المجلة: npj Biological Timing and Sleep، المجلد: 2، العدد: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44323-025-00024-6

تاريخ النشر: 2025-03-08

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44323-025-00024-6

تاريخ النشر: 2025-03-08

تنظيم الغدد الصماء للإيقاعات اليومية

الساعات البيولوجية هي منظمات زمنية داخلية تمكّن الكائنات الحية من التكيف مع الأحداث المتكررة في بيئتها – مثل تتابع الليل والنهار – من خلال التحكم في سلوكيات أساسية مثل تناول الطعام أو دورة النوم والاستيقاظ. تنظم شبكة الساعات الخلوية الشاملة العديد من العمليات الفسيولوجية بما في ذلك النظام الغدد الصماء. تتفاوت مستويات العديد من الهرمونات مثل الميلاتونين، والكورتيزول، وهرمونات الجنس، وهرمون تحفيز الغدة الدرقية، بالإضافة إلى عدد من العوامل الأيضية على مدار اليوم، وبعضها يمكن أن يؤثر بدوره على إيقاعات الساعة البيولوجية. في هذه المراجعة، نقوم بتحليل الطرق الرئيسية التي يمكن أن تنظم بها الهرمونات الإيقاعات البيولوجية في الأنسجة المستهدفة – كعوامل دافعة دورية للإيقاعات الفسيولوجية، وكمنبهات تعيد ضبط مرحلة الساعة في الأنسجة، أو كمنظمات، تؤثر على الإيقاعات اللاحقة بطريقة أكثر استمرارية دون التأثير على الساعة الأساسية. تؤكد هذه البيانات على التفاعل المعقد بين النظام الغدد الصماء والإيقاعات البيولوجية وتقدم طرقًا للتلاعب المحدد بالأنسجة في تنظيم الإيقاعات البيولوجية.

تتعرض معظم الكائنات الحية لتغيرات متكررة في الظروف البيئية وتظهر إيقاعات فسيولوجية على مدار

توجد آلية الساعة الجزيئية في معظم الخلايا، وبالتالي، من أجل توقيت متماسك، يتم مزامنة ساعات الأنسجة المختلفة بواسطة جهاز تنظيم رئيسي يقع في النواة فوق التصالب (SCN) في الوطاء.

ساعات مستقلة عن

ساعات مستقلة عن

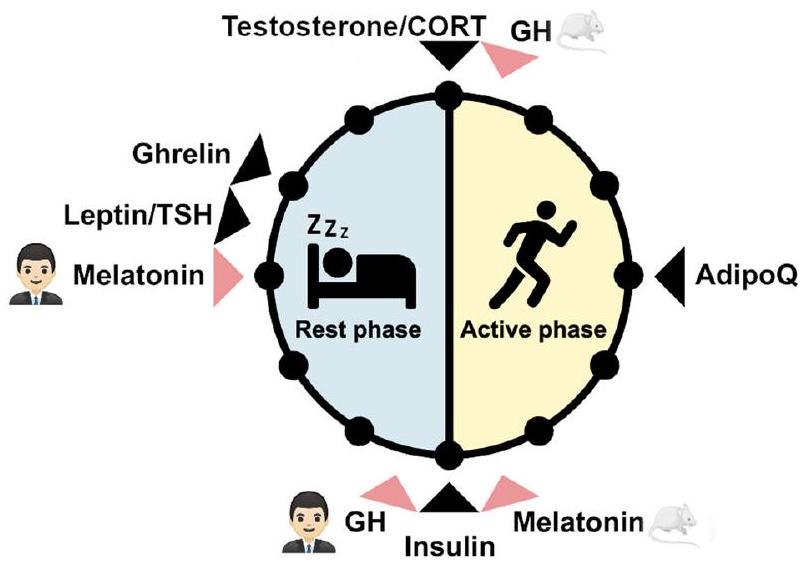

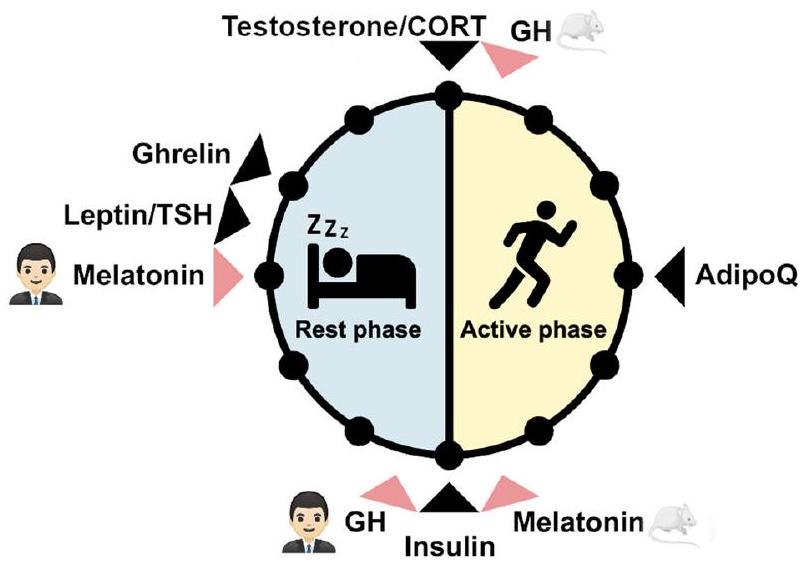

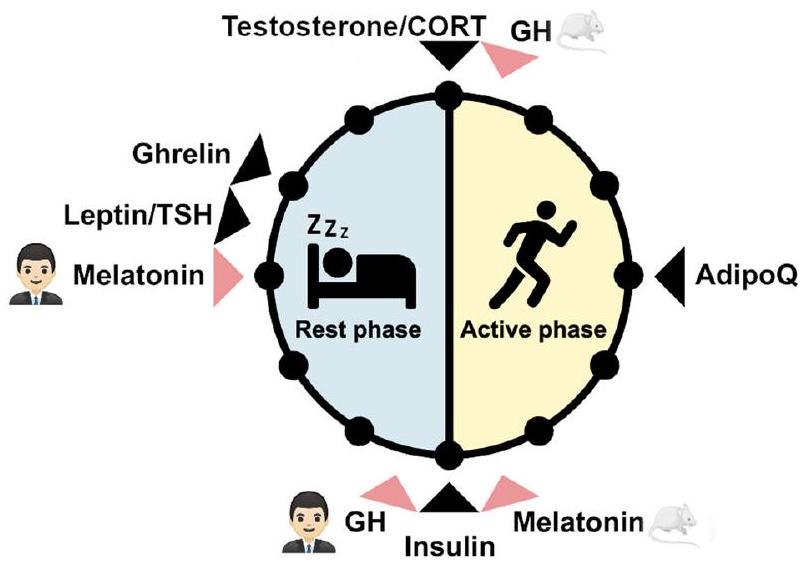

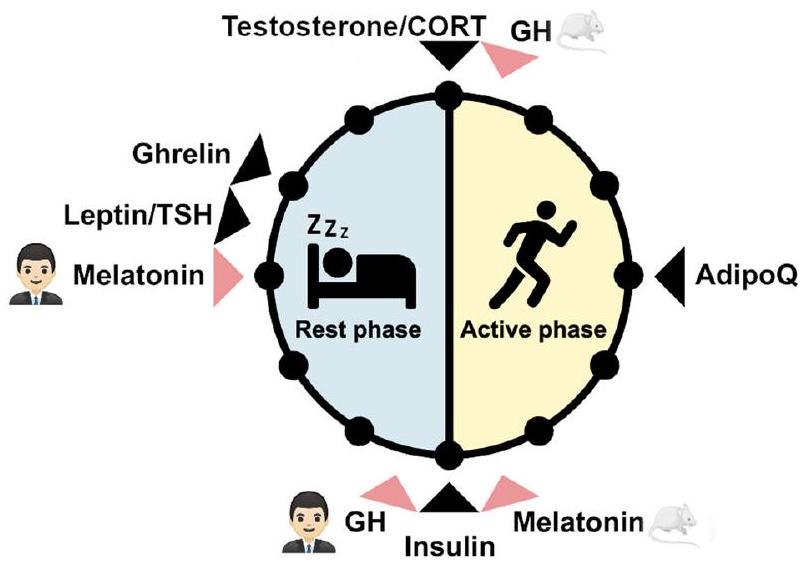

من المعروف أن العديد من الهرمونات تتأرجح على مدار اليوم البالغ 24 ساعة، بما في ذلك الميلاتونين، والجلوكوكورتيكويدات، والستيرويدات الجنسية، وهرمون تحفيز الغدة الدرقية، والعديد من الهرمونات الأيضية مثل الأديبونيكتين، والليبتين، والغريلين، والأنسولين، والجلوكاجون (الشكل 1).

الشكل 1 | أوقات ذروة الهرمونات خلال مرحلة الراحة والنشاط في البشر والقوارض الليلية. يتم الإشارة إلى فترة الوقت التي تصل فيها مستويات الهرمونات إلى ذروتها في البشر والقوارض الليلية بسهم أسود. الهرمونات التي تختلف أوقات ذروتها بين البشر والقوارض الليلية موضحة بسهم أحمر. AdipoQ: أديبونيكتين، CORT: الكورتيزول في البشر والكورتيكوستيرون في الفئران، GH: هرمون النمو، TSH: هرمون تحفيز الغدة الدرقية. صورة الفأر: smart.servier.com.

الشكل 2 | مفهوم التنظيم الغدد الصماء للإيقاعات اليومية. يمكن أن تعمل الهرمونات كمحركات للإيقاع، أو كمنبهات زمنية، أو كمنظمات. الوظيفة كمحرك للإيقاع مستقلة عن الساعة وتتطلب هرمونًا إيقاعيًا يمكنه التأثير على التعبير الجيني الإيقاعي من خلال تفاعلات مباشرة بين الهرمون والهدف. كمنبه زمني، تنظم الهرمونات مباشرة تعبير جينات الساعة في الأنسجة المستهدفة ويمكن أن تغير مرحلة الساعة. كمنظم، تكون الإشارة الهرمونية مستمرة ولكنها قادرة على تعديل الاستقبال الإيقاعي والاستجابة للمؤثرات الخارجية الأخرى في الأنسجة المستهدفة. بهذه الطريقة، يمكن أن تؤدي الفعالية المستمرة على الأنسجة المستهدفة إلى تعديل إيقاعات التعبير الجيني، مما يؤدي إلى استجابة فازية.

تعمل كمنبهات زمنية. وبالمثل، يمكن أن يؤثر الميلاتونين أو الأنسولين على تعبير جينات الساعة البيولوجية في الأنسجة، مما يعيد ضبط الساعات البيولوجية المحلية.

الميلاتونين

الميلاتونين هو هرمون يلعب دورًا حاسمًا في تنظيم إيقاعات الساعة البيولوجية. يعمل كمحرك مباشر لإيقاع الساعة البيولوجية وكمؤشر زمني، ويؤثر بشكل كبير على عمليات فسيولوجية متنوعة.

