DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-48751-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38773174

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-21

روبوتات ميلي خفيفة الوزن وخالية من الانجراف تعمل بالتحكم المغناطيسي عبر الجرافين المحفز بالليزر غير المتناظر

تاريخ القبول: 8 مايو 2024

تاريخ النشر على الإنترنت: 21 مايو 2024

الملخص

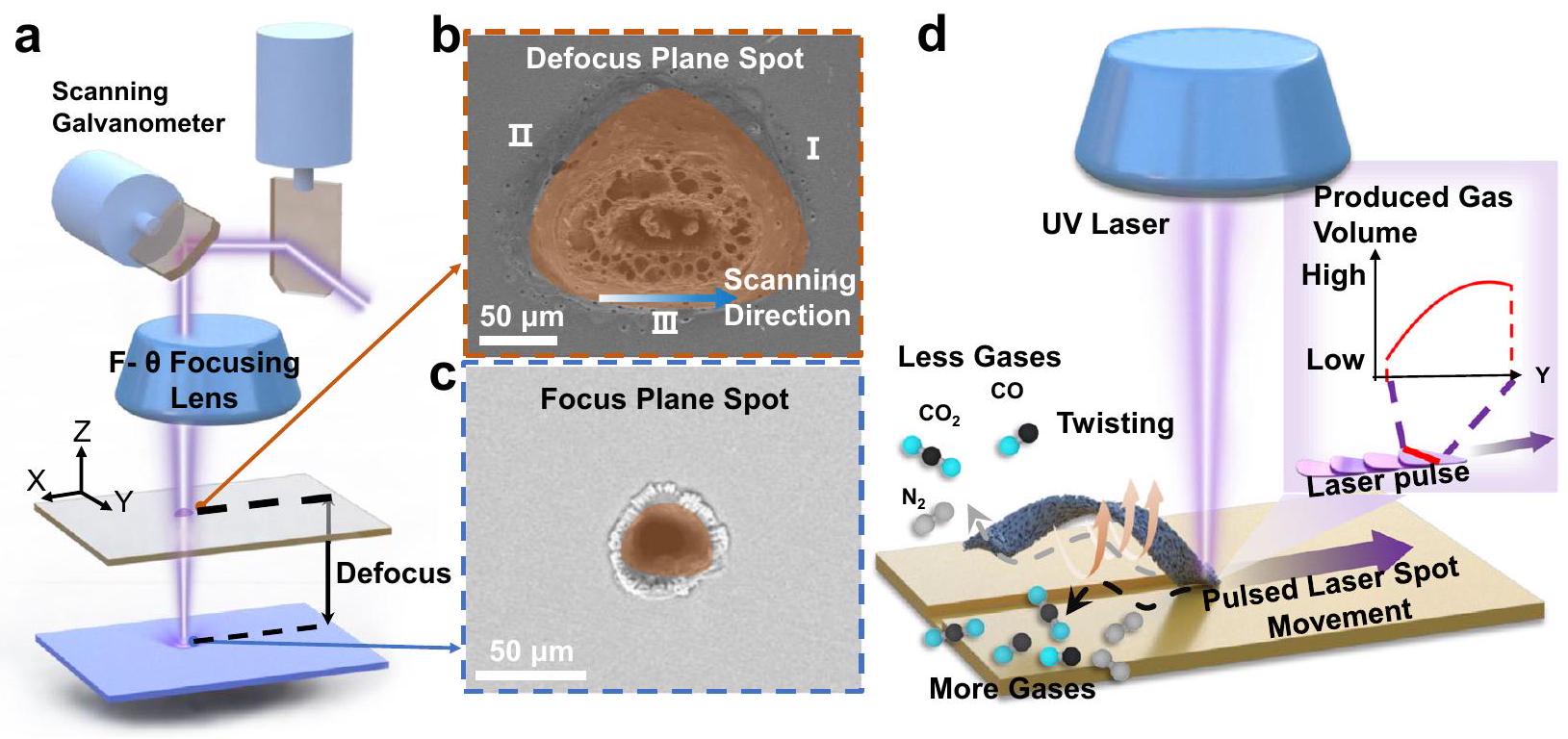

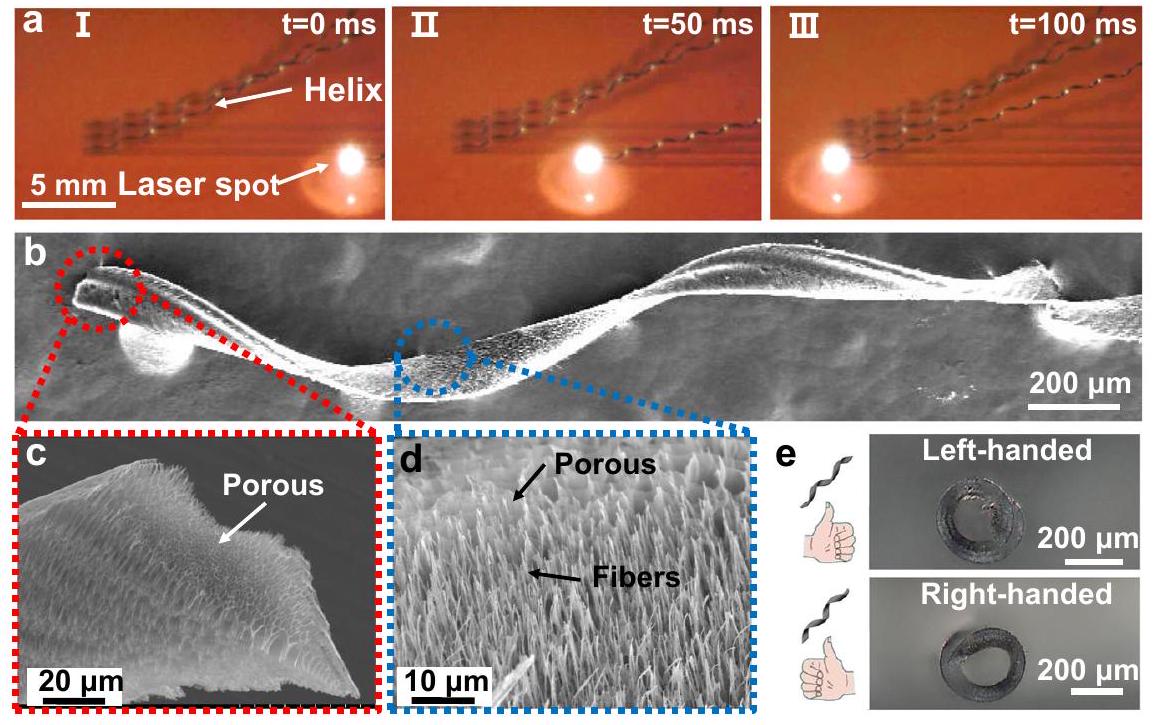

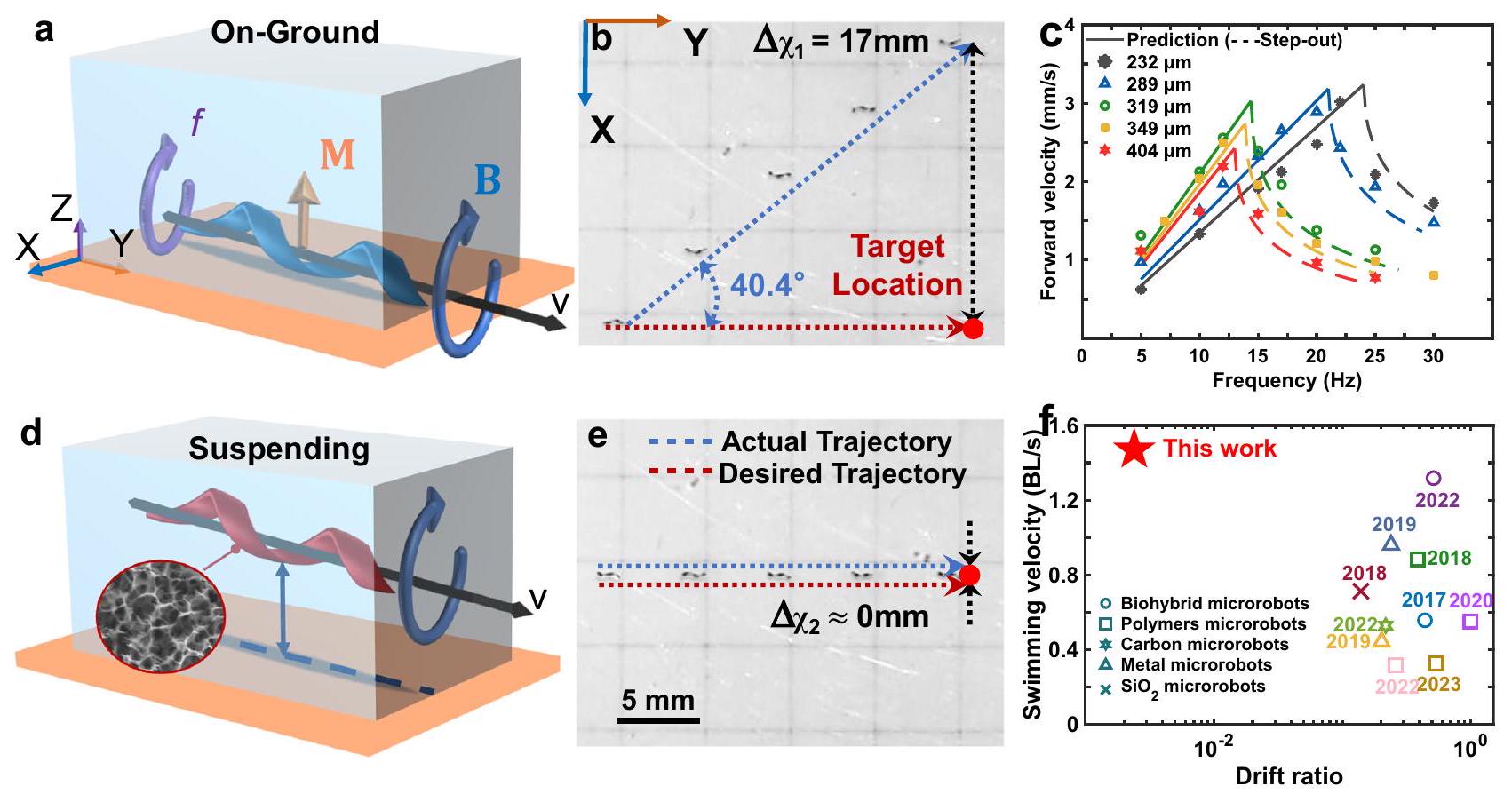

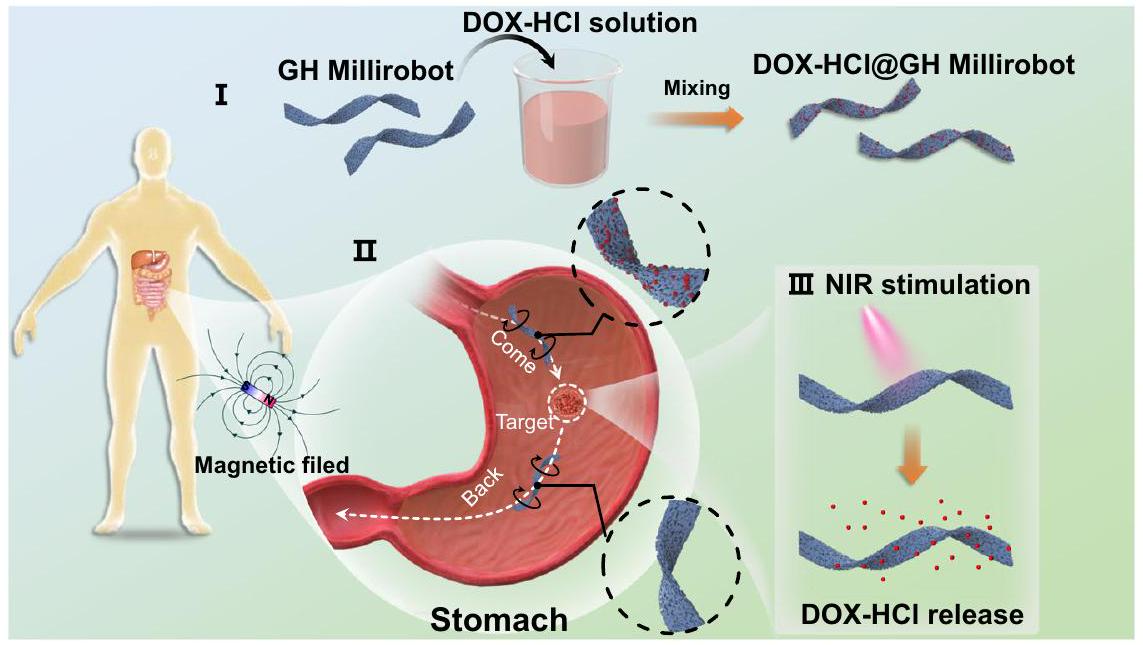

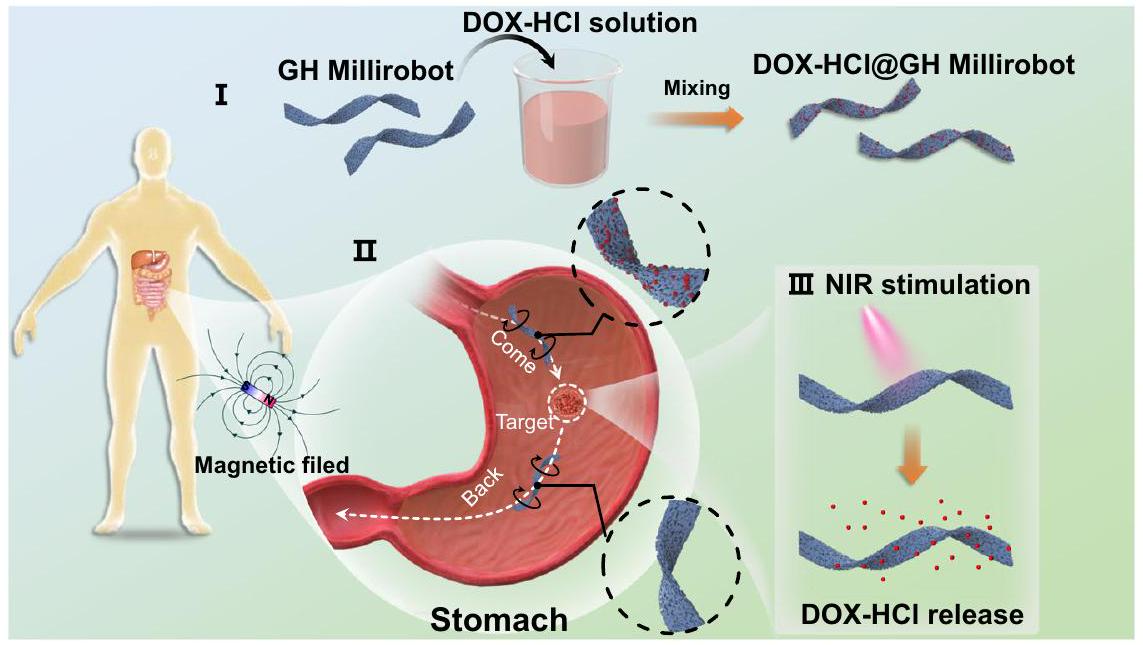

يجب أن تتمتع الروبوتات الدقيقة بتكلفة منخفضة، وحركة فعالة، والقدرة على تتبع مسارات الأهداف بدقة إذا كانت ستستخدم على نطاق واسع. مع المواد الحالية وطرق التصنيع، لا يزال من الصعب تحقيق جميع هذه الميزات في روبوت دقيق واحد. نحن نطور سلسلة من الروبوتات الدقيقة الحلزونية المعتمدة على الجرافين من خلال إدخال تشويه نمط الضوء غير المتماثل