DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-48136-0

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38724490

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-09

استكشاف امتصاص الغاز ومرونة الإطار لـ CALF-20 من خلال التجارب والمحاكاة

تم القبول: 18 أبريل 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 09 مايو 2024

(أ) التحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

في عام 2021، أفادت شركة سيفانتي، بالتعاون مع شركة BASF، بنجاح توسيع إنتاج CALF-20، وهو إطار معدني عضوي مستقر ذو سعة عالية لاحتجاز الكربون بعد الاحتراق.

الرطوبة، بالإضافة إلى المتانة والثبات تجاه البخار، والغازات الحمضية الرطبة، والتعرض المطول لتيار غاز العادم المباشر

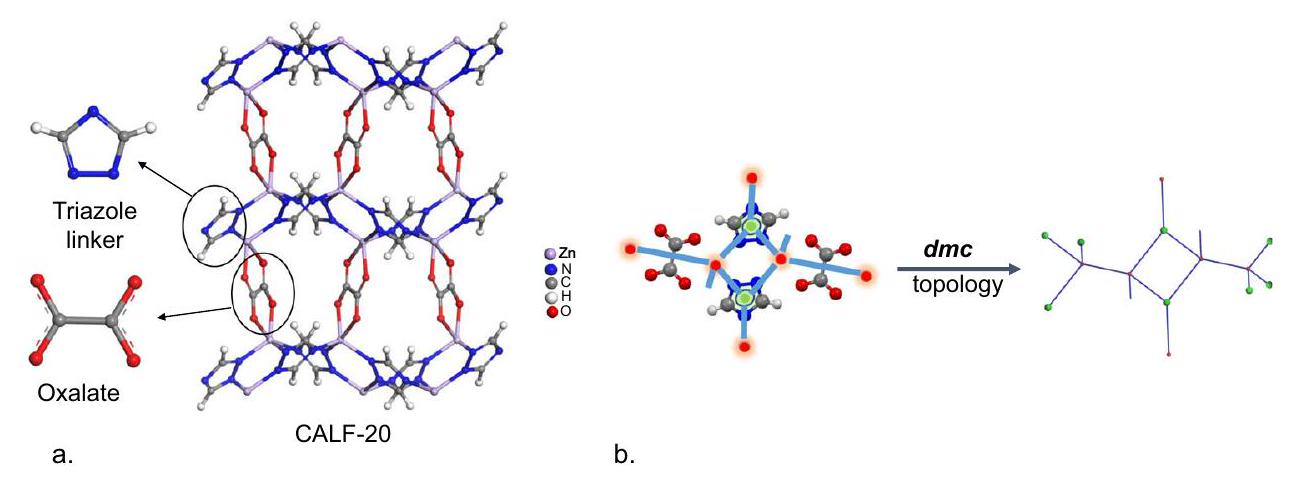

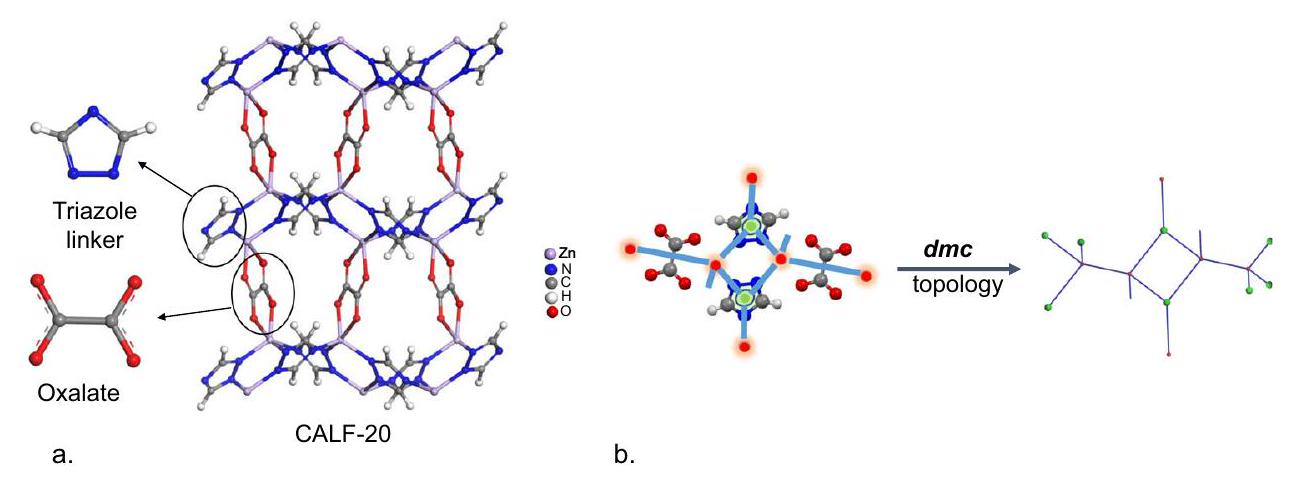

الفروع المستقيمة، على التوالي. تمثل الكرات الحمراء العقد المعدنية وتمثل الكرات الخضراء العقد العضوية، المتصلة عبر ‘فروع’ رابط زرقاء.

النتائج والمناقشة

التوصيف الهندسي وخصائص امتصاص الغاز لـ CALF-20

حوالي

مع رمز الاستجابة السريعة للواقع المعزز (AR) لـ

تم جمعه تحت

تحولات عبر حيود الأشعة السينية للبلورات المسحوقة في الموقع (PXRD). حصلنا على بيانات PXRD تحت تعرضات مختلفة للغاز والسائل (

متجهات الخلية العمودية على طبقات Zn-triazolate. نظام تلوين الذرات هو: رمادي فاتح، زنك؛ أحمر، أكسجين؛ أبيض، هيدروجين؛ أزرق: نيتروجين؛ رمادي: كربون). توزيع أحجام المسام للهيكل التجريبي (أسود)، الهيكل المحسن بواسطة DFT (أخضر)، وتلك المتوسطة على مسارات MD لـ CALF-20 الفارغ والمحمل بالضيوف عند

الماء قادر على إحداث تغييرات أكبر في الإطار مقارنة بجميع الضيوف الآخرين الذين تم مناقشتهم هنا. بعبارة أخرى،

كما هو موضح في الشكل 4c، مع أطوال الخلايا الموضحة في الشكل 4b. يمكننا أن نرى أن هناك مرونة كبيرة حيث يتغير أحد أطوال الخلايا عكسياً مع الآخر: وهذا يتوافق مع الاختلافات الملحوظة في أنماط PXRD لـ CALF-20 عند تعرضه للضيوف (الشكل 3). يتم تثبيط هذا الوضع المرن بشكل كبير عندما تكون الضيوف موجودة في الإطار، كما يتضح من التوزيعات البرتقالية الأضيق في الشكل 4b.

