DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.142213

تاريخ النشر: 2024-04-25

عوامل أداء البيئة والمجتمع والحوكمة (ESG): مراجعة منهجية للأدبيات

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

مراجعة أدبية منهجية

التمويل المستدام

عوامل ESG

البيئة والمجتمع والحوكمة

الملخص

فهم محددات أداء الشركات في مجال البيئة والمجتمع والحوكمة (ESG) ليس فقط هدفًا رئيسيًا في مجال الإدارة الاستراتيجية، ولكنه أيضًا أساسي لمعالجة التحديات البيئية والاجتماعية الأكثر إلحاحًا في العالم وضمان بقاء ESG. حتى الآن، لم يتم إجراء نظرة شاملة على المحددات التي لها أكبر تأثير على معايير ESG. في هذا العمل، تم تحديد وتحليل المحددات الداخلية والخارجية، واستكشاف الأسباب المحتملة للاختلافات في نتائج الأبحاث. تم تطوير هذه المراجعة المنهجية للأدبيات وفقًا لإرشادات PRISMA، التي أدت إلى تحليل محتوى النتائج. تثبت الدراسة الحالية أن الاختلافات في نتائج الأدبيات هي نتيجة مباشرة لعدم اعتبار الباحثين للاستخدامات المختلفة لمزودي بيانات ESG بالإضافة إلى التباين بين الدول. لا تمثل هذه الدراسة فقط الإطار الرائد الأول في هذا الموضوع، ولكن يمكن أن تكون أيضًا دليلًا للشركات التي ترغب في تحسين أدائها في مجال ESG.

1. المقدمة

الأوراق ذات الصلة وفجوة الأدبيات.

| المؤلفون | المنهجية | هدف الدراسة | المحددات | الجغرافيا | قاعدة البيانات المستخدمة | قياس ESG | الإطار الزمني | فرص البحث المستقبلية | ||||||||

| علي وآخرون (2017) | مراجعة أدبية منهجية | تستعرض الدراسة العوامل التي تؤثر على الإفصاح عن المسؤولية الاجتماعية للشركات | داخلي وخارجي | الدول المتقدمة والدول النامية | جوجل سكولار | لا يقدم البحث تحليلًا لمصادر الإفصاحات أو قياسها | حتى عام 2014 |

|

||||||||

| كرايس وجيهيمان (2022) | طرق كمية: نماذج تقسيم التباين | تدرس الدراسة العوامل التي تفسر التباين في أداء ESG بين الشركات | داخلي وخارجي | السياق الأمريكي | – | إحصائيات MSCI ESG KLD |

|

|

||||||||

| ديسلي وآخرون (2022) | طرق كمية: طريقة تقدير النظام GMM ذات الخطوتين | تدرس الدراسة آثار الخصائص المؤسسية على الاستدامة المؤسسية | الحوكمة الداخلية للشركات | الدول الناشئة | – | ريفينيتيف | 2010-2019 | يحتاج الأمر إلى مزيد من البحث لشرح أصول وعوامل الأداء المستدام المختلفة. | ||||||||

| تشن وآخرون (2022) | طرق كمية: نموذج الاختلافات – اللامبالاة (did) | تهدف الدراسة إلى تحليل تأثير الإصلاح المالي الأخضر على درجات ESG للشركات. | تنظيم خارجي | الصين | – | بلومبرغ | 2014-2020 | – مجموعة بيانات ESG واحدة | ||||||||

| أورليتسكي وآخرون (2017) | طرق كمية: ثلاث طرق مختلفة لتحليل تفكيك التباين | تهدف الدراسة إلى تقدير تأثير العوامل الكلية والمتوسطة والصغيرة على CSP | داخلي وخارجي | عينة دولية | – | سستيناليتيكس | 2003-2007 |

|

||||||||

| موونيابين وآخرون (2022) | طرق كمية: الانحدار الخطي المتعدد ذو التأثيرات الثابتة | تهدف الدراسة إلى تقدير تأثير حوكمة الدول على أداء ESG | حوكمة الدول الخارجية | 27 دولة | – | ريفينيتيف | 2015-2019 |

|

||||||||

| كاي وآخرون (2016) | الطرق الكمية: تحليل الانحدار الخطي العادي | تهدف الدراسة إلى تحليل سبب أهمية الدول في CSP | داخلي وخارجي | 36 دولة | – | إحصائيات MSCI ESG KLD | 2006-2011 |

|

||||||||

| أرمينن وآخرون (2017) | طرق كمية: تحليلات الانحدار الخطي | تهدف الدراسة إلى تقدير الفروق بين الصناعات والفروق الدولية في أداء الشركات في المسؤولية الاجتماعية للشركات. | حوكمة الدول الخارجية والصناعة | 52 دولة | – | CSRHUB | 2010-2015 | – تأتي الغالبية العظمى من الشركات من عدد محدود نسبيًا من الدول (الولايات المتحدة، اليابان، المملكة المتحدة) | ||||||||

| المؤلفون | المنهجية | هدف الدراسة | المحددات | الجغرافيا | قاعدة البيانات المستخدمة | قياس ESG | الإطار الزمني | فرص البحث المستقبلية | |||

|

|||||||||||

| غارسيا وأورساتو (2020) | طرق كمية: تحليل الانحدار | تهدف الدراسة إلى تحليل العلاقة بين معايير البيئة والمجتمع والحوكمة (ESG) والأداء المالي | الأداء المالي الداخلي | الدول الناشئة والمتقدمة | – | ريفينيتيف | 2007-2014 | – يمكن أن تشمل الأبحاث المستقبلية أخرى | |||

| غارسيا وآخرون (2017) | طرق كمية: الانحدار الخطي | تدرس الدراسة تأثير الأداء المالي في الشركات العاملة في الصناعات الحساسة | الأداء المالي الداخلي والخارجي والصناعة | دول البريكس | – | ريفينيتيف | 2010-2012 |

|

|||

| شورت وآخرون (2015) | طرق كمية: تحليل RCM | تهدف الدراسة إلى فحص درجة ارتباط المسؤولية الاجتماعية للشركات بالعوامل المتعلقة بالشركة والصناعة والعوامل الزمنية. | داخلي وخارجي | الولايات المتحدة | – | KLD | 2003-2011 |

|

مدرج في التحليل.

لذلك، تهدف مراجعتنا إلى توسيع وتكملة نتائجهم من خلال دمجها مع بقية الأدبيات في عملية التنظيم.

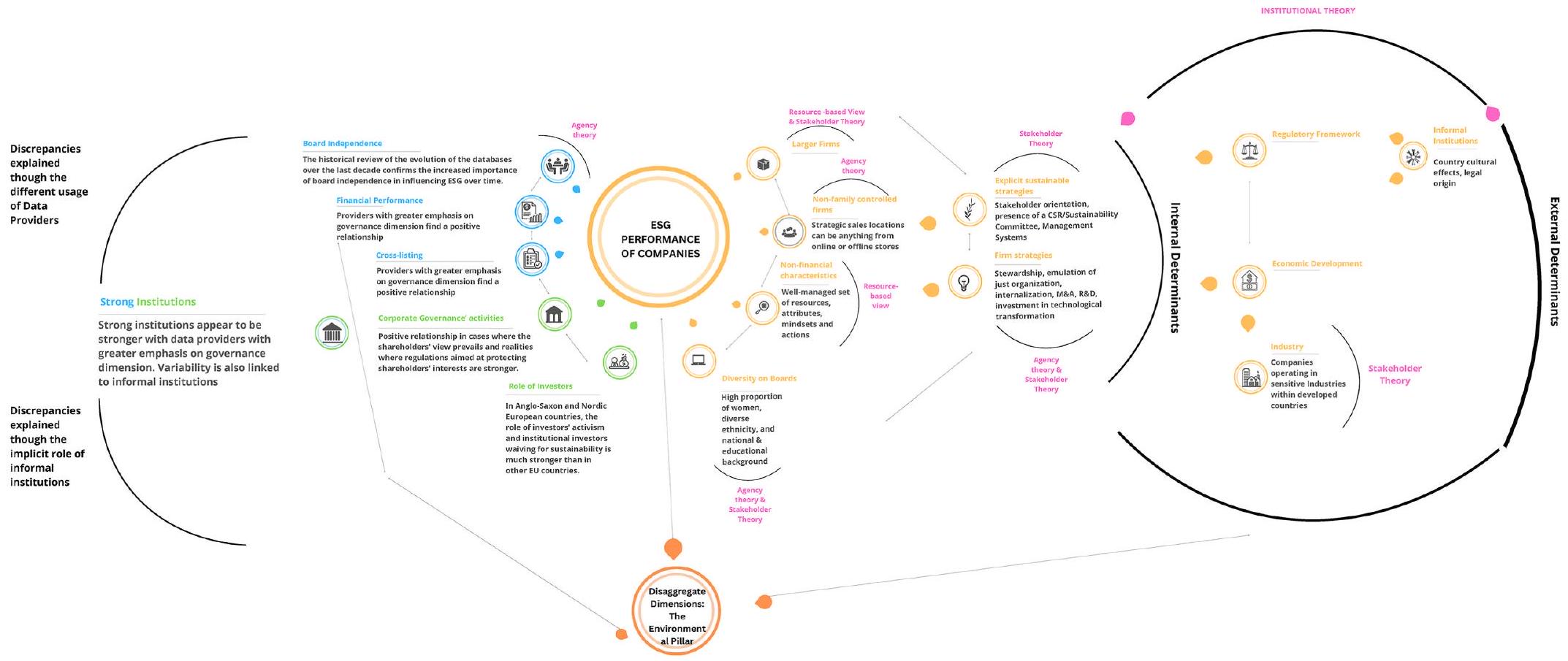

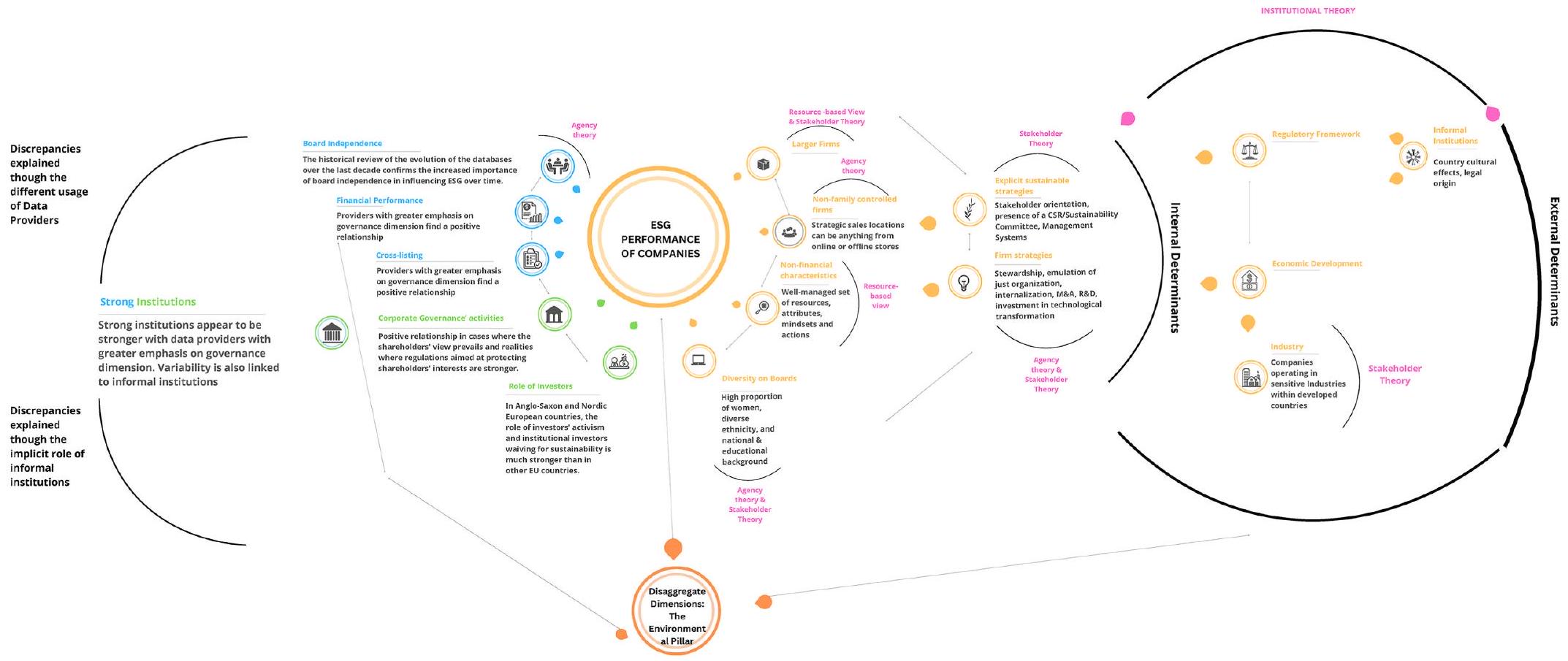

- على عكس أداء الشركات، فإن قياس أداء ESG يفتقر إلى التوحيد القياسي. غالبًا ما تظهر تقييمات ESG من مزودين مختلفين “اختلافات كبيرة” (بيرغ وآخرون، 2022، ص. 1)، مما يؤدي إلى عدم اليقين عند مقارنة ملفات ESG الخاصة بالشركات وصعوبات في تلخيص نتائج دراسات متعددة.

- فيما يتعلق بالبحث في أداء ESG، حصلت كل من الاقتصادات المتقدمة والأسواق الناشئة على اهتمام كبير (لوزانو ومارتينيز-فيريرو، 2022؛ كاي وآخرون، 2016؛ غارسيا وأورساتو، 2020؛ مونيابين وآخرون، 2022). ومع ذلك، كانت استكشاف الفروق بين البلدان كعوامل غير مباشرة للمحددات، لا سيما من حيث حوكمة الشركات وخصائص الشركات، محدودًا. وبالتالي، هناك حالات لا يمكن فيها تعميم بعض النتائج.

- بشكل عام، تركز معظم المقالات أكثر على العوامل الداخلية لأداء ESG بدلاً من العوامل الخارجية. قد يكون ذلك لأن العوامل الداخلية أسهل في القياس والسيطرة، بينما قد تكون العوامل الخارجية أكثر تعقيدًا وصعوبة في التقدير. إن إغفال العوامل الخارجية لأداء ESG يمكن أن يكون مشكلة لأنه قد يؤدي إلى فهم غير مكتمل للعوامل التي تدفع الأداء المستدام على المدى الطويل. تماشيًا مع الرؤى التي قدمها ليانغ ورينيبوج (2017) بشأن المسؤولية الاجتماعية للشركات، فإن الخصائص المعقدة والمترابطة لـ ESG، المدفوعة بالعوامل الخارجية، تشير إلى أنه يجب أن يكون مرتبطًا جوهريًا ليس فقط بقرارات الشركة الفردية، ولكن أيضًا بالتنظيمات والأطر المؤسسية والميول الاجتماعية.

- يمكن أن يؤدي التركيز المحدود على الأعمدة الفردية إلى إضعاف قيمة البحث، حيث أن “العوامل المؤثرة على الأبعاد المختلفة للممارسات والأداء المؤسسي إلى

“ويمكن أن تختلف مكونات G” (موونيابين وآخرون، 2022).

2. الخلفية النظرية

2.1. أهمية المحددات الداخلية والخارجية للتباين في أداء ESG

(خالد وآخرون، 2021) والخصائص غير المالية، مثل الهيكل، والموارد، والعقليات (كاي وآخرون، 2016)، والرئيس التنفيذي (غارسيا-بلاندون وآخرون، 2019)، وخصائص المجلس (بيجي ولوقيل، 2021). تشمل العوامل الخارجية الأطر التنظيمية (أهلستروم ومونسيارديني، 2022)، وتأثيرات الدول (عمر وآخرون، 2020)، والصناعة (شورت وآخرون، 2015)، والوقت (أورليتسكي وآخرون، 2017). في أدبيات الإدارة الاستراتيجية، وجدت الدراسات عمومًا أنه بينما تؤثر كل من عوامل الشركة والصناعة على الأداء المالي المؤسسي، تفسر عوامل مستوى الشركة نسبة أعلى من التباين (شورت وآخرون، 2015)، خاصة بسبب تكويناتها الفريدة من الموارد (بارني، 1991). من حيث أداء ESG، لا يزال من غير الواضح ما إذا كان يمكننا استخلاص استنتاجات مماثلة، ولا تزال الحالة غير مرضية.

