المجلة: JAMA Network Open، المجلد: 7، العدد: 5

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.12687

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38776081

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-22

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.12687

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38776081

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-22

هذه هي النسخة المنشورة من المنشور، المتاحة وفقًا لسياسة الناشر.

تقييم خطر التحيز في التجارب السريرية العشوائية باستخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة

لاي، هونغهاو؛ جي، لونغ؛ صن، مينغياو؛ بان، بي؛ هوانغ، جياجي؛ هو، ليانغينغ؛ يانغ، تشيويو؛ ليو، جيايي؛ ليو، جيانينغ؛ يي، زي يينغ؛ شيا، داني؛ تشاو، وي لونغ؛ وانغ، شياومان؛ ليو، مينغ [و 4 آخرين]

كيفية الاقتباس

لاي، هونغهاو وآخرون. تقييم خطر التحيز في التجارب السريرية العشوائية باستخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة. في: شبكة JAMA المفتوحة، 2024، المجلد 7، العدد

10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.12687

10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.12687

رابط هذا المنشور: https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:177721

DOI المنشور: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.12687

DOI المنشور: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.12687

تحقيق أصلي | الإحصائيات وطرق البحث

تقييم خطر التحيز في التجارب السريرية العشوائية باستخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة

الملخص

الأهمية قد تسهل نماذج اللغة الكبيرة (LLMs) العملية الشاقة للمراجعات المنهجية. ومع ذلك، لا تزال الطرق الدقيقة والموثوقية غير مؤكدة.

الهدف استكشاف جدوى وموثوقية استخدام LLMs لتقييم خطر التحيز (ROB) في التجارب السريرية العشوائية (RCTs).

التصميم، الإعداد، والمشاركون تم إجراء دراسة استقصائية بين 10 أغسطس 2023 و30 أكتوبر 2023. تم اختيار ثلاثين RCTs من المراجعات المنهجية المنشورة.

النتائج الرئيسية والمقاييس تم تطوير موجه هيكلي لتوجيه ChatGPT (LLM 1) وClaude (LLM 2) في تقييم ROB في هذه RCTs باستخدام نسخة معدلة من أداة ROB الخاصة بكوخران التي طورتها مجموعة CLARITY في جامعة مكماستر. تم تقييم كل RCT مرتين بواسطة كلا النموذجين، وتم توثيق النتائج. تمت مقارنة النتائج مع تقييم من 3 خبراء، والذي اعتبر معيارًا قياسيًا. تم حساب معدلات التقييم الصحيحة، الحساسية، الخصوصية، و

النتائج أظهرت كلا النموذجين معدلات تقييم صحيحة عالية. حقق LLM 1 معدل تقييم صحيح متوسط قدره

الاستنتاجات في هذه الدراسة الاستقصائية لتطبيق LLMs لتقييم ROB، أظهر LLM 1 وLLM 2 دقة كبيرة واتساقًا في تقييم RCTs، مما يشير إلى إمكاناتهما كأدوات داعمة في عمليات المراجعة المنهجية.

شبكة JAMA المفتوحة. 2024؛7(5):e2412687. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.12687

نقاط رئيسية

السؤال هل نماذج اللغة الكبيرة موثوقة لتقييم خطر التحيز (ROB) في التجارب السريرية العشوائية (RCTs)؟

النتائج في هذه الدراسة الاستقصائية مع نموذجين كبيرين للغة و3 خبراء يقيمون 30 RCT، تم تطوير موجه هيكلي لتوجيه تقييم ROB، مما أدى إلى معدلات دقة عالية لكلا النموذجين الكبيرين (>84.5%)، مقارنة بالمراجعين البشريين، عبر 10 مجالات محددة.

المعنى تشير هذه النتائج إلى أن نموذجين كبيرين للغة لديهما دقة كبيرة في تقييم ROB في RCTs، مما يشير إلى إمكاناتهما كأدوات داعمة في عمليات المراجعة المنهجية.

محتوى إضافي

تُدرج affiliations المؤلفين ومعلومات المقال في نهاية هذه المقالة.

مقدمة

تجمع المراجعات المنهجية وتقيّم الأبحاث الموجودة، موجهة القرارات السريرية ومعلنة إرشادات الصحة.

يعد تقييم ROB في RCTs المدرجة واحدة من المهام الرئيسية التي يقوم بها مؤلفو المراجعات المنهجية.

لقد أظهرت LLMs

طرق

تم إجراء هذه الدراسة الاستقصائية بين 10 أغسطس و30 أكتوبر 2023، وفقًا لإرشادات الإبلاغ لجمعية الرأي العام الأمريكية (AAPOR).

تشكيل مجموعة العمل

تم تجميع لجنة متعددة التخصصات، تضم 3 خبراء كبار في منهجية الطب القائم على الأدلة (H.L.، B.P.، وL.G.)، و2 من علماء الكمبيوتر (H.L. وJ.H.)، وفريق بحث مكون من 5 باحثين لديهم خلفيات في استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي في الطب القائم على الأدلة (H.L.، M.S.، جيايي ل.، جيانينغ ل.، وW.Z.). طور فريق البحث الموجه، وأجرى الدراسة، وسجل النتائج، وأجرى التحليل الإحصائي. قام خبيرا علوم الكمبيوتر بتحسين الموجه. أشرف الخبراء الثلاثة الكبار على عملية التقييم وطوروا المعيار القياسي للتقييم. أكمل جميع الباحثين تدريبًا لمدة أسبوع حول المراجعات المنهجية لضمان فهم متسق لعملية التقييم.

تطوير الموجه

تضمن تطوير موجه التقييم تحديد معايير من قبل الخبراء الكبار بناءً على الإرشادات (eAppendix 1 في الملحق 1)،

الملحق 1) يتكون من 3 أجزاء: مقدمة تحدد الدور،

اختيار العينة

أولاً، بحثنا في PubMed باستخدام الكلمات الرئيسية المعدلة، أداة كوكراين، خطر التحيز، CLARITY، والتحليل التلوي. تم فحص السجلات بترتيب تنازلي من حيث الأهمية حتى تم العثور على 3 تحليلات تلوي باستخدام أداة كوكراين المعدلة.

تطبيقات نماذج اللغة الكبيرة

للتقييم، تم تطبيق النص النهائي على جميع التجارب السريرية العشوائية باستخدام LLM 1 وLLM 2، مع فترة الوصول التي تمتد من 30 سبتمبر إلى 10 أكتوبر 2023. بينما يسمح LLM 2 للمستخدمين بتحميل ملفات PDF مباشرة، كان تحميل ملفات PDF إلى LLM 1 يتطلب مكونًا إضافيًا منفصلًا في الوقت الذي تم فيه إجراء الدراسة، والذي لم نستخدمه لتجنب التحيز. قمنا أولاً بتحويل ملفات PDF إلى مستندات نصية لضمان أن المعلومات المقدمة لكلا النموذجين كانت متطابقة. عند تقييم ROB لكل تجربة سريرية عشوائية، تم تعريف النتيجة الرئيسية إما كنتيجة محددة من قبل المؤلفين أو، إذا لم يتم تحديدها، كانت النتيجة الأولى المبلغ عنها في الدراسة. تم نسخ المخرجات بدقة إلى مستند (eAppendix 3 في الملحق 1 لـ LLM 1 وeAppendix 4 في الملحق 1 لـ LLM 2). تم استبعاد أي تقييم تم مقاطعته بسبب مشكلات تقنية وتم إعادته على الفور. كانت كل تجربة سريرية عشوائية

