DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2025.104969

تاريخ النشر: 2025-03-11

هضم النشا: تحديث شامل حول آليات التعديل الأساسية وطرق تقييمه في المختبر

– للاستشهاد بهذه النسخة:

معرف HAL: hal-04998681

https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-04998681v1

هضم النشا: تحديث شامل حول آليات التعديل الأساسية وطرق تقييمه في المختبر

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

استجابة جلايسيمية

الألياف الغذائية

الميكروبيوتا

هيكل الغذاء

INFOGEST

الملخص

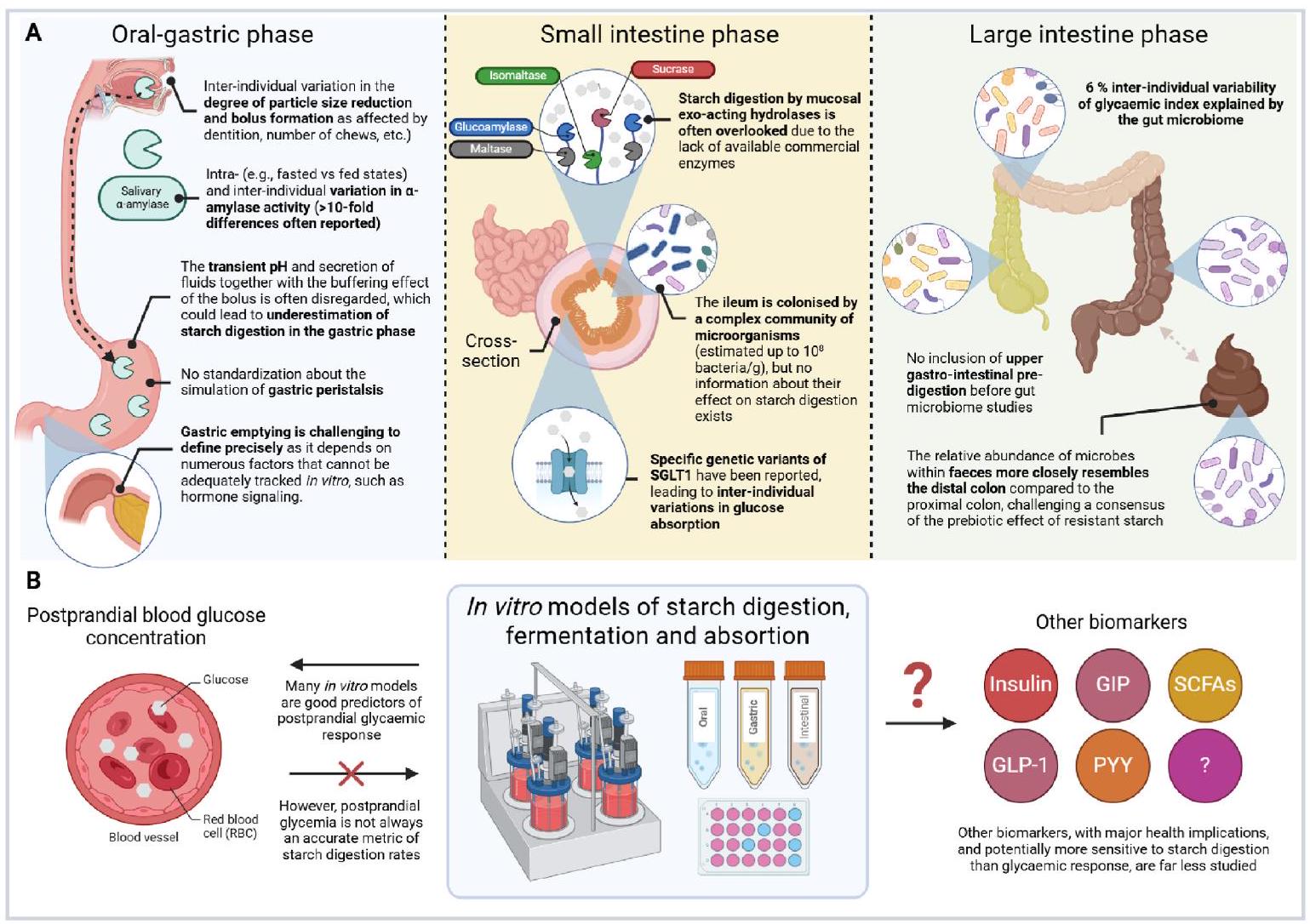

الخلفية: النشا هو الكربوهيدرات السائدة في نظامنا الغذائي وتأثيره على صحة الإنسان مرتبط بشكل معقد بعملية هضمه. ومع ذلك، على الرغم من التقدم الكبير في هذا المجال، لا تزال هناك تناقضات مهمة في كيفية وصف ودراسة هضم النشا في المختبر. النطاق والنهج: كان هدفنا الرئيسي هو تقديم رؤى محدثة حول هضم النشا والتخمر في الجهاز الهضمي البشري، بالإضافة إلى الاستجابات الفسيولوجية ذات الصلة والعوامل الرئيسية للتنوع (بما في ذلك الاختلافات بين الأفراد والاختلافات الهيكلية والتركيبية بين الأطعمة). كما تم تقديم تقييم نقدي لنماذج الهضم وأولويات العمل المستقبلية. هذا العمل هو نتاج تعاون دولي ضمن شبكة بحث INFOGEST. النتائج الرئيسية والاستنتاجات: يتم هضم النشا من خلال العمل المتضافر للإنزيمات الهضمية في اللمعة والحدود الفرشائية. يمكن أن تكون التحولات الميكانيكية والبيوكيميائية التي تحدث خلال المراحل الفموية والمعدية والمعوية حاسمة، مما يساهم بدرجات متفاوتة في عملية الهضم اعتمادًا على خصائص الطعام والخصائص الفردية. تتوفر حاليًا العديد من المنهجيات، مع تعقيد وقدرة متفاوتة على إعادة إنتاج العمليات الهضمية الرئيسية (مثل إفراغ المعدة). يمكن أن تكون بعض مقاييس نتائج القابلية للهضم في المختبر مرتبطة ارتباطًا وثيقًا بنتائج الدراسات في الجسم الحي، مما يظهر الإمكانات الواعدة لهذه الأساليب. ومع ذلك، غالبًا ما تتعرض الأهمية الفسيولوجية لدراسات هضم النشا في المختبر للخطر بسبب نقص التوافق المنهجي (خصوصًا لهضم الفم) وغياب الأحداث الإنزيمية الرئيسية. لذلك، تبرز الحاجة إلى تطوير إرشادات موحدة والتحقق من بروتوكولات المختبر المعدلة لدراسات هضم النشا كأولويات للعمل المستقبلي.

1. المقدمة

2. النشا: الهيكل البنيوي ووجوده في الغذاء

مكون غذائي رئيسي ولبنة أساسية للعديد من المنتجات الغذائية المعالجة المختلفة بما في ذلك الخبز، والبسكويت، والأرز المطبوخ، والبقوليات المعلبة، والمعكرونة، وحبوب الإفطار، والوجبات الخفيفة، ولكن يمكن أيضًا تناولها نيئة (مثل الفواكه النشوية).

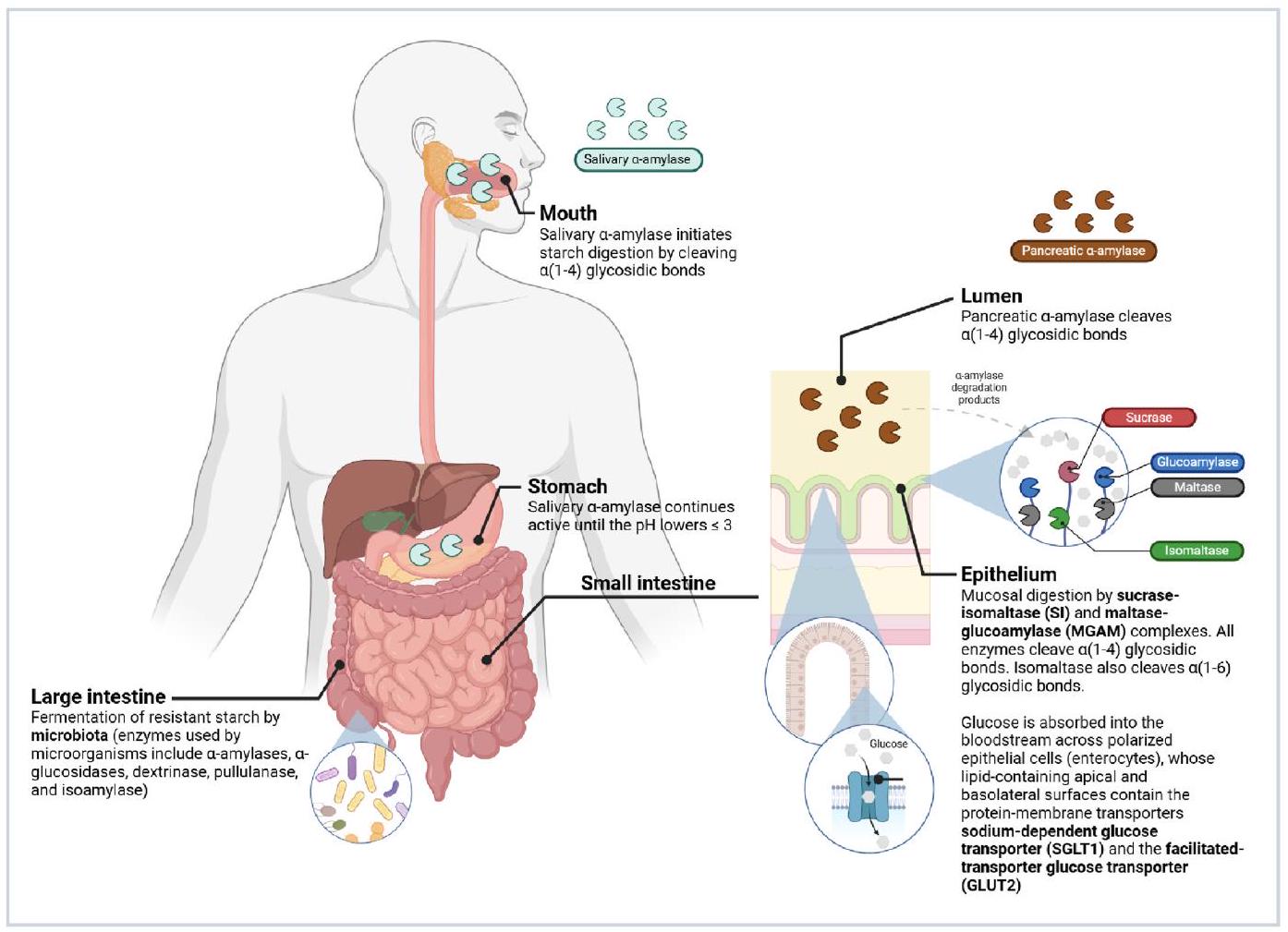

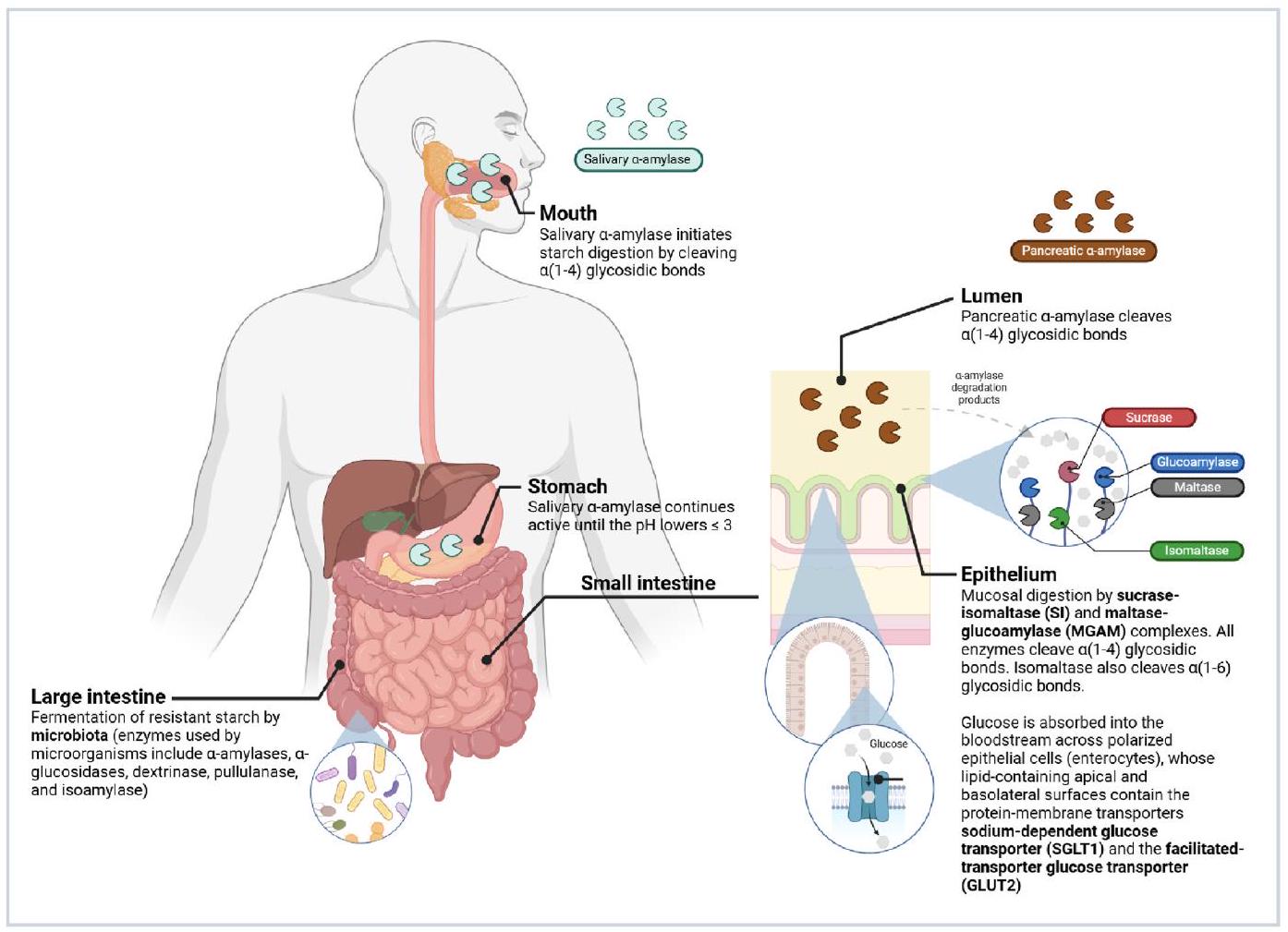

3. هضم النشا والتخمر عبر الجهاز الهضمي البشري

3.1. الفم

2008) ويلعب دورًا في التزليق والهضم الكيميائي للنشا. يتم إفرازه بمعدل

3.2. المعدة

3.3. الأمعاء الدقيقة (تجويف الأمعاء وغشاء الحدود الفرشاة)

لذا يتم تنظيم هضم النشا داخل الاثني عشر بشكل أساسي بواسطة العوامل التي تؤثر على نشاط وإن وصول/ارتباط الركيزة للإنزيمات الأميليوليتية.

