DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-024-02555-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38797862

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-26

نظام الهيدروجيل الديناميكي-الإطار العضوي المعدني يعزز تجديد العظام في التهاب اللثة من خلال توصيل الدواء بشكل محكم

الملخص

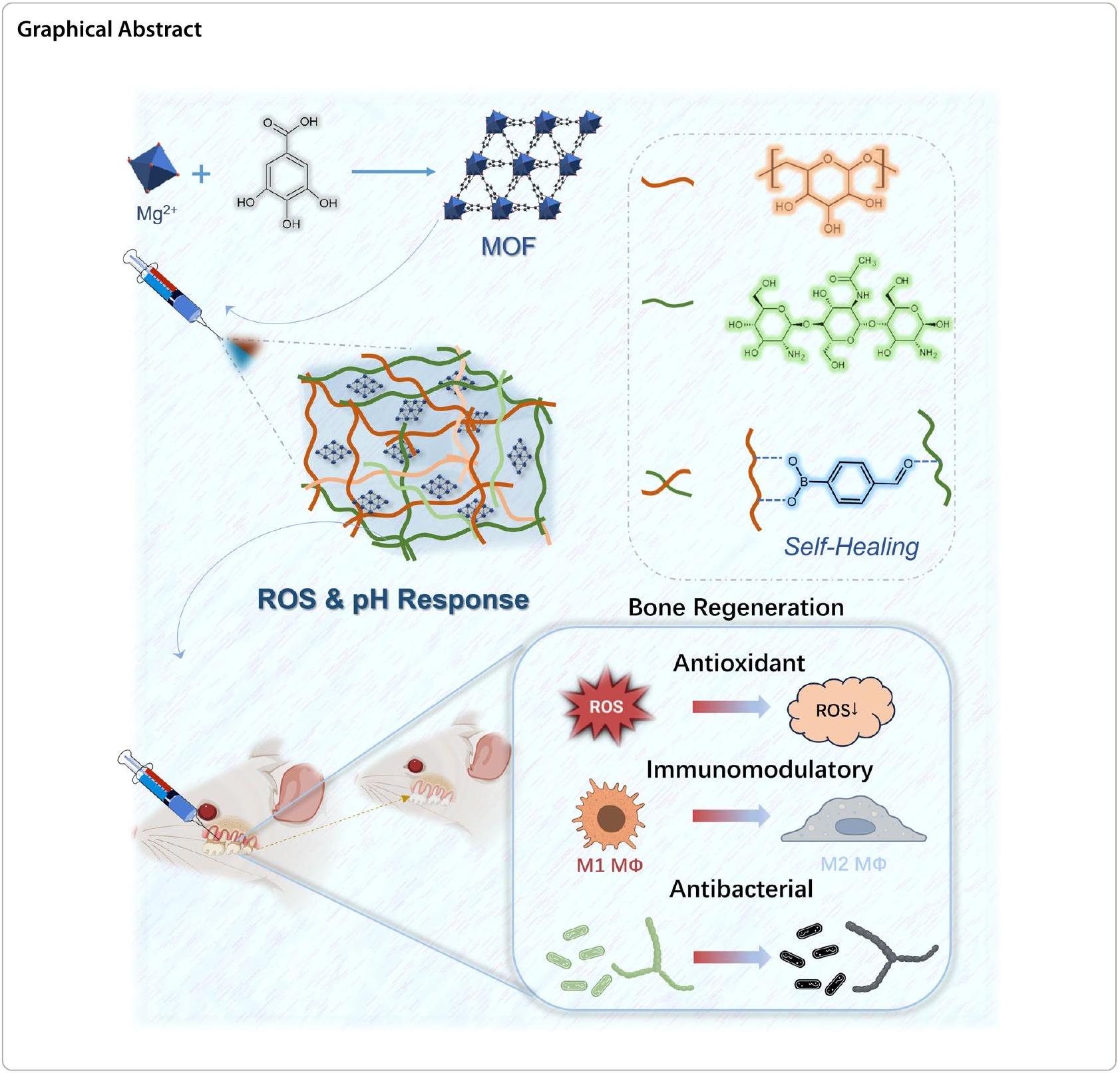

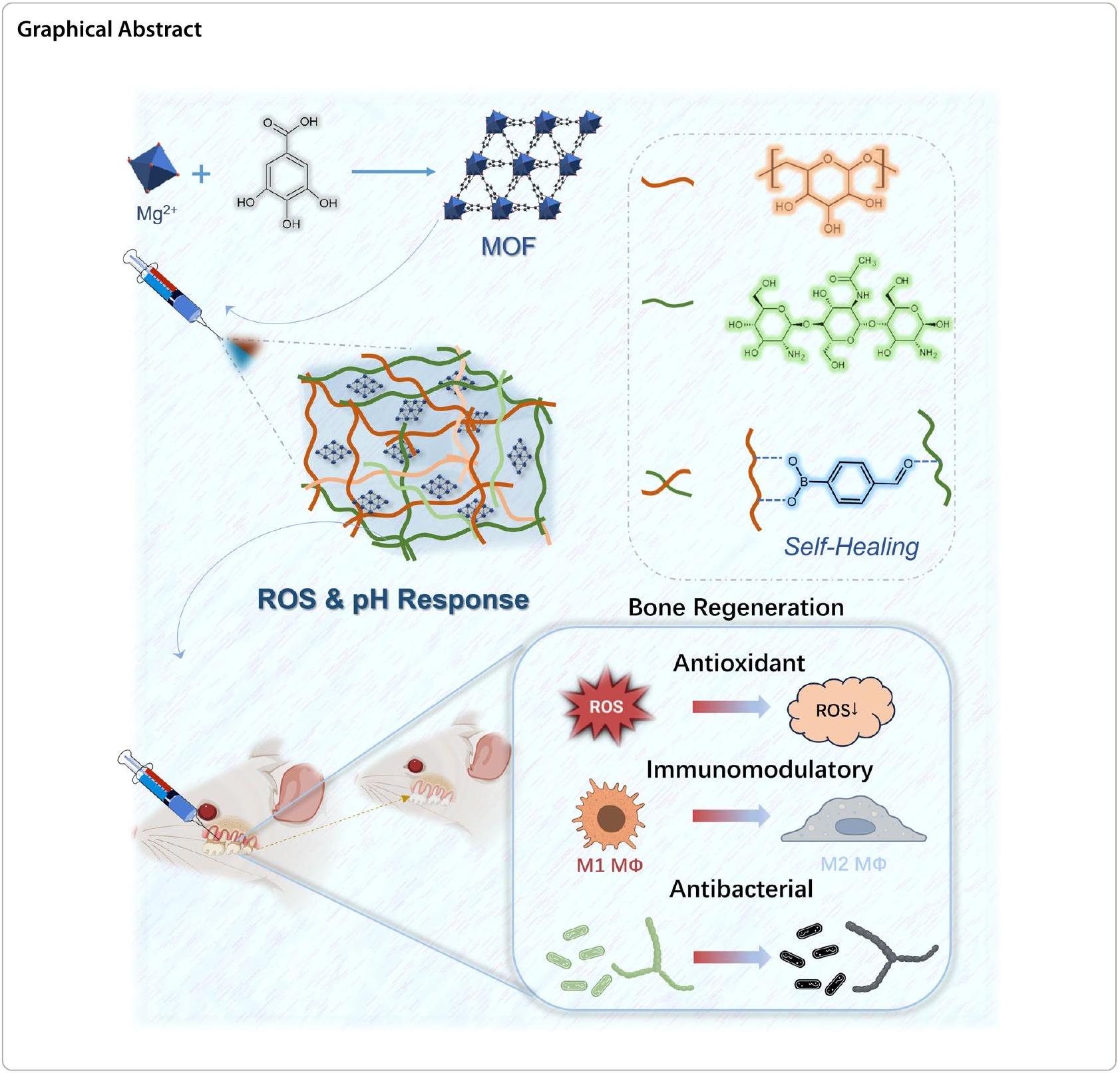

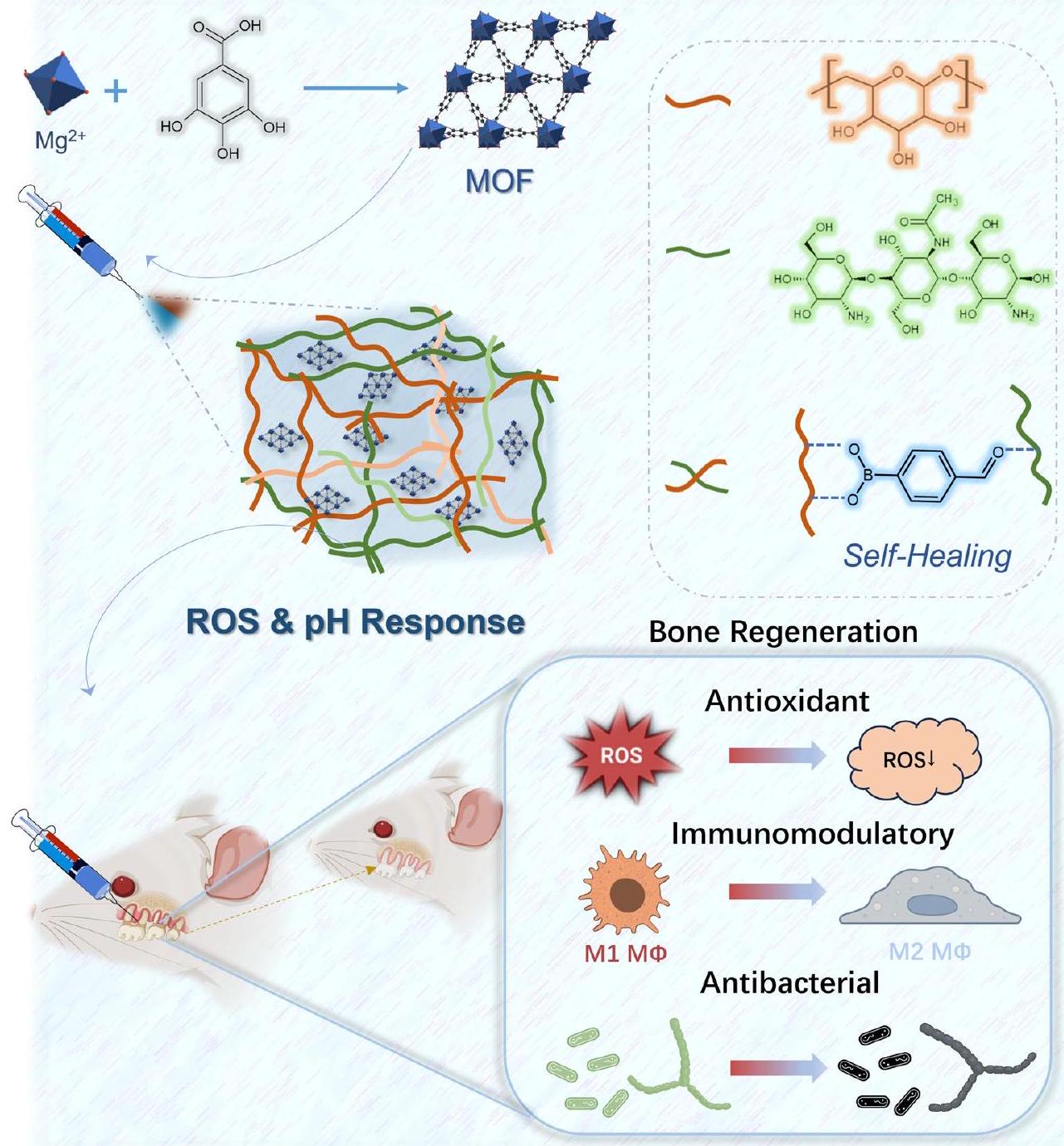

التهاب اللثة هو مرض التهابي مزمن شائع، يؤدي إلى تدهور تدريجي في عظام الفك. تستمر التحديات في تحقيق إصلاح فعال لعظام الفك بسبب تأثير البيئة الميكروبية البكتيرية الفريدة على الاستجابات المناعية. تستكشف هذه الدراسة نهجًا جديدًا يستخدم الأطر المعدنية العضوية (MOFs) (التي تتكون من المغنيسيوم وحمض الجاليك) لتعزيز تجديد العظام في التهاب اللثة، والذي يركز على الأدوار الفسيولوجية لأيونات المغنيسيوم في إصلاح العظام وخصائص حمض الجاليك المضادة للأكسدة والمعدلة للمناعة. ومع ذلك، فإن البيئة الفموية الديناميكية والجيوب اللثوية غير المنتظمة تشكل تحديات لتوصيل الدواء المستدام. تم تصميم نظام هيدروجيل ذكي استجابة، يدمج الكاربوكسي ميثيل كيتوزان (CMCS)، الدكستران (DEX) وحمض 4-فورمال فينيل بورونيك (4-FPBA) لمعالجة هذه المشكلة. يشكل الهيدروجيل القابل للحقن ذاتي الشفاء شبكة مزدوجة الروابط، تضم MOF وتجعل إطلاقه عند الطلب حساسًا لمستويات أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS) ومستويات pH في التهاب اللثة. نسعى لتحليل التأثيرات التآزرية للهيدروجيل مع MOFs في الوظائف المضادة للبكتيريا، وتعديل المناعة وتعزيز تجديد العظام في التهاب اللثة. أثبتت التجارب الحية والمخبرية فعالية النظام في تثبيط التعبير عن الجينات والبروتينات المرتبطة بالالتهاب لتعزيز تجديد العظام اللثوي. يظهر هذا النظام الديناميكي للهيدروجيل مع MOFs وعدًا كمسار علاجي محتمل لمعالجة التحديات في تجديد العظام في التهاب اللثة.

المقدمة

استنادًا إلى الخصائص الفسيولوجية لالتهاب اللثة [5-8]، يتطلب العلاج الفعال وظائف مثل النشاط المضاد للميكروبات، وخصائص مضادة للأكسدة وقدرة على تعزيز تكوين العظام. عمومًا، يتم استخدام فئات مختلفة من المضادات الحيوية لتحقيق الوظائف المذكورة أعلاه [14]. ومع ذلك، فإن الاستخدام المفرط لهذه الأدوية قد يؤدي حتمًا إلى عيوب مثل مقاومة الأدوية وآثار جانبية سلبية [15]. لذلك، بدأ الباحثون تدريجيًا في تحويل تركيزهم نحو استكشاف عوامل علاجية جديدة. في السنوات الأخيرة، حظيت تطبيقات الأطر المعدنية العضوية (MOFs) في مجال الطب الحيوي، وخاصة في توصيل الأدوية وعلاج الأمراض، باهتمام واسع النطاق [16]. الأطر المعدنية العضوية هي فئة من المواد البلورية المسامية المكونة من أيونات معدنية وروابط عضوية، تتميز بمكونات وهياكل قابلة للتخصيص، مما يمكّن من تصميم وتطوير أنظمة متعددة الوظائف مصممة لمختلف الأمراض [17]. وقد تم الإبلاغ عن أن

ومع ذلك، خلال علاج التهاب اللثة، يمكن أن تؤدي البيئة الفموية الديناميكية والمعقدة، بما في ذلك عوامل مثل تدفق اللعاب، والتركيب الكيميائي وتقلبات درجة الحرارة، إلى فقدان سريع لأدوية MOFs [26]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن الهياكل التشريحية غير المنتظمة

للجيوب اللثوية تقدم تحديات محتملة أخرى في علاج التهاب اللثة [27]. لذلك، هناك حاجة لتطوير نظام إطلاق مستدام للتحكم في إطلاق MOFs عند الطلب وتوفير بيئة ميكروبية ملائمة لتجديد العظام في التهاب اللثة. في السنوات الأخيرة، اكتسبت مواد الهيدروجيل القابلة للحقن اهتمامًا تدريجيًا في المجال الطبي الحيوي [28-30]، خاصة الهيدروجيلات الذكية المستجيبة، التي تقدم مزايا فريدة في علاج التهاب اللثة [31، 32]. ومن ثم، تهدف هذه الدراسة إلى بناء هيدروجيل ذكي قابل للحقن استجابة بالتعاون مع MOFs من Mg-GA لعلاج التهاب اللثة. في البداية، اخترنا الكاربوكسي ميثيل كيتوزان (CMCS) والدكستران (DEX) كمكونات رئيسية لبناء الهيدروجيل القابل للحقن. الكاربوكسي ميثيل كيتوزان (CMCS)، هو مشتق من الكيتوزان مع توافق حيوي مشابه وذوبان مائي معزز وخصائص مضادة للبكتيريا [33]، ويستخدم على نطاق واسع في هندسة الأنسجة، وضمادات مضادة للبكتيريا ونظام توصيل الأدوية [34]. وكذلك الدكستران (DEX) هو نوع من المركبات السكرية الخطية التي تنتجها البكتيريا Leuconostoc mesenteroides [35]. هيكل DEX مرتبط بـ

في هذه الدراسة، تم تحميل MOF من Mg-GA في الهلامات الهلامية القابلة للحقن ذاتية الشفاء CSBDX لعلاج التهاب اللثة (الشكل 1). نهدف إلى دراسة إطلاق Mg-GA عند الطلب تحت محفزات البيئة الدقيقة المحددة لالتهاب اللثة، من خلال تعديل تأثيره على تكوين العظام من خلال تنظيم الإجهاد التأكسدي والبيئة المناعية الدقيقة. تهدف الدراسة إلى توضيح التأثيرات التآزرية لخصائص الشفاء الذاتي للهلام ووظائفه المضادة للبكتيريا بالتزامن مع MOF. علاوة على ذلك، نعتزم التحقق من التأثيرات المثبطة على الالتهاب وتعزيز تجديد العظام السنخية لنظام CSBDX@MOF من خلال دراسة التهاب اللثة في الجسم الحي.

