DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85654-3

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39789289

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-09

افتح

أنماط الشكل الخارجي لجمجمة البيسون الأوروبي (Bison bonasus)

الملخص

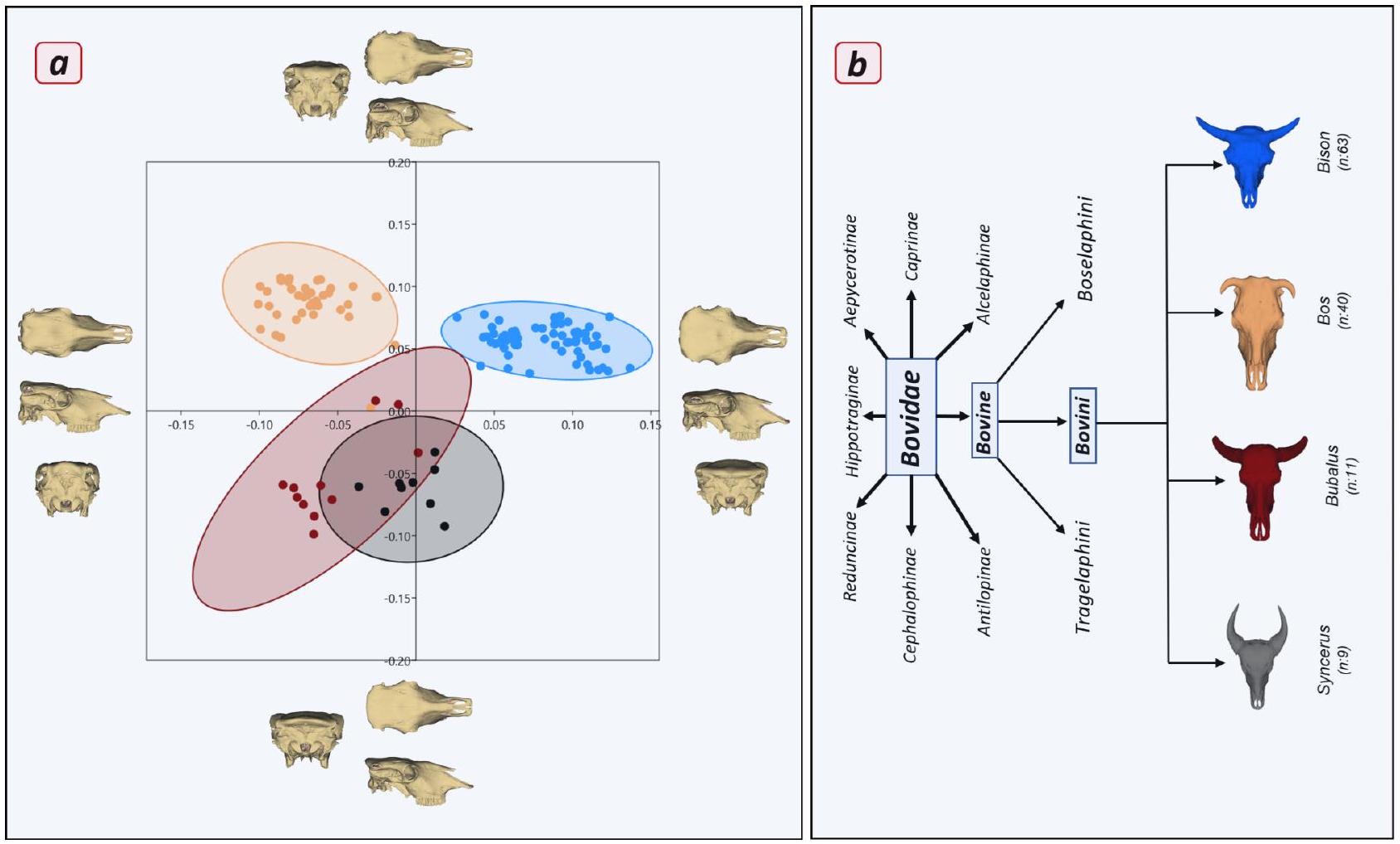

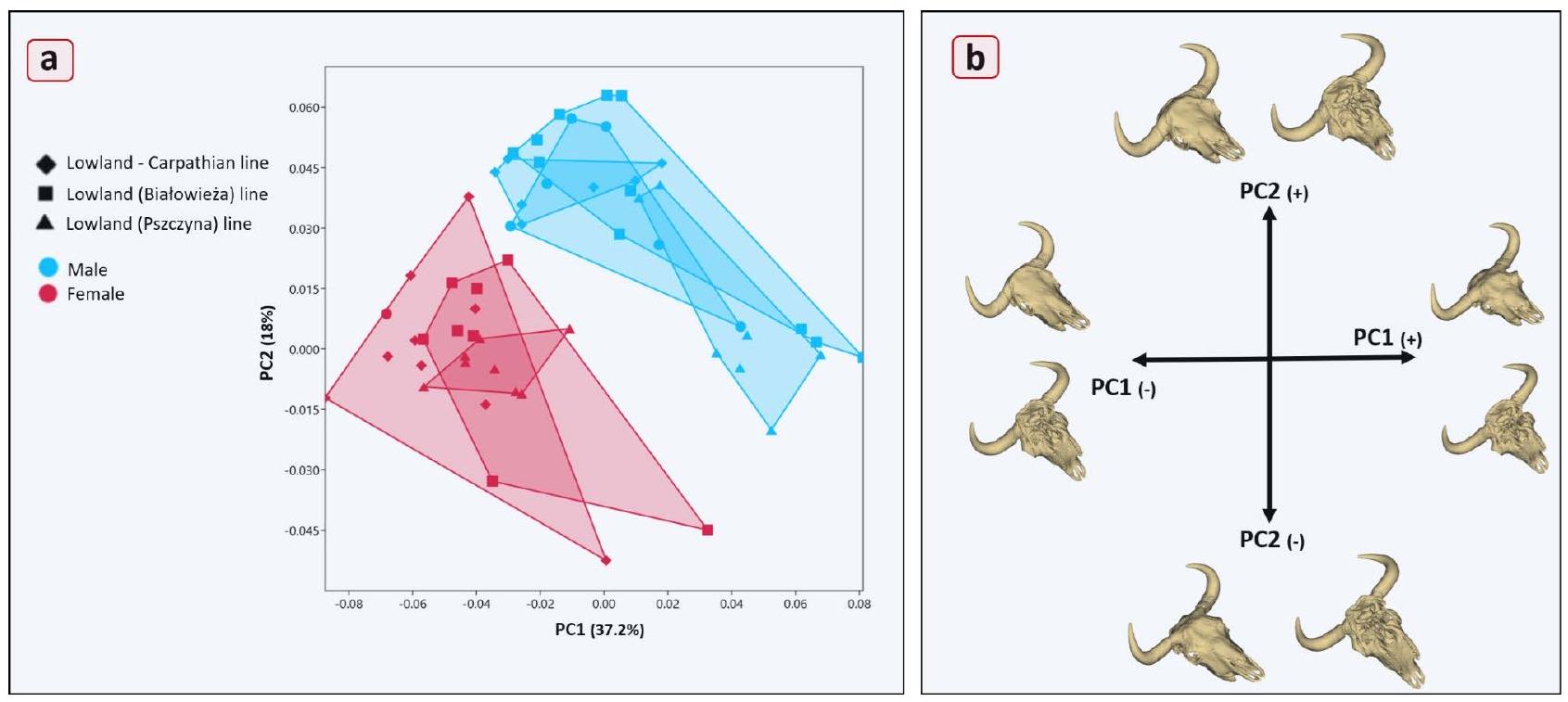

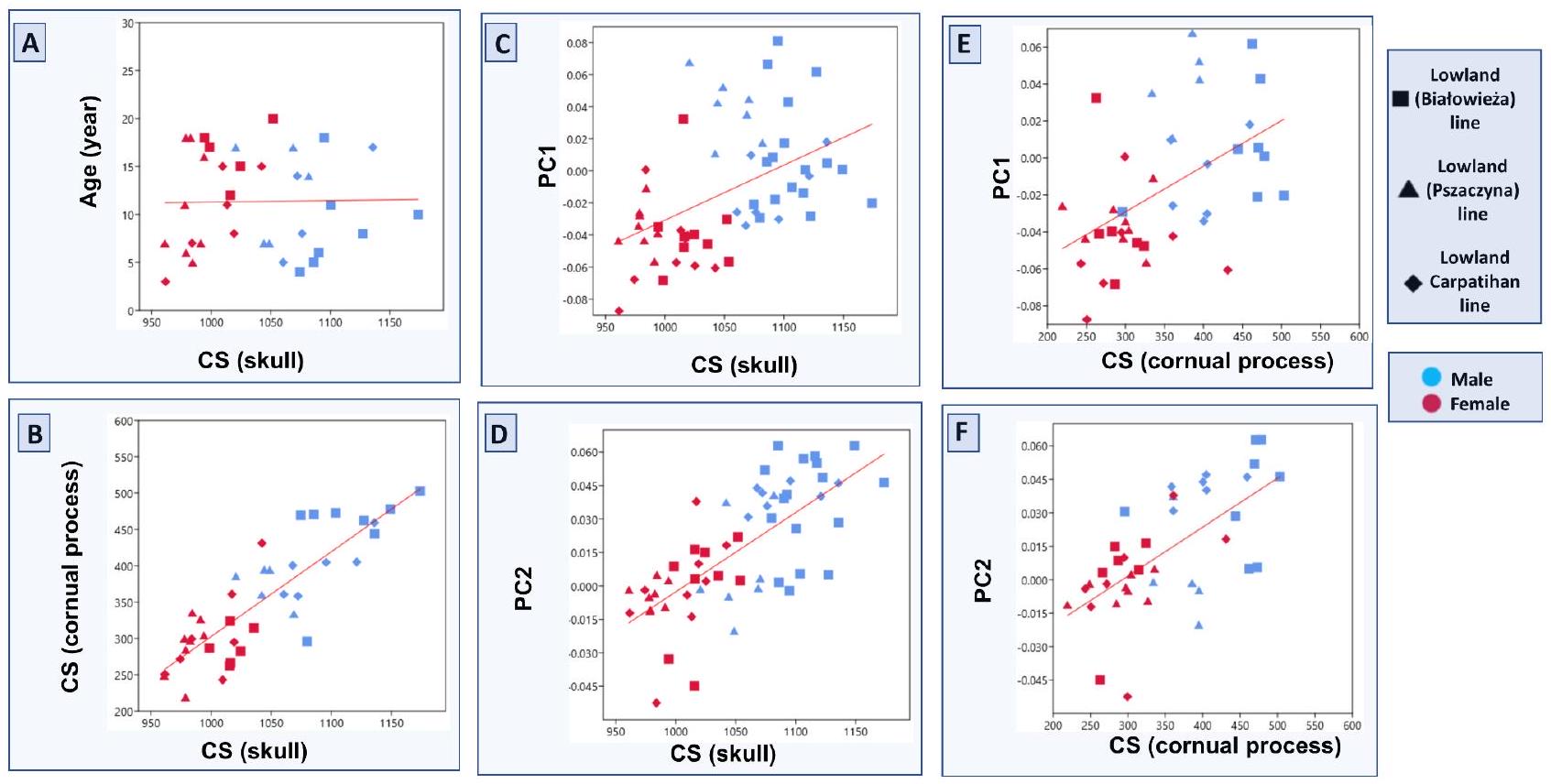

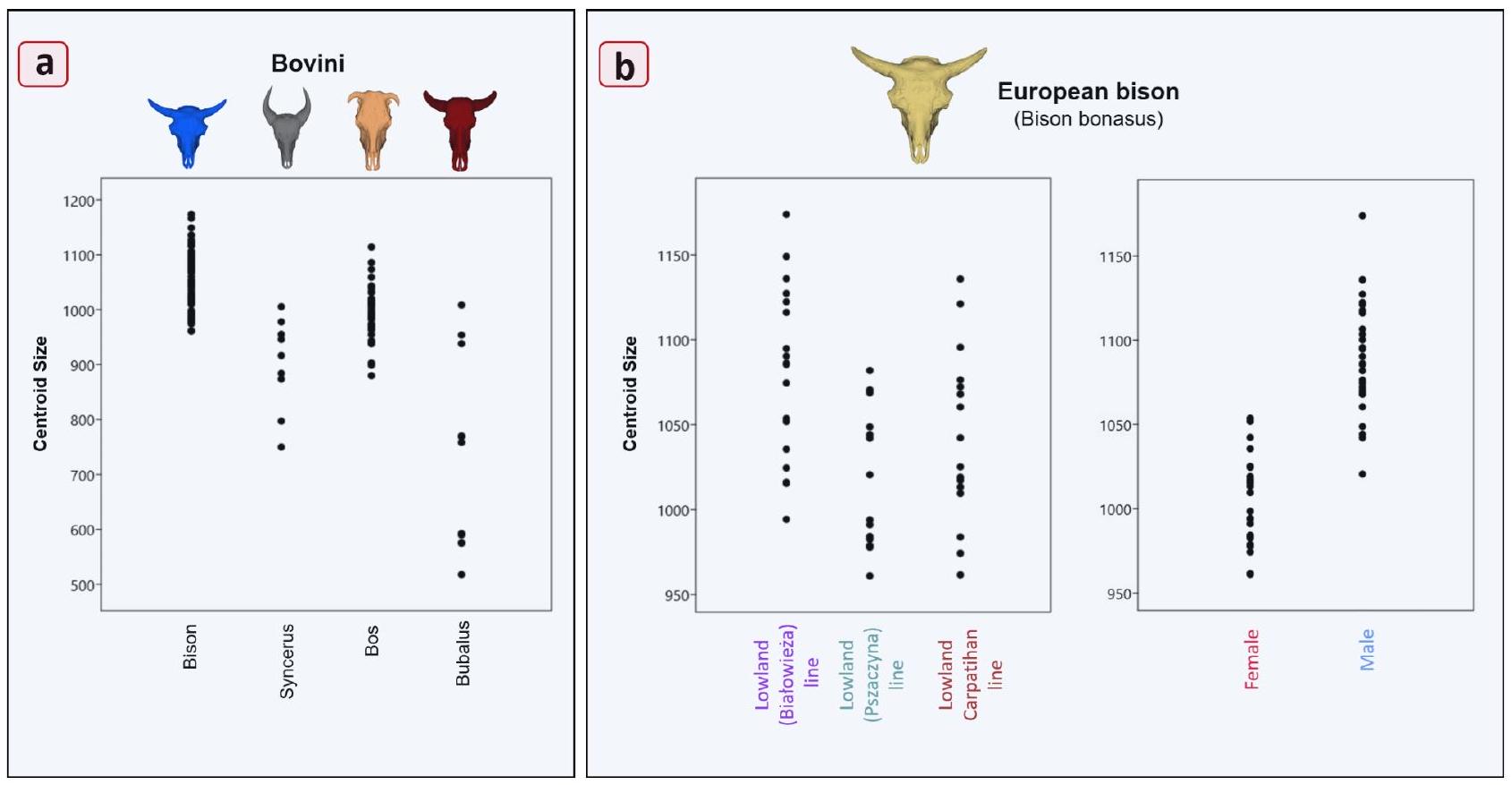

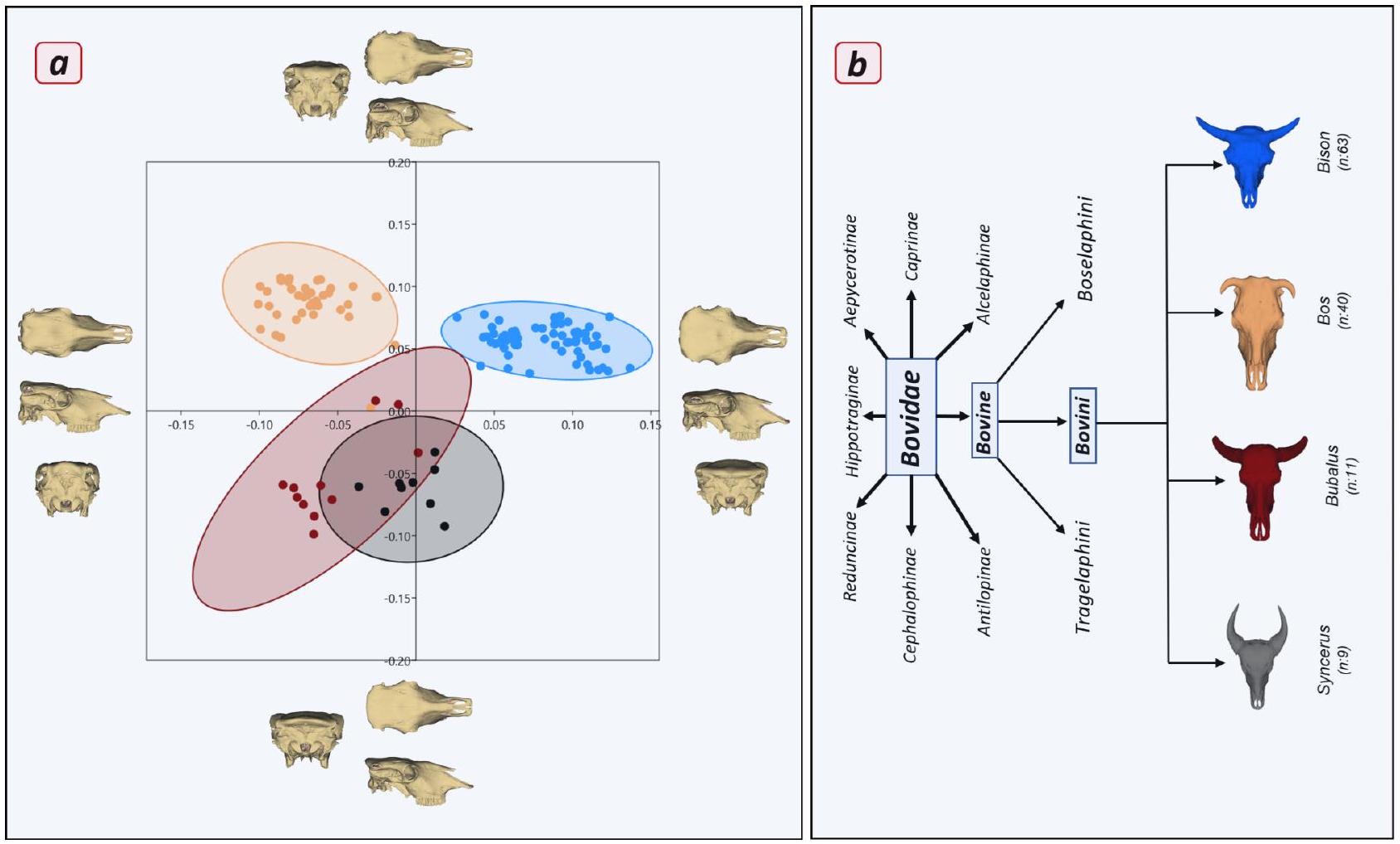

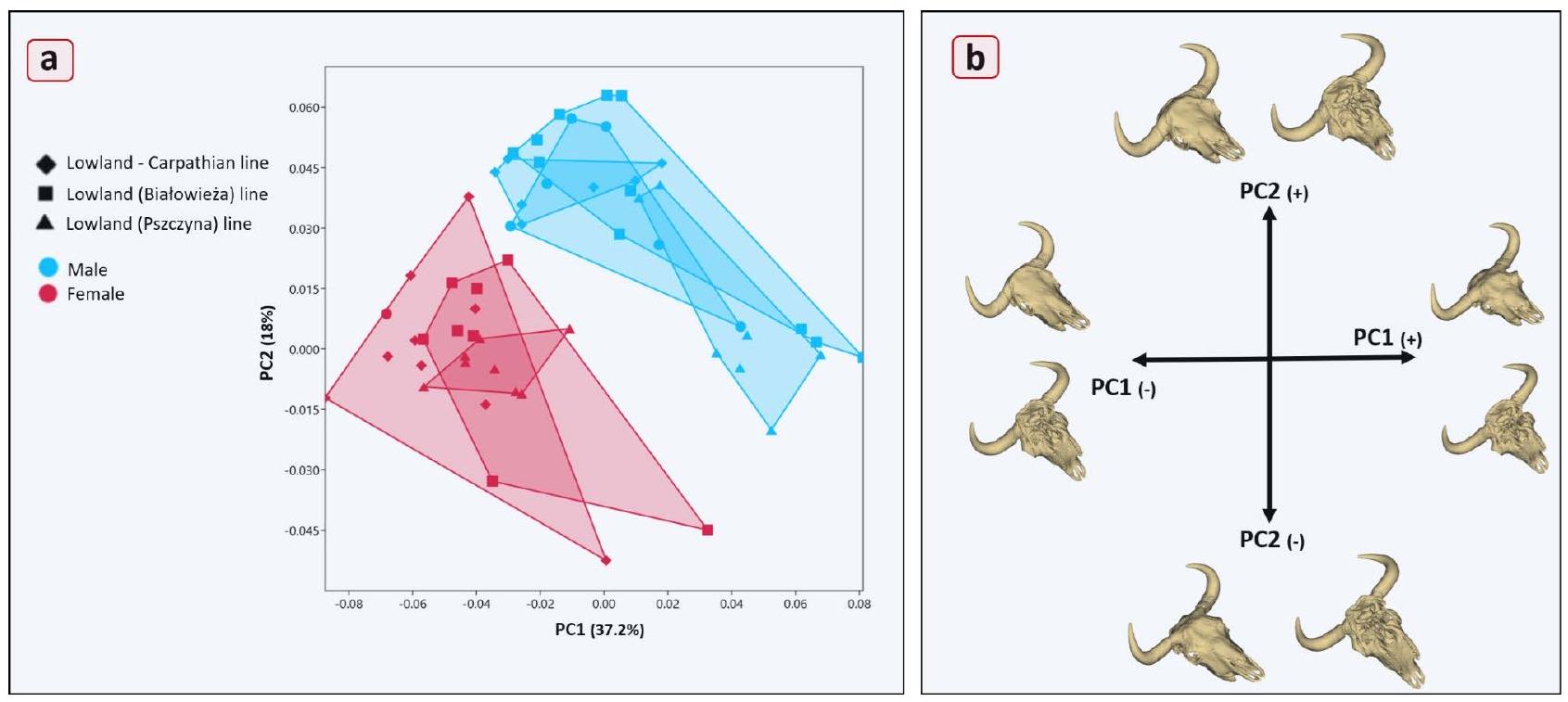

هدفت هذه الدراسة إلى التحقيق في تأثير العوامل البيئية، والاختيار الجنسي، والتنوع الجيني على شكل الجمجمة