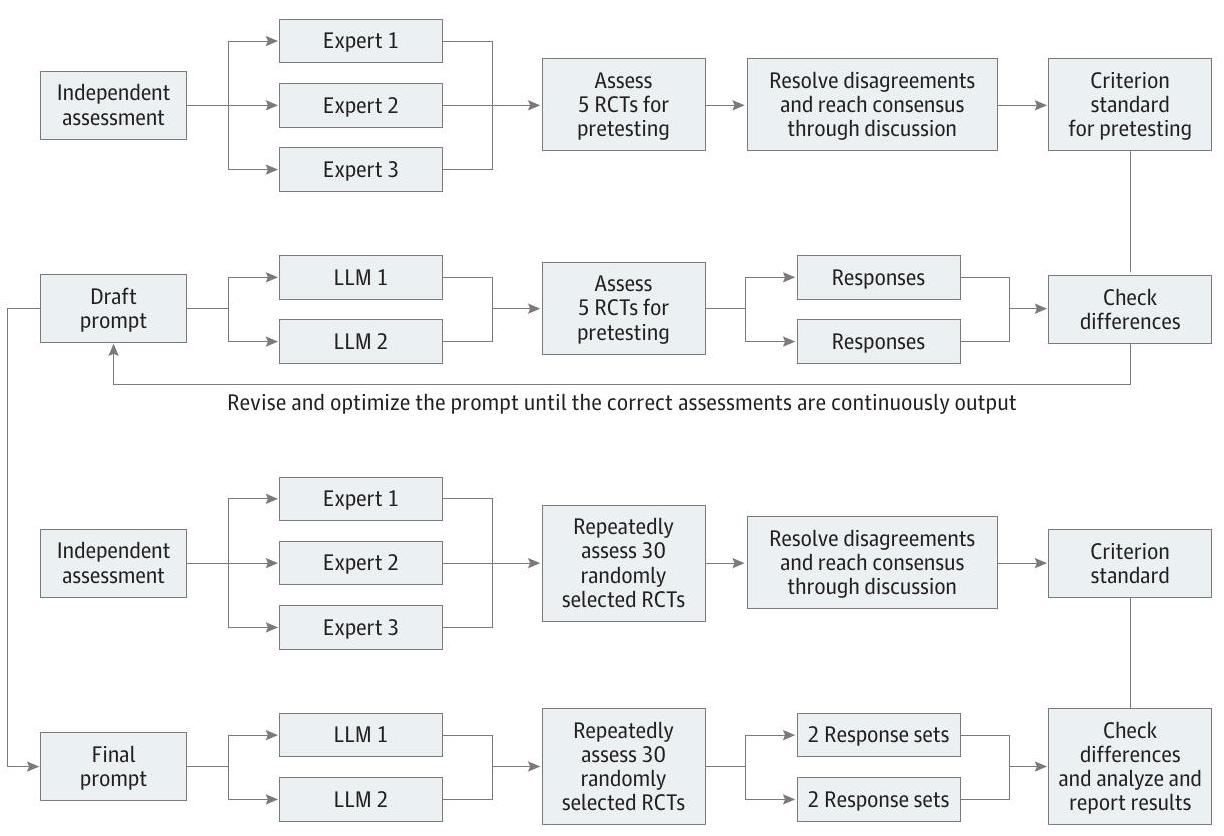

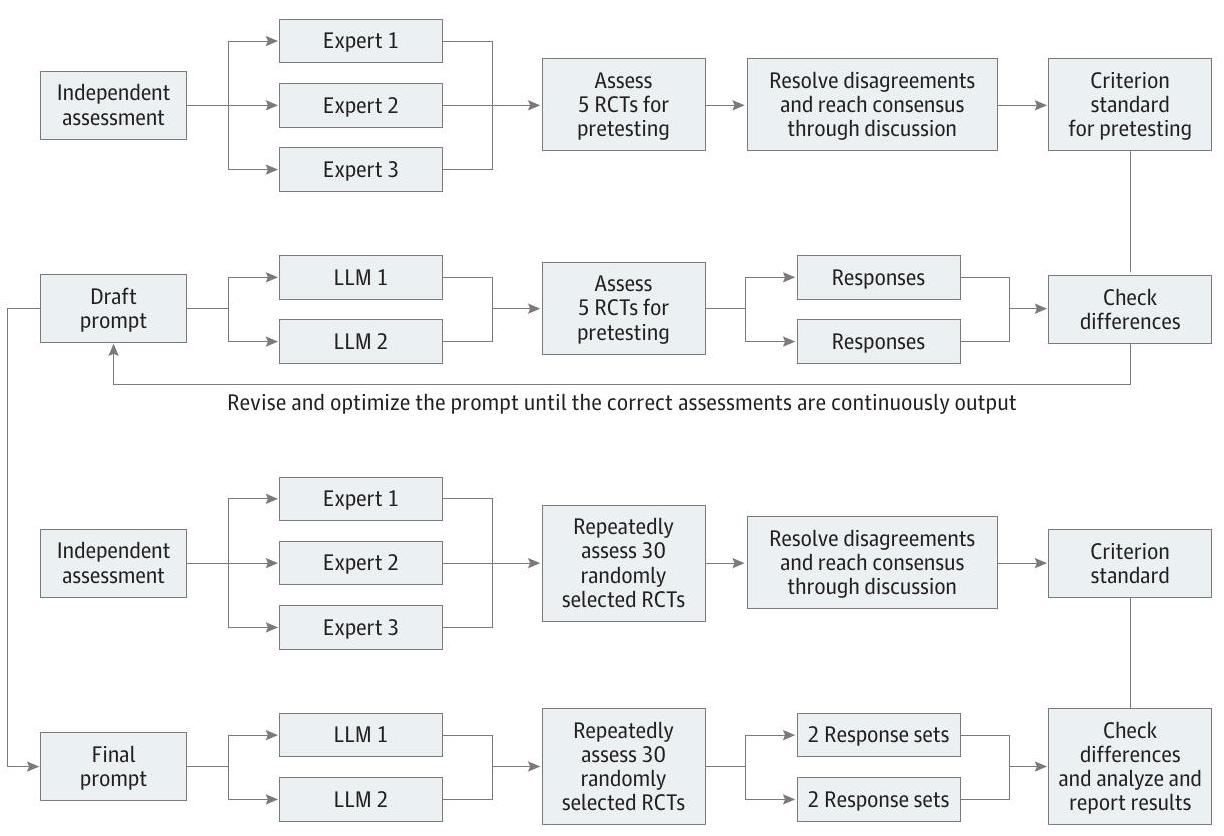

الشكل 1. مخطط تدفق عملية الدراسة الرئيسية

LLM تشير إلى نموذج لغة كبير؛ RCT، تجربة سريرية عشوائية.

تم تقييمه مرتين باستخدام كلا النموذجين اللغويين الكبيرين، مع استخدام نفس الطلب وضمان توافق إصدارات النموذج. طوال العملية، تم الالتزام الصارم بالبروتوكول لضمان دقة نتائج التقييم.

تم تقييمه مرتين باستخدام كلا النموذجين اللغويين الكبيرين، مع استخدام نفس الطلب وضمان توافق إصدارات النموذج. طوال العملية، تم الالتزام الصارم بالبروتوكول لضمان دقة نتائج التقييم.

إنشاء معيار المعيار

قام الخبراء الثلاثة الكبار بتقييم التجارب السريرية العشوائية بشكل مستقل باستخدام المعايير، ثم تم التوفيق بين الاختلافات من خلال التوافق. استمرت هذه المناقشة التكرارية حتى تم التوصل إلى توافق بشأن كل جانب من جوانب تقييم ROB لكل تجربة سريرية عشوائية. شكلت هذه التقييمات المستمدة من التوافق المعيار القياسي (الجدول الإلكتروني 1 في الملحق 1)، مما خدم كمرجع لقياس دقة تقييمات ROB لأدوات LLM.

التحليل الإحصائي

تم إجراء تحليل البيانات باستخدام

الدقة

تم قياس دقة نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في تقييم ROB على المستويات المحددة للدراسة والمجال والمستوى العام باستخدام معدل التقييم الصحيح والحساسية والخصوصية. بالنسبة لدقة المجال المحدد، قمنا أيضًا بحساب الـ

فورمولا 1

القيمة التنبؤية الإيجابية = TP / (TP + FP)

القيمة التنبؤية الإيجابية = TP / (TP + FP)

اختلافات المخاطر (RD) مع

الاتساق

لتقييم موثوقية التقييمات المتكررة لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة، استخدمنا معامل كوهين، الذي يتم اشتقاقه من نسبة الاتفاق الملحوظ (Po) مطروحًا منها التوافق الفعلي الملحوظ بالنسبة لإجمالي عدد الملاحظات (أي، معدل التقييم المتسق) بالإضافة إلى نسبة الاتفاق المتوقع.

نظرًا للإمكانية المحتملة لتجانس تقييمات المخاطر عبر المجالات، والتي قد ترفع بشكل مصطنع من مستوى الاتفاق المتوقع، قمنا بإجراء تحليل حساسية من خلال حساب الكفاءة المعدلة حسب الانتشار والمعدلة حسب التحيز (РАВАк).

علاوة على ذلك، تم حساب RD لمقارنة الفرق في Po بين LLM 1 و LLM 2.

الكفاءة

تم قياس كفاءة عملية التقييم من خلال تسجيل الوقت من تحميل النص إلى إكمال التقييمات الكاملة للنطاق. في هذه الدراسة، دعمت عرض النطاق الترددي للشبكة سرعات التحميل والتنزيل بحوالي 100 ميغابت في الثانية.

النتائج

خصائص التجارب السريرية العشوائية

اخترنا تحليلًا تلويًا واحدًا نُشر في عام 2021،

الدقة

تم تلخيص نتائج التقييم الكاملة في الجدول الإلكتروني 3 والجدول الإلكتروني 4 في الملحق 1. أظهر كل من LLM 1 وLLM 2 دقة جيدة (الجدول والشكل 2). حقق LLM 1 معدل تقييم صحيح متوسط قدره

جدول. الدقة والاتساق المحددين بالنطاق

| مراجع | دقة | الاتساق | |||||

| نسبة التقييم الصحيحة، % | حساسية | خصوصية | درجة F1 | نسبة الاستجابات عالية المخاطر، % | كوهين ك | معدل التقييم المتسق، % | |

| LLM 1 | |||||||

| النطاق 1 | ٥٦.٧٠ | 0.45 | 0.77 | 0.57 | ٣٦.٦٧ | 0.54 | 60.00 |

| النطاق 2 | ٧٠.٠٠ | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.78 | 65.00 | 0.65 | ٧٠.٠٠ |

| النطاق 3.أ | 93.30 | 1.00 | 0.89 | 0.92 | ٤٦.٦٧ | 0.92 | 93.33 |

| النطاق 3.ب | ٩٦.٧٠ | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 50.00 | 0.96 | ٩٦.٦٧ |

| النطاق 3.ج | 93.30 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 0.93 | ٤٨.٣٣ | 0.85 | ٨٦.٦٧ |

| النطاق 3.d | 91.70 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.91 | ٤٦.٦٧ | 0.81 | ٨٣.٣٣ |

| النطاق 3.e | 91.70 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 50.00 | 0.81 | ٨٣.٣٣ |

| النطاق 4 | 78.30 | 0.17 | 0.94 | 0.24 | 8.33 | 0.87 | 90.00 |

| النطاق 5 | ٨٣.٣٠ | غير متوفر | 0.83 | غير متوفر | ١٦.٦٧ | 0.76 | ٨٠.٠٠ |

| النطاق 6 | 90.00 | 0.00 | 0.96 | غير متوفر | 3.33 | 0.91 | 93.33 |

| LLM 2 | |||||||

| النطاق 1 | 80.00 | 0.74 | 0.91 | 0.82 | 50.00 | 0.77 | ٨٠.٠٠ |

| النطاق 2 | ٨٣.٣٠ | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.89 | 73.33 | 0.76 | ٨٠.٠٠ |

| النطاق 3.أ | ٩٨.٣٠ | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.98 | ٤١.٦٧ | 0.96 | ٩٦.٦٧ |

| النطاق 3.b | ٩٦.٧٠ | 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 50.00 | 0.92 | 93.33 |

| النطاق 3.c | 90.00 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.88 | ٤٣.٣٣ | 0.85 | ٨٦.٦٧ |

| النطاق 3.d | 90.00 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.88 | ٤٣.٣٣ | 0.85 | ٨٦.٦٧ |

| النطاق 3.e | 90.00 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.89 | ٤٦.٦٧ | 0.85 | ٨٦.٦٧ |

| النطاق 4 | ٨٣.٣٠ | 0.42 | 0.94 | 0.50 | ١٣.٣٣ | 0.84 | ٨٦.٦٧ |

| النطاق 5 | 90.00 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.25 | 11.67 | 0.83 | ٨٦.٦٧ |

| النطاق 6 | 93.30 | 0.25 | 0.98 | 0.33 | 3.33 | 0.91 | 93.33 |

التجارب السريرية العشوائية (تقييمين لكل تجربة سريرية عشوائية) (الشكل 2). كانت نسبة التقييم الصحيح لـ LLM 2 أعلى بشكل ملحوظ مقارنة بـ LLM 1 (RD، 0.05؛ 95% CI، 0.01-0.09؛

كما هو موضح في الشكل 3 والجدول الإلكتروني 5 والجدول الإلكتروني 6 في الملحق 1، كانت معدلات التقييم الصحيح متشابهة بين النموذجين اللغويين الكبيرين عبر جميع المجالات العشرة. كانت أدنى معدل للتقييم الصحيح للنموذج اللغوي الكبير 1 في المجال 1 (توليد تسلسل عشوائي) عند

في تحليل مخرجات النماذج (الجدول الإلكتروني 9 في الملحق 1)، من إجمالي 155 تقييمًا خاطئًا، كان هناك 89 (

