DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54965-w

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39746976

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-02

فئة جديدة من الأدوية الطاردة للديدان الطبيعية تستهدف استقلاب الدهون

تم القبول: 26 نوفمبر 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 02 يناير 2025

الملخص

الديدان الطفيلية هي تهديد صحي عالمي رئيسي، حيث تصيب ما يقرب من خُمس السكان البشر وتسبب خسائر كبيرة في الثروة الحيوانية والمحاصيل. تزداد مقاومة الأدوية المضادة للديدان القليلة. هنا، نبلغ عن مجموعة من الكحوليات/الأسيتات الدهنية من الأفوكادو (AFAs) التي تظهر نشاطًا قاتلًا للديدان ضد أربعة أنواع من الديدان الطفيلية البيطرية: Brugia pahangi وTeladorsagia circumcincta وHeligmosomoides polygyrus، بالإضافة إلى سلالة مقاومة متعددة الأدوية (UGA) من Haemonchus contortus. تظهر AFA فعالية كبيرة في الفئران المصابة بـ H. polygyrus. في C. elegans، يؤثر التعرض لـ AFA على جميع مراحل التطور، مما يسبب الشلل، وضعف التنفس الميتوكوندري، وزيادة إنتاج أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية، وتلف الميتوكوندريا. في الأجنة، تخترق AFAs قشرة البيضة وتسبب توقفًا سريعًا في التطور. تكشف الاختبارات الجينية والبيوكيميائية أن AFAs تثبط POD-2، الذي يشفر أسيتيل

آثار سلبية على الصحة العامة، والأنظمة الزراعية، وبيئة وحفظ الأنواع البرية

تحتوي على أدوية معتمدة من إدارة الغذاء والدواء ومنتجات طبيعية لنشاط مضاد للديدان واسع الطيف محتمل (البيانات التكميلية 1). من المتوقع أن تكون معظم الجزيئات في هذه المكتبة متوافقة بشكل جيد مع البشر، وهو ما أكدناه من خلال قياس السمية في خط خلايا بشرية. من بين المركبات النشطة بيولوجيًا التي تم تحديدها في الفحص كانت مجموعة من مركبات الكحول الدهني ذات الـ 17 كربون المشابهة هيكلًا الموجودة في مستخلصات الأفوكادو (Persea americana). وجدنا أن هذه المركبات، التي نشير إليها بشكل جماعي باسم كحوليات/أسيتات الأفوكادو (AFAs)، تسبب فتكًا يعتمد على الجرعة في الديدان الطفيلية وتستهدف POD-2 في C. elegans، وهو إنزيم أسيتيل-CoA كربوكسيلاز (ACC) الذي يعد الإنزيم المحدد للسرعة في تخليق الدهون.

