DOI: https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.s441444

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38343429

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-01

هل يعزز أو يعيق الضغط التكنولوجي المدفوع بالذكاء الاصطناعي نية الموظفين في اعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي؟ نموذج وساطة معتدل للتفاعلات العاطفية والكفاءة الذاتية التقنية

الملخص

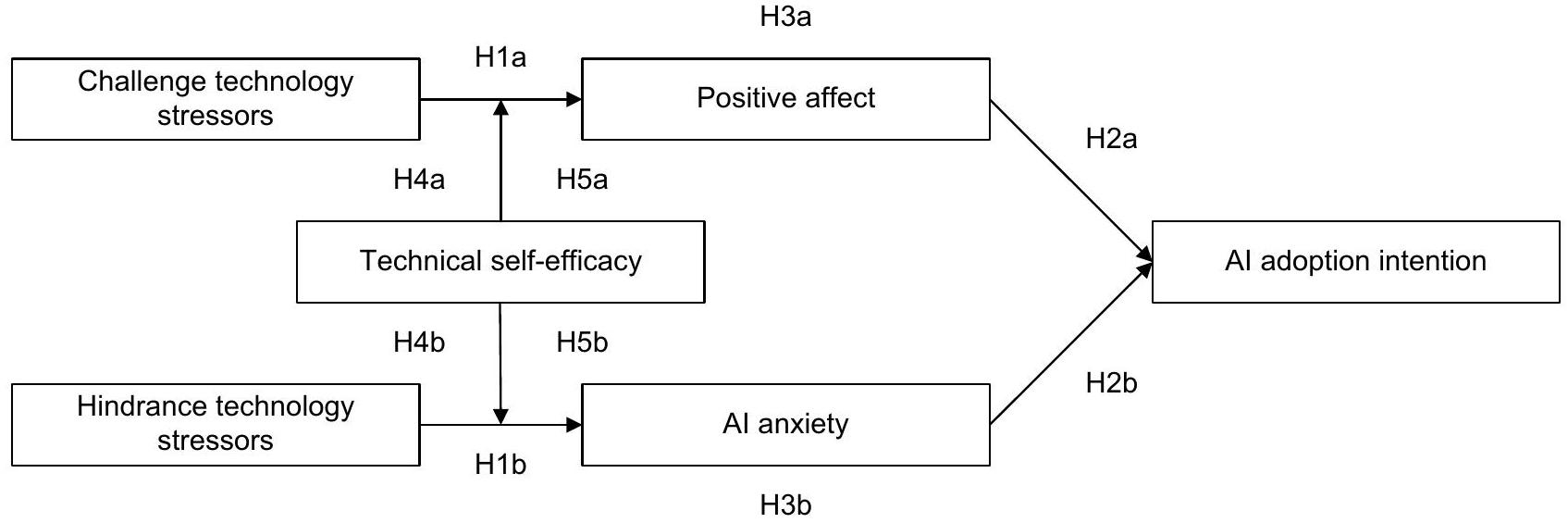

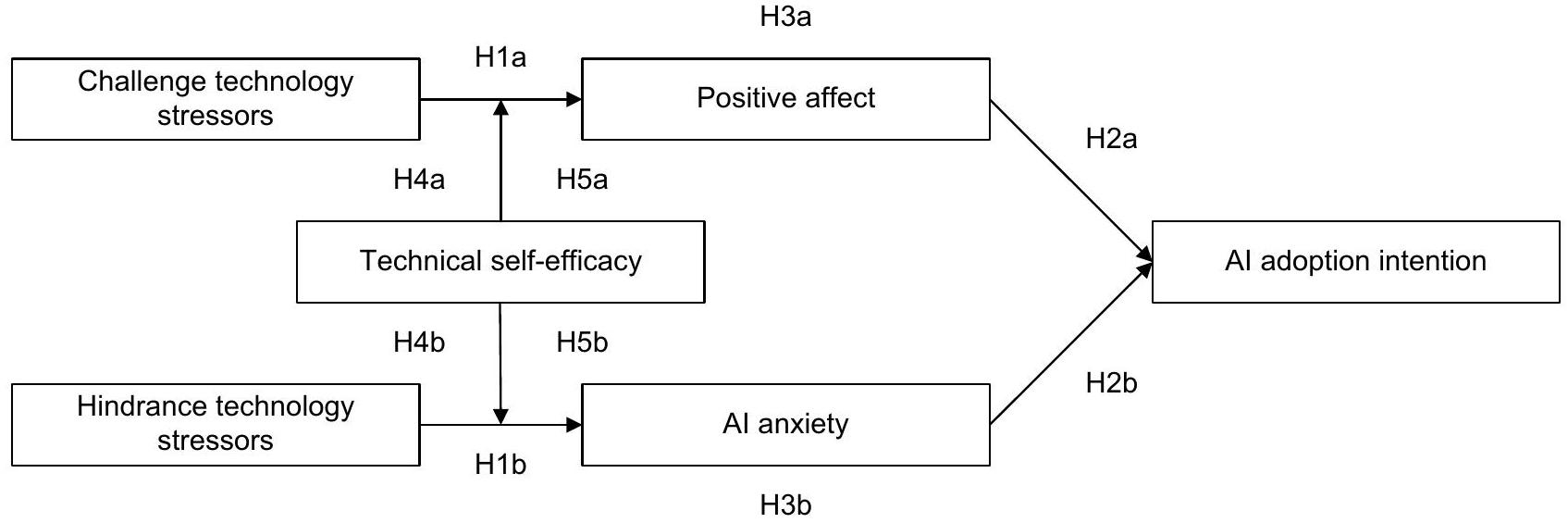

الغرض: إن التكامل المتزايد للذكاء الاصطناعي (AI) داخل المؤسسات يولد ضغطًا تكنولوجيًا كبيرًا بين الموظفين، مما قد يؤثر على نيتهم في اعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي. ومع ذلك، لا تزال الأبحاث الحالية حول الآثار النفسية لهذه الظاهرة غير حاسمة. استنادًا إلى نظرية الأحداث العاطفية (AET) وإطار الضغط التحدي-العيق (CHSF)، تهدف الدراسة الحالية إلى استكشاف “الصندوق الأسود” بين ضغوط التكنولوجيا التحدي والعيق ونية الموظفين في اعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي، بالإضافة إلى شروط الحدود لهذه العلاقة الوسيطة. الطرق: تستخدم الدراسة نهجًا كميًا وتستفيد من بيانات ثلاث موجات. تم جمع البيانات من خلال تقنية العينة الثلجية واستبيان منظم. تتكون العينة من موظفين من 11 منظمة متميزة تقع في مقاطعة قوانغدونغ، الصين. تلقينا 301 استبيان صالح، مما يمثل معدل استجابة إجمالي قدره

المقدمة

المحوري في مشهد الأعمال المعاصر. ومع ذلك، تؤدي متطلبات التكنولوجيا المتغيرة أيضًا إلى ضغط تكنولوجي بين الموظفين، مما يطرح تحديات وعوائق. كيف يمكن تعزيز نية الموظف في اعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي يصبح المفتاح لتحقيق المزايا التنافسية بين الشركات.

الأساس النظري وفرضيات البحث

ضغوط التكنولوجيا المدفوعة بالذكاء الاصطناعي والتحديات وردود الفعل العاطفية

H1b: ترتبط ضغوط التكنولوجيا المعيقة المدفوعة بالذكاء الاصطناعي ارتباطًا إيجابيًا بقلق الذكاء الاصطناعي.

ردود الفعل العاطفية ونية اعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي

H2b. يرتبط قلق الذكاء الاصطناعي ارتباطًا سلبيًا بنية اعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي.

الدور الوسيط لردود الفعل العاطفية

H3b: تؤثر قلق الذكاء الاصطناعي على العلاقة بين ضغوط التكنولوجيا المعيقة ونية اعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي.

