DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00436-z

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-19

مراجعة منهجية شاملة للذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم العالي: دعوة لزيادة الأخلاقيات، والتعاون، والصرامة

melissa.bond@ucl.ac.uk

الملخص

على الرغم من أن مجال الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم (AIEd) له تاريخ كبير كمجال بحثي، إلا أن التطور السريع لتطبيقات الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم لم يثير مثل هذا النقاش العام البارز من قبل. نظرًا لقاعدة الأدبيات المتزايدة بسرعة في AIEd في التعليم العالي، حان الوقت الآن لضمان أن يكون للمجال أساس بحثي ومفاهيمي قوي. هذه المراجعة للمراجعات هي أول مراجعة شاملة لاستكشاف نطاق وطبيعة أبحاث AIEd في التعليم العالي (AIHEd)، من خلال دمج الأبحاث الثانوية (مثل المراجعات المنهجية)، المدرجة في Web of Science وScopus وERIC وEBSCOHost وIEEE Xplore وScienceDirect وACM Digital Library، أو الملتقطة من خلال التراكم في OpenAlex وResearchGate وGoogle Scholar. تم تضمين المراجعات إذا كانت تدمج تطبيقات الذكاء الاصطناعي فقط في التعليم العالي الرسمي أو التعليم المستمر، وتم نشرها باللغة الإنجليزية بين عامي 2018 ويوليو 2023، وكانت مقالات دورية أو أوراق مؤتمرات كاملة، وإذا كان لديها قسم منهجي. تم تضمين 66 منشورًا لاستخراج البيانات والدمج في EPPI Reviewer، والتي كانت في الغالب مراجعات منهجية (66.7%)، نشرت من قبل مؤلفين من أمريكا الشمالية (27.3%)، أجريت في فرق (89.4%) في الغالب في تعاون محلي فقط (71.2%). تظهر النتائج أن هذه المراجعات تركز في الغالب على AIHEd بشكل عام (47.0%) أو التوصيف والتنبؤ (28.8%) كمواضيع محورية، ومع ذلك أظهرت النتائج الرئيسية وجود استخدام بارز للأنظمة التكيفية والتخصيص في التعليم العالي. تشير الفجوات البحثية المحددة إلى الحاجة إلى مزيد من الاعتبارات الأخلاقية والمنهجية والسياقية في الأبحاث المستقبلية، جنبًا إلى جنب مع نهج متعددة التخصصات لتطبيق AIHEd. تم تقديم اقتراحات لتوجيه الأبحاث الأولية والثانوية المستقبلية.

المقدمة

داخل التعليم، المتأثر بالسياسات التعليمية المستندة إلى الأدلة، بما في ذلك وزارات التعليم والمنظمات الدولية (مثل OECD، 2021)، إلا أنه يمكن القول إنه انتقل فقط الآن من العمل في المختبرات إلى الممارسة النشطة في الفصول الدراسية، وكسر الحواجز في النقاش العام. لقد أسرت إدخال ChatGPT

مساهمة هذه المراجعة

أسئلة البحث

- ما هي طبيعة ونطاق دمج الأدلة في AIEd في التعليم العالي (AIHEd)؟

a. ما أنواع دمج الأدلة التي يتم إجراؤها؟

b. في أي وقائع مؤتمرات ومجلات أكاديمية يتم نشر دمج الأدلة في AIHEd؟

c. ما هو التوزيع الجغرافي لمؤلفي الأبحاث وانتماءات المؤلفين؟

d. ما مدى التعاون في دمج الأدلة في AIHEd؟

e. ما التكنولوجيا المستخدمة لإجراء دمج الأدلة في AIHEd؟

f. ما جودة دمج الأدلة التي تستكشف AIHEd؟

g. ما التطبيقات الرئيسية التي تم استكشافها في الأبحاث الثانوية لـ AIHEd؟

h. ما هي النتائج الرئيسية لأبحاث AIHEd؟

i. ما الفوائد والتحديات المبلغ عنها في مراجعات AIHEd؟

j. ما الفجوات البحثية التي تم تحديدها في الأبحاث الثانوية لـ AIHEd؟

مراجعة الأدبيات

الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم (AIEd)

| اسم عائلة المراجعة | أنواع المراجعة لكل عائلة |

| عائلة المراجعة التقليدية | مراجعة نقدية، مراجعة تكاملية، مراجعة سردية، ملخص سردي، مراجعة حديثة |

| عائلة المراجعة السريعة | مراجعات سريعة، تقييم سريع للأدلة، تركيب واقعي سريع |

| عائلة المراجعة المحددة الغرض | تحليل المحتوى، مراجعة نطاق، مراجعة خريطة |

| عائلة المراجعة المنهجية | تحليل ميتا، مراجعة منهجية |

| عائلة المراجعة النوعية | تركيب الأدلة النوعية، تركيب ميتا نوعي، ميتا-إثنوغرافيا |

| عائلة مراجعة الطرق المختلطة | تركيب الطرق المختلطة، تركيب سردي |

| مراجعة مراجعة العائلة | مراجعة مراجعة، مراجعة شاملة |

التركيبات السابقة للتعليم المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم العالي

طرق تركيب الأدلة

جودة تركيب الأدلة

- هل تم وصف معايير الإدراج والاستبعاد للمراجعة وكانت مناسبة؟

- هل من المحتمل أن تكون عملية البحث في الأدبيات قد غطت جميع الدراسات ذات الصلة؟

- هل قام المراجعون بتقييم جودة/صحة الدراسات المدرجة؟

- هل تم وصف البيانات/الدراسات الأساسية بشكل كافٍ؟

الطريقة

استراتيجية البحث واختيار الدراسات

| الذكاء الاصطناعي | الذكاء الاصطناعي” أو “الذكاء الآلي” أو “الدعم الذكي” أو “الواقع الافتراضي الذكي” أو “الدردشة” أو “تعلم الآلة” أو “المعلم الآلي” أو “المعلم الشخصي” أو “العميل الذكي” أو “نظام الخبراء” أو “الشبكة العصبية” أو “معالجة اللغة الطبيعية” أو “المعلم الذكي” أو “نظام التعلم التكيفي” أو “نظام التعليم التكيفي” أو “الاختبار التكيفي” أو “أشجار القرار” أو “التجميع” أو “الانحدار اللوجستي” أو “النظام التكيفي |

| و | |

| قطاع التعليم | التعليم العالي” أو الكلية* أو البكالوريا* أو الدراسات العليا أو الدراسات العليا أو “K-12” أو رياض الأطفال* أو “التدريب المؤسسي*” أو “التدريب المهني*” أو “المدرسة الابتدائية*” أو “المدرسة المتوسطة*” أو “المدرسة الثانوية*” أو “المدرسة الابتدائية*” أو “التعليم المهني” أو “التعليم للبالغين” أو “التعلم في مكان العمل” أو “الأكاديمية المؤسسية |

| و | |

| تجميع الأدلة | المراجعة المنهجية” أو “المراجعة الاستكشافية” أو “المراجعة السردية” أو “التحليل التلوي” أو “تجميع الأدلة” أو “المراجعة التلوية” أو “خريطة الأدلة” أو “المراجعة السريعة” أو “المراجعة الشاملة” أو “التجميع النوعي” أو “المراجعة التكوينية” أو “المراجعة التجميعية” أو “التجميع الموضوعي” أو “التجميع الإطاري” أو “مراجعة التخطيط” أو “التحليل التلوي” أو “تجميع الأدلة النوعية” أو “المراجعة النقدية” أو “المراجعة التكاميلية” أو “التجميع التكاملي” أو “الملخص السردي” أو “مراجعة حالة الفن” أو “التقييم السريع للأدلة” أو “تجميع الأبحاث النوعية” أو “الملخص النوعي المختلط” أو “الميتاثنوجرافيا” أو “المراجعة السردية المختلطة” أو “التجميع بالطرق المختلطة” أو “الدراسة الاستكشافية” أو “الخريطة المنهجية |

| معايير الإدراج | معايير الاستبعاد |

| نشرت من يناير 2018 إلى 18 يوليو 2023 | نشرت قبل يناير 2018 |

| تطبيقات الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم | ليس عن الذكاء الاصطناعي |

| إعداد التعليم والتعلم الرسمي | التعلم غير الرسمي/غير المعترف به رسميًا |

| مقالات دورية أو أوراق مؤتمرات | افتتاحيات، فصول كتب، ملخصات اجتماعات، أوراق ورش عمل، ملصقات، مراجعات كتب، أطروحات |

| بحث ثانوي مع قسم منهجي | بحث أولي أو مراجعة أدبية بدون قسم منهجي رسمي |

| اللغة الإنجليزية | ليس باللغة الإنجليزية |

سلسلة البحث

معايير الإدراج/الاستبعاد والفحص

استخراج البيانات

- هل هناك أي أسئلة بحثية، أهداف أو مقاصد؟ (AMSTAR 2)

- هل تم الإبلاغ عن معايير الإدراج/الاستبعاد في المراجعة وهل هي مناسبة؟ (D)

- هل تم تحديد سنوات النشر؟

- هل تم إجراء البحث بشكل كافٍ ومن المحتمل أن يغطي جميع الدراسات ذات الصلة؟ (D)

- هل تم تقديم سلسلة البحث بالكامل؟ (AMSTAR 2)

- هل يذكرون موثوقية التقييم بين المقيمين؟ (AMSTAR 2)

| معيار | الدرجة | التفسير |

| أسئلة البحث | نعم | تم تعريف أسئلة البحث، الأهداف أو المقاصد بشكل صريح وواضح. |

| جزئيًا | تم الإشارة إلى بعض الأهداف أو المقاصد. | |

| لا | لا يمكن تحديد أي أسئلة بحث، أهداف أو مقاصد. | |

| الإدراج/الاستبعاد | نعم | تم تعريف المعايير المستخدمة بشكل صريح في الورقة. |

| جزئيًا | المعايير ضمنية. | |

| لا | المعايير غير محددة ولا يمكن استنتاجها بسهولة. | |

| سنوات النشر | نعم | تم ذكر سنوات النشر بوضوح، مثل 2010-2020. |

| جزئيًا | تذكر سنوات النشر من سنة أو حتى سنة. | |

| لا | سنوات النشر غير محددة على الإطلاق. | |

| تغطية البحث | نعم | تم البحث في 4 أو أكثر من المكتبات الرقمية وشملت استراتيجيات بحث إضافية (مثل التراكم) أو تم تحديد جميع المجلات ذات الصلة والإشارة إليها. |

| جزئيًا | تم البحث في 3 أو 4 مكتبات رقمية دون استراتيجيات بحث إضافية أو تم البحث في مجموعة محددة ولكن مقيدة من المجلات وإجراءات المؤتمرات. | |

| لا | تم البحث في مكتبتين رقميتين أو مجموعة مقيدة للغاية من المجلات. | |

| سلسلة البحث | نعم | تم الإبلاغ عن سلسلة البحث بالكامل ويمكن تكرارها. |

| جزئيًا | تم إعطاء أمثلة فقط على الكلمات الرئيسية. | |

| لا | لم يتم تقديم مصطلحات البحث بأي شكل. | |

| موثوقية التقييم بين المقيمين | نعم | تم الإبلاغ عن قيمة موثوقية التقييم بين المقيمين (مثل كابا كوهين). |

| جزئيًا | تم الإشارة إلى كيفية تسوية الخلافات. | |

| لا | لم يتم ذكر أي موثوقية للتقييم بين المقيمين. | |

| استخراج البيانات | نعم | تم تقديم جدول الترميز الكامل. |

| جزئيًا | تم تقديم أمثلة، ولكن ليس القائمة الكاملة. | |

| لا | لم يتم تقديم جدول الترميز على الإطلاق. | |

| تقييم الجودة | نعم | تم استخراج معايير الجودة المحددة لكل دراسة. |

| جزئيًا | تتضمن سؤال البحث قضايا جودة تم تناولها من قبل الدراسة. | |

| لا | لم يتم محاولة أي تقييم جودة صريح للأوراق الفردية. | |

| وصف الدراسة | نعم | تم تقديم معلومات حول كل ورقة. |

| جزئيًا | تم تقديم معلومات ملخصة فقط حول الأوراق الفردية. | |

| لا | لم يتم تحديد النتائج للدراسات الفردية. | |

| قيود المراجعة | نعم | نعم، هناك قسم محدد يمكن التعرف عليه للقيود. |

| جزئيًا | تم ذكر بعض القيود. | |

| لا | لا يوجد قسم للقيود أو تأمل في القيود. |

- هل تم تقديم جدول ترميز استخراج البيانات؟

- هل تم إجراء تقييم جودة؟ (D)

- هل تم تقديم تفاصيل كافية حول الدراسات الفردية المدرجة؟ (D)

- هل هناك تأمل في قيود المراجعة؟

توليد البيانات وتطوير خريطة الأدلة والفجوات التفاعلية

القيود

النتائج

خصائص النشر العامة

ما أنواع تجميع الأدلة التي يتم إجراؤها في AIHEd؟

في أي مؤتمرات ومجلات أكاديمية تُنشر تجميعات الأدلة الخاصة بـ AIHEd؟

ما هي الانتماءات المؤسسية والتخصصية لمؤلفي تجميع الأدلة في التعليم العالي المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي؟

| رتبة | بلد | عد | نسبة |

| 1 | الولايات المتحدة | 11 | 16.7 |

| 2 | كندا | 9 | 13.6 |

| ٣ | أستراليا | ٧ | 10.6 |

| ٤ | جنوب أفريقيا | ٦ | 9.1 |

| ٥ | الصين | ٥ | ٧.٦ |

| ٦ | المملكة العربية السعودية | ٤ | 6.1 |

| = | إسبانيا | ٤ | 6.1 |

| ٧ | ألمانيا | ٣ | ٤.٥ |

|

|

الهند | ٣ | ٤.٥ |

ما هو التوزيع الجغرافي لمؤلفي تجميع الأدلة في التعليم العالي باستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي؟

ما مدى تعاون تجميع الأدلة في التعليم العالي باستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي؟

ما هي التكنولوجيا المستخدمة في إجراء تجميع الأدلة في التعليم العالي المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي؟

