DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104949

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-15

تركيز عدسة النظام البيئي على دراسات الابتكار

الاستشهاد بالإصدار المنشور (APA):

ترخيص الوثيقة:

DOI:

حالة الوثيقة وتاريخها:

نسخة الوثيقة:

يرجى التحقق من نسخة الوثيقة لهذا المنشور:

- المخطوطة المقدمة هي نسخة المقال عند التقديم وقبل المراجعة من قبل الأقران. قد تكون هناك اختلافات مهمة بين النسخة المقدمة والنسخة الرسمية المنشورة من السجل. يُنصح الأشخاص المهتمون بالبحث بالاتصال بالمؤلف للحصول على النسخة النهائية من المنشور، أو زيارة DOI لموقع الناشر.

- النسخة النهائية للمؤلف وإثبات المعرض هما نسختان من المنشور بعد مراجعة الأقران.

- تتميز النسخة النهائية المنشورة بالتخطيط النهائي للورقة بما في ذلك رقم المجلد، العدد وأرقام الصفحات.

رابط المنشور

الحقوق العامة

- يمكن للمستخدمين تنزيل ونسخ نسخة واحدة من أي منشور من البوابة العامة لغرض الدراسة الخاصة أو البحث.

- لا يجوز لك توزيع المادة بشكل إضافي أو استخدامها لأي نشاط يهدف إلى الربح أو الكسب التجاري

- يمكنك توزيع عنوان URL الذي يحدد المنشور في البوابة العامة بحرية.

www.tue.nl/taverne

سياسة الإزالة

openaccess@tue.nl

تقديم التفاصيل وسنحقق في ادعائك.

توجيه عدسة النظام البيئي نحو دراسات الابتكار

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

المنصات

خلق القيمة

استحواذ القيمة

التكامل

حوكمة النظام البيئي

الملخص

على مدى ما يقرب من قرن، تم الاعتراف بالدور الرئيسي للابتكار في النمو الاقتصادي ودراسته. اليوم، يتم فهم الابتكارات بشكل متزايد على أنها متجذرة في أنظمة بيئية من الفاعلين المستقلين، سواء كانت شركات أو منظمات أخرى أو أفراد. يساهم هؤلاء الفاعلون بطرق تكاملية لإنشاء عرض قيمة أكبر من مجموع الأجزاء، مع دمج منتجاتهم وعملياتهم التي تجعلها ممكنة من خلال واجهات معيارية بين الفاعلين. هنا نستعرض ظهور عدسة النظام البيئي ضمن دراسات الابتكار في سياق العدد الخاص حول أنظمة الابتكار وابتكار النظام البيئي. بعد تلخيص تاريخ العدد الخاص، نستعرض المقالات التسعة في العدد الخاص ونظهر كيف ترتبط بتعريف الفاعلين، وخلق القيمة المشتركة من قبل الفاعلين، وتنسيق الفاعلين، واستحواذ القيمة من قبل الفاعلين، ثم القضية الكبيرة لتحليل الأنظمة البيئية كوحدة تحليل. من هذا، نقدم اقتراحات للبحث المستقبلي في النظام البيئي، بما في ذلك الفرص لدمج عدسة النظام البيئي مع عدسات أخرى مستخدمة في دراسات الابتكار، وطرق جديدة لدراسة ظواهر النظام البيئي.

1. المقدمة

وصانعو السياسات الآن بشكل متزايد إلى الابتكارات على أنها متجذرة في أنظمة بيئية تتكون من فاعلين مستقلين، بما في ذلك الأفراد والشركات ومنظمات أخرى مثل الجامعات والوكالات العامة. يخلق أعضاء النظام البيئي منتجات وأنظمة تكون قيمتها أكبر من مجموع أجزائها المنفصلة. ثم يستحوذ كل عضو على جزء من “الفائض التكميلي” الناتج – الفرق بين القيمة المشتركة التي أنشأها الجميع ومجموع القيم التي يمكنهم إنشاؤها بشكل منفصل. (تتكون الأنظمة البيئية في العلوم الاجتماعية من فاعلين فرديين وأنواع مختلفة من المنظمات. وهي متميزة عن الأنظمة البيئية “الطبيعية” المكونة من الكائنات الحية والأنواع.)

2. دمج عدسة النظام البيئي ضمن دراسات الابتكار

2.1. تاريخ موجز لدراسات الابتكار

2.2. عدسة النظام البيئي في دراسات الابتكار

المكملون (مطورو تطبيقات البرمجيات) ومستخدمي آيفون.

تمكن الهياكل المودولارية الفاعلين الذين لديهم روابط تنظيمية قليلة جداً من اتخاذ إجراءات تكاملية، لكنها يمكن أن تكون أيضاً عرضة للاختناقات في الأداء في مواقع مختلفة (إيثيراج، 2007؛ أدنر وكابور، 2010؛ بالدوين، 2018؛ هانا وآيزنهاوردت، 2018؛ كابور، 2018). لهذا السبب، يجب الاعتراف بالاعتماد المتبادل في نظام مودولاري وإدارته بشكل صريح من خلال أشكال مختلفة من الحوكمة، مثل المعايير، والقيود على الوصول، أو التفاوض بالإضافة إلى المعاملات والعقود (شتاودنماير وآخرون، 2005؛ كابور ولي، 2013). في نظام بيئي، من غير المرجح أن تكون خيارات الحوكمة ثنائية تشمل فاعلين اثنين، ومن المرجح أن تكون متعددة الأطراف، تشمل مجموعة من الفاعلين وتسهيلها من قبل منسق مركزي (أدنر، 2017؛ أوزونكا وآخرون، 2022).

2.3. إطار لبحث النظام البيئي

- الاستقلالية: الفاعلون في النظام البيئي هم منظمات وأفراد مستقلون. وبالتالي، فإنهم يخضعون لحوكمة موزعة والتقاط القيمة.

- التكامل: يساهم الفاعلون بطرق تكاملية في عرض القيمة المحوري. القيمة المشتركة التي يتم إنشاؤها بواسطة النظام بأكمله أكبر من مجموع قيم الأجزاء المنفصلة.

- الوحدات: المنتجات والعمليات في النظام البيئي هي وحدات ضمن بنية تقنية أكبر.

مجرد مجموع قيمها المنفصلة.

إذا كانت مجموعة من الفاعلين تلبي جميع الشروط الثلاثة، فإنها تتأهل كنظام بيئي ضمن هذا الإطار. من بين جميع الأنظمة البيئية، من المفيد أيضًا التمييز بين الأنظمة البيئية المنصة وغير المنصة. يتم تنسيق الأنظمة البيئية المنصة بواسطة محور مركزي واحد أو أكثر (المنصات). تستخدم الأنظمة البيئية غير المنصة وسائل تنسيق أخرى، بما في ذلك المعاملات الثنائية والعقود، والاتفاقيات متعددة الأطراف التي تنظمها “المنسقون”، والروابط المؤقتة التي تنظمها “مكاملات الأنظمة” (كريتشمر وآخرون، 2022؛ جاكوبيدس وآخرون، 2024؛ بالدوين، 2024، الفصل 3).

مقارنة سمات النظام البيئي.

| نظام بيئي للابتكار | نظام بيئي للمنصة | نظام بيئي ريادي | نظام بيئي للمعرفة | |

| مصدر إنشاء القيمة | ابتكار محوري | منصة محورية | ريادة أعمال إنتاجية | معرفة جديدة |

| الفاعلون النموذجيون | المبتكرون، الموردون، المساهمون | مالك(و) المنصة، المساهمون | رواد الأعمال، الممولون، منظمات البحث، المسرعات | الجامعات، معاهد البحث، الشركات، الوكالات الحكومية |

| التفاعل الأساسي | التدفقات التكنولوجية ومدخلات-مخرجات | التدفقات التكنولوجية والأسواق متعددة الجوانب | تدفقات المعرفة والموارد | تدفقات المعرفة |

| الرابط مع دراسات الابتكار | الابتكار والتغيير التكنولوجي | الابتكار من قبل مالكي المنصات، والمكملين | مجموعات الابتكار والأنظمة الإقليمية | تدفقات المعرفة بين الجامعات والصناعة |

