DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlr.2024.100548

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38649096

تاريخ النشر: 2024-04-21

حمض الدوكوساهيكسانويك الغذائي (DHA) يقلل من تخليق DHA في الكبد عن طريق تثبيط إطالة حمض الإيكوسابنتاينويك

الملخص

حمض الدوكوساهيكسانويك (DHA) وفير في الدماغ حيث ينظم بقاء الخلايا، وتكوين الأعصاب، والالتهاب العصبي. يمكن الحصول على DHA من النظام الغذائي أو تصنيعه من حمض ألفا-لينولينيك (ALA؛ 18:3n-3) من خلال سلسلة من تفاعلات الإشباع والإطالة التي تحدث في الكبد. تشير دراسات التتبع إلى أن DHA الغذائي يمكن أن يقلل من تصنيع نفسه، لكن الآلية لا تزال غير محددة وهي الهدف الرئيسي من هذه المخطوطة. أولاً، نوضح من خلال تتبع

المواد والأساليب

بيان الأخلاقيات

تصميم الدراسة

تم جمع المحاليل المالحة والكبد كما هو موضح أعلاه لتحليل نشاط إنزيمات الكبد في تحويل EPA إلى حمض الدوكوسابنتاينويك n-3 (DPAn-3، 22:5n-3) (ELOVL2/5).

تحليلات الأحماض الدهنية

الذي يدخل إلى جهاز MAT253 IRMS عبر واجهة تدفق مستمر ConFlo IV التي توفر

تحليلات الجينات والإنزيمات

تعليمات الشركة المصنعة. تم إجراء النسخ العكسي PCR الكمي (RT-qPCR) على نظام Bio-Rad CFX96 للوقت الحقيقي. تم تصميم البرايمرات المستخدمة في RT-qPCR عبر الإنترنت باستخدام مكتبة بروب العالمية من روش ومركز تصميم الاختبارات. إجمالي حجم التفاعل لكل عينة (

تم قياسها كزيادة صافية في منتج الأحماض الدهنية غير المشبعة من النوع n-3 الناتج من سلفه n-3 PUFA، محسوبة من الفروق بين القيم الأساسية قبل الحضانة وتلك التي تم الحصول عليها بعد 30 دقيقة من الحضانة. يتم التعبير عن النتائج كـ