في عملية تحويل البوليمر إلى جرافين المحفز بالليزر؛ أدى هذا التشويه إلى التواء تلقائي وتقشير صفائح الجرافين من الركيزة البوليمرية. الطبيعة الخفيفة للجرافين بالتزامن مع الهيكل الدقيق المسامي المحفز بالليزر توفر هيكلًا للروبوت الدقيق بكثافة منخفضة وخصائص عالية من الكارهية للماء على السطح. تم تصنيع روبوتات دقيقة حلزونية مدفوعة مغناطيسيًا ومغطاة بالنيكل مع حركة سريعة، وقدرة ممتازة على تتبع المسارات، وقدرة دقيقة على توصيل الأدوية من الهيكل. من المهم أن هذه الروبوتات الدقيقة عالية الأداء تُصنع بسرعة 77 هيكلًا في الثانية، مما يوضح إمكاناتها في الإنتاج عالي الإنتاجية وعلى نطاق واسع. باستخدام توصيل الأدوية لعلاج سرطان المعدة كمثال، نوضح مزايا الروبوتات الدقيقة الحلزونية المعتمدة على الجرافين من حيث حركتها لمسافات طويلة ونقل الأدوية في بيئة فسيولوجية. تُظهر هذه الدراسة إمكانات الروبوتات الدقيقة الحلزونية المعتمدة على الجرافين لتلبية متطلبات الأداء، والمرونة، وقابلية التوسع، والجدوى الاقتصادية في وقت واحد.