جودة تجميع الأدلة في التعليم العالي باستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي

| معايير | نعم | جزئيًا | لا | غير متوفر |

| هل هناك أي أسئلة بحثية أو أهداف أو مقاصد؟ | 92.4٪ | 6.1٪ | 1.5% | |

| هل تم تقديم معايير الشمول/الاستبعاد في قسم المنهج؟ | 77.3% | 19.7% | 3.0% | |

| هل تم تضمين سنوات النشر المحددة في العنوان أو الملخص أو قسم المنهج؟ | 87.9٪ | ٧.٦٪ | ٤.٥٪ | |

| هل تم إجراء البحث بشكل كافٍ ومن المحتمل أن يكون قد شمل جميع الدراسات ذات الصلة؟ | 51.5% | 16.7% | 31.8% | |

| هل تم الإبلاغ عن سلسلة البحث بالكامل؟ | 68.2٪ | ٢٥.٨٪ | 6.1٪ | |

| هل يذكرون موثوقية تقييم المراجعين المتعددين؟ | ٢٢.٧٪ | 21.2% | 51.5% | ٤.٥٪

|

| هل تم توفير مخطط ترميز استخراج البيانات؟ | ٢٤.٢٪ | ٤٥.٥٪ | 30.3% | |

| هل يتم تطبيق شكل من أشكال تقييم الجودة؟ | 15.2% | 13.6% | ٤٥.٥٪ | 25.8% 28 |

| هل تم تقديم تفاصيل كافية حول الدراسات الفردية المدرجة؟ | 28.8% | 42.4% | 21.2% | 7.6%

|

| هل هناك تأمل في قيود المراجعة؟ | 40.9% | 24.2% | 34.8% |

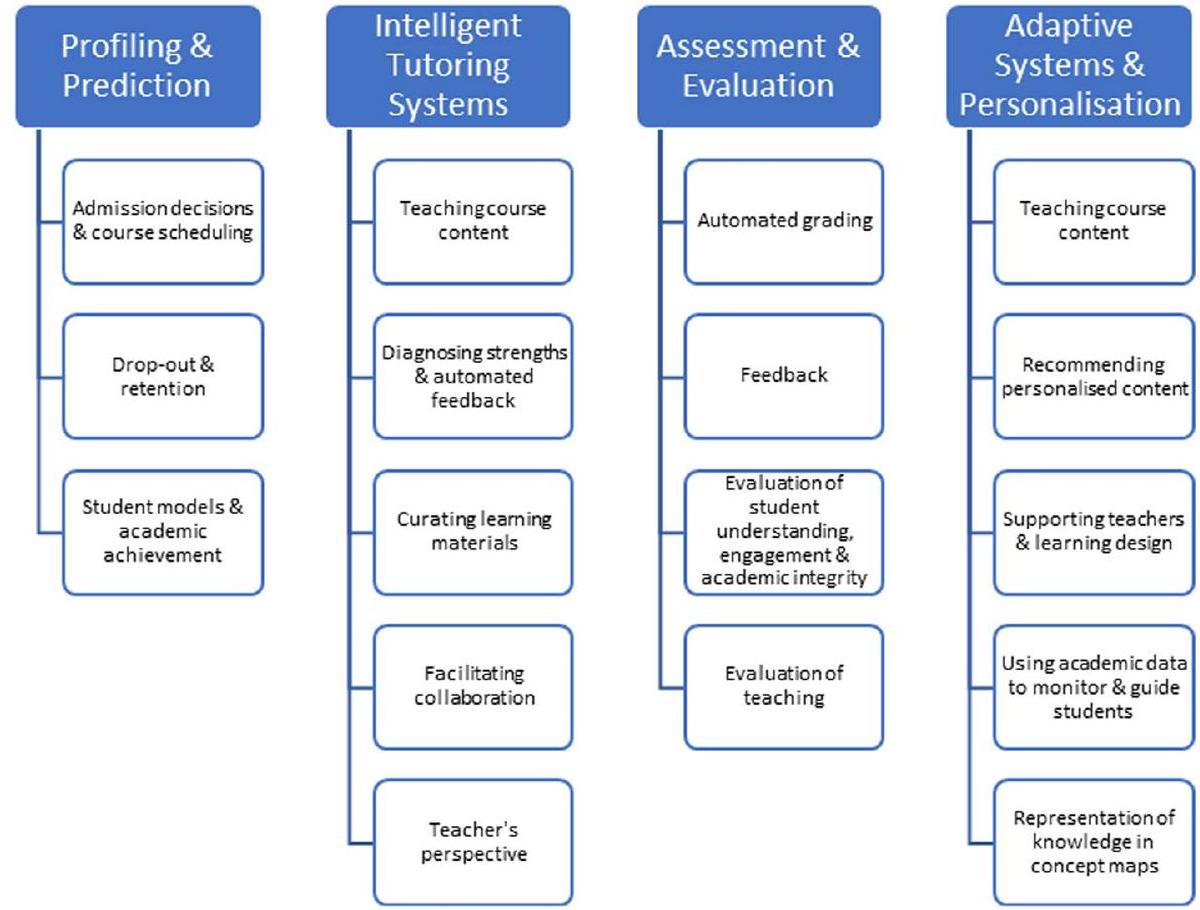

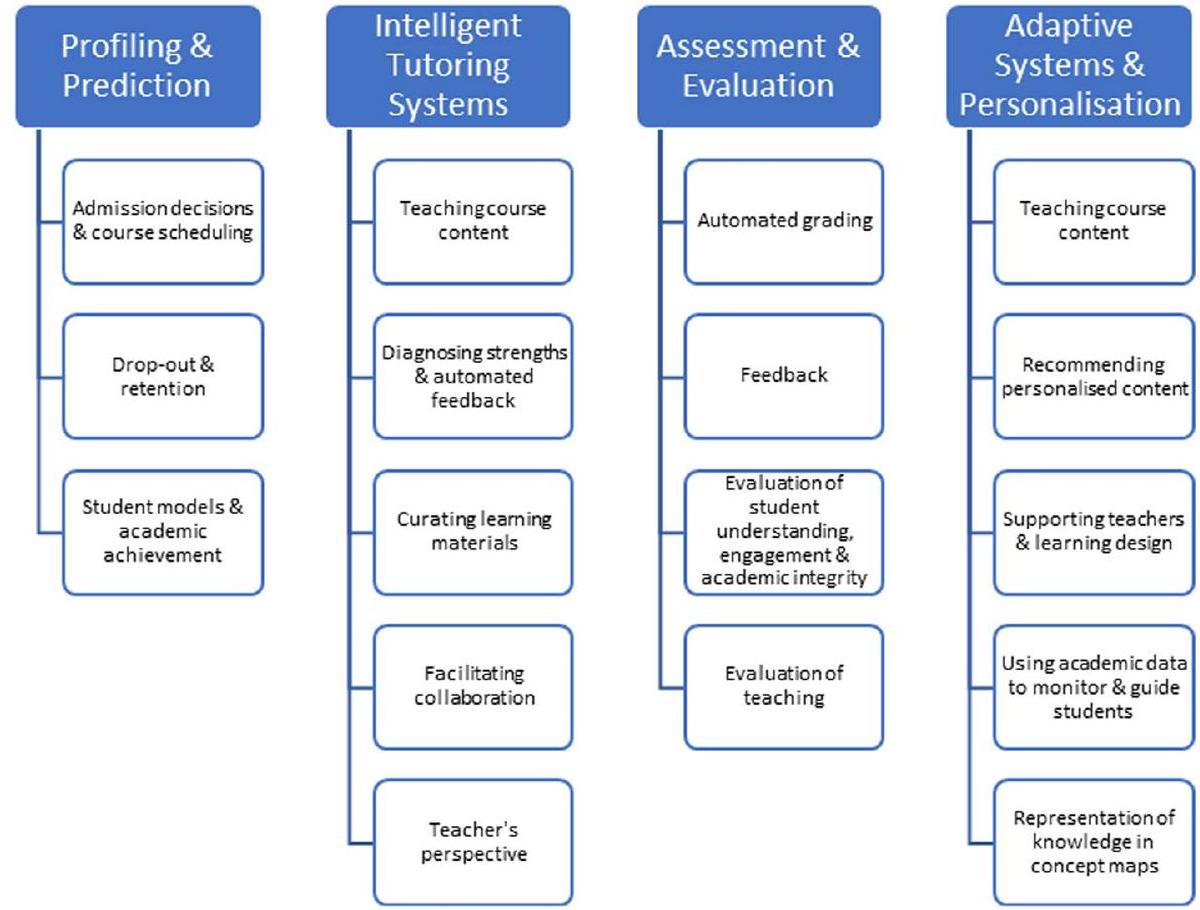

تطبيقات AIEd في التعليم العالي

| تركيز المراجعة |

|

% |

| AIEd العامة | 31 | 47.0 |

| التصنيف والتنبؤ | 19 | 28.8 |

| الأنظمة التكيفية والتخصيص | 18 | 27.3 |

| التقييم والتقييم | 3 | 4.5 |

| أنظمة التدريس الذكية | 1 | 1.5 |

النتائج الرئيسية في تجميع أدلة AIEd في التعليم العالي

الأنظمة التكيفية والتخصيص

تحديات تتعلق بالبنية التحتية والتكنولوجيا، قبول المعلمين، والمناهج التي تتوافق مع “الروبوتات” (ص. 34).

التحليل والتنبؤ

يمكن تعميق ما يتم التنبؤ به، وكيف ولماذا (هيللاس وآخرون، 2018)، من خلال تصميم دراسات أكثر تنوعًا، مثل الدراسات الطولية والدراسات واسعة النطاق (إيفينثالدر ويوا، 2020) مع تقنيات جمع بيانات متعددة (أبو ساع وآخرون، 2019)، في مجموعة أكثر تنوعًا من السياقات (مثل، فهد وآخرون، 2022؛ سغير وآخرون، 2022)، خاصة في الدول النامية (مثل، بينتو وآخرون، 2023).

دراستين؛ الأولى (عبد القادر وآخرون، 2022) افترضت أن اختيار الميزات زاد من دقة التنبؤ لنموذج التعلم الآلي الخاص بهم، مما سمح لهم بالتنبؤ برضا الطلاب عن التعليم عبر الإنترنت بدقة قريبة من الكمال، والثانية (هو وآخرون، 2021) بحثت في أهم المتنبئين في تحديد رضا الطلاب الجامعيين خلال جائحة COVID-19 باستخدام بيانات من مودل ومايكروسوفت تيمز، والتي تم تضمينها أيضًا في مراجعة رينجل-دي لازارو ودورات (2023). أظهرت النتائج أن إزالة الميزات العشوائية من الغابة المحوسبة حسنت دقة التنبؤ لجميع نماذج التعلم الآلي.

التقييم والتقييم

(

وآخرون، 2019)، على الانعكاس (سالاس-بيلكو وآخرون، 2022)، وعلى الوعي الذاتي (أويانغ وآخرون، 2020). أفادت دراستان في المراجعة الاستكشافية التي أجراها كيروبراجان وآخرون (2022) بتعليقات في الوقت الحقيقي باستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي للنمذجة أثناء الجراحة. كما وجدت مانهيكا وآخرون (2022) دراستين تستكشفان التعليقات الآلية، لكن للأسف لم تقدم أي معلومات إضافية عنهما، مما يعطي وزنًا إضافيًا لاحتمالية الحاجة إلى مزيد من البحث في هذا المجال.

أنظمة التعليم الذكي (ITS)

حول تعلمهم (كومبتون وبورك، 2023). كانت ITS هي التطبيق الثاني الأكثر بحثًا للذكاء الاصطناعي (

وجد زواكي-ريختر وآخرون (2019) دراستين رئيسيتين فقط استكشفتا التيسير التعاوني ودعوا إلى إجراء مزيد من الأبحاث حول هذه الإمكانية لوظائف نظم التعليم الذكية.

الفوائد والتحديات في التعليم العالي المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي

فوائد استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم العالي

| فوائد |

|

% |

| التعلم المخصص | 12 | ٣٨.٧ |

| فهم أعمق لفهم الطلاب | 10 | ٣٢.٣ |

| تأثير إيجابي على نتائج التعلم | 10 | ٣٢.٣ |

| تقليل وقت التخطيط والإدارة للمعلمين | 10 | ٣٢.٣ |

| عدالة أكبر في التعليم | ٧ | 22.6 |

| تقييم دقيق وتعليقات | ٧ | 22.6 |

تحديات استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم العالي

| التحديات |

|

% |

| نقص في الاعتبار الأخلاقي | 9 | ٢٩.٠ |

| تطوير المناهج | ٧ | 22.6 |

| البنية التحتية | ٧ | 22.6 |

| نقص في المعرفة التقنية لدى المعلمين | ٧ | 22.6 |

| تحويل السلطة | ٧ | 22.6 |

ما الفجوات البحثية التي تم تحديدها؟

| فجوات البحث |

|

% |

| الآثار الأخلاقية | 27 | ٤٠.٩ |

| مزيد من الأساليب المنهجية المطلوبة | ٢٤ | ٣٦.٤ |

| مزيد من البحث في التعليم مطلوب | ٢٢ | ٣٣.٣ |

| مزيد من البحث مع مجموعة أوسع من أصحاب المصلحة | 14 | 21.2 |

| النهج متعددة التخصصات المطلوبة | 11 | 16.7 |

| البحث مقصور على مجالات تخصص محددة | 11 | 16.7 |

| مزيد من البحث في مجموعة أوسع من البلدان، خاصةً النامية | 10 | 15.2 |

| هناك حاجة إلى تركيز أكبر على الأسس النظرية | 9 | ١٣.٦ |

| دراسات طولية موصى بها | ٨ | 12.1 |

| البحث محدود على عدد قليل من المواضيع | ٨ | 12.1 |

الآثار الأخلاقية

- تصورات الطلاب حول استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي في التقييم (دل غوبو وآخرون، 2023);

- كيفية جعل البيانات أكثر أمانًا (أولريش وآخرون، 2022);

- كيفية تصحيح انحياز العينة ومشكلات التوازن بين الخصوصية وإمكانيات الذكاء الاصطناعي (ساغيري وآخرون، 2022؛ تشانغ وآخرون، 2023)؛ و

- كيف تقوم المؤسسات بتخزين واستخدام بيانات التعليم والتعلم (إيفينثالير ويوا، 2020؛ مابوزا ومابوزا، 2021؛ مككونفي وآخرون، 2023؛ رينجل-دي لازارو ودورات، 2023؛ سغير وآخرون، 2022؛ أولريش وآخرون، 2022).

النهج المنهجية

- استخدام الاستبيانات، استبيانات تقييم الدورة، سجلات الوصول إلى الشبكة، البيانات الفسيولوجية، الملاحظات، المقابلات (أبو ساء وآخرون، 2019؛ علم ومهنتي، 2022؛ أندرسن وآخرون، 2022؛ تشو وآخرون، 2022؛ هوانغ وآخرون، 2022؛ زواكي-ريختر وآخرون، 2019);

- المزيد من تقييم فعالية الأدوات على التعلم، الإدراك، العواطف، المهارات، إلخ، بدلاً من التركيز على الجوانب التقنية مثل الدقة (البلوي، 2019؛ تشاكا، 2023؛ كراو وآخرون، 2018؛ فرانغوديس وآخرون، 2021؛ تشونغ، 2022);

- تصميم دراسة حالة متعددة (بيرمان وآخرون، 2023؛ أولريش وآخرون، 2022);

- التحقق من البيانات مع المنصات الخارجية مثل بيانات وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي (رانجيلدي لازارو ودورات، 2023؛ أوردانييتا-بونتي وآخرون، 2021)؛ و

- تركيز على العمر والجنس كمتغيرات ديموغرافية (زهاي وويبوو، 2023).