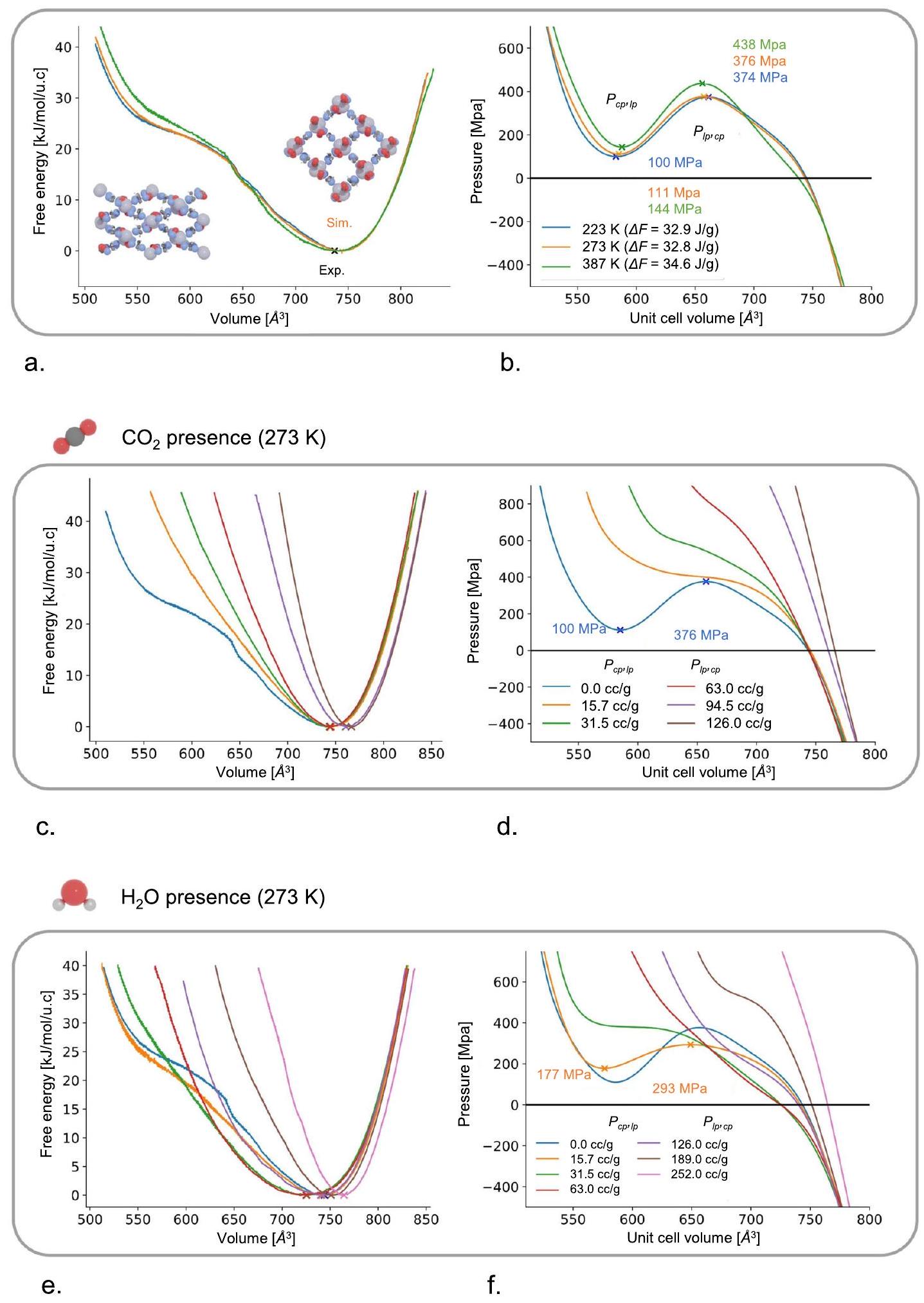

ملفات الطاقة الحرة لنموذج دالة الكثافة الفارغة والمحمّلة بالزوار

حيث لا يُرى هذا لـ

امتصاص الماء في CALF-20

المشتق السالب للطاقة الحرة، كاشفًا عن إمكانية وجود مرحلة cp غير مستقرة عند حجم

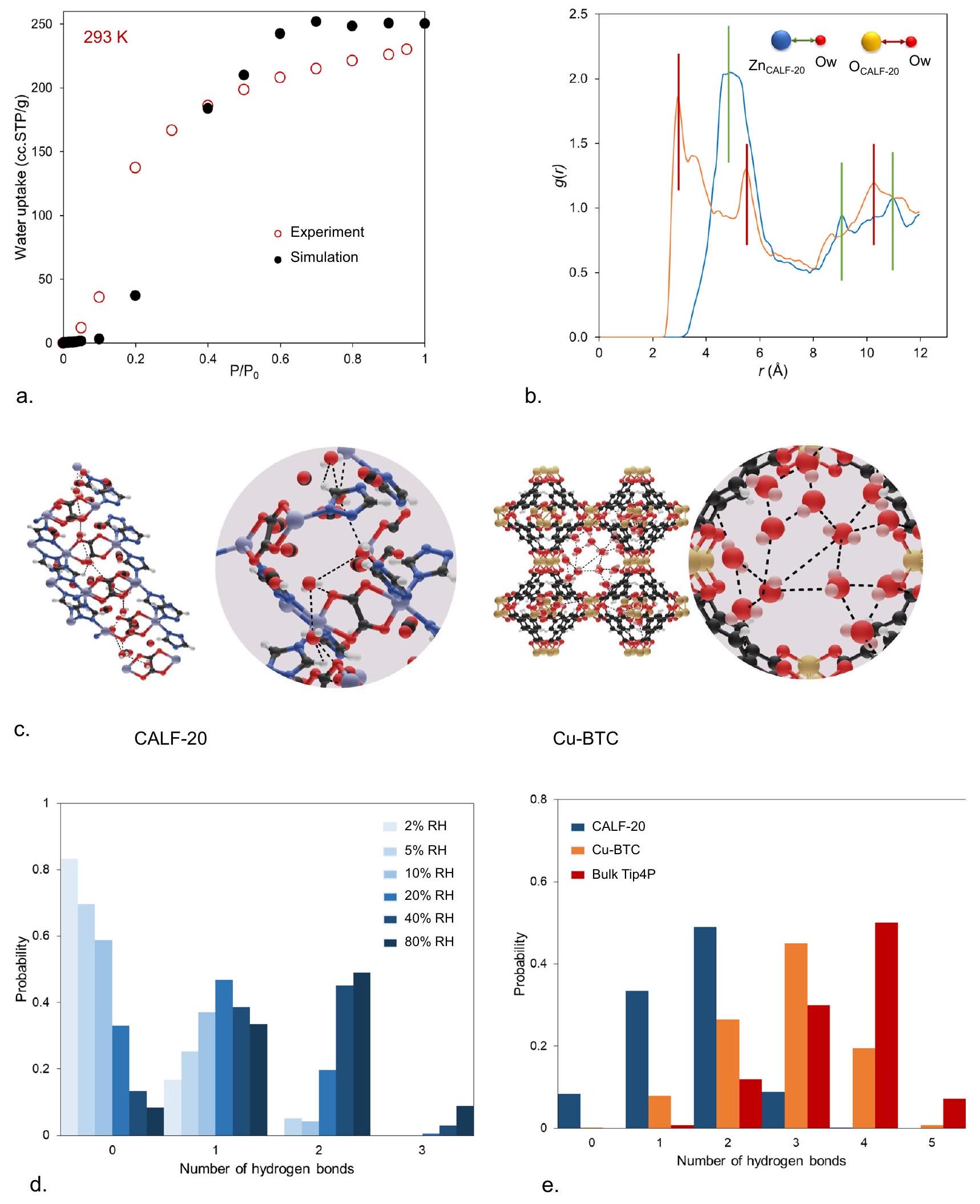

دوال التوزيع الشعاعي بين إطار الزنك وذرة الأكسجين وذرة الأكسجين في الماء لـ

ومقارنة تجمع جزيئات الماء بين CALF-20 و Cu-BTC. د توزيع عدد الروابط الهيدروجينية لمستويات مختلفة من الرطوبة النسبية (RH) في CALF-20. هـ توزيع عدد الروابط الهيدروجينية للماء في

تفاعلات فان دير فالس (vdW) والتفاعلات الكهروستاتيكية لامتصاص الماء في CALF-20 (الشكل التكميلي 3b، c). تمثل التفاعلات الكهروستاتيكية حوالي 73% من إجمالي الطاقة عند مقارنة تفاعلات الماء مع MOF (الشكل التكميلي 3c). كما أن التفاعلات الكهروستاتيكية بين جزيئات الماء هي السائدة وتزداد من

مساحة لمزيد من الممتزات، متوافقة مع الفرضية القائلة بأن الفرق بين الملاحظات التجريبية ومحاكاة مونت كارلو يعود إلى مرونة الإطار تحت امتصاص الضيف. علاوة على ذلك، تم حساب ملفات الطاقة الحرة الكاملة للإطارات الفارغة والمحمّلة بالضيف، باستخدام إمكانيات التعلم الآلي (MLPs) المدربة على بيانات DFT ذات العينة المعززة، مما يوضح المرونة المستحثة للإطار تحت امتصاص الضيف. نلاحظ أن نهجنا في توليد بيانات التدريب لـ MLP على مستوى DFT لتوصيف مرونة الإطار بالكامل كدالة لدرجة الحرارة وامتصاص الضيف لديه القدرة على التوسع بشكل واسع إلى مواد نانوية مسامية أخرى. لقد كانت دراسة مرونة الإطار المستحثة بالضيف على مستوى DFT محدودة في الغالب على تحسينات الطاقة.

