DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-024-03880-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38297263

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-31

دراسة عن وبائيات حمى المالطية في سكان الماشية في المناطق شبه الحضرية والريفية من منطقة ملتان، جنوب البنجاب، باكستان

الملخص

خلفية: داء البروسيلات هو مرض حيواني المنشأ تسببه بكتيريا تنتمي إلى جنس بروسيلة. إنه واحد من أكثر الأمراض البكتيرية الحيوانية المنشأ شيوعًا على مستوى العالم، ولكن للأسف، لا يزال يعتبر مرضًا مهملًا في العالم النامي. بناءً على ذلك، تم إجراء هذه الدراسة لتحديد انتشار وعوامل خطر داء البروسيلات في المجترات الكبيرة في المناطق شبه الحضرية والريفية من منطقة ملتان-باكستان. لهذا الغرض، تم جمع عينات دم (

الخاتمة: في الختام، داء البروسيلات منتشر في المجترات الكبيرة في منطقة ملتان، باكستان. يُقترح وضع وتنفيذ سياسات صارمة للسيطرة الفعالة والوقاية من داء البروسيلات في المنطقة. علاوة على ذلك، فإن الوضع الحالي يتطلب أيضًا تعزيز التنسيق بين التخصصات بين الأطباء البيطريين والأطباء في منظور الصحة الواحدة لضمان وتعزيز أنظمة الرعاية الصحية البشرية والحيوانية في المنطقة.

الكلمات الرئيسية: داء البروسيلات؛ الانتشار، عوامل الخطر، i-ELISA، الكشف الجزيئي، ملتان-باكستان

الخلفية

المرض مرتفع في المناطق الرعوية مقارنة بالمناطق الحضرية [14]. علاوة على ذلك، فإن القدرة على البقاء لبروسيلة في البيئات الباردة والرطبة هي عامل مهم آخر لنقل هذا المرض في الثروة الحيوانية والبشر [15]. تعزز العوامل السلوكية البشرية مثل الظروف غير الصحية وغيرها من الأنشطة التي تعرض الناس للحيوانات المصابة ومنتجاتها فرص الإصابة بالمرض لدى البشر [16]. بشكل عام، يمكن اعتبار المزارعين، وعمال المسالخ، وعمال المختبرات، والأشخاص الذين يشاركون في صناعة الثروة الحيوانية من الفئات عالية المخاطر [17]. العوامل الأخرى التي تعتبر حواجز رئيسية في السيطرة على داء البروسيلات هي السياسات التقليدية للثروة الحيوانية، والتأثيرات السياسية، وعدم كفاية تنفيذ تدابير السيطرة، واستخدام الممارسات التقليدية القديمة، واستهلاك منتجات الألبان غير المبسترة، والتغيرات في نظام تربية الحيوانات، وعدم كفاية التدابير للإبلاغ، والتشخيص والمراقبة لهذا المرض [10]. العلاج المناسب والوقاية من هذا المرض أمر لا بد منه لتجنب الخسائر الاقتصادية في قطاع الثروة الحيوانية. البلدان النامية متأخرة في تنفيذ استراتيجيات القضاء على داء البروسيلات [18-20]. على الرغم من أن منظمة الصحة العالمية (WHO) ومنظمة الصحة الحيوانية العالمية (WOAH) قد وضعت توصيات للقضاء على داء البروسيلات، إلا أنه لا يزال يعتبر تهديدًا صحيًا خطيرًا في البلدان النامية/ المتخلفة لأن تدابير السيطرة على القضاء على داء البروسيلات مكلفة، ومتعبة، وتستغرق وقتًا طويلاً. ومع ذلك، في البلدان الموبوءة، يمكن تجنب حدوثه من خلال التطعيم واستراتيجيات الذبح/ الإعدام [21].

| % الإيجابية مع RBPT (n/T) (95%CI) |

|

|

|||

| VRI | IDEXX | ID.vet | |||

| الإجمالي | 12.45 (61/490) (9.72-15.65) | 12.24 (60/490) (9.52-15.45) | 11.84 (58/490) (9.18-14.95) | 0.089 | 0.956 |

| الماشية | 15.10 (37/245) (10.86-20.10) | 15.92 (39/245) (11.70-21.03) | 15.51 (38/245) (11.28-20.51) | 0.062 | 0.969 |

| الجاموس | 9.79 (24/245) (6.49-14.15) | 8.57 (21/245) (5.56-12.72) | 8.16 (20/245) (5.14-12.31) | 0.٤٣٩ | 0.803 |

| مجتر كبير | إجمالي العينات (ن) | العينات الإيجابية (ن) | % انتشار الأجسام المضادة (95% فترة الثقة) |

|

|

أو | OR (فاصل الثقة 95%) | |

| الحد الأدنى | الحد الأقصى | |||||||

| بشكل عام | ٤٩٠ | ٥٥ | 11.22 (8.59-14.33) | – | – | – | ||

| المواشي | 245 | 31 | 12.65 (8.82-17.44) | 0.316 | 1.004 | 1.33 | 0.76 | 2.37 |

| جاموس | 245 | ٢٤ | 9.80 (6.49-14.15) | |||||

نتائج سلبية [25]. لذلك، من أجل السيطرة الفعالة والوقاية، من الضروري إجراء دراسات حول الحمى المالطية باستخدام أدوات تشخيصية مصلية وجزيئية متطورة لتوليد بيانات أساسية حول انتشارها وعوامل الخطر المرتبطة بها. في باكستان، أفادت بعض الدراسات السابقة بانتشار الحمى المالطية وعوامل الخطر في بعض المناطق المختارة من البلاد [2628]، لكن المعلومات المتعلقة وبائيات الحمى المالطية نادرة/محدودة في جنوب البنجاب، الذي يعد مركز الثروة الحيوانية ويعيش فيه حوالي أكثر من

النتائج

فحص ومقارنة داء البروسيلات باستخدام مستضدات RBPT المتاحة تجارياً

انتشار داء البروسيلات بشكل عام وبحسب الأنواع

الكشف الجزيئي عن أنواع البروسيلة في العينات الإيجابية لاختبار ELISA

انتشار مستوى المزرعة/القطيع حسب مستوى التهسيل

| السكان | بروسيلا spp. % (ن) | ب. أبورتوس (BA) % (ن) | ب. ميلتينسيس (BM) % (ن) | كلا من BA و BM % (ن) |

| من عينات إيجابية لـ ELISA | ||||

| بشكل عام | 100 (55/55) | 80 (44/55) | 20 (11/55) | 5.45 (3/55) |

| المواشي | 100 (31/31) | 80.64 (25/31) | 19.36 (06/31) | 3.22 (31/01) |

| جاموس | 100 (24/24) | 79.17 (19/24) | 20.83 (5/24) | 8.33 (02/24) |

| من إجمالي السكان | ||||

| بشكل عام | 11.22 (55/490) | 8.98 (44/490) | 2.24 (11/490) | 0.61 (03/490) |

| المواشي | 12.65 (31/245) | 10.2 (25/245) | 2.45 (06/245) | 0.41 (01/245) |

| بافالو | 9.80 (24/245) | 7.76 (19/245) | 2.04 (05/245) | 0.82 (02/245) |

ارتباط المعايير الديموغرافية بانتشار حمى المالطية

| الجرابيات الكبيرة | % انتشار (

|

|

|

أو | OR (فاصل الثقة 95%) | |

| الحد الأدنى | الحد الأقصى | |||||

| مستوى القطيع | ||||||

| بشكل عام | 32.83 (22/67) (22.00-44.82) | |||||

| ملتان | 43.75 (7/16) (20.11-69.96) | 0.545 | 1.216 | 2.03 | 0.43 | 10.04 |

| شوجabad | 31.03 (9/29) (16.38-50.00) | 1.2 | 0.3 | 5.02 | ||

| جلالبور بيروالا | 27.27 (6/22) (12.60-50.00) | 1 | ||||

| الماشية الكبيرة حسب التهسيل | ||||||

| ملتان | 12.07 (21/174) (7.85-17.66) | 0.887 | 0.239 | 1.19 | 0.56 | ٢.٥٩ |

| شوجabad | 11.11 (19/171) (7.04-16.78) | 1.08 | 0.5 | 2.39 | ||

| جلالبور بيروالا | 10.34 (15/145) (5.91-16.35) | 1 | ||||

| المواشي | ||||||

| ملتان | 15.05 (14/93) (8.77-23.94) | 0.673 | 0.791 | 1.36 | 0.45 | ٤.٦١ |

| شوجabad | 11.00 (11/100) (5.87-18.72) | 0.95 | 0.3 | ٣.٣٣ | ||

| جلالبور بيروالا | 11.54 (6/52) (5.14-22.66) | 1 | ||||

| بافالو | ||||||

| ملتان | 8.64 (7/81) (3.91-16.91) | 0.862 | 0.298 | 0.88 | 0.27 | 2.82 |

| شوجabad | 11.27 (8/71) (5.01-20.76) | 1.18 | 0.37 | 3.68 | ||

| جلالبور بيروالا | 9.68 (9/93) (4.95-17.43) | 1 | ||||

ارتباط الاضطرابات التناسلية بانتشار حمى المالطية

ارتباط الحالة التعليمية ومستوى الوعي لدى المزارعين بانتشار داء البروسيلات

ذو دلالة إحصائية

نقاش

| الخصائص السكانية | % انتشار (

|

|

قيمة P | أو | OR (فاصل الثقة 95%) | |

| الحد الأدنى | الحد الأقصى | |||||

| العمر (بالسنوات) | ||||||

| بشكل عام | ||||||

|

|

13.67 (19/139) (8.76-20.32) | ٢.٧٧٧ | 0.249 | 1.52 | 0.77 | 0.62 |

|

|

9.45 (29/307) (6.56-13.24) | 1 | ||||

| أكثر من 8 | 15.91 (7/44) (7.21-29.18) | 1.81 | 0.62 | ٤.٦٢ | ||

| المواشي | ||||||

|

|

14.44 (13/90) (8.15-2308) | 0.481 | 0.786 | 1.26 | 0.53 | 2.93 |

|

|

11.80 (17/144) (7.19-18.20) | 1 | ||||

| أكثر من 8 | 9.09 (1/11) (0.46-40.11) | 0.75 | 0.02 | ٥.٨٩ | ||

| جاموس | ||||||

|

|

12.24 (6/49) (5.47-24.06) | ٤.٠٥٢ | 0.132 | 1.75 | 0.51 | ٥.٤ |

|

|

7.36 (12/163) (4.07-12.38) | 1 | ||||

| أكثر من 8 | 18.18 (6/33) (8.22-34.47) | 2.78 | 0.79 | 2.78 | ||

| جنس | ||||||

| بشكل عام | ||||||

| أنثى | 11.30 (52/460) (8.61-14.50) | 0.048 | 0.826 | 1.10 | 0.37 | ٤.٩١ |

| ذكر | 10.00 (3/30) (2.77-25.96) | |||||

| المواشي | ||||||

| أنثى | 12.39 (29/234) (8.61-17.19) | 0.319 | 0.572 | 0.61 | 0.14 | ٤.٥٢ |

| ذكر | 18.18 (2/11) (3.32-50.01) | |||||

| جاموس | ||||||

| أنثى | 10.17 (23/226) (6.69-14.70) | 0.479 | 0.489 | 1.80 | 0.34 | ٤٤.٧٥ |

| ذكر | 5.26 (1/19) (0.26-25.17) | |||||

| سلالة | ||||||

| المواشي | ||||||

| ساهيوال | 6.49 (5/77) (2.59-14.50) | 8.382 | 0.039 | 0.56 | 0.11 | 3.01 |

| فريزيان | 8.88 (4/45) (3.08-20.57) | 0.78 | 0.13 | ٤.٥٥ | ||

| هجين | 11.11 (4/36) (3.88-25.77) | 1 | ||||

| غير مميز | 20.69 (18/87) (12.82-30.27) | 2.08 | 0.61 | 9.12 | ||

| جاموس | ||||||

| نيلي رافي | 7.48 (16/214) (4.50-11.76) | 10.296 | 0.001 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.64 |