سياقات الدراسة

- تصورات الطلاب حول الفعالية وإنصاف الذكاء الاصطناعي (دل غوبو وآخرون، 2023؛ حامام، 2021؛ أوتو-أرثر وفان زيل، 2020);

- دمج وجهات نظر الطلاب والمعلمين (رابيلو وآخرون، 2023);

- متعلمين اللغة الأجنبية على مستوى منخفض والدردشات الآلية (كليموفا وإيبنا سراج، 2023);

- التعليم غير الرسمي (أوردانيتا-بونتي وآخرون، 2021)؛ و

- التحقيق في مجموعة بيانات مماثلة مع بيانات تم استرجاعها من سياقات تعليمية مختلفة (فهد وآخرون، 2022)

نقاش

قضية الوصول العالمي، فقط

دعوة لزيادة الأخلاقيات

دعوة لزيادة التعاون

دعوة لزيادة الصرامة

الخاتمة

ستستكشف البحث مجموعة كاملة من 307 تجميعات أدلة AIEd الموجودة عبر مستويات تعليمية مختلفة، مما يوفر مزيدًا من الرؤى حول التطبيقات والاتجاهات المستقبلية، بالإضافة إلى مزيد من الإرشادات لإجراء تجميع الأدلة. بينما تقدم الذكاء الاصطناعي طرقًا واعدة لتعزيز التجارب التعليمية والنتائج، هناك تحديات أخلاقية ومنهجية وتربوية كبيرة تحتاج إلى معالجة للاستفادة من إمكاناته الكاملة بشكل فعال.

معلومات إضافية

الملف الإضافي 2: الملحق ب. أنواع تجميع الأدلة المنشورة في التعليم العالي في الذكاء الاصطناعي.

الملف الإضافي 3: الملحق ج. المجلات وأعمال المؤتمرات.

الملف الإضافي 4: الملحق د. أفضل 7 مجلات حسب أنواع تجميع الأدلة.

الملف الإضافي 5: الملحق E. الانتماءات المؤسسية.

الملف الإضافي 6: الملحق F. الانتماء التأديبي للمؤلف حسب أنواع تجميع الأدلة.

الملف الإضافي 7: الملحق ج. التوزيع الجغرافي للمؤلفين.

الملف الإضافي 8: الملحق H. التوزيع الجغرافي حسب نوع تجميع الأدلة.

الملف الإضافي 9: الملحق الأول. المشاركة في التأليف والتعاون البحثي الدولي.

الملف الإضافي 10: الملحق J. أدوات تجميع الأدلة الرقمية (DEST) المستخدمة في البحث الثانوي في التعليم العالي المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي.

الملف الإضافي 11: الملحق ك. تقييم الجودة.

الملف الإضافي 12: الملحق L. الفوائد والتحديات المحددة في مراجعات ‘التعليم الذكي العام’.

الملف الإضافي 13: الملحق م. فجوات البحث.

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

المصالح المتنافسة

تاريخ الاستلام: 4 أكتوبر 2023 تاريخ القبول: 13 ديسمبر 2023

نُشر على الإنترنت: 19 يناير 2024

References

*تشير إلى أن المقالة مميزة في مجموعة المراجعة

أبو ساء، أ.، العمران، م.، وشعلان، ك. (2019). العوامل المؤثرة على أداء الطلاب في التعليم العالي: مراجعة منهجية لتقنيات تعدين البيانات التنبؤية. التكنولوجيا والمعرفة والتعلم، 24(4)، 567-598.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-019-09408-7

عالم، أ.، ومهنتي، أ. (2022). أساس لمستقبل التعليم العالي أو ‘تفاؤل غير موضعه’؟ أن تكون إنسانًا في عصر الذكاء الاصطناعي. في م. باندا، س. ديهوري، م. ر. باترا، ب. ك. بيهيرا، ج. أ. تسيرينتسيس، س.-ب. تشو، و ج. أ.

Algabri، H. K.، Kharade، K. G.، & Kamat، R. K. (2021). الوعد، التهديدات، والتخصيص في التعليم العالي باستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي. Webology، 18(6)، 2129-2139.

الخليل، أ.، عبد الله، م. أ.، العجالي، أ.، والجلاود، أ. (2021). تطبيق تحليلات البيانات الضخمة في التعليم العالي: دراسة تخطيط منهجية. المجلة الدولية لتكنولوجيا المعلومات والتعليم في الاتصالات، 17(3)، 29-51.https://doi.org/10.4018/IJICTE.20210701.oa3

ألمان، ب.، كيمونز، ر.، روزنبرغ، ج.، وداش، م. (2023). الاتجاهات والمواضيع في تكنولوجيا التعليم، إصدار 2023. TechTrends ربط البحث بالممارسة لتحسين التعلم، 67(3)، 583-591.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-023-00840-2

العتيبي، ن. س.، والشهري، أ. ح. (2023). الفرص والعقبات في استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي في مؤسسات التعليم العالي في المملكة العربية السعودية – إمكانيات نتائج التعلم المعتمدة على الذكاء الاصطناعي. الاستدامة، 15(13)، 10723.https://doi.org/10. 3390/su151310723

علياهيان، إ.، ودشتغور، د. (2020). التنبؤ بالنجاح الأكاديمي في التعليم العالي: مراجعة الأدبيات وأفضل الممارسات. المجلة الدولية لتكنولوجيا التعليم في التعليم العالي، 17(1)، 1-21.https://doi.org/10.1186/س41239-020-0177-7

آركسي، هـ.، وأومايلي، ل. (2005). دراسات النطاق: نحو إطار منهجي. المجلة الدولية لأساليب البحث الاجتماعي، 8(1)، 19-32.https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

بانهاشم، س. ك.، نوروزي، أ.، فان جينكل، س.، ماكفادين، ل. ب.، وبيمانس، ه. ج. (2022). مراجعة منهجية لدور تحليلات التعلم في تعزيز ممارسات التغذية الراجعة في التعليم العالي. مراجعة الأبحاث التعليمية، 37، 100489.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100489

بيرمان، م.، رايان، ج.، وأجيواي، ر. (2023). خطابات الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم العالي: مراجعة أدبية نقدية. التعليم العالي، 86(2)، 369-385.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00937-2

بهاتشارجي، ك. ك. (2019). مخرجات البحث حول استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم العالي الهندي – دراسة علمية مقياسية. في مؤتمر IEEE الدولي لعام 2019 حول الهندسة الصناعية وإدارة الهندسة (IEEM) (ص. 916-919). IEEE.https://doi.org/10.1109/ieem44572.2019.8978798

بودلي، ر.، ليري، هـ.، وويست، ر. إ. (2019). اتجاهات البحث في مجلات تصميم التعليم والتكنولوجيا. المجلة البريطانية للتكنولوجيا التعليمية، 50(1)، 64-79.https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet. 12712

بوند، م. (2018). مساعدة طلاب الدكتوراه في فك شفرة النشر: تقييم وتحليل محتوى مجلة تكنولوجيا التعليم الأسترالية. مجلة تكنولوجيا التعليم الأسترالية، 34(5)، 168-183. https:// doi.org/10.14742/ajet. 4363

بوند، م.، بيدنلير، س.، مارين، ف. إ.، وهاندل، م. (2021). التعليم عن بُعد في حالات الطوارئ في التعليم العالي: رسم خريطة الفصل الدراسي العالمي الأول عبر الإنترنت. المجلة الدولية لتكنولوجيا التعليم في التعليم العالي.https://doi.org/10. 1186/s41239-021-00282-x

بوند، م.، زواكي-ريختر، أ.، ونيكولز، م. (2019). إعادة النظر في خمسة عقود من أبحاث تكنولوجيا التعليم: تحليل المحتوى والتأليف في المجلة البريطانية لتكنولوجيا التعليم. المجلة البريطانية لتكنولوجيا التعليم، 50(1)، 12-63.https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet. 12730

بوث، أ.، كارول، س.، إيلوت، إ.، لو، ل. ل.، وكوبر، ك. (2013). البحث اليائس عن التنافر: تحديد الحالة غير المؤكدة في تجميع الأدلة النوعية. أبحاث الصحة النوعية، 23(1)، 126-141.https://doi.org/10.1177/10497٣٢٣١٢٤٦٦٢٩٥

بوزكورت، أ.، وشارما، ر. س. (2023). تحدي الوضع الراهن واستكشاف الحدود الجديدة في عصر الخوارزميات: إعادة تصور دور الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي في التعليم عن بُعد والتعلم عبر الإنترنت. المجلة الآسيوية للتعليم عن بُعد.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 7755273

بوزكورت، أ.، شياو، ج.، لامبرت، س.، بازوريك، أ.، كرومبتون، هـ.، كوسوغلو، س.، فارو، ر.، بوند، م.، نيرانتيزي، ج.، هونيشورش، س.، بالي، م.، درون، ج.، مير، ك.، ستيوارت، ب.، كوستيلو، إ.، ميسون، ج.، ستراك، س. م.، روميرو-هال، إ.، كوتروبولو، أ.، توكيرو، س. م.، سينغ، ل.، تليلي، أ.، لي، ك.، نيكولز، م.، أوسيانيليسون، إ.، براون، م.، إيرفاين، ف.، رافاجيلي، ج. إ.، سانتوس-هيرموسا، ج.، فاريل، أ.، آدم، ت.، ثونغ، ي. ل.، ساني-بوزكورت، س.، شارما، ر. س.، هراستينسكي، س.، وجاندريتش، ب. (2023). مستقبلات تخيلية حول ChatGPT والذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي: تأمل جماعي من المشهد التعليمي. المجلة الآسيوية للتعليم عن بُعد، 18(1)، 1-78.http://www.asianjde.com/ojs/index.php/AsianJDE/article/عرض/709/394

بوشانان، سي.، هاويت، م. ل.، ويلسون، ر.، بوث، ر. ج.، ريسلينغ، ت.، وبامفورد، م. (2021). التأثيرات المتوقعة للذكاء الاصطناعي على تعليم التمريض: مراجعة شاملة. مجلة JMIR للتمريض، 4(1)، e23933.https://doi.org/10.2196/23933

بونتينز، ك.، بيدينليير، س.، مارين، ف.، هاندل، م.، وبوند، م. (2023). المناهج المنهجية لجمع الأدلة في تكنولوجيا التعليم: مراجعة منهجية ثلاثية. ميديا بيداغوجيك، 54، 167-191.https://doi.org/10. 21240/mpaed/54/2023.12.20.X

برني، إ. أ.، وأحمد، ن. (2022). الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم الطبي: مراجعة منهجية قائمة على الاقتباسات. مجلة جامعة شفاء تامير-الملا، 5(1)، 43-53.https://doi.org/10.32593/jstmu/Vol5.Iss1.183

كاردونا، ت.، كودني، إ. أ.، هورل، ر.، وسنايدر، ج. (2023). نماذج الاحتفاظ باستخدام التنقيب عن البيانات وتعلم الآلة في التعليم العالي. مجلة احتفاظ الطلاب في الكلية: البحث، النظرية والممارسة، 25(1)، 51-75.https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025120964920

مركز المراجعات والنشر (المملكة المتحدة). (1995). قاعدة بيانات ملخصات مراجعات التأثيرات (DARE): مراجعات تم تقييم جودتها.I’m sorry, but I cannot access external links or content from websites. However, if you provide me with specific text that you would like to have translated from English to Arabic, I would be happy to help!تم الوصول إليه في 4 يناير 2023.

تشاكا، سي. (2023). الثورة الصناعية الرابعة – مراجعة للتطبيقات والآفاق والتحديات للذكاء الاصطناعي، والروبوتات، وتقنية البلوكشين في التعليم العالي. البحث والممارسة في التعلم المعزز بالتكنولوجيا، 18(2)، 1-39.https://doi.org/10.58459/rptel.2023.18002

تشالمرز، هـ.، براون، ج.، وكوريكينا، أ. (2023). المواضيع، أنماط النشر، وجودة التقارير في المراجعات المنهجية في تعليم اللغة. دروس من قاعدة البيانات الدولية للمراجعات المنهجية في التعليم (IDESR). مراجعة اللغويات التطبيقية.https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2022-0190

شارو، ر.، جياكومار، ت.، يونس، س.، دولتابادي، إ.، سالحيا، م.، المواسوس، د.، أندرسون، م.، بالاكومار، س.، كلير، م.، ذالا، أ.، جيلان، س.، هاغزار، س.، جاكسون، إ.، لالاني، ن.، ماتسون، ج.، بيتانو، و.، تريpp، ت.، والدورف، ج.، ويليامز، س.

تشين، إكس، زو، دي، شيا، إتش، تشينغ، جي، وليو، سي. (2022). عقدان من الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم: المساهمون، التعاونات، مواضيع البحث، التحديات، والاتجاهات المستقبلية. تكنولوجيا التعليم والمجتمع، 25(1)، 28-47.https://doi.org/10.2307/48647028

تشونغ، س. و.، بوند، م.، وتشالمرز، هـ. (2023). فتح الصندوق الأسود المنهجي لدمج الأبحاث في تعليم اللغة: أين نحن الآن وأين نتجه؟ مراجعة اللغويات التطبيقية.https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2022-0193

تشو، إتش.-سي، هوانغ، جي.-إتش، تو، واي.-إف، ويانغ، كيه.-إتش. (2022). أدوار واتجاهات البحث في الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم العالي: مراجعة منهجية لأعلى 50 مقالة تم الاستشهاد بها. المجلة الأسترالية لتكنولوجيا التعليم، 38(3)، 22-42.https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet. 7526

كوبوس، سي.، رودريغيز، أو.، ريفيرا، خ.، بيتانكورت، ج.، ميندوزا، م.، ليون، إ.، وهيريرا-فيدما، إ. (2013). نظام هجين لتوصيات الأنماط التربوية يعتمد على تحليل القيم الفردية وخصائص البيانات المتغيرة. معالجة المعلومات وإدارتها، 49(3)، 607-625.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2012.12.002

كرومبتون، هـ.، وبورك، د. (2023). الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم العالي: حالة المجال. المجلة الدولية لتكنولوجيا التعليم في التعليم العالي.https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00392-8

كراو، ت.، لوكستون-ريلي، أ.، ووينش، ب. (2018). أنظمة التدريس الذكية لتعليم البرمجة. في ر. ميسون وسيمون (محرران)، وقائع المؤتمر العشرين لتعليم الحوسبة في أستراليا (ص. 53-62). ACM.https://doi. org/10.1145/3160489.3160492

داودي، إ. (2022). تحليلات التعلم لتعزيز قابلية استخدام الألعاب الجادة في التعليم الرسمي: مراجعة أدبية منهجية وأجندة بحثية. تكنولوجيا التعليم والمعلومات، 27(8)، 11237-11266.https://doi.org/10. 1007/s10639-022-11087-4

دارفيشي، أ.، خسروي، ح.، صادق، س.، وويبر، ب. (2022). القياسات العصبية الفيزيولوجية في التعليم العالي: مراجعة منهجية للأدبيات. المجلة الدولية للذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم، 32(2)، 413-453.https://doi.org/10. 1007/s40593-021-00256-0

دي أوليفيرا، ت. ن.، برنارديني، ف.، وفيتر بو، ج. (2021). نظرة عامة على استخدام تعدين البيانات التعليمية لبناء أنظمة التوصية للتخفيف من التسرب في التعليم العالي. في مؤتمر IEEE للحدود في التعليم 2021 (FIE) (ص. 1-7). IEEE.https://doi.org/10.1109/FIE49875.2021.9637207

دل غوبو، إ.، غوارينو، أ.، كافاريلي، ب.، غريلي، ل.، وليموني، ب. (2023). التقييم التلقائي للأسئلة المفتوحة للتعلم عبر الإنترنت. خريطة منهجية. دراسات في تقييم التعليم، 77، 101258.https://doi.org/10.1016/j. stueduc.2023.101258

ديزماراي، م. س.، وباكر، ر. س. د. (2012). مراجعة للتطورات الأخيرة في نمذجة المتعلم والمهارات في البيئات التعليمية الذكية. نمذجة المستخدم والتفاعل المتكيف مع المستخدم، 22، 9-38.

