المجلة: Scientific Reports، المجلد: 15، العدد: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86679-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39833241

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-20

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86679-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39833241

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-20

افتح

نظام تمارين منظم يعزز الوظيفة اللاإرادية مقارنة بالأنشطة البدنية غير المنظمة في الخيول المسنّة

غالبًا ما تظهر الخيول الأكبر سنًا استجابة تلقائية منخفضة، مما يؤثر على رفاهيتها. بينما يمكن أن يساعد التمرين المنتظم في الحفاظ على الوظيفة التلقائية، فإن تأثير التمرين المنظم على الخيول المسنّة ليس مفهوماً جيدًا. دراسة شملت 27 حصانًا مسنًا فحصت تعديلهم التلقائي على مدى 12 أسبوعًا تحت مستويات نشاط مختلفة. تم تقسيم الخيول إلى ثلاث مجموعات: (1) غير نشطة (SEL)، (2) تلك التي تشارك في أنشطة غير منظمة (RAT)، و(3) تلك التي تتبع نظام تمرين منظم (SER). أظهرت النتائج أن الحد الأدنى ومتوسط معدل ضربات القلب انخفض في مجموعة التمرين المنظم من الأسبوع 10 إلى 12. بالمقابل، لم تُلاحظ أي تغييرات في المجموعات الأخرى. علاوة على ذلك، لم تتغير الفترات بين الضربات في الخيول غير النشطة، وتذبذبت في الخيول المشاركة في أنشطة غير منظمة من الأسبوع 8 إلى

الكلمات الرئيسية: استجابات الإجهاد، الحصان المسن، نمط الحياة الخامل، نظام التمارين المنظم، النشاط البدني غير المنظم، رفاهية الحيوان

تم تدجين الخيول لأغراض بشرية مثل النقل والزراعة والاستخدام العسكري.

يهدف التدريب البدني للخيول إلى تحقيق عدة أهداف رئيسية، بما في ذلك تعزيز أو الحفاظ على الأداء الرياضي الأمثل، وتأخير ظهور التعب، وتقليل خطر الإصابة، والحفاظ على رغبة الحصان في ممارسة التمارين.

فترات تحت تأثير المكونات الودية واللاودية (العصبية المبهمة)، مما يظهر قابلية التكيف ومرونة الأنظمة البيولوجية استجابةً للتحديات المجهدة.

يمكن أن تعكس التعديلات في متغيرات HRV المختلفة مكونات ذاتية معينة. على سبيل المثال، تتأثر التغيرات في فترة النبض إلى النبض (RR)، والانحراف المعياري لفترات RR الطبيعية (SDNN)، والنطاق المنخفض التردد (LF)، ونطاق الطاقة الكلي، والانحراف المعياري لرسم بوانكاري على طول خط الهوية (SD2) بكل من المكونات الودية والمكونات الحائرة.

من المهم أن نلاحظ أن الشيخوخة ليست مرضًا، بل هي حالة يختبر فيها الجسم تراجعًا في كتلة الجسم، والقدرة الهوائية، والمناعة الوظيفية، والوظيفة اللاإرادية مع مرور الوقت.

بينما تم ملاحظة تحسين التنظيم الذاتي بعد برامج التدريب المنظم في الخيول البالغة، لا تزال آثار هذه البرامج على الخيول المسنّة غير مستكشفة إلى حد كبير. علاوة على ذلك، لم يتم توضيح تداعيات الحفاظ على النشاط البدني غير المنظم في الخيول المسنّة المتقاعدة بعد. لذلك، تهدف هذه الدراسة إلى فحص آثار نظام تمرين منظم مقابل النشاط البدني غير المنظم على معدل ضربات القلب أثناء الراحة (HR) والتنظيم الذاتي في الخيول المسنّة المتقاعدة. الفرضية هي أن مستويات النشاط المختلفة ستؤدي إلى اختلافات ملحوظة في معدل ضربات القلب أثناء الراحة والتنظيم الذاتي، مع توقع أن يكون لنظام التمرين المنظم تأثير كبير على كلا المعلمين.

النتائج

لم توجد اختلافات في متوسط العمر (SEL:

طرق المجال الزمني

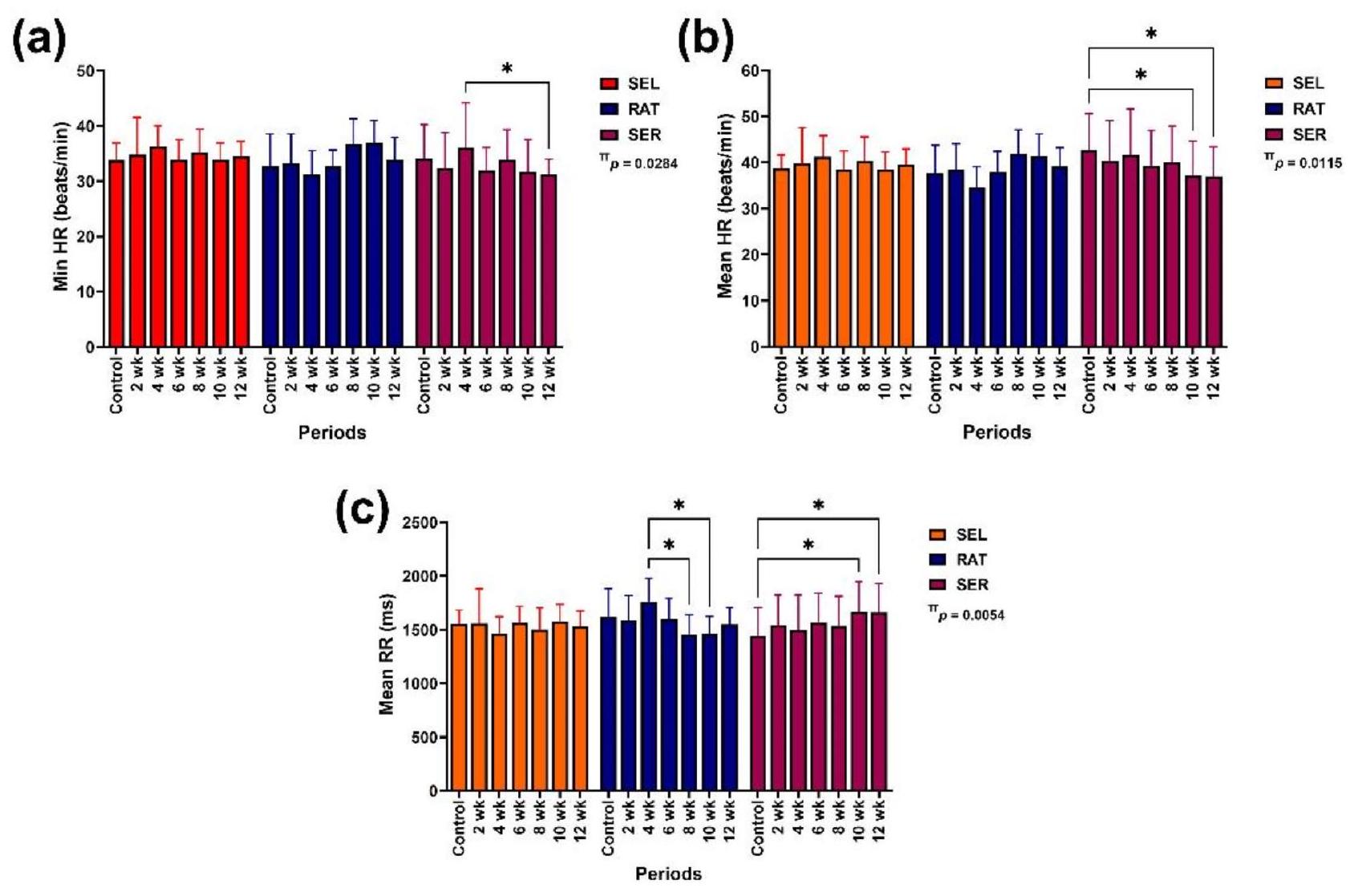

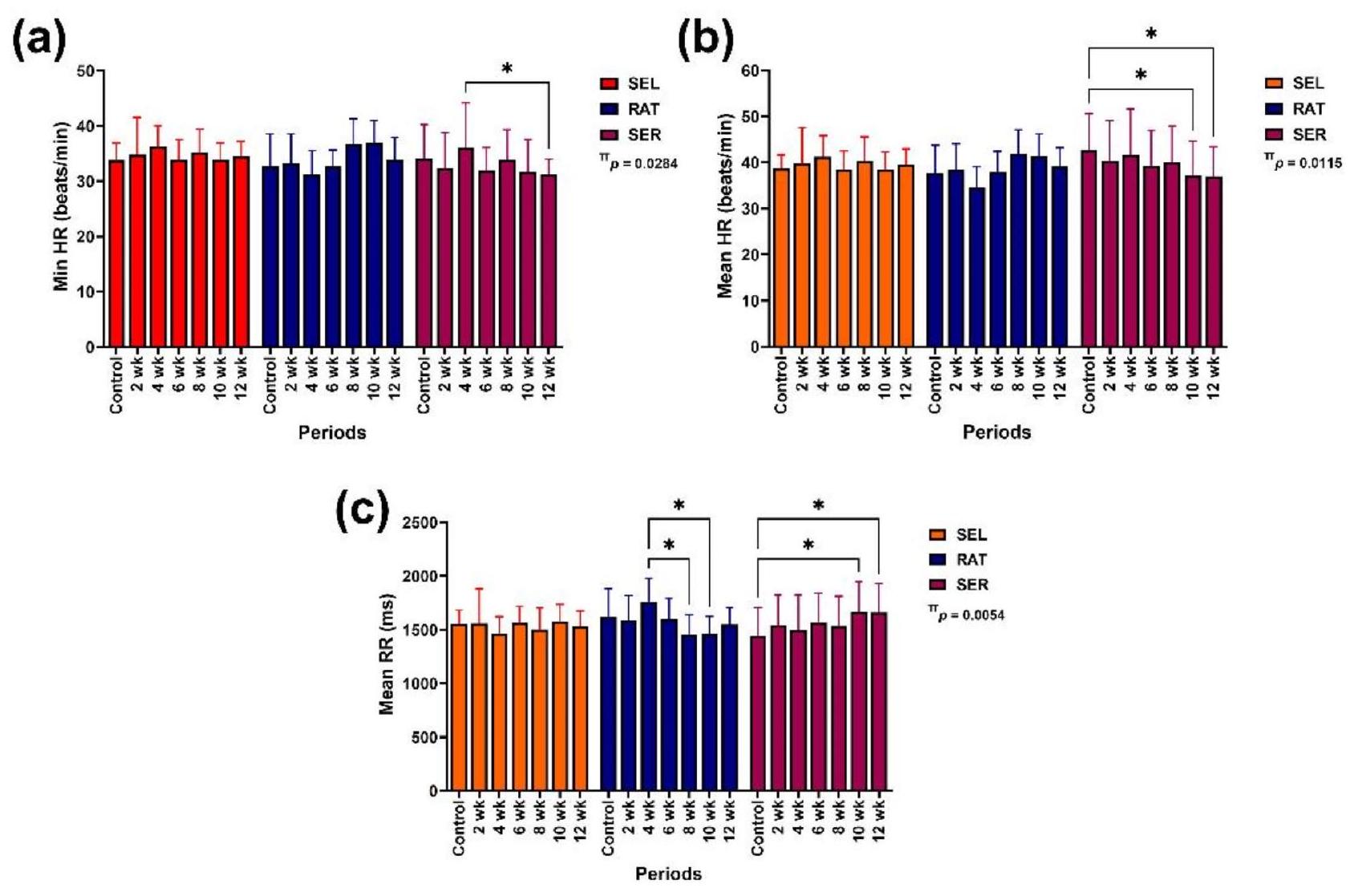

تم ملاحظة تفاعل كبير بين المجموعة والزمن للتغيرات في الحد الأدنى لمعدل ضربات القلب

ظل الحد الأدنى والمتوسط لمعدل ضربات القلب دون تغيير في كل من خيول SEL وRAT. ومع ذلك، في خيول SER، أظهر الحد الأدنى لمعدل ضربات القلب انخفاضًا غير ذي دلالة إحصائية بعد 10 أسابيع.

