DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-05370-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39748358

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-02

مقارنة قوة السحب لطرق مختلفة تعتمد على الأنابيب الدقيقة في إزالة أدوات الأسنان المكسورة: دراسة مخبرية

الملخص

خلفية: يمكن أن يحدث كسر أداة سنية داخل نظام قناة الجذر أثناء علاج قناة الجذر، مما يعقد التنظيف والتشكيل الشامل. وبالتالي، يصبح إدارة الشظية المكسورة أمرًا حيويًا.

الطرق: تم قطع ثمانين ملفًا من النيكل والتيتانيوم (NiTi) #20 (ماني، توشيغي، اليابان) بمقدار 8 مم من الطرف، وثبتت على لوح من الفلين، وتم تصنيفها إلى خمس مجموعات (

الاستنتاج: جميع التقنيات المعتمدة على الميكروتيوب فعالة في إزالة الأدوات المكسورة، مع كون طرق غراء السيانوأكريلات والليزر مناسبة بشكل خاص للحالات التي تتطلب قوة أكبر.

الأهمية السريرية

المقدمة

الأدوات السنية المصنوعة من الفولاذ المقاوم للصدأ (S.S.) وسبائك النيكل والتيتانيوم (Ni-Ti) تستخدم على نطاق واسع بسبب مرونتها الفائقة ومقاومتها المعززة للإجهاد الالتوائي، مما يسهل تحقيق نتائج متوقعة في العلاج السني غير الجراحي [4]. ومع ذلك، يمكن أن تحدث الكسور بشكل غير متعمد حتى عند الالتزام بجميع المبادئ. لذلك، يصبح إزالة الأداة المكسورة من قناة الجذر أمرًا ضروريًا [5].

الإدارة غير الجراحية للأداة المكسورة تتضمن اتخاذ قرار بشأن ما إذا كان يجب إزالة الشظية أو تجاوزها. من المثالي إزالة الأداة المكسورة من قناة الجذر لتسهيل التنظيف والتشكيل الفعال [6]. إزالة أداة منفصلة من قناة الجذر أمر معقد، ويتطلب تدريبًا متخصصًا، وخبرة، وفهمًا عميقًا للطرق والتقنيات والمعدات المتاحة. يعتمد نجاح هذه الإزالة على عوامل تشمل الموقع، والرؤية، والحجم، والطول، ونوع الأداة المكسورة، بالإضافة إلى انحناء ونصف قطر قناة الجذر. كما أن خبرة ومهارات وإرهاق المشغل تؤثر بشكل كبير على النتيجة [7، 8]. تتوفر العديد من الأجهزة والتقنيات والطرق لاسترجاع الأدوات المنفصلة [9].

تم الإبلاغ عن إزالة الشظية باستخدام رؤوس فوق صوتية كنهج فعال، مع معدلات نجاح تتفاوت بشكل كبير من 33 إلى

من بين الطرق العديدة لاستخراج شظية مكسورة من قناة الجذر، تُستخدم تقنيات تعتمد على الميكروتيوب على نطاق واسع بعد الوصول إلى الثلث التاجي.

تم تقديم مجموعة متنوعة من الأطقم الجاهزة إلى السوق لهذا الغرض [13].

تشمل تقنية الميكروتيوب تعديلات مختلفة مثل الميكروتيوب والغراء، الميكروتيوب والسلك، الميكروتيوب والعمود الداخلي، وطريقة تم تقديمها مؤخرًا تتضمن ميكروتيوب وليزر. تتضمن تقنية الميكروتيوب والغراء استخدام غراء سيانوأكريلات، أو أيون زجاجي (GI)، أو مركبات وأسمنتات سنية لتثبيت الأداة المكسورة من خلال الاحتفاظ الميكانيكي. توفر هذه الطريقة وسيلة موثوقة لتأمين إزالة الأداة المكسورة [13، 14]. في تقنية الميكروتيوب والسلك، يتم تشكيل حلقة عن طريق تمرير كلا طرفي السلك عبر الأنبوب. تعمل هذه الحلقة مثل حبل، حيث تلتقط الجزء التاجي من الأداة المكسورة [15]. استنادًا إلى هذه الطريقة، تم تطوير عدة أطقم، بما في ذلك FRS [16]، BTR PEN [17]، وBTEX PEN. يتضمن TEX PEN قلمًا مع ثلاث إبر بمقاييس 25 و27 و30، والتي يتم اختيارها بناءً على حجم القناة. يتم تمرير سلك الفولاذ المقاوم للصدأ عبر الإبرة بطريقة تخلق حلقة في طرف الإبرة. تحتوي الأسلاك على أقطار من

نظرًا لعدم وجود طريقة قياسية لإزالة الأدوات المكسورة من قنوات الجذر ويواجه أطباء الأسنان تحديًا كبيرًا في هذه الحالات، فإن هدف هذه الدراسة هو مقارنة قوى السحب لخمس طرق لاسترجاع الأدوات المكسورة بناءً على تقنية الأنبوب: غراء سيانوأكريلات، راتنج مركب قابل للتصلب بالضوء، سلك، عمود داخلي، وليزر. يجب تحديد اختيار التقنية الأكثر ملاءمة بناءً على الحالة السريرية المحددة وكمية قوة السحب المطلوبة لاسترجاع ناجح. الفرضية الصفرية هي أن قوى السحب لا تختلف بين خمس طرق لاسترجاع الأدوات المكسورة.

المواد والطرق

استخدمت هذه الدراسة ثمانين ملف NiTi #20 (ماني، توشيغي، اليابان) كأدوات علاج الجذور. تم قطع هذه الأدوات بمقدار 8 مم من الطرف باستخدام مثقاب كربيد الشقوق مع جهاز يدوي عالي السرعة. ثم تم وضع الملفات المنفصلة في لوح من الفلين من الطرف، مع التأكد من أن الطرف الحر البالغ طوله 2 مم من الملف يقع فوق سطح اللوح. بناءً على الطريقة المستخدمة، تم تصنيف العينات إلى خمس مجموعات.

المجموعات التجريبية

الجزء المكشوف البالغ طوله 2 مم من الأداة المنفصلة. بناءً على وقت الإعداد من الدراسة الأولية، تم تثبيت الميكروتيوب بلا حركة لمدة 3 دقائق للسماح لللاصق بالتصلب (الشكل 1A).

في المجموعة 2 (الميكروتيوب والراتنج المركب القابل للتصلب بالضوء)، تم استخدام راتنج مركب قابل للتصلب بالضوء (Cirus Flow، إلسودنت، فرنسا) لتثبيت الأداة المكسورة في ميكروتيوب بقياس 21، مشابهة للمجموعة الأولى. تم إدخال ألياف بصرية (Fotona، Light Walker، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) بقطر

في المجموعة 3 (الميكروتيوب والسلك)، تم استخدام BTEX-PEN (Dimotech، دaya Tajhiz Teb Shomal، إيران) لإزالة الأداة المكسورة. تم استخدام إبرة بقياس 25 وسلك بقطر 0.1 مم. تم وضع الحلقة، التي تمثل “الحلقة”، فوق الطرف الحر البالغ طوله 2 مم من الأداة المنفصلة، وتم الإمساك بالشظية في الحلقة (الشكل 1D وE).

في المجموعة 4 (الميكروتيوب والعمود الداخلي)، تم استخدام إبرة سحب نخاع الشوكي بقياس 21 (Dr J، اليابان) كمستخرج. تم تصميم إبرة سحب نخاع الشوكي، التي تحتوي على ثقب قطني يمثل “العمود الداخلي”، لتناسب داخل الإبرة في اتجاه واحد فقط. تم تلميع الطرف الحاد للإبرة

في المجموعة 5 (الميكروتيوب والليزر)، غطت الميكروتيوبات بقياس 21 2 مم من الأدوات المنفصلة فوق سطح لوح الفلين. ثم تم إدخال ألياف بصرية بقطر 200 نانومتر في الميكروتيوبات من الجانب الآخر حتى وصل طرفها إلى الملفات. تم تطبيق الإشعاع باستخدام ليزر Nd: YAG (Fotona، Light Walker، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) لمدة 7 ثوانٍ عند 2 واط و10 هرتز (نبضات في الثانية)، مع الحفاظ على الاتصال بين الألياف البصرية والملف (الشكل 1H). تم قياس الزيادة في درجة الحرارة على السطح الخارجي للميكروتيوب في نقطة اللحام عند درجة حرارة الغرفة باستخدام ثيرموكوبل (DEC، Digital Equipment Corporation، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية).

قياس درجة حرارة السطح الخارجي للجذر

اختبار السحب

التحليل الإحصائي

النتائج

| مجموعات الدراسة | قوة السحب (المتوسط ± SD) |

| الميكروتيوب والسيانوأكريليت |

|

| الميكروتيوب والراتنج المركب |

|

| الميكروتيوب والسلك |

|

| الميكروتيوب والعمود الداخلي |

|

| الميكروتيوب والليزر |

|

قناة الجذر لأسنان الكلاب البشرية المستخرجة، تم قياس زيادة درجة الحرارة عند

المناقشة

توصي الإرشادات عمومًا بمحاولة الإزالة عند الإمكان، مع اعتبار الاحتفاظ فقط إذا كانت الإزالة غير الجراحية غير ناجحة [23]. على الرغم من اقتراح العديد من التقنيات لإزالة الأدوات المكسورة من نظام قناة الجذر، لا يزال من الصعب العثور على طريقة مقبولة عالميًا وآمنة وبسيطة وفعالة من حيث التكلفة مع معدل نجاح مرتفع باستمرار [8].

