DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-023-02261-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38178140

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-04

رؤى جديدة في العلاجات النانوية لالتهاب اللثة: كونشيرتو ثلاثي للنشاط المضاد للميكروبات، تعديل المناعة وتجديد اللثة

الملخص

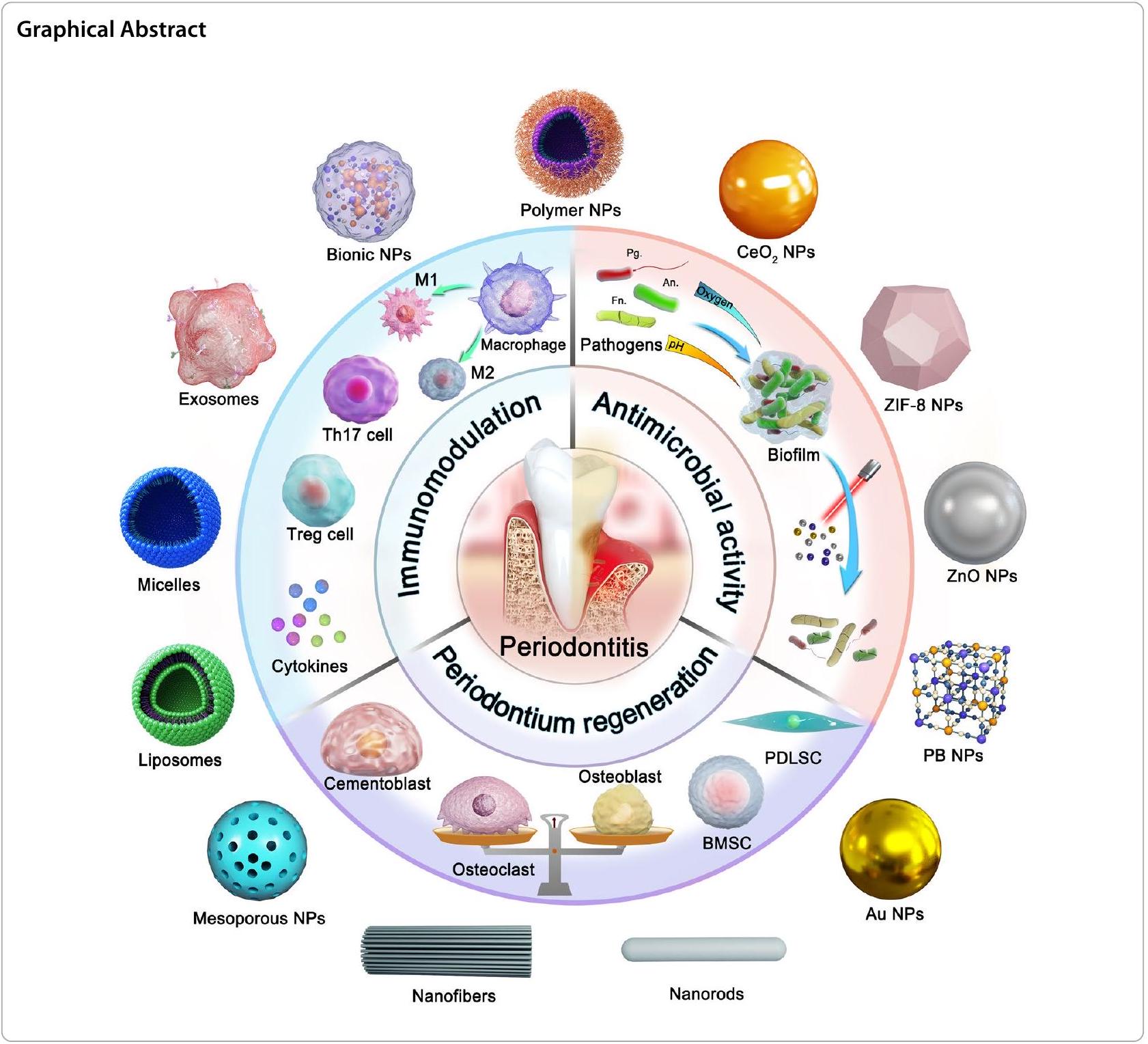

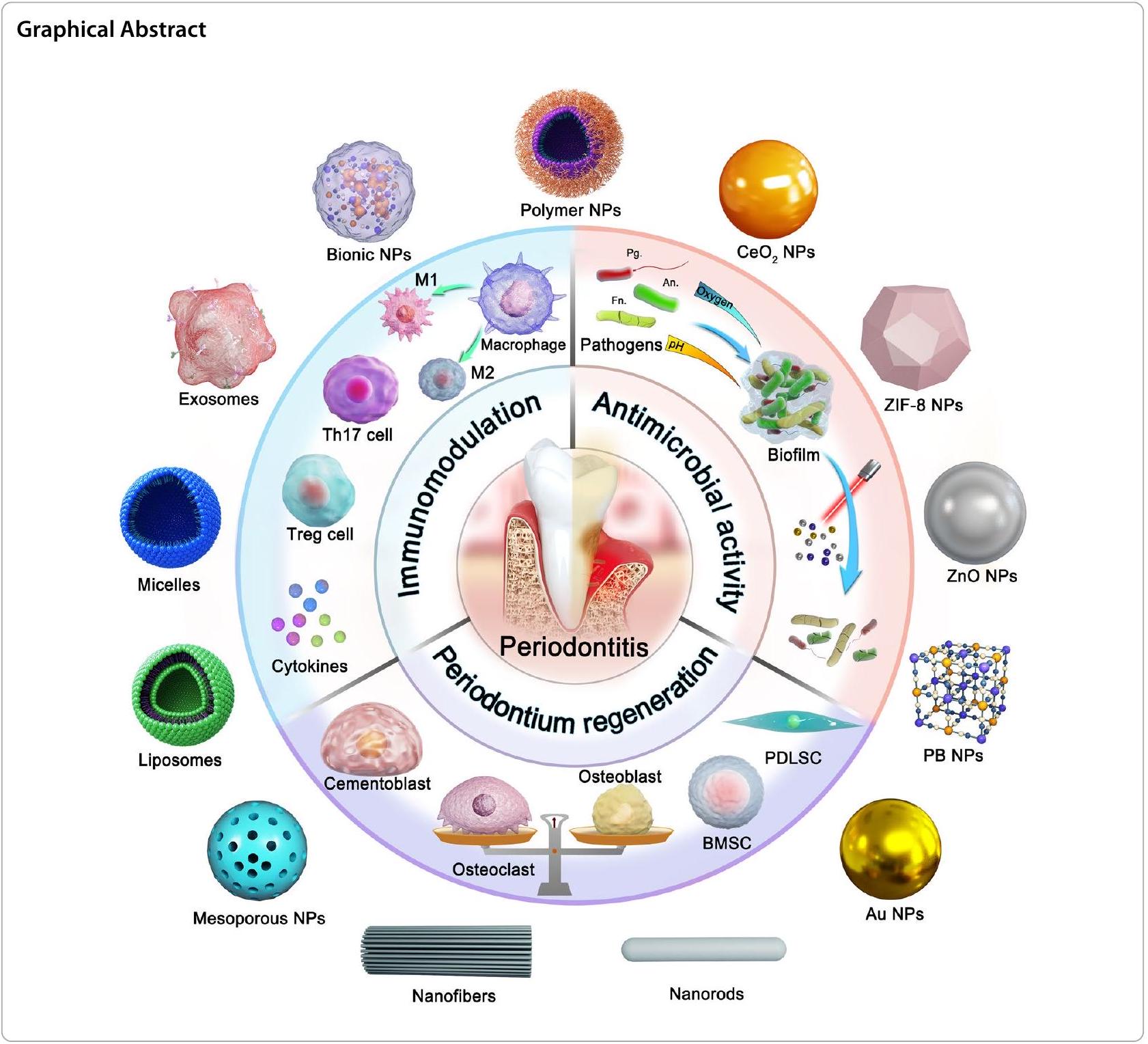

التهاب اللثة هو مرض التهابي مزمن ناتج عن الميكروبيوم المحلي واستجابة الجهاز المناعي للمضيف، مما يؤدي إلى تلف بنية اللثة وحتى فقدان الأسنان. التنظيف العميق وتخطيط الجذور مع استخدام المضادات الحيوية هي الوسائل التقليدية للعلاج غير الجراحي لالتهاب اللثة، لكنها غير كافية للشفاء الكامل بسبب التصاق البكتيريا المستعصي ومقاومة الأدوية. الخيارات العلاجية الجديدة والفعالة في العلاج الدوائي السريري لا تزال نادرة. تحقق العلاجات النانوية استهدافًا خلويًا مستقرًا، واحتفاظًا فمويًا، وإطلاقًا ذكيًا من خلال المرونة الكبيرة في تغيير التركيب الكيميائي أو الخصائص الفيزيائية للجسيمات النانوية. في الوقت نفسه، توفر الحماية ونسبة السطح إلى الحجم العالية للجسيمات النانوية تحميلًا عاليًا للأدوية، مما يضمن فعالية علاجية ملحوظة. حاليًا، يُعد الجمع بين الجسيمات النانوية المتقدمة والاستراتيجيات العلاجية الجديدة أكثر المجالات البحثية نشاطًا في علاج التهاب اللثة. في هذا الاستعراض، نقدم أولاً مسببات التهاب اللثة، ثم نلخص أحدث استراتيجيات العلاج النانوي القائمة على التناغم الثلاثي للنشاط المضاد للبكتيريا، وتنظيم المناعة، وتجديد اللثة، مع التركيز بشكل خاص على آلية العلاج والتصميم المبتكر للأدوية النانوية. أخيرًا، نناقش التحديات وآفاق العلاج النانوي لالتهاب اللثة من منظور مشاكل العلاج الحالية واتجاهات التطوير المستقبلية.

مقدمة

قد يكون العمر عاملاً حاسماً في الاتجاه المتزايد [4]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، هناك أدلة سريرية متزايدة تشير إلى أن التهاب اللثة يشكل عبئًا كبيرًا على نظام الرعاية الصحية العامة بسبب الروابط الوثيقة مع أمراض أخرى مثل السكري، مرض الزهايمر، التهاب المفاصل الروماتويدي، التهاب القولون وحتى السرطان [5-7].

تتمتع الجسيمات النانوية بوعد كبير في معالجة تحديات توصيل الأدوية لعلاج أمراض اللثة. توفر الجسيمات النانوية، بما في ذلك الليبوسومات، والجسيمات النانوية البوليمرية، والميسيلات البوليمرية، والألياف النانوية، مرونة كبيرة في تغيير التركيب الكيميائي والحجم والسطح

الشحنة والخصائص الأخرى، التي يمكن أن تضمن استهدافًا مستقرًا للخلايا واحتفاظًا فمويًا. تشير البيانات الحالية إلى أن الجسيمات النانوية تحمي الأدوية من تأثير الرقم الهيدروجيني والتحلل الإنزيمي في آفة اللثة [12]. من المهم أن يتم تصميم هيكل الجسيمات النانوية للاستجابة لأنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS)، أو الرقم الهيدروجيني، أو آليات الاستجابة للإنزيمات في البيئة الميكروية المرضية من أجل إطلاق دوائي محكم. نلخص استراتيجيات أنظمة التوصيل النانوية لعلاج التهاب اللثة من حيث ثلاثة جوانب رئيسية: العلاج المضاد للبكتيريا، العلاج المناعي المعدل وتجديد الأنسجة (الشكل 1). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن النسبة العالية بين مساحة السطح والحجم للجسيمات النانوية تمكن من تحميل عالي للدواء أو تركيبة الأدوية، مما يؤدي إلى فعالية علاجية تآزرية من خلال الجمع بين جوانب علاجية متعددة. على سبيل المثال، يمكن للجسيمات النانوية المعدنية مثل الفضة والذهب والسيريوم أن تعقم مباشرة أو

ناقش التحديات المستقبلية واتجاهات البحث في أنظمة النانو لعلاج التهاب اللثة.

علم الأمراض الفيزيولوجي لالتهاب اللثة

العدلات، كخط الدفاع الأول في المناعة غير النوعية ضد البكتيريا الممرضة، تحاول ابتلاع أو قتل الممرضات، لكنها تغلبت عليها أعداد كبيرة من الممرضات في التهاب اللثة [24]. كخلايا مقدمة للمستضدات، تعمل الخلايا التغصنية (DCs) كجسر بين الاستجابات المناعية الفطرية والتكيفية في التهاب اللثة [25]. تمتلك الخلايا التغصنية غير الناضجة قدرة عالية على البلعمة وقادرة على التقاط الكائنات الدقيقة الغازية بسرعة [26]. تعرض الخلايا التغصنية الناضجة المستضدات على البداية

تعزيز تمايز خلايا Th 17 أو Treg عن طريق إفراز السيتوكينات لعامل نخر الورم

الاستراتيجيات النانوية لعلاج التهاب اللثة

استراتيجيات العلاج النانوي المضاد للميكروبات

تم تلخيص استراتيجيات علاج التجديد لالتهاب اللثة (الجدول 1).