الدور الوسيط للكفاءة الذاتية التقنية

طريقة البحث

تصميم الدراسة

المشاركون

تدابير

| خصائص | الفئات | تردد | نسبة مئوية (%) |

| جنس | ذكر | 154 | 51.2 |

| أنثى | 147 | ٤٨.٨ | |

| عمر | أقل من 26 عامًا | 68 | 22.6 |

| ٢٦-٣٠ | 72 | ٢٣.٩ | |

| 31-35 | 62 | 20.6 | |

| ٣٦-٤٠ | 51 | 16.9 | |

| فوق سن الأربعين | ٤٨ | 16.0 | |

| الأدوار المهنية | الموظفون العاديون | 114 | ٣٧.٩ |

| عمال الخطوط الأمامية | 135 | ٤٤.٩ | |

| مدراء متوسطون أو كبار | 52 | 17.2 | |

| التعليم | شهادات الكلية أو أقل | ٥٩ | 19.6 |

| شهادات البكالوريوس | 113 | 37.5 | |

| درجات الماجستير أو أعلى | ١٢٩ | 42.9 |

تحديات وضغوط التكنولوجيا المدفوعة بالذكاء الاصطناعي

التأثير الإيجابي

القلق

الكفاءة الذاتية التقنية

نية التبني

متغيرات التحكم

تحليل البيانات

أداة،

النتائج

تباين الطريقة التأكيدية وصلاحية التمييز

الإحصاءات الوصفية والارتباطات

| نموذج القياس |

|

df |

|

CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA |

| نموذج العوامل الستة | 2229.81 | 1259 | 1.77 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| نموذج العوامل الخمسة | ٢٧٠٢.٦٣ | 1264 | 2.14 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.12 | 0.06 |

| نموذج العوامل الأربعة | ٤٤٨٨.٣٠ | 1268 | 3.54 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.14 | 0.09 |

| نموذج العوامل الثلاثة | 7358.06 | 1271 | ٥.٧٨ | 0.67 | 0.65 | 0.18 | 0.13 |

| نموذج العاملين | 9072.86 | 1273 | 7.13 | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.18 | 0.14 |

| نموذج العامل الواحد | 9397.50 | 1274 | 7.38 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.14 | 0.15 |

الاختصارات: CFI، مؤشر الملاءمة المقارن (قيمة القطع، 0.90)؛ TLI، مؤشر تاكر-لويس (قيمة القطع، 0.90)؛ SRMR، الجذر التربيعي المتوسط المعياري (قيمة القطع، 0.05)؛ RMSEA، الجذر التربيعي لمتوسط التقريب (قيمة القطع، 0.06).

| المتغيرات | M | SD | أنا | ٢ | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | ٦ | ٧ | ٨ | 9 |

| أ. الجنس | 0.51 | 0.50 | |||||||||

| 2. العمر | 2.80 | 1.38 | 0.06 | ||||||||

| 3. الموقف | 1.79 | 0.72 | 0.23*** | 0.58*** | |||||||

| 4. التعليم | ٢.٢٣ | 0.76 | 0.13* | 0.51*** | 0.60*** | ||||||

| 5. CTS | 3.26 | 1.09 | 0.23*** | 0.09 | 0.20*** | 0.30*** | |||||

| 6. هيئة تحرير الشام | 3.11 | 1.02 | -0.17** | -0.12* | -0.23*** | -0.28*** | -0.53*** | ||||

| 7. التأثير الإيجابي | 3.33 | 1.17 | 0.14* | 0.09 | 0.20*** | 0.35*** | 0.59*** | -0.55*** | |||

| 8. قلق الذكاء الاصطناعي | 3.01 | 1.11 | -0.20** | -0.04 | -0.22*** | -0.34*** | -0.55*** | 0.55*** | -0.58*** | ||

| 9. الكفاءة الذاتية التقنية | 2.88 | 0.80 | 0.05 | -0.05 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.47*** | -0.02 | 0.40*** | -0.04 | |

| 10. نية اعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي | 3.31 | 1.10 | 0.21*** | 0.13* | 0.24*** | 0.28*** | 0.53*** | -0.53*** | 0.56*** | -0.53*** | 0.10 |

اختبار الفرضيات

| المتغيرات | مي-آي

|

MI-2 XI

|

مي-3 مي

|

مي-4

|

M2-I

|

M2-2 X2

|

M2-3

|

M2-4

|

| ثابت | 1.21*** | 0.89*** | 1.23*** | 0.90*** | 4.31*** | 2.06*** | 4.25*** | 4.97*** |

| جنس | 0.16 | -0.01 | 0.25* | 0.16 | 0.23* | -0.18 | 0.21 | 0.17 |

| عمر | -0.00 | -0.06 | 0.01 | 0.02 | -0.02 | 0.14** | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| موقف | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.08 | -0.06 | 0.08 | 0.06 |

| التعليم | 0.11 | 0.35*** | 0.03 | -0.01 | 0.16 | -0.38*** | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| سي تي إس | 0.48*** | 0.56*** | 0.29*** | |||||

| هيئة تحرير الشام | -0.5|*** | 0.52*** | -0.34*** | |||||

| القلق | 0.49*** | 0.34*** | -0.48*** | -0.32*** | ||||

| أثر | نتائج البوتستراب للتأثير غير المباشر | نتائج البوتستراب للتأثير غير المباشر | ||||||

| M | SE | LLCI | ULCI | M | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.31 | -0.17 | 0.05 | -0.29 | -0.08 | |

الاختصارات: CTS، ضغوط التكنولوجيا التحدي؛ HTS، ضغوط التكنولوجيا المعيقة؛ LL، الحد الأدنى؛ UL، الحد الأقصى؛ CI، فترة الثقة.

| مؤشر | التأثير الإيجابي | القلق | ||||||

| ب | SE | ت | ب | ب | SE | ت | ب | |

| نموذج الاعتدال | ||||||||

| ثابت | 2.77 | 0.15 | 18.20 | <0.001 | ٣.٤٣ | 0.16 | 20.91 | <0.001 |

| جنس | -0.09 | 0.09 | -0.96 | >0.05 | -0.16 | 0.10 | -1.68 | >0.05 |

| عمر | -0.03 | 0.04 | -0.69 | >0.05 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 2.62 | <0.01 |

| موقف | -0.00 | 0.08 | -0.04 | >0.05 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.51 | >0.05 |

| التعليم | 0.22 | 0.08 | 2.80 | <0.01 | -0.33 | 0.08 | -4.08 | <0.001 |

| سي تي إس | 0.74 | 0.05 | 13.71 | <0.001 | ||||

| هيئة تحرير الشام | 0.46 | 0.05 | 9.50 | <0.001 | ||||

| الكفاءة الذاتية التقنية | 0.10 | 0.06 | 1.66 | >0.05 | -0.19 | 0.06 | -3.06 | <0.01 |

| سي تي إس

|

0.51 | 0.04 | 11.87 | <0.001 | ||||

| هيئة تحرير الشام

|

-0.37 | 0.05 | -7.82 | <0.001 | ||||

| نموذج الوساطة المعتدلة | ||||||||

| الكفاءة الذاتية التقنية | أثر غير مباشر | بوت SE | بوت LLCI | بوت ULCI | أثر غير مباشر | بوت SE | بوت LLCI | بوت ULCI |

| مؤشر الوساطة المعتدلة | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.22 |

| التأثير غير المباشر الشرطي عند الكفاءة الذاتية التقنية = م

|

||||||||

| M-ISD | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.23 | -0.24 | 0.08 | -0.41 | -0.12 |

| M+ISD | 0.40 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.65 | -0.05 | 0.04 | -0.14 | 0.02 |

الاختصارات: CTS، ضغوط التكنولوجيا التحدي؛ HTS، ضغوط التكنولوجيا المعيقة؛ LL، الحد الأدنى؛ UL، الحد الأقصى؛ CI، فترة الثقة.