تبدأ المرحلة الأولية في إزالة أداة مكسورة من نظام قناة الجذر بإنشاء مسار مباشر إلى الجزء التاجي من الأداة. بعد ذلك، يجب إزالة جدران العاج المحيطة بالجزء التاجي من الأداة لكشف جزء صغير من الشظية المكسورة. بينما تم اقتراح استخدام مثاقب التريفين لهذه المهمة، فإن رؤوس الموجات فوق الصوتية هي الخيار المفضل بسبب أدائها المتفوق في إزالة العاج بأمان ودقة. في بعض الحالات، يتم إزالة الأداة المكسورة فقط من خلال الاهتزاز بالموجات فوق الصوتية. ومع ذلك، حتى عندما تصبح الشظية المكسورة في القناة فضفاضة وقابلة للحركة، فإن إزالتها لا تزال تمثل تحديًا. أظهرت نتائج الأبحاث الحديثة أن تطبيق الموجات فوق الصوتية يمكن أن يكون إجراءً يستغرق وقتًا طويلاً. قد يؤدي المحاولة العدوانية لإزالة أداة مكسورة من خلال الاهتزاز بالموجات فوق الصوتية، خاصة في الثلث القمي من قناة الجذر أو حول المنحنيات، إلى إزالة مفرطة للعاج الجذري وتطوير أخطاء طبية.

يشير إلى أن التقنيات البديلة قد تكون أكثر ملاءمة لهذه الحالات [27، 28].

وفقًا للدراسة التي أجراها تيروشي وآخرون [16]، يتطلب الأمر حدًا أدنى من التعرض يبلغ 0.7 مم للأداة المكسورة من أجل الاسترجاع الصحيح. من ناحية أخرى، تشير دراسة أخرى إلى أن زيادة الجزء المكشوف من الملف تعزز فعالية إزالته [22]. وبالتالي، في الدراسة الحالية، تم تحديد تعرض الملف عند 2 مم لتحسين فعالية الإزالة المحتملة.

في هذه الدراسة، تم مقارنة فعالية خمس طرق لإزالة الأدوات المنفصلة. تُعتبر طريقة الأنبوب الدقيق والغراء بديلاً أكثر تحفظًا وفعالية من حيث التكلفة وسهولة الوصول مقارنةً بالتقنيات الأخرى. قد تسهل الخصائص الذاتية التصلب واللصق لغراء السيانوأكريلات الالتصاق القوي بالجزء التاجي من الشظية المكسورة، مما يعزز القوة اللازمة للإزالة، بينما يقلل من الضرر الذي يلحق بعاج قناة الجذر. ومع ذلك، تقدم هذه الطريقة تحديات؛ على سبيل المثال، يجب أن يظل الأنبوب الدقيق ثابتًا بينما يتصلب الغراء حول الأداة المكسورة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، قد يكون من الصعب تحقيق ارتباط دقيق بين الغراء والجزء التاجي من الأداة المكسورة، مما يجعلها تقنية حساسة. لذلك، من الضروري أن يكون الارتباط بين الغراء والأداة المنفصلة قويًا بما يكفي لإزالة الشظية بنجاح.

استنادًا إلى نتائج هذه الدراسة، حققت طريقة الأنبوب الدقيق والغراء السيانوأكريليت أعلى قوة سحب، حوالي 64 نيوتن، مقارنة بجميع التقنيات الأخرى التي تم تقييمها. تتماشى نتائجنا مع تلك التي قدمها أولتشاك وآخرون [13]، الذين استخدموا ثلاثة مواد لاصقة مختلفة “راتنج مركب، غراء سيانوأكريليت، وأسمنت GI” في تقنية الأنبوب الدقيق والغراء لإزالة الملفات المكسورة. كشفت نتائجهم أن غراء السيانوأكريليت يظهر رابطة أقوى بكثير مقارنة بالمواد الأخرى. علاوة على ذلك، تدعم الأبحاث التي أجراها فروتا وآخرون [30] جدوى استخدام هذه الطريقة لإزالة الشظايا المكسورة من الثلث القمي لقناة الجذر. على العكس من ذلك، أفاد ويفلماير وآخرون [14] وهاجيwara وآخرون [22] بقوى سحب أقل لغراء السيانوأكريليت (14.7 نيوتن و10.7 نيوتن، على التوالي)، مقارنة بالقيم التي لوحظت في الدراسة الحالية. قد تعود عدة عوامل إلى هذا التباين، بما في ذلك اختلافات في علامة غراء السيانوأكريليت ونوع الملف المستخدم في تلك الدراسات. في الدراسة الحالية، تم استخدام ملفات NiTi K، بينما تم استخدام ملفات SS K في الدراسات المذكورة أعلاه. علاوة على ذلك، قد يكون هناك تفسير آخر وهو أن القطر الداخلي الأصغر

أظهرت مجموعة الأنبوب الدقيق والمركب القابل للتصلب بالضوء أقل قوة سحب.

حوالي 14 نيوتن، مقارنةً بأساليب أخرى في البحث الحالي. ومع ذلك، أفادت دراسة سابقة أجراها ويفلماير وآخرون [14] بقوة سحب تبلغ حوالي 62 نيوتن للمواد المركبة القابلة للتدفق التي يتم علاجها بالضوء، متجاوزة بشكل كبير القوة المسجلة في الدراسة الحالية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، أبرزت نتائج ويفلماير أن قوة السحب للمواد المركبة القابلة للتدفق التي يتم علاجها بالضوء كانت أكبر بكثير من تلك الخاصة بالغراء السيانوأكريلات، مما يعكس اختلافًا مع نتائج دراستنا الحالية. يمكن أن تُعزى الفروقات إلى عدة عوامل، مثل التباينات في الخصائص الفيزيائية والكيميائية للمواد المركبة، والاختلافات في علامات الغراء السيانوأكريلات، والتمييزات في أنواع الملفات المستخدمة في البحث (ملف فولاذي مقاوم للصدأ/H-file مقابل NiTi/K-file). علاوة على ذلك، فإن قطر الألياف الضوئية أمر حاسم في نقل الضوء من جهاز العلاج بالضوء إلى المادة المركبة، مما يؤثر على عملية العلاج. في هذه الدراسة، تم استخدام ألياف ضوئية بقطر

تقنية الحبل مع جهاز الحلقة، التي اقترحها غرين [15] في البداية، تعتمد على طريقة الأنبوب الدقيق والسلك. تم تكييف هذه الطريقة في أجهزة مختلفة لإزالة الأدوات المكسورة. مجموعة BTEX-PEN (Dimotech، دaya Tajhiz Teb Shomal، إيران) هي جهاز متخصص يجمع بين الجودة العالية والفعالية لتوفير قوة إمساك كافية. يبدو أن الوقت المطلوب لإزالة أداة مكسورة باستخدام هذه التقنية عمومًا أقل من الوقت المستغرق عند استخدام أداة فوق صوتية بمفردها [8]. في الطريقة التقليدية، كان الأنبوب يُمسك يدويًا أو باستخدام ملقط، مما جعل إدارته وتوجيهه أمرًا صعبًا للغاية. علاوة على ذلك، لتأمين الحلقة حول الشظية المكسورة، كان يجب لف الأطراف السائبة للسلك باستخدام حامل إبرة. لم تكن هذه المهمة صعبة فحسب، بل كانت غالبًا ما تتطلب مساعدة شخص آخر [15]. لذلك، فإن استخدام قلم لإزالة الشظايا المكسورة يمثل بديلاً أبسط بكثير للطريقة التقليدية [32]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، وفقًا لتيروشي وآخرين [8]، يُوصى باستخدام طريقة الأنبوب الدقيق والسلك لاستخراج الأدوات المكسورة من قناة الجذر التي

لا يمكن إزالته باستخدام رؤوس الموجات فوق الصوتية، لإزالة الشظايا التي تزيد عن 4.5 مم، و/أو للشظايا المكسورة في قنوات الجذر ذات الانحناء الذي يزيد عن 30 درجة. واحدة من التحديات الكبيرة التي تم مواجهتها أثناء تطبيق الأنبوب الدقيق والسلك هي عدم استقرار حلقة السلك حول الشظية المكسورة. على الرغم من المناورة الدقيقة والت placement، قد تصبح حلقة السلك فضفاضة، مما يقلل من فعالية التقنية وقد يؤدي إلى تعقيد الإجراء. تؤكد هذه المشكلة على الحاجة إلى تحسين التقنية في المستقبل. كما تبرز أهمية مهارات وخبرة المشغل في تطبيق تقنية الحلقة بنجاح. ومع ذلك، فإن أحد عيوب هذه الطريقة هو اعتمادها على التكبير. يُوصى بمزيد من البحث لمعالجة هذه القيود وتعزيز القدرة على التنبؤ ونجاح إزالة أدوات الكسر في طب الأسنان الداخلي.

لقد تم اقتراح استخدام ليزر Nd:YAG في لحام سبائك الفولاذ المقاوم للصدأ وسبائك النيكل والتيتانيوم لإنشاء اتصال ثابت. يتم استخدام هذا النوع من الليزر، المزود بألياف بصرية ذات قطر صغير، في طب الأسنان لعلاج الجذور لأغراض التعقيم وإعادة المعالجة، مثل تليين مادة الجوتا-بيرشا، وإزالة المواد السدادة، وتجاوز أو استرجاع الأدوات المكسورة. في الدراسة الحالية، كانت قوة السحب المتوسطة في طريقة الميكروتيوب والليزر حوالي 60 نيوتن، وهو ما كان أعلى بكثير من طرق الميكروتيوب والسلك، والميكروتيوب والمركب القابل للتصلب بالضوء، والميكروتيوب والمحور الداخلي. كانت نتائجنا متعارضة مع نتائج هاجيواara. قد يُعزى هذا التباين إلى عوامل مختلفة، بما في ذلك نوع الليزر، إعدادات جهاز الليزر (الطاقة، التردد، النبض)، نوع الشظية (فولاذ مقاوم للصدأ مقابل نيكل-تيتانيوم/ ملف يدوي مقابل ملف دوار)، وقطر الأنبوب.