تجارب النموذج. يمتلك نظام الهيدروجيل لدينا القدرة على تقديم نهج جديد لتجديد العظام في التهاب اللثة.

طرق وتجارب

المواد

تركيب Mg-GA

تركيب الهيدروجيل

تم خلطها بشكل متجانس وحقنها بسرعة في القالب وتكونت الهلاميات خلال دقائق. تم الحصول على هلاميات CMCS/4FPBA/DEX بنفس الطريقة الموضحة أعلاه دون

توصيف CSBDX

توصيف Mg-GA

توصيف CSBDX@MOF

شكل السطح والمقطع العرضي

وصف خشونة سطح الهيدروجيلات. تم قياس زاوية تماس الماء باستخدام جهاز قياس زاوية التماس DSA-X ROLL. تم قياس شكل قطرة من

الخصائص الميكانيكية

خصائص التورم والانحلال

وزن كـ

خصائص إطلاق الدواء

اختبار مضاد للبكتيريا

التوافق الحيوي

تحضير مستخلصات الهيدروجيل

اختبار تكاثر الخلايا

تم تقييم التكاثر باستخدام مجموعة CCK-8. باختصار، تم إضافة المحلول العامل وتم حضنه لمدة ساعتين في الظلام عند

تلطيخ الخلايا الحية/الميتة

مراقبة شكل الخلايا

اختبارات انحلال الدم

خاصية مضادة للأكسدة

قياس النشاط الكلي لمضادات الأكسدة

تم حساب النشاط وفقًا للصيغة التالية (4).

قياس إزالة الجذور الحرة داخل الخلايا

خاصية تعديل المناعة

تم استخدام تفاعل البوليميراز المتسلسل الكمي (qPCR) للكشف عن تعبير الجينات الالتهابية ومضادة الالتهاب. تم استخراج RNA الخلوي الكلي باستخدام مجموعة تنقية RNA السريعة. تم تحويل RNA إلى cDNA باستخدام مجموعة كواشف PrimeScriptTM RT. تم استخدام نظام qPCR في الوقت الحقيقي (ABI QuantStudio 5، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) للكشف عن تعبير iNOS و COX-2 و IL-6 و TGF-

التمايز العظمي في المختبر

بكثافة قدرها

تجارب الحيوانات

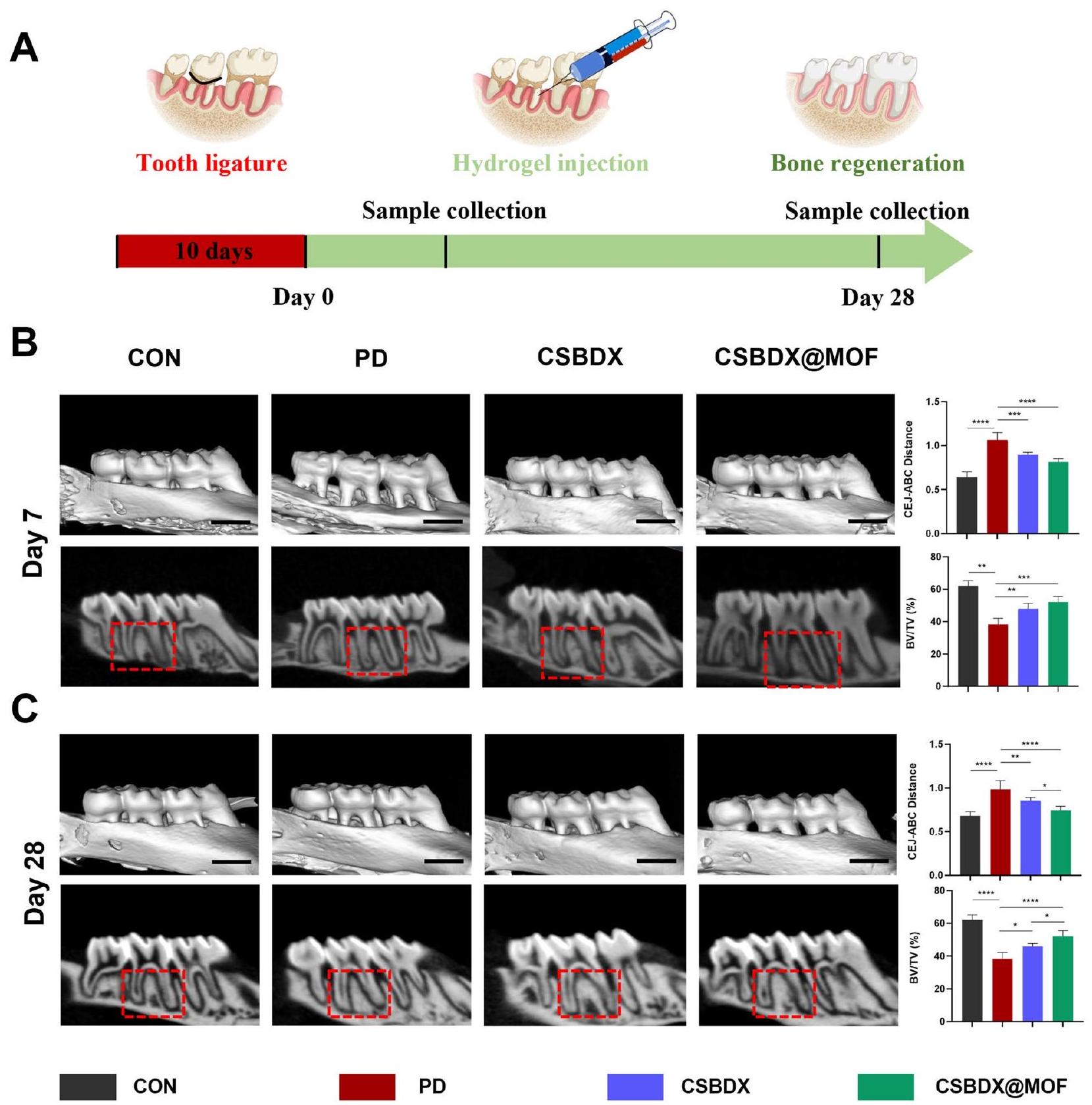

إنشاء نموذج التهاب دواعم السن في الجرذان

تحليل الميكرو-سي تي

التحليل النسيجي

التحليل الإحصائي

النتائج والمناقشة

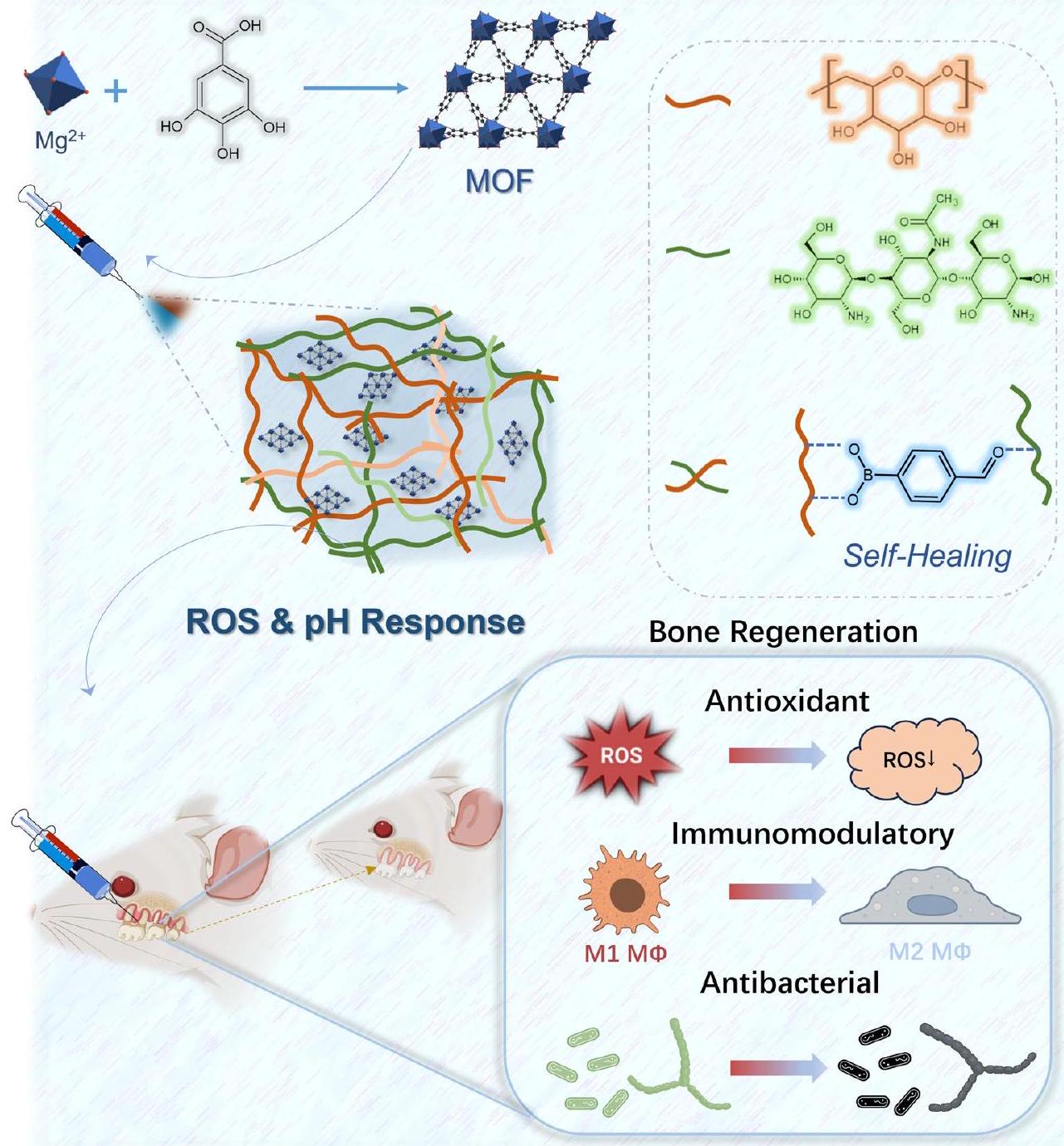

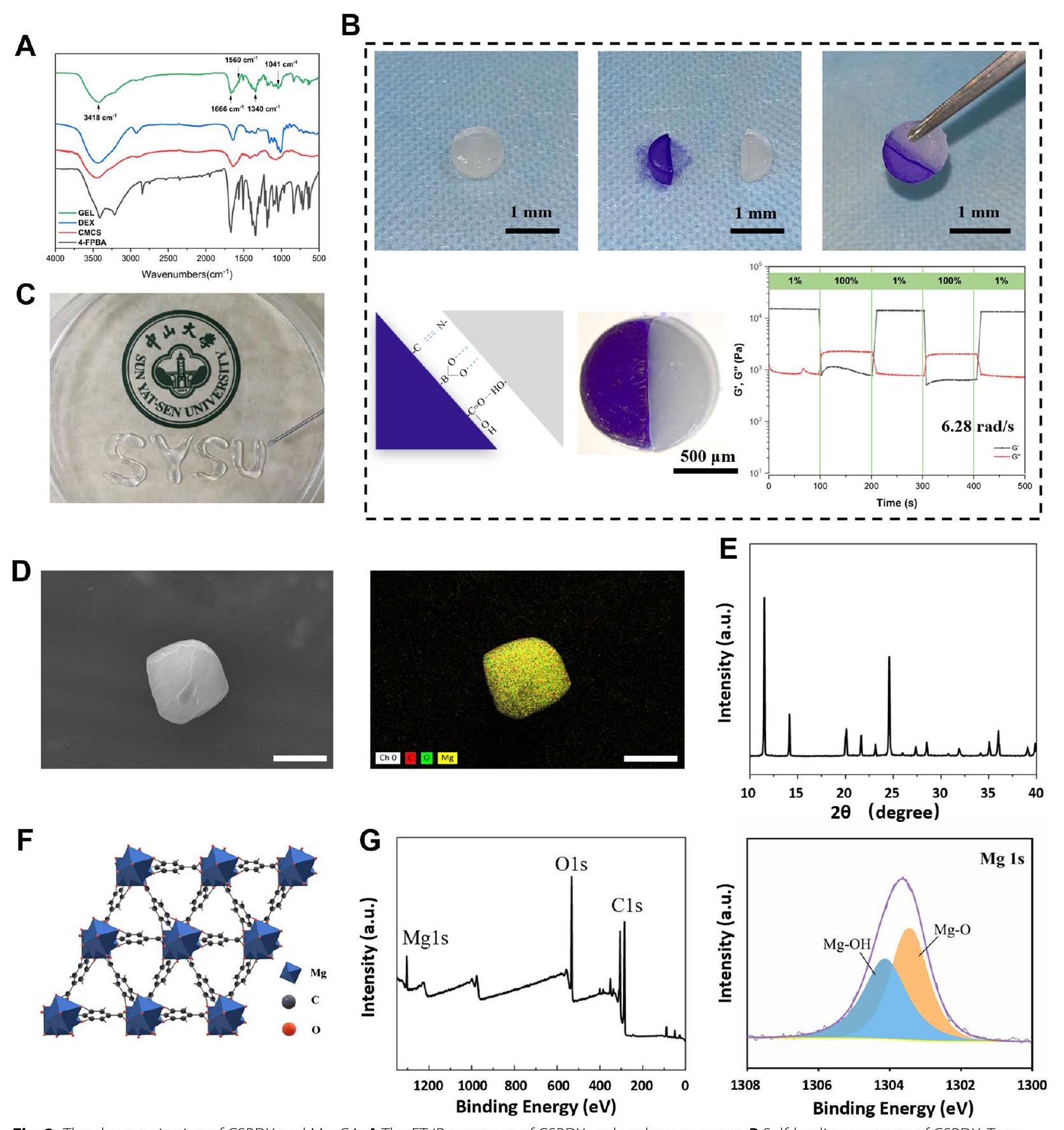

تحضير وتوصيف Mg-GA و CSBDX

(انظر الشكل في الصفحة التالية.)

