DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2024.102521

تاريخ النشر: 2024-03-25

استشهد بالنسخة النهائية:

© 2024 المؤلفون. منشور بواسطة إلسفير المحدودة. هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول بموجب ترخيص CC BY (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

محركات اعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي في التعليم العالي من منظور نظرية السلوك المخطط

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

نظرية السلوك المخطط

التعليم العالي

الملخص

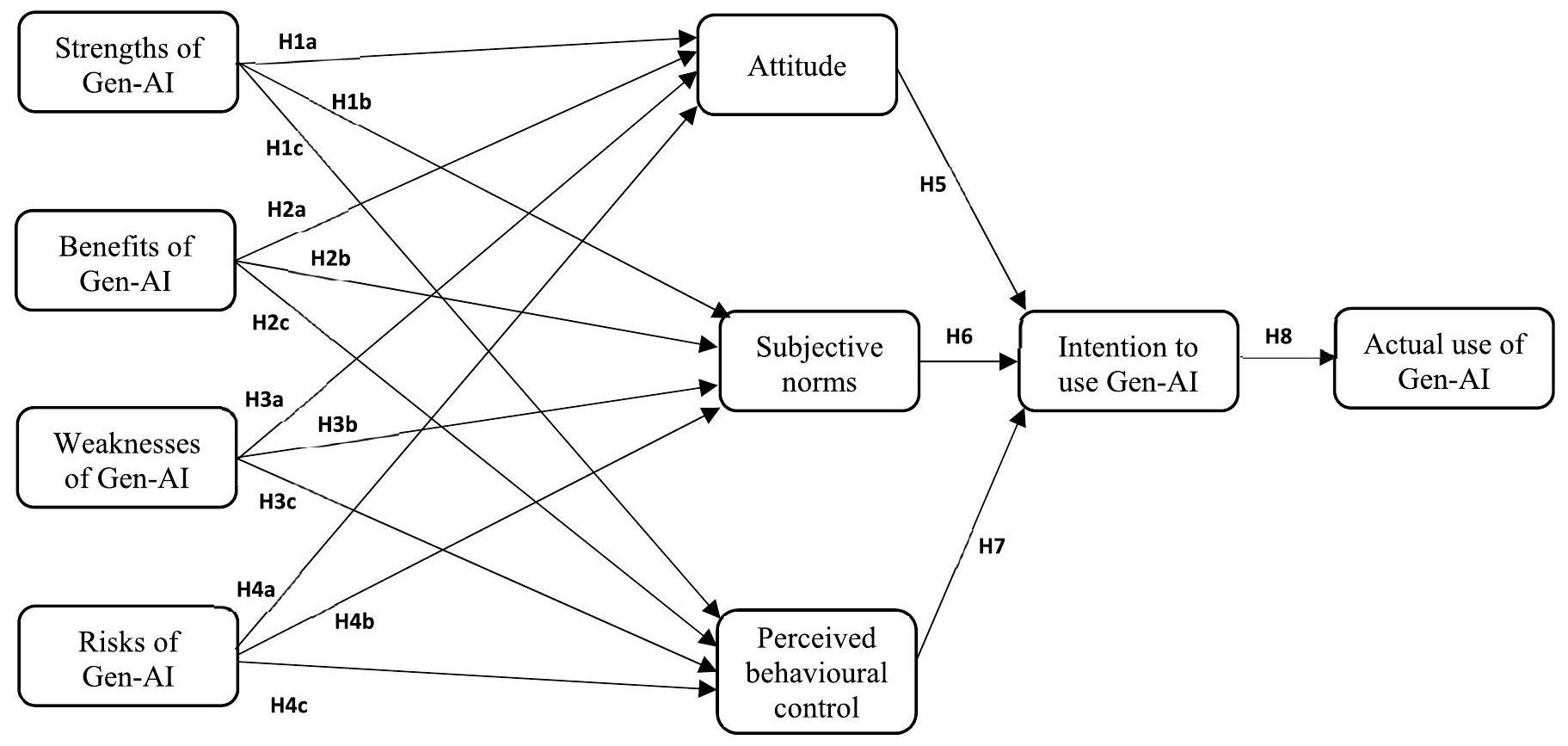

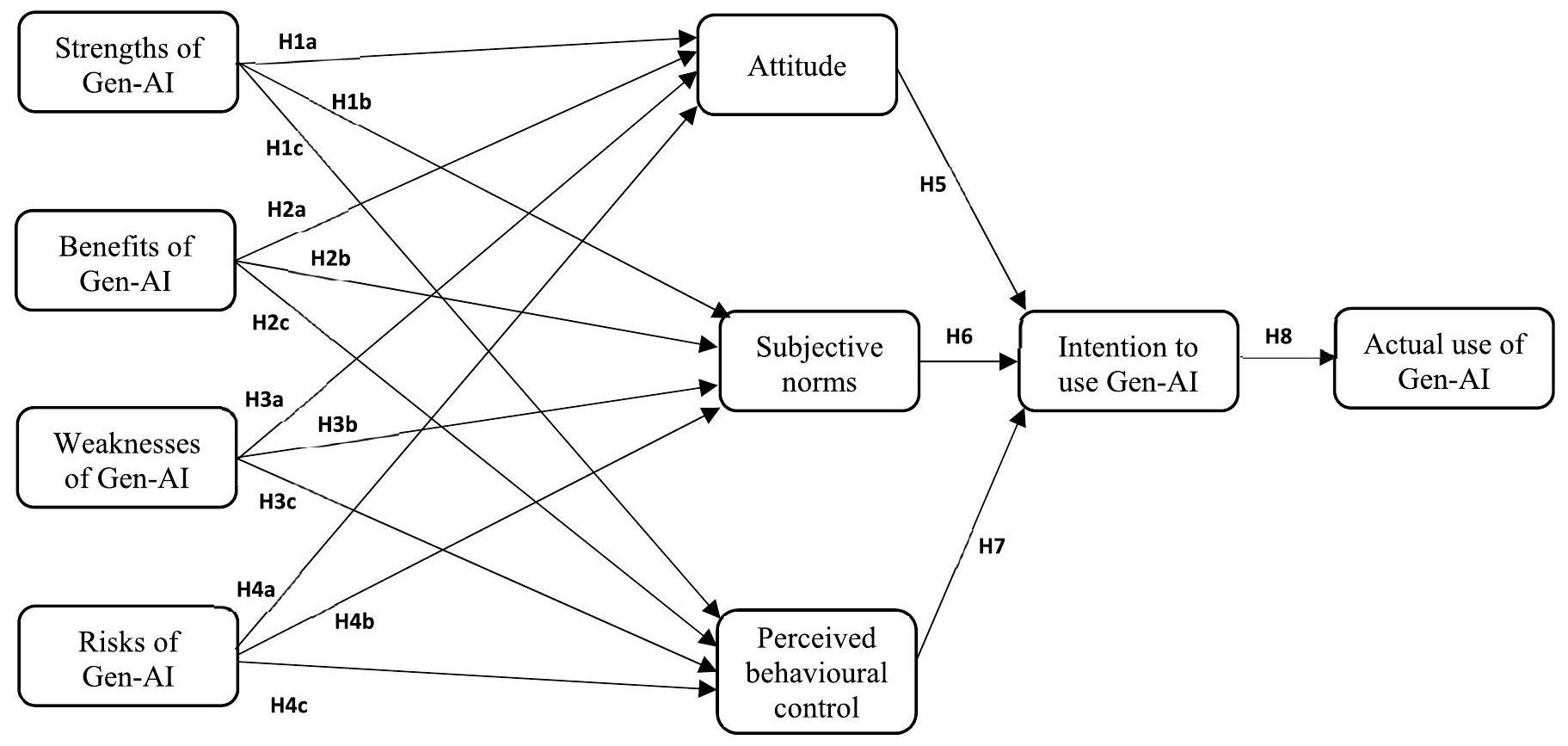

استنادًا إلى نظرية السلوك المخطط (TPB)، تبحث هذه الدراسة في العلاقة بين الفوائد المدركة، والقوى، والضعف، والمخاطر لأدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (GenAI) والعوامل الأساسية لنموذج TPB (أي، الموقف، المعايير الذاتية، والتحكم السلوكي المدرك). كما تبحث الدراسة في الارتباط الهيكلي بين متغيرات TPB ونية استخدام أدوات GenAI، وكيف يمكن أن تؤثر الأخيرة على الاستخدام الفعلي لأدوات GenAI في التعليم العالي. تعتمد الورقة على نهج كمي، معتمدة على استبيان عبر الإنترنت يتم إدارته ذاتيًا بشكل مجهول لجمع بيانات أولية من 130 محاضرًا و168 طالبًا في مؤسسات التعليم العالي (HEIs) في عدة دول، وPLS-SEM لتحليل البيانات. تشير النتائج إلى أنه على الرغم من اختلاف تصورات المحاضرين والطلاب حول المخاطر والضعف لأدوات GenAI، فإن القوى والفوائد المدركة لتقنيات GenAI لها تأثير كبير وإيجابي على مواقفهم، والمعايير الذاتية، والتحكم السلوكي المدرك. تؤثر المتغيرات الأساسية لنموذج TPB بشكل إيجابي وكبير على نوايا المحاضرين والطلاب لاستخدام أدوات GenAI، والتي بدورها تؤثر بشكل كبير وإيجابي على اعتمادهم لمثل هذه الأدوات. تعزز هذه الورقة النظرية من خلال توضيح العوامل التي تشكل اعتماد تقنيات GenAI في HEIs. كما تقدم لأصحاب المصلحة مجموعة متنوعة من الآثار الإدارية والسياسية حول كيفية صياغة قواعد وأنظمة مناسبة للاستفادة من مزايا هذه الأدوات مع التخفيف من آثار عيوبها. كما تم توضيح القيود وفرص البحث المستقبلية.

1. المقدمة

من المناقشات في وسائل الإعلام، والمنتديات عبر الإنترنت، والمجتمعات الأكاديمية [2-8]. نتيجة لذلك، أصبح الباحثون والممارسون مهتمين بشكل متزايد بتداعيات تطبيقات GenAI، خاصة تلك المعتمدة على نماذج اللغة الكبيرة (LLMs)، على التعلم البشري، وتوليد المعرفة، وطبيعة العمل في السنوات القادمة [4]. أشار إيفانوف وسليمان [9] إلى أنه على المدى الطويل، ستحدث الدردشة المعتمدة على LLM ثورة في البحث والتعليم. إذا تم اعتمادها بنجاح، يمكن استخدامها كمدرسين عبر الإنترنت، ومطوري مناهج، ومصححين، ومساهمين في المنشورات الأكاديمية. ستكون LLMs أيضًا ضرورية في إعادة التفكير في التعليم من تفاعلات “المعلم-الطالب” إلى “المعلم-الذكاء الاصطناعي-الطالب” في التعاون [9]، مما يحول

2. مراجعة الأدبيات وتطوير الفرضيات

2.1. نظرية السلوك المخطط

2.2. الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي في التعليم والتعلم

يبدو أن الباحثين يستنتجون أن ظهور الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي يمثل سيفًا ذو حدين، حيث أن من جهة، يوفر دمج الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي في التعليم مجموعة من الفوائد المحتملة لكل من المعلم والمتعلم، ولكن من جهة أخرى، فإنه يطرح أيضًا تحديات جديدة وإمكانية سوء الاستخدام.

2.3. تطوير الفرضيات

تقييمات غير مواتية للنتائج السلوكية [24]. وبالمثل، إذا كانت فوائد GenAI تتماشى مع التوقعات التعليمية أو المجتمعية الأوسع، فمن المحتمل أن تؤثر بشكل إيجابي على المعايير الذاتية، مما يجعلها دافعًا تحفيزيًا لاعتماد التكنولوجيا [25]. وأخيرًا، يمكن أن تعزز الفوائد المتوقعة من GenAI، مثل أتمتة المهام التي تتطلب جهدًا كبيرًا، السيطرة السلوكية المدركة من خلال تعزيز المعتقدات في القدرة على تنفيذ هذه التكنولوجيا بنجاح في البيئات التعليمية [22]. بناءً على ذلك، نفترض أن.

الأدبيات السابقة حول نظرية التخطيط السلوكي [25]. H7 توسع هذا من خلال افتراض أن التحكم السلوكي المدرك الأكبر، الذي يعكس المعتقدات في قدرة الفرد على تنفيذ سلوك، سيؤثر أيضًا بشكل إيجابي على النية لنشر الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي في البيئات التعليمية [22]. أخيرًا، H8 تختتم سلسلة السلوك من خلال اقتراح أن النية، كما تتأثر بالمتغيرات المذكورة أعلاه، ستؤثر إيجابيًا على الاستخدام الفعلي، وهو مبدأ أساسي في نظرية التخطيط السلوكي. وبالتالي، نفترض أن.