ارتفاع في درجة حرارة الأنسجة المحيطة بالجذر [38]. أفاد بودولاك وآخرون [36] أن استخدام ليزر Nd:YAG مع إعداد طاقة

نظرًا لعدم وجود دراسة شاملة تقيم قوة السحب المطلوبة لإزالة الأدوات المكسورة تحت ظروف سريرية متنوعة – مثل نوع الملف المكسور (يدوي أو دوار)، المادة (الفولاذ المقاوم للصدأ أو النيكل-titanium)، طول وقطر الشظية، قطر القناة، درجة انحناء القناة، وموقع الكسر – تستند هذه الدراسة إلى نتائج تيروشي وآخرون [8] لاستنتاج ما يلي: عندما يتجاوز طول الشظية المكسورة 3 مم، ويكون لها قطر أكبر، وتقع في قناة ذات انحناء يزيد عن 30 درجة، أو تقع في المناطق القمية للقناة، فإن قوة سحب أعلى تكون ضرورية للإزالة. وبالتالي، يجب استخدام تقنيات قادرة على exerting قوى سحب أكبر في مثل هذه السيناريوهات، بينما قد تكون الطرق التي تتطلب قوى أقل كافية للظروف الأقل تطلبًا.

لقد كانت الطريقة الأساسية لاستخدام إبرة العمود الفقري تقليديًا تتضمن استخدام أنبوب مع ملف H أو عمود داخلي دون إنشاء نافذة على الأنبوب. ومع ذلك، في هذه الدراسة، قمنا بتعديل التقنية من خلال إنشاء نافذة على الأنبوب باستخدام طاحونة، مما جعل آليتها مشابهة لطريقة IRS [18].

وفقًا لنتائج غادزيلا وآخرين [41]، تتراوح القوة المطلوبة لاستخراج الأسنان بدون صدمة لتمزق ألياف الرباط السني بين 102 و 309 نيوتن. هذه القوى، المطبقة على مدى الزمن، أعلى بشكل ملحوظ من تلك التي تم قياسها في الدراسة الحالية لإزالة الأسنان المكسورة.

الأدوات، التي تراوحت من 14 إلى 64 نيوتن. علاوة على ذلك، أفاد ديترش وآخرون [42] أن قوى الاستخراج باستخدام بنكس

بشكل عام، يتطلب نجاح جميع الطرق لإزالة الأدوات المكسورة معرفة كافية ومهارة وخبرة من المشغل، بالإضافة إلى الوصول إلى معدات تكبير مناسبة مثل الميكروسكوبات الجراحية السنية. يجب ملاحظة أنه قبل إجراء أي إجراء لاسترجاع الأداة المكسورة، يجب تقييم مزايا وعيوب كل طريقة بعناية. علاوة على ذلك، يجب أن يتم اتخاذ القرار بإزالة أو تجاوز أو ترك الشظية المكسورة بناءً على فوائد المريض والحكم السريري. عندما يتم اتخاذ القرار بإزالة الشظية المكسورة من قناة الجذر، يتم تحديد اختيار الطريقة المناسبة بناءً على الظروف الحالية، بما في ذلك الطول والقطر وموقع الأداة المكسورة داخل قناة الجذر، ودرجة انحناء الجذر، والرؤية والوصول إلى الشظية المكسورة، بالإضافة إلى مهارة المشغل في تنفيذ تقنية الاسترجاع.

الخاتمة

شكر وتقدير

رقم التجربة السريرية

مساهمات المؤلفين

الإعداد، علق على النسخ السابقة من المخطوطة. قرأ ووافق على المخطوطة النهائية. م.ك: جمع البيانات والتحليل، علق على النسخ السابقة من المخطوطة. قرأ ووافق على المخطوطة النهائية. ف.هـ: علق على النسخ السابقة من المخطوطة. ب.س: تصور وتصميم الدراسة، إعداد المواد، علق على النسخ السابقة من المخطوطة. قرأ ووافق على المخطوطة النهائية. م.أ: تصور وتصميم الدراسة، إعداد المواد، علق على النسخ السابقة من المخطوطة. قرأ ووافق على المخطوطة النهائية. م.ك: جمع البيانات والتحليل، علق على النسخ السابقة من المخطوطة. قرأ ووافق على المخطوطة النهائية.

ف.هـ: علق على النسخ السابقة من المخطوطة.

ب.س: تصور وتصميم الدراسة، إعداد المواد، علق على النسخ السابقة من المخطوطة. قرأ ووافق على المخطوطة النهائية.

التمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 02 يناير 2025

References

- Amza O, Dimitriu B, Suciu I, Bartok R, Chirila M. Etiology and prevention of an endodontic iatrogenic event: instrument fracture. JML. 2020;13(3):378-381. https://doi.org/10.25122/jml-2020-0137.

- Spili P, Parashos P, Messer HH. The impact of instrument fracture on outcome of endodontic treatment. J Endod. 2005;31(12):845-50. https:// doi.org/10.1097/01.don.0000164127.62864.7c.

- Simon S, Machtou P, Tomson P, Adams N, Lumley P. Influence of fractured instruments on the success rate of endodontic treatment. Dental update. 2008;35(3):172-9. https://doi.org/10.12968/denu.2008.35.3.172

- Zupanc J, Vahdat-Pajouh N, Schäfer E. New thermomechanically treated NiTi alloys-a review. Int Endod J. 2018;51(10):1088-103. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/iej.12924.

- Parashos P, Messer HH. Rotary NiTi instrument fracture and its consequences. J Endod. 2006;32(11):1031-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen. 2006.06.008.

- Nevares G, Cunha RS, Zuolo ML, da Silveira Bueno CE. Success rates for removing or bypassing fractured instruments: a prospective clinical study. J Endod. 2012;38(4):442-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2011.12. 009.

- Terauchi Y, Sexton C, Bakland LK, Bogen G. Factors affecting the removal time of separated instruments. J Endod. 2021;47(8):1245-52. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.joen.2021.05.003.

- Terauchi Y, Ali WT, Abielhassan MM. Present status and future directions: removal of fractured instruments. Int Endod J. 2022;55(3):685-709. https://doi.org/10.1111/iej.13743.

- Rambabu T. Management of fractured endodontic instruments in root canal: a review. JSD. 2020;4(2):40-8. https://doi.org/10.5005/jsd-4-2-40.

- Yang Q, Cheung GS-P, Shen Y, Huang D, Zhou X, Gao Y. The remaining dentin thickness investigation of the attempt to remove broken instrument from mesiobuccal canals of maxillary first molars with virtual simulation technique. BMC Oral Health. 2015;28(15):1-8. https://doi.org/

. - Plotino G, Pameijer CH, Grande NM, Somma F. Ultrasonics in endodontics: a review of the literature. J Endod. 2007;33(2):81-95. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.joen.2006.10.008Get.

- Shaik I, Qadri F, Deshmukh R, Clement C, Patel A, Khan M. Comparing techniques for removal of separated endodontic instruments: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Health Sci. 2022;6(S1):13792-13805. https://doi.org/10.53730/ijhs.v6nS1.8497.

- Olczak K, Grabarczyk J, Szymański W. Removing Fractured Endodontic Files with a Tube Technique-The Strength of the Glued Joint: TubeEndodontic File Setup. Materials. 2023;16(11):4100. https://doi.org/10. 3390/ma16114100.

- Wefelmeier M, Eveslage M, Bürklein S, Ott K, Kaup M. Removing fractured endodontic instruments with a modified tube technique using a lightcuring composite. J Endod. 2015;41(5):733-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. joen.2015.01.018Get.

- Roig-Greene JL. The retrieval of foreign objects from root canals: a simple aid. J Endod. 1983;9(9):394-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0099-2399(83) 80193-9.

- Terauchi Y, O’Leary L, Suda H. Removal of separated files from root canals with a new file-removal system. J Endod. 2006;32(8):789-97. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.joen.2005.12.009.

- Dulundu M, Helvacioglu-Yigit D. The Efficiency of the BTR-Pen System in Removing Different Types of Broken Instruments from Root Canals and Its Effect on the Fracture Resistance of Roots. Materials. 2022;15(17):5816. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15175816.

- Ruddle CJ. Nonsurgical retreatment. J Endod. 2004;30(12):827-45. https:// doi.org/10.1097/01.don.0000145033.15701.2d.

- AI-Zahrani MS, AI-Nazhan S. Retrieval of separated instruments using a combined method with a modified vista dental tip. Saudi Endod J. 2012;2(1):41-5. https://doi.org/10.4103/1658-5984.104421.

- Alomairy KH. Evaluating two techniques on removal of fractured rotary nickel-titanium endodontic instruments from root canals: an in vitro study. J Endod. 2009;35(4):559-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2008.12. 019.

- Mehrpouya M, Gisario A, Elahinia M. Laser welding of NiTi shape memory alloy: A review J Manuf Process. 2018;31(1):162-86. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.jmapro.2017.11.011.

- Hagiwara R, Suehara M, Fujii R, Kato H, Nakagawa KI, Oda Y. Laser welding method for removal of instruments debris from root canals. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 2013;54(2):81-8. https://doi.org/10.2209/tdcpublication.54.81.