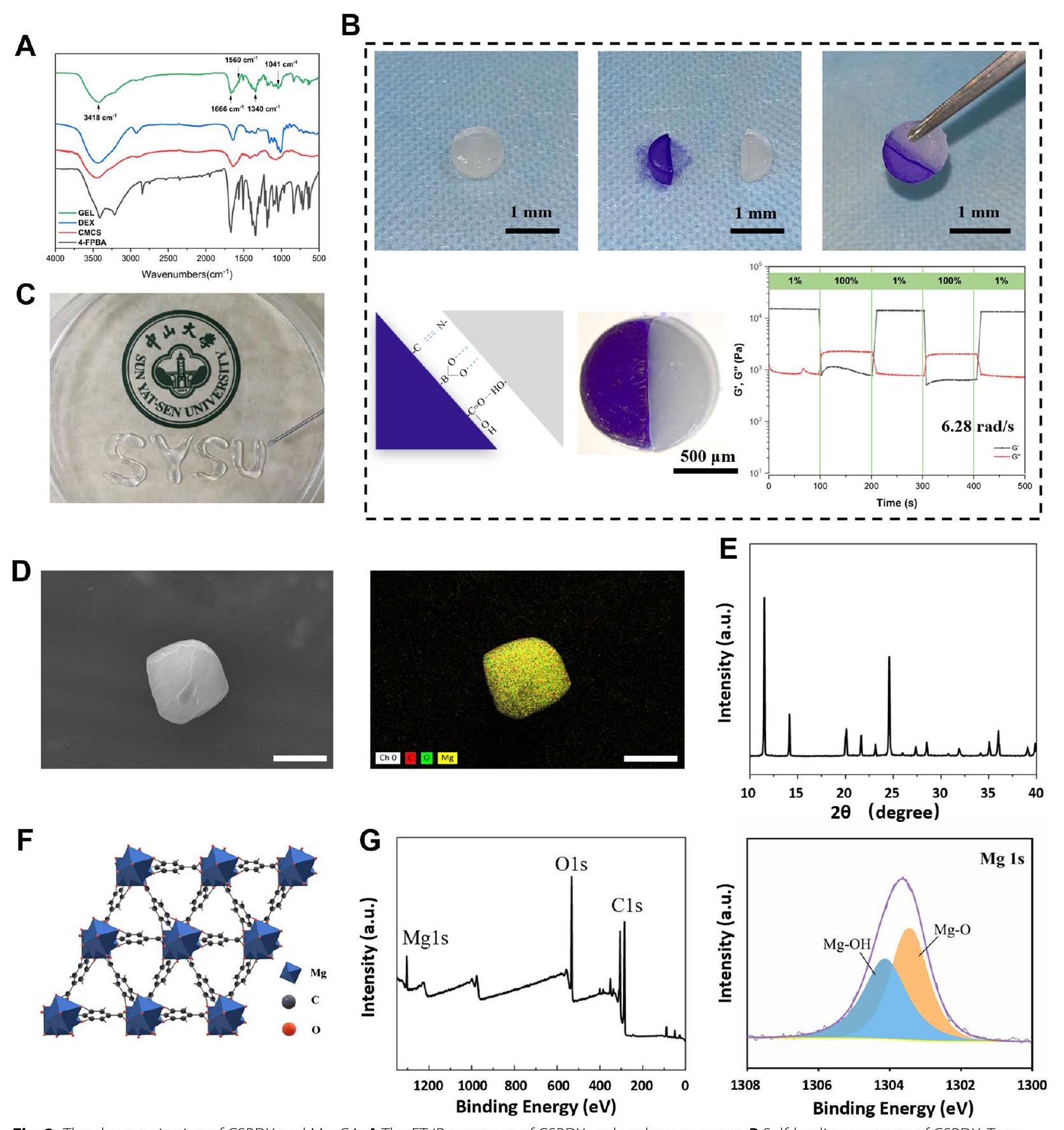

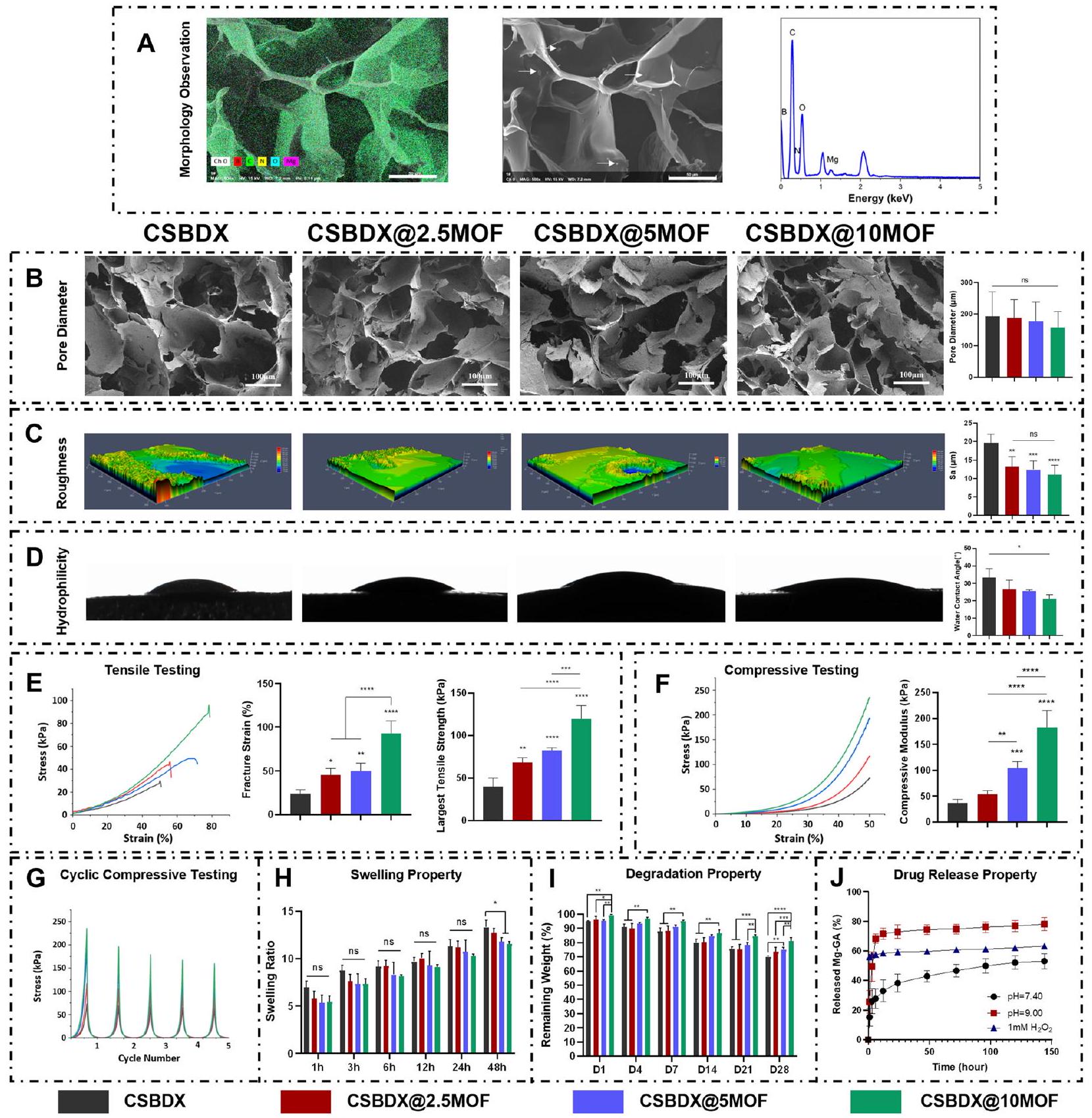

تحضير وتوصيف CSBDX@MOF

الأكسجين والمواد المغذية، مما يعزز تسرب الخلايا ونمو الأنسجة [50، 51]. تم تقييم خشونة السطح وخصائص المحبة للماء لعينات الهيدروجيل أيضًا. أدى إدخال Mg-GA إلى انخفاض كبير في قيمة Sa (متوسط الانحراف الحسابي للملف) ولكنه لم يظهر فرقًا كبيرًا بين ثلاث مجموعات CSBDX@MOF (الشكل 3C). كما هو معروف، فإن السطح الخشن يعزز التصاق الخلايا، والهجرة [52] والتعلق البكتيري [53]. قد تقلل الأسطح ذات الخشونة النسبية الأقل، كما هو موضح في CSBDX@MOF، من التصاق مسببات الأمراض اللثوية، مما يمنع العدوى المستمرة في الأنسجة. أشارت نتائج زاوية تماس الماء إلى محبة ممتازة للماء لجميع عينات الهيدروجيل، مع انخفاض في زاوية تماس الماء والذي تم نسبه إلى وجود مجموعات الهيدروكسيل الفينولية الغنية في MOF من Mg-GA [54] (الشكل 3D). كما هو موضح في الشكل 3E، كانت نسبة الكسر وقوة الشد القصوى لـ CSBDX@MOF أعلى مقارنة بـ CSBDX، حيث أظهرت CSBDX@10MOF أعلى نسبة كسر (حتى

من

وحساسية ROS لـ CSBDX@MOF، المنسوبة إلى تأثيرات التشابك الديناميكي لرابطة البورات الإستر ورابطة الإيمين [44، 45]. لذلك، فإن عملية إطلاق الدواء تستجيب لبيئة pH العالية وROS الدقيقة لالتهاب اللثة، مما يمكّن من إطلاق MOF من Mg-GA عند الطلب، مما يسهل عملية علاج التهاب اللثة.

التأثير المضاد للبكتيريا

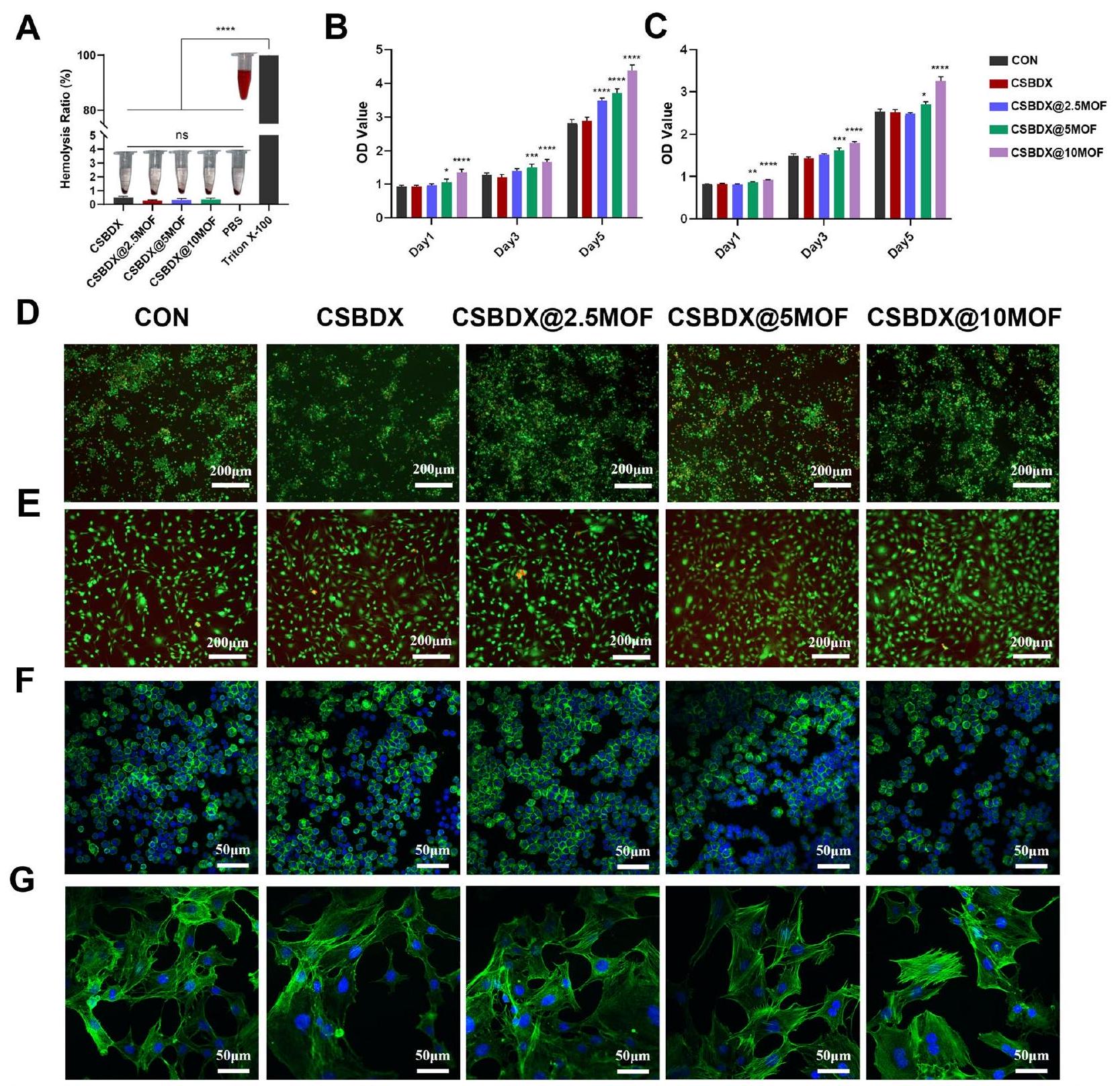

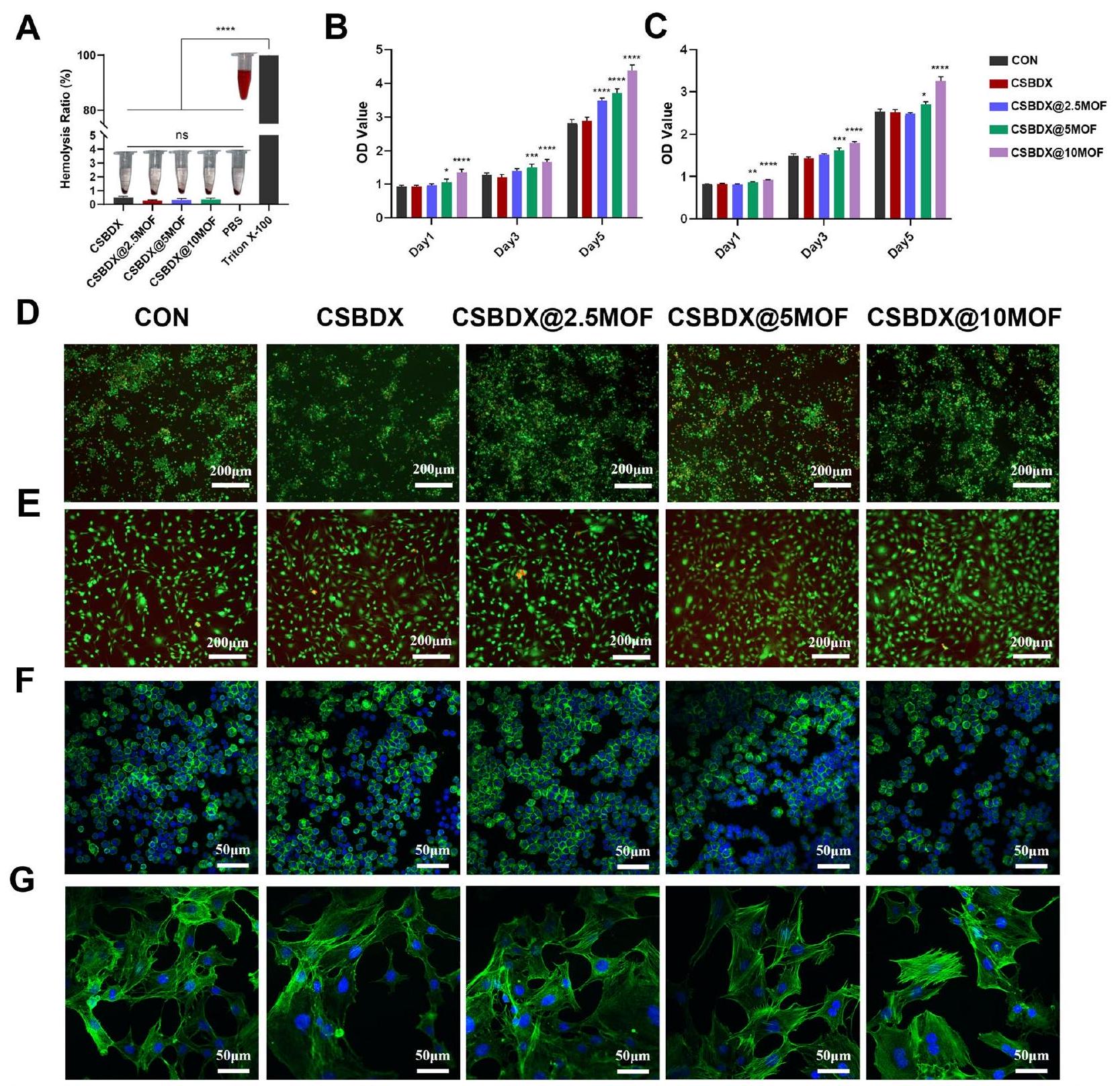

التوافق الحيوي

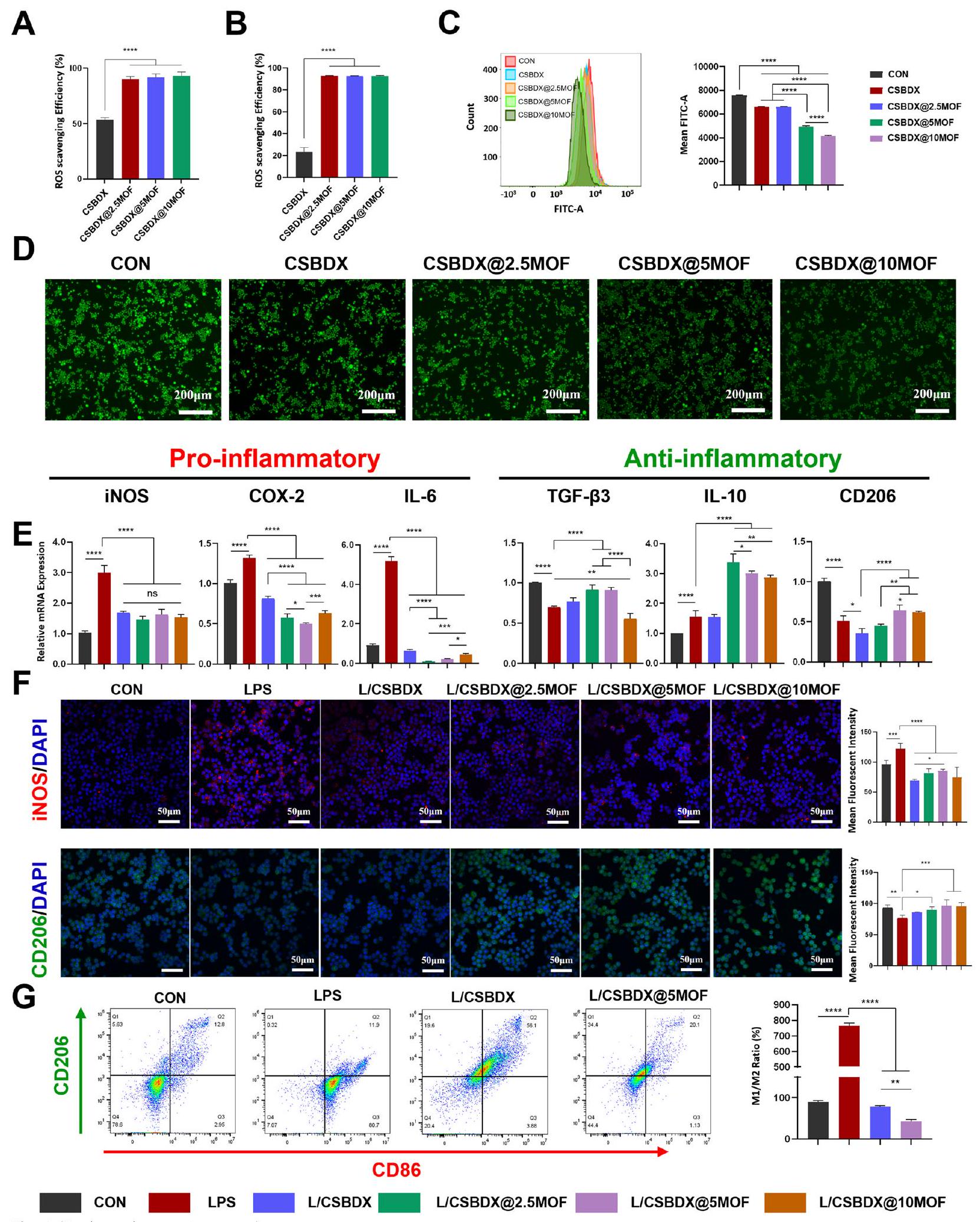

الخاصية المضادة للأكسدة

لتحسين بيئة تجديد العظام في التهاب اللثة.