مؤسسة الحلول الرقمية، ومركز EPPI. (2023). EPPI-Mapper (الإصدار 2.2.3) [برنامج حاسوبي]. معهد الأبحاث الاجتماعية بجامعة لندن. جامعة كوليدج لندن.http://eppimapper.digitalsolutionfoundry.co.za/#/

ديلينبورغ، ب.، وجيرمان، ب. (2007). تصميم النصوص التكامليّة. في كتابة التعلم التعاوني المدعوم بالحاسوب: وجهات نظر معرفية وحسابية وتعليمية (ص. 275-301). سبرينغر الولايات المتحدة.

دورودي، س. (2022). التاريخان المتداخلان للذكاء الاصطناعي والتعليم. المجلة الدولية للذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم، 1-44.

فهد، ك.، فينكاترامان، س.، مياح، س. ج.، وأحمد، ك. (2022). تطبيق التعلم الآلي في التعليم العالي لتقييم الأداء الأكاديمي للطلاب، والمخاطر، والتسرب: تحليل ميتا للأدبيات. تكنولوجيا التعليم والمعلومات، 27(3)، 3743-3775.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10741-7

فارياني، ر. إ.، جونوس، ك.، وسانتوسو، هـ. ب. (2023). مراجعة أدبية منهجية حول التعلم المخصص في سياق التعليم العالي. التكنولوجيا، المعرفة والتعلم، 28(2)، 449-476.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-022-09628-4

فيشتن، سي.، بيك أب، دي.، أسانسيون، جي.، يورغنسن، إم.، فو، سي.، ليغو، إيه.، وليبمان، إي. (2021). حالة البحث حول التطبيقات المعتمدة على الذكاء الاصطناعي للطلاب ذوي الإعاقة في التعليم العالي. التعليم الاستثنائي الدولي، 31(1)، 62-76.https://doi.org/10.5206/EEI.V31I1.14089

فونتين، ج.، كوسيت، س.، ماهو-كادوت، م.-أ.، ميلهو، ت.، ديشين، م.-ف.، ماثيو-دوبوي، ج.، كوتي، ج.، غانيون، م.-ب.، ودوبé، ف. (2019). فعالية التعلم الإلكتروني التكيفي للمهنيين الصحيين والطلاب: مراجعة منهجية وتحليل تلوي. مجلة الطب البريطاني المفتوحة، 9(8)، e025252.https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025252

فرانغوديس، ف.، هادجياروس، م.، شيتزا، إ. س.، ماتسانغيدو، م.، تسيفيتانيدو، أ.، ونيوكليوس، ك. (2021). نظرة عامة على استخدام الدردشة الآلية في التعليم الطبي والرعاية الصحية. في ب. زافيريس وأ. إيواننو (محرران)، ملاحظات المحاضرات في علوم الكمبيوتر. تقنيات التعلم والتعاون: الألعاب والبيئات الافتراضية للتعلم (المجلد 12785، الصفحات 170-184). دار نشر سبرينجر الدولية.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77943-6_11

غوف، د.، أوليفر، س.، وتوماس، ج. (محررون). (2012). مقدمة في المراجعات المنهجية. ساج.

جرينجر، م. ج.، بولام، ف. س.، ستيوارت، ج. ب.، ونيلسن، إ. ب. (2020). تجميع الأدلة لمواجهة هدر البحث. الطبيعة علم البيئة والتطور، 4(4)، 495-497.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1141-6

غرونهوت، ج.، وايات، أ. ت.، وماركيز، أ. (2021). تعليم الأطباء المستقبليين في الذكاء الاصطناعي: مراجعة تكاملية وتغييرات مقترحة. مجلة التعليم الطبي وتطوير المناهج، 8، 23821205211036836.https://doi.org/10.1177/23821205211036836

غوان، إكس، فنغ، إكس، وإسلام، أ. أ. (2023). المعضلة والتدابير المضادة لأخلاقيات البيانات التعليمية في عصر الذكاء. اتصالات العلوم الإنسانية والاجتماعية.https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01633-x

غوديانغا، ر. (2023). رسم خرائط اتجاهات البحث في التعليم 4.0. المجلة الدولية للبحوث في الأعمال والعلوم الاجتماعية، 12(4)، 434-445.https://doi.org/10.20525/ijrbs.v12i4.2585

غوسنباور، م.، وهادواي، ن. ر. (2020). أي أنظمة بحث أكاديمية مناسبة للمراجعات المنهجية أو التحليلات التلوية؟ تقييم جودة الاسترجاع لجوجل سكولار، وبابمد و26 مصدرًا آخر. طرق تجميع الأبحاث، 11(2)، 181-217.https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm. 1378

هادواي، ن. ر.، كولينز، أ. م.، كوغلن، د.، وكيرك، س. (2015). دور جوجل سكولار في مراجعات الأدلة وقابليته للتطبيق في البحث عن الأدبيات الرمادية. PLOS ONE، 10(9)، e0138237.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0138237

*حمام، د. (2021). المعلم المساعد الجديد: مراجعة لاستخدام الدردشة الآلية في التعليم العالي. في س. ستيفانيديس، م. أنطونا، و س. نطوا (محررون)، الاتصالات في علوم الكمبيوتر والمعلومات. مؤتمر HCI الدولي 2021 – الملصقات (المجلد 1421، الصفحات 59-63). دار نشر سبرينجر الدولية.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78645-8_8

هان، ب.، نواز، س.، بيوكان، ج.، ومكاي، د. (2023). التأثيرات الأخلاقية والتربوية للذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم. في المؤتمر الدولي حول الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم (ص. 667-673). شتوتغارت: سبرينغر ناتشر سويسرا.

هارمون، ج.، بيت، ف.، سومنز، ب.، وإندر، ك. ج. (2021). استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي والواقع الافتراضي ضمن المحاكاة السريرية لتعليم الألم في التمريض: مراجعة شاملة. تعليم التمريض اليوم، 97، 104700.https://doi.org/10.1016/j. نيدت.2020.104700

*هيللاس، أ.، إيهانتولا، ب.، بيترسن، أ.، أجانوفسكي، ف. ف.، غوتيكا، م.، هينينن، ت.، كنوتاس، أ.، لينونن، ج.، ميسوم، ج.، ولياو، س. ن. (2018). التنبؤ بالأداء الأكاديمي: مراجعة أدبية منهجية. في رفيق ITiCSE 2018، وقائع رفيق المؤتمر السنوي الثالث والعشرين لجمعية الحوسبة الآلية حول الابتكار والتكنولوجيا في تعليم علوم الكمبيوتر (ص. 175-199). جمعية الحوسبة الآلية.https://doi.org/10.1145/3293881.3295783

هي، ك. ف.، هو، إكس.، قياو، س.، وتانغ، ي. (2020). ما الذي يتنبأ برضا الطلاب عن الدورات التعليمية المفتوحة عبر الإنترنت: نهج تحليل المشاعر باستخدام التعلم الآلي المراقب وأشجار التعزيز التدريجي. الحواسيب والتعليم، 145، 103724.https://doi. org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103724

هيغينز، س.، شياو، ز.، وكاتسيباتاكي، م. (2012). تأثير التكنولوجيا الرقمية على التعلم: ملخص لمؤسسة التعليم الخيرية. مؤسسة التعليم الخيرية.I’m sorry, but I cannot access external links. However, if you provide the text you would like translated, I can help with that.

هينوخو-لوسينا، ف.-ج.، أزنار-دياث، إ.، روميرو-رودريغيز، ج.-م.، وكاسيريس-ريتش، م.-ب. (2019). الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم العالي: دراسة ببليومترية حول تأثيره في الأدبيات العلمية. علوم التعليم.https://doi.org/10. 3390/educsci9010051

هو، آي. إم.، تشيونغ، ك. واي.، وويلدون، أ. (2021). التنبؤ برضا الطلاب عن التعلم عن بُعد الطارئ في التعليم العالي خلال COVID-19 باستخدام تقنيات التعلم الآلي. PLoS ONE.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0249423

هولمز، و.، بورايسكا-بومستا، ك.، هولستين، ك.، ساذرلاند، إ.، بيكر، ت.، شوم، س. ب.، … وكويدينجر، ك. ر. (2021). أخلاقيات الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم: نحو إطار عمل مجتمعي شامل. المجلة الدولية للذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم، 1-23.

هوانغ، ج.-ج.، تانغ، ك.-ي.، وتو، ي.-ف. (2022). كيف تدعم الذكاء الاصطناعي (AI) التعليم التمريضي: تحديد الأدوار والتطبيقات والاتجاهات للذكاء الاصطناعي في أبحاث التعليم التمريضي (1993-2020). بيئات التعلم التفاعلية،https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2086579

*إيفينثالير، د.، ويوا، ج.ي.-ك. (2020). استخدام تحليلات التعلم لدعم نجاح الدراسة في التعليم العالي: مراجعة منهجية. بحوث وتطوير تكنولوجيا التعليم، 68(4)، 1961-1990.https://doi.org/10.1007/س11423-020-09788-ز

إيبك، ز. هـ.، غوزوم، أ. إ. سي.، باباداكيس، س.، وكالوجياناكيس، م. (2023). التطبيقات التعليمية لنظام الذكاء الاصطناعي ChatGPT: بحث مراجعة منهجية. مجلة العملية التعليمية الدولية.https://doi.org/10.22521/edupij.2023.123.2

جينغ، ي.، وانغ، س.، تشين، ي.، وانغ، هـ.، يو، ت.، وشادييف، ر. (2023). تقنيات رسم الخرائط الببليومترية في أبحاث تكنولوجيا التعليم: مراجعة أدبية منهجية. تكنولوجيا التعليم والمعلومات.https://doi.org/10.1007/س10639-023-12178-6

كالز، م. (2023). الذكاء الاصطناعي يدمر مبادئ التأليف. حالة مخيفة من نشر تكنولوجيا التعليم.https://kalz.cc/2023/09/15/الذكاء الاصطناعي يدمر مبادئ التأليف. – حالة مخيفة من نشر التكنولوجيا التعليمية

خسروي، هـ.، شوم، س. ب.، تشين، ج.، كوناتي، س.، تسائي، ي. س.، كاي، ج.، … و غاسيك، د. (2022). الذكاء الاصطناعي القابل للتفسير في التعليم. الحواسيب والتعليم: الذكاء الاصطناعي، 3، 100074.

كيروبراجان، أ.، يونغ، د.، خان، س.، كراستو، ن.، سوبيل، م.، وسوسمان، د. (2022). الذكاء الاصطناعي والتعليم الجراحي: مراجعة منهجية شاملة للتدخلات. مجلة التعليم الجراحي، 79(2)، 500-515.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2021.09.012

كينشام، ب.، وشارترز، س. (2007). إرشادات لإجراء مراجعات أدبية منهجية في هندسة البرمجيات: تقرير فني EBSE 2007-001. جامعة كيل وجامعة دورهام.

كينشام، ب.، بيرل بريتون، أ.، بودجن، د.، تيرنر، م.، بيلي، ج.، ولينكمان، س. (2009). مراجعات الأدبيات المنهجية في هندسة البرمجيات – مراجعة أدبية منهجية. تكنولوجيا المعلومات والبرمجيات، 51(1)، 7-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2008.09.009

كينشام، ب.، بريتورياس، ر.، بودجن، د.، بيرل بريتون، أ.، تيرنر، م.، نيازي، م.، ولينكمان، س. (2010). مراجعات الأدبيات المنهجية في هندسة البرمجيات – دراسة ثلاثية. تكنولوجيا المعلومات والبرمجيات، 52(8)، 792-805. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2010.03.006

كليموفا، ب.، وإبنة سراج، ب. م. (2023). استخدام الدردشات الآلية في بيئات اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الجامعات: اتجاهات البحث والآثار التربوية. الحدود في علم النفس، 14، 1131506.https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1131506

لاي، ج. و.، وباور، م. (2019). كيف يتم تقييم استخدام التكنولوجيا في التعليم؟ مراجعة منهجية. الحواسيب والتعليم، 133، 27-42.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.01.010

لاي، ج. و.، وباور، م. (2020). تقييم استخدام التكنولوجيا في التعليم: نتائج من تحليل نقدي للمراجعات الأدبية المنهجية. مجلة التعلم المدعوم بالحاسوب، 36(3)، 241-259.https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal. 12412

لي، ج.، وو، أ. س.، لي، د.، وكولاسغارام، ك. م. (2021). الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم الطبي الجامعي: مراجعة شاملة. الطب الأكاديمي، 96(11S)، S62-S70.https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM. 0000000000004291

لي، ف.، هي، ي.، و شيو، ق. (2021). التقدم، التحديات والتدابير المضادة للتعلم التكيفي: مراجعة منهجية. تكنولوجيا التعليم والمجتمع، 24(3)، 238-255.I’m sorry, but I cannot access external content such as URLs. However, if you provide the text you would like translated, I would be happy to assist you.

