DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55737-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39833143

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-20

حليب الإبل هو مصدر مهمل للحمى المالطية بين المجتمعات العربية الريفية

تم القبول: 22 ديسمبر 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 20 يناير 2025

الملخص

تصف منظمة الصحة العالمية داء البروسيلات بأنه واحد من الأمراض الحيوانية المنشأ الرائدة في العالم، حيث تُعتبر منطقة الشرق الأوسط نقطة ساخنة عالمية. بروسيلة ميلتينسيس متوطنة بين قطعان الماشية في المنطقة، حيث يحدث الانتقال الحيواني إلى الإنسان عبر استهلاك الحليب الخام، من بين طرق أخرى. يتم التحكم في المرض بشكل كبير من خلال تطعيم قطعان الأغنام الصغيرة والماشية. بسبب التأثيرات الاجتماعية والثقافية والدينية، يُستهلك حليب الإبل (الجمل العربي) بشكل واسع خامًا، بينما يُغلى حليب الأنواع الأخرى من الماشية بشكل كبير. للتحقيق في التأثير المحتمل على الصحة العامة لبروسيلة في الإبل، نقوم بإجراء دراسة مقطعية في جنوب الأردن تشمل 227 قطيعًا و202 أسرة تمتلك الماشية. هنا نوضح أن الاستهلاك اليومي لحليب الإبل الخام مرتبط بحالة إيجابية لبروسيلة بين سكان الدراسة.

حالة إيجابية للفيروس في التحليل متعدد المتغيرات، مما يبرز الحاجة إلى تدابير تحكم مناسبة اجتماعيًا وثقافيًا، مع أهمية التدخلات المستهدفة بين خزان الجمال لتحقيق السيطرة الفعالة.

النتائج

الجمال

| انتشار الأجسام المضادة في السكان | انتشار الأجسام المضادة على مستوى القطيع | |||||||

| الانتشار الظاهر | الانتشار الحقيقي | غير معدّل | معدل* | |||||

| الجمال الإيجابية

|

% | % | (95% فترة الثقة) | قطعان إيجابية

|

% | % | (95% فترة الثقة) | |

| جنوب الأردن (معان والعقبة) | 8/884 | (0.9%) | 1.0% | (0.5-2.1) | 7/227 | ٣.١٪ | 18.7% | (14.3-23.3) |

| معاً | 7/340 | (٢.١٪) | ٢.٤٪ | (1.1-4.8) | 6/81 | ٧.٤٪ | 30.4% | (22.2-39.5) |

| العقبة | 1/544 | (0.2%) | 0.1% | (0.0-1.1) | 1/146 | 0.7% | ٤.٨٪ | (2.1-8.2) |

- تم تعديلها لقيم أداء الاختبار المجمعة؛ كما تم وزن تقدير جنوب الأردن (معان والعقبة) حسب المنطقة.

إيجابي بشأن RBPT و CFT.

القطيع يحتوي على جمل واحد أو أكثر إيجابي، إيجابي في اختبار RBPT وCFT.

عوامل الخطر المحتملة للإصابة. في التحليل الأحادي المتغير، وُجد أن المتغيرات التالية مرتبطة () مع حالة إيجابية للفيروس، المنطقة، شراء الجمال (في العام الماضي)، ممارسات إدارة القطيع المغلق وامتلاك واحدة أو أكثر من الماعز أيضًا (الجدول 2). في التحليل متعدد المتغيرات، كانت الحالة الإيجابية مرتبطة بالمنطقة (معان) وشراء الجمال ; مع أدلة تشير إلى أن ممارسات إدارة القطيع المغلق توفر الحماية (أو ) في نموذج فردي (الخصوصية ناتجة عن غياب أي جِمال إيجابية مأخوذة من بين القطعان المغلقة) (الجدول 3).

البشر

موزون حسب المنطقة

| متغير | ||||||

| الإجمالي (المفقود) | +ve | % | أو | فترة الثقة 95% | ب | |

| 884 جمل تم أخذ عينات منها | ||||||

| فترة الدراسة | ||||||

| 2014-15 | 429 | ٥ | 1.2٪ | 0.94 | 0.26-3.41 | 0.93 |

| 2017-18 | ٤٥٥ | ٥ | 1.1% | |||

| منطقة | ||||||

| معان | ٣٤٠ | ٨ | ٢.٤٪ | 6.53 | 1.62-43.44 | 0.0069 |

| العقبة | 544 | 2 | 0.4% | |||

| جنس | ||||||

| أنثى | 669 | 9 | 1.3% | 2.81 | 0.52-51.96 | 0.26 |

| ذكر | ٢٠٧ (٨) | 1 | 0.5% | |||

| العمر > الوسيط (5 سنوات) | ||||||

| نعم | ٤٠٥ | ٧ | 1.5% | 0.41 | 0.09-1.50 | 0.18 |

| لا | ٤٧٤ (٥) | ٣ | 0.7% | |||

| حجم القطيع > الوسيط (10) | ||||||

| نعم | ٥٥٢ | ٨ | 1.4٪ | 2.43 | 0.60-16.14 | 0.23 |

| لا | ٣٣٢ | 2 | 0.6% | |||

| عدد قطعان الإبل القريبة (ضمن مسافة 15 دقيقة بالسيارة) >20 | ||||||

| نعم | ٣٦٤ | ٦ | 1.6٪ | 2.06 | 0.58-8.10 | 0.26 |

| لا | ٤٩٥ (٢٥) | ٤ | 0.8% | |||

| يتم الاحتفاظ بالقطيع معًا كمجموعة واحدة على مدار السنة | ||||||

| نعم | ٦٠٠ | ٦ | 1.0% | 0.66 | 0.19-2.62 | 0.54 |

| لا | 267 (17) | ٤ | 1.5% | |||

| القطيع على اتصال مع قطعان محلية أخرى | ||||||

| نعم | ٥١٩ | ٨ | 1.3% | 1.15 | 0.32-5.36 | 0.84 |

| لا | 255 (110) | ٣ | 1.2% | |||

| يتم نقل القطيع إلى مناطق بعيدة لأغراض الرعي الموسمي (التنقل الرعوي) | ||||||

| نعم | ٣٦٧ | ٤ | 1.1% | 0.90 | 0.23-3.18 | 0.87 |

| لا | 497 (20) | ٦ | 1.2٪ | |||

| تم شراء جمال جديدة | ||||||

| نعم | 318 | ٧ | ٢.٢٪ | ٤.١٠ | 1.13-19.11 | 0.032 |

| لا | 549 (17) | ٣ | 0.5% | |||

| تُستعير الجمال لأغراض التزاوج | ||||||

| نعم | ٤٤٩ | ٧ | 1.6٪ | 2.19 | 0.60-10.22 | 0.24 |

| لا | 418 (17) | ٣ | 0.7% | |||

| قطيع مغلق | ||||||

| نعم | 142 | 0 | 0.0% | 0.00 | – | 0.056 |

| لا | 713 (29) | 10 | 1.4% | |||

| تُمتلك الأغنام أيضًا | ||||||

| نعم | ٥٣٣ | ٨ | 1.5% | 2.53 | 0.63-16.83 | 0.21 |

| لا | ٣٣٤ (١٧) | 2 | 0.6% | |||

| تُمتلك أيضًا الماعز | ||||||

| نعم | ٦٠٣ | 9 | 1.5% | 3.98 | 0.74-73.67 | 0.12 |

| لا | 264 (17) | 1 | 0.4% | |||

| تم تطعيم قطعان الحيوانات المجترة الصغيرة، حيثما كانت مملوكة، ضد البروسيلات (لقاح Rev 1)

|

||||||

| نعم | 263 | ٤ | 1.5% | 1.17 | 0.26-6.00 | 0.84 |

| لا | 231 (383) | ٣ | 1.3% | |||

| الكلاب موجودة بالقرب من القطيع | ||||||

| نعم | 648 | 9 | 1.4٪ | 3.07 | 0.57-56.79 | 0.22 |

| لا | ٢١٩ (١٧) | 1 | 0.5% | |||

نقاش

| المتغير** | الفئة | OR المعدل مسبقًا

|

قيمة p | OR المعدل بالكامل

|

قيمة p | ||

| المنطقة | معان | 7.11 | 1.75-47.55 | 0.0050 | 6.23 | 1.53-41.81 | 0.0093 |

| العمر | >الوسيط (5 سنوات) | 0.41 | 0.09-1.50 | 0.18 | 0.35 | 0.074-1.32 | 0.12 |

| الجنس | أنثى | 3.56 | 0.64-66.50 | 0.17 | 3.86 | 0.68-72.73 | 0.14 |

| تم شراء الإبل | نعم | 4.32 | 1.19-20.20 | 0.026 | 3.84 | 1.04-18.09 | 0.043 |

| قطيع مغلق

|

نعم | 0.00 | NE | 0.047 | 0.00 | NE | 0.072 |

NE غير قابل للتقدير.

الأنواع بين المجتمعات الإسلامية في الشرق الأوسط وما وراءه

ذبحها، مع كون المشترين المحتملين غير مدركين لتاريخها الإنجابي وحالتها المحتملة الإيجابية للبروسيلات (كما أفاد المشاركون في الدراسة)

| COH (

|

NCOH (

|

كل

|

|||

| العمر* | |||||

| 5-14 | 143 (21.5%) | 47 (24%) | 190 (22%) | ||

| 15-24 | 151 (22.7%) | 50 (25%) | 201 (23%) | ||

| 25-39 | 161 (24.2%) | 40 (20%) | 201 (23%) | ||

| 40-59 | 137 (20.6%) | 44 (22%) | 181 (21%) | ||

|

|

74 (11.1%) | 18 (9%) | 92 (11%) | ||

| الوسيط (المدى interquartile) | 27 (16-45) | ٢٦ (١٥-٤٤) | 27 (16-44) | ||

| جنس | |||||

| أنثى | 384 (57.6%) | 118 (59%) | 401 (46%) | ||

| ذكر | 283 (42.4%) | 82 (41%) | ٤٦٦ (٥٤٪) | ||

| الجنسية** | |||||

| أردني | 565 (93.1%) | 192 (99%) | 757 (95%) | ||

| السعودي | 23 (3.8%) | 0 (0%) | 23 (3%) | ||

| مصري | 8 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (1%) | ||

| سوداني | 8 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (1%) | ||

| آخر | 3 (0.5%) | 2 (1%) | 5 (1%) | ||

| تاريخ البروسيلوز | |||||

| نعم | 18 (2.8%) | 5 (2.6%) | 23 (3%) | ||

| لا | 629 (97.2%) | 189 (97.4%) | 818 (97%) | ||

| التعليم الثانوي | |||||

| نعم | 180 (35.6%) | 53 (37%) | 233 (36%) | ||

| لا | 326 (64.4%) | 90 (63%) | 414 (64%) | ||

| حجم الأسرة (عدد الأعضاء >10) | |||||

| 0-10 | 287 (43.0%) | 76 (38.0%) | 363 (42%) | ||

| 11-20 | ٣٠٩ (٤٦.٣٪) | ١٠٩ (٥٤.٥٪) | 418 (48%) | ||

| >20 | 71 (10.6%) | 15 (7.5%) | 86 (10%) | ||

| الأسرة تمتلك الجمال | |||||

| نعم | 667 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 667 (77%) | ||

| لا | 0 (0%) | 200 (100%) | 200 (23%) | ||

| الأسرة تمتلك الماشية | |||||

| نعم | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| لا | 667 (100%) | 200 (100%) | 867 (100%) | ||

| تملك الأسر حيوانات مجترة صغيرة | |||||

| نعم | 590 (88.5%) | 200 (100%) | 790 (91.1%) | ||

| لا | 77 (11.5%) | 0 (0%) | 77 (8.9%) | ||

| حيثما كانت مملوكة، يتم الإبلاغ عن تلقيح الحيوانات المجترة الصغيرة | |||||

| نعم | 255 (72.9%) | 118 (90.8%) | 373 (77.7%) | ||

| لا | 95 (27.1%) | 12 (9.2%) | 107 (22.3%) | ||

| أي تاريخ من الانخراط في تربية الماشية

|

|||||

| نعم | 571 (85.6%) | 711 (82.0%) | 711 (82%) | ||

| لا | 96 (14.4%) | 156 (18.0%) | 156 (18%) | ||

| متكرر

|

|||||

| نعم | 478 (71.7%) | 577 (66.6%) | 577 (67%) | ||

| لا | 189 (28.3%) | 290 (33.4%) | 290 (33%) | ||

| المنزل المنزلي يحتوي على نظام تبريد الهواء

|

|||||

| نعم | 169 (42.9%) | 56 (31.6%) | 225 (39.4%) | ||

| لا | 225 (57.1%) | 121 (68.4%) | 346 (60.6%) | ||

|

|||||

| معدل* | |||||

| الأفراد الإيجابيون غير المعدلين / إجمالي الأفراد | % | % | (95% فترة الثقة) | ||

| جنوب الأردن (معان والعقبة) |

|

79/667 | (١١.٨٪) | 12.7% | (10.3-15.4) |

|

|

12/200 | (6.0%) | ٨.٢٪ | (4.9-12.5) | |

| جميع الأسر | 91/867 | (10.5%) | ٨.٧٪ | (6.9-10.7) | |

| معاً |

|

68/379 | (١٧.٩٪) | 19.5% | (15.7-23.6) |

|

|

7/99 | (٧.١٪) | 9.0% | (4.4-15.7) | |

| جميع الأسر | 75/478 | (15.7%) | 10.0% | (7.5-12.9) | |

| العقبة |

|

11/288 | (٣.٨٪) | ٤.٨٪ | (2.7-7.7) |

|

|

5/101 | (٥٫٠٪) | 6.2% | (2.6-12.0) | |

| جميع الأسر | 16/389 | (٤.١٪) | ٥.٩٪ | (3.9-8.6) | |

*تم تعديلها لقيم أداء الاختبارات المجمعة، مع تقديرات جنوب الأردن (معان والعقبة) التي تم وزنها أيضًا حسب المنطقة. كما تم تعديل جميع تقديرات الأسر حسب حالة امتلاك الجمال.

