DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-024-00521-3

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-06

كيف تعزز الألعاب التعليمية التعلم في التعليم العالي في مجالات العلوم والتكنولوجيا والهندسة والرياضيات: دراسة مختلطة المنهجيات

الملخص

الخلفية: الطلب على المحترفين ذوي الخبرة في مجالات العلوم والتكنولوجيا والهندسة والرياضيات (STEM) يستمر في النمو. لتلبية هذا الطلب، تسعى الجامعات بنشاط إلى استراتيجيات لجذب المزيد من الطلاب إلى تخصصات STEM وتحسين نتائج تعلمهم. إحدى الطرق الواعدة هي الألعاب التعليمية، وبالتحديد استخدام لوحات المتصدرين. تبحث هذه الدراسة في تأثير الألعاب التعليمية المعتمدة على لوحات المتصدرين على أداء التعلم لـ 175 طالبًا في دورة حساب التفاضل والتكامل، مع التركيز على الأدوار الوسيطة للدافع الذاتي والكفاءة الذاتية، بالإضافة إلى العوامل المحتملة المؤثرة مثل الجنس وخبرة الألعاب. تم استخدام نهج بحث مختلط، يجمع بين تصميم شبه تجريبي قبل الاختبار وبعده مع تسع مقابلات نوعية. النتائج: لوحظ تحسن كبير في أداء التعلم للطلاب في الحالة المعتمدة على الألعاب التعليمية. ومع ذلك، لم يتم العثور على تأثيرات كبيرة تتعلق بالمتغيرات الوسيطة. دعمت التحليلات النوعية هذه النتائج، حيث كشفت أن الطلاب لم يدركوا زيادة في الاستقلالية ضمن الحالة المعتمدة على الألعاب التعليمية، وبدلاً من ذلك، كانت مواضيع الدافع المسيطر سائدة. بينما قدمت لوحة المتصدرين شعورًا بالإنجاز لمعظم المشاركين، لم تُظهر التحليلات الكمية ارتباطًا قويًا بين الكفاءة الذاتية وأداء التعلم. الاستنتاجات: تشير هذه الدراسة إلى أن الألعاب التعليمية المعتمدة على لوحات المتصدرين يمكن أن تعزز أداء التعلم في دورات حساب التفاضل والتكامل على مستوى الجامعة. ومع ذلك، تسلط النتائج الضوء على أهمية تصميم الألعاب التعليمية بعناية، خاصة في كيفية تأثير عناصر اللعبة المختلفة على جوانب دافعية الطلاب.

المقدمة

الإطار المفاهيمي والنظري

تعريف الألعاب التعليمية وعناصر اللعبة

الألعاب التعليمية في التعليم العالي في الرياضيات

الدراسات هي مجال البحث، حيث تهيمن العلوم الصحية والاجتماعية (خاصة علم النفس) في استخدامها، أو الصعوبات التي تواجهها عند محاولة الإبلاغ عن هذه التحليلات بدقة (شولر وآخرون، 2024).

الألعاب التعليمية وأداء التعلم

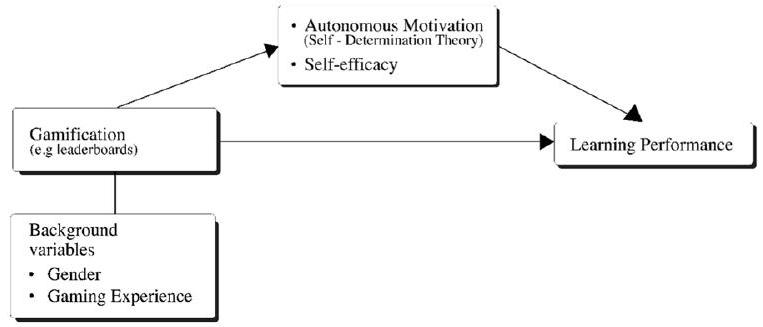

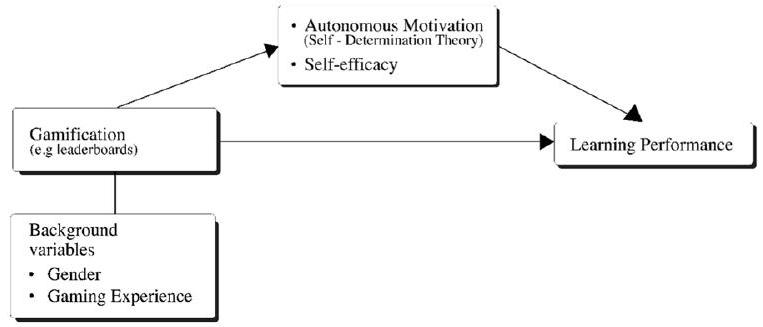

نموذج واحد لدراسة تأثير الألعاب التعليمية على التعلم هو “نظرية التعليم المعتمد على الألعاب” (لاندرز، 2014). تؤكد هذه النظرية على التأثير غير المباشر للألعاب التعليمية على التعلم من خلال الإشارة إلى دور المتغيرات الوسيطة. على سبيل المثال، تفاعل الطلاب المعرضون للوحات المتصدرين (عناصر اللعبة) أكثر من مرة مع مشروع (الوقت المستغرق في سلوك المهمة) مقارنةً بالحالة الضابطة، مما أدى إلى زيادة في أداء التعلم (لاندرز ولاندرز، 2014). حاولت بعض الدراسات استخدام هذه النظرية للألعاب التعليمية (أورتيز-روخاس وآخرون، 2017، 2019). في الدراسة الحالية، بنينا على هذه النظرية، مع اعتبار الدافع الذاتي والكفاءة الذاتية كمتغيرات وسيطة.

الألعاب التعليمية والدافع الذاتي

يتم ملاحظة الدافع المحدد عندما يتعرف الشخص على قيمة نشاط معين (على سبيل المثال، أخذ فصل دراسي لأن الطلاب يعرفون أنه مفيد لاجتياز المادة التالية).

تؤكد نظرية تحديد الذات على كيفية تحقيق كل نوع من أنواع الدافع أو التأكيد على ثلاثة احتياجات نفسية: الحاجة إلى الاستقلالية (كون الفرد متحكمًا في سلوكه)، والكفاءة (تطوير المهارة)، والانتماء (الإحساس بالانتماء إلى مجموعة) (رايان وديتشي، 2000). من المرجح أن تعزز البيئات الم gamified التي تساعد على تلبية هذه الاحتياجات الدافع الذاتي (ميكلر وآخرون، 2017). على سبيل المثال، وصف فان روي وزامان (2017) كيف يدعم الإعداد الم gamified الاستقلالية من خلال السماح للطلاب باختيار أنشطتهم. كما يبدو أنه يلبي حاجتهم إلى الكفاءة، حيث أن الأنشطة تتسم بالتحدي ولكنها قابلة للتحقيق، مع آليات تغذية راجعة (مثل الشارات) تُعلم الطلاب بتقدمهم الإيجابي. أخيرًا، يبدو أن الحاجة إلى الانتماء تتحقق عندما يتم تسهيل التفاعلات. على سبيل المثال، تتيح لوحات المتصدرين للطلاب مقارنة ومشاركة تقدمهم، بالإضافة إلى مناقشة مواقعهم (سايلر وآخرون، 2013). في أبحاث gamification، على حد علمنا، ركز فقط فان روي وزامان (2018) على الدافع الذاتي، مما أظهر زيادة بعد التعرض لعناصر gamified مثل الشارات ولوحات المتصدرين.

يمكن تلبية الاحتياجات التحفيزية في بيئة موجهة للألعاب اعتمادًا على كيفية تنفيذ عناصر اللعبة، وهو مفهوم أطلق عليه ديتردينغ (2011) اسم “القدرة التحفيزية المتموضعة”. على سبيل المثال، بينما تشجع لوحات المتصدرين غالبًا المنافسة بين الأقران ويمكن أن تقلل من الدافع الذاتي (ريف وديتسي، 1996)، إلا أنها يمكن أن تعزز أيضًا الكفاءة وتعزز الاستقلالية الشخصية من خلال تسليط الضوء على التقدم الذاتي. علاوة على ذلك، فإن القدرات التحفيزية ليست مرتبطة بعناصر الألعاب الفردية ولكن تعتمد على النظام الموجه للألعاب بالكامل (ديتردينغ، 2014). لذلك، من الضروري النظر في التفاعل بين العناصر في نظام ما وكيفية تعزيز تركيبتها للدافع الذاتي. ومع ذلك، فإن إحدى الانتقادات لنظرية تحديد الذات هي أنها لا تأخذ في الاعتبار الفروق الفردية (مثل سمات الشخصية، الخلفية الثقافية، القدرات المعرفية) (بولر وفيليبس، 2022). لمعالجة ذلك، تتضمن دراستنا متغيرات أساسية مثل الجنس وخبرة الألعاب لاستكشاف ما إذا كانت هذه الفروق تؤثر على الدافع عند دمجها مع الألعاب.

تحفيز الألعاب والكفاءة الذاتية

(مراقبة أداء الآخرين الناجح)، الإقناع اللفظي (تلقي تعليقات إيجابية أو سلبية حول أداء المهمة)، والحالات الفسيولوجية (مثل مستويات التوتر) (باندورا، 1982). تجسد العديد من عناصر الألعاب التفاعلية التغذية الراجعة حول الأداء الشخصي وأداء الآخرين (بليومرز وآخرون، 2012). على سبيل المثال، توضح كريستي وفوكس (2014) كيف توفر لوحات المتصدرين تغذية راجعة من خلال عرض ترتيب كل طالب. كما يؤكد المؤلفان الآخران كيف تستدعي لوحات المتصدرين تجارب غير مباشرة لأن الطلاب يرون مدى أداء الآخرين. فيما يتعلق بالحالات الفسيولوجية، عندما تكون اللعبة ليست صعبة للغاية ولا سهلة للغاية، فإنها تحفز مستوى مقبول من التوتر أو الإرهاق، مما يعزز الانخراط وإكمال المهمة (كاب، 2012). زادت الأبحاث حول تأثيرات الألعاب التفاعلية على كفاءة الطلاب الذاتية في السنوات الأخيرة. قام أحمد وأسيكصوي (2021) بالتحقيق في تأثير فصل التعلم المقلوب المعزز بالألعاب على كفاءة الذات ومهارات الابتكار لطلاب الفيزياء في مختبر افتراضي. أظهرت النتائج تأثيرًا إيجابيًا على مهارات الابتكار؛ ومع ذلك، لم تظهر كفاءة الذات أي تحسين ملحوظ. قدم تشين وليانغ (2022) دراستهم حول كفاءة الذات كمتغير وسيط، مستكشفين تأثير الألعاب التفاعلية على انخراط الطلاب في الدراسة في فصل تسويق باستخدام استبيانات من 187 طالبًا صينيًا. أظهرت النتائج أن المتعة وكفاءة الذات تؤثران بشكل غير مباشر على الانخراط. في حالة تعليم الرياضيات، الدراسات نادرة وقد أسفرت عن نتائج متناقضة؛ فقد أظهرت بعض الدراسات نتائج إيجابية (بانفيلد وويلكيرسون، 2014)، بينما أفادت أخرى بعدم وجود تأثير ملحوظ (أورتيز-روخاس وآخرون، 2017). تؤكد هذه التناقضات على الحاجة إلى مزيد من البحث حول كفاءة الذات في تعليم الرياضيات.

