DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03341-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39833405

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-01

واجهة دماغ-كمبيوتر عالية الأداء لفك تشفير الأصابع والتحكم في لعبة الطائرات الرباعية لدى فرد مصاب بالشلل

تاريخ القبول: 3 أكتوبر 2024

تاريخ النشر على الإنترنت: 20 يناير 2025

تحقق من التحديثات

□

الملخص

, ظهرت مجموعة متنوعة

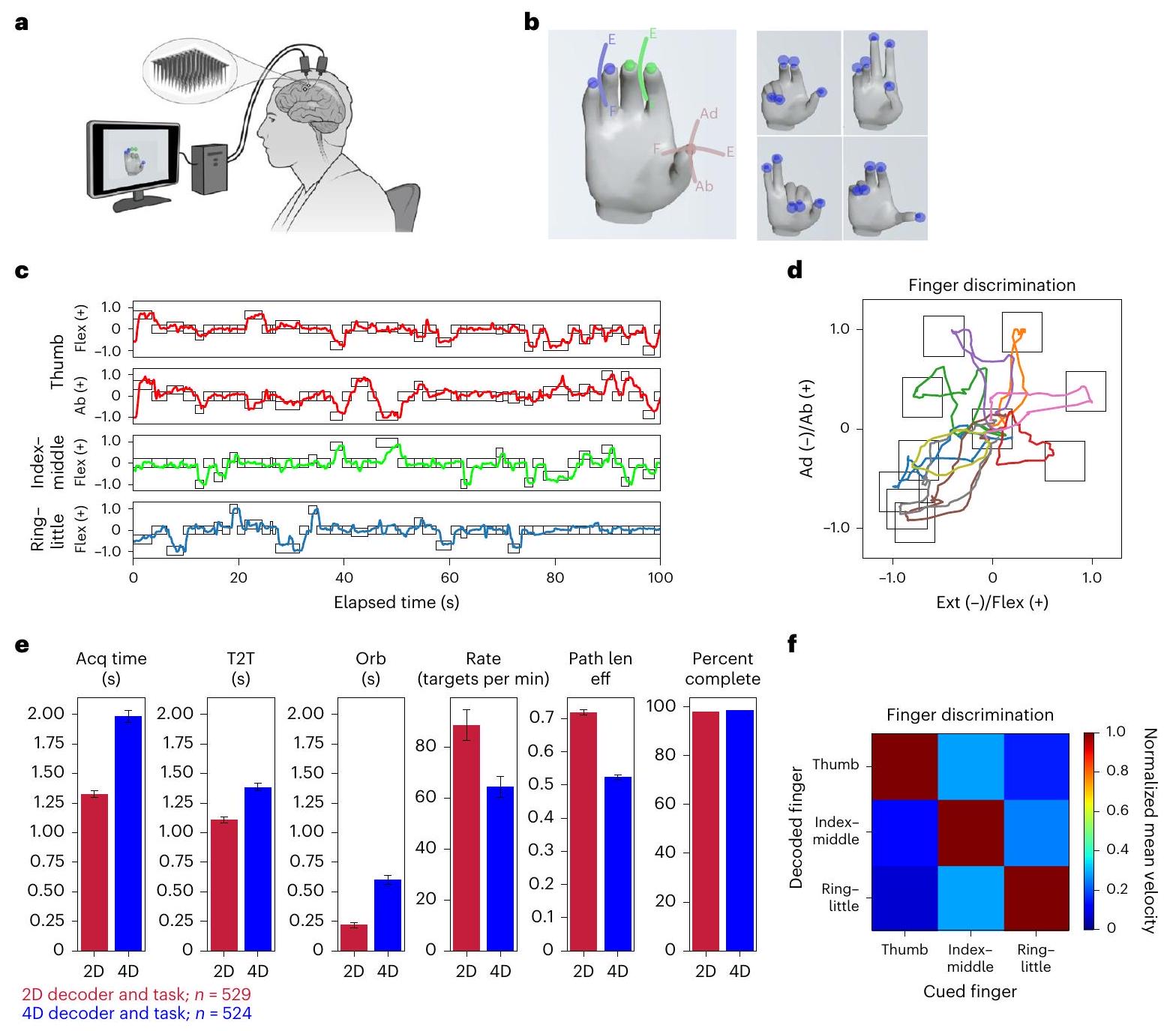

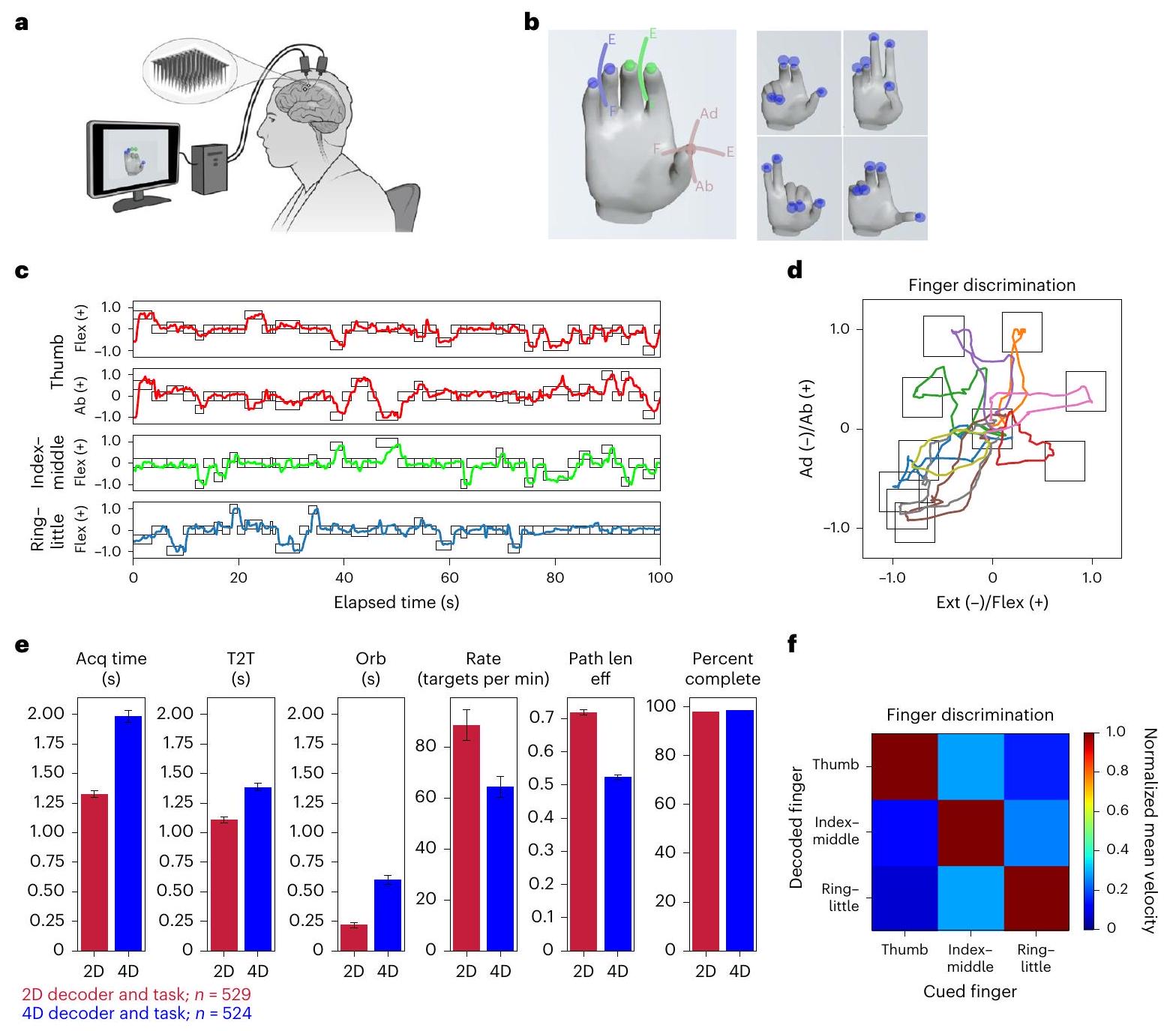

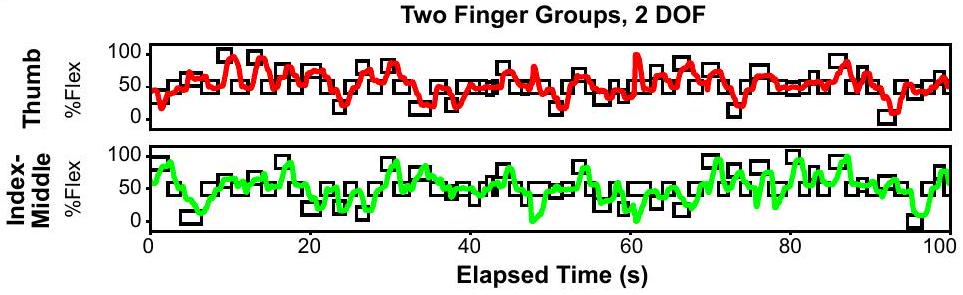

الشكل 1 | نظام iBCI لحركات الأصابع البارعة. أ، تم وضع شاشة الكمبيوتر أمام المشارك بحيث يمكنه أداء مهمة إصبع باستخدام يد افتراضية. خلال التحكم في الحلقة المغلقة، يتم رسم النشاط الكهربائي من المجموعة إلى إشارة تحكم للأصابع الافتراضية. تم تعديل اللوحة من المرجع 27. ب، يسار، يتحرك الإبهام في بعدين، التباعد (Ab) والتقارب (Ad) (الانثناء/التمديد والتباعد/التقارب)، وتتحرك الأصابع الوسطى والخاتمية في قوس أحادي البعد. يمين، تجارب تظهر أهدافًا نموذجية لجميع مجموعات الأصابع الثلاثة لمهمة الأربعة درجات من الحرية. ج، يتم تصوير مقطع زمني مدته 100 ثانية من الحركات المفككة النموذجية لمجموعة الأصابع الثلاثة، مهمة الأربعة درجات من الحرية. يتم وصف المسارات على مدى يتراوح من -1 إلى 1، حيث يشير 1 إلى الانثناء الكامل (flex) أو التباعد (ab) و-1 يشير إلى التمديد (ext) أو التقارب (ad). د، المسارات لكتلة تجريبية توضيحية من 50 تجربة لحركات الإبهام ثنائية الأبعاد، تظهر فقط التجارب التي يتحرك فيها الإبهام لمسافة أكبر من 0.3. يمثل كل لون تجارب متزاوجة متميزة، من المركز إلى الخارج. هـ، إحصائيات ملخصة تقارن بين مهمتي درجتين وأربعة درجات من الحرية لوقت الاكتساب (Acq time)، ووقت الهدف (T2T)، ووقت الدوران (Orb)، ومعدل الاكتساب (Rate)، وكفاءة طول المسار (Path len eff) ونسبة التجارب التي تم إكمالها بنجاح (نسبة الاكتمال). تمثل أشرطة الخطأ الخطأ المعياري للمتوسط. كانت هناك

استعادة الحركة، يمكن أن تمكن التحكم المتقدم في ألعاب الفيديو للأشخاص المصابين بالشلل – وبشكل أوسع، التحكم في الواجهات الرقمية للتواصل الاجتماعي أو العمل عن بُعد.

النتائج

| فك التشفير ثنائي الأبعاد | فك التشفير رباعي الأبعاد | جهاز فك التشفير رباعي الأبعاد (آخر أربع كتل) | |