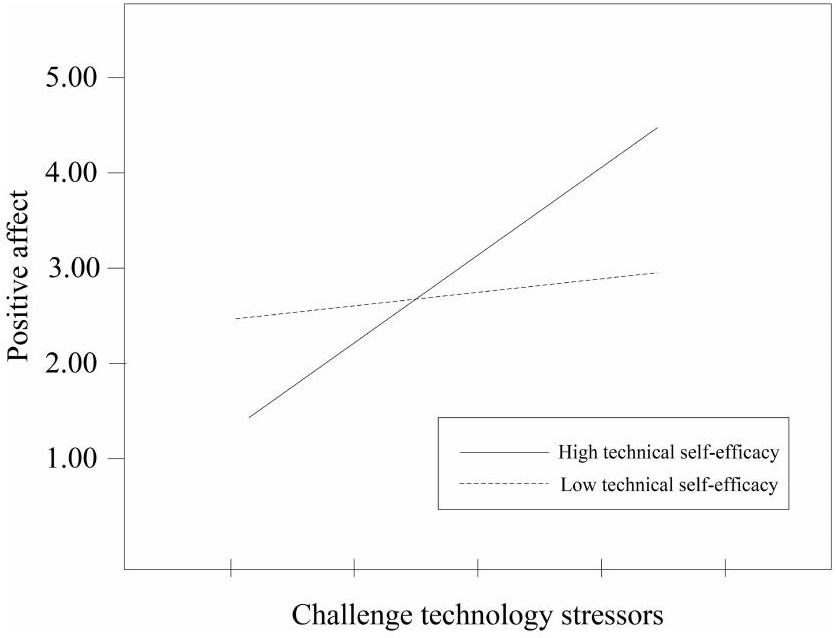

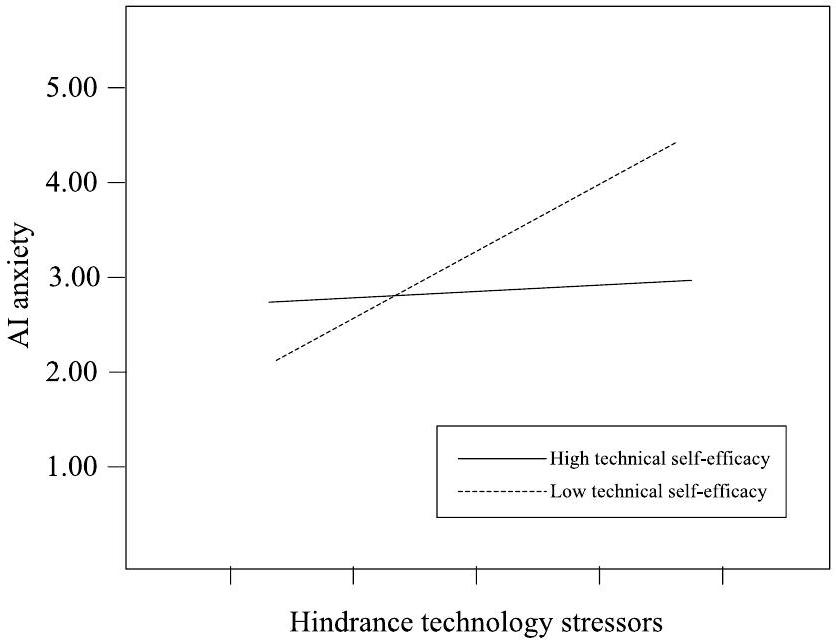

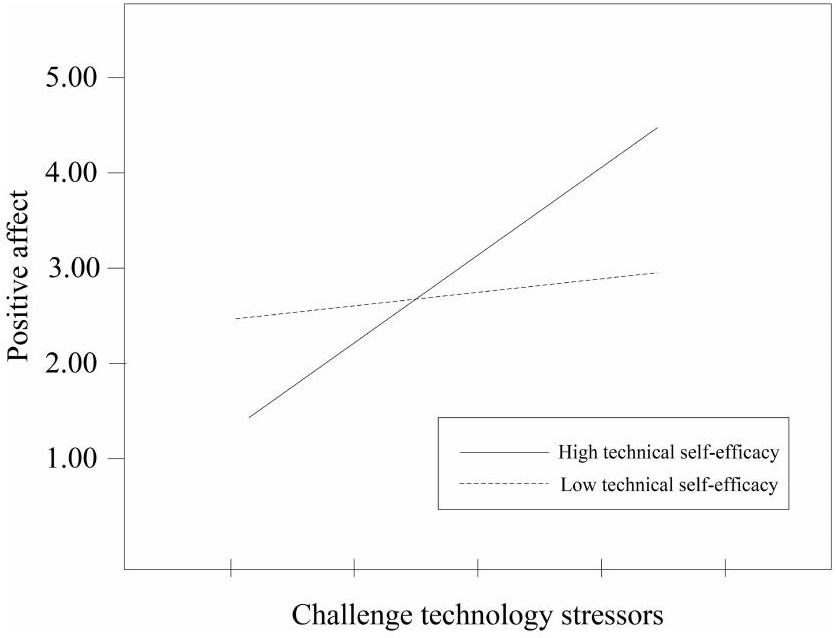

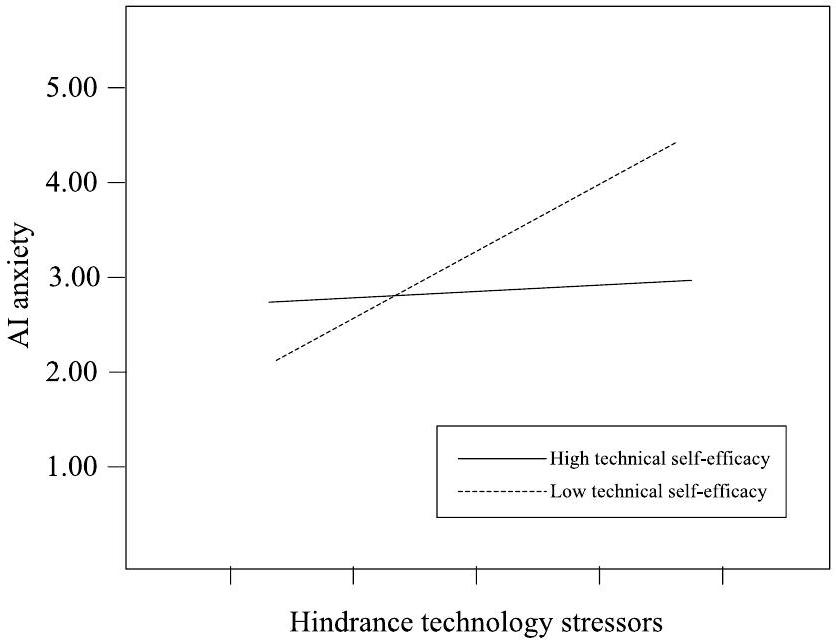

الفعالية. بالمقابل، توضح الشكل 3 أن العلاقة الإيجابية بين ضغوط التكنولوجيا المعوقة المدفوعة بالذكاء الاصطناعي والقلق من الذكاء الاصطناعي أقل وضوحًا بين الأفراد ذوي الكفاءة الذاتية التقنية العالية مقارنةً بأولئك ذوي الكفاءة الذاتية التقنية المنخفضة. وبالتالي، تم دعم الفرضيتين 4 أ و 4 ب.

نقاش

الآثار النظرية

أولاً، تُثري الدراسة الحالية الأدبيات الموجودة حول اعتماد تكنولوجيا الذكاء الاصطناعي من خلال كشف المتغير السابق للتوتر التكنولوجي. لقد أسفرت الأبحاث السابقة حول ما إذا كان التوتر التكنولوجي مفيدًا أو ضارًا للموظفين عن نتائج غير متسقة. تبحث هذه الدراسة في الطبيعة الثنائية للتوتر التكنولوجي، مميزةً بين التوتر التكنولوجي التحدي والتوتر التكنولوجي العائق في سياق تطبيقات الذكاء الاصطناعي، لتعميق فهم نية اعتماد الموظفين للذكاء الاصطناعي.

الدراسة كيف يعتدل الاعتبار الذاتي الفني تأثير ضغط التكنولوجيا المدفوع بالذكاء الاصطناعي على اعتماد التكنولوجيا من خلال ردود الفعل العاطفية، مما يوفر تكملة قيمة لدراسة تطبيقات تكنولوجيا الذكاء الاصطناعي.

