DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-024-09909-7

تاريخ النشر: 2024-08-02

مقالة مراجعة

نظرية التحكم والقيمة: من عواطف الإنجاز إلى نظرية عامة للعواطف الإنسانية

© المؤلفون 2024

الملخص

في نسختها الأصلية، تصف نظرية التحكم والقيمة وتفسر عواطف الإنجاز. مؤخرًا، تم توسيع النظرية لتفسر أيضًا العواطف المعرفية والاجتماعية والوجودية. في هذه المقالة، أستعرض تطور النظرية، من الأعمال الأولية في الثمانينيات إلى النسخ المبكرة من النظرية والنظرية العامة الحديثة للتحكم والقيمة. أقدم ملخصات لمقترحات النظرية المستندة إلى الأدلة حول المقدمات والنتائج وتنظيم العواطف، بما في ذلك الدور المهم بشكل أساسي لتقييمات التحكم والقيمة عبر أنواع مختلفة من العواطف البشرية ذات الصلة بالتعليم (وما بعده). تشمل النظرية تصنيفات وصفية للعواطف بالإضافة إلى مقترحات تفسر (أ) تأثير العوامل الفردية والبيئات الاجتماعية والسياقات الثقافية الاجتماعية على العواطف؛ (ب) آثار العواطف على التعلم والأداء والصحة؛ (ج) السببية المتبادلة التي تربط العواطف والنتائج والمقدمات؛ (د) طرق تنظيم العواطف؛ و (هـ) استراتيجيات التدخل. بعد ذلك، أستعرض أهمية النظرية للممارسة التعليمية، بما في ذلك التقييمات الفردية والواسعة النطاق للعواطف؛ وفهم الطلاب والمعلمين والآباء للعواطف؛ وتغيير الممارسات التعليمية. في الختام، أناقش نقاط القوة في النظرية، والأسئلة المفتوحة، والاتجاهات المستقبلية.

| 1984، 1992 | 2000، 2006 | 2021، 2023 | |||

| تصنيف العواطف | التركيز على القلق |  |

ثنائي الأبعاد (تركيز الكائن × القيمة) |  |

ثلاثي الأبعاد (تركيز الكائن × القيمة × الإثارة) |

| المقدمات | نظرية القيمة المتوقعة للقلق |  |

نظرية التحكم والقيمة لعواطف الإنجاز |  |

نظرية التحكم والقيمة العامة: الإنجاز، العواطف المعرفية، الاجتماعية، والوجودية |

| النتائج | نموذج ثلاثي الأبعاد لآثار العواطف على الأداء |  |

نموذج مدمج في نظرية التحكم والقيمة؛ تمييز بين العواطف الإيجابية المحفزة مقابل المثبطة |  |

نموذج مضاف لآثار الصحة |

مقدمة

الأعمال الأولية ونسخة مبكرة من النظرية

نظرية القيمة المتوقعة العامة للدافع

| قيمة النشاط | قيمة النتيجة | |||

| جوهرية | خارجية | جوهرية | خارجية | |

| إيجابية | السرور، الاهتمام، التدفق، التوافق مع المعايير والهوية | توقع النتائج الإيجابية | السرور؛ التوافق مع المعايير والهوية | توقع النتائج الإيجابية الإضافية |

| سلبية | الانزعاج، النفور، نقص التدفق، نقص التوافق مع المعايير والهوية | توقع النتائج السلبية، بما في ذلك التكاليف (فقدان الوقت، المال، الفرص) | الانزعاج؛ نقص التوافق مع المعايير والهوية | توقع النتائج السلبية الإضافية |

نظرية القيمة المتوقعة للقلق

نموذج التأثيرات العاطفية المعرفية-الدافعية

النسخة المبكرة (2000) من نظرية التحكم-القيمة

نظرية التحكم-القيمة لعواطف الإنجاز

مفهوم وتصنيف عواطف الإنجاز

| تركيز الموضوع | إيجابي

|

سلبي

|

||

| محفز | غير محفز | محفز | غير محفز | |

| إنجاز | ||||

| نشاط | استمتاع | استرخاء | غضب | ملل |

| حماس | إحباط | |||

| نتيجة/ مستقبلية | أمل فرح متوقع | ثقة | قلق | يأس |

| نتيجة/ استرجاعية | فخر | رضا | عار | حزن |

| فرح استرجاعي | راحة | غضب | خيبة أمل | |

| امتنان | ||||

| معرفي | ||||

| رضا | ملل | |||

| عدم توافق المعلومات | دهشة

|

ارتباك إحباط | ||

| اجتماعي | ||||

| ذاتي | فخر | رضا (مع الذات) | عار ذنب | عدم رضا (مع الذات) |

| مرتبط بالآخرين | حب | تعاطف | كراهية | نفور |

| امتنان | غضب | |||

| إعجاب | ازدراء | |||

| رحمة | غيرة | |||

| وجودي | ||||

| صحة، حياة، مرض، موت | سعادة (صحة) | راحة (شفاء) | قلق (مرض، موت) | يأس (مرض، موت) |

المقدمات التقييمية: تصورات السيطرة والقيمة

القيمة المدركة للنتيجة. بناءً على نظرية الإسناد لوينر (1985)، يُعتقد أن مشاعر مثل الفخر، والعار، والامتنان، والغضب بشأن الفشل تعتمد أيضًا على الإسنادات السببية للنتيجة إلى عوامل داخلية مقابل عوامل خارجية (لكن انظر بيكرون، 2006، للاختلافات بين نظرية القيمة والسيطرة ومقترحات وينر).

الآثار: خصوصية المجال لمشاعر الإنجاز

الآثار: العوامل الفردية

الآثار: العوامل الاجتماعية

(1) تؤثر الجودة المعرفية لبيئات الإنجاز، مثل بيئة التعلم في الفصل الدراسي، على اكتساب الكفاءات، والأداء الكفء لأنشطة الإنجاز، وإدراك السيطرة الناتج (على سبيل المثال، بيكرون وآخرون، 2023أ). من خلال تلبية احتياجات الكفاءة (رايان وديشي، 2017)، يمكن أن تعزز البيئات عالية الجودة أيضًا القيمة. متغير حاسم مهم هو مستوى صعوبة المهام. إذا كانت المهام صعبة للغاية، يمكن أن تؤدي نقص السيطرة والمشاعر السلبية. إذا كانت المهام سهلة للغاية، فقد لا تكون ممتعة أيضًا، ويمكن أن تؤدي إلى الملل بدلاً من ذلك.

(2) تؤثر الجودة العاطفية والدافعية للبيئات على تقييمات القيمة، مما يؤثر بالتالي على مشاعر الإنجاز. يمكن أن تأخذ تحفيز القيمة أشكالًا مباشرة وغير مباشرة. تشمل التحفيز المباشر الرسائل اللفظية حول

(3) يمكن أن يؤثر دعم الاستقلالية على كل من السيطرة والقيمة. يُعتقد أن توفير الاختيار بين المهام والاستراتيجيات لأداء المهام يعزز الكفاءة ويحقق الاحتياجات للاستقلالية، مما يعزز السيطرة والقيمة الإيجابية، والعواطف الإيجابية الناتجة (انظر، على سبيل المثال، كوي وآخرون، 2017). هناك حاجة إلى كفاءات كافية لتنظيم الأنشطة الإنجازية ذاتيًا لكي تحدث هذه التأثيرات الإيجابية.

(4) تحدد التوقعات الاجتماعية، وهياكل الأهداف، والتفاعل الاجتماعي الفرص لتجربة النجاح وتلبية الاحتياجات للارتباط. إذا كانت توقعات الآخرين المهمين، مثل المعلمين والآباء، مرتفعة جدًا، فقد يبدو أن النجاح غير قابل للتحقيق، مما يولد القلق واليأس (انظر أيضًا موراياما وآخرون، 2016). وبالمثل، قد تقوض هياكل الأهداف التنافسية تصورات السيطرة. في المقابل، يمكن أن تعزز الهياكل التعاونية المتوازنة الشعور بالسيطرة، وفي نفس الوقت، تعزز القيمة من خلال تلبية الاحتياجات للارتباط.

(5) تشكل التعليقات حول الإنجاز تصورات السيطرة (فورسبلوم وآخرون، 2022)، وتؤثر عواقب الإنجاز (المكافآت المالية، فرص العمل، إلخ) على تصورات القيمة (الخارجية). من مقترحات نظرية القيمة المعرفية، يتضح أن الاختبارات ذات المخاطر العالية يمكن أن تعزز الأهمية المدركة للإنجاز إلى الحد الذي يتم فيه توليد قلق مفرط ويأس لدى العديد من الطلاب والمعلمين.

(6) يتضح من نظرية القيمة المعرفية أن تكوين المجموعات يلعب أيضًا دورًا مهمًا. في نموذج حديث لتأثيرات التركيب على العواطف، دمجت أنا ومارش مقترحات نظرية القيمة المعرفية مع فرضيات من نموذج تأثير السمكة الكبيرة-بركة صغيرة (BFLPE). افترضنا، ووجدنا تجريبيًا، أن كونك عضوًا في مجموعة من ذوي الإنجازات العالية يقلل من الثقة بالنفس والسيطرة المدركة، مما يقلل من العواطف الإيجابية المرتبطة بالإنجاز ويزيد من العواطف السلبية (“تأثير السمكة السعيدة-بركة صغيرة”؛ بيكرون وآخرون، 2019؛ للتعميم عبر البلدان، انظر باساركود وآخرون، 2023).

التأثيرات على التعلم والإنجاز والصحة

مع الزملاء نبهتني إلى أن هذا النموذج كان له قيودان: لم يميز بين العواطف الإيجابية النشطة (مثل الحماس، والفخر) والعواطف الإيجابية غير النشطة (مثل الارتياح، والاسترخاء)، ولم يتناول دور التركيز على الموضوع. في النسخ 2006 وما بعدها من النموذج، تم تناول الفروق بين العواطف الإيجابية النشطة وغير النشطة وأهمية التركيز على الموضوع (بيكرون، 2006؛ بيكرون وآخرون، 2023أ).

