DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae231

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38948324

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-31

يمكن لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة استنتاج الميول النفسية لمستخدمي وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي

الملخص

تظهر نماذج اللغة الكبيرة (LLMs) قدرات تشبه الإنسان بشكل متزايد عبر مجموعة واسعة من المهام. في هذه الورقة، نحقق فيما إذا كانت نماذج اللغة الكبيرة مثل ChatGPT يمكنها استنتاج الميول النفسية لمستخدمي وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي بدقة وما إذا كانت قدرتها على القيام بذلك تختلف عبر المجموعات الاجتماعية والديموغرافية. على وجه التحديد، نختبر ما إذا كان بإمكان GPT-3.5 وGPT-4 استنتاج سمات الشخصية الخمس الكبرى من تحديثات حالة مستخدمي فيسبوك في سيناريو التعلم بدون أمثلة. تظهر نتائجنا ارتباطًا متوسطًا قدره r

1 المقدمة

بينما لم يتم تصميم نماذج اللغة الكبيرة بشكل صريح لالتقاط أو تقليد عناصر من الإدراك البشري وعلم النفس، تشير الأبحاث الحديثة إلى أنه – نظرًا لتدريبها على مجموعات بيانات واسعة من اللغة التي أنشأها البشر – قد تكون قد طورت بشكل عفوي القدرة على القيام بذلك. على سبيل المثال، تظهر نماذج اللغة الكبيرة خصائص مشابهة للقدرات والعمليات الإدراكية التي لوحظت في البشر، بما في ذلك نظرية العقل (أي القدرة على فهم الحالات العقلية لوكلاء آخرين [5])، والتحيزات الإدراكية في اتخاذ القرار [6] والتنشيط الدلالي [7]. وبالمثل، تستطيع نماذج اللغة الكبيرة بشكل فعال توليد رسائل مقنعة مصممة لتناسب ميول نفسية معينة (مثل سمات الشخصية، والقيم الأخلاقية [8]).

هنا، نبحث فيما إذا كانت نماذج اللغة الكبيرة تمتلك جودة أخرى تعتبر إنسانية بشكل أساسي: القدرة على “قراءة” الأشخاص وتكوين انطباعات أولية حول ميولهم النفسية في غياب تفاعل مباشر أو سابق

. كما تظهر الأبحاث تحت مظلة دراسات عدم المعرفة، يمكن للناس أن يكونوا دقيقين بشكل ملحوظ في الحكم على السمات النفسية للغرباء ببساطة من خلال ملاحظة آثار سلوكهم في ظل ظروف معينة [9]. بينما يمكن أن تتأثر مثل هذه الأحكام بالصور النمطية ويمكن أن تختلف دقتها بناءً على السمات التي يتم تقييمها والسياق الذي يتم فيه اتخاذ الأحكام [10]، تشير الأعمال السابقة إلى أن الناس قادرون على التنبؤ بسمات شخصية الغريب من خلال ملاحظة مكاتبهم أو غرف نومهم [11]، أو فحص تفضيلاتهم الموسيقية [12]، أو التمرير عبر ملفاتهم الشخصية على وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي [13].

تظهر الأبحاث الحالية في العلوم الاجتماعية الحاسوبية أن نماذج التعلم الآلي الخاضعة للإشراف قادرة على إجراء تنبؤات مماثلة. أي أنه، نظرًا لوجود مجموعة بيانات كبيرة بما يكفي تشمل كل من السمات الشخصية المبلغ عنها ذاتيًا وآثار الأقدام الرقمية للناس – مثل إعجابات فيسبوك، قوائم التشغيل الموسيقية، أو سجلات التصفح – تكون نماذج التعلم الآلي قادرة على الربط إحصائيًا بين كلا المدخلين بطريقة تسمح لها بالتنبؤ بسمات الشخصية بعد ملاحظة آثار الأقدام الرقمية لشخص ما [14، 15]. وهذا صحيح أيضًا بالنسبة لأشكال مختلفة من بيانات النص، بما في ذلك منشورات وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي [16، 17]، المدونات الشخصية [18]، أو ردود النص القصير التي تم جمعها في سياق طلبات العمل [19].

في هذه الورقة، نختبر ما إذا كانت نماذج اللغة الكبيرة لديها القدرة على إجراء استنتاجات نفسية مماثلة دون أن يتم تدريبها بشكل صريح للقيام بذلك (المعروفة باسم التعلم بدون أمثلة [3]). على وجه التحديد، نستخدم ChatGPT من Open AI (GPT-3.5 وGPT-4 [1]) لاستكشاف ما إذا كانت نماذج اللغة الكبيرة يمكنها استنتاج سمات الشخصية الخمس الكبرى الانفتاح، والضمير، والانبساط، والود، والعصابية [20] لمستخدمي وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي من محتوى تحديثات حالة فيسبوك الخاصة بهم في سيناريو بدون أمثلة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، نختبر التحيزات في أحكام ChatGPT التي قد تنشأ من أساسها في بيانات بشرية متحيزة بنفس القدر. بناءً على الأعمال السابقة التي تسلط الضوء على الصور النمطية الكامنة في نماذج معالجة اللغة الطبيعية المدربة مسبقًا [21، 22]، نستكشف إلى أي مدى تعكس استنتاجات الشخصية التي أجراها ChatGPT التحيزات المتعلقة بالجنس والعمر (مثل التحيزات المحتملة في كيفية الحكم على شخصية الرجال والنساء أو الأشخاص الأكبر سنًا والأصغر سنًا).

2 المنهج

2.1 البيانات والعينة

2.2 القياسات

للحصول على سمات الشخصية المستنتجة من ChatGPT، استخدمنا آخر 200 تحديث حالة على فيسبوك تم إنشاؤها بواسطة كل مستخدم دون معالجة إضافية. كان متوسط طول تحديثات الحالة في عيّنتنا 17.10 كلمة (SD=15.03). تم تقييم تحديثات الحالة باستخدام واجهة برمجة تطبيقات ChatGPT مع GPT-3.5 (الإصدار gpt-3.5-turbo0301) و GPT-4 (الإصدار gpt-4-0314) [1] كنماذج أساسية. لهذا الغرض، تم

لزيادة موثوقية تقديرات الشخصية المستنتجة، استفسرنا من ChatGPT ثلاث مرات لكل استنتاج. كان الاتفاق عبر التقييمات عبر جولات التقييم مرتفعًا لجميع السمات (الانفتاح:

3 النتائج

3.1 هل يمكن لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة استنتاج سمات الشخصية من منشورات وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي؟

