DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01780-z

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38755660

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-16

كيف تؤثر علاقات الأقران على التحصيل الأكاديمي بين طلاب المرحلة المتوسطة: الأدوار الوسيطة لسلسلة الدافع التعليمي والانخراط في التعلم

الملخص

الخلفية على الرغم من الاعتراف بتأثير العلاقات بين الأقران والدافع التعليمي والانخراط في التعلم على التحصيل الأكاديمي، لا يزال هناك فجوة في فهم الآليات المحددة التي تؤثر من خلالها العلاقات بين الأقران على التحصيل الأكاديمي عبر الدافع التعليمي والانخراط في التعلم. الطرق تهدف هذه الدراسة إلى التحقيق في كيفية تأثير العلاقات بين الأقران على التحصيل الأكاديمي لطلاب المدارس الإعدادية من خلال الأدوار الوسيطة المتسلسلة للدافع التعليمي والانخراط في التعلم، باستخدام نموذج النظام الذاتي للتطوير الدافعي كإطار نظري. في يناير 2024، تم اختيار 717 مشاركًا من مدرستين متوسطتين في شرق الصين (متوسط العمر

الخاتمة لتحقيق النجاح الأكاديمي لطلاب المدارس الإعدادية، يجب تنفيذ التدخلات المناسبة لتحسين العلاقات بين الأقران والدافع التعليمي والانخراط في التعلم.

المقدمة

بين الدافع الأكاديمي وتحقيق الرياضيات بين طلاب المدارس الإعدادية [18]. اقترح لييم ومارتن أن الانخراط في المدرسة له تأثير إيجابي على الأداء الأكاديمي [19]. تسلط النتائج الضوء على أهمية النظر في كل من الدافع التعليمي والانخراط في التعلم لفهم التحصيل الأكاديمي.

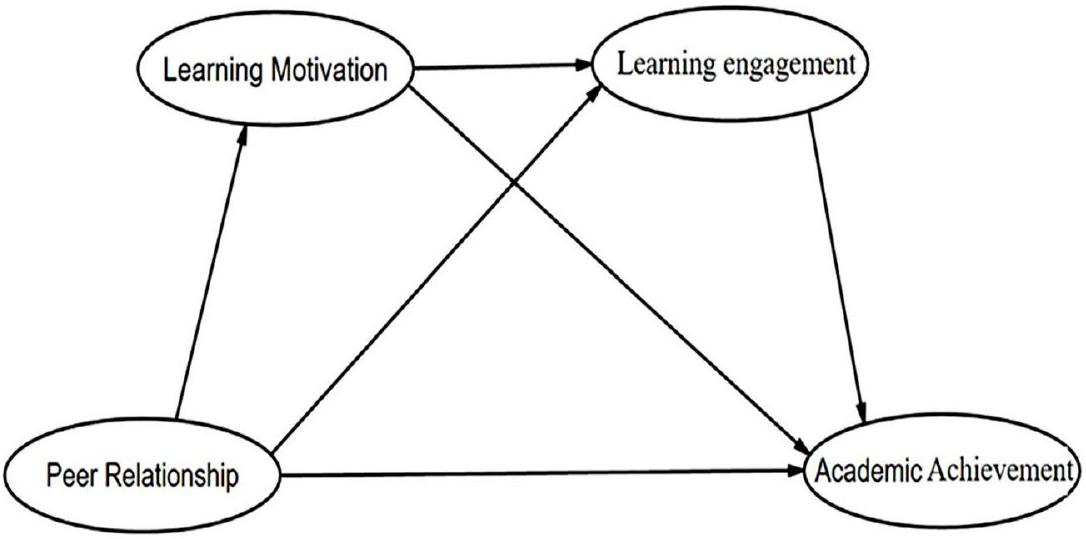

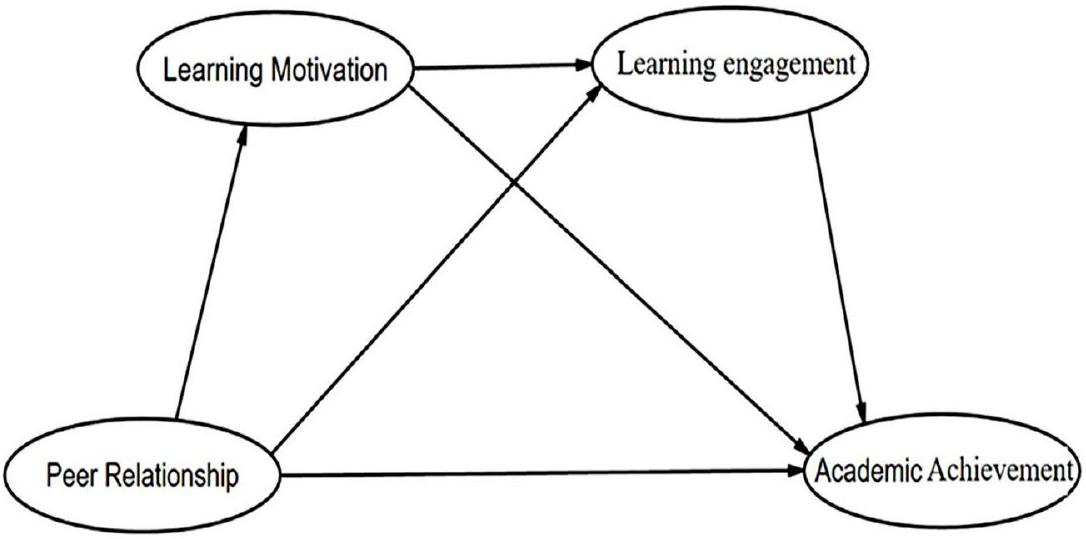

بين العلاقات بين الأقران، ودافع التعلم، والانخراط في التعلم، والإنجاز الأكاديمي. يمكن توضيح العلاقة بين المتغيرات الأربعة وSSMMD كما يلي: تشكل علاقات الأقران، كعنصر من السياق الاجتماعي، معتقدات الفرد الذاتية، والتي تؤثر بشكل كبير على دافعهم للتعلم. الطلاب الذين يمتلكون مستويات أعلى من دافع التعلم هم أكثر عرضة للمشاركة النشطة في أنشطة التعلم (كعنصر من العمل)، ويؤثرون إيجابياً على إنجازهم الأكاديمي (كنتيجة تنموية) [25]. بناءً على هذا النموذج، تفترض هذه الدراسة أن علاقات الأقران (كعامل من عوامل السياق الاجتماعي) قد تؤثر على دافع التعلم لدى المراهقين (كعامل من عوامل النظام الذاتي)، والذي بدوره يؤثر على انخراطهم في التعلم (كعمل فردي)، مما يؤدي في النهاية إلى تأثير إيجابي على الإنجاز الأكاديمي (كنواتج تنموية). يتم تمثيل هذا النموذج النظري في الدراسة بصريًا في الشكل 1.

العلاقات بين الأقران والإنجاز الأكاديمي

بين 596 طالبًا من الأقليات العرقية في المدارس الابتدائية في الصين [28]. علاوة على ذلك، اقترحت الدراسات السابقة أن التأثير الإيجابي للعلاقات بين الأقران على التحصيل الأكاديمي يزداد مع مستوى الصف [29] وأن العلاقات بين الأقران من نفس الجنس مهمة بشكل خاص في التنبؤ بالتحصيل الأكاديمي [19]. بشكل عام، تؤكد هذه النتائج على الدور الحاسم للعلاقات الإيجابية بين الأقران في التحصيل الأكاديمي، مما يبرز أن المراهقين الذين يزرعون علاقات داعمة مع أقرانهم هم أكثر ميلًا لتحقيق النجاح في مساعيهم الأكاديمية. بناءً على ذلك، يتم اقتراح الفرضية التالية.

H1: العلاقات بين الأقران مرتبطة إيجابيًا بالتحصيل الأكاديمي.