سرعة حركتها والانجراف الجانبي

مزايا الروبوتات الدقيقة GH المطورة للحركة لمسافات طويلة ونقل الأدوية في بيئة فسيولوجية.

النتائج

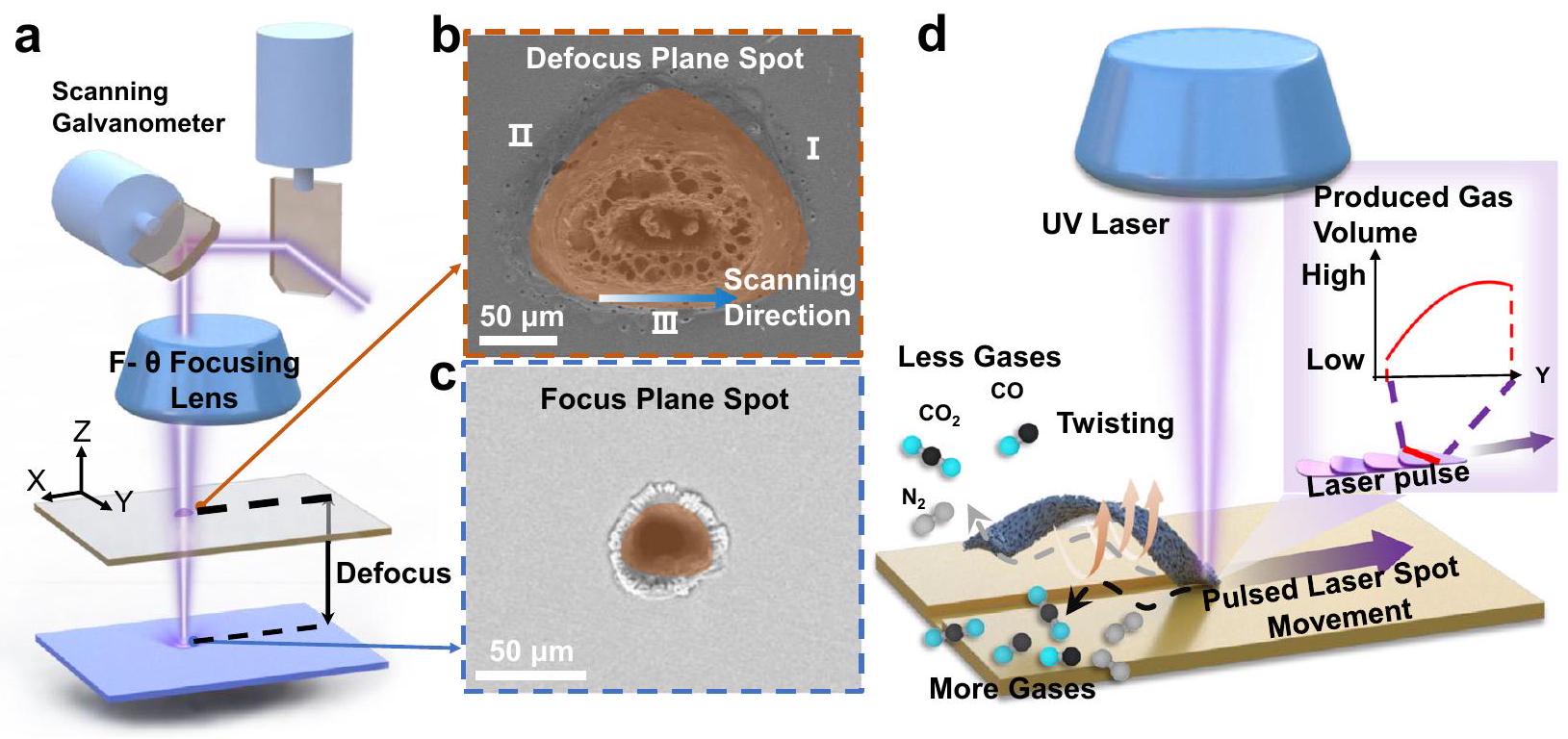

معالجة وتوصيف صفائح LIG الحلزونية المسامية

طائرة.

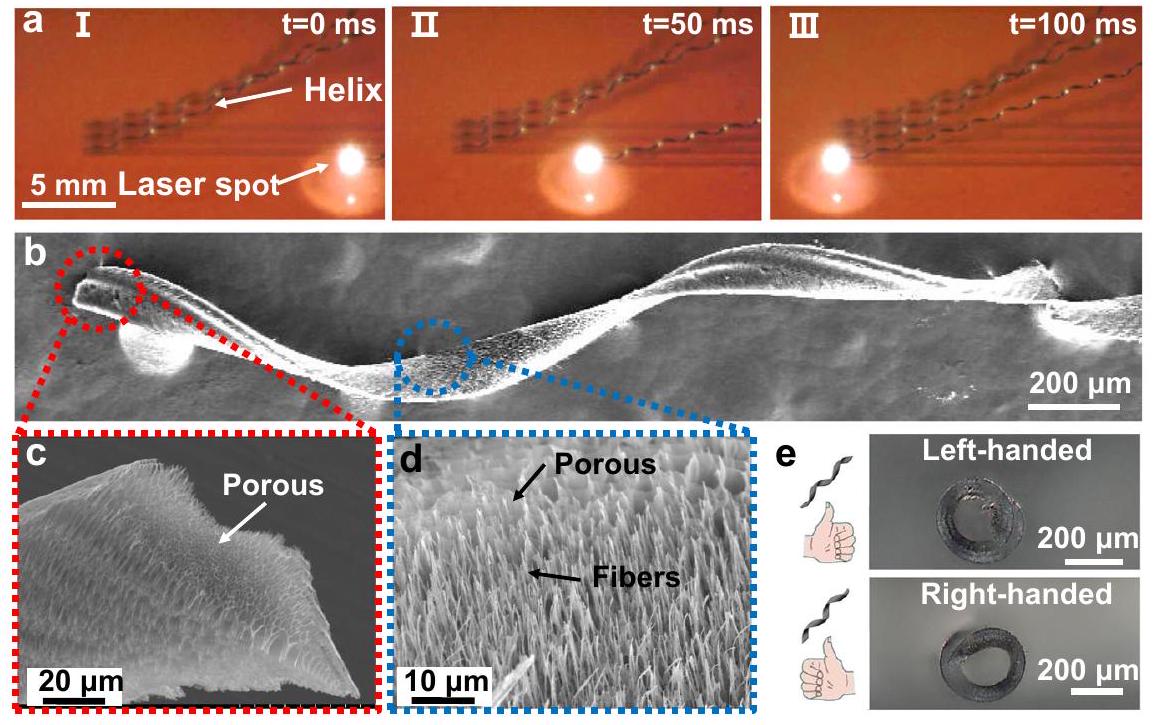

الألياف في السطح السفلي للورقة. تم معالجة أوراق LIG الحلزونية المسامية اليمنى واليسرى من خلال اختيار اتجاهات مسح ليزر مختلفة. تم تكرار هذه التجارب لأكثر من 10 دفعات مختلفة وأسفرت عن نتائج مماثلة.

الذي أدى إلى إنشاء عدد كبير من الميكروثقوب والنانوثقوب

تكون الورقة مغمورة في سائل، مما يمنح الهواء المحبوس فيها طفوًا ملائمًا للورقة؛ علاوة على ذلك، يمكن أن تؤدي خاصية الكارهية للماء لسطح الملي روبوت إلى زيادة تردد الخروج وسرعة السباحة.

