DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-024-06650-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39856711

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-24

معرفة ومواقف وممارسات مربي الماعز الأستراليين تجاه السيطرة على الطفيليات المعوية

الملخص

خلفية: الطفيليات المعوية مثل الديدان الخيطية والكوكيديا مسؤولة عن خسائر اقتصادية كبيرة في صناعة الماعز على مستوى العالم. أدى الاستخدام العشوائي للأدوية المضادة للطفيليات، المسجلة أساسًا للاستخدام في الأغنام والأبقار، في الماعز إلى ظهور طفيليات معوية مقاومة للأدوية. لا يُعرف الكثير عن ممارسات السيطرة على الطفيليات المعوية المستخدمة من قبل مربي الماعز الأستراليين والتي تعتبر حيوية لتحقيق السيطرة المستدامة على الطفيليات الاقتصادية الهامة. توفر الدراسة المبلغ عنها هنا رؤى حول ممارسات السيطرة على الطفيليات المعوية لمربي الماعز الأستراليين بناءً على ردود على استبيان عبر الإنترنت. الطرق: شمل الاستبيان 58 سؤالًا حول ديموغرافيا المزرعة، وإدارة التربية والرعي، ومعرفة الطفيليات المعوية وأهميتها في الماعز الحلوب، وتشخيص العدوى، والأدوية المضادة للطفيليات وخيارات السيطرة البديلة. بعد استبيان تجريبي (

الكلمات الرئيسية: الأدوية المضادة للطفيليات، مقاومة الأدوية المضادة للطفيليات، الماعز الحلوب، الطفيليات المعوية، هيمونشوس كونتورتي، الاستبيان

حاليًا، تعتمد السيطرة على الطفيليات المعوية في الماعز بشكل رئيسي على الاستخدام العشوائي للأدوية المضادة للطفيليات المسجلة أساسًا للاستخدام في الأغنام والأبقار، مما يؤدي إلى مقاومة الأدوية في GINs الاقتصادية الهامة للماعز [21]. مؤخرًا، قام بودينيت وآخرون [22] بمراجعة شاملة للأدبيات حول مقاومة الأدوية المضادة للطفيليات (AR) في GINs للماعز ووجدوا أن جميع الأجناس الرئيسية من الديدان الخيطية (أي، هيمونشوس، تريشسترانغيلوس، تيلادورساجيا، أوزوفاجوستوموم وكوبرية) مقاومة للأدوية المضادة للطفيليات المستخدمة بشكل شائع، مما يشير إلى أن AR أصبحت قضية كبيرة لصناعة الماعز على مستوى العالم. تتعقد هذه الحالة أكثر عندما يكون الاستخدام غير المصرح به للأدوية المضادة للطفيليات شائعًا في الماعز. تشير الدراسات الحالية حول حركية الأدوية إلى أن الماعز يستقلب الأدوية المضادة للطفيليات بشكل أسرع من الأغنام [23-25]. علاوة على ذلك، فإن متطلبات الشركات المصنعة المسجلة للأدوية المضادة للطفيليات لتوفير فترة سحب الحليب تحد من الخيارات المتاحة لمربي الماعز الحلوب للسيطرة على GINs في جميع أنحاء العالم.

نظرًا للتحديات المرتبطة بالسيطرة الكيميائية على طفيليات الماعز، تم إجراء استبيانات في عدة دول لتقييم ممارسات السيطرة على الطفيليات المستخدمة من قبل مربي الماعز [26-35]. ومع ذلك، فإن المعرفة بالطفيليات المعوية، وأهميتها و

ممارسات السيطرة في الماعز الحلوب محدودة. على سبيل المثال، أجرت ثلاث دراسات استبيانات لمربي الماعز الأستراليين، وخاصة مربي الماعز اللحم الموجودين في ولايتين (أي نيو ساوث ويلز وكوينزلاند)، لتقييم ممارسات السيطرة على الطفيليات [36-38]. في الاستبيان الأكثر حداثة، أفاد برونت وآخرون [38] أن

من الجدير بالذكر أن أنظمة الإنتاج، وإدارة الماعز وممارسات التربية تختلف بشكل كبير عن تلك الخاصة بالماعز اللحم، وخاصة الماعز في المراعي، وأنه تم تسجيل دواء واحد فقط، مع فترة سحب الحليب، للاستخدام في الماعز الحلوب ضد الطفيليات الداخلية في أستراليا. في الدراسة المبلغ عنها هنا، استخدمنا استبيانًا عبر الإنترنت لتقييم تصورات وممارسات السيطرة على الطفيليات المعوية لمربي الماعز الحلوب الأستراليين. ستساعد نتائج الدراسة في تحديد التحديات لتحقيق السيطرة المستدامة على الطفيليات الداخلية للماعز مع الخيارات المتاحة المحدودة.

الطرق

مزارع الماعز الحلوب في أستراليا

لا تزال صناعة الماعز الحلوب في أستراليا في مراحلها الأولى مقارنة بصناعات الأغنام والماشية وكذلك صناعات الماعز الحلوب في أماكن أخرى، ولا يُعرف الكثير عن مستويات إنتاج القطيع الوطني أو تأثيره الاقتصادي. يمارس معظم مربي الماعز التزاوج الموسمي، حيث أن نسبة الحمل باستخدام التزاوج الاصطناعي أقل (بشكل رئيسي بسبب المشاكل التقنية) من التزاوج الطبيعي. على الرغم من أن نظام الإنتاج شبه المكثف، الذي يجمع بين الرعي في المراعي المدعومة بمخلفات المحاصيل والعلف الإضافي، هو النوع السائد والمتزايد، إلا أن بعض مزارع الماعز الحلوب الأسترالية تعمل بنظام مكثف (أي عادةً تغذية داخلية وتجارية).

تربية الماعز الحلوب) [39] وأنظمة الإنتاج شبه المكثفة (أي نهج وسيط يتضمن الرعي المنظم، مع وصول محدود إلى المراعي مقارنة بالنظام شبه الواسع وتغذية إضافية أكثر انتظامًا). في كلتا الحالتين، فإن تصميم الحظائر غير المناسب شائع، مما يؤدي إلى ارتفاع تكاليف العمالة، وظروف صحية دون المستوى وقلق بشأن صحة الحيوانات. القيود الصحية الرئيسية هي الديدان المعوية (خاصة للماعز الذي يتغذى على المراعي) [12، 18]، مرض جون [18]، مشاكل التمثيل الغذائي (الإدارة المكثفة مع الحظائر) [40، 41]، الكوكسيديا في الماعز الصغيرة [42]، وفيات الصغار [43، 44]، التهاب المفاصل الدماغي في الماعز [18، 45، 46]، التهاب الضرع [47] ومشاكل القدم [48].

استبيان

تشكل مزارع الماعز الحلوب المسجلة لدى جمعية الماعز الحلوب الأسترالية المحدودة (DGSA) مصدر السكان للدراسة، وكانت مشاركتهم في الدراسة طوعية بالكامل. تم إجراء المسح التجريبي مع 15 مزارع ماعز حلوب وتم استبعاد هذه البيانات من التحليلات النهائية. تم دمج التعليقات الواردة من المسح التجريبي في المسح النهائي. بعد ذلك، تم تسجيل الأعضاء (

تحليلات البيانات

تم استخدام مؤشر التشابه النسبي (PSI) لتقييم تمثيل المزارع المشاركة في صناعة الماعز الحلوب في أستراليا. قام PSI بت quantifying الاتفاق في توزيع التردد لمزارع الماعز الحلوب التي استجابت للاستطلاع، مقسمة حسب الولاية، مع توزيع التردد لمجموع مزارع الماعز الحلوب المسجلة لدى DGSA Ltd في ست ولايات من أستراليا.

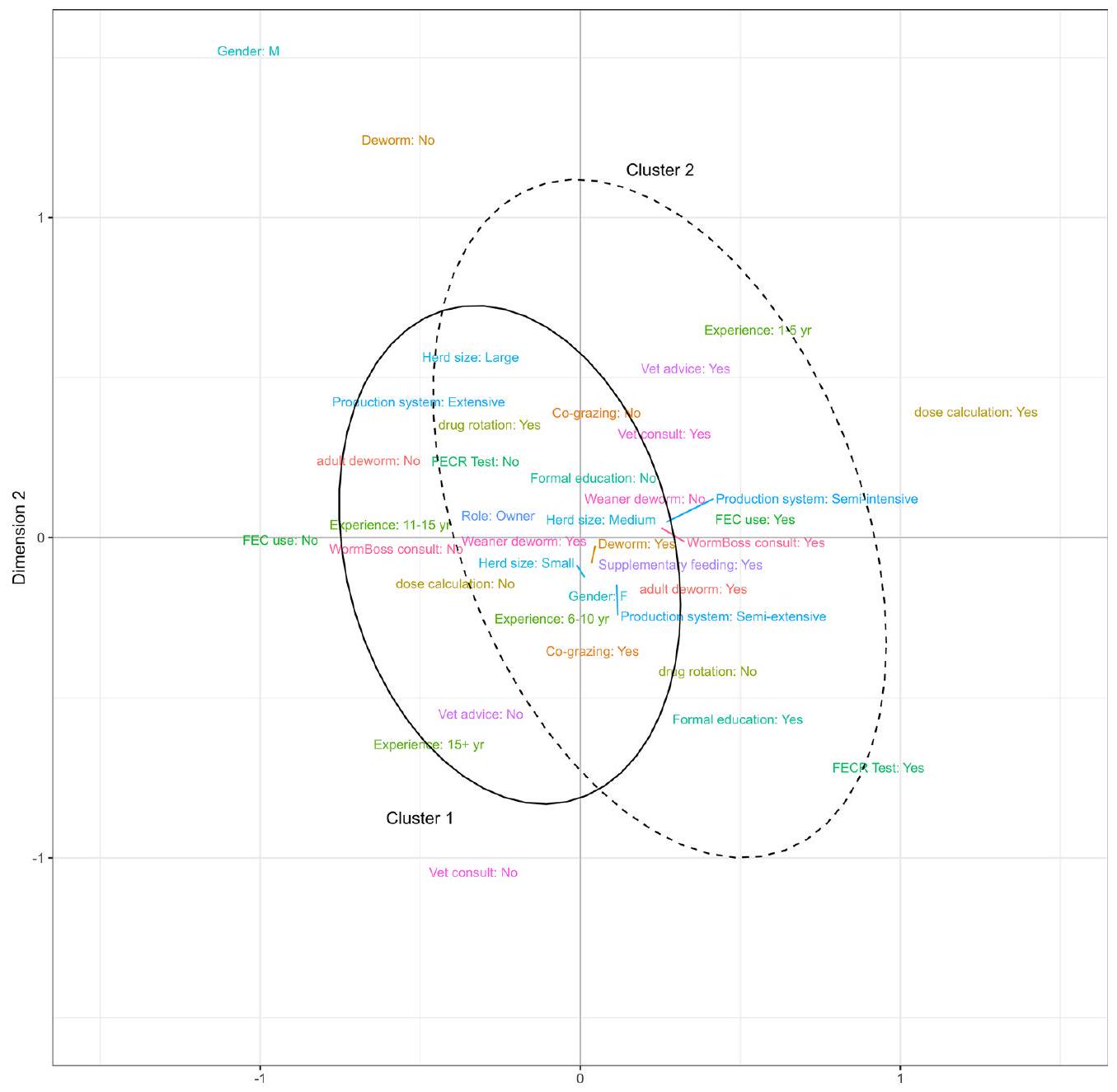

تم إجراء تحليل المراسلات المتعددة (MCA) لتحديد الهياكل الأساسية بين المستجيبين للاستطلاع [51] استنادًا إلى ممارسات التحكم في GIN المختارة في الماعز الموصى بها من قبل WormBoss https://wormboss.com.au (الملف الإضافي 2: الجدول S1). مجموعة

تم إجراء التحليل باستخدام التجميع الهرمي على المكونات الرئيسية (HCPC) باستخدام معيار وورد لتحديد مجموعات المستجيبين الذين أبلغوا عن ممارسات تحكم GIN إما ‘جيدة’ (مثالية) أو ‘سيئة’ (دون المستوى الأمثل). تم استخدام حزمة FactoMine R [52] لتنفيذ MCA و HCPC في R.

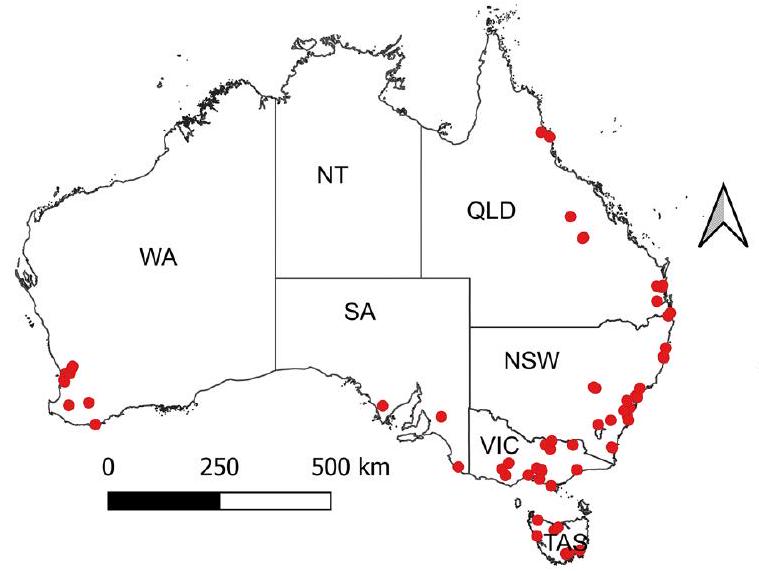

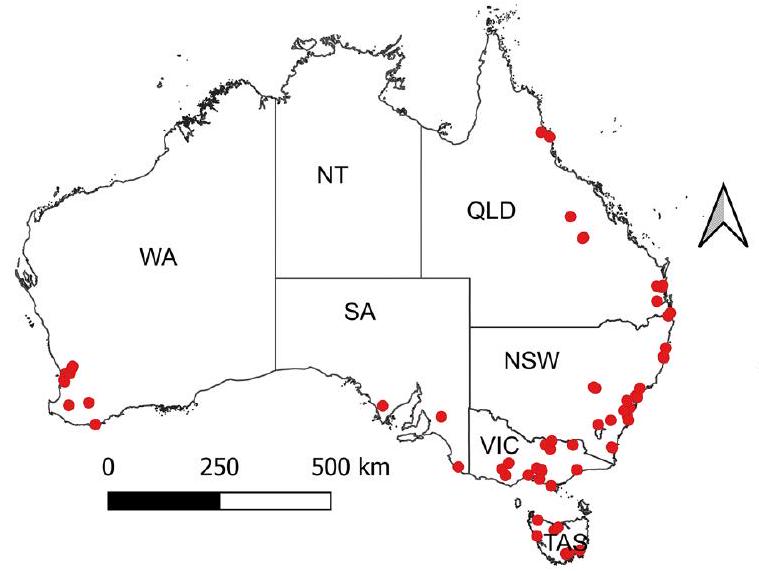

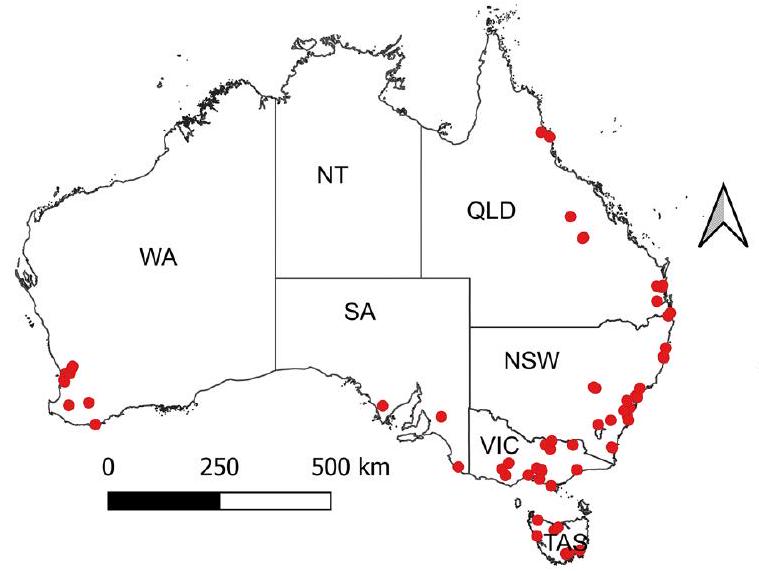

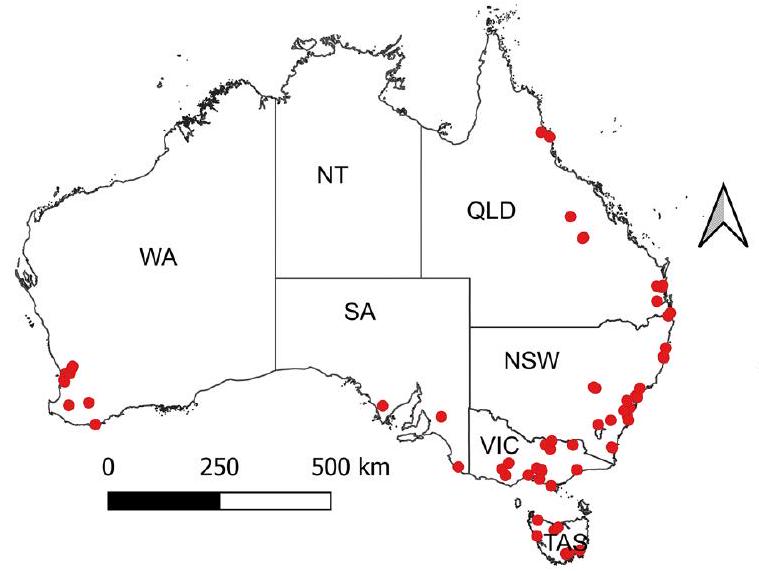

تم إجراء جميع التحليلات وإجراءات تصور البيانات باستخدام R الإصدار 4.3.1 [53] و GraphPad Prism الإصدار 10.3.0 لنظام Windows.www.graphpad.comتم استخدام حزمة برنامج QGIS 3.34 لإنشاء خريطة توضح منطقة الرمز البريدي لمستجيبي الاستطلاع (انظر الشكل 1).

