DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/gh.1288

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38273998

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-01

قلب العالم

]u[دار النشر العالمية

المؤلف المراسل: ماريتشيارا دي تشيزاري

m.dicesare@essex.ac.uk

الكلمات الرئيسية:

للاستشهاد بهذه المقالة:

الملخص

تعتبر الأمراض القلبية الوعائية (CVDs) السبب الرئيسي للوفيات على مستوى العالم. من بين 20.5 مليون وفاة مرتبطة بالأمراض القلبية الوعائية في عام 2021، حدث حوالي 80% منها في البلدان ذات الدخل المنخفض والمتوسط.

باستخدام بيانات من دراسة العبء العالمي للأمراض، وتعاون عوامل خطر الأمراض غير السارية، ومبادرة العد التنازلي للأمراض غير السارية، ومرصد الصحة العالمية التابع لمنظمة الصحة العالمية، وقاعدة بيانات الإنفاق الصحي العالمية التابعة لمنظمة الصحة العالمية، نقدم عبء الأمراض القلبية الوعائية، وعوامل الخطر المرتبطة بها، وعلاقتها بالإنفاق الصحي الوطني، ومؤشر تنفيذ السياسات الحرجة.

تواجه منطقة وسط أوروبا وشرق أوروبا وآسيا الوسطى أعلى مستويات وفيات الأمراض القلبية الوعائية على مستوى العالم. على الرغم من أن مستويات وفيات الأمراض القلبية الوعائية عادة ما تكون أقل في النساء مقارنة بالرجال، إلا أن هذا ليس صحيحًا في معظم

يجب على صانعي السياسات تقييم ملف عوامل الخطر في بلادهم لوضع استراتيجيات فعالة للوقاية من الأمراض القلبية الوعائية وإدارتها. يجب تبني استراتيجيات أساسية مثل تنفيذ برامج التحكم في التبغ الوطنية، وضمان توفر أدوية الأمراض القلبية الوعائية، وإنشاء وحدات متخصصة داخل وزارات الصحة للتعامل مع الأمراض غير السارية في جميع البلدان. كما أن تمويل نظام الرعاية الصحية بشكل كافٍ أمر حيوي، لضمان الوصول المعقول للرعاية لجميع المجتمعات.

المقدمة

الطرق والبيانات

| المؤشر | المصدر | السنة |

| الوفيات | ||

| أمراض القلب الإقفارية | العبء العالمي للأمراض | 1990-2019 |

| السكتة الدماغية | العبء العالمي للأمراض | 1990-2019 |

| جميع الأمراض القلبية الوعائية الأخرى | العبء العالمي للأمراض | 1990-2019 |

| عوامل الخطر | ||

| السكري | تعاون عوامل خطر الأمراض غير السارية | 1975-2014 |

| ارتفاع ضغط الدم | تعاون عوامل خطر الأمراض غير السارية | 1975-2015 |

| السمنة | تعاون عوامل خطر الأمراض غير السارية | 1975-2016 |

| الدهون | تعاون عوامل خطر الأمراض غير السارية | 1975-2018 |

| النشاط البدني | العبء العالمي للأمراض | 1990-2019 |

| تناول الصوديوم | العبء العالمي للأمراض | 1990-2019 |

| استهلاك الكحول | العبء العالمي للأمراض | 1990-2019 |

| تدخين التبغ | العبء العالمي للأمراض | 1990-2019 |

| تلوث الهواء المحيط | العبء العالمي للأمراض | 1990-2019 |

| الوفيات المبكرة (السكتة الدماغية) | العد التنازلي للأمراض غير السارية 2030 | 2015 |

| مؤشر | المصدر | سنة |

| برامج السيطرة على التبغ الوطنية | المرصد الصحي العالمي التابع لمنظمة الصحة العالمية | 2018 |

| سياسة/استراتيجية/خطة عمل لأمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية | المرصد الصحي العالمي التابع لمنظمة الصحة العالمية | ٢٠٢١ |

| وحدة تشغيلية، فرع، أو قسم في وزارة الصحة المسؤول عن الأمراض غير السارية | المرصد الصحي العالمي التابع لمنظمة الصحة العالمية | ٢٠٢١ |

| إرشادات/بروتوكولات/معايير إدارة الأمراض القلبية الوعائية | المرصد الصحي العالمي التابع لمنظمة الصحة العالمية | ٢٠٢١ |

| سياسة/استراتيجية/خطة عمل للحد من قلة النشاط البدني | مرصد الصحة العالمي التابع لمنظمة الصحة العالمية | 2021 |

| سياسة/استراتيجية/خطة عمل للحد من النظام الغذائي غير الصحي المرتبط بالأمراض غير السارية | مرصد الصحة العالمي التابع لمنظمة الصحة العالمية | ٢٠٢١ |

| سياسة/استراتيجية/خطة عمل للحد من الاستخدام الضار للكحول | مرصد الصحة العالمي التابع لمنظمة الصحة العالمية | ٢٠٢١ |

| توفر مثبطات ACE والأسبرين (100 ملغ) وحاصرات بيتا في قطاع الصحة العامة | المرصد الصحي العالمي التابع لمنظمة الصحة العالمية | ٢٠٢١ |

ملاحظة: توفر مثبطات ACE، الأسبرين (100 ملغ) وحاصرات بيتا في القطاع الصحي العام هو مزيج من ثلاثة مؤشرات: 1) توفر مثبطات ACE في القطاع الصحي العام؛ 2) توفر الأسبرين (100 ملغ) في القطاع الصحي العام؛ 3) توفر حاصرات بيتا في القطاع الصحي العام. إذا كانت جميعها متاحة، تم تعيين الدرجة العامة إلى 1، وإذا كان واحد أو أكثر غير متاح، تم تعيين الدرجة العامة إلى 0.

