DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-024-02483-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38689259

تاريخ النشر: 2024-04-30

منصة نانوية مضادة للميكروبات تعتمد على العلاج الضوئي والعلاج بأكسيد النيتريك: نظام متقدم لري قنوات الجذور لعلاج العدوى البكتيرية في طب الأسنان

الملخص

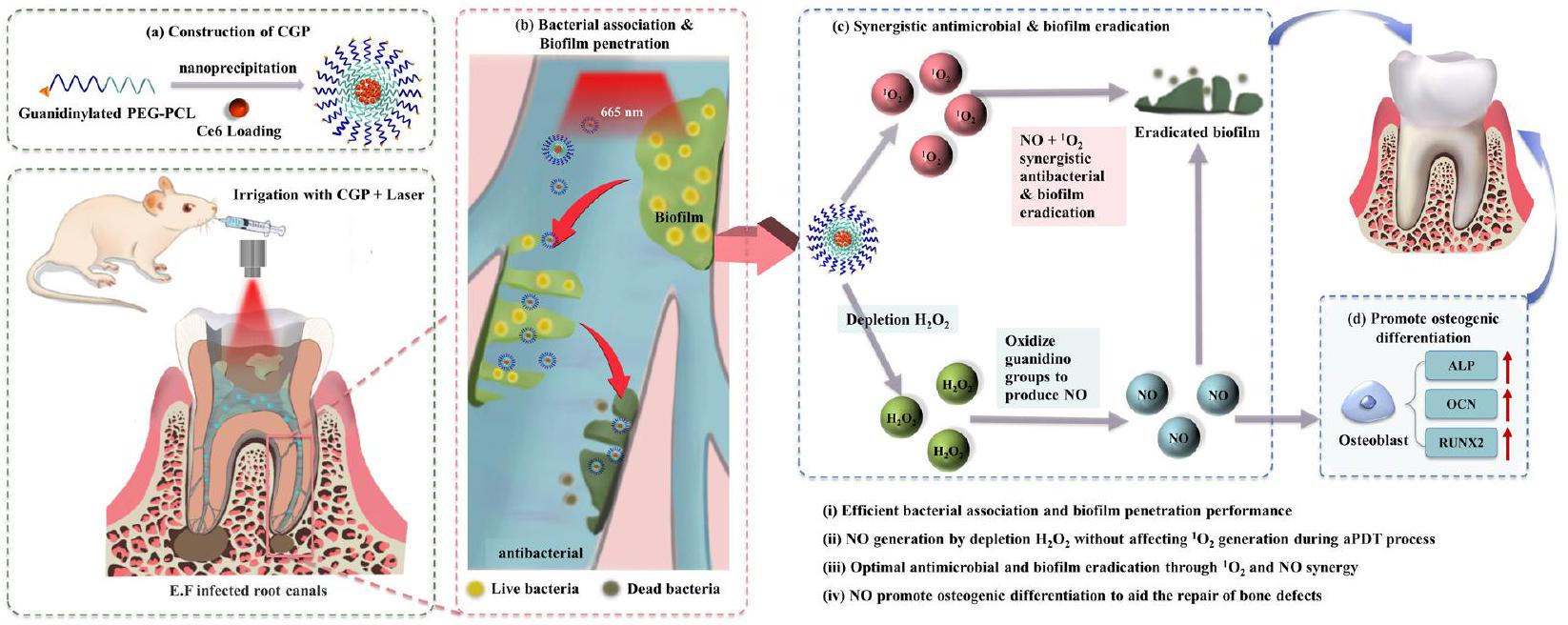

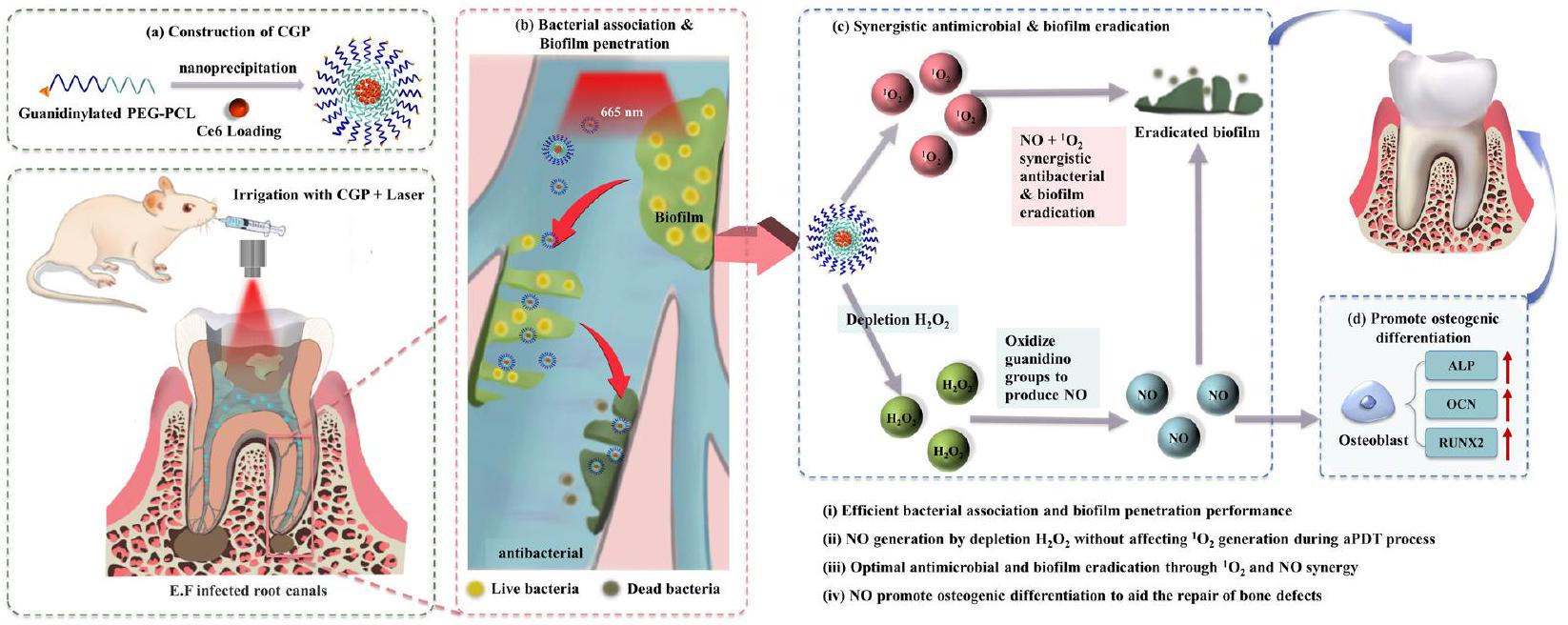

الخلفية: القضايا الرئيسية التي تواجه أثناء علاج التهاب اللثة القمي هي إدارة العدوى البكتيرية وتسهيل إصلاح عيوب العظام السنخية لتقصير مدة المرض. تعتبر المواد المستخدمة في غسل قنوات الجذور التقليدية محدودة في فعاليتها وترتبط بعدة آثار جانبية. تقدم هذه الدراسة علاجًا تآزريًا يعتمد على أكسيد النيتريك (NO) والعلاج الضوئي المضاد للميكروبات (aPDT) لعلاج التهاب اللثة القمي. النتائج: طورت هذه الأبحاث جزيئات نانوية متعددة الوظائف، CGP، باستخدام بولي (إيثيلين جلايكول) المشتق من الجوانيدين.

*المراسلة:

شياوجون كاي

cxj520118@wmu.edu.cn; cxj520118@njtech.edu.cn

يهوى بان

yihuaipan@wmu.edu.cn

مقدمة

يتضمن معالجة قناة الجذر إزالة الأنسجة اللبية المصابة والميكروبات، تليها تعقيم وملء قناة الجذر بمادة غير نشطة. عادةً ما تستخدم هذه العملية التحضير الميكانيكي والري الكيميائي للسيطرة على العدوى. ومع ذلك، فإن التعقيد في تشريح نظام قناة الجذر، إلى جانب الوجود المستمر للأغشية الحيوية، يعيق بشكل كبير فعالية هذه العلاجات. معدل فشل علاج قناة الجذر هو

العلاج الضوئي المضاد للميكروبات (aPDT) هو استراتيجية مضادة للميكروبات فعالة وغير جراحية، توفر تحكمًا زمنيًا ومكانيًا دقيقًا، وخصائص مضادة للميكروبات واسعة الطيف وإزالة الأغشية الحيوية. يعمل من خلال تنشيط المواد الحساسة للضوء باستخدام الليزر عند أطوال موجية محددة، مما يؤدي إلى توليد أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS)، مثل الجذور الهيدروكسيلية، وأنيون السوبر أوكسيد، وبيروكسيد الهيدروجين.

يؤدي إلى استجابة التهابية مستمرة، والتي بدورها يمكن أن تؤثر سلبًا على عملية تكوين العظام. للتغلب على هذه التحديات، ركزت الأبحاث على دمج العلاج الضوئي المعتمد على الأكسجين مع طرق علاجية بديلة. تستكشف هذه الدراسة دمج العلاج الضوئي المعتمد على الأكسجين مع العلاج بالغاز، بهدف تعزيز فعالية القضاء على الأغشية الحيوية والتخفيف من الآثار الضارة لمستويات ROS المرتفعة.

يجمع بين aPDT و NO مسارًا واعدًا لتطوير نظام جديد متعدد الوظائف لري قنوات الجذور. تم تصميم هذه الدراسة لتقييم القدرات المضادة للبكتيريا، وإزالة الأغشية الحيوية، والتمايز العظمي لـ CGP من خلال عد المستعمرات، واختبارات صلاحية البكتيريا الحية/الميتة، وري قنوات الجذور المحاكية، وتجارب التمايز العظمي، بالإضافة إلى الاختبارات العلاجية في نموذج التهاب ذروة الأسنان في الجرذان. بالمقارنة مع NaClO، من المتوقع أن يمتلك CGP خصائص مضادة للميكروبات، بالإضافة إلى قدرات تحكم زمنية ومكانية متفوقة، فضلاً عن قدرة فريدة على تسهيل إصلاح عيوب العظام القمية. نتوقع أن تكون هذه الدراسة قد طورت نظام ري قادرًا على علاج التهاب ذروة الأسنان بأمان وفعالية.

المواد والطرق

المواد

تم الحصول على حمض الأسكوربيك من سيغما-ألدريتش (الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية). كاشف غريس،