النتائج

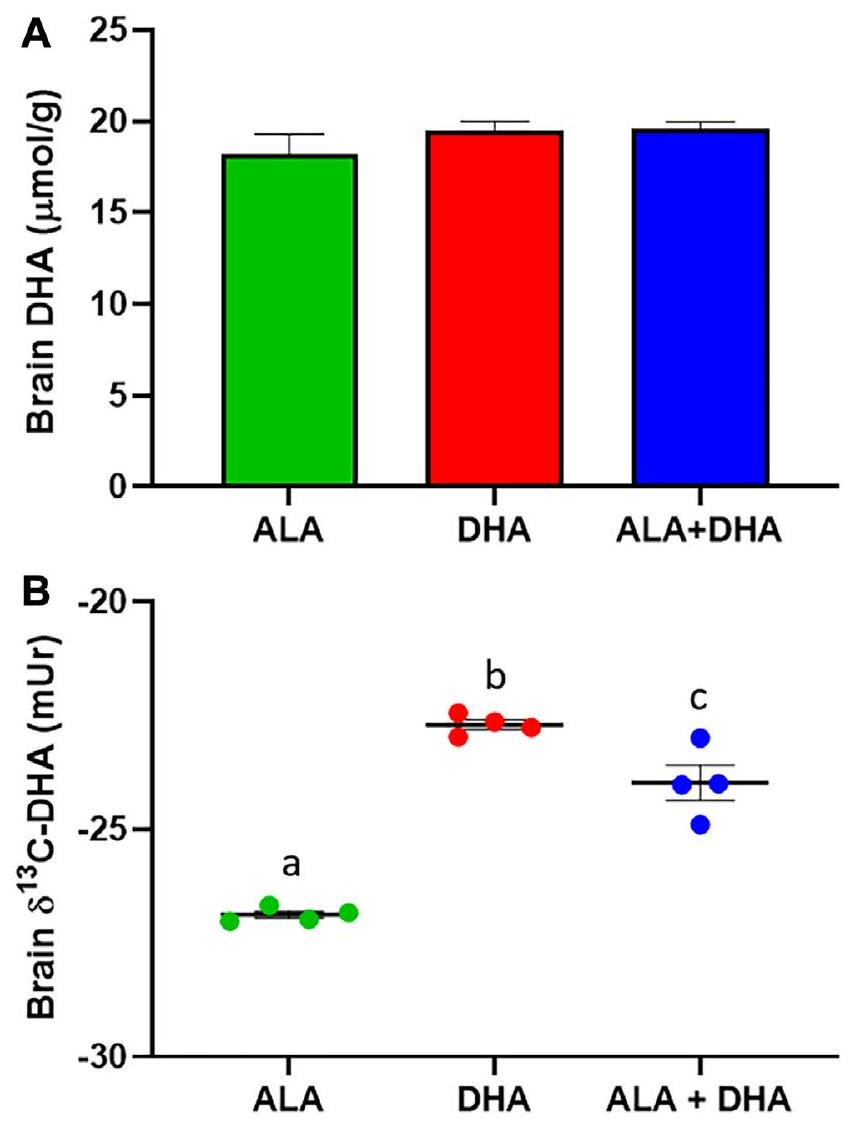

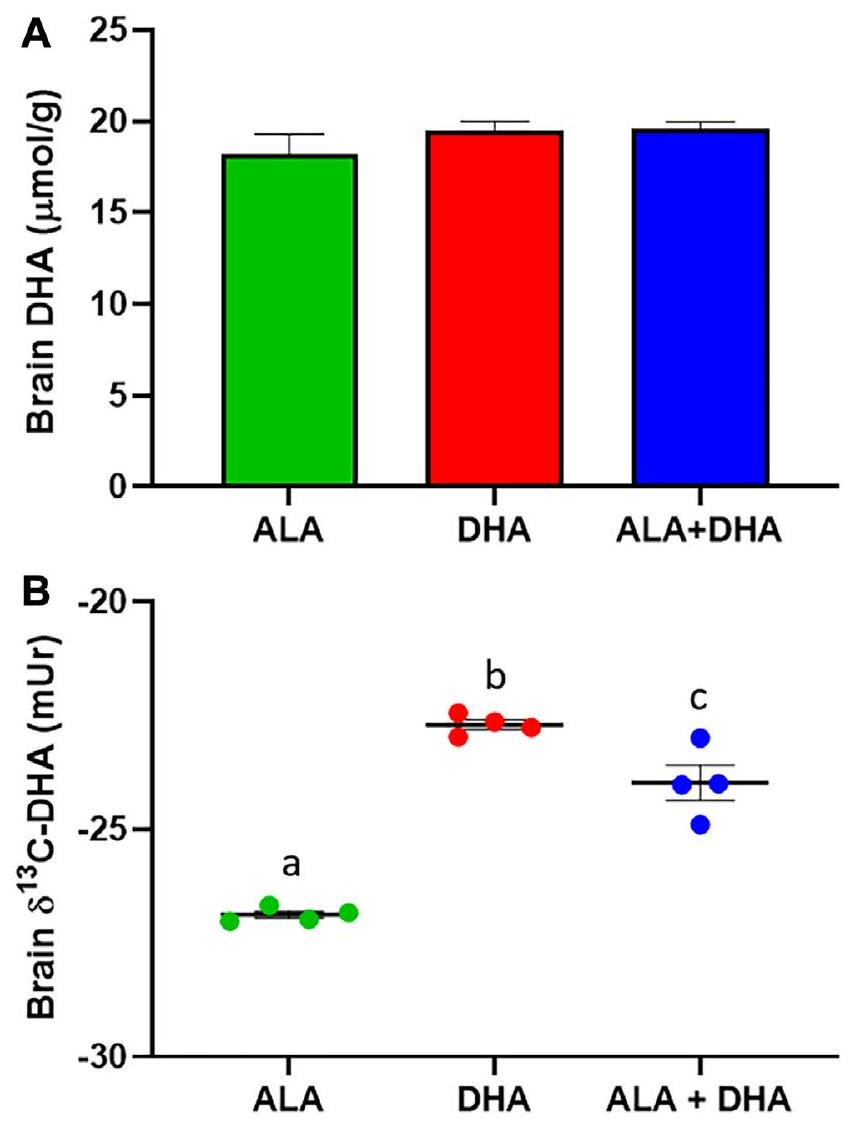

تركيزات DHA في الدماغ و

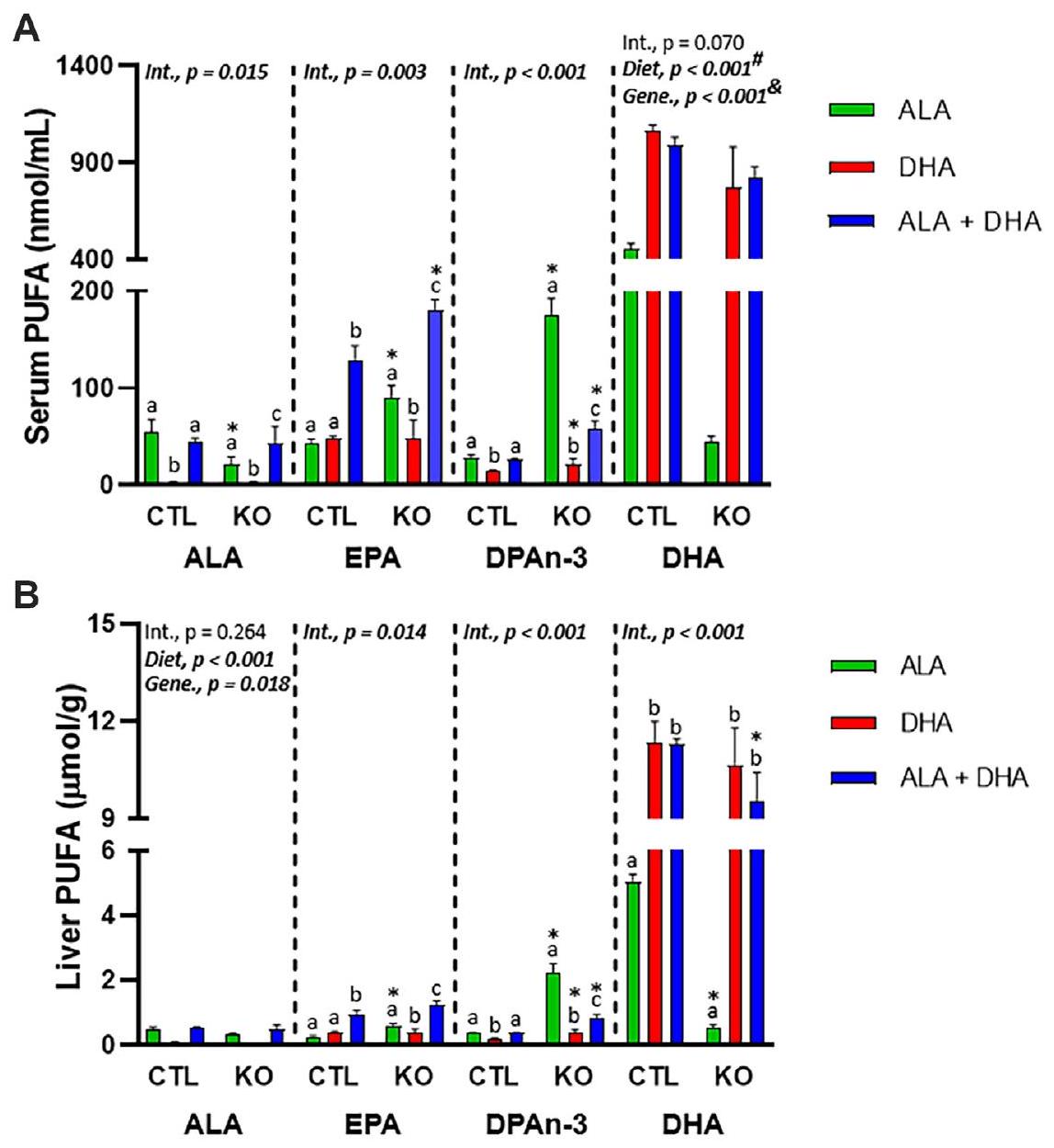

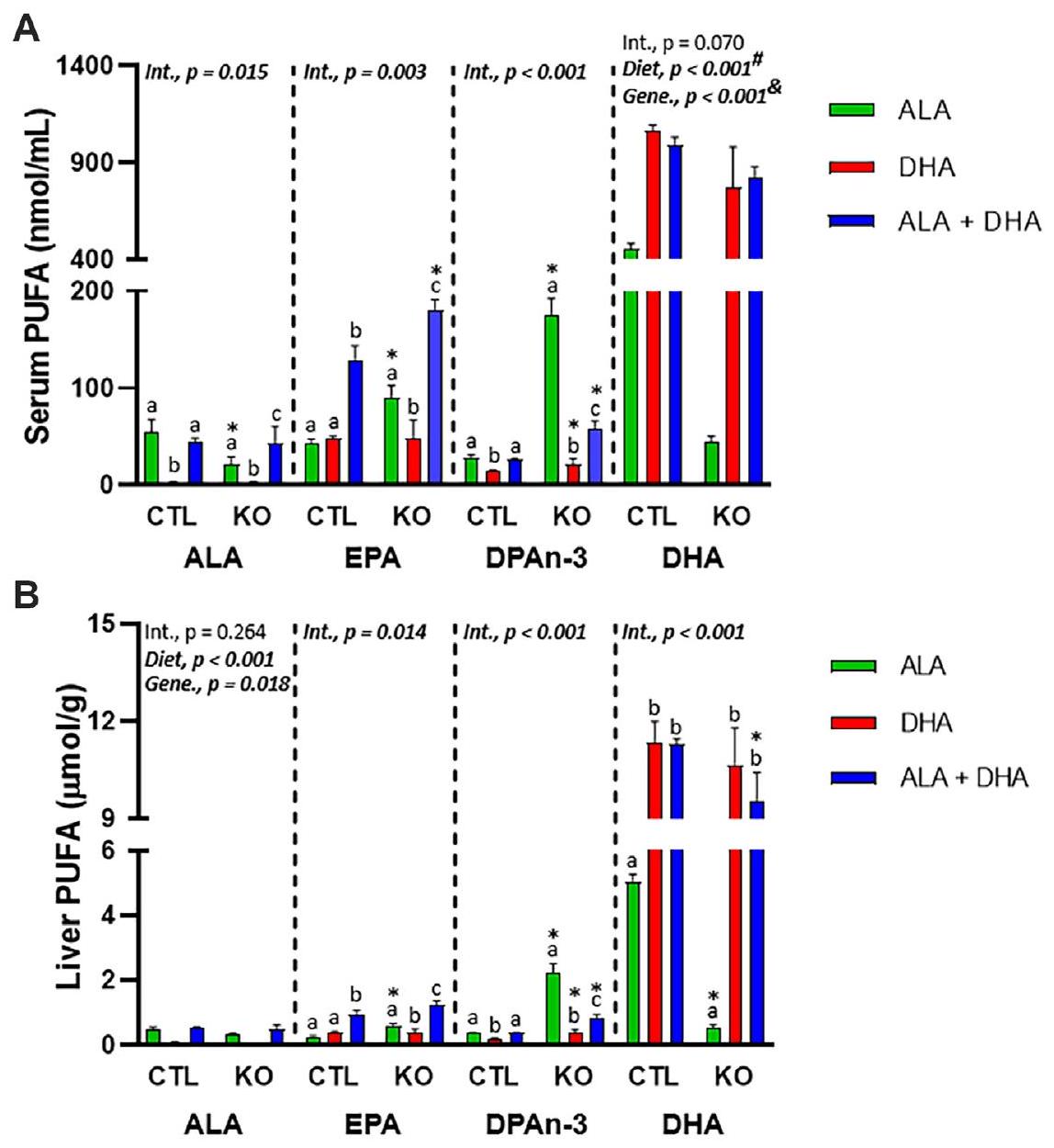

تركيزات الأحماض الدهنية غير المشبعة المتعددة n-3 في المصل والكبد لفئران BALB/c التي تم تغذيتها بـ ALA أو DHA أو ALA + DHA