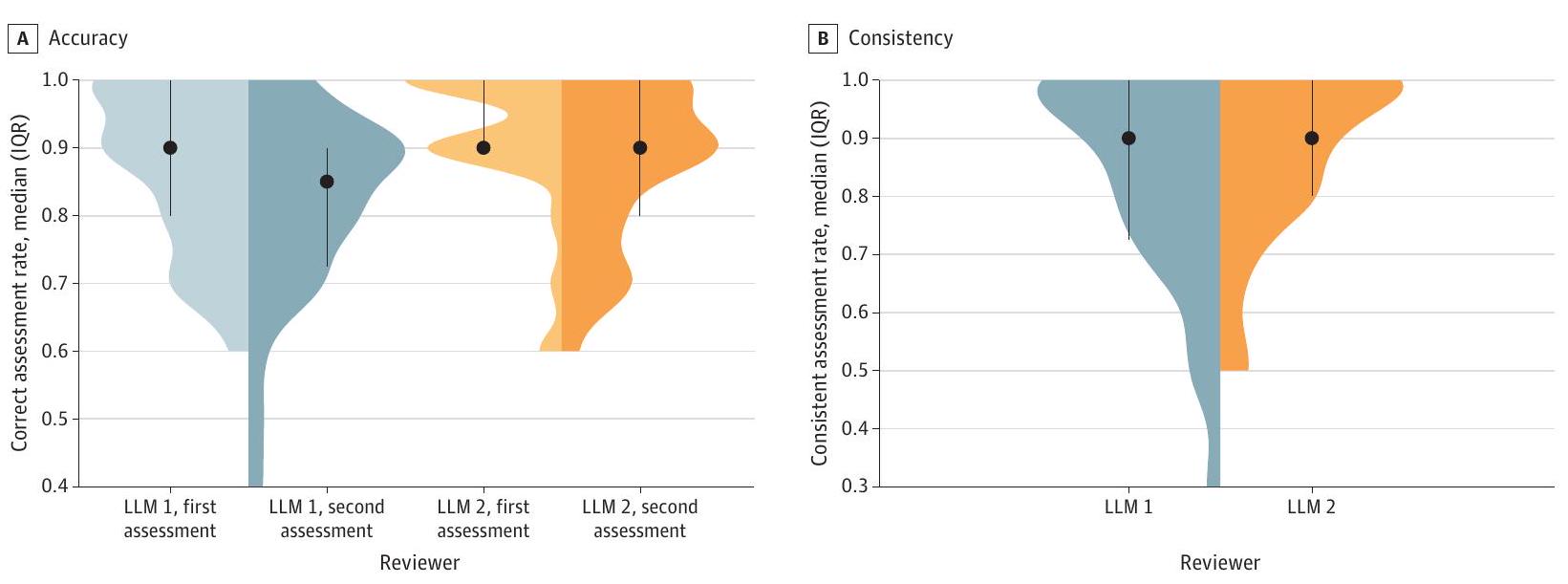

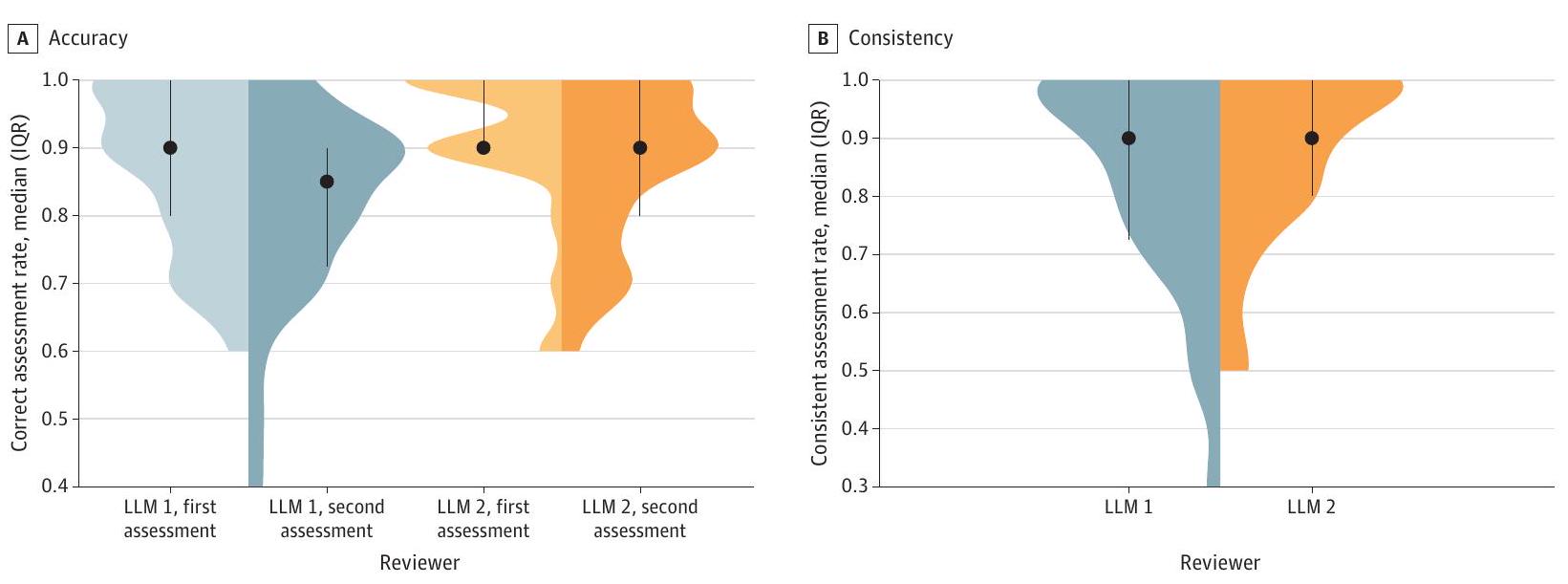

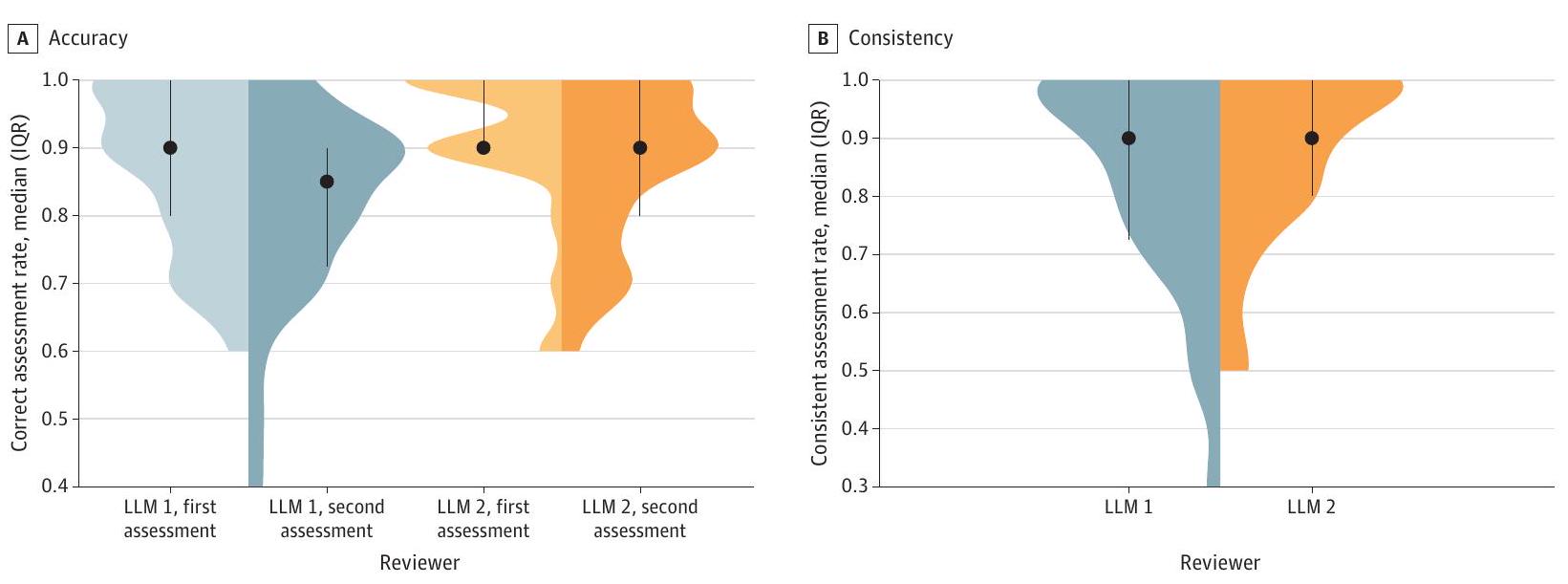

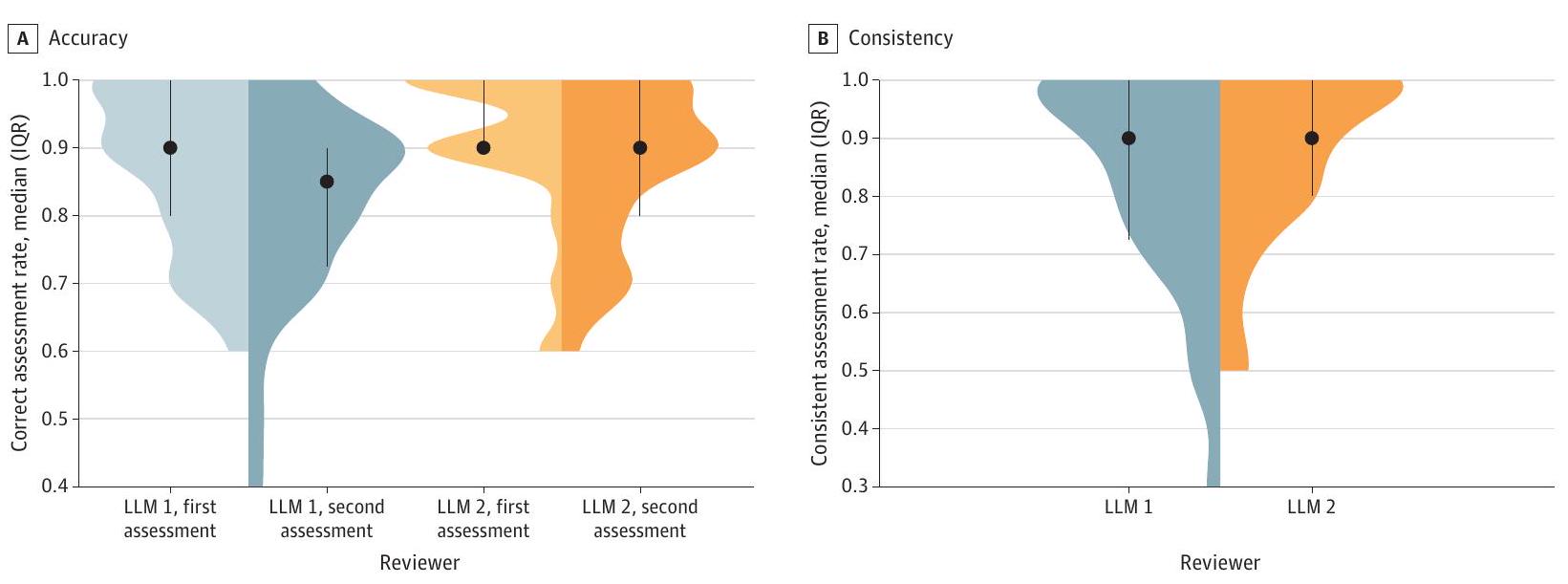

الشكل 2. مقارنة معدلات التقييم الصحيح والمتسق الشاملة لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة (LLMs) 1 و 2 عبر تقييمين متتاليين

الشكل 3. معدلات التقييم الصحيحة والمتسقة لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة (LLMs) 1 و 2 لكل مجال

و 4 (بيانات النتائج المفقودة)، 68 من 90 (

كانت حساسية LLM 1 الإجمالية 0.82

كانت حساسية LLM 2 الأدنى في المجالين 4 و 6 (0.42 و 0.25 على التوالي). تراوحت الخصوصية بين 0.75 و 0.98.

الاتساق

أظهر كل من LLM 1 و LLM 2 معدلات متسقة عالية بشكل عام

على مستوى الدراسة المحددة، أنتج كل من LLM 1 وLLM 2 نتائج متطابقة لـ 12 تجربة عشوائية محكومة في التقييمات المتكررة. كما هو موضح في الجدول الإلكتروني 11 والجدول الإلكتروني 12 في الملحق 1، وجدنا اتفاقات كبيرة أو قريبة من الكمال في معظم التقييمات لكلا النموذجين، وكانت أدنى نسبة متسقة 30% لـ LLM 1 و50% لـ LLM 2. بالنسبة لجميع التقييمات (الجدول الإلكتروني 13 في الملحق 1)، حققت 15 من 30 دراسة

الكفاءة

تراوحت مدة التقييمات التي تم إجراؤها لـ LLM 1 بين 52 و127 ثانية، بمتوسط 77 ثانية لكل تقييم. بالنسبة لـ LLM 2، كان متوسط المدة 53 ثانية (تتراوح بين 36 و87 ثانية).