طرق

محاكاة GCMC لامتصاص الغاز في CALF-20

(MLP) محاكاة الديناميكا الجزيئية لـ CALF-20 الفارغ والمحمل بالضيوف. لتقييم مرونة إطار CALF-20، تم إجراء محاكاة ديناميكا جزيئية في ظروف NPT مع خلية وحدة مرنة بالكامل لكل من الإطار الفارغ والإطار المحمل بالضيوف في

توفر البيانات

References

- Silva, P., Vilela, S. M. F., Tomé, J. P. C. & Almeida Paz, F. A. Multifunctional Metal-Organic Frameworks: From Academia to Industrial Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 6774-6803 (2015).

- Czaja, A. U., Trukhan, N. & Müller, U. Industrial Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1284 (2009).

- Chen, Z. et al. The State of the Field: From Inception to Commercialization of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Faraday Discuss 225, 9-69 (2021).

- Faust, T. MOFs Move to Market. Nat. Chem. 8, 990-991 (2016).

- Ryu, U. et al. Recent Advances in Process Engineering and Upcoming Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 426, 213544 (2021).

- Boyd, P. G. et al. Data-Driven Design of Metal-Organic Frameworks for Wet Flue Gas

Capture. Nature 576, 253-256 (2019). - Benoit, V. et al. A Promising Metal-Organic Framework (MOF), MIL96(Al), for

Separation under Humid Conditions. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 2081-2090 (2018). - Kolle, J. M., Fayaz, M. & Sayari, A. Understanding the Effect of Water on

Adsorption. Chem. Rev. 121, 7280-7345 (2021). - Mason, J. A. et al. Application of a High-Throughput Analyzer in Evaluating Solid Adsorbents for Post-Combustion Carbon Capture via Multicomponent Adsorption of

, and . J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 4787-4803 (2015). - Masala, A. et al.

Capture in Dry and Wet Conditions in UTSA-16 Metal-Organic Framework. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 455-463 (2017). - Kim, E. J. et al. Cooperative Carbon Capture and Steam Regeneration with Tetraamine-Appended Metal-Organic Frameworks. Science 369, 392-396 (2020).

- Shimizu, G. K. H. et al. Metal Organic Framework, Production and Use Thereof. WO2014138878A1, (2014).

- Lin, J.-B. et al. A Scalable Metal-Organic Framework as a Durable Physisorbent for Carbon Dioxide Capture. Science 374, 1464-1469 (2021).

- Shi, Z. et al. Robust Metal-Triazolate Frameworks for

Capture from Flue Gas. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 2750-2754 (2020). - Demessence, A., D’Alessandro, D. M., Foo, M. L. & Long, J. R. Strong

Binding in a Water-Stable, Triazolate-Bridged Metal-Organic Framework Functionalized with Ethylenediamine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 8784-8786 (2009). - Li, S. et al. Two Flexible Cationic Metal-Organic Frameworks with Remarkable Stability for

Separation. Nano Res. 14, 3288-3293 (2021). - Zhang, J.-P., Zhang, Y.-B., Lin, J.-B. & Chen, X.-M. Metal Azolate Frameworks: From Crystal Engineering to Functional Materials. Chem. Rev. 112, 1001-1033 (2012).

- Vaidhyanathan, R. et al. Direct Observation and Quantification of

Binding Within an Amine-Functionalized Nanoporous Solid. Science 330, 650-653 (2010). - Rosen, A. S. et al. Tuning the Redox Activity of Metal-Organic Frameworks for Enhanced, Selective

Binding: Design Rules and Ambient Temperature Chemisorption in a Cobalt-Triazolate Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 4317-4328 (2020). - Rosen, A. S., Notestein, J. M. & Snurr, R. Q. High-Valent Metal-Oxo Species at the Nodes of Metal-Triazolate Frameworks: The Effects of Ligand Exchange and Two-State Reactivity for C-H Bond Activation. Angew. Chem. 132, 19662-19670 (2020).

- Hovington, P. et al. Rapid Cycle Temperature Swing Adsorption Process Using Solid Structured Sorbent for

Capture from Cement Flue Gas. In Proceedings of the 15th Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies Conference 15-18 March 2021; 2021; pp 1-11. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn. 3814414. - Ho, C.-H. & Paesani, F. Elucidating the Competitive Adsorption of

and in CALF-20: New Insights for Enhanced Carbon Capture Metal-Organic Frameworks. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 48287-48295 (2023). - Magnin, Y., Dirand, E., Maurin, G. & Llewellyn, P. L. Abnormal CO2 and

Diffusion in CALF-2O(Zn) Metal-Organic Framework: Fundamental Understanding of CO2 Capture. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 6, 19963-19971 (2023). - Chen, Z. et al. Humidity-Responsive Polymorphism in CALF-20: A Resilient MOF Physisorbent for

Capture. ACS Mater. Lett. 5, 2942-2947 (2023). - Blatov, V. A., Shevchenko, A. P. & Proserpio, D. M. Applied Topological Analysis of Crystal Structures with the Program Package ToposPro. Cryst. Growth Des. 14, 3576-3586 (2014).

- Zoubritzky, L. & Coudert, F.-X. CrystalNets.Jl: Identification of Crystal Topologies. SciPost Chem. 1, 005 (2022).

- Rouquerol, J., Llewellyn, P., Rouquerol, F. Is the Bet Equation Applicable to Microporous Adsorbents? In Characterization of Porous Solids VII; (eds Llewellyn, P. L., Rodriquez-Reinoso, F., Rouqerol, J., Seaton, N.) vol. 160, 49-56 (Elsevier, 2007). https://doi.org/10. 1016/S0167-2991(07)80008-5.

- Gómez-Gualdrón, D. A., Moghadam, P. Z., Hupp, J. T., Farha, O. K. & Snurr, R. Q. Application of Consistency Criteria To Calculate BET Areas of Micro- And Mesoporous Metal-Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 215-224 (2016).

- Chung, Y. G. et al. In Silico Discovery of Metal-Organic Frameworks for Precombustion

Capture Using a Genetic Algorithm. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600909 (2024). - Sturluson, A. et al. The Role of Molecular Modelling and Simulation in the Discovery and Deployment of Metal-Organic Frameworks for Gas Storage and Separation*. Mol. Simul. 45, 1082-1121 (2019).

- Glasby, L. T. et al. Augmented Reality for Enhanced Visualization of MOF Adsorbents. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 63, 5950-5955 (2023).

- Schneemann, A. et al. Flexible Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 6062-6096 (2014).

- Kühne, T. D. et al. CP2K: An Electronic Structure and Molecular Dynamics Software Package – Quickstep: Efficient and Accurate Electronic Structure Calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 194103 (2020).

- Sarkisov, L., Bueno-Perez, R., Sutharson, M. & Fairen-Jimenez, D. Materials Informatics with PoreBlazer v4.0 and the CSD MOF Database. Chem. Mater. 32, 9849-9867 (2020).

- Vanduyfhuys, L. et al. Thermodynamic Insight into StimuliResponsive Behaviour of Soft Porous Crystals. Nat. Commun. 9, 204 (2018).

- Batzner, S. et al. E(3)-Equivariant Graph Neural Networks for DataEfficient and Accurate Interatomic Potentials. Nat. Commun. 13, 2453 (2022).

- Xu, H., Stern, H. A. & Berne, B. J. Can Water Polarizability Be Ignored in Hydrogen Bond Kinetics? J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 2054-2060 (2002).

- Nazarian, D., Camp, J. S., Chung, Y. G., Snurr, R. Q. & Sholl, D. S. Large-Scale Refinement of Metal-Organic Framework Structures Using Density Functional Theory. Chem. Mater. 29, 2521-2528 (2017).

