DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0958344024000302

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-06

تمكين رقمي للطلاب المهاجرين في المناطق الريفية في الصين: الهوية، والاستثمار، والمهارات الرقمية خارج الفصل الدراسي

الملخص

استنادًا إلى نموذج الاستثمار لدارفين ونورتون (2015)، يتناول هذا المقال كيف يتفاوض شينغ وجيمي (كلاهما أسماء مستعارة) كطالبين صينيين ذكور يتعلمون اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية من خلفيات مهاجرة ريفية على هوياتهما ويجمعان مواردهما الاجتماعية والثقافية للاستثمار في المهارات الرقمية المستقلة لتعلم اللغة وتأكيد مكانة شرعية في الفضاءات الحضرية. باستخدام تصميم إثنوغرافي متصل، جمعت هذه الدراسة البيانات من خلال المقابلات، والمجلات الانعكاسية، والقطع الرقمية، والملاحظات في الحرم الجامعي. تم تحليل البيانات باستخدام نهج موضوعي استقرائي بالإضافة إلى طرق تحليل البيانات داخل الحالة وعبر الحالات. تشير النتائج إلى أن شينغ وجيمي عانيا من شعور عميق بالاغتراب والاستبعاد أثناء انتقالهما من الفضاءات الريفية ذات الموارد المحدودة إلى مجال النخبة الحضرية. خضعت علاقات القوة غير المتكافئة في الفصول الدراسية الحضرية لهما إلى هويات ريفية مهمشة وغير كافية من خلال حرمانهما من حق التحدث وسماع صوتهما. ومع ذلك، فإن الانخراط في المهارات الرقمية في العالم الحقيقي سمح لهذين المتعلمين المهاجرين بالوصول إلى مجموعة واسعة من الموارد اللغوية والثقافية والرمزية، مما مكنهما من إعادة تشكيل هوياتهما كمتحدثين شرعيين للغة الإنجليزية. إن اكتساب مثل هذه الشرعية مكنهما من تحدي الإيديولوجيات الاستبعادية السائدة بين الريف والحضر للمطالبة بحق التحدث. ينتهي هذا المقال بتقديم تداعيات لتمكين الطلاب المهاجرين من المناطق الريفية كأعضاء اجتماعيين كفوئين في نظام التعليم العالي الصيني في العصر الرقمي.

1. المقدمة

2. مراجعة الأدبيات

2.1. تعريف المهارات الرقمية

غير متحيزة، فإن الإيديولوجيات الخفية المضمنة في الخوارزميات أو التصميم الاجتماعي التقني يمكن أن تشكل كيفية تقديم المعلومات وإنتاج المعرفة عبر الإنترنت. من الجدير بالذكر أن الاعتراف بأن التكنولوجيا تقدم فرصًا للتغيير الاجتماعي والتواصل العادل، هناك أيضًا مجموعة متزايدة من الأدبيات التي تفحص كيف يمكن إعادة تصميم النصوص، من خلال قدرات الأدوات الرقمية، واستهلاكها لخدمة مصالح جميع المتعلمين من خلال تقويض الإيديولوجيات الاستبعادية والتفاوض على علاقات القوة غير المتكافئة (أفيلا وبانديا، 2013؛ غارسيا، فيرنانديز وأوكونو، 2020). تؤكد هذه الدراسات أيضًا على أن كيفية إدخال المتعلمين إلى مساحات رقمية مختلفة للمشاركة في ممارسات رقمية متنوعة أمر حاسم (غارسيا وآخرون، 2020؛ ليو، 2023أ).

2.2. المهارات الرقمية لمتعلمي اللغات المهاجرين

قد تكون المهارات اللغوية في الحياة اليومية نهجًا فعالًا لدعم تعلمهم للغة وتطوير هويتهم في المجتمع المستضيف.

2.3. تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية والفجوة بين الريف والحضر في الصين

3. الإطار النظري

مبني لأنه يركز على توسيع فهم التجارب الشخصية والمخصصة، بدلاً من السعي لتوليد نتائج قابلة للتعميم تنطبق على مجموعات سكانية أكبر (دافين، 2018). تستند هذه الدراسة أيضًا إلى الإثنوغرافيا المتصلة التي تدمج الثنائيات بين الإنترنت/الافتراضي وoffline/الفيزيائي في دراسات الثقافة الجديدة (لياندر، 2008). يبرز أنه بينما يتحرك متعلمونا بسلاسة ومرونة من وإلى مساحات اجتماعية مختلفة تشكلها التقنيات الرقمية الشاملة، فإنهم في الواقع يشغلون هذه المساحات في الوقت نفسه أو يتنقلون بين العوالم عبر الإنترنت وخارجها ككل بدلاً من مجالات منفصلة (دافين، 2023).

