DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-21210-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39743623

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-02

عدوى الديدان الطفيلية المنقولة عبر التربة ومؤشرات التغذية بين الأطفال (5-9 سنوات) والمراهقين (10-12 سنة) في كاليبار، نيجيريا

الملخص

خلفية تعتبر عدوى الديدان الطفيلية المنقولة بالتربة (STH) قضية صحية عامة هامة في البلدان النامية، حيث تؤثر بشكل خاص على الأطفال.

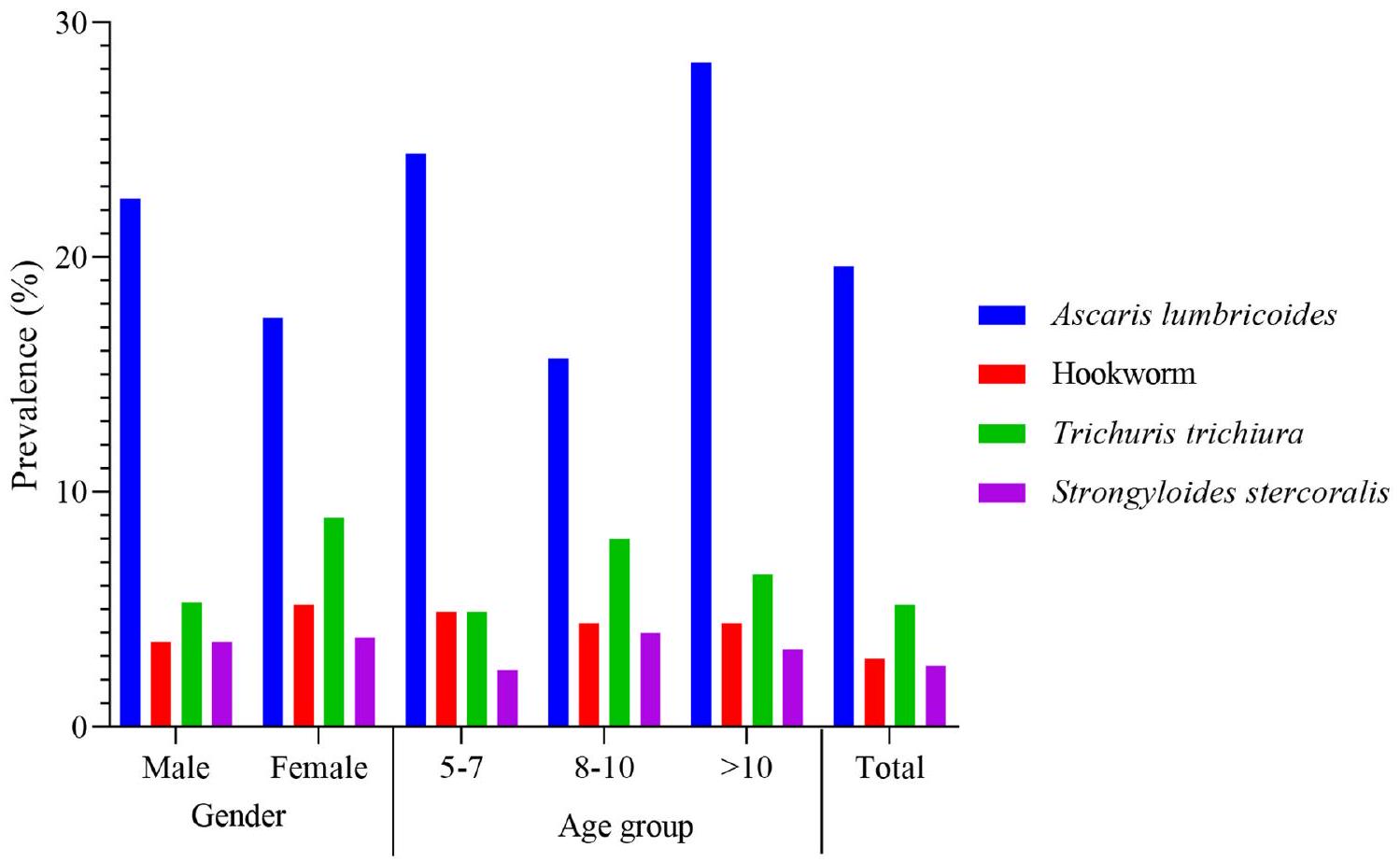

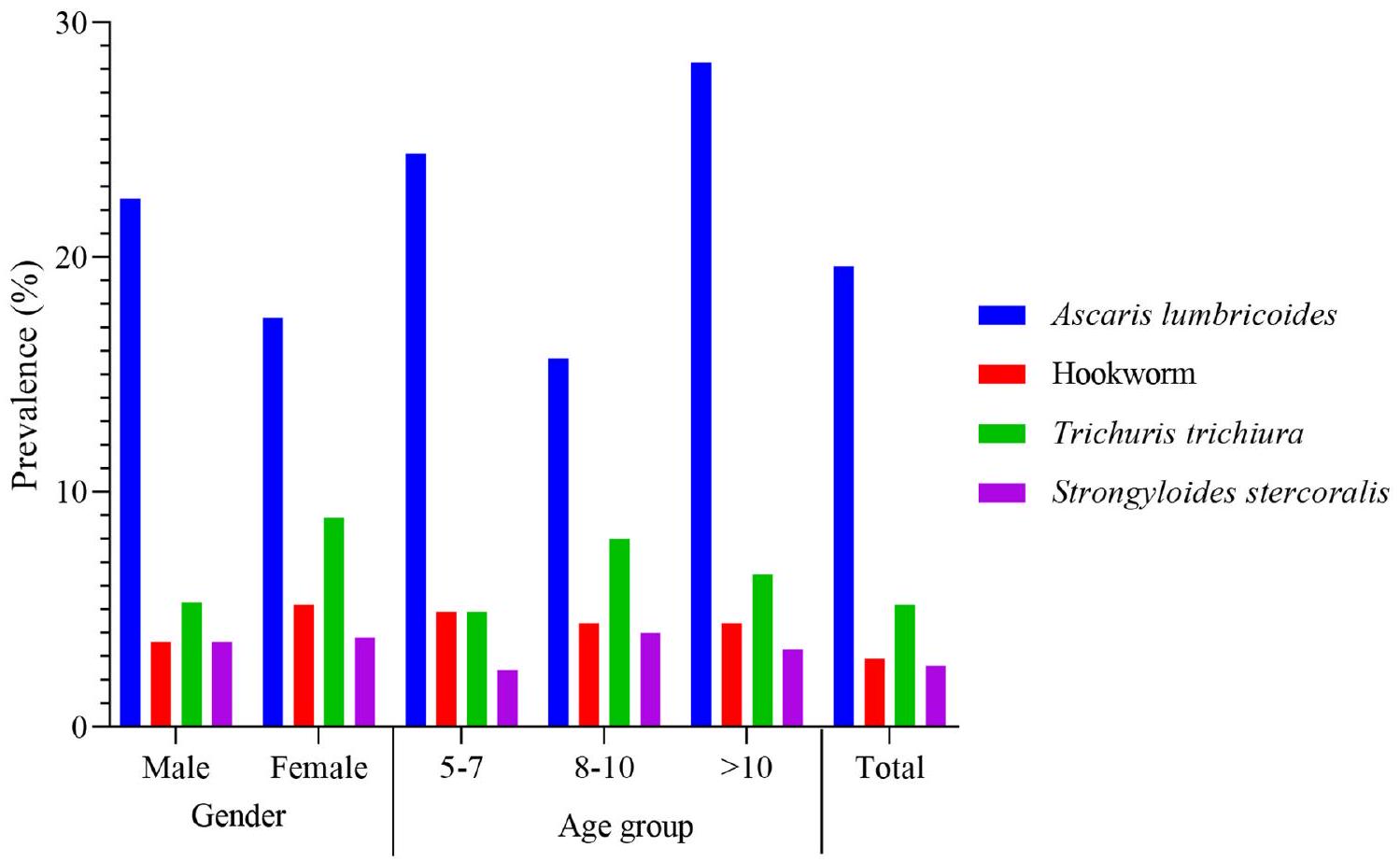

طرق تم إجراء دراسة تحليلية مقطعية داخل المدارس من أبريل إلى يونيو 2023 وشملت 382 مشاركًا في كالابار، نيجيريا. أكمل جميع المشاركين في الدراسة استبيانًا مصممًا لجمع المعلومات حول خصائصهم الديموغرافية ومعرفتهم ومواقفهم وممارساتهم (KAP) بشأن عدوى الديدان الطفيلية المعوية. تم أخذ قياسات أنثروبومترية وفقًا لمعايير منظمة الصحة العالمية (WHO). تم جمع عينات براز طازجة من كل مشارك في الدراسة وفحصها باستخدام تقنية كاتو-كاتز. تم تحليل البيانات باستخدام برنامج STATA، الإصدار 14. تم استخدام نموذج الانحدار اللوجستي الثنائي لتحديد العوامل المتنبئة بعدوى الديدان الطفيلية المعوية وللتحقق من العلاقات بين حالة العدوى وارتفاع معدل التقزم، نقص الوزن، والهزال. النتائج كانت نسبة انتشار الديدان الطفيلية المعوية الإجمالية 28.8%، مع كون أسكاريس لومبريكويدس (19.6%) الأكثر انتشارًا. كانت نسبة انتشار الديدان الطفيلية المعوية أكبر بين الذكور (30.2%) مقارنة بالإناث (27.7%) وكانت أكبر نسبيًا بين المشاركين الذين تتراوح أعمارهم بين 10 سنوات وما فوق (34.8%). سجل جميع المشاركين في الدراسة شدة عدوى خفيفة. كانت معدلات انتشار التقزم، نقص الوزن، والهزال هي

الكلمات المفتاحية: STH، التقزم، سوء التغذية، KAP، عوامل الخطر، أطفال المدارس

الخلفية

في نيجيريا، تعتبر الديدان المعوية شائعة وتمثل قضية صحية عامة هامة [7] وقد أفادت دراسات مختلفة في جميع أنحاء البلاد بانتشار الديدان المعوية يتراوح بين 13.2 إلى

تحتاج الدراسات إلى تقييم المراضة المرتبطة بالديدان المعوية في الأطفال والمراهقين لتقييم فعالية برامج مكافحة الديدان المعوية في البلاد بدقة. تهدف هذه الدراسة إلى التحقيق في انتشار وعوامل خطر عدوى الديدان المعوية وتأثير عدوى الديدان المعوية على المؤشرات الغذائية للأطفال.