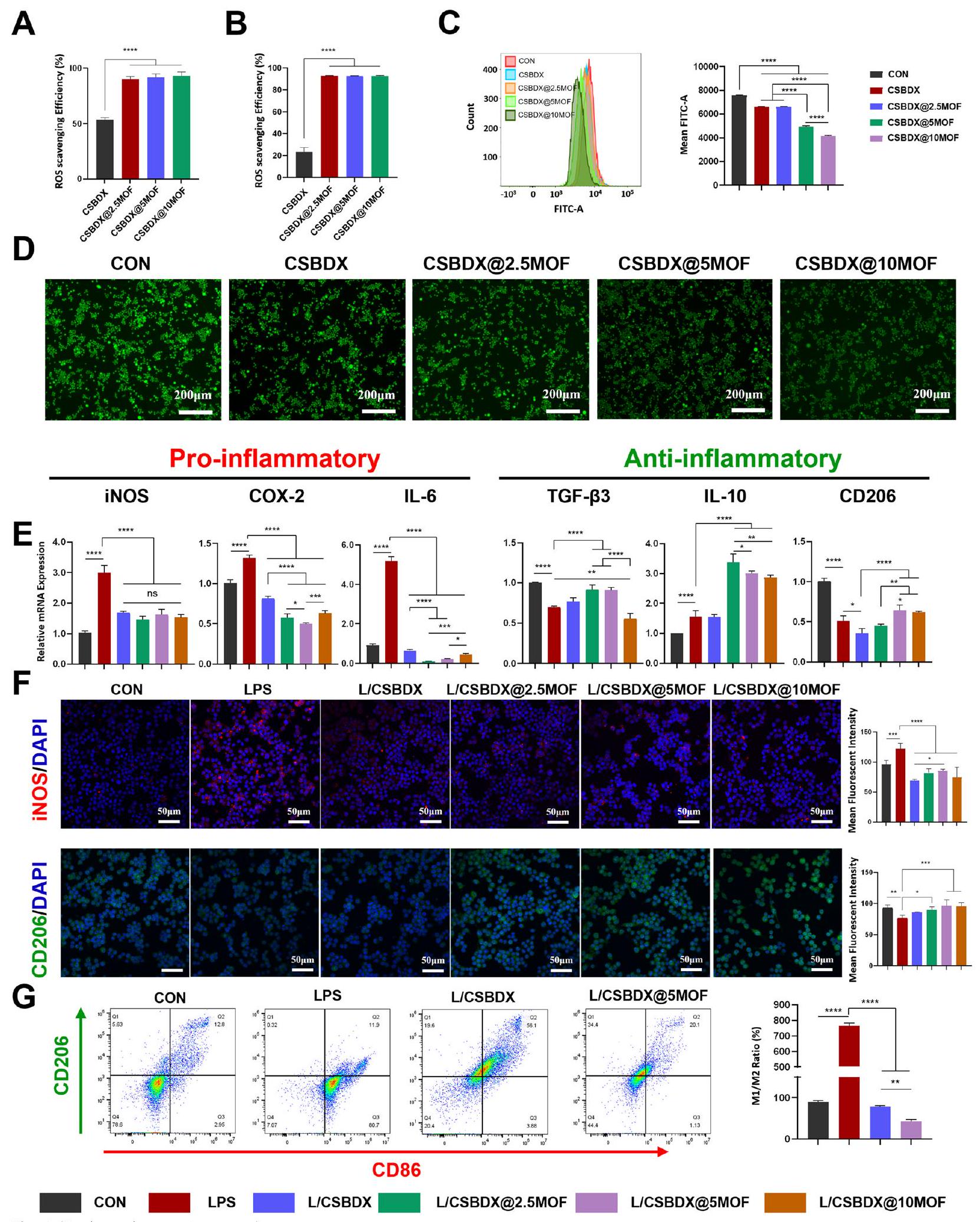

خاصية تعديل المناعة

لبلعميات M1، ويؤدي استقطاب M1 إلى زيادة التعبير عن IL-6 و COX-2 و iNOS ووسائط التهابية أخرى. تحدد البلعميات M2 حل الالتهاب وإعادة بناء العظام، مما يعزز التعبير عن TGF-

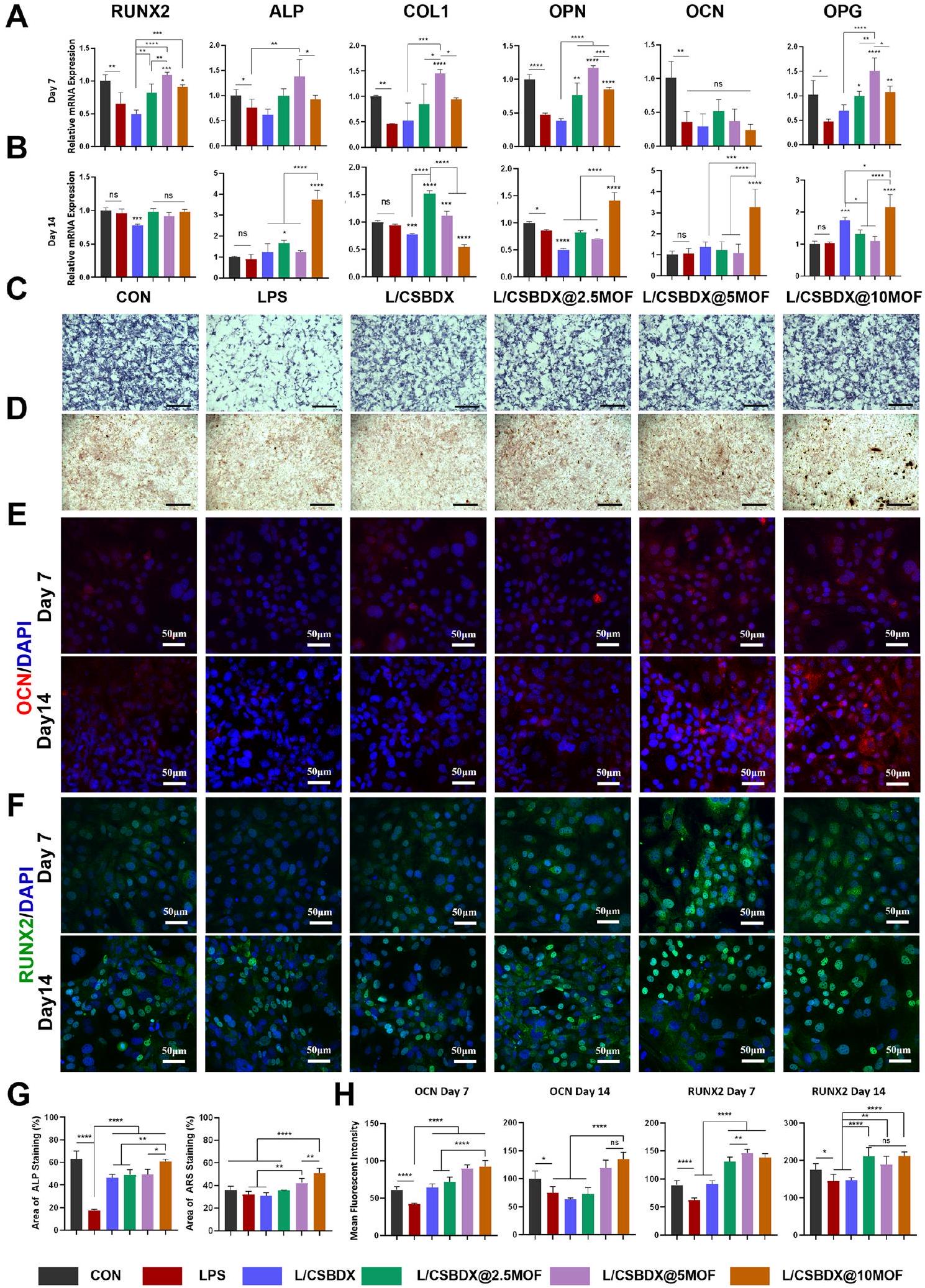

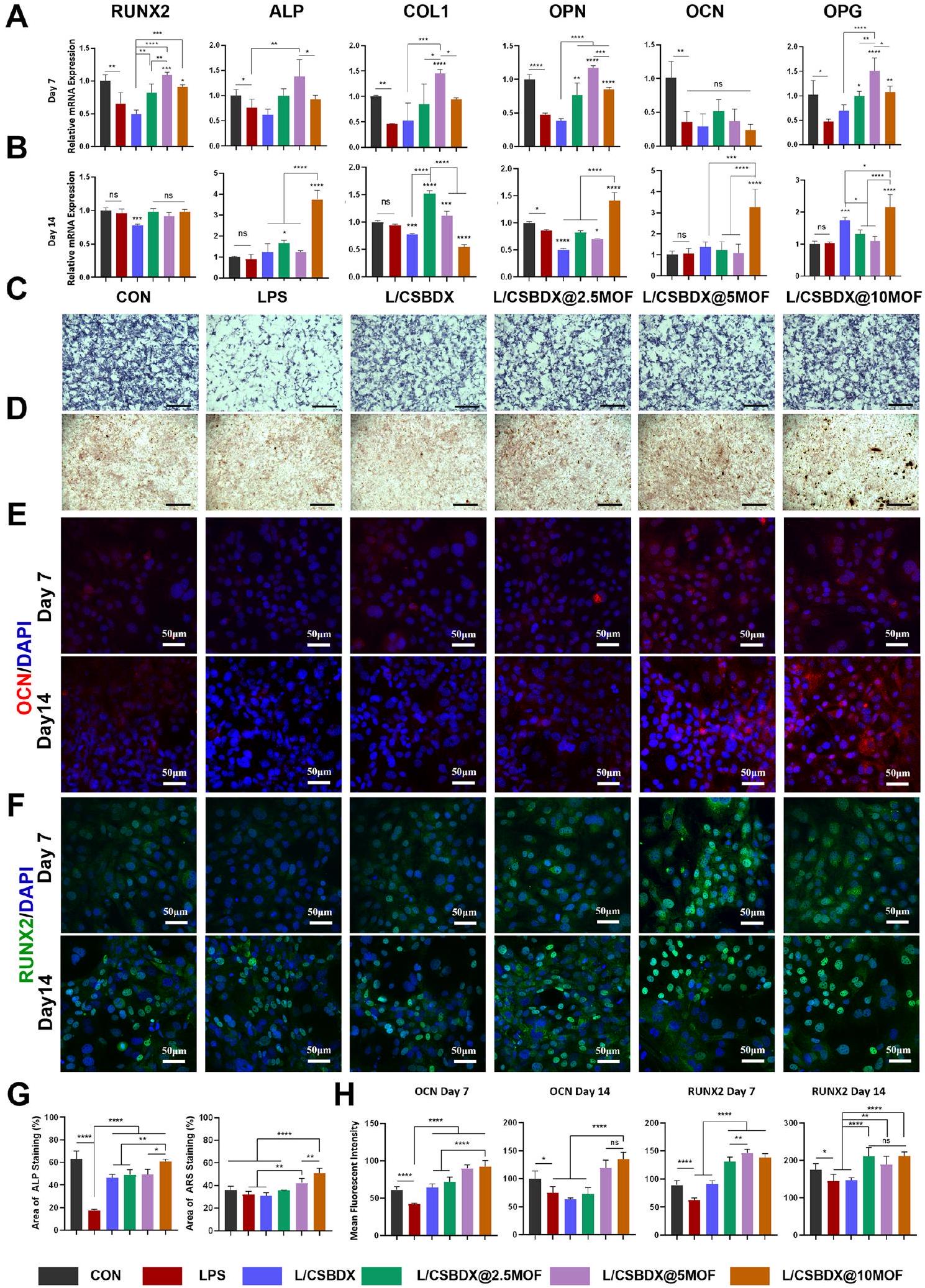

خاصية تكوين العظام في المختبر من خلال تعديل المناعة

التحفيز على تكوين العظام، لوحظت عقيدات كالسيوم ملحوظة في ثلاث مجموعات CSBDX@MOF (الشكل 7D، G). تكوين العظام هو عملية ديناميكية طويلة الأمد، وتختلف التأثيرات المناعية للعظام لنظام الهيدروجيل في التعبير الجيني في مراحل مختلفة من تكوين العظام. قد تُعزى هذه النتائج إلى تأثير تعديل المناعة لوسط البلعميات المهيأ، حيث كانت تركيزات