الصحة العقلية والرفاه النفسي للناس. بنفس المعنى، يمكن اعتبار العواطف السلبية المفرطة المرتبطة بالإنجاز، مثل القلق المفرط من الاختبارات أو الملل، اضطرابات عقلية (انظر بيكرون ولودرر، 2020). ومع ذلك، لا تُعتبر عواطف الإنجاز في التصنيفات الحالية للاضطرابات، مثل الدليل التشخيصي والإحصائي للاضطرابات العقلية (DSM) 5 وتصنيف الأمراض الدولي لمنظمة الصحة العالمية (ICD) 11. تشير نظرية القيمة المعرفية والأدلة الحالية إلى أن العواطف السلبية المفرطة المرتبطة بالإنجاز يمكن أن تكون طويلة الأمد، وأنها يمكن أن تقوض بشكل خطير الوظائف اليومية والرفاه. لذلك، دعونا نعيد النظر في العواطف السلبية المفرطة المرتبطة بالإنجاز كاضطرابات عقلية (تم تضمين قلق الاختبار في ICD 10 ولكن تم إسقاطه لاحقًا؛ بيكرون ولودرر، 2020).

السببية المتبادلة، تنظيم المشاعر، والتدخل

خمسة مجموعات رئيسية. أولاً، يمكن إدارة المشاعر من خلال تعزيز أو قمع عملياتها المكونة بشكل مباشر، مثل تعزيز أو قمع تعبير المشاعر (تنظيم موجه نحو المشاعر). الخيار الثاني هو اختيار أو تعديل المواقف بطريقة تغير المشاعر، مثل اختيار مدرسة تناسب احتياجات الطالب بشكل أفضل، أو اختيار مهام تتناسب مع كفاءات الطالب (تنظيم موجه نحو الموقف). ثالثًا، يمكن إدارة مشاعر الإنجاز من خلال تغيير تقييمات المرء (تنظيم موجه نحو التقييم) أو من خلال إعادة توجيه الانتباه نحو أو بعيدًا عن المحفزات العاطفية، مثل النجاح والفشل (تنظيم موجه نحو الانتباه). أخيرًا، يمكن تنظيم مشاعر الإنجاز من خلال زيادة كفاءات المرء، مما يزيد من احتمالية النجاح ويقوي المشاعر الإيجابية الناتجة (تنظيم موجه نحو الكفاءة). يمكن تصنيف التدخلات التي تستهدف مشاعر الإنجاز بنفس الطريقة (انظر الشكل 3).

العمومية النسبية لمشاعر الإنجاز

الدول. على سبيل المثال، عبر دورات برنامج تقييم الطلاب الدوليين (PISA) لمنظمة التعاون والتنمية الاقتصادية، كانت العلاقات بين استمتاع الطلاب (مثل استمتاع العلوم) أو القلق (مثل قلق الرياضيات) مشابهة عبر مجموعة واسعة من الدول المدرجة (انظر Guo et al.، 2022؛ OECD، 2013). على هذا النحو، تشير الأدلة الحالية إلى أن اقتراحات نظرية التحكم القيمي قابلة للتطبيق عالميًا.

نظرية التحكم القيمي العامة

المشاعر المعرفية

العواطف الاجتماعية

الامتنان، الإعجاب، التعاطف، الكراهية، الغضب، الاحتقار، والحسد (مشاعر اجتماعية متعلقة بالآخرين؛ الجدول 2). تقترح نظرية القيمة العاطفية أن جميع هذه المشاعر تعتمد على القيمة المدركة لسمات وأفعال الذات أو الأشخاص الآخرين، على التوالي. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تعتمد العديد منها أيضًا على تصورات السيطرة.

يتم التسبب في ذلك بواسطة ظروف خارجية، مثل الفقر الذي لا يكون خطأ الشخص الآخر. يتم تحفيز الحسد إذا تم رؤية الصفات القيمة لشخص آخر (مثل الثروة أو الجمال) على أنها ليست ناتجة عن جهد ذاتي، وبالتالي، غير مستحقة (فيذر، 2015). مرة أخرى، يُعتقد أن جميع هذه المشاعر المعتمدة على السيطرة تعتمد على تفاعل تصورات السيطرة والقيمة.

المقدمات البعيدة، التأثيرات على السلوك، والسببية المتبادلة

الآثار على الممارسة التعليمية

تقييم المشاعر

فهم المشاعر

تغيير المشاعر

إلى سياسات تقييم بعيدة عن الاختبارات عالية المخاطر نحو ثقافة خالية من القلق للتعلم من الأخطاء سيكون بمثابة تحول جذري في صنع السياسات التعليمية.

نقاط القوة، والأسئلة المفتوحة، والاتجاهات المستقبلية

مزايا CVT

2022). لشرح أصول مشاعر الإنجاز، يتم دمج مقترحات من نظرية التوقع-القيمة، ونظرية التفسير (وينر، 1985)، ونموذج لازاروس التبادلي (على سبيل المثال، لازاروس وفولكمان، 1984). لشرح التأثيرات على التعلم والإنجاز، تقوم CVT بتوليف مقترحات من نظريات التأثيرات على التحفيز، ونماذج الموارد المعرفية (ماينهاردت وبكرون، 2003؛ ميكلز وروتر-لورينز، 2019)، ونظريات تركز على المشاعر وأنماط التفكير (على سبيل المثال، كلور وهونتسنجير، 2007). بعيدًا عن مجال المشاعر، توفر CVT آفاقًا للتوحيد مع نظرية التحفيز، نظرًا لأن تفسيرات CVT للمشاعر المستقبلية متكافئة من الناحية المفاهيمية مع تفسيرات التحفيز المقدمة من نظرية الكفاءة الذاتية ونظريات التوقع-القيمة. نظرًا للتكامل النظري الذي تقدمه CVT، تظهر النظرية أيضًا “اتساق خارجي” و”تشابه” (غرين، 2022) بالنسبة للنظريات الأخرى في هذا المجال.

أسئلة مفتوحة واتجاهات مستقبلية

التدخلات. بعض هذه الأسئلة المفتوحة والاتجاهات المستقبلية هي كما يلي (للحصول على معالجات أكثر اكتمالًا، انظر بيكرون، 2018، 2021؛ بيكرون وجويتز، 2024ب؛ بيكرون ولينينبرينك-غارسيا، 2014).

تطوير نظرية التحكم والقيمة بشكل أكبر

أي مستوى من الدقة تقع؟ هذا السؤال صعب بشكل خاص للإجابة عليه بالنسبة لتأثيرات المشاعر على الأداء. تفترض نموذج نظرية التحكم والقيمة المعرفية-الدافعية لتأثيرات المشاعر أن المشاعر تؤثر على عمليات الوساطة المختلفة. يمكن أن يختلف توازن التأثيرات على هذه العمليات عبر الأشخاص وظروف المهام، بحيث يمكن أن يكون لنفس المشاعر تأثيرات إيجابية أو سلبية على الأداء. على سبيل المثال، إذا كانت التأثيرات السلبية للقلق على موارد الذاكرة العاملة والدافع الداخلي تفوق التأثيرات الإيجابية على الدافع الخارجي، فإن القلق يجب أن يعيق الأداء. إذا كانت التأثيرات الإيجابية تفوق التأثيرات السلبية على هذه الآليات الوسيطة، فإن القلق يجب أن يعزز الأداء. لتحديد التوازن، هناك حاجة إلى مزيد من العمل على هذه الآليات وتنظيمها الوحدوي.

البحث التجريبي ودراسات التدخل

التقرير الذاتي عرضة لتحيزات الذاكرة وتأثيرات مجموعات الاستجابة (مثل الرغبة الاجتماعية). ثانيًا، التقرير الذاتي ليس مناسبًا بشكل جيد لتقييم العمليات المكونة الفسيولوجية والسلوكية للمشاعر، مثل الإثارة الفسيولوجية والتعبير الوجهي. لقياس المشاعر المستهدفة من قبل نظرية التحكم والقيمة بشكل كامل، من المهم استخدام قنوات متعددة تشمل أيضًا الملاحظة السلوكية، والتحليل الفسيولوجي، والتصوير العصبي (انظر، على سبيل المثال، مارتن وآخرون، 2023، وانظر بيكرون، 2023، للإرشادات المقترحة). هناك حاجة إلى تقدم في هذه المنهجيات لاختبار الديناميات المتعددة المتغيرة والدورات المتعددة من السببية المتبادلة عبر أطر زمنية مختلفة التي تربط المشاعر، والأصول، والنتائج وفقًا لنظرية التحكم والقيمة (على سبيل المثال، باستخدام نمذجة الأنظمة الديناميكية غير الخطية؛ انظر أيضًا مارشاند وهيلبرت، 2023).

الخاتمة

قياس متعدد القنوات، والنمذجة الديناميكية، ودمج المنظورات الفردية والنمطية؛ مزيد من التقدم النظري لشرح تنوع المشاعر عبر الأشخاص والسياقات الاجتماعية والثقافية؛ بالإضافة إلى تطوير تدخلات فعالة وممارسات تعليمية تستهدف المشاعر لتعزيز الصحة العاطفية للطلاب والمعلمين.

