DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2024.106182

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-30

تكوين الأبقار الحلوب التي تعيش مع عجولها سواء بدوام كامل أو جزئي لروابط أمومية قوية

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

الاتصال بين البقرة والعجل

الدافع الأمومي

أقصى سعر مدفوع

طلب المستهلك

الملخص

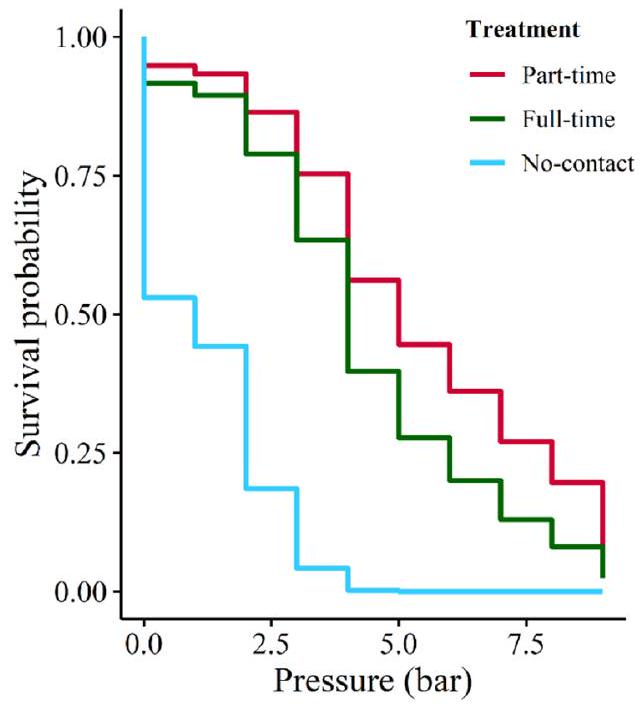

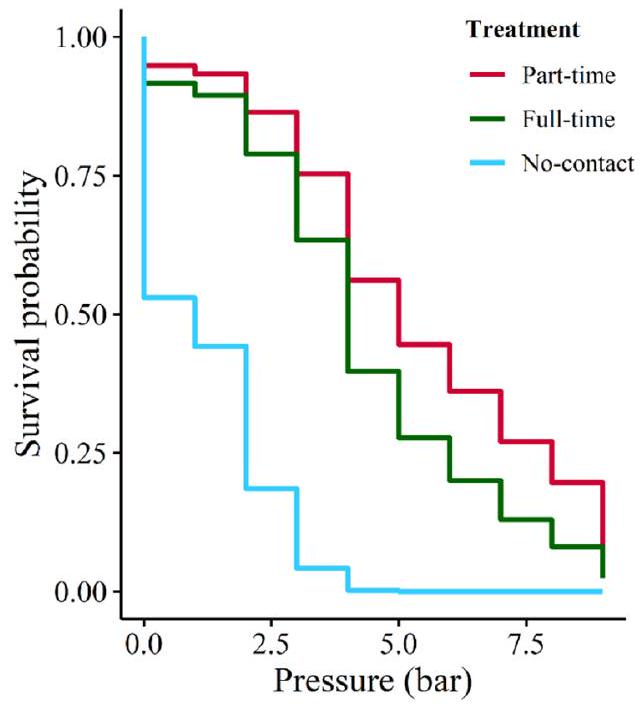

عادةً ما يتم فصل الأبقار الحلوب والعجول بعد فترة وجيزة من الولادة مما يمنع تشكيل رابطة أمومية-فيلية. للسماح ببعض الاتصال بين البقرة والعجل، يُعتقد أن الاتصال الجزئي خلال الأسابيع الأولى هو حل ممكن، لكن من غير المعروف ما إذا كان ذلك يضعف الرابطة الأمومية، أي إذا كان الدافع الأمومي أقل. كانت هذه الدراسة تهدف إلى التحقيق في كيفية تأثير كميات مختلفة من الاتصال بالعجل (بدوام كامل، بدوام جزئي، وعدم الاتصال) على دافع الأمومة لدى الأبقار. باستخدام بوابات دفع هوائية، قمنا بتقييم دافع الأبقار للوصول إلى عجلها الخاص باستخدام طريقة أقصى سعر مدفوع (MPP). لتخفيف الإحباط عند الأسعار المرتفعة، يمكن للأبقار أيضًا الوصول إلى عجل غير مألوف بسعر منخفض ثابت. توقعنا أن الأبقار ستصل إلى العجل غير المألوف عند الوصول إلى أقصى سعر كانت متحفزة لدفعه للوصول إلى عجلها الخاص. بعد 48 ساعة في حظيرة الولادة، تم تخصيص أزواج الأبقار والعجول لثلاثة علاجات مختلفة: بدوام كامل (23 ساعة اتصال/يوم، 28 زوجًا)، بدوام جزئي (10 ساعات اتصال/يوم، 27 زوجًا)، وعدم الاتصال (0 ساعة اتصال/يوم، 26 زوجًا). بعد حوالي 40 يومًا من الولادة، تم تدريب الأبقار على المرور عبر كل من بوابتين: واحدة تؤدي إلى عجلها الخاص وواحدة تؤدي إلى عجل غير مألوف. زاد الوزن على البوابة المؤدية إلى عجل الأبقار الخاص بعد كل مرور، بينما ظلت البوابة المؤدية إلى العجل غير المألوف خفيفة. تم اختبار الأبقار مرة واحدة يوميًا، حتى فشلت في المرور عبر البوابة المؤدية إلى عجلها الخاص لمدة يومين متتاليين. تم تحليل MPP باستخدام نموذج تأثيرات مختلطة من مخاطر كوك. كان عدد الأبقار التي لم تتصل أقل من الأبقار بدوام كامل وبدوام جزئي التي استوفت معايير التعلم. علاوة على ذلك، دفعت الأبقار التي لم تتصل سعرًا أقصى أقل مقارنة بالعلاجات ذات الاتصال، بينما لم يختلف MPP للأبقار بدوام كامل وبدوام جزئي. بقيت معظم الأبقار في صندوق البداية إذا لم تمر عبر البوابة إلى عجلها الخاص، مما يشير إلى أن العجل غير المألوف لا يمكن أن يحل محل عجلها الخاص عند الأسعار المرتفعة. نستنتج أن الأبقار التي لديها اتصال جزئي بالعجل تشكل رابطة أمومية بقوة مماثلة للأبقار التي لديها اتصال بدوام كامل بالعجل. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن الأبقار التي تم فصلها عن عجلها بعد 48 ساعة من الولادة لديها دافع أمومي أضعف بعد 40 يومًا من الولادة.

