DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-023-09841-2

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-15

نظرية الحمل المعرفي وعلاقاتها بالدافعية: منظور نظرية تحديد الذات

© المؤلفون 2024، نشر مصحح 2024

الملخص

على الرغم من أن أبحاث نظرية الحمل المعرفي قد درست العوامل المرتبطة بالدافع، إلا أن هذه الأدبيات قد تم تطويرها بشكل أساسي بمعزل عن بعضها البعض. في هذه المساهمة، هدفنا إلى تعزيز كلا المجالين من خلال دراسة تأثيرات استراتيجيات التعليم على تجربة المتعلمين من الحمل المعرفي والدافع والانخراط والإنجاز. أكمل الطلاب (

نظرية الحمل المعرفي

الدعم والإرشاد التعليمي (إيفانز ومارتن، 2023أ؛ كيرشنر وآخرون، 2006؛ سويلر، 2015).

الحمل المعرفي والدافع

في دراسة لطلاب العلوم في المدارس الثانوية، كانت المشاركة وسيطًا في تأثيرات تعليم تقليل الحمل على الإنجاز، مع تأثيرات كبيرة على مستوى الطلاب والفصول الدراسية (مارتن، جينز، بيرنز، كينيت، مونرو-سميث، وآخرون، 2021b).

نظرية تحديد الذات

تؤثر أسلوب التعليم على الدافعية، وقد توفر تجربة الحمل المعرفي تفسيرًا لسبب حدوث ذلك. في الدراسة الحالية، كما توضح الأقسام التالية، ركزنا على دور أسلوب تحفيز المعلم.

أساليب تحفيز المعلمين

دعم الاستقلالية، الهيكل، والعبء المعرفي

نحو الأنشطة الضرورية للتعلم، مما يقلل من نسبة العبء المعرفي الذي هو خارجي. دعم الاستقلالية هو عمومًا تجربة عاطفية إيجابية، مما يعني أنه قد يؤثر على معتقدات التنظيم الذاتي ويعزز استثمار الجهد العقلي (بلاس وكاليغا، 2019). على سبيل المثال، أظهر دعم الاستقلالية أنه يزيد من جهد الدراسة ويقلل من التسويف على مدار عام دراسي (موراتيديس وآخرون، 2018). بالمقارنة مع التدريس الداعم للاستقلالية، يؤدي التدريس المسيطر إلى سلوكيات واستجابات عاطفية تتطلب موارد انتباهية وتعيق التعلم. في ظل ظروف السيطرة، يجب على الطلاب أن يكونوا قلقين بشأن تجنب المشاكل، وعدم إزعاج المعلم، والامتثال للتوقعات، وإدارة الآثار السلبية لإحباط الاحتياجات النفسية (باتال وآخرون، 2018؛ ريف وآخرون، 2011ب؛ سونينز وآخرون، 2012)، ولا شيء من ذلك يساهم مباشرة في التعلم.

أهداف الدراسة

الطريقة

المشاركون والإجراءات

القياسات

مقياس تعليم تقليل العبء (LRIS)

| الإحصائيات الوصفية والارتباطات. | 1 | 2 | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | ٦ | ٧ | ٨ |

| 1. تعليمات تقليل الحمل | ||||||||

| 2. الحمل المعرفي الزائد | -. 679 – | |||||||

| 3. الحمل المعرفي الجوهري | -. 207 | . 512 | – | |||||

| 4. الدافع (RAI) | . ٥٥١ | -. 519 | -. 370 | – | ||||

| 5. المشاركة | . 646 | -. 517 | -. 385 | . 772 | – | |||

| 6. الانفصال | -. 384 | . 463 | . ٢٠٣ | -. 496 | -. 402 | – | ||

| 7. الدرجة المبلغ عنها من قبل الطالب | . ٢٥١ | -. 324 | -. 404 | . 354 | . 473 | -. 186 | – | |

| 8. الدرجة المبلغ عنها من المدرسة | . ١٣٢ | -. 184 | -. 252 | . 182 | . 229 | -. 203 | . 389 | – |

| عمر | -. 094 | . 028 | -. 001 | -. 066 | -. 094 | . 020 | -. 016 | -. 034 |

| جنس | -. 036 | . 001 | . 061 | . 002 | -. 053 | -. 101 | -. 058 | . ١٠٨ |

| SES | . 093 | -. 060 | -. 044 | . 043 | . 111 | -. 137 | . 140 | . 071 |

| M | ٥.٠٢٦ | ٣.٠٥٨ | ٣.٥١١ | 17.854 | ٤.٨٨٦ | ٢.٥٤٢ | 73.137 | ٢.٧٨٩ |

| SD | 1.356 | 1.584 | 1.483 | ٤.٩٧٩ | 1.083 | 1.383 | 13.472 | . 862 |

| ICC | . 299 | . 242 | . 125 | . ١١٩ | . 177 | . 098 | . 178 | . 453 |

| ICC2 | . 861 | . ٨٢٢ | . 675 | . 664 | . 758 | . 612 | . 744 | . ٨٨٧ |

| أوميغا | . 922 | . 936 | . 916 | . 955 | . 857 | . 842 | – | – |

عبء معرفي

طلاب الرياضيات في المدارس (مارتن وإيفانز، 2018). وجدت مراجعة لهذا النهج في قياس الحمل المعرفي في الدراسات التجريبية (كريغلشتاين وآخرون، 2022) أدلة قوية على الاتساق الداخلي وصلاحية البناء.

