DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-074819

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38191193

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-08

تقييم نماذج التنبؤ السريرية (الجزء 1): من التطوير إلى التحقق الخارجي

المواد الإضافية تُنشر عبر الإنترنت فقط. لعرضها، يرجى زيارة المجلة على الإنترنت.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/

bmj-2023-074819

تم القبول: 04 سبتمبر 2023

الملخص

تقييم أداء نموذج التنبؤ السريري أمر بالغ الأهمية لتحديد دقته التنبؤية في الفئات والسياقات المخصصة للاستخدام. في هذه المقالة، الأولى في سلسلة من ثلاثة أجزاء، يصف كولينز وزملاؤه أهمية التقييم المعنوي باستخدام التحقق الداخلي، والتحقق الداخلي-الخارجي، والتحقق الخارجي، بالإضافة إلى استكشاف التباين، والعدالة، وقابلية التعميم في أداء النموذج.

تُتخذ قرارات الرعاية الصحية للأفراد عادةً بناءً على المخاطر أو الاحتمالات.

على الرغم من العدد المتزايد من النماذج، إلا أن القليل منها يُستخدم بشكل روتيني في الممارسة السريرية بسبب قضايا تشمل تصميم الدراسة واهتمامات التحليل (مثل حجم العينة الصغيرة، والتكيف الزائد)، والتقارير غير المكتملة (مما يؤدي إلى صعوبة في تقييم دراسات نماذج التنبؤ بشكل كامل)، وعدم وجود رابط واضح في اتخاذ القرارات السريرية. من الناحية الأساسية، غالبًا ما يكون هناك غياب أو فشل في تقييم الأداء التنبؤي لنموذج ما بشكل عادل وذو مغزى في السكان المستهدفين التمثيليين والإعدادات السريرية. إن نقص التقييم الشفاف والذو مغزى يعيق الأحكام حول الفائدة المحتملة للنموذج، وما إذا كان جاهزًا للمرحلة التالية من التقييم (مثل التدخل، أو دراسة الجدوى الاقتصادية) أو يحتاج إلى تحديث (مثل إعادة المعايرة). لإدارة هذا العجز، يوضح هذا السلسلة المكونة من ثلاثة أجزاء أهمية تقييم النماذج وكيفية القيام بذلك بشكل جيد، لمساعدة الباحثين في تقديم صورة موثوقة وعادلة عن دقة النموذج التنبؤية.

في هذه المقالة الأولى، نشرح الأسباب وراء تقييم النماذج، ونؤكد أنه يتضمن فحص أداء النموذج التنبؤي في مراحل متعددة، بما في ذلك أثناء تطوير النموذج (التحقق الداخلي) وفي بيانات جديدة (التحقق الخارجي). تتناول الأوراق اللاحقة في هذه السلسلة تصميم الدراسة ومقاييس الأداء المستخدمة لتقييم دقة النموذج التنبؤية (الجزء

لماذا نحتاج إلى تقييم نماذج التنبؤ؟

مجموعة بيانات التطوير ولكن تكون أقل بكثير عند تقييمها في مجموعة بيانات منفصلة، حتى من نفس السكان، مما يجعل النموذج أقل دقة بكثير. التأثير الناتج هو أن النموذج سيكون أقل فائدة وقد يكون ضارًا، بما في ذلك تفاقم الفجوات في توفير الرعاية الصحية أو النتائج الصحية اللاحقة. لذلك، بمجرد تطوير نموذج التنبؤ، من الواضح أنه من المهم إجراء تقييم ذي مغزى لمدى كفاءته.

الصندوق 1: مسرد المصطلحات

معايرة

المعايرة على نطاق واسع

ميل المعايرة

تمييز

فرط التكيف

ضبط المعلمات

انكماش

وجزء 2 من سلسلتنا لمزيد من الشرح التفصيلي

التقييم في تطوير النموذج: أساليب التحقق الداخلي

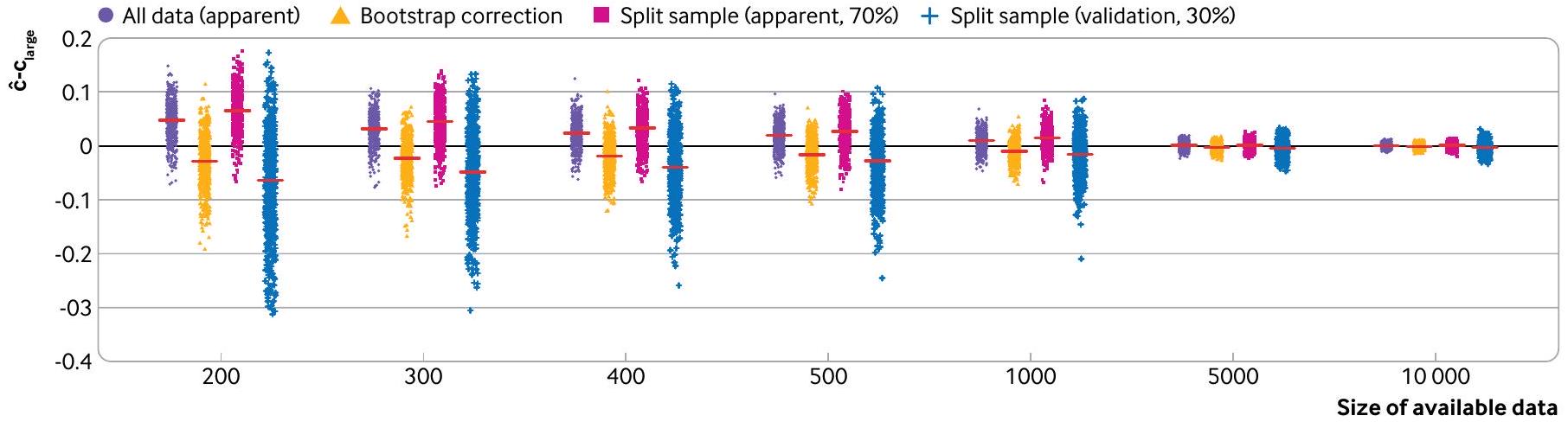

تستند الأساليب المستخدمة على نطاق واسع للتحقق الداخلي إلى تقسيم البيانات (باستخدام مجموعة فرعية من البيانات للتطوير والباقي للتقييم) أو إعادة أخذ العينات (مثل التحقق المتقاطع باستخدام k-fold أو إعادة التقدير؛ الجدول 1). بالنسبة لمجموعات البيانات الكبيرة جدًا، وإجراءات بناء النماذج التي تتطلب حسابات مكثفة (مثل تضمين ضبط المعلمات؛ الصندوق 1)، قد يكون القرار بشأن أي نهج يُستخدم للتحقق الداخلي قرارًا عمليًا. ومع ذلك، فإن بعض الأساليب غير فعالة وغير مفيدة، وخاصة في أحجام العينات الصغيرة، قد تؤدي حتى إلى نتائج متحيزة وغير دقيقة ومتفائلة، وفي النهاية استنتاجات مضللة. لذلك، نصف الآن

الأداء الظاهر

تقسيم عشوائي

BMJ: نُشر لأول مرة كـ 10.1136/bmj-2023-074819 في 8 يناير 2024. تم التنزيل منhttps://www.bmj.com/في 28 أغسطس 2025 بواسطة ضيف. محمي بموجب حقوق الطبع والنشر، بما في ذلك الاستخدامات المتعلقة بتعدين النصوص والبيانات، وتدريب الذكاء الاصطناعي، والتقنيات المماثلة.

| الجدول 1 | طرق مختلفة لتقييم أداء النموذج | |||||||

| نوع التحقق | وصف | تعليقات | |||||

| الأداء الظاهر | أداء النموذج عند تقييمه باستخدام نفس البيانات التي تم استخدامها لتطوير النموذج. | عندما تكون العينة صغيرة إلى متوسطة الحجم (انظر الجزء 3 في هذه السلسلة

|

|||||

| التحقق الداخلي | تقدير أداء النموذج للسكان الأساسيين الذين تم استخدامهم لتطوير النموذج. | توقعات الحد الأدنى، وأحد توصيات تقرير بيان TRIPOD (البند 10b)، هو أن الدراسات التي تطور نموذج توقع يجب أن تقوم بإجراء تحقق داخلي لذلك النموذج في السكان الذين يُقصد استخدامه معهم. تشمل أساليب التحقق الداخلي الشائعة تقسيم البيانات، وطرق مختلفة من التحقق المتقاطع k-fold وbootstrapping. | |||||

| تحقق من صحة العينة المقسمة | عادةً ما يتم تقسيم البيانات (بشكل عشوائي) إلى قسمين: أحدهما يُستخدم لتطوير النموذج، والآخر يُستخدم لتقييم أداء النموذج. | عادةً ما يُنصح بعدم استخدام التحقق من صحة العينة المقسمة. عندما تكون البيانات المتاحة صغيرة إلى متوسطة، فإن تقسيم البيانات سيؤدي إلى إنشاء مجموعة بيانات غير كافية لتطوير النموذج (مما يزيد من احتمال الإفراط في التكيف)، ومجموعة بيانات غير كافية لتقييم أداء النموذج. وعلى العكس، عندما يكون حجم العينة كبيرًا، فإن هناك خطرًا ضئيلًا من الإفراط في التكيف، وبالتالي لا يتم الحصول على معلومات جديدة في تقييم النموذج في بيانات التحقق. كما أن تقسيم مجموعة البيانات عشوائيًا يفتح أيضًا خطر النظرات المتعددة حتى يتم الحصول على نتائج مرضية. | |||||

| التحقق المتقاطع باستخدام k-fold | يتم تقييم أداء النموذج من خلال تقسيم البيانات إلى k مجموعات، حيث

|

|

|||||

| التمويل الذاتي | التعزيز الذاتي هو تقنية إعادة أخذ العينات، حيث يتم إنشاء عينة تعزيز ذاتي عن طريق أخذ عينات عشوائية (مع الاستبدال) من البيانات الأصلية. في التعزيز الذاتي المحسن، يتم تطوير نموذج (تكرار خطوات بناء النموذج المستخدمة لتطوير النموذج على جميع البيانات) في كل عينة تعزيز ذاتي وتقييم أدائه في هذه العينة وكذلك في مجموعة البيانات الأصلية للحصول على تقدير للتفاؤل في أداء النموذج. تتكرر هذه العملية عدة مرات ويتم حساب متوسط التفاؤل، الذي يتم طرحه بعد ذلك من الأداء الظاهر. | ||||||

