DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-025-04700-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40181391

تاريخ النشر: 2025-04-04

ظهور الديدان القوية المقاومة لدوائين في الماعز: أول دليل ظاهري وجيني من محافظة راتشابوري، وسط تايلاند

الملخص

خلفية توفر هذه الدراسة رؤى حاسمة حول انتشار وأنماط مقاومة الأدوية للديدان المعوية القوية (GINs) في الماعز في تايلاند، مع تسليط الضوء على المقاومة للألبندازول والليفاميزول. تشكل الديدان القوية، وخاصة Haemonchus sp. وTrichostrongylus sp.، تهديدًا كبيرًا لصحة الماعز. مع الزيادة العالمية لمقاومة الأدوية المضادة للديدان، فإن اكتشاف مقاومة متعددة الأدوية في سكان الماعز في تايلاند يثير القلق، نظرًا للتجارة المتكررة في استيراد وتصدير الماعز. تتحدى هذه المقاومة استراتيجيات السيطرة الفعالة على الطفيليات. هدفت هذه الدراسة إلى تحديد أنواع الديدان القوية باستخدام كل من الطرق الشكلية والجينية، وتقييم المقاومة للألبندازول والليفاميزول من خلال الأساليب الظاهرة والجزيئية. النتائج أظهرت عينات البراز من 30 مزرعة ماعز في محافظة راتشابوري انتشارًا عاليًا للعدوى بالديدان القوية (87%)، مع اكتشاف Haemonchus sp. وTrichostrongylus sp. في 100% و96% من المزارع، على التوالي. أظهرت الاختبارات الظاهرة مقاومة كبيرة للأدوية، حيث كانت 90% و71% من المزارع تحتوي على تجمعات ديدان قوية مقاومة للألبندازول والليفاميزول، على التوالي. أظهر التحليل الجيني لليرقات المعدية المجمعة أن 100% من المزارع كانت تحتوي على تجمعات ديدان قوية مقاومة للألبندازول، مع 31% مقاومة متماثلة و69% مقاومة غير متماثلة، وTrichostrongylus sp. أظهرت 48% مقاومة متماثلة و52% مقاومة غير متماثلة. بالنسبة لمقاومة الليفاميزول، كانت 92% من المزارع تحتوي على تجمعات ديدان قوية مقاومة، مع ظهور Haemonchus sp.

الخلفية

الديدان الأسطوانية القوية، بما في ذلك الأجناس مثل هيمونشوس، تريشوتراستونغيلوس، كوبرية، شابيرتيا، وأوزوفاجوستوموم، هي الأكثر شيوعًا من الديدان المعوية المعدية التي تصيب الماعز. من بين هذه الأنواع، تشكل هيمونشوس كونتورتوس وأنواع تريشوتراستونغيلوس أكبر تهديد لصحة الماعز.

ظهور مقاومة الأدوية الطاردة للديدان يشكل تحديًا كبيرًا للمزارعين والأطباء البيطريين، مما يؤثر على صحة وإنتاجية الماعز. حيث أن المقاومة تقوض فعالية العلاج، فإن استراتيجيات الإدارة العاجلة مطلوبة للحفاظ على تربية الماعز. تفاقم ممارسات الإدارة السيئة والجرعات غير الصحيحة من إصابات الديدان المعوية [11]. تم الإبلاغ عن مقاومة الديدان الأسطوانية للأدوية الطاردة للديدان، بما في ذلك مقاومة متعددة الأدوية عبر الفئات الثلاث الرئيسية للأدوية الطاردة للديدان – البنزيميدازولات، الإيميدازوثيازولات، واللاكتونات الدائرية، من أوروبا وأستراليا وآسيا [12، 13]. يعتمد الكشف عن مقاومة الأدوية الطاردة للديدان تقليديًا على الطرق الظاهرية، بما في ذلك اختبار فقس البيض (EHT) واختبار تطوير اليرقات (LDT)، بينما يعتمد تقييم فعالية الأدوية على اختبار تقليل عدد البيض في البراز (FECRT). ومع ذلك، فإن الأساليب الجزيئية تكمل بشكل متزايد الطرق الظاهرية، مما يسمح بالكشف الدقيق عن الأليلات المرتبطة بالمقاومة. على سبيل المثال، يتم تحديد مقاومة البنزيميدازول (الألبندازول) من خلال تعدد أشكال النوكليوتيدات المفردة (SNPs) في بيتا-توبولين (

تتركز هذه الدراسة على محافظة راتشابوري في وسط تايلاند، حيث أبلغت الطرق الظاهرية مؤخرًا عن مقاومة مضادات الديدان [25]. أهدافنا هي تحديد أنواع الديدان المعدية التي تصيب الماعز في راتشابوري واكتشاف الجينات المقاومة للأدوية للألبندازول والليفاميزول باستخدام تقنيات ظاهرة وجزيئية. ستوفر هذه النتائج رؤى قيمة للمزارعين والأطباء البيطريين بينما تساهم في الجهود العالمية لإدارة عدوى الديدان المعدية ومكافحة مقاومة مضادات الديدان.

طرق

بيان الأخلاقيات

مزارع الماعز وجمع العينات

تم جمع عينات البراز من المستقيم لكل ماعز باستخدام قفازات نظيفة ووُضعت في أنابيب فالكون سعة 50 مل. ثم تم نقل العينات إلى قسم الديدان الطفيلية، كلية الطب الاستوائي، جامعة ماهيدول، بانكوك، لإجراء مزيد من التحليل.

تحديد وكمية الديدان الطفيلية المعوية الفحص المجهري

التعرف الجزيئي

تم إجراء تفاعل البوليميراز المتسلسل المتداخل باستخدام منطقة الفاصل الداخلي النسخي النووي 2 (ITS2) وجين الرنا الريبوسومي 16S الميتوكوندري (rRNA) لتحديد بيض السستوديات على المستوى الجزيئي. استهدفت البرايمرات النوعية للجنس Haemonchus وTrichostrongylus وOesophagostomum. تبعت برايمرات ITS2 دراسة Income وآخرون (2021)، بينما كانت برايمرات جولة 16S rRNA الأولى مستندة إلى دراسة Chan وآخرون (2020). تم تصميم برايمرات نوعية للجنس لتفاعل البوليميراز المتسلسل المتداخل في هذه الدراسة [20، 28]. باختصار، تم الحصول على تسلسلات جين 16S rRNA المرجعية لـ Haemonchus sp. وTrichostrongylus sp. وOesophagostomum sp. من قاعدة بيانات NCBI وتم محاذاتها باستخدام ClustalX 2.1 [29]. ثم تم تصميم البرايمرات النوعية للجنس ضمن تسلسل منتج PCR من الجولة الأولى من PCR. تم تقييم الخصائص (محتوى GC، حجم المنتج، درجة انصهار، تشكيل حلقة الشعر) والخصوصية للبرايمرات الجديدة.

تم تقييم البرايمرات المصممة باستخدام OligoCalc الإصدار 3.27 و FastPCR [30، 31]. تلخص الجدول 1 البرايمرات المحددة للنوع 16 S المستخدمة في هذه الدراسة، مع درجات حرارة التهجين وأحجام الأمبليكون الخاصة بها.

تم إجراء تضخيم PCR باستخدام جهاز T100

تحليل النشوء والتطور

كشف مقاومة مضادات الديدان

كشف المقاومة الظاهرية للألبندازول من خلال اختبار فقس البيض

لعزل البيض، تم شطف الشرائح الزجاجية بالماء المقطر، وتم نقل حوالي 100 بيضة في 2 مل من الماء إلى كل بئر من صفيحة 24 بئر. تم إعداد تخفيفات الألبندازول عن طريق إذابة 400 ملغ من زينتيل.

كشف المقاومة الظاهرية لليفاميزول من خلال اختبار تطوير اليرقات

| علامة وراثية وجنس | اسم البرايمر والتسلسل (5́-3′) | درجة حرارة التلدين | حجم الأمبليكون |

| 16S هيمونشوس | 16S Hae-F: كاتاتتراتكاجاوا |

|

116 قاعدة أساسية |

| 16S Hae-R: CGTTAAATTAAATAAWAG | |||

| 16S تريكوسرونجيليس | 16S تريشو-F: CTAGGGTAGAATATTATT |

|

173 نقطة أساس |

| 16S تريشو-R: AAAGAAGAACAGTCTTAAT | |||

| 16S أوزوفاجوستوموم | 16S أوزو-ف: CTTCGGAAATTCTTTTTTGG |

|

205 قاعدة زوجية |

| 16S أوزو-R: CTTCTCCCTCTTTAACAAAC |

كشف المقاومة الجينية للألبندازول والليفاميزول عبر تفاعل البوليميراز المتسلسل الكمي باستخدام صبغة SYBR الخضراء الخاصة بالأليلات

خليط رئيسي (نيو إنجلاند بيولوجيكس، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية)،