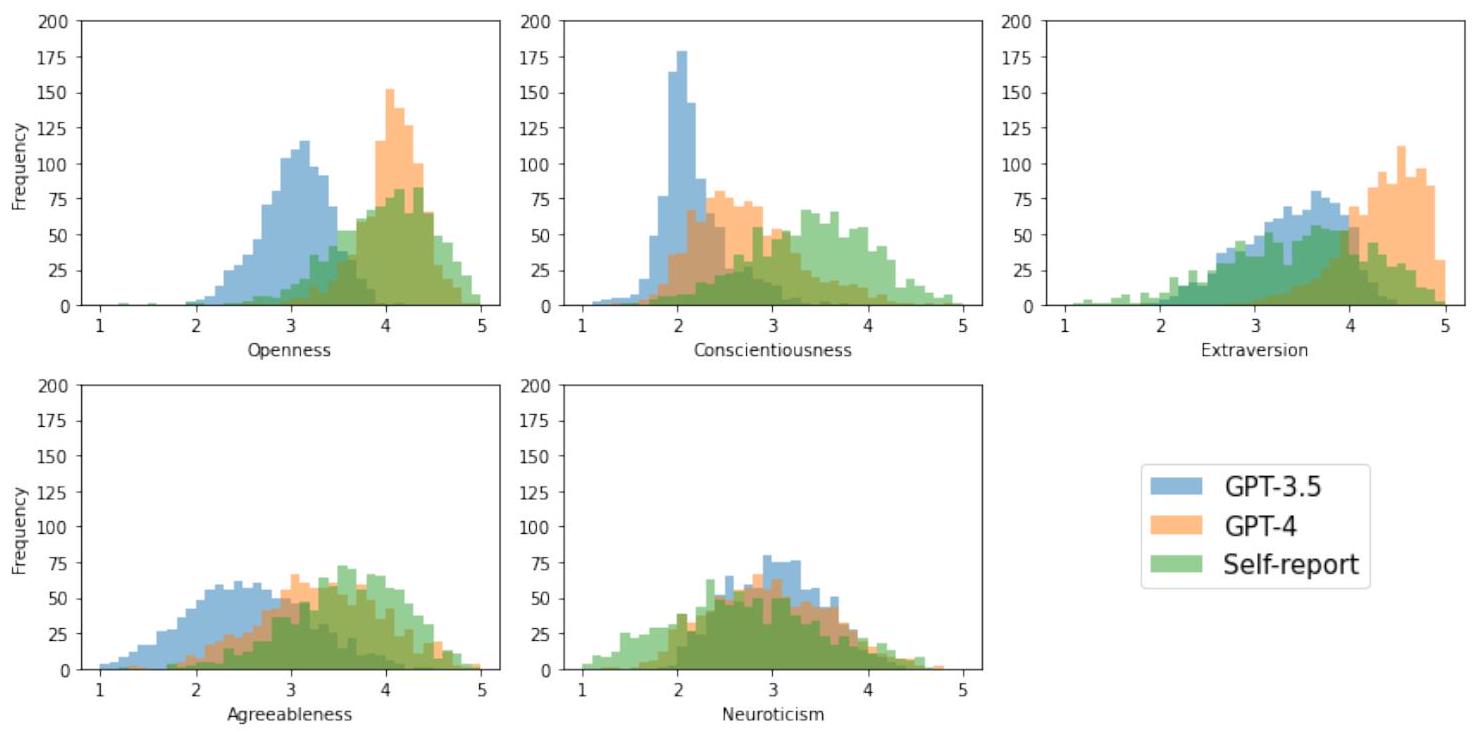

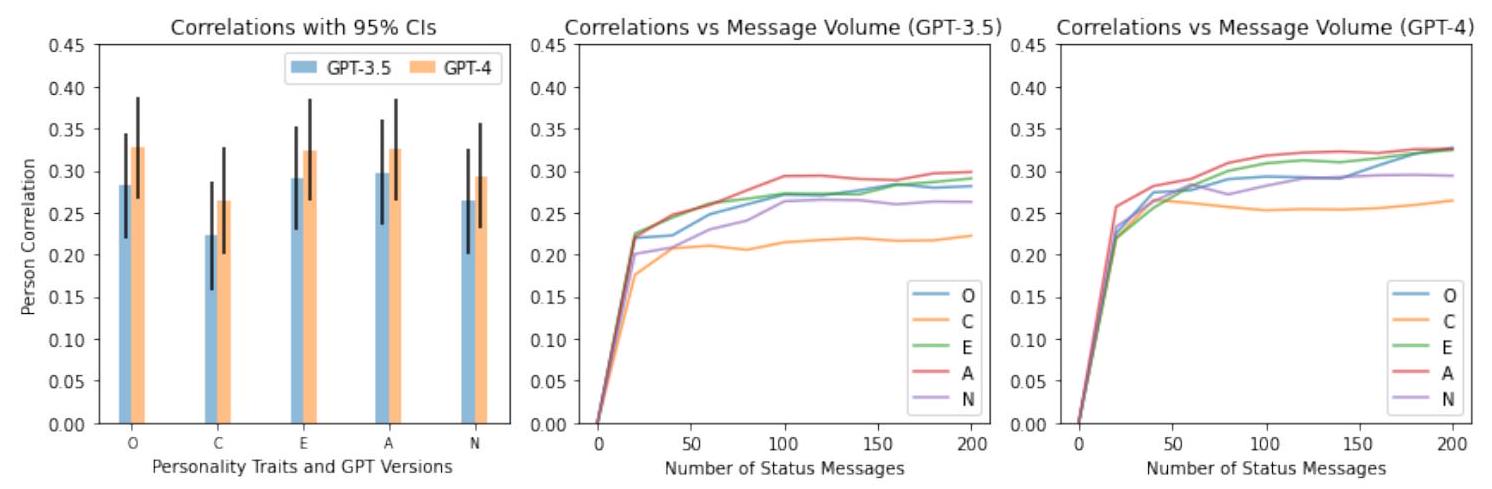

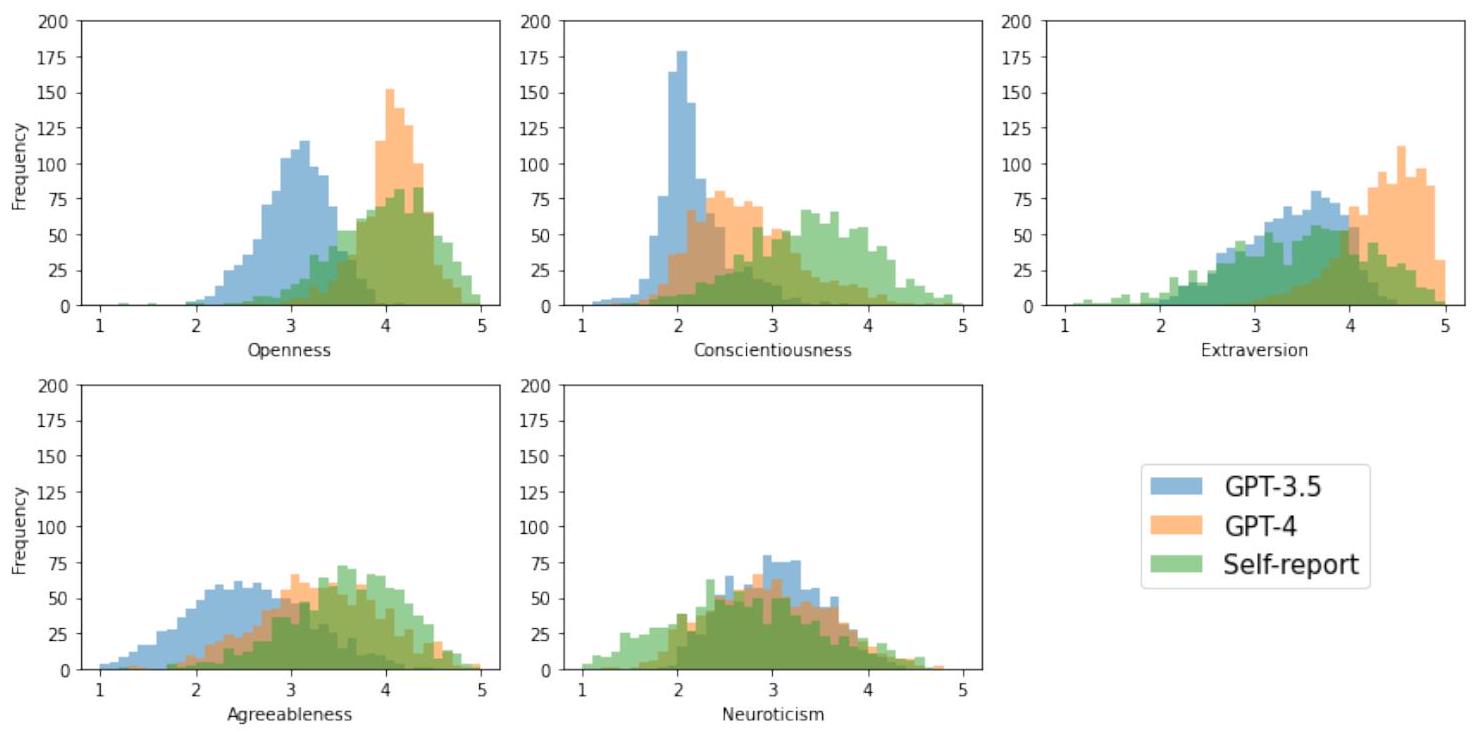

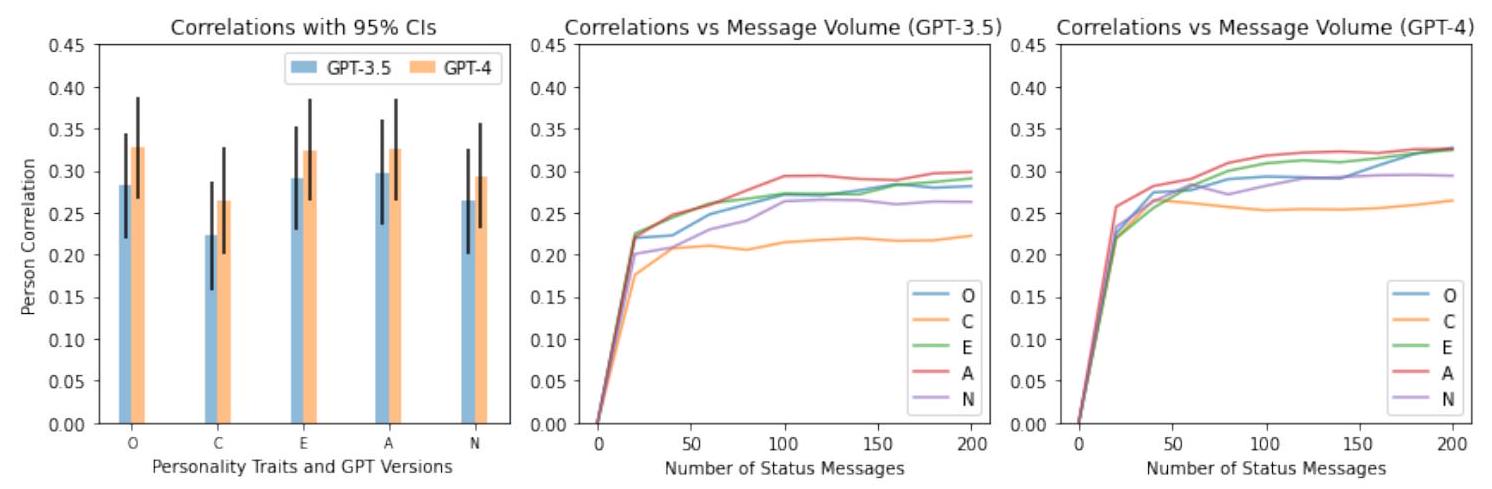

بالإضافة إلى استكشاف قدرة ChatGPT على استنتاج سمات الشخصية من بيانات مستخدمي وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي، اختبرنا أيضًا مدى حساسية هذه القدرة للتغيرات في كمية البيانات المتاحة للاستنتاج. على وجه التحديد، قمنا بحساب الارتباطات بين الدرجات الذاتية المبلغ عنها والدرجات المستنتجة بناءً على أعداد مختلفة من رسائل الحالة. على وجه التحديد، قمنا بحساب الارتباطات التي تم الحصول عليها من الاستنتاجات لكتلة واحدة من رسائل الحالة (20 رسالة حالة) وصولاً إلى عشر كتل (200 رسالة حالة). كما هو متوقع، أدى الوصول إلى المزيد من رسائل الحالة إلى استنتاجات أكثر دقة. ومن الجدير بالذكر، مع ذلك، أن معظم الارتباطات قريبة من أقصى مستوى لها بعد ملاحظة عدد أقل بكثير من العدد النهائي البالغ 200 رسالة حالة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يبدو أن استنتاج بعض السمات حساس بشكل خاص لحجم بيانات الإدخال. على سبيل المثال، استمر دقة النماذج في الزيادة مع مستويات أعلى في حجم الإدخال للانفتاح والانبساط والود والعصابية، بينما كانت فوائد رسائل الحالة الإضافية تتسطح في وقت سابق بالنسبة للضمير. انظر الشكل 2 لتمثيل رسومي و S3 للإحصائيات التفصيلية.