تحفيز الألعاب والمتغيرات الخلفية

تحفيز الألعاب باستخدام لوحات المتصدرين

تمثيل رسومي للنموذج المفاهيمي والنظري

فرضيات البحث

H2: الطلاب المشاركون في دورة حساب معززة بالألعاب يعكسون دافعًا ذاتيًا أعلى وكفاءة ذاتية أعلى من الطلاب في حالة التحكم.

H3: الطلاب المشاركون في دورة حساب معززة بالألعاب يحققون أداءً تعليميًا أعلى من الطلاب في حالة التحكم، مع الأخذ في الاعتبار التأثير الوسيط للتغيرات في الدافع الذاتي، والكفاءة الذاتية، والتفاعل مع المتغيرات المشتركة (الجنس، خبرة الألعاب).

المنهجية

تصميم البحث

مجموعة الدراسة

| المقاييس | الاختبار القبلي | الاختبار البعدي |

| الدافع الذاتي |

|

|

| الكفاءة الذاتية |

|

α=0.89 |

| خبرة الألعاب |

|

الأدوات النوعية

الإجراء

- الأسبوع 1 (الاختبار القبلي): أكمل جميع الطلاب في كل من بيئة البحث التحكمية والتجريبية خلال وقت الحصة، الاستبيانات المختلفة لقياس مستوى كفاءتهم الذاتية، والدافع الذاتي، وخبرة الألعاب، ومعرفة الحساب.

- الأسبوع 2 إلى 7 (بيئة معززة بالألعاب والتحكم): تم تنفيذ نفس الأنشطة التعليمية في كلا حالتي البحث، بما في ذلك الواجبات الإلزامية مثل الواجبات المنزلية، ومشاريع المجموعة، والاختبارات القصيرة، والواجبات الاختيارية مثل اختبارات التقييم الذاتي. ومع ذلك، بالنسبة للطلاب في المجموعة التجريبية، تم تقديم هذه الأنشطة في بيئة معززة بالألعاب.

- الأسبوع 8 و9 (الاختبار البعدي): مشابه للإعداد الخاص بالاختبار القبلي، خلال وقت الحصة، قام الطلاب في كلا حالتي البحث بملء جميع أدوات القياس (الكفاءة الذاتية، الدافع الذاتي، واختبار معرفة الحساب).

تصميم الحالة المعززة بالألعاب

| الفئات | أسئلة نموذجية | |||

| دمج لوحات المتصدرين كعنصر معزز بالألعاب |

|

|||

| لوحات المتصدرين (أفضل الطلاب في لوحة المتصدرين) |

|

|||

| لوحات المتصدرين (الطلاب المتوسطون والمنخفضون في لوحة المتصدرين) | – كيف شعرت/ما كانت أفكارك عندما لم يظهر اسمك في لوحة المتصدرين العامة كل أسبوع؟ | |||

| لوحات المتصدرين والكفاءة الذاتية | – هل كنت متأكدًا خلال أي أسبوع أنك ستدخل في المراكز الثلاثة الأولى؟ |

عند تصميم النهج المعتمد على الألعاب، تم دمج العناصر المحددة لميكانيكيات الألعاب – الديناميات، والميكانيكا، والمكونات – كما أوضحها ويرباخ وآخرون (2012) لجذب الطلاب بطرق متنوعة:

- الديناميات: تم استدعاء مشاعر مثل الفضول من خلال عدم إخبار الطلاب عن النشاط المستقبلي الذي سيتم تضمينه في الترتيب.

- الميكانيكا: نحن نبني على الحظ، والمنافسة، والتغذية الراجعة. كان الحظ (عنصر العشوائية) واضحًا لأن الطلاب لم يعرفوا أي نشاط سيتم اختياره. كان من المتوقع أن يثير ذلك التفاعل والدافع لكل نشاط. عززت الأنشطة الاختيارية شعور الاستقلالية لأن الطلاب كان لديهم حرية الاختيار. كانت طبيعة المنافسة التي أثارتها لوحات المتصدرين تركز على مواقعهم الشخصية: حاول تحسين أدائك مقارنة بالأسبوع السابق. قدمت لوحات المتصدرين أداءهم فيما يتعلق بالتغذية الراجعة. كما أن الأخيرة أثارت أيضًا شعور الكفاءة والفعالية الذاتية.

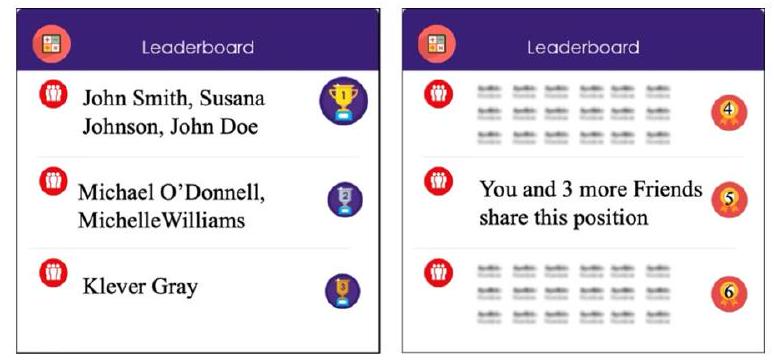

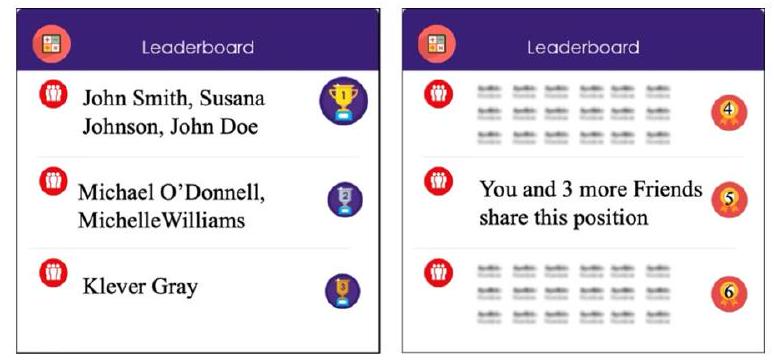

- المكونات: في الحالة التجريبية، تم تصميم نوعين من لوحات المتصدرين، كلاهما دون عرض الدرجات لتجنب الإحباط. كان أحدهما يعرض فقط المراكز الثلاثة الأولى وأسماء الطلاب. تم الإعلان عن هذا الترتيب علنًا من خلال نظام إدارة التعلم في نهاية كل أسبوع لكل دورة تعليمية معتمدة على الألعاب. تم عرض بقية المراكز من خلال لوحة متصدرين نسبية دون تحديد من هو أعلى أو أدنى من الطالب. تم إرسال هذا الترتيب بشكل خاص إلى كل طالب من خلال نظام إدارة التعلم. إذا شارك طالب نفس المركز مع آخرين، فإن المراكز الثلاثة الأولى…

تحليل البيانات

التحليل الكمي

التحليل النوعي

| المتغيرات | حالة التحكم (

|

الحالة التجريبية (

|

| أداء التعلم | ||

| اختبار قبلي | 11.65 (7.57) | 11.72 (6.52) |

| بعد الاختبار | ٢٩.٧١ (١١.٩٥) | ٣٧.٠٣ (٩.٥٤) |

| فرق في أداء التعلم (زيادة التعلم) | 18.06 (8.50) | 25.31 (8.98) |

| الدافع الذاتي (AM) | ||

| اختبار قبلي | 6.02 (0.14) | 6.14 (0.06) |

| بعد الاختبار | 5.93 (0.82) | 5.78 (0.96) |

| الفرق في AM (فرق AM) | -0.10 (0.61) | – 0.36 (0.89) |

| الكفاءة الذاتية | ||

| اختبار تمهيدي | 65.50 (13.43) | 64.02 (17.97) |

| بعد الاختبار | ٧٢.٢٣ (١٥.٥٢) | 72.22 (12.90) |

| فرق في SE (فرق SE) | 6.74 (12.00) | 8.20 (15.10) |

| تجربة الألعاب | 2.75 (0.90) | 2.65 (1.06) |

النتائج

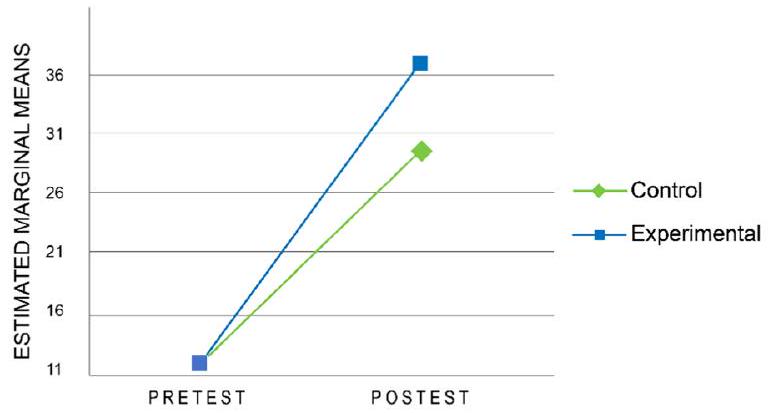

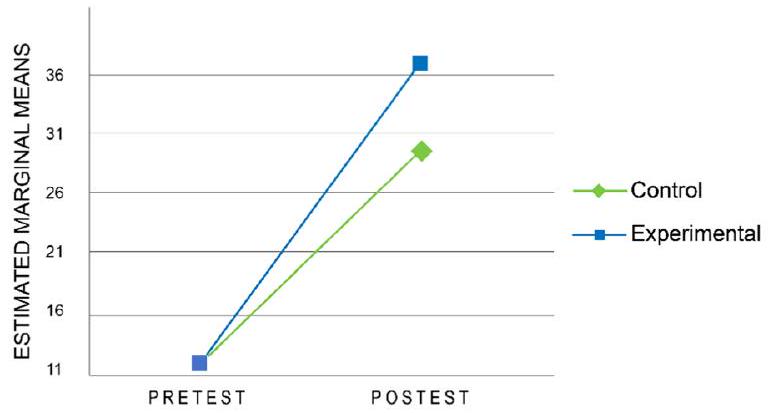

فيما يتعلق بـ H1، كشفت النتائج عن فرق رئيسي كبير في الحالة على مر الزمن،

لتكملة التحليل أعلاه، تم استخدام نموذج مختلط خطي للتنبؤ بأداء تعلم الطلاب، مع تضمين تقاطع عشوائي لأخذ التباين داخل الموضوع في الاعتبار. شملت التأثيرات الثابتة الظروف التجريبية، والوقت، والتفاعل بين الشرط والوقت. وقد أوضح النموذج

