المجلة: Scientific Reports، المجلد: 15، العدد: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79574-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39762311

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-06

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79574-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39762311

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-06

افتح

جزيئات السيلينيوم النانوية المغلفة بالكيتوزان النانوي، المُصنَّعة بطريقة خضراء، كعامل مضاد للفطريات جديد ضد Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: دراسة في المختبر

تم استخدام المبيدات الفطرية الكيميائية للسيطرة على الأمراض الفطرية مثل Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. يجب تقييد هذه المبيدات بسبب سميتها وتطور سلالات مقاومة. لذلك، فإن استخدام المواد الطبيعية على النانو في الإنتاج الزراعي هو بديل محتمل. كان الهدف من هذا العمل هو دراسة الخصائص المضادة للفطريات لمركب نانو (جزيئات السيلينيوم التي تم تصنيعها بطريقة خضراء والمغلفة بالكيتوزان) ضد الفطر الممرض للنبات S. sclerotiorum. تم استخدام الاختزال الكيميائي لإنتاج جزيئات السيلينيوم من مستخلصات قشور الحمضيات، وتم استخدام التجلط الأيوني لإنتاج جزيئات الكيتوزان. تم إنتاج المركب النانوي باستخدام جزيئات السيلينيوم المستقرة بواسطة الكيتوزان والمترابطة مع فوسفات الصوديوم ثلاثي البولي. تم استخدام المجهر الإلكتروني الناقل، وتشتت الضوء الديناميكي، وحيود الأشعة السينية، وطيف الأشعة فوق البنفسجية-المرئية، وطيف الأشعة تحت الحمراء بتحويل فورييه لتوصيف جميع الهياكل النانوية المنتجة. تم التحقيق في النشاط المضاد للفطريات في المختبر والتركيز المثبط الأدنى لجميع الهياكل الضخمة والنانوية في

الكلمات الرئيسية: التخليق الأخضر، الكيتوزان، السيلينيوم، النانو مركب، سكليروتينيا سكليروتيوم

س. سكليروتيوم، أو العفن الأبيض، له تأثيرات سلبية مختلفة على نمو النبات. على سبيل المثال، يمكن أن يتسبب في انخفاض وزن ساق النبات وجذوره، سواء كانت طازجة أو جافة، مما يؤدي إلى موت أنسجة العائل.

س. سكليروتيوم، أو العفن الأبيض، له تأثيرات سلبية مختلفة على نمو النبات. على سبيل المثال، يمكن أن يتسبب في انخفاض وزن ساق النبات وجذوره، سواء كانت طازجة أو جافة، مما يؤدي إلى موت أنسجة العائل.

إنتاج كميات كبيرة من أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية، والسموم، وإنزيمات تكسير جدران الخلايا (CWDEs). تؤدي هذه العملية في النهاية إلى تحفيز موت خلايا العائل وظهور أعراض نخرية.

تظهر الدراسات الحديثة تأثير السيلينيوم المضاد للفطريات ضد S. sclerotiorum كمادة طبيعية على شكل سيلينيت الصوديوم.

تم مؤخرًا اختبار النشاط المضاد للفطريات لجزيئات نانو السيلينيوم المصنعة كيميائيًا ضد S. sclerotiorum

الكيتوزان (CS) هو مبيد فطري طبيعي محتمل تم اختياره في هذه الدراسة مع جزيئات السيلينيوم النانوية لعلاج العدوى بعد الحصاد في الفواكه والخضروات.

تتناول الدراسة الحالية نهجًا منهجيًا لتحضير وتوصيف جزيئات السيلينيوم المغلفة بالشيتيزان النانوي (NCS-Se NPs) التي تم تحضيرها بطريقة خضراء. ستلعب جزيئات الشيتيزان دورًا مزدوجًا كعامل مثبت لجزيئات السيلينيوم وكعامل مضاد للفطريات طبيعي مع جزيئات السيلينيوم ضد نفس المسبب المرضي، S. sclerotiorum. تم اختبار النشاط المضاد للفطريات في الدراسات المخبرية لتركيزات مختلفة من الجزيئات الكبيرة والنانويّة، مقارنةً بالنانوجزيئات الكاملة (NCS-Se NPs)، لدراسة تأثيرها التآزري وتحديد الحد الأدنى من التركيز المثبط (MIC). تم اختبار النشاط المضاد للفطريات للهياكل النانوية عند نفس تركيزات أشكالها الكبيرة، متأثرةً بحجم جزيئاتها. غالبًا ما يكون الحجم أحد العوامل الأكثر أهمية التي تؤثر على النشاط المضاد للفطريات للمادة المختبرة.

النتائج والمناقشة

تحديد العزلة الفطرية

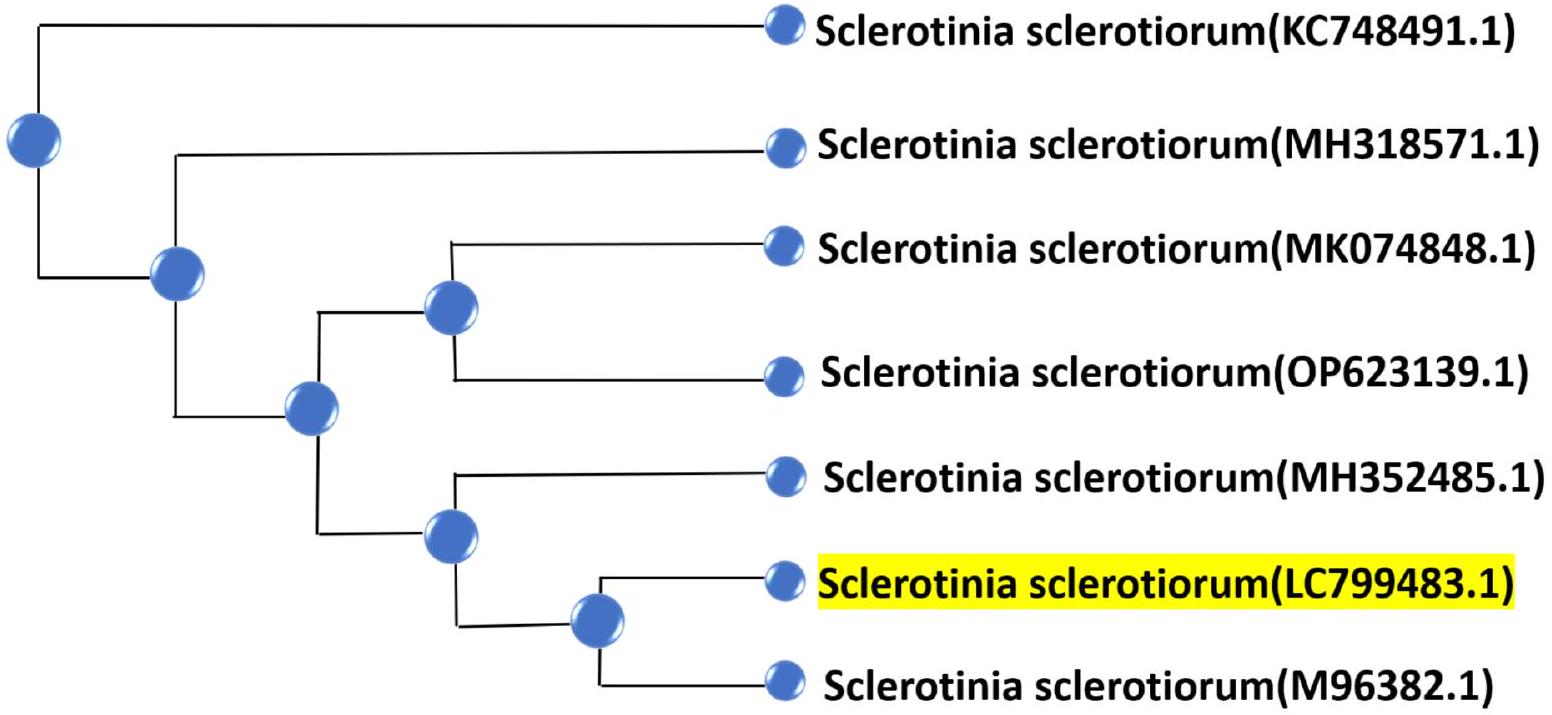

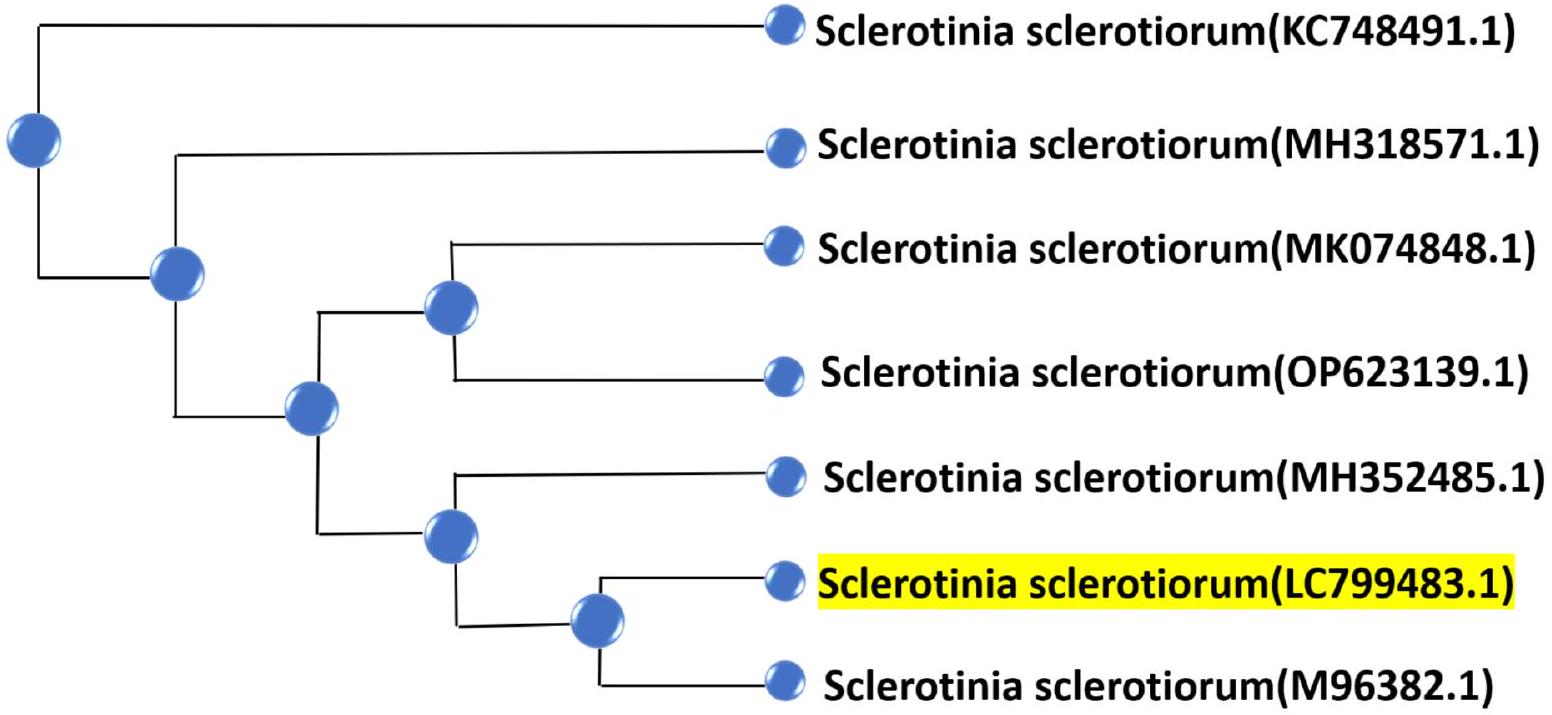

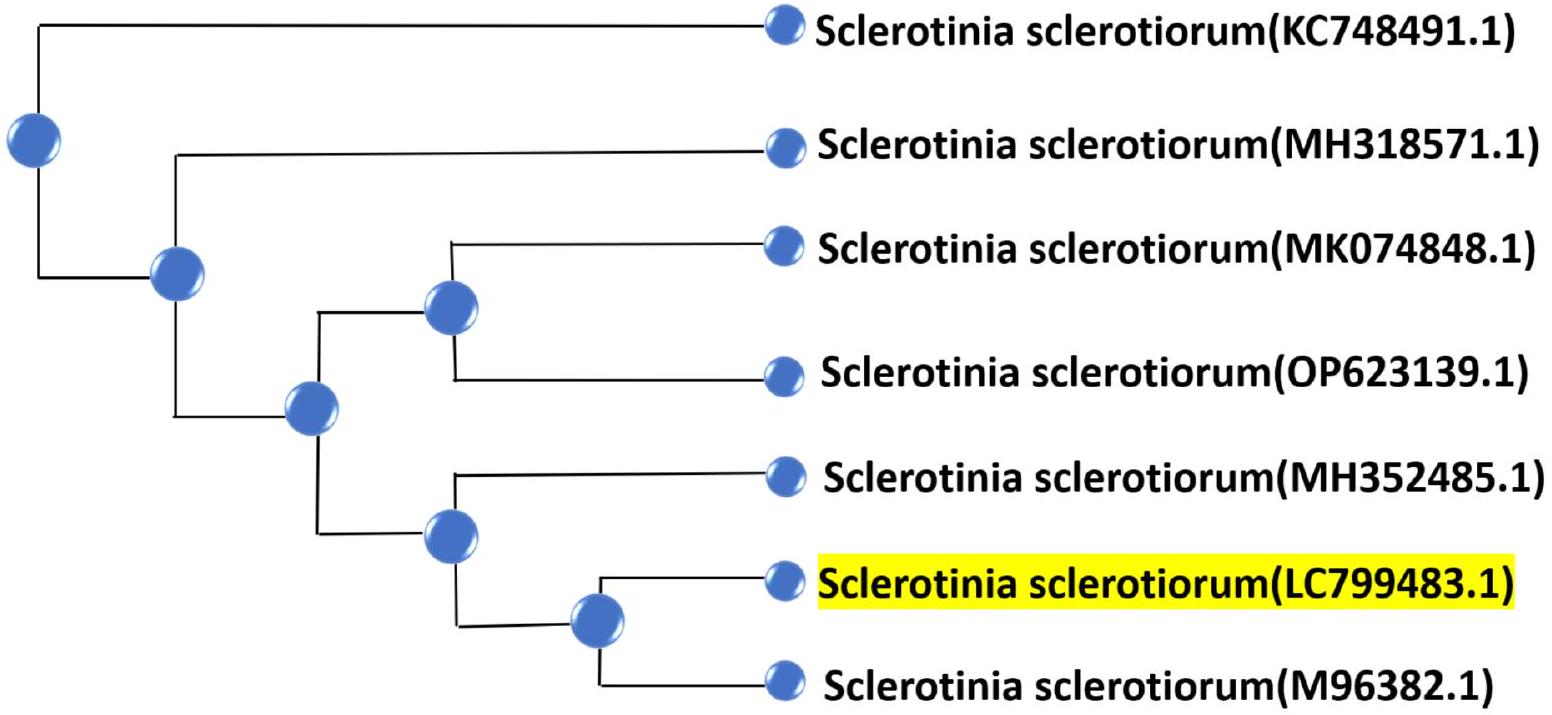

تم تسلسل منطقة ITS الفطرية باستخدام PCR وتم التحقق منها مع قواعد بيانات تسلسل GenBank. تم محاذاة جميع التسلسلات المستخرجة وتحليلها. كان أفضل نموذج استبدال مناسب للمحاذاة هو نموذج كيمورا ذو المعاملين مع توزيع غاما. تم بناء شجرة انضمام الجوار استنادًا إلى تسلسل ITS لجميع السلالات (الشكل 1). أعطى تسلسل ITS تشابهًا عاليًا مع S. sclerotiorum، وكان رقم الوصول للتسلسل هو LC799483.

تحسين التخليق الأخضر لجزيئات السيلينيوم النانوية

تم تحسين عملية التحضير واختيار قشر الحمضيات المناسب لإنتاج الجسيمات النانوية بأحجام أصغر، واستقرار أعلى، وتشتت أفضل. عادةً ما تُعرف الجسيمات النانوية الأصغر بأنها تمتلك نشاطًا مضادًا للفطريات أكثر فعالية من الجسيمات النانوية الأكبر.

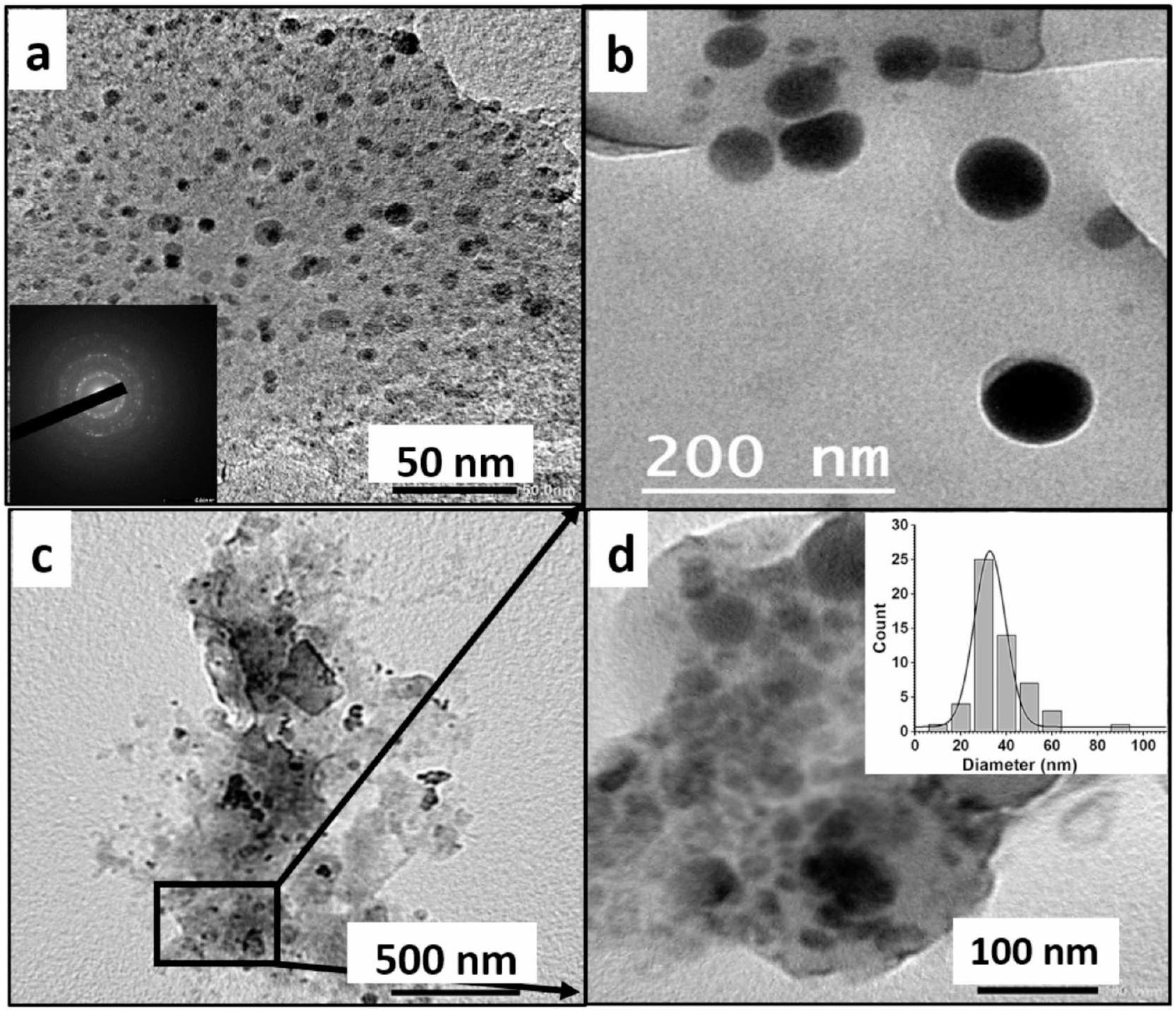

الشكل 2أ، ب يظهر صور TEM لجزيئات L.P. -Se NPs و O.P. -Se NPs، على التوالي، مع عرض توزيع الحجم في الرسم البياني المرفق (في كل منهما). أكدت النتائج التخليق الأخضر لجزيئات Se NPs مع توزيع حجم أفضل لجزيئات L.P. -Se NPs دون تكتلات، كما هو موضح في الشكل 2أ. في هذه الحالة، كان متوسط القطر هو

الشكل 2ج، د يقدم جهد زتا لجزيئات L.P. -Se NPs و O.P. -Se NPs ليكون -19 مللي فولت و +12 مللي فولت، على التوالي. جهد الزتا هو الجهد الكهروستاتيكي عند قياسه عند الطبقة الكهربائية المزدوجة حول جزيء نانوي في المحلول. تحتوي الجزيئات النانوية المحايدة على جهد زتا بين -10 و +10 مللي فولت، بينما تحتوي الجزيئات النانوية الكاتيونية بشدة والجزيئات النانوية الأنيونية بشدة على جهود زتا أكبر من +30 مللي فولت أو أقل من

الشكل 1. شجرة انضمام الجيران لسلالات Sclerotinia sclerotiorum المعزولة. تم إيداع S. sclerotiorum في هذه الدراسة في GeneBank برقم الوصول LC799483.1.