- McGuigan MB, Louca C, Duncan HF. Clinical decision-making after endodontic instrument fracture. BDJ. 2013;214(8):395-400. https://doi.org/10. 1038/sj.bdj.2013.379.

- Vouzara T, Lyroudia K. Separated instrument in endodontics: Frequency, treatment and prognosis. BJDM. 2018;22(3):123-32. https://doi.org/10. 2478/bjdm-2018-0022.

- Souter NJ, Messer HH. Complications associated with fractured file removal using an ultrasonic technique. J Endod. 2005;31(6):450-2. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.don.0000148148.98255.15.

- Pruthi PJ, Nawal RR, Talwar S, Verma M. Comparative evaluation of the effectiveness of ultrasonic tips versus the Terauchi file retrieval kit for the removal of separated endodontic instruments. RDE. 2020;45(2):e14. https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2020.45.e14.

- Yang Q, Shen Y, Huang D, Zhou X, Gao Y, Haapasalo M. Evaluation of two trephine techniques for removal of fractured rotary nickel-titanium instruments from root canals. J Endod. 2017;43(1):116-20. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.joen.2016.09.001.

- Ward JR, Parashos P, Messer HH. Evaluation of an ultrasonic technique to remove fractured rotary nickel-titanium endodontic instruments from root canals: an experimental study. J Endod. 2003;29(11):756-63. https:// doi.org/10.1097/00004770-200311000-00017.

- Korde JM, Kandasubramanian B. Biocompatible alkyl cyanoacrylates and their derivatives as bio-adhesives. Biomater Sci. 2018;6(7):1691-711 . https://doi.org/10.1039/C8BM00312B.

- Frota LMA, Aguiar BA, Aragão MGB, de Vasconcelos BC. Removal of Separated Endodontic K-File with the Aid of Hypodermic Needle and

31. Raja PR. Cyanoacrylate adhesives: A critical review. Reviews of Adhesion and Adhesives. 2016;4(4):398-416. https://doi.org/10.7569/RAA.2016. 097315.

32. Terauchi Y, O’Leary L, Kikuchi I, Asanagi M, Yoshioka T, Kobayashi C, Suda H. Evaluation of the efficiency of a new file removal system in comparison with two conventional systems. J Endod. 2007;33(5):585-8. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2006.12.018.

33. Cruz A, Mercado-Soto CG, Ceja I, Gascón LG, Cholico P, Palafox-Sánchez CA. Removal of an instrument fractured by ultrasound and the instrument removal system under visual magnification. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2015;16(3):238-42. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1668.

34. Perveen A, Molardi C, Fornaini C. Applications of laser welding in dentistry: a state-of-the-art review. Micromachines. 2018;28;9(5):209. https:// doi.org/10.3390/mi9050209.

35. Kamali AS, Deepti J, Karthick A, Prakash V, Andro S. Lasers and its advantages in endodontics-a review. NVEO Journal. 2021;8(4):6386-91. https:// doi.org/10.5152/nnu.2021.1374.

36. Podolak B, Nowicka A, Woźniak K, Szyszka-Sommerfeld L, Dura W, Borawski M, et al. Root Surface Temperature Increases during Root Canal Filling In Vitro with Nd: YAG Laser-Softened Gutta-Percha. J Healthc Eng. 2020;2020(5):8828272. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8828272.

37. Cvikl B, Klimscha J, Holly M, Zeitlinger M, Gruber R, Moritz A. Removal of fractured endodontic instruments using an Nd: YAG laser. Quintessence Int. 2014;45(7):569-75. https://doi.org/10.3290/j.qi.a31961.

38. Palazzi F, Blasi A, Mohammadi Z, Fabbro MD, Estrela C. Penetration of sodium hypochlorite modified with surfactants into root canal dentin. Braz Dent J. 2016;27(2):208-16. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-6440201600 650.

39. Ramsköld LO, Fong CD, Strömberg T. Thermal effects and antibacterial properties of energy levels required to sterilize stained root canals with an Nd: YAG laser. J Endod. 1997;23(2):96-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0099-2399(97)80253-1.

40. Aminsobhani M, Hashemi N, Hamidzadeh F, Sarraf P. Broken Instrument Removal Methods with a Minireview of the Literature. Case Rep Dent. 2024;2024(13):9665987. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/9665987.

41. Gadzella TJ, Hynkova K, Westover L, Addison O, Romanyk DL. A novel method for simulating ex vivo tooth extractions under varying applied loads. Clin Biomech (Bristol). 2023;110:106116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. clinbiomech.2023.106116.

42. Dietrich T, Schmid I, Locher M, Addison O. Extraction force and its determinants for minimally invasive vertical tooth extraction. JMBBM. 2020;105:103711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2020.103711.

ملاحظة الناشر

- *المراسلة:

محسن أمين صباني

maminsobhani@yahoo.com

بگاه سراف

sarraf_p@sina.tums.ac.ir

القائمة الكاملة لمعلومات المؤلف متاحة في نهاية المقال

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-05370-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39748358

Publication Date: 2025-01-02

Comparison of the pull-out force of different microtube-based methods in fractured endodontic instrument removal: An in-vitro study

Abstract

Background The fracture of an endodontic instrument within the root canal system can occur during root canal therapy, complicating thorough cleaning and shaping. Consequently, managing the broken fragment becomes crucial.

Methods Eighty Nickel-titanium (NiTi) #20 K-files (Mani, Tochigi, Japan) were cut 8 mm from the tip, fixed into a corkboard, and classified into five groups (

Conclusion All microtube-based techniques are effective for fractured instrument removal, with cyanoacrylate glue and laser methods being particularly suitable for cases that require higher force.

Clinical Relevance

Introduction

Endodontic instruments fabricated from stainless steel (S.S.) and nickel-titanium (Ni-Ti) alloys are extensively utilized due to their superior flexibility and enhanced resistance to torsional stress, facilitating predictable outcomes in non-surgical endodontic therapy [4]. However, fractures can still occur inadvertently even when all principles are adhered to. Therefore, removing the broken instrument from the root canal becomes essential [5].

Non-surgical management of a fractured instrument involves deciding whether to remove the fragment or bypass it. Optimally, the broken instrument should be removed from the root canal to facilitate effective cleaning and shaping [6]. Removing a separated instrument from the root canal is complex, requiring specialized training, experience, and a deep understanding of the available methods, techniques, and equipment. The success of such removal depends on factors including the location, visibility, size, length, and type of the fractured instrument, as well as the curvature and radius of the root canal. The operator’s experience, skills, and fatigue also significantly impact the outcome [7, 8]. Many devices, techniques, and methods are available for retrieving separated instruments [9].

Removal of the fragment using ultrasonic tips has been reported as an effective approach, with success rates varying widely from 33 to

Among the several methods for extracting a broken fragment from the root canal, microtube-based techniques are widely used after gaining access to the coronal

third. A variety of pre-assembled kits have been introduced to the market for this purpose [13].

The microtube technique includes various modifications such as microtube and glue, microtube and wire, microtube and internal shaft, and a recently introduced method involving a microtube and laser. The microtube and glue technique involves the use of cyanoacrylate glue, glass ionomer (GI), or dental composites and cements to fix the fractured instrument through mechanical retention. This method provides a reliable way to secure the broken instrument removal [13, 14]. In the microtube and wire technique, a loop is formed by passing both ends of the wire through the tube. This loop acts like a lasso, capturing the coronal part of the broken instrument [15]. Based on this method, several kits, including FRS [16], BTR PEN [17], and BTEX PEN, have been developed. TEX PEN includes a pen along with three needles with gauges of 25,27 , and 30 , which are selected based on the size of the canal. The stainless-steel wire is passed through the needle in such a way that a loop is created at the tip of the needle. The wires have diameters of

Since there is no standard method for removing broken instruments from root canals and dentists face a significant challenge in these situations, the aim of this study is to compare the pull-out forces of five broken instrument retrieval methods based on the tube technique: cyanoacrylate glue, light-cured flowable composite, wire, internal shaft, and laser. The choice of the most appropriate technique should be determined by the specific clinical situation and the amount of pull-out force required for successful retrieval. The null hypothesis is that the pull-out forces do not vary among the five broken instrument retrieval methods.

Materials and Methods

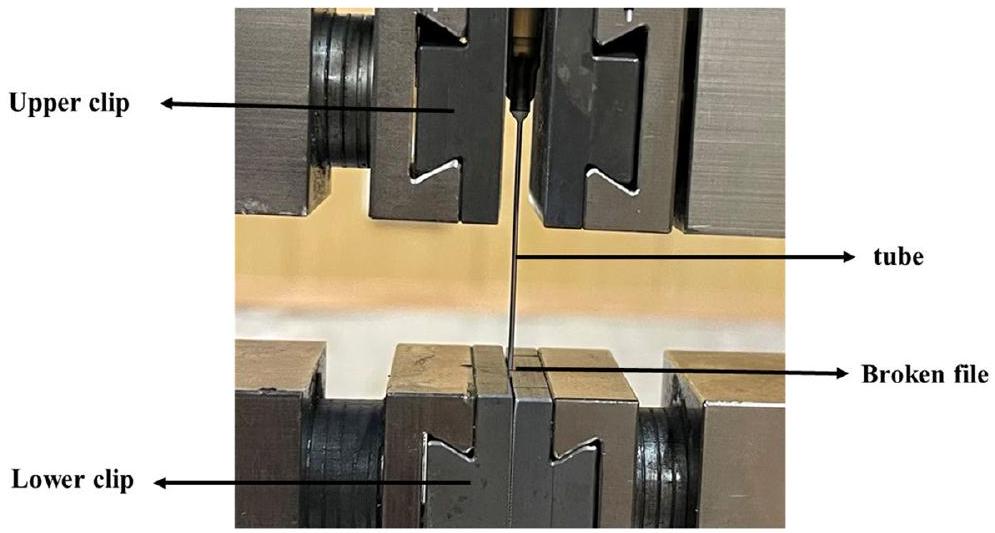

This study utilized eighty NiTi #20 K-files (Mani, Tochigi, Japan) as the endodontic instruments. These instruments were cut 8 mm from the tip using a fissure carbide bur with a high-speed handpiece. The separated files were then placed into a corkboard from the tip, ensuring that the 2 mm free end of the file was located above the board surface. Based on the method used, the specimens were classified into five groups.