- Vandenhaute, S., Cools-Ceuppens, M., DeKeyser, S., Verstraelen, T. & Van Speybroeck, V. Machine Learning Potentials for MetalOrganic Frameworks Using an Incremental Learning Approach. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 19 (2023).

- Dubbeldam, D., Calero, S., Ellis, D. E. & Snurr, R. Q. RASPA: Molecular Simulation Software for Adsorption and Diffusion in Flexible Nanoporous Materials. Mol. Simul. 42, 81-101 (2016).

- Mayo, S. L., Olafson, B. D. & Goddard, W. A. DREIDING: A Generic Force Field for Molecular Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. 94, 8897-8909 (1990).

- Campañá, C., Mussard, B. & Woo, T. K. Electrostatic Potential Derived Atomic Charges for Periodic Systems Using a Modified Error Functional. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 5, 2866-2878 (2009).

- Potoff, J. J. & Siepmann, J. I. Vapor-Liquid Equilibria of Mixtures Containing Alkanes, Carbon Dioxide, and Nitrogen. AIChE J. 47, 1676-1682 (2001).

- Vega, C., Abascal, J. L. F. & Nezbeda, I. Vapor-Liquid Equilibria from the Triple Point up to the Critical Point for the New Generation of TIP4P-like Models: TIP4P/Ew, TIP4P/2005, and TIP4P/Ice. J. Chem. Phys. 125, 34503 (2006).

- Tribello, G. A., Bonomi, M., Branduardi, D., Camilloni, C. & Bussi, G. PLUMED 2: New Feathers for an Old Bird. Comput. Phys. Commun. 185, 604-613 (2014).

- Bonomi, M. et al. Promoting Transparency and Reproducibility in Enhanced Molecular Simulations. Nat. Methods 16, 670-673 (2019).

- Grossfield, A. WHAM: the weighted histogram analysis method, version 2.0.10. http://membrane.urmc.rochester.edu/wordpress/? page_id=126 (2002).

شكر وتقدير

تحت برنامج الزمالات الصناعية (IF2223-110). كما يشكر الدعم من مجلس أبحاث الهندسة والعلوم الفيزيائية (EPSRC) ومركز بيانات البلورات في كامبريدج (CCDC) لتوفير تمويل منح الدكتوراه لـ L.T.G. كما يقر المؤلفون بالدعم المالي من مجلس أبحاث جامعة غنت (BOF). الموارد الحاسوبية (بنية تحتية للحواسيب الفائقة Stevin) والخدمات المقدمة من VSC (مركز الحواسيب الفائقة الفلمنكية)، الممولة من جامعة غنت، وFWO، والحكومة الفلمنكية، قسم EWI. R.O. يقر بالدعم المالي خلال دراسته للدكتوراه من صندوق المنح الدراسية الإندونيسي للتعليم (LPDP) برقم العقد 202002220216006.

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

قسم الهندسة الكيميائية والبيولوجية، جامعة شيفيلد، شيفيلد S1 3JD، المملكة المتحدة. مركز النمذجة الجزيئية (CMM)، جامعة غنت، تكنولوجيا بارك 46، 9052 زوينارد، بلجيكا. شركة سفانتي، 8800 طريق غلينليون، برنابي، كولومبيا البريطانية V5J 5K3، كندا. قسم الهندسة الكيميائية، كلية جامعة لندن، لندن WC1E 7JE، المملكة المتحدة. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: راما أوكتافيان، روبن غويمين.

البريد الإلكتروني: p.moghadam@ucl.ac.uk

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-48136-0

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38724490

Publication Date: 2024-05-09

Gas adsorption and framework flexibility of CALF-20 explored via experiments and simulations

Accepted: 18 April 2024

Published online: 09 May 2024

(A) Check for updates

Abstract

In 2021, Svante, in collaboration with BASF, reported successful scale up of CALF-20 production, a stable MOF with high capacity for post-combustion

humidity, as well as durability and stability towards steam, wet acid gases, and prolonged exposure to direct flue gas stream

straight-through branches, respectively. The red spheres represent metallic nodes and the green spheres represent organic nodes, connected via blue linker ‘branches’.