النتائج

المصدر: معهد قياسات الصحة والتقييم (IHME). تصور بيانات GBD Compare. سياتل، واشنطن: IHME، جامعة واشنطن، 2020. متاح من http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare.

المصدر: معهد قياسات الصحة والتقييم (IHME). تصور بيانات GBD Compare. سياتل، واشنطن: IHME، جامعة واشنطن، 2020. متاح من http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare.

المصدر: معهد قياسات الصحة والتقييم (IHME). تصور بيانات GBD Compare. سياتل، واشنطن: IHME، جامعة واشنطن، 2020. متاح من http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare.

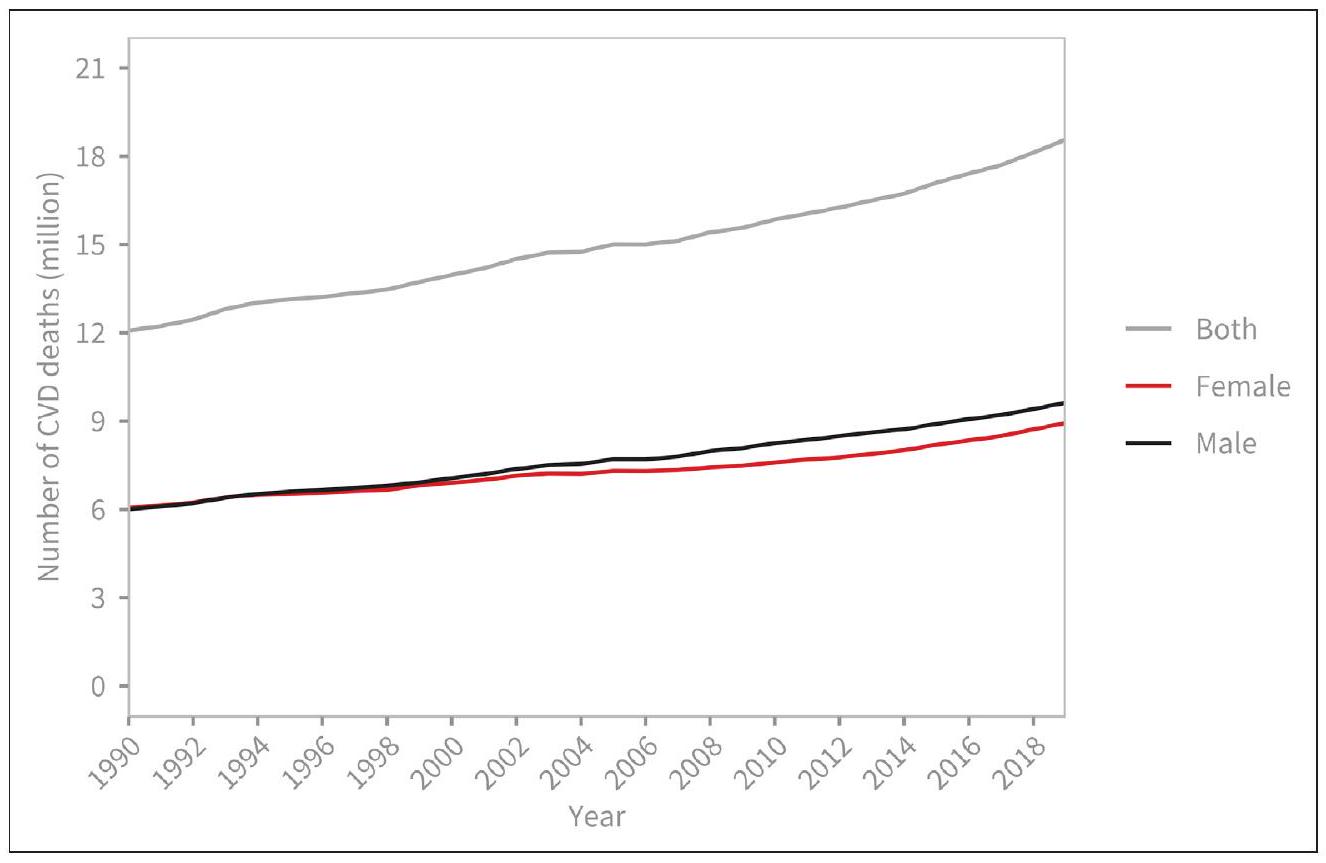

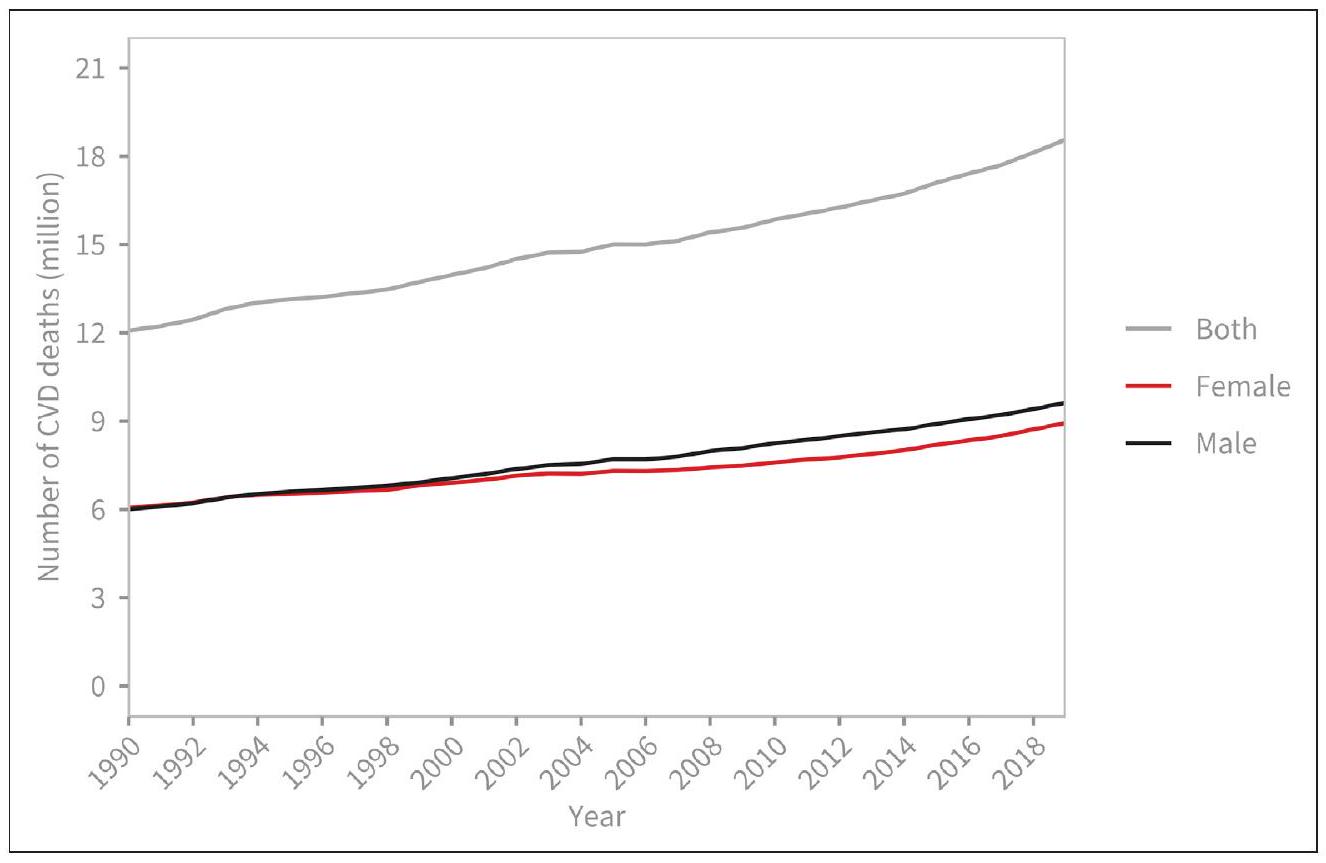

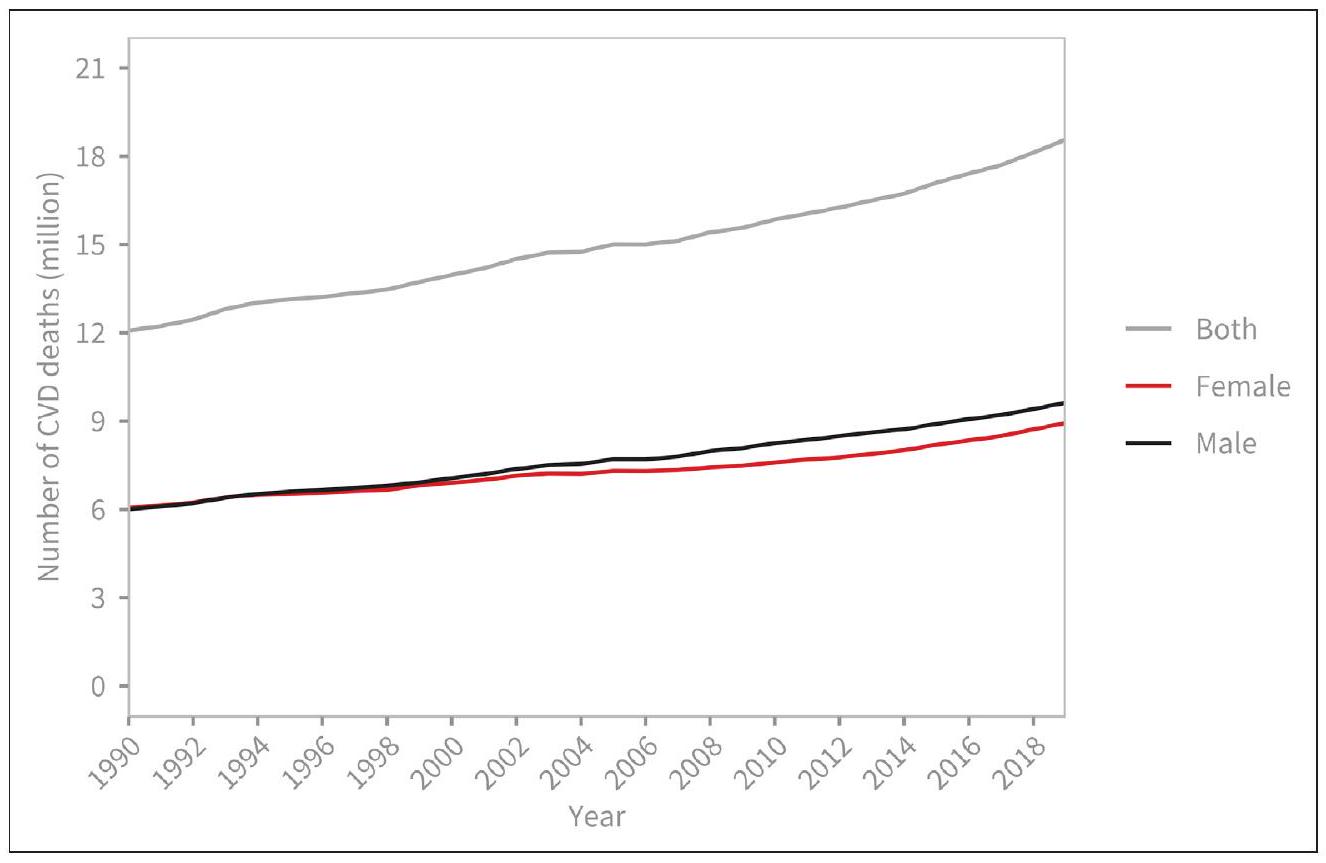

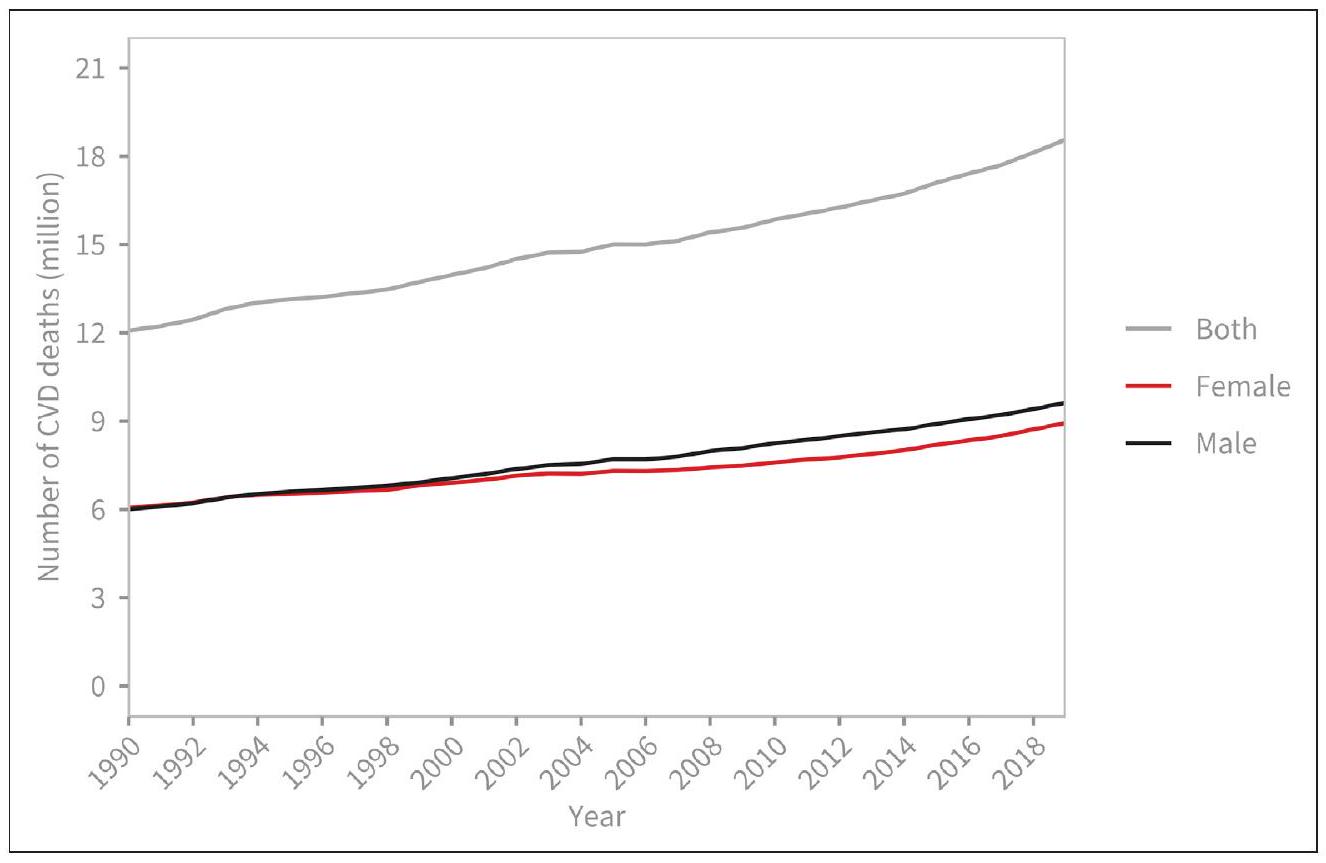

وفيات القلب والأوعية الدموية حسب الجنس

المصدر: معهد قياسات الصحة والتقييم (IHME). تصور بيانات مقارنة GBD. سياتل، واشنطن: IHME، جامعة واشنطن، 2020. متاح من http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare.