من خلال فحص بنية جمجمة البيسون الأوروبي، وهو نوع مهدد بالانقراض، ومقارنته بأنواع أخرى من البقريات. كانت جمجمة البيسون الأوروبي أكبر بكثير من جمجمة الأنواع الأخرى من قبيلة Bovini، وكشفت النتائج عن اختلافات شكلية كبيرة في شكل الجمجمة مقارنة بعينات أخرى من Bovini. أظهرت جمجمة البيسون شكلًا أوسع في المنطقة الجبهية وعملية قرنية موجهة بشكل جانبي أكثر. كما أثر العظم الجبهي بشكل كبير على تنوع شكل الجمجمة داخل الأنواع الفرعية للبيسون الأوروبي. أيضًا، أشارت النتائج إلى أن حجم العمليات القرنية أثر بشكل كبير على شكل الجمجمة. كان لدى ذكور البيسون جماجم أكبر ونتوءات قرنية أكثر تطورًا، ويعتقد أن هذه التغيرات الشكلية في المنطقة الجبهية أثرت أيضًا على المنطقة القفوية، والمنطقة الفكية، وعظام الوجه. علاوة على ذلك، قد تعكس الاختلافات في حجم الجمجمة التي لوحظت بين سلالات Lowland-Pszczyna وLowland-Białowieża، التي تشترك في أصل أقرب من سلالات Lowland-Carpathian، التكيفات البيئية والجينية على مر الزمن. توفر هذه الأبحاث نقطة مرجعية للدراسات المستقبلية حول العوامل البيئية والتطورية التي تؤثر على تنوع جمجمة البيسون، مع آثار كبيرة على الحفاظ على هذا النوع.

البيسون الأوروبي (Bison bonasus)، المعروف باسم الويسنت، هو أكبر ثديي في أوروبا. بعد الحرب العالمية الأولى، واجه هذا النوع خطر الانقراض في البرية، حيث تم قتل آخر فرد في غابة بيلوفيزا في

