DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069241229777

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-01

فك الغموض وتحقيق تشبع البيانات في البحث النوعي من خلال التحليل الموضوعي

الملخص

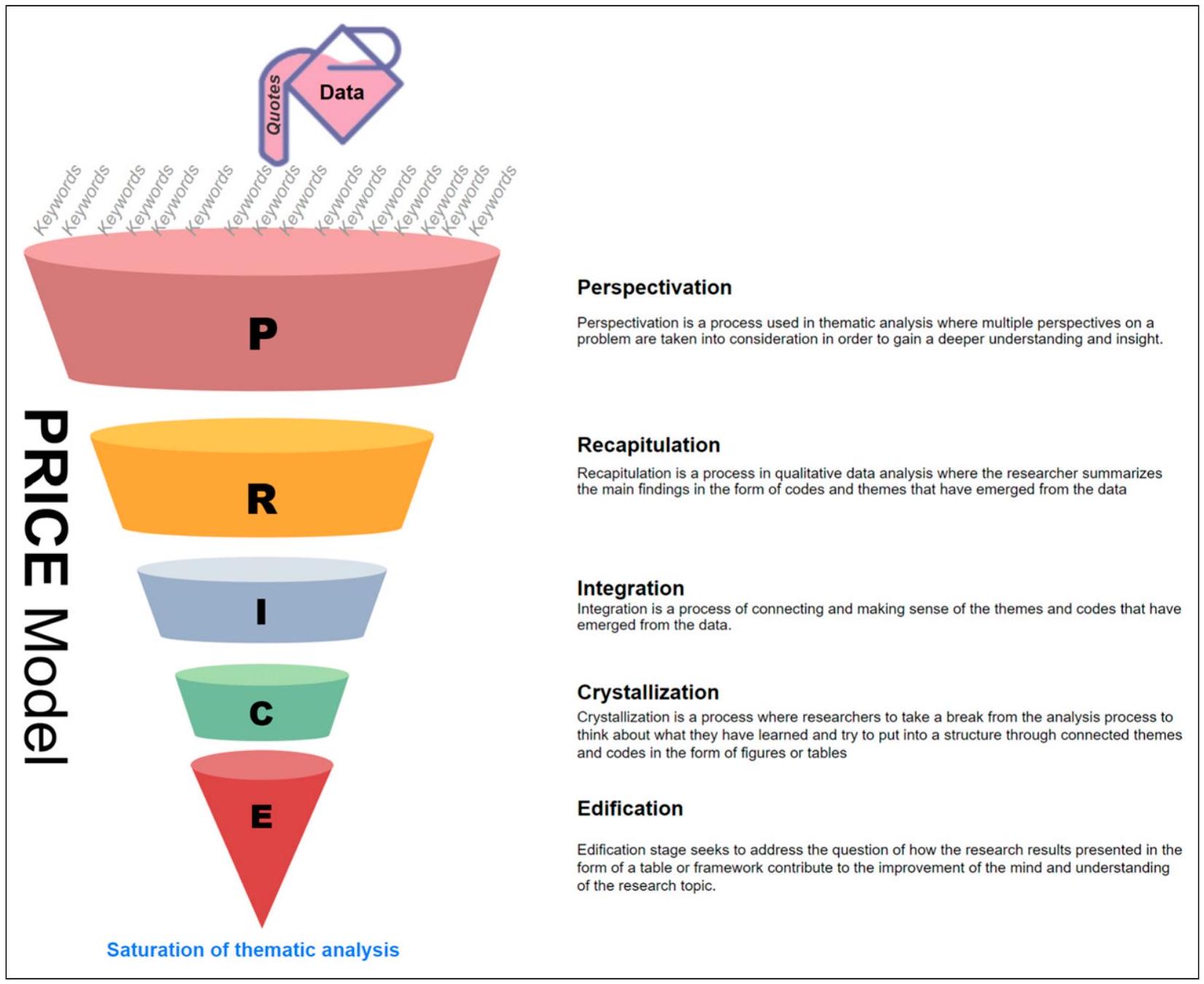

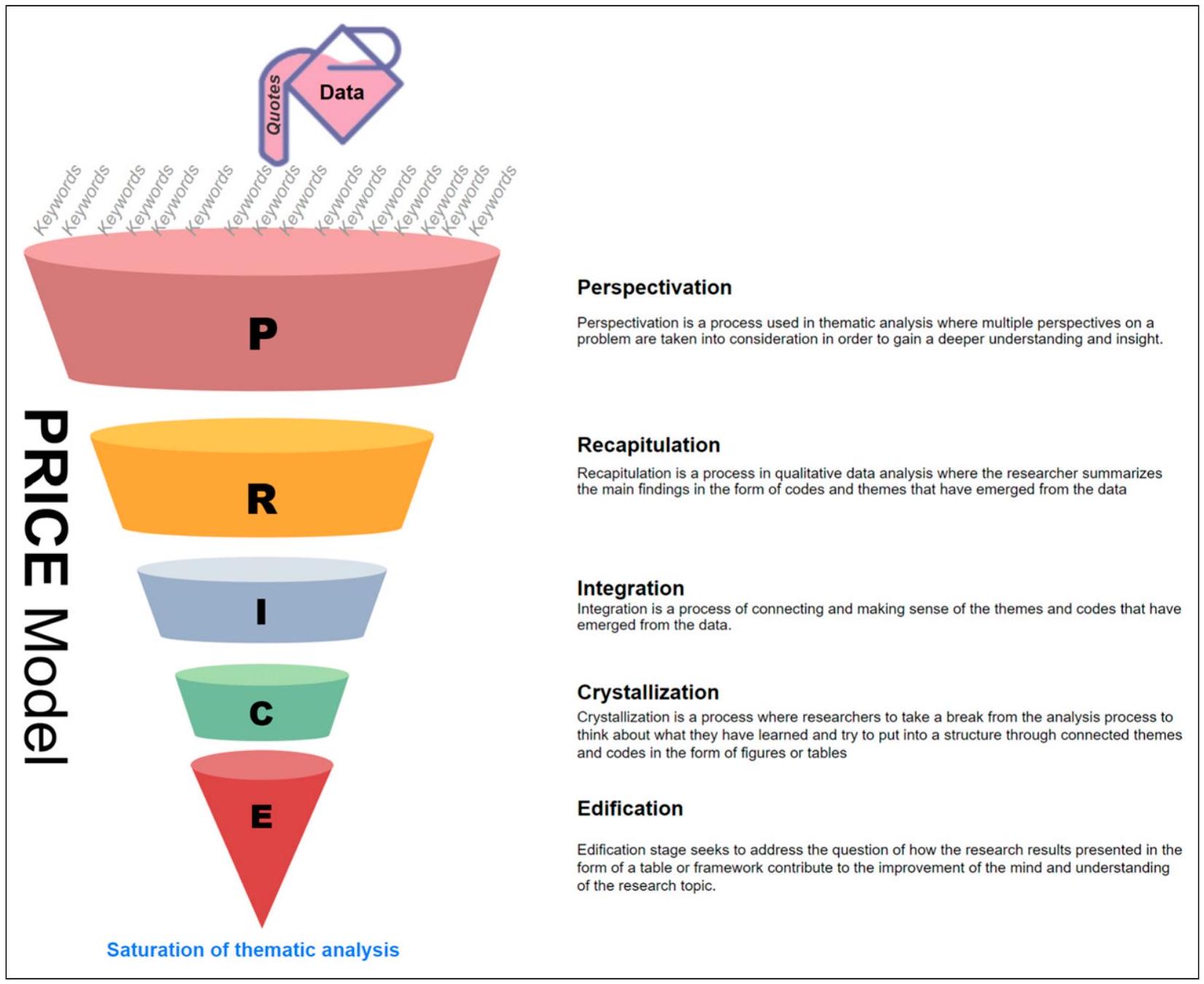

مفهوم التشبع في البحث النوعي هو موضوع نقاش واسع. يشير التشبع إلى النقطة التي لا تظهر فيها بيانات أو مواضيع جديدة من مجموعة البيانات، مما يدل على أن البيانات قد تم استكشافها بالكامل. يعتبر مفهومًا مهمًا لأنه يساعد على ضمان أن النتائج قوية وأن البيانات تُستخدم إلى أقصى إمكاناتها لتحقيق هدف البحث. التشبع، أو النقطة التي لن تؤدي فيها الملاحظات الإضافية للبيانات إلى اكتشاف مزيد من المعلومات المتعلقة بأسئلة البحث، هو جانب مهم من البحث النوعي. ومع ذلك، هناك بعض الغموض والنقاش الدلالي المحيط بمصطلح التشبع، وليس من الواضح دائمًا عدد جولات البحث المطلوبة للوصول إلى التشبع أو المعايير المستخدمة لتحديد ذلك خلال عملية التحليل الموضوعي. تركز هذه الورقة على تحقيق التشبع في سياق التحليل الموضوعي وتطور نهج منهجي لاستخدام البيانات لتبرير مساهمة البحث. وبالتالي، نقدم نموذجًا متميزًا لمساعدة الباحثين على الوصول إلى التشبع من خلال تنقيح أو توسيع الاقتباسات الحالية، الرموز، المواضيع والمفاهيم حسب الحاجة.

الكلمات المفتاحية

المقدمة

فإن فكرة التشبع هي موضوع اختلاف بين الباحثين النوعيين الذين لديهم اختلافات في الرأي بشأن معناها ووضوحها وعمليتها (أوريلي وباركر، 2013؛ ستراوس وكوربين، 1998). في الواقع، ليس من الواضح ما الذي يشمله المصطلح فعليًا (باوين، 2008) وما هي العملية المحددة المطلوبة للمطالبة بأن التشبع قد تم تحقيقه (أوريلي وباركر، 2013). بشكل أساسي، تُستخدم تقديرات القاعدة العامة لتحديد عدد الملاحظات أو المقابلات المطلوبة وتُقدم ادعاءات عن

إعادة النظر في التشبع في البحث النوعي: دمج رؤى الأدبيات الحالية مع النهج المقترح للتشبع

المعايير العملية والوضوح في تحديد المستويات الكافية. التشبع هو إجراء متعدد الأبعاد ومتكرر يهدف إلى تطوير فهم شامل من خلال جمع، جمع، وتحليل البيانات بشكل مستمر، كما وصفه غلاسر وستراوس (1967). تسلط شارماز (2006) الضوء على أن التشبع يتعلق أكثر بشمولية النظرية بدلاً من حجم العينة. يتفق ديوبي وآخرون (2016) وبودي (2016) على أن التشبع يجب أن يؤثر على كل من قابلية التطبيق والصلابة النظرية للتحقيقات. قدم أوركارت (2013) وبيركس وميلز (2015) وجهات نظر أخرى حول التشبع، مؤكدين على تشكيل رموز أو مواضيع جديدة. وهذا يبرز الانتقال نحو البعد التحليلي للبحث. في دراستهم، قدم ستاركس وبراون ترينيداد (2007) مفهوم التشبع النظري كالإدماج الكامل والشامل للبنى الموجودة في البيانات التي تساهم في تطوير النظرية.

