DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41368-023-00266-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38177101

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-05

قدرة تقليل النترات في الميكروبات الفموية متأثرة في التهاب اللثة: الآثار المحتملة لتوافر أكسيد النيتريك النظامي

الملخص

تم اقتراح أن تقليل النترات إلى نتريت بواسطة الميكروبات الفموية مهم لصحة الفم وينتج عنه تكوين أكسيد النيتريك الذي يمكن أن يحسن الظروف القلبية الأيضية. تشير الدراسات حول التركيب البكتيري في اللويحة تحت اللثوية إلى أن البكتيريا المقللة للنترات مرتبطة بصحة اللثة، لكن تأثير التهاب اللثة على قدرة تقليل النترات (NRC) وبالتالي توافر أكسيد النيتريك لم يتم تقييمه. كانت الدراسة الحالية تهدف إلى تقييم كيف يؤثر التهاب اللثة على NRC للميكروبات الفموية. أولاً، تم تحليل بيانات تسلسل 16 S rRNA من خمس دول مختلفة، مما كشف أن البكتيريا المقللة للنترات كانت أقل بشكل ملحوظ في اللويحة تحت اللثوية لمرضى التهاب اللثة مقارنة بالأفراد الأصحاء (

; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41368-023-00266-9

المقدمة

المواد والأساليب

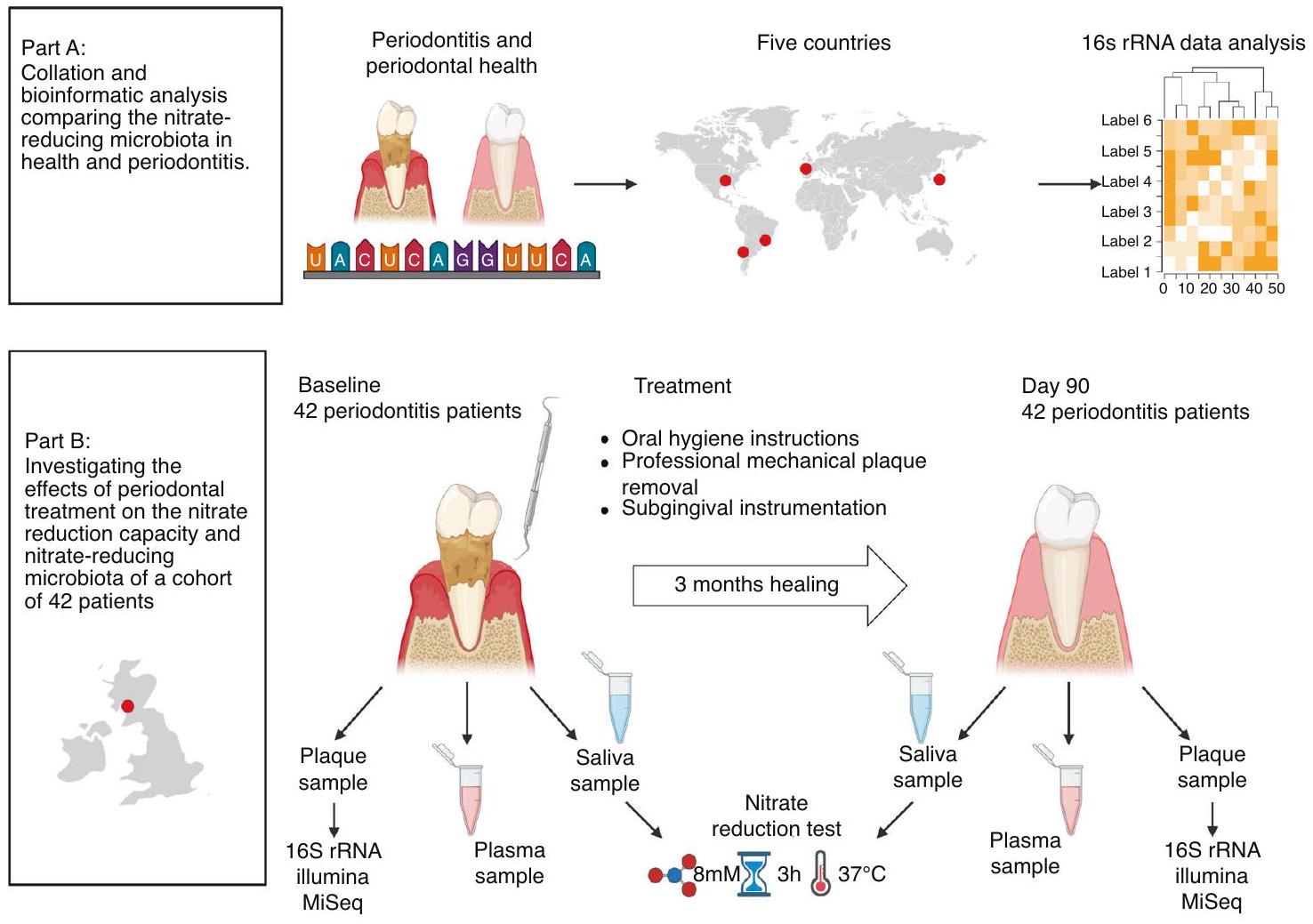