4.2. شينغ وجيمي

4.3. جمع البيانات

4.4. تحليل البيانات

عدة مرات. ثانيًا، تم ترميز جميع البيانات النصية، بما في ذلك المقابلات، وملاحظات الملاحظة الميدانية، والمجلات الانعكاسية، بشكل استقرائي لرسم رموز أولية ووصفاتها المقابلة باستخدام NVivo 12. ثالثًا، تمت مقارنة الرموز باستمرار لتحديد روابطها وصياغة الفئات أو الموضوعات الأكبر (مثل التفاوض على رأس المال في البرية الرقمية). خلال هذه العملية، تم توضيح القطع الرقمية وربطها بالموضوعات الناشئة كأمثلة تكميلية. ثم تم إعادة فحص الموضوعات لتحديد أنماط أكثر استقرارًا ساعدت في معالجة سؤال البحث. في الخطوة الرابعة، استنادًا إلى الرموز الموضوعية التي تم إنشاؤها، كتبت تقريرين عن الحالة يوضحان ممارسات شينغ وجيمي اللغوية وتحولات الهوية عندما ينتقلان بين المساحات عبر الإنترنت وخارجها. ثم تم إجراء تحليل عبر الحالات من خلال مقارنة سردي الحالتين لاستنباط مناقشة موضوعية عميقة. أخيرًا، تم مشاركة التقريرين مع شينغ وجيمي للتحقق من صحة الأعضاء لتحسين مصداقية ودقة تفسيري.

5. النتائج

5.1. حالة شينغ

5.1.1. الهجرة من الريف إلى الحضر والوضع المهمش الأولي في الفضاءات الحضرية

في تخصصي، كنت واحدًا من القلة الذين جاءوا من خلفية ريفية. كان لدى الكثير من زملائي في الصف تجارب في الخارج أو مغامرات ثقافية رائعة قبل الجامعة، بينما لم يكن لدي كل تلك التجارب الفاخرة … بالإضافة إلى ذلك، لم يكن المعلمون يولون الكثير من الاهتمام للطلاب مثلي في الفصل لأنهم اعتقدوا أن الطلاب الريفيين سيئون في اللغة الإنجليزية، على الرغم من أن مهاراتي في التواصل باللغة الإنجليزية كانت بالفعل دون المستوى. لذلك، لم أكن لأحرج نفسي بالتحدث باللغة الإنجليزية أمام الجميع. (المقابلة الأولى)

5.1.2. الاستثمار في المهارات الرقمية في البرية

تلقيت العديد من الاقتراحات القيمة لتعلم اللغة الإنجليزية من طالب أكبر مني سناً، وهو أيضاً من مقاطعة هنان ويقود مجتمعنا الجامعي للغة الإنجليزية. كان يعاني سابقاً من صعوبة في تحدث الإنجليزية، لكنه من خلال الدراسة الذاتية عبر الإنترنت، أصبح واثقاً جداً الآن. بمساعدته، بدأت تدريجياً أدرك مدى أهمية تعلم الإنجليزية عبر الإنترنت وأشعر أن التحدث باللغة الإنجليزية لم يكن شيئاً مخيفاً للغاية.

5.1.3. التنقل في الفضاءات الإيديولوجية للمطالبة بحق التحدث

روى كيف استجاب عندما تعرض شخصيًا للإهانة بسبب المعتقدات التمييزية الخفية ضد العمال المهاجرين من الريف في الفصل الدراسي:

كان هناك وقت تحدث فيه زملائي في الصف عن بنية المدن في الصين في إحدى دروس اللغة الإنجليزية الشفوية. لقد أطلقوا على غطاء المجاري اسم “大豫通宝”.وجادلت بأنني كنت مستخدمًا له. على الرغم من أنني كنت أعلم أنه مزحة، لم أشعر أنه كان صحيحًا. لذا، وقفت وشرحت بجدية لمعلم اللغة الإنجليزية الشفوية من أستراليا [الذي لم يكن يعرف هذا المصطلح المهين] أن مثل هذه التعبيرات المهينة يجب تجنبها في صفنا لأنها مجرد صور نمطية ضد الناس المهاجرين من الريف… كان هذا مستحيلًا بالنسبة لي في الماضي.

5.2. حالة جيمي

5.2.1. الهجرة من الريف إلى الحضر والوضع المهمش الأولي في الفضاءات الحضرية

كنت أدرك الفجوة الكبيرة بيني وبين زملائي في الدراسة. والداي هما عمال مهاجرون من الريف، بينما آباء أصدقائي مهندسون ومعماريون… كان لديهم كل هذه الفرص للتباهي بملابس مصممة أو السفر إلى بلدان أجنبية، بينما كل ما كان يمكنني فعله هو الدراسة بجد. جعلني ذلك أشعر أنني أدنى من أقراني الحضريين. لهذا السبب كنت أحتفظ بنفسي كثيرًا خلال سنتي الدراسية الأولى.