بالنسبة لـ H2، تشير النتائج إلى أنه لم تكن هناك تفاعلات ذات دلالة بين الحالة والوقت في أي من الدافع الذاتي،

| المتغيرات التنبؤية | أثر | تقدير | SE | درجات الحرية | ت | ب |

| (الاعتراض) | (الاعتراض) | ٢٢.٥٢ | 0.71 | 173 | 31.81 | <0.001 |

| الحالة التجريبية | 1-0 | 3.70 | 1.42 | 173 | 2.61 | 0.010 |

| الوقت | 2-1 | 21.69 | 0.82 | 173 | ٢٦.٦٠ | <0.001 |

| شرط * وقت |

|

٧.٢٥ | 1.63 | 173 | ٤.٤٥ | <0.001 |

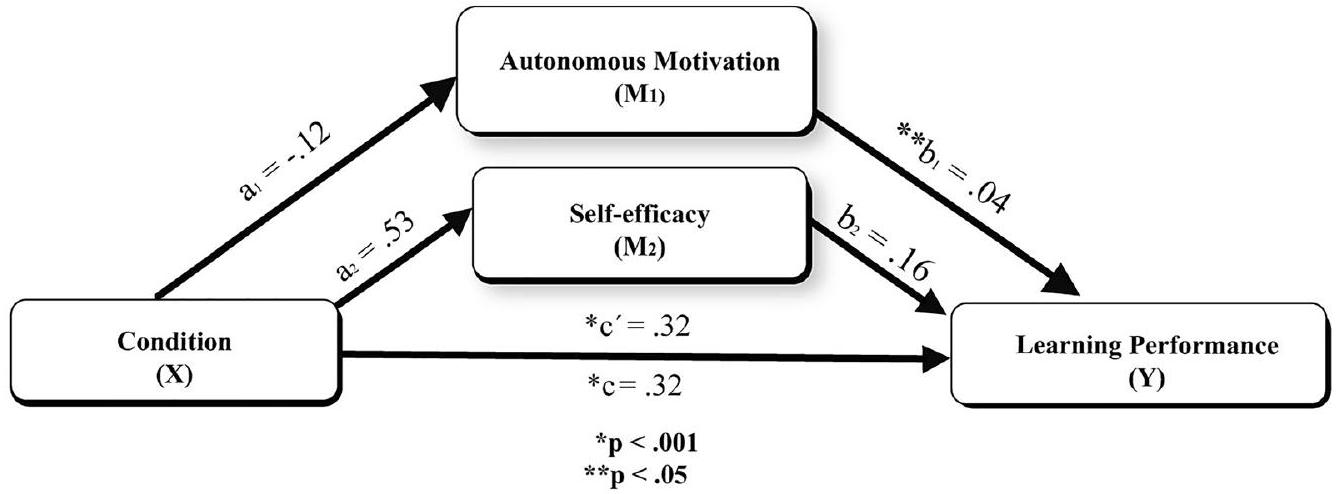

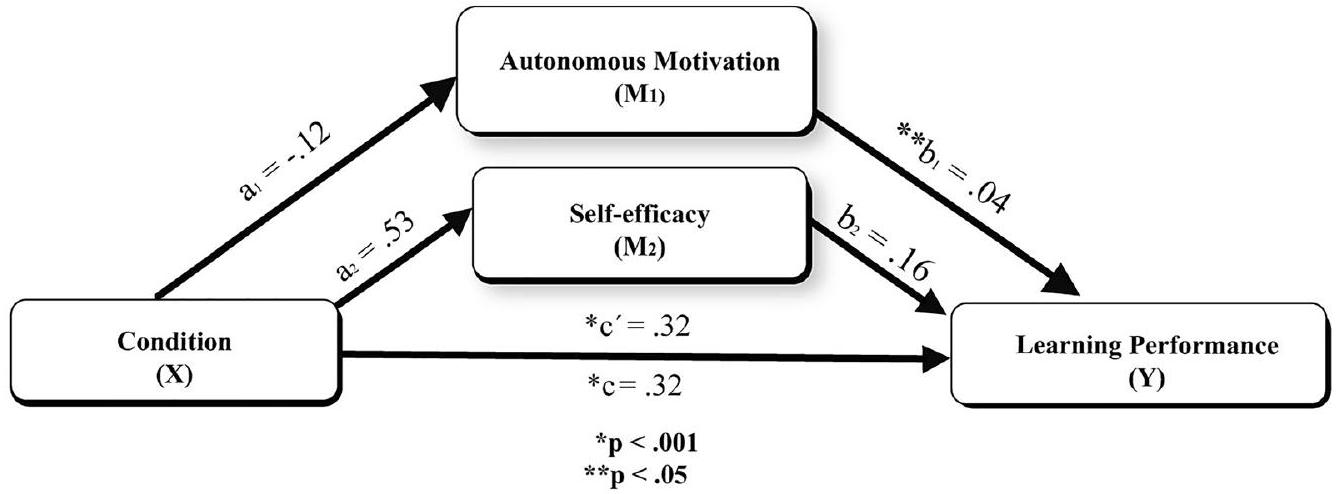

تأثير ذو دلالة إحصائية على مكاسب التعلم. وبالتالي، تم استبعاد كلا المتغيرين من النموذج. وهكذا، استمر تحليل الوساطة مع الدافع الذاتي والكفاءة الذاتية. كما هو موضح في الشكل 4، لم تكن الحالة البحثية مرتبطة بشكل كبير بالدافع الذاتي (a1:

نقاش

فيما يتعلق بالفرضية الثانية، لم تدعم النتائج تأثير الألعاب على الدافع الذاتي والكفاءة الذاتية. على حد علمنا، الدراسة الوحيدة التي قيمت أيضًا الدافع الذاتي – على الرغم من استخدام عناصر ألعاب مختلفة – هي دراسة فان روي وزامان (2018). على عكس نتائجنا، أفادت دراستهم أن الطلاب زادوا من دافعهم الذاتي مع مرور الوقت. توفر تحليلاتنا للبيانات النوعية تفسيرات معقولة. على الرغم من أن التصميم المعتمد على الألعاب كان يهدف إلى تعزيز الدافع الذاتي، إلا أن الطلاب لم يشعروا بذلك. لم يتم الإدلاء بأي تعليقات بشأن الاستقلالية، على الرغم من أن الطلاب كانوا أحرارًا (أو لا) في المشاركة في الأنشطة الاختيارية. كان من المفترض أن تدعم لوحات المتصدرين العلاقة، لكن الطلاب نادرًا ما تفاعلوا مع نتائج بعضهم البعض أو علقوا عليها. الحاجة التحفيزية الوحيدة التي تم ذكرها كانت الكفاءة: اعتبروا لوحة المتصدرين دليلاً، تعطيهم معلومات عن إنجازاتهم الأسبوعية. وبالتالي، تم إدراك لوحة المتصدرين على أنها تدفع المنافسة ضد النفس بدلاً من المنافسة مع الآخرين. يبدو أن هذه النتيجة تتناسب مع نظرية التحفيز الموقعة لدترينغ (2011). على الرغم من أن لوحة المتصدرين عادة ما تُصمم للتنافس مع الآخرين، إلا أن ترتيب إعدادنا تسبب في تأثير عكسي. ومع ذلك، لم يكن هذا التأثير قويًا بما يكفي لإحداث تغييرات كبيرة في الدافع، مما يؤثر على الأداء. النتائج المتعلقة بالكفاءة الذاتية تتماشى مع تلك التي أظهرتها الدراسات السابقة (أورتيز-روخاس وآخرون، 2017، 2019)، حيث لم يتم العثور على أي تأثيرات. تتعارض هذه النتيجة مع التأثيرات الإيجابية التي أبلغ عنها بانفيلد وويلكيرسون (2014). بمساعدة المعلومات النوعية، يمكننا أن نشرح أن كفاءة الطلاب الذاتية أثرت على تركيزهم على فرصهم في النجاح في المادة. ومع ذلك، لم يكن هذا التأثير قويًا بما يكفي للتفاعل مع شروط البحث.

الكفاءة الذاتية أو الدافع الذاتي. هذا يتماشى مع نتائج الدراسات السابقة (أورتيز-روخاس وآخرون، 2017، 2019). هذه النتائج تدحض نظرية لاندير. ومع ذلك، أفادت بعض الدراسات بوجود علاقة مباشرة بين الألعاب التعليمية وأداء التعلم من خلال الوساطة (ديني وآخرون، 2018؛ لانديرز ولانديرز، 2014). ومن ثم، تفسر هذه السيناريوهات الأربعة نقص الروابط في دراستنا. أولاً، لا يتطلب الأمر وجود علاقة سببية لإقامة ارتباط بين الألعاب التعليمية وأداء التعلم. ثانياً، وُجدت علاقة سببية؛ ومع ذلك، فإن المتغيرات الوسيطة المحددة التي تم اختيارها في هذه الدراسة لم تسبب هذا التأثير. ثالثاً، كان للدافع الذاتي أو الكفاءة الذاتية تأثير، لكن الطريقة التي تم قياسها بها أثرت على النتائج. هناك خطر من استخدام استبيانات التقرير الذاتي بسبب احتمال وجود انحياز في الاستجابة (كريتشمان وآخرون، 2014). يشير السيناريو الرابع إلى وجود متغير خارجي يتداخل مع العلاقات السببية. قد تكون بيداغوجيا المعلم قد أثرت على هذه الدراسة. على سبيل المثال، عندما يمنح المعلمون نقاطًا إضافية كمكافآت للتمارين الصفية، يمكن تفسيرها على أنها تحكم خارجي، مما يؤدي إلى زيادة الدافع الخارجي (رايان وديشي، 2000). ومع ذلك، في هذه الدراسة، قمنا بالتحكم في هذا السيناريو من خلال إجراء ملاحظات غير رسمية دورية على أنشطة المعلم لضمان عدم انحراف منهجهم التعليمي الشخصي عن الإعداد الأولي.