ما هي العوامل التي تفسر الأداء المتباين في معايير البيئة والمجتمع والحوكمة (ESG) بين الشركات؟ ما هي المحركات التي تفسر الفجوات في الأدبيات المتعلقة بدور وتأثير هذه العوامل على أداء ESG؟

2.2. أهمية تحليل ESG على المستوى التفصيلي

سلوكيات الفساد، هياكل مجلس الإدارة القائمة على التنوع والعدالة، والشفافية والاستدامة كعناصر مهمة في مهمة الشركة. كما هو متوقع، فإن أداء ESG يزداد مع تحسن أي من أبعاده الثلاثة، مع ثبات الآخرين. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن أن يؤدي التفاعل بينها إلى نتائج تآزرية (هوستيد وفيليو، 2016). في الوقت نفسه، تسلط دراسة كرايس وجيهمان (2022) الضوء على الحاجة إلى التمييز بين المؤشرات الإيجابية والسلبية لتجنب تبسيط الطبيعة المعقدة متعددة الأبعاد لأداء ESG. قد تساعد دراسة مفصلة للعوامل المحددة في توضيح تأثير بعض العناصر لأن هناك ثلاثة أعمدة متميزة تستجيب لوجيستيات متميزة. الهدف الثاني من مراجعتنا هو بالتالي الإجابة على سؤال البحث التالي:

2.3. النظرية في الممارسة: شرح الأطر النظرية

النظريات – النموذجية في مجال الإدارة – قد تم تطبيقها على أداء ESG وما هي تداعياتها العملية. لذلك، فإن السؤال البحثي الثالث هو:

2.4. أداء ESG: إطار مشترك مع مقاييس مختلفة

خصائص متباينة بين مقدمي بيانات ESG المختلفين.

| MSCI ESG | تحليلات KLD | ريفينيتيف (Asset4) | Sustainalytics | ||||||||

| درجة التقييم | CCC إلى AAA | نهج قائم على السرد للتقييم | 0-100 & D- إلى A+ | 0-100 | |||||||

| التاريخ | 1990 | 1988 | 2002 | 1992 | |||||||

| المقر | نيويورك، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية | بوسطن، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية | تورونتو، كندا | أمستردام، هولندا | |||||||

| النطاق | تقييم تعرض الشركات وإدارتها لمخاطر وفرص ESG | “تأثير سلوك الشركات نحو عالم أكثر عدلاً واستدامة” (KLD، 2005) | تم تصميم درجات ESG من ريفينيتيف لقياس الأداء النسبي لـ ESG، والالتزام، والفعالية | قياس تعرض الشركة لمخاطر ESG المادية الخاصة بالصناعة وإدارة تلك المخاطر. | |||||||

| المصادر | إفصاح الشركة + وسائل الإعلام، والمنظمات غير الحكومية، وقواعد بيانات الحكومة + مجموعة بيانات متخصصة للبيانات الكلية | الإفصاح الذاتي | البيانات المعلنة علنًا: مواقع الشركات، تقارير الشركات، مواقع المنظمات غير الحكومية، وسائل الإعلام والأخبار، إيداعات البورصة | الإفصاح العام، وسائل الإعلام والأخبار، تقارير المنظمات غير الحكومية | |||||||

| عدد المعايير | 35 | 178 | 155 | ||||||||

| القضايا الرئيسية | اجتماعية | بيئية | |||||||||

|

|

|

تتغير العوامل وفقًا للمجموعة الصناعية التي تنتمي إليها الشركة | ||||||||

|

|

جدل ESG | |||||||||

| حوكمة الشركات، الشركات | |||||||||||

| الأوزان | كانت الطريقة متسقة من حيث المقاييس | الوزن القياسي لجميع الفئات: البيئة = 42.5%، الاجتماعية 32.5%، الحوكمة

|

انظر أعلاه | ||||||||

| المادية | تُجمع معايير ESG وتُعدل بالنسبة لنظرائها في الصناعة | كانت التقييمات مطلقة: قضايا ذات أهمية عالمية عبر الصناعات مع التركيز على المجتمع، وليس على الشركات. | تم تضمين أوزان فريدة لمقياس ESG (الأهمية) | مؤشرات محددة للصناعة. |

3. طرق البحث

تحسين دقة وكفاءة عمليات البحث، من خلال توفير مفردات موحدة تمكّن المستخدمين من استرجاع المقالات ذات الصلة بسهولة أكبر. تم استخدام التمويل المستدام أيضًا لتضمين الأوراق التي تناولت السياسات التي تعكس النقاشات الأوسع حول دور التمويل في المجتمع (أهلستروم ومونسيارديني، 2022). ‘التمويل المستدام’ هو مصطلح شامل لمجموعة متنوعة من المصطلحات القابلة للتبادل إلى حد كبير: التمويل الاجتماعي؛ الاستثمار الأخلاقي المستدام؛ الاستثمار المسؤول اجتماعيًا؛ الاستثمار المسؤول المستدام (ريزي وآخرون، 2018). يشمل التمويل المستدام أيضًا الفكرة الأولى للاستثمار الأخلاقي: يجب أن يلتزم الاستثمار بنفس المبادئ الأخلاقية التي يلتزم بها المستثمر (دريمبيتيك وآخرون، 2020). نظرًا لأن البحث يعتمد على افتراض التمويل المستدام كـ “نهج أخلاقي فضيل” والعدالة بين الأجيال كهدف للتمويل المستدام، قررنا تضمين مصطلح “أخلاقي” في خوارزميتنا (سوب، 2004). كما تم تضمين الأداء المؤسسي البيئي والاجتماعي والحوكمة كأعمدة فردية في الخوارزمية.

- SCOPUS: مصطلحات الفهرسة (“التمويل المستدام” أو “أداء ESG” أو “مؤشر ESG*” أو “الاستثمار الأخضر” أو “أداء البيئة المؤسسية” أو “الأداء الاجتماعي المؤسسي” أو “أداء الحوكمة الأخلاقية المؤسسية”)“) أو TITLE-ABS-KEY (“التمويل المستدام” أو “أداء ESG” أو “مؤشر ESG”” أو “الاستثمار الأخضر” أو “الأداء البيئي للشركات” أو “الأداء الاجتماعي للشركات” أو “أداء الحوكمة الأخلاقية للشركات*” ) AND (“شركة*” أو “مؤسسة*” أو “عمل”)

- WOS: (“التمويل المستدام” أو “أداء ESG” أو “مؤشر ESG*” أو “الاستثمار الأخضر” أو “الأداء البيئي للشركات” أو “الأداء الاجتماعي للشركات” أو “أداء الحوكمة الأخلاقية للشركات*”) AND (“شركة*” أو “مؤسسة*” أو “عمل”)

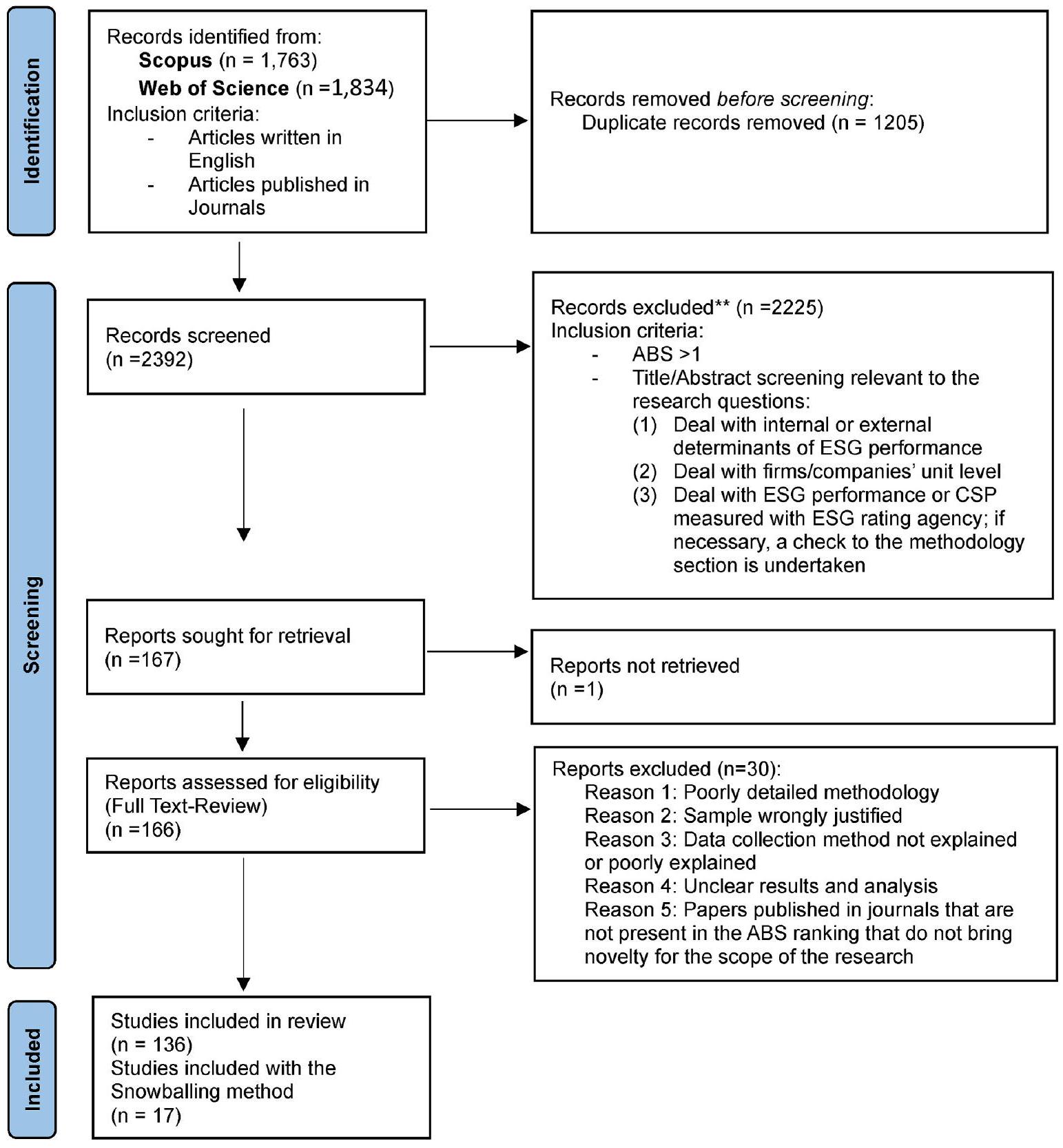

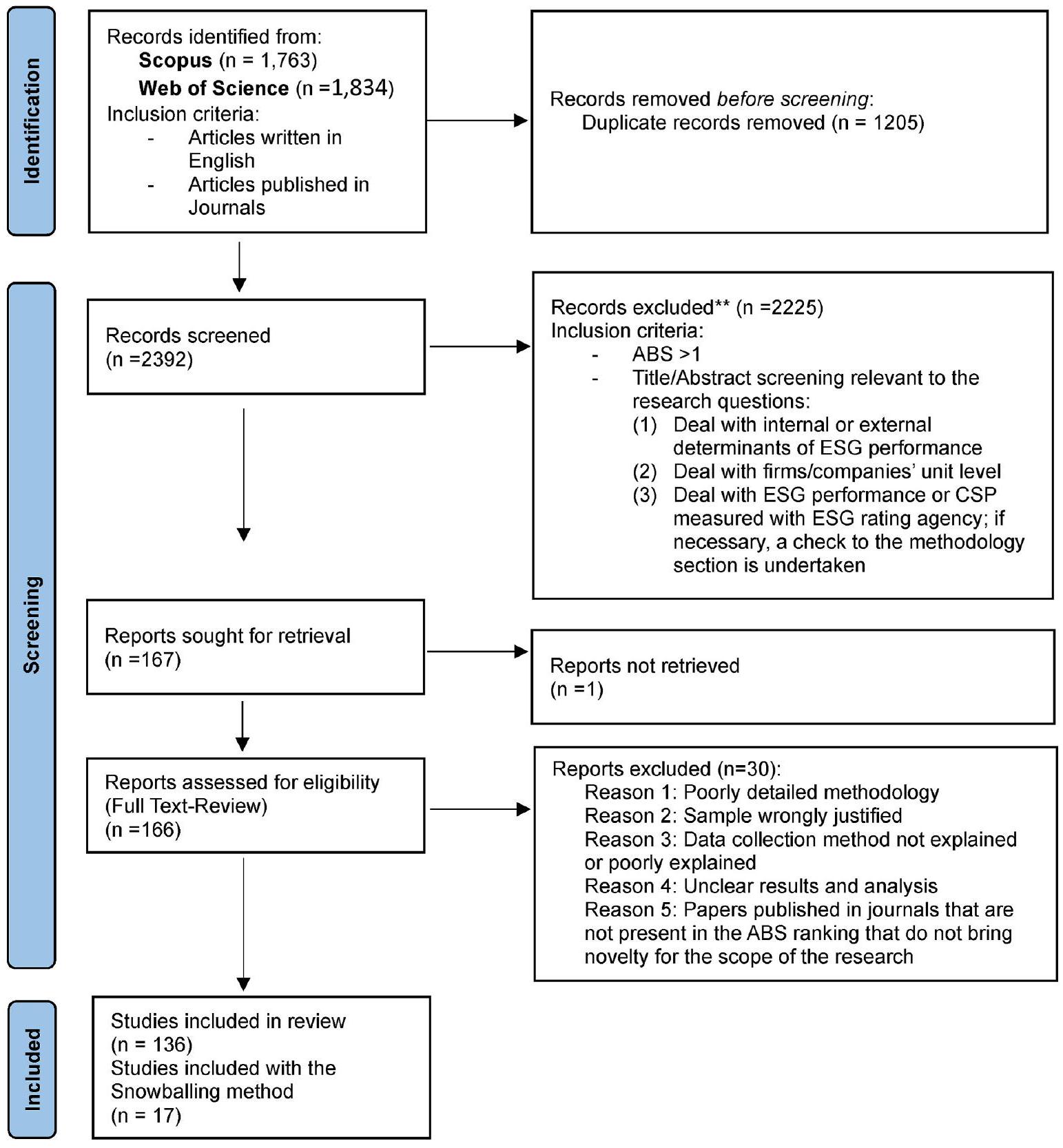

تحديد الدراسات من خلال قواعد البيانات

تضمن ذلك مرحلتين رئيسيتين: فحص العناوين أو الملخصات وتقييم النصوص الكاملة. أولاً، قمنا بتضمين الأوراق المنشورة في المجلات التي تحمل تصنيف رابطة كليات الأعمال المعتمدة (ABS).

4. النتائج

4.1. المحددات الداخلية على أداء ESG

4.1.1. التباين في تأثير الأداء المالي، تنوع المجالس، والتسجيل المتقاطع المفسر: عواقب استخدام قواعد بيانات مختلفة لقياس أداء ESG

الدرجة واستقلالية المجلس.

