DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2024.100171

تاريخ النشر: 2024-03-13

ما هي محو الأمية والكفاءة في الذكاء الاصطناعي؟ إطار شامل لدعمهما

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

كفاءة الذكاء الاصطناعي

التعليم من رياض الأطفال حتى الصف الثاني عشر

تعلم الآلة

محو الأمية البيانات

الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي

الملخص

تعليم الذكاء الاصطناعي في المدارس من رياض الأطفال حتى الصف الثاني عشر هو مبادرة عالمية، ومع ذلك فإن التخطيط وتنفيذ تعليم الذكاء الاصطناعي يمثل تحديًا. تركز الأطر الرئيسية على تحديد المحتوى والمعرفة التقنية (محو الأمية في الذكاء الاصطناعي). تم تطوير معظم التعريفات الحالية لمحو الأمية في الذكاء الاصطناعي لجمهور غير تقني من منظور هندسي وقد لا تكون مناسبة لـ

مقدمة

تقرير عن تعليم الذكاء الاصطناعي. من ناحية أخرى، على عكس التعليم العالي، تصميم

مراجعة الأدبيات

محو الأمية والمهارة في الذكاء الاصطناعي

شرط أساسي لمحو الأمية في الذكاء الاصطناعي. بالنظر إلى العلاقة الوثيقة بين البيانات وتعلم الآلة (فرع من الذكاء الاصطناعي)، تشير محو الأمية البيانية إلى القدرة على فهم، والعمل مع، وتقييم، والجدل حول البيانات كجزء من عملية استقصاء أكثر شمولاً حول العالم [45]، والتي تتداخل إلى حد كبير مع محو الأمية في الذكاء الاصطناعي. علاوة على ذلك، قد لا ترتبط محو الأمية الأخرى، مثل الحاسوبية والعلمية، ارتباطًا وثيقًا بمحو الأمية في الذكاء الاصطناعي. تتضمن محو الأمية الحاسوبية استكشاف وتواصل الأفكار من خلال الشيفرة [44]؛ لذلك، ليست شرطًا أساسيًا لمحو الأمية في الذكاء الاصطناعي التي لا تتطلب كتابة الشيفرات لفهم كيفية عمل الذكاء الاصطناعي. وبالمثل، لا تتطلب محو الأمية في الذكاء الاصطناعي محو الأمية العلمية، التي تشير إلى تقدير طبيعة العلم، ومساهماته، والقيود الأساسية له [22]. تعريف محو الأمية في الذكاء الاصطناعي هو واحد من الأولويات للمحترفين غير المتخصصين في الذكاء الاصطناعي، مما قد يوفر

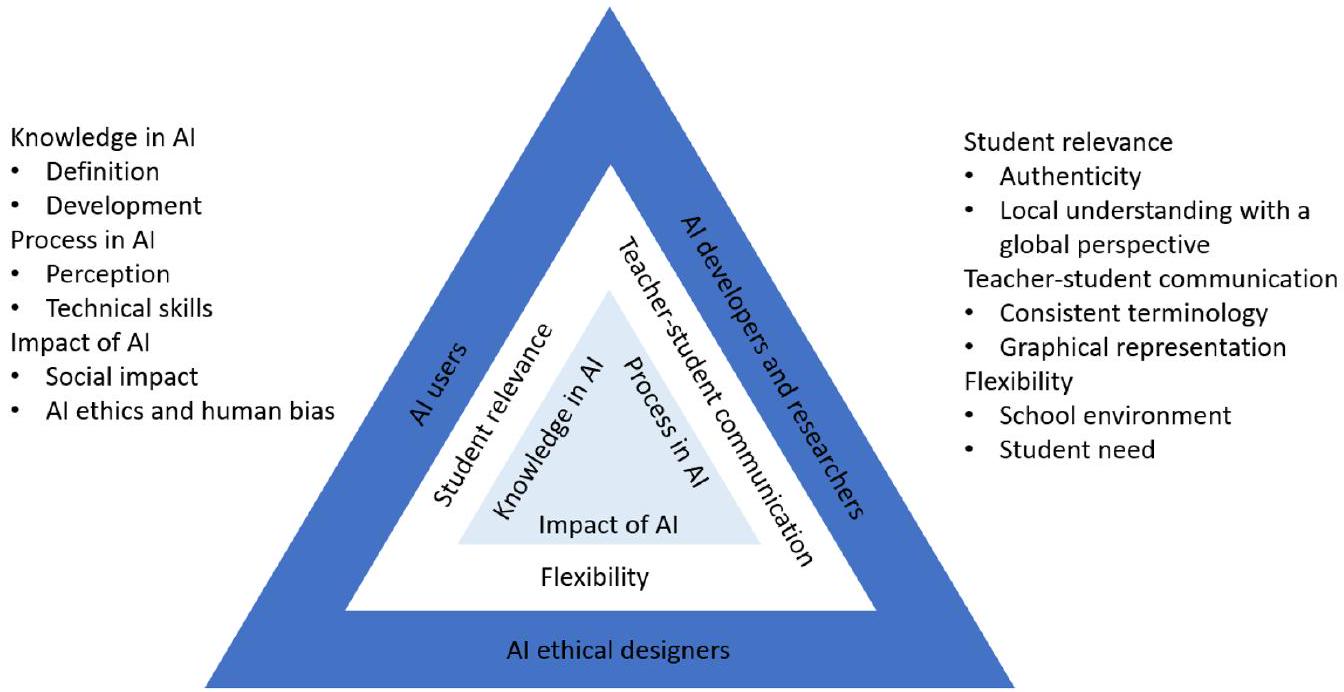

طرق تصميم العمليات والممارسات في سياق تعليم الذكاء الاصطناعي

ثلاثة أطر رئيسية لتعليم الذكاء الاصطناعي في K-12

في السنوات الخمس الماضية. كان أحد الأطر الأولى، المعروف باسم “خمسة أفكار كبيرة في الذكاء الاصطناعي”، قد اقترحه تويريتسكي وآخرون [43]. في عام 2018، كان هناك القليل من التوجيه الخارجي من الأدبيات حول محتوى ونطاق تعليم الذكاء الاصطناعي لطلاب K-12 [42]. بدأت لجنة توجيه AI4K12، التي تتكون من ديفيد تويريتسكي، كريستينا غاردنر-ماكون، فريد مارتن، وديبورا سيهورن، عملها من خلال وضع قائمة. تعمل هذه القائمة كإطار تنظيمي للإرشادات، التي تم تطويرها بناءً على معايير CSTA للحوسبة. تم هيكلة تلك المعايير حول نفس الأفكار الخمس الأساسية [11]. الأفكار الكبيرة الخمس هي:

- الإدراك: تستخدم الحواسيب المستشعرات للحصول على معلومات حول بيئتها. فهم ما تحاول الحواس إخبارنا به هو ما نسميه الإدراك.

- التمثيل والتفكير: تحتفظ الوكلاء بنماذج للعالم وتستخدمها لاتخاذ القرارات. التمثيلات هي القوة الدافعة وراء التفكير، ويستخدمها المفكرون.

- التعلم: يمكن للحواسيب الاستمرار في التعلم من البيانات. من خلال تعديل التمثيلات داخل شجرة القرار أو الشبكة العصبية، ينشئ خوارزمية تعلم الآلة مفكرًا.

- التفاعل الطبيعي: للتواصل مع الناس بطريقة طبيعية، تحتاج الوكلاء الذكية إلى الوصول إلى مجموعة واسعة من المعلومات. تشمل المعلومات الفطرة السليمة، والثقافة، والعواطف البشرية، ومعرفة اللغة.

- الأثر الاجتماعي: سيكون هناك آثار إيجابية وسلبية للذكاء الاصطناعي على المجتمع. تشمل المواضيع الآثار الاقتصادية للأتمتة، والعدالة والشفافية في أنظمة اتخاذ القرار الآلي، والاعتبارات الثقافية لخوارزميات الذكاء الاصطناعي، واستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي من أجل الخير الاجتماعي.

فجوات البحث

هذه الدراسة والطريقة

هدف البحث

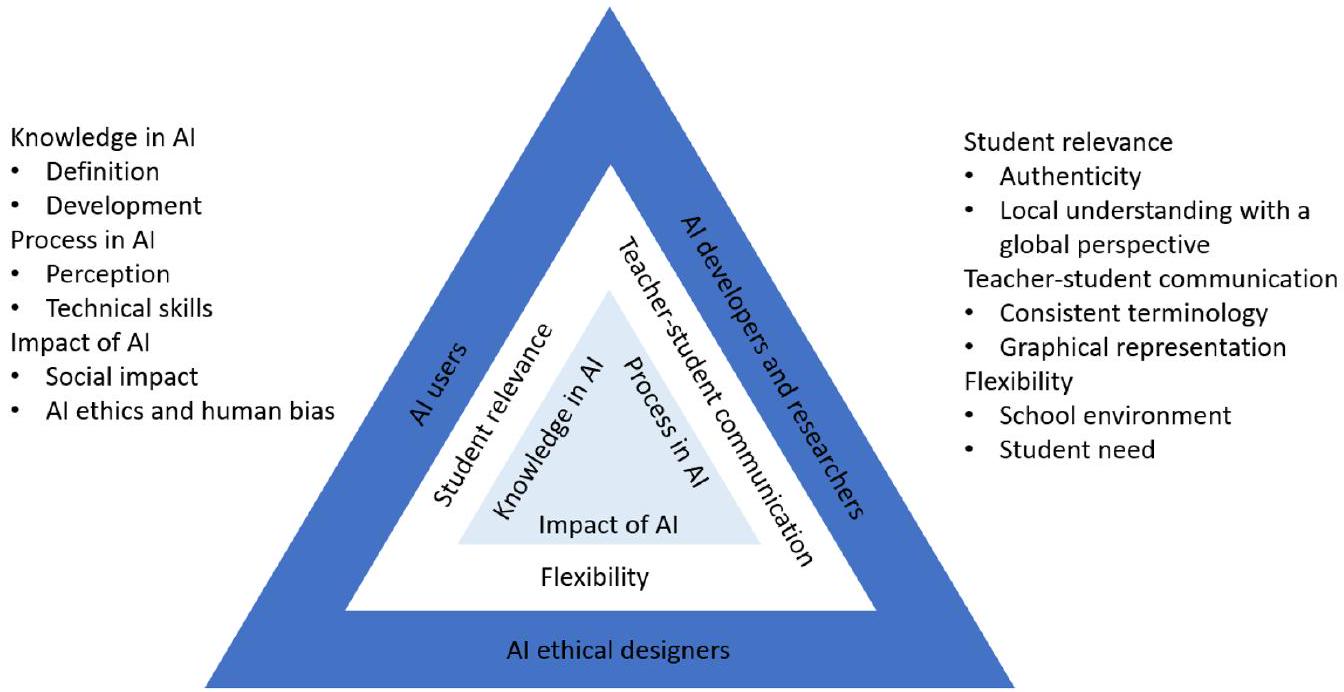

تعريفات معرفة الذكاء الاصطناعي والكفاءة

كما يلي:

