DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-024-02352-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38449005

تاريخ النشر: 2024-03-06

نظام توصيل نانوي مسامي محمّل بالكيرسيتين يعيد تشكيل الميكروبيئة العظمية المناعية لتجديد العظم السنخي في التهاب اللثة عبر مسار miR-21a-5p/PDCD4/NF-κB

الملخص

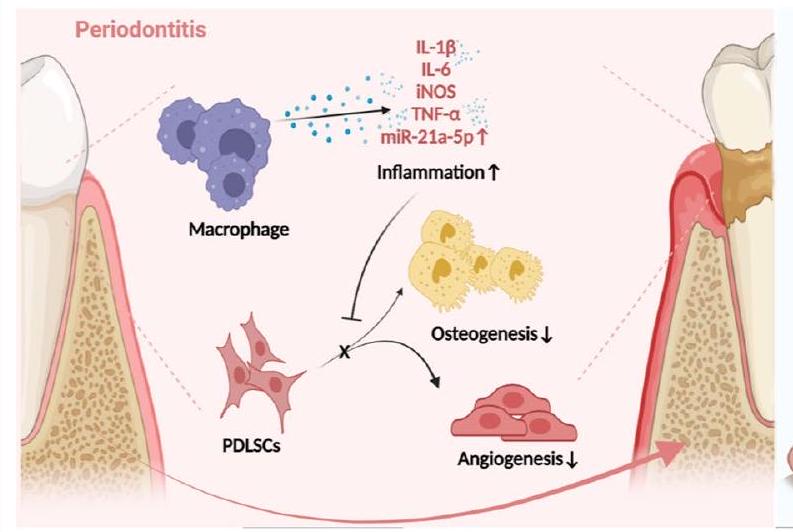

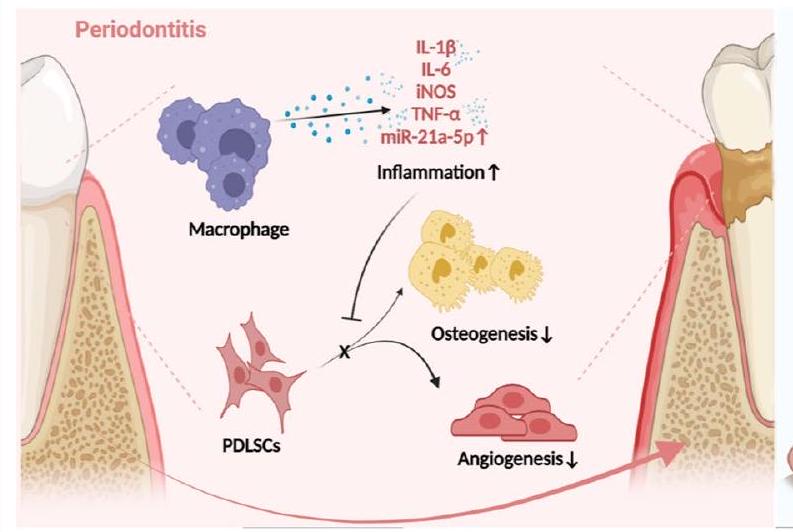

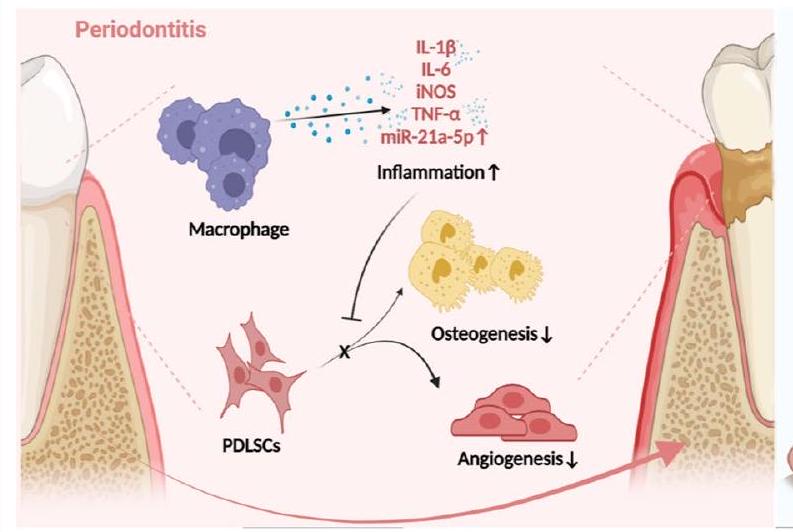

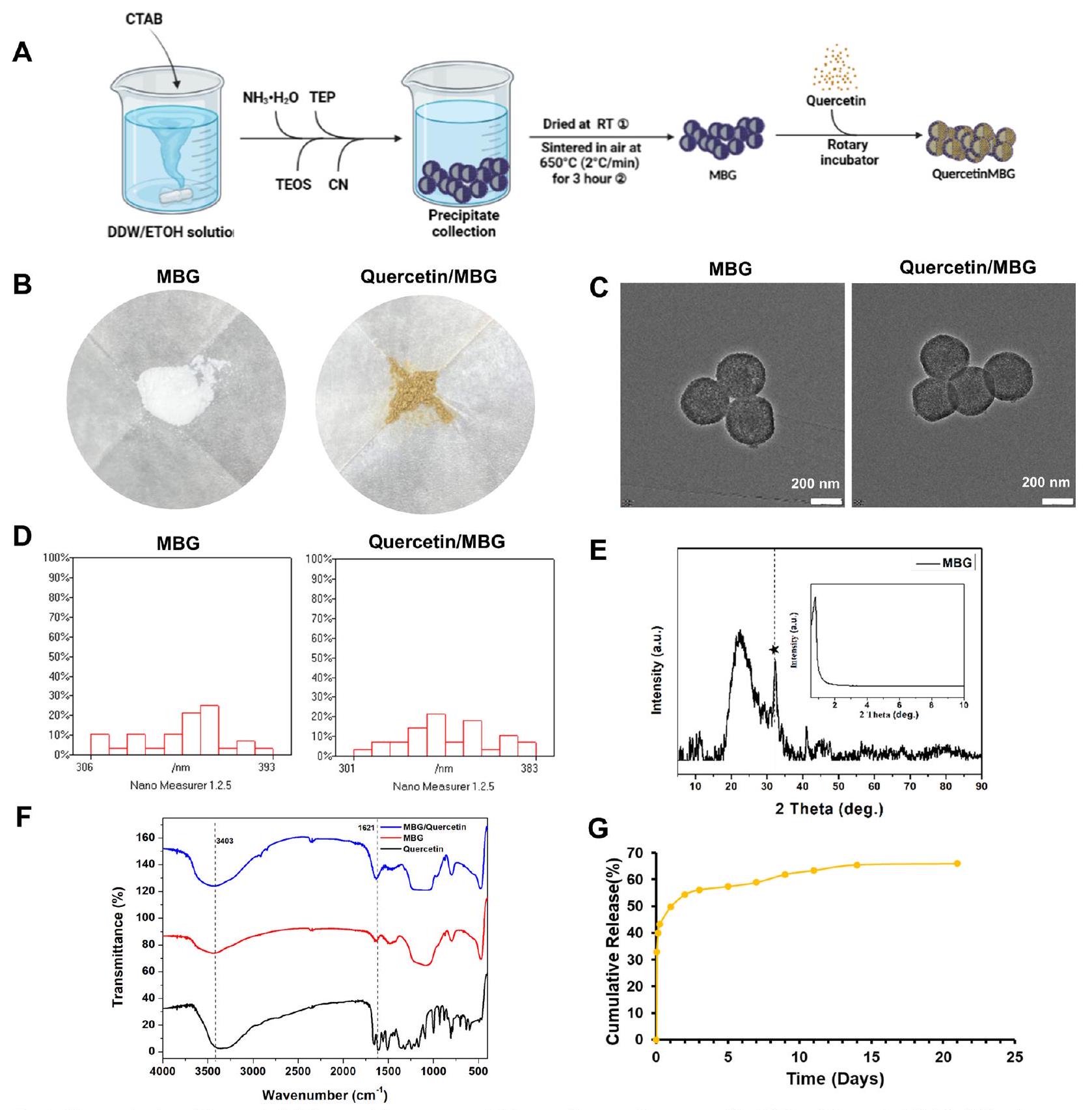

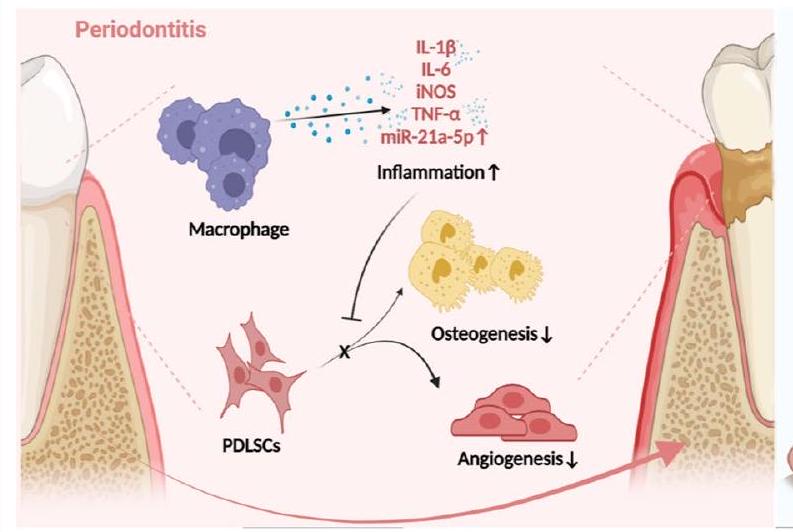

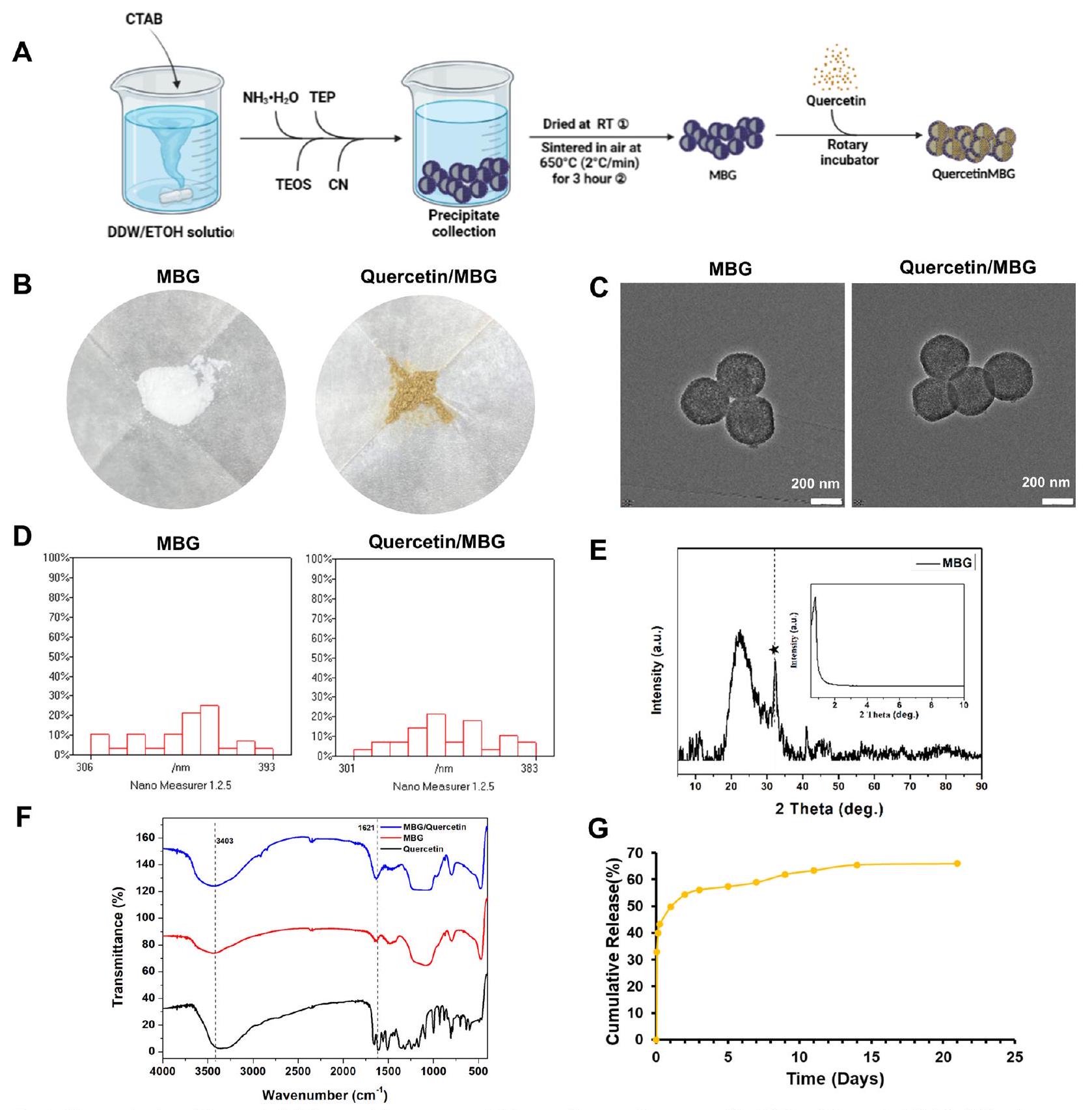

الخلفية: تساهم ضعف تكوين العظام/الأوعية الدموية، والالتهاب المفرط، وعدم التوازن في التوازن المناعي العظمي في مسببات عيب العظم السنخي الناتج عن التهاب اللثة. للأسف، لا تزال هناك نقص في استراتيجيات علاجية مثالية لالتهاب اللثة يمكن أن تجدد العظم السنخي بينما تعيد تشكيل البيئة الدقيقة المناعية العظمية. الكيرسيتين، كفلافونويد أحادي، له أنشطة دوائية متعددة، مثل التأثيرات المعززة للتجديد، ومضادة للالتهابات، ومعدلة للمناعة. على الرغم من طيفه الواسع من الأنشطة الدوائية، فإن التطبيق السريري للكيرسيتين محدود بسبب ذوبانه الضعيف في الماء وتوافره البيولوجي المنخفض. النتائج: في هذه الدراسة، قمنا بتصنيع نظام توصيل نانو محمّل بالكيرسيتين زجاج حيوي مسامي (Quercetin/MBG) مع وظيفة الإفراج المستمر عن الكيرسيتين، والذي يمكن أن يعزز بشكل أفضل تجديد العظام وينظم البيئة الدقيقة المناعية في عيب العظم السنخي مع التهاب اللثة مقارنةً بعلاج MBG النقي. على وجه الخصوص، قلل هذا النظام من تكرار حقن الكيرسيتين مع تحقيق نتائج علاجية مواتية. نظرًا للتأثيرات العلاجية الممتازة التي تحققت من خلال الإفراج المستمر عن الكيرسيتين، قمنا بمزيد من التحقيق في آلياته العلاجية. أظهرت نتائجنا أنه تحت بيئة التهاب اللثة، يمكن أن يستعيد تدخل الكيرسيتين القدرة على تكوين العظام/الأوعية الدموية لخلايا جذعية الرباط السني (PDLSCs)، ويحفز تنظيم المناعة للخلايا البالعة ويؤثر على تأثير تعديل المناعة العظمية. علاوة على ذلك، وجدنا أيضًا أن التأثيرات المعدلة للمناعة العظمية للكيرسيتين عبر الخلايا البالعة يمكن أن تُحجب جزئيًا من خلال التعبير المفرط عن microRNA رئيسي——miR-21a-5p، الذي يعمل من خلال تثبيط تعبير PDCD4 وتنشيط مسار إشارة NF-kB. الخلاصة: باختصار، تُظهر دراستنا أن نظام توصيل النانو المحمّل بالكيرسيتين لديه القدرة على أن يكون نهجًا علاجيًا لإعادة بناء عيوب العظم السنخي في التهاب اللثة. علاوة على ذلك، فإنه يقدم أيضًا

الكلمات الرئيسية: التهاب اللثة، كيرسيتين، تجديد العظم السنخي، تعديل المناعة العظمية، زجاج حيوي مسامي