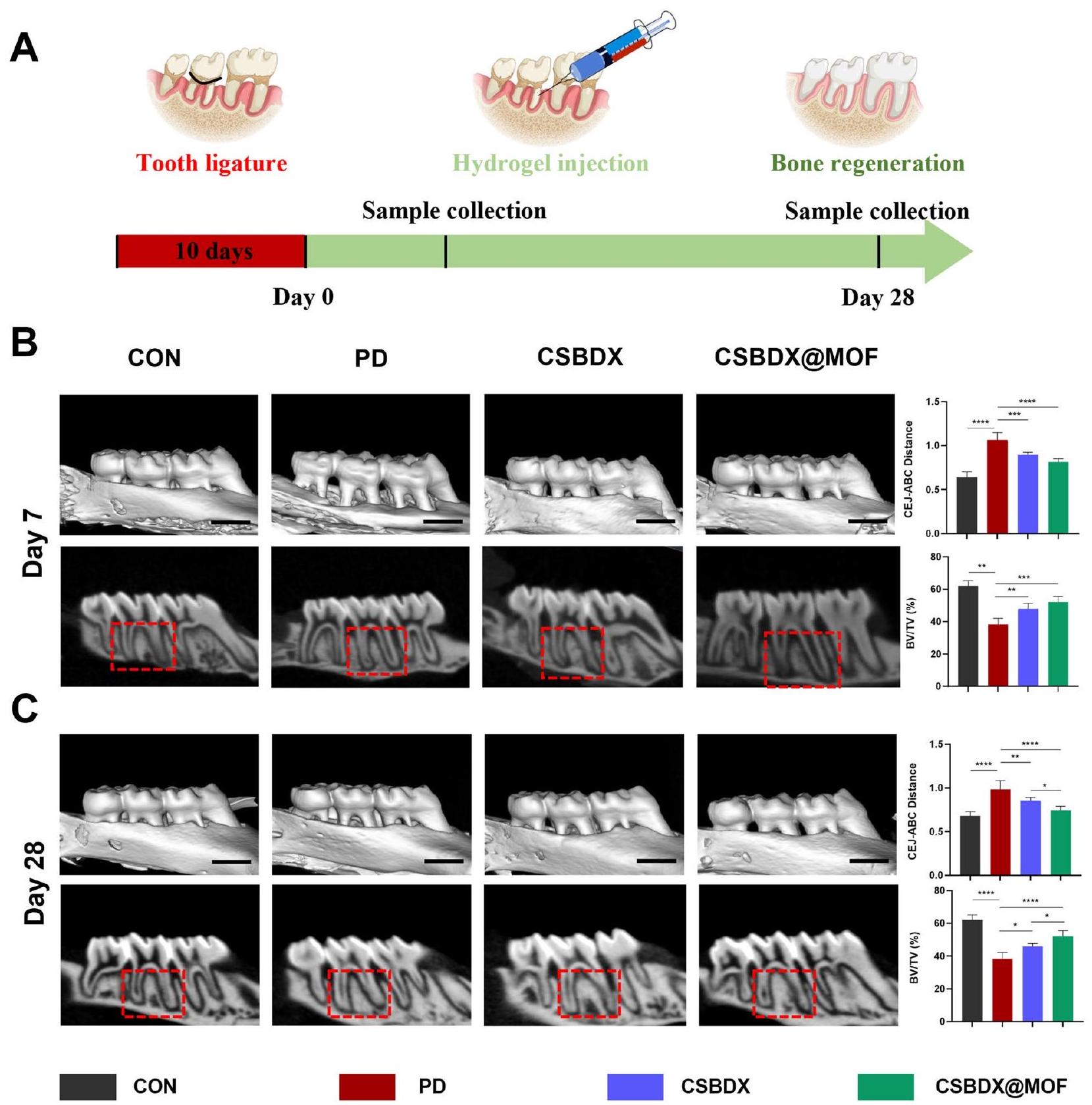

تجديد العظام الفكية في الجسم الحي من خلال تعديل المناعة

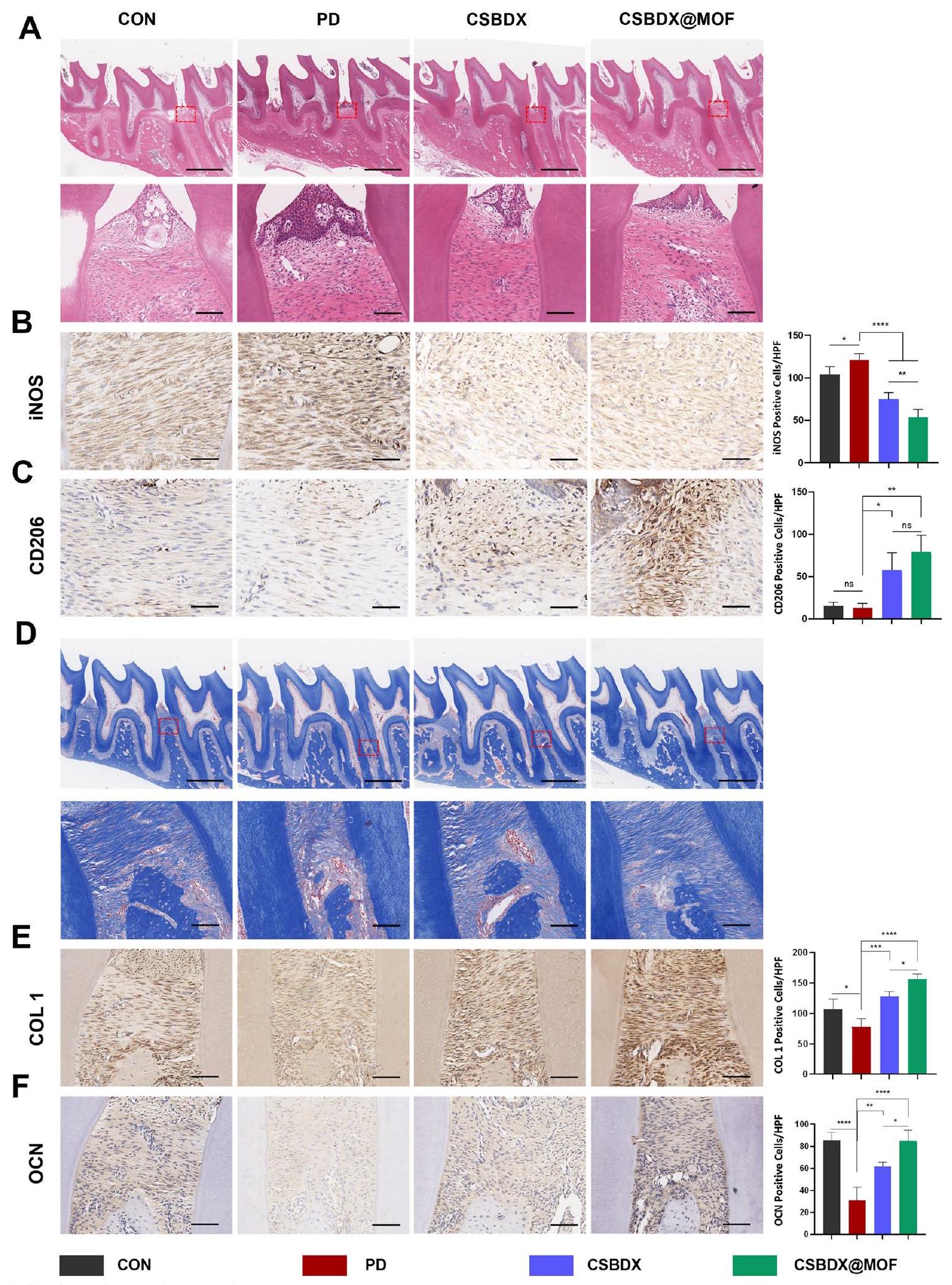

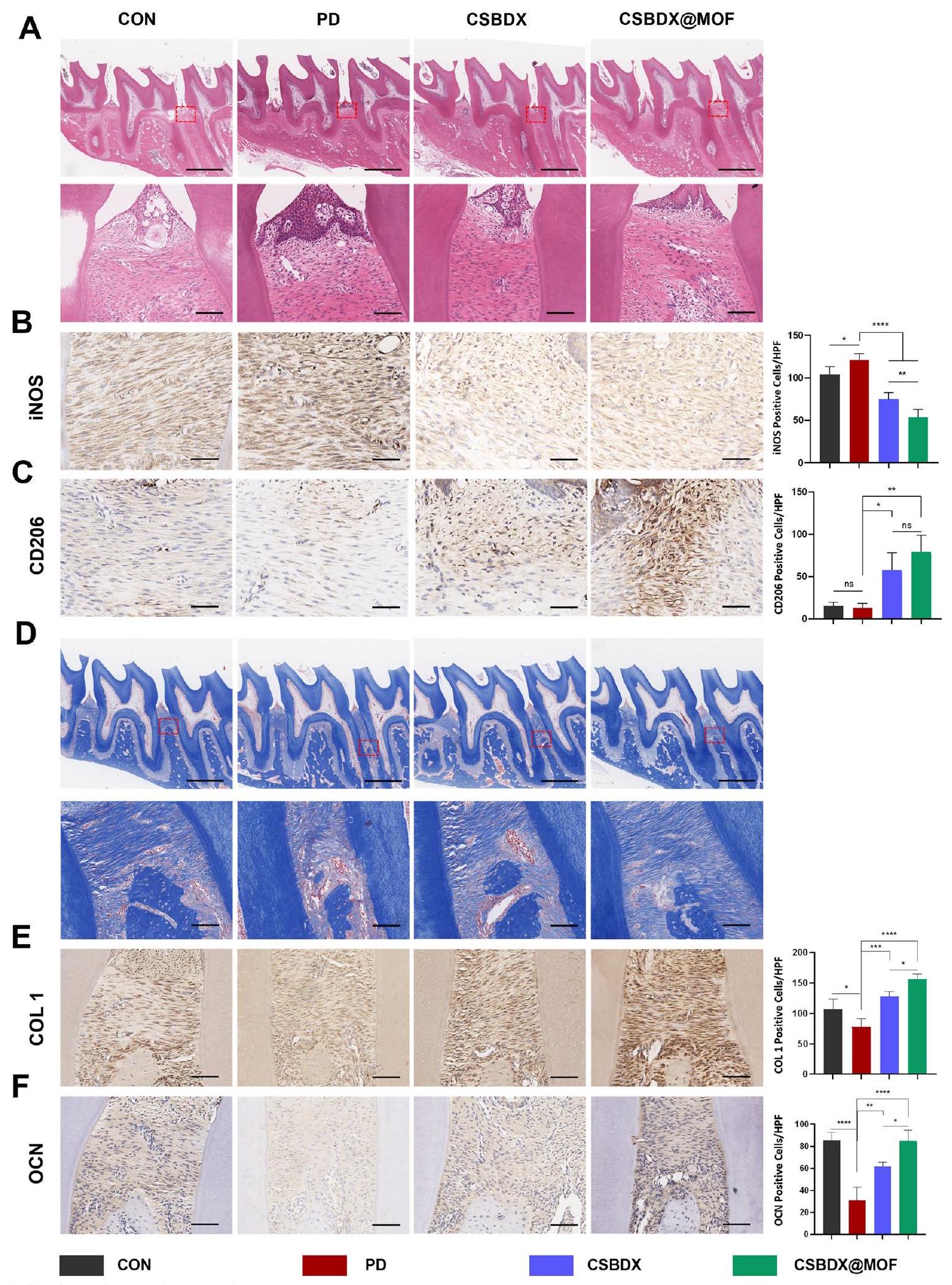

في اليوم الثامن والعشرين. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم استخدام نسبة حجم العظم/إجمالي الحجم (BV/TV) لتقييم جودة العظم السنخي. أظهرت مجموعة PD أدنى نسبة BV/TV، بينما عرضت كل من CSBDX وCSBDX@MOF نتائج مثالية باستمرار. ومن المRemarkably، كانت نسبة BV/TV في مجموعة CSBDX@MOF أعلى بشكل ملحوظ من تلك الموجودة في مجموعة CSBDX في اليوم الثامن والعشرين. وبالتالي، أظهرت مجموعة CSBDX@MOF العلاج الأكثر فعالية لتآكل العظم السنخي الناتج عن التهاب اللثة. تم إجراء صبغ الهيماتوكسيلين والإيوزين (H&E) بالإضافة إلى صبغ المناعية الكيميائية (IHC) لـ iNOS وCD206 في اليوم السابع لتقييم الشكل النسيجي للعظم السنخي وتأثيرات النظام الهيدروجي على المناعة. كما هو موضح في الشكل 9A، دعمت صبغة H&E الاتجاهات التي أظهرتها مسح الميكرو-CT. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، أظهرت مجموعة PD كمية عالية من الخلايا الالتهابية، مما يدل على استمرار وجود ميزات التهاب اللثة. في المقابل، أظهرت المجموعات المعالجة بالهيدروجيل انخفاضًا كبيرًا في الخلايا الالتهابية المتسللة. بالنسبة لصبغة IHC، مقارنةً بمجموعة التحكم، أظهرت مجموعة CSBDX@MOF انخفاضًا كبيرًا في الخلايا الإيجابية لـ iNOS، بينما أظهرت أعلى صبغة لـ CD206 (الشكل 9B، C)، مما يبرز قدراتها القوية المضادة للالتهابات. علاوة على ذلك، تم إجراء صبغ ماسون ثلاثي الألوان وصبغ IHC لـ COL1 وOCN لتقييم ترسب الكولاجين اللثوي وتأثيرات تجديد العظم السنخي لنظام الهيدروجيل في اليوم الثامن والعشرين. كشفت صبغة ماسون ثلاثي الألوان عن وجود رباط لثوي منظم بين العظم السنخي والسن، مصحوبًا بتكوين كولاجين ناضج في مجموعة CSBDX@MOF (الشكل 9D). كما هو موضح في الشكل 9E، F، كشفت صبغة IHC عن انخفاض مستويات التعبير لـ COL1 وOCN في بيئة التهاب اللثة، بينما أظهرت مجموعتا CSBDX وCSBDX@MOF المزيد من الخلايا الإيجابية لـ COL1 وOCN، مع إظهار مجموعة CSBDX@MOF تأثيرات متفوقة. ومع ذلك، نظرًا لأن التهاب اللثة هو مرض مزمن وتجديد العظام يستغرق وقتًا طويلاً، لا يزال يتعين استكشاف التأثير النسبي طويل الأمد لنظام CSBDX وCSBDX@MOF في الجسم الحي. أظهرت الدراسات في المختبر الدور الحاسم لاستقطاب البلعميات في بداية وتقدم التهاب اللثة. تؤكد النتائج المذكورة أعلاه أن تثبيط استقطاب البلعميات M1 يمكن أن يقلل من تعبير السيتوكينات الالتهابية في أنسجة آفات اللثة، وأن تحفيز البلعميات M2 يمكن أن يمنع فقدان العظام. لذلك، يمكن أن يعزز CSBDX@MOF تجديد العظم السنخي من خلال تنظيم استقطاب M1/M2. كما هو متوقع، أظهر نظام الهيدروجيل في هذه الدراسة فعالية تطبيقية في الجسم الحي من خلال تخفيف الالتهاب وتعزيز تجديد العظم السنخي، وذلك بفضل التأثيرات التآزرية لقدرات CMCS المضادة للبكتيريا، وقدرة 4-FPBA الاختزالية.

خصائص وتأثيرات DEX المضادة للالتهابات. بشكل خاص، قدم إدخال MOF بشكل غير مباشر

الخاتمة

معلومات إضافية

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

نُشر على الإنترنت: 26 مايو 2024

References

- Kinane DF, Stathopoulou PG, Papapanou PN. Periodontal diseases. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17038.

- Jepsen S, Suvan J, Deschner J. The association of periodontal diseases with metabolic syndrome and obesity. Periodontol. 2020;83(1):125-53.

- Kwon T, Lamster IB, Levin L. Current concepts in the management of periodontitis. Int Dent J. 2021;71(6):462-76.

- Graziani F, Karapetsa D, Alonso B, et al. Nonsurgical and surgical treatment of periodontitis: how many options for one disease? Periodontol. 2017;75(1):152-88.

- Xu W, Zhou W, Wang H, et al. Roles of porphyromonas gingivalis and its virulence factors in periodontitis. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2020;120:45-84.

- Takahashi N. Oral microbiome metabolism: from “Who Are They?” to “what are they doing?” J Dent Res. 2015;94(12):1628-37.

- Sczepanik FSC, Grossi ML, Casati M, et al. Periodontitis is an inflammatory disease of oxidative stress: we should treat it that way. Periodontol. 2020;84(1):45-68.

- Pan W, Wang Q, Chen Q. The cytokine network involved in the host immune response to periodontitis. Int J Oral Sci. 2019;11(3):30.

- Almubarak A, Tanagala KKK, Papapanou PN, et al. Disruption of monocyte and macrophage homeostasis in periodontitis. Front Immunol. 2020;11:330.

- Cafferata EA, Alvarez C, Diaz KT, et al. Multifunctional nanocarriers for the treatment of periodontitis: Immunomodulatory, antimicrobial, and regenerative strategies. Oral Dis. 2019;25(8):1866-78.

- Chen E, Wang T, Tu Y, et al. ROS-scavenging biomaterials for periodontitis. J Mater Chem B. 2023;11(3):482-99.

- Huang

, Huang L. Periodontal bifunctional biomaterials: progress and perspectives. Materials. 2021;14(24):7588. - Abdo VL, Suarez LJ, de Paula LG, et al. Underestimated microbial infection of resorbable membranes on guided regeneration. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2023;226: 113318.

- Pretzl B, SäLZER S, et al. Administration of systemic antibiotics during non-surgical periodontal therapy-a consensus report. Clin Oral Investig. 2019;23(7):3073-85.

- Khattri S, Nagraj SK, Arora A, Eachempati P, Kusum CK, Bhat KG, Johnson TM, Lodi G, et al. Adjunctive systemic antimicrobials for the non-surgical treatment of periodontitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020. https://doi. org/10.1002/14651858.CD012568.pub2.

- Sun Z, Li T, Mei T, et al. Nanoscale MOFs in nanomedicine applications: from drug delivery to therapeutic agents. J Mater Chem B. 2023;11(15):3273-94.

- Coluccia M, Parisse V, Guglielmi P, et al. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) as biomolecules drug delivery systems for anticancer purposes. Eur J Med Chem. 2022;244: 114801.

- de Baaij JH, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ. Magnesium in man: implications for health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2015;95(1):1-46.

- Yuan Z, Wan Z, Gao C, et al. Controlled magnesium ion delivery system for in situ bone tissue engineering. J Control Release. 2022;350:360-76.