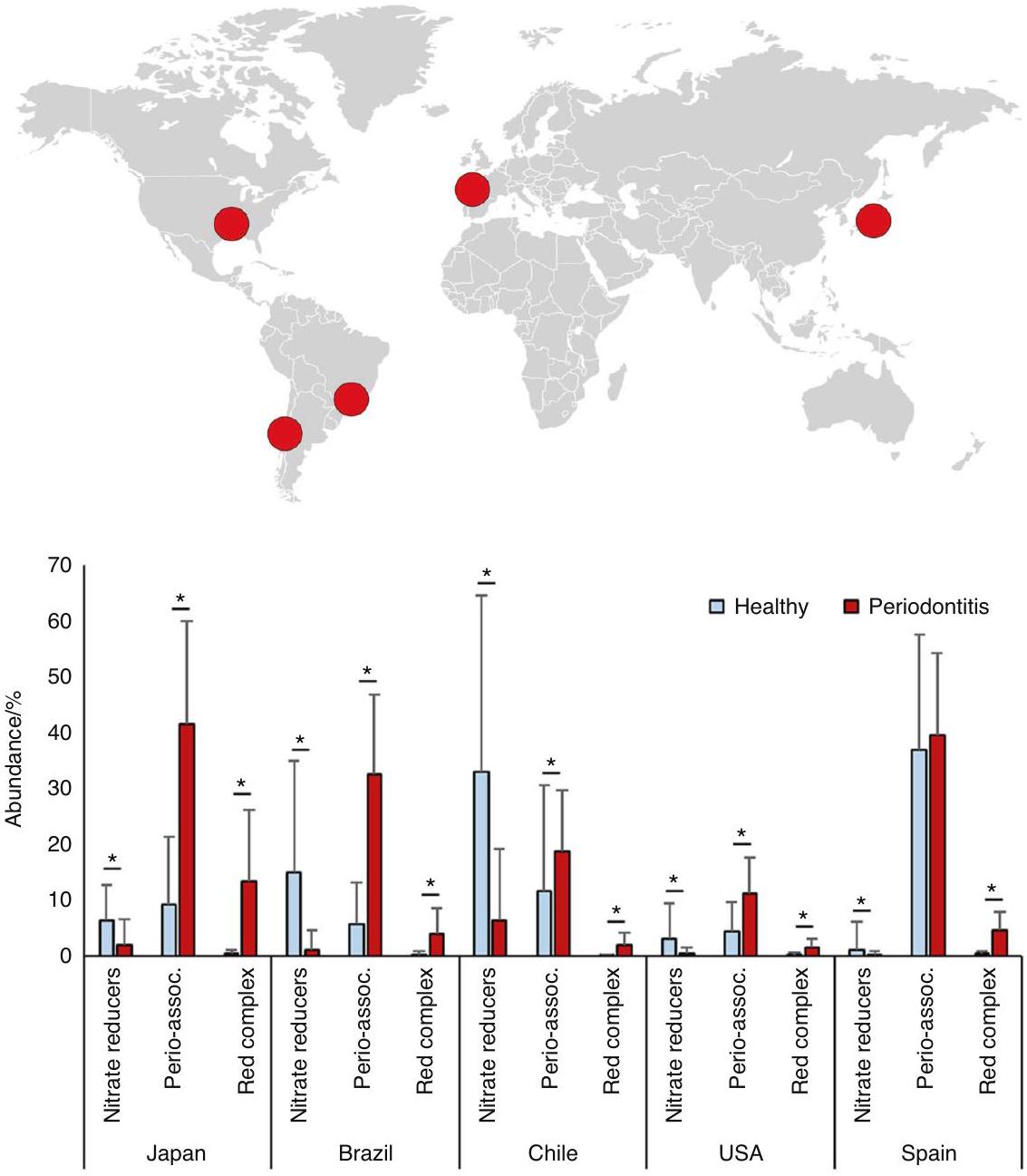

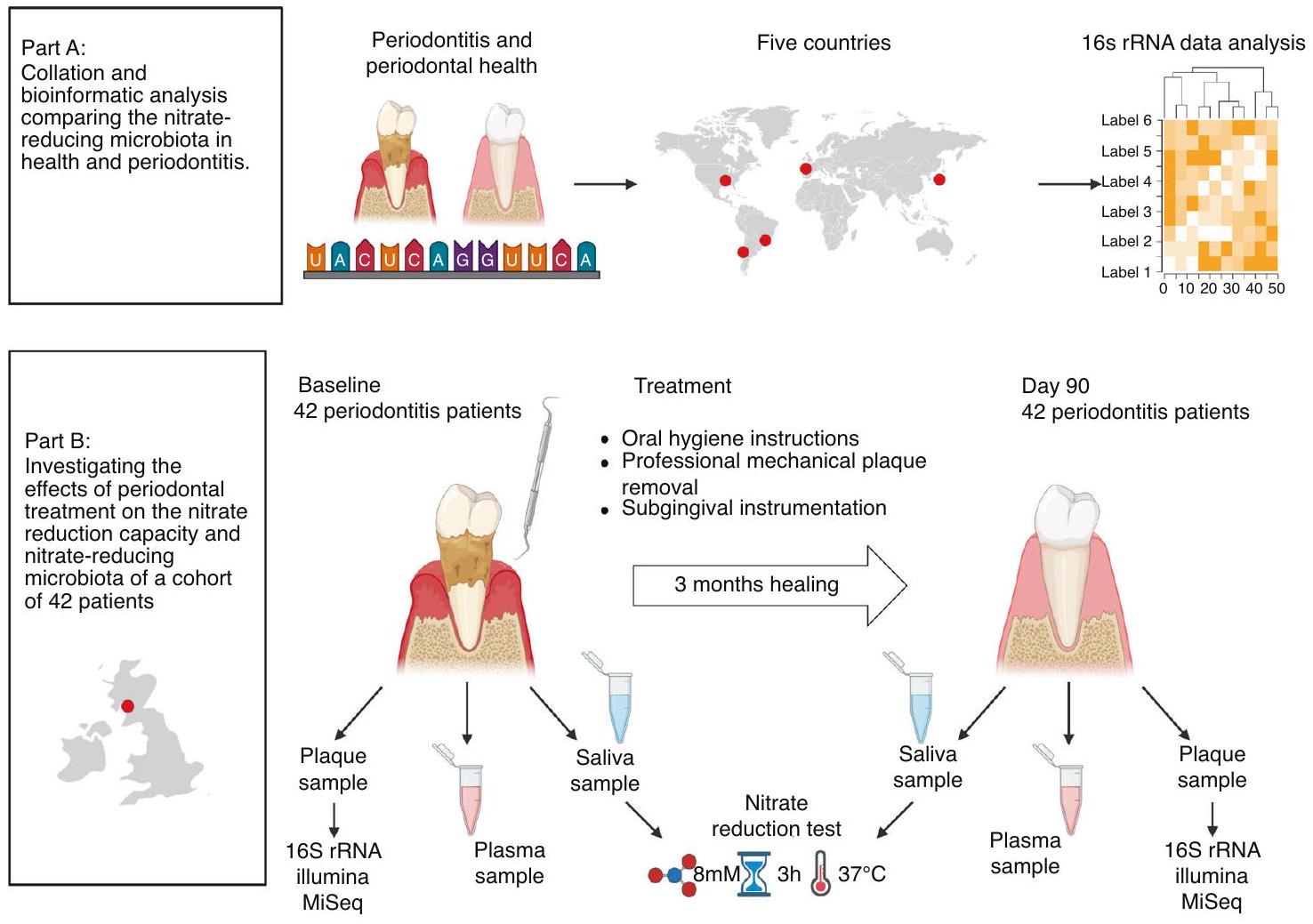

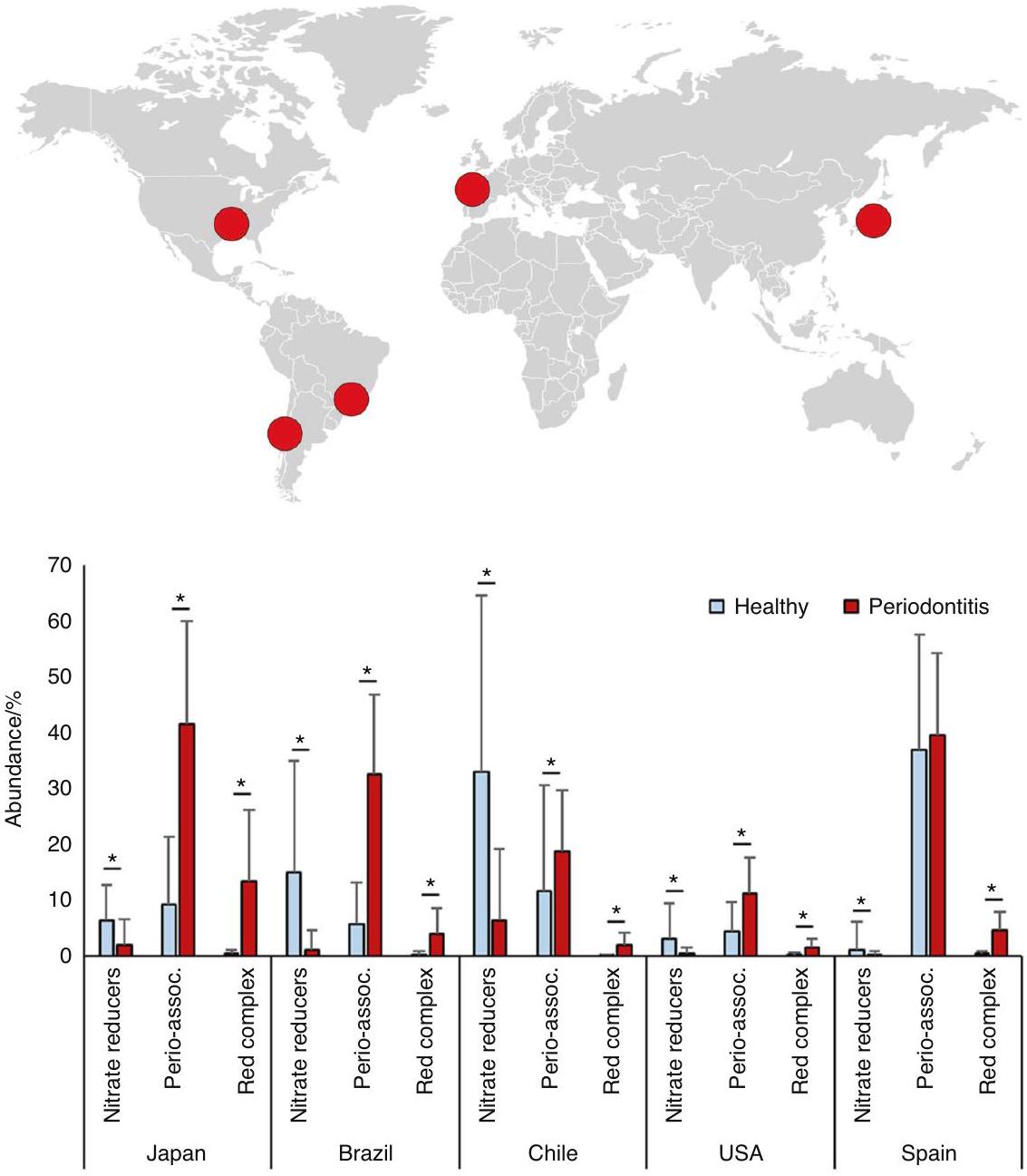

لتقييم ما إذا كان المستوى الإجمالي للبكتيريا المقللة للنترات يمكن أن ينخفض في التهاب اللثة، تم إجراء تحليل معلومات حيوية لخمس مجموعات بيانات للعثور على اختلافات في الميكروبات المقللة للنترات بين صحة اللثة والتهاب اللثة (الشكل 1A). تم اختيار دراسات حيث كانت متوسط عمق الاستكشاف (الفم بالكامل أو المواقع المأخوذة) للأفراد المصابين بالتهاب اللثة على الأقل مرتين أعلى من المجموعة الصحية (الجدول التكميلي 1). تم تنزيل مجموعات البيانات التي تحتوي على بيانات تسلسل 16S rRNA من عينات اللويحات تحت اللثة من قاعدة بيانات NCBI SRA وشملت أفرادًا من دول مختلفة (اليابان،

أثر كبير على تركيب الميكروبات.

لدراسة تأثير العلاج اللثوي على الميكروبات المقللة للنترات، تم استخدام البيانات والعينات من دراسة تم وصفها سابقًا بواسطة دافيسون وآخرون.

روسير وآخرون.

qPCR لروثيا في اللويحات تحت اللثة

تم استخدام الحمض النووي من اللويحات تحت اللثة لقياسات PCR الكمي (qPCR) لتحديد الكمية الإجمالية لخلايا روثيا. على وجه التحديد، تم تضخيم جين اختزال النترات narG لروثيا كما هو موضح بواسطة روسير وآخرون.