الوفيات المبكرة الناتجة عن أمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية

عوامل الخطر

ملاحظة: يتم استخدام اللون الرمادي عندما لا تتوفر تقديرات (مفقودة).

المصدر: العد التنازلي للأمراض غير المعدية [3].

العلاقة بين وفيات أمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية ونفقات الصحة

| المنطقة | % |

| الدخل المرتفع | 97 |

| وسط أوروبا وشرق أوروبا وآسيا الوسطى | 85 |

| أمريكا اللاتينية ومنطقة الكاريبي | 71 |

| شمال إفريقيا والشرق الأوسط | 53 |

| جنوب شرق آسيا وشرق آسيا وأوقيانوسيا | 50 |

| جنوب الصحراء الكبرى | 45 |

| جنوب آسيا | 0 |

ملاحظة (2): تعرض الأرقام الخمسية العالمية التي تقع فيها كل دولة لكل عامل خطر.

القلب العالمي

DOI: 10.5334/gh.1288

المصادر: معهد قياسات الصحة والتقييم (IHME). تصور بيانات مقارنة GBD. سياتل، واشنطن: IHME، جامعة واشنطن، 2020. متاح من http://vizhub. healthdata.org/gbd-compare؛ منظمة الصحة العالمية، قاعدة بيانات نفقات الصحة العالمية. متاح من https://apps.who.int/nha/ قاعدة البيانات/Select/Indicators/en.