أيضًا، كشف التسجيل المتقاطع عن نتائج متناقضة. وفقًا لـ Del Bosco وMisani (2016)، يرتبط التسجيل المتقاطع إيجابيًا فقط بالأداء البيئي والاجتماعي للشركة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، عندما يكون مستوى حماية المستثمر في البورصة التي تسجل فيها الشركة أسهمها مرتفعًا، تحقق الشركة المسجلة بشكل متقاطع درجات بيئية واجتماعية أقل من الشركات التي تسجل في دول ذات مستوى منخفض من حماية المستثمر. على العكس، أظهر Cai et al. (2016) أن أداء ESG أعلى بين الشركات التي تم تداولها على إيصالات الإيداع الأمريكية (ADR)، والتي تستخدم كمؤشر للتسجيل المتقاطع في الولايات المتحدة، وهي دولة تتمتع بنظام قوي جدًا في حماية المستثمر. تبرز خصائص بعد الحوكمة لـ MSCI وRefinitiv، المستخدمة من قبل Cai et al. (2016) وDel Bosco وMisani (2016) الأساليب المختلفة لتعريف وقياس عوامل حوكمة الشركات. في الواقع، تشتهر MSCI بوضع مزيد من التركيز على عوامل الحوكمة، وتركز نهجها بشكل أكبر على الهياكل والعمليات الداخلية للحوكمة. من ناحية أخرى، تأخذ Refinitiv نظرة أوسع تشمل تأثير الشركة على أصحاب المصلحة بخلاف إدارتها فقط. وبالتالي، تختلف النتائج اعتمادًا على ما إذا كانت الحوكمة تهدف إلى ضمان إدارة الشركة بما يتماشى مع أفضل مصالح أصحاب المصلحة أو عندما تكون مرتبطة بشكل مباشر بالأداء المالي والامتثال التنظيمي.

4.1.2. تباين تأثير أنشطة المجلس ودور المستثمرين المفسر: العلاقة الحميمة بين الديناميات الداخلية وأصل القوانين في الدول

العوامل الداخلية على أداء ESG.

| الفئات | فئات فرعية | دليل | دول | المراجع | ||

| استراتيجية الشركة | تقرير وإفصاح ESG | كمية وجودة تقارير معلومات البيئة والمجتمع والحوكمة | السويد | أرفيدسون ودوماي (2022) | ||

| التقارير المتكاملة | عينة دولية؛ جنوب أفريقيا | ميرفيلسكمبر وسترايت (2017)؛ مانيورا (2015)؛ مانس-كيمب وفان دير لوخت (2020) | ||||

| التوجه الاستراتيجي | الوصاية | الدول المتقدمة | شيفرولييه وآخرون (2019) | |||

| توجه استراتيجية المنقب | دول الآسيان | Setiarini وآخرون (2023) | ||||

| محاكاة منظمة عادلة | عينة دولية | جيردي (2001) | ||||

| – | التسجيل المتقاطع | 36 دولة؛ متقدمة وناشئة | كاي وآخرون (2016)؛ ديل بوسكو وميساني (2016) | |||

| – | التدويل المؤسسي | الولايات المتحدة و 43 دولة فرعية | أتيغ وآخرون (2016) | |||

| – | فتح سوق المال | الصين | دينغ وآخرون (2022) | |||

| التكنولوجيا والمنافسة | نفقات البحث والتطوير | 36 دولة | كاي وآخرون (2016) | |||

| – | تكنولوجيا | الدول المتقدمة؛ الصينx2 | غرافلاند وسمد (2015)؛ مينغ وآخرون (2022)؛ لو وآخرون (2023) | |||

| – | التمويل الرقمي | الصين | فانغ وآخرون (2023)؛ مو وآخرون (2023)؛ لي وبانغ (2023)؛ وانغ وآخرون (2023)؛ رين وآخرون (2023) | |||

| حوكمة الاستدامة في الشركة | تعاونية، داخلية، مستعان بها | الدول المتقدمة | هوستد وفيليو (2016) | |||

| تقييمات ESG الفردية الملزمة وفضائح ESG؛ درجة استراتيجية المسؤولية الاجتماعية للشركات؛ كفاءات النسب والمزيج بين الأعمدة في ESG، عقلية ESG | عينة دولية؛ الدول المتقدمة؛ الصين | راجش وراجندران (2020)؛ شينان وآخرون (2023)؛ راجش وآخرون (2022)؛ تشينغ وآخرون (2023) | ||||

|

|

تشن وآخرون (2023)؛ زينغ وآخرون (2023)؛ مالين وميشيلون (2011)؛ شهباز وآخرون (2020)؛ جوندين وآخرون (2021)؛ لوزانو ومارتينيز-فيريرو (2022)؛ باراibar-دييز ودي. أودريوزولا (2019)؛ إبرهاردت-توث (2016)؛ سوتيبون وديشتانابودين (2022)؛ | ||||

| أنظمة الإدارة | أوروبا، شرق آسيا، وأمريكا الشمالية؛ ألمانيا | رونالتر وآخرون (2022)؛ جيب هاردت وآخرون (2023) | ||||

| توجه أصحاب المصلحة | الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية | براور وماهاجان (2013)؛ مالين وميشيلون (2011)؛ براور ورو (2017) | ||||

| سلسلة الإمداد | عينة دولية | داس (2023). | ||||

| الاندماج والاستحواذ | – | 41 دولة؛ الاتحاد الأوروبي؛ الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية | ||||

| باروس وآخرون (2021)؛ تامباكوديس وأناغنوستوبولوس (2020)؛ هيوستن وشان (2022) | ||||||

| خصائص الشركة | الخصائص غير المالية | الهيكل، الثقافة، السمعة، المعرفة؛ القرارات، السمات؛ الأفعال؛ الموارد؛ الأصول، والعقليات؛ الموارد البشرية ورأس المال الفكري | الولايات المتحدة الأمريكيةx2؛ الدول المتقدمة؛ عينة دولية؛ دول جنوب شرق آسيا | كرايس وجيهيمان (2022)؛ شورت وآخرون (2015)؛ أورليتسكي وآخرون (2017)؛ روثنبرغ وآخرون (2017)؛ ليستاري وأدهارياني (2022) | ||

| حجم | 25 دولة ناشئة؛ 36 دولة؛ دول متقدمة؛ | خالد وآخرون (2021)؛ كاي وآخرون (2016)؛ دريمبيتيك وآخرون (2020)؛ | ||||

| الخصائص المالية | الربحية (العائد على الأصول، التدفق النقدي الحر، القيمة السوقية، المبيعات، الموارد الفائضة، الالتزامات والعائد على الأصول)، الرفع المالي، مؤشر المخاطر النظامية | 25 دولة ناشئة؛ عينة دوليةx2؛ 52 دولة؛ بريكس؛ 36 دولة؛ دول متقدمة؛ الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية؛ | خالد وآخرون (2021)؛ غارسيا وأورساتو (2020)؛ تشاو وموريل (2022)؛ شهباز وآخرون (2020)؛ أرمينن وآخرون (2017)؛ غارسيا وآخرون (2017)؛ كاي وآخرون (2016)؛ غارسيا-بلاندون وآخرون (2019)؛ تشوي ولي (2018) | |||

| نقص في الأداء المالي | 27 دولة (دول متقدمة ودول ناشئة) | داسغوبتا (2021) | ||||

| المخاطر المالية | عينة دولية (أساساً من الدول المتقدمة) | شوليه وساندويدي (2018) | ||||

| القيود المالية ومخاطر الضغوط المالية | الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية | شان وآخرون (2016) | ||||

| رؤية المنظمة للشركة | رؤية Slack ورؤية لعدة أصحاب مصلحة | عينة دولية: بشكل رئيسي من الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية | تشيو وشارفمان (2011) | |||

| ميزات الرئيس التنفيذي | السمات الفردية | الخصائص القابلة للملاحظة | الولايات المتحدة الأمريكيةx2؛ الدول المتقدمة؛ الصينx2 | كرايس وجيهيمان (2022)؛ مانر (2010)؛ غارسيا-بلاندون وآخرون (2019)؛ هوانغ وآخرون (2023)؛ | ||

| وانغ وآخرون (2023); | ||||||

| الرئيس التنفيذي للأسرة | كوريا الجنوبية | أري ويوكيونغ (2018) | ||||

| الخصائص غير القابلة للملاحظة | الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية | كانغ (2017) | ||||

| تصور المسؤولية الاجتماعية للشركات | الدنمارك | بيدرسن ونيرغارد (2009) | ||||

| اتخاذ القرار | الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية | وانغ وآخرون (2011) | ||||

| تعويضات المدير التنفيذي | الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية؛ عينة دولية | كانغ (2017)؛ هارت وآخرون (2015)؛ مانر (2010)؛ جانغ وآخرون (2022)؛ كوهين وآخرون (2023)؛ | ||||

| حوكمة الشركات | تنوع مجلس الإدارة | تنوع المجالس | فرنساx2؛ 20 دولة ناشئة؛ عينة دوليةx5؛ الولايات المتحدة؛ 32 دولة؛ | بيجي ولوقيل (2021)؛ كريفو وآخرون (2018)؛ ديسلي وآخرون (2022)؛ حفيظ وترغوت (2013)؛ زانغ (2012)؛ شهباز وآخرون (2020)؛ جوندين وآخرون (2021)؛ لوزانو ومارتينيز-فيريرو (2022)؛ مالين وميشيلون (2011)؛ لويلين ومولر-كاهل (2023)؛ |

| فئات | فئات فرعية | دليل | دول | المراجع |

| نشاط المجلس | تنوع في مجلس الإدارة | فرنسا؛ عينة دوليةx5؛ 20 دولة ناشئة؛ الولايات المتحدةx3؛ إيطالياx2؛ الاتحاد الأوروبي؛ ماليزيا؛ 32 دولة | بيجي ولوقيل (2021)؛ أرايسي وآخرون (2016)؛ زانغ (2012)؛ شهباز وآخرون (2020)؛ غوفيندان وآخرون (2021)؛ لوزانو ومارتينيز-فيريرو (2022)؛ ديسلي وآخرون (2022)؛ مالين وميشيلون (2011)؛ هارجوتو وآخرون (2019)؛ يورك وآخرون (2023)؛ كامبريا وآخرون (2023)؛ سلومكا-غوليمبيوسكا وآخرون (2023)؛ نيرانتزيديس وآخرون (2022)؛ وونغ (2023)؛ لويلين ومولر-كاهل (2023) | |

| اجتماعات | 20 دولة ناشئة؛ عينة دولية؛ | ديسلي وآخرون (2022)؛ شهباز وآخرون (2020)؛ | ||

| مركزية الشبكة للمجلس | المملكة المتحدة | هارجوتو ووانغ (2020) | ||

| مراقبة المجلس والكفاءة | فرنسا؛ الولايات المتحدة الأمريكيةx2؛ عينة دولية | نيخيلي وآخرون (2021)؛ مالين وآخرون (2013)؛ مالين وميشيلون (2011)؛ كاستيو-ميرينو ورودريغيز-بيريز (2021) | ||

| لجان التدقيق | الاتحاد الأوروبي؛ الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية | بوزولي وآخرون (2022)؛ يورك وآخرون (2023)؛ | ||

| مسؤولية المديرين والضباط | الصين | شو وزهاو (2022)؛ تانغ وآخرون (2023)؛ | ||

| الشركات العائلية | فرنسا؛ الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية؛ كوريا الجنوبية؛ 25 دولة؛ دول متقدمة | بيجي ولوقيل (2021)؛ كشميري وماهجان (2014)؛ آري ويوكيونغ (2018)؛ لابيل وآخرون (2018)؛ ريس وروديونوفا (2015) | ||

| علاقة المستثمرين | المستثمرون | الصينx3؛ عينة دوليةx2؛ فرنسا؛ اليابان؛ الاتحاد الأوروبي؛ | هوانغ وآخرون (2022)؛ وانغ وآخرون (2023)؛ باركو وآخرون (2022)؛ تيان وآخرون (2023)؛ جوندان وآخرون (2021)؛ كريفو وآخرون (2018)؛ فوانغ وسوزوكي (2021)؛ فاسان وآخرون (2023)؛ | |

| المستثمرون المؤسسيون | صناديق التقاعد المسؤولة اجتماعياً (SR) | المملكة المتحدة؛ الدول المتقدمةx2؛ الدول الإسكندنافية؛ الولايات المتحدة والمملكة المتحدة؛ الولايات المتحدة؛ الاتحاد الأوروبي؛ الصينx5 | ألدّا (2019)؛ إكلز وكليمنكو (2019)؛ فارد وآخرون (2022)؛ سيمينوفا وهاسل (2019)؛ جيمس وجيفورد (2010)؛ هيوستن وشان (2022)؛ جانجي وفاروني (2018)؛ وانغ وآخرون (2023)؛ جيانغ وآخرون (2022)؛ بينغ وآخرون (2023)؛ هان (2022)؛ ليو وآخرون (2022) |

4.1.3. الرئيس التنفيذي والتمويل الرقمي: الجغرافيا المحدودة تعيق التعميم

et وآخرون، 2023، C، D، F). الاستثناء الوحيد يظهر من دراسة حديثة أجراها كوهين وآخرون (2023). من خلال استخدام عينة دولية من الشركات المتداولة علنًا، يؤكدون أن تنفيذ دفع ESG يتزامن مع تحسينات في النتائج الأساسية لـ ESG. ومع ذلك، من المهم ملاحظة أن قيود الجسم الحالي من الأبحاث لا تزال تعيق إقامة تعميمات نهائية. يمكن استخلاص استنتاجات مماثلة بشأن التمويل الرقمي، الذي يشهد ازدهارًا سريعًا. لقد تم تناول التأثير الإيجابي للتحولات التكنولوجية الرقمية (لو وآخرون، 2023) والتحسينات في القطاع المالي فيما يتعلق بأداء ESG (وانغ وآخرون، 2023؛ لي وبانغ، 2023) مؤخرًا. على الرغم من أن الأدبيات أظهرت أن آثار التمويل الرقمي تكون أكثر وضوحًا في الشركات غير المملوكة للدولة، والشركات الصغيرة، والشركات ذات مستويات أقل من التسويق (مو وآخرون، 2023)، والشركات غير المرتبطة سياسيًا وتلك الموجودة في مناطق ذات مؤسسات عالية الجودة (فانغ وآخرون، 2023)، إلا أن المنطقة الجغرافية تقتصر على الصين، مما يجعل أي تعميم صعب الإثبات.

4.1.4. تقارير الأداء البيئي والاجتماعي والحوكمي: هل هي مؤشر أم لا؟

لقد كانت أجندة التمويل المستدام تعزز أداء ESG أو بدلاً من ذلك، كانت تدفع التأثير السلبي على صناعة تصنيف ESG (أهلستروم ومونسيارديني، 2022).