أسلوب تحفيز المعلم

تحفيز

الخطوبة

فك الارتباط

الدرجات

تحليل البيانات

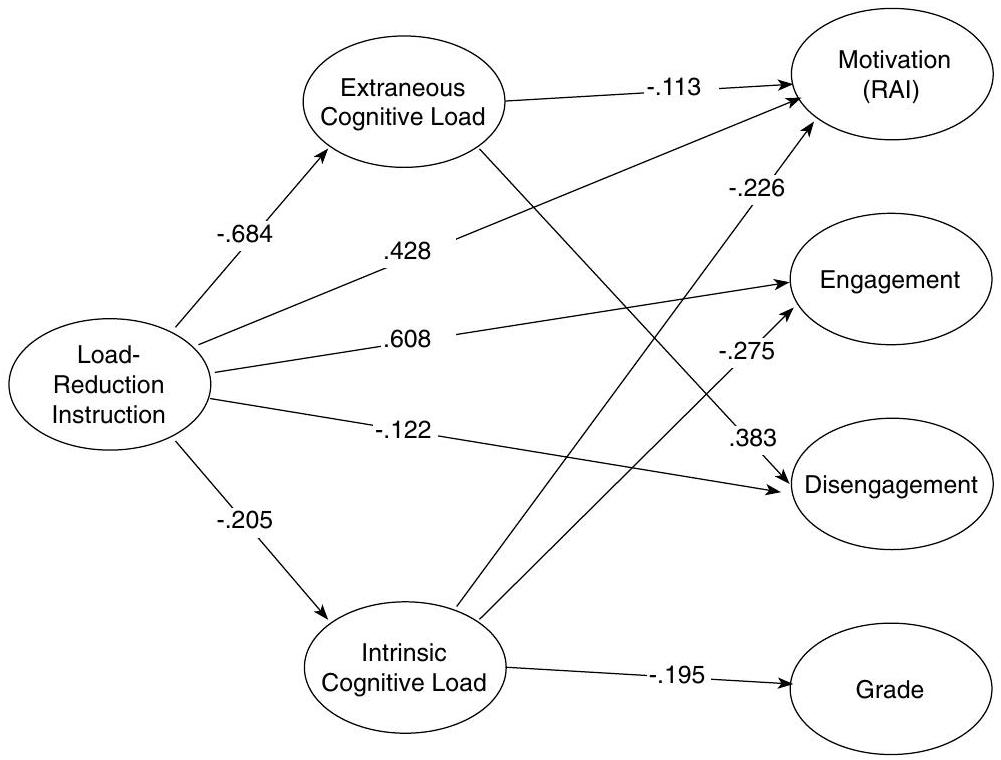

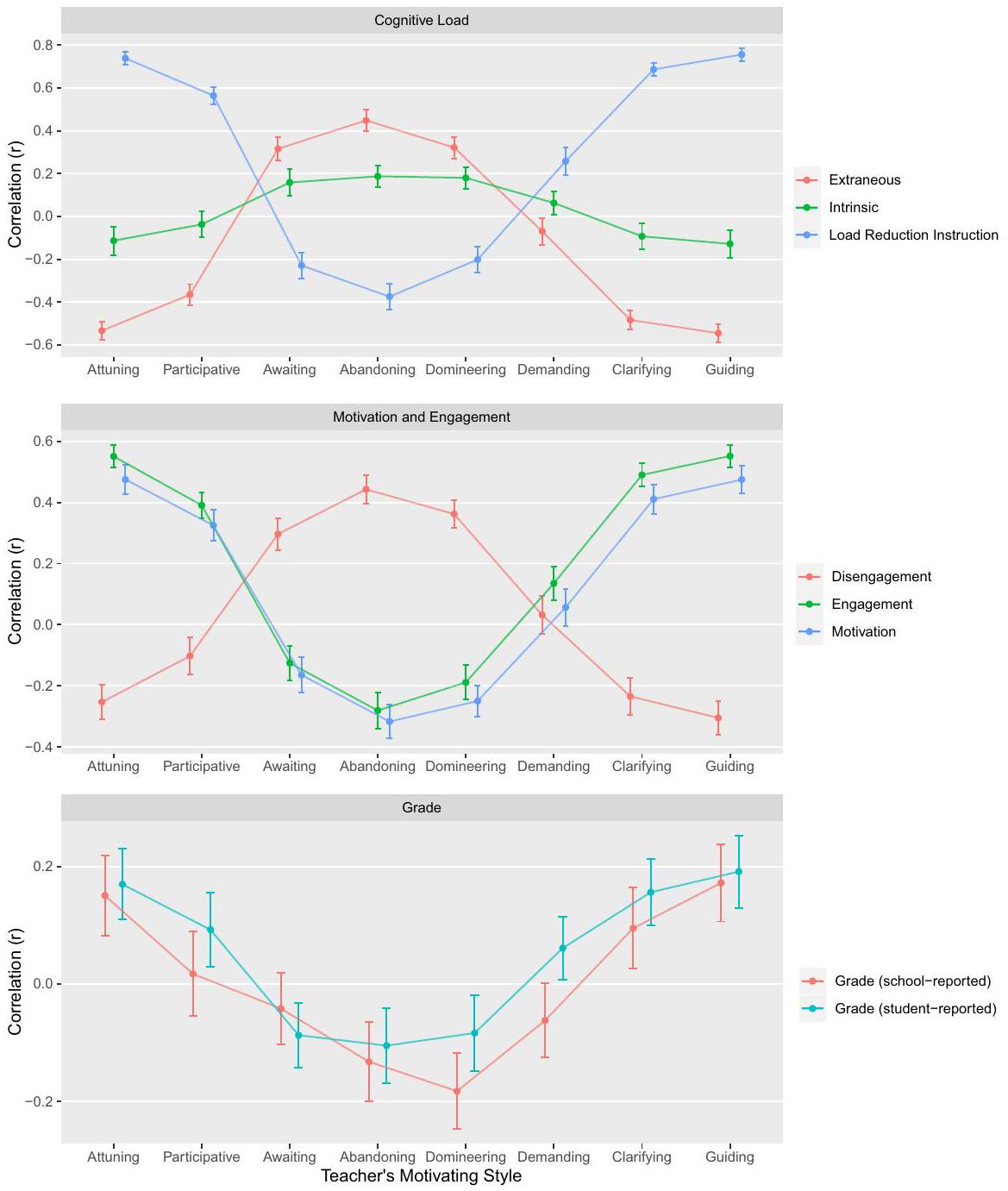

تم التنبؤ بالانسحاب والإنجاز من خلال الحمل المعرفي، ومن ثم تعليم تقليل الحمل. تم تضمين العمر والجنس والوضع الاجتماعي الاقتصادي في النموذج كمتغيرات مصاحبة (أي، تتنبأ بجميع العوامل الأخرى في النموذج). تم تقدير النموذج أولاً كنموذج قياس (تحليل العوامل التأكيدية) مع تقدير جميع الارتباطات الكامنة بحرية، قبل فرض قيود الانحدار (الهيكلية). لم نقم بطرح أي فرضيات (أو نتائج) فيما يتعلق بالوساطة حيث أن النموذج يعتمد على بيانات مقطعية، ولكن من أجل الاكتمال، نبلغ أيضًا عن التأثيرات غير المباشرة. لمعالجة الهدف 2، درسنا أسلوب تحفيز المعلم. باستخدام الهيكل الدائري لأسلوب تحفيز المعلم، قمنا بربط المجالات الفرعية المختلفة داخل نموذج الدائرة بتعليم تقليل الحمل، والحمل المعرفي الداخلي والخارجي، والدافع، والانخراط، والإنجاز. توقعنا نمطًا جيبيًا من الارتباطات بين الأنماط المميزة في الدائرة والنتائج المختلفة المقيمة.

النتائج

الهدف 1: النتائج التحفيزية لتعليم تقليل الحمل

الهدف 2: تأثير أسلوب تحفيز المعلم على الحمل المعرفي

نقاش

عبء المعرفة كعامل سابق للتحفيز والانخراط والتعلم

على سبيل المثال، اقترح أن تجربة الحمل المعرفي الخارجي قد تؤثر على المعتقدات التحفيزية – تحديدًا تقييمات التكلفة، بسبب الجهد المتزايد الذي سيكون مطلوبًا في التفاعلات اللاحقة مع أنشطة التعلم (فيلدون وآخرون، 2019) ومعتقدات الكفاءة الذاتية (فيلدون وآخرون، 2018). كلا البناءين يتعلقان بتوقعات النتائج والجهد المدرك. من خلال تفعيل بناء الدافع الذاتي المستقل، تُظهر الدراسة الحالية أن تقليل الحمل المعرفي قد يسهل أيضًا استيعاب القيمة وتوافق مهام التعلم مع الذات.

أسلوب المعلم التحفيزي والعبء المعرفي

هيكل وأساس الأنشطة التعليمية للطلاب، ورعاية تقدم الطلاب نحو أهداف التعلم. تم دعم نموذج المعلم الدافع (Aelterman & Vansteenkiste، 2023) من خلال البيانات، حيث تم تحديد مستوى ثنائي الأبعاد (أي، تقاطع مستوى دعم الاحتياجات مع مستوى التوجيه) الذي يحدد ثمانية مجالات فرعية قابلة للتحديد. كما تم الافتراض، كانت الأنماط المكتشفة مرتبطة بطريقة مرتبة (أي، جيبية)، حيث كانت المجالات الفرعية المجاورة مرتبطة إيجابيًا، وأصبح النمط يتناقص إيجابيًا وحتى سلبيًا عند الانتقال إلى المجال الفرعي المقابل في النموذج الدائري (Gurtman & Pincus، 2003). عند تنفيذ هذا المقياس، حافظنا على موثوقية هذه الأداة الجديدة (أي، SIS) بما يتجاوز استخدامها السابق في عينات بلجيكية (Aelterman et al.، 2019b) إلى نسخة إنجليزية مع طلاب أستراليين.

ملاحظة حول نظريات الدافع

القيود والاتجاهات للبحوث المستقبلية

في استراتيجيات التعليم (دومين وآخرون، 2020). وبالتالي، للبحوث المستقبلية، نوصي بدراسات تشمل حجم عينة كافٍ على مستوى الفصل لأخذ التباين بين الطلاب والفصول في الاعتبار.

الخاتمة

المتعلمين للانخراط بشكل أعمق في تعلمهم، وقد تدفع المتعلمين حتى للشعور بالإحباط والانفصال. كما أن النتائج الحالية لها تداعيات على المعلمين واستخدامهم لاستراتيجيات التدريس: استراتيجيات تقليل الحمل التعليمي تقلل من الحمل المعرفي وتكون محفزة وجذابة في حد ذاتها. استنادًا إلى هذه النتائج، يبدو أن هناك خطرًا ضئيلًا يواجه الدافع والانخراط من استخدام استراتيجيات التدريس الصريحة لتقليل الحمل المعرفي. خارج استراتيجيات التدريس، فإن أسلوب تحفيز المعلم نفسه له عواقب: محاولات تحفيز الطلاب باستخدام الحوافز الخارجية، أو المطالب المفرطة، أو نقص الهيكل تشكل مخاطر على الطلاب من حيث زيادة الحمل المعرفي وتقليل الدافع والانخراط.

الوصول المفتوح هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام والمشاركة والتكيف والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج في أي وسيلة أو صيغة، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح ما إذا كانت هناك تغييرات قد أُجريت. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة، ما لم يُذكر خلاف ذلك في سطر ائتمان للمادة. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة واستخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، ستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارةhttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

References

Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., Van Keer, H., & Haerens, L. (2016). Changing teachers’ beliefs regarding autonomy support and structure: The role of experienced psychological need satisfaction in teacher training. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 23, 64-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psych sport.2015.10.007

Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., & Haerens, L. (2019a). Correlates of students’ internalization and defiance of classroom rules: A self-determination theory perspective. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 89, 22-40. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep. 12213

Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., Haerens, L., Soenens, B., Fontaine, J. R. J., & Reeve, J. (2019b). Toward an integrative and fine-grained insight in motivating and demotivating teaching styles: The merits of a circumplex approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(3), 497-521. https://doi. org/10.1037/edu0000293

Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1967). Human memory: A proposed system and its control processes. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 2, 89-195.