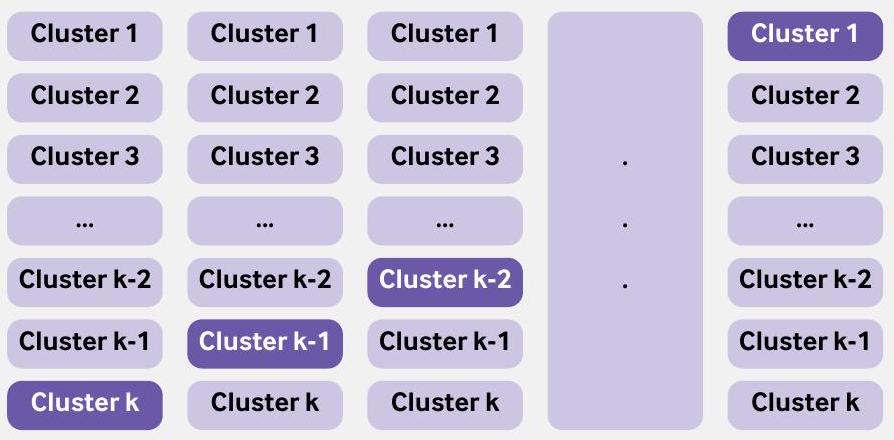

| التحقق المتقاطع الداخلي-الخارجي | تباين في أداء النموذج عبر المجموعات. يمكن أن تكون المجموعة مجموعة بيانات (عندما تتوفر مجموعات بيانات متعددة، مثل من IPDMA) أو مركز (مثل المستشفيات، أو الممارسات العامة). مشابهة لتقنية التحقق المتقاطع k-fold، يتم استخدام جميع المجموعات مع واحدة مستبعدة لتطوير نموذج، ويتم تقييم أدائه على المجموعة المستبعدة. تتكرر هذه العملية مع استبعاد مجموعة مختلفة، بحيث يتم استبعاد كل مجموعة مرة واحدة من التطوير وتستخدم كبيانات اختبار. | تُستخدم جميع البيانات المتاحة لتطوير النموذج، ويتم استخدام IECV لفحص التباين في أداء النموذج. يمكن أيضًا استخدام IECV لاستكشاف المجموعات التي يكون فيها أداء النموذج ضعيفًا (واستكشاف الأسباب)، مما قد يؤدي إلى استبعاد المجموعة من البيانات وتطوير نموذج جديد. | |||||

| التحقق الخارجي |

|

|

|||||

| التحقق الزمني | تقييم أداء نموذج التنبؤ الحالي باستخدام بيانات من نفس الإعداد أو إعداد مشابه في فترة زمنية مختلفة. | في تطوير النموذج، نادراً ما تكون التحقق الزمني مفيداً ويجب تجنبه. ومع ذلك، فإن فهم ما إذا كان أداء النموذج يتغير (وبشكل مهم يتدهور) خلال فترة الدراسة هو أمر مفيد لفهمه ومن الناحية المثالية تصحيحه. | |||||

| التحقق الجغرافي أو المكاني | تقييم أداء نموذج التنبؤ الحالي في البيانات المجمعة من مجموعة مناسبة في مراكز مختلفة (لتطوير النموذج). | في تطوير النموذج، نادراً ما تكون التحقق الجغرافي مفيداً، خاصة عندما يمكن استخدام جميع البيانات لتطوير النموذج ويمكن استكشاف التباين في أداء النموذج عبر مراكز مختلفة باستخدام نهج IECV. إذا كانت البيانات كبيرة بشكل خاص، وكان التحليل مرهقاً من الناحية الحاسوبية، فإن ترك مجموعة (مثل مركز أو دولة) هو حل عملي يمكن النظر فيه. | |||||

| IECV=التحقق المتقاطع الداخلي-الخارجي؛ IPDMA=تحليل البيانات الفردية للمشاركين. | |||||||

التكيف الزائد وإنتاج نموذج غير موثوق به،

نموذج توقع باستخدام نهج عينة مقسمة عشوائيًا. باستخدام نفس النهج كما في السابق، تم تطوير نموذج انحدار لوجستي للتنبؤ بوفاة المرضى خلال 28 يومًا في حالات احتشاء عضلة القلب الحاد باستخدام 14 متغيرًا (العمر، الجنس، ضغط الدم الانقباضي، درجة غلاسكو للغيبوبة، و10 متغيرات ضوضاء). تم ملاءمة النماذج وتقييمها في 500 مجموعة فرعية من بيانات CRASH-2، حيث

مشاركة البيانات، بحيث يتم فرض عينة مقسمة. في هذه الحالات، نوصي بشدة بوجود مجموعات بيانات تطوير واختبار كبيرة جدًا، حيث أن النموذج المطور قد يكون غير مستقر وأداء الاختبار غير موثوق، مما يجعل العملية عديمة الجدوى. يمكن أن تكشف مخاوف أحجام العينات الصغيرة من خلال مخططات عدم الاستقرار وقياسات عدم اليقين.

طرق إعادة العينة: التمهيد والتقاطع المتعدد k

يمكن أن يمنع العبء الحسابي لتنفيذ تقنية البوتستراب استخدام هذه الطريقة في مجموعات البيانات الكبيرة؛ ومع ذلك، في هذه الحالات، لا يتحقق الكثير من استخدام مجموعة البيانات الكاملة لاشتقاق وتقييم نموذج، لأن تقدير الأداء الظاهر يجب أن يكون تقريبًا جيدًا لأداء النموذج في العينة الكبيرة الأساسية.

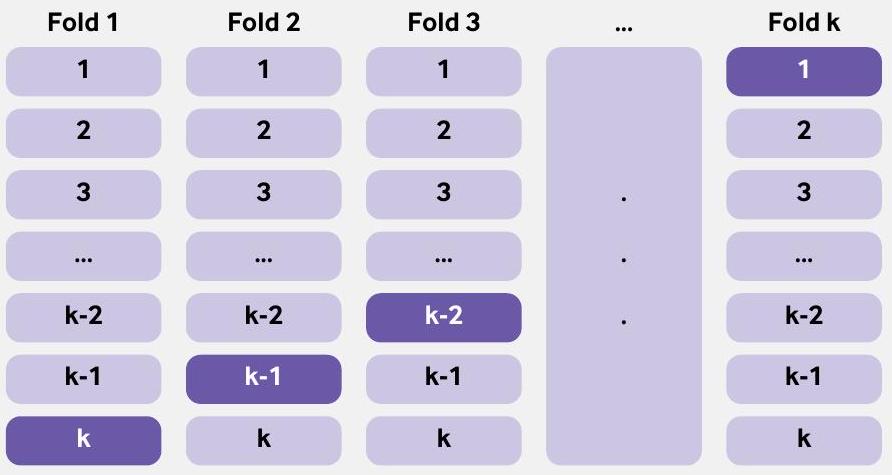

طريقة إعادة العينة الأخرى، التحقق المتقاطع باستخدام k -fold، غالبًا ما تؤدي بشكل مشابه للتقنية المعروفة باسم البوتستراب.مثل

الصندوق 2: استخدام طريقة البوتستراب للتحقق الداخلي

- قم بتطوير نموذج التنبؤ باستخدام البيانات الأصلية بالكامل واحسب الأداء الظاهر.

- قم بإنشاء عينة بوتستراب (بنفس حجم البيانات الأصلية) عن طريق أخذ عينات من الأفراد مع الاستبدال من البيانات الأصلية.

- قم بتطوير نموذج Bootstrap باستخدام عينة Bootstrap (تطبيق جميع طرق النمذجة واختيار المتنبئين، كما في الخطوة 1):

أ. تحديد الأداء الظاهر (مثل، إحصائية c، ميل المعايرة) لهذا النموذج على عينة البوتستراب (أداء البوتستراب).

ب. تحديد أداء نموذج البوتستراب في البيانات الأصلية (أداء الاختبار). - احسب التفاؤل كفرق بين أداء البوتستراب وأداء الاختبار.

- كرر الخطوات من 2 إلى 4 عدة مرات (مثل 500 مرة).

- قم بحساب متوسط تقديرات التفاؤل في الخطوة 5.

- اطرح متوسط التفاؤل (من الخطوة 6) من الأداء الظاهر الذي تم الحصول عليه في الخطوة 1 للحصول على تقدير مصحح للتفاؤل للأداء.

يمكن أيضًا الإبلاغ عن التباين في التقديرات المصححة للتفاؤل، عبر عينات البوتستراب، لإظهار الاستقرار.ستختلف نماذج البوتستراب التي تم إنتاجها في الخطوة 2 (وستختلف عن نموذج التنبؤ الذي تم تطويره على البيانات الكاملة)، ولكن هذه النماذج تستخدم فقط في تقييم الأداء وليس للتنبؤ بالمخاطر الفردية. لقد أظهر ستايربرغ وزملاؤه أن التفاؤل المتوقع يمكن تقديره بدقة باستخدام 200 بوتستراب فقط مع تباين عيني طفيف؛ ومع القوة الحاسوبية الحديثة، نوصي عمومًا بما لا يقل عن 500 بوتستراب. فائدة إضافية من هذه العملية التمهيدية هي أنه يمكن استخدام قيمة ميل المعايرة المصححة بالتفاؤل لضبط النموذج من أي زيادة في التكيف عن طريق تطبيقها كعامل انكماش على معاملات الانحدار الأصلية (تأثيرات المتنبئين).

في طريقة التمهيد، يتم استخدام جميع البيانات المتاحة لتطوير النموذج، ويتم استخدام جميع البيانات المتاحة لتقييم أداء النموذج. يمكن اعتبار التحقق المتقاطع باستخدام k -fold امتدادًا لنهج تقسيم العينة ولكن مع تقليل التحيز والتباين في تقدير أداء النموذج (الصندوق 3).

تقسيم غير عشوائي (خلال تطوير النموذج)

في التحقق الزمني، يتم استخدام بيانات من فترة زمنية واحدة لتطوير نموذج التنبؤ بينما يتم استخدام بيانات من فترة زمنية مختلفة (غير متداخلة) لتقييم أدائه. ومع ذلك، فإن القلق يكمن في اختيار الفترة الزمنية التي يجب استخدامها لتطوير النموذج، وأيها يجب استخدامها للتقييم. قد لا تعكس البيانات من الفترة الزمنية القديمة خصائص المرضى الحالية (المؤشرات والنتائج) أو الرعاية الحالية. وعلى العكس، فإن استخدام الفترة الزمنية الأكثر حداثة لتطوير النموذج يترك البيانات من فترة زمنية قديمة لتقييم الأداء، وبالتالي يوفر فقط معلومات عن دقة التنبؤ في مجموعة تاريخية من المرضى. لا يعد أي من الخيارين مرضيًا، وهذه الطريقة (في لحظة تطوير النموذج) غير موصى بها. على سبيل المثال، أدت التحسينات على مر الزمن في تقنيات الجراحة إلى زيادة عدد المرضى الذين ينجون من الجراحة.

الصندوق 3: استخدام التحقق المتقاطع k-fold للتحقق الداخلي

التقييم أثناء تطوير النموذج: التحقق المتقاطع الداخلي-الخارجي

متاحة وتستخدم لأغراض نموذج التنبؤ.