النتائج

فئة جديدة من الأدوية المضادة للطفيليات

نشاط مضاد للديدان ضد C. elegans و P. pacificus. ج إدماج أسيتات الأفوكادين في

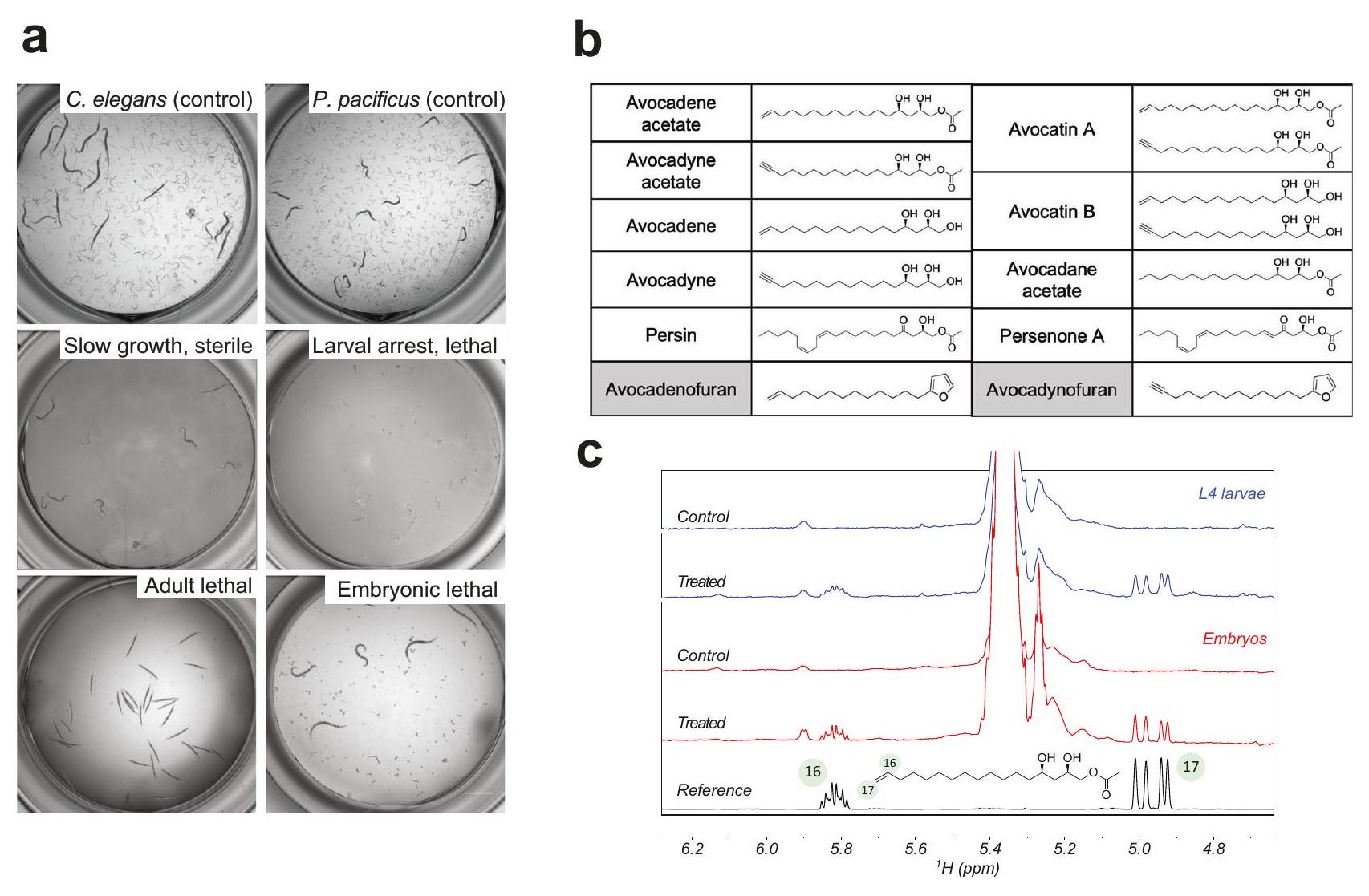

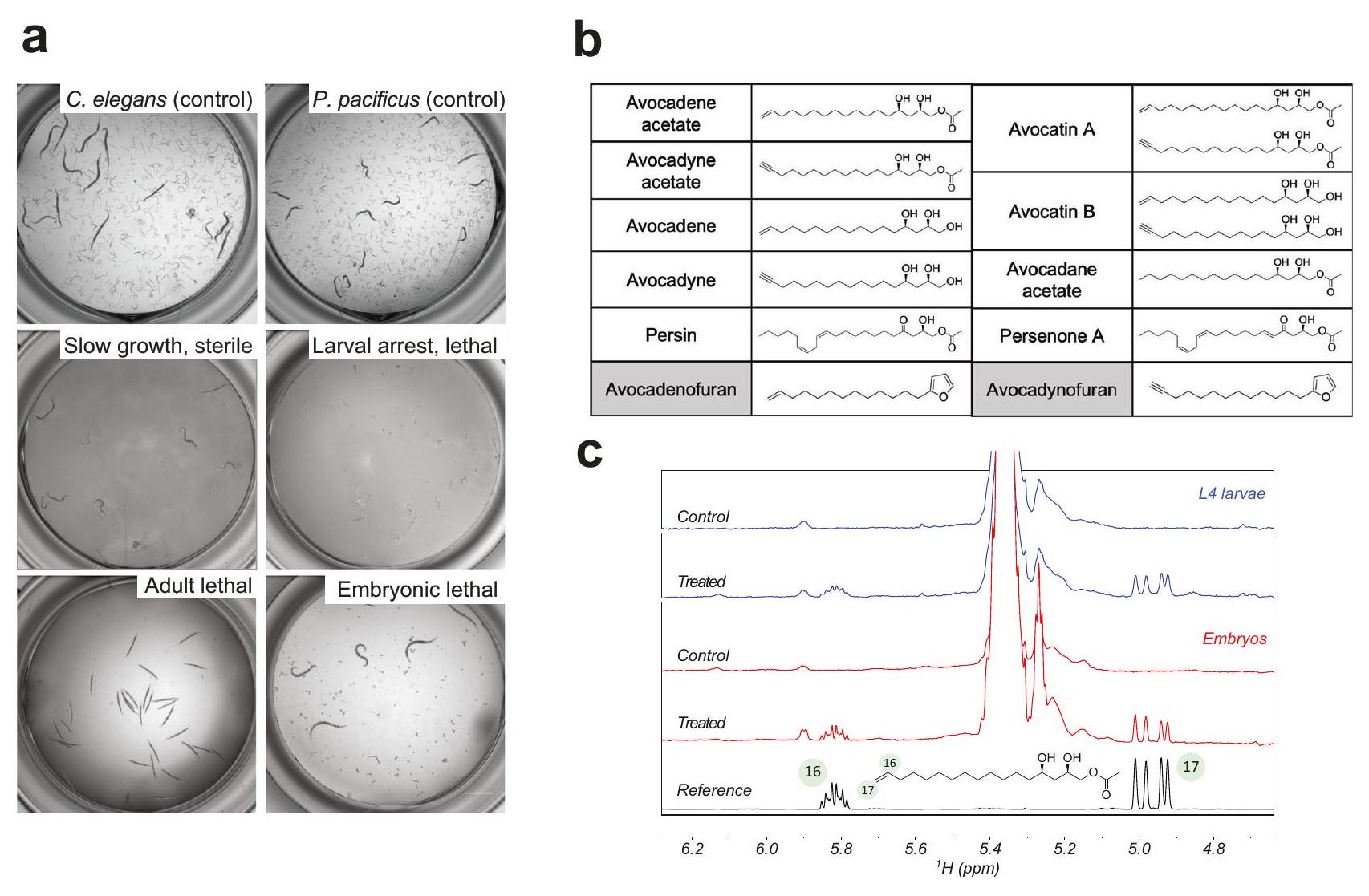

طرق، البيانات التكميلية 2) وأسفرت عن تحديد عائلة من المركبات ذات الصلة المعزولة من الأفوكادو Persea americana التي تسبب مجموعة متنوعة من الظواهر الشديدة في C. elegans (الشكل 1a). تمثل هذه المركبات AFA كحوليات دهنية مشابهة هيكليًا تحتوي على 17 كربونًا ونسخها الأسيتات (الشكل 1b): الأفوكادين ((

احتوت على كميات كبيرة من AFAs بعد

تظهر AFAs نمطًا جديدًا من العمل

| خلاصة | تي. سيركومسينكتا L2 | H. polygyrus L2 | H. contortus (UGA) L2 | بيض H. contortus (UGA) | |||||

| إجمالي | % الفتك | إجمالي | % الفتك | إجمالي | % الفتك | إجمالي | % الفتك | ||

| DMSO | 1% | 32 | 18.8 | 52 | 21.2 | 215 |

|

113 | ٣٣.٦ |

| أفو ب |

|

١١٩ |

|

40 | 100 | ٢٢٣ |

|

89 | 31.5 |

|

|

١١٩ |

|

69 | 100 | ٢٠٩ |

|

30 | 100 | |

| أفو أ |

|

– | – | ٥٥ | 100 | ٢٢٣ |

|

66 | ٣٦.٤ |

|

|

– | – | 76 | 100 | 162 |

|

75 | 100 | |

الخلايا التي تحتوي على ‘-‘ تشير إلى أن الاختبار لم يتم.

| ب. فاهانجي | DMSO |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| إجمالي البالغين | 40 | 32 | 32 | 31 | ٣٦ | ٣٤ | 37 |

| % الفتك/الشلل | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

| إجمالي الإناث | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| % الفتك/الشلل | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 50 | 100 |

| إجمالي الذكور | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| % الفتك/الشلل | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 30 | 90 | 100 |

| إجمالي L3 | 61 | – | – | – | 68 | – | 69 |

| % الفتك | 0 | – | – | – | 100 | – | 100 |

| إجمالي Mfs | ١٠٤ | 154 | 131 | 150 | ١٢٦ | 147 | 163 |

| % الفتك/الشلل | 1.9 | 5.2 | 9.2 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

الخلايا التي تحتوي على ‘-‘ تشير إلى أن الاختبار لم يتم.

| التركيب الجيني | مقاومة | أسيتات الأفوكادو

|

| النوع البري | لا شيء |

|

| تشا-1(ب1152) | الكاربامات/الفوسفات العضوية |

|

| avr-14(ad1302)؛ avr15(ad1051) glc-1(pk54) | إيفرمكتين |

|

| دي إف 17 (أو إكس 175) | إيفرمكتين/ألبندازول |

|

| unc-63(ok1075) | ليفاميزول / مواد مضادة للطفيليات / تيتراهيدروبيريميدينات |

|

| unc-29(e193) | ليفاميزول |

|

| acr-23(ok2804) | مونيبانتيلي |

|

| داف-16(مو86) | أبيجينين |

|

| بن-1(إي1880) | بنزيميدازول |

|

| سلو-1(js379) | إيموديبسيد |

|

النوع البري N2 عند معالجته في مرحلة L1، مما يشير إلى أن مركبات AFA تعمل من خلال آلية مختلفة (الجدول 3، الشكل التكميلي 3). لتوصيف طريقة عمل AFAs بشكل أكبر، قمنا بإجراء طفرات عشوائية في C. elegans باستخدام إيثيل ميثان سلفونات (EMS). على الرغم من إجراء عدة جولات كبيرة من الفحص واختبار مقاومة

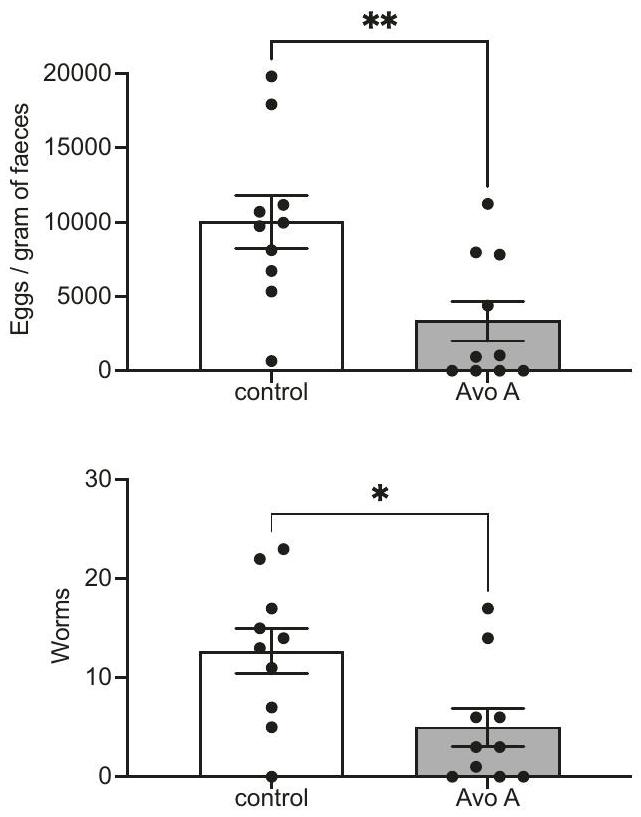

AFAs نشطة في الجسم الحي

تثبط AFAs التنفس في C. elegans

بالإضافة إلى ذلك. رمز اللون وأشرطة الخطأ هي نفسها كما في (ج). كل شريط يمثل عينة واحدة.

كانت هذه التأثيرات أعلى بشكل ملحوظ بشكل عام مقارنةً بالضوابط المعالجة بـ DMSO (اختبار كاي-تربيع)

