DOI: https://doi.org/10.1088/1475-7516/2024/10/035

تاريخ النشر: 2024-10-01

تفضيل قوي للطاقة المظلمة الديناميكية في قياسات DESI BAO وSN

الملخص

تظهر قياسات تذبذبات الصوت الباريونية (BAO) الأخيرة التي أصدرتها DESI، عند دمجها مع بيانات الخلفية الكونية الميكروية (CMB) من بلانك وعينتين مختلفتين من المستعرات العظمى من النوع Ia (بانثيون-بلس و DESY5) تفضيلًا للطاقة المظلمة الديناميكية (DDE) التي تتميز بمعادلة حالة شبيهة بالكيان الحاضر التي عبرت إلى نظام الشبح في الماضي. فرضية أساسية لهذه النتيجة هي افتراض معلمة خطية لتشيفالييه-بولارسكي-ليندر (CPL)

المحتويات

2 نماذج الطاقة المظلمة الديناميكية ….. 5

2.1 معلمة تشيفالييه-بولارسكي-ليندر ….. 5

2.2 المعلمة الأسية ….. 6

2.3 معلمة جاسيال-باجلا-بادمانابهان ….. 6

2.4 المعلمة اللوغاريتمية ….. 6

2.5 معلمة باربوزا-ألكانيز ….. 7

3 الطرق ….. 7

3.1 التحليلات الإحصائية ….. 7

3.2 مجموعات البيانات ….. 8

4 النتائج ….. 9

4.1 النتائج لمعلمة CPL ….. 10

4.2 النتائج للمعلمة الأسية ….. 11

4.3 النتائج لمعلمة JBP ….. 13

4.4 النتائج للمعلمة اللوغاريتمية ….. 15

4.5 النتائج للمعلمة BA ….. 17

5 المناقشات والاستنتاجات ….. 18

A معادلة الحالة، انزياح المحور، وعبور الشبح عبر النماذج المختلفة ….. 21

1 المقدمة

2 نماذج الطاقة المظلمة الديناميكية

2.1 بارامترية شيفالييه-بولارسكي-ليندر

2.2 التمثيل الأسي

2.3 معلمة جسال-باجلا-بادمانابهان

2.4 التمثيل اللوغاريتمي

| معامل | سابق |

|

|

[0.005, 0.1] |

|

|

[0.01, 0.99] |

|

|

[1.61, 3.91] |

|

|

[0.8, 1.2] |

|

|

[0.01، 0.8] |

|

|

[0.5, 10] |

|

|

[-3,1] |

|

|

[-3, 2] |

2.5 باربوزا-ألكانيز التماثل

3 طرق

3.1 التحليلات الإحصائية

تحليلات عبر العينة المتاحة للجمهور Cobaya [390، 391] التي تستخدم تنفيذ تسلسل سرعة السحب السريع [392]. يتم تقييم تقارب سلاسل MCMC المولدة عبر معلمة جيلمان-روبين

3.2 مجموعات البيانات

- بلانك: قياسات تباين درجة حرارة إشعاع الخلفية الكونية الميكروي (CMB) واستقطاب طيف القوة، وطيف القوة المتقاطع، ومزيج طيف قوة عدسات ACT وبلانك. جميع احتمالات CMB المستخدمة في هذا العمل مدرجة أدناه:

(ط) قياسات طيف الطاقة لعدم تجانس درجة الحرارة والاستقطاب،

(ii) قياسات طيف التباينات في درجة الحرارة،

(iii) قياسات طيف استقطاب وضعية E،

(رابعاً) إعادة بناء طيف إمكانيات العدسة، الذي تم الحصول عليه من إصدار بيانات Planck PR4 NPIPE [395] المستخدم بالاقتران مع احتمالية عدسة ACT-DR6 [56، 269]. - DESI: قياسات تذبذبات الصوت الباريونية (BAO) المستخرجة من ملاحظات المجرات والكوازارات [58]، وليمين-

- بانثيون بلس: قياسات معاملات المسافة لـ 1701 منحنى ضوئي لـ 1550 سوبرنوفا من النوع Ia تم تأكيدها طيفياً، مستمدة من ثمانية عشر مسحاً مختلفاً، تم جمعها من عينة بانثيون بلس [55، 358].

- DESY5: قياسات معاملات المسافة لـ 1635 سوبرنوفا من النوع Ia تغطي نطاق الانزياح الأحمر من

4 نتائج

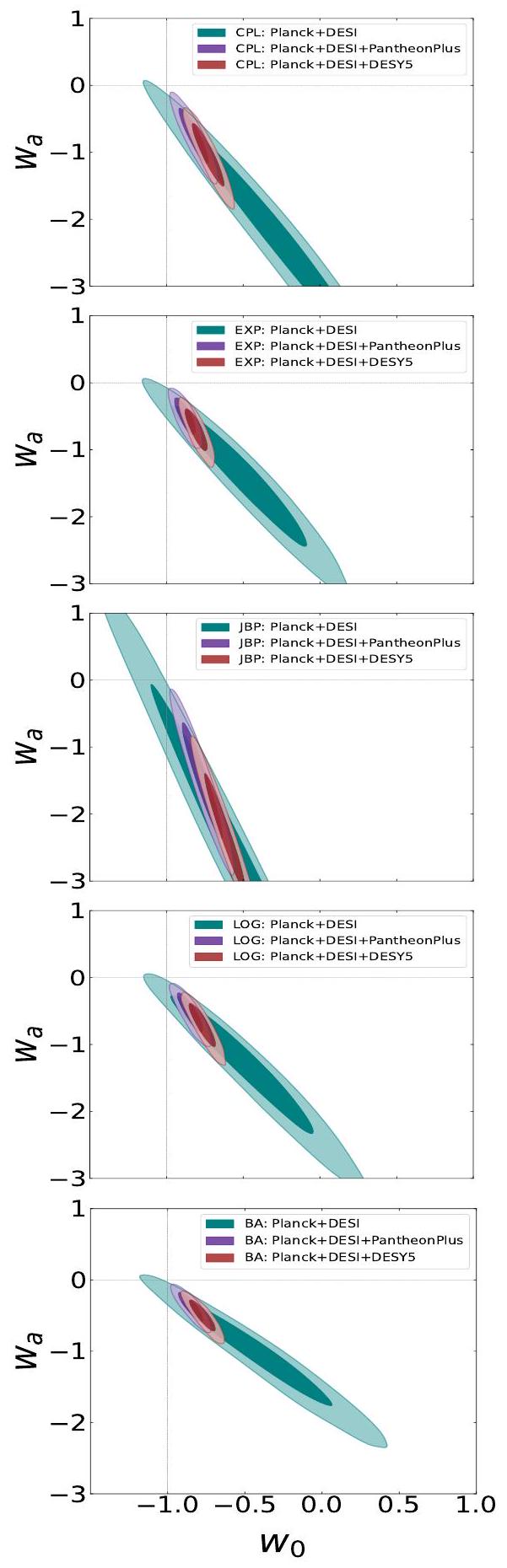

- الجدول 2 والشكل 1 يلخصان القيود العددية وارتباطات المعلمات لحالة CPL الأساسية (2.5). النتائج لهذه الحالة مفصلة في القسم 4.1.

- تقدم الجدول 3 والشكل 2 النتائج للمعامل الأسي (2.6)، الذي تم مناقشته في القسم 4.2.

- توفر الجدول 4 والشكل 3 النتائج لنموذج JBP EoS (2.7)، الذي تم مناقشته في القسم 4.3.

- تلخص الجدول 5 والشكل 4 النتائج للمعلمة اللوغاريتمية (2.8)، المفصلة في القسم 4.4.

- تقدم الجدول 6 والشكل 5 النتائج للمعلمة BA (2.9)، التي تم مناقشتها في القسم 4.5.

4.1 نتائج المعلمة CPL

| معلمة | Planck+DESI | Planck + DESI + PantheonPlus | Planck+DESI+DESY5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-6.8 | -8.4 | -15.2 |

4.2 نتائج المعلمة الأسية

| معلمة | Planck+DESI | Planck + DESI + PantheonPlus | Planck+DESI+DESY5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-6.9 | -7.8 | -15.2 |

4.3 نتائج معلمة JBP

| معلمة | Planck+DESI | Planck + DESI + PantheonPlus | Planck+DESI+DESY5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

< 0.648 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-5.6 | -6.4 | -16.0 |

4.4 النتائج للمعايرة اللوغاريتمية

| معامل | بلانك + ديزي | بلانك + ديزي + بانثيون بلس | بلانك + ديزي + ديزي 5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-6.5 | -9.3 | -14.8 |

4.5 نتائج التوصيف BA

| معامل | بلانك + ديزي | بلانك + ديزي + بانثيون بلس | بلانك + ديزي + ديزي 5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-8.7 | -9.4 | -16.2 |

5 المناقشات والاستنتاجات

نموذج، تتكون جميع هذه المعلمات من اثنين فقط من المعلمات الحرة: القيمة الحالية لمعادلة الحالة (

حتى بمقدار

شكر وتقدير

معادلة الحالة، الانزياح المحوري، وعبور الشبح عبر النماذج المختلفة

| نموذج | مجموعة البيانات |

|

|

|

| CPL | Planck+DESI+PantheonPlus | 0.27 |

|

|

| Planck+DESI+DESY5 | 0.25 |

|

|

|

| أسية | Planck+DESI+PantheonPlus | 0.21 |

|

|

| Planck+DESI+DESY5 | 0.22 |

|

|

|

| JBP | Planck+DESI+PantheonPlus | 0.21 |

|

|

| 4.6 |

|

|

||

| Planck+DESI+DESY5 | 0.21 |

|

|

|

| 4.7 |

|

|

||

| لوغاريتمي | Planck+DESI+PantheonPlus | 0.29 |

|

|

| Planck+DESI+DESY5 | 0.26 |

|

|

|

| BA | Planck+DESI+PantheonPlus | 0.28 |

|

|

| Planck+DESI+DESY5 | 0.28 |

|

|

(ط) الانزياح المحوري

(2) الانزياح الأحمر

- أسية: كما يتضح عند مقارنة الألواح العلوية مع تلك في الصف الثاني من الأعلى في الشكل 7، من منظور ظاهري، يشبه التخصيص الأسّي نموذج CPL عن كثب. تم تسليط الضوء على هذه الشبه بالفعل في النص الرئيسي عند مقارنة التحسين في

- JBP: من بين النماذج الخمسة التي تم تحليلها، تقدم معلمة JBP ظاهرة أكثر دقة فيما يتعلق بتطور معادلة الحالة للطاقة المظلمة. كما هو موضح في الألواح الثالثة من الأعلى في الشكل 7، بسبب طبيعته التربيعية في عامل المقياس، يتقاطع تطور معادلة الحالة ضمن معلمة JBP

- لوغاريتمي: عندما يتعلق الأمر بالمعلمة اللوغاريتمية، فإن سلوك

في الملاءمة للبيانات التي تمتد عبر - BA: وأخيراً وليس آخراً، يتم تقديم تطور

References

[2] Supernova Cosmology Project collaboration, Measurements of

[3] Supernova Search Team collaboration, The farthest known supernova: support for an accelerating universe and a glimpse of the epoch of deceleration, Astrophys. J. 560 (2001) 49 [astro-ph/0104455].

[4] SDSS collaboration, Cosmological parameters from SDSS and WMAP, Phys. Rev. D 69 (2004) 103501 [astro-ph/0310723].

[5] SDSS collaboration, Physical evidence for dark energy, astro-ph/0307335.

[6] Supernova Search Team collaboration, Cosmological results from high-z supernovae, Astrophys. J. 594 (2003) 1 [astro-ph/0305008].

[7] Supernova Cosmology Project collaboration, New constraints on Omega(M), Omega(lambda), and

[8] SDSS collaboration, Cosmological parameter analysis including SDSS Ly-alpha forest and galaxy bias: Constraints on the primordial spectrum of fluctuations, neutrino mass, and dark energy, Phys. Rev. D 71 (2005) 103515 [astro-ph/0407372].

[9] B. Feng, X.-L. Wang and X.-M. Zhang, Dark energy constraints from the cosmic age and supernova, Phys. Lett. B 607 (2005) 35 [astro-ph/0404224].

[10] Supernova Search Team collaboration, Type Ia supernova discoveries at

[11] SNLS collaboration, The Supernova Legacy Survey: Measurement of

[12] SDSS collaboration, Detection of the Baryon Acoustic Peak in the Large-Scale Correlation Function of SDSS Luminous Red Galaxies, Astrophys. J. 633 (2005) 560 [astro-ph/0501171].

[13] D.J. Eisenstein, H.-j. Seo, E. Sirko and D. Spergel, Improving Cosmological Distance Measurements by Reconstruction of the Baryon Acoustic Peak, Astrophys. J. 664 (2007) 675 [astro-ph/0604362].

[14] SDSS collaboration, Cosmological Constraints from the SDSS Luminous Red Galaxies, Phys. Rev. D 74 (2006) 123507 [astro-ph/0608632].

[15] V. Sahni and A. Starobinsky, Reconstructing Dark Energy, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 15 (2006) 2105 [astro-ph/0610026].

[16] ESSENCE collaboration, Observational Constraints on the Nature of the Dark Energy: First Cosmological Results from the ESSENCE Supernova Survey, Astrophys. J. 666 (2007) 694 [astro-ph/0701041].

[17] A. Vikhlinin et al., Chandra Cluster Cosmology Project III: Cosmological Parameter Constraints, Astrophys. J. 692 (2009) 1060 [0812.2720].

[18] D. Stern, R. Jimenez, L. Verde, M. Kamionkowski and S.A. Stanford, Cosmic Chronometers: Constraining the Equation of State of Dark Energy. I: H(z) Measurements, JCAP 02 (2010) 008 [0907.3149].

[19] B.D. Sherwin et al., Evidence for dark energy from the cosmic microwave background alone using the Atacama Cosmology Telescope lensing measurements, Phys. Rev. Lett. 107 (2011) 021302 [1105.0419].

[20] WMAP collaboration, Nine-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Final Maps and Results, Astrophys. J. Suppl. 208 (2013) 20 [1212.5225].

[21] WMAP collaboration, Nine-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Cosmological Parameter Results, Astrophys. J. Suppl. 208 (2013) 19 [1212.5226].

[22] BOSS collaboration, The Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey of SDSS-III, Astron. J. 145 (2013) 10 [1208.0022].

[23] Astro-WISE, KiDS collaboration, The Kilo-Degree Survey, Exper. Astron. 35 (2013) 25 [1206. 1254].

[24] BOSS collaboration, The clustering of galaxies in the SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: baryon acoustic oscillations in the Data Releases 10 and 11 Galaxy samples, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 441 (2014) 24 [1312.4877].

[25] D.H. Weinberg, M.J. Mortonson, D.J. Eisenstein, C. Hirata, A.G. Riess and E. Rozo, Observational Probes of Cosmic Acceleration, Phys. Rept. 530 (2013) 87 [1201.2434].

[26] BOSS collaboration, The clustering of galaxies in the SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: Testing gravity with redshift-space distortions using the power spectrum multipoles, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 443 (2014) 1065 [1312.4611].

[27] BOSS collaboration, Baryon acoustic oscillations in the Lyo forest of BOSS DR11 quasars, Astron. Astrophys. 574 (2015) A59 [1404. 1801].

[28] SDSS collaboration, Improved cosmological constraints from a joint analysis of the SDSS-II and SNLS supernova samples, Astron. Astrophys. 568 (2014) A22 [1401.4064].

[29] BOSS collaboration, Cosmological implications of baryon acoustic oscillation measurements, Phys. Rev. D 92 (2015) 123516 [1411.1074].

[30] A.J. Ross, L. Samushia, C. Howlett, W.J. Percival, A. Burden and M. Manera, The clustering of the SDSS DR7 main Galaxy sample – I. A 4 per cent distance measure at

[31] M. Moresco, L. Pozzetti, A. Cimatti, R. Jimenez, C. Maraston, L. Verde et al., A

[32] M. Moresco, R. Jimenez, L. Verde, A. Cimatti, L. Pozzetti, C. Maraston et al., Constraining the time evolution of dark energy, curvature and neutrino properties with cosmic chronometers, JCAP 12 (2016) 039 [1604.00183].

[33] D. Rubin and B. Hayden, Is the expansion of the universe accelerating? All signs point to yes, Astrophys. J. Lett. 833 (2016) L30 [1610.08972].

[34] BOSS collaboration, The clustering of galaxies in the completed SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: cosmological analysis of the DR12 galaxy sample, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 470 (2017) 2617 [1607.03155].

[35] DES collaboration, The Dark Energy Survey: more than dark energy – an overview, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 460 (2016) 1270 [1601.00329].

[36] B.S. Haridasu, V.V. Luković, R. D’Agostino and N. Vittorio, Strong evidence for an accelerating universe, Astron. Astrophys. 600 (2017) L1 [1702.08244].