- يتم تعريف معرفة الذكاء الاصطناعي بأنها “قدرة الفرد على شرح كيفية عمل تقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي وتأثيرها على المجتمع بوضوح، بالإضافة إلى استخدامها بطريقة أخلاقية ومسؤولة والتواصل والتعاون معها بفعالية في أي بيئة. وهي تركز على المعرفة (أي المعرفة والمهارات).”.

- تُعرَّف كفاءة الذكاء الاصطناعي بأنها “ثقة الفرد وقدرته على شرح كيفية عمل تقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي وتأثيرها على المجتمع بوضوح، بالإضافة إلى استخدامها بطريقة أخلاقية ومسؤولة والتواصل والتعاون معها بفعالية في أي بيئة. يجب أن يكون لديهم الثقة والقدرة على التفكير الذاتي حول فهمهم للذكاء الاصطناعي من أجل التعلم الإضافي. تركز على مدى استخدام الأفراد للذكاء الاصطناعي بطرق مفيدة.”

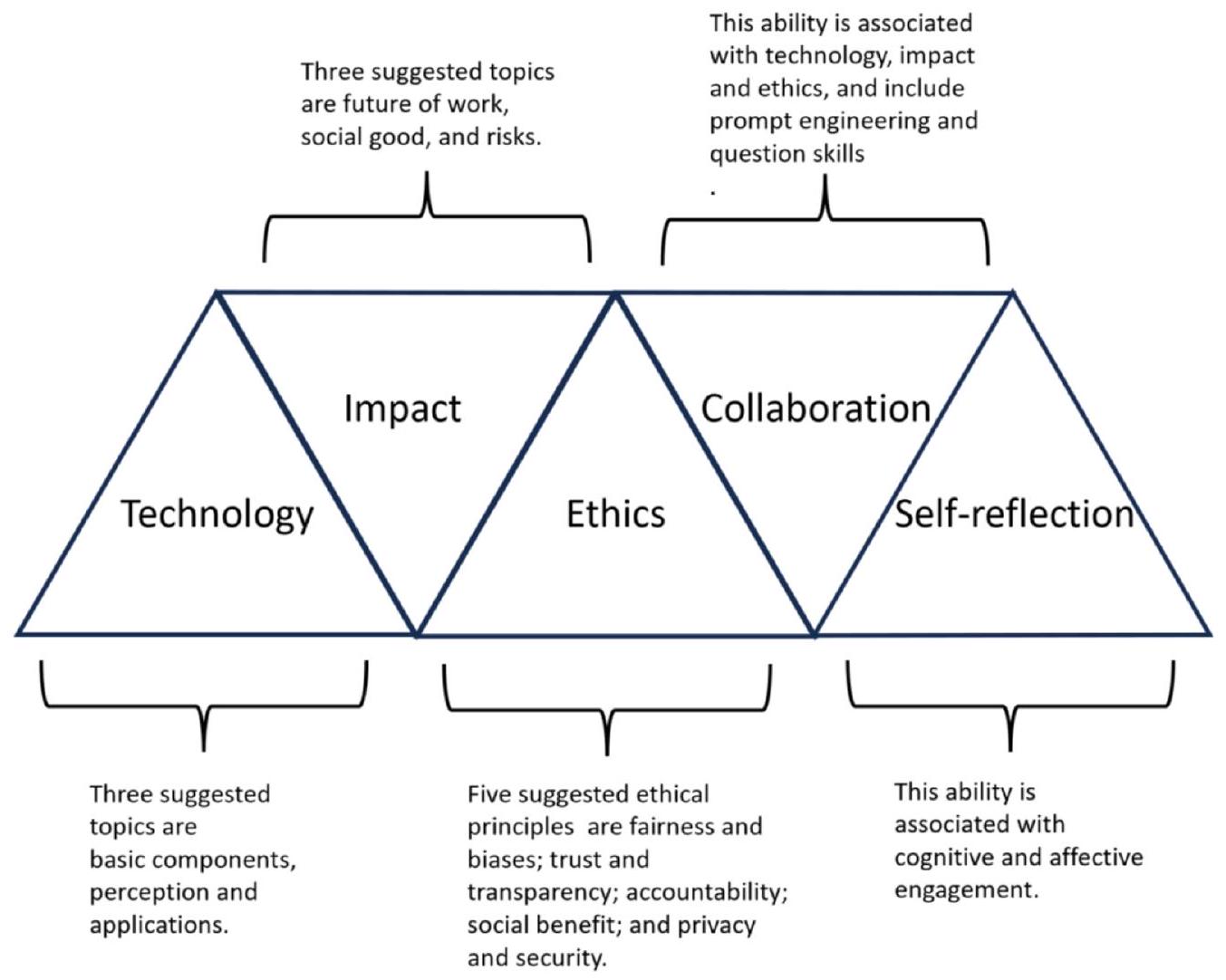

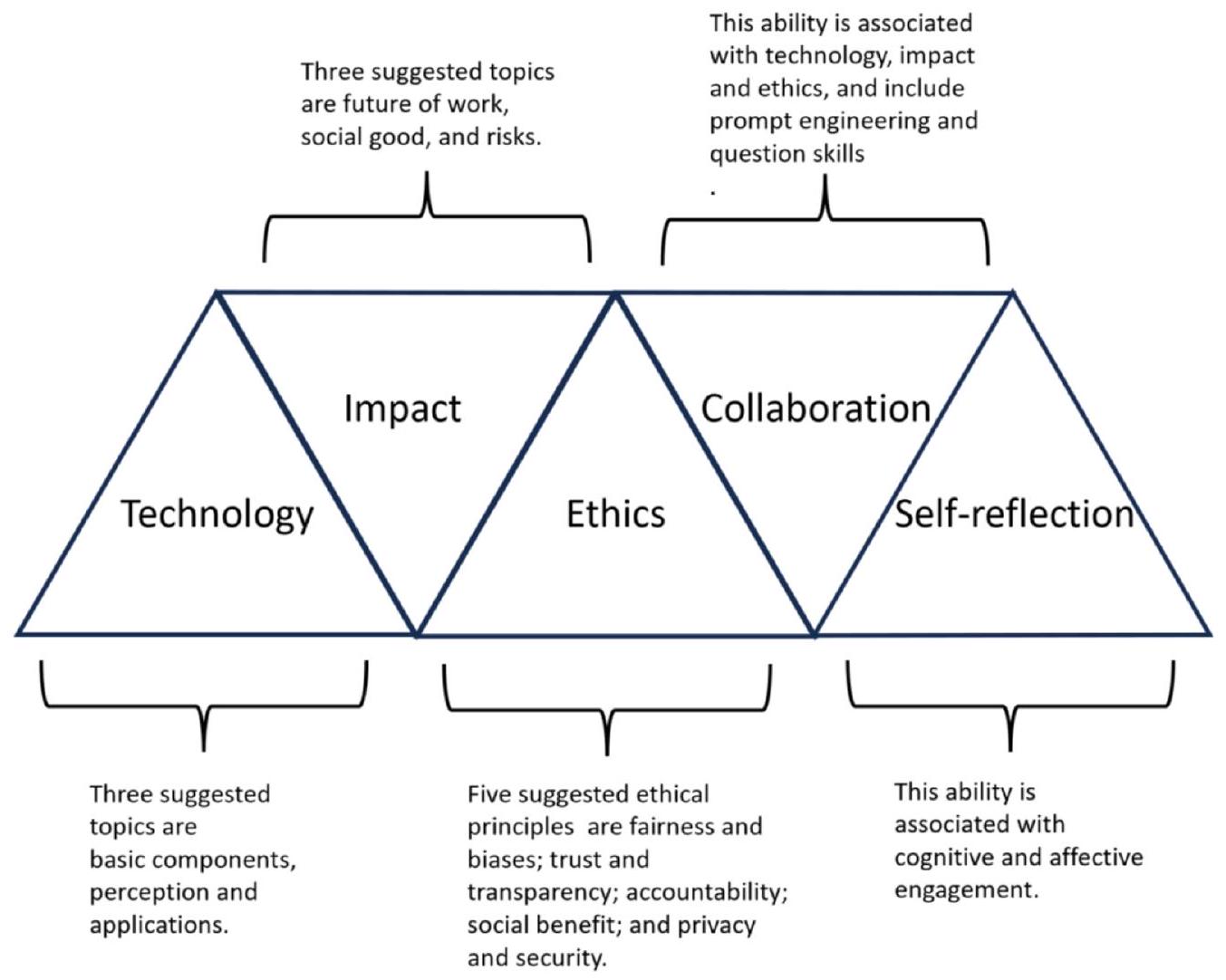

- التكنولوجيا: الثقة والقدرة على شرح كيفية عمل تقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي بوضوح

- الأثر: الثقة والقدرة على شرح كيفية تأثير تقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي على المجتمع بوضوح

- الأخلاقيات: الثقة والقدرة على استخدام تقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي بطريقة أخلاقية ومسؤولة

- التعاون: الثقة والقدرة على التواصل والتعاون بفعالية مع تقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي في أي بيئة

- التأمل الذاتي: الثقة والقدرة على التأمل الذاتي في فهمهم للذكاء الاصطناعي من أجل التعلم الإضافي. الأفراد الذين يمتلكون عقولاً تأملية أقوى هم أكثر احتمالاً لمراجعة معرفتهم بالذكاء الاصطناعي وتحديد المجالات والاحتياجات للتعلم الإضافي.