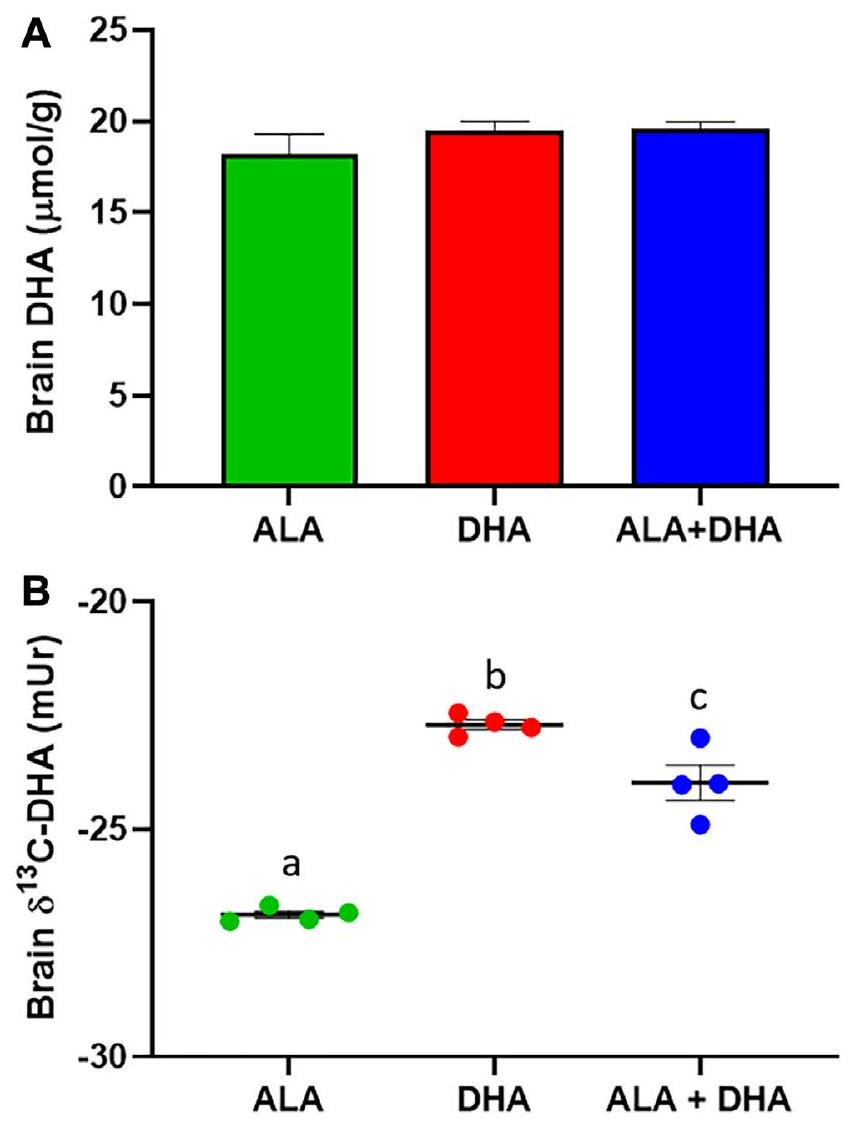

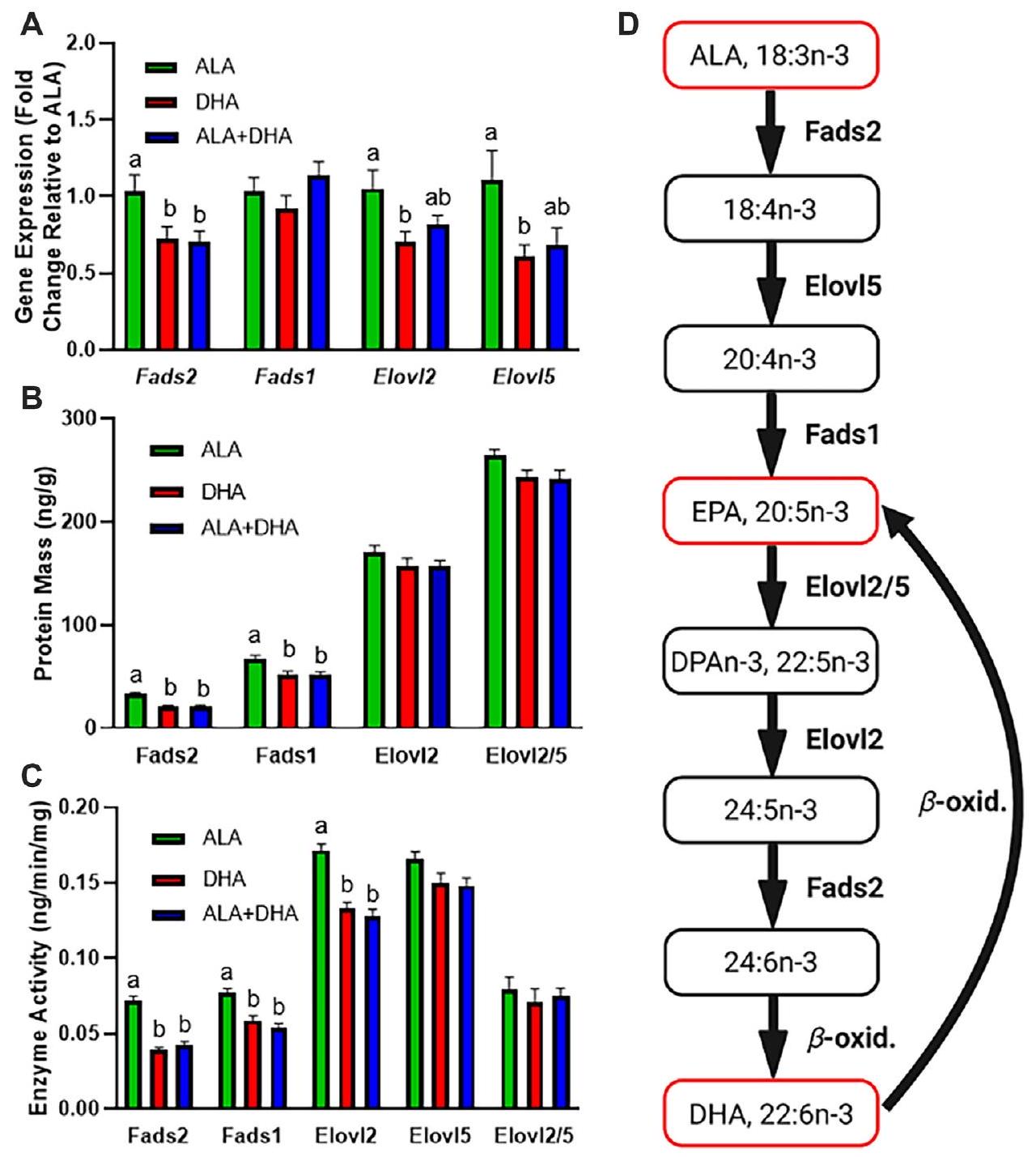

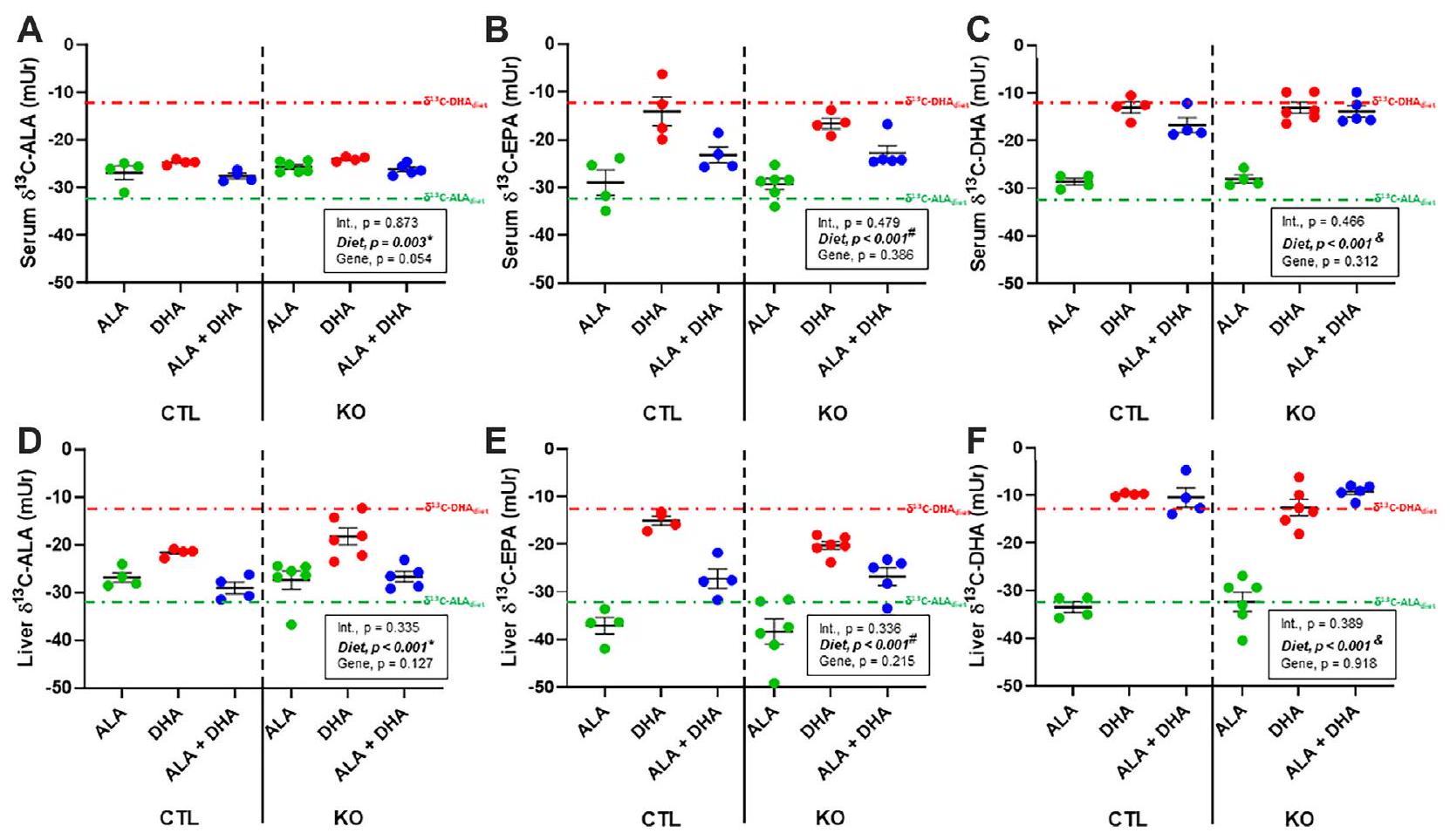

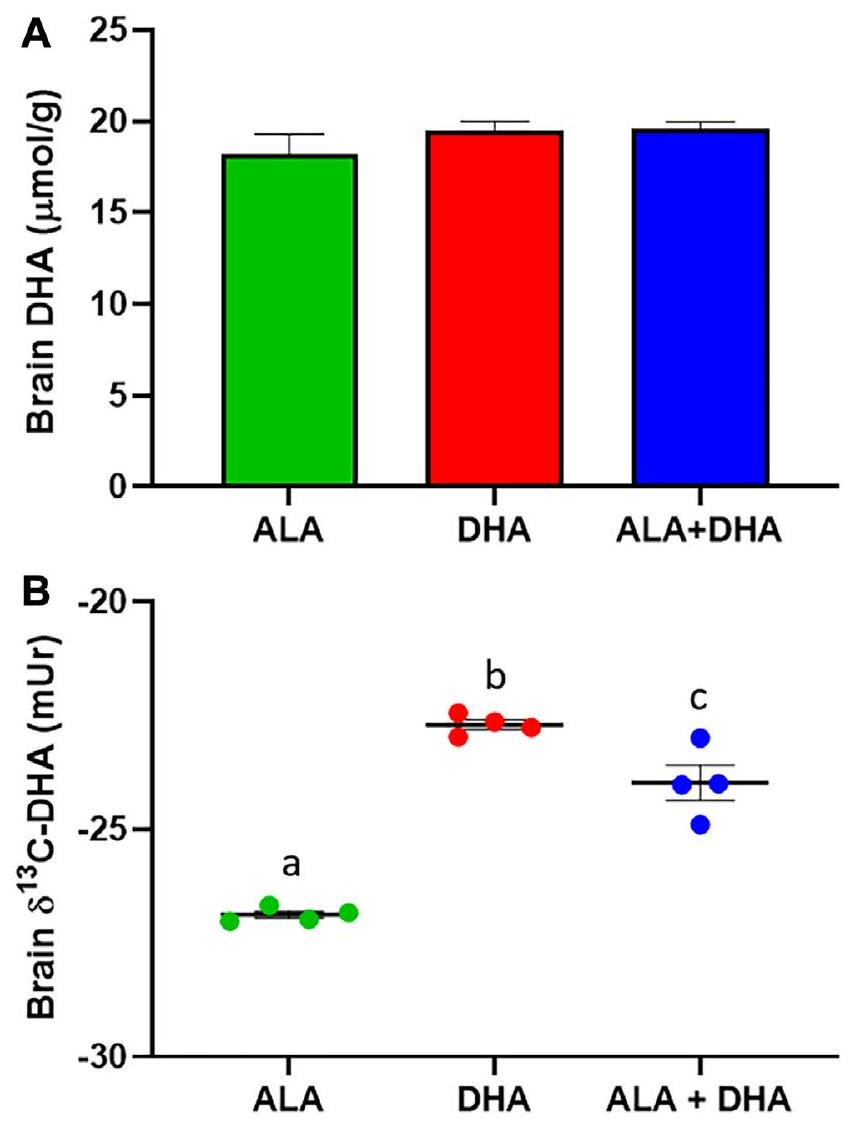

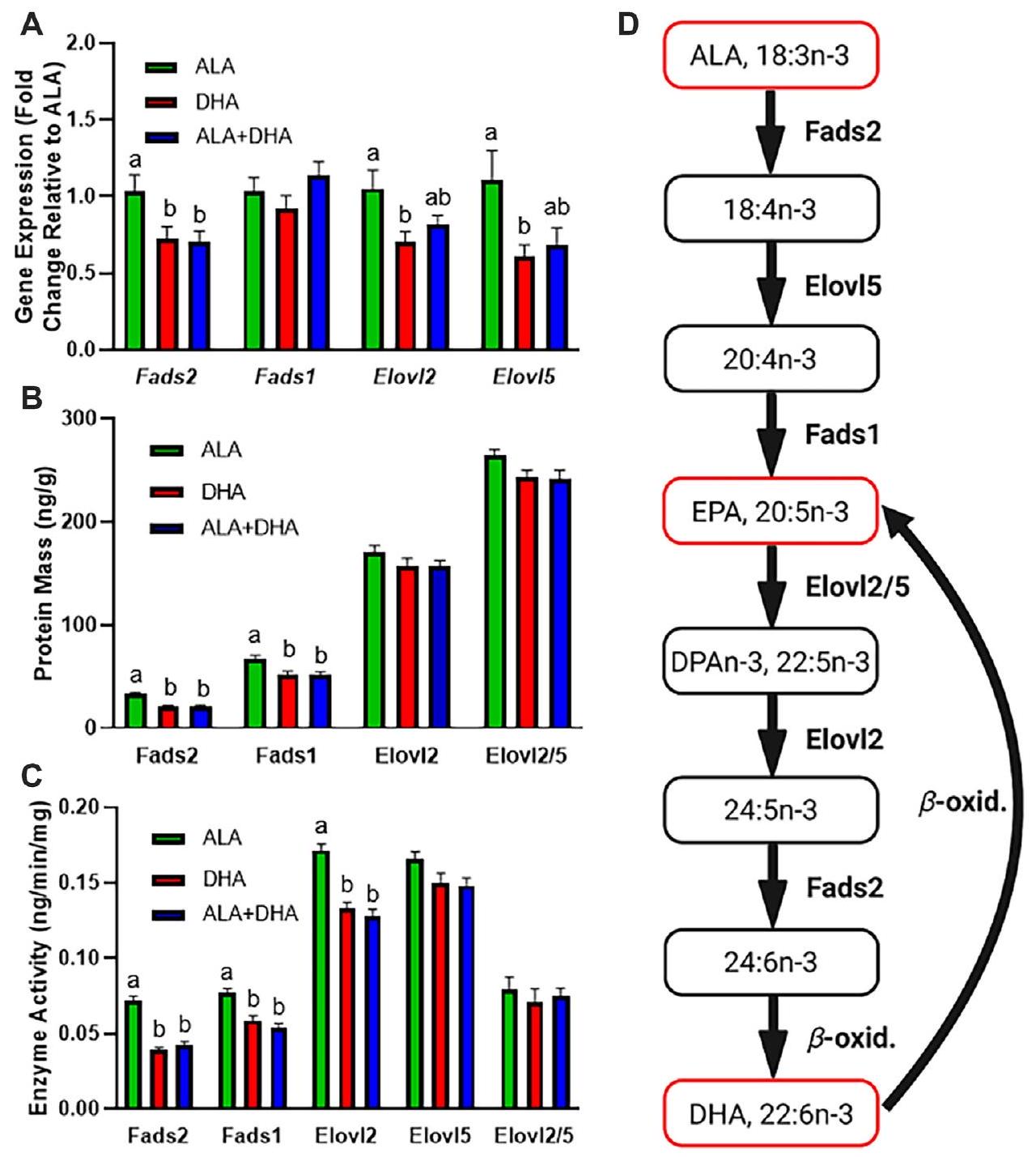

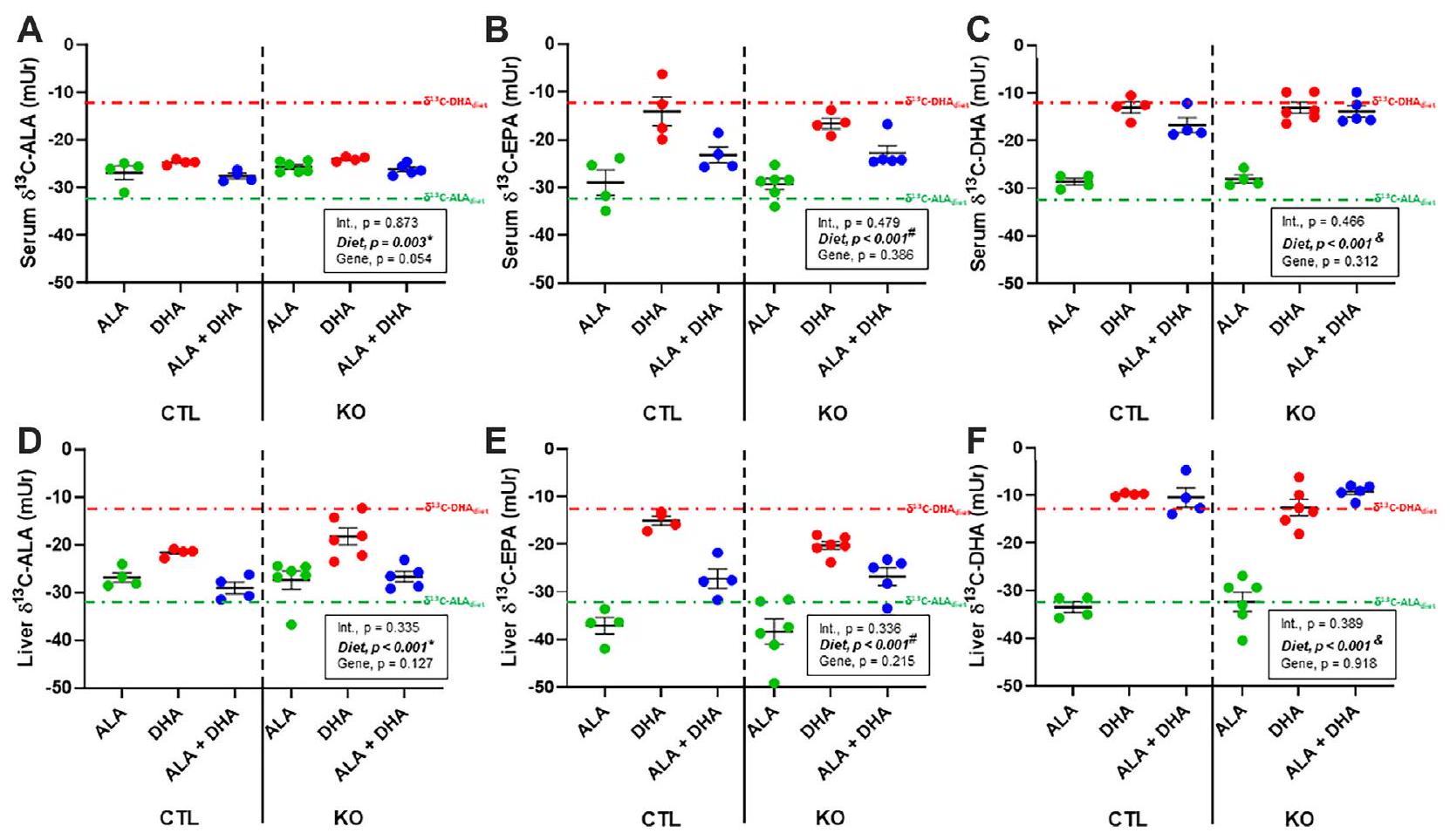

محتوى الكربون-13 من الأحماض الدهنية غير المشبعة n-3 في المصل والكبد لدى فئران BALB/c التي تم تغذيتها بـ ALA أو DHA أو ALA + DHA