تم اختيار قطعان الإبل لتكون مشابهة لتلك الموجودة بين القطعان التي لم يتم اختيارها بطريقة احتمالية، على مدار فترة الدراسة).

طرق

الموافقة الأخلاقية

الجمال

| الفئة* | الإجمالي 867 (مفقود) | +ve | % | أو | فترة الثقة 95% | ب |

| البيانات المكانية | ||||||

| منطقة | ||||||

| معاً | 478 | 75 | 15.7% | 5.32 | 2.42-11.67 | <0.0001 |

| العقبة | ٣٨٩ | 16 | ٤.١٪ | 1.00 | ||

| الفرعية | ||||||

| العقبة الغربية | 186 | ٥ | ٢.٧٪ | 1.00 | 0.0002 | |

| العقبة الشرقية | ٢٠٣ | 11 | 5.4٪ | 2.06 | 0.55-7.70 | |

| معان الشرقية | 222 | 27 | 12.2% | 6.14 | 1.80-20.94 | |

| معان الغربية | 256 | ٤٨ | 18.8% | 9.64 | ٢.٩٦-٣١.٤٥ | |

| منطقة ذات حالة ملكية الجمال | ||||||

| العقبة COH | ٢٨٨ | 11 | 3.8٪ | 1.00 | 0.0001 | |

| العقبة NCOH | ١٠١ | ٥ | 5.0% | 1.29 | 0.27-5.46 | |

| معاً COH | ٣٧٩ | 68 | 17.9% | 6.57 | 2.91-16.85 | |

| معاً NCOH | 99 | ٧ | ٧.١٪ | ٢.١٧ | 0.58-8.11 | |

| المعلومات الشخصية | ||||||

| جنس | ||||||

| أنثى | 401 | ٣٤ | ٨.٥٪ | 0.70 | 0.42-1.18 | 0.18 |

| ذكر | ٤٦٦ | ٥٧ | 12.2% | 1.00 | ||

| عمر | ||||||

| 5-15 | ١٩٠ (٢) | 17 | 8.9٪ | 1.00 | 0.39 | |

| >15-25 | ٢٠١ | 30 | 14.9% | 2.14 | 1.01-4.56 | |

| >25-40 | ٢٠١ | 17 | ٨.٥٪ | 1.45 | 0.62-3.38 | |

| >40-60 | 181 | 19 | 10.5% | 1.62 | 0.72-3.66 | |

| >60 | 92 | ٨ | ٨.٧٪ | 1.35 | 0.47-3.84 | |

| الجنسية | ||||||

| أردني | 757 (66) | 81 | 10.7% | 1.00 | لا | 0.62 |

| مصري | ٨ | 2 | 25.0% | 6.17 | ||

| سوداني | ٨ | 0 | 0.0% | 0.00 | ||

| السعودي | 23 | 0 | 0.0% | 0.00 | ||

| آخر | ٥ | 0 | 0.0% | 0.00 | ||

| موظف منزلي | ||||||

| لا | 832 | 87 | 10.5% | 1.00 | 0.74 | |

| عامل مزرعة | 23 | 2 | 8.7% | 1.11 | 0.19-6.40 | |

| جزار | 12 | 2 | 16.7% | 2.37 | 0.26-21.28 | |

| التعليم الثانوي | ||||||

| نعم | ٢٣٣ (٢١٨) | 17 | ٧.٣٪ | 0.47 | 0.24-0.93 | 0.029 |

| لا | ٤١٦ | ٥٥ | 13.2% | 1.00 | ||

| حالياً في المدرسة (إذا كان

|

||||||

| نعم | 175 (649) | 11 | 6.3% | 0.32 | 0.11-0.92 | 0.035 |

| لا | 43 | ٨ | 18.6٪ | 1.00 | ||

| معلومات الأسرة | ||||||

| نوع السكن المنزلي (خيمة) | ||||||

| نعم | ٢٩٦ | ٤٧ | 15.9% | ٢.٢٩ | 1.11-4.74 | 0.025 |

| لا | 571 | ٤٤ | ٧.٧٪ | 1.00 | ||

| حجم الأسرة | ||||||

| ١-١٠ | ٣٦٣ | ٣٦ | 9.9% | 1.00 | 0.51 | |

| 11-20 | 418 | 43 | 10.3% | 0.91 | 0.42-1.96 | |

| >20 | 86 | 12 | 14.0% | 2.05 | 0.52-8.05 | |

| الفئة* | الإجمالي 867 (مفقود) | +ve | % | أو | فترة الثقة 95% | ب |

| الأسرة تمتلك الجمال | ||||||

| 0 | ٢٠٠ | 12 | 6.0% | 1.00 | 0.33 | |

| 1-6 | 267 | ٢٩ | 10.9٪ | 1.73 | 0.58-5.16 | |

| >6 | ٤٠٠ | 50 | 12.5% | 2.17 | 0.78-6.04 | |

| الأسرة تمتلك أغنام | ||||||

| لا | ٢٤٨ | 17 | 6.9٪ | 1.00 | 0.033 | |

|

|

٣٣٨ | 32 | 9.5% | 1.59 | 0.61-4.16 | |

| >50 | ٢٨١ | 42 | 14.9% | ٣.٥٤ | 1.32-9.53 | |

| الأسرة تمتلك الماعز | ||||||

| لا | ١١٨ | ١٣ | 11.0% | 1.00 | 0.94 | |

|

|

٤٧٩ | 50 | 10.4% | 1.11 | 0.37-3.34 | |

| >50 | ٢٧٠ | ٢٨ | 10.4% | 1.24 | 0.37-4.14 | |

| تم الإبلاغ عن تلقيح الحيوانات المجترة الصغيرة ضد البروسيلات (حيث تمتلك الحيوانات المجترة الصغيرة) | ||||||

| نعم | 373 (387) | ٣٣ | ٨.٨٪ | 0.45 | 0.17-1.18 | 0.10 |

| لا | ١٠٧ | 19 | 17.8% | 1.00 | ||

| استهلاك منتجات الماشية | ||||||

| شرب حليب الإبل النيء | ||||||

| لا | ٤٧٤ | 32 | 6.8٪ | 1.00 | 0.0001 | |

|

|

١٧٦ | ١٣ | ٧.٤٪ | 1.09 | 0.51-2.36 | |

| يومي | 217 | ٤٦ | 21.2% | ٤.٠١ | 2.05-7.82 | |

| الاستهلاك اليومي من الإبل حسب المنطقة | ||||||

| العقبة | 61 | ٣ | ٤.٩٪ | 1.00 | 2.36-62.70 | 0.0047 |

| معاً | 156 | 43 | ٢٧.٦٪ | 9.42 | ||

| شرب حليب الأغنام أو الماعز النيء (امتلاك الأغنام، امتلاك الماعز) | ||||||

| لا | ٧٠٧ | ٥٩ | 8.3٪ | 1.00 | 0.012 | |

|

|

89 | ١٣ | 14.6% | 2.02 | 0.92-4.40 | |

| يومي | 71 | 19 | ٢٦.٨٪ | 2.97 | 1.33-6.60 | |

| استهلاك منتجات الألبان النيئة المصنوعة من حليب المجترات الصغيرة | ||||||

| لا | 630 | ٥٦ | 8.9٪ | 1.00 | 0.054 | |

|

|

١٧٧ | 19 | 10.7% | 1.29 | 0.67-2.49 | |

| يومي | 60 | 16 | ٢٦.٧٪ | 2.80 | 1.21-6.48 | |

| أنشطة المشاركة في الثروة الحيوانية | ||||||

| ولادة الجمال (>أبداً) | ||||||

| نعم | ٢٩٩ | ٤٤ | 14.7% | 1.70 | 0.98-2.94 | 0.058 |

| لا | 568 | ٤٧ | 8.3٪ | 1.00 | ||

| ولادة المجترات الصغيرة

|

||||||

| نعم | ١٢٢ | 27 | ٢٢.١٪ | ٢.٩٥ | 1.58-5.50 | 0.0007 |

| لا | 745 | 64 | ٨.٦٪ | 1.00 | ||

| التخلص من مشيمة الجمل (أبداً) | ||||||

| نعم | 634 | ٥٧ | 9.0% | 1.00 | 0.11 | |

| لا | 233 | ٣٤ | 14.6% | 1.60 | 0.90-. 82 | |

| التخلص من مشيمة الحيوانات المجترة الصغيرة

|

||||||

| نعم | ١١٧ | ٢٢ | 18.8٪ | ٢.٢٧ | 1.18-4.38 | 0.014 |

| لا | 750 | 69 | 9.2% | 1.00 | ||

| ذبح الحيوانات المجترة الصغيرة

|

||||||

| نعم | 82 | 15 | ١٨.٣٪ | 3.02 | 1.36-6.70 | 0.0065 |

| لا | 785 | 76 | 9.7% | 1.00 | ||

| الفئة* | الإجمالي 867 (مفقود) | +ve | % | أو | فترة الثقة 95% | ب |

| بشكل متكرر

|

||||||

| نعم | ٤٣٩ | 61 | 13.9٪ | 1.81 | 0.99-3.28 | 0.053 |

| لا | ٤٢٨ | 30 | ٧٫٠٪ | 1.00 | ||

| بشكل متكرر

|

||||||

| نعم | ٥٠٩ | 73 | 14.3% | 3.06 | 1.62-5.78 | 0.0006 |

| لا | 358 | 18 | ٥٫٠٪ | 1.00 | ||

| بشكل متكرر

|

||||||

| نعم | 577 | 75 | ١٣٫٠٪ | ٢.٤٩ | 1.27-4.89 | 0.0080 |

| لا | ٢٩٠ | 16 | 5.5% | 1.00 | ||

| أي تاريخ لمشاركة الثروة الحيوانية | ||||||

| نعم | 711 | 83 | 11.7% | 2.09 | 0.87-4.99 | 0.099 |

| لا | 156 | ٨ | 5.1٪ | 1.00 | ||

| نظافة اليدين | ||||||

| غسل اليدين أكثر من 5 مرات في اليوم | ||||||

| نعم | 528 | 42 | ٨٫٠٪ | 0.54 | 0.32-0.91 | 0.021 |

| لا | ٣٣٩ | ٤٩ | 14.5% | 1.00 | ||

| صابون مستخدم بالأمس | ||||||

| نعم | 777 | 77 | 9.9% | 0.75 | 0.35-1.63 | 0.47 |

| لا | 90 | 14 | 15.6% | 1.00 | ||

| بشكل متكرر

|

||||||

| لا | 428 | 30 | ٥.٥٪ | 1.00 | 0.0009 | |

| نعم (>5 مرات/اليوم) | 255 | 26 | 9.4% | 1.78 | 0.85-3.69 | |

| نعم (

|

184 | 35 | 18.3% | 3.87 | 1.83-8.15 | |

| بين الأفراد الذين يعملون بشكل متكرر مع الماشية، غسل اليدين أكثر من 5 مرات في اليوم | ||||||

| نعم | ٣٤٢ (٢٩٠) | 32 | 9.4% | 0.46 | 0.25-0.84 | 0.012 |

| لا | 235 | 43 | ١٨.٣٪ | 1.00 | ||

| بين الأفراد الذين يعملون بشكل متكرر مع الماشية، استخدام الصابون أمس | ||||||

| نعم | 504 (290) | 62 | 12.3% | 0.70 | 0.30-1.64 | 0.41 |

| لا | 73 | ١٣ | 17.8% | 1.00 | ||

| بين الأفراد الذين يعملون بشكل متكرر مع الماشية، غسل اليدين مع أو بدون الإبلاغ عن استخدام الصابون يوم أمس | ||||||

|

|

235 (290) | 43 | 18.3% | 1.00 | 0.036 | |

| أكثر من 5 مرات في اليوم بدون صابون | 26 | ٣ | 11.5% | 0.70 | 0.15-3.28 | |

| أكثر من 5 مرات في اليوم بالصابون | 316 | ٢٩ | 9.2% | 0.44 | 0.24-0.82 | |

| تم اختبار قطيع الإبل لوجود الأجسام المضادة لمرض البروسيلا | ||||||

| جمل في القطيع أظهر نتيجة إيجابية للفيروس البروسيللا (إيجابي في اختبار RBPT، تم تأكيد إيجابيته في اختبار CFT) | ||||||

| نعم | ٧ | 2 | ٢٨.٦٪ | 1.00 | 0.36-139.38 | 0.20 |

| لا | ٤٨٩ | ٥٦ | 11.5% | ٧.١٠ | ||

| شرب حليب الإبل حيث تم اختبار إبل في القطيع إيجابي المصل لمرض البروسيلا (إيجابي في اختبار RBPT، مؤكد إيجابي في اختبار CFT) | ||||||