تشير الأدلة إلى أن الميلاتونين يمكن أن يؤثر على الإيقاعات اليومية من خلال التأثير المباشر على نشاط النواة فوق التاجية (SCN) من خلال آليات حادة وآليات إعادة ضبط الساعة. يساعد تأثير الميلاتونين اليومي على فسيولوجيا النواة فوق التاجية في تنسيق توقيت وتزامن مختلف الإيقاعات البيولوجية مثل دورات النوم والاستيقاظ، وإفراز الهرمونات، وتقلبات درجة حرارة الجسم الأساسية.

كزيتجبير، يعمل الميلاتونين كإشارة داخلية تساعد في مزامنة الساعات الداخلية للجسم مع الإشارات الزمنية الخارجية، خاصة في ظروف الإضاءة المنخفضة أو الظلام حيث قد تكون الإشارات الخارجية ضعيفة أو غائبة.

الميلاتونين ينقح سعة وقوة الإيقاعات اليومية. يؤثر على نشاط ويعدل استجابة خلايا الشبكية للضوء. من خلال الإشارة عبر مستقبل الميلاتونين 2 (MT2)، يؤثر الميلاتونين على نشاط خلايا العقدة الشبكية وغيرها من الخلايا العصبية الشبكية، مما يساعد في تنظيم شدة وجودة إشارات الضوء المرسلة إلى النواة فوق التصالبية (SCN). يمكن أن يعدل الميلاتونين الناتج عن الغدة الصنوبرية أيضًا مباشرة حساسية النواة فوق التصالبية للزيتجبيرز، مما يؤثر على الاستقرار العام وقابلية التكيف للنظام اليومي. توجد مستقبلات الميلاتونين (MT1 وMT2) في أنسجة وأعضاء مختلفة.

الجلوكوكورتيكويدات

الجلوكوكورتيكويدات (GCs) هي هرمونات ستيرويدية تُنتَج بواسطة منطقة الفاسيكولاتا في قشرة الغدة الكظرية. تؤثر على العديد من العمليات الفسيولوجية، وأبرزها الأيض والجهاز المناعي.

إيقاع الإفراز مع حدوث ذروات تقريبًا كل 90 دقيقة، على الرغم من أنها أكثر تباينًا في التردد والسعة.

إيقاع الإفراز مع حدوث ذروات تقريبًا كل 90 دقيقة، على الرغم من أنها أكثر تباينًا في التردد والسعة.

تساهم ثلاثة آليات منفصلة في إفراز الجلوكوكورتيكويد الإيقاعي. أولاً، يتم التحكم في محور الوطاء-الغدة النخامية-الكظر (HPA) بواسطة إيقاع يومي عبر إسقاط الأرجينين-فازوبريسين (AVP) من النواة فوق التصالب (SCN) إلى النواة البارافنتريكولارية (PVN)، مما يولد نمط إطلاق إيقاعي في المنطقة السفلية.

عند إطلاقها في مجرى الدم، تمارس الكورتيكوستيرويدات تأثيرها من خلال التفاعل مع نوعين من المستقبلات النووية: MR و GR. بينما يتمتع MR ب affinity أعلى بكثير للكورتيكوستيرويدات مقارنةً بـ GR ويكون مشغولاً بالكامل في معظم أوقات اليوم، فإن GR يتوسط تأثيرات الكورتيكوستيرويدات الفاسية بشكل أكبر. يرتبط بـ GREs لتحفيز التغيرات النسخية في الجينات غير المرتبطة بالساعة وكذلك الجينات المرتبطة بالساعة.

طريقة شائعة أخرى لدراسة وظيفة الكورتيكوستيرويدات في الساعة البيولوجية وتعبير الجينات تتضمن استئصال الغدة الكظرية (ADX). إزالة الغدة الكظرية، وبالتالي استنفاد الكورتيكوستيرويدات، يمكن أن يؤثر على ساعات الأنسجة المحيطية، بما في ذلك تنظيم الجينات الخاصة بالأنسجة بشكل إيجابي وسلبي.

تمتلك الكورتيكوستيرويدات تأثيرات معقدة على تناول الطعام وعمليات الأيض للطاقة، والتي تتضح بشكل خاص من خلال التأثيرات المتباينة تحت الضغط الحاد والمزمن. لها تأثيرات هدم على مخازن الطاقة مثل الأنسجة الدهنية والعضلات، بهدف تحريك الجلوكوز إلى الدم لدعم الدماغ في استجابة القتال أو الهروب. ومع ذلك، عندما يصبح الضغط مزمنًا، تبدأ التأثيرات البنائية لهذا الهرمون في السيطرة. في متلازمة كوشينغ، على سبيل المثال، تعزز مستويات الكورتيكوستيرويدات المرتفعة بشكل مزمن مقاومة الأنسولين وتراكم الدهون في منطقة البطن.

العلاقة بين الكورتيزول (GCs) وتناول الطعام والشهية هي علاقة متبادلة، حيث تؤدي جداول التغذية المضطربة إلى تغيير إيقاع الكورتيزول اليومي، على سبيل المثال في نماذج التغذية النهارية لدى القوارض.

تستهلك مكملات GC المحولة تقريبًا نصف سعراتها الحرارية في المرحلة غير النشطة

تستهلك مكملات GC المحولة تقريبًا نصف سعراتها الحرارية في المرحلة غير النشطة

تفاعلات GC مع الهرمونات الأيضية معقدة وقد تم مراجعتها في أماكن أخرى

الستيرويدات الجنسية

يظهر الاختلاف الجنسي في النظام اليومي من التأثيرات المتنوعة للهرمونات الجنسية على الفسيولوجيا والسلوك، والتي تنظمها محور الوطاء-الغدة النخامية-الخصية (HPG)، وهو آلية مركزية تحكم العمليات التناسلية والتفاعلات الغدد الصماء الأوسع.

تؤثر هرمونات الجنس بشكل كبير على محور الغدة النخامية-الكظرية، حيث يعزز الإستروجين غالبًا نشاط هذا المحور. يزيد الإستراديول من التفعيل الناتج عن الإجهاد على جميع مستويات محور الغدة النخامية-الكظرية، مما يرفع من تعبير هرمون إفراز الكورتيكوتروبين (CRH) وAVP في النواة البارزة، وmRNA الخاص بـ POMC في الغدة النخامية، وحساسية ACTH في الغدد الكظرية.

تلعب الإستروجينات دورًا مهمًا في تنظيم استقلاب الجلوكوز والدهون من خلال تعزيز حساسية الأنسولين، وتعزيز امتصاص الجلوكوز في الأنسجة الطرفية، والتأثير على ملفات الدهون.

مستويات هرمونات الغدة الدرقية، التي تعتبر حاسمة لتنظيم معدل الأيض الأساسي

مستويات هرمونات الغدة الدرقية، التي تعتبر حاسمة لتنظيم معدل الأيض الأساسي

هناك أدلة متزايدة تظهر أن هرمونات الجنس تنظم ليس فقط العمليات التناسلية ولكن أيضًا العمليات غير التناسلية من خلال التفاعل مع الآليات اليومية.

تشير النتائج الأخيرة إلى أن الإستروجين يعدل إيقاع النواة فوق التصالبية (SCN) من خلال الخلايا الدبقية بدلاً من الخلايا العصبية، مستهدفًا بشكل خاص الوصلات الفجوية الخاصة بها واستعادة الإيقاع بعد تثبيط مستقبلات AVP. تظهر الدراسات في المختبر أن الإناث اللواتي لديهن مستويات عالية من الإستروجين، والتي تشبه مرحلة البروإستروس من دورة الشبق، تظهر إيقاعًا قويًا في النواة فوق التصالبية، وقد يكون ذلك بوساطة الوصلات الفجوية الخلوية كما هو موضح في الدراسات المخبرية.

نظرًا لهذه التفاعلات، فإن البحث المستقبلي عبر الأنواع ضروري لتوضيح كيفية تأثير الجنس والهرمونات الجنسية على ضبط الوقت اليومي على المستويات الخلوية والجزيئية. من الضروري أخذ التعبير الديناميكي للإستروجين والبروجستيرون في الاعتبار عبر دورات الشبق والحيض في القوارض والبشر، على التوالي. يصل مستوى الإستروجين إلى ذروته في مرحلة ما قبل الإباضة في الإناث، تليها زيادة في مستوى البروجستيرون بعد الإباضة، مما يشير إلى تأثيرات متباينة على الساعة البيولوجية عبر مراحل دورة التكاثر.

هرمونات الغدة الدرقية

يتم تنظيم تخليق هرمون الغدة الدرقية (TH) بواسطة آلية عصبية غددية تشمل محور الغدة النخامية الدرقية (HPT). تقوم الخلايا العصبية الصغيرة بإفراز هرمون مطلق للغدة الدرقية، مما يحفز الغدة النخامية الأمامية على إفراز هرمون محفز للغدة الدرقية (TSH) في مجرى الدم. يقوم TSH بتحفيز إفراز THs، وخاصة البروهرمون ثيروكسين.

الفئران بينما تعتبر إيقاعات THs اليومية مثيرة للجدل حيث تظهر مستويات THs الكلية والحرّة سعة ضحلة وغالبًا ما تكون غير منتظمة.

الفئران بينما تعتبر إيقاعات THs اليومية مثيرة للجدل حيث تظهر مستويات THs الكلية والحرّة سعة ضحلة وغالبًا ما تكون غير منتظمة.

على الرغم من أن تأثيرات هرمونات الغدة الدرقية في تنظيم استقلاب الطاقة معروفة، إلا أن ما إذا كانت هذه التأثيرات تخضع لتنظيم زمني هو موضوع قيد التحقيق. اقتربنا من هذا السؤال باستخدام نماذج دوائية لتحفيز حالة منخفضة أو مرتفعة من هرمونات الغدة الدرقية، تلتها تحليل النسخ الجيني اليومي لتقييم إمكانية وجود تداخل بين هرمونات الغدة الدرقية والساعة البيولوجية. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن الحالة المرتفعة من هرمونات الغدة الدرقية تزيد بشكل كبير من استهلاك الطاقة ودرجة حرارة الجسم، مما يؤثر على معلمات الإيقاع (مثل MESOR، السعة، والطور) لمئات الجينات المعنية في استقلاب الجلوكوز والدهون والكوليسترول والمواد الغريبة في الكبد.

واحد من المفاهيم التي تظهر من هذه الملاحظات هو دور الإشارات التونية غير الإيقاعية كـ “مضبطات” دورانية (أو tongeber – بالألمانية تعني “مُعطي الصوت” في إشارة إلى مصطلح zeitgeber (“مُعطي الوقت”) الذي يصف مُعدل فاسي للإيقاعات الدورانية). نظرًا لأن THs غير إيقاعية إلى حد كبير، فإنها بالكاد يمكن أن تعمل كمحركات للإيقاع أو zeitgebers. ومع ذلك، من خلال التفاعل مع الإشارات الإيقاعية الداخلية، يمكن أن تؤثر التغيرات في مستويات TH على الوظائف اللاحقة مثل إيقاعات التعبير الجيني. المرشحون لمثل هذه الإيقاعات الداخلية قد يكونون نقل الهرمونات (الامتصاص)، الأيض (ديوديناز)، و/أو تنشيط المستقبلات (THRa وTHR).

