المجلة: Humanities and Social Sciences Communications، المجلد: 12، العدد: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04334-1

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-02

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04334-1

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-02

دور التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال في توقعات التعليم للأطفال الصينيين المتروكين في الريف: تحليل الوساطة المعدل

الوالدان هما أكثر المؤثرين قربًا وتأثيرًا على تطور الطفل. قد تشكل غياب الوالدين بسبب الهجرة في الريف الصيني تهديدًا كبيرًا لتطور التعليم للأطفال المتروكين بسبب نقص التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال. على الرغم من تزايد الاهتمام الأكاديمي، إلا أننا نعرف القليل عن تأثير هجرة الوالدين على التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال أو توقعات التعليم للطلاب الريفيين من حالات ترك مختلفة (أي، ترك من قبل كلا الوالدين؛ ترك من قبل أحد الوالدين؛ أو العيش مع كلا الوالدين). استنادًا إلى البيانات الطولية من مسح التعليم في الصين (

مقدمة

أدى التوسع الاقتصادي السريع في الصين والتحضر بعد إصلاحها الاقتصادي الذي فتح الأبواب، إلى جانب رفع قيود الهجرة الداخلية، إلى حركة غير مسبوقة من الريف إلى المدينة. في عام 2021، انتقل حوالي 292 مليون عامل ريفي إلى المدن بحثًا عن عمل (المكتب الوطني للإحصاء في الصين (2022)). بسبب نظام تسجيل الأسر المزدوج (هوكو) وآلية توزيع الموارد العامة المعتمدة على المكان، لا يُمنح المهاجرون الريفيون الذين ليس لديهم مواطنة حضرية الوصول إلى الخدمات الاجتماعية في مدنهم المضيفة (هي وآخرون 2022). كما أن أطفالهم الريفيين لديهم وصول محدود إلى التعليم العام الحضري (وانغ وزو، 2021؛ تشن وزو، 2024). وبالتالي، على الرغم من الزيادة الطفيفة في عدد الأطفال الريفيين الذين ينتقلون مع والديهم المهاجرين إلى المدن، لا تزال الهجرة الفردية أو هجرة الوالدين فقط (مع ترك الأطفال في القرى) هي السائدة (جين وآخرون 2017). هنا، نعرف “الأطفال المتروكين في الريف” على أنهم الأطفال الذين تقل أعمارهم عن 18 عامًا والذين تُركوا في مواقع أسرهم المسجلة الأصلية عندما يهاجر أحد الوالدين أو كلاهما إلى المناطق الحضرية للعمل (دونغ وآخرون، 2019).

على الرغم من النمو السريع في الاقتصاد الريفي للبلاد، لا تزال هناك فجوة كبيرة بين الريف والحضر في تطوير الطلاب، حيث يظهر الطلاب الريفيون تحصيلًا أكاديميًا أقل، ورفاهية اجتماعية وعاطفية، ودرجات معرفية، وقدرات غير معرفية (عباسي وآخرون 2022؛ تشن وآخرون 2015؛ لو (2012)). بدون مشاركة كافية من الوالدين، يكون الطلاب المتروكون في الريف أكثر عرضة للخطر من أقرانهم غير المتروكين في هذه الجوانب (هانيوم وآخرون 2018؛ هونغ، 2021؛ وين وآخرون 2023). يمثل الطلاب المتروكون أكثر من خُمس إجمالي عدد الأطفال في البلاد (شياو وآخرون 2020)، وتطورهم التعليمي لا يحدد فقط مساراتهم المهنية اللاحقة والتنقل الاجتماعي – بل يؤثر أيضًا على الاستدامة الاقتصادية والانتقال الاجتماعي للبلاد ككل (وو وتشين، 2022).

يلعب الوالدان دورًا مميزًا في التطور الشامل للطفل. إنهم أكثر المؤثرين قربًا وتأثيرًا على هوية الطفل وتطور شخصيته (سيد وسيفج كرينكي، 2013). التفاعل، والإرشاد، والحماية، والرعاية من الوالدين أمر حاسم لنمو الأطفال البدني والاجتماعي والمعرفي والعاطفي (بيرين وآخرون 2016). بالنسبة للتطور التعليمي بشكل خاص، تجعل هويات الوالدين المزدوجة (أي، كأوصياء وكمعلمين) منهم نماذج يحتذى بها لأطفالهم (تشكا وموراتي، 2016). تحدد قيمهم وسلوكهم وتفاعلاتهم مناخ التطور الأسري، الذي يشكل بدوره نتائج تطور الطفل (ميلبي وآخرون 2008).

في الريف الصيني، على الرغم من أن نظريات الهجرة قد تقترح أن هجرة الوالدين ستؤدي إلى تراكم في رأس المال الاقتصادي الأسري وتمكن من زيادة الاستثمار المالي الأسري في التعليم الرسمي وغير الرسمي للأطفال المتروكين، يبدو أن غياب مشاركة الوالدين نتيجة للهجرة قد أضر بالأطفال المتروكين من حيث التطور التعليمي. إنهم يتلقون تواصلًا أقل بين الوالدين والأطفال، ورعاية بدنية، وإشرافًا من الوالدين (عباسي وآخرون 2023؛ هو، 2019؛ روزيل وهيل، 2020). على سبيل المثال، كشفت دراسة تشاو وتشين (2022) أن متوسط درجة التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال بين الأطفال المتروكين في الريف هو

نتائج التعليم للطلاب (وين ولين، 2012). على سبيل المثال، أظهر الأطفال المتروكون في الصين الذين لا يتلقون تواصلًا كافيًا بين الوالدين والأطفال توقعات تعليمية منخفضة وكفاءة ذاتية (هونغ وفولر، 2019).

نتائج التعليم للطلاب (وين ولين، 2012). على سبيل المثال، أظهر الأطفال المتروكون في الصين الذين لا يتلقون تواصلًا كافيًا بين الوالدين والأطفال توقعات تعليمية منخفضة وكفاءة ذاتية (هونغ وفولر، 2019).

تشدد الأدبيات الحالية على أهمية مشاركة الوالدين في تطوير التعليم للأطفال الريفيين وتقترح التأثير السلبي لهجرة الوالدين على مشاركتهم الوالدية المستلمة، والتي يُعتقد بدورها أنها تضر بالتطور التعليمي (زوانغ وآخرون 2024؛ هونغ وفولر، 2019؛ جين وآخرون 2020؛ وانغ، 2014). ومع ذلك، لم تُبذل جهود أكاديمية كبيرة لفك هذا التعقيد وتحديد العلاقات المتبادلة بين هجرة الوالدين، ومشاركة الوالدين، وتطور التعليم للطلاب في الريف الصيني. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، على الرغم من زيادة الدراسات المخصصة للتحقيق في تطوير التعليم للطلاب المتروكين في الريف الصيني، يقتصر العديد منها على هذه الفئة الفرعية على أولئك الذين تُركوا من قبل كلا الوالدين (على سبيل المثال، فو وآخرون 2024؛ شياو وليو 2023). مثل هذا التعريف يستبعد بشكل منهجي الأطفال الريفيين الذين تُركوا بمفردهم من قبل أحد الوالدين ويعيشون مع الوالد الآخر؛ بالنسبة لهؤلاء الأطفال، قد تتأثر مشاركة الوالدين وتطور التعليم أيضًا بهجرة الوالدين ولكن بطرق أقل وضوحًا (سو وآخرون 2017؛ جوانغ وآخرون 2017).

لأسبابٍ عديدة، واستنادًا إلى البيانات الطولية من مسح التعليم الوطني الممثل للصين (CEPS)، تسعى هذه الدراسة إلى الإسهام في الأدبيات من خلال تحديد العلاقة بين التواصل بين الوالدين والأبناء، وهو عنصر أساسي من المشاركة الأبوية، والتوقعات التعليمية، وهو مؤشر حاسم للنتائج التعليمية، بين المراهقين الريفيين الذين لديهم خصائص مختلفة من ترك الأهل (أي، الأطفال الذين تُركوا من قبل كلا الوالدين، LBCB؛ الأطفال الذين تُركوا من قبل أحد الوالدين، LBCS؛ والأطفال غير المتروكين، NLBC). لتحقيق ذلك، نفحص العلاقة بين التواصل بين الوالدين والأبناء وتوقعات الأطفال التعليمية في السياق الريفي الصيني. على وجه التحديد، ندرس كيف تختلف مجموعات المراهقين الريفيين المختلفة من حيث التواصل بين الوالدين والأبناء، مع تأثيرات إضافية على توقعاتهم التعليمية. وهذا يمكننا من تحديد التأثير الوسيط للتواصل بين الوالدين والأبناء على العلاقة بين حالة ترك الأهل للطلاب الريفيين وتوقعاتهم التعليمية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، ننظر أيضًا في كيفية اختلاف العلاقة بين التواصل بين الوالدين والأبناء وتوقعات التعليم بين مجموعات الطلاب الريفيين المختلفة. وبالتالي، نفحص التأثير المعدل لحالة ترك الأهل للأطفال الريفيين على العلاقة بين تواصلهم مع الوالدين وتوقعاتهم التعليمية.

مراجعة الأدبيات

التوقعات التعليمية. يُعرف التوقع التعليمي بأنه أعلى مستوى تعليمي يُتوقع أن يحققه الفرد (Wells et al. 2013). إنه يعكس تقييم الطلاب لقدراتهم الأكاديمية ونجاحهم السابق بالإضافة إلى التقييم الذاتي للتحديات والفرص المتاحة والدعم الخارجي (Andres et al. 2007). تستند المناقشات الأكاديمية حول التوقعات التعليمية إلى نموذج ويسكونسن لتحقيق المكانة، حيث يتم التأكيد على تأثيره الوسيط على العلاقة بين الظروف الخارجية وإنجاز الفرد التعليمي والمهني (Bozick et al. 2010؛ Kristensen et al. 2009). تتشكل توقعات الطلاب التعليمية من خلال عملية التأمل الذاتي بناءً على التفاعل مع الأشخاص المهمين في حياتهم، بما في ذلك والديهم ومعلميهم وأقرانهم (Yuan and Olivos, 2023؛ Nurmi, 2004). تعكس هذه الصورة إلى حد ما مفاهيم بورديو عن العادات ورأس المال الاجتماعي/الثقافي. القيم التعليمية الأبوية وبيئات التعلم المنزلية المتجذرة بعمق في التوجهات الأسرية تشكل توقعات الأطفال التعليمية ومعتقداتهم من خلال عملية الأسرة

التواصل (Coleman, 2001). بين الأسر الريفية الصينية، تساهم التوقعات التعليمية العالية والإيجابية التي يدركها الطلاب الريفيون من الآباء في توقعاتهم التعليمية ودافعهم الداخلي للتعلم (Chen et al. 2023). وهذا يتماشى مع التوقعات العالية الفريدة بين الأطفال المهاجرين في جميع أنحاء العالم (Feliciano and Lanuza, 2016؛ Portes et al. 2010؛ Goyette and Xie, 1999). على سبيل المثال، أشار تحليل Feliciano وLanuza (2016) إلى أن الموارد الثقافية الغنية (مثل: التوقعات العالية من الوالدين، الاهتمام بالمدرسة، وأخلاقيات الالتزام) التي يمتلكها الأطفال في الأسر المهاجرة تساهم في توقعاتهم الأكاديمية العالية.

التواصل (Coleman, 2001). بين الأسر الريفية الصينية، تساهم التوقعات التعليمية العالية والإيجابية التي يدركها الطلاب الريفيون من الآباء في توقعاتهم التعليمية ودافعهم الداخلي للتعلم (Chen et al. 2023). وهذا يتماشى مع التوقعات العالية الفريدة بين الأطفال المهاجرين في جميع أنحاء العالم (Feliciano and Lanuza, 2016؛ Portes et al. 2010؛ Goyette and Xie, 1999). على سبيل المثال، أشار تحليل Feliciano وLanuza (2016) إلى أن الموارد الثقافية الغنية (مثل: التوقعات العالية من الوالدين، الاهتمام بالمدرسة، وأخلاقيات الالتزام) التي يمتلكها الأطفال في الأسر المهاجرة تساهم في توقعاتهم الأكاديمية العالية.

في خطاب التوقعات التعليمية بين الطلاب الريفيين الصينيين، بينما يقيد الوضع الاجتماعي والاقتصادي المنخفض نسبيًا للأسر الريفية الاستثمار المالي الملموس للآباء في تعليم أطفالهم، فإن العوامل الأسرية غير المالية (مثل: التواصل بين الوالدين والأبناء، ورعاية الوالدين والوقت، والتربية السلطوية، وإشراف الوالدين) هي الطرق الحاسمة لتعزيز توقعات الطلاب الريفيين التعليمية (Xu and Montgomery, 2021؛ Chen et al. 2023). علاوة على ذلك، بين هذه العوامل الأبوية الحاسمة، يبرز التواصل بين الوالدين والأبناء عندما يتم اعتبار سكان الطلاب المتروكين (Liu and Leung, 2017). تقيد الانفصال الأسري الناتج عن الهجرة مشاركة الآباء المهاجرين جسديًا في تعليم أطفالهم المتروكين؛ بدلاً من ذلك، تعتبر المحادثات عبر الإنترنت (مكالمات صوتية/مرئية أو رسائل نصية) هي الطريقة التي يحافظون بها على الروابط الأسرية وينقلون قيمهم وتوقعاتهم التعليمية (Ye and Pan, 2011). في هذا السياق، تفحص هذه الدراسة تأثير هجرة الوالدين على التواصل بين الوالدين والأبناء وكذلك الروابط بين التواصل بين الوالدين والأبناء وتوقعات التعليم، بين الأطفال الريفيين ذوي الخصائص المختلفة من ترك الأهل.

