمال ظهور مجموعة تعبيرات الوجه المتعلقة بالألم لدى الخيول، قمنا بتضمين مقاطع فيديو من النقاط الزمنية التي تم فيها تقييم كل حصان بأنه في أعلى مستوى من شدة الألم. تم إجراء تقييم الألم باستخدام مقياس CPS، وهو مقياس الألم الذي ثبت أنه الأفضل في تقييم الألم العظمي لدى الخيول المستريحة.

تم التنبؤ بألم العظام بشكل أفضل بمساعدة مُقرب الأذن (EAD102) (الشكل 2)، حيث “تُسحب الأذن (الأذنان) نحو الخط الأوسط” و”تقل المسافة بين الأذنين”.

تمكنت عدة وحدات تعبير الوجه المتعلقة بالعين من التنبؤ بالألم في هذه الدراسة، مما يؤكد النتائج السابقة حول تعبيرات الوجه المتعلقة بالعين أثناء الألم. كان إغلاق العين بشكل متكرر وطويل (AU143)، وإجراء غمضات طويلة (AU145)، ورفع الجفن العلوي (AU5) بشكل متكرر وطويل مرتبطًا بالألم. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تزامن غمض العين (AU145) بشكل كبير مع وحدات تعبير الوجه الأخرى أثناء الألم الخفيف، وقد تم ربطه بالألم سابقًا – كما هو الحال مع رفع الجفن العلوي (AU5).

هو عامل ضغط داخلي لا يمكن تجنبه

هو عامل ضغط داخلي لا يمكن تجنبه

كانت الغالبية العظمى من الرموز ذات معاملات التنبؤ الإيجابية تنتمي إلى الوجه السفلي. كانت مدة دفع الفك (AD29)، الموصوفة بأنها عندما “يتم دفع الفك السفلي إلى الأمام” أو “تمتد الأسنان السفلية أمام الأسنان العلوية”، تحمل أكبر معامل من بين الرموز التي تنتمي إلى الوجه السفلي. ومع ذلك، عند فحص مجموعة البيانات، وجدنا أنه تم توثيقه ثلاث مرات فقط من بين 37,072 توثيقًا، وأنه كان له مدة أطول في تسلسلات ‘الألم’ مقارنة بتسلسلات ‘عدم الألم’. قد يفسر هذا قيمته التنبؤية التي تم تحديدها في نموذج الانحدار الشبكي المرن (الشكل 2). ومع ذلك، تم اختيار دفع الفك (AD29) سابقًا بواسطة طريقة التزامن في الخيول التي تعاني من الألم السريري.

علاوة على ذلك، حددنا تباينات في AUs/ADs فيما يتعلق بمستوى شدة الألم في الخيول (الجدول 2). باستخدام عدم التماثل في الحركة لتعريف مستوى شدة الألم، يبدو أن الخيول التي تعاني من ألم خفيف كانت لديها رموز تتواجد بشكل متزامن أكثر من الخيول التي تعاني من ألم معتدل. هذه نتيجة مثيرة للاهتمام، تتحدى النظريات السابقة حول الافتراضات المتعلقة بالزيادة المتزامنة في العلاقة الإيجابية والخطية بين أعداد تعبيرات الوجه وشدة الألم. إذا كانت التغيرات الرئيسية في نشاط الوجه تحدث فعليًا عندما تنتقل الخيل من عدم الشعور بالألم إلى الشعور بألم خفيف، فقد يكون من المضلل تقدير مستوى شدة الألم من خلال وجود تعبيرات الوجه. وفقًا للنتائج الحالية، قد تشير الومضة النصفية (AU47) بالاشتراك مع دوران الأذن الفردية (SEAD104) إلى أن الخيل تعاني من ألم معتدل. قد يكون أحد التفسيرات هو أن الخيول ربما تؤدي سلوكيات جسدية مرتبطة بالألم بشكل أكبر خلال الألم المعتدل، مثل التغيرات في الوضعية، وأنها تؤدي إلى تخفيف الألم. وقد تم مناقشة هذا من قبل Ask وآخرين.

بين وجود تعبير وجه قاسي والشدة. ومن ثم، قد يكون مفهوم وجه الألم النموذجي تبسيطًا، وهناك حاجة إلى مزيد من الدراسات حول العلاقة بين شدة الألم وتنوع تعبيرات الوجه.

بين وجود تعبير وجه قاسي والشدة. ومن ثم، قد يكون مفهوم وجه الألم النموذجي تبسيطًا، وهناك حاجة إلى مزيد من الدراسات حول العلاقة بين شدة الألم وتنوع تعبيرات الوجه.

لدراسة العلاقة بين الشدة والنشاط الوجهي، يمكن إضافة درجات الشدة إلى رموز EquiFACS الفردية، كما هو الحال في FACS لدى البشر.

أحد قيود الدراسة الحالية هو أن مقاطع الفيديو المعلّقة تم تسجيلها في وجود المراقبين، لأنه من المعروف أن وجود المراقبين قد يتسبب في اضطراب سلوكيات عدم الراحة لدى الخيول.

في الختام، حددت الدراسة الحالية ستة عشر وحدة تعبيرية (AUs) ووحدات تشخيصية (ADs) مهمة للتعرف على الألم باستخدام النمذجة التنبؤية وطريقة التزامن استنادًا إلى التعليقات التوضيحية لـ

طرق

تمت الموافقة على بروتوكول الدراسة من قبل اللجنة الأخلاقية السويدية (رقم السجل 5.8.18-09822/2018) وفقًا للتشريعات السويدية المتعلقة بتجارب الحيوانات. تم النظر في الاستبدال والتقليل والتحسين بعمق وتم اتباع إرشادات ARRIVE.