النتائج

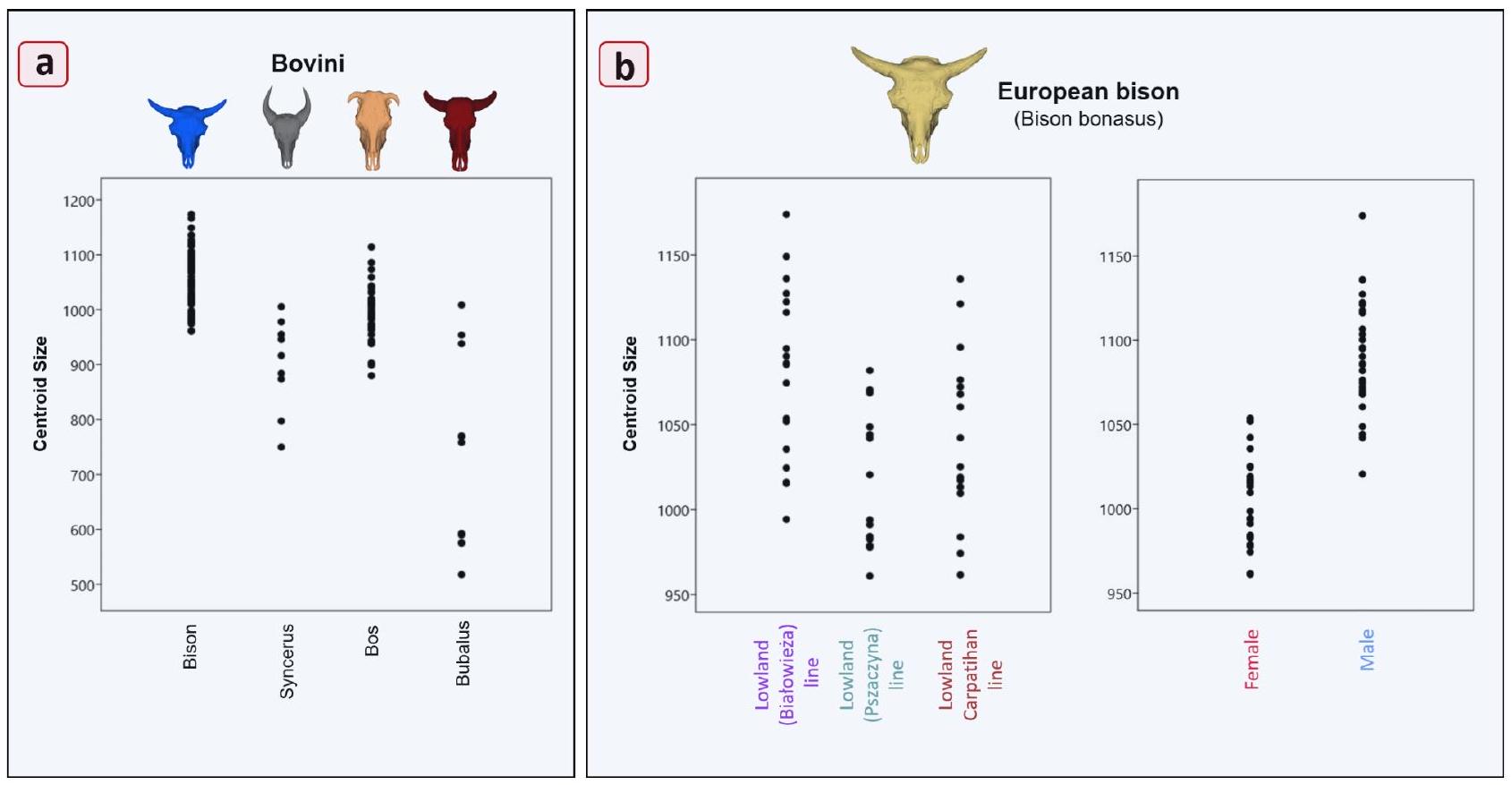

حجم الجمجمة والعملية القرنية

| المجموعة | القياس | الزوج | الفرق | الحد الأدنى CI | الحد الأقصى CI |

|

| Bovini | حجم الجمجمة (CS) | Bison-Syncerus | 151.4489 | 83.4597 | 219.4382 |

|

| Bison -Bos | 56.8076 | 18.2346 | 95.3807 |

|

||

| Bison -Bubalus | 320.4568 | 258.1099 | 382.8037 |

|

||

| Syncerus – Bos | 94.6413 | 24.2511 | 165.0315 |

|

||

| Syncerus – Bubalus | 169.0079 | 83.2522 | 254.7636 |

|

||

| Bos – Bubalus | 263.6492 | 198.6924 | 328.6059 |

|

||

| البيسون الأوروبي (السلالة) | حجم الجمجمة (CS) | Białowieża – Pszczyna | 64.3619 | ٢٧.٤٣٦٧ | ١٠١.٢٨٧ |

|

| بيالوفيزا – الكاربات | ٣٧.٠٧٧٦ | ٠.٨٩١٦ | ٧٣.٢٦٣٦ |

|

||

| بشينا – الكاربات | ٢٧.٢٨٤٣ | -١٣.٦٤٥٣ | ٦٨.٢١٣٩ | ص: ٠.١١١ | ||

| أنثى ذكر | ٨٨.٥٠٨٦ | ٧٢.٢٢٨٨ | ١٠٤.٧٨٨٤ |

|

||

| حجم العملية القرنية (CS) | بيالوفيزا – بشينا | ٦٤.٣٦١٩ | ٢٧.٤٣٦٧ | ١٠١.٢٨٧ |

|

|

| بيالوفيزا – الكاربات | ٣٧.٠٧٧٦ | ٠.٨٩١٦ | ٧٣.٢٦٣٦ |

|

||

| بشينا – الكاربات | ٢٧.٢٨٤٣ | -١٣.٦٤٥٣ | ٦٨.٢١٣٩ | ص: ٠.٢٨٢ | ||

| أنثى ذكر | ٨٨.٥٠٨٦ | ٧٢.٢٢٨٨ | ١٠٤.٧٨٨٤ |

|

تغيرات شكل الجمجمة

اختلافات الشكل بين المجموعات وداخلها

الحجم والشكل

المناقشة

قد تعكس عملية قرون البيسون أيضًا التكيفات مع البيئات التي تعيش فيها هذه الأنواع. تعيش البيسون في المراعي المفتوحة وأطراف الغابات، حيث قد لا تعتمد استراتيجياتها الدفاعية الأساسية بشكل كبير على الأسلحة.

علم الشكل عن طريق exerting الضغط على العظم الجبهي. وهذا بدوره يؤثر على عظام الوجه، مما يساهم في الاختلافات الشكلية المميزة بين الذكور والإناث. تعزز العمليات القرنية المتطورة جيدًا في الذكور نموها غير المتساوي، مما يميز شكل وحجم الجمجمة في أنماط ثنائية الشكل جنسيًا.