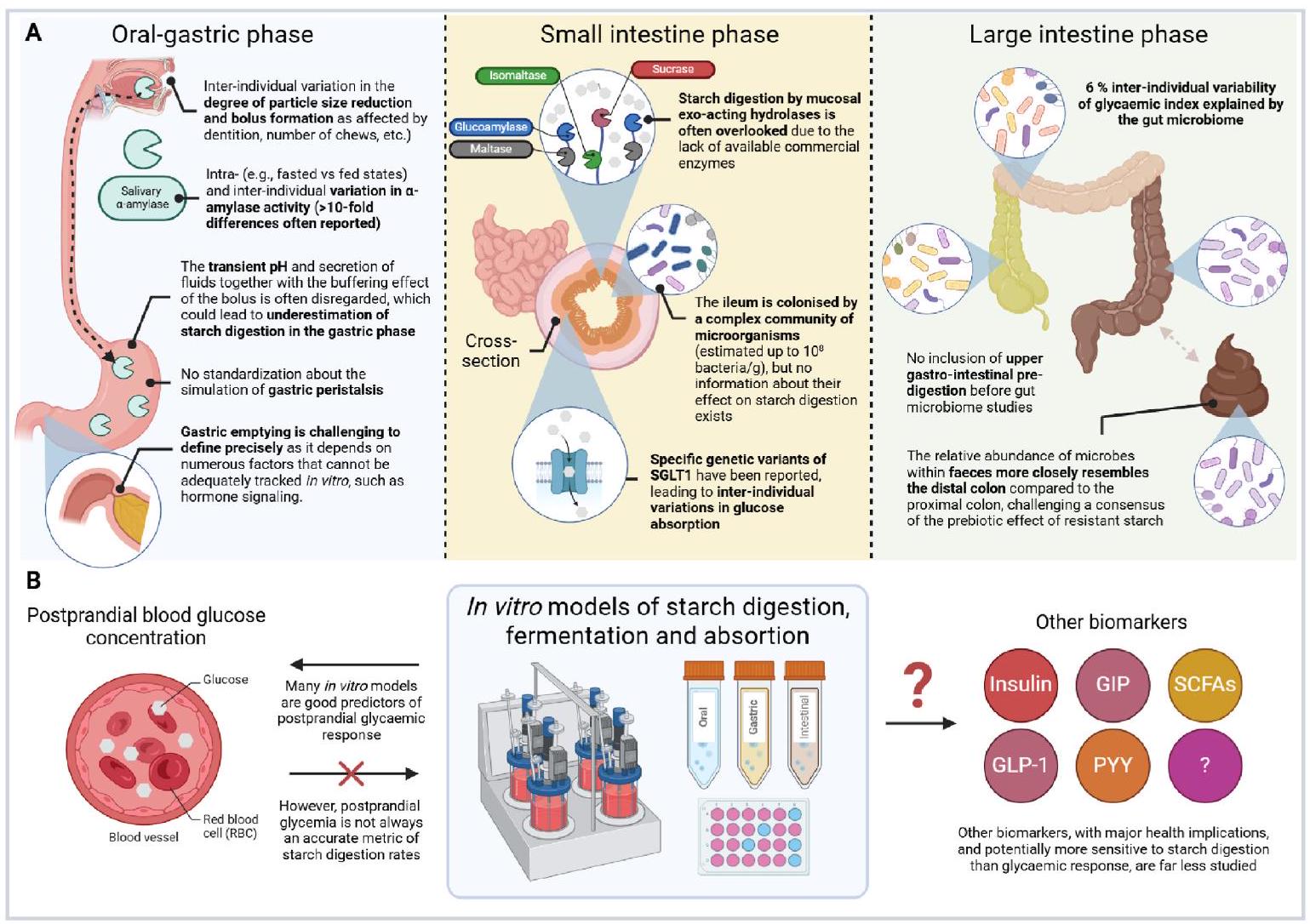

مستعمَرة بواسطة مجتمع معقد من الكائنات الدقيقة (يُقدَّر عددها حتى

3.4. الأمعاء الغليظة

كمية ونوع النشا المستهلك، وتكوين ميكروبيوتا الأمعاء، ووقت انتقال الهضم في القولون (Li، Hu، وآخرون، 2023). تبدأ البكتيريا القولونية عملياتها الأيضية بالالتصاق بمادة النشا، ثم تقوم بتحليلها إلى مركبات أوليغومرية. تنتقل هذه الأوليغومرات إلى الفضاء المحيط بالخلية البكتيرية، حيث تخضع للتحلل الإنزيمي إلى جلوكوز، الذي يتم امتصاصه بعد ذلك في الخلية للاستخدام الأيضي. تمثل قدرة البكتيريا القولونية على الارتباط بالنشا، والوصول إلى هياكلها المتميزة مثل الهياكل البلورية، تكيفات متخصصة ضرورية للوصول التنافسي واستخدام الهياكل الجزيئية للنشا (Deehan وآخرون، 2020). لقد تم الإبلاغ لفترة طويلة عن وجود هذه الآلية الواسعة والمتميزة لاستخدام النشا في البكتيريا سالبة الجرام، وخاصة في شعبة Bacteroidetes (Martens وآخرون، 2009). ومع ذلك، فإن تطوير تقنيات تسلسل الجيل التالي، وخاصة الأساليب المعتمدة على 16S rRNA، قد أشار إلى أن التغيرات في تكوين الميكروبيوتا لا تقتصر على الزيادات في البروبيوتيك مثل أنواع Bifidobacterium وLactobacillus. يمكن أن تقوم Clostridium اللاهوائية، بما في ذلك Ruminococcus وEubacterium وRoseburia وFaecalibacterium وCoprococcus، أيضًا بتخمير النشا (Wang، Wichienchot، وآخرون، 2019)، مع اختلافات ملحوظة في قدرتها على الارتباط والوصول إليه. على سبيل المثال، لا تستطيع Eubacterium rectale الارتباط بالنشا المربوط، بينما تمتلك Eubacterium rectale وRuminococcus bromii قدرة محدودة على النمو على الركيزة. ومع ذلك، أظهرت بكتيريا أخرى التزامًا جيدًا واستخدامًا للنشا المربوط، مثل Bifidobacterium adolescentis وParabacteroides distasonis (Deehan وآخرون، 2020).

4. الاستجابات الفسيولوجية للنشا: الأهمية للتغذية والصحة

وأفرازات الإنزيمات، بما في ذلك ‘كسر الإيليوم’، والشهية، والتمثيل الغذائي (باجيو ودروكر، 2007؛ مالجارز وآخرون، 2008؛ شوارتز وآخرون، 2000). لقد تم مراجعة العواقب الإيجابية للتأثير على إفراز هذه الهرمونات، لا سيما من حيث تنشيط كسر الإيليوم وتعديل استجابات الجلوكوز بعد الوجبات للوجبات اللاحقة في مكان آخر (كونغ وآخرون، 2022).

قد تستفيد النقطة RS5) من المراجعة. يمكن أن يأخذ إطار عمل أكثر شمولاً في الاعتبار الجوانب الحركية للمقاومة، مع التركيز بشكل مثالي على العوامل الرئيسية التي تدفع المقاومة، وتحديداً الخطوات المحددة لمعدل الوصول إلى الإنزيمات وارتباطها بالركيزة والتحويل اللاحق للركيزة إلى منتج بمجرد الارتباط، كما تم الاقتراح سابقًا (Dhital et al.، 2017). في أي حال، فإن التحليلات التلوية الحالية تعتمد على عدد محدود من الدراسات الصغيرة ويتطلب الأمر مزيدًا من التحقيق. من الواضح أن هناك حاجة إلى فهم أفضل للآليات التي يتم من خلالها هضم مصادر النشا المختلفة واستقلابها لتوضيح ما إذا كانت التأثيرات الفسيولوجية الملاحظة ونتائج الصحة ناتجة عن وجود النشا المقاوم أو غياب النشا القابل للهضم.

4.1. الفروق بين الأفراد في وظيفة الهضم والتمثيل الغذائي

في عناصر أخرى من عملية تشكيل الكتلة، مثل زيادة عدد المضغات (Zhu et al., 2014) ودرجة تكسير حجم الجسيمات (Ranawana et al., 2010) تم ربطهما بزيادة تركيزات الجلوكوز في الدم بعد الوجبة. على المستوى الميكانيكي، فإن زيادة تقليل حجم الجسيمات في المرحلة الفموية ستزيد من إطلاق منتجات هضم النشا بواسطة اللعاب.

5. العوامل المؤثرة على قابلية هضم النشا في المنتجات الغذائية

5.1. الهيكل الفائق الجزيئي والجرانيولي الأصلي

جانب الآخر، تؤدي التفاعلات الذاتية للأميلوز أثناء التراجع (

5.2. الحواجز الطبيعية في مصفوفة الأنسجة النباتية

(Noah et al., 1998). إن احتواء النشا بواسطة جدران الخلايا في البقول هو سبب رئيسي للاستجابة الجلايسيمية المنخفضة للبقول المطبوخة بالكامل (Bajka et al., 2023; Petropoulou et al., 2020).

5.3. الهيكل الكلي للطعام

تحلل النشا الأبطأ (Freitas وSouchon وLe Feunteun، 2022؛ Gallo وآخرون، 2022؛ Gkountenoudi-Eskitzi وآخرون، 2023؛ Lazaridou وآخرون، 2014؛ Martinez وRoman وGomez، 2018). توصل Fardet وآخرون (2006)، الذين استعرضوا عدة دراسات حول منتجات الحبوب، إلى استنتاج أن الحفاظ على سلامة هيكل الطعام أثناء الهضم قد يكون عاملاً أكثر أهمية لتقييد تحلل النشا من درجة بلورية النشا أو وجود الألياف الغذائية في المصفوفة المركبة للمنتجات المخبوزة.

5.4. التفاعلات مع مكونات الطعام الأخرى

2021). أخيرًا، تم الإبلاغ على نطاق واسع عن التأثير التآزري للبروتينات والدهون في تقليل هضم النشا (Tang وآخرون، 2019)، مع كون تأثير الدهون في مثل هذه الأنظمة أكثر أهمية (He وآخرون، 2022).