[37] DES collaboration, Dark Energy Survey Year 1 results: Cosmological constraints from cosmic shear, Phys. Rev. D 98 (2018) 043528 [1708.01538].

[38] Pan-STARRS1 collaboration, The Complete Light-curve Sample of Spectroscopically Confirmed SNe Ia from Pan-STARRS1 and Cosmological Constraints from the Combined Pantheon Sample, Astrophys. J. 859 (2018) 101 [1710.00845].

[39] Planck collaboration, Planck 2018 results. I. Overview and the cosmological legacy of Planck, Astron. Astrophys. 641 (2020) A1 [1807.06205].

[40] Planck collaboration, Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters, Astron. Astrophys. 641 (2020) A6 [1807.06209].

[41] A. Gómez-Valent, Quantifying the evidence for the current speed-up of the Universe with low and intermediate-redshift data. A more model-independent approach, JCAP 05 (2019) 026 [1810.02278].

[42] Y. Yang and Y. Gong, The evidence of cosmic acceleration and observational constraints, JCAP 06 (2020) 059 [1912.07375].

[43] ACT collaboration, The Atacama Cosmology Telescope: a measurement of the Cosmic Microwave Background power spectra at 98 and 150 GHz, JCAP 12 (2020) 045 [2007.07289].

[44] ACT collaboration, The Atacama Cosmology Telescope: DR4 Maps and Cosmological Parameters, JCAP 12 (2020) 047 [2007.07288].

[45] EBOSS collaboration, Completed SDSS-IV extended Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: Cosmological implications from two decades of spectroscopic surveys at the Apache Point Observatory, Phys. Rev. D 103 (2021) 083533 [2007.08991].

[46] S. Nadathur, W.J. Percival, F. Beutler and H. Winther, Testing Low-Redshift Cosmic Acceleration with Large-Scale Structure, Phys. Rev. Lett. 124 (2020) 221301 [2001.11044].

[47] B.M. Rose, D. Rubin, A. Cikota, S.E. Deustua, S. Dixon, A. Fruchter et al., Evidence for Cosmic Acceleration is Robust to Observed Correlations Between Type Ia Supernova Luminosity and Stellar Age, Astrophys. J. Lett. 896 (2020) L4 [2002. 12382].

[48] E. Di Valentino, S. Gariazzo, O. Mena and S. Vagnozzi, Soundness of Dark Energy properties, JCAP 07 (2020) 045 [2005. 02062].

[49] KIDS collaboration, KiDS-1000 Cosmology: Cosmic shear constraints and comparison between two point statistics, Astron. Astrophys. 645 (2021) A104 [2007.15633].

[50] KiDS collaboration, KiDS-1000 Cosmology: Constraints beyond flat

[51] SPT-3G collaboration, Measurements of the

[52] DES collaboration, Dark Energy Survey Year 3 results: Cosmological constraints from galaxy clustering and weak lensing, Phys. Rev. D 105 (2022) 023520 [2105.13549].

[53] M. Moresco et al., Unveiling the Universe with emerging cosmological probes, Living Rev. Rel. 25 (2022) 6 [2201.07241].

[54] DES collaboration, Dark Energy Survey Year 3 results: Constraints on extensions to

[55] D. Brout et al., The Pantheon + Analysis: Cosmological Constraints, Astrophys. J. 938 (2022) 110 [2202.04077].

[56] ACT collaboration, The Atacama Cosmology Telescope: DR6 Gravitational Lensing Map and Cosmological Parameters, Astrophys. J. 962 (2024) 113 [2304.05203].

[57] Kilo-Degree Survey, Dark Energy Survey collaboration, DES Y3 + KiDS-1000: Consistent cosmology combining cosmic shear surveys, Open J. Astrophys. 6 (2023) 2305.17173 [2305.17173].

[58] DESI collaboration, DESI 2024 III: Baryon Acoustic Oscillations from Galaxies and Quasars, 2404.03000.

[59] DESI collaboration, DESI 2024: Constraints on Physics-Focused Aspects of Dark Energy using DESI DR1 BAO Data, 2405.13588.

[60] DES collaboration, The Dark Energy Survey: Cosmology Results With

[61] DES collaboration, The Dark Energy Survey Supernova Program: Light curves and 5-Year data release, 2406.05046.

[62] DES collaboration, The Dark Energy Survey Supernova Program: Cosmological Analysis and Systematic Uncertainties, 2401.02945.

[63] T. Buchert, On average properties of inhomogeneous fluids in general relativity. 1. Dust cosmologies, Gen. Rel. Grav. 32 (2000) 105 [gr-qc/9906015].

[64] T. Buchert, On average properties of inhomogeneous fluids in general relativity: Perfect fluid cosmologies, Gen. Rel. Grav. 33 (2001) 1381 [gr-qc/0102049].

[65] T. Buchert, Dark Energy from Structure: A Status Report, Gen. Rel. Grav. 40 (2008) 467 [0707.2153].

[66] P. Hunt and S. Sarkar, Constraints on large scale inhomogeneities from WMAP-5 and SDSS: confrontation with recent observations, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 401 (2010) 547 [0807.4508].

[67] J.T. Nielsen, A. Guffanti and S. Sarkar, Marginal evidence for cosmic acceleration from Type Ia supernovae, Sci. Rep. 6 (2016) 35596 [1506.01354].

[68] I. Tutusaus, B. Lamine, A. Dupays and A. Blanchard, Is cosmic acceleration proven by local cosmological probes?, Astron. Astrophys. 602 (2017) A73 [1706.05036].

[69] L.H. Dam, A. Heinesen and D.L. Wiltshire, Apparent cosmic acceleration from type Ia supernovae, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 472 (2017) 835 [1706.07236].

[70] J. Colin, R. Mohayaee, M. Rameez and S. Sarkar, Evidence for anisotropy of cosmic acceleration, Astron. Astrophys. 631 (2019) L13 [1808.04597].

[71] C. Desgrange, A. Heinesen and T. Buchert, Dynamical spatial curvature as a fit to type Ia supernovae, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 28 (2019) 1950143 [1902.07915].

[72] S.M. Koksbang, Towards statistically homogeneous and isotropic perfect fluid universes with cosmic backreaction, Class. Quant. Grav. 36 (2019) 185004 [1907.08681].

[73] S.M. Koksbang, Another look at redshift drift and the backreaction conjecture, JCAP 10 (2019) 036 [1909. 13489].

[74] A. Heinesen, Reconciling a decelerating Universe with cosmological observations, Phys. Rev. D 107 (2023) L101301 [2212.05568].

[75] V. Sahni and A.A. Starobinsky, The Case for a positive cosmological Lambda term, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 9 (2000) 373 [astro-ph/9904398].

[76] S.M. Carroll, The Cosmological constant, Living Rev. Rel. 4 (2001) 1 [astro-ph/0004075].

[77] P.J.E. Peebles and B. Ratra, The Cosmological Constant and Dark Energy, Rev. Mod. Phys. 75 (2003) 559 [astro-ph/0207347].

[78] T. Padmanabhan, Cosmological constant: The Weight of the vacuum, Phys. Rept. 380 (2003) 235 [hep-th/0212290].

[79] E.J. Copeland, M. Sami and S. Tsujikawa, Dynamics of dark energy, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 15 (2006) 1753 [hep-th/0603057].

[80] R.R. Caldwell and M. Kamionkowski, The Physics of Cosmic Acceleration, Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 59 (2009) 397 [0903.0866].

[81] M. Li, X.-D. Li, S. Wang and Y. Wang, Dark Energy, Commun. Theor. Phys. 56 (2011) 525 [1103.5870].

[82] J. Martin, Everything You Always Wanted To Know About The Cosmological Constant Problem (But Were Afraid To Ask), Comptes Rendus Physique 13 (2012) 566 [1205.3365].

[83] S. Weinberg, The Cosmological Constant Problem, Rev. Mod. Phys. 61 (1989) 1.

[84] L.M. Krauss and M.S. Turner, The Cosmological constant is back, Gen. Rel. Grav. 27 (1995) 1137 [astro-ph/9504003].

[85] S. Weinberg, The Cosmological constant problems, 2, 2000.

[86] V. Sahni, The Cosmological constant problem and quintessence, Class. Quant. Grav. 19 (2002) 3435 [astro-ph/0202076].

[87] J. Yokoyama, Issues on the cosmological constant, 5, 2003.

[88] S. Nobbenhuis, Categorizing different approaches to the cosmological constant problem, Found. Phys. 36 (2006) 613 [gr-qc/0411093].

[89] C.P. Burgess, The Cosmological Constant Problem: Why it’s hard to get Dark Energy from Micro-physics, 2015. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198728856.003.0004.

[90] A. Joyce, B. Jain, J. Khoury and M. Trodden, Beyond the Cosmological Standard Model, Phys. Rept. 568 (2015) 1 [1407.0059].

[91] P. Bull et al., Beyond

[92] B. Wang, E. Abdalla, F. Atrio-Barandela and D. Pavon, Dark Matter and Dark Energy Interactions: Theoretical Challenges, Cosmological Implications and Observational Signatures, Rept. Prog. Phys. 79 (2016) 096901 [1603.08299].

[93] R. Brustein and P.J. Steinhardt, Challenges for superstring cosmology, Phys. Lett. B 302 (1993) 196 [hep-th/9212049].

[94] E. Witten, The Cosmological constant from the viewpoint of string theory, 3, 2000.

[95] S. Kachru, R. Kallosh, A.D. Linde and S.P. Trivedi, De Sitter vacua in string theory, Phys. Rev. D 68 (2003) 046005 [hep-th/0301240].

[96] J. Polchinski, The Cosmological Constant and the String Landscape, 3, 2006.

[97] U.H. Danielsson and T. Van Riet, What if string theory has no de Sitter vacua?, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 27 (2018) 1830007 [1804.01120].

[98] I. Zlatev, L.-M. Wang and P.J. Steinhardt, Quintessence, cosmic coincidence, and the cosmological constant, Phys. Rev. Lett. 82 (1999) 896 [astro-ph/9807002].

[99] D. Pavon and W. Zimdahl, Holographic dark energy and cosmic coincidence, Phys. Lett. B 628 (2005) 206 [gr-qc/0505020].

[100] H.E.S. Velten, R.F. vom Marttens and W. Zimdahl, Aspects of the cosmological “coincidence problem”, Eur. Phys. J. C 74 (2014) 3160 [1410.2509].

[101] A.D. Dolgov, The Problem of vacuum energy and cosmology, 6, 1997.

[102] N. Straumann, The Mystery of the cosmic vacuum energy density and the accelerated expansion of the universe, Eur. J. Phys. 20 (1999) 419 [astro-ph/9908342].

[103] J. Sola, Cosmological constant and vacuum energy: old and new ideas, J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 453 (2013) 012015 [1306.1527].

[104] L. Amendola, Coupled quintessence, Phys. Rev. D 62 (2000) 043511 [astro-ph/9908023].

[105] A.Y. Kamenshchik, U. Moschella and V. Pasquier, An Alternative to quintessence, Phys. Lett.

[106] S. Capozziello, Curvature quintessence, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 11 (2002) 483 [gr-qc/0201033].

[107] M.C. Bento, O. Bertolami and A.A. Sen, Generalized Chaplygin gas, accelerated expansion and dark energy matter unification, Phys. Rev. D 66 (2002) 043507 [gr-qc/0202064].

[108] G. Mangano, G. Miele and V. Pettorino, Coupled quintessence and the coincidence problem, Mod. Phys. Lett. A 18 (2003) 831 [astro-ph/0212518].

[109] G.R. Farrar and P.J.E. Peebles, Interacting dark matter and dark energy, Astrophys. J. 604 (2004) 1 [astro-ph/0307316].

[110] J. Khoury and A. Weltman, Chameleon fields: Awaiting surprises for tests of gravity in space, Phys. Rev. Lett. 93 (2004) 171104 [astro-ph/0309300].

[111] M. Li, A Model of holographic dark energy, Phys. Lett. B 603 (2004) 1 [hep-th/0403127].

[112] L. Amendola, R. Gannouji, D. Polarski and S. Tsujikawa, Conditions for the cosmological viability of

[113] W. Hu and I. Sawicki, Models of

[114] G. Cognola, E. Elizalde, S. Nojiri, S.D. Odintsov, L. Sebastiani and S. Zerbini, A Class of viable modified

[115] S. Nojiri, S.D. Odintsov, M. Sasaki and Y.-l. Zhang, Screening of cosmological constant in non-local gravity, Phys. Lett. B 696 (2011) 278 [1010.5375].

[116] Y.-l. Zhang and M. Sasaki, Screening of cosmological constant in non-local cosmology, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 21 (2012) 1250006 [1108.2112].

[117] M. Rinaldi, Higgs Dark Energy, Class. Quant. Grav. 32 (2015) 045002 [1404.0532].

[118] O. Luongo and H. Quevedo, A Unified Dark Energy Model from a Vanishing Speed of Sound with Emergent Cosmological Constant, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 23 (2014) 1450012.

[119] M. Rinaldi, Dark energy as a fixed point of the Einstein Yang-Mills Higgs Equations, JCAP 10 (2015) 023 [1508.04576].

[120] A. De Felice, L. Heisenberg, R. Kase, S. Mukohyama, S. Tsujikawa and Y.-l. Zhang, Cosmology in generalized Proca theories, JCAP 06 (2016) 048 [1603.05806].

[121] T. Josset, A. Perez and D. Sudarsky, Dark Energy from Violation of Energy Conservation, Phys. Rev. Lett. 118 (2017) 021102 [1604.04183].

[122] C. Burrage and J. Sakstein, A Compendium of Chameleon Constraints, JCAP 11 (2016) 045 [1609.01192].

[123] L. Sebastiani, S. Vagnozzi and R. Myrzakulov, Mimetic gravity: a review of recent developments and applications to cosmology and astrophysics, Adv. High Energy Phys. 2017 (2017) 3156915 [1612.08661].

[124] S. Nojiri, S.D. Odintsov and V.K. Oikonomou, Modified Gravity Theories on a Nutshell: Inflation, Bounce and Late-time Evolution, Phys. Rept. 692 (2017) 1 [1705.11098].

[125] C. Burrage and J. Sakstein, Tests of Chameleon Gravity, Living Rev. Rel. 21 (2018) 1 [1709.09071].

[126] S. Capozziello, R. D’Agostino and O. Luongo, Cosmic acceleration from a single fluid description, Phys. Dark Univ. 20 (2018) 1 [1712.04317].

[127] D. Benisty and E.I. Guendelman, Unified dark energy and dark matter from dynamical spacetime, Phys. Rev. D 98 (2018) 023506 [1802.07981].

[128] A. Casalino, M. Rinaldi, L. Sebastiani and S. Vagnozzi, Mimicking dark matter and dark energy in a mimetic model compatible with GW170817, Phys. Dark Univ. 22 (2018) 108 [1803.02620].

[129] W. Yang, S. Pan, E. Di Valentino, R.C. Nunes, S. Vagnozzi and D.F. Mota, Tale of stable interacting dark energy, observational signatures, and the

[130] E.N. Saridakis, K. Bamba, R. Myrzakulov and F.K. Anagnostopoulos, Holographic dark energy through Tsallis entropy, JCAP 12 (2018) 012 [1806.01301].

[131] L. Visinelli and S. Vagnozzi, Cosmological window onto the string axiverse and the supersymmetry breaking scale, Phys. Rev. D 99 (2019) 063517 [1809.06382].

[132] D. Langlois, Dark energy and modified gravity in degenerate higher-order scalar-tensor (DHOST) theories: A review, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 28 (2019) 1942006 [1811.06271].

[133] D. Benisty, E. Guendelman and Z. Haba, Unification of dark energy and dark matter from diffusive cosmology, Phys. Rev. D 99 (2019) 123521 [1812.06151].

[134] K. Boshkayev, R. D’Agostino and O. Luongo, Extended logotropic fluids as unified dark energy models, Eur. Phys. J. C 79 (2019) 332 [1901.01031].

[135] J.J. Heckman, C. Lawrie, L. Lin, J. Sakstein and G. Zoccarato, Pixelated Dark Energy, Fortsch. Phys. 67 (2019) 1900071 [1901.10489].

[136] R. D’Agostino, Holographic dark energy from nonadditive entropy: cosmological perturbations and observational constraints, Phys. Rev. D 99 (2019) 103524 [1903.03836].

[137] U. Mukhopadhyay, D. Majumdar and D. Adak, Evolution of Dark Energy Perturbations for Slotheon Field and Power Spectrum, Eur. Phys. J. C 80 (2020) 593 [1903.08650].

[138] U. Mukhopadhyay and D. Majumdar, Swampland criteria in the slotheon field dark energy, Phys. Rev. D 100 (2019) 024006 [1904.01455].

[139] U. Mukhopadhyay, A. Paul and D. Majumdar, Addressing the high-

[140] S. Vagnozzi, L. Visinelli, O. Mena and D.F. Mota, Do we have any hope of detecting scattering between dark energy and baryons through cosmology?, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 493 (2020) 1139 [1911.12374].