تحفيز التعلم كوسيط

الانخراط في التعلم كوسيط

لتكريس المزيد من الوقت للأنشطة التعليمية وتحقيق نتائج أكاديمية أفضل في النهاية [47]. وجد لييم ومارتن أن المشاركة النشطة والاستثمار في الأنشطة التعليمية يتنبأ بشكل إيجابي بالنجاح الأكاديمي [19]. دعم وانغ وآخرون ذلك من خلال إظهار أن مستويات أعلى من الانخراط في الفصل مرتبطة بأداء أكاديمي أفضل [4]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، أبرز صقر وآخرون الآثار الطولية للانخراط، موضحين أن المستويات العالية المستدامة من الانخراط تؤدي إلى تحسين النتائج الأكاديمية مع مرور الوقت [48]. مجتمعة، تؤكد هذه الدراسات الحديثة على الدور الحاسم لانخراط الطلاب في تعزيز الإنجاز الأكاديمي.

المواد والأساليب

جمع العينات وجمع البيانات

أدوات البحث

مقياس علاقة الأقران

“اذهب وقدم لهم الراحة.” تم استخدام مقياس ليكرت المكون من 5 نقاط، حيث تتراوح الدرجات من 1 إلى 5 مما يشير إلى “أوافق بشدة” إلى “أعارض بشدة”، مع الإشارة إلى أن الدرجات الأعلى تدل على علاقات أقران أفضل. يتمتع المقياس بموثوقية وصلاحية جيدة، وقد تم التحقق من ذلك من خلال أبحاث حديثة [54].

مقياس دافعية التعلم

مقياس التفاعل في التعلم

الإنجاز الأكاديمي

التحليل الإحصائي

| ديموغرافي | عينة

|

تردد | نسبة مئوية |

| جنس | ذكر | 359 | 50.1% |

| أنثى | 358 | ٤٩.٩٪ | |

| درجة | الصف السابع | 385 | 53.7% |

| الصف الثامن | ٣٣٢ | ٤٦.٣٪ | |

| مقيم | مدينة | ٤٧٦ | 66.4% |

| الريف | 241 | 33.6% | |

| مستوى التعليم للآباء | المدرسة الإعدادية أو أقل | ٣٥٠ | ٤٨.٨٪ |

| المدرسة الثانوية العليا أو المدرسة المهنية | 264 | ٣٦.٨٪ | |

| كلية | 64 | ٨.٩٪ | |

| جامعة | ٣٩ | 5.4٪ | |

| المدرسة الإعدادية أو أقل | ٣٧٢ | 51.9% | |

| مستوى التعليم للآباء | المدرسة الثانوية العليا أو المدرسة المهنية | 242 | 33.8٪ |

| كلية | 66 | 9.2% | |

| جامعة | 37 | 5.2% |

النتائج

تباين الطريقة الشائعة

خصائص العينة

| متغير كامن | بعد | SC | ألف كرونباخ | سي آر | AVE |

| علاقة الأقران (PR) | IR | 0.7720.873 | 0.922 | 0.926 | 0.678 |

| SE | 0.6910.913 | 0.913 | 0.916 | 0.689 | |

| كلور | 0.5950.871 | 0.929 | 0.928 | 0.591 | |

| دافع التعلم (LM) | أنا | 0.5490.909 | 0.936 | 0.947 | 0.566 |

| إم | 0.5480.906 | 0.944 | 0.945 | 0.524 | |

| الانخراط في التعلم | في جي | 0.6380.859 | 0.846 | 0.849 | 0.589 |

| دي دي | 0.5690.909 | 0.940 | 0.942 | 0.675 | |

| AP | 0.6350.809 | 0.885 | 0.887 | 0.614 | |

| علاقة الأقران (PR) | 0.9070.915 | 0.961 | 0.937 | 0.832 | |

| دافع التعلم (LM) | 0.7750.894 | 0.961 | 0.835 | 0.718 | |

| الانخراط في التعلم | 0.8620.915 | 0.946 | 0.862 | 0.678 | |

| التحصيل الأكاديمي | 0.7620.922 | 0.839 | 0.896 | 0.743 | |

| SC=موحد | المعاملات؛ | IR=العلاقات الشخصية | علاقة | سفينة | SE=اجتماعي |

أو مدرسة مهنية،

نموذج القياس

تقدم الجدول 2 نتائج تحليل الموثوقية والصلاحية التوافقية. أظهر نموذج القياس موثوقية مقبولة، كما يتضح من معاملات ألفا كرونباخ التي تتراوح بين 0.839 و 0.961.

نموذج هيكلي

اختبار الفرضية

| متغير محتمل | علاقة الأقران | دافع التعلم | الانخراط في التعلم | التحصيل الأكاديمي |