يعزز التواصل بين الوالدين والأبناء توقعات الطلاب التعليمية. التواصل بين الوالدين والأبناء هو التواصل، سواء كان لفظيًا أو غير لفظي، بين الآباء والأبناء الذي يحدث داخل النظام الأسري (Munz, 2015). إنه مؤشر مهم على العلاقة بين الوالدين والأبناء، وجودته تعكس قوة الحميمية والثقة بين الأطفال ووالديهم (Laursen and Collins, 2004). كما أنه أحد العوامل الأسرية الرئيسية التي تؤثر على توقعات الطلاب التعليمية (Seginer and Vermulst, 2002). هناك نهجان في هذا الصدد. أولاً، تعتبر المحادثات الأسرية بين جيلين قنوات حاسمة لنقل المواقف والقيم والممارسات عبر الأجيال. إحدى المبادئ النظرية الشائعة، كما تم التأكيد عليه في نظرية التعلم الاجتماعي لألبرت باندورا ونظرية نظام الأسرة لموراي بوين، هي الدور المحوري الذي تلعبه التنشئة الاجتماعية الأسرية في تشكيل وجهات نظر الطفل وشخصيته (Bandura (1997)؛ McGinnis and Wright, 2023). تعتبر الملاحظات والانطباعات من التفاعلات الاجتماعية مع الأشخاص المهمين جزءًا لا يتجزأ من إدراك الطفل (Froiland et al. 2013). يعمل الآباء كـ ‘موجهين للتوقعات’ ونماذج يحتذى بها للأطفال (Rumberger, 1983). ضمن الإعداد الأسري ومن خلال الاتصالات الأسرية، يمكن للآباء أن يتواصلوا بشكل مباشر وصريح توقعاتهم التعليمية وبالتالي يساعدون الأطفال في تأسيس مواقفهم التعليمية الخاصة (Fan and Chen, 2001). من خلال التواصل غير المباشر، يمكنهم نقل مواقفهم التعليمية المعترف بها وقيمهم وزرع قيم الأطفال التعليمية الخاصة بهم ومفهوم النجاح الأكاديمي (Nihal Lindberg et al. 2019).

ثانيًا، لا تتشكل مواقف الطلاب التعليمية فقط من خلال بيئتهم الاجتماعية والثقافية الخارجية ولكن تختلف وفقًا لحالتهم النفسية الداخلية (Rothon et al. 2011). من المعروف على نطاق واسع في الأدبيات التعليمية أن الأطفال الذين يتمتعون برفاهية نفسية أفضل يظهرون توقعات تعليمية أعلى، وكفاءة ذاتية، ودافع للتعلم (Ma et al. 2018). في

هذا السياق، يمكن أن يوفر التواصل المفتوح المتكرر بين الوالدين والأبناء للأطفال رعاية أبوية ودفء، مما يحفز بدوره الكفاءة الذاتية وتقدير الذات في التعلم (Bireda and Pillay, 2018؛ Ying et al. 2018). يعتبر هذا التواصل الإيجابي بين الوالدين والأبناء ذا أهمية خاصة للأطفال المتروكين. كشفت الدراسات الدولية أن غياب الوالدين من المحتمل أن يسبب للأطفال اضطرابًا عاطفيًا ويعطل جهودهم التعليمية ويجعلهم يشعرون بخيبة الأمل (Lu (2012)؛ Ren and Treiman, 2016؛ Coe, 2014). أظهر تحليل مقارن أن الأطفال الريفيين الصينيين الذين لديهم والدين مهاجرين، مقارنة بالأطفال غير المتروكين، عانوا من مستوى معيشة أقل ورضا أكاديمي أقل وإحساس أكبر بالوحدة (Su et al. 2013). ومع ذلك، لاحظ المؤلفون أن التواصل الكافي بين الوالدين والأبناء يمكن أن يكون عامل حماية كبير للأطفال المتروكين. يمكن أن يعوض التأثير السلبي لهجرة الوالدين على الرفاهية النفسية وإدراك الحياة إلى حد ما ويحسن توقعات الأطفال المتروكين الأكاديمية، وتقدير الذات، والانخراط في المدرسة، ورضا الحياة (Goings and Shi, 2018؛ Wang et al. 2019؛ Su et al. 2013؛ Sun et al. 2015).

هذا السياق، يمكن أن يوفر التواصل المفتوح المتكرر بين الوالدين والأبناء للأطفال رعاية أبوية ودفء، مما يحفز بدوره الكفاءة الذاتية وتقدير الذات في التعلم (Bireda and Pillay, 2018؛ Ying et al. 2018). يعتبر هذا التواصل الإيجابي بين الوالدين والأبناء ذا أهمية خاصة للأطفال المتروكين. كشفت الدراسات الدولية أن غياب الوالدين من المحتمل أن يسبب للأطفال اضطرابًا عاطفيًا ويعطل جهودهم التعليمية ويجعلهم يشعرون بخيبة الأمل (Lu (2012)؛ Ren and Treiman, 2016؛ Coe, 2014). أظهر تحليل مقارن أن الأطفال الريفيين الصينيين الذين لديهم والدين مهاجرين، مقارنة بالأطفال غير المتروكين، عانوا من مستوى معيشة أقل ورضا أكاديمي أقل وإحساس أكبر بالوحدة (Su et al. 2013). ومع ذلك، لاحظ المؤلفون أن التواصل الكافي بين الوالدين والأبناء يمكن أن يكون عامل حماية كبير للأطفال المتروكين. يمكن أن يعوض التأثير السلبي لهجرة الوالدين على الرفاهية النفسية وإدراك الحياة إلى حد ما ويحسن توقعات الأطفال المتروكين الأكاديمية، وتقدير الذات، والانخراط في المدرسة، ورضا الحياة (Goings and Shi, 2018؛ Wang et al. 2019؛ Su et al. 2013؛ Sun et al. 2015).

تظهر علاقة إيجابية بين التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال وموقف الأطفال التعليمي بشكل واضح بين الأسر الصينية الريفية. هنا، يجب ملاحظة جانبين مهمين من السياق الصيني لفهم أفضل للتوقعات التعليمية بين الطلاب الريفيين الصينيين. أولاً، لا يزال مفهوم البر بالوالدين سائداً في المجتمع الصيني: آلية التبادل بين الأجيال (مثل تربية الأطفال كـ “تأمين” للشيخوخة) تستمر بين الأجيال (غوه، 2011). ثانياً، من المحتمل أن يولي الآباء والأطفال الصينيون أهمية كبيرة للتعليم ويربطون النجاح التعليمي بالتحصيل المهني العالي والوضع الاجتماعي والاقتصادي بسبب معتقداتهم الكونفوشيوسية المتجذرة (كونغ 2015). يعتقد الكثيرون اعتقاداً راسخاً أن التعليم هو الطريق إلى النجاح المهني في المستقبل. نظراً لأن معظم الآباء الريفيين الصينيين يعلقون أهمية كبيرة على التعليم ولديهم توقعات عالية لتعليم أطفالهم (لي وشيا، 2020)، فإن التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال هو قناتهم لنقل القيم التعليمية وبناء توقعات تعليمية خاصة بالأطفال (تشن وآخرون 2023). تعتبر دراسة شيو ومونتغومري (2021) النوعية حول وصول الطلاب الريفيين الصينيين إلى الجامعات النخبوية مثالاً بارزاً. على الرغم من أن الآباء الريفيين مقيدون في قدرتهم على الاستثمار اقتصادياً في تعليم أطفالهم، فإن تعبيرهم اللفظي عن توقعات عالية لأطفالهم وطرق التعليم إلى الجامعات النخبوية يمكن أن يحول ضعف أسرهم المالي إلى قوة – دافع للتعلم وطموحات لتحقيق الإنجازات التعليمية.

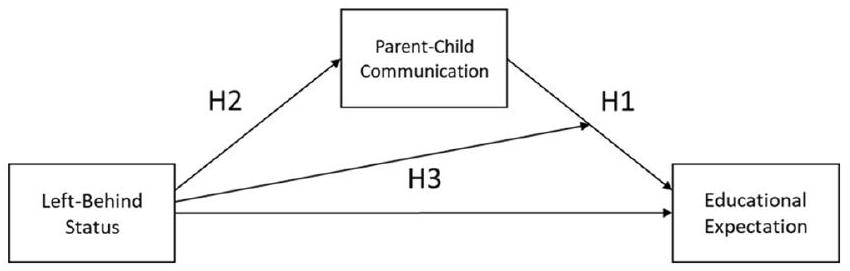

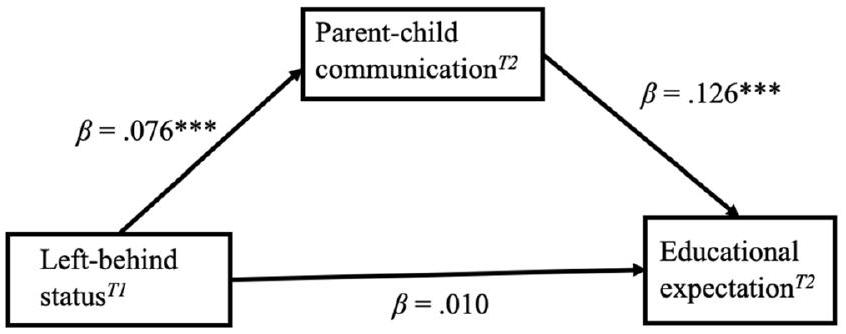

باختصار، يعمل التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال كقناة للآباء لنقل التوقعات التعليمية والقيم والرعاية لأطفالهم. في السياق الصيني، نظراً لأن الآباء عمومًا يحملون موقفًا إيجابيًا تجاه التعليم، فإن المزيد من التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال قد يسهل بشكل أفضل نقل التوقعات التعليمية من الآباء الريفيين إلى أطفالهم ويؤدي إلى توقعات تعليمية أعلى بين هؤلاء الأطفال. لذلك، نقترح الفرضية التالية (انظر الشكل 1):

الشكل 1 النموذج المفاهيمي حول علاقات الوساطة المعتدلة بين حالة الأطفال المتروكين، والتواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال، والتوقعات التعليمية.

الفرضية

التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال عبر مجموعات ريفية مختلفة. بينما يتم التعرف على العلاقة الإيجابية بين التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال وتوقعات الطلاب الريفيين التعليمية، قد تؤثر هجرة الآباء على توقعات الطلاب الريفيين التعليمية بسبب انخفاض التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال. أسباب هذا الانخفاض في التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال مزدوجة. أولاً، تعني الفجوة الجسدية الناتجة عن الهجرة بين الوالدين المهاجرين وأطفالهم المتروكين تقليل الاتصال المباشر. خاصة بالنسبة للآباء الذين ينتقلون عبر خطوط المقاطعات، فإن عيد رأس السنة الصينية هو تقريبًا الوقت الوحيد في السنة الذي يمكنهم فيه العودة إلى الوطن ومقابلة أطفالهم شخصيًا (يي وبان، 2011). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، على الرغم من أن الأطفال المتروكين يعيشون مع أحد الوالدين، فإن تواصلهم بين الوالدين والأطفال يميل إلى أن يكون ضئيلاً. غالبًا ما لا يكون الآباء غير المهاجرين الذين يقيمون مع أطفالهم في القرى الريفية ربات بيوت أو ربات منازل، بل عمال بدوام كامل (مثل العمل الزراعي أو الوظائف اليومية المدفوعة في الصناعة المحلية/البناء) (مورفي، 2020). وقتهم وطاقتهم للتواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال بعد العمل محدودة.

ثانيًا، بديل للمحادثة المباشرة بين الوالدين المهاجرين وأطفالهم المتروكين هو التواصل عبر الإنترنت. أظهرت دراسة أن حوالي تسعين في المئة من التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال بين الآباء المهاجرين الصينيين وأطفالهم المتروكين يحدث افتراضيًا (دوان وآخرون 2014). ومع ذلك، من المحتمل أن يشارك الآباء المهاجرون في المدن في وظائف ثانوية وخدمية ذات أجر منخفض تتميز بجدول عمل غير منتظم وساعات عمل طويلة (رين وآخرون 2017). هذا يقيد التواصل عبر الإنترنت بين الآباء المهاجرين وأطفالهم المتروكين (لي ولي، 2007؛ تونغ وآخرون 2015). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، هناك نقص في الأجهزة الذكية في الأسر الريفية لاستخدامها في التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال (شيو، 2016)، لكن هذا ليس فقط لأسباب مالية. على الرغم من أن العديد من الآباء المهاجرين قادرون على شراء أجهزة ذكية، فإنهم يختارون عدم القيام بذلك، لسببين رئيسيين. أولاً، عندما ينتقل كلا الوالدين إلى المدن للعمل، قد لا يعرف الأجداد المسنون والأطفال المتروكون كيفية استخدام الأجهزة الذكية (يي وبان، 2011). ثانيًا، على الرغم من أن بعض الأطفال المتروكين أو الأطفال المتروكين قد أتقنوا مهارات الهاتف الأساسية، قد يقيد والديهم وصولهم إلى الأجهزة الذكية لأن إدمان الإنترنت والانحرافات الشبابية ذات الصلة تمثل مصدر قلق كبير بين الأطفال المتروكين دون إشراف ورعاية كافية من الوالدين (شيو، 2016؛ رين وآخرون 2017).