طريقة المواد

عينات

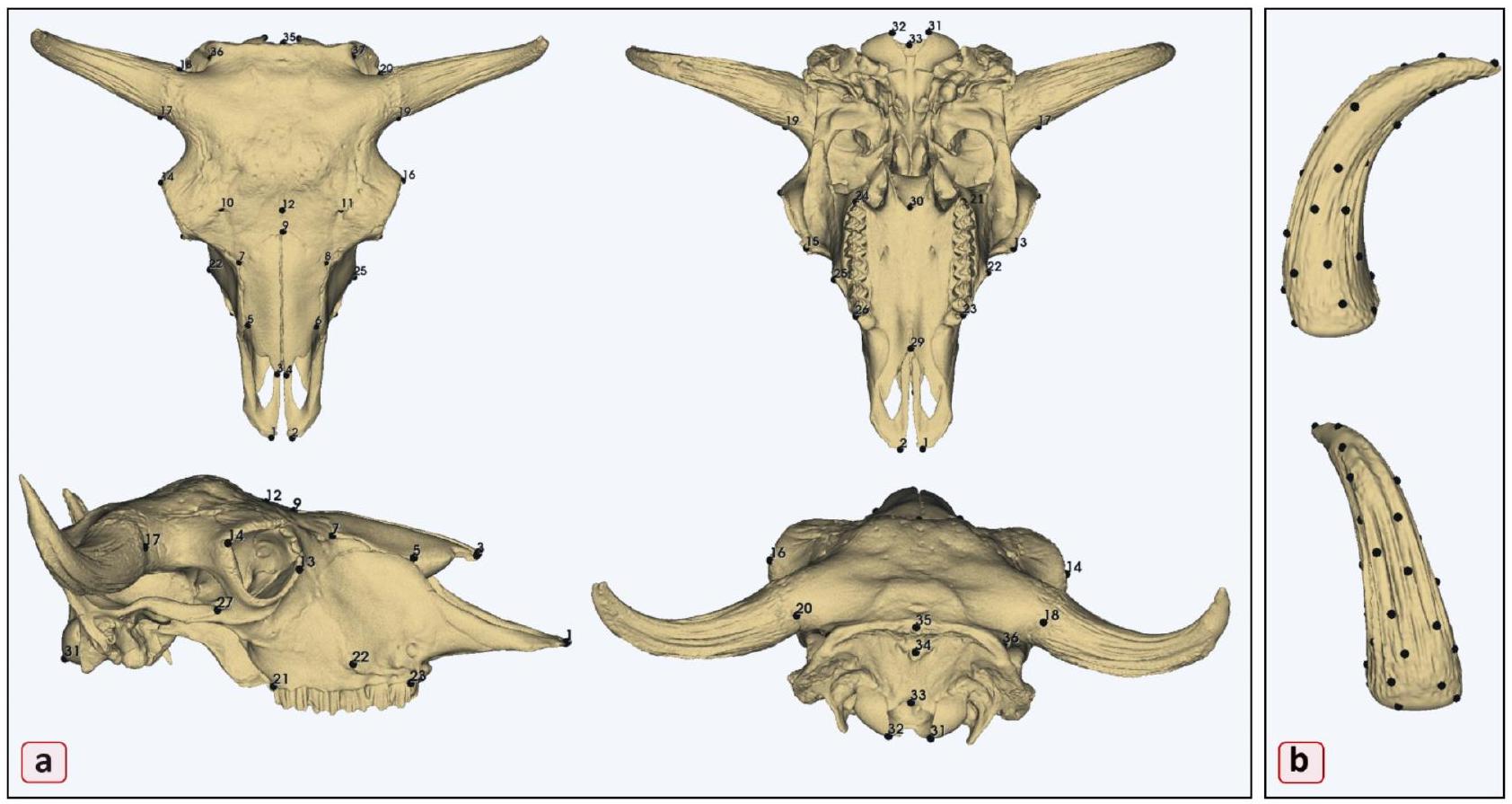

رقمنة العينات وتحديد المعالم

| جمجمة | منطقة | رقم المعلم | وصف المعلم |

| عظام الوجه | منطقة الفك العلوي | 1,2 | بروستيون |

| 21,24 | بعد الأسنان | ||

| ٢٢,٢٥ | نتوءات الوجه | ||

| ٢٣،٢٦ | ضرس | ||

| منطقة الأنف | 3,4 | طرف الأنف من عظام الأنف | |

| ٥،٦ | شَقّ الأنف القاطع | ||

| ٧،٨ | أقصى نهاية أمامية من الغرز الجبهية | ||

| 9 | ناسيون | ||

| منطقة الحنك | ٢٩ | النقطة الأنفية من الحنك الصلب | |

| 30 | نقطة النهاية للحنك الصلب | ||

| المنطقة المدارية | 13,15 | المدار الخارجي | |

| 14,16 | المدار الداخلي | ||

| عظام الدماغ العصبي | المنطقة الجبهية | 10,11 | الثقب فوق المدار |

| 12 | نقطة المنتصف للثقب فوق المدار | ||

| المنطقة القرنية | 17,19 | النقطة الأمامية لعملية القرنية | |

| 18,20 | نقطة النهاية لعملية القرنية | ||

| المنطقة القذالية | 31,32 | النهاية السفلية للنتوءات القذالية | |

| 33 | أوبستيون | ||

| 34 | النتوء القذالي الخارجي | ||

| 35 | قمة العنق | ||

| 36,37 | الحدود الذيلية للحفرة الزمنية | ||

| المنطقة الزمنية | 27,28 | النقطة الأمامية للعملية الزمنية |

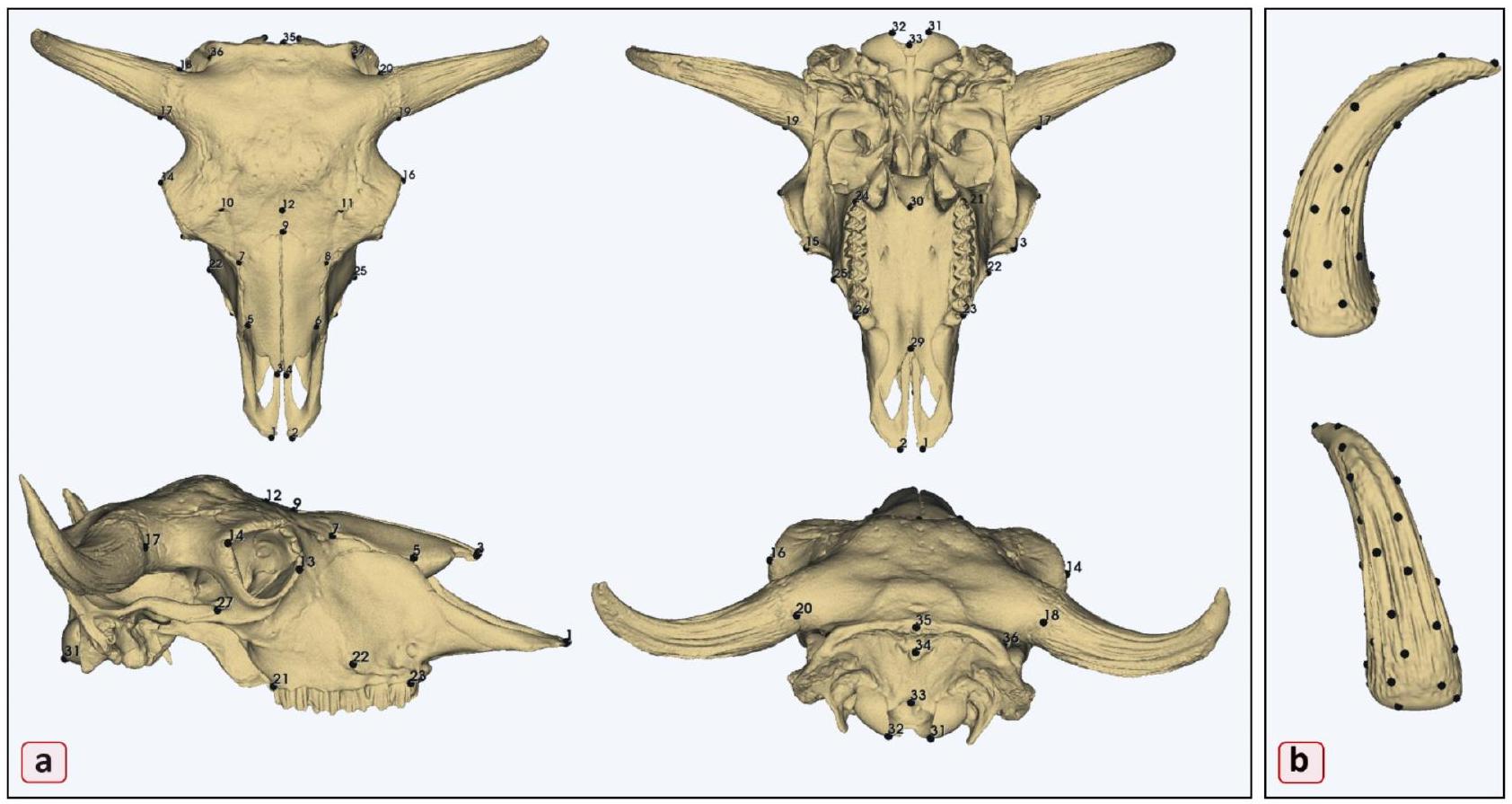

نقاط العينة لضمان تباعد متسق، مما يعزز دقة وقابلية إعادة إنتاج وضع المعالم. تم إنشاء مجموعة المعالم النهائية، التي تتكون من 34 معلمًا شبه، (كما هو موضح بالنقاط السوداء في الشكل 5B). عملية آلية وسعت مجموعة المعالم عبر مجموعة البيانات بأكملها. تم تطبيق مجموعة المسودة على جميع عينات الجمجمة باستخدام توليد المعالم التلقائي عبر محاذاة سحابة النقاط وتحليل المطابقة (ALPACA)