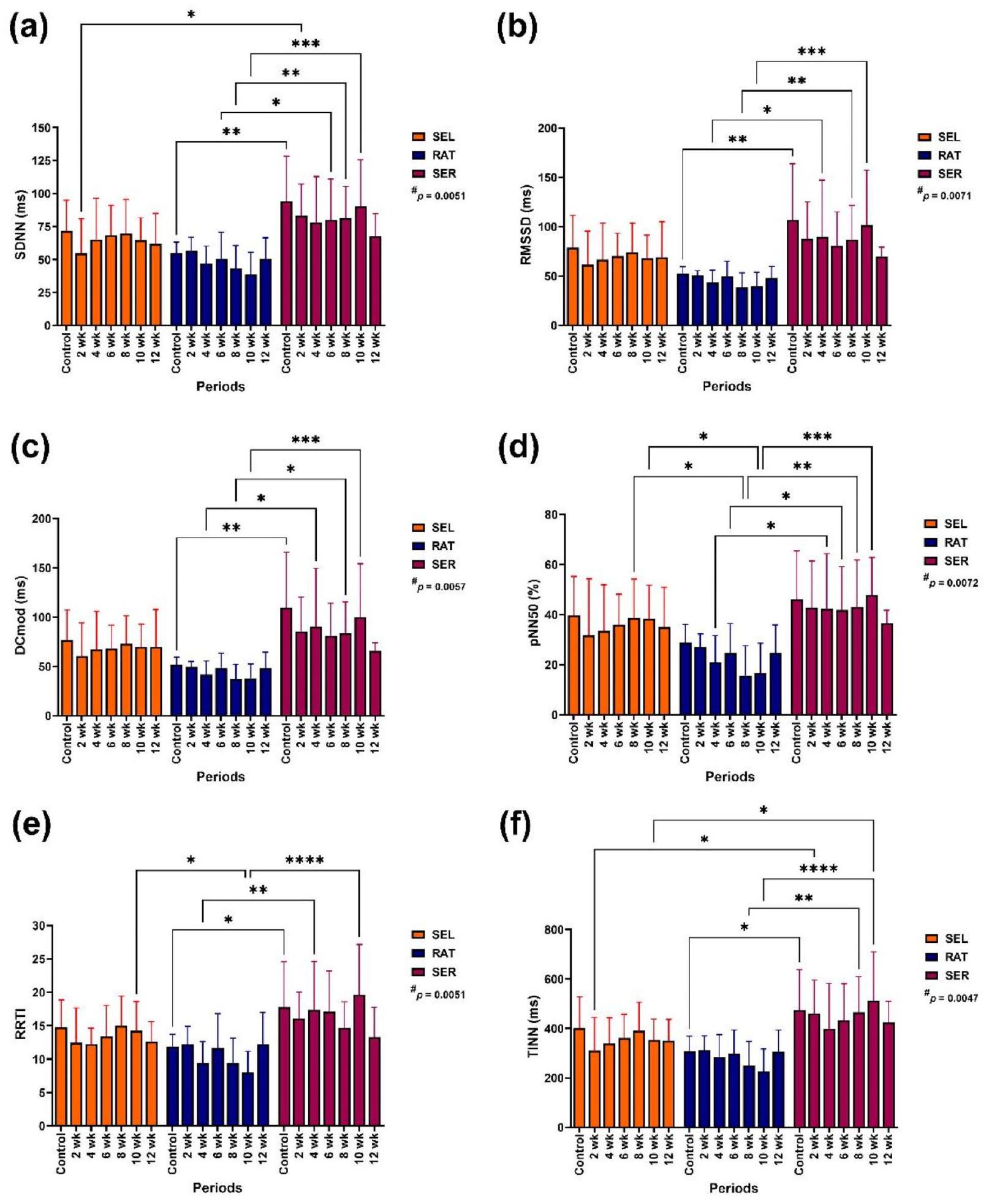

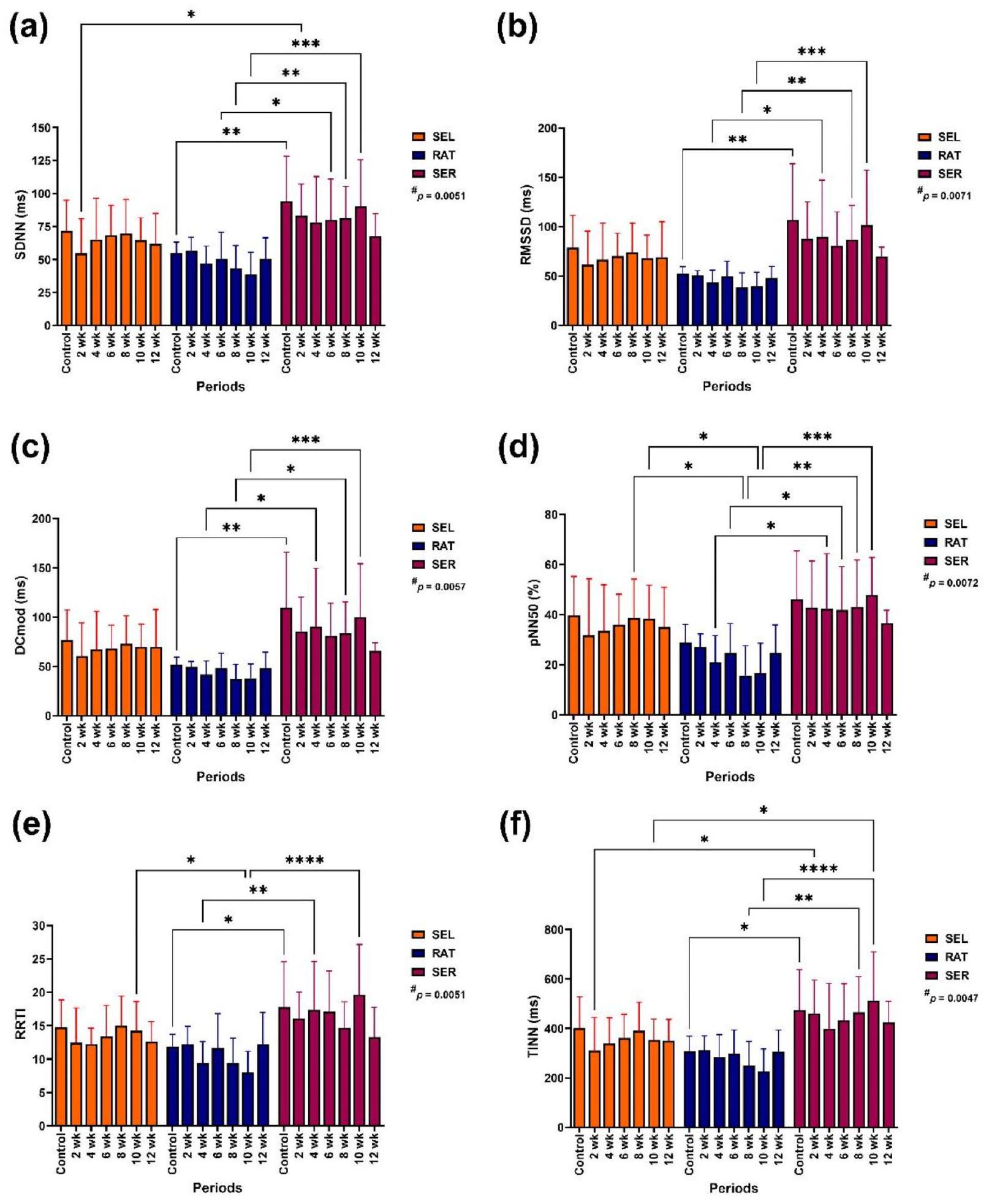

كان SDNN في خيول SER أعلى من خيول RAT قبل الدراسة (الخط الأساسي) في 6 و 8 و 10 أسابيع من الدراسة.

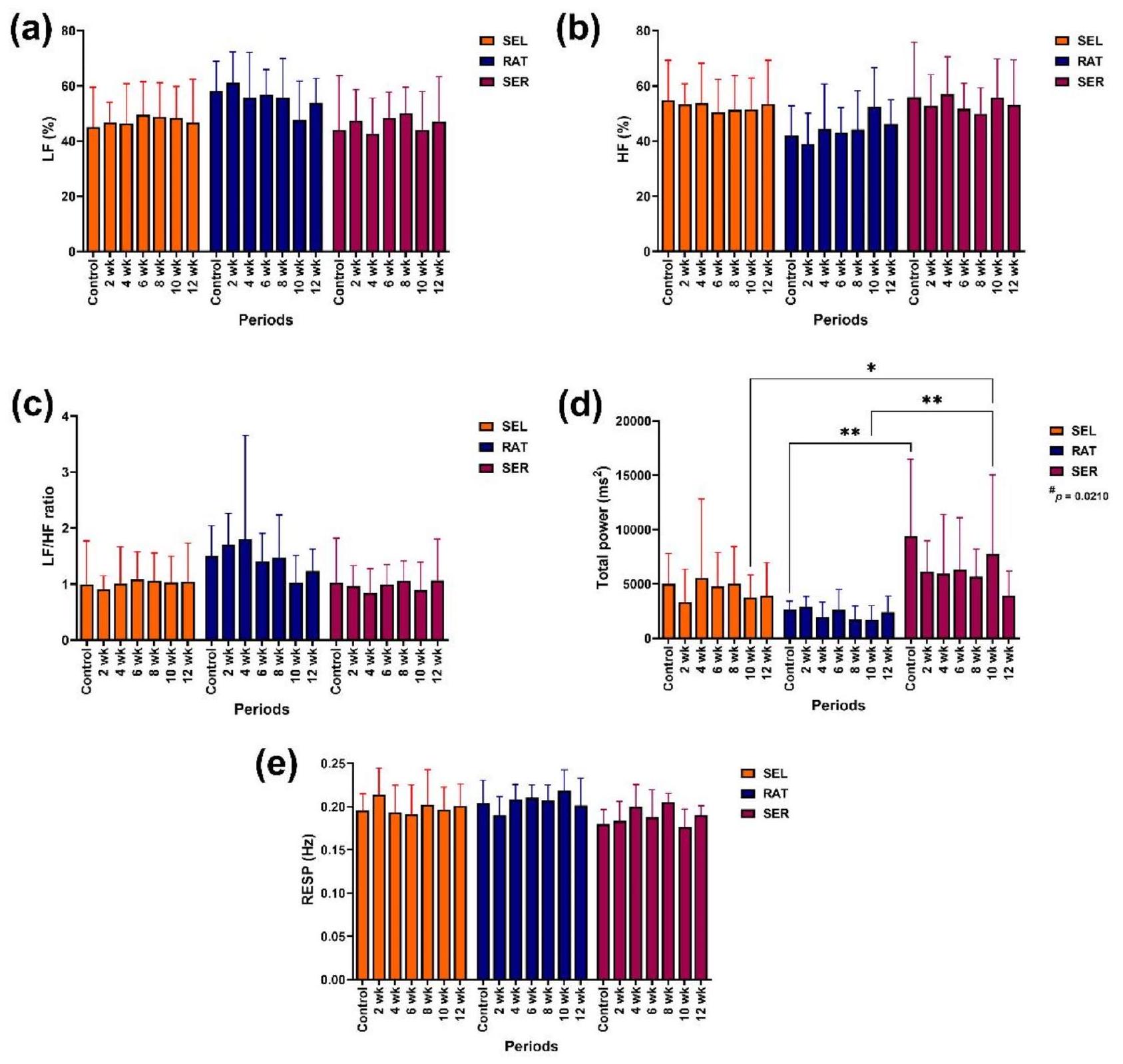

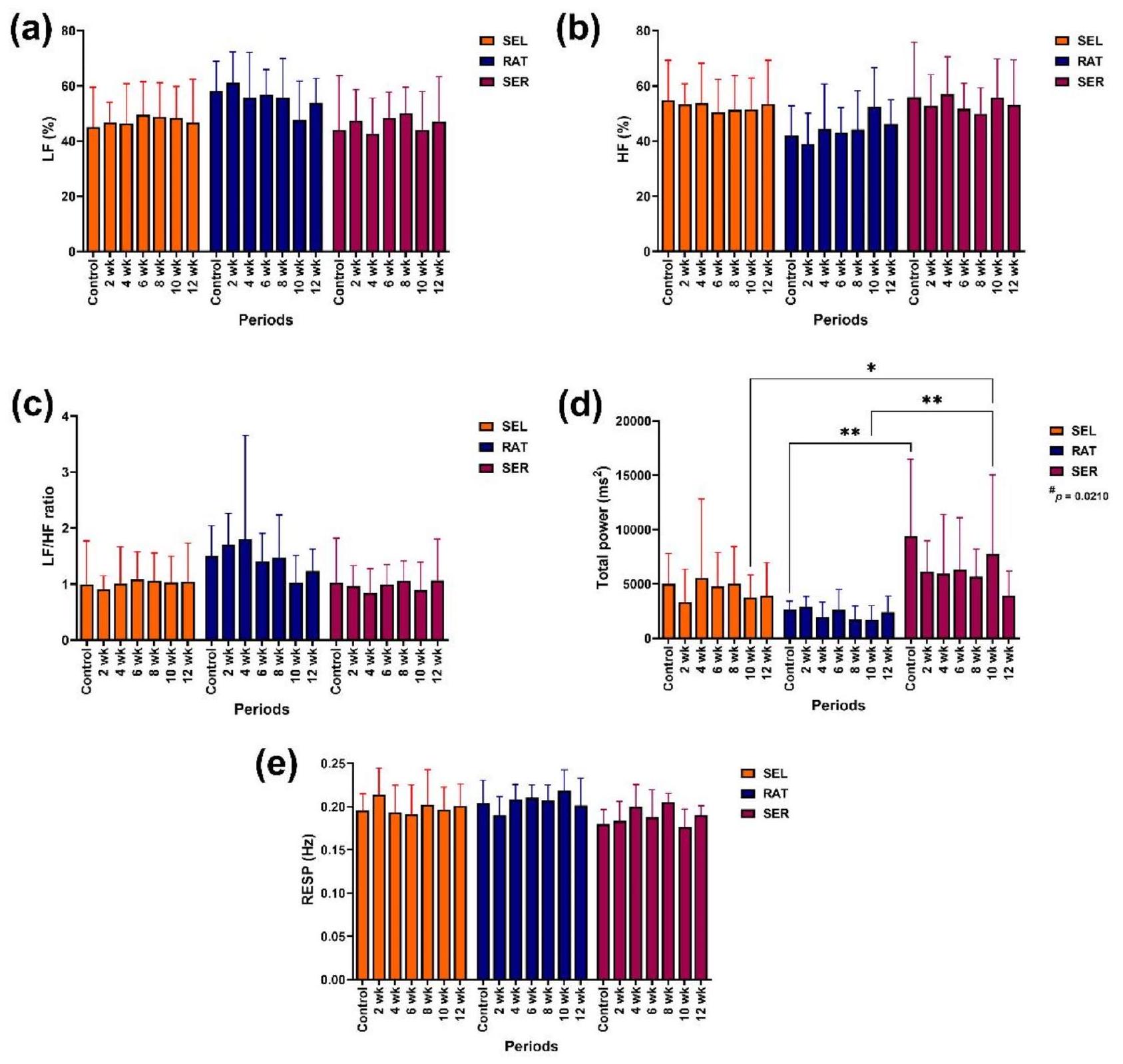

طرق مجال التردد

تفاعل المجموعة مع الزمن، والمجموعة المستقلة والزمن المستقل لم يؤثروا على مساهمات نطاق HF، نطاق LF، نسبة LF/HF أو معدل التنفس (RESP)، على الرغم من أن المجموعة المستقلة وتفاعل المجموعة مع الزمن كانا قريبين من الدلالة في نسبة LF/HF (