3. المنهجية

3.1. إجراءات أخذ العينات وجمع البيانات

3.2. تصميم الاستبيان والقياسات

3.3. تحليل البيانات

4. النتائج

4.1. نماذج القياس

الخصائص السكانية للمشاركين.

| التركيبة السكانية | الفئات | الطلاب | محاضرون | ||

| ن | % | ن | % | ||

| جنس | ذكر | ٨٠ | ٤٧.٦ | 69 | 53.1 |

| أنثى | ٨٨ | 52.4 | 61 | ٤٦.٩ | |

| عمر | 18-30 | ١١٦ | 69.1 | ٧ | ٥.٤ |

| 31-40 | ٣٢ | 19 | 41 | 31.5 | |

| 41-50 | 20 | 11.9 | ٤٤ | ٣٣.٨ | |

| 51-60 | 0 | 0 | ٢٤ | 18.5 | |

| 61+ | 0 | 0 | 14 | 10.8 | |

| تعليمي | الثانوية العامة أو أقل | ٤٦ | ٢٧.٤ | ٥ | 3.9 |

| مستوى | بكالوريوس | 50 | ٢٩.٧ | 2 | 1.5 |

| سيد | 43 | ٢٥.٦ | ٢٢ | 16.9 | |

| دكتوراه | ٢٦ | 15.5 | 98 | 75.4 | |

| الآخرون | ٣ | 1.8 | ٣ | 2.3 | |

| مجال الدراسة/ البحث | العلوم الاجتماعية (مثل: الأعمال، الاقتصاد، السياحة والضيافة، علم النفس، القانون، إلخ) | 134 | 79.8 | ١١٠ | 84.6 |

| التكنولوجيا (مثل الهندسة، الروبوتات، علوم الحاسوب، الميكانيكا، إلخ) | 15 | 8.9 | 12 | 9.2 | |

| الفنون والعلوم الإنسانية (مثل: العمارة، التاريخ، الأدب، الموسيقى، الفلسفة، إلخ) | 12 | 7.1 | ٤ | 3.1 | |

| علوم الحياة والطب الحيوي (مثل: البيولوجيا، الطب، الزراعة، إلخ) | ٥ | ٣ | 2 | 1.5 | |

| العلوم الفيزيائية (مثل علم الفلك، الكيمياء، الفيزياء، الرياضيات، إلخ) | 2 | 1.2 | 2 | 1.5 | |