الشكل 2. صورة TEM لجزيئات Se NPs المصنعة بواسطة (أ) مستخلص قشر الليمون (L.P.- Se NPs) مع رسم بياني مرفق يظهر القطر الذروي عند

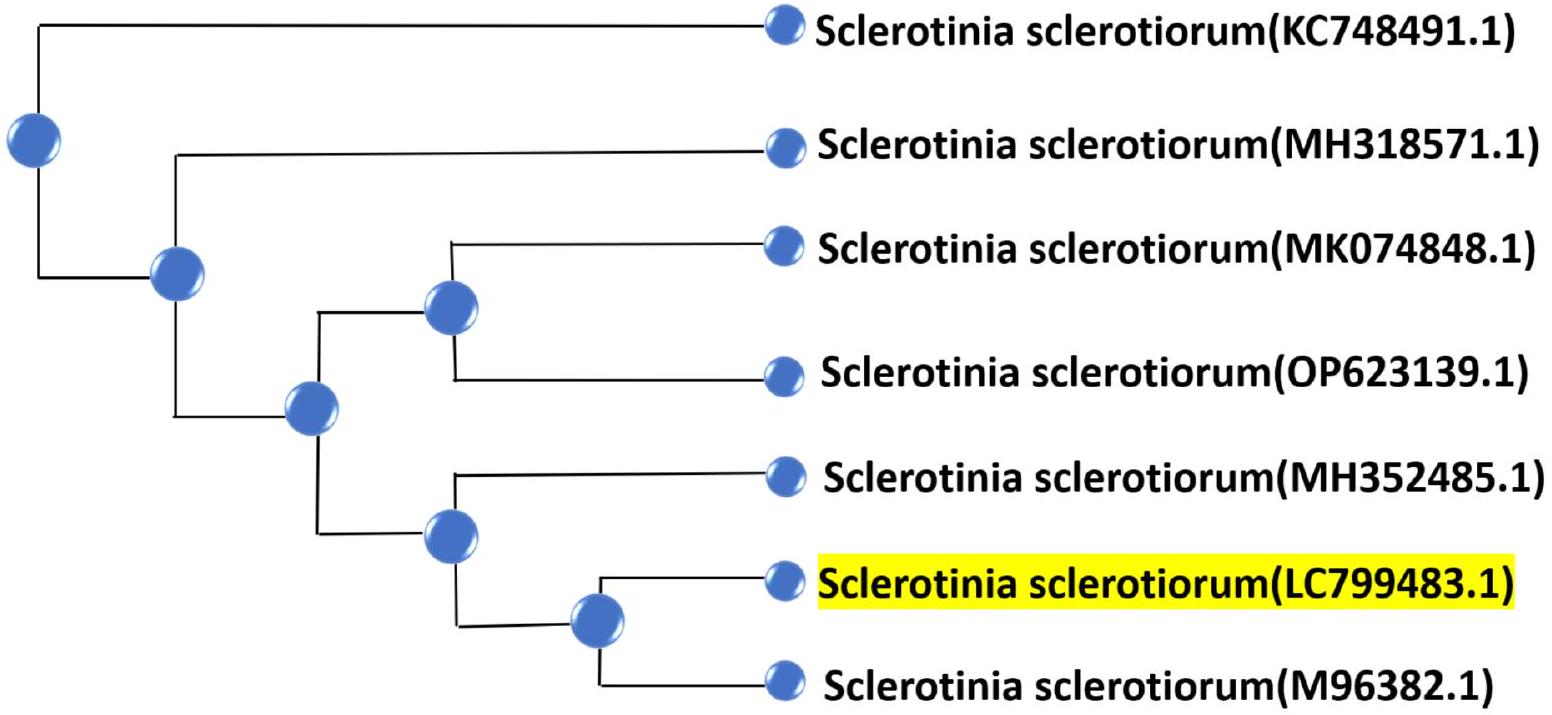

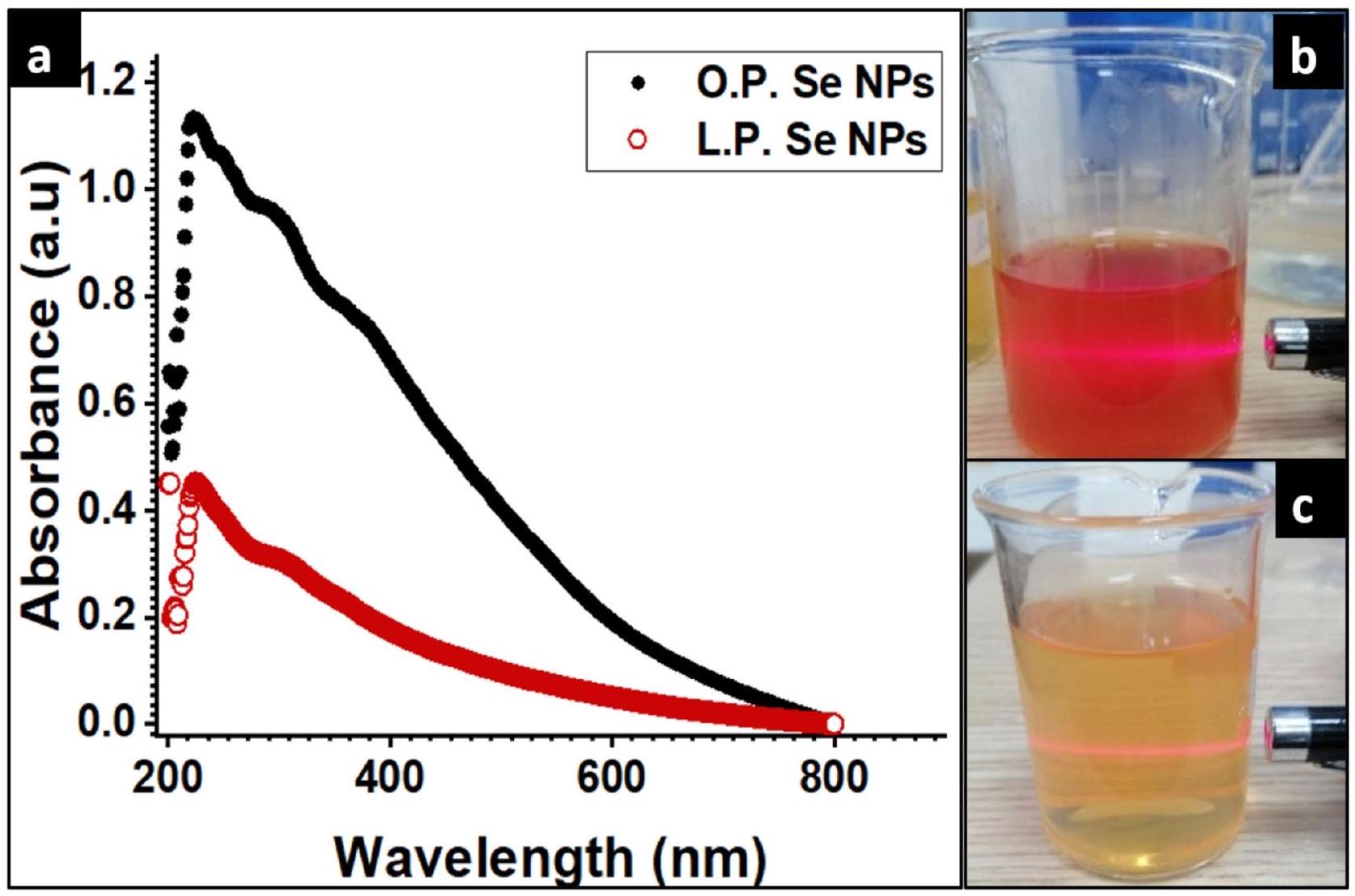

كما هو موضح في الشكل 3أ، كشفت نتائج تحليل UV عن قمم تظهر عند 222 نانومتر و 226 نانومتر في حالة L.P. -Se NPs و O.P. -Se NPs، على التوالي؛ تمثل هذه القمم تكوين جزيئات Se NPs بسبب اختزال أيونات السيلينيت بواسطة حمض الأسكوربيك الموجود في مستخلصات قشر الليمون والبرتقال إلى سيلينيوم عنصري

كما هو موضح في الشكل 3ب، ج، تم استخدام شعاع ليزر في البداية لتأكيد تكوين الجزيئات في كلا الحالتين بسبب تأثير تيندال. تم اختبار تأثير تيندال للتحقق من الهيكل الكولوي والموزع للجزيئات النانوية

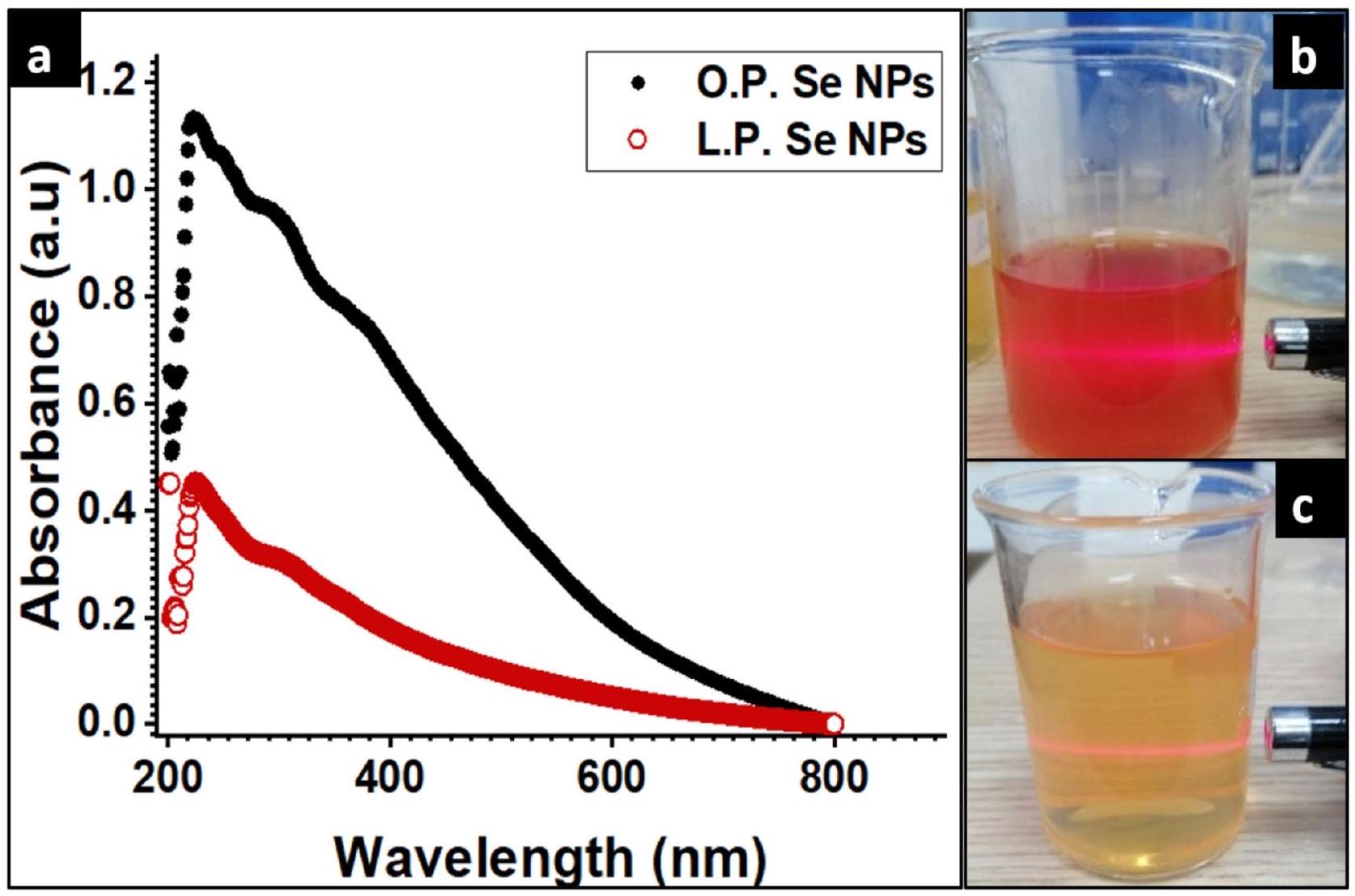

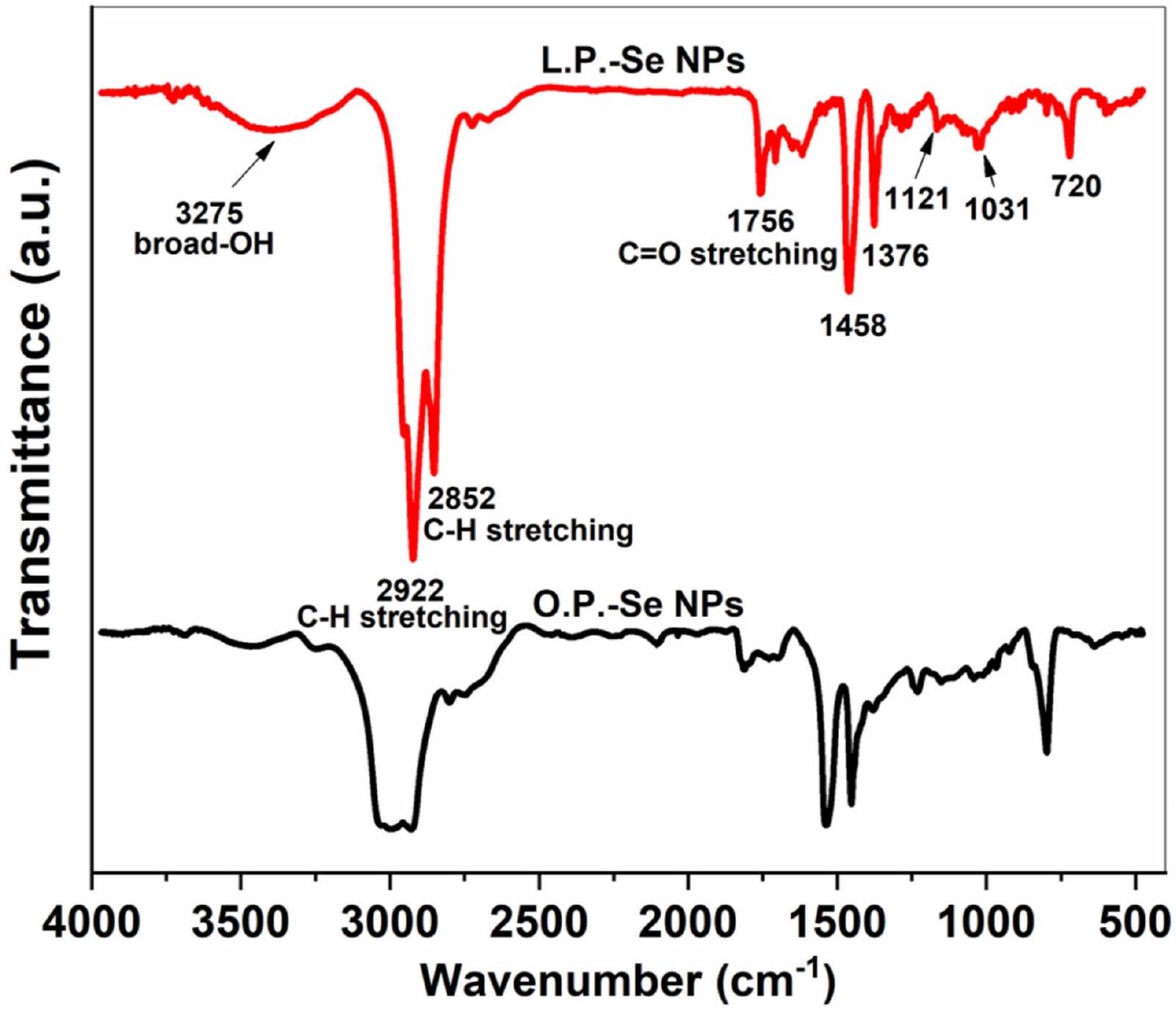

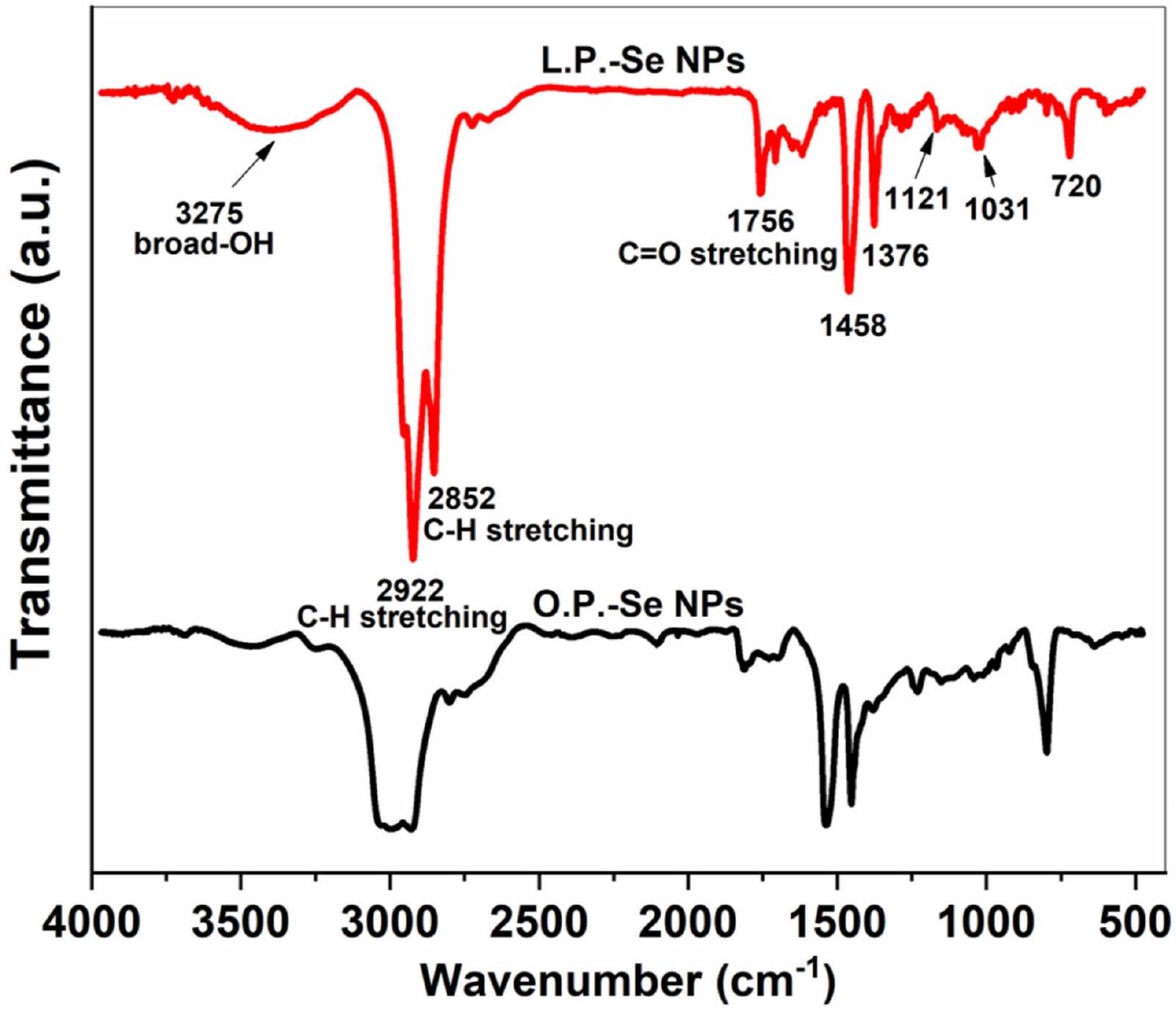

في الشكل 4، قدم تحليل FT-IR التخليق الأخضر لجزيئات Se NPs، باستخدام مستخلص قشر الليمون أو البرتقال، في المنطقة من

كما لوحظ في الشكل 4، فإن شدة معظم نطاقات الامتصاص في حالة L.P. -Se NPs أعلى من نطاقات O.P.-Se NPs. سبب هذا الاختلاف هو انخفاض حجم الجسيمات وزيادة مساحة السطح إلى

الشكل 3. يظهر توصيف الجزيئات المصنعة، (أ) طيف UV لجزيئات O.P.- Se NPs و L.P.- Se NPs (

الشكل 4. طيف FT-IR لجزيئات Se NPs المصنعة بواسطة مستخلصات قشر الليمون والبرتقال.