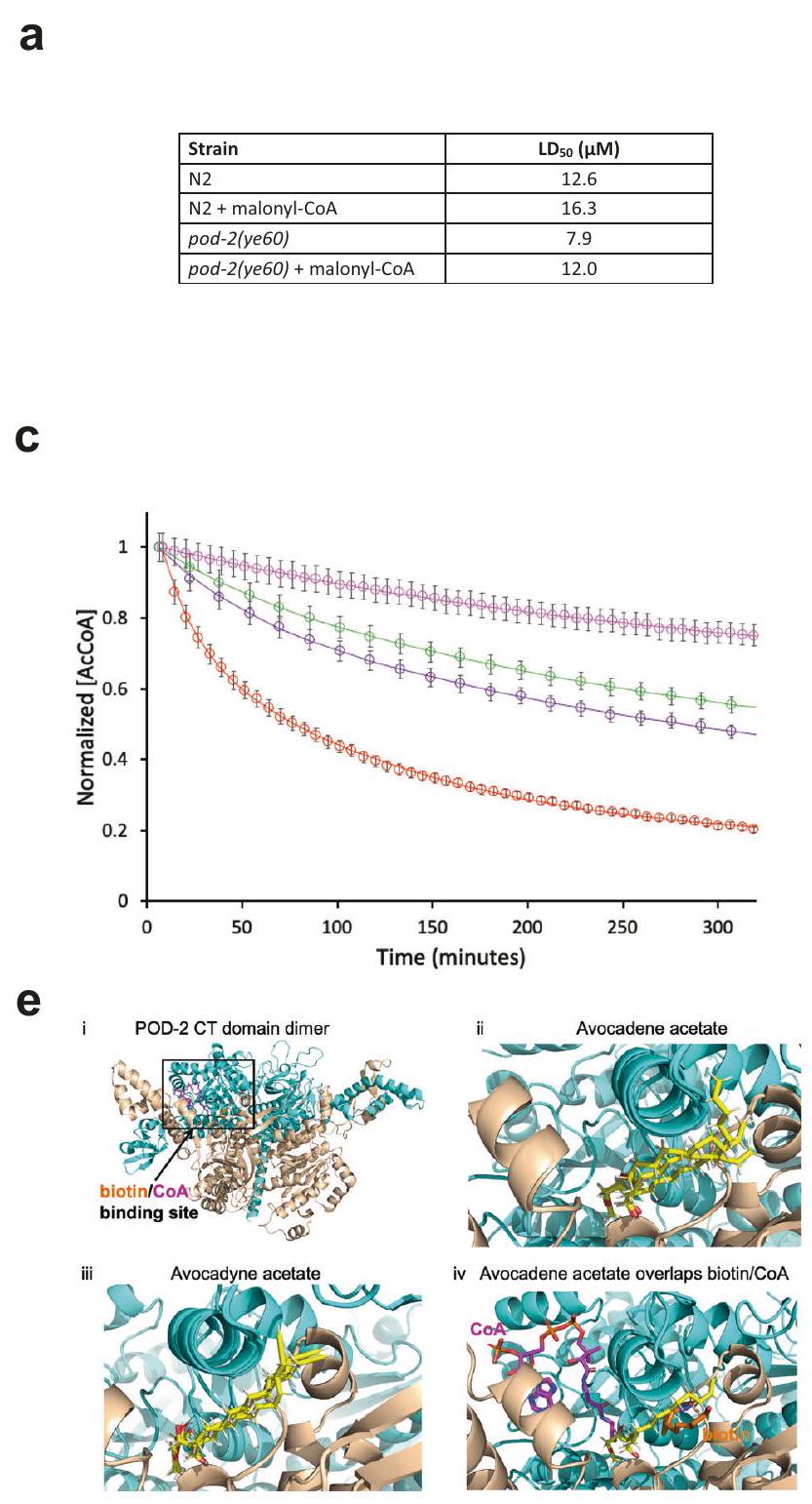

تستهدف AFAs ACC/POD-2

تشير خلايا (AML) إلى تورط الأفوكاتين B في استقلاب الدهون

تكون مثبطة بواسطة نفس الأدوية المضادة للفيروسات في المختبر

نقاش

قياسات معدل استهلاك الأكسجين (OCR) باستخدام محلل Seahorse XFe96

قياس ROS

صبغة ميتو سوكس™ الحمراء

علاج NAC وفيتامين ب12

تمت معالجة الديدان في مرحلة L1 بوجود أو غياب 64 نانومتر من فيتامين B12، تلاها العلاج بـ