1. المقدمة

يسلط الضوء على عدم اليقين المحيط بقوة الرابطة الأمومية وأهمية السلوكيات الأمومية للأبقار الحلوب.

يمكن أن يكون إبقاء البقرة والعجل معًا طوال اليوم والليل تحديًا للمزارع. لذلك، تم اقتراح أنظمة الاتصال بين البقرة والعجل بدوام جزئي كبدائل للاتصال بدوام كامل (بيرتلسن وفارست، 2023؛ سيروفنيك وآخرون، 2020). أظهرت الدراسات السابقة أن الأبقار التي لديها اتصال جزئي بالعجل تقضي وقتًا أقل في تنظيف ورعاية عجولها مقارنة بالأبقار التي لديها اتصال بدوام كامل (بيرتلسن وينسن، 2023؛ ينسن وآخرون، قيد التقديم). ومع ذلك، ليس من الواضح ما إذا كان هذا الانخفاض في الرضاعة والتنظيف يقلل أيضًا من الدافع الأمومي مقارنة بالأبقار بدوام كامل. لذلك، كانت الدراسة الحالية تهدف إلى تحديد دافع الأبقار الحلوب للأمومة والتحقيق في تأثير الاتصال بالعجل (إما بدوام كامل، بدوام جزئي، أو عدمه) على قوة الدافع بعد 40 يومًا من الولادة. افترضنا أن الأبقار التي لديها اتصال بدوام كامل بالعجل تكون أكثر تحفيزًا لاستعادة الاتصال بعجولها من الأبقار التي لديها اتصال جزئي بالعجل، وأن الأبقار التي ليس لديها اتصال بالعجل ستظهر أقل دافع.

2. المواد والأساليب

2.1. الإسكان وعلاجات الاتصال

أقلام الولادة الفردية، وظلت البقرة والعجل معًا في قلم الولادة لمدة تقارب 48 ساعة بعد الولادة (النطاق