3.2 هل تختلف جودة استنتاجات نماذج اللغة الكبيرة عبر المجموعات الديموغرافية؟

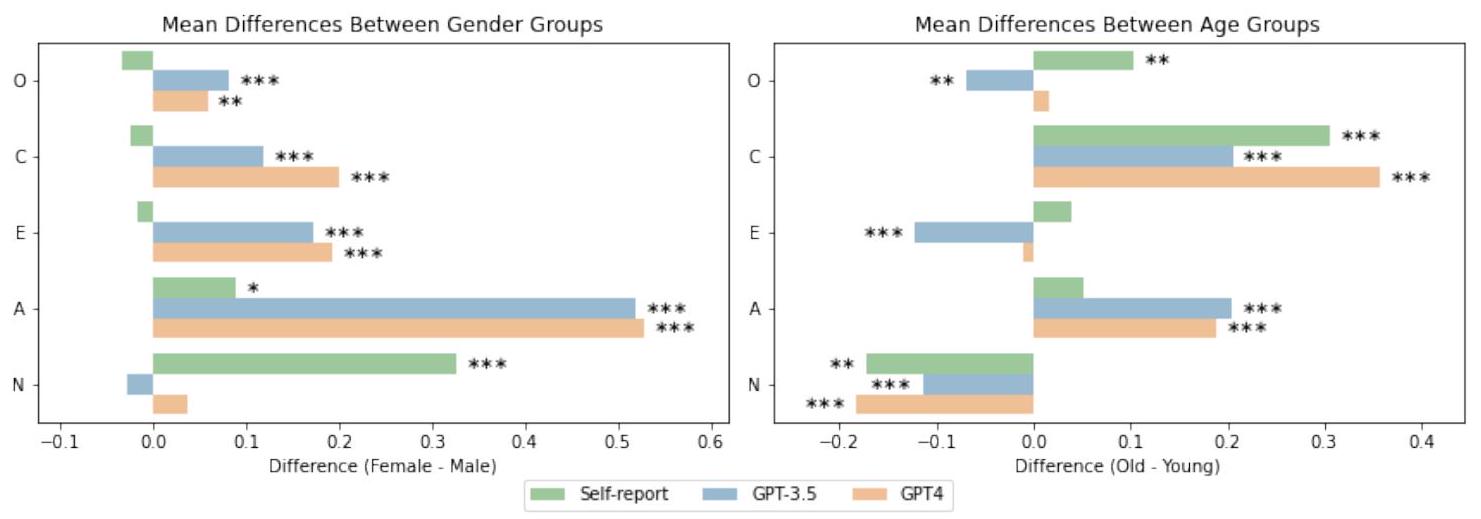

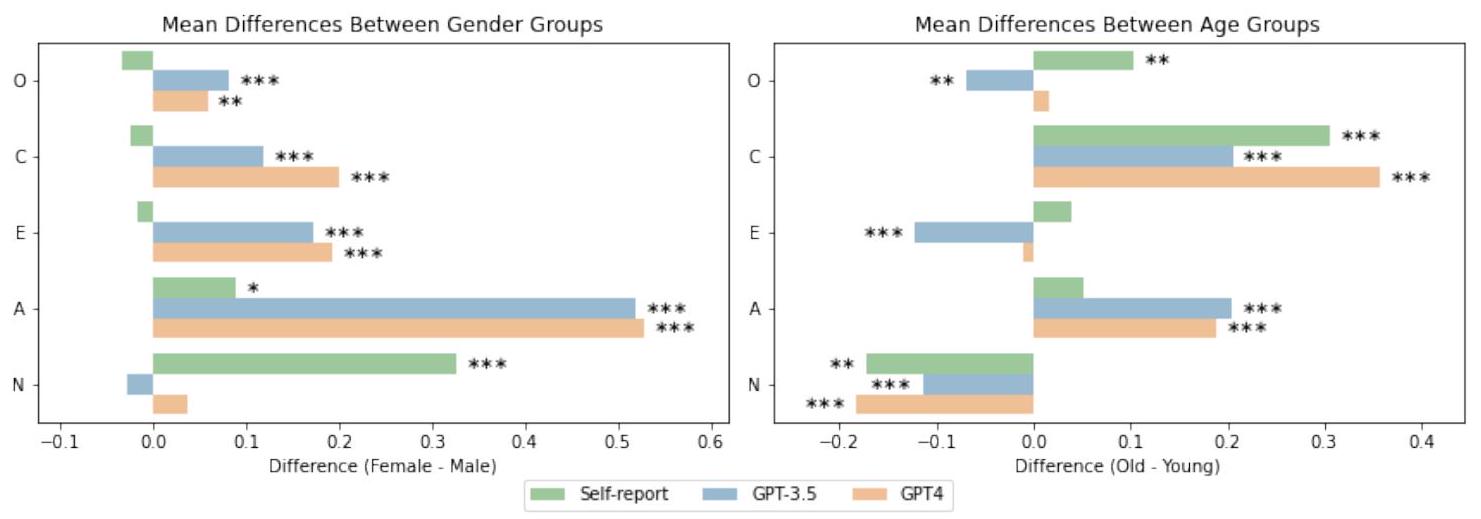

3.2.1 الفروق بين الجنسين

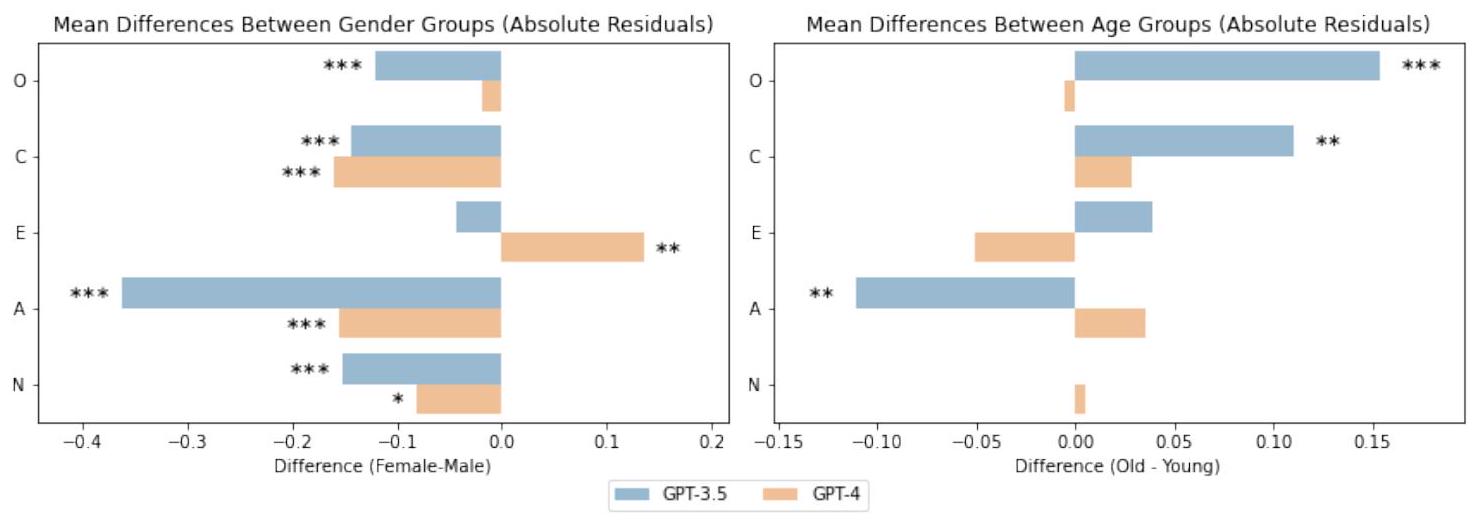

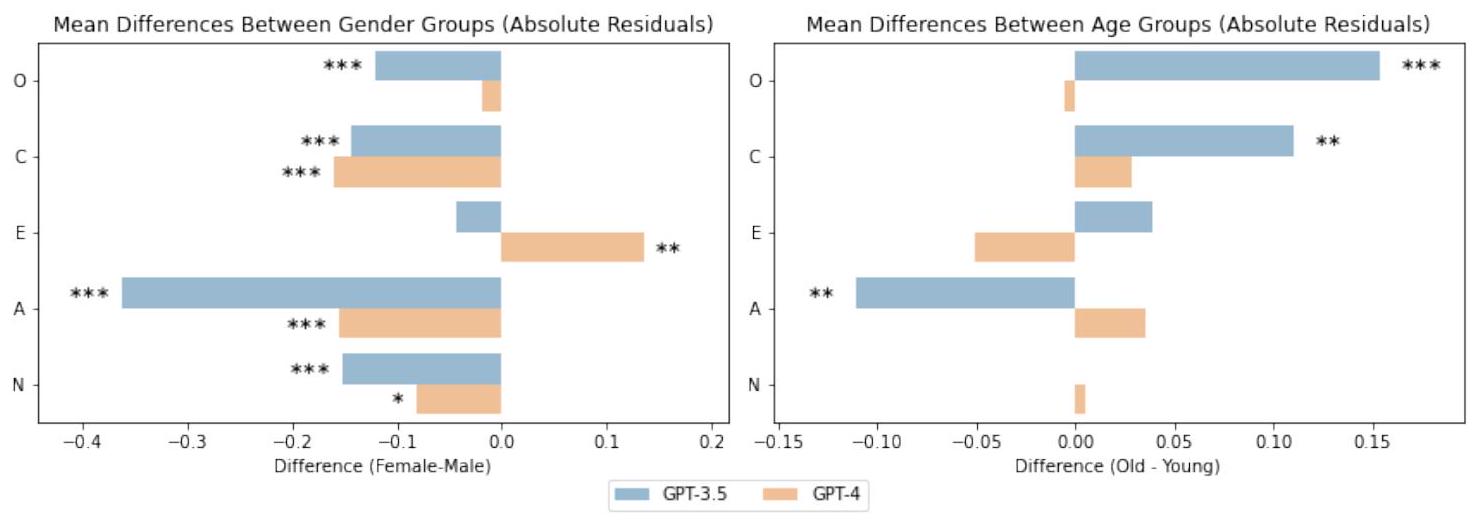

لاستكشاف هذه التحيزات المحتملة بشكل أعمق، قمنا بتحليل المتبقيات بين الدرجات المستنتجة والدرجات المبلغ عنها ذاتيًا كدليل على مدى قدرة GPT على تمثيل سمات الشخصية للمستخدمين الذكور والإناث. تشير النتائج إلى أن استنتاجات شخصية GPT أقل دقة للرجال مقارنة بالنساء. أولاً، لاحظنا متبقيات مطلقة أكبر للمستخدمين الذكور في الضمير (

3.2.2 الفروق العمرية

كما في السابق، نستكشف هذه الاختلافات من خلال تحليل الفروق العمرية في المتبقيات بين الدرجات المبلغ عنها ذاتيًا والدرجات المستنتجة. على عكس تحليلات الجنس، وجدنا عدم اتساق كبير في الاختلافات الجماعية بين GPT-3.5 وGPT-4. بينما أظهرت الاستنتاجات التي قدمها GPT-3.5 متبقيات مطلقة أكبر بشكل ملحوظ للمستخدمين الأكبر سناً في الانفتاح (

3.3 الاتفاق مع تقييمات المراقب من الطرف الثالث

تظهر النتائج أن الارتباطات بين الدرجات المبلغ عنها ذاتيًا وتقييمات المراقب تراوحت من r=. 198 إلى

4 المناقشة

4.1 تفسير النتائج

تساهم دراستنا في مجموعة متزايدة من الأبحاث التي تقارن قدرات LLMs بتلك التي لوحظت في البشر [5، 7، 8]. كما تشير نتائجنا، قد تمتلك LLMs القدرة الشبيهة بالبشر على “توصيف” الأشخاص بناءً على آثارهم السلوكية، دون أن يكون لديها أي تفاعلات مباشرة معهم. على الرغم من أن معظم منشورات وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي لا تحتوي على إشارات صريحة لشخصية الفرد، فإن ChatGPT – تمامًا مثل القضاة البشريين [13، 32] أو النماذج الخاضعة للإشراف [31] – قادر على ترجمة حسابات الأشخاص عن أنشطتهم اليومية وتفضيلاتهم إلى صورة شاملة لميولهم النفسية. تتماشى نتائجنا مع الأعمال السابقة التي تشير إلى أن الانفتاح والانبساطية يمكن استنتاجهما بسهولة أكبر من السمات الأخرى [13، 31]. في الوقت نفسه، كانت استنتاجات LLM أكثر توافقًا مع تقييمات المراقب من التقارير الذاتية في حالة الضمير، مما يشير إلى أن LLMs قد تكرر أيضًا التحيزات في الحكم البشري لبعض السمات.