تجارب RNAi

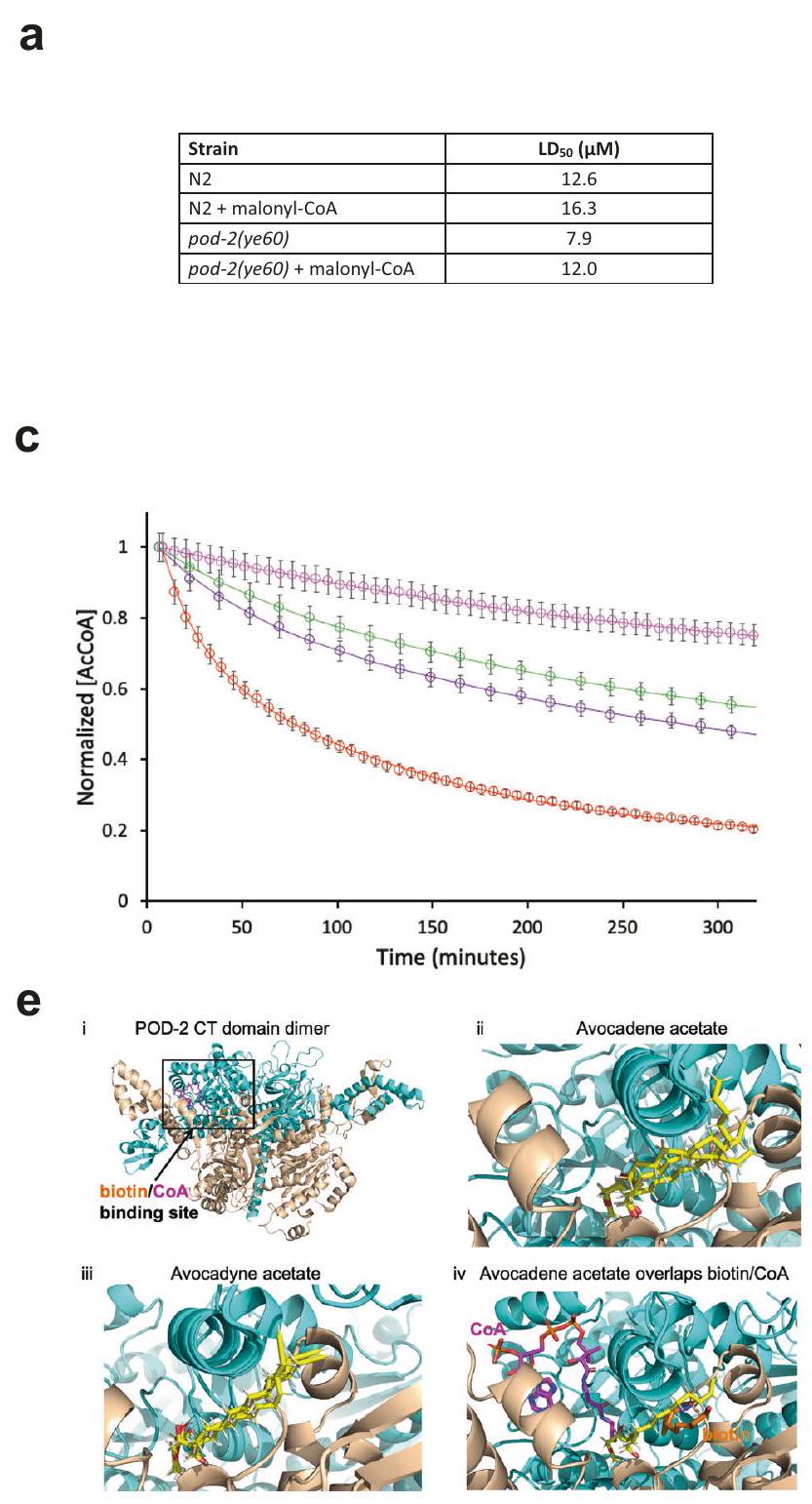

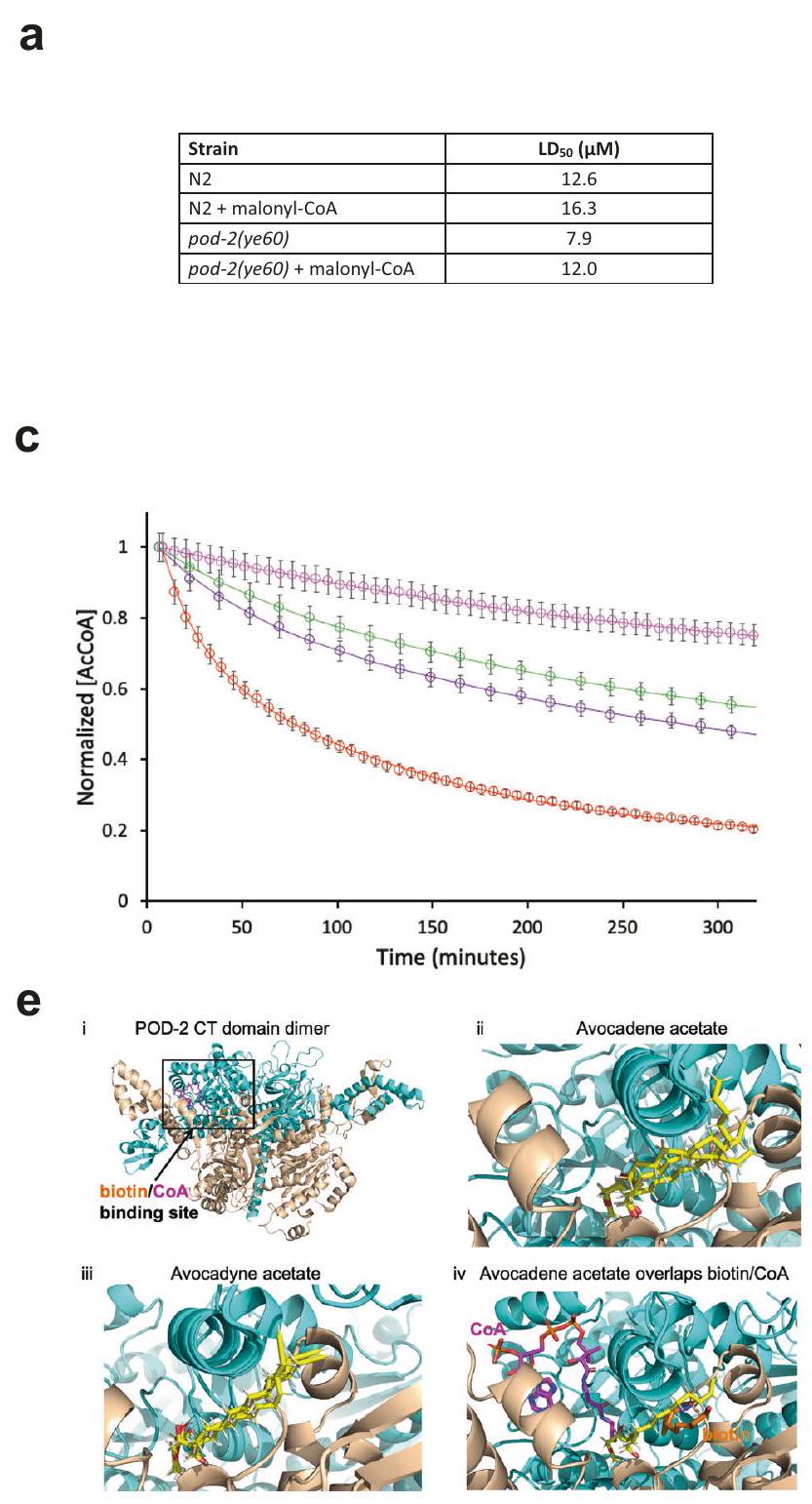

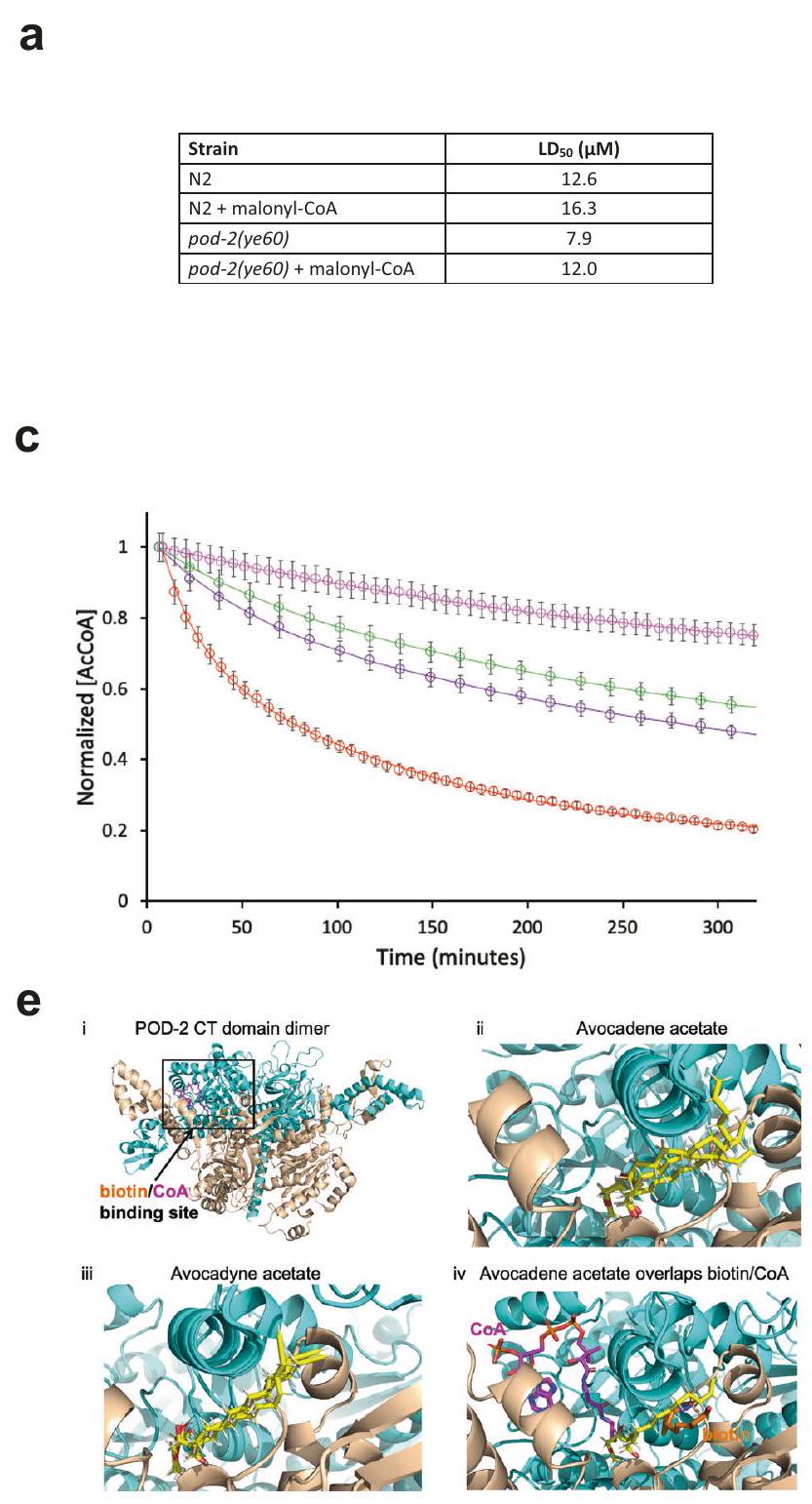

تجارب إنقاذ مالونيل-CoA على WT و pod-2(ye60)

تجارب تحفيز التحلل بواسطة الأوكسين (AID)

الكيمياء الحيوية POD-2

مطيافية الكتلة والبروتيوميات

عمود. تم إعادة تعليق العينات في

النمذجة الحاسوبية

مع 2165 بقايا، تشمل مجالات BC و CT و BCCP. تم نمذجة ثنائي POD-2 والليغاندات المرتبطة به البيوتين و CoA من خلال محاذاة هيكلية باستخدام مجمعات ACC المتماثلة من الخميرة (معرف PDB:

الإحصائيات وإمكانية التكرار

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

References

- Imtiaz, R. et al. Insights from quantitative analysis and mathematical modelling on the proposed WHO 2030 goals for soil-transmitted helminths [version 1; peer review: 2 approved]. Gates Open Res. 3, 1632 (2019).

- Bryant, A. S. & Hallem, E. A. Temperature-dependent behaviors of parasitic helminths. Neurosci Lett 687, 290-303 (2018).

- Learmount, J. et al. Three-year evaluation of best practice guidelines for nematode control on commercial sheep farms in the UK. Vet Parasitol 226, 116-123 (2016).

- Charlier, J. et al. Initial assessment of the economic burden of major parasitic helminth infections to the ruminant livestock industry in Europe. Prev Vet Med. 182, 105103 (2020).

- Siddique, S. & Grundler, F. M. Parasitic nematodes manipulate plant development to establish feeding sites. Curr Opin Microbiol 46, 102-108 (2018).

- Selzer, P. M. & Epe, C. Antiparasitics in animal health: quo vadis? Trends Parasitol 37, 77-89 (2021).

- Blaxter, M. & Koutsovoulos, G. The evolution of parasitism in Nematoda. Parasitology 142, S26-S39 (2015).

- Shih, P. Y. et al. Newly Identified Nematodes from Mono Lake Exhibit Extreme Arsenic Resistance. Curr Biol. 29, 3339-3344.e3334 (2019).

- Gang, S. S. & Hallem, E. A. Mechanisms of host seeking by parasitic nematodes. Mol Biochem Parasitol 208, 23-32 (2016).

- Aleuy, O. A. & Kutz, S. Adaptations, life-history traits and ecological mechanisms of parasites to survive extremes and environmental unpredictability in the face of climate change. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl 12, 308-317 (2020).

- Nixon, S. A. et al. Where are all the anthelmintics? Challenges and opportunities on the path to new anthelmintics. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 14, 8-16 (2020).

- Gasbarre, L. C. Anthelmintic resistance in cattle nematodes in the US. Vet Parasitol 204, 3-11 (2014).

- Geurden, T. et al. Anthelmintic resistance to ivermectin and moxidectin in gastrointestinal nematodes of cattle in Europe. International Journal for Parasitology: Drugs and Drug Resistance 5, 163-171 (2015).

- Prichard, R. K. & Geary, T. G. Perspectives on the utility of moxidectin for the control of parasitic nematodes in the face of developing anthelmintic resistance. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 10, 69-83 (2019).

- Miller, T. W. et al. Avermectins, new family of potent anthelmintic agents: isolation and chromatographic properties. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 15, 368-371 (1979).

- Holden-Dye, L. & Walker, R. J. (2014) Anthelmintic drugs and nematicides: studies in Caenorhabditis elegans. WormBook, 1-29. https://doi.org/10.1895/wormbook.1.143.2.

- Burns, A. R. et al. Caenorhabditis elegans is a useful model for anthelmintic discovery. Nat Commun 6, 7485 (2015).

- Hahnel, S. R., Dilks, C. M., Heisler, I., Andersen, E. C. & Kulke, D. Caenorhabditis elegans in anthelmintic research-Old model, new perspectives. International Journal for Parasitology: Drugs and Drug Resistance 14, 237-248 (2020).

- Min, J. et al. Forward chemical genetic approach identifies new role for GAPDH in insulin signaling. Nat Chem Biol. 3, 55-59 (2007).

- Burns, A. R. et al. The novel nematicide wact- 86 interacts with aldicarb to kill nematodes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 11, e0005502 (2017).

- Bray, M.-A. et al. Cell Painting, a high-content image-based assay for morphological profiling using multiplexed fluorescent dyes. Nat Protoc. 11, 1757-1774 (2016).

- Pearson, Y. E. et al. A statistical framework for high-content phenotypic profiling using cellular feature distributions. Communications Biology 5, 1409 (2022).

- Bond, A. T. & Huffman, D. G. Nematode eggshells: a new anatomical and terminological framework, with a critical review of relevant literature and suggested guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of eggshell imagery. Parasite 30, 6 (2023).

- Oelrichs, P. B. et al. Isolation and identification of a compound from avocado (Persea americana) leaves which causes necrosis of the acinar epithelium of the lactating mammary gland and the myocardium. Natural Toxins 3, 344-349 (1995).

- Crook, M. The dauer hypothesis and the evolution of parasitism: 20 years on and still going strong. Int J Parasitol 44, 1-8 (2014).

- Robertson, E. et al. Demonstration of the anthelmintic potency of marimastat in the heligmosomoides polygyrus rodent model. Journal of parasitology 104, 705-709 (2018).

- Koopman, M. et al. A screening-based platform for the assessment of cellular respiration in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Protoc. 11, 1798-1816 (2016).

- Weisiger, R. A. & Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: organelle specificity. Journal of Biological Chemistry 248, 3582-3592 (1973).

- Dingley, S. et al. Mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction variably increases oxidant stress in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mitochondrion 10, 125-136 (2010).