الحيوانات وتصميم الدراسة

تم نشر معلومات مفصلة عن تصميم الدراسة في مكان آخر

تمت ملاحظة عدم تماثل الحركة مقارنةً بالخط الأساسي (قبل تحفيز العرج). تم إجراء تخفيف الألم عن طريق إخلاء السائل الزليلي وفقًا للإجراءات القياسية السريرية إذا تجاوز العرج

تمت ملاحظة عدم تماثل الحركة مقارنةً بالخط الأساسي (قبل تحفيز العرج). تم إجراء تخفيف الألم عن طريق إخلاء السائل الزليلي وفقًا للإجراءات القياسية السريرية إذا تجاوز العرج

تحليل المشي الموضوعي وتقييم الألم

لكل تحليل موضوعي للمشي، تم تجهيز كل حصان بسبعة علامات كروية مثبتة على الجلد (بقطر 38 مم، كواليسيس AB، غوتنبرغ، السويد)، وسار وهرول في خط مستقيم على أسطح صلبة وناعمة. تم تنفيذ عملية اللنجينغ على سطح ناعم. تم تسجيل مواقع العلامات بواسطة 13 كاميرا لالتقاط الحركة بالأشعة تحت الحمراء (كواليسيس AB، غوتنبرغ، السويد) تعمل بتردد 200 هرتز، وتم تتبعها بواسطة برنامج QTM (الإصدار 2.11-2019.3، كواليسيس AB، غوتنبرغ، السويد)، وتم فحص الصور بصريًا قبل تصدير البيانات وتحليلها في ماتلاب.

تم إجراء تحليل موضوعي أساسي للمشي وتقييمات الألم في الأيام التي سبقت الإدخال. تم إجراء تقييم آخر للألم في صباح يوم الإدخال، مما أسفر عن ثلاث مناسبات تمثل حالة عدم الألم. بعد الإدخال، تم تقييم الألم عندما كان الحصان يستريح في صندوقه قبل وبعد التحليلات الموضوعية للمشي، وأحيانًا أيضًا بين التحليلات الموضوعية للمشي. شمل كل تقييم تسجيلات ألم لمدة دقيقتين باستخدام مقاييس الألم HGS وEQUUS-FAP وEPS، وتسجيل ألم لمدة خمس دقائق باستخدام مقياس الألم العظمي المركب (CPS).

تسجيل الفيديو

قبل وصول الخيول، تم تثبيت أربع كاميرات مراقبة شبكية بالأشعة تحت الحمراء (كاميرا شبكة توريت WDR ExIR، شركة هيكفيجن للتكنولوجيا الرقمية، هانغتشو، الصين) على الجدار أو القضبان في كل زاوية من زوايا حظائر الصناديق، على ارتفاع حوالي 180 سم. تم تثبيت تسعة مصابيح في السقف في كل حظيرة صندوق، على مسافة 75 سم، لتجنب تظليل الوجه أثناء تسجيل الفيديو. إضاءة شريطية (بيضاء باردة،

اختيار مقاطع الفيديو للتعليق

تم اختيار ثلاثة تقييمات للألم أجريت قبل التخدير لتمثيل حالة ‘عدم الألم’. تم اختيار تقييمات الألم التي تمثل حالة ‘الألم’ بناءً على درجات الألم من CPS، وهو مقياس للألم له معايير أداء معروفة.

التعليقات التوضيحية مع EquiFACS

تم تعمية جميع تسلسلات الفيديو وإعادة تسميتها وتوزيعها عشوائيًا بين تسعة معتمدين من EquiFACS.

معالجة البيانات والتحليلات الإحصائية

تم دمج التعليقات في مجموعة بيانات واحدة وخضعت لمزيد من التنظيف. تم إزالة ملفين معلقين لأنهما لم يتم تعليقهما بالكامل. إذا كان

تقييمات الألم المختارة للتعليق باستخدام EquiFACS

الشكل 3. تقييمات الألم المختارة للتعليق لكل حصان. الخيول

تجربته الخيول. تم تحديد مستوى شدة الألم بناءً على زيادة عدم التماثل في الحركة، حيث تم تعيين علامة ‘لا ألم’ (0) تلقائيًا لمقاطع الفيديو المسجلة قبل التحريض. زيادة في

تجربته الخيول. تم تحديد مستوى شدة الألم بناءً على زيادة عدم التماثل في الحركة، حيث تم تعيين علامة ‘لا ألم’ (0) تلقائيًا لمقاطع الفيديو المسجلة قبل التحريض. زيادة في

تم إجراء إحصائيات وصفية ونمذجة انحدار منتظمة في

لتحديد AUs و ADs التي تحدث معًا خلال مستويات مختلفة من شدة الألم، تم استخدام طريقة التزامن الحالية.

توفر البيانات

البيانات المستخدمة للإحصاءات الوصفية ونمذجة التنبؤ متاحة في المواد التكميلية. مجموعة بيانات التعليق الخام متاحة من المؤلف المراسل.

تاريخ الاستلام: 22 ديسمبر 2022؛ تاريخ القبول: 19 ديسمبر 2023

نُشر على الإنترنت: 02 يناير 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 02 يناير 2024

References

- Holmes, T. Q. & Brown, A. F. Champing at the bit for improvements: A review of equine welfare in equestrian sports in the United Kingdom. Animals. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12091186 (2022).

- Douglas, J., Owers, R. & Campbell, M. L. H. Social licence to operate: What can equestrian sports learn from other industries?. Animals. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12151987 (2022).

- Hockenhull, J. & Whay, H. R. A review of approaches to assessing equine welfare. Equine Vet. Educ. 26, 159-166. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/eve. 12129 (2014).

- Dalla Costa, E. et al. Development of the Horse Grimace Scale (HGS) as a pain assessment tool in horses undergoing routine castration. PLoS ONE 9, e92281. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0092281 (2014).

- van Loon, J. P. & Van Dierendonck, M. C. Monitoring acute equine visceral pain with the Equine Utrecht University Scale for Composite Pain Assessment (EQUUS-COMPASS) and the Equine Utrecht University Scale for Facial Assessment of Pain (EQUUSFAP): A scale-construction study. Vet. J. 206, 356-364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2015.08.023 (2015).

- VanDierendonck, M. C. & van Loon, J. P. Monitoring acute equine visceral pain with the Equine Utrecht University Scale for Composite Pain Assessment (EQUUS-COMPASS) and the Equine Utrecht University Scale for Facial Assessment of Pain (EQUUSFAP): A validation study. Vet. J. 216, 175-177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2016.08.004 (2016).

- Gleerup, K. B. & Lindegaard, C. Recognition and quantification of pain in horses: A tutorial review. Equine Vet. Educ. 28, 47-57. https://doi.org/10.1111/eve. 12383 (2015).

- Langford, D. J. et al. Coding of facial expressions of pain in the laboratory mouse. Nat. Methods 7, 447-449. https://doi.org/10. 1038/nmeth. 1455 (2010).

- Prkachin, K. & Solomon, P. E. The structure, reliability and validity of pain expression: Evidence in patients with shoulder pain. Pain 139, 267-274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2008.04.010 (2009).