مؤشر سياسة WHF

المصادر: معهد قياسات الصحة والتقييم (IHME). بيانات مقارنة GBD. سياتل، واشنطن: IHME، جامعة واشنطن، 2020. متاحة من http://vizhub.healthdata. org/gbd-compare; منظمة الصحة العالمية، قاعدة بيانات الإنفاق الصحي العالمي. متاحة من https://apps. who.int/nha/database/Select/Indicators/en. لمواجهة الأمراض غير السارية (الشكل 10).

المصادر: المرصد الصحي العالمي. متاحة من: https://www.who.int/data/gho.

النقاش

- خطة عمل لأمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية؛ P3 وحدة تشغيلية في وزارة الصحة مسؤولة عن الأمراض غير السارية؛ P4 – إرشادات لإدارة أمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية؛ P5 خطة عمل لتقليل قلة النشاط البدني؛ P6 – خطة عمل لتقليل النظام الغذائي غير الصحي المرتبط بالأمراض غير السارية؛ P7 – خطة عمل لتقليل الاستخدام الضار للكحول؛ P8 – توفر أدوية أمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية (مثل مثبطات ACE، الأسبرين، وحاصرات بيتا) في القطاع الصحي العام.

المصادر: الصحة العالمية

المرصد. متاحة من: https://www.who.int/data/gho.

لمواجهة الأمراض غير السارية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يتطلب الأمر أنظمة صحية ومبادرات ممولة بشكل كافٍ حتى تتمكن جميع المجتمعات من الوصول إلى الرعاية التي تحتاجها. إن التقدم المتعثر في صحة القلب والأوعية الدموية ليس فريدًا. عانت تقريبًا كل مبادرة صحية حول العالم بسبب جائحة COVID-19 والبلدان الآن تتصارع مع أي المجالات يجب أن تعطي الأولوية لها بينما تهدف إلى تعزيز وحماية صحة سكانها. نظرًا للعبء الشديد لأمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية من حيث الوفيات والمراضة، لا يمكن إهمال هذا المجال الصحي. سيكافح العالم لتحقيق الأهداف الطموحة المحددة لتقليل الوفيات المبكرة من الأمراض غير السارية بنسبة 25% مقارنة بمستويات 2010، بحلول عام 2025. ومع ذلك، لا يزال هناك وقت لتسريع العمل نحو تحقيق الهدف 3.4 من أهداف التنمية المستدامة المتمثل في تقليل الوفيات المبكرة من الأمراض غير السارية، بما في ذلك أمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية، بمقدار الثلث.