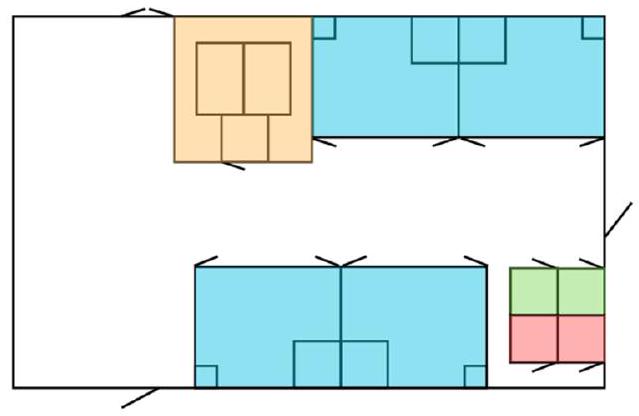

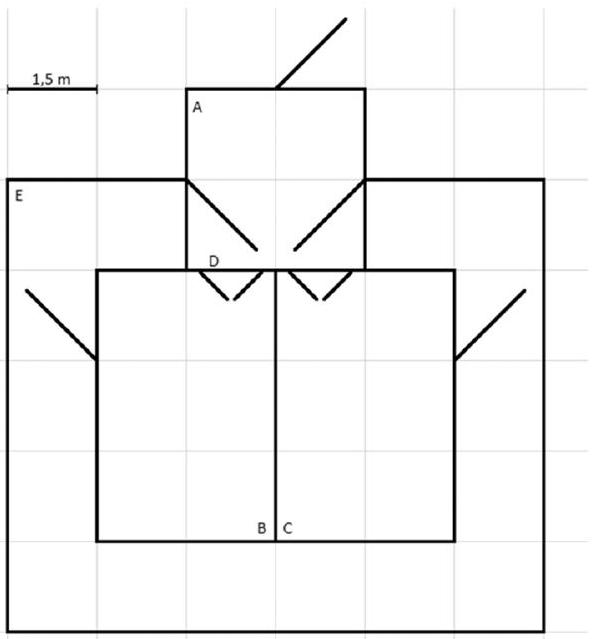

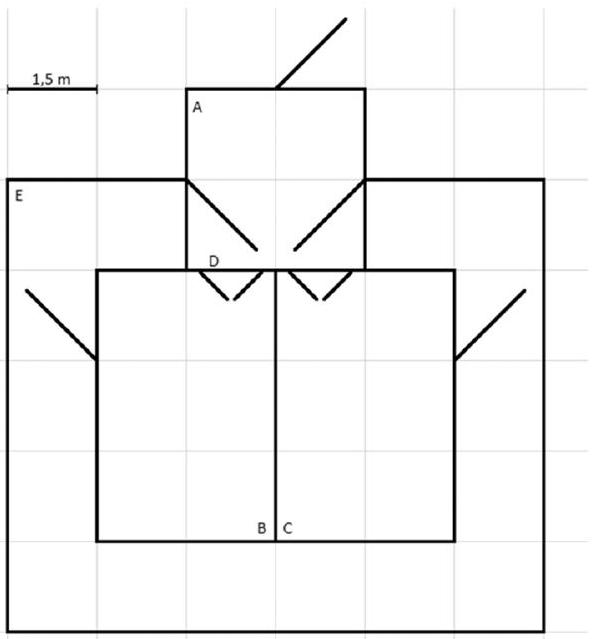

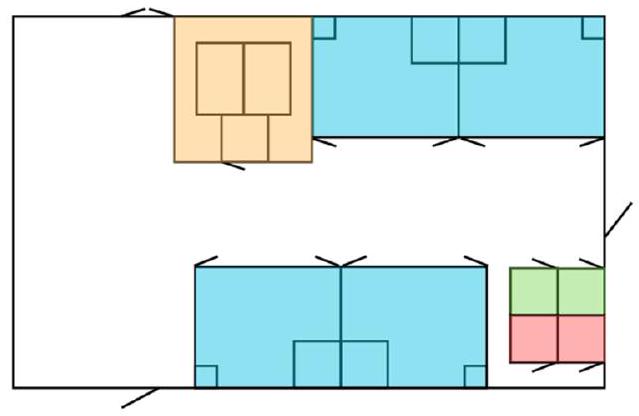

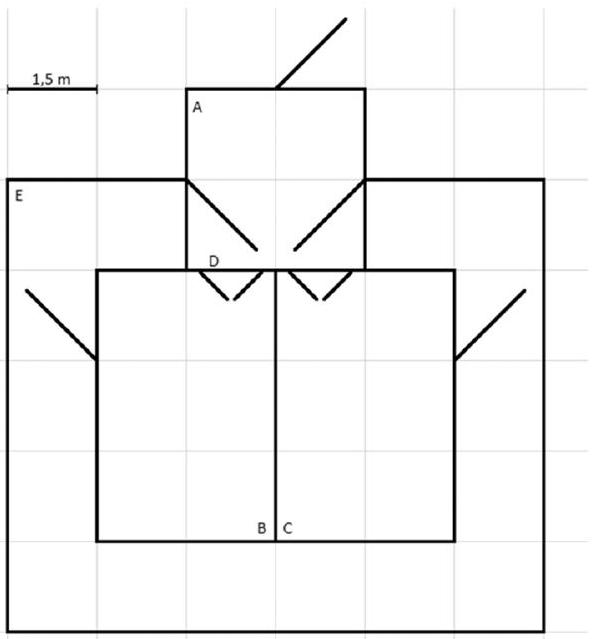

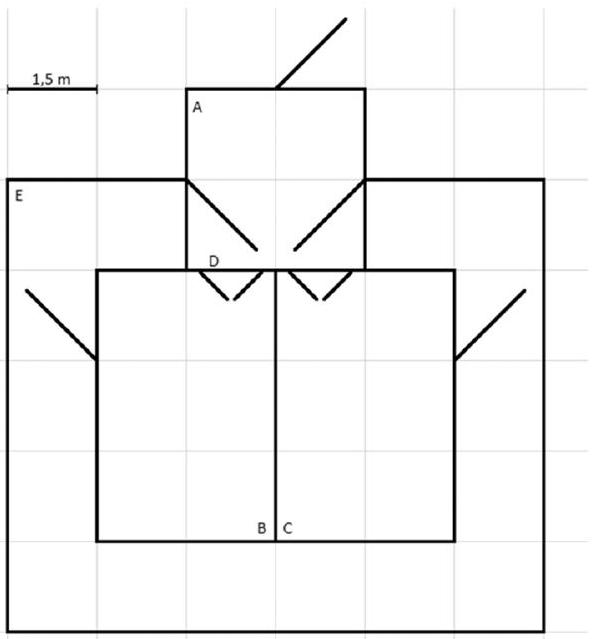

2.2. جهاز الاختبار

2.3. التدريب

الوزن المقابل لكل مستوى ضغط، أي أعلى مستوى من المقاومة الذي ستختبره الأبقار في كل مستوى ضغط، قبل أن تطلق البوابات الضغط. تم وصف إجراء تسجيل الأوزان المقابلة في SM1.

| الضغط (بار) | الوزن (كجم

|

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

|

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

2.3.1. التدريب على اجتياز بوابات الدفع

التبن، والماء خلال فترة الحرمان. لم تر الأبقار التي لا تتصل عجلها الخاص منذ الانفصال بعد 48 ساعة من الولادة.

2.3.2. التدريب على اتخاذ قرار

اختيار البقرة في أول اختيار حر. اجتازت البقرة التدريب إذا مرت عبر إحدى البوابتين (وبالتالي اختارت عجلًا) خلال الدقيقتين، وبدأ الاختبار في اليوم التالي. إذا لم تختار البقرة عجلًا خلال دقيقتين، تم السماح لها بيوم إضافي واحد لاجتياز هذه الخطوة التدريبية. إذا لم تحقق معيار التعلم في هذا اليوم أيضاً، لم يتم تضمينها في الاختبار.