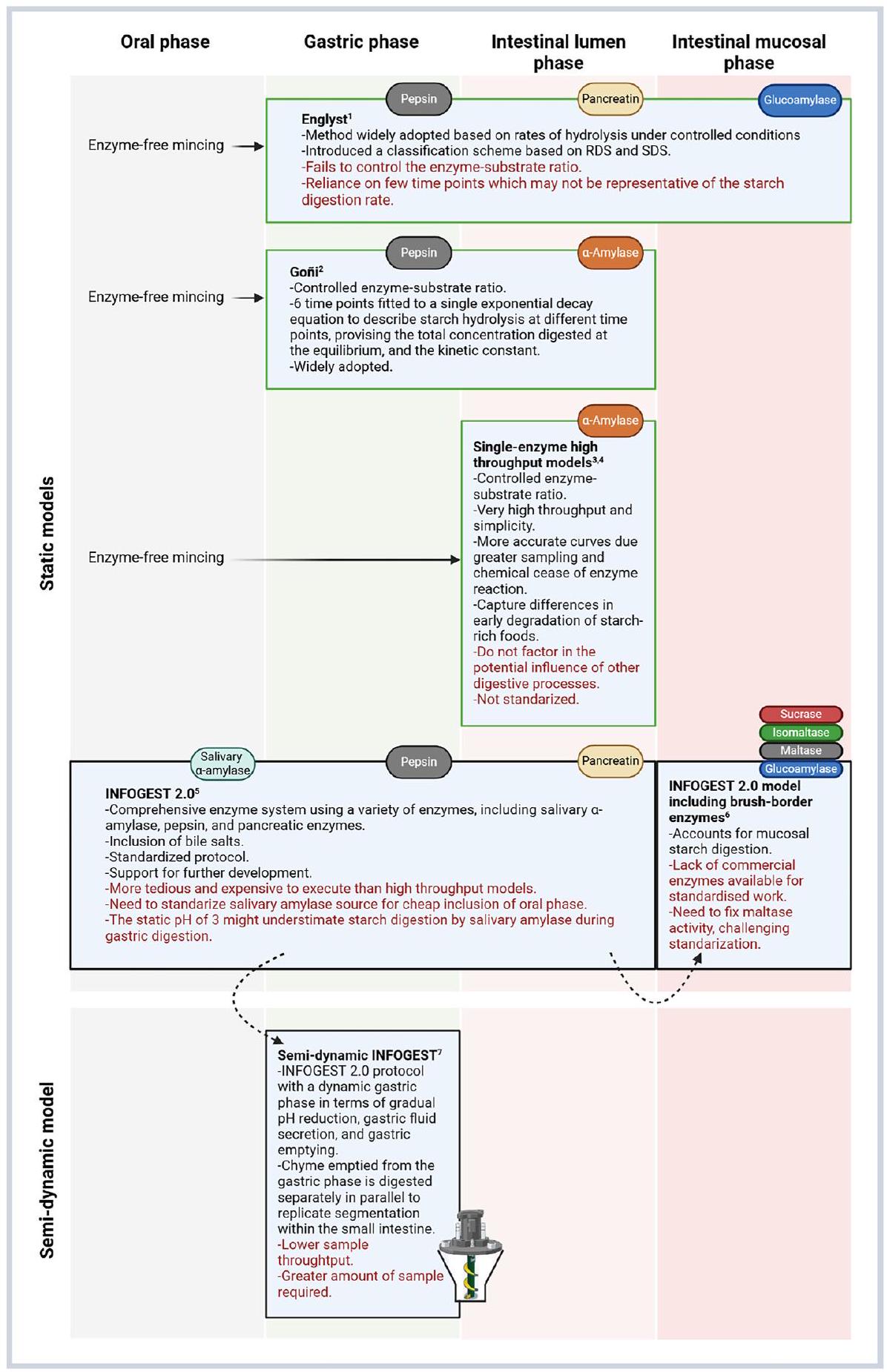

6. التقييم النقدي للطرق المخبرية لدراسات هضم النشا

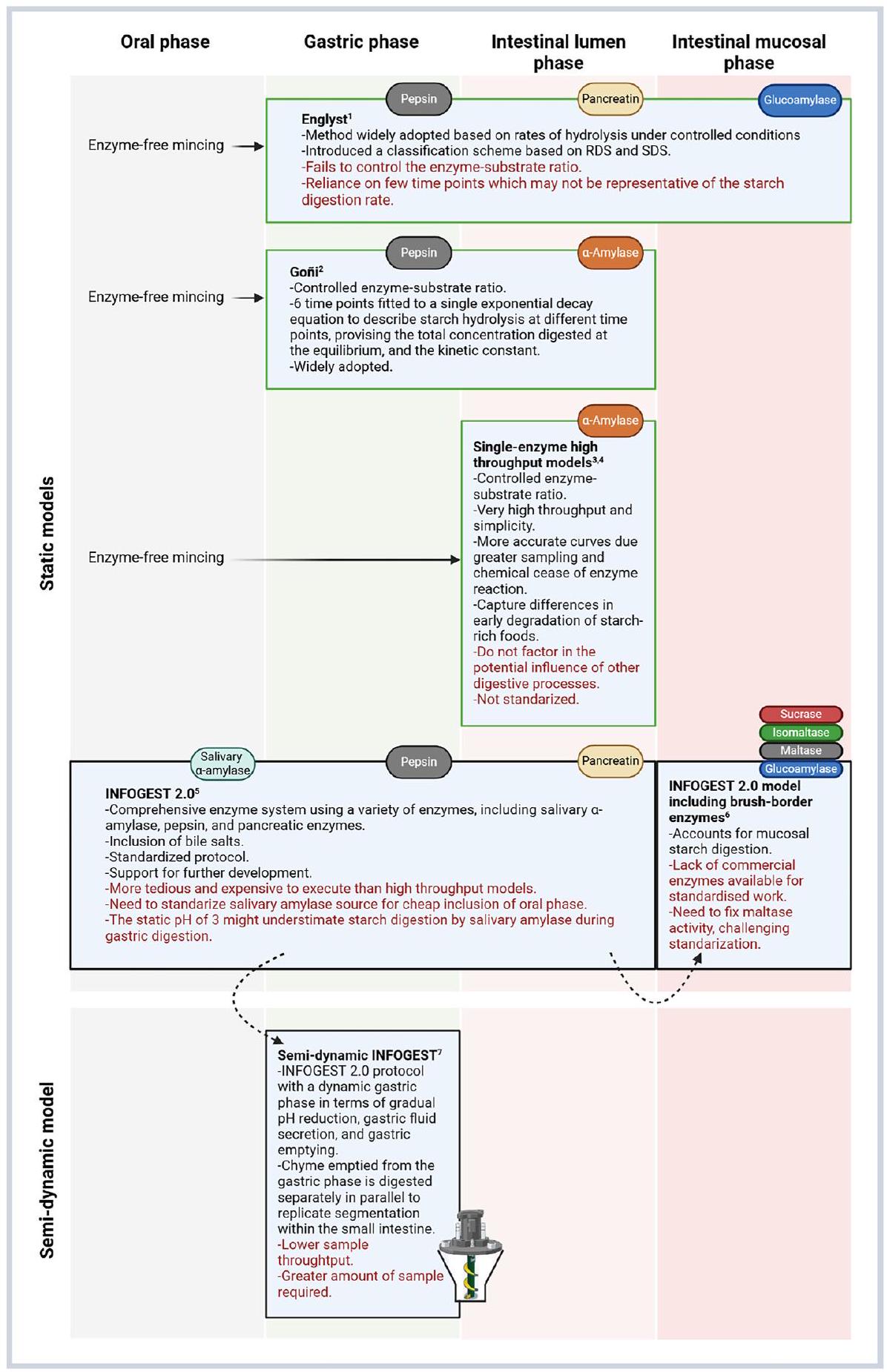

البروتوكولات المقترحة، مع استخدام عدد قليل منها على نطاق واسع، وأحيانًا تصبح موحدة، وجاهزة للتنفيذ باستخدام معدات المختبر التقليدية (الشكل 2). في بعض الحالات، تعتبر الكربوهيدرات واحدة فقط من عدة مغذيات يتم تقييمها في نموذج هضم عام، بينما تركز نماذج أخرى بشكل خاص على هضم النشا. تختلف هذه النماذج في عوامل مهمة مثل ما إذا كانت ثابتة أو ديناميكية، مع إغفال المرحلة الفموية و/أو المعدية، ودرجة الحموضة، ونوع وتركيز الإنزيمات، والمدة، ووجود الإلكتروليتات وأملاح الصفراء (الشكل 2). كما أن

لقد تقدم فهم هضم الأطعمة الغنية بالنشا، وأصبحت نماذج الهضم أكثر تطورًا. في أحد طرفي الطيف، توفر الأساليب البسيطة القائمة على الحركية الإنزيمية ظروفًا محكمة التحكم وتمكن من استخلاص استنتاجات واضحة حول الآليات، لكنها تخاطر بعدم كونها ذات صلة فسيولوجية. يمكن فقط تحديد رؤى حول التحلل المائي للنشا المعتمد على الزمن (أي، معدلات الأميليوليس) خلال الهضم في المختبر، عند اتباع نهج تجريبي حركي (Duijsens et al.، 2022). بينما يمكن تحقيق ذلك باستخدام نماذج ثابتة، فإنها

6.1. نظرة عامة على الطرق المخبرية لمحاكاة هضم النشا في القناة الهضمية العليا

التركيز الكلي المهضوم عند التوازن، والثابت الحركي في أطعمة مختلفة (غوني وآخرون، 1997). تم استخدام النمذجة الرياضية للديناميكا الحركية من الدرجة الأولى لعملية تحليل النشا لتوصيف وكمية أنماط هضم النشا. على سبيل المثال، تم استخدام طريقة لوغاريتم الميل (LOS) لتحديد وكمية الفئات الغذائية المهمة من النشا من خلال تحليل ما إذا كانت عملية تحليل النشا هي عملية من مرحلة واحدة أو عمليتين من الدرجة الأولى الزائفة مع معدلات هضمية مختلفة (إدواردز وآخرون، 2014). ومع ذلك، من المهم ملاحظة أنه في بعض الحالات، تنحرف ديناميات هضم النشا عن سلوك الديناميكا الحركية من الدرجة الأولى الكلاسيكية وتكون النماذج البديلة أكثر ملاءمة (بالاريس بالاريس وآخرون، 2019). بناءً على هذه المبادئ الحركية للإنزيمات، تم إثبات أن اختبارات تحليل النشا البسيطة وعالية الإنتاجية مفيدة لكل من الفهم الميكانيكي وتقدير ومقارنة التأثيرات الجلايسيمية لمنتجات غذائية مختلفة (دويسينس وآخرون، 2022؛ إدواردز وآخرون، 2019؛ لو فونتون وآخرون، 2021؛ نغوين وسوباد، 2018). وبالتالي، على الرغم من بساطتها، فإن هضم المواد الغذائية الغنية بالنشا مع

نظرة عامة على المزايا والقيود الرئيسية لنماذج الهضم في المختبر المختلفة.

| نماذج | المزايا الرئيسية | القيود الرئيسية | ||||||||||||||||||

| اختبارات التحلل النشوي بواسطة إنزيم واحد | ||||||||||||||||||||

| إنغليست (هـ. ن. إنغليست وآخرون، 1992) |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

| بروتوكولات الهضم الثابت | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

– نفس INFOGEST 2.0، ولكن يتضمن إنزيمات الهيدروكسيلاز في غشاء الحدود الشعيرية |

|

||||||||||||||||||

| بروتوكولات الهضم شبه الديناميكية | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

| بروتوكولات الهضم الديناميكية | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

اتجاهات في علوم الغذاء والتكنولوجيا 159 (2025) 104969

| نماذج | المزايا الرئيسية | القيود الرئيسية | ||||||||||

| – بعض النماذج لا تسمح بمرور الهياكل الغذائية الكبيرة | ||||||||||||

| منصات مصغرة | ||||||||||||

| الهضم على شريحة (دي هان وآخرون، 2019) | – يحاكي العمليات الإنزيمية في نظام مصغر – مراقبة في الوقت الحقيقي لهضم المغذيات وتوافرها الحيوي – تحكم عالي في المعايير (مثل: معدلات التدفق، نشاط الإنزيم) | – قدرة مرور محدودة – تحتاج إلى التحقق من صحة البيانات مقابل البيانات الحية – اللمعة الصغيرة لا يمكن أن تستوعب الهياكل الغذائية الأكبر | ||||||||||

| الأمعاء على شريحة (تافيتساين وآخرون، 2024) |

|

|

||||||||||

(دي هان وآخرون، 2019). بالمقابل، تعيد نماذج الأمعاء على شريحة إنشاء بعض جوانب البيئة الدقيقة المعوية مثل بنية الأنسجة ثلاثية الأبعاد، وتنوع الخلايا الظهارية و/أو الإشارات الكيميائية والميكانيكية المختلفة. تم استخدام هذه الأنظمة في دراسات وظيفة حاجز الأمعاء والحالات الالتهابية، بالإضافة إلى تفاعلات الميكروبيوتا، كما تم استعراضه سابقًا (تافيتساين وآخرون، 2024).

6.2. الأولويات المستقبلية

على أساس كل حالة على حدة. أخيرًا، هناك حاجة أيضًا لتقييم قابلية إعادة الإنتاج بين المختبرات لبروتوكولات الهضم التي تركز على هضم النشا والتحقق من صحتها مقابل البيانات الحية.

6.2.1. محاكاة المرحلة الفموية

قد يكون استخدام عينات بشرية مضغوطة خاضعًا لموافقة تنظيمية أخلاقية، ويمكن أن تؤدي التباينات الكبيرة بين الأفراد إلى تحديات جديدة فيما يتعلق بالمعيارية وإمكانية التكرار والتفسير. وبالتالي، على الرغم من تزايد الوعي بأهمية المرحلة الفموية في هضم الأطعمة الغنية بالنشا، لا يوجد حاليًا إجماع حول كيفية تقليد هذه الخطوة. لذلك، هناك حاجة إلى مزيد من العمل لتطوير أفضل الممارسات لمحاكاة المرحلة الفموية لتجارب الهضم في المختبر.

