DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-024-12916-1

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-01

الآثار المترتبة على شرط تلاشي التعقيد في نظرية f(R)

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

الملخص

تقدم هذه الورقة مفهوم التعقيد لزمكان كروي ثابت وتقوم بتمديده إلى

1 المقدمة

تحديًا، بشكل أساسي بسبب التعقيد المتضمن في المشتقات من الدرجة الأعلى للكميات الهندسية. يمكن تحديد مثل هذه الحلول إما تحليليًا أو عدديًا، حيث يعتمد الأخير على توفير شروط أولية أو حدود متوافقة مع السيناريو المحدد قيد النظر. ومع ذلك، للوصول إلى حل، فإن المعلومات الإضافية المتعلقة بالفيزياء المحلية ضرورية. على سبيل المثال، تكشف التحقيقات الأخيرة في الأجسام المدمجة عن وجود عوامل متعددة قد تؤثر على الطبيعة المتجانسة/غير المتجانسة لهذه الهياكل [20-22]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تلعب مكونات فيزيائية أخرى، مثل الكثافة غير المتجانسة، والقص، وتدفق التبدد، أدوارًا محورية في زعزعة استقرار حالة تجانس الضغط [23].

والإنتروبيا ضمن النظام قيد النظر [43-45]. ومع ذلك، واجه هذا التعريف تحديات عند تطبيقه على هيكلين فيزيائيين متميزين، وهما الغاز المثالي والبلورة المثالية، حيث أن خصائصهما متعارضة بطبيعتها، ومع ذلك، لا يظهر كلا النظامين أي تعقيد.