تتفاعل هرمونات الغدة الدرقية أيضًا مع أنظمة الغدد الصماء الأخرى مثل محور HPA. بشكل عام، تؤدي زيادة الكورتيكوستيرويدات إلى تثبيط محور HPT، وبالتالي، فإن الفئران التي تعاني من الإجهاد المزمن لديها مستويات منخفضة من هرمونات الغدة الدرقية.

بشكل عام، تعتبر هرمونات الغدة الدرقية منظمين لعملية الأيض الطاقي اليومي على الرغم من أنها بالكاد تكون إيقاعية على المستوى الهرموني. على الرغم من أن التأثيرات الأيضية المستمرة لهرمونات الغدة الدرقية مثبتة جيدًا، إلا أنه لا يزال غير مؤكد ما إذا كان وقت اليوم يؤثر على تأثيرات هرمونات الغدة الدرقية. لقد تم ملاحظة أدلة على هذا التنظيم في الكبد، ومع ذلك، فإن استجابة هرمونات الغدة الدرقية في أنسجة أخرى، مثل العضلات، على مدار اليوم لا تزال غامضة. علاوة على ذلك، لا يزال الآلية الدقيقة التي من خلالها يحفز مؤشر غير زمني الإيقاعات غير معروفة، ويجب أيضًا اختبار هذا التأثير في أنسجة أخرى. قد يوفر فهم التنظيم الزمني لعمل هرمونات الغدة الدرقية، على سبيل المثال، فوائد لعلاج خلل الأيض المرتبط بالتهاب الكبد الدهني (MASH)، وهي حالة أظهرت فيها ناهضات مستقبلات هرمون الغدة الدرقية بيتا تأثيرات واعدة.

هرمونات الأيض

الأنسجة الدهنية البيضاء (WAT) هي عضو استقلابي مركزي لتنظيم توازن الطاقة. بالإضافة إلى كونها المخزن الرئيسي للطاقة، فهي معروفة جيدًا بنشاطها الغدد الصماء.

تظهر عدة أديبوكينات إيقاعات يومية ويتم تعديل إفرازها بواسطة عوامل داخلية أو بيئية مثل الضوء أو تناول الطعام.

تشير الأدلة الواسعة إلى أن ضعف إفراز الهرمونات الأيضية يمكن أن يخل بنظام الساعة البيولوجية مما يؤدي إلى السمنة وأمراض أيضية أخرى.

يعتمد النسخ اليومي لعدة جينات على تأثير الهرمونات الأيضية

إن التكيف الفعال للإيقاعات الذاتية مع البيئة أمر لا غنى عنه لتحقيق التوازن الأيضي.

إلى اللبتين في البلازما

إلى اللبتين في البلازما

الخاتمة

التفاعلات بين النظام الغدد الصماء والنظام اليومي معقدة. تظهر العديد من الهرمونات تعديلًا يوميًا في أنماط إفرازها و/أو في تأثيرها على الأنسجة المستهدفة. يمكن تصور الأخير من خلال التأثيرات المباشرة على فيزيولوجيا الأنسجة، وإعادة ضبط الساعات المحلية، وتعديل الإيقاعات من خلال التفاعل مع تنظيم إيقاع الأنسجة. يمكن للعديد من الهرمونات – مثل الكورتيكوستيرويدات أو الأنسولين – أن تستخدم أكثر من نوع واحد من العمل، مما يسمح باستجابة يومية أكثر دقة. سيساعد فك هذا التفاعل في فهم أفضل لكيفية تعديل النظام الغدد الصماء للإيقاعات اليومية في الفيزيولوجيا والسلوك، وقد يمكننا من تعديل العمل الهرموني بطريقة محددة للأنسجة في سياق المرض.

توفر البيانات

لم يتم إنشاء أو تحليل أي مجموعات بيانات خلال الدراسة الحالية.

تاريخ الاستلام: 4 سبتمبر 2024؛ تاريخ القبول: 22 يناير 2025؛

نُشر على الإنترنت: 08 مارس 2025

تاريخ الاستلام: 4 سبتمبر 2024؛ تاريخ القبول: 22 يناير 2025؛

نُشر على الإنترنت: 08 مارس 2025

References

- Partch, C. L., Green, C. B. & Takahashi, J. S. Molecular architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Trends Cell Biol. 24, 90-99 (2014).

- Reppert, S. M. & Weaver, D. R. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature 418, 935-941 (2002).

- Begemann, K., Neumann, A.-M. & Oster, H. Regulation and function of extra-SCN circadian oscillators in the brain. Acta Physiol. Oxf. Engl. 229, e13446 (2020).

- Husse, J., Eichele, G. & Oster, H. Synchronization of the mammalian circadian timing system: light can control peripheral clocks independently of the SCN clock: alternate routes of entrainment optimize the alignment of the body’s circadian clock network with external time. BioEssays News Rev. Mol. Cell. Dev. Biol. 37, 1119-1128 (2015).

- Izumo, M. et al. Differential effects of light and feeding on circadian organization of peripheral clocks in a forebrain Bmal1 mutant. eLife 3, e04617 (2014).

- Damiola, F. et al. Restricted feeding uncouples circadian oscillators in peripheral tissues from the central pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Genes Dev. 14, 2950-2961 (2000).

- Gnocchi, D. & Bruscalupi, G. Circadian rhythms and hormonal homeostasis: pathophysiological implications. Biology 6, 10 (2017).

- Rawashdeh, O. & Maronde, E. The hormonal Zeitgeber melatonin: role as a circadian modulator in memory processing. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 5, 27 (2012).

- Balsalobre, A. et al. Resetting of circadian time in peripheral tissues by glucocorticoid signaling. Science 289, 2344-2347 (2000).

- Oster, H. et al. The circadian rhythm of glucocorticoids is regulated by a gating mechanism residing in the adrenal cortical clock. Cell Metab. 4, 163-173 (2006).

- Rose, R. M., Kreuz, L. E., Holaday, J. W., Sulak, K. J. & Johnson, C. E. Diurnal variation of plasma testosterone and cortisol. J. Endocrinol. 54, 177-178 (1972).

- Rahman, S. A. et al. Endogenous circadian regulation of female reproductive hormones. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 104, 6049-6059 (2019).

- Lucke, C., Hehrmann, R., von Mayersbach, K. & von zur Mühlen, A. Studies on circadian variations of plasma TSH, thyroxine and triiodothyronine in man. Acta Endocrinol. 86, 81-88 (1977).

- Yildiz, B. O., Suchard, M. A., Wong, M.-L., McCann, S. M. & Licinio, J. Alterations in the dynamics of circulating ghrelin, adiponectin, and leptin in human obesity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 10434-10439 (2004).

- Malherbe, C., De Gasparo, M., De Hertogh, R. & Hoem, J. J. Circadian variations of blood sugar and plasma insulin levels in man. Diabetologia 5, 397-404 (1969).

- Ruiter, M. et al. The daily rhythm in plasma glucagon concentrations in the rat is modulated by the biological clock and by feeding behavior. Diabetes 52, 1709-1715 (2003).

- Lynch, H. J. Diurnal oscillations in pineal melatonin content. Life Sci. 10, 791-795 (1971).

- Brandenberger, G., Follenius, M., Muzet, A., Ehrhart, J. & Schieber, J. P. Ultradian oscillations in plasma renin activity: their relationships to meals and sleep stages. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 61, 280-284(1985).

- Schüssler, P. et al. Sleep and active renin levels-interaction with age, gender, growth hormone and cortisol. Neuropsychobiology 61, 113-121 (2010).

- Takahashi, Y., Kipnis, D. M. & Daughaday, W. H. Growth hormone secretion during sleep. J. Clin. Investig. 47, 2079-2090 (1968).

- Yurtsever, T. et al. Temporal dynamics of cortisol-associated changes in mRNA expression of glucocorticoid responsive genes FKBP5, GILZ, SDPR, PER1, PER2 and PER3 in healthy humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology 102, 63-67 (2019).

- Hartmann, J. et al. Mineralocorticoid receptors dampen glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity to stress via regulation of FKBP5. Cell Rep. 35, 109185 (2021).

- So, A. Y.-L., Bernal, T. U., Pillsbury, M. L., Yamamoto, K. R. & Feldman, B. J. Glucocorticoid regulation of the circadian clock modulates glucose homeostasis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 17582-17587 (2009).

- Kandalepas, P. C., Mitchell, J. W. & Gillette, M. U. Melatonin signal transduction pathways require E-Box-Mediated transcription of Per1 and Per2 to Reset the SCN Clock at Dusk. PloS ONE 11, e0157824 (2016).

- Tuvia, N. et al. Insulin directly regulates the circadian clock in adipose tissue. Diabetes 70, 1985-1999 https://doi.org/10.2337/ db20-0910 (2021).

- De Assis, L. V. M. & Oster, H. Non-rhythmic modulators of the circadian system: a new class of circadian modulators. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. S1937644824000741 (Elsevier, 2024). https://doi.org/10. 1016/bs.ircmb.2024.04.003.

- Perelis, M. et al. Pancreatic

cell enhancers regulate rhythmic transcription of genes controlling insulin secretion. Science 350, aac4250 (2015). - Stehle, J. H. et al. A survey of molecular details in the human pineal gland in the light of phylogeny, structure, function and chronobiological diseases: molecular details in the human pineal gland. J. Pineal Res. 51, 17-43 (2011).

- Reiter, R. J. Pineal melatonin: cell biology of its synthesis and of its physiological interactions. Endocr. Rev. 12, 151-180 (1991).

- Illnerová, H. & Vaněcek, J. Response of rat pineal serotonin N -acetyltransferase to one min light pulse at different night times. Brain Res. 167, 431-434 (1979).

- Moore, R. Y. Organization and function of a central nervous system circadian oscillator: the suprachiasmatic hypothalamic nucleus. Fed. Protoc. 42, 2783-2789 (1983).

- Zisapel, N. New perspectives on the role of melatonin in human sleep, circadian rhythms and their regulation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 175, 3190-3199 (2018).

- Arendt, J. Melatonin and human rhythms. Chronobiol. Int. 23, 21-37 (2006).

- Crowley, S. J., Lee, C., Tseng, C. Y., Fogg, L. F. & Eastman, C. I. Complete or partial circadian re-entrainment improves performance, alertness, and mood during night-shift work. Sleep 27, 1077-1087 (2004).

- Rawashdeh, O., Hudson, R. L., Stepien, I. & Dubocovich, M. L. Circadian periods of sensitivity for Ramelteon on the onset of runningwheel activity and the peak of suprachiasmatic nucleus neuronal firing rhythms in C3H/HeN mice. Chronobiol. Int. 28, 31-38 (2011).

- Dubocovich, M. L. et al. International Union of basic and clinical pharmacology. LXXV. nomenclature, classification, and pharmacology of G Protein-coupled melatonin receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 62, 343-380 (2010).

- Boiko, D. I. et al. Melatonergic Receptors (Mt1/Mt2) as a potential additional target of novel drugs for depression. Neurochem. Res. 47, 2909-2924 (2022).

- Carrillo-Vico, A., Lardone, P., Álvarez-Sánchez, N., RodríguezRodríguez, A. & Guerrero, J. Melatonin: buffering the immune system. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 8638-8683 (2013).