- Dalla Costa, E. et al. Towards an improved pain assessment in castrated horses using facial expressions (HGS) and circulating miRNAs. Vet. Rec. 188, e82. https://doi.org/10.1002/vetr. 82 (2021).

- DallaCosta, E. et al. Using the Horse Grimace Scale (HGS) to assess pain associated with acute laminitis in horses (Equus caballus). Animals. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani6080047 (2016).

- Marcantonio Coneglian, M., Duarte Borges, T., Weber, S. H., Godoi Bertagnon, H. & Michelotto, P. V. Use of the horse grimace scale to identify and quantify pain due to dental disorders in horses. Appl. Animal Behav. Sci. 225, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. applanim.2020.104970 (2020).

- van Loon, J. P. & Van Dierendonck, M. C. Monitoring equine head-related pain with the Equine Utrecht University scale for facial assessment of pain (EQUUS-FAP). Vet. J. 220, 88-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2017.01.006 (2017).

- van Loon, J. & Van Dierendonck, M. C. Pain assessment in horses after orthopaedic surgery and with orthopaedic trauma. Vet. J. 246, 85-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2019.02.001 (2019).

- Gleerup, K. B., Forkman, B., Lindegaard, C. & Andersen, P. H. An equine pain face. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 42, 103-114. https://doi. org/10.1111/vaa. 12212 (2015).

- Carvalho, J. R. G. et al. Facial expressions of horses using weighted multivariate statistics for assessment of subtle local pain induced by polylactide-based polymers implanted subcutaneously. Animals. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12182400 (2022).

- Hayashi, K. et al. Discordant relationship between evaluation of facial expression and subjective pain rating due to the low pain magnitude. Basic Clin. Neurosci. 9, 43-50. https://doi.org/10.29252/NIRP.BCN.9.1.43 (2018).

- Rhodin, M., Egenvall, A., Haubro Andersen, P. & Pfau, T. Head and pelvic movement asymmetries at trot in riding horses in training and perceived as free from lameness by the owner. PLoS One 12, e0176253. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 01762 53 (2017).

- Kallerud, A. S. et al. Objectively measured movement asymmetry in yearling Standardbred trotters. Equine Vet. J. 53, 590-599. https://doi.org/10.1111/evj. 13302 (2021).

- Bussieres, G. et al. Development of a composite orthopaedic pain scale in horses. Res. Vet. Sci. 85, 294-306. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.rvsc.2007.10.011 (2008).

- Ask, K., Andersen, P. H., Tamminen, L. M., Rhodin, M. & Hernlund, E. Performance of four equine pain scales and their association to movement asymmetry in horses with induced orthopedic pain. Front. Vet. Sci. 9, 938022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets. 2022.938022 (2022).

- Ekman, P. & Friesen, W. V. Facial Action Coding System: Investigator’s Guide (Consulting Psychologists Press, 1978).

- Prkachin, K. Assessing pain by facial expression: Facial expression as nexus. Pain Res. Manag. 14, 53-58. https://doi.org/10.1155/ 2009/542964 (2009).

- Lucey, P. et al. Automatically detecting pain using facial actions. Int. Conf. Affect. Comput. Intell. Interact. Workshops 2009, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACII.2009.5349321 (2009).

- Wiggers, M. Judgments of facial expressions of emotion predicted from facial behavior. J. Nonverbal Behav. 7, 101-116. https:// doi.org/10.1007/BF00986872 (1982).

- Wathan, J., Burrows, A. M., Waller, B. M. & McComb, K. EquiFACS: The equine facial action coding system. PLoS One 10, e0131738. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0131738 (2015).

- Rashid, M., Silventoinen, A., Gleerup, K. B. & Andersen, P. H. Equine Facial Action Coding System for determination of painrelated facial responses in videos of horses. PLoS One 15, e0231608. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0231608 (2020).

- Ask, K., Rhodin, M., Tamminen, L. M., Hernlund, E. & Haubro Andersen, P. Identification of body behaviors and facial expressions associated with induced orthopedic pain in four equine pain scales. Animals. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10112155 (2020).

- Andersen, P. H. et al. Towards machine recognition of facial expressions of pain in horses. Animals. https://doi.org/10.3390/anill 061643 (2021).

- Lundblad, J., Rashid, M., Rhodin, M. & Haubro Andersen, P. Effect of transportation and social isolation on facial expressions of healthy horses. PLoS One 16, e0241532. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0241532 (2021).

- Kunz, M., Meixner, D. & Lautenbacher, S. Facial muscle movements encoding pain-a systematic review. Pain 160, 535-549. https:// doi.org/10.1097/j.pain. 0000000000001424 (2019).

- Wagner, A. E. Effects of stress on pain in horses and incorporating pain scales for equine practice. Vet. Clin. North Am. Equine Pract. 26, 481-492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cveq.2010.07.001 (2010).

- Torcivia, C. & McDonnell, S. In-person caretaker visits disrupt ongoing discomfort behavior in hospitalized equine orthopedic surgical patients. Animals. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10020210 (2020).

- van Loon, J. P. et al. Intra-articular opioid analgesia is effective in reducing pain and inflammation in an equine LPS induced synovitis model. Equine Vet. J. 42, 412-419. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.2010.00077.x (2010).

- Lindegaard, C., Thomsen, M. H., Larsen, S. & Andersen, P. H. Analgesic efficacy of intra-articular morphine in experimentally induced radiocarpal synovitis in horses. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 37, 171-185. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2995.2009.00521.x (2010).

- Palmer, J. L. & Bertone, A. L. Experimentally-induced synovitis as a model for acute synovitis in the horse. Equine Vet. J. 26, 492-495. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.1994.tb04056.x (1994).

- van Loon, J. P. et al. Analgesic and anti-hyperalgesic effects of epidural morphine in an equine LPS-induced acute synovitis model. Vet. J. 193, 464-470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2012.01.015 (2012).

- Van de Water, E. et al. The lipopolysaccharide model for the experimental induction of transient lameness and synovitis in Standardbred horses. Vet. J. 270, 105626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2021.105626 (2021).

- Egan, S., Kearney, C. M., Brama, P. A. J., Parnell, A. C. & McGrath, D. Exploring stable-based behaviour and behaviour switching for the detection of bilateral pain in equines. Appl. Animal Behav. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2021.105214 (2021).