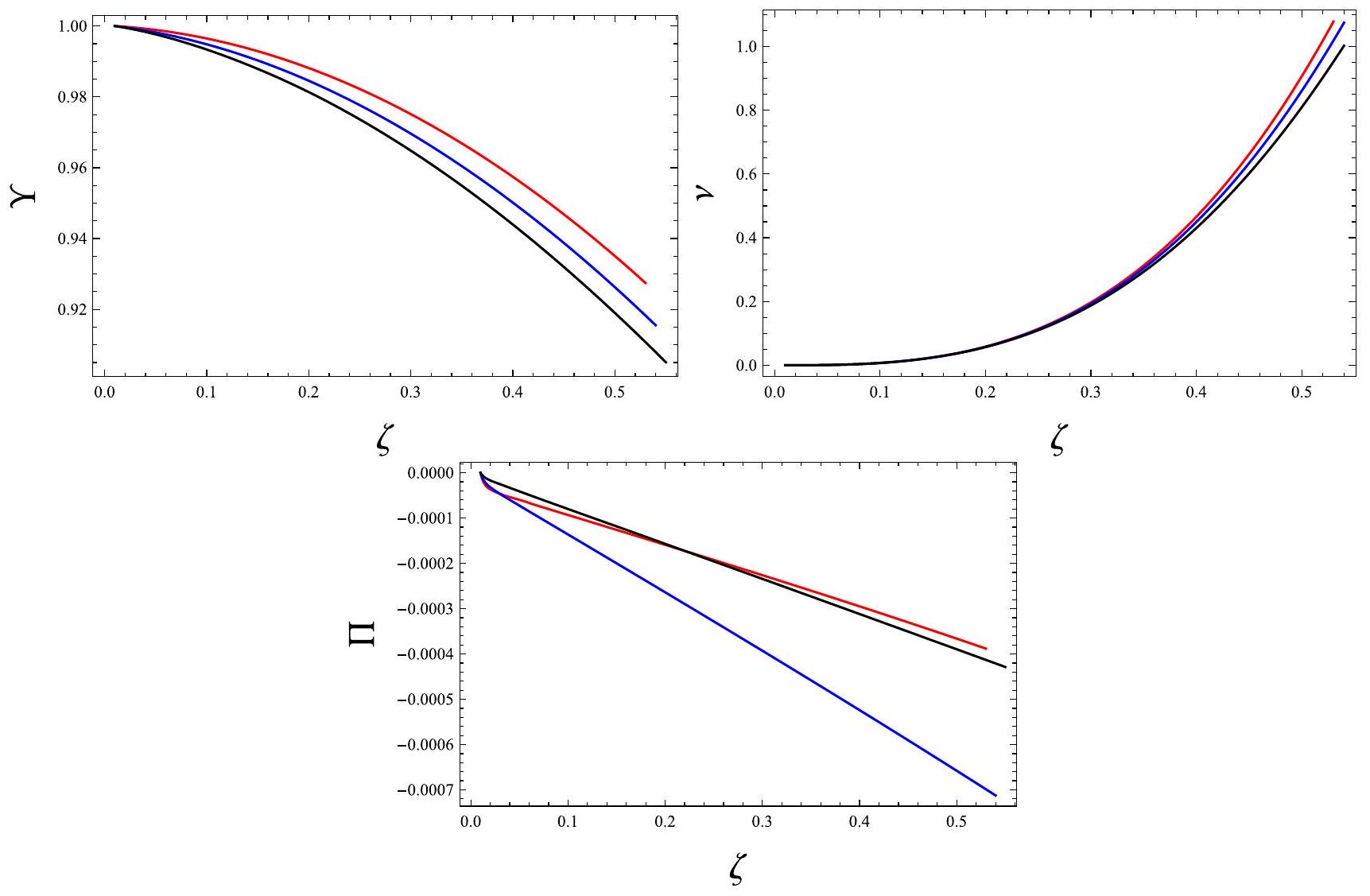

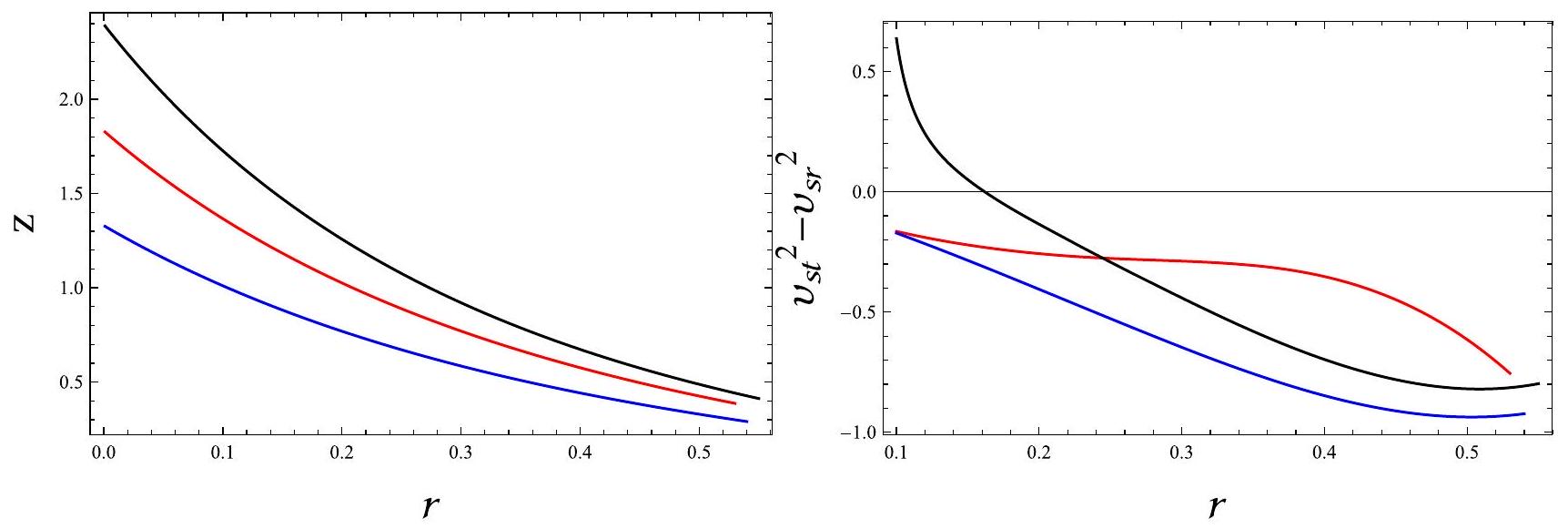

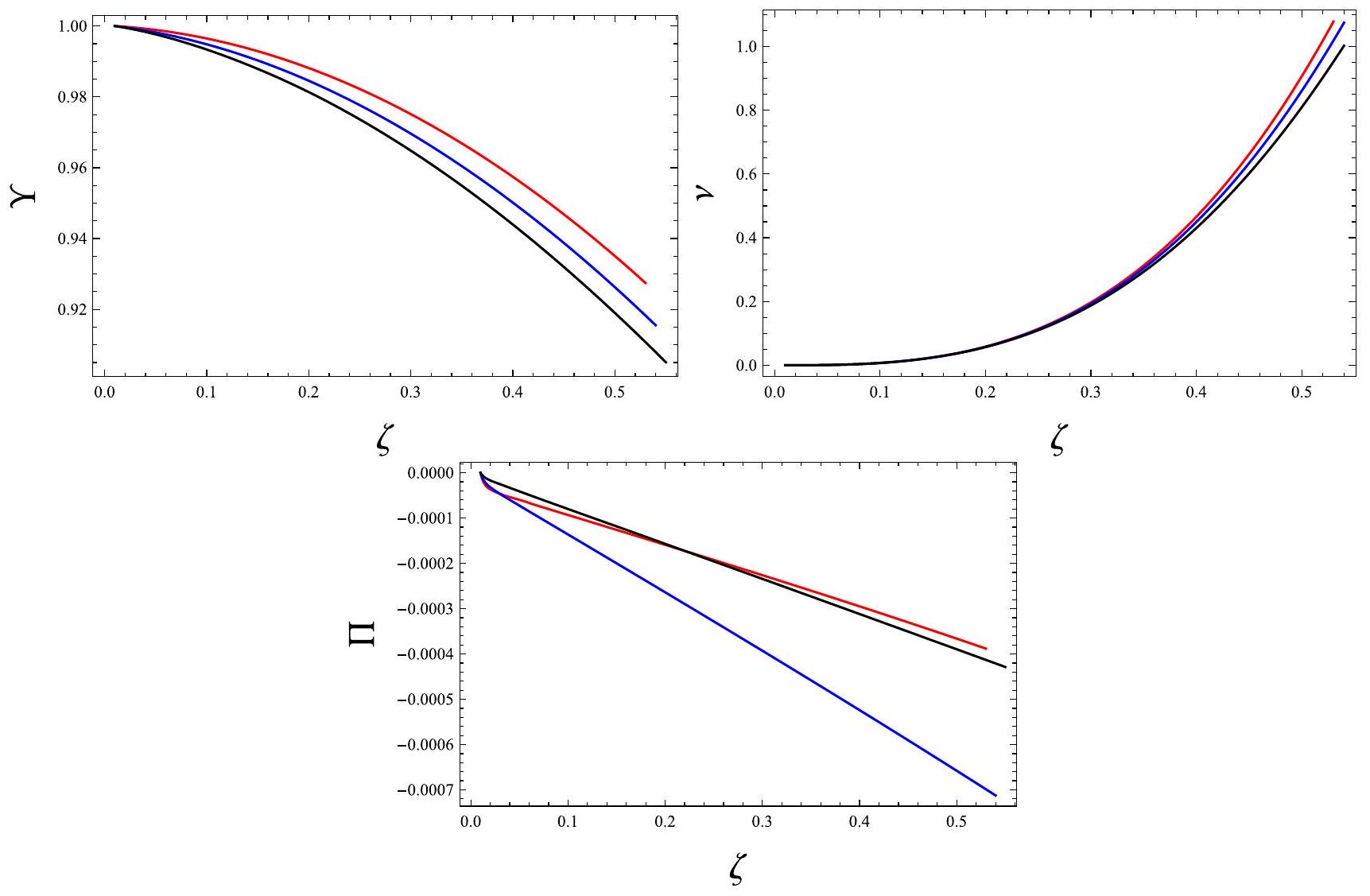

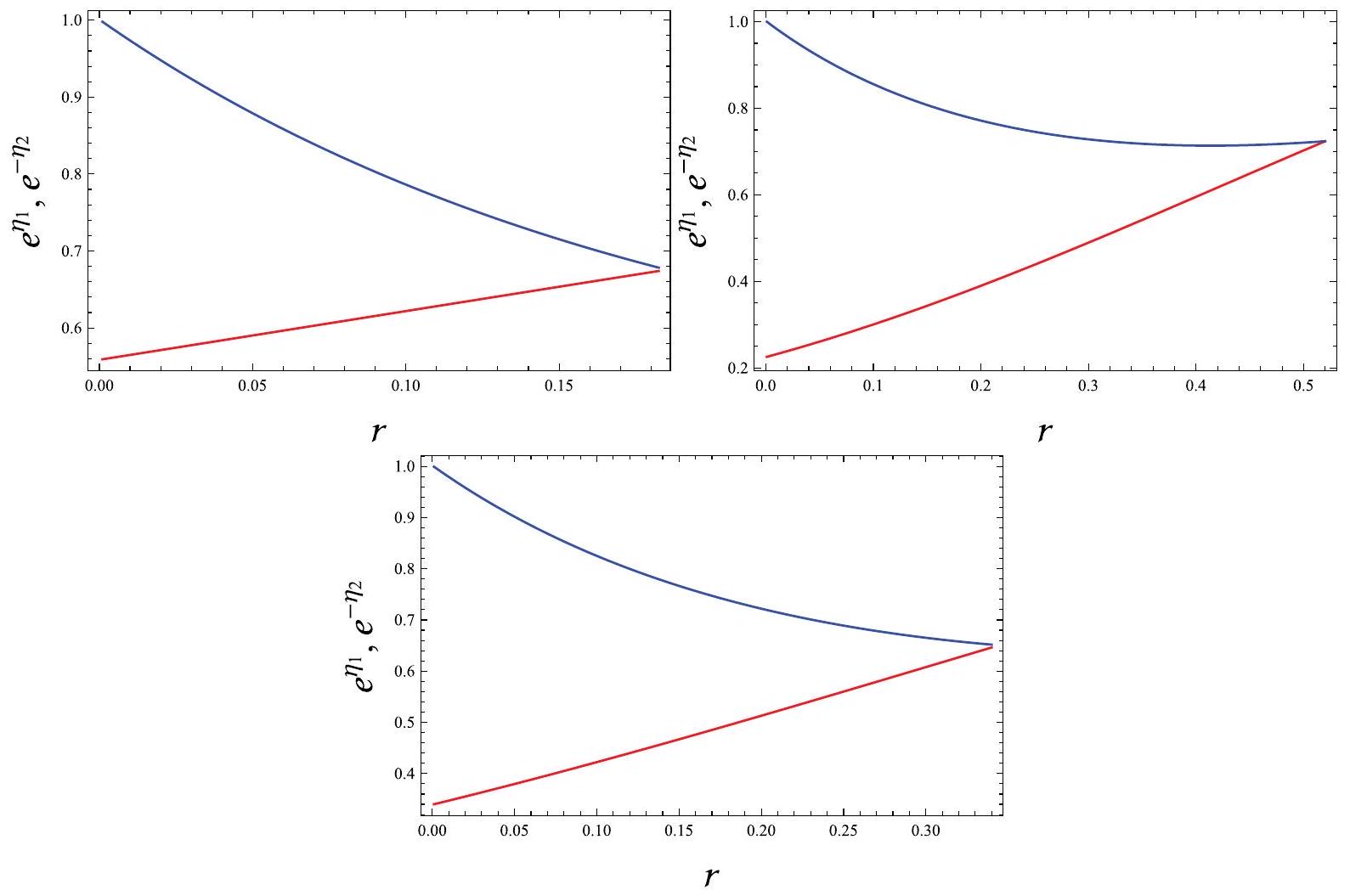

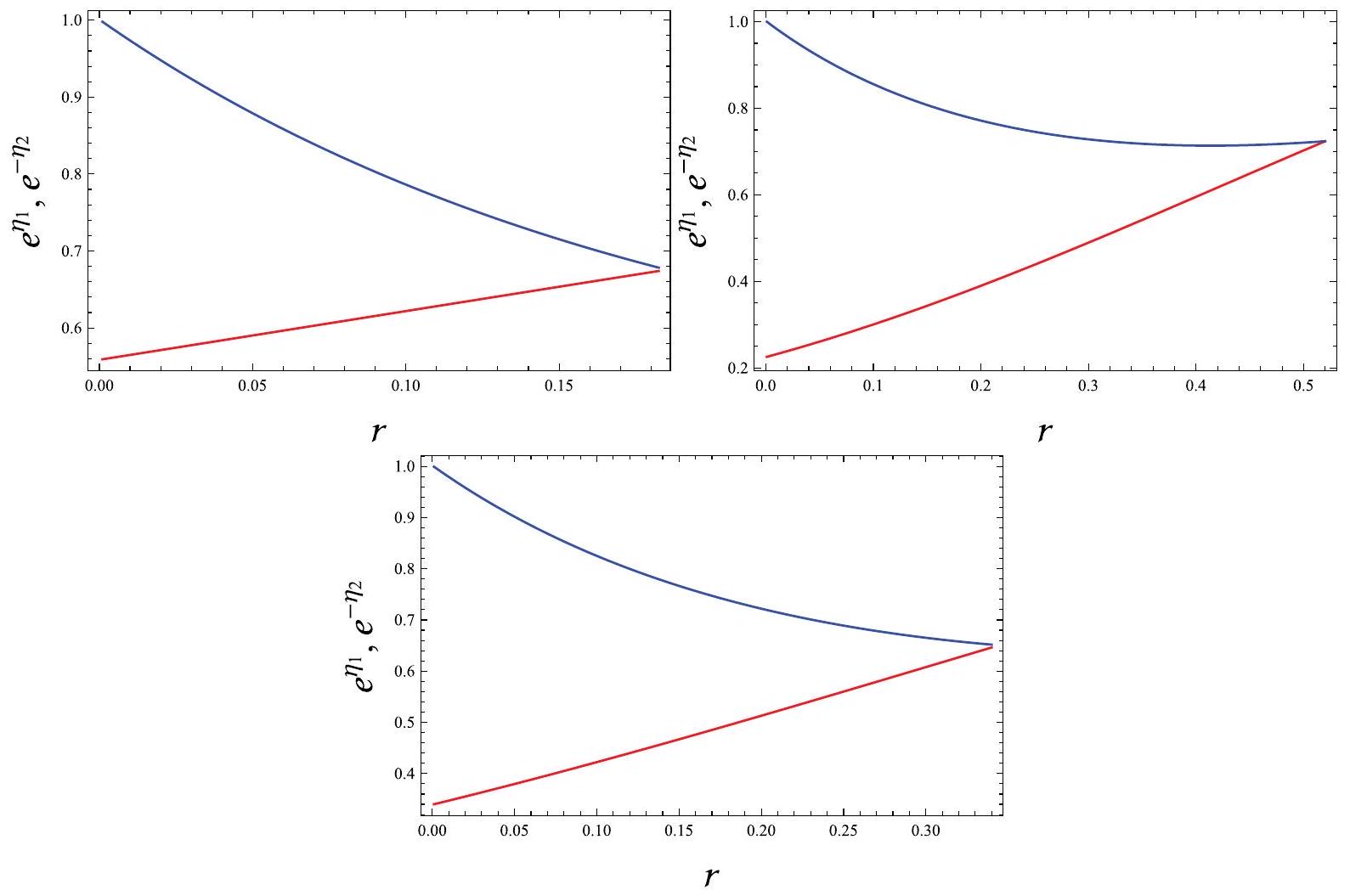

التفسير الرسومي. أخيرًا، يتم تلخيص نتائجنا في القسم الأخير.

أين

أين

-

تشير إلى المشتق التغايري، -

يرمز إلى مشغل دالامبير.

أين

أين

اتباع بعض العلاقات المحددة مثل

أين

أين

الذي تعبيره البديل في شكل كثافة الطاقة المعدلة (9) هو

3 هيكل المتجهات

أين

أين

-

توضح كيف تؤثر كثافة الطاقة المتجانسة على توزيع السائل. -

تحدد عدم التجانس في الكثافة. - يتم التحكم في اللاتناظر المحلي بواسطة العامل

. -

يلعب دور كل من و .

التي تصبح بعد بعض الحسابات الضرورية كـ

من الضروري التأكيد على أن النظام الذي له تعقيد صفري لا يتميز فقط بتكوين متجانس ومتجانس. في الواقع، تشرح المعادلة (30) أيضًا مثل هذا الهيكل (

4 الشروط الفيزيائية للنماذج المدمجة

هذا السياق وتم الالتزام بها من قبل باحثين مختلفين [79،80]. تم توضيح بعض هذه الشروط أدناه.