نسبة الحجم، مما يؤدي إلى زيادة شدة نطاقات الامتصاص في طيف FT-IR حيث تحتوي الجزيئات الأصغر على نسبة أكبر من الذرات على السطح، والتي يمكن أن تتفاعل بشكل أكثر سهولة مع الإشعاع تحت الأحمر الساقط، مما يؤدي إلى إشارة امتصاص أقوى

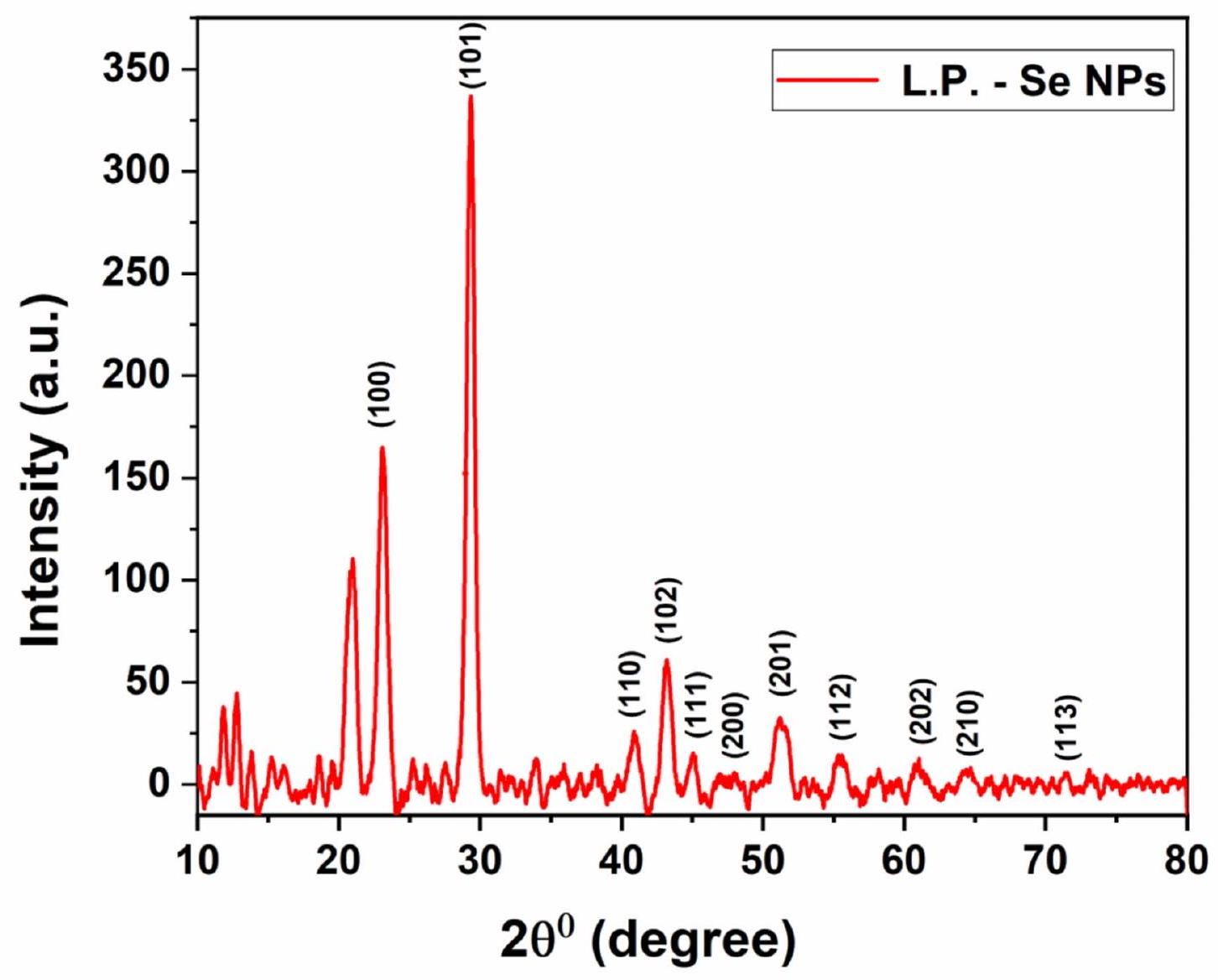

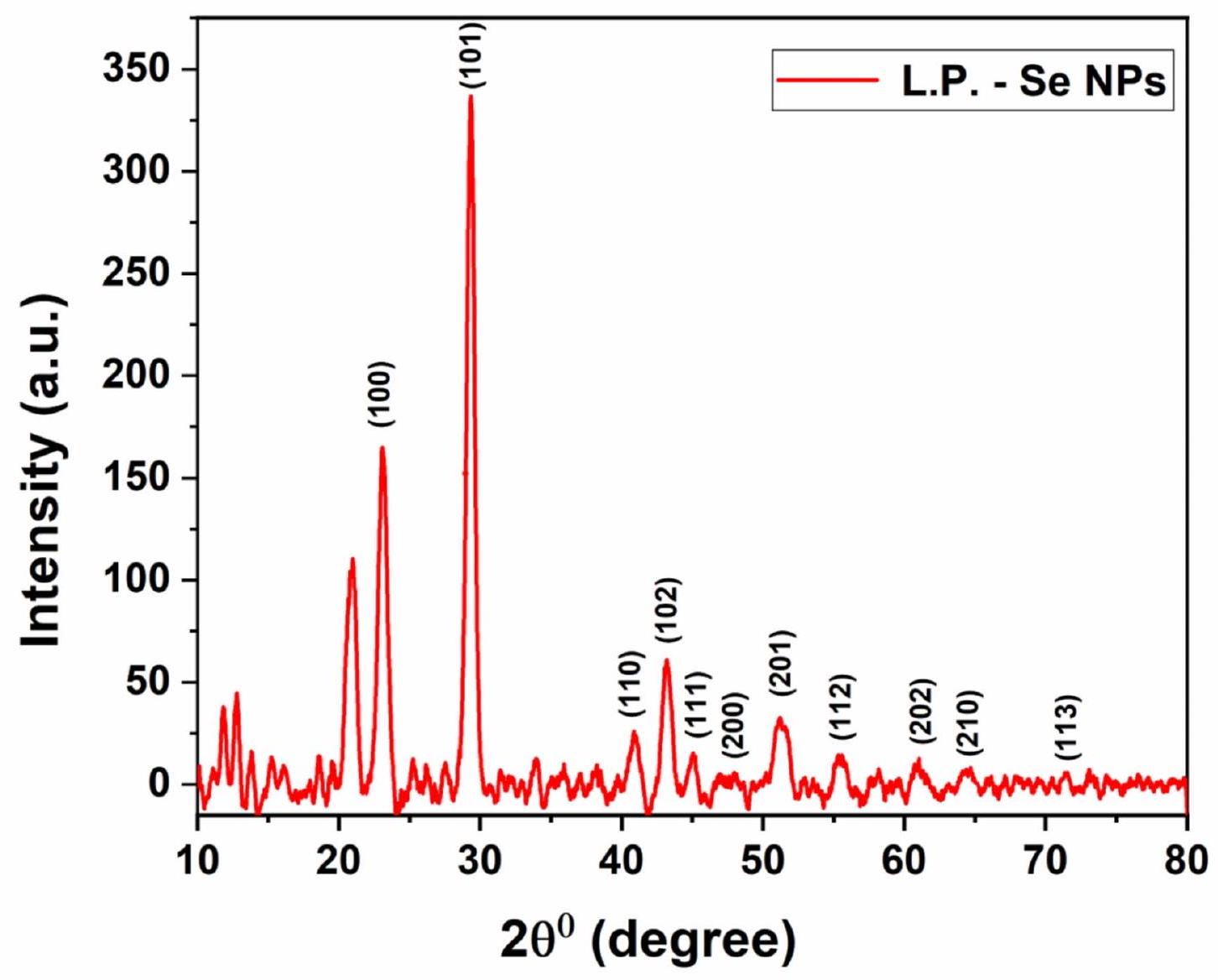

تمت دراسة بلورية L.P. -Se NPs بشكل أكبر باستخدام تحليل حيود الأشعة السينية (XRD). يظهر الشكل 5 نمط XRD نموذجي للهيكل الثلاثي لجزيئات L.P. -Se NPs حيث تتوافق قمم الحيود مع مؤشرات ميلر التالية: (100)، (101)، (110)، (102)، (111)، (200)، (201)، (112)، (202)، (210)، (113). أكدت بعض الدراسات السابقة هذه النتيجة

حجم الجسيمات لجزيئات NPs المصنعة هو أحد العوامل الأكثر أهمية التي تؤثر على النشاط المضاد للميكروبات والفطريات للجزيئات النانوية. لاحظ Sribenjarat وآخرون أن جزيئات Se NPs ذات النطاق الأصغر أظهرت نشاطًا مضادًا للميكروبات أعلى

الشكل 5. نمط XRD لجزيئات L.P.-Se NPs.

تحضير وتوصيف جزيئات CS NPs و NCS-Se NPs

بسبب عدد مجموعات الأمين على سطحها، فإن الطبيعة الكاتيونية للكيتوزان هي سبب جهد الزتا الإيجابي له

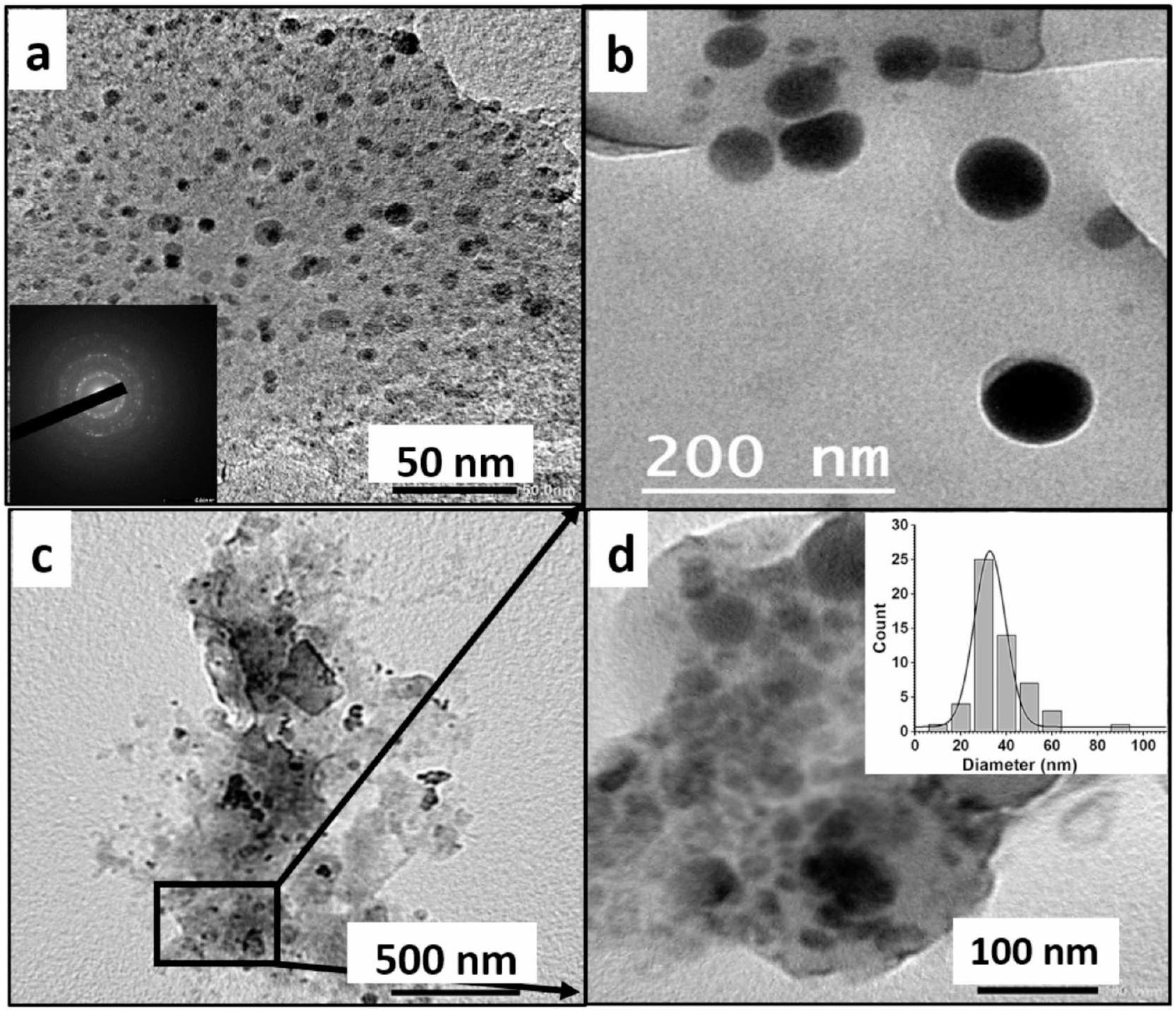

تظهر الصورة TEM في الشكل 6a جزيئات نانوية من CS بحجم جزيئي صغير بمتوسط قطر

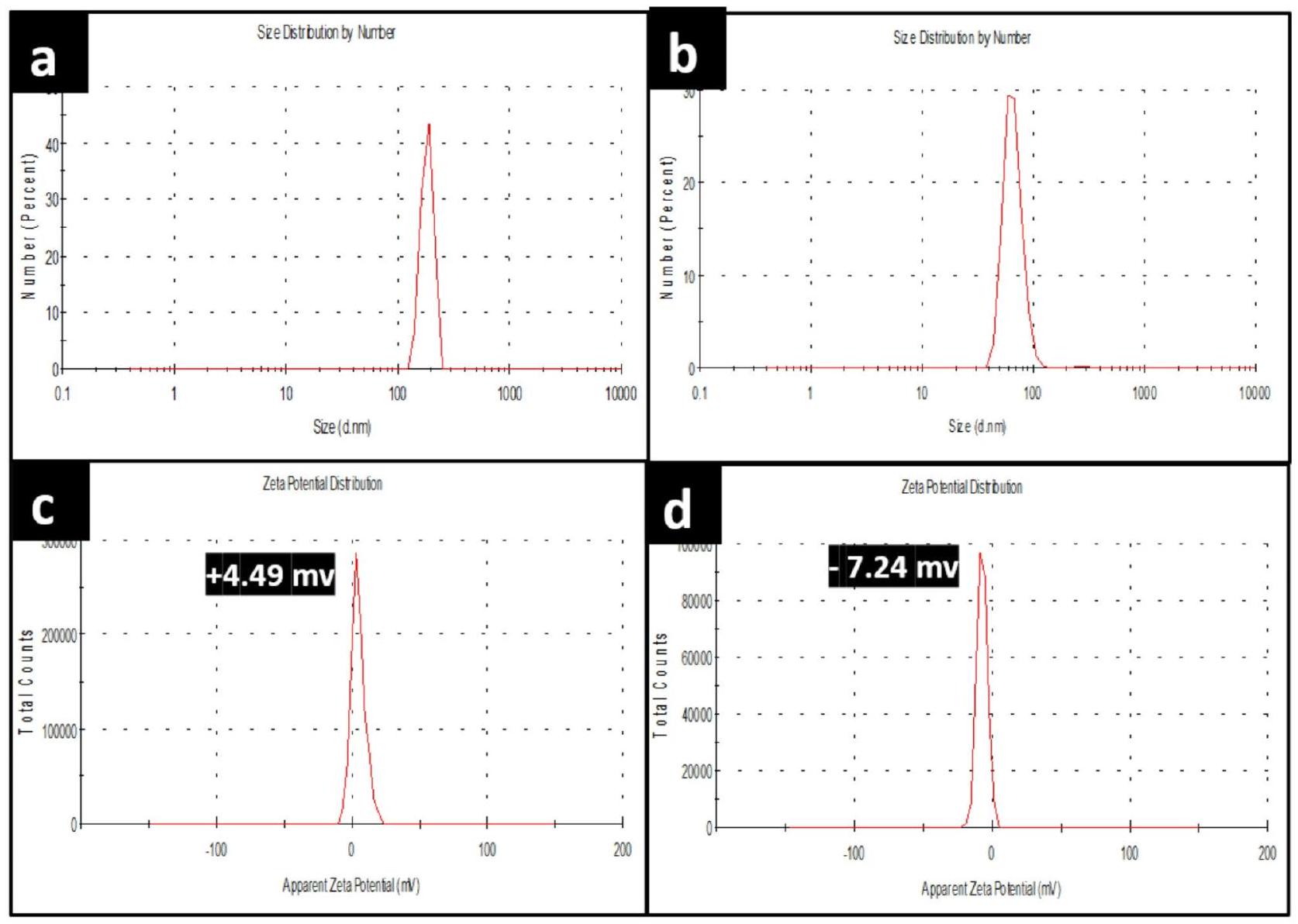

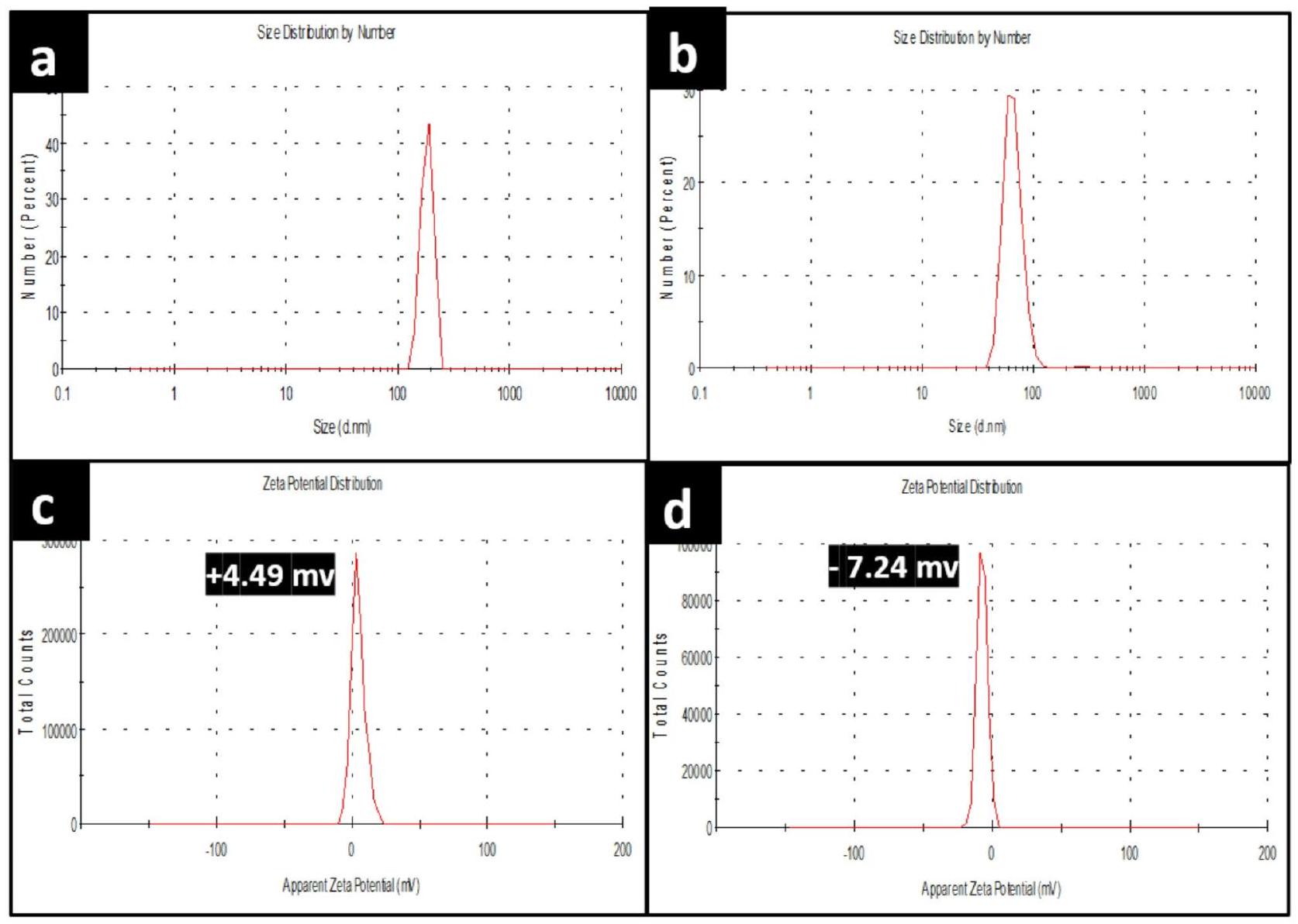

تم استخدام تقنية تشتت الضوء الديناميكي (DLS) لقياس حجم الجسيمات الهيدروديناميكي لجزيئات CS NPs و NCS-Se NPs المحضرة. الشكل 7a b يظهر