Experimental groups

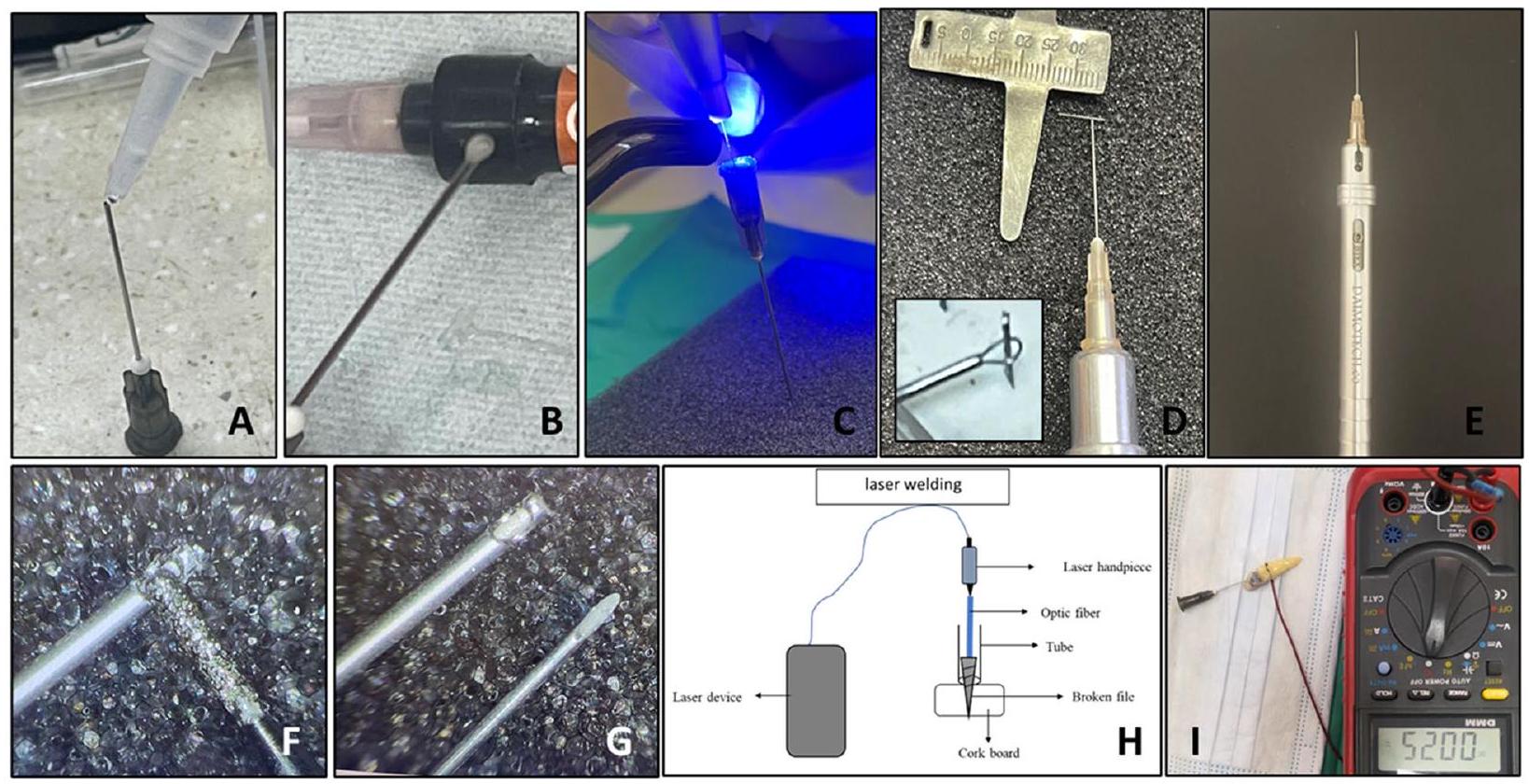

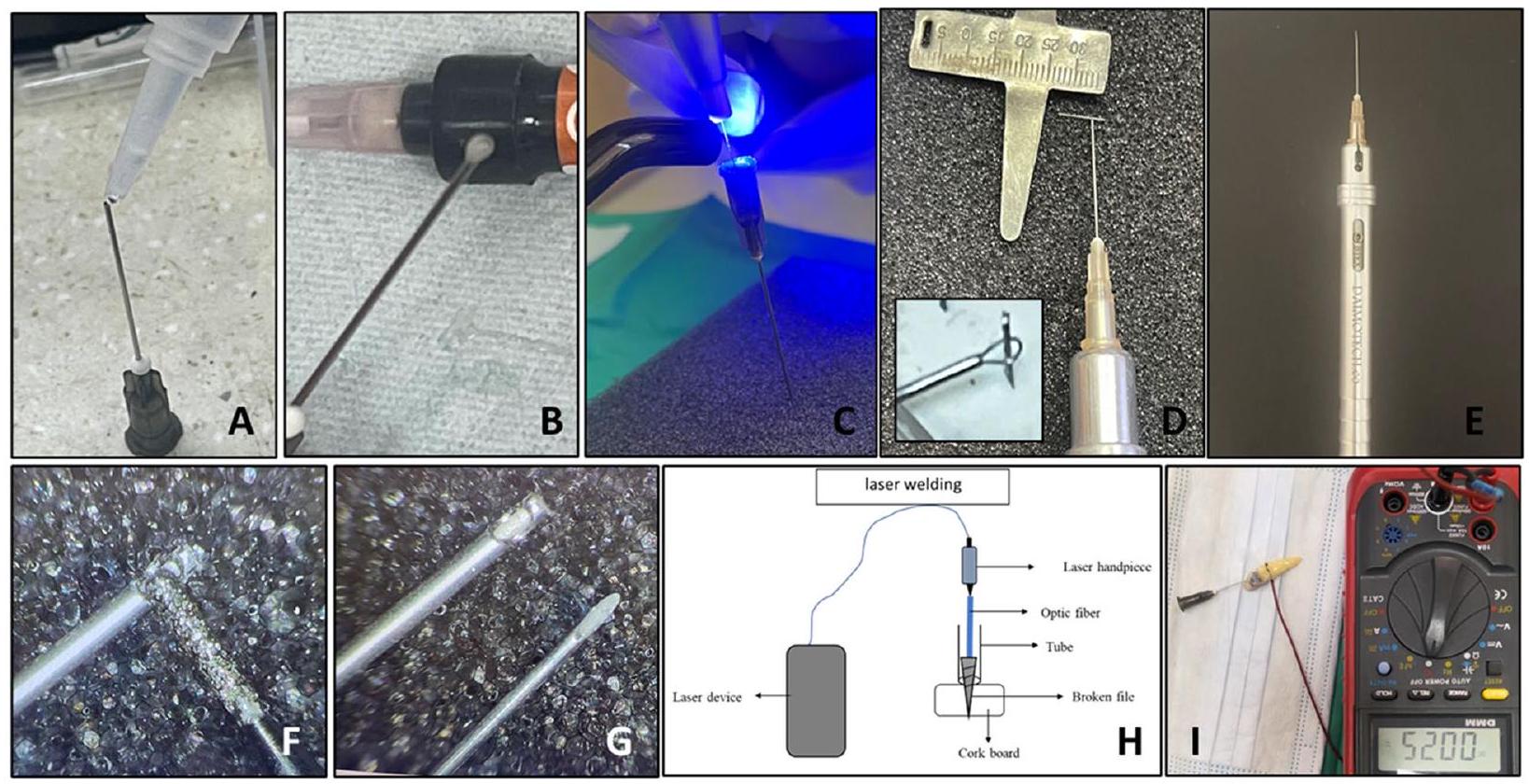

the exposed 2 mm of the separated instrument. Based on the setting time from the pilot study, the microtube was held motionless for 3 min to allow the adhesive to set (Fig. 1A).

In group 2 (microtube and light-cured flowable composite), a light-cured flowable composite resin (Cirus Flow, Elsodent, France) was used to fix the fractured instrument in a 21-gauge microtube, similar to the first group. An optical fiber (Fotona, Light Walker, USA) with a diameter of

In group 3 (microtube and wire), the BTEX-PEN (Dimotech, Daya Tajhiz Teb Shomal, Iran) was used to remove the fractured instrument. A 25-gauge needle and wire with a diameter of 0.1 mm was used. The loop, representing the “lasso,” was placed over the 2 mm free end of the separated instrument, and the fragment was grasped in the loop (Fig. 1D and E).

In group 4 (microtube and internal shaft), a 21-gauge spinal tap needle (Dr J, Japan) was used as an extractor. The spinal tap needle, which has a lumbar puncture representing the “internal shaft,” is designed to fit inside the needle in only one direction. The sharp tip of the needle

In group 5 (microtube and laser), the 21 -gauge microtubes covered the 2 mm of separated instruments above the corkboard surface. An optical fiber with a diameter of 200 nm was then inserted into the microtubes from the other side until its tip reached the files. Irradiation was applied using an Nd: YAG laser (Fotona, Light Walker, USA) for 7 s at 2W and 10 Hz (pulses per second), maintaining contact between the optical fiber and file (Fig. 1H). The increase in temperature on the external surface of the microtube in the welded point was measured at room temperature using a thermocouple (DEC, Digital Equipment Corporation, USA).