وثقت الدراسات التجريبية مستوى أقل من التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال بعد هجرة الآباء (وانغ وآخرون 2019؛ تشاو وتشين، 2022؛ سو وآخرون 2013؛ وانغ وآخرون 2015؛ سو وآخرون 2017). على سبيل المثال، وجدت التحليل المقارن لتشاو وتشين (2022)، باستخدام مجموعة بيانات تمثيلية وطنية، أن متوسط درجة التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال للأطفال المتروكين كان

الفرضية

بالنظر إلى

الدور المعتدل لحالة الأطفال المتروكين. بخلاف النطاق المنخفض، لاحظت الدراسات أن هجرة الآباء تؤثر أيضًا على محتوى وعمق التواصل بين الوالدين المهاجرين وأطفالهم المتروكين (وانغ وآخرون 2015؛ وانغ وآخرون 2019). كشفت دراسة ليو وليونغ (2017) شملت 378 والدًا مهاجرًا من جنوب الصين أن تواصل الآباء المهاجرين مع أطفالهم يميل إلى أن يكون قصيرًا وسطحياً وفوريًا، غالبًا لأغراض الوصول الفوري والطمأنينة، والمعاملات عبر الإنترنت، والمودة، والاسترخاء. كان لدى يي وبان (2011) نفس الملاحظة – أن التواصل الذي يبدأه الآباء المهاجرون يركز على الصحة والسلامة. قد يسألون فقط عن روتينهم اليومي وأدائهم الأكاديمي ولا يشاركون في محادثات أعمق معهم بشأن الأحداث في المدرسة. أفاد ما يقرب من ثلاثة أرباع الطلاب المتروكين الذين شاركوا في استبيان يي وبان (2011) أن محادثاتهم عبر الإنترنت مع آبائهم المهاجرين استمرت

بعيدًا عن قيودها في النقل المباشر للقيم التعليمية بين الأجيال، يهدد التواصل السطحي بين الوالدين المهاجرين وأطفالهم المتروكين الروابط العائلية. اقترحت الدراسة التي أجراها دوان وآخرون (2014) أن

قد تهدد التواصل عبر الإنترنت بين الآباء والأبناء ليس فقط الصحة النفسية للأطفال المتروكين، ولكن أيضًا إدراكهم التعليمي. الأطفال الذين يفشلون في فهم جهود والديهم المهاجرين لتحسين الوضع الاقتصادي للأسرة قد يشعرون بالتخلي ويعانون من التوتر لأنهم يدركون نقص الدعم في تحقيق أهدافهم الأكاديمية (ليانغ وما 2004؛ تشين وآخرون 2023). وبالتالي، بالإضافة إلى فرضيتينا الأوليين، نتوقع أيضًا أن عدد الآباء المقيمين قد يعزز تأثير التواصل بين الآباء والأبناء على توقعات الأطفال التعليمية. وبناءً عليه، نفترض أن (انظر الشكل 1):

فرضية

المنهجية

البيانات. تستند الدراسة إلى بيانات طولية من CEPS (الموجتين الأولى والثانية). تم إطلاق CEPS من قبل مركز أبحاث المسح الوطني في جامعة رينمين في الصين، وهو مسح longitudinal تمثيلي على مستوى البلاد في الصين. يجمع معلومات شاملة من طلاب المدارس المتوسطة، وأولياء أمورهم، والمعلمين، ويحقق في تأثير السياقات الأسرية، وعمليات المدرسة، وهياكل المجتمع والمجتمع على نتائج التعليم للطلاب (شين 2020). سمة أخرى حاسمة لـ CEPS هي أنه يحتوي على موجتين من البيانات. تتيح لنا البيانات الطولية فحص التأثير الزمني لـ اليسار-

خلفية الوضع حول تواصل الآباء والأبناء لدى الطلاب الريفيين وتوقعاتهم التعليمية، والتي قد تكون أفضل من التأثير المتزامن. يتم تقديم تفاصيل حول التحكم في التأثيرات الذاتية في القسم الخاص باستراتيجية التحليل.

خلفية الوضع حول تواصل الآباء والأبناء لدى الطلاب الريفيين وتوقعاتهم التعليمية، والتي قد تكون أفضل من التأثير المتزامن. يتم تقديم تفاصيل حول التحكم في التأثيرات الذاتية في القسم الخاص باستراتيجية التحليل.

تم تطبيق طريقة أخذ العينات متعددة المراحل مع احتمالات تتناسب مع الحجم. في البداية، تم اختيار 28 وحدة أخذ عينة أولية من إجمالي 2870 مقاطعة أو منطقة من نفس المستوى. ثانياً، تم اختيار أربع مدارس من جميع المدارس التي تخدم الصفين السابع والتاسع ضمن الـ 28 وحدة أخذ عينة أولية. في المرحلة الثالثة، تم اختيار فصلين دراسيين من الصف السابع وفصلين دراسيين من الصف التاسع بشكل عشوائي من كل مدرسة عينة. أخيراً، تم دعوة جميع الطلاب من الفصل المختار لإكمال الاستبيان، الذي تم إدارته في شكل استبيان.

المشاركون. شملت دراسة الموجة الأولى 19,487 طالبًا في الصف السابع والتاسع في 2013-2014. تم إجراء دراسة الموجة الثانية بعد عام واحد مع 10,279 طالبًا من الصف السابع فقط من دراسة الموجة الأولى. من بين هؤلاء، تم متابعة 9449 طالبًا بنجاح، بينما فقد 830 طالبًا بسبب الانتقال إلى مدارس أخرى والانسحاب. في موجة 2013-2014، كان 7997 من هؤلاء

إجراءات

حالة الأطفال المتروكين. تشير حالة الأطفال المتروكين إلى عدد الآباء الذين يعيشون معهم في القرى الريفية. تم تصنيف الطلاب الريفيين إلى أطفال غير متروكين يعيشون مع كلا الوالدين (NLBC؛ حالة المتروكين

| الجدول 1 الخصائص السكانية للمشاركين. | ||

| الخصائص السكانية | التردد (

|

نسبة مئوية (%) |

| جنس | ||

| ذكر | ١١٢٥ | 50.6 |

| أنثى | 1099 | ٤٩.٤ |

| عمر | ||

| 12 | 63 | 2.8 |

| ١٣ | 1009 | ٤٥.٢ |

| 14 | 938 | 42.1 |

| 15 | 187 | ٨.٤ |

| 16 | 31 | 1.4 |

| 17 | 1 | 0.04 |

| 18 | 1 | 0.04 |

| حالة الطفل الوحيد | ||

| طفل وحيد | 612 | ٢٦.٩ |

| غير الطفل الوحيد | 1663 | 73.1 |

| حالة المتروكين (عدد الوالدين المقيمين) | ||

| 0 | ٣٣٠ | 14.5 |

| 1 | 297 | 13.1 |

| 2 | 1648 | 72.4 |

التواصل بين الوالدين والطفل. تم قياس التواصل بين الوالدين والطفل في الموجة الأولى باستخدام 10 عناصر. طُلب من المشاركين تقييم تكرار تواصل والديهم (الأب والأم بشكل منفصل؛ خمسة أسئلة لكل منهما) معهم بشأن الأمور التي حدثت في المدرسة، وعلاقاتهم مع الأصدقاء، وعلاقاتهم مع المعلمين، ومزاجهم، وأفكارهم ومشاكلهم. تم حذف السؤال الرابع (المزاج) من الموجة الأولى في الموجة الثانية. لجعل مقاييس التواصل بين الوالدين والطفل في الموجتين قابلة للمقارنة، قمنا بإزالة السؤال الرابع من الموجة الأولى واختيار نفس الأسئلة الأربعة (8 عناصر إجمالاً) لبناء مقياس التواصل بين الوالدين والطفل. تم استخدام مقياس مشابه في دراسات سابقة لقياس التواصل بين الوالدين الصينيين في المناطق الريفية وأطفالهم (على سبيل المثال، سو وآخرون 2013). أظهر مقياسنا المكون من 8 عناصر موثوقية جيدة في كلا الموجتين.

التوقعات التعليمية. تُعرّف التوقعات التعليمية على أنها المستوى الذي يرغب الأفراد في تحقيقه في المدرسة. في كلا الموجتين، تم قياس توقعات المراهقين التعليمية من خلال عنصر واحد (ما هو أعلى مستوى من التعليم تتوقع أن تحصل عليه؟)، والذي تم تطبيقه على نطاق واسع في الدراسات الدولية (فليسيانو، 2006؛ ريمكوتي وآخرون، 2012؛ يو وداراغانوفا، 2015). كانت الإجابات المحتملة هي “التسرب الآن”، “التخرج من المدرسة الإعدادية”، “الذهاب إلى المدرسة الثانوية الفنية أو المدرسة الفنية”، “الذهاب إلى المدرسة الثانوية المهنية”، “الذهاب إلى المدرسة الثانوية العامة”، “التخرج من الكلية المتوسطة”، “الحصول على درجة البكالوريوس”، و”الحصول على درجة الماجستير”، و”الحصول على درجة الدكتوراه”. تم ترميز الردود بشكل مستمر من 1 (التسرب الآن) إلى 9 (الحصول على درجة الدكتوراه).

متغير التحكم. أولاً، تشير نظرية رأس المال لبورديو إلى انتقال رأس المال الاقتصادي العائلي إلى توقعات الطلاب التعليمية وإنجازاتهم اللاحقة (دينغ وو، 2023). أي أن الطلاب الذين يمتلكون موارد تعليمية أفضل من المرجح أن تكون لديهم توقعات تعليمية أعلى. ثانياً، وجدت الدراسات في سياق ريفي صيني أن الفتيات والأبناء الوحيدين من المرجح أن يتلقوا مزيدًا من التواصل من والديهم مقارنةً بالأطفال من عائلات متعددة الأطفال والأولاد، على التوالي (ليو وجيانغ 2021). ثالثاً، تشير الأبحاث في الصين وخارجها إلى أن الآباء الذين يمتلكون مؤهلات تعليمية أعلى يميلون إلى التفاعل بشكل أكثر تكرارًا مع أطفالهم لأنهم أكثر ثقة في القيام بذلك (هان 2023؛ يوي وآخرون 2017). رابعاً، توجد اختلافات بين الطلاب من الجنسين والدرجات المختلفة فيما يتعلق بتوقعاتهم من تحصيلهم التعليمي (ريغسبي وآخرون 2013). لذلك، بالإضافة إلى التحكم في مقاييس الأساس في التحليل (انظر استراتيجية التحليل أدناه)، قمنا أيضًا بالتحكم في العمر، وحالة الطفل الوحيد (

استراتيجية التحليل. لاختبار نموذجنا المفاهيمي في الشكل 1، تم استخدام تحليل المسار مع إجراء من خطوتين. في الخطوة 1، تم اختبار نموذج الوساطة لفحص تأثير الوساطة للتواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال على العلاقة بين حالة البقاء خلف الأهل وتوقعات التعليم (للفرضيتين 1 و2). على وجه التحديد، تم تحليل التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال في الوقت 2 بناءً على حالة البقاء خلف الأهل في الوقت 1، بينما تم تحليل توقعات التعليم في الوقت 2 بناءً على كل من التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال.

| الجدول 2 الإحصائيات الوصفية والارتباطات الثنائية بين المتغيرات. | |||||||||

| م (انحراف معياري) | 1 | ٢ | ٣ | ٤ | |||||

| 1. LBS1 | – | – | |||||||

| 2. PCC1 | 16.52 (3.87) | 0.11 | *** | – | |||||

| 3. PCC2 | 16.58 (3.99) | 0.13 | *** | 0.44 | *** | – | |||

| 4. EE1 | 6.90 (1.66) | 0.02 | 0.19 | *** | 0.14 | *** | – | ||

| 5. EE2 | 6.63 (1.60) | 0.04 | † | 0.15 | *** | 0.20 | *** | 0.52 | *** |

| ملاحظة. حالة LBS1 المتروكة في الوقت 1، PCC1 التواصل بين الوالدين والطفل في الوقت 1، PCC2 التواصل بين الوالدين والطفل في الوقت 2، EE1 التوقعات التعليمية في الوقت 1، EE2 التوقعات التعليمية في الوقت 2.

|

|||||||||

التواصل في الوقت 2 وحالة المتروكين في الوقت 1. الخطوة 2، التي بُنيت على نموذج الوساطة، فحصت التأثير المعتدل لحالة المتروكين على العلاقة بين التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال والتوقعات التعليمية (للفرضية 3). على وجه التحديد، بخلاف التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال في الوقت 2 وحالة المتروكين في الوقت 1، تم إجراء تحليل إضافي للتوقعات التعليمية بناءً على مصطلح التفاعل بين التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال في الوقت 2 وحالة المتروكين في الوقت 1. في هذه الخطوة، تم استخدام تحليل الميل البسيط أيضًا لتوضيح نمط التعديل. بشكل عام، سيوضح النموذج الذي تم اختباره في الخطوة 2 ما إذا كان التأثير الوسيط للتواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال يعتمد على حالة المتروكين، مما يؤدي إلى نموذج وساطة معتدلة (انظر النموذج 74 في هايز (2018) والنموذج 1 في بريشر وآخرون (2007)). تم اتباع مواصفات نموذجنا واختبار مؤشر الوساطة المعتدلة وفقًا لهايز (2018) وبريشر وآخرون (2007). من الجدير بالذكر أنه، عبر الخطوتين 1 و 2، سيتم التحكم في التأثيرات الذاتية للتواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال والتوقعات التعليمية حيث سيتم تحليل التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال والتوقعات التعليمية في الوقت 2 بناءً على التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال والتوقعات التعليمية في الوقت 1.