4.2. العوامل الخارجية على أداء ESG

4.2.1. حوكمة الدولة: المؤسسات والثقافة

العوامل الخارجية على أداء ESG.

| فئات | فئات فرعية | دليل | دول | المراجع |

| الإطار التنظيمي | التشريعات والتوجيهات الأوروبية | السويد؛ الاتحاد الأوروبي؛ | أرفيدسون ودوماي (2022)؛ أهلستروم ومونسيارديني (2022) | |

| التشريعات الوطنية للمبادرات العالمية | الاتفاق العالمي للأمم المتحدة (UNGC) قانون غرينيل II | إسبانيا، فرنسا، اليابان، فرنسا | أورتاس وآخرون (2015) بيجي ولوقيل (2021) | |

| متطلبات الإبلاغ الإلزامي تنظيم البيئة الحكومية | الدول المتقدمة الصين | غرافلاند وسمد (2015) يان وآخرون (2023)؛ لو وتشينغ (2023)؛ زو وآخرون (2023)؛ لي ولي (2022)؛ شو وتان (2023)؛ وانغ وآخرون (2022)؛ تشين وآخرون (2022)؛ هي وآخرون (2023)؛ شيو وآخرون (2023) | ||

| الحوكمة الوطنية/ الإقليمية | المؤسسات الرسمية | الديمقراطية، الاستقرار السياسي والحقوق، الحريات المدنية وجودة التنظيم والمؤسسات، النظام التعليمي، الفساد، التغيير السياسي | 30 دولة؛ الولايات المتحدة مرتين؛ 11 دولة؛ 36 دولة؛ 52 دولة؛ 21 دولة متقدمة؛ الصين ثلاث مرات؛ الأسواق الناشئة؛ 32 دولة | موونيابين وآخرون (2022)؛ كرايس وجيهيمان (2022)؛ أتيغ وآخرون (2016)؛ عمر وآخرون (2020)؛ كاي وآخرون (2016)؛ أرمينين وآخرون (2017)؛ أورليتسكي وآخرون (2017)؛ تشي وآخرون (2022)؛ هوانغ وآخرون (2023)؛ يانغ وآخرون (2023)؛ تشانغ وآخرون (2023)؛ شيو وآخرون (2023)؛ فينوجوبال وآخرون (2023)؛ لويلين ومولر-كاهل (2023)؛ |

| المؤسسات غير الرسمية | الخلفية الثقافية للبلد: الأصل القانوني والتقاليد، الدين، المعتقدات الثقافية | الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية؛ 25 دولة؛ 52 دولة؛ 36 دولة؛ 3 دول؛ 2 دول؛ 64 دولة؛ 49 دولة؛ عينة دولية ×2؛ 32 دولة | كرايس وجيهيمان (2022)؛ لابيل وآخرون (2018)؛ أرمينين وآخرون (2017)؛ كاي وآخرون (2016)؛ أورطاس وآخرون (2015)؛ قويم وآخرون (2022)؛ كاستيو-ميرينو ورودريغيز-بيريز (2021)؛ فوو نين وآخرون (2012)؛ ليانغ ورينيبوج (2017)؛ لوزانو ومارتينيز-فيريرو (2022)؛ فو وآخرون (2022)؛ لويلين ومولر-كاهل (2023) | |

| عدوى دولية | عينة دولية | عمر وآخرون (2020) | ||

| رصد وسائل الإعلام | الإعلام والمنظمات غير الحكومية | الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية؛ الدول المتقدمة؛ بشكل رئيسي الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية واليابان | لي وريفي (2017)؛ جرافلاند وسمد (2015)؛ فو (2023) | |

| صناعة | أنواع | قطاعات مختلفة | الولايات المتحدة؛ 21 دولة متقدمة؛ الولايات المتحدة؛ عينة دولية | كرايس وجيهيمان (2022)؛ أورليتسكي وآخرون (2017)؛ شورت وآخرون (2015)؛ عمر وآخرون (2020) |

| الصناعات الحساسة وعالية التأثير | عينة دولية؛ دول البريكس؛ 52 دولة؛ أستراليا | غارسيا وأورساتو (2020)؛ دو وجيانفي (2023)؛ غارسيا وآخرون (2017)؛ أرمينن وآخرون (2017)؛ غالبراث (2013) | ||

| الرؤية الصناعية والمشاعر | الرؤية الصناعية والمشاعر | عينة دولية؛ اليابان | تشيو وشارفمان (2011)؛ فوانغ وسوزوكي (2021) | |

| فترة | التأثيرات الزمنية | سنة | الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية x2؛ 21 دولة متقدمة؛ أستراليا | كرايس وجيهيمان (2022)؛ أورليتسكي وآخرون (2017)؛ شورت وآخرون (2015)؛ غالبراث (2013) |

| الصدمات الاقتصادية الكلية | أزمة الاقتصاد عام 2008 | 18 دولة متقدمة | كاسلي وآخرون (2021) | |

| – | أزمة ديون السيادة في الاتحاد الأوروبي، مشاكل النظام اليوناني، جائحة كوفيد | عينة دولية | عمر وآخرون (2020)؛ العموش وخطيب (2023) | |

| التنمية الاقتصادية | الناتج المحلي الإجمالي | 52 دولة؛ 49 دولة؛ دول متقدمة؛ عينة دولية | أرمينين وآخرون (2017)؛ فوو نين وآخرون (2012)؛ راجيش وآخرون (2022)؛ لوزانو ومارتينيز-فيريرو (2022) | |

| معامل

|

36 دولة | كاي وآخرون (2016) | ||

| التنمية المالية | 42 دولة في آسيا | نج وآخرون (2020) |

4.2.2. أهمية الصناعة

فكرة أن مقدمي الخدمات قد يعدلون تقييماتهم المتعلقة بالبيئة والمجتمع والحوكمة بناءً على المخاطر والفرص المحددة المرتبطة بكل صناعة، بينما قد يستخدم آخرون نهجًا أكثر معيارية عبر جميع الصناعات. عند استخدام MSCI، الذي لا يعتمد على نهج قائم على الأهمية، تؤثر الصناعة بشكل كبير على الأسواق التي تعتمد معايير ESG (عمر وآخرون، 2020؛ كرايس وجيهيمان، 2022).

4.3. الاستدامة البيئية والاجتماعية وحوكمة الشركات على المستوى التفصيلي: صعود الانتماء الصناعي والأداء المالي على حساب الأداء البيئي

توزيع تأثير العوامل الخارجية على الأعمدة الفردية والمؤشرات الإيجابية والسلبية.

| العوامل الخارجية | المعايير البيئية | المعايير الاجتماعية | معايير الحوكمة | نقاط القوة والاهتمامات | مرجع | ||

| حوكمة الدولة (المؤسسات الرسمية) | + | + (جودة التنظيم) | موونيابين وآخرون (2022) | ||||

| + | Qi وآخرون (2022) | ||||||

| حوكمة الدولة (القوانين) | + | هو وآخرون (2023); | |||||

| حوكمة الدولة + التنمية الاقتصادية | + | أرمينن وآخرون (2017) | |||||

| حوكمة الدولة (المؤسسات غير الرسمية) | + | + | + | أورتاس وآخرون (2015) | |||

| + | Foo Nin وآخرون (2012) | ||||||

| + | + | قويوم وآخرون (2022) | |||||

| صناعة | + | + (المخاوف الاجتماعية) |

|

كرايس وجيهيمان (2022) | |||

| + | + (بعد الموظف) | أرمينن وآخرون (2017) | |||||

| + | + (المجتمعات المحلية) | أورليتسكي وآخرون (2017) | |||||

| + (المخاوف البيئية) | شورت وآخرون (2015) | ||||||

| (صناعة حساسة) | + | غارسيا وآخرون (2017) غالبراث (2013) | |||||

| (تأثير عالٍ) | + | ||||||

| فترة (سنة) |

|

كرايس وجيهيمان (2022) | |||||

| + (مبادرات سلسلة التوريد المسؤولة اجتماعيًا) | أورليتسكي وآخرون (2017) | ||||||

| + (المجتمع المحلي) | – | شورت وآخرون (2015) | |||||

| + | غالبراث (2013) | ||||||

| فترة (أزمة اقتصادية) | -(LMEs) | -(LMEs) | + (الـ CME) | كاسلي وآخرون (2021) | |||

| + (الـ CME) | + (الـ CME) | ||||||

| (جائحة كوفيد-19) | + (خصوصاً الدول النامية) | + (الدول المتقدمة بشكل خاص) | – | العموش وخطيب (2023) |

توزيع تأثير الفروق للعوامل الداخلية على الأعمدة الفردية والمؤشرات الإيجابية والسلبية.

| العامل الداخلي | المعايير البيئية | المعايير الاجتماعية | معايير الحوكمة | نقاط القوة والاهتمامات | مرجع | ||||

| استراتيجية الشركة (التقارير) | – | ميرفلسكمبر وسترايت (2017) | |||||||

| استراتيجية الشركة (التسجيل المزدوج) | – | دل بوسكو وميساني (2016) | |||||||

| استراتيجية الشركة (التدويل) | + | + (المجتمع، التنوع) – (حقوق الإنسان) | + نموذج نقاط القوة في ESG. | أتيغ وآخرون (2016) | |||||

| استراتيجية الشركة (الرقمنة) | + | + | فانغ وآخرون (2023) | ||||||

| استراتيجية الشركة (أنظمة الإدارة) | + (تقليل النفايات واستهلاك الموارد) | + (علاقات العملاء والمساهمين) | + (التواصل الداخلي وزيادة مشاركة المديرين) | رونالتر وآخرون (2022) | |||||

| (لجنة الاستدامة) | + | غوفيندان وآخرون (2021) | |||||||

| خصائص الشركة (غير المالية) | + | + | كرايس وجيهيمان (2022) | ||||||

| + | + (المجتمعات المحلية والموظفين) | + (أبعاد المساهمين) | أورليتسكي وآخرون (2017) | ||||||

| خصائص الشركة (رؤية المنظمة) | + | تشيو وشارفمان (2011) | |||||||

| خصائص الشركة (مالية) | + | أرمينن وآخرون (2017) | |||||||

| + | – | – | غارسيا وآخرون (2017) | ||||||

| المخاطر المالية | + | + | شوليه وساندويدي (2018) | ||||||

| الضغوط المالية | – | -(المجتمع، المنتج) | شان وآخرون (2016) | ||||||

| سمات الرئيس التنفيذي | + كلاهما | كرايس وجيهيمان (2022) | |||||||

| تعويض |

|

كانغ (2017) | |||||||

| حوكمة الشركات (تنوع مجلس الإدارة) |

|

+ (حجم المجلس، التنوع في الجنس والعمر، المديرون الأجانب) |

|

بيجي ولوقيل (2021) | |||||

|

تشانغ (2012) | ||||||||

| + (استقلالية المجلس) | + (مديرو المجتمع المؤثرون، لجنة المسؤولية الاجتماعية للشركات، التنوع الجنسي، المناصب الخارجية) | مالين وميشيلون (2011) | |||||||

| الجنسية والخلفية التعليمية للمجلس مع نقاط القوة | هارجوتو ووانغ (2020) | ||||||||

| + (تنوع الجنس) | غوفيندان وآخرون (2021) | ||||||||

| حوكمة الشركات (مركزية الشبكة) | -(مركزية المعلومات) | هارجوتو ووانغ (2020) | |||||||

| حوكمة الشركات (الموظفين) | -(ممارسات إدارة الموارد البشرية) | روثنبرغ وآخرون (2017) | |||||||

| + (ممثلو مجلس إدارة المساهمين من الموظفين) | + (تمثيل مجلس العمل) | + (ممثلو مجلس الإدارة من الموظفين المساهمين) | نيخلي وآخرون (2021) | ||||||

| الشركات العائلية | – | ريس وروديونوفا (2015) | |||||||

| اختلافات | لا فرق ذو دلالة إحصائية (البيئة) | لا يوجد فرق ذو دلالة إحصائية (المجتمع، رضا العملاء عن جودة المنتج وسلامته، وعلاقات الموظفين). | أري ويوكيونغ (2018) | ||||||

| علاقات المستثمرين وصناديق التقاعد | + | ألدّا (2019) | |||||||

| – المستثمرون المؤسسيون الأجانب المؤهلون | + (تنوع القوى العاملة، جودة المنتج) | + | هان (2022) | ||||||

| مشاعر المستثمرين | – | فوانغ وسوزوكي (2021) |

4.4. الاعتماد المتبادل للنظريات

الأطر النظرية المستخدمة لتحديد العوامل الخارجية والداخلية.

| نظرية | تأكيد أو رفض | المراجع |

| نظرية الشرعية | تأكيد | موونيابين وآخرون (2022)؛ مالين وميشيلون (2011) |

| تمديد | خالد وآخرون (2021) | |

| نظرية أصحاب المصلحة | تأكيد | داس غوبتا (2021)؛ دريمبيتيك وآخرون (2020)؛ تامباكوديس وأناغنوستوبولو (2020)؛ إكليس وكليمنكو (2019)؛ هارجوتو وآخرون (2019)؛ إبرهاردت-توث (2016)؛ أرايسي وآخرون (2016)؛ براور وماهاجان (2013)؛ وونغ وآخرون (2011)؛ مالين وميشيلون (2011)؛ شهباز وآخرون (2020)؛ غوفيندان وآخرون (2021)؛ راجيش وآخرون (2022)؛ قويم وآخرون (2022)؛ رونالتير وآخرون (2022)؛ كاستيلو-ميرينو ورودريغيز-بيريز (2021)؛ باراibar-دييز ودي. أودريوزولا (2019)؛ مينغ وآخرون (2022)؛ وانغ وآخرون (2023)؛ غيب هاردت وآخرون (2023)؛ نيرانتزيديس وآخرون (2022)؛ وانغ وآخرون (2022)؛ تشين وآخرون (2023)؛ داس (2023). |

| تمديد | أورليتسكي وآخرون (2017)؛ هارجوتو ووانغ (2020)؛ خالد وآخرون (2021)؛ براور ورو (2017)؛ العموش وخطيب (2023) | |

| مؤكد جزئيًا | كاسلي وآخرون (2021)؛ غارسيا وآخرون (2017)؛ ألدا (2019)؛ غرافلاند وسمد (2015) | |

| رفض | نيخلي وآخرون (2021)؛ جانجي وفاروني (2018)؛ كريفو وآخرون (2018) | |

| نظرية المؤسسات، فرضية اختلاف المؤسسات (IDH) ونظرية المؤسسات الجديدة | تأكيد | بيجي ولوقيل (2021)؛ غارسيا وأورساتو (2020)؛ تشيو وشارفمان (2011)؛ دريمبيتيك وآخرون (2020)؛ كاسلي وآخرون (2021)؛ أورطاس وآخرون (2015)؛ راجيش وراجندران (2020)؛ غرافلاند وسميت (2015)؛ تشين وآخرون (2022)؛ غيب هاردت وآخرون (2023)؛ لويلين ومولر-كاهل (2023)؛ داس (2023). |

| تمديد | خالد وآخرون (2021)؛ تشين وآخرون (2023)؛ فينوجوبال وآخرون (2023)؛ | |

| رفض مؤكد جزئيًا | غالبراث (2013)؛ ألدا (2019) | |

| نظرية الطبقة العليا | تأكيد | كرايس وجيهيمان (2022)؛ هارجوتو ووانغ (2020)؛ وونغ وآخرون (2011)؛ مانر (2010)؛ بيدرسن ونيرغارد (2009)؛ وانغ وآخرون (2023)؛ |

| تم تأكيد التمديد جزئيًا | تشن وآخرون (2023) بيجي ولوقيل (2021) | |

| نظرية الوكالة | تأكيد | بيجي ولوقيل (2021)؛ لابيل وآخرون (2018)؛ ريس وروديونوفا (2015)؛ آري ويوكيونغ (2018)؛ نخيلي وآخرون (2021)؛ جانجي وفاروني (2018)؛ كانغ (2017)؛ حفيظ وتورغوت (2013)؛ مالين وميشيلون (2011)؛ |

| نظرية | تأكيد أو رفض | المراجع |

| شهباز وآخرون (2020); | ||

| تمديد | خالد وآخرون (2021); | |

| رفض | أرايسي وآخرون (2016)؛ مالين وآخرون (2013)؛ | |

| وجهة نظر قائمة على الموارد (RBV) | تأكيد | غارسيا وأورساتو (2020)؛ هوستد وفيليو (2016)؛ شورت وآخرون (2015)؛ تشيو وشارفمان (2011)؛ روثنبرغ وآخرون (2017)؛ سيتياريني وآخرون (2023) |

| رفض مؤكد جزئيًا | ليستاري وأدهارياني (2022) | |

| نظرية اعتماد الموارد | تأكيد | ديزلي وآخرون (2022)؛ مالين وآخرون. |

| مؤكد جزئيًا | بيجي ولوقيل (2021)؛ حفيظ وترغوت (2013)؛ زانغ (2012)؛ لويلين ومولر-كاهل (2023) | |