Results and discussion

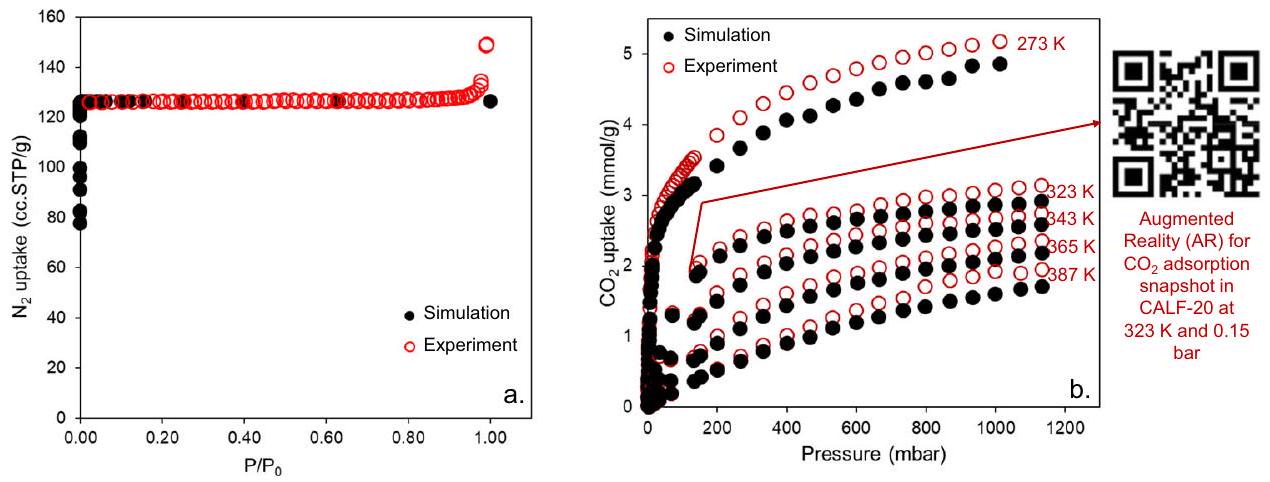

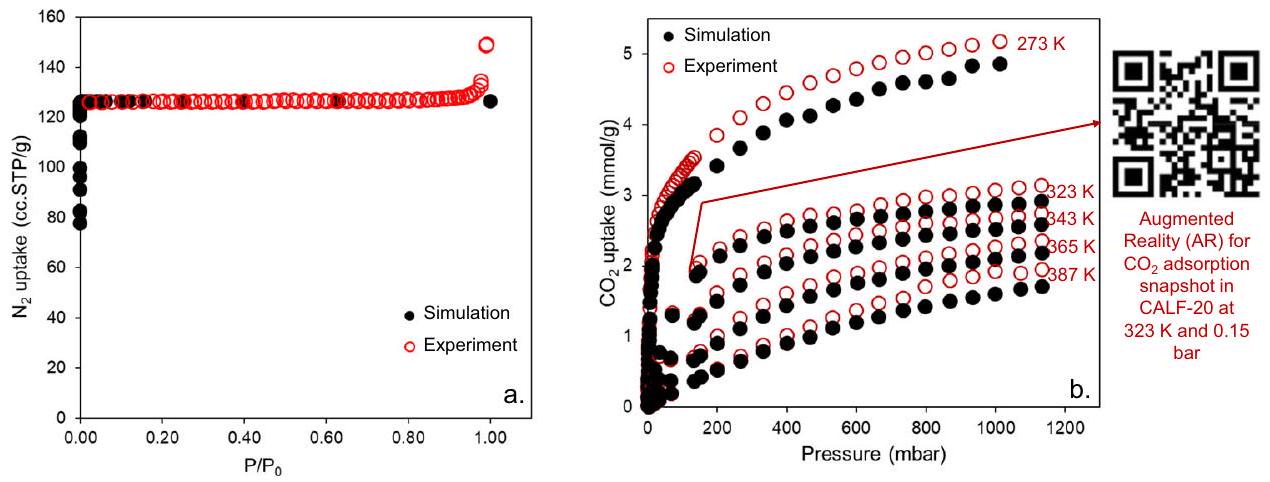

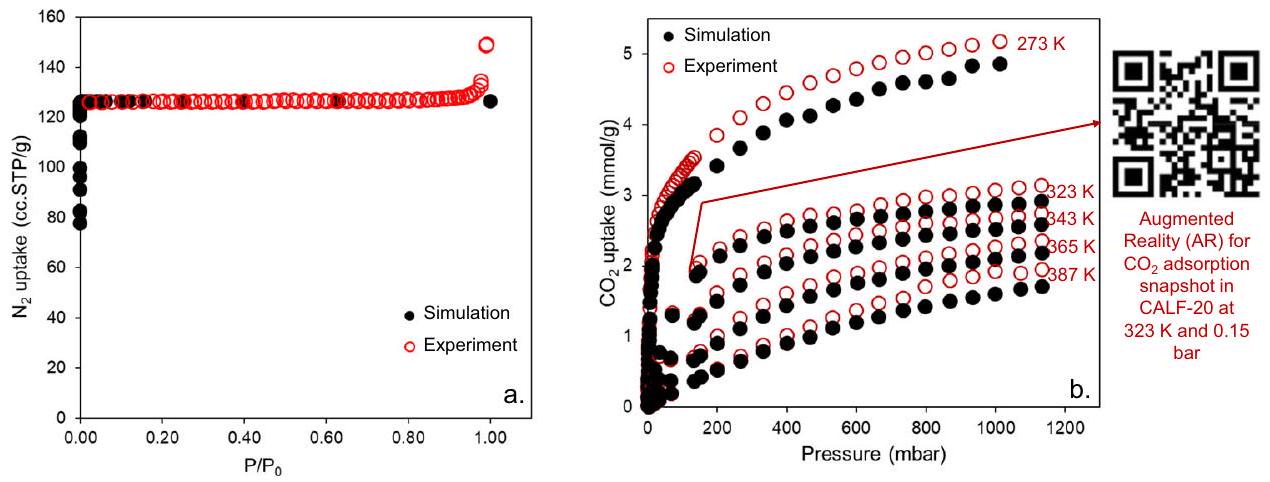

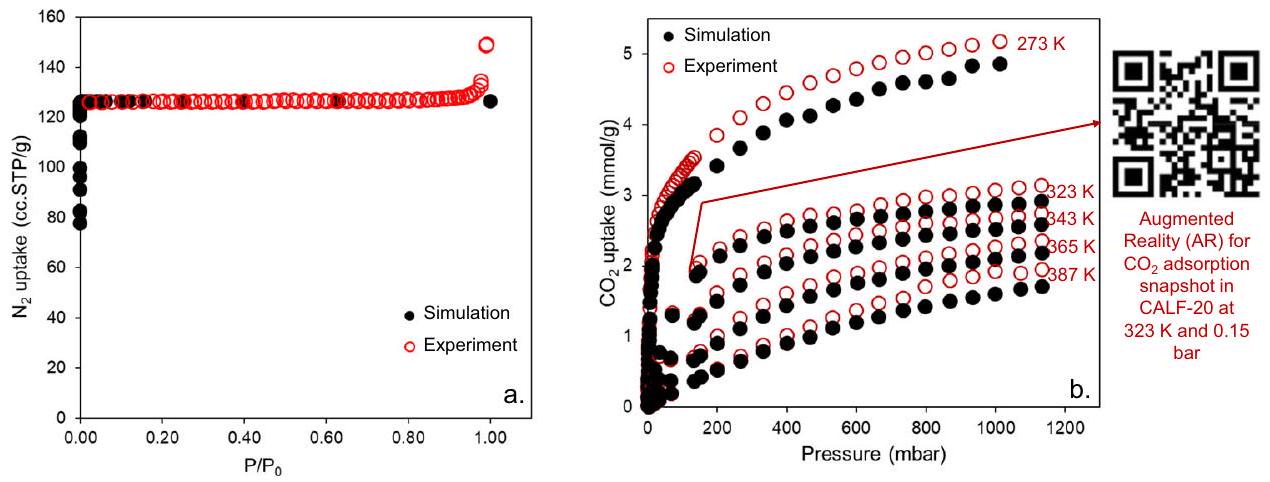

Geometric characterization and gas adsorption properties of CALF-20

ca.

along with QR code for augmented reality (AR) of

collected under

transformations via in-situ powder crystal X-ray diffraction (PXRD). We obtained PXRD data under different gas and liquid exposures (