الملخص الرسومي

الخلفية

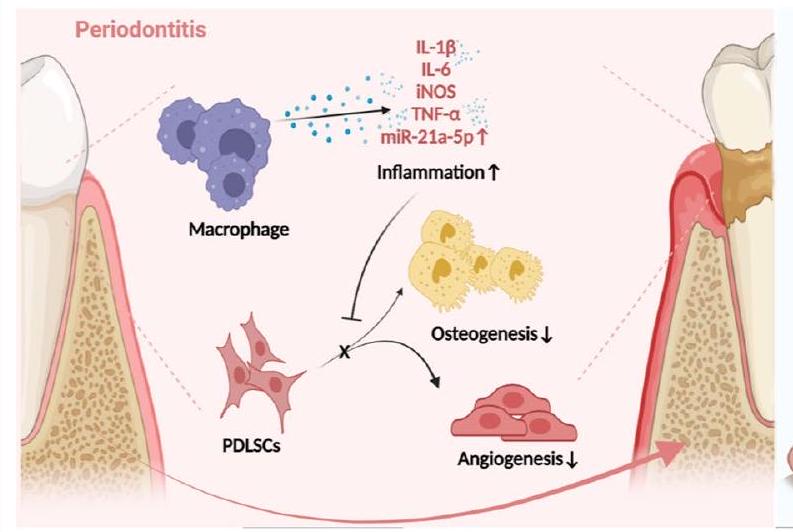

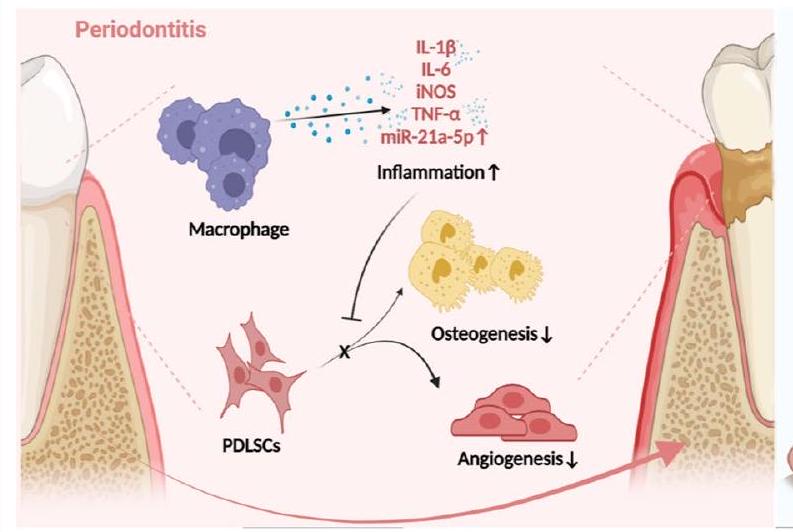

تعتبر PDLSCs، نوع من خلايا الجذعية الميزانشيمية (MSCs)، مرتبطة ارتباطًا وثيقًا بإصلاح العظم السنخي، ولديها إمكانيات واعدة في مجال تجديد اللثة [5]. يمكن أن تعيق الالتهابات المزمنة في التهاب اللثة تكوين العظام/الأوعية الدموية لـ PDLSCs، مما يؤدي إلى اضطراب تجديد اللثة [6]. كخلايا مناعية رئيسية في تطور التهاب اللثة،

تساهم الخلايا البالعة بشكل كبير في التوازن المناعي العظمي [7]. عمومًا، يتم تصنيف الخلايا البالعة عادةً إلى نوعين بناءً على حالة تنشيطها ووظيفتها: النوع M1 المؤيد للالتهابات والنوع M2 المضاد للالتهابات. خلال المرحلة الأولية من الاستجابة الالتهابية في التهاب اللثة، يكون تنشيط النوع M1 مفيدًا للدفاع عن الأنسجة، ولكن إذا استمرت هذه الحالة بعد هذه الفترة، فإنها ستؤدي إلى تدمير لا يمكن عكسه للأنسجة اللثوية [8]. أدى الاستقطاب المفرط للنوع M1 من الخلايا البالعة، كما لوحظ في الدراسات المتعلقة بالتهاب اللثة، إلى تفاقم الاضطرابات المناعية المحلية وأدى إلى تدمير الأنسجة اللثوية، بينما زاد أيضًا من ضعف قدرة PDLSCs على تكوين العظام/الأوعية الدموية وبالتالي تفاقم عدم توازن البيئة الدقيقة المناعية العظمية [9-11]. لذلك، كان من الضروري من الناحية الخلوية استعادة تمايز PDLSCs إلى تكوين العظام/الأوعية الدموية وإعادة تشكيل التوازن المناعي العظمي عبر الخلايا البالعة لإصلاح عيوب العظم السنخي في التهاب اللثة.

ومع ذلك، كدواء صغير جزيئي أحادي، فإن ذوبان الكيرسيتين الضعيف في الماء وتوافره البيولوجي المنخفض يحدان من استخدامه السريري[12]. لذلك، من الضروري إنشاء نظام توصيل دوائي فعال يمكنه الحفاظ على تركيزات مستقرة ومناسبة من الكيرسيتين في الأنسجة المستهدفة للاستخدام السريري. مؤخرًا، يتم اعتبار جزيئات MBG النانوية كحاملات دوائية محتملة لمواقع عيوب العظام، بسبب مساميتها العالية، ومساحة سطحها المحددة، وقدرتها القوية على تحفيز تجديد أنسجة العظام[21]. علاوة على ذلك، أشارت الأبحاث إلى أنه عند استخدام MBG كنظام توصيل دوائي لإصلاح العظام، لم يثير استجابة مناعية غير مواتية في الخلايا البالعة[22،23]. ومن ثم، يُفترض أن نظام توصيل النانو Quercetin/MBG قد يكون له تطبيق محتمل في علاج عيوب العظم السنخي في التهاب اللثة.

تعتبر microRNAs (miRNAs) فئة من RNAs الصغيرة غير المشفرة المحفوظة تطوريًا والتي تنظم التعبير الجيني على مستوى الترجمة[24]. في السنوات الأخيرة، أفادت العديد من الدراسات بوجود علاقة وثيقة بين التهاب اللثة وmiRNAs، مثل miR-21، miR-144، miR-146a، miR-128 وغيرها[25]. علاوة على ذلك، تم الإبلاغ عن أن الكيرسيتين يمكن أن يحفز العديد من miRNAs لتعزيز التمايز العظمي وكذلك تعديل الاستجابة المناعية[26-28]. لذلك، يُفترض أن تلعب miRNAs دورًا محوريًا في تأثيرات تعديل المناعة العظمية للكيرسيتين على التهاب اللثة.

لقد أكدنا أن نظام توصيل الكيرسيتين/MBG النانوي أطلق الكيرسيتين بشكل مستمر وأدى إلى تحسين تجديد العظم السنخي وإعادة تشكيل البيئة الميكروية المناعية العظمية مقارنة بـ MBG النقي. ثم بحثنا في الآلية الخلوية التي من خلالها تدخل الكيرسيتين في تجديد العظم السنخي تحت بيئة التهاب اللثة. لاحظنا أن الكيرسيتين لم يستعد فقط القدرة على تكوين العظام/الأوعية الدموية لخلايا PDLSCs، بل أعاد أيضًا برمجة البلعميات من خلال مسار miR-21a-5p/PDCD4/NF-κB مما أدى إلى إعادة تشكيل البيئة الميكروية المناعية العظمية. باختصار، تشير هذه الدراسة إلى أن نظام توصيل الكيرسيتين المحمّل بالمسام النانوية يحمل إمكانيات كعلاج سريري لإصلاح عيوب العظم السنخي في التهاب اللثة. علاوة على ذلك، فإن التلاعب بـ miR-21a-5p في البلعميات لإعادة تشكيل البيئة الميكروية المناعية العظمية في اللثة يقدم استراتيجية علاجية جديدة لإعادة بناء العظم السنخي في التهاب اللثة.

النتائج

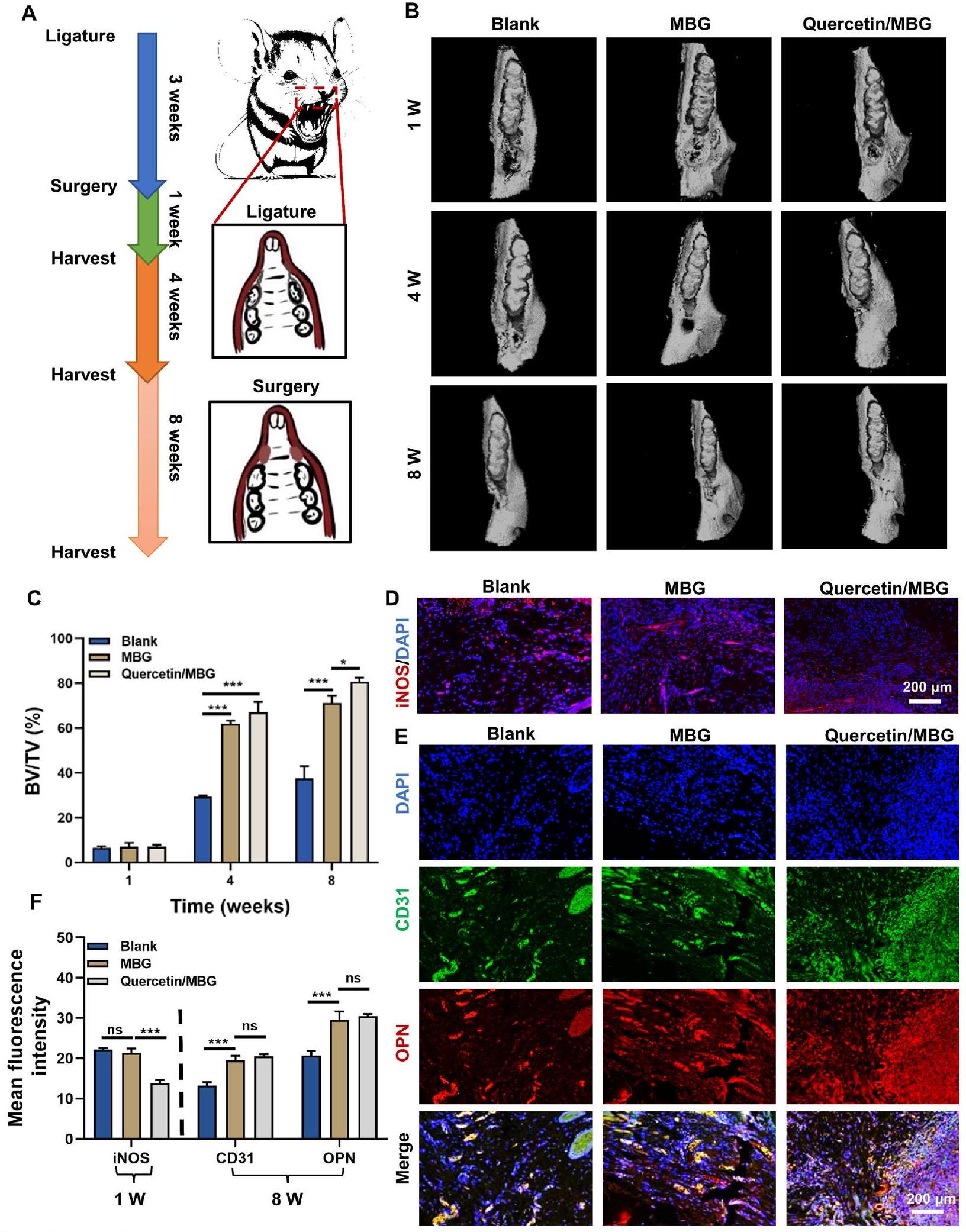

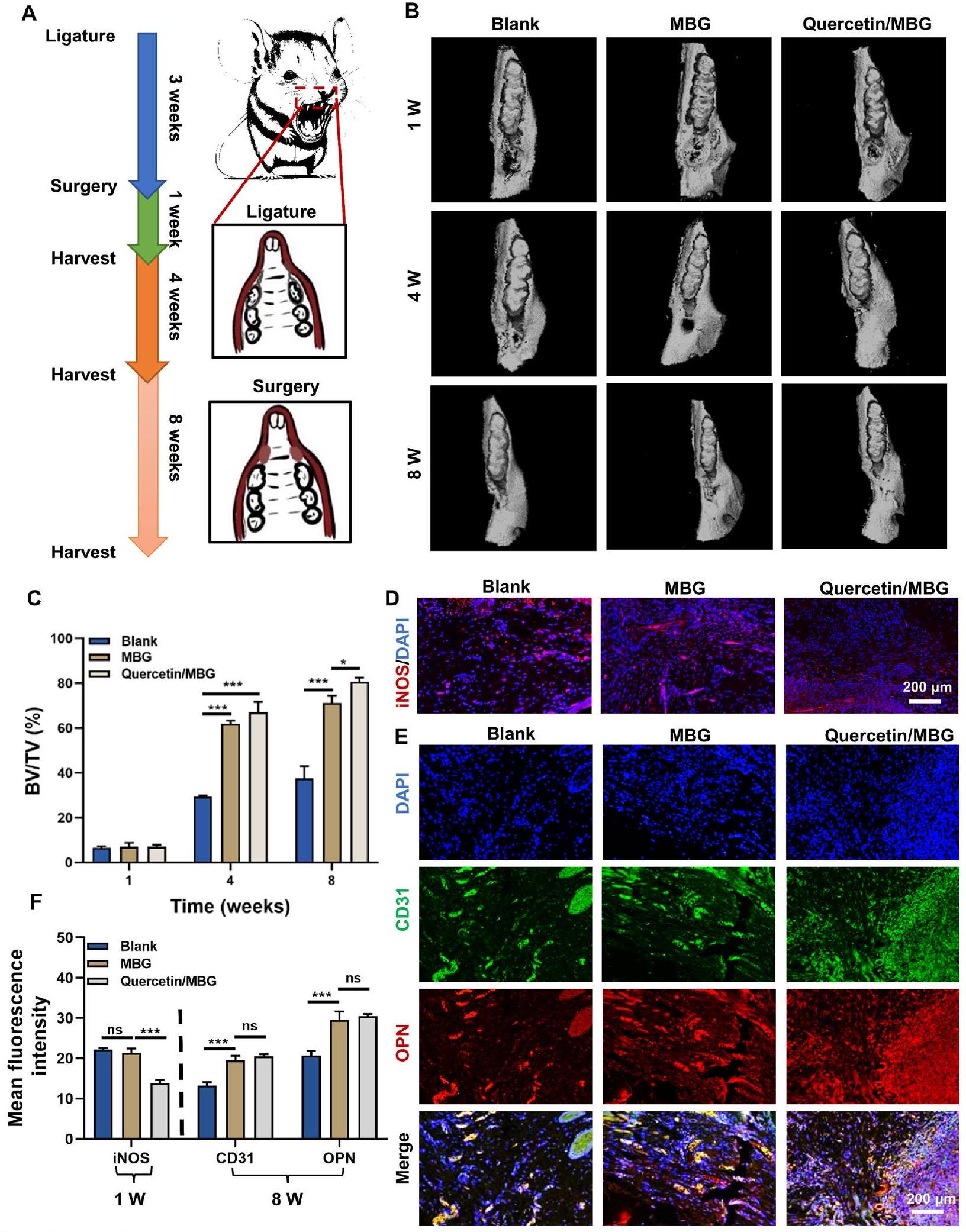

نظام الإفراز المستدام للكويرسيتين عزز تجديد العظم السنخي وخفف الالتهاب المحلي في نموذج عيب العظم السنخي لدى الجرذان مع التهاب اللثة.

الشكل 2 نظام إطلاق الكيرسيتين المستدام عزز تجديد العظام السنخية وخفف الالتهاب المحلي في نموذج عيب العظام السنخية في الجرذان مع التهاب اللثة. أ رسم توضيحي لتصميم التجربة المستخدمة في الدراسة الحيوانية. ب صور إعادة بناء الميكرو-CT لنسيج العظام السنخية. ج تحليل كمي لنسيج العظام السنخية المتكون حديثًا. د صبغة المناعية الفلورية لـ iNOS في العينات المجمعة بعد أسبوع واحد. هـ صبغة المناعية الفلورية لـ CD31 و OPN في العينات المجمعة بعد 8 أسابيع. و تحليل كمي لمتوسط شدة الفلورة لـ iNOS و CD31 و OPN وفقًا لأنماط الصبغة المناعية الموضحة في (د و هـ). (ns، لا يوجد فرق ذو دلالة إحصائية؛

في الختام، أشارت نتائجنا إلى أن الكيرسيتين يمكن أن يعزز بشكل فعال تجديد العظام في مناطق عيوب العظام السنخية في اللثة بينما يتحكم في الالتهاب اللثوي. ثم قمنا بالتحقيق في الآلية الأساسية التي من خلالها يعزز الكيرسيتين تجديد العظام السنخية وينظم الالتهاب في بيئة التهاب اللثة.