على سبيل المثال، تم استخدام التحقق المتقاطع الداخلي-الخارجي في تطوير نموذج ISARIC 4C لتحديد الأفراد المعرضين لزيادة خطر التدهور السريري لدى البالغين المصابين بكوفيد-19 الحاد.

التقييم باستخدام بيانات جديدة: التحقق الخارجي

بعض المجلات ترفض نشر دراسات تطوير النماذج دون وجود تحقق خارجي.

الصندوق 4: التحقق المتقاطع الداخلي-الخارجي

يمكن أن تؤثر حجم العينة غير الكافي، ومعالجة البيانات المفقودة (بما في ذلك المفقودات المهمة)، والتغيرات في الرعاية الصحية على أداء النموذج عند تطبيقه على مجموعة سكانية تمثيلية مستهدفة.

التطوير على الأداء في التحقق الخارجي. وبالتالي، تحتاج معظم نماذج التنبؤ إلى تقييم في بيانات جديدة لإظهار الأماكن التي ينبغي اعتبارها أو عدم اعتبارها للنشر أو لمزيد من تقييم الأثر السريري (على سبيل المثال، في تجربة سريرية عشوائية).

تعتبر التحقق الخارجي ضروريًا لأن التباينات في تقديم الرعاية الصحية، وخصائص المرضى، والخصوصيات المحلية (مثل تعريفات النتائج) ستحدد بشكل طبيعي أداء نموذج التنبؤ المعين. تم اقتراح أطر للمساعدة في تفسير النتائج في التحقق الخارجي من خلال فحص العلاقة (مثل مدى التشابه من حيث مزيج الحالات) بين بيانات التحقق الخارجي وبيانات التطوير، لاستكشاف (على مدى متصل) ما إذا كان التحقق يقيم القابلية للتكرار (البيانات مشابهة لبيانات التطوير) أو القابلية للنقل (البيانات غير مشابهة لبيانات التطوير).

غالبًا ما يتم تضمين التحقق الخارجي في الدراسات التي تطور نموذج التنبؤ. ومع ذلك، كما تم الإشارة إليه سابقًا، في لحظة تطوير النموذج، نوصي عمومًا باستخدام جميع البيانات المتاحة لبناء النموذج، مصحوبةً بالتحقق الداخلي أو التحقق الداخلي-الخارجي المعنوي. إن استخدام جميع البيانات المتاحة لتطوير نموذج يعني أنه يجب بعد ذلك (في معظم الحالات) إجراء دراسات التحقق الخارجي لاحقًا وخارج دراسة تطوير النموذج، كل منها مع هدف محدد.

التقييم في المجموعات الفرعية: تجاوز أداء السكان للمساعدة في فحص العدالة

أظهرت عدم دقة في تقدير درجة خطر فريمينغهام، مع توقعات مفرطة منهجية لدى الرجال عبر جميع الأعمار، ووجود عدم دقة صغيرة في QRISK2 لدى كبار السن.

تقديم تقنية جديدة في الرعاية السريرية، مثل نموذج التنبؤ، والذي من المتوقع أن يزداد فقط مع الزيادة في الاهتمام والاستثمار في الذكاء الاصطناعي وتعلم الآلة، يجب أن يقلل بشكل مثالي ولكن بالتأكيد لا ينبغي أن يخلق أو يزيد من أي تفاوتات في تقديم الرعاية الصحية أو في النتائج الصحية اللاحقة.

الاستنتاجات

الانتماءات المؤلفين

المساهمون: قام GSC و RDR بتصور الورقة وإنتاج المسودة الأولى. قدم جميع المؤلفين تعليقات واقترحوا تغييرات، والتي تم حلها بعد ذلك بواسطة GSC و RDR. GSC هو الضامن. يؤكد المؤلف المراسل أن جميع المؤلفين المدرجين يستوفون معايير التأليف وأنه لم يتم استبعاد أي شخص آخر يستوفي المعايير.

المصالح المتنافسة: جميع المؤلفين قد أكملوا نموذج الإفصاح الموحد ICMJE فيhttps://www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/andأعلن: الدعم من مؤسسة أبحاث السرطان في المملكة المتحدة ومجلس الأبحاث الطبية للعمل المقدم؛ لا توجد علاقات مالية مع أي منظمات قد تكون لها مصلحة في العمل المقدم خلال السنوات الثلاث الماضية؛ لا توجد علاقات أو أنشطة أخرى قد تبدو أنها أثرت على العمل المقدم. GSC و RDR هما محرران إحصائيان لمجلة BMJ.

مشاركة البيانات: بيانات CRASH-2 و CRASH-3 المستخدمة في هذه الورقة متاحة مجانًا علىhttps://freebird.lshtm.ac.ukرمز R المستخدم لإنتاج الأشكال والجداول التكميلية متاح منhttps://github.com/gscollins1973/validationCRASH.

مشاركة المرضى والجمهور: لم يشارك المرضى أو الجمهور في تصميم أو تنفيذ أو تقرير أو نشر بحثنا.

الأصل والمراجعة من قبل الأقران: لم يتم تكليفه، تمت مراجعته من قبل الأقران خارجيًا.

هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول موزعة وفقًا لشروط ترخيص المشاع الإبداعي (CC BY 4.0)، الذي يسمح للآخرين بتوزيع وإعادة مزج وتكييف وبناء على هذا العمل، للاستخدام التجاري، بشرط أن يتم الاستشهاد بالعمل الأصلي بشكل صحيح. انظر:http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

2 غوبتا RK، هاريسون EM، هو A، وآخرون، محققو ISARIC4C. تطوير وتقييم نموذج تدهور ISARIC 4C للبالغين الذين تم إدخالهم إلى المستشفى بسبب COVID-19: دراسة جماعية مستقبلية. لانسيت طب الجهاز التنفسي 2021؛9:349-59. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30559-2

3 ويشارت جي سي، أزاتو إي إم، غرينبرغ دي سي، وآخرون. PREDICT: نموذج تنبؤي جديد في المملكة المتحدة يتنبأ بالنجاة بعد الجراحة لسرطان الثدي الغازي. أبحاث سرطان الثدي 2010؛12:R1. doi:10.1186/bcr2464

4 هدى MT، فيوتريل MS، هارون D، وآخرون. تطوير وتقييم نموذج للتنبؤ بكتلة الدهون لدى الأطفال والمراهقين: تحليل تلوي باستخدام بيانات المشاركين الفردية. BMJ 2019؛ 366: 14293. doi:10.1136/bmj.l4293

5 كريستودولو E، ما J، كولينز GS، ستيربرغ EW، فيرباكل JY، فان كالسير B. مراجعة منهجية تظهر عدم وجود فائدة في الأداء لتعلم الآلة مقارنةً بالانحدار اللوجستي لنماذج التنبؤ السريرية. / علم الأوبئة السريرية 2019؛110:12-22. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.02.004

6 ذيمان ب، ما ج، نافارو كا، وآخرون. يجب تحسين تقارير نماذج التنبؤ السريرية التنبؤية المستندة إلى طرق التعلم الآلي في علم الأورام. / علم الأوبئة السريرية 2021؛138:60-72. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.06.024

7 بيللو V، بيلباسيس L، كونستانتينيديس AK، تزوولكي I، إيفانجيلو E. نماذج التنبؤ بالنتائج في المرضى الذين يعانون من مرض الانسداد الرئوي المزمن: مراجعة منهجية وتقييم نقدي. BMJ 2019؛367: I5358. doi:10.1136/bmj.I5358

8 Damen JAAG، Hooft L، Schuit E، وآخرون. نماذج التنبؤ بمخاطر الأمراض القلبية الوعائية في السكان العامين: مراجعة منهجية. BMJ 2016؛353:i2416. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2416

9 وينانتس إل، فان كالسير بي، كولينز جي إس، وآخرون. نماذج التنبؤ للتشخيص والتنبؤ بفيروس كوفيد-19: مراجعة منهجية وتقييم نقدي. BMJ 2020؛369:m1328. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1328

10 رايلي RD، آرتشر L، سنيل KIE، وآخرون. تقييم نماذج التنبؤ السريرية (الجزء 2): كيفية إجراء دراسة تحقق خارجية. BMJ 2023;383:e074820. doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-074820

12 العدالة AC، كوفينسكي KE، برلين JA. تقييم قابلية تعميم المعلومات التنبؤية. آن إنترن ميد 1999؛130:515-24. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00016

13 كيم دي دبليو، جانغ إتش واي، كو واي، وآخرون. عدم الاتساق في استخدام مصطلح “التحقق” في الدراسات التي تقيم أداء خوارزميات التعلم العميق في تقديم التشخيص من التصوير الطبي. بلس وان 2020؛ 15: e0238908. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0238908

14 سبيرين م، رايلي آر دي، كولينز جي إس، مارتن جي بي. التحقق المستهدف: التحقق من نماذج التنبؤ السريرية في السكان والإعداد المستهدفين. تشخيص التنبؤ والبحث 2022؛6:24. doi:10.1186/s41512-022-00136-8

15 رايلي RD، إنسور J، سنيل KIE، وآخرون. التحقق الخارجي من نماذج التنبؤ السريرية باستخدام مجموعات بيانات كبيرة من سجلات الصحة الإلكترونية أو تحليل البيانات الفردية: الفرص والتحديات. BMJ 2016؛ 353: i3140. doi:10.1136/bmj.i3140

16 فان كالسيرت بي، ستيربرغ إي دبليو، وينانتس إل، فان سمدن إم. لا يوجد شيء يسمى نموذج توقع موثق. بي إم سي ميد 2023؛ 21:70. doi:10.1186/s12916-023-02779-w

17 كولينز جي إس، ريتسما جي بي، ألتمان دي جي، مونس ك جي إم. التقرير الشفاف لنموذج توقع متعدد المتغيرات للتشخيص أو التنبؤ الفردي (TRIPOD): بيان TRIPOD. BMJ 2015؛350:g7594. doi:10.1136/bmj.g7594

18 Moons KGM، ألتمان DG، ريتسما JB، وآخرون. التقرير الشفاف لنموذج التنبؤ المتعدد المتغيرات للتشخيص أو التنبؤ الفردي (TRIPOD): الشرح والتفصيل. آن إنترن ميد 2015؛162:W1-73. doi:10.7326/M14-0698

19 تول DB، جانسن KJ، فيرغوي Y، مونس KG. التحقق من صحة وتحديث وتأثير قواعد التنبؤ السريرية: مراجعة. J Clin Epidemiol 2008؛ 61: 1085-94. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.04.008

20 رايلي RD، إنسور J، سنيل KIE، وآخرون. حساب حجم العينة المطلوب لتطوير نموذج توقع سريري. BMJ 2020؛368:m441. doi:10.1136/bmj.m441

21 رايلي RD، سنيل KI، إنسور J، وآخرون. الحد الأدنى لحجم العينة لتطوير نموذج توقع متعدد المتغيرات: الجزء الثاني – النتائج الثنائية ونتائج الوقت للحدث. ستات ميد 2019؛ 38: 1276-96. doi:10.1002/sim.7992