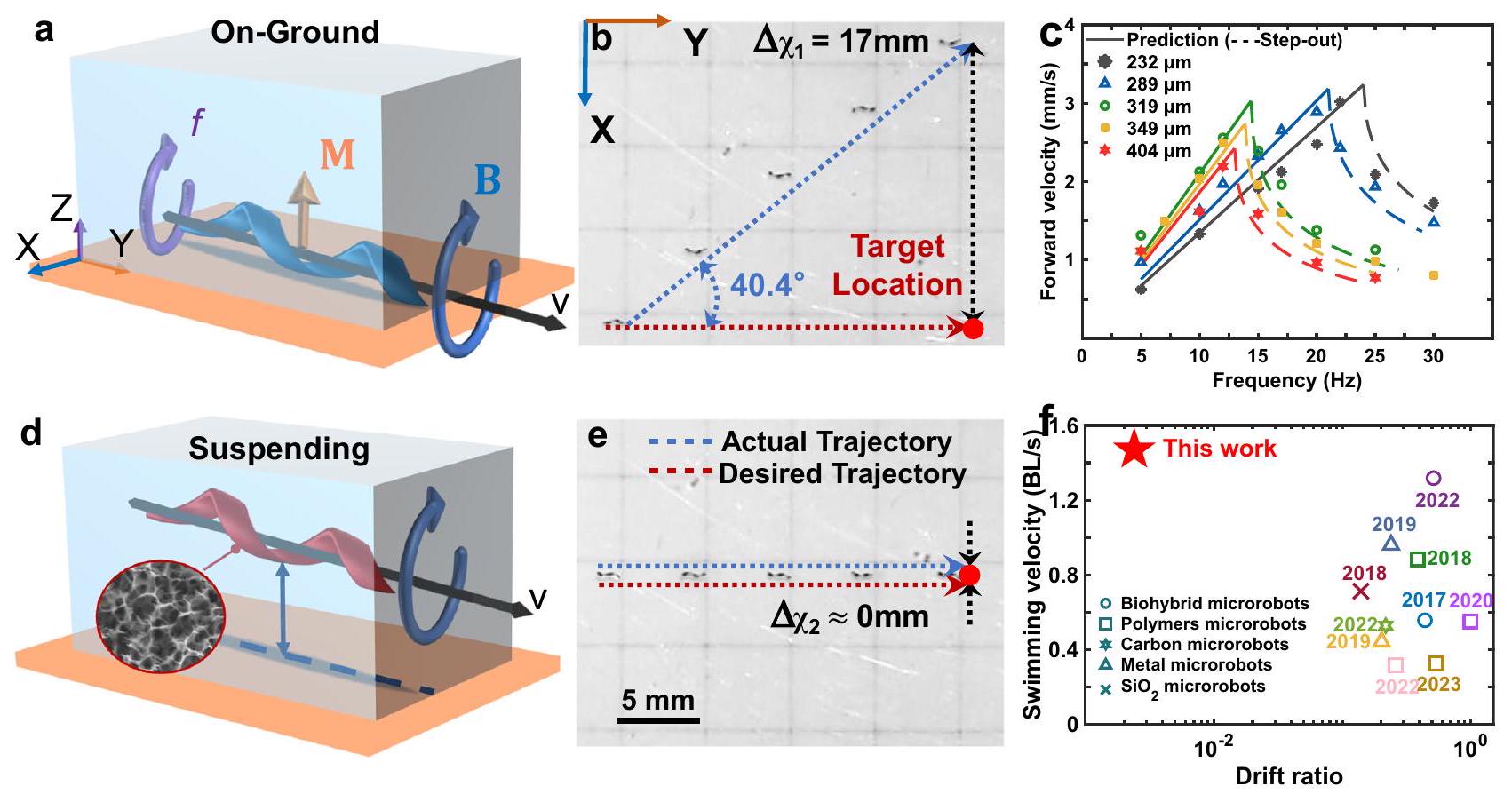

تلاعب وتوصيف الروبوتات الدقيقة من نوع GH

منحنى التنبؤ موضح في الملاحظة التكميلية S1. د مخطط للروبوت المليلي منخفض الكثافة المعلق بالكامل. هـ مخطط زمني لحركة الروبوت المليلي منخفض الكثافة (الروبوت المليلي المعلق). مقياس الرسم: 5 مم.

الميلي روبوتات؛ العزم الذي بدأ دورانها، وتم تحويل حركة التكوين الحلزوني إلى دفع انتقالي. من خلال تغيير اتجاه الدوران ودرجة قوة المجال المغناطيسي، يمكن توجيه الميلي روبوتات GH بشكل اتجاهي. ما لم يُذكر خلاف ذلك، تم قياس حركة الميلي روبوتات GH تحت مجال مغناطيسي بقوة 12 مللي تسلا.

كان المجال المغناطيسي قابلاً للمقارنة مع تلك الخاصة بالروبوتات الصغيرة المدفوعة بالمجال المغناطيسي الأخرى. تحت تردد دوران مرتفع يبلغ 24 هرتز، حقق أخف روبوت حلزوني GH سرعة أمامية عالية من