تركيب جزيئات CGP النانوية

حماية النيتروجين، مع الحفاظ على نسبة مولارية من

الخصائص الفيزيائية الكيميائية لـ CGP

الارتباط البكتيري واختراق الأغشية الحيوية لـ CGP

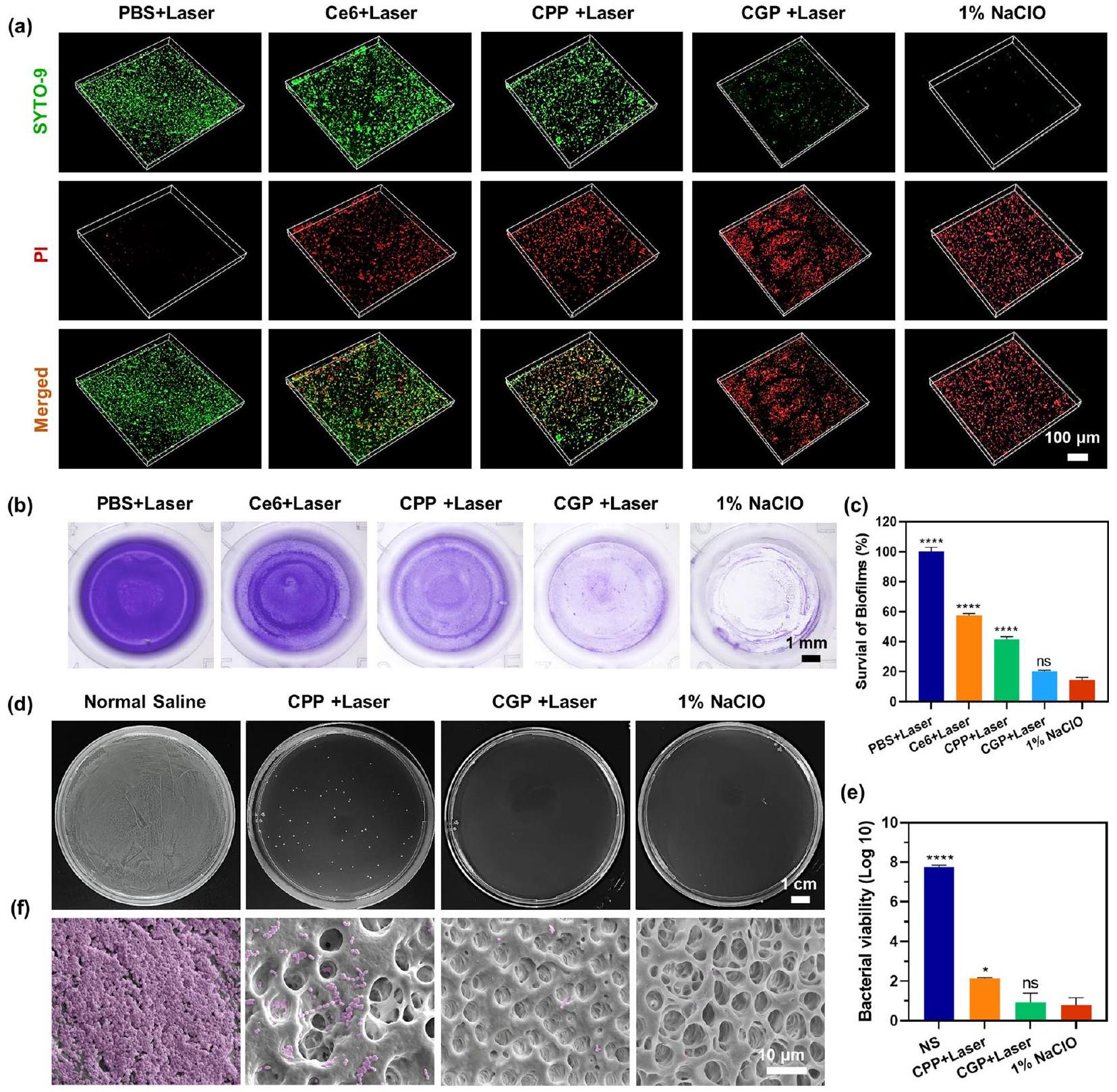

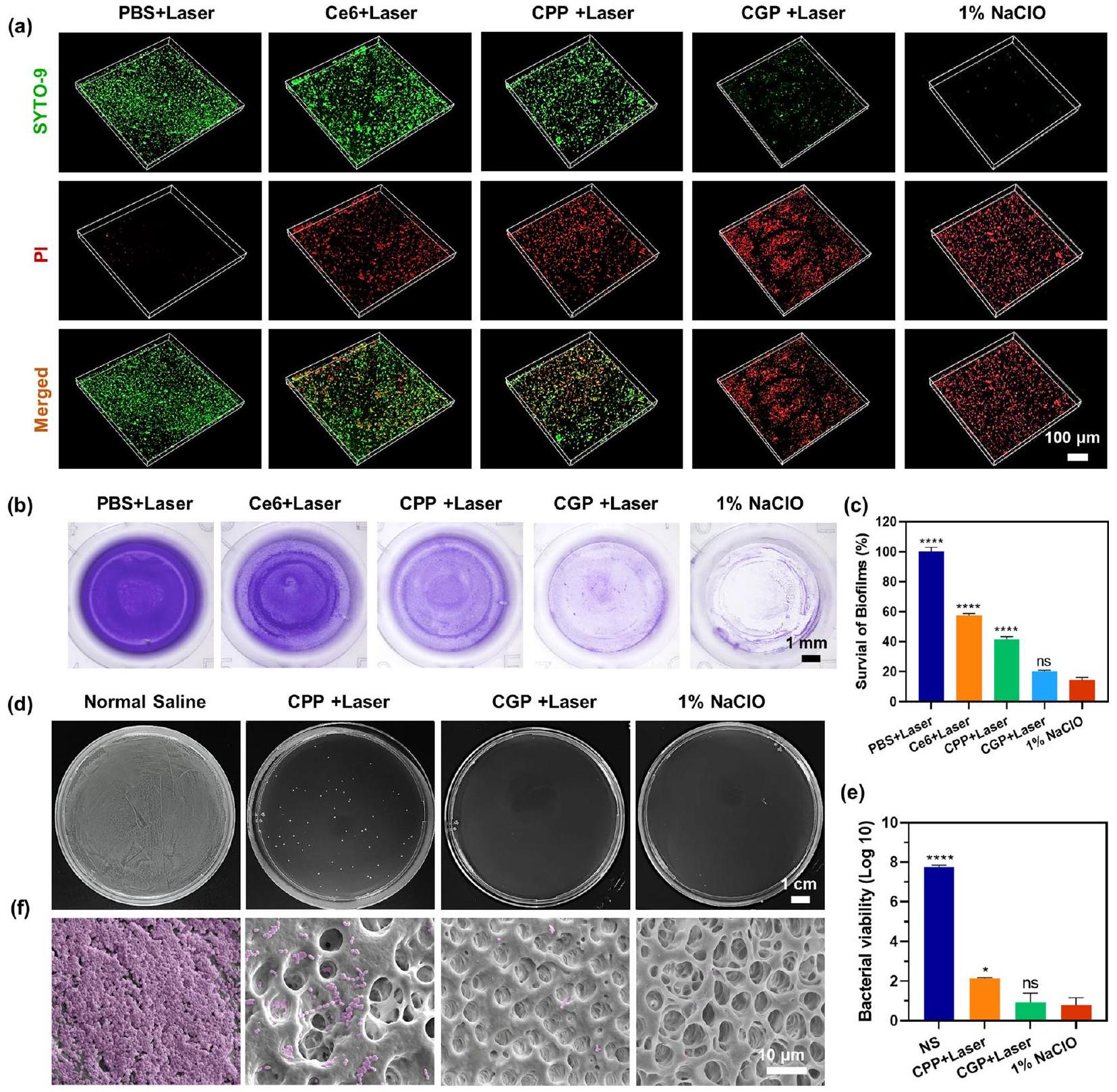

لتقييم خصائص نفاذية الأغشية الحيوية لـ CGP، تم استخدام مجهر المسح الضوئي بالليزر ثلاثي الأبعاد (CLSM، A1، نيكون). SYTO-9 (أخضر،

ثم تم حضنه في حاضنة لاهوائية عند

ملفات تعريف توليد ROS و NO لـ CGP

تصوير

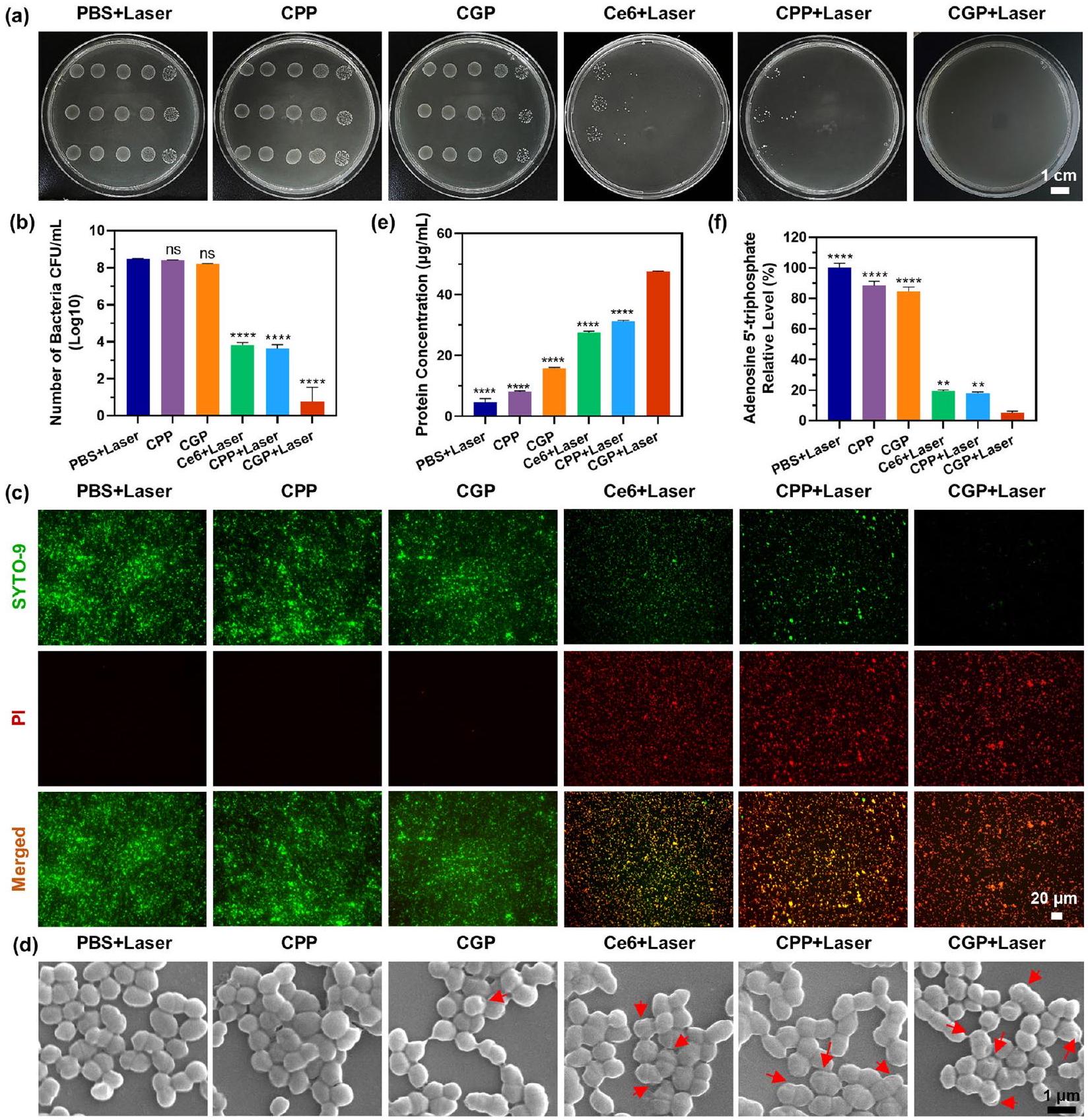

النشاط المضاد للبكتيريا لـ CGP في المختبر

لتقييم الخصائص المضادة للميكروبات لـ CGP بشكل أكبر، تم إجراء اختبار حيوية BacLight الحي/الميت. تم معالجة البكتيريا أولاً كما هو موضح أعلاه. بعد المعالجة، تم طرد تعليق البكتيريا وفصلها لإزالة أي بقايا من CGP. ثم تم إعادة تعليق الرواسب وصبغها بـ SYTO-9 و PI لمدة 15 دقيقة في درجة حرارة الغرفة. ثم، بعد جولة أخرى من الطرد والغسل باستخدام PBS لإزالة الصبغة الزائدة، تم ملاحظة البكتيريا باستخدام ميكروسكوب فلوري مقلوب.

لتصور التغيرات الشكلية في البكتيريا المعالجة بـ CGP+ليزر، تم استخدام المجهر الإلكتروني الماسح (SEM). تم معالجة البكتيريا أولاً كما هو موضح أعلاه. بعد المعالجة، تم طرد خلايا البكتيريا وغسلها مرتين باستخدام NS. ثم تم تثبيت البكتيريا باستخدام 1 مل من

لتجف بشكل طبيعي. أخيرًا، تم رش البكتيريا بالذهب وتمت ملاحظتها باستخدام مجهر إلكتروني ماسح (SU8010، HITACHI). تضمنت مجموعات التحكم لهذه التجارب PBS + ليزر، CPP، CGP، Ce6 + ليزر، و CPP+ليزر.

تسرب البروتين والتغيرات في مستويات ATP في البكتيريا المعالجة بـ CGP

تأثير القضاء على البيوفيلم في المختبر لـ CGP

تم تصوير البيوفيلم المتبقي باستخدام ميكروسكوب مجسم (SMZ 800N، نيكون). بعد التصوير، تم إذابة البيوفيلم المتبقي باستخدام