نقاش

في هذه الدراسة الاستقصائية، أنشأنا محفزًا منظمًا وقابلًا للتطبيق قادرًا على توجيه نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في تقييم مخاطر التحيز في التجارب السريرية العشوائية. أنتجت نماذج اللغة الكبيرة المستخدمة في هذه الدراسة تقييمات كانت قريبة جدًا من تقييمات المراجعين البشريين ذوي الخبرة. توجد أدوات آلية في المراجعات النظامية لكنها غير مستخدمة بشكل كافٍ بسبب صعوبة التشغيل، وسوء تجربة المستخدم، والنتائج غير الموثوقة.

وجدت دراستنا أن كلا من نماذج اللغة الكبيرة أظهرت دقة عالية واتساقًا، مقارنة بالمراجعين البشريين، في تقييم مخاطر التحيز في التجارب السريرية العشوائية. كان لدى النموذج 2 معدل تقييم صحيح أعلى بشكل ملحوظ مقارنة بالنموذج 1. قد تنبع الأسباب المحتملة لهذه الفجوة من الطرق المختلفة لتقديم المقالات. يسمح النموذج 2 بتحميل ملفات PDF مباشرة، مما يحولها تلقائيًا إلى نص للتحليل، بينما كان النموذج 1 يسمح فقط بالنص (كان هذا هو الحال في وقت دراستنا، ولكن يمكن تحميل ملفات PDF بعد تحديث 9 نوفمبر 2023). وبالتالي، يتطلب تحميل ملفات PDF إضافات. نتيجة لذلك، للحفاظ على الاتساق، تم تحويل مقالات التجارب السريرية العشوائية إلى تنسيق نصي قبل التقديم. ومع ذلك، كانت قيود طول النص المختلفة للنموذجين تتطلب تحميل عدة مقاطع بشكل متتابع للنموذج 1، بينما عالج النموذج 2 التحميلات في خطوة واحدة. قد يكون لذلك تأثير على حكم النموذج 1 وقد يفسر المدة الأطول للتقييم مقارنة بالنموذج 2.

أظهرت كل من نماذج اللغة الكبيرة أدنى معدلات التقييم الصحيح في المجال 1، المتعلق بتوليد تسلسلات عشوائية. من بين 38 تقييمًا غير صحيح، كان هناك 30 (

حسب علمنا، هذه الدراسة هي الأولى التي تستكشف بشفافية جدوى تطبيق نماذج اللغة الكبيرة (LLMs) في تقييم مخاطر التحيز (ROB) في التجارب السريرية العشوائية (RCTs). تناولت الدراسة جوانب متعددة من جدوى استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة، بما في ذلك الدقة، والاتساق، والكفاءة. تم اقتراح وتنفيذ طلب مفصل ومنظم وأظهر أداءً جيدًا في التطبيق العملي. تشير نتائجنا أوليًا إلى أنه مع وجود طلب مناسب، يمكن استخدام LLM 1 وLLM 2 جنبًا إلى جنب مع الأداة المعدلة من كوكران لتقييم مخاطر التحيز في التجارب السريرية العشوائية بدقة وكفاءة.

القيود

تحتوي هذه الدراسة الاستقصائية على عدة قيود. أولاً، نظرًا لانخفاض احتمال التقييمات الإيجابية في مجالات معينة، سيكون من الضروري الحصول على عينة كبيرة لاستخلاص استنتاجات قوية. ومع ذلك، بسبب قيود الاستخدام المتعلقة بـ LLM 1 و LLM 2، تم إجراء دراستنا بحجم عينة محدود. ثانيًا، كانت جميع التجارب السريرية العشوائية التي تم تقييمها باللغة الإنجليزية؛ وبالتالي، فإن فعالية هذه الطريقة للأدبيات في لغات أخرى لا تزال غير واضحة. ثالثًا، تم تحديد المعيار المرجعي لهذه البحث بالتوافق بين 3 خبراء كبار. كانت التعليمات المقدمة لـ LLMs لمعالجة تجارب سريرية عشوائية مختلفة موحدة، مما يعني أن المعيار المرجعي تم تأسيسه من أوسع وأعم وجهة نظر. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، في الحفاظ على التناسق مع المعلومات التي تم تحميلها إلى LLMs، لم يأخذ تحديد المعيار المرجعي في الاعتبار المواد التكميلية مثل الملاحق وتفاصيل التسجيل. نظرًا لأنه من الصعب على الذكاء الاصطناعي تفسير الملاحق الطويلة، قد لا تكون LLMs قادرة على إكمال المهمة بشكل مستقل عندما تكون المعلومات الإضافية ضرورية للتقييم الدقيق. ومع ذلك، يمكن التخفيف من هذا القيد في المستقبل من خلال السماح لـ LLMs بالوصول إلى روابط لمصادر خارجية. نظرًا لأن هذه الوظيفة كانت متاحة فقط كنسخة تجريبية خلال دراستنا، لم نستخدمها. رابعًا، أجرت الدراسة تقييمات فقط على النتيجة الرئيسية؛ ومع ذلك، تشير الردود إلى أن LLMs قد تكون لديها القدرة على تقييم جميع النتائج المبلغ عنها في وقت واحد. في الممارسة العملية، يمكن تخصيص التعليمات لتوجيه التقييم نحو نتائج محددة.

الاستنتاجات

في هذه الدراسة الاستقصائية لتطبيق LLMs في تقييم ROB في التجارب السريرية العشوائية، وجدنا أن LLM 1 و LLM 2 حققتا دقة وتناسق ملحوظين عند توجيههما بتعليمات منظمة. من خلال فحص المنطق المقدم ومقارنة تقييمات متعددة عبر نماذج مختلفة، تمكن الباحثون من تحديد وتصحيح جميع الأخطاء تقريبًا بكفاءة.

معلومات المقال

تم قبولها للنشر: 20 مارس 2024.

نشرت: 22 مايو 2024. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.12687

الوصول المفتوح: هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول موزعة بموجب شروط ترخيص CC-BY. © 2024 لاي إتش وآخرون. شبكة JAMA المفتوحة.

نشرت: 22 مايو 2024. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.12687

الوصول المفتوح: هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول موزعة بموجب شروط ترخيص CC-BY. © 2024 لاي إتش وآخرون. شبكة JAMA المفتوحة.

المؤلف المراسل: لونغ جي، دكتور في الطب، مركز أبحاث العلوم الاجتماعية القائمة على الأدلة، كلية الصحة العامة، جامعة لانزهو، رقم 199 طريق دونغغانغ الغربي، منطقة تشنغوان، لانزهو 730000 (gelong2009@163.com).

تبعيات المؤلف: قسم سياسة الصحة والإدارة، كلية الصحة العامة، جامعة لانزهو، لانزهو، الصين (لاي، جي، ق. يانغ، جياي ليو، يي، شيا، تشاو)؛ مركز أبحاث العلوم الاجتماعية القائمة على الأدلة، كلية الصحة العامة، جامعة لانزهو، لانزهو، الصين (لاي، جي، ق. يانغ، جياي ليو، يي، شيا، تشاو)؛ المختبر الرئيسي للطب القائم على الأدلة وترجمة المعرفة في مقاطعة قانسو، لانزهو، الصين (جي، تيان، ك. يانغ)؛ مركز التمريض القائم على الأدلة، كلية التمريض، جامعة لانزهو، لانزهو، الصين (سون)؛ مركز الطب القائم على الأدلة، كلية العلوم الطبية الأساسية، جامعة لانزهو، لانزهو، الصين (بان، هو، وانغ، م. ليو، تيان، ك. يانغ، إستيلي)؛ كلية التمريض، جامعة قانسو للطب الصيني، لانزهو، الصين (هوانغ، جيانينغ ليو)؛ قسم طرق البحث الصحي، الأدلة، والأثر، جامعة مكماستر، أونتاريو، كندا (هو، م. ليو، تالوكدار)؛ معهد الصحة العالمية، جامعة جنيف، جنيف، سويسرا (إستيلي).

مساهمات المؤلف: كان لدى الدكتور لاي وصول كامل إلى جميع البيانات في الدراسة ويتحمل المسؤولية عن سلامة البيانات ودقة تحليل البيانات.

المفهوم والتصميم: لاي، م. ليو، تيان.

الحصول على البيانات أو تحليلها أو تفسيرها: لاي، جي، سون، بان، هوانغ، هو، ق. يانغ، جياي ليو، جيانينغ ليو، يي، شيا، تشاو، وانغ، م. ليو، تالوكدار، ك. يانغ، إستيلي.

الحصول على البيانات أو تحليلها أو تفسيرها: لاي، جي، سون، بان، هوانغ، هو، ق. يانغ، جياي ليو، جيانينغ ليو، يي، شيا، تشاو، وانغ، م. ليو، تالوكدار، ك. يانغ، إستيلي.

كتابة المخطوطة: لاي.

المراجعة النقدية للمخطوطة لمحتوى فكري مهم: جميع المؤلفين.

التحليل الإحصائي: لاي، هو، م. ليو، تيان، إستيلي.

الدعم الإداري أو الفني أو المادي: لاي، سون، بان، هوانغ، جياي ليو، جيانينغ ليو، شيا، تشاو، إستيلي.

الإشراف: جي، بان، ق. يانغ، يي، وانغ، ك. يانغ.

إفصاحات تضارب المصالح: لم يتم الإبلاغ عن أي.

بيان مشاركة البيانات: انظر الملحق 2.

مساهمات إضافية: نود أن نشكر هوارد وايت، دكتور في الفلسفة، الرئيس التنفيذي لشركة كامبل كولابورايشن، على اقتراحاته بشأن مراجعة المقال. لم يتم تعويضه عن مساهماته.

المراجعة النقدية للمخطوطة لمحتوى فكري مهم: جميع المؤلفين.

التحليل الإحصائي: لاي، هو، م. ليو، تيان، إستيلي.

الدعم الإداري أو الفني أو المادي: لاي، سون، بان، هوانغ، جياي ليو، جيانينغ ليو، شيا، تشاو، إستيلي.

الإشراف: جي، بان، ق. يانغ، يي، وانغ، ك. يانغ.

إفصاحات تضارب المصالح: لم يتم الإبلاغ عن أي.

بيان مشاركة البيانات: انظر الملحق 2.

مساهمات إضافية: نود أن نشكر هوارد وايت، دكتور في الفلسفة، الرئيس التنفيذي لشركة كامبل كولابورايشن، على اقتراحاته بشأن مراجعة المقال. لم يتم تعويضه عن مساهماته.