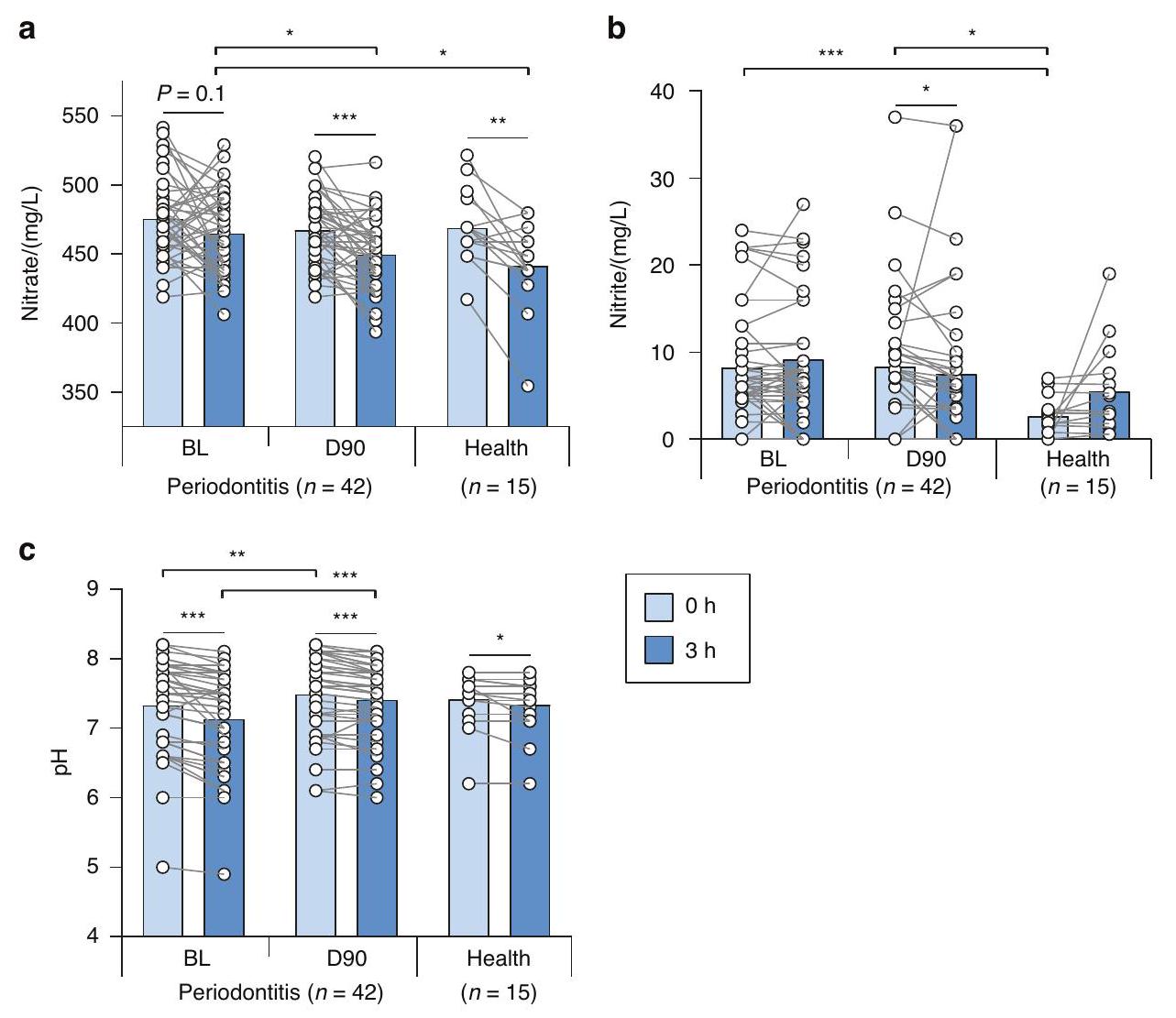

معدل النخر في المرضى الذين يعانون من أمراض اللثة قبل وبعد العلاج اللثوي

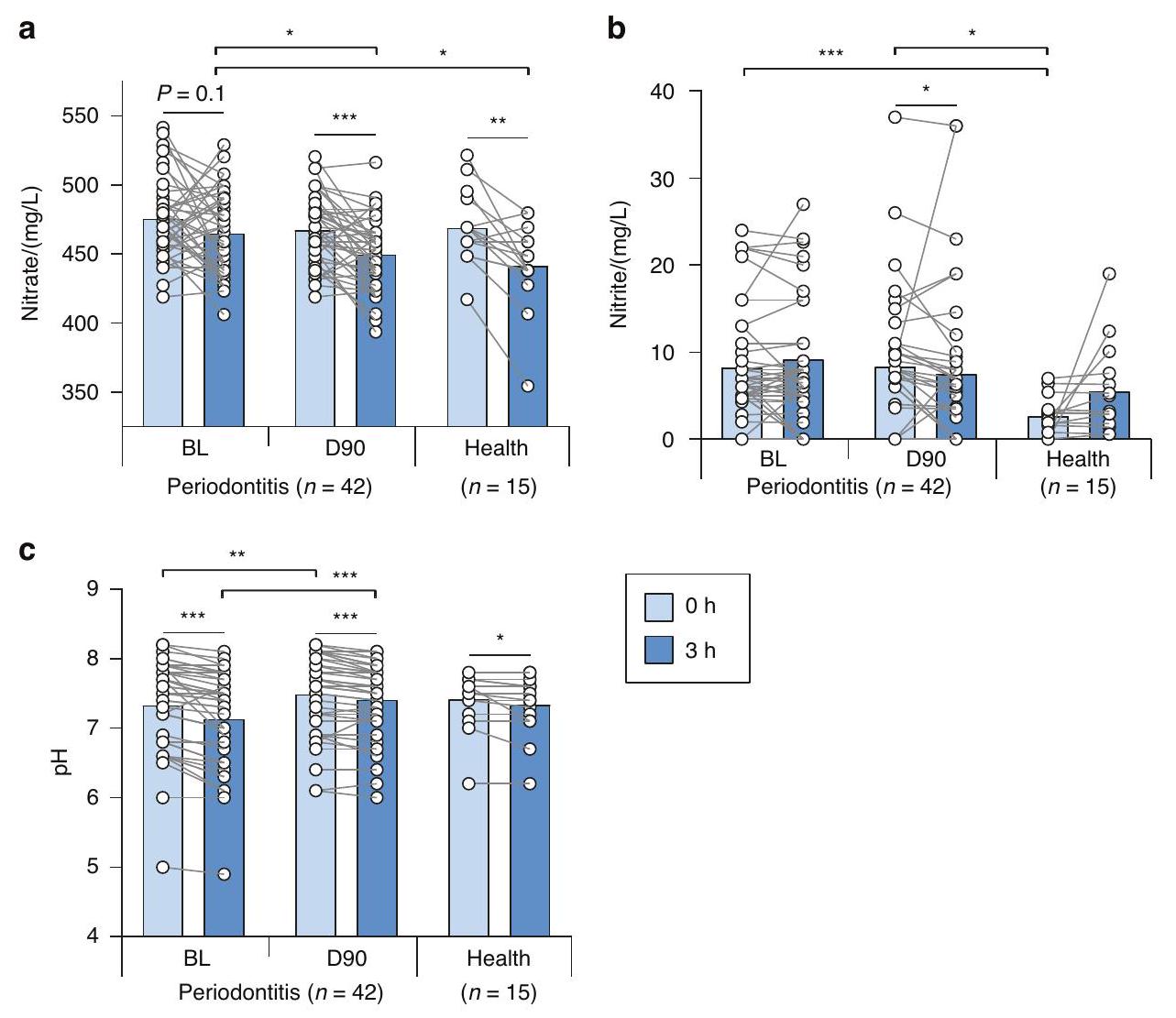

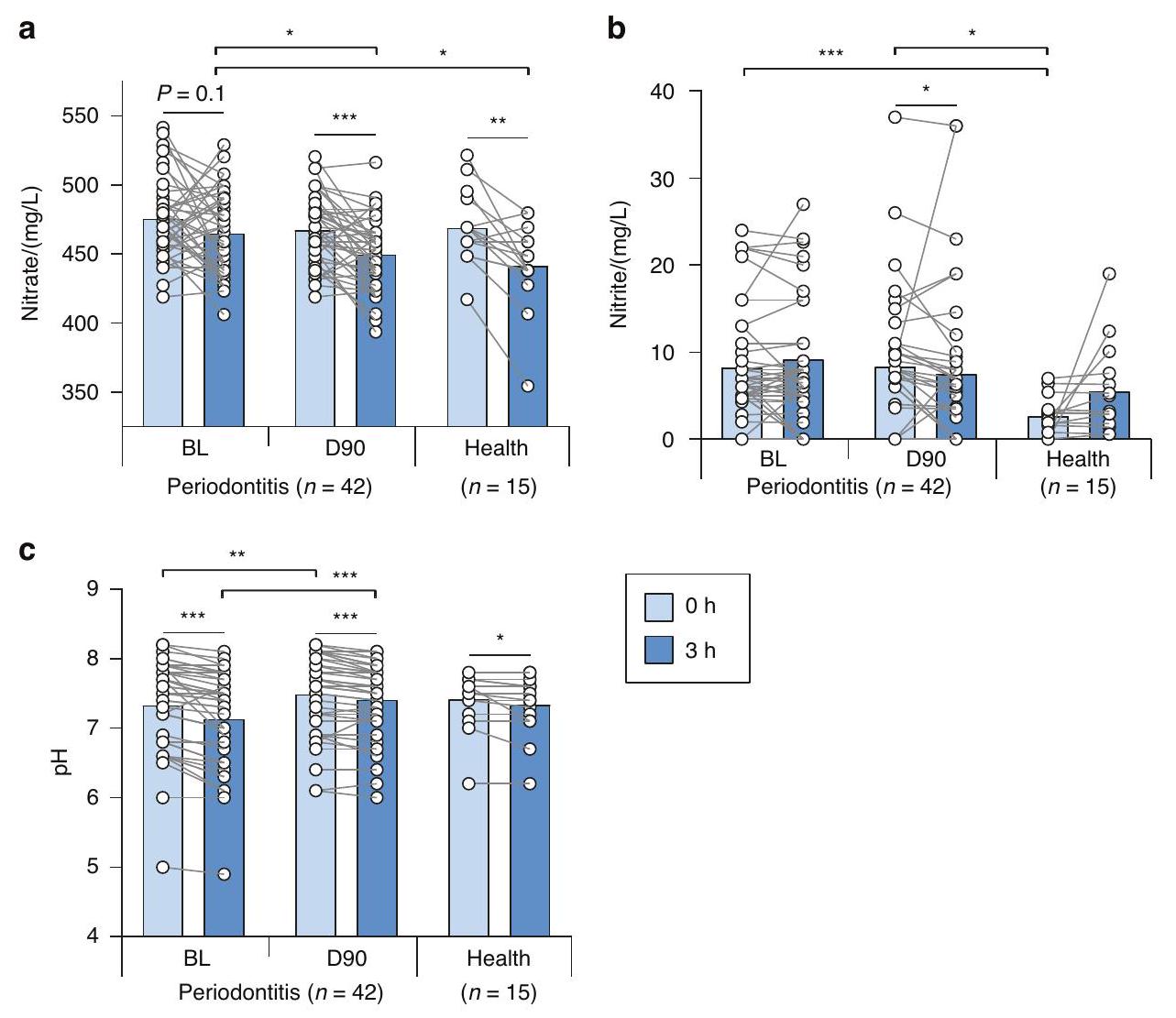

تم استخدام جهاز RQflex 10 Reflectoquant (ميرك ميلبورو، برلنغتون، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) لقياس النترات والنتريت ودرجة الحموضة في اللعاب كما وصفه روسيير وآخرون.

تم تحديد مستويات النترات والنيتريت في البلازما القاعدية قبل وبعد العلاج اللثوي باستخدام الكيمياء الضوئية المعتمدة على الأوزون كما وصفه ليدل وآخرون.

تم إجراء تحليل إحصائي للنترات والنيتريت في اللعاب والبلازما وخلايا روثيا في اللويحة تحت اللثة (المحددة بواسطة qPCR) باستخدام اختبار ويلكوكسون غير المعلمي باستخدام برنامج IBM SPSS للإحصائيات (الإصدار 27) أو GraphPad (الإصدار 9.5.1) واعتُبر ذا دلالة إحصائية عند