تشير الأعمال السابقة بشكل محدد إلى أن نماذج اللغة الكبيرة عرضة للتصنيف النمطي والتحيز فيما يتعلق بالمجموعات الديموغرافية والجغرافية، مما يعكس على الأرجح تمثيل المجموعات في بيانات التدريب الأساسية. في الوقت نفسه، أظهرت الأعمال السابقة اختلافات في استخدام وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي والتعبير الذاتي عبر الإنترنت بين المجموعات الديموغرافية، بما في ذلك العمر والجنس. بينما لا تتحدث الأدبيات السابقة مباشرة عن اختلافات في التعبير عن الشخصية، فإن نمط النتائج الملحوظ يشير إلى أن النساء والأفراد الأصغر سناً يميلون إلى الكشف عن معلومات أكثر دقة حول شخصياتهم عبر الإنترنت.

4.2 القيود والبحوث المستقبلية

ثانيًا، تم الحصول على بيانات النص المستخدمة في تحليلنا من تطبيق MyPersonality على فيسبوك، الذي كان نشطًا بين عامي 2007 و2012. قد تختلف التقاليد اللغوية من هذه الفترة عن اللغة عبر الإنترنت المعاصرة، مما قد يحد من أداء نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في حالة عدم وجود بيانات تدريب جديدة. نتيجة لذلك، نتوقع أن تكون استنتاجات الشخصية لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة أكثر دقة عند تطبيقها على بيانات أكثر حداثة.

ثالثًا، تم الحصول على بياناتنا من مستخدمي فيسبوك الذين تفاعلوا مع تطبيق MyPersonality. وبالتالي، قد لا تكون عيّنتنا ممثلة للسكان الأوسع لمستخدمي وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي (أو الناس بشكل عام)، مما قد يحد من الصلاحية الخارجية لنتائجنا. على سبيل المثال، قد يكون التقدير العام المنخفض لسمات الشخصية مثل الانفتاح ناتجًا عن حقيقة أن مستخدمي MyPersonality كانوا فضوليين ومنفتحين بشكل خاص.

خامسًا، لم تشمل دراستنا ديناميات التفاعلات الحية بين نماذج اللغة الكبيرة والمستخدمين. قد تؤدي التفاعلات في الوقت الحقيقي إلى رؤى مختلفة وتبرز تعقيدات إضافية لم يتم التقاطها في مجموعة بياناتنا النصية الثابتة. ذات صلة، بينما تؤكد أبحاثنا على الإمكانية لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة في تخصيص التفاعلات وتعزيز الحوسبة الاجتماعية، إلا أنها لا تفحص تفاصيل كيفية تنفيذ هذه التخصيصات بشكل فعال.