| نعم | ٤ | 2 | 50٪ | 1.00 | 0.69-851.92 | 0.079 |

| لا | ٢٨١ | ٤٤ | 16% | ٢٤.٣١ | ||

تمت ملاحظته. تم افتراض الحساسية والنوعية أن تكون

| متغير** | فئة | نسبة الأرجحية المعدلة مسبقًا

|

|

تم التعديل بالكامل

|

|

||

| جنس | أنثى | 0.71 | 0.42-1.18 | 0.19 | 0.86 | 0.51-1.45 | 0.57 |

| عمر | ٥-١٥ | 1.00 | 0.25 | 1.00 | 0.12 | ||

| >15-25 | 2.32 | 1.09-4.94 | 2.02 | 1.01-4.15 | |||

| >25-40 | 1.40 | 0.61-3.25 | 0.96 | 0.44-2.08 | |||

| >40-60 | 1.78 | 0.79-4.01 | 1.46 | 0.68-3.17 | |||

| >60 | 1.28 | 0.46-3.61 | 0.88 | 0.33-2.20 | |||

| منطقة | معاً | ٥.٥١ | 2.53-12.03 | <0.0001 | 3.27 | 1.86-6.07 | <0.0001 |

| خيمة السكن الرئيسية | نعم | ٢.٢٥ | 1.15-4.42 | 0.018 | 1.52 | 0.92-2.51 | 0.10 |

| الأسر تمتلك الأغنام | لا | 1.00 | 0.065 | 1.00 | 0.43 | ||

| 1-50 | 1.85 | 0.73-4.66 | 1.22 | 0.63-2.41 | |||

| >50 | 3.04 | 1.19-7.72 | 1.52 | 0.80-2.98 | |||

| ولادة الجمال | نعم | 1.45 | 0.80-2.62 | 0.22 | 0.88 | 0.50-1.54 | 0.65 |

| ولادة المجترات الصغيرة | نعم | 2.45 | 1.31-4.58 | 0.0050 | 1.87 | 1.02-3.39 | 0.044 |

| بشكل متكرر

|

نعم | 2.02 | 1.02-4.03 | 0.045 | 1.30 | 0.68-2.58 | 0.43 |

| غسل اليدين

|

نعم | 0.57 | 0.34-0.98 | 0.041 | 0.64 | 0.39-1.04 | 0.069 |

| شرب حليب الإبل | نادراً/أبداً | 1.00 | 0.0012 | 1.00 | 0.016 | ||

| أسبوعي/شهري | 1.12 | 0.51-2.45 | 1.02 | 0.48-2.06 | |||

| يومي | 3.26 | 1.66-6.41 | ٢.١٩ | 1.23-3.94 | |||

| استهلاك منتجات الألبان من الحيوانات المجترة الصغيرة | نادراً/أبداً | 1.00 | 0.088 | 1.00 | 0.65 | ||

| أسبوعي/شهري | 1.39 | 0.72-2.67 | 1.11 | 0.60-1.99 | |||

| يومي | ٢.٤٦ | 1.08-5.63 | 1.43 | 0.66-2.97 | |||

| شرب حليب الأغنام أو الماعز النيء

|

نادراً/أبداً | 1.00 | 0.0047 | 1.00 | 0.071 | ||

| أسبوعي/شهري | 2.32 | 1.07-5.05 | 1.93 | 0.92-3.82 | |||

| يومي | ٣.١٥ | 1.43-6.93 | 1.96 | 0.95-3.93 | |||

| العمل بشكل متكرر مع الماشية

|

لا يعمل بشكل متكرر مع الماشية | 1.00 | 0.0063 | 1.00 | 0.047 | ||

| العمل بشكل متكرر مع الماشية وغسل اليدين أكثر من 5 مرات في اليوم | 1.45 | 0.68-3.07 | 0.94 | 0.46-1.95 | |||

| العمل بشكل متكرر مع الماشية وغسل اليدين

|

3.03 | 1.42-6.47 | 1.82 | 0.90-3.77 | |||

- في الأشهر الاثني عشر الماضية (باستثناء العمر والجنس).

بسبب التوازي (معامل بيرسون R) تم اختبار هذا المتغير في نموذج متعدد المتغيرات منفصل بدلاً من استهلاك منتجات الألبان الخام من الأغنام أو الماعز. في هذا النموذج، استمر شرب حليب الإبل الخام، وولادة المجترات الصغيرة، والمنطقة في إظهار ارتباط كبير (p< 0.05) مع حالة إيجابية لمستضد بروسيلة.

بسبب التوازي (بيرسون معامل ) مع المتغيرات التي تعمل بشكل متكرر مع الماشية وغسل اليدين تم اختبار هذا المتغير في نموذج متعدد المتغيرات بشكل منفصل بدلاً من العمل بشكل متكرر مع الماشية وغسل اليدين. يوم. في هذا النموذج، شرب حليب الإبل الخام، وولادة المجترات الصغيرة، واستمر الإقليم في إظهار ارتباط كبير ( ) مع حالة إيجابية لمستضد بروسيلة.

الملاحظات في جميع النماذج.

تم استبعادها، مع تعديل المتغير الفردي بعد ذلك في نموذج منفصل باستخدام نفس المتغيرات المشتركة.