| عدد التجارب | 529 | 524 | 192 |

| عدد الأيام | ٣ | ٦ | ٣ |

| وقت الاستحواذ (مللي ثانية) |

|

|

|

| وقت الاستهداف (مللي ثانية) |

|

|

|

| زمن المدار (مللي ثانية) |

|

|

|

| الأهداف في الدقيقة |

|

|

|

| نسبة الإنجاز | 98.1٪ | 98.7٪ | 100% |

| طول المسار |

|

|

|

معدل اكتساب الهدف من

أبعاد النشاط العصبي

أثر عدد درجات الحرية النشطة على فك التشفير

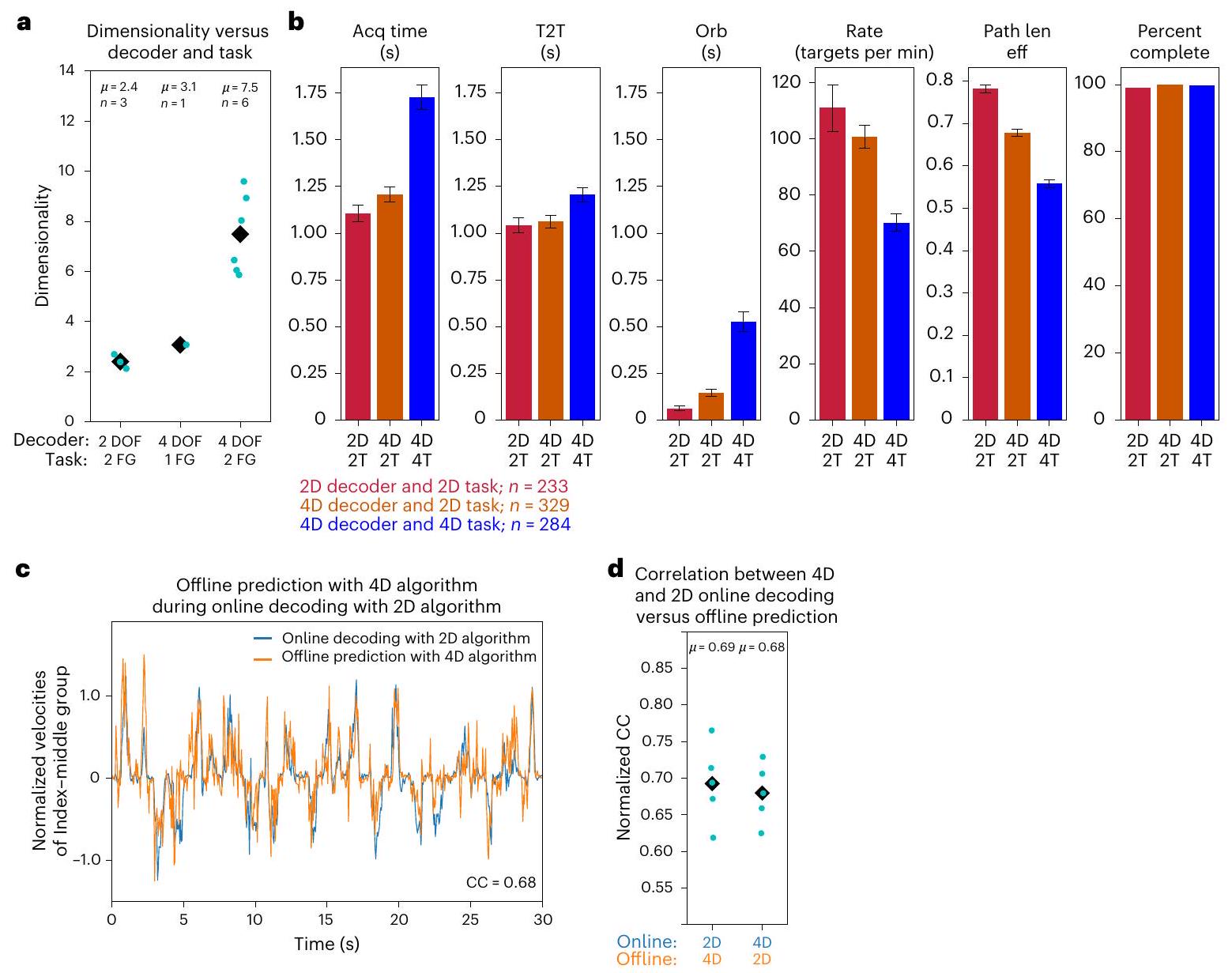

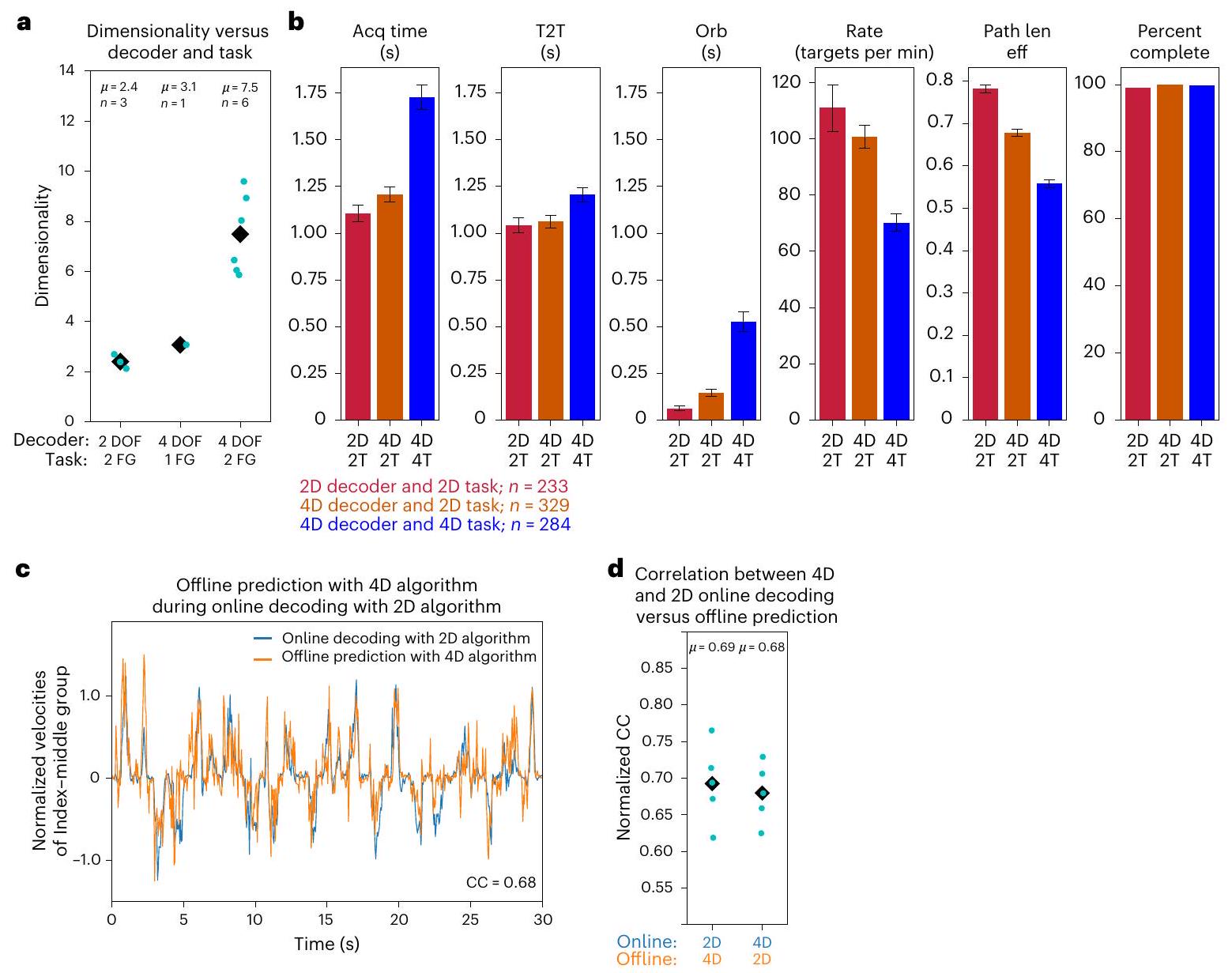

تم استخدام خوارزمية فك التشفير للتنبؤ بسرعات مجموعة المؤشر-الوسطى من نفس الكتلة (برتقالي). يتم إعطاء معامل الارتباط المنظم بين الإشارات عبر الإنترنت وخارج الإنترنت في الزاوية السفلى اليمنى. يتم الإشارة إلى الوحدات بحيث يكون نطاق الحركة لكل درجة حرية هو وحدة واحدة. د، بالنسبة للعشر كتل في المهمة ثنائية الأبعاد، تم استخدام خوارزمية فك التشفير رباعية الأبعاد للتنبؤ بسرعات الأصابع خلال الكتل عبر الإنترنت باستخدام فك التشفير ثنائي الأبعاد (عبر الإنترنت ثنائي الأبعاد باللون الأزرق، خارج الإنترنت رباعي الأبعاد باللون البرتقالي)، وتم استخدام خوارزمية فك التشفير ثنائية الأبعاد للتنبؤ بالسرعات عبر الإنترنت باستخدام فك التشفير رباعي الأبعاد (عبر الإنترنت رباعي الأبعاد باللون الأزرق، خارج الإنترنت ثنائي الأبعاد باللون البرتقالي). يتم تمثيل معامل الارتباط بين الإشارات خارج الإنترنت وعبر الإنترنت بالنقاط ومتوسطه عبر مجموعتي الأصابع. الماس و

لأخذ بعين الاعتبار اضطرابًا في التحويل من النشاط العصبي إلى درجات الحرية

د.ف.

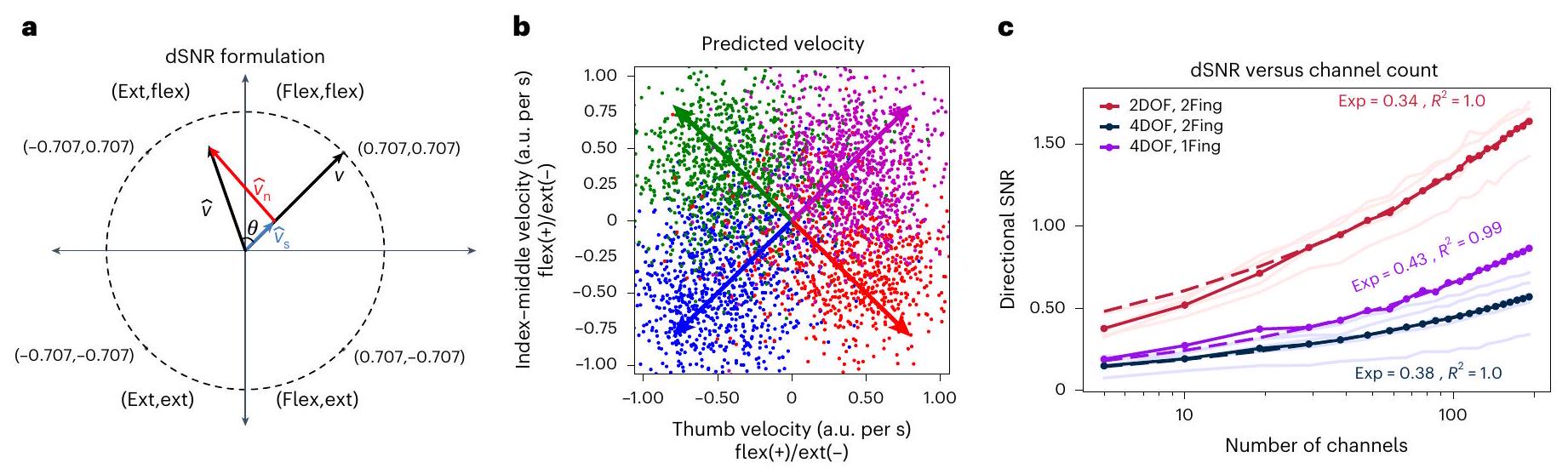

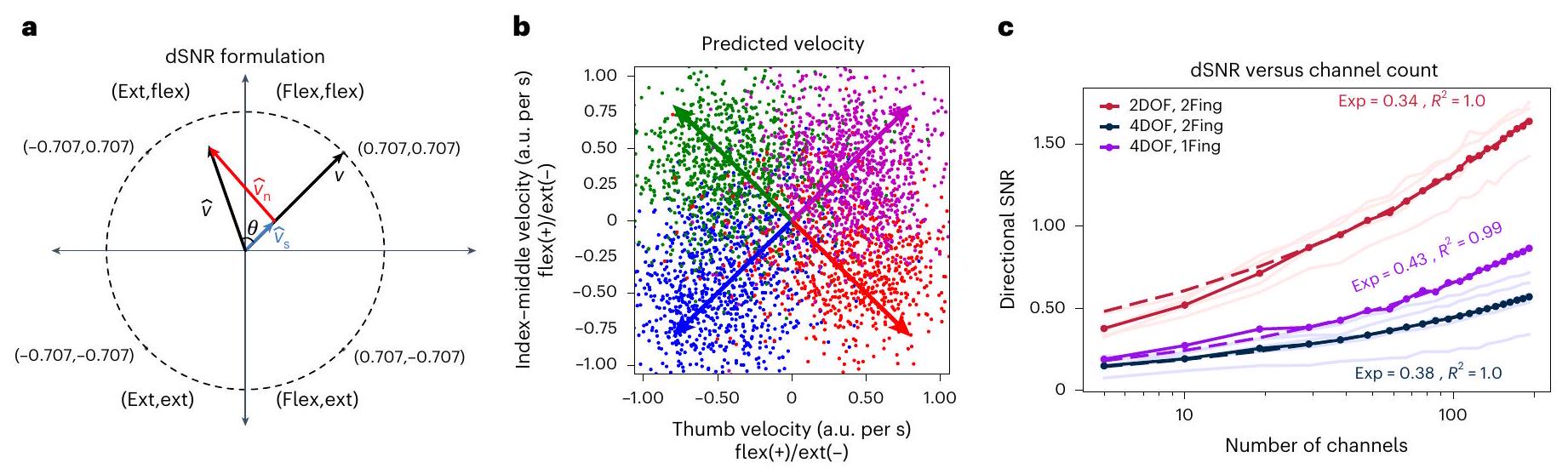

تُستخدم حركات الأصابع المقصودة لحساب dSNR. تمثل الأسهم القيمة المثالية/الحقيقية لكل وضعية إصبع ممكنة بناءً على حركة الإصبع المقصودة المفترضة. ج، يُظهر dSNR كدالة لعدد القنوات لمشفّر الأبعاد الثنائية في مهمة الهدفين/التجربة (2Fing، أحمر)، ومشفّر الأبعاد الرباعية في مهمة الهدفين/التجربة (2Fing، أزرق) ومشفّر الأبعاد الرباعية في مهمة الهدف الواحد/التجربة (1Fing، بنفسجي). يتم تصوير حساب تجريبي لـ dSNR لكل يوم في خطوط ملونة فاتحة والقيمة المتوسطة كخط صلب داكن. تتوافق الخطوط المنقطة مع ملاءمة خطية باستخدام طريقة المربعات الصغرى لـ