مؤكدين على أهمية تجنب عدم الاتساق المنهجي عند دمج أساليب مختلفة. يشجعون على اعتماد وجهة نظر تحليلية فردية، م differentiating بين التحليل الوصفي والتفسيري (TA)، وينفون فكرة تحيز الباحث لصالح الذاتية كأداة بحث. تهدف تعليقاتهم إلى توجيه ممارسة TA الدقيقة، وهي ذات صلة خاصة بالباحثين الذين يسعون لتحقيق إشباع البيانات، مما يبرز الطبيعة التفسيرية لتحديد الموضوعات وأهمية الانعكاسية في العملية. يعيد هذا العمل توجيه الانتباه من النظرية المؤصلة إلى جانب متميز من البحث النوعي، وهو التحليل الموضوعي. بينما تهدف النظرية المؤصلة إلى إنشاء نظريات جديدة، يمكن أن يدعم التحليل الموضوعي هذا الهدف ولكنه يمتلك نطاقًا أوسع، كما ذكر نعيم وآخرون (2023). لذلك، قد لا يكون مفهوم الإشباع كما هو مستخدم في النظرية المؤصلة قابلًا للتطبيق مباشرة على التحليل الموضوعي. تركز هذه الدراسة على تحقيق الإشباع في التحليل الموضوعي، والذي يشير إلى المرحلة التي تم فيها استخدام البيانات بشكل شامل لتحقيق أهداف البحث. على الرغم من أن التحليل الموضوعي والنظرية المؤصلة يشتركان في بعض أوجه التشابه، فإن هذه الورقة تستمد من نهج النظرية المؤصلة نحو الإشباع حيثما كان ذلك مناسبًا، لإبلاغ عملية التحليل الموضوعي بشكل أفضل.

لتحليل عملية جمع البيانات وضمان الإشباع بشكل شامل.

نقاش

توجيه الرؤية

مراقبة أحداث مختلفة في جمع البيانات النوعية. يمكن أن يصل الإبلاغ الصريح عن وجهات نظر مختلفة في تحليل البيانات إلى التشبع لضمان وضوح التحليل.

اختيار الكلمات الرئيسية والاقتباسات الدقيقة

يتجنب (سوء) استخدام الكلمات الجذابة (سيلفرمان، 2017). قد يساعد النظر في الاقتباسات القوية واقتباسات الإثبات الباحث في اختيار الاقتباسات المناسبة. تُظهر الاقتباسات القوية للقارئ أهم نقاط البيانات، ويمكن أيضًا استخدام هذه الاقتباسات لوصف النتائج. تُعرف الاقتباسات القوية بأنها “إحساس بوجودك هناك، بتصور [المشارك]، والشعور بصراعاتهم وعواطفهم” (أمبرت وآخرون، 1995، ص. 885). الاقتباسات القوية “هي أكثر أجزاء البيانات إقناعًا التي لديك، تلك التي توضح نقاطك بفعالية” (برات، 2009، ص. 860). اقترح نعيم وويلسون (2022) أنه إذا كانت بعض الكلمات الرئيسية تُستخدم بشكل شائع من قبل المشاركين وإذا كانت هذه الكلمات الرئيسية يمكن أن تجيب على سؤال البحث من خلال صنع قصة، فيجب اختيار هذه الكلمات الرئيسية القوية، ويجب اختيار جميع الاقتباسات التي تحتوي على هذه الكلمات الرئيسية في المرحلة الأولى من التحليل الموضوعي (نعيم وأوزويم، 2021، 2021ب).

تكرار الكلمات الرئيسية

المقابلات ودورها في تحقيق التشبع. تركز دراسة Guest وآخرون (2017) على مجموعات التركيز، بهدف إنشاء قاعدة أدلة لأحجام العينات غير الاحتمالية اللازمة لتحقيق التشبع. يمكن أن تثري الحقائق والأرقام وتوضح القصص بطرق ملحوظة (Olson، 2000). يواجه الباحثون النوعيون مجموعة فريدة من التحديات عندما يتعلق الأمر باستخدام الأساليب الكمية التي تؤدي إلى نتائج موثوقة. إذا أرادوا أن تكون جهودهم العددية ذات مغزى، سيتعين عليهم تحديد متى وماذا يعدون (DeSantis & Ugarriza، 2000). الطريقة التي يمثل بها المشاركون نفس الوضع من خلال استخدام مفردات وتعبيرات متنوعة لها تأثير كبير على تفسير الأهمية النصية في البحث النوعي. لذلك، لفهم المصطلحات المستخدمة وفهم الآثار العديدة الموجودة في مجموعة بيانات معينة، من الضروري وجود مجموعة واسعة من المصطلحات والتعبيرات (Dey، 2003). تم تقديم نهج كمي من قبل Lowe وآخرون (2018) لتقييم التشبع الموضوعي في تحليل البيانات النوعية. توفر هذه الطريقة أداة قابلة للقياس لتحديد العتبة التي يتم عندها تحقيق التشبع. علاوة على ذلك، فإن تحليل أحجام التأثير في البحث النوعي الذي أجراه Onwuegbuzie (2003) يحظى بتقدير كبير ويساهم بشكل كبير في النقاش الأوسع حول التشبع. علاوة على ذلك، تعتبر الأرقام أدوات بلاغية قوية، مما يمكّن المرء من التأكيد على الصعوبة والتعقيد المتأصلين في البحث النوعي. على سبيل المثال، سيكون من غير المناسب للباحثين تقديم مبررات لأحجام العينات المحدودة ظاهريًا المستخدمة (Greenhalgh & Taylor، 1997؛ Sandelowski، 2001).

تسجيل تردد البيانات

الإشباع في الترميز والموضوعات

وجهة نظر هيكل اللغة

الطرق التي يستخدم بها المتحدثون اللغة لنقل وجهات نظرهم ووجهات نظر الآخرين، بالإضافة إلى العلاقات بين هذه المنظورات. هنا، نستفسر عن كيفية استخدام المشاركين لخيارات لغتهم للتعبير عن وجهات نظر (كلمات رئيسية) ستضفي حيوية على تحليل البيانات، الذي يستكشف الواقع الاجتماعي المبني. إن تحقيق أقصى حيوية للبيانات النوعية المجمعة خلال مرحلة التحليل يتعلق بالمرحلة التي يمتلك فيها الباحث فهمًا شاملاً وعميقًا لكيفية استخدام الكلمات وقادرًا على التقاط وفرة وتعقيد البيانات بناءً على المنظور النظري والمعرفي للبحث.

المنظور النظري

يمكن اعتبار أنواع المفردات المستخدمة للتعبير عن نفس المسألة أو القضية تباينًا. على سبيل المثال، يمكن التعبير عن المشاعر القوية (الرضا، المتعة، خيبة الأمل، الألم) بالإضافة إلى الارتباك والتردد في بعض الاقتباسات، مما سيكون حيوية البيانات. هذه السرعة اللغوية، واللزوجة، والحيوية تتماشى أيضًا مع وجهات النظر الإبستمولوجية للبناء الاجتماعي التي ستؤدي إلى تطوير واقع اجتماعي مُنشأ حول موضوع البحث. وبالتالي، فإن الحيوية النظرية والفلسفية ستؤدي أيضًا إلى تحقيق التوجه. التوجه في تحليل البيانات النوعية يتعلق بالمرحلة التي يمتلك فيها الباحث فهمًا عميقًا للبيانات وقادرًا على إدراكها من وجهات نظر متعددة. يمكن تحقيق ذلك باستخدام السرعة واللزوجة والحيوية في اختيار الكلمات الرئيسية والرموز.

إعادة تلخيص

تم تفكيكها وإعادة تجميعها بطريقة أكثر معنى (ساوندر وآخرون، 2018). يحدث التشبع النظري عندما لا يمكن لأي دليل جديد تحسين جودة النظرية المستمدة (غلاسر وستراوس، 2009). يمكن أن تساعد المنظورات الفلسفية في استكشاف وجهات نظر مختلفة. يتطلب التلخيص، كمفتاح للتشبع، عملية تحليل موضوعي تكرارية، تحدد وتقوم بتنقيح المفاهيم المهمة من خلال النظر في الرموز والمواضيع المطورة.

السياق في البحث الإداري كأجندة تعزز الحوار والفهم والانخراط مع المجتمعات المهمشة التي تم استبعادها تاريخيًا من المجتمع السائد. يتعارض هذا النهج السياسي مع الأساليب الأكثر تقليدية المتبعة في البحث الإداري السائد (سميث، 2002).

التداخل النصي (باختين، 2010). تتضمن إزالة السياق وإعادة السياق تفسير العبارات أو النصوص من خلال وضعها في سياقات جديدة قد لا تتماشى مع السياق الأصلي. العمليات المماثلة شائعة ويمكن ملاحظتها ليس فقط في التداخل النصي للنصوص الكبيرة وعوالم الخطاب الواسعة، ولكن أيضًا في الهيكلة المحلية لتسلسل التفاعل لتطوير المفاهيم من خلال النظر في السياق المحلي والنظري والفلسفي (بيل وآخرون، 2017). إنها تعمل كجسر بين جمع البيانات والتسوية النهائية والتصور. النتيجة النهائية هي ملخص متماسك وواضح للاكتشافات التي يمكن استخدامها لتعزيز الأهداف العامة للدراسة.

الاندماج

قابل للتحقق بين البيانات واستنتاجات الباحث بشأن كل موضوع، فيما يتعلق بالرموز والمواضيع البحثية المقابلة، هو هدف عملية الاندماج. من أجل تقديم تحليل شامل وشامل لنتائج البحث، من الضروري أن تكون المواضيع متماسكة ومتميزة بوضوح عن بعضها البعض (براون وكلارك، 2006). من الضروري إنشاء علاقة تكون شفافة وقابلة للتحقق بين البيانات واستنتاجات الباحث بشأن كل موضوع، مع الأخذ في الاعتبار الرموز والمواضيع ذات الصلة بالدراسة (كوجنو وتوماس، 2016). من أجل التأكد من إثبات جميع الاستنتاجات المستخلصة من البيانات، يمكن تقييم كفاية الإشارة من خلال مقارنة البيانات غير المعالجة بالارتباطات التي تم إنشاؤها بين المواضيع والرموز المطورة ضمن الإطار أو النموذج البحثي النهائي. وفقًا للينكولن وغوبا (1985)، فإن مجرد تقديم جدول أو قائمة بالمواضيع أو عدد المشاركين الذين أيدوا موضوعًا معينًا غير كافٍ. يتحمل المؤلفون عبء إثبات الاعتماد المتبادل والتفاعل بين هذه المفاهيم، كما يتضح من إليوت وآخرون (1999، ص. 223)، من خلال استخدام “قصة/سرد مدفوع بالبيانات، إطار، أو هيكل أساسي للظاهرة أو المجال.” يتطلب ذلك دمج الأفكار التي تم تطويرها سابقًا. “دي سانتيس وأوغاريزا، 2000، ص. 369] يذكران، “يمكن مقارنة المواضيع المحددة جيدًا في دراسات معينة، ومقارنتها، واستخدامها ككتل بناء.”