النتائج

الخصائص العامة لمزارع الماعز الحلوب

من بين 66 مستجيبًا تم تضمينهم في التحليل النهائي، كان أعلى عدد من نيو ساوث ويلز

المتوسط الكلي لمساحة 66 مزرعة كان 76 (النطاق

| سؤال | معنى | الوسيط (Q1، Q3) | الحد الأدنى، الحد الأقصى |

| مساحة المزرعة (فدان) | 76 |

|

0.75، 2000 |

| مساحة الرعي (فدان) | ٥٦ |

|

0.25، 2000 |

| عدد الماعز في العام الماضي | 69 |

|

3, 1,428 |

| – الأطفال (

|

27 |

|

0.700 |

| – الفطام (أكثر من 6 أشهر إلى 1 سنة) | 11 |

|

0,200 |

| – حلبات/إناث الماعز | 27 |

|

0.600 |

| – باكس | ٤ |

|

0,30 |

إدارة تربية الحيوانات والرعي

(86%; 57/66) (الجدول 3). قام معظم المستجيبين (76%، 50/66) بتنظيف الأقلام قبل كل ولادة (ملف إضافي 3: الشكل S1). كانت قش القمح أو رقائق الخشب على الأرضيات الصلبة هي المواد الأكثر استخدامًا كفرش.

تم جمع اللبأ الطازج من الأمهات المحتفظ بها في المزرعة وكان هو المصدر الرئيسي لللبأ للصغار.

| سؤال | مستويات | النسبة المئوية (العدادات) |

| الدور في المزرعة | مالك المزرعة | 94 (62) |

| مدير المزرعة | 5 (3) | |

| عامل موظف | 1 (1) | |

| جنس | أنثى | 91 (60) |

| ذكر | 8 (5) | |

| يفضل عدم الإفصاح | 1 (1) | |

| الخبرة في تربية الماعز (بالسنوات) | 1-5 | ٣٨ (٢٥) |

| ٦-١٠ | 18 (12) | |

| ١١-١٥ | 12 (8) | |

| >15 | 32 (21) | |

| استخدام العقار لتربية الماعز (سنوات) | <1 | 3 (2) |

| ١-١٠ | 62 (41) | |

| 11-20 | 18 (12) | |

| 21-30 | 5 (3) | |

| 31-40 | 8 (5) | |

| >40 | 5 (3) | |

| المؤهل الرسمي | لا | 80 (53) |

| نعم | ٢٠ (١٣) | |

| نوع المؤهل (

|

شهادة في الحيوانات الزراعية | ٣٩ (٥) |

| دبلوم في الحيوانات الزراعية | 31 (4) | |

| تمريض بيطري | 15 (2) | |

| درجة البكالوريوس أو أعلى | 15 (2) |

| سؤال (الردود) | مستويات | النسبة المئوية (العدادات) |

| سلالة

|

أنغلو-نوبى | ٢٥ (٣٥) |

| قزم نيجيري | 16 (22) | |

| سانن | 14 (20) | |

| توغنبرغ | 14 (19) | |

| جبال الألب البريطانية | 9 (12) | |

| جبلي | ٤ (٦) | |

| ميلان الأسترالي | 3 (4) | |

| لامانشا | 2 (3) | |

| البني الأسترالي | 1 (2) | |

| سابل | 1 (2) | |

| الألبان السويسرية | 1 (1) | |

| آخر

|

10 (14) | |

| نظام الإنتاج (

|

نصف موسع | 65 (43) |

| واسع | ٢٣ (١٥) | |

| نصف مكثف | 12 (8) | |

| متوسط مساحة المنطقة المغطاة المخصصة لكل ماعز

|

أكثر من

|

٣٩ (٢٦) |

|

|

17 (11) | |

|

|

15 (10) | |

|

|

12 (8) | |

|

|

9 (6) | |

|

|

5 (3) | |

|

|

3 (2) | |

| مواد الفراش للإيواء الداخلي للإناث

|

أرضية صلبة من قش القمح أو نشارة الخشب | 61 (42) |

| أرضية ترابية | 27 (19) | |

| أرضية مشطوفة مع بلاستيك أو خشب أو معدن ممتد | 9 (6) | |

| لا شيء (الإسكان الداخلي غير متوفر) | 3 (2) | |

| موسم الولادة

|

ربيع | 64 (42) |

| الشتاء | ٢٣ (١٥) | |

| الخريف | 6 (4) | |

| الصيف | 5 (3) | |

| غير موسمي | 3 (2) | |

| متوسط عمر الفطام

|

> 10 أسابيع | ٨٦ (٥٧) |

| 8-10 أسابيع | 14 (9) | |

| تربية الماعز مع أنواع الماشية الأخرى

|

المواشي | 25 (27) |

| خروف | ٢٠ (٢٢) | |

| خيول | 15 (16) | |

| الألباكا/الجمال | 12 (13) | |

| الطيور | 9 (10) | |

| خنازير | 5 (5) | |

| لا شيء | 15 (16) | |

| مشاركة المراعي

|

لا | 42 (28) |

| نعم | ٣٨ (٢٥) | |

| أحيانًا | ٢٠ (١٣) | |

| ممارسة الرعي في المزارع عندما تتشارك المراعي

|

الرعي المشترك مع أنواع الماشية الأخرى | 60 (29) |

| الرعي الدائري | 40 (19) |

| سؤال (الردود) | مستويات | النسبة المئوية (العدادات) |

| أنواع الماشية الأخرى التي ترعى مع الماعز

|

المواشي | ٢٩ (٢٠) |

| خيول | ٢٦ (١٨) | |

| خروف | ٢٠ (١٤) | |

| الألباكا/الجمال | 16 (11) | |

| آخر | 10 (7) | |

| فئة عمرية من الماشية ترعى مع الماعز

|

المواشي بين 1-2 سنة | ٣٥ (٧) |

| المواشي > 2 سنوات | 30 (6) | |

| عجول مفطومة أقل من سنة | 20 (4) | |

| عجول غير مُرضعة | 15 (3) |

معرفة الطفيليات المعوية

من بين 66 مستجيبًا،

الطفيليات، دودة العلق الأسود (Trichostrongylus spp.) (67%; 44/66)، دودة المعدة البنية (T. circumcincta) (65%)، دودة الكبد (F. hepatica) (

أفاد المستجيبون بأن تلوث العلف بالمواد البرازية

مرعى

تشخيص الطفيليات المعوية

الأدوية المضادة للطفيليات وطرق السيطرة الأخرى على الطفيليات المعوية

كان اختيار الأدوية المضادة للطفيليات المتنوعة يختلف بين المزارع ولكنه كان مهيمنًا بواسطة

تركيبة من أربعة أدوية مضادة للطفيليات (أبامكتين، ألبندازول، ليفاميزول وكلوسانتيل) (

نصف المستجيبين (

| سؤال (الردود) | مستويات | النسبة المئوية (العدادات) |

| تم طلب نصيحة بيطرية

|

نعم | ٥٥ (٣٦) |

| لا | ٤٦ (٣٠) | |

| طرق التشخيص المستخدمة

|

عدّ بيض البراز | ٣٣ (٥١) |

| علامات سريرية | 32 (50) | |

| ثقافة اليرقات | 13 (21) | |

| مراقبة الديدان في البراز | 12 (19) | |

| تشريح الجثة | 5 (7) | |

| فحص دموي | 2 (3) | |

| فاماشاك/فقر الدم | 2 (3) | |

| لا شيء | 1 (1) | |

| استخدام FEC (

|

نعم | 67 (44) |

| لا | 32 (21) | |

| لا أعرف | 2 (1) | |

| هدف FEC

|

مراقبة عبء الديدان | ٢٨ (٤١) |

| قرارات التخلص من الديدان | ٢٦ (٣٩) | |

| تقييم فعالية أدوية التخلص من الديدان | 25 (37) | |

| تشخيص الأمراض الناتجة عن الديدان | 21 (31) | |

| اختبار الماعز الجديدة في الحجر الصحي | 1 (1) | |

| موقع اختبار FEC

|

في المزرعة بواسطة الموظفين | 42 (28) |

| مختبر تشخيصي | ٤٠ (٢٦) | |

| عيادة بيطرية | 18 (12) | |

| الماعز المختبر من أجل FEC

|

أطفال

|

16 (31) |

| الرضع (أكثر من 6 أشهر – سنة واحدة) | 20 (39) | |

| الأبقار/الحلابات | 21 (42) | |

| الأغنام الذكور | 13 (26) | |

| باكس | 18 (36) | |

| عمره أكثر من 6 سنوات | 11 (22) |

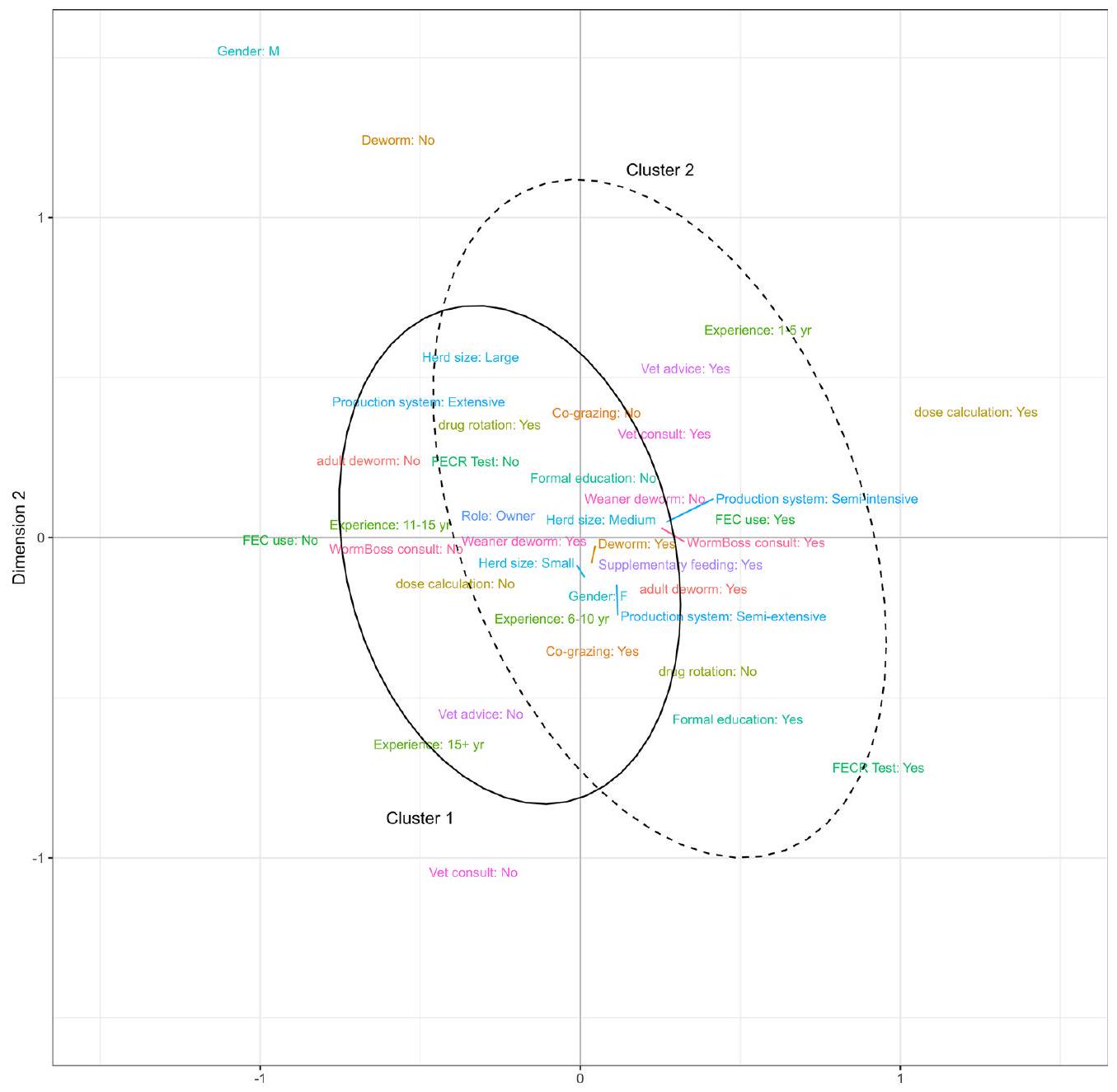

تحليلات المراسلات المتعددة وتحليل المكونات الرئيسية

يحسبون بانتظام الجرعات المناسبة من الأدوية المضادة للطفيليات لماعزهم. بالمقابل، كان المستجيبون في المجموعة 2 يديرون أنظمة إنتاج شبه موسعة أو شبه مكثفة وكان لديهم