- Lewy, A. J., Emens, J., Jackman, A. & Yuhas, K. Circadian uses of melatonin in humans. Chronobiol. Int. 23, 403-412 (2006).

- Srinivasan, V., De Berardis, D., Shillcutt, S. D. & Brzezinski, A. Role of melatonin in mood disorders and the antidepressant effects of agomelatine. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 21, 1503-1522 (2012).

- Rawashdeh, O. & Dubocovich, M. L. Long-term effects of maternal separation on the responsiveness of the circadian system to melatonin in the diurnal nonhuman primate (Macaca mulatta). J. Pineal Res. 56, 254-263 (2014).

- Auger, J.-P. et al. Metabolic rewiring promotes anti-inflammatory effects of glucocorticoids. Nature 629, 184-192 (2024).

- Upton, T. J. et al. High-resolution daily profiles of tissue adrenal steroids by portable automated collection. Sci. Transl. Med. 15, eadg8464 (2023).

- Son, G. H., Chung, S. & Kim, K. The adrenal peripheral clock: glucocorticoid and the circadian timing system. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 32, 451-465 (2011).

- Tousson, E. & MeissI, H. Suprachiasmatic nuclei grafts restore the circadian rhythm in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. J. Neurosci. 24, 2983-2988 (2004).

- Buijs, R. M., Soto-Tinoco, E. & Kalsbeek, A. Circadian control of neuroendocrine systems. in Neuroanatomy of Neuroendocrine Systems (eds. Grinevich, V. & Dobolyi, Á.) 297-315 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86630-3_11.

- Ishida, A. et al. Light activates the adrenal gland: timing of gene expression and glucocorticoid release. Cell Metab. 2, 297-307 (2005).

- Edwards, A. V. & Jones, C. T. Autonomic control of adrenal function. J. Anat. 183, 291-307 (1993).

- Leliavski, A., Shostak, A., Husse, J. & Oster, H. Impaired glucocorticoid production and response to stress in arntl-deficient male mice. Endocrinology 155, 133-142 (2014).

- Yamamoto, T. et al. Acute physical stress elevates mouse period1 mRNA expression in mouse peripheral tissues via a glucocorticoidresponsive element. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42036-42043 (2005).

- Ota, S. M., Kong, X., Hut, R., Suchecki, D. & Meerlo, P. The impact of stress and stress hormones on endogenous clocks and circadian rhythms. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 63, 100931 (2021).

- Wu, T. & Fu, Z. Time-dependent glucocorticoid administration differently affects peripheral circadian rhythm in rats. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 49, 1122-1128 (2017).

- Beta, R. A. A. et al. Core clock regulators in dexamethasone-treated HEK 293T cells at 4 h intervals. BMC Res. Notes 15, 23 (2022).

- Lehmann, M., Haury, K., Oster, H. & Astiz, M. Circadian glucocorticoids throughout development. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1165230 (2023).

- Soták, M. et al. Peripheral circadian clocks are diversely affected by adrenalectomy. Chronobiol. Int. 33, 520-529 (2016).

- Pezük, P., Mohawk, J. A., Wang, L. A. & Menaker, M. Glucocorticoids as entraining signals for peripheral circadian oscillators. Endocrinology 153, 4775-4783 (2012).

- Le Minh, N., Damiola, F., Tronche, F., Schütz, G. & Schibler, U. Glucocorticoid hormones inhibit food-induced phase-shifting of peripheral circadian oscillators. EMBO J. 20, 7128-7136 (2001).

- Zeman, M., Okuliarova, M. & Rumanova, V. S. Disturbances of hormonal circadian rhythms by light pollution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 7255 (2023).

- Rabasa, C. & Dickson, S. L. Impact of stress on metabolism and energy balance. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 9, 71-77 (2016).

- Adam, T. C. & Epel, E. S. Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiol. Behav. 91, 449-458 (2007).

- Le Minh, N. Glucocorticoid hormones inhibit food-induced phaseshifting of peripheral circadian oscillators. EMBO J. 20, 7128-7136 (2001).

- Gallo, P. V. & Weinberg, J. Corticosterone rhythmicity in the rat: interactive effects of dietary restriction and schedule of feeding. J. Nutr. 111, 208-218 (1981).

- Yoshimura, M. et al. Phase-shifting the circadian glucocorticoid profile induces disordered feeding behaviour by dysregulating hypothalamic neuropeptide gene expression. Commun. Biol. 6, 998 (2023).

- Kuckuck, S. et al. Glucocorticoids, stress and eating: the mediating role of appetite-regulating hormones. Obes. Rev. 24, e13539 (2023).

- Sominsky, L. & Spencer, S. J. Eating behavior and stress: a pathway to obesity. Front. Psychol. 5, 434 (2014).

- Giordano, R. et al. Ghrelin, Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis and Cushing’s Syndrome. Pituitary 7, 243-248 (2004).

- Otto, B., Tschop, M., Heldwein, W., Pfeiffer, A. & Diederich, S. Endogenous and exogenous glucocorticoids decrease plasma ghrelin in humans. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 113-117 https://doi.org/10. 1530/eje.0.1510113 (2004).

- Giraldi, F. P. et al. Ghrelin Stimulates Adrenocorticotrophic Hormone (ACTH) Secretion by Human ACTH-Secreting pituitary adenomas in vitro. J. Neuroendocrinol. 19, 208-212 (2007).

- Broglio, F., Gottero, C., Arvat, E. & Ghigo, E. Endocrine and nonendocrine actions of ghrelin. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 59, 109-117 (2003).

- Yan, L. & Silver, R. Resetting the brain clock: time course and localization of mPER1 and mPER2 protein expression in suprachiasmatic nuclei during phase shifts. Eur. J. Neurosci. 19, 1105-1109 (2004).

- Kanda, S. Evolution of the regulatory mechanisms for the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in vertebrates-hypothesis from a comparative view. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 284, 113075 (2019).

- Tsai, H.-W. & Legan, S. J. Loss of luteinizing hormone surges induced by chronic estradiol is associated with decreased activation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Biol. Reprod. 66, 1104-1110 (2002).

- Oduwole, O. O., Huhtaniemi, I. T. & Misrahi, M. The roles of luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone and testosterone in spermatogenesis and folliculogenesis revisited. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 12735 (2021).

- Christensen, A. et al. Hormonal regulation of female reproduction. Horm. Metab. Res. Horm. Stoffwechselforschung Horm. Metab. 44, 587-591 (2012).

- Alvord, V. M., Kantra, E. J. & Pendergast, J. S. Estrogens and the circadian system. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 126, 56-65 (2022).

- Joye, D. A. M. & Evans, J. A. Sex differences in daily timekeeping and circadian clock circuits. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 126, 45-55 (2022).

- Tsunekawa, K. et al. Assessment of exercise-induced stress via automated measurement of salivary cortisol concentrations and the testosterone-to-cortisol ratio: a preliminary study. Sci. Rep. 13, 14532 (2023).

- Thiyagarajan, D. K., Basit, H. & Jeanmonod, R. Physiology, menstrual cycle. in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, 2024).

- Heck, A. L. & Handa, R. J. Sex differences in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis’ response to stress: an important role for gonadal hormones. Neuropsychopharmacology 44, 45-58 (2019).

- Larkin, J. W., Binks, S. L., Li, Y. & Selvage, D. The role of oestradiol in sexually dimorphic hypothalamic-pituitary-adrena axis responses to intracerebroventricular ethanol administration in the rat.

. Neuroendocrinol. 22, 24-32 (2010). - Kitay, J. I. Pituitary-adrenal function in the rat after gonadectomy and gonadal hormone replacement1. Endocrinology 73, 253-260 (1963).

- Stephens, M. A. C., Mahon, P. B., McCaul, M. E. & Wand, G. S. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response to acute psychosocial stress: effects of biological sex and circulating sex hormones. Psychoneuroendocrinology 66, 47-55 (2016).

- Evuarherhe, O. et al. Organizational role for pubertal androgens on adult hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal sensitivity to testosterone in the male rat. J. Physiol. 587, 2977-2985 (2009).

- Yan, H. et al. Estrogen improves insulin sensitivity and suppresses gluconeogenesis via the transcription factor Foxo1. Diabetes 68, 291-304 (2019).

- Parra-Montes de Oca, M. A., Sotelo-Rivera, I., Gutiérrez-Mata, A., Charli, J.-L. & Joseph-Bravo, P. Sex dimorphic responses of the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis to energy demands and stress. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 746924 (2021).

- Griggs, R. C. et al. Effect of testosterone on muscle mass and muscle protein synthesis. J. Appl. Physiol. 66, 498-503 (1989).

- Gery, S., Virk, R. K., Chumakov, K., Yu, A. & Koeffler, H. P. The clock gene Per2 links the circadian system to the estrogen receptor. Oncogene 26, 7916-7920 (2007).

- Xiao, L. et al. Induction of the CLOCK Gene by E2-ERa signaling promotes the proliferation of breast cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 9, e95878 (2014).

- Schlaeger, L. et al. Estrogen-mediated coupling via gap junctions in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 59, 1723-1742 (2024).

- Karatsoreos, I. N., Wang, A., Sasanian, J. & Silver, R. A role for androgens in regulating circadian behavior and the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Endocrinology 148, 5487 (2007).

- Vida, B. et al. Oestrogen receptor

and immunoreactive cells in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of mice: distribution, sex differences and regulation by gonadal hormones. J. Neuroendocrinol. 20, 1270-1277 (2008). - Pilorz, V., Kolms, B. & Oster, H. Rapid jetlag resetting of behavioral, physiological, and molecular rhythms in proestrous female mice. J. Biol. Rhythms 35, 612-627 (2020).

- Meijer, J. H., van der Zee, E. A. & Dietz, M. Glutamate phase shifts circadian activity rhythms in hamsters. Neurosci. Lett. 86, 177-183 (1988).

- Kuljis, D. A. et al. Gonadal- and sex-chromosome-dependent sex differences in the circadian system. Endocrinology 154, 1501-1512 (2013).

- Russell, W. et al. Free triiodothyronine has a distinct circadian rhythm that is delayed but parallels thyrotropin levels. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 93, 2300-2306 (2008).

- Fahrenkrug, J., Georg, B., Hannibal, J. & Jørgensen, H. L. Hypophysectomy abolishes rhythms in rat thyroid hormones but not in the thyroid clock. J. Endocrinol. 233, 209-216 (2017).

- Philippe, J. & Dibner, C. Thyroid circadian timing: roles in physiology and thyroid malignancies. J. Biol. Rhythms 30, 76-83 (2015).

- Mullur, R., Liu, Y.-Y. & Brent, G. A. Thyroid hormone regulation of metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 94, 355-382 (2014).

- Luongo, C., Dentice, M. & Salvatore, D. Deiodinases and their intricate role in thyroid hormone homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 15, 479-488 (2019).

- Groeneweg, S., van Geest, F. S., Peeters, R. P., Heuer, H. & Visser, W. E. Thyroid hormone transporters. Endocr. Rev. 41, 146-201 (2020).

- Sinha, R. A., Singh, B. K. & Yen, P. M. Thyroid hormone regulation of hepatic lipid and carbohydrate metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 25, 538-545 (2014).

- Sinha, R. A., Singh, B. K. & Yen, P. M. Direct effects of thyroid hormones on hepatic lipid metabolism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 14, 259-269 (2018).

- de Assis, L. V. M. et al. Rewiring of liver diurnal transcriptome rhythms by triiodothyronine (T3) supplementation. Elife 11, e79405 (2022).

- de Assis, L. V. M. et al. Tuning of liver circadian transcriptome rhythms by thyroid hormone state in male mice. Sci. Rep. 14, 640 (2024).

- Lincoln, K., Zhou, J., Oster, H. & de Assis, L. V. M. Circadian gating of thyroid hormone action in hepatocytes. Cells 13, 1038 (2024).

- Frick, L. R. et al. Involvement of thyroid hormones in the alterations of T-cell immunity and tumor progression induced by chronic stress. Biol. Psychiatry 65, 935-942 (2009).

- Helmreich, D. L., Parfitt, D. B., Lu, X.-Y., Akil, H. & Watson, S. J. Relation between the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) Axis and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis during Repeated Stress. Neuroendocrinology 81, 183-192 (2005).

- Lo, M. J. et al. Acute effects of thyroid hormones on the production of adrenal cAMP and corticosterone in male rats. Am. J. Physiol. 274, E238-E245 (1998).

- Iglesias, P. & Díez, J. J. Influence of thyroid dysfunction on serum concentrations of adipocytokines. Cytokine 40, 61-70 (2007).

- Harrison, S. A. et al. A Phase 3, randomized, controlled trial of resmetirom in NASH with liver fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 390, 497-509 (2024).

- Kershaw, E. E. & Flier, J. S. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89, 2548-2556 (2004).

- Zwick, R. K., Guerrero-Juarez, C. F., Horsley, V. & Plikus, M. V. Anatomical, physiological, and functional diversity of adipose tissue. Cell Metab. 27, 68-83 (2018).

- Adamczak, M. & Wiecek, A. The adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. Semin. Nephrol. 33, 2-13 (2013).

- Li, Y. et al. Circadian rhythms and obesity: timekeeping governs lipid metabolism. J. Pineal Res. 69, e12682 (2020).

- Wada, T. et al. Adiponectin regulates the circadian rhythm of glucose and lipid metabolism. https://doi.org/10.1530/JOE-22-0006 (2022).

- Gavrila, A. et al. Diurnal and ultradian dynamics of serum adiponectin in healthy men: comparison with leptin, circulating soluble leptin receptor, and cortisol patterns. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88, 2838-2843 (2003).

- Schoeller, D. A., Cella, L. K., Sinha, M. K. & Caro, J. F. Entrainment of the diurnal rhythm of plasma leptin to meal timing. J. Clin. Investig. 100, 1882-1887 (1997).

- Caron, A., Lee, S., Elmquist, J. K. & Gautron, L. Leptin and brain-adipose crosstalks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19, 153-165 (2018).

- Obradovic, M. et al. Leptin and obesity: role and clinical implication. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 585887 (2021).

- Trayhurn, P. & Beattie, J. H. Physiological role of adipose tissue: white adipose tissue as an endocrine and secretory organ. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 60, 329-339 (2001).

- do Nascimento, C. M. O., Ribeiro, E. B. & Oyama, L. M. Metabolism and secretory function of white adipose tissue: effect of dietary fat. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 81, 453-466 (2009).

- Rakshit, K., Qian, J., Ernst, J. & Matveyenko, A. V. Circadian variation of the pancreatic islet transcriptome. Physiol. Genom. 48, 677-687 (2016).

- Schibler, U., Ripperger, J. & Brown, S. A. Peripheral circadian oscillators in mammals: time and food. J. Biol. Rhythms 18, 250-260 (2003).

- Jiang, P. & Turek, F. W. Timing of meals: when is as critical as what and how much. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 312, E369-E380 (2017).

- Adafer, R. et al. Food timing, circadian rhythm and chrononutrition: a systematic review of time-restricted eating’s effects on human health. Nutrients 12, 3770 (2020).

- Weyer, C. et al. Hypoadiponectinemia in obesity and Type 2 diabetes: close association with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86, 1930-1935 (2001).

- Paschos, G. K. et al. Obesity in mice with adipocyte-specific deletion of clock component Arntl. Nat. Med. 18, 1768-1777 (2012).

- Kubota, N. et al. Disruption of adiponectin causes insulin resistance and neointimal formation. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 25863-25866 (2002).

- Grosbellet, E. et al. Circadian phenotyping of obese and diabetic db/ db mice. Biochimie 124, 198-206 (2016).

- Fougeray, T. et al. The hepatocyte insulin receptor is required to program the liver clock and rhythmic gene expression. Cell Rep. 39, 110674 (2022).

- Oishi, K., Yasumoto, Y., Higo-Yamamoto, S., Yamamoto, S. & Ohkura, N. Feeding cycle-dependent circulating insulin fluctuation is not a dominant Zeitgeber for mouse peripheral clocks except in the liver: Differences between endogenous and exogenous insulin effects. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 483, 165-170 (2017).

- Bass, J. & Takahash, J. S. Circadian integration of metabolism and energetics | Science. https://www.science.org/doi/full/10.1126/ science. 1195027 (2010).

- Knutsson, A. & Kempe, A. Shift work and diabetes – A systematic review. Chronobiol. Int. 31, 1146-1151 (2014).

- Swarbrick, M. M. & Havel, P. J. Physiological, pharmacological, and nutritional regulation of circulating adiponectin concentrations in humans. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 6, 87-102 (2008).

- Lee, M.-J. & Fried, S. K. The glucocorticoid receptor, not the mineralocorticoid receptor, plays the dominant role in adipogenesis and adipokine production in human adipocytes. Int. J. Obes. 38, 1228-1233 (2014).

- Ramanjaneya, M. et al. Adiponectin (15-36) stimulates steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein expression and cortisol production in human adrenocortical cells: role of AMPK and MAPK kinase pathways. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813, 802-809 (2011).

- Kuribayashi, S. et al. Association between serum testosterone changes and parameters of the metabolic syndrome. Endocr. J. 71, 1125-1133 (2024).

- Ahrén Diurnal variation in circulating leptin is dependent on gender, food intake and circulating insulin in mice. Acta Physiol. Scand. 169, 325-331 (2000).

- Khodamoradi, K. et al. The role of leptin and low testosterone in obesity. Int. J. Impot. Res. 34, 704-713 (2022).

شكر وتقدير

تم تمويل هذا العمل من قبل مؤسسة الأبحاث الألمانية (أرقام المنح: OS353/10-1 و OS353-11/1؛ معرف المشروع 424957847 – TRR 296 – p13).

مساهمات المؤلفين

كتب المخطوطة ك.ب.، أ.ر.، إ.أ.، ف.ب.، ل.ف.م.أ.، ج.أ.م.، و هـ.أ. قرأ جميع المؤلفين ووافقوا على النسخة النهائية من المخطوطة.

المصالح المتنافسة

يعلن المؤلفون عدم وجود مصالح متنافسة.

معلومات إضافية

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى كيمبرلي بيغمان أو هنريك أوستر.

معلومات إعادة الطباعة والتصاريح متاحة علىhttp://www.nature.com/reprints

ملاحظة الناشر: تظل شركة سبرينجر ناتشر محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

الوصول المفتوح هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي النسب 4.0 الدولية، التي تسمح بالاستخدام والمشاركة والتكيف والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج بأي وسيلة أو صيغة، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح إذا ما تم إجراء تغييرات. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي الخاصة بالمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر الائتمان للمادة. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي الخاصة بالمقالة وكان استخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، فستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارةhttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

© المؤلف(ون) 2025

© المؤلف(ون) 2025

معهد علم الأعصاب، جامعة لوبيك، لوبيك، ألمانيا. مركز الدماغ والسلوك والتمثيل الغذائي، جامعة لوبيك، لوبيك، ألمانيا. مدرسة العلوم الطبية الحيوية، كلية الطب، جامعة كوينزلاند، بريسبان، كوينزلاند، أستراليا. □ البريد الإلكتروني:ki.begemann@uni-luebeck.de; henrik.oster@uni-luebeck.de

Journal: npj Biological Timing and Sleep, Volume: 2, Issue: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44323-025-00024-6

Publication Date: 2025-03-08

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44323-025-00024-6

Publication Date: 2025-03-08

Endocrine regulation of circadian rhythms

Circadian clocks are internal timekeepers enabling organisms to adapt to recurrent events in their environment – such as the succession of day and night-by controlling essential behaviors such as food intake or the sleep-wake cycle. A ubiquitous cellular clock network regulates numerous physiological processes including the endocrine system. Levels of several hormones such as melatonin, cortisol, sex hormones, thyroid stimulating hormone as well as a number of metabolic factors vary across the day, and some of them, in turn, can feedback on circadian clock rhythms. In this review, we dissect the principal ways by which hormones can regulate circadian rhythms in target tissues – as phasic drivers of physiological rhythms, as zeitgebers resetting tissue clock phase, or as tuners, affecting downstream rhythms in a more tonic fashion without affecting the core clock. These data emphasize the intricate interaction of the endocrine system and circadian rhythms and offer inroads into tissue-specific manipulation of circadian organization.

Most organisms are exposed to recurring changes in environmental conditions and express physiological rhythms over the

The molecular clock machinery is found in most cells and, thus, for coherent timing, different tissue clocks are synchronized by a master pacemaker located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus

clocks independent of the

clocks independent of the

Many hormones are known to oscillate throughout the 24 -h day including melatonin, glucocorticoids, sex steroids, thyroid stimulating hormone, and several metabolic hormones such as adiponectin, leptin, ghrelin, insulin, and glucagon (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1 | Peak times of hormones during the rest and active phase in humans and nocturnal rodents. The time window of highest hormone levels in humans and nocturnal rodents is indicated by a black arrow. Hormones with differences in peak time between humans and nocturnal rodents are indicated with a red arrow. AdipoQ: adiponectin, CORT: cortisol in humans and corticosterone in mice, GH: Growth hormone, TSH: Thyroid stimulating hormone. Mouse image: smart.servier.com.

Fig. 2 | Concept of endocrine regulation of circadian rhythms. Hormones can act as rhythm drivers, zeitgebers, or tuners. The function as rhythm driver is clockindependent and requires a rhythmic hormone that can influence rhythmic gene expression via direct hormone-target interactions. As a zeitgeber, hormones directly regulate clock gene expression in target tissues and can shift the phase of the clock. As a tuner, the hormonal signal is tonic but able to modulate the rhythmic reception and response to other external stimuli in the target tissue. In this way, a tonic action on the target tissue can modulate gene expression rhythms, thus eliciting a phasic response.

act as zeitgebers. Similarly, melatonin or insulin can affect tissue clock gene expression, thereby resetting local circadian clocks

Melatonin

Melatonin is a hormone that plays a crucial role in regulating circadian rhythms. It acts as a direct circadian rhythm driver and a zeitgeber, exerting significant influence on various physiological processes

Evidence suggests that melatonin can act on circadian rhythms by directly influencing the activity of the SCN by both acute and clock-resetting mechanisms. Melatonin’s daily action on the SCN physiology helps orchestrate the timing and synchronization of various biological rhythms such as sleep-wake cycles, hormone secretion, and core body temperature fluctuations

As a zeitgeber, melatonin serves as an internal cue that helps synchronize the body’s internal clocks with external time cues, particularly in low-light or dark conditions where external cues might be weak or absent

Melatonin refines the amplitude and robustness of circadian rhythms. It influences the activity and modulates the response of retinal cells to light. By signaling via the melatonin receptor 2 (MT2), melatonin influences the activity of retinal ganglion cells and other retinal neurons, which helps regulate the intensity and quality of the light signals transmitted to the SCN. Pineal melatonin can also directly modulate the sensitivity of the SCN to zeitgebers, thereby influencing the overall stability and adaptability of the circadian system. The two melatonin receptors (MT1 and 2) are found in various tissues and organs

Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids (GCs) are steroid hormones produced by the zona fasciculata of the adrenal cortex. They affect many physiological processes, most notably metabolism and the immune system

rhythm of release with peaks occurring approximately every 90 min , although they are more variable in frequency and amplitude

rhythm of release with peaks occurring approximately every 90 min , although they are more variable in frequency and amplitude

Three separate mechanisms contribute to rhythmic glucocorticoid secretion. Firstly, the hypothalamus-pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis is under circadian control via arginine-vasopressin (AVP) projection from the SCN to the paraventricular nucleus (PVN), generating a rhythmic firing pattern in the downstream region

Once released into the bloodstream, GCs exert their effect via interaction with two types of nuclear receptors: MR and GR. While MR has a much higher affinity to GCs than GR and is at full occupancy at most times of the day, GR mediates more phasic GC effects. It binds GREs to drive transcriptional changes in non-clock as well as clock genes

Another common way to study GC function in the clock and gene expression involves adrenalectomy (ADX). Removing the adrenal gland, and therefore depleting GCs, can affect peripheral tissue clocks, including up- and down-regulation of tissue-specific genes

GCs have complex effects on food intake and energy metabolism, specifically underlined by the diverging effects under acute and chronic stress. It has catabolic effects on energy stores such as adipose tissue and muscle, with the goal of mobilizing glucose into the blood to sustain the brain in the fight-or-flight response. However, when stress becomes chronic, the anabolic effects of this hormone start to prevail. In Cushing’s syndrome, for example, chronically high GC levels promote insulin resistance and central fat accumulation

The relationship between GCs, food intake and appetite is reciprocal, as disrupted feeding schedules shift the daily GC rhythm, for example in rodent daytime feeding paradigms

shifted GC supplementation consume almost half of their calories in the inactive phase

shifted GC supplementation consume almost half of their calories in the inactive phase

GC interactions with metabolic hormones are complex and have been reviewed elsewhere

Sex steroids

Sex dimorphism in the circadian system arises from the diverse effects of sex hormones on physiology and behavior, which are regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, a central mechanism that governs reproductive processes and broader endocrine interactions

Sex hormones exert a significant tonic influence on the HPA axis, with estrogen often enhancing HPA activity. Estradiol increases stress-induced activation at all levels of the HPA axis, elevating corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and AVP expression in the PVN, POMC mRNA in the pituitary, and ACTH sensitivity in the adrenal glands

Estrogen plays a significant role in regulating glucose and fat metabolism by enhancing insulin sensitivity, promoting glucose uptake in peripheral tissues, and influencing lipid profiles

thyroid hormone levels, which are critical for basal metabolic rate regulation

thyroid hormone levels, which are critical for basal metabolic rate regulation

There is growing evidence showing that sex hormones regulate not only reproductive but also non-reproductive processes by interacting with circadian mechanisms

Recent findings suggest that estrogen modifies the SCN rhythm through astrocytes rather than neurons, specifically targeting their gap junctions and restoring rhythmicity after AVP receptor inhibition. In vitro studies show that females with high estrogen levels, resembling the proestrus phase of the estrous cycle, exhibit robust rhythmicity in the SCN, potentially mediated through astrocytic gap junctions as shown in vitro

Given these interactions, future research across species is warranted to elucidate how sex and gonadal hormones influence circadian timekeeping at cellular and molecular levels. Considering dynamic estrogen and progesterone expression across the estrous and menstrual cycles in rodents and humans, respectively, is critical. Estrogen peaks at proestrus before ovulation in females, followed by increased progesterone post-ovulation, suggesting varying effects on the circadian clock across reproductive cycle stages

Thyroid hormones

Thyroid hormone (TH) synthesis is regulated by a neuroendocrine mechanism that involves the HPT axis. Parvocellular neurons release thyrotropin-releasing hormone stimulating the anterior pituitary’s release of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) into the bloodstream. TSH triggers the release of THs, mainly the prohormone thyroxine (

mice whereas the diurnal rhythms of THs are controversial as total and free THs show a shallow amplitude and often arrhythmicity

mice whereas the diurnal rhythms of THs are controversial as total and free THs show a shallow amplitude and often arrhythmicity

Although the effects of THs in regulating energy metabolism are known, whether such effects are subject to temporal regulation is a matter of investigation. We approached this question using pharmacological models to induce a low or high TH state, followed by diurnal transcriptome analysis to evaluate a possible crosstalk between THs and the circadian clock. Notably, a high TH state significantly increases energy expenditure and body temperature, affecting rhythm parameters (e.g., MESOR, amplitude, and phase) of hundreds of genes involved in glucose, lipid, cholesterol, and xenobiotic metabolism in the liver

One of the concepts emerging from these observations is the role of non-rhythmic tonic signals as circadian “tuners” (or tongeber – German for “sound giver” in reference to the term zeitgeber (“time giver”) describing a phasic modulator of circadian rhythms). Since THs are largely arrhythmic, they can hardly act as rhythm drivers or zeitgebers. However, by interacting with intrinsic rhythmic signals changes in TH levels can affect downstream functions such as gene expression rhythms. Candidates for such intrinsic rhythms would be hormone transport (uptake), metabolization (deiodinases), and/or receptor activation (THRa and THR

Thyroid hormones also interact with other endocrine systems such as the HPA axis. In general, increased GCs suppress the HPT axis, thus, chronically stressed mice have reduced thyroid hormone levels

Taken altogether, THs are regulators of circadian energy metabolism despite them being hardly rhythmic at the hormonal level. Although the tonic metabolic effects of thyroid hormones are well-established, it is still uncertain if time of the day influences the effects of thyroid hormones. Evidence of this regulation has been observed in the liver, yet the response of thyroid hormones in other tissues, like muscle, throughout the day is still elusive. Furthermore, the exact mechanism by which a non-temporal cue triggers rhythms is still unknown, and this effect should also be tested in other tissues. Understanding the temporal regulation of thyroid hormone action could, e.g., provide benefits for the treatment of metabolic dysfunction associated steatohepatitis (MASH), a condition where thyroid hormone receptor beta agonist has shown promising effects

Metabolic hormones

White adipose tissue (WAT) is a central metabolic organ to regulate energy homeostasis. In addition to serving as the main store of energy, it is wellknown for its endocrine activity

Several adipokines exhibit diurnal rhythms and their release is modulated by internal or environmental factors such as light or food intake

Extensive evidence suggests that the impairment of metabolic hormone secretion can dysregulate the clock system leading to obesity and other metabolic diseases

The circadian transcription of several genes depends on the action of metabolic hormones

The efficient entrainment of endogenous rhythms to the environment is indispensable for metabolic equilibrium

to leptin in plasma

to leptin in plasma

Conclusion

The interactions between the endocrine and circadian system are complex. Many hormones show circadian modulation in their release patterns and/or in their action at target tissues. The latter can be conceptualized by direct effects on tissue physiology, resetting of local clocks, and modulation of rhythms through interaction with tissue rhythm regulation. Many hormones – such as GCs or insulin – can use more than one type of action, which allows for an even more fine-tuned circadian response. Deciphering this interaction will help in better understanding how the endocrine system modulates daily rhythms of physiology and behavior and may enable us to in a tissue-specific manner modulate hormonal action in the context of disease.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Received: 4 September 2024; Accepted: 22 January 2025;

Published online: 08 March 2025

Received: 4 September 2024; Accepted: 22 January 2025;

Published online: 08 March 2025

References

- Partch, C. L., Green, C. B. & Takahashi, J. S. Molecular architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Trends Cell Biol. 24, 90-99 (2014).

- Reppert, S. M. & Weaver, D. R. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature 418, 935-941 (2002).

- Begemann, K., Neumann, A.-M. & Oster, H. Regulation and function of extra-SCN circadian oscillators in the brain. Acta Physiol. Oxf. Engl. 229, e13446 (2020).

- Husse, J., Eichele, G. & Oster, H. Synchronization of the mammalian circadian timing system: light can control peripheral clocks independently of the SCN clock: alternate routes of entrainment optimize the alignment of the body’s circadian clock network with external time. BioEssays News Rev. Mol. Cell. Dev. Biol. 37, 1119-1128 (2015).

- Izumo, M. et al. Differential effects of light and feeding on circadian organization of peripheral clocks in a forebrain Bmal1 mutant. eLife 3, e04617 (2014).

- Damiola, F. et al. Restricted feeding uncouples circadian oscillators in peripheral tissues from the central pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Genes Dev. 14, 2950-2961 (2000).

- Gnocchi, D. & Bruscalupi, G. Circadian rhythms and hormonal homeostasis: pathophysiological implications. Biology 6, 10 (2017).

- Rawashdeh, O. & Maronde, E. The hormonal Zeitgeber melatonin: role as a circadian modulator in memory processing. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 5, 27 (2012).

- Balsalobre, A. et al. Resetting of circadian time in peripheral tissues by glucocorticoid signaling. Science 289, 2344-2347 (2000).

- Oster, H. et al. The circadian rhythm of glucocorticoids is regulated by a gating mechanism residing in the adrenal cortical clock. Cell Metab. 4, 163-173 (2006).

- Rose, R. M., Kreuz, L. E., Holaday, J. W., Sulak, K. J. & Johnson, C. E. Diurnal variation of plasma testosterone and cortisol. J. Endocrinol. 54, 177-178 (1972).

- Rahman, S. A. et al. Endogenous circadian regulation of female reproductive hormones. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 104, 6049-6059 (2019).

- Lucke, C., Hehrmann, R., von Mayersbach, K. & von zur Mühlen, A. Studies on circadian variations of plasma TSH, thyroxine and triiodothyronine in man. Acta Endocrinol. 86, 81-88 (1977).

- Yildiz, B. O., Suchard, M. A., Wong, M.-L., McCann, S. M. & Licinio, J. Alterations in the dynamics of circulating ghrelin, adiponectin, and leptin in human obesity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 10434-10439 (2004).

- Malherbe, C., De Gasparo, M., De Hertogh, R. & Hoem, J. J. Circadian variations of blood sugar and plasma insulin levels in man. Diabetologia 5, 397-404 (1969).

- Ruiter, M. et al. The daily rhythm in plasma glucagon concentrations in the rat is modulated by the biological clock and by feeding behavior. Diabetes 52, 1709-1715 (2003).

- Lynch, H. J. Diurnal oscillations in pineal melatonin content. Life Sci. 10, 791-795 (1971).