مضاد حيوي

الحجم، مما يحسن فعالية المضاد الميكروبي للإدارة الموضعية [44، 45]. يمكن لجسيمات مينوسكلين النانوية توفير إطلاق مستمر للدواء، وتقليل تكرار الجرعات وتجنب الإفراز المفاجئ للدواء. أظهر الملف الدوائي أن جسيمات مينوسكلين النانوية كان لها أطول مدة تأثير في الأخدود اللثوي، مقارنةً بمرهم هيدروكلوريد المينوسكلين ومحلول المينوسكلين. انخفض تركيز جسيمات مينوسكلين النانوية في الأخدود اللثوي ببطء، مما حافظ على الدواء بتركيز فعال (

| جسيمات نانوية | أنظمة التوصيل | المخدرات | النتيجة | المراجع |

| العبارات الاسمية المصغرة | الجسيمات النانوية البوليمرية | مينوسكلين | تم تحسين معايير اللثة السريرية (عمق جيب اللثة، مؤشر البلاك، ومؤشر اللثة) بشكل ملحوظ. | [45] |

| جسيم نانوي MOX-PLGA | الجسيمات النانوية البوليمرية | هيدروكلوريد موكسيفلوكساسين | الاحتفاظ المطول وإطلاق الدواء لنظام هلامي موضعي محمل بالنانو من الموكسيفلوكساسين في جيوب اللثة | [46] |

| حويصلات مزدوجة التاج محملة بكلوريد سيبروفلوكساسين | الحويصلات | هيدروكلوريد سيبروفلوكساسين | استخدمت الحويصلات ذات التاج المزدوج كحاملات للأدوية، حيث يمكن أن يحقق 50% من الجرعة العادية من المضادات الحيوية الأغراض المضادة للبكتيريا، مما سيقلل من احتمال مقاومة المضادات الحيوية. | [47] |

| جسيمات الذهب النانوية | عناقيد الذهب النانوية | / | تقليل احتمال مقاومة البكتيريا | [50] |

| PCL-OTCz | الجسيمات النانوية البوليمرية | هيدروكلوريد الأوكسي تتراسايكلين وجسيمات أكسيد الزنك النانوية | النشاط المضاد للبكتيريا الممتاز لكلوريد أوكسيتتراسيكلين بالتزامن مع أكسيد الزنك ضد مزارع مختلطة من البكتيريا اللاهوائية سالبة الجرام | [64] |

| جسيمات نانوية مينو-أكسيد الزنك على الألب | نانو-ألبومين | جسيمات أكسيد الزنك النانوية والمينوسكلين | العمل المضاد للبكتيريا التآزري، تقليل جرعة المينوسكلين وتجنب تطور مقاومة الدواء | [65] |

| هلام جسيمات الذهب النانوية المغطاة بثاني أكسيد السيليكون | في نقاط البيع الجديدة | مينوسكلين | القضاء على مسببات الأمراض اللثوية في جيوب اللثة، العلاج الضوئي الحراري للحفاظ على انخفاض احتباس البكتيريا بعد الدواء | [68] |

|

|

نظام التوصيل البوليمري | Ce6 و C6 | نشاط مضاد للبكتيريا قوي ضد الأغشية الحيوية للبلاك | [73] |

| NaYF4-Mn@Ce6@سيلان | الجسيمات النانوية البوليمرية | سي6 | تحقيق تحويل انبعاث الضوء وتعزيز تأثير العلاج الضوئي الديناميكي | [74] |

| جسيمات نانوية TAT-Ce6/TDZ | الجسيمات النانوية البوليمرية | سي6 | عزز اختراق غشاء الخلية البكتيرية من خلال وسيطة ببتيد TAT | [76] |

| جسيمات نانوية “sPDMA@ICG” | نظام التوصيل البوليمري | اللجنة الدولية للحماية | عزز بشكل كبير امتصاص واختراق ICG إلى الخلايا البكتيرية، مظهراً خصائص مضادة للبكتيريا بتآزر بين العلاج الضوئي الحراري (PTT) والعلاج الضوئي الكيميائي (PDT) | [٧٩] |

اقترح شي وزملاؤه تغليف هيدروكلوريد السيبروفلوكساسين في نانوفيسكلات مزدوجة التاج لتقليل جرعة المضاد الحيوي ومقاومة الميكروبات (الشكل 3أ) [47].

عامل مضاد للبكتيريا نانوي معدني

تشكيل مستعمرات بكتيرية مختلطة. أظهر PCL-OTCz نشاطًا مضادًا للبكتيريا قويًا مقارنة بهيدروكلوريد أوكسيتتراسايكلين أو جزيئات أكسيد الزنك النانوية، بشكل فردي.

العلاج الضوئي الحراري/العلاج الضوئي الديناميكي

يشير العلاج المضاد للميكروبات PDT إلى استخدام مادة حساسة للضوء تنتج أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية استجابة لتحفيز الضوء، مما يؤدي إلى أكسدة سريعة للدهون في البكتيريا.

وتدمير الأغشية الدهنية الهشة في علاج التهاب دواعم الأسنان [69، 70]. يُستخدم كلورين e6 (Ce6) على نطاق واسع في العلاج الضوئي الديناميكي بسبب اختراقه القوي للأنسجة، وتوافقه الحيوي العالي، وإنتاجه العالي للأكسجين المفرد [71، 72]. قام صن وآخرون بتحضير نظام توصيل دوائي نانوي بهيكل نواة-قشرة (

شكل وأظهر بنية داخلية أكثر تماسكًا. كان حجم جزيئات جزيئات TAT-Ce6/TDZ النانوية

الأخضر الإندوستيانيني (ICG)، وهو مادة حساسة للضوء ذات خصائص العلاج الضوئي الديناميكي (PDT)، تمت الموافقة عليه للاستخدام السريري من قبل إدارة الغذاء والدواء الأمريكية [77]. استكشف ناجاهارا وآخرون لأول مرة العلاج الضوئي الديناميكي باستخدام المادة الحساسة للضوء الأخضر الإندوستيانيني، التي تمتلك امتصاصًا عاليًا عند أطوال موجية تتراوح بين 800-805 نانومتر [78]. قاموا بتصميم جسيمات نانوية من PLGA محملة بـ ICG ومغطاة بالكيتوزان (ICGNano/c) واستكشفوا العلاج الضوئي الديناميكي لـ ICGNano/c في Pg. أظهرت الدراسة أن ICG-Nano/c مع ليزر ديود منخفض المستوى (

الخصائص. أشارت النتائج إلى أن جزيئات sPDMA@ICG النانوية يمكنها إنتاج أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS) بعد التعرض لإشعاع الليزر، كما تم الكشف عنها بواسطة SOSG. تُظهر صور المجهر المجهري التوافقي أن جزيئات sPDMA@ICG النانوية تتراكم بفعالية داخل الخلايا البكتيرية بعد إعطاء جزيئات sPDMA@ICG النانوية. أظهرت صور المجهر الإلكتروني النافذ أن جزيئات sPDMA@ICG النانوية كانت واضحة على سطح بكتيريا Pg، وأن الغشاء البكتيري تمزق وتفككت الخلايا البكتيرية بعد التعرض لإشعاع الليزر (الشكل 4D). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، قللت جزيئات sPDMA@ICG النانوية مع التعرض لإشعاع الليزر من مساحة نمو الأغشية الحيوية للبلاك المستمدة من نموذج الفئران لالتهاب دواعم السن (الشكل 4E). بعد إعطاء جزيئات sPDMA@ICG النانوية والتعرض لإشعاع الليزر، ارتفعت درجة الحرارة ومستويات ROS في الفئران المصابة بالتهاب دواعم السن، مما يشير إلى أن جزيئات sPDMA@ICG النانوية تمارس تأثيرات علاج حراري ضوئي (PTT) وعلاج ضوئي تفاعلي (PDT) متآزرة في الجسم الحي (الشكل 4F).

استراتيجيات العلاج النانوي المعدلة للمناعة

| جسيمات نانوية | أنظمة التوصيل | المخدرات | النتيجة | المراجع |

| ليبو-آر إس في | الليبوسوم | ريسفيراترول | إعادة برمجة البلاعم من النمط M1 إلى نمط يشبه M2، تعديل البيئة المناعية الدقيقة | [89] |

| DPSC-Exo/CS | الحويصلات الخارجية | / | قمع التهاب اللثة عن طريق تعزيز تحويل البلاعم من النمط الالتهابي إلى النمط المضاد للالتهاب في نسيج اللثة لدى الفئران المصابة بالتهاب اللثة | [90] |

| CeO2@QU | جسيمات نانوية | الكيرسيتين | استُخلصت ROS ونُظمت عملية تحويل البلاعم ذات النمط M1 إلى النمط M2 لتنظيم البيئة المناعية الدقيقة | [14] |

| الدعائم الخارجية ثلاثية الأبعاد | الحويصلات الخارجية | / | تخفيف اختلال توازن خلايا Th17/Treg وتقليل الالتهاب | [99] |

| PDLSC-إكسوس | الحويصلات الخارجية | / | نقلت جسيمات PDLSC-exos الصغيرة miR-155-5p إلى خلايا CD4+ T لتؤثر على توازن Th17/Treg. | [100] |

| نانوالبي إيه/بي إي | الجسيمات النانوية البوليمرية | بايكالين/بايكالين | خفف التعبير عن II-1

|

[104] |

| ممرضات الممارسات المتقدمة (PDA) | جسيمات نانوية من بوليدوبامين | / | يقضي بفعالية على أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية في الجسم، يخفف من الإجهاد التأكسدي ويقلل من الالتهاب الموضعي في اللثة | [105] |

إعادة تشكيل استقطاب البلاعم

طور شي وآخرون ليبوزوم محملاً بالريسفيراترول (Lipo-RSV) لاستقطاب البلاعم من النمط M1 إلى النمط M2 (الشكل 5A) [89]. قام Lipo-RSV بزيادة مستويات التعبير عن الحمض النووي الريبوزي المرسال للعلامات المرتبطة بالنمط M2 (CD206، Arg-1 وChil3)، وخفض مستويات التعبير عن الحمض النووي الريبوزي المرسال لعلامات البلاعم من النمط M1 (CD86، iNOS وCCR7) في البلاعم المنشّطة. زاد علاج Lipo-RSV من نسبة الفئات الفرعية الشبيهة بالنمط M2 (

الجسيمات الخارجية هي جسيمات نانوية الحجم (

تم جمع راسب الإكسوسومات عن طريق الطرد المركزي لعلاج الفئران المصابة بالتهاب دواعم السن [90]. لتعزيز استقرار الإكسوسومات، تم تحضير هلامات الكيتوزان المحملة بإكسوسومات خلايا جذعية من لب الأسنان (DPSCs-Exo/CS) في ثقافة مختلطة مع هلامات الكيتوزان عند

التقاط أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية وتنظيم تحويل البلاعم من النمط M1 إلى النمط M2.

استعادة توازن خلايا Th17/Treg

التوازن بين خلايا Th17 وخلايا Treg أمر حاسم في الاستجابة المناعية اللثوية [94، 95]. يؤدي رد فعل مفرط لخلايا Th17 تجاه الممرضات إلى زيادة تعبير السيتوكينات المؤيدة للالتهاب IL-17 و IL-22 [96]. لقد ثبت أن IL-17 يعزز تعبير RANKL بينما يثبط تعبير OPG في خلايا الرباط اللثوي، مما قد يفسر سبب تعزيز خلايا Th17 لفقدان العظم السنخي [95]. ومع ذلك، يمكن لخلايا Tregs أن تثبط الاستجابة المناعية للمضيف بالتوازن مع خلايا Th17 في اللثة [97، 98]. حتى الآن، لم يتم الإبلاغ عن أي دواء/نظام نانوي ينظم مباشرة توازن خلايا Th17/Treg، لكن تم العثور على أن الإكسوسومات المستمدة من خلايا جذعية من الرباط اللثوي لديها القدرة على تنظيم خلايا Th17/Treg.

وجد تشانغ وآخرون أن الإكسوسومات المستمدة من الخلايا الجذعية الميزنكيمية (3D-exos) يمكن أن تنظم توازن خلايا Th17/Tregs [99]. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن استبدال نظام الزراعة التقليدي ثنائي الأبعاد (2D) بنظام ثلاثي الأبعاد (3D) يمكن أن يزيد من إنتاج الإكسوسومات. كان متوسط حجم الجسيمات للإكسوسومات ثلاثية الأبعاد (3D-exos) هو

حقق تشنغ وآخرون في تأثير الإكسوسومات المستخلصة من خلايا جذعية لغشاء اللثة (PDLSC-exos) على توازن Th17/Treg [100]. تم زيادة التعبير عن عامل النسخ المرتبط بـ Th17 وهو مستقبل الارتباط اليتيم C المرتبط بـ RAR، وتم تقليل التعبير عن عامل النسخ المرتبط بـ Treg وهو الصندوق الأمامي P3 في مرضى التهاب اللثة. هذا يعني أن نسبة Th17/Treg غير متوازنة في مرضى التهاب اللثة. أظهرت النتائج انخفاض CD4 المرتبط بـ Th17.