الكوكيديات

| سؤال (الردود) | مستويات | النسبة المئوية (العدادات) |

| استخدم الأدوية المضادة للطفيليات (

|

نعم | 94 (62) |

| لا | 6 (4) | |

| فئة الدواء المستخدمة (

|

||

| البنزيميدازولات (

|

فينبندازول

|

٨٣ (٣٥) |

| ألبندازول | 14 (6) | |

| BZs غير محددة | 2 (1) | |

| لاكتونات ماكروسيكلية (

|

إيفرمكتين | ٤٠ (١٦) |

| دورامكتين | 30 (12) | |

| أبامكتين | ٢٨ (١١) | |

| موكسيدكتين | 3 (1) | |

| أخرى (

|

ليفاميزول | ٢٦ (٥) |

| تولترزول | ٢٦ (٥) | |

| كلوسانتيل | 21 (4) | |

| سترات المورانتيل | 21 (4) | |

| مونيبانتيلي | 5 (1) | |

| تركيبة تجارية(ات) (

|

4 (BZs + MLs + LEV + كلوسانتيل) | ٥٩ (٤٥) |

| 2 (MLs + مونيبانتيلي) | ٢٤ (١٨) | |

| 2 (MLs + ديركوانتيل) | ٧ (٥) | |

| 3 (BZs + MLs + LEV) | ٧ (٥) | |

| 2 (BZs + LEV) | 2 (2) | |

| 2 (MLs + PZQT) | 1 (1) | |

| تحضير أدوية مضادة للطفيليات المستخدمة

|

عن طريق الفم | 69 (49) |

| قابلة للحقن | 10 (7) | |

| عن طريق الفم وقابلة للحقن | 8 (6) | |

| عن طريق الفم وصب على | 6 (4) | |

| عن طريق الفم، قابلة للحقن وصب على | 4 (3) | |

| صب على | 3 (2) | |

| موسم(ات) الديدان

|

لا جدول ثابت | 38 (48) |

| الربيع | 20 (26) | |

| الخريف | 16 (21) | |

| الصيف | 16 (21) | |

| الشتاء | 14 (18) | |

| تدوير/تغيير أدوية مضادة للطفيليات (

|

لا تدوير | 45 (30) |

| سنويًا | 30 (20) | |

| كل عامين | 23 (15) | |

| كل ثلاث سنوات | 2 (1) | |

نقاش

العدوى الطفيلية المعوية تسببت في خسائر إنتاجية، مما أدى إلى استخدام واسع النطاق للأدوية المضادة للطفيليات (94%; 62/66) المسجلة أساسًا للاستخدام في الأغنام والأبقار. كانت الأدوية المضادة للديدان الأكثر استخدامًا عبارة عن تركيبة تجارية من أربعة أدوية مضادة للديدان (أبامكتين، ألبندازول، ليفاميسول وكلوسانتيل)، تليها BZs وMLs. على الرغم من أن التخلص المستهدف من الديدان كان مستخدمًا في معظم مزارع المستجيبين، إلا أن القليل

[57]. كانت الغالبية العظمى من المستجيبين (

نطاق المنتجات المضادة للطفيليات المسجلة لعلاج الماعز في أستراليا محدود (

يمكن أن يشكل الاستخدام غير المصرح به لمضادات الديدان في الماعز تحديات إضافية عندما تختلف معدلات الجرعات. يُوصى عمومًا بإعطاء ليفاميزول للماعز بجرعة تعادل 1.5 ضعف الجرعة الموصى بها للأغنام [5، 61] ومضادات الديدان الأخرى بجرعة تتراوح بين 1.5 إلى ضعف الجرعة الموصى بها للأغنام [5]. وجدنا أن أكثر من نصف المستجيبين (

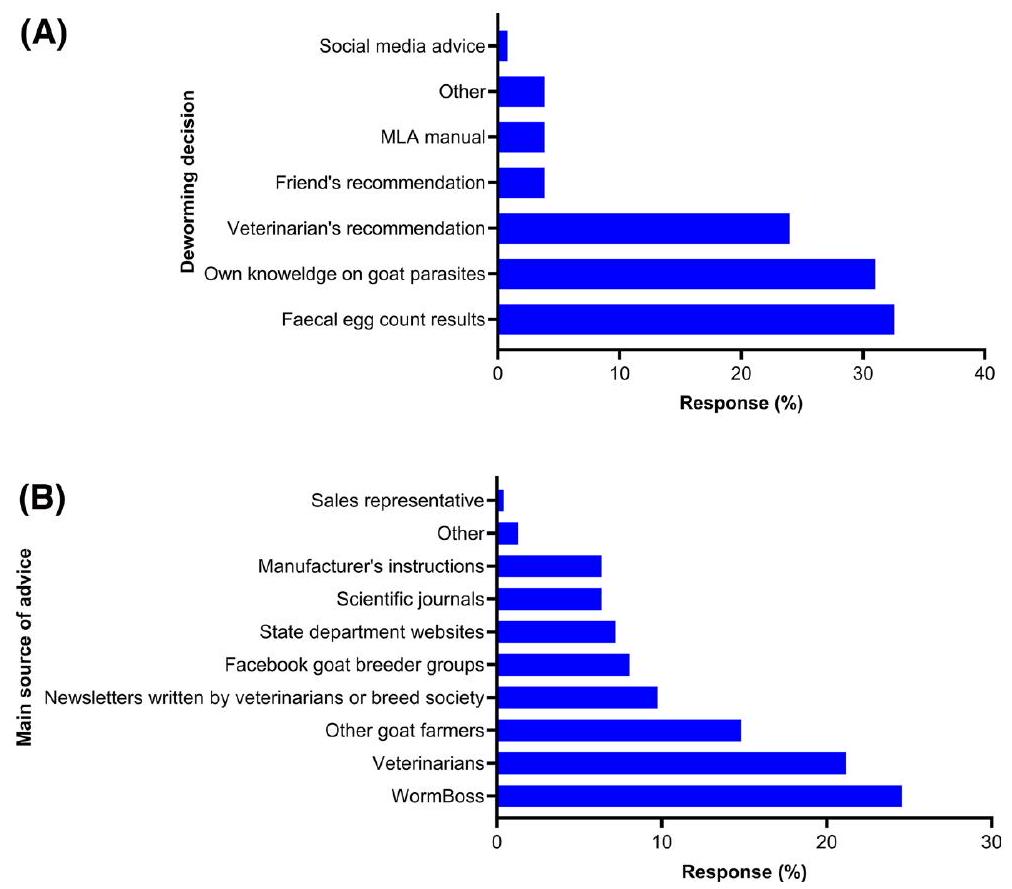

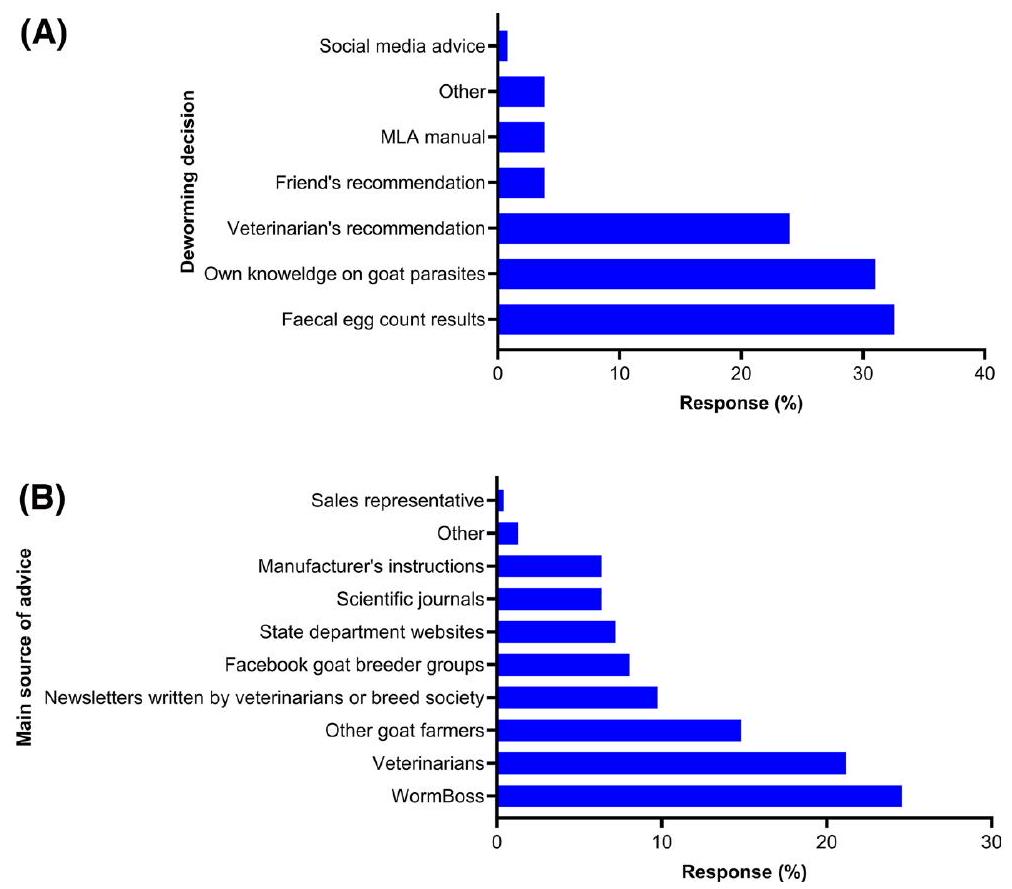

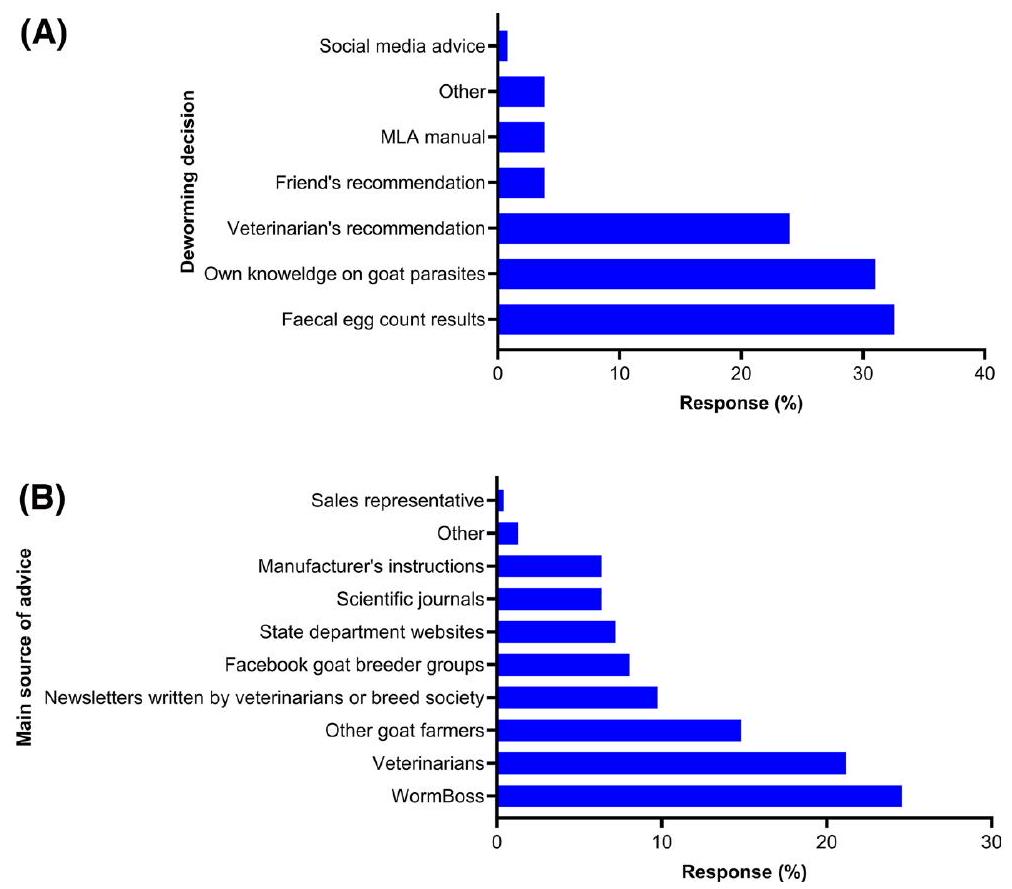

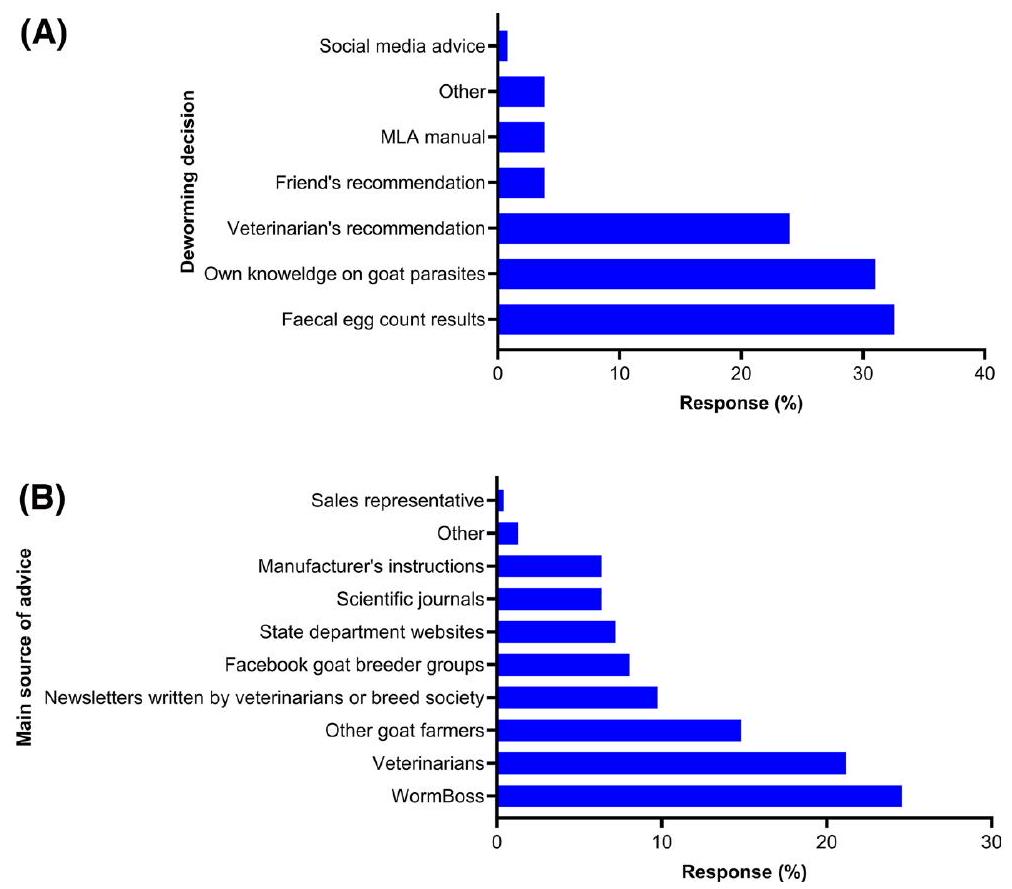

حسب علم المؤلفين، لا يوجد حاليًا منتج مضاد للديدان موصوف للاستخدام في الماعز في أستراليا (https://wormboss.com.au/drenches-for-goats-using-products-correctly-and-legally/). ومع ذلك، كشفت هذه الدراسة أن بعض المزارعين كانوا يستخدمون تحضيرات قابلة للحقن (إيفرمكتين) و/أو تحضيرات سائلة (انظر الجدول 5)؛ هذه النتيجة تتوافق مع نتائج برونت وآخرين [38]. استخدام المنتجات المضادة للطفيليات الموضعية أو القابلة للحقن في الماعز ليس فقط غير فعال ولكن أيضًا سام للماعز حيث أن الماعز يحتوي على دهون تحت الجلد أقل بكثير من الأغنام والماشية (https://wormboss.com.au). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، قد تكون العلاجات غير المصرح بها في الماعز لها فترات انسحاب متغيرة، خاصة بسبب استقلابها المختلف، مما يؤدي إلى دخول الحيوانات أو منتجات الحيوانات إلى أنظمة الإمداد ويشكل خطرًا على الصحة العامة [63]. في أستراليا، يتطلب الاستخدام القانوني للأدوية المضادة للطفيليات التي لم يتم تسجيلها للاستخدام في الماعز وصفة بيطرية غير مصرح بها (https://wormboss.com.au). أظهرت دراستنا أن WormBoss والأطباء البيطريين كانا المصدرين الأكثر موثوقية (108/236) للحصول على نصائح حول استخدام الأدوية المضادة للطفيليات في الماعز الألباني (الشكل 7ب). في الظروف المعطاة، من الحكمة أن يساعد الاستخدام القائم على الوصفات الطبية للأدوية المضادة للطفيليات في تجنب الجرعات الناقصة التي يمكن أن تؤدي إلى مقاومة الأدوية وتشكل مخاطر على سلامة الماعز بالإضافة إلى المخلفات المحتملة في الحليب أو اللحم.