[141] O. Akarsu, J.D. Barrow, L.A. Escamilla and J.A. Vazquez, Graduated dark energy: Observational hints of a spontaneous sign switch in the cosmological constant, Phys. Rev.

[142] E.N. Saridakis, Barrow holographic dark energy, Phys. Rev. D 102 (2020) 123525 [2005.04115].

[143] Ruchika, S.A. Adil, K. Dutta, A. Mukherjee and A.A. Sen, Observational constraints on axion(s) dark energy with a cosmological constant, Phys. Dark Univ. 40 (2023) 101199 [2005.08813].

[144] S.D. Odintsov, V.K. Oikonomou and T. Paul, From a Bounce to the Dark Energy Era with

[145] S.D. Odintsov, V.K. Oikonomou, F.P. Fronimos and K.V. Fasoulakos, Unification of a Bounce with a Viable Dark Energy Era in Gauss-Bonnet Gravity, Phys. Rev. D 102 (2020) 104042 [2010. 13580].

[146] V.K. Oikonomou, Unifying inflation with early and late dark energy epochs in axion

[147] V.K. Oikonomou, Rescaled Einstein-Hilbert Gravity from

[148] S. Vagnozzi, L. Visinelli, P. Brax, A.-C. Davis and J. Sakstein, Direct detection of dark energy: The XENON1T excess and future prospects, Phys. Rev. D 104 (2021) 063023 [2103.15834].

[149] R. Solanki, S.K.J. Pacif, A. Parida and P.K. Sahoo, Cosmic acceleration with bulk viscosity in modified

[150] E.N. Saridakis, Do we need soft cosmology?, Phys. Lett. B 822 (2021) 136649 [2105.08646].

[151] S. Arora, S.K.J. Pacif, A. Parida and P.K. Sahoo, Bulk viscous matter and the cosmic acceleration of the universe in

[152] S. Capozziello, R. D’Agostino and O. Luongo, Thermodynamic parametrization of dark energy, Phys. Dark Univ. 36 (2022) 101045 [2202.03300].

[153] S.A. Narawade, L. Pati, B. Mishra and S.K. Tripathy, Dynamical system analysis for accelerating models in non-metricity

[154] R. D’Agostino, O. Luongo and M. Muccino, Healing the cosmological constant problem during inflation through a unified quasi-quintessence matter field, Class. Quant. Grav. 39 (2022) 195014 [2204.02190].

[155] V.K. Oikonomou and I. Giannakoudi, A panorama of viable

[156] A. Belfiglio, R. Giambò and O. Luongo, Alleviating the cosmological constant problem from particle production, Class. Quant. Grav. 40 (2023) 105004 [2206.14158].

[157] G.G. Luciano and J. Giné, Generalized interacting Barrow Holographic Dark Energy: Cosmological predictions and thermodynamic considerations, Phys. Dark Univ. 41 (2023) 101256 [2210.09755].

[158] S.A. Kadam, J. Levi Said and B. Mishra, Accelerating cosmological models in

[159] Y.C. Ong, An Effective Sign Switching Dark Energy: Lotka-Volterra Model of Two Interacting Fluids, Universe 9 (2023) 437 [2212.04429].

[160] A. Bernui, E. Di Valentino, W. Giarè, S. Kumar and R.C. Nunes, Exploring the Ho tension and the evidence for dark sector interactions from 2D BAO measurements, Phys. Rev. D 107 (2023) 103531 [2301.06097].

[161] G.G. Luciano, Saez-Ballester gravity in Kantowski-Sachs Universe: A new reconstruction paradigm for Barrow Holographic Dark Energy, Phys. Dark Univ. 41 (2023) 101237 [2301.12488].

[162] L. Giani and O.F. Piattella, Induced non-local cosmology, Phys. Dark Univ. 40 (2023) 101219 [2302.06762].

[163] A. Belfiglio, Y. Carloni and O. Luongo, Particle production from non-minimal coupling in a symmetry breaking potential transporting vacuum energy, Phys. Dark Univ. 44 (2024) 101458 [2307.04739].

[164] E. Frion, D. Camarena, L. Giani, T. Miranda, D. Bertacca, V. Marra et al., Bayesian analysis of a Unified Dark Matter model with transition: can it alleviate the

[165] S.A. Adil, U. Mukhopadhyay, A.A. Sen and S. Vagnozzi, Dark energy in light of the early JWST observations: case for a negative cosmological constant?, JCAP 10 (2023) 072 [2307.12763].

[166] S. Halder, S. Pan, P.M. Sá and T. Saha, Coupled phantom cosmological model motivated by the warm inflationary paradigm, 2407.15804.

[167] H. Fischer, C. Käding and M. Pitschmann, Screened Scalar Fields in the Laboratory and the Solar System, Universe 10 (2024) 297 [2405.14638].

[168] A.R. Cooray and D. Huterer, Gravitational lensing as a probe of quintessence, Astrophys. J. Lett. 513 (1999) L95 [astro-ph/9901097].

[169] G. Efstathiou, Constraining the equation of state of the universe from distant type Ia supernovae and cosmic microwave background anisotropies, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 310 (1999) 842 [astro-ph/9904356].

[170] M. Chevallier and D. Polarski, Accelerating universes with scaling dark matter, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 10 (2001) 213 [gr-qc/0009008].

[171] A. Melchiorri, L. Mersini-Houghton, C.J. Odman and M. Trodden, The State of the dark energy equation of state, Phys. Rev. D 68 (2003) 043509 [astro-ph/0211522].

[172] E.V. Linder, Exploring the expansion history of the universe, Phys. Rev. Lett. 90 (2003) 091301 [astro-ph/0208512].

[173] C. Wetterich, Phenomenological parameterization of quintessence, Phys. Lett. B 594 (2004) 17 [astro-ph/0403289].

[174] B. Feng, M. Li, Y.-S. Piao and X. Zhang, Oscillating quintom and the recurrent universe, Phys. Lett. B 634 (2006) 101 [astro-ph/0407432].

[175] J.-Q. Xia, B. Feng and X.-M. Zhang, Constraints on oscillating quintom from supernova, microwave background and galaxy clustering, Mod. Phys. Lett. A 20 (2005) 2409 [astro-ph/0411501].

[176] S. Hannestad and E. Mortsell, Cosmological constraints on the dark energy equation of state and its evolution, JCAP 09 (2004) 001 [astro-ph/0407259].

[177] Y.-g. Gong and Y.-Z. Zhang, Probing the curvature and dark energy, Phys. Rev. D 72 (2005) 043518 [astro-ph/0502262].

[178] H.K. Jassal, J.S. Bagla and T. Padmanabhan, Observational constraints on low redshift evolution of dark energy: How consistent are different observations?, Phys. Rev. D 72 (2005) 103503 [astro-ph/0506748].

[179] S. Nesseris and L. Perivolaropoulos, Comparison of the legacy and gold snia dataset constraints on dark energy models, Phys. Rev. D 72 (2005) 123519 [astro-ph/0511040].

[180] D.-J. Liu, X.-Z. Li, J. Hao and X.-H. Jin, Revisiting the parametrization of Equation of State of Dark Energy via SNIa Data, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 388 (2008) 275 [0804.3829].

[181] E.M. Barboza, Jr. and J.S. Alcaniz, A parametric model for dark energy, Phys. Lett. B 666 (2008) 415 [0805.1713].

[182] J.-Z. Ma and X. Zhang, Probing the dynamics of dark energy with novel parametrizations, Phys. Lett. B 699 (2011) 233 [1102.2671].

[183] I. Sendra and R. Lazkoz, SN and BAO constraints on (new) polynomial dark energy parametrizations: current results and forecasts, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 422 (2012) 776 [1105.4943].

[184] A. De Felice, S. Nesseris and S. Tsujikawa, Observational constraints on dark energy with a fast varying equation of state, JCAP 05 (2012) 029 [1203.6760].

[185] H. Li and X. Zhang, Constraining dynamical dark energy with a divergence-free parametrization in the presence of spatial curvature and massive neutrinos, Phys. Lett. B 713 (2012) 160 [1202.4071].

[186] C.-J. Feng, X.-Y. Shen, P. Li and X.-Z. Li, A New Class of Parametrization for Dark Energy without Divergence, JCAP 09 (2012) 023 [1206.0063].

[187] J. Magaña, V.H. Cárdenas and V. Motta, Cosmic slowing down of acceleration for several dark energy parametrizations, JCAP 10 (2014) 017 [1407.1632].

[188] G. Pantazis, S. Nesseris and L. Perivolaropoulos, Comparison of thawing and freezing dark energy parametrizations, Phys. Rev. D 93 (2016) 103503 [1603.02164].

[189] E. Di Valentino, A. Melchiorri and J. Silk, Reconciling Planck with the local value of

[190] W. Yang, S. Pan and A. Paliathanasis, Latest astronomical constraints on some non-linear parametric dark energy models, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 475 (2018) 2605 [1708.01717].

[191] S. Pan, E.N. Saridakis and W. Yang, Observational Constraints on Oscillating Dark-Energy Parametrizations, Phys. Rev. D 98 (2018) 063510 [1712.05746].

[192] E. Mörtsell and S. Dhawan, Does the Hubble constant tension call for new physics?, JCAP 09 (2018) 025 [1801.07260].

[193] K. Dutta, Ruchika, A. Roy, A.A. Sen and M.M. Sheikh-Jabbari, Beyond

[194] W. Yang, S. Pan, E. Di Valentino and E.N. Saridakis, Observational constraints on dynamical dark energy with pivoting redshift, Universe 5 (2019) 219 [1811.06932].

[195] W. Yang, S. Pan, E. Di Valentino, E.N. Saridakis and S. Chakraborty, Observational constraints on one-parameter dynamical dark-energy parametrizations and the

[196] X. Li and A. Shafieloo, A Simple Phenomenological Emergent Dark Energy Model can Resolve the Hubble Tension, Astrophys. J. Lett. 883 (2019) L3 [1906.08275].

[197] S. Vagnozzi, New physics in light of the

[198] L. Visinelli, S. Vagnozzi and U. Danielsson, Revisiting a negative cosmological constant from low-redshift data, Symmetry 11 (2019) 1035 [1907. 07953].

[199] E. Di Valentino, A. Melchiorri, O. Mena and S. Vagnozzi, Interacting dark energy in the early 2020s: A promising solution to the

[200] K. Dutta, A. Roy, Ruchika, A.A. Sen and M.M. Sheikh-Jabbari, Cosmology with low-redshift observations: No signal for new physics, Phys. Rev. D 100 (2019) 103501 [1908.07267].

[201] E. Di Valentino, A. Melchiorri, O. Mena and S. Vagnozzi, Nonminimal dark sector physics and cosmological tensions, Phys. Rev. D 101 (2020) 063502 [1910.09853].

[202] S. Pan, W. Yang, E. Di Valentino, A. Shafieloo and S. Chakraborty, Reconciling

[203] E.M. Teixeira, A. Nunes and N.J. Nunes, Disformally Coupled Quintessence, Phys. Rev. D 101 (2020) 083506 [1912.13348].

[204] E.M. Teixeira, A. Nunes and N.J. Nunes, Conformally Coupled Tachyonic Dark Energy, Phys. Rev. D 100 (2019) 043539 [1903.06028].

[205] M. Martinelli, N.B. Hogg, S. Peirone, M. Bruni and D. Wands, Constraints on the interacting vacuum-geodesic CDM scenario, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 488 (2019) 3423 [1902.10694].

[206] M. Zumalacarregui, Gravity in the Era of Equality: Towards solutions to the Hubble problem without fine-tuned initial conditions, Phys. Rev. D 102 (2020) 023523 [2003.06396].

[207] N.B. Hogg, M. Bruni, R. Crittenden, M. Martinelli and S. Peirone, Latest evidence for a late time vacuum-geodesic CDM interaction, Phys. Dark Univ. 29 (2020) 100583 [2002.10449].

[208] G. Alestas, L. Kazantzidis and L. Perivolaropoulos,

[209] E. Di Valentino, A. Mukherjee and A.A. Sen, Dark Energy with Phantom Crossing and the

[210] G. Alestas, L. Kazantzidis and L. Perivolaropoulos,

[211] M. Rezaei, T. Naderi, M. Malekjani and A. Mehrabi, A Bayesian comparison between

[212] D. Perkovic and H. Stefancic, Barotropic fluid compatible parametrizations of dark energy, Eur. Phys. J. C 80 (2020) 629 [2004.05342].

[213] H.B. Benaoum, W. Yang, S. Pan and E. Di Valentino, Modified emergent dark energy and its astronomical constraints, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 31 (2022) 2250015 [2008.09098].

[214] S. Kumar, Remedy of some cosmological tensions via effective phantom-like behavior of interacting vacuum energy, Phys. Dark Univ. 33 (2021) 100862 [2102.12902].

[215] S. Vagnozzi, F. Pacucci and A. Loeb, Implications for the Hubble tension from the ages of the oldest astrophysical objects, JHEAp 36 (2022) 27 [2105.10421].

[216] L.A. Escamilla and J.A. Vazquez, Model selection applied to reconstructions of the Dark Energy, Eur. Phys. J. C 83 (2023) 251 [2111.10457].

[217] S. Bag, V. Sahni, A. Shafieloo and Y. Shtanov, Phantom Braneworld and the Hubble Tension, Astrophys. J. 923 (2021) 212 [2107.03271].

[218] A. Theodoropoulos and L. Perivolaropoulos, The Hubble Tension, the M Crisis of Late Time H(z) Deformation Models and the Reconstruction of Quintessence Lagrangians, Universe 7 (2021) 300 [2109.06256].

[219] G. Alestas, D. Camarena, E. Di Valentino, L. Kazantzidis, V. Marra, S. Nesseris et al., Late-transition versus smooth

[220] A.A. Sen, S.A. Adil and S. Sen, Do cosmological observations allow a negative

[221] W. Yang, E. Di Valentino, S. Pan, A. Shafieloo and X. Li, Generalized emergent dark energy model and the Hubble constant tension, Phys. Rev. D 104 (2021) 063521 [2103.03815].

[222] N.B. Hogg and M. Bruni, Shan-Chen interacting vacuum cosmology, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 511 (2022) 4430 [2109.08676].

[223] N. Roy, S. Goswami and S. Das, Quintessence or phantom: Study of scalar field dark energy models through a general parametrization of the Hubble parameter, Phys. Dark Univ. 36 (2022) 101037 [2201.09306].

[224] L. Heisenberg, H. Villarrubia-Rojo and J. Zosso, Simultaneously solving the H0 and

[225] A. Chudaykin, D. Gorbunov and N. Nedelko, Exploring

[226] O. Akarsu, S. Kumar, E. Özülker, J.A. Vazquez and A. Yadav, Relaxing cosmological tensions with a sign switching cosmological constant: Improved results with Planck, BAO, and Pantheon data, Phys. Rev. D 108 (2023) 023513 [2211.05742].

[227] F.B.M.d. Santos, Updating constraints on phantom crossing f

[228] T. Schiavone, G. Montani and F. Bombacigno,

[229] C. van de Bruck, G. Poulot and E.M. Teixeira, Scalar field dark matter and dark energy: a hybrid model for the dark sector, JCAP 07 (2023) 019 [2211.13653].

[230] E. Ozulker, Is the dark energy equation of state parameter singular?, Phys. Rev. D 106 (2022) 063509 [2203.04167].

[231] E.M. Teixeira, B.J. Barros, V.M.C. Ferreira and N. Frusciante, Dissecting kinetically coupled quintessence: phenomenology and observational tests, JCAP 11 (2022) 059 [2207.13682].

[232] I. Ben-Dayan and U. Kumar, Emergent Unparticles Dark Energy can restore cosmological concordance, JCAP 12 (2023) 047 [2302.00067].

[233] M. Ballardini, A.G. Ferrari and F. Finelli, Phantom scalar-tensor models and cosmological tensions, JCAP 04 (2023) 029 [2302.05291].

[234] W. Yang, W. Giarè, S. Pan, E. Di Valentino, A. Melchiorri and J. Silk, Revealing the effects of curvature on the cosmological models, Phys. Rev. D 107 (2023) 063509 [2210.09865].

[235] J. de Cruz Perez and J. Sola Peracaula, Running vacuum in Brans

[236] T. Patil, Ruchika and S. Panda, Coupled quintessence scalar field model in light of observational datasets, JCAP 05 (2024) 033 [2307.03740].

[237] Y. Zhai, W. Giarè, C. van de Bruck, E. Di Valentino, O. Mena and R.C. Nunes, A consistent view of interacting dark energy from multiple CMB probes, JCAP 07 (2023) 032 [2303.08201].

[238] S.A. Adil, O. Akarsu, E. Di Valentino, R.C. Nunes, E. Özülker, A.A. Sen et al., Omnipotent dark energy: A phenomenological answer to the Hubble tension, Phys. Rev. D 109 (2024) 023527 [2306.08046].