أدى الكيرسيتين إلى تعزيز تكوين العظام والأوعية الدموية ومكافحة الالتهاب في خلايا جذع الأنسجة الداعمة للأسنان تحت بيئة التهاب اللثة.

الملف 1: الشكل S2C). استنادًا إلى هذه النتائج، اخترنا تركيزات الكيرسيتين من

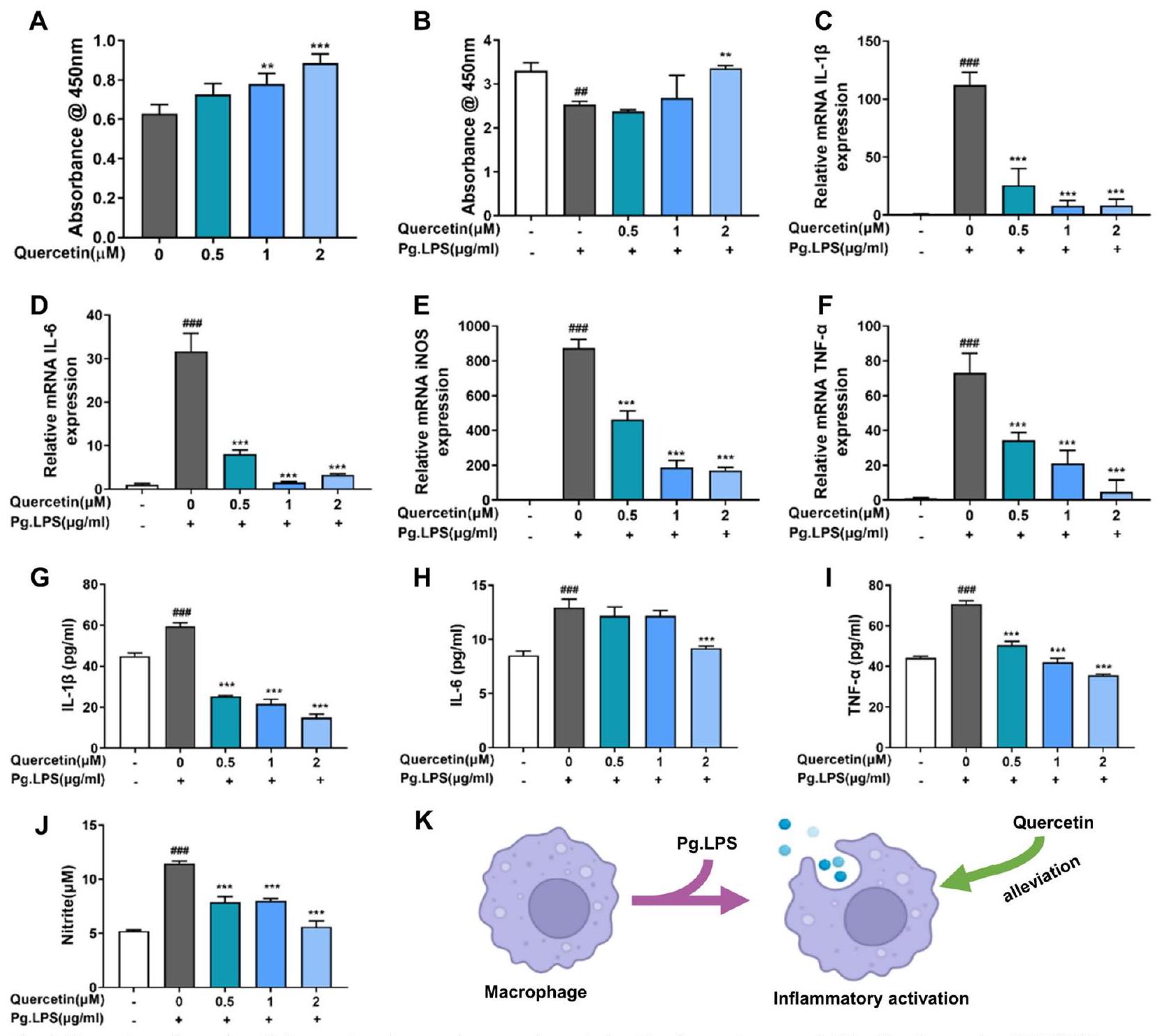

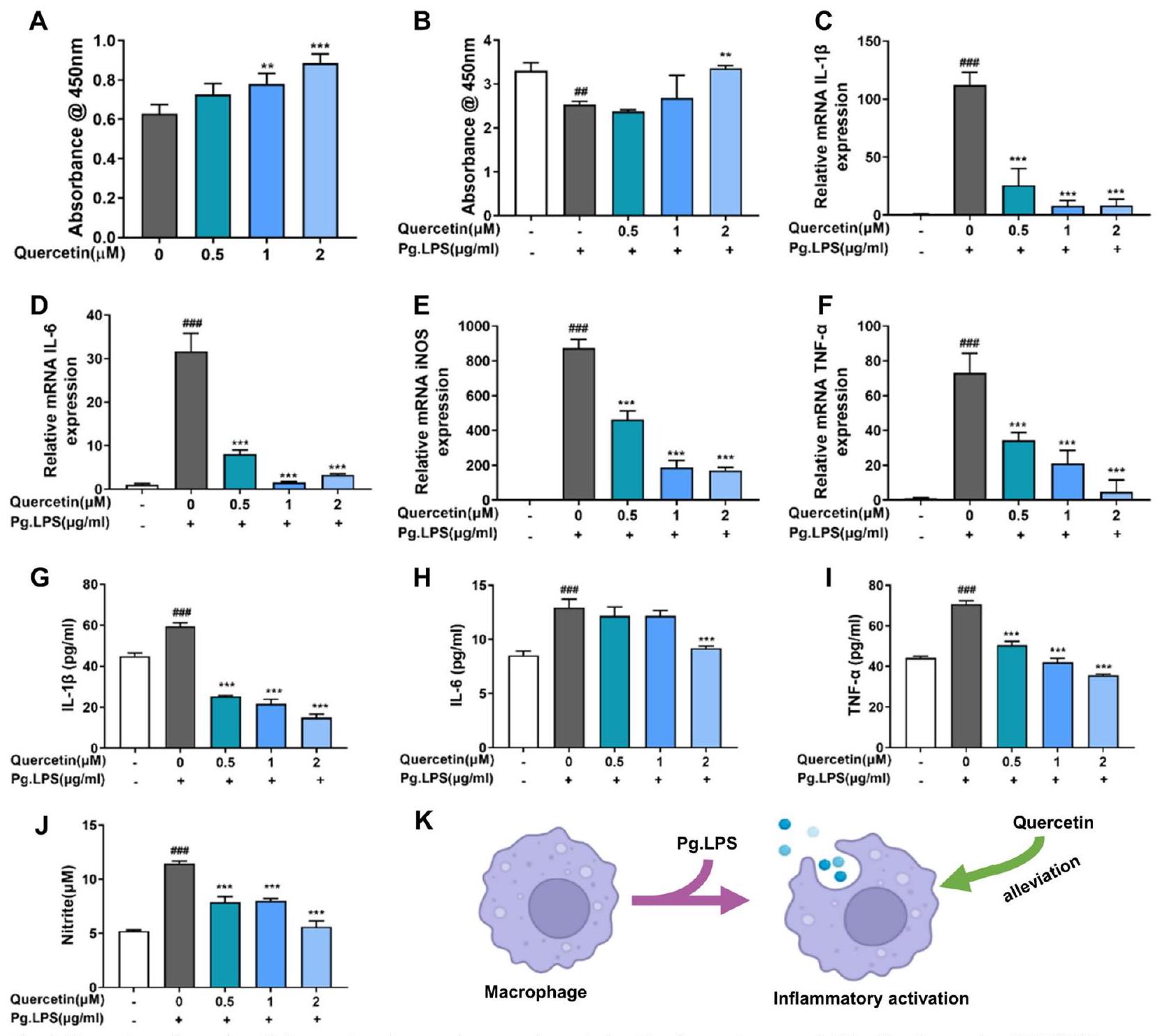

أدى الكيرسيتين إلى مكافحة الالتهاب في البلعميات تحت بيئة التهاب اللثة

(IL-6)، iNOS وعامل نخر الورم-

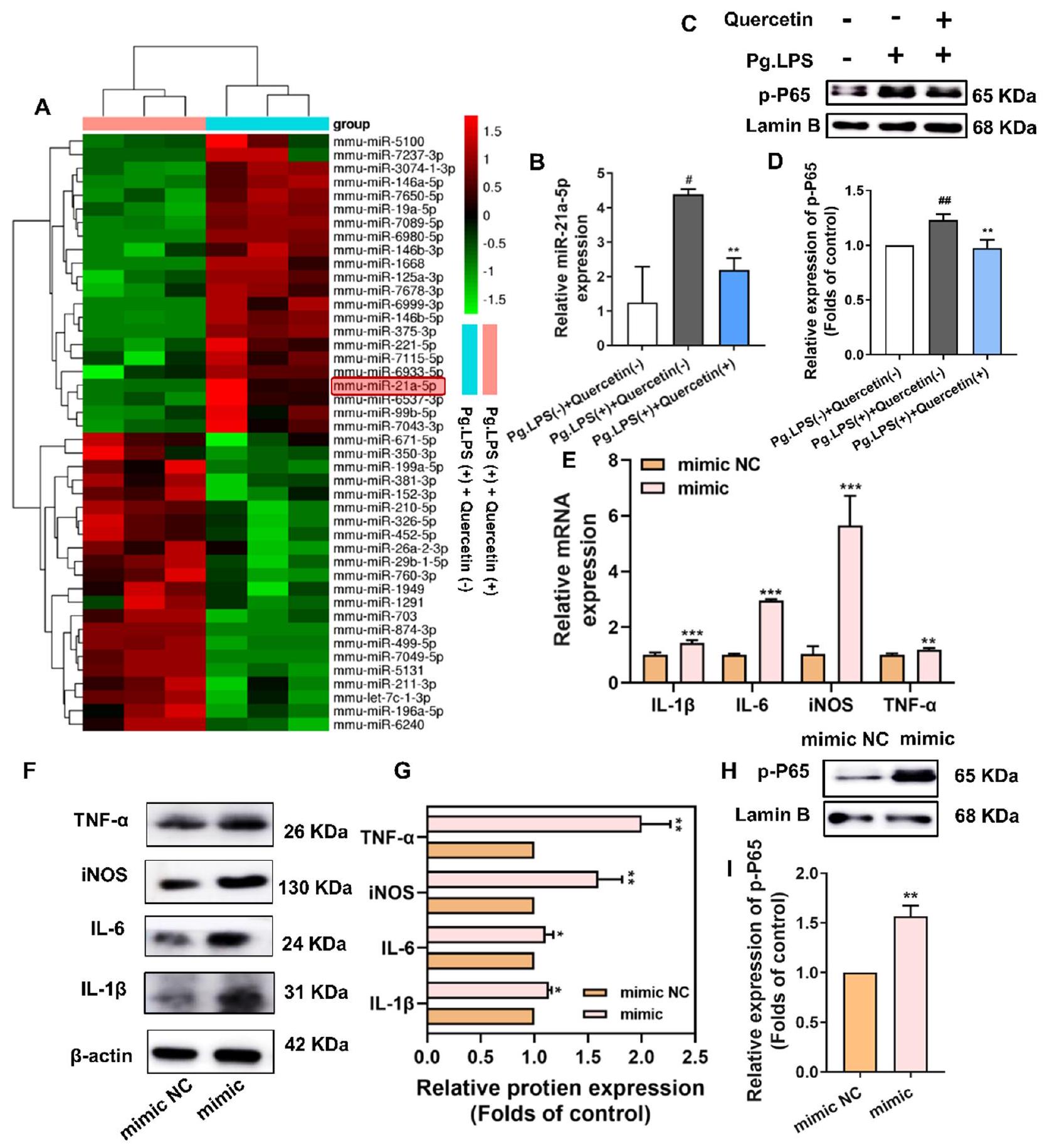

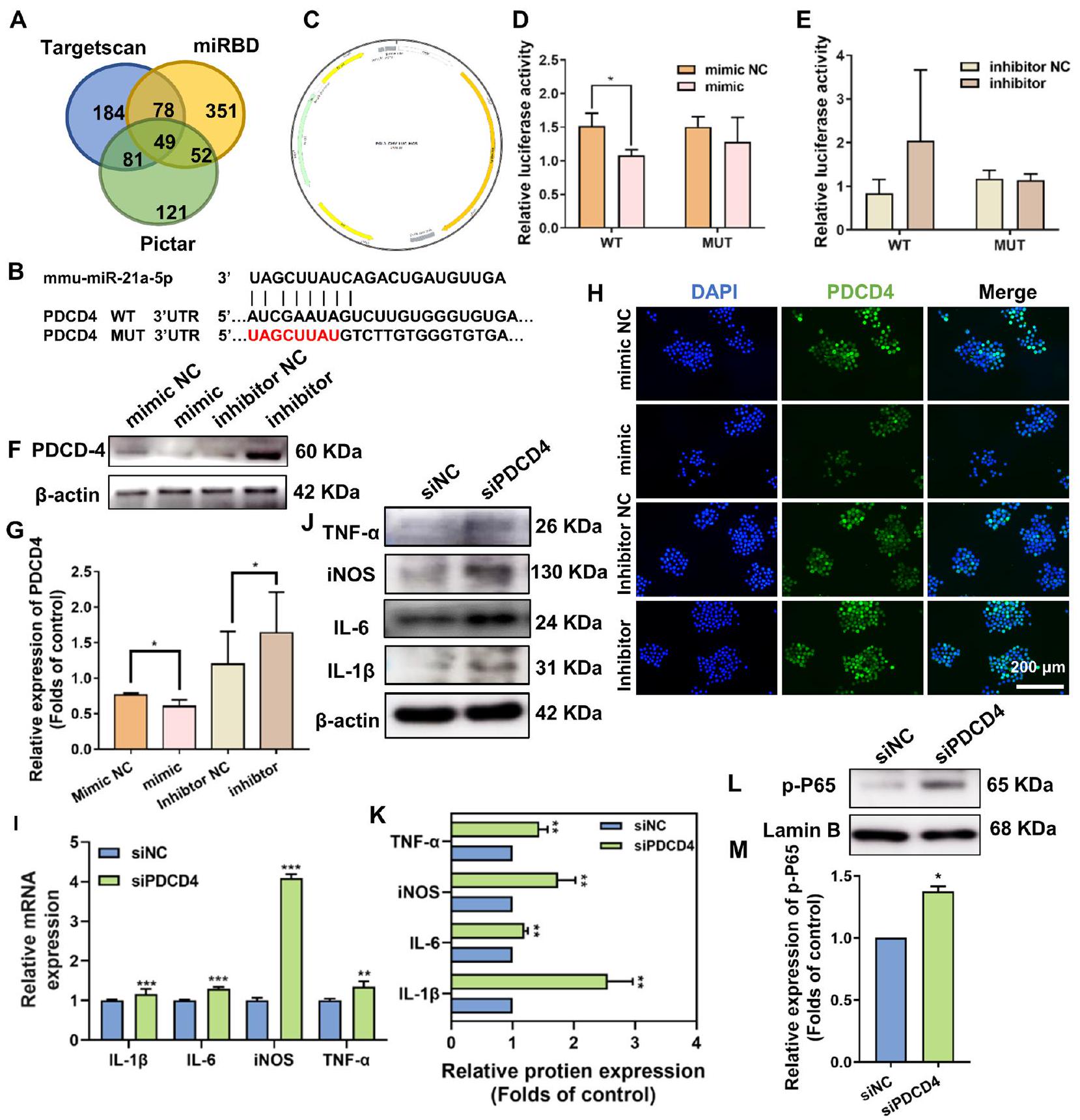

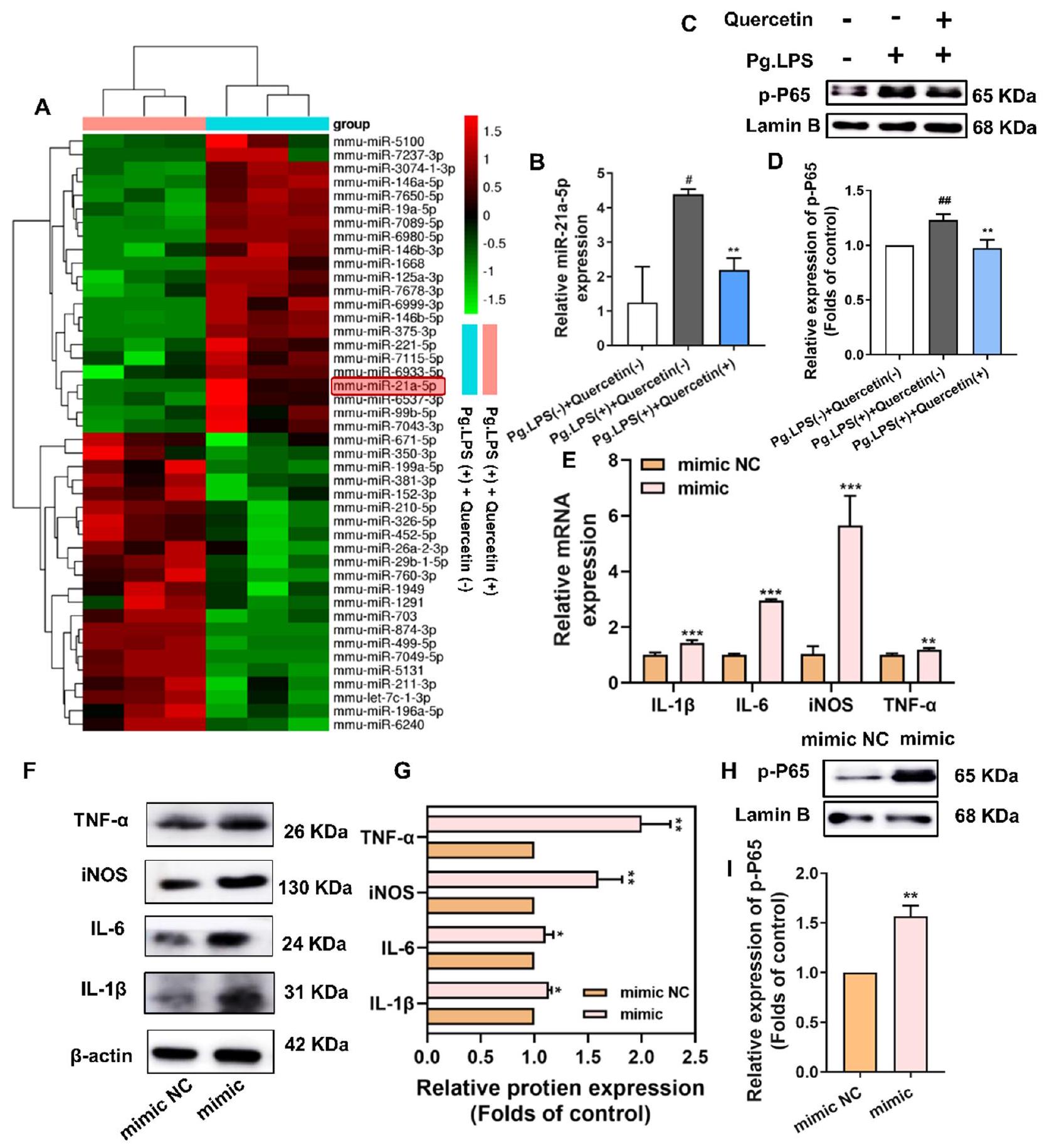

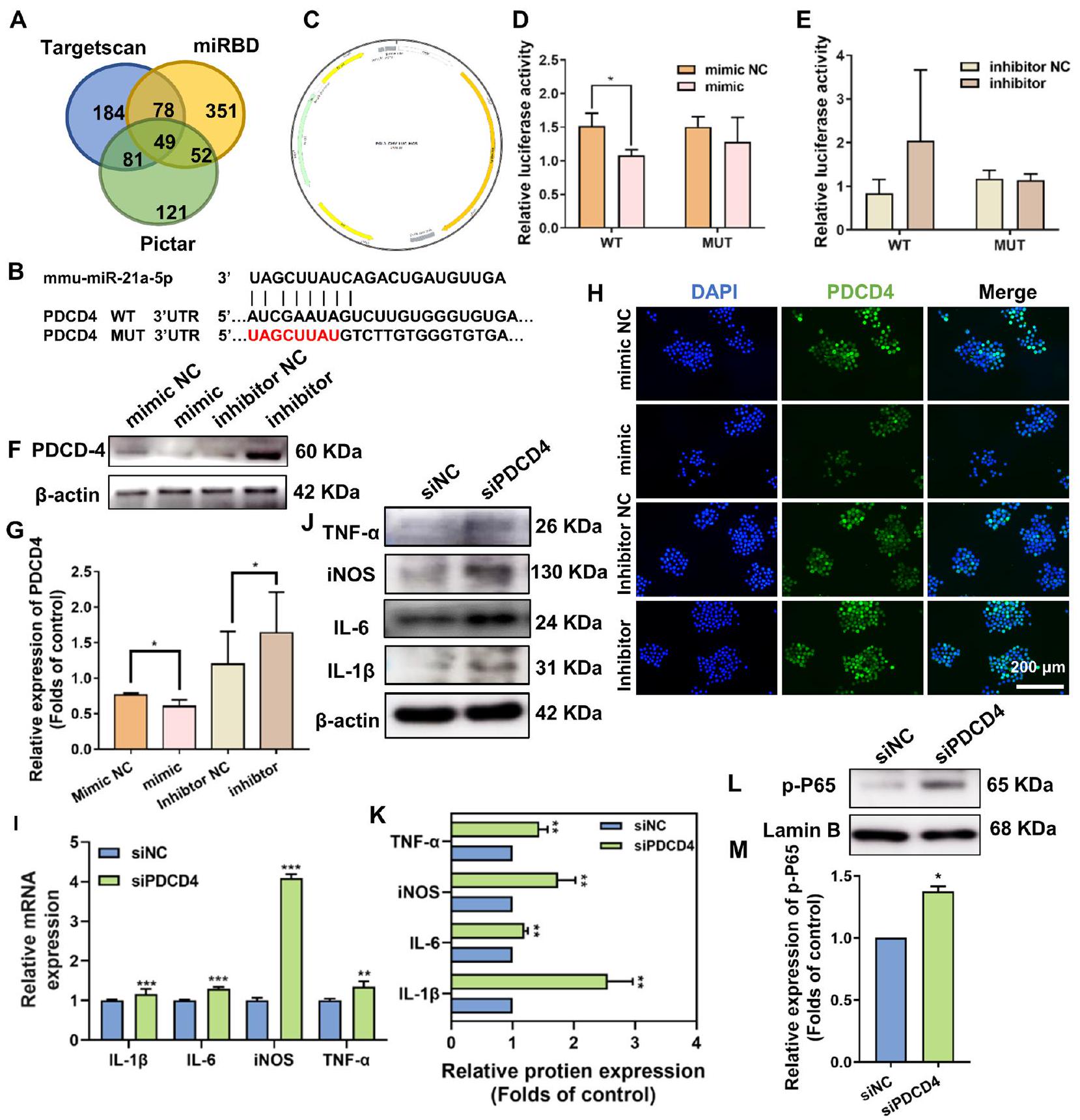

آلية مكافحة الالتهاب للكيرسيتين على البلعميات تحت بيئة التهاب اللثة أوقف الكيرسيتين التفاعل الالتهابي في البلعميات المحفزة بواسطة Pg.LPS من خلال تقليل تعبير miR-21a-5p

أولاً، قمنا بزيادة وتنظيم مستويات miR-21a-5p في خلايا RAW264.7 باستخدام محاكي miR-21a-5p، المثبط، وNC السلبي (الملف الإضافي 1: الشكل S5C). أدى محاكي miR-21a-5p إلى زيادة ملحوظة في مستويات العلامات الالتهابية، بما في ذلك IL-1