6.2.2. أنشطة الإنزيمات في تجويف الأمعاء وحدود الفرشاة

مرحلة الهضم في نموذج INFOGEST 2.0 لأخذ في الاعتبار هضم النشا في الغشاء المخاطي. وقد لوحظ أن إضافة مسحوق الأمعاء الدقيقة للفأر أدت إلى زيادة كبيرة في هضم النشا. ومع ذلك، فإن توحيد نشاط أحد الإنزيمات الأربعة الموجودة على حافة الشعيرات الدموية سيؤدي إلى عدم التوافق مع الإنزيمات الثلاثة الأخرى المعنية في هضم النشا. يبدو أن توحيد نشاط المالتاز (الذي لديه أعلى نشاط) هو النهج الأكثر منطقية، مع القيم المتوسطة المبلغ عنها في البشر من

6.2.3. محاكاة العمليات الديناميكية في الجهاز الهضمي

6.2.4 التكامل مع نماذج أخرى

(البشر) (خوراسانيها et al.، 2023). لإعادة إنشاء البيئات الدقيقة المعوية بشكل أقرب، يمكن الحصول على نماذج ذات تعقيد أعلى من خلال دمج أنواع خلايا مختلفة كما تم مراجعتها مؤخرًا (أسال et al.، 2024). ومع ذلك، قد تكون هناك تحديات مع تعرض مثل هذه النماذج لمحتويات الطعام. يمكن أن تكون الإنزيمات الهضمية وأملاح الصفراء الموجودة في المحتويات ضارة بالخلايا المستخدمة في هذه النماذج. لذلك، من المهم أن نكون على دراية بالمضاعفات المحتملة وكيف يمكن إدارتها حتى يتم أخذ ذلك في الاعتبار عند تصميم دراسة مشتركة للهضم والامتصاص. لمراجعة نقدية لمختلف الأساليب المتاحة، يُشار إلى عمل كوندرشينا et al. (2024) حيث تم تسليط الضوء على الحاجة إلى بروتوكول أو إطار عمل متوافق موحد للدراسات في المختبر التي تركز على امتصاص مكونات الطعام.

الخصائص مثل درجة تحلل النشا ومستويات التحلل الهيكلي لمصفوفة الطعام) قابلة للمقارنة مع السائل الإيلي الذي سيصل إلى القولون في الجسم الحي. النماذج التي تحاول محاكاة جميع مناطق الجهاز الهضمي، مثل SHIME، معقدة ومكلفة وتستغرق وقتًا طويلاً للتشغيل، مما يعني أنه لا يمكن اعتمادها على نطاق واسع. ومع ذلك، حتى عندما لا تكون مثل هذه النماذج متاحة، يمكن إجراء محاكاة كاملة للجهاز الهضمي العلوي بشكل منفصل باستخدام بروتوكولات الهضم في المختبر مثل طرق التوافق الخاصة بـ INFOGEST (Brodkorb et al.، 2019؛ Menard et al.، 2018، 2023؛ Mulet-Cabero et al.، 2020) والتي يمكن أن تتبعها بروتوكولات مصممة خصيصًا للاستخدام بعد عمليات الهضم في المختبر (Pérez-Burillo et al.، 2021).

6.2.5. الفروقات بين مجموعات السكان

6.2.6. التحقق

7. الاستنتاج العام وآفاق المستقبل

تمثل بشكل أفضل مجموعات سكانية فرعية متخصصة، على سبيل المثال تعديل INFOGEST لنمذجة الهضم بشكل أفضل في مجموعات كبار السن والرضع، يوفر حلاً.

- تطوير بروتوكول موحد لهضم المرحلة الفموية لأنواع مختلفة من الطعام يلتقط التحولات الهيكلية والبيوكيميائية التي تحدث في الجسم.

- تأكد من أن الإنزيمات الهضمية الرئيسية مؤخوذة في الاعتبار وأن الانتقالات بين خطوات الهضم تمكن من محاكاة الترتيب الفسيولوجي للأحداث الإنزيمية بدقة.

- تحسين فهم حالات الأمعاء الدقيقة البشرية وتطوير نماذج لمحاكاة هذه المنطقة.

- تطوير أنظمة نماذج متكيفة لتمثيل الفسيولوجيا الفريدة لمجموعات فرعية محددة.

- التكامل بين النماذج العلوية للجهاز الهضمي والسفلية (القولونية) و/أو نماذج الحدود الشعيرية (زراعة الخلايا).

بيان مساهمة مؤلفي CRediT

إقرار التمويل

إعلان عن المصالح المت competing

شكر وتقدير

توفر البيانات

References

Al-Rabadi, G. J. S., Gilbert, R. G., & Gidley, M. J. (2009). Effect of particle size on kinetics of starch digestion in milled barley and sorghum grains by porcine alpha-amylase. Journal of Cereal Science, 50, 198-204.

Alam, S. A., Pentikainen, S., Narvainen, J., Katina, K., Poutanen, K., & Sozer, N. (2019). The effect of structure and texture on the breakdown pattern during mastication and impacts on in vitro starch digestibility of high fibre rye extrudates. Food & Function, 10, 1958-1973.

Alminger, M., Aura, A. M., Bohn, T., Dufour, C., El, S. N., Gomes, A., et al. (2014). In vitro models for studying secondary plant metabolite digestion and bioaccessibility. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 13, 413-436.

Alongi, M., & Anese, M. (2021). Re-thinking functional food development through a holistic approach. Journal of Functional Foods, 81.

Ang, K., Bourgy, C., Fenton, H., Regina, A., Newberry, M., Diepeveen, D., et al. (2020). Noodles made from high amylose wheat flour attenuate postprandial glycaemia in healthy adults. Nutrients, 12.

Ao, Z., Simsek, S., Zhang, G., Venkatachalam, M., Reuhs, B. L., & Hamaker, B. R. (2007). Starch with a slow digestion property produced by altering its chain length, branch density, and crystalline structure. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 55, 4540-4547.

Asal, M., Rep, M., Bontkes, H. J., van Vliet, S. J., Mebius, R. E., & Gibbs, S. (2024). Towards full thickness small intestinal models: Incorporation of stromal cells. Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine, 21, 369-377.

Auricchio, S., Rubino, A., Tosi, R., Semenza, G., Landolt, M., Kistler, H., et al. (1963). Disaccharidase activities in human intestinal mucosa. Enzymologia Biologica et Clinica, 74, 193-208.

Baggio, L. L., & Drucker, D. J. (2007). Biology of incretins: GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology, 132, 2131-2157.

Bai, Y., & Shi, Y. C. (2016). Chemical structures in pyrodextrin determined by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Carbohydrate Polymers, 151, 426-433.

Bajka, B. H., Pinto, A. M., Perez-Moral, N., Saha, S., Ryden, P., Ahn-Jarvis, J., et al. (2023). Enhanced secretion of satiety-promoting gut hormones in healthy humans after consumption of white bread enriched with cellular chickpea flour: A randomized crossover study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 117, 477-489.

Bellmann, S., Minekus, M., Sanders, P., Bosgra, S., & Havenaar, R. (2018). Human glycemic response curves after intake of carbohydrate foods are accurately predicted by combining in vitro gastrointestinal digestion with in silico kinetic modeling. Clinical Nutrition Experimental, 17, 8-22.

Belobrajdic, D. P., Regina, A., Klingner, B., Zajac, I., Chapron, S., Berbezy, P., et al. (2019). High-amylose wheat lowers the postprandial glycemic response to bread in healthy adults: A randomized controlled crossover trial. The Journal of Nutrition, 149, 1335-1345.

Bernfeld, P., Staub, A., & Fischer, E. H. (1948). [On the amylolytic enzymes XI; properties of crystallized human saliva alpha-amylase]. Helvetica Chimica Acta, 31, 2165-2172.

Berry, C. S. (1986). Resistant starch – formation and measurement of starch that Survives exhaustive digestion with amylolytic enzymes during the determination of dietary fiber. Journal of Cereal Science, 4, 301-314.

Berry, S. E., Valdes, A. M., Drew, D. A., Asnicar, F., Mazidi, M., Wolf, J., et al. (2020). Human postprandial responses to food and potential for precision nutrition. Nature Medicine, 26, 964-973.

Bhattarai, R. R., Dhital, S., & Gidley, M. J. (2016). Interactions among macronutrients in wheat flour determine their enzymic susceptibility. Food Hydrocolloids, 61, 415-425.

Bhupathiraju, S. N., Tobias, D. K., Malik, V. S., Pan, A., Hruby, A., Manson, J. E., et al. (2014). Glycemic index, glycemic load, and risk of type 2 diabetes: Results from 3 large US cohorts and an updated meta-analysis. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 100, 218-232.

Birt, D. F., Boylston, T., Hendrich, S., Jane, J. L., Hollis, J., Li, L., et al. (2013). Resistant starch: Promise for improving human health. Advances in Nutrition, 4, 587-601.

Bohn, T., Carriere, F., Day, L., Deglaire, A., Egger, L., Freitas, D., et al. (2018). Correlation between in vitro and in vivo data on food digestion. What can we predict with static in vitro digestion models? Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 58, 2239-2261.

Bojarczuk, A., Khaneghah, A. M., & MarszaLek, K. (2022). Health benefits of resistant starch: A review of the literature. Journal of Functional Foods, 93.

Borah, P. K., Sarkar, A., & Duary, R. K. (2019). Water-soluble vitamins for controlling starch digestion: Conformational scrambling and inhibition mechanism of human pancreatic alpha-amylase by ascorbic acid and folic acid. Food Chemistry, 288, 395-404.

Bordenave, N., Hamaker, B. R., & Ferruzzi, M. G. (2014). Nature and consequences of non-covalent interactions between flavonoids and macronutrients in foods. Food & Function, 5, 18-34.

Bornhorst, G. M. (2017). Gastric mixing during food digestion: Mechanisms and applications. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology, 8, 523-542.

Brennan, C., Blake, D., Ellis, P., & Schofield, J. (1996). Effects of guar galactomannan on wheat bread microstructure and on the in vitro and in vivo digestibility of starch in bread. Journal of Cereal Science, 24, 151-160.

Brennan, C. S., Kuri, V., & Tudorica, C. M. (2004). Inulin-enriched pasta: Effects on textural properties and starch degradation. Food Chemistry, 86, 189-193.

Brighenti, F., Castellani, G., Benini, L., Casiraghi, M. C., Leopardi, E., Crovetti, R., et al. (1995). Effect of neutralized and native vinegar on blood glucose and acetate responses to a mixed meal in healthy subjects. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 49, 242-247.

Brighenti, F., Pellegrini, N., Casiraghi, M. C., & Testolin, G. (1995). In-vitro studies to predict physiological-effects of dietary fiber. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 49, S81-S88.

Brodkorb, A., Egger, L., Alminger, M., Alvito, P., Assuncao, R., Ballance, S., et al. (2019). INFOGEST static in vitro simulation of gastrointestinal food digestion. Nature Protocols, 14, 991-1014.

Buleon, A., Colonna, P., Planchot, V., & Ball, S. (1998). Starch granules: Structure and biosynthesis. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 23, 85-112.

Burton, P., & Lightowler, H. J. (2006). Influence of bread volume on glycaemic response and satiety. British Journal of Nutrition, 96, 877-882.

Burton, P. M., Monro, J. A., Alvarez, L., & Gallagher, E. (2011). Glycemic impact and health: New horizons in white bread formulations. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 51, 965-982.

Butterworth, P. J., Bajka, B. H., Edwards, C. H., Warren, F. J., & Ellis, P. R. (2022). Enzyme kinetic approach for mechanistic insight and predictions of in vivo starch digestibility and the glycaemic index of foods. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 120, 254-264.

Butterworth, P. J., Warren, F. J., & Ellis, P. R. (2011). Human

Camelo-Mendez, G. A., Agama-Acevedo, E., Rosell, C. M., de, J. P.-F. M., & BelloPerez, L. A. (2018). Starch and antioxidant compound release during in vitro gastrointestinal digestion of gluten-free pasta. Food Chemistry, 263, 201-207.

Canas, S., Perez-Moral, N., & Edwards, C. H. (2020). Effect of cooking, 24 h cold storage, microwave reheating, and particle size on in vitro starch digestibility of dry and fresh pasta. Food & Function, 11, 6265-6272.

Carpenter, D., Dhar, S., Mitchell, L. M., Fu, B., Tyson, J., Shwan, N. A., et al. (2015). Obesity, starch digestion and amylase: Association between copy number variants at human salivary (AMY1) and pancreatic (AMY2) amylase genes. Human Molecular Genetics, 24, 3472-3480.

Carpenter, D., Mitchell, L. M., & Armour, J. A. (2017). Copy number variation of human AMY1 is a minor contributor to variation in salivary amylase expression and activity. Human Genomics, 11, 2.

Chapman, R. W., Sillery, J. K., Graham, M. M., & Saunders, D. R. (1985). Absorption of starch by healthy ileostomates: Effect of transit time and of carbohydrate load. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 41, 1244-1248.

Chen, J., Cai, H., Yang, S., Zhang, M., Wang, J., & Chen, Z. (2022). The formation of starch-lipid complexes in instant rice noodles incorporated with different fatty acids: Effect on the structure, in vitro enzymatic digestibility and retrogradation properties during storage. Food Research International, 162, Article 111933.

Chen, X., He, X. W., Zhang, B., Fu, X., Jane, J. L., & Huang, Q. (2017). Effects of adding corn oil and soy protein to corn starch on the physicochemical and digestive properties of the starch. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 104, 481-486.

Chen, X., Zhu, L., Zhang, H., Wu, G., Cheng, L., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Multiscale structure barrier of whole grains and its transformation during heating as starch digestibility controllers in digestive tract: A review. Food Hydrocolloids, 159, Article 110606.

Cheng, M. W., Chegeni, M., Kim, K. H., Zhang, G., Benmoussa, M., Quezada-Calvillo, R., et al. (2014). Different sucrose-isomaltase response of Caco-2 cells to glucose and maltose suggests dietary maltose sensing. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry & Nutrition, 54, 55-60.

Chi, C., Li, X., Huang, S., Chen, L., Zhang, Y., Li, L., et al. (2021). Basic principles in starch multi-scale structuration to mitigate digestibility: A review. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 109, 154-168.

Chi, C., Shi, M., Zhao, Y., Chen, B., He, Y., & Wang, M. (2022). Dietary compounds slow starch enzymatic digestion: A review. Frontiers in Nutrition, 9, Article 1004966.