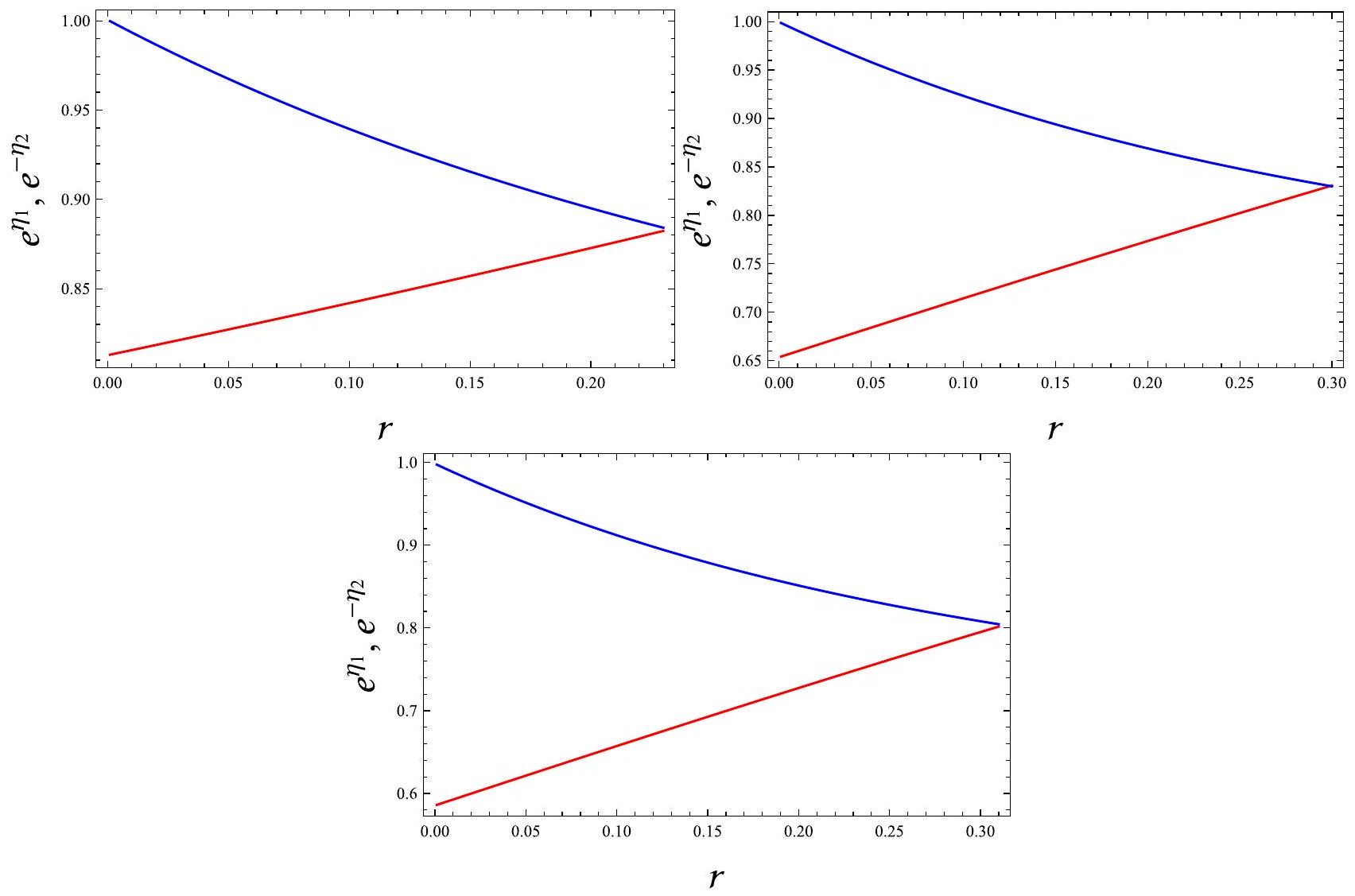

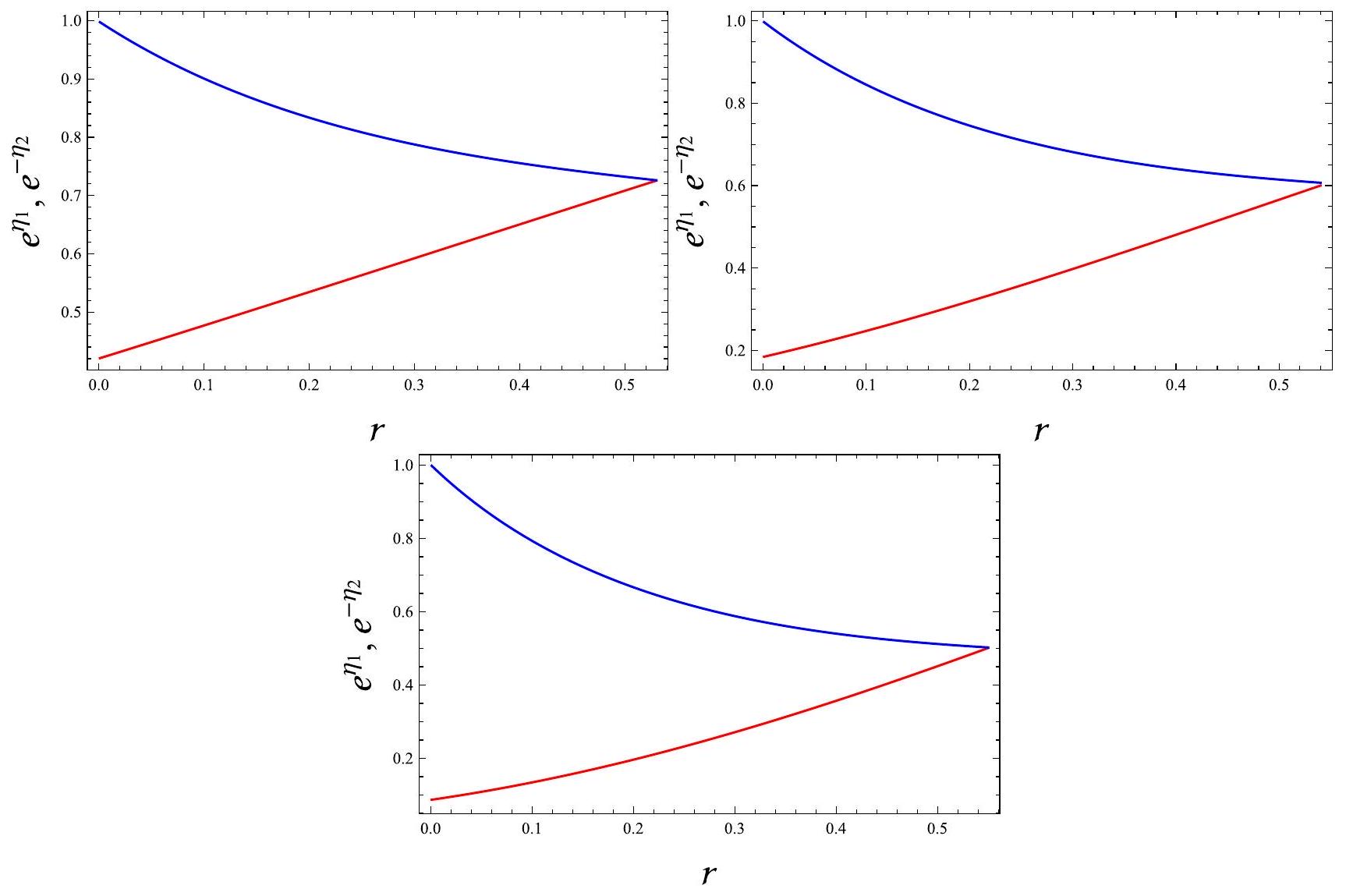

- يجب أن تظهر دوال المقياس الشعاعي/الزماني محدودية، خالية من التفردات وتبقى إيجابية في كل مكان في داخل سائل ذاتي الجاذبية.