| دولة المشاركين | بلغاريا | 26 | 15.5 | ٦ | ٤.٦ |

| إندونيسيا | 20 | 11.9 | ٨ | 6.2 | |

| البرتغال | ١٣ | ٧.٧ | 10 | ٧.٧ | |

| الولايات المتحدة | 10 | 6.0 | ١٣ | 10.0 | |

| فنلندا | 15 | 8.9 | ٥ | 3.8 | |

| عمان | 10 | 6.0 | ٦ | ٤.٦ | |

| بولندا | 10 | 6.0 | ٤ | 3.1 | |

| المملكة المتحدة | ٤ | ٢.٤ | 9 | 6.9 | |

| الهند | ٥ | 3.0 | ٥ | 3.8 | |

| باكستان | ٤ | ٢.٤ | ٤ | 3.1 | |

| إسبانيا | 0 | 0.0 | ٨ | 6.2 | |

| ماليزيا | ٥ | 3.0 | ٢ | 1.5 | |

| مصر | ٤ | ٢.٤ | ٣ | 2.3 | |

| تركيا | 2 | 1.2 | ٥ | 3.8 | |

| اليونان | ٢ | 1.2 | ٤ | 3.1 | |

| هولندا | 2 | 1.2 | ٤ | 3.1 | |

| السويد | 2 | 1.2 | ٣ | 2.3 | |

| تايوان | ٣ | 1.8 | 1 | 0.8 | |

| أستراليا | 1 | 0.6 | ٣ | 2.3 | |

| آخرون | 30 | 17.9 | 27 | 20.8 | |

| إجمالي | 168 | 100.0 | ١٣٠ | 100.0 | |

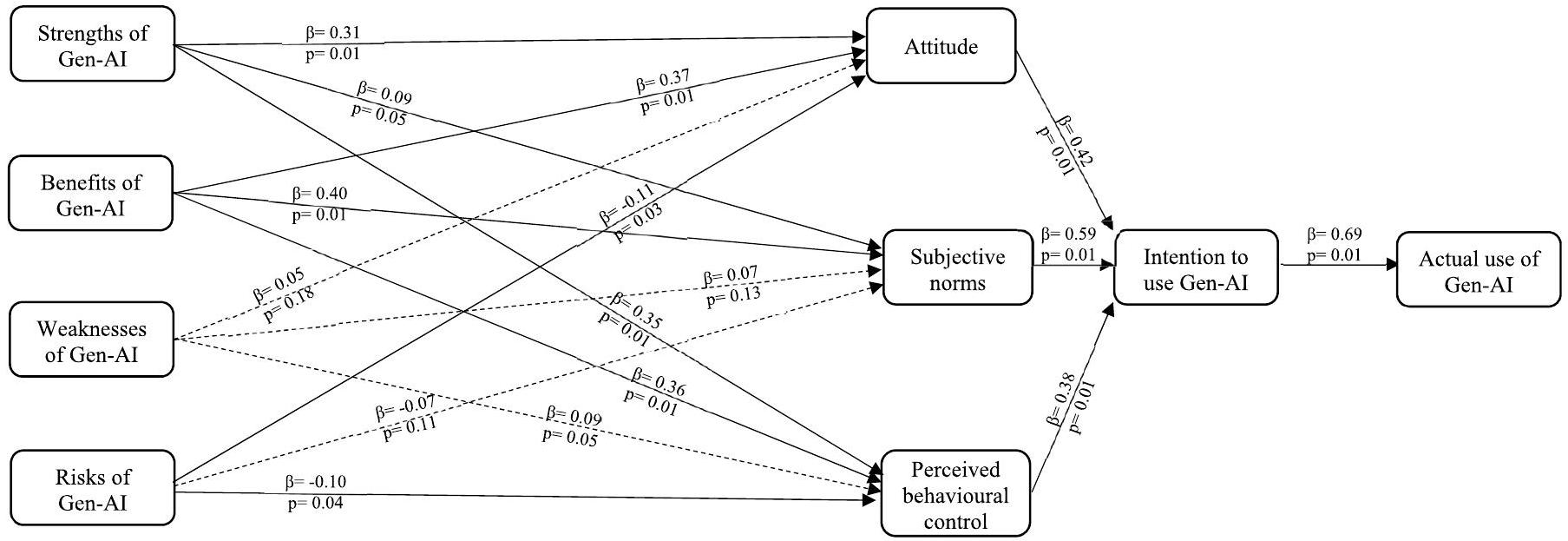

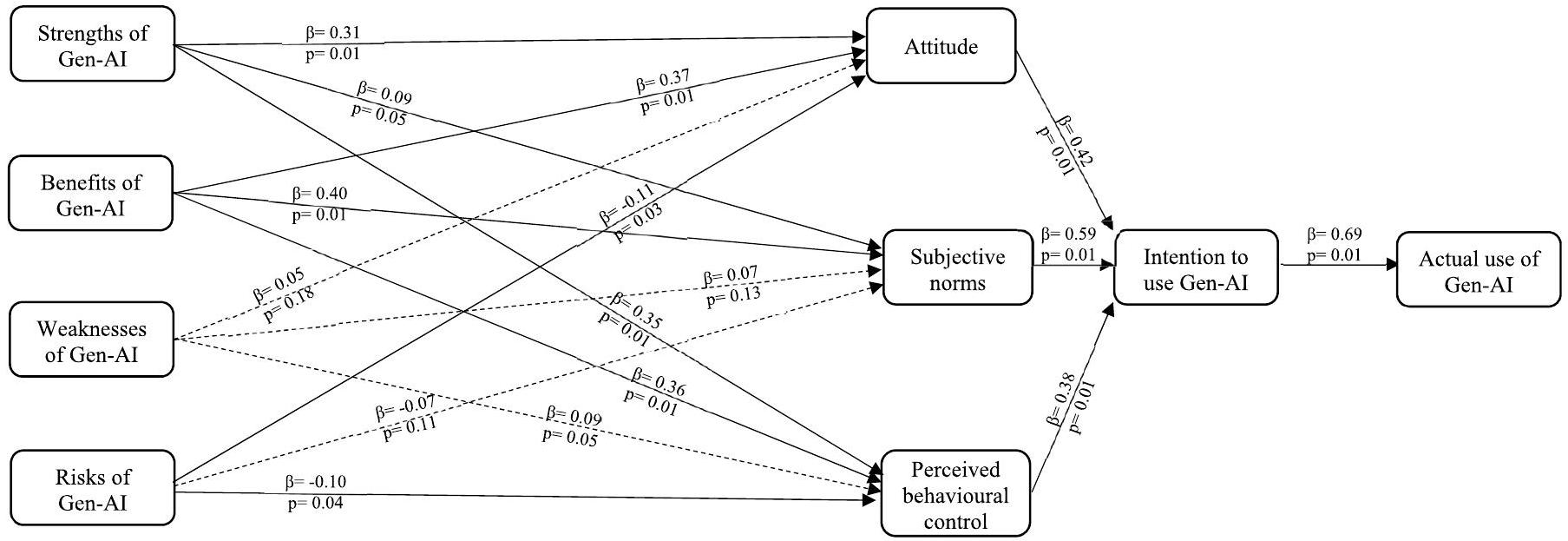

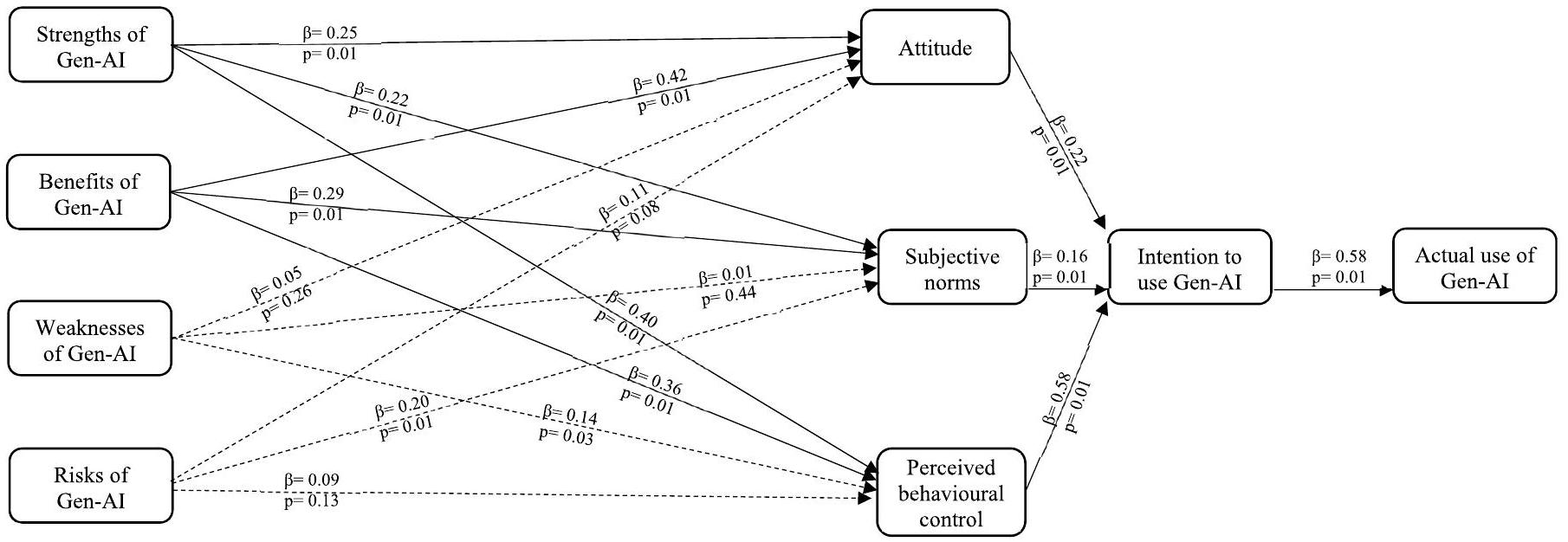

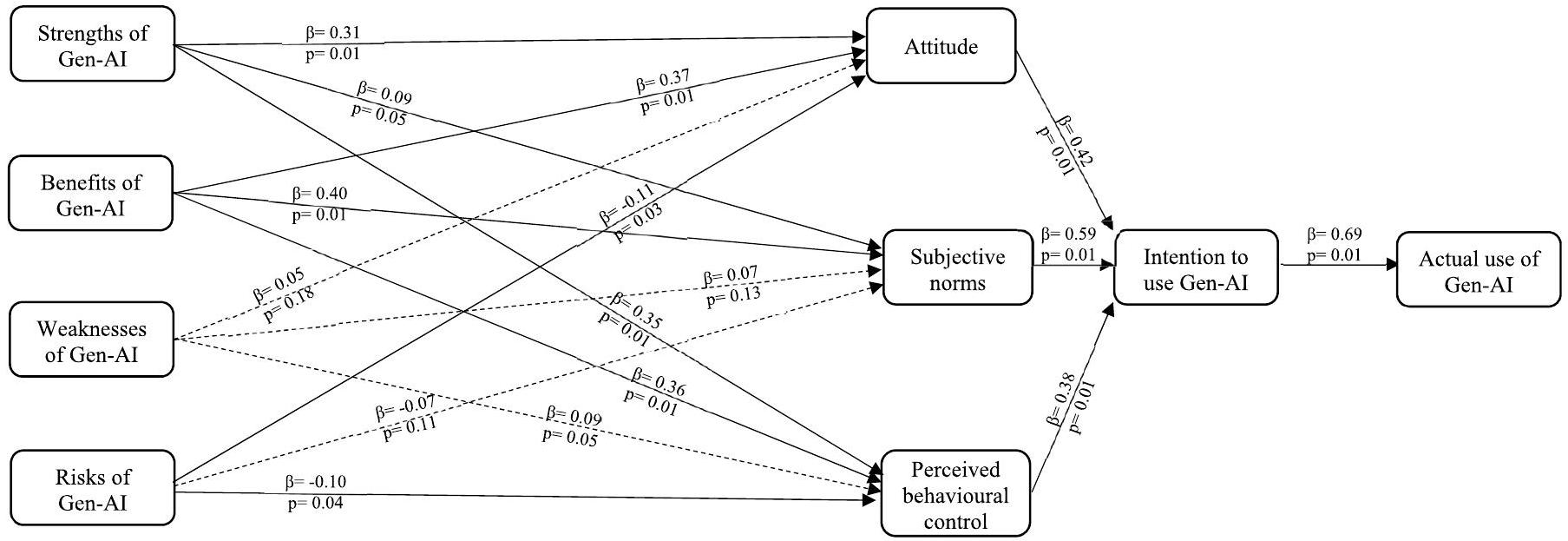

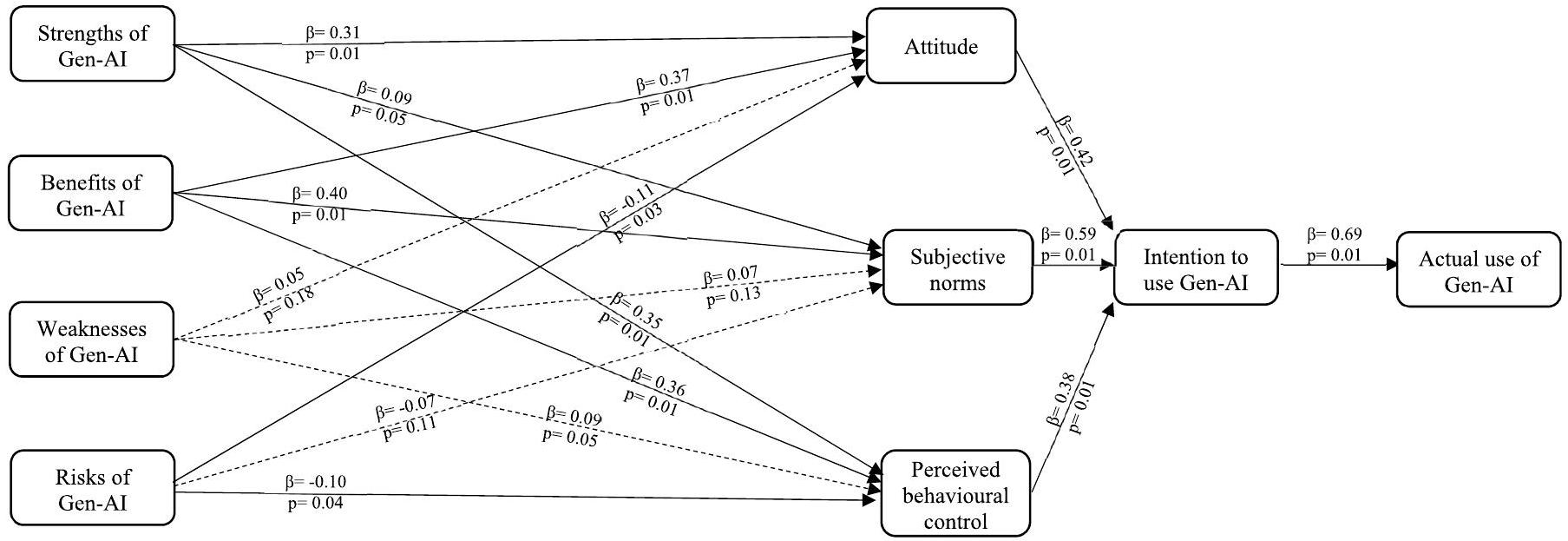

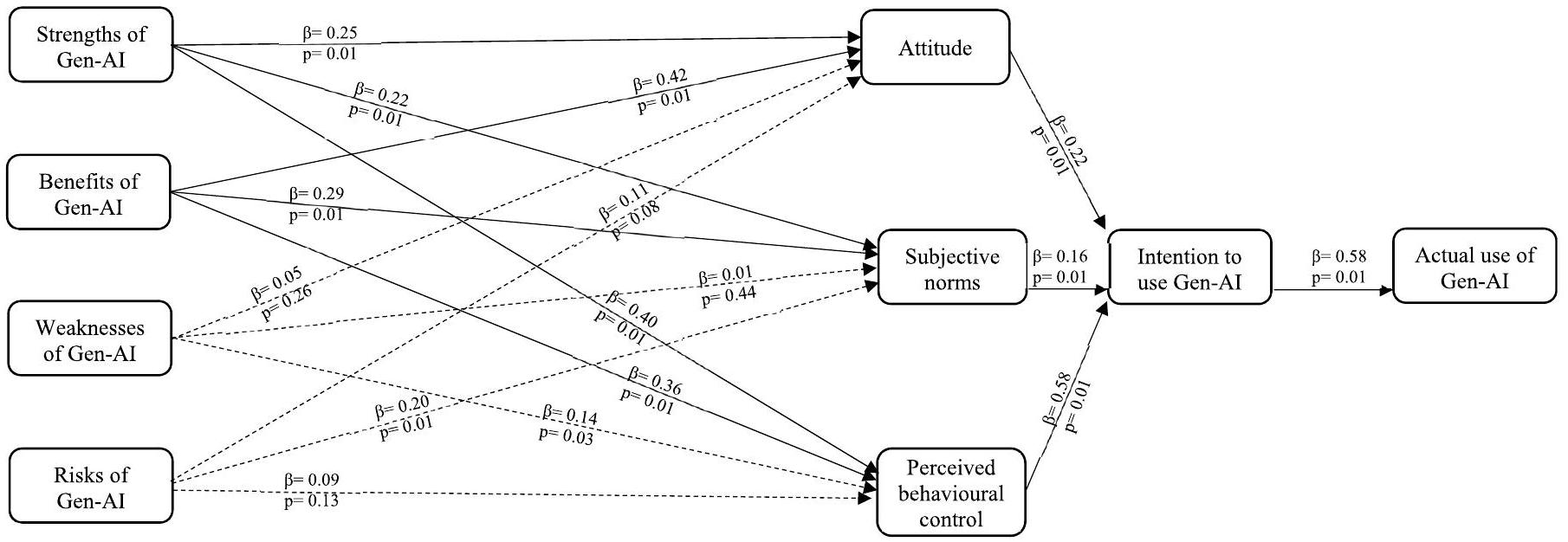

4.2. النماذج الهيكلية

ظل الموقف غير ذي دلالة في النماذج الثلاثة جميعها كما

5. المناقشة والاستنتاجات

5.1. المناقشة والآثار النظرية

الإحصائيات الوصفية ونتائج التقييم لنماذج القياس.

| إجمالي العينة (

|

محاضرون

|

الطلاب

|

|||||||

| إنشاء/عناصر | تحميل المؤشر | الموثوقية المركبة | AVE | تحميل المؤشر | الموثوقية المركبة | AVE | تحميل المؤشر | الموثوقية المركبة | AVE |

| قوة الذكاء الاصطناعي العام | 0.876 | 0.640 | 0.811 | 0.799 | 0.883 | 0.655 | |||

| STRN1 | 0.768 | 0.794 | 0.752 | ||||||

| STRN2 | 0.850 | 0.804 | 0.840 | ||||||

| STRN3 | 0.826 | 0.794 | 0.879 | ||||||

| STRN4 | 0.752 | 0.804 | 0.760 | ||||||

| فوائد الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي | 0.938 | 0.791 | 0.915 | 0.893 | 0.938 | 0.790 | |||

| BNFT1 | 0.892 | 0.916 | 0.878 | ||||||

| BNFT2 | 0.863 | 0.839 | 0.879 | ||||||

| بي إن إف تي 3 | 0.889 | 0.902 | 0.881 | ||||||

| بي إن إف تي 4 | 0.913 | 0.915 | 0.916 | ||||||

| نقاط ضعف الذكاء الاصطناعي العام | 0.873 | 0.580 | 0.866 | 0.776 | 0.854 | 0.593 | |||

| ضعيف1 | 0.816 | 0.795 | 0.782 | ||||||

| ضعيف2 | 0.822 | 0.877 | 0.766 | ||||||

| WEAK3 | 0.719 | 0.780 | 0.770 | ||||||

| WEAK4 | 0.740 | 0.708 | 0.762 | ||||||

| ويك5 | 0.702 | 0.745 | غير متوفر | ||||||

| WEAK6 | غير متوفر | 0.739 | غير متوفر | ||||||

| مخاطر الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي | 0.918 | 0.848 | 0.858 | 0.936 | 0.863 | 0.678 | |||

| RSK1 | 0.921 | 0.936 | 0.863 | ||||||

| RSK2 | 0.921 | 0.936 | 0.857 | ||||||

| RSK3 | غير متوفر | غير متوفر | 0.745 | ||||||

| الموقف | 0.932 | 0.697 | 0.931 | 0.865 | 0.933 | 0.665 | |||

| ATTD1 | 0.787 | 0.747 | 0.830 | ||||||

| ATTD2 | 0.843 | 0.856 | 0.818 | ||||||

| ATTD3 | 0.845 | 0.882 | 0.785 | ||||||

| ATTD4 | 0.848 | 0.924 | 0.804 | ||||||

| ATTD5 | 0.859 | 0.872 | 0.872 | ||||||

| ATTD6 | 0.825 | 0.896 | 0.769 | ||||||

| ATTD7 | غير متوفر | غير متوفر | 0.827 | ||||||

| المعايير الذاتية | 0.930 | 0.816 | 0.921 | 0.929 | 0.909 | 0.770 | |||

| الموضوع 1 | 0.906 | 0.930 | 0.882 | ||||||

| SUBJ2 | 0.912 | 0.928 | 0.897 | ||||||

| SUBJ3 | 0.891 | 0.930 | 0.851 | ||||||

| التحكم السلوكي المدرك | 0.893 | 0.736 | 0.827 | 0.862 | 0.892 | 0.733 | |||

| PRCV1 | 0.827 | 0.817 | 0.836 | ||||||

| PRCV2 | 0.867 | 0.884 | 0.854 | ||||||

| PRCV3 | 0.879 | 0.884 | 0.877 | ||||||

| نية استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي | 0.898 | 0.747 | 0.857 | 0.882 | 0.887 | 0.724 | |||

| INTN1 | 0.856 | 0.876 | 0.843 | ||||||

| INTN2 | 0.872 | 0.884 | 0.862 | ||||||

| INTN3 | 0.864 | 0.886 | 0.848 | ||||||

| الاستخدام الفعلي للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي | 0.922 | 0.855 | 0.858 | 0.936 | 0.909 | 0.833 | |||

| ACTU1 | 0.924 | 0.936 | 0.913 | ||||||

| ACTU2 | 0.924 | 0.936 | 0.913 | ||||||

المزايا التي تقدمها للطلاب والمحاضرين من حيث توفير الوقت وزيادة الإنتاجية، والتحسينات الكبيرة في جودة مخرجات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي مع مرور الوقت قد تكون الأسباب التي تجعل نقاط القوة والفوائد للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي أكثر أهمية بالنسبة للمستجيبين من نقاط الضعف والمخاطر المرتبطة بهذه الأدوات، ولكن يجب أن تقدم الأبحاث المستقبلية إجابة حاسمة على هذا السؤال.