النتائج

الإحصائيات الوصفية. تم تلخيص الإحصائيات الوصفية والارتباطات الثنائية في الجدول 2. بما يتماشى مع النتائج السابقة (مثل، تشاو وتشين، 2022؛ وانغ وآخرون، 2019؛ جوانغ وآخرون، 2017)، كانت درجة التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال التي يتلقاها الأطفال الريفيون في الوقت 2 مرتبطة إيجابيًا بعدد الوالدين المقيمين معهم في القرى.

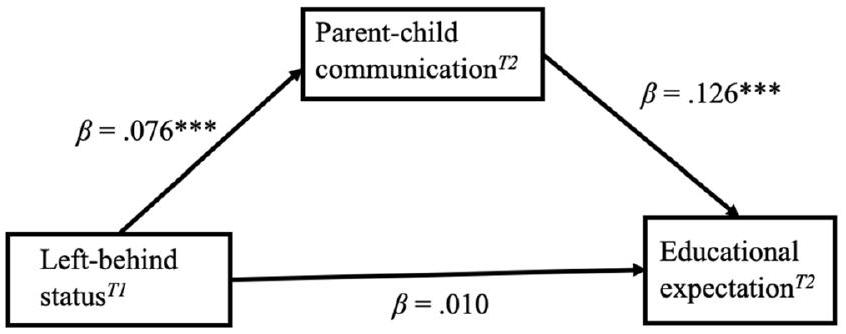

أثر الوساطة في التواصل بين الوالدين والطفل. في الخطوة 1، تم إنشاء نموذج الوساطة لفحص أثر الوساطة للتواصل بين الوالدين والطفل بين حالة ترك الأطفال وتوقعات التعليم. أظهرت تحليل المسار أن نموذج الوساطة كان له ملاءمة جيدة مع البيانات.

الجدول 3 نتائج تحليل المسار في نماذج الوساطة والوساطة التعديلية.

| نموذج الوساطة الخطوة 1 | الخطوة 2 نموذج الوساطة المعتدلة | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| النتيجة: PCC2 | ||||||

| PCC1 | 0.449 | 0.435 | <0.001 | 0.449 | 0.435 | <0.001 |

| LBS1 | 0.413 | 0.076 | <0.001 | 0.413 | 0.076 | <0.001 |

| النتيجة: EE2 | ||||||

| EE1 | 0.489 | 0.507 | <0.001 | 0.487 | 0.505 | <0.001 |

| PCC2 | 0.050 | 0.126 | <0.001 | 0.018 | 0.044 | 0.283 |

| LBS1 | 0.022 | 0.010 | 0.566 | -0.315 | -0.144 | 0.043 |

| PCC2 | ||||||

| ملاحظة. حالة LBS1 المتروكة في الوقت 1، PCC1 التواصل بين الوالدين والطفل في الوقت 1، PCC2 التواصل بين الوالدين والطفل في الوقت 2، EE1 التوقعات التعليمية في الوقت 1، EE2 التوقعات التعليمية في الوقت 2. | ||||||

الشكل 2 نموذج الوساطة المعتدلة بين حالة التخلي، والتواصل بين الوالدين والطفل، والتوقعات التعليمية. ملاحظة.

تم التحكم في التأثيرات الذاتية للتواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال وتوقعات التعليم في النموذج. يمثل المسار العريض تأثير التعديل لحالة ترك الأطفال التي تم اختبارها في الخطوة 2. *

الوقت

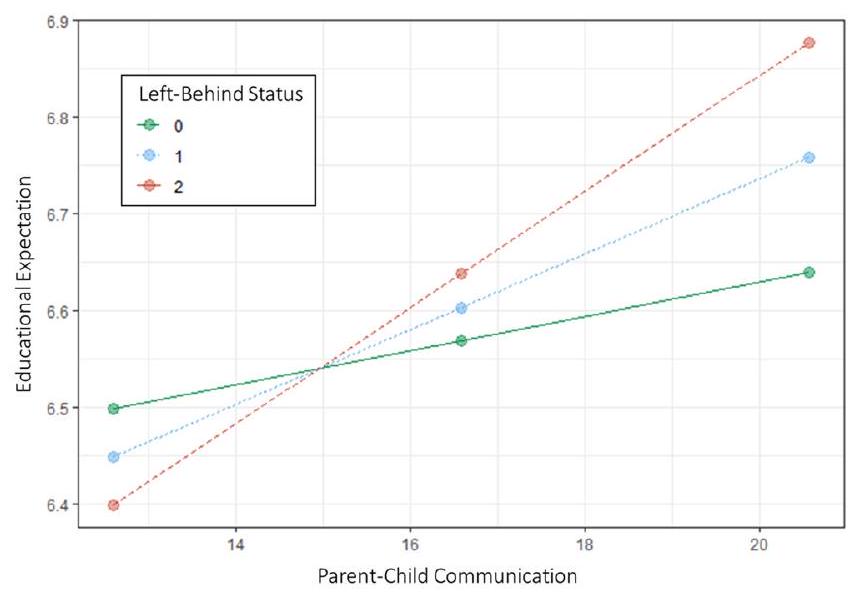

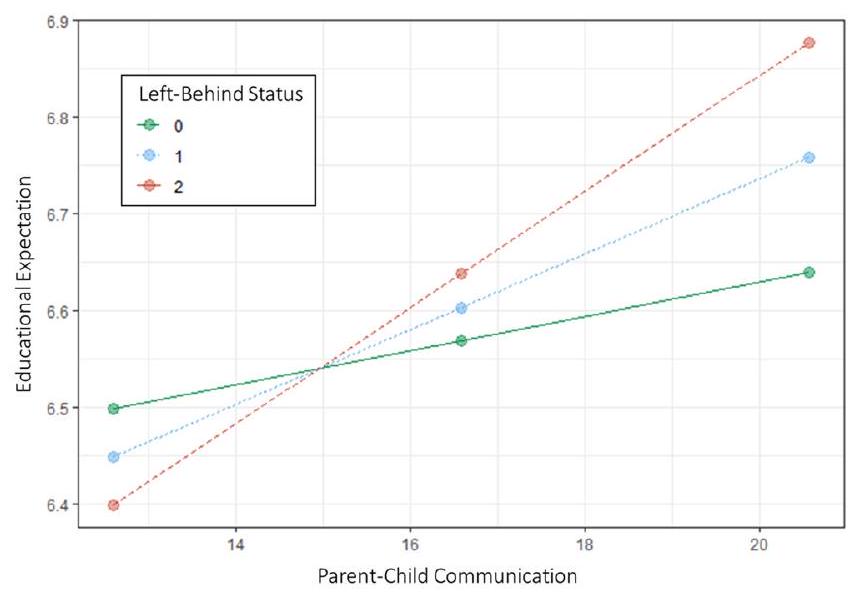

أثر الحالة المتروكة كعامل معتدل. في الخطوة 2، استنادًا إلى نموذج الوساطة في الخطوة 1، قمنا بمزيد من الفحص لمعرفة ما إذا كانت الحالة المتروكة ستعدل العلاقة بين الوالد والطفل

الشكل 3 رسم بياني للمنحدر البسيط لتأثير حالة البقاء خلفًا على العلاقة بين التواصل بين الوالدين والطفل والتوقعات التعليمية.

التواصل وتوقعات التعليم، مما أسفر عن نموذج وساطة معتدل مقترح في الشكل 1. مشابهًا لنموذج الوساطة، كان نموذج الوساطة المعتدل مناسبًا للبيانات بشكل جيد،

من خلال أخذ الخطوتين 1 و 2 معًا في نموذج الوساطة المعدلة، قمنا بفحص ما إذا كان تأثير الوساطة للتواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال يختلف عبر مستويات مختلفة من حالة البقاء خلفًا. وفقًا لـ هايز (2018)، تم حساب مؤشر الوساطة المعدلة ووجد أنه ذو دلالة إحصائية.

تم اختبار نفس مجموعات تحليلات المسار في الخطوتين 1 و 2 مع التحكم في المعلومات الديموغرافية، وهي: العمر، الجنس، حالة الطفل الوحيد، مستوى تعليم الوالدين، الوضع الاقتصادي للأسرة، والموارد التعليمية. لم تكشف النتائج الرئيسية عن تغيير كبير. يتم تقديم معاملات المسار في هذه النماذج في الجدول A1 في الملحق.

نقاش

الشباب هم أصول قيمة للأمة. أكثر من 70 مليون طفل من الأطفال المتروكين في الريف في الصين هم مفتاح لاستدامة الاقتصاد والتنمية الاجتماعية في الصين (وو وتشين، 2022). مثل الصين، تعاني دول أخرى ذات دخل منخفض/متوسط في آسيا وأفريقيا وأوروبا الشرقية وأمريكا اللاتينية أيضًا من نسب كبيرة من الأطفال المتروكين في الريف بسبب هجرة الآباء الداخلية والدولية (تشو وآخرون، 2023). على سبيل المثال، تشير الإحصائيات إلى أن

أثر التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال. لم يتم إجراء تحليل تجريبي كبير على تواصل الوالدين والأطفال لدى الأطفال الريفيين الذين لديهم خصائص مختلفة من ترك الوالدين. الدراسات الأكثر صلة أجرت بشكل رئيسي مقارنات بين الطلاب المتروكين (عادةً LBCB) وأقرانهم غير المتروكين. قامت تحليلنا الكمي المقارن بتصنيف الطلاب الريفيين الصينيين بشكل أكثر تحديدًا إلى ثلاث مجموعات وفقًا لعدد الوالدين الذين يعيشون معهم. أدى هذا المستوى الأكبر من التفاصيل إلى إدراك أن الأطفال الريفيين الذين لديهم عدد أكبر من الوالدين المقيمين من المحتمل أن يتلقوا مستويات أعلى من التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال. تشير النتائج إلى أن هجرة الوالدين تقلل بشكل كبير من مدى التواصل الأسري بين الوالدين المهاجرين والأطفال المتروكين. بالنسبة لـ LBCB، فإن التواصل عبر الإنترنت الذي يتلقونه لا يعادل التواصل الجسدي الذي يتلقاه أقرانهم غير المتروكين. في عصر الإنترنت، الأجهزة الذكية متاحة بسهولة، وقد لا يكون نقص الأجهزة الرقمية هو السبب الرئيسي في ضعف التواصل عبر الإنترنت بين الوالدين والأطفال (Xu، 2016). بدلاً من ذلك، قد يُعزى ذلك إلى جدول العمل غير المنتظم للوالدين المهاجرين ونواياهم للحد من استخدام أطفالهم المتروكين للهواتف المحمولة و/أو الوصول إلى الإنترنت (Li و Li، 2007؛ Ye و Pan، 2011). بالنسبة لـ LBCS، بالإضافة إلى قلة التواصل عبر الإنترنت من الوالد المهاجر، قد يتلقون أيضًا تواصلًا جسديًا أقل من الوالد المقيم مقارنةً بما يتلقاه أقرانهم غير المتروكين من والديهم. تؤدي الهجرة الداخلية إلى تغيير هيكل الأسرة. من المحتمل أن يتلقى NLBC تواصلًا وفيرًا بين الوالدين والأطفال لأن والديهم يمكن أن يعملوا كفريق من اثنين، مما قد يمنحهم مزيدًا من المرونة في التعامل مع الأنشطة الاقتصادية وتربية الأطفال. على العكس من ذلك، فإن الوالد المقيم الوحيد لـ LBCS – الذي يعيش في قرية ريفية – يجب أن يتحمل كل من المسؤوليات الاقتصادية وتربية الأطفال. غالبًا، نظرًا للمعاناة الاقتصادية للعديد من الأسر الريفية، فإن الحصول على ما يكفي من المال يأتي في المقام الأول على قضاء الوقت مع الأطفال (Murphy، 2020).