التطبيقات العملية

القيود والبحث المستقبلي

الخاتمة

بيان الأخلاقيات

الشكر والتقدير

التمويل

الإفصاح

References

- Haenlein M, Kaplan A. A brief history of artificial intelligence: on the past, present, and future of artificial intelligence. Calif Manage Rev. 2019;61 (4):5-14. doi:10.1177/0008125619864925

- Duan Y, Edwards JS, Dwivedi YK. Artificial intelligence for decision making in the era of big data – evolution, challenges and research agenda. Int J Inf Manag. 2019;48:63-71. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.01.021

- Paschen J, Wilson M, Ferreira JJ. Collaborative intelligence: how human and artificial intelligence create value along the B2B sales funnel. Bus Horiz. 2020;63(3):403-414. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2020.01.003

- Belanche D, Casaló LV, Flavián C. Artificial Intelligence in FinTech: understanding robo-advisors adoption among customers. Ind Manag Data Syst. 2019;119(7):1411-1430. doi:10.1108/IMDS-08-2018-0368

- Joehnk J, Weissert M, Wyrtki K. Ready or not, AI comes- An interview study of organizational AI readiness factors. Bus Inf Syst Eng. 2021;63 (1):5-20. doi:10.1007/s12599-020-00676-7

- Nam K, Dutt CS, Chathoth P, Daghfous A, Khan MS. The adoption of artificial intelligence and robotics in the hotel industry: prospects and challenges. Electron Mark. 2021;31(3):553-574. doi:10.1007/s12525-020-00442-3

- Mingotto E, Montaguti F, Tamma M. Challenges in re-designing operations and jobs to embody AI and robotics in services. Findings from a case in the hospitality industry. Electron Mark. 2021;31(3):493-510. doi:10.1007/s12525-020-00439-y

- Lakshmi V, Bahli B. Understanding the robotization landscape transformation: a centering resonance analysis. J Innov Knowl. 2020;5(1):59-67. doi:10.1016/j.jik.2019.01.005

- Braganza A, Chen W, Canhoto A, Sap S. Productive employment and decent work: the impact of AI adoption on psychological contracts, job engagement and employee trust.

Bus Res. 2021;131:485-494. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.08.018 - Cheng B, Lin H, Kong Y. Challenge or hindrance? How and when organizational artificial intelligence adoption influences employee job crafting. J Bus Res. 2023;164:113987. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.113987

- Ghosh B, Daugherty PR, Wilson HJ, Burden A. Taking a systems approach to adopting AI. Harv Bus Rev. 2019;2019:1.

- Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989;13(3):319-340. doi:10.2307/ 249008

- Tornatzky LG, Fleischer M, Chakrabarti AK. The Processes of Technological Innovation. Lexington Books; 1990.

- Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, Davis FD. User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003;27(3):425-478. doi:10.2307/30036540

- Pan Y, Froese F, Liu N, Hu Y, Ye M. The adoption of artificial intelligence in employee recruitment: the influence of contextual factors. Int

Hum Resour Manag. 2022;33(6):1125-1147. doi:10.1080/09585192.2021.1879206 - Sohn K, Kwon O. Technology acceptance theories and factors influencing artificial Intelligence-based intelligent products. Telemat Inform. 2020;47:101324. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2019.101324

- Flavián C, Pérez-Rueda A, Belanche D, Casaló LV. Intention to use analytical artificial intelligence (AI) in services-the effect of technology readiness and awareness. J Serv Manag. 2022;33(2):293-320. doi:10.1108/JOSM-10-2020-0378

- Liu M, Wu J, Zhu C, Hu K. Factors influencing the acceptance of robo-taxi services in China: an extended technology acceptance model analysis. J Adv Transp. 2022;2022:8461212. doi:10.1155/2022/8461212

- Moussawi S, Koufaris M, Benbunan-Fich R. How perceptions of intelligence and anthropomorphism affect adoption of personal intelligent agents. Electron Mark. 2021;31(2):343-364. doi:10.1007/s12525-020-00411-w

- Chen J, Li R, Gan M, Fu Z, Yuan F. Public acceptance of driverless buses in China: an empirical analysis based on an extended UTAUT model. Discrete Dyn Nat Soc. 2020;2020:4318182. doi:10.1155/2020/4318182

- Cao D, Sun Y, Goh E, Wang R, Kuiavska K. Adoption of smart voice assistants technology among Airbnb guests: a revised self-efficacy-based value adoption model (SVAM). Int J Hosp Manag. 2022;101:103124. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.103124

- Yam KC, Tang PM, Jackson JC, Su R, Gray K. The rise of robots increases job insecurity and maladaptive workplace behaviors: multimethod evidence.

Appl Psychol. 2023;108(5):850-870. doi:10.1037/ap10001045 - Wang YY, Wang YS. Development and validation of an artificial intelligence anxiety scale: an initial application in predicting motivated learning behavior. Interact Learn Environ. 2022;30(4):619-634. doi:10.1080/10494820.2019.1674887

- Tarafdar M, Pullins E, Ragu-Nathan TS. Technostress: negative effect on performance and possible mitigations. Inf Syst J. 2015;25(2):103-132. doi:10.1111/isj. 12042

- Saleem F, Malik MI, Qureshi SS, Farid MF, Qamar S. Technostress and employee performance nexus during COVID-19: training and creative self-efficacy as moderators. Front Psychol. 2021;12:595119. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.595119

- Salanova M, Llorens S, Cifre E. The dark side of technologies: technostress among users of information and communication technologies. Int J Psychol. 2013;48(3):422-436. doi:10.1080/00207594.2012.680460

- Chen L, Muthitacharoen A. An empirical investigation of the consequences of technostress: evidence from China. Inf Resour Manag J. 2016;29 (2):14-36. doi:10.4018/IRMJ. 2016040102

- Feng W, Tu R, Lu T, Zhou Z. Understanding forced adoption of self-service technology: the impacts of users’ psychological reactance. Behav Inf Technol. 2019;38(8):820-832. doi:10.1080/0144929X.2018.1557745

- Cavanaugh MA, Boswell WR, Roehling MV, Boudreau JW. An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among U.S. managers.

Appl Psychol. 2000;85(1):65-74. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.85.1.65 - LePine MA. The challenge-hindrance stressor framework: an integrative conceptual review and path forward. Group Organ Manag. 2022;47 (2):223-254. doi:10.1177/10596011221079970

- Benlian A. A daily field investigation of technology-driven spillovers from work to home. MIS Q. 2020;44(3):1259-1300. doi:10.25300/MISQ/2020/14911/

- Yu X, Xu S, Ashton M. Antecedents and outcomes of artificial intelligence adoption and application in the workplace: the socio-technical system theory perspective. Inf Technol People. 2023;36(1):454-474. doi:10.1108/ITP-04-2021-0254

- Parasuraman A, Colby CL. An updated and streamlined technology readiness index: TRI 2.0. J Serv Res. 2015;18(1):59-74. doi:10.1177/ 1094670514539730

- Agogo D, Hess TJ. “How does tech make you feel?” a review and examination of negative affective responses to technology use. Eur J Inf Syst. 2018;27(5):570-599. doi:10.1080/0960085X.2018.1435230

- Lazarus RS. Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. Am Psychol. 1991;46(8):819-834. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.46.8.819

- Li Z, He B, Sun X. Does work stressors lead to abusive supervision? A study of differentiated effects of challenge and hindrance stressors. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2020;13:573-588. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S249071

- Rodell JB, Judge TA. Can “good” stressors spark “bad” behaviors? The mediating role of emotions in links of challenge and hindrance stressors with citizenship and counterproductive behaviors. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94(6):1438-1451. doi:10.1037/a0016752

- Tarafdar M, Bolman Pullins E, Ragu-Nathan TS. Examining impacts of technostress on the professional salesperson’s behavioural performance. J Pers Sell Sales Manag. 2014;34(1):51-69. doi:10.1080/08853134.2013.870184

- Compeau DR, Higgins CA. Computer self-efficacy: development of a measure and initial test. MIS Q. 1995;19(2):189-211. doi:10.2307/249688

- Weiss HM, Cropanzano R. Affective events theory: a theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. In: Staw BM, Cummings LL, editors. Research in Organizational Behavior. Jai Press Inc; 1996:1-74. https://www.webofscience.com/wos/ woscc/summary/b7b37b1a-ffb0-4c3e-a2ff-001699cc6b82-bd627a16/relevance/1. Accessed January 23, 2024.