REFERENCES

- Djulbegovic B, Guyatt GH. Progress in evidence-based medicine: a quarter century on. Lancet. 2017;390 (10092):415-423. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31592-6

- Subbiah V. The next generation of evidence-based medicine. Nat Med. 2023;29(1):49-58. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-02160-z

- Elliott J, Synnot A, Turner T, Living Systematic Review Network, et al. Living systematic review: 1. introduction-the why, what, when, and how. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;91:23-30. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.08.010

- Siemieniuk RA, Bartoszko JJ, Zeraatkar D, et al. Drug treatments for covid-19: living systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m2980. doi:10.1136/bmj.m2980

- Fanaroff AC, Califf RM, Lopes RD. High-quality evidence to inform clinical practice. Lancet. 2019;394(10199): 633-634. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31256-5

- Minozzi S, Cinquini M, Gianola S, Gonzalez-Lorenzo M, Banzi R. The revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) showed low interrater reliability and challenges in its application. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020; 126:37-44. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.06.015

- Savović J, Weeks L, Sterne JA, et al. Evaluation of the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing the risk of bias in randomized trials: focus groups, online survey, proposed recommendations and their implementation. Syst Rev. 2014;3:37. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-3-37

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al; GRADE Working Group. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924-926. doi:10.1136/bmj.39489. 470347.AD

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed. 1000097

- Tool to Assess Risk of Bias in Randomized Controlled Trials DistillerSR. DistillerSR. Accessed October 31, 2023. https://www.distillersr.com/resources/methodological-resources/tool-to-assess-risk-of-bias-in-randomized-controlled-trials-distillersr

- Introducing ChatGPT. Anthropic. Accessed October 31, 2023. https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt

- Introducing Claude. Anthropic. Accessed October 31, 2023. https://www.anthropic.com/index/ introducing-claude

- Omiye JA, Lester JC, Spichak S, Rotemberg V, Daneshjou R. Large language models propagate race-based medicine. NPJ Digit Med. 2023;6(1):195. doi:10.1038/s41746-023-00939-z

- Singhal K, Azizi S, Tu T, et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature. 2023;620(7972): 172-180. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06291-2

- Pitt SC, Schwartz TA, Chu D. AAPOR reporting guidelines for survey studies. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(8):785-786. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0543

- ChatGPT Prompt Engineering for Developers. DeepLearning.AI. Accessed November 6, 2023. https://www. deeplearning.ai/short-courses/chatgpt-prompt-engineering-for-developers/

- R. The R Project for Statistical Computing. Accessed November 9, 2023. https://www.r-project.org/

- McHugh M. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem med (Zagreb). 2012;22(3):276-282. doi:10.11613/ BM.2012.031

- Byrt T, Bishop J, Carlin JB. Bias, prevalence and kappa. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(5):423-429. doi:10.1016/ 0895-4356(93)90018-V

- Hirt J, Meichlinger J, Schumacher P, Mueller G. Agreement in risk of bias assessment between RobotReviewer and human reviewers: an evaluation study on randomised controlled trials in nursing-related Cochrane reviews. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2021;53(2):246-254. doi:10.1111/jnu. 12628

- Shi Q, Nong K, Vandvik P, et al. Benefits and harms of drug treatment for type 2 diabetes: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2023;381:e074068. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022074068

- Pan B, Ge L, Lai H, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of insomnia drugs: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of 153 randomized trials. Drugs. 2023;83(7):587-619. doi:10.1007/s40265-023-01859-8

- Zeraatkar D , Johnston BC , Bartoszko J, et al. Effect of lower versus higher red meat intake on cardiometabolic and cancer outcomes: a systematic review of randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(10):721-731. doi:10. 7326/M19-0622

- Yaskolka Meir A, Tsaban G, Zelicha H, et al. A Green-Mediterranean diet, supplemented with mankai duckweed, preserves iron-homeostasis in humans and is efficient in reversal of anemia in rats. J Nutr. 2019;149

(6):1004-1011. doi:10.1093/jn/nxy321 - Davis CR, Hodgson JM, Woodman R, Bryan J, Wilson C, Murphy KJ. A Mediterranean diet lowers blood pressure and improves endothelial function: results from the MedLey randomized intervention trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(6):1305-1313. doi:10.3945/ajcn.116.146803

- Turner-McGrievy GM, Davidson CR, Wingard EE, Wilcox S, Frongillo EA. Comparative effectiveness of plantbased diets for weight loss: a randomized controlled trial of five different diets. Nutrition. 2015;31(2):350-358. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.09.002

- Murphy KJ, Thomson RL, Coates AM, Buckley JD, Howe PRC. Effects of eating fresh lean pork on cardiometabolic health parameters. Nutrients. 2012;4(7):711-723. doi:10.3390/nu4070711

- Benassi-Evans B, Clifton PM, Noakes M, Keogh JB, Fenech M. High protein-high red meat versus high carbohydrate weight loss diets do not differ in effect on genome stability and cell death in lymphocytes of overweight men. Mutagenesis. 2009;24(3):271-277. doi:10.1093/mutage/gep006

- Griffin HJ, Cheng HL, O’Connor HT, Rooney KB, Petocz P, Steinbeck KS. Higher protein diet for weight management in young overweight women: a 12-month randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15 (6):572-575. doi:10.1111/dom. 12056

- Hunninghake DB, Maki KC, Kwiterovich PO Jr, Davidson MH, Dicklin MR, Kafonek SD. Incorporation of lean red meat into a National Cholesterol Education Program Step I diet: a long-term, randomized clinical trial in free-living persons with hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Nutr. 2000;19(3):351-360. doi:10.1080/07315724.2000.10718931

- de Mello VDF, Zelmanovitz T, Azevedo MJ, de Paula TP, Gross JL. Long-term effect of a chicken-based diet versus enalapril on albuminuria in type 2 diabetic patients with microalbuminuria. J Ren Nutr. 2008;18(5): 440-447. doi:10.1053/j.jrn.2008.04.010

- Poddar KH, Ames M, Hsin-Jen C, Feeney MJ, Wang Y, Cheskin LJ. Positive effect of mushrooms substituted for meat on body weight, body composition, and health parameters. A 1-year randomized clinical trial. Appetite. 2013;71:379-387. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2013.09.008

- Lanza E, Yu B, Murphy G, et al; Polyp Prevention Trial Study Group. The polyp prevention trial continued follow-up study: no effect of a low-fat, high-fiber, high-fruit, and -vegetable diet on adenoma recurrence eight years after randomization. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(9):1745-1752. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0127

- Del Prato S, Camisasca R, Wilson C, Fleck P. Durability of the efficacy and safety of alogliptin compared with glipizide in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a 2-year study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16(12):1239-1246. doi:10.1111/ dom. 12377

- Nahra R, Wang T, Gadde KM, et al. Effects of cotadutide on metabolic and hepatic parameters in adults with overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes: a 54-week randomized phase 2b study. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(6): 1433-1442. doi:10.2337/dc20-2151

- Ikonomidis I, Pavlidis G, Thymis J, et al. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, and their combination on endothelial glycocalyx, arterial function, and myocardial work index in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus after 12-month treatment. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(9):e015716. doi:10.1161/JAHA.119.015716

- Yabiku K, Mutoh A, Miyagi K, Takasu N. Effects of oral antidiabetic drugs on changes in the liver-to-spleen ratio on computed tomography and inflammatory biomarkers in patients with type 2 diabetes and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Ther. 2017;39(3):558-566. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.01.015

- Seino Y, Inagaki N, Haneda M, et al. Efficacy and safety of luseogliflozin added to various oral antidiabetic drugs in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig. 2015;6(4):443-453. doi:10.1111/ jdi. 12316

- Frias JP, Nauck MA, Van J, et al. Efficacy and safety of LY3298176, a novel dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist, in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised, placebo-controlled and active comparator-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10160):2180-2193. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32260-8

- Gao F, Lv X, Mo Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of polyethylene glycol loxenatide as add-on to metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes: a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(12):2375-2383. doi:10.1111/dom. 14163

- Cherney DZI, Ferrannini E, Umpierrez GE, et al. Efficacy and safety of sotagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes and severe renal impairment. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23(12):2632-2642. doi:10.1111/dom. 14513

- Carlson AL, Mullen DM, Mazze R, Strock E, Richter S, Bergenstal RM. Evaluation of insulin glargine and exenatide alone and in combination: a randomized clinical trial with continuous glucose monitoring and ambulatory glucose profile analysis. Endocr Pract. 2019;25(4):306-314. doi:10.4158/EP-2018-0177

- Taskinen MR, Rosenstock J, Tamminen I, et al. Safety and efficacy of linagliptin as add-on therapy to metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(1):65-74. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01326.x

- Yan

, Huang , Ma , et al. A randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, multicenter, controlled trial on brotizolam intervention in outpatients with insomnia. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2013;17(4):239-243. doi:10.3109/ 13651501.2012.735242 - Sivertsen B, Omvik S, Pallesen S, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs zopiclone for treatment of chronic primary insomnia in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(24):2851-2858. doi:10.1001/ jama.295.24.2851

- Black J, Pillar G, Hedner J, et al. Efficacy and safety of almorexant in adult chronic insomnia: a randomized placebo-controlled trial with an active reference. Sleep Med. 2017;36:86-94. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2017.05.009

- Lankford A, Rogowski R, Essink B, Ludington E, Heith Durrence H, Roth T. Efficacy and safety of doxepin 6 mg in a four-week outpatient trial of elderly adults with chronic primary insomnia. Sleep Med. 2012;13(2):133-138. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.09.006

- Fan B, Kang J, He Y, Hao M, Ma S. Efficacy and safety of suvorexant for the treatment of primary insomnia among Chinese: a 6-month randomized double-blind controlled study. Neurol Asia. 2017;22(1):41-47. https://www. nstl.gov.cn/paper_detail.html?id=c7c656ece87218a9c757f49ef6866268

- Randall S, Roehrs TA, Roth T. Efficacy of eight months of nightly zolpidem: a prospective placebo-controlled study. Sleep. 2012;35(11):1551-1557. doi:10.5665/sleep. 2208

- XuH , Zhang C , Qian Y , et al. Efficacy of melatonin for sleep disturbance in middle-aged primary insomnia: a double-blind, randomised clinical trial. Sleep Med. 2020;76:113-119. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2020.10.018

- Allen RP, Mendels J, Nevins DB, Chernik DA, Hoddes E. Efficacy without tolerance or rebound insomnia for midazolam and temazepam after use for one to three months. J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;27(10):768-775. doi:10. 1002/j.1552-4604.1987.tb02994.x

- Mignot E, Mayleben D, Fietze I, et al; investigators. Safety and efficacy of daridorexant in patients with insomnia disorder: results from two multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(2):125-139. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00436-1

- Voshaar RCO, van Balkom AJLM, Zitman FG. Zolpidem is not superior to temazepam with respect to rebound insomnia: a controlled study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004;14(4):301-306. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2003. 09.007

- Jardim PSJ, Rose CJ, Ames HM, Echavez JFM, Van de Velde S, Muller AE. Automating risk of bias assessment in systematic reviews: a real-time mixed methods comparison of human researchers to a machine learning system. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2022;22(1):167. doi:10.1186/s12874-022-01649-y

- Arno A, Thomas J, Wallace B, Marshall IJ, McKenzie JE, Elliott JH. Accuracy and efficiency of machine learningassisted risk-of-bias assessments in “real-world” systematic reviews: a noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(7):1001-1009. doi:10.7326/M22-0092

الملحق 1.