ومع ذلك، تلعب التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال دورًا مهمًا في تطوير التعليم للأطفال. إنه القناة التي يستخدمها الآباء لنقل التوقعات التعليمية والقيم والرعاية لأطفالهم (سيغينر وفيرمولست، 2002). مثل هذه التواصلات اللفظية وغير اللفظية

تُشكّل التعبيرات اللفظية من الآباء مواقف الطلاب التعليمية الخاصة وتعزز من رفاههم النفسي (Froiland et al. 2013; Bireda and Pillay, 2018). في التحليل الحالي، قمنا بالتحقق من العلاقة الإيجابية بين التواصل بين الآباء والأبناء وتوقعات التعليم لدى الطفل في سياق ريفي صيني. يميل الطلاب في المناطق الريفية الذين يتلقون المزيد من التواصل مع آبائهم إلى السعي لتحقيق إنجازات تعليمية أعلى. في الأسر الريفية الصينية، على العموم، على الرغم من أن الظروف الاجتماعية والاقتصادية تقيد الدعم المالي الملموس الذي يمكن أن يتلقاه الأطفال الريفيون، إلا أن التواصل الوفير بين الآباء والأبناء أثبت أنه قادر على بناء دافع التعلم وتوقعات التعليم (Xu and Montgomery, 2021; Chen et al. 2023). أما بالنسبة للأطفال المتروكين بشكل خاص، في حين أن أشكال المشاركة الأبوية الأخرى مقيدة إلى حد كبير بفعل الانفصال الجسدي، يبدو أن التواصل بين الآباء والأبناء هو واحد من الطرق القليلة التي يمكن للآباء المهاجرين من خلالها المشاركة في تعلم ونمو الأطفال. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تشير المنح الدراسية الدولية إلى أن إجازة الوالدين قد تعطي الأطفال المتروكين انطباعًا خاطئًا عن كونهم مهجورين، مما يؤثر سلبًا على صحتهم النفسية ويضر بدافعهم وتوقعاتهم التعليمية (Su et al. 2013; Coe, 2014). تشير نتائجنا إلى أن التواصل المتكرر بين الآباء والأبناء قد يخفف من هذا التأثير السلبي ويحمي توقعات التعليم للأطفال المتروكين (Wang et al. 2019).

تُشكّل التعبيرات اللفظية من الآباء مواقف الطلاب التعليمية الخاصة وتعزز من رفاههم النفسي (Froiland et al. 2013; Bireda and Pillay, 2018). في التحليل الحالي، قمنا بالتحقق من العلاقة الإيجابية بين التواصل بين الآباء والأبناء وتوقعات التعليم لدى الطفل في سياق ريفي صيني. يميل الطلاب في المناطق الريفية الذين يتلقون المزيد من التواصل مع آبائهم إلى السعي لتحقيق إنجازات تعليمية أعلى. في الأسر الريفية الصينية، على العموم، على الرغم من أن الظروف الاجتماعية والاقتصادية تقيد الدعم المالي الملموس الذي يمكن أن يتلقاه الأطفال الريفيون، إلا أن التواصل الوفير بين الآباء والأبناء أثبت أنه قادر على بناء دافع التعلم وتوقعات التعليم (Xu and Montgomery, 2021; Chen et al. 2023). أما بالنسبة للأطفال المتروكين بشكل خاص، في حين أن أشكال المشاركة الأبوية الأخرى مقيدة إلى حد كبير بفعل الانفصال الجسدي، يبدو أن التواصل بين الآباء والأبناء هو واحد من الطرق القليلة التي يمكن للآباء المهاجرين من خلالها المشاركة في تعلم ونمو الأطفال. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تشير المنح الدراسية الدولية إلى أن إجازة الوالدين قد تعطي الأطفال المتروكين انطباعًا خاطئًا عن كونهم مهجورين، مما يؤثر سلبًا على صحتهم النفسية ويضر بدافعهم وتوقعاتهم التعليمية (Su et al. 2013; Coe, 2014). تشير نتائجنا إلى أن التواصل المتكرر بين الآباء والأبناء قد يخفف من هذا التأثير السلبي ويحمي توقعات التعليم للأطفال المتروكين (Wang et al. 2019).

في هذا السياق، تساهم التحليل الحالي في توثيق تأثير التواصل بين الوالدين والأبناء كوسيط في العلاقة بين حالة الطلاب الصينيين في المناطق الريفية الذين تُركوا وراءهم وتوقعاتهم التعليمية. إن الانخفاض في عدد الوالدين المقيمين بسبب هجرة الوالدين يؤدي إلى انخفاض في التواصل بين الوالدين والأبناء، مما يؤثر سلبًا على توقعات الطلاب الريفيين التعليمية. على الرغم من أن الدراسات السابقة (مثل، سو وآخرون 2013) قد ناقشت على نطاق واسع العلاقات بين هجرة الوالدين والتواصل بين الوالدين والأبناء، والعلاقة بين التواصل بين الوالدين والأبناء وتوقعات الطلاب التعليمية، لم تقم أي دراسة بفحص الدور الوسيط للتواصل بين الوالدين والأبناء. ربطت هذه الدراسة حالة الطلاب الصينيين في المناطق الريفية الذين تُركوا وراءهم وتوقعاتهم التعليمية بمدى التواصل الذي تلقوه من والديهم ووجدت أن هجرة الوالدين تضر بتوقعات الطلاب الريفيين التعليمية من خلال انخفاض مدى التواصل بين الوالدين والأبناء. وعلى العكس، تبرز التأثير الوقائي للتواصل بين الوالدين والأبناء على توقعات الطلاب الريفيين الذين تُركوا وراءهم. نظرًا للعلاقة الإيجابية المثبتة بين التواصل بين الوالدين والأبناء وتوقعات التعليم لدى الطلاب الريفيين، فإن إحدى الطرق الممكنة لتحسين توقعات التعليم للأطفال الريفيين الذين تُركوا وراءهم هي توفير مستوى أكبر من التواصل بين الوالدين والأبناء (إما التواصل الجسدي مع الوالدين المقيمين أو التواصل عبر الإنترنت مع الوالدين المهاجرين). تتناغم هذه النتيجة، المستندة إلى سكان ريفيين صينيين، مع دراسات مماثلة عبر العديد من المناطق النامية (مثل، أسيز، 2006؛ هوانغ ويهو، 2012؛ غراهام وآخرون 2012). يمكن أيضًا استخلاص استنتاج مشابه، وهو أن التواصل المنتظم والمتكرر بين الوالدين والأبناء يحسن من قدرة الطلاب الذين تُركوا وراءهم على التكيف ويحافظ على موقفهم الإيجابي وقيمتهم تجاه التعليم.

أثر حالة ترك الأطفال. بالإضافة إلى الأثر الوسيط، تكشف نتائجنا أن حالة ترك الأطفال لدى الطلاب الريفيين تعدل العلاقة الإيجابية بين التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال وتوقعاتهم التعليمية. لاحظنا أن العلاقة الإيجابية بين التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال وتوقعات الطلاب التعليمية أقوى بين الطلاب الريفيين الذين لديهم المزيد من الوالدين المقيمين. تشير هذه النتيجة إلى أن التواصل مع الوالدين يؤثر بشكل مختلف على توقعات التعليم لدى الطلاب الريفيين اعتمادًا على خصائصهم المتعلقة بالترك.

قد يكمن السبب في الاختلاف في محتوى وعمق التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال بين كل من المجموعات الثلاث من الأطفال ووالديهم المقيمين والمهاجرين.

قد يكمن السبب في الاختلاف في محتوى وعمق التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال بين كل من المجموعات الثلاث من الأطفال ووالديهم المقيمين والمهاجرين.

أشارت الدراسات التجريبية المتعلقة بالهجرة الداخلية والدولية باستمرار إلى أن التواصل عبر الإنترنت بين الوالدين المهاجرين وأطفالهم المتروكين لا يمكن مقارنته بالتفاعل وجهًا لوجه (ليو وليونغ، 2017؛ ماهلر، 2001؛ هوانغ وييو، 2012؛ أسيز 2006). على سبيل المثال، أكد الوالدان المهاجران الفلبينيان في بحث أسيز (2006) أن التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال ليس مجرد حديث بل هو قناة للحفاظ على الترابط وتعزيزه. وقد عبروا عن الصعوبة المحبطة في الانخراط في محادثات عميقة مع الأطفال والحفاظ على علاقات أسرية وثيقة من خلال الأجهزة الرقمية. في الصين، أشارت الدراسات أيضًا إلى أن التواصل عبر الإنترنت بين الأطفال المتروكين ووالديهم المهاجرين محدود في العمق (يي وبان، 2011؛ سو وآخرون 2013). يُبلغ عن أن محتوى الحوار عبر الإنترنت سطحي؛ فهو يتناول العديد من جوانب تعليم وحياة الأطفال الريفيين ولكن دون تبادلات ومشاركة عميقة. هذا التواصل الافتراضي بين الوالدين المهاجرين وأطفالهم المتروكين لا يعوق فقط نقل القيم والمعتقدات التعليمية عبر الأجيال ولكنه يعيق أيضًا تقديم الرعاية والدفء الأبوي. وهذا له تأثير سلبي مزدوج على توقعات التعليم لدى الطلاب الريفيين.

من خلال أخذ الآثار الوسيطة والمعدلة الملاحظة معًا، تدعم النتائج الحالية نموذج الوساطة المعدلة فيما يتعلق بحالة ترك الأطفال الريفيين، وتواصلهم مع والديهم، وتوقعاتهم التعليمية. تشير نتائجنا إلى أن الانفصال الجسدي عن الأطفال الناتج عن هجرة الوالدين لا يقلل فقط من درجة التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال بين الوالدين المهاجرين وأطفالهم المتروكين ولكنه يضعف أيضًا تأثير التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال على توقعات التعليم لدى الأطفال الريفيين.

القيود. بينما نعتقد أن نتائج هذا التحليل الممثل وطنيًا تعزز فهمنا للعلاقة المعقدة بين توقعات الوالدين وتطور المراهقين، يجب ملاحظة بعض المخاوف المتعلقة بمقاييس البحث والإطار المفاهيمي. أولاً، فيما يتعلق بتوقعات التعليم، فإن المقياس الذي تم تطبيقه من قبل CFPS يتعلق بتوقعات الطلاب لتحقيق إنجازاتهم التعليمية على المدى الطويل. تم اعتبار توقعات الطلاب لتحقيق إنجازاتهم الأكاديمية على المدى القصير (مثل درجات الامتحانات) أيضًا على نطاق واسع في الدراسات والاستطلاعات الدولية، وإدراجها في نموذجنا قد يكمل نتائجنا. من المحتمل أن يؤثر التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال على مواقف الطلاب الريفيين تجاه أدائهم الأكاديمي على مدى فترة أقصر. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، على الرغم من أن مقاييس التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال وتوقعات التعليم المستخدمة هنا قد تم استخدامها على نطاق واسع في الدراسات الدولية وتم التحقق من موثوقيتها وصلاحيتها، إلا أنها مقاييس ذاتية قد تتعرض لتحيز الرغبة الاجتماعية وتحقيق الذكريات. يجب أن تستخدم الدراسات المستقبلية طرق جمع بيانات متعددة – مثل الملاحظات السلوكية، والمقابلات الثنائية، وتقارير الوالدين – لتوليد بيانات أكثر موضوعية. يمكن أن توفر بيانات المقابلات النوعية من المقابلات الفردية المتعمقة مع الطلاب المتروكين أو المقابلات الثنائية مع الطلاب المتروكين ووالديهم فهمًا أعمق وأكثر دقة لتأثير هجرة الوالدين على تكرار وعمق التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال وتأثير التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال على توقعات التعليم لدى الطلاب.

قيود أخرى هي التباين في العلاقة بين التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال وتوقعات التعليم بين الأطفال المتروكين من قبل الأم أو الأب. نحن

ندرك الآثار غير المتسقة للتواصل الأمومي والأبوي على توقعات التعليم لدى الأطفال. ومع ذلك، نظرًا لأن عدد الأطفال المتروكين في عيّنتنا كان صغيرًا (

ندرك الآثار غير المتسقة للتواصل الأمومي والأبوي على توقعات التعليم لدى الأطفال. ومع ذلك، نظرًا لأن عدد الأطفال المتروكين في عيّنتنا كان صغيرًا (

الآثار العملية. تحتوي النتائج الحالية على عدة آثار عملية لتعزيز توقعات التعليم لدى الأطفال المتروكين في المناطق الريفية. على الرغم من أن الانفصال الناتج عن الهجرة يشكل تهديدًا لتوقعات التعليم لدى الأطفال المتروكين، فإن التواصل المتكرر وعالي الجودة بين الوالدين والأطفال – سواء كان جسديًا أو عبر الإنترنت – يمكن أن يخفف من هذه العلاقة السلبية ويحمي توقعات الأطفال المتروكين بشأن إنجازاتهم التعليمية.