[239] G. Montani, M. De Angelis, F. Bombacigno and N. Carlevaro, Metric

[240] O. Akarsu, E. Di Valentino, S. Kumar, R.C. Nunes, J.A. Vazquez and A. Yadav,

[241] S. Vagnozzi, Seven Hints That Early-Time New Physics Alone Is Not Sufficient to Solve the Hubble Tension, Universe 9 (2023) 393 [2308.16628].

[242] O. Avsajanishvili, G.Y. Chitov, T. Kahniashvili, S. Mandal and L. Samushia, Observational Constraints on Dynamical Dark Energy Models, Universe 10 (2024) 122 [2310.16911].

[243] L. Giani, C. Howlett, K. Said, T. Davis and S. Vagnozzi, An effective description of Laniakea: impact on cosmology and the local determination of the Hubble constant, JCAP

[244] R. Lazkoz, V. Salzano, L. Fernandez-Jambrina and M. Bouhmadi-López, Ripped

[245] L.A. Escamilla, W. Giarè, E. Di Valentino, R.C. Nunes and S. Vagnozzi, The state of the dark energy equation of state circa 2023, JCAP 05 (2024) 091 [2307.14802].

[246] L.A. Escamilla, O. Akarsu, E. Di Valentino and J.A. Vazquez, Model-independent reconstruction of the interacting dark energy kernel: Binned and Gaussian process, JCAP 11 (2023) 051 [2305.16290].

[247] M. Rezaei, S. Pan, W. Yang and D.F. Mota, Evidence of dynamical dark energy in a non-flat universe: current and future observations, JCAP 01 (2024) 052 [2305.18544].

[248] E.M. Teixeira, R. Daniel, N. Frusciante and C. van de Bruck, Forecasts on interacting dark energy with standard sirens, Phys. Rev. D 108 (2023) 084070 [2309.06544].

[249] M. Forconi, W. Giarè, O. Mena, Ruchika, E. Di Valentino, A. Melchiorri et al., A double take on early and interacting dark energy from JWST, JCAP 05 (2024) 097 [2312.11074].

[250] M. Sebastianutti, N.B. Hogg and M. Bruni, The interacting vacuum and tensions: A comparison of theoretical models, Phys. Dark Univ. 46 (2024) 101546 [2312.14123].

[251] W.J. Wolf and P.G. Ferreira, Underdetermination of dark energy, Phys. Rev. D 108 (2023) 103519 [2310.07482].

[252] W. Giarè, E. Di Valentino, E.V. Linder and E. Specogna, Testing

[253] W. Giarè, M.A. Sabogal, R.C. Nunes and E. Di Valentino, Interacting Dark Energy after DESI Baryon Acoustic Oscillation measurements, 2404.15232.

[254] W. Giarè, Y. Zhai, S. Pan, E. Di Valentino, R.C. Nunes and C. van de Bruck, Tightening the reins on non-minimal dark sector physics: Interacting Dark Energy with dynamical and non-dynamical equation of state, 2404.02110.

[255] N. Menci, S.A. Adil, U. Mukhopadhyay, A.A. Sen and S. Vagnozzi, Negative cosmological constant in the dark energy sector: tests from JWST photometric and spectroscopic observations of high-redshift galaxies, 2401.12659.

[256] O. Akarsu, E.O. Colgáin, A.A. Sen and M.M. Sheikh-Jabbari,

[257] E.M. Teixeira, Illuminating the Dark Sector: Searching for new interactions between dark matter and dark energy, 1, 2024.

[258] D. Benisty, S. Pan, D. Staicova, E. Di Valentino and R.C. Nunes, Late-Time constraints on Interacting Dark Energy: Analysis independent of

[259] M. Najafi, S. Pan, E. Di Valentino and J.T. Firouzjaee, Dynamical dark energy confronted with multiple CMB missions, Phys. Dark Univ. 45 (2024) 101539.

[260] H. Moshafi, A. Talebian, E. Yusofi and E. Di Valentino, Observational constraints on the dark energy with a quadratic equation of state, Phys. Dark Univ. 45 (2024) 101524 [2403.02000].

[261] E. Silva, U. Zúñiga Bolaño, R.C. Nunes and E. Di Valentino, Non-Linear Matter Power Spectrum Modeling in Interacting Dark Energy Cosmologies, 2403. 19590.

[262] M. Reyhani, M. Najafi, J.T. Firouzjaee and E. Di Valentino, Structure formation in various dynamical dark energy scenarios, Phys. Dark Univ. 44 (2024) 101477 [2403. 15202].

[263] L.A. Escamilla, S. Pan, E. Di Valentino, A. Paliathanasis, J.A. Vázquez and W. Yang, Oscillations in the Dark?, 2404.00181.

[264] H. Wang, G. Ye and Y.-S. Piao, Impact of evolving dark energy on the search for primordial gravitational waves, 2407.11263.

[265] G. Montani, N. Carlevaro and M. De Angelis, Modified gravity in the presence of matter creation in the late Universe: alleviation of the Hubble tension, 2407.12409.

[266] T.-N. Li, P.-J. Wu, G.-H. Du, S.-J. Jin, H.-L. Li, J.-F. Zhang et al., Constraints on interacting dark energy models from the DESI BAO and DES supernovae data, 2407.14934.

[267] Y. Yang, X. Ren, Q. Wang, Z. Lu, D. Zhang, Y.-F. Cai et al., Quintom cosmology and modified gravity after DESI 2024, 2404.19437.

[268] S. Dwivedi and M. Högås, 2D BAO vs 3D BAO: solving the Hubble tension with alternative cosmological models, 2407.04322.

[269] ACT collaboration, The Atacama Cosmology Telescope: A Measurement of the DR6 CMB Lensing Power Spectrum and Its Implications for Structure Growth, Astrophys. J. 962 (2024) 112 [2304. 05202].

[270] SPT-3G collaboration, SPT-3G: A Next-Generation Cosmic Microwave Background Polarization Experiment on the South Pole Telescope, Proc. SPIE Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 9153 (2014) 91531P [1407. 2973].

[271] SPT-3G collaboration, Measurement of the CMB temperature power spectrum and constraints on cosmology from the SPT-3G 2018 TT, TE, and EE dataset, Phys. Rev. D 108 (2023) 023510 [2212.05642].

[272] A. Lewis and A. Challinor, Weak gravitational lensing of the CMB, Phys. Rept. 429 (2006) 1 [astro-ph/0601594].

[273] W. Giarè, E. Di Valentino, A. Melchiorri and O. Mena, New cosmological bounds on hot relics: axions and neutrinos, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 505 (2021) 2703 [2011.14704].

[274] E. Di Valentino and A. Melchiorri, Neutrino Mass Bounds in the Era of Tension Cosmology, Astrophys. J. Lett. 931 (2022) L18 [2112.02993].

[275] F. D’Eramo, E. Di Valentino, W. Giarè, F. Hajkarim, A. Melchiorri, O. Mena et al., Cosmological bound on the QCD axion mass, redux, JCAP 09 (2022) 022 [2205.07849].

[276] E. Di Valentino, S. Gariazzo, W. Giarè, A. Melchiorri, O. Mena and F. Renzi, Novel model-marginalized cosmological bound on the QCD axion mass, Phys. Rev. D 107 (2023) 103528 [2212.11926].

[277] W. Giarè, O. Mena and E. Di Valentino, Lensing impact on cosmic relics and tensions, Phys. Rev. D 108 (2023) 103539 [2307.14204].

[278] Planck collaboration, Planck 2018 results. VIII. Gravitational lensing, Astron. Astrophys. 641 (2020) A8 [1807.06210].

[279] G. Ye, J.-Q. Jiang and Y.-S. Piao, Shape of CMB lensing in the early dark energy cosmology, Phys. Rev. D 108 (2023) 063512 [2305.18873].

[280] ACT, DES collaboration, Cosmology from cross-correlation of ACT-DR4 CMB lensing and DES-Y3 cosmic shear, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 528 (2024) 2112 [2309.04412].

[281] ACT, DES collaboration, Cosmological constraints from the tomography of DES-Y3 galaxies with CMB lensing from ACT DR4, JCAP 01 (2024) 033 [2306.17268].

[282] ACT, DESI collaboration, The Atacama Cosmology Telescope DR6 and DESI: Structure formation over cosmic time with a measurement of the cross-correlation of CMB Lensing and Luminous Red Galaxies, 2407.04606.

[283] N. Sailer et al., Cosmological constraints from the cross-correlation of DESI Luminous Red Galaxies with CMB lensing from Planck PR4 and ACT DR6, 2407.04607.

[284] ACT collaboration, The Atacama Cosmology Telescope: DR6 Gravitational Lensing and SDSS BOSS cross-correlation measurement and constraints on gravity with the

[285] EUCLID collaboration, Euclid Definition Study Report, 1110.3193.

[286] LSST collaboration, LSST: from Science Drivers to Reference Design and Anticipated Data Products, Astrophys. J. 873 (2019) 111 [0805.2366].

[287] D. Spergel et al., Wide-Field InfraRed Survey Telescope-Astrophysics Focused Telescope Assets WFIRST-AFTA Final Report, 1305.5422.

[288] SKA collaboration, Cosmology with Phase 1 of the Square Kilometre Array: Red Book 2018: Technical specifications and performance forecasts, Publ. Astron. Soc. Austral. 37 (2020) e007 [1811.02743].

[289] E. Di Valentino, O. Mena, S. Pan, L. Visinelli, W. Yang, A. Melchiorri et al., In the realm of the Hubble tension-a review of solutions, Class. Quant. Grav. 38 (2021) 153001 [2103.01183].

[290] L. Perivolaropoulos and F. Skara, Challenges for

[291] E. Abdalla et al., Cosmology intertwined: A review of the particle physics, astrophysics, and cosmology associated with the cosmological tensions and anomalies, JHEAp 34 (2022) 49 [2203.06142].

[292] S. Gariazzo, W. Giarè, O. Mena and E. Di Valentino, How robust are the parameter constraints extending the

[293] R. Bean and A. Melchiorri, Current constraints on the dark energy equation of state, Phys. Rev. D 65 (2002) 041302 [astro-ph/0110472].

[294] S. Hannestad and E. Mortsell, Probing the dark side: Constraints on the dark energy equation of state from CMB, large scale structure and Type Ia supernovae, Phys. Rev. D 66 (2002) 063508 [astro-ph/0205096].

[295] N. Said, C. Baccigalupi, M. Martinelli, A. Melchiorri and A. Silvestri, New Constraints On The Dark Energy Equation of State, Phys. Rev. D 88 (2013) 043515 [1303.4353].

[296] D.L. Shafer and D. Huterer, Chasing the phantom: A closer look at Type Ia supernovae and the dark energy equation of state, Phys. Rev. D 89 (2014) 063510 [1312.1688].

[297] X. Zhang, Impacts of dark energy on weighing neutrinos after Planck 2015, Phys. Rev. D 93 (2016) 083011 [1511.02651].

[298] Y.-Y. Xu and X. Zhang, Comparison of dark energy models after Planck 2015, Eur. Phys. J.

[299] S. Wang, Y.-F. Wang, D.-M. Xia and X. Zhang, Impacts of dark energy on weighing neutrinos: mass hierarchies considered, Phys. Rev. D 94 (2016) 083519 [1608.00672].

[300] S. Vagnozzi, E. Giusarma, O. Mena, K. Freese, M. Gerbino, S. Ho et al., Unveiling

[301] X. Zhang, Weighing neutrinos in dynamical dark energy models, Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 60 (2017) 060431 [1703.00651].

[302] L. Feng, J.-F. Zhang and X. Zhang, Searching for sterile neutrinos in dynamical dark energy cosmologies, Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 61 (2018) 050411 [1706.06913].

[303] D. Wang, Dark Energy Constraints in light of Pantheon SNe Ia, BAO, Cosmic Chronometers and CMB Polarization and Lensing Data, Phys. Rev. D 97 (2018) 123507 [1801.02371].

[304] T. Sprenger, M. Archidiacono, T. Brinckmann, S. Clesse and J. Lesgourgues, Cosmology in the era of Euclid and the Square Kilometre Array, JCAP 02 (2019) 047 [1801.08331].

[305] V. Poulin, K.K. Boddy, S. Bird and M. Kamionkowski, Implications of an extended dark energy cosmology with massive neutrinos for cosmological tensions, Phys. Rev. D 97 (2018) 123504 [1803.02474].

[306] S. Roy Choudhury and A. Naskar, Strong Bounds on Sum of Neutrino Masses in a 12 Parameter Extended Scenario with Non-Phantom Dynamical Dark Energy

[307] DES collaboration, Dark Energy Survey Year 1 Results: Constraints on Extended Cosmological Models from Galaxy Clustering and Weak Lensing, Phys. Rev. D 99 (2019) 123505 [1810.02499].

[308] D. Wang, Exploring new physics beyond the standard cosmology with Dark Energy Survey Year 1 Data, Phys. Dark Univ. 32 (2021) 100810 [1904.00657].

[309] S. Roy Choudhury and S. Hannestad, Updated results on neutrino mass and mass hierarchy from cosmology with Planck 2018 likelihoods, JCAP 07 (2020) 037 [1907.12598].

[310] A. Chudaykin, K. Dolgikh and M.M. Ivanov, Constraints on the curvature of the Universe and dynamical dark energy from the Full-shape and BAO data, Phys. Rev. D 103 (2021) 023507 [2009. 10106].

[311] G. D’Amico, L. Senatore and P. Zhang, Limits on wCDM from the EFTofLSS with the PyBird code, JCAP 01 (2021) 006 [2003.07956].

[312] S. Vagnozzi, A. Loeb and M. Moresco, Eppur è piatto? The Cosmic Chronometers Take on Spatial Curvature and Cosmic Concordance, Astrophys. J. 908 (2021) 84 [2011.11645].

[313] W. Yang, E. Di Valentino, S. Pan, Y. Wu and J. Lu, Dynamical dark energy after Planck CMB final release and

[314] E. Di Valentino, A combined analysis of the

[315] S. Brieden, H. Gil-Marín and L. Verde, Model-agnostic interpretation of 10 billion years of cosmic evolution traced by BOSS and eBOSS data, JCAP 08 (2022) 024 [2204.11868].

[316] C. Grillo, P. Rosati, S.H. Suyu, G.B. Caminha, A. Mercurio and A. Halkola, On the accuracy of time-delay cosmography in the Frontier Fields Cluster MACS J1149.5+2223 with supernova Refsdal, Astrophys. J. 898 (2020) 87 [2001. 02232].

[317] S. Cao, J. Ryan and B. Ratra, Cosmological constraints from Hii starburst galaxy, quasar angular size, and other measurements, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 509 (2022) 4745 [2109.01987].

[318] M. Zhang, B. Wang, P.-J. Wu, J.-Z. Qi, Y. Xu, J.-F. Zhang et al., Prospects for Constraining Interacting Dark Energy Models with 21 cm Intensity Mapping Experiments, Astrophys. J. 918 (2021) 56 [2102.03979].

[319] E.O. Colgáin, M.M. Sheikh-Jabbari and L. Yin, Can dark energy be dynamical?, Phys. Rev. D 104 (2021) 023510 [2104.01930].

[320] Y.-P. Teng, W. Lee and K.-W. Ng, Constraining the dark-energy equation of state with cosmological data, Phys. Rev. D 104 (2021) 083519 [2105.02667].

[321] C. Krishnan, R. Mohayaee, E.O. Colgáin, M.M. Sheikh-Jabbari and L. Yin, Does Hubble tension signal a breakdown in FLRW cosmology?, Class. Quant. Grav. 38 (2021) 184001 [2105.09790].

[322] R.C. Nunes and S. Vagnozzi, Arbitrating the S8 discrepancy with growth rate measurements from redshift-space distortions, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 505 (2021) 5427 [2106.01208].

[323] R.C. Bernardo, D. Grandón, J. Said Levi and V.H. Cárdenas, Parametric and nonparametric methods hint dark energy evolution, Phys. Dark Univ. 36 (2022) 101017 [2111.08289].

[324] G. Bargiacchi, M. Benetti, S. Capozziello, E. Lusso, G. Risaliti and M. Signorini, Quasar cosmology: dark energy evolution and spatial curvature, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 515 (2022) 1795 [2111.02420].

[325] A. Semenaite, A.G. Sánchez, A. Pezzotta, J. Hou, A. Eggemeier, M. Crocce et al., Beyond

[326] P. Carrilho, C. Moretti and A. Pourtsidou, Cosmology with the EFTofLSS and BOSS: dark energy constraints and a note on priors, JCAP 01 (2023) 028 [2207.14784].

[327] D. Wang, Pantheon + constraints on dark energy and modified gravity: An evidence of dynamical dark energy, Phys. Rev. D 106 (2022) 063515 [2207.07164].