صلاحية التمييز (العينة الكلية).

| بناء | فورنيل ولاركَر [53] | ||||||||

| ستران | بي إن إف تي | ضعيف | RSK | ATTD | الموضوع | PRCV | تهيئة | ACTU | |

| ستران | (0.800)* | ||||||||

| بي إن إف تي | 0.657 | (0.889) | |||||||

| ضعيف | -0.079 | -0.017 | (0.762) | ||||||

| RSK | -0.058 | -0.062 | 0.334 | (0.921) | |||||

| ATTD | 0.554 | 0.575 | -0.056 | -0.149 | (0.835) | ||||

| الموضوع | 0.335 | 0.458 | 0.007 | -0.039 | 0.420 | (0.903) | |||

| PRCV | 0.567 | 0.591 | 0.084 | -0.032 | 0.503 | 0.379 | (0.858) | ||

| INTN | 0.586 | 0.668 | -0.009 | -0.095 | 0.582 | 0.527 | 0.709 | (0.864) | |

| ACTU | 0.398 | 0.491 | 0.012 | -0.111 | 0.472 | 0.506 | 0.540 | 0.684 | (0.924) |

| نسب HTMT STRN | بي إن إف تي | ضعيف | RSK | ATTD | الموضوع | PRCV | تهيئة | ACTU | |

| ستران | |||||||||

| بي إن إف تي | 0.766** | ||||||||

| ضعيف | 0.168 | 0.102 | |||||||

| RSK | 0.075 | 0.078 | 0.408 | ||||||

| ATTD | 0.645 | 0.631 | 0.144 | 0.172 | |||||

| الموضوع | 0.394 | 0.509 | 0.066 | 0.053 | 0.468 | ||||

| PRCV | 0.698 | 0.680 | 0.166 | 0.088 | 0.580 | 0.442 | |||

| INTN | 0.717 | 0.767 | 0.139 | 0.115 | 0.670 | 0.615 | 0.858 | ||

| ACTU | 0.487 | 0.564 | 0.056 | 0.135 | 0.543 | 0.590 | 0.651 | 0.823 | |

** القيم الجريئة لنسبة HTMT التي تقل عن 0.90 تشير إلى أن: تلك المتغيرات متميزة عن المتغيرات الأخرى مما يؤكد تفردها.

صلاحية التمييز (المحاضرون).

| بناء | فورنيل ولاركَر [53] | ||||||||

| ستران | بي إن إف تي | ضعيف | RSK | ATTD | الموضوع | PRCV | تهيئة | ACTU | |

| ستران | (0.799) | ||||||||

| بي إن إف تي | 0.549 | (0.893) | |||||||

| ضعيف | -0.112 | -0.009 | (0.776) | ||||||

| RSK | -0.167 | -0.187 | 0.282 | (0.936) | |||||

| ATTD | 0.596 | 0.536 | -0.062 | -0.360 | (0.865) | ||||

| الموضوع | 0.٤٥١ | 0.535 | 0.051 | -0.154 | 0.416 | (0.862) | |||

| PRCV | 0.516 | 0.657 | -0.033 | -0.244 | 0.602 | 0.638 | (0.882) | ||

| INTN | 0.460 | 0.586 | -0.013 | -0.251 | 0.526 | 0.589 | 0.806 | (0.936) | |

| ACTU | 0.297 | 0.452 | 0.008 | -0.174 | 0.426 | 0.303 | 0.488 | 0.527 | (0.814) |

| نسب HTMT | بي إن إف تي | ضعيف | RSK | ATTD | الموضوع | PRCV | تهيئة | ACTU | |

| ستران | |||||||||

| بي إن إف تي | 0.638 | ||||||||

| ضعيف | 0.159 | 0.088 | |||||||

| RSK | 0.200 | 0.211 | 0.330 | ||||||

| ATTD | 0.686 | 0.582 | 0.127 | 0.405 | |||||

| الموضوع | 0.549 | 0.610 | 0.193 | 0.180 | 0.472 | ||||

| PRCV | 0.618 | 0.741 | 0.093 | 0.285 | 0.676 | 0.754 | |||

| INTN | 0.551 | 0.661 | 0.094 | 0.293 | 0.590 | 0.695 | 0.940 | ||

| ACTU | 0.360 | 0.519 | 0.098 | 0.336 | 0.495 | 0.353 | 0.573 | 0.618 | |

** القيم الجريئة لنسبة HTMT التي تقل عن 0.90 تشير إلى أن: تلك المتغيرات متميزة عن المتغيرات الأخرى مما يؤكد تفردها.

علم النفس يشير إلى أن النوايا غالبًا ما تكون محددًا موثوقًا للسلوك اللاحق. إنها نظرة قيمة لفهم العوامل التي تؤثر على اعتماد أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي في الممارسة من قبل كل من المحاضرين والطلاب (على سبيل المثال، المرجع [57،58]).

5.2. الآثار الإدارية والسياسية

صلاحية التمييز (الطلاب).

| بناء | فورنيل ولاركَر [53] | ||||||||

| ستران | بي إن إف تي | ضعيف | RSK | ATTD | الموضوع | PRCV | تهيئة | ACTU | |

| ستران | (0.712) | ||||||||

| بي إن إف تي | 0.688 | (0.889) | |||||||

| ضعيف | -0.077 | 0.002 | (0.692) | ||||||

| RSK | 0.054 | 0.077 | 0.489 | (0.663) | |||||

| ATTD | 0.537 | 0.601 | 0.004 | 0.084 | (0.816) | ||||

| الموضوع | 0.417 | 0.457 | 0.038 | 0.217 | 0.388 | (0.877) | |||

| PRCV | 0.605 | 0.679 | 0.021 | 0.111 | 0.562 | 0.551 | (0.851) | ||

| INTN | 0.349 | 0.426 | 0.044 | 0.084 | 0.414 | 0.457 | 0.576 | (0.913) | |

| ACTU | 0.620 | 0.629 | 0.115 | 0.148 | 0.582 | 0.448 | 0.766 | 0.499 | (0.856) |

| نسب HTMT STRN | بي إن إف تي | ضعيف | RSK | ATTD | الموضوع | PRCV | تهيئة | ACTU | |

| ستران | |||||||||

| بي إن إف تي | 0.745 | ||||||||

| ضعيف | 0.183 | 0.106 | |||||||

| RSK | 0.066 | 0.120 | 0.569 | ||||||

| ATTD | 0.560 | 0.657 | 0.148 | 0.096 | |||||

| الموضوع | 0.493 | 0.520 | 0.158 | 0.180 | 0.441 | ||||

| PRCV | 0.693 | 0.791 | 0.125 | 0.097 | 0.652 | 0.666 | |||

| INTN | 0.341 | 0.500 | 0.084 | 0.113 | 0.484 | 0.554 | 0.715 | ||

| ACTU | 0.691 | 0.728 | 0.139 | 0.137 | 0.672 | 0.538 | 0.941 | 0.615 | |

** القيم الجريئة لنسبة HTMT التي تقل عن 0.90 تشير إلى أن: تلك المتغيرات متميزة عن المتغيرات الأخرى مما يؤكد تفردها.

ملخص نتائج الفرضيات.

| فرضية | نتيجة | |||

| العينة الكلية | محاضرون | الطلاب | ||

| H1a | تؤثر القوة المدركة للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي بشكل إيجابي على الموقف تجاه استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي. | مقبول | مقبول | مقبول |

| H1b | تؤثر القوة المدركة للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي بشكل إيجابي على المعايير الذاتية. | مقبول | مقبول | مقبول |

| H1c | تؤثر القوة المدركة للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي بشكل إيجابي على السيطرة السلوكية المدركة. | مقبول | مقبول | مقبول |

| H2a | تؤثر الفوائد المدركة للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي بشكل إيجابي على الموقف تجاه استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي. | مقبول | مقبول | مقبول |

| H2b | تؤثر الفوائد المدركة للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي بشكل إيجابي على المعايير الذاتية. | مقبول | مقبول | مقبول |

| H2c | تؤثر الفوائد المدركة للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي بشكل إيجابي على السيطرة السلوكية المدركة. | مقبول | مقبول | مقبول |

| H3a | تؤثر نقاط الضعف المتصورة في الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي سلبًا على الموقف تجاه استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي. | مرفوض | مرفوض | مرفوض |

| H3b | تؤثر نقاط الضعف المتصورة للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي سلبًا على المعايير الذاتية. | مرفوض | مرفوض | مرفوض |

| H3c | تؤثر نقاط الضعف المتصورة في الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي سلبًا على السيطرة السلوكية المتصورة. | مرفوض | مرفوض | مرفوض |

| H4a | تؤثر المخاطر المدركة للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي سلبًا على الموقف تجاه استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي. | مقبول | مقبول | مرفوض |

| H4b | تؤثر المخاطر المدركة للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي سلبًا على المعايير الذاتية. | مرفوض | مرفوض | مرفوض |

| H4c | تؤثر المخاطر المدركة للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي سلبًا على السيطرة السلوكية المدركة. | مقبول | مرفوض | مرفوض |

| H5 | الموقف تجاه استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي له تأثير إيجابي على النية لاستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي | مقبول | مقبول | مقبول |

| H6 | المعايير الذاتية المتعلقة بالذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي لها تأثير إيجابي على النية لاستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي | مقبول | مقبول | مقبول |

| H7 | التحكم المدرك فيما يتعلق بالذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي له تأثير إيجابي على نية استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي | مقبول | مقبول | مقبول |

| H8 | نية استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي لها تأثير إيجابي على الاستخدام الفعلي للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي | مقبول | مقبول | مقبول |

إدارة تطبيق الذكاء الاصطناعي العام في البحث والتعليم للتخفيف من آثاره السلبية من خلال إشراك مؤسسات التعليم العالي في العملية. علاوة على ذلك، لدعم الشمولية والتنوع في البحث والتعليم، تحتاج السلطات العامة ومؤسسات التعليم العالي إلى ضمان توفر تقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي العام لجميع المحاضرين والطلاب لضمان قدرتهم التنافسية وقابلية توظيفهم، على سبيل المثال، من خلال حسابات مؤسسية لتطبيقات الذكاء الاصطناعي العام.

5.3. القيود واتجاهات البحث المستقبلية

إعلان الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي في الكتابة العلمية

بيان إعلان المصالح

بيان مساهمة مؤلفي CRediT

توفر البيانات

الملحق 1. التدابير

| المتغيرات | عناصر | مصدر | |||||||||

| قوة الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي |

|

تم تطويره بواسطة المؤلفين | |||||||||

| فوائد الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي |

|

هسو وآخرون [45] وتم توسيعه بواسطة المؤلفين | |||||||||

| نقاط ضعف الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي |

|

تم تطويره بواسطة المؤلفين | |||||||||

| مخاطر الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي |

|

تم تطويره بواسطة المؤلفين | |||||||||

| الموقف |

|

[٤٤] |

| المتغيرات | عناصر | مصدر |

| التحكم السلوكي المدرك | PRCV1- سواء استخدمت الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي أثناء عملي أم لا، فهذا يعتمد تمامًا عليّ. PRCV2- أنا واثق أنه إذا أردت، يمكنني استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي أثناء عملي. | [٤٤] |

| PRCV3- لدي موارد ووقت وفرص لاستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي أثناء عملي | ||

| نية استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي | INTN1- يستحق الأمر استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي أثناء القيام بعملي | [٤٥] |

| INTN2- سأستخدم الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي بشكل متكرر أثناء عملي في المستقبل. | ||

| الاستخدام الفعلي للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي | ACTU1- أستخدم الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي يوميًا | [43] |

| ACTU2- أستخدم الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي بشكل متكرر |

** تمت إزالتها من نموذجين (العينة الكلية والطلاب) بسبب انخفاض تحميل المؤشر.

تمت إزالة نموذج الطلاب فقط بسبب انخفاض تحميل المؤشر.