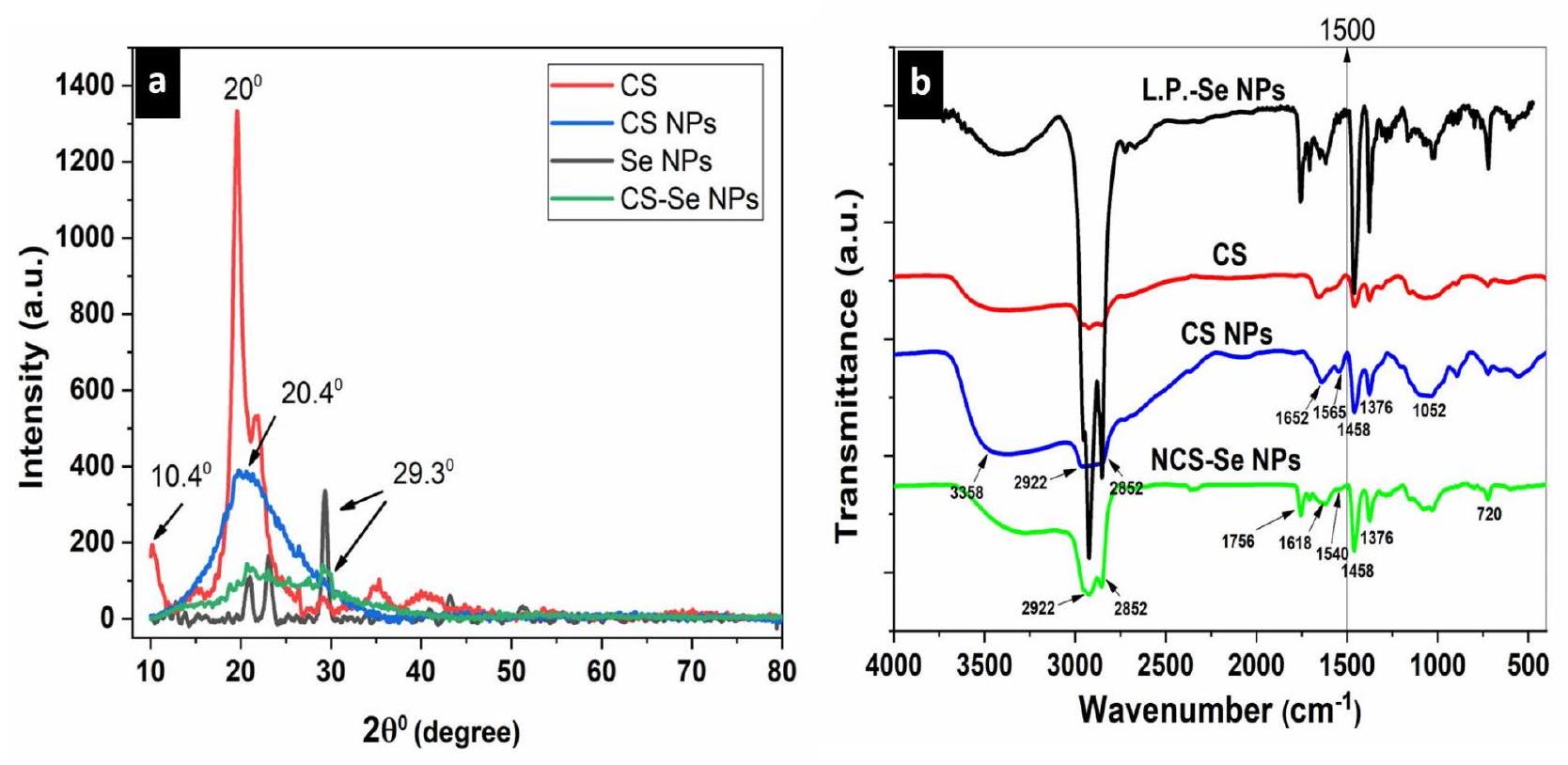

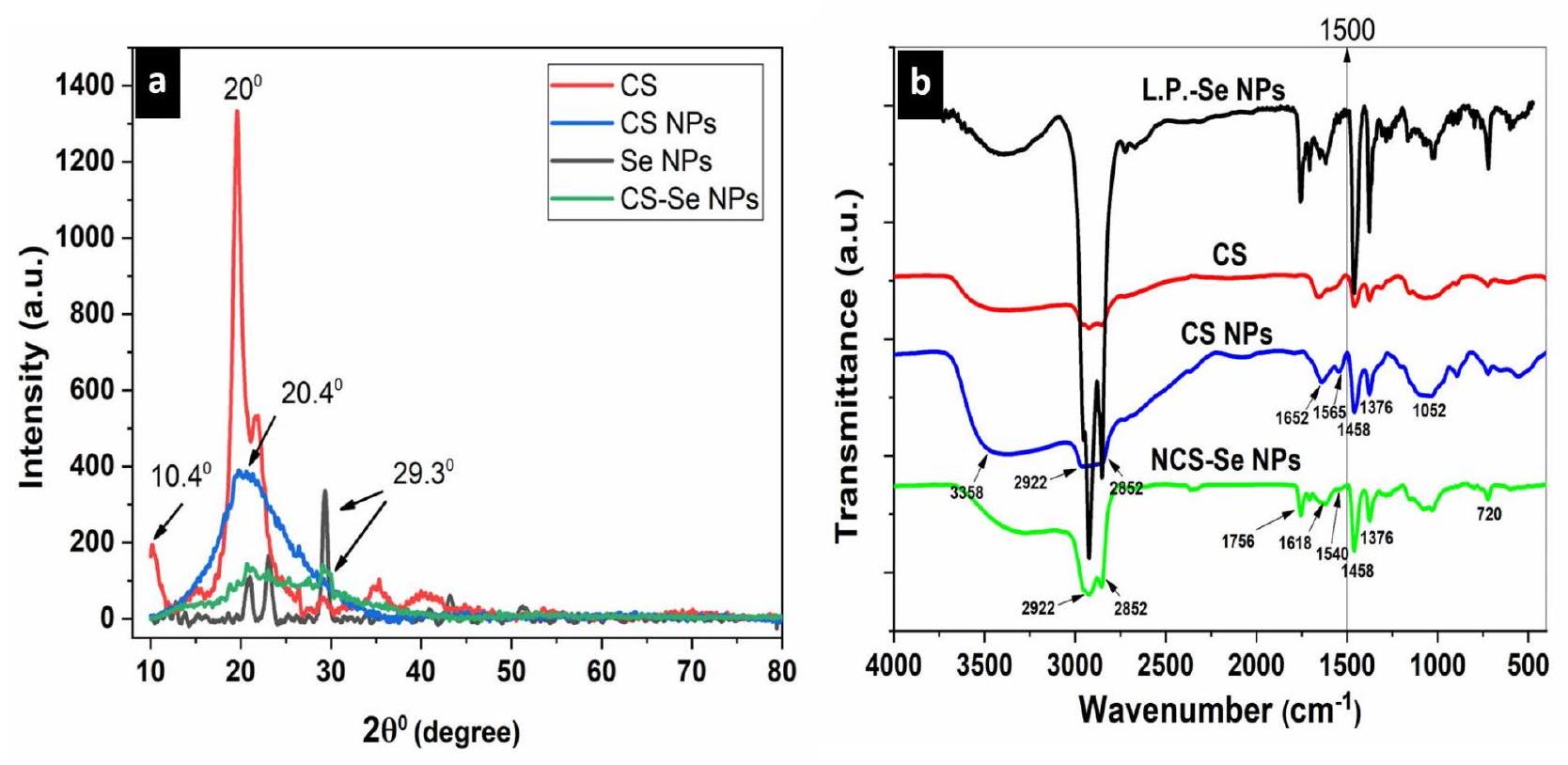

تظهر الشكل 8a نمط حيود الأشعة السينية (XRD) لـ CS و CS NPs و L.P. -Se NPs و NCS-Se NPs. يظهر نمط حيود الأشعة السينية لـ CS NPs قمة بارزة أوسع مع شدة أقل من (CS) عند

الشكل 6. صور TEM لـ (أ) جزيئات CS النانوية مع صورة مصغرة تظهر نمط التشتت متعدد البلورات لجزيئات CS النانوية، (ب) جزيئات Se النانوية، (ج) جزيئات NCS-Se النانوية، (د) لوحة مكبرة من (ج) تظهر جزيئات NCS-Se النانوية مع صورة مصغرة تظهر توزيع الحجم مع قطر ذروة

قد يتسبب السيلينيوم النانوي الموزع بشكل جيد في مصفوفة النانو كومبوزيت في تداخل القمم المميزة لـ Se NPs و CS NPs، ويشير ظهور قمم إضافية في هيكل النانو كومبوزيت إلى أن التفاعلات الأيونية تؤثر على الشبكة البلورية. أكدت الدراسات السابقة هذه النتائج في تحليل حيود الأشعة السينية.

تظهر الشكل 8ب نمط FT-IR لـ CS و CS NPs و NCS-Se NPs و L.P. -Se NPs للتحقيق في التفاعل بين الجزيئات لجزيئات النانو. في النانو كيتوزان، تم ملاحظة عدة قمم للتوصيف. القمة الأولى، عند

الشكل 7. توزيع الحجم لـ (أ) جزيئات نانو الكيتوزان، (ب) جزيئات نانو NCS-Se، وإمكانات زيتا لـ (ج) جزيئات نانو الكيتوزان، و (د) جزيئات نانو NCS-Se، على التوالي.

| الجسيمات النانوية | نطاق الحجم (نانومتر) | القطر المتوسط (نانومتر) | إمكانات زيتا (ملي فولت) |

| إل.بي.-سي |

|

42.28 | -19.0 |

| أو.بي.-سي |

|

85.7 | +12.0 |

| CS |

|

6.43 | +4.49 |

| NCS-Se |

|

٣٢.٧ | -7.24 |

الجدول 1. توزيع حجم الجسيمات وإمكانات زتا لجزيئات السيلينيوم النانوية التي تم تصنيعها حيوياً باستخدام مستخلصات قشور الليمون والبرتقال (L.P.-Se، O.P.-Se)، جزيئات الكيتوزان (CS)، ونانومركبها (NCS-Se).

النشاط المضاد للفطريات في المختبر

اختبار نمو الفطريات

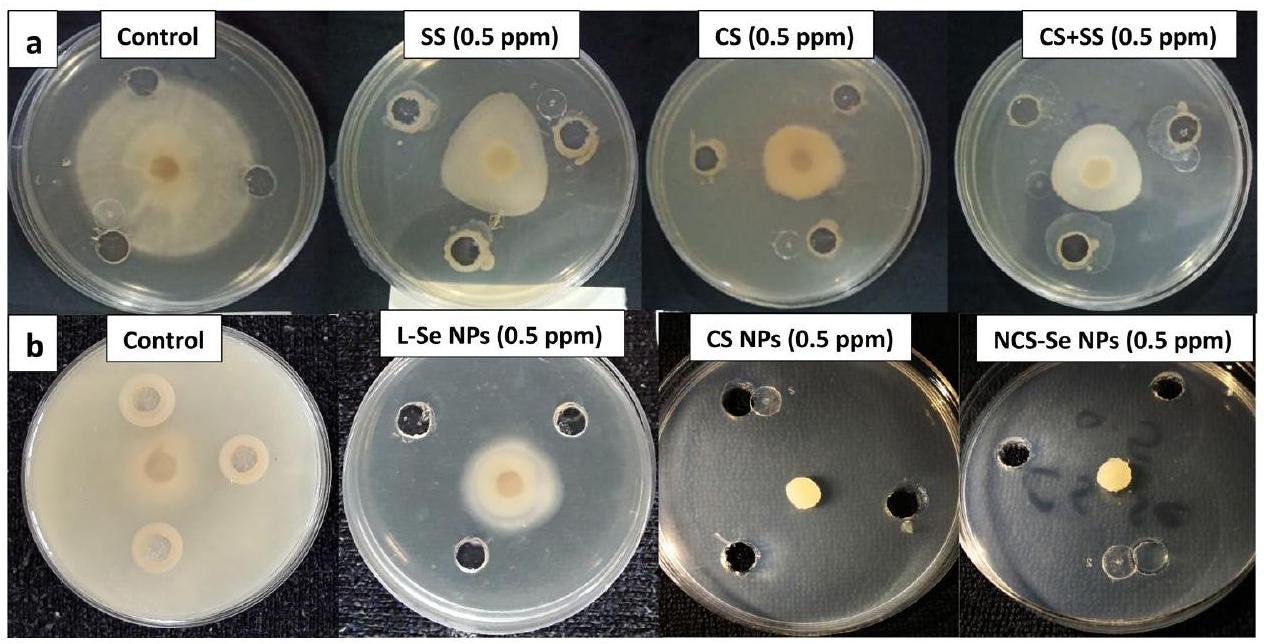

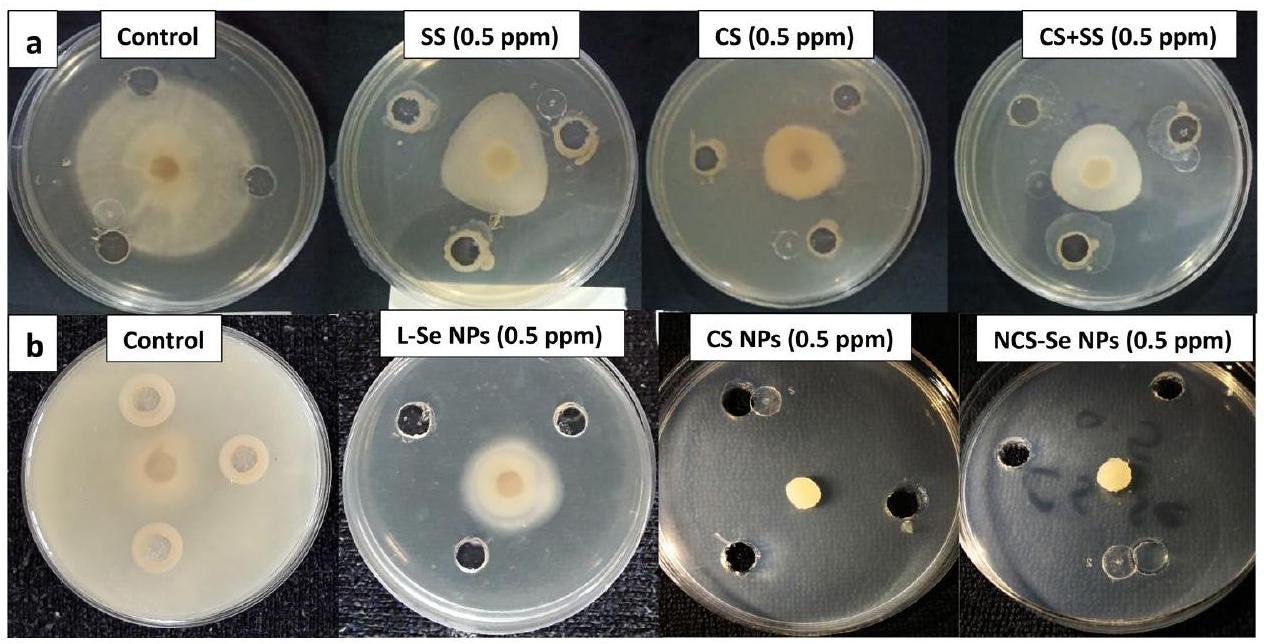

تمت دراسة النشاط المضاد للفطريات للهياكل النانوية الثلاثة المعدة (جسيمات نانوية من الكيتوزان، جسيمات نانوية من السيلينيوم، وجسيمات نانوية من الكيتوزان والسيلينيوم) مقارنة بمصادرها الكبيرة الكيتوزان، والسيلينيوم، ومزيج من الكيتوزان مع السيلينيوم.

جميع القيم المحسوبة في الجدولين أعلاه معروضة كمتوسط

أظهرت النتائج نشاطًا مضادًا للفطريات لجميع المواد السائبة عند جميع التركيزات، كما هو موضح في الجدول 2، والذي يتوافق مع التقارير السابقة حول النشاط المضاد للفطريات لـ CS و SS ضد S. sclerotiorum.

كما هو موضح في الجدول 3، كانت الحد الأدنى من التركيزات المثبطة (MIC) للثلاثة هياكل نانوية عند أدنى تركيزات 0.5 جزء في المليون مع نسب تثبيط تبلغ

الشكل 8. (أ) حيود الأشعة السينية لـ CS، جزيئات CS النانوية، جزيئات L.P.-Se النانوية وجزيئات NCS-Se النانوية & (ب) مطياف الأشعة تحت الحمراء لـ CS، جزيئات CS النانوية، جزيئات L.P.-Se النانوية وجزيئات NCS-Se النانوية.

| التركيز (جزء في المليون) | قطر النمو (سم) | ||

| علاج SS | علاج CS | SS + CS (

|

|

| 0 |

|

|

|

| 0.5 |

|

|

|

| 1 |

|

|

|

| ٥ |

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

| 50 |

|

|

|

| 100 |

|

|

|

| إل إس دي | 0.72 | 0.59 | 0.66 |

الجدول 2. عدد قطر النمو لـ S. sclerotiorum المعالج بتركيزات مختلفة من ثلاثة مواد خام مختبرة (SS، CS، ومزيج من SS + CS)

التأثير المضاد للفطريات لجزيئات نانو LP-Se بتركيز منخفض قدره 0.5 جزء في المليون مع

اختبار الكتلة الحيوية الفطرية

تم تجفيف الكتلة الحيوية الفطرية المحضرة حديثًا المعالجة بكل هيكل نانوي تم اختباره بتركيز الحد الأدنى المثبط (MIC) قدره 0.5 جزء في المليون، بالإضافة إلى التحكم، وتم وزنها بعد خمسة أيام من الحضانة الديناميكية باستخدام جهاز اهتزاز مداري.