يمكن أن يقلل استخدام مضادات الديدان الموصوفة فقط مع استراتيجية تجريد مستهدفة من الضغط الانتقائي المرتبط بمقاومة الأدوية من خلال زيادة عدد السكان المحميين. في الدراسة الحالية،

في الخارج [22]، مع وجود تقارير منشورة محدودة جدًا متاحة في أستراليا [64-67]. ومع ذلك، يُعتقد أن الماعز والأغنام عادة ما تحمل أنواعًا مشابهة من الديدان الأسطوانية وغالبًا ما توجد في نفس المزارع (22 مزرعة في هذا الاستطلاع كانت تمتلك أغنامًا وماعز؛ الجدول 3). نفترض أن وضع مقاومة الأدوية في الماعز في أستراليا قابل للمقارنة مع ما لوحظ في الأغنام [68]. تعتبر المستويات المتزايدة من مقاومة الأدوية لـ

كشفت نتائج MCA أن ممارسات التحكم الأفضل في GIN تم اعتمادها في مزارع الماعز الألباني ذات الأنظمة الإنتاجية شبه المكثفة أو شبه الواسعة، على عكس المزارع ذات الأنظمة الإنتاجية الواسعة؛ حيث شكلت الأولى الغالبية من المستجيبين في الدراسة الحالية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، قام المزارعون الذين لديهم ممارسات جيدة في التحكم في GIN بإجراء FECs وطبقوا استراتيجيات تجريد مستهدفة و/أو استراتيجية للماعز الألباني البالغ. من المثير للاهتمام أن المزارعين في هذه المجموعة أيضًا طلبوا نصيحة بيطرية. ومع ذلك، لم يقوموا بتدوير الأدوية المضادة للطفيليات. قد يكون غياب تدوير الأدوية هذا لأن المزارعين من المحتمل أن يسعوا بنشاط للحصول على نصيحة بيطرية، ومن الممكن أن الأطباء البيطريين لن ينصحوا باستخدام الأدوية المضادة للطفيليات خارج التسمية، خاصة في الماعز الحلوب البالغ، حيث أنه حاليًا لا يوجد سوى دواء مضاد للطفيليات واحد مسجل للاستخدام في الماعز الألباني الأسترالي. على الرغم من أن هذه النتائج مشجعة، يجب على مزارعي الماعز الألباني الذين يستخدمون النظام الإنتاجي الواسع اعتماد هذه الممارسات الأفضل لاتخاذ قرارات مخصصة في المزرعة بناءً على تجريد مستهدف، مما قد يبطئ من تطور مقاومة الأدوية في GINs للماعز.

يمكن استخدام طرق غير كيميائية، مثل التحكم البيولوجي والتطعيم، للسيطرة على الديدان الأسطوانية المقاومة للأدوية في الماعز. في الدراسة الحالية،

بعدم استخدام كريات COWP أكثر من 4 مرات في السنة. وجدنا أن

في هذه الدراسة،

على الرغم من أن الكوكسيديوس هو في الأساس مرض يصيب الصغار، وجدنا أن فقط

. لتحقيق ذلك، من الضروري رفع حظائر الطعام والماء عن الأرض ومنع تسرب الماء، حيث يمكن أن تبقى كيسات الإيميريا حية في الظروف الرطبة. تنشأ تحديات كبيرة في أنظمة إنتاج الماعز الحلوب المكثفة عندما تحدث الولادة عدة مرات على مدار العام للحفاظ على إمدادات الحليب على مدار السنة. إذا استخدم المربي نفس الحظائر باستمرار لمجموعات متعاقبة أو أدخل صغارًا حديثي الولادة إلى حظيرة تحتوي بالفعل على حيوانات أكبر سنًا، فإن الصغار المولودة لاحقًا تتعرض على الفور لتحدٍ ثقيل ويمكن أن تظهر عليها أعراض الكوكسيديوس الشديدة في الأسابيع القليلة الأولى من الحياة [78]. يجب أن يكون مربي الماعز الحلوب الأستراليون على دراية بالعوامل الممرضة وعوامل الخطر البيئية والموطن التي قد تؤدي إلى زيادة حدوث الكوكسيديوس. على سبيل المثال، صغار الماعز في سن صغيرة (أي،

على الرغم من حداثة هذه الدراسة، من المهم تفسير النتائج بعناية بسبب بعض القيود. اعتبارًا من نوفمبر 2023، كان العدد الإجمالي لمربي الماعز الحلوب المسجلين لدى DGSA Ltd هو 456 (تواصل شخصي). يشمل ذلك المربين الذين إما خرجوا من الممارسة أو توقفوا عن عضويتهم، مما يقلل على الأرجح من حجم عينة المصدر لدينا ويزيد من نسبة عينة الدراسة (المستجيبين). ومع ذلك، كانت نسبة الاستجابة لهذه الدراسة 14% (66/456)، على الرغم من أن DGSA Ltd أرسلت تذكيرات متابعة لأعضائها على مدى شهرين. قد تؤدي هذه النسبة المنخفضة للاستجابة إلى إدخال تحيز من خلال تمثيل بعض النتائج بشكل زائد أو ناقص، مما قد يتأثر بإرهاق الاستطلاع. هذه النسبة من الاستجابة (

على الحذف أو استبدال المتوسط للتعامل مع البيانات المفقودة [82].

الاستنتاجات

الاختصارات

| AR | مقاومة الأدوية المضادة للطفيليات |

| DGSA | جمعية الماعز الحلوب الأسترالية المحدودة |

| GINs | الديدان المعوية |

| MCA | تحليلات المراسلات المتعددة |

المعلومات التكميلية

الملف الإضافي 2: الجدول S1. المتغيرات المختارة لتحليل المراسلات المتعددة لتحديد أفضل ممارسات السيطرة على الديدان المعوية في الماعز الحلوب الأسترالية. الجدول S2. الوصول إلى الطعام والماء في مزارع الماعز الحلوب الأسترالية التي استجابت للاستطلاع.

الملف الإضافي 3: الشكل S1. نسبة المستجيبين الذين أبلغوا عن تكرار تنظيف الحظائر قبل كل ولادة في مزارع الماعز الحلوب الأسترالية. الشكل S2. نسبة المستجيبين الذين أبلغوا عن تصوراتهم حول الطفيليات المعوية التي تم تشخيصها في مزارع الماعز الحلوب الأسترالية. الشكل S3. نسبة المستجيبين الذين أبلغوا عن استخدام الأدوية المضادة للطفيليات في الماعز الحلوب الأسترالية. الشكل S4. نسبة المستجيبين الذين أبلغوا عن تصوراتهم حول العلامات السريرية الرئيسية للكوكسيديوس التي لوحظت في الصغار.

الشكر

مساهمات المؤلفين

تنسيق، تصور، مراجعة الكتابة وتحرير. لقد قرأ جميع المؤلفين ووافقوا على النسخة النهائية من المخطوطة.

تمويل

توفر البيانات والمواد

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

موافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

نُشر على الإنترنت: 24 يناير 2025

References

- Van Houtert MF, Sykes AR. Implications of nutrition for the ability of ruminants to withstand gastrointestinal nematode infections. Int J Parasitol. 1996;26:1151-67.

- Waller PJ. Sustainable helminth control of ruminants in developing countries. Vet Parasitol. 1997;71:195-207.

- Githigia SM, Thamsborg SM, Munyua WK, Maingi N. Impact of gastrointestinal helminths on production in goats in Kenya. Small Ruminant Res. 2001;42:21-9.

- Hoste H, Sotiraki S, Landau SY, Jackson F, Beveridge I. Goat-nematode interactions: think differently. Trends Parasitol. 2010;26:376-81.

- Hoste H, Sotiraki S, de Jesús Torres-Acosta JF. Control of endoparasitic nematode infections in goats. Vet Clinic Food Anim Pract. 2011;27:163-73.

- Rinaldi L, Veneziano V, Cringoli G. Dairy goat production and the importance of gastrointestinal strongyle parasitism. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:745-6.

- Fthenakis GC, Papadopoulos E. Impact of parasitism in goat production. Small Ruminant Res. 2018;163:21-3.

- Airs PM, Ventura-Cordero J, Mvula W, Takahashi T, Van Wyk J, Nalivata P, et al. Low-cost molecular methods to characterise gastrointestinal nematode co-infections of goats in Africa. Parasit Vectors. 2023;16:1-15.

- Ghimire TR, Bhattarai N. A survey of gastrointestinal parasites of goats in a goat market in Kathmandu. Nepal J Parasit Dis. 2019;43:686-95.

- Karshima SN, Karshima MN. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence, distribution and nematode species diversity in small ruminants: a Nigerian perspective. J Parasit Dis. 2020;44:702-18.

- Lianou DT, Arsenopoulos K, Michael CK, Mavrogianni VS, Papadopoulos E, Fthenakis GC. Dairy goats helminthosis and its potential predictors in Greece: findings from an extensive countrywide study. Vet Parasitol. 2023;320:109962.

- Maurizio A, Stancampiano L, Tessarin C, Pertile A, Pedrini G, Asti C, et al. Survey on endoparasites of dairy goats in North-Eastern Italy using a farm-tailored monitoring approach. Vet Sci. 2021;8:69.

- Mohammedsalih KM, Khalafalla A, Bashar A, Abakar A, Hessain A, Juma FR, et al. Epidemiology of strongyle nematode infections and first report

of benzimidazole resistance in Haemonchus contortus in goats in South Darfur State, Sudan. BMC Vet Res. 2019;15:1-13. - Radavelli WM, Pazinato R, Klauck V, Volpato A, Balzan A, Rossett J, et al. Occurence of gastrointestinal parasites in goats from the Western Santa Catarina, Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2014;23:101-4.

- Zanzani SA, Gazzonis AL, Di Cerbo A, Varady M, Manfredi MT. Gastrointestinal nematodes of dairy goats, anthelmintic resistance and practices of parasite control in Northern Italy. BMC Vet Res. 2014;10:1-10.

- Levine ND. Nematode parasites of domestic animals and of man. 2nd ed. Minneapolis: Burgess Publishing; 1980.

- Zajac AM. Gastrointestinal nematodes of small ruminants: life cycle, anthelmintics, and diagnosis. Vet Clinic Food Anim Pract. 2006;22:529-41.

- Joe L, Tristan J, Richard S, John WW, Fordyce G. Priority list of endemic diseases for the red meat industries. North Sydney: Meat and Livestock Australia Ltd; 2015.

- Alberti EG, Zanzani SA, Ferrari N, Bruni G, Manfredi MT. Effects of gastrointestinal nematodes on milk productivity in three dairy goat breeds. Small Ruminant Res. 2012;106:12-7.

- Alberti EG, Zanzani SA, Gazzonis AL, Zanatta G, Bruni G, Villa M, et al. Effects of gastrointestinal infections caused by nematodes on milk production in goats in a mountain ecosystem: comparison between a cosmopolite and a local breed. Small Ruminant Res. 2014;120:155-63.

- Paraud C, Chartier C. Facing anthelmintic resistance in goats. In: Simoes J, Gutierrez C, editors. Sustainable goat production in adverse environments. Cham: Springer International; 2017. p. 267-292. https://doi.org/10. 1007/978-3-319-71855-2_16.

- Baudinette E, O’Handley R, Trengove C. Anthelmintic resistance of gastrointestinal nematodes in goats: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vet Parasitol. 2022;312:109809.

- Galtier P, Escoula L, Camguilhem R, Alvinerie M. Comparative bioavailability of levamisole in non-lactating ewes and goats. Ann Rech Vet. 1981;12:109-15.

- Hennessy DR. Physiology, pharmacology and parasitology. Int J Parasitol. 1997;27:145-52.

- Dupuy J, Chartier C, Sutra JF, Alvinerie M. Eprinomectin in dairy goats: dose influence on plasma levels and excretion in milk. Parasitol Res. 2001;87:294-8.

- Kettle PR, Vlassoff A, Reid TC, Hotton CT. A survey of nematode control measures used by milking goat farmers and of anthelmintic resistance on their farms. N Z Vet J. 1983;31:139-43.

- Pearson AB, MacKenzie R. Parasite control in fibre goats: results of a postal questionnaire. N Z Vet J. 1986;34:198-9.

- Maingi N, Bjørn H, Thamsborg SM, Dangolla A, Kyvsgaard NC. A questionnaire survey of nematode parasite control practices on goat farms in Denmark. Vet Parasitol. 1996;66:25-37.

- Scherrer AM, Pomroy WE, Charleston WAG. Anthelmintic usage on goat farms in New Zealand: results of a postal survey. N Z Vet J. 1990;38:133-5.

- Hoste H, Chartier C, Etter E, Goudeau C, Soubirac F, Lefrileux Y. A questionnaire survey on the practices adopted to control gastrointestinal nematode parasitism in dairy goat farms in France. Vet Res Commun. 2000;24:459-69.

- Theodoropoulos G, Theodoropoulos H, Zervas G, Bartziokas E. Nematode parasite control practices of sheep and goat farmers in the region of Trikala, Greece. J Helminthol. 2000;74:89-93.

- Torres-Acosta JFJ, Aguilar-Caballero AJ, Le Bigot C, Hoste H, Canul-Ku HL, Santos-Ricalde R, et al. Comparing different formulae to test for gastrointestinal nematode resistance to benzimidazoles in smallholder goat farms in Mexico. Vet Parasitol. 2005;134:241-8.

- de Sá Guimarães A, Gouveia AMG, do Carmo FB, Gouveia GC, Silva MX, da Silva Vieira L, et al. Management practices to control gastrointestinal parasites in dairy and beef goats in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2011;176:265-69.

- de Waal T, Rinaldi L. Survey of endoparasite and parasite control practices by Irish goat owners. Kukovics S, editor. In: Goat science: from keeping to precision production. Rijeka: IntechOpen; 2023. https://doi.org/10.5772/ intechopen. 104279.

- Rufino-Moya PJ, Leva RZ, Reis LG, García IA, Di Genova DR, Gómez AS, et al. Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites in small ruminant farms in southern Spain. Animals. 2024;14:1668.

- Lyndal-Murphy M, James P, Bowles P, Watts R, Baxendell S. Options for the control of parasites in the Australian goat industry: a situational analysis

of parasites and parasite control. North Sydney: Meat and Livestock Australia Ltd; 2007. - Nogueira M, Gummow B, Gardiner CP, Cavalieri J, Fitzpatrick LA, Parker AJ. A survey of the meat goat industry in Queensland and New South Wales. 2. Herd management, reproductive performance and animal health. Anim Prod Sci. 2015;56:1533-44.

- Brunt LM, Rast L, Hernandez-Jover M, Brockwell YM, Woodgate RG. A producer survey of knowledge and practises on gastrointestinal nematode control within the Australian goat industry. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Rep. 2019;18:100325.

- Zalcman E, Cowled B. Farmer survey to assess the size of the Australian dairy goat industry. Aust Vet J. 2018;96:341-5.

- Mahmood AK, Khan MS, Khan MA, Bilal M, Farooq U. Lactic acidosis in goats: prevalence, intra-ruminal and haematological investigations. J Anim Plant Sci. 2013;23:1527-31.

- Zhang RY, Liu YJ, Yin YY, Jin W, Mao SY, Liu JH. Response of rumen microbiota, and metabolic profiles of rumen fluid, liver and serum of goats to high-grain diets. Animal. 2019;13:1855-64.

- Andrews AH. Some aspects of coccidiosis in sheep and goats. Small Ruminant Res. 2013;110:93-5.

- Anzuino K, Knowles TG, Lee MRF, Grogono-Thomas R. Survey of husbandry and health on UK commercial dairy goat farms. Vet Rec. 2019;185:267-267.

- Todd CG, Bruce B, Deeming L, Zobel G. Survival of replacement kids from birth to mating on commercial dairy goat farms in New Zealand. J Dairy Sci. 2019;102:9382-8.

- Leitner G, Krifucks O, Weisblit L, Lavi Y, Bernstein S, Merin U. The effect of caprine arthritis encephalitis virus infection on production in goats. Vet J. 2010;183:328-31.