الملحق 2. ملاءمة النموذج ومؤشرات الجودة

| مقياس | بشكل عام | محاضرات | الطلاب | القيمة الموصى بها |

| معامل المسار المتوسط (APC) | 0.251، P < 0.001 | 0.266، P < 0.001 | 0.255، P < 0.001 |

|

| متوسط R-squared (ARS) | 0.433،

|

0.474، P < 0.001 | 0.440، P < 0.001 |

|

| متوسط معامل التحديد المعدل (AARS) | 0.426، P < 0.001 |

|

|

|

| متوسط VIF للكتلة (AVIF) | 1.372 | 1.273 | 1.508 | مثاليًا

|

| متوسط عامل التضخم المتعلق بالخطية الكاملة (AFVIF) | 1.989 | ٢.١٠٤ | ٢.١٤١ | من الناحية المثالية

|

| تيننهاوس غوف (غوف) | 0.568 | 0.595 | 0.560 | كبير

|

| نسبة مفارقة سيمبسون (SPR) | 0.938 | 0.938 | 1.000 | مقبول إذا

|

| نسبة مساهمة R-squared (RSCR) | 0.998 | 0.996 | 1.000 | مقبول إذا

|

| نسبة الكبت الإحصائي (SSR) | 1.000 | 0.938 | 0.938 | مقبول إذا

|

| نسبة اتجاه السببية الثنائية غير الخطية (NLBCDR) | 0.875 | 0.844 | 0.906 | مقبول إذا

|

References

[2] O. Ali, P. Murray, M. Momin, F.S. Al-Anzi, The knowledge and innovation challenges of ChatGPT: a scoping review, Technol. Soc. 75 (2023) 102402, https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102402.

[3] S.A. Bin-Nashwan, M. Sadallah, M. Bouteraa, Use of ChatGPT in academia: academic integrity hangs in the balance, Technol. Soc. 75 (2023) 102370, https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102370.

[4] Y.K. Dwivedi, N. Kshetri, L. Hughes, E.L. Slade, A. Jeyaraj, A.K. Kar, A. M. Baabdullah, A. Koohang, V. Raghavan, M. Ahuja, “So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy, Int. J. Inf. Manag. 71 (2023) 102642, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102642.

[5] S. Rice, S.R. Crouse, S.R. Winter, C. Rice, The advantages and limitations of using ChatGPT to enhance technological research, Technol. Soc. 76 (2024) 102426, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102426.

[6] H.S. Sætra, Generative AI: here to stay, but for good? Technol. Soc. 75 (2023) 102372 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102372.

[7] A. Susarla, R. Gopal, J.B. Thatcher, S. Sarker, The Janus effect of generative AI: charting the path for responsible conduct of scholarly activities in information systems, Inf. Syst. Res. 34 (2) (2023) 399-408, https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2023. ed.v34.n2.

[8] R. Vogler, 2023 – an AI university space Odyssey, Retrieved 15th February 2024 from, ROBONOMICS: J. Autom. Econ. 5 (2024) 55, https://journal.robonomics. science/index.php/rj/article/view/55.

[9] S. Ivanov, M. Soliman, Game of algorithms: ChatGPT implications for the future of tourism education and research, J. Tourism Futur. 9 (2) (2023) 214-221, https:// doi.org/10.1108/JTF-02-2023-0038.

[10] T.K. Chiu, The impact of Generative AI (GenAI) on practices, policies and research direction in education: a case of ChatGPT and Midjourney, Interact. Learn. Environ. (2023) 1-17, https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2023.2253861.

[11] M. Farrokhnia, S.K. Banihashem, O. Noroozi, A. Wals, A SWOT analysis of ChatGPT: implications for educational practice and research, Innovat. Educ. Teach. Int. (2023) 1-15, https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2023.2195846.

[12] A. Gilson, C. Safranek, T. Huang, V. Socrates, L. Chi, R.A. Taylor, D. Chartash, How well does ChatGPT do when taking the medical licensing exams? The implications of large language models for medical education and knowledge assessment, medRxiv (2022) 1-9, https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.23.22283901.

[13] F.M. Megahed, Y.-J. Chen, J.A. Ferris, S. Knoth, L.A. Jones-Farmer, How generative AI models such as ChatGPT can be (mis)used in SPC practice, education, and research? An exploratory study, Qual. Eng. 36 (2) (2024) 287-315, https://doi. org/10.1080/08982112.2023.2206479.

[14] S. Biswas, ChatGPT and the future of medical writing, Radiology 307 (2) (2023) e223312, https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.223312.

[15] D.R. Cotton, P.A. Cotton, J.R. Shipway, Chatting and cheating: ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT, Innovat. Educ. Teach. Int. 61 (2) (2024) 228-239, https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2023.2190148.

[16] E. Kasneci, K. Seßler, S. Küchemann, M. Bannert, D. Dementieva, F. Fischer, U. Gasser, G. Groh, S. Günnemann, E. Hüllermeier, ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education, Learn. Indiv Differ 103 (2023) 102274, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2023.102274.

[17] A. Strzelecki, S. ElArabawy, Investigation of the moderation effect of gender and study level on the acceptance and use of generative AI by higher education students: comparative evidence from Poland and Egypt, Br. J. Educ. Technol. (2024), https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet. 13425.

[18] M. Jaboob, M. Hazaimeh, A.M. Al-Ansi, Integration of generative AI techniques and applications in student behavior and cognitive achievement in Arab higher education, Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. (2024) 1-14, https://doi.org/10.1080/ 10447318.2023.2300016.

[19] Y. Wang, W. Zhang, Factors influencing the adoption of generative AI for art designing among Chinese generation Z: a structural equation modeling approach, IEEE Access 11 (2023) 143272-143284, https://doi.org/10.1109/ ACCESS. 2023.3342055.

[20] I. Ajzen, The theory of planned behavior, Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50 (2) (1991) 179-211, https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T.

[21] I. Ajzen, The theory of planned behavior: frequently asked questions, Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2 (4) (2020) 314-324, https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.195.

[22] H. Knauder, C. Koschmieder, Individualized student support in primary school teaching: a review of influencing factors using the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), Teach. Teach. Educ. 77 (2019) 66-76, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. tate.2018.09.012.

[23] T. Teo, C. Beng Lee, Explaining the intention to use technology among student teachers: an application of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), Campus-Wide Inf. Syst. 27 (2) (2010) 60-67, https://doi.org/10.1108/10650741011033035.

[24] M. Bosnjak, I. Ajzen, P. Schmidt, The theory of planned behavior: selected recent advances and applications, Eur. J. Psychol. 16 (3) (2020) 352-356, https://doi. org/10.5964/ejop.v16i3.3107.

[25] M. Conner, C.J. Armitage, Extending the theory of planned behavior: a review and avenues for further research, J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 28 (15) (1998) 1429-1464, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01685.x.

[26] Y. Wang, C. Dong, X. Zhang, Improving MOOC learning performance in China: an analysis of factors from the TAM and TPB, Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 28 (6) (2020) 1421-1433, https://doi.org/10.1002/cae.22310.

[27] J. Cheon, S. Lee, S.M. Crooks, J. Song, An investigation of mobile learning readiness in higher education based on the theory of planned behavior, Comput. Educ. 59 (3) (2012) 1054-1064, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.04.015.

[28] K.M. White, I. Thomas, K.L. Johnston, M.K. Hyde, Predicting attendance at peerassisted study sessions for statistics: role identity and the theory of planned behavior, J. Soc. Psychol. 148 (4) (2008) 473-492, https://doi.org/10.3200/ SOCP.148.4.473-492.

[29] D. Baidoo-Anu, L.O. Ansah, Education in the era of generative artificial intelligence (AI): understanding the potential benefits of ChatGPT in promoting teaching and learning, J. AI 7 (1) (2023) 52-62, https://doi.org/10.61969/jai.1337500.

[30] J. Qadir, Engineering education in the era of ChatGPT: promise and pitfalls of generative AI for education, in: 2023 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Kuwait, Kuwait, 2023, pp. 1-9, https://doi.org/10.1109/ EDUCON54358.2023.10125121.

[31] Stanford, Responsible AI at Stanford, 2023. Retrieved 16th December 2023 from, https://uit.stanford.edu/security/responsibleai.

[32] UNESCO, Generative Artificial Intelligence in Education: what Are the Opportunities and Challenges, 2023. Retrieved 16th December 2023 from, https:// www.unesco.org/en/articles/generative-artificial-intelligence-education-what-are -opportunities-and-challenges.

[33] J. Walmsley, Artificial intelligence and the value of transparency, AI Soc. 36 (2) (2021) 585-595, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-020-01066-z.

[34] S. Noy, W. Zhang, Experimental evidence on the productivity effects of generative artificial intelligence, SSRN 4375283, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4375283, 2023.

[35] M. Shanahan, K. McDonell, L. Reynolds, Role play with large language models, Nature 623 (2023) 493-498, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06647-8.

[36] L. Kohnke, B.L. Moorhouse, D. Zou, ChatGPT for language teaching and learning, 00336882231162868, RELC J. (2023).

[37] I. Carvalho, S. Ivanov, ChatGPT for tourism: applications, benefits and risks, Tour. Rev. 79 (2) (2024) 290-303, https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-02-2023-0088.

[38] E. Bender, T. Gebru, A. McMillan-Major, S. Shmitchell, On the dangers of stochastic parrots: can language models be too big?, in: FAccT ’21: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 2021, pp. 610-623, https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922.

[39] J. Baker-Brunnbauer, TAII framework for trustworthy AI systems, Retrieved 23rd June 2023 from, ROBONOMICS: J. Autom. Econ. 2 (2021) 17, https://journal. robonomics.science/index.php/rj/article/view/17.

[40] Z. Li, The dark side of chatgpt: legal and ethical challenges from stochastic parrots and hallucination, arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.14347, https://doi.org/10.4855 0/arXiv.2304.14347, 2023.

[41] S. Ivanov, The dark side of artificial intelligence in higher education, Serv. Ind. J. 43 (15-16) (2023) 1055-1082, https://doi.org/10.1080/ 02642069.2023 .2258799.

[42] J.F. Hair, C.M. Ringle, M. Sarstedt, PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet, J. Market. Theor. Pract. 19 (2) (2011) 139-152, https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP10696679190202.

[43] W.H. DeLone, E.R. McLean, The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: a ten-year update, J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 19 (4) (2003) 9-30, https://doi.org/ 10.1080/07421222.2003.11045748.

[44] H. Han, L.-T.J. Hsu, C. Sheu, Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: testing the effect of environmental friendly activities, Tourism Manag. 31 (3) (2010) 325-334, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.03.013.

[45] C.-L. Hsu, H.-P. Lu, H.-H. Hsu, Adoption of the mobile Internet: an empirical study of multimedia message service (MMS), Omega 35 (6) (2007) 715-726, https://doi. org/10.1016/j.omega.2006.03.005.

[46] N. Kock, WarpPLS User Manual: Version 8.0 Scriptwarp Systems: Laredo TX, USA, 2022. Retrieved 16th December 2023 from, https://scriptwarp.com/warppls/U serManual_v_8_0.pdf.

[47] N. Kock, L. Gaskins, The mediating role of voice and accountability in the relationship between Internet diffusion and government corruption in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa, Inf. Technol. Dev. 20 (1) (2014) 23-43, https:// doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2013.832129.

[48] J. Henseler, G. Hubona, P.A. Ray, Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: updated guidelines, Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 116 (1) (2016) 2-20, https:// doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382.

[49] M. Soliman, S. Ivanov, C. Webster, The psychological impacts of COVID-19 outbreak on research productivity: a comparative study of tourism and nontourism scholars, J. Tour. Dev. 35 (2021) 23-52, https://doi.org/10.34624/rtd. v0i35.24616.

[50] M. Soliman, R. Sinha, F. Di Virgilio, M.J. Sousa, R. Figueiredo, Emotional intelligence outcomes in higher education institutions: empirical evidence from a Western context, 00332941231197165, Psychol. Rep. (2023), https://doi.org/ 10.1177/00332941231197165.

[51] M.A.Q. Tran, T. Vo-Thanh, M. Soliman, B. Khoury, N.N.T. Chau, Self-compassion, mindfulness, stress, and self-esteem among Vietnamese university students: psychological well-being and positive emotion as mediators, Mindfulness 13 (10) (2022) 2574-2586, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01980-x.

[52] J.F. Hair, M.C. Howard, C. Nitzl, Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis, J. Bus. Res. 109 (2020) 101-110, https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069.

[53] C. Fornell, D.F. Larcker, Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics, J. Market. Res. 18 (3) (1981) 382-388, https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313.

[54] J. Henseler, C.M. Ringle, M. Sarstedt, A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling, J. Acad. Market. Sci. 43 (2015) 115-135, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8.

[55] P.M. Podsakoff, S.B. MacKenzie, J.-Y. Lee, N.P. Podsakoff, Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies, J. Appl. Psychol. 88 (5) (2003) 879, https://doi.org/10.1037/00219010.88.5.879.