فعالية القضاء على البيوفيلم لـ CGP في قنوات الجذر

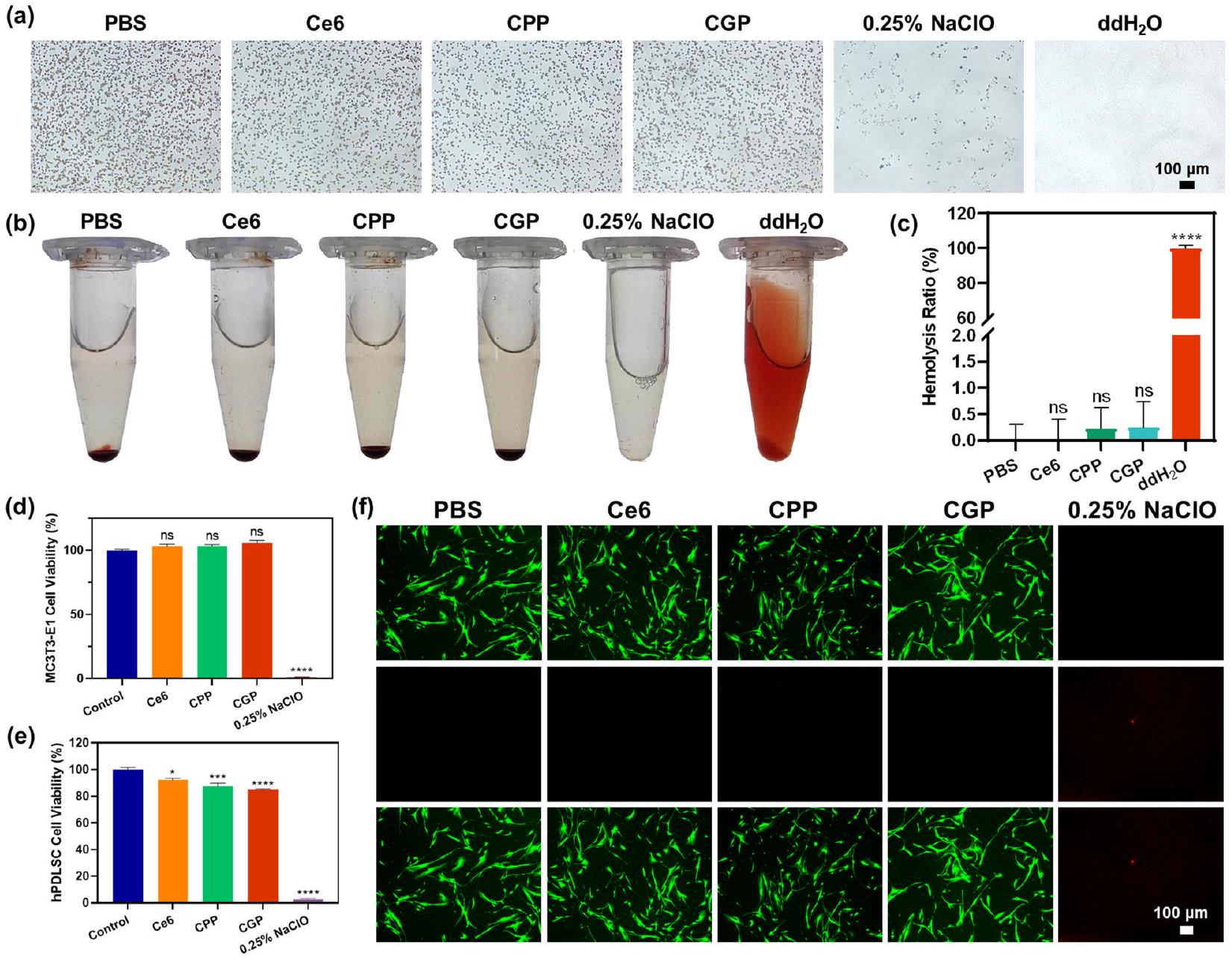

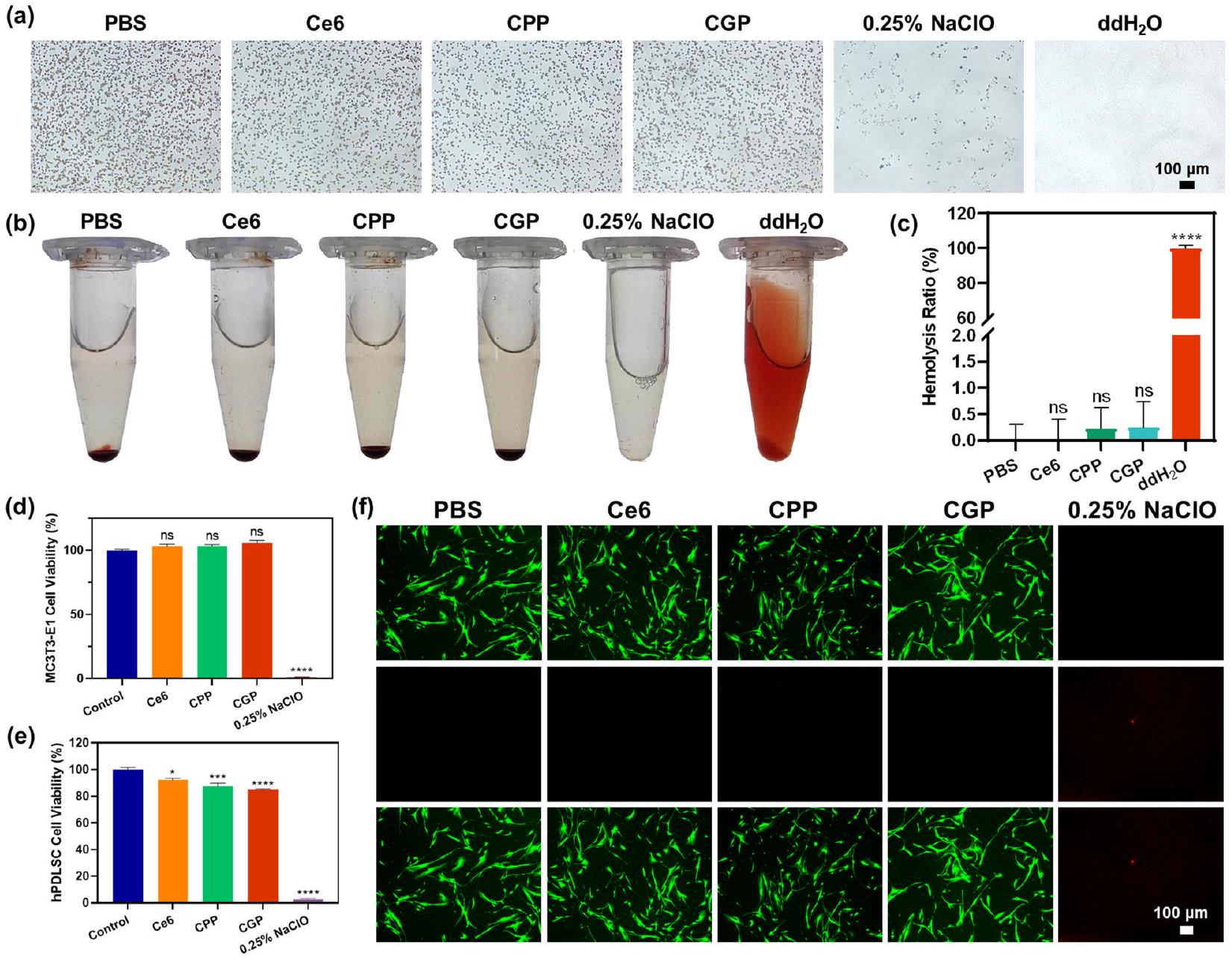

تقييم السلامة الحيوية

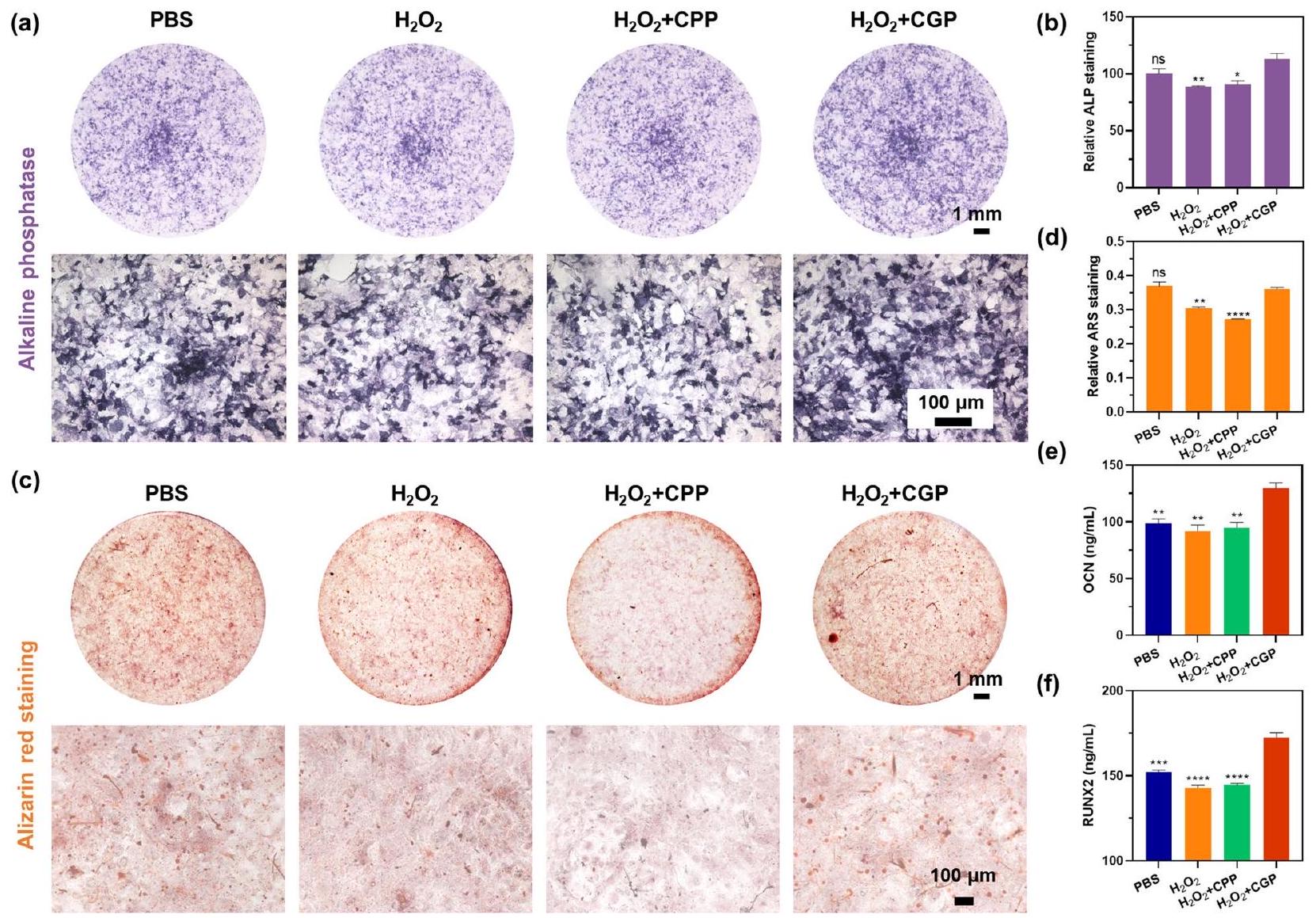

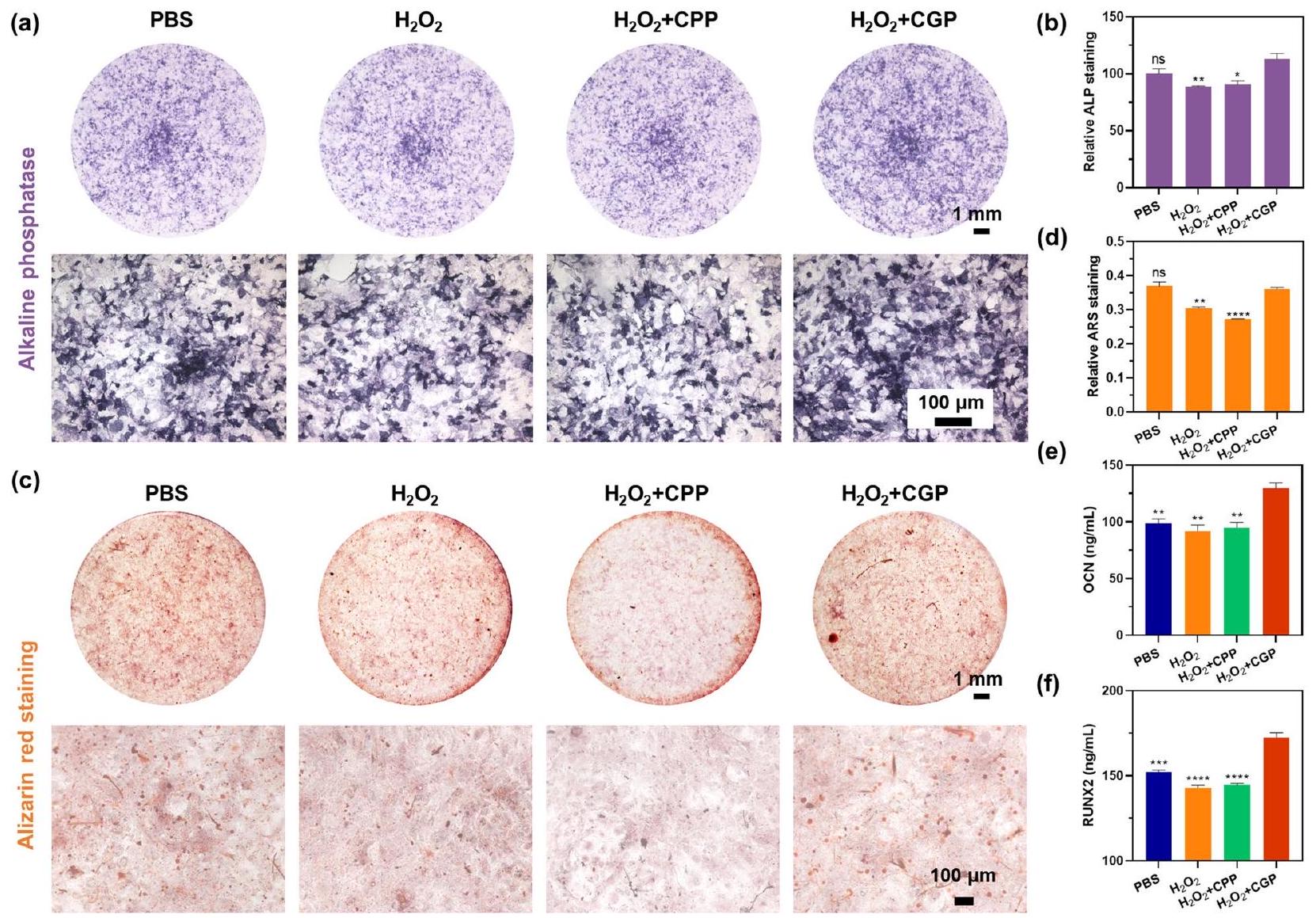

التمايز العظمي في المختبر

CPP.