سادسًا، تُظهر الأبحاث الحالية إمكانيات نماذج اللغة الكبيرة الجاهزة لاستنتاج المتغيرات النفسية باستخدام تقنيات بسيطة مثل التعلم بدون تدريب ونماذج متاحة تجاريًا. من المحتمل أن يتم تحسين الأداء التنبؤي لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة من خلال استراتيجيات تحفيز أكثر تعقيدًا، مثل تحفيز سلسلة الأفكار ومزيج من التعلم في السياق والتدريب الدقيق المراقب. بينما ركزنا عمدًا على التعلم بدون تدريب من أجل تحديد حد أدنى لدقة التنبؤ والتحقيق في القدرة الفطرية لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة على إجراء مثل هذه التنبؤات، يمكن أن تركز الأبحاث المستقبلية على تحديد العوامل التي تعظم دقة التنبؤ. بخلاف نماذج التحفيز الأكثر تعقيدًا، قد يشمل ذلك منح نماذج اللغة الكبيرة الوصول إلى معلومات ديموغرافية للمستخدمين والتي تكون عادةً متاحة للإدراك البشري وقد تؤثر على تفسير الإشارات المتعلقة بالشخصية. على سبيل المثال، قد يتم تفسير محتوى رسائل الحالة بشكل مختلف اعتمادًا على ما إذا كان المستخدم رجلًا يبلغ من العمر 18 عامًا أو امرأة تبلغ من العمر 55 عامًا. قد يؤدي القدرة على تفسير محتوى الرسالة في سياق هوية المرسل إلى تحسين الاستنتاجات، ولكن قد يؤدي أيضًا إلى تضخيم التحيزات الضمنية المعروفة بأنها تستمر في نماذج اللغة.

أخيرًا، بينما نبذل جهدًا لمناقشة الآثار الاجتماعية لنتائجنا (انظر أدناه)، يجب معالجة التوصيات التفصيلية بشأن مخاوف الخصوصية وإمكانية سوء الاستخدام في الأبحاث المستقبلية.

4.3 الآثار

بينما يحمل هذا الديمقراطية فرصًا ملحوظة للاكتشاف العلمي والخدمات المخصصة، فإنه يقدم أيضًا تحديات أخلاقية كبيرة. على وجه التحديد، فإن القدرة على التنبؤ بالاحتياجات النفسية الحميمة والتفضيلات للأشخاص دون علمهم أو موافقتهم تشكل تهديدًا لخصوصية الأشخاص وتقرير المصير [23]. على سبيل المثال، غالبًا ما يشارك المستخدمون المعلومات عبر الإنترنت دون النظر في كيفية استخدام هذه المعلومات من قبل أطراف ثالثة، وقد لا يتماشى استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة للتصنيف النفسي مع نواياهم الأصلية. كما أبرزت حالة كامبريدج أناليتيكا [49] جنبًا إلى جنب مع مجموعة متزايدة من الأبحاث حول الإقناع المخصص والاستهداف النفسي [47، 50، 51]، يمكن بسهولة استخدام الرؤى حول الميول النفسية للأشخاص كسلاح للتأثير على الآراء وتغيير السلوك. وبالتالي، قد يكون من الضروري إدخال حواجز في أنظمة مثل نماذج اللغة الكبيرة تمنع الجهات الفاعلة من الحصول على ملفات نفسية لآلاف أو ملايين المستخدمين. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن المخاوف الموضحة تتماشى مع الدعوات الأخيرة للتنظيم [24-26] وحقيقة أن قانون الذكاء الاصطناعي في الاتحاد الأوروبي [52] يحظر صراحة التعرف على المشاعر في مكان العمل والمؤسسات التعليمية، بالإضافة إلى التقييم الاجتماعي بناءً على السلوك الاجتماعي أو الخصائص الشخصية.

4.4 الخاتمة

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

References

[2] Anthropic, Model Card and Evaluations for Claude Models, 2023. [Online]. Available: https: //www-files.anthropic.com/production/images/Model-Card-Claude-2.pdf

[3] T. Brown et al., “Language Models are Few-Shot Learners,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 33, 2020, pp. 1877-1901. [Online]. Available: https://papers.nips cc/paper/2020/hash/1457c0d6bfcb4967418bfb8ac142f64a-Abstract.html (visited on 01/25/2024).

[4] A. Radford, J. Wu, R. Child, D. Luan, D. Amodei, and I. Sutskever, “Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners,” 2019. [Online]. Available: https: //www. semanticscholar org/paper/Language-Models-are-Unsupervised-Multitask-Learners-Radford-Wu/ 9405cc0d6169988371b2755e573cc28650d14dfe (visited on 08/21/2023).

[5] M. Kosinski, “Theory of Mind Might Have Spontaneously Emerged in Large Language Models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.02083, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2302. 02083 (visited on 09/08/2023).

[6] T. Hagendorff, S. Fabi, and M. Kosinski, “Thinking Fast and Slow in Large Language Models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.05206, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2212. 05206 (visited on 09/08/2023).

[7] J. Digutsch and M. Kosinski, “Overlap in meaning is a stronger predictor of semantic activation in GPT-3 than in humans,” Scientific Reports, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 5035, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-32248-6 (visited on 09/08/2023).

[8] S. C. Matz, J. D. Teeny, S. S. Vaid, H. Peters, G. M. Harari, and M. Cerf, “The potential of generative AI for personalized persuasion at scale,” Scientific Reports, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 4692, 2024, Publisher: Nature Publishing Group. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-53755-0 (visited on 03/01/2024).

[9] L. Albright, D. A. Kenny, and T. E. Malloy, “Consensus in personality judgments at zero acquaintance,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 387-395, 1988.

[10] D. A. Kenny, L. Albright, T. E. Malloy, and D. A. Kashy, “Consensus in interpersonal perception: Acquaintance and the big five,” Psychological Bulletin, vol. 116, no. 2, pp. 245-258, 1994, Place: US Publisher: American Psychological Association.

[12] P. J. Rentfrow and S. D. Gosling, “Message in a Ballad: The Role of Music Preferences in Interpersonal Perception,” Psychological Science, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 236-242, 2006. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01691.x (visited on 09/08/2023).

[13] M. D. Back et al., “Facebook Profiles Reflect Actual Personality, Not Self-Idealization,” Psychological Science, 2010. [Online]. Available: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epub/10.1177/ 0956797609360756 (visited on 01/26/2024).

[14] M. Kosinski, D. Stillwell, and T. Graepel, “Private traits and attributes are predictable from digital records of human behavior,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 110, no. 15, pp. 5802-5805, 2013.

[15] D. Azucar, D. Marengo, and M. Settanni, “Predicting the Big 5 personality traits from digital footprints on social media: A meta-analysis,” Personality and Individual Differences, vol. 124, pp. 150-159, 2018.

[16] H. A. Schwartz et al., “Personality, Gender, and Age in the Language of Social Media: The OpenVocabulary Approach,” PLOS ONE, vol. 8, no. 9, e73791, 2013. [Online]. Available: https : // journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone. 0073791 (visited on 09/07/2023).

[17] G. Park et al., “Automatic personality assessment through social media language,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 108, no. 6, pp. 934-952, 2015.

[18] T. Yarkoni, “Personality in 100,000 Words: A large-scale analysis of personality and word use among bloggers,” Journal of research in personality, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 363-373, 2010. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2885844/(visited on 09/07/2023).

[19] E. Grunenberg, H. Peters, M. J. Francis, M. D. Back, and S. C. Matz, “Machine learning in recruiting: Predicting personality from CVs and short text responses,” Frontiers in Social Psychology, vol. 1, 2024, Publisher: Frontiers. [Online]. Available: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10. 3389/frsps. 2023.1290295 (visited on 05/17/2024).

[20] R. R. McCrae and P. T. Costa Jr., “The five-factor theory of personality,” in Handbook of personality: Theory and research, 3rd ed, New York, NY, US: The Guilford Press, 2008, pp. 159-181.

[21] T. Bolukbasi, K.-W. Chang, J. Zou, V. Saligrama, and A. Kalai, “Man is to computer programmer as woman is to homemaker? debiasing word embeddings,” in Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2016, pp. 4356-4364. (visited on 01/25/2024).

[22] Y. Wan, W. Wang, P. He, J. Gu, H. Bai, and M. Lyu, “BiasAsker: Measuring the Bias in Conversational AI System,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.12434, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/ 2305.12434 (visited on 09/05/2023).

[23] S. C. Matz, R. E. Appel, and M. Kosinski, “Privacy in the age of psychological targeting,” Current Opinion in Psychology, vol. 31, pp. 116-121, 2020.

[24] M. Perc, M. Ozer, and J. Hojnik, “Social and juristic challenges of artificial intelligence,” Palgrave Communications, vol. 5, no. 1, s41599-019-0278-x, 2019. [Online]. Available: https : / /www. nature.com/articles/s41599-019-0278-x (visited on 01/24/2024).

[25] P. Hacker, A. Engel, and M. Mauer, “Regulating ChatGPT and other Large Generative AI Models,” in Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 2023, pp. 1112-1123. [Online]. Available: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3593013. 3594067 (visited on 01/24/2024).

[26] A. Chan, “GPT-3 and InstructGPT: Technological dystopianism, utopianism, and “Contextual” perspectives in AI ethics and industry,” AI and Ethics, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 53-64, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-022-00148-6 (visited on 01/24/2024).