طرق

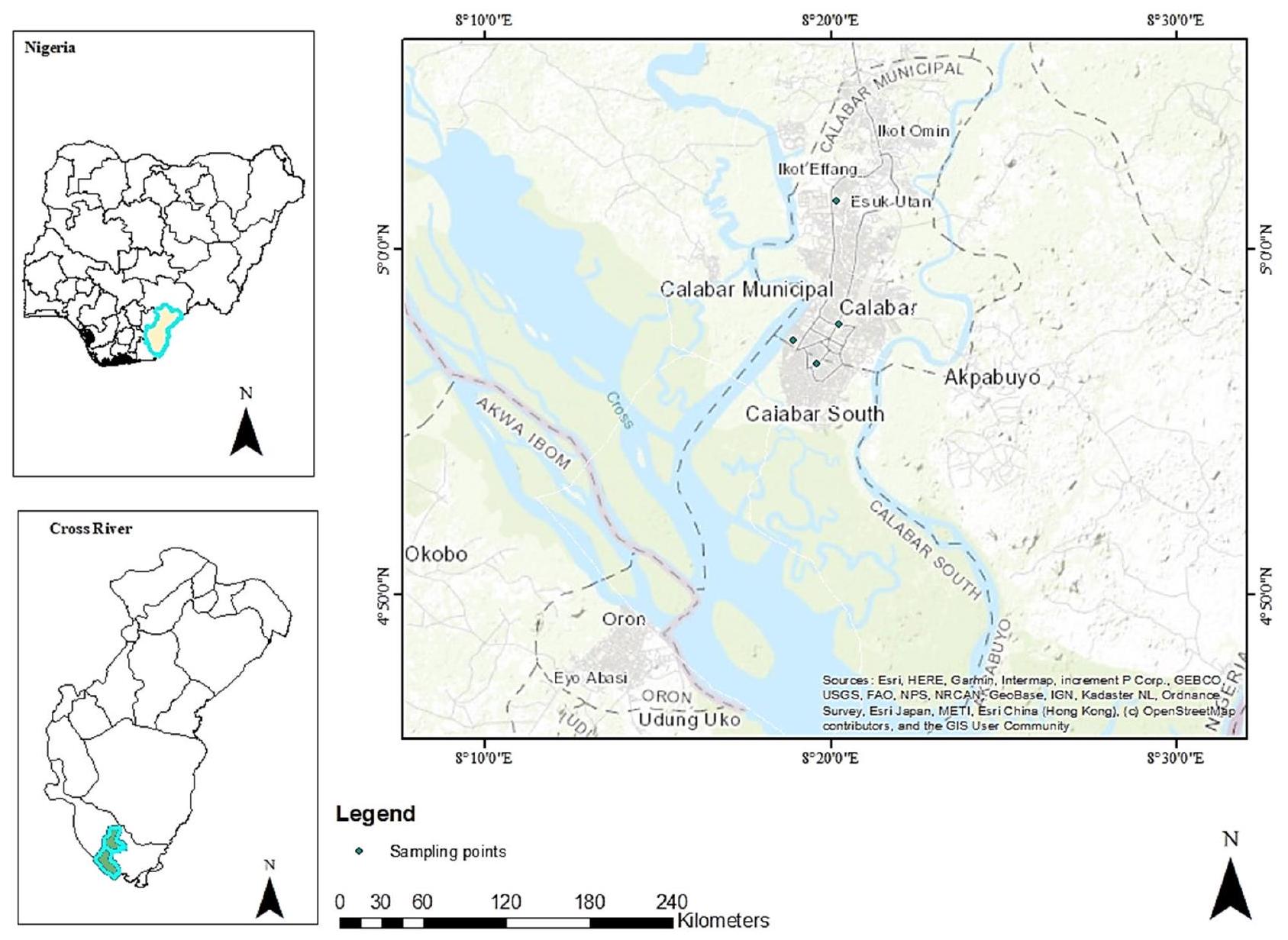

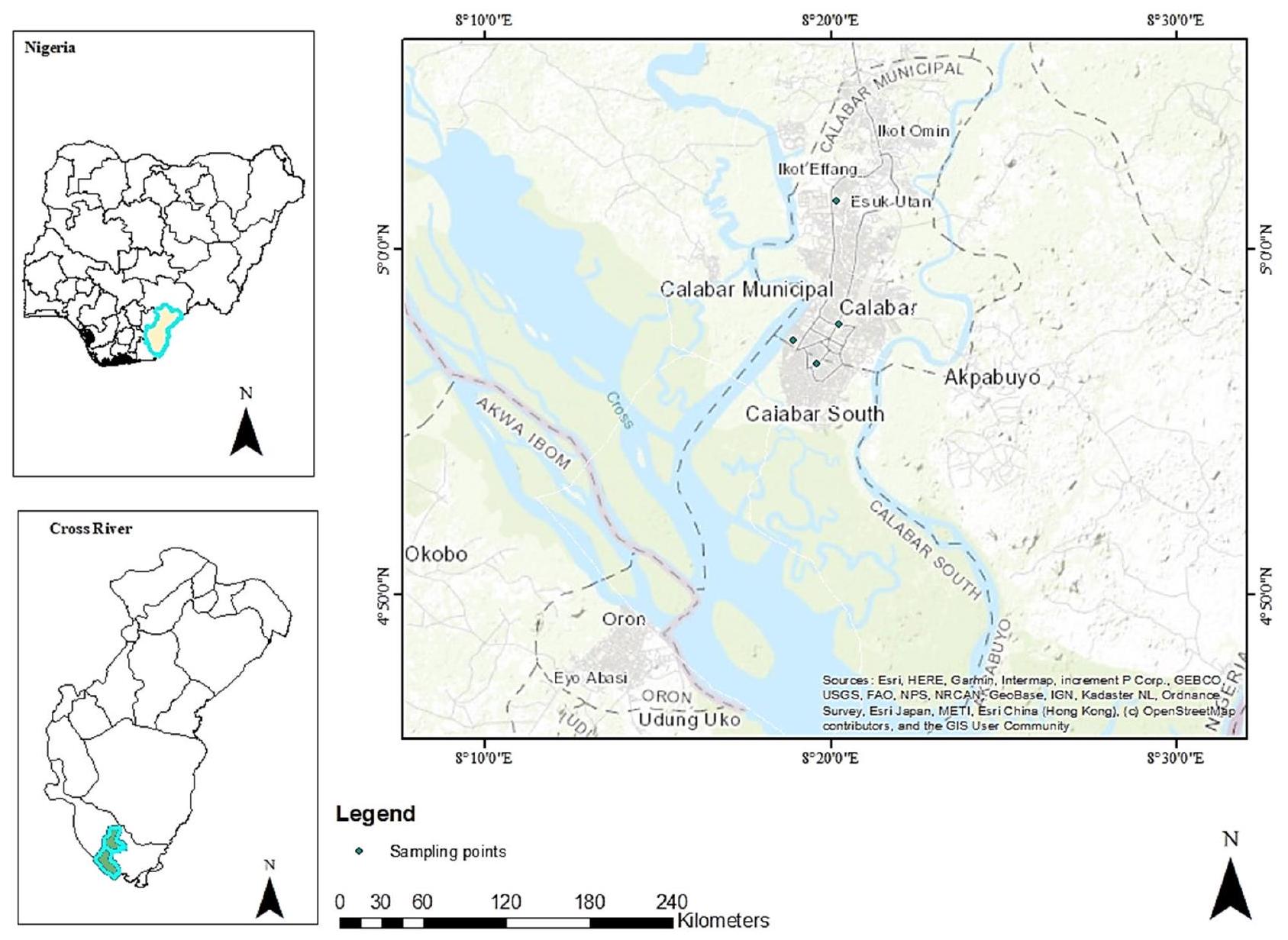

منطقة الدراسة

تصميم الدراسة

تحديد حجم العينة

معايير الشمول والاستبعاد

الاعتبارات الأخلاقية

جمع البيانات

استبيان المعرفة والموقف والممارسة (KAP)

مثل غسل اليدين، التعامل مع الطعام، استخدام المرحاض، وعادات ارتداء الأحذية. تم اختبار الاستبيان مسبقًا في مدرستين مختلفتين. تم اختبار الاستبيان مسبقًا في مدرستين تم اختيارهما عشوائيًا من قائمة وزارة التعليم لتقييم وضوحه وملاءمته وفعاليته. سمح ذلك للباحثين بتحديد وحل أي مشكلات، مما يضمن أن الاستبيان كان مناسبًا للدراسة الرئيسية.

تم إدارة الاستبيان بواسطة اثنين من العاملين في مجال الصحة المدربين، بدعم من معلمي الصف. قرأ العامل الصحي الأول التعليمات والأسئلة للأطفال في الفصل الدراسي، بينما تحرك العامل الصحي الثاني ومعلم الصف لضمان أن جميع التلاميذ فهموا التعليمات وأجابوا على الأسئلة بشكل صحيح.

الفحص الطفيلي

أخيرًا، تم توثيق النتائج في ورقة تقرير مختبر. إذا تم رؤية بيضة واحدة على الأقل أو يرقات (لـ S. stercoralis) على أي من ثلاث شرائح سميكة من كاتو-كاتز، اعتُبر المشارك إيجابيًا. تم ضرب متوسط عدد البيض المحدد حسب النوع من الشرائح الثلاثية من كاتو-كاتز بـ 24 لتقييم شدة

عدوى STH (A. lumbricoides، الدودة الشصية، وT. trichiura) [23]. تم عد البيض لكل نوع من أنواع STH لتحديد انتشار وشدة العدوى (بيض لكل غرام من البراز، EPG). تم تصنيف شدة العدوى لكل نوع على أنها خفيفة أو متوسطة أو شديدة وفقًا لمعايير منظمة الصحة العالمية [24].

تقييم الحالة الغذائية

متغيرات الدراسة

تحليل البيانات

تم استخدام اختبار t لمقارنة متوسط شدة عدوى STH بين الذكور والإناث، بينما تم استخدام ANOVA أحادي الاتجاه لتقييم الفروق في المتوسطات الحسابية لعدوى STH عبر مجموعات عمرية مختلفة.

تم استخدام الإحصائيات الوصفية لتوضيح الخصائص السوسيو ديموغرافية للمشاركين، مع تقديم التكرارات والنسب المئوية للبيانات الفئوية. لفحص العلاقات بين المتغيرات المستقلة والمتغير الناتج، تم تطبيق اختبار كاي-تربيع.

بالنسبة لاستبيان المعرفة والموقف والممارسة (KAP)، تم تخصيص نقطة واحدة لكل إجابة صحيحة في أقسام المعرفة والموقف، وتم خصم نقطة واحدة للإجابات غير الصحيحة، وتم تسجيل إجابات “لا أعرف” بصفر. في قسم الممارسات، تم إعطاء إجابات “أبدًا” درجة صفر، و”بعض الوقت” درجة واحدة، و”دائمًا” درجة اثنين، مما يعكس تكرار السلوك.

تم تصنيف الدرجات العامة للمعرفة والممارسة لدى المشاركين على النحو التالي: الدرجات التي تبلغ 20 أو أكثر تشير إلى معرفة/ممارسة جيدة، والدرجات بين 11 و19 تشير إلى معرفة/ممارسة متوسطة، والدرجات التي تبلغ 10 أو أقل تشير إلى معرفة/ممارسة ضعيفة. على وجه التحديد، بالنسبة لمعرفتهم بانتقال الديدان الطفيلية المعوية (STH) والأعراض، كانت الدرجات من

تم استخدام نموذج الانحدار اللوجستي الثنائي لتحديد العوامل المتنبئة بعدوى الديدان الطفيلية المعوية وفحص

| خاصية | رقم | نسبة مئوية |

| جنس | ||

| ذكر | 169 | ٤٤.٢ |

| أنثى | 213 | ٥٥.٨ |

| الفئة العمرية (سنوات) | ||

| ٥-٧ | 41 | 10.7 |

| 8-10 | 249 | 65.2 |

| >10 | 92 | ٢٤.١ |

| مدرسة | ||

| مدرسة أكيم الابتدائية الحكومية | 100 | 21.2 |

| مدرسة الحكومة الابتدائية في مدينة هينشو | ١٠١ | ٢٦.٤ |

| مدرسة الحكومة الابتدائية في شارع مين | ١٠١ | ٢٦.٤ |

| مدرسة الحكومة الابتدائية إيكوت أنسا | ٨٠ | ٢٠.٩ |

| مهنة الأم | ||

| تاجر | ١١٢ | ٢٩.٣ |

| موظف حكومي | ١٤٤ | ٣٧.٧ |

| عاطل عن العمل | 40 | 10.5 |

| آخرون | 86 | ٢٢.٥ |

| مهنة الأب | ||

| تاجر | ١٣٦ | ٣٥.٦ |

| موظف حكومي | ١٢٢ | 31.9 |

| عاطل عن العمل | 27 | ٧.١ |

| آخرون | 97 | ٢٥.٤ |

النتائج

الخصائص العامة لمشاركي الدراسة

انتشار وشدة الديدان المعوية وخصائص التغذية للمشاركين في الدراسة

بشكل عام، أظهر A. lumbricoides أعلى شدة عدوى

عبر مجموعات عمرية مختلفة، لم تختلف شدة عدوى الديدان الطفيلية المعوية بشكل كبير

معرفة بشيء ما

تم التعرف على الحمى وآلام المعدة بواسطة

تشمل التدابير الوقائية المعترف بها على نطاق واسع غسل الفواكه قبل الاستهلاك

من حيث المعرفة العامة بـ STH، فقط

الوصول إلى المياه، ممارسات الصرف الصحي، ووجهات نظر المشاركين حول الوقاية من الديدان المعوية