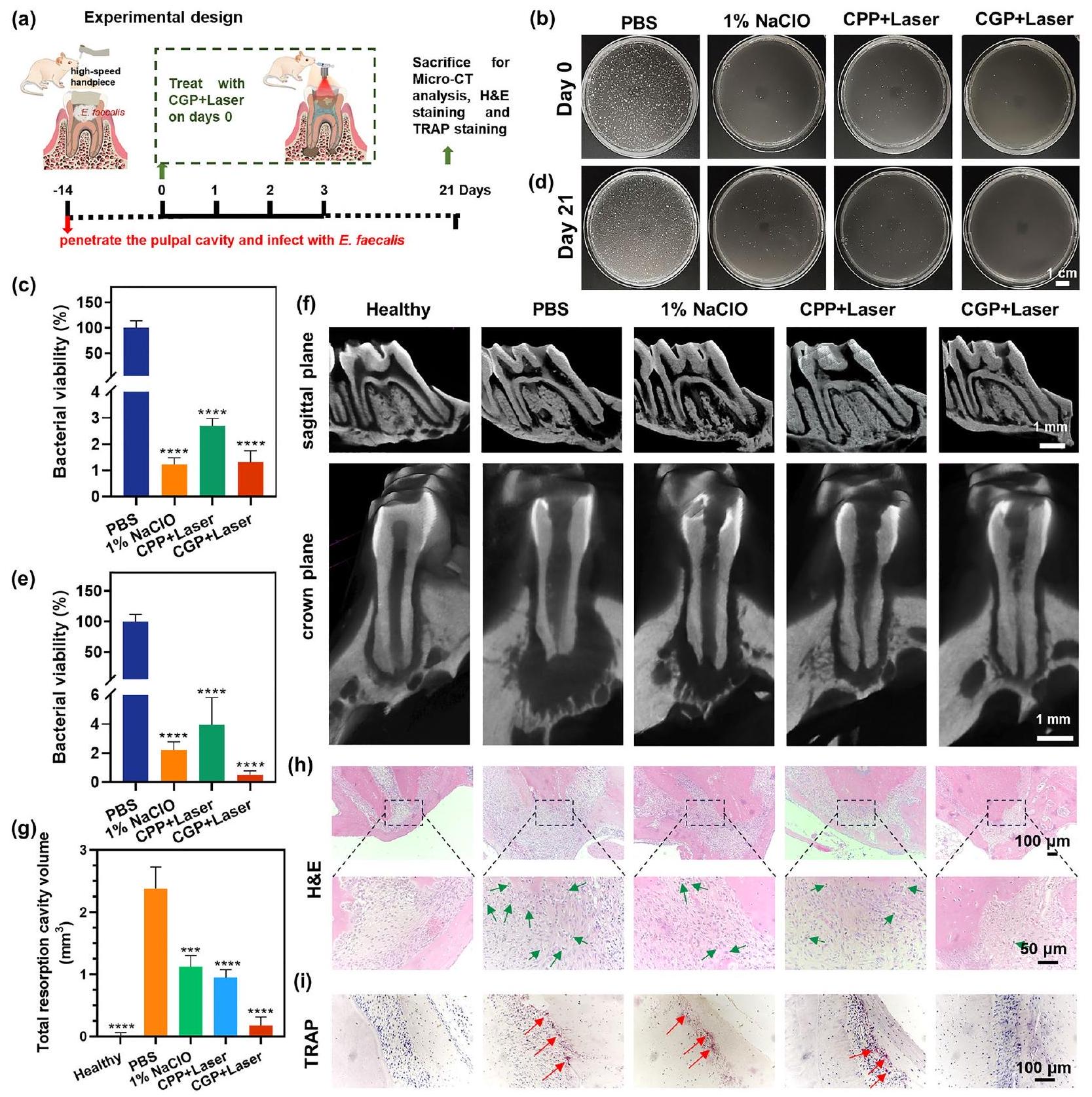

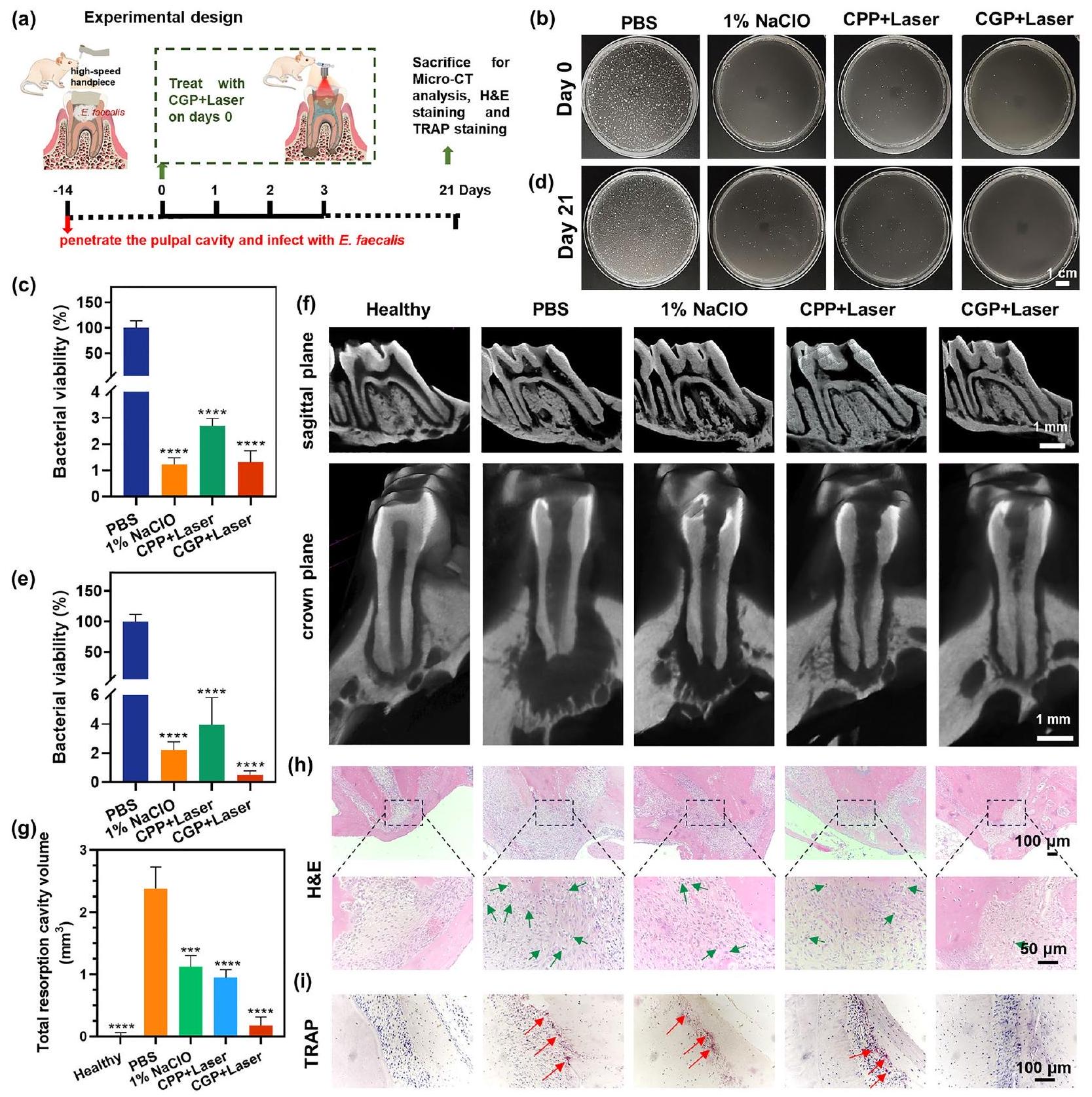

لم تتلق المجموعة الصحية أي علاج. خضعت المجموعات المتبقية للإجراءات التجريبية التالية: أولاً، تم تخدير الفئران باستخدام الإيزوفلوران (RWD Life Science، الصين). بعد ذلك، تم طحن الضرس الأول العلوي الأيسر لكل فأر ميكانيكيًا باستخدام أداة يدوية عالية السرعة بدون ماء للوصول إلى تجويف اللب. ثم تم تشكيل القنوات القريبة باستخدام ملفات K بحجم 10-20# (Dentsply Sirona، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية). بعد ذلك، تم ملء الفراغات بكرات قطن صغيرة تحتوي على تعليق E. faecalis وتم إغلاقها مؤقتًا باستخدام أسمنت أيون زجاجي (GC، اليابان).

لمدة

التحليل الإحصائي

النتائج والمناقشة

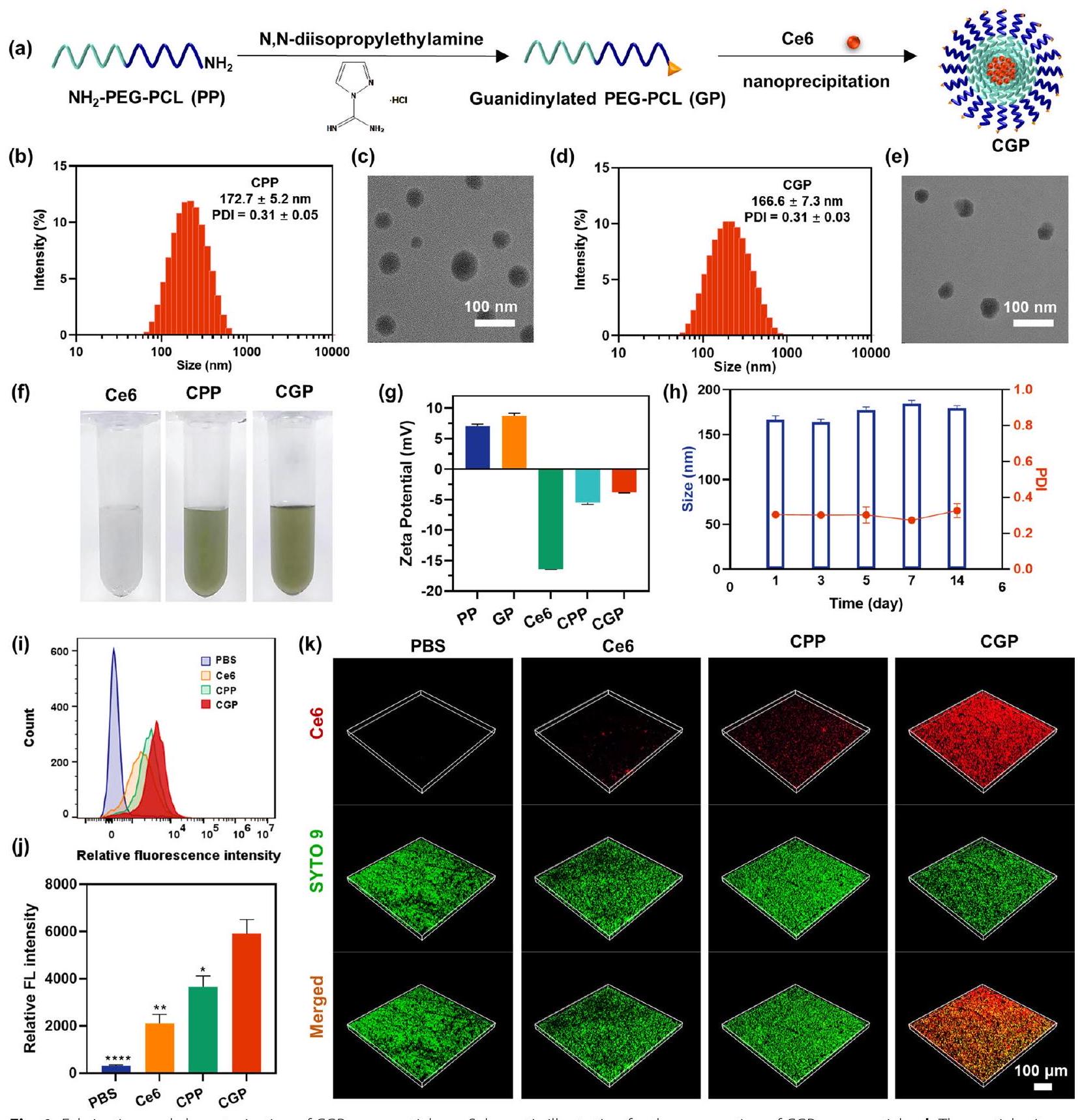

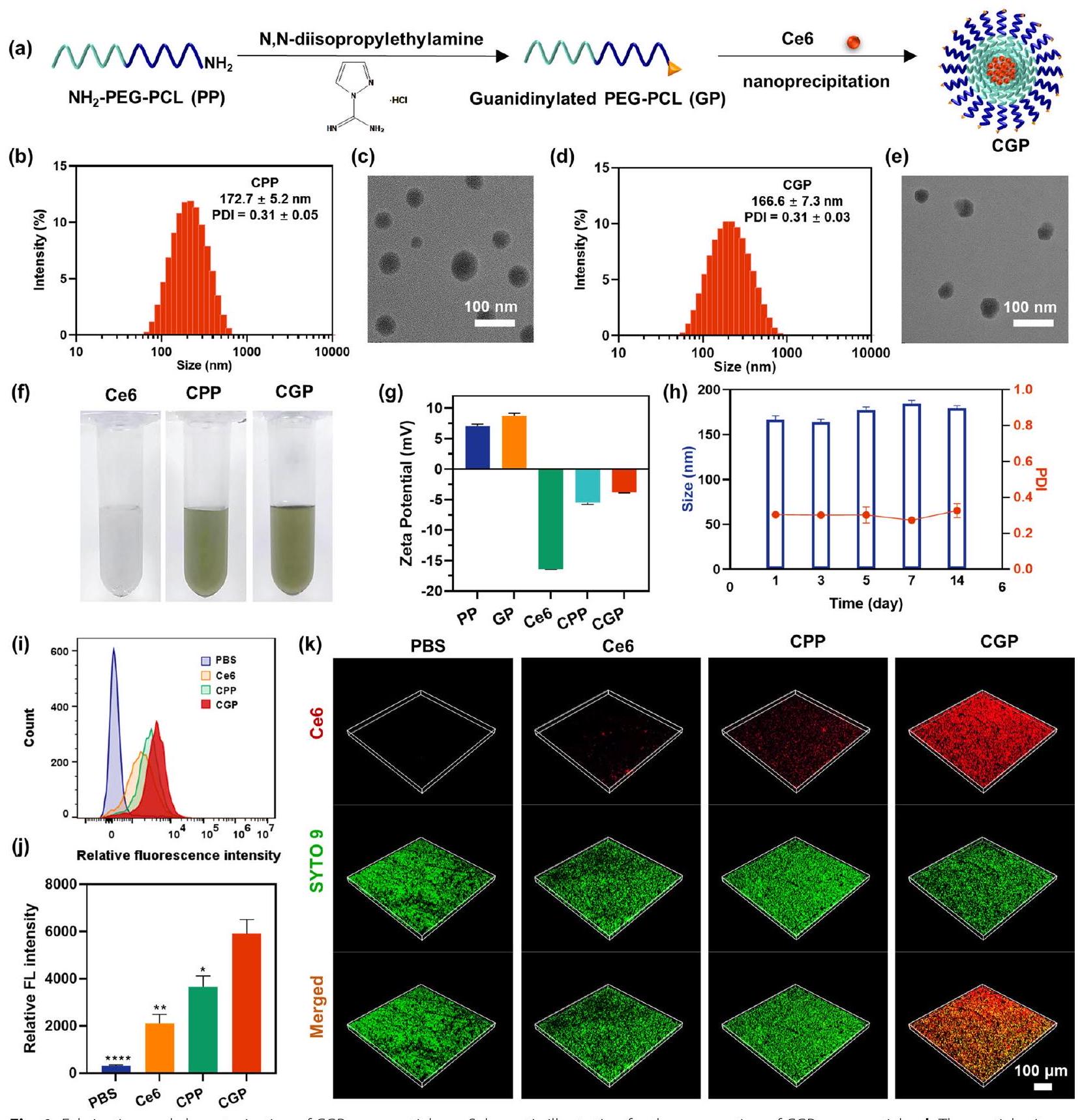

تخليق وتوصيف CGP

اختراق، ويعمل أيضًا كمانح لأكسيد النيتريك. تم تأكيد نجاح عملية الغوانيدينيل من خلال ظهور

(

ال

الارتباط البكتيري ونفاذية الأغشية الحيوية لـ CGP

تتأثر فعالية العوامل المضادة للميكروبات بشكل كبير بقدرتها على اختراق الأغشية الحيوية، والتي تُعرف بأنها تعيق الفعالية العلاجية لمثل هذه العوامل. تم تقييم نفاذية الأغشية الحيوية لـ CGP باستخدام المجهر الضوئي الماسح بالليزر، مع استخدام SYTO-9 كمؤشر لتلوين الأغشية الحيوية. بعد 5 دقائق من التعايش المشترك مع أغشية E. faecalis الحيوية، أظهر تحليل المجهر الضوئي الماسح بالليزر توهجًا أحمر خافتًا ينبعث من Ce 6 داخل الأغشية الحيوية المعالجة بـ Ce 6 الحر، مما يشير إلى اختراق محدود.