- Todhunter, P. G. et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of an equine model of synovitis-induced arthritis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 57, 1080-1093 (1996).

- Wang, G. et al. Changes in synovial fluid inflammatory mediators and cartilage biomarkers after experimental acute equine synovitis. Bull. Vet. Inst. Pulawy 59, 129-134. https://doi.org/10.1515/bvip-2015-0019 (2015).

- Freitas, G. C. et al. Epidural analgesia with morphine or buprenorphine in ponies with lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced carpal synovitis. Can. J. Vet. Res. 75, 141-146 (2011).

- Andreassen, S. M. et al. Changes in concentrations of haemostatic and inflammatory biomarkers in synovial fluid after intraarticular injection of lipopolysaccharide in horses. BMC Vet. Res. 13, 182. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-017-1089-1 (2017).

- de Grauw, J. C., van de Lest, C. H. & van Weeren, P. R. Inflammatory mediators and cartilage biomarkers in synovial fluid after a single inflammatory insult: A longitudinal experimental study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 11, R35. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2640 (2009).

- de Grauw, J. C., van Loon, J. P., van de Lest, C. H., Brunott, A. & van Weeren, P. R. In vivo effects of phenylbutazone on inflammation and cartilage-derived biomarkers in equine joints with acute synovitis. Vet. J. 201, 51-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2014. 03.030 (2014).

- van Loon, J. & Macri, L. Objective assessment of chronic pain in horses using the Horse Chronic Pain Scale (HCPS): A scaleconstruction study. Animals. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11061826 (2021).

- Boutron, I. et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLOS Biol. https://doi.org/10. 1371/journal.pbio. 3000410 (2020).

- Rhodin, M. et al. Vertical movement symmetry of the withers in horses with induced forelimb and hindlimb lameness at trot. Equine Vet. J. 50, 818-824. https://doi.org/10.1111/evj. 12844 (2018).

- MATLAB version 9.7.0.1190202 (R2019b) (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, United States, 2018).

- Serra Bragança, F. M. et al. Quantitative lameness assessment in the horse based on upper body movement symmetry: The effect of different filtering techniques on the quantification of motion symmetry. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. bspc.2019.101674 (2020).

- Roepstorff, C. et al. Reliable and clinically applicable gait event classification using upper body motion in walking and trotting horses. J. Biomech. 114, 110146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2020.110146 (2021).

- Rhodin, M., Pfau, T., Roepstorff, L. & Egenvall, A. Effect of lungeing on head and pelvic movement asymmetry in horses with induced lameness. Vet. J. 198(Suppl 1), e39-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.09.031 (2013).

- Rashid-Engstrom, M., Broome, S., Andersen, P. H., Gleerup, K. B. & Lee, Y. J. What should I annotate? An automatic tool for finding video segments for EquiFACS annotation. Meas. Behav. 164-165 (2018).

- ELAN Linguistic Annotator v. 5.6 (Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, The Language Archive, Nijmegen, 2019).

- R: A Language and Environment fro Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020).

- ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer-Verlag New York, 2016).

- Kuhn, M. Building Predictive Models in R Using the caret Package. J. Stat. Softw. 28, 1-26 (2008). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss. v028.i05

شكر وتقدير

يود المؤلفون أن يشكروا المعلقين على عملهم الشامل والدقيق، ويوهان لوندبلاد على المناقشات القيمة.

مساهمات المؤلفين

تشارك ك.أ.، م.ر.، ب.هـ.أ. و هـ.م. في المسؤولية عن التصور. قام ك.أ.، م.ر.، هـ.م. و ب.هـ.أ. بإجراء تحليل البيانات. قام ك.أ. و م.ر.إ. بتنظيم البيانات وكانا مسؤولين عن الحسابات الإحصائية. كتب ك.أ. النص الرئيسي للمخطوطة. راجع جميع المؤلفين المخطوطة وقدموا مساهمات كبيرة.

تمويل

تم توفير تمويل الوصول المفتوح من قبل الجامعة السويدية للعلوم الزراعية. تم تمويل هذه الدراسة من قبل مجلس الأبحاث السويدي فورماس (2106-01760 (MR)).

المصالح المتنافسة

يعلن المؤلفون عدم وجود مصالح متنافسة.

معلومات إضافية

معلومات إضافية النسخة الإلكترونية تحتوي على مواد إضافية متاحة علىhttps://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50383-y.

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى ك.أ.

معلومات إعادة الطباعة والتصاريح متاحة علىwww.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر: تظل شركة سبرينجر ناتشر محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

معلومات إعادة الطباعة والتصاريح متاحة علىwww.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر: تظل شركة سبرينجر ناتشر محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

الوصول المفتوح هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي النسب 4.0 الدولية، التي تسمح بالاستخدام والمشاركة والتكيف والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج بأي وسيلة أو صيغة، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح ما إذا تم إجراء تغييرات. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي الخاصة بالمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر الائتمان للمادة. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي الخاصة بالمقالة وكان استخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، فستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارةhttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

© المؤلف(ون) 2023

© المؤلف(ون) 2023

قسم التشريح وعلم وظائف الأعضاء والكيمياء الحيوية، الجامعة السويدية للعلوم الزراعية، أوبسالا، السويد. يونيفرس إيه بي، ستوكهولم، السويد. البريد الإلكتروني:كترينا.أask@slu.se

Journal: Scientific Reports, Volume: 14, Issue: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50383-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38167926

Publication Date: 2024-01-02

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50383-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38167926

Publication Date: 2024-01-02

Changes in the equine facial repertoire during different orthopedic pain intensities

A number of facial expressions are associated with pain in horses, however, the entire display of facial activities during orthopedic pain have yet to be described. The aim of the present study was to exhaustively map changes in facial activities in eight resting horses during a progression from sound to mild and moderate degree of orthopedic pain, induced by lipopolysaccharides (LPS) administered in the tarsocrural joint. Lameness progression and regression was measured by objective gait analysis during movement, and facial activities were described by EquiFACS in video sequences (

The horse (Equus caballus) is a popular companion and sports animal, but lately, concerns have been raised about equine welfare

Mild orthopedic pain in horses is commonly assessed during motion through subjectively grading movement asymmetry/lameness or objectively measuring movement asymmetry. However, among e.g., riding horses and Standardbred trotters perceived as sound by their owners, up to

of facial activities/grimaces not included in pain scales could therefore improve the accuracy of assessment of mild orthopedic pain. So may the understanding of how facial activities co-occur during different pain intensities. Hence, exhaustively describing, in a standardized way, all facial activities exhibited is lacking and could contribute to a more reliable assessment tool for early orthopedic pain identification.