التبلور

تثقيف

التثقيف يُستخدم لوصف كيف يمكن أن تساهم نتائج البحث، المقدمة في شكل جداول أو أطر، في نمو وتطور الأفراد، فكريًا وأخلاقيًا وروحيًا. تبدأ عملية التثقيف من خلال تمييز مكونات نظرية شاملة، بالإضافة إلى علاقاتها المتبادلة والمبررات لضمها في النمو العام للنظرية. يستخدم الباحثون فرضية أو اقتراح كأساس لتطوير نظرية أو نموذج. مكونات البيانات التجريبية وعلاقاتها المتبادلة هي العناصر الأساسية لإطار مفاهيمي، يمكن التعبير عنه كاقتراحات. من أجل تحقيق حالة التثقيف الكامل، يجب على الباحث أن يأخذ في الاعتبار متغيرات مختلفة مثل الشمولية، ووجهة النظر، ومدى تضمين السياق. وهذا يتطلب معالجة استفسارات مثل: ما العوامل التي يجب أخذها في الاعتبار لتقديم فهم أكثر شمولاً للظاهرة قيد البحث؟ ما العلاقة بين هذه العوامل؟ ما الذي يبرر اختيار هذه النظرية كضرورية ومناسبة للبحث؟

عناصر غير مرتبطة سابقًا. تشكل المفاهيم التي تتكون منها البيانات الواقعية والروابط بينها اللبنات الأساسية لإطار مفاهيمي، ويمكن التعبير عن علاقات الإطار بين المفاهيم في شكل مقترحات (ريتشاردز، 2015). وفقًا لجيرجن (1982)، من الضروري أن تكون النظريات المستندة إلى التجربة حساسة للسياق. بمعنى، وفقًا للسياقيين، فإنها تتطور بشكل عضوي من التجارب الحياتية للمشاركين والباحث على حد سواء. لذلك، فإن فهم الباحث الخاص يشكل الأساس للعلاقات بين المفاهيم في الإطار المفاهيمي، الذي يُستخدم لتأسيس الرابط بين العوامل المختلفة بطريقة مقترحة. مصدر موثوق حول تطوير النظرية (دوبين، 1978) ينص على أن النظرية الكاملة يجب أن تتضمن العناصر الثلاثة الموضحة أدناه.

بين العوامل، ويجب أن يشرح تدفق القصة لماذا يجب أخذ القصة بهذه الطريقة المحددة. لذلك، اقترح سلام زاده (2020) أنه يجب التحقق من جميع الروابط تجريبيًا قبل أن يمكن استخدام النموذج في الفصل الدراسي؛ وإلا، فإنه يخدم غرضًا ضئيلًا خارج المختبر. من أجل تحقيق ذلك، من الضروري تقديم تفسير للدوافع وراء ما تم إعادة بنائه حديثًا من “ما” و”كيف”.

الخاتمة

تمييز وتصنيف وفحص الموضوعات داخل مجموعة بياناتهم. إنها نهج مميز لتحليل الموضوعات بسبب نهجها الشمولي في تحليل البيانات واستخدام التوجه؛ يمكن أن تساعد الباحثين في تحقيق إشباع البيانات وتوفير إرشادات للمستقبل. نموذج PRICE، على الرغم من أنه يعتمد على النقاش المستمر حول الإشباع في البحث النوعي، يتضمن بشكل أساسي مبادئ ونظريات من النظرية المستندة إلى الأرض وغيرها من المنهجيات النوعية، كل منها مدعوم من منظور فلسفي فريد. يهدف هذا البحث إلى تقديم نهج منهجي لتحقيق الإشباع ضمن هذا الإطار المحدد من خلال تحليل العناصر ذات الصلة بشكل انتقائي. ضمن هذا الإطار المحدد، يتم تحديد الإشباع كنقطة التقاء حيث استخدم الباحثون جميع التطبيقات المحتملة للبيانات، مما يشير إلى انتهاء إجراء جمع البيانات. يمكن أن تستكشف الاستفسارات الإضافية ملاءمة نموذج PRICE لأطر فلسفية ومنهجيات بحثية مختلفة، وفعاليته في تعزيز موثوقية ودقة التحليل النوعي، ودوره في تحسين إجراءات تحليل الموضوعات.

إعلان عن تضارب المصالح

تمويل

بيان أخلاقي

الموافقة الأخلاقية

بيان الامتثال

References

Alasuutari, P. (1995). Researching culture: Qualitative method and cultural studies. Sage.

Ambert, A. M., Adler, P. A., Adler, P., & Detzner, D. F. (1995). Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Journal of Marriage and Family, 57(4), 879-893. https://doi.org/10.2307/ 353409

Auer, P., & di Luzio, A. (Eds.), (1992). The contextualization of language. John Benjamins.

Bansal, P. T., & Corley, K. (2011). The coming of age for qualitative research: Embracing the diversity of qualitative methods. Academy of Management Journal, 54(2), 233-237. https://doi. org/10.5465/amj.2011.60262792

Beck, C. T. (1993). Qualitative research: The evaluation of its credibility, fittingness and auditability. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 15(2), 263-266. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 019394599301500212

Bell, E., Kothiyal, N., & Willmott, H. (2017). Methodology as Technique and the meaning of rigour in globalized management research. British Journal of Management, 28(3), 534-550. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12205

Benbaji, Y. (2004). A demonstrative analysis of ‘open quotation. Mind and Language, 19(5), 534-547. https://doi.org/10.1111/j. 0268-1064.2004.00271.x

Beresford, P., Green, D., Lister, R., & Woodward, K. (1999). Poverty first hand: Poor people speak for themselves. Child Poverty Action Group.

Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1967). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Anchor. Retrieved https://www.amazon.com/The_Social_Construction_ Reality_Sociology/dp/0385058985

Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide. Sage.

Blikstad-Balas, M. (2017). Key challenges of using video when investigating social practices in education: Contextualization, magnification, and representation. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 40(5), 511-523. https://doi. org/10.1080/1743727x.2016.1181162

Boddy, C. R. (2016). Sample size for qualitative research. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 19(4), 426-432. https://doi.org/10.1108/qmr-06-2016-0053

Bowen, G. A. (2008). Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: A research note. Qualitative Research, 8(1), 137-152. https:// doi.org/10.1177/1468794107085301

Bratlie, S. S., Brinchmann, E. I., Melby-Lervåg, M., & Torkildsen, J. v. K. (2022). Morphology – a gateway to advanced language: Meta-analysis of morphological knowledge in languageminority children. Review of Educational Research, 92(4), 614-650. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543211073186

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 24, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2022.2129597

Brown, A. (2010). Qualitative method and compromise in applied social research. Qualitative Research, 10(2), 229-248. https:// doi.org/10.1177/1468794109356743

Burawoy, M. (2009). The extended case method: Four countries, four decades, four great transformations, and one theoretical tradition. Univ of California Press.

Canisius, P. (1987). Perspektivität in Sprache und Text (2nd ed.). Brockmeyer.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2011). Building theory about theory building: What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 36(1), 12-32. https://doi.org/10.5465/ amr.2009.0486

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

Cugno, R., & Thomas, K. (2016). A book review of Laura Ellingson’s engaging crystallization in qualitative research: An introduction. Qualitative Report.

Czarniawska, B. (2016). Reflexivity versus rigor. Management Learning, 47(5), 615-619. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507616663436

Daly, K. J. (2007). Qualitative methods for family studies and human development. Sage.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2011). The Sage handbook of qualitative research. Sage publications.

DeSantis, L., & Ugarriza, D. (2000). The concept of theme as used in qualitative nursing research. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 22(3), 351-372. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 019394590002200308

Dey, I. (2003). Qualitative data analysis: A user friendly guide for social scientists. Routledge.

Diefenbach, T. (2009). Are case studies more than sophisticated storytelling? Methodological problems of qualitative empirical research mainly based on semi-structured interviews. Quality and Quantity, 43(6), 875-894. https://doi.org/10. 1007/s11135-008-9164-0

DiStefano, A. S., Gagneur, A., & Yang, J. S. (2023). Sample size and saturation: A three-phase method for ethnographic research with multiple qualitative data sources. Field Methods.

Dubé, E., Vivion, M., Sauvageau, C., Gagneur, A., Gagnon, R., & Guay, M. (2016). “Nature does things well, why should we interfere?” Vaccine hesitancy among mothers. Qualitative Health Research, 26(3), 411-425. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1049732315573207

Dubin, R. (1978). Theory development. Free Press.

Eisenhardt, K. M., Graebner, M. E., & Sonenshein, S. (2016). Grand challenges and inductive methods: Rigour without rigour mortis. Academy of Management Journal, 59(4), 1113-1123. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.4004

Eldh, A. C., Årestedt, L., & Berterö, C. (2020). Quotations in qualitative studies: Reflections on constituents, custom, and purpose. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 160940692096926. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920969268

related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38(3), 215-229. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466599162782

Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Research, 5(1), 80-92. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 160940690600500107

Fiedler, K., & Semin, G. R. (1992). Attribution and language as a socio-cognitive environment. In G. R. Semin, & K. Fiedler (Eds.), Language, interaction and social cognition (pp. 79-101). Sage Publications, Inc.

Frieze, I. H. (2013). Guidelines for qualitative research being published in Sex Roles. Sex Roles, 69(1-2), 1-2. https://doi.org/10. 1007/s11199-013-0286-z

Fugard, A. J. B., & Potts, H. W. W. (2015). Supporting thinking on sample sizes for thematic analyses: A quantitative tool. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 18(6), 669-684. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2015.1005453

Fusch Ph, D, & Ness, L. R. (2015). Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qualitative Report, 9(20), 1408-1416.