البشر

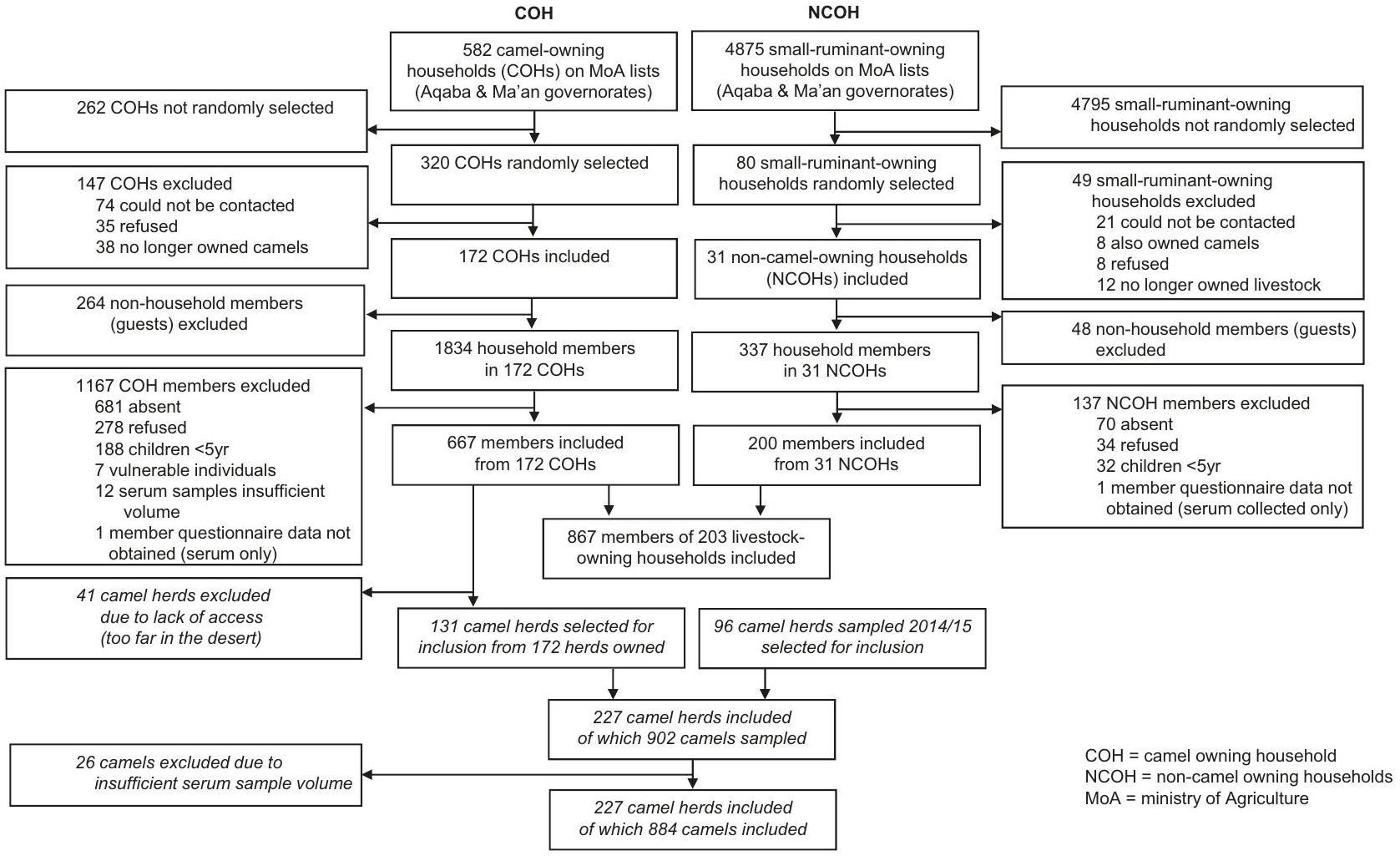

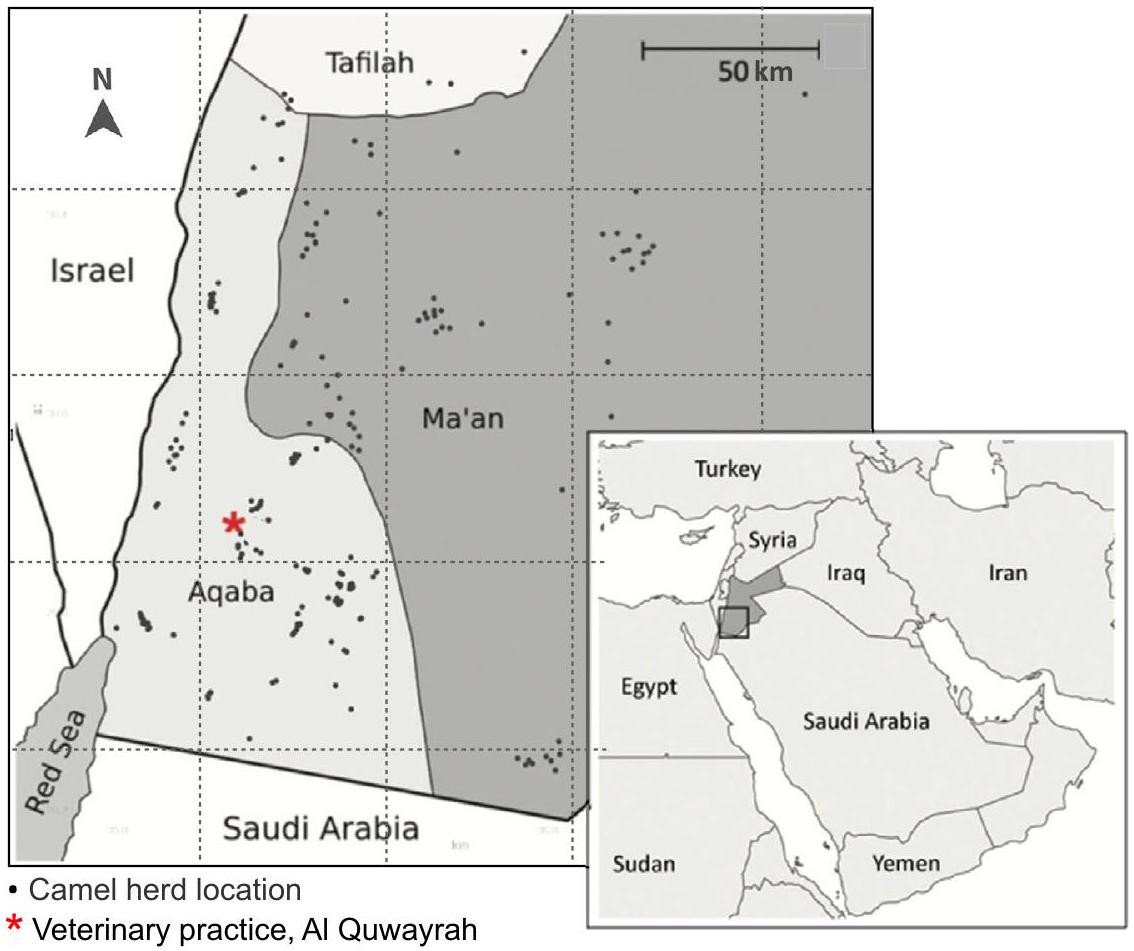

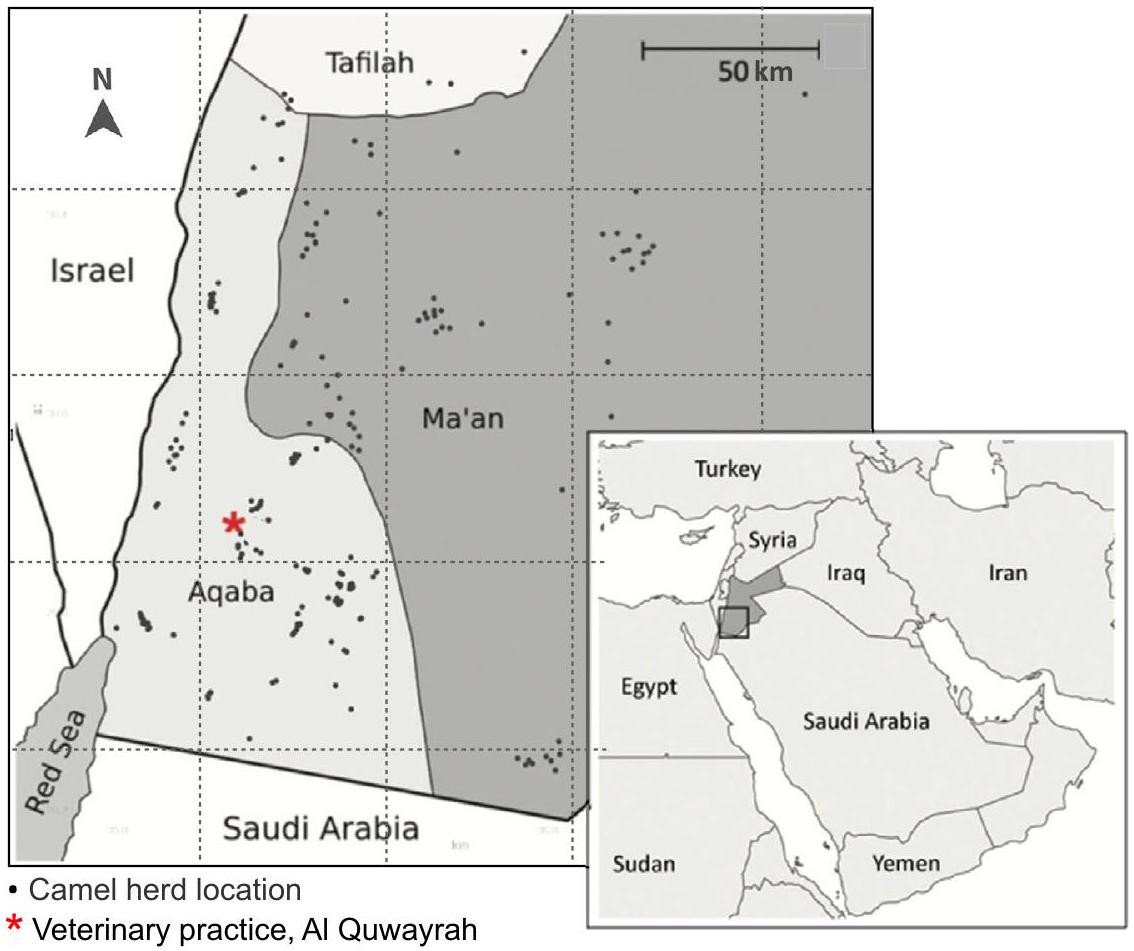

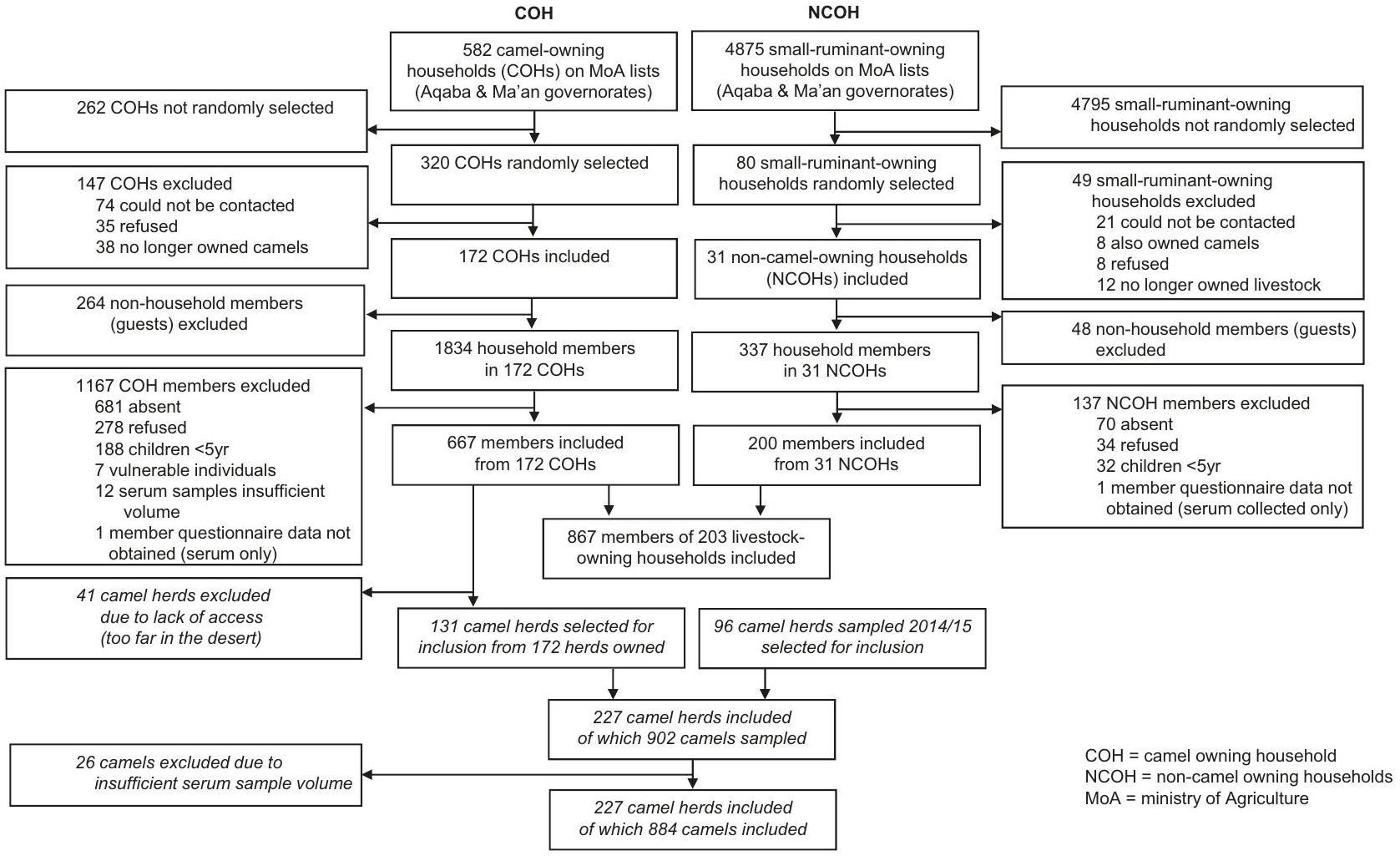

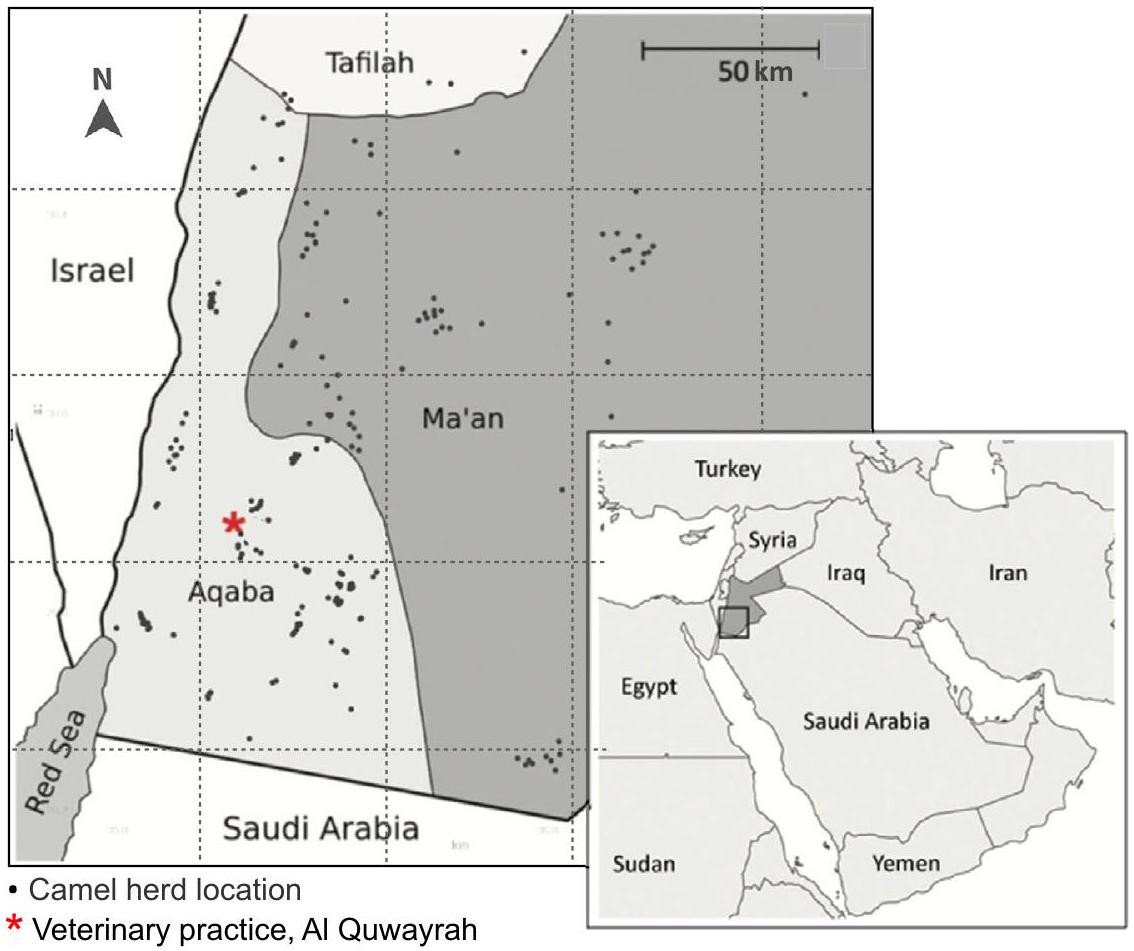

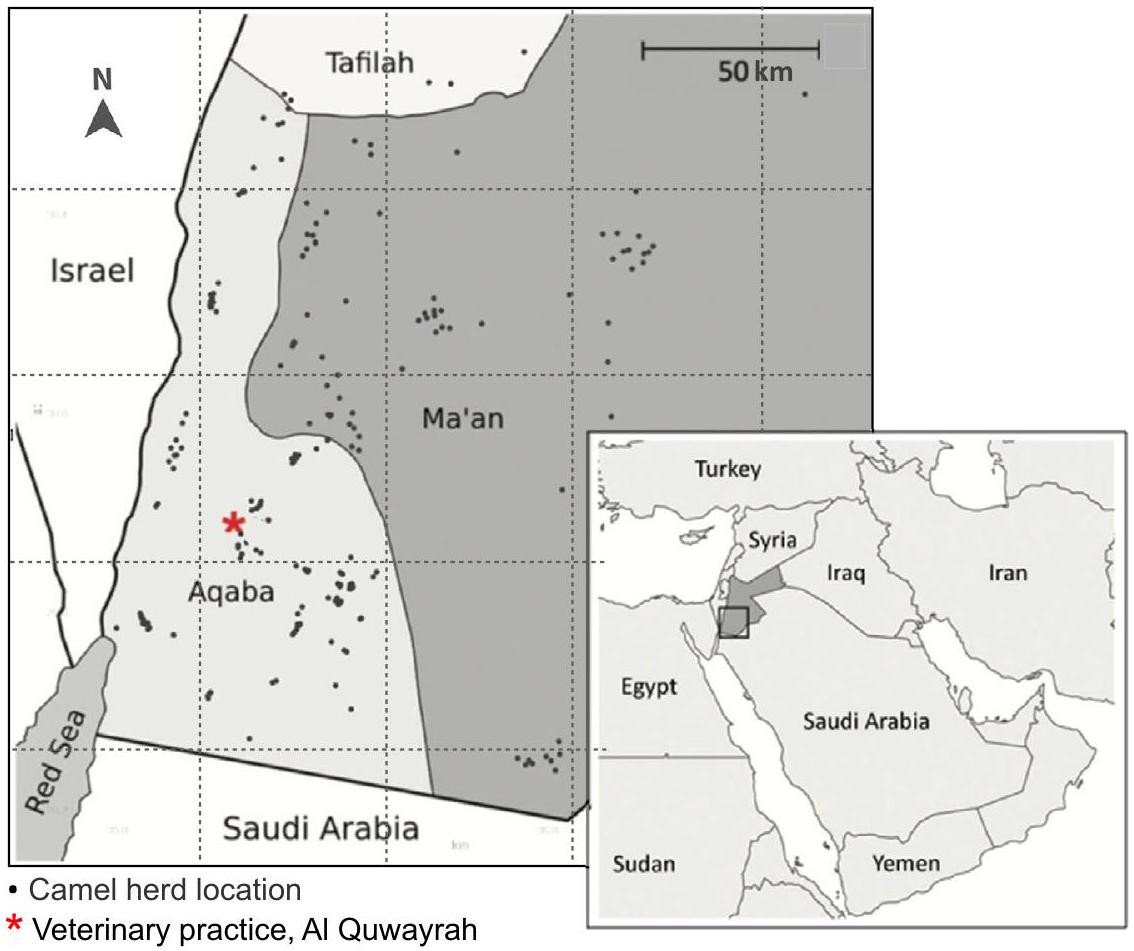

تم اختيار الأسر المالكة للماشية عشوائيًا من قبل أحد المؤلفين المشاركين (SN) باستخدام قوائم عشوائية تم إنشاؤها بواسطة الكمبيوتر (Stata، الإصدار 15.1) من إطار أخذ العينات الذي قدمته وزارة الزراعة، والذي يتضمن قائمة بجميع الأسر التي تمتلك جملًا واحدًا أو أكثر، وقائمة بتلك التي تمتلك أغنامًا أو ماعز، ضمن المناطق الفرعية الأربع (العقبة الشرقية، العقبة الغربية، معان الشرقية، ومعان الغربية) (الشكل 3). كانت كل من المنازل والخيام مؤهلة للإدراج.

تم جمع المعلومات، وتقييم الأهلية، والحصول على الموافقة. تم جمع عينات الدم من الأفراد المشاركين مع إدارة استبيان منظم حول عوامل الخطر المحتملة للتعرض للبروسيلا خلال الأشهر الستة الماضية، بما في ذلك أسئلة تتعلق بالبيانات المكانية، والمعلومات الشخصية (بما في ذلك العمر والجنس (الملاحظ)، ومعلومات الأسرة، واستهلاك الماشية.