المشاركون

تصميم البحث وإجراءاته

التحليلات، الموثوقية والصلاحية

النتائج والمناقشات

المكونات الخمسة في الإطار الشامل

التكنولوجيا

- يجب تدريس المكونات الأساسية، والتعريف، والتاريخ، وتطور الذكاء الاصطناعي في المدارس. تم الاتفاق على التعريف التالي للذكاء الاصطناعي من قبل جميع المشاركين: “يشير الذكاء الاصطناعي إلى قدرة الآلة على أداء مهام تعادل التعلم واتخاذ القرار البشري.” يتماشى هذا التعريف مع نتائج تشيو وآخرين وتوريتسكي وآخرين. يجب على الطلاب فهم المفاهيم الأساسية مثل البيانات الضخمة، وتعلم الآلة، والحوسبة السحابية. يجب عليهم فهم الخصائص الخمس الأساسية والفطرية للبيانات الضخمة، وهي السرعة، والحجم، والقيمة، والتنوع، والموثوقية. لفهم كيفية استخدام آلات الذكاء الاصطناعي للبيانات لتعزيز مهاراتها بشكل صحيح، يجب أن يتناول موضوع تعلم الآلة نماذج التدريب وخوارزميات التعلم. الحوسبة السحابية مطلوبة.

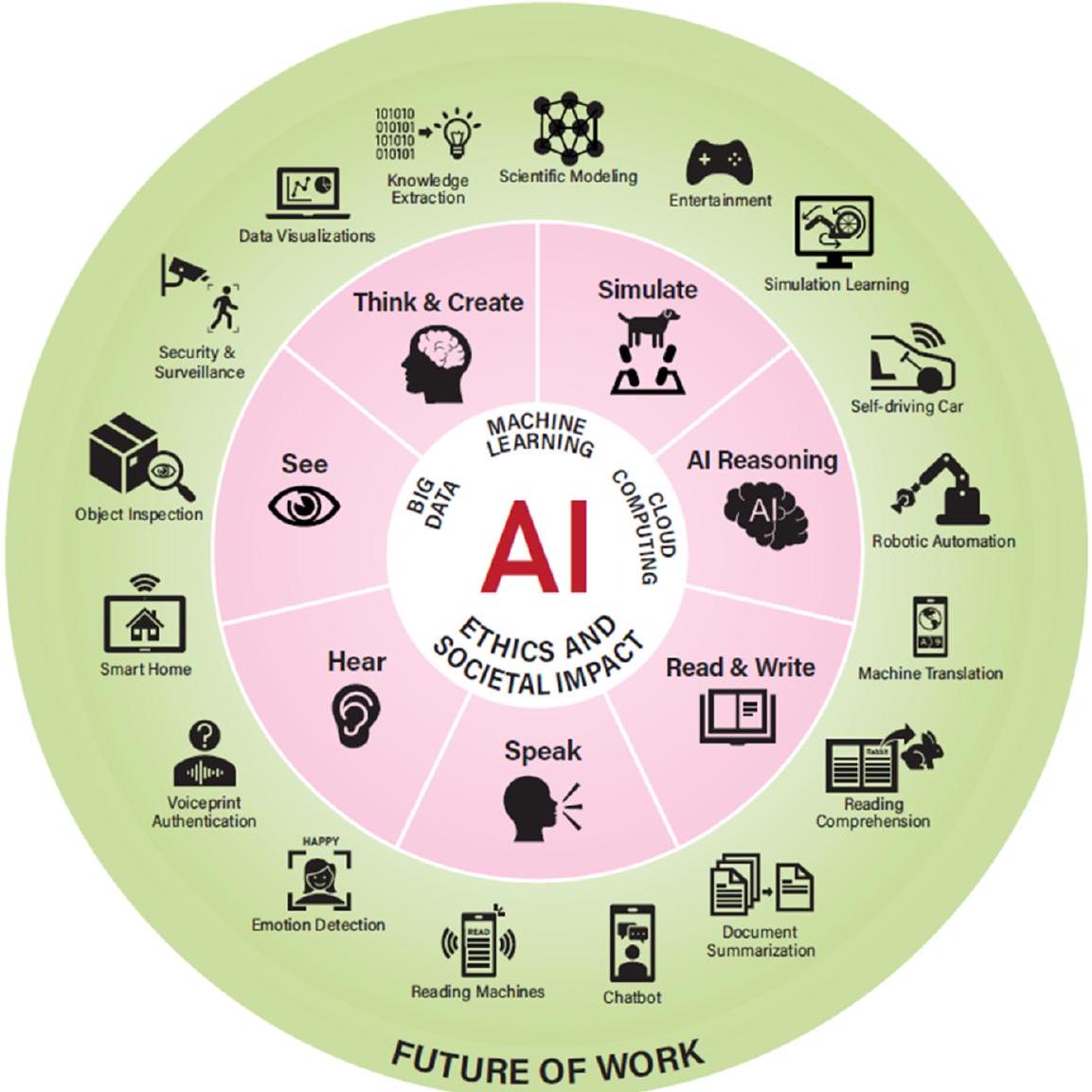

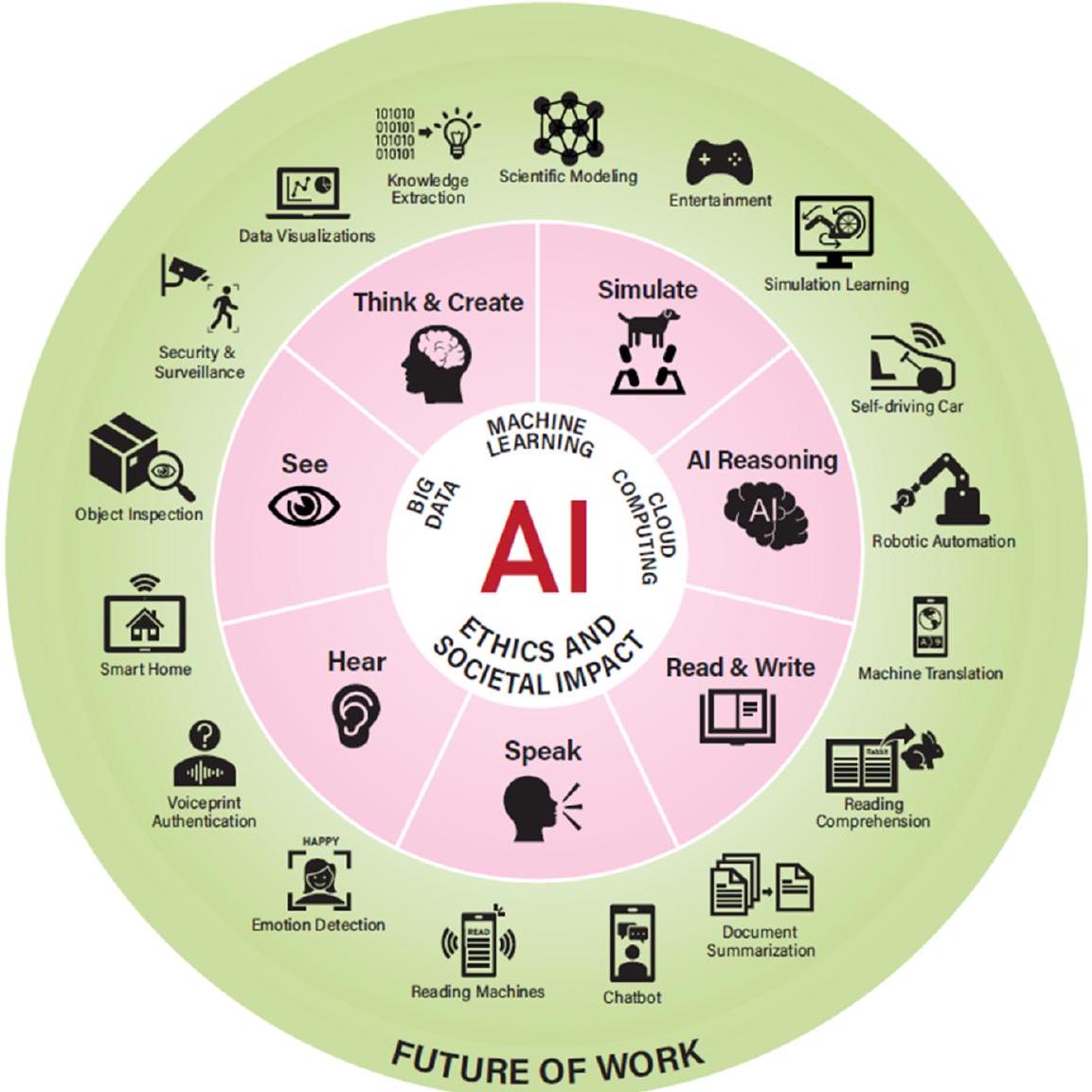

لإجراء معالجة بيانات ضخمة من أجل تدريب النماذج و/أو الخوارزميات بشكل أفضل. علاوة على ذلك، فإن تاريخ وتطور الذكاء الاصطناعي هما موضوعان حاسمان في التعليم من الروضة حتى الصف الثاني عشر. اتفق جميع المشاركين على أنه يجب على الطلاب فهم تاريخ الذكاء الاصطناعي بالإضافة إلى التقدمات المعاصرة مثل “الثورة الصناعية الرابعة” والذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي، مثل ChatGPT وSora. يجب على الطلاب أن يدركوا كيف تختلف آلات الذكاء الاصطناعي عن الآلات غير الذكية. على سبيل المثال، تم تصميم الآلات غير الذكية للإجابة على مشاكلنا من خلال تطبيق القواعد أو الخوارزميات، بينما تستخدم آلات الذكاء الاصطناعي البيانات لتطوير وتجديد القواعد أو النماذج. يجب أن يفهموا أن الذكاء الاصطناعي يغير المفهوم الأساسي لكيفية عمل الآلات وأن “البيانات هي الشيفرة الجديدة”. يجب أن يكون الطلاب الذين أتقنوا المعرفة الأساسية، على وجه الخصوص، قادرين على التعرف على ما إذا كانت التقنيات التي يستخدمونها هي ذكاء اصطناعي وفهم تداعيات ذلك. يجب أن يُطلب منهم أيضًا وصف أنواع البيانات التي يجمعها الذكاء الاصطناعي، وكيف يحلل الذكاء الاصطناعي البيانات، وكيف يتعلم الذكاء الاصطناعي من البيانات. - الإدراك هو الموضوع الثاني في المعرفة الأساسية، وهو متسق مع أبحاث تشيو وآخرون [8] وتوريتسكي وآخرون [42]. أشار المعلمون إلى أن مفهوم الإدراك في دراسة توريتسكي وآخرون [42] مجرد جدًا. لم يفهم الطلاب ما تعنيه هذه الكلمة. اختاروا مفاهيم الحواس البشرية كمواضيع فرعية للإدراك. الحواس البشرية – الرؤية، القراءة، الكتابة؛ التحدث والاستماع؛ التفكير والإبداع؛ الاستدلال والمحاكاة – هي مصطلحات تعكس تعريف الذكاء الاصطناعي. نظرًا لأن هذه المصطلحات ليست تقنية بشكل مفرط، سيفهم كل من الطلاب والمعلمين ما يحتاجون إلى تعلمه أو تدريسه. يجب أن يفهم الطلاب كيف تجمع كل حاسة البيانات وتعالجها.

- الموضوع الثالث هو تطبيقات الذكاء الاصطناعي. أشار المعلمون إلى أن نطاق الموضوع أكبر من عمقه. يجب أن يكون لدى الطلاب فهم شامل لتطبيقات الذكاء الاصطناعي، والتي يجب أن تشمل معظم الصناعات أو جوانب الحياة اليومية مثل الرعاية الصحية، والترفيه، والنقل، واللوجستيات، وما إلى ذلك. يجب عليهم استخدام الإدراك لوصف كيفية عمل كل تطبيق، بالإضافة إلى التعلم الآلي لبناء وتطوير تطبيقات الذكاء الاصطناعي الخاصة بهم.

أثر

- في موضوع مستقبل العمل، يولي الأطفال الصغار قيمة عالية لدراستهم المستقبلية ووظائفهم. يحتاجون إلى فهم أن المزيد من المهن المستقبلية تتطلب معرفة بالذكاء الاصطناعي وأنهم من المرجح بشكل متزايد أن يتعلموا مع الذكاء الاصطناعي في حياتهم ويعملوا مع الذكاء الاصطناعي في وظائفهم.

- الموضوع الفرعي الثاني هو الذكاء الاصطناعي من أجل الخير الاجتماعي. يمكن أن يكون للذكاء الاصطناعي آثار إيجابية وسلبية على المجتمع. وفقًا للمعلمين، يجب على الطلاب أن يتعلموا كيف يحل الذكاء الاصطناعي القضايا المعقدة من خلال معالجة القضايا الاجتماعية والبيئية والصحية العامة الحرجة. بخلاف الفوائد التي يجلبها الذكاء الاصطناعي للمجتمع، يجب على الطلاب أيضًا أن يتعلموا المخاطر.

- الموضوع الأخير هو المخاطر. اتفق جميع المشاركين على أنه يجب على الطلاب أن يكونوا على دراية بالمخاطر المحتملة المرتبطة بالذكاء الاصطناعي. يجب عليهم التحقيق في كيفية تسبب التقنيات الناشئة في المشاكل والأذى في سياقات مختلفة. هذه تتماشى مع الإطارين [4،43] ودراسات أخرى ذات صلة [47،50].