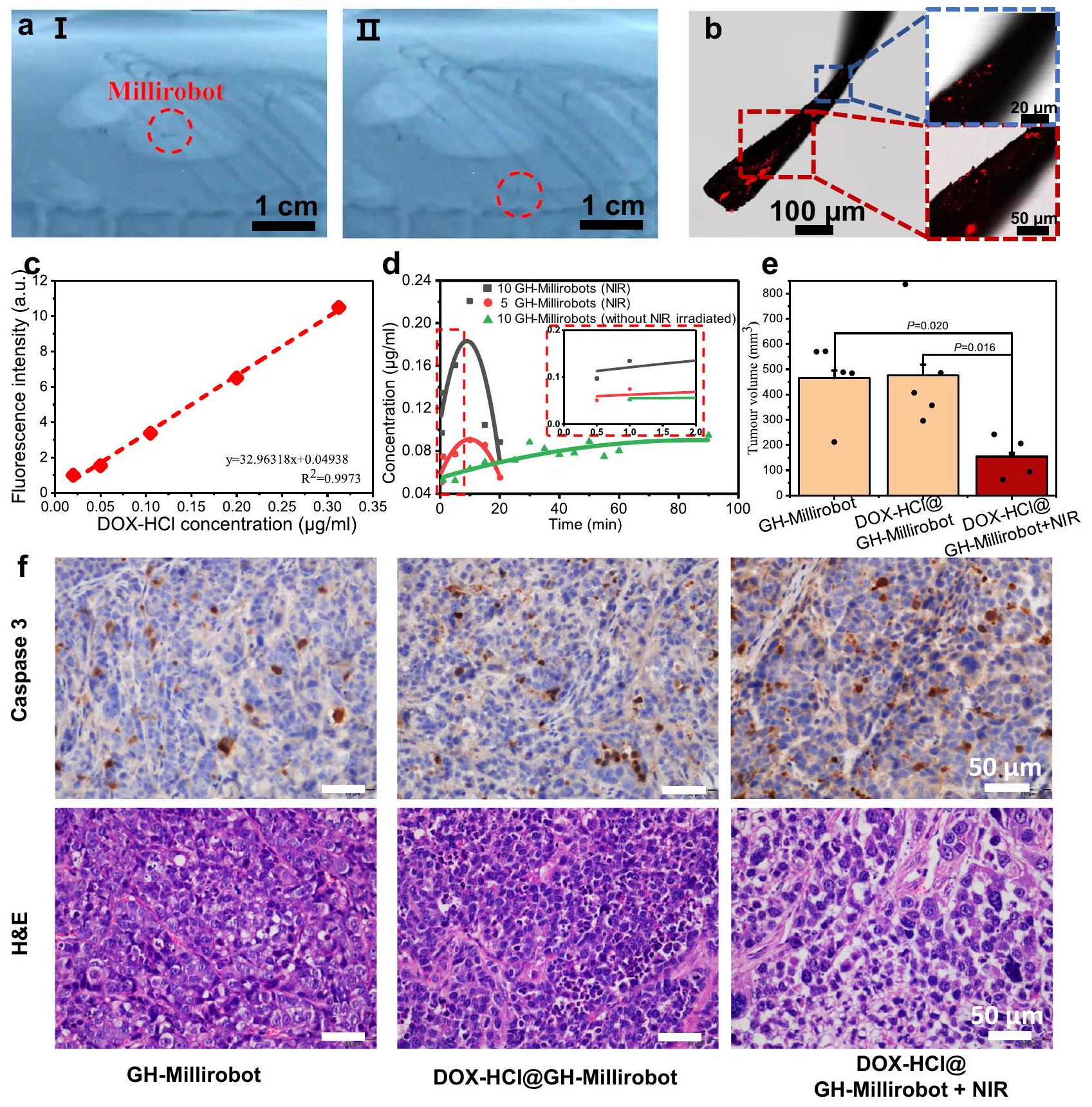

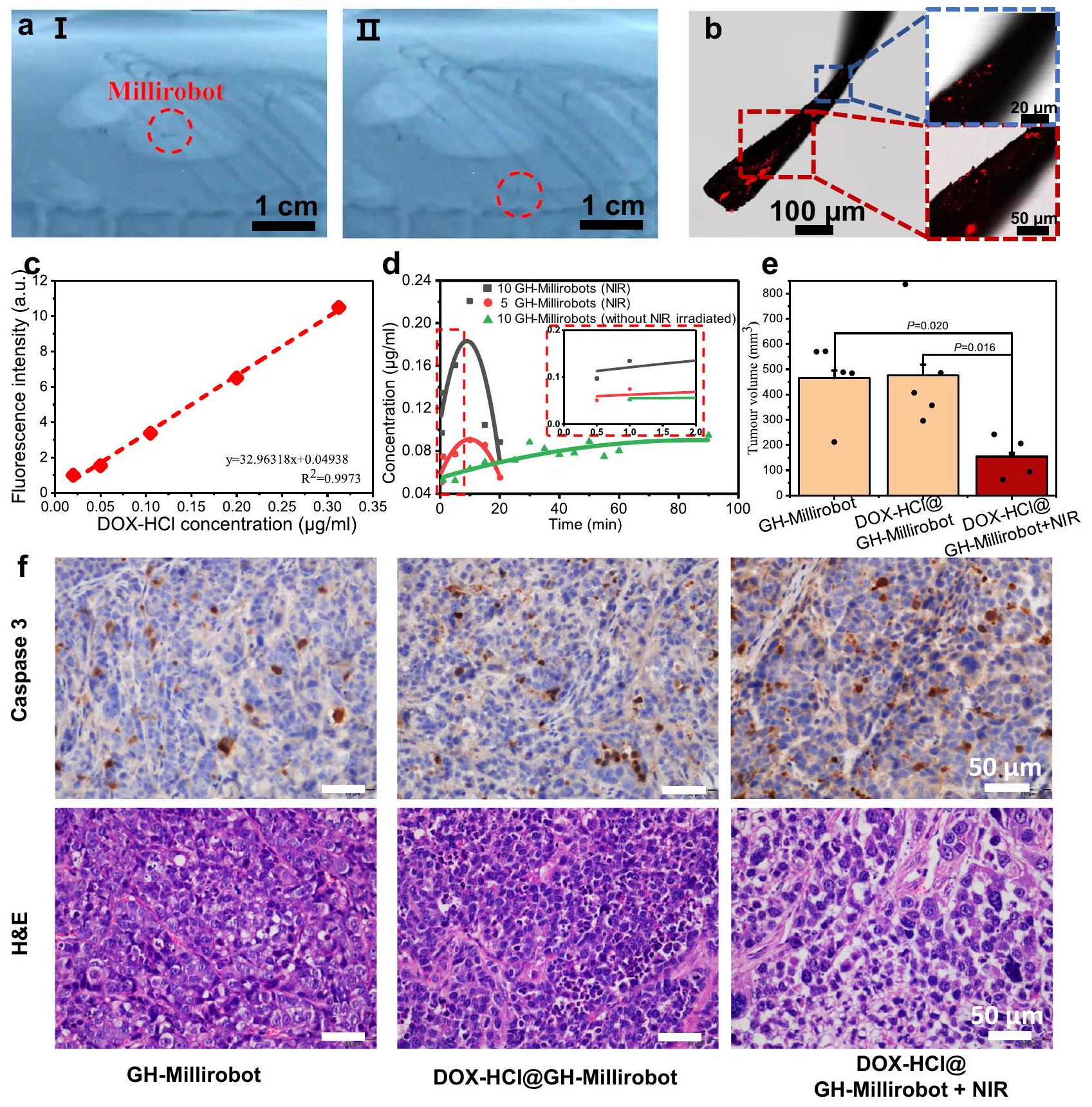

توصيل الأدوية العلاجية

الاضطراب الناتج عن درجات الحرارة العالية المرتبطة بأوقات الإشعاع الممتدة. علاوة على ذلك، كانت كمية الدواء التي أطلقها كل ميلي روبوت GH تقريبًا متساوية بين الدفعات، كما هو موضح في الملاحظة التكميلية S2.

إشعاع في 2 مل من الماء المنزوع الأيونات. تم ملاءمة المنحنيات باستخدام معادلة غاوسية تربيعية. تم بدء عد الفلورية بعد 30 ثانية من بدء إطلاق DOX عند النقطة الزمنية 0. ثم تم أخذ القياسات على فترات زمنية قدرها 1 دقيقة، 5 دقائق، ومن ثم كل 5 دقائق بعد ذلك. يوفر الشكل المصغر عرضًا مكبرًا لفترة الدقيقتين الأوليين. حجم الورم المعدي في ثلاث مجموعات من الفئران. “DOX-HCl@GH-Millirobot” تشير إلى GH-Millirobot المحملة بـ DOX-HCl، (

نقاش

لا يؤدي فقط إلى التواء وتقشير أوراق LIG بشكل عفوي من ركيزة PI، بل يوفر أيضًا للأوراق هيكلًا مساميًا عاليًا. وبالتالي، يتم إنشاء هياكل ميلي روبوت ذات كثافة منخفضة وخصائص طاردة للماء عالية السطح، وتظل الميلي روبوتات الناتجة معلقة بالكامل عند دفعها مغناطيسيًا. تظهر الميلي روبوتات المطلية بالنيكل سرعة حركة مثيرة للإعجاب وقدرة ممتازة على تتبع المسارات المبرمجة، مع انحراف يكاد يكون صفرًا. من خلال تغيير ظروف معالجة الليزر بشكل منهجي، أظهرنا أن طريقة التصنيع المعتمدة توفر إنتاجية عالية (77 هيكل ميلي روبوت في الثانية) وهي قابلة للتحكم ومرنة للغاية؛ يمكن ضبط معلمات هندسية مختلفة مرتبطة بخصائص حركة الميلي روبوتات باستخدام نموذج برامترية. بشكل خاص، فإن الجمع بين سرعة الإنتاج العالية وانخفاض تكلفة المواد الخام يجعل من الممكن الحفاظ على تكلفة كل جهاز ميلي روبوت أقل من سنت واحد: 0.01 دولار أمريكي (ملاحظة إضافية S3). لقد تحققنا من مزايا ميلي روبوتات GH في سياق الحركة لمسافات طويلة وتوصيل الأدوية ضمن بيئة فسيولوجية باستخدام توصيل دواء سرطان المعدة كمثال. تشير هذه الدراسة إلى إمكانيات تكنولوجيا ميلي روبوت GH لتلبية متطلبات تطبيقات متعددة في الوقت نفسه، مثل الأداء والمرونة وقابلية التوسع ومتطلبات الجدوى الاقتصادية.

طرق

بيان الأخلاقيات

تصنيع وتوصيف الروبوتات الميليغرافية GH

التشغيل المغناطيسي وملاحظة المجهر

تحميل وإطلاق DOX-HCI

التلاعب والتصوير في الجسم الحي لروبوتات غرام من نوع ميلي

اختبار السلامة في الجسم الحي

العلاج المضاد للأورام في الجسم الحي

معلق في

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

References

- Dong, Y. et al. Graphene-based helical micromotors constructed by “microscale liquid rope-coil effect” with microfluidics. ACS Nano 14, 16600-16613 (2020).

- Dai, B. et al. Programmable artificial phototactic microswimmer. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 1087-1092 (2016).