المنتجات، أنشطة تربية الماشية ونظافة اليدين (مع استبيان متابعة تم إجراؤه بين أعضاء المجتمع حول ممارسات غلي الحليب). تم إجراء استبيان إضافي لرئيس الأسرة حول عوامل الخطر على مستوى الأسرة، بما في ذلك العمر والجنس لأي أعضاء غير مأخوذين في العينة. تم إجراء الاستبيانات باللهجة المحلية على أجهزة لوحية تعمل بنظام أندرويد باستخدام تطبيق Open Data Kit (الإصدار 1.10). نظرًا للحساسية الثقافية، تم الحصول على معلومات حول جنس المشاركين من خلال ملاحظة المحاور. تم الإبلاغ عن معلومات حول الجنسية بشكل ذاتي، وفقًا لتفاصيل بطاقة الهوية الوطنية أو جواز السفر.

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

References

- World Health Organization. Brucellosis Fact Sheet, WHO, [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ brucellosis (2020).

- World Health Organization. Estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases: foodborne disease burden epidemiology reference group 2007-2015. WHO Geneva, (2015).

- Franc, K. A., Krecek, R. C., Häsler, B. N. & Arenas-Gamboa, A. M. Brucellosis remains a neglected disease in the developing world: a call for interdisciplinary action. BMC Public Health 18, e125 (2018).

- Dean, A. S. et al. Clinical manifestations of human brucellosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6, e1929 (2012).

- Abo-shehada, M. N. & Abu-Halaweh, M. Seroprevalence of Brucella species among women with miscarriage in Jordan. East Mediterr. Health J. 17, 871-874 (2011).

- Radostits O. M., GAY, C., Hinchcliff, K. W. & Constable, P. D. A textbook of the diseases of cattle, horses, sheep, pigs and goats. Veterinary Medicine 10th edition London: Saunders. 1548-1551 (2007).

- Laine, C. G., Johnson, V. E., Scott, H. M. & Arenas-Gamboa, A. M. Global Estimate of Human Brucellosis Incidence. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 29, 1789-1797 (2023).

- Dadar, M. et al. Human brucellosis and associated risk factors in the Middle East region: A comprehensive systematic review, metaanalysis, and meta-regression. Heliyon 10, e34324 (2024).

- Alhussain, H. et al. Seroprevalence of camel brucellosis in Qatar. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 54, e351 (2022).

- Musallam, I. I., Abo-Shehada, M. N., Hegazy, Y. M., Holt, H. R. & Guitian, F. J. Systematic review of brucellosis in the Middle East: disease frequency in ruminants and humans and risk factors for human infection. Epidemiol. Infect. 144, 671-685 (2016).

- Bagheri Nejad, R., Krecek, R. C., Khalaf, O. H., Hailat, N. & ArenasGamboa, A. M. Brucellosis in the Middle East: Current situation and a pathway forward. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14, e0008071 (2020).

- Al-Ani, F. et al. Human and animal brucellosis in the Sultanate of Oman: an epidemiological study. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries 17, 52-58 (2023).

- Al-Marzooqi, W. et al. Seroprevalence and Risk Factors of Brucellosis in Ruminants in Dhofar Province in Southern Oman. Vet. Med Int 2022, e3176147 (2022).

- Shaqra QM, Abu Epidemiological aspects of brucellosis in Jordan. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 16, 581-584 (2000).

- Abutarbush, S. M. et al. Implementation of One Health approach in Jordan: Review and mapping of ministerial mechanisms of zoonotic disease reporting and control, and inter-sectoral collaboration. One Health 15, e100406 (2022).

- McAlester, J. & Kanazawa, Y. Situating zoonotic diseases in peacebuilding and development theories: Prioritizing zoonoses in Jordan. PLoS One 17, e0265508 (2022).

- Abo-Shehada, M. N., Odeh, J. S., Abu-Essud, M. & Abuharfeil, N. Seroprevalence of brucellosis among high risk people in northern Jordan. Int J. Epidemiol. 25, 450-454 (1996).

- Dajani, Y. F., Masoud, A. A. & Barakat, H. F. Epidemiology and diagnosis of human brucellosis in Jordan. J. Trop. Med Hyg. 92, 209-214 (1989).

- Samadi, A., Ababneh, M. M., Giadinis, N. D. & Lafi, S. Q. Ovine and Caprine Brucellosis (Brucella melitensis) in Aborted Animals in Jordanian Sheep and Goat Flocks. Vet. Med Int 2010, e458695 (2010).

- Al-Talafhah, A. H., Lafi, S. Q. & Al-Tarazi, Y. Epidemiology of ovine brucellosis in Awassi sheep in Northern Jordan. Prev. Vet. Med 60, 297-306 (2003).

- Aldomy, F. M., Jahans, K. L. & Altarazi, Y. H. Isolation of Brucella melitensis from aborting ruminants in Jordan. J. Comp. Pathol. 107, 239-42 (1992).

- Musallam, I. I., Abo-Shehada, M., Omar, M. & Guitian, J. Crosssectional study of brucellosis in Jordan: Prevalence, risk factors and spatial distribution in small ruminants and cattle. Prev. Vet. Med 118, 387-96 (2015).

- Abo-Shehada, M. N., Rabi, A. Z. & Abuharfeil, N. The prevalence of brucellosis among veterinarians in Jordan. Ann. Saudi Med 11, 356-357 (1991).

- Al-Amr, M. et al. Epidemiology of human brucellosis in military hospitals in Jordan: A five-year study. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries 16, 1870-1876 (2022).

- Abo-Shehada, M. N. & Abu-Halaweh, M. Risk factors for human brucellosis in northern Jordan. East Mediterr. Health J. 19, 135-140 (2013).

- Issa, H. & Jamal, M. Brucellosis in children in south Jordan. East Mediterr. Health J. 5, 895-902 (1999).

- Galali, Y. & Al-Dmoor, H. M. Miraculous properties of camel milk and perspective of modern science. J. Fam. Med. Dis. Prev. 5, e095 (2019).

- Shimol, S. B. et al. Human brucellosis outbreak acquired through camel milk ingestion in southern Israel. Isr. Med Assoc. J. 14, 475-478 (2012).

- Zhu, S., Zimmerman, D. & Deem, S. L. A review of zoonotic pathogens of dromedary camels. Ecohealth 16, 356-377 (2019).

- Sprague, L. D., Al-Dahouk, S. & Neubauer, H. A review on camel brucellosis: a zoonosis sustained by ignorance and indifference. Pathog. Glob. Health 106, 144-149 (2012).

- Almuzaini, A. M. An epidemiological study of brucellosis in different animal species from the al-qassim region, Saudi Arabia. Vaccines (Basel). 11, e694 (2023).

- Dahl, M. O. Brucellosis in food-producing animals in Mosul, Iraq: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 15, e0235862 (2020).

- Hegazy, Y. M., Moawad, A., Osman, S., Ridler, A. & Guitian, J. Ruminant brucellosis in the Kafr El Sheikh Governorate of the Nile

34. Bardenstein, S., Gibbs, R. E., Yagel, Y., Motro, Y. & Moran-Gilad, J. Brucellosis Outbreak Traced to Commercially Sold Camel Milk through Whole-Genome Sequencing, Israel. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 27, 1728-1731 (2021).

35. Garcell, H. G. et al. Outbreaks of brucellosis related to the consumption of unpasteurized camel milk. J. Infect. Public Health 9, 523-527 (2016).

36. Al-Majali, A. M., Al-Qudah, K. M., Al-Tarazi, Y. H. & Al-Rawashdeh, O. F. Risk factors associated with camel brucellosis in Jordan. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 40, 193-200 (2008).

37. World Organizarion of Animal Health. Manual of diagnostic tests and vaccines for terrestrial animals Ch 3.1.4 (WOAH, Paris, 2022).

38. Mangtani, P. et al. The prevalence and risk factors for human Brucella species infection in a cross-sectional survey of a rural population in Punjab, India. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med Hyg. 114, 255-263 (2020).

39. Alnaeem, A. et al. Some pathological observations on the naturally infected dromedary camels (Camelus dromedarius) with the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in Saudi Arabia 2018-2019. Vet. Q 40, 190-197 (2020).

40. Chatty D. From Camel to Truck: The Bedouin in the Modern World. (White Horse Press, Cambridge, 2013).

41. Qur’an, Al-Ghashiyah (Surra 88), verse 17.

42. Al Zahrani, A. et al. Use of camel urine is of no benefit to cancer patients: observational study and literature review. East Mediterr. Health J. 29, 657-663 (2023).

43. Sahih Al Bukhari, The Book of Medicine (Book 76), Hadith 9.

44. Abutarbush, A. S., Hijazeen, Z., Doodeen, R. & Hawaosha, M. Analysis, description and mapping of camel value chain in jordan ministry of agriculture. Glob. Veterinaria 20, 144-152 (2019).

45. Abuelgasim, K. A. et al. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients with cancer: a cross-sectional survey in Saudi Arabia. BMC Complement Alter. Med 18, e88 (2018).

46. Shaalan, M. A. et al. Brucellosis in children: clinical observations in 115 cases. Int J. Infect. Dis. 6, 182-186 (2002).

47. Musallam, I. I., Abo-Shehada, M. N. & Guitian, J. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices associated with brucellosis in livestock owners in jordan. Am. J. Trop. Med Hyg. 93, 1148-1155 (2015).

48. Holloway, P. et al. Risk factors for middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection among camel populations, Southern Jordan, 2014-2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 27, 2301-2311 (2021).

49. Dadar, M., Tiwari, R., Sharun, K. & Dhama, K. Importance of brucellosis control programs of livestock on the improvement of one health. Vet. Q 41, 137-151 (2021).

50. Radwan, A. I. et al. Control of Brucella melitensis infection in a large camel herd in Saudi Arabia using antibiotherapy and vaccination with Rev. 1 vaccine. Rev. Sci. Tech. 14, 719-732 (1995).

51. Food and Agriculture Organisation, Animal Production and Health Paper 156 Ch. 9 (FAO, Rome, 2003)

52. Holloway, P. et al. A cross-sectional study of Q fever in Camels: Risk factors for infection, the role of small ruminants and public health implications for desert-dwelling pastoral communities. Zoonoses Public Health 70, 238-247 (2023).

53. Ahad, A. A., Megersa, B. & Edao, B. M. Brucellosis in camel, small ruminants, and Somali pastoralists in Eastern Ethiopia: a One Health approach. Front Vet. Sci. 11, e1276275 (2024).

54. Mohammed, A. et al. Seroprevalence and risk factors of brucellosis in dromedary camels (Camelus dromedarius) in Sudan from 1980 to 2020: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vet. Q 43, 1-15 (2023).

55. Dadar, M. & Alamian, S. Isolation of Brucella melitensis from seronegative camel: potential implications in brucellosis control. Prev. Vet. Med 185, e105194 (2020).

56. Blasco, J. M. A review of the use of B. melitensis Rev 1 vaccine in adult sheep and goats. Prev. Vet. Med 31, 275-283 (1997).

57. Vives-Sotoa, M. P.-G. A., Pereirab, J., Rodríguez-Sánchez, J. & Solerac, E. J. What risk do Brucella vaccines pose to humans? A systematic review of the scientific literature on occupational exposure. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 18, e0011889 (2024).

58. Ducrotoy, M. J. et al. Integrated health messaging for multiple neglected zoonoses: Approaches, challenges and opportunities in Morocco. Acta Trop. 152, 17-25 (2015).

59. Mbye, M., Ayyash, M., Abu-Jdayil, B. & Kamal-Eldin, A. The texture of camel milk cheese: effects of milk composition, coagulants, and processing conditions. Front Nutr. 9, e868320 (2022).

60. Al-Zoubi, M. et al. WASH in Islam. Guide on Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) from an Islamic Perspective. (Sanitation for Millions, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Germany 2020).

61. Elsohaby, I. et al. Bayesian Evaluation of Three Serological Tests for Diagnosis of Brucella infections in Dromedary Camels Using Latent Class Models. Prev. Vet. Med 208, e105771 (2022).

62. Khan, F. K. R. et al. Comparative performance study of four different serological tests for the diagnosis of dromedary brucellosis. J. Camel Pract. Res. 23, 213-217 (2016).

63. IDvet. ID Screen

64. Gwida, M. M. et al. Comparison of diagnostic tests for the detection of Brucella spp. in camel sera. BMC Res Notes 4, e525 (2011).

65. Getachew, T., Getachew, G., Sintayehu, G., Getenet, M. & Fasil, A. Bayesian Estimation of Sensitivity and Specificity of Rose Bengal, Complement Fixation, and Indirect ELISA Tests for the Diagnosis of Bovine Brucellosis in Ethiopia. Vet. Med Int 2016, e8032753 (2016).

66. Wernery, U. Camelid brucellosis: a review. Rev. Sci. Tech. 33, 839-857 (2014).

67. Beauvais, W., Orynbayev, M. & Guitian, J. Empirical Bayes estimation of farm prevalence adjusting for multistage sampling and uncertainty in test performance: a Brucella cross-sectional serostudy in southern Kazakhstan. Epidemiol. Infect. 144, 3531-3539 (2016).

68. Serion ELISA classic Brucella spp. IgG. https://www.serion-diagnostics.de/en/products/serion-elisa-classic-antigen/ brucella/ (2023).

69. Al Dahouk, S., Tomaso, H., Nöckler, K., Neubauer, H. & Frangoulidis, D. Laboratory-based diagnosis of brucellosis-a review of the literature. Part II: serological tests for brucellosis. Clin. Lab 49, 577-589 (2003).