الأخلاق

الجماهير التقنية. استخدم المعلمون أخيرًا مبادئ الذكاء الاصطناعي الأخلاقية من IBM كنقطة انطلاق وتوصلوا إلى توافق حول ما يجب تضمينه في هذا الموضوع. اختاروا خمسة منها لأنها أكثر صلة بطلاب المدارس: العدالة والتحيزات؛ الثقة والشفافية؛ المساءلة؛ الفائدة الاجتماعية؛ والخصوصية والأمان.

التعاون

التأمل الذاتي

خمسة تجارب تعليمية أساسية

- المشاركة المجتمعية: وفقًا لكوبر [13] وموني وإدواردز [36]، فإن دمج تعلم الطلاب مع المجتمع هو استراتيجية بيداغوجية هادفة يستخدمها المعلمون لإقامة صلة بين ما يتم تدريسه في الفصل الدراسي ومجتمعات الطلاب المحلية. ونتيجة لذلك، يمكن للطلاب تطبيق أفكارهم بناءً على الملاحظة الشخصية والتفاعل الاجتماعي لتصميم وإيجاد حلول لمشاكل العالم الحقيقي في المجتمع. وهم أكثر ميلاً للاستثمار في التعلم لأن التحديات أكثر صلة وتشجع على مشاركة الطلاب. ستزيد هذه المشاركة المجتمعية من اهتمام الطلاب وحماسهم.

، 28]، مما يؤدي إلى تعليم الذكاء الاصطناعي الأكثر شمولاً وتنوعاً [46]. ستعزز هذه المشاركة المجتمعية الذكاء الاصطناعي من أجل الخير الاجتماعي بينما تنمي أيضاً المواقف الإيجابية للطلاب تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي. علاوة على ذلك، ذكر المعلمون أن نهج التفكير التصميمي – التعاطف، التعريف، التفكير الإبداعي، النموذج الأولي، والاختبار – يجب أن يُستخدم لحل مشاكل المجتمع. لتحقيق تأثير أكبر، يمكن أن تتعلم المشاركة المجتمعية الكثير من التفكير التصميمي [4]. - دراسات حالة عالمية ومحلية: واحدة من الطرق التعليمية الفعالة التي اقترحها المعلمون هي استخدام المقالات الإعلامية لتثقيف الطلاب حول أخلاقيات الذكاء الاصطناعي وتأثيره. يمكن لطلاب المدارس قراءة مقالات ويب متنوعة، ومع ذلك هناك العديد من الخيارات المتحيزة أو الأخبار الكاذبة. هم أقل نضجًا وأقل قدرة على الحكم على موثوقية المقالات. على عكس ما كان عليه الحال قبل عشر سنوات، يتم نشر المزيد من القصص الصحفية نتيجة لتقدم الذكاء الاصطناعي. لقد أصبحت مؤخرًا أكثر سهولة لكل من المعلمين والطلاب. هذه الطريقة تخلق تعلمًا غير تقليدي، مما يجعلها أكثر أصالة وملاءمة. يمكن للطلاب أن يعكسوا بشكل أكثر نشاطًا على القضايا الأخلاقية التي تثيرها القصص الصحفية. علاوة على ذلك، يمكن استخدام هذا الأسلوب التعليمي لتعليم المبادئ الأخلاقية مع التأكيد على أهمية مصادر البيانات. يمكن للمعلمين استخدام ذلك لتوضيح مفاهيم مثل العدالة والتحيز، والثقة والشفافية، والمساءلة.

- الأنشطة العملية: الطلاب محاطون بالذكاء الاصطناعي، لكن ليس كثيرًا في فصولهم الدراسية. يمكن أن تساعد الأنشطة العملية الطلاب على فهم الإدراك بشكل أفضل لأنها تضعهم في مقعد السائق من خلال النشاط البدني والتعلم النشط. يمكن أن يدعم التعلم النشط بدنيًا ثقة الطلاب وقدرتهم على نمذجة العالم وتوليد أفكار إبداعية. قد تسمح هذه الروابط بتصميم واستخدام أدوات متعددة الأجزاء. يمكن للطلاب حل المشكلات التي لا يمكنهم حلها شفهيًا أو بصريًا من خلال نمذجة الأنظمة الفيزيائية بأيديهم. إن طلب من الطلاب استخدام أيديهم لنمذجة الظواهر الفيزيائية باستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي سيطور فهمهم المفاهيمي لإدراك الذكاء الاصطناعي. كما اقترح المعلمون بعض الأفكار العملية: يمكن للطلاب التحقيق في كيفية جمع الذكاء الاصطناعي وفهمه وتحديده للصور، أي تعلم كيفية رؤية الحواسيب للصور. يمكن للطلاب فهم ما يقرؤون ويكتبون نظرًا لأن الذكاء الاصطناعي يفهم اللغات والنصوص، ويمكنهم تطوير محللات نصية لاكتشاف مزاج النصوص. علاوة على ذلك، يعتقد معظم الطلاب أن الذكاء الاصطناعي والروبوتات هما نفس التكنولوجيا. يجب على الطلاب أن يتعلموا كيف يختلف الذكاء الاصطناعي عن الروبوتات من خلال القيام بمشروع عملي يبنون فيه روبوتًا مع التفكير والإدراك. وفقًا للمعلمين، يمكن تعليم المبادئ الأخلاقية، التي غالبًا ما تم تدريسها باستخدام أساليب دراسة الحالة، من خلال الأنشطة العملية. يمكن للطلاب تصميم تطبيقات ذكاء اصطناعي متحيزة واحدة أو أكثر وشرح كيف أدى اختيار مجموعة البيانات إلى النتائج المتحيزة. نتيجة لذلك، يمكن أن تلبي الأنشطة العملية بشكل أفضل احتياجات الطلاب ذوي الفروق الفردية والتعلم وتعزز التعليم الشامل والمتنوع في مجال الذكاء الاصطناعي.