تحليل البيانات

النتائج

تحديد وانتشار وشدة الديدان الخيطية المعوية

التعرف الجزيئي على السستوديات

حالة مقاومة الألبندازول للستروغيليدات التي تصيب الماعز

جرعة تمييزية من

متسقًا مع نتائج EHT الظاهرية، كشفت التحليلات الجينية أن

حالة مقاومة ليفاميزول في الديدان الشريطية التي تصيب الماعز

| منطقة | مزرعة | عدد العينات | بيضة لكل جرام (المتوسط ± الانحراف المعياري) | الحد الأدنى – الحد الأقصى |

| تشوم بوانغ | 1 | ٤ |

|

0-150 |

| 2 | ٣ |

|

0-400 | |

| ٣ | ٧ |

|

0-950 | |

| ٤ | ٦ |

|

0-200 | |

| ٥ | 9 |

|

0-200 | |

| ٦ | ٦ |

|

٧٠٠-١٣٥٠ | |

| إجمالي | ٣٥ |

|

0-1350 | |

| سوان فوينغ | 1 | ٥ |

|

0-550 |

| 2 | ٦ |

|

100-1750 | |

| ٣ | ٣ |

|

٣٥٠-٥٠٠ | |

| ٤ | ٨ |

|

0-2050 | |

| ٥ | ٨ |

|

0-1150 | |

| ٦ | ٣ |

|

0-550 | |

| إجمالي | ٣٣ |

|

0-2050 | |

| بوتارام | 1 | 10 |

|

50-19,650 |

| 2 | ٧ |

|

٥٠-٣٠٠ | |

| ٣ | ٣ | 0 | 0 | |

| ٤ | 10 |

|

0-250 | |

| ٥ | 10 |

|

0-1900 | |

| ٦ | ٨ |

|

50-1900 | |

| إجمالي | ٤٨ |

|

0-19,650 | |

| بان بونغ | 1 | ٣ |

|

0-50 |

| 2 | 1 | 100 | 100 | |

| ٣ | 2 |

|

٢٥٠ | |

| ٤ | 1 | ٧٠٠ | ٧٠٠ | |

| ٥ | ٥ |

|

0-50 | |

| ٦ | ٦ |

|

0-600 | |

| إجمالي | ١٨ |

|

0-700 | |

| بانغ فاي | 1 | ٣ |

|

0-150 |

| ٢ | ٥ |

|

50-450 | |

| ٣ | ٨ |

|

٣٥٠-٢٢٥٠ | |

| ٤ | 11 |

|

100-800 | |

| ٥ | ٧ |

|

0-50 | |

| ٦ | ٥ |

|

0-200 | |

| إجمالي | ٣٩ |

|

0-2250 | |

| بشكل عام | 173 |

|

0-19,650 |

| منطقة | أجناس | ||

| هيمنشوس | تريشوتراستونغيلوس | أيوسوفاجوستوموم | |

| تشوم بوانغ | 100.00 | ٨٣.٣٣ | ٣٣.٣٣ |

| سوان فوانغ | 100.00 | 100.00 | 0 |

| بوتارام | 100.00 | 100.00 | ٦٦.٦٦ |

| بان بونغ | 100.00 | 100.00 | ٤٠.٠٠ |

| بانغ فاي | 100.00 | 100.00 | 0 |

| بشكل عام | 100.00 | ٩٦.٦٧ | ٢٨.٠٠ |

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، أظهر الفحص الجيني لمقاومة الأدوية حساسية أكبر من الطرق الظاهرية. بالنسبة للألبندازول والليفاميزول، حدد التحليل الجزيئي نسبة أعلى من المزارع التي تحتوي على تجمعات قوية مقاومة مقارنةً بالاختبارات الظاهرية. تم تأكيد المزارع التي تم تصنيفها في البداية على أنها حساسة بناءً على الاختبارات الظاهرية لاحقًا على أنها مقاومة (أنماط جينية RR أو RS) من خلال الفحص الجيني. على سبيل المثال، كانت المزرعة رقم 4 في منطقة سوان فوينغ مقاومة للألبندازول عند التحليل الجيني، بينما كانت المزرعة رقم 6 في تشوم بوانغ والمزرعة رقم 3 في بانغ فاي مقاومة لليفاميزول على الرغم من تصنيفها على أنها حساسة في الاختبارات الظاهرية.

نقاش

انتشار مرتفع

تم الإبلاغ عن انتشار مرتفع لعدوى الستروغيلد في الماعز في جنوب تايلاند، وخاصة في ساتون، سونغخلا، باتالونغ، يالا، باتاني، وناراتيوات.

| منطقة | مزرعة | ألبندازول (EHT) | ليفاميزول (LDT) | ||||

| حالة المقاومة |

|

% الفقس في DC

|

حالة المقاومة |

|

% من L1 تتطور إلى L3 في DC

|

||

| تشوم بوانغ | 2 | مقاوم |

|

40 | – | – | – |

| ٦ | مقاوم |

|

٩٨ | عرضة* |

|

0 | |

| سوان فوانغ | 1 | مقاوم |

|

٤٧ | – | – | – |

| 2 | مقاوم |

|

100 | – | – | – | |

| ٣ | عرضة |

|

41 | – | – | – | |

| ٤ | عرضة* |

|

21 | مقاوم |

|

٥٦ | |

| بوتارام | 1 | مقاوم |

|

91 | مقاوم |

|

٥٩ |

| 2 | مقاوم |

|

93 | مقاوم |

|

63 | |

| ٣ | مقاوم |

|

98 | – | – | – | |

| ٤ | مقاوم |

|

100 | مقاوم |

|

68 | |

| ٥ | مقاوم |

|

98 | – | – | – | |

| ٦ | مقاوم |

|

99 | – | – | – | |

| بان بونغ | 1 | مقاوم |

|

97 | – | – | – |

| 2 | مقاوم |

|

99 | – | – | – | |

| ٣ | مقاوم |

|

96 | – | – | – | |

| ٤ | مقاوم |

|

91 | – | – | – | |

| ٦ | مقاوم |

|

90 | مقاوم |

|

73 | |

| بانغ فاي | 2 | مقاوم |

|

97 | – | – | – |

| ٣ | مقاوم |

|

97 | عرضة* |

|

٨ | |

| ٦ | مقاوم |

|

100 | – | – | – | |

| الحي/الأليل | ألبندازول (هيمنشوس) | ألبندازول (تريشوتراستونغيلوس) | ليفاميزول (هيمونشوس) | |||

| مقاوم | عرضة | مقاوم | عرضة | مقاوم | عرضة | |

| تشوم بوانغ | 0.70 | 0.30 | 0.88 | 0.12 | 0.60 | 0.40 |

| سوان فوانغ | 0.70 | 0.30 | 0.90 | 0.10 | 0.40 | 0.60 |

| بوتارام | 0.60 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| بان بونغ | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 0.30 | 0.60 | 0.40 |

| بانغ فاي | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| بشكل عام | 0.65 | 0.35 | 0.74 | 0.26 | 0.52 | 0.48 |

المحافظات [22]. علاوة على ذلك، تم توثيق مقاومة الأدوية المتعددة في أجزاء مختلفة من البلاد [23، 25، 49]. بخلاف مقاومة الألبندازول، تم الإبلاغ عن مقاومة الإيفرمكتين في قطعان الماعز في محافظات سينغ بوري، وخون كاين، وتشايابوم من خلال اختبارات الشكل الظاهري [23، 49]. في محافظة راتشابوري، تم اكتشاف مقاومة الألبندازول والإيفرمكتين في

البلد، تعتبر البنزيميدازولات واللاكتونات الدائرية من أكثر الأدوية المضادة للطفيليات التي يتم استخدامها لعلاج عدوى GIN في المجترات الصغيرة، والتي يستخدمها كل من المزارعين والأطباء البيطريين [50]. وفقًا لبيانات استخدام الأدوية من مزارعي الماعز في هذه الدراسة، كانت الألبندازول والإيفرمكتين هما الأدوية الرئيسية المستخدمة، بينما تم إعطاء اللفاميسول فقط في منطقة تشوم بوانغ. ومع ذلك، على الرغم من استخدامه المحدود، تم اكتشاف مقاومة اللفاميسول. قد يكون أحد العوامل المساهمة في انتشار المقاومة هو حركة الماعز بين المناطق. لم تكن الماعز التي تم فحصها في هذه الدراسة من محافظة راتشابوري فقط، بل تم الحصول عليها أيضًا من محافظات أخرى في شمال شرق، وغرب، ووسط تايلاند. قد يسهل استيراد وتحرك الماعز بين المحافظات انتشار الأليلات المقاومة للأدوية، مما يزيد من تفاقم مقاومة الأدوية المضادة للطفيليات. وبالتالي، ستستمر فعالية العلاجات المضادة للطفيليات لعدوى GIN في الماعز في الانخفاض، مما يؤدي إلى زيادة تكرار الأليلات المقاومة في سكان السترانجيليد.

حجم العينة الصغيرة (

الخاتمة

الاتجاهات من خلال الأبحاث الطولية، وتوضيح آليات المقاومة، وتقييم المركبات البديلة المضادة للطفيليات لضمان فعالية السيطرة على الديدان وتقليل مقاومة الأدوية المضادة للطفيليات في الماعز.

| DC | الجرعة المميزة |

| EHT | اختبار فقس البيض |

| EPG | البيض لكل جرام |

| FECRT | اختبار تقليل عدد بيض البراز |

| GIN | الديدان الخيطية المعوية |

| ITS2 | المسافة الداخلية المنسوخة 2 |

| LDT | اختبار تطوير اليرقات |

| ML | الاحتمالية القصوى |

| NJ | الانضمام الجار |

| qPCR | تفاعل البوليميراز المتسلسل الكمي |

| rRNA | RNA الريبوسومي |

| SNP | تعدد أشكال النوكليوتيد المفرد |

معلومات إضافية

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

الموافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 04 أبريل 2025

References

- Grisi L, Leite RC, Martins JR, Barros AT, Andreotti R, Cançado PH, et al. Reassessment of the potential economic impact of cattle parasites in Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2014;23:150-6.

- Githigia SM, Thamsborg SM, Munyua WK, Maingi N. Impact of gastrointestinal helminths on production in goats in Kenya. Small Rumin Res. 2001;42:21-9.

- Hoste H, Torres-Acosta JFJ. Alternative or improved methods to limit gastro-intestinal parasitism in grazing sheep and goats. Small Rumin Res. 2008;77:159-73.

- Charlier J, Rinaldi L, Musella V, Ploeger HW, Chartier C, Vineer HR, et al. Initial assessment of the economic burden of major parasitic helminth infections to the ruminant livestock industry in Europe. Prev Vet Med. 2020;182:105103.

- Maurizio A, Perrucci S, Tamponi C, Scala A, Cassini R, Rinaldi L, et al. Control of gastrointestinal helminths in small ruminants to prevent anthelmintic resistance: the Italian experience. Parasitology. 2023;150:1105-18.

- Zarlenga DS, Hoberg EP, Tuo W. The identification of Haemonchus species and diagnosis of haemonchosis. Adv Parasitol. 2016;93:145-80.

- Ghadirian E, Arfaa F. First report of human infection with Haemonchus contortus, Ostertagia ostertagi, and Marshallagia marshalli (family Trichostrongylidae) in Iran. J Parasitol. 1973;59:1144-5.

- Boreham RE, McCowan M, Ryan AE, Allworth A, Robson J. Human trichostrongyliasis in Queensland. Pathology. 1995;27:182-5.