تساهم نتائج هذه الدراسة في زيادة المعرفة المتزايدة حول استخدام الألعاب في التعليم، وخاصة في سياق تخصصات العلوم والتكنولوجيا والهندسة والرياضيات في التعليم العالي. لذلك، من المهم النظر في المشهد الأوسع لتطبيقات الألعاب في دورات STEM على مستوى التعليم العالي. على سبيل المثال، في دراسة إيبانيز وآخرون (2014)، حقق طلاب في فصل برمجة C على مستوى الجامعة تحسينًا في أدائهم التعليمي، وتحفيزهم، وانخراطهم بعد تعرضهم لمنصة مخصصة للألعاب (Q-Learning-G)، والتي تضمنت أنشطة عمل لإكمال مهام البرمجة، وأنشطة اجتماعية للتفاعل مع الأقران، وفرص للتغذية الراجعة من خلال تقييم الأقران والاعتراف من خلال لوحات المتصدرين والشارات. وجد كادافيد وغوميز (2015) أن طلابًا من دورة حساب التفاضل والتكامل في كولومبيا قد حسّنوا أدائهم التعليمي بعد استخدام نظام مخصص للألعاب (Ticademia). تشمل الآليات والديناميات والمكونات تتبع التقدم، والنقاط، والترتيب، والمنافسات في الوقت الحقيقي لتطبيق معرفتهم في سياق عملي وتنافسي. مثال آخر موجود في الهندسة (دياث-راميريز، 2020)، حيث استخدم طلاب من دورة بحوث العمليات نظامًا مخصصًا للألعاب حيث كان عليهم التغلب على بعض التحديات والمهام التي تطلبت منهم حل المشكلات أو إكمال المهام المتعلقة بمحتوى الفصل، والمشاركة كفريق لمساعدة الآخرين، واستخدام النقاط، والشارات، والمستويات، و

المكافآت. أظهرت النتائج تحسنًا في الأداء الأكاديمي، وإحساس بالانتماء، والعمل الجماعي. مع استمرار تطور مجال الألعاب التعليمية، فإن البحث المستمر والتطبيقات العملية أمران حاسمان في تحسين الاستراتيجيات المناسبة لتعظيم تأثيرها على نجاح الطلاب.

لذا، فإن هذه الدراسة لها آثار عملية مهمة للمعلمين الذين يسعون إلى دمج الألعاب في ممارساتهم التعليمية ويهدفون إلى تعميق فهمهم لكيفية تأثير لوحات المتصدرين بشكل خاص على نتائج التعلم. أولاً، يمكن أن تعزز الألعاب الأداء التعليمي؛ ومع ذلك، يجب تصميم تنفيذها بعناية، مع الأخذ في الاعتبار تفاعل الديناميات والميكانيكيات والمكونات المتوافقة مع الأهداف التعليمية (دوغال وآخرون، 2021). على سبيل المثال، يمكن أن يساعد إضافة نظام تغذية راجعة، مثل شريط التقدم، الذي يوجه الطلاب أثناء تقدمهم في المحتوى (مثل دورة تعليمية مفتوحة عبر الإنترنت)، في الحفاظ على المشاركة. ثانياً، إحدى النتائج الرئيسية لهذه البحث هي الدور المحدد للوحات المتصدرين في التأثير على الأداء التعليمي. يبدو أن تصميم لوحات المتصدرين لأفضل 3 ولوحات المتصدرين النسبية أكثر فعالية من لوحات المتصدرين المطلقة في تجنب التأثير الضار على الدافع الناتج عن المقارنة المباشرة لأداء الطلاب (هانوس وفوكس، 2015). على الرغم من أن دراستنا لم تكشف عن فرق كبير في الدافع الذاتي، إلا أننا تأكدنا من أن مستوياته لم تنخفض بسبب تصميمات لوحات المتصدرين. ثالثاً، يجب أخذ الفروق الفردية (مثل الجنس ونوع اللاعب) في الاعتبار عند تقييم تأثير الألعاب على التعلم. على سبيل المثال، قد تستفيد العناصر التنافسية مثل لوحات المتصدرين الطلاب الذين يستجيبون بشكل جيد للمكافآت الخارجية (أندرياس وآخرون، 2022). رابعاً، يمكن أن يوفر توسيع استخدام الوسطاء في المزيد من دراسات الألعاب خارج العلوم الاجتماعية والصحة رؤى حول المتغيرات التي تؤثر على تأثيرها في التعليم، مما يمكّن المعلمين من إجراء تعديلات مستنيرة لتعزيز الفعالية. على سبيل المثال، وجد تشين وليانغ (2022) أن الكفاءة الذاتية تتوسط العلاقة بين الألعاب والمشاركة الدراسية. بناءً على نتائجهم، يمكن للمعلمين تصميم تدخلات تعزز ثقة الطلاب بأنفسهم ومشاركتهم.

أخيرًا، تحتوي هذه الدراسة على عدة قيود يمكن للباحثين معالجتها في الأبحاث المستقبلية. أولاً، قد يؤدي الاعتماد على أدوات الإبلاغ الذاتي إلى إدخال تحيز. هذه القيود مرتبطة بمسألة ثانية: بينما جمعنا بيانات نوعية، كانت فقط من الطلاب في المجموعة التجريبية. إن تضمين بيانات من المجموعة الضابطة أمر حاسم للحصول على فهم شامل لكيفية إدراك الطلاب لبيئة تعلمهم. ثالثًا، هناك حاجة إلى بيئة أكثر تحكمًا لتقليل تسرب المشاركين خلال كل من مراحل الاختبار القبلي والاختبار البعدي. رابعًا، على الرغم من أننا أخذنا في الاعتبار التباينات في سلوك المعلم-

قد يكون المعلمون المختلفون المشاركون في فصول مختلفة بمثابة معتدل محتمل. استخدام نفس المعلم عبر ظروف البحث المختلفة من المحتمل أن يوفر نتائج أكثر اتساقًا. خامسًا، يمكن أن يوفر تحليل متغيرات خلفية إضافية، مثل أنواع اللاعبين، رؤى حول كيفية تأثير عناصر اللعبة المحددة على الطلاب. سادسًا، يجب مواصلة دراسة آثار الت gamification في مجالات STEM الأخرى مثل العلوم. سابعًا، من أجل الحصول على صورة أكثر شمولاً عن آثار التدخل، سيكون من المفيد مقارنة النتائج في مجالات STEM وغير STEM.

الخاتمة

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات والمواد

الإعلانات

المصالح المتنافسة

نُشر على الإنترنت: 06 يناير 2025

References

Alamolhoda, M., Ayatollahi, S. M. T., & Bagheri, Z. (2017). A comparative study of the impacts of unbalanced sample sizes on the four synthesized methods of meta-analytic structural equation modeling. BMC Research Notes, 10, 446. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2768-5

An, Y. (2020). Designing effective Gamified learning experiences. International Journal of Technology in Education, 3(2), 62-69.

Andrias, R.M., Sunar, M.S., Sondoh, S.L. (2022). Adaptive Gamification: User/ Player Type and Game Elements Mapping. In: Lv, Z., Song, H. (eds) Intelligent Technologies for Interactive Entertainment. INTETAIN 2021. Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering, vol 429. Springer, Cham. https://doi. org/10.1007/978-3-030-99188-3_15

Baguley, T. (2009). Standardized or simple effect size: What should be reported? British Journal of Psychology, 100(3), 603-617. https://doi.org/10. 1348/000712608X377117

Bai, S., Hew, K. F., & Huang, B. (2020). Does gamification improve student learning outcome? Evidence from a meta-analysis and synthesis of qualitative data in educational contexts. Educational Research Review, 30, 100322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100322

Bandura, A. (1978). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy, 1(4), 139-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6402(78)90002-4

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents, 5(1), 307-337.

Banfield, J., & Wilkerson, B. (2014). Increasing student intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy through gamification pedagogy. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 7(4), 291-298.

Batchelor, R. L., Ali, H., Gardner-Vandy, K. G., Gold, A. U., MacKinnon, J. A., & Asher, P. M. (2021). Reimagining STEM workforce development as a braided river. Eos. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EO157277

Black, A. E., & Deci, E. L. (2000). The effects of instructors’ autonomy support and students’ autonomous motivation on learning organic chemistry: A self-determination theory perspective. Science Education, 84(6), 740-756.

Bleumers, L., All, A., Mariën, I., Shurmans, D., Van Looy, J., Jacobs, A., Willaert, K., De Grove, F., & Stewart, J. (Ed.). (2012). State of play of digital games for empowerment and inclusion: A review of the literature and empirical cases (EUR 25652). Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi. org/10.2791/36295

Bourgonjon, J., Valcke, M., Soetaert, R., & Schellens, T. (2010). Students’ perceptions about the use of video games in the classroom. Computers & Education, 54(4), 1145-1156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.10.022

Cadavid, J. M., & Gómez, L. F. M. (2015). Uso de un entorno virtual de aprendizaje ludificado como estrategia didáctica en un curso de pre-cálculo: Estudio de caso en la Universidad Nacional de Colombia. (2015). RISTI

Castillo-Parra, B., Hidalgo-Cajo, B. G., Vásconez-Barrera, M., & Oleas-López, J. (2022). Gamification in Higher Education: A Review of the Literature. World Journal on Educational Technology: Current Issues, 14(3), 797-816. https://doi.org/10.18844/wjet.v14i3.7341

Chen, J., & Liang, M. (2022). Play hard, study hard? The influence of gamification on students’ study engagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 994700. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.994700

Chernbumroong, S., Sureephong, P., and Muangmoon, O. O. (2017). The effect of leaderboard in different goal-setting levels. In 2017 International Conference on Digital Arts, Media and Technology (ICDAMT) (230-234). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDAMT.2017.7904967

Christy, K. R., & Fox, J. (2014). Leaderboards in a virtual classroom: A test of stereotype threat and social comparison explanations for women’s math performance. Computers & Education, 78, 66-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. compedu.2014.05.005

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

Denden, M., Tlili, A., Essalmi, F., Jemni, M., Chen, N. S., & Burgos, D. (2021). Effects of gender and personality differences on students’ perception of game design elements in educational gamification. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 154, 102674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs. 2021.102674

Deterding, S. (2011). Situated motivational affordances of game elements: A conceptual model. In Gamification: Using game design elements in nongaming contexts, a workshop at CHI , volume 10 .