الهندسة المورفومترية

تحليل الفضاء المورفولوجي: الفروق بين المجموعات وبين الأفراد

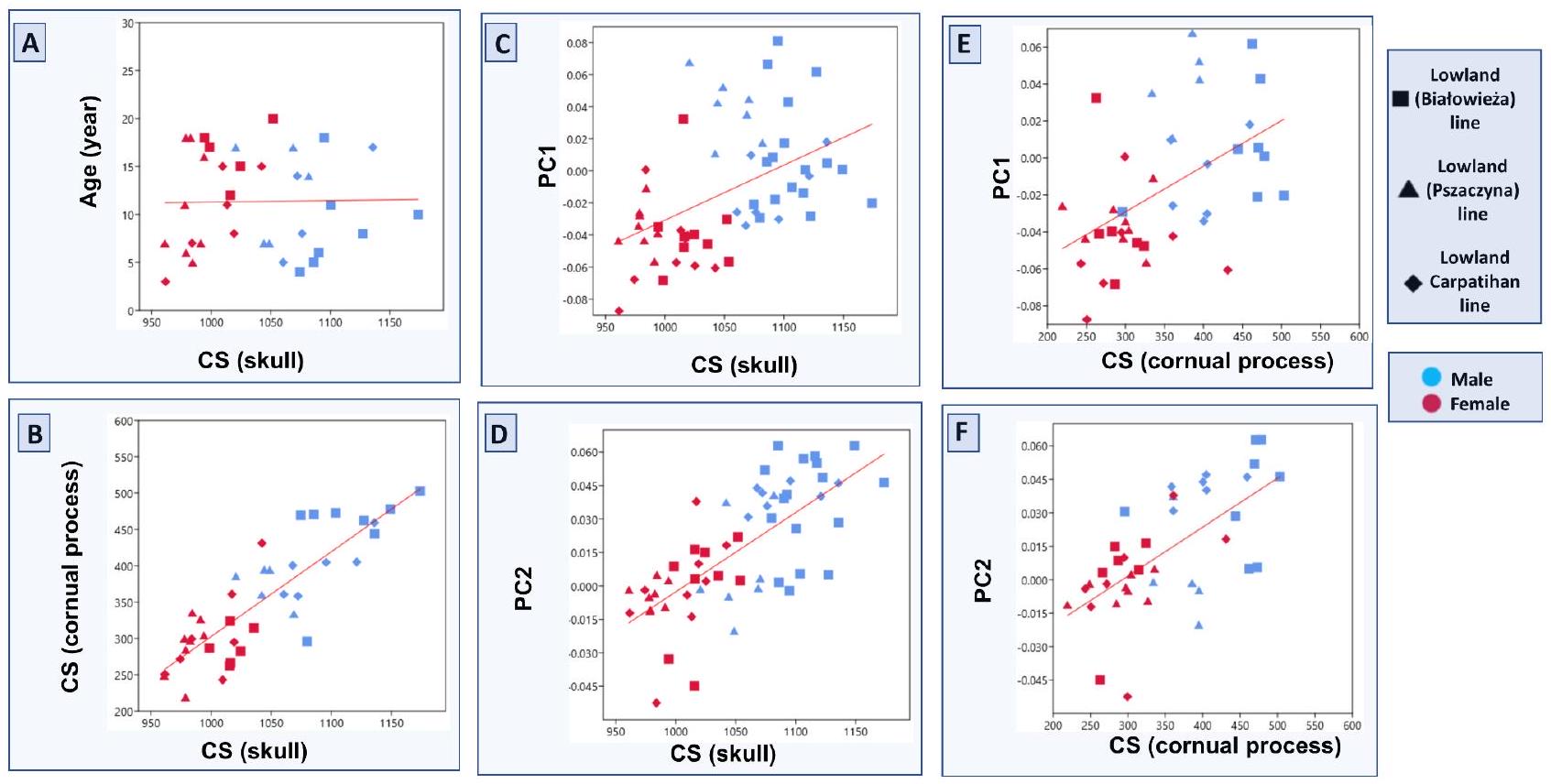

عملية القرنية، الحجم، والعمر

التحليل الإحصائي

توفر البيانات

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 09 يناير 2025

References

- Larska, M., Tomana, J., Krzysiak, M. K., Pomorska-Mól, M. & Socha, W. Prevalence of coronaviruses in European bison (Bison bonasus) in Poland. Sci. Rep. 14, 12928 (2024).

- Olech, W. The number of ancestors and their contribution to European bison (Bison bonasus L.) population. Anim. Sci. 35, 111117 (1999).

- Slatis, H. M. An analysis of inbreeding in the European bison. Genetics 45, 275 (1960).

- Parusel, J. B. What next with Pless line of European bison from Pszczyna-a question on the 155 th anniversary of restitution and breeding? Eur. Bison Conserv. Newsl. 13, 39-56 (2021).

- Plumb, G., Kowalczyk, R. & Hernandez-Blanco, J. A. Bison bonasus. IUCN red list. Threatened Species. https://doi.org/10.2305/IU CN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T2814A45156279.en (2020).

- Haber, A. Phenotypic covariation and morphological diversification in the ruminant skull. Am. Nat. 187(5), 576-591 (2016).

- Janis, C. M. & Theodor, J. M. Cranial and postcranial morphological data in ruminant phylogenetics. Zitteliana 15-31 (2014).

-

- Stankowich, T., & Caro, T. Evolution of weaponry in female bovids. Proc. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 276(1677), 4329-4334 (2009).

- Krasińska, M., Szuma, E., Kobryńczuk, F. & Szara, T. Morphometric variation of the skull during postnatal development in the Lowland European bison Bison bonasus bonasus. Acta Theriol. 53, 193-216 (2008).

- Mysterud, A. et al. Population ecology and conservation of endangered megafauna: The case of European bison in Białowieża Primeval Forest, Poland. Anim. Conserv. 10, 77-87 (2007).

- Zalewski, D., Szczepański, W. & Wołkowycka, M. Characteristics of closed breeding stations of Bison (Bison Bonasus L.) in Poland in the years 1997-2000. Acta Sci. Pol. Silv Colendar Rat. Ind. Lignar. 4, 121-130 (2005).

- Figueirido, B., Tseng, Z. J. & Martín-Serra, A. Skull shape evolution in durophagous carnivorans. Evolution 67(7), 1975-1993 (2013).

- Tokita, M., Yano, W., James, H. F. & Abzhanov, A. Cranial shape evolution in adaptive radiations of birds: Comparative morphometrics of Darwin’s finches and Hawaiian honeycreepers. Proc. R. Soc. B 372, 20150481 (2017).

- Wagner, G. P. What is the promise of developmental evolution? Part I: Why is developmental biology necessary to explain evolutionary innovations? J. Exp. Zool. 288(2), 95-98 (2000).

- Bertossa, R. C. Morphology and behaviour: Functional links in development and evolution. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 366(1574), 2056-2068 (2011).

- Janis, C. M., Constable, E. C., Houpt, K. A., Streich, W. J. & Clauss, M. Comparative ingestive mastication in domestic horses and cattle: A pilot investigation. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 94, 402-409 (2010).

- Sanson, G. The biomechanics of browsing and grazing. Am. J. Bot. 93, 1531-1545 (2006).

- Stankowich, T. & Caro, T. Evolution of weaponry in female bovids. Proc. R. Soc. B. 276, 4329-4334 (2009).

- Kowalczyk, R. et al. Movements of European bison (Bison bonasus) beyond the Białowieża Forest (NE Poland): Range expansion or partial migrations? Acta Theriol. 58, 391-401 (2013).

- Solounias, N. & Moelleken, S. M. Dietary adaptation of some extinct ruminants determined by premaxillary shape. J. Mammal 74, 1059-1971 (1993).

- Tennant, J. P. & MacLeod, N. Snout shape in extant ruminants. PLoS One 9, e112035 (2014).

- Craine, J. M., Towne, E. G., Miller, M. & Fierer, N. Climatic warming and the future of bison as grazers. Sci. Rep. 5, 16738 (2015).

- Nippert, J. B., Culbertson, T. S., Orozco, G. L., Ocheltree, T. W. & Helliker, B. R. Identifying the water sources consumed by bison: Implications for large mammalian grazers worldwide. Ecosphere 4, 1-13 (2013).

- Caro, T. M., Graham, C. M., Stoner, C. J. & Flores, M. M. Correlates of horn and antler shape in bovids and cervids. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 55, 32-41 (2003).

- Tidière, M., Lemaître, J. F., Pélabon, C., Gimenez, O. & Gaillard, J. M. Evolutionary allometry reveals a shift in selection pressure on male horn size. J. Evol. Biol. 30, 1826-1835 (2017).

- Willisch, C. S., Biebach, I., Marreros, N., Ryser-Degiorgis, M. P. & Neuhaus, P. Horn growth and reproduction in a long-lived male mammal: No compensation for poor early-life horn growth. Evol. Biol. 42, 1-11 (2015).

- Buttar, I. & Solounias, N. Specialized position of the horns, and frontal and parietal bones in Bos taurus (Bovini, Artiodactyla), and notes on the evolution of Bos. Ann. Zool. 58, 49-63 (2021).

- Lundrigan, B. Morphology of horns and fighting behavior in the family Bovidae. J. Mammal. 77, 462-475 (1996).

- Bergmann, C. Über die Verhältnisse Der Wärmeökonomie Der Thiere zu Ihrer Grösse. Vandenhoeck Und Ruprecht (1848).

- Bibi, F. & Tyler, J. Evolution of the bovid cranium: Morphological diversification under allometric constraint. Commun. Biol. 5, 69 (2022).

- Tidière, M. et al. Variation in the ontogenetic allometry of horn length in bovids along a body mass continuum. Ecol. Evol. 10, 4104-4114 (2020).

- Packard, G. C. Evolutionary allometry of horn length in the mammalian family Bovidae reconciled by non-linear regression. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 125, 657-663 (2018).

- Cardini, A. & Polly, P. D. Larger mammals have longer faces because of size-related constraints on skull form. Nat. Commun. 4, 2458 (2013).