بالنسبة للتواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال، فإن إحدى الطرق لزيادة التواصل الأبوي الذي يتلقاه الأطفال المتروكون هي أن يبدأ الوالدان المهاجران بمزيد من المكالمات الهاتفية أو الرسائل. يمكن للوالدين إنشاء منصات تواصل عبر الإنترنت مستقرة لإجراء محادثات منتظمة عبر الإنترنت مع أطفالهم. يجب أن تكون هذه المنصات سهلة الاستخدام ومتاحة، وتوفر ميزات مثل مكالمات الفيديو، ومشاركة الملفات، وجدولة المهام لتعزيز التفاعلات المنتظمة والمعنوية. تتطلب هذه التعاون من مقدمي الرعاية المحليين ومعلمي المدارس حيث أن الطلاب المتروكين عادةً لا يمتلكون أجهزة ذكية خاصة بهم. يمكن للوالدين المهاجرين تحديد وقت مع الأجداد، لأولئك الذين يعيشون في المنزل، أو مع معلمي المدارس، لأولئك الذين يقيمون في المدارس، لإجراء محادثات منتظمة عبر الإنترنت مع أطفالهم. علاوة على ذلك، يجب على المكاتب التعليمية المحلية والمنظمات غير الحكومية تنظيم ورش عمل لتعليم مهارات الأبوة والأمومة للوالدين المهاجرين للتركيز على استراتيجيات التواصل عن بُعد، وحل النزاعات، والروابط العاطفية مع أطفالهم المتروكين. يمكن تقديم هذه الورش عبر الإنترنت أو من خلال مراكز المجتمع المحلية. وبالمثل، يجب توفير الدعم والتدريب لمقدمي الرعاية المحليين المسؤولين عن تسهيل التواصل بين الوالدين المهاجرين وأطفالهم المتروكين. يمكن أن يشمل ذلك إرشادات حول مراقبة وقت الشاشة واستخدام الإنترنت للأطفال، وحل المشكلات التقنية، وخلق بيئة ملائمة لتفاعلات الوالدين والأطفال. على مستوى المدرسة، يُوصى بتدخلات قائمة على المدرسة تدمج أنشطة التواصل بين الوالدين والأطفال في المنهج الدراسي للأطفال المتروكين. يمكن أن يتضمن ذلك تخصيص وقت مخصص لمكالمات الفيديو مع الوالدين، وإنشاء مشاريع كتابة رسائل أو رسائل فيديو، أو تنظيم فعاليات عائلية يمكن أن يشارك فيها الوالدين المهاجرين افتراضيًا.

بالإضافة إلى التواصل المنتظم والمتكرر عبر الإنترنت، فإن الزيارات المنزلية الأكثر تكرارًا هي علاج آخر محتمل، إذا كانت الأوضاع المالية للعائلة تسمح بذلك. أما بالنسبة لـ LBCS، فبخلاف زيادة تواصلهم مع الوالد المهاجر، قد تكون الحلول الأكثر قابلية للتطبيق هي تكثيف المحادثات الجسدية مع الوالد المقيم. بالإضافة إلى توسيع العلاقة بين الوالد والطفل.

نقترح أيضًا أن يحتاج كل من الآباء المهاجرين والآباء المقيمين إلى الاستفسار بعمق، من خلال التواصل بين الآباء والأبناء، عن التعليم المدرسي للأطفال المتروكين، والحالة النفسية، والعلاقات الشخصية. يمكن أن يمكّن ذلك الآباء من تقديم الرعاية والدفء لأطفالهم المتروكين والحفاظ على الروابط النفسية للعائلة. وبالمثل، يجب على الآباء استغلال الفرصة للتعبير عن قيمهم التعليمية وتوقعاتهم لأطفالهم المتروكين للتأثير على توقعات الجيل القادم التعليمية. يجب تنفيذ برامج تدخل ذات صلة لتنمية مهارات واستراتيجيات التواصل لدى الآباء الريفيين مع أطفالهم المتروكين لتحسين تقديم رعايتهم الأبوية، وقيمهم التعليمية، ومواقفهم.

نقترح أيضًا أن يحتاج كل من الآباء المهاجرين والآباء المقيمين إلى الاستفسار بعمق، من خلال التواصل بين الآباء والأبناء، عن التعليم المدرسي للأطفال المتروكين، والحالة النفسية، والعلاقات الشخصية. يمكن أن يمكّن ذلك الآباء من تقديم الرعاية والدفء لأطفالهم المتروكين والحفاظ على الروابط النفسية للعائلة. وبالمثل، يجب على الآباء استغلال الفرصة للتعبير عن قيمهم التعليمية وتوقعاتهم لأطفالهم المتروكين للتأثير على توقعات الجيل القادم التعليمية. يجب تنفيذ برامج تدخل ذات صلة لتنمية مهارات واستراتيجيات التواصل لدى الآباء الريفيين مع أطفالهم المتروكين لتحسين تقديم رعايتهم الأبوية، وقيمهم التعليمية، ومواقفهم.

توفر البيانات

تتوفر مجموعات البيانات التي تم إنشاؤها و/أو تحليلها خلال الدراسة الحالية في مسح التعليم في الصين، [http:// ceps.ruc.edu.cn/Arabic/نظرة عامة/نظرة عامة.htm]. مجموعة البيانات (بصيغة .xlsx) لهذا التحليل المحدد متاحة في مستودع داتافيرس، [https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZWBRX0].

تاريخ الاستلام: 27 مارس 2024؛ تاريخ القبول: 19 ديسمبر 2024؛

نُشر على الإنترنت: 02 يناير 2025

نُشر على الإنترنت: 02 يناير 2025

References

Abbasi BN, Luo Z, Sohail A (2023) Effect of parental migration on the noncognitive abilities of left-behind school-going children in rural China. Hum Soc Sci Commun 10(1):1-14

Abbasi BN, Luo Z, Sohail A, Shasha W (2022) Research on non-cognitive ability disparity of Chinese adolescent students: a rural-urban analysis. Glob Econ Rev 51(2):159-174

Andres L, Adamuti-Trache M, Yoon ES, Pidgeon M, Thomsen JP (2007) Educational expectations, parental social class, gender, and postsecondary attainment: a 10 year perspective. Youth Soc 39(2):135-163

Asis MM (2006) Living with migration: experiences of left-behind children in the Philippines. Asian Popul Stud 2(1):45-67

Bandura A (1997). Self-efficacy and health behaviour. In: Baum A, Newman S, Wienman J, West R & McManus C (Eds.) Cambridge handbook of psychology, health and medicine, Cambridge University Press, pp 678

Bennett R, Hosegood V, Newell ML, McGrath N (2015) An approach to measuring dispersed families with a particular focus on children ‘left behind’ by migrant parents: findings from rural South Africa. Popul Space Place 21(4):322-334. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp. 1843

Bireda AD, Pillay J (2018) Perceived parent-child communication and well-being among Ethiopian adolescents. Int J Adolescence Youth 23(1):109-117

Bozick R, Alexander K, Entwisle D, Dauber S, Kerr K (2010) Framing the future: revisiting the place of educational expectations in status attainment. Soc Forces 88(5):2027-2052. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2010.0033

Ceka A, Murati R (2016) The role of parents in the education of children. J Educ Pract 7(5):61-64

Chen LJ, Yang DL & Ren Q (2015) Report on the state of children in China. Chicago, IL: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago. https:// d3qi0qp55mx5f5.cloudfront.net/beijing/i/docs/CFPS-Report-20161.pdf Accessed 0ct 2015

Chen X, Allen JL, Flouri E, Cao X & Hesketh T (2023) Parent-child communication about educational aspirations: experiences of adolescents in rural China. J Child Family Stud 32:2776-2788

Coe C (2014) The scattered family: parenting, African migrants, and global inequality. University of Chicago Press

Coleman JS (2001) Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol 94:S95-S120

Ding Q, Wu Q (2023) Effects of economic capital, cultural capital and social capital on the educational expectation of Chinese migrant children. Appl Res Qual Life 18(3):1407-1432

Dominguez GB & Hall BJ (2022) The health status and related interventions for children left behind due to parental migration in the Philippines: a scoping review. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 28:100566

Dong B, Yu D, Ren Q, Zhao D, Li J, Sun YH (2019) The resilience status of Chinese left-behind children in rural areas: a meta-analysis. Psychol Health Med 24(1):1-3

Duan C, Lv L, Wang Z (2014) Research on left-behind children’s home education and school education. Peking. Univ. Educ. Rev. 12(3):13-29

Abbasi BN, Luo Z, Sohail A, Shasha W (2022) Research on non-cognitive ability disparity of Chinese adolescent students: a rural-urban analysis. Glob Econ Rev 51(2):159-174

Andres L, Adamuti-Trache M, Yoon ES, Pidgeon M, Thomsen JP (2007) Educational expectations, parental social class, gender, and postsecondary attainment: a 10 year perspective. Youth Soc 39(2):135-163

Asis MM (2006) Living with migration: experiences of left-behind children in the Philippines. Asian Popul Stud 2(1):45-67

Bandura A (1997). Self-efficacy and health behaviour. In: Baum A, Newman S, Wienman J, West R & McManus C (Eds.) Cambridge handbook of psychology, health and medicine, Cambridge University Press, pp 678

Bennett R, Hosegood V, Newell ML, McGrath N (2015) An approach to measuring dispersed families with a particular focus on children ‘left behind’ by migrant parents: findings from rural South Africa. Popul Space Place 21(4):322-334. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp. 1843

Bireda AD, Pillay J (2018) Perceived parent-child communication and well-being among Ethiopian adolescents. Int J Adolescence Youth 23(1):109-117

Bozick R, Alexander K, Entwisle D, Dauber S, Kerr K (2010) Framing the future: revisiting the place of educational expectations in status attainment. Soc Forces 88(5):2027-2052. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2010.0033

Ceka A, Murati R (2016) The role of parents in the education of children. J Educ Pract 7(5):61-64

Chen LJ, Yang DL & Ren Q (2015) Report on the state of children in China. Chicago, IL: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago. https:// d3qi0qp55mx5f5.cloudfront.net/beijing/i/docs/CFPS-Report-20161.pdf Accessed 0ct 2015

Chen X, Allen JL, Flouri E, Cao X & Hesketh T (2023) Parent-child communication about educational aspirations: experiences of adolescents in rural China. J Child Family Stud 32:2776-2788

Coe C (2014) The scattered family: parenting, African migrants, and global inequality. University of Chicago Press

Coleman JS (2001) Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol 94:S95-S120

Ding Q, Wu Q (2023) Effects of economic capital, cultural capital and social capital on the educational expectation of Chinese migrant children. Appl Res Qual Life 18(3):1407-1432

Dominguez GB & Hall BJ (2022) The health status and related interventions for children left behind due to parental migration in the Philippines: a scoping review. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 28:100566

Dong B, Yu D, Ren Q, Zhao D, Li J, Sun YH (2019) The resilience status of Chinese left-behind children in rural areas: a meta-analysis. Psychol Health Med 24(1):1-3

Duan C, Lv L, Wang Z (2014) Research on left-behind children’s home education and school education. Peking. Univ. Educ. Rev. 12(3):13-29

Fan X & Chen M (2001) Parental involvement and students’ academic achievement: a meta-analysis. Edu Psychol Rev 13:1-22

Fellmeth G, Rose-Clarke K, Zhao C, Busert LK, Zheng Y, Massazza A, Sonmez H, Eder B, Blewitt A, Lertgrai W, Orcutt M, Ricci K, Mohamed-Ahmed HO, Burns B, Knipe D, Hargreaves S, Hesketh T, Opondo C, Devakumar D (2018) Health impacts of parental migration on left-behind children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 392(10164):2567-2582

Feliciano C (2006) Beyond the family: the influence of premigration group status on the educational expectations of immigrants’ children. Sociol Educ 79(4):281-303. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25054321

Fu W, Zhu Y, Chai H, Xue R (2024) Discrimination perception and problem behaviors of left-behind children in China: the mediating effect of grit and social support. Humanit Social Sci Commun 11(1):1-9

Feliciano C, Lanuza YR (2016) The immigrant advantage in adolescent educational expectations. Int Migr Rev 50(3):758-792

Froiland JM, Peterson A, Davison ML (2013) The long-term effects of early parent involvement and parent expectation in the USA. Sch Psychol Int 34(1):33-50

Gao Y, Bai Y, Ma Y & Shi Y (2019) Parental migration’s effects on the academic and non-academic performance of left-behind children in rural China. China Econ 5:67-80

Goh E (2011) China’s one-child policy and multiple caregiving: raising little suns in Xiamen, Routledge

Goings R, Shi Q (2018) Black male degree attainment: do expectations and aspirations in high school make a difference? Spectr A J Black Men 6(2):1-20

Goyette K & Xie Y (1999) Educational expectations of Asian American youths: determinants and ethnic differences. Sociol Edu 72:22-36

Graham E, Jordan LP, Yeoh BS, Lam T, Asis M, Su-Kamdi (2012) Transnational families and the family nexus: perspectives of Indonesian and Filipino children left behind by migrant parent (s). Environ Plan A 44(4):793-815