[328] M. Koussour, S.K.J. Pacif, M. Bennai and P.K. Sahoo, A New Parametrization of Hubble Parameter in

[329] R.C. Bernardo, D. Grandón, J. Levi Said and V.H. Cárdenas, Dark energy by natural evolution: Constraining dark energy using Approximate Bayesian Computation, Phys. Dark Univ. 40 (2023) 101213 [2211.05482].

[330] S.A. Narawade and B. Mishra, Phantom Cosmological Model with Observational Constraints in

[331] W.-T. Hou, J.-Z. Qi, T. Han, J.-F. Zhang, S. Cao and X. Zhang, Prospects for constraining interacting dark energy models from gravitational wave and gamma ray burst joint observation, JCAP 05 (2023) 017 [2211.10087].

[332] S. Kumar, R.C. Nunes, S. Pan and P. Yadav, New late-time constraints on

[333] R. Bhagat, S.A. Narawade and B. Mishra, Weyl type

[334] A. Mussatayeva, N. Myrzakulov and M. Koussour, Cosmological constraints on dark energy in f(Q) gravity: A parametrized perspective, Phys. Dark Univ. 42 (2023) 101276 [2307.00281].

[335] N.B. Hogg, Constraints on dark energy from TDCOSMO & SLACS lenses, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 528 (2024) L95 [2310.11977].

[336] DESI collaboration, DESI 2024 VI: Cosmological Constraints from the Measurements of Baryon Acoustic Oscillations, 2404.03002.

[337] L. Verde, T. Treu and A.G. Riess, Tensions between the Early and the Late Universe, Nature Astron. 3 (2019) 891 [1907. 10625].

[338] J.-P. Hu and F.-Y. Wang, Hubble Tension: The Evidence of New Physics, Universe 9 (2023) 94 [2302.05709].

[339] W. Giarè, Inflation, the Hubble tension, and early dark energy: An alternative overview, Phys. Rev. D 109 (2024) 123545 [2404.12779].

[340] W. Giarè, CMB Anomalies and the Hubble Tension, 2305. 16919.

[341] R. Mainini, A.V. Maccio, S.A. Bonometto and A. Klypin, Modeling dynamical dark energy, Astrophys. J. 599 (2003) 24 [astro-ph/0303303].

[342] U. Alam, V. Sahni and A.A. Starobinsky, The Case for dynamical dark energy revisited, JCAP 06 (2004) 008 [astro-ph/0403687].

[343] J. Sola and H. Stefancic, Dynamical dark energy or variable cosmological parameters?, Mod. Phys. Lett. A 21 (2006) 479 [astro-ph/0507110].

[344] I. Antoniadis, P.O. Mazur and E. Mottola, Cosmological dark energy: Prospects for a dynamical theory, New J. Phys. 9 (2007) 11 [gr-qc/0612068].

[345] G.-B. Zhao, R.G. Crittenden, L. Pogosian and X. Zhang, Examining the evidence for dynamical dark energy, Phys. Rev. Lett. 109 (2012) 171301 [1207.3804].

[346] J. Solà Peracaula, J. de Cruz Pérez and A. Gómez-Valent, Dynamical dark energy vs.

[347] J. Sola, A. Gomez-Valent and J. de Cruz Pérez, Dynamical dark energy: scalar fields and running vacuum, Mod. Phys. Lett. A 32 (2017) 1750054 [1610.08965].

[348] G.-B. Zhao et al., Dynamical dark energy in light of the latest observations, Nature Astron. 1 (2017) 627 [1701.08165].

[349] W. Yang, N. Banerjee and S. Pan, Constraining a dark matter and dark energy interaction scenario with a dynamical equation of state, Phys. Rev. D 95 (2017) 123527 [1705.09278].

[350] J. Sola Peracaula, A. Gomez-Valent and J. de Cruz Pérez, Signs of Dynamical Dark Energy in Current Observations, Phys. Dark Univ. 25 (2019) 100311 [1811.03505].

[351] S. Pan, W. Yang, E. Di Valentino, E.N. Saridakis and S. Chakraborty, Interacting scenarios with dynamical dark energy: Observational constraints and alleviation of the

[352] C. Escamilla-Rivera and A. Nájera, Dynamical dark energy models in the light of gravitational-wave transient catalogues, JCAP 03 (2022) 060 [2103.02097].

[353] Z.-W. Zhao, Z.-X. Li, J.-Z. Qi, H. Gao, J.-F. Zhang and X. Zhang, Cosmological parameter estimation for dynamical dark energy models with future fast radio burst observations, Astrophys. J. 903 (2020) 83 [2006.01450].

[354] E. Di Valentino, A. Melchiorri, E.V. Linder and J. Silk, Constraining Dark Energy Dynamics in Extended Parameter Space, Phys. Rev. D 96 (2017) 023523 [1704.00762].

[355] E. Di Valentino, A. Melchiorri and J. Silk, Cosmological constraints in extended parameter space from the Planck 2018 Legacy release, JCAP 01 (2020) 013 [1908.01391].

[356] E. Di Valentino, W. Giarè, A. Melchiorri and J. Silk, Health checkup test of the standard cosmological model in view of recent cosmic microwave background anisotropies experiments, Phys. Rev. D 106 (2022) 103506 [2209.12872].

[357] D. Rubin et al., Union Through UNITY: Cosmology with 2,000 SNe Using a Unified Bayesian Framework, 2311.12098.

[358] D. Scolnic et al., The Pantheon + Analysis: The Full Data Set and Light-curve Release, Astrophys. J. 938 (2022) 113 [2112.03863].

[359] M. Cortês and A.R. Liddle, Interpreting DESI’s evidence for evolving dark energy, 2404.08056.

[360] V. Patel and L. Amendola, Comments on the prior dependence of the DESI results, 2407.06586.

[361] L. Orchard and V.H. Cárdenas, Probing Dark Energy Evolution Post-DESI 2024, 2407.05579.

[362] G. Liu, Y. Wang and W. Zhao, Impact of LRG1 and LRG2 in DESI 2024 BAO data on dark energy evolution, 2407.04385.

[363] A. Chudaykin and M. Kunz, Modified gravity interpretation of the evolving dark energy in light of DESI data, 2407. 02558.

[364] A. Notari, M. Redi and A. Tesi, Consistent Theories for the DESI dark energy fit, 2406.08459.

[365] I.D. Gialamas, G. Hütsi, K. Kannike, A. Racioppi, M. Raidal, M. Vasar et al., Interpreting DESI 2024 BAO: late-time dynamical dark energy or a local effect?, 2406.07533.

[366] H. Wang, Z.-Y. Peng and Y.-S. Piao, Can recent DESI BAO measurements accommodate a negative cosmological constant?, 2406.03395.

[367] H. Wang and Y.-S. Piao, Dark energy in light of recent DESI BAO and Hubble tension, 2404.18579.

[368] Y. Carloni, O. Luongo and M. Muccino, Does dark energy really revive using DESI 2024 data?, 2404. 12068.

[369] E.O. Colgáin, M.G. Dainotti, S. Capozziello, S. Pourojaghi, M.M. Sheikh-Jabbari and D. Stojkovic, Does DESI 2024 Confirm

[370] Y. Tada and T. Terada, Quintessential interpretation of the evolving dark energy in light of DESI observations, Phys. Rev. D 109 (2024) L121305 [2404.05722].

[371] W. Yin, Cosmic clues: DESI, dark energy, and the cosmological constant problem, JHEP 05 (2024) 327 [2404.06444].

[372] O. Luongo and M. Muccino, Model independent cosmographic constraints from DESI 2024, 2404.07070.

[373] C.-G. Park, J. de Cruz Perez and B. Ratra, Using non-DESI data to confirm and strengthen the DESI 2024 spatially-flat

[374] D. Shlivko and P.J. Steinhardt, Assessing observational constraints on dark energy, Phys. Lett. B 855 (2024) 138826 [2405.03933].

[375] G. Ye, M. Martinelli, B. Hu and A. Silvestri, Non-minimally coupled gravity as a physically viable fit to DESI 2024 BAO, 2407.15832.

[376] Z. Wang, S. Lin, Z. Ding and B. Hu, The role of LRG1 and LRG2’s monopole in inferring the DESI 2024 BAO cosmology, 2405.02168.

[377] D. Naredo-Tuero, M. Escudero, E. Fernández-Martínez, X. Marcano and V. Poulin, Living at the Edge: A Critical Look at the Cosmological Neutrino Mass Bound, 2407.13831.

[378] R. de Putter and E.V. Linder, Calibrating Dark Energy, JCAP 10 (2008) 042 [0808.0189].

[379] A. Hernández-Almada, M.L. Mendoza-Martínez, M.A. García-Aspeitia and V. Motta, Phenomenological emergent dark energy in the light of DESI Data Release 1, 2407. 09430.

[380] S. Pourojaghi, M. Malekjani and Z. Davari, Cosmological constraints on dark energy parametrizations after DESI 2024: Persistent deviation from standard

[381] O.F. Ramadan, J. Sakstein and D. Rubin, DESI Constraints on Exponential Quintessence, 2405.18747.

[382] K.V. Berghaus, J.A. Kable and V. Miranda, Quantifying Scalar Field Dynamics with DESI 2024 Y1 BAO measurements, 2404.14341.

[383] F.J. Qu, K.M. Surrao, B. Bolliet, J.C. Hill, B.D. Sherwin and H.T. Jense, Accelerated inference on accelerated cosmic expansion: New constraints on axion-like early dark energy with DESI BAO and ACT DR6 CMB lensing, 2404.16805.

[384] P. Adolf, M. Hirsch, S. Krieg, H. Päs and M. Tabet, Fitting the DESI BAO Data with Dark Energy Driven by the Cohen-Kaplan-Nelson Bound, 2406.09964.

[385] C.-P. Ma and E. Bertschinger, Cosmological perturbation theory in the synchronous and conformal Newtonian gauges, Astrophys. J. 455 (1995) 7 [astro-ph/9506072].

[386] N. Dimakis, A. Karagiorgos, A. Zampeli, A. Paliathanasis, T. Christodoulakis and P.A. Terzis, General Analytic Solutions of Scalar Field Cosmology with Arbitrary Potential, Phys. Rev. D 93 (2016) 123518 [1604.05168].

[387] S. Pan, W. Yang and A. Paliathanasis, Imprints of an extended Chevallier-Polarski-Linder parametrization on the large scale of our universe, Eur. Phys. J. C 80 (2020) 274 [1902.07108].

[388] A. Lewis, A. Challinor and A. Lasenby, Efficient computation of CMB anisotropies in closed FRW models, Astrophys. J. 538 (2000) 473 [astro-ph/9911177].

[389] C. Howlett, A. Lewis, A. Hall and A. Challinor, CMB power spectrum parameter degeneracies in the era of precision cosmology, JCAP

[390] A. Lewis and S. Bridle, Cosmological parameters from CMB and other data: A Monte Carlo approach, Phys. Rev. D 66 (2002) 103511 [astro-ph/0205436].

[391] A. Lewis, Efficient sampling of fast and slow cosmological parameters, Phys. Rev. D 87 (2013) 103529 [1304.4473].

[392] R.M. Neal, Taking Bigger Metropolis Steps by Dragging Fast Variables, ArXiv Mathematics e-prints (2005) [math/0502099].

[393] A. Gelman and D.B. Rubin, Inference from Iterative Simulation Using Multiple Sequences, Statist. Sci. 7 (1992) 457.

[394] Planck collaboration, Planck 2018 results. V. CMB power spectra and likelihoods, Astron. Astrophys. 641 (2020) A5 [1907.12875].

[395] J. Carron, M. Mirmelstein and A. Lewis, CMB lensing from Planck PR4 maps, JCAP 09 (2022) 039 [2206.07773].

[396] DESI collaboration, DESI 2024 IV: Baryon Acoustic Oscillations from the Lyman Alpha Forest, 2404.03001.

[397] D. Huterer and M.S. Turner, Probing the dark energy: Methods and strategies, Phys. Rev. D 64 (2001) 123527 [astro-ph/0012510].

[398] A. Albrecht et al., Report of the Dark Energy Task Force, astro-ph/0609591.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1088/1475-7516/2024/10/035

Publication Date: 2024-10-01

Robust Preference for Dynamical Dark Energy in DESI BAO and SN Measurements

Abstract

Recent Baryon Acoustic Oscillation (BAO) measurements released by DESI, when combined with Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) data from Planck and two different samples of Type Ia supernovae (Pantheon-Plus and DESY5) reveal a preference for Dynamical Dark Energy (DDE) characterized by a present-day quintessence-like equation of state that crossed into the phantom regime in the past. A core ansatz for this result is assuming a linear Chevallier-Polarski-Linder (CPL) parameterization

Contents

2 Dynamical Dark Energy Models ….. 5

2.1 Chevallier-Polarski-Linder parametrization ….. 5

2.2 Exponential parametrization ….. 6

2.3 Jassal-Bagla-Padmanabhan parametrization ….. 6

2.4 Logarithmic parametrization ….. 6

2.5 Barboza-Alcaniz parametrization ….. 7

3 Methods ….. 7

3.1 Statistical Analyses ….. 7

3.2 Datasets ….. 8

4 Results ….. 9

4.1 Results for the CPL parameterization ….. 10

4.2 Results for the Exponential parametrization ….. 11

4.3 Results for the JBP parametrization ….. 13

4.4 Results for the Logarithmic parametrization ….. 15

4.5 Results for the BA parametrization ….. 17

5 Discussions and Conclusions ….. 18

A Equation of State, pivot redshift, and phantom crossing across the different models ….. 21

1 Introduction

2 Dynamical Dark Energy Models

2.1 Chevallier-Polarski-Linder parametrization

2.2 Exponential parametrization

2.3 Jassal-Bagla-Padmanabhan parametrization

2.4 Logarithmic parametrization

| Parameter | Prior |

|

|

[0.005, 0.1] |

|

|

[0.01, 0.99] |

|

|

[1.61, 3.91] |

|

|

[0.8, 1.2] |

|

|

[0.01, 0.8] |

|

|

[0.5, 10] |

|

|

[-3,1] |

|

|

[-3, 2] |

2.5 Barboza-Alcaniz parametrization

3 Methods

3.1 Statistical Analyses

analyses via the publicly available sampler Cobaya [390, 391] that employs the fast dragging speed hierarchy implementation [392]. The convergence of the generated MCMC chains is assessed via the Gelman-Rubin parameter

3.2 Datasets

- Planck: Measurements of the Planck CMB temperature anisotropy and polarization power spectra, their cross-spectra, and the combination of the ACT and Planck lensing power spectrum. All CMB likelihoods employed in this work are listed below:

(i) Measurements of the power spectra of temperature and polarization anisotropies,

(ii) Measurements of the spectrum of temperature anisotropies,

(iii) Measurements of the spectrum of E-mode polarization,

(iv) Reconstruction of the spectrum of the lensing potential, obtained by the Planck PR4 NPIPE data release [395] used in combination with ACT-DR6 lensing likelihood [56, 269]. - DESI: Baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO) measurements extracted by observations of galaxies & quasars [58], and Lyman-

- PantheonPlus: Distance moduli measurements of 1701 light curves of 1550 spectroscopically confirmed type Ia SN sourced from eighteen different surveys, gathered from the Pantheon-plus sample [55, 358].