المرفق الإلكتروني 1. مقدمة لتقييم مخاطر التحيز باستخدام أداة كوكراين المعدلة

المرفق الإلكتروني 2. التعليمات لـ LLM 1 و LLM 2 لتقييم مخاطر التحيز في التجارب السريرية العشوائية باستخدام أداة كوكراين المعدلة

المرفق الإلكتروني 3. ردود من LLM 1

المرفق الإلكتروني 4. ردود من LLM 2

الجدول الإلكتروني 1. استجابة المعيار المرجعي لكل تجربة سريرية عشوائية ومجال

الجدول الإلكتروني 2. العتبات لتفسير القيم لكوهين ك

الجدول الإلكتروني 3. نتائج التقييم بواسطة LLM 1 لكل مجال وتجربة سريرية عشوائية

الجدول الإلكتروني 4. نتائج التقييم بواسطة LLM 2 لكل تجربة سريرية عشوائية ومجال

الجدول الإلكتروني 5. الدقة والتناسق المحددين بالمجال للتقييمات بواسطة LLM 1

الجدول الإلكتروني 6. الدقة والتناسق المحددين بالمجال للتقييمات بواسطة LLM 2

الجدول الإلكتروني 7. الدقة المحددة بالدراسة للتقييمات بواسطة LLM 1

الجدول الإلكتروني 8. الدقة المحددة بالدراسة للتقييمات بواسطة LLM 2

الجدول الإلكتروني 9. السبب والمثال للتقييمات الخاطئة لكل مجال

الجدول الإلكتروني 10. التناسق المحدد بالمجال بين 4 تقييمات بواسطة كل من LLM 1 و LLM 2

الجدول الإلكتروني 11. التناسق المحدد بالدراسة بين تقييمين بواسطة LLM 1

الجدول الإلكتروني 12. التناسق المحدد بالدراسة بين تقييمين بواسطة LLM 2

الجدول الإلكتروني 13. التناسق المحدد بالدراسة بين 4 تقييمات بواسطة كل من LLM 1 و LLM 2

المرفق الإلكتروني 2. التعليمات لـ LLM 1 و LLM 2 لتقييم مخاطر التحيز في التجارب السريرية العشوائية باستخدام أداة كوكراين المعدلة

المرفق الإلكتروني 3. ردود من LLM 1

المرفق الإلكتروني 4. ردود من LLM 2

الجدول الإلكتروني 1. استجابة المعيار المرجعي لكل تجربة سريرية عشوائية ومجال

الجدول الإلكتروني 2. العتبات لتفسير القيم لكوهين ك

الجدول الإلكتروني 3. نتائج التقييم بواسطة LLM 1 لكل مجال وتجربة سريرية عشوائية

الجدول الإلكتروني 4. نتائج التقييم بواسطة LLM 2 لكل تجربة سريرية عشوائية ومجال

الجدول الإلكتروني 5. الدقة والتناسق المحددين بالمجال للتقييمات بواسطة LLM 1

الجدول الإلكتروني 6. الدقة والتناسق المحددين بالمجال للتقييمات بواسطة LLM 2

الجدول الإلكتروني 7. الدقة المحددة بالدراسة للتقييمات بواسطة LLM 1

الجدول الإلكتروني 8. الدقة المحددة بالدراسة للتقييمات بواسطة LLM 2

الجدول الإلكتروني 9. السبب والمثال للتقييمات الخاطئة لكل مجال

الجدول الإلكتروني 10. التناسق المحدد بالمجال بين 4 تقييمات بواسطة كل من LLM 1 و LLM 2

الجدول الإلكتروني 11. التناسق المحدد بالدراسة بين تقييمين بواسطة LLM 1

الجدول الإلكتروني 12. التناسق المحدد بالدراسة بين تقييمين بواسطة LLM 2

الجدول الإلكتروني 13. التناسق المحدد بالدراسة بين 4 تقييمات بواسطة كل من LLM 1 و LLM 2

الملحق 2.

بيان مشاركة البيانات

- الاختصارات: LLM، نموذج لغة كبير؛ NA، غير متاح لأن العدد الحقيقي الإيجابي يساوي 0.

Journal: JAMA Network Open, Volume: 7, Issue: 5

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.12687

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38776081

Publication Date: 2024-05-22

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.12687

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38776081

Publication Date: 2024-05-22

This is the published version of the publication, made available in accordance with the publisher’s policy.

Assessing the Risk of Bias in Randomized Clinical Trials With Large Language Models

Lai, Honghao; Ge, Long; Sun, Mingyao; Pan, Bei; Huang, Jiajie; Hou, Liangying; Yang, Qiuyu; Liu, Jiayi; Liu, Jianing; Ye, Ziying; Xia, Danni; Zhao, Weilong; Wang, Xiaoman; Liu, Ming [and 4 more]

How to cite

LAI, Honghao et al. Assessing the Risk of Bias in Randomized Clinical Trials With Large Language Models. In: JAMA network open, 2024, vol. 7, n

10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.12687

10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.12687

This publication URL: https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:177721

Publication DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.12687

Publication DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.12687

Original Investigation | Statistics and Research Methods

Assessing the Risk of Bias in Randomized Clinical Trials With Large Language Models

Abstract

IMPORTANCE Large language models (LLMs) may facilitate the labor-intensive process of systematic reviews. However, the exact methods and reliability remain uncertain.

OBJECTIVE To explore the feasibility and reliability of using LLMs to assess risk of bias (ROB) in randomized clinical trials (RCTs).

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS A survey study was conducted between August 10, 2023, and October 30, 2023. Thirty RCTs were selected from published systematic reviews.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES A structured prompt was developed to guide ChatGPT (LLM 1) and Claude (LLM 2) in assessing the ROB in these RCTs using a modified version of the Cochrane ROB tool developed by the CLARITY group at McMaster University. Each RCT was assessed twice by both models, and the results were documented. The results were compared with an assessment by 3 experts, which was considered a criterion standard. Correct assessment rates, sensitivity, specificity, and

RESULTS Both models demonstrated high correct assessment rates. LLM 1 reached a mean correct assessment rate of

CONCLUSIONS In this survey study of applying LLMs for ROB assessment, LLM 1 and LLM 2 demonstrated substantial accuracy and consistency in evaluating RCTs, suggesting their potential as supportive tools in systematic review processes.

JAMA Network Open. 2024;7(5):e2412687. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.12687

Key Points

Question Are large language models reliable for assessing risk of bias (ROB) in randomized clinical trials (RCTs)?

Findings In this survey study with 2 large language models and 3 experts assessing 30 RCTs, a structured prompt was developed to guide the assessment of ROB, resulting in high accuracy rates for both large language models (>84.5%), compared with human reviewers, across 10 specific domains.

Meaning These findings suggest that 2 large language models have substantial accuracy in assessing ROB in RCTs, suggesting their potential as supportive tools in systematic review processes.

Supplemental content

Author affiliations and article information are listed at the end of this article.

Introduction

Systematic reviews synthesize and evaluate existing research, guiding clinical decisions and informing health guidelines.

The assessment of ROB in the included RCTs is one of the key tasks undertaken by systematic review authors.

LLMs

Methods

This survey study was conducted between August 10, and October 30, 2023, adhering to the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) reporting guideline.

Formation of the Working Group

A multidisciplinary panel was assembled, including 3 senior experts in evidence-based medicine methodology (H.L., B.P., and L.G.), 2 computer scientists (H.L. and J.H.), and a research team of 5 investigators with backgrounds in using artificial intelligence in evidence-based medicine (H.L., M.S., Jiayi L., Jianing L., and W.Z.). The research team developed the prompt, conducted the study, recorded the results, and performed the statistical analysis. The 2 computer science experts refined and optimized the prompt. The 3 senior experts oversaw the assessment process and developed the criterion standard for assessment. All researchers completed a week-long training on systematic reviews to ensure a consistent understanding of the assessment process.

Development of the Prompt

The assessment prompt development involved senior experts setting criteria based on guidelines (eAppendix 1 in Supplement 1),

Supplement 1) consisted of 3 parts: an introduction with setting the role,

Selection of Sample

First, we searched PubMed using the keywords modified, Cochrane tool, risk of bias, CLARITY, and meta-analysis. Records were screened in descending order of relevance until 3 meta-analyses using the modified Cochrane tool

Application of LLMs

For the assessment, the finalized prompt was applied to all RCTs using LLM 1 and LLM 2, with the access time spanning from September 30 to October 10, 2023. Whereas LLM 2 allows users to directly upload PDFs, uploading PDFs to LLM 1 required a separate plugin at the time the study was conducted, which we did not use to avoid bias. We first converted the PDF files into text documents to ensure the information fed to both models was identical. In assessing ROB for each RCT, the primary outcome was defined as either the outcome specified by the authors or, if it was not specified, the first reported outcome in the study. The outputs were accurately transcribed into a document (eAppendix 3 in Supplement 1 for LLM 1 and eAppendix 4 in Supplement 1 for LLM 2). Any assessment interrupted by technical issues was excluded and promptly redone. Each RCT was

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of the Main Study Process

LLM indicates large language model; RCT, randomized clinical trial.

assessed twice with both LLMs, using the same prompt and ensuring consistent model versions. Throughout the process, strict adherence to the protocol was maintained to guarantee the fidelity of the assessment outcomes.

assessed twice with both LLMs, using the same prompt and ensuring consistent model versions. Throughout the process, strict adherence to the protocol was maintained to guarantee the fidelity of the assessment outcomes.

Establishment of the Criterion Standard

The 3 senior experts independently assessed the RCTs using the criteria, then reconciling differences through consensus. This iterative discussion continued until consensus was achieved on each aspect of the ROB assessment for every RCT. These consensus-derived assessments formed the criterion standard (eTable 1 in Supplement 1), serving as a reference to gauge the precision of the ROB evaluations of the LLM tools.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using

Accuracy

Accuracy of the LLMs in ROB assessment was quantified at the study-specific, domain-specific, and overall levels using the correct assessment rate, sensitivity, and specificity. For domain-specific accuracy, we further calculated the

F1

Positive Predictive Value = TP/(TP + FP)

Positive Predictive Value = TP/(TP + FP)

Risk differences (RD) with

Consistency

To evaluate the reliability of the LLMs’ repeated assessments, we used Cohen k , which is derived from the proportion of observed agreement (Po) minus the actual concordance observed relative to the total number of observations (ie, the consistent assessment rate) as well as the proportion of expected agreement

Given the potential homogeneity of risk assessments across domains, which could artificially elevate the expected agreement, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by calculating the prevalenceadjusted and bias-adjusted к (РАВАк).

Furthermore, RD was calculated to compare the difference in Po between LLM 1 and LLM 2.

Efficiency

The efficiency of the assessment process was measured by recording the time from text upload to completion of the full domain assessments. In this study, the network bandwidth supported upload and download speeds of approximately 100 megabits per second.