- Lin S, Yang G, Jiang F, et al. A magnesium-enriched 3D culture system that mimics the bone development microenvironment for vascularized bone regeneration. Adv Sci. 2019;6(12):1900209.

- Zheng Z, Chen Y, Hong H, et al. The “Yin and Yang” of immunomodulatory magnesium-enriched graphene oxide nanoscrolls decorated biomimetic scaffolds in promoting bone regeneration. Adv Healthc Mater. 2021;10(2): e2000631.

- Zahrani NAAL, El-Shishtawy RM, Asiri AM. Recent developments of gallic acid derivatives and their hybrids in medicinal chemistry: a review. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;204:112609.

- Dai Z, Li Z, Zheng W, et al. Gallic acid ameliorates the inflammatory state of periodontal ligament stem cells and promotes pro-osteodifferentiation capabilities of inflammatory stem cell-derived exosomes. Life. 2022;12(9):1392.

- de Melo K, Lisboa LDS, Queiroz MF, et al. Antioxidant activity of fucoidan modified with gallic acid using the redox method. Mar Drugs. 2022;20(8):490.

- Bai J, Zhang Y, Tang C, et al. Gallic acid: pharmacological activities and molecular mechanisms involved in inflammation-related diseases. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;133: 110985.

- Diaz-Salmeron R, Toussaint B, Huang N, et al. Mucoadhesive poloxamerbased hydrogels for the release of HP-

-CD-complexed dexamethasone in the treatment of buccal diseases. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(1):117. - Wang B, Booij-Vrieling HE, Bronkhorst EM, et al. Antimicrobial and antiinflammatory thermo-reversible hydrogel for periodontal delivery. Acta Biomater. 2020;116:259-67.

- Irshad N, Jahanzeb N, Alqasim A, et al. Synthesis and analyses of injectable fluoridated-bioactive glass hydrogel for dental root canal sealing. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(11): e0294446.

- Malik QUA, Iftikhar S, Zahid S, et al. Smart injectable self-setting bioceramics for dental applications. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2020;113: 110956.

- Li W, Liu X, Deng Z, et al. Tough bonding, on-demand debonding, and facile rebonding between hydrogels and diverse metal surfaces. Adv Mater. 2019;31(48): e1904732.

- Wang Y, Li J, Tang M, et al. Smart stimuli-responsive hydrogels for drug delivery in periodontitis treatment. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;162: 114688.

- Sajjad S , Görke O , et al. Acetanilide-loaded injectable hydrogels with enhanced bioactivity and biocompatibility for potential treatment of periodontitis. J Appl Polymer Sci. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1002/app. 55200.

- Chang G, Dang Q, Liu C, et al. Carboxymethyl chitosan and carboxymethyl cellulose based self-healing hydrogel for accelerating diabetic wound healing. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;292: 119687.

- Shariatinia Z. Carboxymethyl chitosan: Properties and biomedical applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;120(Pt B):1406-19.

- Abir F, Barkhordarian S, Sumpio BE. Efficacy of dextran solutions in vascular surgery. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2004;38(6):483-91.

- Zhang M, Huang Y, Pan W, et al. Polydopamine-incorporated dextran hydrogel drug carrier with tailorable structure for wound healing. Carbohydr Polym. 2021;253: 117213.

- Elgamily HM, Gamal AA, Saleh SAA, et al. Microbiological and environmental assessment of human oral dental plaque isolates. Microb Pathog. 2019;135: 103626.

- Hu Q, Lu Y, Luo Y. Recent advances in dextran-based drug delivery systems: from fabrication strategies to applications. Carbohydr Polym. 2021;264: 117999.

- Gao

, Zhang , Jin . Preparation and properties of minocycline-loaded carboxymethyl chitosan gel/alginate nonwovens composite wound dressings. Mar Drugs. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/md17100575. - Ke X, Li M, Wang X, et al. An injectable chitosan/dextran/

-glycerophosphate hydrogel as cell delivery carrier for therapy of myocardial infarction. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;229: 115516. - Xin H. Double-network tough hydrogels: a brief review on achievements and challenges. Gels. 2022;8(4):247.

- Li

, in , Yu Y, et al. In situ rapid-formation sprayable hydrogels for challenging tissue injury management. Adv Mater. 2024. https://doi.org/10. 1002/adma. 202400310. - Li R, Zhou C, Chen J, et al. Synergistic osteogenic and angiogenic effects of KP and QK peptides incorporated with an injectable and self-healing hydrogel for efficient bone regeneration. Bioact Mater. 2022;18:267-83.

-

, et al. ROS-responsive hydrogel coating modified titanium promotes vascularization and osteointegration of bone defects by orchestrating immunomodulation. Biomaterials. 2022;287: 121683. - Lu CH, Yu CH, Yeh YC. Engineering nanocomposite hydrogels using dynamic bonds. Acta Biomater. 2021;130:66-79

- Wu Y, Wang Y, Long L, et al. A spatiotemporal release platform based on pH/ROS stimuli-responsive hydrogel in wound repairing. J Control Release. 2022;341:147-65.

- Wang H, Wang L, Guo S, et al. Rutin-loaded stimuli-responsive hydrogel for anti-inflammation. ACS Appl Mater Interf. 2022. https://doi.org/10. 1021/acsami.2c02295.

- Liang Y, Li Z, Huang Y, et al. Dual-dynamic-bond cross-linked antibacterial adhesive hydrogel sealants with on-demand removability for post-wound-closure and infected wound healing. ACS Nano. 2021;15(4):7078-93.

- Cooper L, Hidalgo T, Gorman M, et al. A biocompatible porous Mg-gallate metal-organic framework as an antioxidant carrier. Chem Commun. 2015;51(27):5848-51.

- Sarker B, Li W, Zheng K, et al. Designing porous bone tissue engineering scaffolds with enhanced mechanical properties from composite hydrogels composed of modified alginate, gelatin, and bioactive glass. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2016;2(12):2240-54.

- Iviglia G, Kargozar S, Baino F. Biomaterials, current strategies, and novel nano-technological approaches for periodontal regeneration. J Funct Biomater. 2019;10(1):3.

- Liang W, He W, Huang R, et al. Peritoneum-inspired janus porous hydrogel with anti-deformation, anti-adhesion, and pro-healing characteristics for abdominal wall defect treatment. Adv Mater. 2022;34(15): e2108992.

- Crawford RJ, Webb HK, Truong VK, et al. Surface topographical factors influencing bacterial attachment. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2012;179-182:142-9.

- Xu Y, Patsis PA, Hauser S, et al. Cytocompatible, injectable, and electroconductive soft adhesives with hybrid covalent/noncovalent dynamic network. Adv Sci. 2019;6(15):1802077.

- Feng

, Zhu , et al. Distribution of 8 periodontal microorganisms in family members of Chinese patients with aggressive periodontitis. Arch Oral Biol. 2015;60(3):400-7. - Liang

, Bai , Niu , et al. High inhabitation activity of CMCS/Phytic acid/Zn(2+) nanoparticles via flash nanoprecipitation (FNP) for bacterial and fungal infections. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;242(Pt 1): 124747. - Zhang B, Jiang Z, Li X, et al. Facile preparation of biocompatible and antibacterial water-soluble films using polyvinyl alcohol/carboxymethyl chitosan blend fibers via centrifugal spinning. Carbohydr Polym. 2023;317: 121062.

- Xu B, Wang H, Wang W, et al. A single-atom nanozyme for wound disinfection applications. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2019;58(15):4911-6.

- Lin Z, Shen D, Zhou W, et al. Regulation of extracellular bioactive cations in bone tissue microenvironment induces favorable osteoimmune conditions to accelerate in situ bone regeneration. Bioact Mater. 2021;6(8):2315-30.

- Furkel J, Knoll M, Din S, et al. C-MORE: a high-content single-cell morphology recognition methodology for liquid biopsies toward personalized cardiovascular medicine. Cell Rep Med. 2021;2(11): 100436.

- Darwish AG, Das PR, Ismail A, et al. untargeted metabolomics and antioxidant capacities of muscadine grape genotypes during berry development. Antioxidants. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10060914.

- Zheng Z, Chen Y, Guo B, Wang Y, Liu W, Sun J, Wang X, et al. Magnesiumorganic framework-based stimuli-responsive systems that optimize the bone microenvironment for enhanced bone regeneration. Chem Eng J. 2020;396: 125241.

- Lin Y, Luo T, Weng A, et al. Gallic acid alleviates gouty arthritis by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pyroptosis through enhancing Nrf2 signaling. Front Immunol. 2020;11: 580593.

- Qiao W, Wong KHM, Shen J, et al. TRPM7 kinase-mediated immunomodulation in macrophage plays a central role in magnesium ion-induced bone regeneration. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):2885.

- Bessa-Gonçalves M, Ribeiro-Machado C, Costa M, Ribeiro CC, Barbosa JN, Barbosa MA, Santos SG, et al. Magnesium incorporation in fibrinogen scaffolds promotes macrophage polarization towards M2 phenotype. Acta Biomater. 2023;155(667):83.

- Li J, Zhao C, Xu Y, et al. Remodeling of the osteoimmune microenvironment after biomaterials implantation in murine tibia: single-cell transcriptome analysis. Bioact Mater. 2023;22:404-22.

- Huang H, Pan W, Wang Y, et al. Nanoparticulate cell-free DNA scavenger for treating inflammatory bone loss in periodontitis. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):5925.

- Tan M, Mosaoa R, Graham GT, et al. Inhibition of the mitochondrial citrate carrier, Slc25a1, reverts steatosis, glucose intolerance, and inflammation in preclinical models of NAFLD/NASH. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27(7):2143-57.

- Bashir KMI, Choi JS. Clinical and physiological perspectives of

-glucans the past, present, and future. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(9):1906. - Zhang

, Huang , Jiang , et al. A novel magnesium ion-incorporating dual-crosslinked hydrogel to improve bone scaffold-mediated osteogenesis and angiogenesis. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2021;121: 111868. - Wu Z, Meng Z, Wu Q, et al. Biomimetic and osteogenic 3D silk fibroin composite scaffolds with nano MgO and mineralized hydroxyapatite for bone regeneration. J Tissue Eng. 2020;11:2041731420967791.

- Oh Y, Ahn CB, Marasinghe M, et al. Insertion of gallic acid onto chitosan promotes the differentiation of osteoblasts from murine bone marrowderived mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;183:1410-8.

- Kang Y, Xu C, Meng L, et al. Exosome-functionalized magnesium-organic framework-based scaffolds with osteogenic, angiogenic and antiinflammatory properties for accelerated bone regeneration. Bioact Mater. 2022;18:26-41.

- Li S, Hua Y, Liao C. Weakening of M1 macrophage and bone resorption in periodontitis cystathionine

-lyase-deficient mice. Oral Dis. 2022. https:// doi.org/10.1111/odi.14374. - Zhuang Z, Yoshizawa-Smith S, Glowacki A, et al. Induction of M2 macrophages prevents bone loss in murine periodontitis models. J Dent Res. 2019;98(2):200-8.

- Chen X , Wan Z , Yang L , et al. Exosomes derived from reparative M 2 -like macrophages prevent bone loss in murine periodontitis models via IL-10 mRNA. J Nanobiotechnology. 2022;20(1):110.

ملاحظة الناشر

- (انظر الشكل في الصفحة التالية.)