[56] F. Kock, A. Berbekova, A.G. Assaf, Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: detection, prevention and control, Tourism Manag. 86 (2021) 104330, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104330.

[57] T. Gundu, Chatbots: a framework for improving information security behaviours using ChatGPT, in: S. Furnell, N. Clarke (Eds.), Human Aspects of Information Security and Assurance, IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, vol. 674, Springer, Cham, 2023, pp. 418-431, https://doi.org/ 10.1007/978-3-031-38530-8_33.

[58] C.S. Shah, S. Mathur, S.K. Vishnoi, Continuance intention of ChatGPT use by students, TDIT 2023, in: S.K. Sharma, Y.K. Dwivedi, B. Metri, B. Lal, A. Elbanna (Eds.), Transfer, Diffusion and Adoption of Next-Generation Digital Technologies, IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, Springer, Cham, 2024, pp. 159-175, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-50188-3_14.

[59] A.M. Al-Zahrani, The impact of generative AI tools on researchers and research: implications for academia in higher education, Innovat. Educ. Teach. Int. (2023) 1-15, https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2023.2271445.

[60] V. Dubljević, Colleges and universities are important stakeholders for regulating large language models and other emerging AI, Technol. Soc. 76 (2024) 102480, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2024.102480.

[61] E.M. Rogers, Diffusion of Innovations, 1983, third ed., The Free Press, London, 1962.

[62] V. Venkatesh, F.D. Davis, A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: four longitudinal field studies, Manag. Sci. 46 (2) (2000) 186-204, https:// doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.46.2.186.11926.

[63] V. Venkatesh, M.G. Morris, G.B. Davis, F.D. Davis, User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view, MIS Q. (2003) 425-478, https://doi.org/

- Corresponding author. Varna University of Management, 13A Oborishte Str., 9000 Varna, Bulgaria.

E-mail addresses: stanislav.ivanov@vumk.eu, info@zangador.institute (S. Ivanov), msoliman.sal@cas.edu.om (M. Soliman), Aarni.Tuomi@haaga-helia.fi (A. Tuomi), nasser2014.sal@cas.edu.om (N.A. Alkathiri), alameer.alalawi@utas.edu.om (A.N. Al-Alawi).

web: http://stanislavivanov.com/.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2024.102521

Publication Date: 2024-03-25

Cite the final publication:

© 2024 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Drivers of generative AI adoption in higher education through the lens of the Theory of Planned Behaviour

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Theory of planned behaviour

Higher education

Abstract

Drawing on the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), this study investigates the relationship between the perceived benefits, strengths, weaknesses, and risks of generative AI (GenAI) tools and the fundamental factors of the TPB model (i.e., attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control). The study also investigates the structural association between the TPB variables and intention to use GenAI tools, and how the latter might affect the actual usage of GenAI tools in higher education. The paper adopts a quantitative approach, relying on an anonymous self-administered online questionnaire to gather primary data from 130 lecturers and 168 students in higher education institutions (HEIs) in several countries, and PLS-SEM for data analysis. The results indicate that although lecturers’ and students’ perceptions of the risks and weaknesses of GenAI tools differ, the perceived strengths and advantages of GenAI technologies have a significant and positive impact on their attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control. The TPB core variables positively and significantly impact lecturers’ and students’ intentions to use GenAI tools, which in turn significantly and positively impact their adoption of such tools. This paper advances theory by outlining the factors shaping the adoption of GenAI technologies in HEIs. It provides stakeholders with a variety of managerial and policy implications for how to formulate suitable rules and regulations to utilise the advantages of these tools while mitigating the impacts of their disadvantages. Limitations and future research opportunities are also outlined.

1. Introduction

of discussions in the media, online forums, and academic communities [2-8]. As a result, researchers and practitioners are becoming increasingly interested in the implications of GenAI applications, especially those based on Large Language Models (LLMs), on human learning, knowledge generation, and the nature of employment in the coming years [4]. Ivanov and Soliman [9] indicated that, in the long run, LLM-based chatbots would revolutionise research and education. If adopted successfully, they could be used as online instructors, curriculum developers, markers, and contributors to scholarly publications. LLMs would also be essential in rethinking education from “teacher-student” interactions to “teacher-AI-student” co-creation [9], shifting

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

2.1. Theory of planned behaviour

2.2. Generative AI in teaching and learning

researchers seem to conclude that the advent of GenAI presents a double-edged sword, whereby on one hand, the integration of GenAI in education offers a range of potential benefits both for the teacher and the learner, but on the other hand, it also brings forward new challenges and potential for misuse [15,16].

2.3. Hypothesis development

unfavourable evaluations of behavioural outcomes [24]. Similarly, if GenAI’s benefits align with broader educational or societal expectations, they are likely to positively affect subjective norms, thereby serving as a motivational driver for technology adoption [25]. Lastly, the anticipated benefits of GenAI, such as the automation of labour-intensive tasks, could enhance perceived behavioural control by bolstering beliefs in the ability to successfully implement this technology in educational settings [22]. Based on this, we hypothesise that.

extant literature on TPB [25]. H7 extends this by positing that greater perceived behavioural control, which reflects beliefs in one’s capability to execute a behaviour, will also positively influence the intention to deploy GenAI in educational settings [22]. Finally, H8 concludes the behavioural chain by suggesting that intention, as influenced by the aforementioned variables, will positively affect actual usage, which is a fundamental tenet of TPB. Thus, we hypothesise that.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sampling and data collection procedures

3.2. Questionnaire design and measures

3.3. Data analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurements models

Demographics characteristics of participants.

| Demographics | Categories | Students | Lecturers | ||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Gender | Male | 80 | 47.6 | 69 | 53.1 |

| Female | 88 | 52.4 | 61 | 46.9 | |

| Age | 18-30 | 116 | 69.1 | 7 | 5.4 |

| 31-40 | 32 | 19 | 41 | 31.5 | |

| 41-50 | 20 | 11.9 | 44 | 33.8 | |

| 51-60 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 18.5 | |

| 61+ | 0 | 0 | 14 | 10.8 | |

| Educational | High school or lower | 46 | 27.4 | 5 | 3.9 |

| level | Bachelor | 50 | 29.7 | 2 | 1.5 |

| Master | 43 | 25.6 | 22 | 16.9 | |

| Doctorate | 26 | 15.5 | 98 | 75.4 | |

| Others | 3 | 1.8 | 3 | 2.3 | |

| Field of study/ research | Social Sciences (e.g. Business, Economics, Tourism and Hospitality, Psychology, Law, etc.) | 134 | 79.8 | 110 | 84.6 |

| Technology (e.g. Engineering, Robotics, Computer Science, Mechanics, etc.) | 15 | 8.9 | 12 | 9.2 | |

| Arts & Humanities (e.g. Architecture, History, Literature, Music, Philosophy, etc.) | 12 | 7.1 | 4 | 3.1 | |

| Life Sciences & Biomedicine (e.g. Biology, Medicine, Agriculture, etc.) | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1.5 | |

| Physical Sciences (e.g. Astronomy, Chemistry, Physics, Mathematics, etc.) | 2 | 1.2 | 2 | 1.5 | |

| Participants country | Bulgaria | 26 | 15.5 | 6 | 4.6 |

| Indonesia | 20 | 11.9 | 8 | 6.2 | |

| Portugal | 13 | 7.7 | 10 | 7.7 | |

| United States | 10 | 6.0 | 13 | 10.0 | |

| Finland | 15 | 8.9 | 5 | 3.8 | |

| Oman | 10 | 6.0 | 6 | 4.6 | |

| Poland | 10 | 6.0 | 4 | 3.1 | |

| United Kingdom | 4 | 2.4 | 9 | 6.9 | |

| India | 5 | 3.0 | 5 | 3.8 | |

| Pakistan | 4 | 2.4 | 4 | 3.1 | |

| Spain | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 6.2 | |

| Malaysia | 5 | 3.0 | 2 | 1.5 | |

| Egypt | 4 | 2.4 | 3 | 2.3 | |

| Turkey | 2 | 1.2 | 5 | 3.8 | |

| Greece | 2 | 1.2 | 4 | 3.1 | |

| Netherlands | 2 | 1.2 | 4 | 3.1 | |

| Sweden | 2 | 1.2 | 3 | 2.3 | |

| Taiwan | 3 | 1.8 | 1 | 0.8 | |

| Australia | 1 | 0.6 | 3 | 2.3 | |

| Others | 30 | 17.9 | 27 | 20.8 | |

| Total | 168 | 100.0 | 130 | 100.0 | |

4.2. Structural models

attitude remained insignificant in all three models as the

5. Discussion and conclusions

5.1. Discussion and theoretical implications

Descriptive statistics and assessment results of the measurement models.

| Total sample (

|

Lecturers (

|

Students (

|

|||||||

| Construct/items | Indicator loading | Composite reliability | AVE | Indicator loading | Composite reliability | AVE | Indicator loading | Composite reliability | AVE |

| Strengths of Gen-AI | 0.876 | 0.640 | 0.811 | 0.799 | 0.883 | 0.655 | |||

| STRN1 | 0.768 | 0.794 | 0.752 | ||||||

| STRN2 | 0.850 | 0.804 | 0.840 | ||||||

| STRN3 | 0.826 | 0.794 | 0.879 | ||||||

| STRN4 | 0.752 | 0.804 | 0.760 | ||||||

| Benefits of Gen-AI | 0.938 | 0.791 | 0.915 | 0.893 | 0.938 | 0.790 | |||

| BNFT1 | 0.892 | 0.916 | 0.878 | ||||||

| BNFT2 | 0.863 | 0.839 | 0.879 | ||||||

| BNFT3 | 0.889 | 0.902 | 0.881 | ||||||

| BNFT4 | 0.913 | 0.915 | 0.916 | ||||||

| Weaknesses of Gen-AI | 0.873 | 0.580 | 0.866 | 0.776 | 0.854 | 0.593 | |||

| WEAK1 | 0.816 | 0.795 | 0.782 | ||||||

| WEAK2 | 0.822 | 0.877 | 0.766 | ||||||

| WEAK3 | 0.719 | 0.780 | 0.770 | ||||||

| WEAK4 | 0.740 | 0.708 | 0.762 | ||||||

| WEAK5 | 0.702 | 0.745 | NA | ||||||

| WEAK6 | NA | 0.739 | NA | ||||||

| Risks of Gen-AI | 0.918 | 0.848 | 0.858 | 0.936 | 0.863 | 0.678 | |||

| RSK1 | 0.921 | 0.936 | 0.863 | ||||||

| RSK2 | 0.921 | 0.936 | 0.857 | ||||||

| RSK3 | NA | NA | 0.745 | ||||||

| Attitude | 0.932 | 0.697 | 0.931 | 0.865 | 0.933 | 0.665 | |||

| ATTD1 | 0.787 | 0.747 | 0.830 | ||||||

| ATTD2 | 0.843 | 0.856 | 0.818 | ||||||

| ATTD3 | 0.845 | 0.882 | 0.785 | ||||||

| ATTD4 | 0.848 | 0.924 | 0.804 | ||||||

| ATTD5 | 0.859 | 0.872 | 0.872 | ||||||

| ATTD6 | 0.825 | 0.896 | 0.769 | ||||||

| ATTD7 | NA | NA | 0.827 | ||||||

| Subjective norms | 0.930 | 0.816 | 0.921 | 0.929 | 0.909 | 0.770 | |||

| SUBJ1 | 0.906 | 0.930 | 0.882 | ||||||

| SUBJ2 | 0.912 | 0.928 | 0.897 | ||||||

| SUBJ3 | 0.891 | 0.930 | 0.851 | ||||||

| Perceived behavioural control | 0.893 | 0.736 | 0.827 | 0.862 | 0.892 | 0.733 | |||

| PRCV1 | 0.827 | 0.817 | 0.836 | ||||||

| PRCV2 | 0.867 | 0.884 | 0.854 | ||||||

| PRCV3 | 0.879 | 0.884 | 0.877 | ||||||

| Intention to use Gen-AI | 0.898 | 0.747 | 0.857 | 0.882 | 0.887 | 0.724 | |||

| INTN1 | 0.856 | 0.876 | 0.843 | ||||||

| INTN2 | 0.872 | 0.884 | 0.862 | ||||||

| INTN3 | 0.864 | 0.886 | 0.848 | ||||||

| Actual use of Gen-AI | 0.922 | 0.855 | 0.858 | 0.936 | 0.909 | 0.833 | |||

| ACTU1 | 0.924 | 0.936 | 0.913 | ||||||

| ACTU2 | 0.924 | 0.936 | 0.913 | ||||||

advantages they give to the students and lecturers in terms of time savings and productivity, and the significant improvements in the quality of GenAI’s outputs over time might be the reasons why the strengths and benefits of GenAI have greater importance for the respondents than the weaknesses and risks associated with these tools but future research needs to provide a definitive answer to this question.