الإعلانات

الوصول المفتوح هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام والمشاركة والتكيف والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج في أي وسيلة أو تنسيق، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح ما إذا كانت قد تم إجراء تغييرات. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر ائتمان للمادة. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة واستخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، ستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارةhttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

References

Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychological Review, 64(6Pt 1), 359-372. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0043445

Barrett, L. F., Lewis, M., & Haviland-Jones, J. M. (Eds.). (2018). Handbook of emotions (

Barroso, C., Ganley, C. M., McGraw, A. L., Geer, E. A., Hart, S. A., & Daucourt, M. C. (2021). A metaanalysis of the relation between math anxiety and math achievement. Psychological Bulletin, 147(2), 134-168. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul000030

Basarkod, G., Marsh, H. W., Guo, J., Parker, P. D., Dicke, T., & Pekrun, R. (2023). The happy-fish-littlepond effect on enjoyment: Generalizability across multiple domains and countries. Learning and Instruction, 85, 101733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2023.101733

Beck, A. T., & Clark, D. A. (1988). Anxiety and depression: An information processing perspective. Anxiety Research, 1(1), 23-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615808808248218

Bieleke, M., Goetz, T., Yanagida, T., Botes, E., Frenzel, A. C., & Pekrun, R. (2023). Measuring emotions in mathematics: The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire-Mathematics (AEQ-M). ZDM-Mathematics Education, 55(2), 269-284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-022-01425-8

Bieleke, M., Gogol, K., Goetz, T., Daniels, L., & Pekrun, R. (2021). The AEQ-S: A short version of the Achievement Emotions Questionnaire. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 65, 101940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101940

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

Camacho-Morles, J., Slemp, G. R., Pekrun, R., Loderer, K., Hou, H., & Oades, L. G. (2021). Activity achievement emotions and academic performance: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 33(3), 1051-1095. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09585-3

Clore, G. L., & Huntsinger, J. R. (2007). How emotions inform judgment and regulate thought. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(9), 393-399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2007.08.005

D’Mello, S., & Graesser, A. (2012). Dynamics of affective states during complex learning. Learning and Instruction, 22(2), 145-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2011.10.001

D’Mello, S., Lehman, B., Pekrun, R., & Graesser, A. (2014). Confusion can be beneficial for learning. Learning and Instruction, 29, 153-170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.05.003

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101859

Feather, N. T. (2015). Analyzing relative deprivation in relation to deservingness, entitlement and resentment. Social Justice Research, 28(1), 7-26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-015-0235-9

Forsblom, L., Pekrun, R., Loderer, K., & Peixoto, F. (2022). Cognitive appraisals, achievement emotions, and students’ math achievement: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(2), 346-367. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000671

Frenzel, A. C., Becker-Kurz, B., Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., & Lüdtke, O. (2018). Emotion transmission in the classroom revisited: A reciprocal effects model of teacher and student enjoyment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(5), 628-639. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000228

Frenzel, A. C., Dindar, M., Pekrun, R., Reck, C., & Marx, A. K. G. (2024). Joy is reciprocally transmitted between teachers and students: Evidence on facial mimicry in the classroom. Learning and Instruction, 91, 101896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2024.101896

Frenzel, A. C., Pekrun, R., & Goetz, T. (2007). Girls and mathematics – a “hopeless” issue? A controlvalue approach to gender differences in emotions towards mathematics. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 22(4), 497-514. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173468

Gigerenzer, G. (2017). A theory integration program. Decision, 4(3), 133-145. https://doi.org/10.1037/ dec0000082

Goetz, T., Bieg, M., Lüdtke, O., Pekrun, R., & Hall, N. C. (2013). Do girls really experience more anxiety in mathematics? Psychological Science, 24(10), 2079-2087. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613486989

Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., Pekrun, R., Hall, N. C., & Lüdtke, O. (2007). Between- and within-domain relations of students’ academic emotions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(4), 715-733. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.4.715

Greene, J. A. (2022). What can educational psychology learn from, and contribute to, theory development scholarship? Educational Psychology Review, 34(4), 3011-3035. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10648-022-09682-5

Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781

Guo, J., Hu, X., Marsh, H. W., & Pekrun, R. (2022). Relations of epistemic beliefs with motivation, achievement, and aspirations in science: Generalizability across 72 societies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(4), 734-751. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000660

Hamaker, E. L. (2023). The within-between dispute in cross-lagged panel research and how to move forward. Psychological Methods. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000600

Hamaker, E. L., Kuiper, R. M., & Grasman, R. P. P. P. (2015). A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychological Methods, 20(1), 102-116. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038889

Hareli, S., & Weiner, B. (2002). Social emotions and personality inferences: A scaffold for a new direction in the study of achievement motivation. Educational Psychologist, 37(3), 183-193. https://doi. org/10.1207/S15326985EP3703_4

Harley, J. M., Pekrun, R., Taxer, J. L., & Gross, J. J. (2019). Emotion regulation in achievement situations: An integrated model. Educational Psychologist., 54(2), 106-126. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 00461520.2019 .1587297

Heckhausen, H. (1980). Motivation und Handeln [Motivation and action]. Springer.

Hoessle, C., Loderer, K., Pekrun, R. (2021, August). Piloting a control-value intervention promoting adaptive achievement emotions in university students. Paper presented at the 19th biennial conference of the European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction (EARLI), online.

Huang, C. (2011). Achievement goals and achievement emotions: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 23(3), 359-388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9155-x

Jirout, J. J., Ruzek, E., Vitiello, V. E., Whittaker, J., & Pianta, R. C. (2023). The association between and development of school enjoyment and general knowledge. Child Devevelopment, 94(2), 119-127. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev. 13878

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-292. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

Lajoie, S. P., & Poitras, E. (2023). Technology-rich learning environments: Theories and methodologies for understanding solo and group learning. In P. A. Schutz & K. Muis (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (4th edition, pp. 630-653). Routledge.

Lazarus, R., & Folkman. S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

Lichtenfeld, S., Pekrun, R., Stupnisky, R. H., Reiss, K., & Murayama, K. (2012). Measuring students’ emotions in the early years: The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire-Elementary School (AEQ-ES). Learning and Individual Differences, 22(2), 190-201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2011.04.009

Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Patall, E. A., & Pekrun, R. (2016). Adaptive motivation and emotion in education: Research and principles for instructional design. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(2), 228-236. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732216644450

Loderer, K., Pekrun, R., & Lester, J. C. (2020). Beyond cold technology: A systematic review and metaanalysis on emotions in technology-based learning environments. Learning and Instruction, 7, 101162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.08.002

Loderer, K., Pekrun, R., & Plass, J. L. (2019). Emotional foundations of game-based learning. In J. L. Plass, B. D. Homer, & R. E. Mayer (Eds.), Handbook of game-based learning (pp. 111-151). MIT Press.

Loewenstein, G. (1994). The psychology of curiosity: A review and reinterpretation. Psychological Bulletin, 116(1), 75-98. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.75

Lüdtke, O., & Robitzsch, A. (2022). A comparison of different approaches for estimating cross-lagged effects from a causal inference perspective. Structural Equation Modeling, 29(6), 888-907. https:// doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2022.2065278

Marchand, G. C., & Hilpert, J. C. (2023). Contributions of complex systems approaches, perspectives, models, and methods in educational psychology. In P. A. Schutz & K. Muis (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (4th edition, pp. 139-161). Routledge.

Marsh, H. W., Parker, P. D., & Pekrun, R. (2019a). Three paradoxical effects on academic self-concept across countries, schools, and students: Frame-of-reference as a unifying theoretical explanation. European Psychologist, 24(3), 231-242. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000332

Marsh, H. W., Pekrun, R., & Lüdtke, O. (2022). Directional ordering of self-concept, school grades, and standardized tests over five years: New tripartite models juxtaposing within- and betweenperson perspectives. Educational Psychology Review, 34, 2697-2744. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10648-022-09662-9

Marsh, H. W., Pekrun, R., Parker, P. D., Murayama, K., Guo, J., Dicke, T., & Arens, A. K. (2019b). The murky distinction between self-concept and self-efficacy: Beware of lurking jingle-jangle fallacies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(2), 331-353. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000281

Martin, A. J., Malmberg, L.-E., Pakarinen, E., Mason, L., & Mainhard, T. (Eds.). (2023). The potential of biophysiology for understanding motivation, engagement, and learning experiences [Special issue]. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(S1). https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep. 12584

Meinhardt, J., & Pekrun, R. (2003). Attentional resource allocation to emotional events: An ERP study. Cognition and Emotion, 17(3), 477-500. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930244000039

Menninghaus, W., Wagner, V., Wassiliwizky, E., Schindler, I., Hanich, J., Jacobsen, T., & Koelsch, S. (2019). What are aesthetic emotions? Psychological Review, 126(2), 171-195. https://doi.org/10. 1037/rev0000135

Mikels, J. A., & Reuter-Lorenz, P. A. (2019). Affective working memory: An integrative psychological construct. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(4), 543-559. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456 91619837597

Murayama, K., Goetz, T., Malmberg, L.-E., Pekrun, R., Tanaka, A., & Martin, A. J. (2017). Within-person analysis in educational psychology: Importance and illustrations. In D. W. Putwain & K. Smart (Eds.), British Journal of Educational Psychology Monograph Series II: Psychological Aspects

of Education – Current Trends: The Role of Competence Beliefs in Teaching and Learning (pp. 71-87). Wiley.

Murayama, K., Pekrun, R., Suzuki, M., Marsh, H. W., & Lichtenfeld, S. (2016). Don’t aim too high for your kids: Parental over-aspiration undermines students’ learning in mathematics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111(5), 166-179. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000079

Neta, M., & Kim, M. J. (2023). Surprise as an emotion: A response to Ortony. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 18(4), 854-862. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916221132789

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD]. (2013). PISA 2012 results (Volume 3): Ready to learn. Students’ engagement, drive and self-beliefs. Author.

Pekrun, R. (1983). Schulische Persönlichkeitsentwicklung. Theoretische Überlegungen und empirische Erhebungen zur Persönlichkeitsentwicklung von Schülern der 5. bis 10. Klassenstufe [Personality development at school: Theoretical models and empirical studies on students’ personality development from grades 5 to 10]. Peter Lang.

Pekrun, R. (1984). An expectancy-value model of anxiety. In R. Schwarzer, C. D. Spielberger, & H. M. van der Ploeg (Eds.), Advances in test anxiety research (Vol. 3, pp. 53-72). Swets & Zeitlinger.

Pekrun, R. (1988). Emotion, Motivation und Persönlichkeit [Emotion, motivation and personality]. Psychologie Verlags Union.

Pekrun, R. (1992a). The expectancy-value theory of anxiety: Overview and implications. In D. G. Forgays, T. Sosnowski, & K. Wrzesniewski (Eds.), Anxiety: Recent developments in self-appraisal, psychophysiological and health research (pp. 23-41). Hemisphere.

Pekrun, R. (1992b). The impact of emotions on learning and achievement: Towards a theory of cognitive/ motivational mediators. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 41(4), 359-376. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1992.tb00712.x

Pekrun, R. (1993). Facets of students’ academic motivation: A longitudinal expectancy-value approach. In M. Maehr & P. Pintrich (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement (8, 139-189). JAI Press.

Pekrun, R. (2000). A social cognitive, control-value theory of achievement emotions. In J. Heckhausen (Ed.), Motivational psychology of human development (pp. 143-163). Elsevier Science.

Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 315341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9029-9

Pekrun, R. (2014). Emotions and learning (Educational Practices Series, Vol. 24). International Academy of Education (IAE) and International Bureau of Education (IBE) of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Geneva, Switzerland. http://www.iaoed. org/downloads/edu-practices_24_eng.pdf

Pekrun, R. (2018). Control-value theory: A social-cognitive approach to achievement emotions. In G. A. D. Liem & D. M. McInerney (Eds.), Big theories revisited 2: A volume of research on sociocultural influences on motivation and learning (pp. 162-190). Information Age Publishing.

Pekrun, R. (2019). The murky distinction between curiosity and interest: State of the art and future directions. Educational Psychology Review, 31(4), 905-914. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10648-019-09512-1

Pekrun, R. (2020). Self-report is indispensable to assess students’ learning. Frontline Learning Research, 8(3), 185-193. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v8i3. 637

Pekrun, R. (2021). Self-appraisals and emotions: A generalized control-value approach. In T. Dicke, F. Guay, H. W. Marsh, R. G. Craven, & D. M. McInerney (Eds.), Self – a multidisciplinary concept (pp. 1-30). Information Age Publishing.

Pekrun, R. (2023). Mind and body in students’ and teachers’ engagement: New evidence, challenges, and guidelines for future research. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(S1), 227-238. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep. 12575

Pekrun, R. (2024). Overcoming fragmentation in motivation science: Why, when, and how should we integrate theories? Educational Psychology Review, 36, 27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-024-09846-5

Pekrun, R., Elliot, A. J., & Maier, M. A. (2009). Achievement goals and achievement emotions: Testing a model of their joint relations with academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(1), 115-135. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013383

Pekrun, R., & Goetz, T. (2024a). Boredom: A control-value theory approach. In M. Bieleke, W. Wolff, & C. Martarelli (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of boredom (pp. 74-89). Routledge.

Pekrun, R., & Goetz, T. (2024b). How universal are academic emotions? A control-value theory perspective. In G. Hagenauer, R. Lazarides, & H. Järvenoja (Eds.), Motivation and emotion in learning and teaching across educational contexts: Theoretical and methodological perspectives and empirical insights (pp. 85-99). Taylor & Francis / Routledge.

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., Barchfeld, P., & Perry, R. P. (2011). Measuring emotions in students’ learning and performance: The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire (AEQ). Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(1), 36-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.10.002

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educational Psychologist, 37(2), 91-105. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3702_4

Pekrun, R., Lichtenfeld, S., Marsh, H. W., Murayama, K., & Goetz, T. (2017a). Achievement emotions and academic performance: Longitudinal models of reciprocal effects. Child Development, 88(5), 1653-1670. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev. 12704

Pekrun, R., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2014). Conclusions and future directions. In R. Pekrun & L. Lin-nenbrink-Garcia (Eds.), International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 659-675). Taylor & Francis.

Pekrun, R., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2022). Academic emotions and student engagement. In A. L. Reschly & S. L. Christenson (Eds.), The handbook of research on student engagement (2nd ed., pp. 109-132). Springer.

Pekrun, R., & Loderer, K. (2020). Control-value theory and students with special needs: Achievement emotion disorders and their links to behavioral disorders and academic difficulties. In A. J. Martin, R. A. Sperling, & K. J. Newton (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology and students with special needs. Taylor & Francis.

Pekrun, R., Marsh, H. W., Elliot, A. J., Stockinger, K., Perry, R. P., Vogl, E., Goetz, T., van Tilburg, W. A. P., Lüdtke, O., & Vispoel, W. P. (2023a). A three-dimensional taxonomy of achievement emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 124(1), 145-178. https://doi.org/10.1037/ pspp0000448

Pekrun, R., Marsh, H. W., Suessenbach, F., Frenzel, A. C., & Goetz, T. (2023b). School grades and students’ emotions: Longitudinal models of within-person reciprocal effects. Learning and Instruction, 83, 101626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2022.101626

Pekrun, R., Murayama, K., Marsh, H. W., Goetz, T., & Frenzel, A. C. (2019). Happy fish in little ponds: Testing a reference group model of achievement and emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 117(1), 166-185. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000230

Pekrun, R., & Stephens, E. J. (2012). Academic emotions. In K. R. Harris, S. Graham, T. Urdan, J. M. Royer, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), APA educational psychology handbook (Vol. 2, pp. 3-31). American Psychological Association.

Pekrun, R., Vogl, E., Muis, K. R., & Sinatra, G. M. (2017b). Measuring emotions during epistemic activities: The Epistemically-Related Emotion Scales. Cognition and Emotion, 31(6), 1268-1276. https:// doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1204989

Peterson, E. G., & Cohen, J. (2019). A case for domain-specific curiosity in mathematics. Educational Psychology Review, 31, 807-832. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09501-4

Price, D. D., Barrell, J. E., & Barrell, J. J. (1985). A quantitative-experiential analysis of human emotions. Motivation and Emotion, 9(1), 19-38. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00991548

Putwain, D. W., Pekrun, R., Nicholson, L. J., Symes, W., Becker, S., & Marsh, H. W. (2018). Controlvalue appraisals, enjoyment, and boredom in mathematics: A longitudinal latent interaction analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 55(6), 1339-1368. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028 31218786689

Quinlan, K. M. (Ed.). (2016). How higher education feels: Poetry that illuminates the experiences of learning, teaching and transformation. Sense Publishers.

Reisenzein, R., Horstmann, G., & Schützwohl, A. (2019). The cognitive-evolutionary model of surprise: A review of the evidence. Topics in Cognitive Science, 11, 50-74. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops. 12292

Roseman, I. J., Spindel, M. S., & Jose, P. E. (1990). Appraisals of emotion-eliciting events: Testing a theory of discrete emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(5), 899-915. https:// doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.899

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press. https://doi.org/10.1521/978.14625/28806

Scherer, K. R., & Moors, A. (2019). The emotion process: Event appraisal and component differentiation. Annual Review of Psychology, 70(1), 719-745. https://doi.org/10.1146/annur ev-psych-122216-011854

Scherer, K. R., Schorr, A., & Johnstone, T. (Eds.). (2001). Appraisal processes in emotion: theory, methods, research. Oxford University Press.

Schönbrodt, F., & Perugini, M. (2013). At what sample size do correlations stabilize? Journal of Research in Personality, 47(5), 609-612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2013.05.009

Shao, K., Pekrun, R., Marsh, H. W., & Loderer, K. (2020). Control-value appraisals, achievement emotions, and foreign language performance: A latent interaction analysis. Learning and Instruction, 69, 101356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101356

Shao, K., Stockinger, K., Marsh, H. W., & Pekrun, R. (2023). Applying control-value theory for examining multiple emotions in second language classrooms: Validating the Achievement Emotions Ques-tionnaire-Second Language Learning. Language Teaching Research. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221144497

Sinha, T. (2022). Enriching problem-solving followed by instruction with explanatory accounts of emotions. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 31(2), 151-198. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2021. 1964506

Skinner, E. A. (1996). A guide to constructs of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(3), 549-570. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.3.549

Steinmayr, R., Crede, J., McElvany, N., & Wirthwein, L. (2016). Subjective well-being, test anxiety, academic achievement: Testing for reciprocal effects. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1994. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01994

Sweller, J. (2023). The development of cognitive load theory: Replication crises and incorporation of other theories can lead to theory expansion. Educational Psychology Review, 35, 95. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10648-023-09817-2

Vansteenkiste, M., Ryan, R. M., & Soenens, B. (2020). Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motivation and Emotion, 44, 1-31. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11031-019-09818-1

von der Embse, N., Jester, D., Roy, D., & Post, J. (2018). Test anxiety effects, predictors, and correlates: A 30-year meta-analytic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 483-493. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.jad.2017.11.048

Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. Wiley.

Wan, S., Lauermann, F., Bailey, D. H., & Eccles, J. S. (2021). When do students begin to think that one has to be either a “math person” or a “language person”? A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 147(9), 867-889. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000340

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4), 548-573.

Williams-Johnson, M., Cross, D., Hong, J., Aultman, L., Osbon, J., & Schutz, P. (2008). “There are no emotions in math”: How teachers approach emotions in the classroom. Teachers College Record, 110(8), 1574-1610. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810811000801

Zeidner, M. (1998). Test anxiety: The state of the art. Plenum.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- This article is part of the Topical Collection on Theory Development in Educational Psychology

Reinhard Pekrun

pekrun@lmu.de

Department of Psychology, University of Essex, Colchester, United Kingdom

Institute for Positive Psychology and Education, Australian Catholic University, Sydney, Australia

3 Department of Psychology, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Munich, Germany

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-024-09909-7

Publication Date: 2024-08-02

REVIEW ARTICLE

Control-Value Theory: From Achievement Emotion to a General Theory of Human Emotions