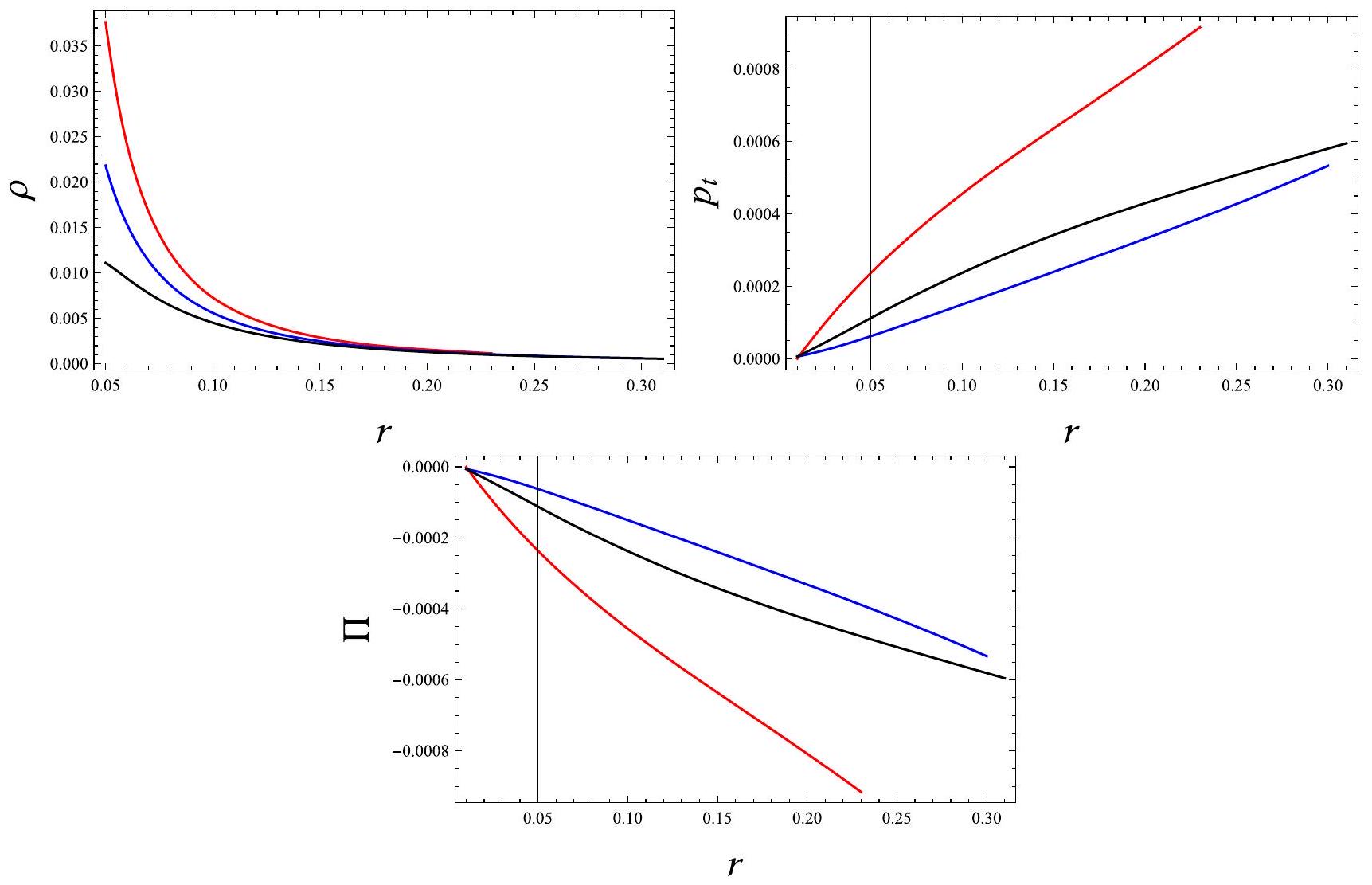

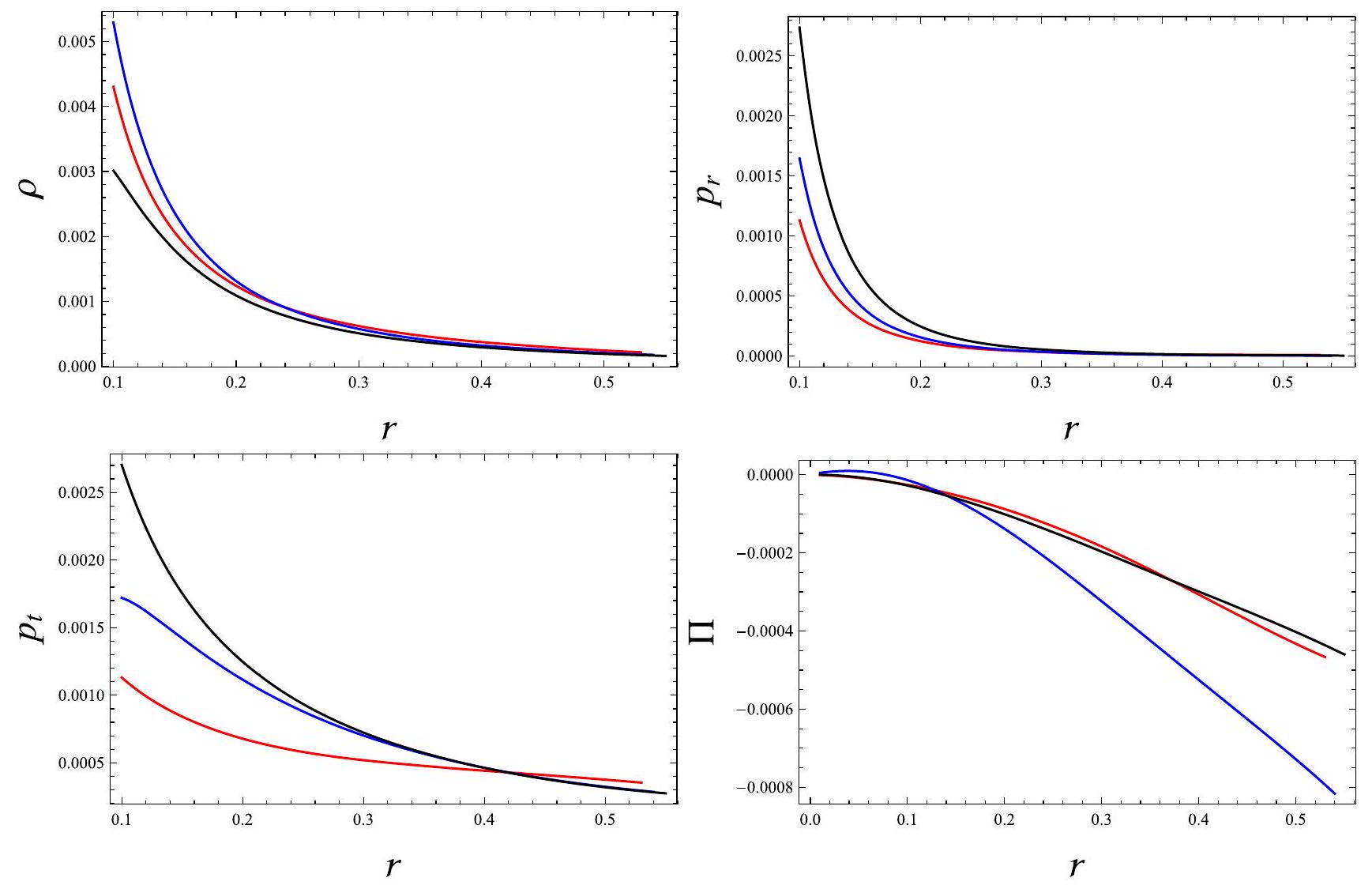

- يجب أن تصل متغيرات المادة، بما في ذلك كثافة الطاقة والضغط، إلى أقصى حد لها في المركز (

)، معبرة عن اتجاه إيجابي محدود عبر النطاق بأكمله. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يجب أن تكون مشتقاتها من الدرجة الأولى صفرًا عند وتتبع اتجاهًا سالبًا نحو الحدود. - في جسم مدمج، يتم ترتيب الجسيمات بطريقة معينة. تخبرنا هذه الترتيبات بمدى قرب هذه الجسيمات من بعضها البعض، مما يحدد في النهاية كثافة ذلك النظام. يمكن أيضًا تعريفها كنسبة الكتلة إلى نصف القطر التي يجب أن تكون بالضرورة أقل من الحد المقترح لتوزيع السائل الكروي المعطى بواسطة [81،82]