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم إجراء تحليل لممارسات الصحة العامة والنظافة حسب الفئة العمرية، مع التركيز على عادات غسل اليدين، واستخدام المرحاض، والمشي حافي القدمين. كشفت النتائج عن اختلافات طفيفة في ممارسات النظافة والصحة العامة عبر الفئات العمرية، على الرغم من أنها ليست ذات دلالة إحصائية. بين الأطفال،

| المتغيرات | رقم | نسبة مئوية |

| سمعت عن STH | ||

| نعم | ٢٦٨ | 70.2 |

| لا | 114 | ٢٩.٨ |

| نقل STH | ||

| امش حافي القدمين | ٥٨ | 15.1 |

| تناول الطعام الملوث | 164 | 42.9 |

| تناول الخضروات غير المطبوخة وغير المغسولة | 60 | 15.7 |

| الاتصال ببراز شخص مصاب | ٤٤ | 11.5 |

| عضة بعوضة | 192 | 50.3 |

| اللعب في المناطق الملوثة | 132 | ٣٤.٦ |

| اللعب بالتربة | 121 | ٣١.٧ |

| اللعب في أماكن متسخة | 68 | 17.8 |

| المعرفة العامة حول انتقال الطفيليات المعوية | ||

| جيد | 64 | 16.8 |

| متوسط | 158 | ٤١.٤ |

| فقير | ١٦٠ | ٤١.٩ |

| المعرفة بعلامات وأعراض الأمراض الطفيلية المعوية | ||

| فقدان الوزن | 78 | ٢٠.٤ |

| ألم في المعدة | 167 | ٤٣.٧ |

| إسهال | ١٤٤ | ٣٧.٧ |

| ضعف النمو | 51 | 13.5 |

| غثيان | ٣٩ | 10.2 |

| فقدان الشهية | 70 | 18.3 |

| فقدان الدم | 65 | 17.0 |

| حمى | 178 | ٤٦.٦ |

| زيادة الوزن | ١٠٢ | ٢٦.٧ |

| ضغط الدم المنخفض | ١١٩ | 31.2 |

| المعرفة العامة حول العلامات والأعراض | ||

| جيد | 19 | ٤.٩٧ |

| متوسط | ١٣٤ | ٣٥.٠٨ |

| فقير | 229 | ٥٩.٩٥ |

| المعرفة حول الوقاية من الأمراض الطفيلية المعوية | ||

| تناول الكثير من الطعام | ٤٧ | 12.3 |

| استخدام شبكة البعوض | 127 | ٣٣.٣ |

| استخدام المرحاض | 96 | ٢٥.١ |

| غسل الفواكه قبل الأكل | ٢٩٣ | ٧٦.٧ |

| غسل يديك قبل الأكل | 287 | 75.1 |

| غسل يديك بعد استخدام المرحاض | ٢٦٠ | 68.1 |

| التمارين الرياضية المنتظمة | ١٠٩ | ٢٨.٥ |

| المعرفة العامة حول الوقاية من الديدان الطفيلية المعوية | ||

| جيد | 52 | 13.6 |

| متوسط | 189 | ٤٩.٥ |

| فقير | 141 | ٣٦.٩ |

| درجة المعرفة العامة | ||

| جيد | 43 | 11.3 |

| متوسط | 237 | 62.0 |

| فقير | ١٠٢ | ٢٦.٧ |

| درجة الموقف العامة | ||

| جيد | 86 | ٢٢.٥ |

| متوسط | 190 | ٤٩.٧ |

| فقير | ١٠٦ | ٢٧.٧٥ |

| درجة الممارسة العامة | ||

| جيد | 87 | 22.8 |

| المتغيرات | رقم | نسبة مئوية |

| متوسط | 191 | 50.0 |

| فقير | ١٠٤ | ٢٧.٢ |

| المتغيرات | التردد (%) | شيء | OR (95% CI) |

|

نسبة الأرجحية (95% فترة الثقة) |

|

|

| إيجابي

|

سلبي،

|

||||||

| جنس | |||||||

| ذكر | 169 (44.2) | 51 (30.2) | 118 (69.8) | مرجع | |||

| أنثى | 213 (55.8) | ٥٩ (٢٧.٧) | 154 (72.3) | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) | 0.595 | 0.7 (0.4-1.2) | 0.329 |

| مصدر مياه الشرب | |||||||

| مياه صالحة للشرب/مياه معبأة/مضخة يدوية | 356 (93.2) | 106 (29.8) | 250 (70.2) | مرجع | |||

| بئر/خزان غير محمي | ٢٦ (٦.٨) | ٤ (١٥.٤) | 22 (84.6) | 0.4 (0.1-1.3) | 0.097 | 0.4 (0.1-1.4) | 0.182 |

| نوع المرحاض | |||||||

| مرحاض | ١٧٦ (٤٦.١) | ٣٨ (٢١.٦) | ١٣٨ (٧٨.٤) | مرجع | |||

| مرحاض حفرة | 182 (47.6) | 67 (36.8) | ١١٥ (٦٣.٢) | 2.1 (1.3-3.4) | 0.002 | 1.0 (0.5-1.8) | 0.942 |

| التبرز في العراء | ٢٤ (٦.٣) | 5 (20.8) | 19 (79.2) | 1.9 (0.3-2.7) | 0.932 | 0.9 (0.2-2.7) | 0.862 |

| تلقيت دواء الديدان من قبل | |||||||

| نعم | ٢٢٣ (٥٨.٤) | 87 (39.0) | ١٣٦ (٦٠.٩) | مرجع | |||

| لا | 159 (41.6) | ٢٣ (١٤.٥) | ١٣٦ (٨٥.٥) | 0.2 (0.1-0.4) | <0.001 | 0.2 (0.1-0.5) | <0.001 |

| غسل اليدين بعد استخدام المرحاض | |||||||

| دائمًا | 131 (34.3) | ٣٧ (٢٨.٢) | 94 (71.8) | مرجع | |||

| أحيانًا | 145 (37.9) | 40 (27.6) | ١٠٥ (٧٢.٤) | 0.9 (0.5-1.6) | 0.903 | 0.9 (0.5-1.7) | 0.941 |

| أبداً | 106 (27.8) | ٣٣ (٣١.١) | 73 (68.8) | 1.1 (0.6-2.0) | 0.628 | 1.1 (0.6-2.1) | 0.615 |

| غسل اليدين قبل وبعد الأكل | |||||||

| دائمًا | 145 (37.9) | ٤٥ (٣١.٠) | 100 (68.9) | مرجع | |||

| أحيانًا | 137 (35.9) | ٤٣ (٣١.٤) | 94 (68.6) | 1.0 (0.6-1.6) | 0.949 | 1.0 (0.6-1.8) | 0.852 |

| أبداً | 100 (26.2) | ٢٢ (٢٢.٠) | 78 (78.0) | 0.6 (0.3-1.1) | 0.120 | 0.5 (0.3-1.1) | 0.١٠٣ |

| غسل الفواكه والخضروات قبل الأكل | |||||||

| دائمًا | 163 (42.7) | ٤٥ (٢٧.٦) | ١١٨ (٧٢.٤) | مرجع | |||

| أحيانًا | ١٢٩ (٣٣.٨) | ٣٣ (٢٥.٦) | 96 (74.4) | 0.9 (0.5-1.5) | 0.698 | 0.9 (0.5-1.7) | 0.984 |

| أبداً | 90 (23.6) | ٣٢ (٣٥.٦) | 58 (64.4) | 1.4 (0.8-2.5) | 0.189 | 1.4 (0.8-2.6) | 0.208 |

| المشي حافي القدمين | |||||||

| دائمًا | ١٣٠ (٣٤.٠) | 40 (30.8) | 90 (69.2) | مرجع | |||

| أحيانًا | 156 (40.9) | 44 (28.2) | ١١٢ (٧١.٨) | 0.8 (0.5-1.4) | 0.636 | 0.8 (0.4-1.4) | 0.465 |

| أبداً | 96 (25.1) | ٢٦ (٢٧.١) | 70 (72.9) | 0.8 (0.4-1.4) | 0.547 | 0.9 (0.4-1.7) | 0.785 |

| يعتقد أن STH هو مرض خطير | |||||||

| نعم | ١٣٩ (٣٦.٤) | ٤٦ (٣٣.١) | 93 (66.9) | مرجع | |||

| لا | 243 (63.6) | 64 (26.3) | 179 (73.7) | 0.7 (0.4-1.1) | 0.161 | 0.7 (0.4-1.1) | 0.212 |

| يؤمن بأن شيئًا ما يمكن منعه | |||||||

| نعم | 340 (89.0) | 96 (28.2) | 244 (71.8) | مرجع | |||

| لا | 42 (10.9) | 14 (33.3) | ٢٨ (٦٦.٧) | 1.2 (0.6-2.5) | 0.492 | 1.0 (0.4-2.1) | 0.954 |

العوامل المرتبطة بعدوى الديدان الطفيلية المعوية

عدوى (أو: 2.1؛ 95% CI: 1.3-3.4؛

المستجيبون الذين لديهم معرفة عامة متوسطة حول انتقال الديدان الطفيلية المعوية (OR: 1.1؛ 95% CI: 0.6-1.9؛

| خاصية | فئة | شيء | OR (فاصل الثقة 95%) |

|

نسبة الأرجحية (95% فترة الثقة) |

|

|

| إيجابي، ن (%) | سلبي، ن (%) | ||||||

| المعرفة العامة بدرجة انتقال الديدان الطفيلية المعوية | جيد | 18 (28.1) | ٤٦ (٧١.٩) | مرجع | |||

| متوسط | ٤٦ (٢٩.١) | ١١٢ (٧٠.٩) | 1.1 (0.6-1.9) | 0.150 | 0.9 (0.8-1.0) | 0.524 | |

| فقير | ٤٦ (٢٨.٨) | 111 (71.3) | 1.0 (0.5-1.9) | 0.090 | 1.3 (0.8-2.0) | 0.306 | |

| درجة المعرفة العامة | جيد | 12 (27.9) | 31 (72.1) | مرجع | |||

| متوسط | 68 (28.7) | 169 (71.3) | 1.0 (0.5-2.1) | 0.917 | 0.9 (0.6-1.3) | 0.701 | |

| فقير | 30 (29.4) | 72 (70.6) | 1.1 (0.5-2.4) | 0.855 | 0.9 (0.6-1.5) | 0.858 | |

| درجة الموقف العامة | جيد | ٣٣ (٣٨.٤) | 53 (61.6) | مرجع | |||

| متوسط | 58 (30.5) | 132 (69.5) | 0.7 (0.4-1.2) | 0.200 | 1.9 (0.8-4.4) | 0.113 | |

| فقير | 19 (17.9) | 87 (82.1) | 0.4 (0.1-0.6) | 0.002 | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | 0.003 | |

| درجة الممارسة العامة | جيد | ٢٣ (٢٦.٤) | 64 (73.6) | مرجع | |||

| متوسط | ٥٦ (٢٩.٣) | 135 (70.7) | 1.1 (0.6-2.0) | 0.621 | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | 0.700 | |

| فقير | ٣١ (٢٩.٨) | 73 (70.2) | 1.1 (0.6-2.2) | 0.607 | 1.1 (0.7-1.4) | 0.440 | |

| متغير | الإجمالي (N) | التقزم

|

نسبة الأرجحية الأحادية (95% فترة الثقة) |

|

نقص الوزن

|

نموذج أحادي المتغير OR (95% CI) |

|

الهدر (%) | نموذج أحادي المتغير OR(95% CI) |

|

| جنس | ||||||||||

| ذكر | 169 | 16 (9.5) | مرجع | 12 (7.1) | مرجع | 10 (5.9) | مرجع | |||

| أنثى | 213 | ٢٤ (١١.٣) | 1.2 (0.6-2.3) | 0.569 | 20 (9.4) | 1.3 (0.6-2.8) | 0.424 | 14 (6.6) | 1.1 (0.4-2.5) | 0.793 |

| فئة العمر | ||||||||||

| ٥-٧ | 41 | 7 (17.1) | مرجع | 6 (14.6) | مرجع | 2 (4.9) | مرجع | |||

| ٨-١٠ | 249 | 27 (10.8) | 0.5 (0.2-1.4) | 0.255 | ٢٣ (٩.٢) | 0.5 (0.2-1.5) | 0.290 | 15 (6.0) | 1.2 (0.2-5.6) | 0.773 |

| >10 | 92 | 6 (6.5) | 0.3 (0.1-1.0) | 0.068 | 3 (3.3) | 0.1 (0.04-0.82) | 0.027 | 7 (7.6) | 1.6 (0.3-8.0) | 0.566 |

| أي شيء | ||||||||||

| إيجابي | ١١٠ | 10 (9.1) | 0.8 (0.3-1.7) | 0.576 | 7 (6.4) | 0.6 (0.2-1.6) | 0.369 | 9 (8.2) | 1.5 (0.6-3.6) | 0.334 |

| سلبي | 272 | 30 (11.0) | مرجع | 25 (9.2) | مرجع | 15 (5.5) | مرجع | |||

العلاقات بين عدوى الديدان الطفيلية ومؤشرات التغذية

لم يكن هناك ارتباط كبير بين التقزم، نقص الوزن، والهزال، وعدوى الديدان المعوية. ومن المثير للاهتمام أن احتمالات التقزم (OR: 0.8؛ 95% CI: 0.3-1.7؛