Bonneville-Roussy, A., Evans, P., Verner-Filion, J., Vallerand, R. J., & Bouffard, T. (2017). Motivation and coping with the stress of assessment: Gender differences in outcomes for university students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 48, 28-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.08.003

Baddeley, A. D. (2012). Working memory: Theories, models, and controversies. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 1-29. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100422

Cook, D. A., Castillo, R. M., Gas, B., & Artino, A. R. (2017). Measuring achievement goal motivation, mindsets and cognitive load: Validation of three instruments’ scores. Medical Education, 51(10), 1061-1074. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu. 13405

Cowan, N. (2010). The magical mystery four: How is working memory capacity limited, and why? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(1), 51-57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721409359277

Cowan, N. (2014). Working memory underpins cognitive development, learning, and education. Educational Psychology Review, 26(2), 197-223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-013-9246-y

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum.

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., & Williams, G. C. (1996). Need satisfaction and the self-regulation of learning. Learning and Individual Differences, 8, 165-183.

Delrue, J., Reynders, B., Broek, G. V., Aelterman, N., De Backer, M., Decroos, S., De Muynck, G.-J., Fontaine, J., Fransen, K., van Puyenbroeck, S., Haerens, L., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2019). Adopting a helicopter-perspective towards motivating and demotivating coaching: A circumplex approach. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 40, 110-126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport. 2018.08.008

Eitel, A., Endres, T., & Renkl, A. (2020). Self-management as a bridge between cognitive load and self-regulated learning: The illustrative case of seductive details. Educational Psychology Review, 32(4), 1073-1087. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09559-5

Evans, P., & Martin, A. J. (2023a). Explicit Instruction. In A. O’Donnell, N. C. Barnes, & J. Reeve (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of educational psychology. Oxford University Press. https://doi. org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199841332.013.53

Evans, P., & Martin, A. J. (2023b). Load reduction instruction: Multilevel effects for motivation, engagement, and achievement in mathematics. Educational Psychology, 1-19. https://doi.org/10. 1080/01443410.2023.2290442

Feldon, D. F., Callan, G., Juth, S., & Jeong, S. (2019). Cognitive load as motivational cost. Educational Psychology Review, 31(2), 319-337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09464-6

Feldon, D. F., Franco, J., Chao, J., Peugh, J., & Maahs-Fladung, C. (2018). Self-efficacy change associated with a cognitive load-based intervention in an undergraduate biology course. Learning and Instruction, 56, 64-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.04.007

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59-109. https://doi.org/10. 3102/00346543074001059

Freer, E., & Evans, P. (2019). Choosing to study music in high school: Teacher support, psychological needs satisfaction, and elective music intentions. Psychology of Music, 47(6), 781-799. https:// doi.org/10.1177/0305735619864634

Gurtman, M. B., & Pincus, A. L. (2003). The circumplex model: Methods and research applications. In Handbook of psychology (pp. 407-428). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471264385.wei0216

Haakma, I., Janssen, M., & Minnaert, A. (2016). A literature review on how need-supportive behavior influences motivation in students with sensory loss. Teaching and Teacher Education, 57, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.02.008

Haakma, I., Janssen, M., & Minnaert, A. (2017). Intervening to improve teachers’ need-supportive behaviour using self-determination theory: Its effects on teachers and on the motivation of students with deafblindness. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 64(3), 310-327. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2016.1213376

Hawthorne, B. S., Vella-Brodrick, D., & A., & Hattie, J. (2019). Well-being as a cognitive load reducing agent: A review of the literature. Frontiers in Education, 4, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3389/ feduc.2019.00121

Hornstra, L., Stroet, K., & Weijers, D. (2021). Profiles of teachers’ need-support: How do autonomy support, structure, and involvement cohere and predict motivation and learning outcomes? Teaching and Teacher Education, 99, 103257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103257

Howard, J. L., Gagné, M., & Bureau, J. S. (2017). Testing a continuum structure of self-determined motivation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 143(12), 1346-1377. https://doi.org/10. 1037/bul0000125

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Jang, H., Reeve, J., & Deci, E. L. (2010). Engaging students in learning activities: It is not autonomy support or structure, but autonomy support and structure. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102, 588-600. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019682

Jang, H., Reeve, J., Ryan, R. M., & Kim, A. (2009). Can self-determination theory explain what underlies the productive, satisfying learning experiences of collectivistically oriented Korean students? Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(3), 644-661. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014 241

Kalyuga, S. (2007). Expertise reversal effect and its implications for learner-tailored instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 19(4), 509-539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-007-9054-3

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75-86.

Krieglstein, F., Beege, M., Rey, G. D., Ginns, P., Krell, M., & Schneider, S. (2022). A systematic metaanalysis of the reliability and validity of subjective cognitive load questionnaires in experimental multimedia learning research. Educational Psychology Review, 34(4), 2485-2541. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10648-022-09683-4

Leppink, J., Paas, F. G. W. C., van Gog, T., van der Vleuten, C. P. M., & van Merriënboer, J. J. G. (2014). Effects of pairs of problems and examples on task performance and different types of cognitive load. Learning and Instruction, 30, 32-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2013.12.001

Likourezos, V., & Kalyuga, S. (2017). Instruction-first and problem-solving-first approaches: Alternative pathways to learning complex tasks. Instructional Science, 45(2), 195-219. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11251-016-9399-4

Litalien, D., Morin, A. J. S., Gagné, M., Vallerand, R. J., Losier, G. F., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Evidence of a continuum structure of academic self-determination: A two-study test using a bifactor-ESEM representation of academic motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 51, 67-82. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.06.010

Mair, P., Groenen, P. J. F., & de Leeuw, J. (2022). More on multidimensional scaling in R: smacof version 2. Journal of Statistical Software, 102(10), 1-47.

Martin, A. J. (2023). Integrating motivation and instruction: Towards a unified approach in educational psychology. Educational Psychology Review, 35(54). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-023-09774-w

Martin, A. J., & Evans, P. (2018). Load reduction instruction: Exploring a framework that assesses explicit instruction through to independent learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 73, 203-214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.03.018

Martin, A. J., Ginns, P., Burns, E. C., Kennett, R., & Pearson, J. (2021a). Load reduction instruction in science and students’ science engagement and science achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(6), 1126-1142. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000552

Martin, A. J., Ginns, P., Burns, E. C., Kennett, R., Munro-Smith, V., Collie, R. J., & Pearson, J. (2021b). Assessing instructional cognitive load in the context of students’ psychological challenge and threat orientations: A multi-level latent profile analysis of students and classrooms. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.656994

Martin, A. J., Ginns, P., Nagy, R. P., Collie, R. J., & Bostwick, K. C. P. (2023). Load reduction instruction in mathematics and English classrooms: A multilevel study of student and teacher reports. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2023.102147

McNeish, D. (2018). Thanks coefficient alpha, we’ll take it from here. Psychological Methods, 23(3), 412-433. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000144

Moreno, R. (2006). Does the modality principle hold for different media? A test of the method-affectslearning hypothesis. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 22(3), 149-158. https://doi.org/10. 1111/j.1365-2729.2006.00170.x

Mouratidis, A., Michou, A., Telli, S., Maulana, R., & Helms-Lorenz, M. (2022). No aspect of structure should be left behind in relation to student autonomous motivation. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(3), 1086-1108. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep. 12489

Mouratidis, A., Michou, A., Aelterman, N., Haerens, L., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2018). Begin-of-schoolyear perceived autonomy-support and structure as predictors of end-of-school-year study efforts and procrastination: The mediating role of autonomous and controlled motivation. Educational Psychology, 38(4), 435-450. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2017.1402863

Nebel, S., Schneider, S., Schledjewski, J., & Rey, G. D. (2017). Goal-setting in educational video games: Comparing goal-setting theory and the goal-free effect. Simulation & Gaming, 48(1), 98-130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878116680869

Oga-Baldwin, W. L. Q., & Nakata, Y. (2015). Structure also supports autonomy: Measuring and defining autonomy-supportive teaching in Japanese elementary foreign language classes: Structure also supports autonomy. Japanese Psychological Research, 57(3), 167-179. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpr. 12077

Patall, E. A., Steingut, R. R., Vasquez, A. C., Trimble, S. S., Pituch, K. A., & Freeman, J. L. (2018). Daily autonomy supporting or thwarting and students’ motivation and engagement in the high school science classroom. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(2), 269-288. https://doi.org/10. 1037/edu0000214

Pitzer, J., & Skinner, E. (2017). Predictors of changes in students’ motivational resilience over the school year: The roles of teacher support, self-appraisals, and emotional reactivity. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 41(1), 15-29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025416642051