Discriminant validity (Total sample).

| Construct | Fornell and Larcker [53] | ||||||||

| STRN | BNFT | WEAK | RSK | ATTD | SUBJ | PRCV | INIT | ACTU | |

| STRN | (0.800)* | ||||||||

| BNFT | 0.657 | (0.889) | |||||||

| WEAK | -0.079 | -0.017 | (0.762) | ||||||

| RSK | -0.058 | -0.062 | 0.334 | (0.921) | |||||

| ATTD | 0.554 | 0.575 | -0.056 | -0.149 | (0.835) | ||||

| SUBJ | 0.335 | 0.458 | 0.007 | -0.039 | 0.420 | (0.903) | |||

| PRCV | 0.567 | 0.591 | 0.084 | -0.032 | 0.503 | 0.379 | (0.858) | ||

| INTN | 0.586 | 0.668 | -0.009 | -0.095 | 0.582 | 0.527 | 0.709 | (0.864) | |

| ACTU | 0.398 | 0.491 | 0.012 | -0.111 | 0.472 | 0.506 | 0.540 | 0.684 | (0.924) |

| HTMT ratios STRN | BNFT | WEAK | RSK | ATTD | SUBJ | PRCV | INIT | ACTU | |

| STRN | |||||||||

| BNFT | 0.766** | ||||||||

| WEAK | 0.168 | 0.102 | |||||||

| RSK | 0.075 | 0.078 | 0.408 | ||||||

| ATTD | 0.645 | 0.631 | 0.144 | 0.172 | |||||

| SUBJ | 0.394 | 0.509 | 0.066 | 0.053 | 0.468 | ||||

| PRCV | 0.698 | 0.680 | 0.166 | 0.088 | 0.580 | 0.442 | |||

| INTN | 0.717 | 0.767 | 0.139 | 0.115 | 0.670 | 0.615 | 0.858 | ||

| ACTU | 0.487 | 0.564 | 0.056 | 0.135 | 0.543 | 0.590 | 0.651 | 0.823 | |

** Bold values HTMT ratio that are lower than 0.90 indicate that: that variable is distinct from other variables confirming its uniqueness.

Discriminant validity (Lecturers).

| Construct | Fornell and Larcker [53] | ||||||||

| STRN | BNFT | WEAK | RSK | ATTD | SUBJ | PRCV | INIT | ACTU | |

| STRN | (0.799) | ||||||||

| BNFT | 0.549 | (0.893) | |||||||

| WEAK | -0.112 | -0.009 | (0.776) | ||||||

| RSK | -0.167 | -0.187 | 0.282 | (0.936) | |||||

| ATTD | 0.596 | 0.536 | -0.062 | -0.360 | (0.865) | ||||

| SUBJ | 0.451 | 0.535 | 0.051 | -0.154 | 0.416 | (0.862) | |||

| PRCV | 0.516 | 0.657 | -0.033 | -0.244 | 0.602 | 0.638 | (0.882) | ||

| INTN | 0.460 | 0.586 | -0.013 | -0.251 | 0.526 | 0.589 | 0.806 | (0.936) | |

| ACTU | 0.297 | 0.452 | 0.008 | -0.174 | 0.426 | 0.303 | 0.488 | 0.527 | (0.814) |

| HTMT ratios | BNFT | WEAK | RSK | ATTD | SUBJ | PRCV | INIT | ACTU | |

| STRN | |||||||||

| BNFT | 0.638 | ||||||||

| WEAK | 0.159 | 0.088 | |||||||

| RSK | 0.200 | 0.211 | 0.330 | ||||||

| ATTD | 0.686 | 0.582 | 0.127 | 0.405 | |||||

| SUBJ | 0.549 | 0.610 | 0.193 | 0.180 | 0.472 | ||||

| PRCV | 0.618 | 0.741 | 0.093 | 0.285 | 0.676 | 0.754 | |||

| INTN | 0.551 | 0.661 | 0.094 | 0.293 | 0.590 | 0.695 | 0.940 | ||

| ACTU | 0.360 | 0.519 | 0.098 | 0.336 | 0.495 | 0.353 | 0.573 | 0.618 | |

** Bold values HTMT ratio that are lower than 0.90 indicate that: that variable is distinct from other variables confirming its uniqueness.

psychology that intentions often serve as a reliable determinant of subsequent behaviour. It is a valuable insight for understanding the factors influencing the adoption of GenAI tools in practice by both lecturers and students (e.g., Ref. [57,58]).

5.2. Managerial and policy implications

Discriminant validity (Students).

| Construct | Fornell and Larcker [53] | ||||||||

| STRN | BNFT | WEAK | RSK | ATTD | SUBJ | PRCV | INIT | ACTU | |

| STRN | (0.712) | ||||||||

| BNFT | 0.688 | (0.889) | |||||||

| WEAK | -0.077 | 0.002 | (0.692) | ||||||

| RSK | 0.054 | 0.077 | 0.489 | (0.663) | |||||

| ATTD | 0.537 | 0.601 | 0.004 | 0.084 | (0.816) | ||||

| SUBJ | 0.417 | 0.457 | 0.038 | 0.217 | 0.388 | (0.877) | |||

| PRCV | 0.605 | 0.679 | 0.021 | 0.111 | 0.562 | 0.551 | (0.851) | ||

| INTN | 0.349 | 0.426 | 0.044 | 0.084 | 0.414 | 0.457 | 0.576 | (0.913) | |

| ACTU | 0.620 | 0.629 | 0.115 | 0.148 | 0.582 | 0.448 | 0.766 | 0.499 | (0.856) |

| HTMT ratios STRN | BNFT | WEAK | RSK | ATTD | SUBJ | PRCV | INIT | ACTU | |

| STRN | |||||||||

| BNFT | 0.745 | ||||||||

| WEAK | 0.183 | 0.106 | |||||||

| RSK | 0.066 | 0.120 | 0.569 | ||||||

| ATTD | 0.560 | 0.657 | 0.148 | 0.096 | |||||

| SUBJ | 0.493 | 0.520 | 0.158 | 0.180 | 0.441 | ||||

| PRCV | 0.693 | 0.791 | 0.125 | 0.097 | 0.652 | 0.666 | |||

| INTN | 0.341 | 0.500 | 0.084 | 0.113 | 0.484 | 0.554 | 0.715 | ||

| ACTU | 0.691 | 0.728 | 0.139 | 0.137 | 0.672 | 0.538 | 0.941 | 0.615 | |

** Bold values HTMT ratio that are lower than 0.90 indicate that: that variable is distinct from other variables confirming its uniqueness.

Summary of the hypotheses results.

| Hypothesis | Result | |||

| Overall sample | Lecturers | Students | ||

| H1a | Perceived strengths of generative AI have a positive effect on attitude towards using generative AI. | Accepted | Accepted | Accepted |

| H1b | Perceived strengths of generative AI have a positive effect on subjective norms. | Accepted | Accepted | Accepted |

| H1c | Perceived strengths of generative AI have a positive effect on perceived behavioural control. | Accepted | Accepted | Accepted |

| H2a | Perceived benefits of generative AI have a positive effect on attitude towards using generative AI. | Accepted | Accepted | Accepted |

| H2b | Perceived benefits of generative AI have a positive effect on subjective norms. | Accepted | Accepted | Accepted |

| H2c | Perceived benefits of generative AI have a positive effect on perceived behavioural control. | Accepted | Accepted | Accepted |

| H3a | Perceived weaknesses of generative AI have a negative effect on attitude towards using generative AI. | Rejected | Rejected | Rejected |

| H3b | Perceived weaknesses of generative AI have a negative effect on subjective norms. | Rejected | Rejected | Rejected |

| H3c | Perceived weaknesses of generative AI have a negative effect on perceived behavioural control. | Rejected | Rejected | Rejected |

| H4a | Perceived risks of generative AI have a negative effect on attitude towards using generative AI. | Accepted | Accepted | Rejected |

| H4b | Perceived risks of generative AI have a negative effect on subjective norms. | Rejected | Rejected | Rejected |

| H4c | Perceived risks of generative AI have a negative effect on perceived behavioural control. | Accepted | Rejected | Rejected |

| H5 | Attitude towards using generative AI has a positive effect on the intention to use generative AI | Accepted | Accepted | Accepted |

| H6 | Subjective norms regarding generative AI have a positive effect on the intention to use generative AI | Accepted | Accepted | Accepted |

| H7 | Perceived control regarding generative AI has a positive effect on the intention to use generative AI | Accepted | Accepted | Accepted |

| H8 | Intention to use generative AI has a positive effect on actual use of generative AI | Accepted | Accepted | Accepted |

manage the application of GenAI in research and education to mitigate its negative impacts [41] by involving HEIs in the process [60]. Furthermore, to support inclusivity and diversity in research and education public authorities and HEIs need to ensure that GenAI technologies are available to all lecturers and students to ensure their competitiveness and employability, e.g. through institutional accounts to GenAI applications.

5.3. Limitations and future research directions

Declaration of generative AI in scientific writing

Declaration of interest statement

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Data availability

Appendix 1. Measures

| Variables | Items | Source | |||||||||

| Strengths of generative AI |

|

Developed by authors | |||||||||

| Benefits of generative AI |

|

Hsu et al. [45] and expanded by the authors | |||||||||

| Weaknesses of generative AI |

|

Developed by authors | |||||||||

| Risks of generative AI |

|

Developed by authors | |||||||||

| Attitude |

|

[44] |

| Variables | Items | Source |

| Perceived behavioural control | PRCV1- Whether or not I use generative AI while doing my work is completely up to me PRCV2- I am confident that if I want, I can use generative AI while doing my work | [44] |

| PRCV3- I have resources, time, and opportunities to use generative AI while doing my work | ||

| Intention to use generative AI | INTN1- It is worth it to use generative AI while doing my work | [45] |

| INTN2- I will frequently use generative AI while doing my work in the future. | ||

| Actual use of generative AI | ACTU1- I use generative AI on a daily basis | [43] |

| ACTU2- I use generative AI frequently |

** Removed from two models (total sample and students) due to low indicator loading.

*Removed only students model due to low indicator loading.

Appendix 2. Model fit and quality indices

| Metric | Overall | Lectures | Students | Recommended value |

| Average path coefficient (APC) | 0.251, P < 0.001 | 0.266, P < 0.001 | 0.255, P < 0.001 |

|

| Average R-squared (ARS) | 0.433,

|

0.474, P < 0.001 | 0.440, P < 0.001 |

|

| Average adjusted R-squared (AARS) | 0.426, P < 0.001 |

|

|

|

| Average block VIF (AVIF) | 1.372 | 1.273 | 1.508 | ideally

|

| Average full collinearity VIF (AFVIF) | 1.989 | 2.104 | 2.141 | ideally

|

| Tenenhaus GoF (GoF) | 0.568 | 0.595 | 0.560 | Large

|

| Simpson’s paradox ratio (SPR) | 0.938 | 0.938 | 1.000 | Acceptable if

|

| R-squared contribution ratio (RSCR) | 0.998 | 0.996 | 1.000 | Acceptable if

|

| Statistical suppression ratio (SSR) | 1.000 | 0.938 | 0.938 | Acceptable if

|

| Nonlinear bivariate causality direction ratio (NLBCDR) | 0.875 | 0.844 | 0.906 | Acceptable if

|

References

[2] O. Ali, P. Murray, M. Momin, F.S. Al-Anzi, The knowledge and innovation challenges of ChatGPT: a scoping review, Technol. Soc. 75 (2023) 102402, https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102402.

[3] S.A. Bin-Nashwan, M. Sadallah, M. Bouteraa, Use of ChatGPT in academia: academic integrity hangs in the balance, Technol. Soc. 75 (2023) 102370, https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102370.

[4] Y.K. Dwivedi, N. Kshetri, L. Hughes, E.L. Slade, A. Jeyaraj, A.K. Kar, A. M. Baabdullah, A. Koohang, V. Raghavan, M. Ahuja, “So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy, Int. J. Inf. Manag. 71 (2023) 102642, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102642.

[5] S. Rice, S.R. Crouse, S.R. Winter, C. Rice, The advantages and limitations of using ChatGPT to enhance technological research, Technol. Soc. 76 (2024) 102426, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102426.

[6] H.S. Sætra, Generative AI: here to stay, but for good? Technol. Soc. 75 (2023) 102372 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102372.