- Lasram, M. M., Dhouib, I. B., Annabi, A., El Fazaa, S. & Gharbi, N. A review on the possible molecular mechanism of action of N -acetylcysteine against insulin resistance and type-2 diabetes development. Clin Biochem. 48, 1200-1208 (2015).

- Bito, T. et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency results in severe oxidative stress, leading to memory retention impairment in Caenorhabditis elegans. Redox biology 11, 21-29 (2017).

- Revtovich, A. V., Lee, R. & Kirienko, N. V. Interplay between mitochondria and diet mediates pathogen and stress resistance in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS genetics 15, e1008011 (2019).

- Hartman, J. H. et al. Swimming Exercise and Transient Food Deprivation in Caenorhabditis elegans Promote Mitochondrial Maintenance and Protect Against Chemical-Induced Mitotoxicity. Sci Rep. 8, 8359 (2018).

- Lee, E. A. et al. Targeting Mitochondria with Avocatin B Induces Selective Leukemia Cell Death. Cancer Res 75, 2478-2488 (2015).

- Tcheng, M. et al. Structure-activity relationship of avocadyne. Food & function 12, 6323-6333 (2021).

- Tcheng, M., Minden, M. D. & Spagnuolo, P. A. Avocado-derived avocadyne is a potent inhibitor of fatty acid oxidation. Journal of Food Biochemistry 46, e13895 (2022).

- Tcheng, M. et al. Very long chain fatty acid metabolism is required in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 137, 3518-3532 (2021).

- Qu, Q., Zeng, F., Liu, X., Wang, Q. J. & Deng, F. Fatty acid oxidation and carnitine palmitoyltransferase I: emerging therapeutic targets in cancer. Cell Death Dis. 7, e2226 (2016).

- Melone, M. A. B. et al. The carnitine system and cancer metabolic plasticity. Cell death & disease 9, 228 (2018).

- Demarquoy, J. & Le Borgne, F. Crosstalk between mitochondria and peroxisomes. World journal of biological chemistry 6, 301 (2015).

- Au, V. et al. CRISPR/Cas9 methodology for the generation of knockout deletions in Caenorhabditis elegans. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics 9, 135-144 (2019).

- Artan, M., Hartl, M., Chen, W. & De Bono, M. Depletion of endogenously biotinylated carboxylases enhances the sensitivity of TurbolD-mediated proximity labeling in Caenorhabditis elegans. Journal of Biological Chemistry 298, 102343 (2022).

- Rappleye, C. A., Tagawa, A., Le Bot, N., Ahringer, J. & Aroian, R. V. Involvement of fatty acid pathways and cortical interaction of the pronuclear complex in Caenorhabditis elegans embryonic polarity. BMC developmental biology 3, 1-15 (2003).

- Watts, J. S., Morton, D. G., Kemphues, K. J. & Watts, J. L. The biotinligating protein BPL-1 is critical for lipid biosynthesis and polarization of the Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. Journal of Biological Chemistry 293, 610-622 (2018).

- Hashimura, H., Ueda, C., Kawabata, J. & Kasai, T. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase inhibitors from avocado (Persea americana Mill) fruits. Bioscience, biotechnology, and biochemistry 65, 1656-1658 (2001).

- Wei, J. & Tong, L. Crystal structure of the 500-kDa yeast acetyl-CoA carboxylase holoenzyme dimer. Nature 526, 723-727 (2015).

- Ahmed, N. et al. Avocatin B Protects Against Lipotoxicity and Improves Insulin Sensitivity in Diet-Induced Obesity. Mol Nutr Food Res. 63, e1900688 (2019).

- Bangar, S. P. et al. Avocado seed discoveries: Chemical composition, biological properties, and industrial food applications. Food Chemistry X, 100507 (2022).

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, D. G. et al. Chemical profile and safety assessment of a food-grade acetogenin-enriched antimicrobial extract from avocado seed. Molecules 24, 2354 (2019).

- Louis, M. L. M. et al. Mosquito larvicidal activity of compounds from unripe fruit peel of avocado (Persea americana Mill.). Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 195, 2636-2647 (2023).

- Soldera-Silva, A. et al. Assessment of anthelmintic activity and bioguided chemical analysis of Persea americana seed extracts. Vet Parasitol 251, 34-43 (2018).

- Rosa, S. S. S. et al. In vitro anthelmintic and cytotoxic activities of extracts of Persea willdenovii Kosterm (Lauraceae). J Helminthol 92, 674-680 (2018).

- Taylor, C. M. et al. Discovery of anthelmintic drug targets and drugs using chokepoints in nematode metabolic pathways. PLoS Pathog 9, e1003505 (2013).

- Gutbrod, P. et al. Inhibition of acetyl-CoA carboxylase by spirotetramat causes growth arrest and lipid depletion in nematodes. Scientific Reports 10, 12710 (2020).

- Starich, T. A., Bai, X. & Greenstein, D. Gap junctions deliver malonylCoA from soma to germline to support embryogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Elife 9, e58619 (2020).

- Hashimshony, T., Feder, M., Levin, M., Hall, B. K. & Yanai, I. Spatiotemporal transcriptomics reveals the evolutionary history of the endoderm germ layer. Nature 519, 219-222 (2015).

- Zhang, H., Tweel, B., Li, J. & Tong, L. Crystal structure of the carboxyltransferase domain of acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase in complex with CP-640186. Structure 12, 1683-1691 (2004).

- Piotto, M., Saudek, V. & Sklenář, V. Gradient-tailored excitation for single-quantum NMR spectroscopy of aqueous solutions. Journal of biomolecular NMR 2, 661-665 (1992).

- Hwang, T.-L. & Shaka, A. Water suppression that works. Excitation sculpting using arbitrary wave-forms and pulsed-field gradients. Journal of Magnetic Resonance, Series A 112, 275-279 (1995).

- Jecock, R. M. & Devaney, E. Expression of small heat shock proteins by the third-stage larva of Brugia pahangi. Molecular and biochemical parasitology 56, 219-226 (1992).

- Burns, A. R. et al. High-throughput screening of small molecules for bioactivity and target identification in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Protoc. 1, 1906-1914 (2006).

- Johnston, C. J. et al. Cultivation of Heligmosomoides polygyrus: an immunomodulatory nematode parasite and its secreted products. JoVE 98, e52412 (2015).

- Spensley, M., Del Borrello, S., Pajkic, D. & Fraser, A. G. Acute effects of drugs on Caenorhabditis elegans movement reveal complex responses and plasticity. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics 8, 2941-2952 (2018).

- Sherman, W., Day, T., Jacobson, M. P., Friesner, R. A. & Farid, R. Novel procedure for modeling ligand/receptor induced fit effects. Journal of medicinal chemistry 49, 534-553 (2006).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تم إعداد شاشة مضادة للديدان بواسطة H.Z.F. وF.R. وP.G.C. قامت F.R. بإجراء تجارب استجابة الجرعة للديدان الخيطية الحرة، وRNAi، وتجارب الحركة وضخ البلعوم وتحليل طفرات الديجون الأوكسينية. قامت S.G. بإجراء تجارب OCR وROS وتوصيف الميتوكوندريا وتجارب تنقية POD-2. قام Y.M. وF.R. وH.Z.F. بإجراء شاشات وراثية EMS للمتغيرات المقاومة. قام Y.M. بإجراء شاشات الطفرات المضادة للديدان وتجارب المجهر الزمني. أعدت S.G. وY.M. عينات لتجارب NMR. قام G.E. وY.H. وG.B. بإجراء تجارب استخراج المركبات وNMR وMass Spectroscopy وتحليل جميع البيانات ذات الصلة. تم إجراء تجارب استجابة الجرعة للديدان الطفيلية في مختبر A.P. تم التخطيط لتجارب الفئران الحية بواسطة H.F. وA.P. وتم تنفيذها بواسطة C.C. في مختبر R.M. الذي ساهم في التحليلات. تم إجراء نمذجة هيكلية للمعلومات الحيوية بواسطة H.H.G. تم إجراء تجارب خلايا الثدييات بواسطة S.K. وX.X. قام Y.P. بإجراء التحليل الإحصائي. قام N.R. بتطوير وتنفيذ قواعد بيانات الفحص وواجهات تسجيل الظواهر. ساعد G.L.B. في التحليل النقدي لتحديد الأهداف. تم تصور المشروع بواسطة H.Z.F. وK.C.G. وF.P. تم كتابة المخطوطة بواسطة H.Z.F. وK.C.G. وF.P.

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

- ¹مركز الجينوميات وعلم الأحياء النظامية، جامعة نيويورك أبوظبي، جزيرة السعديات، أبوظبي، الإمارات العربية المتحدة. ²مركز الجينوميات وعلم الأحياء النظامية، قسم البيولوجيا، جامعة نيويورك، نيويورك، نيويورك، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. ³قسم العلوم الكيميائية، جامعة نابولي “فيديريكو الثاني”، 80138 نابولي، إيطاليا.