| غير مميز | 25.81 (31/8) (12.61-43.38) | |||||

| حجم القطيع (عدد الرؤوس) الإجمالي | ||||||

| الخصائص السكانية | % انتشار (

|

|

قيمة P | أو | OR (فاصل الثقة 95%) | |

| الحد الأدنى | الحد الأقصى | |||||

| حتى 10 | ٢٦.٢٢ (١٦/٦١) (١٥.٨٦-٣٨.٣٧) | ٤٩.١٢٨ | 0.000 | 0.9 | 0.39 | 2.05 |

| من 11 إلى 100 | 5.07 (18/355) (3.13-7.78) | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.29 | ||

| > 100 | 28.38 (21/74) (18.51-39.75) | 1 | ||||

| المواشي | ||||||

| حتى 10 | 30.00 (9/30) (15.81-48.29) | ٣٢.٢٥٩ | 0.000 | 0.79 | 0.24 | 2.54 |

| من 11 إلى 100 | 5.52 (10/181) (2.83-9.76) | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.31 | ||

| > 100 | ٣٥.٢٩ (١٢/٣٤) (١٩.٩٩-٥٣.٠٢) | 1 | ||||

| بوفالو | ||||||

| حتى 10 | 22.58 (7/31) (10.26-40.06) | 18.361 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.27 | ٣.٥٤ |

| من 11 إلى 100 | 4.60 (8/174) (2.04-8.71) | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.53 | ||

| > 100 | 22.50 (9/40) (11.84-37.97) | 1 | ||||

| التوازن العام | ||||||

|

|

11.75 (39/332) (8.63-15.58) | 0.233 | 0.629 | 1.17 | 0.61 | 2.36 |

| >3 | 10.16 (13/128) (5.52-16.57) | |||||

| المواشي | ||||||

|

|

13.89 (25/180) (9.22-19.59) | 1.607 | 0.205 | 1.95 | 0.71 | 7.05 |

| >3 | 7.41 (4/54) (2.56-17.22) | |||||

| جاموس | ||||||

|

|

9.21 (14/152) (5.36-14.92) | 0.474 | 0.491 | 0.73 | 0.30 | 1.85 |

| >3 | 12.16 (9/74) (6.26-21.31) | |||||

| الحمل | ||||||

| بشكل عام | ||||||

| نعم | 12.24 (6/49) (5.47-24.06) | 0.048 | 0.826 | 1.13 | 0.41 | 2.63 |

| لا | 11.19 (46/411) (8.41-14.64) | |||||

| المواشي | ||||||

| نعم | 15.00 (3/20) (4.21-36.94) | 0.137 | 0.711 | 1.32 | 0.28 | ٤.٣٤ |

| لا | 12.15 (26/214) (8.24-17.16) | |||||

| جاموس | ||||||

| نعم | 10.34 (3/29) (2.87-26.87) | 0.001 | 0.974 | 1.06 | 0.23 | 3.42 |

| لا | 10.15 (20/197) (6.40-15.08) | |||||

| حالة البلوغ العامة | ||||||

| الخصائص السكانية | % انتشار (

|

|

قيمة P | أو | OR (فاصل الثقة 95%) | |

| الحد الأدنى | الحد الأقصى | |||||

| العجلات | 16.67 (11/66) (9.14-27.73) | ٢.٢١٠ | 0.137 | 1.73 | 0.80 | 3.49 |

| البالغون | 10.41 (41/394) (7.64-13.76) | |||||

| المواشي | ||||||

| العجلات | 16.67 (5/30) (6.80-34.52) | 0.579 | 0.447 | 1.53 | 0.47 | ٤.١٤ |

| البالغون | 11.76 (24/204) (7.89-16.83) | |||||

| جاموس | ||||||

| العجلات | 16.67 (6/36) (7.51-32.03) | 1.973 | 0.160 | 2.06 | 0.68 | ٥.٥٠ |

| البالغون | 8.95 (17/190) (5.30-13.79) | |||||

| طريقة التلقيح بشكل عام | ||||||

| التلقيح الصناعي | 4.55 (5/110) (1.80-10.14) | 7.436 | 0.024 | 1 | ||

| التكاثر الطبيعي | 14.14 (41/290) (10.39-10.57) | ٣.٤٥ | 1.31 | 11.50 | ||

| غير مخصب | 10.00 (6/60) (4.44-20.38) | 2.32 | 0.56 | 10.08 | ||

| المواشي | ||||||

| التلقيح الصناعي | 4.44 (4/90) (1.52-10.74) | 8.814 | 0.012 | 1 | ||

| التكاثر الطبيعي | 18.10 (21/116) (11.78-26.1) | ٤.٧٢ | 1.51 | 19.67 | ||

| غير مخصب | 14.29 (4/28) (5.02-31.61) | 3.53 | 0.61 | ٢٠.٥٠ | ||

| جاموس | ||||||

| التلقيح الصناعي | 5.00 (1/20) (0.25-23.88) | 1.456 | 0.483 | 1 | ||

| التكاثر الطبيعي | 11.49 (20/174) (7.24-17.07) | ٢.٤٦ | 0.35 | ١٠٧.٥٤ | ||

| غير مخصب | 6.25 (2/32) (1.12-19.59) | 1.26 | 0.06 | 78.57 | ||

| تربية الماعز الصغيرة بشكل مشترك | ||||||

| لا | 9.19 (26/283) (6.23-13.13) | 2.79 | 0.095 | 0.62 | 0.35 | 1.09 |

| نعم | 14.01 (29/207) (9.73-19.44) | |||||

| اضطرابات الإنجاب | %انتشار (

|

|

أو | أو 95% فترة الثقة | قيمة P | ||

| فترة الثقة 95% | الحد الأدنى | الحد الأقصى | |||||

| تاريخ الإجهاض | |||||||

| بشكل عام | |||||||

| نعم | 46.15 (12/26) (28.20-65.92) | ٣٣.٣٨٠ | 8.38 | ٣.٥٥ | 19.56 | 0.000 | |

| لا | 9.22 (40/434) (6.71-12.26) | ||||||

| المواشي | |||||||

| نعم | ٤٧.٠٦ (٨/١٧) (٢٥.٢٩-٧١.٧٩) | ٢٠٫٢٩٠ | 8.17 | ٢.٧٥ | ٢٤.٠٤ | 0.000 | |

| لا | 9.68 (21/217) (6.29-14.37) | ||||||

| جاموس | |||||||

| نعم | 40.00 (4/10) (15.00-71.71) | 10.180 | 6.87 | 1.57 | 27.08 | 0.001 | |

| لا | 8.80 (19/216) (5.51-13.28) | ||||||

| تاريخ التكاثر المتكرر بشكل عام | |||||||

| نعم | ٢٦.٦٧ (١٢/٤٥) (١٤.٨٤-٤١.١٠) | 11.741 | 3.42 | 1.58 | 7.03 | 0.001 | |

| لا | 9.64 (40/415) (7.01-12.81) | ||||||

| المواشي | |||||||

| نعم | 28.00 (7/25) (12.76-47.94) | 6.279 | ٣.٣١ | 1.16 | 8.66 | 0.012 | |

| لا | 10.53 (22/209) (6.74-15.40) | ||||||

| جاموس | |||||||

| نعم | 25.00 (5/20) (10.41-47.40) | 5.274 | 3.51 | 1.02 | 10.44 | 0.022 | |

| لا | 8.74 (18/206) (5.40-13.43) | ||||||

| تاريخ احتباس الأغشية الجنينية بشكل عام | |||||||

| نعم | ٣٨.٨٨ (١٤/٣٦) (٢٤.١٦-٥٥.٧٠) | ٢٩٫٦٤٠ | 6.44 | 2.98 | ١٣.٦٠ | 0.000 | |

| لا | 8.96 (38/424) (6.51-12.06) | ||||||

| المواشي | |||||||

| نعم | 42.85 (6/14) (20.00-68.84) | 12.728 | 6.37 | 1.90 | ٢٠.٣٥ | 0.000 | |

| لا | 10.45 (23/220) (6.87-15.09) | ||||||

| جاموس | |||||||

| نعم | ٣٦.٣٦ (٨/٢٢) (١٨.٧٠-٥٨.٢٤) | 18.283 | 7.12 | ٢.٤٧ | 19.80 | 0.000 | |

| لا | 7.35 (15/204) (4.19-11.84) | ||||||

| المجموعات | إجمالي العينات (ن) | العينات الإيجابية (ن) | العينات السلبية (ن) | % معدل الانتشار (95% CI) | قيمة P |

|

OR | OR(95% CI) | |

| أدنى | أعلى | ||||||||

| الحالة التعليمية للمزارعين | |||||||||

|

|

350 | 50 | 300 | 14.28 (10.90-18.45) | 0.001 | 11.52 | 4.37 | 1.86 | 12.98 |

| فوق المتوسطة | 140 | 5 | 135 | 3.57 (1.41-7.96) | |||||

| الوعي حول حمى البروسيلا | |||||||||

| نعم | 120 | 6 | 114 | 5.00 (2.20-10.52) | 0.013 | 6.179 | 0.35 | 0.13 | 0.79 |

| لا | 370 | 49 | 321 | 13.24 (10.03-17.09) | |||||

تتفق نتائجنا مع نتائج سما وآخرون [51] وخان وآخرون [46] الذين أبلغوا أيضًا عن اختلاف غير ذي دلالة في انتشار حمى البروسيلا حسب الجنس في المجترات الكبيرة. على العكس، تم الإبلاغ عن ارتباط كبير أيضًا بين جنس الحيوان وحمى البروسيلا مع معدلات انتشار أعلى بشكل ملحوظ في الإناث [53، 56]. في منطقة الدراسة، يحتفظ المزارعون فقط بالعجول الإناث لإنتاج الحليب وللحصول على نسل جديد بينما يتم بيع الذكور/ذبحهم في سن مبكرة، لذا يمكننا جمع عدد أقل نسبيًا من عينات المصل من الذكور مقارنة بالإناث. وبناءً عليه، قد يكون الارتباط غير ذي دلالة في دراستنا بسبب حجم العينة الأصغر نسبيًا من الحيوانات الذكورية. في دراستنا، تم تسجيل ارتباط كبير (

مع الفحص غير المناسب للمرض، والنظافة والإدارة [14، 59]. في هذه الدراسة، لم يتم العثور على ارتباط بين انتشار حمى البروسيلا وعدد الولادات في المجترات الكبيرة. سابقًا، أفاد دينكا وآخرون [60] وخان وآخرون [59] أيضًا بنفس النتائج. ومع ذلك، تم الإبلاغ عن اختلاف كبير في انتشار حمى البروسيلا في الماشية التي ليس لديها، أو لديها ولادة واحدة أو ولادات متعددة [53].