معلومات التمويل

المصالح المتنافسة

الانتماءات المؤلفين

معهد الصحة العامة والرفاهية، جامعة إسيكس، كولشستر، المملكة المتحدة

بابلو بيريل (D) orcid.org/0000-0002-2342-301X

قسم وبائيات الأمراض غير السارية، كلية لندن للصحة العامة والطب الاستوائي، لندن، المملكة المتحدة؛ الاتحاد العالمي للقلب، جنيف، سويسرا

شون تايلور (D) orcid.org/0000-0002-5031-3588

الاتحاد العالمي للقلب، جنيف، سويسرا

تشودزيوادزيا كابودولا (D) orcid.org/0000-0002-5867-0336

وحدة أبحاث الصحة العامة والتحولات الصحية في المناطق الريفية (أجينكورت)، كلية الصحة العامة، كلية العلوم الصحية، جامعة ويتواترسراند، جوهانسبرغ، جنوب أفريقيا

أونور بيكسي (د)orcid.org/0000-0002-0513-5292

معهد الصحة العامة والرفاهية، جامعة إسيكس، كولشستر، المملكة المتحدة

توماس أ. غازيان (د)orcid.org/0000-0002-5985-345X

مستشفى بريغهام والنساء، طب القلب، بوسطن، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية؛ كلية الطب بجامعة هارفارد، بوسطن، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

ديانا فاكه مكغي

جمعية القلب الأمريكية، دالاس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

جيريميا موينغي (د)orcid.org/0000-0002-5819-4587

الاتحاد العالمي للقلب، جنيف، سويسرا

بوريانا بروفان

جاغات نارولا (د)orcid.org/0000-0002-0280-3996

مدرسة مكغفرن الطبية في UTHealth، هيوستن، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

دانيال بينيرو (د)orcid.org/0000-0002-0126-8194

قسم الطب، جامعة بوينس آيرس، بوينس آيرس، الأرجنتين

فاوستو ج. بينتو (د)orcid.org/0000-0002-8034-4529

مستشفى سانتا ماريا الجامعي، CAML، CCUL، كلية الطب بجامعة لشبونة، لشبونة، البرتغال

REFERENCES

- Lindstrom M, DeCleene N, Dorsey H, Fuster V, Johnson CO, LeGrand KE, et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks Collaboration, 1990-2021. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022; 80: 2372-2425. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.11.001

- Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). [cited 24 Jul 2023]. Available https://www.who.int/news-room/ fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds).

- NCD Countdown 2030 collaborators. NCD Countdown 2030: pathways to achieving Sustainable Development Goal target 3.4. Lancet. 2020; 396: 918-934. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31761-X

- Website. Available. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/ncd-surveillance-global-monitoringframework.

- NCD Countdown 2030 collaborators. NCD Countdown 2030: worldwide trends in noncommunicable disease mortality and progress towards Sustainable Development Goal target 3.4. Lancet. 2018; 392: 1072-1088. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31992-5

- Website. Available. http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare.

- Homepage > NCD-RisC. [cited 24 Jul 2023]. Available https://ncdrisc.org.

- Global Health Expenditure Database. [cited 24 Jul 2023]. Available. https://apps.who.int/nha/ database.

- Global Health Observatory. [cited 24 Jul 2023]. Available. https://www.who.int/data/gho.

- Finucane MM, Paciorek CJ, Danaei G, Ezzati M. Bayesian Estimation of Population-Level Trends in Measures of Health Status. Stat Sci. 2014; 29: 18-25. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1405.4682; https://doi.org/10.1214/13-STS427

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020; 396: 1204-1222. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9

للاستشهاد بهذه المقالة:

تم القبول: 18 ديسمبر 2023

تم النشر: 25 يناير 2024

حقوق الطبع والنشر:

القلب العالمي هو مجلة مفتوحة الوصول تمت مراجعتها من قبل الأقران تنشرها Ubiquity Press.

- 1 تقرير القلب العالمي، الذي أُطلق في مايو 2023، يهدف إلى تزويد صانعي السياسات والمدافعين حول العالم بالمعلومات اللازمة للمساعدة في تقليل وفيات الأمراض القلبية الوعائية وتسريع التقدم في صحة القلب والأوعية الدموية. تسلط نتائج التقرير الضوء على الاختلافات الرئيسية بين المناطق من حيث عبء الأمراض القلبية الوعائية وعوامل الخطر، فضلاً عن الحواجز الهيكلية وعدم المساواة في صحة القلب والأوعية الدموية، بهدف توجيه صانعي السياسات على المستويات الوطنية والدولية نحو الأولويات التي ينبغي عليهم السعي لمعالجتها. وهو متاح من https:// world-heart-federation.org/resource/world-heart-report-2023.2 تشير الوفيات المبكرة الناتجة عن الأمراض غير المعدية إلى الوفيات التي تحدث بين سن 30 و70 عامًا. هذه الوفيات المبكرة لا تؤدي فقط إلى فقدان كبير في الحياة للأفراد ولكن لها أيضًا تأثيرات أوسع على المجتمعات والاقتصادات، خاصةً لأنها تؤثر على الأفراد ضمن نطاق سن العمل.

- الجدول 3 نسبة الدول التي تنفق على الأقل 5% من الناتج المحلي الإجمالي على الصحة.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/gh.1288

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38273998

Publication Date: 2024-01-01

The Heart of the World

]u[ubiquity press

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Mariachiara Di Cesare

m.dicesare@essex.ac.uk

KEYWORDS:

TO CITE THIS ARTICLE:

Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the leading cause of mortality globally. Of the 20.5 million CVD-related deaths in 2021, approximately 80% occurred in low- and middleincome countries.