Deterding, S. (2014) Eudaimonic Design, or: Six Invitations to Rethink Gamification. Eudaimonic Design, or: Six Invitations to Rehtink Gamification. In: Rethinking Gamification. Edited by Mathias Fuchs, Sonia Fizek, Paolo Ruffino, Niklas Schrape. Lüneburg: meson press 2014, pp. 305-323.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., and Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness: defining “gamification”. In Proceedings of the 15th international academic MindTrek conference: Envisioning future media environments, pages 9-15. https://doi.org/10.1145/2181037.2181040

Díaz-Ramírez, J. (2020). Gamification in engineering education-an empirical assessment on learning and game performance. Heliyon. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04972

Gui, Y., Cai, Z., Yang, Y., Kong, L., Fan, X., & Tai, R. H. (2023). Effectiveness of digital educational game and game design in STEM learning: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of STEM Education, 10(1), 36. https://doi.org/

Hagger, M. S., Hardcastle, S. J., Chater, A., Mallett, C., Pal, S., & Chatzisarantis, N. (2014). Autonomous and controlled motivational regulations for multiple health-related behaviors: Between-and within-participants analyses. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine: An Open Access Journal, 2(1), 565-601. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2014.912945

Hanus, M. D., & Fox, J. (2015). Assessing the effects of gamification in the classroom: A longitudinal study on intrinsic motivation, social comparison, satisfaction, effort, and academic performance. Computers & Education, 80, 152-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.08.019

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1985). Estimation of a single effect size: Parametric and nonparametric methods. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. https://doi. org/10.1016/b978-0-08-057065-5.50010-5

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/10705519909540118

Ibanez, M. B., Di-Serio, A., & Delgado-Kloos, C. (2014). Gamification for engaging computer science students in learning activities: A case study. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 7(3), 291-301. https:// doi.org/10.1109/tlt.2014.2329293

Jent, S., & Janneck, M. (2017). Using Gamification to Enhance User Motivation: The Influence of Gender and Age. Advances in The Human Side of Service Engineering. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60486-2_1

Kapp, K. M. (2012). The gamification of learning and instruction: Game-based methods and strategies for training and education. John Wiley & Sons.

Kleinschmit, A. J., Rosenwald, A., Ryder, E. F., Donovan, S., Murdoch, B., Grandgenett, N. F., Pauley, M., Triplett, E., Tapprich, W., & Morgan, W. (2023). Accelerating STEM education reform: Linked communities of practice promote creation of open educational resources and sustainable professional development. International Journal of STEM Education. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-023-00405-y

Kovácsné Pusztai, K. (2021). Gamification in higher education. Teaching Mathematics and Computer Science, 18(2), 87-106. https://doi.org/10. 5485/tmcs.2020.0510

Kreitchmann, R. S., Abad, F. J., Ponsoda, V., Nieto, M. D., & Morillo, D. (2019). Controlling for response biases in self-report scales: Forced-choice vs. Psychometric modeling of likert items. Frontiers in Psychology. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02309

Landers, R. N. (2014). Developing a theory of gamified learning: Linking serious games and gamification of learning. Simulation & Gaming, 45(6), 752-768. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878114563660

Landers, R. N., & Armstrong, M. B. (2017). Enhancing instructional outcomes with gamification: An empirical test of the Technology-Enhanced Training Effectiveness Model. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 499-507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.031

Landers, R. N., & Landers, A. K. (2014). An empirical test of the theory of gamified learning: The effect of leaderboards on time-on-task and academic performance. Simulation & Gaming, 45(6), 769-785. https:// doi.org/10.1177/1046878114563662

Li, M., Ma, S., & Shi, Y. (2023). Examining the effectiveness of gamification as a tool promoting teaching and learning in educational settings: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1253549. https://doi.org/10. 3389/fpsyg.2023.1253549

Lovasz, A., Bat-Erdene, B., Cukrowska-Torzewska, E., Rigó, M., & Szabó-Morvai, Á. (2023). Competition, subjective feedback, and gender gaps in performance. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 102, 101954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2022.101954

Marczewski, A. (2015). Even Ninja Monkeys Like to Play: Gamification, Game Thinking and Motivational Design. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Mekler, E. D., Brühlmann, F., Tuch, A. N., & Opwis, K. (2017). Towards understanding the effects of individual gamification elements on intrinsic motivation and performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 525-534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.08.048

Mohamed, M., Rasid, N. S. M., Ibrahim, N., & Seshaiyer, P. (2023). Engaging Responsive and Responsible Learning Through Collaborative Teaching in the STEM Classroom. Cases on Responsive and Responsible Learning in Higher Education, 120-133. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-6076-4. ch008

Ortiz Rojas, M. E., Chiluiza, K., and Valcke, M. (2017). Gamification in computer programming: Effects on learning, engagement, self-efficacy and intrinsic motivation. In 11th European Conference on Game-Based Learning (ECGBL), pages 507-514. Acad Conferences LTD.

Ortiz-Rojas, M., Chiluiza, K., & Valcke, M. (2019). Gamification through leaderboards: An empirical study in engineering education. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 27(4), 777-788. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/cae. 12116

the lens of a single theory. In Extended Abstracts of the 2022 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, 261-262. https:// doi.org/10.1145/3505270.3558361

Qin, J. (2023). On the reform of education methods that adapt to STEM development demand. International Journal of Education and Humanities, 6(2), 141-143. https://doi.org/10.54097/ijeh.v6i2.3660

Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Wang, M., Roldan, J. L., & Kunasekaran, P. (2021). Are we in right path for mediation analysis? Reviewing the literature and proposing robust guidelines. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 48, 395-405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.07.013

Reeve, J., & Deci, E. L. (1996). Elements of the competitive situation that affect intrinsic motivation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(1), 24-33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167296221003

Rincon-Flores, E. G., & Santos-Guevara, B. N. (2021). Gamification during Covid-19: Promoting active learning and motivation in higher education. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 37(5), 43-60. https://doi. org/10.14742/ajet. 7157

Ryan, R. M., & Connell, J. P. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 749.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54-67. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Sailer, M., Hense, J., Mandl, H., & Klevers, M. (2013). Psychological perspectives on motivation through gamification. Interaction Design and Architecture(s), 19, 28-37. https://doi.org/10.55612/s-5002-019-002

Sailer, M., Hense, J. U., Mayr, S. K., & Mandl, H. (2017). How gamification motivates: An experimental study of the effects of specific game design elements on psychological need satisfaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 371-380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.033

Sailer, M., & Homner, L. (2020). The gamification of learning: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 32(1), 77-112. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10648-019-09498-w

Schuler, M. S., Coffman, D. L., Stuart, E. A., Nguyen, T. Q., Vegetabile, B., & McCaffrey, D. F. (2024). Practical challenges in mediation analysis: A guide for applied researchers. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10742-024-00327-4

Silva, I., Wong, A., Auria, B., Zambrano, D., & Echeverria, V. (2022). Gamification in Engineering Education: Exploring Students’ Performance, Motivation, and Engagement. IEEE Sixth Ecuador Technical Chapters Meeting (ETCM), 2022, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1109/etcm56276.2022.9935729

Tahir, F., Mitrovic, A., & Sotardi, V. (2021). Do Gaming Experience and Prior Knowledge Matter When Learning with a Gamified ITS? International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), 2021, 75-77. https:// doi.org/10.1109/icalt52272.2021.00030

Ukyo, Y., Noma, H., Maruo, K., & Gosho, M. (2019). Improved small sample inference methods for a mixed-effects model for repeated measures approach in incomplete longitudinal data analysis. Stats, 2(2), 174-188. https://doi.org/10.3390/stats2020013

van Roy, R., & Zaman, B. (2017). Why Gamification Fails in Education and How to Make It Successful: Introducing Nine Gamification Heuristics Based on Self-Determination Theory. Serious Games and Edutainment Applications, 485-509. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51645-5_22

Van Roy, R., & Zaman, B. (2018). Need-supporting gamification in education: An assessment of motivational effects over time. Computers & Education, 127, 283-297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.08.018

Videnovik, M., Vold, T., Kiønig, L., et al. (2023). Game-based learning in computer science education: A scoping literature review. IJ STEM Ed, 10, 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-023-00447-2

Werbach, K., Hunter, D., and Dixon, W. (2012). For the win: How game thinking can revolutionize your business, volume 1. Wharton digital press Philadelphia.

Yan, L. L. L., & Matore, M. E. (2023). Gamification Trend in Students’ Mathematics Learning Through Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 12(1), 400-423. https://doi.org/10.6007/ijarped/v12-i1/15732

Yang, F. M., & Kao, S. T. (2014). Item response theory for measurement validity. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry, 26(3), 171-177. https://doi.org/10.3969/j. issn.1002-0829.2014.03.010

Zahedi, L., Batten, J., Ross, M., Potvin, G., Damas, S., Clarke, P., & Davis, D. (2021). Gamification in education: A mixed-methods study of gender on

computer science students’ academic performance and identity development. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 33, 441-474. https://doi. org/10.1007/s12528-021-09271-5

Zeidan, M., Huang, X., Xiao, L., & Zhao, R. (2022). Improving student engagement using a video-enabled activity-based learning: An exploratory study to STEM preparatory education in UAE. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.47408/jldhe.vi24.888

Zichermann, G., and Cunningham, C. (2011). Gamification by design: Implementing game mechanics in web and mobile apps. ” O’Reilly Media, Inc.”.