الاستنتاجات والتوصيات

طرق

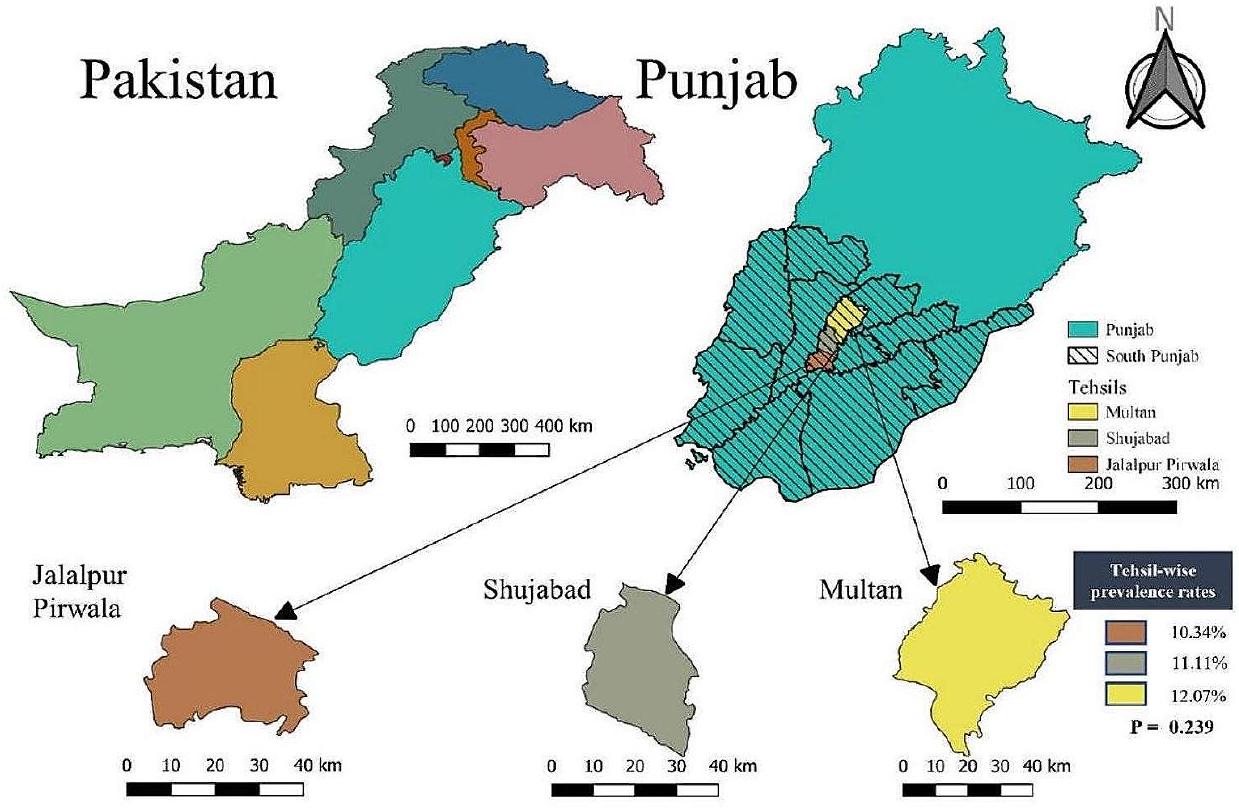

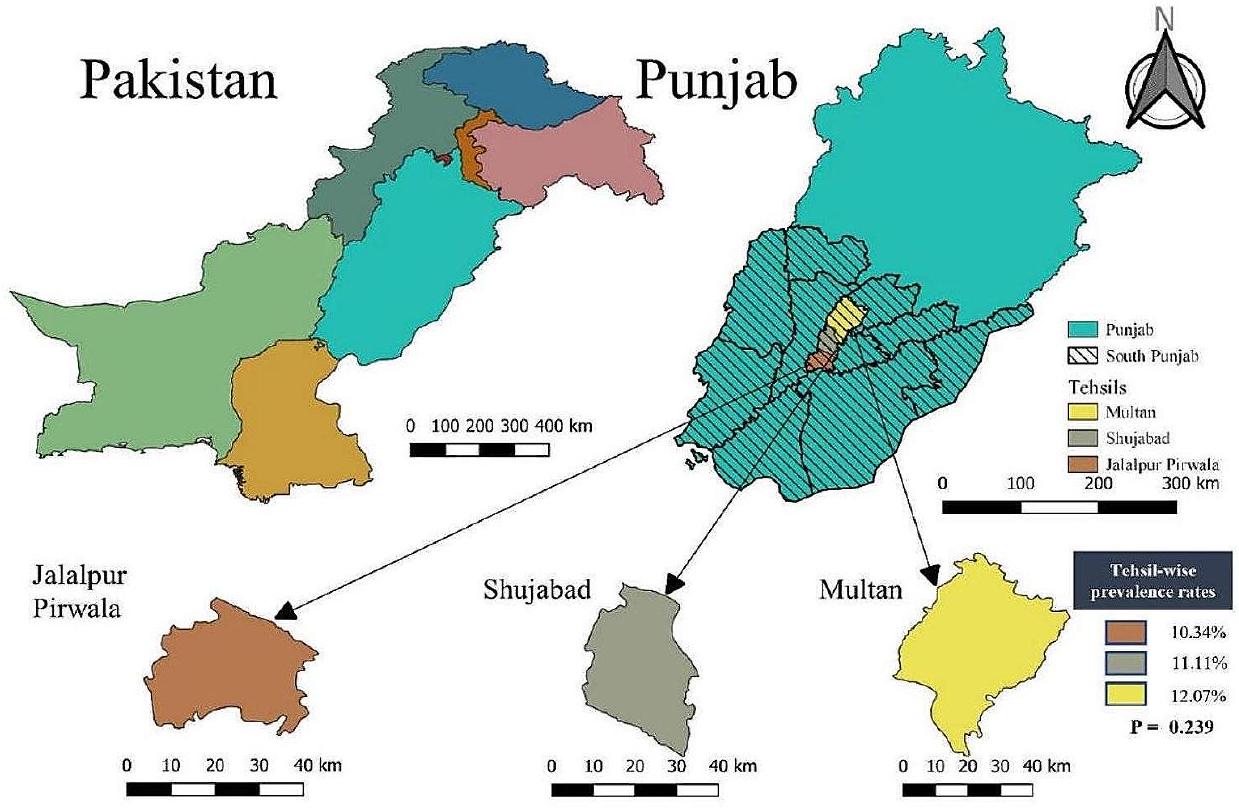

منطقة الدراسة والسكان المستهدفون

تصميم الدراسة وحجم العينة

أخذ عينات الدم

جمع البيانات الوبائية الوصفية

فحص حمى المالطية باستخدام اختبار لوحة روز بنغال (RBPT)

الكشف المصلي عن البروسيلا باستخدام مجموعة ELISA غير المباشرة متعددة الأنواع

الكشف الجزيئي عن أنواع البروسيلة بواسطة تفاعل البوليميراز المتسلسل (PCR)