- Echeverría I, De Miguel R, De Pablo-Maiso L, Glaria I, Benito AA, De Blas I, et al. Multi-platform detection of small ruminant lentivirus antibodies and provirus as biomarkers of production losses. Front Vet Sci. 2020;7:182.

- Dore S, Liciardi M, Amatiste S, Bergagna S, Bolzoni G, Caligiuri V, et al. Survey on small ruminant bacterial mastitis in Italy, 2013-2014. Small Ruminant Res. 2016;141:91-3.

- Battini M, Vieira A, Barbieri S, Ajuda I, Stilwell G, Mattiello S. Invited review: animal-based indicators for on-farm welfare assessment for dairy goats. J Dairy Sci. 2014;97:6625-48.

- Van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45:1-67.

- Feinsinger P, Spears EE, Poole RW. A simple measure of niche breadth. Ecology. 1981;62:27-32.

- Kassambara A. Practical guide to principal component methods in R (multivariate analysis book 2). PCA, M(CA), FAMD, MFA, HCPC, factoextra. 2017. https://www.sthda.com/english/.

- Lê S, Josse J, Husson F. FactoMineR: an R package for multivariate analysis. J Stat Softw. 2008;25:1-18.

- R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2023.

- Holm SA, Sörensen CRL, Thamsborg SM, Enemark HL. Gastrointestinal nematodes and anthelmintic resistance in Danish goat herds. Parasite. 2014;21:37.

- Domke AVM, Chartier C, Gjerde B, Leine N, Vatn S, Østerås O, et al. Worm control practice against gastro-intestinal parasites in Norwegian sheep and goat flocks. Acta Vet Scand. 2011;53:1-9.

- McKenzie RA, Green PE, Thornton AM, Blackall PJ. Feral goats and infectious disease: an abattoir survey. Aust Vet J. 1979;55:441-2.

- Beveridge I, Pullman AL, Henzell R, Martin RR. Helminth parasites of feral goats in South Australia. Aust Vet J. 1987;64:111-2.

- Silva LMR, Carrau T, Vila-Viçosa MJM, Musella V, Rinaldi L, Failing K, et al. Analysis of potential risk factors of caprine coccidiosis. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Rep. 2020;22:100458.

- Jackson F, Varady M, Bartley DJ. Managing anthelmintic resistance in goats: can we learn lessons from sheep? Small Ruminant Res. 2012;103:3-9.

- Playford MC, Smith AN, Love S, Besier RB, Kluver P, Bailey JN. Prevalence and severity of anthelmintic resistance in ovine gastrointestinal nematodes in Australia (2009-2012). Aust Vet J. 2014;92:464-71.

- Chartier C, Pors I, Sutra JF, Alvinerie M. Efficacy and pharmacokinetics of levamisole hydrochloride in goats with nematode infections. Vet Rec. 2000;146:350-1.

- Várady M, Papadopoulos E, Dolinská M, Königová A. Anthelmintic resistance in parasites of small ruminants: sheep versus goats. Helminthologia. 2011;48:137-44.

- Cutress D. Internal parasite control and goats: implications for a growing industry. 2022. http://businesswales.gov.wales/farmingconnect/business. Accessed July 2024.

- Barton NJ, Trainor BL, Urie JS, Atkins JW, Pymans MFS, Wolstencroft IR. Anthelmintic resistance in nematode parasites of goats. Aust Vet J. 1985;62:224-7.

- Veale PI. Resistance to macrocyclic lactones in nematodes of goats. Aust Vet J. 2002;80:303-4.

- Francis EK, Šlapeta J. Refugia or reservoir? Feral goats and their role in the maintenance and circulation of benzimidazole-resistant gastrointestinal nematodes on shared pastures. Parasitology. 2023;150:672-82.

- Gillham RJ, Obendorf DL. Therapeutic failure of levamisole in dairy goats. Aust Vet J. 1985;62:426-7.

- Kotze AC, Hunt PW. The current status and outlook for insecticide, acaricide and anthelmintic resistances across the Australian ruminant livestock industries: assessing the threat these resistances pose to the livestock sector. Aust Vet J. 2023;101:321-33.

- Arsenopoulos KV, Fthenakis GC, Katsarou El, Papadopoulos E. Haemonchosis: a challenging parasitic infection of sheep and goats. Animals. 2021;11:363.

- Healey K, Lawlor C, Knox MR, Chambers M, Lamb J. Field evaluation of Duddingtonia flagrans IAH 1297 for the reduction of worm burden in grazing animals: tracer studies in sheep. Vet Parasitol. 2018;253:48-54.

- Healey K, Lawlor C, Knox MR, Chambers M, Lamb J, Groves P. Field evaluation of Duddingtonia flagrans IAH 1297 for the reduction of worm burden in grazing animals: pasture larval studies in horses, cattle and goats. Vet Parasitol. 2018;258:124-32.

- Maingi N, Krecek RC, van Biljon N. Control of gastrointestinal nematodes in goats on pastures in South Africa using nematophagous fungi Duddingtonia flagrans and selective anthelmintic treatments. Vet Parasitol. 2006;138:328-36.

- Paraud C, Pors I, Chartier C. Efficiency of feeding Duddingtonia flagrans chlamydospores to control nematode parasites of first-season grazing goats in France. Vet Res Commun. 2007;31:305-15.

- Epe C, Holst C, Koopmann R, Schnieder T, Larsen M, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G. Experiences with Duddingtonia flagrans administration to parasitized small ruminants. Vet Parasitol. 2009;159:86-90.

- Vilela VL, Feitosa TF, Braga FR, de Araújo JV, de Oliveira Souto DV. Biological control of goat gastrointestinal helminthiasis by Duddingtonia flagrans in a semi-arid region of the northeastern Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2012;188:127-33.

- de Matos AFIM, Nobre COR, Monteiro JP, Bevilaqua CML, Smith WD, Teixeira M. Attempt to control Haemonchus contortus in dairy goats with Barbervax

, a vaccine derived from the nematode gut membrane glycoproteins. Small Ruminant Res. 2017;151:1-4. - Nobre COR, de Matos AFIM, Monteiro JP, de Souza V, Smith WD, Teixeira M. Benefits of vaccinating goats against Haemonchus contortus during gestation and lactation. Small Ruminant Res. 2020;182:46-51.

- Taylor MA, Coop RL, Wall RL. Veterinary parasitology. 4th ed. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell Science; 2016.

- de Macedo LO, Bezerra-Santos MA, de Mendonça CL, Alves LC, Ramos RAN, de Carvalho GA. Prevalence and risk factors associated with infection by Eimeria spp. in goats and sheep in Northeastern Brazil. J Parasit Dis. 2020;44:607-12.

- Cobanoglu C, Moreo PJ, Warde B. A comparison of mail, fax and webbased survey methods. Int J Mark Res. 2001;43:1-15.

- Miok K, Nguyen-Doan D, Robnik-Šikonja M, Zaharie D. Multiple imputation for biomedical data using Monte Carlo dropout autoencoders. 2019 E-Health and Bioengineering Conference (EHB 2019), 21-23 Nov 2019, Iasi. New York: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers; 2019. p. 1-4.

- Zhong H, Hu W, Penn JM. Application of multiple imputation in dealing with missing data in agricultural surveys: the case of bmp adoption. J Agric Resour Econ. 2018;43:78-102.

ملاحظة الناشر

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-024-06650-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39856711

Publication Date: 2025-01-24

Knowledge, attitudes and practices of Australian dairy goat farmers towards the control of gastrointestinal parasites

Abstract

Background Gastrointestinal parasites such as nematodes and coccidia are responsible for significant economic losses in the goat industry globally. An indiscriminate use of antiparasitic drugs, primarily registered for use in sheep and cattle, in goats has resulted in drug-resistant gastrointestinal parasites. Very little is known about the gastrointestinal parasite control practices used by Australian dairy goat farmers that are pivotal for achieving sustainable control of economically important parasites. The study reported here provides insights into gastrointestinal parasite control practices of Australian dairy goat farmers based on responses to an online survey. Methods The questionnaire comprised 58 questions on farm demography, husbandry and grazing management, knowledge of gastrointestinal parasites and their importance in dairy goats, diagnosis of infections, antiparasitic drugs and alternate control options. After a pilot survey (

Background

Currently, the control of gastrointestinal parasites in goats mainly relies on the indiscriminate use of antiparasitic drugs primarily registered for use in sheep and cattle, resulting in drug resistance in economically important GINs of goats [21]. Recently, Baudinette et al. [22] comprehensively reviewed the literature on anthelmintic resistance (AR) in GINs of goats and found all major nematode genera (i.e., Haemonchus, Trichostrongylus, Teladorsagia, Oesophagostomum and Cooperia) to be resistant to commonly used anthelmintics, indicating that AR is becoming a significant issue for the goat industry globally. This situation is further complicated when the off-label use of antiparasitic drugs is common in goats. Current drug pharmacokinetic studies suggest that goats metabolise anthelmintics faster than sheep [23-25]. Moreover, the requirement for registered manufacturers of anthelmintics to provide a milk withdrawal period limits the options available to dairy goat farmers for controlling GINs worldwide.

Owing to the challenges associated with the chemical control of goat parasites, questionnaire surveys have been conducted in several countries to assess parasite control practices used by goat farmers [26-35]. However, knowledge of gastrointestinal parasites, their significance and

control practices in dairy goats is limited. For instance, three studies have surveyed Australian goat farmers, mainly meat goat farmers located in two states (i.e. New South Wales and Queensland), to assess parasite control practices [36-38]. In the most recent survey, Brunt et al. [38] reported that

It is worth noting that the production systems, management and husbandry practices of dairy goats significantly differ from those of meat goats, particularly the rangeland goats, and that only one drug, with a milk withholding period, is registered for use in dairy goats against internal parasites in Australia. In the study reported here, we used an online questionnaire to assess gastrointestinal parasite control perceptions and practices of Australian dairy goat farmers. The findings of the study will help identify challenges to achieving sustainable control of goat internal parasites with limited available options.

Methods

Dairy goat farms in Australia

The Australian dairy goat industry is still in its infancy compared to the sheep and cattle industries as well as the dairy goat industries elsewhere, and little is known about the national herd’s production levels or economic impact. Most goat farmers practice seasonal breeding, as the percentage of pregnancies using artificial breeding is lower (mainly due to technical problems) than natural mating. Although the semi-extensive production system, which combines grazing on pastures supplemented with crop residues and supplementary feed, is the predominant type and increasing, some Australian dairy goat farms run intensive (i.e. usually indoor feeding and commercial

dairy goat farming) [39] and semi-intensive (i.e. an intermediate approach involving controlled grazing, with limited access to pasture than semi-extensive system and more regular supplementary feeding) production systems. In either case, improper shed design is common, resulting in high labour costs, suboptimal hygienic conditions and animal health concerns. The primary health constraints are GINs (mainly for pasture-fed goats) [12, 18], Johne’s disease [18], metabolic problems (intensive management with shedding) [40,41], coccidiosis in young goats [42], kid mortality [43, 44], caprine arthritis encephalitis [18, 45, 46], mastitis [47] and foot problems [48].

Questionnaire

Dairy goat farms registered with the Dairy Goat Society of Australia Ltd (DGSA) constituted the source population for the survey and their participation in the study was entirely voluntary. The pilot survey was conducted with 15 dairy goat farmers and these data were excluded from the final analyses. The feedback received from the pilot survey was incorporated into the final survey. Subsequently, registered members (

Data analyses

The proportional similarity index (PSI) was used to assess the representativeness of the participating farms in the dairy goat industry of Australia [50]. The PSI quantified the agreement in the frequency distribution of dairy goat farms that responded to the survey, stratified by state, with the frequency distribution of total dairy goat farms registered with DGSA Ltd in six states of Australia.

Multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) was conducted to identify underlying structures among survey respondents [51] based on the selected GIN control practices in goats recommended by WormBoss https:// wormboss.com.au (Additional file 2: Table S1). Cluster

analysis was performed using hierarchical clustering on principal components (HCPC) using Ward’s criterion to identify clusters of respondents who reported either ‘good’ (optimal) or ‘poor’ (suboptimal) GIN control practices. The contributed FactoMine R package [52] was utilised to perform MCA and HCPC in R.

All analyses and data visualisation procedures were performed using R version 4.3.1 [53] and GraphPad Prism version 10.3.0 for Windows (www.graphpad.com). The QGIS 3.34 software package was used to generate a map showing the postcode area of survey respondents (see Fig. 1).

Results

General characteristics of dairy goat farms

Of the 66 respondents included in the final analysis, the highest number was from NSW

The mean total area of the 66 farms was 76 (range

| Question | Mean | Median (Q1, Q3) | Min, Max |

| Farm area (acres) | 76 |

|

0.75, 2,000 |

| Grazing area (acres) | 56 |

|

0.25, 2,000 |

| Number of goats in the last year | 69 |

|

3, 1,428 |

| – Kids (

|

27 |

|

0,700 |

| – Weaners (> 6 months to 1 year) | 11 |

|

0,200 |

| – Milkers/does | 27 |

|

0,600 |

| – Bucks | 4 |

|

0,30 |

Husbandry and grazing management

(86%; 57/66) (Table 3). Most respondents (76%, 50/66) cleaned pens before each kidding (Additional file 3: Figure S1). Wheat straw or wood shavings on solid floors were the most commonly used bedding material (

Fresh colostrum collected from does kept on the farm was the main source of colostrum for kids (