- Watthanakulpanich D, Pongvongsa T, Sanguankiat S, Nuamtanong S, Maipanich W, Yoonuan T, et al. Prevalence and clinical aspects of human Trichostrongylus colubriformis infection in Lao PDR. Acta Trop. 2013;126:37-42.

- Phosuk I, Intapan P, Sanpool O, Janwan P, Thanchomnang T, Sawanyawisuth K, et al. Molecular evidence of Trichostrongylus colubriformis and Trichostrongylus axei infections in humans from Thailand and Lao PDR. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89:376-9.

- Fissiha W, Kinde MZ. Anthelmintic resistance and its mechanism: A review. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:5403-10.

- Dey AR, Begum N, Anisuzzaman MA, Alam MZ. Multiple anthelmintic resistance in gastrointestinal nematodes of small ruminants in Bangladesh. Parasitol Int. 2020;77:102105.

- Potârniche AV, Mickiewicz M, Olah D, Cerbu C, Spînu M, Hari A, et al. First report of anthelmintic resistance in gastrointestinal nematodes in goats in Romania. Animals. 2021;11:2761.

- Silvestre A, Humbert JF. A molecular tool for species identification and benzimidazole resistance diagnosis in larval communities of small ruminant parasites. Exp Parasitol. 2000;95:271-6.

- Silvestre A, Cabaret J. Mutation in position 167 of isotype 1 beta-tubulin gene of trichostrongylid nematodes: role in benzimidazole resistance? Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;120:297-300.

- Santos JML, Monteiro JP, Ribeiro WL, Macedo IT, Camurça-Vasconcelos AL, Vieira LS, et al. Identification and quantification of benzimidazole resistance polymorphisms in Haemonchus contortus isolated in Northeastern Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2014;199:160-4.

- Santos JML, Monteiro JP, Ribeiro WL, Macedo IT, Filho JV, Andre WP, et al. High levels of benzimidazole resistance and

-tubulin isotype 1 SNP F167Y in Haemonchus contortus populations from Ceará State, Brazil. Small Rumi Res. 2017;146:48-52. - Ratanapob N, Arunvipas P, Kasemsuwan S, Phimpraphai W, Panneum S. Prevalence and risk factors for intestinal parasite infection in goats raised in Nakhon pathom Province, Thailand. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2012;44:741-5.

- Kaewnoi D, Kaewmanee S, Wiriyaprom R, Prachantasena S, Pitaksakulrat O, Ngasaman R. Prevalence of zoonotic intestinal parasites in meat goats in Southern Thailand. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2024;24:111-7.

- Income N, Tongshoob J, Taksinoros S, Adisakwattana P, Rotejanaprasert C, Maneekan P. Helminth infections in cattle and goats in Kanchanaburi, Thailand, with focus on Strongyle nematode infections. Vet Sci. 2021;8:324.

- Rerkyusuke S, Lerk-U-Suke S, Mektrirat R, Wiratsudakul A, Kanjampa P, Chaimongkol

, et al. Prevalence and associated risk factors of gastrointestinal parasite infections among meat goats in Khon Kaen Thailand. Vet Med Int. 2024;2024:3267028. - Pitaksakulrat O, Chaiyasaeng M, Artchayasawat A, Eamudomkarn C, Thongsahuan S , Boonmars T. The first molecular identification of benzimidazole resistance in Haemonchus contortus from goats in Thailand. Vet World. 2021;14:764-8.

- Ratanapob N , Thuamsuwan N , Thongyuan S . Anthelmintic resistance status of goat gastrointestinal nematodes in Sing Buri Province, Thailand. Vet World. 2022;15:83-90.

- Sherman DM. The spread of pathogens through trade in small ruminants and their products. Rev Sci Tech. 2011;30:207-17.

- Paduang S, Thongtha R. Study of anthelmintic resistance of gastrointestinal nematodes in goats in Ratchaburi Province. J Kasetsart Vet. 2020;30:1.

- Fisheries MAFF. Food, reference book: manual of veterinary parasitological laboratory techniques. Ministry Agric. 1986;5.

- Cringoli G, Rinaldi L, Veneziano V, Capelli G, Scala A. The influence of flotation solution, sample dilution and the choice of McMaster slide area (volume) on the reliability of the McMaster technique in estimating the faecal egg counts of gastrointestinal strongyles and Dicrocoelium dendriticum in sheep. Vet Parasitol. 2004;123:121-31.

- Chan AHE, Chaisiri K, Morand S, Saralamba N, Thaenkham U. Evaluation and utility of mitochondrial ribosomal genes for molecular systematics of parasitic nematodes. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:364.

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Multiple sequence alignment using ClustalW and ClustalX. Curr Protoc Bioinf. 2002;Chap. 2:Unit 2.3.

- Kibbe WA. OligoCalc: an online oligonucleotide properties calculator. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W43-6.

- Kalendar R, Khassenov B, Ramankulov Y, Samuilova O, Ivanov KI. FastPCR: an in Silico tool for fast primer and probe design and advanced sequence analysis. Genomics. 2017;109:312-9.

- Hall TA, BioEdit. A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for windows 95/98/NT. Nucl Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95-8.

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:1547-9.

- Rambaut A. FigTree v1.3.1. Institute of Evolutionary Biology, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh. 2010. http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/

- Coles GC, Jackson F, Pomroy WE, Prichard RK, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G, Silvestre A, et al. The detection of anthelmintic resistance in nematodes of veterinary importance. Vet Parasitol. 2006;136:167-85.

- Coles GC, Bauer C, Borgsteede F, Geerts S, Klei T, Taylor M, et al. World association for the advancement of veterinary parasitology (W.A.A.V.P.) methods for the detection of anthelmintic resistance in nematodes of veterinary importance. Vet Parasitol. 1992;44:35-44.

- von Samson-Himmelstjerna G, Coles GC, Jackson F, Bauer C, Borgsteede F, Cirak V, et al. Standardization of the egg hatch test for the detection of benzimidazole resistance in parasitic nematodes. Parasitol Res. 2009;105:825-34.

- Araújo-Filho JV, Ribeiro WLC, André WPP, Cavalcante GS, Santos JMLD, Monteiro JP, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic approaches for detection of anthelmintic resistant sheep gastrointestinal nematodes from Brazilian Northeast. Revista Brasileira de parasitologia veterinaria = brazilian. J Veterinary Parasitology: Orgao Oficial Do Colegio Brasileiro De Parasitol Vet. 2021;30:e005021.

- Chagas ACS, Domingues LF, Gaínza YA, Barioni-Júnior W, Esteves SN, Niciura SCM. Target selected treatment with levamisole to control the development of anthelmintic resistance in a sheep flock. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:1131-9.

- Baerman G, Wetzal R, Helminths. 1st ed. 1953. Black well Scientific, Oxford.

- Santos JML, Vasconcelos JF, Frota GA, Freitas EP, Teixeira M, Vieira LDS, et al. Quantitative molecular diagnosis of levamisole resistance in populations of Haemonchus contortus. Exp Parasitol. 2019;205:107734.

- Schoonjans F, Zalata A, Depuydt CE, Comhaire FH. MedCalc: a new computer program for medical statistics. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 1995;48:257-62.

- Junsiri W, Tapo P, Chawengkirttidul R, Watthanadirek A, Poolsawat N, Minsakorn

, et al. The occurrence of gastrointestinal parasitic infections of goats in Ratchaburi, Thailand. Thai J Vet Med. 2021;51:151-60. - Jittapalapong S, Saengow S, Pinyopanuwat N, Chimnoi W, Khachaeram W, Stich RW. Gastrointestinal helminthic and protozoal infections of goats in Satun, Thailand. J Trop Med Parasitol. 2012;35:48-54.

- Azrul LM, Poungpong K, Jittapalapong S, Prasanpanich S. Descriptive prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites in goats from farms in Bangkok and vicinity and the associated risk factors. Annual Res Rev Biology. 2017;16:2.

- Wuthijaree K, Tatsapong P, Lambertz C. The prevalence of intestinal parasite infections in goats from smallholder farms in Northern Thailand. Helminthologia. 2022;59:64-73.

- Phosuk I, Intapan PM, Prasongdee TK, Changtrakul Y, Sanpool O, Janwan P, et al. Human trichostrongyliasis: A hospital case series. Southeast Asian J Trop Med. 2015;46:191-7.

- Mickiewicz M, Czopowicz M, Kawecka-Grochocka E, Moroz A, SzaluśJordanow O, Várady M, et al. The first report of multidrug resistance in gastrointestinal nematodes in goat population in Poland. BMC Vet Res. 2020;16:270.

- Rerkyusuke S, Lamul P, Thipphayathon C, Kanawan K, Porntrakulpipat S. Caprine roundworm nematode resistance to macrocylic lactones in Northeastern Thailand. Vet Integr Sci. 2023;21:623-34.

- Department of Livestock Development. Annual Report 2016. Department of Livestock Development, Ministry of Agricultural and Cooperatives, Bangkok, Thailand. 2016.