2.4. الاختبار: الحد الأقصى للسعر المدفوع (MPP)

نجاح التدريب عبر العلاجات. تم تدريب الأبقار على مدى ثلاثة إلى خمسة أيام، اعتمادًا على مدى سرعة تحقيقها لمعايير التعلم. للنجاح في التدريب والانتقال إلى مرحلة الاختبار، كان يجب على الأبقار تحقيق معيارين للتعلم: 1) اجتياز بوابة مغلقة بمقاومة 0.5 بار و 2) اتخاذ قرار بين عجلها الخاص وعجل غير مألوف.

| علاج | اجتاز التدريب | تدريب فاشل |

| عدم الاتصال | 11 | 15 |

| دوام جزئي | ٢٥ | ٢ |

| دوام كامل | 27 | 1 |

2.5. التحليل الإحصائي

3. النتائج

3.1. التدريب

3.2. الحد الأقصى للسعر المدفوع

3.3. اختيار بديل بسعر أقل – العجل غير المألوف

3.4. الرضاعة

4. المناقشة

استخدام الخيارات البديلة في الفشل الأول والثاني للأبقار للوصول إلى عجلها الخاص. تشمل فقط الأبقار التي اجتازت 1 بار من الضغط، والتي كانت لديها فشلان متتاليان للوصول إلى عجلها الخاص. كما يظهر ما إذا كانت الأبقار قد حاولت أولاً الوصول إلى عجلها الخاص (لمست البوابة بأكتافها) قبل أن تختار إما العجل غير المألوف أو البقاء في صندوق البداية.

| الخيار البديل | حاولت العجل الخاص | لم تحاول العجل الخاص | الإجمالي |

| الفشل الأول | |||

| اختارت العجل غير المألوف | 2 | 7 | 9 |

| بقيت في صندوق البداية | 13 | 21 | 34 |

| الإجمالي | 15 | 28 | 43 |

| الفشل الثاني | |||

| اختارت العجل غير المألوف | 1 | 7 | 8 |

| بقيت في صندوق البداية | 3 | 32 | 35 |

| الإجمالي | 4 | 39 | 43 |

كانت هناك عدد أقل من الأبقار التي لم تتواصل تلبي معايير التعلم في مرحلة التدريب مقارنة بالأبقار في علاجات الاتصال الاثنين، وتلك الأبقار غير المتصلة التي استوفت معايير التعلم كانت لديها MPP أقل من الأبقار من علاجات الاتصال الاثنين. وبالتالي، لم تبدُ الأبقار التي كانت لديها 48 ساعة فقط من الاتصال بالعجول أنها مدفوعة أموميًا بعد 40 يومًا من الولادة. علاوة على ذلك، لم تظهر الأبقار التي لم تتواصل أي تفضيل بين العجلين في أول اختيار حر وقد لا تكون قادرة على التعرف على عجلها الخاص في وقت الاختبار. كلما طالت مدة بقاء البقرة والعجل معًا، كانت الاستجابة للفصل أقوى (راجع ينسن، 2018)، مما قد يشير إلى رابطة أمومية-فيلية أقوى (غوبنيك، 1981). قد تكون قوة دافع الأبقار التي لم تتواصل أقوى لو قضت وقتًا أطول مع عجولها بعد الولادة، أو لو تم اختبارها في وقت سابق. نشجع الدراسات المستقبلية على التحقيق في هذه الجوانب.

لذا فإنهم سيختارون هذا الخيار عندما يصبح السعر للوصول إلى عجلهم الخاص أعلى مما كانوا متحمسين لدفعه. ومع ذلك، تفترض هذه الفرضية درجة من القابلية للاستبدال (هورش، 1980) بين عجل الأبقار الخاص وعجل غير مألوف. حيث استخدمت عدد قليل من الأبقار خيار العجل غير المألوف، يبدو أن القابلية للاستبدال كانت منخفضة جداً. يدعم ذلك النتائج السابقة التي تشير إلى أن الرضاعة والعناية تحدث تقريباً حصرياً بين الأم وعجلها الخاص (جونسن وآخرون، 2015)، والنتائج التي تشير إلى أن الأبقار تتبنى العجول بالتبني بسهولة أكبر عندما يتم إزالة عجلها الخاص بعد فترة قصيرة من الولادة (كنت، 2020). إن استخدام عدد قليل من الأبقار خيار العجل غير المألوف يشير إلى أن أداء السلوكيات الأمومية تجاه عجل غير عجلها الخاص لا يعوض عن العناية بعجلها الخاص. بشكل غير رسمي، بدت الأبقار التي اختارت العجل غير المألوف محبطة؛ حيث صوتت بعضهن ونظرت فوق السياج بحثاً عن عجلها الخاص، بينما دفعت أخريات وصدمن العجل غير المألوف. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، ركضت بقرة واحدة من قلمها إلى ساحة الاختبار ومرت مباشرة عبر البوابة إلى العجل غير المألوف لمدة يومين متتاليين؛ لم تظهر الكثير من الاهتمام بالعجل غير المألوف وبدلاً من ذلك صوتت بشكل متكرر. تفسيرنا لهذه الملاحظات غير الرسمية هو أن بعض الأبقار كانت بالفعل متحمسة للغاية للوصول إلى عجلها الخاص ولكنها كانت مرتبكة بسبب خيار العجلين. قد يؤدي وضع البوابات على جوانب متقابلة من صندوق البداية أو بعيداً عن بعضها البعض إلى جعل الخيار أكثر وضوحاً.