نقاش

كشفت نتائج هذه الدراسة عن انتشار عام للديدان الطفيلية المعوية بنسبة

أشارت دراسة KAP إلى أن

تعزيز المواقف الأفضل وبالتالي تقليل انتشار هذه العدوى.

تشير النتائج أيضًا إلى أن الغالبية العظمى من الأطفال في جميع الفئات العمرية يستخدمون المراحيض البدائية، مما يعكس مستوى معين من الوصول إلى مرافق الصرف الصحي الأساسية. ومع ذلك، فإن الانتشار الأعلى للتغوط في العراء بين المشاركين الذين تتراوح أعمارهم بين

أظهرت الدراسة أن

حوالي

من المدهش أن الأفراد الذين حصلوا على درجات سلبية في المواقف كانوا أقل احتمالاً بشكل كبير للإصابة بعدوى الطفيليات المعوية (OR:

على الرغم من أن معظم المشاركين في الدراسة أفادوا بأن لديهم وصولاً إلى مصادر مياه شرب محسّنة، إلا أن انتشار عدوى الديدان الطفيلية المعوية (STH) ظل مرتفعًا. نظرًا لعدم جمع بيانات حول مستويات الصرف الصحي في الأسر في هذه الدراسة، قد تساهم هذه العوامل غير المقاسة في انتقال الديدان الطفيلية المعوية. ومع ذلك، قد تشير النسبة المنخفضة لعدوى الديدان الشريطية وS. stercoralis التي لوحظت إلى تلوث محدود بالبراز في البيئة، مما يؤدي إلى تقليل خطر العدوى لهذه الطفيليات في منطقة الدراسة. لم يتم العثور على أي ارتباطات بين عدوى الديدان الطفيلية المعوية والمتغيرات مثل الجنس، ونوع الجنس، ومصدر المياه، وغسل اليدين بعد استخدام المرحاض، وغسل اليدين قبل وبعد الوجبات، وغسل الفواكه والخضروات قبل الاستهلاك، والمشي حافي القدمين، أو المعرفة والممارسات العامة المتعلقة بالديدان الطفيلية المعوية بين الأطفال في سن المدرسة، وهو ما يختلف عن نتائج الدراسات السابقة. ومع ذلك، يمكن أن تختلف عوامل الخطر لعدوى الديدان الطفيلية المعوية عبر المواقع اعتمادًا على الجغرافيا، والصرف الصحي البيئي، ونمط الحياة، والممارسات الثقافية للسكان المحليين.

معدلات التقزم الملاحظة (

في دراستنا، لوحظ أن الفتيات يعانين من معدلات أعلى من التقزم، نقص الوزن، والهزال مقارنةً بنظرائهن من الذكور. يمكن تفسير ذلك بالفجوات القائمة على أساس الجنس في التغذية والوصول إلى الرعاية الصحية التي قد تؤثر بشكل غير متناسب على الإناث. على سبيل المثال، قد تحصل الفتيات على وصول أقل إلى الغذاء المغذي أو الخدمات الطبية مقارنةً بالأولاد، مما يزيد من تعرضهن لحالات سوء التغذية مثل التقزم والهزال ونقص الوزن [44]. تتماشى هذه النتائج مع دراسات محمود وآخرون [45]، وييساك وآخرون [46]،

التي أجريت في إثيوبيا وباكستان على التوالي، لكنها تتناقض مع تقارير تشودري وآخرون [47]، بودا وآخرون [48]، وهايلجبرييل [49].

قدمت الأطفال الذين تتراوح أعمارهم بين 8 و 10 سنوات احتمالية أقل للتقزم مقارنةً بأولئك الذين تتراوح أعمارهم بين 5 و 7 سنوات. يتناقض هذا مع النتائج من الدراسات السابقة [50،51]. الأطفال الأصغر سناً، وخاصةً أولئك في الفئة العمرية من 5 إلى 7 سنوات، يميلون إلى أن يكونوا أكثر عرضة للتأثيرات البيئية السلبية مثل ندرة الغذاء، وسوء الصرف الصحي، والوصول المحدود إلى الرعاية الصحية. يمكن أن تعيق هذه العوامل بشكل كبير نموهم وتطورهم، مما يؤدي إلى ارتفاع معدلات التقزم مقارنةً بأولئك من الأطفال الأكبر سناً، الذين قد يكونون قد تجاوزوا سنواتهم الحرجة من الضعف [52]. علاوة على ذلك، قدم الأفراد الذين تزيد أعمارهم عن 10 سنوات احتمالية أقل بشكل ملحوظ للتصنيف كنقص الوزن مقارنةً بأولئك الذين تتراوح أعمارهم بين 5 و 7 سنوات. تتماشى هذه النتائج مع الدراسات التي أجراها ديغاريج وآخرون [53] وإيريسمان وآخرون [54] في إثيوبيا وبوركينا فاسو على التوالي. مع نضوج الأطفال، قد يحصلون على وصول أفضل إلى مجموعة متنوعة من الأطعمة أو يكتسبون عادات غذائية أكثر صحة، مما يعزز وضعهم الغذائي مقارنةً بالأطفال الأصغر سناً، الذين قد لا يزالون يعتمدون على مقدمي الرعاية لتناول وجباتهم [53].

ومع ذلك، كانت احتمالية التعرض للهزال أكبر بين المشاركين الذين تتراوح أعمارهم بين

لم يتم الكشف عن أي ارتباط ذو دلالة إحصائية بين التقزم ونقص الوزن والهزال وعدوى الديدان الطفيلية. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن احتمالية التقزم ونقص الوزن كانت أقل في الأفراد الذين كانت نتائجهم إيجابية لعدوى الديدان الطفيلية مقارنةً بأولئك الذين كانت نتائجهم سلبية. على العكس من ذلك، كانت احتمالية الهزال مرتفعة في الأفراد الإيجابيين لعدوى الديدان الطفيلية مقارنةً بنظرائهم السلبيين. تتماشى هذه النتائج مع نتائج ديغاريج وآخرون [53]. تأثير عدوى الديدان الطفيلية على الحالة الغذائية للمضيف يكون أكثر حدة عندما تكون العدوى طويلة الأمد وشديدة [57]. جميع عدوى الديدان الطفيلية المبلغ عنها في هذه الدراسة كانت من شدة منخفضة.

القيود

حدًا، حيث يمنع تقييم العلاقات السببية بين عدوى الديدان الطفيلية وعوامل الخطر المحددة. علاوة على ذلك، لم تقم الدراسة بقياس تناول المغذيات الدقيقة أو عدد كريات الدم الحمراء في الأطفال. علاوة على ذلك، يمكن أن تؤثر عوامل مثل وجود طفيليات أخرى مثل البلازموديوم، واحتياجات المشاركين الغذائية، والحالة الاجتماعية والاقتصادية بشكل كبير على المؤشرات الغذائية الملاحظة. لذلك، يجب أن تتناول الأبحاث المستقبلية من هذا النوع هذه القيود.

الخاتمة

الشكر

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

الموافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 02 يناير 2025

References

- Pan American Health Organization. Soil transmitted helminthiasis. 2024. htt ps://www.paho.org/en/topics/soil-transmitted-helminthiasis#:~:text=Geoh elminthiasis%20or%20 soil-transmitted%20helminths,Necatamericanus%20 and%20Ancylostoma%20duodenale Accessed 10 May 2024.

- WHO. Ending the neglect to attain the Sustainable Development Goals-A road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021-2030 Geneva. 2020a. https ://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/Ending-the-neglect-to-attain-the-SD Gs—NTD-Roadmap.pdf?ua=1 Accessed 10 May 2024.

- WHO. Guideline: preventive chemotherapy to control soil-transmitted helminth infections in at-risk population groups. 2017. https://iris.who.int/handl e/10665/258983. Accessed 10 May 2024.

- WHO. Intestinal worms: soil-transmitted helminthes. World Health Organization; 2011a.

- Lebu S, Kibone W, Muoghalu CC, Ochaya S, Salzberg A, Bongomin F, Manga M. Soil-transmitted helminths: a critical review of the impact of coinfections and implications for control and elimination. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023;17(8):e0011496. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0011496.

- Quiroz DJG, Del Pilar Agudelo Lopez S, Arango CM, Acosta JEO, Parias LDB, Alzate LU, et al. Prevalence of soil transmitted helminths in school-aged children, Colombia, 2012-2013. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(7):e0007613. htt ps://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007613.

- Idowu OA, Babalola AS, Olapegba T. Prevalence of soil-transmitted helminth infection among children under 2 years from urban and rural settings in Ogun state, Nigeria: implication for control strategy. Gaz Egypt Paediatr Assoc. 2022;70(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43054-021-00096-6.

- Karshima SN. Prevalence and distribution of soil-transmitted helminth infections in Nigerian children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-018-0451-2.

- Imalele EE, Effanga EO, Usang AU. Environmental contamination by soiltransmitted helminths ova and subsequent infection in school-age children in Calabar. Nigeria Sci Afr. 2023a;19:e01580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf. 202 3.e01580.

- Stephenson LS, Lathan MC, Ottesen EA. Malnutrition and parasitic helminthes infections. Parasitology. 2000;121(Suppl):523-8.

- Bain LE, Awah PK, Geraldine N, Kindong NP, Sigal Y, Bernard N, Tanjeko AT. Malnutrition in Sub-saharan Africa: burden, causes and prospects. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;15:120. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2013.15.120.2535.

- Osaro BO, Edet CK, Ben-Osaro NV. Prevalence, pattern and factors associated with undernutrition among primary school aged children in Rivers State Nigeria. Ibom Med J. 2023;16(1):70-80.

- Omage K, Omuemu V. Factors associated with the dietary habits and nutritional status of undergraduate students in a private university in Southern Nigeria. Nigerian J Exp Clin Biosci. 2019;7:7. https://doi.org/10.4103/njecp.nje cp_1_19.

- Ukwajunor EE, Adebayo SB, Gayawan E. Spatio-temporal modelling of severity of malnutrition and its associated risk factors among under five children in Nigeria between 2003 and 2018: bayesian multilevel structured additive regressions. Stat Methods. 2023;32:1743-77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1026 0-023-00711-3.

- Obasohan PE, Walters SJ, Jacques R, et al. Socio-economic, demographic, and contextual predictors of malnutrition among children aged 6-59 months in Nigeria. BMC Nutr. 2024https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-023-00813-x.

