DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-024-00447-4

تاريخ النشر: 2024-03-04

تمكين ChatGPT بآلية توجيه في التعلم المدمج: تأثير التعلم الذاتي التنظيم، ومهارات التفكير العليا، وبناء المعرفة

الملخص

في المشهد المتطور للتعليم العالي، أبرزت التحديات مثل جائحة COVID-19 ضرورة وجود منهجيات تدريس مبتكرة. لقد حفزت هذه التحديات دمج التكنولوجيا في التعليم، لا سيما في بيئات التعلم المدمج، لتعزيز التعلم الذاتي التنظيم (SRL) ومهارات التفكير العليا (HOTS). ومع ذلك، يمكن أن تؤدي زيادة الاستقلالية في التعلم المدمج إلى اضطرابات في التعلم إذا لم يتم معالجة القضايا على الفور. في هذا السياق، يظهر ChatGPT من OpenAI، المعروف بقاعدة معرفته الواسعة وقدرته على تقديم ردود فورية، كمورد تعليمي مهم. ومع ذلك، هناك مخاوف من أن الطلاب قد يصبحون معتمدين بشكل مفرط على مثل هذه الأدوات، مما قد يعيق تطويرهم لمهارات التفكير العليا. لمعالجة هذه المخاوف، يقدم هذه الدراسة أداة التعلم المدعومة بـ ChatGPT المعتمدة على التوجيه (GCLA). تعدل هذه الطريقة استخدام ChatGPT في البيئات التعليمية من خلال تشجيع الطلاب على محاولة حل المشكلات بشكل مستقل قبل طلب المساعدة من ChatGPT. عند الانخراط، يوفر GCLA التوجيه من خلال تلميحات بدلاً من إجابات مباشرة، مما يعزز بيئة ملائمة لتطوير SRL وHOTS. تم استخدام تجربة عشوائية محكومة (RCT) لفحص تأثير GCLA مقارنة باستخدام ChatGPT التقليدي في دورة كيمياء أساسية ضمن بيئة تعلم مدمجة. شملت هذه الدراسة 61 طالبًا جامعيًا من جامعة في تايوان. تكشف النتائج أن GCLA تعزز SRL وHOTS وبناء المعرفة مقارنة باستخدام ChatGPT التقليدي. تتماشى هذه النتائج مباشرة مع الهدف البحثي لتحسين نتائج التعلم من خلال تقديم التوجيه بدلاً من الإجابات من ChatGPT. في الختام، لم يسهل إدخال GCLA تجارب التعلم الأكثر فعالية في بيئات التعلم المدمج فحسب، بل ضمنت أيضًا أن يشارك الطلاب بشكل أكثر نشاطًا في رحلتهم التعليمية. تسلط نتائج هذه الدراسة الضوء على إمكانيات أدوات ChatGPT في تعزيز جودة التعليم العالي، لا سيما في تعزيز المهارات الأساسية مثل التنظيم الذاتي وHOTS. علاوة على ذلك، تقدم هذه البحث رؤى بشأن الاستخدام الأكثر فعالية لـ ChatGPT في التعليم.

المقدمة

- كيف يؤثر GCLA، مقارنة باستخدام ChatGPT التقليدي، على SRL لطلاب التعليم العالي في بيئات التعلم المدمج؟

- كيف يؤثر GCLA، مقارنة باستخدام ChatGPT التقليدي، على تطوير HOTS لدى هؤلاء الطلاب؟

- كيف يؤثر GCLA، مقارنة باستخدام ChatGPT التقليدي، على بناء المعرفة لدى طلاب التعليم العالي في هذه البيئات؟

مراجعة الأدبيات

التعلم الذاتي التنظيم في التعلم المدمج

كفاءتهم التعليمية، مما يضمن إدارة ماهرة لتجارب التعلم ضمن السياقات الغنية لبيئات التعلم المدمجة.

مهارات التفكير العليا

تشات جي بي تي في التعليم

تصميم مساعدة التعلم المعتمدة على تشات جي بي تي (GCLA)

تنفيذ GCLA

| المعلمة | النموذج | الحد الأقصى من الرموز | درجة الحرارة | عقوبة الوجود |

| القيمة | gpt-3.5-turbo-16 k | 4000 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