النتائج

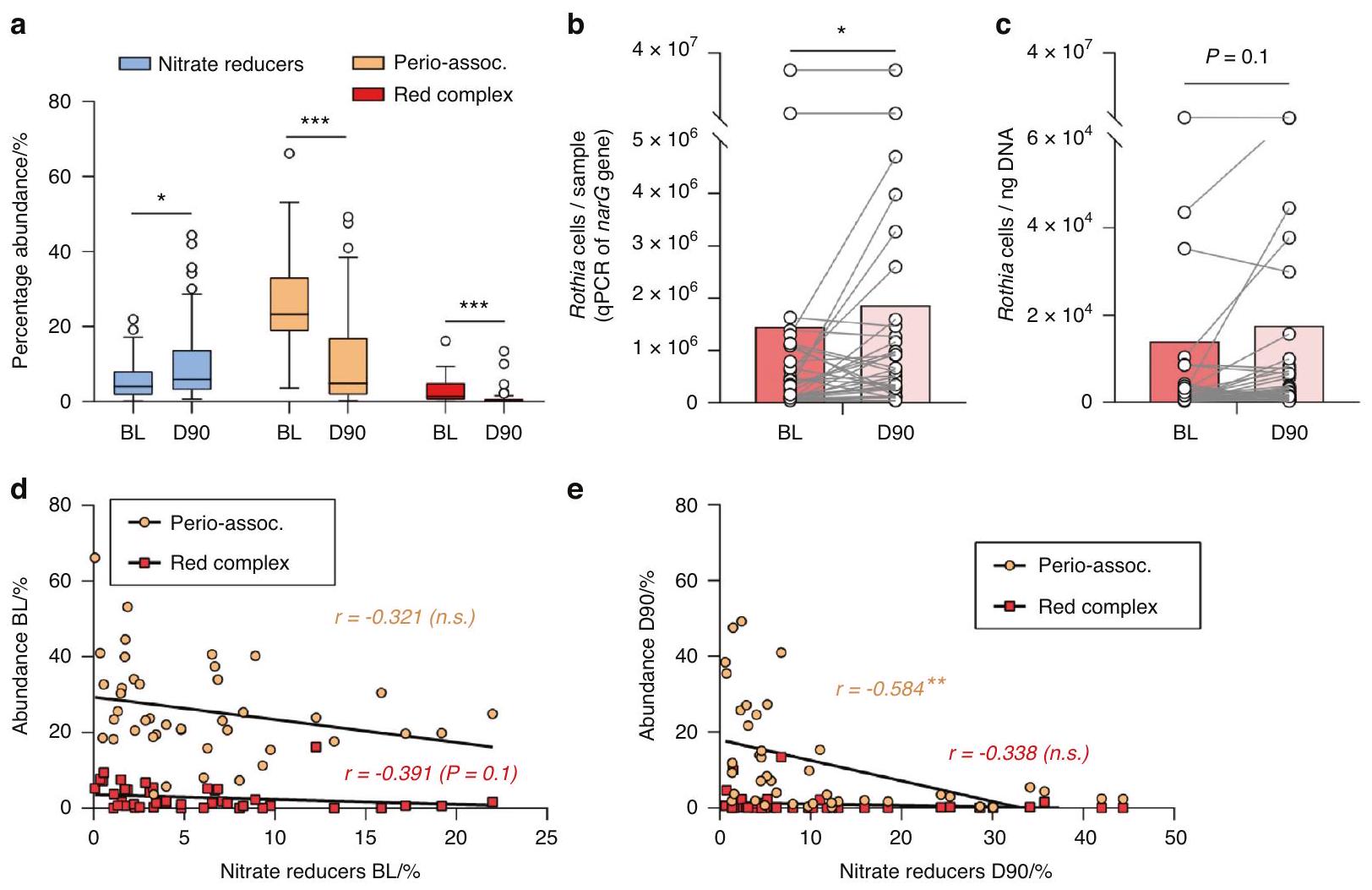

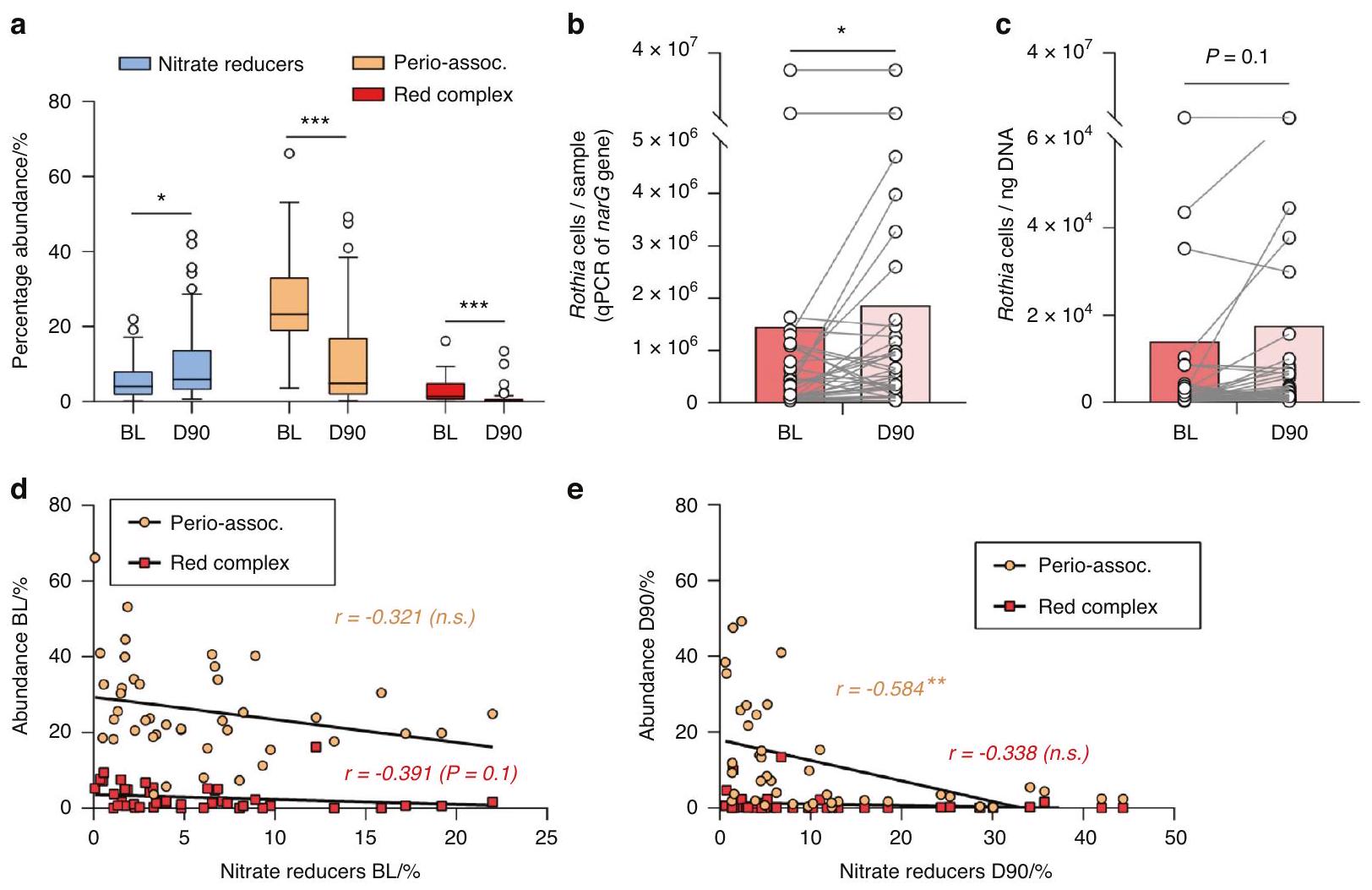

أظهر التركيب البكتيري لعينات تحت اللثة قبل (BL) وبعد (D90) العلاج اللثوي نمطًا متسقًا عبر الأفراد. بالنسبة لخط الأساس، كان هناك زيادة ملحوظة في البكتيريا القادرة على إنتاج النيتريت (الشكل التوضيحي 2)، بما في ذلك البكتيريا المؤكدة التي تقلل النترات (الشكل 3A)، مع نمط معكوس للجراثيم المسببة لأمراض اللثة، بما في ذلك الأنواع الثلاثة من المجمع الأحمر والقائمة الموسعة من البكتيريا المرتبطة بالتهاب اللثة، كما أبلغ عنه جونستون وآخرون سابقًا.

ترتبط بوفرة البكتيريا المخفضة للنترات (

NRC في الصحة والتهاب اللثة

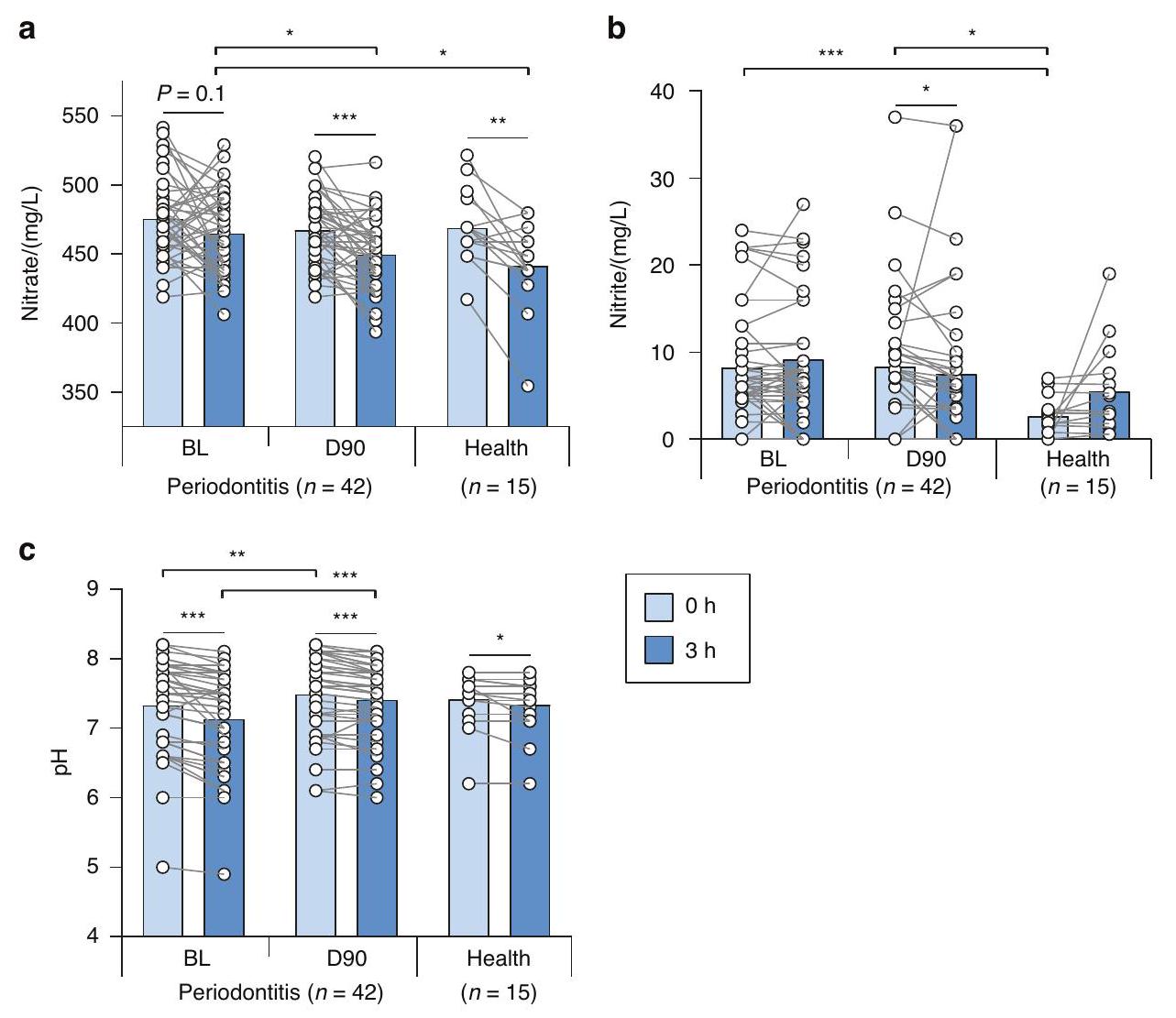

تتفق مع مستويات اللعاب الأساسية من النترات والنترات، كشفت تركيزات النترات والنترات الأساسية في عينات الدم المجمعة من المرضى اللثويين عند الخط الأساسي و 90 يومًا بعد العلاج اللثوي عن عدم وجود اختلافات إحصائية بين هذين الوقتين (الشكل 5A، B). كانت متوسط مستويات البلازما من النترات

النقاش

لمقارنة مستويات البكتيريا المختزلة للنترات تحت اللثة في الصحة والتهاب اللثة، استخدمنا مجموعات بيانات تسلسل 16S من خمس دول مختلفة (اليابان، البرازيل، تشيلي، الولايات المتحدة، وإسبانيا). اتبعت جميع الدول نفس النمط المتمثل في انخفاض الأنواع المرتبطة بالتهاب اللثة وزيادة في البكتيريا المنتجة للنتريت، بما في ذلك الأنواع المؤكدة المختزلة للنترات. هذه النتيجة تتفق مع الدراسات السابقة. على سبيل المثال، فريس وآخرون.

دراسات التسلسل التي تقارن اللويحات تحت اللثة في الصحة والتهاب اللثة، وكذلك التهاب اللثة قبل وبعد العلاج، وجدت أن الأنواع الشائعة المنتجة للنيتريت كانت مرتبطة بصحة اللثة (مثل: ستربتوكوكوس spp.، نيسيريا لونغاتي، نيسيريا سوبفلافا، روثيا أيريا، فيلونيلة بارفولا وجرانوليكاتيلا أديانس). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، وجد فيريس وآخرون أن روثيا كانت الجنس الأكثر ارتباطًا بصحة اللثة، ومع انخفاض الالتهاب بعد العلاج اللثوي، تليها أجناس أخرى منتجة للنيتريت (مثل: نيسيريا، أكتينوميسيس وستربتوكوكوس). تدعم هذه النتائج أيضًا التحليلات المعلوماتية الحيوية لمورك وآخرون.

إشارة انتشار لبعض البكتيريا التي يمكن أن تقلل من تراكم اللويحات.

عند

نقارن بين هذه المجموعات بين التهاب اللثة والصحة أو قبل وبعد العلاج اللثوي). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، أكدت قياسات qPCR للعلامة الحيوية المخفضة للنترات والنوع المرتبط بصحة اللثة روثيا قبل وبعد علاج التهاب اللثة زيادة في خلايا روثيا لكل عينة (

قيود الدراسة وآفاق المستقبل

ملاحظات ختامية

توفر البيانات

الشكر والتقدير

التمويل

معلومات إضافية

REFERENCES

- Theilade, E. The non-specific theory in microbial etiology of inflammatory periodontal diseases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 13, 905-911 (1986).

- Rosier, B. T., Marsh, P. D. & Mira, A. Resilience of the oral microbiota in health: mechanisms that prevent dysbiosis. J. Dent. Res. 97, 371-380 (2018).

- Marsh, P. D. Are dental diseases examples of ecological catastrophes? Microbiology 149, 279-294 (2003).

- Mira, A., Simon-Soro, A. & Curtis, M. A. Role of microbial communities in the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases and caries. J. Clin. Periodontol. 44, S23-S38 (2017).

- Feres, M., Retamal-Valdes, B., Gonçalves, C., Cristina Figueiredo, L. & Teles, F. Did Omics change periodontal therapy? Periodontol 2000 85, 182-209 (2021).