| Question | Levels | Percentage (counts) |

| Role on the farm | Farm owner | 94 (62) |

| Farm manager | 5 (3) | |

| Staff worker | 1 (1) | |

| Gender | Female | 91 (60) |

| Male | 8 (5) | |

| Prefer not to disclose | 1 (1) | |

| Experience in goat farming (years) | 1-5 | 38 (25) |

| 6-10 | 18 (12) | |

| 11-15 | 12 (8) | |

| >15 | 32 (21) | |

| Use of property for goat farming (years) | <1 | 3 (2) |

| 1-10 | 62 (41) | |

| 11-20 | 18 (12) | |

| 21-30 | 5 (3) | |

| 31-40 | 8 (5) | |

| >40 | 5 (3) | |

| Formal qualification | No | 80 (53) |

| Yes | 20 (13) | |

| Type of qualification (

|

Certificate in farm animals | 39 (5) |

| Diploma in farm animals | 31 (4) | |

| Veterinary nursing | 15 (2) | |

| Bachelor’s degree or above | 15 (2) |

| Question (responses) | Levels | Percentage (counts) |

| Breed (

|

Anglo-Nubian | 25 (35) |

| Nigerian Dwarf | 16 (22) | |

| Saanen | 14 (20) | |

| Toggenburg | 14 (19) | |

| British Alpine | 9 (12) | |

| Alpine | 4 (6) | |

| Australian Melaan | 3 (4) | |

| Lamancha | 2 (3) | |

| Australian Brown | 1 (2) | |

| Sable | 1 (2) | |

| Swiss dairy | 1 (1) | |

| Other

|

10 (14) | |

| Production system (

|

Semi-extensive | 65 (43) |

| Extensive | 23 (15) | |

| Semi-intensive | 12 (8) | |

| Average covered area space allowance/housed goat (

|

More than

|

39 (26) |

|

|

17 (11) | |

|

|

15 (10) | |

|

|

12 (8) | |

|

|

9 (6) | |

|

|

5 (3) | |

|

|

3 (2) | |

| Bedding material for indoor housing of does

|

Solid floor with wheat straw or wood shaving | 61 (42) |

| Dirt floor | 27 (19) | |

| Slatted floor with plastic, wood or extended metal | 9 (6) | |

| None (indoor housing not available) | 3 (2) | |

| Kidding season (

|

Spring | 64 (42) |

| Winter | 23 (15) | |

| Autumn | 6 (4) | |

| Summer | 5 (3) | |

| Non-seasonal | 3 (2) | |

| Average weaning age (

|

> 10 weeks | 86 (57) |

| 8-10 weeks | 14 (9) | |

| Keeping goats with other livestock species

|

Cattle | 25 (27) |

| Sheep | 20 (22) | |

| Horses | 15 (16) | |

| Alpacas/camels | 12 (13) | |

| Birds | 9 (10) | |

| Pigs | 5 (5) | |

| None | 15 (16) | |

| Share paddocks (

|

No | 42 (28) |

| Yes | 38 (25) | |

| Occasionally | 20 (13) | |

| Grazing practice of farms when paddocks shared

|

Co-grazing with other livestock species | 60 (29) |

| Rotational grazing | 40 (19) |

| Question (responses) | Levels | Percentage (counts) |

| Other livestock species grazing with goats

|

Cattle | 29 (20) |

| Horses | 26 (18) | |

| Sheep | 20 (14) | |

| Alpacas/camels | 16 (11) | |

| Other | 10 (7) | |

| Age category of cattle grazing with goats (

|

Cattle between 1-2 years | 35 (7) |

| Cattle > 2 years | 30 (6) | |

| Weaned calves < 1 year | 20 (4) | |

| Unweaned calves | 15 (3) |

Knowledge of gastrointestinal parasites

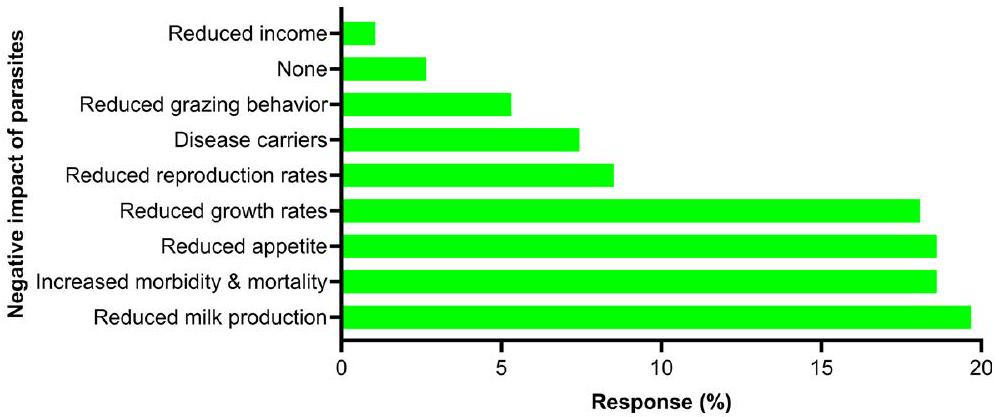

Of the 66 respondents,

parasites, black scour worm (Trichostrongylus spp.) (67%; 44/66), brown stomach worm (T. circumcincta) (65%), liver fluke (F. hepatica) (