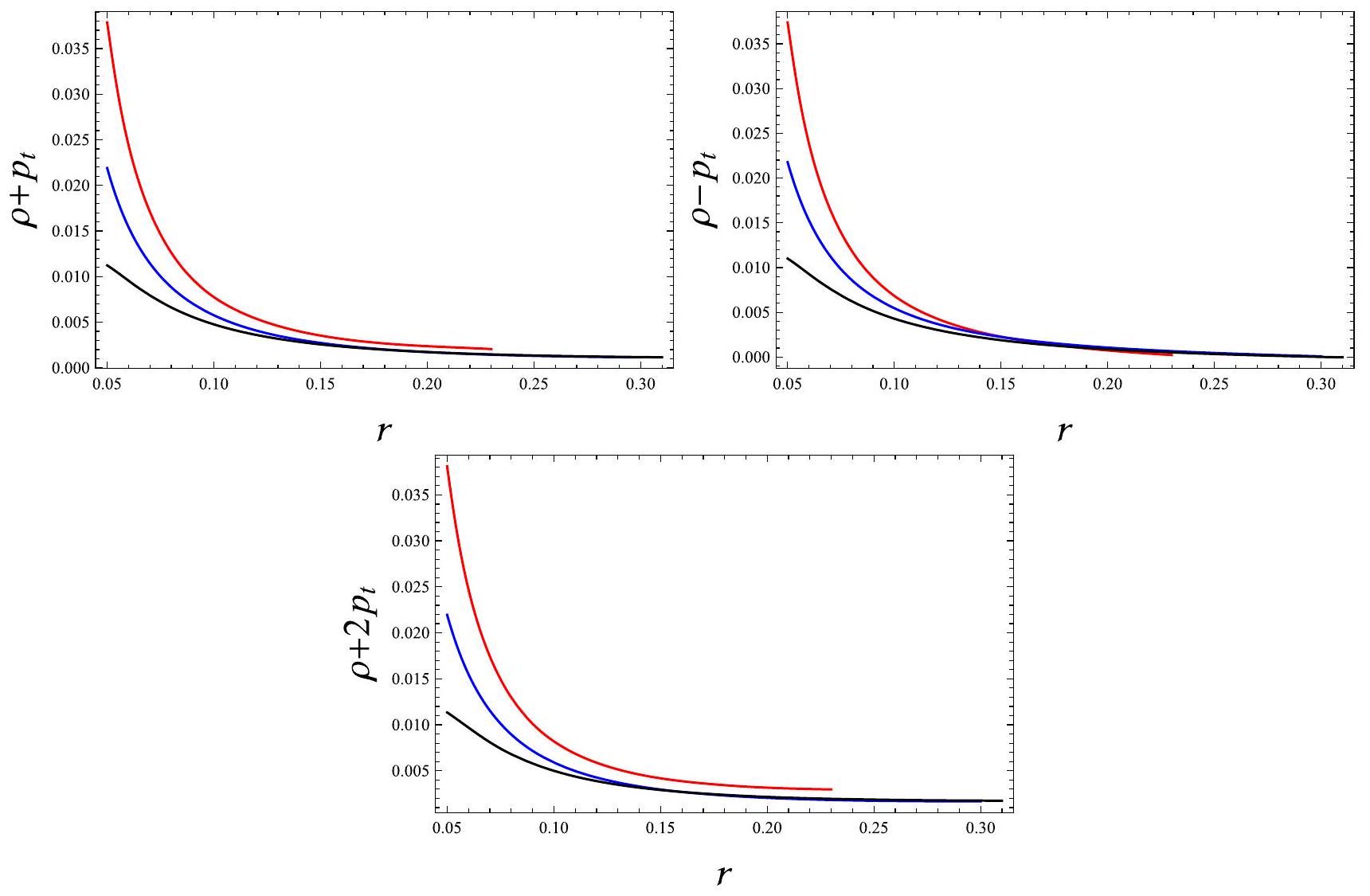

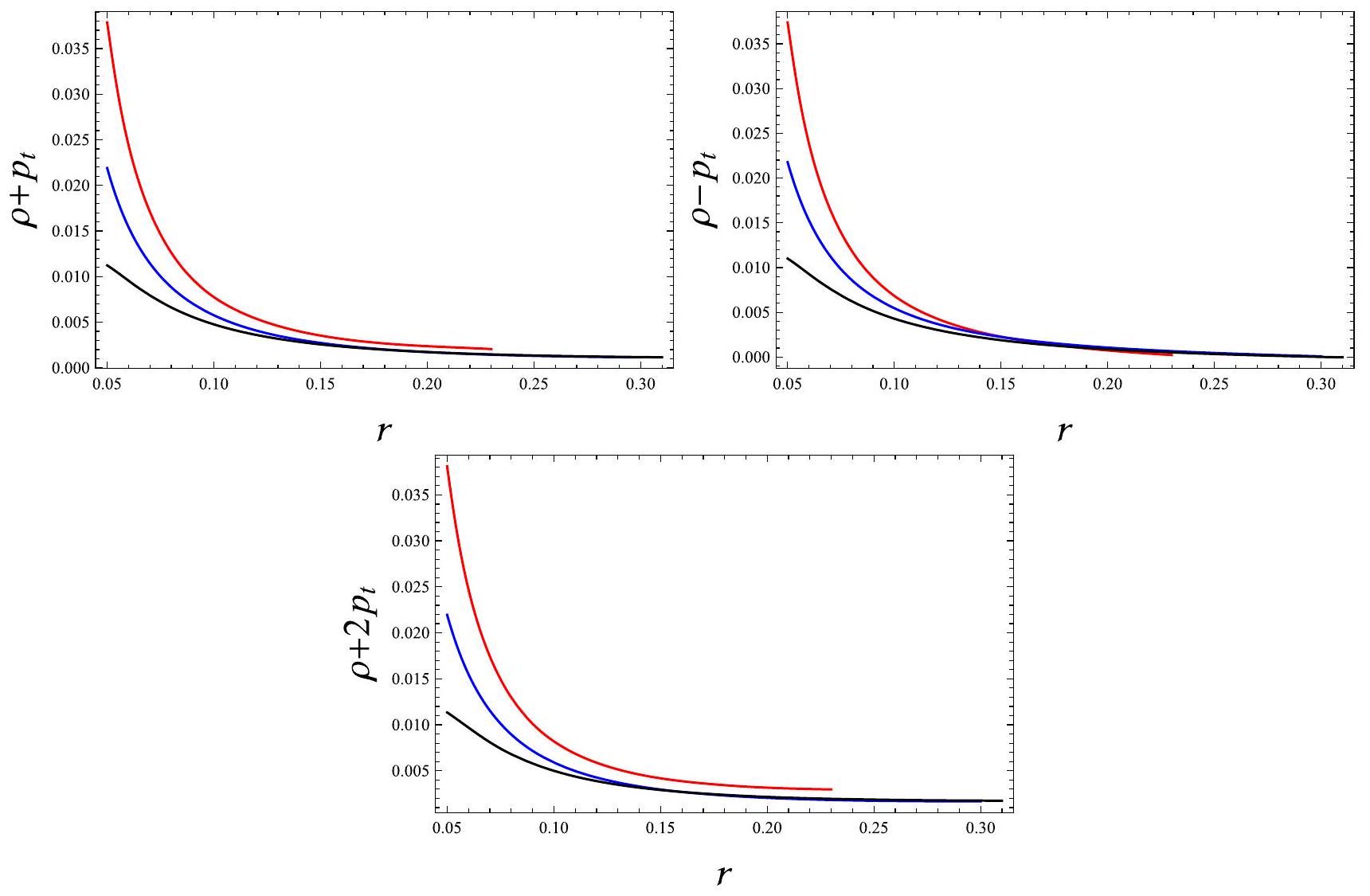

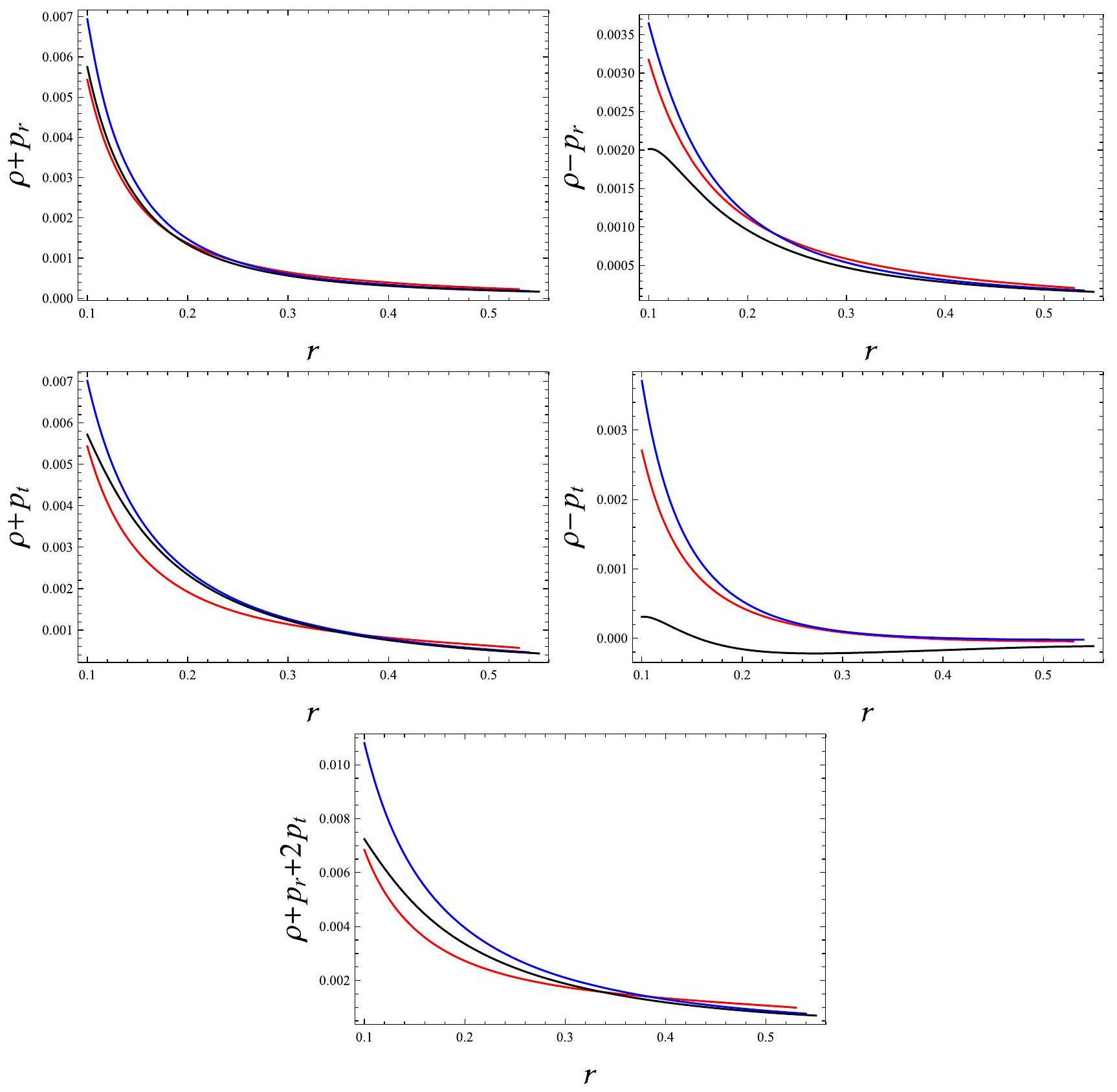

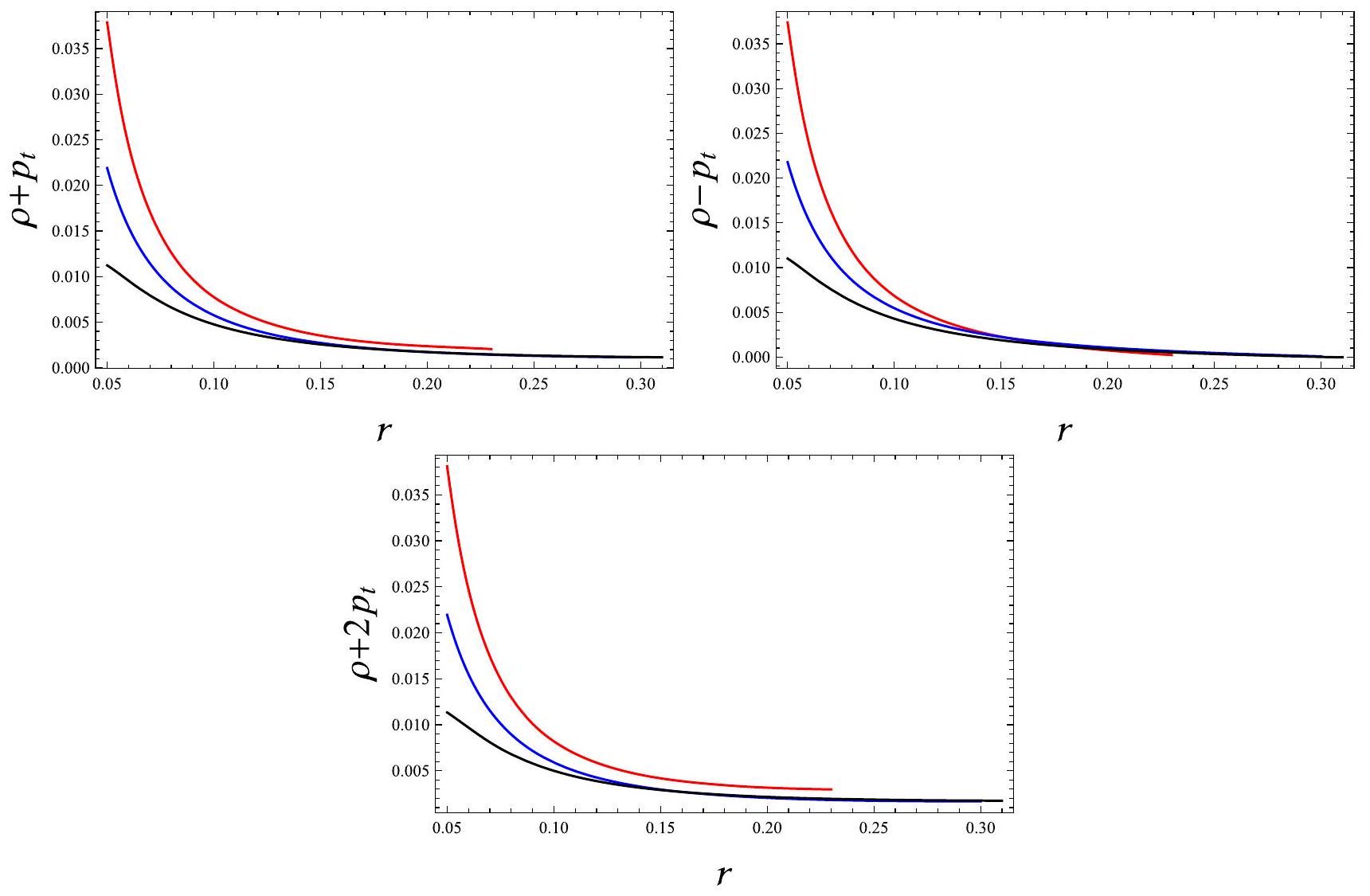

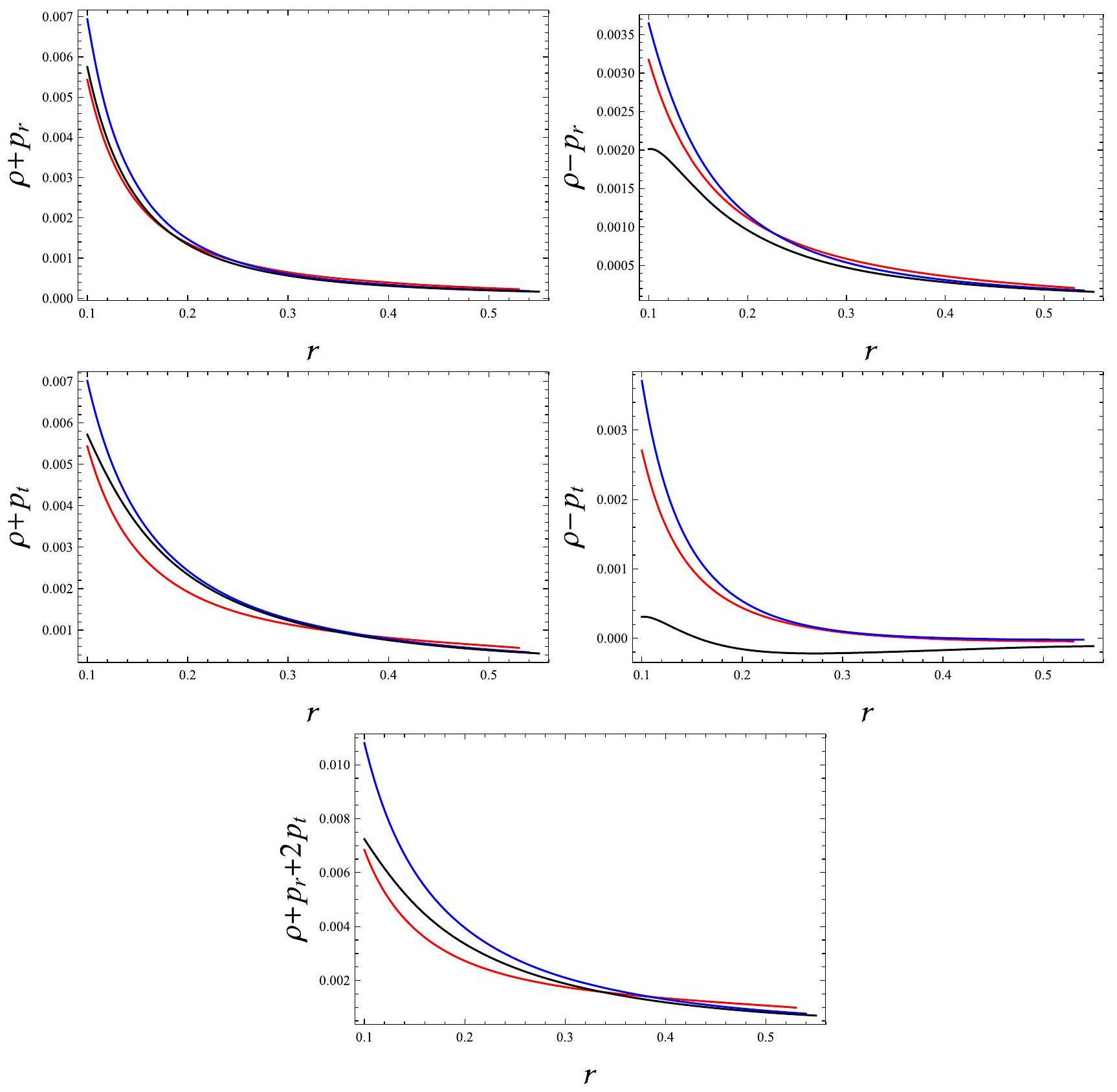

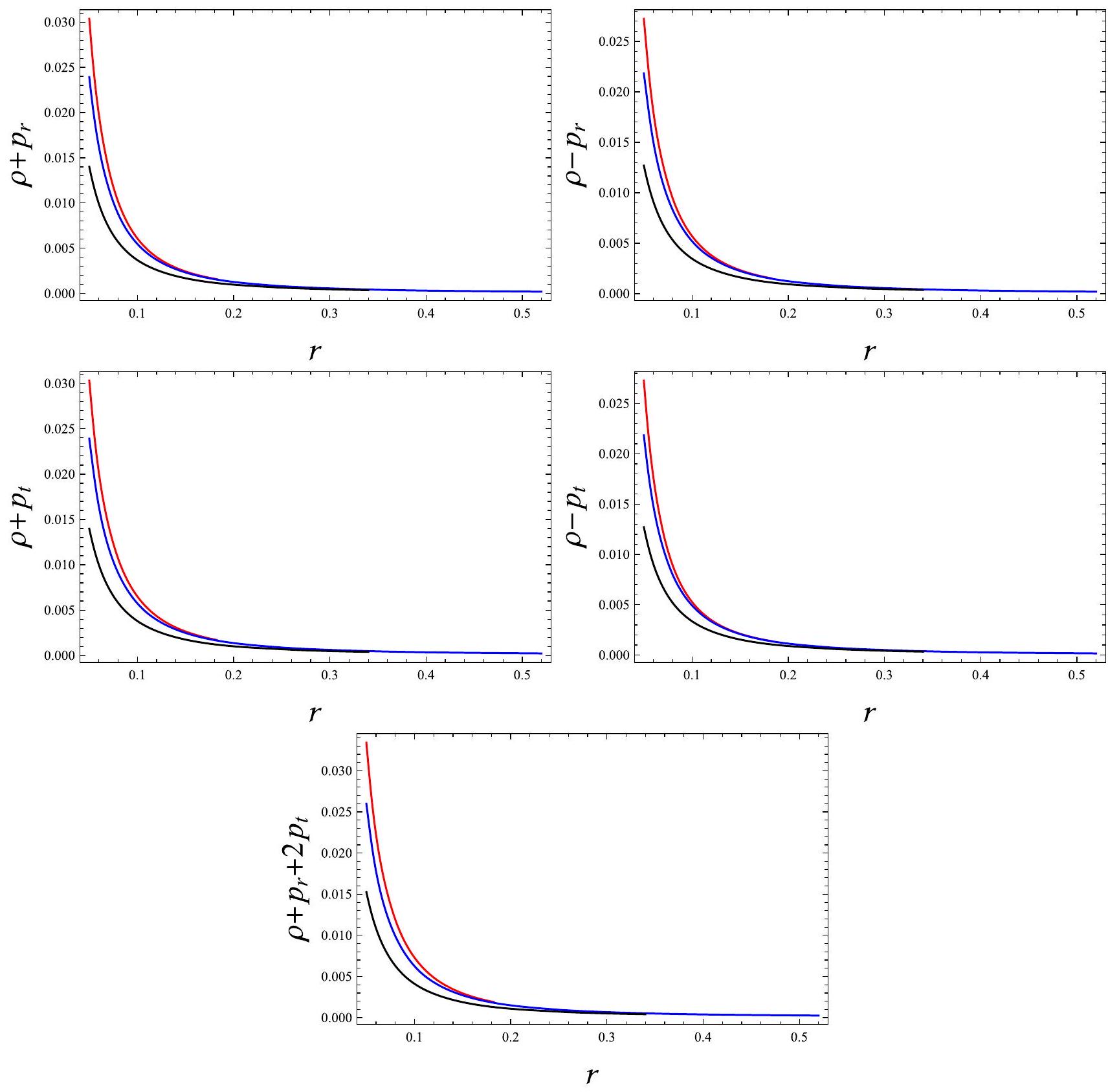

- يمكن ضمان وجود مادة عادية داخل جسم سماوي من خلال تلبية بعض القيود. يُشار إليها بشروط الطاقة التي هي في الواقع تركيبات خطية من معلمات السائل في

. في إعداد السائل قيد النظر، تأخذ هذه القيود الشكل التالي

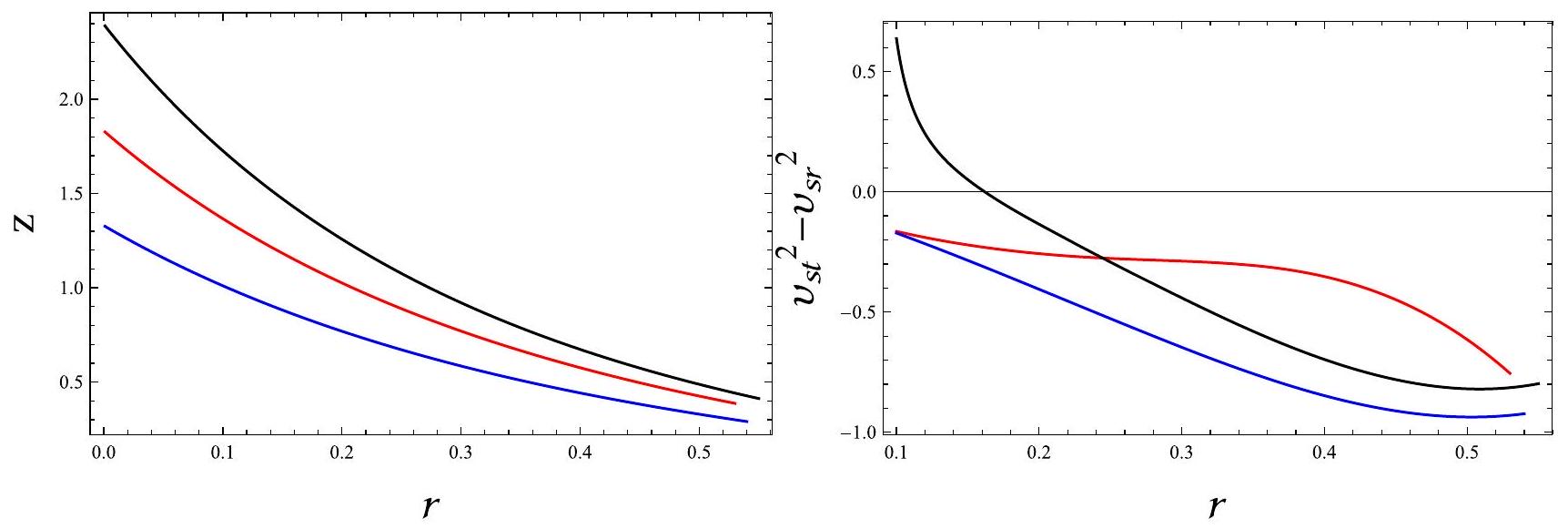

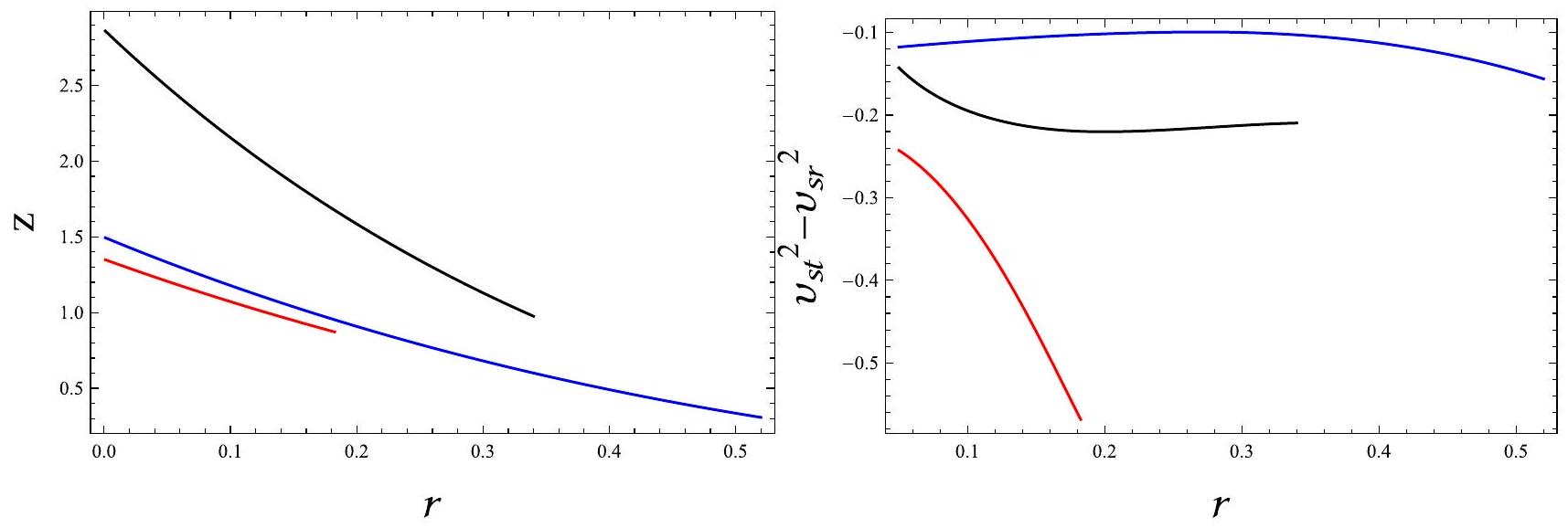

- يمكن تعريف الانزياح الجاذبي في تكوين السائل الداخلي كـ

. نظرًا لأن هذا العامل يعتمد فقط على إمكانات المقياس، فمن الضروري أن ينخفض للخارج. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يجب ألا تتجاوز قيمته 5.211 عند لكي يعتبر النموذج مقبولًا [81]. - لقد حظيت تقييم استقرار النظام الذي انحرف للتو عن التوازن الهيدروستاتيكي باهتمام كبير في الأبحاث الحديثة. قدم هيريرا وآخرون [83،84] مفهوم التشقق، الذي يحدث داخل السائل عندما يتغير الاتجاه الكلي للقوة في الاتجاه الشعاعي عند نقطة معينة بسبب بعض الاضطرابات الخارجية. يعتمد تجنب التشقق على تلبية