Results

Characteristics of the RCTs

We selected 1 meta-analysis published in 2021,

Accuracy

The complete assessment results are summarized in eTable 3 and eTable 4 in Supplement 1. Both LLM 1 and LLM 2 demonstrated good accuracy (Table and Figure 2). LLM 1 achieved a mean correct assessment rate of

Table. Domain-Specific Accuracy and Consistency

| Reviewer | Accuracy | Consistency | |||||

| Correct assessment rate, % | Sensitivity | Specificity | F1 score | Proportion of high risk responses, % | Cohen k | Consistent assessment rate, % | |

| LLM 1 | |||||||

| Domain 1 | 56.70 | 0.45 | 0.77 | 0.57 | 36.67 | 0.54 | 60.00 |

| Domain 2 | 70.00 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.78 | 65.00 | 0.65 | 70.00 |

| Domain 3.a | 93.30 | 1.00 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 46.67 | 0.92 | 93.33 |

| Domain 3.b | 96.70 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 50.00 | 0.96 | 96.67 |

| Domain 3.c | 93.30 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 48.33 | 0.85 | 86.67 |

| Domain 3.d | 91.70 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 46.67 | 0.81 | 83.33 |

| Domain 3.e | 91.70 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 50.00 | 0.81 | 83.33 |

| Domain 4 | 78.30 | 0.17 | 0.94 | 0.24 | 8.33 | 0.87 | 90.00 |

| Domain 5 | 83.30 | NA | 0.83 | NA | 16.67 | 0.76 | 80.00 |

| Domain 6 | 90.00 | 0.00 | 0.96 | NA | 3.33 | 0.91 | 93.33 |

| LLM 2 | |||||||

| Domain 1 | 80.00 | 0.74 | 0.91 | 0.82 | 50.00 | 0.77 | 80.00 |

| Domain 2 | 83.30 | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.89 | 73.33 | 0.76 | 80.00 |

| Domain 3.a | 98.30 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 41.67 | 0.96 | 96.67 |

| Domain 3.b | 96.70 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 50.00 | 0.92 | 93.33 |

| Domain 3.c | 90.00 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 43.33 | 0.85 | 86.67 |

| Domain 3.d | 90.00 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 43.33 | 0.85 | 86.67 |

| Domain 3.e | 90.00 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 46.67 | 0.85 | 86.67 |

| Domain 4 | 83.30 | 0.42 | 0.94 | 0.50 | 13.33 | 0.84 | 86.67 |

| Domain 5 | 90.00 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.25 | 11.67 | 0.83 | 86.67 |

| Domain 6 | 93.30 | 0.25 | 0.98 | 0.33 | 3.33 | 0.91 | 93.33 |

RCTs (2 assessments per each RCT) (Figure 2). LLM 2’s correct assessment rate was significantly higher compared with LLM 1 (RD, 0.05; 95% Cl, 0.01-0.09;

As depicted in Figure 3 and eTable 5 and eTable 6 in Supplement 1, the correct assessment rates were similar between the 2 LLMs across all 10 domains. LLM 1’s lowest correct assessment rate occurred in domain 1 (random sequence generation) at

In analyzing the models’ outputs (eTable 9 in Supplement 1), of the overall 155 wrong assessments, 89 (

Figure 2. Comparison of the Overall Correct and Consistent Assessment Rates of Large Language Models (LLMs) 1 and 2 Across 2 Consecutive Assessments

Figure 3. Correct and Consistent Assessment Rates of Large Language Models (LLMs) 1 and 2 for Each Domain

and 4 (missing outcome data), 68 of 90 (

LLM 1’s overall sensitivity was 0.82 (

LLM 2’s sensitivity was lowest in domains 4 and 6 ( 0.42 and 0.25 , respectively). Specificity ranged between 0.75 and 0.98 . The

Consistency

Both LLM 1 and LLM 2 showcased high overall consistent rates of

On a study-specific level, both LLM 1 and LLM 2 produced identical results for 12 RCTs in repetitive assessments. As shown in eTable 11 and eTable 12 in Supplement 1, we found substantial or near perfect agreements in most assessments for both models, and the lowest consistent rate was 30% for LLM 1 and 50% for LLM 2. For all assessments (eTable 13 in Supplement 1), 15 of 30 studies achieved

Efficiency

The duration of the conducted assessments for LLM 1 ranged between 52 and 127 seconds, with a mean of 77 seconds per assessment. For LLM 2, the mean duration was 53 seconds (range from 36 to 87 seconds).

Discussion

In this survey study, we established a structured and feasible prompt that was capable of guiding LLMs in assessing the ROB in RCTs. The LLMs used in this study produced assessments that were very close to those of experienced human reviewers. Automated tools in systematic reviews exist but are underused due to difficult operation, poor user experience, and unreliable results.

Our study found that both LLMs demonstrated high accuracy and consistency, compared with human reviewers, in assessing the ROB of RCTs. LLM 2 had a significantly higher correct assessment rate compared with LLM 1 . The potential causes for this discrepancy may stem from the different methods of submitting the articles. LLM 2 permits direct PDF file uploads, automatically converting them into text for analysis, while LLM 1 only allowed text (this was the case at the time of our study, but PDFs can be uploaded after the November 9, 2023, update). Thus, uploading PDFs requires additional plugins. Consequently, to maintain consistency, RCT articles were converted to text format before submission. However, the different text length constraints of the 2 LLMs required that multiple segments be uploaded sequentially for LLM 1, whereas LLM 2 processed the uploads in a single step. This could have potentially influenced LLM 1’s judgment and may explain the longer duration of assessment compared with LLM 2.

Both LLMs exhibited the lowest correct assessment rates in domain 1, concerning random sequence generation. Of the 38 incorrect assessments, 30 (

To our knowledge, this study is the first to transparently explore the feasibility of applying LLMs to the assessment of ROB in RCTs. The study addressed multiple aspects of the feasibility of LLM use, including accuracy, consistency, and efficiency. A detailed and structured prompt was proposed and performed commendably in practical application. Our findings preliminarily suggest that with an appropriate prompt, LLM 1 and LLM 2 can be used alongside the modified Cochrane tool to assess the ROB of RCTs accurately and efficiently.

Limitations

This survey study has several limitations. First, given the low probability of positive assessments in certain domains, a large sample would be required to draw robust conclusions. However, due to usage restrictions pertaining to LLM 1 and LLM 2, our study was conducted with a constrained sample size. Second, all RCTs assessed were in English; thus, the efficacy of this method for literature in other languages remains unclear. Third, the criterion standard for this research was determined by consensus among 3 senior experts. The prompt provided to the LLMs for processing different RCTs were uniform, meaning that the criterion standard was established from the broadest and most generic perspective. Additionally, in maintaining consistency with the information uploaded to the LLMs, the determination of the criterion standard did not consider supplementary materials such as appendices and registration details. Because it is challenging for artificial intelligence to interpret lengthy appendices, LLMs may not be capable of completing the task independently when additional information is imperative for accurate assessment. However, this constraint could be mitigated in the future by permitting LLMs access links to external sources. Since this functionality was still available as a beta testing version only during our study, we did not use it. Fourth, the study conducted assessments only on the primary outcome; however, responses indicate that LLMs might have the capability to simultaneously assess all reported outcomes. In practice, the prompt could be tailored to guide the assessment toward specific outcomes.

Conclusions

In this survey study of the application of LLMs to the assessment of ROB in RCTs, we found that LLM 1 and LLM 2 achieved commendable accuracy and consistency when directed by a structured prompt. By scrutinizing the rationale provided and comparing multiple assessments across different models, researchers were able to efficiently identify and correct nearly all errors.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

Accepted for Publication: March 20, 2024.

Published: May 22, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.12687

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License. © 2024 Lai H et al. JAMA Network Open.

Published: May 22, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.12687

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License. © 2024 Lai H et al. JAMA Network Open.

Corresponding Author: Long Ge, MD, Evidence-Based Social Science Research Center, School of Public Health, Lanzhou University, No. 199 Donggang West Road, Chengguan District, Lanzhou 730000 (gelong2009@163.com).

Author Affiliations: Department of Health Policy and Management, School of Public Health, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China (Lai, Ge, Q. Yang, Jiayi Liu, Ye, Xia, Zhao); Evidence-Based Social Science Research Center, School of Public Health, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China (Lai, Ge, Q. Yang, Jiayi Liu, Ye, Xia, Zhao); Key Laboratory of Evidence Based Medicine and Knowledge Translation of Gansu Province, Lanzhou, China (Ge, Tian, K. Yang); Evidence-Based Nursing Center, School of Nursing, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China (Sun); Evidence-Based Medicine Center, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China (Pan, Hou, Wang, M. Liu, Tian, K. Yang, Estill); College of Nursing, Gansu University of Chinese Medicine, Lanzhou, China (Huang, Jianing Liu); Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact, McMaster University, Ontario, Canada (Hou, M. Liu, Talukdar); Institute of Global Health, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland (Estill).

Author Contributions: Dr Lai had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Lai, M. Liu, Tian.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Lai, Ge, Sun, Pan, Huang, Hou, Q. Yang, Jiayi Liu, Jianing Liu, Ye, Xia, Zhao, Wang, M. Liu, Talukdar, K. Yang, Estill.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Lai, Ge, Sun, Pan, Huang, Hou, Q. Yang, Jiayi Liu, Jianing Liu, Ye, Xia, Zhao, Wang, M. Liu, Talukdar, K. Yang, Estill.

Drafting of the manuscript: Lai.

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Lai, Hou, M. Liu, Tian, Estill.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Lai, Sun, Pan, Huang, Jiayi Liu, Jianing Liu, Xia, Zhao, Estill.

Supervision: Ge, Pan, Q. Yang, Ye, Wang, K. Yang.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 2.

Additional Contributions: We would like to thank Howard White, DPhil, CEO Campbell Collaboration, for his suggestions on the revision of the article. He was not compensated for his contributions.

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Lai, Hou, M. Liu, Tian, Estill.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Lai, Sun, Pan, Huang, Jiayi Liu, Jianing Liu, Xia, Zhao, Estill.

Supervision: Ge, Pan, Q. Yang, Ye, Wang, K. Yang.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 2.

Additional Contributions: We would like to thank Howard White, DPhil, CEO Campbell Collaboration, for his suggestions on the revision of the article. He was not compensated for his contributions.

REFERENCES

- Djulbegovic B, Guyatt GH. Progress in evidence-based medicine: a quarter century on. Lancet. 2017;390 (10092):415-423. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31592-6

- Subbiah V. The next generation of evidence-based medicine. Nat Med. 2023;29(1):49-58. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-02160-z

- Elliott J, Synnot A, Turner T, Living Systematic Review Network, et al. Living systematic review: 1. introduction-the why, what, when, and how. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;91:23-30. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.08.010

- Siemieniuk RA, Bartoszko JJ, Zeraatkar D, et al. Drug treatments for covid-19: living systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m2980. doi:10.1136/bmj.m2980

- Fanaroff AC, Califf RM, Lopes RD. High-quality evidence to inform clinical practice. Lancet. 2019;394(10199): 633-634. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31256-5

- Minozzi S, Cinquini M, Gianola S, Gonzalez-Lorenzo M, Banzi R. The revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) showed low interrater reliability and challenges in its application. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020; 126:37-44. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.06.015

- Savović J, Weeks L, Sterne JA, et al. Evaluation of the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing the risk of bias in randomized trials: focus groups, online survey, proposed recommendations and their implementation. Syst Rev. 2014;3:37. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-3-37

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al; GRADE Working Group. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924-926. doi:10.1136/bmj.39489. 470347.AD

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed. 1000097

- Tool to Assess Risk of Bias in Randomized Controlled Trials DistillerSR. DistillerSR. Accessed October 31, 2023. https://www.distillersr.com/resources/methodological-resources/tool-to-assess-risk-of-bias-in-randomized-controlled-trials-distillersr

- Introducing ChatGPT. Anthropic. Accessed October 31, 2023. https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt

- Introducing Claude. Anthropic. Accessed October 31, 2023. https://www.anthropic.com/index/ introducing-claude

- Omiye JA, Lester JC, Spichak S, Rotemberg V, Daneshjou R. Large language models propagate race-based medicine. NPJ Digit Med. 2023;6(1):195. doi:10.1038/s41746-023-00939-z

- Singhal K, Azizi S, Tu T, et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature. 2023;620(7972): 172-180. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06291-2

- Pitt SC, Schwartz TA, Chu D. AAPOR reporting guidelines for survey studies. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(8):785-786. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0543

- ChatGPT Prompt Engineering for Developers. DeepLearning.AI. Accessed November 6, 2023. https://www. deeplearning.ai/short-courses/chatgpt-prompt-engineering-for-developers/

- R. The R Project for Statistical Computing. Accessed November 9, 2023. https://www.r-project.org/