. تشير هذه النتائج إلى أن الإفراط في التعبير عن miR-21a-5p يمكن أن يعزز الاستجابة الالتهابية للبلعميات. لاستكشاف دور miR-21a-5p بشكل أكبر، قمنا بنقل خلايا RAW264.7 باستخدام محاكي miR-21a-5p. كما هو موضح في الشكل 5H، I، زاد نقل محاكي miR-21a-5p بشكل كبير من تعبير p-P65 في النواة، مما أدى إلى تنشيط مسار إشارة NF-кB.

كان PDCD4 هدفًا سفليًا لـ miR-21a-5p ونظم المزيد من الاستجابات الالتهابية للبلعميات من خلال مسار إشارة NF-кB

أظهر الكيرسيتين تأثيرات غير مباشرة مؤيدة لتكوين العظام/الأوعية الدموية عبر miR-21a-5p

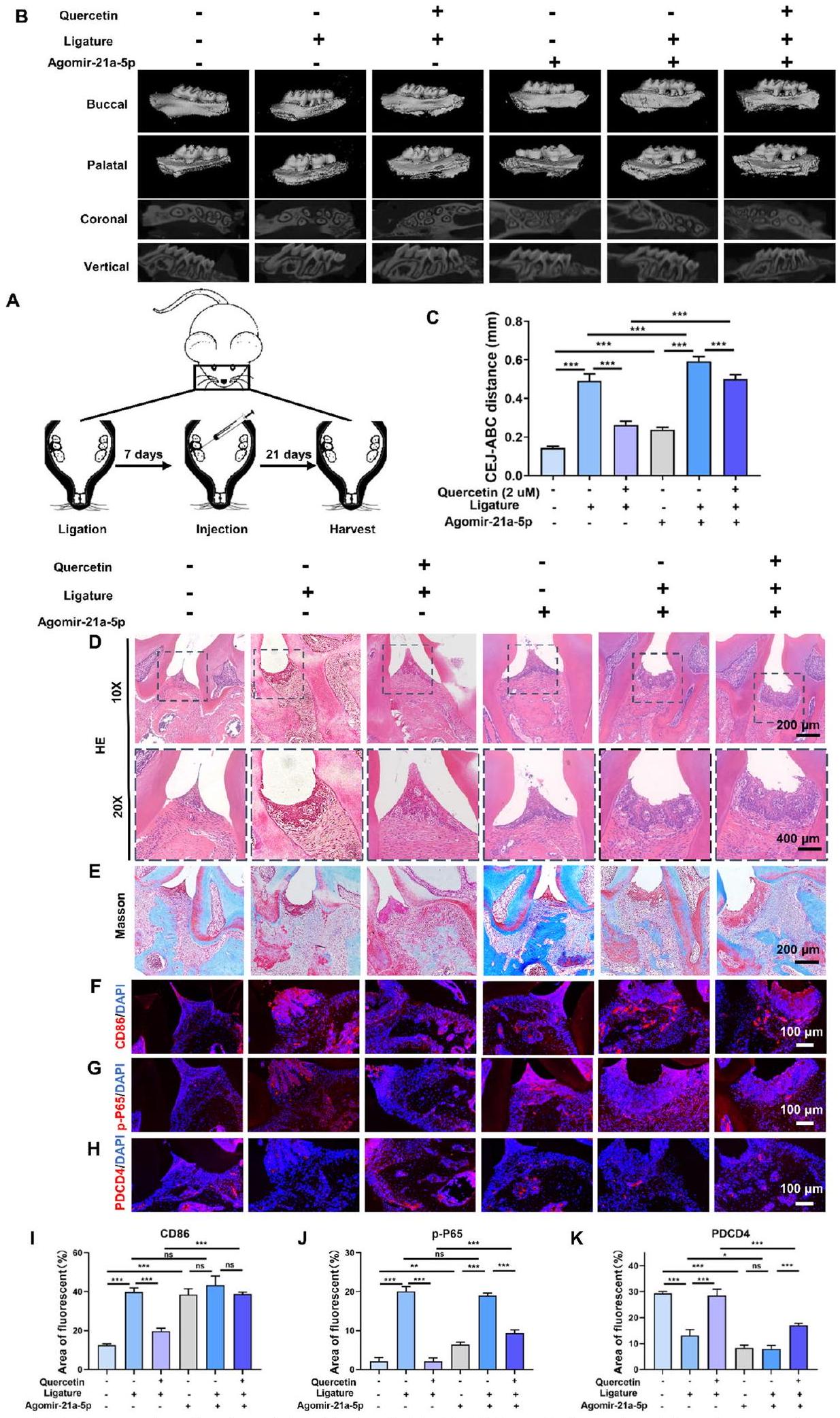

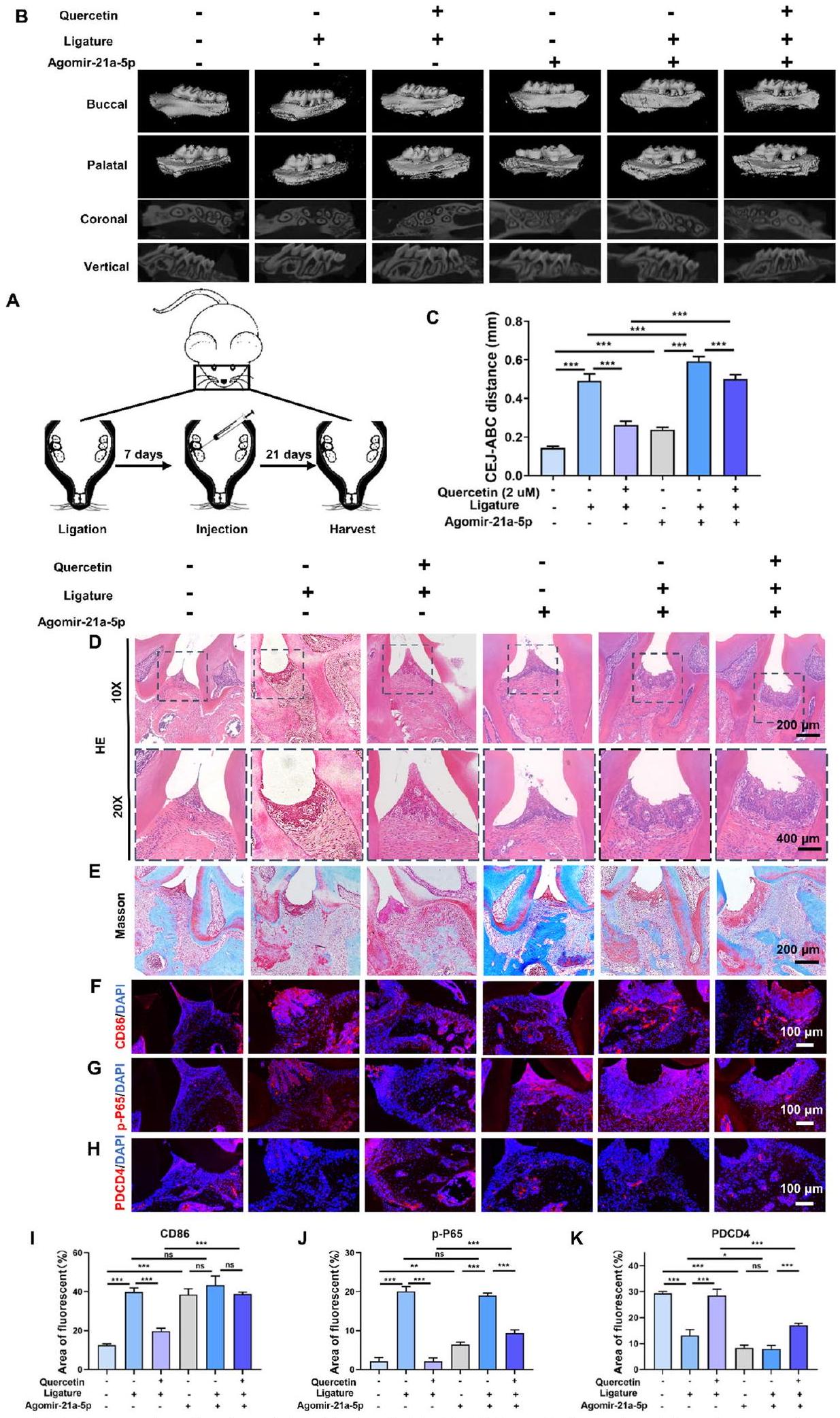

قدم الكيرسيتين تأثيرًا وقائيًا في التهاب اللثة عبر miR-21a-5p

التقييم في المختبر لتأثير MBG على التأثيرات البيولوجية للكويرسيتين

أظهرت الدراسة أعلاه أن الكيرسيتين exerted تأثيرات مناعية من خلال miRNA رئيسي (miR-21a-5p) في البلعميات. لتقييم ما إذا كان MBG يمكن أن يؤثر على الآلية المناعية للكيرسيتين، تم إجراء qRT-PCR. أظهرت النتائج أن MBG لم يؤثر على تعبير miR-21a-5p. علاوة على ذلك، فإن مجموعتي الكيرسيتين ومجموعة الكيرسيتين/MBG قد قمعتا بشكل كبير تعبير miR-21a-5p، الذي تم تنظيمه بشكل زائد بواسطة Pg.LPS، بينما لم يكن هناك فرق كبير بين المجموعتين (الملف الإضافي 1: الشكل S6K).