Plass, J. L., & Kalyuga, S. (2019). Four ways of considering emotion in cognitive load theory. Educational Psychology Review, 31(2), 339-359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09473-5

Plutchik, R., & Conte, H. R. (Eds.). (1997). Circumplex models of personality and emotions. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10261-000

R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Computer software]. http://www.R-project.org

Raftery-Helmer, J. N., & Grolnick, W. S. (2016). Children’s coping with academic failure: Relations with contextual and motivational resources supporting competence. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 36(8), 1017-1041. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431615594459

Ratelle, C. F., Duchesne, S., Litalien, D., & Plamondon, A. (2021). The role of mothers in supporting adaptation in school: A psychological needs perspective. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(1), 197-212. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000455

Ratelle, C. F., Guay, F., Vallerand, R. J., Larose, S., & Senécal, C. B. (2007). Autonomous, controlled, and amotivated types of academic motivation: A person-oriented analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(4), 734-746. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.4.734

Redeker, M., De Vries, R. E., Rouckhout, D., Vermeren, P., & De Fruyt, F. (2014). Integrating leadership: The leadership circumplex. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(3), 435-455. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.738671

Reeve, J. (2009). Why teachers adopt a controlling motivating style toward students and how they can become more autonomy supportive. Educational Psychologist, 44(3), 159-175. https://doi.org/10. 1080/00461520903028990

Reeve, J. (2013). How students create motivationally supportive learning environments for themselves: The concept of agentic engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 579-595. https:// doi.org/10.1037/a0032690

Reeve, J., & Tseng, C. M. (2011a). Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36, 257-267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych. 2011.05.002

Reeve, J., Jang, H.-R., Shin, S. H., Ahn, J. S., Matos, L., & Gargurevich, R. (2022). When students show some initiative: Two experiments on the benefits of greater agentic engagement. Learning and Instruction, 80, 101564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2021.101564

Reeve, J., Jang, H., Carrell, D., Jeon, S., & Barch, J. (2004). Enhancing students’ engagement by increasing teachers’ autonomy support. Motivation and Emotion, 28(2), 147-169. https://doi.org/10. 1023/B:MOEM.0000032312.95499.6f

Rey, G. D., & Buchwald, F. (2011). The expertise reversal effect: Cognitive load and motivational explanations. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 17(1), 33-48. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022 243

Reynders, B., Van Puyenbroeck, S., Ceulemans, E., Vansteenkiste, M., & Vande Broek, G. (2020). How do profiles of need-supportive and controlling coaching relate to team athletes’ motivational outcomes? A person-centered approach. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 42(6), 452-462. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2019-0317

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1-36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Russell, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(6), 1161-1178. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0077714

Ryan, R. M., & Connell, J. P. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 749-761. https:// doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.5.749

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Sheldon, K. M., Osin, E. N., Gordeeva, T. O., Suchkov, D. D., & Sychev, O. A. (2017). Evaluating the dimensionality of self-determination theory’s relative autonomy continuum. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(9), 1215-1238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217711915

Sierens, E., Vansteenkiste, M., Goossens, L., Soenens, B., & Dochy, F. (2009). The synergistic relationship of perceived autonomy support and structure in the prediction of self-regulated learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(1), 57-68. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709908X304398

Skinner, E. A., & Belmont, M. J. (1993). Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(4), 571-581. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.85.4.571

Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A., & Furrer, C. J. (2009). A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: Conceptualization and assessment of children’s behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69(3), 493-525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164408323233

Skulmowski, A., Pradel, S., Kühnert, T., Brunnett, G., & Rey, G. D. (2016). Embodied learning using a tangible user interface: The effects of haptic perception and selective pointing on a spatial learning task. Computers & Education, 92-93, 64-75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.10.011

Soenens, B., Sierens, E., Vansteenkiste, M., Dochy, F., & Goossens, L. (2012). Psychologically controlling teaching: Examining outcomes, antecedents, and mediators. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104, 108-120. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025742

Stroet, K., Opdenakker, M. C., & Minnaert, A. (2015). What motivates early adolescents for school? A longitudinal analysis of associations between observed teaching and motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 42, 129-140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.06.002

Su, Y.-L., & Reeve, J. (2010). A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of intervention programs designed to support autonomy. Educational Psychology Review, 23, 159-188. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10648-010-9142-7

Sweller, J. (2008). Instructional implications of David C Geary’s evolutionary educational psychology. Educational Psychologist, 43(4), 214-216. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520802392208

Sweller, J. (2011). Cognitive load theory. In J. P. Mestre & B. H. Ross (Eds.), The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 55, pp. 37-76). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-387691-1. 00002-8

Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/ 978-1-4419-8126-4

Sweller, J., van Merrienboer, J. J. G., & Paas, F. G. W. C. (1998). Cognitive architecture and instructional design. Educational Psychology Review, 10, 251-296.

Vansteenkiste, M., & Mouratidis, A. (2016). Emerging trends and future directions for the field of motivation psychology: A special issue in honor of Prof. Dr. Willy Lens. Psychologica Belgica, 56(3), 317-341. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb. 354

Vansteenkiste, M., Simons, J., Lens, W., Sheldon, K. M., & Deci, E. L. (2004). Motivating learning, performance, and persistence: The synergistic effects of intrinsic goal contents and autonomy-supportive contexts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(2), 246-260. https://doi.org/10. 1037/0022-3514.87.2.246

Vansteenkiste, M., Sierens, E., Goossens, L., Soenens, B., Dochy, F., Mouratidis, A., Aelterman, N., Haerens, L., & Beyers, W. (2012). Identifying configurations of perceived teacher autonomy support and structure: Associations with self-regulated learning, motivation and problem behavior. Learning and Instruction, 22(6), 431-439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.04.002

Vansteenkiste, M., Aelterman, N., Haerens, L., & Soenens, B. (2019). Seeking stability in stormy educational times: A need-based perspective on (de)motivating teaching grounded in self-determination theory. In E. N. Gonida & M. S. Lemos (Eds.), Motivation in education at a time of global change (Vol. 20, pp. 53-80). Emerald. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0749-742320190000020004

Vermote, B., Aelterman, N., Beyers, W., Aper, L., Buysschaert, F., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2020). The role of teachers’ motivation and mindsets in predicting a (de)motivating teaching style in higher education: A circumplex approach. Motivation and Emotion, 44(2), 270-294. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11031-020-09827-5

Vansteenkiste, M., Aelterman, N., De Muynck, G. J., Haerens, L., Patall, E. A., & Reeve, J. (2018). Fostering personal meaning and self-relevance: A self-determination theory perspective on internalization. Journal of Experimental Education, 86(1), 30-49. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2017. 1381067

Wang, B., Ginns, P., & Mockler, N. (2022). Sequencing tracing with imagination. Educational Psychology Review, 34(1), 421-449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09625-6

Wolters, C. A. (2004). Advancing achievement goal theory: Using goal structures and goal orientations to predict students’ motivation, cognition, and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(2), 236-250. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.2.236

- Paul Evans

paul.evans@unsw.edu.au

School of Education, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Department of Developmental, Personality and Social Psychology, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium 3 Institute for Positive Psychology in Education, Australian Catholic University, Sydney, Australia

4 Melbourne Graduate School of Education, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-023-09841-2

Publication Date: 2024-01-15

Cognitive Load Theory and Its Relationships with Motivation: a Self-Determination Theory Perspective

© The Author(s) 2024, corrected publication 2024

Abstract

Although cognitive load theory research has studied factors associated with motivation, these literatures have primarily been developed in isolation from each other. In this contribution, we aimed to advance both fields by examining the effects of instructional strategies on learners’ experience of cognitive load, motivation, engagement, and achievement. Students (

Cognitive Load Theory

instructional support and guidance (Evans & Martin, 2023a; Kirschner et al., 2006; Sweller, 2015).

Cognitive Load and Motivation

& Evans, 2018). In a study of high school science students, engagement mediated the effects of load reduction instruction on achievement, with large effects at both student and classroom levels (Martin, Ginns, Burns, Kennett, Munro-Smith, et al., 2021b).

Self-Determination Theory

instructional style affects motivation, and the experience of cognitive load may provide an explanation for why this is the case. In the present study, as the following sections outline, we focused on the role of the teacher’s motivating style.