ملاحظة الناشر

- *المراسلة:

أوروسا ثينكام

urusa.tha@mahidol.ac.th

قسم الطفيليات، كلية الطب الاستوائي، جامعة ماهيدول، بانكوك، تايلاند

قسم العلوم الحيوانية التطبيقية والسريرية، كلية العلوم البيطرية، جامعة ماهيدول، ناخون باتوم، تايلاند - تشير علامة الطرح (-) إلى عدم الحصول على بيانات بسبب عدم كفاية البيض المجمعة. تشير علامة النجمة (*) إلى أن نتيجة النمط الجيني المتحصل عليها تتعارض مع حالة مقاومة النمط الظاهري

تشير DC (الجرعة المميزة) إلى الجرعة من الدواء التي من المفترض أن تؤدي إلى وفاة الكائن المستهدف. تشير DC التي تشير إلى مقاومة الألبندازول إلى ، بينما تشير مقاومة اللفاميسول إلى

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-025-04700-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40181391

Publication Date: 2025-04-04

Emergence of dual drug-resistant strongylids in goats: first phenotypic and genotypic evidence from Ratchaburi Province, central Thailand

Abstract

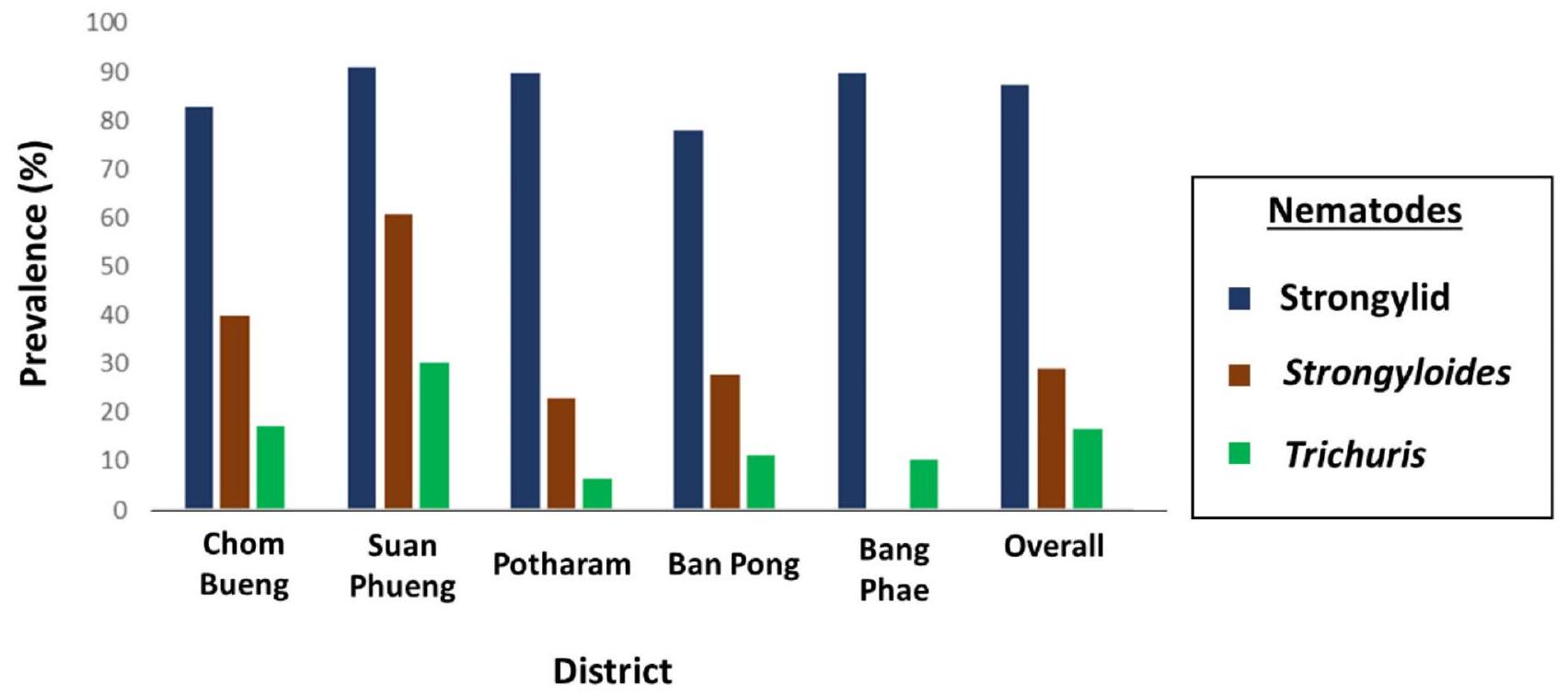

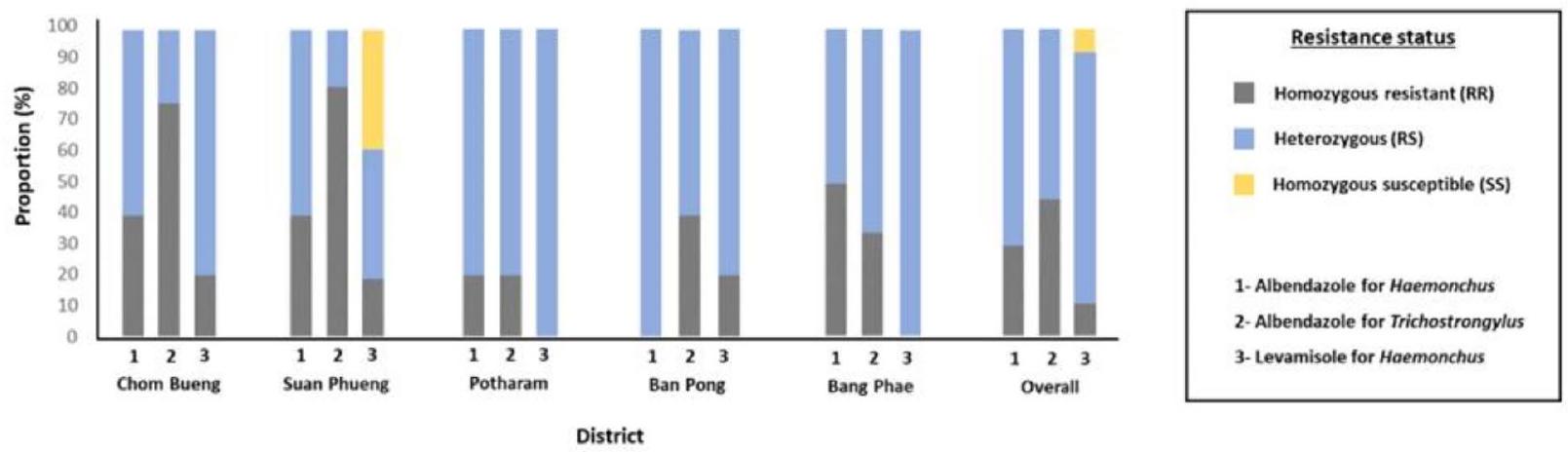

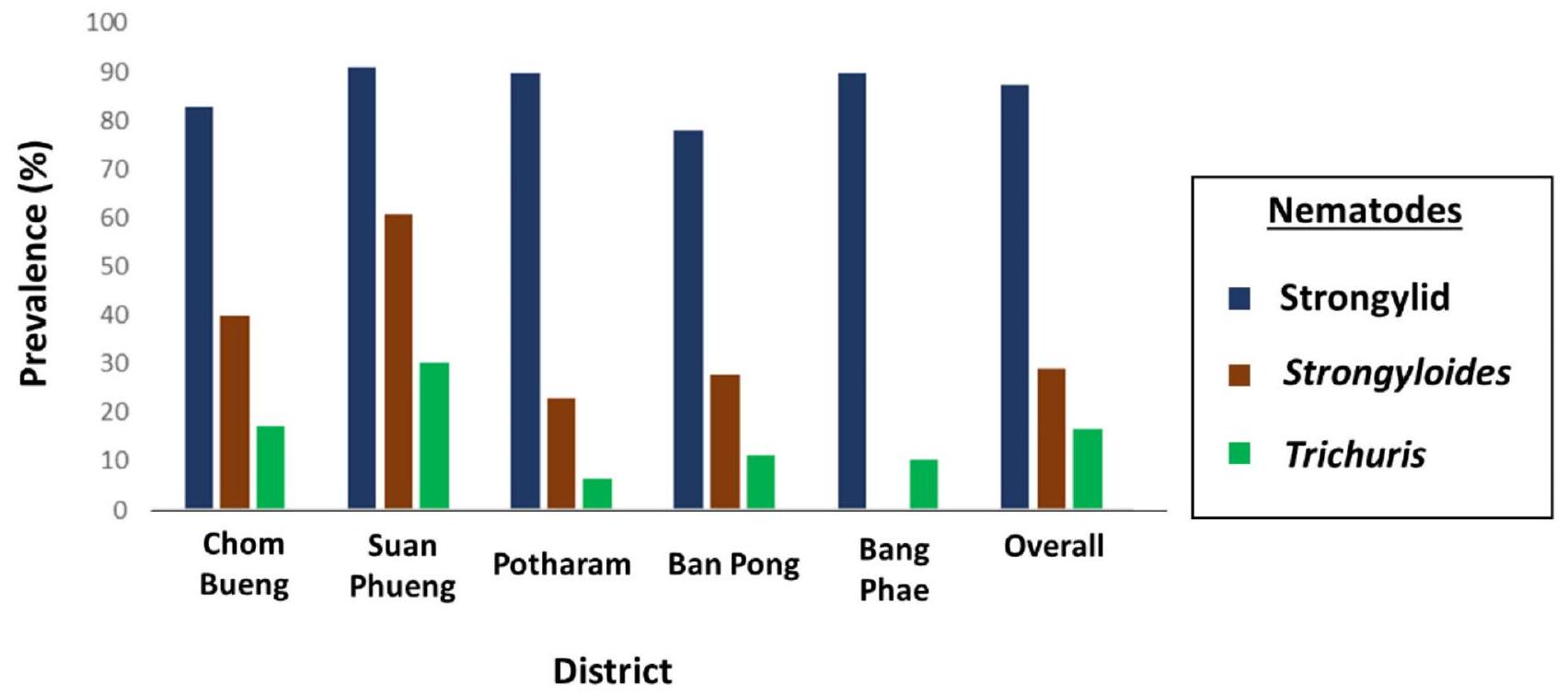

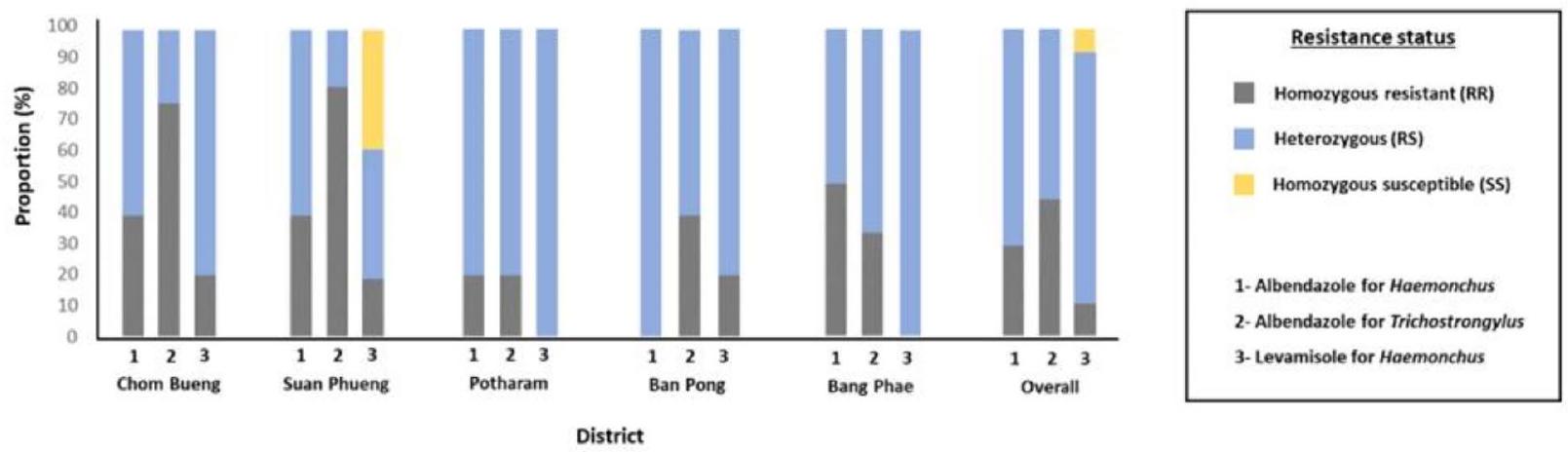

Background This study provides crucial insights into the prevalence and drug resistance patterns of strongylid gastrointestinal nematodes (GINs) in goats in Thailand, highlighting resistance to albendazole and levamisole. Strongylids, particularly Haemonchus sp. and Trichostrongylus sp., pose a significant threat to goat health. With the global rise of anthelmintic resistance, the detection of multidrug resistance in Thailand’s goat population is concerning, given the frequent import and export of goats. This resistance challenges effective parasite control strategies. This study aimed to identify strongylid species using both morphological and genetic methods and to assess resistance to albendazole and levamisole through phenotypic and molecular approaches. Results Fecal samples from 30 goat farms in Ratchaburi Province revealed a high prevalence of strongylid infection (87%), with Haemonchus sp. and Trichostrongylus sp. detected on 100% and 96% of farms, respectively. Phenotypic assays demonstrated significant drug resistance, with 90% and 71% of farms harboring strongylid populations resistant to albendazole and levamisole, respectively. Genotypic analysis of pooled infective larvae showed that 100% of farms had albendazole-resistant strongylid populations, with 31% homozygous and 69% heterozygous resistance, and Trichostrongylus sp. showing 48% homozygous and 52% heterozygous resistance. For levamisole resistance, 92% of farms contained resistant strongylid populations, with Haemonchus sp. exhibiting