5.2.2. الاستثمار في المهارات الرقمية في البرية

5.2.3. التنقل في المساحات الإيديولوجية للمطالبة بحق التحدث

6. المناقشة

سياق الفصل الدراسي. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، من خلال التعرف على كيفية ارتباط الكفاءات الرقمية الإنتاجية لدى شينغ وجيمي بالطريقة التي يتفاوضان بها على الإمكانيات التكنولوجية، ينبغي على معلمي اللغة أن يولوا اهتمامًا خاصًا لتعزيز ميول الطلاب الرقمية التي تعتبر استخدام التكنولوجيا وسيلة لتراكم رأس المال بدلاً من مجرد الترفيه. لتحقيق ذلك، يجب على معلمي اللغة تطوير وعي نقدي حول كيفية تشكيل تاريخ حياة الطلاب المهاجرين من الريف ومسارات تعلمهم لاحتياجاتهم واهتماماتهم التعليمية الشخصية (مثل كيف أصبح شينغ مهتمًا بموسيقى الروك الإنجليزية). الأثر السياسي الأكثر أهمية هو أنه ينبغي على صانعي السياسات والسلطات الجامعية العمل معًا لمساعدة الطلاب المهاجرين من الريف على الاندماج في الفضاء الجامعي الحضري كأعضاء اجتماعيين كفوئين من خلال تقديم المزيد من الدورات التحضيرية المخصصة لمساعدة الطلاب من الريف الصيني على التكيف مع الفروق بين الريف والحضر.

7. الخاتمة

الشكر. أود أن أعبر عن امتناني للمشاركين الذين شاركوا طواعية في هذه الدراسة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، أقدر الدكتور رون دارفين على عمله في مجال محو الأمية وعدم المساواة الرقمية، الذي كان مصدر إلهام كبير لبحثي.

بيان تضارب المصالح. يعلن المؤلف عدم وجود مصالح متنافسة.

بيان أخلاقي. لا توجد قضايا أخلاقية متعلقة بالورقة الحالية. تم إبلاغ المشاركين بأهداف البحث وقدموا موافقتهم لجمع البيانات وتحليلها. تم استخدام أسماء مستعارة لحماية هوياتهم. لم تكن هناك أي تضاربات في المصالح. كما التزمت الدراسة بالإرشادات الأخلاقية لجامعة الصين في هونغ كونغ، مما يضمن سرية المشاركين، والمشاركة الطوعية، واحترام رواياتهم وتجاربهم.

References

Ávila, J. & Pandya, J. Z. (eds.) (2013) Critical digital literacies as social praxis: Intersections and challenges. New York: Peter Lang.

Bourdieu, P. (1984) Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. London: Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (1991) Language and symbolic power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bradley, L. & Al-Sabbagh, K. W. (2022) Mobile language learning designs and contexts for newly arrived migrants. Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 5(3): 179-189. https://doi.org/10.29140/ajal.v5n3.53si5

Darvin,R.(2018)Social class and the unequal digital literacies of youth.Language and Literacy,20(3):26-45.https://doi.org/ 10.20360/langandlit29407

Darvin,R.(2023)Sociotechnical structures,materialist semiotics,and online language learning.Language Learning & Technology,27(2):28-45.https://hdl.handle.net/10125/73502

Darvin,R.&Hafner,C.A.(2022)Digital literacies in TESOL:Mapping out the terrain.TESOL Quarterly,56(3):865-882. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq. 3161

Darvin,R.&Norton,B.(2015)Identity and a model of investment in applied linguistics.Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 35:36-56.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190514000191

Darvin,R.&Norton,B.(2016)Investment and language learning in the 21st century.Langage &Société,3(157):19-38. https://doi.org/10.3917/ls.157.0019

Darvin,R.&Norton,B.(2023)Investment and motivation in language learning:What's the difference?Language Teaching, 56(1):29-40.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444821000057

Duff,P.(2018)Case study research in applied linguistics.New York:Routledge.https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203827147

Garcia,P.,Fernández,C.&Okonkwo,H.(2020)Leveraging technology:How Black girls enact critical digital literacies for social change.Learning,Media and Technology,45(4):345-362.https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1773851

Han,Y.&Reinhardt,J.(2022)Autonomy in the digital wilds:Agency,competence,and self-efficacy in the development of L2 digital identities.TESOL Quarterly,56(3):985-1015.https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq. 3142

Jones,R.H.(2021)The text is reading you:Teaching language in the age of the algorithm.Linguistics and Education,62: Article 100750.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2019.100750

Jones,R.H.&Hafner,C.A.(2021)Understanding digital literacies:A practical introduction(2nd ed.).Abingdon:Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003177647

Kendrick,M.,Early,M.,Michalovich,A.&Mangat,M.(2022)Digital storytelling with youth from refugee backgrounds: Possibilities for language and digital literacy learning.TESOL Quarterly,56(3):961-984.https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq. 3146

Kukulska-Hulme,A.(2009)Will mobile learning change language learning?ReCALL,21(2):157-165.https://doi.org/10.1017/ S0958344009000202

Leander,K.M.(2008)Toward a connective ethnography of online/offline literacy networks.In Coiro,J.,Knobel,M., Lankshear,C.&Leu,D.J.(eds.),Handbook of research on new literacies.New York:Routledge,33-65.