Guang Y, Feng Z, Yang G, Yang Y, Wang L, Dai Q, Hu C, Liu K, Zhang R, Xia F, Zhao M (2017) Depressive symptoms and negative life events: what psycho-social factors protect or harm left-behind children in China? BMC psychiatry 17:1-16

Hannum E, Hu L & Shen W (2018) Short- and long-term outcomes of the left behind in China: education, well-being and life opportunities. Global Edu Monitoring Rep 88

Han J, Hao Y, Cui N, Wang Z, Lyu P, Yue L (2023) Parenting and parenting resources among Chinese parents with children under three years of age: rural and urban differences. BMC Primary Care. 24(1):38. https://doi.org/10. 1186/s12875-023-01993-y

Hayes AF (2018) Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun Monogr 85(1):4-40

He X, Wang H, Friesen D, Shi Y, Chang F, Liu H (2022) Cognitive ability and academic performance among left-behind children: evidence from rural China. Comp A J Comp Int Educ 52(7):1033-1049

Hoang LA, Yeoh BS (2012) Sustaining families across transnational spaces: Vietnamese migrant parents and their left-behind children. Asian Stud Rev 36(3):307-325

Hong Y (2021) The educational hopes and ambitions of left-behind children in rural China: an ethnographic case study, Routledge

Hong Y, & Fuller C (2019) Alone and “left behind”: a case study of “left-behind children” in rural China. Cogent Edu 6:1

Hu S (2019) It’s for our education”: perception of parental migration and resilience among left-behind children in rural China. Soc Indic Res 145(2):641-661

Jin X, Chen W, Sun IY, Liu L (2020) Physical health, school performance and delinquency: a comparative study of left-behind and non-left-behind children in rural China. Child Abus Negl 109:104707

Jin X, Liu H, Liu L (2017) Family education support to rural migrant children in China: evidence from Shenzhen. Eurasia Geogr Econ 58(2):169-200

Kristensen P, Gravseth HM, Bjerkedal T (2009) Educational attainment of Norwegian men: influence of parental and early individual characteristics. J Biosoc Sci 41(6):799-814

Kong PA. Parenting, education, and social mobility in rural China: Cultivating dragons and phoenixes. Routledge; 2015

Laursen B & Collins WA (2004) Parent-child communication during adolescence. In: Vangelisti AL (ed) The routledge handbook of family communication, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp 616

Li P, Li W (2007) Economic status and social attitudes of migrant workers in China. China World Econ 15(4):1-16

Li W, Xie Y (2020) The influence of family background on educational expectations: a comparative study. Chin Sociol Rev 52(3):269-294

Liang Z, Ma Z (2004) Chinaas floating population: new evidence from the 2000 census Popul Develop Rev 30(3):4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2004.00024.x

Liu PL, Leung L (2017) Migrant parenting and mobile phone use: building quality relationships between Chinese migrant workers and their left-behind children. Appl Res Qual Life 12:925-946

Liu Y, Jiang Q (2021) Who benefits from being an only child? A study of parent-child relationship among Chinese junior high school students. Front Psychol 11:608995. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.608995

Fellmeth G, Rose-Clarke K, Zhao C, Busert LK, Zheng Y, Massazza A, Sonmez H, Eder B, Blewitt A, Lertgrai W, Orcutt M, Ricci K, Mohamed-Ahmed HO, Burns B, Knipe D, Hargreaves S, Hesketh T, Opondo C, Devakumar D (2018) Health impacts of parental migration on left-behind children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 392(10164):2567-2582

Feliciano C (2006) Beyond the family: the influence of premigration group status on the educational expectations of immigrants’ children. Sociol Educ 79(4):281-303. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25054321

Fu W, Zhu Y, Chai H, Xue R (2024) Discrimination perception and problem behaviors of left-behind children in China: the mediating effect of grit and social support. Humanit Social Sci Commun 11(1):1-9

Feliciano C, Lanuza YR (2016) The immigrant advantage in adolescent educational expectations. Int Migr Rev 50(3):758-792

Froiland JM, Peterson A, Davison ML (2013) The long-term effects of early parent involvement and parent expectation in the USA. Sch Psychol Int 34(1):33-50

Gao Y, Bai Y, Ma Y & Shi Y (2019) Parental migration’s effects on the academic and non-academic performance of left-behind children in rural China. China Econ 5:67-80

Goh E (2011) China’s one-child policy and multiple caregiving: raising little suns in Xiamen, Routledge

Goings R, Shi Q (2018) Black male degree attainment: do expectations and aspirations in high school make a difference? Spectr A J Black Men 6(2):1-20

Goyette K & Xie Y (1999) Educational expectations of Asian American youths: determinants and ethnic differences. Sociol Edu 72:22-36

Graham E, Jordan LP, Yeoh BS, Lam T, Asis M, Su-Kamdi (2012) Transnational families and the family nexus: perspectives of Indonesian and Filipino children left behind by migrant parent (s). Environ Plan A 44(4):793-815

Guang Y, Feng Z, Yang G, Yang Y, Wang L, Dai Q, Hu C, Liu K, Zhang R, Xia F, Zhao M (2017) Depressive symptoms and negative life events: what psycho-social factors protect or harm left-behind children in China? BMC psychiatry 17:1-16

Hannum E, Hu L & Shen W (2018) Short- and long-term outcomes of the left behind in China: education, well-being and life opportunities. Global Edu Monitoring Rep 88

Han J, Hao Y, Cui N, Wang Z, Lyu P, Yue L (2023) Parenting and parenting resources among Chinese parents with children under three years of age: rural and urban differences. BMC Primary Care. 24(1):38. https://doi.org/10. 1186/s12875-023-01993-y

Hayes AF (2018) Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun Monogr 85(1):4-40

He X, Wang H, Friesen D, Shi Y, Chang F, Liu H (2022) Cognitive ability and academic performance among left-behind children: evidence from rural China. Comp A J Comp Int Educ 52(7):1033-1049

Hoang LA, Yeoh BS (2012) Sustaining families across transnational spaces: Vietnamese migrant parents and their left-behind children. Asian Stud Rev 36(3):307-325

Hong Y (2021) The educational hopes and ambitions of left-behind children in rural China: an ethnographic case study, Routledge

Hong Y, & Fuller C (2019) Alone and “left behind”: a case study of “left-behind children” in rural China. Cogent Edu 6:1

Hu S (2019) It’s for our education”: perception of parental migration and resilience among left-behind children in rural China. Soc Indic Res 145(2):641-661

Jin X, Chen W, Sun IY, Liu L (2020) Physical health, school performance and delinquency: a comparative study of left-behind and non-left-behind children in rural China. Child Abus Negl 109:104707

Jin X, Liu H, Liu L (2017) Family education support to rural migrant children in China: evidence from Shenzhen. Eurasia Geogr Econ 58(2):169-200

Kristensen P, Gravseth HM, Bjerkedal T (2009) Educational attainment of Norwegian men: influence of parental and early individual characteristics. J Biosoc Sci 41(6):799-814

Kong PA. Parenting, education, and social mobility in rural China: Cultivating dragons and phoenixes. Routledge; 2015

Laursen B & Collins WA (2004) Parent-child communication during adolescence. In: Vangelisti AL (ed) The routledge handbook of family communication, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp 616

Li P, Li W (2007) Economic status and social attitudes of migrant workers in China. China World Econ 15(4):1-16

Li W, Xie Y (2020) The influence of family background on educational expectations: a comparative study. Chin Sociol Rev 52(3):269-294

Liang Z, Ma Z (2004) Chinaas floating population: new evidence from the 2000 census Popul Develop Rev 30(3):4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2004.00024.x

Liu PL, Leung L (2017) Migrant parenting and mobile phone use: building quality relationships between Chinese migrant workers and their left-behind children. Appl Res Qual Life 12:925-946

Liu Y, Jiang Q (2021) Who benefits from being an only child? A study of parent-child relationship among Chinese junior high school students. Front Psychol 11:608995. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.608995

Lu Y (2012) Education of children left behind in rural China. J Marriage Fam 74(2):328-341. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00951.x

Ma L, Du X, Hau KT, Liu J (2018) The association between teacher-student relationship and academic achievement in Chinese EFL context: a serial multiple mediation model. Educ Psychol 38(5):687-707. https://doi.org/10. 1080/01443410.2017.1412400

Mahler SJ (2001) Transnational relationships: the struggle to communicate across borders. Identities Glob Stud Cult Power 7(4):583-619. https://doi.org/10. 1080/1070289X.2001.9962679

McGinnis, H, & Wright, AW (2023). Psychological and behavioral factors. In: Halpern-Felsher B (ed), Encyclopedia of child and adolescent health, Academic Press pp 582-598

Melby JN, Conger RD, Fang SA, Wickrama KAS, Conger KJ (2008) Adolescent family experiences and educational attainment during early adulthood. Dev Psychol 44(6):1519, https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0013352

Munz EA (2015) Parent-child communication. In: Munnz EA (ed) The international encyclopedia of interpersonal communication, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, pp 1-5

Murphy R (2020) The children of China’s great migration, Cambridge University Press

National Bureau of Statistics of China (2022) National bureau of statistics of China: 2021 monitoring report on rural migrant workers. http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ zxfb/202302/t20230203_1901452.html Accessed 29 April 2022

Nihal Lindberg E, Yildirim E, Elvan Ö, Öztürk D, Recepoğlu S (2019) Parents’ educational expectations: does It matter for academic success? SDU Int J Educ Stud 6(2):150-160. https://doi.org/10.33710/sduijes. 596569

Nurmi JE (2004) Socialization and self-development: channeling, selection, adjustment, and reflection. In: Lerner RM & Steinberg L (eds) Handbook of adolescent psychology, 2nd edn. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, pp 85-124

Peng B (2021) Chinese migrant parents’ educational involvement: shadow education for left-behind children. Hung. Educ Res J 11(2):101-123. https://doi. org/10.1556/063.2020.00030

Perrin EC, Leslie LK, Boat T (2016) Parenting as primary prevention. JAMA Pediatr 170(7):637-638. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0225

Portes A, Aparicio R, Haller W, Vickstrom E (2010) Moving ahead in Madrid: aspirations and expectations in the Spanish second generation. Int Migr Rev 44(4):767-801. 10.1111%2Fj.1747-7379.2010.00825.x

Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF (2007) Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar Behav Res 42(1):185-227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170701341316

Ren Q, Treiman DJ (2016) The consequences of parental labor migration in China for children’s emotional wellbeing. Soc Sci Res 58:46-67. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.ssresearch.2016.03.003

Ren Y, Yang J, Liu L (2017) Social anxiety and internet addiction among rural leftbehind children: the mediating effect of loneliness. Iran J Public Health 46(12):1659

Rimkute L, Hirvonen R, Tolvanen A, Aunola K, Nurmi JE (2012) Parents’ role in adolescents’ educational expectations. Scand J Educ Res 56(6):571-590. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2011.621133

Rigsby LC, Stull JC, Morse-Kelley N (2013) Determinants of student educational expectations and achievement:Race/ethnicity and gender differences. InSocial and emotional adjustment and family relations in ethnic minorityfamilies, Routledge pp. 201-224

Rothon C, Arephin M, Klineberg E, Cattell V, Stansfeld S (2011) Structural and socio-psychological influences on adolescents’ educational aspirations and subsequent academic achievement. Soc Psychol Educ 14:209-231. https://doi. org/10.1007/s11218-010-9140-0

Rozelle S & Hell N (2020) Invisible China: how the urban-rural divide threatens China’s rise, University of Chicago Press, pp 248

Rumberger RW (1983) Dropping out of high school: the influence of race, sex, and family background. Am Educ Res J 20(2):199-220. https://doi.org/10.3102/ 00028312020002199

Seginer R, Vermulst A (2002) Family environment, educational aspirations, and academic achievement in two cultural settings. J Cross Cultural Psychol 33(6):540-558. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220022102238268

Shen W (2020) A tangled web: the reciprocal relationship between depression and educational outcomes in China. Soc Sci Res 85:102353. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.ssresearch.2019.102353

Su S, Li X, Lin D, Zhu M (2017) Future orientation, social support, and psychological adjustment among left-behind children in rural China: a longitudinal study. Front Psychol 8:1309. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01309

Su S, Li X, Lin D, Xu X, Zhu M (2013) Psychological adjustment among left-behind children in rural China: the role of parental migration and parent-child communication. Child Care Health Dev 39(2):162-170. https://doi.org/10. 1111/j.1365-2214.2012.01400.x

Sun X, Tian Y, Zhang Y, Xie X, Heath MA, Zhou Z (2015) Psychological development and educational problems of left-behind children in rural China. Sch Psychol Int 36(3):227-252. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034314566669

Ma L, Du X, Hau KT, Liu J (2018) The association between teacher-student relationship and academic achievement in Chinese EFL context: a serial multiple mediation model. Educ Psychol 38(5):687-707. https://doi.org/10. 1080/01443410.2017.1412400

Mahler SJ (2001) Transnational relationships: the struggle to communicate across borders. Identities Glob Stud Cult Power 7(4):583-619. https://doi.org/10. 1080/1070289X.2001.9962679