- Yan, X. et al. Multifunctional biohybrid magnetite microrobots for imaging-guided therapy. Sci. Robot 2, q1155 (2017).

- lacovacci, V. et al. An intravascular magnetic catheter enables the retrieval of nanoagents from the bloodstream. Adv. Sci. 5, 1800807 (2018).

- Luo, M., Feng, Y., Wang, T. & Guan, J. Micro-/nanorobots at work in active drug delivery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1706100 (2018).

- Mhanna, R. et al. Artificial bacterial flagella for remotecontrolled targeted single-cell drug delivery. Small 10, 1953-1957 (2014).

- Chen, S. et al. Biodegradable microrobots for DNA vaccine delivery. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 12, 2202921 (2023).

- Lee, J. G. et al. Bubble-based microrobots with rapid circular motions for epithelial pinning and drug delivery. Small 19, 2300409 (2023).

- Zhang, Y., Yan, K., Ji, F. & Zhang, L. Enhanced removal of toxic heavy metals using swarming biohybrid adsorbents. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1806340 (2018).

- Dekanovsky, L. et al. Chemically programmable microrobots weaving a web from hormones. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 711-718 (2020).

- Li, H. et al. Material-engineered bioartificial microorganisms enabling efficient scavenging of waterborne viruses. Nat. Commun. 14, 4658 (2023).

- Maria-Hormigos, R., Mayorga-Martinez, C. C. & Pumera, M. Soft magnetic microrobots for photoactive pollutant removal. Small Method 7, 2201014 (2023).

- Zhang, Y., Yuan, K. & Zhang, L. Micro/nanomachines: from functionalization to sensing and removal. Adv. Mater. Technol. 4, 1800636 (2019).

- Chen, H., Wang, Y., Liu, Y., Zou, Q. & Yu, J. Sensing of fluidic features using colloidal microswarms. ACS Nano 16, 16281-16291 (2022).

- Wang, K. et al. Fluorescent self-propelled covalent organic framework as a microsensor for nitro explosive detection. Appl. Mater. 19, 100550 (2020).

- Xin, C. et al. Conical hollow microhelices with superior swimming capabilities for targeted cargo delivery. Adv. Mater. Today 31, 1808226 (2019).

- Zhou, H., Mayorga-Martinez, C. C., Pané, S., Zhang, L. & Pumera, M. Magnetically driven micro and nanorobots. Chem. Rev. 121, 4999-5041 (2021).

- Mirkovic, T., Zacharia, N. S., Scholes, G. D. & Ozin, G. A. Fuel for thought: chemically powered nanomotors out-swim nature’s flagellated bacteria. ACS Nano 4, 1782-1789 (2010).

- Dong, M. et al. 3D-printed soft magnetoelectric microswimmers for delivery and differentiation of neuron-like cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1910323 (2020).

- Ma, W. & Wang, H. Magnetically driven motile superhydrophobic sponges for efficient oil removal. Appl. Mater. Today 15, 263-266 (2019).

- Zhang, S. et al. Reconfigurable multi-component micromachines driven by optoelectronic tweezers. Nat. Commun. 12, 5349 (2021).

- Zhang, S. et al. Optoelectronic tweezers: a versatile toolbox for nano -/ micro-manipulation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 9203-9242 (2022).

- Wu, X. et al. Light-driven microdrones. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 477 (2022).

- Aghakhani, A., Yasa, O., Wrede, P. & Sitti, M. Acoustically powered surface-slipping mobile microrobots. P. Natl Acad. Sci. Usa. 117, 3469-3477 (2020).

- Park, J., Kim, J. Y., Pané, S., Nelson, B. J. & Choi, H. Acoustically mediated controlled drug release and targeted therapy with degradable 3D porous magnetic microrobots. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 10, 2001096 (2021).

- Aghakhani, A. et al. High shear rate propulsion of acoustic microrobots in complex biological fluids. Sci. Adv. 8, m5126 (2022).

- Ceylan, H. et al. 3D-printed biodegradable microswimmer for theranostic cargo delivery and release. ACS Nano 13, 3353-3362 (2019).

- Wang, X. et al. Surface-chemistry-mediated control of individual magnetic helical microswimmers in a swarm. ACS Nano 12, 6210-6217 (2018).

- Lee, H. & Park, S. Magnetically actuated helical microrobot with magnetic nanoparticle retrieval and sequential dual-drug release abilities. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 15, 27471-27485 (2023).

- Wu, Z. et al. A swarm of slippery micropropellers penetrates the vitreous body of the eye. Sci. Adv. 4, t4388 (2018).

- Walker, D., Käsdorf, B. T., Jeong, H., Lieleg, O. & Fischer, P. Enzymatically active biomimetic micropropellers for the penetration of mucin gels. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500501 (2015).

- Gao, W. et al. Bioinspired helical microswimmers based on vascular plants. Nano Lett. 14, 305-310 (2014).

- Xie, L. et al. Photoacoustic imaging-trackable magnetic microswimmers for pathogenic bacterial infection treatment. ACS Nano 14, 2880-2893 (2020).

- Chen, X. et al. Magnetically driven piezoelectric soft microswimmers for neuron-like cell delivery and neuronal differentiation. Mater. Horiz. 6, 1512-1516 (2019).

- Zhang, L. et al. Characterizing the swimming properties of artificial bacterial flagella. Nano Lett. 9, 3663-3667 (2009).

- Huang, H. et al. Investigation of magnetotaxis of reconfigurable micro-origami swimmers with competitive and cooperative anisotropy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1802110 (2018).

- Nguyen, K. T. et al. A magnetically guided self-rolled microrobot for targeted drug delivery, real-time X-ray imaging, and microrobot retrieval. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 10, 2001681 (2021).

- Yu, Y. et al. Bioinspired helical micromotors as dynamic cell microcarriers. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 12, 16097-16103 (2020).

- Terzopoulou, A. et al. Biodegradable metal-organic frameworkbased microrobots (MOFBOTs). Adv. Healthc. Mater. 9, 2001031 (2020).

- Gong, D., Celi, N., Xu, L., Zhang, D. & Cai, J. CuS nanodots-loaded biohybrid magnetic helical microrobots with enhanced photothermal performance. Mater. Today Chem. 23, 100694 (2022).

- Ma, W. et al. High-throughput and controllable fabrication of helical microfibers by hydrodynamically focusing flow. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 13, 59392-59399 (2021).

- Lombini, M., Diolaiti, E. & Patti, M. Historic evolution of the optical design of the multi conjugate adaptive optics relay for the extremely large telescope. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 486, 320-330 (2019).

- Trappe, N., Murphy, J. A. & Withington, S. The Gaussian beam mode analysis of classical phase aberrations in diffraction-limited optical systems. Eur. J. Phys. 24, 403-412 (2003).

- Chen, Y. et al. Interfacial laser-induced graphene enabling highperformance liquid-solid triboelectric nanogenerator. Adv. Mater. 33, 2104290 (2021).

- Lin, J. et al. Laser-induced porous graphene films from commercial polymers. Nat. Commun. 5, 5714 (2014).

- Liu, Y. et al. Pancake bouncing on superhydrophobic surfaces. Nat. Phys. 10, 515-519 (2014).

- Dreyfus, R. et al. Microscopic artificial swimmers. Nature 437, 862-865 (2005).

- Alcântara, C. C. J. et al. 3D fabrication of fully iron magnetic microrobots. Small 15, 1805006 (2019).

- Cabanach, P. et al. Zwitterionic 3D-printed non-immunogenic stealth microrobots. Adv. Mater. 32, 2003013 (2020).

- Chen, Y. et al. Carbon helical nanorobots capable of cell membrane penetration for single cell targeted SERS bio-sensing and photothermal cancer therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2200600 (2022).

- Zheng, S. et al. Microrobot with Gyroid Surface and Gold Nanostar for High Drug Loading and Near-Infrared-Triggered ChemoPhotothermal Therapy. Pharmaceutics 14, 2393 (2022).

- Elhanafy, A., Abuouf, Y., Elsagheer, S., Ookawara, S. & Ahmed, M. Effect of external magnetic field on realistic bifurcated right coronary artery hemodynamics. Phys. Fluids 35, 61903 (2023).

- Shigemitsu, T. & Ueno, S. Biological and health effects of electromagnetic fields related to the operation of MRI/TMS. Spin 7, 174009 (2017).