عدم المساواة التالية

5 تشكيل نماذج مختلفة

5.1 شرط تعقيد صفري مع ضغط شعاعي صفري

$left.left.+r eta_{1}^{prime 2}+4 eta_{1}^{prime}right}^{2}right]left[pi alpha r^{-1} e^{-eta_{2}}left{2 rleft(eta_{1}^{prime prime}-2 e^{eta_{2}}+2right)right.right.$

$left.-eta_{2}^{prime}left(r eta_{1}^{prime}+4right)+r eta_{1}^{prime 2}+4 eta_{1}^{prime}right}$

$+2 pi]^{-1}-frac{3 r}{pi}left[2 eta_{1}^{prime 2}left{16 alpha+6 alpha r^{2} eta_{2}^{prime prime}right.right.$

$-2 alpha r^{2}left(2 e^{eta_{2}}+1right) eta_{1}^{prime prime}-8 alpha r^{2} e^{eta_{2}}+4 alpha r^{2} e^{2 eta_{2}}$

$left.+4 alpha r^{2}-r^{2} e^{2 eta_{2}}-8 alpha e^{eta_{2}}right}$

$-alpha eta_{2}^{prime 2}left{4left(4left(3 r^{2}+e^{eta_{2}}-2right)+11 r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime prime}right)+left(2 e^{eta_{2}}+15right)right.$

$left.times r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime 2}+12 rleft(e^{eta_{2}}+6right) eta_{1}^{prime}right}$

$+2 eta_{2}^{prime}left{eta_{1}^{prime}left(4 alpha r^{2}left(e^{eta_{2}}+6right) eta_{1}^{prime prime}right.right.$

$-32 alpha-14 alpha r^{2} eta_{2}^{prime prime}+4 alpha r^{2}$

$left.+8 alpha r^{2} e^{eta_{2}}-4 alpha r^{2} e^{2 eta_{2}}+r^{2} e^{2 eta_{2}}+16 alpha e^{eta_{2}}right)$

$+alpha r^{2}left(2 e^{eta_{2}}+1right) eta_{1}^{prime 3}+2 rleft(8 alpha-28 alpha eta_{2}^{prime prime}right.$

$+2 alphaleft(3 e^{eta_{2}}+14right) eta_{1}^{prime prime}+12 alpha e^{eta_{2}}-4 alpha e^{2 eta_{2}}$

$left.left.+12 alpha r eta_{1}^{(3)}+e^{2 eta_{2}}right)+4 alpha rleft(3 e^{eta_{2}}+2right) eta_{1}^{prime 2}right}$

$-alpha r^{2}left(2 e^{eta_{2}}-1right) eta_{1}^{prime 4}+12 alpha r eta_{2}^{prime 3}left(r eta_{1}^{prime}+4right)$

$+4 rleft{4 alphaleft(2 eta_{2}^{(3)}+rleft(left(e^{eta_{2}}-1right)^{2}-eta_{1}^{(4)}right)right.right.$

$left.-4 eta_{1}^{(3)}right)+8 alpha r eta_{2}^{prime prime}left(eta_{1}^{prime prime}+1right)-alpha rleft(2 e^{eta_{2}}+3right) eta_{1}^{prime prime 2}$

$+rleft(4 alpha-8 alpha e^{eta_{2}}+(4 alpha-1) e^{2 eta_{2}}right)$

$left.times eta_{1}^{prime prime}right}+4 r eta_{1}^{prime}left{8 alpha+2 alpha r eta_{2}^{(3)}+16 alpha eta_{2}^{prime prime}right.$

$-2 alphaleft(3 e^{eta_{2}}+4right) eta_{1}^{prime prime}-6 alpha r eta_{1}^{(3)}-12 alpha e^{eta_{2}}$

$left.left.-e^{2 eta_{2}}+4 alpha e^{2 eta_{2}}right}-4 alpha rleft(3 e^{eta_{2}}-2right) eta_{1}^{prime 3}right]$

$-4 e^{eta_{2}} rleft[4 alpha r eta_{1}^{prime 2}left(2 r^{2} e^{eta_{2}}-2 r^{2} eta_{2}^{prime prime}-r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime prime}right.right.$

$left.-2 r^{2}+4 e^{eta_{2}}-12right)-alpha r^{3} eta_{1}^{prime 4}-12 alpha r^{2} eta_{2}^{prime 3}left(r eta_{1}^{prime}+4right)$

$+alpha r eta_{2}^{prime 2}left(44 r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime prime}+11 r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime 2}right.$

$left.+48 r^{2}+48 r eta_{1}^{prime}-64right)-4 rleft{4left(8 alpha-2 alpha r^{2} e^{eta_{2}}right.right.$

$+alpha r^{2} e^{2 eta_{2}}-alpha r^{2} eta_{1}^{(4)}+alpha r^{2}-12 alpha e^{eta_{2}}$

$+2 alpha r eta_{2}^{(3)}+4 alpha e^{2 eta_{2}}-4 alpha r eta_{1}^{(3)}+2 e^{eta_{2}}$

$left.-e^{2 eta_{2}}right)+8 alpha r^{2} eta_{2}^{prime prime}left(eta_{1}^{prime prime}+1right)-4 alphaleft(left(r^{2}+2right) e^{eta_{2}}right.$

$left.left.-r^{2}-4right) eta_{1}^{prime prime}-3 alpha r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime prime 2}right}-8 alpha r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime 3}$

$+8 alpha eta_{1}^{prime}left(2 r^{3} eta_{1}^{(3)}-6 r^{2} eta_{2}^{prime prime}+4 r^{2} e^{eta_{2}}-r^{3} eta_{2}^{(3)}right.$

$left.+2 r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime prime}-4 r^{2}+8 e^{eta_{2}}-16right)-2 eta_{2}^{prime}left{alphaleft(-r^{3}right) eta_{1}^{prime 3}right.$

$+2 alpha r eta_{1}^{prime}left(9 r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime prime}-2 r^{2}-7 r^{2} eta_{2}^{prime prime}right.$

$left.+2 r^{2} e^{eta_{2}}+4 e^{eta_{2}}-28right)-4 alpha r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime 2}$

$+4left(-16 alpha+6 alpha r^{3} eta_{1}^{(3)}-14 alpha r^{2} eta_{2}^{prime prime}+8 alpha r^{2} e^{eta_{2}}right.$

$left.left.left.+12 alpha r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime prime}-r^{2} e^{eta_{2}}+8 alpha e^{eta_{2}}right)right}right]$

$timesleft[2 rleft{2 alpha+(1-2 alpha) e^{eta_{2}}+alpha eta_{1}^{prime prime}right}-alpha eta_{2}^{prime}left(r eta_{1}^{prime}+4right)right.$

$left.+alpha r eta_{1}^{prime 2}+4 alpha eta_{1}^{prime}right]^{-1}=0$.

- بالنسبة لـ

، نحصل على وتصبح الكثافة

- بالنسبة لـ

، نحصل على وتصبح الكثافة

- بالنسبة لـ

، نحصل على وتصبح الكثافة

5.2 بوليتروب يقبل تعقيدًا متلاشيًا

-

يرمز إلى الثابت متعدد الأشكال، -

تشير إلى مؤشر البوليتروبيك، -

هو الأس exponent متعدد الأشكال.

- لـ

نحصل على وتصبح الكثافة

- لـ

نحصل على وتصبح الكثافة

- لـ

نحصل على وتصبح الكثافة

عندما

5.3 شرط تعقيد الاختفاء مع معادلة حالة غير محلية

- لـ

نحصل على وتصبح الكثافة

- لـ

نحصل على وتصبح الكثافة

- لـ

نحصل على وتصبح الكثافة

6 الاستنتاجات

عامل. علاوة على ذلك، قمنا بتقسيم موتر الانحناء بشكل عمودي، مما أدى إلى اشتقاق أربعة مقادير مميزة ترافق كميات فيزيائية متنوعة. لوحظ أن عاملاً يُشار إليه باسم

بيان توفر البيانات لا يحتوي هذا المخطوط على بيانات مرتبطة أو لن يتم إيداع البيانات. [تعليق المؤلفين: هذه دراسة نظرية ولم يتم إدراج أي بيانات تجريبية.]