5. الخاتمة

أصبحت مرتفعة.

بيان مساهمة المؤلفين

إعلان عن تضارب المصالح

شكر وتقدير

الملحق أ. المعلومات الداعمة

References

Bertelsen, M., Vaarst, M., 2023. Shaping cow-calf contact systems: farmers’ motivations and considerations behind a range of different cow-calf contact systems. J. Dairy Sci. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2022-23148.

Boissy, A., Manteuffel, G., Jensen, M.B., Moe, R.O., Spruijt, B., Keeling, L.J., Winckler, C., Forkman, B., Dimitrov, I., Langbein, J., Bakken, M., Veissier, I., Aubert, A., 2007. Assessment of positive emotions in animals to improve their welfare. Physiol. Behav. 92, 375-397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.02.003.

Broom, D.M., 1998. Welfare, stress, and the evolution of feelings. Adv. Study Behav. Busch, G., Weary, D.M., Spiller, A., Von Keyserlingk, M.A.G., 2017. American and German attitudes towards cowcalf separation on dairy farms. PLoS One 12, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0174013.

Dawkins, M.S., 2008. The science of animal suffering. Ethology 114, 937-945. https:// doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0310.2008.01557.x.

Englund, M.D., Cronin, K.A., 2023. Choice, control, and animal welfare: definitions and essential inquiries to advance animal welfare science. Front Vet. Sci. 10, 01-05. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2023.1250251.

Flower, F.C., Weary, D.M., 2003. The effects of early separation on the dairy cow and calf. Anim. Welf. 12, 339-348. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-1591(00)00164-7.

Friend, T.H., 1989. Recognizing behavioral needs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 22, 151-158. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1591(89)90051-8.

Hintze, S., Melotti, L., Colosio, S., Bailoo, J.D., Boada-Saña, M., Würbel, H., Murphy, E., 2018. A cross-species judgement bias task: integrating active trial initiation into a spatial Go/No-go task. Sci. Rep. 8 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23459-3.

Hudson, S.J., Mullord, M.M., 1977. Investigations of maternal bonding in dairy cattle. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 3, 271-276. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3762(77)90008-6.

Hursh, S.R., 1980. Economic concepts for the analysis of behavior. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 32, 219-238. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1980.34-219.

Jensen, M.B., 2011. The early behaviour of cow and calf in an individual calving pen. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 134, 92-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. applanim.2011.06.017.

Jensen, M.B., 2018. The role of social behavior in cattle welfare. in: Advances in Cattle Welfare. Elsevier, pp. 123-155. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-100938-3.00006-1.

Jensen, M.B., Pedersen, L.J., 2008. Using motivation tests to assess ethological needs and preferences. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 113, 340-356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. applanim.2008.02.001.

Jensen, M.B., Munksgaard, L., Pedersen, L.J., Ladewig, J., Matthews, L., 2004. Prior deprivation and reward duration affect the demand function for rest in dairy heifers. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 88, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2004.02.019.

Johnsen, J.F., de Passille, A.M., Mejdell, C.M., Bøe, K.E., Grøndahl, A.M., Beaver, A., Rushen, J., Weary, D.M., 2015. The effect of nursing on the cow-calf bond. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 163, 50-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2014.12.003.

Johnsen, J.F., Johanssen, J.R.E., Aaby, A.V., Kischel, S.G., Ruud, L.E., SokiMakilutila, A., Kristiansen, T.B., Wibe, A.G., Bøe, K.E., Ferneborg, S., 2021. Investigating cow-calf contact in cow-driven systems: behaviour of the dairy cow and calf. J. Dairy Res. 88, 52-55. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022029921000194.

Kent, J.P., 2020. The cow-calf relationship: from maternal responsiveness to the maternal bond and the possibilities for fostering. J. Dairy Res. 87, 101-107. https:// doi.org/10.1017/S0022029920000436.

Kirkden, R.D., Edwards, J.S.S., Broom, D.M., 2003. A theoretical comparison of the consumer surplus and the elasticities of demand as measures of motivational strength. Anim. Behav. 65, 157-178. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.2002.2035.

Kruschwitz, A., Zupan, M., Buchwalder, T., Huber-Eicher, B., 2008. Nest preference of laying hens (Gallus gallus domesticus) and their motivation to exert themselves to gain nest access. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 112, 321-330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. applanim.2007.08.005.

Leotti, L.A., Iyengar, S.S., Ochsner, K.N., 2010. Born to choose: the origins and value of the need for control. Trends Cogn. Sci. 14, 457-463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. tics.2010.08.001.

Mellor, D.J., 2015. Positive animal welfare states and encouraging environment-focused and animal-to-animal interactive behaviours. N. Z. Vet. J. 63, 9-16. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/00480169.2014.926800.

Neave, H.W., Rault, J.-L., Bateson, M., Jensen, E.H., Jensen, M.B., 2023. Assessing the emotional states of dairy cows housed with or without their calves. J. Dairy Sci. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2023-23720.

Placzek, M., Christoph-Schulz, I., Barth, K., 2021. Public attitude towards cow-calf separation and other common practices of calf rearing in dairy farming-a review. Org. Agric. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13165-020-00321-3.

, 2022R Core TeamR: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 2022.

Roadknight, N., Wales, W., Jongman, E., Mansell, P., Hepworth, G., Fisher, A., 2022. Does the duration of repeated temporary separation affect welfare in dairy cow-calf contact systems? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 249 https://doi.org/10.1016/j. applanim.2022.105592.