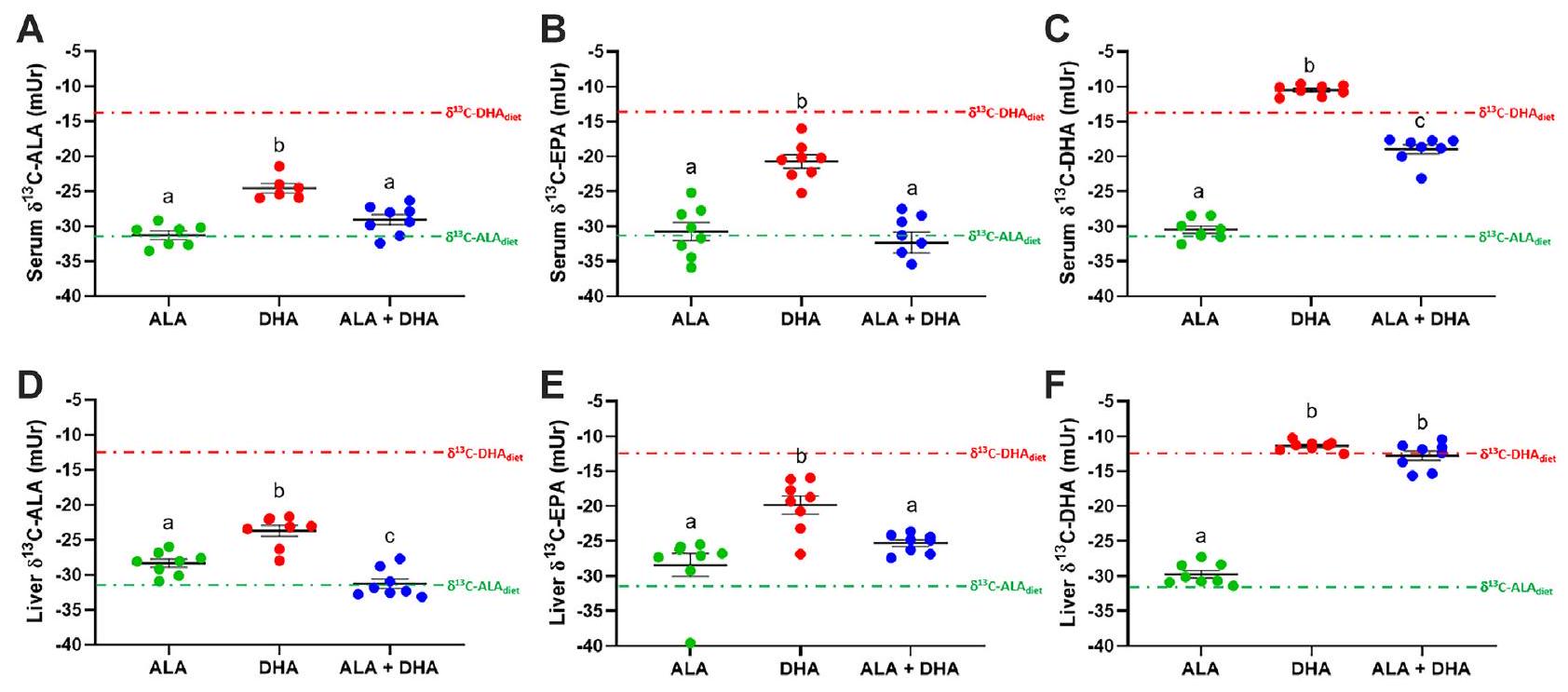

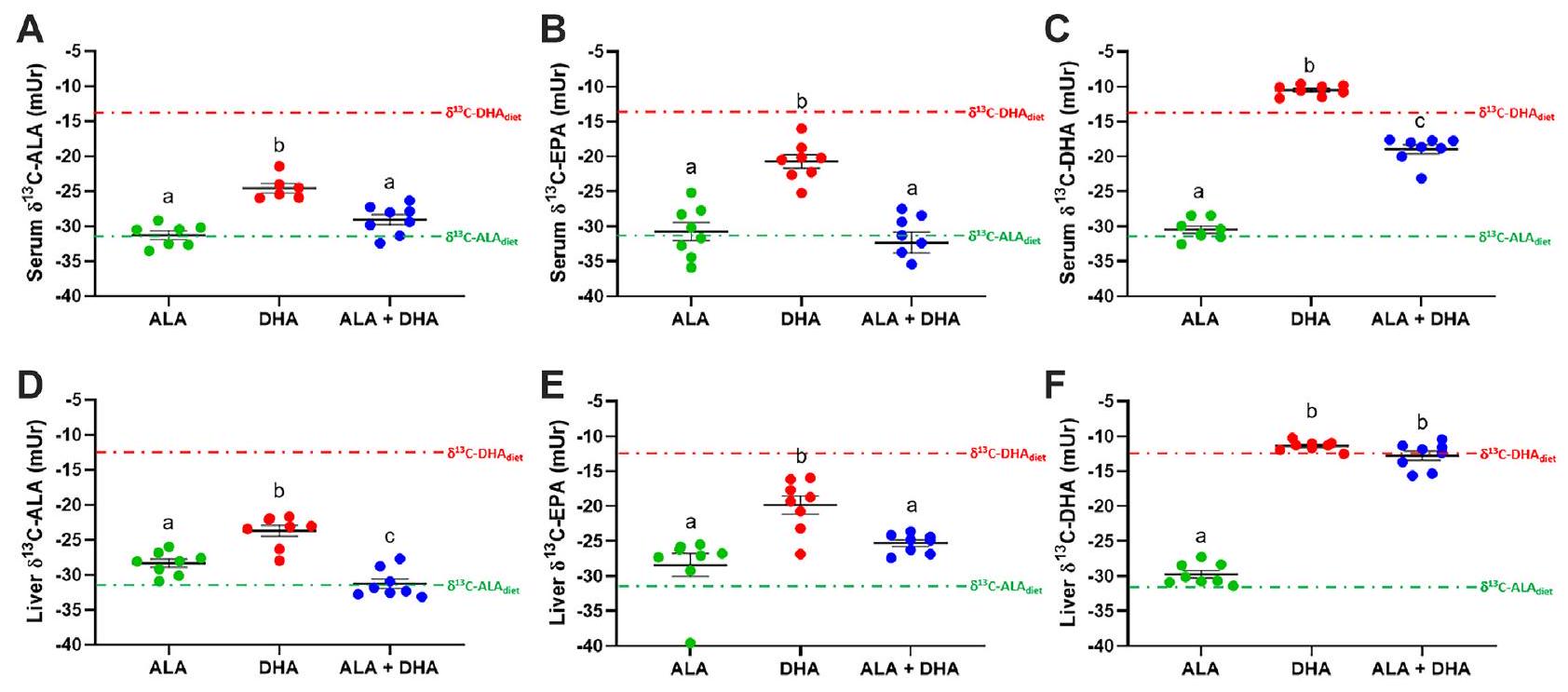

تعبير الجينات في الكبد، محتوى البروتين، ونشاط الإنزيمات في فئران BALB/c التي تم تغذيتها بأنظمة غذائية تحتوي على ALA، DHA، أو ALA + DHA

مستويات السيروم والأحماض الدهنية غير المشبعة من النوع n-3 في الكبد لدى فئران Elovl2 KO المحددة للكبد التي تم تغذيتها بأنظمة غذائية تحتوي على ALA أو DHA أو ALA + DHA

محتوى الكربون-13 من الأحماض الدهنية غير المشبعة n-3 في المصل والكبد لفئران Elovl2 KO المحددة للكبد التي تم تغذيتها بـ ALA أو DHA أو ALA + DHA