Background

Strongylid nematodes, including genera such as Haemonchus, Trichostrongylus, Cooperia, Chabertia, and Oesophagostomum, are the most common GINs infecting goats [5]. Among these, Haemonchus contortus and Trichostrongylus species pose the greatest threat to goat health [6], with

The emergence of anthelmintic resistance poses a significant challenge for farmers and veterinarians, impacting goat health and productivity. As resistance undermines treatment efficacy, urgent management strategies are required to sustain goat farming. Poor management practices and improper dosing further exacerbate GIN infections [11]. Resistance of strongylid nematodes to anthelmintics, including multiple-drug resistance across the three main anthelmintic classes – benzimidazoles, imidazothiazoles, and macrocyclic lactones, have been reported from Europe, Australia, and Asia [12, 13]. Detection of anthelmintic resistance traditionally relies on phenotypic methods, including the egg hatch test (EHT) and larval development test (LDT), while the evaluation of drug efficacy relies on the fecal egg count reduction test (FECRT). However, molecular approaches increasingly complement phenotypic methods, allowing for precise detection of resistance-associated alleles. For instance, benzimidazole (albendazole) resistance is identified through single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the beta-tubulin (

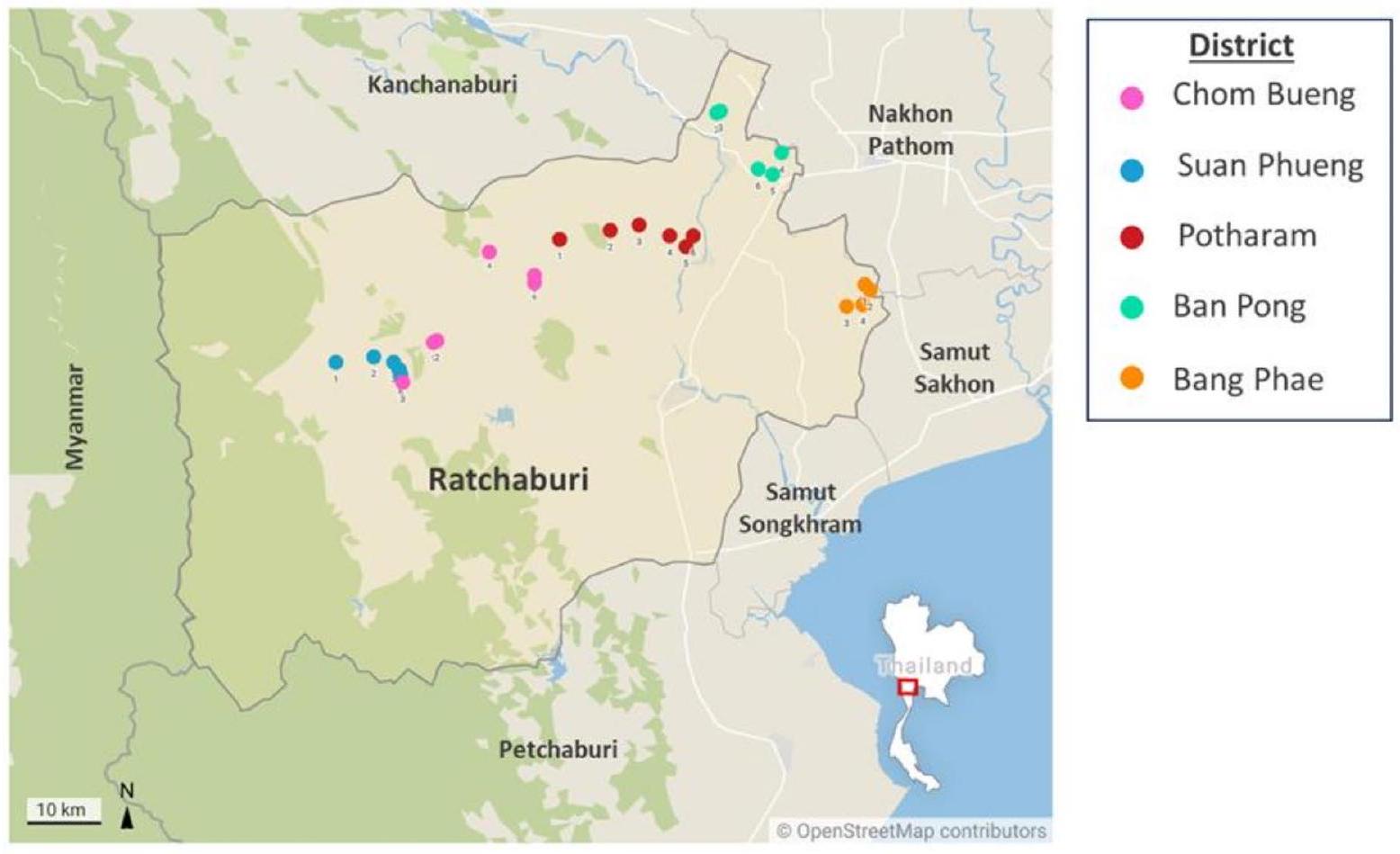

This study focuses on Ratchaburi Province in central Thailand, where phenotypic methods have recently reported anthelmintic resistance [25]. Our objectives are to identify the GIN species infecting goats in Ratchaburi and detect drug-resistant genes for albendazole and levamisole using phenotypic and molecular techniques. This finding will provide valuable insights for farmers and veterinarians while contributing to global efforts to manage GIN infection and combat anthelmintic resistance.