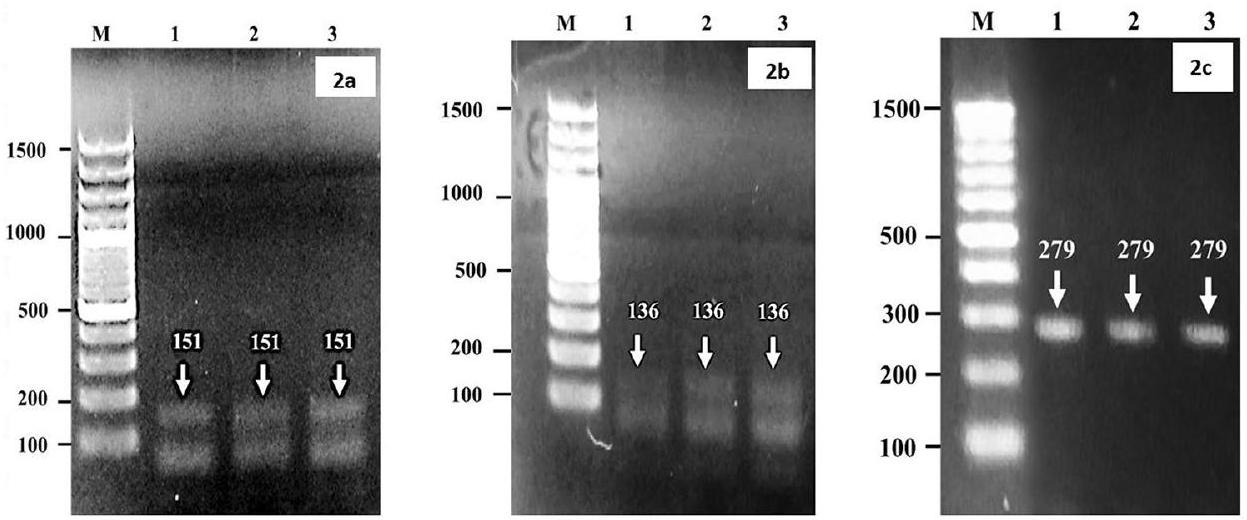

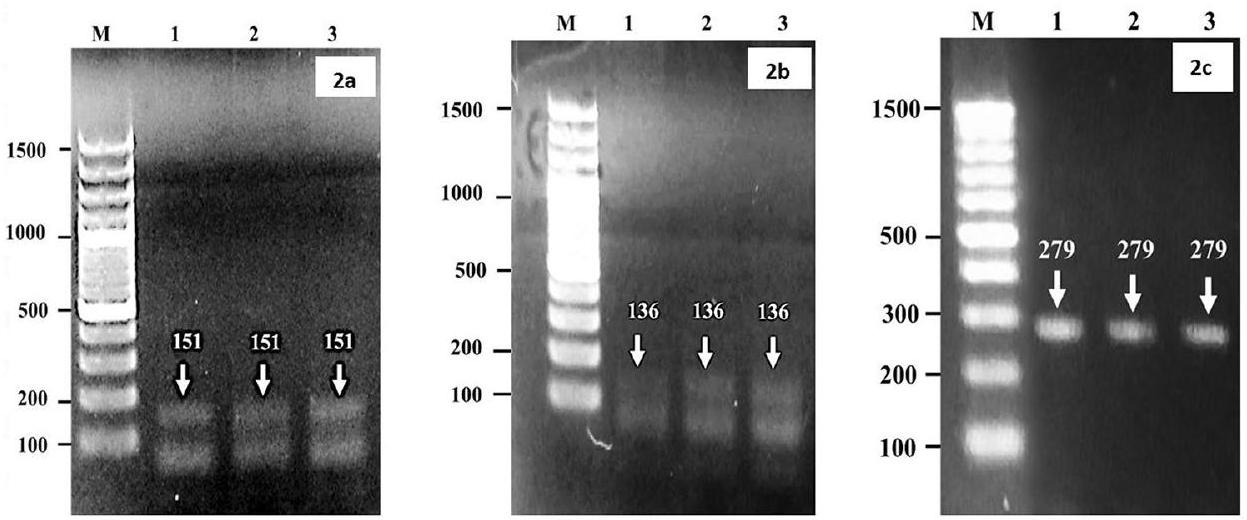

تكبير الجينوم البكتيري لاكتشاف أنواع بروسيلة (B.) مثل B. abortus و B. melitensis باستخدام بادئات محددة للنوع والجنس. تم استخدام بادئات محددة لجنس بروسيلة مع بادئ أمامي (5′ إلى 3′) G CTCGGTTGCCAATATCAATGC وبادئ عكسي (3′ إلى 5′) GGGTAAAGCGTCGCCAGAAG بحجم منتج يبلغ 151 نقطة أساسية؛ بالنسبة لـ B. abortus، بادئ أمامي GCGGCT TTTCTATCACGGTATTC وبادئ عكسي CATGC GCTATGATCTGGTTACG بحجم منتج يبلغ 136 نقطة أساسية، وبالنسبة لـ B. melitensis، بادئ أمامي AACAAGCGGCA CCCCTAAAA وبادئ عكسي CATGCGCTATGA TCTGGTTACG بحجم منتج يبلغ 279 نقطة أساسية تم استخدامها للتكبير [66]. تم رؤية أشرطة الأمبليكون كما هو موضح بواسطة جهاز الإضاءة فوق البنفسجية (الشكل 2a-c). بالنسبة لتفاعل PCR، إجمالي

التحليل الإحصائي

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

تم تنفيذ جميع الطرق وفقًا للإرشادات المؤسسية المتعلقة بالتعامل الإنساني وأخذ العينات من الحيوانات.

موافقة النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

نُشر على الإنترنت: 31 يناير 2024

References

- Ullah Q, Jamil T, Melzer F, Saqib M, Hussain MH, Aslam MA et al. Epidemiology and Associated Risk factors for brucellosis in small ruminants kept at Institutional Livestock Farms in Punjab, Pakistan. Front Veterinary Sci. 2020;7(526).

- Dahourou LD, Ouoba LB, Minoungou L-BG, Tapsoba ARS, Savadogo M, Yougbaré B , et al. Prevalence and factors associated with brucellosis and tuberculosis in cattle from extensive husbandry systems in Sahel and HautsBassins regions, Burkina Faso. Sci Afr. 2023;19:e01570.

- González-Espinoza G, Arce-Gorvel V, Mémet S, Gorvel J-P. Brucella: reservoirs and niches in animals and humans. Pathogens. 2021;10(2):186.

- Corbel MJ. Brucellosis: epidemiology and prevalence worldwide. Brucellosis: clinical and laboratory aspects. CRC Press; 2020. pp. 25-40.

- Dean AS, Crump L, Greter H, Hattendorf J, Schelling E, Zinsstag J. Clinical manifestations of human brucellosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(12):e1929.

- Ibrahim M, Schelling E, Zinsstag J, Hattendorf J, Andargie E, Tschopp R. Sero-prevalence of brucellosis, Q-fever and Rift Valley fever in humans and livestock in Somali Region, Ethiopia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(1):e0008100.

- Edao BM, Ameni G, Assefa Z, Berg S, Whatmore AM, Wood JL. Brucellosis in ruminants and pastoralists in Borena, Southern Ethiopia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(7):e0008461.

- Holt HR, Bedi JS, Kaur P, Mangtani P, Sharma NS, Gill JPS, et al. Epidemiology of brucellosis in cattle and dairy farmers of rural Ludhiana, Punjab. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(3):e0009102.

- Jamil T, Kasi KK, Melzer F, Saqib M, Ullah Q, Khan MR, et al. Revisiting brucellosis in small ruminants of western Border areas in Pakistan. Pathogens. 2020;9(11):929.

- Nejad RB, Krecek RC, Khalaf OH, Hailat N, Arenas Gamboa AM. Brucellosis in the Middle East: current situation and a pathway forward. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(5):e0008071.

- Dadar M, Tiwari R, Sharun K, Dhama K. Importance of brucellosis control programs of livestock on the improvement of one health. Vet Q. 2021;41(1):137-51.

- Zeng J, Duoji C, Yuan Z, Yuzhen S, Fan W, Tian L, et al. Seroprevalence and risk factors for bovine brucellosis in domestic yaks (Bos grunniens) in Tibet, China. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2017;49(7):1339-44.

- Joseph OA, Oluwatoyin AV, Comfort AM, Judy S, Babalola CSI. Risk factors associated with brucellosis among slaughtered cattle: epidemiological insight from two metropolitan abattoirs in Southwestern Nigeria. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2015;5(9):747-53.

- Makita K, Fèvre EM, Waiswa C, Eisler MC, Thrusfield M, Welburn SC. Herd prevalence of bovine brucellosis and analysis of risk factors in cattle in urban and peri-urban areas of the Kampala economic zone, Uganda. BMC Vet Res. 2011;7:60.

- Aune K, Rhyan J, Russell R, Roffe T, Corso B. Environmental persistence of Brucella abortus in the Greater Yellowstone Area. J Wildl Manag. 2012;76:253-61.

- Hegazy YM, Moawad A, Osman S, Ridler A, Guitian J. Ruminant brucellosis in the Kafr El Sheikh Governorate of the Nile Delta, Egypt: prevalence of a neglected zoonosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5(1):e944.

- AI-Shamahy H, Whitty C, Wright S. Risk factors for human brucellosis in Yemen: a case control study. Epidemiol Infect. 2000;125(2):309-13.

- Briones G, Iñón de lannino N, Roset M, Vigliocco A, Paulo PS, Ugalde RA. Brucella abortus cyclic beta-1,2-glucan mutants have reduced virulence in mice and are defective in intracellular replication in HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 2001;69(7):4528-35.

- Memish ZA, Balkhy HH. Brucellosis and international travel. J Travel Med. 2004;11(1):49-55.

- Seleem MN, Boyle SM, Sriranganathan N. Brucellosis: a re-emerging zoonosis. Vet Microbiol. 2010;140(3-4):392-8.

- Zhang N, Huang D, Wu W, Liu J, Liang F, Zhou B, et al. Animal brucellosis control or eradication programs worldwide: a systematic review of experiences and lessons learned. Prev Vet Med. 2018;160:105-15.

- Iqbal M, Fatmi Z, Khan MA. Brucellosis in Pakistan: a neglected zoonotic disease. JPMA The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 2020;70(9):1625-6.

- Franc KA, Krecek RC, Häsler BN, Arenas-Gamboa AM. Brucellosis remains a neglected disease in the developing world: a call for interdisciplinary action. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):125.

- Cadmus S, Adesokan H, Stack J. The use of the milk ring test and rose bengal test in brucellosis control and eradication in Nigeria. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 2008;79(3):113-5.

- Roushan MR, Amiri MJ, Laly A, Mostafazadeh A, Bijani A. Follow-up standard agglutination and 2-mercaptoethanol tests in 175 clinically cured cases of human brucellosis. Int J Infect Diseases: IJID: Official Publication Int Soc Infect Dis. 2010;14(3):e250-3.

- Jamil T, Melzer F, Saqib M, Shahzad A, Khan Kasi K, Hammad Hussain M, et al. Serological and Molecular Detection of Bovine Brucellosis at Institutional Livestock Farms in Punjab, Pakistan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(4):1412.

- Khan AU, Melzer F, Hendam A, Sayour AE, Khan I, Elschner MC et al. Seroprevalence and Molecular Identification of Brucella spp. in bovines in Pakistan-investigating Association with risk factors using machine learning. Front Vet Sci. 2020;7.

- Baig S. Seroprevalence of bovine brucellosis and analysis of risk factors in cattle and livestock Handler’s in Gilgit – Pakistan, 2019. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;101:534.

- Villanueva MA, Mingala CN, Tubalinal GAS, Gaban PBV, Nakajima C, Suzuki Y. Emerging infectious diseases in water buffalo: An economic and public health concern. Emerging Infectious Diseases in Water Buffalo-An Economic and Public Health Concern. 2018.

- Pudake R, Jain U, Kole C, Shakya S, Saxena K. Nano-Biosensing Devices Detecting Biomarkers of Communicable and Non-communicable Diseases of Animals. Biosensors in Agriculture: Recent Trends and Future Perspectives. 2020:415-34.

- Deresa B, Tulu D, Deressa FB. Epidemiological Investigation of Cattle Abortion and Its Association with brucellosis in Jimma Zone, Ethiopia. Veterinary Medicine: Research and Reports. 2020;11:87-98.

- Ukwueze KO, Ishola OO, Dairo MD, Awosanya EJ, Cadmus SI. Seroprevalence of brucellosis and associated factors among livestock slaughtered in OkoOba abattoir, Lagos State, southwestern Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;36(1):53.

- Ntivuguruzwa JB, Kolo FB, Gashururu RS, Umurerwa L, Byaruhanga C, van Heerden H. Seroprevalence and Associated Risk factors of bovine brucellosis at the Wildlife-Livestock-Human interface in Rwanda. Microorganisms. 2020;8(10):1553.