Corrado, M., Zafeiriou, P., Ahn-Jarvis, J. H., Savva, G. M., Edwards, C. H., & Hazard, B. A. (2023). Impact of storage on starch digestibility and texture of a highamylose wheat bread. Food Hydrocolloids, 135, Article 108139.

Costa, J., & Ahluwalia, A. (2019). Advances and current challenges in intestinal in vitro model engineering: A digest. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 7, 144.

Dagbasi, A., Byrne, C., Blunt, D., Serrano-Contreras, J. I., Becker, G. F., Blanco, J. M., et al. (2024). Diet shapes the metabolite profile in an intact human ileum which impacts PYY release. Science Translational Medicine, 16.

Dahlqvist, A. (1962). A method for the determination of amylase in intestinal content. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation, 14, 145-151.

Davenport, H. W. (1992). The gastric mucosal barrier. In H. W. Davenport (Ed.), A history of gastric secretion and digestion (pp. 258-276). New York, NY: Springer New York.

de Almeida Pdel, V., Gregio, A. M., Machado, M. A., de Lima, A. A., & Azevedo, L. R. (2008). Saliva composition and functions: A comprehensive review. The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice, 9, 72-80.

De Haan, P., Ianovska, M. A., Mathwig, K., Van Lieshout, G. A., Triantis, V., Bouwmeester, H., et al. (2019). Digestion-on-a-chip: A continuous-flow modular microsystem recreating enzymatic digestion in the gastrointestinal tract. Lab on a Chip, 19, 1599-1609.

Dedlovskaya, V. (1968). Investigation of pH of contents of the gastro-intestinal tract by a radiotelemetric method. Bulletin of Experimental Biology and Medicine, 66, 1292-1294.

Deehan, E. C., Yang, C., Perez-Munoz, M. E., Nguyen, N. K., Cheng, C. C., Triador, L., et al. (2020). Precision microbiome modulation with discrete dietary fiber structures directs short-chain fatty acid production. Cell Host Microbe, 27, 389-404. e386.

DeMartino, P., & Cockburn, D. W. (2020). Resistant starch: Impact on the gut microbiome and health. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 61, 66-71.

Demuth, T., Edwards, V., Bircher, L., Lacroix, C., Nystrom, L., & Geirnaert, A. (2021). In vitro colon fermentation of soluble arabinoxylan is modified through milling and extrusion. Frontiers in Nutrition, 8, Article 707763.

Dhital, S., Warren, F. J., Butterworth, P. J., Ellis, P. R., & Gidley, M. J. (2017). Mechanisms of starch digestion by alpha-amylase-Structural basis for kinetic properties. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 57, 875-892.

Di Stasio, L., De Caro, S., Marulo, S., Ferranti, P., Picariello, G., & Mamone, G. (2024). Impact of porcine brush border membrane enzymes on INFOGEST in vitro digestion model: A step forward to mimic the small intestinal phase. Food Research International, 197, Article 115300.

Do, D. T., Singh, J., Johnson, S., & Singh, H. (2023). Probing the double-layered cotyledon cell structure of navy beans: Barrier effect of the protein matrix on in vitro starch digestion. Nutrients, 15, 105.

Dobranowski, P. A., & Stintzi, A. (2021). Resistant starch, microbiome, and precision modulation. Gut Microbes, 13, Article 1926842.

Dona, A. C., Pages, G., Gilbert, R. G., & Kuchel, P. W. (2010). Digestion of starch: And kinetic models used to characterise oligosaccharide or glucose release. Carbohydrate Polymers, 80, 599-617.

Donaldson, G. P., Lee, S. M., & Mazmanian, S. K. (2016). Gut biogeography of the bacterial microbiota. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 14, 20-32.

Dong, J. Y., Zhang, Y. H., Wang, P., & Qin, L. Q. (2012). Meta-analysis of dietary glycemic load and glycemic index in relation to risk of coronary heart disease. The American Journal of Cardiology, 109, 1608-1613.

Dreiling, D. A., Triebling, A. T., & Koller, M. (1985). The effect of age on human exocrine pancreatic secretion. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, 52, 336-339.

Dressman, J. B., Berardi, R. R., Dermentzoglou, L. C., Russell, T. L., Schmaltz, S. P., Barnett, J. L., et al. (1990). Upper gastrointestinal (GI) pH in young, healthy men and women. Pharmaceutical Research, 7, 756-761.

Duijsens, D., Pälchen, K., Guevara-Zambrano, J. M., Verkempinck, S. H. E., InfantesGarcia, M. R., Hendrickx, M. E., et al. (2022). Strategic choices for in vitro food digestion methodologies enabling food digestion design. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 126, 61-72.

Duijsens, D., Staes, E., Segers, M., Michels, D., Palchen, K., Hendrickx, M. E., et al. (2024). Single versus multiple metabolite quantification of in vitro starch digestion: A comparison for the case of pulse cotyledon cells. Food Chemistry, 454, Article 139762.

Edwards, C. H., Cochetel, N., Setterfield, L., Perez-Moral, N., & Warren, F. J. (2019). A single-enzyme system for starch digestibility screening and its relevance to understanding and predicting the glycaemic index of food products. Food & Function, 10, 4751-4760.

Edwards, C. H., Grundy, M. M., Grassby, T., Vasilopoulou, D., Frost, G. S., Butterworth, P. J., et al. (2015). Manipulation of starch bioaccessibility in wheat endosperm to regulate starch digestion, postprandial glycemia, insulinemia, and gut hormone responses: A randomized controlled trial in healthy ileostomy participants. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 102, 791-800.

Edwards, C. H., Ryden, P., Mandalari, G., Butterworth, P. J., & Ellis, P. R. (2021). Structure-function studies of chickpea and durum wheat uncover mechanisms by which cell wall properties influence starch bioaccessibility. Nature Food, 2, 118-126.

Edwards, C. H., Warren, F. J., Campbell, G. M., Gaisford, S., Royall, P. G., Butterworth, P. J., et al. (2015). A study of starch gelatinisation behaviour in hydrothermally-processed plant food tissues and implications for in vitro digestibility. Food & Function, 6, 3634-3641.

Edwards, C. H., Warren, F. J., Milligan, P. J., Butterworth, P. J., & Ellis, P. R. (2014). A novel method for classifying starch digestion by modelling the amylolysis of plant foods using first-order enzyme kinetic principles. Food & Function, 5, 2751-2758.

Eelderink, C., Noort, M. W., Sozer, N., Koehorst, M., Holst, J. J., Deacon, C. F., et al. (2015). The structure of wheat bread influences the postprandial metabolic response in healthy men. Food & Function, 6, 3236-3248.

Eelderink, C., Schepers, M., Preston, T., Vonk, R. J., Oudhuis, L., & Priebe, M. G. (2012). Slowly and rapidly digestible starchy foods can elicit a similar glycemic response because of differential tissue glucose uptake in healthy men. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 96, 1017-1024.

EFSA. (2011). Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of a health claim related to “slowly digestible starch in starch-containing foods” and “reduction of post-prandial glycaemic responses” pursuant to Article 13(5) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. EFSA Journal, 9, 2292.

Egger, L., Ménard, O., Delgado-Andrade, C., Alvito, P., Assuncao, R., Balance, S., et al. (2016). The harmonized INFOGEST digestion method: From knowledge to action. Food Research International, 88, 217-225.

Egger, L., Schlegel, P., Baumann, C., Stoffers, H., Guggisberg, D., Brugger, C., et al. (2017). Physiological comparability of the harmonized INFOGEST in vitro digestion method to in vivo pig digestion. Food Research International, 102, 567-574.

El Kaoutari, A., Armougom, F., Gordon, J. I., Raoult, D., & Henrissat, B. (2013). The abundance and variety of carbohydrate-active enzymes in the human gut microbiota. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 11, 497-504.

Englyst, H. N., & Cummings, J. H. (1985). Digestion of the polysaccharides of some cereal foods in the human small intestine. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 42, 778-787.

Englyst, K. N., Englyst, H. N., Hudson, G. J., Cole, T. J., & Cummings, J. H. (1999). Rapidly available glucose in foods: An in vitro measurement that reflects the glycemic response. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 69, 448-454.

Englyst, H. N., Kingman, S. M., & Cummings, J. H. (1992). Classification and measurement of nutritionally important starch fractions. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 46(Suppl 2), S33-S50.

Englyst, H., Wiggins, H. S., & Cummings, J. H. (1982). Determination of the non-starch polysaccharides in plant foods by gas-liquid chromatography of constituent sugars as alditol acetates. Analyst, 107, 307-318.

Faisant, N., Buleon, A., Colonna, P., Molis, C., Lartigue, S., Galmiche, J. P., et al. (1995). Digestion of raw banana starch in the small intestine of healthy humans: Structural features of resistant starch. British Journal of Nutrition, 73, 111-123.

Fardet, A., Leenhardt, F., Lioger, D., Scalbert, A., & Remesy, C. (2006). Parameters controlling the glycaemic response to breads. Nutrition Research Reviews, 19, 18-25.

Farrell, M., Ramne, S., Gouinguenet, P., Brunkwall, L., Ericson, U., Raben, A., et al. (2021). Effect of AMY1 copy number variation and various doses of starch intake on glucose homeostasis: Data from a cross-sectional observational study and a crossover meal study. Genes Nutr, 16, 21.

Ferreira-Lazarte, A., Olano, A., Villamiel, M., & Moreno, F. J. (2017). Assessment of in vitro digestibility of dietary carbohydrates using rat small intestinal extract. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 65, 8046-8053.

Firky, M. E. (1968). Exocrine pancreatic functions in the aged. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 16, 463-467.

Forde, C. G., van Kuijk, N., Thaler, T., de Graaf, C., & Martin, N. (2013). Oral processing characteristics of solid savoury meal components, and relationship with food composition, sensory attributes and expected satiation. Appetite, 60, 208-219.

Freitas, D., Boue, F., Benallaoua, M., Airinei, G., Benamouzig, R., & Le Feunteun, S. (2021). Lemon juice, but not tea, reduces the glycemic response to bread in healthy volunteers: A randomized crossover trial. European Journal of Nutrition, 60, 113-122.

Freitas, D., Boue, F., Benallaoua, M., Airinei, G., Benamouzig, R., Lutton, E., et al. (2022). Glycemic response, satiety, gastric secretions and emptying after bread consumption with water, tea or lemon juice: A randomized crossover intervention using MRI. European Journal of Nutrition, 61, 1621-1636.

Freitas, D., Gómez-Mascaraque, L. G., Le Feunteun, S., & Brodkorb, A. (2023). Boiling vs. baking: Cooking-induced structural transformations drive differences in the starch digestion profiles that are consistent with the glycemic indexes of white and sweet potatoes. Food Structure, 38, Article 100355.

Freitas, D., & Le Feunteun, S. (2019a). Inhibitory effect of black tea, lemon juice, and other beverages on salivary and pancreatic amylases: What impact on bread starch digestion? A dynamic in vitro study. Food Chemistry, 297, Article 124885.

Freitas, D., Le Feunteun, S., Panouille, M., & Souchon, I. (2018). The important role of salivary alpha-amylase in the gastric digestion of wheat bread starch. Food & Function, 9, 200-208.

Freitas, D., Souchon, I., & Le Feunteun, S. (2022). The contribution of gastric digestion of starch to the glycaemic index of breads with different composition or structure. Food & Function, 13, 1718-1724.

Fried, M., Abramson, S., & Meyer, J. H. (1987). Passage of salivary amylase through the stomach in humans. Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 32, 1097-1103.

Fuentes-Zaragoza, E., Riquelme-Navarrete, M. J., Sánchez-Zapata, E., & PérezAlvarez, J. A. (2010). Resistant starch as functional ingredient: A review. Food Research International, 43, 931-942.

Gallego-Lobillo, P., Ferreira-Lazarte, A., Hernández-Hernández, O., & Villamiel, M. (2021). In vitro digestion of polysaccharides: InfoGest protocol and use of small intestinal extract from rat. Food Research International, 140, Article 110054.

Gallo, V., Romano, A., Ferranti, P., D’Auria, G., & Masi, P. (2022). Properties and in vitro digestibility of a bread enriched with lentil flour at different leavening times. Food Structure, 33, Article 100284.

Garcia-Campayo, V., Han, S., Vercauteren, R., & Franck, A. (2018). Digestion of food ingredients and food using an in vitro model integrating intestinal mucosal enzymes. Food and Nutrition Sciences, 9, 711-734.

Gardner, J. D., Ciociola, A. A., & Robinson, M. (2002). Measurement of meal-stimulated gastric acid secretion by in vivo gastric autotitration. Journal of Applied Physiology, 92, 427-434.

Gaviao, M. B., Engelen, L., & van der Bilt, A. (2004). Chewing behavior and salivary secretion. European Journal of Oral Sciences, 112, 19-24.

Gidley, M. J., & Bulpin, P. V. (1989). Aggregation of amylose in aqueous systems – the effect of chain-length on phase-behavior and aggregation kinetics. Macromolecules, 22, 341-346.

Gillard, B. K., Markman, H. C., & Feig, S. A. (1978). Differences between cystic fibrosis and normal saliva

Giuberti, G., Rocchetti, G., & Lucini, L. (2020). Interactions between phenolic compounds, amylolytic enzymes and starch: An updated overview. Current Opinion in Food Science, 31, 102-113.

Gkountenoudi-Eskitzi, I., Kotsiou, K., Irakli, M. N., Lazaridis, A., Biliaderis, C. G., & Lazaridou, A. (2023). In vitro and in vivo glycemic responses and antioxidant potency of acorn and chickpea fortified gluten-free breads. Food Research International, 166, Article 112579.