- DESY5: Distance moduli measurements of 1635 Type Ia SN covering the redshift range of

4 Results

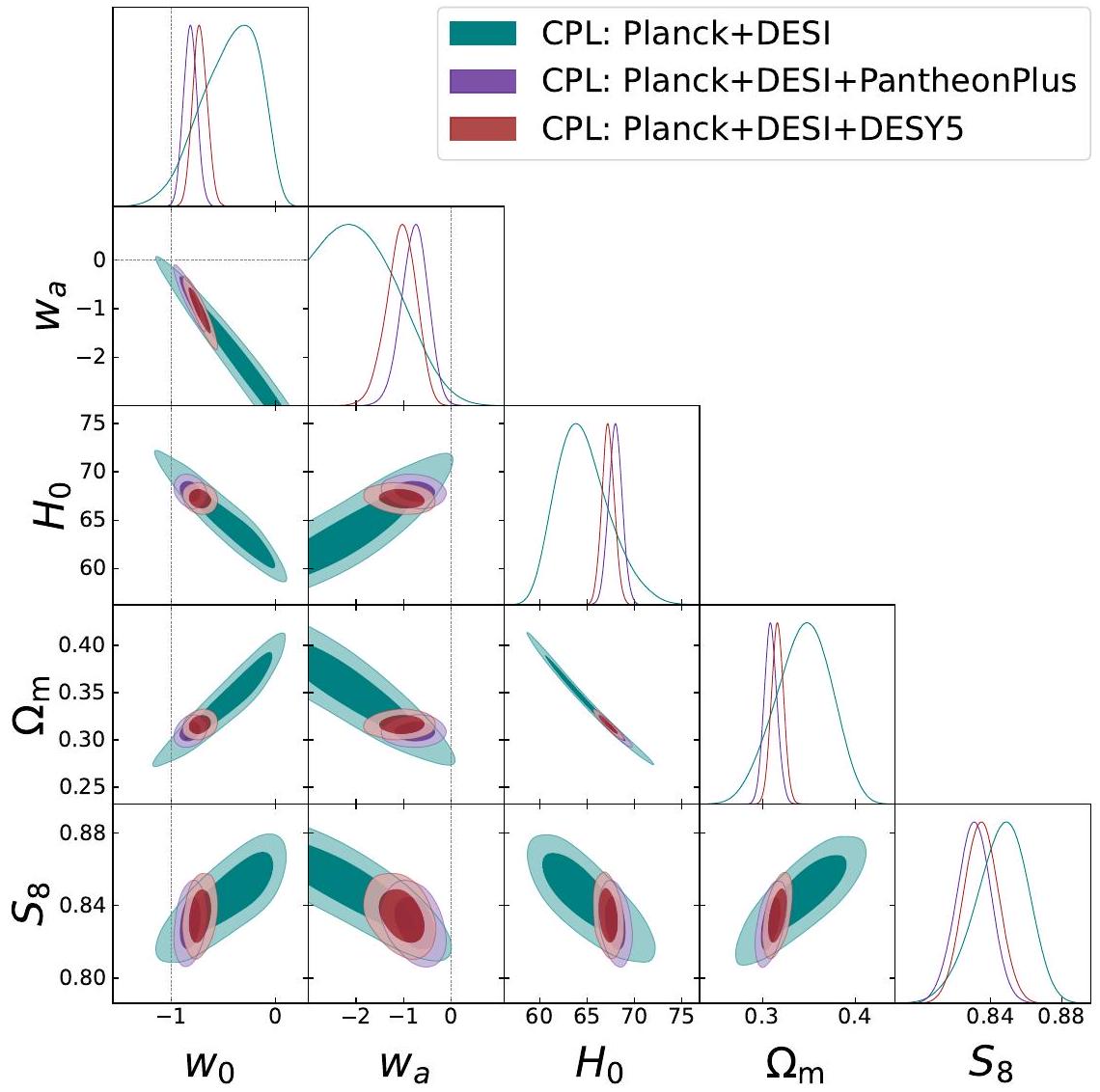

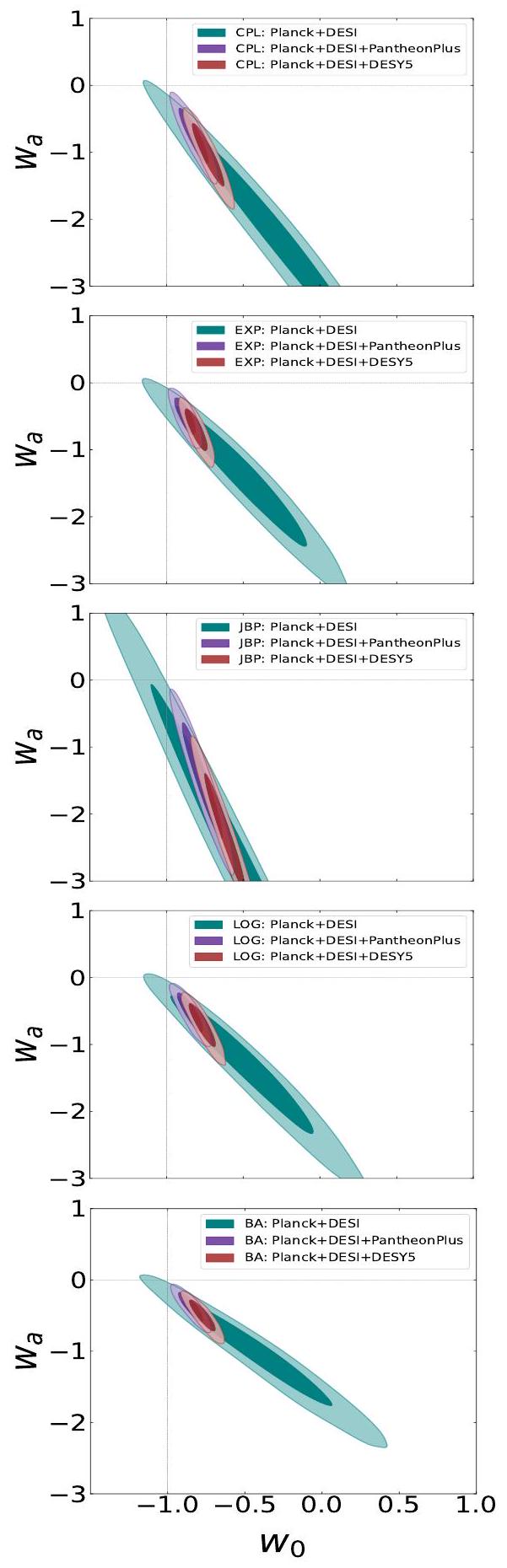

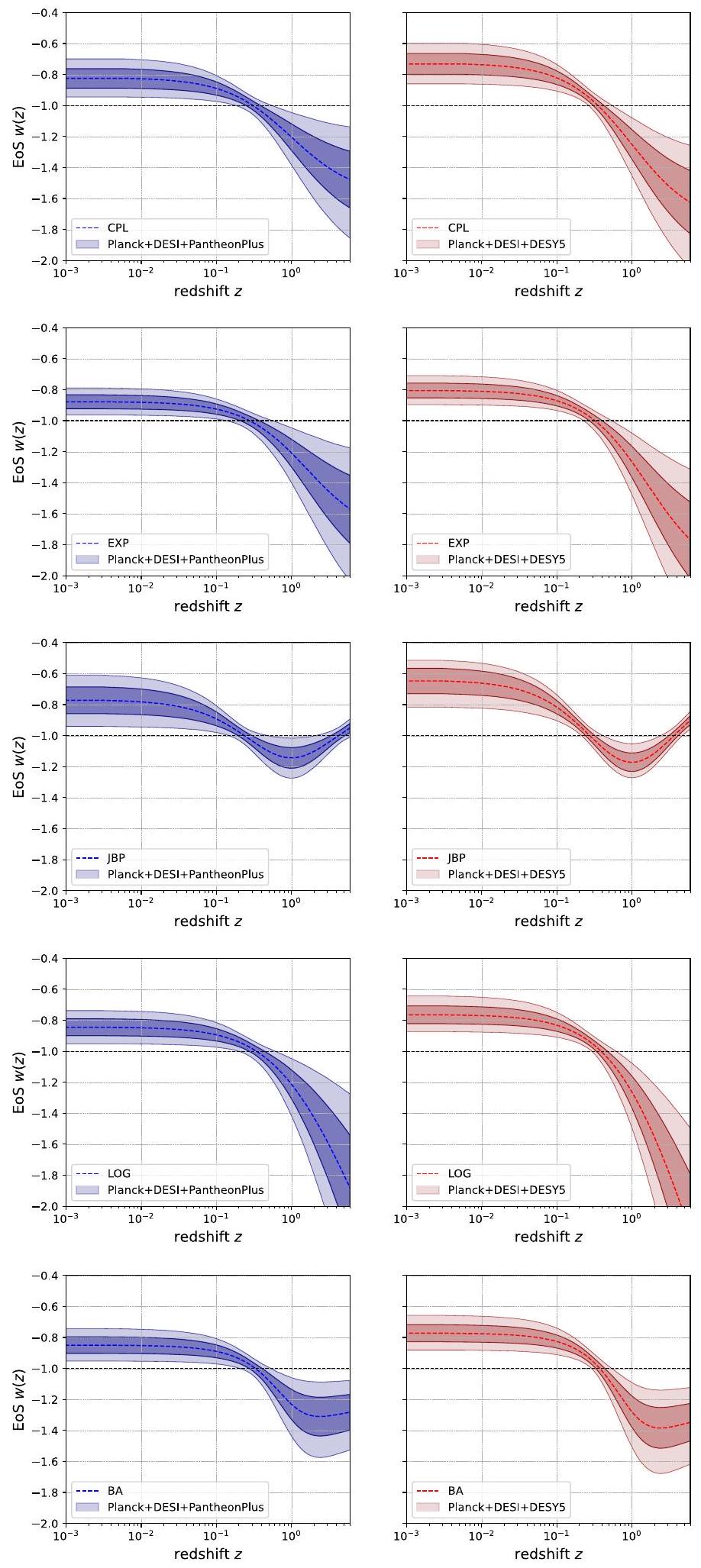

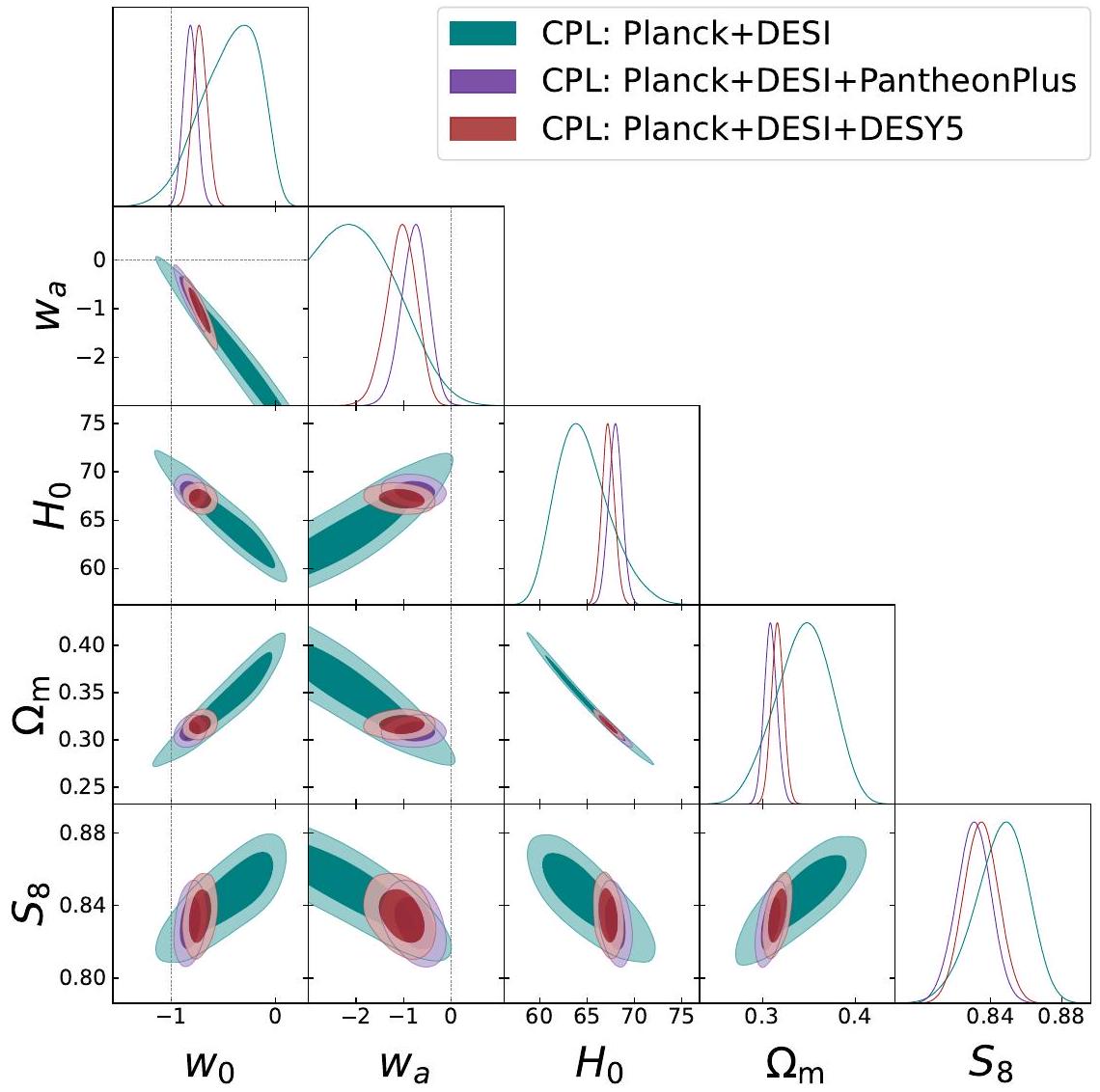

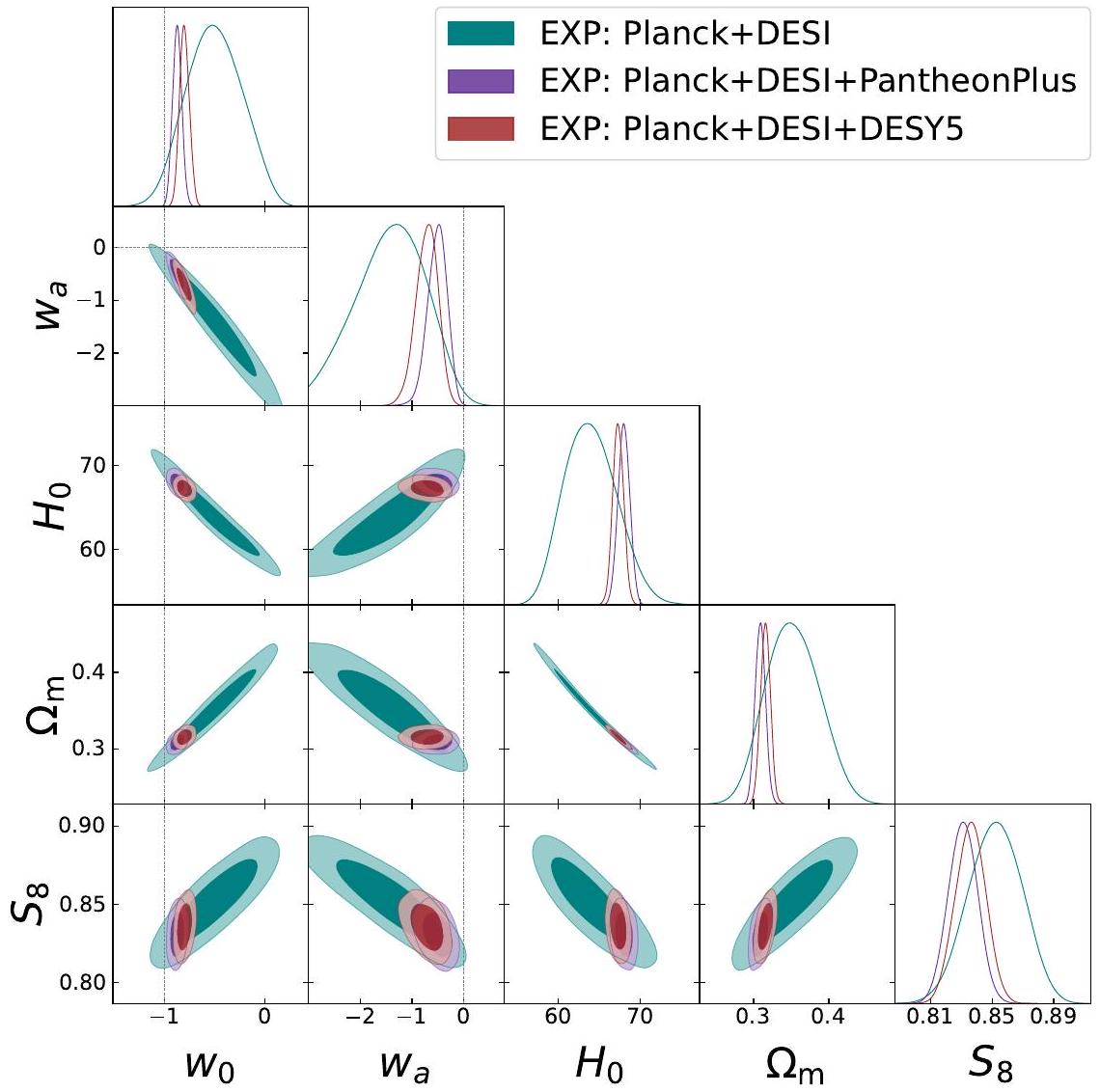

- Table 2 and Figure 1 summarize the numerical constraints and parameter correlations for the baseline CPL case (2.5). The results for this case are detailed in Sec. 4.1.