لم تختلف مساهمات نطاق LF، نطاق HF، نسبة LF/HF و RESP داخل أو بين المجموعات طوال الدراسة. ومع ذلك، كانت الطاقة الكلية في خيول SER أعلى من خيول RAT قبل الدراسة

الشكل 1. آثار أنماط النشاط المختلفة على التغيرات في الحد الأدنى

(الخط الأساسي) وفي 10 أسابيع من الدراسة (

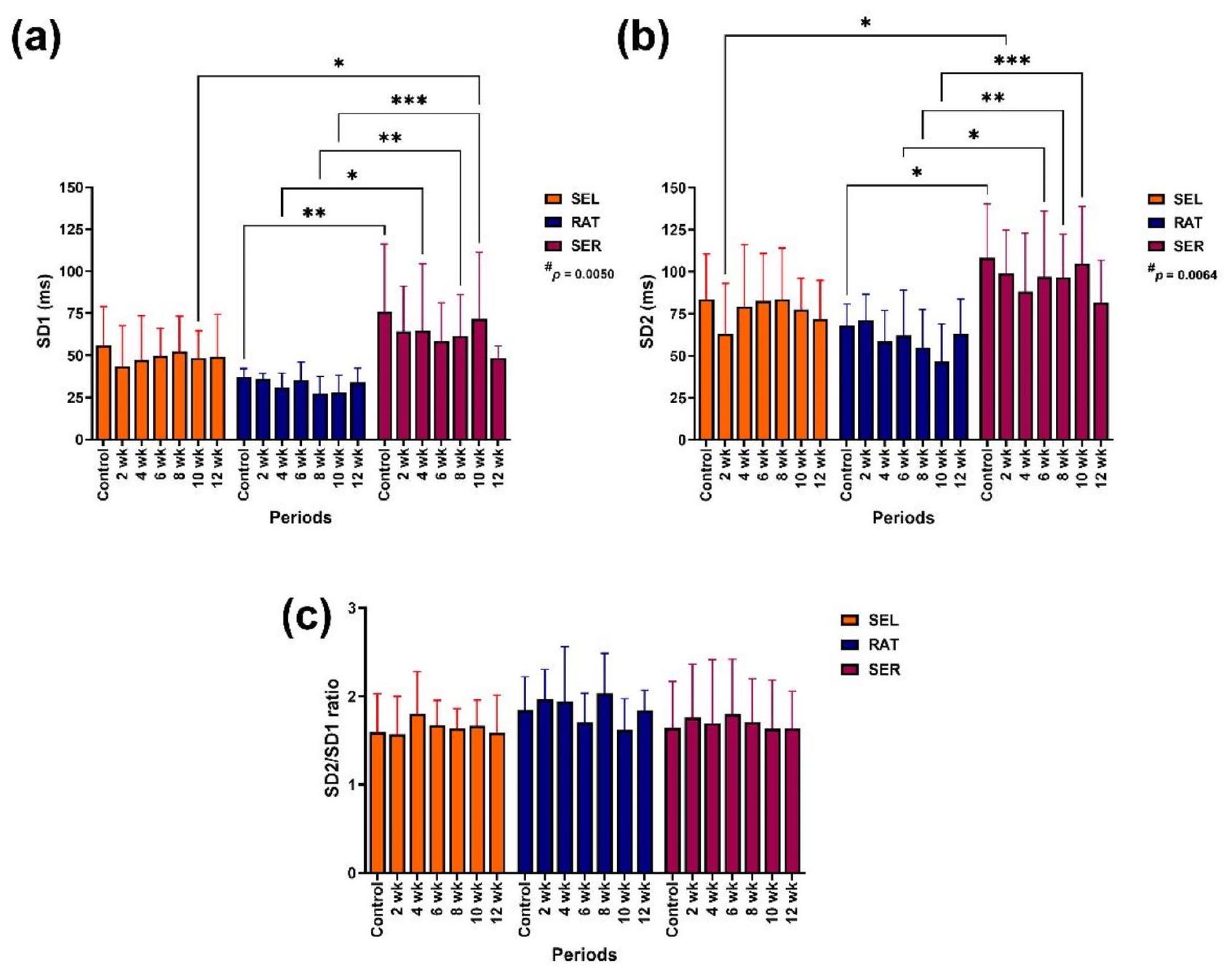

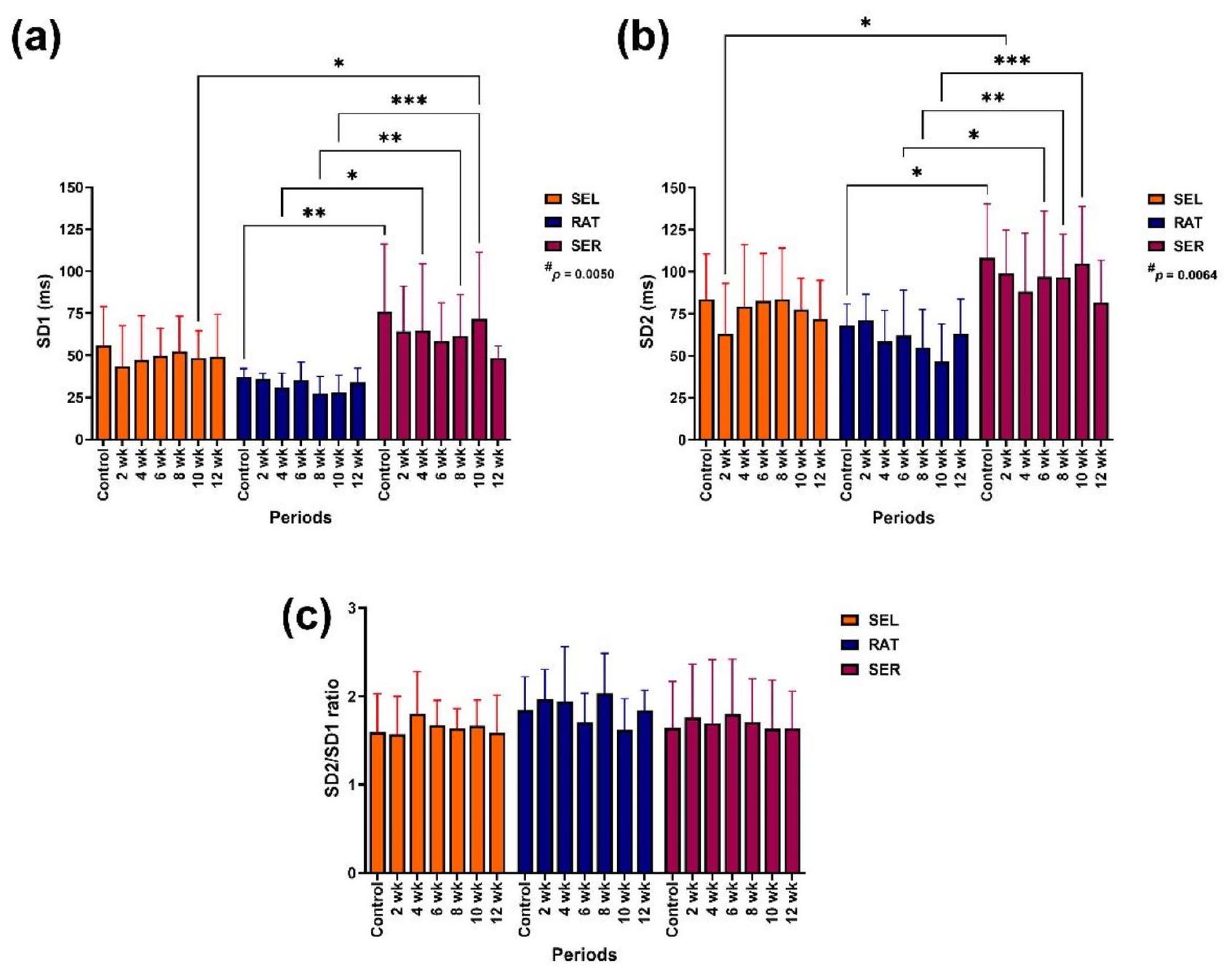

طرق غير خطية

أثرت المجموعة المستقلة على تعديل SD1

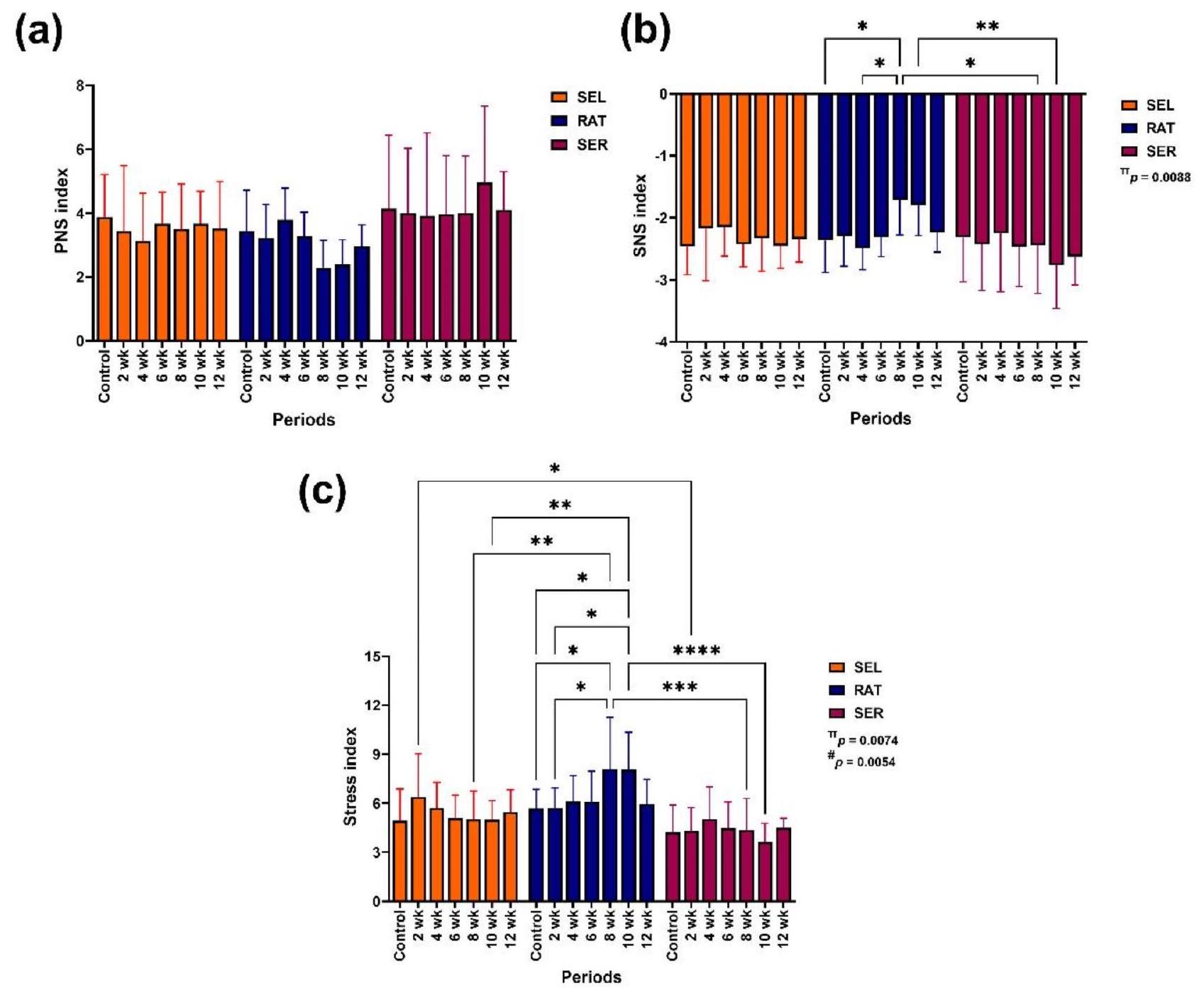

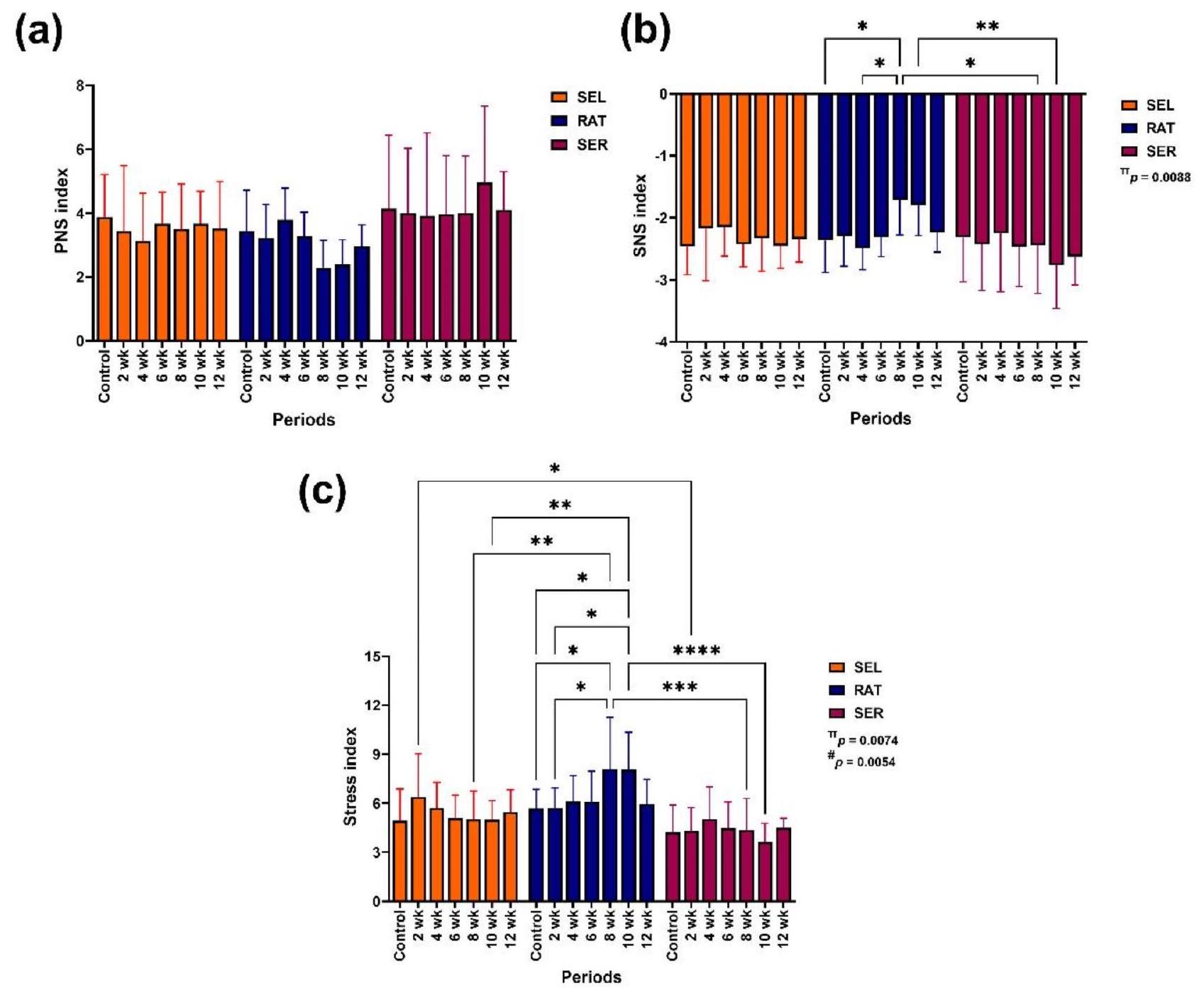

مؤشر الجهاز العصبي الذاتي

أثر تفاعل المجموعة مع الزمن على تعديل مؤشر الجهاز العصبي الودي (SNS)

ظل مؤشر الجهاز العصبي اللاودي (PNS) دون تغيير طوال الدراسة (الشكل 5a). كان مؤشر SNS أقل في خيول SER مقارنة بخيول RAT في 8 و 10 أسابيع من الدراسة (

المناقشة

فحصت هذه الدراسة استجابة HR وتنظيم الجهاز العصبي الذاتي لأنماط النشاط البدني المختلفة في الخيول المسنّة. كشفت عن بعض النتائج المهمة. (1) لوحظ انخفاض في الحد الأدنى والمتوسط من HR، مما يتوافق مع زيادة فترات RR، فقط في خيول SER. (2) كانت متغيرات HRV المختلفة (SDNN، RMSSD، DCmod، pNN50، RRTI، TINN، الطاقة الكلية، SD1 و SD2) أعلى في خيول SER مقارنة بخيول RAT. (3)

الشكل 2. آثار أنماط النشاط المختلفة على التغيرات في متغيرات مجال الزمن: SDNN (أ)، RMSSD (ب)، DCmod (ج)، pNN50 (د)، RRTI (هـ) و TINN (و). # تشير إلى تأثير المجموعة المستقلة.

الشكل 3. آثار مستويات النشاط المختلفة على متغيرات مجال التردد: نطاق LF (أ)، نطاق HF (ب)، نسبة LF/HF (ج)، نطاق الطاقة الكلية (د) و RESP (هـ).

بعض متغيرات HRV في خيول SER (SDNN، TINN، الطاقة الكلية، SD1 و SD2) كانت أيضًا أعلى من خيول SEL. (4) كان مؤشر SNS أقل في خيول SER مقارنة بخيول RAT. (5) كان مؤشر الإجهاد في خيول SER أقل من خيول RAT أو، إلى حد أقل، خيول SEL. تشير هذه النتائج إلى أن الخيول التي تشارك في أنظمة تمارين منظمة تظهر انخفاضًا في HR أثناء الراحة وتنظيمًا أكبر للجهاز العصبي الذاتي مقارنة بتلك التي لديها أنشطة غير منظمة وأنماط حياة مستقرة.

في هذه الدراسة، شاركت خيول SER في برنامج تمارين منظم جيدًا عند شدة منخفضة إلى متوسطة. وقد تم إثبات ذلك من خلال تقلبات HR المتوسطة خلال كل جلسة تمرين، والتي تراوحت من

الشكل 4. آثار مستويات النشاط المختلفة على المتغيرات غير الخطية: SD1 (أ)، SD2 (ب) ونسبة SD2/SD1 (ج). # تشير إلى تأثير المجموعة المستقلة.

في الخيول التي تخضع للتدريب الهوائي

يتأثر تعديل HR بالتفاعل بين الأنشطة الودية واللاودية

تم العثور على متغيرات HRV المختلفة أعلى في خيول SER مقارنة بخيول RAT. تضمنت هذه المتغيرات SDNN، RMSSD، DCmod، pNN50، TINN، RRTI، نطاق الطاقة الكلية، SD1 و SD2. تعكس RMSSD و pNN50 و SD1 التغيرات قصيرة المدى في HR بسبب النشاط اللاودي السائد، بينما تؤثر المكونات الودية واللاودية على تعديلات SDNN و TINN و RRTI و الطاقة الكلية و SD2، مما يعكس HRV بشكل عام.

الشكل 5. آثار مستويات النشاط المختلفة على تعديل مؤشر PNS (أ)، مؤشر SNS (ب) ومؤشر الإجهاد (ج).

أعلى في خيول SER مقارنة بخيول RAT، مما يشير إلى أن الخيول المسنّة التي تشارك في التمارين المنظمة قد تواجه مشاكل قلبية مرتبطة بالعمر أقل من تلك التي تشارك في الأنشطة البدنية غير المنظمة. ومع ذلك، تتطلب هذه النتيجة مزيدًا من التحقق لتأكيد ارتباطها بمشاكل القلب المرتبطة بالعمر في الخيول. علاوة على ذلك، أظهرت خيول SER مستويات أعلى من SDNN و RRTI و TINN و إجمالي طاقة النطاق و SD1 و SD2، مما يعكس تباينًا أعلى في معدل ضربات القلب مقارنة بخيول SEL. كان مؤشر الإجهاد أيضًا أقل مؤقتًا في خيول SER مقارنة بخيول SEL و RAT عند 2 و

اختلفت متغيرات HRV بين المجموعات، لكن لم يُلاحظ أي تباين داخل كل مجموعة. وقد اقترحت تقارير سابقة أن المكون العصب المبهم قد يتم تفعيله بالكامل خلال فترة الراحة في الخيول