Goñi, I., Garcia-Alonso, A., & Saura-Calixto, F. (1997). A starch hydrolysis procedure to estimate glycemic index. Nutrition Research, 17, 427-437.

Goyal, R. K., Guo, Y., & Mashimo, H. (2019). Advances in the physiology of gastric emptying. Neuro-Gastroenterology and Motility, 31, Article e13546.

Granger, D. A., Kivlighan, K. T., El-Sheikh, M., Gordis, E. B., & Stroud, L. R. (2007). Salivary

Gray, G. M. (1992). Starch digestion and absorption in nonruminants. The Journal of Nutrition, 122, 172-177.

Gribble, F. M., & Reimann, F. (2016). Enteroendocrine cells: Chemosensors in the intestinal epithelium. Annual Review of Physiology, 78, 277-299.

Guo, J. Y., Brown, P. R., Tan, L. B., & Kong, L. Y. (2023). Effect of resistant starch consumption on appetite and satiety: A review. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 12.

Guo, J. Y., Tan, L. B., & Kong, L. Y. (2022). Multiple levels of health benefits from resistant starch. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 10.

Gwala, S., Wainana, I., Pallares Pallares, A., Kyomugasho, C., Hendrickx, M., & Grauwet, T. (2019). Texture and interlinked post-process microstructures determine the in vitro starch digestibility of Bambara groundnuts with distinct hard-to-cook levels. Food Research International, 120, 1-11.

Harthoorn, L. F. (2008). Salivary

Hasek, L. Y., Avery, S. E., Chacko, S. K., Fraley, J. K., Vohra, F. A., Quezada-Calvillo, R., et al. (2020). Conditioning with slowly digestible starch diets in mice reduces jejunal alpha-glucosidase activity and glucogenesis from a digestible starch feeding. Nutrition, 78, Article 110857.

He, M., Ding, T., Wu, Y., & Ouyang, J. (2022). Effects of endogenous non-starch nutrients in acorn (quercus wutaishanica blume) kernels on the physicochemical properties and in vitro digestibility of starch. Foods, 11, 825.

Hernandez-Hernandez, O. (2019). In vitro gastrointestinal models for prebiotic carbohydrates: A critical review. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 25, 3478-3483.

Hoebler, C., Devaux, M. F., Karinthi, A., Belleville, C., & Barry, J. L. (2000). Particle size of solid food after human mastication and in vitro simulation of oral breakdown. International Journal of Food Sciences & Nutrition, 51, 353-366.

Hoebler, C., Karinthi, A., Chiron, H., Champ, M., & Barry, J. L. (1999). Bioavailability of starch in bread rich in amylose: Metabolic responses in healthy subjects and starch structure. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 53, 360-366.

Hoebler, C., Karinthi, A., Devaux, M. F., Guillon, F., Gallant, D. J., Bouchet, B., et al. (1998). Physical and chemical transformations of cereal food during oral digestion in human subjects. British Journal of Nutrition, 80, 429-436.

Holland, C., Ryden, P., Edwards, C. H., & Grundy, M. M. (2020). Plant cell walls: Impact on nutrient bioaccessibility and digestibility. Foods, 9, 201.

Htoon, A., Shrestha, A. K., Flanagan, B. M., Lopez-Rubio, A., Bird, A. R., Gilbert, E. P., et al. (2009). Effects of processing high amylose maize starches under controlled

conditions on structural organisation and amylase digestibility. Carbohydrate Polymers, 75, 236-245.

Isenring, J., Bircher, L., Geirnaert, A., & Lacroix, C. (2023). In vitro human gut microbiota fermentation models: Opportunities, challenges, and pitfalls. Microbiome Research Reports, 2, 2.

Ishibashi, T., Matsumoto, S., Harada, H., Ochi, K., Tanaka, J., Seno, T., et al. (1991). [Aging and exocrine pancreatic function evaluated by the recently standardized secretin test]. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi, 28, 599-605.

Jarvis, M. C. (2011). Plant cell walls: Supramolecular assemblies. Food Hydrocolloids, 25, 257-262.

Jarvis, M. C., Briggs, S. P. H., & Knox, J. P. (2003). Intercellular adhesion and cell separation in plants. Plant, Cell and Environment, 26, 977-989.

Jenkins, D. J., Ghafari, H., Wolever, T., Taylor, R., Jenkins, A., Barker, H., et al. (1982). Relationship between rate of digestion of foods and post-prandial glycaemia. Diabetologia, 22, 450-455.

Jenkins, D. J., Thorne, M. J., Camelon, K., Jenkins, A., Rao, A. V., Taylor, R. H., et al. (1982). Effect of processing on digestibility and the blood glucose response: A study of lentils. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 36, 1093-1101.

Ji, H., Hu, J., Zuo, S., Zhang, S., Li, M., & Nie, S. (2022). In vitro gastrointestinal digestion and fermentation models and their applications in food carbohydrates. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 62, 5349-5371.

Johnson, K. L., Gidley, M. J., Bacic, A., & Doblin, M. S. (2018). Cell wall biomechanics: A tractable challenge in manipulating plant cell walls ‘fit for purpose’! Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 49, 163-171.

Jones, B. J., Brown, B. E., Loran, J. S., Edgerton, D., Kennedy, J. F., Stead, J. A., et al. (1983). Glucose absorption from starch hydrolysates in the human jejunum. Gut, 24, 1152-1160.

Kalipatnapu, P., Kelly, R. H., Rao, K. N., & van Thiel, D. H. (1983). Salivary composition: Effects of age and sex. Acta Medica Portuguesa, 4, 327-330.

Karnsakul, W., Luginbuehl, U., Hahn, D., Sterchi, E., Avery, S., Sen, P., et al. (2002). Disaccharidase activities in dyspeptic children: Biochemical and molecular investigations of maltase-glucoamylase activity. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 35, 551-556.

Keenan, M. J., Zhou, J., Hegsted, M., Pelkman, C., Durham, H. A., Coulon, D. B., et al. (2015). Role of resistant starch in improving gut health, adiposity, and insulin resistance. Advances in Nutrition, 6, 198-205.

Keller, J., & Layer, P. (2005). Human pancreatic exocrine response to nutrients in health and disease. Gut, 54(Suppl 6), vi1-28.

Khorasaniha, R., Olof, H., Voisin, A., Armstrong, K., Wine, E., Vasanthan, T., et al. (2023). Diversity of fibers in common foods: Key to advancing dietary research. Food Hydrocolloids, 139, Article 108495.

Kim, B. S., Kim, H. S., Hong, J. S., Huber, K. C., Shim, J. H., & Yoo, S. H. (2013). Effects of amylosucrase treatment on molecular structure and digestion resistance of pregelatinised rice and barley starches. Food Chemistry, 138, 966-975.

Kondrashina, A., Arranz, E., Cilla, A., Faria, M. A., Santos-Hernandez, M., Miralles, B., et al. (2024). Coupling in vitro food digestion with in vitro epithelial absorption; recommendations for biocompatibility. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 64, 9618-9636.

Kondrashina, M., Brodkorb, A., & Giblin, L. (2020). Dairy-derived peptides for satiety. Journal of Functional Foods, 66.

Kong, F., & Singh, R. P. (2010). A human gastric simulator (HGS) to study food digestion in human stomach. Journal of Food Science, 75, E627-E635.

Kong, H., Yu, L., Li, C., Ban, X., Gu, Z., Liu, L., et al. (2022). Perspectives on evaluating health effects of starch: Beyond postprandial glycemic response. Carbohydrate Polymers, 292, Article 119621.

Kopf-Bolanz, K. A., Schwander, F., Gijs, M., Vergeres, G., Portmann, R., & Egger, L. (2012). Validation of an in vitro digestive system for studying macronutrient decomposition in humans. The Journal of Nutrition, 142, 245-250.

Kozu, H., Nakata, Y., Nakajima, M., Neves, M. A., Uemura, K., Sato, S., et al. (2014). Development of a human gastric digestion simulator equipped with peristalsis function for the direct observation and analysis of the food digestion process. Food Science and Technology Research, 20, 225-233.

Lajterer, C., Levi, C. S., & Lesmes, U. (2022). An in vitro digestion model accounting for sex differences in gastro-intestinal functions and its application to study differential protein digestibility. Food Hydrocolloids, 132, Article 107850.

Lazaridou, A., Marinopoulou, A., Matsoukas, N. P., & Biliaderis, C. G. (2014). Impact of flour particle size and autoclaving on

Le Feunteun, S., Verkempinck, S., Floury, J., Janssen, A., Kondjoyan, A., Marze, S., et al. (2021). Mathematical modelling of food hydrolysis during in vitro digestion: From single nutrient to complex foods in static and dynamic conditions. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 116, 870-883.

Le Maux, S., Brodkorb, A., Croguennec, T., Hennessy, A. A., Bouhallab, S., & Giblin, L. (2013).

Lee, B. H., Rose, D. R., Lin, A. H., Quezada-Calvillo, R., Nichols, B. L., & Hamaker, B. R. (2016). Contribution of the individual small intestinal alpha-glucosidases to digestion of unusual alpha-linked glycemic disaccharides. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 64, 6487-6494.

Lee, B. H., Yan, L., Phillips, R. J., Reuhs, B. L., Jones, K., Rose, D. R., et al. (2013). Enzyme-synthesized highly branched maltodextrins have slow glucose generation at the mucosal alpha-glucosidase level and are slowly digestible in vivo. PLoS One, 8, Article e59745.

Lehmann, U., & Robin, F. (2007). Slowly digestible starch – its structure and health implications: A review. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 18, 346-355.

Li, L., Jiang, H. X., Campbell, M., Blanco, M., & Jane, J. L. (2008). Characterization of maize amylose-extender (ae) mutant starches.: Part I: Relationship between resistant starch contents and molecular structures. Carbohydrate Polymers, 74, 396-404.

Li, M., Koecher, K., Hansen, L., & Ferruzzi, M. G. (2017). Phenolics from whole grain oat products as modifiers of starch digestion and intestinal glucose transport. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 65, 6831-6839.

Li, C., Yu, W. W., Wu, P., & Chen, X. D. (2020). Current digestion systems for understanding food digestion in human upper gastrointestinal tract. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 96, 114-126.

Li, H., Zhang, L., Li, J., Wu, Q., Qian, L., He, J., et al. (2024). Resistant starch intake facilitates weight loss in humans by reshaping the gut microbiota. Nature Metabolism, 6, 578-597.

Li, H.-T., Zhang, W., Zhu, H., Chao, C., & Guo, Q. (2023). Unlocking the potential of highamylose starch for gut health: Not all function the same. Fermentation, 9, 134.

Lim, J., Ferruzzi, M. G., & Hamaker, B. R. (2021). Dietary starch is weight reducing when distally digested in the small intestine. Carbohydrate Polymers, 273, Article 118599.

Lin, L. S., Guo, D. W., Huang, J., Zhang, X. D., Zhang, L., & Wei, C. X. (2016). Molecular structure and enzymatic hydrolysis properties of starches from high-amylose maize inbred lines and their hybrids. Food Hydrocolloids, 58, 246-254.

Liu, T. N., Wang, K., Xue, W., Wang, L., Zhang, C. N., Zhang, X. X., et al. (2021). In vitro starch digestibility, edible quality and microstructure of instant rice noodles enriched with rice bran insoluble dietary fiber. Lwt-Food Science and Technology, 142, Article 111008.

Liversey, G. (1994). Energy value of resistant starch. In Proceedings of the concluding plenary meeting of EURESTA (pp. 56-62). EURESTA.

Livesey, G., Taylor, R., Livesey, H. F., Buyken, A. E., Jenkins, D. J. A., Augustin, L. S. A., et al. (2019). Dietary glycemic index and load and the risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and updated meta-analyses of prospective cohort studies. Nutrients, 11, 1280.

Lo Piparo, E., Scheib, H., Frei, N., Williamson, G., Grigorov, M., & Chou, C. J. (2008). Flavonoids for controlling starch digestion: Structural requirements for inhibiting human alpha-amylase. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 51, 3555-3561.

López-Barón, N., Gu, Y., Vasanthan, T., & Hoover, R. (2017). Plant proteins mitigate in vitro wheat starch digestibility. Food Hydrocolloids, 69, 19-27.

López-Barón, N., Sagnelli, D., Blennow, A., Holse, M., Gao, J., Saaby, L., et al. (2018). Hydrolysed pea proteins mitigate in vitro wheat starch digestibility. Food Hydrocolloids, 79, 117-126.

Lopez-Rubio, A., Htoon, A., & Gilbert, E. P. (2007). Influence of extrusion and digestion on the nanostructure of high-amylose maize starch. Biomacromolecules, 8, 1564-1572.

Loret, C., Walter, M., Pineau, N., Peyron, M. A., Hartmann, C., & Martin, N. (2011). Physical and related sensory properties of a swallowable bolus. Physiology & Behavior, 104, 855-864.

Ma, M., Gu, Z., Cheng, L., Li, Z., Li, C., & Hong, Y. (2024). Effect of hydrocolloids on starch digestion: A review. Food Chemistry, 444, Article 138636.

Mackie, A., Mulet-Cabero, A. I., & Torcello-Gomez, A. (2020). Simulating human digestion: Developing our knowledge to create healthier and more sustainable foods. Food & Function, 11, 9397-9431.

Malagelada, J. R., Go, V. L., & Summerskill, W. H. (1979). Different gastric, pancreatic, and biliary responses to solid-liquid or homogenized meals. Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 24, 101-110.