- Brandenberger, G., Follenius, M., Muzet, A., Ehrhart, J. & Schieber, J. P. Ultradian oscillations in plasma renin activity: their relationships to meals and sleep stages. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 61, 280-284(1985).

- Schüssler, P. et al. Sleep and active renin levels-interaction with age, gender, growth hormone and cortisol. Neuropsychobiology 61, 113-121 (2010).

- Takahashi, Y., Kipnis, D. M. & Daughaday, W. H. Growth hormone secretion during sleep. J. Clin. Investig. 47, 2079-2090 (1968).

- Yurtsever, T. et al. Temporal dynamics of cortisol-associated changes in mRNA expression of glucocorticoid responsive genes FKBP5, GILZ, SDPR, PER1, PER2 and PER3 in healthy humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology 102, 63-67 (2019).

- Hartmann, J. et al. Mineralocorticoid receptors dampen glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity to stress via regulation of FKBP5. Cell Rep. 35, 109185 (2021).

- So, A. Y.-L., Bernal, T. U., Pillsbury, M. L., Yamamoto, K. R. & Feldman, B. J. Glucocorticoid regulation of the circadian clock modulates glucose homeostasis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 17582-17587 (2009).

- Kandalepas, P. C., Mitchell, J. W. & Gillette, M. U. Melatonin signal transduction pathways require E-Box-Mediated transcription of Per1 and Per2 to Reset the SCN Clock at Dusk. PloS ONE 11, e0157824 (2016).

- Tuvia, N. et al. Insulin directly regulates the circadian clock in adipose tissue. Diabetes 70, 1985-1999 https://doi.org/10.2337/ db20-0910 (2021).

- De Assis, L. V. M. & Oster, H. Non-rhythmic modulators of the circadian system: a new class of circadian modulators. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. S1937644824000741 (Elsevier, 2024). https://doi.org/10. 1016/bs.ircmb.2024.04.003.

- Perelis, M. et al. Pancreatic

cell enhancers regulate rhythmic transcription of genes controlling insulin secretion. Science 350, aac4250 (2015). - Stehle, J. H. et al. A survey of molecular details in the human pineal gland in the light of phylogeny, structure, function and chronobiological diseases: molecular details in the human pineal gland. J. Pineal Res. 51, 17-43 (2011).

- Reiter, R. J. Pineal melatonin: cell biology of its synthesis and of its physiological interactions. Endocr. Rev. 12, 151-180 (1991).

- Illnerová, H. & Vaněcek, J. Response of rat pineal serotonin N -acetyltransferase to one min light pulse at different night times. Brain Res. 167, 431-434 (1979).

- Moore, R. Y. Organization and function of a central nervous system circadian oscillator: the suprachiasmatic hypothalamic nucleus. Fed. Protoc. 42, 2783-2789 (1983).

- Zisapel, N. New perspectives on the role of melatonin in human sleep, circadian rhythms and their regulation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 175, 3190-3199 (2018).

- Arendt, J. Melatonin and human rhythms. Chronobiol. Int. 23, 21-37 (2006).

- Crowley, S. J., Lee, C., Tseng, C. Y., Fogg, L. F. & Eastman, C. I. Complete or partial circadian re-entrainment improves performance, alertness, and mood during night-shift work. Sleep 27, 1077-1087 (2004).

- Rawashdeh, O., Hudson, R. L., Stepien, I. & Dubocovich, M. L. Circadian periods of sensitivity for Ramelteon on the onset of runningwheel activity and the peak of suprachiasmatic nucleus neuronal firing rhythms in C3H/HeN mice. Chronobiol. Int. 28, 31-38 (2011).

- Dubocovich, M. L. et al. International Union of basic and clinical pharmacology. LXXV. nomenclature, classification, and pharmacology of G Protein-coupled melatonin receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 62, 343-380 (2010).

- Boiko, D. I. et al. Melatonergic Receptors (Mt1/Mt2) as a potential additional target of novel drugs for depression. Neurochem. Res. 47, 2909-2924 (2022).

- Carrillo-Vico, A., Lardone, P., Álvarez-Sánchez, N., RodríguezRodríguez, A. & Guerrero, J. Melatonin: buffering the immune system. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 8638-8683 (2013).

- Lewy, A. J., Emens, J., Jackman, A. & Yuhas, K. Circadian uses of melatonin in humans. Chronobiol. Int. 23, 403-412 (2006).

- Srinivasan, V., De Berardis, D., Shillcutt, S. D. & Brzezinski, A. Role of melatonin in mood disorders and the antidepressant effects of agomelatine. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 21, 1503-1522 (2012).

- Rawashdeh, O. & Dubocovich, M. L. Long-term effects of maternal separation on the responsiveness of the circadian system to melatonin in the diurnal nonhuman primate (Macaca mulatta). J. Pineal Res. 56, 254-263 (2014).

- Auger, J.-P. et al. Metabolic rewiring promotes anti-inflammatory effects of glucocorticoids. Nature 629, 184-192 (2024).

- Upton, T. J. et al. High-resolution daily profiles of tissue adrenal steroids by portable automated collection. Sci. Transl. Med. 15, eadg8464 (2023).

- Son, G. H., Chung, S. & Kim, K. The adrenal peripheral clock: glucocorticoid and the circadian timing system. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 32, 451-465 (2011).

- Tousson, E. & MeissI, H. Suprachiasmatic nuclei grafts restore the circadian rhythm in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. J. Neurosci. 24, 2983-2988 (2004).

- Buijs, R. M., Soto-Tinoco, E. & Kalsbeek, A. Circadian control of neuroendocrine systems. in Neuroanatomy of Neuroendocrine Systems (eds. Grinevich, V. & Dobolyi, Á.) 297-315 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86630-3_11.

- Ishida, A. et al. Light activates the adrenal gland: timing of gene expression and glucocorticoid release. Cell Metab. 2, 297-307 (2005).

- Edwards, A. V. & Jones, C. T. Autonomic control of adrenal function. J. Anat. 183, 291-307 (1993).

- Leliavski, A., Shostak, A., Husse, J. & Oster, H. Impaired glucocorticoid production and response to stress in arntl-deficient male mice. Endocrinology 155, 133-142 (2014).

- Yamamoto, T. et al. Acute physical stress elevates mouse period1 mRNA expression in mouse peripheral tissues via a glucocorticoidresponsive element. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42036-42043 (2005).

- Ota, S. M., Kong, X., Hut, R., Suchecki, D. & Meerlo, P. The impact of stress and stress hormones on endogenous clocks and circadian rhythms. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 63, 100931 (2021).

- Wu, T. & Fu, Z. Time-dependent glucocorticoid administration differently affects peripheral circadian rhythm in rats. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 49, 1122-1128 (2017).

- Beta, R. A. A. et al. Core clock regulators in dexamethasone-treated HEK 293T cells at 4 h intervals. BMC Res. Notes 15, 23 (2022).

- Lehmann, M., Haury, K., Oster, H. & Astiz, M. Circadian glucocorticoids throughout development. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1165230 (2023).

- Soták, M. et al. Peripheral circadian clocks are diversely affected by adrenalectomy. Chronobiol. Int. 33, 520-529 (2016).

- Pezük, P., Mohawk, J. A., Wang, L. A. & Menaker, M. Glucocorticoids as entraining signals for peripheral circadian oscillators. Endocrinology 153, 4775-4783 (2012).

- Le Minh, N., Damiola, F., Tronche, F., Schütz, G. & Schibler, U. Glucocorticoid hormones inhibit food-induced phase-shifting of peripheral circadian oscillators. EMBO J. 20, 7128-7136 (2001).

- Zeman, M., Okuliarova, M. & Rumanova, V. S. Disturbances of hormonal circadian rhythms by light pollution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 7255 (2023).

- Rabasa, C. & Dickson, S. L. Impact of stress on metabolism and energy balance. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 9, 71-77 (2016).

- Adam, T. C. & Epel, E. S. Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiol. Behav. 91, 449-458 (2007).

- Le Minh, N. Glucocorticoid hormones inhibit food-induced phaseshifting of peripheral circadian oscillators. EMBO J. 20, 7128-7136 (2001).

- Gallo, P. V. & Weinberg, J. Corticosterone rhythmicity in the rat: interactive effects of dietary restriction and schedule of feeding. J. Nutr. 111, 208-218 (1981).

- Yoshimura, M. et al. Phase-shifting the circadian glucocorticoid profile induces disordered feeding behaviour by dysregulating hypothalamic neuropeptide gene expression. Commun. Biol. 6, 998 (2023).

- Kuckuck, S. et al. Glucocorticoids, stress and eating: the mediating role of appetite-regulating hormones. Obes. Rev. 24, e13539 (2023).

- Sominsky, L. & Spencer, S. J. Eating behavior and stress: a pathway to obesity. Front. Psychol. 5, 434 (2014).

- Giordano, R. et al. Ghrelin, Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis and Cushing’s Syndrome. Pituitary 7, 243-248 (2004).

- Otto, B., Tschop, M., Heldwein, W., Pfeiffer, A. & Diederich, S. Endogenous and exogenous glucocorticoids decrease plasma ghrelin in humans. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 113-117 https://doi.org/10. 1530/eje.0.1510113 (2004).

- Giraldi, F. P. et al. Ghrelin Stimulates Adrenocorticotrophic Hormone (ACTH) Secretion by Human ACTH-Secreting pituitary adenomas in vitro. J. Neuroendocrinol. 19, 208-212 (2007).

- Broglio, F., Gottero, C., Arvat, E. & Ghigo, E. Endocrine and nonendocrine actions of ghrelin. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 59, 109-117 (2003).

- Yan, L. & Silver, R. Resetting the brain clock: time course and localization of mPER1 and mPER2 protein expression in suprachiasmatic nuclei during phase shifts. Eur. J. Neurosci. 19, 1105-1109 (2004).

- Kanda, S. Evolution of the regulatory mechanisms for the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in vertebrates-hypothesis from a comparative view. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 284, 113075 (2019).

- Tsai, H.-W. & Legan, S. J. Loss of luteinizing hormone surges induced by chronic estradiol is associated with decreased activation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Biol. Reprod. 66, 1104-1110 (2002).

- Oduwole, O. O., Huhtaniemi, I. T. & Misrahi, M. The roles of luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone and testosterone in spermatogenesis and folliculogenesis revisited. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 12735 (2021).

- Christensen, A. et al. Hormonal regulation of female reproduction. Horm. Metab. Res. Horm. Stoffwechselforschung Horm. Metab. 44, 587-591 (2012).

- Alvord, V. M., Kantra, E. J. & Pendergast, J. S. Estrogens and the circadian system. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 126, 56-65 (2022).

- Joye, D. A. M. & Evans, J. A. Sex differences in daily timekeeping and circadian clock circuits. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 126, 45-55 (2022).

- Tsunekawa, K. et al. Assessment of exercise-induced stress via automated measurement of salivary cortisol concentrations and the testosterone-to-cortisol ratio: a preliminary study. Sci. Rep. 13, 14532 (2023).

- Thiyagarajan, D. K., Basit, H. & Jeanmonod, R. Physiology, menstrual cycle. in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, 2024).