Li,H.(2013)Rural students'experiences in a Chinese elite university:Capital,habitus and practices.British Journal of Sociology of Education,34(5-6):829-847.https://www.jstor.org/stable/43818801

Liu,C.&Liu,G.(2023)L2 investment in the transnational context:A case study of PRC scholar students in Singapore.Journal of English and Applied Linguistics,2(2):32-51.https://doi.org/10.59588/2961-3094.1072

Liu,G.(2022)Review of the book Understanding Digital Literacies:A Practical Introduction(2nd ed.).Journal of Second Language Writing,58:Article 100932.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2022.100932

Liu,G.(2023a)Interrogating critical digital literacies in the Chinese context:Insights from an ethnographic case study.Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development.Advance online publication.https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2023. 2241859

Liu,G.(2023b)To transform or not to transform?Understanding the digital literacies of rural lower-class EFL learners. Journal of Language,Identity,and Education.Advance online publication.https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2023.2236217

Liu,G.&Darvin,R.(2024)From rural China to the digital wilds:Negotiating digital repertoires to claim the right to speak online.TESOL Quarterly,58(1):334-362.https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq. 3233

Liu,G.L.,Darvin,R.&Ma,C.(2024)Unpacking the role of motivation and enjoyment in AI-mediated informal digital learning of English(AI-IDLE):A mixed-method investigation in the Chinese context.Computers in Human Behaviors,160: Article 108362.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2024.108362

Liu,G.,Li,W.&Zhang,Y.(2022)Tracing Chinese international students'psychological and academic adjustments in uncertain times:An exploratory case study in the United Kingdom.Frontier in Psychology,13:Article 942227.https://doi. org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.942227

Liu,G.,Ma,C.,Bao,J.&Liu,Z.(2023)Toward a model of informal digital learning of English and intercultural competence:A large-scale structural equation modeling approach.Computer Assisted Language Learning.Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2023.2191652

McLean,C.A.(2010)A space called home:An immigrant adolescent's digital literacy practices.Journal of Adolescent &Adult Literacy,54(1):13-22.https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.54.1.2

National Bureau of Statistics of China(2021) 2021 年农民工监测调查报告[Migrant Labour Monitoring Survey Report 2021].https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-04/29/content_5688043.htm

Norton,B.(2013)Identity and language learning:Extending the conversation(2nd ed.).Bristol:Multilingual Matters.https:// doi.org/10.21832/9781783090563

Norton Peirce,B.(1995)Social identity,investment,and language learning.TESOL Quarterly,29(1):9-31.https://doi.org/10. 2307/3587803

Pennycook,A.&Makoni,S.(2019)Innovations and challenges in applied linguistics from the global south.Abingdon: Routledge.https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429489396

Ragnedda,M.(2017)The third digital divide:A Weberian approach to digital inequalities.Abingdon:Routledge.https://doi. org/10.4324/9781315606002

Sauro,S.&Zourou,K.(2019)What are the digital wilds?Language Learning &Technology,23(1):1-7.https://doi.org/10125/ 44666

Tagg,C.&Seargeant,P.(2021)Context design and critical language/media awareness:Implications for a social digital literacies education.Linguistics and Education,62:Article 100776.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2019.100776

Wu,M.(2023)智能教育背景下英语智慧课堂教育新生态的构建研究[Construction of English smart classroom ecology in the context of the new-era intelligent education].外语电化教学[Computer-Assisted Foreign Language Education],2: 36-41, 110.

Wu,X.&Tarc,P.(2024)Challenges and possibilities in English language learning of rural lower-class Chinese college students:The effect of capital,habitus,and fields.Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development,45(4):957-972. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2021.1931249

Xie,A.&Reay,D.(2020)Successful rural students in China's elite universities:Habitus transformation and inevitable hidden injuries?Higher Education,80(1):21-36.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00462-9

Zhang,Y.&Liu,G.L.(2023)Examining the impacts of learner backgrounds,proficiency level,and the use of digital devices on informal digital learning of English:An explanatory mixed-method study.Computer Assisted Language Learning.Advance online publication.https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2023.2267627

Zhang,Y.&Liu,G.(2024)Revisiting informal digital learning of English(IDLE):A structural equation modeling approach in a university EFL context.Computer Assisted Language Learning,37(7):1904-1936.https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2022. 2134424

عن المؤلف

- استشهد بهذه المقالة: ليو، غ.ل. (2025). التمكين الرقمي للطلاب المهاجرين من الريف في الصين: الهوية، الاستثمار، والمهارات الرقمية خارج الفصل الدراسي. ReCALL 37(2): 215-231.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344024000302

© المؤلفون، 2025. نشرت بواسطة مطبعة جامعة كامبريدج نيابة عن EUROCALL، الجمعية الأوروبية لتعلم اللغة بمساعدة الكمبيوتر. هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول، موزعة بموجب شروط ترخيص المشاع الإبداعي (https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)، الذي يسمح بإعادة الاستخدام والتوزيع والتكاثر غير المقيد، شريطة أن يتم الاستشهاد بالمقالة الأصلية بشكل صحيح. تطبيق شائع لتعلم المفردات الإنجليزية في البر الرئيسي للصين.