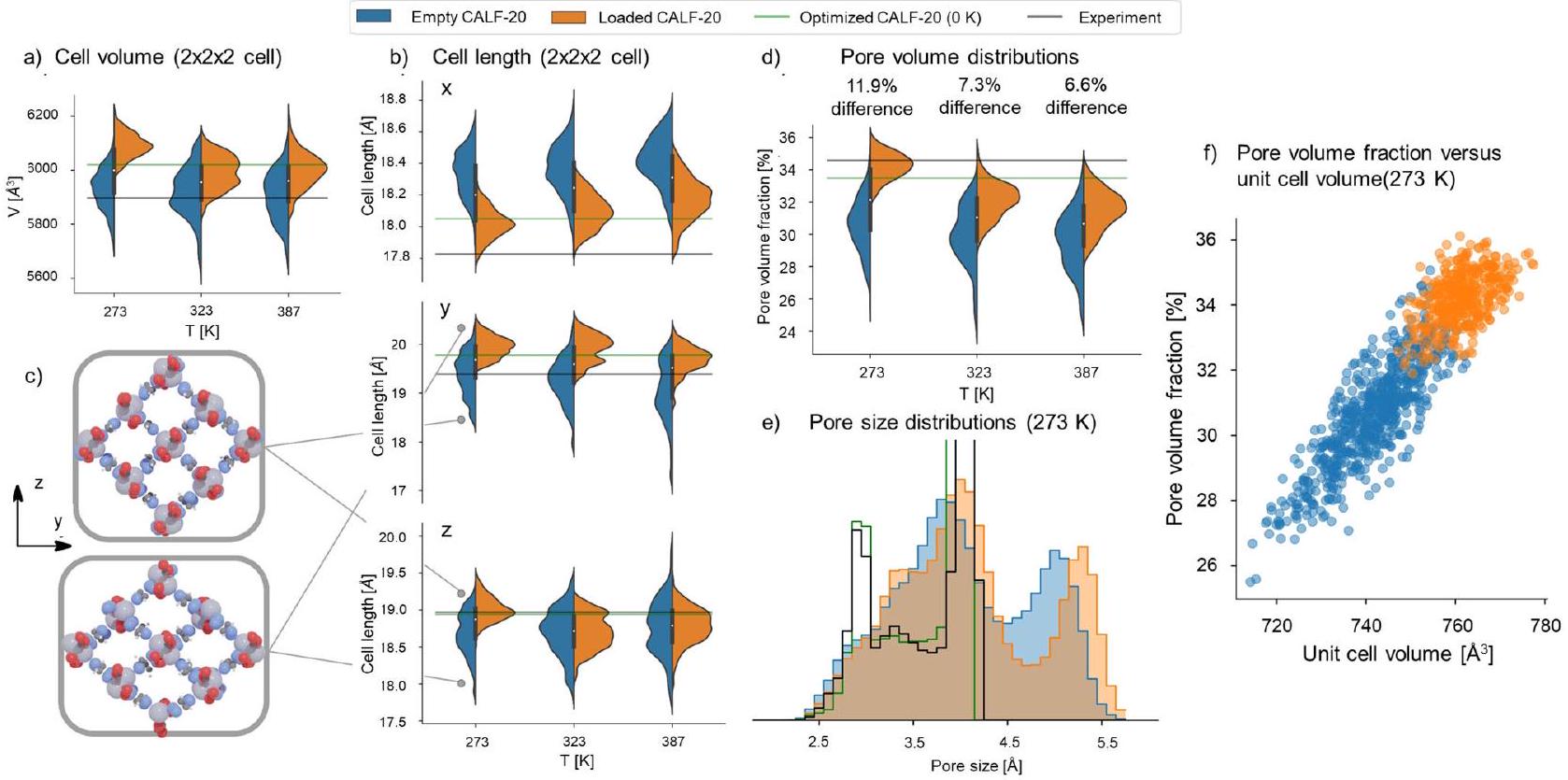

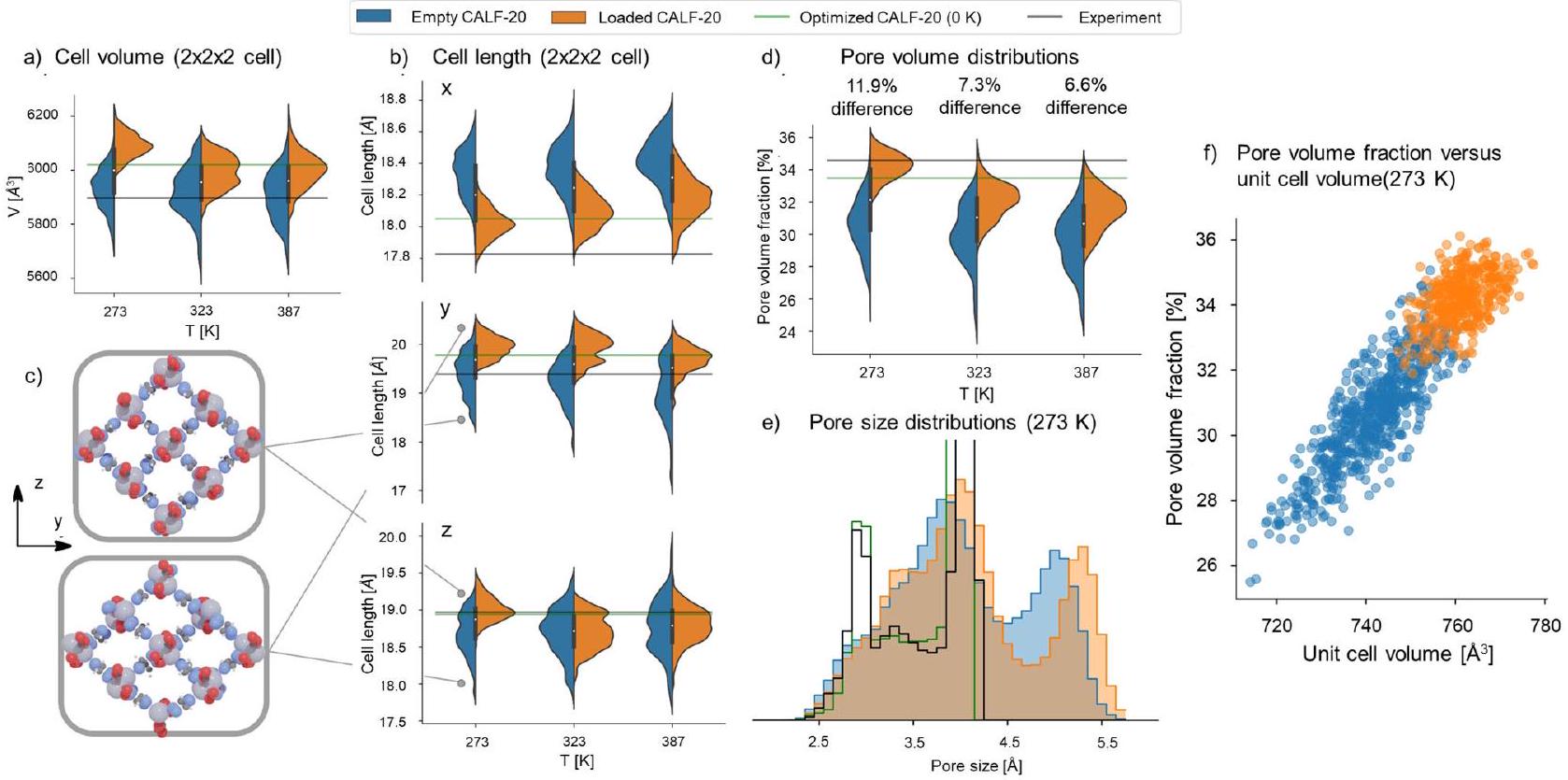

cell vectors perpendicular to the Zn-triazolate layers. Atom coloring scheme is: light gray, zinc; red, oxygen; white, hydrogen; blue: nitrogen; gray: carbon). e Pore size distributions of the experimental structure (black), the DFT optimized structure (green), and those averaged over MD trajectories of the empty and guest-loaded CALF-20 at

water is able to bring more changes to the framework compared to all other guests discussed here. In other words,

which is shown in Fig. 4c, with cell lengths annotated on Fig. 4b. We can see there is significant flexibility where one of the cell lengths varies inversely with the other: this corroborates with the differences observed in the PXRD patterns of CALF-20 upon exposure to guests (Fig. 3). This flexible mode is significantly inhibited when guests are present in the framework, as can be seen from the narrower orange distributions in Fig. 4b.