- المعارض والعروض التقديمية: هذه الاستراتيجية شائعة في نشر أعمال الطلاب، لا سيما في التعلم القائم على المشاريع. إنها تتيح للطلاب توطيد تعلمهم من خلال التواصل حول عملياتهم، والتفكير في منتجاتهم، والتأمل في إجاباتهم. أشار المعلمون في هذا الإطار إلى أنه يجب على الطلاب عرض عملية تعلمهم وأعمال مشاريعهم. وأبرز المعلم في تعليم الذكاء الاصطناعي أنه يجب على الطلاب استخدام المعرفة الأساسية كمعايير لتقديم أعمالهم في المعرض. على سبيل المثال، كيف حصلوا على البيانات أو أنشأوها لبناء الإدراك؟ هل البيانات أخلاقية؟ هل استخدامهم لها أخلاقي؟ ما هو الأثر الاجتماعي لعملهم؟ أي صناعة ستستفيد من منتجاتهم؟ وبناءً عليه، فإن تقديم أعمال مشاريعهم يشجع الطلاب على الاستفادة من اختلافاتهم الفردية.

- التعلم الثقافي: يجب أن تؤخذ القيم الإنسانية والثقافة في الاعتبار عند تعلم الذكاء الاصطناعي. قد تكون البيانات متحيزة بسبب كيفية الحصول عليها أو اختيارها للاستخدام. تلعب القيم الإنسانية والثقافة دورًا كبيرًا في ذلك. قد لا يتم تحديد الإجابة على سؤال “هل هناك تحيز في الذكاء الاصطناعي أم لا” من خلال معرفة الذكاء الاصطناعي ولكن من خلال القيم الإنسانية والثقافة. يجب أن تؤخذ هذان العنصران في الاعتبار من قبل الطلاب أثناء تعلم الذكاء الاصطناعي. على سبيل المثال، عند تطوير مشاريع الذكاء الاصطناعي لمساعدة كبار السن، يتعين على الطلاب احترام ثقافتهم وقيمهم (مثل الطعام والأنظمة الغذائية) ولكن لا يغيرون ثقافتهم. عند مناقشة القضايا الأخلاقية المتعلقة بالسيارات ذاتية القيادة، يجب أن يكون الطلاب على دراية بالقوانين المحلية والمعتقدات الدينية (إيذاء الأبقار في الهند قد يؤدي إلى جرائم خطيرة).

الخير الاجتماعي (مشاركة المجتمع)، صلة الطلاب (مقالات الصحف)، التعلم النشط (أنشطة عملية)، التعاون، والتواصل (عرض تقديمي) (الشكل 2).

اتجاهات البحث المستقبلية والتوصيات

- هندسة الطلب: في هذه التقنية الجديدة، يمكنك إعادة صياغة استفسار، اختيار أسلوب، تقديم مزيد من المعلومات السياقية، أو تعيين دور للذكاء الاصطناعي عند التفاعل مع

. تقتصر الدراسات الحالية حول هذه التقنية على ChatGPT. يتعلق هذا أيضًا بمهاراتنا في طرح الأسئلة. يتم تطوير معظم مهارات طرح الأسئلة لدى الأطفال الصغار في التعليم في المرحلة الابتدائية والثانوية. يجب إجراء مزيد من الدراسات لفهم كيفية تفاعل طلاب المرحلة الابتدائية والثانوية مع الذكاء الاصطناعي، أي، هندسة الطلب أو مهارات طرح الأسئلة للذكاء الاصطناعي. - تعليم علم البيانات: كيفية التواصل مع الذكاء الاصطناعي مرتبط بمن يستخدم البيانات ويفسرها. ترتبط محو الأمية البيانات ارتباطًا وثيقًا بمحو الأمية في الذكاء الاصطناعي [31]. قد يحتاج تعليم علم البيانات ومحو الأمية البيانات إلى أن يتم تضمينها في التعليم في المرحلة الابتدائية والثانوية. حاليًا، يتم تضمين هذه الأمية في مواد الرياضيات أو الذكاء الاصطناعي. يجب إجراء مزيد من الدراسات للتحقيق في كيفية ارتباط محو الأمية البيانات بتطوير محو الأمية في الذكاء الاصطناعي.

- محو الأمية الخوارزمية: للتواصل الكامل مع الذكاء الاصطناعي، قد تكون محو الأمية الخوارزمية مطلوبة. تشمل هذه الأمية الوعي والمعرفة بالخوارزميات، والثقة والاطمئنان للخوارزميات، وتقدير الخوارزميات، وتجنب الخوارزميات [25]. لم يناقش هذا الإطار هذه الأمية. يجب إجراء دراسات مستقبلية لتعريف محو الأمية الخوارزمية وكيف تؤثر على محو الأمية في الذكاء الاصطناعي.

- العقليات الانعكاسية الذاتية: هذه العقلية لم يتم دراستها بشكل كافٍ في تعليم الذكاء الاصطناعي. الذكاء الاصطناعي مختلف عن المواد الأخرى التقليدية، مثل الرياضيات والعلوم في المرحلة الابتدائية والثانوية، وهو في طور النشوء. ترتبط النظرية الاجتماعية المعرفية بالانخراط العاطفي، والتعلم الذاتي المنظم يتعلق بالانعكاس الذاتي. يُوصى بإجراء دراسات مستقبلية لاستخدام النظرية الاجتماعية المعرفية والتعلم الذاتي المنظم لتحديد أساليب التدريس الفعالة لتعزيز العقليات الانعكاسية الذاتية لدى الطلاب.

- البحث التجريبي: لا يزال تعليم الذكاء الاصطناعي جديدًا؛ يجب إجراء مزيد من الدراسات التجريبية لتنقيح تعريف محو الأمية في الذكاء الاصطناعي والكفاءة وإطار تعليم الذكاء الاصطناعي.

الخاتمة والقيود

بيان مساهمة المؤلفين

إعلان عن تضارب المصالح

توفر البيانات

التمويل

الشكر

References

[2] Chiu TKF. Using Self-determination Theory (SDT) to explain student STEM interest and identity development. Instr Sci 2024;58:89-107. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11251-023-09642-8.

[3] Chiu T.K.F. (2023). The impact of Generative AI (GenAI) on practices, policies and research direction in education: A case of ChatGPT and Midjourney, Interactive Learning Environments, Advanced online publication. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/ 10494820.2023.2253861.

[4] Chiu TKF. Applying the Self-determination Theory (SDT) to explain student engagement in online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Res Technol Edu 2022;54(1):14-30. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1891998.

[5] Chiu TKF. A holistic approach to Artificial Intelligence (AI) curriculum for K-12 schools. TechTrends 2021;65:796-807. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-021-00637-1.

[6] Chiu TKF, Chai CS, Williams J, Lin TJ. Teacher professional development on Selfdetermination Theory-based design thinking in STEM education. Edu Technol Soc 2021;24(4):153-65. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48629252.

[7] Chiu TKF, Ismailov M, Zhou X-Y, Xia Q, Au D, Chai CS. Using Self-Determination Theory to explain how community-based learning fosters student interest and identity in integrated STEM education. Int J Sci Math Educ 2023;21:109-30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-023-10382-x.

[8] Chiu TKF, Meng H, Chai CS, King I, Wong S, Yeung Y. Creation and evaluation of a pre-tertiary artificial intelligence (AI) curriculum. IEEE Transac Edu 2022;65(1): 30-9. https://doi.org/10.1109/TE.2021.3085878.

[9] Chiu, T.K.F., Moorhouse, B.L., Chai, C.S., & Ismailov M. (2023). Teacher support and student motivation to learn with artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot, Interactive Learning Environments, Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/10 494820.2023.2172044.

[10] Chiu TKF, Xia Q, Zhou X-Y, Chai CS, Cheng M-T. Systematic literature review on opportunities, challenges, and future research recommendations of artificial intelligence in education. Comput Edu: AI 2023;4:100118. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.caeai.2022.100118.

[11] CSTA. (2017). Computer Science Teachers Association (CSTA) K-12 Computer Science Standards, Revised 2017. https://www.csteachers.org/page/standards. Accessed 12 Nov 2022.

[12] Cooper G. Examining science education in ChatGPT: An exploratory study of generative artificial intelligence. J Sci Educ Technol 2023;32:444-52. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10956-023-10039-y.

[13] Cooper JE. Strengthening the case for community-based learning in teacher education. J Teach Educ 2007;58(3):245-55. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0022487107299979.

[14] Cope B, Kalantzis M, Searsmith D, Cope B, Kalantzis M, Searsmith D. Artificial intelligence for education: Knowledge and its assessment in AI-enabled learning ecologies. Educational Philosophy and Theory 2020;53(12):1229-45. https://doi. org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1728732.

[15] Cypress BS. Rigor or reliability and validity in qualitative research: Perspectives, strategies, reconceptualization, and recommendations. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing 2017;36(4):253-63. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCC.0000000000000253.

[16] Datta P, Whitmore M, Nwankpa JK. A perfect storm: social media news, psychological biases, and AI. Digital Threats: Research and Practice 2021;2(2): 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1145/3428157.

[17] Falloon G. From digital literacy to digital competence: the teacher digital competency (TDC) framework. Educational Technology Research and Development 2020;68:2449-72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09767-4.