واحد من أكبر مواقع تعلم الاستماع والتحدث باللغة الإنجليزية عبر الإنترنت في البر الرئيسي للصين.

مجلة إلكترونية مملوكة للدولة تشارك أصوات جديدة من الصين باللغة الإنجليزية.

يمكن أن يساعد VPN مستخدمي الإنترنت الصينيين في تجاوز جدار الحماية العظيم والوصول إلى المواقع الغربية ومنصات التواصل الاجتماعي مثل يوتيوب وجوجل.

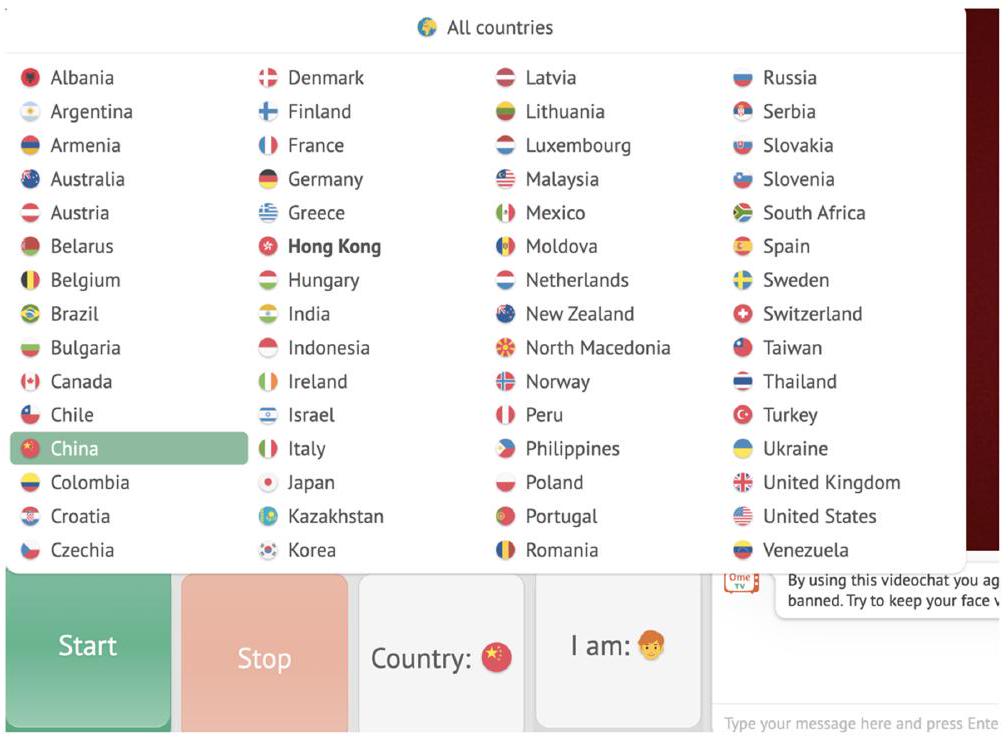

منصة عبر الإنترنت تمكن المستخدمين من تكوين صداقات والتواصل في شكل محادثات فيديو. - ترجمة “6"大豫通宝" حرفيًا إلى عملات نقدية من شعب هنان، مع “大豫” تشير إلى “الهنان العظيم” و”通宝” تعني “عملات نقدية مستخدمة في الصين القديمة”. تم صياغة هذا المصطلح من قبل مستخدمي الإنترنت الصينيين كتعبير مرح ولكنه مهين، ناتج عن مصطلح تمييزي آخر “偷井盖” (فعل سرقة أغطية المجاري العامة). يتم استخدام المصطلحين بشكل شائع للإساءة إلى الناس من الريف في هنان، مما يوحي بأن العمال المهاجرين من هنان يعيلون أنفسهم من خلال سرقة أغطية المجاري.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0958344024000302

Publication Date: 2025-01-06

Digital empowerment for rural migrant students in China: Identity, investment, and digital literacies beyond the classroom