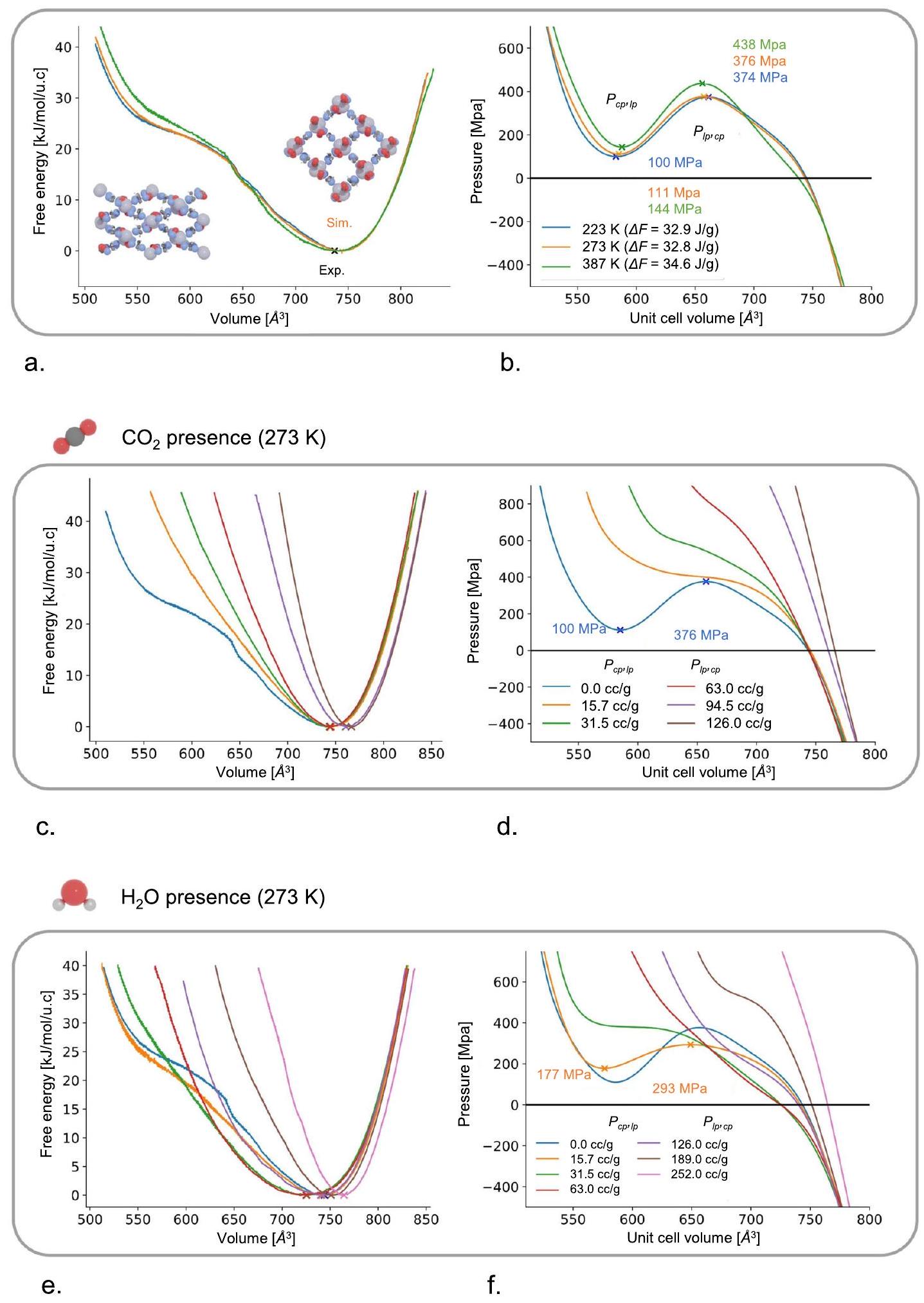

Empty and guest-loaded DFT free energy profiles

where this is not seen for

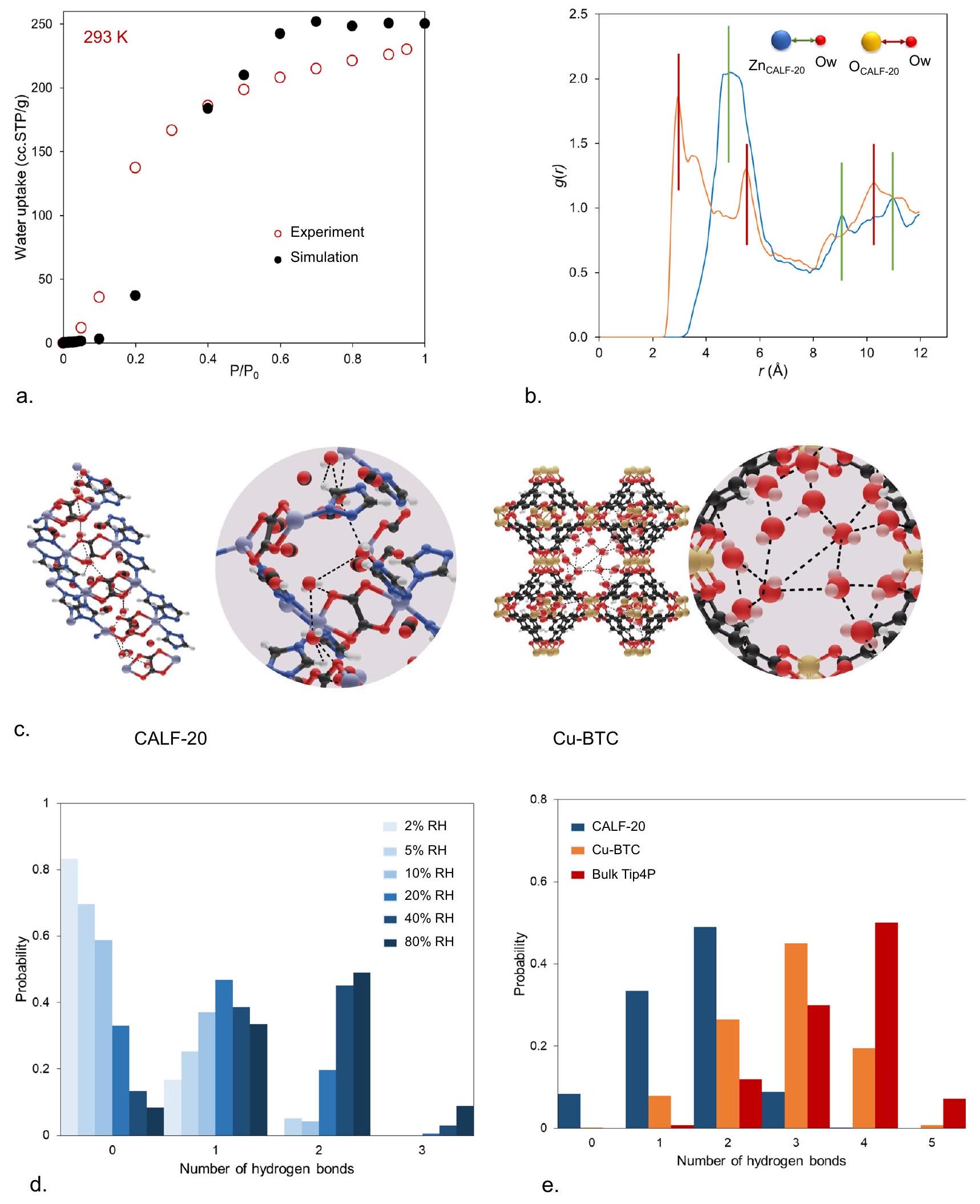

Water adsorption in CALF-20

the negative derivative of the free energy, revealing the possibility of a metastable cp phase at a volume of

b Radial distribution functions between framework Zn and O atom and O atom in water for

and water molecule clustering comparison between CALF-20 and Cu-BTC. d Distribution of the number of hydrogen bonds for different levels of relative humidity (RH) in CALF-20. e Distribution of the number of hydrogen bonds for water at

van der Waals (vdW) and electrostatic interactions for water adsorption in CALF-20 (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c). Electrostatic interactions account for ca. 73% of the total energy when water-MOF interactions are compared (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Electrostatic interactions between water molecules are also dominant and increase from

space for more adsorbates, consistent with the hypothesis that the difference between the experimental observations and the Monte Carlo simulations is due to the flexibility of the framework under guestadsorption. Furthermore, the complete free energy profiles of the empty and guest-loaded frameworks were computed, making use of machine learning potential (MLPs) trained to enhanced sampling DFT data, demonstrating the induced flexibility of the framework under guest adsorption. We note that, our approach of generating training data for an MLP at the DFT level to fully characterize the framework flexibility as a function of temperature and guest adsorption has the promise to be extended widely to other nanoporous materials. The investigation of guest-induced framework flexibility at the DFT level has mostly been limited to energy optimizations

Methods

GCMC simulations of gas adsorption in CALF-20

(MLP) MD simulations of the empty and guest-loaded CALF-20 To assess the flexibility of the CALF-20 framework, NPT MD simulations with a fully flexible unit cell were performed for both the empty and guest-loaded frameworks at

Data availability

References

- Silva, P., Vilela, S. M. F., Tomé, J. P. C. & Almeida Paz, F. A. Multifunctional Metal-Organic Frameworks: From Academia to Industrial Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 6774-6803 (2015).

- Czaja, A. U., Trukhan, N. & Müller, U. Industrial Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1284 (2009).

- Chen, Z. et al. The State of the Field: From Inception to Commercialization of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Faraday Discuss 225, 9-69 (2021).

- Faust, T. MOFs Move to Market. Nat. Chem. 8, 990-991 (2016).

- Ryu, U. et al. Recent Advances in Process Engineering and Upcoming Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 426, 213544 (2021).

- Boyd, P. G. et al. Data-Driven Design of Metal-Organic Frameworks for Wet Flue Gas

Capture. Nature 576, 253-256 (2019). - Benoit, V. et al. A Promising Metal-Organic Framework (MOF), MIL96(Al), for

Separation under Humid Conditions. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 2081-2090 (2018). - Kolle, J. M., Fayaz, M. & Sayari, A. Understanding the Effect of Water on

Adsorption. Chem. Rev. 121, 7280-7345 (2021). - Mason, J. A. et al. Application of a High-Throughput Analyzer in Evaluating Solid Adsorbents for Post-Combustion Carbon Capture via Multicomponent Adsorption of

, and . J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 4787-4803 (2015). - Masala, A. et al.

Capture in Dry and Wet Conditions in UTSA-16 Metal-Organic Framework. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 455-463 (2017). - Kim, E. J. et al. Cooperative Carbon Capture and Steam Regeneration with Tetraamine-Appended Metal-Organic Frameworks. Science 369, 392-396 (2020).

- Shimizu, G. K. H. et al. Metal Organic Framework, Production and Use Thereof. WO2014138878A1, (2014).

- Lin, J.-B. et al. A Scalable Metal-Organic Framework as a Durable Physisorbent for Carbon Dioxide Capture. Science 374, 1464-1469 (2021).