© The Author(s) 2024

Abstract

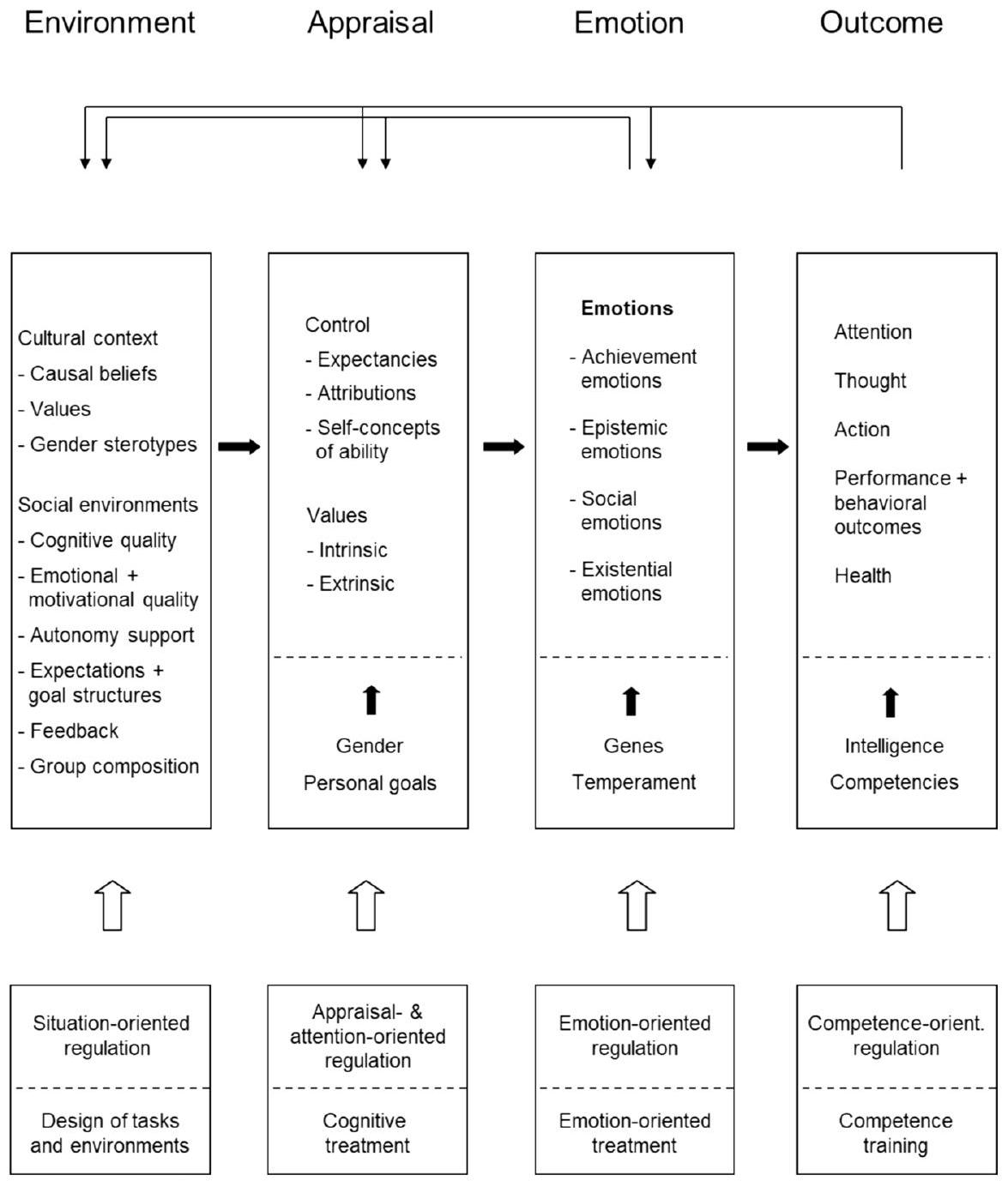

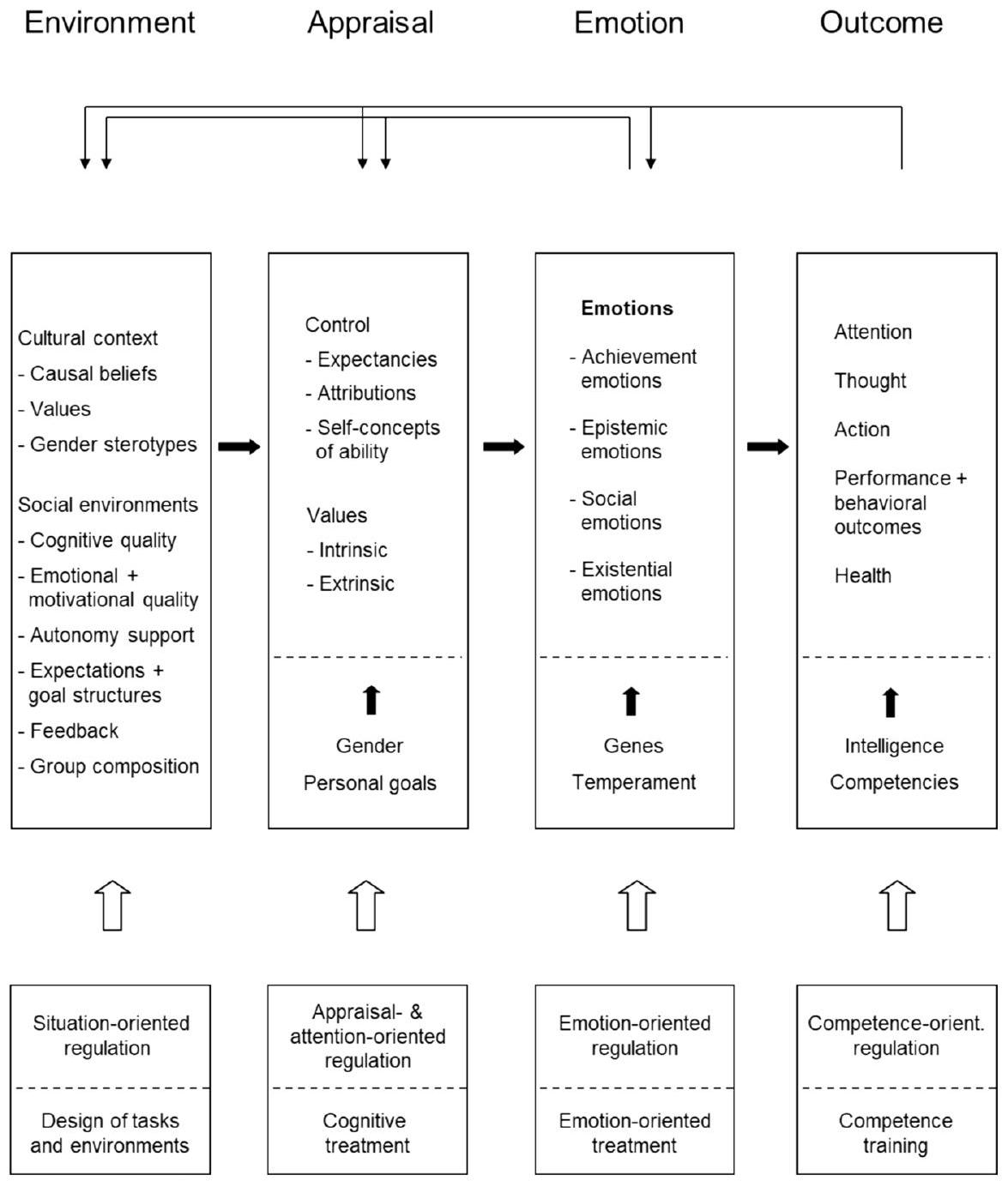

In its original version, control-value theory describes and explains achievement emotions. More recently, the theory has been expanded to also explain epistemic, social, and existential emotions. In this article, I outline the development of the theory, from preliminary work in the 1980s to early versions of the theory and the recent generalized control-value theory. I provide summaries of the theory’s evidence-based propositions on antecedents, outcomes, and regulation of emotions, including the fundamentally important role of control and value appraisals across different types of human emotions that are relevant to education (and beyond). The theory includes descriptive taxonomies of emotions as well as propositions explaining (a) the influence of individual factors, social environments, and socio-cultural contexts on emotions; (b) the effects of emotions on learning, performance, and health; (c) reciprocal causation linking emotions, outcomes, and antecedents; (d) ways to regulate emotions; and (e) strategies for intervention. Subsequently, I outline the relevance of the theory for educational practice, including individual and large-scale assessments of emotions; students’, teachers’, and parents’ understanding of emotions; and change of educational practices. In conclusion, I discuss strengths of the theory, open questions, and future directions.

| 1984, 1992 | 2000, 2006 | 2021, 2023 | |||

| Taxonomy of emotions | Focus on anxiety |  |

2-dimensional (object focus x valence) |  |

3-dimensional (object focus x valence x arousal) |

| Antecedents | Expectancyvalue theory of anxiety |  |

CVT of achievement emotions |  |

Generalized CVT: achievement, epistemic, social, & existential emotions |

| Outcomes | Trichotomous model of emotion effects on performance |  |

Model integrated into CVT; differentiation of positive activating vs. deactivating emotions |  |

Added model of effects on health |

Introduction

Preliminary Work and an Early Version of the Theory

Generalized Expectancy-Value Theory of Motivation

| Activity value | Outcome value | |||

| Intrinsic | Extrinsic | Intrinsic | Extrinsic | |

| Positive | Pleasure, interest, flow, congruency with norms & identity | Expectation of positive outcomes | Pleasure; congruency with norms & identity | Expectation of further positive outcomes |

| Negative | Displeasure, aversion, lack of flow, lack of congruency with norms & identity | Expectation of negative outcomes, including costs (loss of time, money, opportunities) | Displeasure; lack of congruency with norms & identity | Expectation of further negative outcomes |

Expectancy-Value Theory of Anxiety

Cognitive-Motivational Model of Emotion Effects

The Early (2000) Version of Control-Value Theory

Control-Value Theory of Achievement Emotions

Concept and Taxonomy of Achievement Emotions

| Object Focus | Positive

|

Negative

|

||

| Activating | Deactivating | Activating | Deactivating | |

| Achievement | ||||

| Activity | Enjoyment | Relaxation | Anger | Boredom |

| Excitement | Frustration | |||

| Outcome/ prospective | Hope Anticipatory joy | Assurance | Anxiety | Hopelessness |

| Outcome/ retrospective | Pride | Contentment | Shame | Sadness |

| Retrospective joy | Relief | Anger | Disappointment | |

| Gratitude | ||||

| Epistemic | ||||

| Contentment | Boredom | |||

| Incongruity of information | Surprise

|

Confusion Frustration | ||

| Social | ||||

| Self-related | Pride | Satisfaction (with self) | Shame Guilt | Dissatisfaction (with self) |

| Other-related | Love | Sympathy | Hate | Antipathy |

| Gratitude | Anger | |||

| Admiration | Contempt | |||

| Compassion | Envy | |||

| Existential | ||||

| Health, life, disease, death | Happiness (health) | Relief (recovery) | Anxiety (disease, death) | Hopelessness (disease, death) |