3. حول العدد الخاص

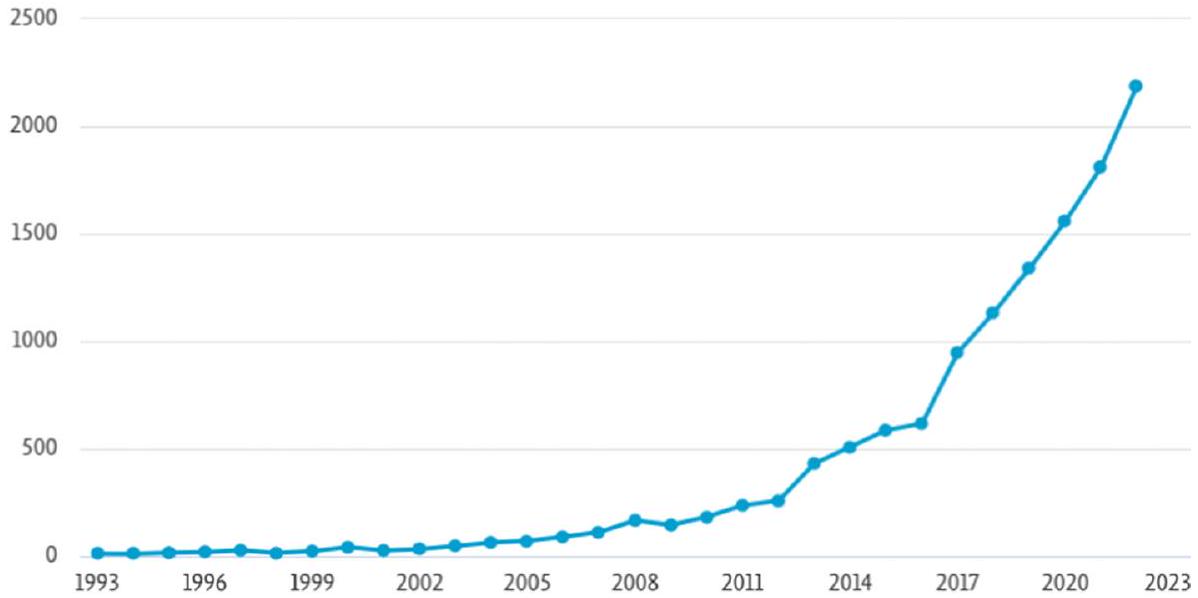

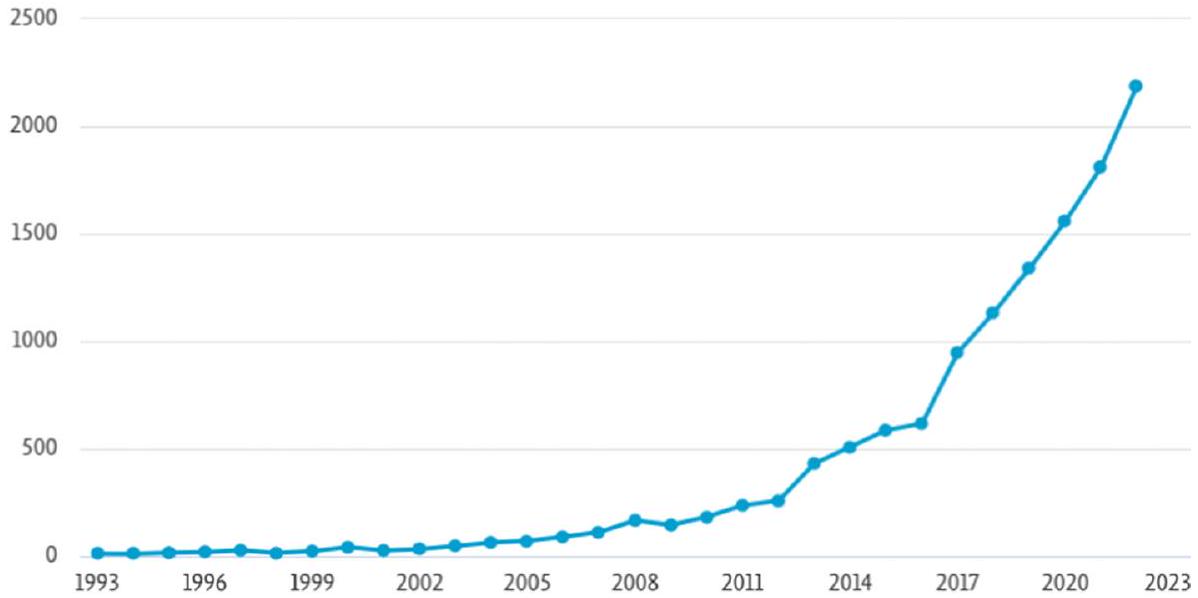

المصدر: إجمالي 12,794 مقالة مدرجة في سكوبس من 1993 إلى 2022 تحتوي على مجال موضوعي يتضمن “بزنس” وعنوان أو ملخص أو كلمات مفتاحية تحتوي على “نظام بيئي” أو “أنظمة بيئية”.

ملخص مقالات العدد الخاص.

| المؤلفون | عنوان | السياق التجريبي | نوع النظام البيئي |

| بورنر وآخرون (2023) | مسار آخر للتكامل: كيف يحدد المستخدمون والوسطاء ويخلقون تركيبات جديدة في نظم الابتكار | منتجات المنزل الذكي | نظام الابتكار، مع كل من المنصات والوسطاء، منسق بواسطة أدوات العمل |

| كوزولينو وجايجر (2024) | تعطيل النظام البيئي والموقف التنظيمي: استراتيجيات دخول منسقي ومكملات الشركات الناشئة في الصحة الرقمية | شركات ناشئة في تكنولوجيا المعلومات الصحية | نظام الابتكار، وليس قائمًا على المنصات |

| جاكوبيديس وآخرون (2024) | الآثار الخارجية والتكاملات في المنصات والأنظمة البيئية: من الحلول الهيكلية إلى الفشل الداخلي | نظرية | منصات الابتكار، منصات المعاملات، جميع نظم الأعمال (ليس فقط نظم الابتكار) |

| كوان وغرب (2023) | الواجهات، التعديل، وظهور النظام البيئي: كيف قامت DARPA بتعديل نظام أشباه الموصلات | أشباه الموصلات بدون مصانع | نظام بيئي مبتكر متعدد الأطراف من تنسيق DARPA |

| ميرك وجيبسِن (2023) | كيف تؤثر المنافسة على الجهود الابتكارية داخل نظام بيئي قائم على المنصات؟ مقارنة بين المساهمين المدفوعين وغير المدفوعين | تطبيقات آيفون المجانية مقابل المدفوعة | نظام الابتكار القائم على المنصات |

| بوجاداس وآخرون (2024) | دور القيمة والتكوين لواجهات برمجة التطبيقات على الويب في نظم الابتكار الرقمي: حالة نظام السفر عبر الإنترنت | مواقع شراء السفر عبر الإنترنت | نظام بيئي معقد مع منصات متعددة |

| رايتر وآخرون (2024) | إدارة أنظمة الابتكار متعددة المستويات | صناعة البنوك الأوروبية | مقارنة بين خمسة أنظمة ابتكار قائمة على المنصات |

| سونغ وآخرون (2024) | من الفضول المبكر إلى شبكة الفضاء الواسعة: ظهور نظام ابتكار الأقمار الصناعية الصغيرة | الأقمار الصناعية الصغيرة | نظام بيئي للابتكار متعدد الأطراف، يتم تنسيقه بواسطة “الجهات الأساسية” التي تقوم باستثمارات متخصصة |

| فان دايك وآخرون (2024) | من المنتج إلى المنصة: كيف تشكل افتراضات واختيارات الشركات القائمة استراتيجيتها للمنصة | مصنعي المعدات الزراعية | مقارنة بين نظامي ابتكار قائمين على المنصات |

4. المواضيع في العدد الخاص

4.1. من هم الفاعلون في النظام البيئي؟

منظمي الرعاية الصحية على التوالي – يمكن أن تلعب دورًا حاسمًا في إجبار الشركات القائمة على تغيير استراتيجياتها وتمكين فرص الدخول للشركات الناشئة المبتكرة.

4.2. كيف يتم إنشاء القيمة المشتركة؟

حول قيمة العرض. وبالمثل، يقارن فان دايك وآخرون الطرق التي اتبعتها شركتان راسختان في صناعة المعدات الزراعية العالمية في اتباع استراتيجيات مختلفة لإدارة الابتكارات التكميلية. أدت استراتيجياتهما المتباينة إلى نتائج مختلفة تمامًا من حيث الكمية وطبيعة التطبيقات المقدمة من قبل المساهمين الخارجيين.

4.3. كيف يتم تنسيق أعضاء النظام البيئي؟

النظم البيئية التي تُرى في صناعة الكمبيوتر.

أخيرًا، عند النظر في قضايا مثل الحوكمة، خلق القيمة، أو الحوافز، كانت الأبحاث السابقة تميل إلى التمييز بين أنواع مختلفة من الفاعلين بناءً على موقعهم الهيكلي داخل النظام البيئي، والذي يُعرف عادةً بأنه الشركة المحورية، المورد أو المكمل (على سبيل المثال، أدنر وكابور، 2010؛ داتي وآخرون، 2018). ومع ذلك، توضح مقالتان في العدد الخاص (رايتير وآخرون، سونغ وآخرون) كيف أن الاختلافات في الأفعال والاستراتيجية في نظام بيئي قد لا تكون دائمًا مدفوعة بموقع الفاعلين الهيكلي. على سبيل المثال، قد تكون الحوافز والمساهمات في القيمة متشابهة بين الموردين والمكملين في شريحة عملاء واحدة، بينما تكون غير متشابهة عبر شريحة عملاء مختلفة. وبالتالي، قد تبحث الأبحاث المستقبلية في الاعتماد المتبادل بين الفاعلين باستخدام تعريفات أكثر أساسية للتكامل، مثل تطبيق ملاحظة ميلغرام وروبرتس (1995) بأن المقياس النهائي للتكامل هو عندما يؤدي غياب المكمل إلى تقليل قيمة العرض.

4.4. من الذي يلتقط القيمة في نظام بيئي وكيف؟

4.5. النظم البيئية كوحدة تحليل

سؤالان رئيسيان: (1) من أين تأتي النظم البيئية؟ و (2) لماذا تتغير؟ كانت إحدى النتائج الشائعة في عدة مقالات هي أن النظم البيئية قد تُنشأ لبدء استراتيجية خلق القيمة لشركة ربحية أو جهة تنظيمية. وبالتالي، يصف كوان وويست تاريخ واجهة رئيسية مكنت من التخصص العمودي داخل صناعة أشباه الموصلات. تم تصميم الواجهة من قبل باحثين أكاديميين ممولين من الحكومة الذين توقعوا أن تقسيم تصميمات الرقائق إلى وحدات سيسمح بتحسين أداء الرقائق بمعدل يتماشى مع ما تنبأ به قانون مور. بدعم من DARPA، نشأت نظام بيئي ثلاثي يتكون من صانعي أدوات EDA، ومصممي الرقائق بدون مصانع، ومصانع أشباه الموصلات، وأصبح تنافسياً مع الشركات المصنعة للأجهزة المتكاملة الراسخة مثل إنتل (بالدوين، 2024، الفصل 8).

5. مستقبل أبحاث النظم البيئية

5.1. المنظورات المتقاربة في دراسات الابتكار

5.1.1. نماذج الأعمال

5.1.2. الابتكار المفتوح

5.1.3. اتحادات البحث، ومنظمات وضع المعايير، ومشاريع المصدر المفتوح

هيكلها وعضويتها أكثر سيولة.

لقد كانت الأبحاث السابقة تميل إلى التركيز على الحوكمة على مستوى واحد ولكن ليس على كلا هذين المستويين من التنظيم. يمكن أن تعترف الأبحاث المستقبلية بالعلاقة الهرمية بين النظام البيئي الأكبر وهذه المنظمات ذات الأغراض الخاصة، وتفحص تفاعلها. على سبيل المثال، متى تقيد معايير النظام البيئي الأكبر سياسات الهيئة الحاكمة المركزية؟ ومتى تؤثر الهيئة المركزية على اتجاه الابتكار في النظام البيئي الأكبر؟ لقد تم دراسة هذه القضايا في سياق مشاريع البرمجيات مفتوحة المصدر والمجتمعات، ولكن ليس في النظم البيئية الابتكارية بشكل عام.