باختصار، يمكن أن يعزز MBG تكوين العظام/الأوعية الدموية دون التأثير على الاستجابة الالتهابية، بينما يمكن أن تعزز إضافة الكيرسيتين تكوين العظام/الأوعية الدموية لخلايا PDLSCs وتمنح خصائص تعديل المناعة لـ MBG (الملف الإضافي 1: الشكل S6L). علاوة على ذلك، أشارت نتائجنا أيضًا إلى أن استخدام MBG

لم تتداخل مع الآلية المناعية للكيرسيتين.

نقاش

المصفوفة خارج الخلوية اللثوية والتمزق المتسارع للأنسجة الداعمة اللثوية الملتهبة. أكدت هذه الدراسة أن الكيرسيتين يمتلك القدرة على استعادة القدرة على التمايز العظمي/الأوعية الدموية بالإضافة إلى تثبيط إنتاج العوامل المؤيدة للالتهابات بما في ذلك IL-6 و TNF-

تعتبر البلعميات مجموعة هامة من خلايا المناعة في تطور التهاب اللثة، حيث تلعب دورًا في البلعمة وتنظيم المناعة. تشير الأدلة الحالية إلى أن نسبة الأنماط الظاهرية المسببة للالتهابات M1 كانت مرتبطة بشكل إيجابي مع تقدم النشاط الالتهابي في اللثة، مما قد يؤدي إلى التهاب مستمر وتلف الأنسجة من خلال إفراز السيتوكينات المسببة للالتهابات، مثل IL-1.

الميكرو RNA، بسبب وظيفته الحاسمة في تعديل الجينات بعد النسخ، كـ RNA داخلي غير مشفر، قد حظي باهتمام كبير في التطبيقات السريرية مثل علاج الالتهابات، وعلاج الأورام، وما إلى ذلك. [52]. وقد أفادت الدراسات أن miR-21 كانت متورطة في التهاب اللثة وأن نقص miR-21 يمكن أن يخفف من تآكل العظم السنخي.

على الرغم من أن تأثير نظام توصيل الكيرسيتين / MBG النانوي على تجديد العظام اللثوية قد تم تقييمه في نموذج عيب العظام السنخية في الجرذان مع التهاب اللثة، إلا أن نماذج القوارض لا يمكن أن تعكس بشكل كامل الوضع الحقيقي للمرض البشري وتلبية احتياجات الترجمة السريرية للمواد الحيوية. لذلك، في الدراسة المستقبلية، نخطط لتقديم حيوانات كبيرة لتقييم التأثير العلاجي لنظام توصيل الكيرسيتين النانوي في تجديد عيوب العظام اللثوية تحت التهاب اللثة.

الخاتمة

محور الإشارات miR-21a-5p/PDCD4/NF-кB وتحسين الميكروبيئة العظمية المناعية عبر البلعميات. وبالتالي، تكشف هذه الدراسة أن نظام التوصيل النانوي القائم على الكيرسيتين يظهر وعدًا كاستراتيجية فعالة لعلاج عيوب العظام السنخية المرتبطة بالتهاب اللثة (الشكل 9).

معلومات إضافية

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات والمواد

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

موافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

تم النشر على الإنترنت: 06 مارس 2024

References

- Kinane DF, Stathopoulou PG, Papapanou PN. Periodontal diseases. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17038.

- Slots J. Periodontitis: facts, fallacies and the future. Periodontol. 2000;2017(75):7-23.

- Gruber R. Osteoimmunology: inflammatory osteolysis and regeneration of the alveolar bone. J Clin Periodontol. 2019;46(Suppl 21):52-69.

- Yang B, Pang X, Li Z, Chen Z, Wang Y. Immunomodulation in the treatment of periodontitis: progress and perspectives. Front Immunol. 2021;12:781378.

- Lin L, Li S, Hu S, Yu W, Jiang B, Mao C, et al. UCHL1 impairs periodontal ligament stem cell osteogenesis in periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2023;102:61-71.

- Zhang Z, Deng M, Hao M, Tang J. Periodontal ligament stem cells in the periodontitis niche: inseparable interactions and mechanisms. J Leukoc Biol. 2021;110:565-76.

- Cui Y, Hong S, Xia Y, Li X, He X, Hu X, et al. Melatonin engineering M2 macrophage-derived exosomes mediate endoplasmic reticulum stress and immune reprogramming for periodontitis therapy. Adv Sci. 2023.

- Metcalfe S, Anselmi N, Escobar A, Visser MB, Kay JG. Innate phagocyte polarization in the oral cavity. Front Immunol. 2021;12:768479.

- Sun X, Gao J, Meng X, Lu X, Zhang L, Chen R. Polarized macrophages in periodontitis: characteristics, function, and molecular signaling. Front Immunol. 2021;12:763334.

- Zhu LF, Li L, Wang XQ, Pan L, Mei YM, Fu YW, et al. M1 macrophages regulate TLR4/AP1 via paracrine to promote alveolar bone destruction in periodontitis. Oral Dis. 2019;25:1972-82.

- Shi J, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Chen R, Wei J, Hou J, et al. Remodeling immune microenvironment in periodontitis using resveratrol liposomes as an antibiotic-free therapeutic strategy. J Nanobiotechnology. 2021;19:429.

- Wang Y, Tao B, Wan Y, Sun Y, Wang L, Sun J, et al. Drug delivery based pharmacological enhancement and current insights of quercetin with therapeutic potential against oral diseases. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;128:110372.

- Zhang W, Jia L, Zhao B, Xiong Y, Wang YN, Liang J, et al. Quercetin reverses TNF-a induced osteogenic damage to human periodontal ligament stem cells by suppressing the NF-kB/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2021;47:39.

- Mooney EC, Holden SE, Xia XJ, Li Y, Jiang M, Banson CN, et al. Quercetin preserves oral cavity health by mitigating inflammation and microbial dysbiosis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:774273.

- Wong SK, Chin KY, Ima-Nirwana S. Quercetin as an agent for protecting the bone: a review of the current evidence. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:6448.

- Zhou Y, Wu Y, Ma W, Jiang X, Takemra A, Uemura M, et al. The effect of quercetin delivery system on osteogenesis and angiogenesis under osteoporotic conditions. J Mater Chem B. 2017;5:612-25.

- Hu Y, Gui Z, Zhou Y, Xia L, Lin K, Xu Y. Quercetin alleviates rat osteoarthritis by inhibiting inflammation and apoptosis of chondrocytes, modulating synovial macrophages polarization to M2 macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;145:146-60.

- Cheng WC, Huang RY, Chiang CY, Chen JK, Liu CH, Chu CL, et al. Ameliorative effect of quercetin on the destruction caused by experimental periodontitis in rats. J Periodontal Res. 2010;45:788-95.

- Kador PF, O’Meara JD, Blessing K, Marx DB, Reinhardt RA. Efficacy of structurally diverse aldose reductase inhibitors on experimental periodontitis in rats. J Periodontol. 2011;82:926-33.

- Napimoga MH, Clemente-Napimoga JT, Macedo CG, Freitas FF, Stipp RN, Pinho-Ribeiro FA, et al. Quercetin inhibits inflammatory bone resorption in a mouse periodontitis model. J Nat Prod. 2013;76:2316-21.

- Arcos D, Portolés MT. Mesoporous bioactive nanoparticles for bone tissue applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:3249.

- Feito MJ, Casarrubios L, Oñaderra M, Gómez-Duro M, Arribas P, PoloMontalvo A, et al. Response of RAW 264.7 and J774A. 1 macrophages to particles and nanoparticles of a mesoporous bioactive glass: a comparative study. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2021;208:112110.

- Gómez-Cerezo N, Casarrubios L, Morales I, Feito MJ, Vallet-Regí M, Arcos D, et al. Effects of a mesoporous bioactive glass on osteoblasts, osteoclasts and macrophages. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2018;528:309-20.

- Shi J, Zhou T, Chen Q. Exploring the expanding universe of small RNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2022;24:415-23.

- Luan X, Zhou X, Fallah P, Pandya M, Lyu H, Foyle D, et al. MicroRNAs: harbingers and shapers of periodontal inflammation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2022;124:85-98.

- Galleggiante V, De Santis S, Liso M, Verna G, Sommella E, Mastronardi M, et al. Quercetin-induced miR-369-3p suppresses chronic inflammatory response targeting C/EBP-

. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2019;63:e1801390. - Zhang Q, Chang B, Zheng G, Du S, Li X. Quercetin stimulates osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells through miRNA-206/connexin 43 pathway. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12:2062-70.

- Wang D, Sun-Waterhouse D, Li F, Xin L, Li D. MicroRNAs as molecular targets of quercetin and its derivatives underlying their biological effects: a preclinical strategy. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019;59:2189-201.

- Vallet-Regí M, Colilla M, Izquierdo-Barba I, Vitale-Brovarone C, Fiorilli S. Achievements in mesoporous bioactive glasses for biomedical applications. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14:2636.

- Gupta S, Majumdar S, Krishnamurthy S. Bioactive glass: a multifunctional delivery system. J Control Release. 2021;335:481-97.

- Chen

, Meng Y, Wang Y, Du C, Yang C. A Biomimetic material with a high bio-responsibility for bone reconstruction and tissue engineering. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2011;22:153-63. - Matsuhashi S, Manirujjaman M, Hamajima H, Ozaki I. Control mechanisms of the tumor suppressor PDCD4: expression and functions. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2304.

- Jing S, Chen H, Liu E, Zhang M, Zeng F, Shen H, et al. Oral pectin/oligochitosan microspheres for colon-specific controlled release of quercetin to treat inflammatory bowel disease. Carbohydr Polym. 2023;316:121025.

- Pan E, Chen H, Wu X, He N, Gan J, Feng H, et al. Protective effect of quercetin on avermectin induced splenic toxicity in carp: resistance to inflammatory response and oxidative damage. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2023;193:105445.

- Adepu S, Ramakrishna S. Controlled drug delivery systems: current status and future directions. Molecules. 2021;26:5905.

- Wei Y, Deng Y, Ma S, Ran M, Jia Y, Meng J, et al. Local drug delivery systems as therapeutic strategies against periodontitis: a systematic review. J Control Release. 2021;333:269-82.

- Casarrubios L, Gómez-Cerezo N, Feito MJ, Vallet-Regí M, Arcos D, Portolés MT. Ipriflavone-loaded mesoporous nanospheres with potential applications for periodontal treatment. Nanomaterials. 2020;10:2573.

- Pan W, Wang Q, Chen Q. The cytokine network involved in the host immune response to periodontitis. Int J Oral Sci. 2019;11:30.

- Han N, Liu Y, Du J, Xu J, Guo L, Liu Y. Regulation of the host immune microenvironment in periodontitis and periodontal bone remodeling. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:3158.

- Queiroz A, Albuquerque-Souza E, Gasparoni LM, de França BN, Pelissari C, Trierveiler M, et al. Therapeutic potential of periodontal ligament stem cells. World J Stem Cells. 2021;13:605-18.

- Wang L, Li X, Song Y, Zhang L, Ye L, Zhou X, et al. NELL1 augments osteogenesis and inhibits inflammation of human periodontal ligament stem cells induced by BMP9. J Periodontol. 2021;93:977-87.

- Plemmenos G, Evangeliou E, Polizogopoulos N, Chalazias A, Deligianni M, Piperi C. Central regulatory role of cytokines in periodontitis and targeting options. Curr Med Chem. 2021;28:3032-58.

- Yin L, Li X, Hou J. Macrophages in periodontitis: a dynamic shift between tissue destruction and repair. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2022;58:336-47.

- Guo X, Wu Z. GABARAP ameliorates IL-1

-induced inflammatory responses and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow-derived stromal cells by activating autophagy. Sci Rep. 2021;11:11561. - Wimalawansa SJ. Nitric oxide and bone. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1192:391-403.

- Liu Y, Fang S, Li X, Feng J, Du J, Guo L, et al. Aspirin inhibits LPS-induced macrophage activation via the NF-kB pathway. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11549.

- Zhao Y, Bai L, Zhang Y, Yao R, Sun Y, Hang R, et al. Type I collagen decorated nanoporous network on titanium implant surface promotes osseointegration through mediating immunomodulation, angiogenesis, and osteogenesis. Biomaterials. 2022;288:121684.

- Ni C, Zhou J, Kong N, Bian T, Zhang Y, Huang X, et al. Gold nanoparticles modulate the crosstalk between macrophages and periodontal ligament cells for periodontitis treatment. Biomaterials. 2019;206:115-32.

- Takeuchi T, Yoshida H, Tanaka S. Role of interleukin-6 in bone destruction and bone repair in rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2021;20:102884.

- Mao CY, Wang YG, Zhang X, Zheng XY, Tang TT, Lu EY. Double-edgedsword effect of IL-1

on the osteogenesis of periodontal ligament stem cells via crosstalk between the NF-kB, MAPK and BMP/Smad signaling pathways. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2296. - Wang S, Xiao L, Prasadam I, Crawford R, Zhou Y, Xiao Y. Inflammatory macrophages interrupt osteocyte maturation and mineralization via regulating the Notch signaling pathway. Mol Med. 2022;28:102.

- Lee SWL, Paoletti C, Campisi M, Osaki T, Adriani G, Kamm RD, et al. MicroRNA delivery through nanoparticles. J Control Release. 2019;313:80-95.

- Chen N, Sui BD, Hu CH, Cao J, Zheng CX, Hou R, et al. microRNA-21 contributes to orthodontic tooth movement. J Dent Res. 2016;95:1425-33.

- Venugopal P, Koshy T, Lavu V, Ranga Rao S, Ramasamy S, Hariharan S, et al. Differential expression of microRNAs let-7a, miR-125b, miR-100, and miR-21 and interaction with NF-kB pathway genes in periodontitis pathogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:5877-84.

- Sirisereephap K, Maekawa T, Tamura H, Hiyoshi T, Domon H, Isono T, et al. Osteoimmunology in periodontitis: local proteins and compounds to alleviate periodontitis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:5540.

- Hu M, Lu Y, Zeng H, Zhang Z, Chen S, Qi Y, et al. MicroRNA-21 maintains hematopoietic stem cell homeostasis through sustaining the NF-kB signaling pathway in mice. Haematologica. 2021;106:412-23.

- Chang WT, Shih JY, Lin YW, Huang TL, Chen ZC, Chen CL, et al. miR-21 upregulation exacerbates pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy in aged hearts. Aging. 2022;14:5925-45.

- Li C, Sun Y, Jiang C, Cao H, Zeng W, Zhang X, et al. Porcine circovirus type 2 infection activates NF-kB pathway and cellular inflammatory responses through circPDCD4/miR-21/PDCD4 axis in porcine kidney 15 cell. Virus Res. 2021;298:198385.

- Gui Q, Lyons DJ, Deeb JG, Belvin BR, Hoffman PS, Lewis JP. Non-human primate macaca mulatta as an animal model for testing efficacy of amixicile as a targeted anti-periodontitis therapy. Front Oral Health. 2021;2:752929.

ملاحظة الناشر

ساهم شي-يوان يانغ ويوه هو بالتساوي في هذا العمل.

*المراسلة:

كاي-لي لين

linkaili@sjtu.edu.cn; Iklecnu@aliyun.com

يوان-جين شو

drxuyuanjin@126.com

القائمة الكاملة لمعلومات المؤلف متاحة في نهاية المقالة- (انظر الشكل في الصفحة التالية.)