- Maier C, Laumer S, Tarafdar M, et al. Challenge and hindrance IS use stressors and appraisals: explaining contrarian associations in post-acceptance IS use behavior. J Assoc Inf Syst. 2021;22(6):1590-1624. doi:10.17705/1jais. 00709

- Wood SJ, Michaelides G. Challenge and hindrance stressors and wellbeing-based work-nonwork interference: a diary study of portfolio workers. Hum Relat. 2016;69(1):111-138. doi:10.1177/0018726715580866

- LePine MA, Zhang Y, Crawford ER, Rich BL. Turning their pain to gain: charismatic leader influence on follower stress appraisal and job performance. Acad Manage J. 2016;59(3):1036-1059. doi:10.5465/amj.2013.0778

- Johnson DG, Verdicchio M. AI anxiety. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol. 2017;68(9):2267-2270. doi:10.1002/asi. 23867

- Georgieff A, Hyee R. Artificial intelligence and employment: new cross-country evidence. Front Artif Intell. 2022;5. doi:10.3389/frai.2022.832736

- Li J, Huang JS. Dimensions of artificial intelligence anxiety based on the integrated fear acquisition theory. Technol Soc. 2020;63:101410. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101410

- Bondanini G, Giorgi G, Ariza-Montes A, Vega-Muñoz A, Andreucci-Annunziata P. Technostress dark side of technology in the workplace: a scientometric analysis. Int

Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):8013. doi:10.3390/ijerph17218013 - Sahu AK, Padhy RK, Dhir A. Envisioning the future of behavioral decision-making: a systematic literature review of behavioral reasoning theory. Australas Mark J. 2020;28(4):145-159. doi:10.1016/j.ausmj.2020.05.001

- Gkinko L, Elbanna A. Hope, tolerance and empathy: employees’ emotions when using an AI-enabled chatbot in a digitalised workplace. Inf Technol People. 2022;35(6):1714-1743. doi:10.1108/ITP-04-2021-0328

- Stam KR, Stanton JM. Events, emotions, and technology: examining acceptance of workplace technology changes. Inf Technol People. 2010;23 (1):23-53. doi:10.1108/09593841011022537

- Chiu YT, Zhu YQ, Corbett J. In the hearts and minds of employees: a model of pre-adoptive appraisal toward artificial intelligence in organizations. Int J Inf Manag. 2021;60:102379. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102379

- Gursoy D, Chi OH, Lu L, Nunkoo R. Consumers acceptance of artificially intelligent (AI) device use in service delivery. Int J Inf Manag. 2019;49:157-169. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.03.008

- Ding Y. Modelling continued use of information systems from a forward-looking perspective: antecedents and consequences of hope and anticipated regret. Inf Manage. 2018;55(4):461-471. doi:10.1016/j.im.2017.11.001

- Chatterjee S, Bhattacharjee KK. Adoption of artificial intelligence in higher education: a quantitative analysis using structural equation modelling. Educ Inf Technol. 2020;25(5):3443-3463. doi:10.1007/s10639-020-10159-7

- Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol. 2001;56 (3):218-226. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

- Huang MH, Rust RT. Artificial Intelligence in Service. J Serv Res. 2018;21(2):155-172. doi:10.1177/1094670517752459

- Evanschitzky H, Iyer GR, Pillai KG, Kenning P, Schuete R. Consumer trial, continuous use, and economic benefits of a retail service innovation: the case of the personal shopping assistant. J Prod Innov Manag. 2015;32(3):459-475. doi:10.1111/jpim.12241

- Kaya F, Aydin F, Schepman A, Rodway P, Yetisensoy O, Kaya MD. The roles of personality traits, AI anxiety, and demographic factors in attitudes toward artificial intelligence. Int J Hum-Comput Interact. 2022. doi:10.1080/10447318.2022.2151730

- Horan KA, Nakahara WH, DiStaso MJ, Jex SM. A review of the challenge-hindrance stress model: recent advances, expanded paradigms, and recommendations for future research. Front Psychol. 2020;11:560346. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.560346

- Yang Y, Li X. The impact of challenge and hindrance stressors on thriving at work double mediation based on affect and motivation. Front Psychol. 2021;12:613871. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.613871

- Huang MH, Rust RT. A strategic framework for artificial intelligence in marketing. J Acad Marking Sci. 2021;49(1):30-50. doi:10.1007/s11747-020-00749-9

- McClure PK. “You’re Fired”, says the robot: the rise of automation in the workplace, technophobes, and fears of unemployment. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2018;36(2):139-156. doi:10.1177/0894439317698637

- Brougham D, Haar J. Smart technology, artificial intelligence, robotics, and algorithms (STARA): employees’ perceptions of our future workplace. J Manag Organ. 2018;24(2):239-257. doi:10.1017/jmo.2016.55

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol. 1982;37(2):122-147. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

- Kim DG, Lee CW. Exploring the roles of self-efficacy and technical support in the relationship between techno-stress and counter-productivity. Sustainability. 2021;13(8):4349. doi:10.3390/su13084349

- Sun LY, Aryee S, Law KS. High-performance human resource practices, citizenship behavior, and organizational performance: a relational perspective. Acad Manage J. 2007;50(3):558-577. doi:10.5465/amj.2007.25525821

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies.

Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879-903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 - Brislin RW. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. Methodology. 1980;1980:389-444.

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063-1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

- Turja T, Rantanen T, Oksanen A. Robot use self-efficacy in healthcare work (RUSH): development and validation of a new measure. AI Soc. 2019;34(1):137-143. doi:10.1007/s00146-017-0751-2

- Karahanna E, Straub D, Chervany N. Information technology adoption across time: a cross-sectional comparison of pre-adoption and post-adoption beliefs. MIS Q Manag Inf Syst. 1999;23(2):183-213. doi:10.2307/249751

- Yi M, Choi H. What drives the acceptance of AI technology?: the role of expectations and experiences. arXiv preprint arXiv. 2023;16:1. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2306.13670

- Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Guilford Press; 2013.

- Kyndt E, Onghena P. The Integration of Work and Learning: tackling the Complexity with Structural Equation Modelling. In: Harteis C, Rausch A, Seifried J editors. Discourses on Professional Learning. Professional and Practice-based Learning. Springer Netherlands; 2014:255-291. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7012-6_14

- Li JJ, Bonn MA, Ye BH. Hotel employee’s artificial intelligence and robotics awareness and its impact on turnover intention: the moderating roles of perceived organizational support and competitive psychological climate. Tour Manag. 2019;73:172-181. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2019.02.006

- Duke AB, Goodman JM, Treadway DC, Breland JW. Perceived organizational support as a moderator of emotional labor/outcomes relationships. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2009;39(5):1013-1034. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2009.00470.x

- Chowdhury S, Dey P, Joel-Edgar S, et al. Unlocking the value of artificial intelligence in human resource management through AI capability framework. Hum Resour Manag Rev. 2023;33(1):100899. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2022.100899

- Nastjuk I, Trang S, Grummeck-Braamt JV, Adam MTP, Tarafdar M. Integrating and synthesising technostress research: a meta-analysis on technostress creators, outcomes, and IS usage contexts. Eur J Inf Syst. 2023;1-22. doi:10.1080/0960085X.2022.2154712

- Wei W, Li L. The impact of artificial intelligence on the mental health of manufacturing workers: the mediating role of overtime work and the work environment. Front Public Health. 2022;10:862407. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.862407

- Gagné M, Parent-Rocheleau X, Bujold A, Gaudet MC, Lirio P. How algorithmic management influences worker motivation: a Self-Determination Theory perspective. Can Psychol. 2022;63(2):247-260. doi:10.1037/cap0000324

- Chang PC, Guo Y, Cai Q, Guo H. Proactive career orientation and subjective career success: a perspective of career construction theory. Behav Sci. 2023;13(6):503. doi:10.3390/bs13060503

البحث النفسي وإدارة السلوك

دوفيبرس

انشر عملك في هذه المجلة

- ملاحظات:

; .

الاختصارات: CTS، ضغوط التكنولوجيا التحدي؛ HTS، ضغوط التكنولوجيا المعيقة.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.s441444

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38343429

Publication Date: 2024-02-01

Does Al-Driven Technostress Promote or Hinder Employees’ Artificial Intelligence Adoption Intention? A Moderated Mediation Model of Affective Reactions and Technical Self-Efficacy

Abstract

Purpose: The increasing integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) within enterprises is generates significant technostress among employees, potentially influencing their intention to adopt AI. However, existing research on the psychological effects of this phenomenon remains inconclusive. Drawing on the Affective Events Theory (AET) and the Challenge-Hindrance Stressor Framework (CHSF), the current study aims to explore the “black box” between challenge and hindrance technology stressors and employees’ intention to adopt AI, as well as the boundary conditions of this mediation relationship. Methods: The study employs a quantitative approach and utilizes three-wave data. Data were collected through the snowball sampling technique and a structured questionnaire survey. The sample comprises employees from 11 distinct organizations located in Guangdong Province, China. We received 301 valid questionnaires, representing an overall response rate of

Introduction

pivotal role in contemporary business landscapes. However, changing technology requirements also lead to technostress among employees, posing challenges and hindrances. How to enhance the employee’s AI adoption intention becomes the key in achieving competitive advantages among corporations.