The Facial Action Coding System (FACS)

The aim of this study was to explore changes in the facial repertoire in resting horses with different intensities of induced acute orthopedic pain. Movement asymmetry was used as a proxy for pain and to define the level of intensity. We tested the predictive performance of facial action units (AUs) and action descriptors (ADs) to identify those important for pain detection, and performed data-driven selection of co-occurring AUs and ADs under different pain intensities. The hypothesis tested that previously described AUs/ADs (half blink, ear rotator, nostril dilator, chin raiser, chewing) can predict pain and co-occur together more frequently in horses with orthopedic pain than without. We also hypothesized that AUs/ADs co-occur less frequently during mild pain than during moderate pain.

Results

Orthopedic pain was successfully induced with intra-articular administration of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) into the hock in all eight horses. The resulting hindlimb lameness and increase in movement asymmetry were confirmed with objective gait analysis during trot. Details on changes in subjectively assessed lameness grades and in objectively measured movement asymmetry have been published elsewhere

Identification of AUs and ADs associated with orthopedic pain

Whether the EquiFACS codes could predict the presence of ‘pain’ or the presence of ‘no pain’ was tested with elastic net regression. Model coefficients are presented in S1 File and plotted in Fig. 1. Those with a coefficient of 0 were considered unable to predict pain. The best predictor for pain chosen by the model was frequent adduction of both ears (EAD102), and duration of one ear rotating (SEAD104) was a weak predictor of pain. Most other ear-related codes were not able to predict pain. Frequent and a long duration of both ears flattening (EAD103) and rotating (EAD104), and frequent adduction of one ear (SEAD102) were associated with no pain. Out of the codes belonging to the upper face, frequency and duration of eye closure (AU143), and duration of blink (AU145) and upper lid raiser (AU5) were classified as predictors of pain. Twelve out of 23 predictors associated with pain were

| Descriptive statistics | Median (1st and 3rd interquartile) | |

| No pain | Pain | |

| Number of annotations per video | 102.5 (65.8, 151.3) | 84.0 (61.0-129.0) |

| Number of annotations per horse | 2314.0 (1822.0, 3267.25) | 1997.5 (1259.0, 2308.0) |

| Duration of annotations (s) | 0.466 (0.340, 0.700) | 0.491 (0.350, 0.750) |

Table 1. Descriptive statistics on the annotation data set. Each annotation represents one specific facial activity. Median, and 1st and 3rd interquartile for the number of annotations per video sequence, the number of annotations per horse and the duration of each annotation in seconds, in video sequences labeled as ‘no pain’ and ‘pain’.

Figure 1. Regressions coefficients in elastic net regression testing the predictive performance of action units (AUs) and action descriptors (ADs). The frequency (‘count’) and duration (‘dur’) of each EquiFACS code are shown. Positive coefficient values indicate an association with presence of pain.

shake side to side (AD84), frequent head nod up and down (AD85), and frequency and duration of swallowing (AD80) were relatively strong predictors of pain. The AUs/ADs associated with no pain were mainly action descriptors: duration of blow (AD133), ear shake (AD87), tongue show (AD19), grooming (AD86), head nod up

and down (AD85), and chewing (AD81), and frequency and duration of jaw sideways (AD30), yawning (AD76), and eye white increase (AD1). Duration of sharp lip puller (AU113), lip corner puller (AU12) and upper lip raiser (AU10), frequency and duration of mouth stretch (AU27), and frequent inner brow raiser (AU101), half blink (AU47) and blink (AU145) were also associated with no pain. Furthermore, horse 3, 5, 6 and 8 were identified as negative predictors of pain in the model.

and down (AD85), and chewing (AD81), and frequency and duration of jaw sideways (AD30), yawning (AD76), and eye white increase (AD1). Duration of sharp lip puller (AU113), lip corner puller (AU12) and upper lip raiser (AU10), frequency and duration of mouth stretch (AU27), and frequent inner brow raiser (AU101), half blink (AU47) and blink (AU145) were also associated with no pain. Furthermore, horse 3, 5, 6 and 8 were identified as negative predictors of pain in the model.

Co-occurrence of AUs and ADs during different levels of pain intensity

On comparing ‘no pain’ video sequences with ‘pain’ sequences, the co-occurrence method identified the following AUs and ADs as conjoined: lower lip depressor (AU16), lips part (AU25), half blink (AU47), single ear forward (SEAD101), and single ear rotator (EAD104) (Fig. 2). AUs and ADs selected by the co-occurrence method for the different levels of pain intensity (defined by movement asymmetry) are presented in Table 2.

Discussion

Resting horses experiencing orthopedic pain show a dynamic facial repertoire consisting of asymmetrical ears, and changes in facial activity in the eye area and lower face. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use EquiFACS and movement asymmetry as outcome measures for studying pain in horses. Both these methods are considered highly objective methods, compared to the visual assessment of lameness and pain. Using these

Figure 2. EquiFACS codes selected by the co-occurrence method and co-occurring significantly more in ‘pain’ than in ‘no pain’ video sequences (

| EquiFACS code | Level of pain intensity | ||||||||

| 0-1 (

|

0-2 (

|

1-2 (

|

|||||||

| Ears | |||||||||

| Single ear forward (SEAD101) |

|

||||||||

| Single ear rotator (SEAD104) |

|

|

|||||||

| Upper face | |||||||||

| Blink (AU145) |

|

||||||||

| Half blink (AU47) |

|

|

|

||||||

| Lower face | |||||||||

| Upper lip raiser (AU10) |

|

||||||||

| Lower lip depressor (AU16) |

|

||||||||

| Lips part (AU25) |

|

||||||||

Table 2. Action units (AUs) and ear action descriptors (EADs) selected by the co-occurrence method. Pain intensity levels were defined based on movement asymmetry. Not all horses experienced both levels of pain intensity, why the number of horses ( n ) experiencing each intensity level is stated in brackets. The frequency of co-occurring AUs and ADs in ‘no pain’ video sequences was compared to the frequency in ‘mild pain intensity’ sequences (

objective methods, it was possible to corroborate some of the earlier findings on facial expressions during pain in horses, such as the presence of asymmetrical ears during pain and the importance of half blink in pain detection. We also identified in more detail other features such as the dynamic lower facial activities during pain, compared to previous studies showing a more stoic lower face. The present study demonstrated that predictive modeling can identify AUs and ADs associated with orthopedic pain, where several AUs and ADs related to the ears, lower face, and eyes, were identified at the peak of pain intensity. From a statistical point of view, when these AUs/ADs occur frequently and for a long duration compared with during baseline, they can indicate pain. However, when assessing pain under clinical settings, the veterinary surgeon rarely knows the baseline state of the equine patient, so it might be difficult to extrapolate these predictions into clinical pain assessments. Therefore, we added the co-occurrence method