الخلايا، وإمكاناتها في علاج التهاب اللثة تحتاج إلى مزيد من الاستكشاف.

تنظيم إفراز السيتوكينات المحفزة/المضادة للالتهابات

استراتيجيات العلاج النانوي لتجديد اللثة

تعزيز تمايز خلايا جذعية لغشاء اللثة

| جسيمات نانوية | أنظمة التوصيل | المخدرات | النتيجة | المراجع |

| جسيمات الذهب النانوية L-Cys | جسيمات الذهب النانوية | / | عزز التكاثر المحفز لخلايا PDLCs البشرية، وزاد من نشاط ALP لديها، ورفع مستويات mRNA لجينات التكوين العظمي | [112] |

| نانو-

|

الجسيمات النانوية البوليمرية | / | زيادة مستويات خلايا PDLSCs البشرية وجينات التكوين العظمي في عظم الأسنان تعزز التمايز العظمي وتساهم في تجديد اللثة | [113] |

| الحويصلات خارج الخلية لخلايا جذعية لب اللبة السنية البشرية | الحويصلات الخارجية | / | زيادة تنظيم مستويات الرنا المرسال لـ Runx2 و OCN في خلايا PDLSCs تعيد التمايز العظمي في خلايا PDLSCs | [116] |

| PLA/CS | الألياف النانوية من PLA/CS | / | عزز التكاثر والتمايز العظمي لخلايا جذعية نخاع العظم وزاد من مستوى التعبير عن الجينات العظمية | [121] |

| بولي لاكتيك أسيد/كالسيوم | الألياف النانوية من PLA/CA | / | زيادة مستويات التعبير عن جينات تمعدن الخلايا وتكوين الوصلات المعدنية في خلايا جذعية نخاع العظم، مما يعزز التمايز العظمي | [122] |

| M2-إكسوس | الحويصلات الخارجية | / | زيادة مستويات التعبير عن تكوين العظام في خلايا جذعية نخاع العظم (BMSCs) مع تقييد مستويات التعبير عن تكوين الخلايا الهادمة للعظم في خلايا بلعمية نخاع العظم (BMDM) | [125] |

| AMG-487 NP | ليبوزومي | AMG-487 NP | قلل من عدد الخلايا البانية للعظم ويمنع فقدان عظم السن | [129] |

| فيبرين-ACP | جسيمات نانوية من الكيتوزان |

|

عزز تمايز خلايا الأسمنت | [134] |

تُعتبر الإكسوسومات المستخلصة من خلايا اللثة السليمة (PDLSCs) مكونات محتملة في التمايز العظمي [114، 115]. قام لي وآخرون بعزل إكسوسومات h-PDLSCs من نسيج الرباط اللثوي المأخوذ من متبرعين أصحاء [116]. كان قطر إكسوسومات h-PDLSCs يبلغ 121.4 نانومتر. قامت إكسوسومات h-PDLSCs برفع مستويات mRNA لكل من RUNX2 وOCN في أربطة اللثة الملتهبة لدى مرضى التهاب اللثة، وعززت تعبير بروتينات OCN المرتبطة بتكوين العظم. كشفت الدراسات الآلية أن إكسوسومات h-PDLSCs تعزز التمايز العظمي من خلال التدخل في مسار إشارات Wnt. كانت مستويات mRNA لكل من Wnt1 وWnt3a وWnt10a و…

تعزيز علاج تمايز خلايا جذعية نخاع العظم

تعطيل تكون الخلايا الهادمة للعظم

جسيمات نانوية تتجمع ذاتياً من حمض البالمتيك والكوليسترول لتعطيل تكوين الخلايا الهادمة للعظم [128، 129]. أظهرت نتائج تلوين TRAP أن تكوين الخلايا الهادمة للعظم تم تثبيطه بعد علاج الليبوزومات المحملة بجسيمات AMG-487 النانوية. أكدت تحليلات إعادة البناء باستخدام الميكرو-CT ذلك.

تسريع تمايز خلايا الأسمنت

يُظهر Fibrin-ACP قدرة قوية على إصلاح أنسجة اللثة من خلال تسريع تجديد الأسمنت.

استراتيجيات العلاج النانوي التآزري

العلاج المضاد للبكتيريا والمعدل للمناعة

| جسيمات نانوية | أنظمة التوصيل | المخدرات | النتيجة | المراجع |

| العلاج المضاد للبكتيريا والمعدل للمناعة | ||||

| MPB-BA | وزارة المالية | بايكالين | زيادة تنظيم تعبير جينات مضادات الأكسدة (SOD-1، CAT وHO-1) لالتقاط أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS) وانخفاض تنظيم عوامل مضادة للالتهابات (TGF-

|

[15] |

| AuAg@PC-Fe | جسيمات نانوية من AuAg | / | العلاج الضوئي الحراري المضاد للميكروبات والمعدل للمناعة لالتهاب دواعم الأسنان | [136] |

| MZ@PNM | جسيمات نانوية مغطاة بغشاء البلاعم | ميترونيدازول | تداخل مع ارتباط Pg بالبلعميات ومنع تحوير Pg لاستجابة الجهاز المناعي المضيف في اللثة | [137] |

| العلاج المضاد للبكتيريا وتجديد اللثة | ||||

| PPZF-JNF | الألياف النانوية | جسيمات نانوية ZIF-8 و FK506 |

|

[140] |

| جيل MA-Z | هيدروجيل | ZIF-8 | أوقف منحنى نمو المكورات العنقودية الذهبية وزاد من مستويات التعبير عن الجينات العظمية (RUNX2، ALP، OCN، COL-1) | [143] |

| CTP-SA | نظام التوصيل البوليمري | / | يمكن إنتاج ROS تحت إشعاع الضوء الأزرق لممارسة تأثيرات مضادة للبكتيريا؛ مناسب

|

[146] |

| العلاج المناعي المعدل وتجديد اللثة | ||||

| جسيمات الذهب النانوية (AuNPs) | جسيمات الذهب النانوية | / | زيادة تعبير مؤشرات M2؛ انخفاض نسبة RANKL/OPG وتعزيز التمايز العظمي | [152] |

| جسيمات نانوية PssL-NAC | الجسيمات النانوية البوليمرية | نَك | انخفاض معدل الاستماتة المحفزة بواسطة LPS ونشاط الخلايا الهادمة للعظم | [153] |

| الجسيمات النانوية الممغنطة | غشاء خلية Treg | جسيمات نانوية من بولي (حمض اللاكتيك-كو-حمض الجليكوليك) | مستهدف

|

[154] |

| العلاج التآزري الثلاثي النمط | ||||

| جسيمات نانوية CeO2@Ce6 | الجسيمات النانوية البوليمرية | سي6 | تنظيم استقطاب البلاعم لتحسين البيئة الدقيقة وزيادة مستويات التعبير الجيني لمؤشرات التكوين العظمي | [155] |

| جسيمات DPPLM النانوية | نظام التوصيل البوليمري | مينوسايكلين حمض ألفا ليبويك | خفض مستوى أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية داخل الخلايا وتعزيز تعبير الجينات العظمية، وتقليل فقدان عظم السنخ | [12] |

استنادًا إلى استراتيجية العلاج التآزري المضاد للميكروبات والمناعي الحراري الضوئي، قام وانغ وزميله بتصميم شبكات معدنية-فينولية (MPNs) محملة بجسيمات نانوية من الذهب والفضة (AuAg@PC-Fe) (الشكل 7ب) [136]. تتكون شبكات MPNs من خلال تنسيق أيونات المعادن والبوليفينولات.

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، انخفض مستوى أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS) بمقدار ثمانية أضعاف في الخلايا البلعمية بعد علاج AuAg@PC-Fe. قام AuAg@PC-Fe بتثبيط تعبير CD86 وتعزيز تعبير CD206 في الخلايا البلعمية، مما يشير إلى أن AuAg@PC-Fe يحفز بفعالية تحول الخلايا البلعمية من النوع M1 إلى النوع M2. أظهرت الدراسات الآلية أن AuAg@PC-Fe يعزز فسفرة Nrf2 من خلال تنشيط مسار الإشارة PI3K/Akt، ويقضي على أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية، ويمنع انتقال P65 إلى النواة في مسار الإشارة NF-κB لتنظيم الاستجابة المناعية.

العلاج المضاد للبكتيريا وتجديد اللثة

هيكل الزئوليت إيميدازول-8 (ZIF-8) يتكون من أيونات الزنك و2-ميثيل إيميدازول. يطلق ZIF-8

الزرع. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، زاد نسبة العظم إلى الحجم (BV/TV) بمقدار

أيون النحاس Cu الناتج عن دوران ROS (

العلاج المناعي المعدل وتجديد اللثة

العلاج التآزري الثلاثي النمط

(السلفيات العظمية) أظهرت قدرة تكوين عظمية كبيرة. تم زيادة تعبير الرنا المرسال للعوامل المرتبطة بتكوين العظم (ALP، COL-1، RUNX-2) في خلايا MC3T3E1 بعد

التحديات والآفاق المستقبلية

الإزالة أم التوازن؟

الاتجاه المستقبلي للعلاج المضاد للميكروبات باستخدام أنظمة التوصيل النانوية.

في البيئة الدقيقة لمرض اللثة، تقوم الخلايا البلعمية المفرطة النشاط أو بعض خلايا T بإنتاج كمية كبيرة من أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS)، ويؤدي تراكم هذه الأنواع إلى تنشيط مسارات الإشارات الالتهابية المرتبطة ونضوج الخلايا الهادمة للعظم، مما يؤدي في النهاية إلى تلف أنسجة اللثة. تهدف استراتيجيات العلاج النانوي الحالية إلى القضاء على أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية كهدف نهائي. ومع ذلك، وجدت عدة دراسات أن المستويات المنخفضة من أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية قد تحمي القدرة التجديدية للخلايا الجذعية [163]. ويرجع ذلك إلى أن المستويات المنخفضة من أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية داخل الخلايا تتوسط التنشيط المؤقت لبروتين كيناز c-Jun N-terminal وتساعد على بقاء الخلية من خلال تنشيط عوامل النسخ activator protein-1 والجينات المضادة للموت المبرمج [163، 164]. لذلك، نحن نفكر فيما إذا كان يمكن الحفاظ على أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية في اللثة عند مستوى منخفض مقبول لتعزيز تجديد اللثة ولعب دور مضاد للبكتيريا دون توليد استجابة مناعية أو إجهاد تأكسدي.

فرص العلاج النانوي المستهدف لالتهاب اللثة

النسيج. يمكن للليبوسوم المحمّل بالجينستين المعدل بالفولات تنظيم محور TLR4/MyD88/NF-кВ في الخلايا البلعمية وتعزيز التمايز العظمي لخلايا جذور اللثة الجذعية [171]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، قد تكون بعض الخلايا المناعية الأخرى (الخلايا التائية، الخلايا البائية، العدلات) وخلايا نسيج اللثة (خلايا جذور اللثة الجذعية، الأرومات الليفية اللثوية، إلخ) أهدافًا محتملة لتنظيم مستهدف لأنظمة توصيل الأدوية النانوية في علاج التهاب اللثة.

فرص الأدوية النانوية المتكاملة مع منصات متعددة

زيادة هجرة وتكاثر خلايا الرباط اللثوي [175].

يرتبط التهاب اللثة بمرض السكري، والتهاب المفاصل الروماتويدي، ومرض الزهايمر، وارتفاع ضغط الدم، وأمراض الأمعاء الالتهابية، وحتى الأمراض المناعية الذاتية والسرطان (الشكل 11) [178-180]. لذلك، تمتلك أنظمة التوصيل النانوية تطبيقات واعدة في علاج التهاب اللثة مع الأمراض المصاحبة. على سبيل المثال، هناك ارتباط ثنائي الاتجاه بين التهاب اللثة ومرض السكري [181]. قد يزيد التهاب اللثة من انتشار مرض السكري ويؤثر على السيطرة الفعالة على مستوى الجلوكوز في الدم [182، 183]. من ناحية أخرى، تؤدي الاضطرابات الأيضية في مرضى السكري إلى إنتاج مفرط للجذور الحرة للأكسجين، والتي لها تأثير ضار على العظم السنخي. كان الضرر في أنسجة اللثة لدى مرضى السكري المصابين بالتهاب اللثة أكثر تدميراً من المرضى المصابين بالتهاب اللثة فقط. لمعالجة هذه المشكلة، طور تشاو وآخرون نظام توصيل دوائي يستجيب للجذور الحرة للأكسجين محمّل…

القدرة العلاجية النانوية للمكونات النشطة الطبيعية

لقد حققت المكونات الطبيعية نتائج تجريبية ممتازة في علاج التهاب دواعم السن. ومع ذلك، فإن معظم المكونات الطبيعية تعاني من ضعف الذوبان ومشاكل في السلامة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، هناك معرفة قليلة بالدراسات الدوائية الحركية داخل الجسم للمكونات النشطة الطبيعية، مما يحد من الترجمة السريرية لهذه المكونات في علاج التهاب دواعم السن. من المتوقع أن يحل استخدام أنظمة توصيل الأدوية النانوية المتقدمة مشاكل تكوين الأدوية للمكونات الطبيعية في المستقبل.