مدرسة العدوى والمناعة، جامعة غلاسكو، اسكتلندا، المملكة المتحدة. المعهد الوطني للبنية الحيوية والأنظمة الحيوية، 00136 روما، إيطاليا. مدرسة التنوع البيولوجي، الصحة الواحدة والطب البيطري، جامعة غلاسكو، اسكتلندا، المملكة المتحدة. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: فاطمة س. رفاعي، سومة جوبيناثان. البريد الإلكتروني:kcg1@nyu.edu; fp1@nyu.edu - (ج) المؤلف(ون) 2024

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54965-w

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39746976

Publication Date: 2025-01-02

A new class of natural anthelmintics targeting lipid metabolism

Accepted: 26 November 2024

Published online: 02 January 2025

Abstract

Parasitic helminths are a major global health threat, infecting nearly one-fifth of the human population and causing significant losses in livestock and crops. Resistance to the few anthelmintic drugs is increasing. Here, we report a set of avocado fatty alcohols/acetates (AFAs) that exhibit nematocidal activity against four veterinary parasitic nematode species: Brugia pahangi, Teladorsagia circumcincta and Heligmosomoides polygyrus, as well as a multidrug resistant strain (UGA) of Haemonchus contortus. AFA shows significant efficacy in H. polygyrus infected mice. In C. elegans, AFA exposure affects all developmental stages, causing paralysis, impaired mitochondrial respiration, increased reactive oxygen species production and mitochondrial damage. In embryos, AFAs penetrate the eggshell and induce rapid developmental arrest. Genetic and biochemical tests reveal that AFAs inhibit POD-2, encoding an acetyl

negative impacts on public health, agricultural systems, and the ecology and conservation of wild species

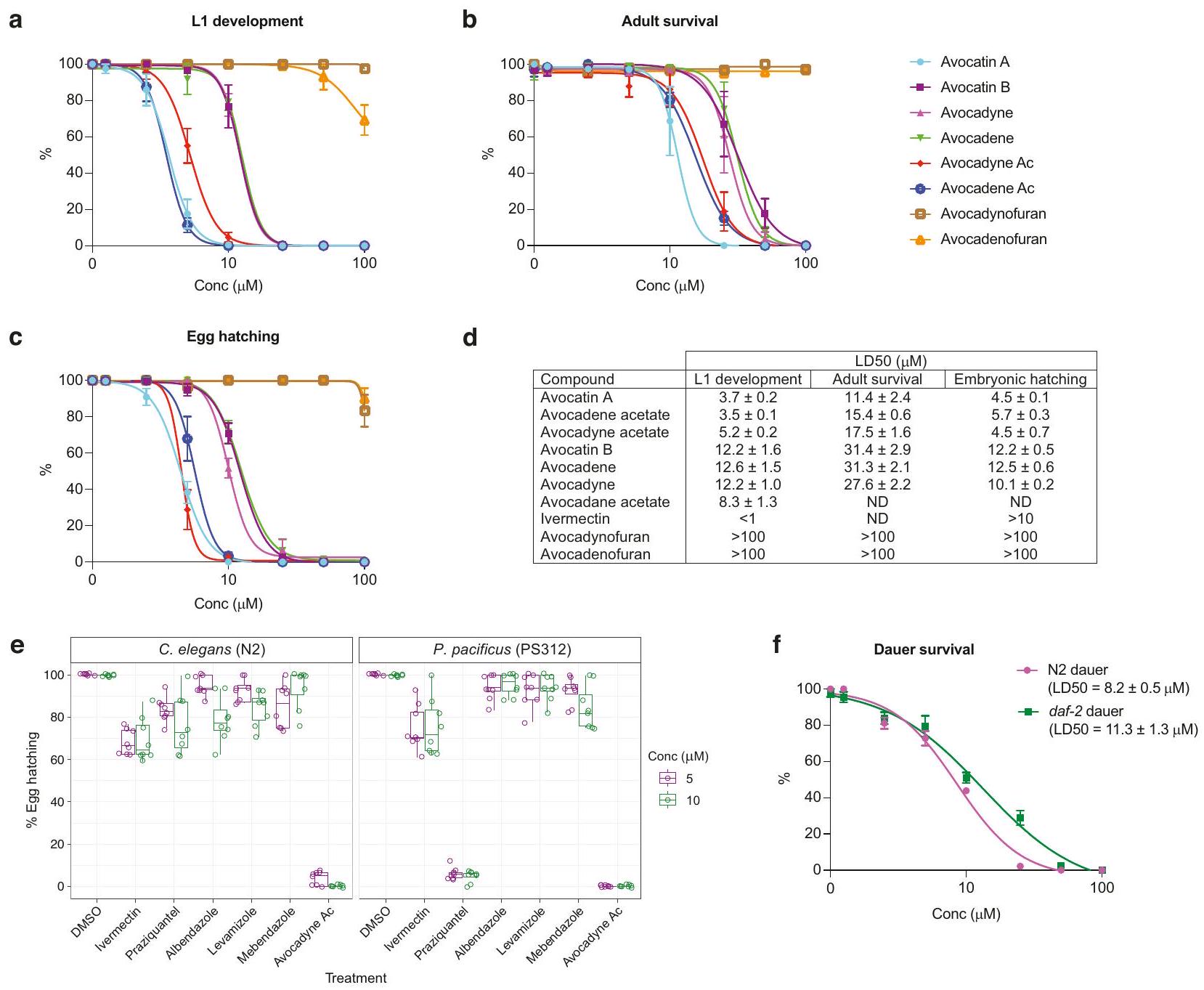

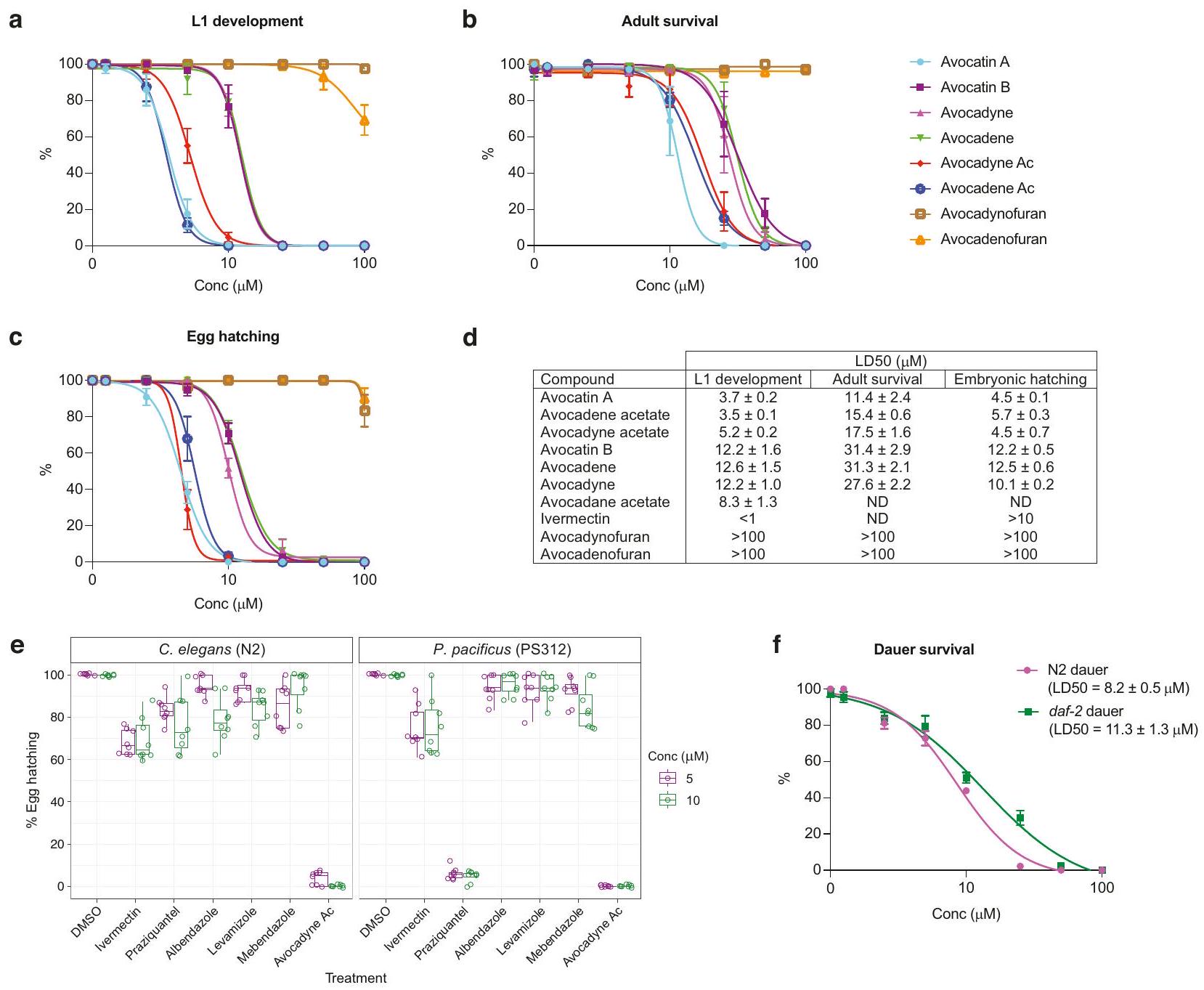

containing FDA-approved drugs and natural products for potential broad-spectrum anthelmintic activity (Supplementary data 1). Most molecules in this library are expected to be well tolerated in humans, which we confirmed by measuring toxicity in a human cell line. Among the bioactive compounds identified in the screen was a group of structurally similar 17-carbon fatty alcohol compounds present in extracts of the avocado Persea americana. We found that these compounds, which we collectively refer to as avocado-derived fatty alcohols/acetates (AFAs), elicit dose-dependent lethality in parasitic nematodes and target C. elegans POD-2, an acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) that is the rate limiting enzyme in lipid biosynthesis.