- Patel, V. G., Oh, W. K. & Galsky, M. D. Treatment of muscle-invasive and advanced bladder cancer in 2020. Ca. Cancer J. Clin. 70, 404-423 (2020).

- Khezri, B. et al. Ultrafast Electrochemical Trigger Drug Delivery Mechanism for Nanographene Micromachines. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1806696 (2019).

- Yang, J. et al. Beyond the Visible: Bioinspired Infrared Adaptive Materials. Adv. Mater. 33, 2004754 (2021).

- Morozov, K. I. & Leshansky, A. M. Dynamics and polarization of superparamagnetic chiral nanomotors in a rotating magnetic field. Nanoscale 6, 12142-12150 (2014).

- Morozov, K. I. & Leshansky, A. M. The chiral magnetic nanomotors. Nanoscale 6, 1580-1588 (2014).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

© المؤلفون 2024

- (ن) تحقق من التحديثات

المختبر الوطني الرئيسي لتقنية ومعدات التصنيع الإلكتروني الدقيق، كلية الهندسة الكهروميكانيكية، جامعة غوانغدونغ للتكنولوجيا، غوانغتشو 510006، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. معهد الطب الطبيعي والكيمياء الخضراء، كلية العلوم الطبية الحيوية والصيدلانية، جامعة غوانغدونغ للتكنولوجيا، غوانغتشو 510006، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. قسم الهندسة الإلكترونية، الجامعة الصينية في هونغ كونغ، شاتين، هونغ كونغ، الصين. كلية علوم المواد والهندسة، معهد جورجيا للتكنولوجيا، أتلانتا، GA 30332، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. البريد الإلكتروني: chenx@gdut.edu.cn; luyj@gdut.edu.cn; nzhao@ee.cuhk.edu.hk

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-48751-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38773174

Publication Date: 2024-05-21

Lightweight and drift-free magnetically actuated millirobots via asymmetric laserinduced graphene

Accepted: 8 May 2024

Published online: 21 May 2024

Abstract

Millirobots must have low cost, efficient locomotion, and the ability to track target trajectories precisely if they are to be widely deployed. With current materials and fabrication methods, achieving all of these features in one millirobot remains difficult. We develop a series of graphene-based helical millirobots by introducing asymmetric light pattern distortion to a laserinduced polymer-to-graphene conversion process; this distortion resulted in the spontaneous twisting and peeling off of graphene sheets from the polymer substrate. The lightweight nature of graphene in combine with the laserinduced porous microstructure provides a millirobot scaffold with a low density and high surface hydrophobicity. Magnetically driven nickel-coated graphene-based helical millirobots with rapid locomotion, excellent trajectory tracking, and precise drug delivery ability were fabricated from the scaffold. Importantly, such high-performance millirobots are fabricated at a speed of 77 scaffolds per second, demonstrating their potential in high-throughput and large-scale production. By using drug delivery for gastric cancer treatment as an example, we demonstrate the advantages of the graphene-based helical millirobots in terms of their long-distance locomotion and drug transport in a physiological environment. This study demonstrates the potential of the graphene-based helical millirobots to meet performance, versatility, scalability, and cost-effectiveness requirements simultaneously.

their movement velocity and lateral drift

advantages of the developed GH millirobots for long-distance locomotion and drug transport in a physiological environment.

Results

Processing and characterization of porous helical LIG sheets

plane.

fibers at the sheet’s bottom surface. e Right- and left-handed porous helical LIG sheets processed by selecting different laser scanning directions. These experiments were repeated for more than 10 different batches and yield similar results.

produced, which resulted in the creation of a substantial number of micropores and nanopores

sheet is immersed in a liquid, with this trapped air conferring favorable buoyancy to the sheet; moreover, the hydrophobicity of the millirobot’s surface can also lead to a greater step-out frequency and higher swimming velocity

Manipulation and characterization of GH millirobots

prediction curve is detailed in Supplementary Note S1. d Schematic of the lowdensity fully suspended GH millirobot. e Time-lapse diagram of the motion of the low-density GH millirobot (suspending GH-millirobot). Scale bar: 5 mm .

millirobots; the torque initiated their rotation, and the helical configuration’s motion was transformed into translational propulsion. Through the alteration of the rotational direction and magnitude of the magnetic field, the GH millirobots could be directionally steered. Unless otherwise specified, the motion of the GH millirobots was measured under a 12 mT magnetic field.

magnetic field were comparable to those of other magnetic-field-driven millirobots. Under a high rotational frequency of 24 Hz , the lightest helical GH millirobot achieved a high forward velocity of

Therapeutic drug delivery

destabilization caused by high temperature associated with extended irradiation times. Furthermore, the quantity of drug released by each GH millirobot was approximately the same between batches, as indicated in Supplementary Note S2

irradiation in 2 mL of deionized water. The curves were fitted using a quadratic Gaussian equation. The fluorescence counting was started 30 s after the initiation of DOX release at time point 0 . Measurements were then taken at intervals of 1 min , 5 min , and subsequently every 5 min thereafter. The inset provides a magnified view of the initial 2-minute period. e Gastric tumor volume in three mice groups. The “DOX-HCl@GH-Millirobot” stand for GH-Millirobot loaded with DOX-HCl, (

Discussion

only induces the spontaneous twisting and peeling off of LIG sheets from a PI substrate but also provides the sheets a highly porous structure. As such, millirobot scaffolds with low density and high surface hydrophobicity are created, and the resultant millirobots remain fully suspended when being propelled magnetically. The nickel-coated GH millirobots exhibit impressive locomotion speed and excellent ability to track programmed trajectories, showing nearly zero deviation. By systematically varying the laser processing conditions, we demonstrated that the adopted fabrication method offers high throughput ( 77 millirobot scaffolds per second) and is highly controllable and versatile; various geometrical parameters linked to the locomotion properties of millirobots can be tuned using a parametric model. In particular, the combination of high production speed and low raw material cost makes it feasible to maintain the cost per millirobot device below one cent: US$0.01 (Supplementary Note S3). We validated the advantages of GH millirobots in the context of longdistance locomotion and drug delivery within a physiological environment by using gastric cancer drug delivery as an example. This study indicates the potential of GH millirobot technology to meet numerous application requirements simultaneously, such as performance, versatility, scalability, and cost-effectiveness requirements.

Methods

Ethics statement

Fabrication and characterization of GH millirobots

Magnetic actuation and microscopy observation

Loading and release of DOX-HCI

In vivo manipulation and imaging of GH millirobots

In vivo safety test

In vivo antitumor therapy

suspended in

Reporting summary

Data availability

References

- Dong, Y. et al. Graphene-based helical micromotors constructed by “microscale liquid rope-coil effect” with microfluidics. ACS Nano 14, 16600-16613 (2020).

- Dai, B. et al. Programmable artificial phototactic microswimmer. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 1087-1092 (2016).

- Yan, X. et al. Multifunctional biohybrid magnetite microrobots for imaging-guided therapy. Sci. Robot 2, q1155 (2017).

- lacovacci, V. et al. An intravascular magnetic catheter enables the retrieval of nanoagents from the bloodstream. Adv. Sci. 5, 1800807 (2018).

- Luo, M., Feng, Y., Wang, T. & Guan, J. Micro-/nanorobots at work in active drug delivery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1706100 (2018).

- Mhanna, R. et al. Artificial bacterial flagella for remotecontrolled targeted single-cell drug delivery. Small 10, 1953-1957 (2014).

- Chen, S. et al. Biodegradable microrobots for DNA vaccine delivery. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 12, 2202921 (2023).

- Lee, J. G. et al. Bubble-based microrobots with rapid circular motions for epithelial pinning and drug delivery. Small 19, 2300409 (2023).

- Zhang, Y., Yan, K., Ji, F. & Zhang, L. Enhanced removal of toxic heavy metals using swarming biohybrid adsorbents. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1806340 (2018).

- Dekanovsky, L. et al. Chemically programmable microrobots weaving a web from hormones. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 711-718 (2020).

- Li, H. et al. Material-engineered bioartificial microorganisms enabling efficient scavenging of waterborne viruses. Nat. Commun. 14, 4658 (2023).

- Maria-Hormigos, R., Mayorga-Martinez, C. C. & Pumera, M. Soft magnetic microrobots for photoactive pollutant removal. Small Method 7, 2201014 (2023).