Measuring the temperature of the outer surface of the root

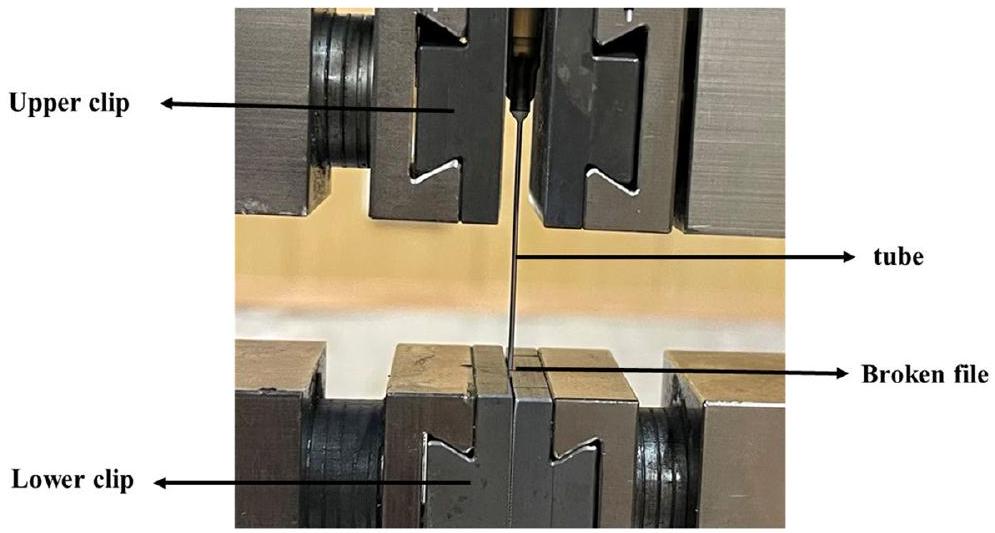

Pull-out test

Statistical analysis

Results

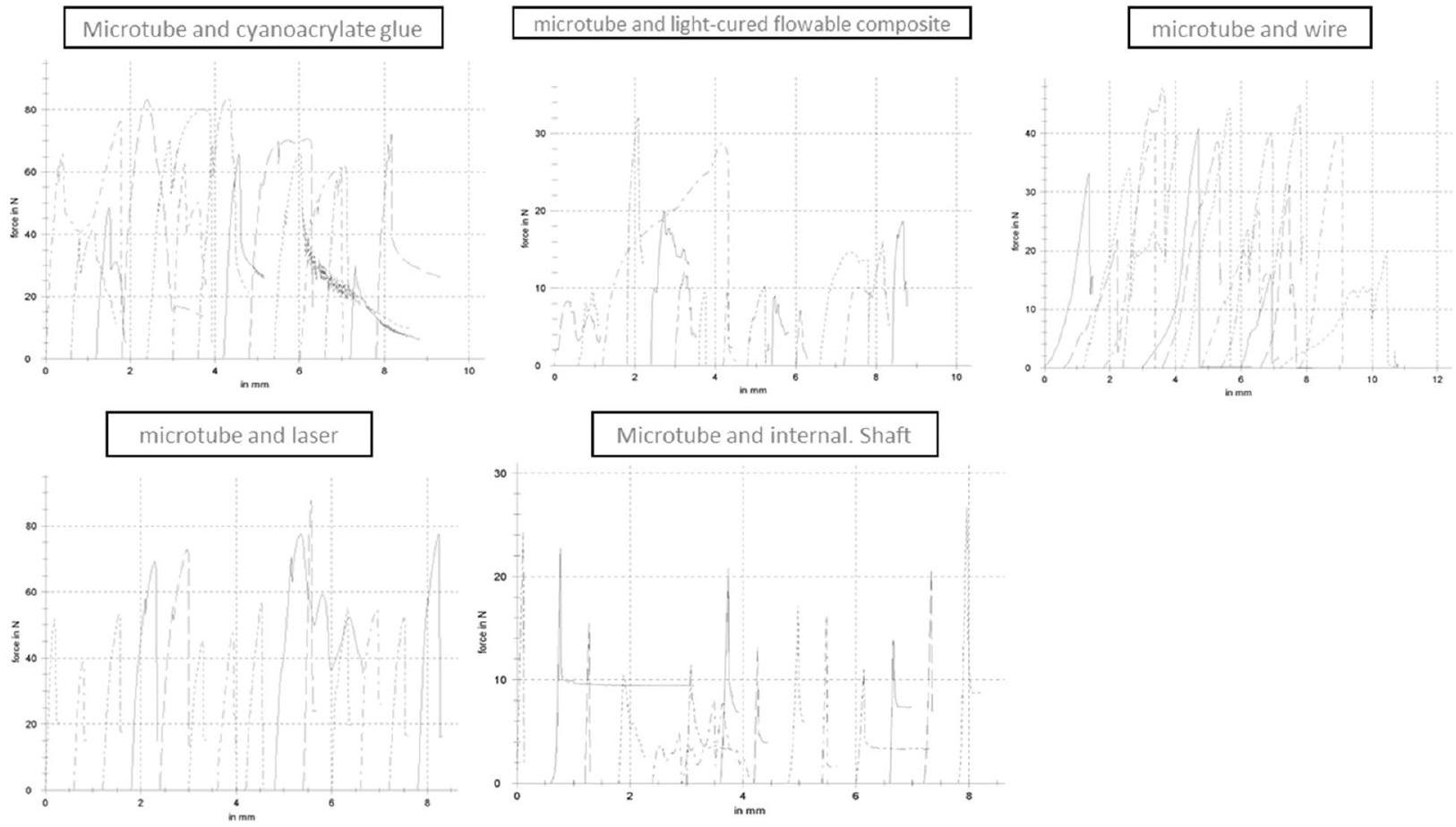

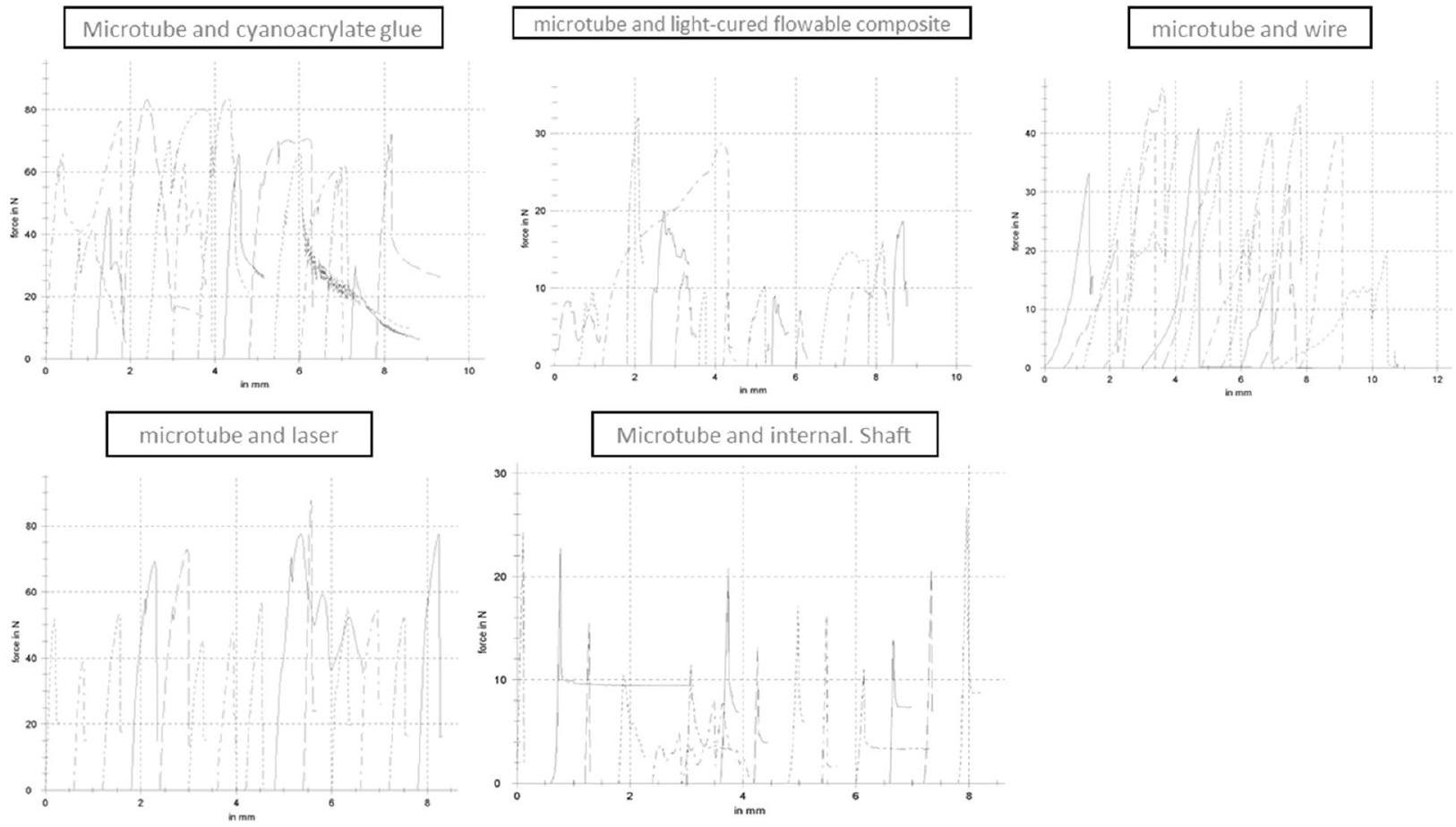

| Study groups | Pull out force (Mean ± SD) |

| Microtube and cyanoacrylate |

|

| Microtube and composite |

|

| Microtube and wire |

|

| Microtube and internal shaft |

|

| Microtube and laser |

|

root canal of human extracted canine teeth, the temperature increase was measured at

Discussion

clinical applicability. Guidelines generally recommend attempting removal when feasible, with retention considered only if non-surgical removal is unsuccessful [23]. Although many techniques have been proposed for broken instrument removal from the root canal system, finding a universally accepted, safe, simple, and cost-effective method with a consistently high success rate remains challenging [8].