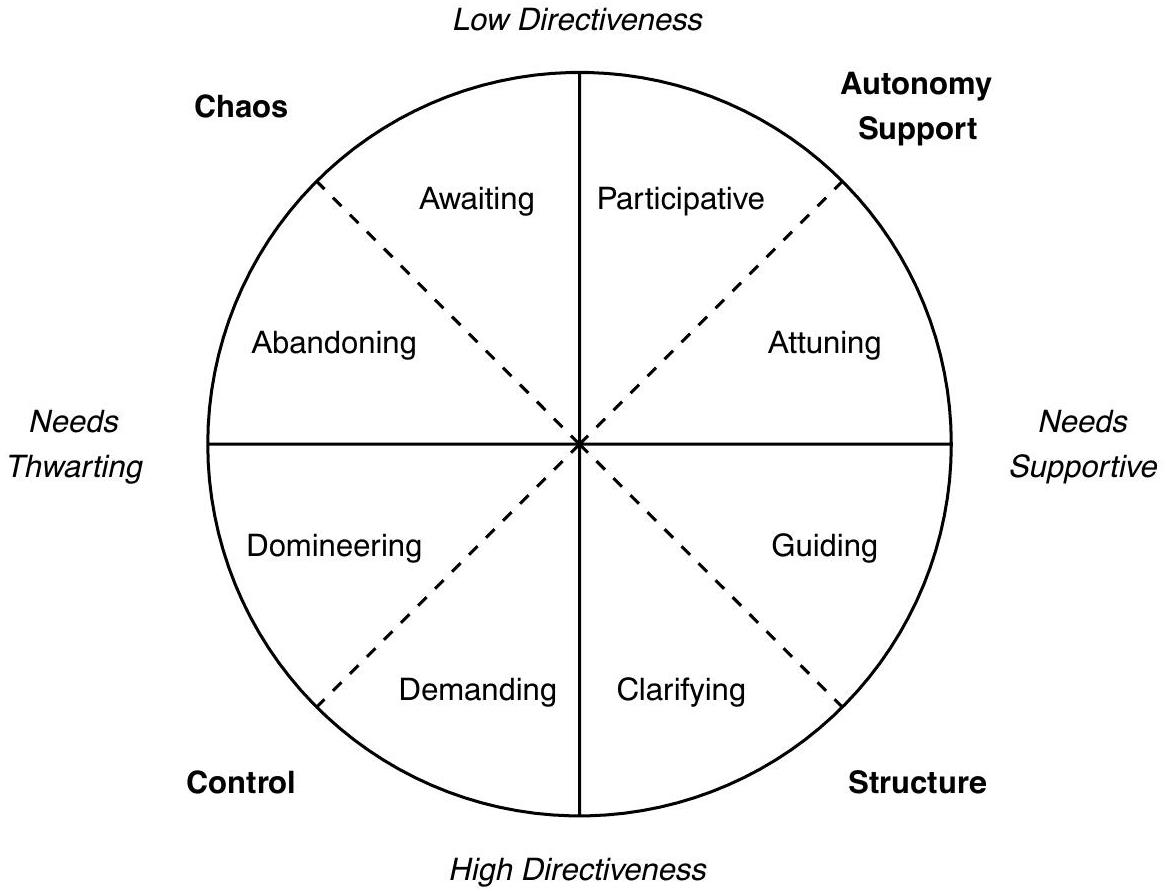

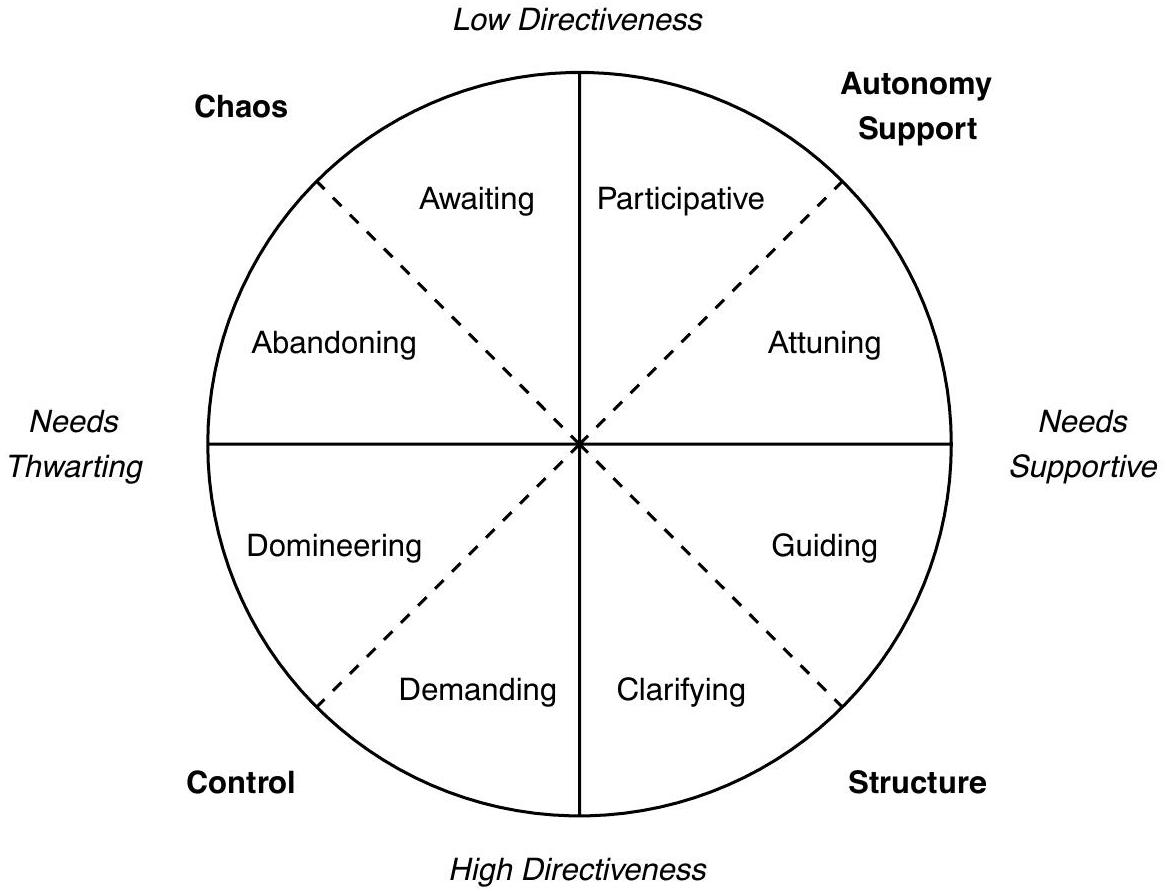

Teachers’ Motivating Styles

Autonomy Support, Structure, and Cognitive Load

towards activities that are necessary for learning, thus reducing the proportion of cognitive load that is extraneous. Autonomy support is generally a positive affective experience, which means that it may influence self-regulation beliefs and promote the investment of mental effort (Plass & Kalyuga, 2019). For example, autonomy support was shown to increase study effort and decrease procrastination over a school year (Mouratidis et al., 2018). In contrast with autonomy-supportive teaching, controlling teaching results in behaviors and affective responses that require attentional resources and impede learning. Under controlling conditions, students have to be concerned with avoiding trouble, not upsetting the teacher, complying with expectations, and managing the negative effects of psychological needs thwarting (Patall et al., 2018; Reeve & Tseng, 2011b; Soenens et al., 2012), none of which contributes directly to learning.

Aims of the Study

Method

Participants and Procedure

Measures

Load Reduction Instruction Scale (LRIS)

| Descriptive statistics and correlations. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 1. Load reduction instruction | ||||||||

| 2. Extraneous cognitive load | -. 679 – | |||||||

| 3. Intrinsic cognitive load | -. 207 | . 512 | – | |||||

| 4. Motivation (RAI) | . 551 | -. 519 | -. 370 | – | ||||

| 5. Engagement | . 646 | -. 517 | -. 385 | . 772 | – | |||

| 6. Disengagement | -. 384 | . 463 | . 203 | -. 496 | -. 402 | – | ||

| 7. Student-reported grade | . 251 | -. 324 | -. 404 | . 354 | . 473 | -. 186 | – | |

| 8. School-reported grade | . 132 | -. 184 | -. 252 | . 182 | . 229 | -. 203 | . 389 | – |

| Age | -. 094 | . 028 | -. 001 | -. 066 | -. 094 | . 020 | -. 016 | -. 034 |

| Gender | -. 036 | . 001 | . 061 | . 002 | -. 053 | -. 101 | -. 058 | . 108 |

| SES | . 093 | -. 060 | -. 044 | . 043 | . 111 | -. 137 | . 140 | . 071 |

| M | 5.026 | 3.058 | 3.511 | 17.854 | 4.886 | 2.542 | 73.137 | 2.789 |

| SD | 1.356 | 1.584 | 1.483 | 4.979 | 1.083 | 1.383 | 13.472 | . 862 |

| ICC | . 299 | . 242 | . 125 | . 119 | . 177 | . 098 | . 178 | . 453 |

| ICC2 | . 861 | . 822 | . 675 | . 664 | . 758 | . 612 | . 744 | . 887 |

| Omega | . 922 | . 936 | . 916 | . 955 | . 857 | . 842 | – | – |

Cognitive Load

school mathematics students (Martin & Evans, 2018). A review of this approach to measuring cognitive load in experimental studies (Krieglstein et al., 2022) found strong evidence for internal consistency and construct validity.