Methods

Ethics statement

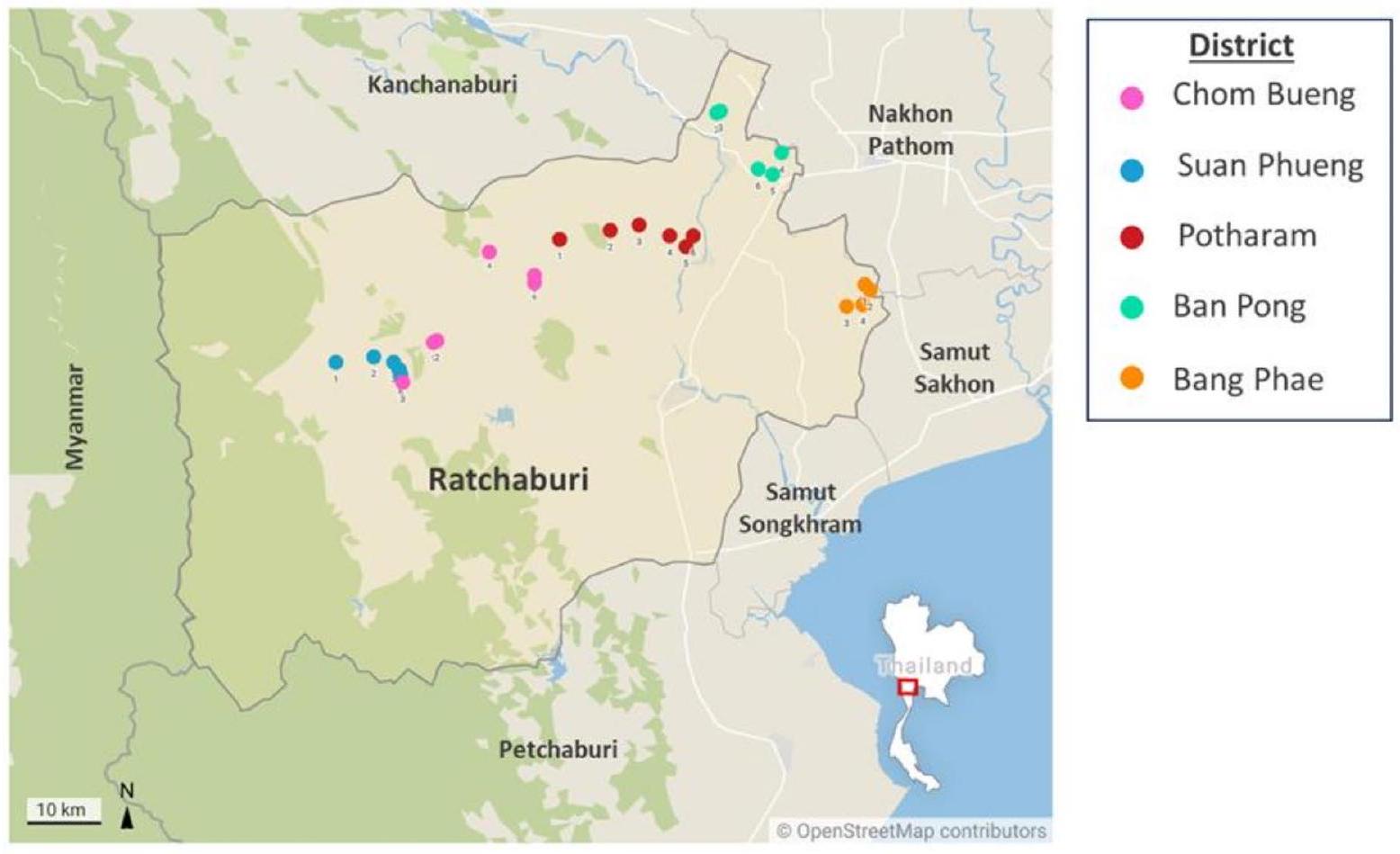

Goat farms and sample collection

Fecal samples were collected from each goat’s rectum using clean gloves and placed in 50 ml Falcon tubes. The samples were then transported to the Department of Helminthology, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok, for further analysis.

Gastrointestinal helminth identification and quantification Microscopic examination

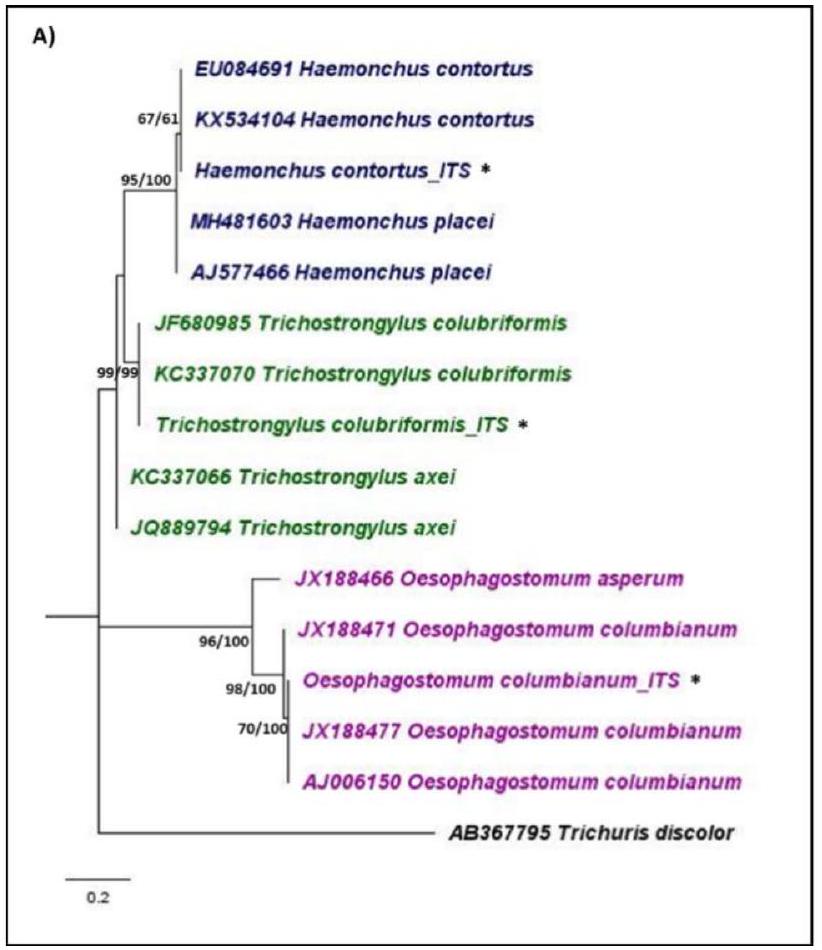

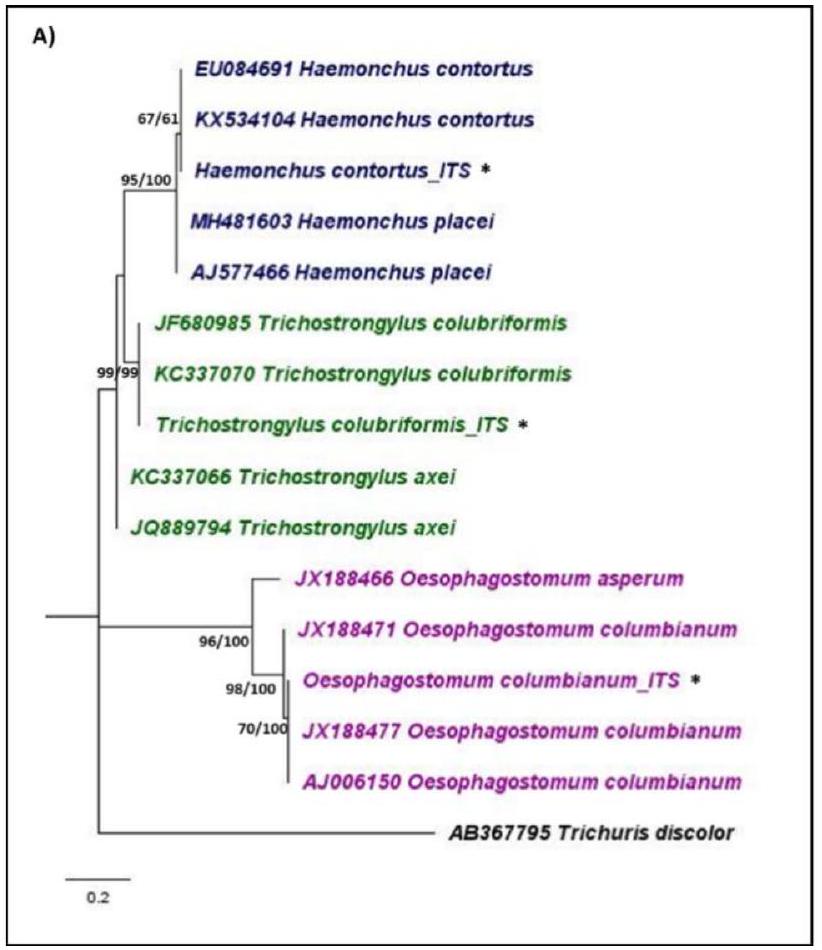

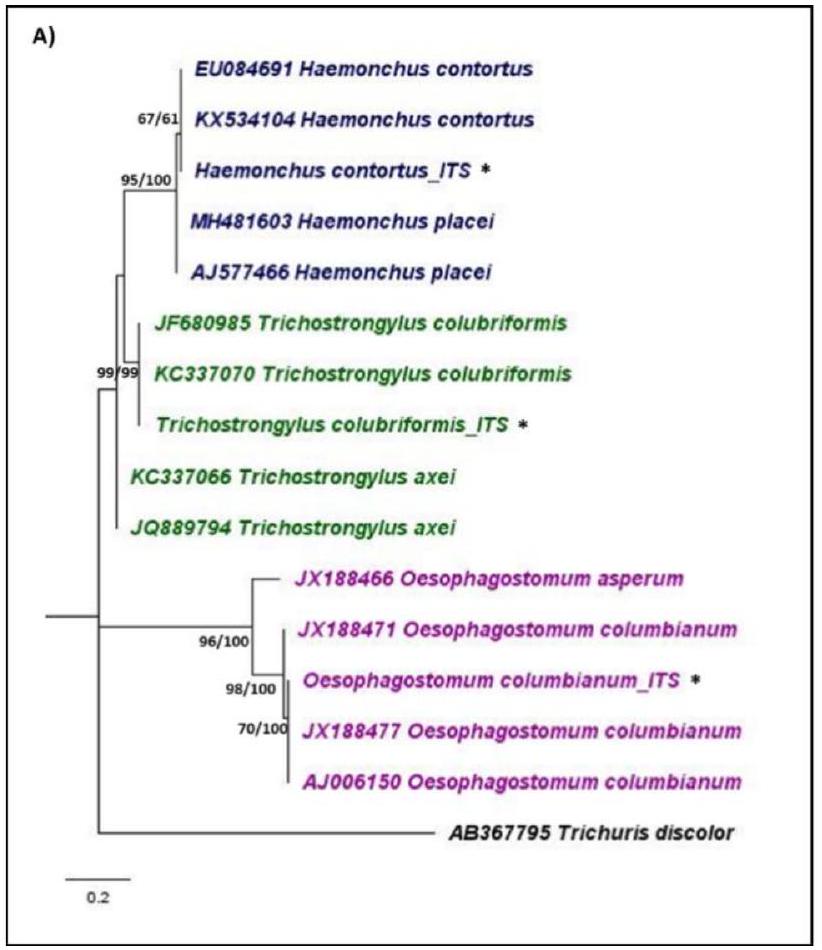

Molecular identification

Nested PCR was conducted using the nuclear internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) region and the mitochondrial 16 S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene to molecularly identify strongylid eggs. Genus-specific primers targeted Haemonchus, Trichostrongylus, and Oesophagostomum. The ITS2 primers followed Income et al. (2021), while the first-round 16 S rRNA primers were based on Chan et al. (2020). Genus-specific primers for nested-PCR were newly designed in this study [20, 28]. Briefly, reference 16S rRNA gene sequences of Haemonchus sp., Trichostrongylus sp., and Oesophagostomum sp. were obtained from the NCBI database and aligned using ClustalX 2.1 [29]. Genus-specific primers were then designed within the PCR amplicon sequence from the first round of PCR. The properties (GC content, amplicon size, melting temperature, hairpin formation) and specificity of the newly

designed primers were evaluated using OligoCalc version 3.27 and FastPCR [30, 31]. Table 1 summarizes the 16 S genus-specific primers used in this study, along with their respective annealing temperature and amplicon sizes.