- Imalele EE, Evbuomwan OI, Osondu-Anyanwu C, Akpan BC. Evaluation of Vegetable Contamination with medically important helminths and protozoans in Calabar, Nigeria. J Adv Biol. 2020;23(9):10-6. https://doi.org/10.9734/ja bb/2020/v23i930176.

- Genet A, Motbainor A, Samuel T, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of soil transmitted helminthiasis among school-age children in wetland and non-wetland areas of Blue Nile Basins, northwest

18. Imalele EE, Braide EI, Emanghe UE, et al. Soil-transmitted helminth infection among school-age children in Ogoja, Nigeria: implication for control. Parasitol Res. 2023b;122:1015-26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-023-07809-3.

19. Bruno T, Omar T. Impact of annual praziquantel treatment on urogenital schistosomiasis in seasonal transmission seasons foci in central Senegal. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(3):10-6.

20. Mationg MLS, Gordon CA, Tallo VL, Olveda RM, Alday PP, Renosa MDC, et al. Status of soil-transmitted helminth infections in schoolchildren in Laguna Province, the Philippines: determined by parasitological and molecular diagnostic techniques. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(11):e0006022. https://doi. org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0006022.

21. Katz N, Chaves A, Pellegrino J. A simple device for quantitative stool thicksmear technique in Schistosoma mansoni. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1972;14(6):397-400.

22. WHO. Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD). Bench Aids for the diagnosis of intestinal parasites. 2019. https://www.who.int/publications/i/ite m/9789241515344. Accessed 10 May 2024.

23. Knopp S, Salim N, Schindler T, Voules DAK, Rothen J, Lweno O, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of Kato-Katz, FLOTAC, Baermann, and PCR methods for the detection of light-intensity hookworm and Strongyloides stercoralis infections in Tanzania. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90:535-45.

24. WHO. Helminth control in school-age children: a guide for managers of control programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2011b. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241548267. Accessed 15 May 2024.

25. WHO. Growth reference data for

26. de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, et al. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(9):660-7. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.07.043497.

27. Usang AU, Imalele EE, Effanga EO, Osondu-Anyanwu C. Prevalence of human intestinal helminthic infections among School-Age Children in Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria. Int J Trop Dis Health. 2020;41(9):55-63. https://doi.org/10. 9734/ijtdh/2020/v41i930318.

28. Chijioke I, Ilechukwu G, Ilechukwu G, Okafor C, Ekejindu I, Sridhar M. A community-based survey of the burden of Ascaris lumbricoides in Enugu. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2011;1(2):165-71.

29. Aemiro A, Menkir S, Girma A. Prevalence of soil-transmitted Helminth infections and Associated Risk factors among School Children in Dembecha Town, Ethiopia. Environ Health Insights. 2024;18. https://doi.org/10.1177/117863022 41245851.

30. Baker SM, Ensink JH. Helminth transmission in simple pit latrines. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106(11):709-10.

31. Farrant O, Marlais T, Houghton J, Goncalves A, Teixeira da Silva Cassama E, Cabral MG, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and health consequences of soiltransmitted helminth infection on the Bijagos Islands, Guinea Bissau: a com-munity-wide cross-sectional study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(12):e0008938. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008938.

32. Muluneh C, Hailu T, Alemu G. Prevalence and Associated factors of soil-transmitted Helminth infections among children living with and without Open Defecation practices in Northwest Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:266-72. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh. 1 9-0704.

33. Hassan AA, Oyebamiji DA, Idowu OF. Spatial patterns of soil-transmitted helminths in the soil environment around Ibadan, an endemic area in southwest Nigeria. Niger J Parasitol. 2017;38:179-84.

34. Kattula D, Sarkar R, Rao Ajjampur SS, Minz S, Levecke B, Muliyil J, Kang G. Prevalence and risk factors for soil transmitted helminth infection among school children in south India. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139(1):76-82.

35. Tekalign E, Bajiro M, Ayana M, et al. Prevalence and intensity of soil-transmitted Helminth infection among Rural Community of Southwest Ethiopia: A Community-based study. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:1-7. https://doi.org/10.1 155/2019/3687873.

36. Pasaribu AP, Alam A, Sembiring K, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of soiltransmitted helminthiasis among school children living in an agricultural area of North Sumatera, Indonesia. BMC Public Health. 2019;19. https://doi.org/10. 1186/s12889-019-7397-6.

37. Eyayu T, Yimer G, Workineh L, et al. Prevalence, intensity of infection and associated risk factors of soil-transmitted helminth infections among school children at Tachgayint Woreda, Northcentral Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0266333. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0266333.

38. Mationg MLS, Williams GM, Tallo VL, et al. Soil-transmitted helminth infections and nutritional indices among Filipino schoolchildren. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:e0010008. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0010008.

39. John C, Poh BK, Jalaludin MY, et al. Exploring disparities in malnutrition among under-five children in Nigeria and potential solutions: a scoping review. Front Nutr. 2024;10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1279130.

40. Ezeh OK, Abir T, Zainol NR, et al. Trends of Stunting Prevalence and its Associated factors among Nigerian children aged

41. Ahmed A, Al-Mekhlafi HM, Al-Adhroey AH, et al. The nutritional impacts of soil-transmitted helminths infections among Orang Asli schoolchildren in rural Malaysia. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-5-11 9.

42. Belizario VY, Liwanag HJC, Naig JRA, et al. Parasitological and nutritional status of school-age and preschool-age children in four villages in Southern Leyte, Philippines: lessons for monitoring the outcome of Community-Led Total Sanitation. Acta Trop. 2015;141:16-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica. 20 14.09.008.

43. WHO. Nutrition Landscape Information System (NLIS) country profile indicators: interpretation guide. 2010. Available from: https://www.who.int/publicat ions/i/item/9789241516952. Accessed 15 June 2024.

44. Belachew T, Hadley C, Lindstrom D, et al. Gender differences in food insecurity and morbidity among adolescents in southwest Ethiopia. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e398-405. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-0944.

45. Mahmood T, Abbas F, Kumar R, et al. Why under five children are stunted in Pakistan? A multilevel analysis of Punjab Multiple indicator Cluster Survey (MICS-2014). BMC Public Health. 2020;20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-02 0-09110-9.

46. Yisak H, Gobena T, Mesfin F. Prevalence and risk factors for under nutrition among children under five at Haramaya district, Eastern Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-015-0535-0.

47. Chowdhury MRK, Rahman MS, Khan MMH, et al. Risk factors for child malnutrition in Bangladesh: a multilevel analysis of a nationwide Population-based survey. J Pediatr. 2016;172:194-201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.01.0 23.

48. Poda GG, Hsu C-Y, Chao JC. -j. factors associated with malnutrition among children < 5 years old in Burkina Faso: evidence from the demographic and health surveys IV 2010. Int J Qual Health Care. 2017;29:901-8. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/intqhc/mzx129.

49. Hailegebriel T. Prevalence and determinants of stunting and Thinness/Wasting among schoolchildren of Ethiopia: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Food Nutr Bull. 2020;41:474-93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0379572120968978.

50. Berhanu A, Garoma S, Arero G, et al. Stunting and associated factors among school-age children (

51. Bloss E, Wainaina F, Bailey R. Prevalence and predictors of underweight, stunting, and wasting among children aged 5 and under in western Kenya. J Trop Pediatr. 2018;50:260-70.

52. Quamme SH, Iversen PO. Prevalence of child stunting in Sub-saharan Africa and its risk factors. Clin Nutr Open Sci. 2022;42:49-61. https://doi.org/10.1016 /j.nutos.2022.01.009.

53. Degarege A, Hailemeskel E, Erko B. Age-related factors influencing the occurrence of undernutrition in northeastern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1490-2.

54. Erismann S, Knoblauch AM, Diagbouga S, Odermatt P, Gerold J, Shrestha A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of undernutrition among schoolchildren in the Plateau Central and Centre-Ouest regions of Burkina Faso. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-016-0230-x.

55. Herrador Z, Sordo L, Gadisa E, Moreno J, Nieto J, Benito A, et al. Crosssectional study of malnutrition and associated factors among school-aged children in rural and urban settings of Fogera and Libo Kemkem districts, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9):e105880.

56. Getaneh Z, Melku M, Geta M, et al. Prevalence and determinants of stunting and wasting among public primary school children in Gondar town, northwest, Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:207. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-01 9-1572-x.

57. Crompton DW, Nesheim MC. Nutritional impact of intestinal helminthiasis during the human life cycle. Annu Rev Nutr. 2002;22:35-59.

ملاحظة الناشر

- *المراسلة:

إديمه إينوجيوموان إيماليل

edemaeddy@gmail.com

القائمة الكاملة لمعلومات المؤلف متاحة في نهاية المقالة

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-21210-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39743623

Publication Date: 2025-01-02

Soil-transmitted helminth infections and nutritional indices among children (

Abstract

Background Soil-transmitted helminth (STH) infections are a significant public health concern in developing countries, particularly affecting children (