70. Ekiri, A. B. et al. Utility of the rose bengal test as a point-of-care test for human brucellosis in endemic african settings: a systematic review. J. Trop. Med 2020, e6586182(2020).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

(ج) المؤلفون 2025

مجموعة الوبائيات البيطرية والاقتصاد والصحة العامة، مركز التعاون التابع لمنظمة الصحة الحيوانية العالمية لتحليل المخاطر والنمذجة، قسم علم الأمراض وعلم السكان، الكلية البيطرية الملكية، هاتفيلد، المملكة المتحدة. ²قسم وبائيات الأمراض المعدية والصحة الدولية، كلية لندن للصحة العامة والطب الاستوائي، لندن، المملكة المتحدة. قسم الوبائيات الطبية والإحصاء الحيوي، معهد كارولينسكا، ستوكهولم، السويد. كلية الطب البيطري، جامعة العلوم والتكنولوجيا الأردنية، إربد، الأردن. قسم طب الأطفال، كلية الطب، جامعة سانت لويس، سانت لويس، ميزوري، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: بونام مانغتاني، خافيير غويتان. البريد الإلكتروني:pholloway3@rvc.ac.uk - *إيجابي على RBPT وإيجابي على CFT أو ELISA.

مرة واحدة، أو أكثر، في السنوات الخمس الماضية.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55737-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39833143

Publication Date: 2025-01-20

Camel milk is a neglected source of brucellosis among rural Arab communities

Accepted: 22 December 2024

Published online: 20 January 2025

Abstract

The World Health Organization describes brucellosis as one of the world’s leading zoonotic diseases, with the Middle East a global hotspot. Brucella melitensis is endemic among livestock populations in the region, with zoonotic transmission occurring via consumption of raw milk, amongst other routes. Control is largely via vaccination of small ruminant and cattle populations. Due to sociocultural and religious influences camel milk (camelus dromedarius) is widely consumed raw, while milk from other livestock species is largely boiled. To investigate the potential public health impact of Brucella in camels we conduct a cross-sectional study in southern Jordan including 227 herds and 202 livestock-owning households. Here we show daily consumption of raw camel milk is associated with Brucella seropositive status among the study population,

seropositive status on multivariable analysis, highlighting the need for socioculturally appropriate control measures, with targeted interventions among the camel reservoir being crucial for effective control.

Results

Camels

| Population seroprevalence | Herd-level seroprevalence | |||||||

| Apparent prevalence | True prevalence | Unadjusted | Adjusted* | |||||

| Positive camels

|

% | % | (95% CI) | Positive herds

|

% | % | (95% CI) | |

| Southern Jordan (Ma’an & Aqaba) | 8/884 | (0.9%) | 1.0% | (0.5-2.1) | 7/227 | 3.1% | 18.7% | (14.3-23.3) |

| Ma’an | 7/340 | (2.1%) | 2.4% | (1.1-4.8) | 6/81 | 7.4% | 30.4% | (22.2-39.5) |

| Aqaba | 1/544 | (0.2%) | 0.1% | (0.0-1.1) | 1/146 | 0.7% | 4.8% | (2.1-8.2) |

- Adjusted for combined test performance values; southern Jordan (Ma’an & Aqaba) estimate also weighted for region.

Positive on RBPT and CFT.

Herd contains one or more positive camels, positive on RBPT and CFT.

potential risk factors for infection. On univariable analysis, the following variables were found to be associated () with seropositive status, region, purchasing camels (in the last year), closed herd management practices and one or more goats also being owned (Table 2). On multivariable analysis, positive status was associated with region (Ma’an) and purchasing camels ; with evidence to suggest closed herd management practices are protective (OR ) in a singular model (singularity being due to the absence of any positive camels sampled from among closed herds) (Table 3).

Humans

weighted for region) being

| Variable | ||||||

| Total (missing) | +ve | % | OR | 95%CI | p | |

| 884 camels sampled | ||||||

| Study period | ||||||

| 2014-15 | 429 | 5 | 1.2% | 0.94 | 0.26-3.41 | 0.93 |

| 2017-18 | 455 | 5 | 1.1% | |||

| Region | ||||||

| Ma’an | 340 | 8 | 2.4% | 6.53 | 1.62-43.44 | 0.0069 |

| Aqaba | 544 | 2 | 0.4% | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 669 | 9 | 1.3% | 2.81 | 0.52-51.96 | 0.26 |

| Male | 207 (8) | 1 | 0.5% | |||

| Age >median ( 5 yr ) | ||||||

| Yes | 405 | 7 | 1.5% | 0.41 | 0.09-1.50 | 0.18 |

| No | 474 (5) | 3 | 0.7% | |||

| Herd size >median (10) | ||||||

| Yes | 552 | 8 | 1.4% | 2.43 | 0.60-16.14 | 0.23 |

| No | 332 | 2 | 0.6% | |||

| Number of camel herds nearby (within a 15-minute drive) >20 | ||||||

| Yes | 364 | 6 | 1.6% | 2.06 | 0.58-8.10 | 0.26 |

| No | 495 (25) | 4 | 0.8% | |||

| Herd is kept together as single group throughout the year | ||||||

| Yes | 600 | 6 | 1.0% | 0.66 | 0.19-2.62 | 0.54 |

| No | 267 (17) | 4 | 1.5% | |||

| Herd has contact with other local herds | ||||||

| Yes | 519 | 8 | 1.3% | 1.15 | 0.32-5.36 | 0.84 |

| No | 255 (110) | 3 | 1.2% | |||

| Herd is moved to distant areas for seasonal grazing purposes (transhumance) | ||||||

| Yes | 367 | 4 | 1.1% | 0.90 | 0.23-3.18 | 0.87 |

| No | 497 (20) | 6 | 1.2% | |||

| New camels are purchased | ||||||

| Yes | 318 | 7 | 2.2% | 4.10 | 1.13-19.11 | 0.032 |

| No | 549 (17) | 3 | 0.5% | |||

| Camels are borrowed for breeding purposes | ||||||

| Yes | 449 | 7 | 1.6% | 2.19 | 0.60-10.22 | 0.24 |

| No | 418 (17) | 3 | 0.7% | |||

| Closed herd | ||||||

| Yes | 142 | 0 | 0.0% | 0.00 | – | 0.056 |

| No | 713 (29) | 10 | 1.4% | |||

| Sheep are also owned | ||||||

| Yes | 533 | 8 | 1.5% | 2.53 | 0.63-16.83 | 0.21 |

| No | 334 (17) | 2 | 0.6% | |||

| Goats are also owned | ||||||

| Yes | 603 | 9 | 1.5% | 3.98 | 0.74-73.67 | 0.12 |

| No | 264 (17) | 1 | 0.4% | |||

| Small ruminant flocks, where owned, have been vaccinated against Brucella (Rev 1 vaccine)

|

||||||

| Yes | 263 | 4 | 1.5% | 1.17 | 0.26-6.00 | 0.84 |

| No | 231 (383) | 3 | 1.3% | |||

| Dogs are present near the herd | ||||||

| Yes | 648 | 9 | 1.4% | 3.07 | 0.57-56.79 | 0.22 |

| No | 219 (17) | 1 | 0.5% | |||

Discussion

| Variable** | Category | A-priori adjusted OR

|

p value | Fully adjusted OR

|

p value | ||

| Region | Ma’an | 7.11 | 1.75-47.55 | 0.0050 | 6.23 | 1.53-41.81 | 0.0093 |

| Age | >median ( 5 yr ) | 0.41 | 0.09-1.50 | 0.18 | 0.35 | 0.074-1.32 | 0.12 |

| Sex | Female | 3.56 | 0.64-66.50 | 0.17 | 3.86 | 0.68-72.73 | 0.14 |

| Camels are purchased | Yes | 4.32 | 1.19-20.20 | 0.026 | 3.84 | 1.04-18.09 | 0.043 |

| Closed herd

|

Yes | 0.00 | NE | 0.047 | 0.00 | NE | 0.072 |

NE non-estimable.

species among Islamic communities in the Middle East and beyond

slaughtered, with potential purchasers then unaware of their reproductive history and potential Brucella positive status (as reported by study participants)

| COH (

|

NCOH (

|

All (

|

|||

| Age* | |||||

| 5-14 | 143 (21.5%) | 47 (24%) | 190 (22%) | ||

| 15-24 | 151 (22.7%) | 50 (25%) | 201 (23%) | ||

| 25-39 | 161 (24.2%) | 40 (20%) | 201 (23%) | ||

| 40-59 | 137 (20.6%) | 44 (22%) | 181 (21%) | ||

|

|

74 (11.1%) | 18 (9%) | 92 (11%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 27 (16-45) | 26 (15-44) | 27 (16-44) | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 384 (57.6%) | 118 (59%) | 401 (46%) | ||

| Male | 283 (42.4%) | 82 (41%) | 466 (54%) | ||

| Nationality** | |||||

| Jordanian | 565 (93.1%) | 192 (99%) | 757 (95%) | ||

| Saudi Arabian | 23 (3.8%) | 0 (0%) | 23 (3%) | ||

| Egyptian | 8 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (1%) | ||

| Sudanese | 8 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (1%) | ||

| Other | 3 (0.5%) | 2 (1%) | 5 (1%) | ||

| History of brucellosis | |||||

| Yes | 18 (2.8%) | 5 (2.6%) | 23 (3%) | ||

| No | 629 (97.2%) | 189 (97.4%) | 818 (97%) | ||

| Secondary education** | |||||

| Yes | 180 (35.6%) | 53 (37%) | 233 (36%) | ||

| No | 326 (64.4%) | 90 (63%) | 414 (64%) | ||

| Household size (no. of members >10) | |||||

| 0-10 | 287 (43.0%) | 76 (38.0%) | 363 (42%) | ||

| 11-20 | 309 (46.3%) | 109 (54.5%) | 418 (48%) | ||

| >20 | 71 (10.6%) | 15 (7.5%) | 86 (10%) | ||

| Household owns camels | |||||

| Yes | 667 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 667 (77%) | ||

| No | 0 (0%) | 200 (100%) | 200 (23%) | ||

| Household owns cattle | |||||

| Yes | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| No | 667 (100%) | 200 (100%) | 867 (100%) | ||

| Household owns small ruminants | |||||

| Yes | 590 (88.5%) | 200 (100%) | 790 (91.1%) | ||

| No | 77 (11.5%) | 0 (0%) | 77 (8.9%) | ||

| Where owned, small ruminants are reported as being vaccinated | |||||

| yes | 255 (72.9%) | 118 (90.8%) | 373 (77.7%) | ||

| No | 95 (27.1%) | 12 (9.2%) | 107 (22.3%) | ||

| Any history of livestock engagement

|

|||||

| Yes | 571 (85.6%) | 711 (82.0%) | 711 (82%) | ||

| No | 96 (14.4%) | 156 (18.0%) | 156 (18%) | ||

| Frequent (

|

|||||

| Yes | 478 (71.7%) | 577 (66.6%) | 577 (67%) | ||

| No | 189 (28.3%) | 290 (33.4%) | 290 (33%) | ||

| Household home has an air-cooling system

|

|||||

| Yes | 169 (42.9%) | 56 (31.6%) | 225(39.4%) | ||

| No | 225 (57.1%) | 121 (68.4%) | 346 (60.6%) | ||

|

|||||

| Adjusted* | |||||

| Unadjusted Positive individuals / total individuals | % | % | (95% CI) | ||

| Southern Jordan (Ma’an & Aqaba) |

|

79/667 | (11.8%) | 12.7% | (10.3-15.4) |

|

|

12/200 | (6.0%) | 8.2% | (4.9-12.5) | |

| All households | 91/867 | (10.5%) | 8.7% | (6.9-10.7) | |

| Ma’an |

|

68/379 | (17.9%) | 19.5% | (15.7-23.6) |

|

|

7/99 | (7.1%) | 9.0% | (4.4-15.7) | |

| All households | 75/478 | (15.7%) | 10.0% | (7.5-12.9) | |

| Aqaba |

|

11/288 | (3.8%) | 4.8% | (2.7-7.7) |

|

|

5/101 | (5.0%) | 6.2% | (2.6-12.0) | |

| All households | 16/389 | (4.1%) | 5.9% | (3.9-8.6) | |

*Adjusted for combined test performance values, with Southern Jordan (Ma’an & Aqaba) estimates also weighted for region. All households estimates are also adjusted for camel owning status.

selected camel herds being similar to those among nonprobabilistically sampled herds, across the study period).