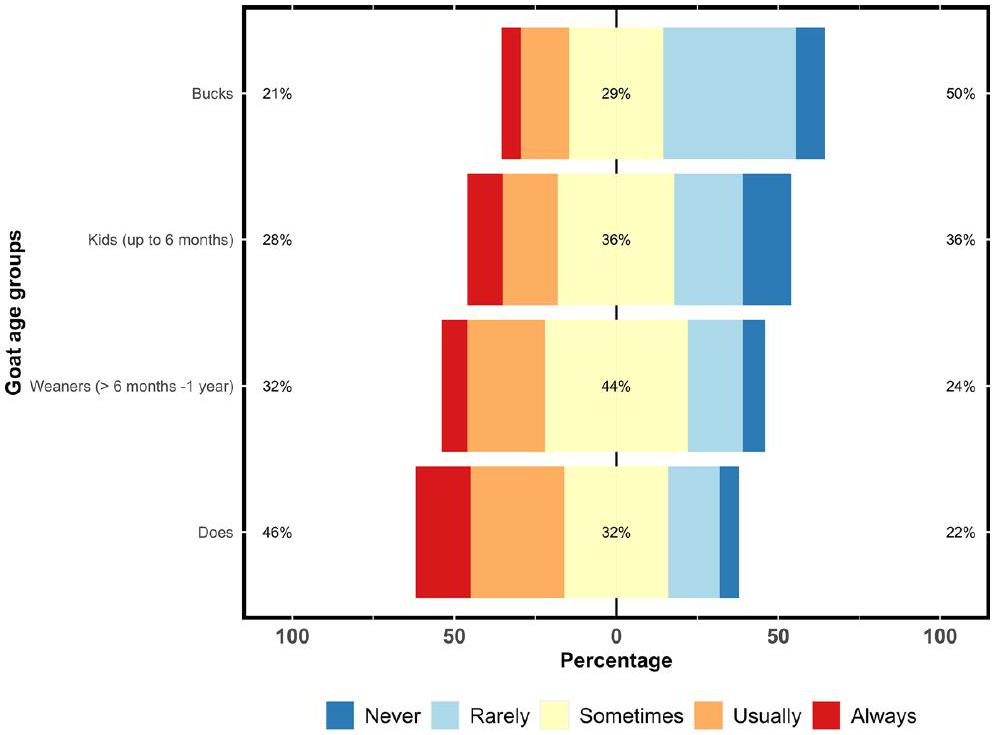

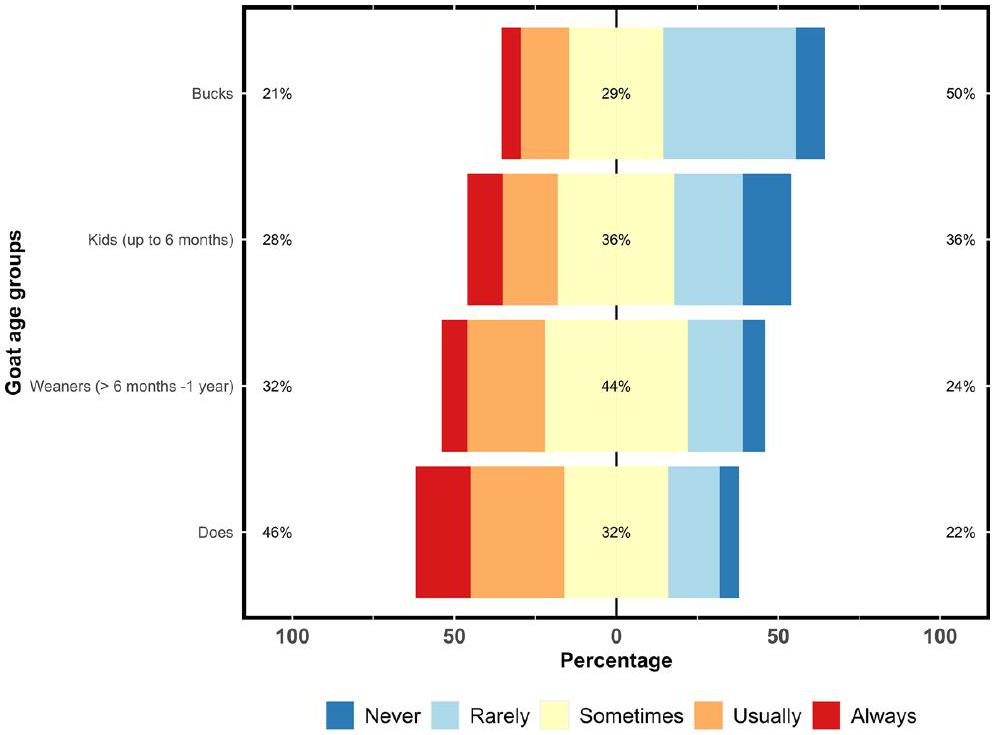

Respondents perceived that contamination of feed with faecal material (

pasture (

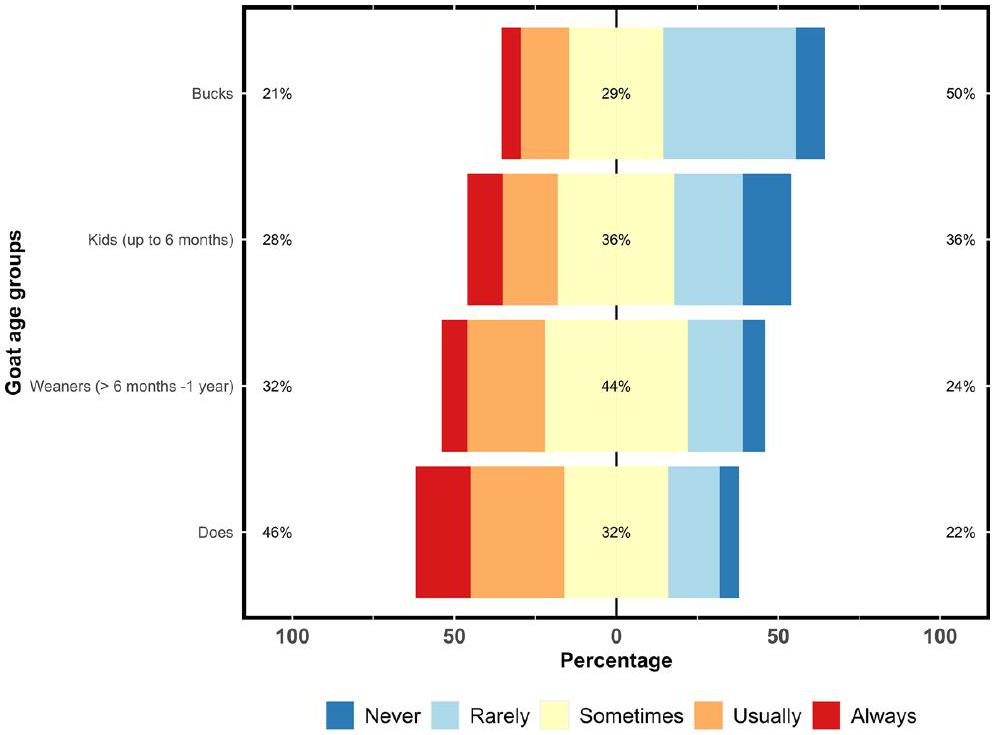

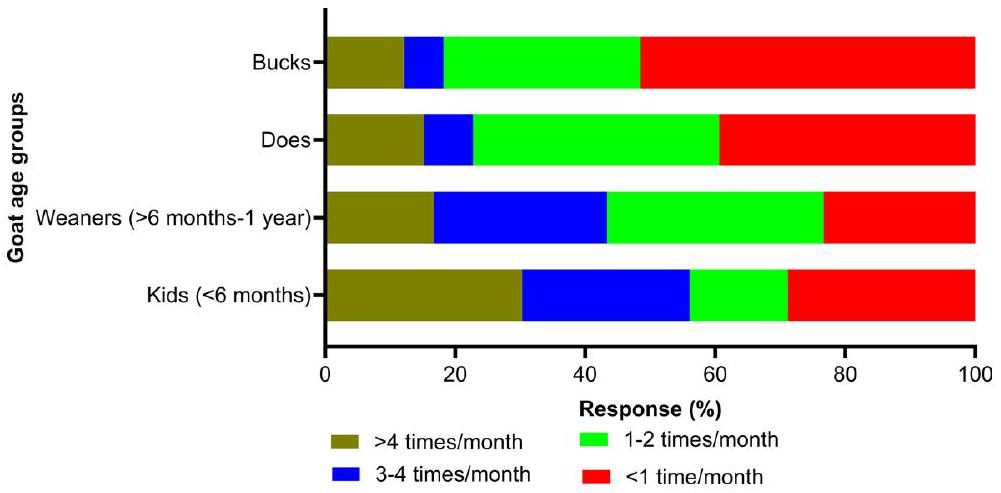

Diagnosis of gastrointestinal parasites

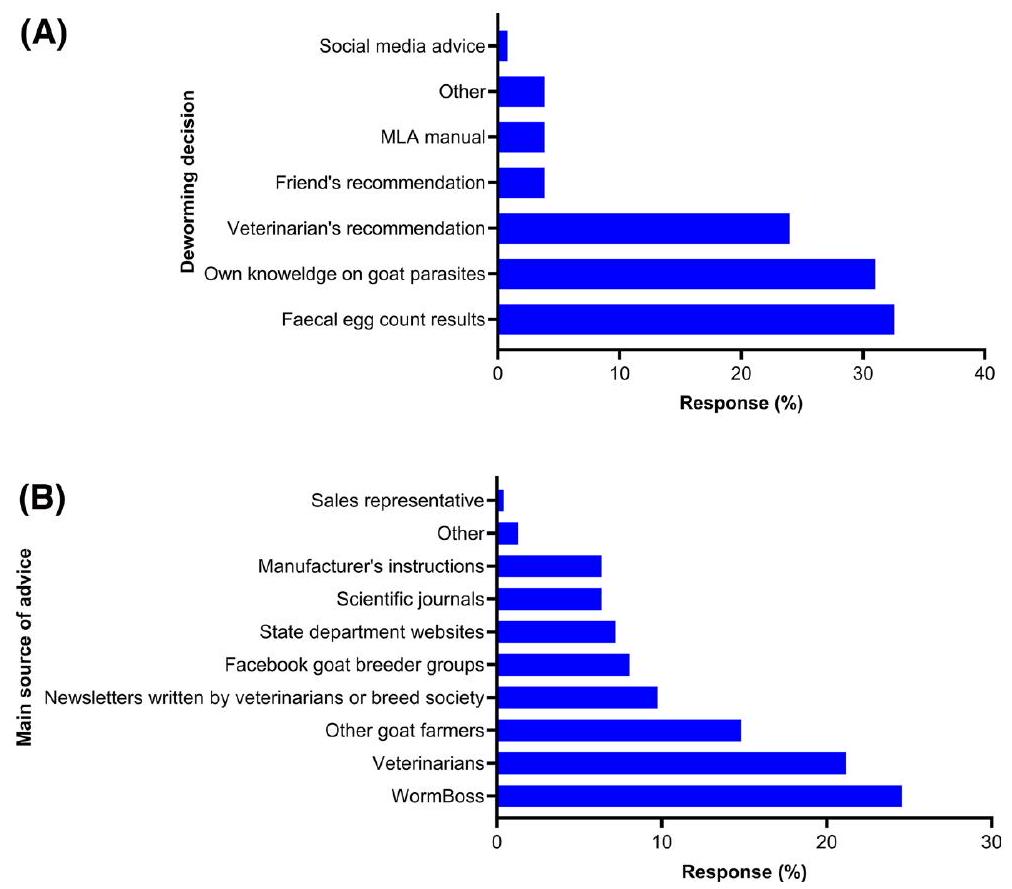

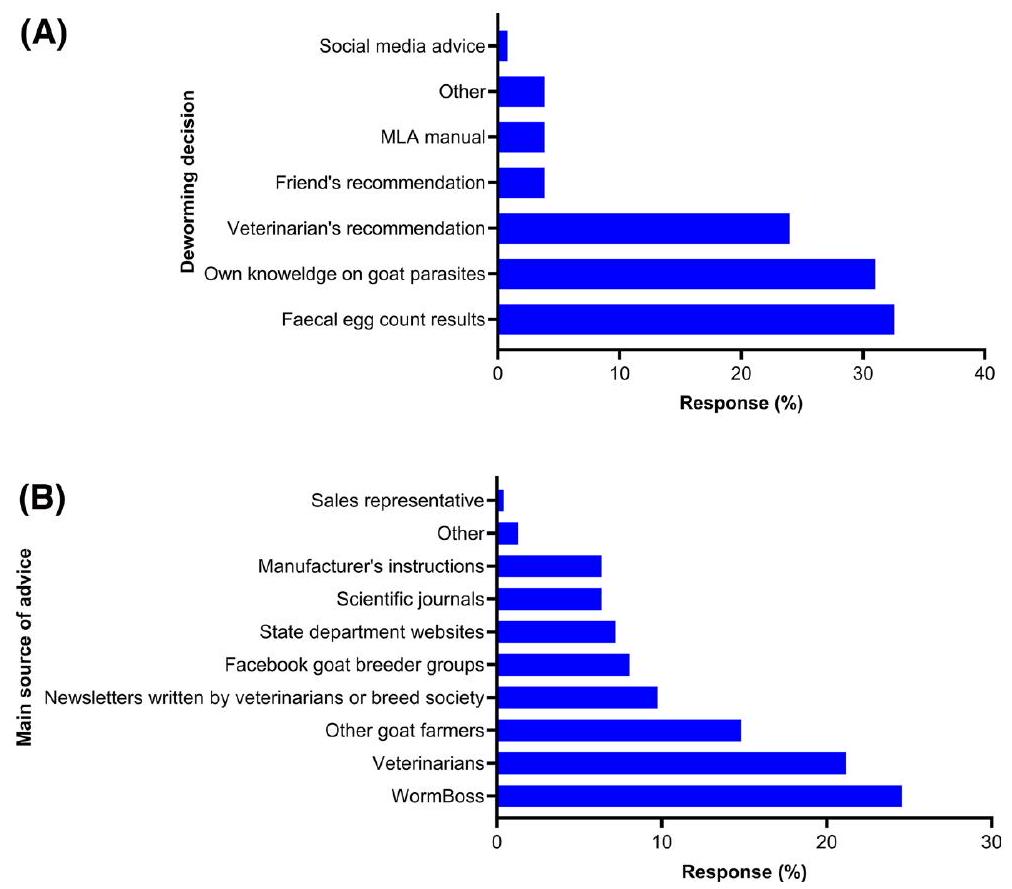

Antiparasitic drugs and other control methods for gastrointestinal parasites

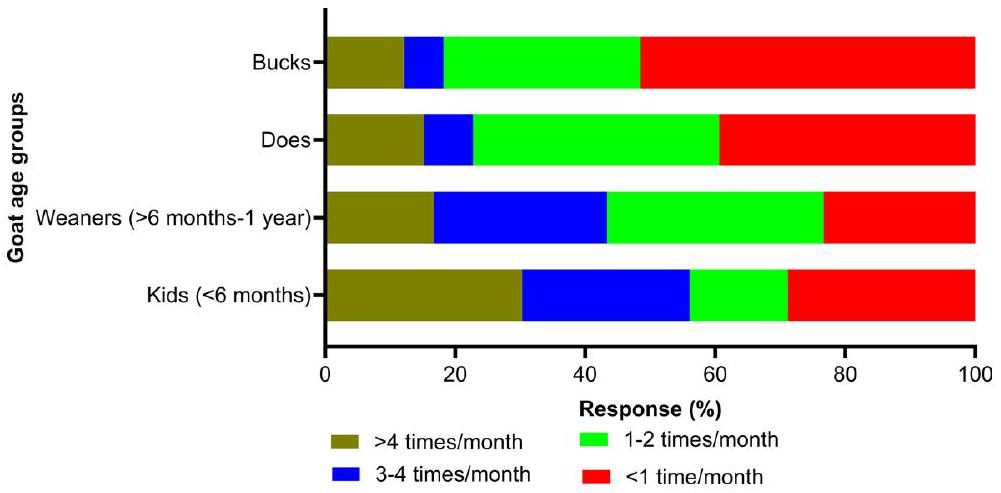

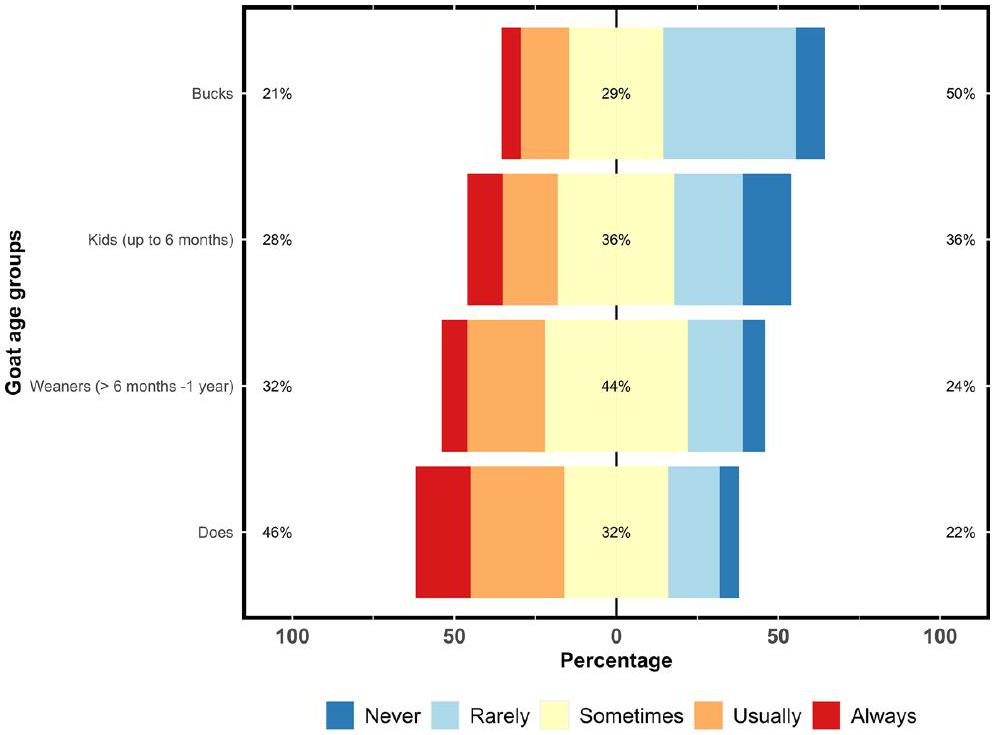

The choice of selecting various antiparasitic drugs varied among farms but it was dominated by a

combination of four anthelmintics (abamectin, albendazole, levamisole and closantel) (

Half of the respondents (

| Question (responses) | Levels | Percentage (counts) |

| Veterinary advice sought (

|

Yes | 55 (36) |

| No | 46 (30) | |

| Diagnostic method(s) used

|

Faecal egg counts | 33 (51) |

| Clinical signs | 32 (50) | |

| Larval culture | 13 (21) | |

| Observation of worms in the faeces | 12 (19) | |

| Post-mortem examination | 5 (7) | |

| Haematological examination | 2 (3) | |

| FAMACHAC/anaemia | 2 (3) | |

| None | 1 (1) | |

| Use of FEC (

|

Yes | 67 (44) |

| No | 32 (21) | |

| Do not know | 2 (1) | |

| Aim of FEC

|

Monitoring of worms burden | 28 (41) |

| Deworming decisions | 26 (39) | |

| Assessing the efficacy of dewormers | 25 (37) | |

| Diagnosing illness due to worms | 21 (31) | |

| Testing new goats in quarantine | 1 (1) | |

| Location of FEC testing (

|

On-farm by the staff | 42 (28) |

| Diagnostic laboratory | 40 (26) | |

| Veterinary clinic | 18 (12) | |

| Goats tested for FEC

|

Kids (

|

16 (31) |

| Weaners (> 6 months – 1 year) | 20 (39) | |

| Does/milkers | 21 (42) | |

| Wethers | 13 (26) | |

| Bucks | 18 (36) | |

| Aged (>6 years) | 11 (22) |

Multiple correspondence and principal component analyses

routinely calculate proper dewormer dosages for their goats. In contrast, respondents in cluster 2 managed semi-extensive or semi-intensive production systems and had

Coccidiosis

| Question (responses) | Levels | Percentage (counts) |

| Use antiparasitic drugs (

|

Yes | 94 (62) |

| No | 6 (4) | |

| Drug class(es) used (

|

||

| Benzimidazoles (

|

Fenbendazole

|

83 (35) |

| Albendazole | 14 (6) | |

| Non-specified BZs | 2 (1) | |

| Macrocyclic lactones (

|

Ivermectin | 40 (16) |

| Doramectin | 30 (12) | |

| Abamectin | 28 (11) | |

| Moxidectin | 3 (1) | |

| Other (

|

Levamisole | 26 (5) |

| Toltrazuril | 26 (5) | |

| Closantel | 21 (4) | |

| Morantel citrate | 21 (4) | |

| Monepantel | 5 (1) | |

| Commercial combination(s) (

|

4 (BZs + MLs + LEV + Closantel) | 59 (45) |

| 2 (MLs + Monepantel) | 24 (18) | |

| 2 (MLs + Derquantel) | 7 (5) | |

| 3 (BZs + MLs + LEV) | 7 (5) | |

| 2 (BZs + LEV) | 2 (2) | |

| 2 (MLs + PZQT) | 1 (1) | |

| Preparation(s) of antiparasitic drugs used

|

Oral | 69 (49) |

| Injectable | 10 (7) | |

| Oral and injectable | 8 (6) | |

| Oral and pour on | 6 (4) | |

| Oral, injectable and pour on | 4 (3) | |

| Pour on | 3 (2) | |

| Season(s) of dewormer

|

No fixed schedule | 38 (48) |

| Spring | 20 (26) | |

| Autumn | 16 (21) | |

| Summer | 16 (21) | |

| Winter | 14 (18) | |

| Rotating/changing antiparasitic drug(s) (

|

No rotation | 45 (30) |

| Annually | 30 (20) | |

| Every two years | 23 (15) | |

| Every three years | 2 (1) | |

Discussion

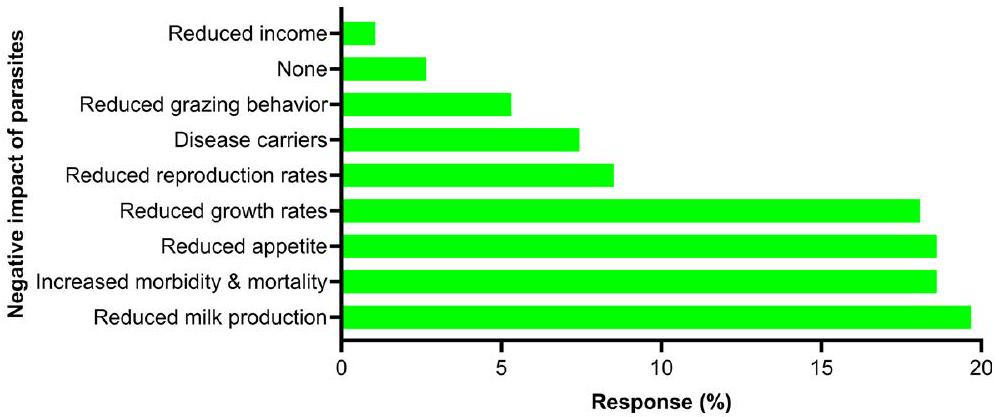

gastrointestinal parasitic infections caused production losses, resulting in widespread use of antiparasitic drugs (94%; 62/66) primarily registered for use in sheep and cattle. The most commonly used anthelmintics were a commercial combination of four anthelmintic drugs (abamectin, albendazole, levamisole and closantel), followed by BZs and MLs. Although targeted deworming was used on most respondents’ farms, very

[57]. An overwhelming majority of respondents (

The range of antiparasitic products registered for treating goats in Australia is limited (

The off-label use of anthelmintics in goats can pose further challenges when the dose rates vary. It is generally recommended to administer levamisole to goats at 1.5 -fold the dose recommended for sheep [5, 61] and other anthelmintics at 1.5- to two fold the sheep dose [5]. We found that over half of the respondents (

To the authors’ knowledge, there is currently no registered topical or injectable anthelmintic product for use in goats in Australia (https://wormboss.com.au/drenches-for-goats-using-products-correctly-and-legally/). However, this study revealed that some farmers were using injectable (ivermectin) and/or pour-on preparations (see Table 5); this finding is in concordance with those of Brunt et al. [38]. Using topical or injectable antiparasitic products in goats is not only ineffective but also toxic to goats as goats have much less subcutaneous fat than sheep and cattle (https://wormboss.com.au). Additionally, unauthorised treatments in goats may have variable withdrawal periods, particularly due to their differing metabolism, leading to animals or animal products entering supply systems and posing a risk to public health [63]. In Australia, the legal use of antiparasitic drugs that are not registered for goat use requires an off-label veterinary prescription (https://wormboss.com.au). Our study showed that WormBoss and veterinarians were the two most trusted sources (108/236) for advice on the use of antiparasitic drugs in dairy goats (Fig. 7b). In the given circumstances, it is prudent that prescription-based use of antiparasitic drugs will help avoid underdosing which can lead to AR and pose risks to the safety of goats as well as the potential residues in milk or meat.

Using prescription-only anthelmintics with a targeted deworming strategy can reduce the selection pressure associated with AR by increasing the refugia population. In the present study,

overseas [22], with very limited published reports available in Australia [64-67]. However, it is believed that goats and sheep typically harbour similar nematode species and are commonly found on the same premises ( 22 farms in this survey owned sheep and goats; Table 3). We assume that the AR situation in goats in Australia is comparable to that observed in sheep [68]. The increasing levels of AR for

The MCA results revealed that better GIN control practices were adopted on dairy goat farms with semiextensive or semi-intensive production systems, in contrast to farms with extensive production systems; the former constituted the majority of respondents in the present study. Additionally, farmers with good GIN control practices conducted FECs and employed targeted and/or strategic deworming strategies for adult dairy goats. Interestingly, farmers in this group also sought veterinary advice. However, they did not rotate antiparasitic drugs. This absence of drug rotation could be because farmers are likely actively seeking veterinary advice, and it is possible that veterinarians will not advise using antiparasitic drugs off-label, particularly in adult milking goats, as currently there is only one antiparasitic drug registered for use in Australian dairy goats. Although these findings are encouraging, dairy goat farmers using the extensive production system should adopt these best practices to make tailored on-farm decisions based on targeted deworming, which could slow the development of AR in GINs of goats.

Non-chemical methods, such as biological control and vaccination, can be used to control drug-resistant nematodes in goats. In the present study,

that COWP boluses are not used more than 4 times per year. We found that

In this study,

Although coccidiosis is mainly a disease of kids, we found that only

goats. To achieve this, it is essential to elevate the feed and water troughs off the ground and prevent water leakage, as Eimeria oocysts can survive in moist conditions. A major challenge in intensive dairy goat production systems arises when kidding occurs multiple times over a year to maintain a consistent year-round milk supply. If the farmer uses the same pens constantly for successive batches or introduces newly born kids to a pen already housing older animals, the kids born later are immediately exposed to a heavy challenge and can show severe coccidiosis in the first few weeks of life [78]. Australian dairy goat farmers should be aware of pathogenic agents and host and environmental risk factors that may lead to a higher incidence of coccidiosis. For example, kids of a young age (i.e.

Despite the novelty of this study, it is important to carefully interpret the results due to certain limitations. As of November 2023, the total number of dairy goat breeders registered with DGSA Ltd was 456 (personal communication). This includes breeders who are either out of practice or have ceased their membership, likely decreasing the size of our source population and increasing the proportion of the study population (respondents). Nevertheless, the response rate for this study was 14% (66/456), despite DGSA Ltd sending follow-up reminders to its members over a period of two months. This low response rate could introduce bias by either over-or-under representing certain results, potentially influenced by survey fatigue. This response rate (

has been favoured over deletion or mean replacement for handling missing data [82].

Conclusions

Abbreviations

| AR | Anthelmintic resistance |

| DGSA | Dairy Goat Society of Australia Ltd |

| GINs | Gastrointestinal nematodes |

| MCA | Multiple correspondence analyses |

Supplementary Information

Additional file 2: Table S1. Variables selected for multiple correspondent analysis to determine the best gastrointestinal nematode control practices in Australian dairy goats. Table S2. Feed and water access at Australian dairy goat farms that responded to the survey.

Additional file 3: Figure S1. Percentage of respondents reporting the frequency of cleaning of pens before each kidding at Australian dairy goat farms. Figure S2. Percentage of respondents reporting their perceptions of gastrointestinal parasites diagnosed at Australian dairy goat farms. Figure S3. Percentage of respondents reporting the use of antiparasitic drugs in Australian dairy goats. Figure S4. Percentage of respondents reporting their perceptions about the main clinical signs of coccidiosis observed in kids.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

curation, conceptualisation, writing-review and editing. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Author details

Published online: 24 January 2025

References

- Van Houtert MF, Sykes AR. Implications of nutrition for the ability of ruminants to withstand gastrointestinal nematode infections. Int J Parasitol. 1996;26:1151-67.

- Waller PJ. Sustainable helminth control of ruminants in developing countries. Vet Parasitol. 1997;71:195-207.