[27] M. Kosinski, S. C. Matz, S. D. Gosling, V. Popov, and D. Stillwell, “Facebook as a research tool for the social sciences: Opportunities, challenges, ethical considerations, and practical guidelines,” The American Psychologist, vol. 70, no. 6, pp. 543-556, 2015.

[28] L. R. Goldberg et al., “The international personality item pool and the future of public-domain personality measures,” Journal of Research in Personality, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 84-96, 2006. [Online]. Available: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0092656605000553 (visited on 09/08/2023).

[29] A. Feingold, “Gender differences in personality: A meta-analysis,” Psychological Bulletin, vol. 116, no. 3, pp. 429-456, 1994.

[31] W. Youyou, M. Kosinski, and D. Stillwell, “Computer-based personality judgments are more accurate than those made by humans,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 112, no. 4, pp. 1036-1040, 2015. [Online]. Available: https: / /www.ncbi.nlm nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4313801/(visited on 01/25/2022).

[32] S. Vazire and S. D. Gosling, “E-Perceptions: Personality Impressions Based on Personal Websites,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 87, no. 1, pp. 123-132, 2004.

[33] S. Abdurahman et al., “Perils and Opportunities in Using Large Language Models in Psychological Research,” https://osf.io/tg79n, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://osf.io/tg79n (visited on 05/12/2024).

[34] E. Durmus et al., “Towards Measuring the Representation of Subjective Global Opinions in Language Models,” arXiv:2306.16388 [cs], 2024, arXiv:2306.16388 [cs]. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv. org/abs/2306.16388 (visited on 05/13/2024).

[35] S. Santurkar, E. Durmus, F. Ladhak, C. Lee, P. Liang, and T. Hashimoto, “Whose Opinions Do Language Models Reflect?” arXiv:2303.17548 [cs], 2023, arXiv:2303.17548 [cs]. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2303. 17548 (visited on 05/13/2024).

[36] M. Atari, M. J. Xue, P. S. Park, D. Blasi, and J. Henrich, “Which Humans?” https://osf.io/5b26t, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://osf.io/5b26t (visited on 05/12/2024).

[37] S. Rathje, D.-M. Mirea, I. Sucholutsky, R. Marjieh, C. Robertson, and J. J. V. Bavel, “GPT is an effective tool for multilingual psychological text analysis,” https://osf.io/sekf5, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://osf.io/sekf5 (visited on 05/12/2024)

[38] S. E. Thayer and S. Ray, “Online Communication Preferences across Age, Gender, and Duration of Internet Use,” CyberPsychology & Behavior, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 432-440, 2006, Publisher: Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers. [Online]. Available: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10. 1089/cpb. 2006.9 .432 (visited on 05/12/2024).

[39] K. Kondakciu, M. Souto, and L. T. Zayer, “Self-presentation and gender on social media: An exploration of the expression of “authentic selves”,” Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 80-99, 2021, Publisher: Emerald Publishing Limited. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-03-2021-0039 (visited on 05/12/2024).

[40] S. Tifferet and I. Vilnai-Yavetz, “Gender differences in Facebook self-presentation: An international randomized study,” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 35, pp. 388-399, 2014. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563214001381 (visited on 05/12/2024).

[41] U. Oberst, V. Renau, A. Chamarro, and X. Carbonell, “Gender stereotypes in Facebook profiles: Are women more female online?” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 60, pp. 559-564, 2016. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563216301480 (visited on 05/12/2024).

[42] G. Roberti, “Female influencers: Analyzing the social media representation of female subjectivity in Italy,” Frontiers in Sociology, vol. 7, 2022, Publisher: Frontiers. [Online]. Available: https: //www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsoc.2022.1024043 (visited on 05/12/2024).

[43] H. Peters, M. Cerf, and S. Matz, “Large Language Models Can Infer Personality from Free-Form User Interactions,” 2024, Publisher: OSF Preprints. [Online]. Available: https: //osf.io/apc5g/ (visited on 05/19/2024).

[44] T. Yang et al., “PsyCoT: Psychological Questionnaire as Powerful Chain-of-Thought for Personality Detection,” arXiv:2310.20256 [cs], 2023, arXiv:2310.20256 [cs]. [Online]. Available: http:// arxiv.org/abs/2310.20256 (visited on 04/17/2024).

[45] S. R. Karra, S. T. Nguyen, and T. Tulabandhula, “Estimating the Personality of White-Box Language Models,” arXiv:2204.12000 [cs], 2023, arXiv:2204.12000 [cs]. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv. org/abs/2204.12000 (visited on 04/23/2024).

[46] P. M. Podsakoff, S. B. MacKenzie, and N. P. Podsakoff, “Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It,” Annual Review of Psychology, vol. 63, no. 1, pp. 539-569, 2012. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710100452 (visited on 09/07/2023).

[48] B. Freiberg and S. C. Matz, “Founder personality and entrepreneurial outcomes: A large-scale field study of technology startups,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 120, no. 19, e2215829120, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas 2215829120 (visited on 09/08/2023).

[49] M. Hu, “Cambridge Analytica’s black box,” Big Data & Society, vol. 7, no. 2, p. 2053951720938 091, 2020. [Online]. Available: https : / / doi . org / 10 . 1177 / 2053951720938091 (visited on 09/07/2023).

[50] J. D. Teeny, J. J. Siev, P. Briñol, and R. E. Petty, “A Review and Conceptual Framework for Understanding Personalized Matching Effects in Persuasion,” Journal of Consumer Psychology, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 382-414, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/ 10.1002/jcpy. 1198 (visited on 09/07/2023).

[51] M. Feinberg and R. Willer, “Moral reframing: A technique for effective and persuasive communication across political divides,” Social and Personality Psychology Compass, vol. 13, no. 12, e12501, 2019.

[52] E. Parliament, Artificial Intelligence Act: Deal on comprehensive rules for trustworthy AI, 2023. [Online]. Available: https: / / www. europarl. europa. eu / news / en / press – room / 20231206IPR15699/artificial-intelligence-act-deal-on-comprehensive-rules-for-trustworthy-ai (visited on 01/25/2024).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae231

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38948324

Publication Date: 2024-05-31

Large Language Models Can Infer Psychological Dispositions of Social Media Users

Abstract

Large Language Models (LLMs) demonstrate increasingly human-like abilities across a wide variety of tasks. In this paper, we investigate whether LLMs like ChatGPT can accurately infer the psychological dispositions of social media users and whether their ability to do so varies across socio-demographic groups. Specifically, we test whether GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 can derive the Big Five personality traits from users’ Facebook status updates in a zero-shot learning scenario. Our results show an average correlation of r

1 Introduction

While LLMs were not explicitly designed to capture or mimic elements of human cognition and psychology, recent research suggests that – given their training on extensive corpora of human-generated language they might have spontaneously developed the capacity to do so. For example, LLMs display properties that are similar to the cognitive abilities and processes observed in humans, including theory of mind (i.e., the ability to understand the mental states of other agents [5]), cognitive biases in decision-making [6] and semantic priming [7]. Similarly, LLMs are able to effectively generate persuasive messages tailored to specific psychological dispositions (e.g., personality traits, moral values [8]).

Here, we examine whether LLMs possess another quality that is fundamentally human: The ability to “read” people and form first impressions about their psychological dispositions in the absence of direct or prior

interaction. As research under the umbrella of zero-acquaintance studies shows, people can be remarkably accurate at judging the psychological traits of strangers simply by observing traces of their behavior under certain conditions [9]. While such judgments can be influenced by stereotypes and their accuracy can vary based on the traits being assessed and the context in which judgments are made [10], past work indicates that people are able to predict a stranger’s personality traits by observing their offices or bedrooms [11], examining their music preferences [12], or scrolling through their social media profiles [13].

Existing research in computational social science shows that supervised machine learning models are able to make similar predictions. That is, given a large enough dataset including both self-reported personality traits and people’s digital footprints – such as Facebook Likes, music playlists, or browsing histories – machine learning models are able to statistically relate both inputs in a way that allows them to predict personality traits after observing a person’s digital footprints [14, 15]. This is also true for various forms of text data, including social media posts [16, 17], personal blogs [18], or short text responses collected in the context of job applications [19].

In this paper, we test whether LLMs have the ability to make similar psychological inferences without having been explicitly trained to do so (known as zero-shot learning [3]). Specifically, we use Open AI’s ChatGPT (GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 [1]) to explore whether LLMs can accurately infer the Big Five personality traits Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism [20] of social media users from the content of their Facebook status updates in a zero-shot scenario. In addition, we test for biases in ChatGPT’s judgments that might arise from its foundation in equally biased human-generated data. Building on previous work highlighting inherent stereotypes in pre-trained NLP models [21, 22], we explore the extent to which the personality inferences made by ChatGPT are indicative of gender and age-related biases (e.g., potential biases in how the personality of men and women or older and younger people is judged).