To increase the probability of horses showing a facial repertoire related to pain, we included video sequences from time points when each horse was assessed to be at its highest level of pain intensity. Pain assessment was performed with CPS, the pain scale found to perform best in assessing orthopedic pain in resting horses

Orthopedic pain was best predicted with the help of ear adductor (EAD102) (Fig. 2), where “the ear(s) are pulled towards the midline” and “the distance between the ears decreases”

Several eye-related AUs/ADs were able to predict pain in the present study, confirming previous findings on eye-related facial expressions during pain. Closing the eye frequently and for a long time (AU143), making long blinks (AU145), and raising the upper eyelid (AU5) frequently and for a long time were associated with pain. In addition, blink (AU145) significantly co-occurred with other AUs/ADs during mild pain, and have been associated with pain previously-as have upper lid raiser (AU5)

is an internal stressor that cannot be avoided

is an internal stressor that cannot be avoided

The majority of codes with positive prediction coefficients belonged to the lower face. Duration of jaw thrust (AD29), described as when “the lower jaw is pushed forward” or “the lower teeth extend in front of the upper teeth”26 had the biggest coefficient out of codes belonging to the lower face. On inspecting the dataset, however, we found that it had only been annotated three times among the 37,072 annotations, and that it had a longer duration in ‘pain’ sequences than in ‘no pain’ sequences. This may explain its predictive value identified in the elastic net regression model (Fig. 2). However, jaw thrust (AD29) has previously been selected by the cooccurrence method in horses with clinical pain

Furthermore, we identified variations in AUs/ADs in relation to the level of pain intensity in horses (Table 2). Using movement asymmetry to define the pain intensity level, it seems like horses experiencing mild pain had more codes co-occurring than horses experiencing moderate pain. This is an interesting finding, questioning previous theories on synchronized increase assumptions on positive and linear correlation between numbers of facial expression and pain intensity. If the major change in facial activity actually take place when the horse goes from experiencing no pain to experiencing mild pain, it might be misleading to approximate the level of pain intensity from the presence of facial expressions. According to the present results, only half blink (AU47) in combination with single ear rotator (SEAD104) may indicate that the horse experiences moderate pain. One explanation might be that horses perhaps perform more pain-related body behavior during moderate pain, such as postural changes, and that they result in pain relief. This was discussed by Ask et al.

between a grimace being present and the intensity. Hence, the concept of one prototypical pain face may be a simplification and further studies are needed on the relationship between pain intensity and facial repertoire.

between a grimace being present and the intensity. Hence, the concept of one prototypical pain face may be a simplification and further studies are needed on the relationship between pain intensity and facial repertoire.

To study the relationship between intensity and facial activity, intensity scores could be added to individual EquiFACS codes, as it is done for FACS in humans

A limitation of the present study is that annotated video sequences were recorded in the presence of observers, because it is known that observer presence may cause horses to disrupt discomfort behaviors

In conclusion, the present study identified sixteen AUs and ADs important for pain recognition using predictive modeling and the co-occurrence method based on annotations of

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the Swedish Ethics Committee (diary number 5.8.18-09822/2018) in accordance with Swedish legislation on animal experiments. Replacement, reduction, and refinement were considered in depth and the ARRIVE guidelines were followed

Animals and study design

Detailed information about the study design has been published elsewhere

movement asymmetry comparable to that at baseline (before lameness induction). Rescue analgesia by evacuation of synovia according to clinical standard procedures was performed if the lameness exceeded

movement asymmetry comparable to that at baseline (before lameness induction). Rescue analgesia by evacuation of synovia according to clinical standard procedures was performed if the lameness exceeded

Objective gait analysis and assessment of pain

For each objective gait analysis, each horse was equipped with seven skin-mounted spherical markers ( 38 mm diameter, Qualisys AB, Gothenburg, Sweden), and walked and trotted in a straight line on hard and soft surfaces. Lunging was performed on a soft surface. Marker positions were recorded by 13 infrared optical motion capture cameras (Qualisys AB, Gothenburg, Sweden) operating at 200 Hz , tracked by QTM software (version 2.11-2019.3, Qualisys AB, Gothenburg, Sweden), and images were visually inspected before exporting and analyzing the data in MatLab

The days prior to induction, baseline objective gait analysis and pain assessments were performed. Another pain assessment was performed on the morning of the induction, resulting in three occasions representing a no pain state. After induction, pain was assessed when the horse was resting in its box stall before and after objective gait analyses, and sometimes also between objective gait analyses. Every assessment included 2 -min pain scorings using the pain scales HGS, EQUUS-FAP, and EPS and a 5 -min pain scoring with the Composite Orthopedic Pain Scale (CPS)

Video recording

Prior to arrival of the horses, four infrared network surveillance cameras (WDR ExIR Turret Network Camera, Hikvision Digital Technology Co., Hangzhou, China) were installed on the wall or the bars in each box stall corner, at a height of approximately 180 cm . Nine lamps were attached to the ceiling in each box stall, at a spacing of 75 cm , to avoid shading of the face during video recording. Strip lighting (cold white,

Selection of video sequences for annotation

Three pain assessments performed prior to induction were selected to represent a ‘no pain’ state. Pain assessments representing a ‘pain’ state were selected based on pain scores from CPS, a pain scale with known performance parameters

Annotations with EquiFACS

All video sequences were blinded, renamed, and randomly distributed among nine EquiFACS-certified

Data processing and statistical analyses

Annotations were merged into one dataset and subjected to further cleaning. Two annotated files were removed since they were not annotated completely. If

Pain assessments selected for annotation with EquiFACS

Figure 3. Pain assessments selected for annotation for each horse. Horses

experienced by the horses. The level of pain intensity was defined based on increase in movement asymmetry, where the ‘no pain’ label (0) was automatically assigned to video sequences recorded before induction. An increase in

experienced by the horses. The level of pain intensity was defined based on increase in movement asymmetry, where the ‘no pain’ label (0) was automatically assigned to video sequences recorded before induction. An increase in

Descriptive statistics and regularized regression modeling were carried out in

To identify AUs and ADs co-occurring together during different levels of pain intensity, the existing cooccurrence method was used

Data availability

Data used for descriptive statistics and predictive modeling are provided in the supplementary materials. The raw annotation dataset is available from the corresponding author

Received: 22 December 2022; Accepted: 19 December 2023

Published online: 02 January 2024

Published online: 02 January 2024

References

- Holmes, T. Q. & Brown, A. F. Champing at the bit for improvements: A review of equine welfare in equestrian sports in the United Kingdom. Animals. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12091186 (2022).