Teacher’s Motivating Style

Motivation

Engagement

Disengagement

Grades

Data Analysis

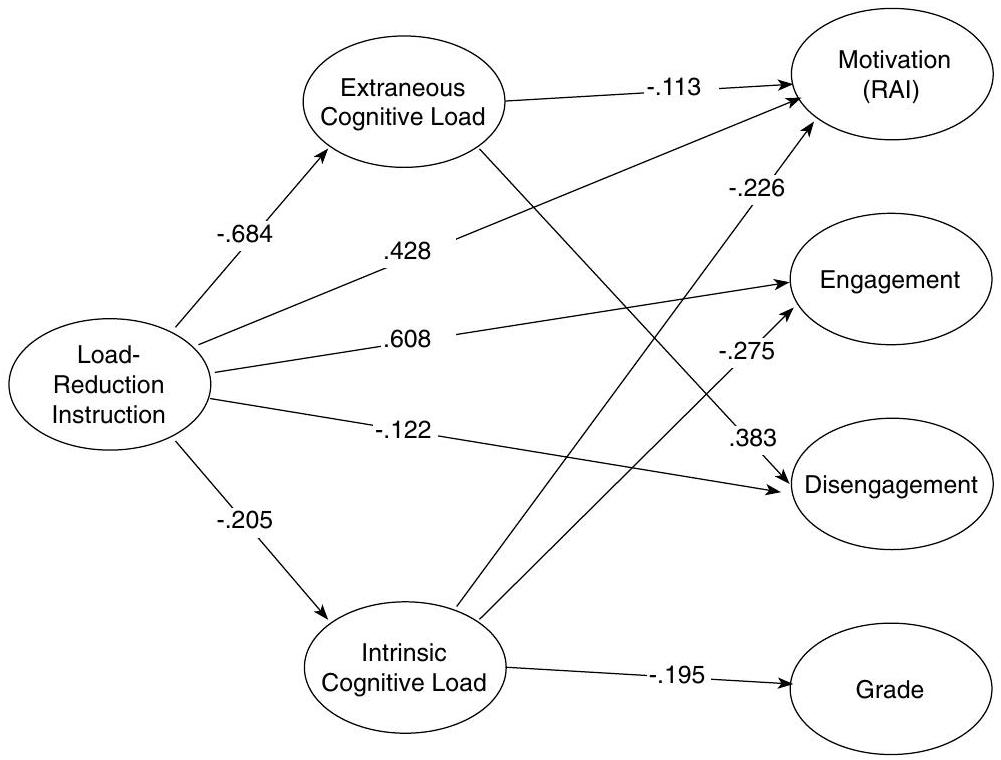

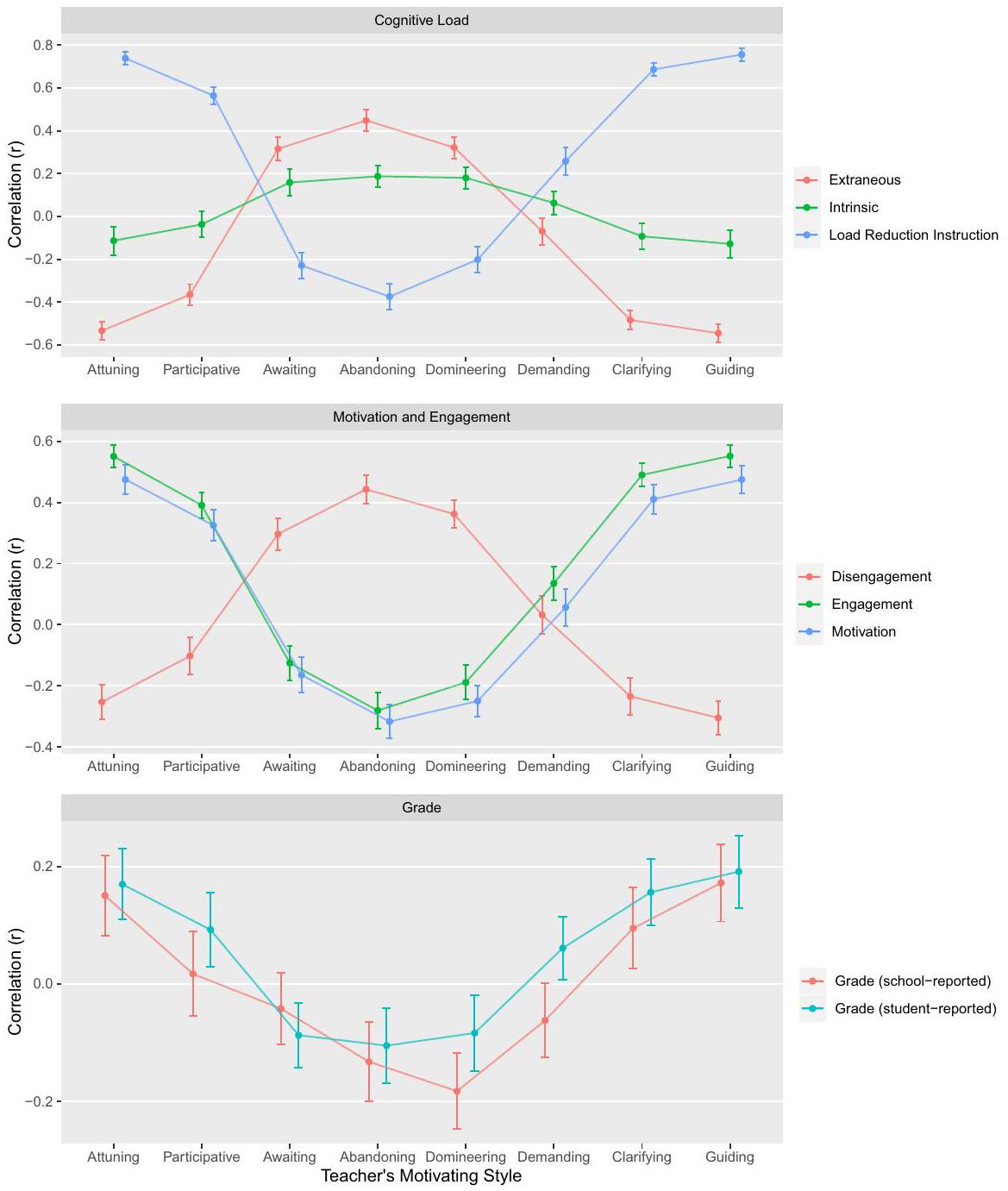

disengagement, and achievement were predicted by cognitive load and, in turn, load reduction instruction. Age, gender, and SES were included in the model as covariates (i.e., predicting all other factors in the model). The model was estimated first as a measurement model (confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)) with all latent correlations freely estimated, before imposing regression (structural) constraints. We did not make any hypotheses (or findings) in relation to mediation as the model is based on cross-sectional data, but for completeness, we also report indirect effects. To address Aim 2, we studied teacher’s motivating style. Using the circumplex structure of the teacher’s motivating style, we correlated the different subareas within the circumplex model with load reduction instruction, intrinsic and extraneous cognitive load, motivation, engagement, and achievement. We expected a sinusoidal pattern of correlations between the discerned styles in the circumplex and the different assessed outcomes.

Results

Aim 1: Motivational Outcomes of Load Reduction Instruction

Aim 2: Effects of Teacher’s Motivation Style on Cognitive Load

Discussion

Cognitive Load as an Antecedent to Motivation, Engagement, and Learning

example, suggested that the experience of extraneous cognitive load may influence motivational beliefs-specifically appraisals of cost, because of the increased effort that would be required on subsequent interactions with learning activities (Feldon et al., 2019) and self-efficacy beliefs (Feldon et al., 2018). Both constructs are concerned with outcome expectations and perceived effort. By operationalizing the SDT construct of autonomous motivation, the present study shows that reducing cognitive load may also facilitate the internalization of value and the alignment of learning tasks with the self.

The Teacher’s Motivating Style and Cognitive Load

structure and rationale of learning activities to students, and to nurture students’ progress towards learning goals. The circumplex model of teachers’ motivating styles (Aelterman & Vansteenkiste, 2023) was supported by the data, identifying a twodimensional plane (i.e., crossing the level of need support with the level of directiveness) situating eight identifiable subareas. As hypothesized, the discerned styles were correlated in an ordered (i.e., sinusoidal) manner, with subareas situated next to each other being positively correlated and the pattern becoming decreasingly positive and even negative when moving to the opposite subarea in the circumplex (Gurtman & Pincus, 2003). In implementing this measure, we upheld the reliability of this new instrument (i.e., the SIS) beyond its previous use in Belgian samples (Aelterman et al., 2019b) to an English version with Australian students.