Theoretical Foundation and Research Hypotheses

Al-Driven Challenge and Hindrance Technology Stressors and Affective Reactions

H1b: AI-driven hindrance technology stressors are positively related to AI anxiety.

Affective Reactions and AI Adoption Intention

H2b. AI anxiety is negatively related to AI adoption intention.

The Mediating Role of Affective Reactions

H3b: AI anxiety mediates the relationship between hindrance technology stressors and AI adoption intention.

The Moderating Role of Technical Self-Efficacy

Research Method

Study Design

Participants

Measures

| Characteristics | Categories | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| Gender | Male | 154 | 51.2 |

| Female | 147 | 48.8 | |

| AGE | Below the age of 26 | 68 | 22.6 |

| 26-30 | 72 | 23.9 | |

| 31-35 | 62 | 20.6 | |

| 36-40 | 51 | 16.9 | |

| Above the age of 40 | 48 | 16.0 | |

| Occupational roles | Ordinary employees | 114 | 37.9 |

| Frontline workers | 135 | 44.9 | |

| Middle or senior managers | 52 | 17.2 | |

| Education | College’s degrees or lower | 59 | 19.6 |

| Bachelor’s degrees | 113 | 37.5 | |

| Master’s degrees or beyond | 129 | 42.9 |

AI-Driven Challenge and Hindrance Technology Stressors

Positive Affect

Al Anxiety

Technical Self-Efficacy

Al Adoption Intention

Control Variables

Data Analysis

tool,

Results

Confirmatory Method Variance and Discriminant Validity

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

| Measurement Model |

|

df |

|

CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA |

| Six-factor model | 2229.81 | 1259 | 1.77 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Five-factor model | 2702.63 | 1264 | 2.14 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.12 | 0.06 |

| Four-factor model | 4488.30 | 1268 | 3.54 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.14 | 0.09 |

| Three-factor model | 7358.06 | 1271 | 5.78 | 0.67 | 0.65 | 0.18 | 0.13 |

| Two-factor model | 9072.86 | 1273 | 7.13 | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.18 | 0.14 |

| One-factor model | 9397.50 | 1274 | 7.38 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.14 | 0.15 |

Abbreviations: CFI, Comparative Fit Index (cutoff value, 0.90); TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index (cutoff value, 0.90); SRMR, Standardized Root Mean square (cutoff value, 0.05); RMSEA, Root Mean Square of Approximation (cutoff value, 0.06).

| Variables | M | SD | I | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| I. Gender | 0.51 | 0.50 | |||||||||

| 2. Age | 2.80 | 1.38 | 0.06 | ||||||||

| 3. Position | 1.79 | 0.72 | 0.23*** | 0.58*** | |||||||

| 4. Education | 2.23 | 0.76 | 0.13* | 0.51*** | 0.60*** | ||||||

| 5. CTS | 3.26 | 1.09 | 0.23*** | 0.09 | 0.20*** | 0.30*** | |||||

| 6. HTS | 3.11 | 1.02 | -0.17** | -0.12* | -0.23*** | -0.28*** | -0.53*** | ||||

| 7. Positive affect | 3.33 | 1.17 | 0.14* | 0.09 | 0.20*** | 0.35*** | 0.59*** | -0.55*** | |||

| 8. AI anxiety | 3.01 | 1.11 | -0.20** | -0.04 | -0.22*** | -0.34*** | -0.55*** | 0.55*** | -0.58*** | ||

| 9. Technical self-efficacy | 2.88 | 0.80 | 0.05 | -0.05 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.47*** | -0.02 | 0.40*** | -0.04 | |

| 10. AI adoption intention | 3.31 | 1.10 | 0.21*** | 0.13* | 0.24*** | 0.28*** | 0.53*** | -0.53*** | 0.56*** | -0.53*** | 0.10 |

Hypotheses Testing

| Variables | MI-I

|

MI-2 XI

|

MI-3 MI

|

MI-4

|

M2-I

|

M2-2 X2

|

M2-3

|

M2-4

|

| Constant | 1.21*** | 0.89*** | 1.23*** | 0.90*** | 4.31*** | 2.06*** | 4.25*** | 4.97*** |

| Gender | 0.16 | -0.01 | 0.25* | 0.16 | 0.23* | -0.18 | 0.21 | 0.17 |

| Age | -0.00 | -0.06 | 0.01 | 0.02 | -0.02 | 0.14** | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Position | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.08 | -0.06 | 0.08 | 0.06 |

| Education | 0.11 | 0.35*** | 0.03 | -0.01 | 0.16 | -0.38*** | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| CTS | 0.48*** | 0.56*** | 0.29*** | |||||

| HTS | -0.5|*** | 0.52*** | -0.34*** | |||||

| Al anxiety | 0.49*** | 0.34*** | -0.48*** | -0.32*** | ||||

| Effect | Bootstrap results for indirect effect | Bootstrap results for indirect effect | ||||||

| M | SE | LLCI | ULCI | M | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.31 | -0.17 | 0.05 | -0.29 | -0.08 | |

Abbreviations: CTS, challenge technology stressors; HTS, hindrance technology stressors; LL, lower limit; UL, upper limit; CI, confidence interval.

| Predictor | Positive Affect | Al Anxiety | ||||||

| B | SE | t | p | B | SE | t | p | |

| Moderation model | ||||||||

| Constant | 2.77 | 0.15 | 18.20 | <0.001 | 3.43 | 0.16 | 20.91 | <0.001 |

| Gender | -0.09 | 0.09 | -0.96 | >0.05 | -0.16 | 0.10 | -1.68 | >0.05 |

| Age | -0.03 | 0.04 | -0.69 | >0.05 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 2.62 | <0.01 |

| Position | -0.00 | 0.08 | -0.04 | >0.05 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.51 | >0.05 |

| Education | 0.22 | 0.08 | 2.80 | <0.01 | -0.33 | 0.08 | -4.08 | <0.001 |

| CTS | 0.74 | 0.05 | 13.71 | <0.001 | ||||

| HTS | 0.46 | 0.05 | 9.50 | <0.001 | ||||

| Technical self-efficacy | 0.10 | 0.06 | 1.66 | >0.05 | -0.19 | 0.06 | -3.06 | <0.01 |

| CTS

|

0.51 | 0.04 | 11.87 | <0.001 | ||||

| HTS

|

-0.37 | 0.05 | -7.82 | <0.001 | ||||

| Moderated mediation model | ||||||||

| Technical self-efficacy | indirect effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | indirect effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| Index of moderated mediation | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.22 |

| Conditional indirect effect at Technical self-efficacy = M

|

||||||||

| M-ISD | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.23 | -0.24 | 0.08 | -0.41 | -0.12 |

| M+ISD | 0.40 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.65 | -0.05 | 0.04 | -0.14 | 0.02 |

Abbreviations: CTS, challenge technology stressors; HTS, hindrance technology stressors; LL, lower limit; UL, upper limit; CI, confidence interval.

efficacy. In contrast, Figure 3 demonstrates that the positive relationship between AI-driven hindrance technology stressors and AI anxiety is less prominent among individuals with high technical self-efficacy when compared to those with low technical self-efficacy. Thus, Hypotheses 4 a and 4 b were supported.

Discussion

Theoretical Implications

First, the current study enriches the existing literature on AI technology adoption by unraveling the antecedent variable of technostress. Previous research on whether technostress is beneficial or detrimental to employees has produced inconsistent results. This study investigates the dualistic nature of technostress, distinguishing challenge and hindrance technostress in the context of AI applications, to deepen the understanding of employees’ AI adoption intention.

study reveals how technical self-efficacy moderates the impact of AI-driven technostress on technology adoption through emotional reactions, providing valuable supplementation to the study of AI technology applications.