5.1.4. الملكية الفكرية (IP)

5.1.5. القدرات التنظيمية

5.1.6. الأنظمة البيئية الريادية والإقليمية

النظام البيئي لتطوير الآخر.

5.1.7. أنظمة المعرفة

5.2. رؤى جديدة من طرق جديدة

6. الخاتمة

بيان مساهمة المؤلفين

إعلان عن تضارب المصالح

توفر البيانات

شكر وتقدير

References

Acs, Z.J., Stam, E., Audretsch, D.B., O’Connor, A., 2017. The lineages of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach. Small Bus. Econ. 49, 1-10.

Adner, R., 2006. Match your innovation strategy to your innovation ecosystem. Harv. Bus. Rev. 84 (4), 98.

Adner, R., 2012. The Wide Lens: A New Strategy for Innovation. Penguin.

Adner, R., 2017. Ecosystem as structure: an actionable construct for strategy. J. Manag. 43 (1), 39-58.

Adner, R., 2021. Winning the Right Game: How to Disrupt, Defend, and Deliver in a Changing World. MIT Press.

Adner, R., Kapoor, R., 2010. Value creation in innovation ecosystems: how the structure of technological interdependence affects firm performance in new technology generations. Strategic Manag. J. 31 (3), 306-333.

Adner, R., Kapoor, R., 2016. Innovation ecosystems and the pace of substitution: reexamining technology S-curves. Strategic Manag. J. 37 (4), 625-648.

Agarwal, S., Kapoor, R., 2022. Value creation tradeoff in business ecosystems: leveraging complementarities while managing interdependencies. Organization Sci. 34 (3), 987-1352.

Altman, E.J., Nagle, F., Tushman, M.L., 2022. The translucent hand of managed ecosystems: engaging communities for value creation and capture. Acad. Manag. Ann. 16 (1), 70-101.

Altman, E.J., Kiron, D., Schwartz, J., Jones, R., 2023. Workforce Ecosystems: Reaching Strategic Goals with People, Partners, and Technologies. MIT Press.

Anderson, P., Tushman, M.L., 1990. Technological discontinuities and dominant designs: a cyclical model of technological change. Adm. Sci. Q. 35 (4), 604-634.

Anderson, P., Tushman, M.L., 2001. Organizational environments and industry exit: the effects of uncertainty, munificence and complexity. Ind. Corp. Chang. 10 (3), 675-711.

Ansari, S., Garud, R., Kumaraswamy, A., 2016. The disruptor’s dilemma: TiVo and the US television ecosystem. Strateg. Manag. J. 37 (9), 1829-1853.

Autio, E., Thomas, L.D., 2021. Researching ecosystems in innovation contexts. Innov. Manag. Rev. 19 (1), 12-25.

Baden-Fuller, C., Haefliger, S., 2013. Business models and technological innovation. Long Range Plann. 46 (6), 419-426.

Baldwin, C.Y., 2008. Where do transactions come from? Modularity, transactions, and the boundaries of firms. Ind. Corp. Chang. 17 (1), 155-195.

Baldwin, C.Y., 2018. Bottlenecks, modules, and dynamic architectural capabilities. In: Teece, D.J., Leih, S. (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Dynamic Capabilities. Oxford University Press.

Baldwin, C.Y., 2024. Design Rules, Volume 2: How Technology Shapes Organizations. MIT Press.

Baldwin, C.Y., Clark, K.B., 1997. Managing in an age of modularity. Harv. Bus. Rev. 75 (5), 84-93.

Baldwin, C.Y., Clark, K.B., 2006. The architecture of participation: does code architecture mitigate free riding in the open source development model? Manag. Sci. 52 (7), 1116-1127.

Baldwin, C.Y., Von Hippel, E., 2011. Modeling a paradigm shift: from producer innovation to user and open collaborative innovation. Organization Sci. 22 (6), 1399-1417.

Baldwin, C.Y., Woodard, C.J., 2009. The architecture of platforms: a unified view. Platforms Markets Innov. 19-44.

Baldwin, C.Y., MacCormack, A.D., Rusnak, J., 2014. Hidden structure: using network methods to map product architecture. Research Policy 43, 1381-1397.

Bogers, M., 2011. The open innovation paradox: knowledge sharing and protection in R&D collaborations. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 14 (1), 93-117.

Bogers, M., Zobel, A.K., Afuah, A., Almirall, E., Brunswicker, S., Dahlander, L., Ter Wal, A.L., 2017. The open innovation research landscape: established perspectives and emerging themes across different levels of analysis. Ind. Innov. 24 (1), 8-40.

Bogers, M., Sims, J., West, J., 2019. What Is an Ecosystem? Incorporating 25 Years of Ecosystem Research. Working Paper. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3437014.

Borner, K., Berends, H., Deken, F., Feldberg, F., 2023. Another pathway to complementarity: how users and intermediaries identify and create new combinations in innovation ecosystems. Res. Policy 52 (7), 104788. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.respol.2023.104788.

Brusoni, Stefano, Prencipe, Andrea, 2001. Unpacking the black box of modularity: technologies, products and organizations. Ind. Corp. Change 10 (1), 179-205.

Brusoni, Stefano, Prencipe, Andrea, Pavitt, Keith, 2001. Knowledge specialization, organizational coupling and the boundaries of the firm: why do firms know more than they make? Adm. Sci. Q. 46 (4), 597-621.

Ceccagnoli, M., Forman, C., Huang, P., Wu, D.J., 2012. Cocreation of value in a platform ecosystem! The case of enterprise software. MIS Q. 263-290.

Cennamo, C., Santalo, J., 2013. Platform competition: strategic trade-offs in platform markets. Strategic Manag. J. 34 (11), 1331-1350.

Cennamo, C., Santaló, J., 2019. Generativity tension and value creation in platform ecosystems. Organ. Sci. 30 (3), 617-641.

Chandler, Alfred D., 1977. The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Chang, L.T., 2009. Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China. Random House Digital, Inc.

Chesbrough, H.W., 2003. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology. Harvard Business Press.

Chesbrough, H., 2020. Open Innovation Results: Going Beyond the Hype and Getting Down to Business. Oxford University Press.

Chesbrough, H., Bogers, M., 2014. Explicating open innovation: Clarifying an emerging paradigm for understanding innovation. In: Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., West, J. (Eds.), New Frontiers in Open Innovation. Oxford University Press, pp. 3-28.

Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., West, J. (Eds.), 2006. Open Innovation: Researching a New Paradigm. Oxford University Press.

Chposky, J., Leonsis, T., 1988. Blue Magic: The People, Power and Politics Behind the IBM Personal Computer. Facts on File Publications, New York, NY.

Christensen, C.M., 2013. The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Harvard Business Review Press.

Clarysse, B., Wright, M., Bruneel, J., Mahajan, A., 2014. Creating value in ecosystems: crossing the chasm between knowledge and business ecosystems. Res. Policy 43 (7), 1164-1176.

Cobben, D., Ooms, W., Roijakkers, N., Radziwon, A., 2022. Ecosystem types: a systematic review on boundaries and goals. J. Bus. Res. 142, 138-164.

Cohen, W.M., 2010. Fifty years of empirical studies of innovative activity and performance. In: Handbook of the Economics of Innovation, 1, pp. 129-213.

Colfer, L.J., Baldwin, C.Y., 2016. The mirroring hypothesis: theory, evidence, and exceptions. Ind. Corp. Change 25 (5), 709-738.

Cozzolino, A., Geiger, S., 2024. Ecosystem disruption and regulatory positioning: entry strategies of digital health startup orchestrators and complementors. Res. Policy 53 (2), 104913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104913.

Cyert, R.M., March, J.G., 1963. A Behavioral Theory of the Firm. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Dahlander, L., Gann, D.M., Wallin, M.W., 2021. How open is innovation? A retrospective and ideas forward. Res. Policy 50 (4), 104218.

Dattée, B., Alexy, O., Autio, E., 2018. Maneuvering in poor visibility: how firms play the ecosystem game when uncertainty is high. Acad. Manage. J. 61 (2), 466-498.

Dosi, G., 1982. Technological paradigms and technological trajectories: a suggested interpretation of the determinants and directions of technical change. Res. Policy 11 (3), 147-162.

Edquist, C., 1997. Systems of Innovation: Technologies, Institutions, and Organizations. Pinter, London.

Eisenmann, T., Parker, G., Van Alstyne, M., 2011. Platform envelopment. Strategic Manag. J. 32 (12), 1270-1285.

Ethiraj, S.K., 2007. Allocation of inventive effort in complex product systems. Strategic Manag. J. 28 (6), 563-584.

Fagerberg, J., Verspagen, B., 2009. Innovation studies-the emerging structure of a new scientific field. Res. Policy 38 (2), 218-233.

Franke, N., von Hippel, E., 2003. Satisfying heterogeneous user needs via innovation toolkits: the case of Apache security software. Res. Policy 32 (7), 1199-1215.

Freeman, C., 1974. The Economics of Industrial Innovation. Penguin, London.

Freeman, C., 1995. The ‘National System of Innovation’ in historical perspective. Camb. J. Econ. 19 (1), 5-24.

Ganco, M., Kapoor, R., Lee, G.K., 2020. From rugged landscapes to rugged ecosystems: structure of interdependencies and firms’ innovative search. Acad. Manage. Rev. 45 (3), 646-674.

Gault, F., 2018. Defining and measuring innovation in all sectors of the economy. Res. Policy 47 (3), 617-622.

Gawer, A., 2021. Digital platforms’ boundaries: the interplay of firm scope, platform sides, and digital interfaces. Long Range Plann. 54 (5), 102045.

Gawer, A., Cusumano, M.A., 2002. Platform Leadership: How Intel, Microsoft, and Cisco Drive Industry Innovation. Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Gawer, A., Phillips, N., 2013. Institutional work as logics shift: the case of Intel’s transformation to platform leader. Organization Stud. 34 (8), 1035-1071.

Granstrand, O., Holgersson, M., 2020. Innovation ecosystems: a conceptual review and a new definition. Technovation 90, 102098.

Grove, Andrew S., 1996. Only the Paranoid Survive. Doubleday, New York.

Hagedoorn, J., Cloodt, M., 2003. Measuring innovative performance: is there an advantage in using multiple indicators? Res. Policy 32 (8), 1365-1379.