| نظرية حافة الزجاج | تأكيد | بيجي ولوقيل (2021) |

| نظرية الهوية الاجتماعية | جزئيًا | بيجي ولوقيل (2021) |

| رفض | نيخلي وآخرون (2021) | |

| تمديد | هوانغ وآخرون، 2023 | |

| القدرات الديناميكية | تأكيد | غارسيا وأورساتو (2020) |

| نظرية الوصاية | تأكيد | شيفرولييه وآخرون (2019)؛ داس (2023). |

| رفض | ليستاري وأدهارياني (2022) | |

| نهج الثروة الاجتماعية والعاطفية (SEW) | رفض | لابيل وآخرون (2018)؛ آري ويوكيونغ (2018) |

| نظرية مالية | رفض التأكيد | تشان وآخرون (2016) أورليتسكي وآخرون (2017) |

| نظرية الاحتمالات | تأكيد | داسغوبتا (2021) |

| نظرية الموارد الفائضة | تأكيد | شوليه وساندويدي (2018)؛ تشوي ولي (2018) |

| مؤكد جزئيًا | دريمبيتيك وآخرون (2020) | |

| رفض | تشاو وموريل (2022) | |

| نظرية رأس المال الاجتماعي | تمديد | هارجوتو ووانغ (2020) |

| نظرية الشبكات الاجتماعية | تمديد | هارجوتو ووانغ (2020) |

| نظرية التحديث البيئي | تأكيد | راجش وراجندران (2020) |

| نظرية الطوارئ | رفض | راجش وراجندران (2020) |

| نظرية المحفظة الحديثة | رفض التأكيد | غانجي وفاروني (2018) إكلس وكليمنكو (2019) |

| نظرية الاتصال بين المجموعات | تأكيد | هارجوتو وآخرون (2019) |

| وجهة نظر تنوع الموارد المعرفية | تأكيد | هارجوتو وآخرون (2019) |

| نظرية التصنيف الاجتماعي | رفض | هارجوتو وآخرون (2019) |

| نموذج التشابه/الجذب | رفض | هارجوتو وآخرون (2019) |

| نظرية الحركة الاجتماعية | تأكيد | سيمينوفا وهسيل (2019) |

| نظرية الإدارة الجيدة | تأكيد | شوليه وساندويدي (2018) |

| نظرية الانتهازية الإدارية | رفض | تشوي ولي (2018) |

| نظرية الوكالة السلوكية | مؤكد جزئيًا | كانغ (2017) |

| نظرية | تأكيد أو رفض | المراجع |

| نظرية النفور من الخسارة | تأكيد | كانغ (2017) |

| نظرية البطولة | رفض/ تمديد | هارت وآخرون (2015) |

| نظرية العدالة | تأكيد/ تمديد | هارت وآخرون (2015) |

| التعقيد التكاملي، أسلوب إدراكي | تأكيد | وانغ وآخرون (2011) |

| نظرية المنظمة | رفض | مالين وميشيلون (2011) |

| نظرية السلطة الإدارية | تأكيد | مانر (2010) |

| نظرية بروز أصحاب المصلحة | تأكيد | جيمس وجيفورد (2010) |

| نظرية العدالة لجون رولز (1971) | مؤكد جزئيًا | جيردي (2001) |

| نظرية بناء الأجندة | مؤكد جزئيًا | لي وريفي (2017) |

| نظرية الإشارة (الإرسال) | تأكيد | وانغ وآخرون (2023)؛ فو (2023) |

| نظرية التنمية المالية | تأكيد | لي وبانغ (2023) |

| نظرية النمو الذاتي | تأكيد | لي وبانغ (2023) |

| نظرية الكتلة الحرجة | تأكيد | نيرانتزيديس وآخرون (2022) |

وأناغنوستوبولو، 2020) وتنفيذ أنظمة الإدارة (رونالتر وآخرون، 2022).

5. المناقشة

هذه المؤسسات الرسمية. على وجه التحديد، قد يكون المزودون الذين يضعون تركيزًا أكبر على عوامل الحوكمة أكثر احتمالًا للعثور على علاقة إيجابية بين الأداء المالي (خالد وآخرون، 2021؛ كرايس وغيمان، 2022)، والإدراج المتقاطع (كاي وآخرون، 2016) والمؤسسات القوية (أتيغ وآخرون، 2016؛ كاي وآخرون، 2016؛ عمر وآخرون، 2020) مع أداء ESG. يمكن للمرء أن يجادل بأنه عند إجراء البحث، يجب على الأكاديميين استخدام العديد من مزودي ESG. على الرغم من أنها دقيقة بشكل عام، فإن استخدام البيانات من مصدرين غير متوافقين جيدًا قد يؤدي إلى مزيج ينتج عنه استنتاجات غير موثوقة. على سبيل المثال، إذا كنت تخدم عملاء من الاتحاد الأوروبي، فإن استخدام بيانات MSCI سيؤدي إلى تصنيف الشركات التي ببساطة لا تتناسب مع وجهة نظر أوروبية لشركة مسؤولة. نظرًا لأن مزودي البيانات هم منتجات لفضائهم وزمانهم الفريد، يجب أن تستخدم الأبحاث المستقبلية حول أداء ESG أكثر من مزود بيانات واحد يتوافق جيدًا في سيناريوهم الثقافي.

أظهر أن فعالية (أو عدمها) مجموعات خصائص مجلس الإدارة لأداء ESG تختلف عبر السياقات المؤسسية (لويلين ومولر-كاهل، 2023) وأهمية أنشطة حوكمة الشركات تختلف بين الولايات القضائية حيث تسود وجهة نظر المساهمين وحيث تكون اللوائح التي تهدف إلى حماية مصالح أصحاب المصلحة أقوى. يبدو أن المستثمرين المؤسسيين يلعبون أيضًا أدوارًا مختلفة بين البلدان. في البلدان الأنغلو-ساكسونية والدول الإسكندنافية الأوروبية، يكون دور نشاط المستثمرين والمستثمرين المؤسسيين في دعم الاستدامة أقوى بكثير من الدول الأخرى في الاتحاد الأوروبي.

نظرية أصحاب المصلحة (أرايسي وآخرون، 2016) ونظرية المؤسسات في استكشاف دوافع أداء ESG. لقد أظهرت وجهة النظر القائمة على الموارد أن أداء ESG يعتمد على الموارد التي تمتلكها الشركة وكيفية تنظيمها (شورت وآخرون، 2015؛ هوستيد وفيليو، 2016؛ روثنبرغ وآخرون، 2017). أكدت نظريتا الوكالة وأصحاب المصلحة أن المجالس المستقلة والمتنوعة من حيث الجنس والمركزة على المسؤولية الاجتماعية تعمل لصالح أداء ESG (شهباز وآخرون، 2020؛ غوفيندان وآخرون، 2021؛ مينغ وآخرون، 2022؛ نيرانزيديس وآخرون، 2022). وُجد أن نظرية المؤسسات أساسية في تفسير دور الضغوط المؤسسية في تشكيل خصائص الشركات (دريمبيتيك وآخرون، 2020؛ غرافلاند وسمد، 2015).

6. الخاتمة والآثار

6.1. أصالة النتائج والآثار الأكاديمية والإدارية والسياسية

وجد أن لديها مستويات أعلى من أداء ESG. أنشطة الرعاية (Chevrollier et al., 2019)، التدويل، الاندماج والاستحواذ، الاستثمار في الابتكار التكنولوجي والبحث والتطوير، ولكن أيضًا الأساليب التي تهدف صراحة إلى الاستدامة، مثل توجيه أصحاب المصلحة، وجود لجنة للاستدامة/المسؤولية الاجتماعية للشركات واعتماد أنظمة الإدارة هي جميعها استراتيجيات ثبت إحصائيًا أنها تزيد من أداء ESG للشركات. في الوقت نفسه، سلط هذا العمل الضوء على التناقضات في الأدبيات حول دور الأداء المالي (Khaled et al., 2021; Crace and Gehman, 2022)، الإدراج المتقاطع (Cai et al., 2016) والمؤسسات القوية (Attig et al., 2016; Cai et al., 2016; Umar et al., 2020). كما تقترح هذه المراجعة اتجاهات مستقبلية للباحثين لمواصلة النقاش حول هذه التناقضات وللتحقيق بشكل أكبر في دور هذه المحددات.