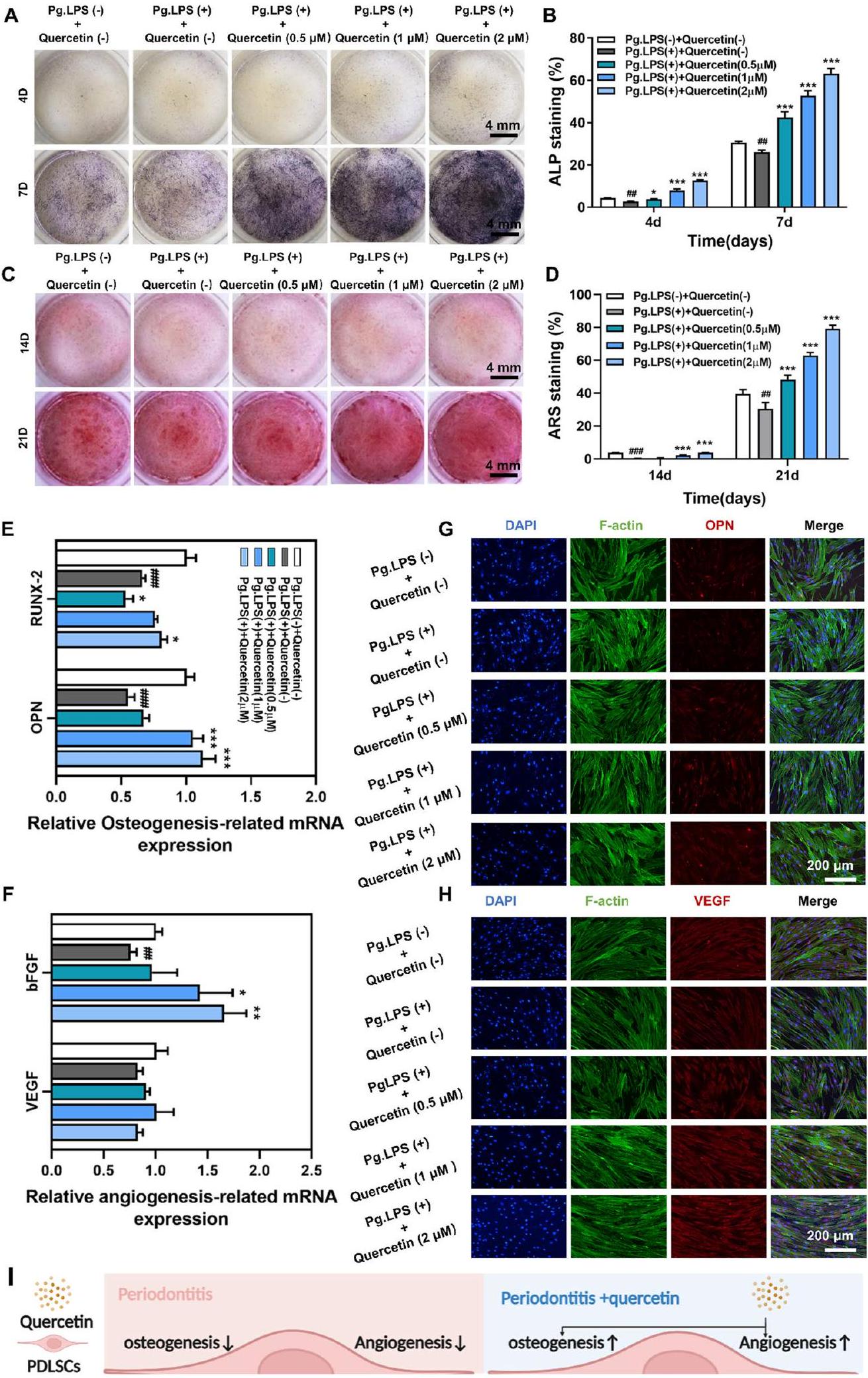

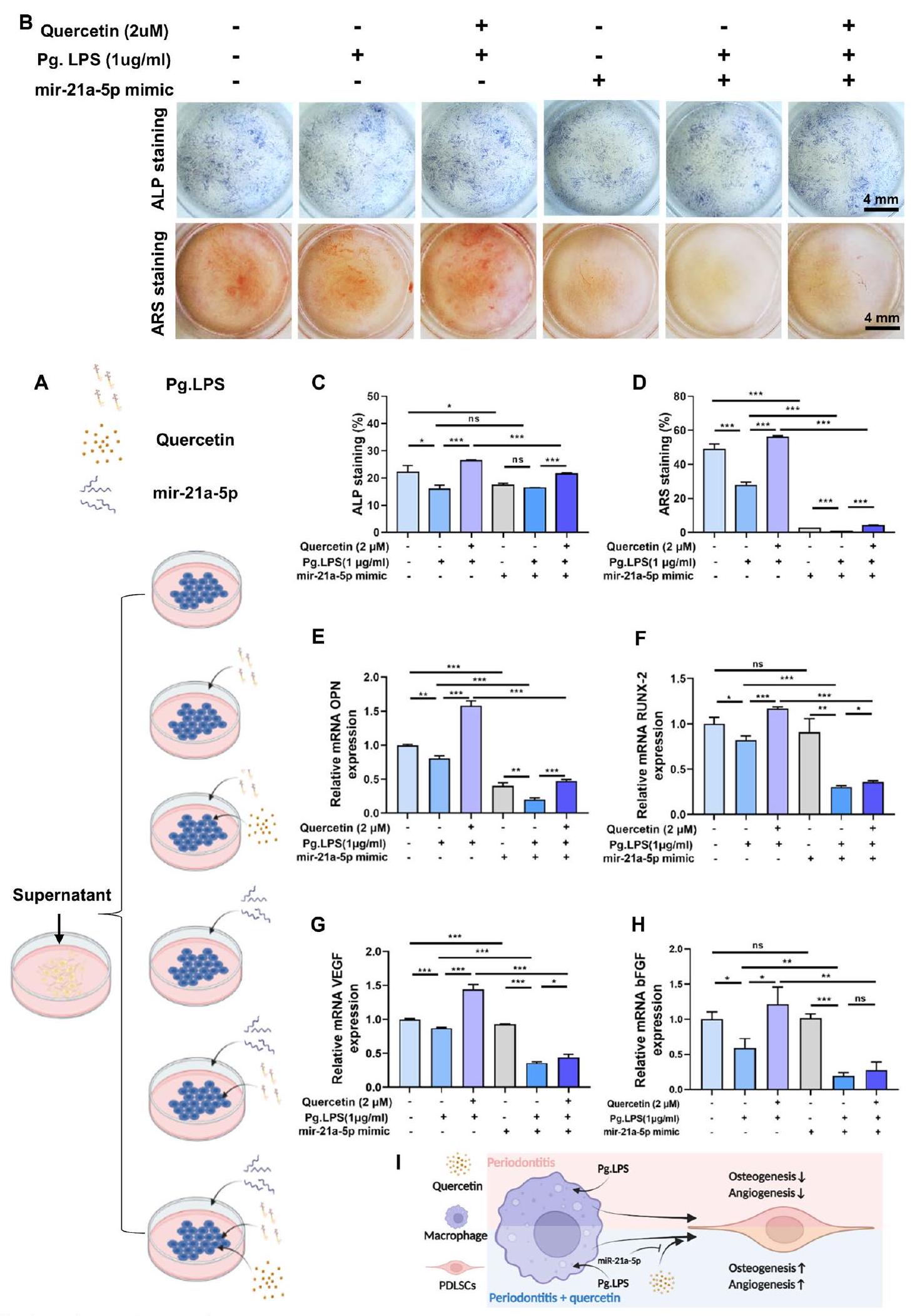

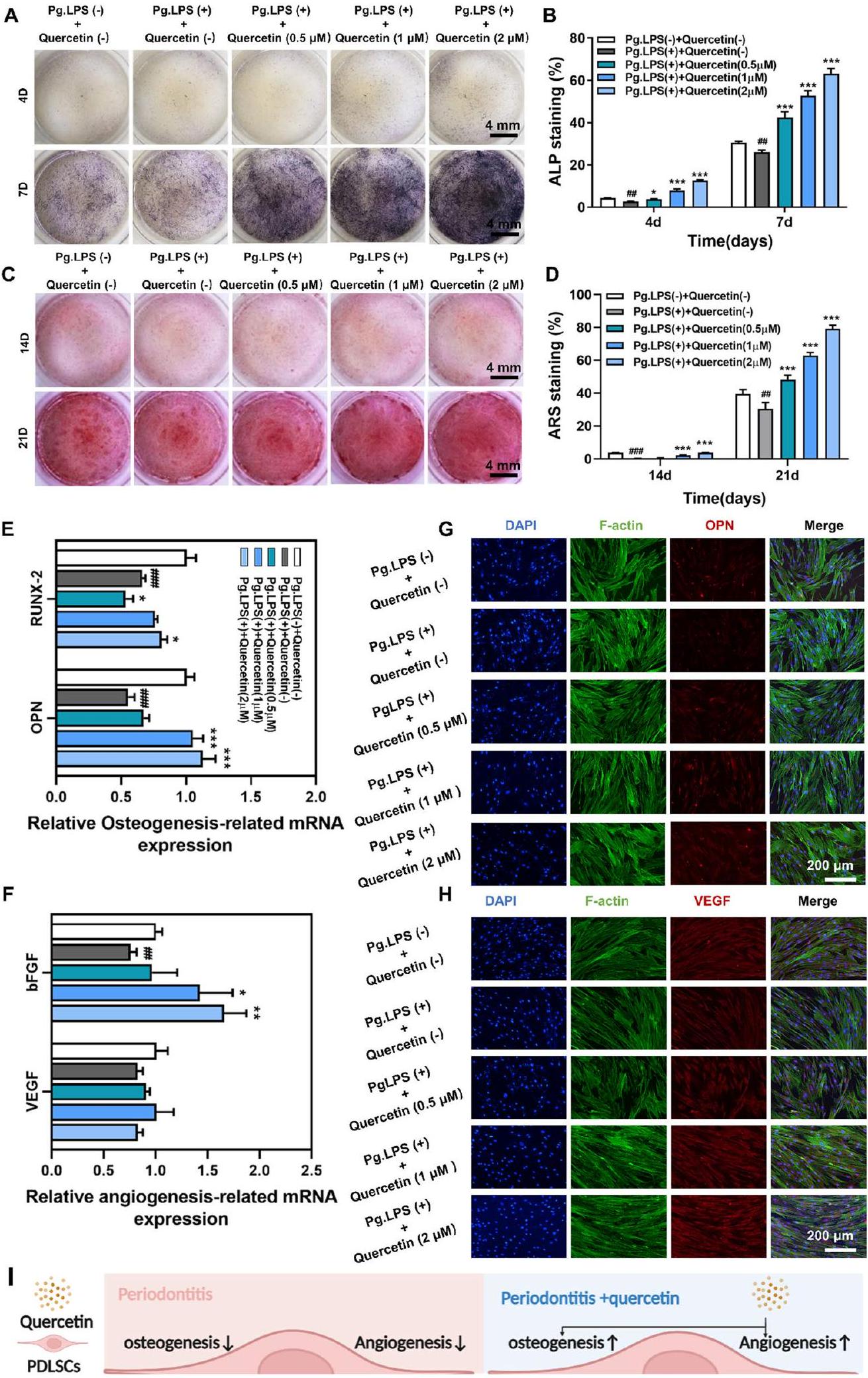

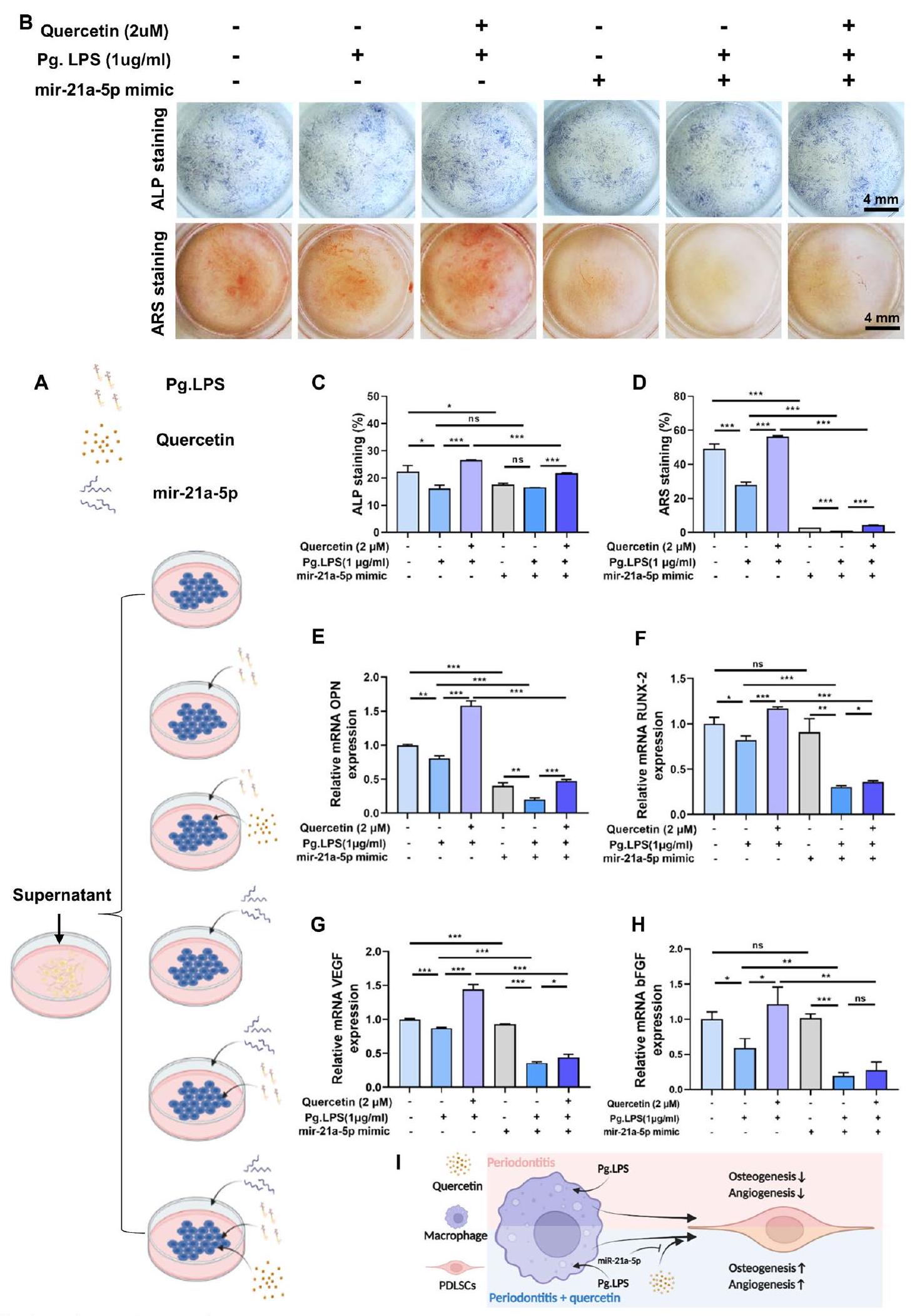

الشكل 3 أظهر الكيرسيتين تأثيرات إيجابية على تكوين العظام/تكوين الأوعية ومضاد للالتهابات في خلايا PDLSCs تحت بيئة التهاب اللثة. أ، ب تلوين ALP ونتائجه الكمية بعد حضانة PDLSCs مع الكيرسيتين لمدة 4 و7 أيام تحت بيئة التهاب اللثة. ج، د تلوين ARS ونتائجه الكمية بعد حضانة PDLSCs مع الكيرسيتين لمدة 14 و21 يومًا تحت بيئة التهاب اللثة. هـ-ز تأثير الكيرسيتين على التعبير عن الجينات المرتبطة بتكوين العظام (OPN وRUNX-2) والجينات المرتبطة بتكوين الأوعية (VEGF وbFGF) في PDLSCs من خلال qRT-PCR. ح تأثير الكيرسيتين على التعبير عن البروتين المرتبط بتكوين العظام (OPN) والبروتين المرتبط بتكوين الأوعية (VEGF) في PDLSCs من خلال تلوين المناعية الفلورية. ط مخطط آلية عمل الكيرسيتين على PDLSCs تحت بيئة التهاب اللثة. (”و مقارنة بمجموعة Pg.LPS (-) + الكيرسيتين (-) ، و مقارنة بمجموعة Pg.LPS (+) + الكيرسيتين (-)؛ البيانات ممثلة كمتوسط SEM، ) - (انظر الشكل في الصفحة التالية.)