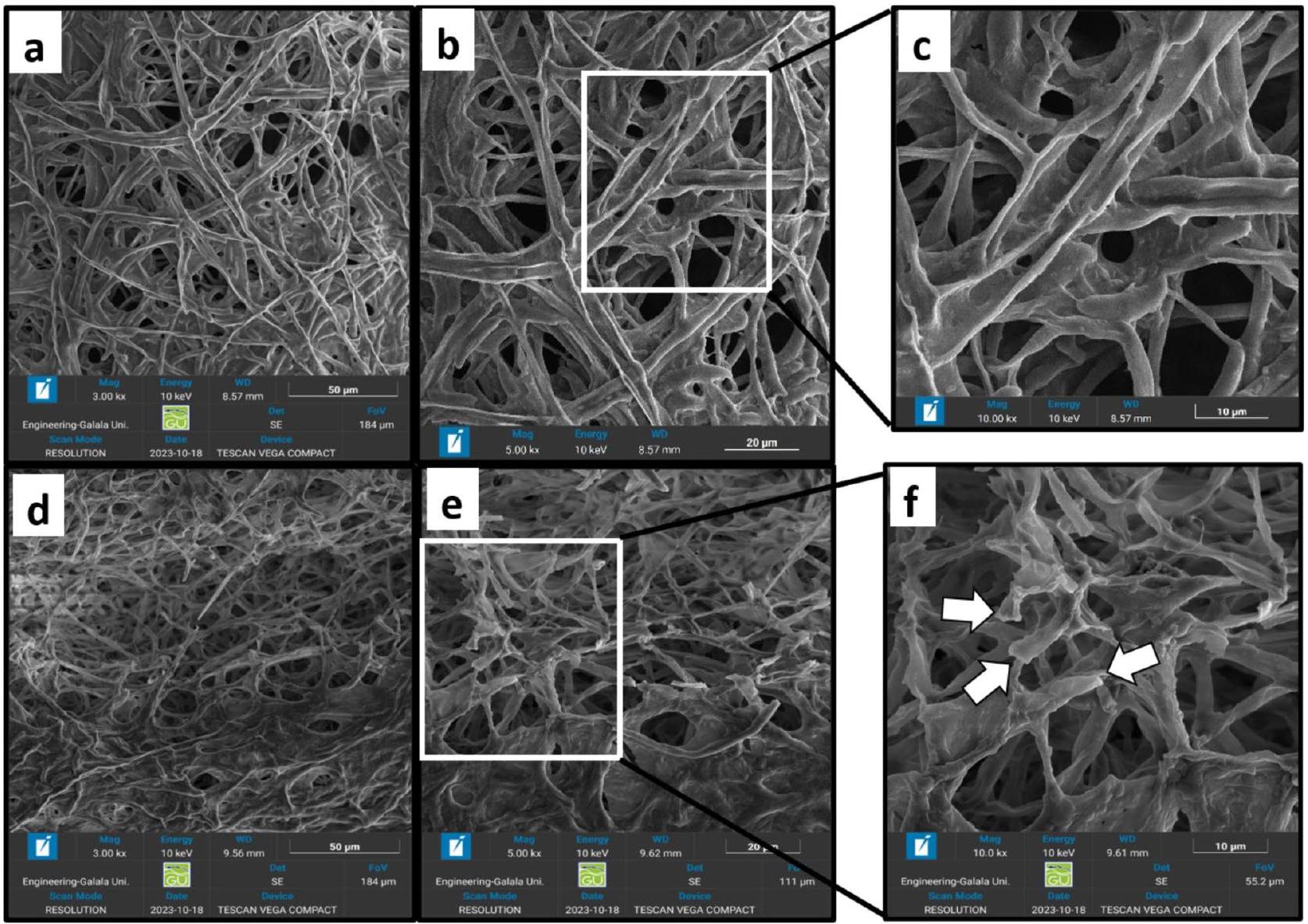

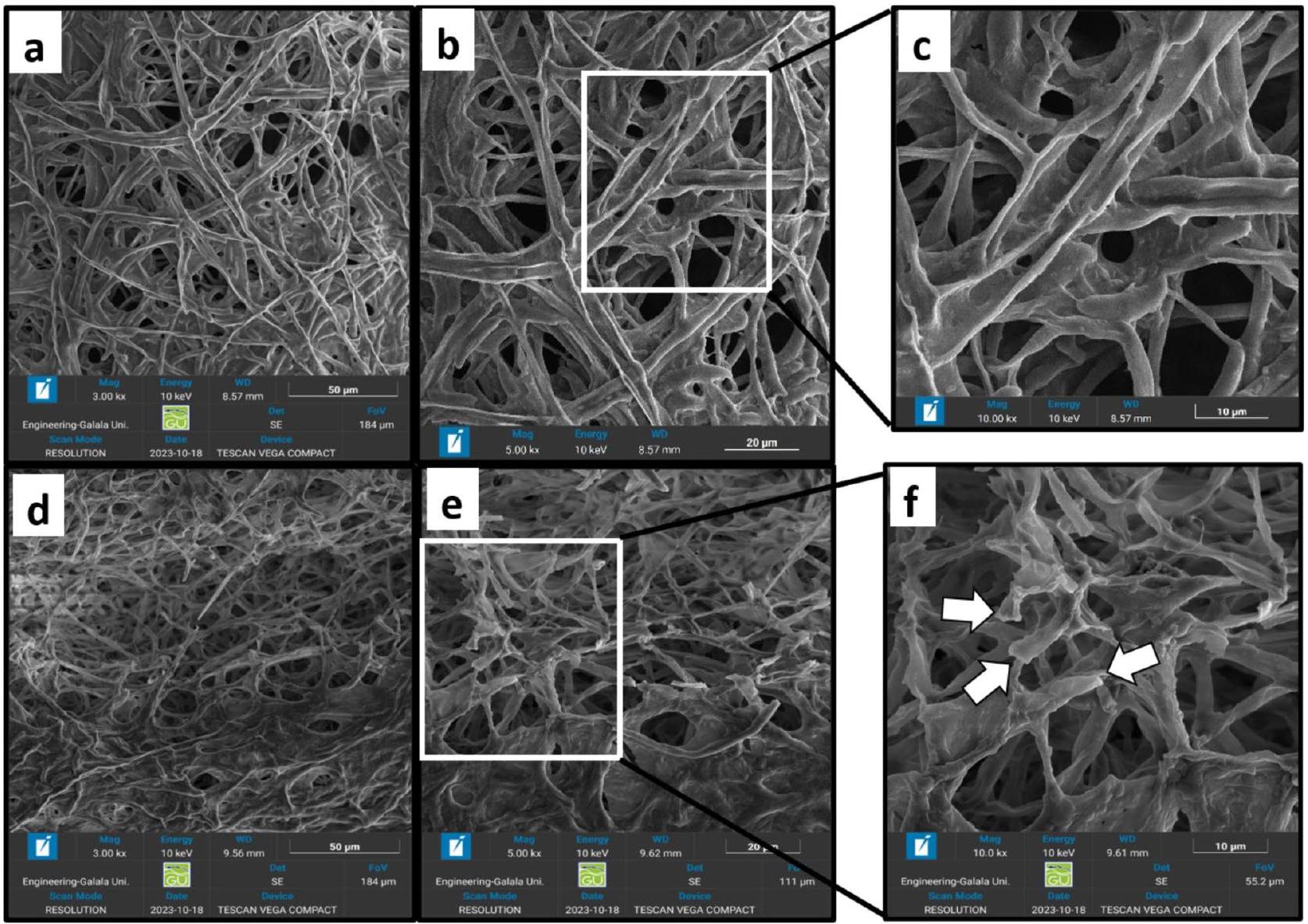

التغيرات الشكلية في خيوط S. sclerotiorum

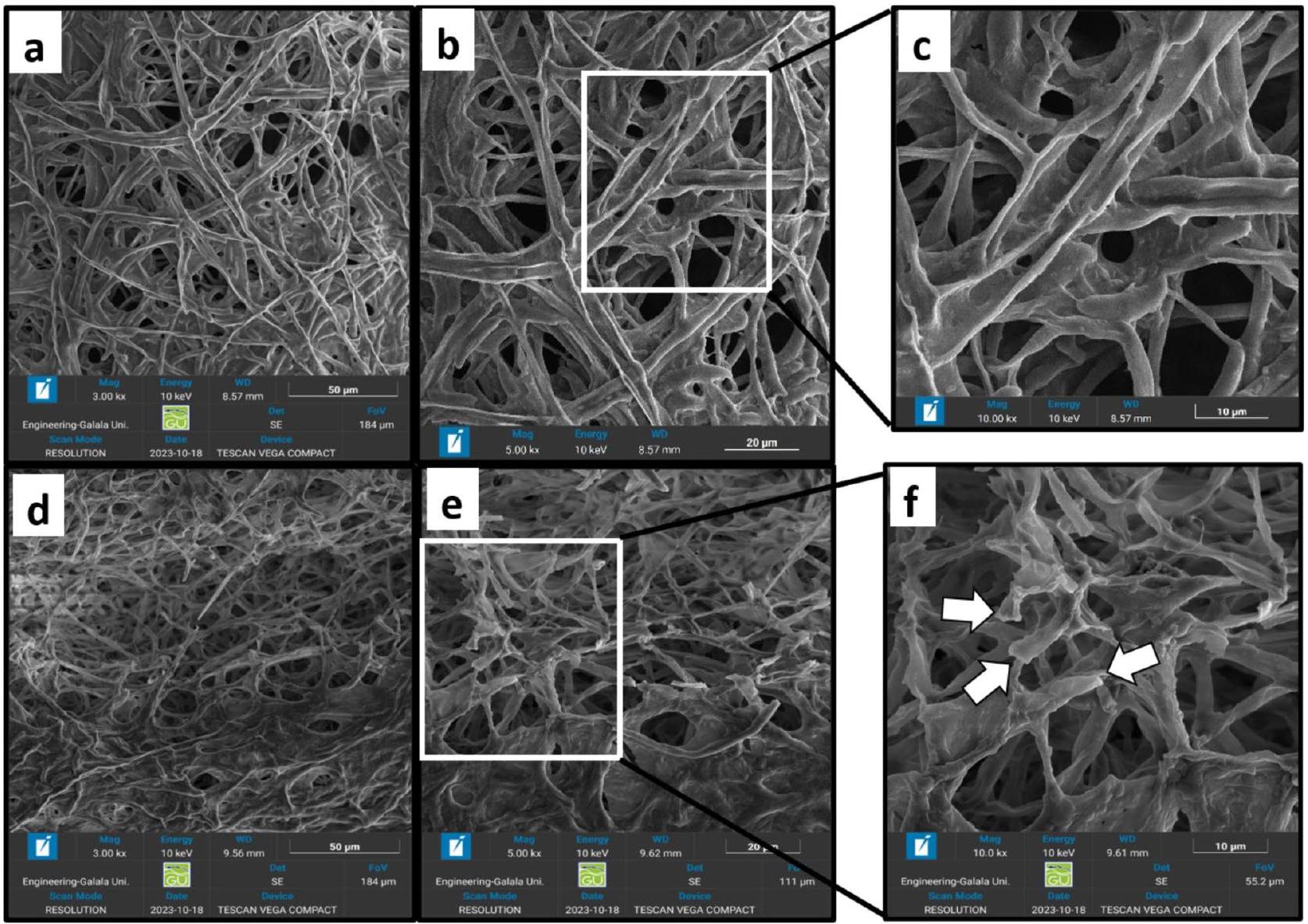

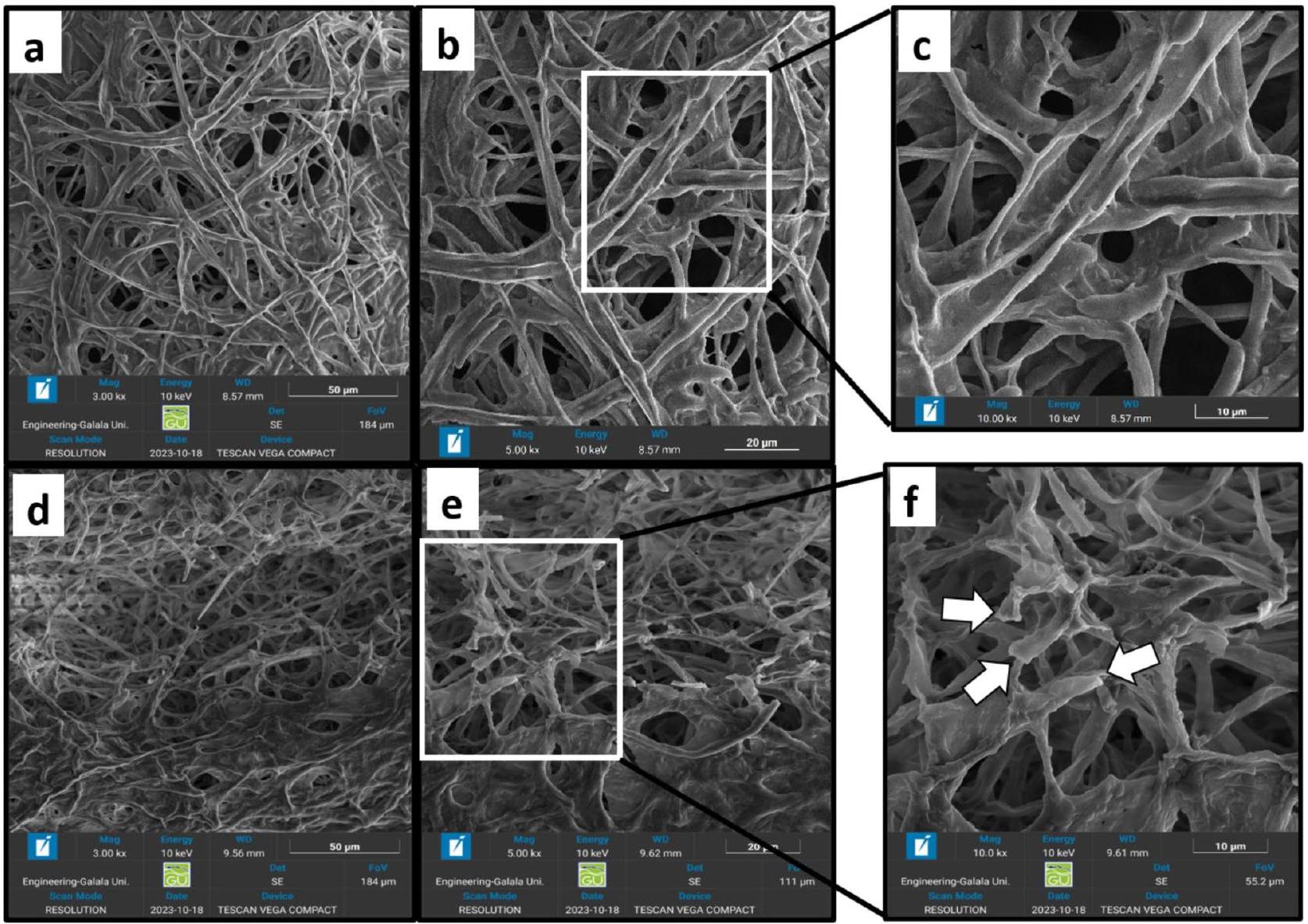

تم الكشف عن التغيرات فوق الهيكلية في خيوط S. sclerotiorum الناتجة عن 0.5 جزء في المليون من جزيئات NCS-Se النانوية باستخدام مجهر إلكتروني مسح (SEM). كانت خيوط S. sclerotiorum غير المعالجة تبدو سليمة وكثيفة وطويلة وأسطوانية، كما هو موضح في الشكل 10a وb وc. في المقابل، أظهرت الخيوط المعالجة بـ 0.5 جزء في المليون من جزيئات NCS-Se النانوية

الشكل 9. نمو الفطريات لـ S. sclerotiorum المعالجة بتركيز الحد الأدنى المثبط (MIC) من (أ) SS، CS، ومزيج من SS + CS

| التركيز (جزء في المليون) | قطر النمو (سم) | ||

| علاج NPs Se | علاج CS NPs | علاج NCS-Se NPs | |

| 0 |

|

|

|

| 0.5 |

|

غير متوفر | غير متوفر |

| 1 |

|

|

غير متوفر |

| ٥ |

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

| 50 |

|

|

|

| 100 |

|

|

|

| إل إس دي | 0.56 | 0.63 | 0.65 |

الجدول 3. عدد أقطار النمو لـ S. sclerotiorum المعالجة بتركيزات مختلفة من ثلاثة هياكل نانوية مختبرة (جزيئات السيلينيوم النانوية، جزيئات الكيتوزان النانوية، وجزيئات الكيتوزان-سيلينيوم النانوية).

| الحضانة الديناميكية

|

تركيز العلاج

|

|||

| تحكم | CS NPs | Se NPs | نقاط NCS-Se | |

| متوسط الكتلة الحيوية

|

|

|

|

|

الجدول 4. وزن الجفاف الناتج من S. sclerotiorum المعالج بـ 0.5 جزء في المليون من جزيئات CS النانوية، وجزيئات Se النانوية، وجزيئات NCS-Se النانوية.

تشوهات وشذوذات في شكلها. تشمل هذه التغيرات الشكلية الانكماش، والانفصال الخلوي، والتشوه، والانهيار في خيوط الفطريات، كما هو موضح في الشكل 10د، هـ، و، وبالتالي، تمزق وتلف

آلية مضادة للفطريات لجزيئات نانو NCS-Se

لقد تم إثبات أن CS و Se يمكن أن يحميان النباتات من العدوى الفطرية.

الشكل 10. صور TEM لخيوط S. sclerotiorum من (أ-ج): صور التحكم و (د-و): صور معالجة 0.5 جزء في المليون من جزيئات NCS-Se.

الشكل 11. مخطط توضيحي يوضح امتصاص جزيئات نانو NCS-Se مع فطريات S. sclerotiorum وتأثيرها الضار.

تم التحقيق. ومع ذلك، فإن تحديد الآلية المضادة للفطريات التي تسببها جزيئات نانو سيلينيوم الكربون (NCS-Se NPs) في خيوط فطر S. sclerotiorum سيساعد في تطوير استراتيجية فعالة وآمنة ومستدامة للسيطرة على S. sclerotiorum وإدارته.

المواد والطرق الكيميائية

تم شراء سيلينيت الصوديوم اللامائي AR من شركة SDFCL، الهند. كيتوزان عالي الوزن الجزيئي بوزن 350 كيلو دالتون ومستوى إزالة الأسيتيل من

عزل وتحديد سلالة الفطر

مرض فطري شائع يسمى تعفن سكليروتينيا، والذي يُطلق عليه أحيانًا العفن الأبيض في بعض المحاصيل، ينجم عن أعضاء فطرية ممرضة من جنس سكليروتينيا. على وجه الخصوص، يُعتبر S. sclerotiorum واحدًا من أكثر الإصابات النباتية ضررًا وانتشارًا. يسبب الفطر الممرض النخرى S. sclerotiorum (ليب.) دي باري أمراضًا في نباتات متنوعة.

تم استرداد 0.5 جرام من الفطريات بعد خمسة أيام من الحضانة في عملية عزل مطحنة الخلاط. تم استخراج الحمض النووي، وتم إجراء تفاعل البوليميراز المتسلسل (PCR) ثلاث مرات. 1x محلول تفاعل البوليميراز المتسلسل،

التركيب الأخضر لجزيئات السيلينيوم النانوية

تم اختيار مستخلصات قشور الحمضيات من الليمون (Citrus limon) والبرتقال (Citrus reticulata)، حيث يحتوي كلاهما على أعلى محتوى من حمض الأسكوربيك.

50 مل من مستخلص قشر الحمضيات الطازج (تم تسخين مستخلص قشر الليمون أو البرتقال بدقة باستخدام جهاز تسخين مغناطيسي مع خلاط، وتم ضبط الظروف على

تحضير محلول CS وجزيئات CS النانوية

تحضير محلول CS

حول

تحضير جزيئات نانوية من الكيتوزان

تم تحضير NP من الكيتوزان باستخدام طريقة التجلط الأيوني بين الكيتوزان وTPP.

تركيب جزيئات نانو NCS-Se

تم تصنيع جزيئات نانو السيلينيوم (Se NPs) بطريقة خضراء كما هو موصوف سابقًا ولكن بوجود الكيتوسان (CS)، مع بعض التعديلات التي وصفها شاو وآخرون.

الذي يؤكد تشكيل جزيئات NCS-Se. تم إزالة CS غير المتفاعل،

الذي يؤكد تشكيل جزيئات NCS-Se. تم إزالة CS غير المتفاعل،

دراسات في المختبر للنشاط المضاد للفطريات

تم تقييم النشاط المضاد للفطريات للمواد الكتلية (CS، SS، ومزيج من كلا المادتين بنسبة

قياس نمو الفطريات

تم عزل S. sclerotiorum من حبة الفاصوليا الخضراء المصابة وتم الاحتفاظ بها على أجار دكستروز البطاطس (PDA). وفقًا لـ Qing و Yao

اختبار الكتلة الحيوية الفطرية

تم إعداد 100 مل من مرق دكستروز البطاطس (PDB) ووضعها في قنينة مخروطية سعة 250 مل. تم تخفيف كل PDP بواسطة MIC لكل هيكل نانوي مختبر (جزيئات Se، NCS، وجزيئات NCS-Se) حتى تم الحصول على التركيزات المختبرة. ثم، تم إدخال أقراص فطرية بقطر 5 مم من الثقافات القديمة (نمت لمدة 10 أيام في درجة حرارة الغرفة) في كل PDB معالج عند

التغيرات الشكلية في خيوط S. sclerotiorum

بعد 18 ساعة من التعرض للحد الأدنى من التركيز المثبط (MIC) لجزيئات NCS-Se النانوية (NPs)، تم تثبيت خيوط S. sclerotiorum باستخدام محلول

توصيف الهياكل النانوية المعدة

مجهر الإلكترون الناقل (TEM)

تم تأكيد تشكيل الهياكل النانوية التالية، جزيئات Se التي تم تصنيعها بطريقة خضراء، جزيئات CS، وجزيئات NCS-Se باستخدام مجهر إلكترون ناقل (TEM) (JEM-2100 PLUS). عند جهد تسريع قدره 200 كيلو فولت، تم استخدام TEM لدراسة الحجم والشكل وحالات التكتل لجزيئات Se، جزيئات CS، وجزيئات NCS-Se. تم وضع قطرة من العينات المخففة على شبكة كربونية مطلية بالنحاس وتركها لتجف لمدة حوالي 15 دقيقة. تم استخدام ورق الترشيح لإزالة العينة الزائدة، ثم تم ترك الشبكة في الهواء لتجف قبل إدخالها إلى TEM.