6.2. قيود البحث والاتجاهات المستقبلية للبحث

تنسيق مصادر التمويل

بيان مساهمة المؤلفين في CRediT

إعلان عن تضارب المصالح

توفر البيانات

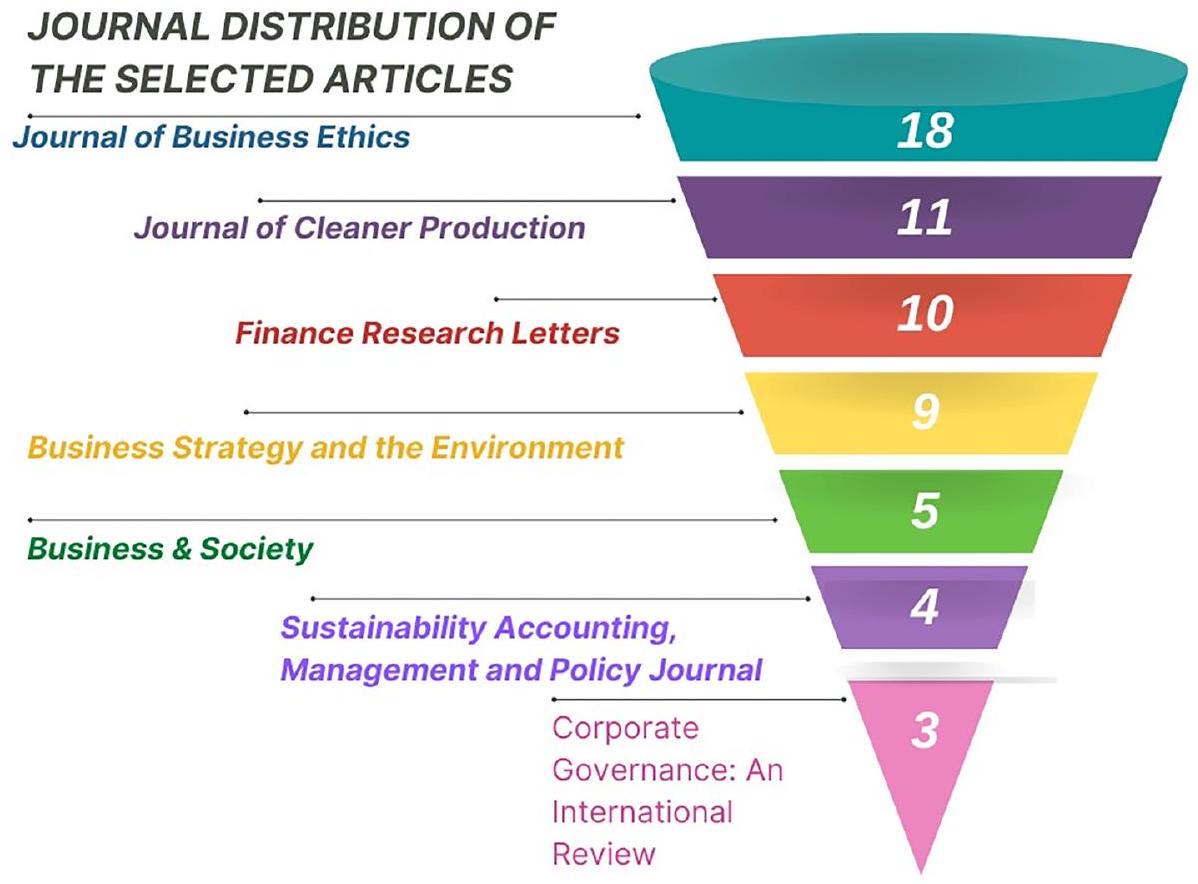

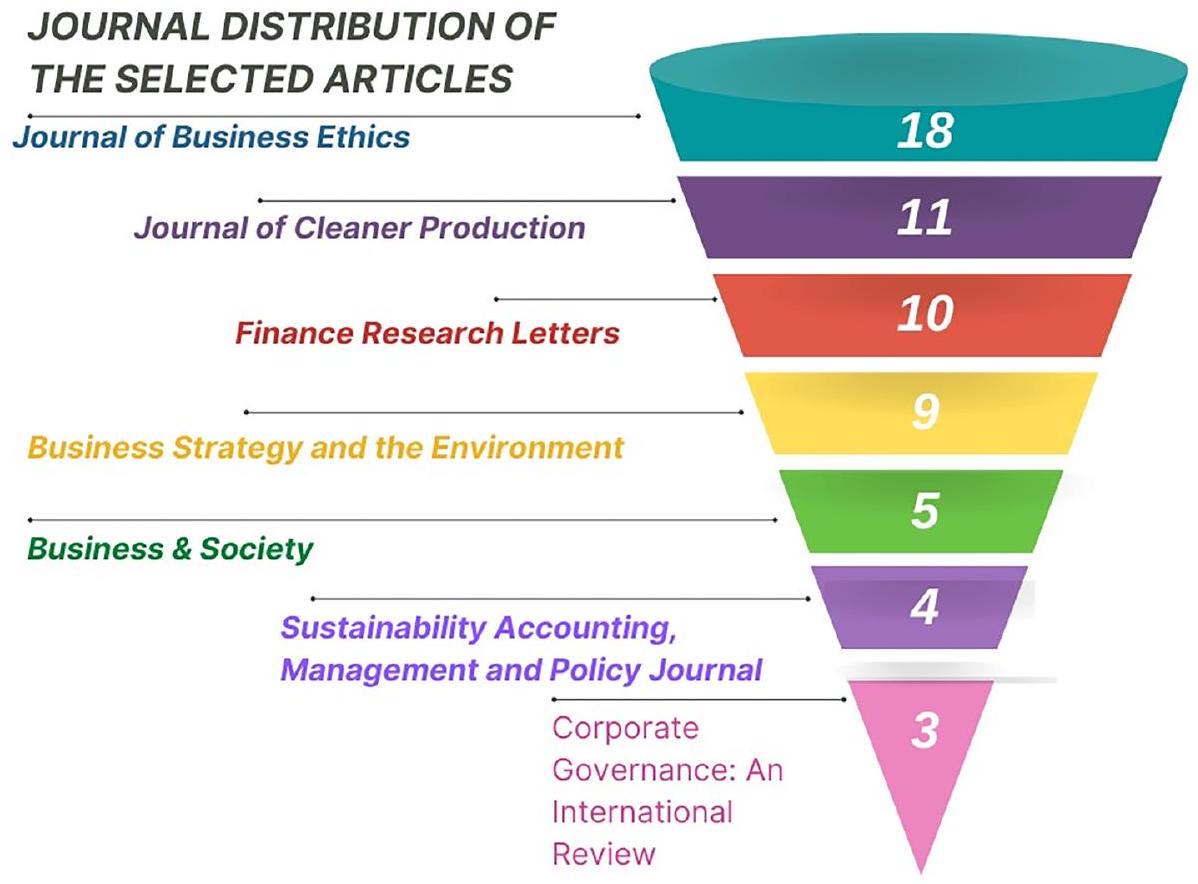

توزيع المجلات للمقالات المختارة

| اسم المجلة | عدد المقالات |

| مجلة أخلاقيات الأعمال | 18 |

| مجلة الإنتاج النظيف | 11 |

| رسائل أبحاث المالية | 10 |

| استراتيجية الأعمال والبيئة | 9 |

| الأعمال والمجتمع | 5 |

| علوم البيئة وبحوث التلوث | 4 |

| مجلة المحاسبة والإدارة والسياسة المستدامة | 4 |

| حوكمة الشركات: مراجعة دولية | 3 |

| النمذجة الاقتصادية | 3 |

| الحدود في علوم البيئة | 3 |

| البحث في الأعمال الدولية والتمويل | 3 |

| الاستدامة | 3 |

| استراتيجية الأعمال والتنمية | 2 |

| حوكمة الشركات | 2 |

| الحدود في علم النفس | 2 |

| مراجعة الأعمال في هارفارد | 2 |

| المجلة الدولية للبحث البيئي والصحة العامة | 2 |

| المراجعة الدولية للتحليل المالي | 2 |

| مجلة الإدارة | 2 |

| المنظمة والبيئة | 2 |

| مجلة تمويل حوض المحيط الهادئ | 2 |

| مجلة الأكاديمية للإدارة | 1 |

| البحوث المحاسبية والتجارية | 1 |

| العلوم التطبيقية | 1 |

| مراجعة الأعمال في منطقة آسيا والمحيط الهادئ | 1 |

| المجلة الآسيوية للمحاسبة والاقتصاد | 1 |

| المجلة الآسيوية للأعمال والمحاسبة | 1 |

| مراجعة بورصة إسطنبول | 1 |

| آفاق الأعمال | 1 |

| المجلة الصينية لأبحاث المحاسبة | 1 |

| حوكمة الشركات: المجلة الدولية للأعمال في المجتمع | 1 |

| المسؤولية الاجتماعية للشركات وإدارة البيئة | 1 |

| الاقتصادي | 1 |

| مراجعة الاقتصاد الشرقي الآسيوي | 1 |

| تمويل الأسواق الناشئة والتجارة | 1 |

| سياسة الطاقة | 1 |

| نظرية ريادة الأعمال والممارسة | 1 |

| البيئة والتنمية والاستدامة | 1 |

| الاقتصاد الأخلاقي | 1 |

| مجلة المالية العالمية | 1 |

| اتصالات العلوم الإنسانية والاجتماعية | 1 |

| المجلة الدولية لحوكمة الأعمال والأخلاقيات | 1 |

| المجلة الدولية لإدارة الضيافة المعاصرة | 1 |

| المجلة الدولية للمالية والاقتصاد | 1 |

| المجلة الدولية للبحوث في التسويق | 1 |

| المجلة الدولية لاقتصاد الإنتاج | 1 |

| المراجعة الدولية للمالية | 1 |

| مجلة بحوث المحاسبة | 1 |

| مجلة اقتصاديات الأعمال والإدارة | 1 |

| مجلة الأعمال في المجتمع | 1 |

| مجلة بحوث الأعمال | 1 |

| مجلة التمويل الشركاتي | 1 |

| مجلة إدارة البيئة | 1 |

| مجلة الاقتصاد المالي | 1 |

| مجلة الأعمال العالمية | 1 |

| قرار الإدارة | 1 |

| الاقتصاد الإداري واتخاذ القرار | 1 |

| مراجعة الأعمال متعددة الجنسيات | 1 |

| بي. إل. أو. إس. وان | 1 |

| مراجعة العلاقات العامة | 1 |

| البحث في الأعمال الدولية والتمويل | 1 |

| مراجعة المالية | 1 |

| مراجعة العلوم الإدارية | 1 |

| أبحاث المؤشرات الاجتماعية | 1 |

| مراجعة المجتمع والأعمال | 1 |

| علوم التخطيط الاجتماعي والاقتصادي | 1 |

| المجلة الجنوب أفريقية للعلوم الاقتصادية وإدارة الأعمال | 1 |

| تنظيم استراتيجي | 1 |

| التنبؤ التكنولوجي والتغيير الاجتماعي | 1 |

| المجلة الدولية لإدارة الموارد البشرية | 1 |

| مجلة المالية | 1 |

| المجلة الأمريكية الشمالية للاقتصاد والمالية | 1 |

| مراجعة الدراسات المالية | 1 |

| مراجعة الأعمال الدولية ثندربيرد | 1 |

الملحق ب

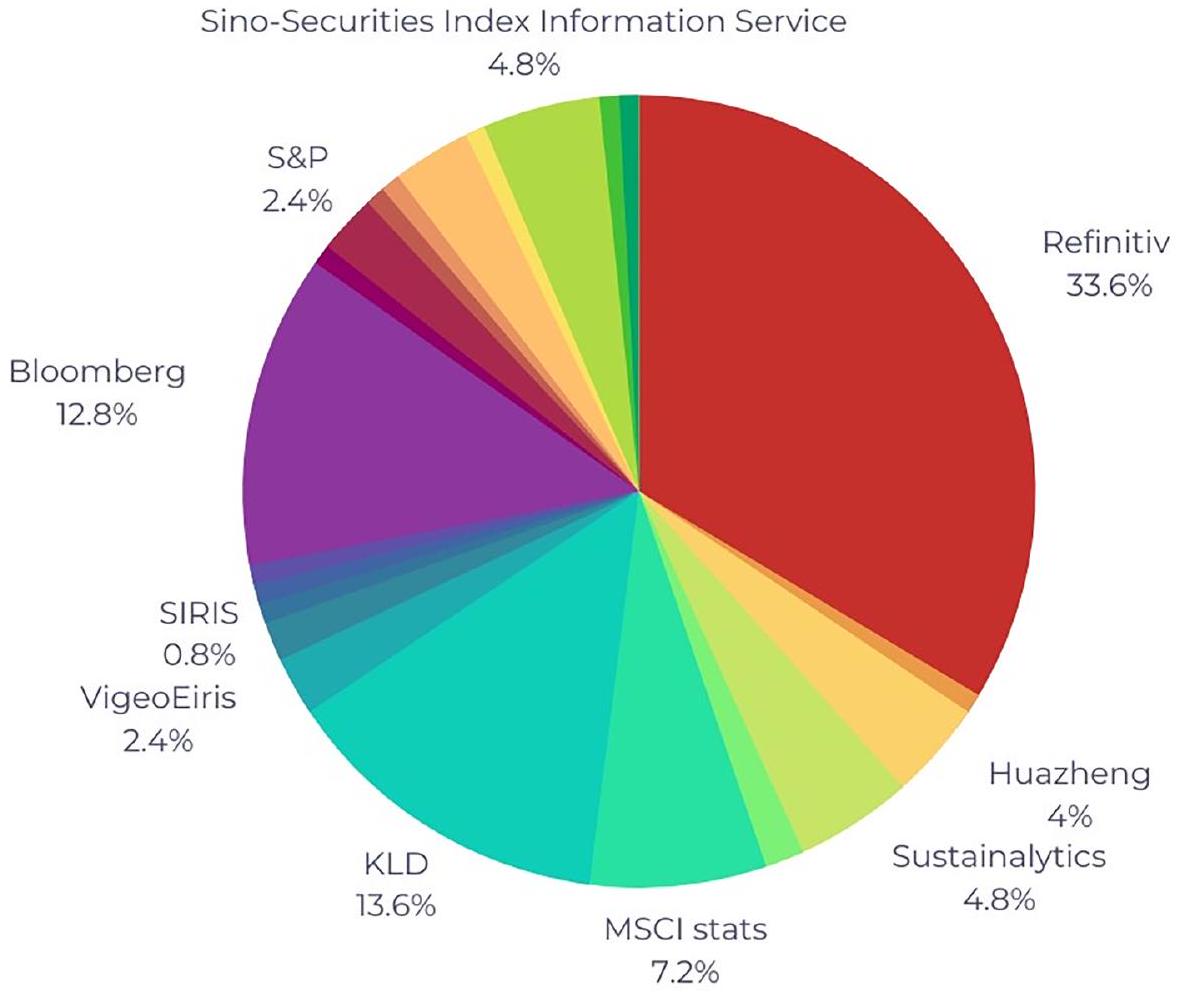

توزيع التقييمات للمقالات المختارة

| ريفينيتيف | ||||||

| ريفينيتيف إيكون |

|

قاعدة بيانات Thomson Reuters ASSET4 (الآن Refinitiv) | ||||

| موونيابين وآخرون (2022)؛ ديسلي وآخرون (2022)؛ باروس وآخرون (2021)؛ رونالتير وآخرون (2022)؛ فو وآخرون (2022)؛ كامبريا وآخرون (2023)؛ بوزولي وآخرون (2022)؛ جيب هاردت وآخرون (2023)؛ كوهين وآخرون (2023)؛ سيتياريني وآخرون (2023)؛ يورك وآخرون (2023)؛ سلومكا-غوليمبيوسكا وآخرون (2023)؛ داس (2023). | (ألدّا، 2019); | داس غوبتا (2021)؛ باركو وآخرون (2022)؛ غارسيا وأورساتو (2020)؛ دريمبيتيك وآخرون (2020)؛ سيمينوفا وهاسل (2019)؛ شولي وسندوي (2018)؛ جانجي وفاروني (2018)؛ مرفلسكمبر وسترايت (2017)؛ مانيورا (2015)؛ ديل بوسكو وميساني (2016)؛ أتيغ وآخرون (2016)؛ أورطاس وآخرون (2015)؛ ريس وروديونوفا (2015)؛ قويم وآخرون (2022)؛ بارايبار-دييز ودي. أودريوزولا (2019)؛ فوانغ وسوزوكي (2021)؛ غارسيا وآخرون (2017)؛ نخيلي وآخرون (2021)؛ تامباكوديس وأناغنوستوبولو (2020)؛ راجيش وراجندران (2020)؛ شهباز وآخرون (2020)؛ راجيش وآخرون (2022)؛ غوفيندان وآخرون (2021)؛ ليستاري وأدهارياني (2022)؛ كاستيو-ميرينو ورودريغيز-بيريز (2021)؛ العموش وخطيب (2023)؛ لوزانو ومارتينيز-فيريرو (2022)؛ فينوجوبال وآخرون (2023)؛ | ||||

| سستيناليتيكس | البحث في الاستثمار المستدام الدولي (SiriPro) – سوتيناليتيكس القديمة | إحصائيات MSCI | KLD – MSCI القديم | |||

| أرفيدسون ودوماي (2022)؛ شيفرولييه وآخرون (2019)؛ هوستد وفيليو (2016)؛ تشاو وموريل (2022)؛ غرافلاند وسمد (2015)؛ كوهين وآخرون (2023) | لابيل وآخرون (2018)؛ أورليتسكي وآخرون (2017)؛ | كرايس وجيهيمان (2022)؛ عمر وآخرون (2020)؛ كاي وآخرون (2016)؛ هارجوتو وآخرون (2019)؛ براور ورو (2017)؛ روثنبرغ وآخرون (2017)؛ تشان وآخرون (2016)؛ أتيغ وآخرون (2016)؛ تشينغ وآخرون (2023)؛ | شورت وآخرون (2015)؛ كشميري وماهجان (2014)؛ تشيو وشارفمان (2011)؛ تشاو وموريل (2022)؛ تشوي ولي (2018)؛ كانغ (2017)؛ هارت وآخرون (2015)؛ براور وماهجان (2013)؛ مالين وآخرون (2013)؛ حفيظ وتورغوت (2013)؛ زانغ (2012)؛ وونغ وآخرون (2011)؛ مالين وميشيلون (2011)؛ مانر (2010)؛ جيردي (2001)؛ لي وريفي (2017)؛ كوهين وآخرون (2023)؛ | |||

| فيجيو إيريس | CSRHub | معهد أبحاث الاستثمار المستدام (SIRIS) | إنوفيست: تقييم القيمة غير الملموسة (IVA) | |||

| بيجي ولوقيل (2021)؛ كاسلي وآخرون (2021)؛ كريفو وآخرون (2018) | أرمينن وآخرون (2017)؛ نيرانتزيديس وآخرون (2022) | غالبراث (2013); | Foo Nin وآخرون (2012) | |||

| تقييمات GMI | ريبريسك | هيكسون | مؤشر KEJI | |||

| أتيغ وآخرون (2016) | هيوستن وشان (2022) | تشي وآخرون (2022)؛ مينغ وآخرون (2022)؛ يانغ وآخرون (2023)؛ وانغ وآخرون (2023)؛ | أري ويوكيونغ (2018) | |||

| سينتاو للتمويل الأخضر | بلومبرغ | موقع HBR | مؤشر داو جونز للاستدامة العالمي (S&P) | |||

| هوانغ وآخرون (2022) | هارجوتو ووانغ (2020)؛ أرايسي وآخرون (2016)؛ مانس-كيمب وفان دير لوخت (2020)؛ نج وآخرون (2020)؛ وانغ وآخرون (2023)؛ صن وسات (2023)؛ لي وبانغ (2023)؛ مو وآخرون (2023)؛ بنغ وآخرون (2023)؛ تشين وآخرون (2022)؛ لي ولي (2022)؛ شو وزهاو (2022)؛ ليو وآخرون (2022)؛ وانغ وآخرون (2022)؛ هوانغ وآخرون (2023)؛ تشين وآخرون (2023)؛ هي وآخرون (2023)؛ | غارسيا-بلاندون وآخرون (2019) | إيبرهاردت-توث (2016)؛ سوتيبون وديشتانابودين (2022)؛ جان وآخرون (2022) | |||

| هيشون. كوم | هوا تشنغ | خدمة معلومات مؤشر الأوراق المالية الصينية | قاعدة بيانات الرياح | |||

| هيشون. كوم | هوا تشنغ | خدمة معلومات مؤشر الأوراق المالية الصينية | قاعدة بيانات الرياح |

| وانغ وآخرون (2023) | سون وآخرون (2023)؛ صن وسات (2023)؛ تشونغ وآخرون (2023)؛ مو وآخرون (2023)؛ لو وآخرون (2023) | وانغ وآخرون (2023)؛ يان وآخرون (2023)؛ فو وآخرون (2022)؛ وانغ وآخرون (2022)؛ تانغ وآخرون (2023)؛ شيوي وآخرون (2023) | شيوي وآخرون (2023); |

| فوتسي راسل | |||

| ونغ (2023); |

References

Al Amosh, H., Khatib, S.F., 2023. ESG performance in the time of COVID-19 pandemic: cross-country evidence. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 30, 39978-39993. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-25050-w.

Alda, M., 2019. Corporate sustainability and institutional shareholders: the pressure of social responsible pension funds on environmental firm practices. Bus. Strat. Environ. 28 (3), 1060-1071. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2301.

Ali, W., Frynas, J.G., Mahmood, Z., 2017. Determinants of corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure in developed and developing countries: a literature review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 24 (4), 273-294. https://doi.org/10.1002/ csr. 1410.

Arayssi, M., Dah, M., Jizi, M., 2016. Women on boards, sustainability reporting and firm performance. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 7 (3), 376-401. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-07-2015-0055.

Ari, K., Youkyoung, L., 2018. Family firms and corporate social performance: evidence from Korean firms. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 24 (5), 693-713. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 13602381.2018.1473323.

Arvidsson, S., Dumay, J., 2022. Corporate ESG reporting quantity, quality, and performance: where to now for environmental policy and practice? Bus. Strat. Environ. 31 (3), 1091-1110. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse. 2937.

Attig, N., Boubakri, N., El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., 2016. Firm internationalization and corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 134 (2), 171-197. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10551-014-2410-6.

Barko, T., Cremers, M., Renneboog, L., 2022. Shareholder engagement on environmental, social, and governance performance. J. Bus. Ethics 180 (2), 777-812. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04850-z.

Barney, J., 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 17, 99-120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108.

Barros, V., V Matos, P., Sarmento, J., Rino Vieira, P., 2021. M&A activity as a driver for better ESG performance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 175 (121338). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121338.

Beji, R., Loukil, N., 2021. Board diversity and corporate social responsibility: empirical evidence from France. J. Bus. Ethics 173 (1), 133-155. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10551-020-04522-4.

Berg, F., Kölbel, J.F., Rigobon, R., 2022. Aggregate confusion: the divergence of ESG RAtings. Rev. Finance 26 (6), 1315-1344. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfac033.

Billio, M., Costola, M., Hristova, I., Latino, C., Pelizzon, L., 2021. Inside the ESG ratings: (Dis)agreement and performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 28 (5), 1426-1445. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr. 2177.

Brower, J., Mahajan, V., 2013. Driven to Be good: a stakeholder theory perspective on the drivers of corporate social performance. J. Bus. Ethics 117 (2), 313-331. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1523-z.

Brower, J., Rowe, K., 2017. Where the eyes go, the body follows?: understanding the impact of strategic orientation on corporate social performance. J. Bus. Res. 79 (C), 134-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.06.004.