- Fero E, Juma A, Koni A, Boci J, Kirandjiski T, Connor R, et al. The seroprevalence of brucellosis and molecular characterization of Brucella species circulating in the beef cattle herds in Albania. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(3):e0229741.

- Shrimali M, Patel S, Chauhan H, Chandel B, Patel A, Sharma K, et al. Seroprevalence of brucellosis in bovine. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2019;8(11):1730-7.

- Madut NA, Muwonge A, Nasinyama GW, Muma JB, Godfroid J, Jubara AS, et al. The sero-prevalence of brucellosis in cattle and their herders in Bahr El Ghazal region, South Sudan. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(6):e0006456.

- Pathak AD, Dubal ZB, Karunakaran M, Doijad SP, Raorane AV, Dhuri RB et al. Apparent seroprevalence, isolation and identification of risk factors for brucellosis among dairy cattle in Goa, India. Comparative immunology, microbiology and infectious diseases. 2016;47:1-6.

- Asgedom H, Damena D, Duguma R. Seroprevalence of bovine brucellosis and associated risk factors in and around Alage district. Ethiopia SpringerPlus. 2016;5(1):1-8.

- Awah-Ndukum J, Mouiche MMM, Kouonmo-Ngnoyum L, Bayang HN, Manchang TK, Poueme RSN, et al. Seroprevalence and risk factors of brucellosis among slaughtered indigenous cattle, abattoir personnel and pregnant women in Ngaoundéré, Cameroon. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):611.

- Chaka H, Aboset G, Garoma A, Gumi B, Thys E. Cross-sectional survey of brucellosis and associated risk factors in the livestock-wildlife interface area of Nechisar National Park, Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2018;50(5):1041-9.

- Bifo H, Gugsa G, Kifleyohannes T, Abebe E, Ahmed M. Sero-prevalence and associated risk factors of bovine brucellosis in Sendafa, Oromia Special Zone surrounding Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(11):e0238212.

- Kamga RMN, Silatsa BA, Farikou O, Kuiate JR, Simo G. Detection of Brucella antibodies in domestic animals of southern Cameroon: implications for the control of brucellosis. Vet Med Sci. 2020;6(3):410-20.

- Yanti Y, Sumiarto B, Kusumastuti T, Panus A, Sodirun S, editors. Seroprevalence and risk factors of brucellosis and the brucellosis model at the individual level of dairy cattle in the West Bandung District, Indonesia, Veterinary World, 14 (1): 1-102021: Abstract.

- Boukary AR, Saegerman C, Abatih E, Fretin D, Alambédji Bada R, De Deken R, et al. Seroprevalence and potential risk factors for Brucella Spp. Infection in traditional cattle, Sheep and Goats Reared in Urban, Periurban and Rural areas of Niger. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e83175.

- Ali S, Akhter S, Neubauer H, Melzer F, Khan I, Abatih EN, et al. Seroprevalence and risk factors associated with bovine brucellosis in the Potohar Plateau, Pakistan. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):73.

- Khan MR, Rehman A, Khalid S, Ahmad MUD, Avais M, Sarwar M, et al. Seroprevalence and Associated Risk factors of bovine brucellosis in District Gujranwala, Punjab, Pakistan. Animals. 2021;11(6):1744.

- Rodriguez-Morales J. A. Climate change, climate variability and brucellosis. Recent patents on anti-infective drug discovery. 2013;8(1):4-12.

- Khan I, Ali S, Hussain R, Raza A, Younus M, Khan N, et al. Serosurvey and potential risk factors of brucellosis in dairy cattle in peri-urban production system in Punjab, Pakistan. Pak Vet J. 2021;41(3):459-62.

- Bakhtullah FP, Shahid M, Basit A, Khan MA, Gul S, Wazir I, et al. Sero-prevalence of brucellosis in cattle in southern area of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Res J Vet Pract. 2014;2(4):63-6.

- Ahmad T, Khan I, Razzaq S, Akhtar R. Prevalence of bovine brucellosis in Islamabad and rawalpindi districts of Pakistan. Pakistan J Zool. 2017;49(3).

- Sima DM, Ifa DA, Merga AL, Tola EH. Seroprevalence of bovine brucellosis and Associated Risk factors in Western Ethiopia. Veterinary Medicine: Research and Reports. 2021;12:317.

- Haileselassie M, Kalayou S, Kyule M, Asfaha M, Belihu K. Effect of Brucella infection on reproduction conditions of female breeding cattle and its public health significance in Western Tigray, northern Ethiopia. Veterinary medicine international. 2011;2011.

- Saeed U, Ali S, LatifT, Rizwan M, Iftikhar A, Ghulam Mohayud Din Hashmi S, et al. Prevalence and spatial distribution of animal brucellosis in central Punjab, Pakistan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6903.

- Patel M, Patel P, Prajapati M, Kanani A, Tyagi K, Fulsoundar A. Prevalence and risk factor’s analysis of bovine brucellosis in peri-urban areas under intensive system of production in Gujarat, India. Vet World. 2014;7(7):509-16.

- França T, Ishikawa L, Zorzella-Pezavento S, Chiuso-Minicucci F, da Cunha MdLRdS, Sartori A. Impact of malnutrition on immunity and infection. J Venom Anim Toxins Including Trop Dis. 2009;15(3):374-90.

- Rahman M, Faruk M, Her M, Kim J, Kang S, Jung S. Prevalence of brucellosis in ruminants in Bangladesh. Vet Med. 2011;56(8):379-85.

- Deka RP, Shome R, Dohoo I, Magnusson U, Randolph DG, Lindahl JF. Seroprevalence and risk factors of Brucella infection in dairy animals in urban and rural areas of Bihar and Assam, India. Microorganisms. 2021;9(4):783.

- Aulakh H, Patil P, Sharma S, Kumar H, Mahajan V, Sandhu K. A study on the epidemiology of bovine brucellosis in Punjab (India) using milk-ELISA. Acta Vet Brno. 2008;77(3):393-9.

- Khan AU, Sayour AE, Melzer F, El-Soally SAGE, Elschner MC, Shell WS, et al. Seroprevalence and molecular identification of Brucella spp. in camels in Egypt. Microorganisms. 2020;8(7):1035.

- Dinka H, Chala R. Seroprevalence study of bovine brucellosis in pastoral and agro-pastoral areas of East Showa Zone, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. American-Eurasian J Agricultural Environ Sci. 2009;6(5):508-12.

- Garry F. Chapter 15 – Miscellaneous Infectious Diseases. In: Divers TJ, Peek SF, editors. Rebhun’s Diseases of Dairy Cattle (Second Edition). Saint Louis: W.B. Saunders; 2008. p. 606-39.

- Batista HR, Passos CTS, Nunes Neto OG, Sarturi C, Coelho APL, Moreira TR, et al. Factors associated with the prevalence of antibodies against Brucella abortus in water buffaloes from Santarém, Lower Amazon region, Brazil. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2020;67(S2):44-8.

- Cárdenas L, Peña M, Melo O, Casal J. Risk factors for new bovine brucellosis infections in Colombian herds. BMC Vet Res. 2019;15(1):81.

- Arif S, Thomson PC, Hernandez-Jover M, McGill DM, Warriach HM, Hayat K, et al. Bovine brucellosis in Pakistan; an analysis of engagement with risk factors in smallholder farmer settings. Veterinary Med Sci. 2019;5(3):390-401.

- Pourhoseingholi MA, Vahedi M, Rahimzadeh M. Sample size calculation in medical studies. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2013;6(1):14-7.

- Probert WS, Schrader KN, Khuong NY, Bystrom SL, Graves MH. Real-time multiplex PCR assay for detection of <i>Brucella spp., <i>B. Abortus, and B. melitensis. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(3):1290-3.

ملاحظة الناشر

ساهم ميان محمد عويس وغوهر خادم بالتساوي في هذا العمل ويتشاركان في المرتبة الأولى كالمؤلفين.

*المراسلة:

ميان محمد عويس

drawaisuaf@gmail.com; muhammadawais@bzu.edu.pk

قائمة كاملة بمعلومات المؤلف متاحة في نهاية المقال

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-024-03880-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38297263

Publication Date: 2024-01-31

A study on the epidemiology of brucellosis in bovine population of peri-urban and rural areas of district Multan, southern Punjab, Pakistan

Abstract

Background Brucellosis is a zoonotic disease caused by a bacterial pathogen belonging to the genus Brucella. It is one of the most frequent bacterial zoonoses globally but unfortunately, it is still considered as a neglected disease in the developing world. Keeping in view, this study was conducted to determine the prevalence and risk determinants of brucellosis in large ruminants of peri-urban and rural areas of district Multan-Pakistan. For this purpose, blood samples (

Conclusion In conclusion, brucellosis is prevalent in large ruminants of district Multan, Pakistan. It is suggested to devise and implement stringent policies for the effective control and prevention of brucellosis in the region. Further, the current situation also warrants the need to strengthen interdisciplinary coordination among veterinarians and physicians in one health perspective to ensure and strengthen the human and animal health care systems in the region.

Keywords Brucellosis; prevalence, Risk determinants, i-ELISA, Molecular detection, Multan-Pakistan

Background

disease is high in pastoral grazing regions as compared to urban areas [14]. Moreover, survival potential of Brucella in cold and humid environments is another important factor for the transmission of this disease in livestock and humans [15]. The human behavioral factors such as unhygienic conditions and other activities that cause the exposure of people to infected animals and their products enhances the chances of disease in humans [16]. On the whole, the farmers, abattoir, laboratory workers, and people that are involved in the livestock industry may be regarded as high risk populations [17]. The other risk factors which serve as main barriers in controlling brucellosis are conventional livestock policies, political influences, inadequate implementation of control measures, usage of old traditional practices, consumption of unpasteurized dairy products, changes in the animal husbandry system and insufficient measures for reporting, diagnosis and surveillance of this disease [10]. The appropriate treatment and prevention of this disease are indispensable to avoid economic losses in the livestock sector. The developing countries are lacking behind in implementing the eradication strategies against brucellosis [18-20]. Although the World Health Organization (WHO) and World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) have devised recommendations for the eradication of brucellosis, but it is still considered a serious health threat in developing/underdeveloped countries because control measures for the eradication of brucellosis are expensive, laborious, and time-consuming. However, in endemic countries, its occurrence can be avoided by vaccination and slaughtering/culling strategies [21].