[18] Gerke S, Minssen T, Cohen G. Ethical and legal challenges of artificial intelligencedriven healthcare. Artificial intelligence in healthcare. Academic Press; 2020. p. 295-336. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818438-7.00012-5.

[19] Ghasemaghaei M. Understanding the impact of big data on firm performance: The necessity of conceptually differentiating among big data characteristics. Int J Inf Manage 2021;57:102055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.102055.

[20] Glatthorn AA, Boschee F, Whitehead BM, Boschee BF. Curriculum leadership: strategies for development and implementation. London: SAGE; 2018.

[21] Grant MM, Branch RM. Project-based learning in a middle school: Tracing abilities through the artifacts of learning. J Res Tech Edu 2005;38(1):65-98. https://doi. org/10.1080/15391523.2005.10782450.

[22] Holbrook J, Rannikmae M. The meaning of scientific literacy. Int J Environ Sci Edu 2009;4(3):275-88.

[23] Holzmeyer C. Beyond ‘AI for Social Good'(AI4SG): social transformations-Not tech-fixes-For health equity. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 2021;46(1-2): 94-125. https://doi.org/10.1080/03080188.2020.1840221.

[24] Hornberger M, Bewersdorff A, Nerdel C. What do university students know about Artificial Intelligence? Development and validation of an AI literacy test. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2023;5:100165. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100165.

[25] Du YR. Personalization, Echo Chambers, News Literacy, and Algorithmic Literacy: A Qualitative Study of AI-Powered News App Users. J Broadcast Electron Media 2023;67(3):246-73. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2023.2182787.

[26] Keefe EB, Copeland SR. What is literacy? The power of a definition. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 2011;36(3-4):92-9. https://doi.org/ 10.2511/027494811800824507.

[27] Kelly AV. The curriculum: theory and practice. 6th ed. London: Sage; 2009.

[28] King NS, Pringle RM. Black girls speak STEM: Counterstories of informal and formal learning experiences. J Res Sci Teach 2019;56(5):539-69. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/tea.21513.

[29] Laupichler MC, Aster A, Raupach T. Delphi study for the development and preliminary validation of an item set for the assessment of non-experts’ AI literacy. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2023;4:100126. https://doi.org/ 10.1075/idj.23.1.03dighttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100126.

[30] Leung L. Validity, reliability, and generalizability in qualitative research. J Family Med Prim Care 2015;4(3):324. https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.161306.

[31] Long D, Magerko B. What is AI literacy? Competencies and design considerations. In: Proceedings of the 2020 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems; 2020. p. 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376727.

[32] Liu P, Yuan W, Fu J, Jiang Z, Hayashi H, Neubig G. Pre-train, prompt, and predict: A systematic survey of prompting methods in natural language processing. ACM Comput Surv 2023;55(9):1-35.

[33] Martin A, Grudziecki J. DigEuLit: Concepts and tools for digital literacy development. Innovation in Teaching and Learning in Information and Computer Sciences 2006;5(4):249-67. https://doi.org/10.11120/ital.2006.05040249.

[34] Marsh CJ, Willis G. Curriculum: alternative approaches, ongoing issues. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice Hall; 2003.

[35] Meskó B. Prompt engineering as an important emerging skill for medical professionals: tutorial. J Med Internet Res 2023;25:e50638. https://doi.org/ 10.2196/50638.

[36] Mooney LA, Edwards B. Experiential learning in sociology: Service learning and other community-based learning initiatives. Teach Sociol 2001;29(2):181-94. https://doi.org/10.2307/1318716.

[37] Priestley M. Whatever happened to curriculum theory? Critical realism and curriculum change. Pedagogy, Culture & Society 2011;19(2):221-37. https://doi. org/10.1080/14681366.2011.582258.

[38] Priestley M, Biesta G, editors. Reinventing the curriculum: new trends in curriculum policy and practice. A&C Black; 2013.

[39] Simmons J, MacLean J. Physical education teachers’ perceptions of factors that inhibit and facilitate the enactment of curriculum change in a high-stakes exam climate. Sport Educ Soc 2018;23(2):186-202. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 13573322.2016.1155444.

[40] Tal T. Pre-service teachers’ reflections on awareness and knowledge following active learning in environmental education. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 2010;19(4):263-76. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/10382046.2010.519146.

[41] Teixeira PJ, Marques MM, Silva MN, Brunet J, Duda J, Haerens L, La Guardia J, Lindwall M, Lonsdale C, Markland D. A Classification of Motivation and Behavior Change Techniques Used in Self-Determination Theory-Based Interventions in Health Contexts. Motiv Sci 2020;6(4):438-55. https://doi.org/10.1037/ mot0000172.

[42] Touretzky DS, Gardner-McCune C, Martin F, Seehorn D. Envisioning AI for K-12: What should every child know about AI?. In: Proceedings of AAAI-19; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v33i01.33019795.

[43] Touretzky D, Gardner-McCune C, Seehorn D. Machine learning and the five big ideas in AI. Int J Artif Intell Educ 2023;33(2):233-66. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s40593-022-00314-1.

[44] Tsarava K, Moeller K, Román-González M, Golle J, Leifheit L, Butz MV, Ninaus M. A cognitive definition of computational thinking in primary education. Comput Educ 2022;179:104425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104425.

[45] Wolff A, Gooch D, Montaner JJC, Rashid U, Kortuem G. Creating an understanding of data literacy for a data-driven society. J Commun Inform 2016;12(3). https:// doi.org/10.15353/joci.v12i3.3275.

[46] Xia Q, Chiu TKF, Lee M, Temitayo I, Dai Y, Chai CS. A self-determination theory design approach for inclusive and diverse artificial intelligence (AI) K-12 education. Comput Educ 2022;189:104582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. compedu.2022.104582.

[47] Williams R, Ali S, Devasia N, DiPaola D, Hong J, Kaputsos SP, Breazeal C. AI+ ethics curricula for middle school youth: Lessons learned from three project-based curricula. Int J Artif Intell Educ 2023;33(2):325-83. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s40593-022-00298-y.

[48] Yannier N, Hudson SE, Koedinger KR, Hirsh-Pasek K, Golinkoff RM, Munakata Y, Brownell SE. Active learning:”Hands-on” meets “minds-on. Science (1979) 2021; 374(6563):26-30. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abj9957.

[49] Zhang C, Lu Y. Study on artificial intelligence: The state of the art and future prospects. J Ind Inf Integr 2021;23:100224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jii.2021.100224.

[50] Zhang H, Lee I, Ali S, DiPaola D, Cheng Y, Breazeal C. Integrating ethics and career futures with technical learning to promote AI literacy for middle school students: An exploratory study. Int J Artif Intell Educ 2023;33(2):290-324. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s40593-022-00293-3.

- Corresponding author at: Faculty of Education, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong.

E-mail addresses: tchiu@cuhk.edu.hk (T.K.F. Chiu), zubairtarar@qu.edu.qa (Z. Ahmad), ismailov.murod.gm@u.tsukuba.ac.jp (M. Ismailov), ismaila.sanusi@uef.fi (I.T. Sanusi).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2024.100171

Publication Date: 2024-03-13

What are artificial intelligence literacy and competency? A comprehensive framework to support them

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

AI competency

K-12 education

Machine learning

Data literacy

Generative AI

Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) education in K-12 schools is a global initiative, yet planning and executing AI education is challenging. The major frameworks are focused on identifying content and technical knowledge (AI literacy). Most of the current definitions of AI literacy for a non-technical audience are developed from an engineering perspective and may not be appropriate for

Introduction

report on AI education. On the other hand, unlike in higher education, designing

Literature review

AI literacy and competency

prerequisite for AI literacy. Considering the close connection between data and machine learning (a branch of AI), data literacy refers to the capacity to understand, work with, evaluate, and argue with data as part of a more comprehensive process of inquiry into the world [45], which largely overlaps with AI literacy. Moreover, the other two literacies, such as computational and scientific, may not closely relate to AI literacy. Computational literacy involves exploring and communicating ideas through code [44]; therefore, it is not necessarily a prerequisite for AI literacy that does not require writing codes to understand how AI works. Similarly, AI literacy does not require scientific literacy, which refers to an appreciation of the nature, contributions, and basic limitations of science [22]. The definition of AI literacy is one of the first for non-AI professionals, which could give

Process and praxis design approaches in AI education context

Three major frameworks for AI education in K-12

research in the past 5 years. One of the first frameworks, known as “Five Big Ideas in AI,” was suggested by Touretzky et al. [43]. In 2018, there was little external guidance from the literature on the content and scope of AI education for K-12 students [42]. The AI4K12 Steering Committee, which consists of David Touretzky, Christina Gardner-McCune, Fred Martin, and Deborah Seehorn, began their work by coming up with a list. This list serves as the organizing framework for the guidelines, which are developed based on the CSTA Computing Standards. Those standards are structured around the same five core ideas [11]. The five big ideas are:

- Perception: Computers use sensors to get information about their environment. Understanding what the senses are trying to tell us is what we call perception.

- Representation and Reasoning: Agents keep models of the world and utilize them to make decisions. Representations are the driving force behind reasoning, and reasoners use them.

- Learning: Computers can keep learning from data. By modifying the representations within a decision tree or neural network, a machine learning algorithm creates a reasoner.

- Natural Interaction: To communicate with people in a natural way, intelligent agents need access to a wide range of information. The information includes common sense, culture, human emotions, and knowledge of language.

- Societal Impact: There will be positive and negative effects of AI on society. The topics include the economic effects of automation, the fairness and transparency of automated decision-making systems, cultural considerations of AI algorithms, and the use of AI for social good.

Research gaps

This study and method

Research goal

The definitions of AI literacy and competency

as follows:

- AI literacy is defined as “an individual’s ability to clearly explain how AI technologies work and impact society, as well as to use them in an ethical and responsible manner and to effectively communicate and collaborate with them in any setting. It focuses on knowing (i.e. knowledge and skills).”.