تشتت الضوء الديناميكي (DLS)

تم قياس حجم الجسيمات لجميع الهياكل النانوية المعدة، جزيئات Se، جزيئات CS، وجزيئات NCS-Se باستخدام جهاز قياس زتا نانو (ZEN3600، مالفرن، المملكة المتحدة) مع نطاق حجم (من

تحليل حيود الأشعة السينية (XRD)

تم إجراء تحليل حيود الأشعة السينية (XRD) لدراسة التركيب البلوري، والتكوين، وحجم الحبيبات للهياكل النانوية باستخدام جهاز حيود الأشعة السينية (جهاز Angstrom -ADX8000) مع مصدر إشعاع CuKal بطول موجي

طيف الأشعة فوق البنفسجية-المرئية (Uv-Vis)

تم تحديد طيف الامتصاص لجميع الهياكل النانوية المعدة باستخدام مطياف الأشعة فوق البنفسجية-المرئية (BioWave3-USA) مع نطاق طول موجي من

مطياف الأشعة تحت الحمراء بتحويل فورييه (FTIR)

شمل التوصيف الإضافي مطياف الأشعة تحت الحمراء بتحويل فورييه (Nicolet

مجهر إلكتروني مس扫描 (SEM)

تمت ملاحظة التغيرات الشكلية في خيوط الممرض بعد المعالجة بالهياكل النانوية من خلال تصوير SEM (TESCAN VEGA COMPACT، برنو، كوهوتوفيتس، جمهورية التشيك) عند جهد تسريع قدره 10 كيلو فولت.

التحليل الإحصائي

تم إجراء التحليل الإحصائي للبيانات المجمعة عبر تحليل ANOVA أحادي الاتجاه (عند

الاستنتاج

بشكل عام، استنتجنا أن جزيئات L.P.-Se تظهر أحجامًا أصغر من

توفر البيانات

جميع البيانات التي تم إنشاؤها أو تحليلها خلال هذه الدراسة مدرجة في هذه المخطوطة.

تاريخ الاستلام: 29 يوليو 2024؛ تاريخ القبول: 11 نوفمبر 2024

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 06 يناير 2025

تاريخ الاستلام: 29 يوليو 2024؛ تاريخ القبول: 11 نوفمبر 2024

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 06 يناير 2025

References

- Perveen, K., Haseeb, A. & Shukla, P. K. Effect of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum on the disease development, growth, oil yield and biochemical changes in plants of Mentha arvensis. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 17 (4), 291-294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2010.05.008 (2010).

- Rollins, J. A. & Dickman, M. B. pH signaling in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: Identification of a pacC/RIM1 homolog. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67 (1), 75-81. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.67.1.75-81.2001 (2001).

- Qin, L. et al. SsCak1 regulates growth and pathogenicity in Sclerotinia Sclerotiorum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (16), 1-14. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/ijms241612610 (2023).

- Ding, Y. et al. Host-Induced Gene silencing of a multifunction gene Sscnd1 enhances Plant Resistance against Sclerotinia Sclerotiorum. Front. Microbiol. 12 (October), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb. 2021.693334 (2021).

- Seifbarghi, S. et al. Changes in the Sclerotinia sclerotiorum transcriptome during infection of Brassica napus. BMC Genom. 18 (1), 1-37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-017-3642-5 (2017).

- Williams, B., Kabbage, M., Kim, H. J., Britt, R. & Dickman, M. B. Tipping the balance: Sclerotinia sclerotiorum secreted oxalic acid suppresses host defenses by manipulating the host redox environment. PLoS Pathog. 7 (6). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat. 10 02107 (2011).

- Chittem, K., Yajima, W. R., Goswami, R. S. & del Río Mendoza, L. E. Transcriptome analysis of the plant pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum interaction with resistant and susceptible canola (Brassica napus) lines. PLoS One. 15 (3), 1-29. https://doi.org/10.13 71/journal.pone. 0229844 (2020).

- Jia, W. et al. Action of selenium against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: Damaging membrane system and interfering with metabolism. Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 150 (June), 10-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2018.06.003 (2018).

- Xu, J. et al. Selenium as a potential fungicide could protect oilseed rape leaves from Sclerotinia sclerotiorum infection. Environ. Pollut. 257, 113495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113495 (2020).

- Fernández-Llamosas, H., Castro, L., Blázquez, M. L., Díaz, E. & Carmona, M. Biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles by Azoarcus Sp. CIB Microb. Cell. Fact. 15 (1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-016-0510-y (2016).

- Wang, H., Zhang, J. & Yu, H. Elemental selenium at nano size possesses lower toxicity without compromising the fundamental effect on selenoenzymes: comparison with selenomethionine in mice. Free Radic Biol. Med. 42 (10), 1524-1533. https://doi.org/10 .1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.02.013 (2007).

- Chen, T., Wong, Y. S., Zheng, W., Bai, Y. & Huang, L. Selenium nanoparticles fabricated in Undaria pinnatifida polysaccharide solutions induce mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in A375 human melanoma cells. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 67 (1), 26-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2008.07.010 (2008).

- Quiterio-Gutiérrez, T. et al. The application of selenium and copper nanoparticles modifies the biochemical responses of tomato plants under stress by Alternaria Solani. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (8). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20081950 (2019).

- Vrandečić, K. et al. Antifungal activities of silver and selenium nanoparticles stabilized with different surface coating agents. Pest Manag Sci. 76 (6), 2021-2029. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps. 5735 (2020).

- Dhawan, G., Singh, I., Dhawan, U. & Kumar, P. Synthesis and characterization of Nanoselenium: A step-by-step guide for undergraduate students. J. Chem. Educ. 98 (9), 2982-2989. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c01467 (2021).

- Cittrarasu, V. et al. Green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles mediated from Ceropegia bulbosa Roxb extract and its cytotoxicity, antimicrobial, mosquitocidal and photocatalytic activities. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80327-9 (2021).

- Alvi, G. B. et al. Biogenic selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) from citrus fruit have anti-bacterial activities. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84099-8 (2021).

- Balakrishnaraja, R., Sasidharan, S. & Biosynthesis of Selenium Nanoparticles Using Citrus Reticulata Peel Extract. Vol 4. (2015).

- Mittal, A. K., Chisti, Y. & Banerjee, U. C. Synthesis of metallic nanoparticles using plant extracts. Biotechnol. Adv. 31 (2), 346-356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.01.003 (2013).

- Rao, A. V. & Rao, L. G. Carotenoids and human health. Pharmacol. Res. 55 (3), 207-216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2007.01.012 (2007).

- Salem, S. S. et al. Green biosynthesis of Selenium nanoparticles using orange peel waste: Characterization, antibacterial and antibiofilm activities against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Life. 12 (6). https://doi.org/10.3390/life12060893 (2022).

- Awad, H. Antifungal potentialities of Chitosan and Trichoderma in controlling Botrytis cinerea, causing strawberry gray mold disease. J. Plant. Prot. Pathol. 8 (8), 371-378. https://doi.org/10.21608/jppp. 2017.46342 (2017).

- Wang, Q., Zuo, J., Wang, Q., Na, Y. & Gao, L. Inhibitory effect of chitosan on growth of the fungal phytopathogen, Sclerotinia Sclerotiorum, and sclerotinia rot of carrot. J. Integr. Agric. 14 (4), 691-697. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2095-3119(14)60800-5 (2015).

- Molloy, C., Cheah, L. H. & Koolaard, J. P. Induced resistance against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in carrots treated with enzymatically hydrolysed chitosan. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 33 (1), 61-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2004.01.009 (2004).

- El-mohamedy, R. S. R., El-aziz, M. E. A. & Kamel, S. Antifungal activity of chitosan nanoparticles against some plant pathogenic fungi in vitro. 21(4):201-209. (2019).

- Slavin, Y. N. & Bach, H. Mechanisms of antifungal properties of metal nanoparticles. Nanomaterials. 12 (24). https://doi.org/10.3 390/nano12244470 (2022).

- Martínez, A. et al. Dual antifungal activity against Candida albicans of copper metallic nanostructures and hierarchical copper oxide marigold-like nanostructures grown in situ in the culture medium. J. Appl. Microbiol. 130 (6), 1883-1892. https://doi.org/1 0.1111/jam. 14859 (2021).

- De La Rosa-García, S. C. et al. Antifungal activity of ZnO and MgO nanomaterials and their mixtures against colletotrichum gloeosporioides strains from tropical fruit. J Nanomater. 2018 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3498527

- Danaei, M. et al. Impact of particle size and polydispersity index on the clinical applications of lipidic nanocarrier systems. Pharmaceutics. 10 (2), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics10020057 (2018).

- Rao, S., Song, Y., Peddie, F. & Evans, A. M. Particle size reduction to the nanometer range: A promising approach to improve buccal absorption of poorly water-soluble drugs. Int. J. Nanomed. 6, 1245-1251. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.s19151 (2011).

- Clogston, J. D. & Patri, A. K. Zeta Potential Measurement. Methods Mol. Biol. 697, 63-70. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-60327-19 8-1_6 (2011).

- Hasani Bijarbooneh, F. et al. Aqueous colloidal stability evaluated by Zeta potential measurement and resultant TiO 2 for superior photovoltaic performance. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 96 (8), 2636-2643. https://doi.org/10.1111/jace. 12371 (2013).

- JAHAN, I. Lemon Peel Extract for synthesizing non-toxic silver nanoparticles through one-step microwave-accelerated Scheme. Kahramanmaraş Sütçü İmam Üniversitesi Tarım ve Doğa. Derg. 24 (1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.18016/ksutarimdoga.vi. 737063 (2021).

- Singh, N., Saha, P., Rajkumar, K. & Abraham, J. Biosynthesis of silver and selenium nanoparticles by Bacillus sp. JAPSK2 and evaluation of antimicrobial activity. Der Pharm. Lett. 6 (1), 175-181 (2014).

- Ramamurthy, C. H. et al. The extra cellular synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles and their free radical scavenging and antibacterial properties. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 102, 808-815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.09.025 (2013).

- Khandsuren, B. & Prokisch, J. The production methods of selenium nanoparticles. Acta Univ. Sapientiae Aliment. 14 (1), 14-43. https://doi.org/10.2478/ausal-2021-0002 (2021).

- Peng, S., McMahon, J. M., Schatz, G. C., Gray, S. K. & Sun, Y. Reversing the size-dependence of surface plasmon resonances. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 107 (33), 14530-14534. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas. 1007524107 (2010).

- İpek, P. et al. Green synthesis and evaluation of antipathogenic, antioxidant, and anticholinesterase activities of gold nanoparticles (au NPs) from Allium cepa L. peel aqueous extract. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 14 (9), 10661-10670. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1 3399-023-04362-y (2024).

- Kelly, K. L., Coronado, E., Zhao, L. L. & Schatz, G. C. The optical properties of metal nanoparticles: The influence of size, shape, and dielectric environment. J. Phys. Chem. B. 107 (3), 668-677. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp026731y (2003).

- Jiang, F., Cai, W. & Tan, G. Facile synthesis and Optical properties of Small Selenium nanocrystals and Nanorods. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 12, 0-5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-017-2165-y (2017).

- Lin, Z. H. & Wang, C. R. C. Evidence on the size-dependent absorption spectral evolution of selenium nanoparticles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 92 (2-3), 591-594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2005.02.023 (2005).

- Wahab, A., Abou Elyazeed, A. M. & Abdalla, A. E. Bioactive compounds in some Citrus peels as affected by drying processes and quality evaluation of cakes supplemented with Citrus peels powder. 44.; (2018).

- El-ghfar, M. H. A. A., Ibrahim, H. M., Hassan, I. M., Abdel Fattah, A. A. & Mahmoud, M. H. Peels of lemon and orange as valueadded ingredients: Chemical and antioxidant properties. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 5 (12), 777-794. https://doi.org/10.2054 6/ijcmas.2016.512.089 (2016).

- Udvardi, B. et al. Effects of particle size on the attenuated total reflection spectrum of minerals. Appl. Spectrosc. 71 (6), 1157-1168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003702816670914 (2017).

- Alagesan, V. & Venugopal, S. Green synthesis of selenium nanoparticle using leaves extract of Withania somnifera and its biological applications and photocatalytic activities. Bionanoscience. 9 (1), 105-116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12668-018-0566-8 (2019).

- Gulley-Stahl, H. J., Haas, J. A., Schmidt, K. A., Evan, A. P. & Sommer, A. J. Attenuated total internal reflection Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy: A quantitative approach for kidney stone analysis. Appl. Spectrosc. 63 (7), 759-766. https://doi.org/10.1366 /000370209788701044 (2009).

- Khater, S., Ali, I., Khater, Ahmed, A. & abd el-megid, S. Preparation and characterization of Chitosan-stabilized selenium nanoparticles for ameliorating experimentally Induced Diabetic Nephropathy in rats. Arab. J. Nucl. Sci. Appl. 0 (0), 1-9. https://do i.org/10.21608/ajnsa.2020.19809.1300 (2020).

- Saeed, M. et al. Assessment of antimicrobial features of selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) using cyclic voltammetric strategy. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 19 (11), 7363-7368. https://doi.org/10.1166/jnn.2019.16627 (2019).

- Sribenjarat, P., Jirakanjanakit, N. & Jirasripongpun, K. Selenium nanoparticles biosynthesized by garlic extract as antimicrobial agent. Sci. Eng. Heal Stud. 14 (1), 22-31 (2020).

- Javed, R. et al. Role of capping agents in the application of nanoparticles in biomedicine and environmental remediation: Recent trends and future prospects. J. Nanobiotechnol. 18 (1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-020-00704-4 (2020).

- Collado-González, M., Montalbán, M. G., Peña-García, J., Pérez-Sánchez, H. & Víllora, G. Díaz Baños FG. Chitosan as stabilizing agent for negatively charged nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 161, 63-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.12.043 (2017).

- Aibani, N., Cuddihy, G. & Wasan, E. K. Chitosan Nanoparticles at the Biological interface: Implications for drug delivery. Published online 2021.

53.Salem,M.F.,Abd-elraoof,W.A.,Tayel,A.A.,Alzuaibr,F.M.&Abonama,O.M.Antifungal application of biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles with pomegranate peels and nanochitosan as edible coatings for citrus green mold protection.J.Nanobiotechnol. Published Online 2022,1-12.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-022-01393-x

54.Alghuthaymi,M.A.et al.Green biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles by cinnamon extract and their antimicrobial activity and application as edible coatings with nano-chitosan.J Food Qual. 2021 (2021).https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6670709

55.Soleimani Asl,S.et al.Chitosan-coated selenium nanoparticles enhance the efficiency of stem cells in the neuroprotection of streptozotocin-induced neurotoxicity in male rats.Int.J.Biochem.Cell.Biol. 141 (September),1-9.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioce 1.2021.106089(2021).

56.Kulikouskaya,V.et al.Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles:A comprehensive study of polymer molecular weight effect on the reaction kinetic,physicochemical properties,and synergetic antibacterial potential.SPE Polym. 3 (2),77-90.https://doi.org/10.10 02/pls2.10069(2022).

57.Rao,L.et al.Chitosan-decorated selenium nanoparticles as protein carriers to improve the in vivo half-life of the peptide therapeutic BAY 55-9837 for type 2 diabetes mellitus.Int.J.Nanomed.9,4819-4828.https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S67871(2014).

58.Shao,C.et al.Chitosan-coated selenium nanoparticles attenuate PRRSV replication and ROS/JNK-mediated apoptosis in vitro. Int.J.Nanomed. 17 (July),3043-3054.https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S370585(2022).

59.Zhihui,J.et al.One-step reinforcement and deacidification of paper.Coatings. 10 (12267),1-15(2020).

60.Thamilarasan,V.et al.Single step fabrication of Chitosan nanocrystals using Penaeus semisulcatus:Potential as New insecticides, antimicrobials and Plant Growth promoters.J.Clust Sci. 29 (2),375-384.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10876-018-1342-1(2018).

61.Ayoub MMH.Incorporated nano-chitosan.Polym.Bull. 0123456789 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00289-023-04768-8(2023).

62.Sheikhalipour,M.et al.Chitosan-selenium nanoparticle(Cs-se np)foliar spray alleviates salt stress in bitter melon.Nanomaterials. 11 (3),1-23.https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11030684(2021).

63.Luo,Y.,Zhang,B.,Cheng,W.H.&Wang,Q.Preparation,characterization and evaluation of selenite-loaded chitosan/TPP nanoparticles with or without zein coating.Carbohydr.Polym. 82 (3),942-951.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.06.029 (2010).

64.Chen,Y.et al.Stability and surface properties of selenium nanoparticles coated with chitosan and sodium carboxymethyl cellulose. Carbohydr.Polym. 278 (17),118859.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118859(2022).

65.Liu,J.,Tian,S.,Meng,X.&Xu,Y.Effects of Chitosan on control of postharvest diseases and physiological responses of tomato fruit.Postharvest Biol.Technol. 44 (3),300-306.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2006.12.019(2007).

66.Ma,Z.,Garrido-Maestu,A.&Jeong,K.C.Application,mode of action,and in vivo activity of chitosan and its micro-and nanoparticles as antimicrobial agents:A review.Carbohydr.Polym. 176 (July),257-265.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.08.082(2017).

67.Wu,Z.et al.Effect of selenium on control of postharvest gray mold of tomato fruit and the possible mechanisms involved.Front. Microbiol. 6 (JAN),1-11.https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01441(2016).

68.Theodoridis,T.&Kraemer,J.No 主観的健康感を中心とした在宅高齢者における健康関連指標に関する共分散構造分析 Title.

69.Smolińska,U.&Kowalska,B.Smolińska-Kowalska2018_Article_BiologicalControlOfTheSoil-bor.pdf.J.Plant.Pathol.Published Online 2018:1-12 .

70.Fatin Najwa,R.&Azrina,A.Comparison of vitamin C content in citrus fruits by titration and high performance liquid chromatography(HPLC)methods.Int.Food Res.J. 24 (2),726-733(2017).

71.Satgurunathan,T.,Bhavan,P.S.&Komathi,S.Green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles from sodium selenite using garlic extract and its enrichment on Artemia Nauplii to feed the freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii post-larvae.Res.J.Chem. Environ. 21 (10),1-12(2017).

72.Nunes,R.,Sousa,Â.,Simaite,A.,Aido,A.&Buzgo,M.Sub-100 nm Chitosan-Triphosphate-DNA nanoparticles for delivery of DNA vaccines †.Published online 2021:1-7.

73.Yao,H.J.&Tian,S.P.Effects of a biocontrol agent and methyl jasmonate on postharvest diseases of peach fruit and the possible mechanisms involved.J.Appl.Microbiol. 98 (4),941-950.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02531.x(2005).

74.Farzand,A.et al.Suppression of sclerotinia sclerotiorum by the induction of systemic resistance and regulation of antioxidant pathways in tomato using fengycin produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42.Biomolecules. 9 (10).https://doi.org/10.3390/b iom9100613(2019).

75.Finney,D.J.Probit analysis:a statistical treatment of the sigmoid response curve.(1952).

54.Alghuthaymi,M.A.et al.Green biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles by cinnamon extract and their antimicrobial activity and application as edible coatings with nano-chitosan.J Food Qual. 2021 (2021).https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6670709

55.Soleimani Asl,S.et al.Chitosan-coated selenium nanoparticles enhance the efficiency of stem cells in the neuroprotection of streptozotocin-induced neurotoxicity in male rats.Int.J.Biochem.Cell.Biol. 141 (September),1-9.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioce 1.2021.106089(2021).

56.Kulikouskaya,V.et al.Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles:A comprehensive study of polymer molecular weight effect on the reaction kinetic,physicochemical properties,and synergetic antibacterial potential.SPE Polym. 3 (2),77-90.https://doi.org/10.10 02/pls2.10069(2022).

57.Rao,L.et al.Chitosan-decorated selenium nanoparticles as protein carriers to improve the in vivo half-life of the peptide therapeutic BAY 55-9837 for type 2 diabetes mellitus.Int.J.Nanomed.9,4819-4828.https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S67871(2014).

58.Shao,C.et al.Chitosan-coated selenium nanoparticles attenuate PRRSV replication and ROS/JNK-mediated apoptosis in vitro. Int.J.Nanomed. 17 (July),3043-3054.https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S370585(2022).

59.Zhihui,J.et al.One-step reinforcement and deacidification of paper.Coatings. 10 (12267),1-15(2020).

60.Thamilarasan,V.et al.Single step fabrication of Chitosan nanocrystals using Penaeus semisulcatus:Potential as New insecticides, antimicrobials and Plant Growth promoters.J.Clust Sci. 29 (2),375-384.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10876-018-1342-1(2018).

61.Ayoub MMH.Incorporated nano-chitosan.Polym.Bull. 0123456789 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00289-023-04768-8(2023).

62.Sheikhalipour,M.et al.Chitosan-selenium nanoparticle(Cs-se np)foliar spray alleviates salt stress in bitter melon.Nanomaterials. 11 (3),1-23.https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11030684(2021).

63.Luo,Y.,Zhang,B.,Cheng,W.H.&Wang,Q.Preparation,characterization and evaluation of selenite-loaded chitosan/TPP nanoparticles with or without zein coating.Carbohydr.Polym. 82 (3),942-951.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.06.029 (2010).