Sankey, C., Henry, S., Górecka-Bruzda, A., Richard-Yris, M.A., Hausberger, M., 2010. The way to a man’s heart is through his stomach: what about horses? PLoS One 5. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0015446.

Sirovica, L.V., Ritter, C., Hendricks, J., Weary, D.M., Gulati, S., von Keyserlingk, M.A.G., 2022. Public attitude toward and perceptions of dairy cattle welfare in cow-calf management systems differing in type of social and maternal contact. J. Dairy Sci. 105, 3248-3268. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2021-21344.

Sirovnik, J., Barth, K., de Oliveira, D., Ferneborg, S., Haskell, M.J., Hillmann, E., Jensen, M.B., Mejdell, C.M., Napolitano, F., Vaarst, M., Verwer, C.M., Waiblinger, S., Zipp, K.A., Johnsen, J.F., 2020. Methodological terminology and definitions for research and discussion of cow-calf contact systems. J. Dairy Res. 87, 108-114. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022029920000564.

Therneau, T.M., 2022. coxme: Mixed Effects Cox Models.

Therneau, T.M., 2023. A Package for Survival Analysis in R.

Tucker, C.B., Munksgaard, L., Mintline, E.M., Jensen, M.B., 2018. Use of a pneumatic push gate to measure dairy cattle motivation to lie down in a deep-bedded area. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 201, 15-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. applanim.2017.12.018.

Wenker, M.L., Bokkers, E.A.M., Lecorps, B., von Keyserlingk, M.A.G., van Reenen, C.G., Verwer, C.M., Weary, D.M., 2020. Effect of cow-calf contact on cow motivation to reunite with their calf. Sci. Rep. 10, 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70927-w.

- Corresponding author.

E-mail address: emma.hvidtfeldt@anivet.au.dk (E.H. Jensen).

Current address: Department of Animal Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette IN, USA 47907

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2024.106182

Publication Date: 2024-01-30

Dairy cows housed both full- and part-time with their calves form strong maternal bonds

A R T I C L E I N F O

Keywords:

Cow-calf contact

Maternal motivation

Maximum price paid

Consumer demand

Abstract

Dairy cow and calf are typically separated shortly after calving preventing the formation of a maternal-filial bond. To allow some cow-calf contact, part-time contact during the first weeks is thought to be a feasible solution, but it is unknown if it weakens maternal bond, i.e., if maternal motivation is lower. This study aimed to investigate how different amounts of calf contact (full-time, part-time, and no contact) affect cows’ maternal motivation. Using pneumatic push gates, we assessed cows’ motivation to access their own calf using the maximum price paid (MPP) method. To mitigate frustration at high prices, cows could also access an unfamiliar calf at a constant low price. We expected that cows would access the unfamiliar calf when reaching the maximum price that they were motivated to pay to access their own calf. Following 48 h in a calving pen, cow-calf pairs were allocated to three different treatments: full-time ( 23 h contact/d, 28 pairs), part-time ( 10 h contact/d, 27 pairs), and no contact ( 0 h contact/d, 26 pairs). Approximately 40 d after calving, cows were trained to pass through each of two push gates: one leading to their own and one leading to an unfamiliar calf. The weight on the gate leading to the cows’ own calf increased following each passing, while the gate leading to the unfamiliar calf remained light. Cows were tested once daily, until they failed to pass through the gate leading to their own calf on two consecutive days. MPP was analysed using a Cox’s proportional hazards mixed effects model. Fewer nocontact cows than full- and part-time cows fulfilled the learning criteria. Furthermore, no-contact cows paid a lower maximum price compared to the two contact treatments, while the MPP of full- and part-time cows did not differ. Most cows remained in the start box if they did not pass the gate to their own calf, indicating that an unfamiliar calf could not substitute for their own calf at high prices. We conclude that cows with part-time calf contact form a maternal bond of similar strength to cows with full-time calf contact. Additionally, cows separated from their calf at 48 h after calving have a weaker maternal motivation at 40 days postpartum.

1. Introduction

highlights uncertainty surrounding the strength of the maternal bond and the importance of maternal behaviours to dairy cows.

Keeping cow and calf together throughout the day and night can prove challenging to the farmer. Therefore, part-time cow-calf-contact systems have been suggested as alternatives to full-time contact (Bertelsen and Vaarst, 2023; Sirovnik et al., 2020). Previous studies have shown that cows with part-time calf contact spend less time grooming and nursing their calves than cows with full-time contact (Bertelsen and Jensen, 2023; Jensen et al., submitted). However, it is unclear whether such reduction in nursing and grooming also reduces maternal motivation compared to full-time cows. Therefore, the present study aimed to quantify dairy cows’ maternal motivation and to investigate the effect of calf contact (either full-time, part-time, or none) on the motivational strength at 40 days postpartum. We hypothesised that cows with full-time calf contact are more motivated to regain contact with their calves than cows with part-time calf contact, and that cows with no calf contact would show the lowest motivation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Housing and contact treatments

individual calving pens, and cow and calf remained together in the calving pen for approximately 48 h postpartum (range

2.2. Test apparatus

2.3. Training

The corresponding weight for each pressure level, i.e., the highest level of resistance the cows would experience on each pressure level, before the gates would release the pressure. The procedure for recording corresponding weights is described in SM1.

| Pressure (bar) | Weight (kg

|

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

|

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

2.3.1. Training to pass push gates

hay, and water during the deprivation period. No-contact cows, until initiation of training, had not seen their own calf since separation at 48 h postpartum.