Methods

Ethical approval

Camels

| Category* | Total 867 (missing) | +ve | % | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Spatial data | ||||||

| Region | ||||||

| Ma’an | 478 | 75 | 15.7% | 5.32 | 2.42-11.67 | <0.0001 |

| Aqaba | 389 | 16 | 4.1% | 1.00 | ||

| Sub-region | ||||||

| Aqaba West | 186 | 5 | 2.7% | 1.00 | 0.0002 | |

| Aqaba East | 203 | 11 | 5.4% | 2.06 | 0.55-7.70 | |

| Ma’an East | 222 | 27 | 12.2% | 6.14 | 1.80-20.94 | |

| Ma’an West | 256 | 48 | 18.8% | 9.64 | 2.96-31.45 | |

| Region with camel owning status | ||||||

| Aqaba COH | 288 | 11 | 3.8% | 1.00 | 0.0001 | |

| Aqaba NCOH | 101 | 5 | 5.0% | 1.29 | 0.27-5.46 | |

| Ma’an COH | 379 | 68 | 17.9% | 6.57 | 2.91-16.85 | |

| Ma’an NCOH | 99 | 7 | 7.1% | 2.17 | 0.58-8.11 | |

| Personal information | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 401 | 34 | 8.5% | 0.70 | 0.42-1.18 | 0.18 |

| Male | 466 | 57 | 12.2% | 1.00 | ||

| Age | ||||||

| 5-15 | 190 (2) | 17 | 8.9% | 1.00 | 0.39 | |

| >15-25 | 201 | 30 | 14.9% | 2.14 | 1.01-4.56 | |

| >25-40 | 201 | 17 | 8.5% | 1.45 | 0.62-3.38 | |

| >40-60 | 181 | 19 | 10.5% | 1.62 | 0.72-3.66 | |

| >60 | 92 | 8 | 8.7% | 1.35 | 0.47-3.84 | |

| Nationality | ||||||

| Jordanian | 757 (66) | 81 | 10.7% | 1.00 | NE | 0.62 |

| Egyptian | 8 | 2 | 25.0% | 6.17 | ||

| Sudanese | 8 | 0 | 0.0% | 0.00 | ||

| Saudi Arabian | 23 | 0 | 0.0% | 0.00 | ||

| Other | 5 | 0 | 0.0% | 0.00 | ||

| Household employee | ||||||

| No | 832 | 87 | 10.5% | 1.00 | 0.74 | |

| Farm Worker | 23 | 2 | 8.7% | 1.11 | 0.19-6.40 | |

| Slaughterer | 12 | 2 | 16.7% | 2.37 | 0.26-21.28 | |

| Secondary education | ||||||

| Yes | 233 (218) | 17 | 7.3% | 0.47 | 0.24-0.93 | 0.029 |

| No | 416 | 55 | 13.2% | 1.00 | ||

| Currently in school (if

|

||||||

| Yes | 175 (649) | 11 | 6.3% | 0.32 | 0.11-0.92 | 0.035 |

| No | 43 | 8 | 18.6% | 1.00 | ||

| Household information | ||||||

| Household dwelling type (tent) | ||||||

| Yes | 296 | 47 | 15.9% | 2.29 | 1.11-4.74 | 0.025 |

| No | 571 | 44 | 7.7% | 1.00 | ||

| Household size | ||||||

| 1-10 | 363 | 36 | 9.9% | 1.00 | 0.51 | |

| 11-20 | 418 | 43 | 10.3% | 0.91 | 0.42-1.96 | |

| >20 | 86 | 12 | 14.0% | 2.05 | 0.52-8.05 | |

| Category* | Total 867 (missing) | +ve | % | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Household owns camels | ||||||

| 0 | 200 | 12 | 6.0% | 1.00 | 0.33 | |

| 1-6 | 267 | 29 | 10.9% | 1.73 | 0.58-5.16 | |

| >6 | 400 | 50 | 12.5% | 2.17 | 0.78-6.04 | |

| Household owns sheep | ||||||

| No | 248 | 17 | 6.9% | 1.00 | 0.033 | |

|

|

338 | 32 | 9.5% | 1.59 | 0.61-4.16 | |

| >50 | 281 | 42 | 14.9% | 3.54 | 1.32-9.53 | |

| Household owns goats | ||||||

| No | 118 | 13 | 11.0% | 1.00 | 0.94 | |

|

|

479 | 50 | 10.4% | 1.11 | 0.37-3.34 | |

| >50 | 270 | 28 | 10.4% | 1.24 | 0.37-4.14 | |

| Small ruminants are reported vaccinated against Brucella (where small ruminants owned) | ||||||

| Yes | 373 (387) | 33 | 8.8% | 0.45 | 0.17-1.18 | 0.10 |

| No | 107 | 19 | 17.8% | 1.00 | ||

| Consumption of livestock products | ||||||

| Drinking raw camels’ milk | ||||||

| No | 474 | 32 | 6.8% | 1.00 | 0.0001 | |

|

|

176 | 13 | 7.4% | 1.09 | 0.51-2.36 | |

| Daily | 217 | 46 | 21.2% | 4.01 | 2.05-7.82 | |

| Daily consumption of camel by region | ||||||

| Aqaba | 61 | 3 | 4.9% | 1.00 | 2.36-62.70 | 0.0047 |

| Ma’an | 156 | 43 | 27.6% | 9.42 | ||

| Drinking raw sheep or goat milk (owning sheep, owning goats) | ||||||

| No | 707 | 59 | 8.3% | 1.00 | 0.012 | |

|

|

89 | 13 | 14.6% | 2.02 | 0.92-4.40 | |

| Daily | 71 | 19 | 26.8% | 2.97 | 1.33-6.60 | |

| Consuming raw dairy products made from small ruminant milk | ||||||

| No | 630 | 56 | 8.9% | 1.00 | 0.054 | |

|

|

177 | 19 | 10.7% | 1.29 | 0.67-2.49 | |

| Daily | 60 | 16 | 26.7% | 2.80 | 1.21-6.48 | |

| Livestock engagement activities | ||||||

| Birthing camels (>never) | ||||||

| Yes | 299 | 44 | 14.7% | 1.70 | 0.98-2.94 | 0.058 |

| No | 568 | 47 | 8.3% | 1.00 | ||

| Birthing small ruminants (

|

||||||

| Yes | 122 | 27 | 22.1% | 2.95 | 1.58-5.50 | 0.0007 |

| No | 745 | 64 | 8.6% | 1.00 | ||

| Disposing of camel afterbirth (>never) | ||||||

| Yes | 634 | 57 | 9.0% | 1.00 | 0.11 | |

| No | 233 | 34 | 14.6% | 1.60 | 0.90-. 82 | |

| Disposing of small ruminant afterbirth (

|

||||||

| Yes | 117 | 22 | 18.8% | 2.27 | 1.18-4.38 | 0.014 |

| No | 750 | 69 | 9.2% | 1.00 | ||

| Slaughtering small ruminants (

|

||||||

| Yes | 82 | 15 | 18.3% | 3.02 | 1.36-6.70 | 0.0065 |

| No | 785 | 76 | 9.7% | 1.00 | ||

| Category* | Total 867 (missing) | +ve | % | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Frequently (

|

||||||

| Yes | 439 | 61 | 13.9% | 1.81 | 0.99-3.28 | 0.053 |

| No | 428 | 30 | 7.0% | 1.00 | ||

| Frequently (

|

||||||

| Yes | 509 | 73 | 14.3% | 3.06 | 1.62-5.78 | 0.0006 |

| No | 358 | 18 | 5.0% | 1.00 | ||

| Frequently (

|

||||||

| Yes | 577 | 75 | 13.0% | 2.49 | 1.27-4.89 | 0.0080 |

| No | 290 | 16 | 5.5% | 1.00 | ||

| Any history livestock engagement | ||||||

| Yes | 711 | 83 | 11.7% | 2.09 | 0.87-4.99 | 0.099 |

| No | 156 | 8 | 5.1% | 1.00 | ||

| Hand hygiene | ||||||

| Hand washing >5 times / day | ||||||

| Yes | 528 | 42 | 8.0% | 0.54 | 0.32-0.91 | 0.021 |

| No | 339 | 49 | 14.5% | 1.00 | ||

| Used soap yesterday | ||||||

| Yes | 777 | 77 | 9.9% | 0.75 | 0.35-1.63 | 0.47 |

| No | 90 | 14 | 15.6% | 1.00 | ||

| Frequently (

|

||||||

| No | 428 | 30 | 5.5% | 1.00 | 0.0009 | |

| Yes (>5 times/day) | 255 | 26 | 9.4% | 1.78 | 0.85-3.69 | |

| Yes (

|

184 | 35 | 18.3% | 3.87 | 1.83-8.15 | |

| Among individuals frequently working with livestock, handwashing >5 times day | ||||||

| Yes | 342 (290) | 32 | 9.4% | 0.46 | 0.25-0.84 | 0.012 |

| No | 235 | 43 | 18.3% | 1.00 | ||

| Among individuals frequently working with livestock, use of soap yesterday | ||||||

| Yes | 504 (290) | 62 | 12.3% | 0.70 | 0.30-1.64 | 0.41 |

| No | 73 | 13 | 17.8% | 1.00 | ||

| Among individuals frequently working with livestock, handwashing with or without reported use of soap yesterday | ||||||

|

|

235 (290) | 43 | 18.3% | 1.00 | 0.036 | |

| >5 times/day without soap | 26 | 3 | 11.5% | 0.70 | 0.15-3.28 | |

| >5 times/day with soap | 316 | 29 | 9.2% | 0.44 | 0.24-0.82 | |

| Camel herd tested for brucella seropositivity | ||||||

| A camel in the herd tested seropositive for Brucella (positive on RBPT, confirmed positive on CFT) | ||||||

| Yes | 7 | 2 | 28.6% | 1.00 | 0.36-139.38 | 0.20 |

| No | 489 | 56 | 11.5% | 7.10 | ||

| Drinking camel milk where a camel in the herd tested seropositive for Brucella (positive on RBPT, confirmed positive on CFT) | ||||||

| Yes | 4 | 2 | 50% | 1.00 | 0.69-851.92 | 0.079 |

| No | 281 | 44 | 16% | 24.31 | ||

observed. Sensitivity and specificity were assumed to be

| Variable** | Category | A-priori adjusted OR

|

|

Fully adjusted OR

|

|

||

| Sex | Female | 0.71 | 0.42-1.18 | 0.19 | 0.86 | 0.51-1.45 | 0.57 |

| Age | 5-15 | 1.00 | 0.25 | 1.00 | 0.12 | ||

| >15-25 | 2.32 | 1.09-4.94 | 2.02 | 1.01-4.15 | |||

| >25-40 | 1.40 | 0.61-3.25 | 0.96 | 0.44-2.08 | |||

| >40-60 | 1.78 | 0.79-4.01 | 1.46 | 0.68-3.17 | |||

| >60 | 1.28 | 0.46-3.61 | 0.88 | 0.33-2.20 | |||

| Region | Ma’an | 5.51 | 2.53-12.03 | <0.0001 | 3.27 | 1.86-6.07 | <0.0001 |

| Primary dwelling tent | Yes | 2.25 | 1.15-4.42 | 0.018 | 1.52 | 0.92-2.51 | 0.10 |

| Household own sheep | No | 1.00 | 0.065 | 1.00 | 0.43 | ||

| 1-50 | 1.85 | 0.73-4.66 | 1.22 | 0.63-2.41 | |||

| >50 | 3.04 | 1.19-7.72 | 1.52 | 0.80-2.98 | |||

| Birthing camels | Yes | 1.45 | 0.80-2.62 | 0.22 | 0.88 | 0.50-1.54 | 0.65 |

| Birthing small ruminants | Yes | 2.45 | 1.31-4.58 | 0.0050 | 1.87 | 1.02-3.39 | 0.044 |

| Frequently (

|

Yes | 2.02 | 1.02-4.03 | 0.045 | 1.30 | 0.68-2.58 | 0.43 |

| Handwashing

|

Yes | 0.57 | 0.34-0.98 | 0.041 | 0.64 | 0.39-1.04 | 0.069 |

| Drinking camel milk | Rarely/never | 1.00 | 0.0012 | 1.00 | 0.016 | ||

| Weekly/monthly | 1.12 | 0.51-2.45 | 1.02 | 0.48-2.06 | |||

| Daily | 3.26 | 1.66-6.41 | 2.19 | 1.23-3.94 | |||

| Consuming small ruminant dairy products | Rarely/never | 1.00 | 0.088 | 1.00 | 0.65 | ||

| Weekly/monthly | 1.39 | 0.72-2.67 | 1.11 | 0.60-1.99 | |||

| Daily | 2.46 | 1.08-5.63 | 1.43 | 0.66-2.97 | |||

| Drinking raw sheep or goat milk

|

Rarely/never | 1.00 | 0.0047 | 1.00 | 0.071 | ||

| Weekly/monthly | 2.32 | 1.07-5.05 | 1.93 | 0.92-3.82 | |||

| Daily | 3.15 | 1.43-6.93 | 1.96 | 0.95-3.93 | |||

| Frequently working with livestock (

|

Not frequently working with livestock | 1.00 | 0.0063 | 1.00 | 0.047 | ||

| Frequently working with livestock & hand washing >5 times/day | 1.45 | 0.68-3.07 | 0.94 | 0.46-1.95 | |||

| Frequently working with livestock & hand washing

|

3.03 | 1.42-6.47 | 1.82 | 0.90-3.77 | |||

- In the last 12 months (with exception of age and sex).

Due to collinearity (Pearson R coefficient ) with consumption of raw sheep or goat dairy products this variable was tested in separate multivariable model in place of consumption of raw sheep or goat dairy products. In this model drinking raw camel milk, birthing small ruminants and region continued to demonstrate significant association (p< 0.05 ) with Brucella seropositive status.

Due to collinearity (Pearson coefficient ) with the variables frequently working with livestock and handwashing day, this variable was tested in separate multivariable model in place of frequently working with livestock and handwashing day. In this model drinking raw camel milk, birthing small ruminants and region continued to demonstrate significant association( ) with Brucella seropositive status.

observations in all models.

excluded, with the singular variable then adjusted in a separate model using the same covariates.

Humans

livestock-owning households in four sub-regions of southern Jordan (Aqaba East, Aqaba West, Ma’an East, and Ma’an West) (Fig. 3). Livestock-owning households were randomly selected by a co-author (SN) using computer-generated randomisation lists (Stata, version 15.1) from a sampling frame provided by the MoA, comprising a list of all households owning one or more camels, and a list of those owning sheep or goats, within the four sub-regions. Both house and tent dwellings were eligible for inclusion.

information, assessed eligibility, and obtained consent. Blood samples were collected from participating individuals together with administration of a structured questionnaire regarding potential risk factors for Brucella exposure during the previous 6 months, including questions regarding spatial data, personal information (including age and sex (observed), household information, consumption of livestock

products, livestock engagement activities and hand hygiene (with a follow-up questionnaire administered among COH regarding milk boiling practices). An additional questionnaire was administered to the household head regarding household-level risk factors, including age and sex of any unsampled members. Questionnaires were administered in the local dialect on android tablets using the application Open Data Kit (version 1.10). Due to cultural sensitivity, information regarding participant sex was obtained from interviewer observation. Information regarding nationality was self-reported, according to national identity card or passport details.