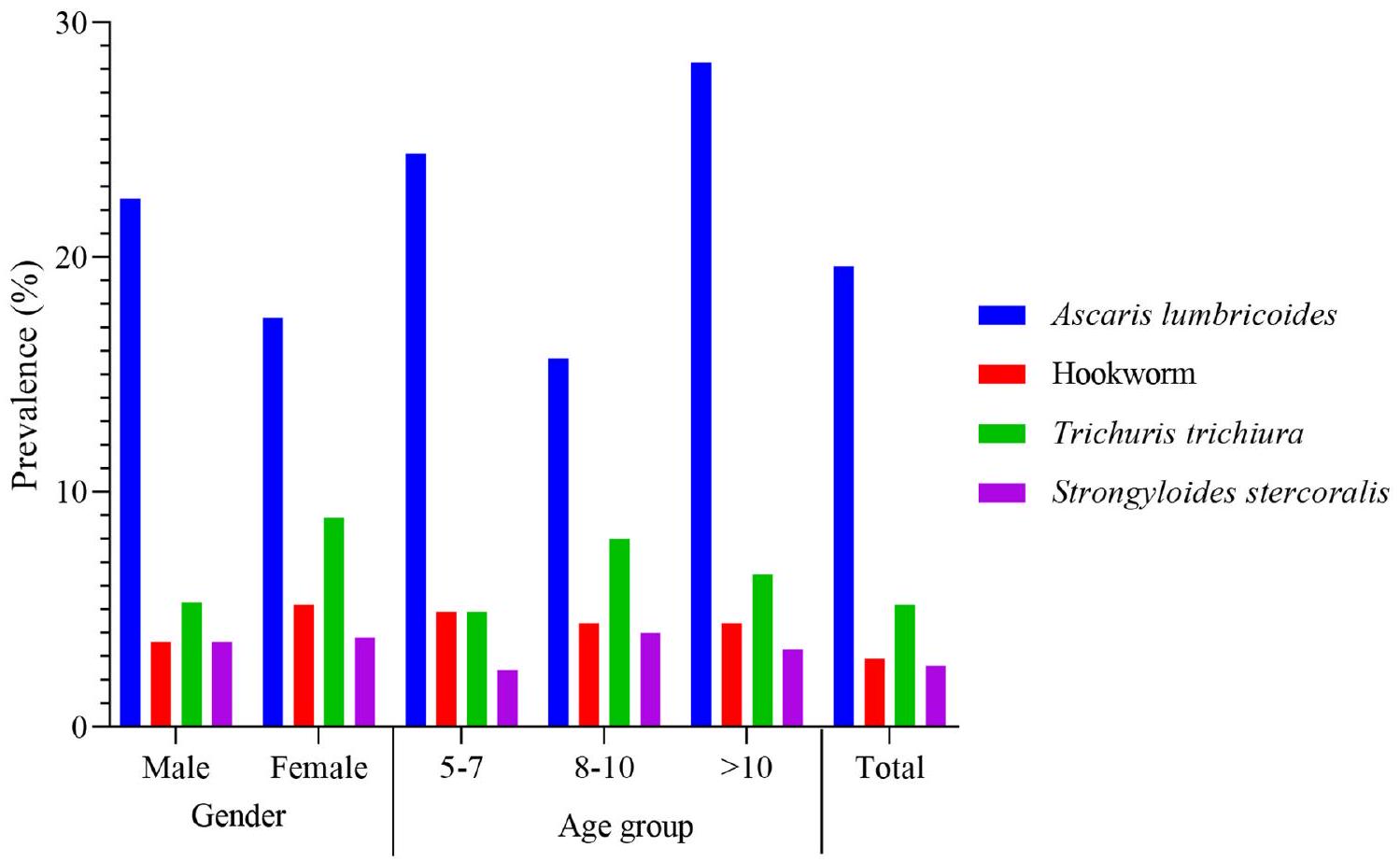

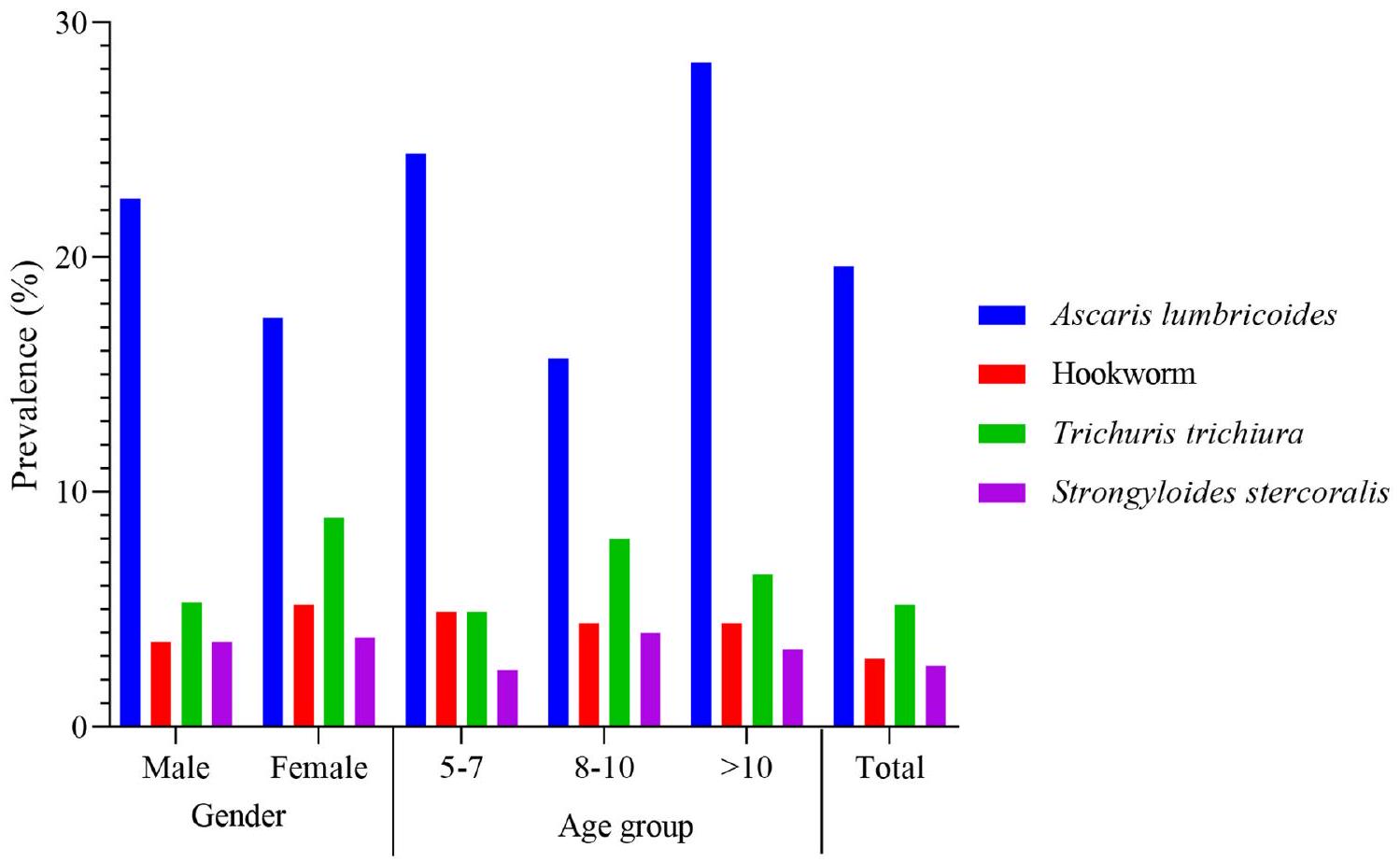

Methods An analytical cross-sectional study was conducted within schools and took place from April to June 2023 and involved 382 participants in Calabar, Nigeria. All participants in the study completed a questionnaire designed to gather information on their demographics and knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) regarding STH infections. Anthropometric measurements were taken according to World Health Organisation (WHO) standards. Fresh faecal samples were collected from each study participant and examined via the Kato-Katz technique. The data were analysed using STATA software, version 14. A binomial logistic regression model was used to identify predictors of STH infections and to examine the associations between STH infection status and stunting, underweight, and wasting. Results The overall prevalence of STHs was 28.8%, with Ascaris lumbricoides (19.6%) being the most prevalent. The prevalence of STHs was greater among males (30.2%) than females (27.7%) and was relatively greater among participants aged 10 years and above (34.8%). All study participants recorded light infection intensities. The prevalence rates of stunting, underweight, and wasting were

Keywords STH, Stunting, Malnutrition, KAP, Risk factors, School children

Background

In Nigeria, STHs are prevalent and represent a significant public health issue [7] and various studies across the country have reported the prevalence of STH ranging from 13.2 to

studies are needed to evaluate the morbidity related to STH in children and adolescents to accurately assess the effectiveness of STH control programmes in the country. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence and risk factors of STH infections and the effect of STH infections on nutritional indices of children (

Methods

Study area

Study design

Sample size determination

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Ethical considerations

Data collection

Knowledge attitude and practice (KAP) questionnaire

such as hand washing, food handling, toilet use, and footwear habits. The questionnaire underwent a pretest at two different schools The questionnaire was pretested at two randomly selected schools from a Ministry of Education list to evaluate its clarity, relevance, and effectiveness. This allowed researchers to identify and resolve any issues, ensuring the questionnaire was suitable for the main study.

The questionnaire was administered by two trained health extension workers, with support from the class teachers. The first health extension worker read out the instructions and questions to the children in the classroom, whereas the second health extension worker and the class teacher moved around to ensure that all the pupils understood the instructions and answered the questions correctly.

Parasitological examination

Finally, the results were documented on a laboratory report sheet. If at least one egg or larvae (for S. stercoralis) were seen on any of the three Kato-Katz thick smear slides, the participant was considered positive. The spe-cies-specific average egg count from the triplicate KatoKatz slides was multiplied by 24 to evaluate the intensity

of STH infection (A. lumbricoides, Hookworm, and T. trichiura) [23]. The number of eggs for each STH species was counted to determine the prevalence and intensity of infection (eggs per gram of faeces, EPG). The infection intensity for each species was classified as light, moderate, or heavy according to the WHO criteria [24].

Nutritional status assessment

Study variables

Data analysis

A t-test was used to compare the mean intensity of STH infections between males and females, whereas one-way ANOVA was used to assess differences in the arithmetic means of STH infections across various age

groups. Descriptive statistics were employed to outline the sociodemographic traits of the participants, presenting frequencies and percentages for categorical data. To examine the relationships between independent variables and the outcome variable, the chi-square test was applied.

For the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) questionnaire, each correct answer in the knowledge and attitude sections was assigned one point, incorrect answers received minus one point, and “do not know” responses were scored zero. In the practices section, “Never” responses were given a score of zero, “Some of the time” were given a score of one, and “Always” were given a score of two, reflecting the frequency of the behaviour.

The participants’ overall knowledge and practice scores were categorised as follows: scores of 20 or more indicated good knowledge/practice, scores between 11 and 19 indicated average knowledge/practice, and scores of 10 or less indicated poor knowledge/practice. Specifically, for knowledge of STH transmission and symptoms, scores of

Binomial logistic regression model was used to identify predictors of STH infections and to examine the

| Characteristic | Number | Percentage |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 169 | 44.2 |

| Female | 213 | 55.8 |

| Age-group (Years) | ||

| 5-7 | 41 | 10.7 |

| 8-10 | 249 | 65.2 |

| >10 | 92 | 24.1 |

| School | ||

| Government Primary School Akim | 100 | 21.2 |

| Government Primary School Henshaw Town | 101 | 26.4 |

| Government Primary School Mayne Avenue | 101 | 26.4 |

| Government Primary School Ikot Ansa | 80 | 20.9 |

| Mother’s Occupation | ||

| Trader | 112 | 29.3 |

| Civil servant | 144 | 37.7 |

| Unemployed | 40 | 10.5 |

| Others | 86 | 22.5 |

| Father’s Occupation | ||

| Trader | 136 | 35.6 |

| Civil servant | 122 | 31.9 |

| Unemployed | 27 | 7.1 |

| Others | 97 | 25.4 |

Results

General characteristics of the study participants

Prevalence and intensity of STH and nutritional characteristics of the study participants

Overall, A. lumbricoides presented the highest infection intensity

Across different age groups, the intensity of STH infections did not significantly differ (

Knowledge of STH

Fever and stomach ache were recognized by

The preventive measures most widely recognized included washing fruits before consumption (

In terms of overall knowledge of STH, only

Water access, sanitation practices, and perceptions of STH prevention among respondents

Additionally, an analysis of sanitation and hygiene practices by age group was conducted, with a focus on handwashing habits, toilet use, and walking barefoot. The results revealed slight variations in hygiene and sanitation practices across age groups, though not statistically significant. Among children,

| Variables | Number | Percentage |

| Heard about STH | ||

| Yes | 268 | 70.2 |

| No | 114 | 29.8 |

| STH Transmission | ||

| Walk barefoot | 58 | 15.1 |

| Eating contaminated food | 164 | 42.9 |

| Eating undercooked and unwashed vegetables | 60 | 15.7 |

| Contact with faeces of an infected person | 44 | 11.5 |

| Mosquito bite | 192 | 50.3 |

| Playing in contaminated areas | 132 | 34.6 |

| Playing with soil | 121 | 31.7 |

| Playing in dirty places | 68 | 17.8 |

| Overall STH transmission knowledge | ||

| Good | 64 | 16.8 |

| Average | 158 | 41.4 |

| Poor | 160 | 41.9 |

| Knowledge about STH signs and symptoms | ||

| Weight loss | 78 | 20.4 |

| Stomach ache | 167 | 43.7 |

| Diarrhoea | 144 | 37.7 |

| Growth impairment | 51 | 13.5 |

| Nausea | 39 | 10.2 |

| Loss of appetite | 70 | 18.3 |

| Blood loss | 65 | 17.0 |

| Fever | 178 | 46.6 |

| Overweight | 102 | 26.7 |

| Low blood pressure | 119 | 31.2 |

| Overall knowledge about signs and symptoms | ||

| Good | 19 | 4.97 |

| Average | 134 | 35.08 |

| Poor | 229 | 59.95 |

| Knowledge about STH prevention | ||

| Eating too much food | 47 | 12.3 |

| Using mosquito net | 127 | 33.3 |

| Using the toilet | 96 | 25.1 |

| Washing fruits before eating | 293 | 76.7 |

| Washing your hands before eating | 287 | 75.1 |

| Washing your hands after using the toilet | 260 | 68.1 |

| Regular exercise | 109 | 28.5 |

| Overall knowledge about STH prevention | ||

| Good | 52 | 13.6 |

| Average | 189 | 49.5 |

| Poor | 141 | 36.9 |

| Overall knowledge score | ||

| Good | 43 | 11.3 |

| Average | 237 | 62.0 |

| Poor | 102 | 26.7 |

| Overall attitude score | ||

| Good | 86 | 22.5 |

| Average | 190 | 49.7 |

| Poor | 106 | 27.75 |

| Overall practice score | ||

| Good | 87 | 22.8 |

| Variables | Number | Percentage |

| Average | 191 | 50.0 |

| Poor | 104 | 27.2 |

| Variables | Frequency (%) | STH | OR (95% CI) |

|

AOR (95% CI) |

|

|

| Positive,

|

Negative,

|

||||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 169 (44.2) | 51 (30.2) | 118 (69.8) | Reference | |||