الشكل 7 أظهر الكيرسيتين تأثيرات غير مباشرة إيجابية على تكوين العظام/تكوين الأوعية عبر miR-21a-5p. أ توضيح تخطيطي لتجربة الزراعة المشتركة. ب-د تلوين ALP، تلوين ARS ونتائجها الكمية لـ PDLSCs المزروعة مع CM المجمعة من البلعميات لمدة 7 و21 يومًا. هـ-ح التعبير عن الجينات المرتبطة بتكوين العظام (OPN وRUNX-2) والجينات المرتبطة بتكوين الأوعية (VEGF وbFGF) في PDLSCs المزروعة مع CM المجمعة من البلعميات من خلال qRT-PCR. ط مخطط آلية عمل الكيرسيتين وmiR-21a-5p على تعديل المناعة العظمية بين البلعميات وPDLSCs تحت بيئة التهاب اللثة. (ns، لا يوجد فرق ذو دلالة؛و ؛ البيانات ممثلة كمتوسط SEM، )

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-024-02352-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38449005

Publication Date: 2024-03-06

Check for updates

Quercetin-loaded mesoporous nano-delivery system remodels osteoimmune microenvironment to regenerate alveolar bone in periodontitis via the miR-21a-5p/PDCD4/ NF-кB pathway

Abstract

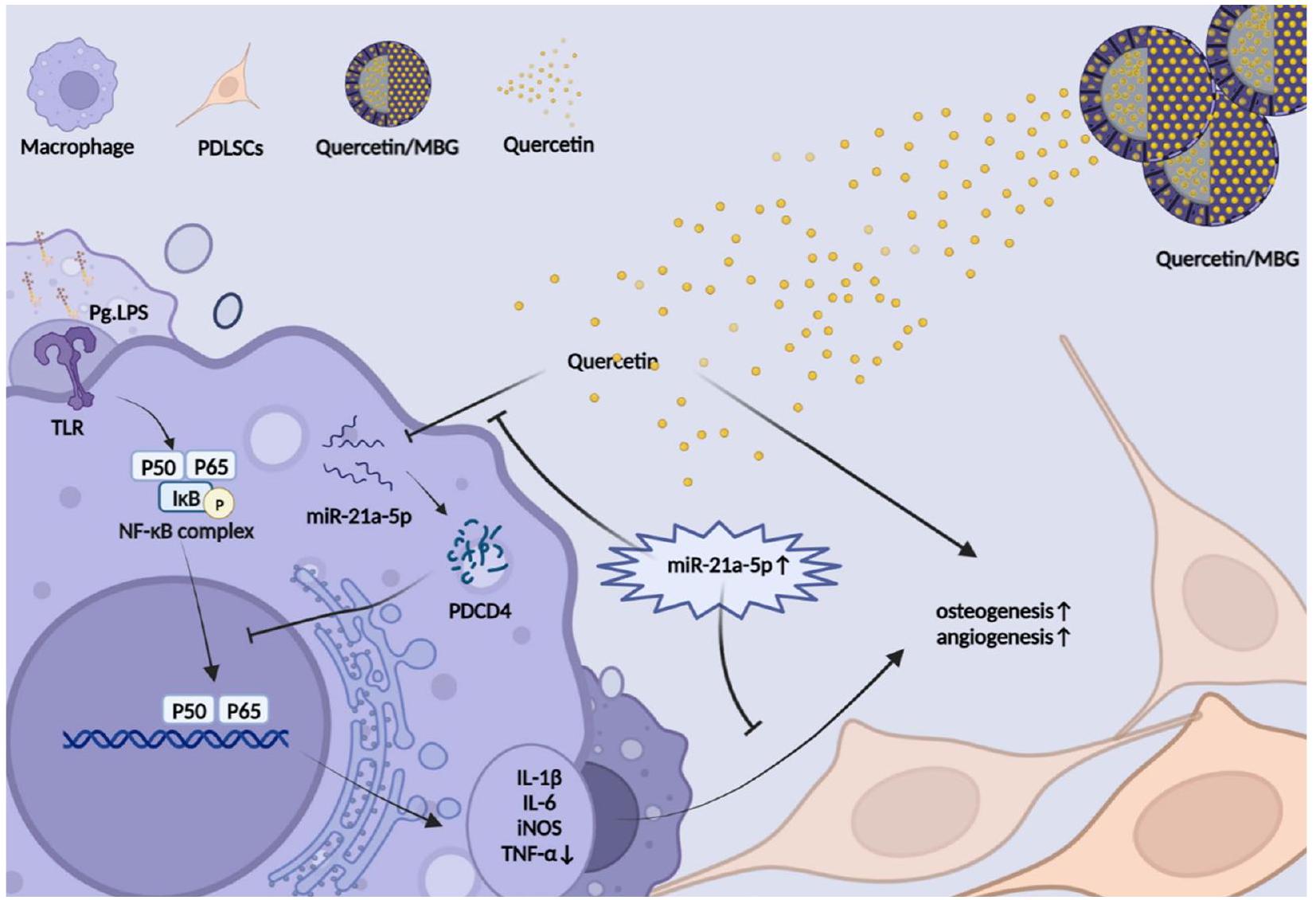

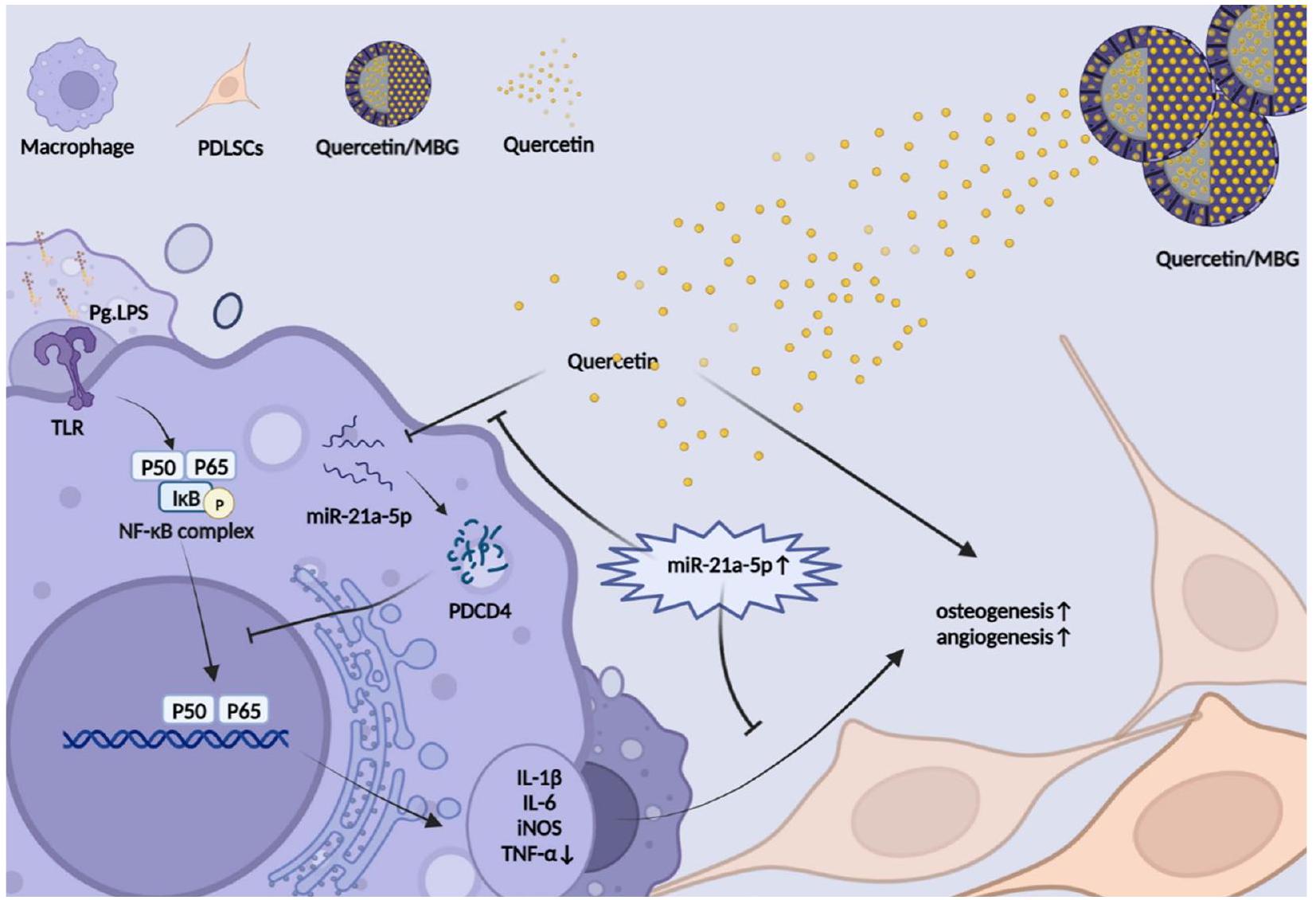

Background Impaired osteo-/angiogenesis, excessive inflammation, and imbalance of the osteoimmune homeostasis are involved in the pathogenesis of the alveolar bone defect caused by periodontitis. Unfortunately, there is still a lack of ideal therapeutic strategies for periodontitis that can regenerate the alveolar bone while remodeling the osteoimmune microenvironment. Quercetin, as a monomeric flavonoid, has multiple pharmacological activities, such as pro-regenerative, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory effects. Despite its vast spectrum of pharmacological activities, quercetin’s clinical application is limited due to its poor water solubility and low bioavailability. Results In this study, we fabricated a quercetin-loaded mesoporous bioactive glass (Quercetin/MBG) nano-delivery system with the function of continuously releasing quercetin, which could better promote the bone regeneration and regulate the immune microenvironment in the alveolar bone defect with periodontitis compared to pure MBG treatment. In particular, this nano-delivery system effectively decreased injection frequency of quercetin while yielding favorable therapeutic results. In view of the above excellent therapeutic effects achieved by the sustained release of quercetin, we further investigated its therapeutic mechanisms. Our findings indicated that under the periodontitis microenvironment, the intervention of quercetin could restore the osteo-/angiogenic capacity of periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs), induce immune regulation of macrophages and exert an osteoimmunomodulatory effect. Furthermore, we also found that the above osteoimmunomodulatory effects of quercetin via macrophages could be partially blocked by the overexpression of a key microRNA——miR-21a-5p, which worked through inhibiting the expression of PDCD4 and activating the NF-kB signaling pathway. Conclusion In summary, our study shows that quercetin-loaded mesoporous nano-delivery system has the potential to be a therapeutic approach for reconstructing alveolar bone defects in periodontitis. Furthermore, it also offers

Keywords Periodontitis, Quercetin, Alveolar bone regeneration, Osteoimmunomodulation, Mesoporous bioactive glass

Graphical Abstract

Background

PDLSCs, a type of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), are closely associated with alveolar bone repair, which have promising potential in the field of periodontal regeneration [5]. The osteo-/angiogenesis of PDLSCs could be hindered by the chronic inflammation in periodontitis, leading to periodontal regeneration disorder [6]. As a key immune cell in the development of periodontitis,

macrophages contribute significantly to osteoimmune homeostasis [7]. Generally, macrophages are typically classified into two phenotypes based on their activation status and function: the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype and the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype. During the initial phase of the inflammatory response in periodontitis, the activation of M1 phenotype is beneficial for tissue defense, but if this state persists beyond this period, it would lead to irreversible destruction of periodontal tissue [8]. Excessive M1 polarization of macrophages, as observed in periodontitis-related studies, worsened local immune disorders and led to destruction of periodontal tissue, while also further weakening the already delicate osteo-/angiogenesis capacity of PDLSCs and thereby exacerbating the osteoimmune microenvironment imbalance [9-11]. Therefore, restoring osteo-/angiogenic differentiation of PDLSCs and remodeling osteoimmune homeostasis via macrophages were cytologically critical for repairing alveolar bone defects in periodontitis.

However,as a monomeric small molecule drug,querce- tin's poor water solubility and low bioavailability limit its clinical use[12].Thus,it is essential to create an effective drug delivery system that can sustain stable and suitable concentrations of quercetin in targeted tissues for clini- cal use.Recently,MBG nanoparticles are being consid- ered as potential drug carriers for bone defect sites,due to their high porosity,specific surface area,and strong ability to stimulate bone tissue regeneration[21].Fur- thermore,researches indicated that when MBG was uti- lized as a drug delivery system for bone repair,it did not elicit an unfavorable immune response in macrophages [22,23].Hence,it is assumed that the Quercetin/MBG nano-delivery system may have potential application in the treatment of alveolar bone defects in periodontitis.

MicroRNAs(miRNAs)are a class of evolutionarily conserved non-coding small RNAs that regulate gene expression at the translational level[24].In recent years, many studies have reported a close relationship between periodontitis and miRNAs,such as miR-21、miR-144、miR-146a、miR-128 and etc.[25].Furthermore,it has been reported that quercetin can induce various miRNAs to promote osteogenic differentiation as well as modulate the immune response[26-28].Therefore,it is hypothe- sized that miRNAs play a pivotal role in the osteoimmu- noregulatory effects of quercetin on periodontitis.

We confirmed that the Quercetin/MBG nano-deliv- ery system consistently released quercetin and resulted in better alveolar bone regeneration and osteoimmune microenvironment remodeling compared to pure MBG. Then,we investigated the cytological mechanism by which quercetin intervened in regenerating alveolar bone under the periodontitis microenvironment.We observed that quercetin not only restored the osteo-/ angiogenic capacity of PDLSCs,but also reprogrammed macrophages through the miR-21a-5p/PDCD4/NF-кВ pathway thereby remodeling the osteoimmune micro- environment.In summary,this study suggests that the quercetin-loaded mesoporous nano-delivery system holds potential as a clinical therapy for repairing alveo- lar bone defects in periodontitis.Moreover,manipulating miR-21a-5p in macrophages to remodel the periodontal osteoimmune microenvironment offers a novel thera- peutic strategy for rebuilding the alveolar bone in periodontitis.

Results

Quercetin sustained-release system strengthened alveolar bone regeneration and relieved local inflammation in a rat alveolar bone defect model with periodontitis

Fig. 2 Quercetin sustained-release system strengthened alveolar bone regeneration and relieved local inflammation in a rat alveolar bone defect model with periodontitis. A Scheme illustration of the experimental design used for the animal study. B Micro-CT reconstruction images of the alveolar bone tissue. C Quantitative analysis of the newly formed alveolar bone tissue. D Immunofluorescence staining of iNOS in samples collected in 1 week. E Immunofluorescence staining of CD31 and OPN in samples collected in 8 weeks. F Quantitative analysis of the mean fluorescence intensity of iNOS, CD31and OPN according to the immunostaining patterns shown in (D and E). (ns, no significant difference;

In conclusion, our findings suggested that quercetin could effectively promote bone regeneration in areas of periodontal alveolar bone defects while controlling periodontal inflammation. We then investigated the underlying mechanism by which quercetin promoted alveolar bone regeneration and regulated inflammation in the periodontitis microenvironment.

Quercetin performed pro-osteo-/angiogenesis and anti-inflammation of PDLSCs under periodontitis microenvironment

file 1: Fig. S2C). Based on these findings, we selected quercetin concentrations of

Quercetin performed anti-inflammation of macrophages under periodontitis microenvironment

(IL-6), iNOS and Tumor necrosis factor-

Anti-inflammatory mechanism of quercetin on macrophages under periodontitis microenvironment Quercetin hindered the inflammatory reaction in Pg.LPS -stimulated macrophages through decreasing the expression of miR-21a-5p

Firstly, we effectively upregulated and downregulated the levels of miR-21a-5p in RAW264.7 cells using miR-21a-5p mimic, inhibitor, and their negative control (NC) (Additional file 1: Fig. S5C). miR-21a-5p mimic yielded significantly increased levels of pro-inflammatory markers, including IL-1

tests. These findings suggest that the overexpression of miR-21a-5p could strengthen the inflammatory response of macrophages. To investigate miR-21a-5p’s role further, we transfected RAW264.7 cells with miR-21a-5p mimic. As shown in Fig. 5H, I, the transfection of miR-21a-5p mimic significantly increased the expression of p-P65 in the nucleus, resulting in the activation of the NF-кB signaling pathway.