McGinnis, H, & Wright, AW (2023). Psychological and behavioral factors. In: Halpern-Felsher B (ed), Encyclopedia of child and adolescent health, Academic Press pp 582-598

Melby JN, Conger RD, Fang SA, Wickrama KAS, Conger KJ (2008) Adolescent family experiences and educational attainment during early adulthood. Dev Psychol 44(6):1519, https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0013352

Munz EA (2015) Parent-child communication. In: Munnz EA (ed) The international encyclopedia of interpersonal communication, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, pp 1-5

Murphy R (2020) The children of China’s great migration, Cambridge University Press

National Bureau of Statistics of China (2022) National bureau of statistics of China: 2021 monitoring report on rural migrant workers. http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ zxfb/202302/t20230203_1901452.html Accessed 29 April 2022

Nihal Lindberg E, Yildirim E, Elvan Ö, Öztürk D, Recepoğlu S (2019) Parents’ educational expectations: does It matter for academic success? SDU Int J Educ Stud 6(2):150-160. https://doi.org/10.33710/sduijes. 596569

Nurmi JE (2004) Socialization and self-development: channeling, selection, adjustment, and reflection. In: Lerner RM & Steinberg L (eds) Handbook of adolescent psychology, 2nd edn. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, pp 85-124

Peng B (2021) Chinese migrant parents’ educational involvement: shadow education for left-behind children. Hung. Educ Res J 11(2):101-123. https://doi. org/10.1556/063.2020.00030

Perrin EC, Leslie LK, Boat T (2016) Parenting as primary prevention. JAMA Pediatr 170(7):637-638. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0225

Portes A, Aparicio R, Haller W, Vickstrom E (2010) Moving ahead in Madrid: aspirations and expectations in the Spanish second generation. Int Migr Rev 44(4):767-801. 10.1111%2Fj.1747-7379.2010.00825.x

Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF (2007) Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar Behav Res 42(1):185-227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170701341316

Ren Q, Treiman DJ (2016) The consequences of parental labor migration in China for children’s emotional wellbeing. Soc Sci Res 58:46-67. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.ssresearch.2016.03.003

Ren Y, Yang J, Liu L (2017) Social anxiety and internet addiction among rural leftbehind children: the mediating effect of loneliness. Iran J Public Health 46(12):1659

Rimkute L, Hirvonen R, Tolvanen A, Aunola K, Nurmi JE (2012) Parents’ role in adolescents’ educational expectations. Scand J Educ Res 56(6):571-590. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2011.621133

Rigsby LC, Stull JC, Morse-Kelley N (2013) Determinants of student educational expectations and achievement:Race/ethnicity and gender differences. InSocial and emotional adjustment and family relations in ethnic minorityfamilies, Routledge pp. 201-224

Rothon C, Arephin M, Klineberg E, Cattell V, Stansfeld S (2011) Structural and socio-psychological influences on adolescents’ educational aspirations and subsequent academic achievement. Soc Psychol Educ 14:209-231. https://doi. org/10.1007/s11218-010-9140-0

Rozelle S & Hell N (2020) Invisible China: how the urban-rural divide threatens China’s rise, University of Chicago Press, pp 248

Rumberger RW (1983) Dropping out of high school: the influence of race, sex, and family background. Am Educ Res J 20(2):199-220. https://doi.org/10.3102/ 00028312020002199

Seginer R, Vermulst A (2002) Family environment, educational aspirations, and academic achievement in two cultural settings. J Cross Cultural Psychol 33(6):540-558. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220022102238268

Shen W (2020) A tangled web: the reciprocal relationship between depression and educational outcomes in China. Soc Sci Res 85:102353. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.ssresearch.2019.102353

Su S, Li X, Lin D, Zhu M (2017) Future orientation, social support, and psychological adjustment among left-behind children in rural China: a longitudinal study. Front Psychol 8:1309. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01309

Su S, Li X, Lin D, Xu X, Zhu M (2013) Psychological adjustment among left-behind children in rural China: the role of parental migration and parent-child communication. Child Care Health Dev 39(2):162-170. https://doi.org/10. 1111/j.1365-2214.2012.01400.x

Sun X, Tian Y, Zhang Y, Xie X, Heath MA, Zhou Z (2015) Psychological development and educational problems of left-behind children in rural China. Sch Psychol Int 36(3):227-252. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034314566669

Syed M, Seiffge-Krenke I (2013) Personality development from adolescence to emerging adulthood: linking trajectories of ego development to the family context and identity formation. J Personal Soc Psychol 104(2):371. https:// doi.org/10.1037/a0030070

Tong Y, Luo W, Piotrowski M (2015) The association between parental migration and childhood illness in rural China. Eur J Popul 31:561-586. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10680-015-9355-z

Tong Y, Luo W, Piotrowski M (2015) The association between parental migration and childhood illness in rural China. Eur J Popul 31:561-586. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10680-015-9355-z

Wang F, Lin L, Xu M, Li L, Lu J, Zhou X (2019) Mental health among left-behind children in rural China in relation to parent-child communication. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(10):1855

Wang H, Zhu R (2021) Social spillovers of China’s left-behind children in the classroom. Labour Econ 69:101958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2020. 101958

Wang L, Feng Z, Yang G, Yang Y, Dai Q, Hu C, Liu K, Guang Y, Zhang R, Xia F, Zhao M (2015) The epidemiological characteristics of depressive symptoms in the left-behind children and adolescents of Chongqing in China. J Affect Disord 177:36-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.002

Wang SX (2014) The effect of parental migration on the educational attainment of their left-behind children in rural China. BE J Econ Anal Policy 14(3):1037-1080. https://doi.org/10.1515/bejeap-2013-0067

Wells RS, Seifert TA, Saunders DB (2013) Gender and realized educational expectations: the roles of social origins and significant others. Res High Educ 54:599-626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-013-9308-5

Wen M, Lin D (2012) Child development in rural China: children left behind by their migrant parents and children of nonmigrant families. Child Dev 83(1):120-136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01698.x

Wen M, Wang W, Ahmmad Z, Jin L (2023) Parental migration and self-efficacy among rural-origin adolescents in China: patterns and mechanisms. J Commun Psychol 51(2):626-647. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop. 22976

Wu Q, Lu D, Kang M (2015) Social capital and the mental health of children in rural China with different experiences of parental migration. Soc Sci Med 132:270-277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.050

Wu Z & Qin Y (2022) Report of rural education development in China (20202022), Chineese edition, China Science Publishing & Media

Wang H, Zhu R (2021) Social spillovers of China’s left-behind children in the classroom. Labour Econ 69:101958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2020. 101958

Wang L, Feng Z, Yang G, Yang Y, Dai Q, Hu C, Liu K, Guang Y, Zhang R, Xia F, Zhao M (2015) The epidemiological characteristics of depressive symptoms in the left-behind children and adolescents of Chongqing in China. J Affect Disord 177:36-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.002

Wang SX (2014) The effect of parental migration on the educational attainment of their left-behind children in rural China. BE J Econ Anal Policy 14(3):1037-1080. https://doi.org/10.1515/bejeap-2013-0067

Wells RS, Seifert TA, Saunders DB (2013) Gender and realized educational expectations: the roles of social origins and significant others. Res High Educ 54:599-626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-013-9308-5

Wen M, Lin D (2012) Child development in rural China: children left behind by their migrant parents and children of nonmigrant families. Child Dev 83(1):120-136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01698.x

Wen M, Wang W, Ahmmad Z, Jin L (2023) Parental migration and self-efficacy among rural-origin adolescents in China: patterns and mechanisms. J Commun Psychol 51(2):626-647. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop. 22976

Wu Q, Lu D, Kang M (2015) Social capital and the mental health of children in rural China with different experiences of parental migration. Soc Sci Med 132:270-277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.050

Wu Z & Qin Y (2022) Report of rural education development in China (20202022), Chineese edition, China Science Publishing & Media

Xiao Y, He L, Chang W, Zhang S, Wang R, Chen X, Li X, Wang Z, Risch HA (2020) Self-harm behaviors, suicidal ideation, and associated factors among rural left-behind children in west China. Ann. Epidemiol. 42:42-49. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.12.014

Xiao J, Liu X (2023) How does family cultural capital influence the individuals’ development?-case study about left-behind children in China. Asia Pacific Edu Rev 24(1):167-178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-022-09744-x

Xu JH (2016) Media discourse on cell phone technology and “left-behind children” in China. Glob Media J 9(1):87

Xu Y, Montgomery C (2021) Understanding the complexity of Chinese rural parents’ roles in their children’s access to elite universities. Br J Sociol Educ 42(4):555-570. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2021.1872364

Ye J, Pan L (2011) Differentiated childhoods: impacts of rural labor migration on left-behind children in China. J peasant Stud 38(2):355-377. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/03066150.2011.559012

Xiao J, Liu X (2023) How does family cultural capital influence the individuals’ development?-case study about left-behind children in China. Asia Pacific Edu Rev 24(1):167-178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-022-09744-x

Xu JH (2016) Media discourse on cell phone technology and “left-behind children” in China. Glob Media J 9(1):87

Xu Y, Montgomery C (2021) Understanding the complexity of Chinese rural parents’ roles in their children’s access to elite universities. Br J Sociol Educ 42(4):555-570. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2021.1872364

Ye J, Pan L (2011) Differentiated childhoods: impacts of rural labor migration on left-behind children in China. J peasant Stud 38(2):355-377. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/03066150.2011.559012

Ying L, Zhou H, Yu S, Chen C, Jia X, Wang Y, Lin C (2018) Parent-child communication and self-esteem mediate the relationship between interparental conflict and children’s depressive symptoms. Child Care Health Dev 44(6):908-915. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch. 12610

Yu, M, & Daraganova, G (2015). The educational expectations of Australian children and their mothers. In Australian Institute of Family Studies, The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children Annual Statistical Report 2014 (pp. 105-129). Melbourne: AIFS

Yue A, Shi Y, Luo R, Chen J, Garth J, Zhang J, Medina A, Kotb S, Rozelle S (2017) China’s invisible crisis: Cognitive delays among rural toddlers and the absence of modern parenting. China J 78(1):50-80. https://doi.org/10.1086/692290

Yuan X, Olivos F (2023) Conformity or contrast? simultaneous effect of grademates and classmates on students’ educational aspirations. Soc Sci Res 114:102908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2023.102908

Yue A, Shi Y, Luo R, Chen J, Garth J, Zhang J, Medina A, Kotb S, Rozelle S(2017) China’s invisible crisis: Cognitive delays among rural toddlers and the absence of modern parenting China J 78(1):50-80. https://doi.org/10.1086/ 692290

Yu, M, & Daraganova, G (2015). The educational expectations of Australian children and their mothers. In Australian Institute of Family Studies, The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children Annual Statistical Report 2014 (pp. 105-129). Melbourne: AIFS

Yue A, Shi Y, Luo R, Chen J, Garth J, Zhang J, Medina A, Kotb S, Rozelle S (2017) China’s invisible crisis: Cognitive delays among rural toddlers and the absence of modern parenting. China J 78(1):50-80. https://doi.org/10.1086/692290

Yuan X, Olivos F (2023) Conformity or contrast? simultaneous effect of grademates and classmates on students’ educational aspirations. Soc Sci Res 114:102908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2023.102908

Yue A, Shi Y, Luo R, Chen J, Garth J, Zhang J, Medina A, Kotb S, Rozelle S(2017) China’s invisible crisis: Cognitive delays among rural toddlers and the absence of modern parenting China J 78(1):50-80. https://doi.org/10.1086/ 692290

Zhao C, Chen B (2022) Parental migration and non-cognitive abilities of leftbehind children in rural China: causal effects by an instrumental variable approach. Child Abus Negl 123:105389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu. 2021.105389

Zheng X, Zhou Y (2024) Social spillovers of parental absence: the classroom peer effects of ‘left-behind’ children on household human capital investments in rural China. J Dev Stud 60(2):288-308

Zhuang J, Ng JC, Wu Q (2024) I am better because of your expectation: examining how left-behind status moderates the mediation effect of perceived parental educational expectation on cognitive ability among Chinese rural students. Child Care Health Dev 50(4):e13283

Zhuang, J, & Wu, Q (2024). Interventions for left-behind children in Mainland China: a scoping review. Child Youth Serv Rev 166:107933

Zhu Z, Wang Y, Pan X. (2023) Health problems faced by left-behind children in low/middle-income countries. BMJ Global Health. 8(8):e013502. https://doi. org/10.1136/bmjgh-2023-013502

Zhuang J, Ng JC, Wu Q (2024) I am better because of your expectation: examining how left-behind status moderates the mediation effect of perceived parental educational expectation on cognitive ability among Chinese rural students. Child Care Health Dev 50(4):e13283

Zhuang, J, & Wu, Q (2024). Interventions for left-behind children in Mainland China: a scoping review. Child Youth Serv Rev 166:107933

Zhu Z, Wang Y, Pan X. (2023) Health problems faced by left-behind children in low/middle-income countries. BMJ Global Health. 8(8):e013502. https://doi. org/10.1136/bmjgh-2023-013502

مساهمات المؤلفين