- Chen, T., Marsh, P. D. & Al-Hebshi, N. N. SMDI: An index for measuring subgingival microbial dysbiosis. J. Dent. Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345211035775 (2021).

- Rosier, B. T. et al. The importance of nitrate reduction for oral health. J. Dent. Res. 101, 887-897 (2022).

- Vanhatalo, A. et al. Nitrate-responsive oral microbiome modulates nitric oxide homeostasis and blood pressure in humans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 124, 21-30 (2018).

- Rosier, B. T., Buetas, E., Moya-Gonzalvez, E. M., Artacho, A. & Mira, A. Nitrate as a potential prebiotic for the oral microbiome. Sci. Rep. 10, 12895 (2020).

- Hajishengallis, G. Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 30-44 (2015).

- Hajishengallis, G. & Chavakis, T. Local and systemic mechanisms linking periodontal disease and inflammatory comorbidities. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 21, 426-440 (2021).

- Beck, J. D., Papapanou, P. N., Philips, K. H. & Offenbacher, S. Periodontal medicine: 100 Years of progress. J. Dent. Res. 98, 1053-1062 (2019).

- Schreiber, F. et al. Denitrification in human dental plaque. BMC Biol. 8, 24 (2010).

- Hyde, E. R. et al. Metagenomic analysis of nitrate-reducing bacteria in the oral cavity: implications for nitric oxide homeostasis. PLOS ONE 26, 3 (2014).

- Aerts, A., Dendale, P., Strobel, G. & Block, P. Sublingual nitrates during head-up tilt testing for the diagnosis of vasovagal syncope. Am. Heart J. 133, 504-507 (1997).

- Goh, C. E. et al. Nitrite generating and depleting capacity of the oral microbiome and cardiometabolic risk: results from ORIGINS. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 11, e023038 (2022).

- Hezel, M. P. & Weitzberg, E. The oral microbiome and nitric oxide homoeostasis. Oral. Dis. 21, 7-16 (2015).

- Lundberg, J. O., Carlström, M. & Weitzberg, E. Metabolic effects of dietary nitrate in health and disease. Cell Metab. 28, 9-22 (2018).

Rosier et al.

10

19. Morou-Bermúdez, E., Torres-Colón, J. E., Bermúdez, N. S., Patel, R. P. & Joshipura, K. J. Pathways linking oral bacteria, nitric oxide metabolism, and health. J. Dent. Res. 101, 623-631 (2022).

20. Kapil, V. et al. Physiological role for nitrate-reducing oral bacteria in blood pressure control. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 55, 93-100 (2013).

21. Backlund, C. J., Sergesketter, A. R., Offenbacher, S. & Schoenfisch, M. H. Antibacterial efficacy of exogenous nitric oxide on periodontal pathogens. J. Dent. Res. 93, 1089-1094 (2014).

22. Lanas, A. Role of nitric oxide in the gastrointestinal tract. Arthritis Res. Ther. 10, S4 (2008).

23. Schairer, D. O., Chouake, J. S., Nosanchuk, J. D. & Friedman, A. J. The potential of nitric oxide releasing therapies as antimicrobial agents. Virulence 3, 271-279 (2012).

24. Rosier, B. T. et al. A single dose of nitrate increases resilience against acidification derived from sugar fermentation by the oral microbiome. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 11, 692883 (2021).

25. Ikeda, E. et al. Japanese subgingival microbiota in health vs disease and their roles in predicted functions associated with periodontitis. Odontology 108, 280-291 (2020).

26. Pérez-Chaparro, P. J. et al. Do different probing depths exhibit striking differences in microbial profiles? J. Clin. Periodontol. 45, 26-37 (2018).

27. Abusleme, L. et al. The subgingival microbiome in health and periodontitis and its relationship with community biomass and inflammation. ISME J. 7, 1016-1025 (2013).

28. Griffen, A. L. et al. Distinct and complex bacterial profiles in human periodontitis and health revealed by 16 S pyrosequencing. ISME J. 6, 1176-1185 (2012).

29. Camelo-Castillo, A. J. et al. Subgingival microbiota in health compared to periodontitis and the influence of smoking. Front. Microbiol. 6, 119 (2015).

30. Arredondo, A. et al. Comparative 16 S rRNA gene sequencing study of subgingival microbiota of healthy subjects and patients with periodontitis from four different countries. J. Clin. Periodontol. 50, 1176-1187 (2023).

31. Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from llumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581-583 (2016).

32. Team, R. C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing http:// www.R-project.org/, http://www.R-project.org/ (2014).

33. Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590-D596 (2013).

34. Yilmaz, P. et al. The SILVA and “All-species Living Tree Project (LTP)” taxonomic frameworks. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D643-D648 (2014).

35. Socransky, S. S., Haffajee, A. D., Cugini, M. A., Smith, C. & Kent, R. L. Jr. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J. Clin. Periodontol. 25, 134-144 (1998).

36. Pérez-Chaparro, P. J. et al. Newly identified pathogens associated with periodontitis: a systematic review. J. Dent. Res. 93, 846-858 (2014).

37. Davison, E. et al. The subgingival plaque microbiome, systemic antibodies against bacteria and citrullinated proteins following periodontal therapy. Pathogens 10, 193 (2021).

38. Johnston, W. et al. Mechanical biofilm disruption causes microbial and immunological shifts in periodontitis patients. Sci. Rep. 11, 9796 (2021).

39. Sanz, M. et al. EFP Workshop participants and methodological consultants. Treatment of stage I-III periodontitis-the EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Periodontol. 47, 4-60 (2020).

40. Papapanou, P. N. et al. Periodontitis: consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the classification of periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions. J. Periodontol. 89, S173-S182 (2018).

41. Johnston, W. The Host and Microbial Response to Non-surgical Periodontal Therapy. (University of Glasgow, 2021).

42. Darcey, J. & Ashley, M. See you in three months! The rationale for the three monthly periodontal recall interval: a risk based approach. Br. Dent. J. 211, 379-385 (2011).

43. Herrera, D. et al. EFP workshop participants and methodological consultant treatment of stage IV periodontitis: the EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Periodontol. 49, 4-71 (2022).

44. Rosier, B. T., Moya-Gonzalvez, E. M., Corell-Escuin, P. & Mira, A. Isolation and characterization of nitrate-reducing bacteria as potential probiotics for oral and systemic health. Front. Microbiol. 11, 555465 (2020).

45. Liddle, L. et al. Variability in nitrate-reducing oral bacteria and nitric oxide metabolites in biological fluids following dietary nitrate administration: an assessment of the critical difference. Nitric Oxide 82, 1-10 (2019).

46. Lin, H. & Peddada, S. D. Analysis of compositions of microbiomes with bias correction. Nat. Commun. 11, 3514 (2020).

47. Meuric, V. et al. Signature of microbial dysbiosis in periodontitis. Appl Environ. Microbiol. 83, e00462-17 (2017).

48. Mazurel, D. et al. Nitrate and a nitrate-reducing Rothia aeria strain as potential prebiotic or synbiotic treatments for periodontitis. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 9, 40 (2023).

49. Mantilla Gomez, S. M. et al. Tongue coating and salivary bacterial counts in healthy/gingivitis subjects and periodontitis patients. J. Clin. Periodontol. 28, 970-978 (2001).

50. Burleigh, M. C. et al. Salivary nitrite production is elevated in individuals with a higher abundance of oral nitrate-reducing bacteria. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 120, 80-88 (2018).

51. Liddle, L. et al. Reduced nitric oxide synthesis in winter: a potential contributing factor to increased cardiovascular risk. Nitric Oxide 127, 1-9 (2022).

52. Webb, A. J. et al. Acute blood pressure lowering, vasoprotective, and antiplatelet properties of dietary nitrate via bioconversion to nitrite. Hypertension 51, 784-790 (2008).

53. Larsen, F. J., Ekblom, B., Sahlin, K., Lundberg, J. O. & Weitzberg, E. Effects of dietary nitrate on blood pressure in healthy volunteers. N. Engl. J. Med. 355, 2792-2793 (2006).

54. Fernandes, D. et al. Local delivery of nitric oxide prevents endothelial dysfunction in periodontitis. Pharm. Res. 188, 106616 (2022).

55. Bahadoran, Z., Ghasemi, A., Mirmiran, P., Azizi, F. & Hadaegh, F. Beneficial effects of inorganic nitrate/nitrite in type 2 diabetes and its complications. Nutr. Metab. 12, 16 (2015).

56. Joshipura, K. J., Muñoz-Torres, F. J., Morou-Bermudez, E. & Patel, R. P. Over-thecounter mouthwash use and risk of pre-diabetes/diabetes. Nitric Oxide 71, 14-20 (2017).

57. Ghasemi, A. & Jeddi, S. Anti-obesity and anti-diabetic effects of nitrate and nitrite. Nitric Oxide 70, 9-24 (2017).

58. Preshaw, P. M. et al. Periodontitis and diabetes: a two-way relationship. Diabetologia 55, 21-31 (2012).

59. Kebschull, M., Demmer, R. T. & Papapanou, P. N. Gum bug, leave my heart alone!”-epidemiologic and mechanistic evidence linking periodontal infections and atherosclerosis. J. Dent. Res. 89, 879-902 (2010).

60. Tashie, W. et al. Altered bioavailability of nitric oxide and L-arginine is a key determinant of endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 3251956 (2020).