| % Seropositivity with RBPT (n/T) (95%CI) |

|

|

|||

| VRI | IDEXX | ID.vet | |||

| Overall | 12.45 (61/490) (9.72-15.65) | 12.24 (60/490) (9.52-15.45) | 11.84 (58/490) (9.18-14.95) | 0.089 | 0.956 |

| Cattle | 15.10 (37/245) (10.86-20.10) | 15.92 (39/245) (11.70-21.03) | 15.51 (38/245) (11.28-20.51) | 0.062 | 0.969 |

| Buffalo | 9.79 (24/245) (6.49-14.15) | 8.57 (21/245) (5.56-12.72) | 8.16 (20/245) (5.14-12.31) | 0.439 | 0.803 |

| Large Ruminant | Total samples (n) | Positive samples (n) | % Seroprevalence (95% CI) |

|

|

OR | OR (95% CI) | |

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||||||

| Overall | 490 | 55 | 11.22 (8.59-14.33) | – | – | – | ||

| Cattle | 245 | 31 | 12.65 (8.82-17.44) | 0.316 | 1.004 | 1.33 | 0.76 | 2.37 |

| Buffalo | 245 | 24 | 9.80 (6.49-14.15) | |||||

negative results [25]. So, for effective control and prevention, it is imperative to conduct studies on brucellosis using sophisticated serological and molecular diagnostic tools to generate baseline data on its prevalence and associated risk factors. In Pakistan, some previous studies have reported the prevalence and risk determinants of brucellosis in some selected districts of the country [2628], but information regarding the epidemiology of brucellosis is scarce/ limited in southern Punjab which is the hub of livestock and inhabits approximately more than

Results

Screening and comparison of brucellosis using different commercially available RBPT antigens

Overall and species-wise prevalence of brucellosis

Molecular detection of Brucella species in ELISA positive samples

Farm/herd level and tehsil wise prevalence

| Population | Brucella Spp. % (n) | B. abortus (BA) % (n) | B. melitensis (BM) % (n) | Both BA & BM % (n) |

| Out of ELISA positive samples | ||||

| Overall | 100 (55/55) | 80 (44/55) | 20 (11/55) | 5.45 (3/55) |

| Cattle | 100 (31/31) | 80.64 (25/31) | 19.36 (06/31) | 3.22 (01/31) |

| Buffalo | 100 (24/24) | 79.17 (19/24) | 20.83 (5/24) | 8.33 (02/24) |

| Out of total population | ||||

| Overall | 11.22 (55/490) | 8.98 (44/490) | 2.24 (11/490) | 0.61 (03/490) |

| Cattle | 12.65 (31/245) | 10.2 (25/245) | 2.45 (06/245) | 0.41 (01/245) |

| Buffalo | 9.80 (24/245) | 7.76 (19/245) | 2.04 (05/245) | 0.82 (02/245) |

Association of demographic parameters with the prevalence of brucellosis

| Large Ruminants | % Prevalence (

|

|

|

OR | OR(95% CI) | |

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||

| Herd-Level | ||||||

| Overall | 32.83 (22/67) (22.00-44.82) | |||||

| Multan | 43.75 (7/16) (20.11-69.96) | 0.545 | 1.216 | 2.03 | 0.43 | 10.04 |

| Shujabad | 31.03 (9/29) (16.38-50.00) | 1.2 | 0.3 | 5.02 | ||

| Jalalpur Pirwala | 27.27 (6/22) (12.60-50.00) | 1 | ||||

| Tehsil-wise Overall large ruminants | ||||||

| Multan | 12.07 (21/174) (7.85-17.66) | 0.887 | 0.239 | 1.19 | 0.56 | 2.59 |

| Shujabad | 11.11 (19/171) (7.04-16.78) | 1.08 | 0.5 | 2.39 | ||

| Jalalpur Pirwala | 10.34 (15/145) (5.91-16.35) | 1 | ||||

| Cattle | ||||||

| Multan | 15.05 (14/93) (8.77-23.94) | 0.673 | 0.791 | 1.36 | 0.45 | 4.61 |

| Shujabad | 11.00 (11/100) (5.87-18.72) | 0.95 | 0.3 | 3.33 | ||

| Jalalpur Pirwala | 11.54 (6/52) (5.14-22.66) | 1 | ||||

| Buffalo | ||||||

| Multan | 8.64 (7/81) (3.91-16.91) | 0.862 | 0.298 | 0.88 | 0.27 | 2.82 |

| Shujabad | 11.27 (8/71) (5.01-20.76) | 1.18 | 0.37 | 3.68 | ||

| Jalalpur Pirwala | 9.68 (9/93) (4.95-17.43) | 1 | ||||

Association of reproductive disorders with prevalence of brucellosis

Association of educational status and awareness level of farmers with prevalence of brucellosis

statistically significant

Discussion

| Demographic Characters | % Prevalence (

|

|

P-Value | OR | OR (95% CI) | |

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| Overall | ||||||

|

|

13.67 (19/139) (8.76-20.32) | 2.777 | 0.249 | 1.52 | 0.77 | 0.62 |

|

|

9.45 (29/307) (6.56-13.24) | 1 | ||||

| More than 8 | 15.91 (7/44) (7.21-29.18) | 1.81 | 0.62 | 4.62 | ||

| Cattle | ||||||

|

|

14.44 (13/90) (8.15-2308) | 0.481 | 0.786 | 1.26 | 0.53 | 2.93 |

|

|

11.80 (17/144) (7.19-18.20) | 1 | ||||

| More than 8 | 9.09 (1/11) (0.46-40.11) | 0.75 | 0.02 | 5.89 | ||

| Buffalo | ||||||

|

|

12.24 (6/49) (5.47-24.06) | 4.052 | 0.132 | 1.75 | 0.51 | 5.4 |

|

|

7.36 (12/163) (4.07-12.38) | 1 | ||||

| More than 8 | 18.18 (6/33) (8.22-34.47) | 2.78 | 0.79 | 2.78 | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Overall | ||||||

| Female | 11.30 (52/460) (8.61-14.50) | 0.048 | 0.826 | 1.10 | 0.37 | 4.91 |

| Male | 10.00 (3/30) (2.77-25.96) | |||||

| Cattle | ||||||

| Female | 12.39 (29/234) (8.61-17.19) | 0.319 | 0.572 | 0.61 | 0.14 | 4.52 |

| Male | 18.18 (2/11) (3.32-50.01) | |||||

| Buffalo | ||||||

| Female | 10.17 (23/226) (6.69-14.70) | 0.479 | 0.489 | 1.80 | 0.34 | 44.75 |

| Male | 5.26 (1/19) (0.26-25.17) | |||||

| Breed | ||||||

| Cattle | ||||||

| Sahiwal | 6.49 (5/77) (2.59-14.50) | 8.382 | 0.039 | 0.56 | 0.11 | 3.01 |

| Friesian | 8.88 (4/45) (3.08-20.57) | 0.78 | 0.13 | 4.55 | ||

| Crossbred | 11.11 (4/36) (3.88-25.77) | 1 | ||||

| Non-descript | 20.69 (18/87) (12.82-30.27) | 2.08 | 0.61 | 9.12 | ||

| Buffalo | ||||||

| Nili Ravi | 7.48 (16/214) (4.50-11.76) | 10.296 | 0.001 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.64 |

| Non-descript | 25.81 (8/31) (12.61-43.38) | |||||

| Herd size (No. of heads) Overall | ||||||

| Demographic Characters | % Prevalence (

|

|

P-Value | OR | OR(95% CI) | |

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||

| Up to 10 | 26.22 (16/61) (15.86-38.37) | 49.128 | 0.000 | 0.9 | 0.39 | 2.05 |

| From 11 to 100 | 5.07 (18/355) (3.13-7.78) | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.29 | ||

| > 100 | 28.38 (21/74) (18.51-39.75) | 1 | ||||

| Cattle | ||||||

| Up to 10 | 30.00 (9/30) (15.81-48.29) | 32.259 | 0.000 | 0.79 | 0.24 | 2.54 |

| From 11 to 100 | 5.52 (10/181) (2.83-9.76) | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.31 | ||

| > 100 | 35.29 (12/34) (19.99-53.02) | 1 | ||||

| Buffalo | ||||||

| Up to 10 | 22.58 (7/31) (10.26-40.06) | 18.361 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.27 | 3.54 |

| From 11 to 100 | 4.60 (8/174) (2.04-8.71) | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.53 | ||