Galvin, R. (2015). How many interviews are enough? Do qualitative interviews in building energy consumption research produce reliable knowledge? Journal of Building Engineering, 1, 2-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2014.12.001

Ganle, J. K. (2016). Hegemonic masculinity, HIV/AIDS risk perception, and sexual behavior change among young people in Ghana. Qualitative Health Research, 26(6), 763-781. https:// doi.org/10.1177/1049732315573204

Ganong, L., Coleman, M., & Jamison, T. B. (2011). Patterns of stepchild-stepparent relationship development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73(2), 396-413. https://doi.org/10.1111/j. 1741-3737.2010.00814.x

Gephart, R. P. (2004). Qualitative research and the academy of management journal. Academy of Management Journal, 47(4), 454-462. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2004.14438580

Gergen, K. (1982). Toward transformation in social knowledge. Springer-Verlag.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2009). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research (4th ed.). Aldine.

Goldberg, A. E. (2009). Lesbian and heterosexual preadoptive couples’ openness to transracial adoption. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79(1), 103-117. https://doi.org/10.1037/ a0015354

Gómez-Chacón, D. L. (2015). Claustrum animae” or the edification of the soul. The building scenes in the cloister of santa maria la Real de Nieva (segovia). Anales de Historia del Arte, 24(0), 59-77. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_anha.2014.v24.48691

Gordon, J. (2020). The turn of the page: Spoken quotation in shared reading. Classroom Discourse, 11(4), 366-387. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/19463014.2019.1665562

& W. Kallmeyer (Eds.), Perspective and perspectivation in discourse (pp. 1-11). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Greenhalgh, T., & Taylor, R. (1997). How to read a paper: Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research). British Medical Journal, 315(7110), 740-743. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315. 7110.740

Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis. Sage Publications.

Guest, G., Namey, E., & McKenna, K. (2017). How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes. Field Methods, 29(1), 3-22. https:// doi.org/10.1177/1525822×16639015

Gugiu, C., Randall, J., Gibbons, E., Hunter, T., Naegeli, A., & Symonds, T. (2020). PNS217 bootstrap saturation: A quantitative approach for supporting data saturation in sample sizes in qualitative research. Value in Health, 23(2), S677. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jval.2020.08.1661

Gumperz, J. (1982). Discourse strategies. Cambridge University Press.

Gumperz, J. (1992). Contextualization revisited. In P. Auer, & A. di Luzio (Eds.), The contextualization of language (pp. 39-53). John Benjamins.

Gunji, N. (2017). Heike paintings in the early edo period: Edification and ideology for elite men and women. Archives of Asian Art, 67(1), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1215/00666637-3788627

Hammersley, M. (2015). Sampling and thematic analysis: A response to fugard and Potts. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 18(6), 687-688. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 13645579.2015.1005456

Härtel, C. E. J., & O’Connor, J. M. (2014). Contextualizing research: Putting context back into organizational behavior research. Journal of Management and Organization, 20(4), 417-422. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2014.61

Hennink, M., & Kaiser, B. N. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science & Medicine, 292, 114523. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523

Hill, R., & Hansen, D. A. (1960). The identification of conceptual frameworks utilized in family study. Marriage and Family Living, 22(4), 299-311. https://doi.org/10.2307/347242

Hollenbach, J. A., Holcomb, C., Hurley, C. K., Mabdouly, A., Maiers, M., Noble, J. A., Robinson, J., Schmidt, A. H., Shi, L., Turner, V., Yao, Y., & Mack, S. J. (2012). 16th IHIW: Immunogenomic data-management methods. Report from the immunogenomic data analysis working group (IDAWG). International Journal of Immunogenetics, 40(1), 46-53. https:// doi.org/10.1111/iji. 12026

Holloway, I., & Wheeler, S. (1996). Qualitative research in nursing. Blackwell Science.

Kerr, C., Nixon, A., & Wild, D. (2010). Assessing and demonstrating data saturation in qualitative inquiry supporting patient-reported outcomes research. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, 10(3), 269-281. https://doi.org/10.1586/ erp.10.30

Klag, M., & Langley, A. (2013). Approaching the conceptual leap in qualitative research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15(2), 149-166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370. 2012.00349.x

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Reliability in content analysis: Some common misconceptions and recommendations. Human Communication Research, 30(3), 411-433. https://doi.org/10. 1093/hcr/30.3.411

LaDonna, K. A., Artino, A. R., & Balmer, D. F. (2021). Beyond the guise of saturation: Rigor and qualitative interview data. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 13(5), 607-611. https://doi. org/10.4300/JGME-D-21-00752.1

Langley, A. (2013). Approaching the conceptual leap in qualitative research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15(2), 149-166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2012. 00349.x

Lowe, A., Norris, A. C., Farris, A. J., & Babbage, D. R. (2018). Quantifying thematic saturation in qualitative data analysis. Field Methods, 30(3), 191-207. https://doi.org/10.1177/

Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., & Dorrit Guassora, A. (2015). Sample size in qualitative interview studies guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753-1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444

Márquez, F. P. G., & Muñoz, J. M. C. (2012). A pattern recognition and data analysis method for maintenance management. International Journal of Systems Science, 43(6), 1014-1028. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207720903045809

Matthews, S. H. (2005). Crafting qualitative research articles on marriages and families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(4), 799-808. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00176.x

McLaren, P. G., & Durepos, G. (2021). A call to practice context in management and organization studies. Journal of Management Inquiry, 30(1), 74-84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492619837596

Mees-Buss, J., Welch, C., & Piekkari, R. (2020). From templates to heuristics: How and why to move beyond the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 25(2), 405-429. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428120967716

Morse, J. M. (1994). Designing funded qualitative research. Sage.

Morse, J. M., Barrett, M., Mayan, M., Olson, K., & Spiers, J. (2002). Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in

qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1(2), 13-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690200100202

Mwita, K. (2022). Factors influencing data saturation in qualitative studies. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science 11(4), 414-420. https://doi.org/10.20525/ijrbs. v11i4.1776

Naeem, M., & Ozuem, W. (2021a). Developing UGC social brand engagement model: Insights from diverse consumers. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 20(2), 426-439. https://doi.org/10.1002/ cb. 1873

Naeem, M., & Ozuem, W. (2021b). The role of social media in internet banking transition during COVID-19 pandemic: Using multiple methods and sources in qualitative research. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 60, 102483-102483. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102483

Naeem, M., & Ozuem, W. (2022). Understanding misinformation and rumors that generated panic buying as a social practice during COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from twitter, YouTube and focus group interviews. Information Technology and People, 35(7), 2140-2166. https://doi.org/10.1108/itp-01-2021-0061

Naeem, M., Ozuem, W., Howell, K., & Ranfagni, S. (2022). Understanding the process of meanings, materials, and competencies in adoption of mobile banking. Electronic Markets, 32(4), 2445-2469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-022-00610-7

Naeem, M., Ozuem, W., Howell, K., & Ranfagni, S. (2023). A step-by-step process of thematic analysis to develop a conceptual model in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22, 16094069231205789. https://doi.org/10. 1177/16094069231205789

Nazir, Z., Shahzad, K., Malik, M. K., Anwar, W., Bajwa, I. S., & Mehmood, K. (2022). Authorship attribution for a resource poor language-Urdu. ACM Transactions on Asian and LowResource Language Information Processing, 21(3), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1145/3487061

Nelson, J. (2017). Using conceptual depth criteria: Addressing the challenge of reaching saturation in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 17(5), 554-570. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1468794116679873

Neuman, W. L (2018). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Pearson.

Nguyen, D. C., & Tull, J. (2022). Context and contextualization: The extended case method in qualitative international business research. Journal of World Business, 57(5), 101348. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jwb.2022.101348

Olson, T. (2000). Numbers, narratives, and nursing history. The Social Science Journal, 37(1), 137-144. https://doi.org/10. 1016/s0362-3319(99)00060-9

Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2003). Effect sizes in qualitative research: A prolegomenon. Quality and Quantity, 37(4), 393-409. https:// doi.org/10.1023/a:1027379223537

O’Reilly, M, & Parker, N. (2013). Unsatisfactory saturation: A critical exploration of the notion of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 13(2), 190-197. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112446106

Pratt, M. G. (2009). From the editors: For the lack of a boilerplate: Tips on writing up (and reviewing) qualitative research. Academy of Management Journal, 52(5), 856-862. https://doi. org/10.5465/amj.2009.44632557

Ramezani, R. (2021). A language-independent authorship attribution approach for author identification of text documents. Expert Systems with Applications, 180, 115139. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.eswa.2021.115139

Reay, T., & Whetten, D. A. (2011). What constitutes a theoretical contribution in family business? Family Business Review, 24(2), 105-110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486511406427

Reuber, A. R., & Fischer, E. (2021). Putting qualitative international business research in context(s). Journal of International Business Studies, 53, 27-38. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-021-00478-3

Richards, K. A. R. (2015). Role socialization theory: The sociopolitical realities of teaching physical education. European Physical Education Review, 21(3), 379-393. https://doi.org/10. 1177/1356336×15574367

Rogers, M. (2015). Contextualizing theories and practices of bricolage research. Qualitative Report.

Rousseau, D. M., & Fried, Y. (2001). Editorial: Location, location, location: Contextualizing organizational research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1002/job. 78

Roy, K., Zvonkovic, A., Goldberg, A., Sharp, E., & LaRossa, R. (2015). Sampling richness and qualitative integrity: Challenges for research with families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(1), 243-260. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf. 12147

Sacks, H. (1972a). An initial investigation of the usability of conversational data for doing sociology. In D. Sudnow (Ed.), Studies in social interaction.

Sacks, H. (1972b). On the analyzability of stories by children. In J.J. Gumperz, & D.H. Hymes (Eds.), Directions in sociolinguistics: The ethnography of communication. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Sagarra, N., & Ellis, N. C. (2013). From seeing adverbs to seeing verbal morphology: Language experience and adult acquisition of L2 tense. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 35(2), 261-290. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0272263112000885

Salamzadeh, A. (2020). What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Journal of Organizational Culture, Communications and Conflict, 24(1), 1-2.

Saldana, J. M. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

Sandelowski, M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing and Health, 18(2), 179-183. https://doi. org/10.1002/nur.4770180211

Sandelowski, M. (2001). Real qualitative researchers do not count: The use of numbers in qualitative research. Research in Nursing and Health, 24(3), 230-240. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur. 1025

Sandelowski, M. (2003). Tables or tableaux? The challenges of writing and reading mixed methods studies. In A. Tashakkori, &

C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research (pp. 143-165): Sage.

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinxs, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality and Quantity, 52(4), 1893-1907. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

Schlechtweg, M., & Härtl, H. (2020). Do we pronounce quotation? An analysis of name-informing and non-name-informing contexts. Language and Speech, 63(4), 769-798. https://doi.org/10. 1177/0023830919893393

Silverman, D. (2017). How was it for you? The interview society and the irresistible rise of the (poorly analyzed) interview. Qualitative Research, 17(2), 144-158. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1468794116668231

Sinkovics, N. (2018). Pattern matching in qualitative analysis. The sage handbook of qualitative business and management research methods, 468-485.