Cai, Y., Pan, C.H., Statman, M., 2016. Why do countries matter so much in corporate social performance? J. Corp. Finance 41 (C), 591-609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jcorpfin.2016.09.004.

Cambrea, D.R., Paolone, F., Cucari, N., 2023. Advisory or monitoring role in ESG scenario: which women directors are more influential in the Italian context? Bus. Strat. Environ. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3366.

Cassely, L., Larbi, S., Revelli, C., Lacroux, A., 2021. Corporate social performance (CSP) in time of economic crisis. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 12 (5), 913-942. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-07-2020-0262.

Castillo-Merino, D., Rodríguez-Pérez, G., 2021. The effects of legal origin and corporate governance on financial firms’ sustainability performance. Sustainability 13 (8233). https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158233.

Chan, C., Chou, D., Lo, H., 2016. Do financial constraints matter when firms engage in CSR? N. Am. J. Econ. Finance 39, 241-259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. najef.2016.10.009.

Chen, J., Yang, Y., Liu, R., Geng, Y., Ren, X., 2023. Green bond issuance and corporate ESG performance: the perspective of internal attention and external supervision. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 10 (1). https://doi.org/10.1057/ s41599-023-01941-2.

Cheng, L.T., Lee, S.-k., Li, S.K., Tsang, C.K., 2023. Understanding resource deployment efficiency for ESG and financial performance: a dea approach. Res. Int. Bus. Finance 65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2023.101941.

Chollet, P., Sandwidi, B.W., 2018. CSR engagement and financial risk: a virtuous circle? International evidence. Global Finance J. 38 (C), 65-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. gfj.2018.03.004.

Cohen, S., Kadach, I., Ormazabal, G., Reichelstein, S., 2023. Executive compensation tied to ESG performance: international evidence. J. Account. Res. 61 (3), 805-853. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12481.

Crace, L., Gehman, J., 2022. What really explains ESG performance? Disentangling the asymmetrical drivers of the triple bottom line. Organ. Environ. 36 (1), 150-178. https://doi.org/10.1177/10860266221079408.

Crifo, P., Escrig-Olmedo, E., Mottis, N., 2018. Corporate governance as a key driver of corporate sustainability in France: the role of board members and investor relations. J. Bus. Ethics 159 (4), 1127-1146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3866-6.

Cruz, C., Larraza-Kintana, M., Garcés-Galdeano, L., Berrone, P., 2014. Are family firms really more socially responsible? Entrep. Theory Pract. 38 (6), 1295-1316. https:// doi.org/10.1111/etap. 12125.

Damodaran, A., 2023. ESG Is beyond Redemption: May it RIP. Financial Times.

Das, A., 2023. Predictive value of supply chain sustainability initiatives for ESGperformance: a study of large multinationals. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. https://doi. org/10.1108/MBR-09-2022-0149.

DasGupta, R., 2021. Financial performance shortfall, ESG controversies, and ESG performance: evidence from firms around the world. Finance Res. Lett. 46 (PB) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.102487.

Del Bosco, B., Misani, N., 2016. The effect of cross-listing on the environmental, social, and governance performance of firms. J. World Bus. 51 (6), 977-990. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jwb.2016.08.002.

Deng, P., Wen, J., He, W., Chen, Y.-E., Wang, Y.-P., 2022. Capital market opening and ESG performance. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 1540496X.2022.2094761.

Disli, M., Yilmaz, M., Mohamed, F., 2022. Board characteristics and sustainability performance: empirical evidence from emerging markets. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 13 (4), 929-952. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-09-2020-0313.

Drempetic, S., Klein, C., Zwergel, B., 2020. The influence of firm size on the ESG score: corporate sustainability ratings under review. J. Bus. Ethics 167 (2), 333-360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04164-1.

Du, L., Jianfei, S., 2023. Washing away their stigma? The ESG of “Sin” firms. Finance Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2023.103938.

Eberhardt-Toth, E., 2016. Who should be on a board corporate social responsibility committee? J. Clean. Prod. 140 (3), 1926-1935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jclepro.2016.08.127.

Eccles, R.G., Klimenko, S., 2019. The investor revolution. Harv. Bus. Rev. 97, 106-116.

European Commission, 2023a. EU taxonomy for sustainable activities. https://finance. ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance/tools-and-standards/eu-taxonomy-sustainable -activities_en#:~:text=The%20EU%20taxonomy%20allows%20financial%20and% 20non-financial%20companies,economic%20activities%20that%20can%20be% 20considered%20environmentally%20sustainable.

European Commission, 2023b. Proposal for a regulation of the European parliament and of the council on the transparency and integrity of environmental, social and governance (ESG) rating activities. COM(2023) 314 final.

Fasan, M., Zaro, E.S., Zaro, C.S., Schiavon, C., Bagarotto, E.-M., 2023. Do deviations from shareholder democracy harm sustainability? An empirical analysis of multiple voting shares in Europe. Int. J. Bus. Govern. Ethics 17 (2), 111-130. https://doi.org/ 10.1504/IJBGE. 2023. 129417.

Freeman, R.E., 1984. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Cambridge University Press.

Freeman, R., McVea, J., 2000. A stakeholder approach to strategic management. In: Hitt, M., Freeman, M.E., Harrison, J. (Eds.), Handbook of Strategic Managment. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford.

Friedman, M., 1970. The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. N. Y. Times Mag. 13, 32-33.

Fu, L., 2023. Why bad news can Be good news: the signaling feedback effect of negative media coverage of corporate irresponsibility. Organ. Environ. 36 (1), 98-125. https://doi.org/10.1177/10860266221108704.

Fu, P., Narayan, S.W., Weber, O., Tian, Y., Ren, Y.-S., 2022. Does local confucian culture affect corporate environmental, social, and governance ratings? Evidence from China. Sustainability 14 (24). https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416374.

Galbreath, J., 2013. ESG in focus: the Australian evidence. J. Bus. Ethics 118 (3), 529-541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1607-9.

Gangi, F., Varrone, N., 2018. Screening activities by socially responsible funds: a matter of agency? J. Clean. Prod. 197 (1), 842-855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jclepro.2018.06.228.

Garcia, A., Orsato, R., 2020. Testing the institutional difference hypothesis: a study about environmental, social, governance, and financial performance. Business Strategy and the Environmnet 29 (1), 3261-3272. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2570.

Garcia, A., Mendes-Da-Silva, W., Orsato, R., 2017. Sensitive industries produce better ESG performance: evidence from emerging markets. J. Clean. Prod. 150 (1137), 135-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.02.180, 150.

Garcia-Blandon, J., Argilés-Bosch, J.M., Ravenda, D., 2019. Exploring the relationship between CEO characteristics and performance. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 20 (6), 1064-1082. https://doi.org/10.3846/jbem.2019.10447.

Gebhardt, M., Thun, T.W., Seefloth, M., Zuelch, H., 2023. Managing sustainability-Does the integration of environmental, social and governance key performance. Bus. Strat. Environ. 32 (4), 2175-2192. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse. 3242.

Gerde, V.W., 2001. The design dimensions of the just organization: an empirical test of the relation between organization design and corporate social performance. Bus. Soc. 40 (4), 472-477. https://doi.org/10.1177/000765030104000406.

Govindan, K., Kilic, M., Uyar, A., Karaman, A., 2021. Drivers and value-relevance of CSR performance in the logistics sector: a cross-country firm-level investigation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 231 (107835) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2020.107835.

Graafland, J., Smid, H., 2015. Competition and institutional drivers of corporate social performance. Economist 163 (3), 303-322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-015-9255-y.

Hafsi, T., Turgut, G., 2013. Boardroom diversity and its effect on social performance: conceptualization and empirical evidence. J. Bus. Ethics 112 (3), 463-479. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1272-z.

Han, H., 2022. Does increasing the QFII quota promote Chinese institutional investors to drive ESG? Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting & Economics. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/16081625.2022.2156362.

Harjoto, M., Laksmana, I., Yang, Y., 2019. Board nationality and educational background diversity and corporate social performance. Corp. Govern. 19 (2), 217-239. https:// doi.org/10.1108/CG-04-2018-0138.

Hart, T.A., David, P., Shao, F., Fox, C.J., Westermann-Behaylo, M., 2015. An examination of the impact of executive compensation disparity on corporate social performance. Strat. Organ. 13 (3), 200-223. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127015585103.

He, X., Jing, Q., Chen, H., 2023. The impact of environmental tax laws on heavypolluting enterprise ESG performance: a stakeholder behavior perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 344 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118578.

Huang, W., Luo, Y., Wang, X., Xiao, L., 2022. Controlling shareholder pledging and corporate ESG behavior. Res. Int. Bus. Finance 61, 101655. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ribaf.2022.101655.

Huang, M., Li, M., Li, X., 2023. Do non-local CEOs affect environmental, social and governance performance? Manag. Decis. 61 (8), 2354-2373. https://doi.org/ 10.1108/MD-07-2022-1004.

Jiang, Y., Wang, C., Li, S., Wan, J., 2022. Do institutional investors’ corporate site visits improve ESG performance? Evidence from China. Pac. Basin Finance J. 76 https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2022.101884.

Kang, J., 2017. Unobservable CEO characteristics and CEO compensation as correlated determinants of CSP. Bus. Soc. 56 (3), 419-453. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0007650314568862.

Khaled, R., Ali, H., Mohamed, E., 2021. The Sustainable Development Goals and corporate sustainability performance: mapping, extent and determinants. J. Clean. Prod. 311, 127599 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127599.

Labelle, R., Hafsi, T., Francoeur, C., al, e., 2018. Family firms’ corporate social performance: a calculated quest for socioemotional wealth. J. Bus. Ethics 148, 511-525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2982-9.

Lee, S., Riffe, D., 2017. Who sets the corporate social responsibility agenda in the news media? Unveiling the agenda-building process of corporations and a monitoring group. Publ. Relat. Rev. 43 (2), 293-305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. pubrev.2017.02.007.

Lestari, N.I., Adhariani, D., 2022. Can intellectual capital contribute to financial and nonfinancial performances during normal and crisis situations? Business Strategy & Development 5 (4), 390-404. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsd2.206.

Lewellyn, K., Muller-Kahle, M., 2023. ESG leaders or laggards? A configurational analysis of ESG performance. Bus. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1177/00076503231182688.

Li, J., Li, S., 2022. Environmental protection tax, corporate ESG performance, and green technological innovation. Front. Environ. Sci. 10 https://doi.org/10.3389/ fenvs. 2022.982132.

Li, W., Pang, W., 2023. The impact of digital inclusive finance on corporate ESG performance: based on the perspective of corporate green technology innovation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 30 (24), 65314-65327. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11356-023-27057-3.

Liang, H., Renneboog, L., 2017. On the foundations of corporate social responsibility. J. Finance 72, 853-910. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12487.

Liu, J., Xiong, X., Gao, Y., Zhang, J., 2022. The impact of institutional investors on ESG: evidence from China. Account. Finance. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.13011.

Lozano, B.M., Martinez-Ferrero, J., 2022. Do emerging and developed countries differ in terms of sustainable performance? Analysis of board, ownership and country-level factors. Res. Int. Bus. Finance 62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2022.101688.

Lu, S., Cheng, B., 2023. Does environmental regulation affect firms’ ESG performance? Evidence from China. Manag. Decis. Econ. 44 (4), 2004-2009. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/mde. 3796.

Mallin, C., Michelon, G., Raggi, D., 2013. Monitoring intensity and stakeholders’ orientation: how does governance affect social and environmental disclosure? J. Bus. Ethics 114 (1), 29-43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1324-4.

Maniora, J., 2015. Is integrated reporting really the superior mechanism for the integration of ethics into the core business model? An empirical analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 140, 755-786. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2874-z.

Manner, M., 2010. The impact of CEO characteristics on corporate social performance. J. Bus. Ethics 93 (Suppl. 1), 53-72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0626-7.

Meng, S., Su, H., Yu, J., 2022. Digital transformation and corporate social performance: how do board independence and institutional ownership matter? Front. Psychol. 13 https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYG.2022.915583.

Mervelskemper, L., Streit, D., 2017. Enhancing market valuation of ESG performance: is integrated reporting keeping its promise? Bus. Strat. Environ. 26 (4), 536-549. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse. 1935.

Mooneeapen, O., Abhayawansa, S., Mamode Khan, N., 2022. The influence of the country governance environment on corporate environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 13 (4), 953-985. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-07-2021-0298.

Mu, W., Liu, K., Tao, Y., Ye, Y., 2023. Digital finance and corporate ESG. Finance Res. Lett. 51 (C) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2022.103426.

Nekhili, M., Boukadhaba, A., Nagati, H., 2021. The ESG-financial performance relationship: does the type of employee board representation matter? Corp. Govern. Int. Rev. 29 (2), 134-161. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg. 12345.

Nerantzidis, M., Tzeremes, P., Koutoupis, A., Pourgias, A., 2022. Exploring the black box: board gender diversity and corporate social performance. Finance Res. Lett. 48 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2022.102987.

Ng, T., Lye, C., Chan, K., Lim, Y., Lim, Y., 2020. Sustainability in asia: the roles of financial development in environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance. Soc. Indicat. Res. 150 (1), 17-44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02288-w.

Ortas, E., Álvarez, I., Jaussaud, J., Garayar, A., 2015. The impact of institutional and social context on corporate environmental, social and governance performance of companies committed to voluntary corporate social responsibility initiatives. J. Clean. Prod. 108, 673-684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.06.089.

Peng, H., Zhang, Z., Goodell, J.W., Li, M., 2023. Socially responsible investing: is it for real or just for show? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 86 https://doi.org/10.1016/j. irfa.2023.102553.

Pozzoli, M., Pagani, A., Paolone, F., 2022. The impact of audit committee characteristics on ESG performance in the European Union member states: empirical evidence before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.jclepro.2022.133411.

Qiang, S., Gang, C., Dawei, H., 2023. Environmental cooperation system, ESG performance and corporate green innovation: empirical evidence from China. Front. Psychol. 14 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1096419.

Qoyum, A., Sakti, M.R., Thaker, H.M., AlHashfi, R.U., 2022. Does the islamic label indicate good environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance? Evidence from sharia-compliant firms in Indonesia and Malaysia. Borsa Istanbul Review 22 (2), 306-320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2021.06.001.

Rajesh, R., Rajeev, A., Rajendran, C., 2022. Corporate social performances of firms in select developed economies: a comparative study. Soc. Econ. Plann. Sci. 81 (C) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2021.101194.

Rawls, J., 1971. A Theory of Justice. Belknap Press/Harvard University Press.

Rees, W., Rodionova, T., 2015. The influence of family ownership on corporate social responsibility: an international analysis of publicly listed companies. Corp. Govern. Int. Rev. 23 (3), 184-202. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg. 12086.

Ren, X., Zeng, G., Zhao, Y., 2023. Digital finance and corporate ESG performance: empirical evidence from listed companies in China. Pac. Basin Finance J. 79 https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2023.102019.

Rizzi, F., Pellegrini, C., Battaglia, M., 2018. The structuring of social finance: emerging approaches for supporting environmentally and socially impactful projects. J. Clean. Prod. 170, 805-817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclep.

Ronalter, L., Bernardo, M., Romaní, J., 2022. Quality and environmental management systems as business tools to enhance ESG performance: a cross-regional empirical study. Environ. Dev. Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02425-0.

Rothenberg, S., Hull, C.E., Tang, Z., 2017. The impact of human resource management on corporate social performance strengths and concerns. Bus. Soc. 56 (3), 391-418. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650315586594.

Sauer, P.C., Seuring, S., 2023. How to conduct systematic literature reviews in management research: a guide in 6 steps and 14 decisions. Review of Managerial Science 17, 1899-1933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-023-00668-3.

Semenova, N., Hassel, L., 2019. Private engagement by Nordic institutional investors on environmental, social, and governance risks in global companies. Corp. Govern. Int. Rev. 27 (2), 144-161. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12267.