مما أدى إلى متغيرات HRV متسقة عبر فترة الدراسة. بالنسبة لخيول SER، انخفض متوسط معدل ضربات القلب بعد نظام التمارين المنظم على الرغم من عدم حدوث تغيير في النشاط العصب المبهم. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، مع عدم وجود تباين في مؤشر PNS، كان مؤشر SNS أقل في خيول SER مقارنة بخيول RAT. تشير هذه النتائج إلى انخفاض تدريجي في دور المكون الودي استجابةً لنظام التمارين المنظم، مما يؤدي إلى انخفاض معدل ضربات القلب في الخيول المسنّة، بما يتماشى مع التقارير السابقة

مما أدى إلى متغيرات HRV متسقة عبر فترة الدراسة. بالنسبة لخيول SER، انخفض متوسط معدل ضربات القلب بعد نظام التمارين المنظم على الرغم من عدم حدوث تغيير في النشاط العصب المبهم. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، مع عدم وجود تباين في مؤشر PNS، كان مؤشر SNS أقل في خيول SER مقارنة بخيول RAT. تشير هذه النتائج إلى انخفاض تدريجي في دور المكون الودي استجابةً لنظام التمارين المنظم، مما يؤدي إلى انخفاض معدل ضربات القلب في الخيول المسنّة، بما يتماشى مع التقارير السابقة

تشابهت متغيرات HRV الأساسية في خيول SER و RAT بشكل وثيق مع تلك الموجودة في خيول SEL في بداية الدراسة. ومع ذلك، قد توجد تحيزات عند تضمين الخيول المتقاعدة التي عاشت نمط حياة مستقر، سواء تم تقديمها لبرنامج تمارين منظم أو استمرت في روتينها المستقر. بالنسبة للتدريب المنظم الذي استمر 12 أسبوعًا، تم اختيار الخيول المسنّة المستقرة التي لديها القدرة على إكمال نظام التمارين (مثل: درجة حالة الجسم المقبولة، التكوين المناسب للحوافر والأطراف، والألفة مع بروتوكول التمرين) بشكل أساسي لمجموعة SER. قد يعني هذا المعيار الاختياري قيم متغيرات HRV أعلى قليلاً في مجموعة SER مقارنة بمجموعة SEL. من المهم، على عكس الخيول المسنّة في المجموعات الأخرى، كانت الخيول في مجموعة RAT مشغولة باستمرار في أنشطة بدنية غير منظمة قبل الدراسة. قد يكون هذا قد عرضهم لتجربة الإجهاد المزمن، مما أدى إلى متغيرات HRV أقل قليلاً من خيول SEL ولكن أقل بكثير من خيول SER في بداية الدراسة (الجدول S2). على الرغم من أن نظام التمارين المنظم أظهر القدرة على الحفاظ على الاستجابات اللاإرادية، إلا أن تأثير هذا النظام على التكيف العضلي والوظائف الإنزيمية ذات الصلة في الخيول المسنّة يتطلب مزيدًا من التحقيق.

واجهت الدراسة تحديًا بسبب العدد المحدود من الخيول المسنّة الصحية المتاحة، خاصة لأولئك الذين قاموا بالنشاط البدني أو نظام التمارين المنظم. أدى ذلك إلى حجم عينة صغيرة لجميع مجموعات الدراسة. هذه هي القيود الرئيسية للدراسة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، قد يكون إدراج الخيول من جنسيات مختلفة وخصائص فردية قد ساهم في التباينات في الاستجابات اللاإرادية داخل كل مجموعة. علاوة على ذلك، من المحتمل أن تؤدي مستويات اللياقة البدنية المتفاوتة بين الخيول في مجموعة RAT إلى استجابات لاإرادية مختلفة أثناء أداء الأنشطة غير المنظمة. لذلك، يجب تفسير نتائج الدراسة المتعلقة بالتنظيم اللاإرادي بحذر.

الخاتمة

أظهرت الخيول المسنّة المشاركة في برنامج تمارين منظم تحسينات في كل من اللياقة البدنية والتنظيم اللاإرادي مقارنة بتلك التي لديها أنشطة غير منظمة أو نمط حياة مستقر. على العكس من ذلك، أظهرت الخيول المسنّة التي تشارك في نشاط بدني غير منظم آثارًا سلبية محتملة. توفر هذه النتائج رؤى قيمة حول كيفية تأثير مستويات النشاط المختلفة على التنظيم اللاإرادي في الخيول المسنّة المتقاعدة. تحمل الدراسة تداعيات كبيرة على الرفاهية، مما يشير إلى الحاجة إلى ممارسات إدارة لتعزيز الرفاهية، والحفاظ على الرفاهية، وإلى حد ما، الحفاظ على القيمة الاقتصادية للخيول المسنّة بعد التقاعد. بينما توجد أدلة على القدرة على الحفاظ على الاستجابات اللاإرادية، هناك حاجة إلى مزيد من البحث لاستكشاف التكيفات العضلية والوظائف الإنزيمية ذات الصلة الناتجة عن نظام التمارين المنظم في الخيول المسنّة.