Smith, A.D. (2002). From process data to publication: A personal sensemaking. Journal of Management Inquiry, 11(4), 383-406. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492602238847

Smith, K.G., & Hitt, M. (Eds.), (2005). Great minds in management: The process of theory development. Oxford University Press.

Stake, R. E. (2010). Qualitative research: Studying how things work: Guilford Press.

Starks, H., & Brown Trinidad, S. (2007). Choose your method: A comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qualitative Health Research, 17(10), 1372-1380. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307307031

Stewart, H., Gapp, R., & Harwood, I. (2017). Exploring the alchemy of qualitative management research: Seeking trustworthiness, credibility and rigor through crystallization. Qualitative Report, 22(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2017.2604

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1997). Grounded theory in practice. Sage Publications.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage.

Sujatha, R., & Alva, J. (2020). Effectiveness of cognitive edification programme on knowledge and reported practice of early ambulation among nursing students in a selected nursing institute. Nursing Journal of India, 111(3), 108-113.

Tran, V. T., Porcher, R., Tran, V. C., & Ravaud, P. (2017). Predicting data saturation in qualitative surveys with mathematical models from ecological research. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 82, 71-78.

Urquhart, C. (2013). Quantitative approaches. Research, evaluation and audit: Key steps in demonstrating your value (p. 121).

Van Dijk, T. A. (1984). Prejudice and discourse: An analysis of ethnic prejudice in cognition and conversation. John Benjamins.

Van Maanen, J. (2010). A song for my supper: More tales of the field. Organizational Research Methods, 13(2), 240-255. https://doi. org/10.1177/1094428109343968

Van Maanen, J., Sorensen, J. B., & Mitchell, T. R. (2007). The interplay between theory and method. Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1145-1154. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007. 26586080

Von, C. S. (1989). Referential movement in descriptive and narrative discourse. In R. Dietrich, & C. F. Graumann (Eds.), Language processing in social context. Elsevier Science Publishers B.V. [pages not specified]).

Wallas, G. (1926). The art of thought. Harcourt Brace.

Welch, C., Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, E., Piekkari, R., & Plakoyiannaki, E. (2022). Reconciling theory and context: How the case study can set a new agenda for international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 53(1), 4-26. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-021-00484-5

Whetten, D. A. (1989). What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 490-495. https://doi. org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308371

White, C., Woodfield, K., Ritchie, J., & Ormston, R. (2014). Writing up qualitative research. In J. Ritchie, J. Lewis, C. Nicholls McNaughton, & R. Ormston (Eds.), Qualitative research practice (pp. 368-400). Sage.

Wicker, A. W. (1985). Getting out of our conceptual ruts: Strategies for expanding conceptual frameworks. American Psychologist, 40(10), 1094-1103. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.40.10.1094

Wolcott, H. (1990). Writing up qualitative research. Sage Publications.

Wray, N., Markovic, M., & Manderson, L. (2007). ‘Researcher saturation’: The impact of data triangulation and intensiveresearch practices on the researcher and qualitative research process. Qualitative Health Research, 17(10), 1392-1402. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973230730830

- ‘The School of Business and Technology, University of Gloucestershire, UK

Business School for the Creative Industries, University for the Creative Arts, UK

Newcastle Business School, Northumbria University, UK

Department of Economics and Business, University of Florence, Italy

Corresponding Author:

Muhammad Naeem, School of Business & Management, University of Gloucestershire, Arden House, Middlemarch Park, Coventry CV3 4JF, UK.

Email: dr.muhammadnaeem222@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069241229777

Publication Date: 2024-01-01

Demystification and Actualisation of Data Saturation in Qualitative Research Through Thematic Analysis

Abstract

The concept of saturation in qualitative research is a widely debated topic. Saturation refers to the point at which no new data or themes are emerging from the data set, which indicates that the data have been fully explored. It is considered an important concept as it helps to ensure that the findings are robust and that the data are being used to their full potential to achieve the research aim. Saturation, or the point at which further observation of data will not lead to the discovery of more information related to the research questions, is an important aspect of qualitative research. However, there is some mystification and semantic debate surrounding the term saturation, and it is not always clear how many rounds of research are needed to reach saturation or what criteria are used to make that determination during the thematic analysis process. This paper focuses on the actualisation of saturation in the context of thematic analysis and develops a systematic approach to using data to justify the contribution of research. Consequently, we introduce a distinct model to help researchers reach saturation through refining or expanding existing quotations, codes, themes and concepts as necessary.

Keywords

Introduction

the idea of saturation is a subject of difference among qualitative researchers who have differences in opinion regarding its meaning, clarity, and practicality (O’Reilly & Parker, 2013; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Indeed, it is unclear what the term actually encompasses (Bowen, 2008) and what specific process is required to claim that saturation has been accomplished (O’Reilly & Parker, 2013). Fundamentally, rule-of-thumb estimates are used to determine how many observations or interviews are needed and claims of

Revisiting Saturation in Qualitative Research: Integrating Current Literature Insights with the Proposed Saturation Approach

practical standards and clarity in identifying sufficient levels. Saturation is a multifaceted and repetitive procedure that aims to develop a thorough understanding by continuously gathering, collecting, and analysing data, as described by Glaser and Strauss (1967). Charmaz (2006) highlight that saturation pertains more to the comprehensiveness of the theory rather than the size of the sample. Dube et al. (2016) and Boddy (2016) agree, asserting that saturation should impact both the applicability and theoretical soundness of investigations. Urquhart (2013) and Birks and Mills (2015) have offered other perspectives on saturation, emphasising the formation of new codes or themes. This highlights a transition towards the analytical dimension of research. In their study, Starks and Brown Trinidad (2007) introduce the concept of theoretical saturation as the complete and thorough inclusion of constructs found in the data that contribute to the development of the theory.

emphasising the importance of avoiding methodological inconsistency when combining different approaches. They promote the adoption of an individual’s analytical viewpoint, differentiating between descriptive and interpretive Transactional Analysis (TA), and refute the notion of researcher bias in favour of subjectivity as a research instrument. Their commentary aims to guide rigorous TA practice, especially relevant for researchers striving for data saturation, emphasizing the interpretative nature of identifying themes and the importance of reflexivity in the process. This work redirects the attention from grounded theory to a distinct facet of qualitative research, namely thematic analysis. While grounded theory aims to create new theories, thematic analysis can also support this goal but has a broader scope, as mentioned by Naeem et al. (2023). Therefore, the concept of saturation as used in grounded theory may not be directly applicable to thematic analysis. This study focuses on the attainment of saturation in thematic analysis, which refers to the stage where the data has been exhaustively employed to fulfil the research objectives. Although thematic analysis and grounded theory share some similarities, this paper draws from the grounded theory approach to saturation where relevant, to better inform the thematic analysis process.

qualitative case study to thoroughly analyse the process of collecting data and ensuring saturation.