| علاقة الأقران | 0.912 | |||

| دافع التعلم | 0.534 | 0.847 | ||

| الانخراط في التعلم | 0.303 | 0.322 | 0.823 | |

| التحصيل الأكاديمي | 0.340 | 0.346 | 0.329 | 0.862 |

| مؤشر الملاءمة | القيم المقترحة | قيمة هذه الدراسة |

| CMIN/DF(

|

>1 و <3 |

|

| جذر متوسط مربع خطأ التقريب (RMSEA) | <0.08 | 0.014 |

| مؤشر ملاءمة النموذج (GFI) | >0.90 | 0.946 |

| مؤشر ملاءمة التكيف المعدل (AGFI) | >0.90 | 0.942 |

| مؤشر الملاءمة التزايدي (NFI) | >0.90 | 0.946 |

| مؤشر الملاءمة المقارن (CFI) | >0.90 | 0.993 |

| مؤشر توكر-لويس (TLI) | >0.90 | 0.993 |

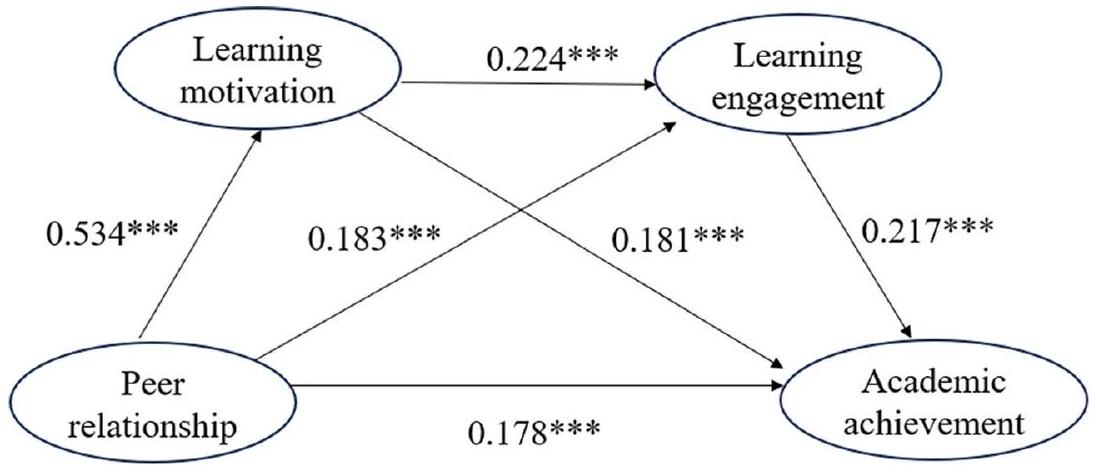

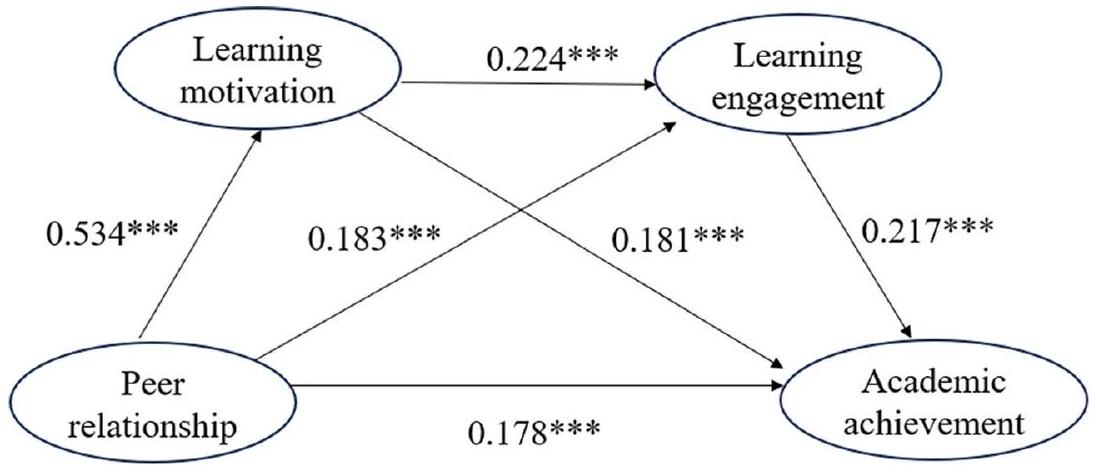

تحليلات تأثير العلاقة بين الأقران على التحصيل الأكاديمي

| فرضية | مسار | تقديرات غير مفهومة | ت | توقيع | تقديرات الوقوف | اختبار الفرضية |

| H1 | العلاقات العامة

|

1.313 | ٣.٧١٢ | *** | 0.178 | مدعوم |

| H2 | العلاقات العامة

|

0.318 | 12.232 | *** | 0.534 | مدعوم |

| H3 | LM

|

٢.٢٣٩ | ٣.٥١٢ | *** | 0.181 | مدعوم |

| H5 | العلاقات العامة

|

0.134 | ٣.٥٤٥ | *** | 0.183 | مدعوم |

| H6 |

|

0.274 | ٤.٠٣٣ | *** | 0.224 | مدعوم |

| H7 | لي

|

2.192 | ٤.٨٧٥ | *** | 0.217 | مدعوم |

فترات الثقة المصححة من التحيز (

تأثير دافع التعلم يمثل

نقاش

| علاقة المسار | تقدير نقطي | ناتج المعامل | التمويل الذاتي | |||||

| فترة الثقة 95% مصححة للانحياز | فترة الثقة النسبية 95% | |||||||

| SE | ت | أخفض | علوي | أخفض | علوي | |||

| اختبار التأثيرات غير المباشرة والمباشرة والإجمالية | ||||||||

| ديستال إي |

|

0.191 | 0.072 | ٢.٦٥٣ | 0.076 | 0.365 | 0.059 | 0.339 |

| LMIE |

|

0.713 | 0.286 | ٢.٤٩٣ | 0.193 | 1.326 | 0.191 | 1.321 |

| لي |

|

0.293 | 0.127 | 2.307 | 0.081 | 0.585 | 0.076 | 0.584 |

| رباط | التأثير غير المباشر الكلي | 1.198 | 0.312 | 3.840 | 0.656 | 1.907 | 0.635 | 1.870 |

| دي | العلاقات العامة

|

1.313 | 0.354 | ٣.٧١٢ | 0.487 | ٢.١٧٨ | 0.496 | 2.179 |

| تي إي | التأثير الكلي | ٢.٥١٠ | 0.404 | ٦.٢١٣ | 1.745 | 3.309 | 1.740 | ٣.٢٩٠ |

| نسبة التأثيرات غير المباشرة | ||||||||

| P1 | ديستال إي/تي | 0.160 | 0.078 | 2.051 | 0.057 | 0.394 | 0.051 | 0.344 |

| P2 | LMIE/TIE | 0.595 | 0.137 | ٤.٣٤٣ | 0.257 | 0.787 | 0.258 | 0.789 |

| P3 | لي/تي | 0.245 | 0.112 | ٢.١٨٨ | 0.065 | 0.495 | 0.076 | 0.502 |

| P4 | ربط/تكنولوجيا التعليم | 0.477 | 0.128 | ٣.٧٢٧ | 0.256 | 0.777 | 0.256 | 0.777 |

| P5 | دي/تي | 0.523 | 0.128 | ٤.٠٨٦ | 0.223 | 0.744 | 0.223 | 0.744 |

العلاقة بين العلاقات الزملائية والتحصيل الأكاديمي لطلاب المرحلة المتوسطة.

أظهرت نتائج الدراسة أن الانخراط في التعلم كان له دور وسيط جزئي في العلاقة بين العلاقات مع الأقران والتحصيل الأكاديمي بين طلاب المدارس الإعدادية. وهذا يشير إلى أن مستوى عالٍ من الانخراط في التعلم يمكن أن يساعد في توضيح سبب ميل طلاب المدارس الإعدادية الذين يطورون علاقات إيجابية مع أقرانهم إلى إظهار أداء أكاديمي محسّن. عندما تكون لدى الطلاب علاقات إيجابية مع أقرانهم، ينعكس انخراطهم المتزايد في التعلم في مشاركتهم النشطة في الصف، ورغبتهم في إكمال الواجبات، وسعيهم النشط للحصول على فرص تعلم إضافية، مما يؤدي في النهاية إلى تحسين التحصيل الأكاديمي. تتماشى هذه النتيجة مع الأبحاث السابقة، التي تفترض أن الانخراط في التعلم هو عامل محوري يربط بين العلاقات مع الأقران والتحصيل الأكاديمي لطلاب المدارس الإعدادية. ستساعد الروابط التي يشكلها المراهقون مع أقرانهم في زيادة المشاركة في العملية التعليمية، مما سيؤدي بدوره إلى تحسين الأداء الأكاديمي. وقد قدمت هذه النتيجة مزيدًا من الأدلة على أن الانخراط في التعلم يلعب دورًا مهمًا في الربط بين العلاقات مع الأقران والتحصيل الأكاديمي.

كشفت الدراسة أيضًا أن دافع التعلم والانخراط في التعلم لعبا دور الوساطة المتسلسل في العلاقة بين العلاقات الزملائية والإنجاز الأكاديمي، وهو أحد أكثر الاستنتاجات إثارة للدهشة التي تم التوصل إليها من التحقيق. تتماشى هذه النتيجة مع نموذج النظام الذاتي لتطوير الدافع [20]، الذي يقترح أن التفاعلات الإيجابية والدعم من الأقران يساهمان في تطوير دافع التعلم لدى الأفراد. هذا الدافع، بدوره، يؤثر على مستوى انخراطهم في التعلم، مما يؤدي إلى تحسين الإنجاز الأكاديمي. علاوة على ذلك، كشفت الدراسة أن دافع التعلم لدى طلاب المدارس الإعدادية ساهم بشكل أقل في مستوى انخراطهم في التعلم.

كان الدافع للتعلم، لأن الدافع يلعب دورًا حاسمًا في تحفيز اهتمامهم وجهودهم واستمرارهم في المهام الأكاديمية [49].

الآثار النظرية والعملية

الارتباط، والإنجاز الأكاديمي باستخدام نموذج النظام الذاتي للتطوير التحفيزي، والذي قد يوفر رؤى للبحوث المستقبلية في دول أخرى. ثانياً، يستكشف الآلية الوسيطة بين علاقات الأقران وإنجاز الطلاب في المدارس الإعدادية من خلال فحص أدوار الدافع للتعلم والانخراط في التعلم. يمكن أن تُثري هذه النظرة الجديدة فهمنا للرابط بين علاقات الأقران والإنجاز الأكاديمي بين طلاب المدارس الإعدادية.

القيود واتجاهات البحث المستقبلية

شكر وتقدير

غير قابل للتطبيق.

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

تمت الموافقة عليها من قبل جميع المؤلفين. تم تنفيذ جميع الطرق وفقًا للإرشادات واللوائح ذات الصلة. تم اعتماد الاستبيان والمنهجية لهذه الدراسة من قبل لجنة الأخلاقيات البحثية في كلية التربية بجامعة قوفو العادية قبل جمع البيانات.

موافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

الموافقة المستنيرة

تاريخ الاستلام: 25 أبريل 2023 / تاريخ القبول: 9 مايو 2024

References

- Marsh HW, McCallum JH. The measurement of academic achievement: methods and background. Wiley; 1984.

- Hattie J, Visible Learning. A synthesis of over 800 Meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge; 2009.

- Genesee F, Lindholm-Leary K, Saunders W, Christian D. Educating English Language Learners. Cambridge.UK: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

- Wang

, Deng , Du . Harsh parenting and academic achievement in Chinese adolescents: potential mediating roles of effortful control and classroom engagement. J Sch Psychol. 2017;SX002244051730095-. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2017.09.002. - Corcoran RP, Cheung A, Kim E, Xie C. Effective Universal school-based social and emotional learning programs for improving academic achievement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Educational Res Rev. 2017;S1747938:X17300611-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. edurev.2017.12.001.

- Cheng L, Li M, Kirby JR, Qiang H, Wade-Woolley L. English language immersion and students’ academic achievement in English, Chinese and mathematics. Evaluation Res Educ. 2010;23(3):151-69. https://doi.org/10.1080/0950079 0.2010.489150.

- Zhang W, Zhang L, Chen L, Ji L, Deater-Deckard K. Developmental changes in longitudinal associations between academic achievement and psychopathological symptoms from late childhood to middle adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(2):178-88. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12927.

- Steinmayr R, Meiner A, Weideinger AF, Wirthwein L. Academic achievement. UK: Oxford University Press; 2014.

- Wang M, Kiuru N, Degol JL, Salmela-Aro K. Friends, academic achievement, and school engagement during adolescence: a social network approach to peer influence and selection effects. Learn Instruction. 2018;58:148-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.06.003.

- Wei Y. Study on the influence of school factors on self-esteem development of children. Psychol Dev Educ. 1998;2:12-6.

- Gallardo LO, Barrasa A, Fabricio G. Positive peer relationships and academic achievement across early and mid-adolescence. Social Behav Personality:An Int J. 2016;44(10):1637-48. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2016.44.10.1637.

- Dogan U, Student, Engagement. Academic Self-efficacy, and academic motivation as predictors of academic achievement. Anthropol. 2015;20(3):553-61. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720073.2015.11891759.

- Tanaka M. Examining kanji learning motivation using self-determination theory. System. 2013;41:804-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2013.08.004.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2020;101860-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. cedpsych.2020.101860.

- Schaufeli WB, Martinez IM, Pinto AM, Salanova M, Bakker AB. Burnout and Engagement in University students: a cross-national study. J Cross-Cult Psychol. 2002;33:464-81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022102033005003.

- Li Y, Yao C, Zeng S, Wang X, Lu T, Li C, Lan J, You X. How social networking site addiction drives university students’ academic achievement: the mediating role of learning engagement. J Pac Rim Psychol. 2019;13:e19. https://doi. org/10.1017/prp.2019.12.

- Wentzel KR. Peer relationships, motivation, and academic achievement at school. In: Elliot AJ, Dweck CS, Yeager DS, editors. Handbook of competence and motivation: theory and application. The Guilford; 2017. pp. 586-603.

- Li L, Peng Z, Lu L, Liao H, Li H, Peer relationships, self-efficacy, academic motivation, and mathematics achievement in Zhuang adolescents: a Moderated Mediation Model. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;105358. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105358.

- Liem GA, Martin AJ. Peer relationships and adolescents’ academic and non-academic outcomes: same-sex and opposite-sex peer effects and the mediating role of school engagement. Br J Educ Psychol. 2011;81(2):183-206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2010.02013.x.

- Connell JP, Wellborn JG. Competence, autonomy, and relatedness: a motivational analysis of self-system processes. In: Gunnar MR, Sroufe LA, editors. The Minnesota symposia on child psychology. Self-processes and development. Volume 23. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1991. pp. 43-77.

- Skinner E, Furrer C, Marchand G, Kindermann T. Engagement and disaffection in the classroom: part of a larger motivational dynamic? J Educ Psychol. 2008;100(4):765-81. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012840.

- Deci E. Intrinsic motivation. New York, NY: Plenum; 1975.

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Springer Science + Business Media; 1985. P.11.

- Wang M, Wang M, Wang J. Parental conflict damages academic performance in adolescents: the mediating roles of Effortful Control and Classroom Participation. Psychol Dev Educ. 2018;34(04):434-42.

- Wu H, Li S, Zheng J, Guo J. Medical students’ motivation and academic performance: the mediating roles of self-efficacy and learning engagement. Med Educ Online. 2020;25(1):1742964. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.202 0.1742964.

- Ma D. Research on the relationship between parent-child relationship, peer relationship and academic performance of junior high school students [Unpublished manuscript]. Qufu Normal University, China; 2020.

- Jacobson LT, Burdsal CA. Academic Performance in Middle School: Friendship Influences. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice. 2012; 2(3). Retrieved from https://journals.ku.edu/gjcpp/article/view/20901.

- Li L, Liu Y, Peng Z, Liao M, Lu L, Liao H, Li H. Peer relationships, motivation, self-efficacy, and science literacy in ethnic minority adolescents in China: a moderated mediation model. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;119:105524-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105524.

- Llorca A, Cristina Richaud M, Malonda E. Parenting, peer relationships, academic self-efficacy, and academic achievement: Direct and mediating effects. Front Psychol. 2017;8:316809. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02120.

- Li M, Frieze IH, Nokes-Malach TJ, Cheong J. Do friends always help your studies? Mediating processes between social relations and academic motivation. Soc Psychol Educ. 2013;16:129-49. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11218-012-9203-5.

- Kuo YC, Walker AE, Schroder KEE, Belland BR. Interaction, internet selfefficacy, and self-regulated learning as predictors of student satisfaction in online education courses. Internet High Educ. 2014;20:35-50. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2013.10.001.

- Wentzel KR, Muenks K, McNeish D, Russell S. Peer and teacher supports in relation to motivation and effort: a multi-level study. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2017;49:32-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.11.002.

- Huangfu Q, Wei N, Zhang R, Tang Y, Luo G. Social support and continuing motivation in chemistry: the mediating roles of interest in chemistry and chemistry self-efficacy. Chem Educ Res Pract. 2023;24(2):478-93. https://doi. org/10.1039/D2RP00165A.

- Juvonen J, Graham S. Bullying in schools: the power of bullies and the plight of victims. Ann Rev Psychol. 2014;65:159-85. https://doi.org/10.1146/ annurev-psych-010213-115030.

- Wentzel KR, Barry CM, Caldwell KA. Friendships in middle school: influences on motivation and school adjustment. J Educ Psychol. 2004;96(2):195. https:// doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.2.195.

- Tella A. The impact of motivation on student’s academic achievement and learning outcomes in mathematics among secondary school students in Nigeria. Eurasia J Math Sci Technol Educ. 2007;3(2):149-56. https://doi. org/10.12973/ejmste/75390.

- Law KMY, Geng S, Li T. Student enrollment, motivation and learning performance in a blended learning environment: the mediating effects of social, teaching, and cognitive presence. Comput Educ. 2019;S0360131519300508-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.02.021.

- Datu JAD, Yang W. Academic buoyancy, academic motivation, and academic achievement among Filipino high school students. Curr Psychol. 2021;40:3958-65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00358-y.

- Lepper M, Corpus J, Iyengar S. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations in the classroom: age differences and academic correlates. J Educ Psychol. 2005;97(2):184-96. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.2.184.

- Meng

. The relationship between student motivation and academic performance: the mediating role of online learning behavior. Qual Assur Educ. 2022;31(1):167-80. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-02-2022-0046. - Martin AJ, Dowson M, Interpersonal relationships, motivation, engagement, and achievement: Yields for theory, current issues, and educational practice. Rev Educ Res. 2009;79(1):327-65. https://doi. org/10.3102/0034654308325583.