اعتماد دقة فك التشفير على عدد القنوات

المرتفع

ترجمة إشارة إصبع iBCI للتحكم في الطائرة الرباعية الافتراضية

| رقم. | يوم | مهمة | لا | عمق المجال | كتل OL (التجارب) | كتل CL (التجارب)

|

وقت تدريب CL (دقائق) | شكل | ملاحظات |

| 1 | ٢٣٩٥ | فك تشفير إصبع CL | 1 | ٤ | 2 (200) | 7 (467) | ٢٤.٣ | 1، 3، ED 3، ED 4 | |

| 2 | 2400 | فك تشفير إصبع CL | 2 | ٤ | 2 (200) | 3 (180) | 9.8 | 1، 3، ED 3، ED 4 | |

| ٣ | 2402 | فك تشفير إصبع CL | ٣ | ٤ | 2 (200) | 5 (252) | 14.1 | 1، 3، ED 3-5 | |

| 3ب | +5 (250) | 16.3 | ED 5 | ||||||

| ٤ | 2407 | فك تشفير إصبع CL | ٤ | 2 | 2 (200) | 2 (100) | ٥.٩ | 1، 3، ED 3، ED 4 | |

| ٥ | ٢٤٠٩ | فك تشفير إصبع CL | ٥ | ٤ | 2 (200) | 9 (450) | ٢٥.٧ | 1، 3، ED 3-5 | |

| ٦ | ٢ | 2 (200) | 2 (100) | 11.1 | 1، 3، ED 3، ED 4 | ||||

| ٦ | 2423 | فك تشفير إصبع CL | ٧ | ٤ | 2 (200) | 12 (585) | ٣٥.٨ | 1-3، ED 1، ED 3-5 | تم استخدام بيانات الحلقة المفتوحة لرسم الارتباك في الشكل الإضافي 1. وتم استخدام بيانات الحلقة المغلقة في الأشكال 2-4. |

| 7ب | +2 (100) | ٥.٥ | 2، ED 5 | ||||||

| ٨ | 2 | 2 (200) | 7 (297) | ٢٠.٢ | 1، ED 3، ED 4 | تمت محاولة الإفراط في تدريب جهاز فك التشفير من خلال إعادة تدريبه على العديد من الكتل المغلقة بعد الانتهاء من 100% من التجارب. | |||

| 8ب | +3 (150) | 5.1 | 2، 3، ED 5 | يتضمن 1 كتلة (50 تجربة) باستخدام جهاز فك التشفير 4D | |||||

| ٧ | ٢٤٣٠ | فك تشفير إصبع CL | 9 | ٤ | 2 (200) | 3 (150) | 8.2 | 1، ED 3، ED 4 | |

| 9ب | +2 (100) | 5.1 | 2، ED 5 | ||||||

| 9c | +1 (50) | 2.5 | 2، ED 5 | ||||||

| 9د | +7 (331) | 16.8 | 1-3 التعليمات 5 | مستخدم في الشكل 3 لمزيد من التجارب (مقارنة بالكتل السابقة) | |||||

| 9e | +1 (50) | 2.0 | 1-3، ED 5 | مستخدم في الشكل 3 لمزيد من التجارب (مقارنة بالكتل السابقة) | |||||

| 10 | 2 | 1 (100) | 1 (50) | 1.5 | 2، 3، ED 5 | مستخدم في الشكل 3 لمزيد من التجارب (مقارنة بالكتل السابقة) | |||

| 10ب | +1 (50) | 1.5 | 2، 3، ED 5 | مستخدم في الشكل 3 لمزيد من التجارب (مقارنة بالكتل السابقة) | |||||

| 10 سنت | +1 (50) | 2.0 | 2أ، 3 | مستخدم في الشكل 3 لمزيد من التجارب (مقارنةً بالكتل السابقة) | |||||

| ٨ | 2520 | مسار عقبات مراقبة الجودة | 11 | ٤ | 2 (200) | 3 (150) | 8.3 | ||

| 11ب | +4 (200) | 10.3 | ٤ | ||||||

| 11ج | +2 (100) | 5.8 | |||||||

| 11د | +2 (100) | ٤.٧ | |||||||

| 9 | 2569 | خواتم عشوائية لمراقبة الجودة | 12 | ٤ | 2 (200) | 6 (269) | ٢٠.٤ | تم تنفيذ الكتل المفتوحة باستخدام مرجع متوسط مشترك، بينما استخدمت الكتل المغلقة مرجع الانحدار الخطي. |

ليس فقط من خلال دقة فك الشفرات ولكن أيضًا إلى حد كبير من خلال العوامل السلوكية، حيث قد يجد حتى المشغلون الأصحاء الذين يستخدمون جهاز التحكم أحادي اليد لطائرة رباعية المراوح أن المهمة تمثل تحديًا.

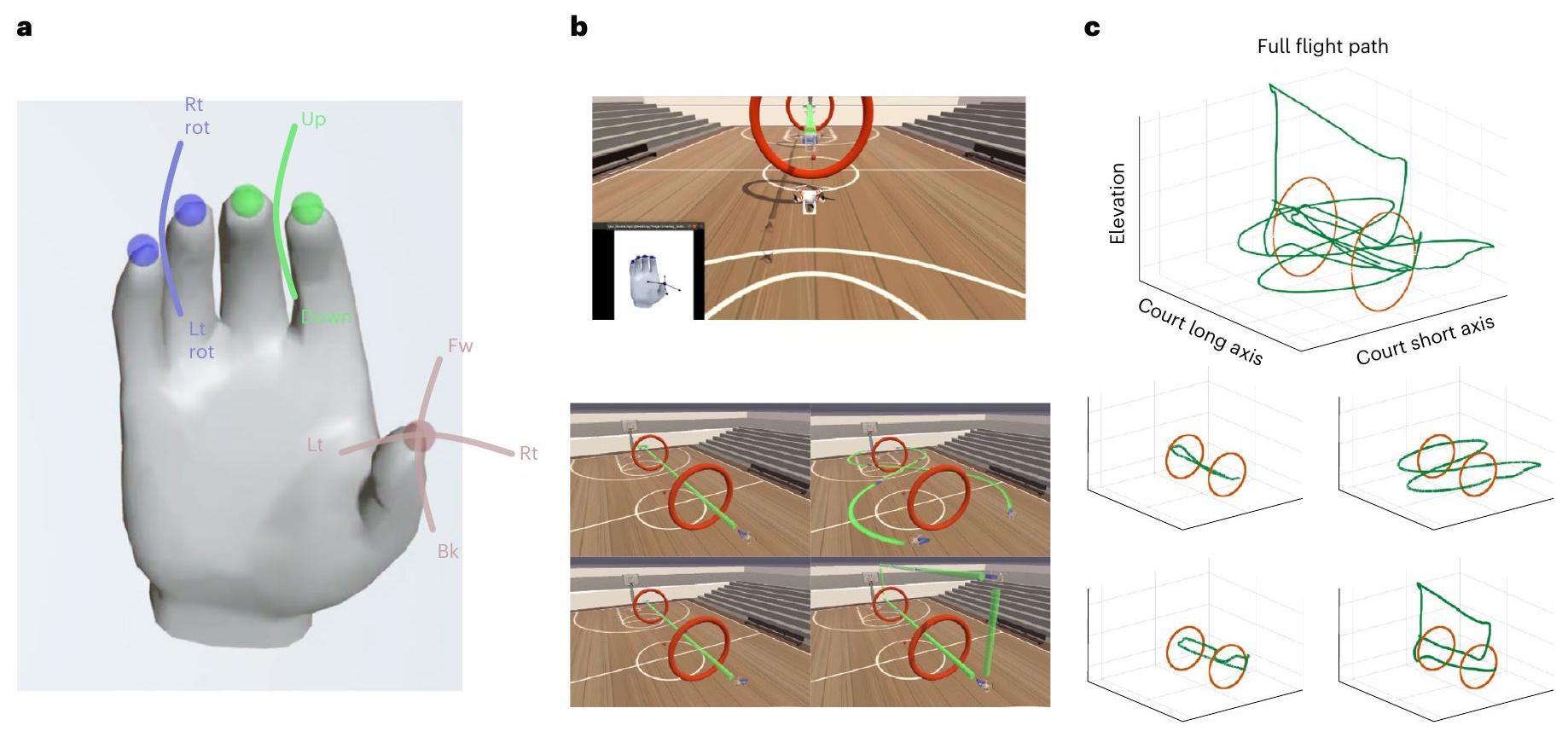

تجربة المستخدم

يتطلب المسار من الطائرة بدون طيار التحرك للأمام، والدوران، والتحرك للأمام مرة أخرى عبر نفس الحلقات للعودة إلى نقطة البداية (لفة واحدة). يتطلب المسار في أعلى اليمين من المشارك التحرك للأمام والدوران في نفس الوقت لإكمال مسارين على شكل ‘ثمانية’ حول الحلقات والعودة إلى نقطة البداية (لفة واحدة). يتطلب المسار في أسفل اليسار منه التحرك إلى اليسار عبر كلا الحلقات، التوقف ثم التحرك إلى اليمين مرة أخرى عبر الحلقات (لفة واحدة). يتطلب المسار في أسفل اليمين التحرك للأمام عبر الحلقات، وزيادة الارتفاع، ثم التحرك للخلف فوق الحلقات، وتقليل الارتفاع، ثم التحرك للأمام عبر كلا الحلقات إلى نقطة النهاية (1.5 لفة). ج، في الأعلى، مسار طيران كامل نموذجي خلال كتلة من دورة العقبات. في الأسفل، يتم فصل مسار الطيران إلى لفات تتوافق مع المسار المخطط لكل لفة في

“وقت التدريب” حتى يتمكن من تحسين أدائه وصرح مرة بأنه “أشعر أننا يمكن أن نعمل حتى الساعة 9 الليلة”. لم يبدو أن التعب كان عاملاً في التحكم بالطائرة الرباعية، حيث لم يطلب T5 أبداً إنهاء أو تقصير أي من الجلسات التسع المضمنة في هذه الدراسة. في النهاية، كان هذا العمل تتويجاً لهدف طويل الأمد رآه كل من فريق البحث والمشارك كإنجاز تعاوني مشترك.

والتحكم في الطائرة الرباعية موضحًا أن التحكم في الطائرة الرباعية كان “أكثر حساسية من الأصابع” وأنه كان عليه “أن يلمسها في اتجاه”. كما أكد على أهمية تخصيص الأصابع وكيف أن فشل التخصيص يؤدي إلى تدهور الأداء: “عندما تسحب لأسفل بإصبعك [الصغير]، من المفترض أن تبقى الأصابع الأخرى [المجموعات] هناك… لكنهم يتتبعون مع [الإصبع الصغير]، وهو ما يشتت انتباهي وكل شيء ينزل إلى اليسار بدلاً من أن يكون مجرد يسار أو أيًا كان”.

نقاش

مؤشرات رقمية، ونقاط نهاية وأزرار. ومع ذلك، فإن معظم الأبحاث السابقة والتطوير التجاري قد ركزت على استخدام واجهات التحكم الدماغية للتحكم في المؤشر ثنائي الأبعاد / النقر

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

References

- Armour, B. S., Courtney-Long, E. A., Fox, M. H., Fredine, H. & Cahill, A. Prevalence and causes of paralysis-United States, 2013. Am. J. Public Health 106, 1855-1857 (2016).

- Trezzini, B., Brach, M., Post, M. & Gemperli, A. Prevalence of and factors associated with expressed and unmet service needs reported by persons with spinal cord injury living in the community. Spinal Cord 57, 490-500 (2019).

- Cairns, P. et al. Enabled players: the value of accessible digital games. Games Cult. 16, 262-282 (2021).

- Tabacof, L., Dewil, S., Herrera, J. E., Cortes, M. & Putrino, D. Adaptive esports for people with spinal cord injury: new frontiers for inclusion in mainstream sports performance. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.612350 (2021).

- Beeston, J., Power, C., Cairns, P. & Barlet, M. in Computers Helping People with Special Needs (eds Miesenberger, K. & Kouroupetroglou, G.) 245-253 (Springer, 2018).

- Porter, J. R. & Kientz, J. A. An empirical study of issues and barriers to mainstream video game accessibility. In Proc. 15th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (ed. Lewis, C.) 1-8 (ACM, 2013).

- Taheri, A., Weissman, Z. & Sra, M. Design and evaluation of a hands-free video game controller for individuals with motor impairments. Front. Comp. Sci. 3, 751455.1 (2021).

- Nuyujukian, P. et al. Cortical control of a tablet computer by people with paralysis. PLoS ONE 13, eO2O4566 (2018).

- Flesher, S. N. et al. A brain-computer interface that evokes tactile sensations improves robotic arm control. Science 372, 831-836 (2021).

- Ajiboye, A. B. et al. Restoration of reaching and grasping movements through brain-controlled muscle stimulation in a person with tetraplegia: a proof-of-concept demonstration. Lancet 389, 1821-1830 (2017).

- Carmena, J. M. et al. Learning to control a brain-machine interface for reaching and grasping by primates. PLoS Biol. 1, e42 (2003).

- Collinger, J. L. et al. High-performance neuroprosthetic control by an individual with tetraplegia. Lancet 381, 557-564 (2013).

- Hochberg, L. R. et al. Reach and grasp by people with tetraplegia using a neurally controlled robotic arm. Nature 485, 372-375 (2012).