Abstract

Drawing upon Darvin and Norton’s (2015) model of investment, this article examines how Xing and Jimmy (both pseudonyms) as two male Chinese English as a foreign language learners from rural migrant backgrounds negotiate their identities and assemble their social and cultural resources to invest in autonomous digital literacies for language learning and the assertion of a legitimate place in urban spaces. Employing a connective ethnographic design, this study collected data through interviews, reflexive journals, digital artifacts, and on-campus observations. Data were analyzed using an inductive thematic approach as well as within- and cross-case data analysis methods. The findings indicate that Xing and Jimmy experienced a profound sense of alienation and exclusion as they migrated from under-resourced rural spaces to the urban elite field. The unequal power relations in urban classrooms subjected them to marginalized and inadequate rural identities by denying them the right to speak and be heard. However, engaging with digital literacies in the wild allowed these migrant learners to access a wide range of linguistic, cultural, and symbolic resources, empowering them to reframe their identities as legitimate English speakers. The acquisition of such legitimacy enabled them to challenge the prevailing rural-urban exclusionary ideologies to claim the right to speak. This article closes by offering implications for empowering rural migrant students as socially competent members of the Chinese higher education system in the digital age.

1. Introduction

2. Literature review

2.1. Defining digital literacies

unbiased, the hidden ideologies embedded in algorithms or sociotechnical design can shape how information is given and knowledge is produced online. Notably, recognizing that technology presents opportunities for social change and equitable communications, there is also a growing body of literature that examines how texts, through the affordances of digital tools, can be redesigned and consumed to serve the interests of all learners by subverting exclusionary ideologies and negotiating inequitable power relationships (Ávila & Pandya, 2013; Garcia, Fernández & Okonkwo, 2020). These studies also emphasize that how learners are ushered into different digital spaces to participate in diverse digital practices is critical (Garcia et al., 2020; Liu, 2023a).

2.2. Digital literacies of migrant language learners

literacies in the wild may be an effective approach to supporting their language learning and identity development in the receiving society.

2.3. English language learning and rural-urban divide in China

3. Theoretical framework

based because it focuses on extending the understanding of personal and particularized experiences, rather than aiming to generate generalizable findings applicable to larger populations (Duff, 2018). This study also draws upon connective ethnography that collapses the binaries between online/virtual and offline/physical in New Literacy Studies (Leander, 2008). It highlights that while our learners move fluidly and flexibly from and to different social spaces shaped by ubiquitous digital technologies, they are in effect occupying these spaces simultaneously or navigating online and offline worlds as an entirety rather than separate fields (Darvin, 2023).

4.2. Xing and Jimmy

4.3. Data collection

4.4. Data analysis

multiple times. Second, all textual data, including the interviews, observation field notes, and reflexive journals, were coded inductively to map out initial codes and their corresponding descriptors using NVivo 12. Third, the codes were compared constantly to locate their links and formulate the larger categories or themes (e.g. negotiating capital in the digital wilds). During this process, digital artifacts were annotated and linked to the emergent themes as complementary examples. Then the themes were re-examined to identify more stable patterns that helped to address the research question. In the fourth step, based on the established thematic codes, I wrote two case reports demonstrating Xing’s and Jimmy’s literacy practices and identity shifts when moving across online and offline spaces. Then a cross-case analysis was undertaken by comparing the two case narratives to elicit in-depth thematic discussion. Finally, the two case reports were shared with Xing and Jimmy for member checking to improve the credibility and accuracy of my interpretations.

5. Findings

5.1. The case of Xing

5.1.1. Rural-urban migration and the initial marginalized status in urban spaces

In my major, I was one of the rare folks who hailed from a rural background. A lot of my classmates had been abroad or had all these cool cross-cultural adventures before college, while I didn’t have all those fancy experiences … On top of that, the teachers didn’t give much attention to students like me in class because they believed rural students were terrible at English, though my English communication skills were indeed below standard. So, I wasn’t about to embarrass myself by speaking English in front of everyone. (Interview I)

5.1.2. Investing in digital literacies in the wild

I received many valuable English learning suggestions from an upperclassman who is also from Henan province and is leading our undergraduate English society. He used to struggle with his spoken English, but through self-study online, he has become very confident now. With his help, I gradually started to know how important it is to learn English online and feel that English speaking was not such a terrifying thing. (Interview II)

5.1.3. Navigating ideological spaces to claim the right to speak

recounted how he responded when being personally affronted by hidden discriminatory beliefs against rural migrant workers in the classroom:

There was a time when my classmates talked about China's city infrastructure in one oral- English class.They called the manhole cover"大豫通宝"and argued I was a user of it. Though I knew it was a joke,I didn't feel like it was right.So,I stood up and seriously explained to the oral-English teacher from Australia[who didn't know this derogatory term] that such insulting expressions should be avoided in our classroom because it's just stereotypes against rural migrant people ...This would be impossible for the past"me." (Interview III)

5.2.The case of Jimmy

5.2.1.Rural-urban migration and the initial marginalized status in urban spaces

I could realize the huge background gap between me and my classmates.My parents are rural migrant workers,while my friends'parents are engineers and architects ...They had all these opportunities to flaunt designer clothes or jet off to foreign lands,while all I could do was studying hard.It made me feel like I was inferior to my urban peers.That's why I kept to myself a lot during my first year of studies.(Interview I)