| > 100 | 22.50 (9/40) (11.84-37.97) | 1 | ||||

| Parity Overall | ||||||

|

|

11.75 (39/332) (8.63-15.58) | 0.233 | 0.629 | 1.17 | 0.61 | 2.36 |

| >3 | 10.16 (13/128) (5.52-16.57) | |||||

| Cattle | ||||||

|

|

13.89 (25/180) (9.22-19.59) | 1.607 | 0.205 | 1.95 | 0.71 | 7.05 |

| >3 | 7.41 (4/54) (2.56-17.22) | |||||

| Buffalo | ||||||

|

|

9.21 (14/152) (5.36-14.92) | 0.474 | 0.491 | 0.73 | 0.30 | 1.85 |

| >3 | 12.16 (9/74) (6.26-21.31) | |||||

| Pregnancy | ||||||

| Overall | ||||||

| Yes | 12.24 (6/49) (5.47-24.06) | 0.048 | 0.826 | 1.13 | 0.41 | 2.63 |

| No | 11.19 (46/411) (8.41-14.64) | |||||

| Cattle | ||||||

| Yes | 15.00 (3/20) (4.21-36.94) | 0.137 | 0.711 | 1.32 | 0.28 | 4.34 |

| No | 12.15 (26/214) (8.24-17.16) | |||||

| Buffalo | ||||||

| Yes | 10.34 (3/29) (2.87-26.87) | 0.001 | 0.974 | 1.06 | 0.23 | 3.42 |

| No | 10.15 (20/197) (6.40-15.08) | |||||

| Puberty Status Overall | ||||||

| Demographic Characters | % Prevalence (

|

|

P-Value | OR | OR(95% CI) | |

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||

| Heifers | 16.67 (11/66) (9.14-27.73) | 2.210 | 0.137 | 1.73 | 0.80 | 3.49 |

| Adults | 10.41 (41/394) (7.64-13.76) | |||||

| Cattle | ||||||

| Heifers | 16.67 (5/30) (6.80-34.52) | 0.579 | 0.447 | 1.53 | 0.47 | 4.14 |

| Adults | 11.76 (24/204) (7.89-16.83) | |||||

| Buffalo | ||||||

| Heifers | 16.67 (6/36) (7.51-32.03) | 1.973 | 0.160 | 2.06 | 0.68 | 5.50 |

| Adults | 8.95 (17/190) (5.30-13.79) | |||||

| Mode of insemination Overall | ||||||

| Artificial Insemination | 4.55 (5/110) (1.80-10.14) | 7.436 | 0.024 | 1 | ||

| Natural Breeding | 14.14 (41/290) (10.39-10.57) | 3.45 | 1.31 | 11.50 | ||

| Not Inseminated | 10.00 (6/60) (4.44-20.38) | 2.32 | 0.56 | 10.08 | ||

| Cattle | ||||||

| Artificial Insemination | 4.44 (4/90) (1.52-10.74) | 8.814 | 0.012 | 1 | ||

| Natural Breeding | 18.10 (21/116) (11.78-26.1) | 4.72 | 1.51 | 19.67 | ||

| Not Inseminated | 14.29 (4/28) (5.02-31.61) | 3.53 | 0.61 | 20.50 | ||

| Buffalo | ||||||

| Artificial Insemination | 5.00 (1/20) (0.25-23.88) | 1.456 | 0.483 | 1 | ||

| Natural Breeding | 11.49 (20/174) (7.24-17.07) | 2.46 | 0.35 | 107.54 | ||

| Not Inseminated | 6.25 (2/32) (1.12-19.59) | 1.26 | 0.06 | 78.57 | ||

| Co-raising of small ruminants | ||||||

| No | 9.19 (26/283) (6.23-13.13) | 2.79 | 0.095 | 0.62 | 0.35 | 1.09 |

| Yes | 14.01 (29/207) (9.73-19.44) | |||||

| Reproductive disorders | %Prevalence (

|

|

OR | OR 95% CI | P-Value | ||

| 95% CI | Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||

| Abortion History | |||||||

| Overall | |||||||

| Yes | 46.15 (12/26) (28.20-65.92) | 33.380 | 8.38 | 3.55 | 19.56 | 0.000 | |

| No | 9.22 (40/434) (6.71-12.26) | ||||||

| Cattle | |||||||

| Yes | 47.06 (8/17) (25.29-71.79) | 20.290 | 8.17 | 2.75 | 24.04 | 0.000 | |

| No | 9.68 (21/217) (6.29-14.37) | ||||||

| Buffalo | |||||||

| Yes | 40.00 (4/10) (15.00-71.71) | 10.180 | 6.87 | 1.57 | 27.08 | 0.001 | |

| No | 8.80 (19/216) (5.51-13.28) | ||||||

| Repeat Breeding History Overall | |||||||

| Yes | 26.67 (12/45) (14.84-41.10) | 11.741 | 3.42 | 1.58 | 7.03 | 0.001 | |

| No | 9.64 (40/415) (7.01-12.81) | ||||||

| Cattle | |||||||

| Yes | 28.00 (7/25) (12.76-47.94) | 6.279 | 3.31 | 1.16 | 8.66 | 0.012 | |

| No | 10.53 (22/209) (6.74-15.40) | ||||||

| Buffalo | |||||||

| Yes | 25.00 (5/20) (10.41-47.40) | 5.274 | 3.51 | 1.02 | 10.44 | 0.022 | |

| No | 8.74 (18/206) (5.40-13.43) | ||||||

| History of retention of fetal membranes Overall | |||||||

| Yes | 38.88 (14/36) (24.16-55.70) | 29.640 | 6.44 | 2.98 | 13.60 | 0.000 | |

| No | 8.96 (38/424) (6.51-12.06) | ||||||

| Cattle | |||||||

| Yes | 42.85 (6/14) (20.00-68.84) | 12.728 | 6.37 | 1.90 | 20.35 | 0.000 | |

| No | 10.45 (23/220) (6.87-15.09) | ||||||

| Buffalo | |||||||

| Yes | 36.36 (8/22) (18.70-58.24) | 18.283 | 7.12 | 2.47 | 19.80 | 0.000 | |

| No | 7.35 (15/204) (4.19-11.84) | ||||||

| Groups | Total samples (n) | Positive samples (n) | Negative samples (n) | % Prevalence (95% CI) | P-value |

|

OR | OR(95% CI) | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Educational status of Farmers | |||||||||

|

|

350 | 50 | 300 | 14.28 (10.90-18.45) | 0.001 | 11.52 | 4.37 | 1.86 | 12.98 |

| Above Matric | 140 | 5 | 135 | 3.57 (1.41-7.96) | |||||

| Awareness about Brucellosis | |||||||||

| Yes | 120 | 6 | 114 | 5.00 (2.20-10.52) | 0.013 | 6.179 | 0.35 | 0.13 | 0.79 |

| No | 370 | 49 | 321 | 13.24 (10.03-17.09) | |||||

area. In agreement to our findings, Sima et al. [51] and Khan et al. [46] also reported a non-significant difference in gender-wise prevalence of brucellosis in large ruminants. Conversely, a significant association had also been reported between animal sex and brucellosis with predominantly higher prevalence rates in females [53, 56]. In study area, farmers retain only female calves for milk production and to get next progeny whereas males are being sold out/slaughtered at early age, so we could collect relatively smaller number of sera samples from males as compared to females. Accordingly, a non-significant association in our study might be due to relatively smaller sample size of male animals. In our study, a significant association (

protocols along with inappropriate disease screening, hygiene and management [14, 59]. In this study, no association was found between prevalence of brucellosis and number of parities in large ruminants. Previously, Dinka et al. [60] and Khan et al. [59] also reported similar findings. However, a significant difference has been reported in prevalence of brucellosis in cattle with no, single or multiple parities [53].

Conclusions and recommendations

Methods

Study area and target population

Study Design and Sample size

Blood sampling

Descriptive epidemiological data collection

Screening of brucellosis using Rose Bengal plate test (RBPT)

Serological detection of brucellosis by using Indirect multispecies ELISA Kit

Molecular detection of Brucella species by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

amplification of bacterial genome for the detection of Brucella (B.) species viz. B. abortus and B. melitensis by using genus and species-specific primers. Specific primers for Brucella Genus with forward primer (5′ to 3′) G CTCGGTTGCCAATATCAATGC and reverse primer (3′ to 5′) GGGTAAAGCGTCGCCAGAAG with product size of 151 bp ; for B. abortus forward primer GCGGCT TTTCTATCACGGTATTC and reverse primer CATGC GCTATGATCTGGTTACG with product size of 136 bp and for B. melitensis forward primer AACAAGCGGCA CCCCTAAAA and reverse primer CATGCGCTATGA TCTGGTTACG with product size of 279 pb were used for amplification [66]. The bands of amplicons as seen by UV-transilluminator (Fig. 2a-c). For PCR reaction, a total of

Statistical analysis

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the methods were performed in accordance with the institutional guidelines regarding humane handling and sampling from animals.

Consent of publication

Competing interests

Author details

Published online: 31 January 2024

References

- Ullah Q, Jamil T, Melzer F, Saqib M, Hussain MH, Aslam MA et al. Epidemiology and Associated Risk factors for brucellosis in small ruminants kept at Institutional Livestock Farms in Punjab, Pakistan. Front Veterinary Sci. 2020;7(526).

- Dahourou LD, Ouoba LB, Minoungou L-BG, Tapsoba ARS, Savadogo M, Yougbaré B , et al. Prevalence and factors associated with brucellosis and tuberculosis in cattle from extensive husbandry systems in Sahel and HautsBassins regions, Burkina Faso. Sci Afr. 2023;19:e01570.

- González-Espinoza G, Arce-Gorvel V, Mémet S, Gorvel J-P. Brucella: reservoirs and niches in animals and humans. Pathogens. 2021;10(2):186.

- Corbel MJ. Brucellosis: epidemiology and prevalence worldwide. Brucellosis: clinical and laboratory aspects. CRC Press; 2020. pp. 25-40.

- Dean AS, Crump L, Greter H, Hattendorf J, Schelling E, Zinsstag J. Clinical manifestations of human brucellosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(12):e1929.

- Ibrahim M, Schelling E, Zinsstag J, Hattendorf J, Andargie E, Tschopp R. Sero-prevalence of brucellosis, Q-fever and Rift Valley fever in humans and livestock in Somali Region, Ethiopia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(1):e0008100.

- Edao BM, Ameni G, Assefa Z, Berg S, Whatmore AM, Wood JL. Brucellosis in ruminants and pastoralists in Borena, Southern Ethiopia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(7):e0008461.

- Holt HR, Bedi JS, Kaur P, Mangtani P, Sharma NS, Gill JPS, et al. Epidemiology of brucellosis in cattle and dairy farmers of rural Ludhiana, Punjab. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(3):e0009102.

- Jamil T, Kasi KK, Melzer F, Saqib M, Ullah Q, Khan MR, et al. Revisiting brucellosis in small ruminants of western Border areas in Pakistan. Pathogens. 2020;9(11):929.

- Nejad RB, Krecek RC, Khalaf OH, Hailat N, Arenas Gamboa AM. Brucellosis in the Middle East: current situation and a pathway forward. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(5):e0008071.

- Dadar M, Tiwari R, Sharun K, Dhama K. Importance of brucellosis control programs of livestock on the improvement of one health. Vet Q. 2021;41(1):137-51.

- Zeng J, Duoji C, Yuan Z, Yuzhen S, Fan W, Tian L, et al. Seroprevalence and risk factors for bovine brucellosis in domestic yaks (Bos grunniens) in Tibet, China. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2017;49(7):1339-44.

- Joseph OA, Oluwatoyin AV, Comfort AM, Judy S, Babalola CSI. Risk factors associated with brucellosis among slaughtered cattle: epidemiological insight from two metropolitan abattoirs in Southwestern Nigeria. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2015;5(9):747-53.

- Makita K, Fèvre EM, Waiswa C, Eisler MC, Thrusfield M, Welburn SC. Herd prevalence of bovine brucellosis and analysis of risk factors in cattle in urban and peri-urban areas of the Kampala economic zone, Uganda. BMC Vet Res. 2011;7:60.

- Aune K, Rhyan J, Russell R, Roffe T, Corso B. Environmental persistence of Brucella abortus in the Greater Yellowstone Area. J Wildl Manag. 2012;76:253-61.

- Hegazy YM, Moawad A, Osman S, Ridler A, Guitian J. Ruminant brucellosis in the Kafr El Sheikh Governorate of the Nile Delta, Egypt: prevalence of a neglected zoonosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5(1):e944.

- AI-Shamahy H, Whitty C, Wright S. Risk factors for human brucellosis in Yemen: a case control study. Epidemiol Infect. 2000;125(2):309-13.

- Briones G, Iñón de lannino N, Roset M, Vigliocco A, Paulo PS, Ugalde RA. Brucella abortus cyclic beta-1,2-glucan mutants have reduced virulence in mice and are defective in intracellular replication in HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 2001;69(7):4528-35.

- Memish ZA, Balkhy HH. Brucellosis and international travel. J Travel Med. 2004;11(1):49-55.

- Seleem MN, Boyle SM, Sriranganathan N. Brucellosis: a re-emerging zoonosis. Vet Microbiol. 2010;140(3-4):392-8.

- Zhang N, Huang D, Wu W, Liu J, Liang F, Zhou B, et al. Animal brucellosis control or eradication programs worldwide: a systematic review of experiences and lessons learned. Prev Vet Med. 2018;160:105-15.