- Pandarinath, C. et al. High performance communication by people with paralysis using an intracortical brain-computer interface. eLife 6, e18554 (2017).

- Velliste, M., Perel, S., Spalding, M. C., Whitford, A. S. & Schwartz, A. B. Cortical control of a prosthetic arm for self-feeding. Nature 453, 1098-1101 (2008).

- Hochberg, L. R. et al. Neuronal ensemble control of prosthetic devices by a human with tetraplegia. Nature 442, 164-171 (2006).

- Wodlinger, B. et al. Ten-dimensional anthropomorphic arm control in a human brain-machine interface: difficulties, solutions, and limitations. J. Neural Eng. 12, 016011 (2014).

- Guan, C. et al. Decoding and geometry of ten finger movements in human posterior parietal cortex and motor cortex. J. Neural Eng. 20, 036020 (2023).

- Jorge, A., Royston, D. A., Tyler-Kabara, E. C., Boninger, M. L. & Collinger, J. L. Classification of individual finger movements using intracortical recordings in human motor cortex. Neurosurgery 87, 630-638 (2020).

- Bouton, C. E. et al. Restoring cortical control of functional movement in a human with quadriplegia. Nature 533, 247-250 (2016).

- Nakanishi, Y. et al. Decoding fingertip trajectory from electrocorticographic signals in humans. Neurosci. Res. 85, 20-27 (2014).

- Nason, S. R. et al. Real-time linear prediction of simultaneous and independent movements of two finger groups using an intracortical brain-machine interface. Neuron 109, 3164-3177. e3168 (2021).

- Willsey, M. S. et al. Real-time brain-machine interface in non-human primates achieves high-velocity prosthetic finger movements using a shallow feedforward neural network decoder. Nat. Commun. 13, 6899 (2022).

- Nason, S. R. et al. A low-power band of neuronal spiking activity dominated by local single units improves the performance of brain-machine interfaces. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4, 973-983 (2020).

- Costello, J. T. et al. Balancing memorization and generalization in RNNs for high performance brain-machine interfaces. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.28.542435 (2023).

- Shah, N. P. et al. Pseudo-linear summation explains neural geometry of multi-finger movements in human premotor cortex. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.11.561982 (2023).

- Willett, F. R., Avansino, D. T., Hochberg, L. R., Henderson, J. M. & Shenoy, K. V. High-performance brain-to-text communication via handwriting. Nature 593, 249-254 (2021).

- Griffin, D. M., Hoffman, D. S. & Strick, P. L. Corticomotoneuronal cells are “functionally tuned”. Science 350, 667-670 (2015).

- Sakellaridi, S. et al. Intrinsic variable learning for brain-machine interface control by human anterior intraparietal cortex. Neuron 102, 694-705. e693 (2019).

- Willett, F. R. et al. Hand knob area of premotor cortex represents the whole body in a compositional way. Cell 181, 396-409. e326 (2020).

- Zhang, C. Y. et al. Preservation of partially mixed selectivity in human posterior parietal cortex across changes in task context. Eneuro 7, ENEURO.0222-19.2019 (2020).

- Kryger, M. et al. Flight simulation using a brain-computer interface: a pilot, pilot study. Exp. Neurol. 287, 473-478 (2017).

- Gilja, V. et al. A high-performance neural prosthesis enabled by control algorithm design. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 1752 (2012).

- Kao, J. C., Nuyujukian, P., Ryu, S. I. & Shenoy, K. V. A high-performance neural prosthesis incorporating discrete state selection with hidden Markov models. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 64, 935-945 (2016).

- LaFleur, K. et al. Quadcopter control in three-dimensional space using a noninvasive motor imagery-based brain-computer interface. J. Neural Eng. 10, 046003 (2013).

- Essential facts about the computer and video game industry. Entertainment Software Association www.theesa.com/resource/2 021-essential-facts-about-the-video-game-industry/ (2021).

- Raith, L. et al. Massively multiplayer online games and well-being: a systematic literature review. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.698799 (2021).

- Adeane, A. Quad gods: the world-class gamers who play with their mouths. BBC www.bbc.com/news/stories-55811621 (2021).

- Willett, F. R. et al. A high-performance speech neuroprosthesis. Nature 620, 1031-1036 (2023).

- Card, N. S. et al. An accurate and rapidly calibrating speech neuroprosthesis. N. Engl. J. Med. 391, 609-618 (2024).

(c) The Author(s) 2025

طرق

التجربة السريرية والمشارك

جلسات المشارك

مهام الأصابع

تم الإشارة لتحريك مجموعات الأصابع في نفس الوقت من وضع ‘محايد’ مركزي نحو أهداف عشوائية ضمن نطاق الحركة النشط. بمجرد الوصول إلى الهدف، كان مطلوبًا أن تكون جميع الأصابع داخل الهدف لمدة 500 مللي ثانية ليتم إكمال التجربة بنجاح. في التجربة التالية، تم وضع الأهداف مرة أخرى في المركز. كان عرض الهدف هو

مهام الطائرات الرباعية

أكمل جميع أجزاء مسار العقبات بأسرع ما يمكن وبأكبر قدر من الدقة. أكمل المسار 12 مرة إجمالاً، وخلال هذه الجولات المكتملة، لم يتم فرض أي عقوبة لعدم البقاء بالضبط على المسار، أو ضرب الحلقات أو تفويت الحلقات (حيث أنه فاتته حلقتان من أصل 168 حلقة ممكنة).

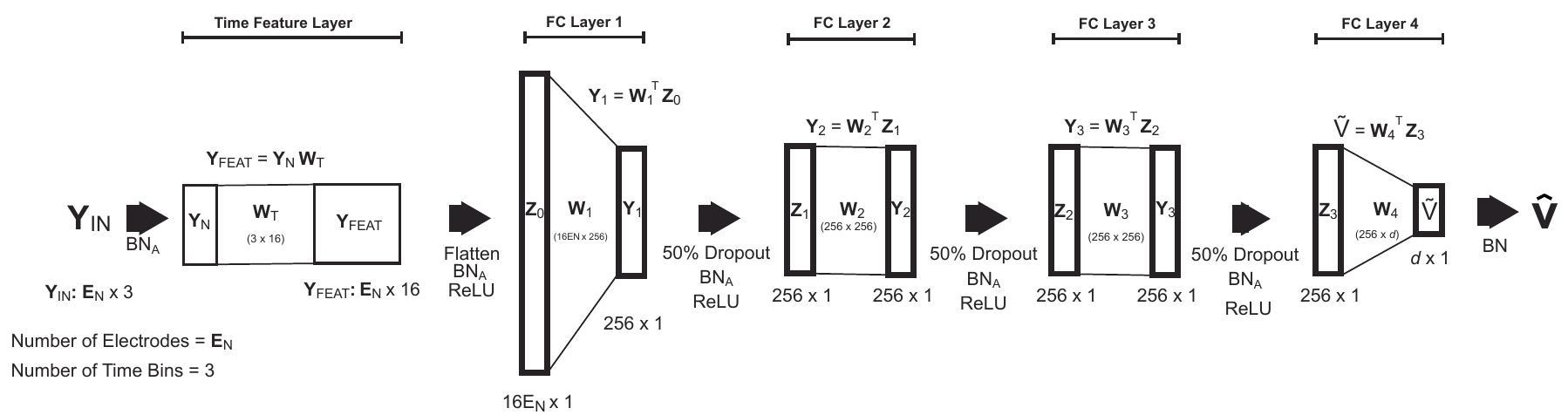

خوارزمية فك التشفير

برنامج فك التشفير ذو الحلقة المغلقة

تدريب الخوارزمية

خطأ متوسط المربعات (torch.nn.MSELoss) بين سرعات الأصابع الفعلية خلال تدريب الحلقة المفتوحة ومخرجات الخوارزمية باستخدام خوارزمية تحسين آدم

نظام BCI ومعالجة الإشارات في الواجهة الأمامية

بروتوكولات التدريب لبرنامج فك التشفير 4D

بروتوكولات التدريب لشفرة ثنائية الأبعاد

المقاييس عبر الإنترنت

التحليلات غير المتصلة بالإنترنت

(الإصدار 1.12.0)، torchvision (الإصدار 0.13.0)، numpy (الإصدار 1.21.5)، matplotlib (الإصدار 3.5.3)، PIL (الإصدار 9.0.1) و sklearn (الإصدار 1.0.2). تم تفصيل مصفوفات الالتباس وتحليلات الأبعاد في الطرق التكميلية وهي مشابهة للتحليلات في التقارير السابقة.

نسبة الإشارة إلى الضوضاء. على الرغم من أنه تم اقتراح مقاييس نسبة الإشارة إلى الضوضاء للتحليلات غير المتصلة، إلا أن هناك نسبة إشارة إلى ضوضاء قائمة على المتجهات

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

References

- Deo, D. R. et al. Brain control of bimanual movement enabled by recurrent neural networks. Sci. Rep. 14, 1598 (2024).

- Shah, S., Dey, D., Lovett, C. & Kapoor, A. Airsim: high-fidelity visual and physical simulation for autonomous vehicles. In Field and Service Robotics: Results of the 11th International Conference (eds Hutter, M. & Siegwart, R.) 621-635 (Springer, 2018).

- Ioffe, S. & Szegedy, C. Batch normalization: accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. In Proc. 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning (eds Bach, F. & Blei, D.) 448-456 (JMLR, 2015).

- He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Delving deep into rectifiers: surpassing human-level performance on imagenet classification. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 1026-1034 (IEEE, 2015).

- Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1412.6980 (2014).

- Perge, J. A. et al. Intra-day signal instabilities affect decoding performance in an intracortical neural interface system. J. Neural Eng. 10, 036004 (2013).

- Liu, R. et al. Drop, swap, and generate: a self-supervised approach for generating neural activity. Adv. Neural Inf. Process Syst. 34, 10587-10599 (2021).

- Sussillo, D., Stavisky, S. D., Kao, J. C., Ryu, S. I. & Shenoy, K. V. Making brain-machine interfaces robust to future neural variability. Nat. Commun. 7, 13749 (2016).

- Jarosiewicz, B. et al. Virtual typing by people with tetraplegia using a self-calibrating intracortical brain-computer interface. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 313ra179-313ra179 (2015).

- Wilson, G. H. et al. Long-term unsupervised recalibration of cursor BCls. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi. org/10.1101/2023.02.03.527022 (2023).

- Degenhart, A. D. et al. Stabilization of a brain-computer interface via the alignment of low-dimensional spaces of neural activity. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4, 672-685 (2020).

- Karpowicz, B. M. et al. Stabilizing brain-computer interfaces through alignment of latent dynamics. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.06.487388 (2022).

- Tse, D. & Viswanath, P. Fundamentals of Wireless Communication (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2005).

- Willsey, M. et al. Data from: a high-performance brain-computer interface for finger decoding and quadcopter game control in an individual with paralysis [Dataset]. Dryad. https://doi.org/10.5061/ dryad.1jwstqk4f (2024).

شكر وتقدير

تحذير: جهاز تجريبي. محدود بموجب القانون الفيدرالي للاستخدام التجريبي فقط.

مساهمات المؤلفين

و F.R.W.; التحقق: M.S.W.، N.P.S.، D.T.A. و F.R.W.; التحليل الرسمي: M.S.W.; التحقيق: M.S.W.، N.P.S.، D.T.A.، N.V.H.، R.M.J.، F.B.K.، F.R.W. و J.M.H.; الكتابة – المسودة الأصلية: M.S.W.; الكتابة – المراجعة والتحرير: M.S.W.، N.P.S.، D.T.A.، N.V.H.، R.M.J.، F.B.K.، L.R.H.، F.R.W. و J.M.H.; الإشراف: M.S.W.، F.R.W. و J.M.H.; إدارة المشروع: L.R.H. و J.M.H.; الحصول على التمويل: L.R.H. و J.M.H.

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

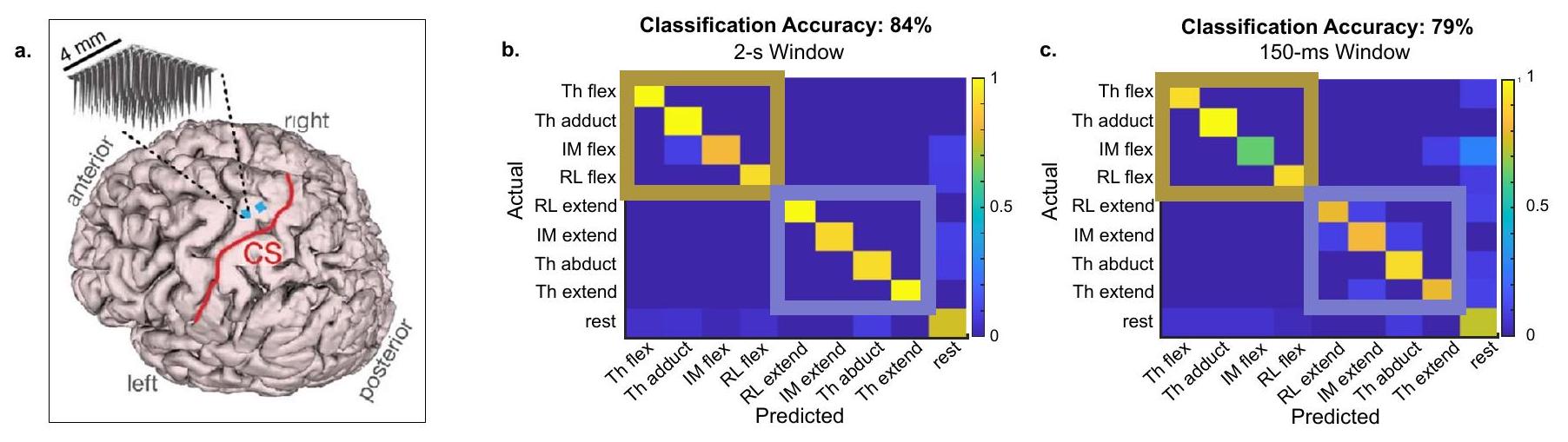

2016. الخط الأحمر يشير إلى الشق المركزي (CS). لوحة من Deo وآخرون.