The initial phase in removing a broken instrument from the root canal system begins with creating a direct path to the coronal portion of the instrument. Following this, the dentinal walls surrounding the coronal part of the instrument must be removed to expose a small portion of the broken fragment [24]. While trephine burs have been suggested for this task, ultrasonic tips are the preferred choice due to their superior performance in safely and precisely removing dentin [12]. In certain instances, the broken instrument is removed solely by ultrasonic agitation. However, even when the broken fragment in the canal becomes loose and mobile, its removal still presents a challenge [25]. Recent research findings have shown that ultrasonic application can be a time-consuming procedure [26]. Aggressively attempting to remove a broken instrument through ultrasonic agitation, particularly in the apical third of the root canal or around curves, may lead to excessive removal of radicular dentin and the development of iatrogenic errors. This

suggests that alternative techniques may be more suitable for these situations [27, 28].

According to the study by Terauchi et al. [16], a minimum exposure of 0.7 mm of the broken instrument is required for proper retrieval. On the other hand, another study suggests that increasing the exposed portion of the file enhances the effectiveness of its removal [22]. Consequently, in the present study, the file exposure has been set at 2 mm to potentially improve removal efficacy.

In this study, the efficacy of five methods for separated instrument removal was compared. The microtube and glue method is recognized as a more conservative, costeffective, and accessible alternative compared to other techniques [13]. The self-curing and adhesive properties of cyanoacrylate glue may facilitate a strong attachment to the coronal portion of the broken fragment, enhancing the force for removal, while reducing damage to the root canal dentin [29]. Nevertheless, this method presents challenges; for instance, the microtube must remain stationary while the glue sets around the broken instrument. Additionally, it can be difficult to achieve a precise bond between the glue and the coronal section of the broken instrument, making it a sensitive technique [30]. Thus, it is essential that the bond between the glue and the separated instrument is robust enough to successfully remove the fragment [31].

Based on the findings of this study, the microtube and cyanoacrylate glue method achieved the highest pull-out force, approximately 64 N , compared to all other techniques evaluated. Our findings are in line with those of Olczak et al. [13], who employed three different adhesive materials “composite resin, cyanoacrylate glue, and GI cement” in the microtube-and-glue technique for removing broken files. Their results revealed that cyanoacrylate glue exhibits a significantly stronger bond compared to the other materials. Furthermore, research by Frota et al. [30], supports the viability of using this method to removal of broken fragments from the apical third of the root canal.On the contrary, Wefelmeier et al. [14] and Hagiwara et al. [22] reported lower pull-out forces for cyanoacrylate glue ( 14.7 N and 10.7 N , respectively), compared to the values observed in the present study. Several factors may account for this discrepancy, including variations in the brand of cyanoacrylate glue and the type of file utilized in those studies. In the current study, NiTi K-files were employed, whereas SS K-files were used in the aforementioned studies. Furthermore, another possible explanation is that the smaller inner diameter

The microtube and light-cure flowable composite group demonstrated the lowest pull-out force,

approximately 14 N , compared to other methods in the current research. However, a previous study by Wefelmeier et al. [14] reported a pull-out force of about 62 N for the light-cure flowable composite, significantly surpassing the force recorded in the present study. Additionally, Wefelmeier’s findings highlighted that the pull-out force for the light-cure flowable composite was significantly greater than that of cyanoacrylate glue, presenting a disagreement with the results of our current study. The differences can be attributed to several factors, such as variations in the physical and chemical characteristics of the composites, disparities in the brands of cyanoacrylate glue, and distinctions in the types of files employed in the research (stainless steel/H-file vs. NiTi/K-file). Moreover, the diameter of the optical fiber is critical in transmitting light from the light-curing device to the composite material, thereby affecting the curing process. In this study, an optical fiber with a diameter of

The lasso technique with loop device, initially proposed by Greene [15], is based on the microtube and wire method. This method has been adapted into various devices for broken instrument removal. The BTEX-PEN kit (Dimotech, Daya Tajhiz Teb Shomal, Iran) is a specialized device that combines fine quality and effectiveness to provide sufficient gripping force. It appears that the time required to remove a broken instrument using this technique is generally less than when using an ultrasonic instrument alone [8]. In the traditional approach, the tube was either held manually or with forceps, making its management and steering quite challenging. Furthermore, to secure the loop around the fractured fragment, the loose ends of the wire had to be wound using a needle holder. This task was not only difficult but often necessitated the help of another individual [15].Therefore, the use of a pen for broken fragment removal presents a significantly simpler alternative to the conventional method [32].Additionally, according to Terauchi et al. [8], the microtube and wire method is recommended for extracting broken instruments from the root canal that

cannot be removed with ultrasonic tips, for removing fragments that are longer than 4.5 mm , and/or for fragments fractured in root canals with a curvature greater than 30 degrees. One significant challenge encountered during the application of the microtube and wire is the instability of the wire loop around the broken fragment. Despite careful manipulation and placement, the wire loop may become loose, reducing the efficacy of the technique and potentially complicating the procedure. This issue emphasizes the need for future refinement of the technique. It also highlights the importance of operator skills and experience in successfully applying the loop technique. However, a drawback of this method is its reliance on magnification [33]. Further research is recommended to address this limitation and enhance the predictability and success of fracture instrument removal in endodontics.

The Nd:YAG laser has been suggested for welding SS and Ni-Ti alloys to establish a fixed connection [34]. This type of laser, equipped with a small diameter optic fiber, is utilized in endodontics for both disinfection [35] and retreatment purposes, such as softening gutta-percha, removal of sealers [36], and either bypassing or retrieving broken instruments [22, 37].In the current study, the average pull-out force in the microtube and laser method was about 60 N , which was significantly higher than the methods of microtube and wire, microtube and light-cured flowable composite, and microtube and internal shaft. Our results were contrary to Hagiwara’s findings [22]. This discrepancy may be attributed to different factors, including the type of laser, laser device settings (power, frequency, pulse), type of fragment (SS vs. NiTi/ hand file vs. rotary file), and the diameter of the tube

rise in temperature of the adjacent periradicular tissues [38].Podolak et al. [36] reported that the application of the Nd:YAG laser with a power setting of

As no comprehensive study has assessed the pull-out force required to remove fractured instruments under varying clinical conditions-such as the type of fractured file (manual or rotary), material (SS or NiTi), fragment length and diameter, canal diameter, degree of canal curvature, and fracture location-this study draws on the findings of Terauchi et al. [8] to infer the following: When the fractured fragment exceeds 3 mm in length, has a larger diameter, is located in a canal with a curvature greater than 30 degrees, or is situated in the apical regions of the canal, a higher pull-out force is necessary for removal. Consequently, techniques capable of exerting greater pull-out forces should be employed in such scenarios, whereas methods requiring lower forces may suffice for less demanding conditions.

The primary method for using a spinal needle has traditionally involved using a tube with an H-file or internal shaft without creating a window on the tube. However, in this study, we modified the technique by creating a window on the tube using a grinder, thereby making its mechanism similar to the IRS method [18]. A

According to the findings of Gadzella et al. [41], the force required for atraumatic tooth extraction to rupture PDL fibers ranges from 102 to 309 N . These forces, applied over time, are notably higher than those measured in the present study for removing broken

instruments, which ranged from 14 to 64 N . Furthermore, Dietrich et al. [42] reported that extraction forces using the Benex

In general, the success of all methods for broken instrument removal requires sufficient knowledge, skill, and experience of the operator, along with access to appropriate magnification equipment such as dental operating microscopes. It should be noted that before performing any procedure for broken instrument retrieval, the advantages and disadvantages of each method should be carefully assessed. Furthermore, the decision to remove, bypass, or leave the broken fragment should always be made based on patient benefits and clinical judgment. When the decision is made to remove the broken fragment from the root canal, the choice of the appropriate method is determined based on existing conditions, including the length, diameter, and location of the broken instrument within the root canal, the degree of root curvature, visibility and access to the broken fragment, as well as the operator’s skill in performing the retrieval technique.

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Clinical Trial Number

Authors’ contributions

preparation, commented on previous versions of the manuscript. read and approved the final manuscript. M.K: data collection and analysis, commented on previous versions of the manuscript. read and approved the final manuscript. F.H: commented on previous versions of the manuscript. P.S:study conception and design,Material preparation, commented on previous versions of the manuscript. read and approved the final manuscript. M.A: study conception and design,Material preparation, commented on previous versions of the manuscript. read and approved the final manuscript. M.K: data collection and analysis, commented on previous versions of the manuscript. read and approved the final manuscript.

F.H: commented on previous versions of the manuscript.