PCR amplification was carried out using a T100

Phylogenetic analysis

Anthelmintic resistance detection

Phenotypic resistance detection of albendazole via egg hatch test

To isolate the eggs, coverslips were rinsed with distilled water, and approximately 100 eggs in 2 ml of water were transferred to each well of a 24 -well plate. Albendazole dilutions were prepared by dissolving 400 mg Zentel

Phenotypic resistance detection of levamisole via larva development test

| Genetic marker and genus | Primer name and sequence (5́-3′) | Annealing temperature | Amplicon size |

| 16S Haemonchus | 16S Hae-F: CATATTTRATCCAGAWG |

|

116 bp |

| 16S Hae-R: CGTTAAATTAAATAAWAG | |||

| 16S Trichostrongylus | 16S Tricho-F: CTAGGGTAGAATATTATT |

|

173 bp |

| 16S Tricho-R: AAAGAAGAACAGTCTTAAT | |||

| 16S Oesophagostomum | 16S Oeso-F: CTTCGGAAATTCTTTTTTGG |

|

205 bp |

| 16S Oeso-R: CTTCTCCCTCTTTAACAAAC |

Genotypic resistance detection of albendazole and levamisole via allele-specific SYBR green qPCR

master mix (New England Biolabs, MA, USA),

Data analysis

Results

Identification, prevalence, and intensity of gastrointestinal nematodes

Molecular identification of strongylids

Albendazole resistance status of strongylids infecting goats

discriminating dose of

Consistent with the phenotypic EHT results, the genotypic analysis revealed that

Levamisole resistance status of strongylids infecting goats

| District | Farm | No. of samples | Egg per gram (mean ± SD) | Min – max |

| Chom Bueng | 1 | 4 |

|

0-150 |

| 2 | 3 |

|

0-400 | |

| 3 | 7 |

|

0-950 | |

| 4 | 6 |

|

0-200 | |

| 5 | 9 |

|

0-200 | |

| 6 | 6 |

|

700-1350 | |

| Total | 35 |

|

0-1350 | |

| Suan Phueng | 1 | 5 |

|

0-550 |

| 2 | 6 |

|

100-1750 | |

| 3 | 3 |

|

350-500 | |

| 4 | 8 |

|

0-2050 | |

| 5 | 8 |

|

0-1150 | |

| 6 | 3 |

|

0-550 | |

| Total | 33 |

|

0-2050 | |

| Potharam | 1 | 10 |

|

50-19,650 |

| 2 | 7 |

|

50-300 | |

| 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 | 10 |

|

0-250 | |

| 5 | 10 |

|

0-1900 | |

| 6 | 8 |

|

50-1900 | |

| Total | 48 |

|

0-19,650 | |

| Ban Pong | 1 | 3 |

|

0-50 |

| 2 | 1 | 100 | 100 | |

| 3 | 2 |

|

250 | |

| 4 | 1 | 700 | 700 | |

| 5 | 5 |

|

0-50 | |

| 6 | 6 |

|

0-600 | |

| Total | 18 |

|

0-700 | |

| Bang Phae | 1 | 3 |

|

0-150 |

| 2 | 5 |

|

50-450 | |

| 3 | 8 |

|

350-2250 | |

| 4 | 11 |

|

100-800 | |

| 5 | 7 |

|

0-50 | |

| 6 | 5 |

|

0-200 | |

| Total | 39 |

|

0-2250 | |

| Overall | 173 |

|

0-19,650 |

| District | Genera | ||

| Haemonchus | Trichostrongylus | Oesophagostomum | |

| Chom Bueng | 100.00 | 83.33 | 33.33 |

| Suan Phueng | 100.00 | 100.00 | 0 |

| Potharam | 100.00 | 100.00 | 66.66 |

| Ban Pong | 100.00 | 100.00 | 40.00 |

| Bang Phae | 100.00 | 100.00 | 0 |

| Overall | 100.00 | 96.67 | 28.00 |

Additionally, genotypic screening of drug resistance demonstrated greater sensitivity than phenotypic methods. For albendazole and levamisole, molecular analysis identified a higher percentage of farms with resistant strongylid populations than phenotypic tests. Farms initially classified as susceptible based on phenotypic assays were later confirmed as resistant (RR or RS genotypes) through genotypic screening. For example, farm number 4 in Suan Phueng district tested resistant to albendazole upon genotypic analysis, while farm number 6 in Chom Bueng and farm number 3 in Bang Phae were found to be resistant to levamisole despite being classified as susceptible in phenotypic tests.

Discussion

A high prevalence

A high prevalence of strongylid infection in goats has been reported in southern Thailand, particularly in Satun, Songkhla, Pattalung, Yala, Pattani, and Narathiwat

| District | Farm | Albendazole (EHT) | Levamisole (LDT) | ||||

| Resistance status |

|

% hatch at DC

|

Resistance status |

|

% of L1 develop to L3 at DC

|

||

| Chom Bueng | 2 | Resistant |

|

40 | – | – | – |

| 6 | Resistant |

|

98 | Susceptible* |

|

0 | |

| Suan Phueng | 1 | Resistant |

|

47 | – | – | – |

| 2 | Resistant |

|

100 | – | – | – | |

| 3 | Susceptible |

|

41 | – | – | – | |

| 4 | Susceptible* |

|

21 | Resistant |

|

56 | |

| Potharam | 1 | Resistant |

|

91 | Resistant |

|

59 |

| 2 | Resistant |

|

93 | Resistant |

|

63 | |

| 3 | Resistant |

|

98 | – | – | – | |

| 4 | Resistant |

|

100 | Resistant |

|

68 | |

| 5 | Resistant |

|

98 | – | – | – | |

| 6 | Resistant |

|

99 | – | – | – | |

| Ban Pong | 1 | Resistant |

|

97 | – | – | – |

| 2 | Resistant |

|

99 | – | – | – | |

| 3 | Resistant |

|

96 | – | – | – | |

| 4 | Resistant |

|

91 | – | – | – | |

| 6 | Resistant |

|

90 | Resistant |

|

73 | |

| Bang Phae | 2 | Resistant |

|

97 | – | – | – |

| 3 | Resistant |

|

97 | Susceptible* |

|

8 | |

| 6 | Resistant |

|

100 | – | – | – | |

| District/allele | Albendazole (Haemonchus) | Albendazole (Trichostrongylus) | Levamisole (Haemonchus) | |||

| Resistant | Susceptible | Resistant | Susceptible | Resistant | Susceptible | |

| Chom Bueng | 0.70 | 0.30 | 0.88 | 0.12 | 0.60 | 0.40 |

| Suan Phueng | 0.70 | 0.30 | 0.90 | 0.10 | 0.40 | 0.60 |

| Potharam | 0.60 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Ban Pong | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 0.30 | 0.60 | 0.40 |

| Bang Phae | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Overall | 0.65 | 0.35 | 0.74 | 0.26 | 0.52 | 0.48 |

provinces [22]. Moreover, multiple drug resistance has been documented in various parts of the country [23, 25, 49]. Aside from albendazole resistance, ivermectin resistance has been reported in goat herds in Sing Buri, Khon Kaen, and Chaiyaphum Provinces through phenotypic tests [23, 49]. In Ratchaburi Province, albendazole and ivermectin resistance was detected in

country, benzimidazoles and macrocyclic lactones are the most commonly administered anthelmintic drugs for GIN infections in small ruminants, used by both farmers and veterinarians [50]. According to drug usage data from goat farmers in this study, albendazole and ivermectin were the primary anthelmintics used, with levamisole being administered only in Chom Bueng district. However, despite its limited use, levamisole resistance was still detected. A possible contributing factor to the spread of resistance is the movement of goats between regions. The goats examined in this study were not solely from Ratchaburi Province but were also sourced from other provinces in the Northeast, Western, and Central parts of Thailand. The importation and interprovincial movement of goats may facilitate the dissemination of drugresistant alleles, exacerbating anthelmintic resistance. Consequently, the efficacy of anthelmintic treatments for GIN infections in goats will continue to decline, leading to an increased frequency of resistant alleles in strongylid population.

The small sample size (

Conclusion

trends through longitudinal research, elucidating resistance mechanisms, and evaluating alternative anthelmintic compounds to ensure effective helminth control and mitigate anthelmintic resistance in goats.

| DC | Discriminating dose |

| EHT | Egg hatch test |

| EPG | Eggs per gram |

| FECRT | Fecal egg count reduction test |

| GIN | Gastrointestinal nematode |

| ITS2 | Internal transcribed spacer 2 |

| LDT | Larval development test |

| ML | Maximum-likelihood |

| NJ | Neighbor-joining |

| qPCR | Quantitative PCR |

| rRNA | Ribosomal RNA |

| SNP | Single nucleotide polymorphism |

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Published online: 04 April 2025

References

- Grisi L, Leite RC, Martins JR, Barros AT, Andreotti R, Cançado PH, et al. Reassessment of the potential economic impact of cattle parasites in Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2014;23:150-6.

- Githigia SM, Thamsborg SM, Munyua WK, Maingi N. Impact of gastrointestinal helminths on production in goats in Kenya. Small Rumin Res. 2001;42:21-9.

- Hoste H, Torres-Acosta JFJ. Alternative or improved methods to limit gastro-intestinal parasitism in grazing sheep and goats. Small Rumin Res. 2008;77:159-73.

- Charlier J, Rinaldi L, Musella V, Ploeger HW, Chartier C, Vineer HR, et al. Initial assessment of the economic burden of major parasitic helminth infections to the ruminant livestock industry in Europe. Prev Vet Med. 2020;182:105103.

- Maurizio A, Perrucci S, Tamponi C, Scala A, Cassini R, Rinaldi L, et al. Control of gastrointestinal helminths in small ruminants to prevent anthelmintic resistance: the Italian experience. Parasitology. 2023;150:1105-18.