Maljaars, P. W., Peters, H. P., Mela, D. J., & Masclee, A. A. (2008). Ileal brake: A sensible food target for appetite control. A review. Physiology & Behavior, 95, 271-281.

Mandel, A. L., Peyrot des Gachons, C., Plank, K. L., Alarcon, S., & Breslin, P. A. (2010). Individual differences in AMY1 gene copy number, salivary alpha-amylase levels, and the perception of oral starch. PLoS One, 5, Article e13352.

Marciani, L., Gowland, P. A., Fillery-Travis, A., Manoj, P., Wright, J., Smith, A., et al. (2001). Assessment of antral grinding of a model solid meal with echo-planar imaging. American Journal of Physiology – Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 280, G844-G849.

Martens, B. M. J., Bruininx, E. M. A. M., Gerrits, W. J. J., & Schols, H. A. (2020). The importance of amylase action in the porcine stomach to starch digestion kinetics. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 267, Article 114546.

Martens, E. C., Koropatkin, N. M., Smith, T. J., & Gordon, J. I. (2009). Complex glycan catabolism by the human gut microbiota: The Bacteroidetes sus-like paradigm. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 284, 24673-24677.

Martinez, M. M. (2021). Starch nutritional quality: Beyond intraluminal digestion in response to current trends. Current Opinion in Food Science, 38, 112-121.

Martinez, M. M., Li, C., Okoniewska, M., Mukherjee, I., Vellucci, D., & Hamaker, B. (2018). Slowly digestible starch in fully gelatinized material is structurally driven by molecular size and A and B1 chain lengths. Carbohydrate Polymers, 197, 531-539.

Martinez, M. M., Roman, L., & Gomez, M. (2018). Implications of hydration depletion in the in vitro starch digestibility of white bread crumb and crust. Food Chemistry, 239, 295-303.

Matthan, N. R., Ausman, L. M., Meng, H., Tighiouart, H., & Lichtenstein, A. H. (2016). Estimating the reliability of glycemic index values and potential sources of methodological and biological variability. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 104, 1004-1013.

Maurer, A. H. (2015). Gastrointestinal motility, part 1: Esophageal transit and gastric emptying. Journal of Nuclear Medicine, 56, 1229-1238.

Menard, O., Bourlieu, C., De Oliveira, S. C., Dellarosa, N., Laghi, L., Carriere, F., et al. (2018). A first step towards a consensus static in vitro model for simulating full-term infant digestion. Food Chemistry, 240, 338-345.

Ménard, O., Picque, D., & Dupont, D. (2015). The DIDGI® system. The impact of food bioactives on health: In vitro and ex vivo models.

Mikolajczyk, A. E., Watson, S., Surma, B. L., & Rubin, D. T. (2015). Assessment of tandem measurements of pH and total gut transit time in healthy volunteers. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology, 6, e100.

Miles, M. J., Morris, V. J., Orford, P. D., & Ring, S. G. (1985). The roles of amylose and amylopectin in the gelation and retrogradation of starch. Carbohydrate Research, 135, 271-281.

Minderhoud, I. M., Mundt, M. W., Roelofs, J. M., & Samsom, M. (2004). Gastric emptying of a solid meal starts during meal ingestion: Combined study using 13C-octanoic acid breath test and Doppler ultrasonography. Absence of a lag phase in 13C-octanoic acid breath test. Digestion, 70, 55-60.

Minekus, M. (2015). The TNO gastro-intestinal model (TIM). Springer International Publishing.

Minekus, M., Alminger, M., Alvito, P., Ballance, S., Bohn, T., Bourlieu, C., et al. (2014). A standardised static in vitro digestion method suitable for food – an international consensus. Food & Function, 5, 1113-1124.

Mirrahimi, A., de Souza, R. J., Chiavaroli, L., Sievenpiper, J. L., Beyene, J., Hanley, A. J., et al. (2012). Associations of glycemic index and load with coronary heart disease events: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohorts. Journal of the American Heart Association, 1, Article e000752.

Mishra, S., Monro, J., & Hedderley, D. (2008). Effect of processing on slowly digestible starch and resistant starch in potato. Starch – Stärke, 60, 500-507.

Monro, J., & Mishra, S. (2022). In vitro digestive analysis of digestible and resistant starch fractions, with concurrent Glycemic Index determination, in whole grain wheat products minimally processed for reduced glycaemic impact. Foods, 11, 1904.

Moongngarm, A., Bronlund, J. E., Grigg, N., & Sriwai, N. (2012). Chewing behavior and bolus properties as affected by different rice types. International Journal of Medical and Biological Sciences, 6, 51-56.

Morell, P., Hernando, I., & Fiszman, S. M. (2014). Understanding the relevance of inmouth food processing. A review of techniques. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 35, 18-31.

Moretton, M., Alongi, M., Melchior, S., & Anese, M. (2023). Adult and elderly in vitro digestibility patterns of proteins and carbohydrates as affected by different commercial bread types. Food Research International, 167, Article 112732.

Muir, J. G., & O’Dea, K. (1993). Validation of an in vitro assay for predicting the amount of starch that escapes digestion in the small intestine of humans. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 57, 540-546.

Mulet-Cabero, A. I., Egger, L., Portmann, R., Menard, O., Marze, S., Minekus, M., et al. (2020). A standardised semi-dynamic in vitro digestion method suitable for food – an international consensus. Food & Function, 11, 1702-1720.

Mullie, P., Koechlin, A., Boniol, M., Autier, P., & Boyle, P. (2016). Relation between breast cancer and high glycemic index or glycemic load: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 56, 152-159.

Nadia, J., Bronlund, J., Singh, R. P., Singh, H., & Bornhorst, G. M. (2021). Structural breakdown of starch-based foods during gastric digestion and its link to glycemic response: In vivo and in vitro considerations. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 20, 2660-2698.

Nadia, J., Bronlund, J. E., Singh, H., Singh, R. P., & Bornhorst, G. M. (2022). Contribution of the proximal and distal gastric phases to the breakdown of cooked starch-rich solid foods during static in vitro gastric digestion. Food Research International, 157, Article 111270.

Nadia, J., Olenskyj, A. G., Subramanian, P., Hodgkinson, S., Stroebinger, N., Estevez, T. G., et al. (2022). Influence of food macrostructure on the kinetics of acidification in the pig stomach after the consumption of rice- and wheat-based foods: Implications for starch hydrolysis and starch emptying rate. Food Chemistry, 394, Article 133410.

Nassar, M., Hiraishi, N., Islam, M. S., Otsuki, M., & Tagami, J. (2014). Age-related changes in salivary biomarkers. Journal of Dental Sciences, 9, 85-90.

Nater, U. M., Rohleder, N., Schlotz, W., Ehlert, U., & Kirschbaum, C. (2007). Determinants of the diurnal course of salivary alpha-amylase. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 32, 392-401.

Nguyen, G. T., & Sopade, P. A. (2018). Modeling starch digestograms: Computational characteristics of kinetic models for in vitro starch digestion in food research. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 17, 1422-1445.

Noah, L., Guillon, F., Bouchet, B., Buleon, A., Molis, C., Gratas, M., et al. (1998). Digestion of carbohydrate from white beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in healthy humans. The Journal of Nutrition, 128, 977-985.

Nugent, A. P. (2005). Health properties of resistant starch. Nutrition Bulletin, 30, 27-54.

Ohland, C. L., & Jobin, C. (2015). Microbial activities and intestinal homeostasis: A delicate balance between health and disease. Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 1, 28-40.

Oku, T., Tanabe, K., Ogawa, S., Sadamori, N., & Nakamura, S. (2011). Similarity of hydrolyzing activity of human and rat small intestinal disaccharidases. Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology, 4, 155-161.

Palchen, K., Michels, D., Duijsens, D., Gwala, S., Pallares Pallares, A., Hendrickx, M., et al. (2021). In vitro protein and starch digestion kinetics of individual chickpea cells: From static to more complex in vitro digestion approaches. Food & Function, 12, 7787-7804.

Pallares Pallares, A., Loosveldt, B., Karimi, S. N., Hendrickx, M., & Grauwet, T. (2019). Effect of process-induced common bean hardness on structural properties of in vivo

generated boluses and consequences for in vitro starch digestion kinetics. British Journal of Nutrition, 122, 388-399.

Passannanti, F., Nigro, F., Gallo, M., Tornatore, F., Frasso, A., Saccone, G., et al. (2017). In vitro dynamic model simulating the digestive tract of 6-month-old infants. PLoS One, 12, Article e0189807.

Pérez-Burillo, S., Molino, S., Navajas-Porras, B., Valverde-Moya, Á. J., HinojosaNogueira, D., López-Maldonado, A., et al. (2021). An in vitro batch fermentation protocol for studying the contribution of food to gut microbiota composition and functionality. Nature Protocols, 16, 3186-3209.

Perry, G. H., Dominy, N. J., Claw, K. G., Lee, A. S., Fiegler, H., Redon, R., et al. (2007). Diet and the evolution of human amylase gene copy number variation. Nature Genetics, 39, 1256-1260.

Petropoulou, K., Salt, L. J., Edwards, C. H., Warren, F. J., Garcia-Perez, I., Chambers, E. S., et al. (2020). A natural mutation in Pisum sativum L. (pea) alters starch assembly and improves glucose homeostasis in humans. Nature Food, 1, 693-704.

Peyron, M. A., & Woda, A. (2016). An update about artificial mastication. Current Opinion in Food Science, 9, 21-28.

Pico, J., Corbin, S., Ferruzzi, M. G., & Martinez, M. M. (2019). Banana flour phenolics inhibit trans-epithelial glucose transport from wheat cakes in a coupled in vitro digestion/Caco-2 cell intestinal model. Food & Function, 10, 6300-6311.

Priebe, M. G., Eelderink, C., Wachters-Hagedoorn, R. E., & Vonk, R. J. (2018). Starch digestion and applications of slowly available starch. In M. Sjöö, & L. Nilsson (Eds.), Starch in food (pp. 805-826). Woodhead Publishing.

Prochazkova, N., Falony, G., Dragsted, L. O., Licht, T. R., Raes, J., & Roager, H. M. (2023). Advancing human gut microbiota research by considering gut transit time. Gut, 72, 180-191.

Prodan, A., Brand, H. S., Ligtenberg, A. J., Imangaliyev, S., Tsivtsivadze, E., van der Weijden, F., et al. (2015). Interindividual variation, correlations, and sex-related differences in the salivary biochemistry of young healthy adults. European Journal of Oral Sciences, 123, 149-157.

Pugh, J. E., Cai, M., Altieri, N., & Frost, G. (2023). A comparison of the effects of resistant starch types on glycemic response in individuals with type 2 diabetes or prediabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Nutrition, 10, Article 1118229.

Qadir, N., & Wani, I. A. (2022). In-vitro digestibility of rice starch and factors regulating its digestion process: A review. Carbohydrate Polymers, 291, Article 119600.

Quezada-Calvillo, R., Robayo-Torres, C. C., Ao, Z., Hamaker, B. R., Quaroni, A., Brayer, G. D., et al. (2007). Luminal substrate “brake” on mucosal maltaseglucoamylase activity regulates total rate of starch digestion to glucose. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 45, 32-43.

Ranawana, V., Monro, J. A., Mishra, S., & Henry, C. J. (2010). Degree of particle size breakdown during mastication may be a possible cause of interindividual glycemic variability. Nutrition Research, 30, 246-254.

Read, N. W., Welch, I. M., Austen, C. J., Barnish, C., Bartlett, C. E., Baxter, A. J., et al. (1986). Swallowing food without chewing; a simple way to reduce postprandial glycaemia. British Journal of Nutrition, 55, 43-47.

Ribeiro, N. C. B. V., Ramer-Tait, A. E., & Cazarin, C. B. B. (2022). Resistant starch: A promising ingredient and health promoter. PharmaNutrition, 21.

Roman, L., Gomez, M., Hamaker, B. R., & Martinez, M. M. (2019). Banana starch and molecular shear fragmentation dramatically increase structurally driven slowly digestible starch in fully gelatinized bread crumb. Food Chemistry, 274, 664-671.

Roman, L., Gomez, M., Li, C., Hamaker, B. R., & Martinez, M. M. (2017). Biophysical features of cereal endosperm that decrease starch digestibility. Carbohydrate Polymers, 165, 180-188.

Roman, L., & Martinez, M. M. (2019). Structural basis of Resistant Starch (RS) in bread: Natural and commercial alternatives. Foods, 8, 267.

Roman, L., Yee, J., Hayes, A. M. R., Hamaker, B. R., Bertoft, E., & Martinez, M. M. (2020). On the role of the internal chain length distribution of amylopectins during retrogradation: Double helix lateral aggregation and slow digestibility. Carbohydrate Polymers, 246, Article 116633.

Rossiter, M. A., Barrowman, J. A., Dand, A., & Wharton, B. A. (1974). Amylase content of mixed saliva in children. Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica, 63, 389-392.

Ruigrok, R., Weersma, R. K., & Vich Vila, A. (2023). The emerging role of the small intestinal microbiota in human health and disease. Gut Microbes, 15, Article 2201155.

Schwingshackl, L., & Hoffmann, G. (2013). Long-term effects of low glycemic index/load vs. high glycemic index/load diets on parameters of obesity and obesity-associated risks: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Diseases, 23, 699-706.

Seidelmann, S. B., Feofanova, E., Yu, B., Franceschini, N., Claggett, B., Kuokkanen, M., et al. (2018). Genetic variants in SGLT1, glucose tolerance, and cardiometabolic risk. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 72, 1763-1773.