| Female | 213 (55.8) | 59 (27.7) | 154 (72.3) | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) | 0.595 | 0.7 (0.4-1.2) | 0.329 |

| Source of Drinking Water | |||||||

| Potable water/bottled water/hand pump | 356 (93.2) | 106 (29.8) | 250 (70.2) | Reference | |||

| Unprotected well/Reservoir | 26 (6.8) | 4 (15.4) | 22 (84.6) | 0.4 (0.1-1.3) | 0.097 | 0.4 (0.1-1.4) | 0.182 |

| Type of Toilet | |||||||

| Water Closet | 176 (46.1) | 38 (21.6) | 138 (78.4) | Reference | |||

| Pit Toilet | 182 (47.6) | 67 (36.8) | 115 (63.2) | 2.1 (1.3-3.4) | 0.002 | 1.0 (0.5-1.8) | 0.942 |

| Open defecation | 24 (6.3) | 5 (20.8) | 19 (79.2) | 1.9 (0.3-2.7) | 0.932 | 0.9 (0.2-2.7) | 0.862 |

| Received worm medicine before | |||||||

| Yes | 223 (58.4) | 87 (39.0) | 136 (60.9) | Reference | |||

| No | 159 (41.6) | 23 (14.5) | 136 (85.5) | 0.2 (0.1-0.4) | <0.001 | 0.2 (0.1-0.5) | <0.001 |

| Washing hands after using the toilet | |||||||

| Always | 131 (34.3) | 37 (28.2) | 94 (71.8) | Reference | |||

| Sometimes | 145 (37.9) | 40 (27.6) | 105 (72.4) | 0.9 (0.5-1.6) | 0.903 | 0.9 (0.5-1.7) | 0.941 |

| Never | 106 (27.8) | 33 (31.1) | 73 (68.8) | 1.1 (0.6-2.0) | 0.628 | 1.1 (0.6-2.1) | 0.615 |

| Washing hands before and after eating | |||||||

| Always | 145 (37.9) | 45 (31.0) | 100 (68.9) | Reference | |||

| Sometimes | 137 (35.9) | 43 (31.4) | 94 (68.6) | 1.0 (0.6-1.6) | 0.949 | 1.0 (0.6-1.8) | 0.852 |

| Never | 100 (26.2) | 22 (22.0) | 78 (78.0) | 0.6 (0.3-1.1) | 0.120 | 0.5 (0.3-1.1) | 0.103 |

| Washing fruits and vegetables before eating | |||||||

| Always | 163 (42.7) | 45 (27.6) | 118 (72.4) | Reference | |||

| Sometimes | 129 (33.8) | 33 (25.6) | 96 (74.4) | 0.9 (0.5-1.5) | 0.698 | 0.9 (0.5-1.7) | 0.984 |

| Never | 90 (23.6) | 32 (35.6) | 58 (64.4) | 1.4 (0.8-2.5) | 0.189 | 1.4 (0.8-2.6) | 0.208 |

| Walking barefooted | |||||||

| Always | 130 (34.0) | 40 (30.8) | 90 (69.2) | Reference | |||

| Sometimes | 156 (40.9) | 44 (28.2) | 112 (71.8) | 0.8 (0.5-1.4) | 0.636 | 0.8 (0.4-1.4) | 0.465 |

| Never | 96 (25.1) | 26 (27.1) | 70 (72.9) | 0.8 (0.4-1.4) | 0.547 | 0.9 (0.4-1.7) | 0.785 |

| Believe STH is a serious disease | |||||||

| Yes | 139 (36.4) | 46 (33.1) | 93 (66.9) | Reference | |||

| No | 243 (63.6) | 64 (26.3) | 179 (73.7) | 0.7 (0.4-1.1) | 0.161 | 0.7 (0.4-1.1) | 0.212 |

| Believe STH can be prevented | |||||||

| Yes | 340 (89.0) | 96 (28.2) | 244 (71.8) | Reference | |||

| No | 42 (10.9) | 14 (33.3) | 28 (66.7) | 1.2 (0.6-2.5) | 0.492 | 1.0 (0.4-2.1) | 0.954 |

Factors associated with STH infection

infection (OR: 2.1; 95% CI: 1.3-3.4;

The respondents with average overall knowledge of STH transmission (OR: 1.1; 95% CI: 0.6-1.9;

| Characteristic | Category | STH | OR(95% CI) |

|

AOR (95% CI) |

|

|

| Positive, n (%) | Negative, n (%) | ||||||

| Overall knowledge of STH Transmission score | Good | 18 (28.1) | 46 (71.9) | Reference | |||

| Average | 46 (29.1) | 112 (70.9) | 1.1 (0.6-1.9) | 0.150 | 0.9 (0.8-1.0) | 0.524 | |

| Poor | 46 (28.8) | 111 (71.3) | 1.0 (0.5-1.9) | 0.090 | 1.3 (0.8-2.0) | 0.306 | |

| Overall knowledge score | Good | 12 (27.9) | 31 (72.1) | Reference | |||

| Average | 68 (28.7) | 169 (71.3) | 1.0 (0.5-2.1) | 0.917 | 0.9 (0.6-1.3) | 0.701 | |

| Poor | 30 (29.4) | 72 (70.6) | 1.1 (0.5-2.4) | 0.855 | 0.9 (0.6-1.5) | 0.858 | |

| Overall attitude score | Good | 33 (38.4) | 53 (61.6) | Reference | |||

| Average | 58 (30.5) | 132 (69.5) | 0.7 (0.4-1.2) | 0.200 | 1.9 (0.8-4.4) | 0.113 | |

| Poor | 19 (17.9) | 87 (82.1) | 0.4 (0.1-0.6) | 0.002 | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | 0.003 | |

| Overall practice score | Good | 23 (26.4) | 64 (73.6) | Reference | |||

| Average | 56 (29.3) | 135 (70.7) | 1.1 (0.6-2.0) | 0.621 | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | 0.700 | |

| Poor | 31 (29.8) | 73 (70.2) | 1.1 (0.6-2.2) | 0.607 | 1.1 (0.7-1.4) | 0.440 | |

| Variable | Total (N) | Stunting

|

Univariate OR (95% CI) |

|

Underweight

|

Univariate OR (95% CI) |

|

Wasting (%) | Univariate OR(95% CI) |

|

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 169 | 16 (9.5) | Reference | 12 (7.1) | Reference | 10 (5.9) | Reference | |||

| Female | 213 | 24 (11.3) | 1.2 (0.6-2.3) | 0.569 | 20 (9.4) | 1.3 (0.6-2.8) | 0.424 | 14 (6.6) | 1.1 (0.4-2.5) | 0.793 |

| Age-Group | ||||||||||

| 5-7 | 41 | 7 (17.1) | Reference | 6 (14.6) | Reference | 2 (4.9) | Reference | |||

| 8-10 | 249 | 27 (10.8) | 0.5 (0.2-1.4) | 0.255 | 23 (9.2) | 0.5 (0.2-1.5) | 0.290 | 15 (6.0) | 1.2 (0.2-5.6) | 0.773 |

| >10 | 92 | 6 (6.5) | 0.3 (0.1-1.0) | 0.068 | 3 (3.3) | 0.1 (0.04-0.82) | 0.027 | 7 (7.6) | 1.6 (0.3-8.0) | 0.566 |

| Any STH | ||||||||||

| Positive | 110 | 10 (9.1) | 0.8 (0.3-1.7) | 0.576 | 7 (6.4) | 0.6 (0.2-1.6) | 0.369 | 9 (8.2) | 1.5 (0.6-3.6) | 0.334 |

| Negative | 272 | 30 (11.0) | Reference | 25 (9.2) | Reference | 15 (5.5) | Reference | |||

Associations between STH infection and nutritional indicators

There was no significant association between stunting, underweight, wasting, and STH infection. Interestingly, the odds of being stunted (OR: 0.8; 95% CI: 0.3-1.7;

Discussion

Findings from this study revealed an overall STH prevalence of

The KAP survey indicated that

foster better attitudes and subsequently reduce the prevalence and spread of these infections.

Also, findings indicate that the majority of children across all age groups use pit toilets, reflecting some level of access to basic sanitation facilities. However, the higher prevalence of open defecation among participants aged

The study revealed that

Approximately

Surprisingly, individuals with lower attitude scores were significantly less likely to acquire an STH infection (OR:

Although most participants in the study reported having access to improved drinking water sources, the prevalence of STH infections remained elevated. Since data on household sanitation levels were not gathered in this study, these unmeasured factors may contribute to STH transmission. However, the low prevalence of hookworm and S. stercoralis infections observed may indicate limited faecal contamination in the environment, resulting in a reduced infection risk for these parasites in the study area. No associations were found between STH infections and variables such as sex, gender, water source, handwashing after toilet use, handwashing before and after meals, washing fruits and vegetables before consumption, walking barefoot, or overall knowledge and practices regarding STH among school-aged children, which differs from the findings of previous studies [3437]. Nonetheless, risk factors for STH infections can vary across locations depending on the geography, environmental sanitation, lifestyle, and cultural practices of the local population [38].

The observed rates of stunting (

In our study, female children were observed to have higher rates of stunting, underweight, and wasting than their male counterparts. This may be explained by gen-der-based disparities in nutrition and healthcare access may disproportionately impact females. For example, girls might receive less access to nutritious food or medical services than boys do, increasing their susceptibility to malnutrition-related conditions such as stunting, wasting, and underweight [44]. These findings align with the studies of Mahmood et al. [45], and Yisak et al. [46],

which were conducted in Ethiopia, and Pakistan, respectively, but contrast with the reports of Chowdhury et al. [47], Poda et al. [48], and Hailegebriel [49].

Children between the ages of 8 and 10 years presented a lower likelihood of stunting than those between 5 and 7 years. This contrasts with findings from previous studies [50,51]. Younger children, particularly those in the 5-7 years of age range, tend to be more susceptible to adverse environmental influences such as food scarcity, inadequate sanitation, and limited access to health care. These factors can significantly hinder their growth and development, resulting in elevated stunting rates compared with those of older children, who may have outgrown their most critical years of vulnerability [52]. Furthermore, individuals above the age of 10 years presented a notably lower likelihood of being classified as underweight than did those between the ages of 5 and 7 years. These findings align with the studies conducted by Degarege et al. [53] and Erismann et al. [54] in Ethiopia and Burkina Faso, respectively. As children mature, they may gain improved access to a more diverse range of foods or acquire healthier eating practices, thereby enhancing their nutritional status compared to younger children, who may still be dependent on caregivers for their meals [53].

Nevertheless, the likelihood of experiencing wasting was greater among participants aged

No statistically significant correlation was detected between stunting, underweight, and wasting and STH infection. Notably, the likelihood of being stunted and underweight was lower in individuals who tested positive for STH than in those who were negative. In contrast, the likelihood of wasting was elevated in STH-positive individuals relative to their negative counterparts. These findings align with the results of Degarege et al. [53]. The impact of helminth infections on a host’s nutritional status is more severe when infections are prolonged and intense [57]. All the STH infections reported in this study were of low intensity.

Limitations

limitation, as it precludes the evaluation of causal relationships between STH and the identified risk factors. Furthermore, the study did not measure micronutrient intake or red blood cell counts in the children. Moreover, factors like the presence of other parasites such as Plasmodium, participants’ dietary needs, and socio-economic status can greatly impact the nutritional indices observed. Therefore, future research of a similar nature should address these limitations.