Practical Implications

Limitation and Future Research

Conclusion

Ethics Statement

Acknowledgments

Funding

Disclosure

References

- Haenlein M, Kaplan A. A brief history of artificial intelligence: on the past, present, and future of artificial intelligence. Calif Manage Rev. 2019;61 (4):5-14. doi:10.1177/0008125619864925

- Duan Y, Edwards JS, Dwivedi YK. Artificial intelligence for decision making in the era of big data – evolution, challenges and research agenda. Int J Inf Manag. 2019;48:63-71. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.01.021

- Paschen J, Wilson M, Ferreira JJ. Collaborative intelligence: how human and artificial intelligence create value along the B2B sales funnel. Bus Horiz. 2020;63(3):403-414. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2020.01.003

- Belanche D, Casaló LV, Flavián C. Artificial Intelligence in FinTech: understanding robo-advisors adoption among customers. Ind Manag Data Syst. 2019;119(7):1411-1430. doi:10.1108/IMDS-08-2018-0368

- Joehnk J, Weissert M, Wyrtki K. Ready or not, AI comes- An interview study of organizational AI readiness factors. Bus Inf Syst Eng. 2021;63 (1):5-20. doi:10.1007/s12599-020-00676-7

- Nam K, Dutt CS, Chathoth P, Daghfous A, Khan MS. The adoption of artificial intelligence and robotics in the hotel industry: prospects and challenges. Electron Mark. 2021;31(3):553-574. doi:10.1007/s12525-020-00442-3

- Mingotto E, Montaguti F, Tamma M. Challenges in re-designing operations and jobs to embody AI and robotics in services. Findings from a case in the hospitality industry. Electron Mark. 2021;31(3):493-510. doi:10.1007/s12525-020-00439-y

- Lakshmi V, Bahli B. Understanding the robotization landscape transformation: a centering resonance analysis. J Innov Knowl. 2020;5(1):59-67. doi:10.1016/j.jik.2019.01.005

- Braganza A, Chen W, Canhoto A, Sap S. Productive employment and decent work: the impact of AI adoption on psychological contracts, job engagement and employee trust.

Bus Res. 2021;131:485-494. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.08.018 - Cheng B, Lin H, Kong Y. Challenge or hindrance? How and when organizational artificial intelligence adoption influences employee job crafting. J Bus Res. 2023;164:113987. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.113987

- Ghosh B, Daugherty PR, Wilson HJ, Burden A. Taking a systems approach to adopting AI. Harv Bus Rev. 2019;2019:1.

- Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989;13(3):319-340. doi:10.2307/ 249008

- Tornatzky LG, Fleischer M, Chakrabarti AK. The Processes of Technological Innovation. Lexington Books; 1990.

- Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, Davis FD. User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003;27(3):425-478. doi:10.2307/30036540

- Pan Y, Froese F, Liu N, Hu Y, Ye M. The adoption of artificial intelligence in employee recruitment: the influence of contextual factors. Int

Hum Resour Manag. 2022;33(6):1125-1147. doi:10.1080/09585192.2021.1879206 - Sohn K, Kwon O. Technology acceptance theories and factors influencing artificial Intelligence-based intelligent products. Telemat Inform. 2020;47:101324. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2019.101324

- Flavián C, Pérez-Rueda A, Belanche D, Casaló LV. Intention to use analytical artificial intelligence (AI) in services-the effect of technology readiness and awareness. J Serv Manag. 2022;33(2):293-320. doi:10.1108/JOSM-10-2020-0378

- Liu M, Wu J, Zhu C, Hu K. Factors influencing the acceptance of robo-taxi services in China: an extended technology acceptance model analysis. J Adv Transp. 2022;2022:8461212. doi:10.1155/2022/8461212

- Moussawi S, Koufaris M, Benbunan-Fich R. How perceptions of intelligence and anthropomorphism affect adoption of personal intelligent agents. Electron Mark. 2021;31(2):343-364. doi:10.1007/s12525-020-00411-w

- Chen J, Li R, Gan M, Fu Z, Yuan F. Public acceptance of driverless buses in China: an empirical analysis based on an extended UTAUT model. Discrete Dyn Nat Soc. 2020;2020:4318182. doi:10.1155/2020/4318182

- Cao D, Sun Y, Goh E, Wang R, Kuiavska K. Adoption of smart voice assistants technology among Airbnb guests: a revised self-efficacy-based value adoption model (SVAM). Int J Hosp Manag. 2022;101:103124. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.103124

- Yam KC, Tang PM, Jackson JC, Su R, Gray K. The rise of robots increases job insecurity and maladaptive workplace behaviors: multimethod evidence.

Appl Psychol. 2023;108(5):850-870. doi:10.1037/ap10001045 - Wang YY, Wang YS. Development and validation of an artificial intelligence anxiety scale: an initial application in predicting motivated learning behavior. Interact Learn Environ. 2022;30(4):619-634. doi:10.1080/10494820.2019.1674887

- Tarafdar M, Pullins E, Ragu-Nathan TS. Technostress: negative effect on performance and possible mitigations. Inf Syst J. 2015;25(2):103-132. doi:10.1111/isj. 12042

- Saleem F, Malik MI, Qureshi SS, Farid MF, Qamar S. Technostress and employee performance nexus during COVID-19: training and creative self-efficacy as moderators. Front Psychol. 2021;12:595119. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.595119

- Salanova M, Llorens S, Cifre E. The dark side of technologies: technostress among users of information and communication technologies. Int J Psychol. 2013;48(3):422-436. doi:10.1080/00207594.2012.680460

- Chen L, Muthitacharoen A. An empirical investigation of the consequences of technostress: evidence from China. Inf Resour Manag J. 2016;29 (2):14-36. doi:10.4018/IRMJ. 2016040102

- Feng W, Tu R, Lu T, Zhou Z. Understanding forced adoption of self-service technology: the impacts of users’ psychological reactance. Behav Inf Technol. 2019;38(8):820-832. doi:10.1080/0144929X.2018.1557745

- Cavanaugh MA, Boswell WR, Roehling MV, Boudreau JW. An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among U.S. managers.

Appl Psychol. 2000;85(1):65-74. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.85.1.65 - LePine MA. The challenge-hindrance stressor framework: an integrative conceptual review and path forward. Group Organ Manag. 2022;47 (2):223-254. doi:10.1177/10596011221079970

- Benlian A. A daily field investigation of technology-driven spillovers from work to home. MIS Q. 2020;44(3):1259-1300. doi:10.25300/MISQ/2020/14911/

- Yu X, Xu S, Ashton M. Antecedents and outcomes of artificial intelligence adoption and application in the workplace: the socio-technical system theory perspective. Inf Technol People. 2023;36(1):454-474. doi:10.1108/ITP-04-2021-0254

- Parasuraman A, Colby CL. An updated and streamlined technology readiness index: TRI 2.0. J Serv Res. 2015;18(1):59-74. doi:10.1177/ 1094670514539730

- Agogo D, Hess TJ. “How does tech make you feel?” a review and examination of negative affective responses to technology use. Eur J Inf Syst. 2018;27(5):570-599. doi:10.1080/0960085X.2018.1435230

- Lazarus RS. Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. Am Psychol. 1991;46(8):819-834. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.46.8.819

- Li Z, He B, Sun X. Does work stressors lead to abusive supervision? A study of differentiated effects of challenge and hindrance stressors. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2020;13:573-588. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S249071

- Rodell JB, Judge TA. Can “good” stressors spark “bad” behaviors? The mediating role of emotions in links of challenge and hindrance stressors with citizenship and counterproductive behaviors. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94(6):1438-1451. doi:10.1037/a0016752

- Tarafdar M, Bolman Pullins E, Ragu-Nathan TS. Examining impacts of technostress on the professional salesperson’s behavioural performance. J Pers Sell Sales Manag. 2014;34(1):51-69. doi:10.1080/08853134.2013.870184

- Compeau DR, Higgins CA. Computer self-efficacy: development of a measure and initial test. MIS Q. 1995;19(2):189-211. doi:10.2307/249688

- Weiss HM, Cropanzano R. Affective events theory: a theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. In: Staw BM, Cummings LL, editors. Research in Organizational Behavior. Jai Press Inc; 1996:1-74. https://www.webofscience.com/wos/ woscc/summary/b7b37b1a-ffb0-4c3e-a2ff-001699cc6b82-bd627a16/relevance/1. Accessed January 23, 2024.