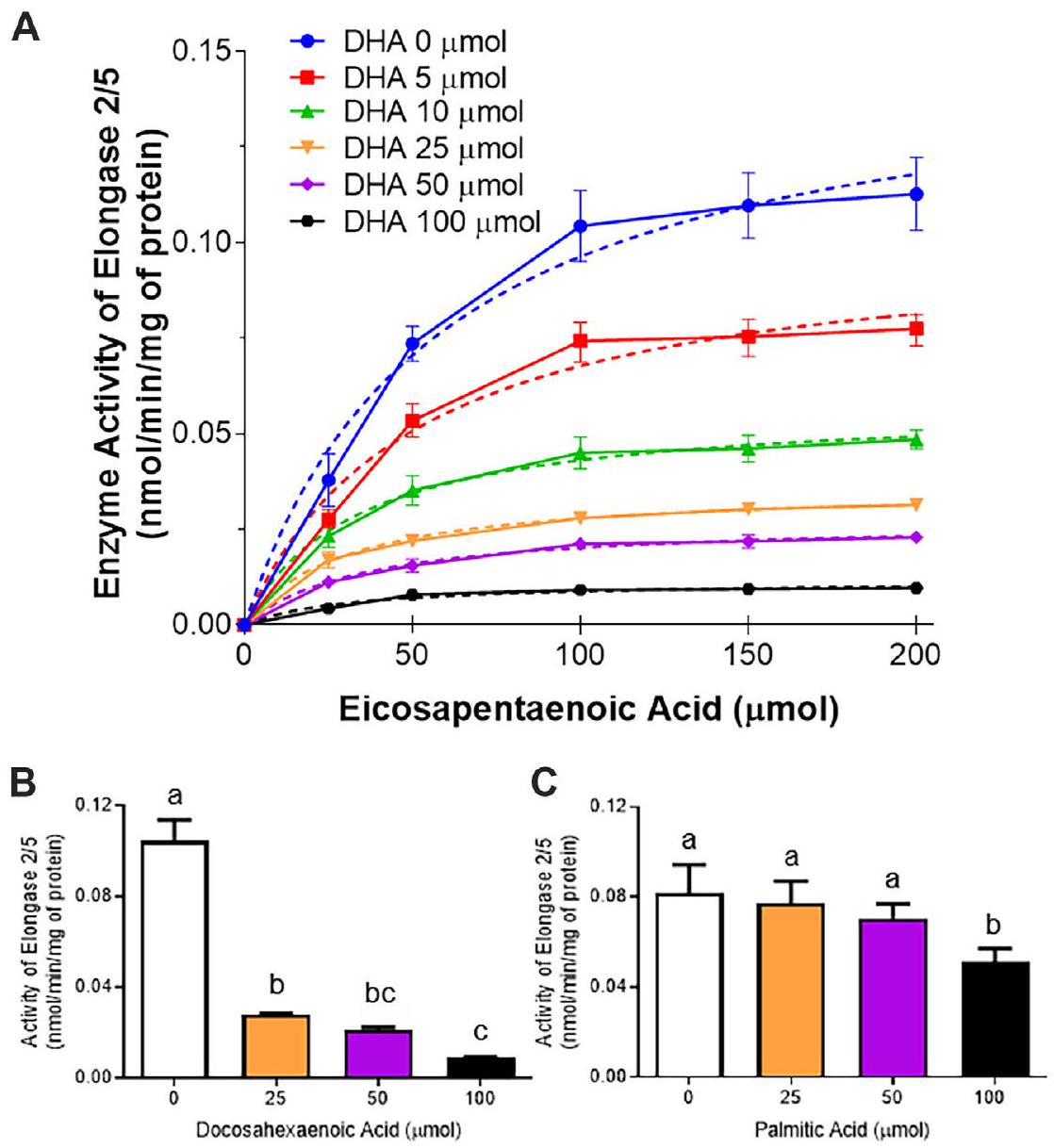

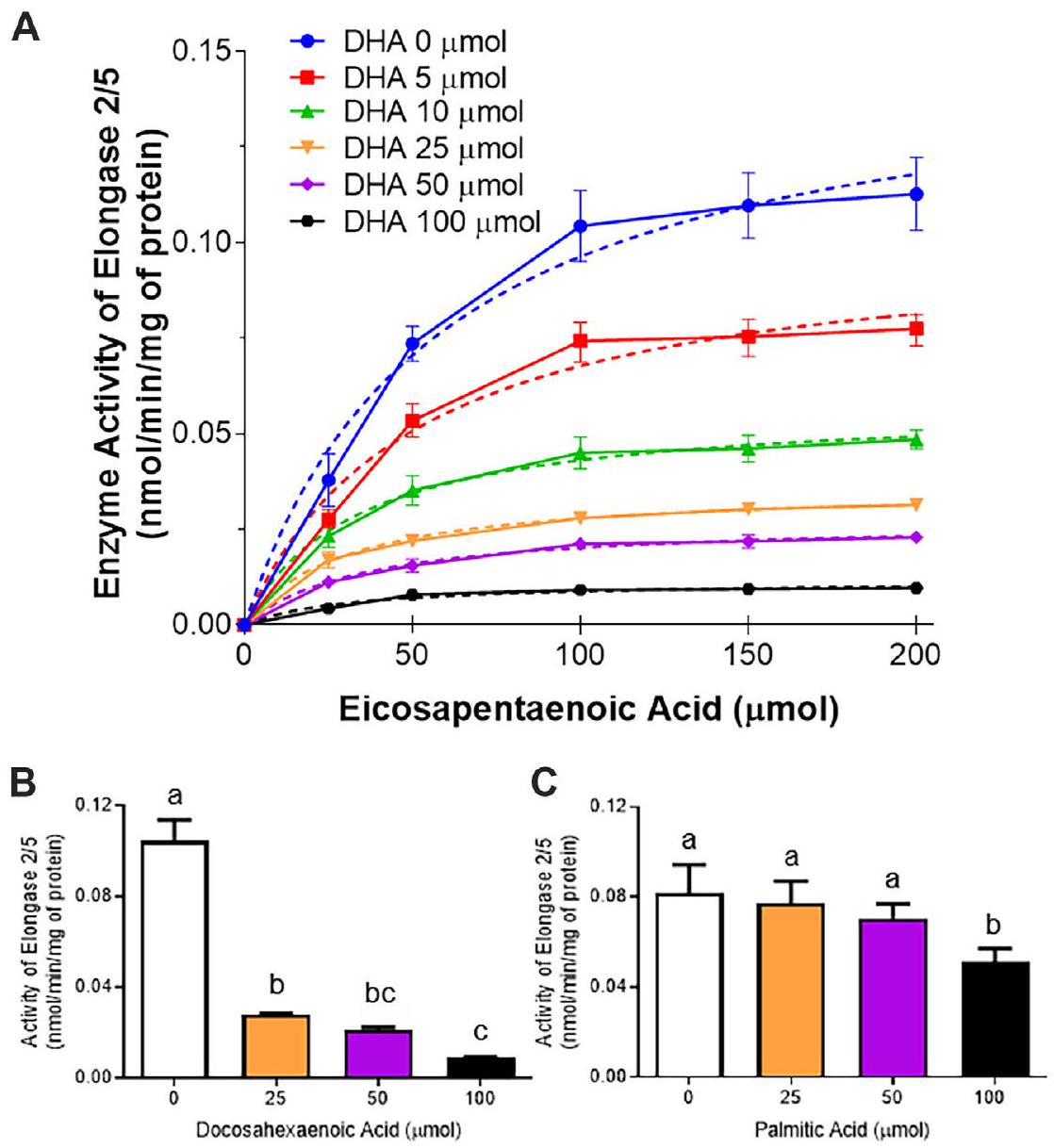

تثبيط DHA لـ ELOVL2/5 (EPA

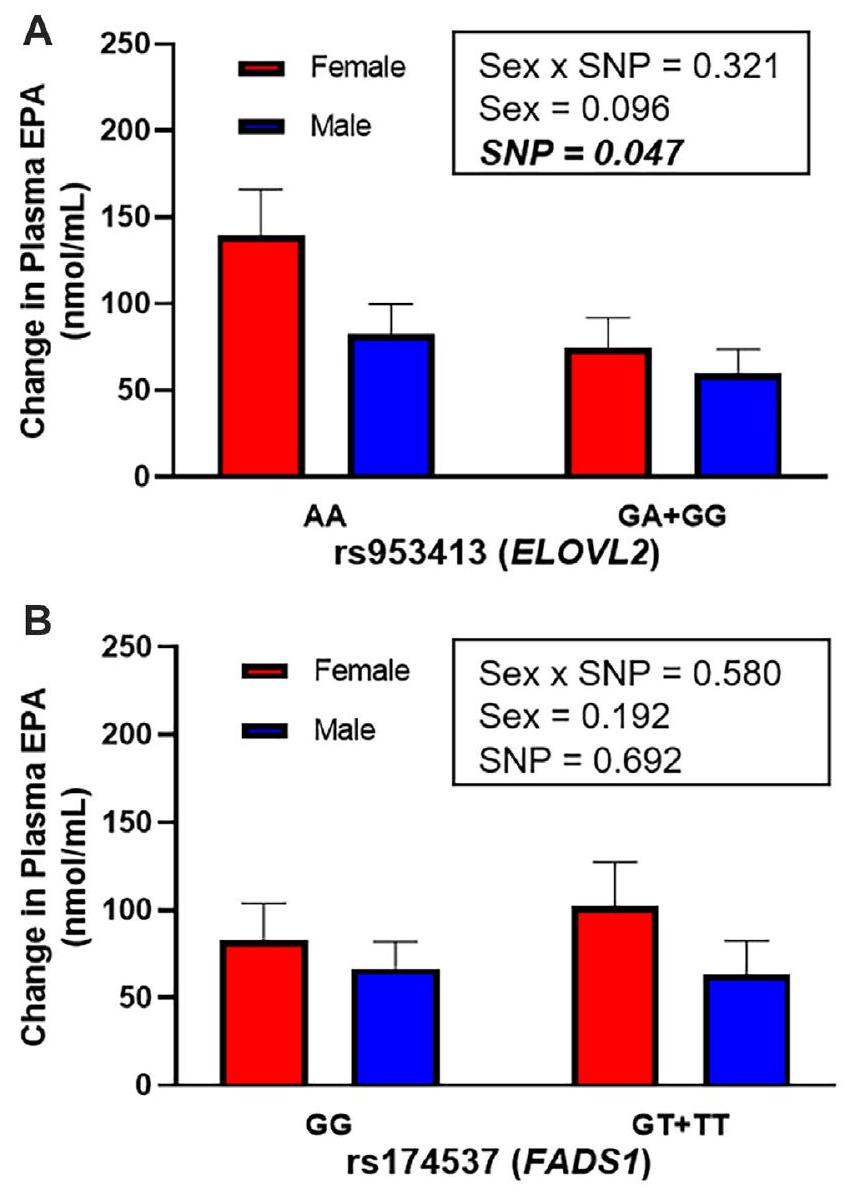

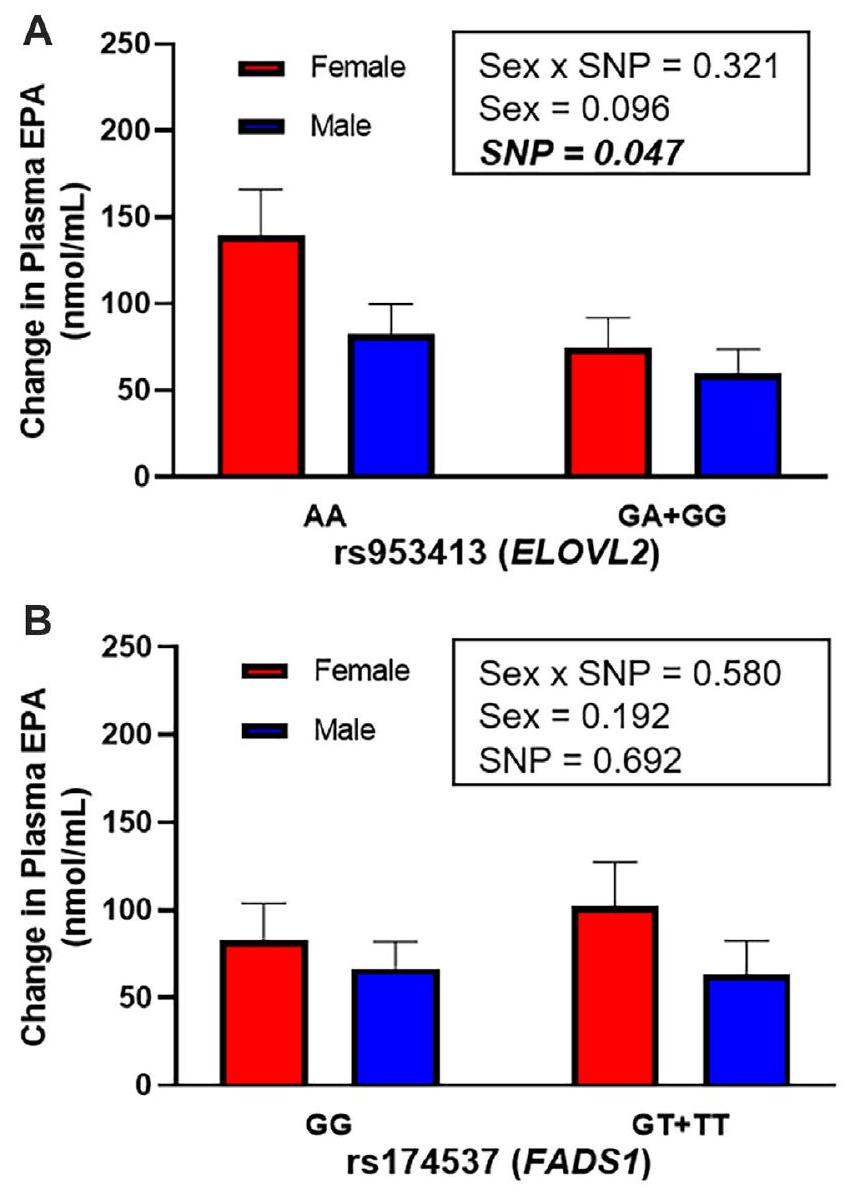

تغيير في مستويات EPA في البلازما لدى البشر الذين تم تزويدهم بـ

نقاش

بشكل خاص بواسطة ELOVL2، كهدف مثبط جديد ومهم لـ DHA من خلال مسار التغذية الراجعة السلبية. بشكل جماعي، تُظهر أعمالنا للمرة الأولى أن DHA الغذائي يقلل من تخليق نفسه في الكبد عن طريق تثبيط إطالة EPA.

مسار التخليق الحيوي (50). مقارنةً بتغذية ALA، بدا أن DHA يقلل من تعبير mRNA لـ Elovl2 و Elovl5؛ ومع ذلك، لم يتم الوصول إلى الدلالة في مجموعة ALA + DHA، ولم يترجم هذا الانخفاض إلى محتوى بروتين أقل. علاوة على ذلك، لم تؤثر تغذية DHA على نشاط ELOVL5 أو النشاط المشترك لـ ELOVL2/5؛ ومع ذلك، كان نشاط ELOVL2 أقل في كلا مجموعتي تغذية DHA مقارنةً بمجموعة تغذية ALA. هناك قيود على اختبار نشاط الإنزيم: (1) الميكروسومات هي قطع مجزأة من الشبكة الإندوبلازمية التي قد لا تمثل الدعم الهيكلي الطبيعي لإنزيمات الإطالة والتشبع، و(2) قد يتغير تركيب الأحماض الدهنية التي تتعرض لها الميكروسومات المعزولة مقارنةً بالخلايا السليمة. ومع ذلك، أظهرنا أن نشاط ELOVL2 ينخفض بشكل مستقل عن التغيرات في محتوى البروتين، مما يشير إلى أن DHA يمارس تعديلات بعد الترجمة على ELOVL2، ولكن ليس على ELOVL5.

هناك مصدران للأحماض الدهنية، مثلما في مجموعة نظامنا الغذائي ALA + DHA، يمكن حساب المساهمة النسبية لـ ALA و DHA في EPA.

نسب DHA:EPA في الكبد

قياس تثبيط إطالة EPA. على العكس من ذلك، عندما يكون DHA غائبًا في النظام الغذائي، كما هو شائع لدى النباتيين وأولئك الذين لا يتناولون الأسماك، فإن إطالة EPA لا تتعرض للتثبيط، ويمكن استخدام ALA لتخليق DHA. هناك حاجة لأعمال مستقبلية تفحص تأثيرات التطور، والوراثة، والضغط على استجابة هذا المسار. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تظهر أدبيات تشير إلى أن DHA قد يغير التأثيرات الناتجة عن EPA. لم تكن التجارب السريرية العشوائية التي تستخدم مكملات مختلطة من EPA/DHA لتقليل نقاط نهاية الأمراض القلبية الوعائية ناجحة.