22 شاكور هـ، روبرتس آي، باوتيستا ر، وآخرون، متعاونون في تجربة CRASH-2. تأثيرات حمض الترانيكساميك على الوفاة، والأحداث الوعائية الانسدادية، ونقل الدم في مرضى الصدمة الذين يعانون من نزيف كبير (CRASH-2): تجربة عشوائية محكومة بالدواء الوهمي. لانسيت 2010؛376:23-32. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60835-5

23 ستايربرغ EW. التحقق في أبحاث التنبؤ: الهدر الناتج عن تقسيم البيانات. / علم الأوبئة السريرية 2018;103:131-3. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.07.010

24 رايلي RD، سنيل KIE، إنسور J، وآخرون. الحد الأدنى لحجم العينة لتطوير نموذج توقع متعدد المتغيرات: الجزء الأول – النتائج المستمرة. ستات ميد 2019؛ 38: 1262-75. doi:10.1002/sim.7993

25 فان سمدن م، دي غروت جا، مونس كج، وآخرون. لا يوجد مبرر لمعيار متغير واحد لكل 10 أحداث في تحليل الانحدار اللوجستي الثنائي. BMC ميد ريس ميثودول 2016؛ 16:163. doi:10.1186/s12874-016-0267-3

26 فان سمدن م، مونس ك جي، دي غروت ج أ، وآخرون. حجم العينة لنماذج التنبؤ اللوجستي الثنائي: ما وراء معايير الأحداث لكل متغير. طرق إحصائية في البحث الطبي 2019؛ 28: 2455-74. doi:10.1177/0962280218784726

27 رايلي RD، كولينز GS، إنسور J، وآخرون. حسابات الحد الأدنى لحجم العينة للتحقق الخارجي من نموذج التنبؤ السريري مع نتيجة زمنية. ستات ميد 2022؛ 41: 1280-95. doi:10.1002/sim.9275

28 سنيل كيه، آرتشر ل، إنسور ج، وآخرون. التحقق الخارجي من نماذج التنبؤ السريرية: كانت حسابات حجم العينة المعتمدة على المحاكاة أكثر موثوقية من القواعد العامة. مجلة الوبائيات السريرية 2021؛ 135: 79-89. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.011

29 أرشر إل، سنيل كيه آي إي، إنسور ج، هودا إم تي، كولينز جي إس، رايلي آر دي. الحد الأدنى لحجم العينة للتحقق الخارجي من نموذج التنبؤ السريري مع نتيجة مستمرة. ستات ميد 2021؛ 40: 133-46. doi:10.1002/sim.8766

30 ستايربرغ EW، هاريل FEJr، بورس بوم GJJM، إيكيما نس MJC، فيرغوي Y، هابما JDF. التحقق الداخلي من النماذج التنبؤية: كفاءة بعض الإجراءات لتحليل الانحدار اللوجستي. J Clin Epidemiol 2001؛54:774-81. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(01)003419

31 رايلي RD، كولينز GS. استقرار نماذج التنبؤ السريرية التي تم تطويرها باستخدام طرق إحصائية أو تعلم الآلة [إنترنت]. arXiv؛ 2022 [تم الاستشهاد به في 4 يناير 2023]. متوفر من:https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.01061

32 هاريل FEJr، لي KL، مارك DB. نماذج التنبؤ متعددة المتغيرات: قضايا في تطوير النماذج، تقييم الافتراضات والملاءمة، وقياس وتقليل الأخطاء. إحصاء الطب 1996؛ 15: 361-87. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4

33 مارتن جي بي، رايلي آر دي، كولينز جي إس، سبيرين م. تطوير نماذج التنبؤ السريرية عند الالتزام بالحد الأدنى من العينة

BMJ: نُشر لأول مرة كـ 10.1136/bmj-2023-074819 في 8 يناير 2024. تم التنزيل منhttps://www.bmj.com/في 28 أغسطس 2025 بواسطة ضيف. محمي بموجب حقوق الطبع والنشر، بما في ذلك الاستخدامات المتعلقة بتعدين النصوص والبيانات، وتدريب الذكاء الاصطناعي، والتقنيات المماثلة.

توصيات الحجم: أهمية قياس تباين البوتستراب في ضبط المعلمات والأداء التنبؤي. طرق إحصائية في البحث الطبي 2021؛30:2545-61. doi:10.1177/09622802211046388

34 ستايربرغ EW، بليكر SE، مول HA، جروبي DE، مونس KGM. التحقق الداخلي والخارجي من النماذج التنبؤية: دراسة محاكاة للتحيز والدقة في عينات صغيرة. / علم الأوبئة السريرية 2003؛ 56: 441-7. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00047-7

35 ستايربرغ EW. نماذج التنبؤ السريرية: نهج عملي للتطوير والتحقق والتحديث. الطبعة الثانية. سبرينغر، 2019. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-16399-0.

36 هاريل FEJr. استراتيجيات نمذجة الانحدار: مع تطبيقات على النماذج الخطية، والانحدار اللوجستي والترتيبي، وتحليل البقاء. الطبعة الثانية. سبرينجر، 2015. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-194257.

38 هيكي جي إل، غرانت إس دبليو، مورفي جي جي، وآخرون. الاتجاهات الديناميكية في جراحة القلب: لماذا لم يعد نموذج يوروسكور اللوجستي مناسبًا لجراحة القلب المعاصرة وآثار ذلك على نماذج المخاطر المستقبلية. المجلة الأوروبية لجراحة القلب والصدر 2013؛43:1146-52. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezs584

39 جنكينز د. التحديث المستمر ومراقبة نماذج التنبؤ السريرية: هل حان الوقت لأنظمة التنبؤ الديناميكية؟ 2021؛7.

40 Booth S، Riley RD، Ensor J، Lambert PC، Rutherford MJ. إعادة ضبط الزمن لتحسين تطوير نماذج التنبؤ وتوقعات المخاطر في البيئات التي تتحسن فيها معدلات البقاء مع مرور الوقت. Int/ Epidemiol 2020؛49:1316-25. doi:10.1093/ije/dyaa030

41 هيبيسلي-كوك ج، كوبرلاند س، فينوجرادوفا ي، وآخرون. التنبؤ بمخاطر القلب والأوعية الدموية في إنجلترا وويلز: الاشتقاق والتأكيد المستقبلي لـ QRISK2. BMJ 2008؛ 336: 1475-82. doi:10.1136/bmj.39609.449676.25

42 رايلي آر، تيرني ج، ستيوارت ل، محررون. تحليل البيانات الفردية للمتعاونين: دليل لأبحاث الرعاية الصحية. وايلي، 2021. doi:10.1002/9781119333784.

43 ستايربرغ EW، هاريل FEJr. تحتاج نماذج التنبؤ إلى التحقق الداخلي المناسب، والتحقق الداخلي الخارجي، والتحقق الخارجي. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;69:245-7. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.04.005

44 روستون بي، بارمار إم كي بي، سيلفستر آر. بناء وتحقق من نموذج تنبؤي عبر عدة دراسات، مع تطبيق في سرطان المثانة السطحي. إحصاء الطب 2004؛ 23: 907-26. doi:10.1002/sim.1691

45 تاكادا تي، نيجمان إس، دينكاساس إس، وآخرون. ساعدت عملية التحقق المتبادل الداخلي-الخارجي في تقييم قابلية تعميم نماذج التنبؤ في مجموعات البيانات الكبيرة المجمعة. / علم الأوبئة السريرية 2021؛ 137: 8391. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.025

47 ديبري TPA، كولينز GS، رايلي RD، وآخرون. التقرير الشفاف لنماذج التنبؤ متعددة المتغيرات التي تم تطويرها أو التحقق من صحتها باستخدام بيانات مجمعة: قائمة فحص TRIPOD-Cluster. BMJ 2023؛380:e071018. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-071018

48 ديبري TPA، كولينز GS، رايلي RD، وآخرون. التقرير الشفاف لنماذج التنبؤ متعددة المتغيرات التي تم تطويرها أو التحقق من صحتها باستخدام بيانات مجمعة (TRIPOD-Cluster): الشرح والتفصيل. BMJ 2023؛380:e071058. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-071058

50 كولينز جي إس، ألتمن دي جي. التنبؤ بخطر الإصابة بأمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية على مدى 10 سنوات في المملكة المتحدة: التحقق المستقل والخارجي من نسخة محدثة من QRISK2. BMJ 2012؛344:e4181. doi:10.1136/bmj.e4181

51 نيفين ل، محررو مجلة PLOS للطب. تعزيز الاستخدام المفيد لتعلم الآلة في الرعاية الصحية والطب: نحو فهم مجتمعي. PLoS Med 2018؛ 15: e1002708. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002708

52 كولينز جي إس، دي غروت جي إيه، داتون إس، وآخرون. التحقق الخارجي من نماذج التنبؤ متعددة المتغيرات: مراجعة منهجية للسلوك والتقارير المنهجية. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014؛ 14:40. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-14-40

53 Moons KGM، ألتمان DG، فيرغوي Y، رويستون P. التنبؤ والبحث التنبؤي: تطبيق وتأثير النماذج التنبؤية في الممارسة السريرية. BMJ 2009؛ 338: b606. doi:10.1136/bmj.b606

54 ديبري TPA، فيرغوي Y، كوفيبرج H، نيبور D، ستيربرغ EW، مونس KGM. إطار جديد لتعزيز تفسير دراسات التحقق الخارجي لنماذج التنبؤ السريرية. J Clin Epidemiol 2015؛ 68: 279-89. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.06.018

55 كابيتزا ف، كامباجنر أ، سوارس ف، وآخرون. أهمية أن تكون خارجيًا. رؤى منهجية للتحقق الخارجي من نماذج التعلم الآلي في الطب. طرق الحوسبة والبرامج الحيوية 2021؛ 208: 106288. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2021.106288

56 ألتمان دي جي، فيرغوي ي، رويستون بي، مونس ك جي إم. التنبؤ والبحث التنبؤي: التحقق من نموذج تنبؤي. BMJ 2009؛ 338: b605. doi:10.1136/bmj.b605

57 ديفيس SE، لاسكو TA، تشين G، سيو ED، ماثيني ME. انحراف المعايرة في نماذج الانحدار وتعلم الآلة لإصابة الكلى الحادة. مجلة جمعية المعلومات الطبية الأمريكية 2017؛ 24: 1052-61. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocx030

58 ويسلر بي إس، نيلسون ج، بارك جي، وآخرون. التحقق الخارجي من نماذج التنبؤ السريري القلبي الوعائي: مراجعة شاملة للأدبيات. دائرة نتائج الجودة القلبية الوعائية 2021؛14:e007858. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.121.007858