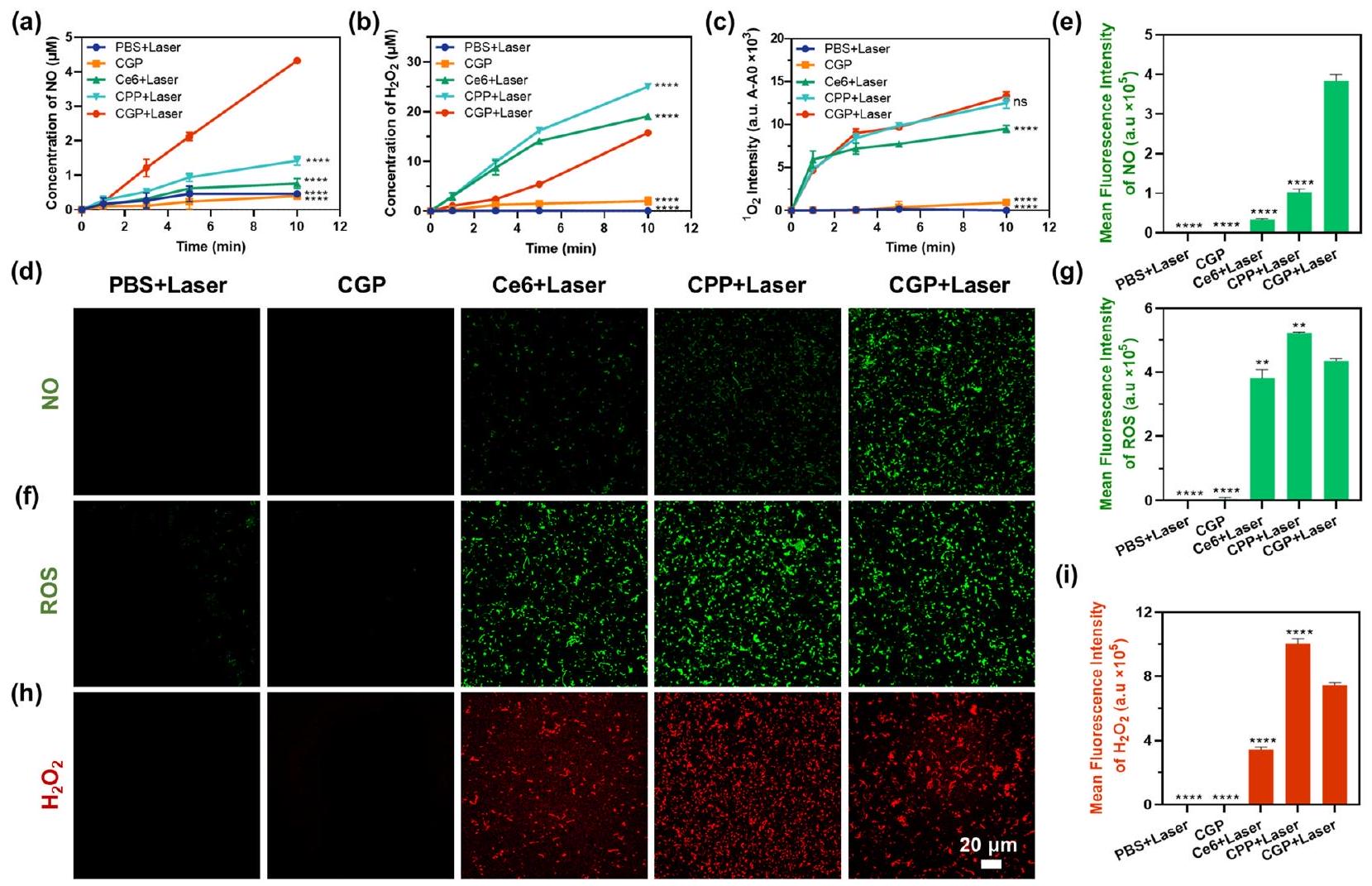

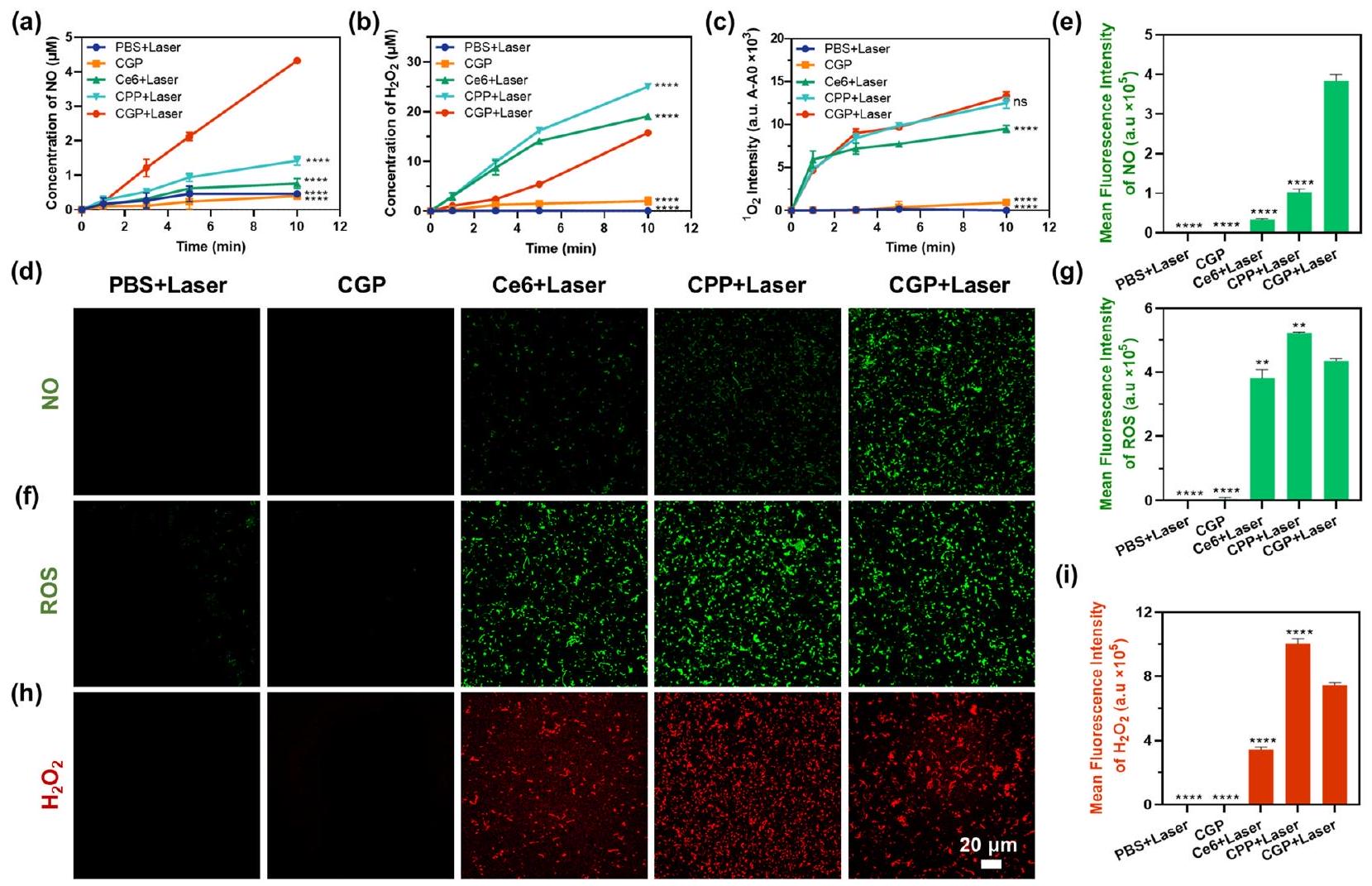

توليد الجذور الحرة والأكسيد النيتريكي المدفوع بالعلاج الضوئي المعتمد على الأدوية

لتأكيد النتائج المذكورة أعلاه، استخدمنا التصوير المجهري بالليزر المتقارب لمراقبة إنتاج NO و ROS و

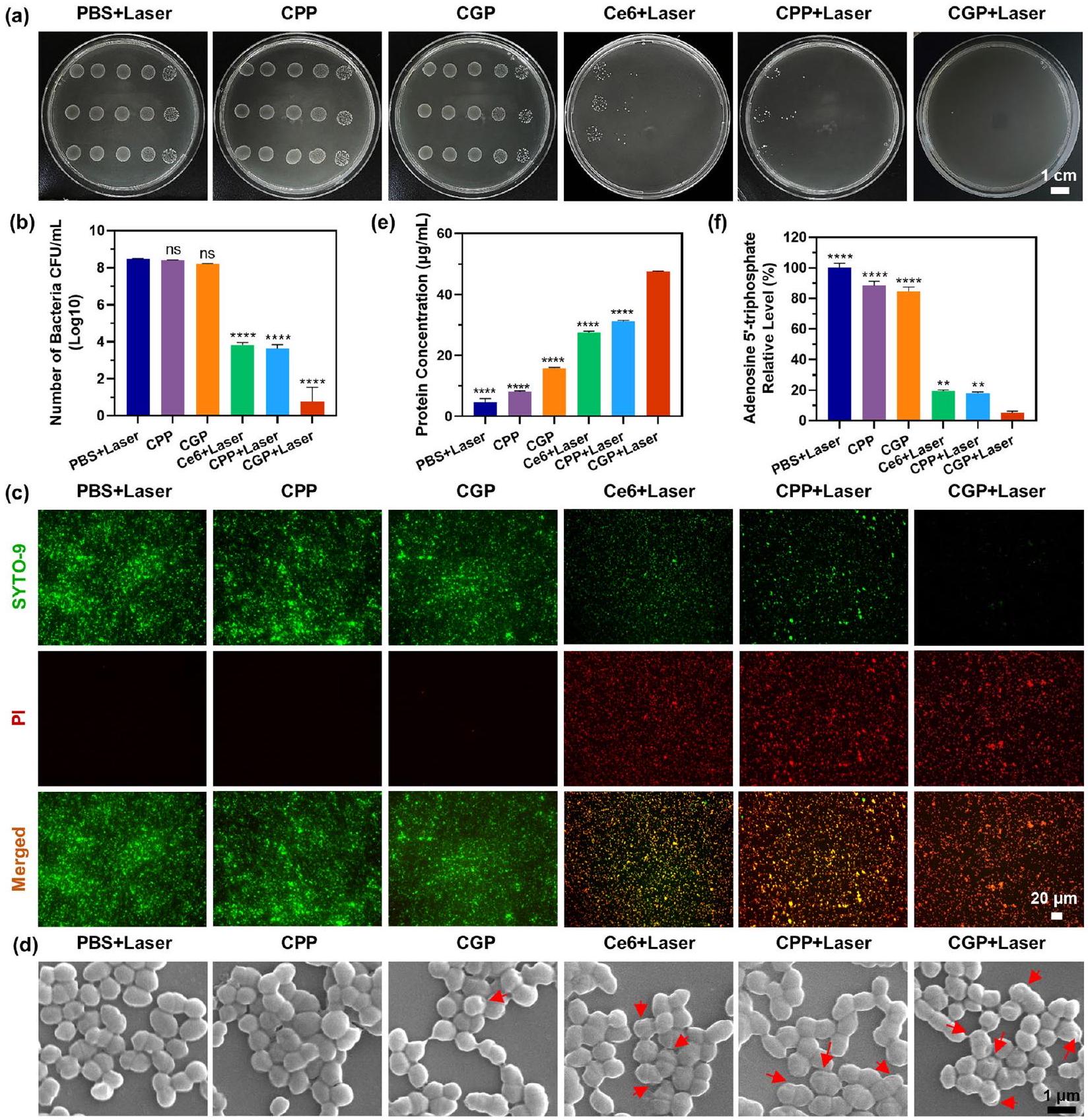

التأثير المضاد للميكروبات لـ CGP في المختبر

تأثير مضاد للميكروبات قوي يسهل من خلال الجمع بين العلاج الضوئي المعتمد على الأكسجين (aPDT) وأكسيد النيتريك (NO). لتوضيح التأثيرات على سلامة الخلايا البكتيرية، استخدمنا مجموعة اختبار الحية/الميتة BacLight. في هذه المجموعة، يتمكن صبغة الحمض النووي الفلورية الخضراء SYTO-9 من اختراق جميع البكتيريا، بينما يمكن لصبغة PI اختراق الأغشية المتضررة فقط.