Shalon, D., Culver, R. N., Grembi, J. A., Folz, J., Treit, P. V., Shi, H., et al. (2023). Profiling the human intestinal environment under physiological conditions. Nature, 617, 581-591.

Simonian, H. P., Vo, L., Doma, S., Fisher, R. S., & Parkman, H. P. (2005). Regional postprandial differences in pH within the stomach and gastroesophageal junction. Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 50, 2276-2285.

Simsek, M., Quezada-Calvillo, R., Ferruzzi, M. G., Nichols, B. L., & Hamaker, B. R. (2015). Dietary phenolic compounds selectively inhibit the individual subunits of maltase-glucoamylase and sucrase-isomaltase with the potential of modulating glucose release. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 63, 3873-3879.

Sousa, R., Recio, I., Heimo, D., Dubois, S., Moughan, P. J., Hodgkinson, S. M., et al. (2023). In vitro digestibility of dietary proteins and in vitro DIAAS analytical

workflow based on the INFOGEST static protocol and its validation with in vivo data. Food Chemistry, 404, Article 134720.

Southgate, D. A. (1969a). Determination of carbohydrates in foods. I. Available carbohydrate. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 20, 326-330.

Southgate, D. A. (1969b). Determination of carbohydrates in foods. II. Unavailable carbohydrates. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 20, 331-335.

Strahler, J., Mueller, A., Rosenloecher, F., Kirschbaum, C., & Rohleder, N. (2010). Salivary

Stylianopoulos, C. L. (2012). Carbohydrates: Requirements and dietary importance. In B. Caballero, L. H. Allen, & A. Prentice (Eds.), Encyclopedia of human nutrition (2nd ed., pp. 316-321). Academic press.

Sun, S. L., Jin, Y. Z., Hong, Y., Gu, Z. B., Cheng, L., Li, Z. F., et al. (2021). Effects of fatty acids with various chain lengths and degrees of unsaturation on the structure, physicochemical properties and digestibility of maize starch-fatty acid complexes. Food Hydrocolloids, 110, Article 106224.

Sun, Y. M., Zhong, C., Zhou, Z. L., Lei, Z. X., & Langrish, T. A. G. (2022). A review of in vitro methods for measuring the glycemic index of single foods: Understanding the interaction of mass transfer and reaction engineering by dimensional analysis. Processes, 10.

Taavitsainen, S., Juuti-Uusitalo, K., Kurppa, K., Lindfors, K., Kallio, P., & Kellomäki, M. (2024). Gut-on-chip devices as intestinal inflammation models and their future for studying multifactorial diseases. Frontiers in Lab on a Chip Technologies, 2.

Tagliasco, M., Font, G., Renzetti, S., Capuano, E., & Pellegrini, N. (2024). Role of particle size in modulating starch digestibility and textural properties in a rye bread model system. Food Research International, 190, Article 114565.

Tagliasco, M., Tecuanhuey, M., Reynard, R., Zuliani, R., Pellegrini, N., & Capuano, E. (2022). Monitoring the effect of cell wall integrity in modulating the starch digestibility of durum wheat during different steps of bread making. Food Chemistry, 396, Article 133678.

Tang, M., Wang, L., Cheng, X., Wu, Y., & Ouyang, J. (2019). Non-starch constituents influence the in vitro digestibility of naked oat (Avena nuda L.) starch. Food Chemistry, 297, Article 124953.

Thuenemann, E. C., Mandalari, G., Rich, G. T., & Faulks, R. M. (2015). Dynamic gastric model (DGM). In K. Verhoeckx, P. Cotter, I. Lopez-Exposito, C. Kleiveland, T. Lea, A. Mackie, et al. (Eds.), The impact of food bioactives on health: In vitro and ex vivo models (pp. 47-59). Cham (CH): Springer.

Tily, H., Patridge, E., Cai, Y., Gopu, V., Gline, S., Genkin, M., et al. (2022). Gut microbiome activity contributes to prediction of individual variation in glycemic response in adults. Diabetes Therapy, 13, 89-111.

Van de Wiele, T., Van den Abbeele, P., Ossieur, W., Possemiers, S., & Marzorati, M. (2015). The simulator of the human intestinal microbial Ecosystem (SHIME®). In K. Verhoeckx, P. Cotter, I. Lopez-Exposito, C. Kleiveland, T. Lea, A. Mackie, et al. (Eds.), The impact of food bioactives on health: In vitro and ex vivo models (pp. 305-317). Cham (CH): Springer International Publishing.

van Leeuwen, P. T., Brul, S., Zhang, J., & Wortel, M. T. (2023). Synthetic microbial communities (SynComs) of the human gut: Design, assembly, and applications. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 47, Article fuad012.

van Stegeren, A. H., Wolf, O. T., & Kindt, M. (2008). Salivary alpha amylase and cortisol responses to different stress tasks: Impact of sex. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 69, 33-40.

Varriano-Marston, E., Ke, V., Huang, G., & Ponte, J. (1980). Comparison of methods to determine starch gelatinization in bakery foods. Cereal Chemistry, 57, 242-248.

Vega-Lopez, S., Ausman, L. M., Griffith, J. L., & Lichtenstein, A. H. (2007). Interindividual variability and intra-individual reproducibility of glycemic index values for commercial white bread. Diabetes Care, 30, 1412-1417.

Vellas, B., Balas, D., Moreau, J., Bouisson, M., Senegas-Balas, F., Guidet, M., et al. (1988). Exocrine pancreatic secretion in the elderly. International Journal of Pancreatology, 3, 497-502.

Vernon-Carter, E. J., Alvarez-Ramirez, J., Meraz, M., Bello-Perez, L. A., & Garcia-Diaz, S. (2020). Canola oil/candelilla wax oleogel improves texture, retards staling and reduces in vitro starch digestibility of maize tortillas. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 100, 1238-1245.

Versantvoort, C. H., Oomen, A. G., Van de Kamp, E., Rompelberg, C. J., & Sips, A. J. (2005). Applicability of an in vitro digestion model in assessing the bioaccessibility of mycotoxins from food. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 43, 31-40.

Versantvoort, C. H. M., & Rompelberg, C. (2004). Development and applicability of an in vitro digestion model. In Assessing the bioaccessibility of contaminants from food.

Walther, B., Lett, A. M., Bordoni, A., Tomas-Cobos, L., Nieto, J. A., Dupont, D., et al. (2019). GutSelf: Interindividual variability in the processing of dietary compounds by the human gastrointestinal tract. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 63, Article e1900677.

Wang, T. L., Bogracheva, T. Y., & Hedley, C. L. (1998). Starch: As simple as A, B, C? Journal of Experimental Botany, 49, 481-502.

Wang, S. J., Li, C. L., Copeland, L., Niu, Q., & Wang, S. (2015). Starch retrogradation: A comprehensive review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 14, 568-585.

Wang, K. L., Li, M., Han, Q. Y., Fu, R., & Ni, Y. Y. (2021). Inhibition of

Wang, M. M., Wichienchot, S., He, X. W., Fu, X., Huang, Q., & Zhang, B. (2019). In vitro colonic fermentation of dietary fibers: Fermentation rate, short-chain fatty acid production and changes in microbiota. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 88, 1-9.

Wang, J., Wu, P., Liu, M., Liao, Z., Wang, Y., Dong, Z., et al. (2019). An advanced near real dynamic in vitro human stomach system to study gastric digestion and emptying of beef stew and cooked rice. Food & Function, 10, 2914-2925.

Wolever, T. M. (2016). Personalized nutrition by prediction of glycaemic responses: Fact or fantasy? European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 70, 411-413.

Woolnough, J. W., Bird, A. R., Monro, J. A., & Brennan, C. S. (2010). The effect of a brief salivary alpha-amylase exposure during chewing on subsequent in vitro starch digestion curve profiles. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 11, 2780-2790.

Woolnough, J. W., Monro, J. A., Brennan, C. S., & Bird, A. R. (2008). Simulating human carbohydrate digestion: A review of methods and the need for standardisation. International Journal of Food Science and Technology, 43, 2245-2256.

Worning, H., & Mullertz, S. (1966). pH and pancreatic enzymes in the human duodenum during digestion of a standard meal. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology, 1, 268-283.

Xiao, J., Kai, G., Yamamoto, K., & Chen, X. (2013). Advance in dietary polyphenols as alpha-glucosidases inhibitors: A review on structure-activity relationship aspect. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 53, 818-836.

Xiong, W., Devkota, L., Zhang, B., Muir, J., & Dhital, S. (2022). Intact cells: “Nutritional capsules” in plant foods. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 21, 1198-1217.

Yang, Z., Zhang, Y., Wu, Y., & Ouyang, J. (2023). Factors influencing the starch digestibility of starchy foods: A review. Food Chemistry, 406, Article 135009.

Yang, C., Zhong, F., Douglas Goff, H., & Li, Y. (2019). Study on starch-protein interactions and their effects on physicochemical and digestible properties of the blends. Food Chemistry, 280, 51-58.

Zeevi, D., Korem, T., Zmora, N., Israeli, D., Rothschild, D., Weinberger, A., et al. (2015). Personalized nutrition by prediction of glycemic responses. Cell, 163, 1079-1094.

Zheng, J., Huang, S., Zhao, R., Wang, N., Kan, J., & Zhang, F. (2021). Effect of four viscous soluble dietary fibers on the physicochemical, structural properties, and in vitro digestibility of rice starch: A comparison study. Food Chemistry, 362, Article 130181.

Zhong, F., Li, Y., Noe, K. M., Wei, L., Chen, M., & Nsor-Atindana, J. (2018). Implications of static in vitro digestion of starch in the presence of dietary fiber. Frontiers of Agricultural Science and Engineering, 5, 340-350.

Zhu, Y., Hsu, W. H., & Hollis, J. H. (2014). Increased number of chews during a fixedamount meal suppresses postprandial appetite and modulates glycemic response in older males. Physiology & Behavior, 133, 136-140.

Zhu, Y., Wen, P., Wang, P., Li, Y., Tong, Y., Ren, F., et al. (2022). Influence of native cellulose, microcrystalline cellulose and soluble cellodextrin on inhibition of starch digestibility. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 219, 491-499.

- Abbreviations: DS, Digestible starch; GI, Glycaemic Index; PA, Pancreatic

-amylase; RDS, Rapidly digestible starch; RS, Resistant starch; SDS, Slowly digestible starch. - Corresponding author. Teagasc Food Research Centre, Moorepark, Fermoy, Co Cork P61 C996, Ireland.

** Corresponding author. Center for Innovative Food (CiFOOD), Department of Food Science, Aarhus University, Agro Food Park 48, Aarhus N 8200, Denmark.

*** Corresponding author. Quadram Institute Bioscience, Norwich Research Park, NR4 7UQ, Norwich, United Kingdom.

E-mail addresses: daniela.freitas@teagasc.ie (D. Freitas), mm@food.au.dk, mmartinez@uva.es (M.M. Martinez), cathrina.edwards@quadram.ac.uk (C.H. Edwards).

These authors contributed equally.

- Corresponding author. Teagasc Food Research Centre, Moorepark, Fermoy, Co Cork P61 C996, Ireland.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2025.104969

Publication Date: 2025-03-11

Starch digestion: A comprehensive update on the underlying modulation mechanisms and its in vitro assessment methodologies

– To cite this version:

HAL Id: hal-04998681

https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-04998681v1

Starch digestion: A comprehensive update on the underlying modulation mechanisms and its in vitro assessment methodologies

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Glycaemic response

Dietary fibre

Microbiota

Food structure

INFOGEST

Abstract

Background: Starch is the predominant carbohydrate in our diets and its impact on human health is intricately linked with its digestive process. However, despite major advancements in the field, important inconsistencies in how starch digestion is described and studied in vitro still persist. Scope and approach: Our main objective was to provide up-to-date insights on starch digestion and fermentation in the human gastrointestinal tract, as well as related physiological responses and main drivers of variability (including inter-individual variations and structural and compositional differences between foods). A critical appraisal of digestion models and future work priorities is also presented. This work is the product of an international collaboration within the INFOGEST research network. Key findings and conclusions: Starch digestion is accomplished by the concerted action of luminal and brushborder hydrolases. Mechanical and biochemical transformations occurring throughout oral, gastric and intestinal phases can be determinant, contributing to different extents to the digestive process depending on food properties and individual characteristics. Numerous methodologies, with varying complexity and capacity to reproduce key digestive processes (e.g., gastric emptying), are currently available. Some in vitro digestibility outcome measures can be closely correlated with the outcomes of in vivo studies, demonstrating the promising potential of these approaches. However, the physiological relevance of in vitro starch digestion studies is often compromised by the lack of methodological consensus (particularly for oral digestion) and omission of key enzymatic events. Therefore, the need to develop harmonized guidelines and validate in vitro protocols adapted to starch digestion studies stand out as priority areas for future work.

1. Introduction

2. Starch: structural architecture and occurrence in food

major nutritional component and building block of many different processed food products including bread, biscuits, cooked rice, canned pulses, pasta, breakfast cereals, and snacks, but may also be ingested raw (e.g., starchy fruits).

3. Starch digestion and fermentation through the human gastrointestinal tract

3.1. Mouth

2008) and plays a role in lubrication and biochemical digestion of starch. It is secreted at a rate of

3.2. Stomach

3.3. Small intestine (lumen and brush border membrane)

2021). Starch digestion within the duodenum is thus regulated mostly by factors affecting the activity and substrate access/binding of amylolytic enzymes.

colonised by a complex community of microorganisms (estimated up to

3.4. Large intestine