Reporting summary

Data availability

References

- World Health Organization. Brucellosis Fact Sheet, WHO, [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ brucellosis (2020).

- World Health Organization. Estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases: foodborne disease burden epidemiology reference group 2007-2015. WHO Geneva, (2015).

- Franc, K. A., Krecek, R. C., Häsler, B. N. & Arenas-Gamboa, A. M. Brucellosis remains a neglected disease in the developing world: a call for interdisciplinary action. BMC Public Health 18, e125 (2018).

- Dean, A. S. et al. Clinical manifestations of human brucellosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6, e1929 (2012).

- Abo-shehada, M. N. & Abu-Halaweh, M. Seroprevalence of Brucella species among women with miscarriage in Jordan. East Mediterr. Health J. 17, 871-874 (2011).

- Radostits O. M., GAY, C., Hinchcliff, K. W. & Constable, P. D. A textbook of the diseases of cattle, horses, sheep, pigs and goats. Veterinary Medicine 10th edition London: Saunders. 1548-1551 (2007).

- Laine, C. G., Johnson, V. E., Scott, H. M. & Arenas-Gamboa, A. M. Global Estimate of Human Brucellosis Incidence. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 29, 1789-1797 (2023).

- Dadar, M. et al. Human brucellosis and associated risk factors in the Middle East region: A comprehensive systematic review, metaanalysis, and meta-regression. Heliyon 10, e34324 (2024).

- Alhussain, H. et al. Seroprevalence of camel brucellosis in Qatar. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 54, e351 (2022).

- Musallam, I. I., Abo-Shehada, M. N., Hegazy, Y. M., Holt, H. R. & Guitian, F. J. Systematic review of brucellosis in the Middle East: disease frequency in ruminants and humans and risk factors for human infection. Epidemiol. Infect. 144, 671-685 (2016).

- Bagheri Nejad, R., Krecek, R. C., Khalaf, O. H., Hailat, N. & ArenasGamboa, A. M. Brucellosis in the Middle East: Current situation and a pathway forward. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14, e0008071 (2020).

- Al-Ani, F. et al. Human and animal brucellosis in the Sultanate of Oman: an epidemiological study. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries 17, 52-58 (2023).

- Al-Marzooqi, W. et al. Seroprevalence and Risk Factors of Brucellosis in Ruminants in Dhofar Province in Southern Oman. Vet. Med Int 2022, e3176147 (2022).

- Shaqra QM, Abu Epidemiological aspects of brucellosis in Jordan. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 16, 581-584 (2000).

- Abutarbush, S. M. et al. Implementation of One Health approach in Jordan: Review and mapping of ministerial mechanisms of zoonotic disease reporting and control, and inter-sectoral collaboration. One Health 15, e100406 (2022).

- McAlester, J. & Kanazawa, Y. Situating zoonotic diseases in peacebuilding and development theories: Prioritizing zoonoses in Jordan. PLoS One 17, e0265508 (2022).

- Abo-Shehada, M. N., Odeh, J. S., Abu-Essud, M. & Abuharfeil, N. Seroprevalence of brucellosis among high risk people in northern Jordan. Int J. Epidemiol. 25, 450-454 (1996).

- Dajani, Y. F., Masoud, A. A. & Barakat, H. F. Epidemiology and diagnosis of human brucellosis in Jordan. J. Trop. Med Hyg. 92, 209-214 (1989).

- Samadi, A., Ababneh, M. M., Giadinis, N. D. & Lafi, S. Q. Ovine and Caprine Brucellosis (Brucella melitensis) in Aborted Animals in Jordanian Sheep and Goat Flocks. Vet. Med Int 2010, e458695 (2010).

- Al-Talafhah, A. H., Lafi, S. Q. & Al-Tarazi, Y. Epidemiology of ovine brucellosis in Awassi sheep in Northern Jordan. Prev. Vet. Med 60, 297-306 (2003).

- Aldomy, F. M., Jahans, K. L. & Altarazi, Y. H. Isolation of Brucella melitensis from aborting ruminants in Jordan. J. Comp. Pathol. 107, 239-42 (1992).

- Musallam, I. I., Abo-Shehada, M., Omar, M. & Guitian, J. Crosssectional study of brucellosis in Jordan: Prevalence, risk factors and spatial distribution in small ruminants and cattle. Prev. Vet. Med 118, 387-96 (2015).

- Abo-Shehada, M. N., Rabi, A. Z. & Abuharfeil, N. The prevalence of brucellosis among veterinarians in Jordan. Ann. Saudi Med 11, 356-357 (1991).

- Al-Amr, M. et al. Epidemiology of human brucellosis in military hospitals in Jordan: A five-year study. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries 16, 1870-1876 (2022).

- Abo-Shehada, M. N. & Abu-Halaweh, M. Risk factors for human brucellosis in northern Jordan. East Mediterr. Health J. 19, 135-140 (2013).

- Issa, H. & Jamal, M. Brucellosis in children in south Jordan. East Mediterr. Health J. 5, 895-902 (1999).

- Galali, Y. & Al-Dmoor, H. M. Miraculous properties of camel milk and perspective of modern science. J. Fam. Med. Dis. Prev. 5, e095 (2019).

- Shimol, S. B. et al. Human brucellosis outbreak acquired through camel milk ingestion in southern Israel. Isr. Med Assoc. J. 14, 475-478 (2012).

- Zhu, S., Zimmerman, D. & Deem, S. L. A review of zoonotic pathogens of dromedary camels. Ecohealth 16, 356-377 (2019).

- Sprague, L. D., Al-Dahouk, S. & Neubauer, H. A review on camel brucellosis: a zoonosis sustained by ignorance and indifference. Pathog. Glob. Health 106, 144-149 (2012).

- Almuzaini, A. M. An epidemiological study of brucellosis in different animal species from the al-qassim region, Saudi Arabia. Vaccines (Basel). 11, e694 (2023).

- Dahl, M. O. Brucellosis in food-producing animals in Mosul, Iraq: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 15, e0235862 (2020).

- Hegazy, Y. M., Moawad, A., Osman, S., Ridler, A. & Guitian, J. Ruminant brucellosis in the Kafr El Sheikh Governorate of the Nile

34. Bardenstein, S., Gibbs, R. E., Yagel, Y., Motro, Y. & Moran-Gilad, J. Brucellosis Outbreak Traced to Commercially Sold Camel Milk through Whole-Genome Sequencing, Israel. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 27, 1728-1731 (2021).

35. Garcell, H. G. et al. Outbreaks of brucellosis related to the consumption of unpasteurized camel milk. J. Infect. Public Health 9, 523-527 (2016).

36. Al-Majali, A. M., Al-Qudah, K. M., Al-Tarazi, Y. H. & Al-Rawashdeh, O. F. Risk factors associated with camel brucellosis in Jordan. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 40, 193-200 (2008).

37. World Organizarion of Animal Health. Manual of diagnostic tests and vaccines for terrestrial animals Ch 3.1.4 (WOAH, Paris, 2022).

38. Mangtani, P. et al. The prevalence and risk factors for human Brucella species infection in a cross-sectional survey of a rural population in Punjab, India. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med Hyg. 114, 255-263 (2020).

39. Alnaeem, A. et al. Some pathological observations on the naturally infected dromedary camels (Camelus dromedarius) with the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in Saudi Arabia 2018-2019. Vet. Q 40, 190-197 (2020).

40. Chatty D. From Camel to Truck: The Bedouin in the Modern World. (White Horse Press, Cambridge, 2013).

41. Qur’an, Al-Ghashiyah (Surra 88), verse 17.

42. Al Zahrani, A. et al. Use of camel urine is of no benefit to cancer patients: observational study and literature review. East Mediterr. Health J. 29, 657-663 (2023).

43. Sahih Al Bukhari, The Book of Medicine (Book 76), Hadith 9.

44. Abutarbush, A. S., Hijazeen, Z., Doodeen, R. & Hawaosha, M. Analysis, description and mapping of camel value chain in jordan ministry of agriculture. Glob. Veterinaria 20, 144-152 (2019).

45. Abuelgasim, K. A. et al. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients with cancer: a cross-sectional survey in Saudi Arabia. BMC Complement Alter. Med 18, e88 (2018).

46. Shaalan, M. A. et al. Brucellosis in children: clinical observations in 115 cases. Int J. Infect. Dis. 6, 182-186 (2002).

47. Musallam, I. I., Abo-Shehada, M. N. & Guitian, J. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices associated with brucellosis in livestock owners in jordan. Am. J. Trop. Med Hyg. 93, 1148-1155 (2015).

48. Holloway, P. et al. Risk factors for middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection among camel populations, Southern Jordan, 2014-2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 27, 2301-2311 (2021).

49. Dadar, M., Tiwari, R., Sharun, K. & Dhama, K. Importance of brucellosis control programs of livestock on the improvement of one health. Vet. Q 41, 137-151 (2021).

50. Radwan, A. I. et al. Control of Brucella melitensis infection in a large camel herd in Saudi Arabia using antibiotherapy and vaccination with Rev. 1 vaccine. Rev. Sci. Tech. 14, 719-732 (1995).

51. Food and Agriculture Organisation, Animal Production and Health Paper 156 Ch. 9 (FAO, Rome, 2003)

52. Holloway, P. et al. A cross-sectional study of Q fever in Camels: Risk factors for infection, the role of small ruminants and public health implications for desert-dwelling pastoral communities. Zoonoses Public Health 70, 238-247 (2023).

53. Ahad, A. A., Megersa, B. & Edao, B. M. Brucellosis in camel, small ruminants, and Somali pastoralists in Eastern Ethiopia: a One Health approach. Front Vet. Sci. 11, e1276275 (2024).

54. Mohammed, A. et al. Seroprevalence and risk factors of brucellosis in dromedary camels (Camelus dromedarius) in Sudan from 1980 to 2020: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vet. Q 43, 1-15 (2023).

55. Dadar, M. & Alamian, S. Isolation of Brucella melitensis from seronegative camel: potential implications in brucellosis control. Prev. Vet. Med 185, e105194 (2020).

56. Blasco, J. M. A review of the use of B. melitensis Rev 1 vaccine in adult sheep and goats. Prev. Vet. Med 31, 275-283 (1997).

57. Vives-Sotoa, M. P.-G. A., Pereirab, J., Rodríguez-Sánchez, J. & Solerac, E. J. What risk do Brucella vaccines pose to humans? A systematic review of the scientific literature on occupational exposure. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 18, e0011889 (2024).

58. Ducrotoy, M. J. et al. Integrated health messaging for multiple neglected zoonoses: Approaches, challenges and opportunities in Morocco. Acta Trop. 152, 17-25 (2015).

59. Mbye, M., Ayyash, M., Abu-Jdayil, B. & Kamal-Eldin, A. The texture of camel milk cheese: effects of milk composition, coagulants, and processing conditions. Front Nutr. 9, e868320 (2022).

60. Al-Zoubi, M. et al. WASH in Islam. Guide on Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) from an Islamic Perspective. (Sanitation for Millions, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Germany 2020).

61. Elsohaby, I. et al. Bayesian Evaluation of Three Serological Tests for Diagnosis of Brucella infections in Dromedary Camels Using Latent Class Models. Prev. Vet. Med 208, e105771 (2022).

62. Khan, F. K. R. et al. Comparative performance study of four different serological tests for the diagnosis of dromedary brucellosis. J. Camel Pract. Res. 23, 213-217 (2016).

63. IDvet. ID Screen

64. Gwida, M. M. et al. Comparison of diagnostic tests for the detection of Brucella spp. in camel sera. BMC Res Notes 4, e525 (2011).

65. Getachew, T., Getachew, G., Sintayehu, G., Getenet, M. & Fasil, A. Bayesian Estimation of Sensitivity and Specificity of Rose Bengal, Complement Fixation, and Indirect ELISA Tests for the Diagnosis of Bovine Brucellosis in Ethiopia. Vet. Med Int 2016, e8032753 (2016).

66. Wernery, U. Camelid brucellosis: a review. Rev. Sci. Tech. 33, 839-857 (2014).

67. Beauvais, W., Orynbayev, M. & Guitian, J. Empirical Bayes estimation of farm prevalence adjusting for multistage sampling and uncertainty in test performance: a Brucella cross-sectional serostudy in southern Kazakhstan. Epidemiol. Infect. 144, 3531-3539 (2016).

68. Serion ELISA classic Brucella spp. IgG. https://www.serion-diagnostics.de/en/products/serion-elisa-classic-antigen/ brucella/ (2023).

69. Al Dahouk, S., Tomaso, H., Nöckler, K., Neubauer, H. & Frangoulidis, D. Laboratory-based diagnosis of brucellosis-a review of the literature. Part II: serological tests for brucellosis. Clin. Lab 49, 577-589 (2003).

70. Ekiri, A. B. et al. Utility of the rose bengal test as a point-of-care test for human brucellosis in endemic african settings: a systematic review. J. Trop. Med 2020, e6586182(2020).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

(c) The Author(s) 2025

Veterinary Epidemiology, Economics and Public Health Group, WOAH Collaborating Centre for Risk Analysis and Modelling, Department of Pathobiology and Population Sciences, The Royal Veterinary College, Hatfield, UK. ²Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology and International Health, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK. Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden. Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan. Department of Paediatrics, School of Medicine, Saint Louis University, St Louis, MO, USA. These authors contributed equally: Punam Mangtani, Javier Guitian. e-mail: pholloway3@rvc.ac.uk - *Positive on RBPT and positive on CFT or ELISA.

TOnce, or more, in the past 5 years.