- Kobryńczuk, F., Krasińska, M. & Szara, T. Sexual dimorphism in skulls of the lowland European bison, Bison bonasus bonasus. Ann. Zool. 45, 335-340 (2008).

- Szara, T., Klich, D., Wójcik, A. M. & Olech, W. Temporal trends in skull morphology of the European bison from the 1950s to the present day. Diversity 15, 377 (2023).

- Morena, S., Barba, S. & Álvaro-Tordesillas, A. Shining 3D EinScan-Pro, application and validation in the field of cultural heritage, from the Chillida-Leku Museum to the archaeological museum of Sarno. Int. Arch. Photogramm. ISPRS Arch. 42, 135-142 (2019).

- Bookstein, F. L. Morphometric Tools for Landmark data: Geometry and Biology (Cambridge University Press, 1997).

- Çakar, B. et al. Comparison of skull morphometric characteristics of simmental and holstein cattle breeds. Animals 14, 2085 (2024).

- Özkan, E., Siddiq, A. B., Kahvecioğlu, K. O., Öztürk, M. & Onar, V. Morphometric analysis of the skulls of domestic cattle (Bos taurus L.) and water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis L.) in Turkey. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 43, 532-539 (2019).

- Porto, A., Rolfe, S. & Maga, A. M. ALPACA: A fast and accurate computer vision approach for automated landmarking of threedimensional biological structures. Methods Ecol. Evol. 12, 2129-2144 (2021).

- Beinat, A. & Crosilla, F. Generalised Procrustes Analysis for size and Shape 3-D Object Reconstructions 345-353 (Optical, 2001).

- Stuart, M. A geometric approach to principal components analysis. Am. Stat. 36, 365-367 (1982).

- Rolfe, S. et al. SlicerMorph: An open and extensible platform to retrieve, visualize and analyse 3D morphology. Methods Ecol. Evol. 12, 1816-1825 (2021).

- Viacava, P., Baker, A. M., Blomberg, S. P., Phillips, M. J. & Weisbecker, V. Using 3D geometric morphometrics to aid taxonomic and ecological understanding of a recent speciation event within a small Australian marsupial (Antechinus: Dasyuridae). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 196(3), 963-978 (2022).

- Adams, D. C. & Otárola-Castillo, E. Geomorph: An R package for the collection and analysis of geometric morphometric shape data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 4(4), 393-399 (2013).

- Hammer, Ø. & Harper, D. A. Past: Ualeontological statistics software package for educaton and data anlysis. Palaeont Electr. 4, 1 (2001).

- Minervino, A. H. H., Zava, M., Vecchio, D. & Borghese, A. Bubalus bubalis: A short story. Front. vet. sci. 7, 570413 (2020).

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

الإعلانات

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

يجب توجيه المراسلات وطلبات المواد إلى T.S.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على www.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر تظل Springer Nature محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

© المؤلفون 2025

قسم التشريح، كلية الطب البيطري، جامعة إسطنبول-جيراه باشا، 34320 إسطنبول، تركيا.

قسم العلوم الشكلية، معهد الطب البيطري، جامعة وارسو لعلوم الحياة SGGW، 02-776 وارسو، بولندا. البريد الإلكتروني: tomasz_szara@sggw.edu.pl

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85654-3

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39789289

Publication Date: 2025-01-09

OPEN

Morphological patterns of the European bison (Bison bonasus) skull

Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the effects of environmental factors, sexual selection, and genetic variation on skull morphology by examining the skull structure of the European bison, a species at risk of extinction, and comparing it to other bovid species. The skull of the European bison was significantly bigger than that of other species of the tribe Bovini, and the results revealed considerable morphological differences in skull shape compared to other Bovini samples. The bison skull exhibited a broader shape in the frontal region and a more laterally oriented cornual process. The frontal bone also significantly influenced skull shape variation within the European bison subspecies. Also, the findings indicated that cornual processes size significantly affected skull shape. Male Bison had larger skulls and more developed cornual ridges, and these morphological changes in the frontal region are thought to have also influenced the nuchal region, maxillary region, and facial bones. Furthermore, the differences in skull size observed between the Lowland-Pszczyna and Lowland-Białowieża lines, which share a closer origin than the Lowland-Carpathian lines, may reflect environmental and genetic adaptations over time. This research provides a reference point for future studies on the ecological and evolutionary factors influencing bison skull variations, with significant implications for the conservation of this species.

The European bison (Bison bonasus), known as the wisent, is Europe’s largest mammal. Following World War I, the species faced extinction in the wild, with the last individual being killed in the Białowieża Forest in

Results

Skull and cornual process size

| Group | Measurement | Pair | Difference | Lower CI | Upper CI |

|

| Bovini | Skull size (CS) | Bison-Syncerus | 151.4489 | 83.4597 | 219.4382 |

|

| Bison -Bos | 56.8076 | 18.2346 | 95.3807 |

|

||

| Bison -Bubalus | 320.4568 | 258.1099 | 382.8037 |

|

||

| Syncerus – Bos | 94.6413 | 24.2511 | 165.0315 |

|

||

| Syncerus – Bubalus | 169.0079 | 83.2522 | 254.7636 |

|

||

| Bos – Bubalus | 263.6492 | 198.6924 | 328.6059 |

|

||

| European bison (Line) | Skull size (CS) | Białowieża – Pszczyna | 64.3619 | 27.4367 | 101.287 |

|

| Białowieża – Carpathian | 37.0776 | 0.8916 | 73.2636 |

|

||

| Pszczyna – Carpathian | 27.2843 | -13.6453 | 68.2139 | p: 0.111 | ||

| Female Male | 88.5086 | 72.2288 | 104.7884 |

|

||

| Cornual process Size (CS) | Białowieża – Pszczyna | 64.3619 | 27.4367 | 101.287 |

|

|

| Białowieża – Carpathian | 37.0776 | 0.8916 | 73.2636 |

|

||

| Pszczyna – Carpathian | 27.2843 | -13.6453 | 68.2139 | p: 0.282 | ||

| Female Male | 88.5086 | 72.2288 | 104.7884 |

|

Skull shape variations

Inter- and intragroup shape differences

Size and shape

Discussion

of the bison’s cornual process could also reflect adaptations to the environments in which these species live. Bison inhabit open grasslands and forest edges, where their primary defensive strategies may not rely heavily on weapons

morphology by exerting pressure on the frontal bone. This, in turn, affects the facial bones, contributing to the distinct morphological differences between males and females. The well-developed cornual processes in males reinforce their allometric growth, further differentiating skull shape and size in sexually dimorphic patterns

Material method

Samples

Specimen digitization and landmarking

| Skull | Area | Landmark No | Landmark description |

| Facial bones | Maxillary area | 1,2 | Prosthion |

| 21,24 | Postdentale | ||

| 22,25 | facial tuberosities | ||

| 23,26 | Premolar | ||

| Nasal area | 3,4 | Rostral end of nasal bones | |

| 5,6 | Naso-incisive notch | ||

| 7,8 | The most rostral end of the frontal suture | ||

| 9 | Nasion | ||

| Palate area | 29 | The rostral point of the hard palate | |

| 30 | The end point of the hard palate | ||

| Orbital area | 13,15 | Entorbitale | |

| 14,16 | Ectorbitale | ||

| Neurocranial bones | Frontal area | 10,11 | Supraorbital foramen |

| 12 | Middle point of the supraorbital foramen | ||

| Cornual area | 17,19 | The rostral point of the cornual process | |

| 18,20 | The end point of the cornual process | ||

| Occipital area | 31,32 | Lower end of the occipital condyles | |

| 33 | Opisthion | ||

| 34 | The external occipital protuberance | ||

| 35 | Nuchal crest | ||

| 36,37 | Caudal border of temporal fossa | ||

| Temporal area | 27,28 | The rostral point of the temporal process |

of the sampling points were adjusted to ensure consistent spacing, enhancing the precision and reproducibility of the landmark placement. The final landmark set, comprising 34 semilandmarks, was generated (as shown by black dots in Fig. 5B). An automated process extended the landmark set across the entire dataset. The draft set was applied to all skull specimens using Automatic Landmark Generation via Point Cloud Alignment and Correspondence Analysis (ALPACA)

Geometric morphometrics

Morphospace analysis: inter- and intragroup differences

Cornual process, size, and age

Statistical analysis

Data availability

Published online: 09 January 2025

References

- Larska, M., Tomana, J., Krzysiak, M. K., Pomorska-Mól, M. & Socha, W. Prevalence of coronaviruses in European bison (Bison bonasus) in Poland. Sci. Rep. 14, 12928 (2024).

- Olech, W. The number of ancestors and their contribution to European bison (Bison bonasus L.) population. Anim. Sci. 35, 111117 (1999).