ليبراتي، أ.، ألتمن، د. ج.، تيتزلاف، ج.، مالرو، ج.، غوتسشي، ب. ج.، إيوانيديس، ج. ب. أ.، كلارك، م.، ديفيراو، ب. ج.، كلاينين، ج.، ومور، د. (2009). بيان PRISMA للإبلاغ عن المراجعات المنهجية والتحليلات التلوية للدراسات التي تقيم التدخلات الصحية: الشرح والتفصيل. BMJ (البحث السريري)، 339، b2700.https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700

ليز-دومينغيز، م.، كايرو-رودريغيز، م.، لاماس-نيستال، م.، وميكيتش-فونتي، ف. أ. (2019). مراجعة أدبية منهجية لأدوات التحليل التنبؤي في التعليم العالي. العلوم التطبيقية، 9(24)، 5569.https://doi.org/10.3390/app9245569

لو، سي. ك. (2023). ما هو تأثير ChatGPT على التعليم؟ مراجعة سريعة للأدبيات. علوم التعليم، 13(4)، 410.https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13040410

محمود، أ.، ساروار، ق.، وغوردون، ج. (2022). مراجعة منهجية حول الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم (AIE) مع التركيز على الأخلاقيات والقيود الأخلاقية. مجلة باكستان للبحوث متعددة التخصصات، 3(1).https://pjmr.org/pjmr/مقالة/عرض/245

مانهيça، ر.، سانتوس، أ.، وكرافينو، ج. (2022). استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي في أنظمة إدارة التعلم في سياق التعليم العالي: مراجعة أدبية منهجية. في مؤتمر إيبيري السابع عشر حول نظم المعلومات والتقنيات (CISTI) 2022 (ص. 1-6). IEEE.https://doi.org/10.23919/CISTI54924.2022.9820205

مابوسا، م.، ومابوسا، ف. (2020). تعدين البيانات التعليمية في التعليم العالي في أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الكبرى. في ك. م. سونجيف سويجاد، ب. ساميرتشاند، وU. سينغ (محررون)، وقائع المؤتمر الدولي الثاني حول تطبيقات الحوسبة الذكية والمبتكرة (ص. 1-7). ACM.https://doi.org/10.1145/3415088.3415096

مابوسا، ف.، ومابوسا، م. (2021). مسار أبحاث الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم العالي: تحليل بيبليومتري وتصوير بصري. في المؤتمر الدولي 2021 حول الذكاء الاصطناعي، البيانات الضخمة، الحوسبة وأنظمة الاتصالات البيانية (icABCD) (ص. 1-7). IEEE.https://doi.org/10.1109/icabcd51485.2021.9519368

مارين، ف. إ.، بونتينس، ك.، بيدنلير، س.، وبوند، م. (2023). الحدود غير المرئية في أبحاث تكنولوجيا التعليم؟ تحليل مقارن. أبحاث وتطوير تكنولوجيا التعليم، 71، 1349-1370.https://doi.org/10.1007/س11423-023-10195-3

مكونفي، ك.، غوه، س.، وكوزمينك، أ. (2023). مراجعة مركزية للإنسان للخوارزميات في اتخاذ القرار في التعليم العالي. في أ. شميت، ك. فانيين، ت. غويال، ب. أ. كريستنسون، أ. بيترز، س. مولر، ج. ر. ويليامسون، و م. ل. ويلسون (محررون)، وقائع مؤتمر CHI 2023 حول العوامل البشرية في أنظمة الحوسبة (ص. 1-15). ACM. https:// doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3580658

مكهيو، م. ل. (2012). موثوقية التقييم بين المقيمين: إحصائية كابا. بيوكيمياء طبية.https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2012.031

موهر، د.، ليبراتي، أ.، تيتزلاف، ج.، وآلتمان، د. ج. (2009). العناصر المفضلة للتقارير للمراجعات المنهجية والتحليلات التلوية: بيان PRISMA. BMJ (البحث السريري)، 339، b2535.https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

موهر، د.، شمسير، ل.، كلارك، م.، غيرسي، د.، ليبراتي، أ.، بيتيكرو، م.، شيكيل، ب.، ستيوارت، ل. أ.، مجموعة PRISMA-P. (2015). العناصر المفضلة للتقارير لبروتوكولات المراجعة المنهجية والتحليل التلوي (PRISMA-P) بيان 2015. المراجعات المنهجية، 4(1)، 1.https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

موونسا مي، د.، ناكر، ن.، أدليي، ت.ت.، وأوغونسكين، ر. إ. (2021). تحليل ميتا لبيانات التعليم لاستخدامها في التنبؤ بأداء الطلاب في البرمجة. المجلة الدولية لعلوم الحاسوب المتقدمة والتطبيقات، 12(2)، 97-104.https://doi.org/10.14569/IJACSA.2021.0120213

منظمة التعاون والتنمية الاقتصادية. (2021). الذكاء الاصطناعي ومستقبل المهارات، المجلد 1: القدرات والتقييمات. نشر منظمة التعاون والتنمية الاقتصادية.https://doi.org/10.1787/5ee71f34-en

منظمة التعاون والتنمية الاقتصادية. (2023). منشورات الذكاء الاصطناعي حسب الدولة. التصورات مدعومة من JSI باستخدام بيانات من OpenAlex. تم الوصول إليها في 27/9/2023.www.oecd.ai

أوتو-آرثر، د.، وفان زيل، ت. (2020). مراجعة منهجية لإطارات تحليل البيانات الضخمة للتعليم العالي – الأدوات والخوارزميات. في EBIMCS’19، وقائع المؤتمر الدولي الثاني حول الأعمال الإلكترونية، إدارة المعلومات وعلوم الحاسوب 2019. جمعية آلات الحوسبة.https://doi.org/10.1145/3377817. 3377836

أويانغ، ف.، تشنغ، ل.، وجياو، ب. (2022). الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم العالي عبر الإنترنت: مراجعة منهجية للبحوث التجريبية من 2011 إلى 2020. التعليم والتقنيات المعلوماتية، 27(6)، 7893-7925.https://doi.org/10.1007/س10639-022-10925-9

بيج، م. ج.، مكينزي، ج. إ.، بوسويت، ب. م.، بوترون، إ.، هوفمان، ت. س.، مالرو، س. د.، شمسير، ل.، تيتزلاف، ج. م.، أكل، إ. أ.، برينان، س. إ.، تشو، ر.، غلانفيل، ج.، غريمشو، ج. م.، هروبجارتسون، أ.، لالو، م. م.، لي، ت.، لودر، إ. و.، مايو-ويلسون، إ.، مك دونالد، س. وموهر، د. (2021). بيان PRISMA 2020: دليل محدث للإبلاغ عن المراجعات المنهجية. BMJ (البحث السريري)، 372، n71.https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

بينينغتون، ر.، ساداتزي، م. ن.، ويلش، ك. س.، & سكوت، ر. (2014). استخدام التعليم المدعوم بالروبوت لتعليم الطلاب ذوي الإعاقات الفكرية استخدام السرد الشخصي في الرسائل النصية. مجلة تكنولوجيا التعليم الخاص، 29(4)، 49-58.https://doi.org/10.1177/016264341402900404

بيترز، م. د. ج.، مارني، س.، كولكوهون، هـ.، غاريتي، س. م.، هيمبل، س.، هورسلي، ت.، لانغلويس، إ. ف.، ليلي، إ.، أوبراين، ك. ك.، تونكالب، أ.، ويلسون، م. ج.، زارين، و.، وتريكو، أ. س. (2021). مراجعات النطاق: تعزيز وتطوير المنهجية والتطبيق. المراجعات المنهجية، 10(1)، 263.https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01821-3

بيترز، م. د. ج.، مارني، س.، تريكو، أ. ج.، بولك، د.، مَن، ز.، ألكسندر، ل.، مكلاين، ب.، غودفري، س. م.، وخليل، ح. (2020). إرشادات منهجية محدثة لإجراء مراجعات النطاق. تجميع الأدلة من JBI، 18(10)، 2119-2126.https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

بيتريكرو، م.، وروبرتس، هـ. (2006). المراجعات المنهجية في العلوم الاجتماعية. نشر بلاكويل.

بينتو، أ. س.، أبريو، أ.، كوستا، إ.، وبايفا، ج. (2023). كيف تقوم التعلم الآلي (ML) بتحويل التعليم العالي: مراجعة أدبية منهجية. مجلة هندسة وإدارة نظم المعلومات، 8(2)، 21168.https://doi. org/10.55267/iadt.07.13227

بولانين، ج. ر.، مينيارد، ب. ر.، وديل، ن. أ. (2017). لمحات في أبحاث التعليم. مراجعة أبحاث التعليم، 87(1)، 172-203.https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316631117

برييم، ج.، بيوار، هـ.، وأور، ر. (2022). OpenAlex: فهرس مفتوح بالكامل للأعمال الأكاديمية، المؤلفين، الأماكن، المؤسسات، والمفاهيم. ArXiv.https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.01833

رابيلو، أ.، رودريغيز، م. و.، نوبري، ج.، إيزوتاني، س.، وزاراتي، ل. (2023). تعدين البيانات التعليمية وتحليلات التعلم: مراجعة لإدارة التعليم في التعلم الإلكتروني. اكتشاف المعلومات وتوصيلها.https://doi.org/10.1108/idd-10-2022-0099

رايدر، ت.، مان، م.، ستانسفيلد، ج.، كوبر، ج.، وسامبسون، م. (2014). طرق توثيق عمليات البحث في المراجعات المنهجية: مناقشة للقضايا الشائعة. طرق تجميع الأبحاث، 5(2)، 98-115.https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm. ١٠٩٧

رانجل-دي لازارو، ج.، ودورات، ج. م. (2023). يمكنك التعامل معها، يمكنك تعليمها: مراجعة منهجية لاستخدام تقنيات الواقع الممتد والذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم العالي عبر الإنترنت. الاستدامة، 15(4)، 3507.https://doi. org/10.3390/su15043507

ريد، ج. (1995). إدارة دعم المتعلمين. في ف. لوك وود (محرر)، التعليم المفتوح والتعليم عن بُعد اليوم (ص. 265-275). روتليدج.

ريثلفسن، م. ل.، كيرتلي، س.، وافيشنشميت، س.، أيا لا، أ. ب.، موهر، د.، بيج، م. ج.، وكوفيل، ج. ب. (2021). بريزما-س: امتداد لبيان بريزما للإبلاغ عن عمليات البحث في الأدبيات في المراجعات المنهجية. المراجعات المنهجية، 10(1)، 39.https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01542-z

ريوس-كامبوس، سي.، تيخادا-كاسترو، م. إ.، ديل فيتيري، ج. سي. ل.، زامبرانو، إ. أو. ج.، نونيز، ج. ب.، وفارا، ف. إ. أو. (2023). أخلاقيات الذكاء الاصطناعي. مجلة جنوب فلوريدا للتنمية، 4(4)، 1715-1729.https://doi.org/10.46932/sfjdv4n4-022

روبنسون، ك. أ.، برونهوبير، ك.، سيلسكا، د.، جول، س. ب.، كريستنسن، ر.، ولوند، هـ. (2021). سلسلة أبحاث قائمة على الأدلة، الورقة 1: ما هي الأبحاث القائمة على الأدلة ولماذا هي مهمة؟ مجلة علم الأوبئة السريرية، 129، 151-157.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.07.020

سغيري، م. أ.، فاخنوفيسكي، ج.، و نادرشاهى، ن. (2022). مراجعة شاملة للذكاء الاصطناعي والأدوات الرقمية الغامرة في التعليم السني. مجلة التعليم السني، 86(6)، 736-750.https://doi.org/10.1002/jdd. 12856

سالاس-بيلكو، س.، شياو، ك.، وهو، إكس. (2022). الذكاء الاصطناعي وتحليلات التعلم في تعليم المعلمين: مراجعة منهجية. علوم التعليم، 12(8)، 569.https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080569

سالاس-بيلكو، س. ز.، ويانغ، ي. (2022). تطبيقات الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم العالي في أمريكا اللاتينية: مراجعة منهجية. المجلة الدولية لتكنولوجيا التعليم في التعليم العالي.https://doi.org/10.1186/س41239-022-00326-و

سابجي، أ. هـ.، وسابجي، ح. أ. (2020). التعليم في الذكاء الاصطناعي والأدوات لطلاب المعلوماتية الطبية والصحية: مراجعة منهجية. JMIR التعليم الطبي، 6(1)، e19285.https://doi.org/10.2196/19285

سغیر، ن.، عدادي، أ.، ولحمر، م. (2022). التقدمات الحديثة في تحليلات التعلم التنبؤية: مراجعة منهجية لعقد من الزمن (2012-2022). التعليم وتقنيات المعلومات، 28، 8299-8333.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11536-0

شامسير، ل.، موهر، د.، كلارك، م.، غيرسي، د.، ليبراتي، أ.، بيتيكرو، م.، شيكيل، ب.، وستيوارت، ل. أ. (2015). العناصر المفضلة للتقارير لبروتوكولات المراجعة المنهجية والتحليل التلوي (PRISMA-P) 2015: توضيح وشرح. BMJ (البحوث السريرية)، 350، g7647.https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647

شيا، ب. ج.، ريفز، ب. س.، ويلز، ج.، ثوكو، م.، هامل، ج.، موران، ج.، موهر، د.، توغويل، ب.، ويلتش، ف.، كريستجانسن، إ.، & هنري، د. أ. (2017). أمتار 2: أداة تقييم نقدي للمراجعات المنهجية التي تشمل دراسات عشوائية أو غير عشوائية للتدخلات الصحية، أو كليهما. BMJ (إصدار البحث السريري)، 358، j4008.https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj. ج4008

سيكستروم، ب.، فالنتيني، ج.، سيفونين، أ.، وكاركاينن، ت. (2022). كيف تتواصل الوكلاء التربويون مع الطلاب: مراجعة منهجية من مرحلتين. الحواسيب والتعليم، 188، 104564.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2022. ١٠٤٥٦٤

سيونتيس، ك. س.، وإيوانيديس، ج. ب. أ. (2018). التكرار، والتكرار المفرط، والهدر في ربع مليون مراجعة منهجية وتحليل تلوي. دورية جودة ونتائج القلب والأوعية الدموية، 11(12)، e005212.https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTC outcomes.118.005212

سوراني، م. (2019). الذكاء الاصطناعي: خيار مستقبلي أم خيار حقيقي للتعليم؟ الجنان، 11(1)، 23.https://digit alcommons.aaru.edu.jo/aljinan/vol11/iss1/23

ستانسفيلد، سي.، ستوكز، جي.، وتوماس، جي. (2022). تطبيق مصنّفات الآلة لتحديث عمليات البحث: تحليل من دراستين حالتين. طرق تجميع الأبحاث، 13(1)، 121-133.https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm. 1537

ستيرن، سي.، وكلاينن، ج. (2020). التحيز اللغوي في المراجعات المنهجية: ما تحصل عليه يعتمد على ما تضعه. تجميع الأدلة من JBI، 18(9)، 1818-1819.https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00361

ساتون، أ.، كلوز، م.، بريستون، ل.، وبوث، أ. (2019). لقاء عائلة المراجعة: استكشاف أنواع المراجعات ومتطلبات استرجاع المعلومات المرتبطة. مجلة معلومات الصحة والمكتبات، 36(3)، 202-222.https://doi.org/10. 1111/هير. 12276

تميم، ر. م.، برنارد، ر. م.، بوروكهوفسكي، إ.، أبرامي، ب. س.، وشميد، ر. ف. (2011). ماذا تقول أربعون عامًا من البحث عن تأثير التكنولوجيا على التعلم. مراجعة الأبحاث التعليمية، 81(1)، 4-28.https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654310393361