تم تنفيذه باستخدام التحويلات الخطية

أ.

ب.

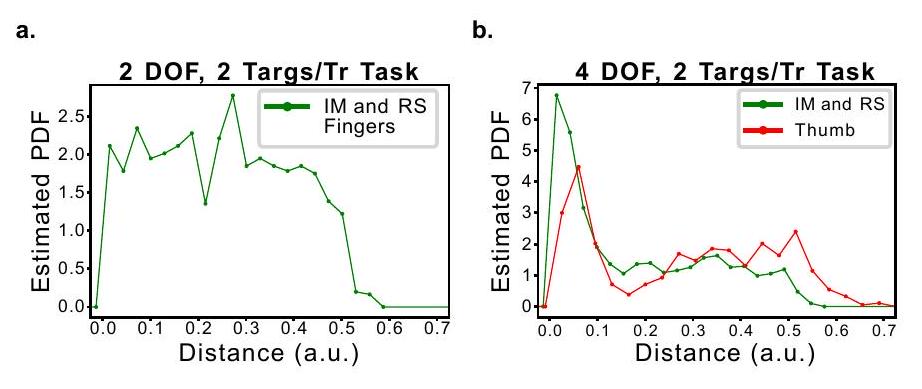

مهمة ذات درجتين من الحرية

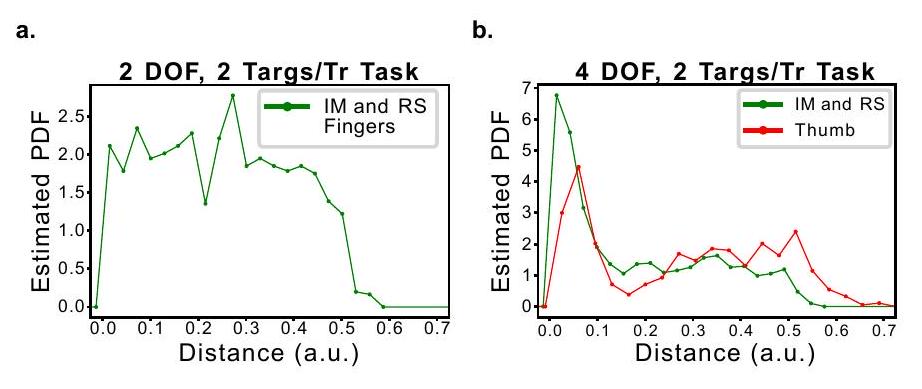

يمثل المنحنى المسافات المجمعة لثني/مد إصبع IM وإصبع RL، ويمثل المنحنى البرتقالي المسافة ثنائية الأبعاد للإبهام (مجمعة من المكونات ثنائية الأبعاد للثني/المد والابتعاد/الاقتراب) للتجارب التي استخدمت جهاز فك التشفير رباعي الأبعاد والمهمة في الشكل 1e. وحدات عشوائية، DOF، درجة الحرية؛ PDF، دالة توزيع الاحتمالات.

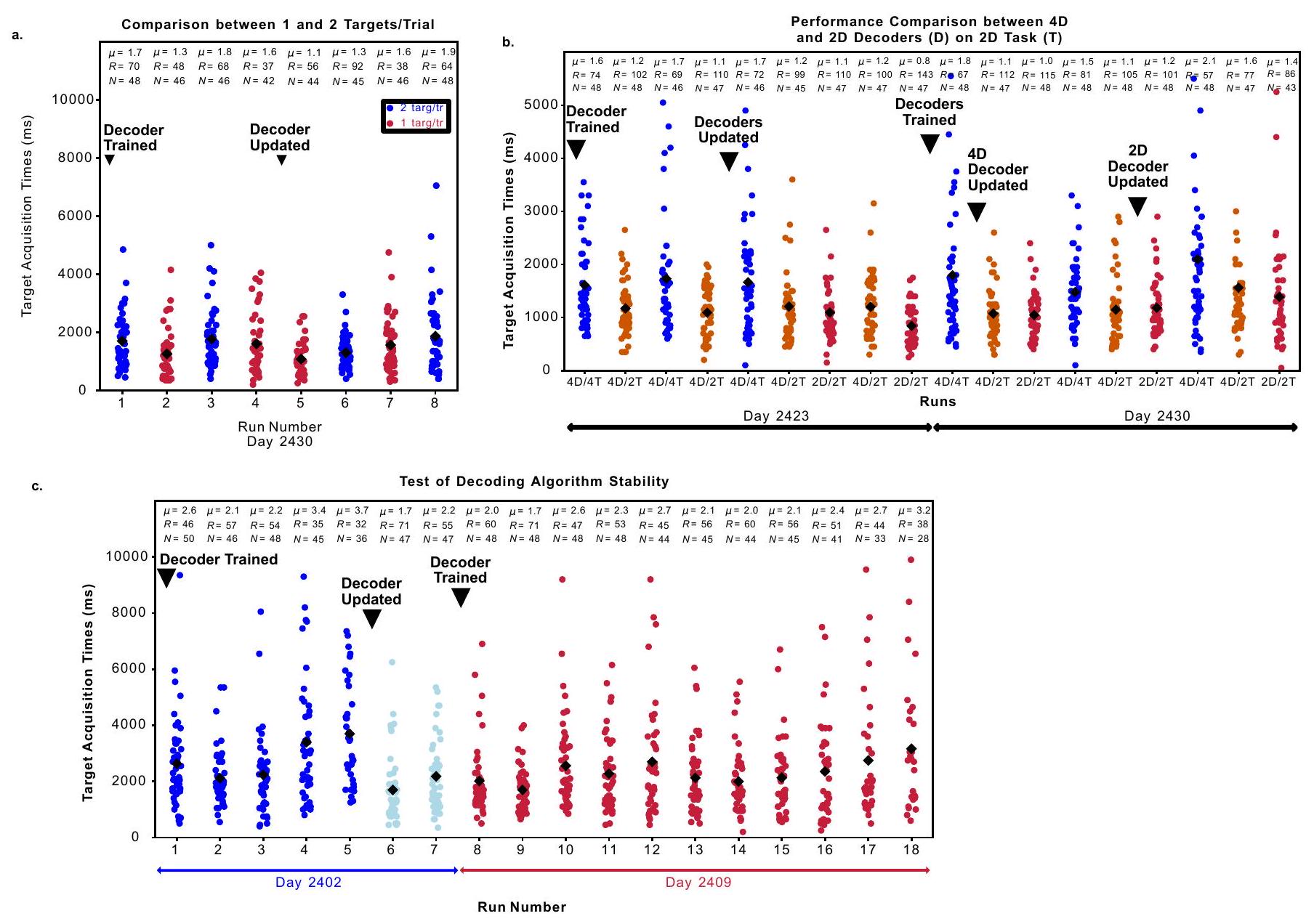

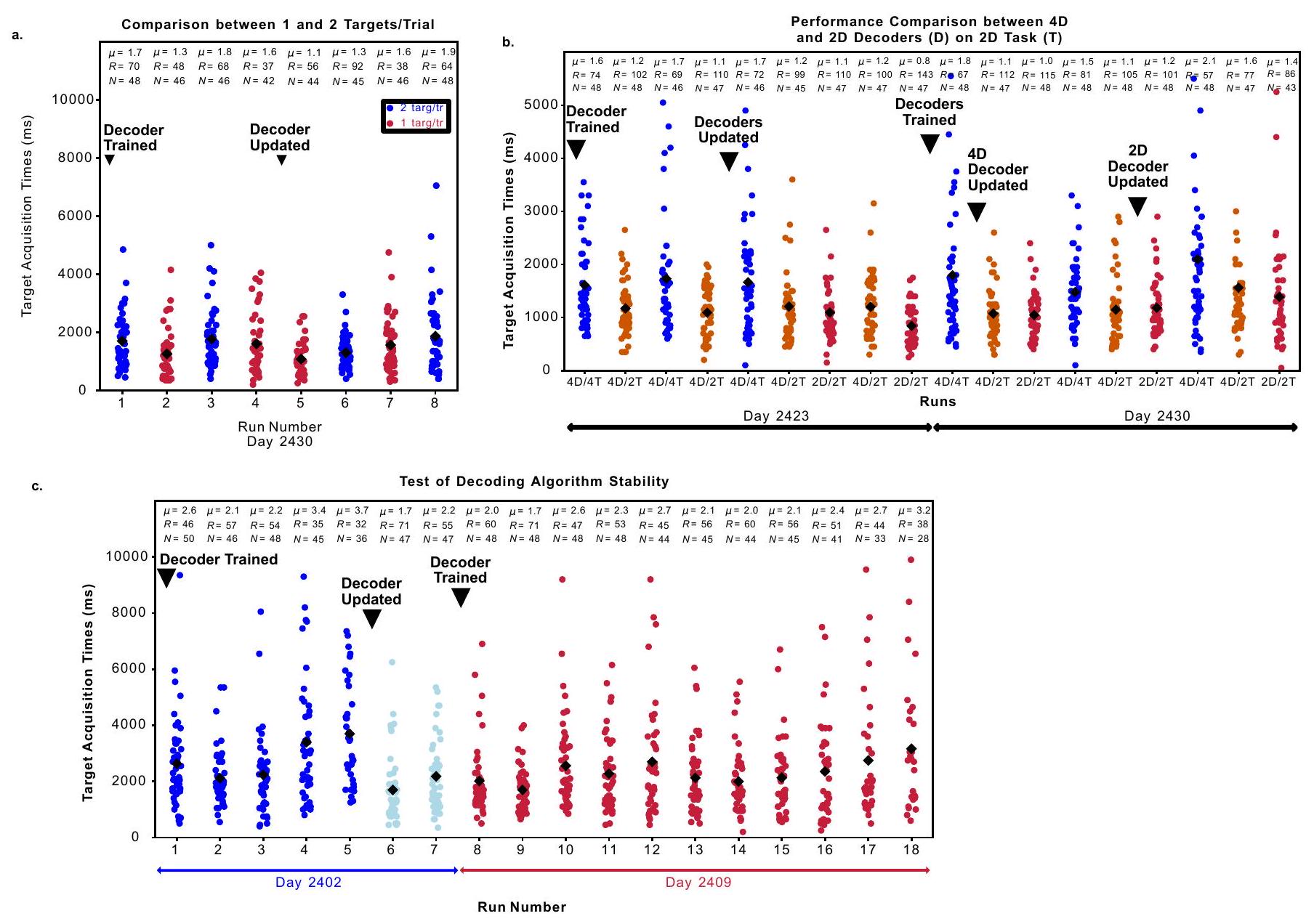

تمثل المجموعة كتل متتالية دون إعادة تدريب ما لم يُذكر خلاف ذلك. تشير التسميات 4D/4T إلى تشغيل وحدة فك التشفير 4D على 4T؛ 4D/2T تشير إلى وحدة فك التشفير 4D على 2T؛ و 2D/2T تشير إلى وحدة فك التشفير 2D على 2T. ج، اختبار استقرار وحدة فك التشفير لمدة يومين تجريبيين باستخدام وحدة فك التشفير 4-DOF لهدفين جديدين/تجربة. بالنسبة للأيام 2402 (الأزرق والفاتح) و2409 (الأحمر)، تم تدريب وحدة فك التشفير (مثلث مقلوب مع “وحدة فك التشفير مدربة”) ثم استخدمت في كتل متتالية حتى لم يكن بالإمكان إكمال التجارب بشكل موثوق. في اليوم 2402، تم إعادة تدريب وحدة فك التشفير (“وحدة فك التشفير محدثة”) لإظهار استعادة الأداء في كتلتين لاحقتين (الفاتح الأزرق).

| 1 هدف/تجربة جديدة | هدفين/تجربة جديدة | |

| عدد التجارب | 178 | 187 |

| عدد الأيام | 1 | 1 |

| وقت الاستحواذ

|

|

|

| وقت الاستهداف

|

|

|

| زمن المدارات

|

|

|

| الأهداف في الدقيقة |

|

|

| نسبة الإنجاز |

|

|

| طول المسار |

|

|

| فك التشفير ثنائي الأبعاد، مهمة ثنائية الأبعاد | فك التشفير رباعي الأبعاد، مهمة رباعية الأبعاد | فك التشفير 4D، مهمة 2D | |

| عدد التجارب | 233 | 284 | ٣٢٩ |

| عدد الأيام | ٣ | ٣ | ٣ |

| وقت الاستحواذ (مللي ثانية) |

|

|

|

| وقت الاستهداف (مللي ثانية) |

|

|

|

| زمن المدار (مللي ثانية) |

|

|

|

| الأهداف في الدقيقة |

|

|

|

| نسبة الإنجاز | 99.1٪ | 99.6% | 100% |

| طول المسار |

|

|

|

محفظة الطبيعة

| المؤلف (المؤلفون) المراسلون: |

|

||

| آخر تحديث بواسطة المؤلف(ين): | 20 سبتمبر 2024 |

ملخص التقرير

الإحصائيات

□

□

□

□

□

□ لتحليل بايزي، معلومات حول اختيار القيم الأولية وإعدادات سلسلة ماركوف مونت كارلو

□ لتصميمات هرمية ومعقدة، تحديد المستوى المناسب للاختبارات والتقارير الكاملة عن النتائج

□ تقديرات أحجام التأثير (مثل حجم تأثير كوهين)

تم التأكيد

□ حجم العينة بالضبط

□ بيان حول ما إذا كانت القياسات قد أُخذت من عينات متميزة أو ما إذا كانت نفس العينة قد تم قياسها عدة مرات

يجب أن تُوصف الاختبارات الشائعة فقط بالاسم؛ واصفًا التقنيات الأكثر تعقيدًا في قسم الطرق.