Discussion

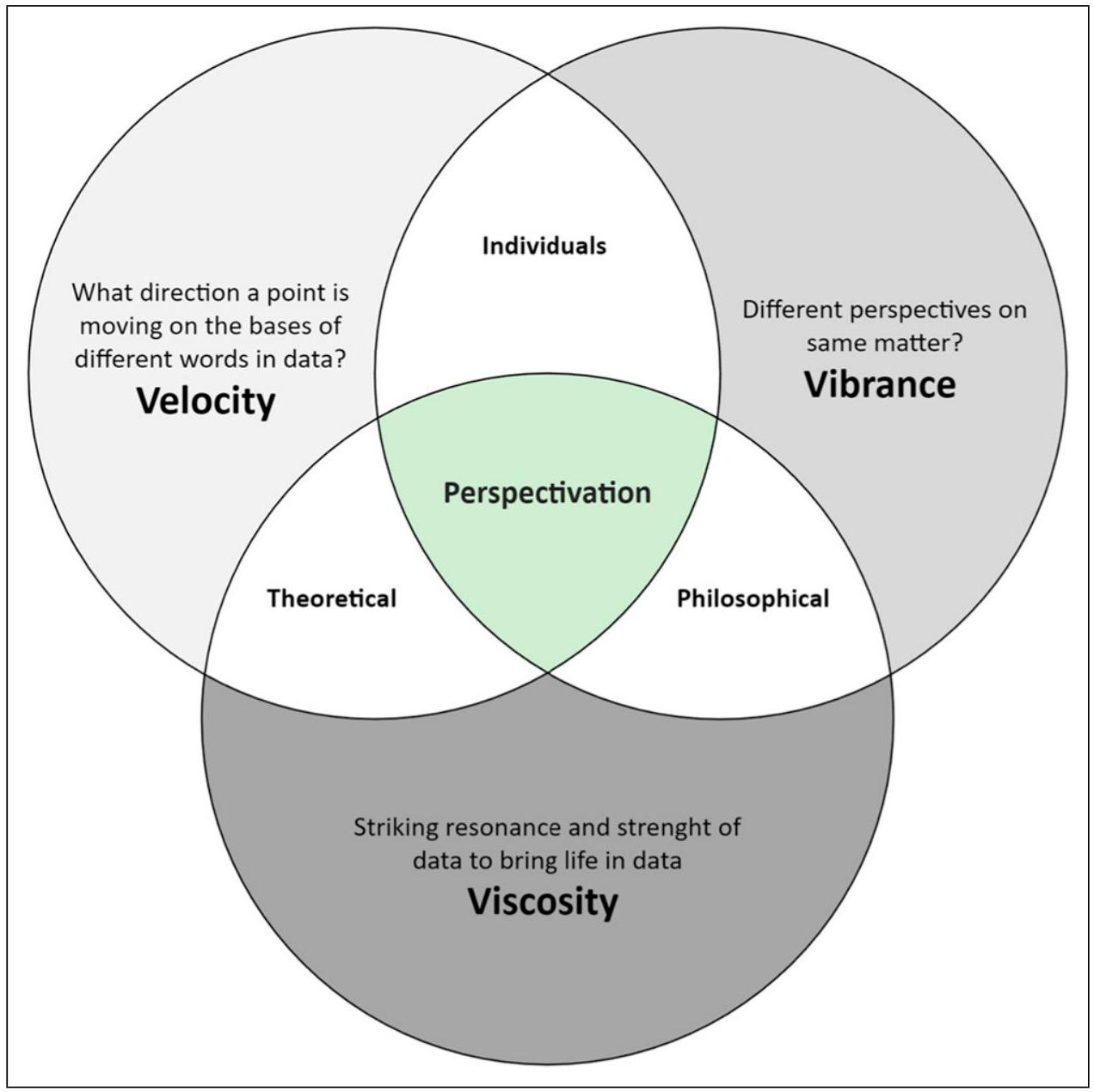

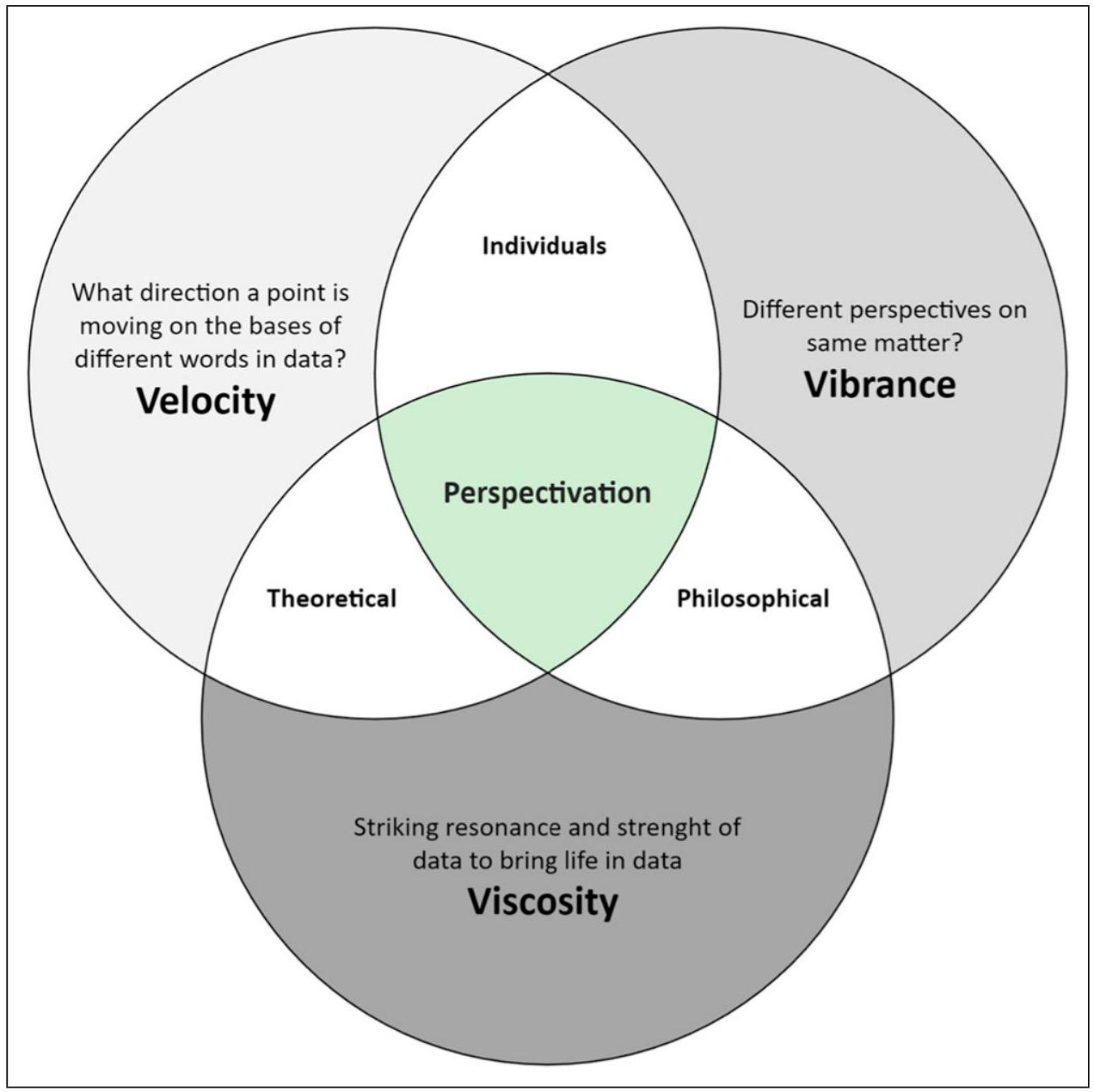

Perspectivation

observation of different events in qualitative data collection. The explicit reporting of different perspectives in the data analysis can reach saturation to ensure the clarity of the analysis.

Selection of Accurate Keywords and Quotes

avoids the (mis)use of catchy words (Silverman, 2017). Consideration of power quotes and proof quotes might help a researcher to choose appropriate quotes. Power quotations show the reader the most important data points, and these quotes can also be used to describe the results. Power quotes are defined as a “sense of being there, of visualising the [participant], feeling their conflict and emotions” (Ambert et al., 1995, p. 885). Power quotes “are the most compelling bits of data you have, the ones that effectively illustrate your points” (Pratt, 2009, p. 860). Naeem and Wilson (2022) suggested that if some keywords are commonly used by the participants and if these keywords can answer the research question through making a story, then these strong keywords should be selected, and all quotations containing these keywords should be selected at the first stage of the thematic analysis (Naeem & Ozuem, 2021, 2021b).

Frequency of Keywords

interviews and their role in achieving saturation. Guest et al., (2017) study shifts focus to focus groups, aiming to establish an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes necessary for saturation. Facts and figures can enrich and elucidate stories in remarkable ways (Olson, 2000). Qualitative researchers face a unique set of challenges when it comes to utilising quantitative methods that yield credible findings. If they want their numerical efforts to matter, they will have to determine when and what to count (DeSantis & Ugarriza, 2000). The manner in which the participants represent the same situation through the use of varied vocabulary and expressions has a substantial effect on the interpretation of the textual significance in qualitative research. Therefore, for researchers to comprehend the terminology utilised and fully understand the numerous implications present in a specific dataset, a wide array of terms and expressions is necessary (Dey, 2003). A quantitative approach is introduced by Lowe et al. (2018) to assess thematic saturation in qualitative data analysis. This method provides a quantifiable tool for identifying the threshold at which saturation is achieved. Furthermore, the analysis of effect sizes in qualitative research conducted by Onwuegbuzie (2003) is highly regarded and significantly contributes to the broader discourse surrounding saturation. Moreover, numbers serve as potent rhetorical devices, enabling one to emphasise the arduousness and intricacy inherent in qualitative research. For example, it would be inappropriate for researchers to offer justifications for the seemingly limited sample sizes employed (Greenhalgh & Taylor, 1997; Sandelowski, 2001).

Recording the Frequency of Data

Saturation in Coding and Theming

Language Structure Perspective

the ways in which speakers use language to convey their own and other people’s points of view, as well as the relationships between these perspectives. Here, we inquire as to how participants make use of their language options to express viewpoints (keywords) that will bring vibrancy to the data analysis, which explores socially constructed reality. Attaining the utmost vividness of the gathered qualitative data during the analysis phase pertains to the stage at which the researcher possesses a thorough and profound comprehension of how words have been employed and is capable of capturing the abundance and intricacy of the data based on the theoretical and epistemological standpoint of the research.

Theoretical Perspective

types of vocabulary used to express the same matter or issue can be considered variance. For example, strong emotions (satisfaction, enjoyment, disappointment, hurt) as well as confusion and hesitancy might be expressed in some quotes, which will be the vibrancy of the data. This linguistic velocity, viscosity and vibrancy is also aligned with social constructionist epistemological perspectives that would lead to the development of a socially constructed reality of the research topic. Consequently, theoretical and philosophical vibrancy would also lead to achieve perspectivation. Perspectivation in qualitative data analysis pertains to the stage where the researcher possesses a profound comprehension of the data and is capable of perceiving it from many viewpoints. This can be achieved using velocity, viscosity and vibrancy in the selection of keywords and codes.

Recapitulation

apart and reassembled in a more meaningful way (Saunder et al., 2018). Theoretical saturation occurs when no new evidence can improve the quality of the derived theory (Glaser & Strauss, 2009). Philosophical perspectives can help to explore different perspectives. Recapitulation, as a key to saturation, requires the iterative process of thematic analysis, which identifies and refines important concepts through consideration of the developed codes and themes.

contextualization in management research as an agenda that promotes dialogue, understanding, and engagement with marginalized communities that have been historically excluded from mainstream society. This political approach is in contrast to the more conventional approaches taken in mainstream management research (Smith, 2002).

intertextuality (Bakhtin, 2010). Decontextualization and recontextualization involve the interpretation of utterances or texts by placing them in new contexts that may not align with the original context. Similar processes are widespread and can be observed not only in the intertextuality of large texts and extensive discourse worlds, but also in the local structuring of interaction sequences to develop the concepts through consideration of the local, theoretical and philosophical context (Bell et al., 2017). It serves as a bridge between the data collection and the final contextualisation and conceptualisation. The ultimate result is a cohesive and lucid synopsis of the discoveries that may be utilised to bolster the overarching study goals.

Integration

verifiable connection between the data and the researcher’s deductions regarding each theme, in relation to the corresponding research codes and themes, is the aim of the integration process. In order to present a thorough and inclusive analysis of the research outcomes, it is essential that the themes are coherent and clearly differentiated from each other (Braun & Clarke, 2006). It is imperative to establish a correlation that is both transparent and verifiable between the data and the researcher’s deductions regarding each theme, taking into account the relevant codes and themes of the study (Cugno & Thomas, 2016). In order to ascertain the substantiation of all deductions made from the data, referential adequacy can be evaluated by juxtaposing the unprocessed data with the correlations established between the developed themes and codes within the ultimate research framework or model. According to Lincoln and Guba (1985), merely providing a table or a list of themes or the number of participants who endorsed a specific theme is insufficient. The authors bear the onus of demonstrating the interdependence and interaction of these concepts, as illustrated by Elliott et al. (1999, p. 223), through the use of a “data-driven story/narrative, framework, or underlying structure for the phenomenon or domain.” This necessitates the integration of previously developed ideas. “DeSantis & Ugarriza, 2000, p. 369] state, “Well-defined themes in particular studies can be compared, contrasted, and utilised as building blocks.”

Crystallisation

Edification

same root. Edification is used to describe how research results, presented in the form of tables or frameworks, can contribute to the growth and development of individuals, intellectually, morally and spiritually. The process of edification commences by discerning the constituents of a comprehensive theory, as well as their interrelationships and the justifications for their inclusion in the overall growth of the theory. Researchers utilise a proposition or hypothesis as a foundation to develop a theory or model. The constituents of empirical data and their interrelationships are the fundamental elements of a conceptual framework, which can be articulated as propositions. In order to achieve the state of complete edification, the researcher must take into account various variables such as thoroughness, perspective, and the extent to which context is incorporated. This entails addressing inquiries such as: What factors should be considered to present a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under investigation? What is the relationship between the factors? What justifies the selection of this theory as necessary and suitable for the research?

previously unrelated elements. The concepts that make up real-world data and the connections between them form the building blocks of a conceptual framework, and the framework’s relations between concepts can be expressed in the form of propositions (Richards, 2015). According to Gergen (1982), it is essential for experience-based theories to be sensitive to context. Meaning, according to contextualists, they develop organically out of the lived experiences of participants and the researcher alike. Therefore, the researcher’s own understanding forms the basis for the relationships among concepts in the conceptual framework, which is used to establish the link between various factors in a propositional fashion. An authoritative source on theory development (Dubin, 1978) states that a full theory must include the three elements described below.

between factors, and the flow of the story should explain why the story needs to be taken in that specific way. Therefore, Salamzadeh (2020) suggested that all connections must be empirically verified before the model can be used in the classroom; otherwise, it serves little purpose outside of the lab. In order to accomplish this, it is necessary to provide an explanation for the motivations behind the newly reconstructed what’s and how’s.