Results

Novel class of anthelmintics

anthelmintic activity against C. elegans and P. pacificus. c Incorporation of avocadene acetate in

methods, Supplementary data 2) and resulted in the identification of a family of related compounds isolated from the avocado Persea americana that cause a variety of severe phenotypes in C. elegans (Fig. 1a). These AFA compounds represent structurally similar 17-carbon fatty alcohols and their acetate variants (Fig. 1b): avocadene ((

contained significant amounts of AFAs following

AFAs show a new mode of action

| Conc. | T. circumcincta L2 | H. polygyrus L2 | H. contortus (UGA) L2 | H. contortus (UGA) eggs | |||||

| Total | % lethality | Total | % lethality | Total | % lethality | Total | % lethality | ||

| DMSO | 1% | 32 | 18.8 | 52 | 21.2 | 215 |

|

113 | 33.6 |

| Avo B |

|

119 |

|

40 | 100 | 223 |

|

89 | 31.5 |

|

|

119 |

|

69 | 100 | 209 |

|

30 | 100 | |

| Avo A |

|

– | – | 55 | 100 | 223 |

|

66 | 36.4 |

|

|

– | – | 76 | 100 | 162 |

|

75 | 100 | |

Cells with ‘-‘ indicate that the assay was not performed.

| B. pahangi | DMSO |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total adults | 40 | 32 | 32 | 31 | 36 | 34 | 37 |

| % lethality/paralysis | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

| Total females | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| % lethality/paralysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 50 | 100 |

| Total males | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| % lethality/paralysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 30 | 90 | 100 |

| Total L3 | 61 | – | – | – | 68 | – | 69 |

| % lethality | 0 | – | – | – | 100 | – | 100 |

| Total Mfs | 104 | 154 | 131 | 150 | 126 | 147 | 163 |

| % lethality/paralysis | 1.9 | 5.2 | 9.2 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Cells with ‘-‘ indicate that the assay was not performed.

| Genotype | Resistance | Avocadene Acetate

|

| wild-type | None |

|

| cha-1(p1152) | Carbamates/organophosphates |

|

| avr-14(ad1302); avr15(ad1051) glc-1(pk54) | Ivermectin |

|

| dyf-17 (ox175) | Ivermectin/albendazole |

|

| unc-63(ok1075) | Levamizole/anti-parasitic reagents/ Tetrahydropyrimidines |

|

| unc-29(e193) | Levamizole |

|

| acr-23(ok2804) | Monepantel |

|

| daf-16(mu86) | Apigenin |

|

| ben-1(e1880) | Benzimidazole |

|

| slo-1(js379) | Emodepside |

|

wild type N2 when treated at the L1 stage, indicating that AFA compounds act through a different mechanism (Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 3). To further characterize the mode of action of AFAs, we performed random mutagenesis in C. elegans using ethylmethanesulfonate (EMS). Despite performing several large rounds of screening and testing the resistance of

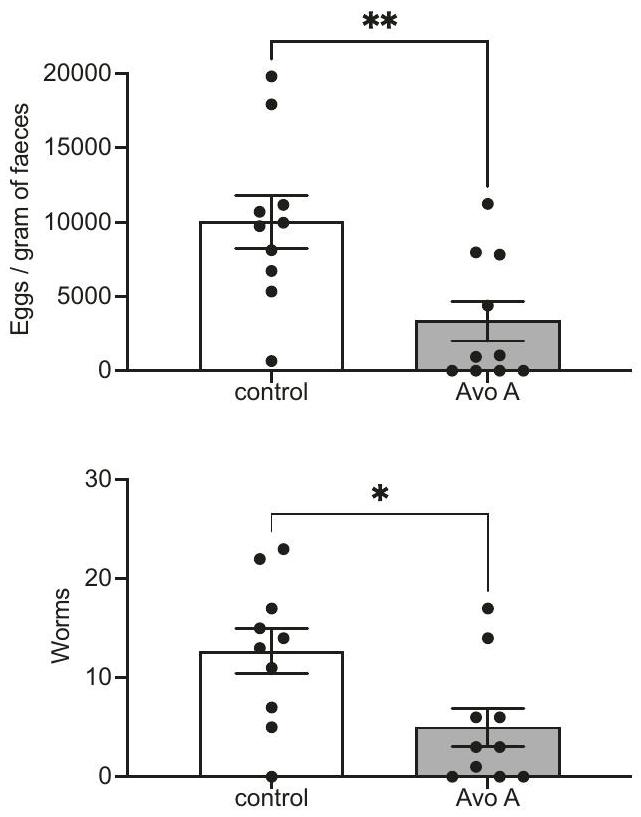

AFAs are active in vivo

AFAs inhibit respiration in C. elegans

addition. The color code and the error bars are the same as in (c). Each bar represents a single sample (

these effects was significantly higher overall in comparison with DMSOtreated controls (Chi-square test

AFAs target ACC/POD-2

(AML) cells suggested an involvement of avocatin B in lipid metabolism

be inhibited by the same AFAs in vitro

Discussion

Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) measurements using the Seahorse XFe96 analyzer

ROS measurement

MitoSOX™ red staining

NAC and vitamin B12 treatment

acetate or DMSO and survival was scored after 2 days. Similarly, L1 stage worms were treated in the presence or absence of 64 nM vitamin B12, followed by treatment with

RNAi experiments

Malonyl-CoA rescue experiments on WT and pod-2(ye60)

Auxin-inducible degron (AID) experiments

POD-2 biochemistry

Mass spectrometry and proteomics

column. Samples were resuspended in

Computational modeling

with 2165 residues, includes the BC, CT and BCCP domains. The POD-2 dimer and its bound ligands biotin and CoA were modeled by structural alignment using solved yeast ACC homodimer complexes (PDB ID:

Statistics and reproducibility

Reporting summary

Data availability

References

- Imtiaz, R. et al. Insights from quantitative analysis and mathematical modelling on the proposed WHO 2030 goals for soil-transmitted helminths [version 1; peer review: 2 approved]. Gates Open Res. 3, 1632 (2019).

- Bryant, A. S. & Hallem, E. A. Temperature-dependent behaviors of parasitic helminths. Neurosci Lett 687, 290-303 (2018).

- Learmount, J. et al. Three-year evaluation of best practice guidelines for nematode control on commercial sheep farms in the UK. Vet Parasitol 226, 116-123 (2016).

- Charlier, J. et al. Initial assessment of the economic burden of major parasitic helminth infections to the ruminant livestock industry in Europe. Prev Vet Med. 182, 105103 (2020).

- Siddique, S. & Grundler, F. M. Parasitic nematodes manipulate plant development to establish feeding sites. Curr Opin Microbiol 46, 102-108 (2018).

- Selzer, P. M. & Epe, C. Antiparasitics in animal health: quo vadis? Trends Parasitol 37, 77-89 (2021).

- Blaxter, M. & Koutsovoulos, G. The evolution of parasitism in Nematoda. Parasitology 142, S26-S39 (2015).

- Shih, P. Y. et al. Newly Identified Nematodes from Mono Lake Exhibit Extreme Arsenic Resistance. Curr Biol. 29, 3339-3344.e3334 (2019).

- Gang, S. S. & Hallem, E. A. Mechanisms of host seeking by parasitic nematodes. Mol Biochem Parasitol 208, 23-32 (2016).

- Aleuy, O. A. & Kutz, S. Adaptations, life-history traits and ecological mechanisms of parasites to survive extremes and environmental unpredictability in the face of climate change. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl 12, 308-317 (2020).

- Nixon, S. A. et al. Where are all the anthelmintics? Challenges and opportunities on the path to new anthelmintics. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 14, 8-16 (2020).

- Gasbarre, L. C. Anthelmintic resistance in cattle nematodes in the US. Vet Parasitol 204, 3-11 (2014).

- Geurden, T. et al. Anthelmintic resistance to ivermectin and moxidectin in gastrointestinal nematodes of cattle in Europe. International Journal for Parasitology: Drugs and Drug Resistance 5, 163-171 (2015).

- Prichard, R. K. & Geary, T. G. Perspectives on the utility of moxidectin for the control of parasitic nematodes in the face of developing anthelmintic resistance. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 10, 69-83 (2019).

- Miller, T. W. et al. Avermectins, new family of potent anthelmintic agents: isolation and chromatographic properties. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 15, 368-371 (1979).

- Holden-Dye, L. & Walker, R. J. (2014) Anthelmintic drugs and nematicides: studies in Caenorhabditis elegans. WormBook, 1-29. https://doi.org/10.1895/wormbook.1.143.2.

- Burns, A. R. et al. Caenorhabditis elegans is a useful model for anthelmintic discovery. Nat Commun 6, 7485 (2015).

- Hahnel, S. R., Dilks, C. M., Heisler, I., Andersen, E. C. & Kulke, D. Caenorhabditis elegans in anthelmintic research-Old model, new perspectives. International Journal for Parasitology: Drugs and Drug Resistance 14, 237-248 (2020).

- Min, J. et al. Forward chemical genetic approach identifies new role for GAPDH in insulin signaling. Nat Chem Biol. 3, 55-59 (2007).

- Burns, A. R. et al. The novel nematicide wact- 86 interacts with aldicarb to kill nematodes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 11, e0005502 (2017).

- Bray, M.-A. et al. Cell Painting, a high-content image-based assay for morphological profiling using multiplexed fluorescent dyes. Nat Protoc. 11, 1757-1774 (2016).

- Pearson, Y. E. et al. A statistical framework for high-content phenotypic profiling using cellular feature distributions. Communications Biology 5, 1409 (2022).

- Bond, A. T. & Huffman, D. G. Nematode eggshells: a new anatomical and terminological framework, with a critical review of relevant literature and suggested guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of eggshell imagery. Parasite 30, 6 (2023).