- McHugh M. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem med (Zagreb). 2012;22(3):276-282. doi:10.11613/ BM.2012.031

- Byrt T, Bishop J, Carlin JB. Bias, prevalence and kappa. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(5):423-429. doi:10.1016/ 0895-4356(93)90018-V

- Hirt J, Meichlinger J, Schumacher P, Mueller G. Agreement in risk of bias assessment between RobotReviewer and human reviewers: an evaluation study on randomised controlled trials in nursing-related Cochrane reviews. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2021;53(2):246-254. doi:10.1111/jnu. 12628

- Shi Q, Nong K, Vandvik P, et al. Benefits and harms of drug treatment for type 2 diabetes: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2023;381:e074068. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022074068

- Pan B, Ge L, Lai H, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of insomnia drugs: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of 153 randomized trials. Drugs. 2023;83(7):587-619. doi:10.1007/s40265-023-01859-8

- Zeraatkar D , Johnston BC , Bartoszko J, et al. Effect of lower versus higher red meat intake on cardiometabolic and cancer outcomes: a systematic review of randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(10):721-731. doi:10. 7326/M19-0622

- Yaskolka Meir A, Tsaban G, Zelicha H, et al. A Green-Mediterranean diet, supplemented with mankai duckweed, preserves iron-homeostasis in humans and is efficient in reversal of anemia in rats. J Nutr. 2019;149

(6):1004-1011. doi:10.1093/jn/nxy321 - Davis CR, Hodgson JM, Woodman R, Bryan J, Wilson C, Murphy KJ. A Mediterranean diet lowers blood pressure and improves endothelial function: results from the MedLey randomized intervention trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(6):1305-1313. doi:10.3945/ajcn.116.146803

- Turner-McGrievy GM, Davidson CR, Wingard EE, Wilcox S, Frongillo EA. Comparative effectiveness of plantbased diets for weight loss: a randomized controlled trial of five different diets. Nutrition. 2015;31(2):350-358. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.09.002

- Murphy KJ, Thomson RL, Coates AM, Buckley JD, Howe PRC. Effects of eating fresh lean pork on cardiometabolic health parameters. Nutrients. 2012;4(7):711-723. doi:10.3390/nu4070711

- Benassi-Evans B, Clifton PM, Noakes M, Keogh JB, Fenech M. High protein-high red meat versus high carbohydrate weight loss diets do not differ in effect on genome stability and cell death in lymphocytes of overweight men. Mutagenesis. 2009;24(3):271-277. doi:10.1093/mutage/gep006

- Griffin HJ, Cheng HL, O’Connor HT, Rooney KB, Petocz P, Steinbeck KS. Higher protein diet for weight management in young overweight women: a 12-month randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15 (6):572-575. doi:10.1111/dom. 12056

- Hunninghake DB, Maki KC, Kwiterovich PO Jr, Davidson MH, Dicklin MR, Kafonek SD. Incorporation of lean red meat into a National Cholesterol Education Program Step I diet: a long-term, randomized clinical trial in free-living persons with hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Nutr. 2000;19(3):351-360. doi:10.1080/07315724.2000.10718931

- de Mello VDF, Zelmanovitz T, Azevedo MJ, de Paula TP, Gross JL. Long-term effect of a chicken-based diet versus enalapril on albuminuria in type 2 diabetic patients with microalbuminuria. J Ren Nutr. 2008;18(5): 440-447. doi:10.1053/j.jrn.2008.04.010

- Poddar KH, Ames M, Hsin-Jen C, Feeney MJ, Wang Y, Cheskin LJ. Positive effect of mushrooms substituted for meat on body weight, body composition, and health parameters. A 1-year randomized clinical trial. Appetite. 2013;71:379-387. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2013.09.008

- Lanza E, Yu B, Murphy G, et al; Polyp Prevention Trial Study Group. The polyp prevention trial continued follow-up study: no effect of a low-fat, high-fiber, high-fruit, and -vegetable diet on adenoma recurrence eight years after randomization. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(9):1745-1752. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0127

- Del Prato S, Camisasca R, Wilson C, Fleck P. Durability of the efficacy and safety of alogliptin compared with glipizide in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a 2-year study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16(12):1239-1246. doi:10.1111/ dom. 12377

- Nahra R, Wang T, Gadde KM, et al. Effects of cotadutide on metabolic and hepatic parameters in adults with overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes: a 54-week randomized phase 2b study. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(6): 1433-1442. doi:10.2337/dc20-2151

- Ikonomidis I, Pavlidis G, Thymis J, et al. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, and their combination on endothelial glycocalyx, arterial function, and myocardial work index in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus after 12-month treatment. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(9):e015716. doi:10.1161/JAHA.119.015716

- Yabiku K, Mutoh A, Miyagi K, Takasu N. Effects of oral antidiabetic drugs on changes in the liver-to-spleen ratio on computed tomography and inflammatory biomarkers in patients with type 2 diabetes and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Ther. 2017;39(3):558-566. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.01.015

- Seino Y, Inagaki N, Haneda M, et al. Efficacy and safety of luseogliflozin added to various oral antidiabetic drugs in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig. 2015;6(4):443-453. doi:10.1111/ jdi. 12316

- Frias JP, Nauck MA, Van J, et al. Efficacy and safety of LY3298176, a novel dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist, in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised, placebo-controlled and active comparator-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10160):2180-2193. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32260-8

- Gao F, Lv X, Mo Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of polyethylene glycol loxenatide as add-on to metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes: a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(12):2375-2383. doi:10.1111/dom. 14163

- Cherney DZI, Ferrannini E, Umpierrez GE, et al. Efficacy and safety of sotagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes and severe renal impairment. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23(12):2632-2642. doi:10.1111/dom. 14513

- Carlson AL, Mullen DM, Mazze R, Strock E, Richter S, Bergenstal RM. Evaluation of insulin glargine and exenatide alone and in combination: a randomized clinical trial with continuous glucose monitoring and ambulatory glucose profile analysis. Endocr Pract. 2019;25(4):306-314. doi:10.4158/EP-2018-0177

- Taskinen MR, Rosenstock J, Tamminen I, et al. Safety and efficacy of linagliptin as add-on therapy to metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(1):65-74. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01326.x

- Yan

, Huang , Ma , et al. A randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, multicenter, controlled trial on brotizolam intervention in outpatients with insomnia. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2013;17(4):239-243. doi:10.3109/ 13651501.2012.735242 - Sivertsen B, Omvik S, Pallesen S, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs zopiclone for treatment of chronic primary insomnia in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(24):2851-2858. doi:10.1001/ jama.295.24.2851

- Black J, Pillar G, Hedner J, et al. Efficacy and safety of almorexant in adult chronic insomnia: a randomized placebo-controlled trial with an active reference. Sleep Med. 2017;36:86-94. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2017.05.009

- Lankford A, Rogowski R, Essink B, Ludington E, Heith Durrence H, Roth T. Efficacy and safety of doxepin 6 mg in a four-week outpatient trial of elderly adults with chronic primary insomnia. Sleep Med. 2012;13(2):133-138. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.09.006

- Fan B, Kang J, He Y, Hao M, Ma S. Efficacy and safety of suvorexant for the treatment of primary insomnia among Chinese: a 6-month randomized double-blind controlled study. Neurol Asia. 2017;22(1):41-47. https://www. nstl.gov.cn/paper_detail.html?id=c7c656ece87218a9c757f49ef6866268

- Randall S, Roehrs TA, Roth T. Efficacy of eight months of nightly zolpidem: a prospective placebo-controlled study. Sleep. 2012;35(11):1551-1557. doi:10.5665/sleep. 2208

- XuH , Zhang C , Qian Y , et al. Efficacy of melatonin for sleep disturbance in middle-aged primary insomnia: a double-blind, randomised clinical trial. Sleep Med. 2020;76:113-119. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2020.10.018

- Allen RP, Mendels J, Nevins DB, Chernik DA, Hoddes E. Efficacy without tolerance or rebound insomnia for midazolam and temazepam after use for one to three months. J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;27(10):768-775. doi:10. 1002/j.1552-4604.1987.tb02994.x

- Mignot E, Mayleben D, Fietze I, et al; investigators. Safety and efficacy of daridorexant in patients with insomnia disorder: results from two multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(2):125-139. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00436-1

- Voshaar RCO, van Balkom AJLM, Zitman FG. Zolpidem is not superior to temazepam with respect to rebound insomnia: a controlled study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004;14(4):301-306. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2003. 09.007

- Jardim PSJ, Rose CJ, Ames HM, Echavez JFM, Van de Velde S, Muller AE. Automating risk of bias assessment in systematic reviews: a real-time mixed methods comparison of human researchers to a machine learning system. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2022;22(1):167. doi:10.1186/s12874-022-01649-y

- Arno A, Thomas J, Wallace B, Marshall IJ, McKenzie JE, Elliott JH. Accuracy and efficiency of machine learningassisted risk-of-bias assessments in “real-world” systematic reviews: a noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(7):1001-1009. doi:10.7326/M22-0092

SUPPLEMENT 1.

eAppendix 1. Introduction for assessing risk of bias using the modified Cochrane tool

eAppendix 2. Prompt for LLM 1 and LLM 2 to assess risk of bias in randomized clinical trials with the modified Cochrane tool

eAppendix 3. Responses from LLM 1

eAppendix 4. Responses from LLM 2

eTable 1. The criterion standard response for each randomized clinical trial and domain

eTable 2. Thresholds to interpret the values for Cohen’s k

eTable 3. The results of assessment by LLM 1 for each domain and RCT

eTable 4. The results of assessment by LLM 2 for each RCT and domain

eTable 5. The domain-specific accuracy and consistency of assessments by LLM 1

eTable 6. The domain-specific accuracy and consistency of assessments by LLM 2

eTable 7. The study-specific accuracy of assessments by LLM 1

eTable 8. The study-specific accuracy of assessments by LLM 2

eTable 9. The reason and example of wrong assessments for each domain

eTable 10. The domain-specific consistency between 4 assessments by both LLM 1 and LLM 2

eTable 11. The study-specific consistency between 2 assessments by LLM 1

eTable 12. The study-specific consistency between 2 assessments by LLM 2

eTable 13. The study-specific consistency between 4 assessments by both LLM 1 and LLM 2

eAppendix 2. Prompt for LLM 1 and LLM 2 to assess risk of bias in randomized clinical trials with the modified Cochrane tool

eAppendix 3. Responses from LLM 1

eAppendix 4. Responses from LLM 2

eTable 1. The criterion standard response for each randomized clinical trial and domain

eTable 2. Thresholds to interpret the values for Cohen’s k

eTable 3. The results of assessment by LLM 1 for each domain and RCT

eTable 4. The results of assessment by LLM 2 for each RCT and domain

eTable 5. The domain-specific accuracy and consistency of assessments by LLM 1

eTable 6. The domain-specific accuracy and consistency of assessments by LLM 2

eTable 7. The study-specific accuracy of assessments by LLM 1

eTable 8. The study-specific accuracy of assessments by LLM 2

eTable 9. The reason and example of wrong assessments for each domain

eTable 10. The domain-specific consistency between 4 assessments by both LLM 1 and LLM 2

eTable 11. The study-specific consistency between 2 assessments by LLM 1

eTable 12. The study-specific consistency between 2 assessments by LLM 2

eTable 13. The study-specific consistency between 4 assessments by both LLM 1 and LLM 2

SUPPLEMENT 2.

Data Sharing Statement

- Abbreviations: LLM, large language model; NA, not available because the true positive number is equal to 0 .