- Shao Y, Kang S. The association between peer relationship and learning engagement among adolescents the chain mediating roles of self-efficacy and academic resilience. Front Psychol. 2022;13:938756. https://doi. org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.938756.

- Kiefer SM, Alley KM, Ellerbrock CR. Teacher and peer support for young adolescents’ motivation, engagement, and school belonging. RMLE Online. 2015;38(8):1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404476.2015.11641184.

- Valiente C, Swanson J, DeLay D, Fraser AM, Parker JH. Emotion-related socialization in the classroom: Considering the roles of teachers, peers, and the classroom context. Dev Psychol. 2020;56(3):578-94. https://doi.org/10.1037/ dev0000863.

- Lee J, Song H, Hong AJ. Exploring factors, and indicators for measuring students’ sustainable engagement in e-learning. Sustainability. 2019;11(4):985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11040985.

- Yuan J, Kim C. The effects of autonomy support on student engagement in peer assessment. Educ Tech Res Dev. 2018;66:25-52. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11423-017-9538-x.

- Kim HJ, Hong AJ, Song HD. The roles of academic engagement and digital readiness in students’ achievements in university e-learning environments. Int J Educational Technol High Educ. 2019;16(1):1-18. https://doi. org/10.1186/s41239-019-0152-3.

- Saqr M, López-Pernas S, Helske S, Hrastinski S. The longitudinal association between engagement and achievement varies by time, students’ profiles, and achievement state: a full program study. Comput Educ. 2023;199:104787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2023.104787.

- An F, Yu J, Xi L. Relationship between perceived teacher support and learning engagement among adolescents: mediation role of technology acceptance and learning motivation. Front Psychol. 2022;13:992464. https://doi. org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.992464.

- Semenova T. The role of learners’ motivation in MOOC completion. Open Learning: J Open Distance e-Learning. 2020;1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/02 680513.2020.1766434.

- Froiland JM, Worrell FC. Intrinsic motivation, learning goals, engagement, and achievement in a diverse high school. Psychol Sch. 2016;53(3):321-36. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21901.

- Huang

, Yang . Research on the relationships among learning motivation, learning engagement, and learning effectiveness. Educational Rev. 2021;5(6):182-90. https://doi.org/10.26855/er.2021.06.004. - Zhang W, Xu M, Su H. Dance with structural equations. Xiamen: Xiamen University; 2020.

- Li J, Wang J, Li JY, Qian S, Jia RX, Wang YQ, … Xu Y. How do socioeconomic status relate to social relationships among adolescents: a school-based study in East China.BMC pediatrics. 2020; 20:1-10. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s12887-020-02175-w.

- Amabile TM, Hill KG, Hennessey BA, Tighe EM. The work preference inventory: assessing intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1994;66(5):950. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.66.5.950.

- Chi L, Xin Z. Measurement of college students’ learning motivation and its relationship with self-efficacy. Psychol Dev Educ. 2006; (02): 64-70.

- Fang L, Shi K, Zhang K. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the learning engagement scale. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2008;6:618-20.

- Schaufeli WB, Salanova M, Gonzalez-roma V, Bakker AB. The measurement of Engagement and Burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor Analytic Approach. J Happiness Stud. 2002;3:71-92. https://doi.org/10.102 3/a:1015630930326.

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP. Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and recommendations on how to control it. Ann Rev Psychol. 2012;63:539-69. https://doi.org/10.1146/ annurev-psych-120710-100452.

- Zhou H, Long LR. Statistical remedies for common method biases. Adv Psychol Sci. 2004;12:942-50. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879.

- Hair JF, BlackWC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. 8th ed. Multivariate data analysis (2019). Andover, Hampshire: Cengage learning EMEA; 2019.

- Yockey RD. In: Translating C, Liu, Wu Z, editors. SPSS is actually very simple. Beijing: China Renmin University; 2010.

- Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981;66(6):39-50. https:// doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104.

- Jackson DL, Gillaspy JA Jr, Purc-Stephenson R. Reporting practices in confirmatory factor analysis: an overview and some recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2009;14(1):6-23. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014694.

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155-9. https://doi. org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155.

- Cheung MWL. Comparison of approaches to constructing confidence intervals for Mediating effects using Structural equation models. Structural equation modeling: a Multidisciplinary Journal. 2007; 14(2): 227-46. https:// doi.org/10.1080/10705510709336745.

- Cheung GW, Lau RS. Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables. Organizational Res Methods. 2007;11(2):296-325. https://doi. org/10.1177/1094428107300343.

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Mahwah: Erlbaum; 2008.

- Escalante MN, Fernández-Zabala A, Goñi Palacios E, Izar-de-la-Fuente DI. School Climate and Perceived academic achievement: direct or resiliencemediated relationship? Sustainability. 2020;13(1):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ su13010068.

- Berndt TJ. Friends’ influence on student adjustment to school. Educational Psychol. 1999;34(1):15-28. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3401_2.

- Chen

, French . Children’s social competence in cultural context. Ann Rev Psychol. 2008;59:591-616. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev. psych.59.103006.093606. - Véronneau MH, Dishion TJ. Predicting change in early adolescent problem behavior in the middle school years: a mesosystemic perspective on parenting and peer experiences. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38:1125-37. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9431-0.

- Lubbers MJ, Van Der Werf MPC, Snijders TAB, Creemers BPM, Kuyper H. The impact of peer relations on academic progress in junior high. J Sch Psychol. 2006;44(6):491-512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2006.07.005.

- Wentzel KR, Jablansky S, Scalise NR. Peer social acceptance and academic achievement: a meta-analytic study. J Educ Psychol. 2021;113(1):157-80. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu000046883.

- Chen JJL. Relation of academic support from parents, teachers, and peers to Hong Kong adolescents’ academic achievement: The mediating role of academic engagement. Genetic, social, and general psychology monographs. 2005; 131(2): 77-127. https://doi.org/10.3200/MONO.131.2.77-127.

- Chen

. The effect of thematic video-based instruction on learning and motivation in e-learning. Int J Phys Sci. 2012;7(6):957-65. https://doi.org/10.5897/ IJPS11.1788.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

College of Foreign Languages, Qufu Normal University, Qufu, China

College of Economics and Management, Tarim University, Alar, China Shandong Vocational Animal Science and Veterinary College, Weifang, China - Note PR=Peer Relationship, LM=Learning Motivation, LE=Learning Engagement, AA=academic achievement, IE=Indirect effect, TIE=Total Indirect Effect, DE=Direct Effect, TE=Total Effect, DIE=Distal Indirect Effect

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01780-z

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38755660

Publication Date: 2024-05-16

How peer relationships affect academic achievement among junior high school students: The chain mediating roles of learning motivation and learning engagement

Abstract

Background Despite the recognition of the impact of peer relationships, learning motivation, and learning engagement on academic achievement, there is still a gap in understanding the specific mechanisms through which peer relationships impact academic achievement via learning motivation and learning engagement. Methods This study aims to investigate how peer relationships affect junior high school students’ academic achievement through the chain mediating roles of learning motivation and learning engagement, employing the self-system model of motivational development as the theoretical framework. In January 2024, 717 participants were selected from two middle schools in eastern China (mean age

Conclusion For junior high school students to achieve academic success, the appropriate interventions should be implemented to improve peer relationships, learning motivation, and learning engagement.

Introduction

between academic motivation and mathematics achievement among junior high school students [18]. Liem and Martin posited that school engagement has a positive impact on academic performance [19]. The findings highlight the importance of considering both learning motivation and learning engagement in understanding academic achievement.

between peer relationships, learning motivation, learning engagement, and academic achievement. The relationship between the four variables and SSMMD can be elaborated as follows: Peer relationships, as a component of the social context, shapes an individual’s self-beliefs, which significantly influences their learning motivation. Students who possess higher levels of learning motivation are more likely to get active engagement in learning activities (as a component of the action), and impact their academic achievement positively (as a developmental outcome) [25]. Based on this model, this study hypothesizes that peer relationships (as a social context factor) may influence adolescents’ learning motivation (as a self-system factor), which in turn affects their learning engagement (as individual action), ultimately resulting in a positive impact on academic achievement (as developmental outcomes). This theoretical model in the study is visually represented in Fig. 1.