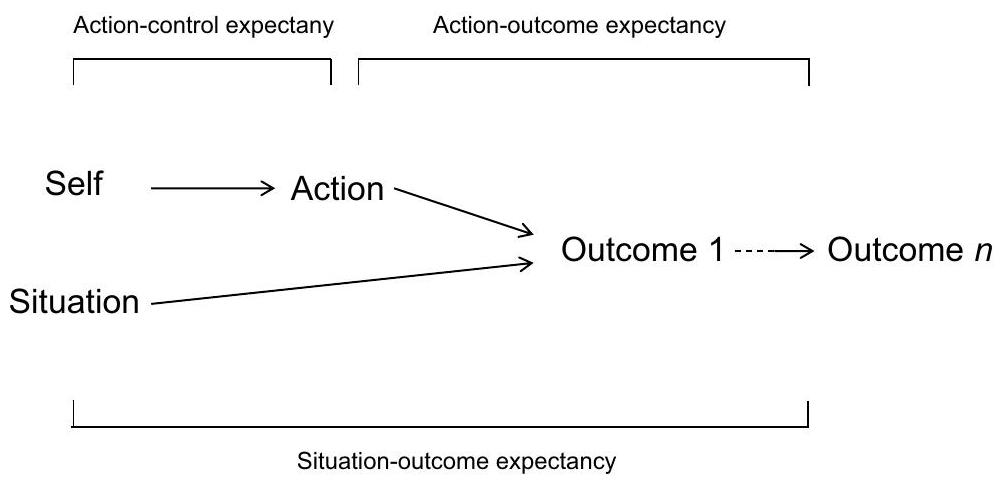

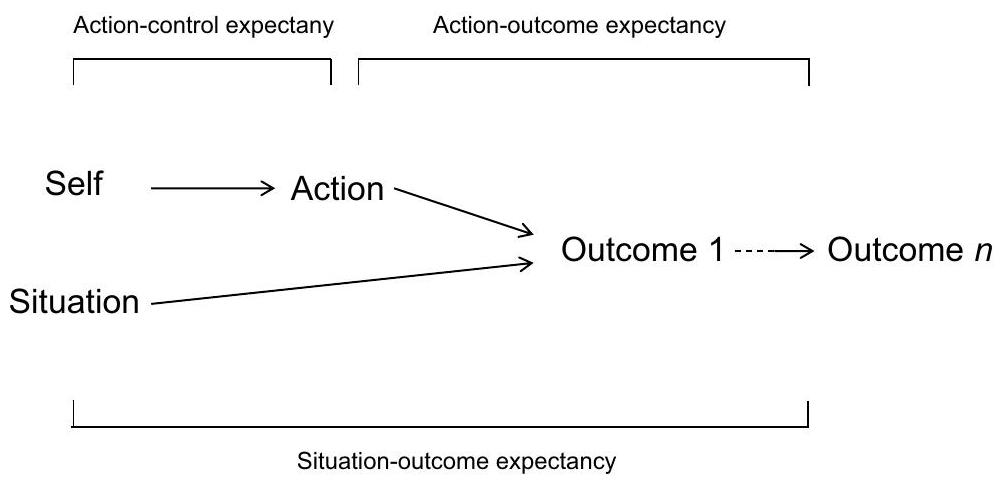

Appraisal Antecedents: Perceptions of Control and Value

the perceived value of the outcome. Following up on Weiner’s (1985) attributional theory, emotions like pride, shame, gratitude, and anger about failure are thought to additionally depend on causal attributions of the outcome to internal versus external factors (but see Pekrun, 2006, for differences between CVT and Weiner’s propositions).

Implications: Domain Specificity of Achievement Emotions

Implications: Individual Antecedents

Implications: Social Antecedents

(1) The cognitive quality of achievement environments, such as the learning environment in the classroom, influences the acquisition of competencies, the competent performance of achievement activities, and resulting control perceptions (e.g., Pekrun et al., 2023a). By fulfilling needs for competence (Ryan & Deci, 2017), high-quality environments can also boost value. A critically important variable is the difficulty level of tasks. If tasks are too demanding, lack of control and negative emotions can result. If tasks are too easy, they may not be enjoyable either, and boredom can result instead.

(2) The emotional and motivational quality of environments impacts value appraisals, thus influencing achievement emotions. Value induction can take both direct and indirect forms. Direct induction includes verbal messages about the

(3) Autonomy support can influence both control and value. Providing choice between tasks and strategies to perform tasks is thought to promote competence and fulfill needs for autonomy, thus boosting control, positive value, and the resulting positive emotions (see, e.g., Cui et al., 2017). Sufficient competencies to self-regulate achievement activities are needed for these positive effects to occur.

(4) Social expectations, goal structures, and social interaction define opportunities to experience success and fulfill needs for relatedness. If expectations of significant others, such as teachers and parents, are too high, then success may seem unattainable, thus, generating anxiety and hopelessness (see also Murayama et al., 2016). Similarly, competitive goal structures may undermine perceptions of control. In contrast, well-calibrated cooperative structures can promote a sense of control and, at the same time, promote value by meeting needs for relatedness.

(5) Feedback about achievement shapes perceptions of control (Forsblom et al., 2022), and the consequences of achievement (financial gratifications, career opportunities etc.) influence perceptions of (extrinsic) value. From CVT propositions, it follows that high-stakes testing can boost the perceived importance of achievement to the extent that excessive anxiety and hopelessness are generated in many students and teachers.

(6) It follows from CVT that the composition of groups also plays an important role. In a recent model of compositional effects on emotions, Marsh and I combined CVT propositions with hypotheses from his big-fish-little-pond effect (BFLPE) model. We hypothesized, and found empirically, that being a member of a group of high achievers reduces self-confidence and perceived control, thereby decreasing positive achievement emotions and exacerbating negative emotions (“happy-fish-little-pond effect”; Pekrun et al., 2019; for a generalization across countries, see Basarkod et al., 2023).

Effects on Learning, Achievement, and Health

with colleagues alerted me to the fact that this model had two limitations: It did not differentiate between positive activating emotions (e.g., excitement, pride) and positive deactivating emotions (e.g., relief, relaxation), and it did not address the role of object focus. In the 2006 and subsequent versions of the model, differences between activating and deactivating positive emotions and the importance of object focus are addressed (Pekrun, 2006; Pekrun et al., 2023a).

people’s mental health and psychological wellbeing. In the same vein, excessive negative achievement emotions, such as excessive test anxiety or boredom, could be considered mental disorders (see Pekrun & Loderer, 2020). Nevertheless, achievement emotions are not considered in current classifications of disorders, such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) 5 and the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 11. CVT and the extant evidence suggest that excessive negative achievement emotions can be long-lasting, and that they can severely undermine everyday functioning and wellbeing. We have therefore called for re-considering excessive negative achievement emotions as mental disorders (test anxiety was included in the ICD 10 but was subsequently dropped; Pekrun & Loderer, 2020).

Reciprocal Causation, Emotion Regulation, and Intervention

five major groups. First, emotions can be managed by directly enhancing or suppressing their component processes, such as enhancing or suppressing the expression of emotion (emotion-oriented regulation). A second option is to select or modify situations in a way that changes emotions, such as selecting a school that better fits a student’s needs, or selecting tasks that match a student’s competencies (situation-oriented regulation). Third, achievement emotions can be managed by changing one’s appraisals (appraisal-oriented regulation) or by refocusing attention towards or away from emotional stimuli, such as success and failure (attentionoriented regulation). Finally, achievement emotions can be regulated by increasing one’s competencies, thus increasing the likelihood of success and strengthening the resulting positive emotions (competence-oriented regulation). Interventions targeting achievement emotions can be grouped in the same way (see Fig. 3).

Relative Universality of Achievement Emotions

countries. For example, across cycles of the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), relations between students’ enjoyment (such as science enjoyment) or anxiety (such as math anxiety) were similar across the broad range of countries included (see Guo et al., 2022; OECD, 2013). As such, the extant evidence suggests that CVT propositions are universally applicable.

Generalized Control-Value Theory

Epistemic Emotions

Social Emotions

gratitude, admiration, compassion, hate, anger, contempt, and envy (other-related social emotions; Table 2). CVT proposes that all these emotions depend on the perceived value of attributes and actions of oneself or other persons, respectively. In addition, many of them also depend on perceptions of control.

is caused by external circumstances, such as poverty not being the other person’s own fault. Envy is prompted if another person’s valued attributes (such as wealth or beauty) are seen as not being self-generated, thus, being undeserved (Feather, 2015). Again, all these control-dependent emotions are thought to depend on the interplay of perceptions of control and value.

Distal Antecedents, Effects on Behavior, and Reciprocal Causation

Implications for Educational Practice

Assessment of Emotions

Understanding Emotions

Changing Emotions

assessment policies away from high-stakes testing and towards an anxiety-free culture of learning from mistakes would amount to a radical shift in educational policymaking.

Strengths, Open Questions, and Future Directions

Virtues of CVT

2022). To explain the origins of achievement emotions, propositions from expec-tancy-value theory, attributional theory (Weiner, 1985), and Lazarus’s transactional model (e.g., Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) are integrated. To explain effects on learning and achievement, CVT synthesizes propositions from theories of effects on motivation, cognitive resources models (Meinhardt & Pekrun, 2003; Mikels & Reu-ter-Lorenz, 2019), and theories focusing on emotions and modes of thinking (e.g., Clore & Huntsinger, 2007). Beyond the emotion domain, CVT provides prospects for unification with motivation theory, given that CVT’s explanations of prospective emotions are conceptually equivalent with the explanations of motivation provided by self-efficacy theory and expectancy-value theories. Given the theoretical integration offered by CVT, the theory also shows “external consistency” and “analogy” (Greene, 2022) relative to other theories in the field.

Open Questions and Future Directions

interventions. A few of these open questions and future directions are the following (for more complete treatments, see Pekrun, 2018, 2021; Pekrun & Goetz, 2024b; Pekrun & Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2014).

Further Developing CVT

which level of granularity are they located? This question is especially difficult to answer for effects of emotions on performance. CVT’s cognitive-motivational model of emotion effects posits that emotions influence various mediating processes. The balance of effects on these processes can vary across persons and task conditions, such that one and the same emotion can have positive or negative overall effects on performance. For example, if the negative effects of anxiety on working memory resources and intrinsic motivation outweigh positive effects on extrinsic motivation, then anxiety should impair performance. If positive effects outweigh negative effects on these mediating mechanisms, then anxiety should boost performance. To define the balance, further work on these mechanisms and their modular organization is needed.