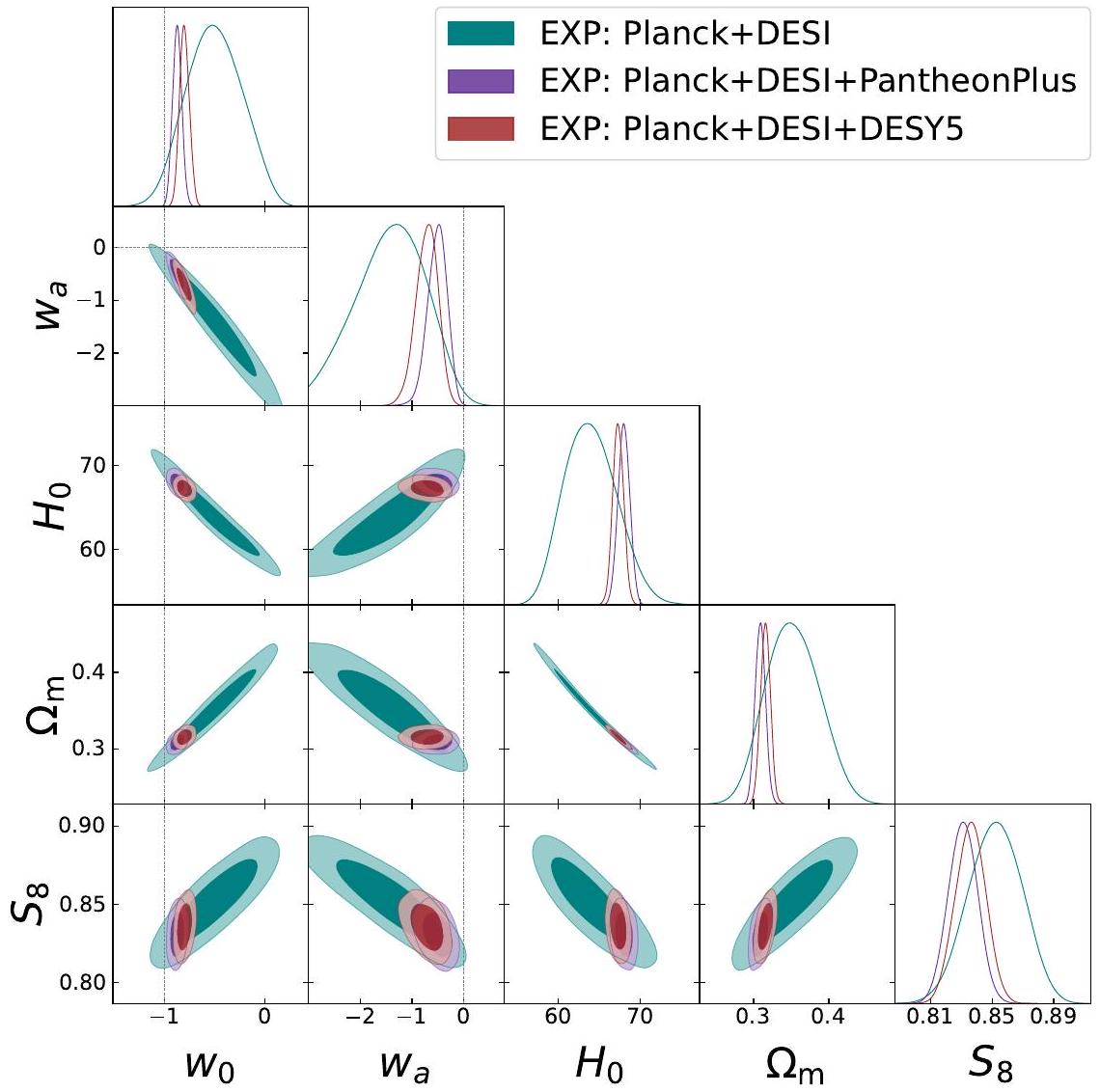

- Table 3 and Figure 2 present the results for the exponential parameterization (2.6), discussed in Sec. 4.2.

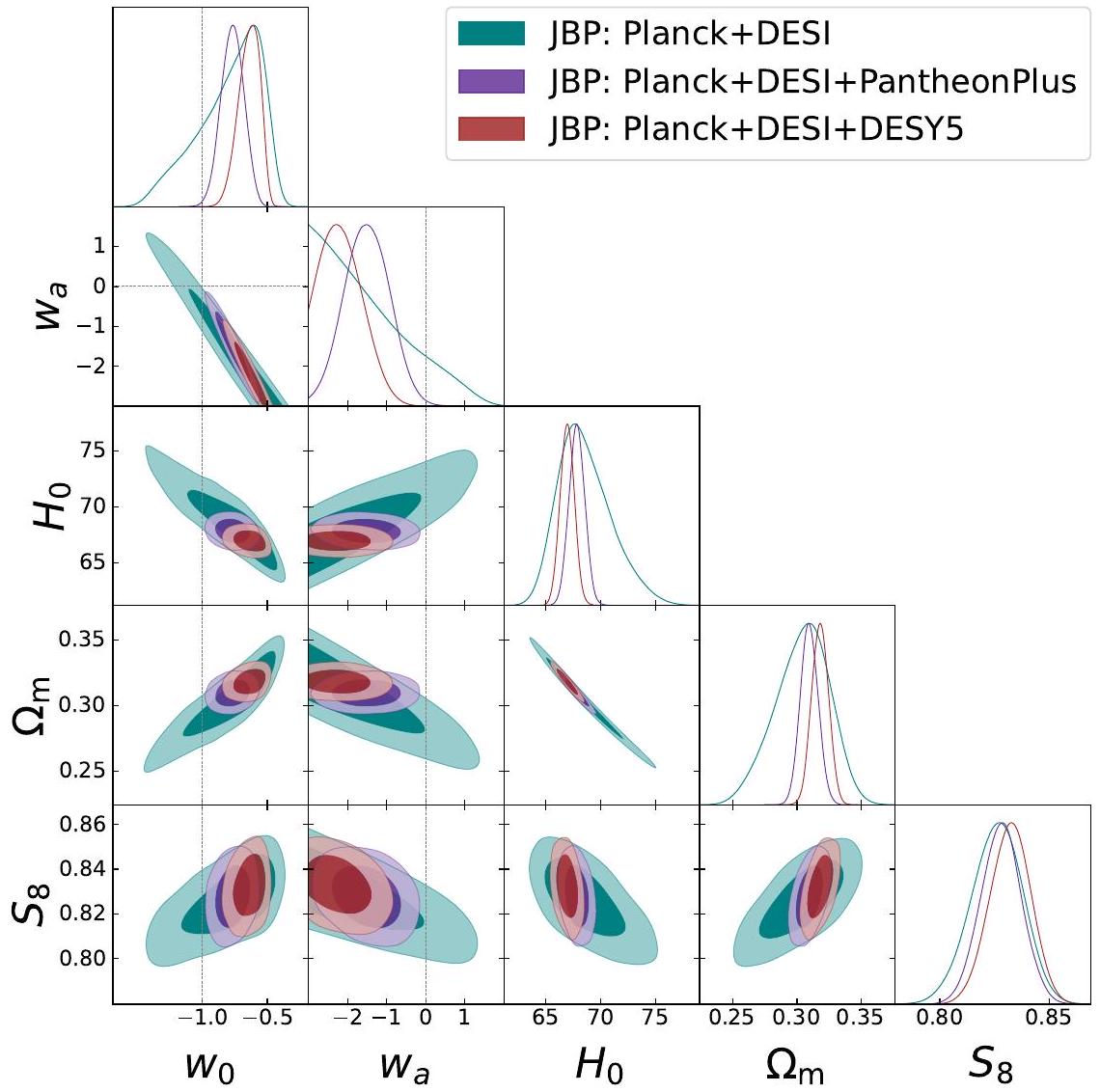

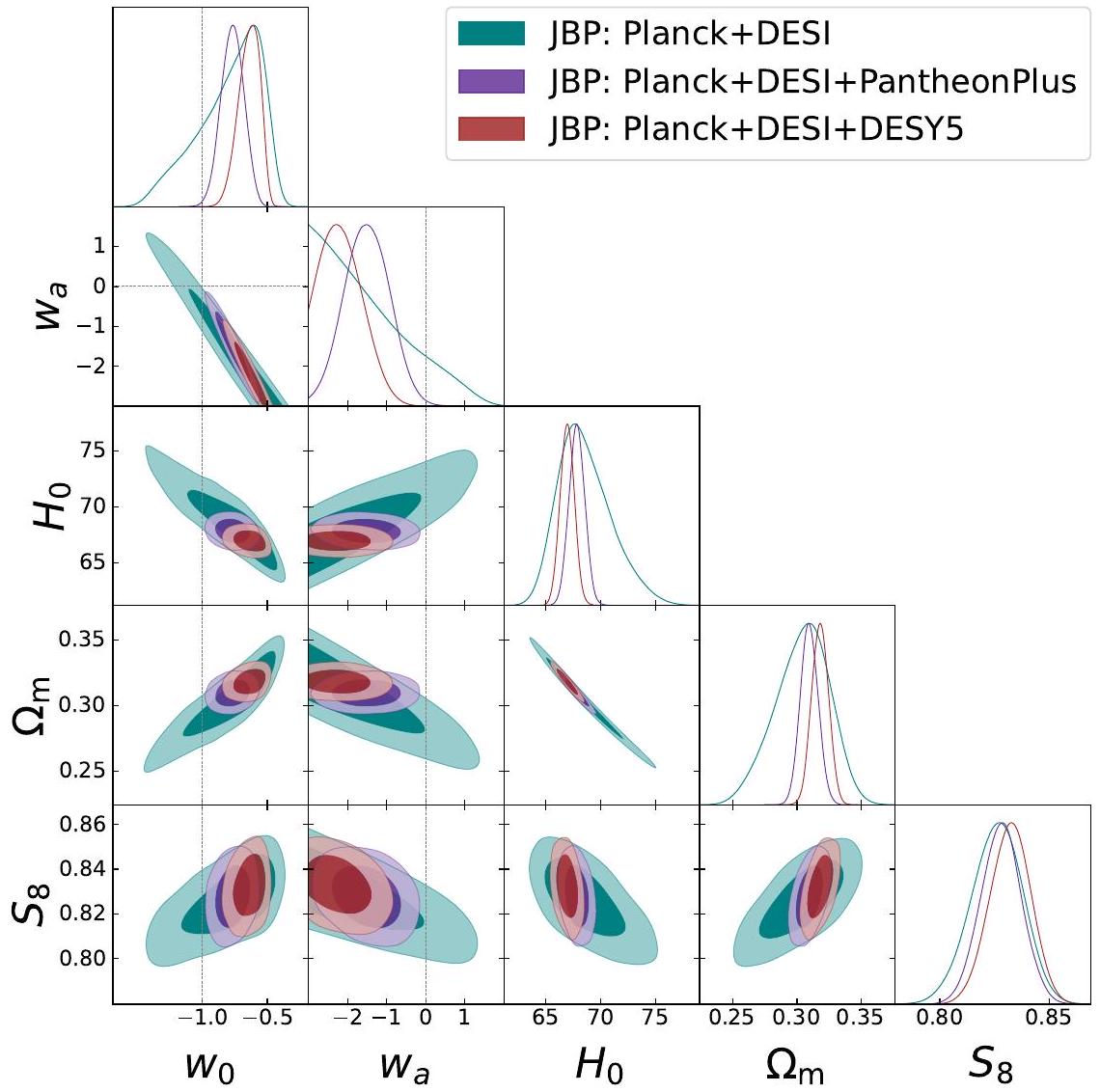

- Table 4 and Figure 3 provide the results for the JBP EoS (2.7), discussed in Sec. 4.3.

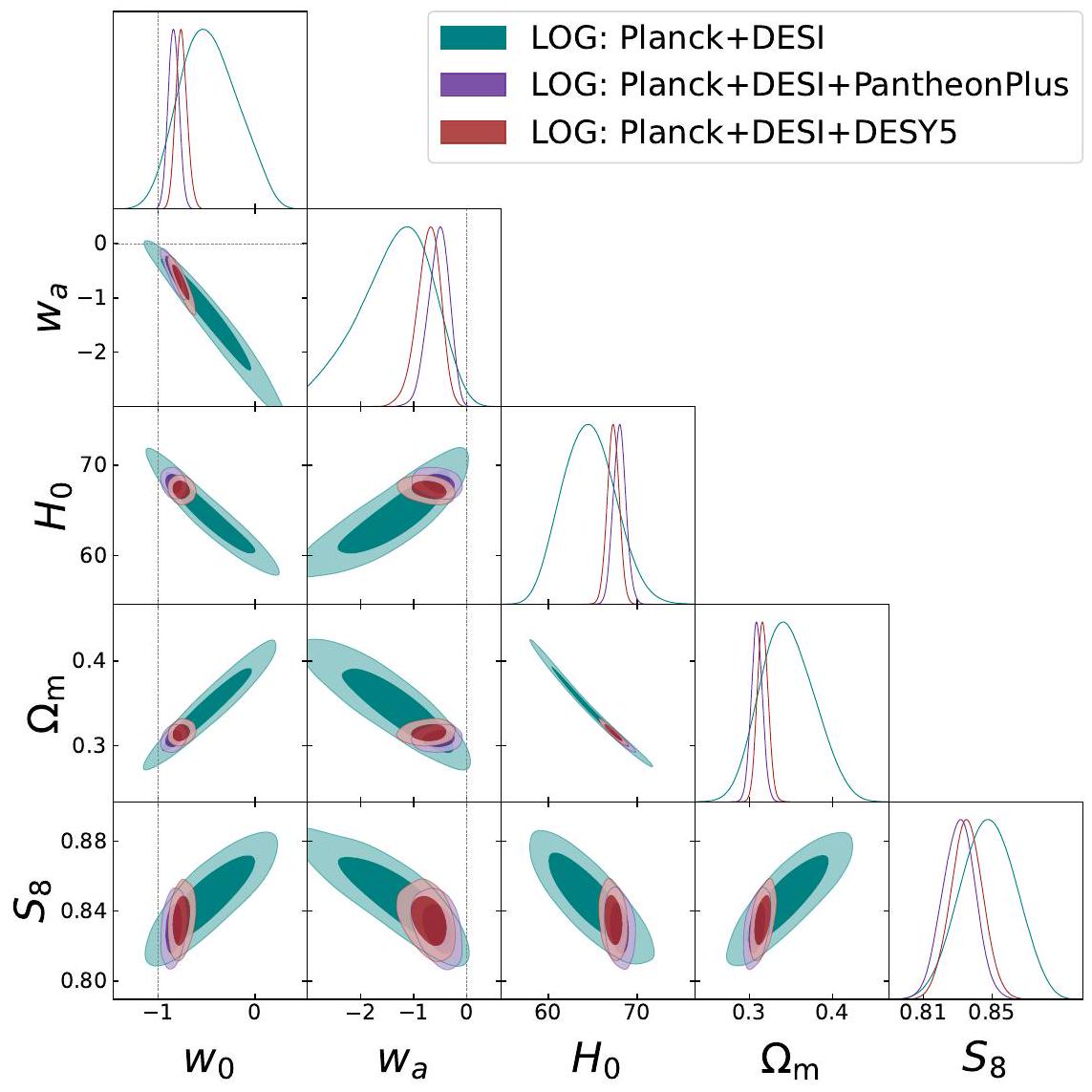

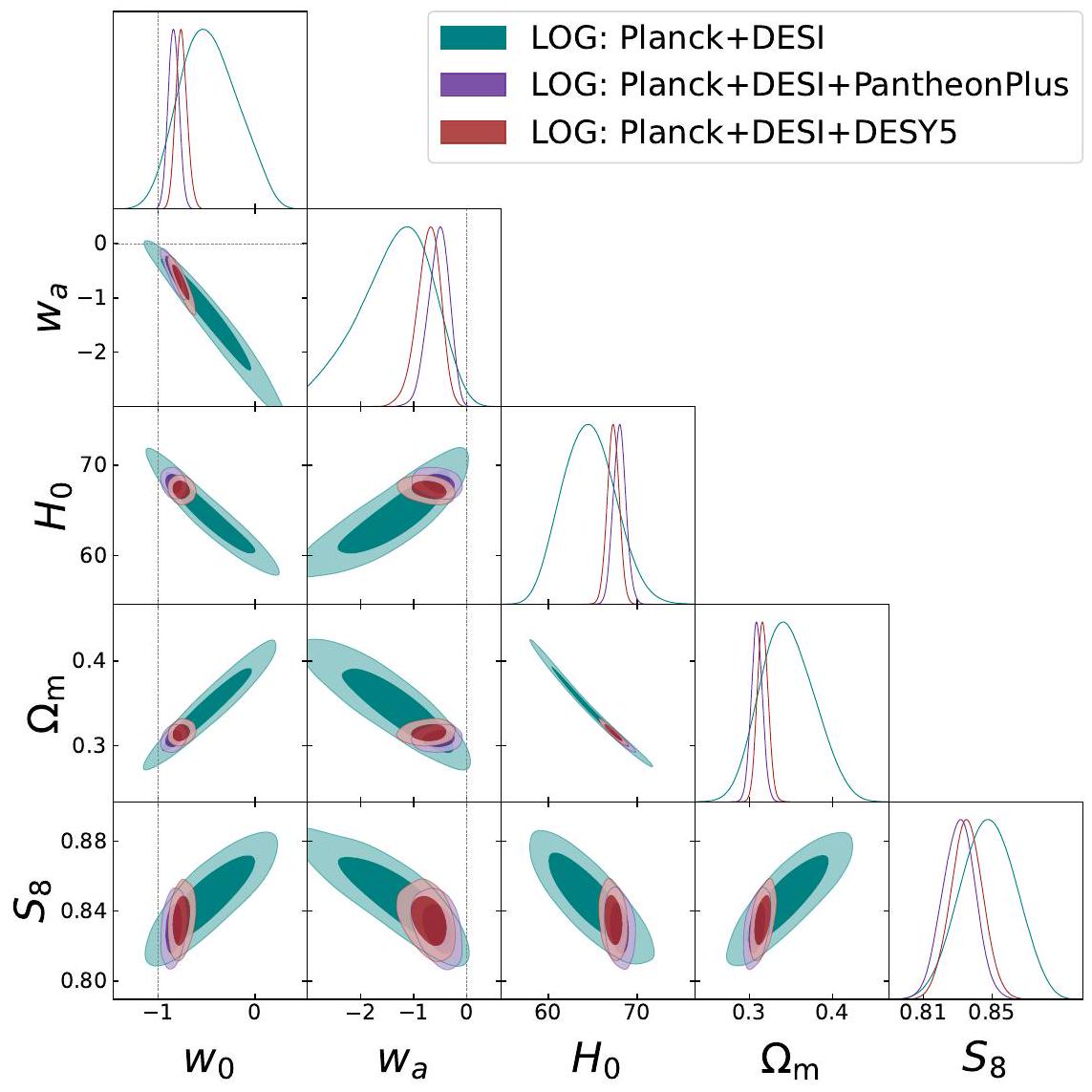

- Table 5 and Figure 4 summarize the results for the logarithmic parameterization (2.8), detailed in Sec. 4.4.