الخاتمة

العلاج والابتكارات في تصميم أنظمة التوصيل النانوية. بشكل عام، أظهرت العلاجات النانوية إمكانات كبيرة على المستويات قبل السريرية، لكن أداؤها السريري لا يزال بحاجة إلى التقييم. هناك حاجة إلى المزيد من العمل لتحسين تطوير استراتيجيات علاجية نانوية جديدة. نعتقد أن الاستراتيجيات العلاجية النانوية ستوفر قريبًا فرصًا جديدة لعلاج التهاب دواعم الأسنان، مما يخفف من معاناة المرضى والعبء الطبي على المجتمع.

الاختصارات

| ABC | حدبة العظم السنخي |

| ALP | الفوسفاتاز القلوي |

| Au NBPs | الهرمونات النانوية الذهبية |

| AuNPs | جسيمات الذهب النانوية |

| BMDM | البلعميات المشتقة من نخاع العظم |

| BMSCs | خلايا جذعية من نخاع العظم |

| BV/TV | حجم العظم/حجم النسيج |

| C5aR | مستقبل المكون 5a |

| Ce6 | كلورين e6 |

| CEJ | وصلة الميناء بالأسمنت |

|

|

جسيمات أكسيد السيريوم النانوية |

| CXCL | رابطة كيموكين C-X-C |

| COL-1 | الكولاجين النوع الأول |

| CXCR3 | مستقبل كيموكين C-X-C 3 |

| DCs | الخلايا التغصنية |

| Fn | فيوزوباكتيريوم نوكلاتوم |

| Gel MA | جيلاتين ميثاكريلات |

| ICG | الأخضر الإندوكاينيني |

| IFN-

|

إنترفيرون-

|

| IL | إنترلوكين |

| LPS | ليبوبوليساكاريد |

| Micro-CT | التصوير المقطعي المحوسب الدقيق |

| NF-kB | عامل النسخ النووي-كابا-بي |

| NIR | الأشعة تحت الحمراء القريبة |

| OCN | أوستيوكالسين |

| OPG | أوستيوبرتينجرين |

| PDLSCs | خلايا جذعية من غشاء دواعم السن |

| PDT | العلاج الضوئي الديناميكي |

| Pg | بورفيروموناس جينجيفاليس |

| PLGA | بولي (D, L-لاكتيد-كو-جليكوليد) |

| PTT | العلاج الحراري الضوئي |

| RANKL | المحفز لمستقبل عامل النسخ النووي كابا-بي |

| RNA-seq | تسلسل الحمض النووي الريبي |

| ROS | أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية |

| RUNX2 | عامل النسخ المرتبط بـ Runt 2 |

| SEM | المجهر الإلكتروني الماسح |

| STAT | ناقل الإشارة ومنشط النسخ |

| Tb.N | عدد العظام الإسفنجية |

| TEM | المجهر الإلكتروني الناقل |

| TGF-

|

عامل النمو المحول-

|

| Th- | خلايا T المساعدة |

| TNF-a | عامل نخر الورم-ألفا |

| TRAP | الفوسفاتاز الحمضي المقاوم للطرطرات |

| Treg | خلايا T التنظيمية |

| ZIF-8 | هيكل الزيوليت الإيميدازولي-8 |

| ZnO | أكسيد الزنك |

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

توفر البيانات والمواد

الإعلانات

الموافقة الأخلاقية والموافقة على المشاركة

الموافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

نشر عبر الإنترنت: 04 يناير 2024

References

- Peres

, Macpherson LMD, Weyant RJ, Daly B, Venturelli R, Mathur MR, Listl S, Celeste RK, Guarnizo-Herreño CC, Kearns C, et al. Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. Lancet. 2019;394:249-60. - Jiao J, Jing W, Si Y, Feng X, Tai B, Hu D, Lin H, Wang B, Wang C, Zheng S, et al. The prevalence and severity of periodontal disease in Mainland China: data from the Fourth National Oral Health Survey (2015-2016). J Clin Periodontol. 2021;48:168-79.

- Eke PI, Wei L, Borgnakke WS, Thornton-Evans G, Zhang XY, Lu H, Mcguire LC, Genco RJ. Periodontitis prevalence in adults

years of age, in the USA. Periodontol. 2000;2016(72):76-95. - Luo LS, Luan HH, Wu L, Shi YJ, Wang YB, Huang Q, Xie WZ, Zeng XT. Secular trends in severe periodontitis incidence, prevalence and disability-adjusted life years in five Asian countries: a comparative study from 1990 to 2017. J Clin Periodontol. 2021;48:627-37.

- Hajishengallis G. Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:30-44.

- Zieba M, Chaber P, Duale K, Martinka Maksymiak M, Basczok M, Kowalczuk M, Adamus G. Polymeric carriers for delivery systems in the treatment of chronic periodontal disease. Polymers (Basel). 2020;12:1574.

- Hajishengallis G. Interconnection of periodontal disease and comorbidities: Evidence, mechanisms, and implications. Periodontol 2000. 2022;89:9-18.

- Kim WJ, Soh Y, Heo SM. Recent advances of therapeutic targets for the treatment of periodontal disease. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 2021;29:263-7.

- Sgolastra F, Petrucci A, Ciarrocchi I, Masci C, Spadaro A. Adjunctive systemic antimicrobials in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Periodontal Res. 2020;56:236-48.

- Kherul Anuwar AH, Saub R, Safii SH, Ab-Murat N, Mohd Taib MS, Mamikutty R, Ng CW. Systemic antibiotics as an adjunct to subgingival debridement: a network meta-analysis. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022;11:1716.

- Kinane DF, Stathopoulou PG, Papapanou PN. Periodontal diseases. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17038.

- Wang L, Li Y, Ren M, Wang X, Li L, Liu F, Lan Y, Yang S, Song J. pH and lipase-responsive nanocarrier-mediated dual drug delivery system to treat periodontitis in diabetic rats. Bioact Mater. 2022;18:254-66.

- Ding Y, Wang Y, Li J, Tang M, Chen H, Wang G, Guo J, Gui S. Microemul-sion-thermosensitive gel composites as in situ-forming drug reservoir for periodontitis tissue repair through alveolar bone and collagen regeneration strategy. Pharm Dev Technol. 2023;28:30-9.

- Wang Y, Li C, Wan Y, Qi M, Chen Q, Sun Y, Sun X, Fang J, Fu L, Xu L, et al. Quercetin-loaded ceria nanocomposite potentiate dual-directional immunoregulation via macrophage polarization against periodontal inflammation. Small. 2021;17:e2101505.

- Tian Y, Li Y, Liu J, Lin Y, Jiao J, Chen B, Wang W, Wu S, Li C. Photothermal therapy with regulated Nrf2/NF-kappaB signaling pathway for treating bacteria-induced periodontitis. Bioact Mater. 2022;9:428-45.

- Hajishengallis G, Chavakis T, Lambris JD. Current understanding of periodontal disease pathogenesis and targets for host-modulation therapy. Periodontol 2000. 2020;84:14-34.

- Lamont RJ, Koo H, Hajishengallis G. The oral microbiota: dynamic communities and host interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16:745-59.

- Abdulkareem AA, AI-Taweel FB, AI-Sharqi AJB, Gul SS, Sha A, Chapple ILC. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of periodontitis: from symbiosis to dysbiosis. J Oral Microbiol. 2023;15:2197779.

- Pai SI, Matheus HR, Guastaldi FPS. Effects of periodontitis on cancer outcomes in the era of immunotherapy. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2023;4:e166-75.

- Dewhirst FE, Chen T, Izard J, Paster BJ, Tanner AC, Yu WH, Lakshmanan A, Wade WG. The human oral microbiome. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:5002-17.

- Benoit DSW, Sims KR Jr, Fraser D. Nanoparticles for oral biofilm treatments. ACS Nano. 2019;13:4869-75.

- Su X, Zhang J, Qin X. CD40 up-regulation on dendritic cells correlates with Th17/Treg imbalance in chronic periodontitis in young population. Innate Immun. 2020;26:482-9.

- Wei Y, Deng Y, Ma S, Ran M, Jia Y, Meng J, Han F, Gou J, Yin T, He H, et al. Local drug delivery systems as therapeutic strategies against periodontitis: a systematic review. J Control Release. 2021;333:269-82.

- Uriarte SM, Edmisson JS, Jimenez-Flores E. Human neutrophils and oral microbiota: a constant tug-of-war between a harmonious and a discordant coexistence. Immunol Rev. 2016;273:282-98.

- Zhu Y, Winer D, Goh C, Shrestha A. Injectable thermosensitive hydrogel to modulate tolerogenic dendritic cells under hyperglycemic condition. Biomater Sci. 2023;11:2091-102.

- Wilensky A, Segev H, Mizraji G, Shaul Y, Capucha T, Shacham M, Hovav AH . Dendritic cells and their role in periodontal disease. Oral Dis. 2014;20:119-26.

- Zou J, Zeng Z, Xie W, Zeng Z. Immunotherapy with regulatory T and B cells in periodontitis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;109:108797.

- Arun KV, Talwar A, Kumar TS. T-helper cells in the etiopathogenesis of periodontal disease: a mini review. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2011;15:4-10.

- Jiang

, Huang W, Huang R, Zhao , Chen C. mTOR signaling in the regulation of CD4 +T cell subsets in periodontal diseases. Front Immunol. 2022;13: 827461. - Kidd P. Th1/Th2 balance: the hypothesis, its limitations, and implications for health and disease. Altern Med Rev. 2003;8:223-46.

- El-Awady AR, Elashiry M, Morandini AC, Meghil MM, Cutler CW. Dendritic cells a critical link to alveolar bone loss and systemic disease risk in periodontitis: immunotherapeutic implications. Periodontol 2000. 2022;89:41-50.

- Meghil MM, Ghaly M, Cutler CW. A tale of two fimbriae: how invasion of dendritic cells by Porphyromonas gingivalis disrupts DC maturation and depolarizes the T-cell-mediated immune response. Pathogens. 2022;11:328.

- Fu J, Huang Y, Bao T, Liu C, Liu X, Chen X. The role of Th17 cells/IL-17A in

and the strategic therapy targeting on IL-17A. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19:98. - Zhang Z, Deng M, Hao M, Tang J. Periodontal ligament stem cells in the periodontitis niche: inseparable interactions and mechanisms. J Leukoc Biol. 2021;110:565-76.

- Cafferata EA, Terraza-Aguirre C, Barrera R, Faundez N, Gonzalez N, Rojas C, Melgar-Rodriguez S, Hernandez M, Carvajal P, Cortez C, et al. Interleukin-35 inhibits alveolar bone resorption by modulating the Th17/Treg imbalance during periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47:676-88.

- Cheng R, Wu Z, Li M, Shao M, Hu T. Interleukin-1 beta is a potential therapeutic target for periodontitis: a narrative review. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12:2.

- Pan W, Wang Q, Chen Q. The cytokine network involved in the host immune response to periodontitis. Int J Oral Sci. 2019;11:30.

- Vaquette C, Pilipchuk SP, Bartold PM, Hutmacher DW, Giannobile WV, Ivanovski S. Tissue engineered constructs for periodontal regeneration: current status and future perspectives. Adv Healthc Mater. 2018;7:e1800457.

- Makabenta JMV, Nabawy A, Li CH, Schmidt-Malan S, Patel R, Rotello VM. Nanomaterial-based therapeutics for antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19:23-36.

- Mi G, Shi D, Wang M, Webster TJ. Reducing bacterial infections and biofilm formation using nanoparticles and nanostructured antibacterial surfaces. Adv Healthc Mater. 2018;7:e1800103.

- Mehta D, Saini V, Aggarwal B, Khan A, Bajaj A. Unlocking the bacterial membrane as a therapeutic target for next-generation antimicrobial amphiphiles. Mol Aspects Med. 2021;81:100999.