توفر البيانات

بيانات إضافية

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تحليل؛ أ. ح. م.، س. ل.، ج. م.، د. م. م. و ر. ب. ب. تصور؛ أ. ح. م.، ج. س.-ج. و ر. ب. ب. تحقق؛ أ. ح. م. تصور؛ أ. ح. م. كتابة المسودة الأصلية؛ ر. ف.، ب. ج. ك.، ج. س.، ر. د. ر.، م. ج.-س.، ج. س.-ج.، س. ل.، ج. م.، د. م. م. و ر. ب. ب. كتابة-مراجعة وتحرير؛ س. ل.، ج. م.، د. م. م. و ر. ب. ب. إشراف؛ ج. س.-ج.، ج. م.، د. م. م. و ر. ب. ب. موارد؛ د. م. م. و ر. ب. ب. إدارة المشروع؛ ر. ب. ب. الحصول على التمويل.

معرفات ORCID للمؤلفين

ميليسا غونزاليس-سوتو (دhttps://orcid.org/0000-0003-43095604

تعارض المصالح

الاختصارات

REFERENCES

- Bazinet, R. P., and Laye, S. (2014) Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their metabolites in brain function and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15, 771-785

- Dyall, S. C., Balas, L., Bazan, N. G., Brenna, J. T., Chiang, N., da Costa Souza, F., et al. (2022) Polyunsaturated fatty acids and fatty acid-derived lipid mediators: recent advances in the understanding of their biosynthesis, structures, and functions. Prog. Lipid Res. 86, 101165

- Lee, J. W., Huang, B. X., Kwon, H., Rashid, M. A., Kharebava, G., Desai, A., et al. (2016) Orphan GPR110 (ADGRF1) targeted by Ndocosahexaenoylethanolamine in development of neurons and cognitive function. Nat. Commun. 7, 13123

- Liu, J., Sahin, C., Ahmad, S., Magomedova, L., Zhang, M., Jia, Z., et al. (2022) The omega-3 hydroxy fatty acid 7(S)-HDHA is a high-affinity PPARalpha ligand that regulates brain neuronal morphology. Sci. Signal. 15, eabol857

- Dalli, J., and Serhan, C. N. (2018) Immunoresolvents signaling molecules at intersection between the brain and immune system. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 50, 48-54

- Lukiw, W. J., Cui, J. G., Marcheselli, V. L., Bodker, M., Botkjaer, A., Gotlinger, K., et al. (2005) A role for docosahexaenoic acidderived neuroprotectin D1 in neural cell survival and Alzheimer disease. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 2774-2783

- Park, T., Chen, H., and Kim, H. Y. (2019) GPR110 (ADGRF1) mediates anti-inflammatory effects of N-docosahexaenoylethanolamine. J. Neuroinflammation. 16, 225

- Akbar, M., Calderon, F., Wen, Z., and Kim, H. Y. (2005) Docosahexaenoic acid: a positive modulator of Akt signaling in neuronal survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 102, 10858-10863

- Asatryan, A., and Bazan, N. G. (2017) Molecular mechanisms of signaling via the docosanoid neuroprotectin D1 for cellular homeostasis and neuroprotection. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 12390-12397

- Chen, C. T., Domenichiello, A. F., Trepanier, M. O., Liu, Z., Masoodi, M., and Bazinet, R. P. (2013) The low levels of eicosapentaenoic acid in rat brain phospholipids are maintained via multiple redundant mechanisms. J. Lipid Res. 54, 2410-2422

- Igarashi, M., Ma, K., Chang, L., Bell, J. M., Rapoport, S. I., and DeMar, J. C., Jr. (2006) Low liver conversion rate of alphalinolenic to docosahexaenoic acid in awake rats on a high-docosahexaenoate-containing diet. J. Lipid Res. 47, 1812-1822

- Scott, B. L., and Bazan, N. G. (1989) Membrane docosahexaenoate is supplied to the developing brain and retina by the liver. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86, 2903-2907

- Valenzuela, R., Metherel, A. H., Cisbani, G., Smith, M. E., Choui-nard-Watkins, R., Klievik, B. J., et al. (2023) Protein concentrations and activities of fatty acid desaturase and elongase enzymes in liver, brain, testicle, and kidney from mice: substrate dependency. Biofactors. 50, 89-100

- Igarashi, M., DeMar, J. C., Jr., Ma, K., Chang, L., Bell, J. M., and Rapoport, S. I. (2007) Docosahexaenoic acid synthesis from alpha-linolenic acid by rat brain is unaffected by dietary n-3 PUFA deprivation. J. Lipid Res. 48, 1150-1158

- Igarashi, M., DeMar, J. C., Jr., Ma, K., Chang, L., Bell, J. M., and Rapoport, S. I. (2007) Upregulated liver conversion of alphalinolenic acid to docosahexaenoic acid in rats on a 15 week n-3 PUFA-deficient diet. J. Lipid Res. 48, 152-164

- von Schacky, C., and Weber, P. C. (1985) Metabolism and effects on platelet function of the purified eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids in humans. J. Clin. Invest. 76, 2446-2450

- Conquer, J. A., and Holub, B. J. (1996) Supplementation with an algae source of docosahexaenoic acid increases (n-3) fatty acid status and alters selected risk factors for heart disease in vegetarian subjects. J. Nutr. 126, 3032-3039

- Rambjor, G. S., Walen, A. I., Windsor, S. L., and Harris, W. S. (1996) Eicosapentaenoic acid is primarily responsible for hypotriglyceridemic effect of fish oil in humans. Lipids. 31 Suppl, S45-S49

- Conquer, J. A., and Holub, B. J. (1997) Dietary docosahexaenoic acid as a source of eicosapentaenoic acid in vegetarians and omnivores. Lipids. 32, 341-345

- Stark, K. D., and Holub, B. J. (2004) Differential eicosapentaenoic acid elevations and altered cardiovascular disease risk factor responses after supplementation with docosahexaenoic acid in postmenopausal women receiving and not receiving hormone replacement therapy. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 79, 765-773

- Schuchardt, J. P., Ostermann, A. I., Stork, L., Kutzner, L., Kohrs, H., Greupner, T., et al. (2016) Effects of docosahexaenoic acid supplementation on PUFA levels in red blood cells and plasma. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 115, 12-23

- Allaire, J., Harris, W. S., Vors, C., Charest, A., Marin, J., Jackson, K. H., et al. (2017) Supplementation with high-dose docosahexaenoic acid increases the Omega-3 Index more than high-dose eicosapentaenoic acid. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 120, 8-14

- Guo, X. F., Sinclair, A. J., Kaur, G., and Li, D. (2018) Differential effects of EPA, DPA and DHA on cardio-metabolic risk factors in high-fat diet fed mice. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 136, 47-55

- Metherel, A. H., Irfan, M., Klingel, S. L., Mutch, D. M., and Bazinet, R. P. (2019) Compound-specific isotope analysis reveals no retroconversion of DHA to EPA but substantial conversion of EPA to DHA following supplementation: a randomized control trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 110, 823-831

- Willumsen, N., Vaagenes, H., Lie, O., Rustan, A. C., and Berge, R. K. (1996) Eicosapentaenoic acid, but not docosahexaenoic acid, increases mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and upregulates 2,

26. Depner, C. M., Philbrick, K. A., and Jump, D. B. (2013) Docosahexaenoic acid attenuates hepatic inflammation, oxidative stress, and fibrosis without decreasing hepatosteatosis in a Ldlr(-/-) mouse model of western diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Nutr. 143, 315-323

27. Suzuki-Kemuriyama, N., Matsuzaka, T., Kuba, M., Ohno, H., Han, S. I., Takeuchi, Y., et al. (2016) Different effects of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids on atherogenic high-fat diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. PLoS One. 11, e0157580

28. Lytle, K. A., Wong, C. P., and Jump, D. B. (2017) Docosahexaenoic acid blocks progression of western diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in obese Ldlr-/- mice. PLoS One. 12, e0173376

29. Metherel, A. H., Domenichiello, A. F., Kitson, A. P., Lin, Y. H., and Bazinet, R. P. (2017) Serum n-3 tetracosapentaenoic acid and tetracosahexaenoic acid increase following higher dietary alpha-linolenic acid but not docosahexaenoic acid. Lipids. 52, 167-172

30. Leng, S., Winter, T., and Aukema, H. M. (2018) Dietary ALA, EPA and DHA have distinct effects on oxylipin profiles in female and male rat kidney, liver and serum. J. Nutr. Biochem. 57, 228-237

31. Metherel, A. H., Lacombe, R. J. S., Aristizabal Henao, J. J., MorinRivron, D., Kitson, A. P., Hopperton, K. E., et al. (2018) Two weeks of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) supplementation increases synthesis-secretion kinetics of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids compared to 8 weeks of DHA supplementation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 60, 24-34

32. Drouin, G., Catheline, D., Guillocheau, E., Gueret, P., Baudry, C., Le Ruyet, P., et al. (2019) Comparative effects of dietary n-3 docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), DHA and EPA on plasma lipid parameters, oxidative status and fatty acid tissue composition.

33. Schlenk, H., Sand, D. M., and Gellerman, J. L. (1969) Retroconversion of docosahexaenoic acid in the rat. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 187, 201-207

34. Lacombe, R. J. S., and Bazinet, R. P. (2021) Natural abundance carbon isotope ratio analysis and its application in the study of diet and metabolism. Nutr. Rev. 79, 869-888

35. Meier-Augenstein, W. (1999) Applied gas chromatography coupled to isotope ratio mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 842, 351-371

36. Metherel, A. H., Chouinard-Watkins, R., Trepanier, M. O., Lacombe, R. J. S., and Bazinet, R. P. (2017) Retroconversion is a minor contributor to increases in eicosapentaenoic acid following docosahexaenoic acid feeding as determined by compound specific isotope analysis in rat liver. Nutr. Metab. (Lond.). 14, 75

37. Lacombe, R. J. S., Lee, C. C., and Bazinet, R. P. (2020) Turnover of brain DHA in mice is accurately determined by tracer-free natural abundance carbon isotope ratio analysis. J. Lipid Res. 61, 116-126

38. Domenichiello, A. F., Kitson, A. P., Metherel, A. H., Chen, C. T., Hopperton, K. E., Stavro, P. M., et al. (2017) Whole-body docosahexaenoic acid synthesis-secretion rates in rats are constant across a large range of dietary alpha-linolenic acid intakes.

39. Metherel, A. H., Lacombe, R. J. S., Chouinard-Watkins, R., and Bazinet, R. P. (2019) Docosahexaenoic acid is both a product of and a precursor to tetracosahexaenoic acid in the rat. J. Lipid Res. 60, 412-420

40. Klingel, S. L., Metherel, A. H., Irfan, M., Rajna, A., Chabowski, A., Bazinet, R. P., et al. (2019) EPA and DHA have divergent effects on serum triglycerides and lipogenesis, but similar effects on lipoprotein lipase activity: a randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 110, 1502-1509

41. Folch, J., Lees, M., and Sloane Stanley, G. H. (1957) A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226, 497-509

42. Metherel, A. H., Irfan, M., Klingel, S. L., Mutch, D. M., and Bazinet, R. P. (2021) Higher increase in plasma DHA in females compared to males following EPA supplementation may be influenced by a polymorphism in ELOVL2: an exploratory study. Lipids. 56, 211-228

43. Klingel, S. L., Roke, K., Hidalgo, B., Aslibekyan, S., Straka, R. J., An, P., et al. (2017) Sex differences in blood HDL-c, the total

cholesterol/HDL-c ratio, and palmitoleic acid are not associated with variants in common candidate genes. Lipids. 52, 969-980

44. Su, H. M., and Brenna, J. T. (1998) Simultaneous measurement of desaturase activities using stable isotope tracers or a nontracer method. Anal. Biochem. 261, 43-50

45. Valenzuela, R., Barrera, C., Gonzalez-Astorga, M., Sanhueza, J., and Valenzuela, A. (2014) Alpha linolenic acid (ALA) from Rosa canina, sacha inchi and chia oils may increase ALA accretion and its conversion into n-3 LCPUFA in diverse tissues of the rat. Food Funct. 5, 1564-1572

46. Giuliano, V., Lacombe, R. J. S., Hopperton, K. E., and Bazinet, R. P. (2018) Applying stable carbon isotopic analysis at the natural abundance level to determine the origin of docosahexaenoic acid in the brain of the fat-1 mouse. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 1863, 1388-1398

47. Lacombe, R. J. S., Giuliano, V., Colombo, S. M., Arts, M. T., and Bazinet, R. P. (2017) Compound-specific isotope analysis resolves the dietary origin of docosahexaenoic acid in the mouse brain. J. Lipid Res. 58, 2071-2081