Using data from the Global Burden of Disease Study, NCD Risk Factor Collaboration, NCD Countdown initiative, WHO Global Health Observatory, and WHO Global Health Expenditure database, we present the burden of CVDs, associated risk factors, their association with national health expenditures, and an index of critical policy implementation.

The Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia region face the highest levels of CVD mortality globally. Although CVD mortality levels are generally lower in women than men, this is not true in almost

Policymakers must assess their country’s risk factor profile to craft effective strategies for CVD prevention and management. Fundamental strategies such as the implementation of National Tobacco Control Programmes, ensuring the availability of CVD medications, and establishing specialised units within health ministries to tackle non-communicable diseases should be embraced in all countries. Adequate healthcare system funding is equally vital, ensuring reasonable access to care for all communities.

INTRODUCTION

METHODS AND DATA

| INDICATOR | SOURCE | YEAR |

| Mortality | ||

| Ischemic heart disease | Global burden of disease | 1990-2019 |

| Stroke | Global burden of disease | 1990-2019 |

| All other CVDs | Global burden of disease | 1990-2019 |

| Risk factors | ||

| Diabetes | NCD risk factor collaboration | 1975-2014 |

| Raised blood pressure | NCD risk factor collaboration | 1975-2015 |

| Obesity | NCD risk factor collaboration | 1975-2016 |

| Lipids | NCD risk factor collaboration | 1975-2018 |

| Physical activity | Global burden of disease | 1990-2019 |

| Sodium intake | Global burden of disease | 1990-2019 |

| Alcohol consumption | Global burden of disease | 1990-2019 |

| Tobacco smoking | Global burden of disease | 1990-2019 |

| Ambient air pollution | Global burden of disease | 1990-2019 |

| Premature mortality (stroke) | NCD Countdown 2030 | 2015 |

| INDICATOR | SOURCE | YEAR |

| National tobacco control programmes | WHO Global Health Observatory | 2018 |

| Policy/strategy/action plan for CVD | WHO Global Health Observatory | 2021 |

| Operational Unit, Branch, or Dept. in Ministry of Health with responsibility for NCDs | WHO Global Health Observatory | 2021 |

| Guidelines/protocols/standards for the management of cardiovascular diseases | WHO Global Health Observatory | 2021 |

| Policy/strategy/action plan to reduce physical inactivity | WHO Global Health Observatory | 2021 |

| Policy/strategy/action plan to reduce unhealthy diet related to NCDs | WHO Global Health Observatory | 2021 |

| Policy/strategy/action plan to reduce the harmful use of alcohol | WHO Global Health Observatory | 2021 |

| Availability of ACE inhibitors, Aspirin ( 100 mg ) and Beta blockers in the public health sector | WHO Global Health Observatory | 2021 |

Note: Availability of ACE inhibitors, Aspirin ( 100 mg ) and Beta blockers in the public health sector is a combination of the three indicators 1) availability of ACE inhibitors in the public health sector; 2) availability of Aspirin ( 100 mg ) in the public health sector; 3) availability of Beta blockers in the public health sector. If all 3 available the overall score was set to 1 if one or more not available the overall score was set to 0 .

RESULTS

Source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD Compare Data Visualization. Seattle, WA: IHME, University of Washington, 2020. Available from http://vizhub.healthdata. org/gbd-compare.

Source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD Compare Data Visualization. Seattle, WA: IHME, University of Washington, 2020. Available from http://vizhub.healthdata. org/gbd-compare.

Source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD Compare Data Visualization. Seattle, WA: IHME, University of Washington, 2020. Available from http://vizhub.healthdata. org/gbd-compare.

CARDIOVASCULAR DEATHS BY SEX

Source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD Compare Data Visualization. Seattle, WA: IHME, University of Washington, 2020. Available from http://vizhub.healthdata. org/gbd-compare.

CVD PREMATURE MORTALITY

RISK FACTORS

Note: Grey colour is used when no estimates were available (missing).

Source: NCD Countdown [3].

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CVD MORTALITY AND HEALTH EXPENDITURE

| REGION | % |

| High-income | 97 |

| Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia | 85 |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 71 |

| North Africa and Middle East | 53 |

| Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Oceania | 50 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 45 |

| South Asia | 0 |

Note (2): The figures display the global quintile into which each country falls for each risk factor.

Global Heart

DOI: 10.5334/gh. 1288

Sources: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD Compare Data Visualization. Seattle, WA: IHME, University of Washington, 2020. Available from http://vizhub. healthdata.org/gbd-compare; World Health Organization, Global Health Expenditure Database. Available from https://apps.who.int/nha/ database/Select/Indicators/en.

WHF POLICY INDEX

Sources: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD Compare Data Visualization. Seattle, WA: IHME, University of Washington, 2020. Available from http://vizhub.healthdata. org/gbd-compare; World Health Organization, Global Health Expenditure Database. Available from https://apps. who.int/nha/database/Select/ Indicators/en. to NCDs (Figure 10).