61. Altemani, F., Barrett, H. L., Callaway, L. K., McIntyre, H. D., & Dekker Nitert, M. Reduced abundance of nitrate-reducing bacteria in the oral microbiota of women with future preeclampsia. Nutrients 14, 1139 (2022).

62. Kim, A. J., Lo, A. J., Pullin, D. A., Thornton-Johnson, D. S. & Karimbux, N. Y. Scaling and root planing treatment for periodontitis to reduce preterm birth and low birth weight: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Periodontol. 83, 1508-1519 (2012).

63. Tonetti, M. S. et al. Treatment of periodontitis and endothelial function. N. Engl. J. Med. 356, 911-920 (2018).

64. Monaghan, C. et al. The effects of two different doses of ultraviolet-A light exposure on nitric oxide metabolites and cardiorespiratory outcomes. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 118, 1043-1052 (2018).

65. Liddle, L. et al. Variability in nitrate-reducing oral bacteria and nitric oxide metabolites in biological fluids following dietary nitrate administration: an assessment of the critical difference. Nitric Oxide 83, 1-10 (2019).

66. Jiang, Y. et al. Comparison of red-complex bacteria between saliva and subgingival plaque of periodontitis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 11, 727732 (2021).

Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

© The Author(s) 2024, corrected publication 2024

Department of Genomics and Health, FISABIO Foundation, Center for Advanced Research in Public Health, Valencia, Spain; Department of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow, UK; Oral Sciences, University of Glasgow Dental School, School of Medicine, Dentistry and Nursing, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK; Sport and Physical Activity Research Institute, University of the West of Scotland, Blantyre, Scotland; Instituto de Biomedicina de Valencia, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (IBV-CSIC), Valencia, Spain and CIBER Center for Epidemiology and Public Health, Madrid, Spain Correspondence: Alex Mira (mira_ale@gva.es)

These authors contributed equally: Bob T. Rosier, William Johnston

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41368-023-00266-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38177101

Publication Date: 2024-01-05

Nitrate reduction capacity of the oral microbiota is impaired in periodontitis: potential implications for systemic nitric oxide availability

Abstract

The reduction of nitrate to nitrite by the oral microbiota has been proposed to be important for oral health and results in nitric oxide formation that can improve cardiometabolic conditions. Studies of bacterial composition in subgingival plaque suggest that nitrate-reducing bacteria are associated with periodontal health, but the impact of periodontitis on nitrate-reducing capacity (NRC) and, therefore, nitric oxide availability has not been evaluated. The current study aimed to evaluate how periodontitis affects the NRC of the oral microbiota. First, 16 S rRNA sequencing data from five different countries were analyzed, revealing that nitratereducing bacteria were significantly lower in subgingival plaque of periodontitis patients compared with healthy individuals (

; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41368-023-00266-9

INTRODUCTION

MATERIALS AND METHODS

To evaluate if the total level of nitrate-reducing bacteria could decrease in periodontitis, bioinformatic analysis of five datasets was performed to find differences in the nitrate-reducing microbiota between periodontal health and periodontitis (Fig. 1A). Specifically, studies were selected where the average probing depth (entire mouth or sampled sites) of the periodontitis individuals was at least two times higher than the healthy group (Supplementary Table 1). Datasets containing 16S rRNA sequencing data from subgingival plaque samples were downloaded from the NCBI SRA Database and included individuals from different countries (Japan,

significant effect on microbiota composition.

To study the effect of periodontal treatment on the nitrate-reducing microbiota, data and samples were used from a study previously described by Davison et al.

Rosier et al.

qPCR of Rothia in subgingival plaque

The subgingival plaque DNA was used for quantitative PCR (qPCR) measurements to determine the total amount of Rothia cells. Specifically, the Rothia nitrate reductase narG gene was amplified as described by Rosier et al.

The NRC in periodontal patients before and after periodontal treatment (

For nitrate, nitrite and pH measurements in saliva, the RQflex 10 Reflectoquant (Merck Millipore, Burlington, Massachusetts, USA) reflectometer was used as described by Rosier et al.

The basal plasma nitrate and nitrite levels were determined before and after periodontal treatment using ozone-based chemiluminescence as described by Liddle et al.

Statistical analysis of nitrate and nitrite in saliva and plasma and Rothia cells in subgingival plaque (determined by qPCR) was performed using a nonparametric Wilcoxon test using IBM SPSS statistics (version 27) or GraphPad (version 9.5.1) and considered statistically significant at

RESULTS

The bacterial composition of subgingival samples before (BL) and after (D90) periodontal treatment showed a consistent pattern across individuals. Relative to baseline, there was a significant increase in bacteria capable of producing nitrite (Supplementary Fig. 2), including confirmed nitrate-reducing bacteria (Fig. 3A), with an opposite pattern for periodontal pathogens, including both the three species of the red complex and the extended list of periodontitis-associated bacteria, as reported previously by Johnston et al.

correlated with the abundance of nitrate-reducing bacteria (

NRC in health and periodontitis

In agreement with the basal salivary levels of nitrate and nitrite, the basal nitrate and nitrite concentrations in blood samples collected in periodontal patients at baseline and 90 days after the periodontal treatment revealed no statistical differences between these two-time points (Fig. 5A, B). The average plasma nitrate levels were

DISCUSSION

To compare the subgingival levels of nitrate-reducing bacteria in health and periodontitis, we used 16 S sequencing datasets of five different countries (Japan, Brazil, Chile, USA, and Spain). All countries followed the same pattern of a decrease in periodontitis-associated species and an increase in nitriteproducing bacteria, including confirmed nitrate-reducing species. This finding is in agreement with previous studies. For example, Feres et al.

sequencing studies comparing subgingival plaque in health and periodontitis, as well as periodontitis before and after treatment and found that common nitrite-producing species were associated with periodontal health (e.g., Steptococcus spp., Neisseria longate, Neisseria subflava, Rothia aeria, Veilonella Parvula and Granulicatella adiacens). Additionally, Feres et al. found that Rothia was the genus with the strongest association with periodontal health, and with reduced inflammation after periodontal treatment, followed by other nitrite-producing genera (e.g., Neisseria, Actinomyces and Steptococcus). These results are further supported by bioinformatic analyses of Meuric et al.

dispersal signal for some bacteria that could reduce plaque accumulation.

at

comparing these groups between periodontitis and health or before and after periodontal treatment). Additionally, qPCR measurements of the nitrate-reducing biomarker and periodontal-health-associated genus Rothia before and after periodontitis treatment confirmed an increase of Rothia cells per sample (

Study limitations and future perspectives

Concluding remarks

DATA AVAILABILITY

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

FUNDING

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

REFERENCES

- Theilade, E. The non-specific theory in microbial etiology of inflammatory periodontal diseases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 13, 905-911 (1986).

- Rosier, B. T., Marsh, P. D. & Mira, A. Resilience of the oral microbiota in health: mechanisms that prevent dysbiosis. J. Dent. Res. 97, 371-380 (2018).

- Marsh, P. D. Are dental diseases examples of ecological catastrophes? Microbiology 149, 279-294 (2003).

- Mira, A., Simon-Soro, A. & Curtis, M. A. Role of microbial communities in the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases and caries. J. Clin. Periodontol. 44, S23-S38 (2017).

- Feres, M., Retamal-Valdes, B., Gonçalves, C., Cristina Figueiredo, L. & Teles, F. Did Omics change periodontal therapy? Periodontol 2000 85, 182-209 (2021).

- Chen, T., Marsh, P. D. & Al-Hebshi, N. N. SMDI: An index for measuring subgingival microbial dysbiosis. J. Dent. Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345211035775 (2021).

- Rosier, B. T. et al. The importance of nitrate reduction for oral health. J. Dent. Res. 101, 887-897 (2022).

- Vanhatalo, A. et al. Nitrate-responsive oral microbiome modulates nitric oxide homeostasis and blood pressure in humans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 124, 21-30 (2018).

- Rosier, B. T., Buetas, E., Moya-Gonzalvez, E. M., Artacho, A. & Mira, A. Nitrate as a potential prebiotic for the oral microbiome. Sci. Rep. 10, 12895 (2020).

- Hajishengallis, G. Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 30-44 (2015).

- Hajishengallis, G. & Chavakis, T. Local and systemic mechanisms linking periodontal disease and inflammatory comorbidities. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 21, 426-440 (2021).

- Beck, J. D., Papapanou, P. N., Philips, K. H. & Offenbacher, S. Periodontal medicine: 100 Years of progress. J. Dent. Res. 98, 1053-1062 (2019).

- Schreiber, F. et al. Denitrification in human dental plaque. BMC Biol. 8, 24 (2010).

- Hyde, E. R. et al. Metagenomic analysis of nitrate-reducing bacteria in the oral cavity: implications for nitric oxide homeostasis. PLOS ONE 26, 3 (2014).

- Aerts, A., Dendale, P., Strobel, G. & Block, P. Sublingual nitrates during head-up tilt testing for the diagnosis of vasovagal syncope. Am. Heart J. 133, 504-507 (1997).

- Goh, C. E. et al. Nitrite generating and depleting capacity of the oral microbiome and cardiometabolic risk: results from ORIGINS. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 11, e023038 (2022).

- Hezel, M. P. & Weitzberg, E. The oral microbiome and nitric oxide homoeostasis. Oral. Dis. 21, 7-16 (2015).