P.S:study conception and design,Material preparation, commented on previous versions of the manuscript. read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Competing interests

Author details

Published online: 02 January 2025

References

- Amza O, Dimitriu B, Suciu I, Bartok R, Chirila M. Etiology and prevention of an endodontic iatrogenic event: instrument fracture. JML. 2020;13(3):378-381. https://doi.org/10.25122/jml-2020-0137.

- Spili P, Parashos P, Messer HH. The impact of instrument fracture on outcome of endodontic treatment. J Endod. 2005;31(12):845-50. https:// doi.org/10.1097/01.don.0000164127.62864.7c.

- Simon S, Machtou P, Tomson P, Adams N, Lumley P. Influence of fractured instruments on the success rate of endodontic treatment. Dental update. 2008;35(3):172-9. https://doi.org/10.12968/denu.2008.35.3.172

- Zupanc J, Vahdat-Pajouh N, Schäfer E. New thermomechanically treated NiTi alloys-a review. Int Endod J. 2018;51(10):1088-103. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/iej.12924.

- Parashos P, Messer HH. Rotary NiTi instrument fracture and its consequences. J Endod. 2006;32(11):1031-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen. 2006.06.008.

- Nevares G, Cunha RS, Zuolo ML, da Silveira Bueno CE. Success rates for removing or bypassing fractured instruments: a prospective clinical study. J Endod. 2012;38(4):442-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2011.12. 009.

- Terauchi Y, Sexton C, Bakland LK, Bogen G. Factors affecting the removal time of separated instruments. J Endod. 2021;47(8):1245-52. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.joen.2021.05.003.

- Terauchi Y, Ali WT, Abielhassan MM. Present status and future directions: removal of fractured instruments. Int Endod J. 2022;55(3):685-709. https://doi.org/10.1111/iej.13743.

- Rambabu T. Management of fractured endodontic instruments in root canal: a review. JSD. 2020;4(2):40-8. https://doi.org/10.5005/jsd-4-2-40.

- Yang Q, Cheung GS-P, Shen Y, Huang D, Zhou X, Gao Y. The remaining dentin thickness investigation of the attempt to remove broken instrument from mesiobuccal canals of maxillary first molars with virtual simulation technique. BMC Oral Health. 2015;28(15):1-8. https://doi.org/

. - Plotino G, Pameijer CH, Grande NM, Somma F. Ultrasonics in endodontics: a review of the literature. J Endod. 2007;33(2):81-95. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.joen.2006.10.008Get.

- Shaik I, Qadri F, Deshmukh R, Clement C, Patel A, Khan M. Comparing techniques for removal of separated endodontic instruments: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Health Sci. 2022;6(S1):13792-13805. https://doi.org/10.53730/ijhs.v6nS1.8497.

- Olczak K, Grabarczyk J, Szymański W. Removing Fractured Endodontic Files with a Tube Technique-The Strength of the Glued Joint: TubeEndodontic File Setup. Materials. 2023;16(11):4100. https://doi.org/10. 3390/ma16114100.

- Wefelmeier M, Eveslage M, Bürklein S, Ott K, Kaup M. Removing fractured endodontic instruments with a modified tube technique using a lightcuring composite. J Endod. 2015;41(5):733-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. joen.2015.01.018Get.

- Roig-Greene JL. The retrieval of foreign objects from root canals: a simple aid. J Endod. 1983;9(9):394-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0099-2399(83) 80193-9.

- Terauchi Y, O’Leary L, Suda H. Removal of separated files from root canals with a new file-removal system. J Endod. 2006;32(8):789-97. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.joen.2005.12.009.

- Dulundu M, Helvacioglu-Yigit D. The Efficiency of the BTR-Pen System in Removing Different Types of Broken Instruments from Root Canals and Its Effect on the Fracture Resistance of Roots. Materials. 2022;15(17):5816. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15175816.

- Ruddle CJ. Nonsurgical retreatment. J Endod. 2004;30(12):827-45. https:// doi.org/10.1097/01.don.0000145033.15701.2d.

- AI-Zahrani MS, AI-Nazhan S. Retrieval of separated instruments using a combined method with a modified vista dental tip. Saudi Endod J. 2012;2(1):41-5. https://doi.org/10.4103/1658-5984.104421.

- Alomairy KH. Evaluating two techniques on removal of fractured rotary nickel-titanium endodontic instruments from root canals: an in vitro study. J Endod. 2009;35(4):559-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2008.12. 019.

- Mehrpouya M, Gisario A, Elahinia M. Laser welding of NiTi shape memory alloy: A review J Manuf Process. 2018;31(1):162-86. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.jmapro.2017.11.011.

- Hagiwara R, Suehara M, Fujii R, Kato H, Nakagawa KI, Oda Y. Laser welding method for removal of instruments debris from root canals. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 2013;54(2):81-8. https://doi.org/10.2209/tdcpublication.54.81.

- McGuigan MB, Louca C, Duncan HF. Clinical decision-making after endodontic instrument fracture. BDJ. 2013;214(8):395-400. https://doi.org/10. 1038/sj.bdj.2013.379.

- Vouzara T, Lyroudia K. Separated instrument in endodontics: Frequency, treatment and prognosis. BJDM. 2018;22(3):123-32. https://doi.org/10. 2478/bjdm-2018-0022.

- Souter NJ, Messer HH. Complications associated with fractured file removal using an ultrasonic technique. J Endod. 2005;31(6):450-2. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.don.0000148148.98255.15.

- Pruthi PJ, Nawal RR, Talwar S, Verma M. Comparative evaluation of the effectiveness of ultrasonic tips versus the Terauchi file retrieval kit for the removal of separated endodontic instruments. RDE. 2020;45(2):e14. https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2020.45.e14.

- Yang Q, Shen Y, Huang D, Zhou X, Gao Y, Haapasalo M. Evaluation of two trephine techniques for removal of fractured rotary nickel-titanium instruments from root canals. J Endod. 2017;43(1):116-20. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.joen.2016.09.001.

- Ward JR, Parashos P, Messer HH. Evaluation of an ultrasonic technique to remove fractured rotary nickel-titanium endodontic instruments from root canals: an experimental study. J Endod. 2003;29(11):756-63. https:// doi.org/10.1097/00004770-200311000-00017.

- Korde JM, Kandasubramanian B. Biocompatible alkyl cyanoacrylates and their derivatives as bio-adhesives. Biomater Sci. 2018;6(7):1691-711 . https://doi.org/10.1039/C8BM00312B.

- Frota LMA, Aguiar BA, Aragão MGB, de Vasconcelos BC. Removal of Separated Endodontic K-File with the Aid of Hypodermic Needle and

31. Raja PR. Cyanoacrylate adhesives: A critical review. Reviews of Adhesion and Adhesives. 2016;4(4):398-416. https://doi.org/10.7569/RAA.2016. 097315.

32. Terauchi Y, O’Leary L, Kikuchi I, Asanagi M, Yoshioka T, Kobayashi C, Suda H. Evaluation of the efficiency of a new file removal system in comparison with two conventional systems. J Endod. 2007;33(5):585-8. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2006.12.018.

33. Cruz A, Mercado-Soto CG, Ceja I, Gascón LG, Cholico P, Palafox-Sánchez CA. Removal of an instrument fractured by ultrasound and the instrument removal system under visual magnification. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2015;16(3):238-42. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1668.

34. Perveen A, Molardi C, Fornaini C. Applications of laser welding in dentistry: a state-of-the-art review. Micromachines. 2018;28;9(5):209. https:// doi.org/10.3390/mi9050209.

35. Kamali AS, Deepti J, Karthick A, Prakash V, Andro S. Lasers and its advantages in endodontics-a review. NVEO Journal. 2021;8(4):6386-91. https:// doi.org/10.5152/nnu.2021.1374.

36. Podolak B, Nowicka A, Woźniak K, Szyszka-Sommerfeld L, Dura W, Borawski M, et al. Root Surface Temperature Increases during Root Canal Filling In Vitro with Nd: YAG Laser-Softened Gutta-Percha. J Healthc Eng. 2020;2020(5):8828272. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8828272.

37. Cvikl B, Klimscha J, Holly M, Zeitlinger M, Gruber R, Moritz A. Removal of fractured endodontic instruments using an Nd: YAG laser. Quintessence Int. 2014;45(7):569-75. https://doi.org/10.3290/j.qi.a31961.

38. Palazzi F, Blasi A, Mohammadi Z, Fabbro MD, Estrela C. Penetration of sodium hypochlorite modified with surfactants into root canal dentin. Braz Dent J. 2016;27(2):208-16. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-6440201600 650.

39. Ramsköld LO, Fong CD, Strömberg T. Thermal effects and antibacterial properties of energy levels required to sterilize stained root canals with an Nd: YAG laser. J Endod. 1997;23(2):96-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0099-2399(97)80253-1.

40. Aminsobhani M, Hashemi N, Hamidzadeh F, Sarraf P. Broken Instrument Removal Methods with a Minireview of the Literature. Case Rep Dent. 2024;2024(13):9665987. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/9665987.

41. Gadzella TJ, Hynkova K, Westover L, Addison O, Romanyk DL. A novel method for simulating ex vivo tooth extractions under varying applied loads. Clin Biomech (Bristol). 2023;110:106116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. clinbiomech.2023.106116.

42. Dietrich T, Schmid I, Locher M, Addison O. Extraction force and its determinants for minimally invasive vertical tooth extraction. JMBBM. 2020;105:103711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2020.103711.

Publisher’s Note

- *Correspondence:

Mohsen Aminsobhani

maminsobhani@yahoo.com

Pegah Sarraf

sarraf_p@sina.tums.ac.ir

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article