ملاحظة الناشر

- *المراسلات:

مارغاريتا أورتيز-روخاس

margarita.ortiz@cti.espol.edu.ec

مركز تكنولوجيا المعلومات، المدرسة العليا البوليتكنيكية في ليتورال، إسبول، حرم غوستافو غاليندو كيلومتر 30.5 طريق محيطي، صندوق بريد 09-01-5863، غواياكيل، غواياس، الإكوادور

قسم الدراسات التعليمية، جامعة غنت، ه. دونانلاان 2، 9000 غنت، بلجيكا

مركز الأبحاث والخدمات التعليمية، المدرسة العليا البوليتكنيكية في ليتورال، إسبول، حرم غوستافو غاليندو كيلومتر 30.5 طريق محيطي، صندوق بريد 09-01-5863، غواياكيل، غواياس، الإكوادور - © المؤلف(ون) 2025. الوصول المفتوح. هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي النسب-غير التجاري-عدم الاشتقاق 4.0 الدولية، التي تسمح بأي استخدام غير تجاري، ومشاركة، وتوزيع، واستنساخ في أي وسيلة أو صيغة، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلف(ين) الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح إذا كنت قد قمت بتعديل المادة المرخصة. ليس لديك إذن بموجب هذه الرخصة لمشاركة المواد المعدلة المشتقة من هذه المقالة أو أجزاء منها. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي الخاصة بالمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر الائتمان للمادة. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي الخاصة بالمقالة واستخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، ستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارة http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-024-00521-3

Publication Date: 2025-01-06

How gamification boosts learning in STEM higher education: a mixed methods study

Abstract

Background The demand for professionals with expertise in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) continues to grow. To meet this demand, universities are actively seeking strategies to engage more students in STEM disciplines and improve their learning outcomes. One promising approach is gamification, specifically using leaderboards. This study investigates the impact of leaderboard-based gamification on the learning performance of 175 students in a calculus course, with a focus on the mediating roles of autonomous motivation and self-efficacy, as well as potential moderating factors such as gender and gaming experience. A mixed-method research approach was employed, combining a pretest-posttest quasi-experimental design with nine qualitative interviews. Results A significant improvement in learning performance for students in the gamified condition was observed. However, no significant effects were found related to the mediating variables. Qualitative analysis supported these findings, revealing that students did not perceive an increase in autonomy within the gamified condition, and instead, themes of controlled motivation were prevalent. While the leaderboard provided a sense of achievement for most participants, the quantitative analysis did not show a strong correlation between self-efficacy and learning performance. Conclusions This study suggests that leaderboard-based gamification can enhance learning performance in calculus courses at the university level. However, the findings highlight the importance of careful gamification design, particularly in how different game elements influence students’ motivational aspects.

Introduction

Conceptual and theoretical framework

Defining gamification and game elements

Gamification in mathematics higher education

studies could be the field of research, where health and social sciences (especially psychology) are predominant in its use, or the difficulties faced when attempting to report these analyses accurately (Schuler et al., 2024).

Gamification and learning performance

One model to study the impact of gamification on learning is the “theory of gamified instructions” (Landers, 2014). This theory emphasizes the indirect impact of gamification on learning by pointing to the role of mediating variables. For instance, students exposed to leaderboards (game elements) interacted more times with a project (time spent on task behavior) than in the control condition, causing an increase in learning performance (Landers & Landers, 2014). A few studies have attempted to use this theory for gamification (Ortiz-Rojas et al., 2017, 2019). In the present study, we built on this theory, considering autonomous motivation and self-efficacy as the mediating variables.

Gamification and autonomous motivation

acquired as a student). Identified motivation is observed when a person identifies with the value of a specific activity (e.g., taking a class because students know that it is useful to pass the next subject).

Self-Determination Theory stresses how each type of motivation fulfils or stresses three psychological needs: the need for autonomy (being in control of one’s behavior), competence (developing mastery), and relatedness (sense of belonging to a group) (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Gamified environments that help to satisfy these needs are more likely to promote autonomous motivation (Mekler et al., 2017). For instance, Van Roy and Zaman (2017) described how a gamified setting supports autonomy by allowing students to choose their activities. It also seems to satisfy their need for competence, as the activities are challenging yet achievable, with feedback mechanisms (e.g., badges) informing students of their positive progress. Finally, the need for relatedness seems to be fulfilled when interactions are facilitated. For example, leaderboards allow students to compare and share their progress, as well as discuss their positions (Sailer et al., 2013). In gamification research, to the best of our knowledge, only Van Roy and Zaman (2018) focused on autonomous motivation, demonstrating an increase after exposure to gamified elements like badges and leaderboards.

Motivational needs can be satisfied in a gamified setting depending on how game elements are implemented, a concept Deterding (2011) termed “situated motivational affordance.” For example, while leaderboards often encourage peer competition and can reduce autonomous motivation (Reeve and Deci, 1996), they can also enhance competence and foster personal autonomy by highlighting self-progress. Moreover, motivational affordances are not tied to individual gamification elements but depend on the entire gamified system (Deterding, 2014). Therefore, it is essential to consider the interplay between elements in a system and how their combination promotes autonomous motivation. However, one critique of SelfDetermination Theory is that it does not account for individual differences (e.g., personality traits, cultural background, cognitive abilities) (Poeller & Phillips, 2022). To address this, our study incorporates ground variables such as gender and gaming experience to explore whether these differences impact motivation when combined with gamification.

Gamification and self-efficacy

(observing others’ successful performance), verbal persuasion (receiving positive or negative feedback about task performance), and physiological states (e.g., stress levels) (Bandura, 1982). Many gamification elements embody feedback on personal and others’ performances (Bleumers et al., 2012). For instance, Christy and Fox (2014) demonstrate how leaderboards provide feedback by showing each student’s ranking position. The latter authors also stress how leaderboards invoke vicarious experiences because students see how well others perform. In terms of physiological states, when a game is neither too difficult nor too easy, it induces an acceptable level of stress or exhaustion, thereby promoting engagement and task completion (Kapp, 2012). Research on the effects of gamification on student self-efficacy has increased in recent years. Ahmed and Asiksoy (2021) investigated the impact of a gamified flipped learning class on the self-efficacy and innovation skills of physics students in a virtual laboratory. The results show a positive impact on innovation skills; however, self-efficacy showed no significant improvement. Chen and Liang (2022) presented their study on self-efficacy as a mediating variable, exploring the impact of gamification on students’ study engagement in a marketing class using surveys from 187 Chinese students. The results showed that enjoyment and selfefficacy indirectly influence engagement. In the case of mathematics education, studies are scarce and have yielded contradictory results; some have shown positive results (Banfield & Wilkerson, 2014), while others have reported no significant effect (Ortiz-Rojas et al., 2017). These discrepancies underscore the need for further research on self-efficacy in mathematics education.

Gamification and background variables

Gamification using leaderboards

Graphic representation of the conceptual and theoretical model

Research hypotheses

H2: Students involved in a gamified calculus course reflect higher autonomous motivation and higher selfefficacy than students in a control condition.

H3: Students involved in a gamified calculus course attain higher learning performance than students in a control condition, considering the mediating effect of the changes in autonomous motivation, self-efficacy, and interaction with co-variables (gender, gaming experience).

Methodology

Research design

Study group

| Scales | Pretest | Posttest |

| Autonomous Motivation |

|

|

| Self-Efficacy |

|

α=0.89 |

| Gaming Experience |

|

Qualitative instruments

Procedure

- Week 1 (pre-test): All students in both the control and experimental research setting-completed during class time, the various questionnaires to gauge their level of self-efficacy, self-motivation, gaming experience, and calculus knowledge.

- Week 2 through 7 (gamified and control setting): The same instructional activities were carried out in both research conditions, including compulsory assignments like homework, group projects, quizzes, and optional assignments like self-assessment quizzes. However, for students in the experimental group these activities were presented in a gamified setting.

- Week 8 and 9 (post-test): Comparable to the pre-test set-up, during class time, students in both research conditions filled out all the measurement instruments (self-efficacy, autonomous motivation, and the calculus knowledge test).

Design of the gamified condition

| Categories | Sample questions | |||

| Incorporation of leaderboards as a gamified element |

|

|||

| Leaderboards (Top students in leaderboard) |

|

|||

| Leaderboards (Middle and low students in leaderboard) | – How did you feel/what were your thoughts when your name did not appear in the public leaderboard each week? | |||

| Leaderboards and self-efficacy | -Were you certain during any week that you were going to make it in the top 3 ? |

When designing the gamified approach, the specific elements of gamification-dynamics, mechanics, and components-as outlined by Werbach et al. (2012) were incorporated to engage students in various ways:

- Dynamics: Emotions such as curiosity were invoked by not telling students about the future activity to be included in the ranking.

- Mechanics: We build on chance, competition, and feedback. Chance (an element of randomness) was apparent because the students did not know which activity would be selected. This was expected to invoke engagement and motivation for each activity. The optional activities fostered a sense of autonomy because the students had freedom to choose. The nature of the competition invoked by the leaderboards centered on their personal positions: try to improve compared to the previous week. Leaderboards presented their performance regarding feedback. The latter also induced a sense of competence and self-efficacy.