Empirical Research and Intervention Studies

self-report is subject to memory biases and the influence of response sets (such as social desirability). Second, self-report is not well suited to assess the physiological and behavioral component processes of emotions, like physiological arousal and facial expression. To more fully measure the emotions targeted by CVT, it is important to use multiple channels also including behavioral observation, physiological analysis, and neuro-imaging (see, e.g., Martin et al., 2023, and see Pekrun, 2023, for proposed guidelines). Advances in these methodologies are needed to more fully test the multivariate dynamics and multiple loops of reciprocal causation across different timeframes that link emotions, origins, and outcomes according to CVT (e.g., using nonlinear dynamic systems modeling; see also Marchand & Hilpert, 2023).

Conclusion

multi-channel measurement, dynamic modelling, and an integration of idiographic and nomothetic perspectives; further theoretical advances to more fully explain the diversity of emotions across persons and sociocultural contexts; as well as development of effective interventions and educational practices that target emotions to promote students’ and teachers’ affective health.

Declarations

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/.

References

Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychological Review, 64(6Pt 1), 359-372. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0043445

Barrett, L. F., Lewis, M., & Haviland-Jones, J. M. (Eds.). (2018). Handbook of emotions (

Barroso, C., Ganley, C. M., McGraw, A. L., Geer, E. A., Hart, S. A., & Daucourt, M. C. (2021). A metaanalysis of the relation between math anxiety and math achievement. Psychological Bulletin, 147(2), 134-168. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul000030

Basarkod, G., Marsh, H. W., Guo, J., Parker, P. D., Dicke, T., & Pekrun, R. (2023). The happy-fish-littlepond effect on enjoyment: Generalizability across multiple domains and countries. Learning and Instruction, 85, 101733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2023.101733

Beck, A. T., & Clark, D. A. (1988). Anxiety and depression: An information processing perspective. Anxiety Research, 1(1), 23-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615808808248218

Bieleke, M., Goetz, T., Yanagida, T., Botes, E., Frenzel, A. C., & Pekrun, R. (2023). Measuring emotions in mathematics: The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire-Mathematics (AEQ-M). ZDM-Mathematics Education, 55(2), 269-284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-022-01425-8

Bieleke, M., Gogol, K., Goetz, T., Daniels, L., & Pekrun, R. (2021). The AEQ-S: A short version of the Achievement Emotions Questionnaire. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 65, 101940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101940

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

Camacho-Morles, J., Slemp, G. R., Pekrun, R., Loderer, K., Hou, H., & Oades, L. G. (2021). Activity achievement emotions and academic performance: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 33(3), 1051-1095. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09585-3

Clore, G. L., & Huntsinger, J. R. (2007). How emotions inform judgment and regulate thought. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(9), 393-399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2007.08.005

D’Mello, S., & Graesser, A. (2012). Dynamics of affective states during complex learning. Learning and Instruction, 22(2), 145-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2011.10.001

D’Mello, S., Lehman, B., Pekrun, R., & Graesser, A. (2014). Confusion can be beneficial for learning. Learning and Instruction, 29, 153-170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.05.003

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101859

Feather, N. T. (2015). Analyzing relative deprivation in relation to deservingness, entitlement and resentment. Social Justice Research, 28(1), 7-26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-015-0235-9

Forsblom, L., Pekrun, R., Loderer, K., & Peixoto, F. (2022). Cognitive appraisals, achievement emotions, and students’ math achievement: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(2), 346-367. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000671

Frenzel, A. C., Becker-Kurz, B., Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., & Lüdtke, O. (2018). Emotion transmission in the classroom revisited: A reciprocal effects model of teacher and student enjoyment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(5), 628-639. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000228

Frenzel, A. C., Dindar, M., Pekrun, R., Reck, C., & Marx, A. K. G. (2024). Joy is reciprocally transmitted between teachers and students: Evidence on facial mimicry in the classroom. Learning and Instruction, 91, 101896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2024.101896

Frenzel, A. C., Pekrun, R., & Goetz, T. (2007). Girls and mathematics – a “hopeless” issue? A controlvalue approach to gender differences in emotions towards mathematics. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 22(4), 497-514. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173468

Gigerenzer, G. (2017). A theory integration program. Decision, 4(3), 133-145. https://doi.org/10.1037/ dec0000082

Goetz, T., Bieg, M., Lüdtke, O., Pekrun, R., & Hall, N. C. (2013). Do girls really experience more anxiety in mathematics? Psychological Science, 24(10), 2079-2087. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613486989

Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., Pekrun, R., Hall, N. C., & Lüdtke, O. (2007). Between- and within-domain relations of students’ academic emotions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(4), 715-733. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.4.715

Greene, J. A. (2022). What can educational psychology learn from, and contribute to, theory development scholarship? Educational Psychology Review, 34(4), 3011-3035. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10648-022-09682-5

Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781

Guo, J., Hu, X., Marsh, H. W., & Pekrun, R. (2022). Relations of epistemic beliefs with motivation, achievement, and aspirations in science: Generalizability across 72 societies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(4), 734-751. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000660

Hamaker, E. L. (2023). The within-between dispute in cross-lagged panel research and how to move forward. Psychological Methods. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000600

Hamaker, E. L., Kuiper, R. M., & Grasman, R. P. P. P. (2015). A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychological Methods, 20(1), 102-116. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038889

Hareli, S., & Weiner, B. (2002). Social emotions and personality inferences: A scaffold for a new direction in the study of achievement motivation. Educational Psychologist, 37(3), 183-193. https://doi. org/10.1207/S15326985EP3703_4

Harley, J. M., Pekrun, R., Taxer, J. L., & Gross, J. J. (2019). Emotion regulation in achievement situations: An integrated model. Educational Psychologist., 54(2), 106-126. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 00461520.2019 .1587297

Heckhausen, H. (1980). Motivation und Handeln [Motivation and action]. Springer.

Hoessle, C., Loderer, K., Pekrun, R. (2021, August). Piloting a control-value intervention promoting adaptive achievement emotions in university students. Paper presented at the 19th biennial conference of the European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction (EARLI), online.

Huang, C. (2011). Achievement goals and achievement emotions: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 23(3), 359-388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9155-x

Jirout, J. J., Ruzek, E., Vitiello, V. E., Whittaker, J., & Pianta, R. C. (2023). The association between and development of school enjoyment and general knowledge. Child Devevelopment, 94(2), 119-127. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev. 13878

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-292. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

Lajoie, S. P., & Poitras, E. (2023). Technology-rich learning environments: Theories and methodologies for understanding solo and group learning. In P. A. Schutz & K. Muis (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (4th edition, pp. 630-653). Routledge.

Lazarus, R., & Folkman. S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

Lichtenfeld, S., Pekrun, R., Stupnisky, R. H., Reiss, K., & Murayama, K. (2012). Measuring students’ emotions in the early years: The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire-Elementary School (AEQ-ES). Learning and Individual Differences, 22(2), 190-201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2011.04.009

Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Patall, E. A., & Pekrun, R. (2016). Adaptive motivation and emotion in education: Research and principles for instructional design. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(2), 228-236. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732216644450

Loderer, K., Pekrun, R., & Lester, J. C. (2020). Beyond cold technology: A systematic review and metaanalysis on emotions in technology-based learning environments. Learning and Instruction, 7, 101162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.08.002

Loderer, K., Pekrun, R., & Plass, J. L. (2019). Emotional foundations of game-based learning. In J. L. Plass, B. D. Homer, & R. E. Mayer (Eds.), Handbook of game-based learning (pp. 111-151). MIT Press.

Loewenstein, G. (1994). The psychology of curiosity: A review and reinterpretation. Psychological Bulletin, 116(1), 75-98. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.75

Lüdtke, O., & Robitzsch, A. (2022). A comparison of different approaches for estimating cross-lagged effects from a causal inference perspective. Structural Equation Modeling, 29(6), 888-907. https:// doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2022.2065278

Marchand, G. C., & Hilpert, J. C. (2023). Contributions of complex systems approaches, perspectives, models, and methods in educational psychology. In P. A. Schutz & K. Muis (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (4th edition, pp. 139-161). Routledge.

Marsh, H. W., Parker, P. D., & Pekrun, R. (2019a). Three paradoxical effects on academic self-concept across countries, schools, and students: Frame-of-reference as a unifying theoretical explanation. European Psychologist, 24(3), 231-242. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000332

Marsh, H. W., Pekrun, R., & Lüdtke, O. (2022). Directional ordering of self-concept, school grades, and standardized tests over five years: New tripartite models juxtaposing within- and betweenperson perspectives. Educational Psychology Review, 34, 2697-2744. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10648-022-09662-9

Marsh, H. W., Pekrun, R., Parker, P. D., Murayama, K., Guo, J., Dicke, T., & Arens, A. K. (2019b). The murky distinction between self-concept and self-efficacy: Beware of lurking jingle-jangle fallacies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(2), 331-353. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000281

Martin, A. J., Malmberg, L.-E., Pakarinen, E., Mason, L., & Mainhard, T. (Eds.). (2023). The potential of biophysiology for understanding motivation, engagement, and learning experiences [Special issue]. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(S1). https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep. 12584

Meinhardt, J., & Pekrun, R. (2003). Attentional resource allocation to emotional events: An ERP study. Cognition and Emotion, 17(3), 477-500. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930244000039

Menninghaus, W., Wagner, V., Wassiliwizky, E., Schindler, I., Hanich, J., Jacobsen, T., & Koelsch, S. (2019). What are aesthetic emotions? Psychological Review, 126(2), 171-195. https://doi.org/10. 1037/rev0000135

Mikels, J. A., & Reuter-Lorenz, P. A. (2019). Affective working memory: An integrative psychological construct. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(4), 543-559. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456 91619837597

Murayama, K., Goetz, T., Malmberg, L.-E., Pekrun, R., Tanaka, A., & Martin, A. J. (2017). Within-person analysis in educational psychology: Importance and illustrations. In D. W. Putwain & K. Smart (Eds.), British Journal of Educational Psychology Monograph Series II: Psychological Aspects

of Education – Current Trends: The Role of Competence Beliefs in Teaching and Learning (pp. 71-87). Wiley.

Murayama, K., Pekrun, R., Suzuki, M., Marsh, H. W., & Lichtenfeld, S. (2016). Don’t aim too high for your kids: Parental over-aspiration undermines students’ learning in mathematics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111(5), 166-179. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000079

Neta, M., & Kim, M. J. (2023). Surprise as an emotion: A response to Ortony. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 18(4), 854-862. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916221132789

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD]. (2013). PISA 2012 results (Volume 3): Ready to learn. Students’ engagement, drive and self-beliefs. Author.