2.3.2. Training to make a choice

the cow’s choice in the first free choice. The cow passed training if she passed through one of the two gates (and thus chose a calf) within the 2 minutes, and testing began the following day. If the cow did not choose a calf within 2 minutes, she was permitted one extra day to pass this training step. If she did not meet the learning criterion on this day either, she was not included for testing.

2.4. Testing: Maximum price paid (MPP)

Training success across the treatments. Cows were trained over three to five days, depending on how quickly they met the learning criteria. To pass training and continue to the testing phase, the cows had to meet two learning criteria: 1) passing a closed gate with 0.5 bar of resistance and 2) making a choice between their own and an unfamiliar calf.

| Treatment | Passed training | Failed training |

| No-contact | 11 | 15 |

| Part-time | 25 | 2 |

| Full-time | 27 | 1 |

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Training

3.2. Maximum price paid

3.3. Choice of lower price alternative – the unfamiliar calf

3.4. Nursing

4. Discussion

The use of alternative options in the cows’ first and second fail to reach their own calf. Included are only cows that passed 1 bar of pressure, and who had two consecutive fails to reach their own calf. Also shown is whether the cows first tried to access their own calf (touched the gate with their shoulders) before they chose either the unfamiliar calf or to stay in the start box.

| Alternative choice | Tried own calf | Did not try own calf | Total |

| First fail | |||

| Chose unfamiliar calf | 2 | 7 | 9 |

| Stayed in start box | 13 | 21 | 34 |

| Total | 15 | 28 | 43 |

| Second fail | |||

| Chose unfamiliar calf | 1 | 7 | 8 |

| Stayed in start box | 3 | 32 | 35 |

| Total | 4 | 39 | 43 |

Fewer no-contact cows met the learning criteria in the training phase compared to cows on the two contact treatments, and those non-contact cows that did meet the learning criteria had a lower MPP than cows from the two contact treatments. Thus, cows with only 48 h of calf contact did not appear to be maternally motivated 40 days postpartum. Furthermore, no-contact cows showed no preference among the two calves in the first free choice and may not have been able to recognise their own calf at the time of testing. The longer cow and calf are kept together, the stronger are the response to separation (reviewed by Jensen, 2018), which could indicate a stronger maternal-filial bond (Gubernick, 1981). The strength of no-contact cows’ motivation may have been stronger had they spent more time with their calves after calving, or had they been tested at an earlier point. We encourage future studies to investigate these aspects.

they would therefore choose this option when the price to reach their own calf became higher than what they were motivated to pay. This hypothesis, however, assumes a degree of substitutability (Hursh, 1980) between cows’ own calf and an unfamiliar calf. As only few cows utilised the unfamiliar calf option, it appears that substitutability was very low. This is supported by previous findings that nursing and grooming almost exclusively happen between the dam and her own calf (Johnsen et al., 2015), and findings that cows more easily adopt foster calves when their own calf has been removed shortly after calving (Kent, 2020). That only few cows utilised the unfamiliar calf option suggests that performing maternal behaviours towards a calf other than her own does not substitute for caring for her own calf. Anecdotally, cows choosing the unfamiliar calf appeared frustrated; some vocalised and looked over the fence for their own calf, while others pushed and headbutted the unfamiliar calf. Additionally, one cow ran from her home pen to the test arena and straight through the gate to the unfamiliar calf two days in a row; she did not show much interest in the unfamiliar calf and instead repeatedly vocalised. Our interpretation of these anecdotal observations is that some cows were indeed highly motivated to reach their own calf but confused by the choice of two calves. Placing the gates on opposite sides of the start box or further apart from each other could possibly make the choice clearer.

5. Conclusion

became high.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Declaration of Competing Interest

Acknowledgements

Appendix A. Supporting information

References

Bertelsen, M., Vaarst, M., 2023. Shaping cow-calf contact systems: farmers’ motivations and considerations behind a range of different cow-calf contact systems. J. Dairy Sci. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2022-23148.

Boissy, A., Manteuffel, G., Jensen, M.B., Moe, R.O., Spruijt, B., Keeling, L.J., Winckler, C., Forkman, B., Dimitrov, I., Langbein, J., Bakken, M., Veissier, I., Aubert, A., 2007. Assessment of positive emotions in animals to improve their welfare. Physiol. Behav. 92, 375-397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.02.003.

Broom, D.M., 1998. Welfare, stress, and the evolution of feelings. Adv. Study Behav. Busch, G., Weary, D.M., Spiller, A., Von Keyserlingk, M.A.G., 2017. American and German attitudes towards cowcalf separation on dairy farms. PLoS One 12, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0174013.

Dawkins, M.S., 2008. The science of animal suffering. Ethology 114, 937-945. https:// doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0310.2008.01557.x.

Englund, M.D., Cronin, K.A., 2023. Choice, control, and animal welfare: definitions and essential inquiries to advance animal welfare science. Front Vet. Sci. 10, 01-05. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2023.1250251.

Flower, F.C., Weary, D.M., 2003. The effects of early separation on the dairy cow and calf. Anim. Welf. 12, 339-348. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-1591(00)00164-7.

Friend, T.H., 1989. Recognizing behavioral needs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 22, 151-158. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1591(89)90051-8.

Hintze, S., Melotti, L., Colosio, S., Bailoo, J.D., Boada-Saña, M., Würbel, H., Murphy, E., 2018. A cross-species judgement bias task: integrating active trial initiation into a spatial Go/No-go task. Sci. Rep. 8 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23459-3.