المواد والأساليب

موافقة الأخلاقيات

حصل بروتوكول دراسة الحيوانات على موافقة لجنة رعاية واستخدام الحيوانات المؤسسية في جامعة كاسيتسارت (ACKU65-VET-005 و ACKU66-VET-089). تأكدنا من أن جميع الطرق تم تنفيذها وفقًا للإرشادات واللوائح ذات الصلة، مع الالتزام بإرشادات ARRIVE.

الخيول

تم اختيار سبعة وعشرون حصانًا مسنًا من سلالة مختلطة من نادي محبي الخيول في باتوم ثاني، تايلاند، لهذه الدراسة. كانت هذه الخيول قد شاركت سابقًا في الرياضات الفروسية وتقاعدت من المنافسة حوالي سن 15 عامًا. بعد تقاعدها، عاشت إما حياة مستقرة أو استمرت في الأنشطة البدنية. تم إيواؤها في

بروتوكول التجربة

تم إجراء التجارب في نادي محبي الخيول في باتوم ثاني، تايلاند، لمدة 12 أسبوعًا متتاليًا بين مايو ويوليو 2023. خلال هذه الفترة، تراوحت الرطوبة النسبية بين 61 و

| ترتيب التدريب | المشي | الدقائق | نمط التدريب |

| 1 | المشي | 5 | النمط 1 |

| 2 | الهرولة | 10 | |

| 3 | المشي | 1 | |

| 4 | الهرولة | 10 | |

| 5 | المشي | 1 | |

| 6 | العدو | 5 | النمط 2 |

| 7 | المشي | 1 | |

| 8 | العدو | 5 | |

| 9 | المشي | 1 | |

| 10 | الهرولة | 10 | النمط 3 |

| 11 | المشي | 5 |

الجدول 1. أنماط التدريب في الخيول المسنّة التي تمارس نظام التمارين المنظم.

ركوب، مصمم وفقًا لاحتياجات عملاء اليوم قبل بدء الدراسة. تم تعيينهم للحفاظ على نشاطهم البدني غير المنظم (RAT)، والذي شمل حوالي 20 إلى 30 دقيقة من التمارين يوميًا، ثلاثة إلى أربعة أيام في الأسبوع، على مدى فترة 12 أسبوعًا. في أيام عدم التمرين، قضوا أيضًا بضع ساعات في الحظيرة. (3) تتكون المجموعة الثالثة من تسعة خيول مسنّة غير نشطة أخرى (خمسة ذكور وأربع إناث) بمتوسط عمر قدره

جمع البيانات واكتسابها

تم تسجيل فترات RR كل أسبوعين لحساب متغيرات HRV، مما يوفر رؤى حول التنظيم الذاتي. كانت الخيول في هذه الدراسة مزودة بجهاز مراقبة معدل ضربات القلب (HRM) من Polar Electro Oy، كيمبلي، فنلندا. تم التحقق من صحة هذا الجهاز سهل الاستخدام لقياس معدل ضربات القلب وHRV

ثم تم ربط الساعة الرياضية ببرنامج Polar FlowSync (https://flow.polar.com/، تم الوصول إليه في 29 سبتمبر 2024) لتحميل بيانات فترات RR وتصديرها كملفات CSV. تم استخدام هذه الوثائق لحساب متغيرات HRV عبر برنامج Kubios premium (Kubios HRV Scientific؛ https://www.kubios.com/ hrv-premium/) وتم الإبلاغ عنها كملفات MATLAB MAT. لضمان توافق فترات RR، تم ضبط تصحيح الأثر التلقائي لاستبعاد اكتشافات الضربات المفقودة أو الزائدة أو غير المتوافقة والضربات غير الطبيعية، مثل الانقباضات البطينية المبكرة أو غيرها من عدم انتظام ضربات القلب في سلسلة زمنية لفترات RR. تم ضبط الكشف التلقائي عن الضوضاء على مستوى متوسط لاستبعاد مقاطع الضوضاء التي تشوه عدة ضربات متتالية، مما يؤثر على دقة تحليل HRV. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم استخدام طريقة الأولويات السلسة لإزالة عدم استقرارية سلسلة زمنية لفترات RR. تم ضبط تردد القطع لإزالة الاتجاه عند 0.035 هرتز، كما هو موضح في دليل المستخدم (https://www.kubios.com/downloads/Kubios_HRV_Users_Guide.pdf، تم الوصول إليه في 29 سبتمبر 2024). تم التعبير عن متغيرات HRV في ثلاثة طرق مجال، كما هو موضح في الجدول 2، وتم الإبلاغ عنها بفواصل زمنية مدتها أسبوعين لمدة 12 أسبوعًا متتاليًا.

التحليل الإحصائي

تم إجراء التحليل الإحصائي للبيانات باستخدام GraphPad Prism الإصدار 10.4.0 (GraphPad Software Inc.، سان دييغو، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية). نظرًا لوجود بيانات مفقودة في تحليل HRV، تم تقييم التأثيرات المستقلة للمجموعة والوقت وتأثير التفاعل بين المجموعة والوقت على معدل ضربات القلب وتعديل HRV بواسطة نموذج التأثيرات المختلطة (الحد الأقصى المقيد للاحتمالية؛ REML) مع تصحيح Greenhouse-Geisser. تم تنفيذ اختبار Tukey’s post hoc للمقارنات داخل المجموعة وبين المجموعات في أوقات محددة. تم استخدام اختبار Shapiro-Wilk للتحقق من التوزيع الطبيعي للبيانات عند الضرورة. نظرًا لتوزيع البيانات بشكل طبيعي، تم استخدام ANOVA أحادي الاتجاه، تلاه اختبارات المقارنات المتعددة لـ Tukey، لتقدير التغيرات في أعمار الخيول وأوزانها. تم التعبير عن النتائج كمتوسط ± انحراف معياري، و

| المتغير | الوحدة | الوصف |

| متغيرات المجال الزمني | ||

| Min HR | نبضات/دقيقة | أدنى معدل ضربات قلب |

| Mean HR | نبضات/دقيقة | متوسط معدل ضربات القلب |

| Mean RR | مللي ثانية | متوسط فترة الضربات |

| SDNN | مللي ثانية | الانحراف المعياري لفترات RR الطبيعية |

| RMSSD | مللي ثانية | الجذر التربيعي لمتوسط الفروق بين فترات RR المتتالية |

| pNN50 | % | عدد أزواج فترات RR المتتالية التي تختلف بأكثر من 50 مللي ثانية (NN50) مقسومًا على العدد الإجمالي لفترات RR |

| DCmod | مللي ثانية | قدرة التباطؤ المعدلة، محسوبة كفرق نقطتين |

| TINN | مللي ثانية | التداخل المثلثي لفترات RR الطبيعية، محسوبة من عرض قاعدة الرسم البياني الذي يعرض فترات RR |

| RRTI | – | مؤشر مثلثي لفترات RR، محسوب من تكامل كثافة الرسم البياني لفترات RR مقسومًا على ارتفاعه |

| مؤشر الضغط | – | الجذر التربيعي لمؤشر ضغط بايفسكي

|

| متغيرات المجال الترددي | ||

| LF | % | القوة النسبية للنطاق الترددي المنخفض (عتبة نطاق التردد

|

| HF | % | القوة النسبية للنطاق الترددي العالي (عتبة نطاق التردد

|

| RESP | هرتز | معدل التنفس المقدر من تسجيلات فترات RR |

| LF/HF ratio | – | نسبة تحليل النطاق الترددي للإشارة إلى توازن السمبثاوي والباراسمبثاوي |

| Total power |

|

إجمالي طيف الطاقة |

| متغيرات غير خطية | ||

| SD1 | مللي ثانية | الانحراف المعياري لرسم Poincaré العمودي على خط الهوية |

| SD2 | مللي ثانية | الانحراف المعياري لرسم Poincaré على طول خط الهوية |

| SD2/SD1 ratio | – | نسبة التحليل غير الخطي للإشارة إلى توازن السمبثاوي والباراسمبثاوي |

| مؤشرات الجهاز العصبي الذاتي | ||

| مؤشر PNS | – | مؤشر الجهاز العصبي الباراسمبثاوي، المحسوب بناءً على متوسط فترة RR، RMSSD وSD1، يعكس النشاط الباراسمبثاوي |

| مؤشر SNS | – | مؤشر الجهاز العصبي السمبثاوي، المحدد بناءً على متوسط معدل ضربات القلب، مؤشر الإجهاد وSD2، يمثل النشاط السمبثاوي |

الجدول 2. متغيرات HRV المقاسة في الخيول المسنّة بمستويات نشاط مختلفة.

توفر البيانات

البيانات الأصلية المقدمة في الدراسة متاحة علنًا على https://www.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27233970.

تم الاستلام: 22 نوفمبر 2024؛ تم القبول: 13 يناير 2025

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 20 يناير 2025

تم الاستلام: 22 نوفمبر 2024؛ تم القبول: 13 يناير 2025

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 20 يناير 2025

References

- Bokonyi, S. History of horse domestication. Anim. Genet. Resour. Inf. 6, 29-34. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1014233900004089 (1987).

- Holmes, T. Q. & Brown, A. F. Champing at the Bit for Improvements: A Review of Equine Welfare in Equestrian Sports in the United Kingdom. Animals 12 (2022).

- Lester, G. D. in Equine sports medicine and surgery: basic and clinical sciences of the equine athlete (ed K. W. Hinchcliff, Kaneps, A., Geor R. J.) 1037-1043 (2004).

- Marlin, D. & Nankervis, K. J. Equine exercise physiology 1-6 (Blackwell Science Ltd, 2002).

- Rivero, J. L. L. et al. Effects of intensity and duration of exercise on muscular responses to training of thoroughbred racehorses. J. Appl. Physiol. 102, 1871-1882. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.01093.2006 (2007).

- Evans, D. L. & Rose, R. J. Cardiovascular and respiratory responses to submaximal exercise training in the thoroughbred horse. Pflügers Archiv. 411, 316-321. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00585121 (1988).

- Siqueira, R. F., Teixeira, M. S., Perez, F. P. & Gulart, L. S. Effect of lunging exercise program with Pessoa training aid on cardiac physical conditioning predictors in adult horses. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-4162-12972 (2023).

- Cottin, F. et al. Effect of Exercise Intensity and Repetition on Heart Rate Variability during Training in Elite trotting horse. Int. J. Sports Med. 26, 859-867. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2005-837462 (2005).

- Betros, C. L., McKeever, N. M., Filho, M., Malinowski, H. C., McKeever, K. H. & K. & Effect of training on intrinsic and resting heart rate and plasma volume in young and old horses. Comp. Exerc. Physiol. 9, 43-50. https://doi.org/10.3920/CEP12020 (2013).

- Kuwahara, M., Hiraga, A., Kai, M., Tsubone, H. & Sugano, S. Influence of training on autonomic nervous function in horses: evaluation by power spectral analysis of heart rate variability. Equine Vet. J. 31, 178-180. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.1999 .tb05213.x (1999).

- Coelho, C. S. et al. Training Effects on the Stress Predictors for Young Lusitano Horses Used in Dressage. Animals 12 (2022).

- Votion, D. M., Gnaiger, E., Lemieux, H., Mouithys-Mickalad, A. & Serteyn, D. Physical fitness and mitochondrial respiratory capacity in horse skeletal muscle. PLoS One. 7, e34890. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0034890 (2012).

- Rietbroek, N. J. et al. Effect of exercise on development of capillary supply and oxidative capacity in skeletal muscle of horses. Am. J. Vet. Res. 68, 1226-1231. https://doi.org/10.2460/ajvr.68.11.1226 (2007).

- Votion, D. M. et al. Alterations in mitochondrial respiratory function in response to endurance training and endurance racing. Equine Vet. J. 42, 268-274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.2010.00271.x (2010).

- Graham-Thiers, P. M. & Bowen, L. K. Improved ability to maintain fitness in horses during large pasture turnout. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 33, 581-585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2012.09.001 (2013).

- Huangsaksri, O. et al. Physiological stress responses in horses participating in novice endurance rides. Heliyon https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31874 (2024).

- Sanigavatee, K. et al. Hematological and physiological responses in polo ponies with different field-play positions during low-goal polo matches. PLoS One. 19, e0303092. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0303092 (2024).

- von Lewinski, M. et al. Cortisol release, heart rate and heart rate variability in the horse and its rider: different responses to training and performance. Vet. J. 197, 229-232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2012.12.025 (2013).

- Szabó, C., Vizesi, Z. & Vincze, A. Heart rate and heart rate variability of amateur show jumping horses competing on different levels. Animals 11, 693. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11030693 (2021). https://doi.org/https://doi

- Von Borell, E. et al. Heart rate variability as a measure of autonomic regulation of cardiac activity for assessing stress and welfare in farm animals-A review. Physiol. Behav. 92, 293-316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.01.007 (2007).

- Stucke, D., Große Ruse, M. & Lebelt, D. Measuring heart rate variability in horses to investigate the autonomic nervous system activity – pros and cons of different methods. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 166, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2015.02.007 (2015).

- Shaffer, F. & Ginsberg, J. P. An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Front. Public. Health https://doi.org/10.3389/f pubh.2017.00258 (2017).