Setiarini, A., Gani, L., Diyanty, V., Adhariani, D., 2023. Strategic orientation, risk-taking, corporate life cycle and environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices: evidence from ASEAN countries. Business Strategy and Development 6 (3), 491-502. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsd2.257.

Shahbaz, M., Karaman, A.S., Kilic, M., Uyar, A., 2020. Board attributes, CSR engagement, and corporate performance: what is the nexus in the energy sector? Energy Pol. 143 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111582.

Sheehan, N.T., Vaidyanathan, G., Fox, K.A., Klassen, M., 2023. Making the invisible, visible: overcoming barriers to ESG performance with an ESG mindset. Bus. Horiz. 66 (2), 265-276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2022.07.003.

Short, J.C., McKenny, A.F., Ketchen, D.J., Snow, C.C., Hult, G.T., 2015. An empirical examination of firm, industry, and temporal effects on corporate social performance. Bus. Soc. 55 (8) https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650315574848.

Shu, H., Tan, W., 2023. Does carbon control policy risk affect corporate ESG performance? Econ. Modell. 120 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2022.106148.

Słomka-Gołębiowska, A., De Masi, S., Zambelli, S., Paci, A., 2023. Towards higher sustainability: if you want something done, ask a chairwoman. Finance Res. Lett. 58 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2023.104308.

Soppe, A., 2004. Sustainable corporate finance. J. Bus. Ethics 53 (1/2), 213-224. https:// doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.00000.

Suttipun, M., Dechthanabodin, P., 2022. Environmental, social and governance (ESG) committees and performance in Thailand. Asian J. Bus. Account. 15 (2), 205-220. https://doi.org/10.22452/ajba.vol15no2.7.

Tang, S.L., He, L.F., Su, F., Zhou, X.Y., 2023. Does directors’ and officers’ liability insurance improve corporate ESG performance? Evidence from China. Int. J. Finance Econ.

Tian, Z., Zhu, B., Lu, Y., 2023. The governance of non-state shareholders and corporate ESG: empirical evidence from China. Finance Res. Lett. 56 https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.frl.2023.104162.

Venugopal, A., Al-Shammari, M., Thotapalli, P.M.V., Fuad, M., 2023. Liabilities of origin and its influence on firm’s corporate social performance? A study of emerging market multinational corporations. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 65 (5), 519-531. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.22354.

Vuong, N., Suzuki, Y., 2021. The motivating role of sentiment in ESG performance: evidence from Japanese companies. East Asian Economic Review 25 (2), 125-150. https://doi.org/10.11644/KIEP.EAER.2021.25.2.393.

Wang, L., Le, Q., Peng, M., Zeng, H., Kong, L., 2022. Does central environmental protection inspection improve corporate environmental, social, and governance performance? Evidence from China. Bus. Strat. Environ. 1-23. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/bse. 3280.

Wang, L., Qi, J., Zhuang, H., 2023. Monitoring or collusion? Multiple large shareholders and corporate ESG performance: evidence from China”,2023. Finance Res. Lett. 53 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2023.103673.

Wang, W., Sun, Z., Wang, W., Hua, Q., Wu, F., 2023. The impact of environmental uncertainty on ESG performance: emotional vs. rational. J. Clean. Prod. 397 https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136528.

Wang, Y., Lin, Y., Fu, X., Chen, S., 2023. Institutional ownership heterogeneity and ESG performance: evidence from China. Finance Res. Lett. 51 https://doi.org/10.1016/j. frl.2022.103448.

Wang, L., Zhang, Y., Qi, C., 2023. Does the CEOs’ hometown identity matter for firms’ environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 30 (26), 69054-69063. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-27349-8.

Wong, S.L., 2023. The impact of female representation and ethnic diversity in committees on environmental, social and governance performance in Malaysia. Soc. Bus. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBR-02-2023-0052.

Wong, E.M., Ormiston, M.E., Tetlock, P.E., 2011. The effects of top management team integrative complexity and decentralized decision making on corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. J. 54 (6), 1207-1228. https://doi.org/10.5465/ amj.2008.0762.

Xu, H., Zhao, J., 2022. Can directors’ and officers’ liability insurance improve corporate ESG performance? Front. Environ. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.949982.

Xue, Q., Wang, H., Bai, C., 2023. Local green finance policies and corporate ESG performance. Int. Rev. Finance 1-29. https://doi.org/10.1111/irfi.12417.

Xue, Q., Wang, H., Ji, X., Wei, J., 2023a. Local government centralization and corporate ESG performance: evidence from China’s county-to-district reform. China Journal of Accounting Research 16 (3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjar.2023.100314.

Yan, Y., Cheng, Q., Huang, M., Lin, Q., Lin, W., 2023. Government environmental regulation and corporate ESG performance: evidence from natural resource accountability audits in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 20 (1). https://doi. org/10.3390/ijerph20010447.

Yang, C., Hao, W., Song, D., 2023. The effect of political turnover on corporate ESG performance: evidence from China. PLoS One 18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone. 0288789.

Yorke, S.M., Donkor, A., Appiagyei, K., 2023. Experts on boards audit committee and sustainability performance: the role of gender. J. Clean. Prod. 414 https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137553.

Zhang, D., Meng, L., Zhang, J., 2023. Environmental subsidy disruption, skill premiums and ESG performance. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 90 https://doi.org/10.1016/j. irfa.2023.102862.

Zhao, X., Murrell, A., 2022. Does A virtuous circle really exist? Revisiting the causal linkage between CSP and CFP. J. Bus. Ethics 177, 173-192. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10551-021-04769-5.

Zhu, N., Zhou, Y., Zhang, S., Yan, J., 2023. Tax incentives and environmental, social, and governance performance: empirical evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 30 (19), 54899-54913. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-26112-3.

- Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: alice.martiny@santannapisa.it (A. Martiny), Jonathan.taglialatela@polimi.it (J. Taglialatela), francesco.testa@santannapisa.it (F. Testa), Fabio. iraldo@santannapisa.it (F. Iraldo).Some papers used in this Review refer to Thomson Reuters Asset4, which has undergone several name changes: Refinitiv first and in 2023 rebranded as LSEG Data & Analytics.

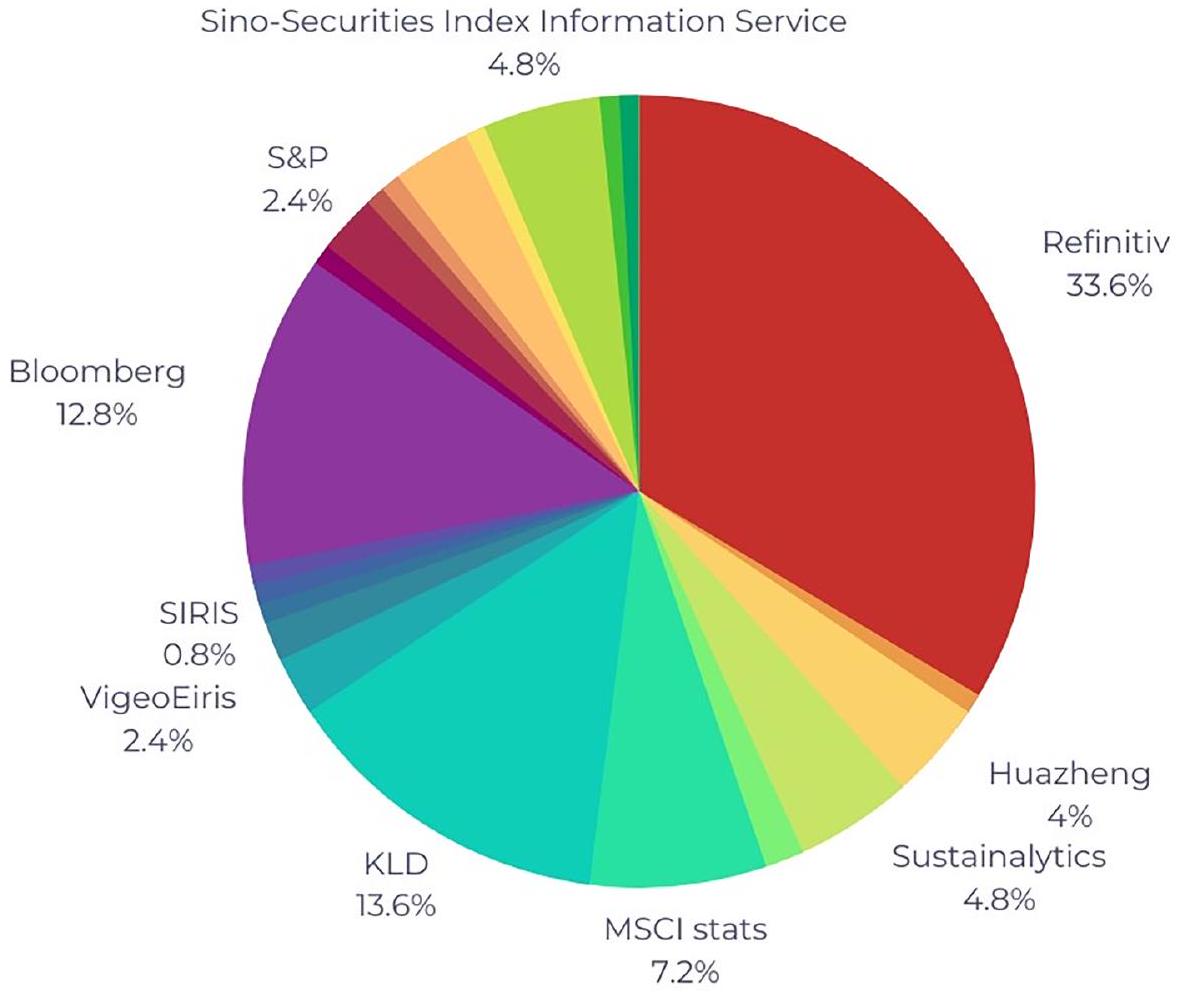

Kinder, Lydenberg, Domini and Co., Inc. Snowballing methodology for paper selection involves expanding the list of papers by examining references, citation searches, and assessing relevance to systematically identify relevant research papers on a specific topic. In the graphic Refinitiv percentage also includes Thomson/Reuters and Datastream. Complete information is to be retrieved in Appendix B. - LMEs: Liberal Market Economies.

CMEs: Coordinated Market Economies.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.142213

Publication Date: 2024-04-25

Determinants of environmental social and governance (ESG) performance: A systematic literature review

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Systematic literature review

Sustainable finance

ESG determinants

Environmental, Social and Governance

Abstract

Understanding the determinants of firms’ ESG performance is not only a key goal of the strategic management field, but it is also fundamental for addressing the world’s most pressing environmental and social challenges and guarantee the survival of ESG as well. To date, no comprehensive overview has been carried out of the determinants that have the greatest impact on ESG criteria. In this work, internal and external determinants are identified and analysed, and the potential causes of the discrepancies in research findings are explored. This Systematic Literature Review was developed in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines, whose process led to a content analysis of the results. The current study proves that the discrepancies in literature findings are a direct consequence of the lack of consideration by scholars of the different usage of ESG data providers as well as the variance among countries. Not only does this study represent the first pioneering framework on the topic, but it could also serve as a guidebook for firms wishing to improve their ESG performance.

1. Introduction

Relevant papers and literature gap.

| Authors | Methodology | Aim of the Study | Determinants | Geography | Database used | ESG measurement | Time Frame | Opportunities for Future Research | ||||||||

| Ali et al. (2017) | Systematic Literature Review | The study reviews the determinants driving CSR disclosure | Internal and External | Developed Countries and Developing Countries | Google Scholar | The paper does not give an analysis of the sources of the disclosures or their measurement | Until 2014 |

|

||||||||

| Crace and Gehman (2022) | Quantitative methods: variance partitioning models | The study analyses what factors explain variation in ESG performance between firms | Internal and External | U.S context | – | MSCI ESG KLD STATS |

|

|

||||||||

| Disli et al. (2022) | Quantitative methods: two-step system GMM estimation method | The study investigates the effects of corporate attributes on corporate sustainability | Internal corporate governance | Emerging Countries | – | Refinitiv | 2010-2019 | – More research is needed to explain the origins and different determinants of sustainability performance | ||||||||

| Chen et al. (2022) | Quantitative methods: differences- indifferences (did) model | The study aims to analyse the impact of green financial reform on the ESG scores of enterprises. | External regulation | China | – | Bloomberg | 2014-2020 | – Single ESG dataset | ||||||||

| Orlitzky et al. (2017) | Quantitative methods: three different methods of variance decomposition analysis | The study aims to estimate the influence of macro, meso and micro factors on CSP | Internal and External | International Sample | – | Sustainalytics | 2003-2007 |

|

||||||||

| Mooneeapen et al. (2022) | Quantitative methods: fixed effects multiple linear regression | The study aims to estimate the influence of country governance on ESG performance | External country governance | 27 countries | – | Refinitiv | 2015-2019 |

|

||||||||

| Cai et al. (2016) | Quantitative methods: OLS regression | The study aims to analyse why countries matter so much in CSP | Internal and External | 36 countries | – | MSCI ESG KLD STATS | 2006-2011 |

|

||||||||

| Arminen et al. (2017) | Quantitative methods: linear regression analyses | The study aims to estimate interindustry and international differences of companies’ CSP | External country governance and industry | 52 countries | – | CSRHUB | 2010-2015 | – A clear majority of the companies come from a relatively limited number of countries (U.S, Japan, U.K) | ||||||||

| Authors | Methodology | Aim of the Study | Determinants | Geography | Database used | ESG measurement | Time Frame | Opportunities for Future Research | |||

|

|||||||||||

| Garcia and Orsato (2020) | Quantitative methods: regression analysis | The study aims to analyse the relationship between ESG and financial performance | Internal financial performance | Emerging and Developed Countries | – | Refinitiv | 2007-2014 | – Future research can include other | |||

| Garcia et al. (2017) | Quantitative methods: linear regression | The study investigates the influence of financial performance in firms of sensitive industries | Internal and External financial performance and industry | BRICS countries | – | Refinitiv | 2010-2012 |

|

|||

| Short et al. (2015) | Quantitative methods: RCM analysis | The study aims to examine the degree to which CSP is related to firm, industry, and temporal factors | Internal and External | U.S | – | KLD | 2003-2011 |

|

included in the analysis.

Therefore, our review aims at extending and complementing their findings by integrating them with the rest of the literature in the process of systematization.

- Contrary to firm performance, the measurement of ESG performance lacks standardisation. ESG ratings from different providers often exhibit “substantial disagreements” (Berg et al., 2022, pag.1), resulting in uncertainty when comparing companies’ ESG profiles and difficulties in synthesizing the findings of multiple studies.

- In terms of research on ESG performance, both developed economies and emerging markets have garnered significant attention (Lozano and Martinez-Ferrero, 2022; Cai et al., 2016; Garcia and Orsato, 2020; Mooneeapen et al., 2022). However, the exploration of differences among countries as indirect drivers of determinants, particularly in terms of corporate governance and firm characteristics, has been limited. Consequently, there are instances where the generalization of certain findings is not possible.

- In general, most articles focus more on internal determinants of ESG performance than external ones. This may be because internal determinants are easier to measure and control, while external determinants may be more complex and difficult to quantify. Neglecting external determinants of ESG performance can be problematic because it may lead to an incomplete understanding of the factors that drive long-term sustainable performance. In alignment with the insights offered by Liang and Renneboog (2017) concerning CSR, the intricate and interdependent qualities of ESG, driven by externalities, imply that it should be intrinsically connected not just to a company’s individual decisions, but also to regulations, institutional frameworks, and societal inclinations.

- Limited focus on the singular pillars can weaken the value of research, as the “factors influencing various dimensions of corporate practices and performance to

and G components can differ” (Mooneeapen et al., 2022).

2. Theoretical background

2.1. The importance of the internal and external determinants of variation in ESG performance