48. Domenichiello, A. F., Chen, C. T., Trepanier, M. O., Stavro, P. M., and Bazinet, R. P. (2014) Whole body synthesis rates of DHA from alpha-linolenic acid are greater than brain DHA accretion and uptake rates in adult rats. J. Lipid Res. 55, 62-74

49. DeNiro, M. J., and Epstein, S. (1977) Mechanism of carbon isotope fractionation associated with lipid synthesis. Science. 197, 261-263

50. Gregory, M. K., Gibson, R. A., Cook-Johnson, R. J., Cleland, L. G., and James, M. J. (2011) Elongase reactions as control points in long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid synthesis. PLoS One. 6, e29662

51. Wang, Y., Botolin, D., Christian, B., Busik, J., Xu, J., and Jump, D. B. (2005) Tissue-specific, nutritional, and developmental regulation of rat fatty acid elongases. J. Lipid Res. 46, 706-715

52. Pauter, A. M., Olsson, P., Asadi, A., Herslof, B., Csikasz, R. I., Zadravec, D., et al. (2014) Elov12 ablation demonstrates that systemic DHA is endogenously produced and is essential for lipid homeostasis in mice. J. Lipid Res. 55, 718-728

53. Metherel, A. H., and Bazinet, R. P. (2019) Updates to the n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis pathway: DHA synthesis rates, tetracosahexaenoic acid and (minimal) retroconversion. Prog. Lipid Res. 76, 101008

54. Bazinet, R. P., Weis, M. T., Rapoport, S. I., and Rosenberger, T. A. (2006) Valproic acid selectively inhibits conversion of arachidonic acid to arachidonoyl-CoA by brain microsomal longchain fatty acyl-CoA synthetases: relevance to bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 184, 122-129

55. Gotoh, N., Nagao, K., Ishida, H., Nakamitsu, K., Yoshinaga, K., Nagai, T., et al. (2018) Metabolism of natural highly unsaturated fatty acid, tetracosahexaenoic acid (24:6n-3), in C57BL/KsJ-db/ db mice. J. Oleo Sci. 67, 1597-1607

56. Liu, L., Hu, Q., Wu, H., Wang, X., Gao, C., Chen, G., et al. (2018) Dietary DHA/EPA ratio changes fatty acid composition and attenuates diet-induced accumulation of lipid in the liver of ApoE(-/-) mice. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 6256802

57. Alsaleh, A., Maniou, Z., Lewis, F. J., Hall, W. L., Sanders, T. A., and O’Dell, S. D. (2014) ELOVL2 gene polymorphisms are associated with increases in plasma eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid proportions after fish oil supplement. Genes Nutr. 9, 362

58. Pan, G., Cavalli, M., Carlsson, B., Skrtic, S., Kumar, C., and Wadelius, C. (2020) rs953413 regulates polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolism by modulating ELOVL2 expression. iScience. 23, 100808

59. Pal, A., Metherel, A. H., Fiabane, L., Buddenbaum, N., Bazinet, R. P., and Shaikh, S. R. (2020) Do eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid have the potential to compete against each other? Nutrients. 12, 3718

60. Le, V. T., Knight, S., Watrous, J. D., Najhawan, M., Dao, K., McCubrey, R. O., et al. (2023) Higher docosahexaenoic acid levels lower the protective impact of eicosapentaenoic acid on longterm major cardiovascular events. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1229130

61. ASCEND Study Collaborative Group, Bowman, L., Mafham, M., Wallendszus, K., Stevens, W., Buck, G., et al. (2018) Effects of n-3 fatty acid supplements in diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 1540-1550

62. Manson, J. E., Cook, N. R., Lee, I. M., Christen, W., Bassuk, S. S., Mora, S., et al. (2019) Marine n-3 fatty acids and prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 23-32

63. Bhatt, D. L., Steg, P. G., Miller, M., Brinton, E. A., Jacobson, T. A., Ketchum, S. B., et al. (2019) Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 11-22

64. Yokoyama, M., Origasa, H., Matsuzaki, M., Matsuzawa, Y., Saito, Y., Ishikawa, Y., et al. (2007) Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on major coronary events in hypercholesterolaemic patients

(JELIS): a randomised open-label, blinded endpoint analysis. Lancet. 369, 1090-1098

65. Firth, J., Teasdale, S. B., Allott, K., Siskind, D., Marx, W., Cotter, J., et al. (2019) The efficacy and safety of nutrient supplements in the treatment of mental disorders: a meta-review of metaanalyses of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry. 18, 308-324

- *For correspondence: Adam H. Metherel, adam.metherel@utoronto.ca.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlr.2024.100548

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38649096

Publication Date: 2024-04-21

Dietary docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) downregulates liver DHA synthesis by inhibiting eicosapentaenoic acid elongation

Abstract

DHA is abundant in the brain where it regulates cell survival, neurogenesis, and neuroinflammation. DHA can be obtained from the diet or synthesized from alpha-linolenic acid (ALA; 18:3n-3) via a series of desaturation and elongation reactions occurring in the liver. Tracer studies suggest that dietary DHA can downregulate its own synthesis, but the mechanism remains undetermined and is the primary objective of this manuscript. First, we show by tracing

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement

Study design

saline and livers collected as described above for future analysis of liver enzyme activity for the conversion of EPA to n-3 docosapentaenoic acid (DPAn-3, 22:5n-3) (ELOVL2/5).

Fatty acid analyses

which enters the MAT253 IRMS via a ConFlo IV continuous flow interface providing the

Gene and enzyme analyses

manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcriptionquantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was conducted on a Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time system. The primers used for RT-qPCR were designed online using the Roche Universal Probe Library and Assay Design Center. A total reaction volume per sample (

were measured as net increase of n-3 PUFA product produced from precursor n-3 PUFA, calculated from the differences between baseline values prior to incubation and those obtained after 30 min incubation. Results are expressed as

RESULTS

Brain DHA concentrations and

Serum and liver n-3 PUFA concentrations of BALB/c mice fed ALA, DHA, or ALA + DHA

Serum and liver n-3 PUFA carbon-13 content of BALB/c mice fed ALA, DHA, or ALA + DHA

Liver gene expression, protein content, and enzyme activity of BALB/c mice fed ALA, DHA, or ALA + DHA diets

Serum and liver n-3 PUFA levels of liver-specific Elovl2 KO mice fed ALA, DHA, or ALA + DHA diets

Serum and liver n-3 PUFA carbon-13 content of liver-specific Elovl2 KO mice fed ALA, DHA, or ALA + DHA

DHA inhibition of ELOVL2/5 (EPA

Change in plasma EPA levels in humans supplemented with

DISCUSSION

particular by ELOVL2, as a novel and important inhibitory target of DHA via a negative feedback pathway. Collectively, our work demonstrates for the first time that dietary DHA downregulates its own synthesis in the liver by inhibiting EPA elongation.

biosynthesis pathway (50). DHA compared to ALA feeding appeared to lower mRNA expression of Elovl2 and Elovl5; however, significance was not reached in the ALA + DHA group, and this lowering did not translate to lower protein content. Furthermore, DHA feeding did not affect ELOVL5 activity or the combined ELOVL2/5 activity; however, ELOVL2 activity was lower in both DHA fed groups compared to the ALA fed group. There are limitations of the enzyme activity assay: (1) microsomes are fragmented pieces of the endoplasmic reticulum that may not represent the normal structural support for the elongase and desaturase enzymes, and (2) the fatty acid composition that the isolated microsomes are exposed to may be altered compared to the intact cell. Nevertheless, we demonstrated that ELOVL2 activity is lowered independent of changes in protein content, suggesting that DHA exerts posttranslational modifications on ELOVL2, but not ELOVL5.

there are two sources of fatty acids, such as in our ALA + DHA diet group, the relative contribution of ALA and DHA to EPA can be calculated

liver DHA:EPA proportions

measure the inhibition of EPA elongation. Conversely, when DHA is absent in the diet, as would be common in vegans and those who do not consume fish, EPA elongation is not inhibited, and ALA can be used to synthesize DHA. Future work examining the effects of development, genetics, and stress on the responsiveness of this pathway are warranted. Beyond this, a literature is emerging suggesting that DHA may alter the effects from EPA (59, 60). RCTs using mixed EPA/DHA supplements to reduce cardiovascular disease end points have been unsuccessful

Data availability

Supplemental data

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

analysis; A. H. M., S. L., C. M., D. M. M. and R. P. B. conceptualization; A. H. M., C. C.-G., and R. P. B. validation; A. H. M. visualization; A. H. M. writing-original draft; R. V., B. J. K., G. C., R. D. R., M. G.-S., C. C.-G., S. L., C. M., D. M. M., and R. P. B. writing-review and editing; S. L., C. M., D. M. M., and R. P. B. supervision; C. C.-G., C. M., D. M. M., and R. P. B. resources; D. M. M. and R. P. B. project administration; R. P. B. funding acquisition.

Author ORCIDs

Melissa Gonzalez-Soto (D https://orcid.org/0000-0003-43095604

Conflict of interest

Abbreviations

REFERENCES

- Bazinet, R. P., and Laye, S. (2014) Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their metabolites in brain function and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15, 771-785

- Dyall, S. C., Balas, L., Bazan, N. G., Brenna, J. T., Chiang, N., da Costa Souza, F., et al. (2022) Polyunsaturated fatty acids and fatty acid-derived lipid mediators: recent advances in the understanding of their biosynthesis, structures, and functions. Prog. Lipid Res. 86, 101165

- Lee, J. W., Huang, B. X., Kwon, H., Rashid, M. A., Kharebava, G., Desai, A., et al. (2016) Orphan GPR110 (ADGRF1) targeted by Ndocosahexaenoylethanolamine in development of neurons and cognitive function. Nat. Commun. 7, 13123

- Liu, J., Sahin, C., Ahmad, S., Magomedova, L., Zhang, M., Jia, Z., et al. (2022) The omega-3 hydroxy fatty acid 7(S)-HDHA is a high-affinity PPARalpha ligand that regulates brain neuronal morphology. Sci. Signal. 15, eabol857

- Dalli, J., and Serhan, C. N. (2018) Immunoresolvents signaling molecules at intersection between the brain and immune system. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 50, 48-54

- Lukiw, W. J., Cui, J. G., Marcheselli, V. L., Bodker, M., Botkjaer, A., Gotlinger, K., et al. (2005) A role for docosahexaenoic acidderived neuroprotectin D1 in neural cell survival and Alzheimer disease. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 2774-2783

- Park, T., Chen, H., and Kim, H. Y. (2019) GPR110 (ADGRF1) mediates anti-inflammatory effects of N-docosahexaenoylethanolamine. J. Neuroinflammation. 16, 225

- Akbar, M., Calderon, F., Wen, Z., and Kim, H. Y. (2005) Docosahexaenoic acid: a positive modulator of Akt signaling in neuronal survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 102, 10858-10863

- Asatryan, A., and Bazan, N. G. (2017) Molecular mechanisms of signaling via the docosanoid neuroprotectin D1 for cellular homeostasis and neuroprotection. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 12390-12397

- Chen, C. T., Domenichiello, A. F., Trepanier, M. O., Liu, Z., Masoodi, M., and Bazinet, R. P. (2013) The low levels of eicosapentaenoic acid in rat brain phospholipids are maintained via multiple redundant mechanisms. J. Lipid Res. 54, 2410-2422

- Igarashi, M., Ma, K., Chang, L., Bell, J. M., Rapoport, S. I., and DeMar, J. C., Jr. (2006) Low liver conversion rate of alphalinolenic to docosahexaenoic acid in awake rats on a high-docosahexaenoate-containing diet. J. Lipid Res. 47, 1812-1822

- Scott, B. L., and Bazan, N. G. (1989) Membrane docosahexaenoate is supplied to the developing brain and retina by the liver. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86, 2903-2907

- Valenzuela, R., Metherel, A. H., Cisbani, G., Smith, M. E., Choui-nard-Watkins, R., Klievik, B. J., et al. (2023) Protein concentrations and activities of fatty acid desaturase and elongase enzymes in liver, brain, testicle, and kidney from mice: substrate dependency. Biofactors. 50, 89-100

- Igarashi, M., DeMar, J. C., Jr., Ma, K., Chang, L., Bell, J. M., and Rapoport, S. I. (2007) Docosahexaenoic acid synthesis from alpha-linolenic acid by rat brain is unaffected by dietary n-3 PUFA deprivation. J. Lipid Res. 48, 1150-1158