- Iqbal M, Fatmi Z, Khan MA. Brucellosis in Pakistan: a neglected zoonotic disease. JPMA The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 2020;70(9):1625-6.

- Franc KA, Krecek RC, Häsler BN, Arenas-Gamboa AM. Brucellosis remains a neglected disease in the developing world: a call for interdisciplinary action. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):125.

- Cadmus S, Adesokan H, Stack J. The use of the milk ring test and rose bengal test in brucellosis control and eradication in Nigeria. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 2008;79(3):113-5.

- Roushan MR, Amiri MJ, Laly A, Mostafazadeh A, Bijani A. Follow-up standard agglutination and 2-mercaptoethanol tests in 175 clinically cured cases of human brucellosis. Int J Infect Diseases: IJID: Official Publication Int Soc Infect Dis. 2010;14(3):e250-3.

- Jamil T, Melzer F, Saqib M, Shahzad A, Khan Kasi K, Hammad Hussain M, et al. Serological and Molecular Detection of Bovine Brucellosis at Institutional Livestock Farms in Punjab, Pakistan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(4):1412.

- Khan AU, Melzer F, Hendam A, Sayour AE, Khan I, Elschner MC et al. Seroprevalence and Molecular Identification of Brucella spp. in bovines in Pakistan-investigating Association with risk factors using machine learning. Front Vet Sci. 2020;7.

- Baig S. Seroprevalence of bovine brucellosis and analysis of risk factors in cattle and livestock Handler’s in Gilgit – Pakistan, 2019. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;101:534.

- Villanueva MA, Mingala CN, Tubalinal GAS, Gaban PBV, Nakajima C, Suzuki Y. Emerging infectious diseases in water buffalo: An economic and public health concern. Emerging Infectious Diseases in Water Buffalo-An Economic and Public Health Concern. 2018.

- Pudake R, Jain U, Kole C, Shakya S, Saxena K. Nano-Biosensing Devices Detecting Biomarkers of Communicable and Non-communicable Diseases of Animals. Biosensors in Agriculture: Recent Trends and Future Perspectives. 2020:415-34.

- Deresa B, Tulu D, Deressa FB. Epidemiological Investigation of Cattle Abortion and Its Association with brucellosis in Jimma Zone, Ethiopia. Veterinary Medicine: Research and Reports. 2020;11:87-98.

- Ukwueze KO, Ishola OO, Dairo MD, Awosanya EJ, Cadmus SI. Seroprevalence of brucellosis and associated factors among livestock slaughtered in OkoOba abattoir, Lagos State, southwestern Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;36(1):53.

- Ntivuguruzwa JB, Kolo FB, Gashururu RS, Umurerwa L, Byaruhanga C, van Heerden H. Seroprevalence and Associated Risk factors of bovine brucellosis at the Wildlife-Livestock-Human interface in Rwanda. Microorganisms. 2020;8(10):1553.

- Fero E, Juma A, Koni A, Boci J, Kirandjiski T, Connor R, et al. The seroprevalence of brucellosis and molecular characterization of Brucella species circulating in the beef cattle herds in Albania. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(3):e0229741.

- Shrimali M, Patel S, Chauhan H, Chandel B, Patel A, Sharma K, et al. Seroprevalence of brucellosis in bovine. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2019;8(11):1730-7.

- Madut NA, Muwonge A, Nasinyama GW, Muma JB, Godfroid J, Jubara AS, et al. The sero-prevalence of brucellosis in cattle and their herders in Bahr El Ghazal region, South Sudan. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(6):e0006456.

- Pathak AD, Dubal ZB, Karunakaran M, Doijad SP, Raorane AV, Dhuri RB et al. Apparent seroprevalence, isolation and identification of risk factors for brucellosis among dairy cattle in Goa, India. Comparative immunology, microbiology and infectious diseases. 2016;47:1-6.

- Asgedom H, Damena D, Duguma R. Seroprevalence of bovine brucellosis and associated risk factors in and around Alage district. Ethiopia SpringerPlus. 2016;5(1):1-8.

- Awah-Ndukum J, Mouiche MMM, Kouonmo-Ngnoyum L, Bayang HN, Manchang TK, Poueme RSN, et al. Seroprevalence and risk factors of brucellosis among slaughtered indigenous cattle, abattoir personnel and pregnant women in Ngaoundéré, Cameroon. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):611.

- Chaka H, Aboset G, Garoma A, Gumi B, Thys E. Cross-sectional survey of brucellosis and associated risk factors in the livestock-wildlife interface area of Nechisar National Park, Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2018;50(5):1041-9.

- Bifo H, Gugsa G, Kifleyohannes T, Abebe E, Ahmed M. Sero-prevalence and associated risk factors of bovine brucellosis in Sendafa, Oromia Special Zone surrounding Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(11):e0238212.

- Kamga RMN, Silatsa BA, Farikou O, Kuiate JR, Simo G. Detection of Brucella antibodies in domestic animals of southern Cameroon: implications for the control of brucellosis. Vet Med Sci. 2020;6(3):410-20.

- Yanti Y, Sumiarto B, Kusumastuti T, Panus A, Sodirun S, editors. Seroprevalence and risk factors of brucellosis and the brucellosis model at the individual level of dairy cattle in the West Bandung District, Indonesia, Veterinary World, 14 (1): 1-102021: Abstract.

- Boukary AR, Saegerman C, Abatih E, Fretin D, Alambédji Bada R, De Deken R, et al. Seroprevalence and potential risk factors for Brucella Spp. Infection in traditional cattle, Sheep and Goats Reared in Urban, Periurban and Rural areas of Niger. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e83175.

- Ali S, Akhter S, Neubauer H, Melzer F, Khan I, Abatih EN, et al. Seroprevalence and risk factors associated with bovine brucellosis in the Potohar Plateau, Pakistan. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):73.

- Khan MR, Rehman A, Khalid S, Ahmad MUD, Avais M, Sarwar M, et al. Seroprevalence and Associated Risk factors of bovine brucellosis in District Gujranwala, Punjab, Pakistan. Animals. 2021;11(6):1744.

- Rodriguez-Morales J. A. Climate change, climate variability and brucellosis. Recent patents on anti-infective drug discovery. 2013;8(1):4-12.

- Khan I, Ali S, Hussain R, Raza A, Younus M, Khan N, et al. Serosurvey and potential risk factors of brucellosis in dairy cattle in peri-urban production system in Punjab, Pakistan. Pak Vet J. 2021;41(3):459-62.

- Bakhtullah FP, Shahid M, Basit A, Khan MA, Gul S, Wazir I, et al. Sero-prevalence of brucellosis in cattle in southern area of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Res J Vet Pract. 2014;2(4):63-6.

- Ahmad T, Khan I, Razzaq S, Akhtar R. Prevalence of bovine brucellosis in Islamabad and rawalpindi districts of Pakistan. Pakistan J Zool. 2017;49(3).

- Sima DM, Ifa DA, Merga AL, Tola EH. Seroprevalence of bovine brucellosis and Associated Risk factors in Western Ethiopia. Veterinary Medicine: Research and Reports. 2021;12:317.

- Haileselassie M, Kalayou S, Kyule M, Asfaha M, Belihu K. Effect of Brucella infection on reproduction conditions of female breeding cattle and its public health significance in Western Tigray, northern Ethiopia. Veterinary medicine international. 2011;2011.

- Saeed U, Ali S, LatifT, Rizwan M, Iftikhar A, Ghulam Mohayud Din Hashmi S, et al. Prevalence and spatial distribution of animal brucellosis in central Punjab, Pakistan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6903.

- Patel M, Patel P, Prajapati M, Kanani A, Tyagi K, Fulsoundar A. Prevalence and risk factor’s analysis of bovine brucellosis in peri-urban areas under intensive system of production in Gujarat, India. Vet World. 2014;7(7):509-16.

- França T, Ishikawa L, Zorzella-Pezavento S, Chiuso-Minicucci F, da Cunha MdLRdS, Sartori A. Impact of malnutrition on immunity and infection. J Venom Anim Toxins Including Trop Dis. 2009;15(3):374-90.

- Rahman M, Faruk M, Her M, Kim J, Kang S, Jung S. Prevalence of brucellosis in ruminants in Bangladesh. Vet Med. 2011;56(8):379-85.

- Deka RP, Shome R, Dohoo I, Magnusson U, Randolph DG, Lindahl JF. Seroprevalence and risk factors of Brucella infection in dairy animals in urban and rural areas of Bihar and Assam, India. Microorganisms. 2021;9(4):783.

- Aulakh H, Patil P, Sharma S, Kumar H, Mahajan V, Sandhu K. A study on the epidemiology of bovine brucellosis in Punjab (India) using milk-ELISA. Acta Vet Brno. 2008;77(3):393-9.

- Khan AU, Sayour AE, Melzer F, El-Soally SAGE, Elschner MC, Shell WS, et al. Seroprevalence and molecular identification of Brucella spp. in camels in Egypt. Microorganisms. 2020;8(7):1035.

- Dinka H, Chala R. Seroprevalence study of bovine brucellosis in pastoral and agro-pastoral areas of East Showa Zone, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. American-Eurasian J Agricultural Environ Sci. 2009;6(5):508-12.

- Garry F. Chapter 15 – Miscellaneous Infectious Diseases. In: Divers TJ, Peek SF, editors. Rebhun’s Diseases of Dairy Cattle (Second Edition). Saint Louis: W.B. Saunders; 2008. p. 606-39.

- Batista HR, Passos CTS, Nunes Neto OG, Sarturi C, Coelho APL, Moreira TR, et al. Factors associated with the prevalence of antibodies against Brucella abortus in water buffaloes from Santarém, Lower Amazon region, Brazil. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2020;67(S2):44-8.

- Cárdenas L, Peña M, Melo O, Casal J. Risk factors for new bovine brucellosis infections in Colombian herds. BMC Vet Res. 2019;15(1):81.

- Arif S, Thomson PC, Hernandez-Jover M, McGill DM, Warriach HM, Hayat K, et al. Bovine brucellosis in Pakistan; an analysis of engagement with risk factors in smallholder farmer settings. Veterinary Med Sci. 2019;5(3):390-401.

- Pourhoseingholi MA, Vahedi M, Rahimzadeh M. Sample size calculation in medical studies. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2013;6(1):14-7.

- Probert WS, Schrader KN, Khuong NY, Bystrom SL, Graves MH. Real-time multiplex PCR assay for detection of <i>Brucella spp., <i>B. Abortus, and B. melitensis. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(3):1290-3.

Publisher’s Note

Mian Muhammad Awais and Gohar Khadim contributed equally to this work and share the 1st authorship.

*Correspondence:

Mian Muhammad Awais

drawaisuaf@gmail.com; muhammadawais@bzu.edu.pk

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article