- Guentsch A, Jentsch H, Pfister W, Hoffmann T, Eick S. Moxifloxacin as an adjunctive antibiotic in the treatment of severe chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1894-903.

- Mudgil M, Pawar PK. Preparation and in vitro/ex vivo evaluation of moxifloxacin-loaded PLGA nanosuspensions for ophthalmic application. Sci Pharm. 2013;81:591-606.

- Pinon-Segundo E, Ganem-Quintanar A, Alonso-Perez V, QuintanarGuerrero D. Preparation and characterization of triclosan nanoparticles for periodontal treatment. Int J Pharm. 2005;294:217-32.

- Yao W, Xu P, Pang Z, Zhao J, Chai Z, Li X, Li H, Jiang M, Cheng H, Zhang B, Cheng N. Local delivery of minocycline-loaded PEG-PLA nanoparticles for the enhanced treatment of periodontitis in dogs. Int J Nanomed. 2014;9:3963-70.

- Beg S, Dhiman S, Sharma T, Jain A, Sharma RK, Jain A, Singh B. Stimuli responsive in situ gelling systems loaded with PLGA nanoparticles of moxifloxacin hydrochloride for effective treatment of periodontitis. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2020;21:76.

- Xi Y, Wang Y, Gao J, Xiao Y, Du J. Dual corona vesicles with intrinsic antibacterial and enhanced antibiotic delivery capabilities for effective treatment of biofilm-induced periodontitis. ACS Nano. 2019;13:13645-57.

- Gold K, Slay B, Knackstedt M, Gaharwar AK. Antimicrobial activity of metal and metal-oxide based nanoparticles. Adv Therap. 2018;1:1700033.

- Wang Y, Malkmes MJ, Jiang C, Wang P, Zhu L, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Huang H, Jiang L. Antibacterial mechanism and transcriptome analysis of ultra-small gold nanoclusters as an alternative of harmful antibiotics against Gram-negative bacteria. J Hazard Mater. 2021;416:126236.

- Zhang Y, Chen R, Wang Y, Wang P, Pu J, Xu X, Chen F, Jiang L, Jiang Q, Yan F. Antibiofilm activity of ultra-small gold nanoclusters against Fusobacterium nucleatum in dental plaque biofilms. J Nanobiotechnol. 2022;20:470.

- Amna T, Hassan MS, Sheikh FA, Lee HK, Seo KS, Yoon D, Hwang IH. Zinc oxide-doped poly(urethane) spider web nanofibrous scaffold via one-step electrospinning: a novel matrix for tissue engineering. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:1725-34.

- Anitha S, Brabu B, John Thiruvadigal D, Gopalakrishnan C, Natarajan TS. Optical, bactericidal and water repellent properties of electrospun nano-composite membranes of cellulose acetate and ZnO . Carbohydr Polym. 2013;97:856-63.

- Kasraei S, Sami L, Hendi S, Alikhani MY, Rezaei-Soufi L, Khamverdi Z. Antibacterial properties of composite resins incorporating silver and zinc oxide nanoparticles on Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus. Restor Dent Endod. 2014;39:109-14.

- Krol A, Pomastowski P, Rafinska K, Railean-Plugaru V, Buszewski B. Zinc oxide nanoparticles: synthesis, antiseptic activity and toxicity mechanism. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2017;249:37-52.

- Liu Y, He L, Mustapha A, Li H, Hu ZQ, Lin M. Antibacterial activities of zinc oxide nanoparticles against Escherichia coli O157:H7. J Appl Microbiol. 2009;107:1193-201.

- Sirelkhatim A, Mahmud S, Seeni A, Kaus NHM, Ann LC, Bakhori SKM, Hasan H, Mohamad D. Review on zinc oxide nanoparticles: antibacterial activity and toxicity mechanism. Nanomicro Lett. 2015;7:219-42.

- Adams LK, Lyon DY, Alvarez PJJ. Comparative eco-toxicity of nanoscale

, and ZnO water suspensions. Water Res. 2006;40:3527-32. - Pasquet J, Chevalier Y, Pelletier J, Couval E, Bouvier D, Bolzinger M-A. The contribution of zinc ions to the antimicrobial activity of zinc oxide. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2014;457:263-74.

- Sanchez-Lopez E, Gomes D, Esteruelas G, Bonilla L, Lopez-Machado AL, Galindo R, Cano A, Espina M, Ettcheto M, Camins A, et al. Metal-based nanoparticles as antimicrobial agents: an overview. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2020;10:292.

- Lakshmi Prasanna V, Vijayaraghavan R. Insight into the mechanism of antibacterial activity of ZnO : surface defects mediated reactive oxygen species even in the dark. Langmuir. 2015;31:9155-62.

- Madhumitha G, Elango G, Roopan SM. Biotechnological aspects of ZnO nanoparticles: overview on synthesis and its applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;100:571-81.

- Munchow EA, Albuquerque MT, Zero B, Kamocki K, Piva E, Gregory RL, Bottino MC. Development and characterization of novel ZnO-loaded electrospun membranes for periodontal regeneration. Dent Mater. 2015;31:1038-51.

- Augustine R, Dominic EA, Reju I, Kaimal B, Kalarikkal N, Thomas S. Electrospun polycaprolactone membranes incorporated with ZnO nanoparticles as skin substitutes with enhanced fibroblast proliferation and wound healing. RSC Adv. 2014;4:24777-85.

- Dias AM, da Silva FG, Monteiro APF, Pinzon-Garcia AD, Sinisterra RD, Cortes ME. Polycaprolactone nanofibers loaded oxytetracycline hydrochloride and zinc oxide for treatment of periodontal disease. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2019;103:109798.

- Mou J, Liu Z, Liu J, Lu J, Zhu W, Pei D. Hydrogel containing minocycline and zinc oxide-loaded serum albumin nanopartical for periodontitis application: preparation, characterization and evaluation. Drug Deliv. 2019;26:179-87.

- Chen Y, Gao Y, Chen Y, Liu L, Mo A, Peng Q. Nanomaterials-based photothermal therapy and its potentials in antibacterial treatment. J Control Release. 2020;328:251-62.

- Zheng Y, Wei M, Wu H, Li F, Ling D. Antibacterial metal nanoclusters. J Nanobiotechnol. 2022;20:328.

- Lin J, He Z, Liu F, Feng J, Huang C, Sun X, Deng H. Hybrid hydrogels for synergistic periodontal antibacterial treatment with sustained drug release and NIR-responsive photothermal effect. Int J Nanomed. 2020;15:5377-87.

- Zhong Y, Zheng XT, Zhao S, Su X, Loh XJ. Stimuli-activable metal-bearing nanomaterials and precise on-demand antibacterial strategies. ACS Nano. 2022;16:19840-72.

- Jia Q, Song Q, Li P, Huang W. Rejuvenated photodynamic therapy for bacterial infections. Adv Healthc Mater. 2019;8:e1900608.

- Zhao J, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Wu H, Li J, Zhao Y, Zhang L, Zou D, Li Z, Wang S. Synthetic and biodegradable molybdenum(IV) diselenide triggers the cascade photo- and immunotherapy of tumor. Adv Healthc Mater. 2022;11:2200524.

- Fu X, Yang Z, Deng T, Chen J, Wen Y, Fu X, Zhou L, Zhu Z, Yu C. A natural polysaccharide mediated MOF-based Ce6 delivery system with improved biological properties for photodynamic therapy. J Mater Chem B. 2020;8:1481-8.

- Sun X, Wang L, Lynch CD, Sun X, Li X, Qi M, Ma C, Li C, Dong B, Zhou Y, Xu HHK. Nanoparticles having amphiphilic silane containing Chlorin e6 with strong anti-biofilm activity against periodontitis-related pathogens. J Dent. 2019;81:70-84.

- Zhang T, Ying D, Qi M, Li X, Fu L, Sun X, Wang L, Zhou Y. Anti-biofilm property of bioactive upconversion nanocomposites containing chlorin e6 against periodontal pathogens. Molecules. 2019;24:2692.

- Chen B, Dong B, Wang J, Zhang S, Xu L, Yu W, Song H. Amphiphilic silane modified NaYF4:Yb, Er loaded with Eu(TTA,3(TPPO,2 nanoparticles and their multi-functions: dual mode temperature sensing and cell imaging. Nanoscale. 2013;5:8541-9.

- Li Z, Pan W, Shi E, Bai L, Liu H, Li C, Wang Y, Deng J, Wang Y. A multifunctional nanosystem based on bacterial cell-penetrating photosensitizer for fighting periodontitis via combining photodynamic and antibiotic therapies. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2021;7:772-86.

- Zhang H, Zhang X, Zhu X, Chen J, Chen Q, Zhang H, Hou L, Zhang Z. NIR light-induced tumor phototherapy using photo-stable ICG delivery system based on inorganic hybrid. Nanomedicine. 2018;14:73-84.

- Nagahara A, Mitani A, Fukuda M, Yamamoto H, Tahara K, Morita I, Ting CC, Watanabe T, Fujimura T, Osawa K, et al. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy using a diode laser with a potential new photosensitizer, indocyanine green-loaded nanospheres, may be effective for the clearance of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Periodontal Res. 2013;48:591-9.

- Shi E, Bai L, Mao L, Wang H, Yang X, Wang Y, Zhang M, Li C, Wang Y. Selfassembled nanoparticles containing photosensitizer and polycationic brush for synergistic photothermal and photodynamic therapy against periodontitis. J Nanobiotechnol. 2021;19:413.

- Yang B, Pang X, Li Z, Chen Z, Wang Y. Immunomodulation in the treatment of periodontitis: progress and perspectives. Front Immunol. 2021;12:781378.

- Balta MG, Papathanasiou E, Blix IJ, Van Dyke TE. Host modulation and treatment of periodontal disease. J Dent Res. 2021;100:798-809.

- Xu XW, Liu X, Shi C, Sun HC. Roles of immune cells and mechanisms of immune responses in periodontitis. Chin J Dent Res. 2021;24:219-30.

- Sun X, Gao J, Meng X, Lu X, Zhang L, Chen R. Polarized macrophages in periodontitis: characteristics, function, and molecular signaling. Front Immunol. 2021;12:763334.

- Funes SC, Rios M, Escobar-Vera J, Kalergis AM. Implications of macrophage polarization in autoimmunity. Immunology. 2018;154:186-95.

- Boutilier AJ, Elsawa SF. Macrophage polarization states in the tumor microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:6995.

- Chanmee T, Ontong P, Konno K, Itano N. Tumor-associated macrophages as major players in the tumor microenvironment. Cancers (Basel). 2014;6:1670-90.

- Huang

. Polarizing macrophages in vitro. In: Rousselet G, editor. Macrophages. Methods in molecular biology. New York: Springer; 2018. p. 119-26. - Wang LX, Zhang SX, Wu HJ, Rong XL, Guo J. M2b macrophage polarization and its roles in diseases. J Leukoc Biol. 2019;106:345-58.

- Shi J, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Chen R, Wei J, Hou J, Wang B, Lai H, Huang Y. Remodeling immune microenvironment in periodontitis using resveratrol liposomes as an antibiotic-free therapeutic strategy. J Nanobiotechnol. 2021;19:429.

- Shen Z, Kuang S, Zhang Y, Yang M, Qin W, Shi X, Lin Z. Chitosan hydrogel incorporated with dental pulp stem cell-derived exosomes alleviates periodontitis in mice via a macrophage-dependent mechanism. Bioact Mater. 2020;5:1113-26.

- Figueiredo RDA, Ortega AC, Gonzalez Maldonado LA, Castro RD, Avila-Campos MJ, Rossa C, Aquino SG. Perillyl alcohol has antibacterial effects and reduces ROS production in macrophages. J Appl Oral Sci. 2020;28:e20190519.

- Kim J, Kim HY, Song SY, Go SH, Sohn HS, Baik S, Soh M, Kim K, Kim D, Kim HC, et al. Synergistic oxygen generation and reactive oxygen species scavenging by manganese ferrite/ceria co-decorated nanoparticles for rheumatoid arthritis treatment. ACS Nano. 2019;13:3206-17.

- Yang B, Chen Y, Shi J. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-based nanomedicine. Chem Rev. 2019;119:4881-985.

- Deng J, Lu C, Zhao Q, Chen K, Ma S, Li Z. The Th17/Treg cell balance: crosstalk among the immune system, bone and microbes in periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 2022;57:246-55.

- Kini V, Mohanty I, Telang G, Vyas N. Immunopathogenesis and distinct role ofTh17 in periodontitis: a review. J Oral Biosci. 2022;64:193-201.

- Mousset CM, Hobo W, Woestenenk R, Preijers F, Dolstra H, van der Waart AB. Comprehensive phenotyping of T cells using flow cytometry. Cytometry A. 2019;95:647-54.

- Gaffen SL, Moutsopoulos NM. Regulation of host-microbe interactions at oral mucosal barriers by type 17 immunity. Sci Immunol. 2020;5:eaau4594.