إن إدخال PI يسبب تقليل في فلورية SYTO 9. كما هو موضح في الشكل 3c، لم تُلاحظ إشارات فلورية لـ PI في E. faecalis المعالجة بـ PBS + ليزر، CPP، و CGP، مما يشير إلى أن البكتيريا لديها أغشية سليمة. أظهرت E. faecalis المعالجة بـ CPP + ليزر و Ce6 + ليزر فلورية خضراء وحمراء قوية نسبيًا، مما يدل على حدوث اضطراب معتدل في أغشية البكتيريا. بالمقابل، أظهرت البكتيريا المعالجة بـ CGP + ليزر فلورية حمراء قوية وفلورية خضراء ضعيفة، مما يدل على تلف شديد في أغشية البكتيريا. تؤكد هذه النتائج أن التأثير المضاد للميكروبات لـ CGP + ليزر يتفوق على CPP + ليزر، مما يشير إلى التأثير التآزري المضاد للميكروبات لـ aPDT و NO. علاوة على ذلك، استكشفت الدراسة الآلية المضادة للميكروبات للجزيئات النانوية من خلال تسرب البروتين، والتغيرات في مستويات ATP، والتغيرات في شكل البكتيريا.

القضاء على الأغشية الحيوية لـ CGP في المختبر

يجب الاعتراف بالآثار الجانبية الشديدة والسمية المعروفة. وبالتالي، نعتقد أن CGP لا يزال يحمل إمكانيات للتطبيق في ري قنوات الجذور. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، كان من الواضح أن فعالية المضادات الميكروبية والقضاء على الأغشية الحيوية لـ

مجموعة، مما يسمح بتحليل أكثر تركيزًا على الخصائص القوية المستهدفة للبيوفيلم لـ CGP.

تشجيعًا من النتائج الإيجابية لتقنية CGP + الليزر في صبغ البكتيريا الحية/الميتة وصبغ الكريستال البنفسجي، قمنا بزراعة أغشية حيوية لبكتيريا E. faecalis في قنوات الجذور لأسنان بشرية مستخرجة لتقييم فعالية القضاء على الأغشية الحيوية. كما هو موضح في الشكل 4d و e، تم ملاحظة حيوية البكتيريا بعد علاج CPP + الليزر عند

اختبارات التوافق الدموي والتوافق الحيوي

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، كانت قابلية بقاء الخلايا لـ CGP باستمرار أكبر من

تمت ملاحظة فلوريسcence حمراء ملحوظة من صبغة PI (الشكل 5f). كما هو متوقع، أظهر NaClO سمية خلوية ملحوظة، مع أقل من

التمايز العظمي في المختبر

تشير هذه النتائج إلى قمع ملحوظ للتمايز العظمي في وجود

يوجد عادةً في الحالات الالتهابية [52]. ومع ذلك، يبدو أن إدخال CGP يعاكس هذا التأثير المثبط. الآلية الكامنة وراء هذه الظاهرة تتضمن استهلاك

العلاج في الجسم الحي لالتهاب جذر السن

عند الإصابة، تم علاج الجرذان بمحلول PBS،

البيانات الكمية المعروضة في الشكل 7 ج، كان حجم تجويف الامتصاص

تأثير الإخراج لـ NaClO، مما يسبب سمية الأنسجة المحيطة بالذروة [54]. تم استخدام طريقة الري باستخدام الحقنة التقليدية في هذه الدراسة، وكان الإخراج القمي لا مفر منه باستثناء أنظمة الري ذات الضغط السلبي [55]. من المRemarkably، كانت تجويف الامتصاص لـ CGP+Laser

وخصائص إذابة الأنسجة. ونعتقد أن CGP + الليزر يمكن أن يكون بديلاً جذابًا في بعض الحالات. علاوة على ذلك، قد يحمل وعدًا في علاج أمراض اللثة، وإدارة عدوى الأغشية الحيوية الأخرى، وتطبيقات متنوعة أخرى.

الاستنتاجات

| اختصارات | |

| AP | التهاب جذر السن |

| NaClO | هيبوكلوريت الصوديوم |

| aPDT | العلاج الضوئي المضاد للميكروبات |

| روس | أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية |

|

|

بيروكسيد الهيدروجين |

|

|

الأكسجين الأحادي |

| لا | أكسيد النيتريك |

| جي-بيغ-بي سي إل | بوليمر غوانيدينيلاتي بولي (إيثيلين غليكول) – بولي (ɛ-كابرو لاكتون) |

|

|

بولي (إيثيلين غليكول) – بولي (ديلتا-كابرو لاكتون) طرفه أميني |

| سي 6 | كلورين e6 |

| CGP | جي-بيغ-بي سي إل محمّل بـ Ce6 |

| CPP |

|

| بي بي | جزيئات نانوية فارغة NH2-PEG-PCL |

| طبيب عام | جزيئات نانوية فارغة من G-PEG-PCL |

| E. faecalis | إنتيروكوكوس فاسياليس |

| PBS | محلول ملحي معزز بالفوسفات |

| NS | محلول ملحي عادي |

| فخ | فوسفاتاز الحمض المقاوم للتارتارات |

| هو | الهيماتوكسيلين-إيوزين |

| SOSG | مستشعر الأكسجين الأحادي الأخضر |

| دي سي إف إتش – دي إيه | ديكلوروديهيدروفلورسئين داي أستات |

| داف-إف إم دا | 3-أمينو، 4-أمينوميثيل-2’، 7′-ديفلوريسئين، داي أسيتيت |

| ATP | تغيرات في الأدينوزين 5′-ثلاثي الفوسفات |

| خلايا جذعية من نسيج اللثة البشري | خلايا جذعية من الرباط اللثوي البشري |

| ALP | الفوسفاتاز القلوي |

| إليزا | اختبار الامتزاز المناعي المرتبط بالإنزيم |

| OCN | أوستيوكالسين |

| RUNX2 | عامل النسخ المرتبط بـ Runt 2 |

| CLSM | ميكروسكوب المسح بالليزر المتماسك |

معلومات إضافية

استقرار CGP خلال 14 يومًا.

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

موافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

نُشر على الإنترنت: 30 أبريل 2024

References

- Kakehashi S, Stanley HR, Fitzgerald RJ. The effects of surgical exposures of dental pulps in germ-free and conventional laboratory rats. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1965;20:340-9.

- Shah AC, Leong KK, Lee MK, Allareddy V. Outcomes of hospitalizations attributed to periapical abscess from 2000 to 2008: a longitudinal trend analysis. J Endod. 2013;39:1104-10.

- Tiburcio-Machado CS, Michelon C, Zanatta FB, Gomes MS, Marin JA, Bier CA. The global prevalence of apical periodontitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Endod J. 2021;54:712-35.

- Persoon IF, Ozok AR. Definitions and epidemiology of endodontic infections. Curr Oral Health Rep. 2017;4:278-85.

- Distel JW, Hatton JF, Gillespie MJ. Biofilm formation in medicated root canals. J Endod. 2002;28:689-93.

- Mah TF, Pitts B, Pellock B, Walker GC, Stewart PS, O’Toole GA. A genetic basis for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm antibiotic resistance. Nature. 2003:426:306-10.

- Zehnder M. Root canal irrigants. J Endod. 2006;32:389-98.

- AI-Sebaei MO, Halabi OA, El-Hakim IE. Sodium hypochlorite accident resulting in life-threatening airway obstruction during root canal treatment: a case report. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2015;7:41-4.

- Ortiz-Alves T, Diaz-Sanchez R, Gutierrez-Perez JL, Gonzalez-Martin M, Serrera-Figallo MA, Torres-Lagares D. Bone necrosis as a complication of sodium hypochlorite extrusion. A case report. J Clin Exp Dent. 2022;14:e885-889.

- Xu R, Guo D, Zhou X, Sun J, Zhou Y, Fan Y, Zhou X, Wan M, Du W, Zheng L. Disturbed bone remodelling activity varies in different stages of experimental, gradually progressive apical periodontitis in rats. Int J Oral Sci. 2019;11:27.

- Xiao F, Cao B, Wang C, Guo X, Li M, Xing D, Hu X. Pathogen-specific polymeric antimicrobials with significant membrane disruption and enhanced photodynamic damage to inhibit highly opportunistic bacteria. ACS Nano. 2019;13:1511-25.

- Wang D, Niu L, Qiao ZY, Cheng DB, Wang J, Zhong Y, Bai F, Wang H, Fan H. Synthesis of self-assembled porphyrin nanoparticle photosensitizers. ACS Nano. 2018;12:3796-803.

- Zhu J, Tian J, Yang C, Chen J, Wu L, Fan M, Cai X. L-Arg-rich amphiphilic dendritic peptide as a versatile NO donor for NO/photodynamic synergistic treatment of bacterial infections and promoting wound healing. Small. 2021;17: e2101495.

- Carrinho PM, Andreani DIK, Morete VA, Iseri S, Navarro RS, Villaverde AB. A study on the macroscopic morphometry of the lesion area on diabetic ulcers in humans treated with photodynamic therapy using two methods of measurement. Photomed Laser Surg. 2018;36:44-50.

- de Vasconcelos Catao MH, Nonaka CF, de Albuquerque Jr RL, de BentoOliveira Costa PMR. Effects of red laser, infrared, photodynamic therapy, and green LED on the healing process of third-degree burns: clinical and histological study in rats. Lasers Med Sci. 2015;30:421-8.

- Gong J, Park H, Lee J, Seo H, Lee S. Effect of photodynamic therapy on multispecies biofilms, including Streptococcus mutans, Lactobacillus casei, and Candida albicans. Photobiomodul Photomed Laser Surg. 2019;37:282-7.

- Wan SS, Zeng JY, Cheng H, Zhang XZ. ROS-induced NO generation for gas therapy and sensitizing photodynamic therapy of tumor. Biomaterials. 2018;185:51-62.

- Xiu W, Gan S, Wen Q, Qiu Q, Dai S, Dong H, Li Q, Yuwen L, Weng L, Teng Z, et al. Biofilm microenvironment-responsive nanotheranostics for dualmode imaging and hypoxia-relief-enhanced photodynamic therapy of bacterial infections. Research (Wash D C). 2020;2020:9426453.

- Cao H, Zhong S, Wang Q, Chen C, Tian J, Zhang W. Enhanced photodynamic therapy based on an amphiphilic branched copolymer with pendant vinyl groups for simultaneous GSH depletion and Ce6 release. J Mater Chem B. 2020;8:478-83.

- Sun X, Sun J, Lv J, Dong B, Liu M, Liu J, Sun L, Zhang G, Zhang L, Huang G, et al. Ce6-C6-TPZ co-loaded albumin nanoparticles for synergistic combined PDT-chemotherapy of cancer. J Mater Chem B. 2019;7:5797-807.

- Liu HD, Ren MX, Li Y, Zhang RT, Ma NF, Li TL, Jiang WK, Zhou Z, Yao XW, Liu ZY, Yang M. Melatonin alleviates hydrogen peroxide induced oxidative damage in MC3T3-E1 cells and promotes osteogenesis by activating SIRT1. Free Radic Res. 2022;56:63-76.

- Sheppard AJ, Barfield AM, Barton S, Dong Y. Understanding reactive oxygen species in bone regeneration: a glance at potential therapeutics and bioengineering applications. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10: 836764.

- Zhang J, Guo H, Liu M, Tang K, Li S, Fang Q, Du H, Zhou X, Lin X, Yang Y. Recent design strategies for boosting chemodynamic therapy of bacterial infections. Exploration. 2023;2023:20230087.

- Liu R, Peng Y, Lu L, Peng S, Chen T, Zhan M. Near-infrared light-triggered nano-prodrug for cancer gas therapy. J Nanobiotechnol. 2021;19:443.

- Yang Z, Chen H. Recent deveolpment of multifunctional responsive gas-releasing nanoplatforms for tumor therapeutic application. Nano Res. 2023;16:3924-38.

- Opoku-Damoah

hang . Therapeutic gas-releasing nanomedicines with controlled release: advances and perspectives. Exploration (Beijing). 2022;2:20210181. - Backlund CJ, Sergesketter AR, Offenbacher S, Schoenfisch MH. Antibacterial efficacy of exogenous nitric oxide on periodontal pathogens. J Dent Res. 2014;93:1089-94.

- Barui AK, Nethi SK, Patra CR. Investigation of the role of nitric oxide driven angiogenesis by zinc oxide nanoflowers. J Mater Chem B. 2017;5:3391-403.

- Qian Y, Chug MK, Brisbois EJ. Nitric oxide-releasing silicone oil with tunable payload for antibacterial applications. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2022;5:3396-404.

- Lv X, Jiang J, Ren J, Li H, Yang D, Song X, Hu Y, Wang W, Dong X. Nitric oxide-assisted photodynamic therapy for enhanced penetration and hypoxic bacterial biofilm elimination. Adv Healthc Mater. 2023;12: e2302031.

- Li G, Yu S, Xue W, Ma D, Zhang W. Chitosan-graft-PAMAM loading nitric oxide for efficient antibacterial application. Chem Eng J. 2018;347:923-31.

- Saura M, Tarin C, Zaragoza C. Recent insights into the implication of nitric oxide in osteoblast differentiation and proliferation during bone development. Sci World J. 2010;10:624-32.

- Won JE, Kim WJ, Shim JS, Ryu JJ. Guided bone regeneration with a nitricoxide releasing polymer inducing angiogenesis and osteogenesis in critical-sized bone defects. Macromol Biosci. 2022;22: e2200162.

- Yasuhara R, Suzawa T, Miyamoto Y, Wang X, Takami M, Yamada A, Kamijo R. Nitric oxide in pulp cell growth, differentiation, and mineralization. J Dent Res. 2007;86:163-8.

- Izawa H, Kinai M, Ifuku S, Morimoto M, Saimoto H. Guanidinylated chitosan inspired by arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptides. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;125:901-5.

- Khan NF, Nakamura H, Izawa H, Ifuku S, Kadowaki D, Otagiri M, Anraku M. Evaluation of the safety and gastrointestinal migration of guanidinylated chitosan after oral administration to rats. J Funct Biomater. 2023;14:340.