- Igarashi, M., DeMar, J. C., Jr., Ma, K., Chang, L., Bell, J. M., and Rapoport, S. I. (2007) Upregulated liver conversion of alphalinolenic acid to docosahexaenoic acid in rats on a 15 week n-3 PUFA-deficient diet. J. Lipid Res. 48, 152-164

- von Schacky, C., and Weber, P. C. (1985) Metabolism and effects on platelet function of the purified eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids in humans. J. Clin. Invest. 76, 2446-2450

- Conquer, J. A., and Holub, B. J. (1996) Supplementation with an algae source of docosahexaenoic acid increases (n-3) fatty acid status and alters selected risk factors for heart disease in vegetarian subjects. J. Nutr. 126, 3032-3039

- Rambjor, G. S., Walen, A. I., Windsor, S. L., and Harris, W. S. (1996) Eicosapentaenoic acid is primarily responsible for hypotriglyceridemic effect of fish oil in humans. Lipids. 31 Suppl, S45-S49

- Conquer, J. A., and Holub, B. J. (1997) Dietary docosahexaenoic acid as a source of eicosapentaenoic acid in vegetarians and omnivores. Lipids. 32, 341-345

- Stark, K. D., and Holub, B. J. (2004) Differential eicosapentaenoic acid elevations and altered cardiovascular disease risk factor responses after supplementation with docosahexaenoic acid in postmenopausal women receiving and not receiving hormone replacement therapy. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 79, 765-773

- Schuchardt, J. P., Ostermann, A. I., Stork, L., Kutzner, L., Kohrs, H., Greupner, T., et al. (2016) Effects of docosahexaenoic acid supplementation on PUFA levels in red blood cells and plasma. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 115, 12-23

- Allaire, J., Harris, W. S., Vors, C., Charest, A., Marin, J., Jackson, K. H., et al. (2017) Supplementation with high-dose docosahexaenoic acid increases the Omega-3 Index more than high-dose eicosapentaenoic acid. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 120, 8-14

- Guo, X. F., Sinclair, A. J., Kaur, G., and Li, D. (2018) Differential effects of EPA, DPA and DHA on cardio-metabolic risk factors in high-fat diet fed mice. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 136, 47-55

- Metherel, A. H., Irfan, M., Klingel, S. L., Mutch, D. M., and Bazinet, R. P. (2019) Compound-specific isotope analysis reveals no retroconversion of DHA to EPA but substantial conversion of EPA to DHA following supplementation: a randomized control trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 110, 823-831

- Willumsen, N., Vaagenes, H., Lie, O., Rustan, A. C., and Berge, R. K. (1996) Eicosapentaenoic acid, but not docosahexaenoic acid, increases mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and upregulates 2,

26. Depner, C. M., Philbrick, K. A., and Jump, D. B. (2013) Docosahexaenoic acid attenuates hepatic inflammation, oxidative stress, and fibrosis without decreasing hepatosteatosis in a Ldlr(-/-) mouse model of western diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Nutr. 143, 315-323

27. Suzuki-Kemuriyama, N., Matsuzaka, T., Kuba, M., Ohno, H., Han, S. I., Takeuchi, Y., et al. (2016) Different effects of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids on atherogenic high-fat diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. PLoS One. 11, e0157580

28. Lytle, K. A., Wong, C. P., and Jump, D. B. (2017) Docosahexaenoic acid blocks progression of western diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in obese Ldlr-/- mice. PLoS One. 12, e0173376

29. Metherel, A. H., Domenichiello, A. F., Kitson, A. P., Lin, Y. H., and Bazinet, R. P. (2017) Serum n-3 tetracosapentaenoic acid and tetracosahexaenoic acid increase following higher dietary alpha-linolenic acid but not docosahexaenoic acid. Lipids. 52, 167-172

30. Leng, S., Winter, T., and Aukema, H. M. (2018) Dietary ALA, EPA and DHA have distinct effects on oxylipin profiles in female and male rat kidney, liver and serum. J. Nutr. Biochem. 57, 228-237

31. Metherel, A. H., Lacombe, R. J. S., Aristizabal Henao, J. J., MorinRivron, D., Kitson, A. P., Hopperton, K. E., et al. (2018) Two weeks of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) supplementation increases synthesis-secretion kinetics of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids compared to 8 weeks of DHA supplementation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 60, 24-34

32. Drouin, G., Catheline, D., Guillocheau, E., Gueret, P., Baudry, C., Le Ruyet, P., et al. (2019) Comparative effects of dietary n-3 docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), DHA and EPA on plasma lipid parameters, oxidative status and fatty acid tissue composition.

33. Schlenk, H., Sand, D. M., and Gellerman, J. L. (1969) Retroconversion of docosahexaenoic acid in the rat. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 187, 201-207

34. Lacombe, R. J. S., and Bazinet, R. P. (2021) Natural abundance carbon isotope ratio analysis and its application in the study of diet and metabolism. Nutr. Rev. 79, 869-888

35. Meier-Augenstein, W. (1999) Applied gas chromatography coupled to isotope ratio mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 842, 351-371

36. Metherel, A. H., Chouinard-Watkins, R., Trepanier, M. O., Lacombe, R. J. S., and Bazinet, R. P. (2017) Retroconversion is a minor contributor to increases in eicosapentaenoic acid following docosahexaenoic acid feeding as determined by compound specific isotope analysis in rat liver. Nutr. Metab. (Lond.). 14, 75

37. Lacombe, R. J. S., Lee, C. C., and Bazinet, R. P. (2020) Turnover of brain DHA in mice is accurately determined by tracer-free natural abundance carbon isotope ratio analysis. J. Lipid Res. 61, 116-126

38. Domenichiello, A. F., Kitson, A. P., Metherel, A. H., Chen, C. T., Hopperton, K. E., Stavro, P. M., et al. (2017) Whole-body docosahexaenoic acid synthesis-secretion rates in rats are constant across a large range of dietary alpha-linolenic acid intakes.

39. Metherel, A. H., Lacombe, R. J. S., Chouinard-Watkins, R., and Bazinet, R. P. (2019) Docosahexaenoic acid is both a product of and a precursor to tetracosahexaenoic acid in the rat. J. Lipid Res. 60, 412-420

40. Klingel, S. L., Metherel, A. H., Irfan, M., Rajna, A., Chabowski, A., Bazinet, R. P., et al. (2019) EPA and DHA have divergent effects on serum triglycerides and lipogenesis, but similar effects on lipoprotein lipase activity: a randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 110, 1502-1509

41. Folch, J., Lees, M., and Sloane Stanley, G. H. (1957) A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226, 497-509

42. Metherel, A. H., Irfan, M., Klingel, S. L., Mutch, D. M., and Bazinet, R. P. (2021) Higher increase in plasma DHA in females compared to males following EPA supplementation may be influenced by a polymorphism in ELOVL2: an exploratory study. Lipids. 56, 211-228

43. Klingel, S. L., Roke, K., Hidalgo, B., Aslibekyan, S., Straka, R. J., An, P., et al. (2017) Sex differences in blood HDL-c, the total

cholesterol/HDL-c ratio, and palmitoleic acid are not associated with variants in common candidate genes. Lipids. 52, 969-980

44. Su, H. M., and Brenna, J. T. (1998) Simultaneous measurement of desaturase activities using stable isotope tracers or a nontracer method. Anal. Biochem. 261, 43-50

45. Valenzuela, R., Barrera, C., Gonzalez-Astorga, M., Sanhueza, J., and Valenzuela, A. (2014) Alpha linolenic acid (ALA) from Rosa canina, sacha inchi and chia oils may increase ALA accretion and its conversion into n-3 LCPUFA in diverse tissues of the rat. Food Funct. 5, 1564-1572

46. Giuliano, V., Lacombe, R. J. S., Hopperton, K. E., and Bazinet, R. P. (2018) Applying stable carbon isotopic analysis at the natural abundance level to determine the origin of docosahexaenoic acid in the brain of the fat-1 mouse. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 1863, 1388-1398

47. Lacombe, R. J. S., Giuliano, V., Colombo, S. M., Arts, M. T., and Bazinet, R. P. (2017) Compound-specific isotope analysis resolves the dietary origin of docosahexaenoic acid in the mouse brain. J. Lipid Res. 58, 2071-2081

48. Domenichiello, A. F., Chen, C. T., Trepanier, M. O., Stavro, P. M., and Bazinet, R. P. (2014) Whole body synthesis rates of DHA from alpha-linolenic acid are greater than brain DHA accretion and uptake rates in adult rats. J. Lipid Res. 55, 62-74

49. DeNiro, M. J., and Epstein, S. (1977) Mechanism of carbon isotope fractionation associated with lipid synthesis. Science. 197, 261-263

50. Gregory, M. K., Gibson, R. A., Cook-Johnson, R. J., Cleland, L. G., and James, M. J. (2011) Elongase reactions as control points in long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid synthesis. PLoS One. 6, e29662

51. Wang, Y., Botolin, D., Christian, B., Busik, J., Xu, J., and Jump, D. B. (2005) Tissue-specific, nutritional, and developmental regulation of rat fatty acid elongases. J. Lipid Res. 46, 706-715

52. Pauter, A. M., Olsson, P., Asadi, A., Herslof, B., Csikasz, R. I., Zadravec, D., et al. (2014) Elov12 ablation demonstrates that systemic DHA is endogenously produced and is essential for lipid homeostasis in mice. J. Lipid Res. 55, 718-728

53. Metherel, A. H., and Bazinet, R. P. (2019) Updates to the n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis pathway: DHA synthesis rates, tetracosahexaenoic acid and (minimal) retroconversion. Prog. Lipid Res. 76, 101008

54. Bazinet, R. P., Weis, M. T., Rapoport, S. I., and Rosenberger, T. A. (2006) Valproic acid selectively inhibits conversion of arachidonic acid to arachidonoyl-CoA by brain microsomal longchain fatty acyl-CoA synthetases: relevance to bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 184, 122-129

55. Gotoh, N., Nagao, K., Ishida, H., Nakamitsu, K., Yoshinaga, K., Nagai, T., et al. (2018) Metabolism of natural highly unsaturated fatty acid, tetracosahexaenoic acid (24:6n-3), in C57BL/KsJ-db/ db mice. J. Oleo Sci. 67, 1597-1607

56. Liu, L., Hu, Q., Wu, H., Wang, X., Gao, C., Chen, G., et al. (2018) Dietary DHA/EPA ratio changes fatty acid composition and attenuates diet-induced accumulation of lipid in the liver of ApoE(-/-) mice. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 6256802

57. Alsaleh, A., Maniou, Z., Lewis, F. J., Hall, W. L., Sanders, T. A., and O’Dell, S. D. (2014) ELOVL2 gene polymorphisms are associated with increases in plasma eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid proportions after fish oil supplement. Genes Nutr. 9, 362

58. Pan, G., Cavalli, M., Carlsson, B., Skrtic, S., Kumar, C., and Wadelius, C. (2020) rs953413 regulates polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolism by modulating ELOVL2 expression. iScience. 23, 100808

59. Pal, A., Metherel, A. H., Fiabane, L., Buddenbaum, N., Bazinet, R. P., and Shaikh, S. R. (2020) Do eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid have the potential to compete against each other? Nutrients. 12, 3718

60. Le, V. T., Knight, S., Watrous, J. D., Najhawan, M., Dao, K., McCubrey, R. O., et al. (2023) Higher docosahexaenoic acid levels lower the protective impact of eicosapentaenoic acid on longterm major cardiovascular events. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1229130

61. ASCEND Study Collaborative Group, Bowman, L., Mafham, M., Wallendszus, K., Stevens, W., Buck, G., et al. (2018) Effects of n-3 fatty acid supplements in diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 1540-1550

62. Manson, J. E., Cook, N. R., Lee, I. M., Christen, W., Bassuk, S. S., Mora, S., et al. (2019) Marine n-3 fatty acids and prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 23-32

63. Bhatt, D. L., Steg, P. G., Miller, M., Brinton, E. A., Jacobson, T. A., Ketchum, S. B., et al. (2019) Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 11-22

64. Yokoyama, M., Origasa, H., Matsuzaki, M., Matsuzawa, Y., Saito, Y., Ishikawa, Y., et al. (2007) Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on major coronary events in hypercholesterolaemic patients

(JELIS): a randomised open-label, blinded endpoint analysis. Lancet. 369, 1090-1098

65. Firth, J., Teasdale, S. B., Allott, K., Siskind, D., Marx, W., Cotter, J., et al. (2019) The efficacy and safety of nutrient supplements in the treatment of mental disorders: a meta-review of metaanalyses of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry. 18, 308-324

- *For correspondence: Adam H. Metherel, adam.metherel@utoronto.ca.