5.2.2. Investing in digital literacies in the wild

5.2.3. Navigating ideological spaces to claim the right to speak

6. Discussion

classroom context. Additionally, recognizing how Xing’s and Jimmy’s productive digital literacies are inseparable from the way they negotiate technological affordances, language teachers ought to pay special attention to fostering students’ digital dispositions that view technology use as a way of capital accumulation rather than simply entertainment. Language teachers, to this end, should develop a critical awareness of how rural migrant students’ life histories and learning trajectories shape their personalized learning needs and interests (e.g. how Xing became interested in English rock music). The most important policy implication is that policymakers and university authorities should work together to help rural migrant students integrate into the urban university space as socially competent members by offering more tailored preparation courses to help students from rural China adapt to rural-urban differences.

7. Conclusion

Acknowledgements. I extend my gratitude to the participants who willingly took part in this study. Additionally, I appreciate Dr Ron Darvin for his work on literacy and digital inequity, which has served as a significant source of inspiration for my research.

Conflict of interest statement. The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical statement. There is no ethical issue involved in the present paper. Participants were informed of the research objectives and provided consent for data collection and analysis. Pseudonyms were used to protect their identities. No conflicts of interest were present. The study also adhered to the ethical guidelines of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, ensuring participant anonymity, voluntary participation, and respect for their narratives and experiences.

References

Ávila, J. & Pandya, J. Z. (eds.) (2013) Critical digital literacies as social praxis: Intersections and challenges. New York: Peter Lang.

Bourdieu, P. (1984) Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. London: Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (1991) Language and symbolic power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bradley, L. & Al-Sabbagh, K. W. (2022) Mobile language learning designs and contexts for newly arrived migrants. Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 5(3): 179-189. https://doi.org/10.29140/ajal.v5n3.53si5

Darvin,R.(2018)Social class and the unequal digital literacies of youth.Language and Literacy,20(3):26-45.https://doi.org/ 10.20360/langandlit29407

Darvin,R.(2023)Sociotechnical structures,materialist semiotics,and online language learning.Language Learning & Technology,27(2):28-45.https://hdl.handle.net/10125/73502

Darvin,R.&Hafner,C.A.(2022)Digital literacies in TESOL:Mapping out the terrain.TESOL Quarterly,56(3):865-882. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq. 3161

Darvin,R.&Norton,B.(2015)Identity and a model of investment in applied linguistics.Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 35:36-56.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190514000191

Darvin,R.&Norton,B.(2016)Investment and language learning in the 21st century.Langage &Société,3(157):19-38. https://doi.org/10.3917/ls.157.0019

Darvin,R.&Norton,B.(2023)Investment and motivation in language learning:What's the difference?Language Teaching, 56(1):29-40.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444821000057

Duff,P.(2018)Case study research in applied linguistics.New York:Routledge.https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203827147

Garcia,P.,Fernández,C.&Okonkwo,H.(2020)Leveraging technology:How Black girls enact critical digital literacies for social change.Learning,Media and Technology,45(4):345-362.https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1773851

Han,Y.&Reinhardt,J.(2022)Autonomy in the digital wilds:Agency,competence,and self-efficacy in the development of L2 digital identities.TESOL Quarterly,56(3):985-1015.https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq. 3142

Jones,R.H.(2021)The text is reading you:Teaching language in the age of the algorithm.Linguistics and Education,62: Article 100750.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2019.100750

Jones,R.H.&Hafner,C.A.(2021)Understanding digital literacies:A practical introduction(2nd ed.).Abingdon:Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003177647

Kendrick,M.,Early,M.,Michalovich,A.&Mangat,M.(2022)Digital storytelling with youth from refugee backgrounds: Possibilities for language and digital literacy learning.TESOL Quarterly,56(3):961-984.https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq. 3146

Kukulska-Hulme,A.(2009)Will mobile learning change language learning?ReCALL,21(2):157-165.https://doi.org/10.1017/ S0958344009000202

Leander,K.M.(2008)Toward a connective ethnography of online/offline literacy networks.In Coiro,J.,Knobel,M., Lankshear,C.&Leu,D.J.(eds.),Handbook of research on new literacies.New York:Routledge,33-65.