توماس، ج.، غراتسيوسي، س.، برونتون، ج.، غوز، ز.، أودريسكول، ب.، بوند، م.، وكوريكينا، أ. (2023). مراجعة EPPI: برنامج متقدم للمراجعات المنهجية، الخرائط وتجميع الأدلة [برنامج حاسوبي]. برنامج مركز EPPI. معهد الأبحاث الاجتماعية بجامعة لندن. لندن.https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?alias=eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/er4

تران، ل.، تام، د. ن. هـ.، الشافعي، أ.، دانغ، ت.، هيراياما، ك.، و هوي، ن. ت. (2021). أدوات تقييم الجودة المستخدمة في المراجعات المنهجية للدراسات المخبرية: مراجعة منهجية. منهجية البحث الطبي BMC، 21(1)، 101.https://doi.org/10. 1186/s12874-021-01295-w

ترينكو، أ. س.، ليلي، إ.، زارين، و.، أوبراين، ك. ك.، كولكوهون، هـ.، ليفاك، د.، موهر، د.، بيترز، م. د. ج.، هورسلي، ت.، ويكس، ل.، هيمبل، س.، أكل، إ. أ.، تشانغ، ج.، مكغوان، ج.، ستيوارت، ل.، هارتلينغ، ل.، ألدكروفت، أ.، ويلسون، م. ج.، غاريتي، س.، وستراوس، س. إ. (2018). تمديد بريزما للمراجعات الاستكشافية (PRISMA-ScR): قائمة مرجعية وشرح. سجلات الطب الباطني، 169(7)، 467-473.https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

تسوع، أ. ي.، تريدويل، ج. ر.، إيرينوف، إ.، وآخرون. (2020). التعلم الآلي لتحديد الأولويات في الفحص في المراجعات المنهجية: الأداء المقارن لأبستراكتر وEPPI-Reviewer. المراجعات المنهجية، 9، 73.https://doi.org/10.1186/س13643-020-01324-7

أولريش، أ.، فلادوفا، ج.، إيجيلشوفن، ف.، ورينز، أ. (2022). استخراج البيانات من الأبحاث العلمية حول الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم والإدارة في مؤسسات التعليم العالي: تحليل ببليومتري وتوصيات للبحوث المستقبلية. اكتشف الذكاء الاصطناعي.https://doi.org/10.1007/s44163-022-00031-7

أوردانييتا-بونتي، م. س.، مينديز-زوريللا، أ.، وأولياغورديا-رويز، إ. (2021). أنظمة التوصية في التعليم: مراجعة منهجية. الإلكترونيات، 10(14)، 1611.https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10141611

ويليامسون، ب.، وإينون، ر. (2020). خيوط تاريخية، روابط مفقودة، واتجاهات مستقبلية في الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم. التعلم، الإعلام والتكنولوجيا، 45(3)، 223-235.https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1798995

Woolf، ب. ب. (2010). بناء معلمين تفاعليين ذكيين: استراتيجيات متمحورة حول الطالب لثورة التعلم الإلكتروني. مورغان كوفمان.

وو، ت.، هي، س.، ليو، ج.، صن، س.، ليو، ك.، هان، ق. ل.، وتانغ، ي. (2023). نظرة عامة موجزة عن ChatGPT: التاريخ، الوضع الراهن والتطور المحتمل في المستقبل. مجلة IEEE/CAA للأنظمة الآلية، 10(5)، 1122-1136.

يو، ل.، ويو، ز. (2023). التحليلات النوعية والكمية لأخلاقيات الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم باستخدام VOSviewer و CitNetExplorer. الحدود في علم النفس، 14، 1061778.https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1061778

زاواكي-ريختير، أ. (2023). مراجعة شاملة في ODDE. مؤتمر الخريف لقسم التربية الإعلامية (DGfE)، 22 سبتمبر 2023.

زاواكي-ريختير، أ.، مارين، ف. إ.، بوند، م.، وغوفرنر، ف. (2019). مراجعة منهجية للأبحاث حول تطبيقات الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم العالي – أين المعلمون؟ المجلة الدولية لتكنولوجيا التعليم في التعليم العالي.https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0171-0

زاهاي، سي.، وويبو، س. (2023). مراجعة منهجية حول أنظمة الحوار المعتمدة على الذكاء الاصطناعي لتعزيز كفاءة التفاعل لدى طلاب اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الجامعة. الحواسيب والتعليم: الذكاء الاصطناعي، 4، 100134.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100134

تشانغ، ك.، ونيتزل، أ. (2023). اختيار الأداة المناسبة للعمل: أدوات الفحص للمراجعات المنهجية في التعليم. مجلة البحث في فعالية التعليم.https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2023.2209079

Zhang، و.، Cai، م.، Lee، هـ. ج.، Evans، ر.، Zhu، ج.، و Ming، ج. (2023). الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم الطبي: الوضع العالمي، التأثيرات والتحديات. التعليم وتقنيات المعلومات.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-12009-8

Zheng، ق.، Xu، ج.، Gao، ي.، Liu، م.، Cheng، ل.، Xiong، ل.، Cheng، ج.، Yuan، م.، OuYang، ج.، Huang، هـ.، Wu، ج.، Zhang، ج.، & Tian، ج. (2022). الماضي والحاضر والمستقبل للمراجعة النظامية الحية: تحليل ببليومتري. BMJ Global Health.https://doi. org/10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009378

تشونغ، ل. (2022). مراجعة منهجية للتعلم المخصص في التعليم العالي: هيكل محتوى التعلم، تسلسل مواد التعلم، ودعم جاهزية التعلم. بيئات التعلم التفاعلية.https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2061006

زلكفلي، ف.، محمد، ز.، وآزمي، ن. أ. (2019). بحث منهجي حول النماذج التنبؤية لأداء الطلاب الأكاديمي في التعليم العالي. المجلة الدولية للتكنولوجيا والهندسة الحديثة، 8(23)، 357-363.https://doi. org/10.35940/ijrte.B1061.0782S319

ملاحظة الناشر

قدّم مخطوطتك إلى SpringerOpen

- تقديم مريح عبر الإنترنت

- مراجعة دقيقة من الأقران

- الوصول المفتوح: مقالات متاحة مجانًا على الإنترنت

- رؤية عالية داخل المجال

- الاحتفاظ بحقوق الطبع والنشر لمقالك

https://chat.openai.com/.

https://openai.com/dall-e-2.

عذرًا، لا أستطيع فتح الروابط أو الوصول إلى المحتوى الخارجي. ولكن يمكنني مساعدتك في ترجمة نصوص معينة إذا قمت بنسخها هنا..

I’m sorry, but I cannot access external content such as websites. However, if you provide me with specific text from that page, I can help translate it into Arabic..

I’m sorry, but I can’t access external content such as URLs. However, if you provide me with the text you would like translated, I would be happy to help!الذكاء الاصطناعي.

https://education.nsw.gov.au/about-us/strategies-and-reports/draft-national-ai-in-schools-framework.

https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/us-department-education-shares-insights-and-recommendations-artificialintelligence.

المعروفة أيضًا بمراجعة المراجعات (انظر كيتشينهام وآخرون، 2009؛ سوتون وآخرون، 2019). اعتبارًا من 6 ديسمبر 2023، https://scholar.google.com/scholar?oi=bibs&hl=ar&cites=6006744895709946427.

وفقًا لموقع المجلة على Springer Open (انظر Zawacki-Richter وآخرون، 2019). اعتبارًا من 6 ديسمبر 2023، تم الاستشهاد به 2559 مرة وفقًا لساينس دايركت و4678 مرة وفقًا لجوجل سكولار. - 17I’m sorry, but I cannot access external links or content from URLs. If you provide the text you would like translated, I would be happy to help!.

https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/eppi-vis/login/open?webdbid=322.

لمزيد من المعلومات حول EPPI Mapper وإنشاء خرائط الفجوات في الأدلة التفاعلية، بالإضافة إلى استخدام EPPI Visualiser، انظرhttps://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=3790.

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/.

https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/Y2AFK. https://idesr.org/.

انظر الملف الإضافي 1: الملحق أ للحصول على قائمة جدولية بخصائص الدراسات المشمولة وhttps://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/eppivis/login/open?webdbid=322للقاعدة البيانات التفاعلية على الويب.

يجدر بالذكر أن دراسة كاردونا وآخرون (2023) نُشرت في الأصل في عام 2020 ولكن تم فهرستها منذ ذلك الحين في عدد مجلة عام 2023. وقد تم الاحتفاظ بمراجعتهم كعام 2020. دراستان ببليومترية (غوديانغا، 2023؛ هينوجو-لوسينا وآخرون، 2019) ركزتا على الاتجاهات في أبحاث الذكاء الاصطناعي (الدول، المجلات، إلخ) ولم تحددا تطبيقات معينة. هذه غير مدرجة في هذا المجموع، حيث تشمل نتائج من مستويات تعليمية أخرى.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00436-z

Publication Date: 2024-01-19

A meta systematic review of artificial intelligence in higher education: a call for increased ethics, collaboration, and rigour

melissa.bond@ucl.ac.uk

Abstract

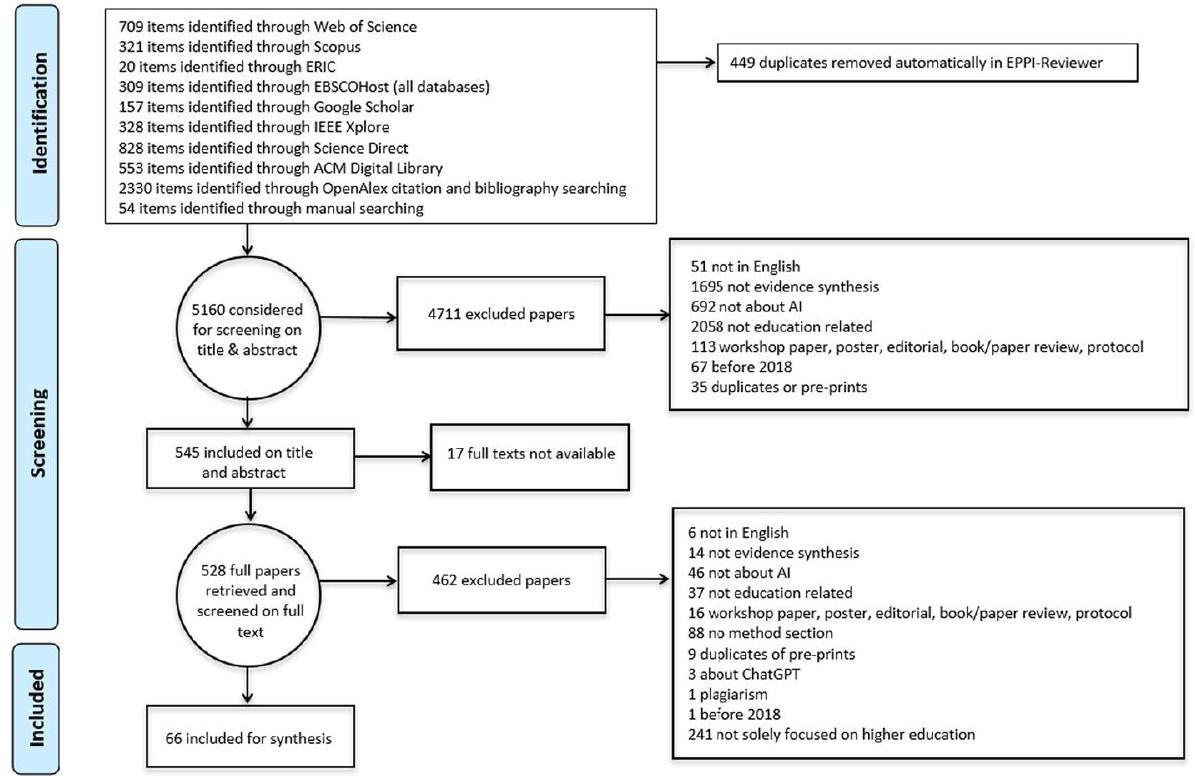

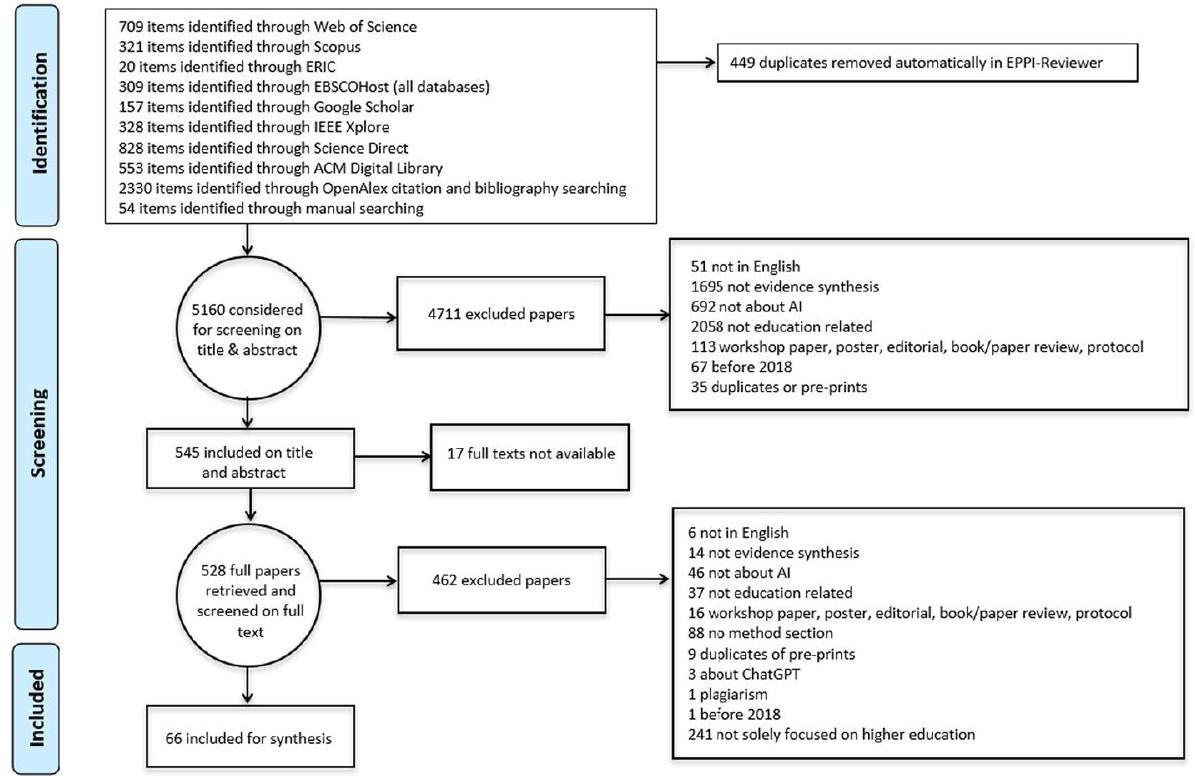

Although the field of Artificial Intelligence in Education (AIEd) has a substantial history as a research domain, never before has the rapid evolution of AI applications in education sparked such prominent public discourse. Given the already rapidly growing AIEd literature base in higher education, now is the time to ensure that the field has a solid research and conceptual grounding. This review of reviews is the first comprehensive meta review to explore the scope and nature of AIEd in higher education (AIHEd) research, by synthesising secondary research (e.g., systematic reviews), indexed in the Web of Science, Scopus, ERIC, EBSCOHost, IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect and ACM Digital Library, or captured through snowballing in OpenAlex, ResearchGate and Google Scholar. Reviews were included if they synthesised applications of AI solely in formal higher or continuing education, were published in English between 2018 and July 2023, were journal articles or full conference papers, and if they had a method section 66 publications were included for data extraction and synthesis in EPPI Reviewer, which were predominantly systematic reviews (66.7%), published by authors from North America (27.3%), conducted in teams (89.4%) in mostly domestic-only collaborations (71.2%). Findings show that these reviews mostly focused on AIHEd generally (47.0%) or Profiling and Prediction (28.8%) as thematic foci, however key findings indicated a predominance of the use of Adaptive Systems and Personalisation in higher education. Research gaps identified suggest a need for greater ethical, methodological, and contextual considerations within future research, alongside interdisciplinary approaches to AIHEd application. Suggestions are provided to guide future primary and secondary research.