- Components: In the experimental condition, two types of leaderboards were designed, both without showing scores to avoid discouragement. One only showed the top three positions and students’ names. This ranking was publicly announced through the learning management system at the end of each week for each gamified course. The rest of the positions were shown through a relative leaderboard without specifying who was above or below the student. This ranking was privately sent to each student through the learning management system. If a student shared the same position with others, the top three leader-

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis

Qualitative analysis

| Variables | Control Condition (

|

Experimental Condition (

|

| Learning Performance | ||

| Pre-test | 11.65 (7.57) | 11.72 (6.52) |

| Post-test | 29.71 (11.95) | 37.03 (9.54) |

| Difference in Learning Performance (Learning Gain) | 18.06 (8.50) | 25.31 (8.98) |

| Autonomous Motivation (AM) | ||

| Pre-test | 6.02 (0.14) | 6.14 (0.06) |

| Post-test | 5.93 (0.82) | 5.78 (0.96) |

| Difference in AM (Diff AM) | -0.10 (0.61) | – 0.36 (0.89) |

| Self-Efficacy | ||

| Pre-Test | 65.50 (13.43) | 64.02 (17.97) |

| Post-Test | 72.23 (15.52) | 72.22 (12.90) |

| Difference in SE (Diff SE) | 6.74 (12.00) | 8.20 (15.10) |

| Gaming Experience | 2.75 (0.90) | 2.65 (1.06) |

Results

Regarding H1, the results revealed a significant main difference in the condition over time,

To complement the above analysis, a linear mixed model was used to predict students’ learning performance, incorporating a random intercept to account for within-subject variability. The fixed effects included experimental conditions, time, and the interaction between condition and time. The model explained

Concerning H2, the results indicate that there were no significant interactions of condition over time in either Autonomous Motivation,

| Predictor variables | Effect | Estimate | SE | Degrees of freedom | t | p |

| (Intercept) | (Intercept) | 22.52 | 0.71 | 173 | 31.81 | <0.001 |

| Experimental Condition | 1-0 | 3.70 | 1.42 | 173 | 2.61 | 0.010 |

| Time | 2-1 | 21.69 | 0.82 | 173 | 26.60 | <0.001 |

| Condition * Time |

|

7.25 | 1.63 | 173 | 4.45 | <0.001 |

a statistically significant effect on learning gain. Hence, both variables were excluded from the model. Thus, the mediation analysis continued with autonomous motivation and self-efficacy. As shown in Fig. 4, the research condition was not significantly related to autonomous motivation (a1:

Discussion

With respect to the second hypothesis, the results did not support the effect of gamification on autonomous motivation and self-efficacy. To the best of our knowledge, the only study that also evaluated autonomous motivation -though using different game elementsis that of Van Roy and Zaman (2018). Contrary to our findings, their study reported that students increased their autonomous motivation over time. Our analysis of the qualitative data provides plausible explanations. Although the gamified design was meant to boost autonomous motivation, students did not experience this. No comments were made regarding autonomy, although the students were free (not) to engage in optional activities. Leaderboards were supposed to support relatedness, but students rarely interacted with or commented on each other’s results. The only motivational need mentioned was competence: they considered the leaderboard a guide, giving them information about their weekly achievements. Thus, the leaderboard was perceived as pushing competition against oneself rather than with others. This finding appears to fit Deterding’s (2011) situated motivational theory. Although a leaderboard is usually designed to compete with others, the arrangement of our setup caused the opposite effect. However, this effect was still not sufficiently strong to cause substantial changes in motivation, which affects performance. The results regarding self-efficacy are in line with those of previous studies (Ortiz-Rojas et al., 2017, 2019), where no effects were found. This finding contradicts the positive effects reported by Banfield and Wilkerson (2014). With the help of qualitative information, we can explain that students’ self-efficacy influenced their focus on their chances of succeeding in the subject. Nevertheless, this impact was not sufficiently strong to interact with research conditions.

self-efficacy or autonomous motivation. This is consistent with the results of previous studies (Ortiz-Rojas et al., 2017, 2019). These results refute the theory of Lander. Nevertheless, some studies have reported a direct relationship between gamification and learning performance through mediation (Denny et al., 2018; Landers & Landers, 2014). Hence, these four scenarios explain the lack of connections in our study. First, a causal relationship is not required to establish a connection between gamification and learning performance. Second, a causal relationship was found; however, the specific mediation variables chosen in this study did not cause this effect. Third, autonomous motivation or self-efficacy did have an effect, but the way it was measured affected the results. There is a risk of using self-report questionnaires because of the potential response bias (Kreitchmann et al., 2014). The fourth scenario points to an external variable interfering with causal relationships. Teacher pedagogy may have influenced this study. For instance, when teachers give extra points as rewards for class exercises, they can be interpreted as having external control, causing extrinsic motivation to increase (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Nevertheless, in this study, we controlled this scenario by making informal periodical observations of teacher activities to ensure that their personal teaching methodology did not deviate from the initial setup.

The findings of this study contribute to the growing body of research on gamification specifically within the context of STEM disciplines in higher education. Therefore, it is important to consider the broader landscape of gamification applications in STEM courses at the higher education level. For example, in Ibanez et al. (2014), students of a C-Programming class at the university level improved their learning performance, motivation, and engagement after being exposed to a gamified platform (Q-Learning-G), which included work activities for completing programming tasks, social activities for interacting with peers, and feedback opportunities through peer assessment and recognition through leaderboards and badges. Cadavid and Gómez (2015) found that students from an undergraduate pre-calculus course in Colombia improved their learning performance after using a gamified system (Ticademia). The mechanics, dynamics, and components include progress tracking, points, rankings, and real-time duels to apply their knowledge in a practical and competitive context. Another example is found in engineering (Díaz-Ramírez, 2020), where students from an operations research course used a gamified system where they had to overcome some challenges and assignments that required them to solve problems or complete tasks related to the class content, participate as a team helping others, and use points, badges, levels, and

rewards. The results indicated an improvement in academic performance, sense of belonging, and teamwork. As the field of gamification continues to evolve, ongoing research and practical implications are crucial in refining appropriate strategies to maximize their impact on student success.

Hence, this study has important practical implications for educators who seek to incorporate gamification into their teaching practices and aim to deepen their understanding of how leaderboards specifically affect learning outcomes. First, gamification can enhance learning performance; however, its implementation must be carefully designed, considering the interplay of dynamics, mechanics, and components aligned with educational goals (Duggal et al., 2021). For instance, adding a feedback system, such as a progress bar, that guides students as they advance in content (e.g., a MOOC), can help maintain engagement. Second, a key finding of this research is the specific role of leaderboards in influencing learning performance. Designing Top 3 and relative leaderboards seems more effective than absolute leaderboards in avoiding the detrimental impact on motivation that comes from directly comparing students’ performances (Hanus & Fox, 2015). Although our study did not reveal a significant difference in autonomous motivation, we ensured that its levels did not decline because of the leaderboard designs. Third, Individual differences (e.g., gender and player type) should be considered when assessing the impact of gamification on learning. For instance, competitive elements such as leaderboards may benefit students who respond well to external rewards (Andrias et al., 2022). Fourth, expanding the use of mediators in more gamification studies beyond social sciences and health can provide insights into the variables affecting their impact on education, enabling teachers to make informed adjustments to enhance effectiveness. For example, Chen and Liang (2022) found that selfefficacy mediates the relationship between gamification and study engagement. Due to their results, teachers can design interventions that boost students’ self-confidence and engagement.

Finally, this study has several limitations that can be addressed by researchers in future research. First, the reliance on self-reporting instruments may introduce bias. This limitation is related to a second issue: while we collected qualitative data, it was only from students in the experimental group. Including data from the control group is crucial for gaining a comprehensive understanding of how students perceive their learning environment. Third, a more controlled setting is needed to minimize participant dropout during both the pre-test and post-test phases. Fourth, although we accounted for variations in teacher behavior-a

potential moderator-different teachers were involved in different classes. Using the same teacher through various research conditions would likely provide more consistent results. Fifth, analyzing additional background variables, such as player types, could offer insights into how specific game elements affect students. Sixth, continue the study of the effects of gamification in other STEM areas such as Science. Seventh, for the purpose of obtaining a more comprehensive picture of the intervention’s effects, it would be beneficial to compare the results in STEM and non-STEM fields.

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Declarations

Competing interests

Published online: 06 January 2025

References

Alamolhoda, M., Ayatollahi, S. M. T., & Bagheri, Z. (2017). A comparative study of the impacts of unbalanced sample sizes on the four synthesized methods of meta-analytic structural equation modeling. BMC Research Notes, 10, 446. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2768-5

An, Y. (2020). Designing effective Gamified learning experiences. International Journal of Technology in Education, 3(2), 62-69.

Andrias, R.M., Sunar, M.S., Sondoh, S.L. (2022). Adaptive Gamification: User/ Player Type and Game Elements Mapping. In: Lv, Z., Song, H. (eds) Intelligent Technologies for Interactive Entertainment. INTETAIN 2021. Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering, vol 429. Springer, Cham. https://doi. org/10.1007/978-3-030-99188-3_15

Baguley, T. (2009). Standardized or simple effect size: What should be reported? British Journal of Psychology, 100(3), 603-617. https://doi.org/10. 1348/000712608X377117

Bai, S., Hew, K. F., & Huang, B. (2020). Does gamification improve student learning outcome? Evidence from a meta-analysis and synthesis of qualitative data in educational contexts. Educational Research Review, 30, 100322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100322

Bandura, A. (1978). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy, 1(4), 139-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6402(78)90002-4

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents, 5(1), 307-337.

Banfield, J., & Wilkerson, B. (2014). Increasing student intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy through gamification pedagogy. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 7(4), 291-298.

Batchelor, R. L., Ali, H., Gardner-Vandy, K. G., Gold, A. U., MacKinnon, J. A., & Asher, P. M. (2021). Reimagining STEM workforce development as a braided river. Eos. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EO157277

Black, A. E., & Deci, E. L. (2000). The effects of instructors’ autonomy support and students’ autonomous motivation on learning organic chemistry: A self-determination theory perspective. Science Education, 84(6), 740-756.

Bleumers, L., All, A., Mariën, I., Shurmans, D., Van Looy, J., Jacobs, A., Willaert, K., De Grove, F., & Stewart, J. (Ed.). (2012). State of play of digital games for empowerment and inclusion: A review of the literature and empirical cases (EUR 25652). Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi. org/10.2791/36295

Bourgonjon, J., Valcke, M., Soetaert, R., & Schellens, T. (2010). Students’ perceptions about the use of video games in the classroom. Computers & Education, 54(4), 1145-1156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.10.022

Cadavid, J. M., & Gómez, L. F. M. (2015). Uso de un entorno virtual de aprendizaje ludificado como estrategia didáctica en un curso de pre-cálculo: Estudio de caso en la Universidad Nacional de Colombia. (2015). RISTI

Castillo-Parra, B., Hidalgo-Cajo, B. G., Vásconez-Barrera, M., & Oleas-López, J. (2022). Gamification in Higher Education: A Review of the Literature. World Journal on Educational Technology: Current Issues, 14(3), 797-816. https://doi.org/10.18844/wjet.v14i3.7341

Chen, J., & Liang, M. (2022). Play hard, study hard? The influence of gamification on students’ study engagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 994700. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.994700

Chernbumroong, S., Sureephong, P., and Muangmoon, O. O. (2017). The effect of leaderboard in different goal-setting levels. In 2017 International Conference on Digital Arts, Media and Technology (ICDAMT) (230-234). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDAMT.2017.7904967

Christy, K. R., & Fox, J. (2014). Leaderboards in a virtual classroom: A test of stereotype threat and social comparison explanations for women’s math performance. Computers & Education, 78, 66-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. compedu.2014.05.005

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

Denden, M., Tlili, A., Essalmi, F., Jemni, M., Chen, N. S., & Burgos, D. (2021). Effects of gender and personality differences on students’ perception of game design elements in educational gamification. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 154, 102674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs. 2021.102674

Deterding, S. (2011). Situated motivational affordances of game elements: A conceptual model. In Gamification: Using game design elements in nongaming contexts, a workshop at CHI , volume 10 .