- Andreev K, Bianchi C, Laursen JS, Citterio L, Hein-Kristensen L, Gram L, Kuzmenko I, Olsen CA, Gidalevitz D. Guanidino groups greatly enhance the action of antimicrobial peptidomimetics against bacterial cytoplasmic membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2014;1838:2492-502.

- Hu D, Deng Y, Jia F, Jin Q, Ji J. Surface charge switchable supramolecular nanocarriers for nitric oxide synergistic photodynamic eradication of biofilms. ACS Nano. 2020;14:347-59.

- Liu H, Yu Y, Xue T, Gan C, Xie Y, Wang D, Li P, Qian Z, Ye T. A nonenzymatic electrochemical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide in vitro and in vivo fibrosis models. Chin Chem Lett. 2024;35: 108574.

- Xiu W, Shan J, Yang K, Xiao H, Yuwen L, Wang L. Recent development of nanomedicine for the treatment of bacterial biofilm infections. VIEW. 2021;2:20200065.

- Gollmer A, Arnbjerg J, Blaikie FH, Pedersen BW, Breitenbach T, Daasbjerg K, Glasius M, Ogilby PR. Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green

: photochemical behavior in solution and in a mammalian cell. Photochem Photobiol. 2011;87:671-9. - Huysseune A, Larsen UG, Larionova D, Matthiesen CL, Petersen SV, Muller M, Witten PE. Bone formation in zebrafish: the significance of DAF-FM DA staining for nitric oxide detection. Biomolecules. 2023;13:1780.

- Eruslanov E, Kusmartsev S. Identification of ROS using oxidized DCFDA and flow-cytometry. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;594:57-72.

- Hsu Y-J, Nain A, Lin Y-F, Tseng Y-T, Li Y-J, Sangili A, Srivastava P, Yu H-L, Huang Y-F, Huang C-C. Self-redox reaction driven in situ formation of Cu2O/Ti3C2Tx nanosheets boost the photocatalytic eradication of multi-drug resistant bacteria from infected wound. J Nanobiotechnol. 2022;20:235.

- Votyakova TV, Reynolds IJ. Detection of hydrogen peroxide with Amplex Red: interference by NADH and reduced glutathione auto-oxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;431:138-44.

- Skulachev V. Bioenergetic aspects of apoptosis, necrosis and mitoptosis. Apoptosis. 2006;11:473-85.

- Veisi H. Sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl). Synlett. 2007;2007:2607-8.

- Puchtler H, Meloan SN. TERRY MS: On the history and mechanism of alizarin and alizarin red S stains for calcium. J Histochem Cytochem. 1969;17:110-24.

- Xiao G, Cui Y, Ducy P, Karsenty G, Franceschi RT. Ascorbic acid-dependent activation of the osteocalcin promoter in MC3T3-E1 preosteoblasts:

requirement for collagen matrix synthesis and the presence of an intact OSE2 sequence. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:1103-13. - Kawane T, Qin X, Jiang Q, Miyazaki T, Komori H, Yoshida CA, MatsuuraKawata VKdS, Sakane C, Matsuo Y, Nagai K. Runx2 is required for the proliferation of osteoblast progenitors and induces proliferation by regulating Fgfr2 and Fgfr3. Sci Rep. 2018;8:13551.

- Seweryn A, Alicka M, Fal A, Kornicka-Garbowska K, Lawniczak-Jablonska K, Ozga M, Kuzmiuk P, Godlewski M, Marycz K. Hafnium (IV) oxide obtained by atomic layer deposition (ALD) technology promotes early osteogenesis via activation of Runx2-OPN-mir21A axis while inhibits osteoclasts activity. J Nanobiotechnol. 2020;18:1-16.

- Wittmann C, Chockley P, Singh SK, Pase L, Lieschke GJ, Grabher C. Hydrogen peroxide in inflammation: messenger, guide, and assassin. Adv Hematol. 2012;2012: 541471.

- Luo X, Wan Q, Cheng L, Xu R. Mechanisms of bone remodeling and therapeutic strategies in chronic apical periodontitis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12: 908859.

- Cai C, Chen

, Y, Jiang . Advances in the role of sodium hypochlorite irrigant in chemical preparation of root canal treatment. Biomed Res Int. 2023;2023:8858283. - Azim AA, Aksel H, Margaret Jefferson M, Huang GT. Comparison of sodium hypochlorite extrusion by five irrigation systems using an artificial root socket model and a quantitative chemical method. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22:1055-61.

- Mei Z, Gao D, Hu D, Zhou H, Ma T, Huang L, Liu X, Zheng R, Zheng H, Zhao P, et al. Activatable NIR-II photoacoustic imaging and photochemical synergistic therapy of MRSA infections using miniature Au/Ag nanorods. Biomaterials. 2020;251: 120092.

- Badran Z, Rahman B, De Bonfils P, Nun P, Coeffard V, Verron E. Antibacterial nanophotosensitizers in photodynamic therapy: an update. Drug Discov Today. 2023;28: 103493.

- Swimberghe RCD, Coenye T, De Moor RJG, Meire MA. Biofilm model systems for root canal disinfection: a literature review. Int Endod J. 2019;52:604-28.

ملاحظة الناشر

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-024-02483-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38689259

Publication Date: 2024-04-30

Photodynamic and nitric oxide

Check for updates therapy-based synergistic antimicrobial nanoplatform: an advanced root canal irrigation system for endodontic bacterial infections

Abstract

Background The main issues faced during the treatment of apical periodontitis are the management of bacterial infection and the facilitation of the repair of alveolar bone defects to shorten disease duration. Conventional root canal irrigants are limited in their efficacy and are associated with several side effects. This study introduces a synergistic therapy based on nitric oxide (NO) and antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) for the treatment of apical periodontitis. Results This research developed a multifunctional nanoparticle, CGP, utilizing guanidinylated poly (ethylene glycol)poly (

*Correspondence:

Xiaojun Cai

cxj520118@wmu.edu.cn; cxj520118@njtech.edu.cn

Yihuai Pan

yihuaipan@wmu.edu.cn

Introduction

at addressing AP, involves the removal of infected pulp tissue and microorganisms, followed by disinfection and filling of the root canal with an inert material. This process typically employs mechanical preparation and chemical irrigation for infection control. However, the complex anatomy of the root canal system, along with the persistent presence of biofilms, significantly hinders the effectiveness of these treatments. The failure rate of root canal treatment is

Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) is an efficient, non-invasive antimicrobial strategy, which offers precise temporal and spatial control, broad-spectrum antimicrobial and biofilm eradication properties [11]. It operates by activating photosensitizers with lasers at specific wavelengths, leading to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydroxyl radicals, superoxide anion, hydrogen peroxide

lead to a persistent inflammatory response, which, in turn, can adversely affect the process of osteogenesis [21, 22]. To overcome these challenges, research has focused on combining aPDT with alternative therapeutic approaches [23,24]. This study explores the combination of aPDT with gas therapy, aiming to enhance biofilm eradication efficacy and mitigate the detrimental effects of elevated ROS levels.

The combination of aPDT and NO offers a promising pathway for developing a new multifunctional root canal irrigation system. This study is designed to assess the antibacterial, biofilm eradication, and osteogenic differentiation capabilities of CGP through colony counting, live/dead bacterial viability assays, simulated root canal irrigation, and osteogenic differentiation experiments, along with therapeutic testing in a rat AP model. Compared to NaClO , CGP is anticipated to possess not only antimicrobial properties but also superior temporal and spatial control abilities, as well as a unique capacity to facilitate the repair of apical bone defects. We anticipate that this study has developed an irrigation system capable of safely and effectively treating AP.

Materials and methods

Materials

ascorbic acid were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). The Griess reagent,

Synthesis of CGP nanoparticles

nitrogen protection, maintaining a molar ratio of

Physicochemical characterization of CGP

Bacterial association and biofilm penetration of CGP

To assess the biofilm permeation properties of CGP, three-dimensional confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM, A1, Nikon) was utilized. SYTO-9 (green,

was then incubated in an anaerobic incubator at

ROS and NO generation profiles of CGP

Imaging of

Antibacterial activity of CGP in vitro

To further evaluate the antimicrobial properties of CGP, a live/dead BacLight viability assay was conducted. The bacteria were first treated as described above. After treatment, the bacterial suspension was centrifuged and washed to remove any residues of CGP. The pellet was then resuspended and stained with SYTO-9 and PI for 15 min at room temperature. Then, after another round of centrifuged and washed with PBS to remove excess stain, the bacteria were observed using an inverted fluorescence microscope.

To visualize the morphological changes in bacteria treated with CGP+Laser, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was utilized. Bacteria were first treated as described above. After treatment, the bacterial cells were centrifuged and washed twice with NS. The bacteria were then fixed using 1 mL of

dry naturally. Finally, the bacteria were sputtered with gold and observed with a scanning electron microscope (SU8010, HITACHI). Control groups for these experiments included PBS + Laser, CPP, CGP, Ce6 + Laser, and CPP+Laser.

Protein leakage and changes in ATP levels in CGP-treated bacteria

In vitro biofilm eradication effect of CGP

and the residual biofilms were photographed with a stereomicroscope (SMZ 800N, Nikon). After photographing, the residual biofilm was dissolved with

Biofilm eradication efficacy of CGP in root canals

Biosafety assessment

Osteogenic differentiation in vitro

In vivo treatment of apical periodontitis

After 2 weeks, the cements were removed, followed by the irrigation of the root canals using

of 5 min . Thereafter, sterile paper points were inserted into the canals to collect residual bacteria, which were then placed into EP tubes containing 1 mL of NS and stored at

Statistical analysis

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization of CGP

penetration, and additionally functions as a nitric oxide donor. The successful guanidinylation was confirmed by the emergence of of

(

The

Bacterial association and biofilm permeation of CGP

The efficacy of antimicrobial agents is significantly influenced by their ability to penetrate biofilms, which are known to hinder the therapeutic effectiveness of such agents [38]. The biofilm permeability of CGP was assessed using a CLSM, employing SYTO-9 as an indicator for biofilm staining. After 5 min of co-incubation with E. faecalis biofilm, CLSM analysis showed a faint red fluorescence emanating from Ce 6 within the biofilm treated with free Ce 6 , suggesting limited penetration.

ROS and NO generation driven by aPDT

To corroborate the aforementioned results, we employed CLSM to observe the production of NO, ROS, and

Antimicrobial effect of CGP in vitro

potent antimicrobial effect facilitated by the combination of aPDT and NO. To further elucidate the effects on bacterial cell integrity, we utilized the live/dead BacLight viability kit. Within this kit, the green fluorescent nucleic acid dye SYTO-9 penetrates and labels all bacteria, while PI can only penetrate compromised membranes

and the insertion of PI causes a reduction of SYTO 9 fluorescence. As shown in Fig. 3c, PI fluorescence signals were hardly observed in the E. faecalis treated with PBS + Laser, CPP, and CGP, suggesting that the bacteria have intact membranes. CPP + Laser and Ce6 + Lasertreated E. faecalis exhibited relatively strong green and red fluorescence, indicating a moderate disruption of the bacterial membranes. In contrast, the CGP + Lasertreated bacteria exhibited strong red fluorescence and weak green fluorescence, indicating severe damage to the bacterial membranes. These results confirm that the antimicrobial effect of CGP + Laser is superior to that of CPP + Laser, thus indicating the synergistic antimicrobial effect of aPDT and NO. Furthermore, the study explored the antimicrobial mechanism of the nanoparticles through protein leakage, changes in alterations in ATP levels, and alterations in bacterial morphology.

Biofilm eradication of CGP in vitro

for severe side effects and well-known cytotoxicity must be acknowledged. Consequently, we believe that CGP still holds potential for application in root canal irrigation. In addition, it was evident that the antimicrobial and biofilm eradication efficacies of free

group, allowing for a more focused analysis on the potent biofilm-targeting properties of CGP.

Encouraged by the favorable outcomes of CGP + Laser in live/dead bacterial staining and crystal violet staining, we proceeded to cultivate E. faecalis biofilms in the root canals of extracted human teeth to assess the biofilm eradication efficacy. As shown in Fig. 4d and e, the bacterial viability post CPP + Laser treatment was observed at

Hemocompatibility and biocompatibility assays

Besides, the cell viability of CGP was consistently >

significant red fluorescence from PI staining observed (Fig. 5f). As predicted, NaClO exhibited pronounced cytotoxicity, with less than

Osteogenic differentiation in vitro

These results indicate a notable suppression of osteogenic differentiation in the presence of

is commonly present in inflammatory conditions [52]. However, the introduction of CGP appears to counteract this inhibitory effect. The mechanism underlying this phenomenon involves the consumption of

In vivo treatment of apical periodontitis

of infection, the rats were treated with PBS,

quantitative data presented in Fig. 7 g , the volume of the resorption cavity was

the extrusion effect of NaClO , causing periapical tissue toxicity [54]. The conventional syringe irrigation method was employed in this study, and apical extrusion was inevitable except for negative pressure irrigation systems [55]. Remarkably, the resorption cavity of CGP+Laser was

and tissue-dissolving characteristics. And we believe that CGP + Laser can serve as a compelling alternative in certain cases. Furthermore, it may hold promise in periodontal therapy, managing other biofilm infections, and various other applications.