Haki, K., Blaschke, M., Aier, S., Winter, R., Tilson, D., 2022. Dynamic capabilities for transitioning from product platform ecosystem to innovation platform ecosystem. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 1-19.

Hannah, D.P., Eisenhardt, K.M., 2018. How firms navigate cooperation and competition in nascent ecosystems. Strateg. Manag. J. 39 (12), 3163-3192.

Heaton, S., Siegel, D.S., Teece, D.J., 2019. Universities and innovation ecosystems: a dynamic capabilities perspective. Industrial Corp. Change 28 (4), 921-939.

Helfat, C.E., 2000. Guest editor’s introduction to the special issue: the evolution of firm capabilities. Strategic Manag. J. 21 (10-11), 955-959.

Helfat, C.E., Peteraf, M.A., 2015. Managerial cognitive capabilities and the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities. Strategic Manag. J. 36 (6), 831-850.

Helfat, C.E., Raubitschek, R.S., 2018. Dynamic and integrative capabilities for profiting from innovation in digital platform-based ecosystems. Res. Policy 47 (8), 1391-1399.

Helper, S., Sako, M., 2010. Management innovation in supply chain: appreciating Chandler in the twenty-first century. Industrial Corp. Change 19 (2), 399-429.

Henderson, R.M., Clark, K.B., 1990. Architectural innovation: the reconfiguration of existing systems and the failure of established firms. Adm. Sci. Q. 35 (1), 9-30.

Holgersson, M., Baldwin, C.Y., Chesbrough, H., Bogers, M.L., 2022. The forces of ecosystem evolution. Calif. Manage. Rev. 64 (3), 5-23.

Iansiti, Marco, Levien, Roy, 2004. The Keystone Advantage: What the New Dynamics of Business Ecosystems Mean for Strategy, Innovation, and Sustainability. Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Intel Oral History Panel, 2008. Computer History Museum, Mountain View, CA. http://ar chive.computerhistory.org/resources/text/oral_history/Intel_386_Business_Strategy/ 102701962.05.01.pdf. August 14, (viewed April 18, 2017).

Jacobides, M.G., Cennamo, C., Gawer, A., 2024. Externalities and complementarities in platforms and ecosystems: from structural solutions to endogenous failures. Res. Policy 53 (1), 104906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104906.

Järvi, K., Almpanopoulou, A., Ritala, P., 2018. Organization of knowledge ecosystems: prefigurative and partial forms. Res. Policy 47 (8), 1523-1537.

Jones, S.L., Leiponen, A., Vasudeva, G., 2021. The evolution of cooperation in the face of conflict: evidence from the innovation ecosystem for mobile telecom standards development. Strategic Manag. J. 42 (4), 710-740.

Kamien, M.I., Schwartz, N.L., 1982. Market Structure and Innovation. Cambridge University Press.

Kapoor, R., 2018. Ecosystems: broadening the locus of value creation. J. Organ. Des. 7 (1), 1-16.

Kapoor, R., Agarwal, S., 2017. Sustaining superior performance in business ecosystems: evidence from application software developers in the iOS and Android smartphone ecosystems. Organization Sci. 28 (3), 531-551.

Kapoor, R., Lee, J.M., 2013. Coordinating and competing in ecosystems: how organizational forms shape new technology investments. Strategic Manag. J. 34 (3), 274-296.

Kapoor, R., McGrath, P.J., 2014. Unmasking the interplay between technology evolution and R&D collaboration: evidence from the global semiconductor manufacturing industry, 1990-2010. Res. Policy 43 (3), 555-569.

Klepper, S., 1996. Entry, exit, growth, and innovation over the product life cycle. Am. Econ. Rev. 562-583.

Klepper, S., 1997. Industry life cycles. Ind. Corp. Change 6 (1), 145-182.

Kretschmer, T., Leiponen, A., Schilling, M., Vasudeva, G., 2022. Platform ecosystems as meta-organizations: implications for platform strategies. Strategic Manag. J. 43 (3), 405-424.

Kuan, J., West, J., 2023. Interfaces, modularity and ecosystem emergence: how DARPA modularized the semiconductor ecosystem. Res. Policy 52 (8), 104789. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104789.

Laursen, K., Salter, A., 2006. Open for innovation: the role of openness in explaining innovation performance among UK manufacturing firms. Strategic Manag. J. 27 (2), 131-150.

Laursen, K., Salter, A., 2014. The paradox of openness: appropriability, external search and collaboration. Res. Policy 43 (5), 867-878.

Lee, S., Kim, W., Lee, H., Jeon, J., 2016. Identifying the structure of knowledge networks in the US mobile ecosystems: patent citation analysis. Tech. Anal. Strat. Manag. 28 (4), 411-434.

Locke, R.M., 1996. The composite economy: local politics and industrial change in contemporary Italy. Econ. Soc. 25 (4), 483-510.

MacCormack, Alan, Rusnak, John, Baldwin, Carliss, 2006. Exploring the structure of complex software designs: an empirical study of open source and proprietary code. Manag. Sci. 52 (7), 1015-1030.

MacCormack, Alan, Baldwin, Carliss, Rusnak, John, 2012. Exploring the duality between product and organizational architectures: a test of the “mirroring” hypothesis. Res. Policy 41 (8), 1309-1324.

Malerba, F., 2002. Sectoral systems of innovation and production. Res. Policy 31 (2), 247-264.

Martin, B.R., 2012. The evolution of science policy and innovation studies. Res. Policy 41 (7), 1219-1239.

Milgrom, P., Roberts, J., 1995. Complementarities and fit strategy, structure, and organizational change in manufacturing. J. Account. Econ. 19 (2), 179-208.

Miric, M., Jeppesen, L.B., 2023. How does competition influence innovative effort within a platform-based ecosystem? Contrasting paid and unpaid contributors. Res. Policy 52 (7), 104790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104790.

Moore, J.F., 1993. Predators and prey: a new ecology of competition. Harv. Bus. Rev. 71 (3), 75-86.

Morris, Charles R., Ferguson, Charles H., 1993. How Architecture Wins Technology Wars, March-April. Harvard Business Review, pp. 86-96.

Mowery, D.C., Nelson, R.R. (Eds.), 1999. Sources of Industrial Leadership. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Nelson, Richard R. (Ed.), 1993. National Innovation Systems: A Comparative Analysis. Oxford University Press, New York.

Nelson, R.R., Winter, S.G., 1982. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Harvard University Press.

Nicotra, M., Romano, M., Del Giudice, M., Schillaci, C.E., 2018. The causal relation between entrepreneurial ecosystem and productive entrepreneurship: a measurement framework. J. Technol. Transfer. 43 (3), 640-673.

Olk, P., West, J., 2020. The relationship of industry structure to open innovation: cooperative value creation in pharmaceutical consortia. R&D Manag. 50 (1), 116-135.

Olk, P., West, J., 2023. Distributed governance of a complex ecosystem: how R&D consortia orchestrate the Alzheimer’s knowledge ecosystem. Calif. Manage. Rev. 65 (2), 93-128.

Parker, G., Van Alstyne, M., Jiang, X., 2017. Platform ecosystems. MIS Q. 41 (1), 255-266.

Parnas, David L., 1972. A technique for software module specification with examples. Commun. ACM 15, 330-336.

Parnas, David L., 1972b. On the Criteria to Be Used in Decomposing Systems into Modules. In: Communications of the ACM 15: 1053-58. Software Fundamentals: Collected Papers of David Parnas. Addison-Wesley, Boston MA reprinted in Hoffman and Weiss (eds.).

Parnas, David L., 2001. In: Hoffman, D.M., Weiss, D.M. (Eds.), Software Fundamentals: Collected Papers by David L. Parnas. Addison-Wesley, Boston MA.

Pavitt, K., 1984. Sectoral patterns of technical change: towards a taxonomy and a theory. Res. Policy 13 (6), 343-373.

Pavitt, K., 1999. Technology, Management and Systems of Innovation. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Pujadas, R., Valderrama, E., Venters, W., 2024. The value and structuring role of web APIs in digital innovation ecosystems: the case of the online travel ecosystem. Res. Policy 53 (2), 104931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104931.

Qiu, Y., Gopal, A., Hann, I.H., 2017. Logic pluralism in mobile platform ecosystems: a study of indie app developers on the iOS app store. Inf. Syst. Res. 28 (2), 225-249.

Randhawa, K., West, J., Skellern, K., Josserand, E., 2021. Evolving a value chain to an open innovation ecosystem: cognitive engagement of stakeholders in customizing medical implants. Calif. Manage. Rev. 63 (2), 101-134.

Randhawa, K., Wilden, R., Akaka, M.A., 2022. Innovation intermediaries as collaborators in shaping service ecosystems: the importance of dynamic capabilities. Ind. Mark. Manag. 103, 183-197.

Reiter, A., Stonig, J., Frankenberger, K., 2024. Managing multi-tiered innovation ecosystems. Res. Policy 53 (1), 104905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. respol.2023.104905.

Reypens, C., Lievens, A., Blazevic, V., 2021. Hybrid orchestration in multi-stakeholder innovation networks: practices of mobilizing multiple, diverse stakeholders across organizational boundaries. Organization Stud. 42 (1), 61-83.

Rietveld, J., Schilling, M.A., Bellavitis, C., 2019. Platform strategy: managing ecosystem value through selective promotion of complements. Organization Sci. 30 (6), 1232-1251.

Rohrbeck, R., Hölzle, K., Gemünden, H.G., 2009. Opening up for competitive advantage-how Deutsche Telekom creates an open innovation ecosystem. R&D Manag. 39 (4), 420-430.

Rosenberg, N., 1982. Inside the Black Box: Technology and Economics. Cambridge University Press.

Sako, M., Helper, S., 1998. Determinants of trust in supplier relations: evidence from the automotive industry in Japan and the United States. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 34 (3), 387-417.

Saxenian, A., 1996. Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128, With a New Preface by the Author. Harvard University Press.

Schäper, T., Jung, C., Foege, J.N., Bogers, M.L.A.M., Fainshmidt, S., Nüesch, S., 2023. The S -shaped relationship between open innovation and financial performance: a longitudinal perspective using a novel text-based measure. Res. Policy 52 (6), 104764.

Schmookler, J., 1966. Invention and Economic Growth. Harvard University Press.

Schreieck, M., Wiesche, M., Krcmar, H., 2021. Capabilities for value co-creation and value capture in emergent platform ecosystems: A longitudinal case study of SAP’s cloud platform. J. Inf. Technol. 36 (4), 365-390. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 02683962211023780.

Schumpeter, Joseph A., 1942. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. Harper & Brothers, New York.

Simcoe, T., 2006. Open standards and intellectual property rights. In: Open Innovation: Researching a New Paradigm. Oxford University Press.

Simon, H.A., 1947. Administrative Behavior. Simon and Schuster.

Simon, Herbert A., 1962. The Architecture of Complexity. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 106: 467-482, reprinted in Simon (1981) The Sciences of the Artificial, 2nd ed. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 193-229.

Simon, Herbert A., 1969. The Sciences of the Artificial. MIT Press, Cambridge MA.

Smith, K., 2006. Measuring innovation. In: Fagerberg, Jan, Mowery, David C. (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Innovation (Oxford).

Snihur, Y., Zott, C., Amit, R., 2021. Managing the value appropriation dilemma in business model innovation. Strat. Sci. 6 (1), 22-38. https://doi.org/10.1287/ stsc.2020.0113.

Song, Y., Gnyawali, D., Qian, L., 2024. From early curiosity to space wide web: the emergence of the small satellite innovation ecosystem. Res. Policy 53 (2), 104932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104932.

Stam, E., 2015. Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: a sympathetic critique. Eur. Plan. Stud. 23 (9), 1759-1769. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 09654313.2015.1061484.

Staudenmayer, Nancy, Tripsas, Mary, Tucci, Christopher L., 2005. Interfirm modularity and its implications for product development. J. Product Innov. Manag. 22 (4), 303-321.

Sturgeon, Timothy J., 2002. Modular production networks: a new American model of industrial organization. Ind. Corp. Change 11 (3), 451-496.

Sturgeon, T.J., Kawakami, M., 2011. Global value chains in the electronics industry: characteristics, crisis, and upgrading opportunities for firms from developing countries. Int. J. Technol. Learn. Innov. Develop. 4 (1-3), 120-147.

Suarez, F.F., 2004. Battles for technological dominance: an integrative framework. Res. Policy 33 (2), 271-286.

Sydow, J., Windeler, A., Schubert, C., Möllering, G., 2012. Organizing R&D consortia for path creation and extension: the case of semiconductor manufacturing technologies. Organ. Stud. 33 (7), 907-936.

Teece, D.J., 1986. Profiting from technological innovation: implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Res. Policy 15 (6), 285-305.

Teece, D.J., 2006. Reflections on “profiting from innovation”. Res. Policy 35 (8), 1131-1146.

Teece, D.J., 2009. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management: Organizing for innovation and growth. Oxford University Press.

Teece, D.J., 2018. Profiting from innovation in the digital economy: enabling technologies, standards, and licensing models in the wireless world. Res. policy 47 (8), 1367-1387.

Thun, E., Taglioni, D., Sturgeon, T., Dallas, M.P., 2022. Massive Modularity: Understanding Industry Organization in the Digital Age-The Case of Mobile Phone Handsets. No. 10164. The World Bank.

Toh, P.K., Miller, C.D., 2017. Pawn to save a chariot, or drawbridge into the fort? Firms’ disclosure during standard setting and complementary technologies within ecosystems. Strategic Manag. J. 38 (11), 2213-2236.

Tushman, M.L., Anderson, P., 1986. Technological discontinuities and organizational environments. Adm. Sci. Q. 31 (3), 439-465.

Utterback, J.M., Abernathy, W.J., 1975. A dynamic model of process and product innovation. Omega 3 (6), 639-656.

Uzunca, B., Sharapov, D., Tee, R., 2022. Governance rigidity, industry evolution, and value capture in platform ecosystems. Res. Policy 51 (7), 104560.

van der Borgh, M., Cloodt, M., Romme, A.G.L., 2012. Value creation by knowledge-based ecosystems: evidence from a field study. R&D Manag. 42 (2), 150-169.

van Dyck, M., Lüttgens, D., Diener, K., Piller, F., Pollok, P., 2024. From product to platform: how incumbents’ assumptions and choices shape their platform strategy. Res. Policy 53 (1), 104904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104904.

von Hippel, E., 1988. The Sources of Innovation (Oxford).

von Hippel, E., 2005. Democratizing Innovation. MIT Press.

von Hippel, E., 2019. Free Innovation. MIT Press.

West, J., 2014. Challenges of funding open innovation platforms: lessons from Symbian Ltd. In: Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., West, J. (Eds.), New Frontiers in Open Innovation. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 71-93.

West, J., Dedrick, J., 2000. Innovation and control in standards architectures: the rise and fall of Japan’s PC-98. Inform. Syst. Res. 11 (2), 197-216.

West, J., Gallagher, S., 2006. Challenges of open innovation: the paradox of firm investment in open-source software. R&D Manag. 36 (3), 319-331.

West, J., Wood, D., 2013. Evolving an open ecosystem: the rise and fall of the Symbian platform. Adv. Strateg. Manag. 30, 27-68.

Womack, J.P., Jones, D.T., Roos, D., 1990. The Machine That Changed the World: The Story of Lean Production. Rawson Associates, New York, NY.

Wurth, B., Stam, E., Spigel, B., 2022. Toward an entrepreneurial ecosystem research program. Entrep. Theory Pract. 46 (3), 729-778.

Zhu, F., Iansiti, M., 2012. Entry into platform-based markets. Strategic Manag. J. 33 (1), 88-106.

Zott, C., Amit, R., Massa, L., 2011. The business model: recent developments and future research. J. Manag. 37 (4), 1019-1042.

- Corresponding author.

E-mail address: dr.joel.west@gmail.com (J. West).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104949

Publication Date: 2024-01-15

Focusing the ecosystem lens on innovation studies

Citation for published version (APA):

Document license:

DOI:

Document status and date:

Document Version:

Please check the document version of this publication:

- A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher’s website.

- The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review.

- The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers.

Link to publication

General rights

- Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research.

- You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain

- You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal.

www.tue.nl/taverne

Take down policy

openaccess@tue.nl

providing details and we will investigate your claim.

Focusing the ecosystem lens on innovation studies

A R T I C L E I N F O

Keywords:

Platforms

Value creation

Value capture

Complementarity

Ecosystem governance

Abstract

For nearly a century, the key role of innovation in economic growth has been acknowledged and studied. Today, innovations are increasingly understood as being embedded in ecosystems of autonomous actors, whether firms, other organizations, or individuals. These actors contribute in complementary ways to create a value proposition that is greater than the sum of the parts, with the integration of their products and processes made possible by modular interfaces between actors. Here we review the emergence of the ecosystem lens within innovation studies in the context of the Special Issue on Innovation Ecosystems and Ecosystem Innovation. After summarizing the history of the special issue, we review the nine articles in the special issue and show how they relate to defining the actors, joint value creation by the actors, coordinating the actors, value capture by the actors, and then the large issue of analyzing ecosystems as the unit of analysis. From this, we offer suggestions for future ecosystem research, including opportunities to combine the ecosystem lens with other lenses used in innovation studies, and new methods for studying ecosystem phenomena.

1. Introduction

and policymakers now increasingly view innovations as embedded in ecosystems made up of autonomous actors, including individuals, firms and other organizations such as universities and public agencies. Members of an ecosystem create products and systems whose value is greater than the sum of their separate parts. Each member then captures a part of the resulting “complementary surplus” – the difference between the joint value created by all and the sum of the values they could create separately. (Ecosystems in the social sciences are made up of individual actors and various kinds of organizations. They are distinct from “natural” ecosystems made up of organisms and species.)

2. Incorporating an ecosystem lens within innovation studies

2.1. A brief history of innovation studies

2.2. The ecosystem lens in innovation studies

complementors (application software developers), and iPhone users.

Modular architectures enable actors with very few organizational ties to take complementary actions, but they can also be subject to performance bottlenecks at different locations (Ethiraj, 2007; Adner and Kapoor, 2010; Baldwin, 2018; Hannah and Eisenhardt, 2018; Kapoor, 2018). For this reason, the interdependencies in a modular system must be explicitly recognized and managed through different forms of governance, e.g., via standards, restrictions on access, or negotiation as well as transactions and contracts (Staudenmayer et al., 2005; Kapoor and Lee, 2013). In an ecosystem, governance choices are less likely to be bilateral involving two actors and more likely to be multilateral, involving a group of actors and facilitated by a focal orchestrator (Adner, 2017; Uzunca et al., 2022).

2.3. A framework for ecosystem research

- Autonomy: The actors in the ecosystem are autonomous organizations and individuals. As such, they are subject to distributed governance and value capture.

- Complementarity: The actors contribute in complementary ways to a focal value proposition. The joint value created by the whole system is greater than the sum of the values of the separate parts.

- Modularity: The products and processes in the ecosystem are modules within a larger technical architecture.

simply the sum of their separate values.

If a group of actors satisfies all three conditions, they qualify as an ecosystem within this framework. Among all ecosystems, it is also useful to distinguish between platform ecosystems and non-platform ecosystems. Platform ecosystems are coordinated by one or more central hubs (platforms). Non-platform ecosystems use other means of coordination, including bilateral transactions and contracts, multilateral agreements arranged by “orchestrators,” and temporary linkages organized by “system integrators” (Kretschmer et al., 2022; Jacobides et al., 2024; Baldwin, 2024, Ch. 3).

Comparing ecosystem attributes.

| Innovation ecosystem | Platform ecosystem | Entrepreneurial ecosystem | Knowledge ecosystem | |

| Source of value creation | Focal innovation | Focal platform | Productive entrepreneurship | Novel knowledge |

| Typical actors | Innovators, Suppliers, Complementors | Platform owner(s), Complementors | Entrepreneurs, Funders, Research Organizations, Accelerators | Universities, research institutes, firms, government agencies |

| Primary Interaction | Technological and inputoutput flows | Technological and multi-sided markets | Knowledge and resource flows | Knowledge flows |

| Link with Innovation studies | Innovation and technological change | Innovation by platform owners, complementors | Innovation clusters and regional ecosystems | University-industry knowledge flows |

3. About the special issue

Source: A total of 12,794 Scopus-indexed articles from 1993 to 2022 that have a Subject Area containing “busi” and Title, Abstract or Keywords that contain “ecosystem” or “ecosystems”.

Summary of special issue articles.

| Authors | Title | Empirical context | Type of ecosystem |

| Borner et al. (2023) | Another pathway to complementarity: How users and intermediaries identify and create new combinations in innovation ecosystems | Smart home products | Innovation ecosystem, w/ both platforms and intermediaries, coordinated by toolkits |

| Cozzolino and Geiger (2024) | Ecosystem disruption and regulatory positioning: Entry strategies of digital health startup orchestrators and complementors | Healthcare IT startups | Innovation ecosystem, not platform-based |

| Jacobides et al. (2024) | Externalities and complementarities in platforms and ecosystems: From structural solutions to eendogenous failures | Theory | Innovation platforms, transaction platforms, all business ecosystems (not only innovation ecosystems) |

| Kuan and West (2023) | Interfaces, modularity and ecosystem emergence: How DARPA modularized the semiconductor ecosystem | Fabless semiconductors | Multilateral innovation ecosystem orchestrated by DARPA |

| Miric and Jeppesen (2023) | How does competition influence innovative effort within a platform-based ecosystem? Contrasting paid and unpaid contributors | Free vs. paid iPhone apps | Platform-based innovation ecosystem |

| Pujadas et al. (2024) | The value and structuring role of web APIs in digital innovation ecosystems: The case of the online travel ecosystem | Online travel purchase sites | Complex ecosystem with multiple platforms |

| Reiter et al. (2024) | Managing multi-tiered innovation ecosystems | European banking industry | Comparison of five platform-based innovation ecosystems |

| Song et al. (2024) | From early curiosity to space wide web: The emergence of the small satellite innovation ecosystem | Small satellites | Multilateral innovation ecosystem, orchestrated by “core actors” making specialized investments |

| van Dyck et al. (2024) | From product to platform: How incumbents’ assumptions and choices shape their platform strategy | Agricultural equipment manufacturers | Comparison of two nascent platformbased innovation ecosystems |

4. Themes in the special issue

4.1. Who are the actors in an ecosystem?

healthcare regulators respectively – can play a crucial role both in forcing incumbents to change strategies and enabling entry opportunities for innovative startups.

4.2. How is joint value created?

about the value proposition. Similarly, van Dyck et al. contrast the ways in which two established incumbents in the global agricultural equipment industry pursued different strategies for managing complementary innovations. Their divergent strategies resulted in very different results for both the quantity and nature of the applications provided by thirdparty complementors.

4.3. How are ecosystem members coordinated?

ecosystems seen in the computer industry.

Finally, when considering issues such as governance, value creation, or incentives, prior research has tended to distinguish between different types of actors based on their structural position within the ecosystem typically defined as focal firm, supplier or complementor (e.g., Adner and Kapoor, 2010; Dattée et al., 2018). However, two articles in the special issue (Reiter et al., Song et al.) illustrate how differences in actions and strategy in an ecosystem may not always be driven by structural position of the actors. For example, the incentives and contributions to value may be similar between suppliers and complementors in one customer segment, while dissimilar across a different customer segment. Future research might thus examine interdependence between actors using more fundamental definitions of complementarity, such as by applying Milgrom and Roberts’ (1995) observation that the ultimate measure of complementarity is when absence of the complementor reduces the value of the offering.

4.4. Who captures value in an ecosystem and how?

4.5. Ecosystems as the unit of analysis

two key questions: (1) where do ecosystems come from? and (2) why do they change? A common finding in several articles was that ecosystems may be created to jump-start the value creation strategy of a for-profit firm or a regulator. Thus, Kuan & West describe the history of a key interface that enabled vertical specialization within the semiconductor industry. The interface was prototyped by government-funded academic researchers who predicted that the modularization of chip designs would allow chip performance to continue to improve at the rate predicted by Moore’s Law. With DARPA’s backing, a tripartite ecosystem made up of EDA toolmakers, fabless chip designers, and semiconductor foundries arose and became competitive with established integrated device manufacturers like Intel (Baldwin, 2024, Ch. 8).

5. The future of ecosystem research

5.1. Convergent perspectives in innovation studies

5.1.1. Business models

5.1.2. Open innovation

5.1.3. Research consortia, standards-setting organizations, and open source projects

structure and membership are more fluid.

Prior research has tended to focus on governance at one but not both of these levels of organization. Future research could recognize the hierarchical relation between the larger ecosystem and these specialpurpose organizations, and examine their interaction. For example, when do the norms of the larger ecosystem constrain the policies of the central governing body? And when does the center affect the direction of innovation of the larger ecosystem? These issues have been studied in the context of open source software projects and communities, but not in innovation ecosystems more generally.

5.1.4. Intellectual property (IP)

5.1.5. Organizational capabilities

5.1.6. Entrepreneurial and regional ecosystems

ecosystem can enable, constrain or accelerate the development of the other.

5.1.7. Knowledge ecosystems

5.2. New insights from new methods

6. Conclusion

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Declaration of competing interest

Data availability

Acknowledgements

References

Acs, Z.J., Stam, E., Audretsch, D.B., O’Connor, A., 2017. The lineages of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach. Small Bus. Econ. 49, 1-10.

Adner, R., 2006. Match your innovation strategy to your innovation ecosystem. Harv. Bus. Rev. 84 (4), 98.

Adner, R., 2012. The Wide Lens: A New Strategy for Innovation. Penguin.

Adner, R., 2017. Ecosystem as structure: an actionable construct for strategy. J. Manag. 43 (1), 39-58.

Adner, R., 2021. Winning the Right Game: How to Disrupt, Defend, and Deliver in a Changing World. MIT Press.

Adner, R., Kapoor, R., 2010. Value creation in innovation ecosystems: how the structure of technological interdependence affects firm performance in new technology generations. Strategic Manag. J. 31 (3), 306-333.

Adner, R., Kapoor, R., 2016. Innovation ecosystems and the pace of substitution: reexamining technology S-curves. Strategic Manag. J. 37 (4), 625-648.

Agarwal, S., Kapoor, R., 2022. Value creation tradeoff in business ecosystems: leveraging complementarities while managing interdependencies. Organization Sci. 34 (3), 987-1352.

Altman, E.J., Nagle, F., Tushman, M.L., 2022. The translucent hand of managed ecosystems: engaging communities for value creation and capture. Acad. Manag. Ann. 16 (1), 70-101.

Altman, E.J., Kiron, D., Schwartz, J., Jones, R., 2023. Workforce Ecosystems: Reaching Strategic Goals with People, Partners, and Technologies. MIT Press.

Anderson, P., Tushman, M.L., 1990. Technological discontinuities and dominant designs: a cyclical model of technological change. Adm. Sci. Q. 35 (4), 604-634.

Anderson, P., Tushman, M.L., 2001. Organizational environments and industry exit: the effects of uncertainty, munificence and complexity. Ind. Corp. Chang. 10 (3), 675-711.

Ansari, S., Garud, R., Kumaraswamy, A., 2016. The disruptor’s dilemma: TiVo and the US television ecosystem. Strateg. Manag. J. 37 (9), 1829-1853.

Autio, E., Thomas, L.D., 2021. Researching ecosystems in innovation contexts. Innov. Manag. Rev. 19 (1), 12-25.

Baden-Fuller, C., Haefliger, S., 2013. Business models and technological innovation. Long Range Plann. 46 (6), 419-426.

Baldwin, C.Y., 2008. Where do transactions come from? Modularity, transactions, and the boundaries of firms. Ind. Corp. Chang. 17 (1), 155-195.

Baldwin, C.Y., 2018. Bottlenecks, modules, and dynamic architectural capabilities. In: Teece, D.J., Leih, S. (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Dynamic Capabilities. Oxford University Press.

Baldwin, C.Y., 2024. Design Rules, Volume 2: How Technology Shapes Organizations. MIT Press.

Baldwin, C.Y., Clark, K.B., 1997. Managing in an age of modularity. Harv. Bus. Rev. 75 (5), 84-93.

Baldwin, C.Y., Clark, K.B., 2006. The architecture of participation: does code architecture mitigate free riding in the open source development model? Manag. Sci. 52 (7), 1116-1127.

Baldwin, C.Y., Von Hippel, E., 2011. Modeling a paradigm shift: from producer innovation to user and open collaborative innovation. Organization Sci. 22 (6), 1399-1417.

Baldwin, C.Y., Woodard, C.J., 2009. The architecture of platforms: a unified view. Platforms Markets Innov. 19-44.

Baldwin, C.Y., MacCormack, A.D., Rusnak, J., 2014. Hidden structure: using network methods to map product architecture. Research Policy 43, 1381-1397.

Bogers, M., 2011. The open innovation paradox: knowledge sharing and protection in R&D collaborations. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 14 (1), 93-117.

Bogers, M., Zobel, A.K., Afuah, A., Almirall, E., Brunswicker, S., Dahlander, L., Ter Wal, A.L., 2017. The open innovation research landscape: established perspectives and emerging themes across different levels of analysis. Ind. Innov. 24 (1), 8-40.

Bogers, M., Sims, J., West, J., 2019. What Is an Ecosystem? Incorporating 25 Years of Ecosystem Research. Working Paper. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3437014.

Borner, K., Berends, H., Deken, F., Feldberg, F., 2023. Another pathway to complementarity: how users and intermediaries identify and create new combinations in innovation ecosystems. Res. Policy 52 (7), 104788. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.respol.2023.104788.

Brusoni, Stefano, Prencipe, Andrea, 2001. Unpacking the black box of modularity: technologies, products and organizations. Ind. Corp. Change 10 (1), 179-205.

Brusoni, Stefano, Prencipe, Andrea, Pavitt, Keith, 2001. Knowledge specialization, organizational coupling and the boundaries of the firm: why do firms know more than they make? Adm. Sci. Q. 46 (4), 597-621.

Ceccagnoli, M., Forman, C., Huang, P., Wu, D.J., 2012. Cocreation of value in a platform ecosystem! The case of enterprise software. MIS Q. 263-290.

Cennamo, C., Santalo, J., 2013. Platform competition: strategic trade-offs in platform markets. Strategic Manag. J. 34 (11), 1331-1350.

Cennamo, C., Santaló, J., 2019. Generativity tension and value creation in platform ecosystems. Organ. Sci. 30 (3), 617-641.

Chandler, Alfred D., 1977. The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Chang, L.T., 2009. Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China. Random House Digital, Inc.

Chesbrough, H.W., 2003. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology. Harvard Business Press.

Chesbrough, H., 2020. Open Innovation Results: Going Beyond the Hype and Getting Down to Business. Oxford University Press.

Chesbrough, H., Bogers, M., 2014. Explicating open innovation: Clarifying an emerging paradigm for understanding innovation. In: Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., West, J. (Eds.), New Frontiers in Open Innovation. Oxford University Press, pp. 3-28.

Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., West, J. (Eds.), 2006. Open Innovation: Researching a New Paradigm. Oxford University Press.

Chposky, J., Leonsis, T., 1988. Blue Magic: The People, Power and Politics Behind the IBM Personal Computer. Facts on File Publications, New York, NY.

Christensen, C.M., 2013. The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Harvard Business Review Press.

Clarysse, B., Wright, M., Bruneel, J., Mahajan, A., 2014. Creating value in ecosystems: crossing the chasm between knowledge and business ecosystems. Res. Policy 43 (7), 1164-1176.

Cobben, D., Ooms, W., Roijakkers, N., Radziwon, A., 2022. Ecosystem types: a systematic review on boundaries and goals. J. Bus. Res. 142, 138-164.

Cohen, W.M., 2010. Fifty years of empirical studies of innovative activity and performance. In: Handbook of the Economics of Innovation, 1, pp. 129-213.

Colfer, L.J., Baldwin, C.Y., 2016. The mirroring hypothesis: theory, evidence, and exceptions. Ind. Corp. Change 25 (5), 709-738.

Cozzolino, A., Geiger, S., 2024. Ecosystem disruption and regulatory positioning: entry strategies of digital health startup orchestrators and complementors. Res. Policy 53 (2), 104913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104913.

Cyert, R.M., March, J.G., 1963. A Behavioral Theory of the Firm. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Dahlander, L., Gann, D.M., Wallin, M.W., 2021. How open is innovation? A retrospective and ideas forward. Res. Policy 50 (4), 104218.

Dattée, B., Alexy, O., Autio, E., 2018. Maneuvering in poor visibility: how firms play the ecosystem game when uncertainty is high. Acad. Manage. J. 61 (2), 466-498.

Dosi, G., 1982. Technological paradigms and technological trajectories: a suggested interpretation of the determinants and directions of technical change. Res. Policy 11 (3), 147-162.

Edquist, C., 1997. Systems of Innovation: Technologies, Institutions, and Organizations. Pinter, London.

Eisenmann, T., Parker, G., Van Alstyne, M., 2011. Platform envelopment. Strategic Manag. J. 32 (12), 1270-1285.

Ethiraj, S.K., 2007. Allocation of inventive effort in complex product systems. Strategic Manag. J. 28 (6), 563-584.

Fagerberg, J., Verspagen, B., 2009. Innovation studies-the emerging structure of a new scientific field. Res. Policy 38 (2), 218-233.

Franke, N., von Hippel, E., 2003. Satisfying heterogeneous user needs via innovation toolkits: the case of Apache security software. Res. Policy 32 (7), 1199-1215.

Freeman, C., 1974. The Economics of Industrial Innovation. Penguin, London.

Freeman, C., 1995. The ‘National System of Innovation’ in historical perspective. Camb. J. Econ. 19 (1), 5-24.

Ganco, M., Kapoor, R., Lee, G.K., 2020. From rugged landscapes to rugged ecosystems: structure of interdependencies and firms’ innovative search. Acad. Manage. Rev. 45 (3), 646-674.

Gault, F., 2018. Defining and measuring innovation in all sectors of the economy. Res. Policy 47 (3), 617-622.

Gawer, A., 2021. Digital platforms’ boundaries: the interplay of firm scope, platform sides, and digital interfaces. Long Range Plann. 54 (5), 102045.

Gawer, A., Cusumano, M.A., 2002. Platform Leadership: How Intel, Microsoft, and Cisco Drive Industry Innovation. Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Gawer, A., Phillips, N., 2013. Institutional work as logics shift: the case of Intel’s transformation to platform leader. Organization Stud. 34 (8), 1035-1071.

Granstrand, O., Holgersson, M., 2020. Innovation ecosystems: a conceptual review and a new definition. Technovation 90, 102098.

Grove, Andrew S., 1996. Only the Paranoid Survive. Doubleday, New York.

Hagedoorn, J., Cloodt, M., 2003. Measuring innovative performance: is there an advantage in using multiple indicators? Res. Policy 32 (8), 1365-1379.

Haki, K., Blaschke, M., Aier, S., Winter, R., Tilson, D., 2022. Dynamic capabilities for transitioning from product platform ecosystem to innovation platform ecosystem. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 1-19.

Hannah, D.P., Eisenhardt, K.M., 2018. How firms navigate cooperation and competition in nascent ecosystems. Strateg. Manag. J. 39 (12), 3163-3192.

Heaton, S., Siegel, D.S., Teece, D.J., 2019. Universities and innovation ecosystems: a dynamic capabilities perspective. Industrial Corp. Change 28 (4), 921-939.

Helfat, C.E., 2000. Guest editor’s introduction to the special issue: the evolution of firm capabilities. Strategic Manag. J. 21 (10-11), 955-959.

Helfat, C.E., Peteraf, M.A., 2015. Managerial cognitive capabilities and the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities. Strategic Manag. J. 36 (6), 831-850.

Helfat, C.E., Raubitschek, R.S., 2018. Dynamic and integrative capabilities for profiting from innovation in digital platform-based ecosystems. Res. Policy 47 (8), 1391-1399.

Helper, S., Sako, M., 2010. Management innovation in supply chain: appreciating Chandler in the twenty-first century. Industrial Corp. Change 19 (2), 399-429.

Henderson, R.M., Clark, K.B., 1990. Architectural innovation: the reconfiguration of existing systems and the failure of established firms. Adm. Sci. Q. 35 (1), 9-30.

Holgersson, M., Baldwin, C.Y., Chesbrough, H., Bogers, M.L., 2022. The forces of ecosystem evolution. Calif. Manage. Rev. 64 (3), 5-23.

Iansiti, Marco, Levien, Roy, 2004. The Keystone Advantage: What the New Dynamics of Business Ecosystems Mean for Strategy, Innovation, and Sustainability. Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Intel Oral History Panel, 2008. Computer History Museum, Mountain View, CA. http://ar chive.computerhistory.org/resources/text/oral_history/Intel_386_Business_Strategy/ 102701962.05.01.pdf. August 14, (viewed April 18, 2017).

Jacobides, M.G., Cennamo, C., Gawer, A., 2024. Externalities and complementarities in platforms and ecosystems: from structural solutions to endogenous failures. Res. Policy 53 (1), 104906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104906.

Järvi, K., Almpanopoulou, A., Ritala, P., 2018. Organization of knowledge ecosystems: prefigurative and partial forms. Res. Policy 47 (8), 1523-1537.

Jones, S.L., Leiponen, A., Vasudeva, G., 2021. The evolution of cooperation in the face of conflict: evidence from the innovation ecosystem for mobile telecom standards development. Strategic Manag. J. 42 (4), 710-740.

Kamien, M.I., Schwartz, N.L., 1982. Market Structure and Innovation. Cambridge University Press.

Kapoor, R., 2018. Ecosystems: broadening the locus of value creation. J. Organ. Des. 7 (1), 1-16.

Kapoor, R., Agarwal, S., 2017. Sustaining superior performance in business ecosystems: evidence from application software developers in the iOS and Android smartphone ecosystems. Organization Sci. 28 (3), 531-551.

Kapoor, R., Lee, J.M., 2013. Coordinating and competing in ecosystems: how organizational forms shape new technology investments. Strategic Manag. J. 34 (3), 274-296.

Kapoor, R., McGrath, P.J., 2014. Unmasking the interplay between technology evolution and R&D collaboration: evidence from the global semiconductor manufacturing industry, 1990-2010. Res. Policy 43 (3), 555-569.

Klepper, S., 1996. Entry, exit, growth, and innovation over the product life cycle. Am. Econ. Rev. 562-583.

Klepper, S., 1997. Industry life cycles. Ind. Corp. Change 6 (1), 145-182.

Kretschmer, T., Leiponen, A., Schilling, M., Vasudeva, G., 2022. Platform ecosystems as meta-organizations: implications for platform strategies. Strategic Manag. J. 43 (3), 405-424.

Kuan, J., West, J., 2023. Interfaces, modularity and ecosystem emergence: how DARPA modularized the semiconductor ecosystem. Res. Policy 52 (8), 104789. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104789.

Laursen, K., Salter, A., 2006. Open for innovation: the role of openness in explaining innovation performance among UK manufacturing firms. Strategic Manag. J. 27 (2), 131-150.

Laursen, K., Salter, A., 2014. The paradox of openness: appropriability, external search and collaboration. Res. Policy 43 (5), 867-878.

Lee, S., Kim, W., Lee, H., Jeon, J., 2016. Identifying the structure of knowledge networks in the US mobile ecosystems: patent citation analysis. Tech. Anal. Strat. Manag. 28 (4), 411-434.

Locke, R.M., 1996. The composite economy: local politics and industrial change in contemporary Italy. Econ. Soc. 25 (4), 483-510.

MacCormack, Alan, Rusnak, John, Baldwin, Carliss, 2006. Exploring the structure of complex software designs: an empirical study of open source and proprietary code. Manag. Sci. 52 (7), 1015-1030.

MacCormack, Alan, Baldwin, Carliss, Rusnak, John, 2012. Exploring the duality between product and organizational architectures: a test of the “mirroring” hypothesis. Res. Policy 41 (8), 1309-1324.

Malerba, F., 2002. Sectoral systems of innovation and production. Res. Policy 31 (2), 247-264.

Martin, B.R., 2012. The evolution of science policy and innovation studies. Res. Policy 41 (7), 1219-1239.

Milgrom, P., Roberts, J., 1995. Complementarities and fit strategy, structure, and organizational change in manufacturing. J. Account. Econ. 19 (2), 179-208.

Miric, M., Jeppesen, L.B., 2023. How does competition influence innovative effort within a platform-based ecosystem? Contrasting paid and unpaid contributors. Res. Policy 52 (7), 104790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104790.