Li,H.(2013)Rural students'experiences in a Chinese elite university:Capital,habitus and practices.British Journal of Sociology of Education,34(5-6):829-847.https://www.jstor.org/stable/43818801

Liu,C.&Liu,G.(2023)L2 investment in the transnational context:A case study of PRC scholar students in Singapore.Journal of English and Applied Linguistics,2(2):32-51.https://doi.org/10.59588/2961-3094.1072

Liu,G.(2022)Review of the book Understanding Digital Literacies:A Practical Introduction(2nd ed.).Journal of Second Language Writing,58:Article 100932.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2022.100932

Liu,G.(2023a)Interrogating critical digital literacies in the Chinese context:Insights from an ethnographic case study.Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development.Advance online publication.https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2023. 2241859

Liu,G.(2023b)To transform or not to transform?Understanding the digital literacies of rural lower-class EFL learners. Journal of Language,Identity,and Education.Advance online publication.https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2023.2236217

Liu,G.&Darvin,R.(2024)From rural China to the digital wilds:Negotiating digital repertoires to claim the right to speak online.TESOL Quarterly,58(1):334-362.https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq. 3233

Liu,G.L.,Darvin,R.&Ma,C.(2024)Unpacking the role of motivation and enjoyment in AI-mediated informal digital learning of English(AI-IDLE):A mixed-method investigation in the Chinese context.Computers in Human Behaviors,160: Article 108362.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2024.108362

Liu,G.,Li,W.&Zhang,Y.(2022)Tracing Chinese international students'psychological and academic adjustments in uncertain times:An exploratory case study in the United Kingdom.Frontier in Psychology,13:Article 942227.https://doi. org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.942227

Liu,G.,Ma,C.,Bao,J.&Liu,Z.(2023)Toward a model of informal digital learning of English and intercultural competence:A large-scale structural equation modeling approach.Computer Assisted Language Learning.Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2023.2191652

McLean,C.A.(2010)A space called home:An immigrant adolescent's digital literacy practices.Journal of Adolescent &Adult Literacy,54(1):13-22.https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.54.1.2

National Bureau of Statistics of China(2021) 2021 年农民工监测调查报告[Migrant Labour Monitoring Survey Report 2021].https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-04/29/content_5688043.htm

Norton,B.(2013)Identity and language learning:Extending the conversation(2nd ed.).Bristol:Multilingual Matters.https:// doi.org/10.21832/9781783090563

Norton Peirce,B.(1995)Social identity,investment,and language learning.TESOL Quarterly,29(1):9-31.https://doi.org/10. 2307/3587803

Pennycook,A.&Makoni,S.(2019)Innovations and challenges in applied linguistics from the global south.Abingdon: Routledge.https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429489396

Ragnedda,M.(2017)The third digital divide:A Weberian approach to digital inequalities.Abingdon:Routledge.https://doi. org/10.4324/9781315606002

Sauro,S.&Zourou,K.(2019)What are the digital wilds?Language Learning &Technology,23(1):1-7.https://doi.org/10125/ 44666

Tagg,C.&Seargeant,P.(2021)Context design and critical language/media awareness:Implications for a social digital literacies education.Linguistics and Education,62:Article 100776.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2019.100776

Wu,M.(2023)智能教育背景下英语智慧课堂教育新生态的构建研究[Construction of English smart classroom ecology in the context of the new-era intelligent education].外语电化教学[Computer-Assisted Foreign Language Education],2: 36-41, 110.

Wu,X.&Tarc,P.(2024)Challenges and possibilities in English language learning of rural lower-class Chinese college students:The effect of capital,habitus,and fields.Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development,45(4):957-972. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2021.1931249

Xie,A.&Reay,D.(2020)Successful rural students in China's elite universities:Habitus transformation and inevitable hidden injuries?Higher Education,80(1):21-36.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00462-9

Zhang,Y.&Liu,G.L.(2023)Examining the impacts of learner backgrounds,proficiency level,and the use of digital devices on informal digital learning of English:An explanatory mixed-method study.Computer Assisted Language Learning.Advance online publication.https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2023.2267627

Zhang,Y.&Liu,G.(2024)Revisiting informal digital learning of English(IDLE):A structural equation modeling approach in a university EFL context.Computer Assisted Language Learning,37(7):1904-1936.https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2022. 2134424

About the author

- Cite this article: Liu, G.L. (2025). Digital empowerment for rural migrant students in China: Identity, investment, and digital literacies beyond the classroom. ReCALL 37(2): 215-231. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344024000302

© The Author(s), 2025. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of EUROCALL, the European Association for Computer-Assisted Language Learning. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution and reproduction, provided the original article is properly cited. A popular English vocabulary learning application in mainland China.

One of the largest online English listening and speaking learning websites in mainland China.

A state-owned online magazine that shares fresh voices from China in English.

VPN enables Chinese internet users to get around the Great Firewall and access Western websites and social media platforms such as YouTube and Google.

A online platform that enables users to make friends and network in the form of video chats. - 6"大豫通宝"literally translates to the cash coins of the Henan people,with"大豫"referring to"the great Henan"and"通宝"meaning"cash coins used in ancient China".This term was coined by Chinese netizens as a playful yet derogatory expression,stemming from another discriminatory term"偷井盖"(the act of stealing public manhole covers).The two terms are commonly used to denigrate rural people from Henan,insinuating that Henan's rural migrant workers sustain themselves by pilfering manhole covers.