- Karthikeyan B. Talwar, Arun KV, Kalaivani S: Evaluation of transcription factor that regulates

helper 17 and regulatory cells function in periodontal health and disease. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7:S672-676. - Zhang Y, Chen J, Fu H, Kuang S, He F, Zhang M, Shen Z, Qin W, Lin Z, Huang S. Exosomes derived from 3D-cultured MSCs improve therapeutic effects in periodontitis and experimental colitis and restore the Th17 cell/Treg balance in inflamed periodontium. Int J Oral Sci. 2021;13:43.

- Zheng Y, Dong C, Yang J, Jin Y, Zheng W, Zhou Q, Liang Y, Bao L, Feng G, Ji J, et al. Exosomal microRNA-155-5p from PDLSCs regulated Th17/Treg balance by targeting sirtuin-1 in chronic periodontitis. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:20662-74.

- Prasad R, Suchetha A, Lakshmi P, Darshan MB, Apoorva SM, Ashit GB. Interleukin-11 – its role in the vicious cycle of inflammation, periodontitis and diabetes: a clinicobiochemical cross-sectional study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2015;19:159-63.

- Toker H, Gorgun EP, Korkmaz EM, Yuce HB, Poyraz O. The effects of IL-10 gene polymorphism on serum, and gingival crevicular fluid levels of IL-6 and IL-10 in chronic periodontitis. J Appl Oral Sci. 2018;26:e20170232.

- Zhang Q, Chen B, Yan F, Guo J, Zhu X, Ma S, Yang W. Interleukin-10 inhibits bone resorption: a potential therapeutic strategy in periodontitis and other bone loss diseases. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:284836.

- Li X, Luo W, Ng TW, Leung PC, Zhang C, Leung KC, Jin L. Nanoparticleencapsulated baicalein markedly modulates pro-inflammatory response in gingival epithelial cells. Nanoscale. 2017;9:12897-907.

- Bao X, Zhao J, Sun J, Hu M, Yang X. Polydopamine nanoparticles as efficient scavengers for reactive oxygen species in periodontal disease. ACS Nano. 2018;12:8882-92.

- Liu X, He X, Jin D, Wu S, Wang H, Yin M, Aldalbahi A, El-Newehy M, Mo X, Wu J. A biodegradable multifunctional nanofibrous membrane for periodontal tissue regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2020;108:207-22.

- Liang Y, Luan X, Liu X. Recent advances in periodontal regeneration: a biomaterial perspective. Bioact Mater. 2020;5:297-308.

- Liu J, Wang H, Zhang L, Li X, Ding X, Ding G, Wei F. Periodontal ligament stem cells promote polarization of M2 macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2022;111:1185-97.

- Lee JS, Lee JB, Cha JK, Choi EY, Park SY, Cho KS, Kim CS. Chemokine in inflamed periodontal tissues activates healthy periodontal-ligament stem cell migration. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44:530-9.

- Zhou M, Liu N, Zhang Q, Tian T, Ma Q, Zhang T, Cai X. Effect of tetrahedral DNA nanostructures on proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of human periodontal ligament stem cells. Cell Prolif. 2019;52:e12566.

- Li C, Li Z, Zhang Y, Fathy AH, Zhou M. The role of the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway in the proliferation of gold nanoparticle-treated human periodontal ligament stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:214.

- Zhang S, Zhou H, Kong N, Wang Z, Fu H, Zhang Y, Xiao Y, Yang W, Yan F. l-cysteine-modified chiral gold nanoparticles promote periodontal tissue regeneration. Bioact Mater. 2021;6:3288-99.

- Liu J, Dai Q, Weir MD, Schneider A, Zhang C, Hack GD, Oates TW, Zhang K, Li A, Xu HHK. Biocompatible nanocomposite enhanced osteogenic and cementogenic differentiation of periodontal ligament stem cells in vitro for periodontal regeneration. Materials (Basel). 2020;13:4951.

- Xie L, Chen J, Ren X, Zhang M, Thuaksuban N, Nuntanaranont T, Guan Z. Alteration of circRNA and IncRNA expression profile in exosomes derived from periodontal ligament stem cells undergoing osteogenic differentiation. Arch Oral Biol. 2021;121:104984.

- Zhang Z, Shuai Y, Zhou F, Yin J, Hu J, Guo S, Wang Y, Liu W. PDLSCs regulate angiogenesis of periodontal ligaments via VEGF transferred by exosomes in periodontitis. Int J Med Sci. 2020;17:558-67.

- Lei F, Li M, Lin T, Zhou H, Wang F, Su X. Treatment of inflammatory bone loss in periodontitis by stem cell-derived exosomes. Acta Biomater. 2022;141:333-43.

- Liu W, Konermann A, Guo T, Jager A, Zhang L, Jin Y. Canonical Wnt signaling differently modulates osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow and from periodontal ligament under inflammatory conditions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1840:1125-34.

- Calabrese EJ. Hormesis and bone marrow stem cells: enhancing cell proliferation, differentiation and resilience to inflammatory stress. Chem Biol Interact. 2022;351:109730.

- Wang Y, Li J, Zhou J, Qiu Y, Song J. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound enhances bone marrow-derived stem cells-based periodontal regenerative therapies. Ultrasonics. 2022;121:106678.

- Lu L, Liu Y, Zhang X, Lin J. The therapeutic role of bone marrow stem cell local injection in rat experimental periodontitis. J Oral Rehabil. 2020;47(Suppl 1):73-82.

- Shen R, Xu W, Xue Y, Chen L, Ye H, Zhong E, Ye Z, Gao J, Yan Y. The use of chitosan/PLA nano-fibers by emulsion eletrospinning for periodontal tissue engineering. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2018;46:419-30.

- Ye Z, Xu W, Shen R, Yan Y. Emulsion electrospun PLA/calcium alginate nanofibers for periodontal tissue engineering. J Biomater Appl. 2020;34:763-77.

- AIQranei MS, Chellaiah MA. Osteoclastogenesis in periodontal diseases: possible mediators and mechanisms. J Oral Biosci. 2020;62:123-30.

- Kitaura H, Marahleh A, Ohori F, Noguchi T, Shen WR, Qi J, Nara Y, Pramusita A, Kinjo R, Mizoguchi I. Osteocyte-related cytokines regulate osteoclast formation and bone resorption. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:5169.

- Chen X, Wan Z, Yang L, Song S, Fu Z, Tang K, Chen L, Song Y. Exosomes derived from reparative M 2 -like macrophages prevent bone loss in murine periodontitis models via IL-10 mRNA. J Nanobiotechnol. 2022;20:110.

- Bakheet SA, Alrwashied BS, Ansari MA, Nadeem A, Attia SM, Alanazi MM, Aldossari AA, Assiri MA, Mahmood HM, Al-Mazroua HA, Ahmad SF. CXC chemokine receptor 3 antagonist AMG487 shows potent anti-arthritic effects on collagen-induced arthritis by modifying B cell inflammatory profile. Immunol Lett. 2020;225:74-81.

- Hiyari S, Green E, Pan C, Lari S, Davar M, Davis R, Camargo PM, Tetradis S, Lusis AJ, Pirih FQ. Genomewide association study identifies Cxcl family members as partial mediators of LPS-induced periodontitis. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33:1450-63.

- Cui ZK, Bastiat G, Jin C, Keyvanloo A, Lafleur M. Influence of the nature of the sterol on the behavior of palmitic acid/sterol mixtures and their derived liposomes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1798:1144-52.

- Lari S, Hiyari S, de Araujo Silva DN, de Brito BB, Ishii M, Monajemzadeh S, Cui ZK, Tetradis S, Lee M, Pirih FQ. Local delivery of a CXCR3 antagonist decreases the progression of bone resorption induced by LPS injection in a murine model. Clin Oral Investig. 2022;26:5163-9.

- Menicanin D, Hynes K, Han J, Gronthos S, Bartold PM. Cementum and periodontal ligament regeneration. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;881:207-36.

- Bozbay E, Dominici F, Gokbuget AY, Cintan S, Guida L, Aydin MS, Mariotti A, Pilloni A. Preservation of root cementum: a comparative evaluation of power-driven versus hand instruments. Int J Dent Hyg. 2018;16:202-9.

- Wang H, Wang X, Ma L, Huang X, Peng Y, Huang H, Gao X, Chen Y, Cao Z. PGC-1 alpha regulates mitochondrial biogenesis to ameliorate hypoxia-inhibited cementoblast mineralization. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2022;1516:300-11.

- Wang Y, Li Y, Shao P, Wang L, Bao X, Hu M. IL1 beta inhibits differentiation of cementoblasts via microRNA-325-3p. J Cell Biochem. 2020;121:2606-17.

- Park CH, Oh JH, Jung HM, Choi Y, Rahman SU, Kim S, Kim TI, Shin HI, Lee YS, Yu FH, et al. Effects of the incorporation of epsilon-aminocaproic acid/chitosan particles to fibrin on cementoblast differentiation and cementum regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2017;61:134-43.

- Chen E, Wang T, Tu Y, Sun Z, Ding Y, Gu Z, Xiao S. ROS-scavenging biomaterials for periodontitis. J Mater Chem B. 2023;11:482-99.

- Wang H, Wang D, Huangfu H, Lv H, Qin Q, Ren S, Zhang Y, Wang L, Zhou Y. Branched AuAg nanoparticles coated by metal-phenolic networks for treating bacteria-induced periodontitis via photothermal antibacterial and immunotherapy. Mater Des. 2022;224:111401.

- Yan N, Xu J, Liu G, Ma C, Bao L, Cong Y, Wang Z, Zhao Y, Xu W, Chen C. Penetrating macrophage-based nanoformulation for periodontitis treatment. ACS Nano. 2022;16:18253-65.

- Chen J, Zhang X, Huang C, Cai H, Hu S, Wan Q, Pei X, Wang J. Osteogenic activity and antibacterial effect of porous titanium modified with metal-organic framework films. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2017;105:834-46.

- Zhong L, Chen J, Ma Z, Feng H, Chen S, Cai H, Xue Y, Pei X, Wang J, Wan Q. 3D printing of metal-organic framework incorporated porous scaffolds to promote osteogenic differentiation and bone regeneration. Nanoscale. 2020;12:24437-49.

- Sun M, Liu Y, Jiao K, Jia W, Jiang K, Cheng Z, Liu G, Luo Y. A periodontal tissue regeneration strategy via biphasic release of zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 and FK506 using a uniaxial electrospun Janus nanofiber. J Mater Chem B. 2022;10:765-78.

- Liu Y, Zhu Z, Pei X, Zhang X, Cheng X, Hu S, Gao X, Wang J, Chen J, Wan Q. ZIF-8-modified multifunctional bone-adhesive hydrogels promoting angiogenesis and osteogenesis for bone regeneration. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12:36978-95.

- Xue Y, Zhu Z, Zhang X, Chen J, Yang X, Gao X, Zhang S, Luo F, Wang J, Zhao W, et al. Accelerated bone regeneration by MOF modified multifunctional membranes through enhancement of osteogenic and angiogenic performance. Adv Healthc Mater. 2021;10:e2001369.

- Liu Y, Li T, Sun M, Cheng Z, Jia W, Jiao K, Wang S, Jiang K, Yang Y, Dai Z, et al. ZIF-8 modified multifunctional injectable photopolymerizable GelMA hydrogel for the treatment of periodontitis. Acta Biomater. 2022;146:37-48.

- Dong Z, Lin Y, Xu S, Chang L, Zhao X, Mei X, Gao X. NIR-triggered tea polyphenol-modified gold nanoparticles-loaded hydrogel treats periodontitis by inhibiting bacteria and inducing bone regeneration. Mater Des. 2023;225:111487.

- Burghardt I, Lüthen F, Prinz C, Kreikemeyer B, Zietz C, Neumann H-G, Rychly J. A dual function of copper in designing regenerative implants. Biomaterials. 2015;44:36-44.

- Xu Y, Zhao S, Weng Z, Zhang W, Wan X, Cui T, Ye J, Liao L, Wang X. Jelly-inspired injectable guided tissue regeneration strategy with shape auto-matched and dual-light-defined antibacterial/osteogenic pattern switch properties. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12:54497-506.

- Liu J, Ouyang Y, Zhang Z, Wen S, Pi Y, Chen D, Su Z, Liang Z, Guo L, Wang Y. The role of Th17 cells: explanation of relationship between periodontitis and COPD? Inflamm Res. 2022;71:1011-24.

- Beklen A, Ainola M, Hukkanen M, Gurgan C, Sorsa T, Konttinen YT. MMPs, IL-1, and TNF are regulated by IL-17 in periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2007;86:347-51.

- Cavalla F, Hernandez M. Polarization profiles of T lymphocytes and macrophages responses in periodontitis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2022;1373:195-208.