Peer relationships and academic achievement

among 596 ethnic minority junior school students in China [28]. Moreover, previous studies have suggested that the positive impact of peer relationships on academic achievement increases with grade level [29] and that same-gender peer relationships are particularly important in predicting academic achievement [19]. Overall, these findings emphasize the critical role of positive peer relationships in academic achievement, highlighting that adolescents who cultivate supportive relationships with their peers are more inclined to achieve success in their academic pursuits. On the basis of this, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H1: Peer relationships are positively correlated with academic achievement.

Learning motivation as a mediator

Learning engagement as a mediator

to devote more time to learning activities and ultimately achieve better academic outcomes [47]. Liem and Martin found that active participation and investment in learning activities positively predict academic success [19]. Wang et al. further supported this by demonstrating that higher levels of classroom engagement are associated with better academic performance [4]. Additionally, Saqr et al. highlighted the longitudinal effects of engagement, showing that sustained high levels of engagement lead to improved academic outcomes over time [48]. Taken together, these recent studies underscore the critical role of student engagement in fostering academic achievement.

Materials and methods

Sampling and data collection

Research instruments

Peer relationship scale

go comfort them.”). The 5 -point Likert scale was used, with scores ranging from 1 to 5 indicating “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”, with higher scores indicating higher peer relationships. The scale has good reliability and validity, which has been validated by recent research [54].

Learning motivation scale

Learning engagement scale

Academic achievement

Statistical analysis

| Demographic | Sample(

|

Frequency | Percentage |

| Gender | Male | 359 | 50.1% |

| Female | 358 | 49.9% | |

| Grade | Grade Seven | 385 | 53.7% |

| Grade Eight | 332 | 46.3% | |

| Resident | Town | 476 | 66.4% |

| Countryside | 241 | 33.6% | |

| Fathers’ educational level | Junior high school or below | 350 | 48.8% |

| Senior high school or vocational school | 264 | 36.8% | |

| College | 64 | 8.9% | |

| university | 39 | 5.4% | |

| Junior high school or below | 372 | 51.9% | |

| Fathers’ educational level | Senior high school or vocational school | 242 | 33.8% |

| College | 66 | 9.2% | |

| university | 37 | 5.2% |

Results

Common method variance

Sample characteristics

| Latent variable | Dimension | SC | Cronbach’s a | CR | AVE |

| Peer relationship (PR) | IR | 0.7720.873 | 0.922 | 0.926 | 0.678 |

| SE | 0.6910.913 | 0.913 | 0.916 | 0.689 | |

| Cl | 0.5950.871 | 0.929 | 0.928 | 0.591 | |

| Learning motivation(LM) | IM | 0.5490.909 | 0.936 | 0.947 | 0.566 |

| EM | 0.5480.906 | 0.944 | 0.945 | 0.524 | |

| Learning engagement(LE) | VG | 0.6380.859 | 0.846 | 0.849 | 0.589 |

| DD | 0.5690.909 | 0.940 | 0.942 | 0.675 | |

| AP | 0.6350.809 | 0.885 | 0.887 | 0.614 | |

| Peer relationship (PR) | 0.9070.915 | 0.961 | 0.937 | 0.832 | |

| Learning motivation(LM) | 0.7750.894 | 0.961 | 0.835 | 0.718 | |

| Learning engagement(LE) | 0.8620.915 | 0.946 | 0.862 | 0.678 | |

| Academic achievement(AA) | 0.7620.922 | 0.839 | 0.896 | 0.743 | |

| SC=standardized | coefficients; | IR=interpersonal | relation | ship; | SE=social |

or vocational school,

Measurement model

Table 2 presents the results of the reliability and convergent validity analysis. The measurement model demonstrated acceptable reliability, as indicated by Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.839 to 0.961 .

Structural model

Hypothesis test

| Potential variable | Peer relationship | Learning motivation | Learning engagement | Academic achievement |

| Peer relationship | 0.912 | |||

| Learning motivation | 0.534 | 0.847 | ||

| Learning engagement | 0.303 | 0.322 | 0.823 | |

| Academic achievement | 0.340 | 0.346 | 0.329 | 0.862 |

| Fit index | Suggested values | Value of this study |

| CMIN/DF(

|

>1 & <3 |

|

| Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) | <0.08 | 0.014 |

| Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) | >0.90 | 0.946 |

| Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) | >0.90 | 0.942 |

| Incremental Fit Index (NFI) | >0.90 | 0.946 |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | >0.90 | 0.993 |

| Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) | >0.90 | 0.993 |

Analyses of the mediating effect of peer relationship on academic achievement

| Hypothesis | Path | Unstand estimates | t | Sig. | Stand estimates | Hypothesis test |

| H1 | PR

|

1.313 | 3.712 | *** | 0.178 | Supported |

| H2 | PR

|

0.318 | 12.232 | *** | 0.534 | Supported |

| H3 | LM

|

2.239 | 3.512 | *** | 0.181 | Supported |

| H5 | PR

|

0.134 | 3.545 | *** | 0.183 | Supported |

| H6 |

|

0.274 | 4.033 | *** | 0.224 | Supported |

| H7 | LE

|

2.192 | 4.875 | *** | 0.217 | Supported |

bias-corrected confidence intervals (

effect of learning motivation accounts for

Discussion

| Path relationship | Point estimate | Product of coefficient | Bootstrapping | |||||

| Bias-corrected 95% CI | Percentile 95% CI | |||||||

| SE | t | Lower | upper | lower | upper | |||

| Test of indirect, direct and total effects | ||||||||

| DistallE |

|

0.191 | 0.072 | 2.653 | 0.076 | 0.365 | 0.059 | 0.339 |

| LMIE |

|

0.713 | 0.286 | 2.493 | 0.193 | 1.326 | 0.191 | 1.321 |

| LEIE |

|

0.293 | 0.127 | 2.307 | 0.081 | 0.585 | 0.076 | 0.584 |

| TIE | Total indirect effect | 1.198 | 0.312 | 3.840 | 0.656 | 1.907 | 0.635 | 1.870 |

| DE | PR

|

1.313 | 0.354 | 3.712 | 0.487 | 2.178 | 0.496 | 2.179 |

| TE | total effect | 2.510 | 0.404 | 6.213 | 1.745 | 3.309 | 1.740 | 3.290 |

| Percentage of indirect effects | ||||||||

| P1 | DistallE/TIE | 0.160 | 0.078 | 2.051 | 0.057 | 0.394 | 0.051 | 0.344 |

| P2 | LMIE/TIE | 0.595 | 0.137 | 4.343 | 0.257 | 0.787 | 0.258 | 0.789 |

| P3 | LEIE/TIE | 0.245 | 0.112 | 2.188 | 0.065 | 0.495 | 0.076 | 0.502 |

| P4 | TIE/TE | 0.477 | 0.128 | 3.727 | 0.256 | 0.777 | 0.256 | 0.777 |

| P5 | DE/TE | 0.523 | 0.128 | 4.086 | 0.223 | 0.744 | 0.223 | 0.744 |

the correlation between peer relationships and junior high school students’ academic achievement.

The results of the study demonstrated that learning engagement also partially mediated the association between peer relationships and academic achievement among junior high school students. This suggests that a high level of learning engagement can help elucidate why junior high school students who foster positive relationships with their peers tend to exhibit improved academic performance. When students have positive peer relationships, their increased learning engagement is reflected in their active participation in class, eagerness to complete assignments, and proactive pursuit of additional learning opportunities, ultimately leading to enhanced academic achievement [19]. This finding aligns with prior research [73, 74], which postulates that learning engagement is a pivotal factor linking peer relationships and junior high school students’ academic achievement. The connections that teenagers forge with their contemporaries will facilitate increased participation in the educational process, which in turn will lead to enhanced academic performance [75]. The finding provided more evidence that learning engagement plays a significant role in the link between peer relationships and academic achievement.