- Slatis, H. M. An analysis of inbreeding in the European bison. Genetics 45, 275 (1960).

- Parusel, J. B. What next with Pless line of European bison from Pszczyna-a question on the 155 th anniversary of restitution and breeding? Eur. Bison Conserv. Newsl. 13, 39-56 (2021).

- Plumb, G., Kowalczyk, R. & Hernandez-Blanco, J. A. Bison bonasus. IUCN red list. Threatened Species. https://doi.org/10.2305/IU CN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T2814A45156279.en (2020).

- Haber, A. Phenotypic covariation and morphological diversification in the ruminant skull. Am. Nat. 187(5), 576-591 (2016).

- Janis, C. M. & Theodor, J. M. Cranial and postcranial morphological data in ruminant phylogenetics. Zitteliana 15-31 (2014).

-

- Stankowich, T., & Caro, T. Evolution of weaponry in female bovids. Proc. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 276(1677), 4329-4334 (2009).

- Krasińska, M., Szuma, E., Kobryńczuk, F. & Szara, T. Morphometric variation of the skull during postnatal development in the Lowland European bison Bison bonasus bonasus. Acta Theriol. 53, 193-216 (2008).

- Mysterud, A. et al. Population ecology and conservation of endangered megafauna: The case of European bison in Białowieża Primeval Forest, Poland. Anim. Conserv. 10, 77-87 (2007).

- Zalewski, D., Szczepański, W. & Wołkowycka, M. Characteristics of closed breeding stations of Bison (Bison Bonasus L.) in Poland in the years 1997-2000. Acta Sci. Pol. Silv Colendar Rat. Ind. Lignar. 4, 121-130 (2005).

- Figueirido, B., Tseng, Z. J. & Martín-Serra, A. Skull shape evolution in durophagous carnivorans. Evolution 67(7), 1975-1993 (2013).

- Tokita, M., Yano, W., James, H. F. & Abzhanov, A. Cranial shape evolution in adaptive radiations of birds: Comparative morphometrics of Darwin’s finches and Hawaiian honeycreepers. Proc. R. Soc. B 372, 20150481 (2017).

- Wagner, G. P. What is the promise of developmental evolution? Part I: Why is developmental biology necessary to explain evolutionary innovations? J. Exp. Zool. 288(2), 95-98 (2000).

- Bertossa, R. C. Morphology and behaviour: Functional links in development and evolution. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 366(1574), 2056-2068 (2011).

- Janis, C. M., Constable, E. C., Houpt, K. A., Streich, W. J. & Clauss, M. Comparative ingestive mastication in domestic horses and cattle: A pilot investigation. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 94, 402-409 (2010).

- Sanson, G. The biomechanics of browsing and grazing. Am. J. Bot. 93, 1531-1545 (2006).

- Stankowich, T. & Caro, T. Evolution of weaponry in female bovids. Proc. R. Soc. B. 276, 4329-4334 (2009).

- Kowalczyk, R. et al. Movements of European bison (Bison bonasus) beyond the Białowieża Forest (NE Poland): Range expansion or partial migrations? Acta Theriol. 58, 391-401 (2013).

- Solounias, N. & Moelleken, S. M. Dietary adaptation of some extinct ruminants determined by premaxillary shape. J. Mammal 74, 1059-1971 (1993).

- Tennant, J. P. & MacLeod, N. Snout shape in extant ruminants. PLoS One 9, e112035 (2014).

- Craine, J. M., Towne, E. G., Miller, M. & Fierer, N. Climatic warming and the future of bison as grazers. Sci. Rep. 5, 16738 (2015).

- Nippert, J. B., Culbertson, T. S., Orozco, G. L., Ocheltree, T. W. & Helliker, B. R. Identifying the water sources consumed by bison: Implications for large mammalian grazers worldwide. Ecosphere 4, 1-13 (2013).

- Caro, T. M., Graham, C. M., Stoner, C. J. & Flores, M. M. Correlates of horn and antler shape in bovids and cervids. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 55, 32-41 (2003).

- Tidière, M., Lemaître, J. F., Pélabon, C., Gimenez, O. & Gaillard, J. M. Evolutionary allometry reveals a shift in selection pressure on male horn size. J. Evol. Biol. 30, 1826-1835 (2017).

- Willisch, C. S., Biebach, I., Marreros, N., Ryser-Degiorgis, M. P. & Neuhaus, P. Horn growth and reproduction in a long-lived male mammal: No compensation for poor early-life horn growth. Evol. Biol. 42, 1-11 (2015).

- Buttar, I. & Solounias, N. Specialized position of the horns, and frontal and parietal bones in Bos taurus (Bovini, Artiodactyla), and notes on the evolution of Bos. Ann. Zool. 58, 49-63 (2021).

- Lundrigan, B. Morphology of horns and fighting behavior in the family Bovidae. J. Mammal. 77, 462-475 (1996).

- Bergmann, C. Über die Verhältnisse Der Wärmeökonomie Der Thiere zu Ihrer Grösse. Vandenhoeck Und Ruprecht (1848).

- Bibi, F. & Tyler, J. Evolution of the bovid cranium: Morphological diversification under allometric constraint. Commun. Biol. 5, 69 (2022).

- Tidière, M. et al. Variation in the ontogenetic allometry of horn length in bovids along a body mass continuum. Ecol. Evol. 10, 4104-4114 (2020).

- Packard, G. C. Evolutionary allometry of horn length in the mammalian family Bovidae reconciled by non-linear regression. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 125, 657-663 (2018).

- Cardini, A. & Polly, P. D. Larger mammals have longer faces because of size-related constraints on skull form. Nat. Commun. 4, 2458 (2013).

- Kobryńczuk, F., Krasińska, M. & Szara, T. Sexual dimorphism in skulls of the lowland European bison, Bison bonasus bonasus. Ann. Zool. 45, 335-340 (2008).

- Szara, T., Klich, D., Wójcik, A. M. & Olech, W. Temporal trends in skull morphology of the European bison from the 1950s to the present day. Diversity 15, 377 (2023).

- Morena, S., Barba, S. & Álvaro-Tordesillas, A. Shining 3D EinScan-Pro, application and validation in the field of cultural heritage, from the Chillida-Leku Museum to the archaeological museum of Sarno. Int. Arch. Photogramm. ISPRS Arch. 42, 135-142 (2019).

- Bookstein, F. L. Morphometric Tools for Landmark data: Geometry and Biology (Cambridge University Press, 1997).

- Çakar, B. et al. Comparison of skull morphometric characteristics of simmental and holstein cattle breeds. Animals 14, 2085 (2024).

- Özkan, E., Siddiq, A. B., Kahvecioğlu, K. O., Öztürk, M. & Onar, V. Morphometric analysis of the skulls of domestic cattle (Bos taurus L.) and water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis L.) in Turkey. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 43, 532-539 (2019).

- Porto, A., Rolfe, S. & Maga, A. M. ALPACA: A fast and accurate computer vision approach for automated landmarking of threedimensional biological structures. Methods Ecol. Evol. 12, 2129-2144 (2021).

- Beinat, A. & Crosilla, F. Generalised Procrustes Analysis for size and Shape 3-D Object Reconstructions 345-353 (Optical, 2001).

- Stuart, M. A geometric approach to principal components analysis. Am. Stat. 36, 365-367 (1982).

- Rolfe, S. et al. SlicerMorph: An open and extensible platform to retrieve, visualize and analyse 3D morphology. Methods Ecol. Evol. 12, 1816-1825 (2021).

- Viacava, P., Baker, A. M., Blomberg, S. P., Phillips, M. J. & Weisbecker, V. Using 3D geometric morphometrics to aid taxonomic and ecological understanding of a recent speciation event within a small Australian marsupial (Antechinus: Dasyuridae). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 196(3), 963-978 (2022).

- Adams, D. C. & Otárola-Castillo, E. Geomorph: An R package for the collection and analysis of geometric morphometric shape data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 4(4), 393-399 (2013).

- Hammer, Ø. & Harper, D. A. Past: Ualeontological statistics software package for educaton and data anlysis. Palaeont Electr. 4, 1 (2001).

- Minervino, A. H. H., Zava, M., Vecchio, D. & Borghese, A. Bubalus bubalis: A short story. Front. vet. sci. 7, 570413 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Declarations

Competing interests

Additional information

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to T.S.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

© The Author(s) 2025

Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Istanbul University-Cerrahpasa, 34320 Istanbul, Turkey.

Department of Morphological Sciences, Institute of Veterinary Medicine, Warsaw University of Life SciencesSGGW, 02-776 Warsaw, Poland. email: tomasz_szara@sggw.edu.pl