- Maier C, Laumer S, Tarafdar M, et al. Challenge and hindrance IS use stressors and appraisals: explaining contrarian associations in post-acceptance IS use behavior. J Assoc Inf Syst. 2021;22(6):1590-1624. doi:10.17705/1jais. 00709

- Wood SJ, Michaelides G. Challenge and hindrance stressors and wellbeing-based work-nonwork interference: a diary study of portfolio workers. Hum Relat. 2016;69(1):111-138. doi:10.1177/0018726715580866

- LePine MA, Zhang Y, Crawford ER, Rich BL. Turning their pain to gain: charismatic leader influence on follower stress appraisal and job performance. Acad Manage J. 2016;59(3):1036-1059. doi:10.5465/amj.2013.0778

- Johnson DG, Verdicchio M. AI anxiety. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol. 2017;68(9):2267-2270. doi:10.1002/asi. 23867

- Georgieff A, Hyee R. Artificial intelligence and employment: new cross-country evidence. Front Artif Intell. 2022;5. doi:10.3389/frai.2022.832736

- Li J, Huang JS. Dimensions of artificial intelligence anxiety based on the integrated fear acquisition theory. Technol Soc. 2020;63:101410. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101410

- Bondanini G, Giorgi G, Ariza-Montes A, Vega-Muñoz A, Andreucci-Annunziata P. Technostress dark side of technology in the workplace: a scientometric analysis. Int

Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):8013. doi:10.3390/ijerph17218013 - Sahu AK, Padhy RK, Dhir A. Envisioning the future of behavioral decision-making: a systematic literature review of behavioral reasoning theory. Australas Mark J. 2020;28(4):145-159. doi:10.1016/j.ausmj.2020.05.001

- Gkinko L, Elbanna A. Hope, tolerance and empathy: employees’ emotions when using an AI-enabled chatbot in a digitalised workplace. Inf Technol People. 2022;35(6):1714-1743. doi:10.1108/ITP-04-2021-0328

- Stam KR, Stanton JM. Events, emotions, and technology: examining acceptance of workplace technology changes. Inf Technol People. 2010;23 (1):23-53. doi:10.1108/09593841011022537

- Chiu YT, Zhu YQ, Corbett J. In the hearts and minds of employees: a model of pre-adoptive appraisal toward artificial intelligence in organizations. Int J Inf Manag. 2021;60:102379. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102379

- Gursoy D, Chi OH, Lu L, Nunkoo R. Consumers acceptance of artificially intelligent (AI) device use in service delivery. Int J Inf Manag. 2019;49:157-169. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.03.008

- Ding Y. Modelling continued use of information systems from a forward-looking perspective: antecedents and consequences of hope and anticipated regret. Inf Manage. 2018;55(4):461-471. doi:10.1016/j.im.2017.11.001

- Chatterjee S, Bhattacharjee KK. Adoption of artificial intelligence in higher education: a quantitative analysis using structural equation modelling. Educ Inf Technol. 2020;25(5):3443-3463. doi:10.1007/s10639-020-10159-7

- Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol. 2001;56 (3):218-226. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

- Huang MH, Rust RT. Artificial Intelligence in Service. J Serv Res. 2018;21(2):155-172. doi:10.1177/1094670517752459

- Evanschitzky H, Iyer GR, Pillai KG, Kenning P, Schuete R. Consumer trial, continuous use, and economic benefits of a retail service innovation: the case of the personal shopping assistant. J Prod Innov Manag. 2015;32(3):459-475. doi:10.1111/jpim.12241

- Kaya F, Aydin F, Schepman A, Rodway P, Yetisensoy O, Kaya MD. The roles of personality traits, AI anxiety, and demographic factors in attitudes toward artificial intelligence. Int J Hum-Comput Interact. 2022. doi:10.1080/10447318.2022.2151730

- Horan KA, Nakahara WH, DiStaso MJ, Jex SM. A review of the challenge-hindrance stress model: recent advances, expanded paradigms, and recommendations for future research. Front Psychol. 2020;11:560346. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.560346

- Yang Y, Li X. The impact of challenge and hindrance stressors on thriving at work double mediation based on affect and motivation. Front Psychol. 2021;12:613871. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.613871

- Huang MH, Rust RT. A strategic framework for artificial intelligence in marketing. J Acad Marking Sci. 2021;49(1):30-50. doi:10.1007/s11747-020-00749-9

- McClure PK. “You’re Fired”, says the robot: the rise of automation in the workplace, technophobes, and fears of unemployment. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2018;36(2):139-156. doi:10.1177/0894439317698637

- Brougham D, Haar J. Smart technology, artificial intelligence, robotics, and algorithms (STARA): employees’ perceptions of our future workplace. J Manag Organ. 2018;24(2):239-257. doi:10.1017/jmo.2016.55

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol. 1982;37(2):122-147. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

- Kim DG, Lee CW. Exploring the roles of self-efficacy and technical support in the relationship between techno-stress and counter-productivity. Sustainability. 2021;13(8):4349. doi:10.3390/su13084349

- Sun LY, Aryee S, Law KS. High-performance human resource practices, citizenship behavior, and organizational performance: a relational perspective. Acad Manage J. 2007;50(3):558-577. doi:10.5465/amj.2007.25525821

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies.

Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879-903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 - Brislin RW. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. Methodology. 1980;1980:389-444.

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063-1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

- Turja T, Rantanen T, Oksanen A. Robot use self-efficacy in healthcare work (RUSH): development and validation of a new measure. AI Soc. 2019;34(1):137-143. doi:10.1007/s00146-017-0751-2

- Karahanna E, Straub D, Chervany N. Information technology adoption across time: a cross-sectional comparison of pre-adoption and post-adoption beliefs. MIS Q Manag Inf Syst. 1999;23(2):183-213. doi:10.2307/249751

- Yi M, Choi H. What drives the acceptance of AI technology?: the role of expectations and experiences. arXiv preprint arXiv. 2023;16:1. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2306.13670

- Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Guilford Press; 2013.

- Kyndt E, Onghena P. The Integration of Work and Learning: tackling the Complexity with Structural Equation Modelling. In: Harteis C, Rausch A, Seifried J editors. Discourses on Professional Learning. Professional and Practice-based Learning. Springer Netherlands; 2014:255-291. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7012-6_14

- Li JJ, Bonn MA, Ye BH. Hotel employee’s artificial intelligence and robotics awareness and its impact on turnover intention: the moderating roles of perceived organizational support and competitive psychological climate. Tour Manag. 2019;73:172-181. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2019.02.006

- Duke AB, Goodman JM, Treadway DC, Breland JW. Perceived organizational support as a moderator of emotional labor/outcomes relationships. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2009;39(5):1013-1034. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2009.00470.x

- Chowdhury S, Dey P, Joel-Edgar S, et al. Unlocking the value of artificial intelligence in human resource management through AI capability framework. Hum Resour Manag Rev. 2023;33(1):100899. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2022.100899

- Nastjuk I, Trang S, Grummeck-Braamt JV, Adam MTP, Tarafdar M. Integrating and synthesising technostress research: a meta-analysis on technostress creators, outcomes, and IS usage contexts. Eur J Inf Syst. 2023;1-22. doi:10.1080/0960085X.2022.2154712

- Wei W, Li L. The impact of artificial intelligence on the mental health of manufacturing workers: the mediating role of overtime work and the work environment. Front Public Health. 2022;10:862407. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.862407

- Gagné M, Parent-Rocheleau X, Bujold A, Gaudet MC, Lirio P. How algorithmic management influences worker motivation: a Self-Determination Theory perspective. Can Psychol. 2022;63(2):247-260. doi:10.1037/cap0000324

- Chang PC, Guo Y, Cai Q, Guo H. Proactive career orientation and subjective career success: a perspective of career construction theory. Behav Sci. 2023;13(6):503. doi:10.3390/bs13060503

Psychology Research and Behavior Management

Dovepress

Publish your work in this journal

- Notes:

; .

Abbreviations: CTS, challenge technology stressors; HTS, hindrance technology stressors.