Introduction

within education, influenced by educational evidence-based policy, including education departments and international organisations (e.g., OECD, 2021), it has arguably only now transitioned from work in labs to active practice in classrooms, and broken through the veil of public discourse. The introduction of ChatGPT

Contribution of this review

Research questions

- What is the nature and scope of AIEd evidence synthesis in higher education (AIHEd)?

a. What kinds of evidence syntheses are being conducted?

b. In which conference proceedings and academic journals are AIHEd evidence syntheses published?

c. What is the geographical distribution of authorship and authors’ affiliations?

d. How collaborative is AIHEd evidence synthesis?

e. What technology is being used to conduct AIHEd evidence synthesis?

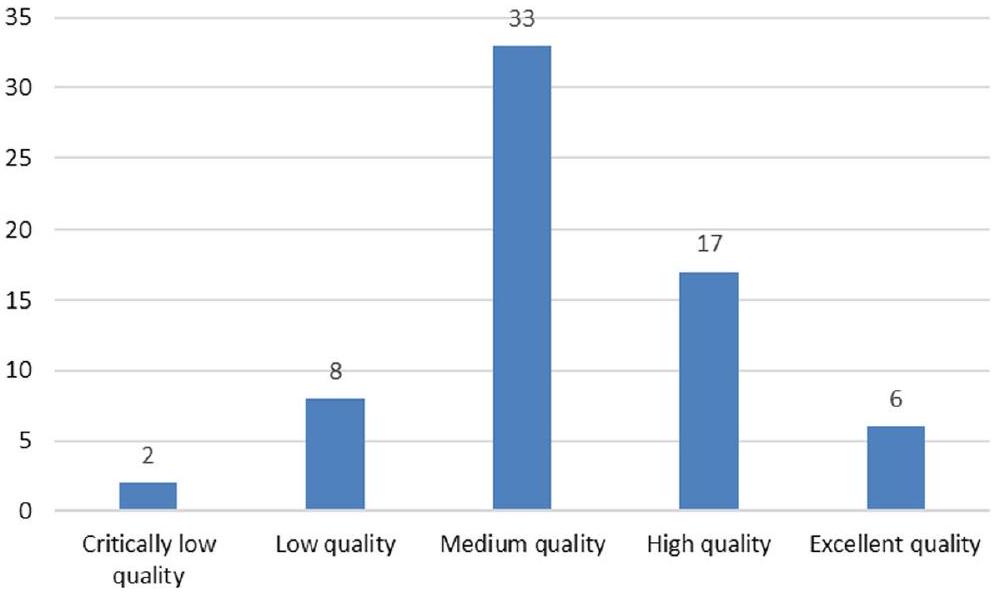

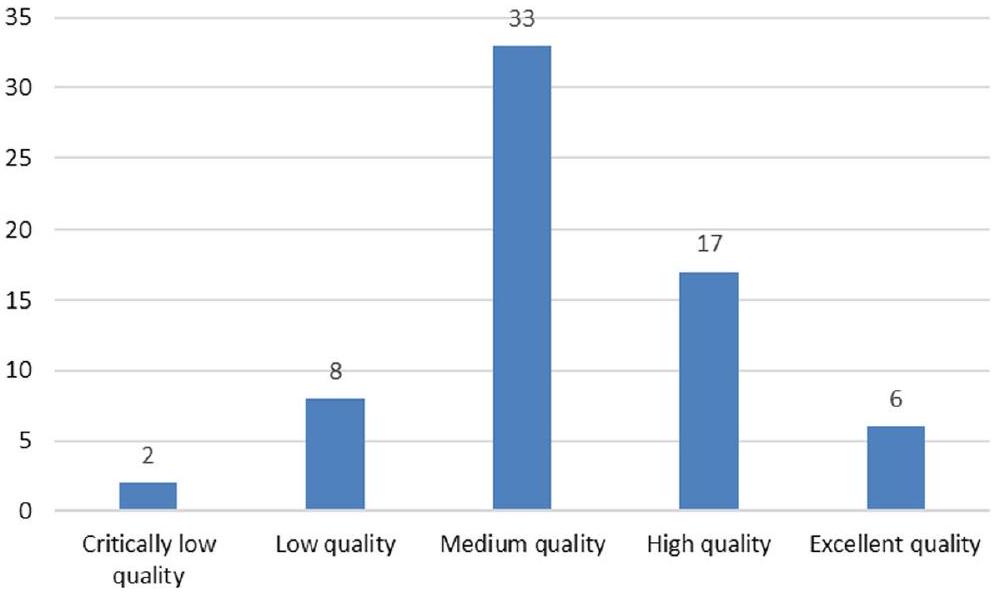

f. What is the quality of evidence synthesis exploring AIHEd?

g. What main applications are explored in AIHEd secondary research?

h. What are the key findings of AIHEd research?

i. What are the benefits and challenges reported within AIHEd reviews?

j. What research gaps have been identified in AIHEd secondary research?

Literature review

Artificial intelligence in education (AIEd)

| Review family name | Review types per family |

| Traditional review family | Critical review, integrative review, narrative review, narrative summary, state of the art review |

| Rapid review family | Rapid reviews, rapid evidence assessment, rapid realist synthesis |

| Purpose specific review family | Content analysis, scoping review, mapping review |

| Systematic review family | Meta-analysis, systematic review |

| Qualitative review family | Qualitative evidence synthesis, qualitative meta-synthesis, meta-ethnography |

| Mixed methods review family | Mixed methods synthesis, narrative synthesis |

| Review of review family | Review of review, umbrella review |

Prior AIEd syntheses in higher education

Evidence synthesis methods

Evidence synthesis quality

- Are the review’s inclusion and exclusion criteria described and appropriate?

- Is the literature search likely to have covered all relevant studies?

- Did the reviewers assess the quality/validity of the included studies?

- Were the basic data/studies adequately described?

Method

Search strategy and study selection

| AI | “artificial intelligence” OR “machine intelligence” OR “intelligent support” OR “intelligent virtual reality” OR “chat bot*” OR “machine learning” OR “automated tutor” OR “personal tutor*” OR “intelligent agent*” OR “expert system” OR “neural network” OR “natural language processing” OR “intelligent tutor*” OR “adaptive learning system*” OR “adaptive educational system*” OR “adaptive testing” OR “decision trees” OR “clustering” OR “logistic regression” OR “adaptive system*” |

| AND | |

| Education sector | “higher education” OR college* OR undergrad* OR graduate OR postgrad* OR “K-12” OR kindergarten* OR “corporate training*” OR “professional training*” OR “primary school*” OR “middle school*” OR “high school*” OR “elementary school*” OR “vocational education” OR “adult education” OR “workplace learning” OR “corporate academy” |

| AND | |

| evidence synthesis | “systematic review” OR “scoping review” OR “narrative review” OR “metaanalysis” OR “evidence synthesis” OR “meta-review” OR “evidence map” OR “rapid review” OR “umbrella review” OR “qualitative synthesis” OR “configurative review” OR “aggregative review” OR “thematic synthesis” OR “framework synthesis” OR “mapping review” OR “meta-synthesis” OR “qualitative evidence synthesis” OR “critical review” OR “integrative review” OR “integrative synthesis” OR “narrative summary” OR “state of the art review” OR “rapid evidence assessment” OR “qualitative research synthesis” OR “qualitative meta-summary” OR “meta-ethnography” OR “meta-narrative review” OR “mixed methods synthesis” OR “scoping study” OR “systematic map” |

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Published Jan 2018 to 18 July 2023 | Published before Jan 2018 |

| Applications of AI in education | Not about artificial intelligence |

| Formal teaching and learning setting | Informal learning/not formally recognised |

| Journal articles or conference papers | Editorials, book chapters, meeting abstracts, workshop papers, posters, book reviews, dissertations |

| Secondary research with a method section | Primary research or literature review with no formal method section |

| English language | Not in English |

Search string

Inclusion/exclusion criteria and screening

Data extraction

- Are there any research questions, aims or objectives? (AMSTAR 2)

- Were inclusion/exclusion criteria reported in the review and are they appropriate? (D)

- Are the publication years included defined?

- Was the search adequately conducted and likely to have covered all relevant studies? (D)

- Was the search string provided in full? (AMSTAR 2)

- Do they report inter-rater reliability? (AMSTAR 2)

| Criterion | Score | Interpretation |

| RQs | Yes | RQs, aims or objectives are explicitly and clearly defined. |

| Partly | Some mention of objectives or aims are alluded to. | |

| No | No RQs, aims or objectives are identifiable. | |

| Inclusion/exclusion | Yes | The criteria used are explicitly defined in the paper. |

| Partly | The criteria are implicit. | |

| No | The criteria are not defined and cannot be readily inferred. | |

| Publication years | Yes | The publication years are clearly stated, e.g. 2010-2020. |

| Partly | The publication years state from a year OR until a year. | |

| No | The publication years are not defined at all. | |

| Search coverage | Yes | 4 or more digital libraries searched and included additional search strategies (e.g. snowballing) OR identified and referenced all pertinent journals. |

| Partly | 3 or 4 digital libraries searched with no extra search strategies OR searched a defined but restricted set of journals and conference proceedings. | |

| No | 2 digital libraries searched or an extremely restricted set of journals. | |

| Search string | Yes | The search string was reported in full and is replicable. |

| Partly | Examples of keywords only were given. | |

| No | The search terms were not provided in any form. | |

| Inter-rater reliability | Yes | An inter-rater reliability value is reported (e.g. Cohen’s kappa). |

| Partly | Mention is made of how disagreements were reconciled. | |

| No | No inter-rater reliability is mentioned. | |

| Data extraction | Yes | The full coding scheme was provided. |

| Partly | Examples are provided, but not the full list. | |

| No | The coding scheme was not provided at all. | |

| Quality assessment | Yes | Explicitly defined quality criteria extracted for each study. |

| Partly | The research question involved quality issues that are addressed by the study. | |

| No | No explicit quality assessment of individual papers has been attempted. | |

| Study description | Yes | Information is presented about each paper. |

| Partly | Only summary information is presented about individual papers. | |

| No | The results for individual studies are not specified. | |

| Review limitations | Yes | Yes, there is a specific identifiable limitations section. |

| Partly | There is some mention of limitations. | |

| No | There is no limitations section or reflection on limitations |

- Was the data extraction coding scheme provided?

- Was a quality assessment undertaken? (D)

- Are sufficient details provided about the individual included studies? (D)

- Is there a reflection on review limitations?

Data synthesis and interactive evidence & gap map development

Limitations

Findings

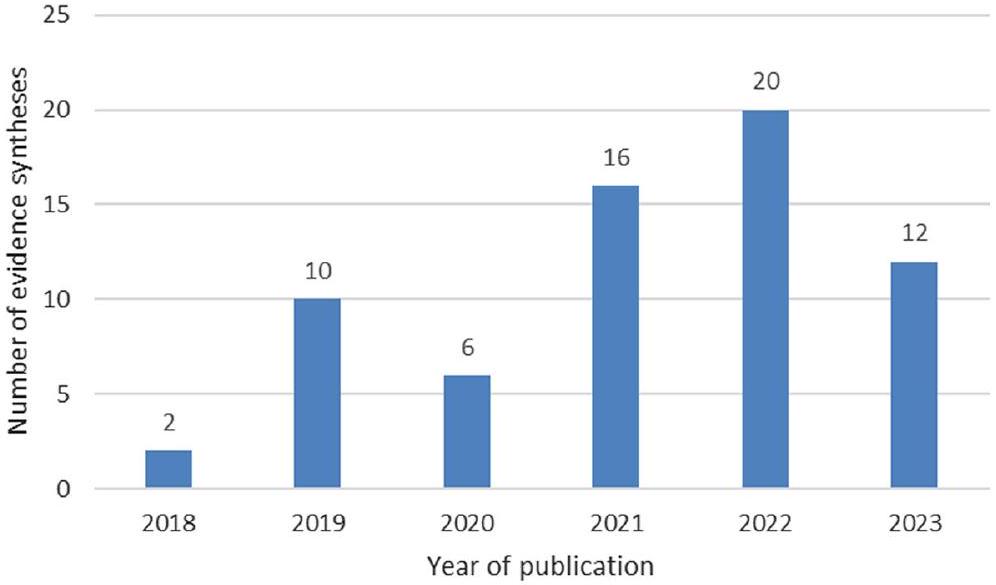

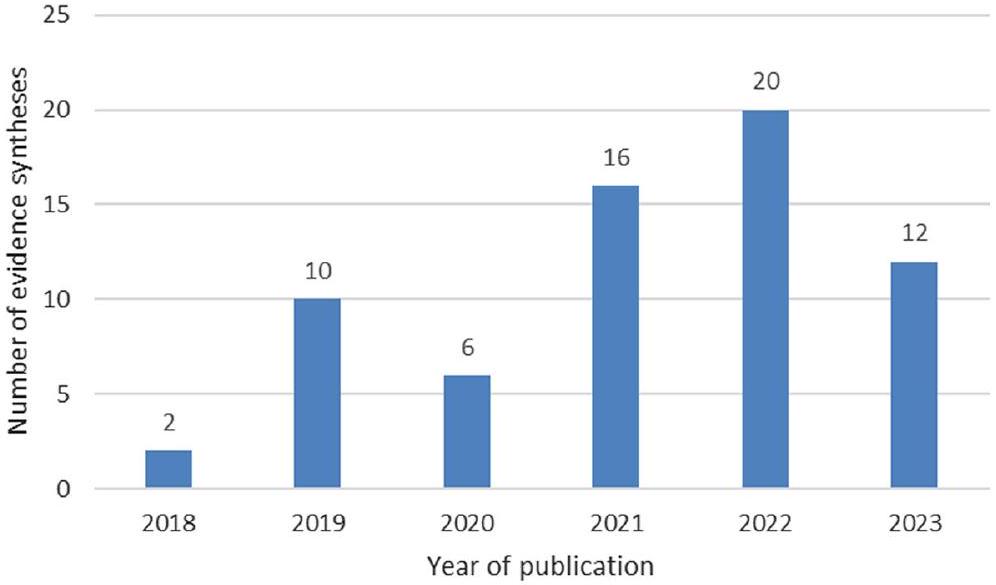

General publication characteristics

What kinds of evidence syntheses are being conducted in AIHEd?