Conclusion

discerning, classifying, and scrutinising themes within their dataset. It is a distinctive approach to thematic analysis due to its holistic approach to data analysis and utilisation of perspectivation; it can assist researchers in achieving data saturation and provide guidance for the future. The PRICE model, although based on the ongoing discussion on saturation in qualitative research, primarily incorporates principles and theories from grounded theory and other qualitative methodologies, each of which is supported by a unique philosophical standpoint. This research aims to provide a systematic approach to achieving saturation within this specific framework by selectively analysing relevant elements. Within this particular framework, saturation is delineated as the juncture wherein researchers have fully used all potential applications of the data, indicating the conclusion of the data collection procedure. Further inquiries could explore the suitability of the PRICE model for different philosophical frameworks and research methodologies, its effectiveness in strengthening the dependability and precision of qualitative analysis, and its role in improving theme analysis procedures.

Declaration of conflicting interests

Funding

Ethical Statement

Ethical Approval

Compliance Statement

References

Alasuutari, P. (1995). Researching culture: Qualitative method and cultural studies. Sage.

Ambert, A. M., Adler, P. A., Adler, P., & Detzner, D. F. (1995). Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Journal of Marriage and Family, 57(4), 879-893. https://doi.org/10.2307/ 353409

Auer, P., & di Luzio, A. (Eds.), (1992). The contextualization of language. John Benjamins.

Bansal, P. T., & Corley, K. (2011). The coming of age for qualitative research: Embracing the diversity of qualitative methods. Academy of Management Journal, 54(2), 233-237. https://doi. org/10.5465/amj.2011.60262792

Beck, C. T. (1993). Qualitative research: The evaluation of its credibility, fittingness and auditability. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 15(2), 263-266. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 019394599301500212

Bell, E., Kothiyal, N., & Willmott, H. (2017). Methodology as Technique and the meaning of rigour in globalized management research. British Journal of Management, 28(3), 534-550. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12205

Benbaji, Y. (2004). A demonstrative analysis of ‘open quotation. Mind and Language, 19(5), 534-547. https://doi.org/10.1111/j. 0268-1064.2004.00271.x

Beresford, P., Green, D., Lister, R., & Woodward, K. (1999). Poverty first hand: Poor people speak for themselves. Child Poverty Action Group.

Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1967). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Anchor. Retrieved https://www.amazon.com/The_Social_Construction_ Reality_Sociology/dp/0385058985

Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide. Sage.

Blikstad-Balas, M. (2017). Key challenges of using video when investigating social practices in education: Contextualization, magnification, and representation. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 40(5), 511-523. https://doi. org/10.1080/1743727x.2016.1181162

Boddy, C. R. (2016). Sample size for qualitative research. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 19(4), 426-432. https://doi.org/10.1108/qmr-06-2016-0053

Bowen, G. A. (2008). Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: A research note. Qualitative Research, 8(1), 137-152. https:// doi.org/10.1177/1468794107085301

Bratlie, S. S., Brinchmann, E. I., Melby-Lervåg, M., & Torkildsen, J. v. K. (2022). Morphology – a gateway to advanced language: Meta-analysis of morphological knowledge in languageminority children. Review of Educational Research, 92(4), 614-650. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543211073186

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 24, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2022.2129597

Brown, A. (2010). Qualitative method and compromise in applied social research. Qualitative Research, 10(2), 229-248. https:// doi.org/10.1177/1468794109356743

Burawoy, M. (2009). The extended case method: Four countries, four decades, four great transformations, and one theoretical tradition. Univ of California Press.

Canisius, P. (1987). Perspektivität in Sprache und Text (2nd ed.). Brockmeyer.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2011). Building theory about theory building: What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 36(1), 12-32. https://doi.org/10.5465/ amr.2009.0486

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

Cugno, R., & Thomas, K. (2016). A book review of Laura Ellingson’s engaging crystallization in qualitative research: An introduction. Qualitative Report.

Czarniawska, B. (2016). Reflexivity versus rigor. Management Learning, 47(5), 615-619. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507616663436

Daly, K. J. (2007). Qualitative methods for family studies and human development. Sage.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2011). The Sage handbook of qualitative research. Sage publications.

DeSantis, L., & Ugarriza, D. (2000). The concept of theme as used in qualitative nursing research. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 22(3), 351-372. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 019394590002200308

Dey, I. (2003). Qualitative data analysis: A user friendly guide for social scientists. Routledge.

Diefenbach, T. (2009). Are case studies more than sophisticated storytelling? Methodological problems of qualitative empirical research mainly based on semi-structured interviews. Quality and Quantity, 43(6), 875-894. https://doi.org/10. 1007/s11135-008-9164-0

DiStefano, A. S., Gagneur, A., & Yang, J. S. (2023). Sample size and saturation: A three-phase method for ethnographic research with multiple qualitative data sources. Field Methods.

Dubé, E., Vivion, M., Sauvageau, C., Gagneur, A., Gagnon, R., & Guay, M. (2016). “Nature does things well, why should we interfere?” Vaccine hesitancy among mothers. Qualitative Health Research, 26(3), 411-425. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1049732315573207

Dubin, R. (1978). Theory development. Free Press.

Eisenhardt, K. M., Graebner, M. E., & Sonenshein, S. (2016). Grand challenges and inductive methods: Rigour without rigour mortis. Academy of Management Journal, 59(4), 1113-1123. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.4004

Eldh, A. C., Årestedt, L., & Berterö, C. (2020). Quotations in qualitative studies: Reflections on constituents, custom, and purpose. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 160940692096926. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920969268

related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38(3), 215-229. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466599162782

Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Research, 5(1), 80-92. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 160940690600500107

Fiedler, K., & Semin, G. R. (1992). Attribution and language as a socio-cognitive environment. In G. R. Semin, & K. Fiedler (Eds.), Language, interaction and social cognition (pp. 79-101). Sage Publications, Inc.

Frieze, I. H. (2013). Guidelines for qualitative research being published in Sex Roles. Sex Roles, 69(1-2), 1-2. https://doi.org/10. 1007/s11199-013-0286-z

Fugard, A. J. B., & Potts, H. W. W. (2015). Supporting thinking on sample sizes for thematic analyses: A quantitative tool. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 18(6), 669-684. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2015.1005453

Fusch Ph, D, & Ness, L. R. (2015). Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qualitative Report, 9(20), 1408-1416.

Galvin, R. (2015). How many interviews are enough? Do qualitative interviews in building energy consumption research produce reliable knowledge? Journal of Building Engineering, 1, 2-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2014.12.001

Ganle, J. K. (2016). Hegemonic masculinity, HIV/AIDS risk perception, and sexual behavior change among young people in Ghana. Qualitative Health Research, 26(6), 763-781. https:// doi.org/10.1177/1049732315573204

Ganong, L., Coleman, M., & Jamison, T. B. (2011). Patterns of stepchild-stepparent relationship development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73(2), 396-413. https://doi.org/10.1111/j. 1741-3737.2010.00814.x

Gephart, R. P. (2004). Qualitative research and the academy of management journal. Academy of Management Journal, 47(4), 454-462. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2004.14438580

Gergen, K. (1982). Toward transformation in social knowledge. Springer-Verlag.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2009). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research (4th ed.). Aldine.

Goldberg, A. E. (2009). Lesbian and heterosexual preadoptive couples’ openness to transracial adoption. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79(1), 103-117. https://doi.org/10.1037/ a0015354

Gómez-Chacón, D. L. (2015). Claustrum animae” or the edification of the soul. The building scenes in the cloister of santa maria la Real de Nieva (segovia). Anales de Historia del Arte, 24(0), 59-77. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_anha.2014.v24.48691

Gordon, J. (2020). The turn of the page: Spoken quotation in shared reading. Classroom Discourse, 11(4), 366-387. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/19463014.2019.1665562

& W. Kallmeyer (Eds.), Perspective and perspectivation in discourse (pp. 1-11). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Greenhalgh, T., & Taylor, R. (1997). How to read a paper: Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research). British Medical Journal, 315(7110), 740-743. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315. 7110.740

Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis. Sage Publications.

Guest, G., Namey, E., & McKenna, K. (2017). How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes. Field Methods, 29(1), 3-22. https:// doi.org/10.1177/1525822×16639015

Gugiu, C., Randall, J., Gibbons, E., Hunter, T., Naegeli, A., & Symonds, T. (2020). PNS217 bootstrap saturation: A quantitative approach for supporting data saturation in sample sizes in qualitative research. Value in Health, 23(2), S677. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jval.2020.08.1661

Gumperz, J. (1982). Discourse strategies. Cambridge University Press.

Gumperz, J. (1992). Contextualization revisited. In P. Auer, & A. di Luzio (Eds.), The contextualization of language (pp. 39-53). John Benjamins.

Gunji, N. (2017). Heike paintings in the early edo period: Edification and ideology for elite men and women. Archives of Asian Art, 67(1), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1215/00666637-3788627

Hammersley, M. (2015). Sampling and thematic analysis: A response to fugard and Potts. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 18(6), 687-688. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 13645579.2015.1005456

Härtel, C. E. J., & O’Connor, J. M. (2014). Contextualizing research: Putting context back into organizational behavior research. Journal of Management and Organization, 20(4), 417-422. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2014.61

Hennink, M., & Kaiser, B. N. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science & Medicine, 292, 114523. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523

Hill, R., & Hansen, D. A. (1960). The identification of conceptual frameworks utilized in family study. Marriage and Family Living, 22(4), 299-311. https://doi.org/10.2307/347242

Hollenbach, J. A., Holcomb, C., Hurley, C. K., Mabdouly, A., Maiers, M., Noble, J. A., Robinson, J., Schmidt, A. H., Shi, L., Turner, V., Yao, Y., & Mack, S. J. (2012). 16th IHIW: Immunogenomic data-management methods. Report from the immunogenomic data analysis working group (IDAWG). International Journal of Immunogenetics, 40(1), 46-53. https:// doi.org/10.1111/iji. 12026

Holloway, I., & Wheeler, S. (1996). Qualitative research in nursing. Blackwell Science.