□ وصف لجميع المتغيرات المرافقة التي تم اختبارها

□ وصف لأي افتراضات أو تصحيحات، مثل اختبارات الطبيعية والتعديل للمقارنات المتعددة

ل

ل

البرمجيات والشيفرة

جمع البيانات

تم تطوير عرض الإصبع الافتراضي في Unity (2021.3.9f1). استخدم بيئة الطائرة الرباعية المعتمدة على الفيزياء مكون Microsoft AirSim كمحاكي لطائرة رباعية في Unity (2019.3.12f1). يقوم معالج الإشارة العصبية بإرسال الإشارة الرقمية إلى جهاز SuperLogics يعمل بنظام Simulink Real-Time (v2019، Mathworks، ناتيك، ماساتشوستس). تواصل هذا الكمبيوتر مع جهاز كمبيوتر يعمل بنظام Linux ويستخدم Ubuntu مع Python (v3.7.11)، PyTorch (v1.12.1،https://pytorch.org/)، وRedis (v7.02)، حيث تم تنفيذ الشيفرة المخصصة لفك التشفير، والتحكم في البيئة الافتراضية في Unity، وتدريب الشبكة العصبية. تم توصيل النظام بالكامل بجهاز كمبيوتر إضافي يعمل بنظام Windows ويستخدم Matlab (v2019، Mathworks، ناتيك، ماساتشوستس) الذي تم توصيله بالنظام لإيقاف وبدء التجارب خلال الجلسات.

تم إجراء التحليلات غير المتصلة بالإنترنت باستخدام بايثون (الإصدار 3.9.12) من خلال دفتر ملاحظات Jupyterhttps://jupyter.org/) وفي Matlab (v2022a، Mathworks، ناتيك، ماساتشوستس). تم استخدام الحزم التالية في بايثون: scipy (v1.7.3)، torch (v1.12.0)، torchvision (v0.13.0)، numpy (v1.21.5)، matplotlib (v3.5.3)، PIL (v9.0.1)، sklearn (v1.0.2). إصدارات حزم Jupyter الأساسية هي: IPython 8.2.0، ipykernel 6.9.1، ipywidgets 7.6.5، jupyter_client 6.1.12، jupyter_core 4.9.2، jupyter_server 1.13.5، jupyterlab 3.3.2، nbclient 0.5.13، nbconvert 6.4.4، nbformat 5.3.0، notebook 6.4.8، qtconsole 5.3.0، traitlets 5.1.1.

بيانات

معلومات السياسة حول توفر البيانات

- رموز الانضمام، معرفات فريدة، أو روابط ويب لمجموعات البيانات المتاحة للجمهور

- وصف لأي قيود على توفر البيانات

- بالنسبة لمجموعات البيانات السريرية أو بيانات الطرف الثالث، يرجى التأكد من أن البيان يتماشى مع سياستنا.

البحث الذي يتضمن مشاركين بشريين، بياناتهم، أو مواد بيولوجية

تم تسجيل المشارك T5 في تجربة BrainGate 2 السريرية بعد استيفاء معايير الإدراج بناءً جزئيًا على خصائص المرض. تتوفر معايير الإدراج والاستبعاد على الإنترنت.ClinicalTrials.gov). تم متابعة هذه التحقيق كجزء من مقياس النتائج الثانوية للتجربة السريرية. فيما يتعلق بالتحيزات المحتملة في الاختيار، يمكن أن تؤدي معايير الإدراج والاستبعاد الصارمة إلى اختيار مشاركين أكثر صحة من السكان النموذجيين الذين يعانون من الشلل.

التقارير الخاصة بالمجال

علوم الحياة □ العلوم السلوكية والاجتماعية □ العلوم البيئية والتطورية والبيئية

لنسخة مرجعية من الوثيقة بجميع الأقسام، انظرnature.com/documents/nr-reporting-summary-flat.pdf

تصميم دراسة العلوم الحياتية

| حجم العينة | لم يتم إجراء حساب لحجم العينة. تم جمع البيانات من مشارك واحد لتوصيف أداء واجهة الدماغ-الكمبيوتر. عدد التجارب قابل للمقارنة مع دراسات مماثلة، وتم تقدير عدم اليقين في تقديرات الأداء باستخدام الخطأ المعياري للمتوسط. |

| استبعاد البيانات | لم يتم استبعاد أي بيانات. تم إجراء جلسات فك الشيفرة باستخدام الأصابع على مدى سلسلة من الأيام (من مارس إلى أبريل 2023). تم عرض دورة العقبات ذات الأربعة درجات من الحرية ومهمة الحلقة العشوائية في يوم واحد بعد جلسات تمهيدية لتطوير كل مهمة. |

| التكرار | تم تقييم النتائج الأولية لفك تشفير الأصابع بنجاح وتم تأكيدها في 7 أيام مستقلة دون استبعاد. |

| العشوائية | لم يكن هناك توزيع عشوائي للمشاركين على مجموعات العلاج حيث كان هناك مشارك واحد فقط. كان هناك توزيع عشوائي لمواقع أهداف الأصابع من المركز إلى الخارج لتجميع عشوائي لمساحة الأهداف المحتملة. |

| مُعَمي | لم يكن هناك أي تعمية مرتبطة بمجموعات العلاج حيث كان هناك مشارك واحد فقط مسجل. لم يكن من الممكن تعمية المشارك عن المهمة التي كان يؤديها. |

التقارير عن مواد وأنظمة وطرق محددة

| المواد والأنظمة التجريبية | طرق | ||

| غير متوفر | مشارك في الدراسة | غير متوفر | مشارك في الدراسة |

| إكس | □ |  |

□ |

| إكس | □ | إكس | □ |

| إكس | □ | ||

| إكس | □ | ||

| إكس | □ | ||

| إكس | □ | ||

النباتات

غير متوفر

غير متوفر

غير متوفر

- ¹قسم جراحة الأعصاب، جامعة ستانفورد، ستانفورد، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. ²قسم جراحة الأعصاب، جامعة ميتشيغان، آن آربر، ميشيغان، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03341-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39833405

Publication Date: 2025-01-01

A high-performance brain-computer interface for finger decoding and quadcopter game control in an individual with paralysis

Accepted: 3 October 2024

Published online: 20 January 2025

Check for updates

Abstract

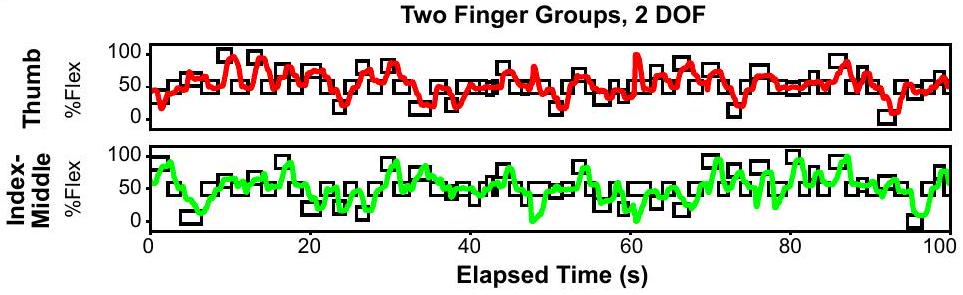

People with paralysis express unmet needs for peer support, leisure activities and sporting activities. Many within the general population rely on social media and massively multiplayer video games to address these needs. We developed a high-performance, finger-based brain-computer-interface system allowing continuous control of three independent finger groups, of which the thumb can be controlled in two dimensions, yielding a total of four degrees of freedom. The system was tested in a human research participant with tetraplegia due to spinal cord injury over sequential trials requiring fingers to reach and hold on targets, with an average acquisition rate of 76 targets per minute and completion time of

of themes emerged (for example, recreation, artistic expression, social connectedness); however, in those with disabilities, many expressed a theme of enablement, meaning both equality with able-bodied players and overcoming their disability. Even with assistive/adaptive technologies, gamers with motor impairments often have to play at an easier level of difficulty

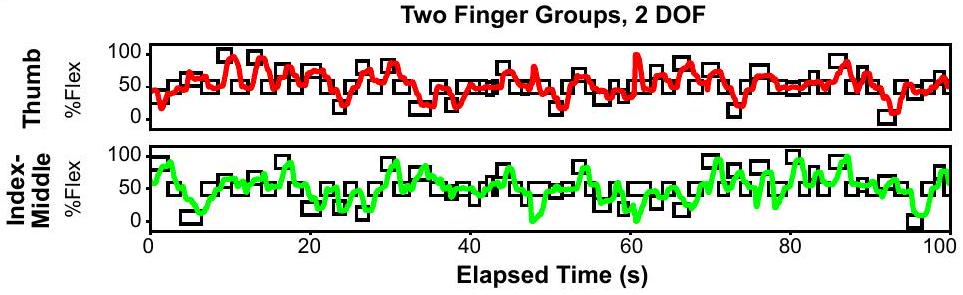

illustrative 50-trial block of 2D thumb movements, showing only trials where the thumb travels a distance greater than 0.3. Each color represents distinct paired, center-out-center trial. e, Summary statistics comparing the two- and four-DOF tasks for acquisition time (Acq time), time to target (T2T), orbiting time (Orb), acquisition rate (Rate), path length efficiency (Path len eff) and the percent of trials successfully completed (Percent complete). The error bars represent the standard error of the mean. There were

motor restoration, could enable sophisticated control of video games for people with paralysis-and, more broadly, control of digital interfaces for social networking or remote work.

Results

| 2D decoder | 4D decoder | 4D decoder (last four blocks) | |

| Number of trials | 529 | 524 | 192 |

| Number of days | 3 | 6 | 3 |

| Acquisition time (ms) |

|

|

|

| Time to target (ms) |

|

|

|

| Orbiting time (ms) |

|

|

|

| Targets per minute |

|

|

|

| Percent completed | 98.1% | 98.7% | 100% |

| Path length |

|

|

|

(a target acquisition rate of

Dimensionality of the neural activity

Effect of number of active DOF on decoding

decoding algorithm was used to predict index-middle group velocities from the same block (orange). The normalized CC between the online and offline signals is given in the bottom-right corner. Units are denoted so that the range of motion for each DOF is unity. d, For the ten blocks on the 2D task, the 4D decoding algorithm was used to predict finger velocities during online blocks using the 2D decoder (online 2D in blue, offline 4D in orange), and the 2D decoding algorithm was used to predict online velocities using the 4D decoder (online 4D in blue, offline 2D in orange). CC between the offline and online signals is represented by dots and averaged across both finger groups. The diamond and

to account for a perturbation in the mapping from neural activity to the DOF

d.f.

intended finger movements are used to calculate dSNR. The arrows represent the ideal/truth value for each possible finger position based on the assumed intended finger movement. c, The dSNR as a function of channel count for the 2D decoder on the two-target/trial task (2Fing, red), 4D decoder on the two-target/ trial task (2Fing, blue) and 4D decoder on the one target/trial task (1Fing, purple). An empirical calculation of dSNR for each day is depicted in lightly colored lines and the mean value as the dark solid line. The dashed lines correspond to a linear, least-squares fit for the