The study further revealed that learning motivation and learning engagement played a chain mediation role in the association between peer relationships and academic achievement, which is one of the most astonishing conclusions drawn from the investigation. This result aligns with the self-system model of motivational development [20], which suggests that positive interactions and support from peers contribute to the development of individuals’ learning motivation. This motivation, in turn, influences their level of learning engagement, leading to improved academic achievement. Furthermore, the study revealed that junior high school students’ learning motivation contributed less to their level of learning engagement (

was learning motivation, because motivation plays a crucial role in driving their interest, effort, and persistence in academic tasks [49].

The theoretical and practical implications

engagement, and academic achievement utilizing the self-system model of motivational development, which may provide insights for future research in other countries. Secondly, it explores the mediating mechanism between peer relationships and junior high school students’ academic achievement through examining the roles of learning motivation and learning engagement. The novel perspective can enrich our understanding of the link between peer relationships and academic achievement among junior high school students.

Limitations and future research directions

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

seen and approved by all authors. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The questionnaire and methodology for this study was approved by the research ethics committee of the College of Education at Qufu Normal University before data collection.

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Informed consent

Received: 25 April 2023 / Accepted: 9 May 2024

References

- Marsh HW, McCallum JH. The measurement of academic achievement: methods and background. Wiley; 1984.

- Hattie J, Visible Learning. A synthesis of over 800 Meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge; 2009.

- Genesee F, Lindholm-Leary K, Saunders W, Christian D. Educating English Language Learners. Cambridge.UK: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

- Wang

, Deng , Du . Harsh parenting and academic achievement in Chinese adolescents: potential mediating roles of effortful control and classroom engagement. J Sch Psychol. 2017;SX002244051730095-. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2017.09.002. - Corcoran RP, Cheung A, Kim E, Xie C. Effective Universal school-based social and emotional learning programs for improving academic achievement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Educational Res Rev. 2017;S1747938:X17300611-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. edurev.2017.12.001.

- Cheng L, Li M, Kirby JR, Qiang H, Wade-Woolley L. English language immersion and students’ academic achievement in English, Chinese and mathematics. Evaluation Res Educ. 2010;23(3):151-69. https://doi.org/10.1080/0950079 0.2010.489150.

- Zhang W, Zhang L, Chen L, Ji L, Deater-Deckard K. Developmental changes in longitudinal associations between academic achievement and psychopathological symptoms from late childhood to middle adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(2):178-88. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12927.

- Steinmayr R, Meiner A, Weideinger AF, Wirthwein L. Academic achievement. UK: Oxford University Press; 2014.

- Wang M, Kiuru N, Degol JL, Salmela-Aro K. Friends, academic achievement, and school engagement during adolescence: a social network approach to peer influence and selection effects. Learn Instruction. 2018;58:148-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.06.003.

- Wei Y. Study on the influence of school factors on self-esteem development of children. Psychol Dev Educ. 1998;2:12-6.

- Gallardo LO, Barrasa A, Fabricio G. Positive peer relationships and academic achievement across early and mid-adolescence. Social Behav Personality:An Int J. 2016;44(10):1637-48. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2016.44.10.1637.

- Dogan U, Student, Engagement. Academic Self-efficacy, and academic motivation as predictors of academic achievement. Anthropol. 2015;20(3):553-61. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720073.2015.11891759.

- Tanaka M. Examining kanji learning motivation using self-determination theory. System. 2013;41:804-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2013.08.004.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2020;101860-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. cedpsych.2020.101860.

- Schaufeli WB, Martinez IM, Pinto AM, Salanova M, Bakker AB. Burnout and Engagement in University students: a cross-national study. J Cross-Cult Psychol. 2002;33:464-81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022102033005003.

- Li Y, Yao C, Zeng S, Wang X, Lu T, Li C, Lan J, You X. How social networking site addiction drives university students’ academic achievement: the mediating role of learning engagement. J Pac Rim Psychol. 2019;13:e19. https://doi. org/10.1017/prp.2019.12.

- Wentzel KR. Peer relationships, motivation, and academic achievement at school. In: Elliot AJ, Dweck CS, Yeager DS, editors. Handbook of competence and motivation: theory and application. The Guilford; 2017. pp. 586-603.

- Li L, Peng Z, Lu L, Liao H, Li H, Peer relationships, self-efficacy, academic motivation, and mathematics achievement in Zhuang adolescents: a Moderated Mediation Model. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;105358. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105358.

- Liem GA, Martin AJ. Peer relationships and adolescents’ academic and non-academic outcomes: same-sex and opposite-sex peer effects and the mediating role of school engagement. Br J Educ Psychol. 2011;81(2):183-206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2010.02013.x.

- Connell JP, Wellborn JG. Competence, autonomy, and relatedness: a motivational analysis of self-system processes. In: Gunnar MR, Sroufe LA, editors. The Minnesota symposia on child psychology. Self-processes and development. Volume 23. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1991. pp. 43-77.

- Skinner E, Furrer C, Marchand G, Kindermann T. Engagement and disaffection in the classroom: part of a larger motivational dynamic? J Educ Psychol. 2008;100(4):765-81. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012840.

- Deci E. Intrinsic motivation. New York, NY: Plenum; 1975.

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Springer Science + Business Media; 1985. P.11.

- Wang M, Wang M, Wang J. Parental conflict damages academic performance in adolescents: the mediating roles of Effortful Control and Classroom Participation. Psychol Dev Educ. 2018;34(04):434-42.

- Wu H, Li S, Zheng J, Guo J. Medical students’ motivation and academic performance: the mediating roles of self-efficacy and learning engagement. Med Educ Online. 2020;25(1):1742964. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.202 0.1742964.

- Ma D. Research on the relationship between parent-child relationship, peer relationship and academic performance of junior high school students [Unpublished manuscript]. Qufu Normal University, China; 2020.

- Jacobson LT, Burdsal CA. Academic Performance in Middle School: Friendship Influences. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice. 2012; 2(3). Retrieved from https://journals.ku.edu/gjcpp/article/view/20901.

- Li L, Liu Y, Peng Z, Liao M, Lu L, Liao H, Li H. Peer relationships, motivation, self-efficacy, and science literacy in ethnic minority adolescents in China: a moderated mediation model. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;119:105524-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105524.

- Llorca A, Cristina Richaud M, Malonda E. Parenting, peer relationships, academic self-efficacy, and academic achievement: Direct and mediating effects. Front Psychol. 2017;8:316809. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02120.

- Li M, Frieze IH, Nokes-Malach TJ, Cheong J. Do friends always help your studies? Mediating processes between social relations and academic motivation. Soc Psychol Educ. 2013;16:129-49. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11218-012-9203-5.

- Kuo YC, Walker AE, Schroder KEE, Belland BR. Interaction, internet selfefficacy, and self-regulated learning as predictors of student satisfaction in online education courses. Internet High Educ. 2014;20:35-50. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2013.10.001.

- Wentzel KR, Muenks K, McNeish D, Russell S. Peer and teacher supports in relation to motivation and effort: a multi-level study. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2017;49:32-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.11.002.

- Huangfu Q, Wei N, Zhang R, Tang Y, Luo G. Social support and continuing motivation in chemistry: the mediating roles of interest in chemistry and chemistry self-efficacy. Chem Educ Res Pract. 2023;24(2):478-93. https://doi. org/10.1039/D2RP00165A.

- Juvonen J, Graham S. Bullying in schools: the power of bullies and the plight of victims. Ann Rev Psychol. 2014;65:159-85. https://doi.org/10.1146/ annurev-psych-010213-115030.