- Douglas, J., Owers, R. & Campbell, M. L. H. Social licence to operate: What can equestrian sports learn from other industries?. Animals. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12151987 (2022).

- Hockenhull, J. & Whay, H. R. A review of approaches to assessing equine welfare. Equine Vet. Educ. 26, 159-166. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/eve. 12129 (2014).

- Dalla Costa, E. et al. Development of the Horse Grimace Scale (HGS) as a pain assessment tool in horses undergoing routine castration. PLoS ONE 9, e92281. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0092281 (2014).

- van Loon, J. P. & Van Dierendonck, M. C. Monitoring acute equine visceral pain with the Equine Utrecht University Scale for Composite Pain Assessment (EQUUS-COMPASS) and the Equine Utrecht University Scale for Facial Assessment of Pain (EQUUSFAP): A scale-construction study. Vet. J. 206, 356-364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2015.08.023 (2015).

- VanDierendonck, M. C. & van Loon, J. P. Monitoring acute equine visceral pain with the Equine Utrecht University Scale for Composite Pain Assessment (EQUUS-COMPASS) and the Equine Utrecht University Scale for Facial Assessment of Pain (EQUUSFAP): A validation study. Vet. J. 216, 175-177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2016.08.004 (2016).

- Gleerup, K. B. & Lindegaard, C. Recognition and quantification of pain in horses: A tutorial review. Equine Vet. Educ. 28, 47-57. https://doi.org/10.1111/eve. 12383 (2015).

- Langford, D. J. et al. Coding of facial expressions of pain in the laboratory mouse. Nat. Methods 7, 447-449. https://doi.org/10. 1038/nmeth. 1455 (2010).

- Prkachin, K. & Solomon, P. E. The structure, reliability and validity of pain expression: Evidence in patients with shoulder pain. Pain 139, 267-274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2008.04.010 (2009).

- Dalla Costa, E. et al. Towards an improved pain assessment in castrated horses using facial expressions (HGS) and circulating miRNAs. Vet. Rec. 188, e82. https://doi.org/10.1002/vetr. 82 (2021).

- DallaCosta, E. et al. Using the Horse Grimace Scale (HGS) to assess pain associated with acute laminitis in horses (Equus caballus). Animals. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani6080047 (2016).

- Marcantonio Coneglian, M., Duarte Borges, T., Weber, S. H., Godoi Bertagnon, H. & Michelotto, P. V. Use of the horse grimace scale to identify and quantify pain due to dental disorders in horses. Appl. Animal Behav. Sci. 225, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. applanim.2020.104970 (2020).

- van Loon, J. P. & Van Dierendonck, M. C. Monitoring equine head-related pain with the Equine Utrecht University scale for facial assessment of pain (EQUUS-FAP). Vet. J. 220, 88-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2017.01.006 (2017).

- van Loon, J. & Van Dierendonck, M. C. Pain assessment in horses after orthopaedic surgery and with orthopaedic trauma. Vet. J. 246, 85-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2019.02.001 (2019).

- Gleerup, K. B., Forkman, B., Lindegaard, C. & Andersen, P. H. An equine pain face. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 42, 103-114. https://doi. org/10.1111/vaa. 12212 (2015).

- Carvalho, J. R. G. et al. Facial expressions of horses using weighted multivariate statistics for assessment of subtle local pain induced by polylactide-based polymers implanted subcutaneously. Animals. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12182400 (2022).

- Hayashi, K. et al. Discordant relationship between evaluation of facial expression and subjective pain rating due to the low pain magnitude. Basic Clin. Neurosci. 9, 43-50. https://doi.org/10.29252/NIRP.BCN.9.1.43 (2018).

- Rhodin, M., Egenvall, A., Haubro Andersen, P. & Pfau, T. Head and pelvic movement asymmetries at trot in riding horses in training and perceived as free from lameness by the owner. PLoS One 12, e0176253. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 01762 53 (2017).

- Kallerud, A. S. et al. Objectively measured movement asymmetry in yearling Standardbred trotters. Equine Vet. J. 53, 590-599. https://doi.org/10.1111/evj. 13302 (2021).

- Bussieres, G. et al. Development of a composite orthopaedic pain scale in horses. Res. Vet. Sci. 85, 294-306. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.rvsc.2007.10.011 (2008).

- Ask, K., Andersen, P. H., Tamminen, L. M., Rhodin, M. & Hernlund, E. Performance of four equine pain scales and their association to movement asymmetry in horses with induced orthopedic pain. Front. Vet. Sci. 9, 938022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets. 2022.938022 (2022).

- Ekman, P. & Friesen, W. V. Facial Action Coding System: Investigator’s Guide (Consulting Psychologists Press, 1978).

- Prkachin, K. Assessing pain by facial expression: Facial expression as nexus. Pain Res. Manag. 14, 53-58. https://doi.org/10.1155/ 2009/542964 (2009).

- Lucey, P. et al. Automatically detecting pain using facial actions. Int. Conf. Affect. Comput. Intell. Interact. Workshops 2009, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACII.2009.5349321 (2009).

- Wiggers, M. Judgments of facial expressions of emotion predicted from facial behavior. J. Nonverbal Behav. 7, 101-116. https:// doi.org/10.1007/BF00986872 (1982).

- Wathan, J., Burrows, A. M., Waller, B. M. & McComb, K. EquiFACS: The equine facial action coding system. PLoS One 10, e0131738. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0131738 (2015).

- Rashid, M., Silventoinen, A., Gleerup, K. B. & Andersen, P. H. Equine Facial Action Coding System for determination of painrelated facial responses in videos of horses. PLoS One 15, e0231608. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0231608 (2020).