- Lundberg, J. O., Carlström, M. & Weitzberg, E. Metabolic effects of dietary nitrate in health and disease. Cell Metab. 28, 9-22 (2018).

Rosier et al.

10

19. Morou-Bermúdez, E., Torres-Colón, J. E., Bermúdez, N. S., Patel, R. P. & Joshipura, K. J. Pathways linking oral bacteria, nitric oxide metabolism, and health. J. Dent. Res. 101, 623-631 (2022).

20. Kapil, V. et al. Physiological role for nitrate-reducing oral bacteria in blood pressure control. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 55, 93-100 (2013).

21. Backlund, C. J., Sergesketter, A. R., Offenbacher, S. & Schoenfisch, M. H. Antibacterial efficacy of exogenous nitric oxide on periodontal pathogens. J. Dent. Res. 93, 1089-1094 (2014).

22. Lanas, A. Role of nitric oxide in the gastrointestinal tract. Arthritis Res. Ther. 10, S4 (2008).

23. Schairer, D. O., Chouake, J. S., Nosanchuk, J. D. & Friedman, A. J. The potential of nitric oxide releasing therapies as antimicrobial agents. Virulence 3, 271-279 (2012).

24. Rosier, B. T. et al. A single dose of nitrate increases resilience against acidification derived from sugar fermentation by the oral microbiome. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 11, 692883 (2021).

25. Ikeda, E. et al. Japanese subgingival microbiota in health vs disease and their roles in predicted functions associated with periodontitis. Odontology 108, 280-291 (2020).

26. Pérez-Chaparro, P. J. et al. Do different probing depths exhibit striking differences in microbial profiles? J. Clin. Periodontol. 45, 26-37 (2018).

27. Abusleme, L. et al. The subgingival microbiome in health and periodontitis and its relationship with community biomass and inflammation. ISME J. 7, 1016-1025 (2013).

28. Griffen, A. L. et al. Distinct and complex bacterial profiles in human periodontitis and health revealed by 16 S pyrosequencing. ISME J. 6, 1176-1185 (2012).

29. Camelo-Castillo, A. J. et al. Subgingival microbiota in health compared to periodontitis and the influence of smoking. Front. Microbiol. 6, 119 (2015).

30. Arredondo, A. et al. Comparative 16 S rRNA gene sequencing study of subgingival microbiota of healthy subjects and patients with periodontitis from four different countries. J. Clin. Periodontol. 50, 1176-1187 (2023).

31. Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from llumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581-583 (2016).

32. Team, R. C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing http:// www.R-project.org/, http://www.R-project.org/ (2014).

33. Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590-D596 (2013).

34. Yilmaz, P. et al. The SILVA and “All-species Living Tree Project (LTP)” taxonomic frameworks. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D643-D648 (2014).

35. Socransky, S. S., Haffajee, A. D., Cugini, M. A., Smith, C. & Kent, R. L. Jr. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J. Clin. Periodontol. 25, 134-144 (1998).

36. Pérez-Chaparro, P. J. et al. Newly identified pathogens associated with periodontitis: a systematic review. J. Dent. Res. 93, 846-858 (2014).

37. Davison, E. et al. The subgingival plaque microbiome, systemic antibodies against bacteria and citrullinated proteins following periodontal therapy. Pathogens 10, 193 (2021).

38. Johnston, W. et al. Mechanical biofilm disruption causes microbial and immunological shifts in periodontitis patients. Sci. Rep. 11, 9796 (2021).

39. Sanz, M. et al. EFP Workshop participants and methodological consultants. Treatment of stage I-III periodontitis-the EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Periodontol. 47, 4-60 (2020).

40. Papapanou, P. N. et al. Periodontitis: consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the classification of periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions. J. Periodontol. 89, S173-S182 (2018).

41. Johnston, W. The Host and Microbial Response to Non-surgical Periodontal Therapy. (University of Glasgow, 2021).

42. Darcey, J. & Ashley, M. See you in three months! The rationale for the three monthly periodontal recall interval: a risk based approach. Br. Dent. J. 211, 379-385 (2011).

43. Herrera, D. et al. EFP workshop participants and methodological consultant treatment of stage IV periodontitis: the EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Periodontol. 49, 4-71 (2022).

44. Rosier, B. T., Moya-Gonzalvez, E. M., Corell-Escuin, P. & Mira, A. Isolation and characterization of nitrate-reducing bacteria as potential probiotics for oral and systemic health. Front. Microbiol. 11, 555465 (2020).

45. Liddle, L. et al. Variability in nitrate-reducing oral bacteria and nitric oxide metabolites in biological fluids following dietary nitrate administration: an assessment of the critical difference. Nitric Oxide 82, 1-10 (2019).

46. Lin, H. & Peddada, S. D. Analysis of compositions of microbiomes with bias correction. Nat. Commun. 11, 3514 (2020).

47. Meuric, V. et al. Signature of microbial dysbiosis in periodontitis. Appl Environ. Microbiol. 83, e00462-17 (2017).

48. Mazurel, D. et al. Nitrate and a nitrate-reducing Rothia aeria strain as potential prebiotic or synbiotic treatments for periodontitis. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 9, 40 (2023).

49. Mantilla Gomez, S. M. et al. Tongue coating and salivary bacterial counts in healthy/gingivitis subjects and periodontitis patients. J. Clin. Periodontol. 28, 970-978 (2001).

50. Burleigh, M. C. et al. Salivary nitrite production is elevated in individuals with a higher abundance of oral nitrate-reducing bacteria. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 120, 80-88 (2018).

51. Liddle, L. et al. Reduced nitric oxide synthesis in winter: a potential contributing factor to increased cardiovascular risk. Nitric Oxide 127, 1-9 (2022).

52. Webb, A. J. et al. Acute blood pressure lowering, vasoprotective, and antiplatelet properties of dietary nitrate via bioconversion to nitrite. Hypertension 51, 784-790 (2008).

53. Larsen, F. J., Ekblom, B., Sahlin, K., Lundberg, J. O. & Weitzberg, E. Effects of dietary nitrate on blood pressure in healthy volunteers. N. Engl. J. Med. 355, 2792-2793 (2006).

54. Fernandes, D. et al. Local delivery of nitric oxide prevents endothelial dysfunction in periodontitis. Pharm. Res. 188, 106616 (2022).

55. Bahadoran, Z., Ghasemi, A., Mirmiran, P., Azizi, F. & Hadaegh, F. Beneficial effects of inorganic nitrate/nitrite in type 2 diabetes and its complications. Nutr. Metab. 12, 16 (2015).

56. Joshipura, K. J., Muñoz-Torres, F. J., Morou-Bermudez, E. & Patel, R. P. Over-thecounter mouthwash use and risk of pre-diabetes/diabetes. Nitric Oxide 71, 14-20 (2017).

57. Ghasemi, A. & Jeddi, S. Anti-obesity and anti-diabetic effects of nitrate and nitrite. Nitric Oxide 70, 9-24 (2017).

58. Preshaw, P. M. et al. Periodontitis and diabetes: a two-way relationship. Diabetologia 55, 21-31 (2012).

59. Kebschull, M., Demmer, R. T. & Papapanou, P. N. Gum bug, leave my heart alone!”-epidemiologic and mechanistic evidence linking periodontal infections and atherosclerosis. J. Dent. Res. 89, 879-902 (2010).

60. Tashie, W. et al. Altered bioavailability of nitric oxide and L-arginine is a key determinant of endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 3251956 (2020).

61. Altemani, F., Barrett, H. L., Callaway, L. K., McIntyre, H. D., & Dekker Nitert, M. Reduced abundance of nitrate-reducing bacteria in the oral microbiota of women with future preeclampsia. Nutrients 14, 1139 (2022).

62. Kim, A. J., Lo, A. J., Pullin, D. A., Thornton-Johnson, D. S. & Karimbux, N. Y. Scaling and root planing treatment for periodontitis to reduce preterm birth and low birth weight: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Periodontol. 83, 1508-1519 (2012).

63. Tonetti, M. S. et al. Treatment of periodontitis and endothelial function. N. Engl. J. Med. 356, 911-920 (2018).

64. Monaghan, C. et al. The effects of two different doses of ultraviolet-A light exposure on nitric oxide metabolites and cardiorespiratory outcomes. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 118, 1043-1052 (2018).

65. Liddle, L. et al. Variability in nitrate-reducing oral bacteria and nitric oxide metabolites in biological fluids following dietary nitrate administration: an assessment of the critical difference. Nitric Oxide 83, 1-10 (2019).

66. Jiang, Y. et al. Comparison of red-complex bacteria between saliva and subgingival plaque of periodontitis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 11, 727732 (2021).

Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

© The Author(s) 2024, corrected publication 2024

Department of Genomics and Health, FISABIO Foundation, Center for Advanced Research in Public Health, Valencia, Spain; Department of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow, UK; Oral Sciences, University of Glasgow Dental School, School of Medicine, Dentistry and Nursing, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK; Sport and Physical Activity Research Institute, University of the West of Scotland, Blantyre, Scotland; Instituto de Biomedicina de Valencia, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (IBV-CSIC), Valencia, Spain and CIBER Center for Epidemiology and Public Health, Madrid, Spain Correspondence: Alex Mira (mira_ale@gva.es)

These authors contributed equally: Bob T. Rosier, William Johnston