- Papathanasiou E, Conti P, Carinci F, Lauritano D, Theoharides TC. IL-1 superfamily members and periodontal diseases. J Dent Res. 2020;99:1425-34.

- Plemmenos G, Evangeliou E, Polizogopoulos N, Chalazias A, Deligianni M , Piperi C. Central regulatory role of cytokines in periodontitis and targeting options. Curr Med Chem. 2021;28:3032-58.

- Ni C, Zhou J, Kong N, Bian T, Zhang Y, Huang X, Xiao Y, Yang W, Yan F. Gold nanoparticles modulate the crosstalk between macrophages and periodontal ligament cells for periodontitis treatment. Biomaterials. 2019;206:115-32.

- Qiu X, Yu Y, Liu H, Li X, Sun W, Wu W, Liu C, Miao L. Remodeling the periodontitis microenvironment for osteogenesis by using a reactive oxygen species-cleavable nanoplatform. Acta Biomater. 2021;135:593-605.

- Li S, Wang L, Gu Y, Lin L, Zhang M, Jin M, Mao C, Zhou J, Zhang W, Huang

, et al. Biomimetic immunomodulation by crosstalk with nanoparticulate regulatory T cells. Matter. 2021;4:3621-45. - Sun Y, Sun X, Li X, Li W, Li C, Zhou Y, Wang L, Dong B. A versatile nanocomposite based on nanoceria for antibacterial enhancement and protection from aPDT-aggravated inflammation via modulation of macrophage polarization. Biomaterials. 2021;268:120614.

- Zhang Y, Wang X, Li H, Ni C, Du Z, Yan F. Human oral microbiota and its modulation for oral health. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;99:883-93.

- Fan R, Zhou Y, Chen X, Zhong X, He F, Peng W, Li L, Wang X, Xu Y. Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles promote apoptosis via msRNA-regulated DNA methylation in periodontitis. Microbiol Spectr. 2023;11:e0328822.

- Bustamante M, Oomah BD, Mosi-Roa Y, Rubilar M, Burgos-Diaz C. Probiotics as an adjunct therapy for the treatment of halitosis, dental caries and periodontitis. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2020;12:325-34.

- Zidar A, Kristl J, Kocbek P, Zupancic S. Treatment challenges and delivery systems in immunomodulation and probiotic therapies for periodontitis. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2021;18:1229-44.

- Wang J, Liu Y, Wang W, Ma J, Zhang M, Lu X, Liu J, Kou Y. The rationale and potential for using Lactobacillus in the management of periodontitis. J Microbiol. 2022;60:355-63.

- Jung JI, Kim YG, Kang CH, Imm JY. Effects of Lactobacillus curvatus MG5246 on inflammatory markers in Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopol-ysaccharide-sensitized human gingival fibroblasts and periodontitis rat model. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2022;31:111-20.

- Esteban-Fernández A, Ferrer MD, Zorraquín-Peña I, López-López A. Mira MVM-AA: in vitro beneficial effects of Streptococcus dentisani as potencial oral probiotic for periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 2019;90:1346-55.

- Mittal M, Siddiqui MR, Tran K, Reddy SP, Malik AB. Reactive oxygen species in inflammation and tissue injury. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:1126-67.

- Tan DQ, Suda T. Reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial homeostasis as regulators of stem cell fate and function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2018;29:149-68.

- Del Castillo LF, Schlegel Gomez R, Pelka M, Hornstein OP, Johannessen AC, von den Driesch P. Immunohistochemical localization of very late activation integrins in healthy and diseased human gingiva. J Periodontal Res. 1996;31:36-42.

- Haapasalmi K, Mäkelä M, Oksala O, Heino J, Yamada KM, Uitto VJ, Larjava H. Expression of epithelial adhesion proteins and integrins in chronic inflammation. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:193.

- Hersel U, Dahmen C, Kessler H. RGD modified polymers: biomaterials for stimulated cell adhesion and beyond. Biomaterials. 2003;24:4385-415.

- Ruoslahti E. RGD and other recognition sequences for integrins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:697-715.

- Yao W, Xu P, Zhao J, Ling L, Li X, Zhang B, Cheng N, Pang Z. RGD functionalized polymeric nanoparticles targeting periodontitis epithelial cells for the enhanced treatment of periodontitis in dogs. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2015;458:14-21.

- He XT, Li X, Zhang M, Tian BM, Sun LJ, Bi CS, Deng DK, Zhou H, Qu HL, Wu C, Chen FM. Role of molybdenum in material immunomodulation and periodontal wound healing: targeting immunometabolism and mitochondrial function for macrophage modulation. Biomaterials. 2022;283:121439.

- Wang G, Peng C, Tang M, Wang Y, Li J, Chen H, Chang X, Shu Z, He N , Guo J, Gui S. Simultaneously boosting inflammation resolution and osteogenic differentiation in periodontitis using folic acidmodified liposome-thermosensitive hydrogel composites. Mater Des. 2023;234:112314.

- Wang Y, Li J, Tang M, Peng C, Wang G, Wang J, Wang X, Chang X, Guo J, Gui S. Smart stimuli-responsive hydrogels for drug delivery in periodontitis treatment. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;162:114688.

- Li N, Xie L, Wu Y, Wu Y, Liu Y, Gao Y, Yang J, Zhang X, Jiang L. Dexametha-sone-loaded zeolitic imidazolate frameworks nanocomposite hydrogel with antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects for periodontitis treatment. Mater Today Bio. 2022;16:100360.

- Tang J, Yi W, Yan J, Chen Z, Fan H, Zaldivar-Silva D, Agüero L, Wang S. Highly absorbent bio-sponge based on carboxymethyl chitosan/ poly-

-glutamic acid/platelet-rich plasma for hemostasis and wound healing. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;247:125754. - Chew JRJ, Chuah SJ, Teo KYW, Zhang S, Lai RC, Fu JH, Lim LP, Lim SK, Toh WS. Mesenchymal stem cell exosomes enhance periodontal ligament cell functions and promote periodontal regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2019;89:252-64.

- Zhang X, Zhao J, Xie P, Wang S. Biomedical applications of electrets: recent advance and future perspectives. J Funct Biomater. 2023;14:320.

- Yu B, Qiao Z, Cui J, Lian M, Han Y, Zhang X, Wang W, Yu X, Yu H, Wang X , Lin K. A host-coupling bio-nanogenerator for electrically stimulated osteogenesis. Biomater. 2021;276:120997.

- Gonzalez-Febles J, Sanz M. Periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis: what have we learned about their connection and their treatment? Periodontol 2000. 2021;87:181-203.

- Ray RR. Periodontitis: an oral disease with severe consequences. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2023;195:17-32.

- Newman KL, Kamada N. Pathogenic associations between oral and gastrointestinal diseases. Trends Mol Med. 2022;28:1030-9.

- Li B, Xin Z, Gao S, Li Y, Guo S, Fu Y, Xu R, Wang D, Cheng J, Liu L, et al. SIRT6-regulated macrophage efferocytosis epigenetically controls inflammation resolution of diabetic periodontitis. Theranostics. 2023;13:231-49.

- Guru SR, Aghanashini S. Impact of scaling and root planing on salivary and serum plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression in patients with periodontitis with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Periodontol. 2023;94:20-30.

- Wu CZ, Yuan YH, Liu HH, Li SS, Zhang BW, Chen W, An ZJ, Chen SY, Wu YZ, Han B, et al. Epidemiologic relationship between periodontitis and type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20:204.

- Zhao X, Yang Y, Yu J, Ding R, Pei D, Zhang Y, He G, Cheng Y, Li A. Injectable hydrogels with high drug loading through B-N coordination and ROS-triggered drug release for efficient treatment of chronic periodontitis in diabetic rats. Biomaterials. 2022;282:121387.

- Wang H, Chang X, Ma Q, Sun B, Li H, Zhou J, Hu Y, Yang X, Li J, Chen X, Song J. Bioinspired drug-delivery system emulating the natural bone healing cascade for diabetic periodontal bone regeneration. Bioact Mater. 2023;21:324-39.

- Hajishengallis G, Chavakis T. Local and systemic mechanisms linking periodontal disease and inflammatory comorbidities. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21:426-40.

- Inchingolo AD, Inchingolo AM, Malcangi G, Avantario P, Azzollini D, Buongiorno S, Viapiano F, Campanelli M, Ciocia AM, De Leonardis N, et al. Effects of resveratrol, curcumin and quercetin supplementation on bone metabolism-a systematic review. Nutrients. 2022;14:3519.

- Cao JH, Xue R, He B. Quercetin protects oral mucosal keratinocytes against lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory toxicity by suppressing the AKT/AMPK/mTOR pathway. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2021;43:519-26.

- Taskan MM, Gevrek F. Quercetin decreased alveolar bone loss and apoptosis in experimentally induced periodontitis model in wistar rats. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem. 2020;19:436-48.

- Bhattarai G, Poudel SB, Kook SH, Lee JC. Resveratrol prevents alveolar bone loss in an experimental rat model of periodontitis. Acta Biomater. 2016;29:398-408.

- Li Y, Jiao J, Qi Y, Yu W, Yang S, Zhang J, Zhao J. Curcumin: a review of experimental studies and mechanisms related to periodontitis treatment. J Periodontal Res. 2021;56:837-47.

- Zheng XY, Mao CY, Qiao H, Zhang X, Yu L, Wang TY, Lu EY. Plumbagin suppresses chronic periodontitis in rats via down-regulation of TNF-alpha, IL-1 beta and IL-6 expression. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2017;38:1150-60.

ملاحظة الناشر

هل أنت مستعد لتقديم بحثك؟ اختر BMC واستفد من:

- تقديم سريع ومريح عبر الإنترنت

- مراجعة دقيقة من قبل باحثين ذوي خبرة في مجالك

- نشر سريع عند القبول

- دعم لبيانات البحث، بما في ذلك أنواع البيانات الكبيرة والمعقدة

- الوصول المفتوح الذهبي الذي يعزز التعاون الأوسع وزيادة الاقتباسات

- أقصى قدر من الرؤية لبحثك: أكثر من 100 مليون مشاهدة للموقع سنويًا

ساهم جياكسين لي ويوشياو وانغ بالتساوي في الورقة.

*للتواصل:

منغجي لي

limj@ahtcm.edu.cn

شوانغيينغ جوي

guishy0520@126.com

جيان قوه

guoj0719@126.com

القائمة الكاملة لمعلومات المؤلف متاحة في نهاية المقالة

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-023-02261-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38178140

Publication Date: 2024-01-04

New insights into nanotherapeutics for periodontitis: a triple concerto of antimicrobial activity, immunomodulation and periodontium regeneration

Abstract

Periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory disease caused by the local microbiome and the host immune response, resulting in periodontal structure damage and even tooth loss. Scaling and root planning combined with antibiotics are the conventional means of nonsurgical treatment of periodontitis, but they are insufficient to fully heal periodontitis due to intractable bacterial attachment and drug resistance. Novel and effective therapeutic options in clinical drug therapy remain scarce. Nanotherapeutics achieve stable cell targeting, oral retention and smart release by great flexibility in changing the chemical composition or physical characteristics of nanoparticles. Meanwhile, the protectiveness and high surface area to volume ratio of nanoparticles enable high drug loading, ensuring a remarkable therapeutic efficacy. Currently, the combination of advanced nanoparticles and novel therapeutic strategies is the most active research area in periodontitis treatment. In this review, we first introduce the pathogenesis of periodontitis, and then summarize the state-of-the-art nanotherapeutic strategies based on the triple concerto of antibacterial activity, immunomodulation and periodontium regeneration, particularly focusing on the therapeutic mechanism and ingenious design of nanomedicines. Finally, the challenges and prospects of nano therapy for periodontitis are discussed from the perspective of current treatment problems and future development trends.

Introduction

age may be a critical factor for the increasing trend [4]. In addition, there is growing clinical evidence that periodontitis places a huge burden on the public health care system due to the close links to other diseases such as diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, colitis and even cancer [5-7].

Nanoparticles have significant promise for addressing the challenges of periodontal drug delivery. Nanoparticles, including liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, polymeric micelles and nanofibers, provide great flexibility in changing chemical composition, size, surface

charge and other characteristics, which can ensure stable cell targeting and oral retention. Existing data suggest that nanoparticles protect drugs from pH influence and enzymatic degradation in the periodontal lesion [12]. Importantly, the nanoparticle structure can be designed to respond to reactive oxygen species (ROS), pH , or enzyme-response mechanisms in the pathological microenvironment for controlled drug release. We summarize nano delivery systems strategies for the treatment of periodontitis in terms of three main aspects: antibacterial therapy, immunomodulatory therapy and tissue regeneration (Fig. 1). In addition, the high surface area to volume ratio of nanoparticles enables high drug or drug combination loading, resulting in synergistic therapeutic efficacy by combining multiple treatment aspects. For example, metal nanoparticles such as silver, gold, and cerium, can directly sterilize or

discuss the future challenges and research directions of nano systems for periodontitis treatment.