- Mourot, L., Bouhaddi, M., Perrey, S., Rouillon, J. D. & Regnard, J. Quantitative Poincaré plot analysis of heart rate variability: effect of endurance training. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 91, 79-87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-003-0917-0 (2004).

- Ishizaka, S., Aurich, J. E., Ille, N., Aurich, C. & Nagel, C. Acute physiological stress response of horses to different potential shortterm stressors. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 54, 81-86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2017.02.013 (2017).

- Becker-Birck, M. et al. Cortisol release and heart rate variability in sport horses participating in equestrian competitions. J. Vet. Behav. 8, 87-94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2012.05.002 (2013).

- Nyerges-Bohák, Z. et al. Heart rate variability in horses with and without severe equine asthma. Equine Vet. J. https://doi.org/10.1 111/evj. 14414 (2024).

- Janczarek, I., Kędzierski, W., Wilk, I., Wnuk-Pawlak, E. & Rakowska, A. Comparison of daily heart rate variability in old and young horses: a preliminary study. J. Vet. Behav. 38, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2020.05.005 (2020).

- Sanigavatee, K. et al. Comparison of daily heart rate and heart rate variability in trained and sedentary aged horses. J. Equine Vet. 137, 105094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2024.105094 (2024).

- Cottin, F., Barrey, E., Lopes, P. & Billat, V. Effect of repeated exercise and recovery on heart rate variability in elite trotting horses during high intensity interval training. Equine Vet. J. 38, 204-209. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.2006.tb05540.x (2006).

- Younes, M., Robert, C., Barrey, E. & Cottin, F. Effects of Age, Exercise Duration, and Test Conditions on Heart Rate Variability in Young Endurance Horses. Front. Physiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2016.00155 (2016).

- Reed, S. A., LaVigne, E. K., Jones, A. K., Patterson, D. F. & Schauer, A. L. Horse species symposium: The aging horse: Effects of inflammation on muscle satellite cells 1, 2. J. Anim. Sci. 93, 862-870. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2014-8448 (2015).

- Harrington McKeever, K. Aging and how it affects the physiological response to exercise in the horse. Clin. Tech. Equine Pract. 2, 258-265. https://doi.org/10.1053/S1534-7516(03)00068-4 (2003).

- Baragli, P., Vitale, V., Banti, L. & Sighieri, C. Effect of aging on behavioural and physiological responses to a stressful stimulus in horses (Equus caballus). Behaviour 151, 1513-1533. https://doi.org/10.1163/1568539X-00003197 (2014).

- Horohov, D. W. et al. Effect of exercise on the immune response of young and old horses. Am. J. Vet. Res. 60, 643-647. https://doi. org/10.2460/ajvr.1999.60.05.643 (1999).

- Betros, C. L., McKeever, K. H., Kearns, C. F. & Malinowski, K. Effects of ageing and training on maximal heart rate and VO2max. Equine Vet. J. 34, 100-105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.2002.tb05399.x (2002).

- McKeever, K. H. Exercise and Rehabilitation of older horses. Vet. Clin. North. Am. Equine Pract. 32, 317-332. https://doi.org/10.1 016/j.cveq.2016.04.008 (2016). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/

- Keadle, T. L., Pourciau, S. S., Melrose, P. A., Kammerling, S. G. & Horohov, D. W. Acute exercises stress modulates immune function in unfit horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 13, 226-231. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0737-0806(06)81019-1 (1993).

- Kim, J. et al. Exercise training increases oxidative capacity and attenuates exercise-induced ultrastructural damage in skeletal muscle of aged horses. J. Appl. Physiol. 98, 334-342. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00172.2003 (2005).

- Waran, N., McGreevy, P. & Casey, R. A. In The Welfare of Horses (ed. Waran, N.) 194-201 (Springer Netherlands, 2007).

- Vincent, T. L. et al. Retrospective study of predictive variables for maximal heart rate (HRmax) in horses undergoing strenuous treadmill exercise. Equine Vet. J. 38, 146-152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.2006.tb05531.x (2006).

- Manohar, M. Equine exercise physiology 2 132-147 (ICEEP, 1987).

- Chanda, M., Srikuea, R., Cherdchutam, W., Chairoungdua, A. & Piyachaturawat, P. Modulating effects of exercise training regimen on skeletal muscle properties in female polo ponies. BMC Vet. Res. 12, 245. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-016-0874-6 (2016).

- Medicine, A. in ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 3-6 (ed Pescatello LS Thompson WR GN) (Wolters Kluwer Health, 2010).

- Agüera, E. et al. Blood parameter and heart rate response to training in andalusian horses. J. Physiol. Biochem. 51, 55-64 (1995).

- Ringmark, S. et al. Reduced high intensity training distance had no effect on VLa4 but attenuated heart rate response in 2-3-yearold standardbred horses. Acta Vet. Scand. 57, 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13028-015-0107-1 (2015).

- Bauer, A. et al. Deceleration capacity of heart rate as a predictor of mortality after myocardial infarction: cohort study. Lancet 367, 1674-1681. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68735-7 (2006).

- Nasario-Junior, O., Benchimol-Barbosa, P. R. & Nadal, J. Refining the deceleration capacity index in phase-rectified signal averaging to assess physical conditioning level. J. Electrocardiol. 47, 306-310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2013.12.006 (2014).

- Yang, L. et al. in 2017 10th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, BioMedical Engineering and Informatics (CISPBMEI). pp. 1-5.

- Liu, X., Xiang, L. & Tong, G. Predictive values of heart rate variability, deceleration and acceleration capacity of heart rate in postinfarction patients with LVEF

. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 25, e12771. https://doi.org/10.1111/anec. 12771 (2020). - Nyerges-Bohák, Z., Nagy, K., Rózsa, L., Póti, P. & Kovács, L. Heart rate variability before and after 14 weeks of training in Thoroughbred horses and standardbred trotters with different training experience. PLoS One. 16, e0259933. https://doi.org/10.13 71/journal.pone. 0259933 (2021).

- Frippiat, T., van Beckhoven, C., Moyse, E. & Art, T. Accuracy of a heart rate monitor for calculating heart rate variability parameters in exercising horses. J. Equine Vet. 104, 103716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2021.103716 (2021).

- Kapteijn, C. M. et al. Measuring heart rate variability using a heart rate monitor in horses (Equus caballus) during groundwork. Front. Vet. Sci. 9, 939534. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2022.939534 (2022).

- Ille, N., Erber, R., Aurich, C. & Aurich, J. Comparison of heart rate and heart rate variability obtained by heart rate monitors and simultaneously recorded electrocardiogram signals in nonexercising horses. J. Vet. Behav. 9, 341-346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jve b.2014.07.006 (2014).

- Huangsaksri, O. et al. Physiological stress responses in horses participating in novice endurance rides. Heliyon 10, e31874. https:/ /doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31874 (2024). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/

- Poochipakorn, C. et al. Effect of Exercise in a Vector-Protected Arena for preventing African horse sickness transmission on physiological, biochemical, and behavioral variables of horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 131, 104934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2023.1 04934 (2023).

- Huangsaksri, O., Wonghanchao, T., Sanigavatee, K., Poochipakorn, C. & Chanda, M. Heart rate and heart rate variability in horses undergoing hot and cold shoeing. PLoS One. 19, e0305031. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0305031 (2024).

- Frippiat, T., van Beckhoven, C., van Gasselt, V. J., Dugdale, A. & Vandeweerd, J. M. Effect of gait on, and repeatability of heart rate and heart rate variability measurements in exercising Warmblood dressage horses. Comp. Exerc. Physiol.. https://doi.org/10.1163/ 17552559-20220044 (2023).

- Baevsky, R. & Berseneva, A. Use KARDIVAR system for determination of the stress level and estimation of the body adaptability. Standards of measurements and physiological interpretation. Moscow-Prague 41 (2008).

الشكر والتقدير

يود المؤلفون أن يعبروا عن امتنانهم لـ Vaewratt Kamonkon، مدير نادي محبي الخيول، لتخصيص خيولهم لهذه الدراسة.

مساهمات المؤلفين

K.S. وC.P. وT.W. وM.C. ساهموا في التصور، البرمجيات، الموارد والتصور؛ K.S. وC.P. وO.H. وS.V. وS.P. وW.C. وS.W. وT.W. وM.C. شاركوا في المنهجية، التحقق، التحليل الرسمي والتحقيق؛ K.S. وC.P. وO.H. وT.W. وM.C. ساهموا في تنسيق البيانات؛ K.S. وT.W. وM.C. شاركوا في الحصول على التمويل، كتبوا المسودة الأصلية للمخطوطة؛ T.W. وM.C. أشرفوا على هذا المشروع، كتبوا، راجعوا وحرروا المسودة النهائية للمخطوطة. جميع المؤلفين قرأوا ووافقوا على النسخة المنشورة من المخطوطة.

التمويل

تم تمويل هذا البحث من قبل المجلس الوطني للبحوث في تايلاند (أرقام الاتصال N41A661096 وN41A650067) وكلية الطب البيطري، جامعة كاسيتسارت (VET.KU2024-03 وVET.KU202405). تم تمويل APC من قبل كلية الطب البيطري، جامعة كاسيتسارت.

الإعلانات

المصالح المتنافسة

يعلن المؤلفون عدم وجود مصالح متنافسة.

الموافقة الأخلاقية

حصل بروتوكول دراسة الحيوانات على موافقة لجنة رعاية واستخدام الحيوانات المؤسسية في جامعة كاسيتسارت (ACKU65-VET-005 وACKU66-VET-089). لقد تأكدنا من أن جميع الطرق تم تنفيذها وفقًا للإرشادات واللوائح ذات الصلة، مع الالتزام بإرشادات ARRIVE.

الموافقة المستنيرة

تم الحصول عليها من مالكي جميع الخيول المشاركة في الدراسة.

معلومات إضافية

معلومات إضافية النسخة عبر الإنترنت تحتوي على مواد إضافية متاحة على https://doi.org/1 0.1038/s41598-025-86679-4.

يجب توجيه المراسلات وطلبات المواد إلى T.W. أو M.C.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على www.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر تظل Springer Nature محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على www.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر تظل Springer Nature محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

الوصول المفتوح هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام غير التجاري، والتي تسمح بأي استخدام غير تجاري، ومشاركة، وتوزيع وإعادة إنتاج في أي وسيلة أو صيغة، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح إذا قمت بتعديل المادة المرخصة. ليس لديك إذن بموجب هذه الرخصة لمشاركة المواد المعدلة المشتقة من هذه المقالة أو أجزاء منها. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر الائتمان للمادة. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة واستخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، ستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارة http://creativecommo ns.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

© المؤلفون 2025

© المؤلفون 2025

برنامج الدراسات السريرية البيطرية، كلية الطب البيطري، جامعة كاسيتسارت، حرم كامفانغ ساين، كامفانغ ساين، ناخون باتوم 73140، تايلاند. مركز البحث والابتكار البيطري، كلية الطب البيطري، جامعة كاسيتسارت، حرم بانغ خين، بانكوك 10900، تايلاند. قسم علوم الطب البيطري للحيوانات الكبيرة والحياة البرية، كلية الطب البيطري، جامعة كاسيتسارت، حرم كامفانغ ساين، كامفانغ ساين، ناخون باتوم 73140، تايلاند. برنامج العلوم البيطرية، كلية الطب البيطري، جامعة كاسيتسارت، حرم بانغ خين، بانكوك 10900، تايلاند. البريد الإلكتروني: thita.wo@ku.th; fvetmtcd@ku.ac.th

Journal: Scientific Reports, Volume: 15, Issue: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86679-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39833241

Publication Date: 2025-01-20

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86679-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39833241

Publication Date: 2025-01-20

OPEN

A structured exercise regimen enhances autonomic function compared to unstructured physical activities in geriatric horses

Older horses often show reduced autonomic responses, affecting their well-being. While regular exercise can help maintain autonomic function, the impact of structured exercise on geriatric horses is not well understood. A study involving 27 geriatric horses examined their autonomic modulation over 12 weeks under different activity levels. Horses were divided into three groups: ( 1 ) sedentary (SEL), (2) those participating in unstructured activities (RAT), and (3) those following a structured exercise regimen (SER). Results showed that the minimum and average heart rates decreased in the structured exercise group from weeks 10 to 12 . In contrast, no changes were observed in the other groups. Furthermore, beat-to-beat intervals did not change in sedentary horses, fluctuated in horses engaged in unstructured activities from weeks 8 to

Keywords Stress responses, Aged horse, Sedentary lifestyle, Structured exercise regimen, Unstructured physical activity, Animal welfare

Horses have been domesticated for human purposes such as transportation, agriculture and military use

Physical training for horses aims to achieve several key goals, including enhancing or preserving optimal sports performance, delaying the onset of fatigue, reducing the risk of injury and maintaining the horse’s willingness to exercise

intervals under the influence of the sympathetic and parasympathetic (vagal) components, demonstrating the adaptability and flexibility of biological systems in response to stressful challenges

Modification of various HRV variables can reflect specific autonomic components. For example, changes in beat-to-beat (RR) interval, the standard deviation of normal-to-normal RR intervals (SDNN), the lowfrequency (LF) band, the total power band and the standard deviation of the Poincaré plot along the line of identity (SD2) are influenced by both sympathetic and vagal components

Importantly, ageing is not a disease but a condition in which the body experiences a decline in body mass, aerobic capacity, functional immunity and autonomic function with time

While the enhancement of autonomic regulation has been noted following structured training programs in adult horses, the effects of such programs on geriatric horses remain largely unexplored. Furthermore, the implications of maintaining unstructured physical activity in retired geriatric horses have yet to be clarified. Therefore, this study aims to examine the effects of a structured exercise regimen versus unstructured physical activity on resting heart rate (HR) and autonomic regulation in retired geriatric horses. The hypothesis is that different levels of activity will result in notable differences in resting HR and autonomic regulation, with the structured exercise regimen expected to have a significant impact on both parameters.