- Wentzel KR, Barry CM, Caldwell KA. Friendships in middle school: influences on motivation and school adjustment. J Educ Psychol. 2004;96(2):195. https:// doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.2.195.

- Tella A. The impact of motivation on student’s academic achievement and learning outcomes in mathematics among secondary school students in Nigeria. Eurasia J Math Sci Technol Educ. 2007;3(2):149-56. https://doi. org/10.12973/ejmste/75390.

- Law KMY, Geng S, Li T. Student enrollment, motivation and learning performance in a blended learning environment: the mediating effects of social, teaching, and cognitive presence. Comput Educ. 2019;S0360131519300508-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.02.021.

- Datu JAD, Yang W. Academic buoyancy, academic motivation, and academic achievement among Filipino high school students. Curr Psychol. 2021;40:3958-65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00358-y.

- Lepper M, Corpus J, Iyengar S. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations in the classroom: age differences and academic correlates. J Educ Psychol. 2005;97(2):184-96. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.2.184.

- Meng

. The relationship between student motivation and academic performance: the mediating role of online learning behavior. Qual Assur Educ. 2022;31(1):167-80. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-02-2022-0046. - Martin AJ, Dowson M, Interpersonal relationships, motivation, engagement, and achievement: Yields for theory, current issues, and educational practice. Rev Educ Res. 2009;79(1):327-65. https://doi. org/10.3102/0034654308325583.

- Shao Y, Kang S. The association between peer relationship and learning engagement among adolescents the chain mediating roles of self-efficacy and academic resilience. Front Psychol. 2022;13:938756. https://doi. org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.938756.

- Kiefer SM, Alley KM, Ellerbrock CR. Teacher and peer support for young adolescents’ motivation, engagement, and school belonging. RMLE Online. 2015;38(8):1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404476.2015.11641184.

- Valiente C, Swanson J, DeLay D, Fraser AM, Parker JH. Emotion-related socialization in the classroom: Considering the roles of teachers, peers, and the classroom context. Dev Psychol. 2020;56(3):578-94. https://doi.org/10.1037/ dev0000863.

- Lee J, Song H, Hong AJ. Exploring factors, and indicators for measuring students’ sustainable engagement in e-learning. Sustainability. 2019;11(4):985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11040985.

- Yuan J, Kim C. The effects of autonomy support on student engagement in peer assessment. Educ Tech Res Dev. 2018;66:25-52. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11423-017-9538-x.

- Kim HJ, Hong AJ, Song HD. The roles of academic engagement and digital readiness in students’ achievements in university e-learning environments. Int J Educational Technol High Educ. 2019;16(1):1-18. https://doi. org/10.1186/s41239-019-0152-3.

- Saqr M, López-Pernas S, Helske S, Hrastinski S. The longitudinal association between engagement and achievement varies by time, students’ profiles, and achievement state: a full program study. Comput Educ. 2023;199:104787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2023.104787.

- An F, Yu J, Xi L. Relationship between perceived teacher support and learning engagement among adolescents: mediation role of technology acceptance and learning motivation. Front Psychol. 2022;13:992464. https://doi. org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.992464.

- Semenova T. The role of learners’ motivation in MOOC completion. Open Learning: J Open Distance e-Learning. 2020;1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/02 680513.2020.1766434.

- Froiland JM, Worrell FC. Intrinsic motivation, learning goals, engagement, and achievement in a diverse high school. Psychol Sch. 2016;53(3):321-36. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21901.

- Huang

, Yang . Research on the relationships among learning motivation, learning engagement, and learning effectiveness. Educational Rev. 2021;5(6):182-90. https://doi.org/10.26855/er.2021.06.004. - Zhang W, Xu M, Su H. Dance with structural equations. Xiamen: Xiamen University; 2020.

- Li J, Wang J, Li JY, Qian S, Jia RX, Wang YQ, … Xu Y. How do socioeconomic status relate to social relationships among adolescents: a school-based study in East China.BMC pediatrics. 2020; 20:1-10. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s12887-020-02175-w.

- Amabile TM, Hill KG, Hennessey BA, Tighe EM. The work preference inventory: assessing intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1994;66(5):950. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.66.5.950.

- Chi L, Xin Z. Measurement of college students’ learning motivation and its relationship with self-efficacy. Psychol Dev Educ. 2006; (02): 64-70.

- Fang L, Shi K, Zhang K. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the learning engagement scale. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2008;6:618-20.

- Schaufeli WB, Salanova M, Gonzalez-roma V, Bakker AB. The measurement of Engagement and Burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor Analytic Approach. J Happiness Stud. 2002;3:71-92. https://doi.org/10.102 3/a:1015630930326.

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP. Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and recommendations on how to control it. Ann Rev Psychol. 2012;63:539-69. https://doi.org/10.1146/ annurev-psych-120710-100452.

- Zhou H, Long LR. Statistical remedies for common method biases. Adv Psychol Sci. 2004;12:942-50. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879.

- Hair JF, BlackWC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. 8th ed. Multivariate data analysis (2019). Andover, Hampshire: Cengage learning EMEA; 2019.

- Yockey RD. In: Translating C, Liu, Wu Z, editors. SPSS is actually very simple. Beijing: China Renmin University; 2010.

- Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981;66(6):39-50. https:// doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104.

- Jackson DL, Gillaspy JA Jr, Purc-Stephenson R. Reporting practices in confirmatory factor analysis: an overview and some recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2009;14(1):6-23. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014694.

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155-9. https://doi. org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155.

- Cheung MWL. Comparison of approaches to constructing confidence intervals for Mediating effects using Structural equation models. Structural equation modeling: a Multidisciplinary Journal. 2007; 14(2): 227-46. https:// doi.org/10.1080/10705510709336745.

- Cheung GW, Lau RS. Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables. Organizational Res Methods. 2007;11(2):296-325. https://doi. org/10.1177/1094428107300343.

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Mahwah: Erlbaum; 2008.

- Escalante MN, Fernández-Zabala A, Goñi Palacios E, Izar-de-la-Fuente DI. School Climate and Perceived academic achievement: direct or resiliencemediated relationship? Sustainability. 2020;13(1):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ su13010068.

- Berndt TJ. Friends’ influence on student adjustment to school. Educational Psychol. 1999;34(1):15-28. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3401_2.

- Chen

, French . Children’s social competence in cultural context. Ann Rev Psychol. 2008;59:591-616. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev. psych.59.103006.093606. - Véronneau MH, Dishion TJ. Predicting change in early adolescent problem behavior in the middle school years: a mesosystemic perspective on parenting and peer experiences. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38:1125-37. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9431-0.

- Lubbers MJ, Van Der Werf MPC, Snijders TAB, Creemers BPM, Kuyper H. The impact of peer relations on academic progress in junior high. J Sch Psychol. 2006;44(6):491-512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2006.07.005.

- Wentzel KR, Jablansky S, Scalise NR. Peer social acceptance and academic achievement: a meta-analytic study. J Educ Psychol. 2021;113(1):157-80. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu000046883.

- Chen JJL. Relation of academic support from parents, teachers, and peers to Hong Kong adolescents’ academic achievement: The mediating role of academic engagement. Genetic, social, and general psychology monographs. 2005; 131(2): 77-127. https://doi.org/10.3200/MONO.131.2.77-127.

- Chen

. The effect of thematic video-based instruction on learning and motivation in e-learning. Int J Phys Sci. 2012;7(6):957-65. https://doi.org/10.5897/ IJPS11.1788.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

College of Foreign Languages, Qufu Normal University, Qufu, China

College of Economics and Management, Tarim University, Alar, China Shandong Vocational Animal Science and Veterinary College, Weifang, China - Note PR=Peer Relationship, LM=Learning Motivation, LE=Learning Engagement, AA=academic achievement, IE=Indirect effect, TIE=Total Indirect Effect, DE=Direct Effect, TE=Total Effect, DIE=Distal Indirect Effect