- Shi, Z. et al. Robust Metal-Triazolate Frameworks for

Capture from Flue Gas. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 2750-2754 (2020). - Demessence, A., D’Alessandro, D. M., Foo, M. L. & Long, J. R. Strong

Binding in a Water-Stable, Triazolate-Bridged Metal-Organic Framework Functionalized with Ethylenediamine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 8784-8786 (2009). - Li, S. et al. Two Flexible Cationic Metal-Organic Frameworks with Remarkable Stability for

Separation. Nano Res. 14, 3288-3293 (2021). - Zhang, J.-P., Zhang, Y.-B., Lin, J.-B. & Chen, X.-M. Metal Azolate Frameworks: From Crystal Engineering to Functional Materials. Chem. Rev. 112, 1001-1033 (2012).

- Vaidhyanathan, R. et al. Direct Observation and Quantification of

Binding Within an Amine-Functionalized Nanoporous Solid. Science 330, 650-653 (2010). - Rosen, A. S. et al. Tuning the Redox Activity of Metal-Organic Frameworks for Enhanced, Selective

Binding: Design Rules and Ambient Temperature Chemisorption in a Cobalt-Triazolate Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 4317-4328 (2020). - Rosen, A. S., Notestein, J. M. & Snurr, R. Q. High-Valent Metal-Oxo Species at the Nodes of Metal-Triazolate Frameworks: The Effects of Ligand Exchange and Two-State Reactivity for C-H Bond Activation. Angew. Chem. 132, 19662-19670 (2020).

- Hovington, P. et al. Rapid Cycle Temperature Swing Adsorption Process Using Solid Structured Sorbent for

Capture from Cement Flue Gas. In Proceedings of the 15th Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies Conference 15-18 March 2021; 2021; pp 1-11. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn. 3814414. - Ho, C.-H. & Paesani, F. Elucidating the Competitive Adsorption of

and in CALF-20: New Insights for Enhanced Carbon Capture Metal-Organic Frameworks. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 48287-48295 (2023). - Magnin, Y., Dirand, E., Maurin, G. & Llewellyn, P. L. Abnormal CO2 and

Diffusion in CALF-2O(Zn) Metal-Organic Framework: Fundamental Understanding of CO2 Capture. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 6, 19963-19971 (2023). - Chen, Z. et al. Humidity-Responsive Polymorphism in CALF-20: A Resilient MOF Physisorbent for

Capture. ACS Mater. Lett. 5, 2942-2947 (2023). - Blatov, V. A., Shevchenko, A. P. & Proserpio, D. M. Applied Topological Analysis of Crystal Structures with the Program Package ToposPro. Cryst. Growth Des. 14, 3576-3586 (2014).

- Zoubritzky, L. & Coudert, F.-X. CrystalNets.Jl: Identification of Crystal Topologies. SciPost Chem. 1, 005 (2022).

- Rouquerol, J., Llewellyn, P., Rouquerol, F. Is the Bet Equation Applicable to Microporous Adsorbents? In Characterization of Porous Solids VII; (eds Llewellyn, P. L., Rodriquez-Reinoso, F., Rouqerol, J., Seaton, N.) vol. 160, 49-56 (Elsevier, 2007). https://doi.org/10. 1016/S0167-2991(07)80008-5.

- Gómez-Gualdrón, D. A., Moghadam, P. Z., Hupp, J. T., Farha, O. K. & Snurr, R. Q. Application of Consistency Criteria To Calculate BET Areas of Micro- And Mesoporous Metal-Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 215-224 (2016).

- Chung, Y. G. et al. In Silico Discovery of Metal-Organic Frameworks for Precombustion

Capture Using a Genetic Algorithm. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600909 (2024). - Sturluson, A. et al. The Role of Molecular Modelling and Simulation in the Discovery and Deployment of Metal-Organic Frameworks for Gas Storage and Separation*. Mol. Simul. 45, 1082-1121 (2019).

- Glasby, L. T. et al. Augmented Reality for Enhanced Visualization of MOF Adsorbents. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 63, 5950-5955 (2023).

- Schneemann, A. et al. Flexible Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 6062-6096 (2014).

- Kühne, T. D. et al. CP2K: An Electronic Structure and Molecular Dynamics Software Package – Quickstep: Efficient and Accurate Electronic Structure Calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 194103 (2020).

- Sarkisov, L., Bueno-Perez, R., Sutharson, M. & Fairen-Jimenez, D. Materials Informatics with PoreBlazer v4.0 and the CSD MOF Database. Chem. Mater. 32, 9849-9867 (2020).

- Vanduyfhuys, L. et al. Thermodynamic Insight into StimuliResponsive Behaviour of Soft Porous Crystals. Nat. Commun. 9, 204 (2018).

- Batzner, S. et al. E(3)-Equivariant Graph Neural Networks for DataEfficient and Accurate Interatomic Potentials. Nat. Commun. 13, 2453 (2022).

- Xu, H., Stern, H. A. & Berne, B. J. Can Water Polarizability Be Ignored in Hydrogen Bond Kinetics? J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 2054-2060 (2002).

- Nazarian, D., Camp, J. S., Chung, Y. G., Snurr, R. Q. & Sholl, D. S. Large-Scale Refinement of Metal-Organic Framework Structures Using Density Functional Theory. Chem. Mater. 29, 2521-2528 (2017).

- Vandenhaute, S., Cools-Ceuppens, M., DeKeyser, S., Verstraelen, T. & Van Speybroeck, V. Machine Learning Potentials for MetalOrganic Frameworks Using an Incremental Learning Approach. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 19 (2023).

- Dubbeldam, D., Calero, S., Ellis, D. E. & Snurr, R. Q. RASPA: Molecular Simulation Software for Adsorption and Diffusion in Flexible Nanoporous Materials. Mol. Simul. 42, 81-101 (2016).

- Mayo, S. L., Olafson, B. D. & Goddard, W. A. DREIDING: A Generic Force Field for Molecular Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. 94, 8897-8909 (1990).

- Campañá, C., Mussard, B. & Woo, T. K. Electrostatic Potential Derived Atomic Charges for Periodic Systems Using a Modified Error Functional. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 5, 2866-2878 (2009).

- Potoff, J. J. & Siepmann, J. I. Vapor-Liquid Equilibria of Mixtures Containing Alkanes, Carbon Dioxide, and Nitrogen. AIChE J. 47, 1676-1682 (2001).

- Vega, C., Abascal, J. L. F. & Nezbeda, I. Vapor-Liquid Equilibria from the Triple Point up to the Critical Point for the New Generation of TIP4P-like Models: TIP4P/Ew, TIP4P/2005, and TIP4P/Ice. J. Chem. Phys. 125, 34503 (2006).

- Tribello, G. A., Bonomi, M., Branduardi, D., Camilloni, C. & Bussi, G. PLUMED 2: New Feathers for an Old Bird. Comput. Phys. Commun. 185, 604-613 (2014).

- Bonomi, M. et al. Promoting Transparency and Reproducibility in Enhanced Molecular Simulations. Nat. Methods 16, 670-673 (2019).

- Grossfield, A. WHAM: the weighted histogram analysis method, version 2.0.10. http://membrane.urmc.rochester.edu/wordpress/? page_id=126 (2002).

Acknowledgements

under the Industrial Fellowships programme (IF2223-110). He also acknowledges support from the Engineering and Physical Science Research Council (EPSRC) and the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC) for the provision of Ph.D studentship funding to L.T.G. The authors also acknowledge financial support from the Research Board of Ghent University (BOF). The computational resources (Stevin Supercomputer Infrastructure) and services provided by the VSC (Flemish Supercomputer Center), funded by Ghent University, FWO, and the Flemish Government, department EWI. R.O. acknowledges funding support during his Ph.D. study from the Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP) with contract no. 202002220216006.

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

© The Author(s) 2024

Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, The University of Sheffield, Sheffield S1 3JD, UK. Center for Molecular Modeling (CMM), Ghent University, Technologiepark 46, 9052 Zwijnaarde, Belgium. Svante Inc., 8800 Glenlyon Pkwy, Burnaby, BC V5J 5K3, Canada. Department of Chemical Engineering, University College London, London WC1E 7JE, UK. These authors contributed equally: Rama Oktavian, Ruben Goeminne.

e-mail: p.moghadam@ucl.ac.uk