- Zhang, Y., Yuan, K. & Zhang, L. Micro/nanomachines: from functionalization to sensing and removal. Adv. Mater. Technol. 4, 1800636 (2019).

- Chen, H., Wang, Y., Liu, Y., Zou, Q. & Yu, J. Sensing of fluidic features using colloidal microswarms. ACS Nano 16, 16281-16291 (2022).

- Wang, K. et al. Fluorescent self-propelled covalent organic framework as a microsensor for nitro explosive detection. Appl. Mater. 19, 100550 (2020).

- Xin, C. et al. Conical hollow microhelices with superior swimming capabilities for targeted cargo delivery. Adv. Mater. Today 31, 1808226 (2019).

- Zhou, H., Mayorga-Martinez, C. C., Pané, S., Zhang, L. & Pumera, M. Magnetically driven micro and nanorobots. Chem. Rev. 121, 4999-5041 (2021).

- Mirkovic, T., Zacharia, N. S., Scholes, G. D. & Ozin, G. A. Fuel for thought: chemically powered nanomotors out-swim nature’s flagellated bacteria. ACS Nano 4, 1782-1789 (2010).

- Dong, M. et al. 3D-printed soft magnetoelectric microswimmers for delivery and differentiation of neuron-like cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1910323 (2020).

- Ma, W. & Wang, H. Magnetically driven motile superhydrophobic sponges for efficient oil removal. Appl. Mater. Today 15, 263-266 (2019).

- Zhang, S. et al. Reconfigurable multi-component micromachines driven by optoelectronic tweezers. Nat. Commun. 12, 5349 (2021).

- Zhang, S. et al. Optoelectronic tweezers: a versatile toolbox for nano -/ micro-manipulation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 9203-9242 (2022).

- Wu, X. et al. Light-driven microdrones. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 477 (2022).

- Aghakhani, A., Yasa, O., Wrede, P. & Sitti, M. Acoustically powered surface-slipping mobile microrobots. P. Natl Acad. Sci. Usa. 117, 3469-3477 (2020).

- Park, J., Kim, J. Y., Pané, S., Nelson, B. J. & Choi, H. Acoustically mediated controlled drug release and targeted therapy with degradable 3D porous magnetic microrobots. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 10, 2001096 (2021).

- Aghakhani, A. et al. High shear rate propulsion of acoustic microrobots in complex biological fluids. Sci. Adv. 8, m5126 (2022).

- Ceylan, H. et al. 3D-printed biodegradable microswimmer for theranostic cargo delivery and release. ACS Nano 13, 3353-3362 (2019).

- Wang, X. et al. Surface-chemistry-mediated control of individual magnetic helical microswimmers in a swarm. ACS Nano 12, 6210-6217 (2018).

- Lee, H. & Park, S. Magnetically actuated helical microrobot with magnetic nanoparticle retrieval and sequential dual-drug release abilities. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 15, 27471-27485 (2023).

- Wu, Z. et al. A swarm of slippery micropropellers penetrates the vitreous body of the eye. Sci. Adv. 4, t4388 (2018).

- Walker, D., Käsdorf, B. T., Jeong, H., Lieleg, O. & Fischer, P. Enzymatically active biomimetic micropropellers for the penetration of mucin gels. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500501 (2015).

- Gao, W. et al. Bioinspired helical microswimmers based on vascular plants. Nano Lett. 14, 305-310 (2014).

- Xie, L. et al. Photoacoustic imaging-trackable magnetic microswimmers for pathogenic bacterial infection treatment. ACS Nano 14, 2880-2893 (2020).

- Chen, X. et al. Magnetically driven piezoelectric soft microswimmers for neuron-like cell delivery and neuronal differentiation. Mater. Horiz. 6, 1512-1516 (2019).

- Zhang, L. et al. Characterizing the swimming properties of artificial bacterial flagella. Nano Lett. 9, 3663-3667 (2009).

- Huang, H. et al. Investigation of magnetotaxis of reconfigurable micro-origami swimmers with competitive and cooperative anisotropy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1802110 (2018).

- Nguyen, K. T. et al. A magnetically guided self-rolled microrobot for targeted drug delivery, real-time X-ray imaging, and microrobot retrieval. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 10, 2001681 (2021).

- Yu, Y. et al. Bioinspired helical micromotors as dynamic cell microcarriers. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 12, 16097-16103 (2020).

- Terzopoulou, A. et al. Biodegradable metal-organic frameworkbased microrobots (MOFBOTs). Adv. Healthc. Mater. 9, 2001031 (2020).

- Gong, D., Celi, N., Xu, L., Zhang, D. & Cai, J. CuS nanodots-loaded biohybrid magnetic helical microrobots with enhanced photothermal performance. Mater. Today Chem. 23, 100694 (2022).

- Ma, W. et al. High-throughput and controllable fabrication of helical microfibers by hydrodynamically focusing flow. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 13, 59392-59399 (2021).

- Lombini, M., Diolaiti, E. & Patti, M. Historic evolution of the optical design of the multi conjugate adaptive optics relay for the extremely large telescope. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 486, 320-330 (2019).

- Trappe, N., Murphy, J. A. & Withington, S. The Gaussian beam mode analysis of classical phase aberrations in diffraction-limited optical systems. Eur. J. Phys. 24, 403-412 (2003).

- Chen, Y. et al. Interfacial laser-induced graphene enabling highperformance liquid-solid triboelectric nanogenerator. Adv. Mater. 33, 2104290 (2021).

- Lin, J. et al. Laser-induced porous graphene films from commercial polymers. Nat. Commun. 5, 5714 (2014).

- Liu, Y. et al. Pancake bouncing on superhydrophobic surfaces. Nat. Phys. 10, 515-519 (2014).

- Dreyfus, R. et al. Microscopic artificial swimmers. Nature 437, 862-865 (2005).

- Alcântara, C. C. J. et al. 3D fabrication of fully iron magnetic microrobots. Small 15, 1805006 (2019).

- Cabanach, P. et al. Zwitterionic 3D-printed non-immunogenic stealth microrobots. Adv. Mater. 32, 2003013 (2020).

- Chen, Y. et al. Carbon helical nanorobots capable of cell membrane penetration for single cell targeted SERS bio-sensing and photothermal cancer therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2200600 (2022).

- Zheng, S. et al. Microrobot with Gyroid Surface and Gold Nanostar for High Drug Loading and Near-Infrared-Triggered ChemoPhotothermal Therapy. Pharmaceutics 14, 2393 (2022).

- Elhanafy, A., Abuouf, Y., Elsagheer, S., Ookawara, S. & Ahmed, M. Effect of external magnetic field on realistic bifurcated right coronary artery hemodynamics. Phys. Fluids 35, 61903 (2023).

- Shigemitsu, T. & Ueno, S. Biological and health effects of electromagnetic fields related to the operation of MRI/TMS. Spin 7, 174009 (2017).

- Patel, V. G., Oh, W. K. & Galsky, M. D. Treatment of muscle-invasive and advanced bladder cancer in 2020. Ca. Cancer J. Clin. 70, 404-423 (2020).

- Khezri, B. et al. Ultrafast Electrochemical Trigger Drug Delivery Mechanism for Nanographene Micromachines. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1806696 (2019).

- Yang, J. et al. Beyond the Visible: Bioinspired Infrared Adaptive Materials. Adv. Mater. 33, 2004754 (2021).

- Morozov, K. I. & Leshansky, A. M. Dynamics and polarization of superparamagnetic chiral nanomotors in a rotating magnetic field. Nanoscale 6, 12142-12150 (2014).

- Morozov, K. I. & Leshansky, A. M. The chiral magnetic nanomotors. Nanoscale 6, 1580-1588 (2014).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

© The Author(s) 2024

- (n) Check for updates

State Key Laboratory of Precision Electronic Manufacturing Technology and Equipment, School of Electromechanical Engineering, Guangdong University of Technology, Guangzhou 510006, PR China. Institute of Natural Medicine and Green Chemistry, School of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Guangdong University of Technology, Guangzhou 510006, PR China. Department of Electronic Engineering, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong, China. School of Materials Science and Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA 30332, USA. e-mail: chenx@gdut.edu.cn; luyj@gdut.edu.cn; nzhao@ee.cuhk.edu.hk