٥٩ فان كالسـتر ب، وينانتس ل، تيمرمان د، ستايربرغ إي دبليو، كولينز جي إس. التحليلات التنبؤية في الرعاية الصحية: كيف يمكننا أن نعرف أنها تعمل؟/ جمعية المعلومات الطبية الأمريكية ٢٠١٩؛٢٦:١٦٥١-٤. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocz130

٦٠ بارك ي، هو ج، سينغ م، وآخرون. مقارنة الطرق لتقليل التحيز من نماذج التنبؤ السريرية للاكتئاب بعد الولادة. شبكة جراحة جاما ٢٠٢١؛٤:e٢١٣٩٠٩. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.3909

٦١ غاناباثي س، بالمر ج، ألدرمان ج إي، وآخرون. معالجة التحيز في مجموعات بيانات الذكاء الاصطناعي من خلال مبادرة STANDING Together. الطب الطبيعي ٢٠٢٢؛٢٨:٢٢٣٢-٣. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01987-w

٦٢ فياس د أ، آيزنشتاين ل ج، جونز د س. مخفي في العلن إعادة النظر في استخدام تصحيح العرق في الخوارزميات السريرية. نيو إنجلاند جورنال أوف ميديسن ٢٠٢٠؛٣٨٣:٨٧٤-٨٢. doi:10.1056/NEJMms2004740

٦٣ جونسون-مان سي إن، لوفتس ت ج، بيهوريك أ. العدالة والذكاء الاصطناعي في الرعاية الجراحية. جراحة جاما ٢٠٢١؛١٥٦:٥٠٩-١٠. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2020.7208

٦٤ باولس ج ك، كينت د م. غير متساوي بشكل متوقع: فهم ومعالجة المخاوف من أن التنبؤ السريري الخوارزمي قد يزيد من الفجوات الصحية. NPJ Digit Med ٢٠٢٠؛٣:٩٩. doi:10.1038/s41746-020-0304-9

- نقاط ملخصة

تستخدم نماذج التنبؤ السريرية مجموعة من المتغيرات لتقدير مخاطر النتائج للأفرادتقييم أداء نموذج التنبؤ أمر بالغ الأهمية ودراسات التحقق ضرورية، حيث يمكن أن يكون النموذج المطور بشكل سيء ضارًا أو يزيد من الفجوات في تقديم الرعاية الصحية أو نتائج الرعاية الصحية اللاحقةيجب أن يتم تقييم أداء النموذج في مجموعات بيانات تمثل السكان المستهدفين المقصودين لتنفيذ النموذجغالبًا ما يبدو أداء النموذج التنبؤي ممتازًا في مجموعة بيانات التطوير ولكنه يكون أقل بكثير عند تقييمه في مجموعة بيانات منفصلة، حتى من نفس السكان

يجب تجنب تقسيم البيانات في لحظة تطوير النموذج بشكل عام لأنه يتخلص من البيانات مما يؤدي إلى نموذج أقل موثوقية، بينما يترك عددًا قليلًا جدًا من البيانات لتقييم أدائه بشكل موثوق

يجب بذل جهود منسقة لاستغلال جميع البيانات المتاحة لبناء أفضل نموذج ممكن، مع استخدام أفضل لطرق إعادة العينة للتحقق الداخلي، والتحقق الداخلي-الخارجي لتقييم أداء النموذج وقابليته للتعميم عبر المجموعات

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-074819

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38191193

Publication Date: 2024-01-08

Evaluation of clinical prediction models (part 1): from development to external validation

Additional material is published online only. To view please visit the journal online.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/

bmj-2023-074819

Accepted: 04 September 2023

Abstract

Evaluating the performance of a clinical prediction model is crucial to establish its predictive accuracy in the populations and settings intended for use. In this article, the first in a three part series, Collins and colleagues describe the importance of a meaningful evaluation using internal, internal-external, and external validation, as well as exploring heterogeneity, fairness, and generalisability in model performance.

Healthcare decisions for individuals are routinely made on the basis of risk or probability.

Despite the increasing number of models, very few are routinely used in clinical practice owing to issues including study design and analysis concerns (eg, small sample size, overfitting), incomplete reporting (leading to difficulty in fully appraising prediction model studies), and no clear link into clinical decision making. Fundamentally, there is often an absence or failure to fairly and meaningfully evaluate the predictive performance of a model in representative target populations and clinical settings. Lack of transparent and meaningful evaluation obfuscates judgments about the potential usefulness of the model, and whether it is ready for next stage of evaluation (eg, an intervention, or cost effectiveness study) or requires updating (eg, recalibration). To manage this deficit, this three part series outlines the importance of model evaluation and how to undertake it well, to help researchers provide a reliable and fair picture of a model’s predictive accuracy.

In this first article, we explain the rationale for model evaluation, and emphasise that it involves examining a model’s predictive performance at multiple stages, including at model development (internal validation) and in new data (external validation). Subsequent papers in this series consider the study design and performance measures used to evaluate the predictive accuracy of a model (part

Why do we need to evaluate prediction models?

development dataset butbemuch lower when evaluated in a separate dataset, even from the same population, often rendering the model much less accurate. The downstream effect is that the model will be less useful and even potentially harmful, including exacerbating inequalities in either provision of healthcare or subsequent healthcare outcomes. Therefore, once a prediction model has been developed, it is clearly important to carry out a meaningful evaluation of how well it performs.