Kerr, C., Nixon, A., & Wild, D. (2010). Assessing and demonstrating data saturation in qualitative inquiry supporting patient-reported outcomes research. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, 10(3), 269-281. https://doi.org/10.1586/ erp.10.30

Klag, M., & Langley, A. (2013). Approaching the conceptual leap in qualitative research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15(2), 149-166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370. 2012.00349.x

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Reliability in content analysis: Some common misconceptions and recommendations. Human Communication Research, 30(3), 411-433. https://doi.org/10. 1093/hcr/30.3.411

LaDonna, K. A., Artino, A. R., & Balmer, D. F. (2021). Beyond the guise of saturation: Rigor and qualitative interview data. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 13(5), 607-611. https://doi. org/10.4300/JGME-D-21-00752.1

Langley, A. (2013). Approaching the conceptual leap in qualitative research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15(2), 149-166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2012. 00349.x

Lowe, A., Norris, A. C., Farris, A. J., & Babbage, D. R. (2018). Quantifying thematic saturation in qualitative data analysis. Field Methods, 30(3), 191-207. https://doi.org/10.1177/

Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., & Dorrit Guassora, A. (2015). Sample size in qualitative interview studies guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753-1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444

Márquez, F. P. G., & Muñoz, J. M. C. (2012). A pattern recognition and data analysis method for maintenance management. International Journal of Systems Science, 43(6), 1014-1028. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207720903045809

Matthews, S. H. (2005). Crafting qualitative research articles on marriages and families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(4), 799-808. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00176.x

McLaren, P. G., & Durepos, G. (2021). A call to practice context in management and organization studies. Journal of Management Inquiry, 30(1), 74-84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492619837596

Mees-Buss, J., Welch, C., & Piekkari, R. (2020). From templates to heuristics: How and why to move beyond the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 25(2), 405-429. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428120967716

Morse, J. M. (1994). Designing funded qualitative research. Sage.

Morse, J. M., Barrett, M., Mayan, M., Olson, K., & Spiers, J. (2002). Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in

qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1(2), 13-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690200100202

Mwita, K. (2022). Factors influencing data saturation in qualitative studies. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science 11(4), 414-420. https://doi.org/10.20525/ijrbs. v11i4.1776

Naeem, M., & Ozuem, W. (2021a). Developing UGC social brand engagement model: Insights from diverse consumers. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 20(2), 426-439. https://doi.org/10.1002/ cb. 1873

Naeem, M., & Ozuem, W. (2021b). The role of social media in internet banking transition during COVID-19 pandemic: Using multiple methods and sources in qualitative research. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 60, 102483-102483. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102483

Naeem, M., & Ozuem, W. (2022). Understanding misinformation and rumors that generated panic buying as a social practice during COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from twitter, YouTube and focus group interviews. Information Technology and People, 35(7), 2140-2166. https://doi.org/10.1108/itp-01-2021-0061

Naeem, M., Ozuem, W., Howell, K., & Ranfagni, S. (2022). Understanding the process of meanings, materials, and competencies in adoption of mobile banking. Electronic Markets, 32(4), 2445-2469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-022-00610-7

Naeem, M., Ozuem, W., Howell, K., & Ranfagni, S. (2023). A step-by-step process of thematic analysis to develop a conceptual model in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22, 16094069231205789. https://doi.org/10. 1177/16094069231205789

Nazir, Z., Shahzad, K., Malik, M. K., Anwar, W., Bajwa, I. S., & Mehmood, K. (2022). Authorship attribution for a resource poor language-Urdu. ACM Transactions on Asian and LowResource Language Information Processing, 21(3), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1145/3487061

Nelson, J. (2017). Using conceptual depth criteria: Addressing the challenge of reaching saturation in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 17(5), 554-570. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1468794116679873

Neuman, W. L (2018). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Pearson.

Nguyen, D. C., & Tull, J. (2022). Context and contextualization: The extended case method in qualitative international business research. Journal of World Business, 57(5), 101348. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jwb.2022.101348

Olson, T. (2000). Numbers, narratives, and nursing history. The Social Science Journal, 37(1), 137-144. https://doi.org/10. 1016/s0362-3319(99)00060-9

Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2003). Effect sizes in qualitative research: A prolegomenon. Quality and Quantity, 37(4), 393-409. https:// doi.org/10.1023/a:1027379223537

O’Reilly, M, & Parker, N. (2013). Unsatisfactory saturation: A critical exploration of the notion of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 13(2), 190-197. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112446106

Pratt, M. G. (2009). From the editors: For the lack of a boilerplate: Tips on writing up (and reviewing) qualitative research. Academy of Management Journal, 52(5), 856-862. https://doi. org/10.5465/amj.2009.44632557

Ramezani, R. (2021). A language-independent authorship attribution approach for author identification of text documents. Expert Systems with Applications, 180, 115139. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.eswa.2021.115139

Reay, T., & Whetten, D. A. (2011). What constitutes a theoretical contribution in family business? Family Business Review, 24(2), 105-110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486511406427

Reuber, A. R., & Fischer, E. (2021). Putting qualitative international business research in context(s). Journal of International Business Studies, 53, 27-38. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-021-00478-3

Richards, K. A. R. (2015). Role socialization theory: The sociopolitical realities of teaching physical education. European Physical Education Review, 21(3), 379-393. https://doi.org/10. 1177/1356336×15574367

Rogers, M. (2015). Contextualizing theories and practices of bricolage research. Qualitative Report.

Rousseau, D. M., & Fried, Y. (2001). Editorial: Location, location, location: Contextualizing organizational research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1002/job. 78

Roy, K., Zvonkovic, A., Goldberg, A., Sharp, E., & LaRossa, R. (2015). Sampling richness and qualitative integrity: Challenges for research with families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(1), 243-260. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf. 12147

Sacks, H. (1972a). An initial investigation of the usability of conversational data for doing sociology. In D. Sudnow (Ed.), Studies in social interaction.

Sacks, H. (1972b). On the analyzability of stories by children. In J.J. Gumperz, & D.H. Hymes (Eds.), Directions in sociolinguistics: The ethnography of communication. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Sagarra, N., & Ellis, N. C. (2013). From seeing adverbs to seeing verbal morphology: Language experience and adult acquisition of L2 tense. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 35(2), 261-290. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0272263112000885

Salamzadeh, A. (2020). What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Journal of Organizational Culture, Communications and Conflict, 24(1), 1-2.

Saldana, J. M. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

Sandelowski, M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing and Health, 18(2), 179-183. https://doi. org/10.1002/nur.4770180211

Sandelowski, M. (2001). Real qualitative researchers do not count: The use of numbers in qualitative research. Research in Nursing and Health, 24(3), 230-240. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur. 1025

Sandelowski, M. (2003). Tables or tableaux? The challenges of writing and reading mixed methods studies. In A. Tashakkori, &

C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research (pp. 143-165): Sage.

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinxs, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality and Quantity, 52(4), 1893-1907. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

Schlechtweg, M., & Härtl, H. (2020). Do we pronounce quotation? An analysis of name-informing and non-name-informing contexts. Language and Speech, 63(4), 769-798. https://doi.org/10. 1177/0023830919893393

Silverman, D. (2017). How was it for you? The interview society and the irresistible rise of the (poorly analyzed) interview. Qualitative Research, 17(2), 144-158. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1468794116668231

Sinkovics, N. (2018). Pattern matching in qualitative analysis. The sage handbook of qualitative business and management research methods, 468-485.

Smith, A.D. (2002). From process data to publication: A personal sensemaking. Journal of Management Inquiry, 11(4), 383-406. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492602238847

Smith, K.G., & Hitt, M. (Eds.), (2005). Great minds in management: The process of theory development. Oxford University Press.

Stake, R. E. (2010). Qualitative research: Studying how things work: Guilford Press.

Starks, H., & Brown Trinidad, S. (2007). Choose your method: A comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qualitative Health Research, 17(10), 1372-1380. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307307031

Stewart, H., Gapp, R., & Harwood, I. (2017). Exploring the alchemy of qualitative management research: Seeking trustworthiness, credibility and rigor through crystallization. Qualitative Report, 22(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2017.2604

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1997). Grounded theory in practice. Sage Publications.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage.

Sujatha, R., & Alva, J. (2020). Effectiveness of cognitive edification programme on knowledge and reported practice of early ambulation among nursing students in a selected nursing institute. Nursing Journal of India, 111(3), 108-113.

Tran, V. T., Porcher, R., Tran, V. C., & Ravaud, P. (2017). Predicting data saturation in qualitative surveys with mathematical models from ecological research. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 82, 71-78.

Urquhart, C. (2013). Quantitative approaches. Research, evaluation and audit: Key steps in demonstrating your value (p. 121).

Van Dijk, T. A. (1984). Prejudice and discourse: An analysis of ethnic prejudice in cognition and conversation. John Benjamins.

Van Maanen, J. (2010). A song for my supper: More tales of the field. Organizational Research Methods, 13(2), 240-255. https://doi. org/10.1177/1094428109343968

Van Maanen, J., Sorensen, J. B., & Mitchell, T. R. (2007). The interplay between theory and method. Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1145-1154. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007. 26586080

Von, C. S. (1989). Referential movement in descriptive and narrative discourse. In R. Dietrich, & C. F. Graumann (Eds.), Language processing in social context. Elsevier Science Publishers B.V. [pages not specified]).

Wallas, G. (1926). The art of thought. Harcourt Brace.

Welch, C., Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, E., Piekkari, R., & Plakoyiannaki, E. (2022). Reconciling theory and context: How the case study can set a new agenda for international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 53(1), 4-26. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-021-00484-5

Whetten, D. A. (1989). What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 490-495. https://doi. org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308371

White, C., Woodfield, K., Ritchie, J., & Ormston, R. (2014). Writing up qualitative research. In J. Ritchie, J. Lewis, C. Nicholls McNaughton, & R. Ormston (Eds.), Qualitative research practice (pp. 368-400). Sage.

Wicker, A. W. (1985). Getting out of our conceptual ruts: Strategies for expanding conceptual frameworks. American Psychologist, 40(10), 1094-1103. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.40.10.1094

Wolcott, H. (1990). Writing up qualitative research. Sage Publications.

Wray, N., Markovic, M., & Manderson, L. (2007). ‘Researcher saturation’: The impact of data triangulation and intensiveresearch practices on the researcher and qualitative research process. Qualitative Health Research, 17(10), 1392-1402. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973230730830

- ‘The School of Business and Technology, University of Gloucestershire, UK

Business School for the Creative Industries, University for the Creative Arts, UK

Newcastle Business School, Northumbria University, UK

Department of Economics and Business, University of Florence, Italy

Corresponding Author:

Muhammad Naeem, School of Business & Management, University of Gloucestershire, Arden House, Middlemarch Park, Coventry CV3 4JF, UK.

Email: dr.muhammadnaeem222@gmail.com