Pathophysiology of periodontitis

Neutrophils, as the first line of nonspecific immunity against pathogenic bacteria, attempt to engulf or kill pathogens, but they are overwhelmed by a large number of pathogens in periodontitis [24]. As antigen-presenting cells, dendritic cells (DCs) bridge the innate and adaptive immune responses in periodontitis [25]. Immature DCs have a high phagocytosis capacity and are able to rapidly capture invading microorganisms [26]. Mature DCs present antigens to the initial

promote Th 17 or Treg cells differentiation by releasing the cytokines of tumor necrosis factor

Nanotherapeutic strategies for periodontitis

Antimicrobial nanotherapeutic strategies

regeneration treatment strategies for periodontitis are summarized (Table 1).

Antibiotic

size, thus improving the antimicrobial efficacy of topical administration [44, 45]. MIN-NPs can provide sustained drug release, reduce the frequency of administration and avoid burst release of the drug. The pharmacokinetic profile showed that MIN-NPs had the longest duration of action in the gingival sulcus, compared to minocycline hydrochloride ointment and minocycline solution. The concentration of MIN-NPs in the gingival sulcus decreased slowly, maintaining the drug at an effective concentration (

| Nanoparticles | Delivery systems | Drugs | Outcome | References |

| MIN-NPs | Polymeric nanoparticles | Minocycline | Clinical periodontal parameters (periodontal pocket depth, plaque index and gingival index) were significantly improved | [45] |

| MOX-PLGA nanoparticle | Polymeric nanoparticles | Moxifloxacin hydrochloride | Prolonged retention and drug release of a nanoloaded moxifloxacin in situ gel system in periodontal pockets | [46] |

| Ciprofloxacin hydrochloride loaded dual corona vesicles | Vesicles | Ciprofloxacin hydrochloride | Used double crown vesicles as drug carriers, 50% of the normal dose of antibiotics can achieve antibacterial purposes, which will reduce the possibility of antibiotic resistance | [47] |

| AuNCs | Au nanoclusters | / | Reduce the possibility of bacterial resistance | [50] |

| PCL-OTCz | Polymeric nanoparticles | Oxytetracycline hydrochloride and ZnO NPs | Excellent antibacterial activity of oxytetracycline hydrochloride in synergy with ZnO against mixed cultures of Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria | [64] |

| Mino-ZnO@Alb NPs | Nano-albumin | ZnO NPs and minocycline | Synergistic antibacterial action, reduced the dosage of Minocycline and avoiding the development of drug resistance | [65] |

| Gel MA-Au NBPs@SiO2 | Au NBPs | Minocycline | Eliminated periodontal pathogens in periodontal pockets, photothermal treatment to maintain low bacterial retention after medication | [68] |

|

|

Polymeric delivery system | Ce6 and C6 | Strong antibacterial activity against plaque biofilms | [73] |

| NaYF4-Mn@Ce6@silane | Polymeric nanoparticles | Ce6 | Realized the conversion of light emission and enhance the PDT effect | [74] |

| TAT-Ce6/TDZ NPs | Polymeric nanoparticles | Ce6 | Promoted the penetration of the bacterial cell membrane through the mediation of TAT peptide | [76] |

| sPDMA@ICG NPs | Polymeric delivery system | ICG | Significantly promoted the adsorption and penetration of ICG into bacterial cells, exhibiting synergistic antibacterial properties of PTT and PDT | [79] |

Xi and his colleagues proposed the encapsulate the ciprofloxacin hydrochloride in dual corona nanovesicles to reduce the antibiotic dose and antimicrobial resistance (Fig. 3A) [47]. The

Metallic nano-antibacterial agent

form mixed bacterial cultures. PCL-OTCz showed powerful antibacterial activity compared with oxytetracycline hydrochloride or ZnO nanoparticles, individually.

Photothermal/photodynamic therapy

PDT antimicrobial therapy refers to the use of a photosensitizer that produces ROS in response to light stimulation, thus leading to rapid oxidation of lipids in bacteria,

and the destruction of fragile lipid membranes in periodontitis treatment [69, 70]. Chlorin e6 (Ce6) is widely used in PDT therapy because of its strong tissue penetration, great biocompatibility and high yield of singlet oxygen [71, 72]. Sun et al. prepared a core-shell structure nanodrug delivery system (

shape and exhibited a more compact inner structure. The particle size of TAT-Ce6/TDZ NPs was

Indocyanine green (ICG), a photosensitizer with PDT properties, has been approved for clinical use by the US Food and Drug Administration [77]. Nagahara et al. first explored PDT of photosensitizer indocyanine green, which has high absorption at a wavelengths of 800805 nm [78]. They designed ICG-loaded PLGA nanospheres coated with chitosan (ICGNano/c) and explored the PDT of ICGNano/c in Pg. The study showed that ICG-Nano/c with low-level diode laser (

properties. The results suggested that sPDMA@ICG NPs can produce ROS after laser irradiation, as detected by SOSG. Confocal microscopy images show that sPDMA@ ICG NPs are effectively accumulate in bacterial cells after the administration of sPDMA@ICG NPs. TEM images showed that sPDMA@ICG NPs were clearly visible on the surface of Pg, and that the bacterial film ruptured and bacterial cells disintegrated after laser irradiation (Fig. 4D). In addition, sPDMA@ICG NPs with laser irradiation reduced the growing area of plaque biofilms derived derive from a rat model of periodontitis (Fig. 4E). After sPDMA@ICG NPs administration and laser irradiation, temperature and ROS levels were increased in rats with periodontitis, indicating that sPDMA@ICG NPs exert synergistic PTT and PDT effects in vivo (Fig. 4F).

Immunomodulatory nanotherapeutic strategies

| Nanoparticles | Delivery systems | Drugs | Outcome | References |

| Lipo-RSV | Liposome | Resveratrol | Reprogramed the macrophages from M1- to M2-like phenotype, adjustment of the immune microenvironment | [89] |

| DPSC-Exo/CS | Exosomes | / | Suppressed periodontal inflammation by promoting the conversion of macrophages from a pro-inflammatory to an anti-inflammatory phenotype in the periodontium of mice with periodontitis | [90] |

| CeO2@QU | Nanoparticles | Quercetin | Scavenged ROS and regulated the conversion of M1 phenotype macrophages to the M2 phenotype to regulate the immune microenvironment | [14] |

| 3D-exos | Exosomes | / | Alleviated Th17 cell/Treg imbalance and reduce inflammation | [99] |

| PDLSC-exos | Exosomes | / | PDLSC-exos transferred miR-155-5p into CD4 + T cells to affecting the Th17/Treg homeostasis | [100] |

| Nano-BA/BE | Polymeric nanoparticles | Baicalein/Baicalin | Alleviated the expression of II-1

|

[104] |

| PDA NPs | Polydopamine nanoparticles | / | Effectively scavenges ROS in the body, relieves oxidative stress and reduces local periodontal inflammation | [105] |

Remodeling macrophage polarization

Shi et al. developed a liposome loaded with resveratrol (Lipo-RSV) to polarize macrophages from the M1 to M2 phenotype (Fig. 5A) [89]. Lipo-RSV upregulated the mRNA expression levels of M2-related markers (CD206, Arg-1 and Chil3), and downregulated the mRNA expression levels of M1 macrophage markers (CD86, iNOS and CCR7) in activated macrophages. Lipo-RSV treatment increased the percentage of M2-like subpopulations (

Exosomes are nanosized (

collected their exosome pellets by centrifugation for the treatment of mice with periodontitis [90]. To enhance the stability of the exosomes, chitosan hydrogels loaded with dental pulp stem cell exosomes (DPSCs-Exo/CS) were prepared in mixed culture with chitosan hydrogels at

scavenging ROS and regulating the conversion of M1 phenotype macrophages to the M2 phenotype.

Restoring Th17/Treg cells balance

between Th17 and Treg cells is crucial in the periodontal immune response [94, 95]. Overreaction of Th17 cells to pathogens leads to increased expression of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-17 and IL-22 [96]. IL-17 has been shown to boost RANKL expression while inhibiting OPG expression in periodontal ligament cells, which might explain why Th17 cells promote alveolar bone loss [95]. However, Tregs can suppress the host immune response in equilibrium with Th17 cells in the periodontium [97, 98]. To date, no drug/nanosystem has been reported to directly regulate the Th17/Treg cells balance, but exosomes derived from periodontal ligament stem cells have been found to have the potential to regulate Th17/Treg cells.

Zhang et al. found that exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells (3D-exos) could regulate Th17/Tregs cell balance [99]. Notably, replacing the traditional 2D culture system with a 3D system could increase exosome production. The average particle size of the 3D-exos was

Zheng et al. investigated the effect of exosomes from periodontal membrane stem cells (PDLSC-exos) on Th17/Treg balance [100]. The expression of the Th17related transcription factor RAR-related orphan receptor C was upregulated and the Treg-related transcription factor forkhead Box P3 was down-regulated in periodontitis patients. This means that the Th17/Treg ratio is unbalanced in patients with periodontitis. The results showed lower Th17-related CD4

cells, and their potential in the treatment of periodontitis needs to be further explored.

Regulating pro-/anti-inflammatory cytokine secretion

Periodontium regeneration nanotherapeutics strategies

Promoting periodontal membrane stem cell differentiation

| Nanoparticles | Delivery systems | Drugs | Outcome | References |

| L-Cys-AuNPs | Au nanoparticles | / | Promoted proliferation of human PDLCs, enhances their ALP activity and upregulated mRNA levels of osteogenic genes | [112] |

| Nano-

|

Polymeric nanoparticles | / | Increased levels of human PDLSCs and osteogenic genes in dental bone promote osseous differentiation and contribute to periodontium regeneration | [113] |

| h-PDLSCs-exosomes | Exosomes | / | Upregulated of Runx2 and OCN mRNA levels in PDLSCs restores osteogenic differentiation in PDLSCs | [116] |

| PLA/CS | PLA/CS nanofiber | / | Promoted proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs and upregulated the expression level of osteogenic genes | [121] |

| PLA/CA | PLA/CA nanofiber | / | Increased expression levels of cell mineralization genes and formation of mineralized junctions BMSCs, promoting osteogenic differentiation | [122] |

| M2-Exos | Exosomes | / | Increased expression levels of osteogenesis in BMSCs while restrained expression levels of osteoclast formation in BMDM | [125] |

| AMG-487 NP | Liposomal | AMG-487 NP | Reduced the number of osteoblasts and inhibits alveolar bone loss | [129] |

| Fibrin-ACP | Chitosan nanoparticles |

|

Promoted the differentiation of cementoblasts | [134] |

Exosomes derived from healthy PDLSCs are potential components of osteogenic differentiation [114, 115]. Lei et al. isolated h-PDLSCs-exosomes from periodontal ligament tissue derived from healthy donors [116]. The diameter of h-PDLSCs-exosomes was 121.4 nm . h-PDLSCs-exosomes upregulated the mRNA levels of RUNX2 and OCN in the inflammatory periodontal ligaments of patients with periodontitis and promoted the expression of OCN osteogenesis-related proteins. Mechanistic studies found that h-PDLSCs-exosomes promote osteogenic differentiation by intervening Wnt signaling pathway. The mRNA levels of Wnt1, Wnt3a, Wnt10a, and

Promoting bone marrow stem cell differentiation therapy

Disturbing osteoclastogenesis

nanoparticles self-assembled from palmitic acid and cholesterol to disturb ostecoclastogenesis [128, 129]. TRAP staining results showed that ostecoclastogenesis was inhibited after AMG-487 NPs-loaded liposome treatment. Micro-CT reconstruction analysis confirmed a

Accelerating cementoblast differentiation

that Fibrin-ACP exhibits powerful periodontal tissue repair potential by accelerating cementum regeneration.

Synergistic nanotherapeutic strategies

Antibacterial and immunomodulatory therapy

| Nanoparticles | Delivery systems | Drugs | Outcome | References |

| Antibacterial and immunomodulatory therapy | ||||

| MPB-BA | MOF | Baicalein | Up-regulated of antioxidant genes (SOD-1, CAT and HO-1) expression to scavenge ROS and down-regulation of anti-inflammatory factors (TGF-

|

[15] |

| AuAg@PC-Fe | AuAg nanoparticles | / | Photothermal antimicrobial and immunomodulatory treatment periodontitis | [136] |

| MZ@PNM | Macrophage membrane coating nanoparticles | Metronidazole | Interfered with the binding of Pg to macrophages and preventing Pg subversion of periodontal host immune response | [137] |

| Antibacterial and periodontium regeneration therapy | ||||

| PPZF-JNF | Nanofibers | ZIF-8 NPs and FK506 |

|

[140] |