Conclusions

| Abbreviations | |

| AP | Apical periodontitis |

| NaClO | Sodium hypochlorite |

| aPDT | Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

|

|

Hydrogen peroxide |

|

|

Singlet oxygen |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| G-PEG-PCL | Guanidinylated poly (ethylene glycol)-poly(ɛ-caprolactone) |

|

|

Amino-terminated poly (ethylene glycol)-poly(દ-caprolactone) |

| Ce6 | Chlorin e6 |

| CGP | G-PEG-PCL loaded with Ce6 |

| CPP |

|

| PP | Blank NH2-PEG-PCL nanoparticles |

| GP | Blank G-PEG-PCL nanoparticles |

| E. faecalis | Enterococcus faecalis |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| NS | Normal saline |

| TRAP | Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase |

| HE | Hematoxylin-eosin |

| SOSG | Singlet oxygen sensor green |

| DCFH-DA | Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate |

| DAF-FM DA | 3-Amino,4-aminomethyl-2′,7′-difluorescein, diacetate |

| ATP | Alterations in adenosine 5′-triphosphate |

| hPDLSCs | Human periodontal ligament stem cells |

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| OCN | Osteocalcin |

| RUNX2 | Runt-related transcription factor 2 |

| CLSM | Confocal laser scanning microscope |

Supplementary Information

of G-PEG-PCL. Fig. S2. The stability of CGP during 14 days. Fig.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Published online: 30 April 2024

References

- Kakehashi S, Stanley HR, Fitzgerald RJ. The effects of surgical exposures of dental pulps in germ-free and conventional laboratory rats. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1965;20:340-9.

- Shah AC, Leong KK, Lee MK, Allareddy V. Outcomes of hospitalizations attributed to periapical abscess from 2000 to 2008: a longitudinal trend analysis. J Endod. 2013;39:1104-10.

- Tiburcio-Machado CS, Michelon C, Zanatta FB, Gomes MS, Marin JA, Bier CA. The global prevalence of apical periodontitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Endod J. 2021;54:712-35.

- Persoon IF, Ozok AR. Definitions and epidemiology of endodontic infections. Curr Oral Health Rep. 2017;4:278-85.

- Distel JW, Hatton JF, Gillespie MJ. Biofilm formation in medicated root canals. J Endod. 2002;28:689-93.

- Mah TF, Pitts B, Pellock B, Walker GC, Stewart PS, O’Toole GA. A genetic basis for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm antibiotic resistance. Nature. 2003:426:306-10.

- Zehnder M. Root canal irrigants. J Endod. 2006;32:389-98.

- AI-Sebaei MO, Halabi OA, El-Hakim IE. Sodium hypochlorite accident resulting in life-threatening airway obstruction during root canal treatment: a case report. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2015;7:41-4.

- Ortiz-Alves T, Diaz-Sanchez R, Gutierrez-Perez JL, Gonzalez-Martin M, Serrera-Figallo MA, Torres-Lagares D. Bone necrosis as a complication of sodium hypochlorite extrusion. A case report. J Clin Exp Dent. 2022;14:e885-889.

- Xu R, Guo D, Zhou X, Sun J, Zhou Y, Fan Y, Zhou X, Wan M, Du W, Zheng L. Disturbed bone remodelling activity varies in different stages of experimental, gradually progressive apical periodontitis in rats. Int J Oral Sci. 2019;11:27.

- Xiao F, Cao B, Wang C, Guo X, Li M, Xing D, Hu X. Pathogen-specific polymeric antimicrobials with significant membrane disruption and enhanced photodynamic damage to inhibit highly opportunistic bacteria. ACS Nano. 2019;13:1511-25.

- Wang D, Niu L, Qiao ZY, Cheng DB, Wang J, Zhong Y, Bai F, Wang H, Fan H. Synthesis of self-assembled porphyrin nanoparticle photosensitizers. ACS Nano. 2018;12:3796-803.

- Zhu J, Tian J, Yang C, Chen J, Wu L, Fan M, Cai X. L-Arg-rich amphiphilic dendritic peptide as a versatile NO donor for NO/photodynamic synergistic treatment of bacterial infections and promoting wound healing. Small. 2021;17: e2101495.

- Carrinho PM, Andreani DIK, Morete VA, Iseri S, Navarro RS, Villaverde AB. A study on the macroscopic morphometry of the lesion area on diabetic ulcers in humans treated with photodynamic therapy using two methods of measurement. Photomed Laser Surg. 2018;36:44-50.

- de Vasconcelos Catao MH, Nonaka CF, de Albuquerque Jr RL, de BentoOliveira Costa PMR. Effects of red laser, infrared, photodynamic therapy, and green LED on the healing process of third-degree burns: clinical and histological study in rats. Lasers Med Sci. 2015;30:421-8.

- Gong J, Park H, Lee J, Seo H, Lee S. Effect of photodynamic therapy on multispecies biofilms, including Streptococcus mutans, Lactobacillus casei, and Candida albicans. Photobiomodul Photomed Laser Surg. 2019;37:282-7.

- Wan SS, Zeng JY, Cheng H, Zhang XZ. ROS-induced NO generation for gas therapy and sensitizing photodynamic therapy of tumor. Biomaterials. 2018;185:51-62.

- Xiu W, Gan S, Wen Q, Qiu Q, Dai S, Dong H, Li Q, Yuwen L, Weng L, Teng Z, et al. Biofilm microenvironment-responsive nanotheranostics for dualmode imaging and hypoxia-relief-enhanced photodynamic therapy of bacterial infections. Research (Wash D C). 2020;2020:9426453.

- Cao H, Zhong S, Wang Q, Chen C, Tian J, Zhang W. Enhanced photodynamic therapy based on an amphiphilic branched copolymer with pendant vinyl groups for simultaneous GSH depletion and Ce6 release. J Mater Chem B. 2020;8:478-83.

- Sun X, Sun J, Lv J, Dong B, Liu M, Liu J, Sun L, Zhang G, Zhang L, Huang G, et al. Ce6-C6-TPZ co-loaded albumin nanoparticles for synergistic combined PDT-chemotherapy of cancer. J Mater Chem B. 2019;7:5797-807.

- Liu HD, Ren MX, Li Y, Zhang RT, Ma NF, Li TL, Jiang WK, Zhou Z, Yao XW, Liu ZY, Yang M. Melatonin alleviates hydrogen peroxide induced oxidative damage in MC3T3-E1 cells and promotes osteogenesis by activating SIRT1. Free Radic Res. 2022;56:63-76.

- Sheppard AJ, Barfield AM, Barton S, Dong Y. Understanding reactive oxygen species in bone regeneration: a glance at potential therapeutics and bioengineering applications. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10: 836764.

- Zhang J, Guo H, Liu M, Tang K, Li S, Fang Q, Du H, Zhou X, Lin X, Yang Y. Recent design strategies for boosting chemodynamic therapy of bacterial infections. Exploration. 2023;2023:20230087.

- Liu R, Peng Y, Lu L, Peng S, Chen T, Zhan M. Near-infrared light-triggered nano-prodrug for cancer gas therapy. J Nanobiotechnol. 2021;19:443.

- Yang Z, Chen H. Recent deveolpment of multifunctional responsive gas-releasing nanoplatforms for tumor therapeutic application. Nano Res. 2023;16:3924-38.

- Opoku-Damoah

hang . Therapeutic gas-releasing nanomedicines with controlled release: advances and perspectives. Exploration (Beijing). 2022;2:20210181. - Backlund CJ, Sergesketter AR, Offenbacher S, Schoenfisch MH. Antibacterial efficacy of exogenous nitric oxide on periodontal pathogens. J Dent Res. 2014;93:1089-94.

- Barui AK, Nethi SK, Patra CR. Investigation of the role of nitric oxide driven angiogenesis by zinc oxide nanoflowers. J Mater Chem B. 2017;5:3391-403.

- Qian Y, Chug MK, Brisbois EJ. Nitric oxide-releasing silicone oil with tunable payload for antibacterial applications. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2022;5:3396-404.

- Lv X, Jiang J, Ren J, Li H, Yang D, Song X, Hu Y, Wang W, Dong X. Nitric oxide-assisted photodynamic therapy for enhanced penetration and hypoxic bacterial biofilm elimination. Adv Healthc Mater. 2023;12: e2302031.

- Li G, Yu S, Xue W, Ma D, Zhang W. Chitosan-graft-PAMAM loading nitric oxide for efficient antibacterial application. Chem Eng J. 2018;347:923-31.

- Saura M, Tarin C, Zaragoza C. Recent insights into the implication of nitric oxide in osteoblast differentiation and proliferation during bone development. Sci World J. 2010;10:624-32.

- Won JE, Kim WJ, Shim JS, Ryu JJ. Guided bone regeneration with a nitricoxide releasing polymer inducing angiogenesis and osteogenesis in critical-sized bone defects. Macromol Biosci. 2022;22: e2200162.

- Yasuhara R, Suzawa T, Miyamoto Y, Wang X, Takami M, Yamada A, Kamijo R. Nitric oxide in pulp cell growth, differentiation, and mineralization. J Dent Res. 2007;86:163-8.

- Izawa H, Kinai M, Ifuku S, Morimoto M, Saimoto H. Guanidinylated chitosan inspired by arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptides. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;125:901-5.

- Khan NF, Nakamura H, Izawa H, Ifuku S, Kadowaki D, Otagiri M, Anraku M. Evaluation of the safety and gastrointestinal migration of guanidinylated chitosan after oral administration to rats. J Funct Biomater. 2023;14:340.

- Andreev K, Bianchi C, Laursen JS, Citterio L, Hein-Kristensen L, Gram L, Kuzmenko I, Olsen CA, Gidalevitz D. Guanidino groups greatly enhance the action of antimicrobial peptidomimetics against bacterial cytoplasmic membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2014;1838:2492-502.

- Hu D, Deng Y, Jia F, Jin Q, Ji J. Surface charge switchable supramolecular nanocarriers for nitric oxide synergistic photodynamic eradication of biofilms. ACS Nano. 2020;14:347-59.

- Liu H, Yu Y, Xue T, Gan C, Xie Y, Wang D, Li P, Qian Z, Ye T. A nonenzymatic electrochemical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide in vitro and in vivo fibrosis models. Chin Chem Lett. 2024;35: 108574.

- Xiu W, Shan J, Yang K, Xiao H, Yuwen L, Wang L. Recent development of nanomedicine for the treatment of bacterial biofilm infections. VIEW. 2021;2:20200065.

- Gollmer A, Arnbjerg J, Blaikie FH, Pedersen BW, Breitenbach T, Daasbjerg K, Glasius M, Ogilby PR. Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green

: photochemical behavior in solution and in a mammalian cell. Photochem Photobiol. 2011;87:671-9. - Huysseune A, Larsen UG, Larionova D, Matthiesen CL, Petersen SV, Muller M, Witten PE. Bone formation in zebrafish: the significance of DAF-FM DA staining for nitric oxide detection. Biomolecules. 2023;13:1780.

- Eruslanov E, Kusmartsev S. Identification of ROS using oxidized DCFDA and flow-cytometry. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;594:57-72.

- Hsu Y-J, Nain A, Lin Y-F, Tseng Y-T, Li Y-J, Sangili A, Srivastava P, Yu H-L, Huang Y-F, Huang C-C. Self-redox reaction driven in situ formation of Cu2O/Ti3C2Tx nanosheets boost the photocatalytic eradication of multi-drug resistant bacteria from infected wound. J Nanobiotechnol. 2022;20:235.

- Votyakova TV, Reynolds IJ. Detection of hydrogen peroxide with Amplex Red: interference by NADH and reduced glutathione auto-oxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;431:138-44.

- Skulachev V. Bioenergetic aspects of apoptosis, necrosis and mitoptosis. Apoptosis. 2006;11:473-85.

- Veisi H. Sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl). Synlett. 2007;2007:2607-8.

- Puchtler H, Meloan SN. TERRY MS: On the history and mechanism of alizarin and alizarin red S stains for calcium. J Histochem Cytochem. 1969;17:110-24.

- Xiao G, Cui Y, Ducy P, Karsenty G, Franceschi RT. Ascorbic acid-dependent activation of the osteocalcin promoter in MC3T3-E1 preosteoblasts:

requirement for collagen matrix synthesis and the presence of an intact OSE2 sequence. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:1103-13. - Kawane T, Qin X, Jiang Q, Miyazaki T, Komori H, Yoshida CA, MatsuuraKawata VKdS, Sakane C, Matsuo Y, Nagai K. Runx2 is required for the proliferation of osteoblast progenitors and induces proliferation by regulating Fgfr2 and Fgfr3. Sci Rep. 2018;8:13551.

- Seweryn A, Alicka M, Fal A, Kornicka-Garbowska K, Lawniczak-Jablonska K, Ozga M, Kuzmiuk P, Godlewski M, Marycz K. Hafnium (IV) oxide obtained by atomic layer deposition (ALD) technology promotes early osteogenesis via activation of Runx2-OPN-mir21A axis while inhibits osteoclasts activity. J Nanobiotechnol. 2020;18:1-16.

- Wittmann C, Chockley P, Singh SK, Pase L, Lieschke GJ, Grabher C. Hydrogen peroxide in inflammation: messenger, guide, and assassin. Adv Hematol. 2012;2012: 541471.

- Luo X, Wan Q, Cheng L, Xu R. Mechanisms of bone remodeling and therapeutic strategies in chronic apical periodontitis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12: 908859.

- Cai C, Chen

, Y, Jiang . Advances in the role of sodium hypochlorite irrigant in chemical preparation of root canal treatment. Biomed Res Int. 2023;2023:8858283. - Azim AA, Aksel H, Margaret Jefferson M, Huang GT. Comparison of sodium hypochlorite extrusion by five irrigation systems using an artificial root socket model and a quantitative chemical method. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22:1055-61.

- Mei Z, Gao D, Hu D, Zhou H, Ma T, Huang L, Liu X, Zheng R, Zheng H, Zhao P, et al. Activatable NIR-II photoacoustic imaging and photochemical synergistic therapy of MRSA infections using miniature Au/Ag nanorods. Biomaterials. 2020;251: 120092.

- Badran Z, Rahman B, De Bonfils P, Nun P, Coeffard V, Verron E. Antibacterial nanophotosensitizers in photodynamic therapy: an update. Drug Discov Today. 2023;28: 103493.

- Swimberghe RCD, Coenye T, De Moor RJG, Meire MA. Biofilm model systems for root canal disinfection: a literature review. Int Endod J. 2019;52:604-28.