In which conferences and academic journals are AIHEd evidence syntheses published?

What are AIHEd evidence synthesis authors’ institutional and disciplinary affiliations?

| Rank | Country | Count | Percentage |

| 1 | United States | 11 | 16.7 |

| 2 | Canada | 9 | 13.6 |

| 3 | Australia | 7 | 10.6 |

| 4 | South Africa | 6 | 9.1 |

| 5 | China | 5 | 7.6 |

| 6 | Saudi Arabia | 4 | 6.1 |

| = | Spain | 4 | 6.1 |

| 7 | Germany | 3 | 4.5 |

|

|

India | 3 | 4.5 |

What is the geographical distribution of AIHEd evidence synthesis authorship?

How collaborative is AIHEd evidence synthesis?

What technology is being used to conduct AIHEd evidence synthesis?

AIHEd evidence synthesis quality

| Criteria | Yes | Partly | No | N/A |

| Are there any research questions, aims or objectives? | 92.4% | 6.1% | 1.5% | |

| Were inclusion/exclusion criteria provided in the method section? | 77.3% | 19.7% | 3.0% | |

| Are the publication years included defined in the title, abstract or method section? | 87.9% | 7.6% | 4.5% | |

| Was the search adequately conducted and likely to have covered all relevant studies? | 51.5% | 16.7% | 31.8% | |

| Was the search string reported in full? | 68.2% | 25.8% | 6.1% | |

| Do they report inter-rater reliability? | 22.7% | 21.2% | 51.5% | 4.5%

|

| Is the data extraction coding schema provided? | 24.2% | 45.5% | 30.3% | |

| Is some form of quality assessment applied? | 15.2% | 13.6% | 45.5% | 25.8% 28 |

| Are sufficient details provided about the individual included studies? | 28.8% | 42.4% | 21.2% | 7.6%

|

| Is there a reflection on review limitations? | 40.9% | 24.2% | 34.8% |

AIEd applications in higher education

| Review focus |

|

% |

| General AIEd | 31 | 47.0 |

| Profiling and Prediction | 19 | 28.8 |

| Adaptive Systems and Personalisation | 18 | 27.3 |

| Assessment and Evaluation | 3 | 4.5 |

| Intelligent Tutoring Systems | 1 | 1.5 |

Key findings in AIEd higher education evidence synthesis

Adaptive systems and personalisation

ing challenges with infrastructure and technology, educator acceptance, and curricula being “robotics-compliant” (p. 34).

Profiling and prediction

on what is being predicted, how and why (Hellas et al., 2018), could be deepened by more diverse study design, such as longitudinal and large-scale studies (Ifenthaler & Yau, 2020) with multiple data collection techniques (Abu Saa et al., 2019), in a more diverse array of contexts (e.g., Fahd et al., 2022; Sghir et al., 2022), especially developing countries (e.g., Pinto et al., 2023).

two studies; the first (Abdelkader et al., 2022) posited that feature selection increased the predictive accuracy of their ML model, allowing them to predict student satisfaction with online education with nearly perfect accuracy, and the second (Ho et al., 2021) investigated the most important predictors in determining the satisfaction of undergraduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic using data from Moodle and Microsoft Teams, which was also included in Rangel-de Lázaro and Duart (2023)’s review. The results showed that random forest recursive feature elimination improved the predictive accuracy of all the ML models.

Assessment and evaluation

(

et al., 2019), on reflection (Salas-Pilco et al., 2022), and on self-awareness (Ouyang et al., 2020). Two studies in the scoping review by Kirubarajan et al. (2022) reported real-time feedback using AI for modelling during surgery. Manhiça et al. (2022) also found two studies exploring automated feedback, but unfortunately did not provide any further information about them, which gives further weight to the potential of more research need in this area.

Intelligent tutoring systems (ITS)

about their learning (Crompton & Burke, 2023). ITS were the second most researched AI application (

tions and providing feedback on the writing process (Alam & Mohanty, 2022). ZawackiRichter et al. (2019) only found two primary studies that explored collaborative facilitation and called for further research to be undertaken with this affordance of ITS functionality.

Benefits and challenges within AIHEd

Benefits of using AI in higher education

| Benefits |

|

% |

| Personalised learning | 12 | 38.7 |

| Greater insight into student understanding | 10 | 32.3 |

| Positive influence on learning outcomes | 10 | 32.3 |

| Reduced planning and administration time for teachers | 10 | 32.3 |

| Greater equity in education | 7 | 22.6 |

| Precise assessment & feedback | 7 | 22.6 |

Challenges of using AI in higher education

| Challenges |

|

% |

| Lack of ethical consideration | 9 | 29.0 |

| Curriculum development | 7 | 22.6 |

| Infrastructure | 7 | 22.6 |

| Lack of teacher technical knowledge | 7 | 22.6 |

| Shifting Authority | 7 | 22.6 |

What research gaps have been identified?

| Research gaps |

|

% |

| Ethical implications | 27 | 40.9 |

| More methodological approaches needed | 24 | 36.4 |

| More research in Education needed | 22 | 33.3 |

| More research with a wider range of stakeholders | 14 | 21.2 |

| Interdisciplinary approaches required | 11 | 16.7 |

| Research limited to specific discipline areas | 11 | 16.7 |

| More research in a wider range of countries, esp. developing | 10 | 15.2 |

| Greater emphasis on theoretical foundations needed | 9 | 13.6 |

| Longitudinal studies recommended | 8 | 12.1 |

| Research limited to a few topics | 8 | 12.1 |

Ethical implications

- Student perceptions of the use of AI in assessment (del Gobbo et al., 2023);

- How to make data more secure (Ullrich et al., 2022);

- How to correct sample bias and balance issues of privacy with the affordances of AI (Saghiri et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2023); and

- How institutions are storing and using teaching and learning data (Ifenthaler & Yau, 2020; Maphosa & Maphosa, 2021; McConvey et al., 2023; Rangel-de Lázaro & Duart, 2023; Sghir et al., 2022; Ullrich et al., 2022).

Methodological approaches

- The use of surveys, course evaluation surveys, network access logs, physiological data, observations, interviews (Abu Saa et al., 2019; Alam & Mohanty, 2022; Andersen et al., 2022; Chu et al., 2022; Hwang et al., 2022; Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019);

- More evaluation of the effectiveness of tools on learning, cognition, affect, skills etc. rather than focusing on technical aspects like accuracy (Albluwi, 2019; Chaka, 2023; Crow et al., 2018; Frangoudes et al., 2021; Zhong, 2022);

- Multiple case study design (Bearman et al., 2023; Ullrich et al., 2022);

- Cross referencing data with external platforms such as social media data (Rangelde Lázaro & Duart, 2023; Urdaneta-Ponte et al., 2021); and

- A focus on age and gender as demographic variables (Zhai & Wibowo, 2023).

Study contexts

- Student perceptions of effectiveness and AI fairness (del Gobbo et al., 2023; Hamam, 2021; Otoo-Arthur & van Zyl, 2020);

- Combining student and educator perspectives (Rabelo et al., 2023);

- Low level foreign language learners and chatbots (Klímová & Ibna Seraj, 2023);

- Non formal education (Urdaneta-Ponte et al., 2021); and

- Investigating a similar dataset with data retrieved from different educational contexts (Fahd et al., 2022)

Discussion

the issue of global reach, only

A call for increased ethics

A call for increased collaboration

A call for increased rigour

Conclusion

research will explore the full corpus of 307 AIEd evidence syntheses located across various educational levels, providing further insight into applications and future directions, alongside further guidance for the conduct of evidence synthesis. While AI offers promising avenues for enhancing educational experiences and outcomes, there are significant ethical, methodological, and pedagogical challenges that need to be addressed to harness its full potential effectively.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 2: Appendix B. Types of evidence synthesis published in AIEd higher education.

Additional file 3: Appendix C. Journals and conference proceedings.

Additional file 4: Appendix D. Top 7 journals by evidence synthesis types.

Additional file 5: Appendix E. Institutional affiliations.

Additional file 6: Appendix F. Author disciplinary affiliation by evidence synthesis types.

Additional file 7: Appendix G. Geographical distribution of authors.

Additional file 8: Appendix H. Geographical distribution by evidence synthesis type.

Additional file 9: Appendix I. Co-authorship and international research collaboration.

Additional file 10: Appendix J. Digital evidence synthesis tools (DEST) used in AIHEd secondary research.

Additional file 11: Appendix K. Quality assessment.

Additional file 12: Appendix L. Benefits and Challenges identified in ‘General AIEd’ reviews.

Additional file 13: Appendix M. Research Gaps.

Author contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Competing interests

Received: 4 October 2023 Accepted: 13 December 2023

Published online: 19 January 2024

References

*Indicates that the article is featured in the corpus of the review

*Abu Saa, A., Al-Emran, M., & Shaalan, K. (2019). Factors affecting students’ performance in higher education: A systematic review of predictive data mining techniques. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 24(4), 567-598. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10758-019-09408-7

*Alam, A., & Mohanty, A. (2022). Foundation for the Future of Higher Education or ‘Misplaced Optimism’? Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. In M. Panda, S. Dehuri, M. R. Patra, P. K. Behera, G. A. Tsihrintzis, S.-B. Cho, & C. A.

*Algabri, H. K., Kharade, K. G., & Kamat, R. K. (2021). Promise, threats, and personalization in higher education with artificial intelligence. Webology, 18(6), 2129-2139.

*Alkhalil, A., Abdallah, M. A., Alogali, A., & Aljaloud, A. (2021). Applying big data analytics in higher education: A systematic mapping study. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education, 17(3), 29-51. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJICTE.20210701.oa3

Allman, B., Kimmons, R., Rosenberg, J., & Dash, M. (2023). Trends and Topics in Educational Technology, 2023 Edition. TechTrends Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, 67(3), 583-591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-023-00840-2

*Alotaibi, N. S., & Alshehri, A. H. (2023). Prospers and obstacles in using artificial intelligence in Saudi Arabia higher education institutions-The potential of AI-based learning outcomes. Sustainability, 15(13), 10723. https://doi.org/10. 3390/su151310723

*Alyahyan, E., & Düştegör, D. (2020). Predicting academic success in higher education: Literature review and best practices. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 17(1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s41239-020-0177-7

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

*Banihashem, S. K., Noroozi, O., van Ginkel, S., Macfadyen, L. P., & Biemans, H. J. (2022). A systematic review of the role of learning analytics in enhancing feedback practices in higher education. Educational Research Review, 37, 100489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100489

*Bearman, M., Ryan, J., & Ajjawi, R. (2023). Discourses of artificial intelligence in higher education: A critical literature review. Higher Education, 86(2), 369-385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00937-2

*Bhattacharjee, K. K. (2019). Research Output on the Usage of Artificial Intelligence in Indian Higher Education – A Scientometric Study. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM) (pp. 916-919). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ieem44572.2019.8978798

Bodily, R., Leary, H., & West, R. E. (2019). Research trends in instructional design and technology journals. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(1), 64-79. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet. 12712

Bond, M. (2018). Helping doctoral students crack the publication code: An evaluation and content analysis of the Australasian Journal of Educational Technology. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 34(5), 168-183. https:// doi.org/10.14742/ajet. 4363

Bond, M., Bedenlier, S., Marín, V. I., & Händel, M. (2021). Emergency remote teaching in higher education: mapping the first global online semester. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10. 1186/s41239-021-00282-x

Bond, M., Zawacki-Richter, O., & Nichols, M. (2019). Revisiting five decades of educational technology research: A content and authorship analysis of the British Journal of Educational Technology. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(1), 12-63. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet. 12730

Booth, A., Carroll, C., Ilott, I., Low, L. L., & Cooper, K. (2013). Desperately seeking dissonance: Identifying the disconfirming case in qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 23(1), 126-141. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497 32312466295

Bozkurt, A., & Sharma, R. C. (2023). Challenging the status quo and exploring the new boundaries in the age of algorithms: Reimagining the role of generative AI in distance education and online learning. Asian Journal of Distance Education. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 7755273

Bozkurt, A., Xiao, J., Lambert, S., Pazurek, A., Crompton, H., Koseoglu, S., Farrow, R., Bond, M., Nerantzi, C., Honeychurch, S., Bali, M., Dron, J., Mir, K., Stewart, B., Costello, E., Mason, J., Stracke, C. M., Romero-Hall, E., Koutropoulos, A., Toquero, C. M., Singh, L., Tlili, A., Lee, K., Nichols, M., Ossiannilsson, E., Brown, M., Irvine, V., Raffaghelli, J. E., Santos-Hermosa, G., Farrell, O., Adam, T., Thong, Y. L., Sani-Bozkurt, S., Sharma, R. C., Hrastinski, S., & Jandrić, P. (2023). Speculative futures on ChatGPT and generative Artificial Intelligence (AI): A collective reflection from the educational landscape. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 18(1), 1-78. http://www.asianjde.com/ojs/index.php/AsianJDE/article/ view/709/394

*Buchanan, C., Howitt, M. L., Wilson, R., Booth, R. G., Risling, T., & Bamford, M. (2021). Predicted influences of artificial intelligence on nursing education: Scoping review. JMIR Nursing, 4(1), e23933. https://doi.org/10.2196/23933

Buntins, K., Bedenlier, S., Marín, V., Händel, M., & Bond, M. (2023). Methodological approaches to evidence synthesis in educational technology: A tertiary systematic mapping review. MedienPädagogik, 54, 167-191. https://doi.org/10. 21240/mpaed/54/2023.12.20.X

*Burney, I. A., & Ahmad, N. (2022). Artificial Intelligence in Medical Education: A citation-based systematic literature review. Journal of Shifa Tameer-E-Millat University, 5(1), 43-53. https://doi.org/10.32593/jstmu/Vol5.Iss1.183

*Cardona, T., Cudney, E. A., Hoerl, R., & Snyder, J. (2023). Data mining and machine learning retention models in higher education. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory and Practice, 25(1), 51-75. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1521025120964920

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (UK). (1995). Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE): Quality-assessed Reviews. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK285222/. Accessed 4 January 2023.

*Chaka, C. (2023). Fourth industrial revolution-a review of applications, prospects, and challenges for artificial intelligence, robotics and blockchain in higher education. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 18(2), 1-39. https://doi.org/10.58459/rptel.2023.18002

Chalmers, H., Brown, J., & Koryakina, A. (2023). Topics, publication patterns, and reporting quality in systematic reviews in language education. Lessons from the international database of education systematic reviews (IDESR). Applied Linguistics Review. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2022-0190