Deterding, S. (2014) Eudaimonic Design, or: Six Invitations to Rethink Gamification. Eudaimonic Design, or: Six Invitations to Rehtink Gamification. In: Rethinking Gamification. Edited by Mathias Fuchs, Sonia Fizek, Paolo Ruffino, Niklas Schrape. Lüneburg: meson press 2014, pp. 305-323.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., and Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness: defining “gamification”. In Proceedings of the 15th international academic MindTrek conference: Envisioning future media environments, pages 9-15. https://doi.org/10.1145/2181037.2181040

Díaz-Ramírez, J. (2020). Gamification in engineering education-an empirical assessment on learning and game performance. Heliyon. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04972

Gui, Y., Cai, Z., Yang, Y., Kong, L., Fan, X., & Tai, R. H. (2023). Effectiveness of digital educational game and game design in STEM learning: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of STEM Education, 10(1), 36. https://doi.org/

Hagger, M. S., Hardcastle, S. J., Chater, A., Mallett, C., Pal, S., & Chatzisarantis, N. (2014). Autonomous and controlled motivational regulations for multiple health-related behaviors: Between-and within-participants analyses. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine: An Open Access Journal, 2(1), 565-601. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2014.912945

Hanus, M. D., & Fox, J. (2015). Assessing the effects of gamification in the classroom: A longitudinal study on intrinsic motivation, social comparison, satisfaction, effort, and academic performance. Computers & Education, 80, 152-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.08.019

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1985). Estimation of a single effect size: Parametric and nonparametric methods. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. https://doi. org/10.1016/b978-0-08-057065-5.50010-5

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/10705519909540118

Ibanez, M. B., Di-Serio, A., & Delgado-Kloos, C. (2014). Gamification for engaging computer science students in learning activities: A case study. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 7(3), 291-301. https:// doi.org/10.1109/tlt.2014.2329293

Jent, S., & Janneck, M. (2017). Using Gamification to Enhance User Motivation: The Influence of Gender and Age. Advances in The Human Side of Service Engineering. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60486-2_1

Kapp, K. M. (2012). The gamification of learning and instruction: Game-based methods and strategies for training and education. John Wiley & Sons.

Kleinschmit, A. J., Rosenwald, A., Ryder, E. F., Donovan, S., Murdoch, B., Grandgenett, N. F., Pauley, M., Triplett, E., Tapprich, W., & Morgan, W. (2023). Accelerating STEM education reform: Linked communities of practice promote creation of open educational resources and sustainable professional development. International Journal of STEM Education. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-023-00405-y

Kovácsné Pusztai, K. (2021). Gamification in higher education. Teaching Mathematics and Computer Science, 18(2), 87-106. https://doi.org/10. 5485/tmcs.2020.0510

Kreitchmann, R. S., Abad, F. J., Ponsoda, V., Nieto, M. D., & Morillo, D. (2019). Controlling for response biases in self-report scales: Forced-choice vs. Psychometric modeling of likert items. Frontiers in Psychology. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02309

Landers, R. N. (2014). Developing a theory of gamified learning: Linking serious games and gamification of learning. Simulation & Gaming, 45(6), 752-768. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878114563660

Landers, R. N., & Armstrong, M. B. (2017). Enhancing instructional outcomes with gamification: An empirical test of the Technology-Enhanced Training Effectiveness Model. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 499-507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.031

Landers, R. N., & Landers, A. K. (2014). An empirical test of the theory of gamified learning: The effect of leaderboards on time-on-task and academic performance. Simulation & Gaming, 45(6), 769-785. https:// doi.org/10.1177/1046878114563662

Li, M., Ma, S., & Shi, Y. (2023). Examining the effectiveness of gamification as a tool promoting teaching and learning in educational settings: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1253549. https://doi.org/10. 3389/fpsyg.2023.1253549

Lovasz, A., Bat-Erdene, B., Cukrowska-Torzewska, E., Rigó, M., & Szabó-Morvai, Á. (2023). Competition, subjective feedback, and gender gaps in performance. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 102, 101954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2022.101954

Marczewski, A. (2015). Even Ninja Monkeys Like to Play: Gamification, Game Thinking and Motivational Design. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Mekler, E. D., Brühlmann, F., Tuch, A. N., & Opwis, K. (2017). Towards understanding the effects of individual gamification elements on intrinsic motivation and performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 525-534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.08.048

Mohamed, M., Rasid, N. S. M., Ibrahim, N., & Seshaiyer, P. (2023). Engaging Responsive and Responsible Learning Through Collaborative Teaching in the STEM Classroom. Cases on Responsive and Responsible Learning in Higher Education, 120-133. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-6076-4. ch008

Ortiz Rojas, M. E., Chiluiza, K., and Valcke, M. (2017). Gamification in computer programming: Effects on learning, engagement, self-efficacy and intrinsic motivation. In 11th European Conference on Game-Based Learning (ECGBL), pages 507-514. Acad Conferences LTD.

Ortiz-Rojas, M., Chiluiza, K., & Valcke, M. (2019). Gamification through leaderboards: An empirical study in engineering education. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 27(4), 777-788. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/cae. 12116

the lens of a single theory. In Extended Abstracts of the 2022 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, 261-262. https:// doi.org/10.1145/3505270.3558361

Qin, J. (2023). On the reform of education methods that adapt to STEM development demand. International Journal of Education and Humanities, 6(2), 141-143. https://doi.org/10.54097/ijeh.v6i2.3660

Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Wang, M., Roldan, J. L., & Kunasekaran, P. (2021). Are we in right path for mediation analysis? Reviewing the literature and proposing robust guidelines. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 48, 395-405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.07.013

Reeve, J., & Deci, E. L. (1996). Elements of the competitive situation that affect intrinsic motivation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(1), 24-33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167296221003

Rincon-Flores, E. G., & Santos-Guevara, B. N. (2021). Gamification during Covid-19: Promoting active learning and motivation in higher education. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 37(5), 43-60. https://doi. org/10.14742/ajet. 7157

Ryan, R. M., & Connell, J. P. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 749.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54-67. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Sailer, M., Hense, J., Mandl, H., & Klevers, M. (2013). Psychological perspectives on motivation through gamification. Interaction Design and Architecture(s), 19, 28-37. https://doi.org/10.55612/s-5002-019-002

Sailer, M., Hense, J. U., Mayr, S. K., & Mandl, H. (2017). How gamification motivates: An experimental study of the effects of specific game design elements on psychological need satisfaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 371-380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.033

Sailer, M., & Homner, L. (2020). The gamification of learning: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 32(1), 77-112. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10648-019-09498-w

Schuler, M. S., Coffman, D. L., Stuart, E. A., Nguyen, T. Q., Vegetabile, B., & McCaffrey, D. F. (2024). Practical challenges in mediation analysis: A guide for applied researchers. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10742-024-00327-4

Silva, I., Wong, A., Auria, B., Zambrano, D., & Echeverria, V. (2022). Gamification in Engineering Education: Exploring Students’ Performance, Motivation, and Engagement. IEEE Sixth Ecuador Technical Chapters Meeting (ETCM), 2022, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1109/etcm56276.2022.9935729

Tahir, F., Mitrovic, A., & Sotardi, V. (2021). Do Gaming Experience and Prior Knowledge Matter When Learning with a Gamified ITS? International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), 2021, 75-77. https:// doi.org/10.1109/icalt52272.2021.00030

Ukyo, Y., Noma, H., Maruo, K., & Gosho, M. (2019). Improved small sample inference methods for a mixed-effects model for repeated measures approach in incomplete longitudinal data analysis. Stats, 2(2), 174-188. https://doi.org/10.3390/stats2020013

van Roy, R., & Zaman, B. (2017). Why Gamification Fails in Education and How to Make It Successful: Introducing Nine Gamification Heuristics Based on Self-Determination Theory. Serious Games and Edutainment Applications, 485-509. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51645-5_22

Van Roy, R., & Zaman, B. (2018). Need-supporting gamification in education: An assessment of motivational effects over time. Computers & Education, 127, 283-297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.08.018

Videnovik, M., Vold, T., Kiønig, L., et al. (2023). Game-based learning in computer science education: A scoping literature review. IJ STEM Ed, 10, 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-023-00447-2

Werbach, K., Hunter, D., and Dixon, W. (2012). For the win: How game thinking can revolutionize your business, volume 1. Wharton digital press Philadelphia.

Yan, L. L. L., & Matore, M. E. (2023). Gamification Trend in Students’ Mathematics Learning Through Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 12(1), 400-423. https://doi.org/10.6007/ijarped/v12-i1/15732

Yang, F. M., & Kao, S. T. (2014). Item response theory for measurement validity. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry, 26(3), 171-177. https://doi.org/10.3969/j. issn.1002-0829.2014.03.010

Zahedi, L., Batten, J., Ross, M., Potvin, G., Damas, S., Clarke, P., & Davis, D. (2021). Gamification in education: A mixed-methods study of gender on

computer science students’ academic performance and identity development. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 33, 441-474. https://doi. org/10.1007/s12528-021-09271-5

Zeidan, M., Huang, X., Xiao, L., & Zhao, R. (2022). Improving student engagement using a video-enabled activity-based learning: An exploratory study to STEM preparatory education in UAE. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.47408/jldhe.vi24.888

Zichermann, G., and Cunningham, C. (2011). Gamification by design: Implementing game mechanics in web and mobile apps. ” O’Reilly Media, Inc.”.

Publisher’s Note

- *Correspondence:

Margarita Ortiz-Rojas

margarita.ortiz@cti.espol.edu.ec

Centro de Tecnologías de Información, Escuela Superior Politécnica del Litoral, ESPOL, Campus Gustavo Galindo Km. 30.5 Vía Perimetral, P.O. Box 09-01-5863, Guayaquil, Guayas, Ecuador

Department of Educational Studies, Ghent University, H. Dunantlaan 2, 9000 Ghent, Belgium

Centro de Investigaciones y Servicios Educativos, Escuela Superior Politécnica del Litoral, ESPOL, Campus Gustavo Galindo Km. 30.5 Vía Perimetral, P.O. Box 09-01-5863, Guayaquil, Guayas, Ecuador - © The Author(s) 2025. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.