- Heck, A. L. & Handa, R. J. Sex differences in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis’ response to stress: an important role for gonadal hormones. Neuropsychopharmacology 44, 45-58 (2019).

- Larkin, J. W., Binks, S. L., Li, Y. & Selvage, D. The role of oestradiol in sexually dimorphic hypothalamic-pituitary-adrena axis responses to intracerebroventricular ethanol administration in the rat.

. Neuroendocrinol. 22, 24-32 (2010). - Kitay, J. I. Pituitary-adrenal function in the rat after gonadectomy and gonadal hormone replacement1. Endocrinology 73, 253-260 (1963).

- Stephens, M. A. C., Mahon, P. B., McCaul, M. E. & Wand, G. S. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response to acute psychosocial stress: effects of biological sex and circulating sex hormones. Psychoneuroendocrinology 66, 47-55 (2016).

- Evuarherhe, O. et al. Organizational role for pubertal androgens on adult hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal sensitivity to testosterone in the male rat. J. Physiol. 587, 2977-2985 (2009).

- Yan, H. et al. Estrogen improves insulin sensitivity and suppresses gluconeogenesis via the transcription factor Foxo1. Diabetes 68, 291-304 (2019).

- Parra-Montes de Oca, M. A., Sotelo-Rivera, I., Gutiérrez-Mata, A., Charli, J.-L. & Joseph-Bravo, P. Sex dimorphic responses of the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis to energy demands and stress. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 746924 (2021).

- Griggs, R. C. et al. Effect of testosterone on muscle mass and muscle protein synthesis. J. Appl. Physiol. 66, 498-503 (1989).

- Gery, S., Virk, R. K., Chumakov, K., Yu, A. & Koeffler, H. P. The clock gene Per2 links the circadian system to the estrogen receptor. Oncogene 26, 7916-7920 (2007).

- Xiao, L. et al. Induction of the CLOCK Gene by E2-ERa signaling promotes the proliferation of breast cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 9, e95878 (2014).

- Schlaeger, L. et al. Estrogen-mediated coupling via gap junctions in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 59, 1723-1742 (2024).

- Karatsoreos, I. N., Wang, A., Sasanian, J. & Silver, R. A role for androgens in regulating circadian behavior and the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Endocrinology 148, 5487 (2007).

- Vida, B. et al. Oestrogen receptor

and immunoreactive cells in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of mice: distribution, sex differences and regulation by gonadal hormones. J. Neuroendocrinol. 20, 1270-1277 (2008). - Pilorz, V., Kolms, B. & Oster, H. Rapid jetlag resetting of behavioral, physiological, and molecular rhythms in proestrous female mice. J. Biol. Rhythms 35, 612-627 (2020).

- Meijer, J. H., van der Zee, E. A. & Dietz, M. Glutamate phase shifts circadian activity rhythms in hamsters. Neurosci. Lett. 86, 177-183 (1988).

- Kuljis, D. A. et al. Gonadal- and sex-chromosome-dependent sex differences in the circadian system. Endocrinology 154, 1501-1512 (2013).

- Russell, W. et al. Free triiodothyronine has a distinct circadian rhythm that is delayed but parallels thyrotropin levels. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 93, 2300-2306 (2008).

- Fahrenkrug, J., Georg, B., Hannibal, J. & Jørgensen, H. L. Hypophysectomy abolishes rhythms in rat thyroid hormones but not in the thyroid clock. J. Endocrinol. 233, 209-216 (2017).

- Philippe, J. & Dibner, C. Thyroid circadian timing: roles in physiology and thyroid malignancies. J. Biol. Rhythms 30, 76-83 (2015).

- Mullur, R., Liu, Y.-Y. & Brent, G. A. Thyroid hormone regulation of metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 94, 355-382 (2014).

- Luongo, C., Dentice, M. & Salvatore, D. Deiodinases and their intricate role in thyroid hormone homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 15, 479-488 (2019).

- Groeneweg, S., van Geest, F. S., Peeters, R. P., Heuer, H. & Visser, W. E. Thyroid hormone transporters. Endocr. Rev. 41, 146-201 (2020).

- Sinha, R. A., Singh, B. K. & Yen, P. M. Thyroid hormone regulation of hepatic lipid and carbohydrate metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 25, 538-545 (2014).

- Sinha, R. A., Singh, B. K. & Yen, P. M. Direct effects of thyroid hormones on hepatic lipid metabolism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 14, 259-269 (2018).

- de Assis, L. V. M. et al. Rewiring of liver diurnal transcriptome rhythms by triiodothyronine (T3) supplementation. Elife 11, e79405 (2022).

- de Assis, L. V. M. et al. Tuning of liver circadian transcriptome rhythms by thyroid hormone state in male mice. Sci. Rep. 14, 640 (2024).

- Lincoln, K., Zhou, J., Oster, H. & de Assis, L. V. M. Circadian gating of thyroid hormone action in hepatocytes. Cells 13, 1038 (2024).

- Frick, L. R. et al. Involvement of thyroid hormones in the alterations of T-cell immunity and tumor progression induced by chronic stress. Biol. Psychiatry 65, 935-942 (2009).

- Helmreich, D. L., Parfitt, D. B., Lu, X.-Y., Akil, H. & Watson, S. J. Relation between the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) Axis and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis during Repeated Stress. Neuroendocrinology 81, 183-192 (2005).

- Lo, M. J. et al. Acute effects of thyroid hormones on the production of adrenal cAMP and corticosterone in male rats. Am. J. Physiol. 274, E238-E245 (1998).

- Iglesias, P. & Díez, J. J. Influence of thyroid dysfunction on serum concentrations of adipocytokines. Cytokine 40, 61-70 (2007).

- Harrison, S. A. et al. A Phase 3, randomized, controlled trial of resmetirom in NASH with liver fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 390, 497-509 (2024).

- Kershaw, E. E. & Flier, J. S. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89, 2548-2556 (2004).

- Zwick, R. K., Guerrero-Juarez, C. F., Horsley, V. & Plikus, M. V. Anatomical, physiological, and functional diversity of adipose tissue. Cell Metab. 27, 68-83 (2018).

- Adamczak, M. & Wiecek, A. The adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. Semin. Nephrol. 33, 2-13 (2013).

- Li, Y. et al. Circadian rhythms and obesity: timekeeping governs lipid metabolism. J. Pineal Res. 69, e12682 (2020).

- Wada, T. et al. Adiponectin regulates the circadian rhythm of glucose and lipid metabolism. https://doi.org/10.1530/JOE-22-0006 (2022).

- Gavrila, A. et al. Diurnal and ultradian dynamics of serum adiponectin in healthy men: comparison with leptin, circulating soluble leptin receptor, and cortisol patterns. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88, 2838-2843 (2003).

- Schoeller, D. A., Cella, L. K., Sinha, M. K. & Caro, J. F. Entrainment of the diurnal rhythm of plasma leptin to meal timing. J. Clin. Investig. 100, 1882-1887 (1997).

- Caron, A., Lee, S., Elmquist, J. K. & Gautron, L. Leptin and brain-adipose crosstalks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19, 153-165 (2018).

- Obradovic, M. et al. Leptin and obesity: role and clinical implication. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 585887 (2021).

- Trayhurn, P. & Beattie, J. H. Physiological role of adipose tissue: white adipose tissue as an endocrine and secretory organ. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 60, 329-339 (2001).

- do Nascimento, C. M. O., Ribeiro, E. B. & Oyama, L. M. Metabolism and secretory function of white adipose tissue: effect of dietary fat. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 81, 453-466 (2009).

- Rakshit, K., Qian, J., Ernst, J. & Matveyenko, A. V. Circadian variation of the pancreatic islet transcriptome. Physiol. Genom. 48, 677-687 (2016).

- Schibler, U., Ripperger, J. & Brown, S. A. Peripheral circadian oscillators in mammals: time and food. J. Biol. Rhythms 18, 250-260 (2003).

- Jiang, P. & Turek, F. W. Timing of meals: when is as critical as what and how much. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 312, E369-E380 (2017).

- Adafer, R. et al. Food timing, circadian rhythm and chrononutrition: a systematic review of time-restricted eating’s effects on human health. Nutrients 12, 3770 (2020).

- Weyer, C. et al. Hypoadiponectinemia in obesity and Type 2 diabetes: close association with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86, 1930-1935 (2001).

- Paschos, G. K. et al. Obesity in mice with adipocyte-specific deletion of clock component Arntl. Nat. Med. 18, 1768-1777 (2012).

- Kubota, N. et al. Disruption of adiponectin causes insulin resistance and neointimal formation. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 25863-25866 (2002).

- Grosbellet, E. et al. Circadian phenotyping of obese and diabetic db/ db mice. Biochimie 124, 198-206 (2016).

- Fougeray, T. et al. The hepatocyte insulin receptor is required to program the liver clock and rhythmic gene expression. Cell Rep. 39, 110674 (2022).

- Oishi, K., Yasumoto, Y., Higo-Yamamoto, S., Yamamoto, S. & Ohkura, N. Feeding cycle-dependent circulating insulin fluctuation is not a dominant Zeitgeber for mouse peripheral clocks except in the liver: Differences between endogenous and exogenous insulin effects. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 483, 165-170 (2017).

- Bass, J. & Takahash, J. S. Circadian integration of metabolism and energetics | Science. https://www.science.org/doi/full/10.1126/ science. 1195027 (2010).

- Knutsson, A. & Kempe, A. Shift work and diabetes – A systematic review. Chronobiol. Int. 31, 1146-1151 (2014).

- Swarbrick, M. M. & Havel, P. J. Physiological, pharmacological, and nutritional regulation of circulating adiponectin concentrations in humans. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 6, 87-102 (2008).

- Lee, M.-J. & Fried, S. K. The glucocorticoid receptor, not the mineralocorticoid receptor, plays the dominant role in adipogenesis and adipokine production in human adipocytes. Int. J. Obes. 38, 1228-1233 (2014).

- Ramanjaneya, M. et al. Adiponectin (15-36) stimulates steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein expression and cortisol production in human adrenocortical cells: role of AMPK and MAPK kinase pathways. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813, 802-809 (2011).

- Kuribayashi, S. et al. Association between serum testosterone changes and parameters of the metabolic syndrome. Endocr. J. 71, 1125-1133 (2024).

- Ahrén Diurnal variation in circulating leptin is dependent on gender, food intake and circulating insulin in mice. Acta Physiol. Scand. 169, 325-331 (2000).

- Khodamoradi, K. et al. The role of leptin and low testosterone in obesity. Int. J. Impot. Res. 34, 704-713 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the German Research Foudation (grant numbers: OS353/10-1 and OS353-11/1; Project-ID 424957847 – TRR 296 – p13).

Author contributions

K.B., O.R., I.O., V.P., L.V.M.A., J.O.M., and H.O. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Kimberly Begemann or Henrik Oster.

Reprints and permissions information is available at http://www.nature.com/reprints

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

© The Author(s) 2025

© The Author(s) 2025

Institute of Neurobiology, University of Lübeck, Lübeck, Germany. Center of Brain, Behavior, and Metabolism, University of Lübeck, Lübeck, Germany. School of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia. □ e-mail: ki.begemann@uni-luebeck.de; henrik.oster@uni-luebeck.de