- Oelrichs, P. B. et al. Isolation and identification of a compound from avocado (Persea americana) leaves which causes necrosis of the acinar epithelium of the lactating mammary gland and the myocardium. Natural Toxins 3, 344-349 (1995).

- Crook, M. The dauer hypothesis and the evolution of parasitism: 20 years on and still going strong. Int J Parasitol 44, 1-8 (2014).

- Robertson, E. et al. Demonstration of the anthelmintic potency of marimastat in the heligmosomoides polygyrus rodent model. Journal of parasitology 104, 705-709 (2018).

- Koopman, M. et al. A screening-based platform for the assessment of cellular respiration in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Protoc. 11, 1798-1816 (2016).

- Weisiger, R. A. & Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: organelle specificity. Journal of Biological Chemistry 248, 3582-3592 (1973).

- Dingley, S. et al. Mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction variably increases oxidant stress in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mitochondrion 10, 125-136 (2010).

- Lasram, M. M., Dhouib, I. B., Annabi, A., El Fazaa, S. & Gharbi, N. A review on the possible molecular mechanism of action of N -acetylcysteine against insulin resistance and type-2 diabetes development. Clin Biochem. 48, 1200-1208 (2015).

- Bito, T. et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency results in severe oxidative stress, leading to memory retention impairment in Caenorhabditis elegans. Redox biology 11, 21-29 (2017).

- Revtovich, A. V., Lee, R. & Kirienko, N. V. Interplay between mitochondria and diet mediates pathogen and stress resistance in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS genetics 15, e1008011 (2019).

- Hartman, J. H. et al. Swimming Exercise and Transient Food Deprivation in Caenorhabditis elegans Promote Mitochondrial Maintenance and Protect Against Chemical-Induced Mitotoxicity. Sci Rep. 8, 8359 (2018).

- Lee, E. A. et al. Targeting Mitochondria with Avocatin B Induces Selective Leukemia Cell Death. Cancer Res 75, 2478-2488 (2015).

- Tcheng, M. et al. Structure-activity relationship of avocadyne. Food & function 12, 6323-6333 (2021).

- Tcheng, M., Minden, M. D. & Spagnuolo, P. A. Avocado-derived avocadyne is a potent inhibitor of fatty acid oxidation. Journal of Food Biochemistry 46, e13895 (2022).

- Tcheng, M. et al. Very long chain fatty acid metabolism is required in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 137, 3518-3532 (2021).

- Qu, Q., Zeng, F., Liu, X., Wang, Q. J. & Deng, F. Fatty acid oxidation and carnitine palmitoyltransferase I: emerging therapeutic targets in cancer. Cell Death Dis. 7, e2226 (2016).

- Melone, M. A. B. et al. The carnitine system and cancer metabolic plasticity. Cell death & disease 9, 228 (2018).

- Demarquoy, J. & Le Borgne, F. Crosstalk between mitochondria and peroxisomes. World journal of biological chemistry 6, 301 (2015).

- Au, V. et al. CRISPR/Cas9 methodology for the generation of knockout deletions in Caenorhabditis elegans. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics 9, 135-144 (2019).

- Artan, M., Hartl, M., Chen, W. & De Bono, M. Depletion of endogenously biotinylated carboxylases enhances the sensitivity of TurbolD-mediated proximity labeling in Caenorhabditis elegans. Journal of Biological Chemistry 298, 102343 (2022).

- Rappleye, C. A., Tagawa, A., Le Bot, N., Ahringer, J. & Aroian, R. V. Involvement of fatty acid pathways and cortical interaction of the pronuclear complex in Caenorhabditis elegans embryonic polarity. BMC developmental biology 3, 1-15 (2003).

- Watts, J. S., Morton, D. G., Kemphues, K. J. & Watts, J. L. The biotinligating protein BPL-1 is critical for lipid biosynthesis and polarization of the Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. Journal of Biological Chemistry 293, 610-622 (2018).

- Hashimura, H., Ueda, C., Kawabata, J. & Kasai, T. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase inhibitors from avocado (Persea americana Mill) fruits. Bioscience, biotechnology, and biochemistry 65, 1656-1658 (2001).

- Wei, J. & Tong, L. Crystal structure of the 500-kDa yeast acetyl-CoA carboxylase holoenzyme dimer. Nature 526, 723-727 (2015).

- Ahmed, N. et al. Avocatin B Protects Against Lipotoxicity and Improves Insulin Sensitivity in Diet-Induced Obesity. Mol Nutr Food Res. 63, e1900688 (2019).

- Bangar, S. P. et al. Avocado seed discoveries: Chemical composition, biological properties, and industrial food applications. Food Chemistry X, 100507 (2022).

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, D. G. et al. Chemical profile and safety assessment of a food-grade acetogenin-enriched antimicrobial extract from avocado seed. Molecules 24, 2354 (2019).

- Louis, M. L. M. et al. Mosquito larvicidal activity of compounds from unripe fruit peel of avocado (Persea americana Mill.). Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 195, 2636-2647 (2023).

- Soldera-Silva, A. et al. Assessment of anthelmintic activity and bioguided chemical analysis of Persea americana seed extracts. Vet Parasitol 251, 34-43 (2018).

- Rosa, S. S. S. et al. In vitro anthelmintic and cytotoxic activities of extracts of Persea willdenovii Kosterm (Lauraceae). J Helminthol 92, 674-680 (2018).

- Taylor, C. M. et al. Discovery of anthelmintic drug targets and drugs using chokepoints in nematode metabolic pathways. PLoS Pathog 9, e1003505 (2013).

- Gutbrod, P. et al. Inhibition of acetyl-CoA carboxylase by spirotetramat causes growth arrest and lipid depletion in nematodes. Scientific Reports 10, 12710 (2020).

- Starich, T. A., Bai, X. & Greenstein, D. Gap junctions deliver malonylCoA from soma to germline to support embryogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Elife 9, e58619 (2020).

- Hashimshony, T., Feder, M., Levin, M., Hall, B. K. & Yanai, I. Spatiotemporal transcriptomics reveals the evolutionary history of the endoderm germ layer. Nature 519, 219-222 (2015).

- Zhang, H., Tweel, B., Li, J. & Tong, L. Crystal structure of the carboxyltransferase domain of acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase in complex with CP-640186. Structure 12, 1683-1691 (2004).

- Piotto, M., Saudek, V. & Sklenář, V. Gradient-tailored excitation for single-quantum NMR spectroscopy of aqueous solutions. Journal of biomolecular NMR 2, 661-665 (1992).

- Hwang, T.-L. & Shaka, A. Water suppression that works. Excitation sculpting using arbitrary wave-forms and pulsed-field gradients. Journal of Magnetic Resonance, Series A 112, 275-279 (1995).

- Jecock, R. M. & Devaney, E. Expression of small heat shock proteins by the third-stage larva of Brugia pahangi. Molecular and biochemical parasitology 56, 219-226 (1992).

- Burns, A. R. et al. High-throughput screening of small molecules for bioactivity and target identification in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Protoc. 1, 1906-1914 (2006).

- Johnston, C. J. et al. Cultivation of Heligmosomoides polygyrus: an immunomodulatory nematode parasite and its secreted products. JoVE 98, e52412 (2015).

- Spensley, M., Del Borrello, S., Pajkic, D. & Fraser, A. G. Acute effects of drugs on Caenorhabditis elegans movement reveal complex responses and plasticity. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics 8, 2941-2952 (2018).

- Sherman, W., Day, T., Jacobson, M. P., Friesner, R. A. & Farid, R. Novel procedure for modeling ligand/receptor induced fit effects. Journal of medicinal chemistry 49, 534-553 (2006).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

anthelmintic screen was set up by H.Z.F., F.R. and P.G.C. F.R. carried out the free-living nematode dose-response experiments, RNAi, motility and pharyngeal pumping assays and auxin degron mutants analysis. S.G. performed the OCR, ROS, mitochondrial characterization, and POD-2 purification experiments. Y.M., F.R. and H.Z.F. performed EMS genetics screens for resistant mutants. Y.M. performed anthelmintic mutant screens and time-lapse microscopy. S.G. and Y.M. prepared samples for NMR experiments. G.E., Y.H. and G.B. carried out compound extraction, NMR and Mass Spectroscopy experiments and analyzed all related data. Parasitic worm dose-response experiments were carried out in the laboratory of A.P. In vivo mouse experiments were planned by H.F. and A.P. and performed by C.C. in the laboratory of R.M, who contributed to the analyses. Bioinformatics structural modeling was performed by H.H.G. Mammalian cell experiments were performed by S.K. and X.X. Y.P. conducted statistical analysis. N.R. developed and implemented screening databases and phenotype scoring user interfaces. G.L.B. helped with critical analysis for target identification. The project was conceived by H.Z.F., K.C.G. and F.P. The manuscript was written by H.Z.F., K.C.G. and F.P.

Competing interests

Additional information

- ¹Center for Genomics and Systems Biology, New York University Abu Dhabi, Saadiyat Island, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. ²Center for Genomics and Systems Biology, Department of Biology, New York University, New York, NY, USA. ³Dipartimento di Scienze Chimiche, Università di Napoli “Federico II”, 80138 Naples, Italy.

School of Infection and Immunity, University of Glasgow, Scotland, UK. Istituto Nazionale Biostrutture e Biosistemi, 00136 Rome, Italy. School of Biodiversity, One Health and Veterinary Medicine, University of Glasgow, Scotland, UK. These authors contributed equally: Fathima S. Refai, Suma Gopinadhan. e-mail: kcg1@nyu.edu; fp1@nyu.edu - (c) The Author(s) 2024