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Author details

Published online: 02 January 2025

References

- Pan American Health Organization. Soil transmitted helminthiasis. 2024. htt ps://www.paho.org/en/topics/soil-transmitted-helminthiasis#:~:text=Geoh elminthiasis%20or%20 soil-transmitted%20helminths,Necatamericanus%20 and%20Ancylostoma%20duodenale Accessed 10 May 2024.

- WHO. Ending the neglect to attain the Sustainable Development Goals-A road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021-2030 Geneva. 2020a. https ://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/Ending-the-neglect-to-attain-the-SD Gs—NTD-Roadmap.pdf?ua=1 Accessed 10 May 2024.

- WHO. Guideline: preventive chemotherapy to control soil-transmitted helminth infections in at-risk population groups. 2017. https://iris.who.int/handl e/10665/258983. Accessed 10 May 2024.

- WHO. Intestinal worms: soil-transmitted helminthes. World Health Organization; 2011a.

- Lebu S, Kibone W, Muoghalu CC, Ochaya S, Salzberg A, Bongomin F, Manga M. Soil-transmitted helminths: a critical review of the impact of coinfections and implications for control and elimination. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023;17(8):e0011496. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0011496.

- Quiroz DJG, Del Pilar Agudelo Lopez S, Arango CM, Acosta JEO, Parias LDB, Alzate LU, et al. Prevalence of soil transmitted helminths in school-aged children, Colombia, 2012-2013. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(7):e0007613. htt ps://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007613.

- Idowu OA, Babalola AS, Olapegba T. Prevalence of soil-transmitted helminth infection among children under 2 years from urban and rural settings in Ogun state, Nigeria: implication for control strategy. Gaz Egypt Paediatr Assoc. 2022;70(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43054-021-00096-6.

- Karshima SN. Prevalence and distribution of soil-transmitted helminth infections in Nigerian children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-018-0451-2.

- Imalele EE, Effanga EO, Usang AU. Environmental contamination by soiltransmitted helminths ova and subsequent infection in school-age children in Calabar. Nigeria Sci Afr. 2023a;19:e01580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf. 202 3.e01580.

- Stephenson LS, Lathan MC, Ottesen EA. Malnutrition and parasitic helminthes infections. Parasitology. 2000;121(Suppl):523-8.

- Bain LE, Awah PK, Geraldine N, Kindong NP, Sigal Y, Bernard N, Tanjeko AT. Malnutrition in Sub-saharan Africa: burden, causes and prospects. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;15:120. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2013.15.120.2535.

- Osaro BO, Edet CK, Ben-Osaro NV. Prevalence, pattern and factors associated with undernutrition among primary school aged children in Rivers State Nigeria. Ibom Med J. 2023;16(1):70-80.

- Omage K, Omuemu V. Factors associated with the dietary habits and nutritional status of undergraduate students in a private university in Southern Nigeria. Nigerian J Exp Clin Biosci. 2019;7:7. https://doi.org/10.4103/njecp.nje cp_1_19.

- Ukwajunor EE, Adebayo SB, Gayawan E. Spatio-temporal modelling of severity of malnutrition and its associated risk factors among under five children in Nigeria between 2003 and 2018: bayesian multilevel structured additive regressions. Stat Methods. 2023;32:1743-77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1026 0-023-00711-3.

- Obasohan PE, Walters SJ, Jacques R, et al. Socio-economic, demographic, and contextual predictors of malnutrition among children aged 6-59 months in Nigeria. BMC Nutr. 2024https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-023-00813-x.

- Imalele EE, Evbuomwan OI, Osondu-Anyanwu C, Akpan BC. Evaluation of Vegetable Contamination with medically important helminths and protozoans in Calabar, Nigeria. J Adv Biol. 2020;23(9):10-6. https://doi.org/10.9734/ja bb/2020/v23i930176.

- Genet A, Motbainor A, Samuel T, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of soil transmitted helminthiasis among school-age children in wetland and non-wetland areas of Blue Nile Basins, northwest

18. Imalele EE, Braide EI, Emanghe UE, et al. Soil-transmitted helminth infection among school-age children in Ogoja, Nigeria: implication for control. Parasitol Res. 2023b;122:1015-26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-023-07809-3.

19. Bruno T, Omar T. Impact of annual praziquantel treatment on urogenital schistosomiasis in seasonal transmission seasons foci in central Senegal. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(3):10-6.

20. Mationg MLS, Gordon CA, Tallo VL, Olveda RM, Alday PP, Renosa MDC, et al. Status of soil-transmitted helminth infections in schoolchildren in Laguna Province, the Philippines: determined by parasitological and molecular diagnostic techniques. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(11):e0006022. https://doi. org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0006022.

21. Katz N, Chaves A, Pellegrino J. A simple device for quantitative stool thicksmear technique in Schistosoma mansoni. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1972;14(6):397-400.

22. WHO. Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD). Bench Aids for the diagnosis of intestinal parasites. 2019. https://www.who.int/publications/i/ite m/9789241515344. Accessed 10 May 2024.

23. Knopp S, Salim N, Schindler T, Voules DAK, Rothen J, Lweno O, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of Kato-Katz, FLOTAC, Baermann, and PCR methods for the detection of light-intensity hookworm and Strongyloides stercoralis infections in Tanzania. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90:535-45.

24. WHO. Helminth control in school-age children: a guide for managers of control programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2011b. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241548267. Accessed 15 May 2024.

25. WHO. Growth reference data for

26. de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, et al. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(9):660-7. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.07.043497.

27. Usang AU, Imalele EE, Effanga EO, Osondu-Anyanwu C. Prevalence of human intestinal helminthic infections among School-Age Children in Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria. Int J Trop Dis Health. 2020;41(9):55-63. https://doi.org/10. 9734/ijtdh/2020/v41i930318.

28. Chijioke I, Ilechukwu G, Ilechukwu G, Okafor C, Ekejindu I, Sridhar M. A community-based survey of the burden of Ascaris lumbricoides in Enugu. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2011;1(2):165-71.

29. Aemiro A, Menkir S, Girma A. Prevalence of soil-transmitted Helminth infections and Associated Risk factors among School Children in Dembecha Town, Ethiopia. Environ Health Insights. 2024;18. https://doi.org/10.1177/117863022 41245851.

30. Baker SM, Ensink JH. Helminth transmission in simple pit latrines. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106(11):709-10.

31. Farrant O, Marlais T, Houghton J, Goncalves A, Teixeira da Silva Cassama E, Cabral MG, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and health consequences of soiltransmitted helminth infection on the Bijagos Islands, Guinea Bissau: a com-munity-wide cross-sectional study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(12):e0008938. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008938.

32. Muluneh C, Hailu T, Alemu G. Prevalence and Associated factors of soil-transmitted Helminth infections among children living with and without Open Defecation practices in Northwest Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:266-72. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh. 1 9-0704.

33. Hassan AA, Oyebamiji DA, Idowu OF. Spatial patterns of soil-transmitted helminths in the soil environment around Ibadan, an endemic area in southwest Nigeria. Niger J Parasitol. 2017;38:179-84.

34. Kattula D, Sarkar R, Rao Ajjampur SS, Minz S, Levecke B, Muliyil J, Kang G. Prevalence and risk factors for soil transmitted helminth infection among school children in south India. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139(1):76-82.

35. Tekalign E, Bajiro M, Ayana M, et al. Prevalence and intensity of soil-transmitted Helminth infection among Rural Community of Southwest Ethiopia: A Community-based study. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:1-7. https://doi.org/10.1 155/2019/3687873.

36. Pasaribu AP, Alam A, Sembiring K, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of soiltransmitted helminthiasis among school children living in an agricultural area of North Sumatera, Indonesia. BMC Public Health. 2019;19. https://doi.org/10. 1186/s12889-019-7397-6.

37. Eyayu T, Yimer G, Workineh L, et al. Prevalence, intensity of infection and associated risk factors of soil-transmitted helminth infections among school children at Tachgayint Woreda, Northcentral Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0266333. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0266333.

38. Mationg MLS, Williams GM, Tallo VL, et al. Soil-transmitted helminth infections and nutritional indices among Filipino schoolchildren. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:e0010008. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0010008.

39. John C, Poh BK, Jalaludin MY, et al. Exploring disparities in malnutrition among under-five children in Nigeria and potential solutions: a scoping review. Front Nutr. 2024;10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1279130.

40. Ezeh OK, Abir T, Zainol NR, et al. Trends of Stunting Prevalence and its Associated factors among Nigerian children aged

41. Ahmed A, Al-Mekhlafi HM, Al-Adhroey AH, et al. The nutritional impacts of soil-transmitted helminths infections among Orang Asli schoolchildren in rural Malaysia. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-5-11 9.

42. Belizario VY, Liwanag HJC, Naig JRA, et al. Parasitological and nutritional status of school-age and preschool-age children in four villages in Southern Leyte, Philippines: lessons for monitoring the outcome of Community-Led Total Sanitation. Acta Trop. 2015;141:16-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica. 20 14.09.008.

43. WHO. Nutrition Landscape Information System (NLIS) country profile indicators: interpretation guide. 2010. Available from: https://www.who.int/publicat ions/i/item/9789241516952. Accessed 15 June 2024.

44. Belachew T, Hadley C, Lindstrom D, et al. Gender differences in food insecurity and morbidity among adolescents in southwest Ethiopia. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e398-405. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-0944.

45. Mahmood T, Abbas F, Kumar R, et al. Why under five children are stunted in Pakistan? A multilevel analysis of Punjab Multiple indicator Cluster Survey (MICS-2014). BMC Public Health. 2020;20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-02 0-09110-9.

46. Yisak H, Gobena T, Mesfin F. Prevalence and risk factors for under nutrition among children under five at Haramaya district, Eastern Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-015-0535-0.

47. Chowdhury MRK, Rahman MS, Khan MMH, et al. Risk factors for child malnutrition in Bangladesh: a multilevel analysis of a nationwide Population-based survey. J Pediatr. 2016;172:194-201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.01.0 23.

48. Poda GG, Hsu C-Y, Chao JC. -j. factors associated with malnutrition among children < 5 years old in Burkina Faso: evidence from the demographic and health surveys IV 2010. Int J Qual Health Care. 2017;29:901-8. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/intqhc/mzx129.

49. Hailegebriel T. Prevalence and determinants of stunting and Thinness/Wasting among schoolchildren of Ethiopia: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Food Nutr Bull. 2020;41:474-93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0379572120968978.

50. Berhanu A, Garoma S, Arero G, et al. Stunting and associated factors among school-age children (

51. Bloss E, Wainaina F, Bailey R. Prevalence and predictors of underweight, stunting, and wasting among children aged 5 and under in western Kenya. J Trop Pediatr. 2018;50:260-70.

52. Quamme SH, Iversen PO. Prevalence of child stunting in Sub-saharan Africa and its risk factors. Clin Nutr Open Sci. 2022;42:49-61. https://doi.org/10.1016 /j.nutos.2022.01.009.

53. Degarege A, Hailemeskel E, Erko B. Age-related factors influencing the occurrence of undernutrition in northeastern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1490-2.

54. Erismann S, Knoblauch AM, Diagbouga S, Odermatt P, Gerold J, Shrestha A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of undernutrition among schoolchildren in the Plateau Central and Centre-Ouest regions of Burkina Faso. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-016-0230-x.

55. Herrador Z, Sordo L, Gadisa E, Moreno J, Nieto J, Benito A, et al. Crosssectional study of malnutrition and associated factors among school-aged children in rural and urban settings of Fogera and Libo Kemkem districts, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9):e105880.

56. Getaneh Z, Melku M, Geta M, et al. Prevalence and determinants of stunting and wasting among public primary school children in Gondar town, northwest, Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:207. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-01 9-1572-x.

57. Crompton DW, Nesheim MC. Nutritional impact of intestinal helminthiasis during the human life cycle. Annu Rev Nutr. 2002;22:35-59.

Publisher’s note

- *Correspondence:

Edema Enogiomwan Imalele

edemaeddy@gmail.com

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article