[7] A. Susarla, R. Gopal, J.B. Thatcher, S. Sarker, The Janus effect of generative AI: charting the path for responsible conduct of scholarly activities in information systems, Inf. Syst. Res. 34 (2) (2023) 399-408, https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2023. ed.v34.n2.

[8] R. Vogler, 2023 – an AI university space Odyssey, Retrieved 15th February 2024 from, ROBONOMICS: J. Autom. Econ. 5 (2024) 55, https://journal.robonomics. science/index.php/rj/article/view/55.

[9] S. Ivanov, M. Soliman, Game of algorithms: ChatGPT implications for the future of tourism education and research, J. Tourism Futur. 9 (2) (2023) 214-221, https:// doi.org/10.1108/JTF-02-2023-0038.

[10] T.K. Chiu, The impact of Generative AI (GenAI) on practices, policies and research direction in education: a case of ChatGPT and Midjourney, Interact. Learn. Environ. (2023) 1-17, https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2023.2253861.

[11] M. Farrokhnia, S.K. Banihashem, O. Noroozi, A. Wals, A SWOT analysis of ChatGPT: implications for educational practice and research, Innovat. Educ. Teach. Int. (2023) 1-15, https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2023.2195846.

[12] A. Gilson, C. Safranek, T. Huang, V. Socrates, L. Chi, R.A. Taylor, D. Chartash, How well does ChatGPT do when taking the medical licensing exams? The implications of large language models for medical education and knowledge assessment, medRxiv (2022) 1-9, https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.23.22283901.

[13] F.M. Megahed, Y.-J. Chen, J.A. Ferris, S. Knoth, L.A. Jones-Farmer, How generative AI models such as ChatGPT can be (mis)used in SPC practice, education, and research? An exploratory study, Qual. Eng. 36 (2) (2024) 287-315, https://doi. org/10.1080/08982112.2023.2206479.

[14] S. Biswas, ChatGPT and the future of medical writing, Radiology 307 (2) (2023) e223312, https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.223312.

[15] D.R. Cotton, P.A. Cotton, J.R. Shipway, Chatting and cheating: ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT, Innovat. Educ. Teach. Int. 61 (2) (2024) 228-239, https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2023.2190148.

[16] E. Kasneci, K. Seßler, S. Küchemann, M. Bannert, D. Dementieva, F. Fischer, U. Gasser, G. Groh, S. Günnemann, E. Hüllermeier, ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education, Learn. Indiv Differ 103 (2023) 102274, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2023.102274.

[17] A. Strzelecki, S. ElArabawy, Investigation of the moderation effect of gender and study level on the acceptance and use of generative AI by higher education students: comparative evidence from Poland and Egypt, Br. J. Educ. Technol. (2024), https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet. 13425.

[18] M. Jaboob, M. Hazaimeh, A.M. Al-Ansi, Integration of generative AI techniques and applications in student behavior and cognitive achievement in Arab higher education, Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. (2024) 1-14, https://doi.org/10.1080/ 10447318.2023.2300016.

[19] Y. Wang, W. Zhang, Factors influencing the adoption of generative AI for art designing among Chinese generation Z: a structural equation modeling approach, IEEE Access 11 (2023) 143272-143284, https://doi.org/10.1109/ ACCESS. 2023.3342055.

[20] I. Ajzen, The theory of planned behavior, Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50 (2) (1991) 179-211, https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T.

[21] I. Ajzen, The theory of planned behavior: frequently asked questions, Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2 (4) (2020) 314-324, https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.195.

[22] H. Knauder, C. Koschmieder, Individualized student support in primary school teaching: a review of influencing factors using the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), Teach. Teach. Educ. 77 (2019) 66-76, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. tate.2018.09.012.

[23] T. Teo, C. Beng Lee, Explaining the intention to use technology among student teachers: an application of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), Campus-Wide Inf. Syst. 27 (2) (2010) 60-67, https://doi.org/10.1108/10650741011033035.

[24] M. Bosnjak, I. Ajzen, P. Schmidt, The theory of planned behavior: selected recent advances and applications, Eur. J. Psychol. 16 (3) (2020) 352-356, https://doi. org/10.5964/ejop.v16i3.3107.

[25] M. Conner, C.J. Armitage, Extending the theory of planned behavior: a review and avenues for further research, J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 28 (15) (1998) 1429-1464, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01685.x.

[26] Y. Wang, C. Dong, X. Zhang, Improving MOOC learning performance in China: an analysis of factors from the TAM and TPB, Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 28 (6) (2020) 1421-1433, https://doi.org/10.1002/cae.22310.

[27] J. Cheon, S. Lee, S.M. Crooks, J. Song, An investigation of mobile learning readiness in higher education based on the theory of planned behavior, Comput. Educ. 59 (3) (2012) 1054-1064, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.04.015.

[28] K.M. White, I. Thomas, K.L. Johnston, M.K. Hyde, Predicting attendance at peerassisted study sessions for statistics: role identity and the theory of planned behavior, J. Soc. Psychol. 148 (4) (2008) 473-492, https://doi.org/10.3200/ SOCP.148.4.473-492.

[29] D. Baidoo-Anu, L.O. Ansah, Education in the era of generative artificial intelligence (AI): understanding the potential benefits of ChatGPT in promoting teaching and learning, J. AI 7 (1) (2023) 52-62, https://doi.org/10.61969/jai.1337500.

[30] J. Qadir, Engineering education in the era of ChatGPT: promise and pitfalls of generative AI for education, in: 2023 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Kuwait, Kuwait, 2023, pp. 1-9, https://doi.org/10.1109/ EDUCON54358.2023.10125121.

[31] Stanford, Responsible AI at Stanford, 2023. Retrieved 16th December 2023 from, https://uit.stanford.edu/security/responsibleai.

[32] UNESCO, Generative Artificial Intelligence in Education: what Are the Opportunities and Challenges, 2023. Retrieved 16th December 2023 from, https:// www.unesco.org/en/articles/generative-artificial-intelligence-education-what-are -opportunities-and-challenges.

[33] J. Walmsley, Artificial intelligence and the value of transparency, AI Soc. 36 (2) (2021) 585-595, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-020-01066-z.

[34] S. Noy, W. Zhang, Experimental evidence on the productivity effects of generative artificial intelligence, SSRN 4375283, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4375283, 2023.

[35] M. Shanahan, K. McDonell, L. Reynolds, Role play with large language models, Nature 623 (2023) 493-498, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06647-8.

[36] L. Kohnke, B.L. Moorhouse, D. Zou, ChatGPT for language teaching and learning, 00336882231162868, RELC J. (2023).

[37] I. Carvalho, S. Ivanov, ChatGPT for tourism: applications, benefits and risks, Tour. Rev. 79 (2) (2024) 290-303, https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-02-2023-0088.

[38] E. Bender, T. Gebru, A. McMillan-Major, S. Shmitchell, On the dangers of stochastic parrots: can language models be too big?, in: FAccT ’21: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 2021, pp. 610-623, https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922.

[39] J. Baker-Brunnbauer, TAII framework for trustworthy AI systems, Retrieved 23rd June 2023 from, ROBONOMICS: J. Autom. Econ. 2 (2021) 17, https://journal. robonomics.science/index.php/rj/article/view/17.

[40] Z. Li, The dark side of chatgpt: legal and ethical challenges from stochastic parrots and hallucination, arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.14347, https://doi.org/10.4855 0/arXiv.2304.14347, 2023.

[41] S. Ivanov, The dark side of artificial intelligence in higher education, Serv. Ind. J. 43 (15-16) (2023) 1055-1082, https://doi.org/10.1080/ 02642069.2023 .2258799.

[42] J.F. Hair, C.M. Ringle, M. Sarstedt, PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet, J. Market. Theor. Pract. 19 (2) (2011) 139-152, https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP10696679190202.

[43] W.H. DeLone, E.R. McLean, The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: a ten-year update, J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 19 (4) (2003) 9-30, https://doi.org/ 10.1080/07421222.2003.11045748.

[44] H. Han, L.-T.J. Hsu, C. Sheu, Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: testing the effect of environmental friendly activities, Tourism Manag. 31 (3) (2010) 325-334, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.03.013.

[45] C.-L. Hsu, H.-P. Lu, H.-H. Hsu, Adoption of the mobile Internet: an empirical study of multimedia message service (MMS), Omega 35 (6) (2007) 715-726, https://doi. org/10.1016/j.omega.2006.03.005.

[46] N. Kock, WarpPLS User Manual: Version 8.0 Scriptwarp Systems: Laredo TX, USA, 2022. Retrieved 16th December 2023 from, https://scriptwarp.com/warppls/U serManual_v_8_0.pdf.

[47] N. Kock, L. Gaskins, The mediating role of voice and accountability in the relationship between Internet diffusion and government corruption in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa, Inf. Technol. Dev. 20 (1) (2014) 23-43, https:// doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2013.832129.

[48] J. Henseler, G. Hubona, P.A. Ray, Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: updated guidelines, Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 116 (1) (2016) 2-20, https:// doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382.

[49] M. Soliman, S. Ivanov, C. Webster, The psychological impacts of COVID-19 outbreak on research productivity: a comparative study of tourism and nontourism scholars, J. Tour. Dev. 35 (2021) 23-52, https://doi.org/10.34624/rtd. v0i35.24616.

[50] M. Soliman, R. Sinha, F. Di Virgilio, M.J. Sousa, R. Figueiredo, Emotional intelligence outcomes in higher education institutions: empirical evidence from a Western context, 00332941231197165, Psychol. Rep. (2023), https://doi.org/ 10.1177/00332941231197165.

[51] M.A.Q. Tran, T. Vo-Thanh, M. Soliman, B. Khoury, N.N.T. Chau, Self-compassion, mindfulness, stress, and self-esteem among Vietnamese university students: psychological well-being and positive emotion as mediators, Mindfulness 13 (10) (2022) 2574-2586, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01980-x.

[52] J.F. Hair, M.C. Howard, C. Nitzl, Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis, J. Bus. Res. 109 (2020) 101-110, https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069.

[53] C. Fornell, D.F. Larcker, Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics, J. Market. Res. 18 (3) (1981) 382-388, https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313.

[54] J. Henseler, C.M. Ringle, M. Sarstedt, A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling, J. Acad. Market. Sci. 43 (2015) 115-135, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8.

[55] P.M. Podsakoff, S.B. MacKenzie, J.-Y. Lee, N.P. Podsakoff, Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies, J. Appl. Psychol. 88 (5) (2003) 879, https://doi.org/10.1037/00219010.88.5.879.

[56] F. Kock, A. Berbekova, A.G. Assaf, Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: detection, prevention and control, Tourism Manag. 86 (2021) 104330, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104330.

[57] T. Gundu, Chatbots: a framework for improving information security behaviours using ChatGPT, in: S. Furnell, N. Clarke (Eds.), Human Aspects of Information Security and Assurance, IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, vol. 674, Springer, Cham, 2023, pp. 418-431, https://doi.org/ 10.1007/978-3-031-38530-8_33.

[58] C.S. Shah, S. Mathur, S.K. Vishnoi, Continuance intention of ChatGPT use by students, TDIT 2023, in: S.K. Sharma, Y.K. Dwivedi, B. Metri, B. Lal, A. Elbanna (Eds.), Transfer, Diffusion and Adoption of Next-Generation Digital Technologies, IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, Springer, Cham, 2024, pp. 159-175, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-50188-3_14.

[59] A.M. Al-Zahrani, The impact of generative AI tools on researchers and research: implications for academia in higher education, Innovat. Educ. Teach. Int. (2023) 1-15, https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2023.2271445.

[60] V. Dubljević, Colleges and universities are important stakeholders for regulating large language models and other emerging AI, Technol. Soc. 76 (2024) 102480, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2024.102480.

[61] E.M. Rogers, Diffusion of Innovations, 1983, third ed., The Free Press, London, 1962.

[62] V. Venkatesh, F.D. Davis, A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: four longitudinal field studies, Manag. Sci. 46 (2) (2000) 186-204, https:// doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.46.2.186.11926.

[63] V. Venkatesh, M.G. Morris, G.B. Davis, F.D. Davis, User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view, MIS Q. (2003) 425-478, https://doi.org/

- Corresponding author. Varna University of Management, 13A Oborishte Str., 9000 Varna, Bulgaria.

E-mail addresses: stanislav.ivanov@vumk.eu, info@zangador.institute (S. Ivanov), msoliman.sal@cas.edu.om (M. Soliman), Aarni.Tuomi@haaga-helia.fi (A. Tuomi), nasser2014.sal@cas.edu.om (N.A. Alkathiri), alameer.alalawi@utas.edu.om (A.N. Al-Alawi).

web: http://stanislavivanov.com/.