Moore, J.F., 1993. Predators and prey: a new ecology of competition. Harv. Bus. Rev. 71 (3), 75-86.

Morris, Charles R., Ferguson, Charles H., 1993. How Architecture Wins Technology Wars, March-April. Harvard Business Review, pp. 86-96.

Mowery, D.C., Nelson, R.R. (Eds.), 1999. Sources of Industrial Leadership. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Nelson, Richard R. (Ed.), 1993. National Innovation Systems: A Comparative Analysis. Oxford University Press, New York.

Nelson, R.R., Winter, S.G., 1982. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Harvard University Press.

Nicotra, M., Romano, M., Del Giudice, M., Schillaci, C.E., 2018. The causal relation between entrepreneurial ecosystem and productive entrepreneurship: a measurement framework. J. Technol. Transfer. 43 (3), 640-673.

Olk, P., West, J., 2020. The relationship of industry structure to open innovation: cooperative value creation in pharmaceutical consortia. R&D Manag. 50 (1), 116-135.

Olk, P., West, J., 2023. Distributed governance of a complex ecosystem: how R&D consortia orchestrate the Alzheimer’s knowledge ecosystem. Calif. Manage. Rev. 65 (2), 93-128.

Parker, G., Van Alstyne, M., Jiang, X., 2017. Platform ecosystems. MIS Q. 41 (1), 255-266.

Parnas, David L., 1972. A technique for software module specification with examples. Commun. ACM 15, 330-336.

Parnas, David L., 1972b. On the Criteria to Be Used in Decomposing Systems into Modules. In: Communications of the ACM 15: 1053-58. Software Fundamentals: Collected Papers of David Parnas. Addison-Wesley, Boston MA reprinted in Hoffman and Weiss (eds.).

Parnas, David L., 2001. In: Hoffman, D.M., Weiss, D.M. (Eds.), Software Fundamentals: Collected Papers by David L. Parnas. Addison-Wesley, Boston MA.

Pavitt, K., 1984. Sectoral patterns of technical change: towards a taxonomy and a theory. Res. Policy 13 (6), 343-373.

Pavitt, K., 1999. Technology, Management and Systems of Innovation. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Pujadas, R., Valderrama, E., Venters, W., 2024. The value and structuring role of web APIs in digital innovation ecosystems: the case of the online travel ecosystem. Res. Policy 53 (2), 104931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104931.

Qiu, Y., Gopal, A., Hann, I.H., 2017. Logic pluralism in mobile platform ecosystems: a study of indie app developers on the iOS app store. Inf. Syst. Res. 28 (2), 225-249.

Randhawa, K., West, J., Skellern, K., Josserand, E., 2021. Evolving a value chain to an open innovation ecosystem: cognitive engagement of stakeholders in customizing medical implants. Calif. Manage. Rev. 63 (2), 101-134.

Randhawa, K., Wilden, R., Akaka, M.A., 2022. Innovation intermediaries as collaborators in shaping service ecosystems: the importance of dynamic capabilities. Ind. Mark. Manag. 103, 183-197.

Reiter, A., Stonig, J., Frankenberger, K., 2024. Managing multi-tiered innovation ecosystems. Res. Policy 53 (1), 104905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. respol.2023.104905.

Reypens, C., Lievens, A., Blazevic, V., 2021. Hybrid orchestration in multi-stakeholder innovation networks: practices of mobilizing multiple, diverse stakeholders across organizational boundaries. Organization Stud. 42 (1), 61-83.

Rietveld, J., Schilling, M.A., Bellavitis, C., 2019. Platform strategy: managing ecosystem value through selective promotion of complements. Organization Sci. 30 (6), 1232-1251.

Rohrbeck, R., Hölzle, K., Gemünden, H.G., 2009. Opening up for competitive advantage-how Deutsche Telekom creates an open innovation ecosystem. R&D Manag. 39 (4), 420-430.

Rosenberg, N., 1982. Inside the Black Box: Technology and Economics. Cambridge University Press.

Sako, M., Helper, S., 1998. Determinants of trust in supplier relations: evidence from the automotive industry in Japan and the United States. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 34 (3), 387-417.

Saxenian, A., 1996. Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128, With a New Preface by the Author. Harvard University Press.

Schäper, T., Jung, C., Foege, J.N., Bogers, M.L.A.M., Fainshmidt, S., Nüesch, S., 2023. The S -shaped relationship between open innovation and financial performance: a longitudinal perspective using a novel text-based measure. Res. Policy 52 (6), 104764.

Schmookler, J., 1966. Invention and Economic Growth. Harvard University Press.

Schreieck, M., Wiesche, M., Krcmar, H., 2021. Capabilities for value co-creation and value capture in emergent platform ecosystems: A longitudinal case study of SAP’s cloud platform. J. Inf. Technol. 36 (4), 365-390. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 02683962211023780.

Schumpeter, Joseph A., 1942. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. Harper & Brothers, New York.

Simcoe, T., 2006. Open standards and intellectual property rights. In: Open Innovation: Researching a New Paradigm. Oxford University Press.

Simon, H.A., 1947. Administrative Behavior. Simon and Schuster.

Simon, Herbert A., 1962. The Architecture of Complexity. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 106: 467-482, reprinted in Simon (1981) The Sciences of the Artificial, 2nd ed. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 193-229.

Simon, Herbert A., 1969. The Sciences of the Artificial. MIT Press, Cambridge MA.

Smith, K., 2006. Measuring innovation. In: Fagerberg, Jan, Mowery, David C. (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Innovation (Oxford).

Snihur, Y., Zott, C., Amit, R., 2021. Managing the value appropriation dilemma in business model innovation. Strat. Sci. 6 (1), 22-38. https://doi.org/10.1287/ stsc.2020.0113.

Song, Y., Gnyawali, D., Qian, L., 2024. From early curiosity to space wide web: the emergence of the small satellite innovation ecosystem. Res. Policy 53 (2), 104932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104932.

Stam, E., 2015. Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: a sympathetic critique. Eur. Plan. Stud. 23 (9), 1759-1769. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 09654313.2015.1061484.

Staudenmayer, Nancy, Tripsas, Mary, Tucci, Christopher L., 2005. Interfirm modularity and its implications for product development. J. Product Innov. Manag. 22 (4), 303-321.

Sturgeon, Timothy J., 2002. Modular production networks: a new American model of industrial organization. Ind. Corp. Change 11 (3), 451-496.

Sturgeon, T.J., Kawakami, M., 2011. Global value chains in the electronics industry: characteristics, crisis, and upgrading opportunities for firms from developing countries. Int. J. Technol. Learn. Innov. Develop. 4 (1-3), 120-147.

Suarez, F.F., 2004. Battles for technological dominance: an integrative framework. Res. Policy 33 (2), 271-286.

Sydow, J., Windeler, A., Schubert, C., Möllering, G., 2012. Organizing R&D consortia for path creation and extension: the case of semiconductor manufacturing technologies. Organ. Stud. 33 (7), 907-936.

Teece, D.J., 1986. Profiting from technological innovation: implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Res. Policy 15 (6), 285-305.

Teece, D.J., 2006. Reflections on “profiting from innovation”. Res. Policy 35 (8), 1131-1146.

Teece, D.J., 2009. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management: Organizing for innovation and growth. Oxford University Press.

Teece, D.J., 2018. Profiting from innovation in the digital economy: enabling technologies, standards, and licensing models in the wireless world. Res. policy 47 (8), 1367-1387.

Thun, E., Taglioni, D., Sturgeon, T., Dallas, M.P., 2022. Massive Modularity: Understanding Industry Organization in the Digital Age-The Case of Mobile Phone Handsets. No. 10164. The World Bank.

Toh, P.K., Miller, C.D., 2017. Pawn to save a chariot, or drawbridge into the fort? Firms’ disclosure during standard setting and complementary technologies within ecosystems. Strategic Manag. J. 38 (11), 2213-2236.

Tushman, M.L., Anderson, P., 1986. Technological discontinuities and organizational environments. Adm. Sci. Q. 31 (3), 439-465.

Utterback, J.M., Abernathy, W.J., 1975. A dynamic model of process and product innovation. Omega 3 (6), 639-656.

Uzunca, B., Sharapov, D., Tee, R., 2022. Governance rigidity, industry evolution, and value capture in platform ecosystems. Res. Policy 51 (7), 104560.

van der Borgh, M., Cloodt, M., Romme, A.G.L., 2012. Value creation by knowledge-based ecosystems: evidence from a field study. R&D Manag. 42 (2), 150-169.

van Dyck, M., Lüttgens, D., Diener, K., Piller, F., Pollok, P., 2024. From product to platform: how incumbents’ assumptions and choices shape their platform strategy. Res. Policy 53 (1), 104904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104904.

von Hippel, E., 1988. The Sources of Innovation (Oxford).

von Hippel, E., 2005. Democratizing Innovation. MIT Press.

von Hippel, E., 2019. Free Innovation. MIT Press.

West, J., 2014. Challenges of funding open innovation platforms: lessons from Symbian Ltd. In: Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., West, J. (Eds.), New Frontiers in Open Innovation. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 71-93.

West, J., Dedrick, J., 2000. Innovation and control in standards architectures: the rise and fall of Japan’s PC-98. Inform. Syst. Res. 11 (2), 197-216.

West, J., Gallagher, S., 2006. Challenges of open innovation: the paradox of firm investment in open-source software. R&D Manag. 36 (3), 319-331.

West, J., Wood, D., 2013. Evolving an open ecosystem: the rise and fall of the Symbian platform. Adv. Strateg. Manag. 30, 27-68.

Womack, J.P., Jones, D.T., Roos, D., 1990. The Machine That Changed the World: The Story of Lean Production. Rawson Associates, New York, NY.

Wurth, B., Stam, E., Spigel, B., 2022. Toward an entrepreneurial ecosystem research program. Entrep. Theory Pract. 46 (3), 729-778.

Zhu, F., Iansiti, M., 2012. Entry into platform-based markets. Strategic Manag. J. 33 (1), 88-106.

Zott, C., Amit, R., Massa, L., 2011. The business model: recent developments and future research. J. Manag. 37 (4), 1019-1042.

- Corresponding author.

E-mail address: dr.joel.west@gmail.com (J. West).