64.Chen,Y.et al.Stability and surface properties of selenium nanoparticles coated with chitosan and sodium carboxymethyl cellulose. Carbohydr.Polym. 278 (17),118859.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118859(2022).

65.Liu,J.,Tian,S.,Meng,X.&Xu,Y.Effects of Chitosan on control of postharvest diseases and physiological responses of tomato fruit.Postharvest Biol.Technol. 44 (3),300-306.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2006.12.019(2007).

66.Ma,Z.,Garrido-Maestu,A.&Jeong,K.C.Application,mode of action,and in vivo activity of chitosan and its micro-and nanoparticles as antimicrobial agents:A review.Carbohydr.Polym. 176 (July),257-265.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.08.082(2017).

67.Wu,Z.et al.Effect of selenium on control of postharvest gray mold of tomato fruit and the possible mechanisms involved.Front. Microbiol. 6 (JAN),1-11.https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01441(2016).

68.Theodoridis,T.&Kraemer,J.No 主観的健康感を中心とした在宅高齢者における健康関連指標に関する共分散構造分析 Title.

69.Smolińska,U.&Kowalska,B.Smolińska-Kowalska2018_Article_BiologicalControlOfTheSoil-bor.pdf.J.Plant.Pathol.Published Online 2018:1-12 .

70.Fatin Najwa,R.&Azrina,A.Comparison of vitamin C content in citrus fruits by titration and high performance liquid chromatography(HPLC)methods.Int.Food Res.J. 24 (2),726-733(2017).

71.Satgurunathan,T.,Bhavan,P.S.&Komathi,S.Green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles from sodium selenite using garlic extract and its enrichment on Artemia Nauplii to feed the freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii post-larvae.Res.J.Chem. Environ. 21 (10),1-12(2017).

72.Nunes,R.,Sousa,Â.,Simaite,A.,Aido,A.&Buzgo,M.Sub-100 nm Chitosan-Triphosphate-DNA nanoparticles for delivery of DNA vaccines †.Published online 2021:1-7.

73.Yao,H.J.&Tian,S.P.Effects of a biocontrol agent and methyl jasmonate on postharvest diseases of peach fruit and the possible mechanisms involved.J.Appl.Microbiol. 98 (4),941-950.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02531.x(2005).

74.Farzand,A.et al.Suppression of sclerotinia sclerotiorum by the induction of systemic resistance and regulation of antioxidant pathways in tomato using fengycin produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42.Biomolecules. 9 (10).https://doi.org/10.3390/b iom9100613(2019).

75.Finney,D.J.Probit analysis:a statistical treatment of the sigmoid response curve.(1952).

الشكر والتقدير

نود أن نشكر الدكتور أحمد إبراهيم، والدكتور أحمد م. الخواجة، والدكتور خالد السيد مصطفى (جامعة الجلالة، مدينة الجلالة، السويس، مصر) على مساعدتهم في تقنيات التوصيف المستخدمة في هذه الدراسة.

مساهمات المؤلفين

كان محمد م. دسوقي له دور أساسي في تنفيذ الجوانب العملية للمشروع، وتحليل البيانات، وصياغة المسودة الأولية. قدمت رادوا ح. أبو صالح الإشراف طوال المشروع وكانت مسؤولة عن مراجعة المسودة النهائية للمخطوطة. ساهم طارق أ. أ. موسى في تصميم التجارب، وساعد في العمل العملي، وشارك في تحليل البيانات ومراجعة المسودة النهائية للمخطوطة. كانت هبة م. فهمي مشاركة في تصور العمل، وساعدت في العمل العملي، وساهمت في تحليل البيانات والنقاش، ومراجعة المسودة النهائية للمخطوطة.

التمويل

تم توفير تمويل الوصول المفتوح من قبل هيئة العلوم والتكنولوجيا والابتكار (STDF) بالتعاون مع بنك المعرفة المصري (EKB).

الإعلانات

المصالح المتنافسة

يعلن المؤلفون عدم وجود مصالح متنافسة.

معلومات إضافية

يجب توجيه المراسلات وطلبات المواد إلى ر. ح. أ. – س. أو ط. أ. أ. م.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على www. nature. com/reprints.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على www. nature. com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر: تظل Springer Nature محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

الوصول المفتوح: هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام والمشاركة والتكيف والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج في أي وسيلة أو صيغة، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح ما إذا كانت هناك تغييرات قد تم إجراؤها. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر الائتمان للمادة. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة واستخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، ستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارة http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

© المؤلفون 2024

© المؤلفون 2024

قسم الفيزياء الحيوية، كلية العلوم، جامعة القاهرة، الجيزة، مصر. برنامج علوم النانو والتكنولوجيا، كلية العلوم، جامعة الجلالة، مدينة الجلالة، مدينة الجلالة الجديدة 43511، السويس، مصر. مجموعة الفيزياء الحيوية، قسم الفيزياء، كلية العلوم، جامعة المنصورة، المنصورة، مصر. قسم علم النبات والميكروبيولوجيا، كلية العلوم، جامعة القاهرة، الجيزة، مصر. البريد الإلكتروني: R.H.Saleh@gu.edu.eg; tmoussa@sci.cu.edu.eg

Journal: Scientific Reports, Volume: 15, Issue: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79574-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39762311

Publication Date: 2025-01-06

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79574-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39762311

Publication Date: 2025-01-06

OPEN

Nano-chitosan-coated, greensynthesized selenium nanoparticles as a novel antifungal agent against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: in vitro study

Chemical fungicides have been used to control fungal diseases like Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. These fungicides must be restricted because of their toxicity and the development of resistance strains. Therefore, utilizing natural nanoscale materials in agricultural production is a potential alternative. This work aimed to investigate the antifungal properties of a nanocomposite (nano-chitosan-coated, green-synthesized selenium nanoparticles) against the plant pathogenic fungus S. sclerotiorum. Chemical reduction was used to produce selenium nanoparticles from citrus peel extracts, and ionotropic gelation was used to produce chitosan nanoparticles. The nanocomposite has been produced using selenium nanoparticles stabilized by chitosan and cross-linked with sodium tripolyphosphate. Transmission electron microscopy, dynamic light scattering, X-ray diffraction, UV-VIS spectroscopy, and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy were used to characterize all produced nanostructures. The in vitro antifungal activity and minimum inhibitory concentration of all bulk and nanostructures are investigated at

Keywords Green Synthesis, Chitosan, Selenium, Nanocomposite, Sclerotinia Sclerotiorum

S. sclerotiorum, or white mould, generally has different adverse effects on plant development. For instance, it can cause decreases in the weight of the plant’s stem and root, whether fresh or dry, resulting in the death of host tissues

S. sclerotiorum, or white mould, generally has different adverse effects on plant development. For instance, it can cause decreases in the weight of the plant’s stem and root, whether fresh or dry, resulting in the death of host tissues

producing substantial quantities of reactive oxygen species, toxins, and cell wall-degrading enzymes (CWDEs). This process ultimately results in the induction of host cell death and the manifestation of necrotic symptoms

Recent studies demonstrate the antifungal action of selenium against S. sclerotiorum as a natural material in the form of sodium selenite

The antifungal activity of the chemically synthesized Se NPs against S. sclerotiorum was recently tested

Chitosan(CS) is a potential natural fungicide selected in this study with Se NPs to treat postharvest infections in fruits and vegetables

The current study details a systematic approach for preparing and characterizing nano-chitosan-coated green synthesized selenium nanoparticles (NCS-Se NPs). CS NPs will play a dual role as a stabilizing agent for Se NPs and as a natural antifungal agent with Se NPs against the same causal pathogen, S. sclerotiorum. In vitro studies tested the antifungal activity of different concentrations of the bulk and Nanoparticles, compared to the whole nanocomposite (NCS-Se NPs), to study its synergistic effect and determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). The antifungal activity of the nanostructures was tested at the same concentrations of their bulk forms, influenced by their particle size. The size is often one of the most critical factors affecting the antifungal activity of the tested material

Results and discussion

Identification of the fungal isolate

The fungal ITS region’s PCR was sequenced and checked with the GenBank sequence databases. All obtained sequences were aligned and analyzed. The best-fitting substitution model for the alignment was the Kimura 2 parameter model with gamma distribution. A neighbor-joining tree was constructed based on the ITS sequence of all strains (Fig. 1). The ITS sequence gave high similarities with S. sclerotiorum, and the sequence had accession number LC799483.

Optimization of the green synthesis of Se NPs

The preparation process and selection of the proper citrus peel were optimized to produce NPs with smaller particle sizes, higher stability, and dispersity. Typically, smaller NPs are known to have more potent antifungal activity than larger NPs

Figure 2a, b shows TEM images for L.P. -Se NPs and O.P. -Se NPs, respectively, showing size distribution histogram (inset in each). The results confirmed the green synthesis of Se NPs with better size distribution of L.P. -Se NPs with no aggregations, as shown in Fig. 2a. In this case, the average diameter was

Figure 2c, d presents the zeta potential of L.P. -Se NPs and O.P. -Se NPs to be -19 mv and +12 mv , respectively. The zeta potential is the electrostatic potential when measured at the electrical double layer around a nanoparticle in solution. Neutral nanoparticles have a zeta potential between -10 and +10 mV , whereas strongly cationic and strongly anionic nanoparticles have zeta potentials more enormous than +30 mV or less than

Fig. 1. A neighbor-joining tree for the isolated Sclerotinia sclerotiorum strains. The S. sclerotiorum in this study was deposited in GeneBank with accession number LC799483.1.

Fig. 2. TEM Image of Se NPs synthesized by (a) lemon-peel extract (L.P.- Se NPs) with an inset histogram showing the peak diameter at

As shown in Fig. 3a, the results of UV analysis revealed peaks that are displayed at 222 nm and 226 nm in the case of L.P. -Se NPs and O.P. -Se NPs, respectively; these peaks represent the formation of Se NPs due to the reduction of selenite ions by ascorbic acid found in lemon-peel and orange-peel extracts into elemental selenium

As shown in Fig. 3b, c, a laser beam was used initially to confirm the formation of NPs in both cases due to the Tyndall effect. The Tyndall effect was tested to verify the colloidal and dispersed structure of nanoparticles

In Fig. 4, FT-IR analysis presented the green synthesis of Se NPs, using lemon or orange-peel extract, in the region from

As observed in Fig. 4, the intensity of most absorption bands in the case of L.P. -Se NPs is higher than O.P.-Se NP bands. The reason for this difference is due to the decrease in particle size and the increase in surface area to

Fig. 3. Shows the characterization of the synthesized NPs, (a) UV spectroscopy of green synthesized O.P.- Se NPs, and L.P.- Se NPs (

Fig. 4. FT-IR spectroscopy of Se NPs synthesized by lemon and orange-peel extracts.

volume ratio, leading to higher intensity of absorption bands in the FT-IR spectrum as smaller particles have a more significant proportion of atoms on the surface, which can interact more readily with the incident infrared radiation, resulting in a stronger absorption signal

The crystallinity of L.P. -Se NPs was further investigated using X-ray powder Diffraction (XRD) analysis. Figure 5 shows a typical XRD pattern of the triagonal structure of L.P. -Se NPs in which the diffraction peaks correspond to the following miller indices: (100), (101), (110), (102), (111), (200), (201), (112), (202), (210), (113). Some previous studies confirmed this result

The particle size of synthesized NPs is one of the most critical factors affecting the antimicrobial and antifungal activity of NPs. Sribenjarat et al.. noted that Se NPs with a smaller size range showed higher antimicrobial activity

Fig. 5. XRD pattern of L.P.-Se NPs.

Preparation and characterization of CS NPs and NCS-Se NPs

Due to the number of amino groups on its surface, The cationic nature of chitosan is the reason for its positive zeta potential

Figure 6a shows the TEM image of CS NPs with a tiny particle size of an average diameter of

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) technique has been used to measure the hydrodynamic particle size of prepared CS NPs and NCS-Se NPs. Figure 7a b shows

Figure 8a shows the XRD pattern of CS, CS NPs, L.P. -Se NPs, and NCS-Se NPs. XRD pattern of CS NPs exhibits a broader prominent peak with lower intensity than (CS) at

Fig. 6. TEM images of (a) CS NPs with an inset showing the polycrystalline diffraction pattern of CS NPs, (b) Se NPs, (c) NCS-Se NPs, (d) zoom-in panel from (C) showing NCS-Se NPs with inset showing size distribution with peak Diameter of

The well-dispersed nano-selenium in the nanocomposite matrix may cause the distinctive XRD peaks of Se NPs and CS NPs to overlap, and the appearance of additional peaks in the nanocomposite structure suggests that ionic interactions are influencing the crystal lattice. Previous studies confirmed these XRD results

Figure 8b shows the FT-IR pattern of CS, CS NPs, NCS-Se NPs, and L.P. -Se NPs to investigate the intermolecular interaction of nanoparticles. In nano-chitosan, several characterization peaks were noted. The first peak, at

Fig. 7. Size distribution of (a) CS NPs, (b) NCS-Se NPs, and zeta potential of (c) CS NPs, and (d) NCS-Se NPs, respectively.

| Nanoparticles | Size Range (nm) | Mean Diameter (nm) | Zeta Potential (mv) |

| L.P.-Se |

|

42.28 | -19.0 |

| O.P.-Se |

|

85.7 | +12.0 |

| CS |

|

6.43 | +4.49 |

| NCS-Se |

|

32.7 | -7.24 |

Table 1. Particle size distribution and zeta potential of biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using lemon and orange-peel extracts (L.P.-Se, O.P.-Se), chitosan nanoparticles (CS), and their nanocomposite (NCS-Se).

In vitro antifungal activity

Mycelial growth assay

The antifungal activity of the three prepared nanostructures (CS NPs, L.P. -Se NPs, and NCS-Se NPs) had been studied compared to their bulk sources CS, SS, and a mixture of CS with SS (

All calculated values in the above two tables are shown as mean

The results showed an antifungal activity of all bulk materials at all concentrations, as shown in Table 2, which agrees with previous reports on the antifungal activity of CS and SS against S. sclerotiorum

As shown in Table 3, among all inhibitory concentrations, the MIC of the three nanostructures was also at minimum concentrations of 0.5 ppm with inhibitory percentages of

Fig. 8. (a) XRD of CS, CS NPs, L.P.- Se NPs & NCS-Se NPs & (b) FT-IR of CS, CS NPs, L.P.-Se NPs & NCS-Se NPs.

| Concentration (ppm) | Growth Diameter (cm) | ||

| SS treatment | CS Treatment | SS + CS (

|

|

| 0 |

|

|

|

| 0.5 |

|

|

|

| 1 |

|

|

|

| 5 |

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

| 50 |

|

|

|

| 100 |

|

|

|

| LSD | 0.72 | 0.59 | 0.66 |

Table 2. Growth diameter count of S. sclerotiorum treated with different concentrations of three tested bulk materials (SS, CS, and mixture of SS + CS (

The antifungal effect of LP- Se NPs at a low concentration of 0.5 ppm with

Mycelial biomass assay

Freshly prepared fungal biomass treated with each tested nanostructure with the MIC of 0.5 ppm , besides control, were dried and weighed after five days of dynamic incubation using an orbital shaker at

Morphological changes in S. sclerotiorum hyphae

The Ultrastructural changes in the hyphae of S. sclerotiorum caused by 0.5 ppm of NCS-Se NPs were detected using a scanning electron microscope (SEM). The untreated hyphae of S. sclerotiorum appeared intact, dense, long, and cylindrical, as shown in Fig. 10a, b, c. In contrast, hyphae treated with 0.5 ppm NCS-Se NPs showed

Fig. 9. The mycelial growth of S. sclerotiorum treated with MIC of (a) SS, CS, and mixture of SS + CS (

| Concentration (ppm) | Growth Diameter (cm) | ||

| Se NPs treatment | CS NPs Treatment | NCS-Se NPs Treatment | |

| 0 |

|

|

|

| 0.5 |

|

N/A | N/A |

| 1 |

|

|

N/A |

| 5 |

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

| 50 |

|

|

|

| 100 |

|

|

|

| LSD | 0.56 | 0.63 | 0.65 |

Table 3. Growth diameter count of S. sclerotiorum treated with different concentrations of three tested nanostructures (Se NPs, CS NPs, and NCS-Se NPs).

| Dynamic incubation

|

Treatment concentration

|

|||

| Control | CS NPs | Se NPs | NCS-Se NPs | |

| Average biomass

|

|

|

|

|

Table 4. Dry weight yield of S. sclerotiorum treated with 0.5 ppm of CS NPs, Se NPs, and NCS-Se NPs.

deformities and abnormalities in their morphology. These morphological changes include shrinkage, plasmolysis, distortion, and breakdown of fungal hyphae, as shown in Fig. 10d, e, f, and therefore, rupture and damage of

Antifungal mechanism of NCS-Se NPs

It has been demonstrated that CS and Se can protect plants from fungal infections

Fig. 10. TEM images of S. sclerotiorum hyphae of (a-c): control micrographs and (d-f): 0.5 ppm of NCS-Se NPs treatment micrographs.

Fig. 11. Schematic diagram showing the adsorption of NCS-Se NPs with S. sclerotiorum mycelia and their damage effect.

investigated. However, identifying the antifungal mechanism that NCS-Se NPs caused to S. sclerotiorum mycelia would aid in developing an efficient, safe, and sustainable strategy for controlling and managing S. sclerotiorum.

Materials and methods Chemicals

Sodium selenite anhydrous AR was purchased from SDFCL Co., India. High molecular weight Chitosan of 350 KD and Deacetylation level of

Isolation and identification of fungal strain

A common fungal disease called Sclerotinia rot, sometimes called white mould on some crops, is brought on by phytopathogenic members of the Sclerotinia genus. Specifically, S. sclerotiorum is regarded as one of the most pernicious and widespread plant infections. Necrotrophic fungal pathogen S. sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary causes diseases in various plants

A mixer mill isolation process recovered 0.5 g of fungal mycelium after five days of incubation. DNA was extracted, and a triplicate polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was conducted. 1x PCR buffer,

Green synthesis of Se NPs

Citrus limon (lemon) and Citrus reticulata (orange) are the citrus peel extracts selected, as both contain the highest ascorbic acid content

50 ml of the freshly prepared citrus peel extract (lemon or orange-peel extract was precisely heated using a magnetic hot plate stirrer, and conditions were adjusted to

Preparation of CS solution and CS NPs

Preparation of CS solution

About

Preparation of CS NPs

CS NPs were prepared using the ionotropic gelation method between CS and TPP

Synthesis of NCS- Se NPs

NCS-Se NPs were green synthesized as Se NPs as described before but in the presence of CS, with some modifications described by Shao et al.

which confirms the formation of NCS-Se NPs. The unreacted CS,

which confirms the formation of NCS-Se NPs. The unreacted CS,

In vitro studies of antifungal activity

Antifungal activity of the bulk materials (CS, SS, and a mixture of both materials with a ratio

Mycelial growth measurement

S. sclerotiorum was isolated from the infected green bean and kept on potato dextrose agar (PDA). According to Qing and Yao

Mycelial biomass assay

100 ml of potato dextrose broth (PDB) was prepared and placed in a 250 ml conical flask. Each PDP was diluted by the MIC of each tested nanostructure (Se NPs, NCS, and NCS-Se NPs) until the tested concentrations were obtained. Then, mycelial disks with 5 mm – diameter from old cultures ( 10 days grown at room temperature) were inserted into each treated PDB at

Morphological changes in S. sclerotiorum hyphae

After 18 h of exposure to the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of NCS-Se nanoparticles (NPs), S. sclerotiorum hyphae were fixed with a

Characterization of the prepared nanostructures

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The formation of the following nanostructures, green synthesized Se NPs, CS NPs, and NCS-Se NPs was confirmed using a Transmission electron microscope (TEM) (JEM-2100 PLUS). At an accelerating voltage of 200 KV , TEM was used to study the size, shape, and agglomeration states of Se NPs, CS NPs, and NCS-Se NPs. A drop of the diluted samples was placed on a copper-coated carbon grid and allowed to dry for about 15 min . A filter paper was used to remove the excess sample, and then the grid was left in the air to dry before being introduced to the TEM.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS)

The particle size of all prepared nanostructures, Se NPs, CS NPs, and NCS-Se NPs was measured using the Zeta sizer nano series (ZEN3600, Malvern, UK) with a size range (of

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis

X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD) was done to study the crystal structure, composition, and grain size of nanostructures using an X-ray diffractometer (Angstrom -ADX8000 diffractometer) with CuKal-radiation source of wavelength

Ultraviolet-visible (Uv-Vis) spectroscopy

The absorption spectrum of all prepared nanostructures was determined using UV-Vis. Spectrophotometer (BioWave3-USA) with a wavelength range of

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

Further characterization involved Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (Nicolet

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The morphological changes in the hyphae of the pathogen after treatment with the nanostructures were observed through SEM imaging (TESCAN VEGA COMPACT, Brno, Kohoutovice, Czech) at an accelerating voltage of 10 KeV .