PDCD4 was a downstream target of miR-21a-5p and further regulated inflammatory responses of macrophages through the NF-кB signaling pathway

Quercetin performed indirect pro-osteo-/angiogenic effects via miR-21a-5p

Quercetin provided the protective effect in periodontitis via miR-21a-5p

In vitro evaluation of MBG’s influence on quercetin’s biological effects

The study above demonstrated that quercetin exerted immunomodulatory effects through a key miRNA (miR-21a-5p) in macrophages. To evaluate whether MBG could affect the immunomodulatory mechanism of quercetin, qRT-PCR was performed. The result indicatde that MBG did not affect the expression of miR -21a-5p. Moreover, both the Quercetin and the Quercetin/MBG groups significantly suppressed the expression of miR-21a-5p, which was up-regulated by Pg.LPS, while there was no significant difference between the two groups (Additional file 1: Fig. S6K).

In summary, MBG could promote osteo-/angiogenesis without affecting the inflammatory response, while the addition of quercetin could further enhance osteo-/ angiogenesis of PDLSCs and confer immunomodulatory properties to MBG (Additional file 1: Fig. S6L). Furthermore, our findings also indicated that the use of MBG

did not interfere the immunomodulatory mechanism of quercetin.

Discussion

of periodontal extracellular matrix and the accelerated rupture of inflamed periodontal supporting tissues [42]. This study affirmed that quercetin possessed the ability to restore osteo-/angiogenic differentiation capacity as well as inhibit the pro-inflammatory factors’ production including IL-6 and TNF-

Macrophages are an important subset of immune cells in the development of periodontitis, which play roles in phagocytosis and immune regulation. Current evidence suggested that the proportion of pro-inflammatory M1 phenotypes was positively correlated with the progression of periodontal inflammatory activity, which could lead to sustained inflammation and tissue damage through the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1

miRNA, due to its critical function in post-transcriptional gene modification, as a non-coding endogenous RNA, has gained tremendous attention in clinical applications such as inflammation therapy, tumor treatment etc. [52]. Studies have reported that miR-21 were involved in the periodontitis and the deficiency of miR-21 could alleviate alveolar bone

Although the effect of Quercetin /MBG nano-delivery system on periodontal bone regeneration has been evaluated in a rat alveolar bone defect model with periodontitis, rodent models cannot fully reflect the real human disease situation and meet the needs of clinical translation of biomaterials [59]. Therefore, in the future study, we plan to introduce large animals to further evaluate the therapeutic effect of the quercetin nano-delivery system in regenerating periodontal bone defects under periodontitis.

Conclusion

miR-21a-5p/PDCD4/NF-кB signaling axis and optimize the osteoimmune microenvironment via macrophages. Thus, this study reveals that nano-delivery system based on quercetin shows promise as an effective strategy for the treatment of alveolar bone defects with periodontitis (Fig. 9).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Author details

Published online: 06 March 2024

References

- Kinane DF, Stathopoulou PG, Papapanou PN. Periodontal diseases. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17038.

- Slots J. Periodontitis: facts, fallacies and the future. Periodontol. 2000;2017(75):7-23.

- Gruber R. Osteoimmunology: inflammatory osteolysis and regeneration of the alveolar bone. J Clin Periodontol. 2019;46(Suppl 21):52-69.

- Yang B, Pang X, Li Z, Chen Z, Wang Y. Immunomodulation in the treatment of periodontitis: progress and perspectives. Front Immunol. 2021;12:781378.

- Lin L, Li S, Hu S, Yu W, Jiang B, Mao C, et al. UCHL1 impairs periodontal ligament stem cell osteogenesis in periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2023;102:61-71.

- Zhang Z, Deng M, Hao M, Tang J. Periodontal ligament stem cells in the periodontitis niche: inseparable interactions and mechanisms. J Leukoc Biol. 2021;110:565-76.

- Cui Y, Hong S, Xia Y, Li X, He X, Hu X, et al. Melatonin engineering M2 macrophage-derived exosomes mediate endoplasmic reticulum stress and immune reprogramming for periodontitis therapy. Adv Sci. 2023.

- Metcalfe S, Anselmi N, Escobar A, Visser MB, Kay JG. Innate phagocyte polarization in the oral cavity. Front Immunol. 2021;12:768479.

- Sun X, Gao J, Meng X, Lu X, Zhang L, Chen R. Polarized macrophages in periodontitis: characteristics, function, and molecular signaling. Front Immunol. 2021;12:763334.

- Zhu LF, Li L, Wang XQ, Pan L, Mei YM, Fu YW, et al. M1 macrophages regulate TLR4/AP1 via paracrine to promote alveolar bone destruction in periodontitis. Oral Dis. 2019;25:1972-82.

- Shi J, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Chen R, Wei J, Hou J, et al. Remodeling immune microenvironment in periodontitis using resveratrol liposomes as an antibiotic-free therapeutic strategy. J Nanobiotechnology. 2021;19:429.

- Wang Y, Tao B, Wan Y, Sun Y, Wang L, Sun J, et al. Drug delivery based pharmacological enhancement and current insights of quercetin with therapeutic potential against oral diseases. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;128:110372.

- Zhang W, Jia L, Zhao B, Xiong Y, Wang YN, Liang J, et al. Quercetin reverses TNF-a induced osteogenic damage to human periodontal ligament stem cells by suppressing the NF-kB/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2021;47:39.

- Mooney EC, Holden SE, Xia XJ, Li Y, Jiang M, Banson CN, et al. Quercetin preserves oral cavity health by mitigating inflammation and microbial dysbiosis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:774273.

- Wong SK, Chin KY, Ima-Nirwana S. Quercetin as an agent for protecting the bone: a review of the current evidence. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:6448.

- Zhou Y, Wu Y, Ma W, Jiang X, Takemra A, Uemura M, et al. The effect of quercetin delivery system on osteogenesis and angiogenesis under osteoporotic conditions. J Mater Chem B. 2017;5:612-25.

- Hu Y, Gui Z, Zhou Y, Xia L, Lin K, Xu Y. Quercetin alleviates rat osteoarthritis by inhibiting inflammation and apoptosis of chondrocytes, modulating synovial macrophages polarization to M2 macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;145:146-60.

- Cheng WC, Huang RY, Chiang CY, Chen JK, Liu CH, Chu CL, et al. Ameliorative effect of quercetin on the destruction caused by experimental periodontitis in rats. J Periodontal Res. 2010;45:788-95.

- Kador PF, O’Meara JD, Blessing K, Marx DB, Reinhardt RA. Efficacy of structurally diverse aldose reductase inhibitors on experimental periodontitis in rats. J Periodontol. 2011;82:926-33.

- Napimoga MH, Clemente-Napimoga JT, Macedo CG, Freitas FF, Stipp RN, Pinho-Ribeiro FA, et al. Quercetin inhibits inflammatory bone resorption in a mouse periodontitis model. J Nat Prod. 2013;76:2316-21.

- Arcos D, Portolés MT. Mesoporous bioactive nanoparticles for bone tissue applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:3249.

- Feito MJ, Casarrubios L, Oñaderra M, Gómez-Duro M, Arribas P, PoloMontalvo A, et al. Response of RAW 264.7 and J774A. 1 macrophages to particles and nanoparticles of a mesoporous bioactive glass: a comparative study. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2021;208:112110.

- Gómez-Cerezo N, Casarrubios L, Morales I, Feito MJ, Vallet-Regí M, Arcos D, et al. Effects of a mesoporous bioactive glass on osteoblasts, osteoclasts and macrophages. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2018;528:309-20.

- Shi J, Zhou T, Chen Q. Exploring the expanding universe of small RNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2022;24:415-23.

- Luan X, Zhou X, Fallah P, Pandya M, Lyu H, Foyle D, et al. MicroRNAs: harbingers and shapers of periodontal inflammation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2022;124:85-98.

- Galleggiante V, De Santis S, Liso M, Verna G, Sommella E, Mastronardi M, et al. Quercetin-induced miR-369-3p suppresses chronic inflammatory response targeting C/EBP-

. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2019;63:e1801390. - Zhang Q, Chang B, Zheng G, Du S, Li X. Quercetin stimulates osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells through miRNA-206/connexin 43 pathway. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12:2062-70.

- Wang D, Sun-Waterhouse D, Li F, Xin L, Li D. MicroRNAs as molecular targets of quercetin and its derivatives underlying their biological effects: a preclinical strategy. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019;59:2189-201.

- Vallet-Regí M, Colilla M, Izquierdo-Barba I, Vitale-Brovarone C, Fiorilli S. Achievements in mesoporous bioactive glasses for biomedical applications. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14:2636.

- Gupta S, Majumdar S, Krishnamurthy S. Bioactive glass: a multifunctional delivery system. J Control Release. 2021;335:481-97.

- Chen

, Meng Y, Wang Y, Du C, Yang C. A Biomimetic material with a high bio-responsibility for bone reconstruction and tissue engineering. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2011;22:153-63. - Matsuhashi S, Manirujjaman M, Hamajima H, Ozaki I. Control mechanisms of the tumor suppressor PDCD4: expression and functions. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2304.

- Jing S, Chen H, Liu E, Zhang M, Zeng F, Shen H, et al. Oral pectin/oligochitosan microspheres for colon-specific controlled release of quercetin to treat inflammatory bowel disease. Carbohydr Polym. 2023;316:121025.

- Pan E, Chen H, Wu X, He N, Gan J, Feng H, et al. Protective effect of quercetin on avermectin induced splenic toxicity in carp: resistance to inflammatory response and oxidative damage. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2023;193:105445.

- Adepu S, Ramakrishna S. Controlled drug delivery systems: current status and future directions. Molecules. 2021;26:5905.

- Wei Y, Deng Y, Ma S, Ran M, Jia Y, Meng J, et al. Local drug delivery systems as therapeutic strategies against periodontitis: a systematic review. J Control Release. 2021;333:269-82.

- Casarrubios L, Gómez-Cerezo N, Feito MJ, Vallet-Regí M, Arcos D, Portolés MT. Ipriflavone-loaded mesoporous nanospheres with potential applications for periodontal treatment. Nanomaterials. 2020;10:2573.

- Pan W, Wang Q, Chen Q. The cytokine network involved in the host immune response to periodontitis. Int J Oral Sci. 2019;11:30.

- Han N, Liu Y, Du J, Xu J, Guo L, Liu Y. Regulation of the host immune microenvironment in periodontitis and periodontal bone remodeling. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:3158.

- Queiroz A, Albuquerque-Souza E, Gasparoni LM, de França BN, Pelissari C, Trierveiler M, et al. Therapeutic potential of periodontal ligament stem cells. World J Stem Cells. 2021;13:605-18.

- Wang L, Li X, Song Y, Zhang L, Ye L, Zhou X, et al. NELL1 augments osteogenesis and inhibits inflammation of human periodontal ligament stem cells induced by BMP9. J Periodontol. 2021;93:977-87.

- Plemmenos G, Evangeliou E, Polizogopoulos N, Chalazias A, Deligianni M, Piperi C. Central regulatory role of cytokines in periodontitis and targeting options. Curr Med Chem. 2021;28:3032-58.

- Yin L, Li X, Hou J. Macrophages in periodontitis: a dynamic shift between tissue destruction and repair. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2022;58:336-47.

- Guo X, Wu Z. GABARAP ameliorates IL-1

-induced inflammatory responses and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow-derived stromal cells by activating autophagy. Sci Rep. 2021;11:11561. - Wimalawansa SJ. Nitric oxide and bone. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1192:391-403.

- Liu Y, Fang S, Li X, Feng J, Du J, Guo L, et al. Aspirin inhibits LPS-induced macrophage activation via the NF-kB pathway. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11549.

- Zhao Y, Bai L, Zhang Y, Yao R, Sun Y, Hang R, et al. Type I collagen decorated nanoporous network on titanium implant surface promotes osseointegration through mediating immunomodulation, angiogenesis, and osteogenesis. Biomaterials. 2022;288:121684.

- Ni C, Zhou J, Kong N, Bian T, Zhang Y, Huang X, et al. Gold nanoparticles modulate the crosstalk between macrophages and periodontal ligament cells for periodontitis treatment. Biomaterials. 2019;206:115-32.

- Takeuchi T, Yoshida H, Tanaka S. Role of interleukin-6 in bone destruction and bone repair in rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2021;20:102884.

- Mao CY, Wang YG, Zhang X, Zheng XY, Tang TT, Lu EY. Double-edgedsword effect of IL-1

on the osteogenesis of periodontal ligament stem cells via crosstalk between the NF-kB, MAPK and BMP/Smad signaling pathways. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2296. - Wang S, Xiao L, Prasadam I, Crawford R, Zhou Y, Xiao Y. Inflammatory macrophages interrupt osteocyte maturation and mineralization via regulating the Notch signaling pathway. Mol Med. 2022;28:102.

- Lee SWL, Paoletti C, Campisi M, Osaki T, Adriani G, Kamm RD, et al. MicroRNA delivery through nanoparticles. J Control Release. 2019;313:80-95.

- Chen N, Sui BD, Hu CH, Cao J, Zheng CX, Hou R, et al. microRNA-21 contributes to orthodontic tooth movement. J Dent Res. 2016;95:1425-33.

- Venugopal P, Koshy T, Lavu V, Ranga Rao S, Ramasamy S, Hariharan S, et al. Differential expression of microRNAs let-7a, miR-125b, miR-100, and miR-21 and interaction with NF-kB pathway genes in periodontitis pathogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:5877-84.

- Sirisereephap K, Maekawa T, Tamura H, Hiyoshi T, Domon H, Isono T, et al. Osteoimmunology in periodontitis: local proteins and compounds to alleviate periodontitis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:5540.

- Hu M, Lu Y, Zeng H, Zhang Z, Chen S, Qi Y, et al. MicroRNA-21 maintains hematopoietic stem cell homeostasis through sustaining the NF-kB signaling pathway in mice. Haematologica. 2021;106:412-23.

- Chang WT, Shih JY, Lin YW, Huang TL, Chen ZC, Chen CL, et al. miR-21 upregulation exacerbates pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy in aged hearts. Aging. 2022;14:5925-45.

- Li C, Sun Y, Jiang C, Cao H, Zeng W, Zhang X, et al. Porcine circovirus type 2 infection activates NF-kB pathway and cellular inflammatory responses through circPDCD4/miR-21/PDCD4 axis in porcine kidney 15 cell. Virus Res. 2021;298:198385.

- Gui Q, Lyons DJ, Deeb JG, Belvin BR, Hoffman PS, Lewis JP. Non-human primate macaca mulatta as an animal model for testing efficacy of amixicile as a targeted anti-periodontitis therapy. Front Oral Health. 2021;2:752929.

Publisher’s Note

Shi-Yuan Yang and Yue Hu are contributed equally to this work.

*Correspondence:

Kai-Li Lin

linkaili@sjtu.edu.cn; Iklecnu@aliyun.com

Yuan-Jin Xu

drxuyuanjin@126.com

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article- (See figure on next page.)

Fig. 3 Quercetin performed pro-osteo-/angiogenesis and anti-inflammation of PDLSCs under periodontitis microenvironment. A, B ALP staining and its quantitative results after incubation of PDLSCs with quercetin for 4 and 7 days under periodontitis microenvironment. C, D ARS staining and its quantitative results after incubation of PDLSCs with quercetin for 14 and 21 days under periodontitis microenvironment. E-G Effect of quercetin on the expression of osteogenic-related genes (OPN and RUNX-2) and angiogenic-related genes (VEGF and bFGF) of PDLSCs through qRT-PCR. H Effect of quercetin on the expression of osteogenic-related protein (OPN) and angiogenic-related protein (VEGF) of PDLSCs through immunofluorescence staining. I Schematic of the pharmacological mechanism of quercetin on PDLSCs under periodontitis microenvironment. (”and compared to Pg.LPS (-) + Quercetin (-) group, and compared to Pg.LPS (+) + Quercetin (-) group; Data are represented as the mean SEM, ) - (See figure on next page.)

Fig. 7 Quercetin performed indirect pro-osteo-/angiogenic effects via miR-21a-5p. A Schematic illustration of the co-culture experiment. B-D ALP staining, ARS staining and their quantitative results of PDLSCs cultured with the CM collected from macrophages for 7 and 21 days. E-H The expression of osteogenic-related (OPN and RUNX-2) and angiogenic-related (VEGF and bFGF) genes of PDLSCs cultured with the CM collected from macrophages through qRT-PCR. I Schematic of the pharmacological mechanism of quercetin and miR-21a-5p on osteoimmunomodulation between macrophages and PDLSCs under periodontitis microenvironment. (ns, no significant difference;and ; Data are represented as the mean SEM, )