Pekrun, R. (1983). Schulische Persönlichkeitsentwicklung. Theoretische Überlegungen und empirische Erhebungen zur Persönlichkeitsentwicklung von Schülern der 5. bis 10. Klassenstufe [Personality development at school: Theoretical models and empirical studies on students’ personality development from grades 5 to 10]. Peter Lang.

Pekrun, R. (1984). An expectancy-value model of anxiety. In R. Schwarzer, C. D. Spielberger, & H. M. van der Ploeg (Eds.), Advances in test anxiety research (Vol. 3, pp. 53-72). Swets & Zeitlinger.

Pekrun, R. (1988). Emotion, Motivation und Persönlichkeit [Emotion, motivation and personality]. Psychologie Verlags Union.

Pekrun, R. (1992a). The expectancy-value theory of anxiety: Overview and implications. In D. G. Forgays, T. Sosnowski, & K. Wrzesniewski (Eds.), Anxiety: Recent developments in self-appraisal, psychophysiological and health research (pp. 23-41). Hemisphere.

Pekrun, R. (1992b). The impact of emotions on learning and achievement: Towards a theory of cognitive/ motivational mediators. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 41(4), 359-376. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1992.tb00712.x

Pekrun, R. (1993). Facets of students’ academic motivation: A longitudinal expectancy-value approach. In M. Maehr & P. Pintrich (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement (8, 139-189). JAI Press.

Pekrun, R. (2000). A social cognitive, control-value theory of achievement emotions. In J. Heckhausen (Ed.), Motivational psychology of human development (pp. 143-163). Elsevier Science.

Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 315341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9029-9

Pekrun, R. (2014). Emotions and learning (Educational Practices Series, Vol. 24). International Academy of Education (IAE) and International Bureau of Education (IBE) of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Geneva, Switzerland. http://www.iaoed. org/downloads/edu-practices_24_eng.pdf

Pekrun, R. (2018). Control-value theory: A social-cognitive approach to achievement emotions. In G. A. D. Liem & D. M. McInerney (Eds.), Big theories revisited 2: A volume of research on sociocultural influences on motivation and learning (pp. 162-190). Information Age Publishing.

Pekrun, R. (2019). The murky distinction between curiosity and interest: State of the art and future directions. Educational Psychology Review, 31(4), 905-914. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10648-019-09512-1

Pekrun, R. (2020). Self-report is indispensable to assess students’ learning. Frontline Learning Research, 8(3), 185-193. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v8i3. 637

Pekrun, R. (2021). Self-appraisals and emotions: A generalized control-value approach. In T. Dicke, F. Guay, H. W. Marsh, R. G. Craven, & D. M. McInerney (Eds.), Self – a multidisciplinary concept (pp. 1-30). Information Age Publishing.

Pekrun, R. (2023). Mind and body in students’ and teachers’ engagement: New evidence, challenges, and guidelines for future research. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(S1), 227-238. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep. 12575

Pekrun, R. (2024). Overcoming fragmentation in motivation science: Why, when, and how should we integrate theories? Educational Psychology Review, 36, 27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-024-09846-5

Pekrun, R., Elliot, A. J., & Maier, M. A. (2009). Achievement goals and achievement emotions: Testing a model of their joint relations with academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(1), 115-135. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013383

Pekrun, R., & Goetz, T. (2024a). Boredom: A control-value theory approach. In M. Bieleke, W. Wolff, & C. Martarelli (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of boredom (pp. 74-89). Routledge.

Pekrun, R., & Goetz, T. (2024b). How universal are academic emotions? A control-value theory perspective. In G. Hagenauer, R. Lazarides, & H. Järvenoja (Eds.), Motivation and emotion in learning and teaching across educational contexts: Theoretical and methodological perspectives and empirical insights (pp. 85-99). Taylor & Francis / Routledge.

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., Barchfeld, P., & Perry, R. P. (2011). Measuring emotions in students’ learning and performance: The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire (AEQ). Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(1), 36-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.10.002

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educational Psychologist, 37(2), 91-105. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3702_4

Pekrun, R., Lichtenfeld, S., Marsh, H. W., Murayama, K., & Goetz, T. (2017a). Achievement emotions and academic performance: Longitudinal models of reciprocal effects. Child Development, 88(5), 1653-1670. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev. 12704

Pekrun, R., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2014). Conclusions and future directions. In R. Pekrun & L. Lin-nenbrink-Garcia (Eds.), International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 659-675). Taylor & Francis.

Pekrun, R., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2022). Academic emotions and student engagement. In A. L. Reschly & S. L. Christenson (Eds.), The handbook of research on student engagement (2nd ed., pp. 109-132). Springer.

Pekrun, R., & Loderer, K. (2020). Control-value theory and students with special needs: Achievement emotion disorders and their links to behavioral disorders and academic difficulties. In A. J. Martin, R. A. Sperling, & K. J. Newton (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology and students with special needs. Taylor & Francis.

Pekrun, R., Marsh, H. W., Elliot, A. J., Stockinger, K., Perry, R. P., Vogl, E., Goetz, T., van Tilburg, W. A. P., Lüdtke, O., & Vispoel, W. P. (2023a). A three-dimensional taxonomy of achievement emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 124(1), 145-178. https://doi.org/10.1037/ pspp0000448

Pekrun, R., Marsh, H. W., Suessenbach, F., Frenzel, A. C., & Goetz, T. (2023b). School grades and students’ emotions: Longitudinal models of within-person reciprocal effects. Learning and Instruction, 83, 101626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2022.101626

Pekrun, R., Murayama, K., Marsh, H. W., Goetz, T., & Frenzel, A. C. (2019). Happy fish in little ponds: Testing a reference group model of achievement and emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 117(1), 166-185. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000230

Pekrun, R., & Stephens, E. J. (2012). Academic emotions. In K. R. Harris, S. Graham, T. Urdan, J. M. Royer, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), APA educational psychology handbook (Vol. 2, pp. 3-31). American Psychological Association.

Pekrun, R., Vogl, E., Muis, K. R., & Sinatra, G. M. (2017b). Measuring emotions during epistemic activities: The Epistemically-Related Emotion Scales. Cognition and Emotion, 31(6), 1268-1276. https:// doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1204989

Peterson, E. G., & Cohen, J. (2019). A case for domain-specific curiosity in mathematics. Educational Psychology Review, 31, 807-832. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09501-4

Price, D. D., Barrell, J. E., & Barrell, J. J. (1985). A quantitative-experiential analysis of human emotions. Motivation and Emotion, 9(1), 19-38. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00991548

Putwain, D. W., Pekrun, R., Nicholson, L. J., Symes, W., Becker, S., & Marsh, H. W. (2018). Controlvalue appraisals, enjoyment, and boredom in mathematics: A longitudinal latent interaction analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 55(6), 1339-1368. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028 31218786689

Quinlan, K. M. (Ed.). (2016). How higher education feels: Poetry that illuminates the experiences of learning, teaching and transformation. Sense Publishers.

Reisenzein, R., Horstmann, G., & Schützwohl, A. (2019). The cognitive-evolutionary model of surprise: A review of the evidence. Topics in Cognitive Science, 11, 50-74. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops. 12292

Roseman, I. J., Spindel, M. S., & Jose, P. E. (1990). Appraisals of emotion-eliciting events: Testing a theory of discrete emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(5), 899-915. https:// doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.899

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press. https://doi.org/10.1521/978.14625/28806

Scherer, K. R., & Moors, A. (2019). The emotion process: Event appraisal and component differentiation. Annual Review of Psychology, 70(1), 719-745. https://doi.org/10.1146/annur ev-psych-122216-011854

Scherer, K. R., Schorr, A., & Johnstone, T. (Eds.). (2001). Appraisal processes in emotion: theory, methods, research. Oxford University Press.

Schönbrodt, F., & Perugini, M. (2013). At what sample size do correlations stabilize? Journal of Research in Personality, 47(5), 609-612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2013.05.009

Shao, K., Pekrun, R., Marsh, H. W., & Loderer, K. (2020). Control-value appraisals, achievement emotions, and foreign language performance: A latent interaction analysis. Learning and Instruction, 69, 101356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101356

Shao, K., Stockinger, K., Marsh, H. W., & Pekrun, R. (2023). Applying control-value theory for examining multiple emotions in second language classrooms: Validating the Achievement Emotions Ques-tionnaire-Second Language Learning. Language Teaching Research. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221144497

Sinha, T. (2022). Enriching problem-solving followed by instruction with explanatory accounts of emotions. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 31(2), 151-198. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2021. 1964506

Skinner, E. A. (1996). A guide to constructs of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(3), 549-570. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.3.549

Steinmayr, R., Crede, J., McElvany, N., & Wirthwein, L. (2016). Subjective well-being, test anxiety, academic achievement: Testing for reciprocal effects. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1994. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01994

Sweller, J. (2023). The development of cognitive load theory: Replication crises and incorporation of other theories can lead to theory expansion. Educational Psychology Review, 35, 95. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10648-023-09817-2

Vansteenkiste, M., Ryan, R. M., & Soenens, B. (2020). Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motivation and Emotion, 44, 1-31. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11031-019-09818-1

von der Embse, N., Jester, D., Roy, D., & Post, J. (2018). Test anxiety effects, predictors, and correlates: A 30-year meta-analytic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 483-493. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.jad.2017.11.048

Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. Wiley.

Wan, S., Lauermann, F., Bailey, D. H., & Eccles, J. S. (2021). When do students begin to think that one has to be either a “math person” or a “language person”? A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 147(9), 867-889. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000340

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4), 548-573.

Williams-Johnson, M., Cross, D., Hong, J., Aultman, L., Osbon, J., & Schutz, P. (2008). “There are no emotions in math”: How teachers approach emotions in the classroom. Teachers College Record, 110(8), 1574-1610. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810811000801

Zeidner, M. (1998). Test anxiety: The state of the art. Plenum.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- This article is part of the Topical Collection on Theory Development in Educational Psychology

Reinhard Pekrun

pekrun@lmu.de

Department of Psychology, University of Essex, Colchester, United Kingdom

Institute for Positive Psychology and Education, Australian Catholic University, Sydney, Australia

3 Department of Psychology, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Munich, Germany