Hudson, S.J., Mullord, M.M., 1977. Investigations of maternal bonding in dairy cattle. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 3, 271-276. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3762(77)90008-6.

Hursh, S.R., 1980. Economic concepts for the analysis of behavior. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 32, 219-238. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1980.34-219.

Jensen, M.B., 2011. The early behaviour of cow and calf in an individual calving pen. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 134, 92-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. applanim.2011.06.017.

Jensen, M.B., 2018. The role of social behavior in cattle welfare. in: Advances in Cattle Welfare. Elsevier, pp. 123-155. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-100938-3.00006-1.

Jensen, M.B., Pedersen, L.J., 2008. Using motivation tests to assess ethological needs and preferences. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 113, 340-356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. applanim.2008.02.001.

Jensen, M.B., Munksgaard, L., Pedersen, L.J., Ladewig, J., Matthews, L., 2004. Prior deprivation and reward duration affect the demand function for rest in dairy heifers. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 88, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2004.02.019.

Johnsen, J.F., de Passille, A.M., Mejdell, C.M., Bøe, K.E., Grøndahl, A.M., Beaver, A., Rushen, J., Weary, D.M., 2015. The effect of nursing on the cow-calf bond. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 163, 50-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2014.12.003.

Johnsen, J.F., Johanssen, J.R.E., Aaby, A.V., Kischel, S.G., Ruud, L.E., SokiMakilutila, A., Kristiansen, T.B., Wibe, A.G., Bøe, K.E., Ferneborg, S., 2021. Investigating cow-calf contact in cow-driven systems: behaviour of the dairy cow and calf. J. Dairy Res. 88, 52-55. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022029921000194.

Kent, J.P., 2020. The cow-calf relationship: from maternal responsiveness to the maternal bond and the possibilities for fostering. J. Dairy Res. 87, 101-107. https:// doi.org/10.1017/S0022029920000436.

Kirkden, R.D., Edwards, J.S.S., Broom, D.M., 2003. A theoretical comparison of the consumer surplus and the elasticities of demand as measures of motivational strength. Anim. Behav. 65, 157-178. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.2002.2035.

Kruschwitz, A., Zupan, M., Buchwalder, T., Huber-Eicher, B., 2008. Nest preference of laying hens (Gallus gallus domesticus) and their motivation to exert themselves to gain nest access. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 112, 321-330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. applanim.2007.08.005.

Leotti, L.A., Iyengar, S.S., Ochsner, K.N., 2010. Born to choose: the origins and value of the need for control. Trends Cogn. Sci. 14, 457-463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. tics.2010.08.001.

Mellor, D.J., 2015. Positive animal welfare states and encouraging environment-focused and animal-to-animal interactive behaviours. N. Z. Vet. J. 63, 9-16. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/00480169.2014.926800.

Neave, H.W., Rault, J.-L., Bateson, M., Jensen, E.H., Jensen, M.B., 2023. Assessing the emotional states of dairy cows housed with or without their calves. J. Dairy Sci. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2023-23720.

Placzek, M., Christoph-Schulz, I., Barth, K., 2021. Public attitude towards cow-calf separation and other common practices of calf rearing in dairy farming-a review. Org. Agric. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13165-020-00321-3.

, 2022R Core TeamR: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 2022.

Roadknight, N., Wales, W., Jongman, E., Mansell, P., Hepworth, G., Fisher, A., 2022. Does the duration of repeated temporary separation affect welfare in dairy cow-calf contact systems? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 249 https://doi.org/10.1016/j. applanim.2022.105592.

Sankey, C., Henry, S., Górecka-Bruzda, A., Richard-Yris, M.A., Hausberger, M., 2010. The way to a man’s heart is through his stomach: what about horses? PLoS One 5. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0015446.

Sirovica, L.V., Ritter, C., Hendricks, J., Weary, D.M., Gulati, S., von Keyserlingk, M.A.G., 2022. Public attitude toward and perceptions of dairy cattle welfare in cow-calf management systems differing in type of social and maternal contact. J. Dairy Sci. 105, 3248-3268. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2021-21344.

Sirovnik, J., Barth, K., de Oliveira, D., Ferneborg, S., Haskell, M.J., Hillmann, E., Jensen, M.B., Mejdell, C.M., Napolitano, F., Vaarst, M., Verwer, C.M., Waiblinger, S., Zipp, K.A., Johnsen, J.F., 2020. Methodological terminology and definitions for research and discussion of cow-calf contact systems. J. Dairy Res. 87, 108-114. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022029920000564.

Therneau, T.M., 2022. coxme: Mixed Effects Cox Models.

Therneau, T.M., 2023. A Package for Survival Analysis in R.

Tucker, C.B., Munksgaard, L., Mintline, E.M., Jensen, M.B., 2018. Use of a pneumatic push gate to measure dairy cattle motivation to lie down in a deep-bedded area. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 201, 15-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. applanim.2017.12.018.

Wenker, M.L., Bokkers, E.A.M., Lecorps, B., von Keyserlingk, M.A.G., van Reenen, C.G., Verwer, C.M., Weary, D.M., 2020. Effect of cow-calf contact on cow motivation to reunite with their calf. Sci. Rep. 10, 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70927-w.

- Corresponding author.

E-mail address: emma.hvidtfeldt@anivet.au.dk (E.H. Jensen).

Current address: Department of Animal Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette IN, USA 47907