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the collected data was performed via the ONE-WAY ANOVA analysis (at

Conclusion

Generally, we concluded that L.P.-Se NPs exhibit smaller sizes of

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript.

Received: 29 July 2024; Accepted: 11 November 2024

Published online: 06 January 2025

Received: 29 July 2024; Accepted: 11 November 2024

Published online: 06 January 2025

References

- Perveen, K., Haseeb, A. & Shukla, P. K. Effect of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum on the disease development, growth, oil yield and biochemical changes in plants of Mentha arvensis. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 17 (4), 291-294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2010.05.008 (2010).

- Rollins, J. A. & Dickman, M. B. pH signaling in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: Identification of a pacC/RIM1 homolog. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67 (1), 75-81. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.67.1.75-81.2001 (2001).

- Qin, L. et al. SsCak1 regulates growth and pathogenicity in Sclerotinia Sclerotiorum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (16), 1-14. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/ijms241612610 (2023).

- Ding, Y. et al. Host-Induced Gene silencing of a multifunction gene Sscnd1 enhances Plant Resistance against Sclerotinia Sclerotiorum. Front. Microbiol. 12 (October), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb. 2021.693334 (2021).

- Seifbarghi, S. et al. Changes in the Sclerotinia sclerotiorum transcriptome during infection of Brassica napus. BMC Genom. 18 (1), 1-37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-017-3642-5 (2017).

- Williams, B., Kabbage, M., Kim, H. J., Britt, R. & Dickman, M. B. Tipping the balance: Sclerotinia sclerotiorum secreted oxalic acid suppresses host defenses by manipulating the host redox environment. PLoS Pathog. 7 (6). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat. 10 02107 (2011).

- Chittem, K., Yajima, W. R., Goswami, R. S. & del Río Mendoza, L. E. Transcriptome analysis of the plant pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum interaction with resistant and susceptible canola (Brassica napus) lines. PLoS One. 15 (3), 1-29. https://doi.org/10.13 71/journal.pone. 0229844 (2020).

- Jia, W. et al. Action of selenium against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: Damaging membrane system and interfering with metabolism. Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 150 (June), 10-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2018.06.003 (2018).

- Xu, J. et al. Selenium as a potential fungicide could protect oilseed rape leaves from Sclerotinia sclerotiorum infection. Environ. Pollut. 257, 113495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113495 (2020).

- Fernández-Llamosas, H., Castro, L., Blázquez, M. L., Díaz, E. & Carmona, M. Biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles by Azoarcus Sp. CIB Microb. Cell. Fact. 15 (1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-016-0510-y (2016).

- Wang, H., Zhang, J. & Yu, H. Elemental selenium at nano size possesses lower toxicity without compromising the fundamental effect on selenoenzymes: comparison with selenomethionine in mice. Free Radic Biol. Med. 42 (10), 1524-1533. https://doi.org/10 .1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.02.013 (2007).

- Chen, T., Wong, Y. S., Zheng, W., Bai, Y. & Huang, L. Selenium nanoparticles fabricated in Undaria pinnatifida polysaccharide solutions induce mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in A375 human melanoma cells. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 67 (1), 26-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2008.07.010 (2008).

- Quiterio-Gutiérrez, T. et al. The application of selenium and copper nanoparticles modifies the biochemical responses of tomato plants under stress by Alternaria Solani. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (8). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20081950 (2019).

- Vrandečić, K. et al. Antifungal activities of silver and selenium nanoparticles stabilized with different surface coating agents. Pest Manag Sci. 76 (6), 2021-2029. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps. 5735 (2020).

- Dhawan, G., Singh, I., Dhawan, U. & Kumar, P. Synthesis and characterization of Nanoselenium: A step-by-step guide for undergraduate students. J. Chem. Educ. 98 (9), 2982-2989. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c01467 (2021).

- Cittrarasu, V. et al. Green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles mediated from Ceropegia bulbosa Roxb extract and its cytotoxicity, antimicrobial, mosquitocidal and photocatalytic activities. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80327-9 (2021).

- Alvi, G. B. et al. Biogenic selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) from citrus fruit have anti-bacterial activities. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84099-8 (2021).

- Balakrishnaraja, R., Sasidharan, S. & Biosynthesis of Selenium Nanoparticles Using Citrus Reticulata Peel Extract. Vol 4. (2015).

- Mittal, A. K., Chisti, Y. & Banerjee, U. C. Synthesis of metallic nanoparticles using plant extracts. Biotechnol. Adv. 31 (2), 346-356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.01.003 (2013).

- Rao, A. V. & Rao, L. G. Carotenoids and human health. Pharmacol. Res. 55 (3), 207-216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2007.01.012 (2007).

- Salem, S. S. et al. Green biosynthesis of Selenium nanoparticles using orange peel waste: Characterization, antibacterial and antibiofilm activities against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Life. 12 (6). https://doi.org/10.3390/life12060893 (2022).

- Awad, H. Antifungal potentialities of Chitosan and Trichoderma in controlling Botrytis cinerea, causing strawberry gray mold disease. J. Plant. Prot. Pathol. 8 (8), 371-378. https://doi.org/10.21608/jppp. 2017.46342 (2017).

- Wang, Q., Zuo, J., Wang, Q., Na, Y. & Gao, L. Inhibitory effect of chitosan on growth of the fungal phytopathogen, Sclerotinia Sclerotiorum, and sclerotinia rot of carrot. J. Integr. Agric. 14 (4), 691-697. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2095-3119(14)60800-5 (2015).

- Molloy, C., Cheah, L. H. & Koolaard, J. P. Induced resistance against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in carrots treated with enzymatically hydrolysed chitosan. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 33 (1), 61-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2004.01.009 (2004).

- El-mohamedy, R. S. R., El-aziz, M. E. A. & Kamel, S. Antifungal activity of chitosan nanoparticles against some plant pathogenic fungi in vitro. 21(4):201-209. (2019).

- Slavin, Y. N. & Bach, H. Mechanisms of antifungal properties of metal nanoparticles. Nanomaterials. 12 (24). https://doi.org/10.3 390/nano12244470 (2022).

- Martínez, A. et al. Dual antifungal activity against Candida albicans of copper metallic nanostructures and hierarchical copper oxide marigold-like nanostructures grown in situ in the culture medium. J. Appl. Microbiol. 130 (6), 1883-1892. https://doi.org/1 0.1111/jam. 14859 (2021).

- De La Rosa-García, S. C. et al. Antifungal activity of ZnO and MgO nanomaterials and their mixtures against colletotrichum gloeosporioides strains from tropical fruit. J Nanomater. 2018 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3498527

- Danaei, M. et al. Impact of particle size and polydispersity index on the clinical applications of lipidic nanocarrier systems. Pharmaceutics. 10 (2), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics10020057 (2018).

- Rao, S., Song, Y., Peddie, F. & Evans, A. M. Particle size reduction to the nanometer range: A promising approach to improve buccal absorption of poorly water-soluble drugs. Int. J. Nanomed. 6, 1245-1251. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.s19151 (2011).

- Clogston, J. D. & Patri, A. K. Zeta Potential Measurement. Methods Mol. Biol. 697, 63-70. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-60327-19 8-1_6 (2011).

- Hasani Bijarbooneh, F. et al. Aqueous colloidal stability evaluated by Zeta potential measurement and resultant TiO 2 for superior photovoltaic performance. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 96 (8), 2636-2643. https://doi.org/10.1111/jace. 12371 (2013).

- JAHAN, I. Lemon Peel Extract for synthesizing non-toxic silver nanoparticles through one-step microwave-accelerated Scheme. Kahramanmaraş Sütçü İmam Üniversitesi Tarım ve Doğa. Derg. 24 (1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.18016/ksutarimdoga.vi. 737063 (2021).

- Singh, N., Saha, P., Rajkumar, K. & Abraham, J. Biosynthesis of silver and selenium nanoparticles by Bacillus sp. JAPSK2 and evaluation of antimicrobial activity. Der Pharm. Lett. 6 (1), 175-181 (2014).

- Ramamurthy, C. H. et al. The extra cellular synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles and their free radical scavenging and antibacterial properties. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 102, 808-815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.09.025 (2013).

- Khandsuren, B. & Prokisch, J. The production methods of selenium nanoparticles. Acta Univ. Sapientiae Aliment. 14 (1), 14-43. https://doi.org/10.2478/ausal-2021-0002 (2021).

- Peng, S., McMahon, J. M., Schatz, G. C., Gray, S. K. & Sun, Y. Reversing the size-dependence of surface plasmon resonances. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 107 (33), 14530-14534. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas. 1007524107 (2010).

- İpek, P. et al. Green synthesis and evaluation of antipathogenic, antioxidant, and anticholinesterase activities of gold nanoparticles (au NPs) from Allium cepa L. peel aqueous extract. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 14 (9), 10661-10670. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1 3399-023-04362-y (2024).

- Kelly, K. L., Coronado, E., Zhao, L. L. & Schatz, G. C. The optical properties of metal nanoparticles: The influence of size, shape, and dielectric environment. J. Phys. Chem. B. 107 (3), 668-677. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp026731y (2003).

- Jiang, F., Cai, W. & Tan, G. Facile synthesis and Optical properties of Small Selenium nanocrystals and Nanorods. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 12, 0-5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-017-2165-y (2017).

- Lin, Z. H. & Wang, C. R. C. Evidence on the size-dependent absorption spectral evolution of selenium nanoparticles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 92 (2-3), 591-594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2005.02.023 (2005).

- Wahab, A., Abou Elyazeed, A. M. & Abdalla, A. E. Bioactive compounds in some Citrus peels as affected by drying processes and quality evaluation of cakes supplemented with Citrus peels powder. 44.; (2018).

- El-ghfar, M. H. A. A., Ibrahim, H. M., Hassan, I. M., Abdel Fattah, A. A. & Mahmoud, M. H. Peels of lemon and orange as valueadded ingredients: Chemical and antioxidant properties. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 5 (12), 777-794. https://doi.org/10.2054 6/ijcmas.2016.512.089 (2016).

- Udvardi, B. et al. Effects of particle size on the attenuated total reflection spectrum of minerals. Appl. Spectrosc. 71 (6), 1157-1168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003702816670914 (2017).

- Alagesan, V. & Venugopal, S. Green synthesis of selenium nanoparticle using leaves extract of Withania somnifera and its biological applications and photocatalytic activities. Bionanoscience. 9 (1), 105-116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12668-018-0566-8 (2019).

- Gulley-Stahl, H. J., Haas, J. A., Schmidt, K. A., Evan, A. P. & Sommer, A. J. Attenuated total internal reflection Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy: A quantitative approach for kidney stone analysis. Appl. Spectrosc. 63 (7), 759-766. https://doi.org/10.1366 /000370209788701044 (2009).

- Khater, S., Ali, I., Khater, Ahmed, A. & abd el-megid, S. Preparation and characterization of Chitosan-stabilized selenium nanoparticles for ameliorating experimentally Induced Diabetic Nephropathy in rats. Arab. J. Nucl. Sci. Appl. 0 (0), 1-9. https://do i.org/10.21608/ajnsa.2020.19809.1300 (2020).

- Saeed, M. et al. Assessment of antimicrobial features of selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) using cyclic voltammetric strategy. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 19 (11), 7363-7368. https://doi.org/10.1166/jnn.2019.16627 (2019).

- Sribenjarat, P., Jirakanjanakit, N. & Jirasripongpun, K. Selenium nanoparticles biosynthesized by garlic extract as antimicrobial agent. Sci. Eng. Heal Stud. 14 (1), 22-31 (2020).

- Javed, R. et al. Role of capping agents in the application of nanoparticles in biomedicine and environmental remediation: Recent trends and future prospects. J. Nanobiotechnol. 18 (1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-020-00704-4 (2020).

- Collado-González, M., Montalbán, M. G., Peña-García, J., Pérez-Sánchez, H. & Víllora, G. Díaz Baños FG. Chitosan as stabilizing agent for negatively charged nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 161, 63-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.12.043 (2017).

- Aibani, N., Cuddihy, G. & Wasan, E. K. Chitosan Nanoparticles at the Biological interface: Implications for drug delivery. Published online 2021.

53.Salem,M.F.,Abd-elraoof,W.A.,Tayel,A.A.,Alzuaibr,F.M.&Abonama,O.M.Antifungal application of biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles with pomegranate peels and nanochitosan as edible coatings for citrus green mold protection.J.Nanobiotechnol. Published Online 2022,1-12.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-022-01393-x

54.Alghuthaymi,M.A.et al.Green biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles by cinnamon extract and their antimicrobial activity and application as edible coatings with nano-chitosan.J Food Qual. 2021 (2021).https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6670709

55.Soleimani Asl,S.et al.Chitosan-coated selenium nanoparticles enhance the efficiency of stem cells in the neuroprotection of streptozotocin-induced neurotoxicity in male rats.Int.J.Biochem.Cell.Biol. 141 (September),1-9.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioce 1.2021.106089(2021).

56.Kulikouskaya,V.et al.Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles:A comprehensive study of polymer molecular weight effect on the reaction kinetic,physicochemical properties,and synergetic antibacterial potential.SPE Polym. 3 (2),77-90.https://doi.org/10.10 02/pls2.10069(2022).

57.Rao,L.et al.Chitosan-decorated selenium nanoparticles as protein carriers to improve the in vivo half-life of the peptide therapeutic BAY 55-9837 for type 2 diabetes mellitus.Int.J.Nanomed.9,4819-4828.https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S67871(2014).

58.Shao,C.et al.Chitosan-coated selenium nanoparticles attenuate PRRSV replication and ROS/JNK-mediated apoptosis in vitro. Int.J.Nanomed. 17 (July),3043-3054.https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S370585(2022).

59.Zhihui,J.et al.One-step reinforcement and deacidification of paper.Coatings. 10 (12267),1-15(2020).

60.Thamilarasan,V.et al.Single step fabrication of Chitosan nanocrystals using Penaeus semisulcatus:Potential as New insecticides, antimicrobials and Plant Growth promoters.J.Clust Sci. 29 (2),375-384.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10876-018-1342-1(2018).

61.Ayoub MMH.Incorporated nano-chitosan.Polym.Bull. 0123456789 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00289-023-04768-8(2023).

62.Sheikhalipour,M.et al.Chitosan-selenium nanoparticle(Cs-se np)foliar spray alleviates salt stress in bitter melon.Nanomaterials. 11 (3),1-23.https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11030684(2021).

63.Luo,Y.,Zhang,B.,Cheng,W.H.&Wang,Q.Preparation,characterization and evaluation of selenite-loaded chitosan/TPP nanoparticles with or without zein coating.Carbohydr.Polym. 82 (3),942-951.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.06.029 (2010).

64.Chen,Y.et al.Stability and surface properties of selenium nanoparticles coated with chitosan and sodium carboxymethyl cellulose. Carbohydr.Polym. 278 (17),118859.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118859(2022).

65.Liu,J.,Tian,S.,Meng,X.&Xu,Y.Effects of Chitosan on control of postharvest diseases and physiological responses of tomato fruit.Postharvest Biol.Technol. 44 (3),300-306.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2006.12.019(2007).

66.Ma,Z.,Garrido-Maestu,A.&Jeong,K.C.Application,mode of action,and in vivo activity of chitosan and its micro-and nanoparticles as antimicrobial agents:A review.Carbohydr.Polym. 176 (July),257-265.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.08.082(2017).

67.Wu,Z.et al.Effect of selenium on control of postharvest gray mold of tomato fruit and the possible mechanisms involved.Front. Microbiol. 6 (JAN),1-11.https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01441(2016).

68.Theodoridis,T.&Kraemer,J.No 主観的健康感を中心とした在宅高齢者における健康関連指標に関する共分散構造分析 Title.

69.Smolińska,U.&Kowalska,B.Smolińska-Kowalska2018_Article_BiologicalControlOfTheSoil-bor.pdf.J.Plant.Pathol.Published Online 2018:1-12 .

70.Fatin Najwa,R.&Azrina,A.Comparison of vitamin C content in citrus fruits by titration and high performance liquid chromatography(HPLC)methods.Int.Food Res.J. 24 (2),726-733(2017).

71.Satgurunathan,T.,Bhavan,P.S.&Komathi,S.Green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles from sodium selenite using garlic extract and its enrichment on Artemia Nauplii to feed the freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii post-larvae.Res.J.Chem. Environ. 21 (10),1-12(2017).

72.Nunes,R.,Sousa,Â.,Simaite,A.,Aido,A.&Buzgo,M.Sub-100 nm Chitosan-Triphosphate-DNA nanoparticles for delivery of DNA vaccines †.Published online 2021:1-7.

73.Yao,H.J.&Tian,S.P.Effects of a biocontrol agent and methyl jasmonate on postharvest diseases of peach fruit and the possible mechanisms involved.J.Appl.Microbiol. 98 (4),941-950.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02531.x(2005).

74.Farzand,A.et al.Suppression of sclerotinia sclerotiorum by the induction of systemic resistance and regulation of antioxidant pathways in tomato using fengycin produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42.Biomolecules. 9 (10).https://doi.org/10.3390/b iom9100613(2019).

75.Finney,D.J.Probit analysis:a statistical treatment of the sigmoid response curve.(1952).

54.Alghuthaymi,M.A.et al.Green biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles by cinnamon extract and their antimicrobial activity and application as edible coatings with nano-chitosan.J Food Qual. 2021 (2021).https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6670709

55.Soleimani Asl,S.et al.Chitosan-coated selenium nanoparticles enhance the efficiency of stem cells in the neuroprotection of streptozotocin-induced neurotoxicity in male rats.Int.J.Biochem.Cell.Biol. 141 (September),1-9.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioce 1.2021.106089(2021).

56.Kulikouskaya,V.et al.Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles:A comprehensive study of polymer molecular weight effect on the reaction kinetic,physicochemical properties,and synergetic antibacterial potential.SPE Polym. 3 (2),77-90.https://doi.org/10.10 02/pls2.10069(2022).

57.Rao,L.et al.Chitosan-decorated selenium nanoparticles as protein carriers to improve the in vivo half-life of the peptide therapeutic BAY 55-9837 for type 2 diabetes mellitus.Int.J.Nanomed.9,4819-4828.https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S67871(2014).

58.Shao,C.et al.Chitosan-coated selenium nanoparticles attenuate PRRSV replication and ROS/JNK-mediated apoptosis in vitro. Int.J.Nanomed. 17 (July),3043-3054.https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S370585(2022).

59.Zhihui,J.et al.One-step reinforcement and deacidification of paper.Coatings. 10 (12267),1-15(2020).

60.Thamilarasan,V.et al.Single step fabrication of Chitosan nanocrystals using Penaeus semisulcatus:Potential as New insecticides, antimicrobials and Plant Growth promoters.J.Clust Sci. 29 (2),375-384.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10876-018-1342-1(2018).

61.Ayoub MMH.Incorporated nano-chitosan.Polym.Bull. 0123456789 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00289-023-04768-8(2023).

62.Sheikhalipour,M.et al.Chitosan-selenium nanoparticle(Cs-se np)foliar spray alleviates salt stress in bitter melon.Nanomaterials. 11 (3),1-23.https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11030684(2021).

63.Luo,Y.,Zhang,B.,Cheng,W.H.&Wang,Q.Preparation,characterization and evaluation of selenite-loaded chitosan/TPP nanoparticles with or without zein coating.Carbohydr.Polym. 82 (3),942-951.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.06.029 (2010).

64.Chen,Y.et al.Stability and surface properties of selenium nanoparticles coated with chitosan and sodium carboxymethyl cellulose. Carbohydr.Polym. 278 (17),118859.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118859(2022).

65.Liu,J.,Tian,S.,Meng,X.&Xu,Y.Effects of Chitosan on control of postharvest diseases and physiological responses of tomato fruit.Postharvest Biol.Technol. 44 (3),300-306.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2006.12.019(2007).

66.Ma,Z.,Garrido-Maestu,A.&Jeong,K.C.Application,mode of action,and in vivo activity of chitosan and its micro-and nanoparticles as antimicrobial agents:A review.Carbohydr.Polym. 176 (July),257-265.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.08.082(2017).

67.Wu,Z.et al.Effect of selenium on control of postharvest gray mold of tomato fruit and the possible mechanisms involved.Front. Microbiol. 6 (JAN),1-11.https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01441(2016).

68.Theodoridis,T.&Kraemer,J.No 主観的健康感を中心とした在宅高齢者における健康関連指標に関する共分散構造分析 Title.