A Note on Theories of Motivation

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

instructional strategies (Domen et al., 2020). Thus, for future research, we recommend studies that include sufficient sample size at the classroom level to account for variability between both students and classrooms.

Conclusion

learners to engage more deeply in their learning, and may even prompt learners to become frustrated and disengage. The present findings also have implications for teachers and their use of teaching strategies: load reduction instruction strategies reduce cognitive load and are themselves motivating and engaging. Based on these findings, it seems that there is minimal risk posed for motivation and engagement by using explicit teaching strategies to reduce cognitive load. Outside of instructional strategies, the teacher’s motivating style itself has consequences: attempts to motivate students using external contingencies, excessive demands, or a lack of structure pose risks to students in terms of increased cognitive load and reduced motivation and engagement.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/.

References

Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., Van Keer, H., & Haerens, L. (2016). Changing teachers’ beliefs regarding autonomy support and structure: The role of experienced psychological need satisfaction in teacher training. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 23, 64-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psych sport.2015.10.007

Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., & Haerens, L. (2019a). Correlates of students’ internalization and defiance of classroom rules: A self-determination theory perspective. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 89, 22-40. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep. 12213

Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., Haerens, L., Soenens, B., Fontaine, J. R. J., & Reeve, J. (2019b). Toward an integrative and fine-grained insight in motivating and demotivating teaching styles: The merits of a circumplex approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(3), 497-521. https://doi. org/10.1037/edu0000293

Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1967). Human memory: A proposed system and its control processes. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 2, 89-195.

Bonneville-Roussy, A., Evans, P., Verner-Filion, J., Vallerand, R. J., & Bouffard, T. (2017). Motivation and coping with the stress of assessment: Gender differences in outcomes for university students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 48, 28-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.08.003

Baddeley, A. D. (2012). Working memory: Theories, models, and controversies. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 1-29. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100422

Cook, D. A., Castillo, R. M., Gas, B., & Artino, A. R. (2017). Measuring achievement goal motivation, mindsets and cognitive load: Validation of three instruments’ scores. Medical Education, 51(10), 1061-1074. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu. 13405

Cowan, N. (2010). The magical mystery four: How is working memory capacity limited, and why? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(1), 51-57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721409359277

Cowan, N. (2014). Working memory underpins cognitive development, learning, and education. Educational Psychology Review, 26(2), 197-223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-013-9246-y

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum.

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., & Williams, G. C. (1996). Need satisfaction and the self-regulation of learning. Learning and Individual Differences, 8, 165-183.

Delrue, J., Reynders, B., Broek, G. V., Aelterman, N., De Backer, M., Decroos, S., De Muynck, G.-J., Fontaine, J., Fransen, K., van Puyenbroeck, S., Haerens, L., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2019). Adopting a helicopter-perspective towards motivating and demotivating coaching: A circumplex approach. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 40, 110-126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport. 2018.08.008

Eitel, A., Endres, T., & Renkl, A. (2020). Self-management as a bridge between cognitive load and self-regulated learning: The illustrative case of seductive details. Educational Psychology Review, 32(4), 1073-1087. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09559-5

Evans, P., & Martin, A. J. (2023a). Explicit Instruction. In A. O’Donnell, N. C. Barnes, & J. Reeve (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of educational psychology. Oxford University Press. https://doi. org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199841332.013.53

Evans, P., & Martin, A. J. (2023b). Load reduction instruction: Multilevel effects for motivation, engagement, and achievement in mathematics. Educational Psychology, 1-19. https://doi.org/10. 1080/01443410.2023.2290442

Feldon, D. F., Callan, G., Juth, S., & Jeong, S. (2019). Cognitive load as motivational cost. Educational Psychology Review, 31(2), 319-337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09464-6

Feldon, D. F., Franco, J., Chao, J., Peugh, J., & Maahs-Fladung, C. (2018). Self-efficacy change associated with a cognitive load-based intervention in an undergraduate biology course. Learning and Instruction, 56, 64-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.04.007

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59-109. https://doi.org/10. 3102/00346543074001059

Freer, E., & Evans, P. (2019). Choosing to study music in high school: Teacher support, psychological needs satisfaction, and elective music intentions. Psychology of Music, 47(6), 781-799. https:// doi.org/10.1177/0305735619864634

Gurtman, M. B., & Pincus, A. L. (2003). The circumplex model: Methods and research applications. In Handbook of psychology (pp. 407-428). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471264385.wei0216

Haakma, I., Janssen, M., & Minnaert, A. (2016). A literature review on how need-supportive behavior influences motivation in students with sensory loss. Teaching and Teacher Education, 57, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.02.008

Haakma, I., Janssen, M., & Minnaert, A. (2017). Intervening to improve teachers’ need-supportive behaviour using self-determination theory: Its effects on teachers and on the motivation of students with deafblindness. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 64(3), 310-327. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2016.1213376

Hawthorne, B. S., Vella-Brodrick, D., & A., & Hattie, J. (2019). Well-being as a cognitive load reducing agent: A review of the literature. Frontiers in Education, 4, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3389/ feduc.2019.00121

Hornstra, L., Stroet, K., & Weijers, D. (2021). Profiles of teachers’ need-support: How do autonomy support, structure, and involvement cohere and predict motivation and learning outcomes? Teaching and Teacher Education, 99, 103257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103257

Howard, J. L., Gagné, M., & Bureau, J. S. (2017). Testing a continuum structure of self-determined motivation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 143(12), 1346-1377. https://doi.org/10. 1037/bul0000125

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Jang, H., Reeve, J., & Deci, E. L. (2010). Engaging students in learning activities: It is not autonomy support or structure, but autonomy support and structure. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102, 588-600. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019682

Jang, H., Reeve, J., Ryan, R. M., & Kim, A. (2009). Can self-determination theory explain what underlies the productive, satisfying learning experiences of collectivistically oriented Korean students? Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(3), 644-661. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014 241

Kalyuga, S. (2007). Expertise reversal effect and its implications for learner-tailored instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 19(4), 509-539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-007-9054-3

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75-86.

Krieglstein, F., Beege, M., Rey, G. D., Ginns, P., Krell, M., & Schneider, S. (2022). A systematic metaanalysis of the reliability and validity of subjective cognitive load questionnaires in experimental multimedia learning research. Educational Psychology Review, 34(4), 2485-2541. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10648-022-09683-4

Leppink, J., Paas, F. G. W. C., van Gog, T., van der Vleuten, C. P. M., & van Merriënboer, J. J. G. (2014). Effects of pairs of problems and examples on task performance and different types of cognitive load. Learning and Instruction, 30, 32-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2013.12.001

Likourezos, V., & Kalyuga, S. (2017). Instruction-first and problem-solving-first approaches: Alternative pathways to learning complex tasks. Instructional Science, 45(2), 195-219. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11251-016-9399-4

Litalien, D., Morin, A. J. S., Gagné, M., Vallerand, R. J., Losier, G. F., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Evidence of a continuum structure of academic self-determination: A two-study test using a bifactor-ESEM representation of academic motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 51, 67-82. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.06.010

Mair, P., Groenen, P. J. F., & de Leeuw, J. (2022). More on multidimensional scaling in R: smacof version 2. Journal of Statistical Software, 102(10), 1-47.

Martin, A. J. (2023). Integrating motivation and instruction: Towards a unified approach in educational psychology. Educational Psychology Review, 35(54). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-023-09774-w

Martin, A. J., & Evans, P. (2018). Load reduction instruction: Exploring a framework that assesses explicit instruction through to independent learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 73, 203-214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.03.018

Martin, A. J., Ginns, P., Burns, E. C., Kennett, R., & Pearson, J. (2021a). Load reduction instruction in science and students’ science engagement and science achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(6), 1126-1142. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000552

Martin, A. J., Ginns, P., Burns, E. C., Kennett, R., Munro-Smith, V., Collie, R. J., & Pearson, J. (2021b). Assessing instructional cognitive load in the context of students’ psychological challenge and threat orientations: A multi-level latent profile analysis of students and classrooms. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.656994

Martin, A. J., Ginns, P., Nagy, R. P., Collie, R. J., & Bostwick, K. C. P. (2023). Load reduction instruction in mathematics and English classrooms: A multilevel study of student and teacher reports. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2023.102147

McNeish, D. (2018). Thanks coefficient alpha, we’ll take it from here. Psychological Methods, 23(3), 412-433. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000144

Moreno, R. (2006). Does the modality principle hold for different media? A test of the method-affectslearning hypothesis. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 22(3), 149-158. https://doi.org/10. 1111/j.1365-2729.2006.00170.x