- Zarlenga DS, Hoberg EP, Tuo W. The identification of Haemonchus species and diagnosis of haemonchosis. Adv Parasitol. 2016;93:145-80.

- Ghadirian E, Arfaa F. First report of human infection with Haemonchus contortus, Ostertagia ostertagi, and Marshallagia marshalli (family Trichostrongylidae) in Iran. J Parasitol. 1973;59:1144-5.

- Boreham RE, McCowan M, Ryan AE, Allworth A, Robson J. Human trichostrongyliasis in Queensland. Pathology. 1995;27:182-5.

- Watthanakulpanich D, Pongvongsa T, Sanguankiat S, Nuamtanong S, Maipanich W, Yoonuan T, et al. Prevalence and clinical aspects of human Trichostrongylus colubriformis infection in Lao PDR. Acta Trop. 2013;126:37-42.

- Phosuk I, Intapan P, Sanpool O, Janwan P, Thanchomnang T, Sawanyawisuth K, et al. Molecular evidence of Trichostrongylus colubriformis and Trichostrongylus axei infections in humans from Thailand and Lao PDR. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89:376-9.

- Fissiha W, Kinde MZ. Anthelmintic resistance and its mechanism: A review. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:5403-10.

- Dey AR, Begum N, Anisuzzaman MA, Alam MZ. Multiple anthelmintic resistance in gastrointestinal nematodes of small ruminants in Bangladesh. Parasitol Int. 2020;77:102105.

- Potârniche AV, Mickiewicz M, Olah D, Cerbu C, Spînu M, Hari A, et al. First report of anthelmintic resistance in gastrointestinal nematodes in goats in Romania. Animals. 2021;11:2761.

- Silvestre A, Humbert JF. A molecular tool for species identification and benzimidazole resistance diagnosis in larval communities of small ruminant parasites. Exp Parasitol. 2000;95:271-6.

- Silvestre A, Cabaret J. Mutation in position 167 of isotype 1 beta-tubulin gene of trichostrongylid nematodes: role in benzimidazole resistance? Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;120:297-300.

- Santos JML, Monteiro JP, Ribeiro WL, Macedo IT, Camurça-Vasconcelos AL, Vieira LS, et al. Identification and quantification of benzimidazole resistance polymorphisms in Haemonchus contortus isolated in Northeastern Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2014;199:160-4.

- Santos JML, Monteiro JP, Ribeiro WL, Macedo IT, Filho JV, Andre WP, et al. High levels of benzimidazole resistance and

-tubulin isotype 1 SNP F167Y in Haemonchus contortus populations from Ceará State, Brazil. Small Rumi Res. 2017;146:48-52. - Ratanapob N, Arunvipas P, Kasemsuwan S, Phimpraphai W, Panneum S. Prevalence and risk factors for intestinal parasite infection in goats raised in Nakhon pathom Province, Thailand. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2012;44:741-5.

- Kaewnoi D, Kaewmanee S, Wiriyaprom R, Prachantasena S, Pitaksakulrat O, Ngasaman R. Prevalence of zoonotic intestinal parasites in meat goats in Southern Thailand. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2024;24:111-7.

- Income N, Tongshoob J, Taksinoros S, Adisakwattana P, Rotejanaprasert C, Maneekan P. Helminth infections in cattle and goats in Kanchanaburi, Thailand, with focus on Strongyle nematode infections. Vet Sci. 2021;8:324.

- Rerkyusuke S, Lerk-U-Suke S, Mektrirat R, Wiratsudakul A, Kanjampa P, Chaimongkol

, et al. Prevalence and associated risk factors of gastrointestinal parasite infections among meat goats in Khon Kaen Thailand. Vet Med Int. 2024;2024:3267028. - Pitaksakulrat O, Chaiyasaeng M, Artchayasawat A, Eamudomkarn C, Thongsahuan S , Boonmars T. The first molecular identification of benzimidazole resistance in Haemonchus contortus from goats in Thailand. Vet World. 2021;14:764-8.

- Ratanapob N , Thuamsuwan N , Thongyuan S . Anthelmintic resistance status of goat gastrointestinal nematodes in Sing Buri Province, Thailand. Vet World. 2022;15:83-90.

- Sherman DM. The spread of pathogens through trade in small ruminants and their products. Rev Sci Tech. 2011;30:207-17.

- Paduang S, Thongtha R. Study of anthelmintic resistance of gastrointestinal nematodes in goats in Ratchaburi Province. J Kasetsart Vet. 2020;30:1.

- Fisheries MAFF. Food, reference book: manual of veterinary parasitological laboratory techniques. Ministry Agric. 1986;5.

- Cringoli G, Rinaldi L, Veneziano V, Capelli G, Scala A. The influence of flotation solution, sample dilution and the choice of McMaster slide area (volume) on the reliability of the McMaster technique in estimating the faecal egg counts of gastrointestinal strongyles and Dicrocoelium dendriticum in sheep. Vet Parasitol. 2004;123:121-31.

- Chan AHE, Chaisiri K, Morand S, Saralamba N, Thaenkham U. Evaluation and utility of mitochondrial ribosomal genes for molecular systematics of parasitic nematodes. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:364.

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Multiple sequence alignment using ClustalW and ClustalX. Curr Protoc Bioinf. 2002;Chap. 2:Unit 2.3.

- Kibbe WA. OligoCalc: an online oligonucleotide properties calculator. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W43-6.

- Kalendar R, Khassenov B, Ramankulov Y, Samuilova O, Ivanov KI. FastPCR: an in Silico tool for fast primer and probe design and advanced sequence analysis. Genomics. 2017;109:312-9.

- Hall TA, BioEdit. A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for windows 95/98/NT. Nucl Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95-8.

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:1547-9.

- Rambaut A. FigTree v1.3.1. Institute of Evolutionary Biology, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh. 2010. http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/

- Coles GC, Jackson F, Pomroy WE, Prichard RK, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G, Silvestre A, et al. The detection of anthelmintic resistance in nematodes of veterinary importance. Vet Parasitol. 2006;136:167-85.

- Coles GC, Bauer C, Borgsteede F, Geerts S, Klei T, Taylor M, et al. World association for the advancement of veterinary parasitology (W.A.A.V.P.) methods for the detection of anthelmintic resistance in nematodes of veterinary importance. Vet Parasitol. 1992;44:35-44.

- von Samson-Himmelstjerna G, Coles GC, Jackson F, Bauer C, Borgsteede F, Cirak V, et al. Standardization of the egg hatch test for the detection of benzimidazole resistance in parasitic nematodes. Parasitol Res. 2009;105:825-34.

- Araújo-Filho JV, Ribeiro WLC, André WPP, Cavalcante GS, Santos JMLD, Monteiro JP, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic approaches for detection of anthelmintic resistant sheep gastrointestinal nematodes from Brazilian Northeast. Revista Brasileira de parasitologia veterinaria = brazilian. J Veterinary Parasitology: Orgao Oficial Do Colegio Brasileiro De Parasitol Vet. 2021;30:e005021.

- Chagas ACS, Domingues LF, Gaínza YA, Barioni-Júnior W, Esteves SN, Niciura SCM. Target selected treatment with levamisole to control the development of anthelmintic resistance in a sheep flock. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:1131-9.

- Baerman G, Wetzal R, Helminths. 1st ed. 1953. Black well Scientific, Oxford.

- Santos JML, Vasconcelos JF, Frota GA, Freitas EP, Teixeira M, Vieira LDS, et al. Quantitative molecular diagnosis of levamisole resistance in populations of Haemonchus contortus. Exp Parasitol. 2019;205:107734.

- Schoonjans F, Zalata A, Depuydt CE, Comhaire FH. MedCalc: a new computer program for medical statistics. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 1995;48:257-62.

- Junsiri W, Tapo P, Chawengkirttidul R, Watthanadirek A, Poolsawat N, Minsakorn

, et al. The occurrence of gastrointestinal parasitic infections of goats in Ratchaburi, Thailand. Thai J Vet Med. 2021;51:151-60. - Jittapalapong S, Saengow S, Pinyopanuwat N, Chimnoi W, Khachaeram W, Stich RW. Gastrointestinal helminthic and protozoal infections of goats in Satun, Thailand. J Trop Med Parasitol. 2012;35:48-54.

- Azrul LM, Poungpong K, Jittapalapong S, Prasanpanich S. Descriptive prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites in goats from farms in Bangkok and vicinity and the associated risk factors. Annual Res Rev Biology. 2017;16:2.

- Wuthijaree K, Tatsapong P, Lambertz C. The prevalence of intestinal parasite infections in goats from smallholder farms in Northern Thailand. Helminthologia. 2022;59:64-73.

- Phosuk I, Intapan PM, Prasongdee TK, Changtrakul Y, Sanpool O, Janwan P, et al. Human trichostrongyliasis: A hospital case series. Southeast Asian J Trop Med. 2015;46:191-7.

- Mickiewicz M, Czopowicz M, Kawecka-Grochocka E, Moroz A, SzaluśJordanow O, Várady M, et al. The first report of multidrug resistance in gastrointestinal nematodes in goat population in Poland. BMC Vet Res. 2020;16:270.

- Rerkyusuke S, Lamul P, Thipphayathon C, Kanawan K, Porntrakulpipat S. Caprine roundworm nematode resistance to macrocylic lactones in Northeastern Thailand. Vet Integr Sci. 2023;21:623-34.

- Department of Livestock Development. Annual Report 2016. Department of Livestock Development, Ministry of Agricultural and Cooperatives, Bangkok, Thailand. 2016.

Publisher’s note

- *Correspondence:

Urusa Thaenkham

urusa.tha@mahidol.ac.th

Department of Helminthology, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

Department of Pre-Clinic and Applied Animal Science, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Mahidol University, Nakhon Pathom, Thailand - A dash (-) indicates no data was obtained due to insufficient eggs collected. An asterisk (*) indicates that the genotype result obtained contrasted with the phenotype resistance status

DC (discriminating dose) indicates the dose of the drug that is supposed to result in the mortality of the target organism. The DC indicating albendazole resistance is , while for levamisole is