- AI competency is defined as “an individual’s confidence and ability to clearly explain how AI technologies work and impact society, as well as to use them in an ethical and responsible manner and to effectively communicate and collaborate with them in any setting. They should have the confidence and ability to self-reflect on their AI understanding for further learning. It focuses on how well individuals use AI in beneficial ways.”.

- Technology: confidence and ability to clearly explain how AI technologies work

- Impact: confidence and ability to clearly explain how AI technologies impact society

- Ethics: confidence and ability to use AI technologies in an ethical and responsible manner

- Collaboration: confidence and ability to effectively communicate and collaborate with AI technologies in any setting

- Self-reflection: confidence and ability to self-reflect on their AI understanding for further learning. Individuals with stronger selfreflective mindsets are more likely to keep reviewing their AI knowledge and identify areas and needs for further learning.

Participants

Research design and procedure

Analyses, reliability and validity

Results and discussions

The five components in the comprehensive framework

Technology

- In the basic components, the definition, history, and development of AI should be taught in schools [49]. The following definition of AI was agreed upon by all the participants: “AI refers to a machine’s ability to do tasks equivalent to human learning and decision-making.”. This definition is consistent with the findings of Chiu et al. [8] and Touretzky et al. [42]. The students must understand essential concepts such as big data, machine learning, and cloud computing. They must understand the five primary and inherent characteristics of big data, which are velocity, volume, value, variety, and veracity [19]. To properly understand how AI machines use data to enhance their skills, the topic of machine learning should encompass training models and learning algorithms [4,10]. Cloud computing is required

for huge data processing in order to better train models and/or algorithms. Furthermore, the history and development of AI are critical topics in K-12. All the participants agreed that the students should understand AI history as well as contemporary advancements such as the “fourth industrial revolution” and generative AI, e.g., ChatGPT and Sora [12,49]. The students must comprehend how AI machines differ from non-AI machines. Non-AI machines, for example, have been designed to answer our problems by applying rules or algorithms, whereas AI machines use data to develop and regenerate the rules or models. They should understand that AI is changing the fundamental concept of how machines work and that “data are the new code” [49]. The students who have mastered the essential knowledge, in particular, should be able to recognize if the technologies they are employing are AI and comprehend the ramifications of this. They should also be required to describe what types of data AI collects, how AI analyzes data, and how AI learns from data. - Perception is the second topic in core knowledge, which is consistent with the research of Chiu et al. [8] and Touretzky et al. [42]. The teachers indicated that the concept of perception in Touretzky et al. study [42] is too abstract. The students did not understand what this word meant. They chose human sensor concepts as perception subtopics. Human sensors-see, read, and write; speak and hear; think and create; reason and simulate-are terms that reflect the definition of AI. Because these terminologies are not overly technical, both students and teachers will understand what they need to learn or teach. The students should understand how each sensor collects and processes data.

- The third topic is AI applications. The teachers highlighted that the topic’s breadth is more significant than its depth. The students should have a thorough understanding of AI applications, which should include most industries or aspects of daily life such as healthcare, entertainment, transport, logistics, etc. They should employ perception to describe how each application functions, as well as machine learning to construct and develop their own AI applications.

Impact

- On the topic of the future of work, young children place a high value on their future studies and employment. They need to understand that more future vocations demand AI literacy and that they are increasingly likely to learn with AI in their lives and work with AI in their jobs.

- The second subtopic is AI for social good. AI can have both positive and harmful effects on society. According to the teachers, the students should learn how AI solves complicated issues by addressing critical social, environmental, and public health concerns [23]. Other than the benefits AI brings to society, students should also learn the risks.

- The last topic is risk. All the participants agreed that the students should be aware of the potential risks associated with AI. They should investigate how emerging technologies cause trouble and harm in various contexts. These are aligned with the two frameworks [4,43] and other related studies [47,50].

Ethics

technical audiences. The teachers finally used IBM AI ethical principles as a starting point and reached a consensus on what to include in this topic. They chose five of them because they are more relevant to school students: fairness and biases; trust and transparency; accountability; social benefit; and privacy and security [18].

Collaboration

Self-reflection

Five essential learning experiences

- Community engagement: According to Cooper [13] and Mooney & Edwards [36], integrating student learning with the community is a purposeful pedagogical strategy used by instructors to make a connection between what is taught in the classroom and the students’ local communities. As a result, students can apply their ideas based on personal observation and social interaction to design and find solutions to real-world problems in a community. They are more inclined to invest more in learning since the challenges are more relevant and encourage student participation. This community involvement will increase students’ interest and enthusiasm

, 28], resulting in more inclusive and diverse AI education [46]. This community involvement will promote AI for social good while also cultivating students’ positive attitudes toward AI. Furthermore, the teachers stated that the design thinking approach-empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test-should be used to solve community problems. To have a greater impact, community participation may learn a lot from design thinking [4]. - Global and local case studies: One of the effective teaching methods proposed by the teachers is using media articles to educate about AI ethics and impact. School students can read various web articles, yet there are many biased options or fake news [16]. They are less mature and less capable of judging the reliability of the articles. Unlike ten years ago, more newspaper stories are being published as a result of AI advancement. They have recently become more accessible to both teachers and students. This method creates non-textbook learning, making it more authentic and relevant. Students can more actively reflect on ethical issues raised in newspaper stories [40]. Furthermore, this teaching style can be utilized to teach ethical principles while emphasizing the importance of data sources. This can be used by teachers to illustrate concepts such as fairness and bias, trust and transparency, and accountability.

- Hands-on activities: Students are surrounded by AI, but not so much in their classrooms. Hands-on activities could help students learn perception better because they put them more in the driver’s seat through physical activity and active learning [48]. Physically active learning can support students’ confidence and ability to model the world and generate creative ideas [48]. These connections may allow multipart tool design and use. Students can solve problems they cannot solve orally or visually by modeling physical systems with their hands [46]. Asking students to use their hands to model physical phenomena using AI will develop their conceptual understanding of AI perception. The teachers also suggested some practical ideas: students could investigate how AI can collect, understand, and identify images, i.e., learn how computers see images. Students can understand what they read and write since AI understands languages and text, and they can develop text analyzers to detect text moods. Furthermore, most students believe AI and robotics are the same technology. Students should learn how AI differs from robotics by doing a hands-on project in which they build a robot with reasoning and perception. According to the teachers, ethical principles, which were often taught using case-study approaches, can be taught through hands-on activities. Students could design one or more biased AI apps and explain how the dataset selection resulted in the biased results. As a result, hands-on activities can better cater to students with individual and learning differences and promote inclusive and diverse AI education [46].

- Exhibitions and presentations: This strategy is prevalent in the dissemination of student work, particularly in project-based learning. It allows students to consolidate their learning by communicating their processes, thinking about their products, and reflecting on their answers [21]. Teachers indicated in this framework that students should display their learning process and project work. The teacher highlighted in AI education that students should use core knowledge as criteria to present their work in the exhibition. For example, how did they acquire or create the data for building the perception? Are the data ethical? Is their use moral? What is the social impact of their work? What industry will acquire their products? Accordingly, presenting their project work encourages students to tap into their individual differences.

- Cultural learning: Human values and culture should be considered when learning AI. Data may be biased due to how it is obtained or chosen for usage. Human values and culture play a significant role in this. The answer to the questionAI bias or not”” may not be determined by AI knowledge but by human values and culture. These two elements must be considered by students while learning AI. For example, when developing AI projects to help the elderly, students are obliged to respect their culture and values (e.g., food and diets) but not change theirs. When discussing ethical issues related to driverless cars, students must be aware of local laws and religious beliefs (hurting cows in India may result in serious crimes).

social good (community participation), students’ relevancy (newspaper articles), active learning (hands-on activities), collaboration, and communication (presentation) (Fig. 2).

Future research directions and recommendations

- Prompt engineering: In this new technique, you may rephrase a query, select a style, provide more contextual information, or assign a role to AI when interacting with

. The current studies on this technique are restricted to ChatGPT. This is also related to our questioning skills. Most of the young children’s questioning skills are developed in K-12 education. More studies should be conducted to understand how K-12 students interact with AI, i.e., prompt engineering or questioning skills for AI. - Data science education: how to communicate with AI is associated with who to use and interpret data. Data literacy is strongly associated with AI literacy [31]. Data science education and data literacy may need to be included in K-12 education. Currently, this literacy is embedded in mathematics or AI subjects. More studies should be conducted to investigate how data literacy relates to AI literacy development.

- Algorithmic Literacy: To fully communicate with AI, algorithmic literacy may be needed. This literacy includes awareness and knowledge of algorithms, trust and confidence in algorithms, algorithm appreciation, and algorithm avoidance [25] This framework did not discuss this literacy. Future studies should be conducted to define algorithmic literacy and how it affects AI literacy.

- Self-reflective mindsets: this mindset is understudied in AI education. AI is different from other typical subjects, such as mathematics and sciences in K-12, and is emerging. Social cognitive theory is related to emotional engagement, and self-regulated learning concerns self-reflection. Future studies are recommended to use social cognitive theory and self-regulated learning to identify effective pedagogies to nurture students’ self-reflective mindsets.

- Empirical research: AI education is still new; more empirical studies should be conducted to refine the definition of AI literacy and competency and the AI education framework.

Conclusion and limitations

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Declaration of competing interest

Data availability

Funding

Acknowledgements

References

[2] Chiu TKF. Using Self-determination Theory (SDT) to explain student STEM interest and identity development. Instr Sci 2024;58:89-107. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11251-023-09642-8.

[3] Chiu T.K.F. (2023). The impact of Generative AI (GenAI) on practices, policies and research direction in education: A case of ChatGPT and Midjourney, Interactive Learning Environments, Advanced online publication. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/ 10494820.2023.2253861.

[4] Chiu TKF. Applying the Self-determination Theory (SDT) to explain student engagement in online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Res Technol Edu 2022;54(1):14-30. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1891998.