2 Method

2.1 Data and Sampling

2.2 Measures

To obtain inferred personality traits from ChatGPT, we used the last 200 Facebook status updates generated by each user without additional preprocessing. The average length of status updates in our sample was 17.10 words (SD=15.03). Status updates were scored using the ChatGPT API with GPT-3.5 (version gpt-3.5-turbo0301) and GPT-4 (version gpt-4-0314) [1] as underlying models. For this purpose, the status updates were

To boost the reliability of the inferred personality estimates, we queried ChatGPT three times for each inference. Agreement across ratings across rating rounds was high for all traits (Openness:

3 Results

3.1 Can LLMs Infer Personality Traits From Social Media Posts?

In addition to exploring the capacity of ChatGPT to infer personality traits from social media user data, we also tested the extent to which this capacity is sensitive to changes in the amount of data that was available for inference. Specifically, we computed correlations between self-reported and inferred personality scores based on different numbers of status messages. Specifically, we computed correlations obtained from inferences for a single chunk of status messages (20 status messages) all the way up to ten chunks (200 status messages). As expected, having access to more status messages resulted in more accurate inferences. Notably, however, most correlations are close to their maximum level after observing far less than the ultimate number of 200 status messages. In addition, the inference of certain traits seems to be particularly susceptible to the volume of input data. For example, the models’ accuracy kept increasing with higher levels in input volume for Openness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism, while the benefits of additional status messages leveled off earlier for Conscientiousness. See Figure 2 for a graphical representation and S3 for detailed statistics.

3.2 Does the Quality of LLM Inferences Vary Across Demographic Groups?

3.2.1 Gender Differences

To further explore these potential biases, we analyzed the residuals between inferred scores and self-reported scores as an indication of how well GPT is able to represent the personality traits of male and female users. The findings suggest that GPT’s personality inferences are less accurate for men than women. First, we observed larger absolute residuals for male users in Conscientiousness (

3.2.2 Age Differences

As before, we further explore these differences by analyzing age differences in the residuals between selfreported and inferred scores. Unlike in the analyses of gender, we found substantial inconsistency in the group differences between GPT-3.5 and GPT-4. While the inferences made by GPT-3.5 showed significantly larger absolute residuals for older users in Openness (

3.3 Agreement With Third-Person Observer Ratings

The results show that correlations between self-reported scores and observer ratings ranged from r=. 198 to

4 Discussion

4.1 Interpretation of Results

Our study contributes to a growing body of research comparing the abilities of LLMs to those observed in humans [5, 7, 8]. As our findings suggest, LLMs might have the human-like ability to “profile” people based on their behavioral traces, without ever having had direct interactions with them. Although most social media posts do not contain explicit references to a person’s character, ChatGPT – just like human judges [13, 32] or supervised models [31] – is able to translate people’s accounts of their daily activities and preferences into a holistic picture of their psychological dispositions. Our results are aligned with previous work suggesting that Openness and Extraversion are more easily inferred than other traits [13, 31]. At the same time, LLM inferences were more congruent with observer ratings than self-reports in the case of Conscientiousness, indicating that LLMs may also replicate biases in human judgment for certain traits.

Specifically, past work indicates that LLMs are susceptible to stereotyping and bias with regard to demographic and geographic groups | 21, 33-37], likely reflecting groups’ representation in the underlying training data. At the same time, past work has shown differences in social media use and online self-expression across demographic groups, including age and gender [38-42]. While the past literature does not directly speak to differences in personality expression, the observed pattern of results would indicate that women and younger individuals tend to reveal more accurate information about their personalities online.

4.2 Limitations and Future Research

Second, the text data used in our analysis was obtained from the MyPersonality Facebook application [27], which was active between 2007 and 2012. Linguistic conventions from this period might differ from contemporary online language, potentially limiting the zero-shot performance of LLMs, which have been trained on newer data. As a result, we would expect the personality inferences of LLMs to be even more accurate when applied to more contemporary data.

Third, our data was sourced from Facebook users who interacted with the MyPersonality application. As such, our sample might not be representative of the broader population of social media users (or people more generally), which could limit the external validity of our findings. For example, the general underestimation of personality traits such as Openness might be due to the fact that myPersonality users were particularly curious and open-minded.

Fifth, our study did not encompass the dynamics of live interactions between LLMs and users. Real-time interactions might yield different insights and highlight additional complexities not captured in our static textual data set [43]. Relatedly, while our research underscores the potential for LLMs in personalizing interactions and enhancing social computing, it does not examine the specifics of how these personalizations can be effectively implemented.

Sixth, the current research demonstrates the potential of out-of-the-box LLMs for inferring psychological variables using simple techniques such as zero-shot learning and commercially available models. It is likely that the predictive performance of LLMs could be improved through more sophisticated prompting strategies, such as chain-of-thought prompting [44] and a combination of in-context learning and supervised fine-tuning [45]. While we purposefully focused on zero-shot learning in order to establish a lower bound of predictive accuracy and investigate LLMs’ inherent ability to make such predictions, future research could focus on identifying levers that maximize predictive accuracy. Aside from more sophisticated prompting paradigms, this could include giving LLMs access to users’ demographic information which is typically available to human perception and could moderate the interpretation of personality-related signals. For example, the content of status messages may be interpreted differently depending on whether the user is an 18-year-old man or a 55-year-old woman. Being able to interpret message content in the context of sender identity could lead to improved inferences, but could also amplify implicit biases that are known to persist in language models [21, 33, 35].

Finally, while we make an effort to discuss the societal implications of our findings (see below), detailed recommendations regarding privacy concerns and the potential for misuse should be addressed in future research.

4.3 Implications

While this democratization holds remarkable opportunities for scientific discovery and personalized services, it also introduces considerable ethical challenges. Specifically, the ability to predict people’s intimate psychological needs and preferences without their knowledge or consent poses a threat to people’s privacy and self-determination [23]. For instance, users often share information online without considering how this information can be used by third parties and the use of LLMs for psychological profiling may not align with their original intentions. As the case of Cambridge Analytica [49] alongside a growing body of research on personalized persuasion and psychological targeting [47, 50, 51] has highlighted, insights into people’s psychological dispositions can easily be weaponized to sway opinions and change behavior. Consequently, it might be necessary to introduce guardrails into systems like LLMs that prevent actors from obtaining psychological profiles of thousands or millions of users. Notably, the outlined concerns are aligned with recent calls for regulation [24-26] and the fact that the EU AI Act [52] explicitly bans emotion recognition in the workplace and educational institutions, as well as social scoring based on social behavior or personal characteristics.

4.4 Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

References

[2] Anthropic, Model Card and Evaluations for Claude Models, 2023. [Online]. Available: https: //www-files.anthropic.com/production/images/Model-Card-Claude-2.pdf

[3] T. Brown et al., “Language Models are Few-Shot Learners,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 33, 2020, pp. 1877-1901. [Online]. Available: https://papers.nips cc/paper/2020/hash/1457c0d6bfcb4967418bfb8ac142f64a-Abstract.html (visited on 01/25/2024).

[4] A. Radford, J. Wu, R. Child, D. Luan, D. Amodei, and I. Sutskever, “Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners,” 2019. [Online]. Available: https: //www. semanticscholar org/paper/Language-Models-are-Unsupervised-Multitask-Learners-Radford-Wu/ 9405cc0d6169988371b2755e573cc28650d14dfe (visited on 08/21/2023).

[5] M. Kosinski, “Theory of Mind Might Have Spontaneously Emerged in Large Language Models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.02083, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2302. 02083 (visited on 09/08/2023).

[6] T. Hagendorff, S. Fabi, and M. Kosinski, “Thinking Fast and Slow in Large Language Models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.05206, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2212. 05206 (visited on 09/08/2023).

[7] J. Digutsch and M. Kosinski, “Overlap in meaning is a stronger predictor of semantic activation in GPT-3 than in humans,” Scientific Reports, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 5035, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-32248-6 (visited on 09/08/2023).

[8] S. C. Matz, J. D. Teeny, S. S. Vaid, H. Peters, G. M. Harari, and M. Cerf, “The potential of generative AI for personalized persuasion at scale,” Scientific Reports, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 4692, 2024, Publisher: Nature Publishing Group. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-53755-0 (visited on 03/01/2024).

[9] L. Albright, D. A. Kenny, and T. E. Malloy, “Consensus in personality judgments at zero acquaintance,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 387-395, 1988.

[10] D. A. Kenny, L. Albright, T. E. Malloy, and D. A. Kashy, “Consensus in interpersonal perception: Acquaintance and the big five,” Psychological Bulletin, vol. 116, no. 2, pp. 245-258, 1994, Place: US Publisher: American Psychological Association.

[12] P. J. Rentfrow and S. D. Gosling, “Message in a Ballad: The Role of Music Preferences in Interpersonal Perception,” Psychological Science, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 236-242, 2006. [Online]. Available: https: //doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01691.x (visited on 09/08/2023).

[13] M. D. Back et al., “Facebook Profiles Reflect Actual Personality, Not Self-Idealization,” Psychological Science, 2010. [Online]. Available: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epub/10.1177/ 0956797609360756 (visited on 01/26/2024).