Results

No differences existed in average age (SEL:

Time domain methods

A significant group-by-time interaction was observed for changes in minimum HR (

The minimum and mean HR remained unchanged in both SEL and RAT horses. However, in SER horses, the minimum HR showed a non-significant reduction at 10 weeks (

SDNN in SER horses was higher than in RAT horses before the study (baseline) at 6,8 and 10 weeks of the study (

Frequency domain methods

Group-by-time interaction, independent group and independent time did not affect the contributions of HF band, LF band, LF/HF ratio or respiratory rate (RESP), even though the independent group and group-bytime interaction were almost significant in LF/HF ratio (

The contributions of LF band, HF band, LF/HF ratio and RESP did not differ within or between groups throughout the study. However, the total power in SER horses was higher than in RAT horses before the study

Fig. 1. The effects of different activity modalities on changes in minimum

(baseline) and at 10 weeks of the study (

Nonlinear methods

The independent group affected the modification of SD1

Autonomic nervous system index

The effect of group-by-time interaction impacted modulation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) index

The parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) index remained unchanged throughout the study (Fig. 5a). The SNS index was lower in SER horses than in RAT horses at 8 and 10 weeks of the study (

Discussion

This study examined the HR and autonomic regulation responses to different physical modalities in geriatric horses. It revealed some significant findings. (1) A decrease in minimum and mean HR, corresponding to increased RR intervals, was only observed in SER horses. (2) Various HRV variables (SDNN, RMSSD, DCmod, pNN50, RRTI, TINN, total power, SD1 and SD2) were higher in SER horses compared to RAT horses. (3)

Fig. 2. The effects of different activity modalities on changes in time domain variables: SDNN (a), RMSSD (b), DCmod (c), pNN50 (d), RRTI (e) and TINN (f). # indicates independent group effect.

Fig. 3. The effects of different activity levels on frequency domain variables: LF band (a), HF band (b), LF/ HF ratio (c), total power band (d) and RESP (e).

Some HRV variables in SER horses (SDNN, TINN, total power, SD1 and SD2) were also higher than in SEL horses. (4) The SNS index was lower in SER horses compared to RAT horses. (5) The stress index in SER horses was lower than in RAT horses or, to a lesser extent, SEL horses. These results suggest that horses engaged in structured exercise regimens exhibit reduced resting HR and greater autonomic regulation compared to those with unstructured activities and sedentary lifestyles.

In this study, SER horses participated in a well-regimented exercise programme at a low-to-moderate intensity. This was evidenced by the average HR fluctuations during each exercise session, which ranged from

Fig. 4. The effects of different activity levels on nonlinear variables: SD1 (a), SD2 (b) and SD2/SD1 ratio (c). # indicates independent group effect.

in horses undergoing aerobic training

The modulation of HR is influenced by the interplay between sympathetic and vagal activities

Various HRV variables were found to be higher in SER horses compared to RAT horses. These variables comprised SDNN, RMSSD, DCmod, pNN50, TINN, RRTI, total power band, SD1 and SD2. RMSSD, pNN50 and SD1 reflect short-term variations in HR due to predominant vagal activity, whereas sympathetic and vagal components affect modulations of SDNN, TINN, RRTI, total power and SD2, reflecting overall HRV

Fig. 5. The effects of different activity levels on modification of PNS index (a), SNS index (b) and stress index (c).

higher in SER horses than in RAT horses, suggesting that aged horses participating in structured exercise might experience fewer age-related cardiac issues than those involved in unstructured physical activities. Nevertheless, this finding requires further validation to confirm its association with age-related cardiac problems in horses. Furthermore, the SER horses exhibited higher SDNN, RRTI, TINN, total power band, SD1 and SD2, reflecting higher HR variations than SEL horses. The stress index was also temporally lower in SER horses than in SEL and RAT horses at 2 and

The HRV variables differed between the groups, but no variation was observed within each group. Previous reports have suggested that the vagal component may be fully activated during the resting period in horses

leading to consistent HRV variables across the study period. For the SER horses, the mean HR decreased after the structured exercise regimen despite no change in vagal activity. Additionally, with no variation in the PNS index, the SNS index was lower in SER horses compared to RAT horses. These findings suggest a gradual reduction in the role of the sympathetic component in response to a structured exercise regimen, resulting in a decreased resting HR in aged horses, consistent with previous reports

leading to consistent HRV variables across the study period. For the SER horses, the mean HR decreased after the structured exercise regimen despite no change in vagal activity. Additionally, with no variation in the PNS index, the SNS index was lower in SER horses compared to RAT horses. These findings suggest a gradual reduction in the role of the sympathetic component in response to a structured exercise regimen, resulting in a decreased resting HR in aged horses, consistent with previous reports

The baseline HRV variables in the SER and RAT horses closely resembled those in SEL horses at the start of the study. However, biases may exist when including retired-aged horses who have led a sedentary lifestyle, whether they were introduced to a structured exercise programme or continuing their sedentary routine. For the 12-week structured training, sedentary aged horses with the potential to complete the exercise regimen (e.g. acceptable body condition score, appropriate hoof and limb conformation, and familiarity with lunging protocol) were primarily chosen for the SER group. This selection criterion could mean slightly higher HRV variable values in the SER group compared to the SEL group. Importantly, unlike the aged horses in the other groups, the horses in the RAT group were consistently engaged in unstructured physical activities before the study. This may have predisposed them to experience chronic stress, resulting in HRV variables slightly lower than the SEL horses but significantly lower than the SER horses at the beginning of the study (Table S2). Although the structured exercise regimen showed the potential to maintain autonomic responses, the impact of this exercise regimen on muscular adaptation and related enzymatic functions in geriatric horses requires further investigation.

The study faced a challenge due to the limited number of healthy geriatric horses available, especially for those who performed the physical activity or structured exercise regimen. This resulted in a small sample size for all study groups. This is the primary limitation of the study. Additionally, the inclusion of horses of different sexes and individual characteristics may have contributed to variations in autonomic responses within each group. Furthermore, the varying levels of physical fitness among the horses in the RAT group likely led to differing autonomic responses while performing unstructured activities. Therefore, the study results concerning autonomic regulation must be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

Geriatric horses participating in a structured exercise programme showed improvements in both physical fitness and autonomic regulation compared to those with unstructured activities or a sedentary lifestyle. Conversely, aged horses engaging in unstructured physical activity demonstrated potentially negative effects. These findings provide valuable insights into how different activity levels affect autonomic regulation in retired geriatric horses. The study has significant welfare implications, suggesting the need for management practices to enhance wellbeing, maintain welfare and, to some extent, preserve the economic value of geriatric horses after retirement. While there is evidence of the potential to sustain autonomic responses, further research is necessary to explore the muscular adaptations and related enzymatic functions arising from a structured exercise regimen in geriatric horses.

Materials and methods

Ethics approval

The animal study protocol received approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Kasetsart University (ACKU65-VET-005 and ACKU66-VET-089). We ensured that all methods were conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, adhering to the ARRIVE guidelines.

Horses

Twenty-seven mixed-breed geriatric horses from the Horse Lover’s Club in Pathum Thani, Thailand, were selected for this study. These horses had previously participated in equestrian sports and retired from competition around the age of 15 years. Following their retirement, they either lived sedentarily or continued with physical activities. They were housed in

Experimental protocol

The experiments were conducted at the Horse Lover’s Club in Pathum Thani, Thailand, for 12 consecutive weeks between May and July 2023. During this period, the relative humidity ranged from 61 to

| Training order | Gait | Minutes | Training pattern |

| 1 | Walk | 5 | Pattern 1 |

| 2 | Trot | 10 | |

| 3 | Walk | 1 | |

| 4 | Trot | 10 | |

| 5 | Walk | 1 | |

| 6 | Canter | 5 | Pattern 2 |

| 7 | Walk | 1 | |

| 8 | Canter | 5 | |

| 9 | Walk | 1 | |

| 10 | Trot | 10 | Pattern 3 |

| 11 | Walk | 5 |

Table 1. Training patterns in aged horses practising structured exercise regimen.

riding, tailored to the needs of the day’s clients prior to the start of the study. They were assigned to maintain their unstructured physical activity (RAT), which involved approximately 20 to 30 min of exercise per day, three to four days a week, over a 12 -week period. On non-exercise days, they also spent a few hours in the paddock. (3) The third group comprised another nine sedentary geriatric horses (five geldings and four mares) with an average age of

Data collection and acquisition

The RR intervals were recorded biweekly to calculate HRV variables, providing insight into autonomic regulation. The horses in this study were equipped with an HR monitoring (HRM) device from Polar Electro Oy, Kempele, Finland. This user-friendly device has been validated for measuring HR and HRV

The sports watch was then linked to the Polar FlowSync program (https://flow.polar.com/, accessed on 29 September 2024) to upload the RR interval data and export them as CSV files. These documents were used to compute the HRV variables via the Kubios premium software (Kubios HRV Scientific; https://www.kubios.com/ hrv-premium/) and reported as MATLAB MAT files. To ensure the aligned RR intervals, the automatic artefact correction was set to exclude missing, extra or misaligned beat detections and ectopic beats, such as premature ventricular contractions or other arrhythmias in the RR interval time series. The automatic noise detection was set at a medium level to exclude noise segments that distorted several consecutive beats, thereby affecting the accuracy of HRV analysis. Additionally, the smoothness priors method was used to remove RR interval time series nonstationarities. The cutoff frequency for trend removal was set at 0.035 Hz , as outlined by the user guideline (https://www.kubios.com/downloads/Kubios_HRV_Users_Guide.pdf, accessed on 29 September 2024). The HRV variables were expressed in three domain methods, as shown in Table 2, and reported at 2-week intervals for a consecutive 12 weeks.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.4.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Due to missing data on HRV analysis, the independent effects of group and time and the interaction effect of group-by-time on HR and HRV modulation were evaluated by the mixed-effects model (restricted maximum likelihood; REML) with Greenhouse-Geisser correction. Tukey’s post hoc test was implemented for within-group and between-group comparisons at specific times. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to verify the normal distribution of the data when necessary. Due to the normally distributed data, the oneway ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests, was employed to estimate variations in the horses’ age and weight. The results were expressed as mean ± SD, and

| Variable | Unit | Description |

| Time domain variables | ||

| Min HR | beats/min | Minimum heart rate |

| Mean HR | beats/min | Mean heart rate |

| Mean RR | ms | Mean beat-to-beat interval |

| SDNN | ms | Standard deviation of normal-to-normal RR intervals |

| RMSSD | ms | Root mean square of differences between successive RR intervals |

| pNN50 | % | Number of successive RR interval pairs differing by more than 50 ms (NN50) divided by the total number of RR intervals |

| DCmod | ms | Modified deceleration capacity, computed as a two-point difference |

| TINN | ms | Triangular interpolation of normal-to-normal intervals, computed from the baseline width of a histogram displaying RR intervals |

| RRTI | – | RR triangular index, computed from the integral of the density of the RR interval histogram divided by its height |

| Stress index | – | Square root of Baevsky’s stress index

|

| Frequency domain variables | ||

| LF | % | Relative power of the low-frequency band (frequency band threshold

|

| HF | % | Relative power of the high-frequency band (frequency band threshold

|

| RESP | Hz | Respiratory rate estimated from RR interval recordings |

| LF/HF ratio | – | Ratio of frequency band analysis to indicate sympathovagal balance |

| Total power |

|

Total power band spectrum |

| Nonlinear variables | ||

| SD1 | ms | Standard deviation of the Poincaré plot perpendicular to the line of identity |

| SD2 | ms | Standard deviation of the Poincaré plot along the line of identity |

| SD2/SD1 ratio | – | Ratio of nonlinear analysis to indicate sympathovagal balance |

| Autonomic nervous system indexes | ||

| PNS index | – | Parasympathetic nervous system index, calculated based on mean RR interval, RMSSD and SD1, reflects parasympathetic activity |

| SNS index | – | Sympathetic nervous system index, determined based on mean HR, stress index and SD2, represents sympathetic activity |

Table 2. HRV variables measured in geriatric horses with different activity levels.

Data availability

The original data presented in the study are openly available at https://www.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27233970.

Received: 22 November 2024; Accepted: 13 January 2025

Published online: 20 January 2025

Received: 22 November 2024; Accepted: 13 January 2025

Published online: 20 January 2025

References

- Bokonyi, S. History of horse domestication. Anim. Genet. Resour. Inf. 6, 29-34. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1014233900004089 (1987).

- Holmes, T. Q. & Brown, A. F. Champing at the Bit for Improvements: A Review of Equine Welfare in Equestrian Sports in the United Kingdom. Animals 12 (2022).

- Lester, G. D. in Equine sports medicine and surgery: basic and clinical sciences of the equine athlete (ed K. W. Hinchcliff, Kaneps, A., Geor R. J.) 1037-1043 (2004).