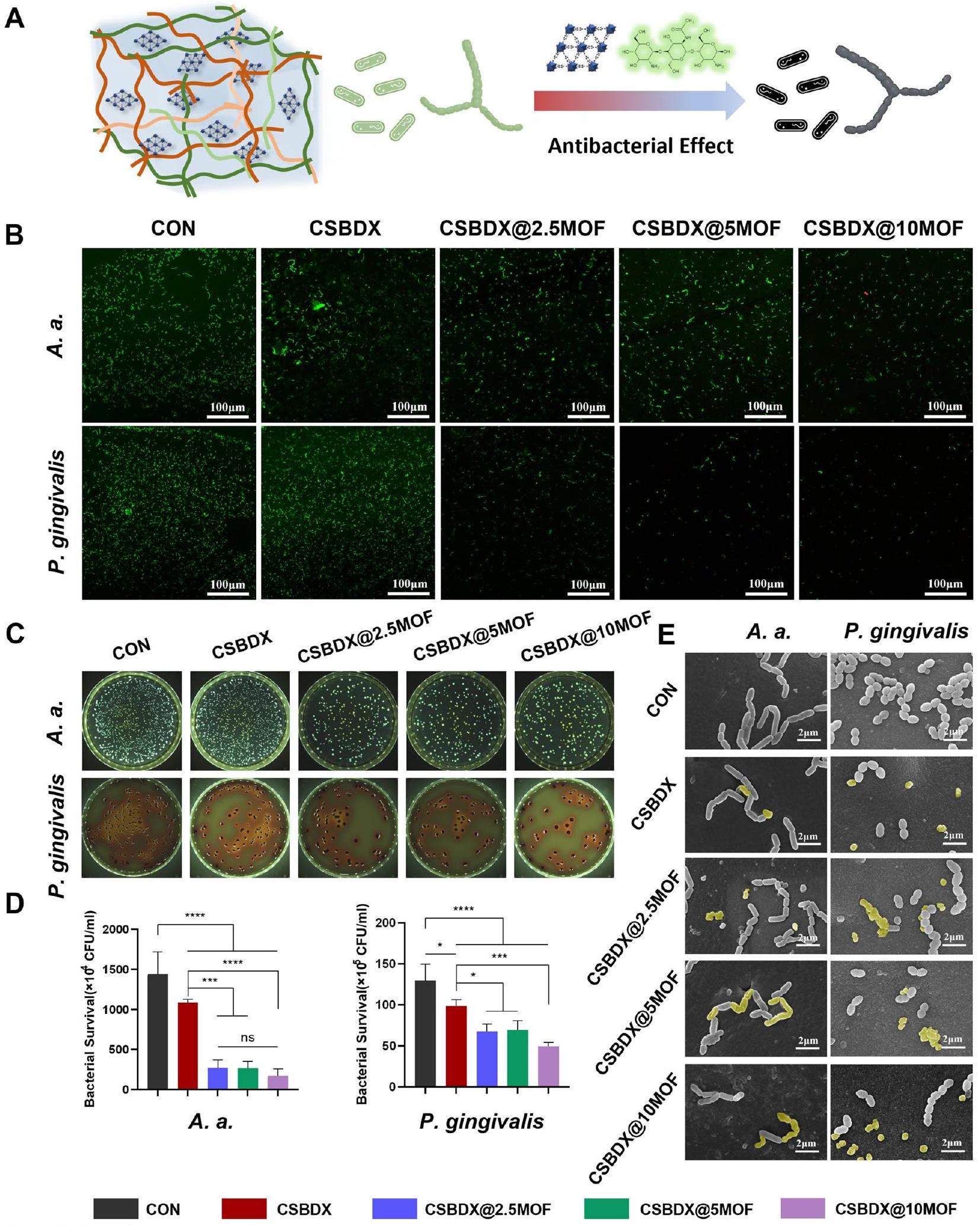

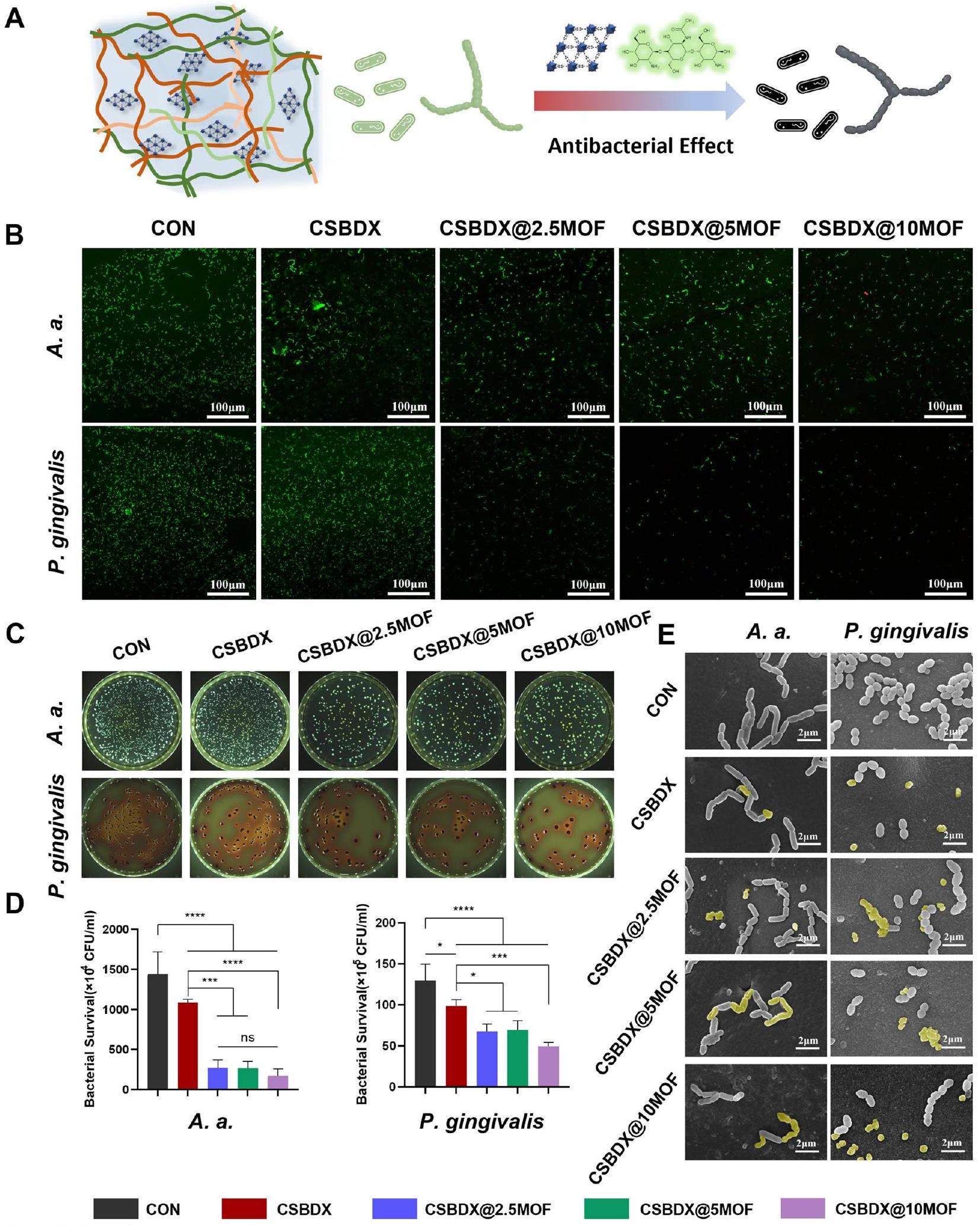

الشكل 4 تأثير مضاد للبكتيريا. أ الرسم التخطيطي لتأثير النظام الهيدروجيلي المضاد للبكتيريا على A. a.. جينجيفاليس. ب صور تمثيلية لتلوين البكتيريا الحية/الميتة لـ A. a. و P. gingivalis بعد زراعة مشتركة مع الهيدروجيل (شريط صور تمثيلية لتمثيل مستعمرات البكتيريا ورسم بياني لبقاء البكتيريا من . أ. و . جينجيفاليس بعد زراعة مشتركة مع الهيدروجيل والتحليل الإحصائي المقابل لبقاء البكتيريا ( ). الصور المجهرية الإلكترونية الممثلة لـ . أ. و . جينجيفاليس بعد زراعة مشتركة مع الهيدروجيل ( تشير الألوان الزائفة الصفراء إلى البكتيريا المكدسة والمجعدة. لا دلالة - الشكل 6 الخصائص المضادة للأكسدة والمعدلة للمناعة لـ CSBDX@MOF. التحليل الكمي لكفاءة إزالة الجذور الحرة DPPHA و ABTS B للهيدروجيل. ج بيانات تدفق الخلايا التمثيلية ومتوسط شدة الفلورسنت لـ DCF في RAW264.7 المعالجة بـ

مع مستخلصات الهيدروجيل. د صور صبغة DCFH-DA التمثيلية في RAW264.7 المعالجة بـ 300 مم H2O2 (بار ). الجينات النسبية (مؤيدة للالتهاب: iNOS، COX-2 و IL-6. مضادة للالتهاب: TGF- تعبيرات IL-10 و CD206) E وتعبيرات البروتينات المرتبطة باستقطاب البلعميات (iNOS و CD206) في خلايا RAW264.7 المرباة مع مستخلصات الهيدروجيل مع تحفيز بي.جي.-إل.بي.إس لـ تدفق السيتومترية لعلامات سطح استقطاب البلعميات (CD86 و CD206). : : : : - (انظر الشكل في الصفحة التالية.)

الشكل 7 التأثير العظمي لـ CSBDX@MOF. التعبير الجيني النسبي لـ RUNX2 و ALP و COL1 و OPN و OCN و OPG في خلايا MC3T3 المرباة في وسط مهيأ من البلعميات في اليوم السابعواليوم الرابع عشر صبغة C ALP لخلايا MC3T3 المرباة في وسط مهيأ من البلعميات في اليوم السابع (شريط تلوين D ARS لخلايا MC3T3 المرباة في وسط مهيأ من البلعميات في اليوم الحادي والعشرين (شريط ). الصور التمثيلية المناعية الفلورية لـ OCN (E) و RUNX2 (F) لخلايا MC3T3 المرباة في وسط مهيأ من البلعميات في اليوم السابع والرابع عشر (شريط ). ج التحليل الإحصائي لمساحة صبغة ALP و ARS. التحليل الإحصائي لشدة الفلورسنت المتوسطة (MFI) لـ OCN و RUNX2 ). لا دلالة - (انظر الشكل في الصفحة التالية.)

الشكل 9 التقييم النسيجي للتعديل المناعي، ترسب الكولاجين وتجديد العظم الهوائي للهيدروجيل. صور صبغة H&E التمثيلية في اليوم السابع( علوي صور تمثيلية للتلوين المناعي النسيجي لـ iNOS و CD206 في اليوم السابع والتحليل الإحصائي للخلايا الإيجابية لـ iNOS و CD206 لكل مجال عالي القوة (HPF) صور صبغ التريكروم لممثل ماسون (بار علوي، شريط صور تمثيلية للتلوين المناعي النسيجي لـ COL1 E و OCN F في اليوم الثامن والعشرين والتحليل الإحصائي للخلايا الإيجابية لـ COL 1 و OCN لكل مجال عالي الطاقة (بار ). *: لا دلالة

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-024-02555-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38797862

Publication Date: 2024-05-26

Dynamic hydrogel-metal-organic

Check for updates framework system promotes bone regeneration in periodontitis through controlled drug delivery

Abstract

Periodontitis is a prevalent chronic inflammatory disease, which leads to gradual degradation of alveolar bone. The challenges persist in achieving effective alveolar bone repair due to the unique bacterial microenvironment’s impact on immune responses. This study explores a novel approach utilizing Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) (comprising magnesium and gallic acid) for promoting bone regeneration in periodontitis, which focuses on the physiological roles of magnesium ions in bone repair and gallic acid’s antioxidant and immunomodulatory properties. However, the dynamic oral environment and irregular periodontal pockets pose challenges for sustained drug delivery. A smart responsive hydrogel system, integrating Carboxymethyl Chitosan (CMCS), Dextran (DEX) and 4-formylphenylboronic acid (4-FPBA) was designed to address this problem. The injectable self-healing hydrogel forms a dual-crosslinked network, incorporating the MOF and rendering its on-demand release sensitive to reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and pH levels of periodontitis. We seek to analyze the hydrogel’s synergistic effects with MOFs in antibacterial functions, immunomodulation and promotion of bone regeneration in periodontitis. In vivo and in vitro experiment validated the system’s efficacy in inhibiting inflammation-related genes and proteins expression to foster periodontal bone regeneration. This dynamic hydrogel system with MOFs, shows promise as a potential therapeutic avenue for addressing the challenges in bone regeneration in periodontitis.

Introduction

Based on the physiological characteristics of periodontitis [5-8], effective treatment necessitates functions such as antimicrobial activity, antioxidant property and pro-osteogenesis capacity. Generally, various classes of antibiotics are utilized to achieve the aforementioned functions [14]. However, the widespread misuse of these drugs may inevitably lead to drawbacks such as drug resistance and adverse side effects [15]. Therefore, researchers are gradually shifting their focus towards the exploration of novel therapeutic agents. In recent years, the application of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) in the field of biomedicine, particularly in drug delivery and disease treatment, has garnered widespread attention [16]. MOFs are a class of porous crystalline materials composed of metal ions and organic linkers, characterized by customizable components and structures, enabling the design and development of multifunctional systems tailored to various diseases [17]. It has been reported that

However, during the treatment of periodontitis, the dynamic and complex oral environment, including factors such as saliva flow, chemical composition and temperature fluctuations, can lead to rapid loss of MOFs drugs [26]. Additionally, the irregular anatomical

structures of periodontal pockets further present potential challenges in the treatment of periodontitis [27]. Therefore, there is a need to develop a sustained release system for controlling the on-demand release of MOFs and providing a favorable microenvironment for bone regeneration in periodontitis. In recent years, injectable hydrogel materials have gradually gained attention in the biomedical field [28-30], especially smart responsive hydrogels, which offer unique advantages in periodontitis treatment [31, 32]. Hence, this study aims to construct a dynamic responsive smart injectable hydrogel in conjunction with MOFs of Mg-GA for the treatment of periodontitis. Initially, we have selected Carboxymethyl Chitosan (CMCS) and Dextran (DEX) as the primary components for constructing the injectable hydrogel. Carboxymethyl chitosan (CMCS), a derivative of chitosan with similar biocompatibility and enhanced water solubility and antibacterial property [33], is widely used in tissue engineering, anti-bacterial dressing and drug delivery system [34]. As well as Dextran (DEX) is a kind of linear polysaccharide compound produced by bacteria Leuconostoc mesenteroides [35]. The backbone of DEX is linked with

In this study, the MOF of Mg-GA was loaded into CSBDX injectable self-healing hydrogels for the treatment of periodontitis (Fig. 1). We aim to investigate in-depth the on-demand release of Mg -GA under the specific microenvironment stimuli of periodontitis, by modulating its impact on osteogenesis through the regulation of oxidative stress and the immune microenvironment. The study aims to elucidate the synergistic effects of the hydrogel’s self-healing properties and antibacterial functions in conjunction with the MOF. Furthermore, we intend to validate the inhibitory effects on inflammation and promotion of alveolar bone regeneration of the CSBDX@MOF system through in vivo periodontitis

model experiments. Our hydrogel system holds the potential to offer a novel approach for bone regeneration in periodontitis.

Methods and experiments

Materials

Synthesis of Mg-GA

Synthesis of the hydrogels

homogenously mixed and quickly injected into the mold and hydrogels were formed within minutes. CMCS/4FPBA/DEX hydrogels were obtained in the same way as described above without

Characterization of CSBDX

Characterization of Mg-GA

Characterization of CSBDX@MOF

Surface and cross-section morphology

describe the surface roughness of hydrogels. The water contact angle was measured using a DSA-X ROLL contact angle measuring instrument. The profile of a drop of

Mechanical properties

Swelling and degradation properties

weighed as

Drug release properties

Antibacterial test

Biocompatibility

Preparation of hydrogel extracts

Cell proliferation assay

proliferation was evaluated using the CCK-8 kit. Briefly, the working solution was added and incubated for 2 h in the dark at

Live/dead cell staining

Cell morphology observation

Hemolysis assays

Antioxidant property

Total antioxidant activity measurement

activity was calculated according to the following formula (4).

Intracellular ROS scavenging measurement

Immunomodulatory property

reaction ( qPCR ) was used to detect the expression of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory genes. The total cellular RNA was extracted using the RNA-Quick Purification Kit. RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScriptTM RT reagent kit. The real-time qPCR system (ABI QuantStudio 5, USA) was used to detect the expression of iNOS, COX-2, IL-6, TGF-

Osteogenic differentiation in vitro

at a density of

Animal experiments

Rat periodontitis model establishment

Micro-CT analysis

Histological analysis

Statistical analysis

Results and discussion

Preparation and characterization of Mg-GA and CSBDX

(See figure on next page.)

Preparation and characterization of CSBDX@MOF

of oxygen and nutrients, promoting cellular infiltration and tissue ingrowth [50, 51]. Surface roughness and hydrophilicity of the hydrogel samples were also evaluated. Introduction of Mg -GA led to a significant decrease in the Sa value (arithmetical mean deviation of the profile) but showed no significant difference among the three CSBDX@MOF groups (Fig. 3C). As it is wellknown, a rough surface favors cell adhesion, migration [52] and bacterial attachment [53]. Surfaces with relatively lower roughness, as seen in CSBDX@MOF, might reduce the adherence of periodontal pathogens, preventing persistent tissue infections. Water contact angle results indicated excellent hydrophilicity for all hydrogel samples, with a decrease in water contact angle which was attributed to the rich phenolic hydroxyl groups present in the MOF of Mg-GA [54] (Fig. 3D). As depicted in Fig. 3E, the fracture strain and maximum tensile strength of CSBDX@MOF were higher compared to CSBDX, with CSBDX@10MOF exhibiting the highest fracture strain (up to

of

and ROS sensitivity of CSBDX@MOF, attributed to the dynamic crosslinking effects of borate ester bonds and imine bonds [44, 45]. Therefore, the drug release process is responsive to the high pH and ROS microenvironment of periodontitis, enabling on-demand release of MOF of Mg-GA, thereby facilitating the treatment process of periodontitis.

Antibacterial effect

Biocompatibility

Antioxidant property

conditions for the improvement of the bone regeneration microenvironment in periodontitis.

Immunomodulatory property

of M1 macrophages, and M1 polarization upregulates the expression of IL-6, COX-2, iNOS, and other inflammatory mediators. M2 macrophages determine the resolution of inflammation and bone reconstruction, promoting the expression of TGF-

Osteogenesis property in vitro through immunomodulation

osteogenic induction, noticeable calcium nodules were observed in the three CSBDX@MOF group (Fig. 7D, G). Osteogenesis is a dynamic long-term process, and the osteoimmunomodulatory effects of the hydrogel system vary in gene expression at different stages of osteogenesis. These outcomes may be attributed to the immunomodulatory effect of macrophage conditioned medium, for the concentration of free

Alveolar bone regeneration in vivo through immunomodulation

group on the 28th day. Additionally, bone volume/total volume (BV/TV) ratio was employed to assess alveolar bone quality. The PD group exhibited the lowest BV/TV, whereas both CSBDX and CSBDX@MOF consistently displayed optimal outcomes. Remarkably, the BV/TV ratio of CSBDX@MOF was significantly higher than that in the CSBDX group on the 28th day. Consequently, the CSBDX@MOF group showed the most effective treatment for periodontitis-induced alveolar bone resorption. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining as well as Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for iNOS and CD206 on the 7th day were performed to evaluate histological morphology of alveolar bone and immunomodulatory effects of the hydrogel system. As depicted in Fig. 9A, H&E staining supported the trends of micro-CT scanning. Besides, the PD group exhibited a high quantity of inflammatory cells, indicating the sustained presence of periodontitis features. In contrast, the hydrogel-treated groups showed a significant reduction in infiltrating inflammatory cells. For IHC staining, compared to the control group, the CSBDX@MOF group exhibited a significant reduction in iNOS-positive cells, while displaying the highest CD206 staining (Fig. 9B, C), highlighting its robust anti-inflammatory capabilities. Furthermore, Masson’s trichrome staining and IHC staining for COL1 and OCN were conducted to evaluate periodontal collagen deposit and alveolar bone regeneration effects of the hydrogel system on the 28th day. Masson’s trichrome staining revealed the presence of an organized periodontal ligament between the alveolar bone and tooth, accompanied by mature collagen formation in the CSBDX@ MOF group (Fig. 9D). As depicted in Fig. 9E, F IHC staining revealed decreased expression levels of COL1 and OCN in the periodontitis environment, whereas the CSBDX and CSBDX@MOF groups showed more COL1 and OCN-positive cells, with the CSBDX@MOF group demonstrating superior effects. However, for periodontitis is a chronic disease and bone regeneration takes a long time, the relative long-term osteogenic effect of CSBDX and CSBDX@MOF system in vivo remains to be explored. In vitro studies have indicated the critical role of macrophage polarization in the onset and progression of periodontitis [67]. The aforementioned results validate that inhibiting M1 macrophage polarization can reduce the expression of inflammatory cytokines in periodontal lesion tissues [74], and inducing M2 macrophages can prevent bone loss [75, 76]. Therefore, CSBDX@MOF can promote alveolar bone regeneration by regulating M1/ M2 polarization. As anticipated, the hydrogel system in this study demonstrated application efficacy in vivo by alleviating inflammation and promoting alveolar bone regeneration, attributed to the synergistic effects of CMCS’s antibacterial capabilities, 4-FPBA’s reductive

properties and DEX’s anti-inflammatory effects. Particularly, the introduction of MOF indirectly provided

Conclusion

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Data Availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Competing interests

Author details

Published online: 26 May 2024

References

- Kinane DF, Stathopoulou PG, Papapanou PN. Periodontal diseases. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17038.

- Jepsen S, Suvan J, Deschner J. The association of periodontal diseases with metabolic syndrome and obesity. Periodontol. 2020;83(1):125-53.