- Ask, K., Rhodin, M., Tamminen, L. M., Hernlund, E. & Haubro Andersen, P. Identification of body behaviors and facial expressions associated with induced orthopedic pain in four equine pain scales. Animals. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10112155 (2020).

- Andersen, P. H. et al. Towards machine recognition of facial expressions of pain in horses. Animals. https://doi.org/10.3390/anill 061643 (2021).

- Lundblad, J., Rashid, M., Rhodin, M. & Haubro Andersen, P. Effect of transportation and social isolation on facial expressions of healthy horses. PLoS One 16, e0241532. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0241532 (2021).

- Kunz, M., Meixner, D. & Lautenbacher, S. Facial muscle movements encoding pain-a systematic review. Pain 160, 535-549. https:// doi.org/10.1097/j.pain. 0000000000001424 (2019).

- Wagner, A. E. Effects of stress on pain in horses and incorporating pain scales for equine practice. Vet. Clin. North Am. Equine Pract. 26, 481-492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cveq.2010.07.001 (2010).

- Torcivia, C. & McDonnell, S. In-person caretaker visits disrupt ongoing discomfort behavior in hospitalized equine orthopedic surgical patients. Animals. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10020210 (2020).

- van Loon, J. P. et al. Intra-articular opioid analgesia is effective in reducing pain and inflammation in an equine LPS induced synovitis model. Equine Vet. J. 42, 412-419. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.2010.00077.x (2010).

- Lindegaard, C., Thomsen, M. H., Larsen, S. & Andersen, P. H. Analgesic efficacy of intra-articular morphine in experimentally induced radiocarpal synovitis in horses. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 37, 171-185. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2995.2009.00521.x (2010).

- Palmer, J. L. & Bertone, A. L. Experimentally-induced synovitis as a model for acute synovitis in the horse. Equine Vet. J. 26, 492-495. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.1994.tb04056.x (1994).

- van Loon, J. P. et al. Analgesic and anti-hyperalgesic effects of epidural morphine in an equine LPS-induced acute synovitis model. Vet. J. 193, 464-470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2012.01.015 (2012).

- Van de Water, E. et al. The lipopolysaccharide model for the experimental induction of transient lameness and synovitis in Standardbred horses. Vet. J. 270, 105626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2021.105626 (2021).

- Egan, S., Kearney, C. M., Brama, P. A. J., Parnell, A. C. & McGrath, D. Exploring stable-based behaviour and behaviour switching for the detection of bilateral pain in equines. Appl. Animal Behav. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2021.105214 (2021).

- Todhunter, P. G. et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of an equine model of synovitis-induced arthritis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 57, 1080-1093 (1996).

- Wang, G. et al. Changes in synovial fluid inflammatory mediators and cartilage biomarkers after experimental acute equine synovitis. Bull. Vet. Inst. Pulawy 59, 129-134. https://doi.org/10.1515/bvip-2015-0019 (2015).

- Freitas, G. C. et al. Epidural analgesia with morphine or buprenorphine in ponies with lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced carpal synovitis. Can. J. Vet. Res. 75, 141-146 (2011).

- Andreassen, S. M. et al. Changes in concentrations of haemostatic and inflammatory biomarkers in synovial fluid after intraarticular injection of lipopolysaccharide in horses. BMC Vet. Res. 13, 182. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-017-1089-1 (2017).

- de Grauw, J. C., van de Lest, C. H. & van Weeren, P. R. Inflammatory mediators and cartilage biomarkers in synovial fluid after a single inflammatory insult: A longitudinal experimental study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 11, R35. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2640 (2009).

- de Grauw, J. C., van Loon, J. P., van de Lest, C. H., Brunott, A. & van Weeren, P. R. In vivo effects of phenylbutazone on inflammation and cartilage-derived biomarkers in equine joints with acute synovitis. Vet. J. 201, 51-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2014. 03.030 (2014).

- van Loon, J. & Macri, L. Objective assessment of chronic pain in horses using the Horse Chronic Pain Scale (HCPS): A scaleconstruction study. Animals. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11061826 (2021).

- Boutron, I. et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLOS Biol. https://doi.org/10. 1371/journal.pbio. 3000410 (2020).

- Rhodin, M. et al. Vertical movement symmetry of the withers in horses with induced forelimb and hindlimb lameness at trot. Equine Vet. J. 50, 818-824. https://doi.org/10.1111/evj. 12844 (2018).

- MATLAB version 9.7.0.1190202 (R2019b) (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, United States, 2018).

- Serra Bragança, F. M. et al. Quantitative lameness assessment in the horse based on upper body movement symmetry: The effect of different filtering techniques on the quantification of motion symmetry. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. bspc.2019.101674 (2020).

- Roepstorff, C. et al. Reliable and clinically applicable gait event classification using upper body motion in walking and trotting horses. J. Biomech. 114, 110146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2020.110146 (2021).

- Rhodin, M., Pfau, T., Roepstorff, L. & Egenvall, A. Effect of lungeing on head and pelvic movement asymmetry in horses with induced lameness. Vet. J. 198(Suppl 1), e39-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.09.031 (2013).

- Rashid-Engstrom, M., Broome, S., Andersen, P. H., Gleerup, K. B. & Lee, Y. J. What should I annotate? An automatic tool for finding video segments for EquiFACS annotation. Meas. Behav. 164-165 (2018).

- ELAN Linguistic Annotator v. 5.6 (Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, The Language Archive, Nijmegen, 2019).

- R: A Language and Environment fro Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020).

- ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer-Verlag New York, 2016).

- Kuhn, M. Building Predictive Models in R Using the caret Package. J. Stat. Softw. 28, 1-26 (2008). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss. v028.i05

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the annotators for their exhaustive and thorough work, and Johan Lundblad for valuable discussions.

Author contributions

K.A., M.R., P.H.A. and E.H. shared responsibility for the conceptualization. K.A., M.R., E.H. and P.H.A. performed the data analysis. K.A. and M.R.E. curated the data and were responsible for the statistical computations. K.A. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript and made substantial contributions.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. This study was funded by Svenska Forskningsrådet Formas (2106-01760 (MR)).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41598-023-50383-y.

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to K.A.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

© The Author(s) 2023

© The Author(s) 2023

Department of Anatomy, Physiology and Biochemistry, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden. Univrses AB, Stockholm, Sweden. email: katrina.ask@slu.se