[14] M. Kosinski, D. Stillwell, and T. Graepel, “Private traits and attributes are predictable from digital records of human behavior,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 110, no. 15, pp. 5802-5805, 2013.

[15] D. Azucar, D. Marengo, and M. Settanni, “Predicting the Big 5 personality traits from digital footprints on social media: A meta-analysis,” Personality and Individual Differences, vol. 124, pp. 150-159, 2018.

[16] H. A. Schwartz et al., “Personality, Gender, and Age in the Language of Social Media: The OpenVocabulary Approach,” PLOS ONE, vol. 8, no. 9, e73791, 2013. [Online]. Available: https : // journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone. 0073791 (visited on 09/07/2023).

[17] G. Park et al., “Automatic personality assessment through social media language,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 108, no. 6, pp. 934-952, 2015.

[18] T. Yarkoni, “Personality in 100,000 Words: A large-scale analysis of personality and word use among bloggers,” Journal of research in personality, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 363-373, 2010. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2885844/(visited on 09/07/2023).

[19] E. Grunenberg, H. Peters, M. J. Francis, M. D. Back, and S. C. Matz, “Machine learning in recruiting: Predicting personality from CVs and short text responses,” Frontiers in Social Psychology, vol. 1, 2024, Publisher: Frontiers. [Online]. Available: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10. 3389/frsps. 2023.1290295 (visited on 05/17/2024).

[20] R. R. McCrae and P. T. Costa Jr., “The five-factor theory of personality,” in Handbook of personality: Theory and research, 3rd ed, New York, NY, US: The Guilford Press, 2008, pp. 159-181.

[21] T. Bolukbasi, K.-W. Chang, J. Zou, V. Saligrama, and A. Kalai, “Man is to computer programmer as woman is to homemaker? debiasing word embeddings,” in Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2016, pp. 4356-4364. (visited on 01/25/2024).

[22] Y. Wan, W. Wang, P. He, J. Gu, H. Bai, and M. Lyu, “BiasAsker: Measuring the Bias in Conversational AI System,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.12434, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/ 2305.12434 (visited on 09/05/2023).

[23] S. C. Matz, R. E. Appel, and M. Kosinski, “Privacy in the age of psychological targeting,” Current Opinion in Psychology, vol. 31, pp. 116-121, 2020.

[24] M. Perc, M. Ozer, and J. Hojnik, “Social and juristic challenges of artificial intelligence,” Palgrave Communications, vol. 5, no. 1, s41599-019-0278-x, 2019. [Online]. Available: https : / /www. nature.com/articles/s41599-019-0278-x (visited on 01/24/2024).

[25] P. Hacker, A. Engel, and M. Mauer, “Regulating ChatGPT and other Large Generative AI Models,” in Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 2023, pp. 1112-1123. [Online]. Available: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3593013. 3594067 (visited on 01/24/2024).

[26] A. Chan, “GPT-3 and InstructGPT: Technological dystopianism, utopianism, and “Contextual” perspectives in AI ethics and industry,” AI and Ethics, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 53-64, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-022-00148-6 (visited on 01/24/2024).

[27] M. Kosinski, S. C. Matz, S. D. Gosling, V. Popov, and D. Stillwell, “Facebook as a research tool for the social sciences: Opportunities, challenges, ethical considerations, and practical guidelines,” The American Psychologist, vol. 70, no. 6, pp. 543-556, 2015.

[28] L. R. Goldberg et al., “The international personality item pool and the future of public-domain personality measures,” Journal of Research in Personality, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 84-96, 2006. [Online]. Available: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0092656605000553 (visited on 09/08/2023).

[29] A. Feingold, “Gender differences in personality: A meta-analysis,” Psychological Bulletin, vol. 116, no. 3, pp. 429-456, 1994.

[31] W. Youyou, M. Kosinski, and D. Stillwell, “Computer-based personality judgments are more accurate than those made by humans,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 112, no. 4, pp. 1036-1040, 2015. [Online]. Available: https: / /www.ncbi.nlm nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4313801/(visited on 01/25/2022).

[32] S. Vazire and S. D. Gosling, “E-Perceptions: Personality Impressions Based on Personal Websites,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 87, no. 1, pp. 123-132, 2004.

[33] S. Abdurahman et al., “Perils and Opportunities in Using Large Language Models in Psychological Research,” https://osf.io/tg79n, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://osf.io/tg79n (visited on 05/12/2024).

[34] E. Durmus et al., “Towards Measuring the Representation of Subjective Global Opinions in Language Models,” arXiv:2306.16388 [cs], 2024, arXiv:2306.16388 [cs]. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv. org/abs/2306.16388 (visited on 05/13/2024).

[35] S. Santurkar, E. Durmus, F. Ladhak, C. Lee, P. Liang, and T. Hashimoto, “Whose Opinions Do Language Models Reflect?” arXiv:2303.17548 [cs], 2023, arXiv:2303.17548 [cs]. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2303. 17548 (visited on 05/13/2024).

[36] M. Atari, M. J. Xue, P. S. Park, D. Blasi, and J. Henrich, “Which Humans?” https://osf.io/5b26t, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://osf.io/5b26t (visited on 05/12/2024).

[37] S. Rathje, D.-M. Mirea, I. Sucholutsky, R. Marjieh, C. Robertson, and J. J. V. Bavel, “GPT is an effective tool for multilingual psychological text analysis,” https://osf.io/sekf5, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://osf.io/sekf5 (visited on 05/12/2024)

[38] S. E. Thayer and S. Ray, “Online Communication Preferences across Age, Gender, and Duration of Internet Use,” CyberPsychology & Behavior, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 432-440, 2006, Publisher: Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers. [Online]. Available: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10. 1089/cpb. 2006.9 .432 (visited on 05/12/2024).

[39] K. Kondakciu, M. Souto, and L. T. Zayer, “Self-presentation and gender on social media: An exploration of the expression of “authentic selves”,” Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 80-99, 2021, Publisher: Emerald Publishing Limited. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-03-2021-0039 (visited on 05/12/2024).

[40] S. Tifferet and I. Vilnai-Yavetz, “Gender differences in Facebook self-presentation: An international randomized study,” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 35, pp. 388-399, 2014. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563214001381 (visited on 05/12/2024).

[41] U. Oberst, V. Renau, A. Chamarro, and X. Carbonell, “Gender stereotypes in Facebook profiles: Are women more female online?” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 60, pp. 559-564, 2016. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563216301480 (visited on 05/12/2024).

[42] G. Roberti, “Female influencers: Analyzing the social media representation of female subjectivity in Italy,” Frontiers in Sociology, vol. 7, 2022, Publisher: Frontiers. [Online]. Available: https: //www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsoc.2022.1024043 (visited on 05/12/2024).

[43] H. Peters, M. Cerf, and S. Matz, “Large Language Models Can Infer Personality from Free-Form User Interactions,” 2024, Publisher: OSF Preprints. [Online]. Available: https: //osf.io/apc5g/ (visited on 05/19/2024).

[44] T. Yang et al., “PsyCoT: Psychological Questionnaire as Powerful Chain-of-Thought for Personality Detection,” arXiv:2310.20256 [cs], 2023, arXiv:2310.20256 [cs]. [Online]. Available: http:// arxiv.org/abs/2310.20256 (visited on 04/17/2024).

[45] S. R. Karra, S. T. Nguyen, and T. Tulabandhula, “Estimating the Personality of White-Box Language Models,” arXiv:2204.12000 [cs], 2023, arXiv:2204.12000 [cs]. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv. org/abs/2204.12000 (visited on 04/23/2024).

[46] P. M. Podsakoff, S. B. MacKenzie, and N. P. Podsakoff, “Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It,” Annual Review of Psychology, vol. 63, no. 1, pp. 539-569, 2012. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710100452 (visited on 09/07/2023).

[48] B. Freiberg and S. C. Matz, “Founder personality and entrepreneurial outcomes: A large-scale field study of technology startups,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 120, no. 19, e2215829120, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas 2215829120 (visited on 09/08/2023).

[49] M. Hu, “Cambridge Analytica’s black box,” Big Data & Society, vol. 7, no. 2, p. 2053951720938 091, 2020. [Online]. Available: https : / / doi . org / 10 . 1177 / 2053951720938091 (visited on 09/07/2023).

[50] J. D. Teeny, J. J. Siev, P. Briñol, and R. E. Petty, “A Review and Conceptual Framework for Understanding Personalized Matching Effects in Persuasion,” Journal of Consumer Psychology, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 382-414, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/ 10.1002/jcpy. 1198 (visited on 09/07/2023).

[51] M. Feinberg and R. Willer, “Moral reframing: A technique for effective and persuasive communication across political divides,” Social and Personality Psychology Compass, vol. 13, no. 12, e12501, 2019.

[52] E. Parliament, Artificial Intelligence Act: Deal on comprehensive rules for trustworthy AI, 2023. [Online]. Available: https: / / www. europarl. europa. eu / news / en / press – room / 20231206IPR15699/artificial-intelligence-act-deal-on-comprehensive-rules-for-trustworthy-ai (visited on 01/25/2024).