Mouratidis, A., Michou, A., Telli, S., Maulana, R., & Helms-Lorenz, M. (2022). No aspect of structure should be left behind in relation to student autonomous motivation. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(3), 1086-1108. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep. 12489

Mouratidis, A., Michou, A., Aelterman, N., Haerens, L., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2018). Begin-of-schoolyear perceived autonomy-support and structure as predictors of end-of-school-year study efforts and procrastination: The mediating role of autonomous and controlled motivation. Educational Psychology, 38(4), 435-450. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2017.1402863

Nebel, S., Schneider, S., Schledjewski, J., & Rey, G. D. (2017). Goal-setting in educational video games: Comparing goal-setting theory and the goal-free effect. Simulation & Gaming, 48(1), 98-130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878116680869

Oga-Baldwin, W. L. Q., & Nakata, Y. (2015). Structure also supports autonomy: Measuring and defining autonomy-supportive teaching in Japanese elementary foreign language classes: Structure also supports autonomy. Japanese Psychological Research, 57(3), 167-179. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpr. 12077

Patall, E. A., Steingut, R. R., Vasquez, A. C., Trimble, S. S., Pituch, K. A., & Freeman, J. L. (2018). Daily autonomy supporting or thwarting and students’ motivation and engagement in the high school science classroom. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(2), 269-288. https://doi.org/10. 1037/edu0000214

Pitzer, J., & Skinner, E. (2017). Predictors of changes in students’ motivational resilience over the school year: The roles of teacher support, self-appraisals, and emotional reactivity. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 41(1), 15-29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025416642051

Plass, J. L., & Kalyuga, S. (2019). Four ways of considering emotion in cognitive load theory. Educational Psychology Review, 31(2), 339-359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09473-5

Plutchik, R., & Conte, H. R. (Eds.). (1997). Circumplex models of personality and emotions. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10261-000

R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Computer software]. http://www.R-project.org

Raftery-Helmer, J. N., & Grolnick, W. S. (2016). Children’s coping with academic failure: Relations with contextual and motivational resources supporting competence. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 36(8), 1017-1041. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431615594459

Ratelle, C. F., Duchesne, S., Litalien, D., & Plamondon, A. (2021). The role of mothers in supporting adaptation in school: A psychological needs perspective. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(1), 197-212. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000455

Ratelle, C. F., Guay, F., Vallerand, R. J., Larose, S., & Senécal, C. B. (2007). Autonomous, controlled, and amotivated types of academic motivation: A person-oriented analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(4), 734-746. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.4.734

Redeker, M., De Vries, R. E., Rouckhout, D., Vermeren, P., & De Fruyt, F. (2014). Integrating leadership: The leadership circumplex. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(3), 435-455. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.738671

Reeve, J. (2009). Why teachers adopt a controlling motivating style toward students and how they can become more autonomy supportive. Educational Psychologist, 44(3), 159-175. https://doi.org/10. 1080/00461520903028990

Reeve, J. (2013). How students create motivationally supportive learning environments for themselves: The concept of agentic engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 579-595. https:// doi.org/10.1037/a0032690

Reeve, J., & Tseng, C. M. (2011a). Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36, 257-267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych. 2011.05.002

Reeve, J., Jang, H.-R., Shin, S. H., Ahn, J. S., Matos, L., & Gargurevich, R. (2022). When students show some initiative: Two experiments on the benefits of greater agentic engagement. Learning and Instruction, 80, 101564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2021.101564

Reeve, J., Jang, H., Carrell, D., Jeon, S., & Barch, J. (2004). Enhancing students’ engagement by increasing teachers’ autonomy support. Motivation and Emotion, 28(2), 147-169. https://doi.org/10. 1023/B:MOEM.0000032312.95499.6f

Rey, G. D., & Buchwald, F. (2011). The expertise reversal effect: Cognitive load and motivational explanations. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 17(1), 33-48. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022 243

Reynders, B., Van Puyenbroeck, S., Ceulemans, E., Vansteenkiste, M., & Vande Broek, G. (2020). How do profiles of need-supportive and controlling coaching relate to team athletes’ motivational outcomes? A person-centered approach. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 42(6), 452-462. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2019-0317

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1-36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Russell, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(6), 1161-1178. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0077714

Ryan, R. M., & Connell, J. P. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 749-761. https:// doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.5.749

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Sheldon, K. M., Osin, E. N., Gordeeva, T. O., Suchkov, D. D., & Sychev, O. A. (2017). Evaluating the dimensionality of self-determination theory’s relative autonomy continuum. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(9), 1215-1238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217711915

Sierens, E., Vansteenkiste, M., Goossens, L., Soenens, B., & Dochy, F. (2009). The synergistic relationship of perceived autonomy support and structure in the prediction of self-regulated learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(1), 57-68. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709908X304398

Skinner, E. A., & Belmont, M. J. (1993). Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(4), 571-581. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.85.4.571

Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A., & Furrer, C. J. (2009). A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: Conceptualization and assessment of children’s behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69(3), 493-525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164408323233

Skulmowski, A., Pradel, S., Kühnert, T., Brunnett, G., & Rey, G. D. (2016). Embodied learning using a tangible user interface: The effects of haptic perception and selective pointing on a spatial learning task. Computers & Education, 92-93, 64-75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.10.011

Soenens, B., Sierens, E., Vansteenkiste, M., Dochy, F., & Goossens, L. (2012). Psychologically controlling teaching: Examining outcomes, antecedents, and mediators. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104, 108-120. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025742

Stroet, K., Opdenakker, M. C., & Minnaert, A. (2015). What motivates early adolescents for school? A longitudinal analysis of associations between observed teaching and motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 42, 129-140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.06.002

Su, Y.-L., & Reeve, J. (2010). A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of intervention programs designed to support autonomy. Educational Psychology Review, 23, 159-188. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10648-010-9142-7

Sweller, J. (2008). Instructional implications of David C Geary’s evolutionary educational psychology. Educational Psychologist, 43(4), 214-216. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520802392208

Sweller, J. (2011). Cognitive load theory. In J. P. Mestre & B. H. Ross (Eds.), The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 55, pp. 37-76). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-387691-1. 00002-8

Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/ 978-1-4419-8126-4

Sweller, J., van Merrienboer, J. J. G., & Paas, F. G. W. C. (1998). Cognitive architecture and instructional design. Educational Psychology Review, 10, 251-296.

Vansteenkiste, M., & Mouratidis, A. (2016). Emerging trends and future directions for the field of motivation psychology: A special issue in honor of Prof. Dr. Willy Lens. Psychologica Belgica, 56(3), 317-341. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb. 354

Vansteenkiste, M., Simons, J., Lens, W., Sheldon, K. M., & Deci, E. L. (2004). Motivating learning, performance, and persistence: The synergistic effects of intrinsic goal contents and autonomy-supportive contexts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(2), 246-260. https://doi.org/10. 1037/0022-3514.87.2.246

Vansteenkiste, M., Sierens, E., Goossens, L., Soenens, B., Dochy, F., Mouratidis, A., Aelterman, N., Haerens, L., & Beyers, W. (2012). Identifying configurations of perceived teacher autonomy support and structure: Associations with self-regulated learning, motivation and problem behavior. Learning and Instruction, 22(6), 431-439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.04.002

Vansteenkiste, M., Aelterman, N., Haerens, L., & Soenens, B. (2019). Seeking stability in stormy educational times: A need-based perspective on (de)motivating teaching grounded in self-determination theory. In E. N. Gonida & M. S. Lemos (Eds.), Motivation in education at a time of global change (Vol. 20, pp. 53-80). Emerald. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0749-742320190000020004

Vermote, B., Aelterman, N., Beyers, W., Aper, L., Buysschaert, F., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2020). The role of teachers’ motivation and mindsets in predicting a (de)motivating teaching style in higher education: A circumplex approach. Motivation and Emotion, 44(2), 270-294. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11031-020-09827-5

Vansteenkiste, M., Aelterman, N., De Muynck, G. J., Haerens, L., Patall, E. A., & Reeve, J. (2018). Fostering personal meaning and self-relevance: A self-determination theory perspective on internalization. Journal of Experimental Education, 86(1), 30-49. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2017. 1381067

Wang, B., Ginns, P., & Mockler, N. (2022). Sequencing tracing with imagination. Educational Psychology Review, 34(1), 421-449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09625-6

Wolters, C. A. (2004). Advancing achievement goal theory: Using goal structures and goal orientations to predict students’ motivation, cognition, and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(2), 236-250. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.2.236

- Paul Evans

paul.evans@unsw.edu.au

School of Education, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Department of Developmental, Personality and Social Psychology, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium 3 Institute for Positive Psychology in Education, Australian Catholic University, Sydney, Australia

4 Melbourne Graduate School of Education, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia