DOI: https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.38418

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-30

نمذجة التفاعل بين مصداقية المعلم، تأكيد المعلم، وانخراط طلاب تخصص اللغة الإنجليزية أكاديميًا: نهج مختلط متسلسل

الملخص

اعتمادًا على نهج مختلط متسلسل، قامت الدراسة الحالية بفحص تصورات طلاب تخصص اللغة الإنجليزية حول دور تأكيد المعلم ومصداقية المعلم في تعزيز مشاركتهم الأكاديمية في السياق الصيني. ومن خلال تطبيق برنامج WeChat، تم تقديم ثلاثة مقاييس لـ 1168 طالبًا من تخصص اللغة الإنجليزية تم اختيارهم من فصول مختلفة لتعليم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية. ولأغراض التثليث، تم دعوة 40 مشاركًا للمشاركة في جلسات المقابلة أيضًا. أظهرت فحص الارتباطات بين المفاهيم وجود ارتباط قوي بين مشاركة الطلاب الأكاديمية وتأكيد المعلم، بالإضافة إلى ارتباط وثيق بين مشاركة الطلاب الأكاديمية ومصداقية المعلم. وهذا يدل على أن المشاركة الأكاديمية لطلاب اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الصين مرتبطة بهذه السلوكيات الشخصية للمعلم. كما تم فحص مساهمة تأكيد المعلم ومصداقيته في مشاركة طلاب اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الصين باستخدام تحليل المسار، والذي أظهر أن مشاركة طلاب اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الصين كانت متوقعة من خلال مصداقية المعلم وتأكيده. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، المقابلة

أثبتت النتائج الدور الأساسي لهذين السلوكين في التواصل في زيادة انخراط الطلاب الصينيين. قد تكون النتائج لها بعض الدلالات الملحوظة لمعلمي المعلمين ومدرسي اللغة.

1. المقدمة

قال إن تأثير خصائص المعلم الشخصية على انخراط متعلمي اللغة الإنجليزية في الأكاديميا لم يحظ بالاهتمام الكافي. وبالتالي، فإن ما إذا كانت المتغيرات الشخصية للمعلم يمكن أن تحدث تغييرات كبيرة في انخراط متعلمي اللغة الإنجليزية في الأكاديميا لا يزال موضع تساؤل. تسعى هذه الدراسة الحالية إلى معالجة هذا السؤال من خلال فحص كيفية اختلاف انخراط طلاب اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الأكاديميا كدالة لسلوكيات المعلمين الإيجابية الشخصية.

2. مراجعة الأدبيات

2.1. تأكيد المعلم

2.2. مصداقية المعلم

كما أشار بانفيلد وآخرون (2006)، قام أرسطو بتصنيف أساليب الإقناع إلى ثلاث فئات مختلفة، بما في ذلك (أ) الإيثوس (أي مصداقية/موثوقية المرسل)، (ب) اللوغوس (أي المنطق المستخدم لإثبات ادعاء ما)، و(ج) الباثوس (أي النداءات العاطفية/الملهمة). من بين هذه الفئات، يُعتبر الإيثوس الوسيلة الأكثر قوة للإقناع التي يمكن من خلالها للمتحدث أن يقنع جمهوره بفعالية (بيشغدام وآخرون، 2019). الإيثوس/مصداقية المصدر كمفهوم معقد يتكون من ثلاثة أبعاد: الكفاءة، والموثوقية، والرعاية (تيفن وهانسون، 2004؛ وانغ وآخرون، 2022). بينما يتعلق البعد الأول من مصداقية المصدر بمعرفة المتحدثين ومهاراتهم وقدراتهم، فإن الموثوقية والرعاية تتعلق بشخصية المتحدثين. عند توسيع هذه الأبعاد إلى التعليم، تتعلق الكفاءة بكيفية إدراك الطلاب بشكل إيجابي لمعرفتهم وقدراتهم التعليمية (تيفن وهانسون، 2004؛ زهي وانغ، 2023). تشير الموثوقية إلى مقدار الصدق الذي يظهره المعلمون في تفاعلاتهم مع طلابهم (تيفن، 2007). أما الرعاية، كالبعد الأخير، فتتناول الانتباه المستمر للمعلمين لاحتياجات ورغبات الطلاب (تشانغ، 2009).

مصداقية المعلم كمتنبئ مهم لمشاركة الطلاب. مجتمعة، كشفت نتائج الدراسة أن مشاركة الطلاب في بيئات التعلم تعتمد بشكل صارم على مصداقية معلميهم. على الرغم من هذه المحاولات، لا يزال فحص مصداقية المعلم فيما يتعلق بسلوكيات الطلاب الأكاديمية في مراحله الأولى. علاوة على ذلك، فإن القليل من الدراسات قد بحثت في تداعيات مصداقية المعلم في سياقات تعليم اللغة. لسد هذه الفجوة، في هذا البحث، استكشفنا تصورات مجموعة من طلاب اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية حول مستوى مصداقية معلميهم.

2.3. الانخراط الأكاديمي

تحديد محددات انخراط طلاب اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية. سعت الدراسة الحالية إلى معالجة هذه الفجوة من خلال فحص قوة تأكيد المعلم ومصداقيته في التنبؤ بانخراط طلاب اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية.

2.4. النماذج النظرية للتفاعل بين سلوكيات التواصل للمعلم وسلوكيات الطلاب الأكاديمية

RQ2: إلى أي مدى، إن وجد، تتنبأ مصداقية المعلم وتأكده بشكل كبير بانخراط الطلاب الصينيين الأكاديمي؟

3. المنهجية

3.1. المشاركون

3.2. الأدوات

3.2.1. مقياس تأكيد المعلم (TCS)

3.2.2. مقياس مصداقية المصدر (SCS)

(

3.2.3. مقياس انخراط العمل في أوترخت للطلاب (UWES-S)

3.2.4. المقابلات شبه المنظمة

3.3. الإجراء

من الطلاب الصينيين من تخصصات اللغة الإنجليزية الذين تم تجنيدهم من مقاطعات مختلفة عبر البر الرئيسي الصيني. ثم، تم توزيع الاستبيانات عبر الإنترنت على هؤلاء الطلاب (

3.4. التحليل

إجابات المشاركين في المقابلات. ساعدهم ذلك على أن يصبحوا على دراية بأي تفاصيل مهمة. ثم، في المرحلة التالية، مروا عبر ثلاث مراحل من الترميز المفتوح، وإنشاء الفئات، والتجريد لترميز ردود المشاركين في المقابلات. في المرحلة الأولى، قام المحللون بفحص النصوص وقدموا بعض الرموز المؤقتة، وفقًا لذلك. ثم، خلال المرحلة الثانية، ربطوا الرموز الأولية وصنفوها تحت عناوين أعلى. أخيرًا، في المرحلة الأخيرة، تم تسمية كل فئة باستخدام كلمات ذات خصائص محتوى. بعد ذلك، لقياس اتفاقية الترميز بين المحللين، تم استخدام ألفا كريبندورف (

4. النتائج

4.1. معالجة البيانات

| كولموغوروف-سميرنوف

|

|||

| الإحصائية | df | Sig. | |

| تأكيد المعلم | .05 | 1168 | .12 |

| موثوقية المعلم | .08 | 1168 | .09 |

| مشاركة الطلاب الأكاديمية | .07 | 1168 | .06 |

| المقاييس | المكونات الفرعية | ألفا كرونباخ |

| TCS | – | .92 |

| عامل الكفاءة | .80 | |

| عامل الرعاية/ النية الطيبة | .73 | |

| SCS | عامل الموثوقية | .77 |

| المقياس الكلي | .93 | |

| UWES-S | الحيوية | .80 |

| التفاني | .71 | |

| الامتصاص | .70 | |

| المقياس الكلي | .95 |

| الاستبيانات | CR | AVE | MSV | M axR(H) |

| TCS | 0.889 | 0.855 | 0.427 | 0.968 |

| SCS | 0.757 | 0.753 | 0.107 | 0.976 |

| UWES-S | 0.969 | 0.692 | 0.427 | 0.975 |

4.2. النتائج الكمية

| التأكيد | الموثوقية | مشاركة الأكاديمية | |

| التأكيد | 1 | ||

| 1168 | |||

| الموثوقية | .72** | 1 | |

| . 000 | |||

| 1168 | 1168 | ||

| مشاركة الأكاديمية | .38** | .33** | 1 |

| . 000 | . 000 | ||

| 1168 | 1168 | 1168 |

| الحيوية | التفاني | الامتصاص | |

| التأكيد |

|

|

|

| الموثوقية |

|

|

|

كما هو موضح في الجدول 5، وُجدت علاقات إيجابية ذات دلالة بين جميع مكونات مشاركة الطلاب الأكاديمية وتأكيد المعلم العام وموثوقيته. مقارنةً بالمكونات الأخرى لمشاركة الطلاب الأكاديمية، كان التفاني مرتبطًا بشكل أكبر بتأكيد المعلم (

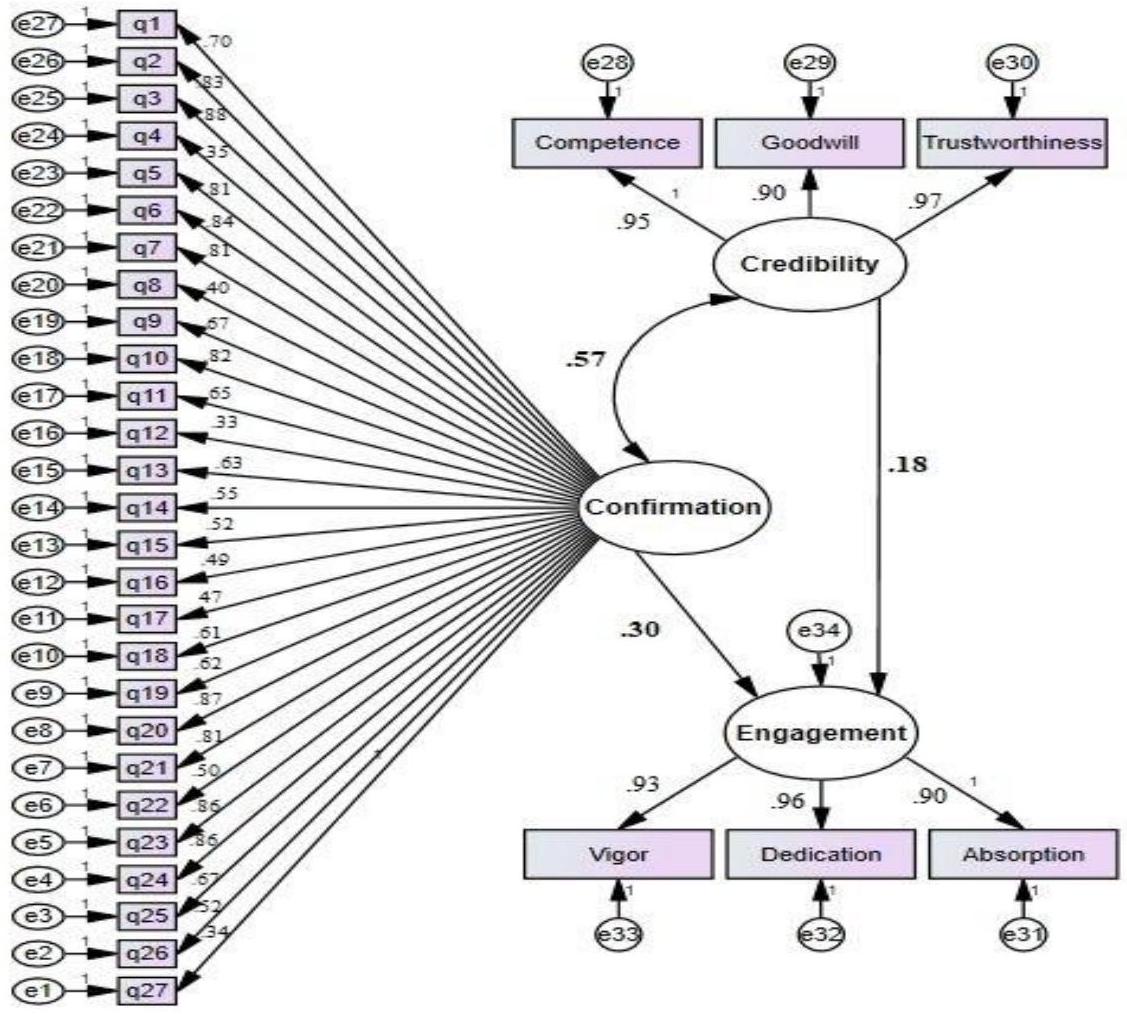

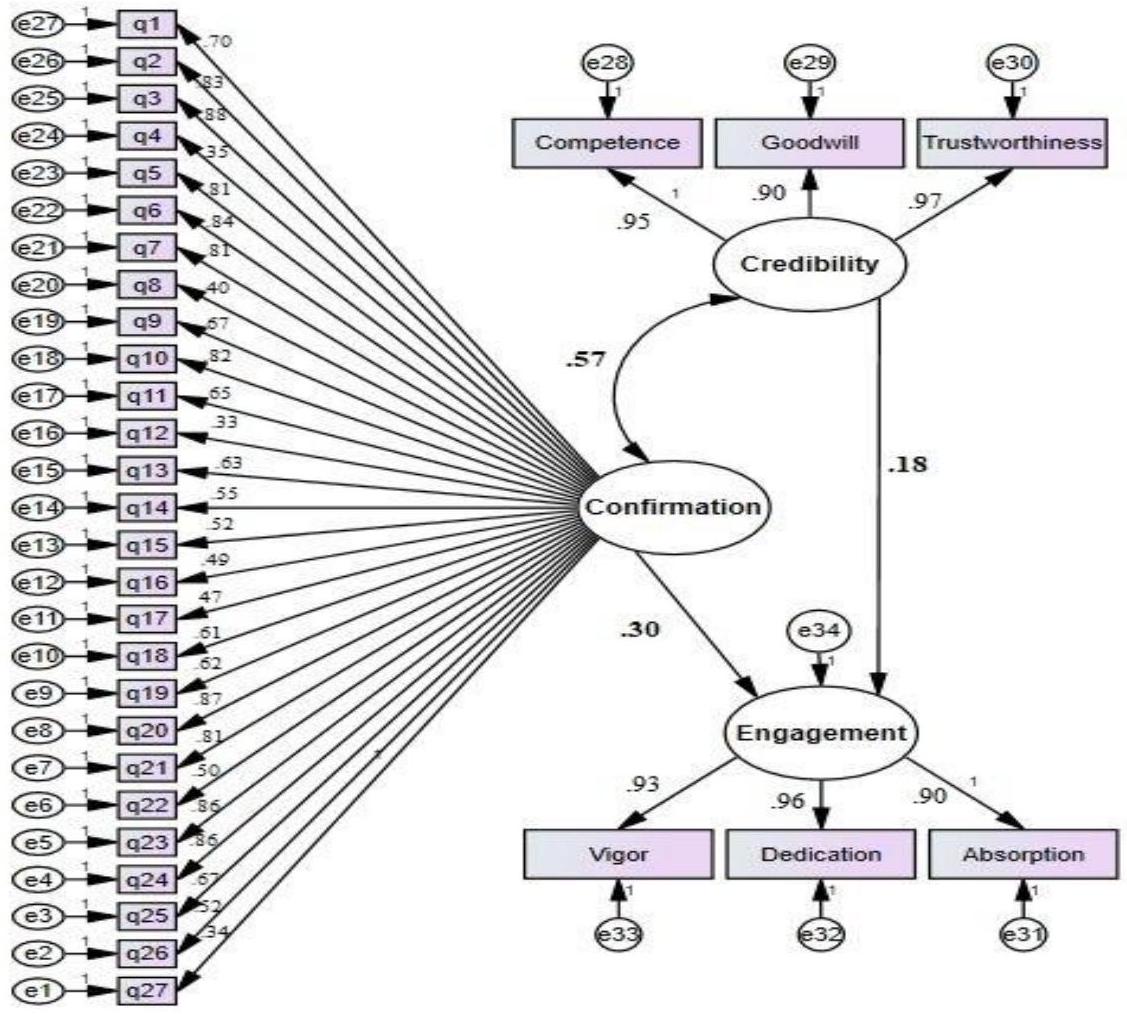

4.2.2. RQ2: إلى أي مدى، إن وجد، تتنبأ موثوقية المعلم وتأكيد المعلم بشكل كبير بمشاركة الطلاب الأكاديمية الصينية؟

تظهر توافقًا جيدًا مع البيانات المجمعة. كما تشير الجدول 6، كانت جميع مؤشرات التوافق مقبولة للغاية، مما يوضح أن النموذج المقترح يتمتع بصلاحية عالية.

| X2/ df | جي إف آي | CFI | لا يوجد معلومات | RMSEA | |

| تناسب مقبول |

|

|

|

|

|

| نموذج | 2.92 | .93 | .94 | .95 | .07 |

4.2. النتائج النوعية

P9: التأكيدات التي أتلقاها عادةً من معلم اللغة الإنجليزية الخاص بي تشجعني على المشاركة في أنشطة الصف.

توفير التأكيد للمتعلمين يمكن أن يعزز تفاعلهم مع بيئة تعلم اللغة.

من المرجح أن يشارك الطلاب في أنشطة الصف عندما يشعرون بالتقدير.

تأكيد المعلم أو موافقته يجعلني واثقًا بما يكفي للمشاركة بنشاط في أنشطة التعلم.

| المواضيع | الموضوعات الفرعية | تردد | نسبة مئوية |

| تأكيد المعلم | – | 30 |

|

| مصداقية المعلم | الموثوقية، الرعاية/النية الطيبة، الكفاءة | 20 |

|

| تقرير | – | 15 |

|

| رعاية المعلم | – | 12 |

|

| قرب المعلم | القرب اللفظي، القرب غير اللفظي | 10 |

|

| إجمالي | 87 | 100 |

كما توضح الجدول 7، كانت مصداقية المعلم (الثقة، العناية/النوايا الحسنة، الكفاءة) موضوعًا متكررًا آخر.

الطلاب كعامل مهم في مشاركتهم الأكاديمية. تضيء الاقتباسات التالية على القوة التنبؤية لمصداقية المعلم:

يمكن لمعلم لغة متمكن أن يلهمني لأصبح متعلماً نشطاً في بيئة الفصل الدراسي.

بالنسبة لي، المعلمون الموثوقون يجيدون تحسين مشاركة طلابهم الأكاديمية.

أعتقد أن goodwill المعلم يمكن أن يزرع علاقة إيجابية بين المعلم والطالب ويخلق بيئة تعليمية جيدة يمكن أن تزيد بشكل كبير من مشاركة الطلاب الأكاديمية.

P8: أعتقد أن وجود علاقة قوية وإيجابية بين المعلمين والطلاب يمكن أن يحفزهم على المشاركة في عملية اكتساب اللغة.

استخدام تعبيرات الوجه والإيماءات ولغة الجسد لا يمكّن معلمي اللغة من خلق بيئة تعليمية حيوية فحسب، بل يساعدهم أيضًا على إشراك الطلاب في عملية التعلم.

5. المناقشة

التي أظهرت قيمة مصداقية المعلم في تحفيز تعلم الطلاب (فرنانديس، 2019)، والاستعداد للتواصل (لي، 2020)، والرغبة في حضور الدروس (هو ووانغ، 2023؛ بيشغدام وآخرون، 2019؛ بيشغدام وآخرون، 2023). جميع هذه الدراسات السابقة حددت مدى تأثير وجهات نظر الطلاب ومواقفهم تجاه كفاءة معلميهم ونواياهم الحسنة وموثوقيتهم على سلوكياتهم في الفصل الدراسي، بما في ذلك انخراطهم الأكاديمي.

6. الاستنتاجات، الآثار، القيود، والاتجاهات للبحوث المستقبلية

سياق اللغة. وبالتالي، قد لا يمكن تعميم نتائج هذه الدراسة على سياقات تعليم اللغة الإنجليزية الأخرى. لتحديد أي تناقضات في النتائج، يجب على التحقيقات المستقبلية تكرار هذا الموضوع في بيئات تعليمية أخرى. ثانياً، لم يتم قياس أو التحكم في تأثيرات العوامل الظرفية، بما في ذلك الجنس والعمر والتخصص. لتحقيق نتائج أكثر دقة، يُنصح بشدة بإجراء المزيد من الاستفسارات للقيام بذلك. ثالثاً، تم استقصاء الطلاب فقط في هذه الدراسة. لتقديم صورة أكثر شمولاً عن القضية، هناك حاجة لإجراء دراسات مستقبلية تشمل مقابلة بعض المعلمين أيضاً. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فيما يتعلق بنواقص الأدبيات الحالية، هناك بعض التوصيات الهامة الأخرى التي تحتاج إلى الذكر أيضاً. للبدء، هناك نقص في الأبحاث التجريبية حول كيفية تأثير العوامل الإيجابية في العلاقات الشخصية للمعلمين، ولا سيما التأكيد والمصداقية، على مشاركة الطلاب. وبالتالي، يجب تكريس المزيد من الاهتمام الأكاديمي لهذه المتغيرات الشخصية وتأثيراتها التعليمية المحتملة. بعد ذلك، على الرغم من أن الخلفية الثقافية قد تشكل تصورات المشاركين (شي ودرخشان، 2021)، إلا أن القليل من الدراسات حول تأكيد المعلم والمصداقية أخذت الفروق الثقافية في الاعتبار (على سبيل المثال، بيشغدام وآخرون، 2023). لمعرفة إلى أي مدى قد تؤثر الفروق الثقافية على مواقف الطلاب تجاه هذه المتغيرات الشخصية الإيجابية، هناك حاجة لإجراء المزيد من الدراسات عبر الثقافات في هذا الصدد. هناك فجوة أخرى تحتاج إلى معالجة وهي أنه بينما حصلت سلوكيات الاتصال الإيجابية، ولا سيما المصداقية، على اهتمام كافٍ في التعليم السائد، فقد تم تجاهلها إلى حد ما في سياق التعليم اللغوي. لذلك، هناك حاجة لإجراء دراسات مستقبلية في هذا المجال في سياقات اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية واللغة الإنجليزية كلغة ثانية.

شكر وتقدير

References

Baralt, M. (2012). Coding qualitative data. In A. M ackey & S. M. Gass (Eds.), Research methods in second language acquisition (pp. 222-244). Blackwell.

BERA. (2011). Ethical guidelines for educational research. Retrieved from http:// content.yudu.com/Library/A2xnp5/Bera/resources/index.htm?referrerUrl =http://free.yudu.com/item/details/2023387/Bera

Berg, B. L. (2002). An introduction to content analysis. In B. L. Berg (Ed.), Qualitative research methods for the social sciences (pp. 174-199). Allyn & Bacon.

Buckner, M . M ., & Frisby, B. N. (2015). Feeling valued matters: An examination of instructor confirmation and instructional dissent. Communication Studies, 66(3), 398-413. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2015.1024873

Burnard, P. (1996). Teaching the analysis of textual data: An experiential approach. Nurse Education Today, 16(4), 278-281.

Campbell, L. C., Eichhorn, K. C., Basch, C., & Wolf, R. (2009). Exploring the relationship between teacher confirmation, gender, and student effort in the college classroom. Human Communication, 12(4), 447-464.

Carmona-Halty, M ., Salanova, M ., Llorens, S., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2021). Linking positive emotions and academic performance: The mediated role of academic psychological capital and academic engagement. Current Psychology, 40, 2938-2947. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00227-8

Carver, C., Jung, D., & Gurzynski-Weiss, L. (2021). Examining learner engagement in relationship to learning and communication mode. In P. Hiver, A. H. Al-Hoorie, & S. Mercer (Eds.), Student engagement in the language classroom (pp. 120142). M ultilingual M atters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788923613-010

Croucher, S. M., Rahmani, D., Galy-Badenas, F., Zeng, C., Albuquerque, A., Attarieh, M., & Nshom, E. N. (2021). Exploring the relationship between teacher confirmation and student motivation: The United States and Finland. In M. D. López-Jiménez & J. Sánchez-Torres (Eds.), Intercultural competence past, present, and future: Respecting the past, problems in the present, and forging the future (pp. 101-120). Springer.

Derakhshan, A. (2021). The predictability of Turkman students’ academic engagement through Persian language teachers’ nonverbal immediacy and

credibility. Journal of Teaching Persian to Speakers of Other Languages, 10(21), 3-24. https://doi.org/10.30479/JTPSOL.2021.14654.1506

Derakhshan, A. (2022). The “5Cs” positive teacher interpersonal behaviors: Implications for learner empowerment and learning in an L2 context. Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/9783031165276

Derakhshan, A., Eslami, Z. R., Curle, S., & Zhaleh, K. (2022). Exploring the validity of immediacy and burnout scales in an EFL context: The predictive role of teacher-student interpersonal variables in university students’ experience of academic burnout. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 12(1), 87-115. http://dx.doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2022.12.1.5

Derakhshan, A., Fathi, J., Pawlak, M., & Kruk, M. (2022). Classroom social climate, growth language mindset, and student engagement: The mediating role of boredom in learning English as a foreign language. Journal of Multilingual and M ulticultural Development._https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2099407

Dewaele, J.-M., & Li, C. (2021). Teacher enthusiasm and students’ social-behavioral learning engagement: The mediating role of student enjoyment and boredom in Chinese EFL classes. Language Teaching Research, 25(6), 922945. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211014538

Dogan, U. (2015). Student engagement, academic self-efficacy, and academic motivation as predictors of academic performance. The Anthropologist, 20(3), 553-561. https:// doi.org/10.1080/ 09720073.2015.11891759

Dörnyei, Z, & Csizér, K. (2012). How to design and analyze surveys in second language acquisition research. In A. M ackey & S. M . Gass (Eds.), Research methods in second language acquisition: A practical guide (pp. 74-94). Blackwell.

Ellis, K. (2000). Perceived teacher confirmation: The development and validation of an instrument and two studies of the relationship to cognitive and affective learning. Human Communication Research, 26(2), 264-291. https:// doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2000.tb00758.x

Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107-115.

Fernandes, C. (2019). The relationship between teacher communication, and teacher credibility, student motivation, and academic achievement in India (Doctoral Dissertation, University of Oregon). ProQuest Dissertations Publishing Publication (No. 10980753).

Finn, J. D. (1989). Withdrawing from school. Review of Educational Research, 59(2), 117-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/00346543059002117

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218-226. https:// doi.org/ 10.1037/ 0003-066X.56.3.218

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1367-1377. https:// doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1512

Fredrickson, B. L., & Branigan, C. (2005). Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cognition & Emotion, 19(3), 313-332. https:// doi.org/ 10.1080/ 02699930441000238

Friedman, D. A. (2012). How to collect and analyze qualitative data. In A. M ackey & S. M. Gass (Eds.), Research methods in second language acquisition: A practical guide (pp. 180-200). Blackwell.

Ghelichli, Y., Seyyedrezaei, S. H., Barani, G., & M azandarani, O. (2020). The relationship between dimensions of student engagement and language learning motivation among Iranian EFL learners. International Journal of Foreign Language Teaching and Research, 8(31), 43-57.

Goldman, Z. W., & Goodboy, A. K. (2014). M aking students feel better: Examining the relationships between teacher confirmation and college students’ emotional outcomes. Communication Education, 63(3), 259-277.

Goldman, Z. W., Claus, C. J., & Goodboy, A. K. (2018). A conditional process analysis of the teacher confirmation – student learning relationship. Communication Quarterly, 66(3), 245-264. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 01463373.2017.1356339

Goodboy, A. K., & M yers, S. A. (2008). The effect of teacher confirmation on student communication and learning outcomes. Communication Education, 57(2), 153-179. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520701787777

Gray, D. L., Anderman, E. M ., & O’Connell, A. A. (2011). Associations of teacher credibility and teacher affinity with learning outcomes in health classrooms. Social Psychology of Education, 14(2), 185-208. https://doi.org/10. 1007/s11218-010-9143-x

Gupta, M ., & Pandey, J. (2018). Impact of student engagement on affective learning: Evidence from a large Indian university. Current Psychology, 37(1), 414421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9522-3

Hsu, C. F. (2012). The influence of vocal qualities and confirmation of nonnative English-speaking teachers on student receiver apprehension, affective

learning, and cognitive learning. Communication Education, 61(1), 4-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2011.615410

Hsu, C. F., & Huang, I. (2017). Are international students quiet in class? The influence of teacher confirmation on classroom apprehension and willingness to talk in class. Journal of International Students, 7(1), 38-52.

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation M odeling, 6(1), 1-55. https:// doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hu, S., & Kuh, G. D. (2002). Being (dis)engaged in educationally purposeful activities: The influences of student and institutional characteristics. Research in Higher Education, 43(5), 555-575. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020114231387

Hu, L., & Wang, Y. (2023). The predicting role of EFL teachers’ immediacy behaviors in students’ willingness to communicate and academic engagement. BMC Psychology, 11(318), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01378-x

Imlawi, J., Gregg, D., & Karimi, J. (2015). Student engagement in course-based social networks: The impact of instructor credibility and use of communication. Computers & Education, 88, 84-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.04.015

Jiang, A. L., & Zhang, L. J. (2021). University teachers’ teaching style and their students’ agentic engagement in EFL learning in China: A self-determination theory and achievement goal theory integrated perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 704269. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.704269

Kahn, P., Everington, L., Kelm, K., Reid, I., & Watkins, F. (2017). Understanding student engagement in online learning environments: The role of reflexivity. Educational Technology Research and Development, 65, 203-218. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016-9484-z

Khajavy, G. H. (2021). M odeling the relations between foreign language engagement, emotions, grit and reading achievement. In P. Hiver, A. H. Al-Hoorie, & S. M ercer (Eds.), Student engagement in the language classroom (pp. 241-259). Multilingual M atters.

Kuh, G. D. (2009). The national survey of student engagement: Conceptual and empirical foundations. New Directions for Institutional Research, 2(141), 5-20.

Kuh, G. D., Kinzie, J. L., Buckley, J. A., Bridges, B. K., & Hayek, J. C. (2006) (Eds.), What matters to student success? A review of the literature. National Postsecondary Education Cooperative.

Lauermann, F., & Berger, J. L. (2021). Linking teacher self-efficacy and responsibility with teachers’ self-reported and student-reported motivating styles and student engagement. Learning and Instruction, 76, 101441. https:// doi. org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101441

Lee, J. H. (2020). Relationships among students’ perceptions of native and nonnative EFL teachers’ immediacy behaviours and credibility and students’ willingness to communicate in class. Oxford Review of Education, 46(2), 153168. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 03054985.2019.1642187

M acIntyre, P. D., Ross, J., & Clément, R. (2019). Emotions are motivating. In M. Lamb, K. Csizér, A. Henry, & S. Ryan (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of motivation for language learning (pp. 183-202). Springer. https://doi.org/10. 1007/978-3-030-28380-3_9

M artin, A. J., & Collie, R. J. (2019). Teacher-student relationships and students’ engagement in high school: Does the number of negative and positive relationships with teachers matter? Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(5), 861-876. https:// doi.org/10.1037/edu0000317

M cCroskey, J. C., & Teven, J. J. (2013). Source credibility measures. M easurement Instrument Database for the Social Science.

M ercer, S. (2019). Language learner engagement: Setting the scene. In X. Gao (Ed.), Second handbook of English language teaching (pp. 643-660). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02899-2_40

M ercer, S., & Dörnyei, Z. (2020). Engaging language learners in contemporary classrooms. Cambridge University Press.

M ercer, S., M acIntyre, P., Gregersen, T., & Talbot, K. (2018). Positive language education: Combining positive education and language education. Theory and Practice of Second Language Acquisition, 4(2), 11-31.

M ottet, T. P., Frymier, A. B., & Beebe, S. A. (2006). Theorizing about instructional communication. In T. P. M ottet, V. P. Richmond, & J. C. M cCroskey (Eds.), Handbook of instructional communication: Rhetorical and relational perspectives (pp. 255-282). Allyn & Bacon.

Nassaji, H. (2020). Good qualitative research. Language Teaching Research, 24(4), 427-431. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820941288

Pan, Z., Wang, Y., & Derakhshan, A. (2023). Unpacking Chinese EFL students’ academic engagement and psychological well-being: The roles of language teachers’ affective scaffolding. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 52(5), 1799-1819. https:// doi.org/ 10.1007/ s10936-023-09974-z

Pawlak, M . (2014). Investigating learner engagement with oral corrective feedback: Aims, methodology, outcomes. In A. Łyda & K. Szcześniak (Eds.), Awareness in action. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-00461-7_5

Ramshe, M. H., Ghazanfari, M ., & Ghonsooly, B. (2019). The role of personal best goals in EFL learners’ behavioural, cognitive, and emotional engagement. International Journal of Instruction, 12(1), 1627-1638.

Reeve, J., & Tseng, C. M . (2011). Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(4), 257-267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.05.002

Salanova, M., Schaufeli, W., M artínez, I., & Bresó, E. (2010). How obstacles and facilitators predict academic performance: The mediating role of study burnout and engagement. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 23(1), 53-70. https://doi.org/10. 1080/10615800802609965

Schaufeli, W. B. (2013). What is engagement. In C. Truss, K. Alfes, R. Delbridge, A. Shantz, & E. Soane (Eds.), Employee engagement in theory and practice (pp. 15-36). Routledge.

Schaufeli, W. B., M artinez, I. M ., Pinto, A. M ., Salanova, M ., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(5), 464-481. https:// doi. org/10.1 177/0022022102033005003

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71-92.

Schrodt, P., & Finn, A. N. (2011). Students’ perceived understanding: An alternative measure and its associations with perceived teacher confirmation, verbal aggressiveness, and credibility. Communication Education, 60(2), 231-254. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 03634523.2010.535007

Shappie, A. T., & Debb, S. M . (2019). African American student achievement and the historically Black University: The role of student engagement. Current Psychology, 38(6), 1649-1661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9723-4

Sidelinger, R. J., & Booth-Butterfield, M. (2010). Co-constructing student involvement: An examination of teacher confirmation and student-to-student connectedness in the college classroom. Communication Education, 59(2), 165-184. https:// doi.org/10.1080/ 03634520903390867

Teven, J. J. (2007). Effects of supervisor social influence, nonverbal immediacy, and biological sex on subordinates’ perceptions of job satisfaction, liking, and supervisor credibility. Communication Quarterly, 55(2), 155-177. https:// doi. org/10.1080/01463370601036036

Teven, J. J., & Hanson, T. L. (2004). The impact of teacher immediacy and perceived caring on teacher competence and trustworthiness. Communication Quarterly, 52(1), 39-53. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 01463370409370177

Tibbles, D., Richmond, V. P., M cCroskey, J. C., & Weber, K. (2008). Organizational orientations in an instructional setting. Communication Education, 57(3), 389-407. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520801930095

Tsang, A., & Dewaele, J.-M . (2023). The relationships between young FL learners’ classroom emotions (anxiety, boredom, & enjoyment), engagement, and FL proficiency. Applied Linguistics Review. https:// doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2022-0077

Wang, Y., & Derakhshan, A. (2023). Enhancing Chinese and Iranian EFL students’ willingness to attend classes: The role of teacher confirmation and caring. Porta Linguarum, 39(1),165-192. http://doi.org/ 10.30827/portalin.vi39.23625

Wang, Y., Derakhshan A., & Pan, Z. (2022). Positioning an agenda on a loving pedagogy in second language acquisition: Conceptualization, practice, and research. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 894190. https://doi.org/10.33 89/fpsyg.2022.894190.

Wang, Y., Derakhshan, A., & Zhang, L. J. (2021). Researching and practicing positive psychology in second/foreign language learning and teaching: The past, current status and future directions. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 110. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.731721.

Xie, F., & Derakhshan, A. (2021). A conceptual review of positive teacher interpersonal communication behaviors in the instructional context. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 2623. https:// doi.org/ 10.3389/fpsyg. 2021.708490

Zepke, N., & Leach, L. (2010). Improving student engagement: Ten proposals for action. Active Learning in Higher Education, 11(3), 167-177. https://doi. org/10.1177/1469787410379680

Zhang, Q. (2009). Perceived teacher credibility and student learning: Development of a multicultural model. Western Journal of Communication, 73(3), 326-347. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570310903082073

Zhang, Q., & Zhang, J. (2013). Instructors’ positive emotions: Effects on student engagement and critical thinking in US and Chinese classrooms. Communication Education, 62(4), 395-411. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 03634523.2013.828842

Zhang, Z V., & Hyland, K. (2022). Fostering student engagement with feedback: An integrated approach. Assessing Writing, 51, 100586. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.asw.2021.100586

الملحق أ

مقياس تأكيد المعلم (TCS)

معلمتي في اللغة الإنجليزية…

- يُعبر عن اهتمامه/اهتمامها بما إذا كان الطلاب يتعلمون.

- يدل على أنه/أنها يقدّر أسئلة أو تعليقات الطلاب.

- يبذل جهدًا للتعرف على الطلاب.

- يقلل من شأن الطلاب أو يحط من قدرهم عندما يشاركون في الصف.

- تحقق من فهم الطلاب قبل الانتقال إلى النقطة التالية.

- يقدم تعليقات شفهية أو مكتوبة على أعمال الطلاب.

- يُقيم اتصالاً بالعين خلال محاضرات الصف.

- يتحدث بتعالٍ مع الطلاب.

- يكون فظًا في الرد على تعليقات أو أسئلة بعض الطلاب خلال الحصة.

- يستخدم أسلوب تدريس تفاعلي.

- يستمع بانتباه عندما يطرح الطلاب أسئلة أو يقدمون تعليقات خلال الحصة.

- يظهر سلوكًا متعجرفًا.

- يستغرق وقتًا للإجابة على أسئلة الطلاب بشكل كامل.

- يحرج الطلاب أمام الفصل.

- يُبلغ أنه/أنها ليس لديه/لديها وقت للاجتماع مع الطلاب.

- يخيف الطلاب.

- يبدي تفضيلًا لطلاب معينين.

- يقلل من شأن الطلاب عندما يذهبون إلى المعلم طلبًا للمساعدة خارج الفصل.

- يبتسم للفصل.

- يُعبر عن اعتقاده بأن الطلاب يمكنهم تحقيق أداء جيد في الصف.

- متاح للإجابة على الأسئلة قبل وبعد الحصة.

- غير مستعد للاستماع إلى الطلاب الذين يختلفون.

- يستخدم مجموعة متنوعة من تقنيات التدريس لمساعدة الطلاب على فهم محتوى الدورة.

- يسأل الطلاب عن رأيهم في سير الدرس و/أو كيف تسير المهام.

- يُدمج التمارين في المحاضرات عند الاقتضاء.

- مستعد للانحراف قليلاً عن المحاضرة عندما يطرح الطلاب أسئلة.

- يركز على عدد قليل من الطلاب خلال الحصص بينما يتجاهل الآخرين.

الملحق ب

مقياس مصداقية المصدر (SCS)

| 1) | ذكي | ١٢٣٤٥٦٧ | غير ذكي |

| 2) | غير مدرب | ١٢٣٤٥٦٧ | مدرب |

| 3) | تهتم بي | ١٢٣٤٥٦٧ | لا يهتم بي |

| ٤) | صادق | ١٢٣٤٥٦٧ | غير أمين |

| 5) | يأخذ مصلحتي في الاعتبار | ١٢٣٤٥٦٧ | لا يهتم بمصالحي |

| 6) | غير موثوق به | ١٢٣٤٥٦٧ | موثوق به |

| ٧) | غير خبير | ١٢٣٤٥٦٧ | خبير |

| 8) | متمركز حول الذات | ١٢٣٤٥٦٧ | غير أناني |

| 9) | مهتم بي | ١٢٣٤٥٦٧ | لا يهتم بي |

| 10) | مُشَرَّف | ١٢٣٤٥٦٧ | غير شريف |

| 11) | مُطلَع | ١٢٣٤٥٦٧ | غير مطلع |

| 12) | أخلاقي | ١٢٣٤٥٦٧ | غير أخلاقي |

| 13) | غير كفء | ١٢٣٤٥٦٧ | كفء |

| 14) | غير أخلاقي | ١٢٣٤٥٦٧ | أخلاقي |

| 15) | غير حساس | ١٢٣٤٥٦٧ | حساس |

| 16) | مشرق | ١٢٣٤٥٦٧ | غبي |

| 17) | مزيف | ١٢٣٤٥٦٧ | صادق |

| 18) | عدم الفهم | ١٢٣٤٥٦٧ | فهم |

الملحق ج

مقياس التفاعل العملي في أوترخت للطلاب (UWES-S)

حيوية

- عندما أدرس، أشعر بالقوة العقلية.

- يمكنني الاستمرار لفترة طويلة جداً عندما أكون أدرس.

- عندما أدرس، أشعر أنني مليء بالطاقة.

- عندما أدرس أشعر بالقوة والنشاط.

- عندما أستيقظ في الصباح، أشعر برغبة في الذهاب إلى الصف.

إهداء

- أجد دراستي مليئة بالمعنى والهدف.

- دراستي تلهمني.

- أنا متحمس لدراستي.

- أنا فخور بدراستي.

- أجد دراستي تحديًا.

امتصاص

- الوقت يمر بسرعة عندما أدرس.

- عندما أدرس، أنسى كل شيء آخر من حولي.

- أشعر بالسعادة عندما أدرس بجد.

- أندمج تمامًا عندما أدرس.

الملحق د

أسئلة المقابلة

- ما هي سلوكيات المعلم الدولية التي تشعر أنها تؤثر بشكل أكبر على مشاركتك في سياق الفصل الدراسي؟ (يرجى الشرح)

- إلى أي مدى يمكن أن تشجع كفاءة معلم اللغة الإنجليزية لديك، ونواياه الحسنة، وموثوقيته على مشاركتك في أنشطة الفصل الدراسي؟ (يرجى الشرح)

- هل تعتقد أن تأكيد المعلمين لك مهم لمشاركتك الأكاديمية؟ لماذا؟ أو لماذا لا؟ (يرجى الشرح)

- هل لديك أي تعليقات إضافية حول الآثار الإيجابية لمصداقية المعلم والتأكيد على مشاركتك الأكاديمية؟

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.38418

Publication Date: 2024-01-30

Modeling the interaction between teacher credibility, teacher confirmation, and English major students’ academic engagement: A sequential mixed-methods approach

Abstract

Adopting a sequential mixed-methods approach, the current inquiry examined English major students’ perceptions of the role of teacher confirmation and teacher credibility in enhancing their academic engagement in the Chinese context. In doing so, through WeChat messenger, three scales were provided to 1168 English major students chosen from different English as a foreign language (EFL) classes. For the sake of triangulation, 40 participants were invited to take part in interview sessions as well. The inspection of the correlations between the constructs indicated a strong association between student academic engagement and teacher confirmation as well as a close connection between student academic engagement and teacher credibility. This showed that the academic engagement of Chinese EFL students is tied to these teacher interpersonal behaviors. The contribution of teacher confirmation and credibility to Chinese EFL students’ academic engagement was also examined using path analysis, which demonstrated that Chinese EFL students’ academic engagement was predicted by teacher credibility and confirmation. Additionally, the interview

outcomes proved the integral role of these two communication behaviors in increasing Chinese students’ engagement. Findings may have some noteworthy implications for teacher educators and language instructors.

1. Introduction

said, the influence of teacher interpersonal characteristics on English language learners’ academic engagement has received inadequate attention. Thus, whether teacher interpersonal variables can bring about significant changes in the academic engagement of English learners is open to question. The present investigation strives to address this question by examining how EFL students’ academic engagement varies as a function of teachers’ positive interpersonal behaviors.

2. Literature review

2.1. Teacher confirmation

2.2. Teacher credibility

noted by Banfield et al. (2006), Aristotle grouped persuasion mode into three different categories, including (a) ethos (i.e., the credibility/believability of a communicator), (b) logos (i.e., the reasoning used to prove an assertion), and (c) pathos (i.e., the emotional/inspirational appeals). Among them, ethos is deemed as the most potent means of persuasion through which an orator can effectively convince his/her audience (Pishghadam et al., 2019). Ethos/source credibility as a complex concept comprises three dimensions: competence, trustworthiness, and caring (Teven & Hanson, 2004; Wang et al., 2022). While the first dimension of source credibility has something to do with speakers’ knowledge, skills, and abilities, trustworthiness and caring are related to the personality of speakers. Extending these dimensions to education, competence pertains to how positively students perceive their instructors’ knowledge and teaching abilities (Teven & Hanson, 2004; Zhi & Wang, 2023). Trustworthiness refers to the amount of honesty instructors demonstrate in interactions with their pupils (Teven, 2007). Caring, as the last dimension, deals with instructors’ continual attention to students’ needs, wants, and desires (Zhang, 2009).

teacher credibility as a significant predictor of student engagement. Taken together, the study outcomes divulged that students’ involvement in learning environments strictly depends on their teachers’ credibility. Despite such attempts, the examination of teacher credibility in relation to students’ academic behaviors is still in its infancy. Moreover, few studies have investigated the implications of teacher credibility in language education contexts. To fill this lacuna, in this research, we explored a group of EFL students’ perceptions of their instructors’ level of credibility.

2.3. Academic engagement

identify the predictors of EFL students’ engagement. The present study sought to address this gap by examining the power of teacher confirmation and credibility in predicting EFL students’ academic engagement.

2.4. Theoretical models of the interplay between teacher communication behaviors and student academic behaviors

RQ2: To what extent, if any, do teacher credibility and teacher confirmation significantly predict Chinese students’ academic engagement?

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Teacher Confirmation Scale (TCS)

3.2.2. Source Credibility Scale (SCS)

(

3.2.3. Utrecht Work Engagement Scale for Students (UWES-S)

3.2.4. Semi-structured interviews

3.3. Procedure

of Chinese students of English majors recruited from different provinces across the Chinese mainland. Then, the online questionnaires were administered to those students (

3.4. Analysis

of interviewees’ answers. This helped them become aware of any important details. Then, at the next stage, they went through the three phases of open coding, creating categories, and abstraction to codify interviewees’ responses. In the first phase, the analysts scrutinized the transcripts and offered some tentative codes, accordingly. Then, during the second phase, they linked the initial codes and categorized them into higher-order headings. Finally, at the last phase, each category was named using content-characteristic words. Following that, to measure the intercoder agreement, Krippendorff’s alpha (

4. Results

4.1. Data preprocessing

| Kolmogorov-Smirnov

|

|||

| Statistic | df | Sig. | |

| Teacher confirmation | .05 | 1168 | .12 |

| Teacher credibility | .08 | 1168 | .09 |

| Student academic engagement | .07 | 1168 | .06 |

| Scales | Subscales | Cronbach alpha |

| TCS | – | .92 |

| Competence factor | .80 | |

| Caring/ goodwill factor | .73 | |

| SCS | Trustworthiness factor | .77 |

| Overall scale | .93 | |

| UWES-S | Vigor | .80 |

| Dedication | .71 | |

| Absorption | .70 | |

| Overall scale | .95 |

| Questionnaires | CR | AVE | MSV | M axR(H) |

| TCS | 0.889 | 0.855 | 0.427 | 0.968 |

| SCS | 0.757 | 0.753 | 0.107 | 0.976 |

| UWES-S | 0.969 | 0.692 | 0.427 | 0.975 |

4.2. The quantitative results

| Confirmation | Credibility | Academic engagement | |

| Confirmation | 1 | ||

| 1168 | |||

| Credibility | .72** | 1 | |

| . 000 | |||

| 1168 | 1168 | ||

| Academic engagement | .38** | .33** | 1 |

| . 000 | . 000 | ||

| 1168 | 1168 | 1168 |

| Vigor | Dedication | Absorption | |

| Confirmation |

|

|

|

| Credibility |

|

|

|

As shown in Table 5, positive significant relationships were found between all the components of student academic engagement and overall teacher confirmation and credibility. Compared to the other components of student academic engagement, dedication was more significantly correlated with teacher confirmation (

4.2.2. RQ2: To what extent, if any, do teacher credibility and teacher confirmation significantly predict Chinese students’ academic engagement?

exhibit good fit to the collected data. As Table 6 indicates, all the fit indices were highly acceptable, illustrating that the suggested model enjoyed high validity.

| X2/ df | GFI | CFI | NFI | RMSEA | |

| Acceptable fit |

|

|

|

|

|

| Model | 2.92 | .93 | .94 | .95 | .07 |

4.2. The qualitative findings

P9: The confirmations that I typically receive from my English language teacher encourage me to engage in class activities.

P10: Providing confirmation to learners can foster their engagement with the language learning environment.

P14: Students are more likely to participate in class activities when they feel acknowledged.

P17: The teacher’s confirmation or approval makes me confident enough to actively participate in learning activities.

| Themes | Sub-themes | Frequency | Percentage |

| Teacher confirmation | – | 30 |

|

| Teacher credibility | Trustworthiness, caring/goodwill, competence | 20 |

|

| Rapport | – | 15 |

|

| Teacher care | – | 12 |

|

| Teacher immediacy | Verbal immediacy, nonverbal immediacy | 10 |

|

| Total | 87 | 100 |

As Table 7 demonstrates, teacher credibility (trustworthiness, caring/goodwill, competence) was another recurrent theme (

students as a significant antecedent of their academic engagement. The following excerpts illuminate the predictive power of teacher credibility:

P7: A knowledgeable language teacher can inspire me to become an active learner in classroom environment.

P16: To me, trustworthy teachers are good at improving their students’ academic engagement.

P23: I believe that teacher goodwill can cultivate a positive teacher-student relationship and create a good instructional-learning environment in which students’ academic engagement can be dramatically increased.

P8: I think a strong and positive connection between teachers and students can trigger them take part in the language acquisition process.

P34: The use of facial expressions, gestures, and body language not only enables language teachers to create a lively learning environment but also helps them to involve students in the learning process.

5. Discussion

that demonstrated the value of teacher credibility for students’ learning motivation (Fernandes, 2019), WTC (Lee, 2020), and willingness to attend classes (Hu & Wang, 2023; Pishghadam et al., 2019; Pishghadam et al., 2023). All these previous studies identified the extent to which students’ classroom behaviors, including their academic engagement, can be influenced by their viewpoints and attitudes towards their teachers’ competence, goodwill, and trustworthiness.

6. Conclusions, implications, limitations, and directions for future research

language context. Thus, the findings of this study may not be generalized to other English education contexts. To identify any discrepancies in the findings, future investigations should replicate this topic in other educational settings. Second, the effects of situational factors, including gender, age, and major, were not measured nor controlled. To attain more accurate findings, further inquiries are firmly advised to do so. Third, only students were surveyed and interviewed in this study. To offer a more comprehensive picture of the issue, future studies are required to interview some teachers as well. Besides, with regard to the shortcomings of the existing literature, some other critical recommendations need to be mentioned as well. To start with, there is a dearth of empirical research on how teachers’ positive interpersonal factors, notably confirmation and credibility, may result in student engagement. As such, much more academic attention should be devoted to these interpersonal variables and their potential educational consequences. Next, even though cultural background may shape the perceptions of participants (Xie & Derakhshan, 2021), only a few studies on teacher confirmation and credibility have taken cultural differences into account (e.g., Pishghadam et al., 2023). To find out to what extent cultural differences may affect students’ attitudes toward these positive interpersonal variables, more cross-cultural studies need to be undertaken in this regard. Another lacuna that needs to be addressed is that while positive communication behaviors, notably credibility, have received adequate attention in mainstream education, they have been somehow overlooked in the language instructional context. Future studies in this area are therefore required to be conducted in EFL and ESL contexts.

Acknowledgement

References

Baralt, M. (2012). Coding qualitative data. In A. M ackey & S. M. Gass (Eds.), Research methods in second language acquisition (pp. 222-244). Blackwell.

BERA. (2011). Ethical guidelines for educational research. Retrieved from http:// content.yudu.com/Library/A2xnp5/Bera/resources/index.htm?referrerUrl =http://free.yudu.com/item/details/2023387/Bera

Berg, B. L. (2002). An introduction to content analysis. In B. L. Berg (Ed.), Qualitative research methods for the social sciences (pp. 174-199). Allyn & Bacon.

Buckner, M . M ., & Frisby, B. N. (2015). Feeling valued matters: An examination of instructor confirmation and instructional dissent. Communication Studies, 66(3), 398-413. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2015.1024873

Burnard, P. (1996). Teaching the analysis of textual data: An experiential approach. Nurse Education Today, 16(4), 278-281.

Campbell, L. C., Eichhorn, K. C., Basch, C., & Wolf, R. (2009). Exploring the relationship between teacher confirmation, gender, and student effort in the college classroom. Human Communication, 12(4), 447-464.

Carmona-Halty, M ., Salanova, M ., Llorens, S., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2021). Linking positive emotions and academic performance: The mediated role of academic psychological capital and academic engagement. Current Psychology, 40, 2938-2947. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00227-8

Carver, C., Jung, D., & Gurzynski-Weiss, L. (2021). Examining learner engagement in relationship to learning and communication mode. In P. Hiver, A. H. Al-Hoorie, & S. Mercer (Eds.), Student engagement in the language classroom (pp. 120142). M ultilingual M atters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788923613-010

Croucher, S. M., Rahmani, D., Galy-Badenas, F., Zeng, C., Albuquerque, A., Attarieh, M., & Nshom, E. N. (2021). Exploring the relationship between teacher confirmation and student motivation: The United States and Finland. In M. D. López-Jiménez & J. Sánchez-Torres (Eds.), Intercultural competence past, present, and future: Respecting the past, problems in the present, and forging the future (pp. 101-120). Springer.

Derakhshan, A. (2021). The predictability of Turkman students’ academic engagement through Persian language teachers’ nonverbal immediacy and

credibility. Journal of Teaching Persian to Speakers of Other Languages, 10(21), 3-24. https://doi.org/10.30479/JTPSOL.2021.14654.1506

Derakhshan, A. (2022). The “5Cs” positive teacher interpersonal behaviors: Implications for learner empowerment and learning in an L2 context. Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/9783031165276

Derakhshan, A., Eslami, Z. R., Curle, S., & Zhaleh, K. (2022). Exploring the validity of immediacy and burnout scales in an EFL context: The predictive role of teacher-student interpersonal variables in university students’ experience of academic burnout. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 12(1), 87-115. http://dx.doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2022.12.1.5

Derakhshan, A., Fathi, J., Pawlak, M., & Kruk, M. (2022). Classroom social climate, growth language mindset, and student engagement: The mediating role of boredom in learning English as a foreign language. Journal of Multilingual and M ulticultural Development._https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2099407

Dewaele, J.-M., & Li, C. (2021). Teacher enthusiasm and students’ social-behavioral learning engagement: The mediating role of student enjoyment and boredom in Chinese EFL classes. Language Teaching Research, 25(6), 922945. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211014538

Dogan, U. (2015). Student engagement, academic self-efficacy, and academic motivation as predictors of academic performance. The Anthropologist, 20(3), 553-561. https:// doi.org/10.1080/ 09720073.2015.11891759

Dörnyei, Z, & Csizér, K. (2012). How to design and analyze surveys in second language acquisition research. In A. M ackey & S. M . Gass (Eds.), Research methods in second language acquisition: A practical guide (pp. 74-94). Blackwell.

Ellis, K. (2000). Perceived teacher confirmation: The development and validation of an instrument and two studies of the relationship to cognitive and affective learning. Human Communication Research, 26(2), 264-291. https:// doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2000.tb00758.x

Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107-115.

Fernandes, C. (2019). The relationship between teacher communication, and teacher credibility, student motivation, and academic achievement in India (Doctoral Dissertation, University of Oregon). ProQuest Dissertations Publishing Publication (No. 10980753).

Finn, J. D. (1989). Withdrawing from school. Review of Educational Research, 59(2), 117-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/00346543059002117

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218-226. https:// doi.org/ 10.1037/ 0003-066X.56.3.218

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1367-1377. https:// doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1512

Fredrickson, B. L., & Branigan, C. (2005). Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cognition & Emotion, 19(3), 313-332. https:// doi.org/ 10.1080/ 02699930441000238

Friedman, D. A. (2012). How to collect and analyze qualitative data. In A. M ackey & S. M. Gass (Eds.), Research methods in second language acquisition: A practical guide (pp. 180-200). Blackwell.

Ghelichli, Y., Seyyedrezaei, S. H., Barani, G., & M azandarani, O. (2020). The relationship between dimensions of student engagement and language learning motivation among Iranian EFL learners. International Journal of Foreign Language Teaching and Research, 8(31), 43-57.

Goldman, Z. W., & Goodboy, A. K. (2014). M aking students feel better: Examining the relationships between teacher confirmation and college students’ emotional outcomes. Communication Education, 63(3), 259-277.

Goldman, Z. W., Claus, C. J., & Goodboy, A. K. (2018). A conditional process analysis of the teacher confirmation – student learning relationship. Communication Quarterly, 66(3), 245-264. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 01463373.2017.1356339

Goodboy, A. K., & M yers, S. A. (2008). The effect of teacher confirmation on student communication and learning outcomes. Communication Education, 57(2), 153-179. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520701787777

Gray, D. L., Anderman, E. M ., & O’Connell, A. A. (2011). Associations of teacher credibility and teacher affinity with learning outcomes in health classrooms. Social Psychology of Education, 14(2), 185-208. https://doi.org/10. 1007/s11218-010-9143-x

Gupta, M ., & Pandey, J. (2018). Impact of student engagement on affective learning: Evidence from a large Indian university. Current Psychology, 37(1), 414421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9522-3

Hsu, C. F. (2012). The influence of vocal qualities and confirmation of nonnative English-speaking teachers on student receiver apprehension, affective

learning, and cognitive learning. Communication Education, 61(1), 4-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2011.615410

Hsu, C. F., & Huang, I. (2017). Are international students quiet in class? The influence of teacher confirmation on classroom apprehension and willingness to talk in class. Journal of International Students, 7(1), 38-52.

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation M odeling, 6(1), 1-55. https:// doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hu, S., & Kuh, G. D. (2002). Being (dis)engaged in educationally purposeful activities: The influences of student and institutional characteristics. Research in Higher Education, 43(5), 555-575. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020114231387

Hu, L., & Wang, Y. (2023). The predicting role of EFL teachers’ immediacy behaviors in students’ willingness to communicate and academic engagement. BMC Psychology, 11(318), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01378-x

Imlawi, J., Gregg, D., & Karimi, J. (2015). Student engagement in course-based social networks: The impact of instructor credibility and use of communication. Computers & Education, 88, 84-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.04.015

Jiang, A. L., & Zhang, L. J. (2021). University teachers’ teaching style and their students’ agentic engagement in EFL learning in China: A self-determination theory and achievement goal theory integrated perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 704269. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.704269

Kahn, P., Everington, L., Kelm, K., Reid, I., & Watkins, F. (2017). Understanding student engagement in online learning environments: The role of reflexivity. Educational Technology Research and Development, 65, 203-218. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016-9484-z

Khajavy, G. H. (2021). M odeling the relations between foreign language engagement, emotions, grit and reading achievement. In P. Hiver, A. H. Al-Hoorie, & S. M ercer (Eds.), Student engagement in the language classroom (pp. 241-259). Multilingual M atters.

Kuh, G. D. (2009). The national survey of student engagement: Conceptual and empirical foundations. New Directions for Institutional Research, 2(141), 5-20.

Kuh, G. D., Kinzie, J. L., Buckley, J. A., Bridges, B. K., & Hayek, J. C. (2006) (Eds.), What matters to student success? A review of the literature. National Postsecondary Education Cooperative.

Lauermann, F., & Berger, J. L. (2021). Linking teacher self-efficacy and responsibility with teachers’ self-reported and student-reported motivating styles and student engagement. Learning and Instruction, 76, 101441. https:// doi. org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101441

Lee, J. H. (2020). Relationships among students’ perceptions of native and nonnative EFL teachers’ immediacy behaviours and credibility and students’ willingness to communicate in class. Oxford Review of Education, 46(2), 153168. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 03054985.2019.1642187

M acIntyre, P. D., Ross, J., & Clément, R. (2019). Emotions are motivating. In M. Lamb, K. Csizér, A. Henry, & S. Ryan (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of motivation for language learning (pp. 183-202). Springer. https://doi.org/10. 1007/978-3-030-28380-3_9

M artin, A. J., & Collie, R. J. (2019). Teacher-student relationships and students’ engagement in high school: Does the number of negative and positive relationships with teachers matter? Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(5), 861-876. https:// doi.org/10.1037/edu0000317

M cCroskey, J. C., & Teven, J. J. (2013). Source credibility measures. M easurement Instrument Database for the Social Science.

M ercer, S. (2019). Language learner engagement: Setting the scene. In X. Gao (Ed.), Second handbook of English language teaching (pp. 643-660). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02899-2_40

M ercer, S., & Dörnyei, Z. (2020). Engaging language learners in contemporary classrooms. Cambridge University Press.

M ercer, S., M acIntyre, P., Gregersen, T., & Talbot, K. (2018). Positive language education: Combining positive education and language education. Theory and Practice of Second Language Acquisition, 4(2), 11-31.

M ottet, T. P., Frymier, A. B., & Beebe, S. A. (2006). Theorizing about instructional communication. In T. P. M ottet, V. P. Richmond, & J. C. M cCroskey (Eds.), Handbook of instructional communication: Rhetorical and relational perspectives (pp. 255-282). Allyn & Bacon.

Nassaji, H. (2020). Good qualitative research. Language Teaching Research, 24(4), 427-431. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820941288

Pan, Z., Wang, Y., & Derakhshan, A. (2023). Unpacking Chinese EFL students’ academic engagement and psychological well-being: The roles of language teachers’ affective scaffolding. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 52(5), 1799-1819. https:// doi.org/ 10.1007/ s10936-023-09974-z

Pawlak, M . (2014). Investigating learner engagement with oral corrective feedback: Aims, methodology, outcomes. In A. Łyda & K. Szcześniak (Eds.), Awareness in action. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-00461-7_5

Ramshe, M. H., Ghazanfari, M ., & Ghonsooly, B. (2019). The role of personal best goals in EFL learners’ behavioural, cognitive, and emotional engagement. International Journal of Instruction, 12(1), 1627-1638.

Reeve, J., & Tseng, C. M . (2011). Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(4), 257-267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.05.002

Salanova, M., Schaufeli, W., M artínez, I., & Bresó, E. (2010). How obstacles and facilitators predict academic performance: The mediating role of study burnout and engagement. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 23(1), 53-70. https://doi.org/10. 1080/10615800802609965

Schaufeli, W. B. (2013). What is engagement. In C. Truss, K. Alfes, R. Delbridge, A. Shantz, & E. Soane (Eds.), Employee engagement in theory and practice (pp. 15-36). Routledge.

Schaufeli, W. B., M artinez, I. M ., Pinto, A. M ., Salanova, M ., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(5), 464-481. https:// doi. org/10.1 177/0022022102033005003

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71-92.

Schrodt, P., & Finn, A. N. (2011). Students’ perceived understanding: An alternative measure and its associations with perceived teacher confirmation, verbal aggressiveness, and credibility. Communication Education, 60(2), 231-254. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 03634523.2010.535007

Shappie, A. T., & Debb, S. M . (2019). African American student achievement and the historically Black University: The role of student engagement. Current Psychology, 38(6), 1649-1661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9723-4

Sidelinger, R. J., & Booth-Butterfield, M. (2010). Co-constructing student involvement: An examination of teacher confirmation and student-to-student connectedness in the college classroom. Communication Education, 59(2), 165-184. https:// doi.org/10.1080/ 03634520903390867

Teven, J. J. (2007). Effects of supervisor social influence, nonverbal immediacy, and biological sex on subordinates’ perceptions of job satisfaction, liking, and supervisor credibility. Communication Quarterly, 55(2), 155-177. https:// doi. org/10.1080/01463370601036036

Teven, J. J., & Hanson, T. L. (2004). The impact of teacher immediacy and perceived caring on teacher competence and trustworthiness. Communication Quarterly, 52(1), 39-53. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 01463370409370177

Tibbles, D., Richmond, V. P., M cCroskey, J. C., & Weber, K. (2008). Organizational orientations in an instructional setting. Communication Education, 57(3), 389-407. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520801930095

Tsang, A., & Dewaele, J.-M . (2023). The relationships between young FL learners’ classroom emotions (anxiety, boredom, & enjoyment), engagement, and FL proficiency. Applied Linguistics Review. https:// doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2022-0077

Wang, Y., & Derakhshan, A. (2023). Enhancing Chinese and Iranian EFL students’ willingness to attend classes: The role of teacher confirmation and caring. Porta Linguarum, 39(1),165-192. http://doi.org/ 10.30827/portalin.vi39.23625

Wang, Y., Derakhshan A., & Pan, Z. (2022). Positioning an agenda on a loving pedagogy in second language acquisition: Conceptualization, practice, and research. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 894190. https://doi.org/10.33 89/fpsyg.2022.894190.

Wang, Y., Derakhshan, A., & Zhang, L. J. (2021). Researching and practicing positive psychology in second/foreign language learning and teaching: The past, current status and future directions. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 110. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.731721.

Xie, F., & Derakhshan, A. (2021). A conceptual review of positive teacher interpersonal communication behaviors in the instructional context. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 2623. https:// doi.org/ 10.3389/fpsyg. 2021.708490

Zepke, N., & Leach, L. (2010). Improving student engagement: Ten proposals for action. Active Learning in Higher Education, 11(3), 167-177. https://doi. org/10.1177/1469787410379680

Zhang, Q. (2009). Perceived teacher credibility and student learning: Development of a multicultural model. Western Journal of Communication, 73(3), 326-347. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570310903082073

Zhang, Q., & Zhang, J. (2013). Instructors’ positive emotions: Effects on student engagement and critical thinking in US and Chinese classrooms. Communication Education, 62(4), 395-411. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 03634523.2013.828842

Zhang, Z V., & Hyland, K. (2022). Fostering student engagement with feedback: An integrated approach. Assessing Writing, 51, 100586. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.asw.2021.100586

APPENDIX A

Teacher Confirmation Scale (TCS)

My English teacher…

- Communicates that he/she is interested in whether students are learning.

- Indicates that he/she appreciates students’ questions or comments.

- Makes an effort to get to know students.

- Belittles or puts students down when they participate in class.

- Checks on students’ understanding before going on to the next point.

- Gives oral or written feedback on students’ work.

- Establishes eye contact during class lectures.

- Talks down to students.

- Is rude in responding to some students’ comments or questions during class.

- Uses an interactive teaching style.

- Listens attentively when students ask questions or make comments during class.

- Displays arrogant behavior.

- Takes time to answer students’ questions fully.

- Embarrasses students in front of the class.

- Communicates that he/she doesn’t have time to meet with students.

- Intimidates students.

- Shows favoritism to certain students.

- Puts students down when they go to the teacher for help outside of class.

- Smiles at the class.

- Communicates that he/she believes that students can do well in the class.

- Is available for questions before and after class.

- Is unwilling to listen to students who disagree.

- Uses a variety of teaching techniques to help students understand course material.

- Asks students how they think the class is going and/or how assignments are coming along.

- Incorporates exercises into lectures when appropriate.

- Is willing to deviate slightly from the lecture when students ask questions.

- Focuses on only a few students during classes while ignoring others.

APPENDIX B

Source Credibility Scale (SCS)

| 1) | Intelligent | 1234567 | Unintelligent |

| 2) | Untrained | 1234567 | Trained |

| 3) | Cares about me | 1234567 | Doesn’t care about me |

| 4) | Honest | 1234567 | Dishonest |

| 5) | Has my interests at heart | 1234567 | Doesn’t have my interests at heart |

| 6) | Untrustworthy | 1234567 | Trustworthy |

| 7) | Inexpert | 1234567 | Expert |

| 8) | Self-centered | 1234567 | Not self-centered |

| 9) | Concerned with me | 1234567 | Not concerned with me |

| 10) | Honorable | 1234567 | Dishonorable |

| 11) | Informed | 1234567 | Uninformed |

| 12) | Moral | 1234567 | Immoral |

| 13) | Incompetent | 1234567 | Competent |

| 14) | Unethical | 1234567 | Ethical |

| 15) | Insensitive | 1234567 | Sensitive |

| 16) | Bright | 1234567 | Stupid |

| 17) | Phony | 1234567 | Genuine |

| 18) | Not understanding | 1234567 | Understanding |

APPENDIX C

Utrecht Work Engagement Scale for Students (UWES-S)

Vigor

- When I’m studying, I feel mentally strong.

- I can continue for a very long time when I am studying.

- When I study, I feel like I am bursting with energy.

- When studying I feel strong and vigorous.

- When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to class.

Dedication

- I find my studies to be full of meaning and purpose.

- My studies inspire me.

- I am enthusiastic about my studies.

- I am proud of my studies.

- I find my studies challenging.

Absorption

- Time flies when I am studying.

- When I am studying, I forget everything else around me.

- I feel happy when I am studying intensely.

- I get carried away when I am studying.

APPENDIX D

Interview questions

- What teacher international behaviors do you feel most impact your engagement in classroom context? (Please explain)

- To what extent can your English teacher’s competence, goodwill, and trustworthiness encourage you to take part in classroom activities? (Please explain)

- Do you think being confirmed by teachers is important for your academic engagement? Why? or Why not? (Please explain)

- Do you have any further comments on the positive effects of teacher credibility and confirmation on your academic engagement?