Box 1: Glossary of terms

Calibration

Calibration-in-the-large

Calibration slope

Discrimination

Overfitting

Parameter tuning

Shrinkage

and part 2 of our series for more detailed explanation

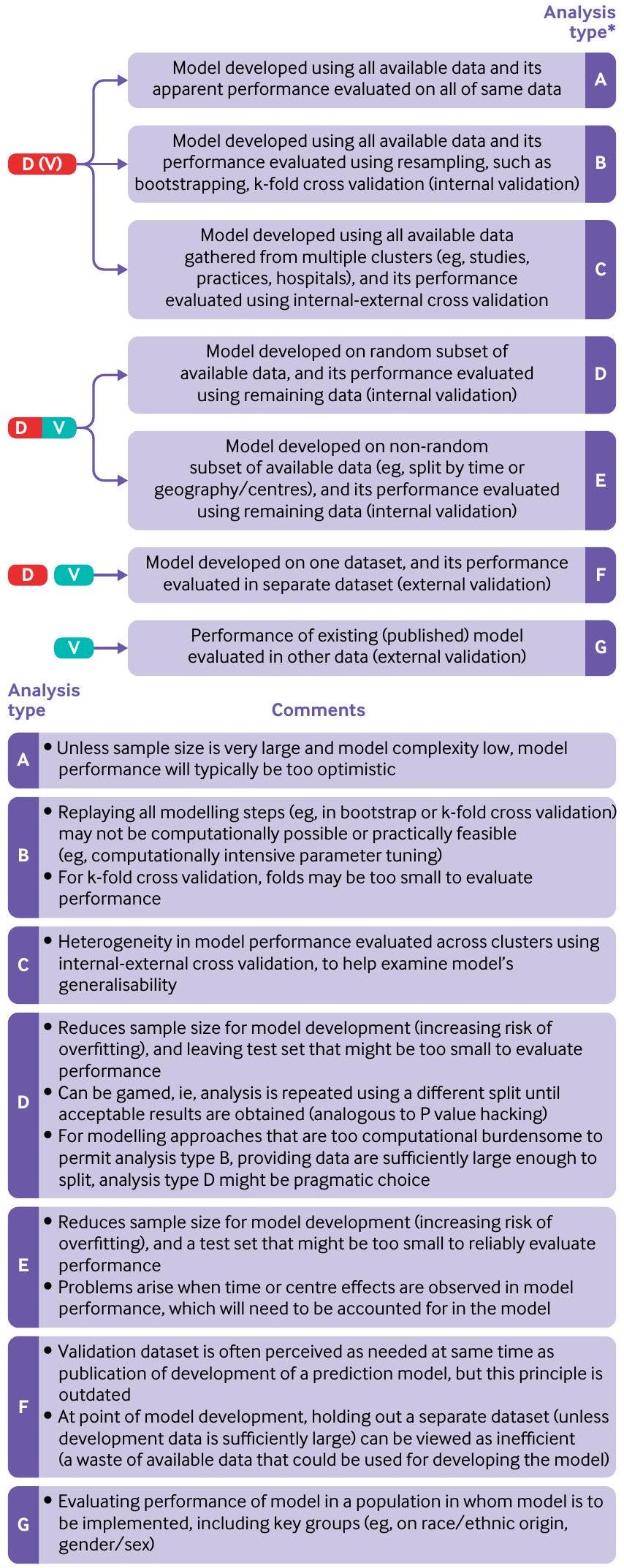

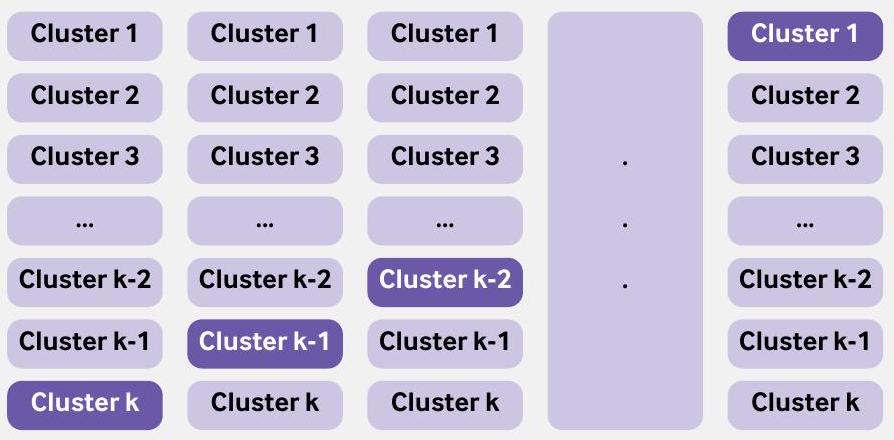

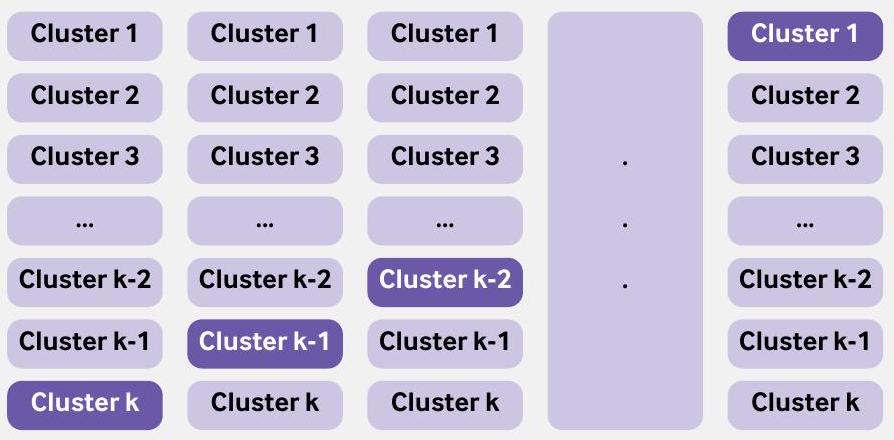

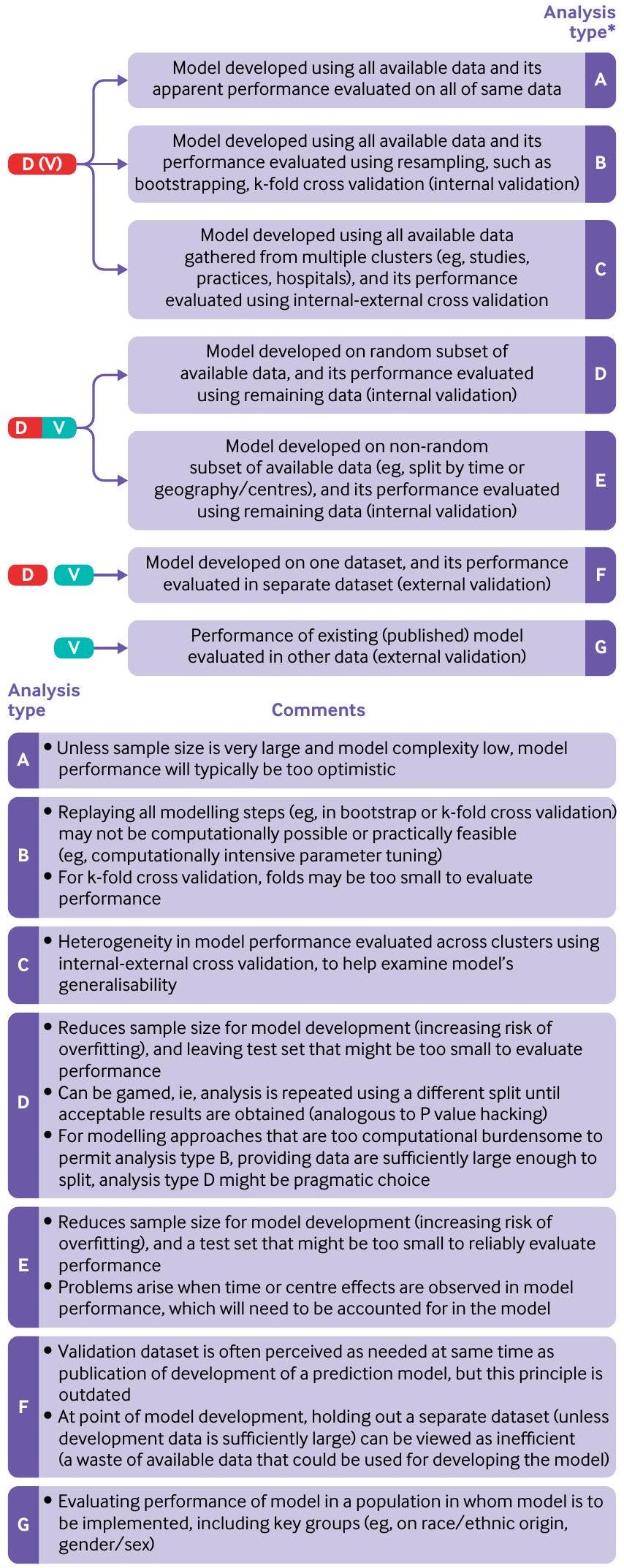

Evaluation at model development: internal validation approaches

Widely used approaches for internal validation are based on data splitting (using a subset of the data for development and the remainder for evaluation) or resampling (eg, k-fold cross validation or bootstrapping; table 1). For very large datasets, and computationally intensive model building procedures (eg, including parameter tuning; box 1), the decision on which approach is used for internal validation could be a pragmatic one. Nevertheless, some approaches are inefficient and uninformative, and, especially in small sample sizes, might even lead to biased, imprecise and optimistic results and ultimately misleading conclusions. Therefore, we now describe

Apparent performance

Random split

BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj-2023-074819 on 8 January 2024. Downloaded from https://www.bmj.com/ on 28 August 2025 by guest. Protected by copyright, including for uses related to text and data mining, Al training, and similar technologies.

| Table 1 | Different approaches for evaluating model performance | |||||||

| Type of validation | Description | Comments | |||||

| Apparent performance | Performance of the model when evaluated in the same data used to develop the model. | When the sample is of small to moderate size (see part 3 in this series

|

|||||

| Internal validation | Estimating model performance for the underlying population used to develop the model. | A minimal expectation, and one of the TRIPOD statement reporting recommendations (item 10b), is that studies developing a prediction model should carry out an internal validation of that model in the population in whom it is intended to be used. Common internal validation approaches include data splitting, and variations of k-fold cross validation and bootstrapping. | |||||

| Split sample validation | Data are (usually randomly) split into two: one used to develop the model, one used to evaluate the performance of the model. | Split sample validation is generally advised against. When the available data are small to moderate, splitting data will create a dataset that is insufficient for model development (increasing the likelihood of overfitting), and a dataset that is insufficient to evaluate the performance of the model. Conversely when the sample size is large, there is little risk of overfitting, and thus no new information is gained in evaluating the model in the validation data. Randomly splitting the dataset also opens up the danger of multiple looks until satisfactory results are obtained. | |||||

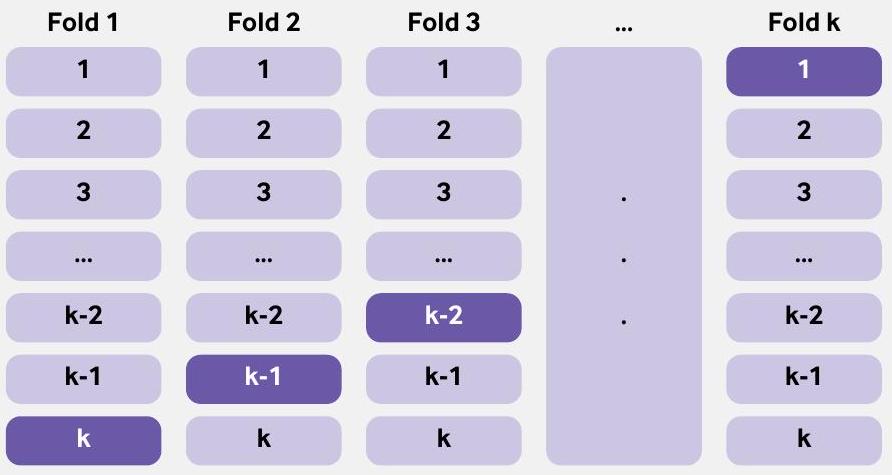

| k-fold cross validation | Model performance is evaluated by splitting the data into k groups, where

|

|

|||||

| Bootstrapping | Bootstrapping is a resampling technique, where a bootstrap sample is created by randomly sampling (with replacement) from the original data. In the enhanced bootstrap, a model is developed (repeating the model building steps used to develop the model on all the data) in each bootstrap sample and its performance evaluated in this sample as well as the original dataset to get an estimate of optimism of model performance. This process is repeated many times and the average optimism calculated, which is then subtracted from the apparent performance. | ||||||

| Internal-external cross validation | Heterogeneity in performance of the model across clusters. A cluster could be a dataset (when multiple datasets are available, eg, from an IPDMA) or centre (eg, hospitals, general practices). Similar to k -fold cross validation, all clusters with one omitted are used to develop a model, and its performance evaluated on the omitted cluster. This process is repeated taking out a different cluster, so that each cluster is omitted once from the development and used as a test dataset. | All available data are used to develop the model and IECV is used to examine heterogeneity in model performance. IECV can also be used to explore clusters where model performance is poor (and explore reasons), which could lead to dropping the cluster from the data and a new model developed. | |||||

| External validation |

|

|

|||||

| Temporal validation | Evaluating the performance of an existing prediction model in data from the same or similar setting in a different time period. | At model development, temporal validation is rarely useful and should be avoided. However, understanding whether model performance is changing (and importantly deteriorating) over the study period is useful to understand and ideally rectify. | |||||

| Geographical or spatial validation | Evaluating the performance of an existing prediction model in data collected from an appropriate population in different centres (to the model development). | At model development, geographical validation is rarely useful, particularly when all the data can be used to develop the model and heterogeneity in model performance across different centres can be explore using the IECV approach. If data are particularly large, and analysis computationally burdensome, then leaving out a cluster (eg, a centre or country) is a pragmatic compromise that can be considered. | |||||

| IECV=internal-external cross validation; IPDMA=individual participant data meta-analysis. | |||||||

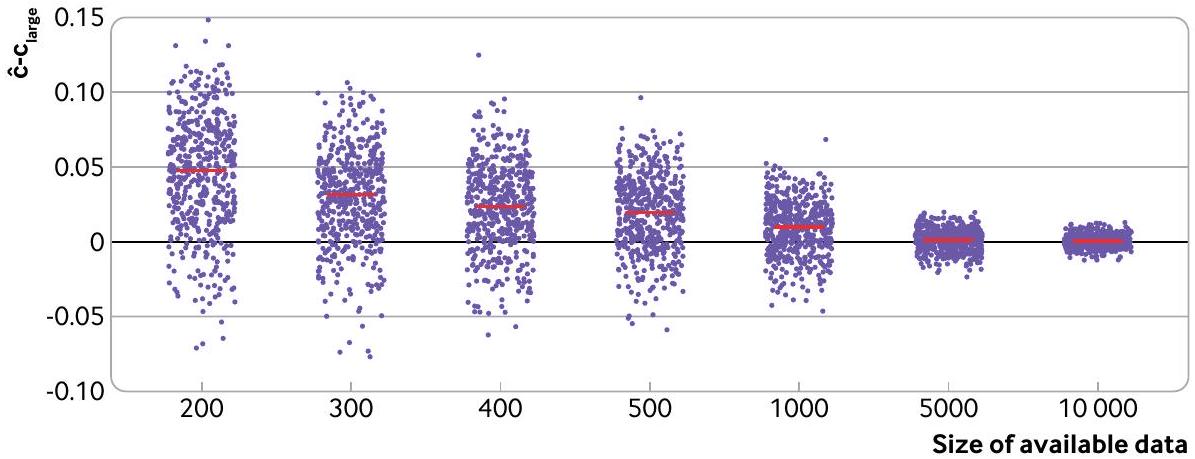

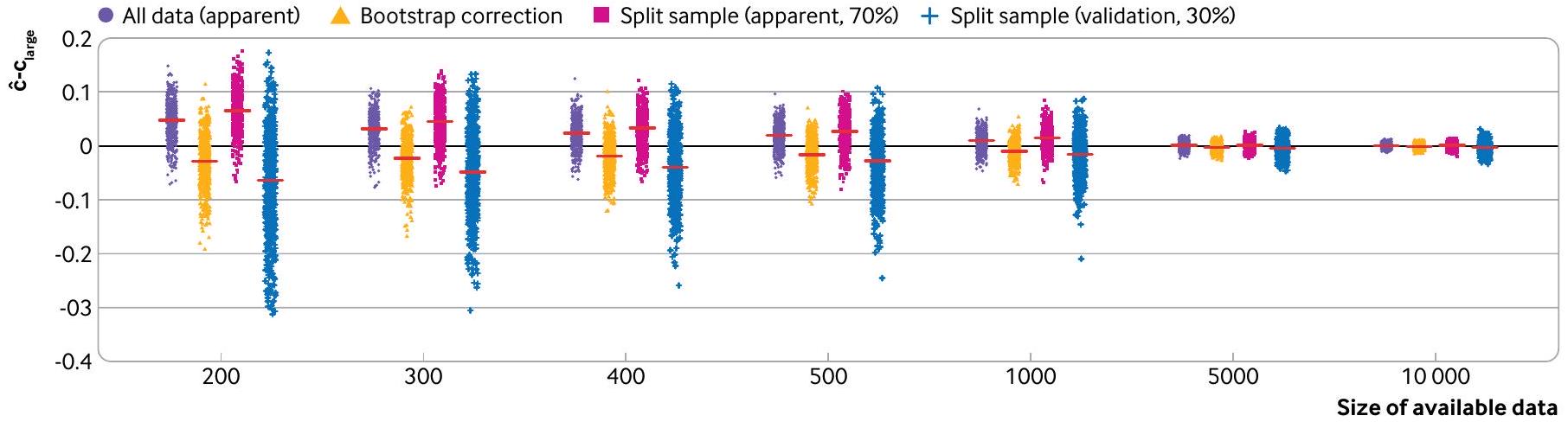

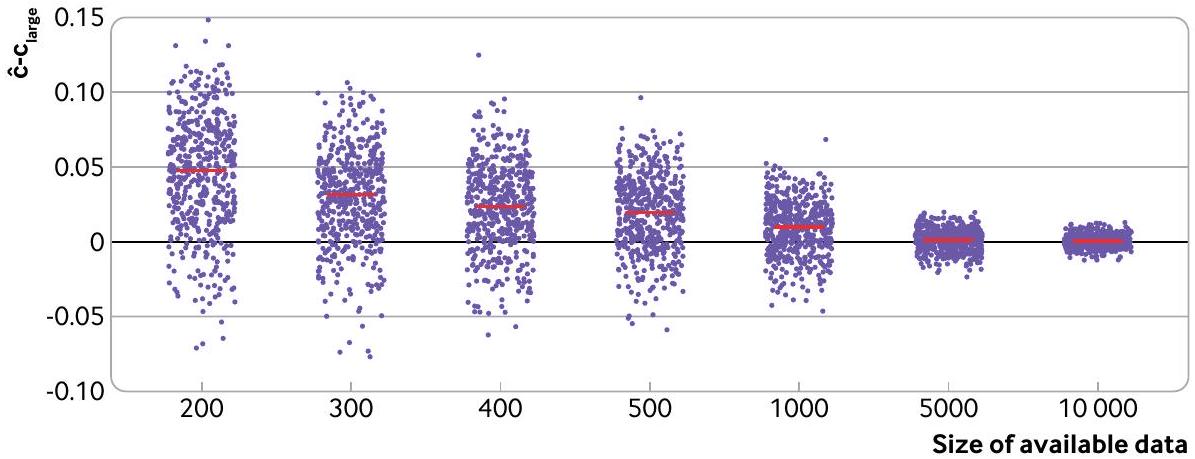

overfitting and producing an unreliable model,

a prediction model using a random split sample approach. Using the same approach as before, a logistic regression model for predicting 28 day mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction was developed using 14 predictors (age, sex, systolic blood pressure, Glasgow coma score, and 10 noise predictors). The models are fit and evaluated in 500 split sample subsets of the CRASH-2 data, whereby

data sharing, such that a split sample is enforced. In these situations, we strongly recommended having very large development and test datasets, as otherwise the developed model might be unstable and test performance unreliable, rendering the process futile. Concerns of small sample sizes can be revealed by instability plots and measures of uncertainty.

Resampling approaches: bootstrapping and k -fold cross validation

datasets, the computational burden to carry out bootstrapping can prohibit its use; in these instances, however, little is achieved over using the entire dataset to both derive and evaluate a model, because the estimate of apparent performance should be a good approximation of the underlying large sample performance of the model.

Another resampling method, k -fold cross validation, will often perform comparably to bootstrapping.Like

Box 2: Using bootstrapping for internal validation

- Develop the prediction model using the entire original data and calculate the apparent performance.

- Generate a bootstrap sample (of the same size as the original data), by sampling individuals with replacement from the original data.

- Develop a bootstrap model using the bootstrap sample (applying all the same modelling and predictor selection methods, as in step 1):

a. Determine the apparent performance (eg, c statistic, calibration slope) of this model on the bootstrap sample (bootstrap performance).

b. Determine the performance of the bootstrap model in the original data (test performance). - Calculate the optimism as the difference between the bootstrap performance and the test performance.

- Repeat steps 2 to 4 many times (eg, 500 times).

- Average the estimates of optimism in step 5.

- Subtract the average optimism (from step 6) from the apparent performance obtained in step 1 to obtain an optimism corrected estimate of performance.

The variability in the optimism corrected estimates, across the bootstrap samples, can also be reported to demonstrate stability.The bootstrap models produced in step 2 will vary (and differ from the prediction model developed on the entire data), but these bootstrap models are only used in the evaluation of performance and not for individual risk prediction. Steyerberg and colleagues have shown that the expected optimism could precisely be estimated with as few as 200 bootstraps with minor sampling variability; with modern computational power, we generally recommend at least 500 bootstraps. An additional benefit of this bootstrap process is that the value of optimism corrected calibration slope can be used to adjust the model from any overfitting by applying it as shrinkage factor to the original regression coefficients (predictor effects).

bootstrapping, all available data are used to develop the model, and all available data are used to evaluate model performance. k -fold cross validation can be seen an extension of the split sample approach but with a reduction in the bias and variability in estimation of model performance (box 3).

Non-random split (at model development)

In a temporal validation, data from one time period are used to develop the prediction model while data from a different (non-overlapping) time period are used to evaluate its performance. The concern, though, is selecting which time period should be used to develop the model, and which to use for evaluation. Using data from the older time period for model development might not reflect current patient characteristics (predictors and outcomes) or current care. Conversely, using the more contemporary time period to develop the model leaves the data from an older time period to evaluate the performance, and so only provides information on the predictive accuracy in a historical cohort of patients. Neither option is satisfactory, and this approach (at the moment of model development) is not recommended. For example, improvements over time in surgical techniques have led to larger number of patients surviving surgery,

Box 3: Use of k -fold cross validation for internal validation

Evaluation at model development: internal-external cross validation

available and used for prediction model purposes.

For example, internal-external cross validation was used in the development of the ISARIC 4C model to identify individuals at increased risk of clinical deterioration in adults with acute covid-19.

Evaluation using new data: external validation

Some journals refuse to publish model development studies without an external validation

Box 4: Internal-external cross validation

inadequate sample size, handling of missing data (including missing important predictors), and changes in health care could all affect the model performance when applied to a target representative population.

development on performance at external validation. Thus, most prediction models need evaluation in new data to demonstrate where they should and should not be considered for deployment or further evaluation of clinical impact (eg, in a randomised clinical trial

External validations are needed because variations in healthcare provision, patient demographics, and local idiosyncrasies (eg, in outcome definitions) will naturally dictate the performance of a particular prediction model. Frameworks have been proposed to aid the interpretation of findings at external validation by examining the relatedness (eg, how similar in terms of case mix) of the external validation data to the development data, to explore (on a continuum) whether the validation assesses reproducibility (data are similar to the development data) or transportability (data are dissimilar to the development data).

External validation is sometimes included in studies developing a prediction model. However, as noted earlier, at the moment of model development, we generally recommend that all available data should be used to build the model, accompanied by a meaningful internal or internal-external cross validation. Using all the available data to develop a model implies that external validation studies should then (in most instances) be done subsequently and outside the model development study, each with a specific

Evaluation in subgroups: going beyond population performance to help examine fairness

demonstrated miscalibration of the Framingham risk score, with systematic overprediction in men across all ages, and a small miscalibration of QRISK2 in those of older age.

Introducing a new technology in clinical care, such as a prediction model, which is expected only to increase with the surge in interest and investment in artificial intelligence and machine learning, should ideally reduce but certainly not create or exacerbate any disparities in either provision of healthcare or indeed subsequent healthcare outcomes.

Conclusions

AUTHOR AFFILIATIONS

Contributors: GSC and RDR conceived the paper and produced the first draft. All authors provided comments and suggested changes, which were then resolved by GSC and RDR. GSC is the guarantor. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at https://www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/and declare: support from Cancer Research UK and the Medical Research Council for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. GSC and RDR are statistical editors for The BMJ.

Data sharing: The CRASH-2 and CRASH-3 data used in this paper are freely available at https://freebird.lshtm.ac.uk. The R code used to produce the figures and supplementary tables is available from https://github.com/gscollins1973/validationCRASH.

Patient and public involvement: Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination of our research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

2 Gupta RK, Harrison EM, Ho A, et al, ISARIC4C Investigators. Development and validation of the ISARIC 4C Deterioration model for adults hospitalised with COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2021;9:349-59. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30559-2

3 Wishart GC, Azzato EM, Greenberg DC, et al. PREDICT: a new UK prognostic model that predicts survival following surgery for invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2010;12:R1. doi:10.1186/bcr2464

4 Hudda MT, Fewtrell MS, Haroun D, et al. Development and validation of a prediction model for fat mass in children and adolescents: metaanalysis using individual participant data. BMJ 2019;366:14293. doi:10.1136/bmj.l4293

5 Christodoulou E, Ma J, Collins GS, Steyerberg EW, Verbakel JY, Van Calster B. A systematic review shows no performance benefit of machine learning over logistic regression for clinical prediction models. / Clin Epidemiol 2019;110:12-22. doi:10.1016/j. jclinepi.2019.02.004

6 Dhiman P, Ma J, Navarro CA, et al. Reporting of prognostic clinical prediction models based on machine learning methods in oncology needs to be improved. / Clin Epidemiol 2021;138:60-72. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.06.024

7 Bellou V, Belbasis L, Konstantinidis AK, Tzoulaki I, Evangelou E. Prognostic models for outcome prediction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and critical appraisal. BMJ 2019;367:I5358. doi:10.1136/bmj.I5358

8 Damen JAAG, Hooft L, Schuit E, et al. Prediction models for cardiovascular disease risk in the general population: systematic review. BMJ 2016;353:i2416. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2416

9 Wynants L, Van Calster B, Collins GS, et al. Prediction models for diagnosis and prognosis of covid-19: systematic review and critical appraisal. BMJ 2020;369:m1328. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1328

10 Riley RD, Archer L, Snell KIE, et al. Evaluation of clinical prediction models (part 2): how to undertake an external validation study. BMJ 2023;383:e074820. doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-074820

12 Justice AC, Covinsky KE, Berlin JA. Assessing the generalizability of prognostic information. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:515-24. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00016

13 Kim DW, Jang HY, Ko Y, et al. Inconsistency in the use of the term “validation” in studies reporting the performance of deep learning algorithms in providing diagnosis from medical imaging. PLOS One 2020;15:e0238908. doi:10.1371/journal.pone. 0238908

14 Sperrin M, Riley RD, Collins GS, Martin GP. Targeted validation: validating clinical prediction models in their intended population and setting. Diagn Progn Res 2022;6:24. doi:10.1186/s41512-022-00136-8

15 Riley RD, Ensor J, Snell KIE, et al. External validation of clinical prediction models using big datasets from e-health records or IPD meta-analysis: opportunities and challenges. BMJ 2016;353:i3140. doi:10.1136/bmj.i3140

16 Van Calster B, Steyerberg EW, Wynants L, van Smeden M. There is no such thing as a validated prediction model. BMC Med 2023;21:70. doi:10.1186/s12916-023-02779-w

17 Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KGM. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. BMJ 2015;350:g7594. doi:10.1136/bmj.g7594

18 Moons KGM, Altman DG, Reitsma JB, et al. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:W1-73. doi:10.7326/M14-0698

19 Toll DB, Janssen KJ, Vergouwe Y, Moons KG. Validation, updating and impact of clinical prediction rules: a review. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:1085-94. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.04.008

20 Riley RD, Ensor J, Snell KIE, et al. Calculating the sample size required for developing a clinical prediction model. BMJ 2020;368:m441. doi:10.1136/bmj.m441

21 Riley RD, Snell KI, Ensor J, et al. Minimum sample size for developing a multivariable prediction model: PART II – binary and time-to-event outcomes. Stat Med 2019;38:1276-96. doi:10.1002/sim. 7992

22 Shakur H, Roberts I, Bautista R, et al, CRASH-2 trial collaborators. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2010;376:23-32. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60835-5

23 Steyerberg EW. Validation in prediction research: the waste by data splitting. / Clin Epidemiol 2018;103:131-3. doi:10.1016/j. jclinepi.2018.07.010

24 Riley RD, Snell KIE, Ensor J, et al. Minimum sample size for developing a multivariable prediction model: Part I – Continuous outcomes. Stat Med 2019;38:1262-75. doi:10.1002/sim. 7993

25 van Smeden M, de Groot JA, Moons KG, et al. No rationale for 1 variable per 10 events criterion for binary logistic regression analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol 2016;16:163. doi:10.1186/s12874-016-0267-3

26 van Smeden M, Moons KG, de Groot JA, et al. Sample size for binary logistic prediction models: Beyond events per variable criteria. Stat Methods Med Res 2019;28:2455-74. doi:10.1177/0962280218784726

27 Riley RD, Collins GS, Ensor J, et al. Minimum sample size calculations for external validation of a clinical prediction model with a time-toevent outcome. Stat Med 2022;41:1280-95. doi:10.1002/sim. 9275

28 Snell KIE, Archer L, Ensor J, et al. External validation of clinical prediction models: simulation-based sample size calculations were more reliable than rules-of-thumb. J Clin Epidemiol 2021;135:79-89. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.011

29 Archer L, Snell KIE, Ensor J, Hudda MT, Collins GS, Riley RD. Minimum sample size for external validation of a clinical prediction model with a continuous outcome. Stat Med 2021;40:133-46. doi:10.1002/ sim. 8766

30 Steyerberg EW, Harrell FEJr, Borsboom GJJM, Eijkemans MJC, Vergouwe Y, Habbema JDF. Internal validation of predictive models: efficiency of some procedures for logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2001;54:774-81. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(01)003419

31 Riley RD, Collins GS. Stability of clinical prediction models developed using statistical or machine learning methods [Internet]. arXiv; 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 4]. Available from: https://arxiv.org/ abs/2211.01061

32 Harrell FEJr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med 1996;15:361-87. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4

33 Martin GP, Riley RD, Collins GS, Sperrin M. Developing clinical prediction models when adhering to minimum sample

BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj-2023-074819 on 8 January 2024. Downloaded from https://www.bmj.com/ on 28 August 2025 by guest. Protected by copyright, including for uses related to text and data mining, Al training, and similar technologies.

size recommendations: The importance of quantifying bootstrap variability in tuning parameters and predictive performance. Stat Methods Med Res 2021;30:2545-61. doi:10.1177/09622802211046388

34 Steyerberg EW, Bleeker SE, Moll HA, Grobbee DE, Moons KGM. Internal and external validation of predictive models: a simulation study of bias and precision in small samples. / Clin Epidemiol 2003;56:441-7. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00047-7

35 Steyerberg EW. Clinical prediction models: a practical approach to development, validation, and updating. 2nd ed. Springer, 2019. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-16399-0.

36 Harrell FEJr. Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic and ordinal regression, and survival analysis. 2nd ed. Springer, 2015. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-194257.

38 Hickey GL, Grant SW, Murphy GJ, et al. Dynamic trends in cardiac surgery: why the logistic EuroSCORE is no longer suitable for contemporary cardiac surgery and implications for future risk models. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2013;43:1146-52. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ ezs584

39 Jenkins DA. Continual updating and monitoring of clinical prediction models: time for dynamic prediction systems? 2021;7.

40 Booth S, Riley RD, Ensor J, Lambert PC, Rutherford MJ. Temporal recalibration for improving prognostic model development and risk predictions in settings where survival is improving over time. Int/ Epidemiol 2020;49:1316-25. doi:10.1093/ije/dyaa030

41 Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Vinogradova Y, et al. Predicting cardiovascular risk in England and Wales: prospective derivation and validation of QRISK2. BMJ 2008;336:1475-82. doi:10.1136/ bmj.39609.449676.25

42 Riley R, Tierney J, Stewart L, eds. Individual participant data meta-analysis: a handbook for healthcare research. Wiley, 2021. doi:10.1002/9781119333784.

43 Steyerberg EW, Harrell FEJr. Prediction models need appropriate internal, internal-external, and external validation. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;69:245-7. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.04.005

44 Royston P, Parmar MKB, Sylvester R. Construction and validation of a prognostic model across several studies, with an application in superficial bladder cancer. Stat Med 2004;23:907-26. doi:10.1002/ sim. 1691

45 Takada T, Nijman S, Denaxas S, et al. Internal-external crossvalidation helped to evaluate the generalizability of prediction models in large clustered datasets. / Clin Epidemiol 2021;137:8391. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.025

47 Debray TPA, Collins GS, Riley RD, et al. Transparent reporting of multivariable prediction models developed or validated using clustered data: TRIPOD-Cluster checklist. BMJ 2023;380:e071018. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-071018

48 Debray TPA, Collins GS, Riley RD, et al. Transparent reporting of multivariable prediction models developed or validated using clustered data (TRIPOD-Cluster): explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2023;380:e071058. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-071058

50 Collins GS, Altman DG. Predicting the 10 year risk of cardiovascular disease in the United Kingdom: independent and external validation of an updated version of QRISK2. BMJ 2012;344:e4181. doi:10.1136/bmj.e4181

51 Nevin L, PLOS Medicine Editors. Advancing the beneficial use of machine learning in health care and medicine: Toward a community understanding. PLoS Med 2018;15:e1002708. doi:10.1371/ journal.pmed. 1002708

52 Collins GS, de Groot JA, Dutton S, et al. External validation of multivariable prediction models: a systematic review of methodological conduct and reporting. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:40. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-14-40

53 Moons KGM, Altman DG, Vergouwe Y, Royston P. Prognosis and prognostic research: application and impact of prognostic models in clinical practice. BMJ 2009;338:b606. doi:10.1136/bmj.b606

54 Debray TPA, Vergouwe Y, Koffijberg H, Nieboer D, Steyerberg EW, Moons KGM. A new framework to enhance the interpretation of external validation studies of clinical prediction models. J Clin Epidemiol 2015;68:279-89. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.06.018

55 Cabitza F, Campagner A, Soares F, et al. The importance of being external. methodological insights for the external validation of machine learning models in medicine. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2021;208:106288. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2021.106288

56 Altman DG, Vergouwe Y, Royston P, Moons KGM. Prognosis and prognostic research: validating a prognostic model. BMJ 2009;338:b605. doi:10.1136/bmj.b605

57 Davis SE, Lasko TA, Chen G, Siew ED, Matheny ME. Calibration drift in regression and machine learning models for acute kidney injury. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2017;24:1052-61. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocx030

58 Wessler BS, Nelson J, Park JG, et al. External Validations of Cardiovascular Clinical Prediction Models: A Large-Scale Review of the Literature. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2021;14:e007858. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.121.007858

59 Van Calster B, Wynants L, Timmerman D, Steyerberg EW, Collins GS. Predictive analytics in health care: how can we know it works?/ Am Med Inform Assoc 2019;26:1651-4. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocz130

60 Park Y, Hu J, Singh M, et al. Comparison of Methods to Reduce Bias From Clinical Prediction Models of Postpartum Depression. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e213909. doi:10.1001/ jamanetworkopen.2021.3909

61 Ganapathi S, Palmer J, Alderman JE, et al. Tackling bias in Al health datasets through the STANDING Together initiative. Nat Med 2022;28:2232-3. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01987-w

62 Vyas DA, Eisenstein LG, Jones DS. Hidden in Plain Sight Reconsidering the Use of Race Correction in Clinical Algorithms. N Engl J Med 2020;383:874-82. doi:10.1056/NEJMms2004740

63 Johnson-Mann CN, Loftus TJ, Bihorac A. Equity and Artificial Intelligence in Surgical Care. JAMA Surg 2021;156:509-10. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2020.7208

64 Paulus JK, Kent DM. Predictably unequal: understanding and addressing concerns that algorithmic clinical prediction may increase health disparities. NPJ Digit Med 2020;3:99. doi:10.1038/s41746-020-0304-9

- SUMMARY POINTS

Clinical prediction models use a combination of variables to estimate outcome risk for individualsEvaluating the performance of a prediction model is critically important and validation studies are essential, as a poorly developed model could be harmful or exacerbate disparities in either provision of health care or subsequent healthcare outcomesEvaluating model performance should be carried out in datasets that are representative of the intended target populations for the model’s implementationA model’s predictive performance will often appear to be excellent in the development dataset but be much lower when evaluated in a separate dataset, even from the same population

Splitting data at the moment of model development should generally be avoided as it discards data leading to a more unreliable model, whilst leaving too few data to reliably evaluate its performance

Concerted efforts should be made to exploit all available data to build the best possible model, with better use of resampling methods for internal validation, and internal-external validation to evaluate model performance and generalisability across clusters