Dependency of decoding accuracy on channel count

the high

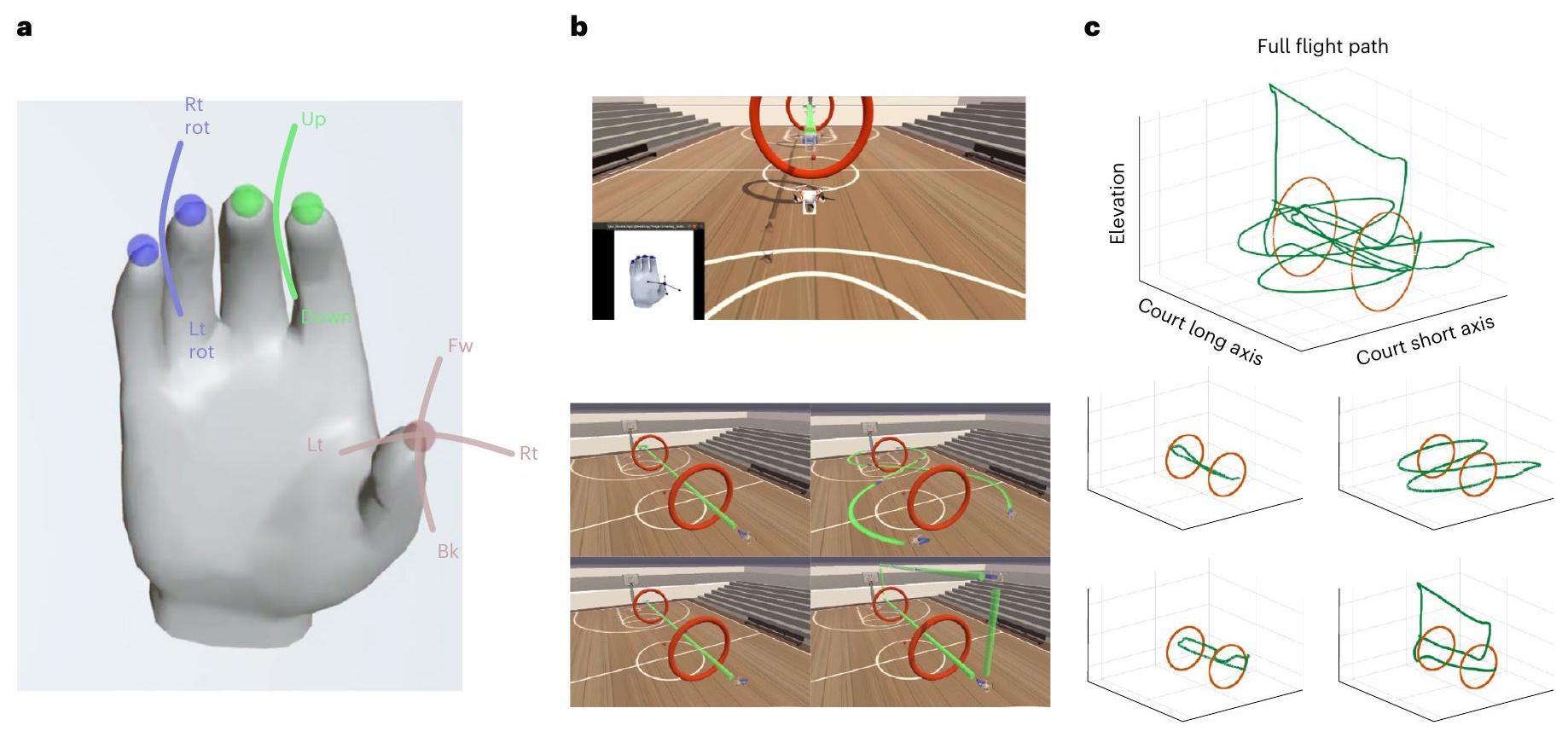

Translation of a finger iBCI to virtual quadcopter control

| Sno. | Day | Task | D no. | DOF | OL blocks (trials) | CL blocks (trials)

|

CL training time (min) | Figure | Notes |

| 1 | 2395 | CL finger decoding | 1 | 4 | 2 (200) | 7 (467) | 24.3 | 1, 3, ED 3, ED 4 | |

| 2 | 2400 | CL finger decoding | 2 | 4 | 2 (200) | 3 (180) | 9.8 | 1, 3, ED 3, ED 4 | |

| 3 | 2402 | CL finger decoding | 3 | 4 | 2 (200) | 5 (252) | 14.1 | 1, 3, ED 3-5 | |

| 3b | +5 (250) | 16.3 | ED 5 | ||||||

| 4 | 2407 | CL finger decoding | 4 | 2 | 2 (200) | 2 (100) | 5.9 | 1, 3, ED 3, ED 4 | |

| 5 | 2409 | CL finger decoding | 5 | 4 | 2 (200) | 9 (450) | 25.7 | 1, 3, ED 3-5 | |

| 6 | 2 | 2 (200) | 2 (100) | 11.1 | 1, 3, ED 3,ED 4 | ||||

| 6 | 2423 | CL finger decoding | 7 | 4 | 2 (200) | 12 (585) | 35.8 | 1-3, ED 1, ED 3-5 | Open-loop data were used for the confusion plots in Extended Data Fig. 1. Closed-loop data were used in Figs. 2-4. |

| 7b | +2 (100) | 5.5 | 2, ED 5 | ||||||

| 8 | 2 | 2 (200) | 7 (297) | 20.2 | 1, ED 3, ED 4 | Attempted to overtrain the decoder by ReFIT training it over many closed-loop blocks after 100% of trials were completed | |||

| 8b | +3 (150) | 5.1 | 2, 3, ED 5 | Includes 1 block (50 trials) using the 4D decoder | |||||

| 7 | 2430 | CL finger decoding | 9 | 4 | 2 (200) | 3 (150) | 8.2 | 1, ED 3, ED 4 | |

| 9b | +2 (100) | 5.1 | 2, ED 5 | ||||||

| 9c | +1 (50) | 2.5 | 2, ED 5 | ||||||

| 9d | +7 (331) | 16.8 | 1-3 ED 5 | Used in Fig. 3 for more trials (than earlier blocks) | |||||

| 9e | +1 (50) | 2.0 | 1-3, ED 5 | Used in Fig. 3 for more trials (than earlier blocks) | |||||

| 10 | 2 | 1 (100) | 1 (50) | 1.5 | 2, 3, ED 5 | Used in Fig. 3 for more trials (than earlier blocks) | |||

| 10b | +1 (50) | 1.5 | 2, 3,ED 5 | Used in Fig. 3 for more trials (than earlier blocks) | |||||

| 10c | +1 (50) | 2.0 | 2a, 3 | Used in Fig. 3 for more trials (than earlier blocks) | |||||

| 8 | 2520 | QC obstacle course | 11 | 4 | 2 (200) | 3 (150) | 8.3 | ||

| 11b | +4 (200) | 10.3 | 4 | ||||||

| 11c | +2 (100) | 5.8 | |||||||

| 11d | +2 (100) | 4.7 | |||||||

| 9 | 2569 | QC random rings | 12 | 4 | 2 (200) | 6 (269) | 20.4 | Open-loop blocks were performed using common average referencing, and closed-loop blocks used linear regression referencing |

not only by decoding accuracy but also largely by behavioral factors, as even able-bodied operators using a unimanual quadcopter control might find the task challenging.

User experience

path requires the quadcopter to move forward, turn around and move forward through the same rings to return to the starting point (one lap). The top-right path requires the participant to simultaneously move forward and turn to complete two ‘figure-8’ paths around the rings and back to the starting point (one lap). The bottom-left path requires him to move left through both rings, stop and then move right back through the rings (one lap). The bottom-right path requires moving forward through the rings, increasing the elevation, moving backward over top of the rings, decreasing elevation and then moving forward through both rings to the ending point (1.5 laps). c, Top, an exemplary full-flight path during a block of the obstacle course. Bottom, the flight path is separated into laps corresponding to the planned flight path for each lap in

“stick time” so he could improve his performance and exclaimed once that “I feel like we can work until 9 tonight”. Fatigue did not appear to be a factor in quadcopter control, with T5 never requesting to terminate or shorten any of the nine sessions included in this study. Ultimately, this work was the culmination of a long-held goal seen by both the research team and the participant as a joint collaborative achievement.

and quadcopter control explaining that the quadcopter control was “more sensitive than fingers” and he just had “to tickle it a direction”. He also emphasized the importance of individualization of the fingers and how failure of individualization degrades performance: “when you pull down with your [little finger], the other two finger [groups] are supposed to just stay there… but they track with the [little finger], which is what throws me off and the whole thing goes down and to the left instead of just left or whatever it is”.

Discussion

digital cursors, endpoints and buttons. However, most past research and commercial development has focused on using BCIs for 2D point/ click cursor control

Online content

References

- Armour, B. S., Courtney-Long, E. A., Fox, M. H., Fredine, H. & Cahill, A. Prevalence and causes of paralysis-United States, 2013. Am. J. Public Health 106, 1855-1857 (2016).

- Trezzini, B., Brach, M., Post, M. & Gemperli, A. Prevalence of and factors associated with expressed and unmet service needs reported by persons with spinal cord injury living in the community. Spinal Cord 57, 490-500 (2019).

- Cairns, P. et al. Enabled players: the value of accessible digital games. Games Cult. 16, 262-282 (2021).

- Tabacof, L., Dewil, S., Herrera, J. E., Cortes, M. & Putrino, D. Adaptive esports for people with spinal cord injury: new frontiers for inclusion in mainstream sports performance. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.612350 (2021).

- Beeston, J., Power, C., Cairns, P. & Barlet, M. in Computers Helping People with Special Needs (eds Miesenberger, K. & Kouroupetroglou, G.) 245-253 (Springer, 2018).

- Porter, J. R. & Kientz, J. A. An empirical study of issues and barriers to mainstream video game accessibility. In Proc. 15th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (ed. Lewis, C.) 1-8 (ACM, 2013).

- Taheri, A., Weissman, Z. & Sra, M. Design and evaluation of a hands-free video game controller for individuals with motor impairments. Front. Comp. Sci. 3, 751455.1 (2021).

- Nuyujukian, P. et al. Cortical control of a tablet computer by people with paralysis. PLoS ONE 13, eO2O4566 (2018).

- Flesher, S. N. et al. A brain-computer interface that evokes tactile sensations improves robotic arm control. Science 372, 831-836 (2021).

- Ajiboye, A. B. et al. Restoration of reaching and grasping movements through brain-controlled muscle stimulation in a person with tetraplegia: a proof-of-concept demonstration. Lancet 389, 1821-1830 (2017).

- Carmena, J. M. et al. Learning to control a brain-machine interface for reaching and grasping by primates. PLoS Biol. 1, e42 (2003).

- Collinger, J. L. et al. High-performance neuroprosthetic control by an individual with tetraplegia. Lancet 381, 557-564 (2013).

- Hochberg, L. R. et al. Reach and grasp by people with tetraplegia using a neurally controlled robotic arm. Nature 485, 372-375 (2012).

- Pandarinath, C. et al. High performance communication by people with paralysis using an intracortical brain-computer interface. eLife 6, e18554 (2017).

- Velliste, M., Perel, S., Spalding, M. C., Whitford, A. S. & Schwartz, A. B. Cortical control of a prosthetic arm for self-feeding. Nature 453, 1098-1101 (2008).

- Hochberg, L. R. et al. Neuronal ensemble control of prosthetic devices by a human with tetraplegia. Nature 442, 164-171 (2006).

- Wodlinger, B. et al. Ten-dimensional anthropomorphic arm control in a human brain-machine interface: difficulties, solutions, and limitations. J. Neural Eng. 12, 016011 (2014).

- Guan, C. et al. Decoding and geometry of ten finger movements in human posterior parietal cortex and motor cortex. J. Neural Eng. 20, 036020 (2023).

- Jorge, A., Royston, D. A., Tyler-Kabara, E. C., Boninger, M. L. & Collinger, J. L. Classification of individual finger movements using intracortical recordings in human motor cortex. Neurosurgery 87, 630-638 (2020).

- Bouton, C. E. et al. Restoring cortical control of functional movement in a human with quadriplegia. Nature 533, 247-250 (2016).

- Nakanishi, Y. et al. Decoding fingertip trajectory from electrocorticographic signals in humans. Neurosci. Res. 85, 20-27 (2014).

- Nason, S. R. et al. Real-time linear prediction of simultaneous and independent movements of two finger groups using an intracortical brain-machine interface. Neuron 109, 3164-3177. e3168 (2021).

- Willsey, M. S. et al. Real-time brain-machine interface in non-human primates achieves high-velocity prosthetic finger movements using a shallow feedforward neural network decoder. Nat. Commun. 13, 6899 (2022).

- Nason, S. R. et al. A low-power band of neuronal spiking activity dominated by local single units improves the performance of brain-machine interfaces. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4, 973-983 (2020).

- Costello, J. T. et al. Balancing memorization and generalization in RNNs for high performance brain-machine interfaces. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.28.542435 (2023).

- Shah, N. P. et al. Pseudo-linear summation explains neural geometry of multi-finger movements in human premotor cortex. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.11.561982 (2023).

- Willett, F. R., Avansino, D. T., Hochberg, L. R., Henderson, J. M. & Shenoy, K. V. High-performance brain-to-text communication via handwriting. Nature 593, 249-254 (2021).

- Griffin, D. M., Hoffman, D. S. & Strick, P. L. Corticomotoneuronal cells are “functionally tuned”. Science 350, 667-670 (2015).

- Sakellaridi, S. et al. Intrinsic variable learning for brain-machine interface control by human anterior intraparietal cortex. Neuron 102, 694-705. e693 (2019).

- Willett, F. R. et al. Hand knob area of premotor cortex represents the whole body in a compositional way. Cell 181, 396-409. e326 (2020).

- Zhang, C. Y. et al. Preservation of partially mixed selectivity in human posterior parietal cortex across changes in task context. Eneuro 7, ENEURO.0222-19.2019 (2020).

- Kryger, M. et al. Flight simulation using a brain-computer interface: a pilot, pilot study. Exp. Neurol. 287, 473-478 (2017).

- Gilja, V. et al. A high-performance neural prosthesis enabled by control algorithm design. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 1752 (2012).

- Kao, J. C., Nuyujukian, P., Ryu, S. I. & Shenoy, K. V. A high-performance neural prosthesis incorporating discrete state selection with hidden Markov models. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 64, 935-945 (2016).