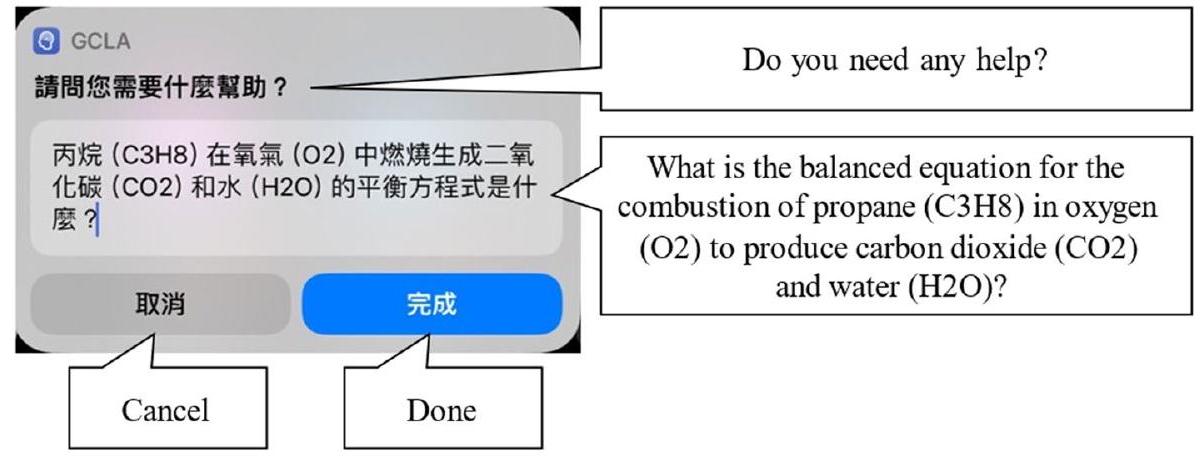

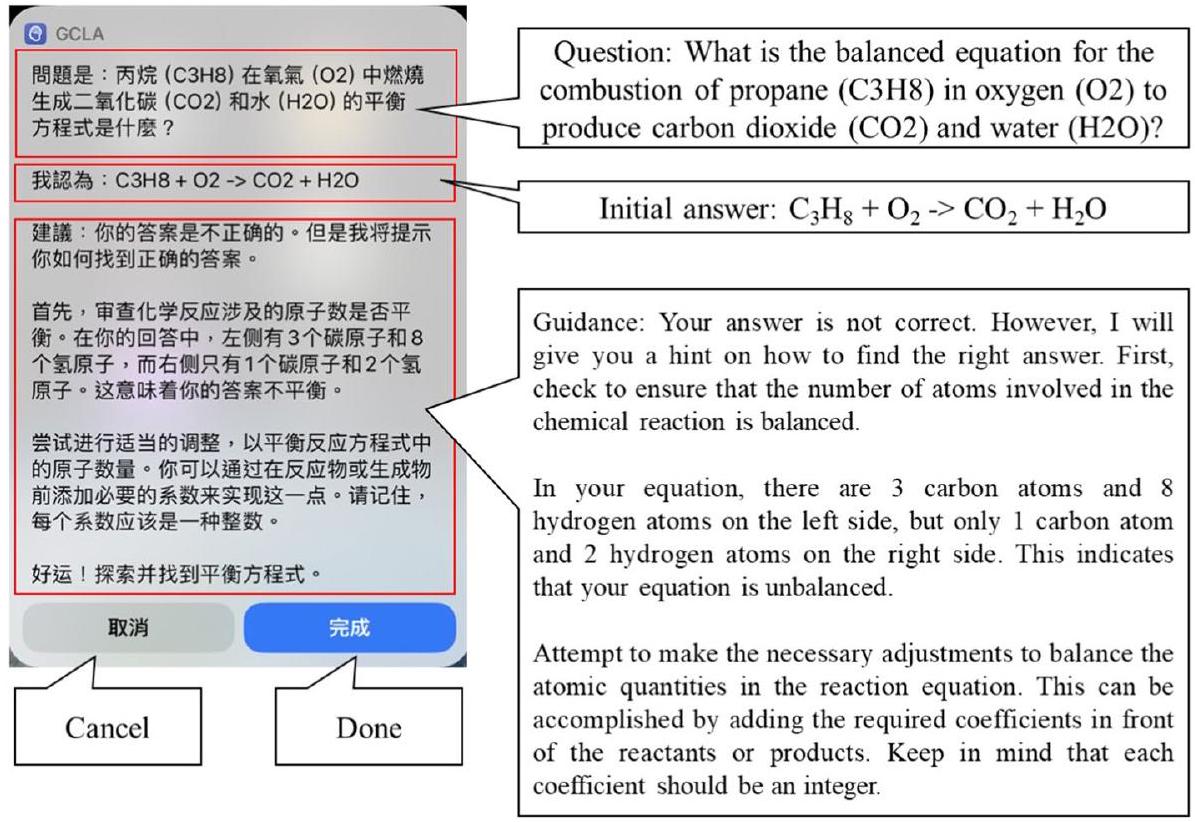

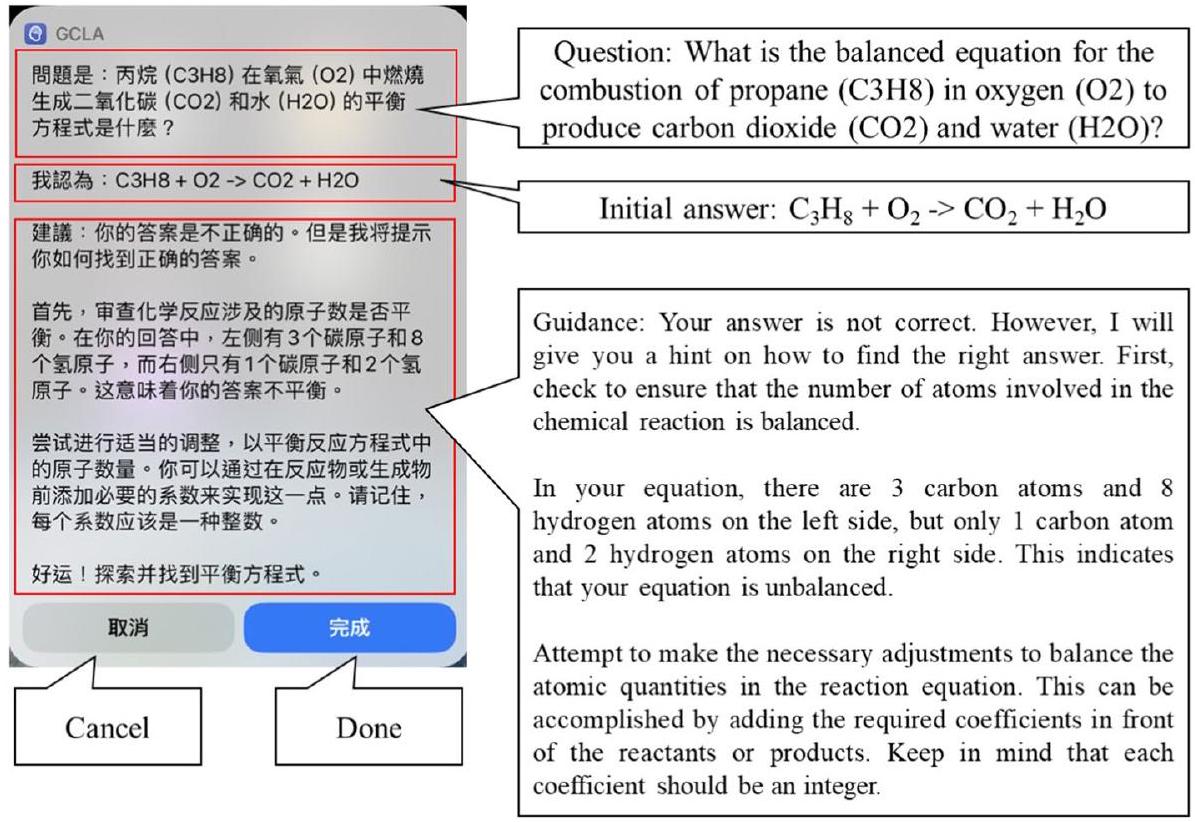

مثال على استخدام GCLA

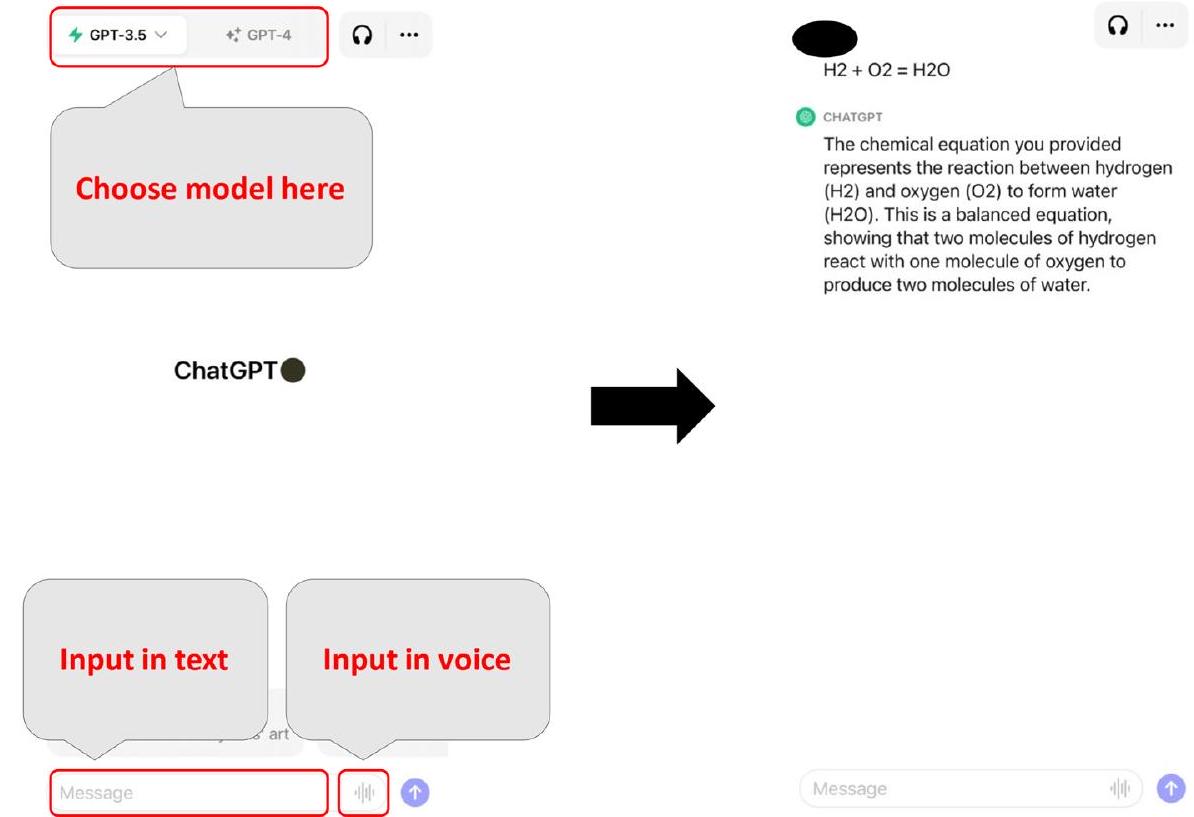

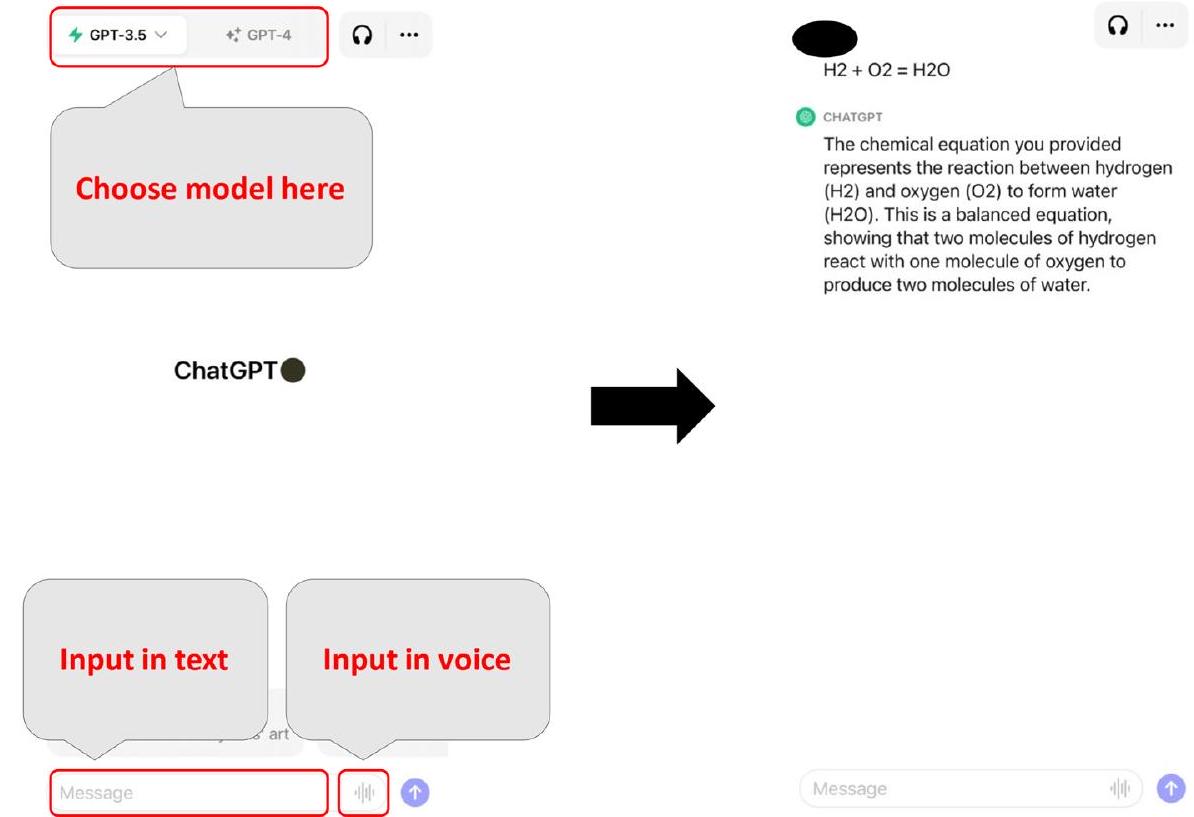

مقارنة ChatGPT على iOS

المنهجية

تصميم البحث

السكان

حجم العينة وتقنية العينة

الطريقة الأكثر عملية واقتصادية لتجنيد المشاركين لهذه الدراسة، نظرًا للقيود الزمنية والموارد.

القياس

خصوصًا في سياق أكاديمي. يتكون مقياس SRL من ثلاثة أبعاد رئيسية وتسعة أبعاد فرعية، ويستخدم مقياس ليكرت من خمس نقاط للإجابات. تم تأكيد موثوقيته وصلاحيته في دراسات سابقة (Chen et al.، 2001؛ Guay et al.، 2000؛ Wang et al.، 2016).

موثوقية القياس

| التفكير النقدي | حل المشكلات | الإبداع | |

| الموثوقية الأصلية | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.80 |

| الموثوقية المعدلة | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.72 |

| البعد | البعد الفرعي | موثوقية |

| الدافع (مرحلة التفكير المسبق) | الدافع الداخلي | 0.86 |

| التنظيم المحدد | 0.88 | |

| تنظيم خارجي | 0.79 | |

| عدم الدافع | 0.80 | |

| الانخراط (مرحلة الأداء) | الانخراط المعرفي | 0.85 |

| الارتباط العاطفي | 0.81 | |

| الانخراط السلوكي | 0.75 | |

| الانخراط الاجتماعي | 0.77 | |

| الكفاءة الذاتية (مرحلة التأمل الذاتي) | الكفاءة الذاتية | 0.79 |

تفاصيل الاختبار القبلي والاختبار البعدي

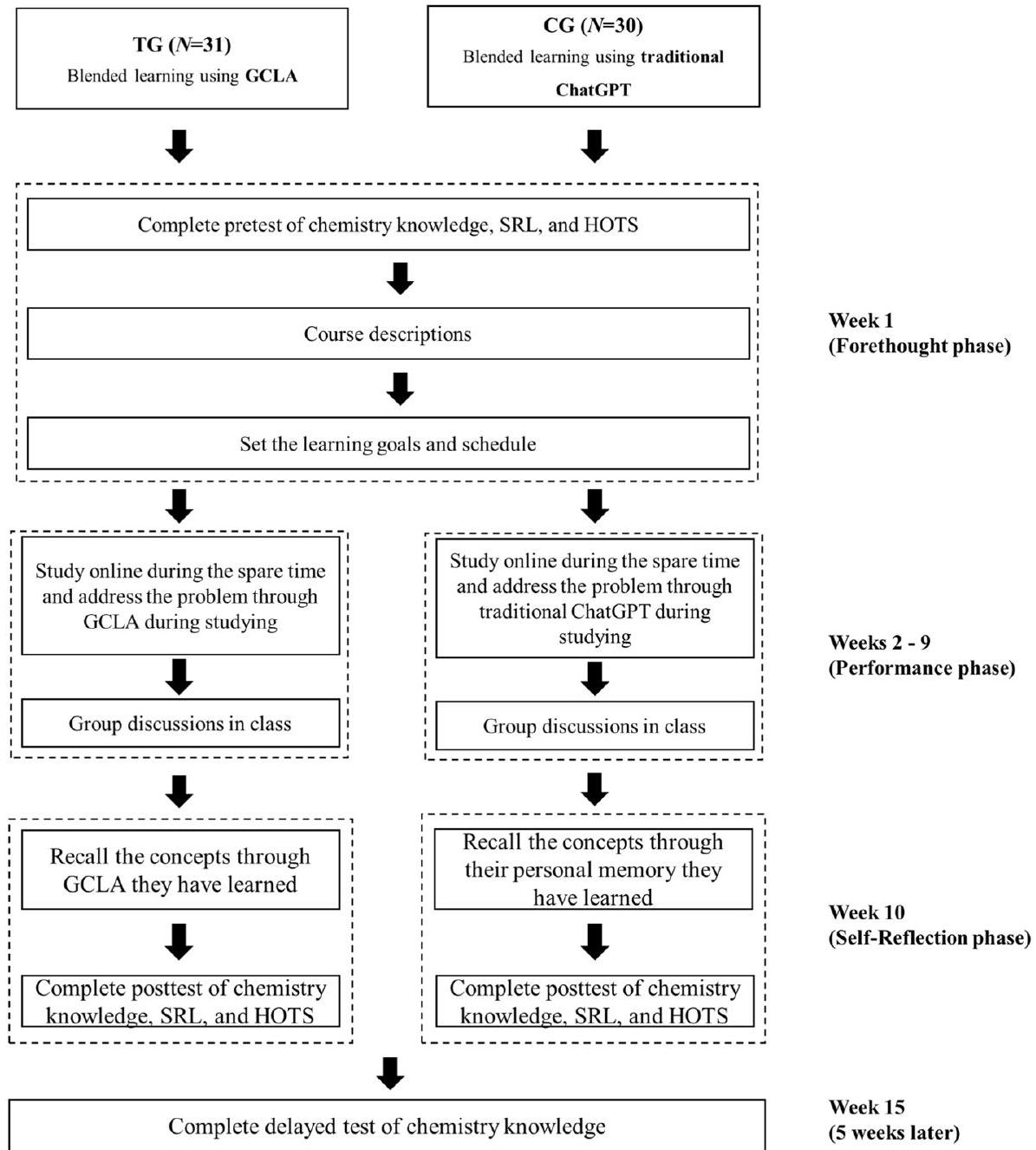

منهجية التعليم

- الأسبوع 1: مرحلة التفكير المسبق

- الأسبوع 2 إلى 9: مرحلة الأداء

- الأسبوع 10: مرحلة التأمل الذاتي

| مرحلة SRL | وصف TG | وصف CG |

| مرحلة التفكير المسبق | قبل الغوص في دراسة الكيمياء، يجب على الطلاب تحديد أهداف تعلم يومية ومراقبة إنجازاتهم. | قبل الغوص في دراسة الكيمياء، يجب على الطلاب تحديد أهداف تعلم يومية ومراقبة إنجازاتهم. |

| مرحلة الأداء | عندما يواجه الطلاب تحديات في دراستهم، يمكنهم اللجوء إلى GCLA لمعالجة هذه الصعوبات. | عند مواجهة التحديات في دراستهم، يمكن للطلاب اللجوء إلى ChatGPT على نظام iOS للحصول على المساعدة. |

| مرحلة التأمل الذاتي | فحص السجلات المؤرشفة في ملف سجل التعلم يسمح بالتفكير في الدروس الماضية ويساعد في الاحتفاظ بالمفاهيم. | شجع الطلاب على التأمل في تجاربهم في الفصل واسترجاع المفاهيم من خلال الاستناد إلى ذكرياتهم الشخصية |

استخدام ChatGPT على نظام iOS خلال نفس المرحلة والاعتماد على الذاكرة للمهام التأملية في الأسبوع الأخير. يوضح الجدول 4 الاختلافات في ديناميات التعلم الذاتي بين مجموعة التجربة ومجموعة التحكم طوال مدة الدراسة.

المتغيرات

طرق التحليل والأدوات الإحصائية

- الإحصائيات الوصفية: لوصف خصائص العينة ودرجات المتغيرات التابعة لكل مجموعة.

- تحليل التباين المشروط (ANCOVA): لمقارنة متوسط درجات المتغيرات التابعة بين المجموعات، مع تعديل تأثيرات المتغيرات المرافقة.

- حجم التأثير: لقياس حجم الفرق بين المجموعات، باستخدام إيتا تربيع الجزئي

) كمؤشر. - البرمجيات الإحصائية: لإجراء تحليل البيانات، باستخدام JAMOVI الإصدار 2.4 (المشروع، 2023).

النتائج

أثر GCLA على التعلم الذاتي المنظم (SRL)

| متغير | اختبار ليفين | |

|

|

|

|

| الدافع الداخلي | 0.104 | 0.749 |

| التنظيم المحدد | 1.82 | 0.182 |

| تنظيم خارجي | 2.43 | 0.124 |

| عدم الدافع | 0.075 | 0.785 |

| الانخراط المعرفي | 0.٣٢٣ | 0.572 |

| الانخراط السلوكي | 0.124 | 0.726 |

| الارتباط العاطفي | ٢.٢١ | 0.143 |

| الكفاءة الذاتية | 0.029 | 0.866 |

| تي جي (

|

سي جي

|

|||||||

| اختبار قبلي | بعد الاختبار | اختبار قبلي | بعد الاختبار | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| الدافع الداخلي | 16.2 | 1.88 | 18.9 | 2.82 | 16.0 | ٢.٤٦ | 16.1 | 2.55 |

| التنظيم المحدد | 14.8 | 2.32 | 19.1 | ٣.٥٠ | 14.7 | 1.45 | 17.8 | 2.53 |

| تنظيم خارجي | 15.4 | 2.01 | 18.1 | 1.53 | 15.8 | ٢.٢٦ | 17.3 | ٢.٢٦ |

| عدم الدافع | 11.2 | 1.64 | 8.53 | 2.73 | 11.6 | 1.71 | 12.0 | 2.73 |

| الانخراط المعرفي | ٢٥.٣ | 3.49 | ٣٤.٥ | 2.58 | ٢٤.٩ | 3.35 | ٢٧.٤ | 2.72 |

| الانخراط السلوكي | 17.0 | 1.28 | ٢٠.١ | 1.71 | 16.9 | 2.16 | 17.4 | 1.33 |

| الارتباط العاطفي | 12.6 | 1.60 | 13.5 | 1.21 | 12.5 | 2.32 | 12.8 | 1.53 |

| الكفاءة الذاتية | ٢٥.٨ | 2.53 | 31.2 | ٣.٩٠ | ٢٥.٧ | 2.79 | ٢٥.٨ | ٤.١٦ |

| متغير | SS | df | المتوسط التربيعي | ف | ب | جزئي

|

| الدافع الداخلي | ١٢٠.٤ | 1 | 120.41 | 17.13 | <0.001*** | 0.228 |

| التنظيم المحدد | ٢٤.٦ | 1 | ٢٤.٦ | 2.94 | 0.092 | 0.048 |

| تنظيم خارجي | 11.8 | 1 | 11.8 | 3.33 | 0.073 | 0.054 |

| عدم الدافع | 185.98 | 1 | 185.98 | ٢٤.٦٢ | <0.001*** | 0.298 |

| الانخراط المعرفي | 778.4 | 1 | 778.4 | ٤٨.٦٠ | <0.001*** | 0.369 |

| الانخراط السلوكي | ١٣٣ | 1 | 132.88 | 41.4 | <0.001*** | 0.333 |

| الارتباط العاطفي | ٥.٩٨ | 1 | ٥.٩٨ | 3.12 | 0.082 | 0.051 |

| الكفاءة الذاتية | ٤٣٧.٠٦ | 1 | ٤٣٧.٠٦ | ٢٦.٤٦ | <0.001*** | 0.313 |

| متغير | اختبار ليفين | |

|

|

|

|

| التفكير النقدي | 1.22 | 0.273 |

| حل المشكلات | 0.13 | 0.719 |

| الإبداع | 0.261 | 0.611 |

| تي جي (

|

سي جي

|

|||||||

| اختبار قبلي | بعد الاختبار | اختبار قبلي | بعد الاختبار | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| التفكير النقدي | ١٣.٠ | 1.47 | 17.3 | ٢.١٩ | ١٣.٠ | 1.52 | 13.8 | 2.00 |

| حل المشكلات | 12.3 | 1.05 | 15.9 | 2.01 | 12.0 | 2.01 | 13.1 | 1.96 |

| الإبداع | 9.58 | 1.39 | 11.0 | 1.18 | 9.47 | 1.11 | 10.1 | 1.07 |

| متغير | SS | df | المتوسط التربيعي | ف | ب | جزئي

|

| التفكير النقدي | 182.17 | 1 | 182.17 | ٤١.٧٣ | <0.001*** | 0.418 |

| حل المشكلات | ١٣٠.٦ | 1 | ١٣٠.٦ | ٣٨.٧ | <0.001*** | 0.400 |

| الإبداع | 10.63 | 1 | 10.63 | 8.98 | 0.004** | 0.134 |

أثر GCLA على مهارات التفكير العليا (HOTS)

أثر GCLA على بناء المعرفة

| متغير | اختبار ليفين | |

|

|

|

|

| اختبار ما بعد المعرفة الكيميائية | 1.22 | 0.273 |

| اختبار متأخر لمعرفه الكيمياء | 0.13 | 0.719 |

| تي جي (

|

سي جي

|

|||

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| اختبار تمهيدي لمعلومات الكيمياء | 63.3 | 11.8 | 62.0 | 7.80 |

| اختبار ما بعد المعرفة الكيميائية | 79.7 | 6.77 | ٧٤.٧ | ٨.٥٥ |

| اختبار متأخر لمعلومات الكيمياء | ٧٥.٩ | 6.36 | 69.3 | 6.94 |

| متغير | SS | df | المتوسط التربيعي | ف | ب | جزئي

|

| اختبار ما بعد المعرفة الكيميائية | ٣٥٧ | 1 | ٣٥٧ | 6.10 | 0.017* | 0.100 |

| اختبار متأخر لمعرفه الكيمياء | ٢٨٠ | 1 | ٢٨٠ | 8.20 | 0.006** | 0.124 |

نقاش

أثر GCLA على التعلم الذاتي المنظم (SRL)

أثر الدعم في الوقت المناسب على دافعية الطلاب – عامل حاسم لنجاح الطلاب في التعليم العالي، كما أكد وو وآخرون (2023a).

أثر GCLA على مهارات التفكير العليا

أثر GCLA على بناء المعرفة

اكتساب المعرفة في بيئات التعليم العالي. كما هو موضح في الجدولين 12 و 13، أظهر المتعلمون في التعليم العالي الذين استخدموا GCLA أداءً متفوقًا في كل من تقييمات الاختبار بعد التعليم والاختبار المتأخر مقارنةً بأقرانهم الذين استخدموا أدوات ChatGPT التقليدية.

الآثار

الآثار النظرية

الآثار العملية

تقدم الطلاب وأدائهم من خلال ملف سجل التعلم. علاوة على ذلك، يمكن دمج GCLA بسهولة في منصات التعلم المدمج والمناهج الحالية، حيث إنه متوافق مع أجهزة آبل ويمكن تخصيصه وفقًا لأهداف التعلم والسياقات المختلفة.

الخاتمة

القيود

الاتجاهات المستقبلية

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

توفر البيانات والمواد

الإعلانات

المصالح المتنافسة

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 04 مارس 2024

References

Adeshola, I., & Adepoju, A. P. (2023). The opportunities and challenges of ChatGPT in education. Interactive Learning Environments. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2023.2253858

Al-Husban, N. A. (2020). Critical thinking skills in asynchronous discussion forums: A case study. International Journal of Technology in Education, 3(2), 82-91.

Al Mamun, M. A., & Lawrie, G. (2023). Student-content interactions: Exploring behavioural engagement with selfregulated inquiry-based online learning modules. Smart Learning Environments, 10(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s40561-022-00221-x

Bernardo, A. B., Galve-González, C., Núñez, J. C., & Almeida, L. S. (2022). A path model of university dropout predictors: The role of satisfaction, the use of self-regulation learning strategies and students’ engagement. Sustainability. https:// doi.org/10.3390/su14031057

Brookhart, S. M. (2010). How to assess higher-order thinking skills in your classroom. Ascd.

Carvalho, A. R., & Santos, C. (2022). Developing peer mentors’ collaborative and metacognitive skills with a technologyenhanced peer learning program. Computers and Education Open, 3, 100070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2021. 100070

Chan, C. K. Y., & Hu, W. (2023). Students’ voices on generative AI: Perceptions, benefits, and challenges in higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s41239-023-00411-8

Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organizational Research Methods, 4(1), 62-83. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810141004

Chen, T., Luo, H., Feng, Q., & Li, G. (2023). Effect of technology acceptance on blended learning satisfaction: The serial mediation of emotional experience, social belonging, and higher-order thinking. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4442.

Cheng, S.-C., Hwang, G.-J., & Lai, C.-L. (2020). Effects of the group leadership promotion approach on students’ higher order thinking awareness and online interactive behavioral patterns in a blended learning environment. Interactive Learning Environments, 28(2), 246-263. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1636075

Conklin, W. (2011). Higher-order thinking skills to develop 21st century learners. Teacher Created Materials.

Cooper, G. (2023). Examining science education in ChatGPT: An exploratory study of generative artificial intelligence. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 32(3), 444-452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-023-10039-y

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

Dale, R. (2021). GPT-3: What’s it good for? Natural Language Engineering, 27(1), 113-118.

Dellatola, E., Daradoumis, T., & Dimitriadis, Y. (2020). Exploring students’ engagement within a collaborative inquiry-based language learning activity in a blended environment. In S. Yu, M. Ally, & A. Tsinakos (Eds.), Emerging technologies and pedagogies in the curriculum (pp. 355-375). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-0618-5_21

Ding, L., Li, T., Jiang, S., & Gapud, A. (2023). Students’ perceptions of using ChatGPT in a physics class as a virtual tutor. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s41239-023-00434-1

Doo, M. Y., & Bonk, C. J. (2020). The effects of self-efficacy, self-regulation and social presence on learning engagement in a large university class using flipped Learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 36(6), 997-1010. https://doi. org/10.1111/jcal. 12455

Ettinger, A. (2020). What BERT is not: Lessons from a new suite of psycholinguistic diagnostics for language models. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 8, 34-48. https://doi.org/10.1162/tacl_a_00298

Gan, W., Sun, Y., Peng, X., & Sun, Y. (2020). Modeling learner’s dynamic knowledge construction procedure and cognitive item difficulty for knowledge tracing. Applied Intelligence, 50(11), 3894-3912. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10489-020-01756-7

Giacumo, L. A., & Savenye, W. (2020). Asynchronous discussion forum design to support cognition: Effects of rubrics and instructor prompts on learner’s critical thinking, achievement, and satisfaction. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(1), 37-66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-019-09664-5

Göçmen, Ö., & Coşkun, H. (2022). Do De Bono’s green hat and green-red combination increase creativity in brainstorming on individuals and dyads? Thinking Skills and Creativity, 46, 101185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2022.101185

Gong, Z., Lee, L.-H., Soomro, S. A., Nanjappan, V., & Georgiev, G. V. (2022). A systematic review of virtual brainstorming from the perspective of creativity: Affordances, framework, and outlook. Digital Creativity, 33(2), 96-127. https://doi. org/10.1080/14626268.2022.2064879

Guay, F., Vallerand, R. J., & Blanchard, C. (2000). On the assessment of situational intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The Situational Motivation Scale (SIMS). Motivation and Emotion, 24(3), 175-213. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005614228 250

Hershcovits, H., Vilenchik, D., & Gal, K. (2020). Modeling engagement in self-directed learning systems using principal component analysis. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 13(1), 164-171. https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2019. 2922902

Hood, N., Littlejohn, A., & Milligan, C. (2015). Context counts: How learners’ contexts influence learning in a MOOC. Computers & Education, 91, 83-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.10.019

Hsia, L.-H., & Hwang, G.-J. (2020). From reflective thinking to learning engagement awareness: A reflective thinking promoting approach to improve students’ dance performance, self-efficacy and task load in flipped learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(6), 2461-2477. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet. 12911

Hwang, G.-J., & Lai, C.-L. (2017). Facilitating and bridging out-of-class and in-class learning: An interactive e-book-based flipped learning approach for math courses. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 20(1), 184-197.

Hwang, G.-J., Lai, C.-L., Liang, J.-C., Chu, H.-C., & Tsai, C.-C. (2018). A long-term experiment to investigate the relationships between high school students’ perceptions of mobile learning and peer interaction and higher-order thinking tendencies. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66(1), 75-93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-017-9540-3

Hwang, G.-J., Yin, C., & Chu, H.-C. (2019). The era of flipped learning: Promoting active learning and higher order thinking with innovative flipped learning strategies and supporting systems. Interactive Learning Environments, 27(8), 991-994. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1667150

Jansen, T., & Möller, J. (2022). Teacher judgments in school exams: Influences of students’ lower-order-thinking skills on the assessment of students’ higher-order-thinking skills. Teaching and Teacher Education, 111, 103616. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103616

Kasneci, E., Sessler, K., Küchemann, S., Bannert, M., Dementieva, D., Fischer, F., Gasser, U., Groh, G., Günnemann, S., Hüllermeier, E., Krusche, S., Kutyniok, G., Michaeli, T., Nerdel, C., Pfeffer, J., Poquet, O., Sailer, M., Schmidt, A., Seidel, T., Stadler, M., Kasneci, G. (2023). ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learning and Individual Differences, 103, 102274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2023.102274

Kohnke, L., Moorhouse, B. L., & Zou, D. (2023). ChatGPT for language teaching and learning. RELC Journal, 54(2), 537-550. https://doi.org/10.1177/00336882231162868

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 212-218.

Kuo, Y.-R., Tuan, H.-L., & Chin, C.-C. (2020). The influence of inquiry-based teaching on male and female students’ motivation and engagement. Research in Science Education, 50(2), 549-572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-018-9701-3

Labadze, L., Grigolia, M., & Machaidze, L. (2023). Role of AI chatbots in education: Systematic literature review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00426-1

Lee, H.-Y., Cheng, Y.-P., Wang, W.-S., Lin, C.-J., & Huang, Y.-M. (2023a). Exploring the learning process and effectiveness of STEM education via learning behavior analysis and the interactive-constructive-active-passive framework. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 61(5), 951-976. https://doi.org/10.1177/07356331221136888

Lee, H.-Y., Lin, C.-J., Wang, W.-S., Chang, W.-C., & Huang, Y.-M. (2023b). Precision education via timely intervention in K-12 computer programming course to enhance programming skill and affective-domain learning objectives. International Journal of STEM Education, 10(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-023-00444-5

Lu, K., Pang, F., & Shadiev, R. (2021a). Understanding the mediating effect of learning approach between learning factors and higher order thinking skills in collaborative inquiry-based learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 69(5), 2475-2492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-021-10025-4

Lu, K., Yang, H. H., Shi, Y., & Wang, X. (2021b). Examining the key influencing factors on college students’ higher-order thinking skills in the smart classroom environment. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-020-00238-7

Mali, D., & Lim, H. (2021). How do students perceive face-to-face/blended learning as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic? The International Journal of Management Education, 19(3), 100552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100552

Mamun, M. A. A., Lawrie, G., & Wright, T. (2020). Instructional design of scaffolded online learning modules for self-directed and inquiry-based learning environments. Computers & Education, 144, 103695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019. 103695

Menon, D., & Azam, S. (2021). Investigating preservice teachers’ science teaching self-efficacy: An analysis of reflective practices. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 19(8), 1587-1607. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10763-020-10131-4

Montenegro-Rueda, M., Fernández-Cerero, J., Fernández-Batanero, J. M., & López-Meneses, E. (2023). Impact of the implementation of ChatGPT in education: A systematic review. Computers, 12(8), 153.

O’Riordan, T., Millard, D. E., & Schulz, J. (2021). Is critical thinking happening? Testing content analysis schemes applied to MOOC discussion forums. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 29(4), 690-709. https://doi.org/10.1002/cae. 22314

Pedaste, M., Mäeots, M., Siiman, L. A., de Jong, T., van Riesen, S. A. N., Kamp, E. T., Manoli, C. C., Zacharia, Z. C., & Tsourlidaki, E. (2015). Phases of inquiry-based learning: Definitions and the inquiry cycle. Educational Research Review, 14, 47-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.02.003

Phungsuk, R., Viriyavejakul, C., & Ratanaolarn, T. (2017). Development of a problem-based learning model via a virtual learning environment. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 38(3), 297-306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjss.2017.01.001

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). Chapter 14—The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 451-502). Academic Press.

project, T. J. (2023). jamovi. In https://www.jamovi.org/

Rabin, E., Henderikx, M., Yoram, M. K., & Kalz, M. (2020). What are the barriers to learners’ satisfaction in MOOCs and what predicts them? The role of age, intention, self-regulation, self-efficacy and motivation. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 36(3), 119-131.

Radford, A., Narasimhan, K., Salimans, T., & Sutskever, I. (2018). Improving language understanding by generative pre-training, https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/openai-assets/research-covers/language-unsupervised/language_understand ing_paper.pdf

Rasheed, R. A., Kamsin, A., & Abdullah, N. A. (2020). Challenges in the online component of blended learning: A systematic review. Computers & Education, 144, 103701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103701

Salah Dogham, R., Elcokany, N. M., Saber Ghaly, A., Dawood, T. M. A., Aldakheel, F. M., Llaguno, M. B. B., & Mohsen, D. M. (2022). Self-directed learning readiness and online learning self-efficacy among undergraduate nursing students. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences, 17, 100490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjans.2022.100490

Schraw, G., & Moshman, D. (1995). Metacognitive theories. Educational Psychology Review, 7(4), 351-371. https://doi.org/10. 1007/BF02212307

Snodin, N. S. (2013). The effects of blended learning with a CMS on the development of autonomous learning: A case study of different degrees of autonomy achieved by individual learners. Computers & Education, 61, 209-216. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.10.004

Stephen, J. S., Rockinson-Szapkiw, A. J., & Dubay, C. (2020). Persistence model of non-traditional online learners: Self-efficacy, self-regulation, and self-direction. American Journal of Distance Education, 34(4), 306-321. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923 647.2020.1745619

Stojanov, A. (2023). Learning with ChatGPT 3.5 as a more knowledgeable other: An autoethnographic study. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00404-7

Tawfik, A. A., Graesser, A., Gatewood, J., & Gishbaugher, J. (2020). Role of questions in inquiry-based instruction: Towards a design taxonomy for question-asking and implications for design. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(2), 653-678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09738-9

Valentine, A., Belski, I., & Hamilton, M. (2017). Developing creativity and problem-solving skills of engineering students: A comparison of web- and pen-and-paper-based approaches. European Journal of Engineering Education, 42(6), 1309-1329. https://doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2017.1291584

van Kesteren, M. T. R., & Meeter, M. (2020). How to optimize knowledge construction in the brain. NPJ Science of Learning, 5(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-020-0064-y

Wang, M.-T., Fredricks, J. A., Ye, F., Hofkens, T. L., & Linn, J. S. (2016). The math and science engagement scales: Scale development, validation, and psychometric properties. Learning and Instruction, 43, 16-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc. 2016.01.008

Wu, T.-T., Lee, H.-Y., Li, P.-H., Huang, C.-N., & Huang, Y.-M. (2023a). Promoting self-regulation progress and knowledge construction in blended learning via ChatGPT-based learning aid. Journal of Educational Computing Research. https://doi.org/10. 1177/07356331231191125

Wu, T.-T., Lee, H.-Y., Wang, W.-S., Lin, C.-J., & Huang, Y.-M. (2023b). Leveraging computer vision for adaptive learning in STEM education: Effect of engagement and self-efficacy. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00422-5

Zhang, M., & Li, J. (2021). A commentary of GPT-3 in MIT Technology Review 2021. Fundamental Research, 1(6), 831-833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fmre.2021.11.011

Zhou, M., & Lam, K. K. L. (2019). Metacognitive scaffolding for online information search in K-12 and higher education settings: A systematic review. Educational Technology Research and Development, 67(6), 1353-1384. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11423-019-09646-7

Zhu, M., Bonk, C. J., & Doo, M. Y. (2020). Self-directed learning in MOOCs: Exploring the relationships among motivation, selfmonitoring, and self-management. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(5), 2073-2093. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s11423-020-09747-8

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Chapter 2—Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13-39). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012109890-2/ 50031-7

Zimmerman, B. J. (2008). Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. American Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 166-183. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831207312909

ملاحظة الناشر

حصل هسين-يو لي على درجة البكالوريوس في قسم تطبيق التكنولوجيا وتطوير الموارد البشرية، جامعة تايوان الوطنية، تايوان، جمهورية الصين، في عام 2019، وحصل على درجة الماجستير في قسم علوم الهندسة، جامعة تشنغ كونغ الوطنية، تايوان، جمهورية الصين، في عام 2021. وهو حاليًا يسعى للحصول على درجة الدكتوراه في علوم الهندسة في جامعة تشنغ كونغ الوطنية، تايوان، جمهورية الصين. تشمل اهتماماته البحثية تكنولوجيا التعليم، وتحليل التعلم، ورؤية الكمبيوتر، والذكاء الاصطناعي.

الأبحاث وتحرير 3 قضايا خاصة في المجلات المفهرسة في SSCI، كان أيضًا يشغل منصب مدير تخصصات تعليم العلوم التطبيقية وتعليم الهندسة المبتكرة في وزارة العلوم والتكنولوجيا في تايوان. الدكتور هوانغ هو عضو كبير في IEEE وأصبح زميلًا في جمعية الكمبيوتر البريطانية في عام 2011. حصل الدكتور هوانغ على العديد من جوائز البحث، مثل جائزة تايوان الوطنية للبحث المتميز في عامي 2011 و2014، الممنوحة لأفضل 100 عالم في تايوان. وفقًا لورقة نشرت في BJET، يحتل المرتبة الثالثة عالميًا من حيث عدد أوراق تكنولوجيا التعليم المنشورة في الفترة من 2012 إلى 2017.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-024-00447-4

Publication Date: 2024-03-04

Empowering ChatGPT with guidance mechanism in blended learning: effect of self-regulated learning, higher-order thinking skills, and knowledge construction

Check for updates

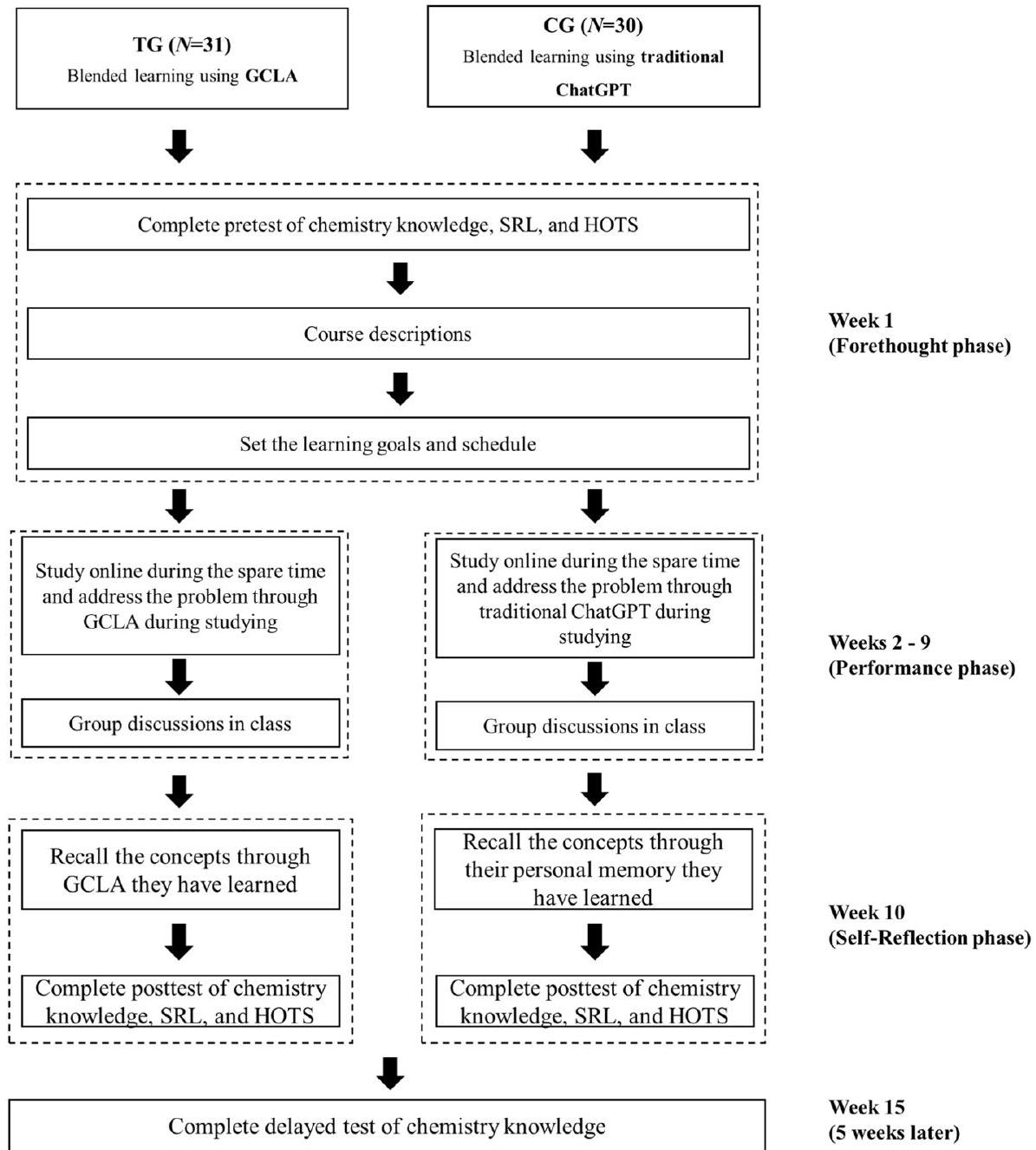

Abstract

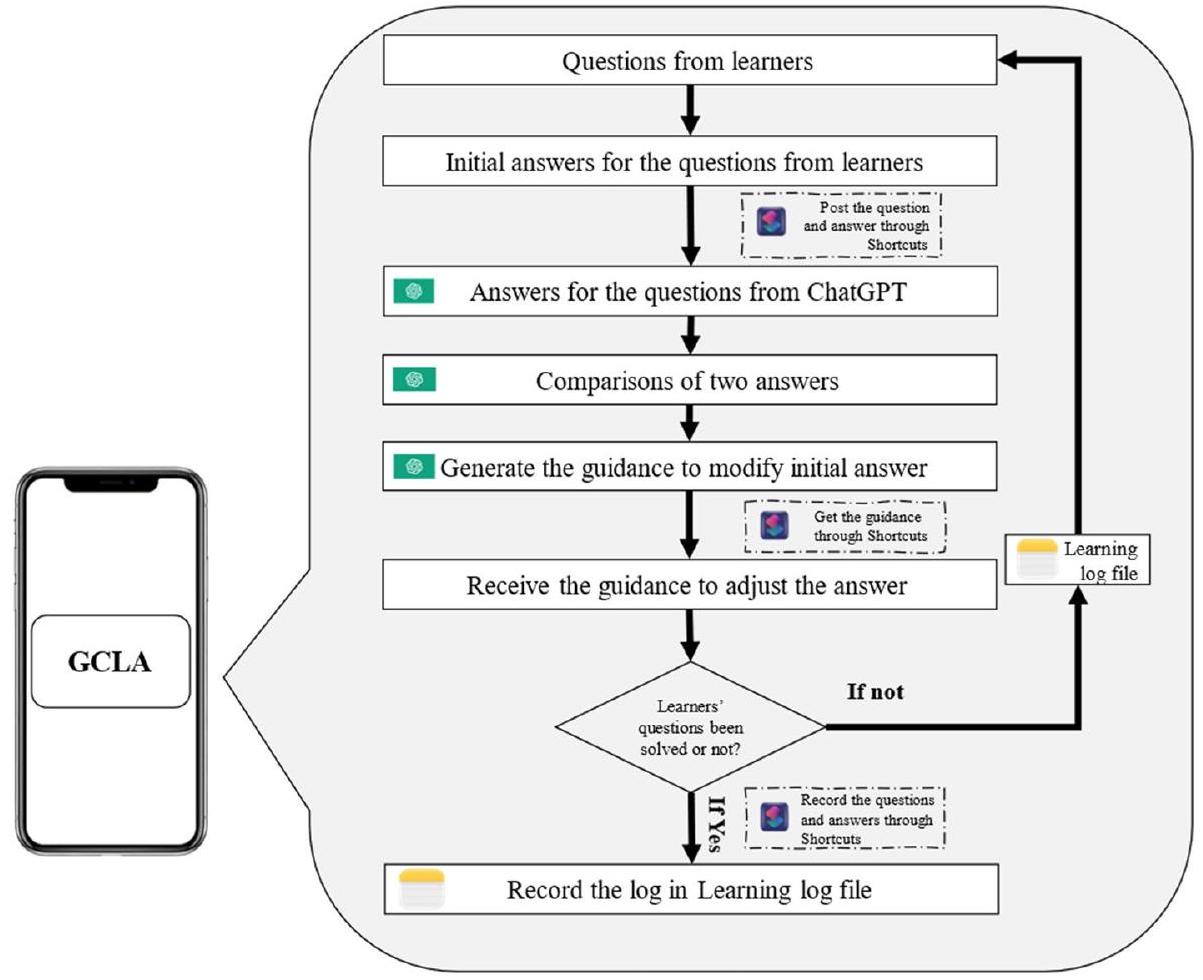

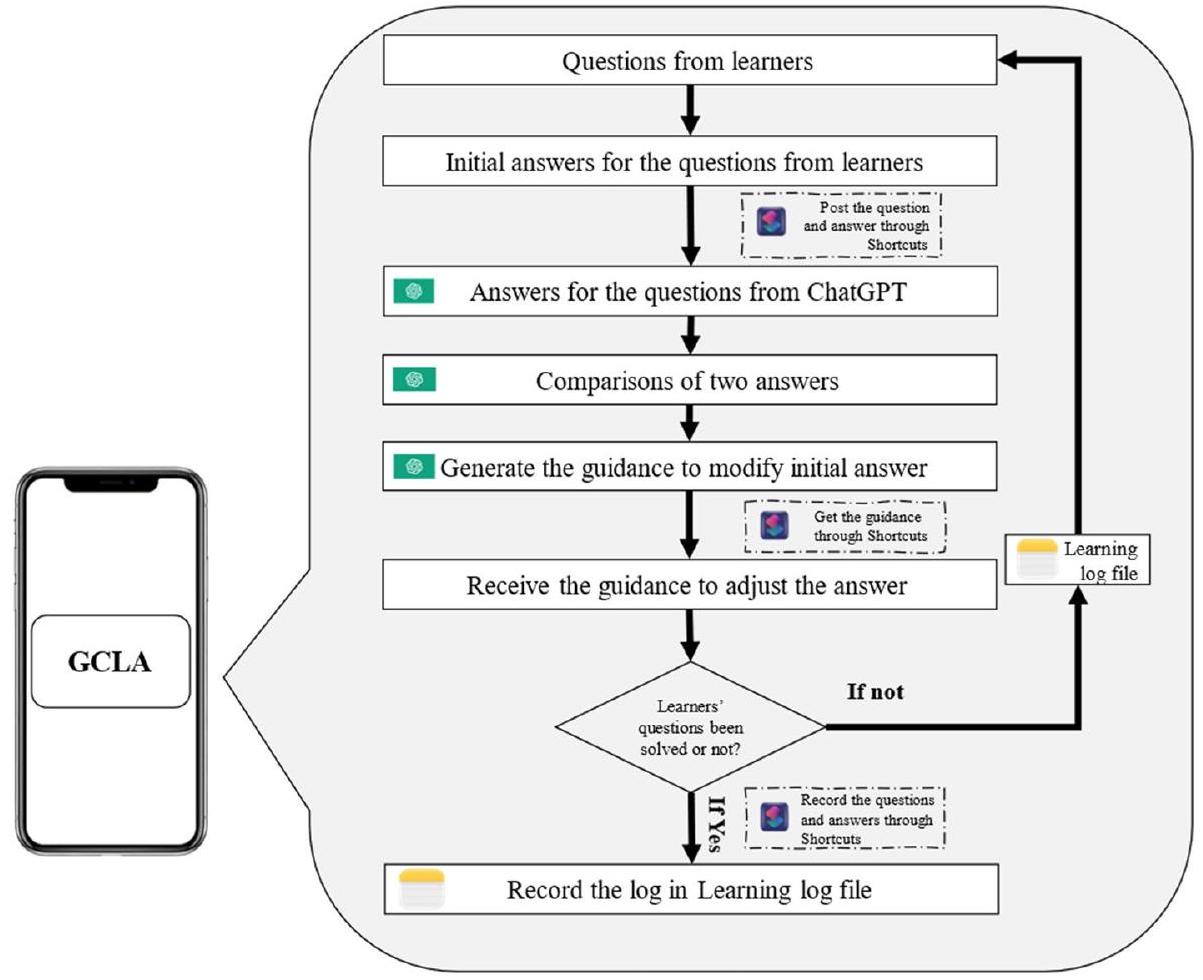

In the evolving landscape of higher education, challenges such as the COVID-19 pandemic have underscored the necessity for innovative teaching methodologies. These challenges have catalyzed the integration of technology into education, particularly in blended learning environments, to bolster self-regulated learning (SRL) and higherorder thinking skills (HOTS). However, increased autonomy in blended learning can lead to learning disruptions if issues are not promptly addressed. In this context, OpenAl’s ChatGPT, known for its extensive knowledge base and immediate feedback capability, emerges as a significant educational resource. Nonetheless, there are concerns that students might become excessively dependent on such tools, potentially hindering their development of HOTS. To address these concerns, this study introduces the Guidance-based ChatGPT-assisted Learning Aid (GCLA). This approach modifies the use of ChatGPT in educational settings by encouraging students to attempt problem-solving independently before seeking ChatGPT assistance. When engaged, the GCLA provides guidance through hints rather than direct answers, fostering an environment conducive to the development of SRL and HOTS. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) was employed to examine the impact of the GCLA compared to traditional ChatGPT use in a foundational chemistry course within a blended learning setting. This study involved 61 undergraduate students from a university in Taiwan. The findings reveal that the GCLA enhances SRL, HOTS, and knowledge construction compared to traditional ChatGPT use. These results directly align with the research objective to improve learning outcomes through providing guidance rather than answers by ChatGPT. In conclusion, the introduction of the GCLA has not only facilitated more effective learning experiences in blended learning environments but also ensured that students engage more actively in their educational journey. The implications of this study highlight the potential of ChatGPT-based tools in enhancing the quality of higher education, particularly in fostering essential skills such as self-regulation and HOTS. Furthermore, this research offers insights regarding the more effective use of ChatGPT in education.

Introduction

- How does the GCLA, compared to traditional ChatGPT use, affect the SRL of higher education students in blended learning environments?

- How does the GCLA, compared to traditional ChatGPT use, influence the development of HOTS in these students?

- How does the GCLA, compared to traditional ChatGPT use, impact knowledge construction in higher education students in these environments?

Literature review

Self-regulated learning in blended learning

learning proficiency, ensuring adept management of learning experiences within the rich contexts of blended learning environments.

Higher-order thinking skills

ChatGPT in education

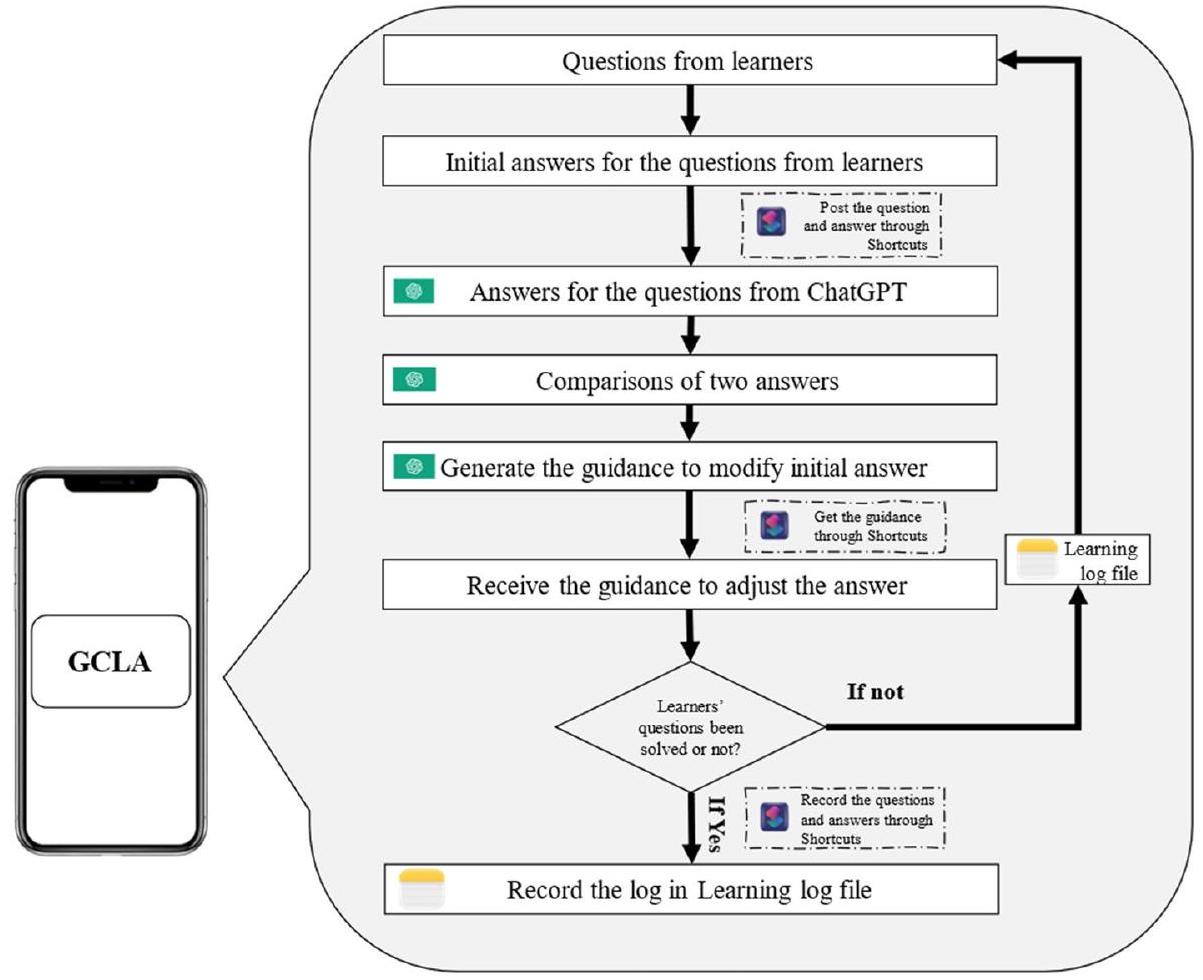

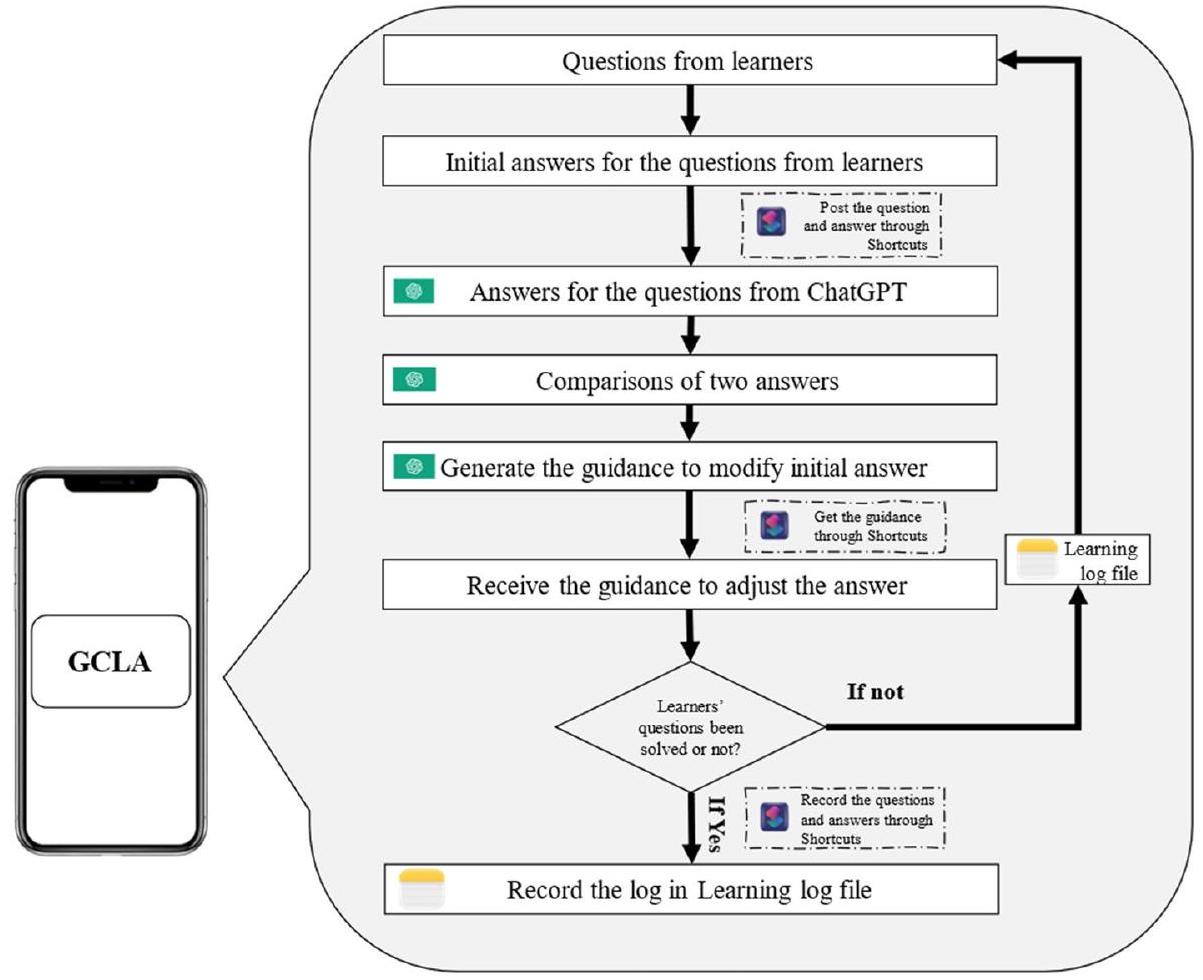

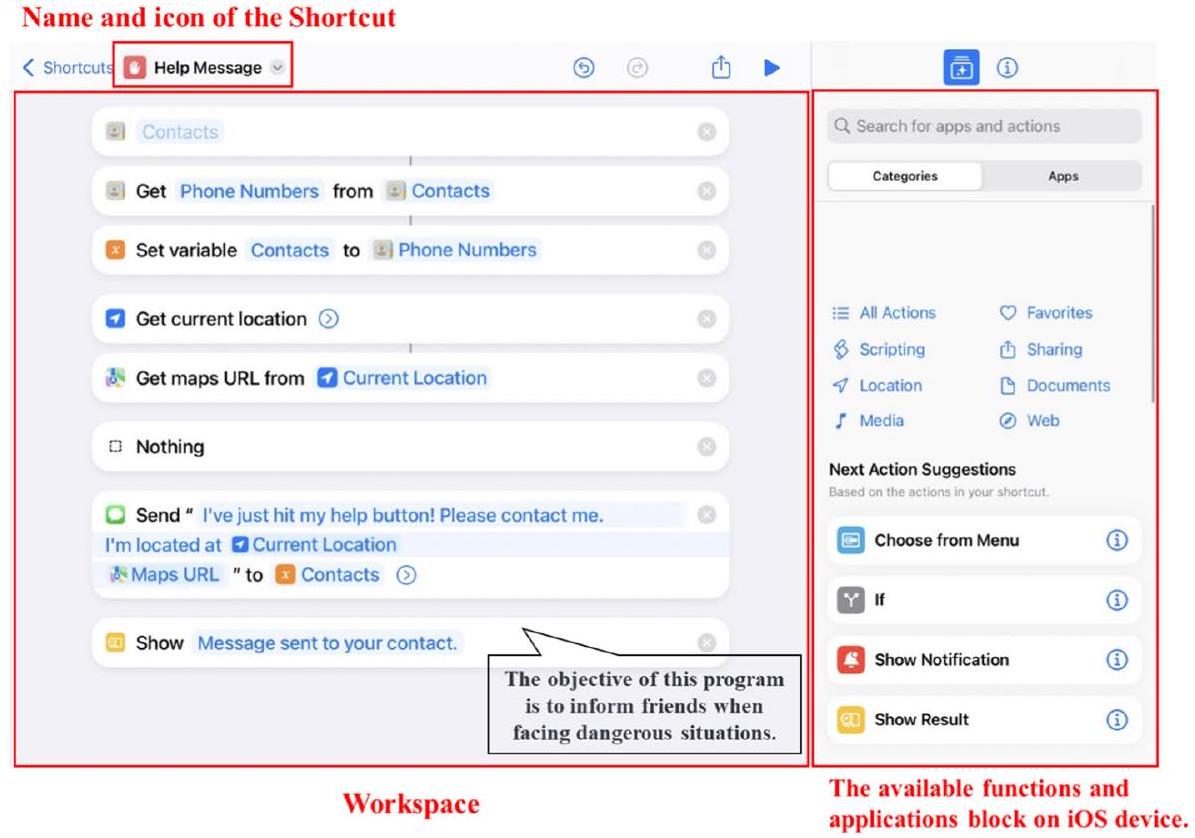

The design of guidance-based ChatGPT-assisted learning aid (GCLA)

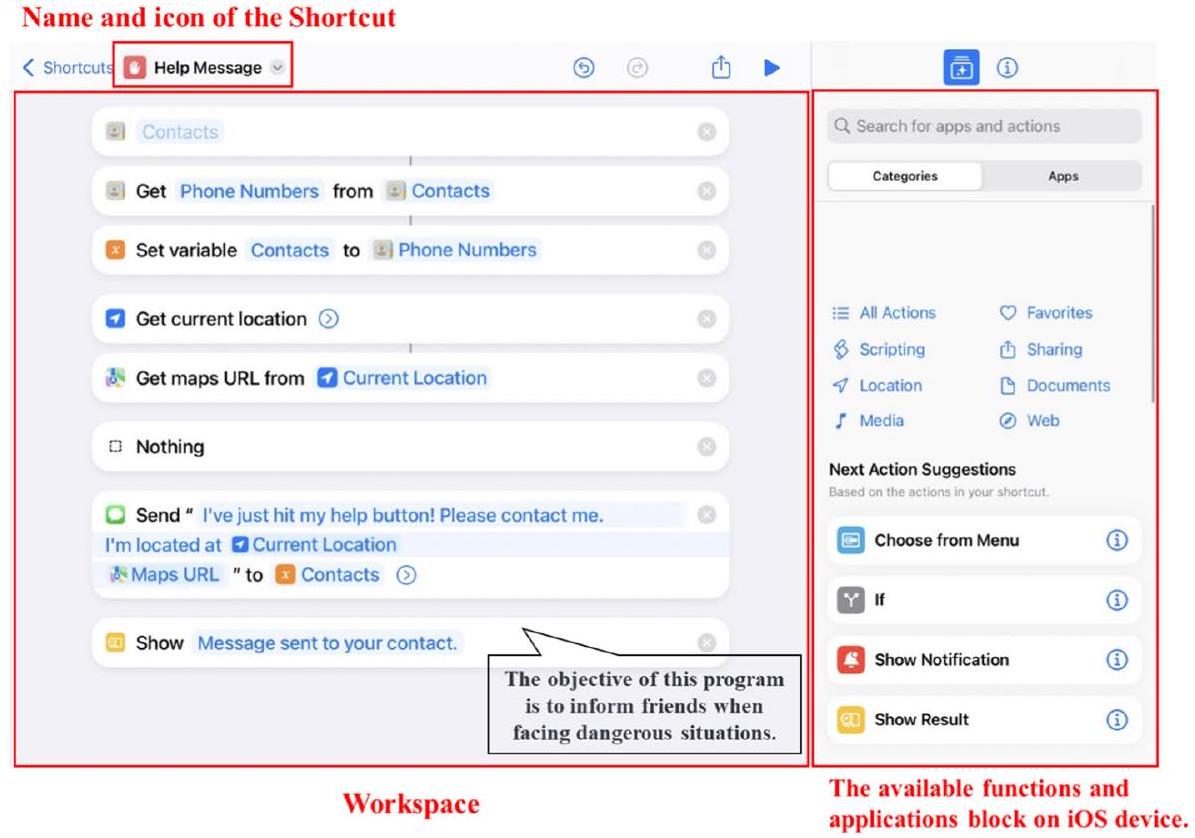

The implementation of GCLA

| Parameter | Model | Max_tokens | Temperature | Presence_penalty |

| Value | gpt-3.5-turbo-16 k | 4000 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

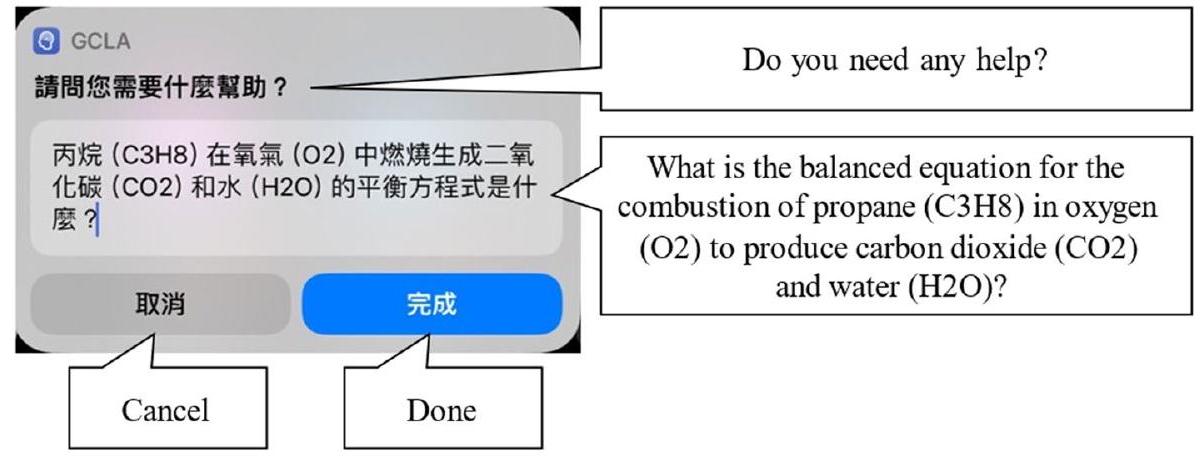

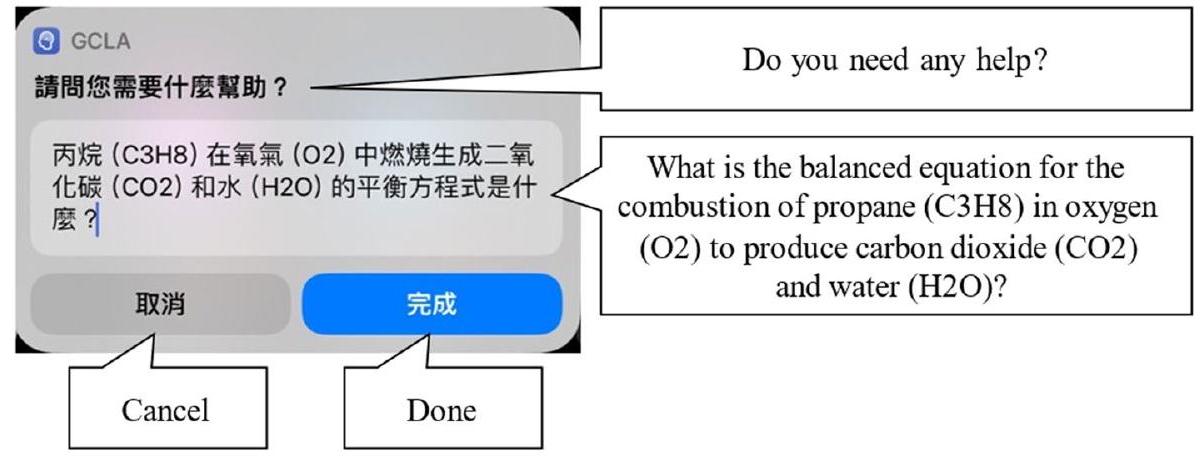

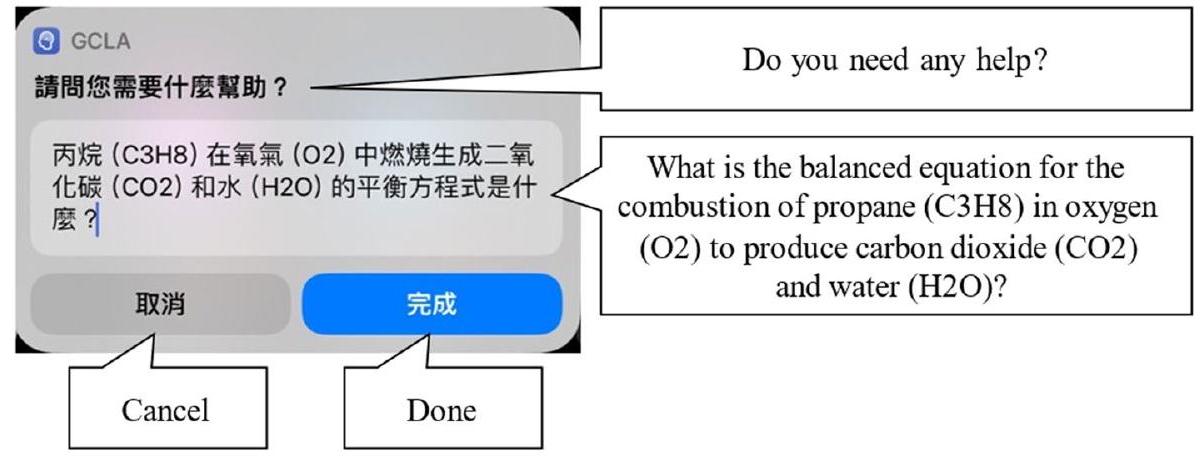

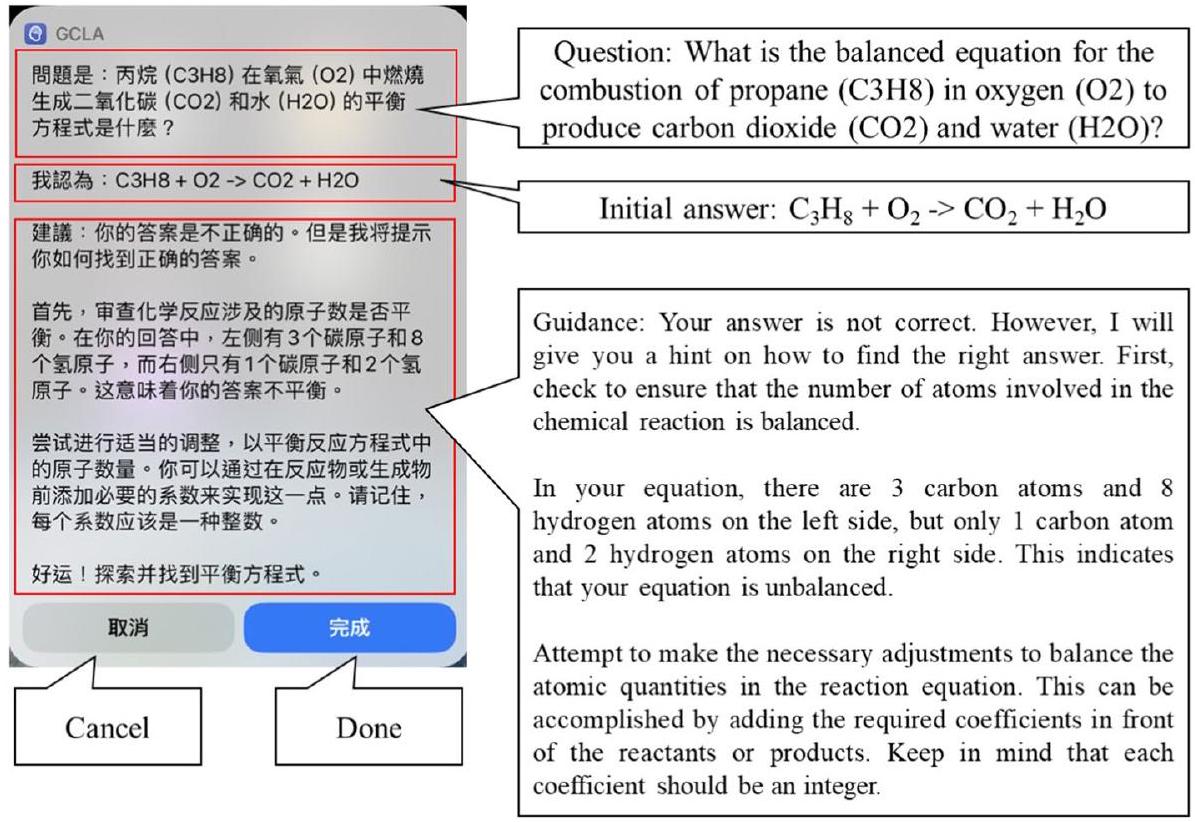

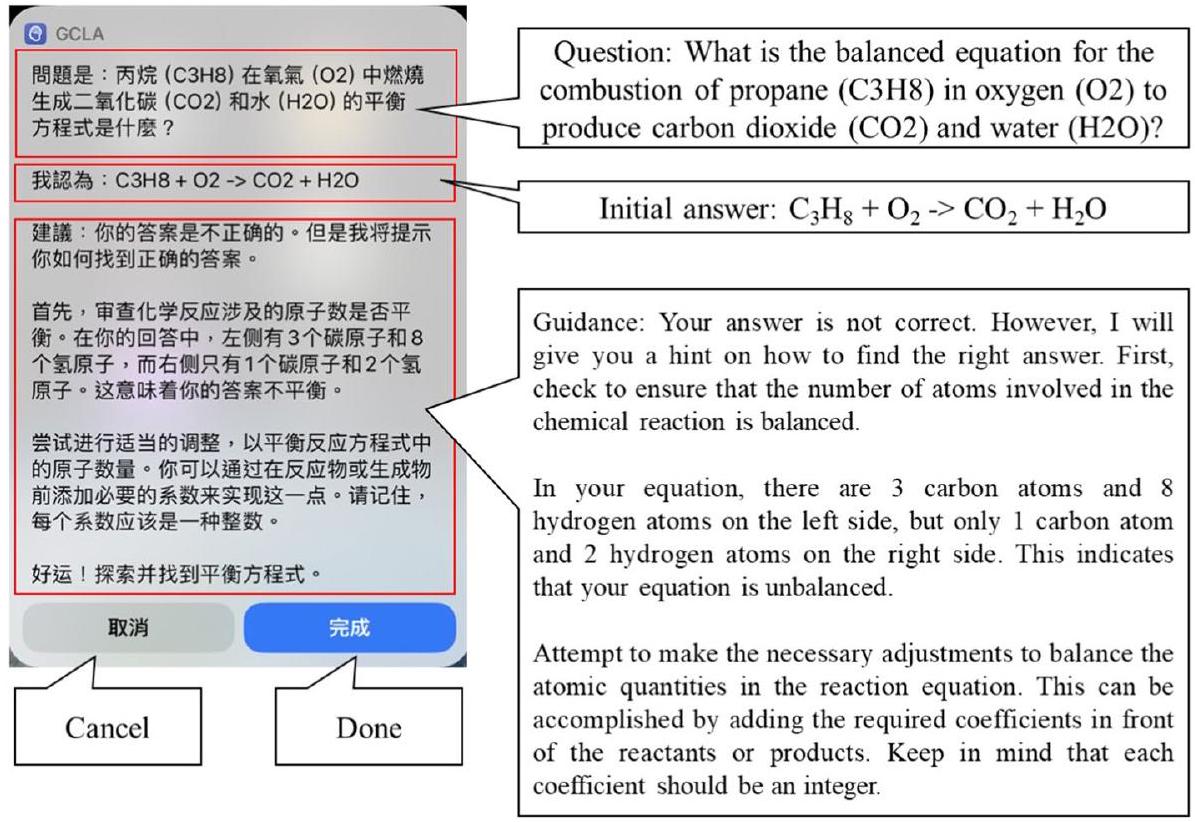

The example of using GCLA

The comparison of ChatGPT on iOS

Methodology

Research design

Population

Sample size and sampling technique

the most practical and economical way to recruit participants for this study, given the time and resource constraints.

Measurement

particularly in an academic context. The SRL scale, comprising three primary dimensions and nine sub-dimensions, uses a five-point Likert scale for responses. Its reliability and validity were confirmed in prior studies (Chen et al., 2001; Guay et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2016).

Reliability of the measurement

| Critical thinking | Problem-solving | Creativity | |

| Original reliability | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.80 |

| Revised reliability | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.72 |

| Dimension | Sub-dimension | Reliability |

| Motivation (Forethought phase) | Intrinsic motivation | 0.86 |

| Identified regulation | 0.88 | |

| External regulation | 0.79 | |

| Amotivation | 0.80 | |

| Engagement (Performance phase) | Cognitive engagement | 0.85 |

| Emotional engagement | 0.81 | |

| Behavioral engagement | 0.75 | |

| Social engagement | 0.77 | |

| Self-efficacy (Self-reflection phase) | Self-efficacy | 0.79 |

Details of pre-test of and post-test

Instruction methodology

- Week 1: Forethought phase

- Weeks 2 to 9: Performance phase

- Week 10: Self-reflection phase

| SRL phase | TG description | CG description |

| Forethought phase | Before diving into the study of chemistry, students should set daily learning objectives and monitor their achievements | Before diving into the study of chemistry, students should set daily learning objectives and monitor their achievements |

| Performance phase | When faced with challenges in their studies, students can turn to GCLA to address these difficulties | When facing challenges in their studies, students can turn to ChatGPT on iOS for assistance |

| Self-reflection phase | Examining the archived entries in the learning log file allows for reflection on past lessons and aids in the retention of concepts | Encourage students to reflect on their classroom experiences and recall concepts by drawing upon their personal memories |

using ChatGPT on iOS during the same phase and relied on memory for reflective tasks in the final week. Table 4 delineates the variations in SRL dynamics between the TG and CG throughout the study’s duration.

Variables

Methods of analysis and statistical tools

- Descriptive statistics: To describe the sample characteristics and the scores of the dependent variables for each group.

- Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA): To compare the mean scores of the dependent variables between the groups, adjusting for the effects of the covariates.

- Effect size: To measure the magnitude of the difference between the groups, using partial eta-squared (

) as the index. - Statistical software: To perform the data analysis, using JAMOVI version 2.4 (project, 2023).

Results

The impact of GCLA on self-regulated learning (SRL)

| Variable | Levene’s test | |

|

|

|

|

| Intrinsic motivation | 0.104 | 0.749 |

| Identified regulation | 1.82 | 0.182 |

| External regulation | 2.43 | 0.124 |

| Amotivation | 0.075 | 0.785 |

| Cognitive engagement | 0.323 | 0.572 |

| Behavioral engagement | 0.124 | 0.726 |

| Emotional engagement | 2.21 | 0.143 |

| Self-efficacy | 0.029 | 0.866 |

| TG (

|

CG (

|

|||||||

| Pre-test | Post-test | Pre-test | Post-test | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Intrinsic motivation | 16.2 | 1.88 | 18.9 | 2.82 | 16.0 | 2.46 | 16.1 | 2.55 |

| Identified regulation | 14.8 | 2.32 | 19.1 | 3.50 | 14.7 | 1.45 | 17.8 | 2.53 |

| External regulation | 15.4 | 2.01 | 18.1 | 1.53 | 15.8 | 2.26 | 17.3 | 2.26 |

| Amotivation | 11.2 | 1.64 | 8.53 | 2.73 | 11.6 | 1.71 | 12.0 | 2.73 |

| Cognitive engagement | 25.3 | 3.49 | 34.5 | 2.58 | 24.9 | 3.35 | 27.4 | 2.72 |

| Behavioral engagement | 17.0 | 1.28 | 20.1 | 1.71 | 16.9 | 2.16 | 17.4 | 1.33 |

| Emotional engagement | 12.6 | 1.60 | 13.5 | 1.21 | 12.5 | 2.32 | 12.8 | 1.53 |

| Self-efficacy | 25.8 | 2.53 | 31.2 | 3.90 | 25.7 | 2.79 | 25.8 | 4.16 |

| Variable | SS | df | Mean square | F | p | Partial

|

| Intrinsic motivation | 120.4 | 1 | 120.41 | 17.13 | <0.001*** | 0.228 |

| Identified regulation | 24.6 | 1 | 24.6 | 2.94 | 0.092 | 0.048 |

| External regulation | 11.8 | 1 | 11.8 | 3.33 | 0.073 | 0.054 |

| Amotivation | 185.98 | 1 | 185.98 | 24.62 | <0.001*** | 0.298 |

| Cognitive engagement | 778.4 | 1 | 778.4 | 48.60 | <0.001*** | 0.369 |

| Behavioral engagement | 133 | 1 | 132.88 | 41.4 | <0.001*** | 0.333 |

| Emotional engagement | 5.98 | 1 | 5.98 | 3.12 | 0.082 | 0.051 |

| Self-efficacy | 437.06 | 1 | 437.06 | 26.46 | <0.001*** | 0.313 |

| Variable | Levene’s test | |

|

|

|

|

| Critical thinking | 1.22 | 0.273 |

| Problem-solving | 0.13 | 0.719 |

| Creativity | 0.261 | 0.611 |

| TG (

|

CG (

|

|||||||

| Pre-test | Post-test | Pre-test | Post-test | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Critical thinking | 13.0 | 1.47 | 17.3 | 2.19 | 13.0 | 1.52 | 13.8 | 2.00 |

| Problem-solving | 12.3 | 1.05 | 15.9 | 2.01 | 12.0 | 2.01 | 13.1 | 1.96 |

| Creativity | 9.58 | 1.39 | 11.0 | 1.18 | 9.47 | 1.11 | 10.1 | 1.07 |

| Variable | SS | df | Mean Square | F | p | Partial

|

| Critical thinking | 182.17 | 1 | 182.17 | 41.73 | <0.001*** | 0.418 |

| Problem-solving | 130.6 | 1 | 130.6 | 38.7 | <0.001*** | 0.400 |

| Creativity | 10.63 | 1 | 10.63 | 8.98 | 0.004** | 0.134 |

The impact of GCLA on higher-order thinking skills (HOTS)

The impact of GCLA on knowledge construction

| Variable | Levene’s test | |

|

|

|

|

| Post-test for chemistry knowledge | 1.22 | 0.273 |

| Delayed test for chemistry knowledge | 0.13 | 0.719 |

| TG (

|

CG (

|

|||

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Pre-test for chemistry knowledge | 63.3 | 11.8 | 62.0 | 7.80 |

| Post-test for chemistry knowledge | 79.7 | 6.77 | 74.7 | 8.55 |

| Delayed test for chemistry knowledge | 75.9 | 6.36 | 69.3 | 6.94 |

| Variable | SS | df | Mean Square | F | p | Partial

|

| Post-test for chemistry knowledge | 357 | 1 | 357 | 6.10 | 0.017* | 0.100 |

| Delayed test for chemistry knowledge | 280 | 1 | 280 | 8.20 | 0.006** | 0.124 |

Discussion

The impact of GCLA on self-regulated learning (SRL)

the impact of timely support on student motivation-a critical factor for student success in higher education, as emphasized by Wu et al. (2023a).

The impact of GCLA on higher-order thinking skills (HOTS)

The impact of GCLA on knowledge construction

knowledge acquisition in higher education settings. As delineated in Tables 12 and 13, higher education learners using the GCLA displayed superior performance in both post-test and delayed test evaluations when compared to peers using conventional ChatGPT tools.

Implications

Theoretical implications

Practical implications

students’ progress and performance through the learning log file. Moreover, the GCLA can be easily integrated into existing blended learning platforms and curricula, as it is compatible with Apple devices and can be customized according to different learning objectives and contexts.

Conclusion

Limitations

Future directions

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Declarations

Competing interests

Published online: 04 March 2024

References

Adeshola, I., & Adepoju, A. P. (2023). The opportunities and challenges of ChatGPT in education. Interactive Learning Environments. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2023.2253858

Al-Husban, N. A. (2020). Critical thinking skills in asynchronous discussion forums: A case study. International Journal of Technology in Education, 3(2), 82-91.

Al Mamun, M. A., & Lawrie, G. (2023). Student-content interactions: Exploring behavioural engagement with selfregulated inquiry-based online learning modules. Smart Learning Environments, 10(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s40561-022-00221-x

Bernardo, A. B., Galve-González, C., Núñez, J. C., & Almeida, L. S. (2022). A path model of university dropout predictors: The role of satisfaction, the use of self-regulation learning strategies and students’ engagement. Sustainability. https:// doi.org/10.3390/su14031057

Brookhart, S. M. (2010). How to assess higher-order thinking skills in your classroom. Ascd.

Carvalho, A. R., & Santos, C. (2022). Developing peer mentors’ collaborative and metacognitive skills with a technologyenhanced peer learning program. Computers and Education Open, 3, 100070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2021. 100070

Chan, C. K. Y., & Hu, W. (2023). Students’ voices on generative AI: Perceptions, benefits, and challenges in higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s41239-023-00411-8

Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organizational Research Methods, 4(1), 62-83. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810141004

Chen, T., Luo, H., Feng, Q., & Li, G. (2023). Effect of technology acceptance on blended learning satisfaction: The serial mediation of emotional experience, social belonging, and higher-order thinking. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4442.

Cheng, S.-C., Hwang, G.-J., & Lai, C.-L. (2020). Effects of the group leadership promotion approach on students’ higher order thinking awareness and online interactive behavioral patterns in a blended learning environment. Interactive Learning Environments, 28(2), 246-263. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1636075

Conklin, W. (2011). Higher-order thinking skills to develop 21st century learners. Teacher Created Materials.

Cooper, G. (2023). Examining science education in ChatGPT: An exploratory study of generative artificial intelligence. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 32(3), 444-452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-023-10039-y

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

Dale, R. (2021). GPT-3: What’s it good for? Natural Language Engineering, 27(1), 113-118.

Dellatola, E., Daradoumis, T., & Dimitriadis, Y. (2020). Exploring students’ engagement within a collaborative inquiry-based language learning activity in a blended environment. In S. Yu, M. Ally, & A. Tsinakos (Eds.), Emerging technologies and pedagogies in the curriculum (pp. 355-375). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-0618-5_21

Ding, L., Li, T., Jiang, S., & Gapud, A. (2023). Students’ perceptions of using ChatGPT in a physics class as a virtual tutor. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s41239-023-00434-1

Doo, M. Y., & Bonk, C. J. (2020). The effects of self-efficacy, self-regulation and social presence on learning engagement in a large university class using flipped Learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 36(6), 997-1010. https://doi. org/10.1111/jcal. 12455

Ettinger, A. (2020). What BERT is not: Lessons from a new suite of psycholinguistic diagnostics for language models. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 8, 34-48. https://doi.org/10.1162/tacl_a_00298

Gan, W., Sun, Y., Peng, X., & Sun, Y. (2020). Modeling learner’s dynamic knowledge construction procedure and cognitive item difficulty for knowledge tracing. Applied Intelligence, 50(11), 3894-3912. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10489-020-01756-7

Giacumo, L. A., & Savenye, W. (2020). Asynchronous discussion forum design to support cognition: Effects of rubrics and instructor prompts on learner’s critical thinking, achievement, and satisfaction. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(1), 37-66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-019-09664-5

Göçmen, Ö., & Coşkun, H. (2022). Do De Bono’s green hat and green-red combination increase creativity in brainstorming on individuals and dyads? Thinking Skills and Creativity, 46, 101185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2022.101185

Gong, Z., Lee, L.-H., Soomro, S. A., Nanjappan, V., & Georgiev, G. V. (2022). A systematic review of virtual brainstorming from the perspective of creativity: Affordances, framework, and outlook. Digital Creativity, 33(2), 96-127. https://doi. org/10.1080/14626268.2022.2064879

Guay, F., Vallerand, R. J., & Blanchard, C. (2000). On the assessment of situational intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The Situational Motivation Scale (SIMS). Motivation and Emotion, 24(3), 175-213. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005614228 250

Hershcovits, H., Vilenchik, D., & Gal, K. (2020). Modeling engagement in self-directed learning systems using principal component analysis. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 13(1), 164-171. https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2019. 2922902

Hood, N., Littlejohn, A., & Milligan, C. (2015). Context counts: How learners’ contexts influence learning in a MOOC. Computers & Education, 91, 83-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.10.019

Hsia, L.-H., & Hwang, G.-J. (2020). From reflective thinking to learning engagement awareness: A reflective thinking promoting approach to improve students’ dance performance, self-efficacy and task load in flipped learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(6), 2461-2477. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet. 12911

Hwang, G.-J., & Lai, C.-L. (2017). Facilitating and bridging out-of-class and in-class learning: An interactive e-book-based flipped learning approach for math courses. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 20(1), 184-197.

Hwang, G.-J., Lai, C.-L., Liang, J.-C., Chu, H.-C., & Tsai, C.-C. (2018). A long-term experiment to investigate the relationships between high school students’ perceptions of mobile learning and peer interaction and higher-order thinking tendencies. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66(1), 75-93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-017-9540-3

Hwang, G.-J., Yin, C., & Chu, H.-C. (2019). The era of flipped learning: Promoting active learning and higher order thinking with innovative flipped learning strategies and supporting systems. Interactive Learning Environments, 27(8), 991-994. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1667150

Jansen, T., & Möller, J. (2022). Teacher judgments in school exams: Influences of students’ lower-order-thinking skills on the assessment of students’ higher-order-thinking skills. Teaching and Teacher Education, 111, 103616. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103616

Kasneci, E., Sessler, K., Küchemann, S., Bannert, M., Dementieva, D., Fischer, F., Gasser, U., Groh, G., Günnemann, S., Hüllermeier, E., Krusche, S., Kutyniok, G., Michaeli, T., Nerdel, C., Pfeffer, J., Poquet, O., Sailer, M., Schmidt, A., Seidel, T., Stadler, M., Kasneci, G. (2023). ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learning and Individual Differences, 103, 102274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2023.102274

Kohnke, L., Moorhouse, B. L., & Zou, D. (2023). ChatGPT for language teaching and learning. RELC Journal, 54(2), 537-550. https://doi.org/10.1177/00336882231162868

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 212-218.

Kuo, Y.-R., Tuan, H.-L., & Chin, C.-C. (2020). The influence of inquiry-based teaching on male and female students’ motivation and engagement. Research in Science Education, 50(2), 549-572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-018-9701-3

Labadze, L., Grigolia, M., & Machaidze, L. (2023). Role of AI chatbots in education: Systematic literature review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00426-1

Lee, H.-Y., Cheng, Y.-P., Wang, W.-S., Lin, C.-J., & Huang, Y.-M. (2023a). Exploring the learning process and effectiveness of STEM education via learning behavior analysis and the interactive-constructive-active-passive framework. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 61(5), 951-976. https://doi.org/10.1177/07356331221136888

Lee, H.-Y., Lin, C.-J., Wang, W.-S., Chang, W.-C., & Huang, Y.-M. (2023b). Precision education via timely intervention in K-12 computer programming course to enhance programming skill and affective-domain learning objectives. International Journal of STEM Education, 10(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-023-00444-5

Lu, K., Pang, F., & Shadiev, R. (2021a). Understanding the mediating effect of learning approach between learning factors and higher order thinking skills in collaborative inquiry-based learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 69(5), 2475-2492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-021-10025-4

Lu, K., Yang, H. H., Shi, Y., & Wang, X. (2021b). Examining the key influencing factors on college students’ higher-order thinking skills in the smart classroom environment. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-020-00238-7

Mali, D., & Lim, H. (2021). How do students perceive face-to-face/blended learning as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic? The International Journal of Management Education, 19(3), 100552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100552

Mamun, M. A. A., Lawrie, G., & Wright, T. (2020). Instructional design of scaffolded online learning modules for self-directed and inquiry-based learning environments. Computers & Education, 144, 103695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019. 103695

Menon, D., & Azam, S. (2021). Investigating preservice teachers’ science teaching self-efficacy: An analysis of reflective practices. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 19(8), 1587-1607. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10763-020-10131-4

Montenegro-Rueda, M., Fernández-Cerero, J., Fernández-Batanero, J. M., & López-Meneses, E. (2023). Impact of the implementation of ChatGPT in education: A systematic review. Computers, 12(8), 153.

O’Riordan, T., Millard, D. E., & Schulz, J. (2021). Is critical thinking happening? Testing content analysis schemes applied to MOOC discussion forums. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 29(4), 690-709. https://doi.org/10.1002/cae. 22314

Pedaste, M., Mäeots, M., Siiman, L. A., de Jong, T., van Riesen, S. A. N., Kamp, E. T., Manoli, C. C., Zacharia, Z. C., & Tsourlidaki, E. (2015). Phases of inquiry-based learning: Definitions and the inquiry cycle. Educational Research Review, 14, 47-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.02.003

Phungsuk, R., Viriyavejakul, C., & Ratanaolarn, T. (2017). Development of a problem-based learning model via a virtual learning environment. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 38(3), 297-306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjss.2017.01.001

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). Chapter 14—The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 451-502). Academic Press.

project, T. J. (2023). jamovi. In https://www.jamovi.org/

Rabin, E., Henderikx, M., Yoram, M. K., & Kalz, M. (2020). What are the barriers to learners’ satisfaction in MOOCs and what predicts them? The role of age, intention, self-regulation, self-efficacy and motivation. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 36(3), 119-131.

Radford, A., Narasimhan, K., Salimans, T., & Sutskever, I. (2018). Improving language understanding by generative pre-training, https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/openai-assets/research-covers/language-unsupervised/language_understand ing_paper.pdf

Rasheed, R. A., Kamsin, A., & Abdullah, N. A. (2020). Challenges in the online component of blended learning: A systematic review. Computers & Education, 144, 103701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103701

Salah Dogham, R., Elcokany, N. M., Saber Ghaly, A., Dawood, T. M. A., Aldakheel, F. M., Llaguno, M. B. B., & Mohsen, D. M. (2022). Self-directed learning readiness and online learning self-efficacy among undergraduate nursing students. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences, 17, 100490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjans.2022.100490

Schraw, G., & Moshman, D. (1995). Metacognitive theories. Educational Psychology Review, 7(4), 351-371. https://doi.org/10. 1007/BF02212307

Snodin, N. S. (2013). The effects of blended learning with a CMS on the development of autonomous learning: A case study of different degrees of autonomy achieved by individual learners. Computers & Education, 61, 209-216. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.10.004

Stephen, J. S., Rockinson-Szapkiw, A. J., & Dubay, C. (2020). Persistence model of non-traditional online learners: Self-efficacy, self-regulation, and self-direction. American Journal of Distance Education, 34(4), 306-321. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923 647.2020.1745619

Stojanov, A. (2023). Learning with ChatGPT 3.5 as a more knowledgeable other: An autoethnographic study. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00404-7

Tawfik, A. A., Graesser, A., Gatewood, J., & Gishbaugher, J. (2020). Role of questions in inquiry-based instruction: Towards a design taxonomy for question-asking and implications for design. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(2), 653-678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09738-9

Valentine, A., Belski, I., & Hamilton, M. (2017). Developing creativity and problem-solving skills of engineering students: A comparison of web- and pen-and-paper-based approaches. European Journal of Engineering Education, 42(6), 1309-1329. https://doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2017.1291584

van Kesteren, M. T. R., & Meeter, M. (2020). How to optimize knowledge construction in the brain. NPJ Science of Learning, 5(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-020-0064-y

Wang, M.-T., Fredricks, J. A., Ye, F., Hofkens, T. L., & Linn, J. S. (2016). The math and science engagement scales: Scale development, validation, and psychometric properties. Learning and Instruction, 43, 16-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc. 2016.01.008

Wu, T.-T., Lee, H.-Y., Li, P.-H., Huang, C.-N., & Huang, Y.-M. (2023a). Promoting self-regulation progress and knowledge construction in blended learning via ChatGPT-based learning aid. Journal of Educational Computing Research. https://doi.org/10. 1177/07356331231191125

Wu, T.-T., Lee, H.-Y., Wang, W.-S., Lin, C.-J., & Huang, Y.-M. (2023b). Leveraging computer vision for adaptive learning in STEM education: Effect of engagement and self-efficacy. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00422-5

Zhang, M., & Li, J. (2021). A commentary of GPT-3 in MIT Technology Review 2021. Fundamental Research, 1(6), 831-833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fmre.2021.11.011

Zhou, M., & Lam, K. K. L. (2019). Metacognitive scaffolding for online information search in K-12 and higher education settings: A systematic review. Educational Technology Research and Development, 67(6), 1353-1384. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11423-019-09646-7

Zhu, M., Bonk, C. J., & Doo, M. Y. (2020). Self-directed learning in MOOCs: Exploring the relationships among motivation, selfmonitoring, and self-management. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(5), 2073-2093. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s11423-020-09747-8

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Chapter 2—Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13-39). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012109890-2/ 50031-7

Zimmerman, B. J. (2008). Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. American Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 166-183. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831207312909

Publisher’s Note

Hsin-Yu Lee received his B.S. degree in the Department of Technology Application and Human Resource Development, National Taiwan Normal University, Taiwan, R.O.C., in 2019, and received the M.S. degree in the Department of Engineering Science, National Cheng-Kung University, Taiwan, R.O.C., in 2021. He is currently pursuing his Ph.D. degree in engineering science at National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan, R.O.C. His research interests include educational technology, learning analytics, computer vision and artificial intelligence.

papers and editing 3 special issues in SSCI-indexed journals, he was also serving as the directors of Disciplines of Applied Science Education and Innovative Engineering Education in Taiwan’s Ministry of Science and Technology. Dr. Huang is a senior member of the IEEE and became Fellow of British Computer Society in 2011. Dr. Huang has received many research awards, such as Taiwan’s National Outstanding Research Award in 2011 and 2014, given to Taiwan’s top 100 scholars. According to a paper published in BJET, he is ranked no. 3 in the world on terms of the number of educational technology papers published in the period 2012 to 2017.