- Marlin, D. & Nankervis, K. J. Equine exercise physiology 1-6 (Blackwell Science Ltd, 2002).

- Rivero, J. L. L. et al. Effects of intensity and duration of exercise on muscular responses to training of thoroughbred racehorses. J. Appl. Physiol. 102, 1871-1882. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.01093.2006 (2007).

- Evans, D. L. & Rose, R. J. Cardiovascular and respiratory responses to submaximal exercise training in the thoroughbred horse. Pflügers Archiv. 411, 316-321. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00585121 (1988).

- Siqueira, R. F., Teixeira, M. S., Perez, F. P. & Gulart, L. S. Effect of lunging exercise program with Pessoa training aid on cardiac physical conditioning predictors in adult horses. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-4162-12972 (2023).

- Cottin, F. et al. Effect of Exercise Intensity and Repetition on Heart Rate Variability during Training in Elite trotting horse. Int. J. Sports Med. 26, 859-867. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2005-837462 (2005).

- Betros, C. L., McKeever, N. M., Filho, M., Malinowski, H. C., McKeever, K. H. & K. & Effect of training on intrinsic and resting heart rate and plasma volume in young and old horses. Comp. Exerc. Physiol. 9, 43-50. https://doi.org/10.3920/CEP12020 (2013).

- Kuwahara, M., Hiraga, A., Kai, M., Tsubone, H. & Sugano, S. Influence of training on autonomic nervous function in horses: evaluation by power spectral analysis of heart rate variability. Equine Vet. J. 31, 178-180. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.1999 .tb05213.x (1999).

- Coelho, C. S. et al. Training Effects on the Stress Predictors for Young Lusitano Horses Used in Dressage. Animals 12 (2022).

- Votion, D. M., Gnaiger, E., Lemieux, H., Mouithys-Mickalad, A. & Serteyn, D. Physical fitness and mitochondrial respiratory capacity in horse skeletal muscle. PLoS One. 7, e34890. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0034890 (2012).

- Rietbroek, N. J. et al. Effect of exercise on development of capillary supply and oxidative capacity in skeletal muscle of horses. Am. J. Vet. Res. 68, 1226-1231. https://doi.org/10.2460/ajvr.68.11.1226 (2007).

- Votion, D. M. et al. Alterations in mitochondrial respiratory function in response to endurance training and endurance racing. Equine Vet. J. 42, 268-274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.2010.00271.x (2010).

- Graham-Thiers, P. M. & Bowen, L. K. Improved ability to maintain fitness in horses during large pasture turnout. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 33, 581-585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2012.09.001 (2013).

- Huangsaksri, O. et al. Physiological stress responses in horses participating in novice endurance rides. Heliyon https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31874 (2024).

- Sanigavatee, K. et al. Hematological and physiological responses in polo ponies with different field-play positions during low-goal polo matches. PLoS One. 19, e0303092. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0303092 (2024).

- von Lewinski, M. et al. Cortisol release, heart rate and heart rate variability in the horse and its rider: different responses to training and performance. Vet. J. 197, 229-232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2012.12.025 (2013).

- Szabó, C., Vizesi, Z. & Vincze, A. Heart rate and heart rate variability of amateur show jumping horses competing on different levels. Animals 11, 693. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11030693 (2021). https://doi.org/https://doi

- Von Borell, E. et al. Heart rate variability as a measure of autonomic regulation of cardiac activity for assessing stress and welfare in farm animals-A review. Physiol. Behav. 92, 293-316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.01.007 (2007).

- Stucke, D., Große Ruse, M. & Lebelt, D. Measuring heart rate variability in horses to investigate the autonomic nervous system activity – pros and cons of different methods. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 166, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2015.02.007 (2015).

- Shaffer, F. & Ginsberg, J. P. An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Front. Public. Health https://doi.org/10.3389/f pubh.2017.00258 (2017).

- Mourot, L., Bouhaddi, M., Perrey, S., Rouillon, J. D. & Regnard, J. Quantitative Poincaré plot analysis of heart rate variability: effect of endurance training. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 91, 79-87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-003-0917-0 (2004).

- Ishizaka, S., Aurich, J. E., Ille, N., Aurich, C. & Nagel, C. Acute physiological stress response of horses to different potential shortterm stressors. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 54, 81-86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2017.02.013 (2017).

- Becker-Birck, M. et al. Cortisol release and heart rate variability in sport horses participating in equestrian competitions. J. Vet. Behav. 8, 87-94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2012.05.002 (2013).

- Nyerges-Bohák, Z. et al. Heart rate variability in horses with and without severe equine asthma. Equine Vet. J. https://doi.org/10.1 111/evj. 14414 (2024).

- Janczarek, I., Kędzierski, W., Wilk, I., Wnuk-Pawlak, E. & Rakowska, A. Comparison of daily heart rate variability in old and young horses: a preliminary study. J. Vet. Behav. 38, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2020.05.005 (2020).

- Sanigavatee, K. et al. Comparison of daily heart rate and heart rate variability in trained and sedentary aged horses. J. Equine Vet. 137, 105094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2024.105094 (2024).

- Cottin, F., Barrey, E., Lopes, P. & Billat, V. Effect of repeated exercise and recovery on heart rate variability in elite trotting horses during high intensity interval training. Equine Vet. J. 38, 204-209. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.2006.tb05540.x (2006).

- Younes, M., Robert, C., Barrey, E. & Cottin, F. Effects of Age, Exercise Duration, and Test Conditions on Heart Rate Variability in Young Endurance Horses. Front. Physiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2016.00155 (2016).

- Reed, S. A., LaVigne, E. K., Jones, A. K., Patterson, D. F. & Schauer, A. L. Horse species symposium: The aging horse: Effects of inflammation on muscle satellite cells 1, 2. J. Anim. Sci. 93, 862-870. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2014-8448 (2015).

- Harrington McKeever, K. Aging and how it affects the physiological response to exercise in the horse. Clin. Tech. Equine Pract. 2, 258-265. https://doi.org/10.1053/S1534-7516(03)00068-4 (2003).

- Baragli, P., Vitale, V., Banti, L. & Sighieri, C. Effect of aging on behavioural and physiological responses to a stressful stimulus in horses (Equus caballus). Behaviour 151, 1513-1533. https://doi.org/10.1163/1568539X-00003197 (2014).

- Horohov, D. W. et al. Effect of exercise on the immune response of young and old horses. Am. J. Vet. Res. 60, 643-647. https://doi. org/10.2460/ajvr.1999.60.05.643 (1999).

- Betros, C. L., McKeever, K. H., Kearns, C. F. & Malinowski, K. Effects of ageing and training on maximal heart rate and VO2max. Equine Vet. J. 34, 100-105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.2002.tb05399.x (2002).

- McKeever, K. H. Exercise and Rehabilitation of older horses. Vet. Clin. North. Am. Equine Pract. 32, 317-332. https://doi.org/10.1 016/j.cveq.2016.04.008 (2016). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/

- Keadle, T. L., Pourciau, S. S., Melrose, P. A., Kammerling, S. G. & Horohov, D. W. Acute exercises stress modulates immune function in unfit horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 13, 226-231. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0737-0806(06)81019-1 (1993).

- Kim, J. et al. Exercise training increases oxidative capacity and attenuates exercise-induced ultrastructural damage in skeletal muscle of aged horses. J. Appl. Physiol. 98, 334-342. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00172.2003 (2005).

- Waran, N., McGreevy, P. & Casey, R. A. In The Welfare of Horses (ed. Waran, N.) 194-201 (Springer Netherlands, 2007).

- Vincent, T. L. et al. Retrospective study of predictive variables for maximal heart rate (HRmax) in horses undergoing strenuous treadmill exercise. Equine Vet. J. 38, 146-152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.2006.tb05531.x (2006).

- Manohar, M. Equine exercise physiology 2 132-147 (ICEEP, 1987).

- Chanda, M., Srikuea, R., Cherdchutam, W., Chairoungdua, A. & Piyachaturawat, P. Modulating effects of exercise training regimen on skeletal muscle properties in female polo ponies. BMC Vet. Res. 12, 245. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-016-0874-6 (2016).

- Medicine, A. in ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 3-6 (ed Pescatello LS Thompson WR GN) (Wolters Kluwer Health, 2010).

- Agüera, E. et al. Blood parameter and heart rate response to training in andalusian horses. J. Physiol. Biochem. 51, 55-64 (1995).

- Ringmark, S. et al. Reduced high intensity training distance had no effect on VLa4 but attenuated heart rate response in 2-3-yearold standardbred horses. Acta Vet. Scand. 57, 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13028-015-0107-1 (2015).

- Bauer, A. et al. Deceleration capacity of heart rate as a predictor of mortality after myocardial infarction: cohort study. Lancet 367, 1674-1681. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68735-7 (2006).

- Nasario-Junior, O., Benchimol-Barbosa, P. R. & Nadal, J. Refining the deceleration capacity index in phase-rectified signal averaging to assess physical conditioning level. J. Electrocardiol. 47, 306-310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2013.12.006 (2014).

- Yang, L. et al. in 2017 10th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, BioMedical Engineering and Informatics (CISPBMEI). pp. 1-5.

- Liu, X., Xiang, L. & Tong, G. Predictive values of heart rate variability, deceleration and acceleration capacity of heart rate in postinfarction patients with LVEF

. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 25, e12771. https://doi.org/10.1111/anec. 12771 (2020). - Nyerges-Bohák, Z., Nagy, K., Rózsa, L., Póti, P. & Kovács, L. Heart rate variability before and after 14 weeks of training in Thoroughbred horses and standardbred trotters with different training experience. PLoS One. 16, e0259933. https://doi.org/10.13 71/journal.pone. 0259933 (2021).

- Frippiat, T., van Beckhoven, C., Moyse, E. & Art, T. Accuracy of a heart rate monitor for calculating heart rate variability parameters in exercising horses. J. Equine Vet. 104, 103716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2021.103716 (2021).

- Kapteijn, C. M. et al. Measuring heart rate variability using a heart rate monitor in horses (Equus caballus) during groundwork. Front. Vet. Sci. 9, 939534. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2022.939534 (2022).

- Ille, N., Erber, R., Aurich, C. & Aurich, J. Comparison of heart rate and heart rate variability obtained by heart rate monitors and simultaneously recorded electrocardiogram signals in nonexercising horses. J. Vet. Behav. 9, 341-346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jve b.2014.07.006 (2014).

- Huangsaksri, O. et al. Physiological stress responses in horses participating in novice endurance rides. Heliyon 10, e31874. https:/ /doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31874 (2024). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/

- Poochipakorn, C. et al. Effect of Exercise in a Vector-Protected Arena for preventing African horse sickness transmission on physiological, biochemical, and behavioral variables of horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 131, 104934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2023.1 04934 (2023).

- Huangsaksri, O., Wonghanchao, T., Sanigavatee, K., Poochipakorn, C. & Chanda, M. Heart rate and heart rate variability in horses undergoing hot and cold shoeing. PLoS One. 19, e0305031. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0305031 (2024).

- Frippiat, T., van Beckhoven, C., van Gasselt, V. J., Dugdale, A. & Vandeweerd, J. M. Effect of gait on, and repeatability of heart rate and heart rate variability measurements in exercising Warmblood dressage horses. Comp. Exerc. Physiol.. https://doi.org/10.1163/ 17552559-20220044 (2023).

- Baevsky, R. & Berseneva, A. Use KARDIVAR system for determination of the stress level and estimation of the body adaptability. Standards of measurements and physiological interpretation. Moscow-Prague 41 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend our gratitude to Vaewratt Kamonkon, director of the Horse Lover’s Club, for allocating their horses for this study.

Author contributions

K.S., C.P., T.W. and M.C. contributed to conceptualisation, software, resources and visualisation; K.S., C.P., O.H., S.V., S.P., W.C., S.W., T.W. and M.C. involved in methodology, validation, formal analysis and investigation; K.S., C.P., O.H., T.W. and M.C contributed to data curation; K.S., T.W. and M.C involved in funding acquisition, wrote the original draft of the manuscript; T.W. and M.C supervised this project, wrote, reviewed and edited the final draft of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Research Council of Thailand (contact nos. N41A661096 and N41A650067) and the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kasetsart University (VET.KU2024-03 and VET.KU202405). The APC was funded by the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kasetsart University.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The animal study protocol received approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Kasetsart University (ACKU65-VET-005 and ACKU66-VET-089). We ensured that all methods were conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, adhering to the ARRIVE guidelines.

Informed consent

was obtained from the owners of all horses involved in the study.

Additional information

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/1 0.1038/s41598-025-86679-4.

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to T.W. or M.C.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommo ns.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

© The Author(s) 2025

© The Author(s) 2025

Veterinary Clinical Studies Program, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kasetsart University, Kamphaeng Saen Campus, Kamphaeng Saen, Nakhon Pathom 73140, Thailand. Center for Veterinary Research and Innovation, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kasetsart University, Bang Khen Campus, Bangkok 10900, Thailand. Department of Large Animal and Wildlife Clinical Science, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kasetsart University, Kamphaeng Saen Campus, Kamphaeng Saen, Nakhon Pathom 73140, Thailand. Veterinary Science Program, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kasetsart University, Bang Khen Campus, Bangkok 10900, Thailand. email: thita.wo@ku.th; fvetmtcd@ku.ac.th