- Githigia SM, Thamsborg SM, Munyua WK, Maingi N. Impact of gastrointestinal helminths on production in goats in Kenya. Small Ruminant Res. 2001;42:21-9.

- Hoste H, Sotiraki S, Landau SY, Jackson F, Beveridge I. Goat-nematode interactions: think differently. Trends Parasitol. 2010;26:376-81.

- Hoste H, Sotiraki S, de Jesús Torres-Acosta JF. Control of endoparasitic nematode infections in goats. Vet Clinic Food Anim Pract. 2011;27:163-73.

- Rinaldi L, Veneziano V, Cringoli G. Dairy goat production and the importance of gastrointestinal strongyle parasitism. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:745-6.

- Fthenakis GC, Papadopoulos E. Impact of parasitism in goat production. Small Ruminant Res. 2018;163:21-3.

- Airs PM, Ventura-Cordero J, Mvula W, Takahashi T, Van Wyk J, Nalivata P, et al. Low-cost molecular methods to characterise gastrointestinal nematode co-infections of goats in Africa. Parasit Vectors. 2023;16:1-15.

- Ghimire TR, Bhattarai N. A survey of gastrointestinal parasites of goats in a goat market in Kathmandu. Nepal J Parasit Dis. 2019;43:686-95.

- Karshima SN, Karshima MN. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence, distribution and nematode species diversity in small ruminants: a Nigerian perspective. J Parasit Dis. 2020;44:702-18.

- Lianou DT, Arsenopoulos K, Michael CK, Mavrogianni VS, Papadopoulos E, Fthenakis GC. Dairy goats helminthosis and its potential predictors in Greece: findings from an extensive countrywide study. Vet Parasitol. 2023;320:109962.

- Maurizio A, Stancampiano L, Tessarin C, Pertile A, Pedrini G, Asti C, et al. Survey on endoparasites of dairy goats in North-Eastern Italy using a farm-tailored monitoring approach. Vet Sci. 2021;8:69.

- Mohammedsalih KM, Khalafalla A, Bashar A, Abakar A, Hessain A, Juma FR, et al. Epidemiology of strongyle nematode infections and first report

of benzimidazole resistance in Haemonchus contortus in goats in South Darfur State, Sudan. BMC Vet Res. 2019;15:1-13. - Radavelli WM, Pazinato R, Klauck V, Volpato A, Balzan A, Rossett J, et al. Occurence of gastrointestinal parasites in goats from the Western Santa Catarina, Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2014;23:101-4.

- Zanzani SA, Gazzonis AL, Di Cerbo A, Varady M, Manfredi MT. Gastrointestinal nematodes of dairy goats, anthelmintic resistance and practices of parasite control in Northern Italy. BMC Vet Res. 2014;10:1-10.

- Levine ND. Nematode parasites of domestic animals and of man. 2nd ed. Minneapolis: Burgess Publishing; 1980.

- Zajac AM. Gastrointestinal nematodes of small ruminants: life cycle, anthelmintics, and diagnosis. Vet Clinic Food Anim Pract. 2006;22:529-41.

- Joe L, Tristan J, Richard S, John WW, Fordyce G. Priority list of endemic diseases for the red meat industries. North Sydney: Meat and Livestock Australia Ltd; 2015.

- Alberti EG, Zanzani SA, Ferrari N, Bruni G, Manfredi MT. Effects of gastrointestinal nematodes on milk productivity in three dairy goat breeds. Small Ruminant Res. 2012;106:12-7.

- Alberti EG, Zanzani SA, Gazzonis AL, Zanatta G, Bruni G, Villa M, et al. Effects of gastrointestinal infections caused by nematodes on milk production in goats in a mountain ecosystem: comparison between a cosmopolite and a local breed. Small Ruminant Res. 2014;120:155-63.

- Paraud C, Chartier C. Facing anthelmintic resistance in goats. In: Simoes J, Gutierrez C, editors. Sustainable goat production in adverse environments. Cham: Springer International; 2017. p. 267-292. https://doi.org/10. 1007/978-3-319-71855-2_16.

- Baudinette E, O’Handley R, Trengove C. Anthelmintic resistance of gastrointestinal nematodes in goats: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vet Parasitol. 2022;312:109809.

- Galtier P, Escoula L, Camguilhem R, Alvinerie M. Comparative bioavailability of levamisole in non-lactating ewes and goats. Ann Rech Vet. 1981;12:109-15.

- Hennessy DR. Physiology, pharmacology and parasitology. Int J Parasitol. 1997;27:145-52.

- Dupuy J, Chartier C, Sutra JF, Alvinerie M. Eprinomectin in dairy goats: dose influence on plasma levels and excretion in milk. Parasitol Res. 2001;87:294-8.

- Kettle PR, Vlassoff A, Reid TC, Hotton CT. A survey of nematode control measures used by milking goat farmers and of anthelmintic resistance on their farms. N Z Vet J. 1983;31:139-43.

- Pearson AB, MacKenzie R. Parasite control in fibre goats: results of a postal questionnaire. N Z Vet J. 1986;34:198-9.

- Maingi N, Bjørn H, Thamsborg SM, Dangolla A, Kyvsgaard NC. A questionnaire survey of nematode parasite control practices on goat farms in Denmark. Vet Parasitol. 1996;66:25-37.

- Scherrer AM, Pomroy WE, Charleston WAG. Anthelmintic usage on goat farms in New Zealand: results of a postal survey. N Z Vet J. 1990;38:133-5.

- Hoste H, Chartier C, Etter E, Goudeau C, Soubirac F, Lefrileux Y. A questionnaire survey on the practices adopted to control gastrointestinal nematode parasitism in dairy goat farms in France. Vet Res Commun. 2000;24:459-69.

- Theodoropoulos G, Theodoropoulos H, Zervas G, Bartziokas E. Nematode parasite control practices of sheep and goat farmers in the region of Trikala, Greece. J Helminthol. 2000;74:89-93.

- Torres-Acosta JFJ, Aguilar-Caballero AJ, Le Bigot C, Hoste H, Canul-Ku HL, Santos-Ricalde R, et al. Comparing different formulae to test for gastrointestinal nematode resistance to benzimidazoles in smallholder goat farms in Mexico. Vet Parasitol. 2005;134:241-8.

- de Sá Guimarães A, Gouveia AMG, do Carmo FB, Gouveia GC, Silva MX, da Silva Vieira L, et al. Management practices to control gastrointestinal parasites in dairy and beef goats in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2011;176:265-69.

- de Waal T, Rinaldi L. Survey of endoparasite and parasite control practices by Irish goat owners. Kukovics S, editor. In: Goat science: from keeping to precision production. Rijeka: IntechOpen; 2023. https://doi.org/10.5772/ intechopen. 104279.

- Rufino-Moya PJ, Leva RZ, Reis LG, García IA, Di Genova DR, Gómez AS, et al. Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites in small ruminant farms in southern Spain. Animals. 2024;14:1668.

- Lyndal-Murphy M, James P, Bowles P, Watts R, Baxendell S. Options for the control of parasites in the Australian goat industry: a situational analysis

of parasites and parasite control. North Sydney: Meat and Livestock Australia Ltd; 2007. - Nogueira M, Gummow B, Gardiner CP, Cavalieri J, Fitzpatrick LA, Parker AJ. A survey of the meat goat industry in Queensland and New South Wales. 2. Herd management, reproductive performance and animal health. Anim Prod Sci. 2015;56:1533-44.

- Brunt LM, Rast L, Hernandez-Jover M, Brockwell YM, Woodgate RG. A producer survey of knowledge and practises on gastrointestinal nematode control within the Australian goat industry. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Rep. 2019;18:100325.

- Zalcman E, Cowled B. Farmer survey to assess the size of the Australian dairy goat industry. Aust Vet J. 2018;96:341-5.

- Mahmood AK, Khan MS, Khan MA, Bilal M, Farooq U. Lactic acidosis in goats: prevalence, intra-ruminal and haematological investigations. J Anim Plant Sci. 2013;23:1527-31.

- Zhang RY, Liu YJ, Yin YY, Jin W, Mao SY, Liu JH. Response of rumen microbiota, and metabolic profiles of rumen fluid, liver and serum of goats to high-grain diets. Animal. 2019;13:1855-64.

- Andrews AH. Some aspects of coccidiosis in sheep and goats. Small Ruminant Res. 2013;110:93-5.

- Anzuino K, Knowles TG, Lee MRF, Grogono-Thomas R. Survey of husbandry and health on UK commercial dairy goat farms. Vet Rec. 2019;185:267-267.

- Todd CG, Bruce B, Deeming L, Zobel G. Survival of replacement kids from birth to mating on commercial dairy goat farms in New Zealand. J Dairy Sci. 2019;102:9382-8.

- Leitner G, Krifucks O, Weisblit L, Lavi Y, Bernstein S, Merin U. The effect of caprine arthritis encephalitis virus infection on production in goats. Vet J. 2010;183:328-31.

- Echeverría I, De Miguel R, De Pablo-Maiso L, Glaria I, Benito AA, De Blas I, et al. Multi-platform detection of small ruminant lentivirus antibodies and provirus as biomarkers of production losses. Front Vet Sci. 2020;7:182.

- Dore S, Liciardi M, Amatiste S, Bergagna S, Bolzoni G, Caligiuri V, et al. Survey on small ruminant bacterial mastitis in Italy, 2013-2014. Small Ruminant Res. 2016;141:91-3.

- Battini M, Vieira A, Barbieri S, Ajuda I, Stilwell G, Mattiello S. Invited review: animal-based indicators for on-farm welfare assessment for dairy goats. J Dairy Sci. 2014;97:6625-48.

- Van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45:1-67.

- Feinsinger P, Spears EE, Poole RW. A simple measure of niche breadth. Ecology. 1981;62:27-32.

- Kassambara A. Practical guide to principal component methods in R (multivariate analysis book 2). PCA, M(CA), FAMD, MFA, HCPC, factoextra. 2017. https://www.sthda.com/english/.

- Lê S, Josse J, Husson F. FactoMineR: an R package for multivariate analysis. J Stat Softw. 2008;25:1-18.

- R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2023.

- Holm SA, Sörensen CRL, Thamsborg SM, Enemark HL. Gastrointestinal nematodes and anthelmintic resistance in Danish goat herds. Parasite. 2014;21:37.

- Domke AVM, Chartier C, Gjerde B, Leine N, Vatn S, Østerås O, et al. Worm control practice against gastro-intestinal parasites in Norwegian sheep and goat flocks. Acta Vet Scand. 2011;53:1-9.

- McKenzie RA, Green PE, Thornton AM, Blackall PJ. Feral goats and infectious disease: an abattoir survey. Aust Vet J. 1979;55:441-2.

- Beveridge I, Pullman AL, Henzell R, Martin RR. Helminth parasites of feral goats in South Australia. Aust Vet J. 1987;64:111-2.

- Silva LMR, Carrau T, Vila-Viçosa MJM, Musella V, Rinaldi L, Failing K, et al. Analysis of potential risk factors of caprine coccidiosis. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Rep. 2020;22:100458.

- Jackson F, Varady M, Bartley DJ. Managing anthelmintic resistance in goats: can we learn lessons from sheep? Small Ruminant Res. 2012;103:3-9.

- Playford MC, Smith AN, Love S, Besier RB, Kluver P, Bailey JN. Prevalence and severity of anthelmintic resistance in ovine gastrointestinal nematodes in Australia (2009-2012). Aust Vet J. 2014;92:464-71.

- Chartier C, Pors I, Sutra JF, Alvinerie M. Efficacy and pharmacokinetics of levamisole hydrochloride in goats with nematode infections. Vet Rec. 2000;146:350-1.

- Várady M, Papadopoulos E, Dolinská M, Königová A. Anthelmintic resistance in parasites of small ruminants: sheep versus goats. Helminthologia. 2011;48:137-44.

- Cutress D. Internal parasite control and goats: implications for a growing industry. 2022. http://businesswales.gov.wales/farmingconnect/business. Accessed July 2024.

- Barton NJ, Trainor BL, Urie JS, Atkins JW, Pymans MFS, Wolstencroft IR. Anthelmintic resistance in nematode parasites of goats. Aust Vet J. 1985;62:224-7.

- Veale PI. Resistance to macrocyclic lactones in nematodes of goats. Aust Vet J. 2002;80:303-4.

- Francis EK, Šlapeta J. Refugia or reservoir? Feral goats and their role in the maintenance and circulation of benzimidazole-resistant gastrointestinal nematodes on shared pastures. Parasitology. 2023;150:672-82.

- Gillham RJ, Obendorf DL. Therapeutic failure of levamisole in dairy goats. Aust Vet J. 1985;62:426-7.

- Kotze AC, Hunt PW. The current status and outlook for insecticide, acaricide and anthelmintic resistances across the Australian ruminant livestock industries: assessing the threat these resistances pose to the livestock sector. Aust Vet J. 2023;101:321-33.

- Arsenopoulos KV, Fthenakis GC, Katsarou El, Papadopoulos E. Haemonchosis: a challenging parasitic infection of sheep and goats. Animals. 2021;11:363.

- Healey K, Lawlor C, Knox MR, Chambers M, Lamb J. Field evaluation of Duddingtonia flagrans IAH 1297 for the reduction of worm burden in grazing animals: tracer studies in sheep. Vet Parasitol. 2018;253:48-54.

- Healey K, Lawlor C, Knox MR, Chambers M, Lamb J, Groves P. Field evaluation of Duddingtonia flagrans IAH 1297 for the reduction of worm burden in grazing animals: pasture larval studies in horses, cattle and goats. Vet Parasitol. 2018;258:124-32.

- Maingi N, Krecek RC, van Biljon N. Control of gastrointestinal nematodes in goats on pastures in South Africa using nematophagous fungi Duddingtonia flagrans and selective anthelmintic treatments. Vet Parasitol. 2006;138:328-36.

- Paraud C, Pors I, Chartier C. Efficiency of feeding Duddingtonia flagrans chlamydospores to control nematode parasites of first-season grazing goats in France. Vet Res Commun. 2007;31:305-15.

- Epe C, Holst C, Koopmann R, Schnieder T, Larsen M, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G. Experiences with Duddingtonia flagrans administration to parasitized small ruminants. Vet Parasitol. 2009;159:86-90.

- Vilela VL, Feitosa TF, Braga FR, de Araújo JV, de Oliveira Souto DV. Biological control of goat gastrointestinal helminthiasis by Duddingtonia flagrans in a semi-arid region of the northeastern Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2012;188:127-33.

- de Matos AFIM, Nobre COR, Monteiro JP, Bevilaqua CML, Smith WD, Teixeira M. Attempt to control Haemonchus contortus in dairy goats with Barbervax

, a vaccine derived from the nematode gut membrane glycoproteins. Small Ruminant Res. 2017;151:1-4. - Nobre COR, de Matos AFIM, Monteiro JP, de Souza V, Smith WD, Teixeira M. Benefits of vaccinating goats against Haemonchus contortus during gestation and lactation. Small Ruminant Res. 2020;182:46-51.

- Taylor MA, Coop RL, Wall RL. Veterinary parasitology. 4th ed. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell Science; 2016.

- de Macedo LO, Bezerra-Santos MA, de Mendonça CL, Alves LC, Ramos RAN, de Carvalho GA. Prevalence and risk factors associated with infection by Eimeria spp. in goats and sheep in Northeastern Brazil. J Parasit Dis. 2020;44:607-12.

- Cobanoglu C, Moreo PJ, Warde B. A comparison of mail, fax and webbased survey methods. Int J Mark Res. 2001;43:1-15.

- Miok K, Nguyen-Doan D, Robnik-Šikonja M, Zaharie D. Multiple imputation for biomedical data using Monte Carlo dropout autoencoders. 2019 E-Health and Bioengineering Conference (EHB 2019), 21-23 Nov 2019, Iasi. New York: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers; 2019. p. 1-4.

- Zhong H, Hu W, Penn JM. Application of multiple imputation in dealing with missing data in agricultural surveys: the case of bmp adoption. J Agric Resour Econ. 2018;43:78-102.

Publisher’s Note

- *Correspondence:

Abdul Jabbar

jabbara@unimelb.edu.au

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article