Sources: Global Health Observatory. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho.

DISCUSSION

- Action plan for CVDs; P3 Operational Unit in Ministry of Health with responsibility for NCDs; P4 – Guidelines for the management of CVDs; P5 Action plan to reduce physical inactivity; P6 – Action plan to reduce unhealthy diet related to NCDs; P7 – Action plan to reduce the harmful use of alcohol; P8 – Availability of CVD drugs (e.g., ACE inhibitors, aspirin, and Beta blockers) in the public health sector.

Sources: Global Health

Observatory. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho.

for tackling NCDs. Additionally, it requires adequately funded health systems and initiatives so that all communities can access the care they need. The stalling progress in cardiovascular health is not unique. Almost every health initiative around the world suffered because of the COVID-19 pandemic and countries are now grappling with which areas to prioritise as they aim to boost and protect the health of their populations. Given the severe burden of CVDs both in terms of mortality and morbidity, this area of health cannot be neglected. The world will struggle to meet the ambitious targets set to reduce premature mortality from NCDs by 25% compared to 2010 levels, by 2025. There is still time, however, to accelerate action toward meeting Sustainable Development Goal 3.4 of reducing by one-third premature mortality from NCDs, including cardiovascular diseases.

FUNDING INFORMATION

COMPETING INTERESTS

AUTHOR AFFILIATIONS

Institute of Public Health and Wellbeing, University of Essex, Colchester, UK

Pablo Perel (D) orcid.org/0000-0002-2342-301X

Department of Non-Communicable Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK; World Heart Federation, Geneva, Switzerland

Sean Taylor (D) orcid.org/0000-0002-5031-3588

World Heart Federation, Geneva, Switzerland

Chodziwadziwa Kabudula (D) orcid.org/0000-0002-5867-0336

MRC/Wits Rural Public Health and Health Transitions Research Unit (Agincourt), School of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

Honor Bixby (D) orcid.org/0000-0002-0513-5292

Institute of Public Health and Wellbeing, University of Essex, Colchester, UK

Thomas A. Gaziano (D) orcid.org/0000-0002-5985-345X

Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Cardiovascular Medicine, Boston, USA; Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA

Diana Vaca McGhie

American Heart Association, Dallas, USA

Jeremiah Mwangi (D) orcid.org/0000-0002-5819-4587

World Heart Federation, Geneva, Switzerland

Borjana Pervan

Jagat Narula (D) orcid.org/0000-0002-0280-3996

McGovern Medical School at UTHealth, Houston, USA

Daniel Pineiro (D) orcid.org/0000-0002-0126-8194

Department of Medicine, University of Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Fausto J. Pinto (D) orcid.org/0000-0002-8034-4529

Santa Maria University Hospital, CAML, CCUL, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal

REFERENCES

- Lindstrom M, DeCleene N, Dorsey H, Fuster V, Johnson CO, LeGrand KE, et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks Collaboration, 1990-2021. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022; 80: 2372-2425. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.11.001

- Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). [cited 24 Jul 2023]. Available https://www.who.int/news-room/ fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds).

- NCD Countdown 2030 collaborators. NCD Countdown 2030: pathways to achieving Sustainable Development Goal target 3.4. Lancet. 2020; 396: 918-934. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31761-X

- Website. Available. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/ncd-surveillance-global-monitoringframework.

- NCD Countdown 2030 collaborators. NCD Countdown 2030: worldwide trends in noncommunicable disease mortality and progress towards Sustainable Development Goal target 3.4. Lancet. 2018; 392: 1072-1088. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31992-5

- Website. Available. http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare.

- Homepage > NCD-RisC. [cited 24 Jul 2023]. Available https://ncdrisc.org.

- Global Health Expenditure Database. [cited 24 Jul 2023]. Available. https://apps.who.int/nha/ database.

- Global Health Observatory. [cited 24 Jul 2023]. Available. https://www.who.int/data/gho.

- Finucane MM, Paciorek CJ, Danaei G, Ezzati M. Bayesian Estimation of Population-Level Trends in Measures of Health Status. Stat Sci. 2014; 29: 18-25. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1405.4682; https://doi.org/10.1214/13-STS427

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020; 396: 1204-1222. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9

TO CITE THIS ARTICLE:

Accepted: 18 December 2023

Published: 25 January 2024

COPYRIGHT:

Global Heart is a peer-reviewed open access journal published by Ubiquity Press.

- 1 The World Heart Report, launched in May 2023, is aimed at equipping policymakers and advocates around the world with the information needed to help reduce CVD deaths and accelerate progress in cardiovascular health. The report findings highlight the main differences between geographies in terms of CVD burden and risk factors, as well as structural barriers and inequities in CVD health, with the goal of guiding policymakers at national and international levels toward the priorities they should seek to address. It is available from https:// world-heart-federation.org/resource/world-heart-report-2023.2 Premature mortality from non-communicable diseases refers to deaths occurring between the ages of 30 and 70 years. These premature deaths not only result in a significant loss of life for individuals but also have broader impacts on societies and economies, particularly as they affect individuals within the working age range.

- Table 3 Proportion of countries spending at least 5% of GDP on health.