[5] Chiu TKF. A holistic approach to Artificial Intelligence (AI) curriculum for K-12 schools. TechTrends 2021;65:796-807. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-021-00637-1.

[6] Chiu TKF, Chai CS, Williams J, Lin TJ. Teacher professional development on Selfdetermination Theory-based design thinking in STEM education. Edu Technol Soc 2021;24(4):153-65. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48629252.

[7] Chiu TKF, Ismailov M, Zhou X-Y, Xia Q, Au D, Chai CS. Using Self-Determination Theory to explain how community-based learning fosters student interest and identity in integrated STEM education. Int J Sci Math Educ 2023;21:109-30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-023-10382-x.

[8] Chiu TKF, Meng H, Chai CS, King I, Wong S, Yeung Y. Creation and evaluation of a pre-tertiary artificial intelligence (AI) curriculum. IEEE Transac Edu 2022;65(1): 30-9. https://doi.org/10.1109/TE.2021.3085878.

[9] Chiu, T.K.F., Moorhouse, B.L., Chai, C.S., & Ismailov M. (2023). Teacher support and student motivation to learn with artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot, Interactive Learning Environments, Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/10 494820.2023.2172044.

[10] Chiu TKF, Xia Q, Zhou X-Y, Chai CS, Cheng M-T. Systematic literature review on opportunities, challenges, and future research recommendations of artificial intelligence in education. Comput Edu: AI 2023;4:100118. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.caeai.2022.100118.

[11] CSTA. (2017). Computer Science Teachers Association (CSTA) K-12 Computer Science Standards, Revised 2017. https://www.csteachers.org/page/standards. Accessed 12 Nov 2022.

[12] Cooper G. Examining science education in ChatGPT: An exploratory study of generative artificial intelligence. J Sci Educ Technol 2023;32:444-52. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10956-023-10039-y.

[13] Cooper JE. Strengthening the case for community-based learning in teacher education. J Teach Educ 2007;58(3):245-55. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0022487107299979.

[14] Cope B, Kalantzis M, Searsmith D, Cope B, Kalantzis M, Searsmith D. Artificial intelligence for education: Knowledge and its assessment in AI-enabled learning ecologies. Educational Philosophy and Theory 2020;53(12):1229-45. https://doi. org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1728732.

[15] Cypress BS. Rigor or reliability and validity in qualitative research: Perspectives, strategies, reconceptualization, and recommendations. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing 2017;36(4):253-63. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCC.0000000000000253.

[16] Datta P, Whitmore M, Nwankpa JK. A perfect storm: social media news, psychological biases, and AI. Digital Threats: Research and Practice 2021;2(2): 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1145/3428157.

[17] Falloon G. From digital literacy to digital competence: the teacher digital competency (TDC) framework. Educational Technology Research and Development 2020;68:2449-72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09767-4.

[18] Gerke S, Minssen T, Cohen G. Ethical and legal challenges of artificial intelligencedriven healthcare. Artificial intelligence in healthcare. Academic Press; 2020. p. 295-336. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818438-7.00012-5.

[19] Ghasemaghaei M. Understanding the impact of big data on firm performance: The necessity of conceptually differentiating among big data characteristics. Int J Inf Manage 2021;57:102055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.102055.

[20] Glatthorn AA, Boschee F, Whitehead BM, Boschee BF. Curriculum leadership: strategies for development and implementation. London: SAGE; 2018.

[21] Grant MM, Branch RM. Project-based learning in a middle school: Tracing abilities through the artifacts of learning. J Res Tech Edu 2005;38(1):65-98. https://doi. org/10.1080/15391523.2005.10782450.

[22] Holbrook J, Rannikmae M. The meaning of scientific literacy. Int J Environ Sci Edu 2009;4(3):275-88.

[23] Holzmeyer C. Beyond ‘AI for Social Good'(AI4SG): social transformations-Not tech-fixes-For health equity. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 2021;46(1-2): 94-125. https://doi.org/10.1080/03080188.2020.1840221.

[24] Hornberger M, Bewersdorff A, Nerdel C. What do university students know about Artificial Intelligence? Development and validation of an AI literacy test. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2023;5:100165. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100165.

[25] Du YR. Personalization, Echo Chambers, News Literacy, and Algorithmic Literacy: A Qualitative Study of AI-Powered News App Users. J Broadcast Electron Media 2023;67(3):246-73. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2023.2182787.

[26] Keefe EB, Copeland SR. What is literacy? The power of a definition. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 2011;36(3-4):92-9. https://doi.org/ 10.2511/027494811800824507.

[27] Kelly AV. The curriculum: theory and practice. 6th ed. London: Sage; 2009.

[28] King NS, Pringle RM. Black girls speak STEM: Counterstories of informal and formal learning experiences. J Res Sci Teach 2019;56(5):539-69. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/tea.21513.

[29] Laupichler MC, Aster A, Raupach T. Delphi study for the development and preliminary validation of an item set for the assessment of non-experts’ AI literacy. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2023;4:100126. https://doi.org/ 10.1075/idj.23.1.03dighttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100126.

[30] Leung L. Validity, reliability, and generalizability in qualitative research. J Family Med Prim Care 2015;4(3):324. https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.161306.

[31] Long D, Magerko B. What is AI literacy? Competencies and design considerations. In: Proceedings of the 2020 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems; 2020. p. 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376727.

[32] Liu P, Yuan W, Fu J, Jiang Z, Hayashi H, Neubig G. Pre-train, prompt, and predict: A systematic survey of prompting methods in natural language processing. ACM Comput Surv 2023;55(9):1-35.

[33] Martin A, Grudziecki J. DigEuLit: Concepts and tools for digital literacy development. Innovation in Teaching and Learning in Information and Computer Sciences 2006;5(4):249-67. https://doi.org/10.11120/ital.2006.05040249.

[34] Marsh CJ, Willis G. Curriculum: alternative approaches, ongoing issues. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice Hall; 2003.

[35] Meskó B. Prompt engineering as an important emerging skill for medical professionals: tutorial. J Med Internet Res 2023;25:e50638. https://doi.org/ 10.2196/50638.

[36] Mooney LA, Edwards B. Experiential learning in sociology: Service learning and other community-based learning initiatives. Teach Sociol 2001;29(2):181-94. https://doi.org/10.2307/1318716.

[37] Priestley M. Whatever happened to curriculum theory? Critical realism and curriculum change. Pedagogy, Culture & Society 2011;19(2):221-37. https://doi. org/10.1080/14681366.2011.582258.

[38] Priestley M, Biesta G, editors. Reinventing the curriculum: new trends in curriculum policy and practice. A&C Black; 2013.

[39] Simmons J, MacLean J. Physical education teachers’ perceptions of factors that inhibit and facilitate the enactment of curriculum change in a high-stakes exam climate. Sport Educ Soc 2018;23(2):186-202. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 13573322.2016.1155444.

[40] Tal T. Pre-service teachers’ reflections on awareness and knowledge following active learning in environmental education. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 2010;19(4):263-76. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/10382046.2010.519146.

[41] Teixeira PJ, Marques MM, Silva MN, Brunet J, Duda J, Haerens L, La Guardia J, Lindwall M, Lonsdale C, Markland D. A Classification of Motivation and Behavior Change Techniques Used in Self-Determination Theory-Based Interventions in Health Contexts. Motiv Sci 2020;6(4):438-55. https://doi.org/10.1037/ mot0000172.

[42] Touretzky DS, Gardner-McCune C, Martin F, Seehorn D. Envisioning AI for K-12: What should every child know about AI?. In: Proceedings of AAAI-19; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v33i01.33019795.

[43] Touretzky D, Gardner-McCune C, Seehorn D. Machine learning and the five big ideas in AI. Int J Artif Intell Educ 2023;33(2):233-66. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s40593-022-00314-1.

[44] Tsarava K, Moeller K, Román-González M, Golle J, Leifheit L, Butz MV, Ninaus M. A cognitive definition of computational thinking in primary education. Comput Educ 2022;179:104425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104425.

[45] Wolff A, Gooch D, Montaner JJC, Rashid U, Kortuem G. Creating an understanding of data literacy for a data-driven society. J Commun Inform 2016;12(3). https:// doi.org/10.15353/joci.v12i3.3275.

[46] Xia Q, Chiu TKF, Lee M, Temitayo I, Dai Y, Chai CS. A self-determination theory design approach for inclusive and diverse artificial intelligence (AI) K-12 education. Comput Educ 2022;189:104582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. compedu.2022.104582.

[47] Williams R, Ali S, Devasia N, DiPaola D, Hong J, Kaputsos SP, Breazeal C. AI+ ethics curricula for middle school youth: Lessons learned from three project-based curricula. Int J Artif Intell Educ 2023;33(2):325-83. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s40593-022-00298-y.

[48] Yannier N, Hudson SE, Koedinger KR, Hirsh-Pasek K, Golinkoff RM, Munakata Y, Brownell SE. Active learning:”Hands-on” meets “minds-on. Science (1979) 2021; 374(6563):26-30. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abj9957.

[49] Zhang C, Lu Y. Study on artificial intelligence: The state of the art and future prospects. J Ind Inf Integr 2021;23:100224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jii.2021.100224.

[50] Zhang H, Lee I, Ali S, DiPaola D, Cheng Y, Breazeal C. Integrating ethics and career futures with technical learning to promote AI literacy for middle school students: An exploratory study. Int J Artif Intell Educ 2023;33(2):290-324. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s40593-022-00293-3.

- Corresponding author at: Faculty of Education, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong.

E-mail addresses: tchiu@cuhk.edu.hk (T.K.F. Chiu), zubairtarar@qu.edu.qa (Z. Ahmad), ismailov.murod.gm@u.tsukuba.ac.jp (M. Ismailov), ismaila.sanusi@uef.fi (I.T. Sanusi).