- LaFleur, K. et al. Quadcopter control in three-dimensional space using a noninvasive motor imagery-based brain-computer interface. J. Neural Eng. 10, 046003 (2013).

- Essential facts about the computer and video game industry. Entertainment Software Association www.theesa.com/resource/2 021-essential-facts-about-the-video-game-industry/ (2021).

- Raith, L. et al. Massively multiplayer online games and well-being: a systematic literature review. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.698799 (2021).

- Adeane, A. Quad gods: the world-class gamers who play with their mouths. BBC www.bbc.com/news/stories-55811621 (2021).

- Willett, F. R. et al. A high-performance speech neuroprosthesis. Nature 620, 1031-1036 (2023).

- Card, N. S. et al. An accurate and rapidly calibrating speech neuroprosthesis. N. Engl. J. Med. 391, 609-618 (2024).

(c) The Author(s) 2025

Methods

Clinical trial and participant

Participant sessions

Finger tasks

was cued to simultaneously move the finger groups from a center ‘neutral’ position toward random targets within the active range of motion. Once reaching the target, all fingers were required to be within the target for 500 ms for the trial to be successfully completed. On the subsequent trial, targets were placed back at the center. The target width was

Quadcopter tasks

complete all segments of the obstacle course as quickly and accurately as possible. He completed the course a total of 12 times, and during these completed runs, no penalty was assessed for not staying exactly on course, hitting rings or missing rings (he did miss two of the total 168 possible rings).

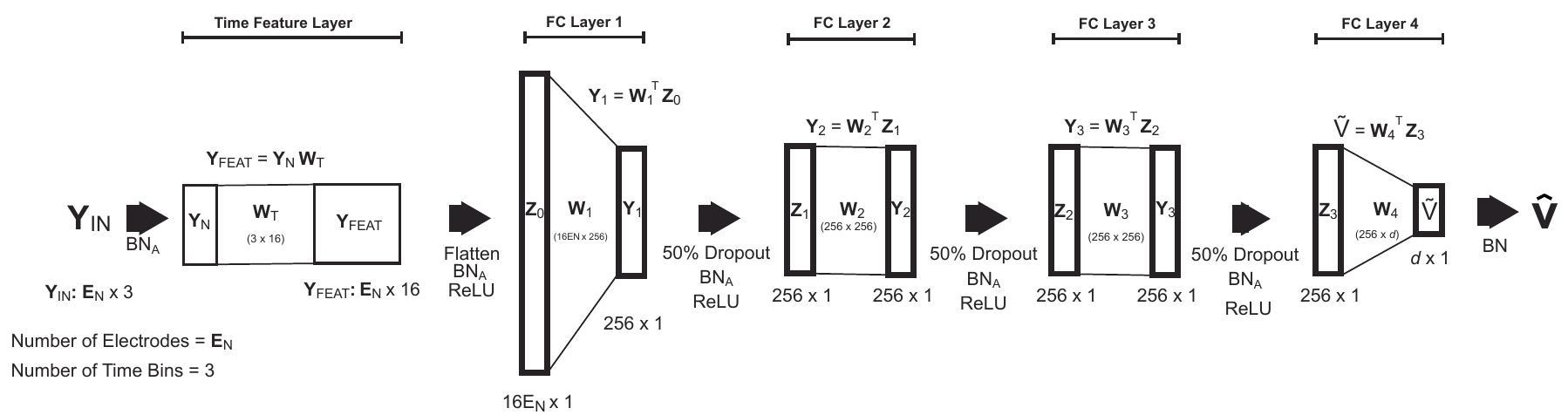

Decoding algorithm

Closed-loop decoding software

Algorithm training

mean-squared error (torch.nn.MSELoss) between the actual finger velocities during open-loop training and the algorithm output using the Adam optimization algorithm

BCI rig and front-end signal processing

Training protocols for the 4D decoder

Training protocols for the 2D decoder

Online metrics

Offline analyses

(v.1.12.0), torchvision (v.0.13.0), numpy (v.1.21.5), matplotlib (v.3.5.3), PIL (v.9.0.1) and sklearn (v.1.0.2). Confusion matrices and dimensionality analyses are detailed in the Supplementary Methods and are similar to analyses in previous reports

dSNR. Although SNR metrics have been proposed for offline analyses, a vector-based SNR

Reporting summary

Data availability

Code availability

References

- Deo, D. R. et al. Brain control of bimanual movement enabled by recurrent neural networks. Sci. Rep. 14, 1598 (2024).

- Shah, S., Dey, D., Lovett, C. & Kapoor, A. Airsim: high-fidelity visual and physical simulation for autonomous vehicles. In Field and Service Robotics: Results of the 11th International Conference (eds Hutter, M. & Siegwart, R.) 621-635 (Springer, 2018).

- Ioffe, S. & Szegedy, C. Batch normalization: accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. In Proc. 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning (eds Bach, F. & Blei, D.) 448-456 (JMLR, 2015).

- He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Delving deep into rectifiers: surpassing human-level performance on imagenet classification. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 1026-1034 (IEEE, 2015).

- Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1412.6980 (2014).

- Perge, J. A. et al. Intra-day signal instabilities affect decoding performance in an intracortical neural interface system. J. Neural Eng. 10, 036004 (2013).

- Liu, R. et al. Drop, swap, and generate: a self-supervised approach for generating neural activity. Adv. Neural Inf. Process Syst. 34, 10587-10599 (2021).

- Sussillo, D., Stavisky, S. D., Kao, J. C., Ryu, S. I. & Shenoy, K. V. Making brain-machine interfaces robust to future neural variability. Nat. Commun. 7, 13749 (2016).

- Jarosiewicz, B. et al. Virtual typing by people with tetraplegia using a self-calibrating intracortical brain-computer interface. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 313ra179-313ra179 (2015).

- Wilson, G. H. et al. Long-term unsupervised recalibration of cursor BCls. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi. org/10.1101/2023.02.03.527022 (2023).

- Degenhart, A. D. et al. Stabilization of a brain-computer interface via the alignment of low-dimensional spaces of neural activity. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4, 672-685 (2020).

- Karpowicz, B. M. et al. Stabilizing brain-computer interfaces through alignment of latent dynamics. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.06.487388 (2022).

- Tse, D. & Viswanath, P. Fundamentals of Wireless Communication (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2005).

- Willsey, M. et al. Data from: a high-performance brain-computer interface for finger decoding and quadcopter game control in an individual with paralysis [Dataset]. Dryad. https://doi.org/10.5061/ dryad.1jwstqk4f (2024).

Acknowledgements

CAUTION: Investigational Device. Limited by Federal Law to Investigational Use.

Author contributions

and F.R.W.; Validation: M.S.W., N.P.S., D.T.A. and F.R.W.; Formal analysis: M.S.W.; Investigation: M.S.W., N.P.S., D.T.A., N.V.H., R.M.J., F.B.K., F.R.W. and J.M.H.; Writing—original draft: M.S.W.; Writing—review and editing: M.S.W., N.P.S., D.T.A., N.V.H., R.M.J., F.B.K., L.R.H., F.R.W. and J.M.H.; Supervision: M.S.W., F.R.W. and J.M.H.; Project administration: L.R.H. and J.M.H.; Funding acquisition: L.R.H. and J.M.H.

Competing interests

Additional information

2016. The red line indicates the central sulcus (CS). Panel from Deo et al.

implemented with affine

a.

b.

the 2-DOF task,

curve represents combined IM finger and RL finger flexion/extension distances, and the orange curve represents the 2D distance for the thumb (combining the 2D components of flexion/extension and abduction/adduction) for trials using the 4D decoder and task in Fig. 1e. a.u., arbitrary units; DOF, degree of freedom; PDF, probability distribution function.

collection represent consecutive blocks without re-training unless otherwise indicated. The labels 4D/4T indicate the 4D decoder run on 4T; 4D/2T indicates the 4D decoder on 2T; and 2D/2T indicates the 2D decoder on 2T. c, Decoder stability test for 2 trial days using the 4-DOF decoder for 2 new targets/trial. For days 2402 (blue and light blue) and 2409 (red), the decoder was trained (upside down triangle with “Decoder Trained”) and then used in consecutive blocks until trials could not be reliably completed. On day 2402 , the decoder was retrained (“Decoder Updated”) to demonstrate the recovery of performance on 2 subsequent blocks (light blue).

| 1 New target/trial | 2 New targets/trial | |

| Number of trials | 178 | 187 |

| Number of days | 1 | 1 |

| Acquisition time

|

|

|

| Time to target

|

|

|

| Orbiting time

|

|

|

| Targets per minute |

|

|

| Percent completed |

|

|

| Path length |

|

|

| 2D Decoder, 2D task | 4D Decoder, 4D task | 4D Decoder, 2D task | |

| Number of trials | 233 | 284 | 329 |

| Number of days | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Acquisition time (ms) |

|

|

|

| Time to target (ms) |

|

|

|

| Orbiting time (ms) |

|

|

|

| Targets per minute |

|

|

|

| Percent completed | 99.1% | 99.6% | 100% |

| Path length |

|

|

|

natureportfolio

| Corresponding author(s): |

|

||

| Last updated by author(s): | Sep 20, 2024 |

Reporting Summary

Statistics

□

□

□

□

□

□ For Bayesian analysis, information on the choice of priors and Markov chain Monte Carlo settings

□ For hierarchical and complex designs, identification of the appropriate level for tests and full reporting of outcomes

□ Estimates of effect sizes (e.g. Cohen’s

Confirmed

□ The exact sample size

□ A statement on whether measurements were taken from distinct samples or whether the same sample was measured repeatedly

Only common tests should be described solely by name; describe more complex techniques in the Methods section.

□ A description of all covariates tested

□ A description of any assumptions or corrections, such as tests of normality and adjustment for multiple comparisons

“

L

L

Software and code

Data collection

The virtual finger display was developed in Unity (2021.3.9f1). A physics-based quadcopter environment used the Microsoft AirSim plugin41 as a quadcopter simulator in Unity (2019.3.12f1). The Neural Signal Processor sends the digital signal to a SuperLogics machine running Simulink Real-Time (v2019, Mathworks, Natick, MA). This computer communicated with a Linux computer running Ubuntu with Python (v3.7.11), PyTorch (v1.12.1, https://pytorch.org/), and Redis (v7.02), where custom code performed decoding, control of the virtual environment in Unity, and training of the neural network. The entire system was interfaced with an additional Windows computer running Matlab (v2019, Mathworks, Natick, MA) that was interfaced with the system to stop and start experimental runs during sessions.

The offline analyses were conducted in Python (v3.9.12) using a Jupyter notebook (https://jupyter.org/) and in Matlab (v2022a, Mathworks, Natick, MA). The following python packages were used: scipy (v1.7.3), torch (v1.12.0), torchvision (v0.13.0), numpy (v1.21.5), matplotlib (v3.5.3), PIL (v9.0.1), sklearn (v1.0.2). The versions of the Jupyter core packages are: IPython 8.2.0, ipykernel 6.9.1, ipywidgets 7.6.5, jupyter_client 6.1.12, jupyter_core 4.9.2, jupyter_server 1.13.5, jupyterlab 3.3.2, nbclient 0.5.13, nbconvert 6.4.4, nbformat 5.3.0, notebook 6.4.8, qtconsole 5.3.0, traitlets 5.1.1.

Data

Policy information about availability of data

- Accession codes, unique identifiers, or web links for publicly available datasets

- A description of any restrictions on data availability

- For clinical datasets or third party data, please ensure that the statement adheres to our policy

Research involving human participants, their data, or biological material

Participant T5 was enrolled in the BrainGate 2 clinical trial after meeting inclusion criteria based in part on disease characteristics. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are available online (ClinicalTrials.gov). This investigation was pursued as part of the secondary outcome measure of the clinical trial. Regarding potential selection biases, the strict inclusion and exclusion criteria could lead to selecting healthier participants than the typical population with paralysis.

Field-specific reporting

Life sciences □ Behavioural & social sciences □ Ecological, evolutionary & environmental sciences

For a reference copy of the document with all sections, see nature.com/documents/nr-reporting-summary-flat.pdf

Life sciences study design

| Sample size | No sample-size calculation was performed. Data were collected in a single participant to characterize the performance of a brain-computer interface. The number of trials are comparable to similar studies, and uncertainty in performance estimates were quantified using the standard error of the mean. |

| Data exclusions | No data was excluded. Finger decoding sessions were performed over a series of days (from March to April, 2023). The 4DOF obstacle course and random ring task were demonstrated on a single day after preliminary sessions to develop each task. |

| Replication | Primary results of finger decoding were evaluated successfully confirmed on 7 independent days without exclusion. |

| Randomization | There was not randomization of participants to treatment groups as there was only one participant. There was randomization of the positions of center-out-center finger targets to randomly sample the potential target space. |

| Blinding | There was no blinding related to treatment groups as there was only one participant enrolled. It was not possible to blind the participant to the task he was performing. |

Reporting for specific materials, systems and methods

| Materials & experimental systems | Methods | ||

| n/a | Involved in the study | n/a | Involved in the study |

| X | □ |  |

□ |

| X | □ | X | □ |

| X | □ | ||

| X | □ | ||

| X | □ | ||

| X | □ | ||

Plants

n/a

n/a

n/a

- ¹Department of Neurosurgery, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA. ²Department of Neurosurgery, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.