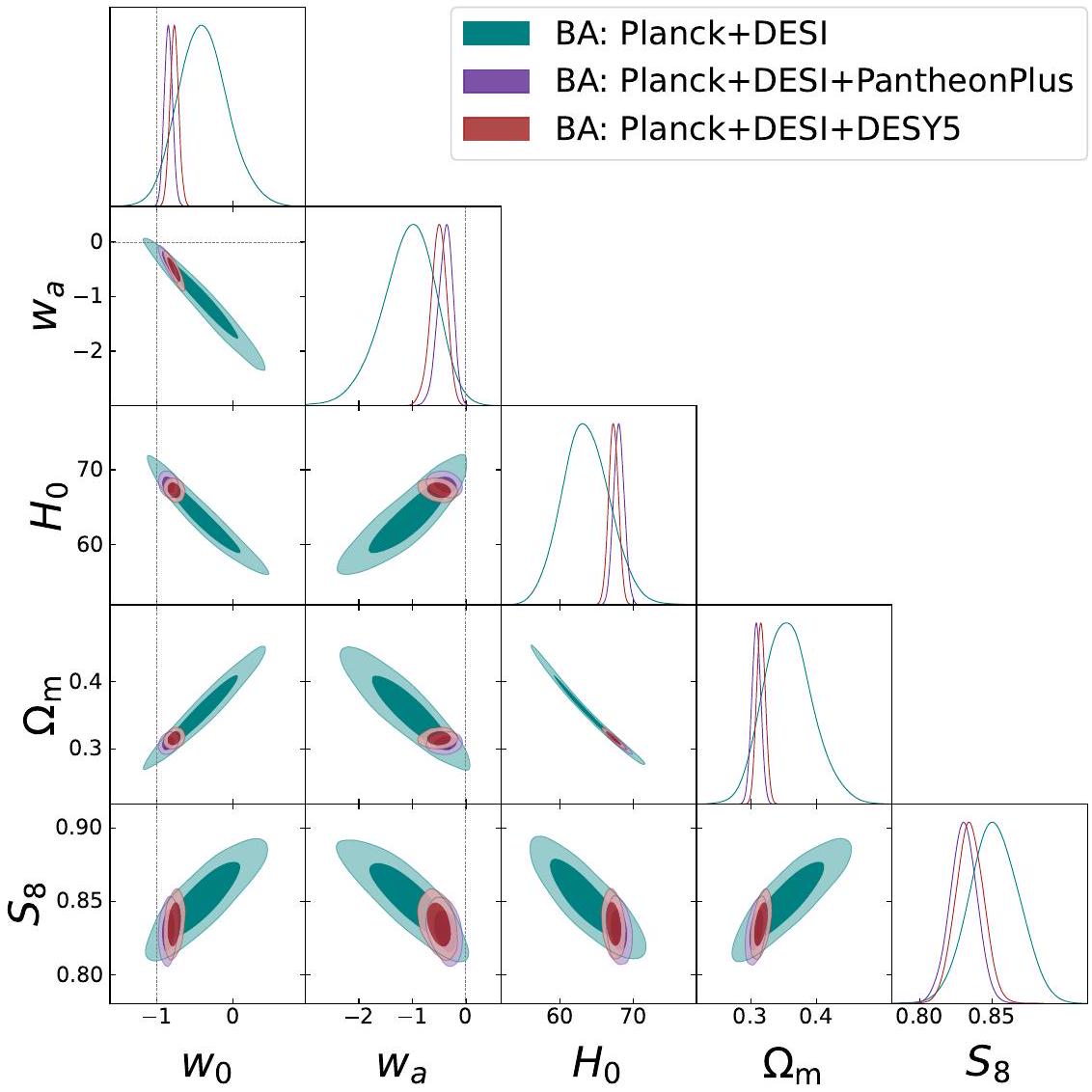

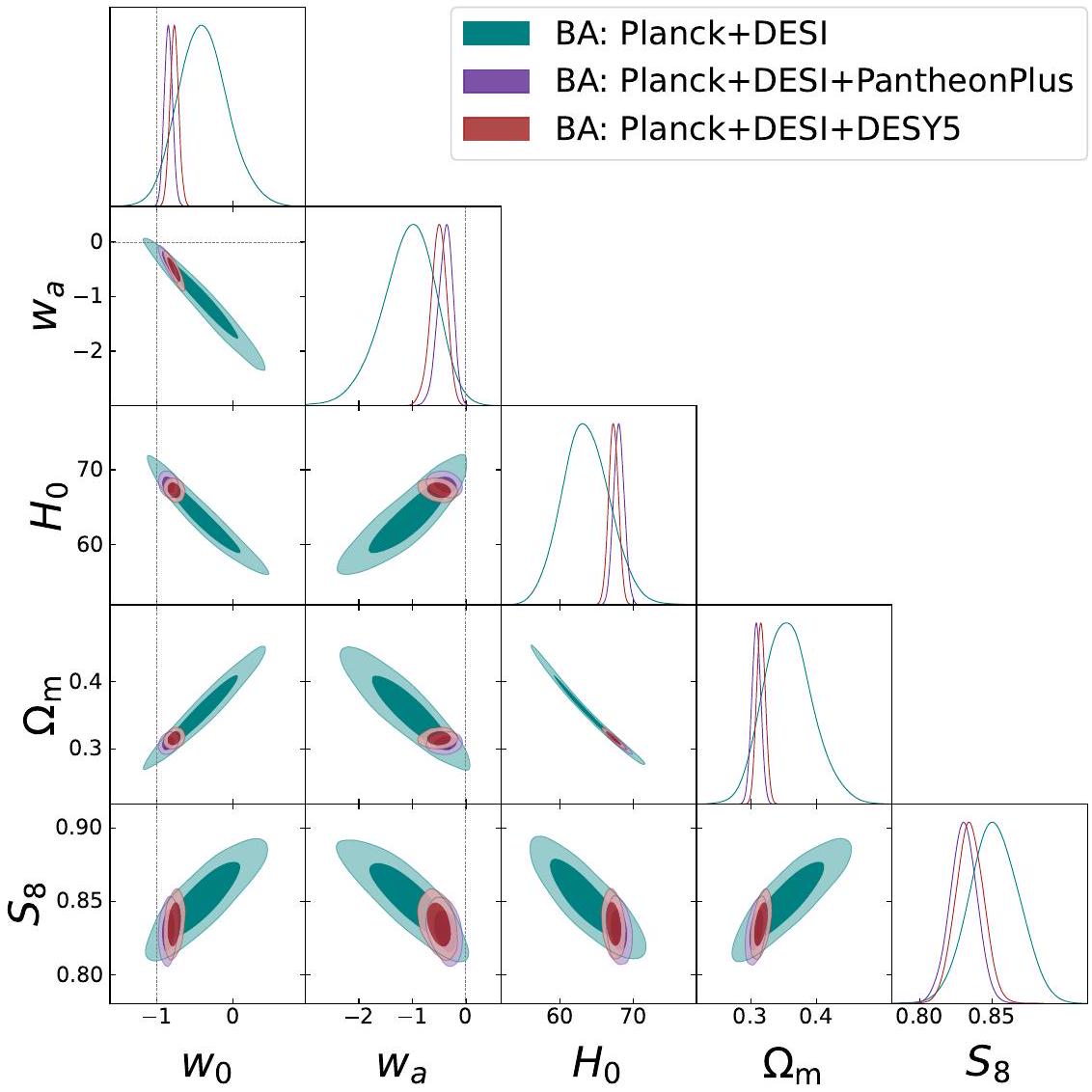

- Table 6 and Figure 5 present the results for the BA parameterization (2.9), discussed in Sec. 4.5.

4.1 Results for the CPL parameterization

| Parameter | Planck+DESI | Planck + DESI + PantheonPlus | Planck+DESI+DESY5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-6.8 | -8.4 | -15.2 |

4.2 Results for the Exponential parametrization

| Parameter | Planck+DESI | Planck + DESI + PantheonPlus | Planck+DESI+DESY5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-6.9 | -7.8 | -15.2 |

4.3 Results for the JBP parametrization

| Parameter | Planck+DESI | Planck + DESI + PantheonPlus | Planck+DESI+DESY5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

< 0.648 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-5.6 | -6.4 | -16.0 |

4.4 Results for the Logarithmic parametrization

| Parameter | Planck+DESI | Planck + DESI + PantheonPlus | Planck+DESI+DESY5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-6.5 | -9.3 | -14.8 |

4.5 Results for the BA parametrization

| Parameter | Planck+DESI | Planck + DESI + PantheonPlus | Planck+DESI+DESY5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-8.7 | -9.4 | -16.2 |

5 Discussions and Conclusions

model, all these parameterizations consist of only two free parameters: the present-day value of the equation of state (

by up to a factor of

Acknowledgments

A Equation of State, pivot redshift, and phantom crossing across the different models

| Model | Dataset |

|

|

|

| CPL | Planck+DESI+PantheonPlus | 0.27 |

|

|

| Planck+DESI+DESY5 | 0.25 |

|

|

|

| Exponential | Planck+DESI+PantheonPlus | 0.21 |

|

|

| Planck+DESI+DESY5 | 0.22 |

|

|

|

| JBP | Planck+DESI+PantheonPlus | 0.21 |

|

|

| 4.6 |

|

|

||

| Planck+DESI+DESY5 | 0.21 |

|

|

|

| 4.7 |

|

|

||

| Logarithmic | Planck+DESI+PantheonPlus | 0.29 |

|

|

| Planck+DESI+DESY5 | 0.26 |

|

|

|

| BA | Planck+DESI+PantheonPlus | 0.28 |

|

|

| Planck+DESI+DESY5 | 0.28 |

|

|

(i) the pivot redshift

(ii) the redshift

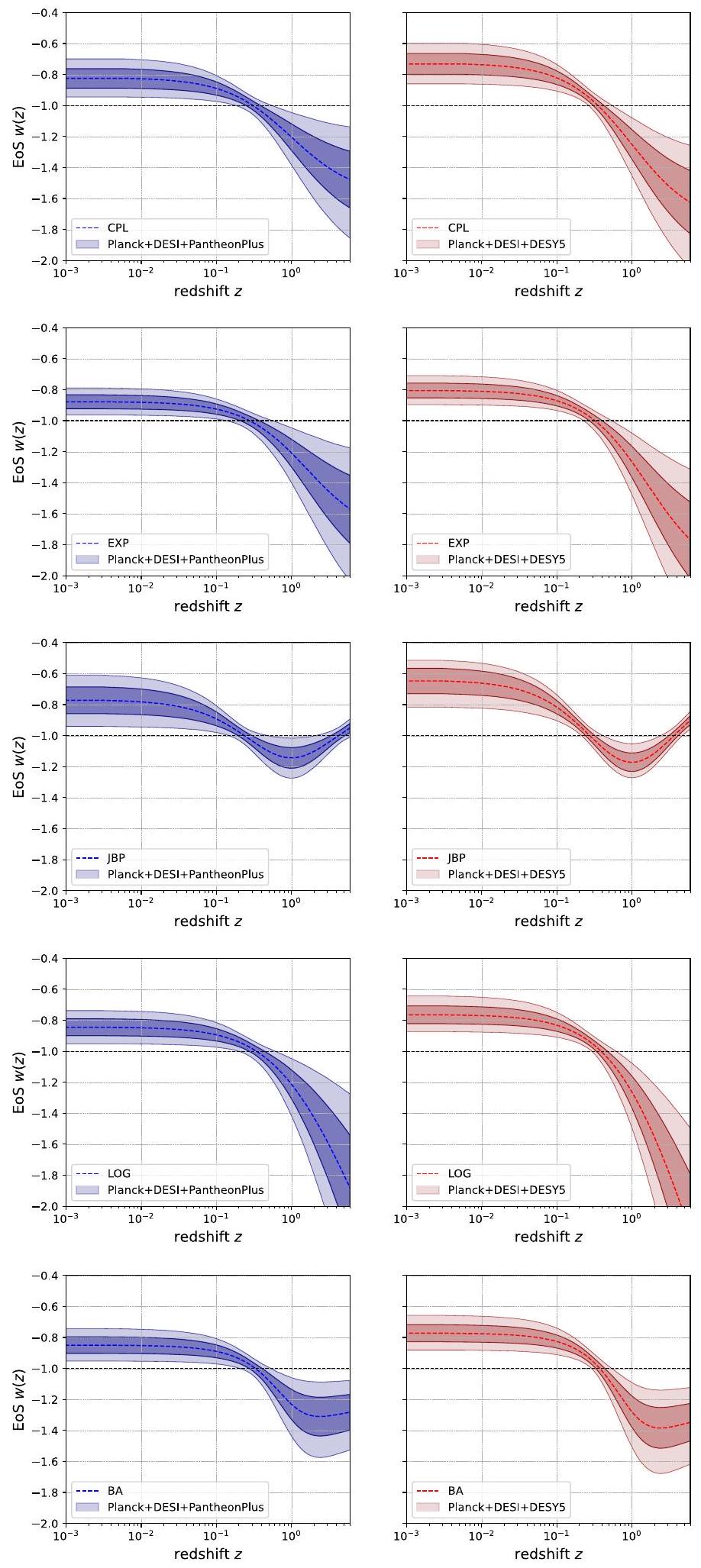

- Exponential: As seen when comparing the top panels with those in the second row from the top in Fig. 7, from a phenomenological perspective, the exponential parameterization closely resembles the CPL model. This similarity was already highlighted in the main text when comparing the improvement in

- JBP: Among the five models analyzed, the JBP parameterization presents a more nuanced phenomenology regarding the evolution of the DE EoS. As shown in the third panels from the top in Fig. 7, due to its quadratic nature in the scale factor, the evolution of the EoS within the JBP parameterization crosses

- Logarithmic: When it comes to the logarithmic parameterization, the behavior of

in the fit to data spanning - BA: Last but not least, the evolution of

References

[2] Supernova Cosmology Project collaboration, Measurements of

[3] Supernova Search Team collaboration, The farthest known supernova: support for an accelerating universe and a glimpse of the epoch of deceleration, Astrophys. J. 560 (2001) 49 [astro-ph/0104455].

[4] SDSS collaboration, Cosmological parameters from SDSS and WMAP, Phys. Rev. D 69 (2004) 103501 [astro-ph/0310723].

[5] SDSS collaboration, Physical evidence for dark energy, astro-ph/0307335.

[6] Supernova Search Team collaboration, Cosmological results from high-z supernovae, Astrophys. J. 594 (2003) 1 [astro-ph/0305008].

[7] Supernova Cosmology Project collaboration, New constraints on Omega(M), Omega(lambda), and

[8] SDSS collaboration, Cosmological parameter analysis including SDSS Ly-alpha forest and galaxy bias: Constraints on the primordial spectrum of fluctuations, neutrino mass, and dark energy, Phys. Rev. D 71 (2005) 103515 [astro-ph/0407372].

[9] B. Feng, X.-L. Wang and X.-M. Zhang, Dark energy constraints from the cosmic age and supernova, Phys. Lett. B 607 (2005) 35 [astro-ph/0404224].

[10] Supernova Search Team collaboration, Type Ia supernova discoveries at

[11] SNLS collaboration, The Supernova Legacy Survey: Measurement of

[12] SDSS collaboration, Detection of the Baryon Acoustic Peak in the Large-Scale Correlation Function of SDSS Luminous Red Galaxies, Astrophys. J. 633 (2005) 560 [astro-ph/0501171].