- Kwon T, Lamster IB, Levin L. Current concepts in the management of periodontitis. Int Dent J. 2021;71(6):462-76.

- Graziani F, Karapetsa D, Alonso B, et al. Nonsurgical and surgical treatment of periodontitis: how many options for one disease? Periodontol. 2017;75(1):152-88.

- Xu W, Zhou W, Wang H, et al. Roles of porphyromonas gingivalis and its virulence factors in periodontitis. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2020;120:45-84.

- Takahashi N. Oral microbiome metabolism: from “Who Are They?” to “what are they doing?” J Dent Res. 2015;94(12):1628-37.

- Sczepanik FSC, Grossi ML, Casati M, et al. Periodontitis is an inflammatory disease of oxidative stress: we should treat it that way. Periodontol. 2020;84(1):45-68.

- Pan W, Wang Q, Chen Q. The cytokine network involved in the host immune response to periodontitis. Int J Oral Sci. 2019;11(3):30.

- Almubarak A, Tanagala KKK, Papapanou PN, et al. Disruption of monocyte and macrophage homeostasis in periodontitis. Front Immunol. 2020;11:330.

- Cafferata EA, Alvarez C, Diaz KT, et al. Multifunctional nanocarriers for the treatment of periodontitis: Immunomodulatory, antimicrobial, and regenerative strategies. Oral Dis. 2019;25(8):1866-78.

- Chen E, Wang T, Tu Y, et al. ROS-scavenging biomaterials for periodontitis. J Mater Chem B. 2023;11(3):482-99.

- Huang

, Huang L. Periodontal bifunctional biomaterials: progress and perspectives. Materials. 2021;14(24):7588. - Abdo VL, Suarez LJ, de Paula LG, et al. Underestimated microbial infection of resorbable membranes on guided regeneration. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2023;226: 113318.

- Pretzl B, SäLZER S, et al. Administration of systemic antibiotics during non-surgical periodontal therapy-a consensus report. Clin Oral Investig. 2019;23(7):3073-85.

- Khattri S, Nagraj SK, Arora A, Eachempati P, Kusum CK, Bhat KG, Johnson TM, Lodi G, et al. Adjunctive systemic antimicrobials for the non-surgical treatment of periodontitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020. https://doi. org/10.1002/14651858.CD012568.pub2.

- Sun Z, Li T, Mei T, et al. Nanoscale MOFs in nanomedicine applications: from drug delivery to therapeutic agents. J Mater Chem B. 2023;11(15):3273-94.

- Coluccia M, Parisse V, Guglielmi P, et al. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) as biomolecules drug delivery systems for anticancer purposes. Eur J Med Chem. 2022;244: 114801.

- de Baaij JH, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ. Magnesium in man: implications for health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2015;95(1):1-46.

- Yuan Z, Wan Z, Gao C, et al. Controlled magnesium ion delivery system for in situ bone tissue engineering. J Control Release. 2022;350:360-76.

- Lin S, Yang G, Jiang F, et al. A magnesium-enriched 3D culture system that mimics the bone development microenvironment for vascularized bone regeneration. Adv Sci. 2019;6(12):1900209.

- Zheng Z, Chen Y, Hong H, et al. The “Yin and Yang” of immunomodulatory magnesium-enriched graphene oxide nanoscrolls decorated biomimetic scaffolds in promoting bone regeneration. Adv Healthc Mater. 2021;10(2): e2000631.

- Zahrani NAAL, El-Shishtawy RM, Asiri AM. Recent developments of gallic acid derivatives and their hybrids in medicinal chemistry: a review. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;204:112609.

- Dai Z, Li Z, Zheng W, et al. Gallic acid ameliorates the inflammatory state of periodontal ligament stem cells and promotes pro-osteodifferentiation capabilities of inflammatory stem cell-derived exosomes. Life. 2022;12(9):1392.

- de Melo K, Lisboa LDS, Queiroz MF, et al. Antioxidant activity of fucoidan modified with gallic acid using the redox method. Mar Drugs. 2022;20(8):490.

- Bai J, Zhang Y, Tang C, et al. Gallic acid: pharmacological activities and molecular mechanisms involved in inflammation-related diseases. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;133: 110985.

- Diaz-Salmeron R, Toussaint B, Huang N, et al. Mucoadhesive poloxamerbased hydrogels for the release of HP-

-CD-complexed dexamethasone in the treatment of buccal diseases. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(1):117. - Wang B, Booij-Vrieling HE, Bronkhorst EM, et al. Antimicrobial and antiinflammatory thermo-reversible hydrogel for periodontal delivery. Acta Biomater. 2020;116:259-67.

- Irshad N, Jahanzeb N, Alqasim A, et al. Synthesis and analyses of injectable fluoridated-bioactive glass hydrogel for dental root canal sealing. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(11): e0294446.

- Malik QUA, Iftikhar S, Zahid S, et al. Smart injectable self-setting bioceramics for dental applications. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2020;113: 110956.

- Li W, Liu X, Deng Z, et al. Tough bonding, on-demand debonding, and facile rebonding between hydrogels and diverse metal surfaces. Adv Mater. 2019;31(48): e1904732.

- Wang Y, Li J, Tang M, et al. Smart stimuli-responsive hydrogels for drug delivery in periodontitis treatment. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;162: 114688.

- Sajjad S , Görke O , et al. Acetanilide-loaded injectable hydrogels with enhanced bioactivity and biocompatibility for potential treatment of periodontitis. J Appl Polymer Sci. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1002/app. 55200.

- Chang G, Dang Q, Liu C, et al. Carboxymethyl chitosan and carboxymethyl cellulose based self-healing hydrogel for accelerating diabetic wound healing. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;292: 119687.

- Shariatinia Z. Carboxymethyl chitosan: Properties and biomedical applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;120(Pt B):1406-19.

- Abir F, Barkhordarian S, Sumpio BE. Efficacy of dextran solutions in vascular surgery. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2004;38(6):483-91.

- Zhang M, Huang Y, Pan W, et al. Polydopamine-incorporated dextran hydrogel drug carrier with tailorable structure for wound healing. Carbohydr Polym. 2021;253: 117213.

- Elgamily HM, Gamal AA, Saleh SAA, et al. Microbiological and environmental assessment of human oral dental plaque isolates. Microb Pathog. 2019;135: 103626.

- Hu Q, Lu Y, Luo Y. Recent advances in dextran-based drug delivery systems: from fabrication strategies to applications. Carbohydr Polym. 2021;264: 117999.

- Gao

, Zhang , Jin . Preparation and properties of minocycline-loaded carboxymethyl chitosan gel/alginate nonwovens composite wound dressings. Mar Drugs. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/md17100575. - Ke X, Li M, Wang X, et al. An injectable chitosan/dextran/

-glycerophosphate hydrogel as cell delivery carrier for therapy of myocardial infarction. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;229: 115516. - Xin H. Double-network tough hydrogels: a brief review on achievements and challenges. Gels. 2022;8(4):247.

- Li

, in , Yu Y, et al. In situ rapid-formation sprayable hydrogels for challenging tissue injury management. Adv Mater. 2024. https://doi.org/10. 1002/adma. 202400310. - Li R, Zhou C, Chen J, et al. Synergistic osteogenic and angiogenic effects of KP and QK peptides incorporated with an injectable and self-healing hydrogel for efficient bone regeneration. Bioact Mater. 2022;18:267-83.

-

, et al. ROS-responsive hydrogel coating modified titanium promotes vascularization and osteointegration of bone defects by orchestrating immunomodulation. Biomaterials. 2022;287: 121683. - Lu CH, Yu CH, Yeh YC. Engineering nanocomposite hydrogels using dynamic bonds. Acta Biomater. 2021;130:66-79

- Wu Y, Wang Y, Long L, et al. A spatiotemporal release platform based on pH/ROS stimuli-responsive hydrogel in wound repairing. J Control Release. 2022;341:147-65.

- Wang H, Wang L, Guo S, et al. Rutin-loaded stimuli-responsive hydrogel for anti-inflammation. ACS Appl Mater Interf. 2022. https://doi.org/10. 1021/acsami.2c02295.

- Liang Y, Li Z, Huang Y, et al. Dual-dynamic-bond cross-linked antibacterial adhesive hydrogel sealants with on-demand removability for post-wound-closure and infected wound healing. ACS Nano. 2021;15(4):7078-93.

- Cooper L, Hidalgo T, Gorman M, et al. A biocompatible porous Mg-gallate metal-organic framework as an antioxidant carrier. Chem Commun. 2015;51(27):5848-51.

- Sarker B, Li W, Zheng K, et al. Designing porous bone tissue engineering scaffolds with enhanced mechanical properties from composite hydrogels composed of modified alginate, gelatin, and bioactive glass. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2016;2(12):2240-54.

- Iviglia G, Kargozar S, Baino F. Biomaterials, current strategies, and novel nano-technological approaches for periodontal regeneration. J Funct Biomater. 2019;10(1):3.

- Liang W, He W, Huang R, et al. Peritoneum-inspired janus porous hydrogel with anti-deformation, anti-adhesion, and pro-healing characteristics for abdominal wall defect treatment. Adv Mater. 2022;34(15): e2108992.

- Crawford RJ, Webb HK, Truong VK, et al. Surface topographical factors influencing bacterial attachment. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2012;179-182:142-9.

- Xu Y, Patsis PA, Hauser S, et al. Cytocompatible, injectable, and electroconductive soft adhesives with hybrid covalent/noncovalent dynamic network. Adv Sci. 2019;6(15):1802077.

- Feng

, Zhu , et al. Distribution of 8 periodontal microorganisms in family members of Chinese patients with aggressive periodontitis. Arch Oral Biol. 2015;60(3):400-7. - Liang

, Bai , Niu , et al. High inhabitation activity of CMCS/Phytic acid/Zn(2+) nanoparticles via flash nanoprecipitation (FNP) for bacterial and fungal infections. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;242(Pt 1): 124747. - Zhang B, Jiang Z, Li X, et al. Facile preparation of biocompatible and antibacterial water-soluble films using polyvinyl alcohol/carboxymethyl chitosan blend fibers via centrifugal spinning. Carbohydr Polym. 2023;317: 121062.

- Xu B, Wang H, Wang W, et al. A single-atom nanozyme for wound disinfection applications. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2019;58(15):4911-6.

- Lin Z, Shen D, Zhou W, et al. Regulation of extracellular bioactive cations in bone tissue microenvironment induces favorable osteoimmune conditions to accelerate in situ bone regeneration. Bioact Mater. 2021;6(8):2315-30.

- Furkel J, Knoll M, Din S, et al. C-MORE: a high-content single-cell morphology recognition methodology for liquid biopsies toward personalized cardiovascular medicine. Cell Rep Med. 2021;2(11): 100436.

- Darwish AG, Das PR, Ismail A, et al. untargeted metabolomics and antioxidant capacities of muscadine grape genotypes during berry development. Antioxidants. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10060914.

- Zheng Z, Chen Y, Guo B, Wang Y, Liu W, Sun J, Wang X, et al. Magnesiumorganic framework-based stimuli-responsive systems that optimize the bone microenvironment for enhanced bone regeneration. Chem Eng J. 2020;396: 125241.

- Lin Y, Luo T, Weng A, et al. Gallic acid alleviates gouty arthritis by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pyroptosis through enhancing Nrf2 signaling. Front Immunol. 2020;11: 580593.

- Qiao W, Wong KHM, Shen J, et al. TRPM7 kinase-mediated immunomodulation in macrophage plays a central role in magnesium ion-induced bone regeneration. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):2885.

- Bessa-Gonçalves M, Ribeiro-Machado C, Costa M, Ribeiro CC, Barbosa JN, Barbosa MA, Santos SG, et al. Magnesium incorporation in fibrinogen scaffolds promotes macrophage polarization towards M2 phenotype. Acta Biomater. 2023;155(667):83.

- Li J, Zhao C, Xu Y, et al. Remodeling of the osteoimmune microenvironment after biomaterials implantation in murine tibia: single-cell transcriptome analysis. Bioact Mater. 2023;22:404-22.

- Huang H, Pan W, Wang Y, et al. Nanoparticulate cell-free DNA scavenger for treating inflammatory bone loss in periodontitis. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):5925.

- Tan M, Mosaoa R, Graham GT, et al. Inhibition of the mitochondrial citrate carrier, Slc25a1, reverts steatosis, glucose intolerance, and inflammation in preclinical models of NAFLD/NASH. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27(7):2143-57.

- Bashir KMI, Choi JS. Clinical and physiological perspectives of

-glucans the past, present, and future. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(9):1906. - Zhang

, Huang , Jiang , et al. A novel magnesium ion-incorporating dual-crosslinked hydrogel to improve bone scaffold-mediated osteogenesis and angiogenesis. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2021;121: 111868. - Wu Z, Meng Z, Wu Q, et al. Biomimetic and osteogenic 3D silk fibroin composite scaffolds with nano MgO and mineralized hydroxyapatite for bone regeneration. J Tissue Eng. 2020;11:2041731420967791.

- Oh Y, Ahn CB, Marasinghe M, et al. Insertion of gallic acid onto chitosan promotes the differentiation of osteoblasts from murine bone marrowderived mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;183:1410-8.

- Kang Y, Xu C, Meng L, et al. Exosome-functionalized magnesium-organic framework-based scaffolds with osteogenic, angiogenic and antiinflammatory properties for accelerated bone regeneration. Bioact Mater. 2022;18:26-41.

- Li S, Hua Y, Liao C. Weakening of M1 macrophage and bone resorption in periodontitis cystathionine

-lyase-deficient mice. Oral Dis. 2022. https:// doi.org/10.1111/odi.14374. - Zhuang Z, Yoshizawa-Smith S, Glowacki A, et al. Induction of M2 macrophages prevents bone loss in murine periodontitis models. J Dent Res. 2019;98(2):200-8.

- Chen X , Wan Z , Yang L , et al. Exosomes derived from reparative M 2 -like macrophages prevent bone loss in murine periodontitis models via IL-10 mRNA. J Nanobiotechnology. 2022;20(1):110.

Publisher’s Note

- *Correspondence:

Xinchun Zhang

zhxinch@mail.sysu.edu.cn

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article - (See figure on next page.)

Fig. 4 Antibacterial effect. A The schematic illustration of antibacterial effect of hydrogel system on A. a. and. gingivalis. B Representative images of Live/dead bacteria staining of A. a. and P. gingivalis after co-culture with hydrogel (bar ). C Representative images of colony formation assay and bacterial survival histogram of . a. and . gingivalis after co-culture with hydrogel and corresponding statistical analysis of bacterial survival ( ). E Representative SEM images of . a. and . gingivalis after co-culture with hydrogel ( ). Yellow pseudo-color indicates the stacked and crumpled bacteria. , ns no significance - Fig. 6 The antioxidant and immunomodulatory properties of CSBDX@MOF. The quantitative analysis of DPPHA and ABTS B radical scavenging efficiency of hydrogel. C Representative flow cytometry data and mean fluorescence intensity of DCF in RAW264.7 treated with

with hydrogel extracts. D Representative DCFH-DA staining images of in RAW264.7 treated with 300 Mm H 2 O 2 (bar ). Relative gene (pro-inflammatory: iNOS, COX-2 and IL-6. Anti-inflammatory: TGF- , IL-10 and CD206) expressions E and macrophage polarization-related protein (iNOS and CD206) expressions in RAW264.7 incubated with hydrogel extracts with stimulation of P.g.-LPS for Flow cytometry of macrophage polarization surface markers (CD86 and CD206). : : : : - (See figure on next page.)

Fig. 7 The osteogenic effect of CSBDX@MOF. Relative gene expression of RUNX2, ALP, COL1, OPN, OCN and OPG in MC3T3 cells incubated with macrophage conditioned medium on 7th dayand 14th day . C ALP staining of MC3T3 cells incubated with macrophage conditioned medium on 7th day (bar ). D ARS staining of MC3T3 cells incubated with macrophage conditioned medium on 21st day (bar ). The representative immunofluorescence images of OCN (E) and RUNX2 (F) of MC3T3 cells incubated with macrophage conditioned medium on 7th and 14th day (bar ). G The statistical analysis of area of ALP and ARS staining. The statistical analysis of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of OCN and RUNX2 ( ). , ns no significance - (See figure on next page.)

Fig. 9 Histological evaluation of immunomodulatory, collagen deposit and alveolar bone regeneration of hydrogels. Representative H&E staining images on the 7th day( upper, lower). Representative immunohistochemical staining images of iNOS and CD206 C on the 7th day and the statistical analysis of positive cells of iNOS and CD206 per HPF ( ). Representative Masson’s trichrome staining images (bar upper, bar lower). Representative immunohistochemical staining images of COL1 E and OCN F on the 28th day and the statistical analysis of positive cells of COL 1 and OCN per HPF (bar ). *: , ns no significance