تمويل من SCOAP

References

- A.G. Riess et al., Astron. J. 116, 1009 (1998)

- S. Perlmutter et al., Astrophys. J. 517, 565 (1999)

- M. Tegmark et al., Phys. Rev. D 69, 103501 (2004)

- C.L. Bennett et al., Astrophys. J. 583, 1 (2003)

- D.N. Spergel et al., Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 148, 175 (2003)

- R.R. Caldwell, Phys. Lett. B 545, 23 (2002)

- S. Nojiri, S.D. Odintsov, Phys. Lett. B 565, 1 (2003)

- A. Sen, J. High Energy Phys. 04, 048 (2002)

- V. Gorini, A. Kamenshchik, U. Moschella, Phys. Rev. D 67, 063509 (2003)

- S. Nojiri, S.D. Odintsov, Phys. Rev. D 74, 086005 (2006)

- S. Capozziello, P. Martin-Moruno, C. Rubano, Phys. Lett. B 664, 12 (2008)

- S. Nojiri, S.D. Odintsov, TSPU Bulletin N8(110), 7 (2011)

- A.D. Felice, S. Tsujikawa, Living Rev. Relativ. 13, 3 (2010)

- J.L. Said, K.Z. Adami, Phys. Rev. D 83, 043008 (2011)

- S.K. Tripathy, B. Mishra, Eur. Phys. J. Plus 131, 273 (2016)

- A.S. Agrawal, S.K. Tripathy, B. Mishra, Chin. J. Phys. 71, 333 (2021)

- A.V. Astashenok, S. Capozziello, S.D. Odintsov, Phys. Lett. B 742, 160 (2015)

- G. Mustafa, I. Hussain, M.F. Shamir, Universe 6, 48 (2020)

- M.F. Shamir, A. Malik, G. Mustafa, Chin. J. Phys. 73, 634 (2021)

- L. Herrera, N.O. Santos, Phys. Rep. 286, 53 (1997)

- J. Ovalle, Phys. Rev. D 95, 104019 (2017)

- J. Ovalle, R. Casadio, R. da Rocha, A. Sotomayor, Eur. Phys. J. C 78, 122 (2018)

- L. Herrera, Phys. Rev. D 101, 104024 (2020)

- L. Herrera, J. Ospino, A. Di Prisco, Phys. Rev. D 77, 027502 (2008)

- G. Abellán, P. Bargueño, E. Contreras, E. Fuenmayor, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 29, 2050082 (2020)

- S. Chandrasekhar, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 93, 390 (1933)

- F.K. Liu, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 281, 197 (1996)

- G. Abellán, E. Fuenmayor, L. Herrera, Phys. Dark Universe 28, 100549 (2020)

- R.F. Tooper, Astrophys. J. 140, 434 (1964)

- S.A. Bludman, Astrophys. J. 183, 637 (1973)

- L. Herrera, W. Barreto, Phys. Rev. D 88, 084022 (2013)

- L. Herrera, A. Di Prisco, W. Barreto, J. Ospino, Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 46, 1827 (2014)

- G. Abellán, E. Fuenmayor, E. Contreras, L. Herrera, Phys. Dark Universe 30, 100632 (2020)

- K.R. Karmarkar, Proc. Indian Acad. Sci. Sect. A 27, 56 (1948)

- K.N. Singh, S.K. Maurya, F. Rahaman, F. Tello-Ortiz, Eur. Phys. J. C 79, 381 (2019)

- J. Ospino, L.A. Núñez, Eur. Phys. J. C 80, 166 (2020)

- G. Mustafa et al., Phys. Dark Universe 31, 100747 (2021)

- A. Ramos, C. Arias, E. Fuenmayor, E. Contreras, Eur. Phys. J. C 81, 203 (2021)

- M. Sharif, T. Naseer, Phys. Scr. 97, 055004 (2022)

- M. Sharif, T. Naseer, Phys. Scr. 97, 125016 (2022)

- L. Herrera, A. Di Prisco, J. Ospino, E. Fuenmayor, J. Math. Phys. 42, 2129 (2001)

- T. Naseer, M. Sharif, A. Fatima, S. Manzoor, Chin. J. Phys. 86, 350 (2023)

- R. López-Ruiz, H.L. Mancini, X. Calbet, Phys. Lett. A 209, 321 (1995)

- X. Calbet, R. López-Ruiz, Phys. Rev. E 63, 066116 (2001)

- C.P. Panos, N.S. Nikolaidis, K.C. Chatzisavvas, C.C. Tsouros, Phys. Lett. A 373, 2343 (2009)

- L. Herrera, Phys. Rev. D 97, 044010 (2018)

- L. Bel, Ann. Inst. Henri Poincaré 17, 37 (1961)

- L. Herrera, J. Ospino, A. Di Prisco, E. Fuenmayor, O. Troconis, Phys. Rev. D 79, 064025 (2009)

- L. Herrera, A. Di Prisco, J. Ospino, Phys. Rev. D 98, 104059 (2018)

- L. Herrera, A. Di Prisco, J. Ospino, Phys. Rev. D 99, 044049 (2019)

- M. Sharif, T. Naseer, Eur. Phys. J. Plus 137, 1304 (2022)

- M. Sharif, T. Naseer, Class. Quantum Gravity 40, 035009 (2023)

- M. Sharif, T. Naseer, Phys. Dark Universe 42, 101324 (2023)

- M. Sharif, T. Naseer, Ann. Phys. 453, 169311 (2023)

- M. Sharif, T. Naseer, Chin. J. Phys. 86, 596 (2023)

- M. Sharif, T. Naseer, Ann. Phys. 459, 169527 (2023)

- G. Abbas, H. Nazar, Eur. Phys. J. C 78, 510 (2018)

- G. Abbas, H. Nazar, Eur. Phys. J. C 78, 957 (2018)

- R. Manzoor, W. Shahid, Phys. Dark Universe 33, 100844 (2021)

- M. Sharif, T. Naseer, Chin. J. Phys. 77, 2655 (2022)

- M. Sharif, T. Naseer, Eur. Phys. J. Plus 137, 947 (2022)

- Z. Yousaf et al., Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 495, 4334 (2020)

- Z. Yousaf, M.Z. Bhatti, T. Naseer, Ann. Phys. 420, 168267 (2020)

- Z. Yousaf, M.Z. Bhatti, T. Naseer, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 29, 2050061 (2020)

- Z. Yousaf et al., Phys. Dark Universe 29, 100581 (2020)

- Z. Yousaf, M.Z. Bhatti, T. Naseer, Phys. Dark Universe 28, 100535 (2020)

- Z. Yousaf, M.Z. Bhatti, T. Naseer, Eur. Phys. J. Plus 135, 353 (2020)

- C. Arias, E. Contreras, E. Fuenmayor, A. Ramos, Ann. Phys. 436, 168671 (2022)

- T. Koivisto, Class. Quantum Gravity 23, 4289 (2006)

- K. Kainulainen, J. Piilonen, V. Reijonen, D. Sunhede, Phys. Rev. D 76, 024020 (2007)

- A.A. Starobinsky, Phys. Lett. B 91, 99 (1980)

- D. Kazanas, Astrophys. J. 241, L59 (1980)

- A.H. Guth, Phys. Rev. D 23, 347 (1981)

- A.A. Starobinsky, J. Exp. Theor. Phys. Lett. 30, 682 (1979)

- A.A. Starobinsky, Sov. Astron. Lett. 9, 302 (1983)

- M. Zubair, G. Abbas, Astrophys. Space Sci. 361, 342 (2016)

- R.C. Tolman, Phys. Rev. 35, 875 (1930)

- H. Hernández, L.A. Núñez, Can. J. Phys. 82, 29 (2004)

- M.S.R. Delgaty, K. Lake, Comput. Phys. Commun. 115, 395 (1998)

- B.V. Ivanov, Eur. Phys. J. C 77, 738 (2017)

- H.A. Buchdahl, Phys. Rev. 116, 1027 (1959)

- A. Alho, J. Natário, P. Pani, G. Raposo, Phys. Rev. D 106, L041502 (2022)

- L. Herrera, Phys. Lett. A 165, 206 (1992)

- H. Abreu, H. Hernández, L.A. Núñez, Class. Quantum Gravity 24, 4631 (2007)

- P.S. Florides, Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 337, 529 (1974)

e-mails: tayyabnaseer48@yahoo.com; tayyab.naseer@math.uol.edu.pk

e-mail: msharif.math@pu.edu.pk (corresponding author)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-024-12916-1

Publication Date: 2024-06-01

Implications of vanishing complexity condition in f(R) theory

© The Author(s) 2024

Abstract

This paper introduces the concept of complexity for a static spherical spacetime and extends it to the modified

1 Introduction

challenging, primarily due to the intricate involvement of higher-order derivatives of geometric quantities. Such solutions can be determined either analytically or numerically, the latter contingent upon the provision of initial or boundary conditions compatible with the specific scenario under consideration. However, to arrive at a solution, supplementary information concerning local physics is indispensable. For instance, recent investigations into compact objects reveal the potential existence of multiple factors that affect the isotropic/anisotropic nature of these structures [20-22]. Additionally, other physical components, such as inhomogeneous density, shear and dissipation flux, play pivotal roles in destabilizing the condition of pressure isotropy [23].

and entropy within the system under consideration [43-45]. However, this definition faced challenges when applied to two distinct physical structures, namely an ideal gas and a perfect crystal, as their properties are inherently opposite, yet both systems exhibit no complexity.

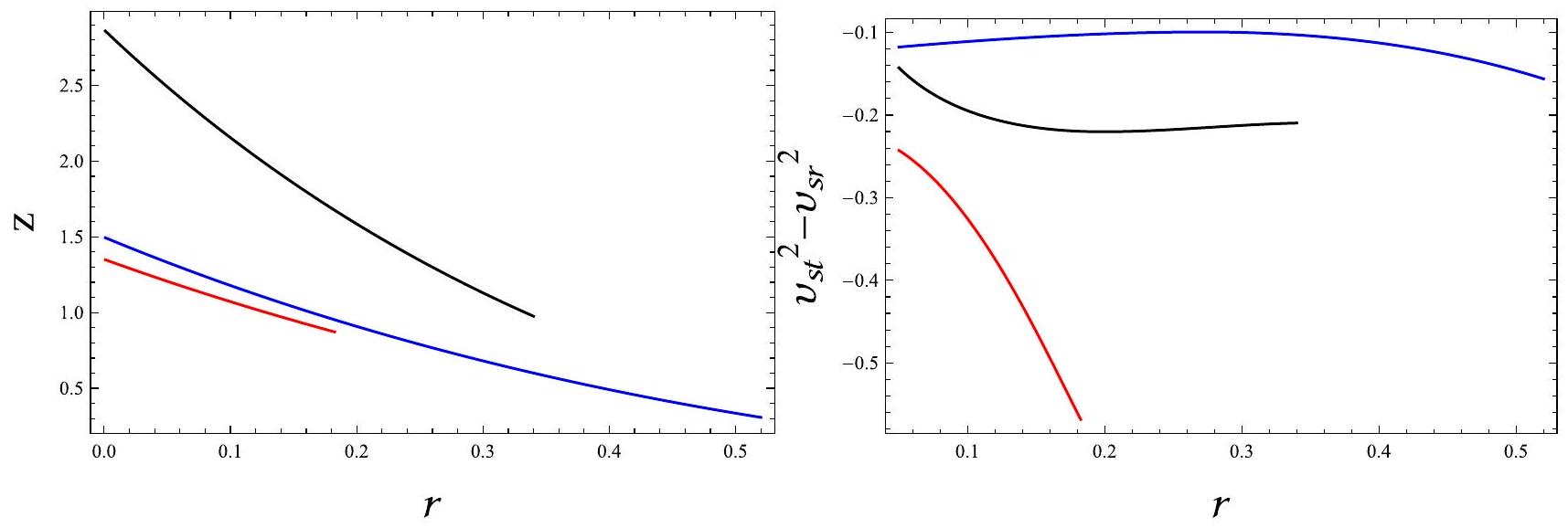

graphical interpretation. Finally, our results are summarized in the last section.

where

where

-

indicates the covariant derivative, -

symbolizes the d’Alembert operator.

where

where

following some particular relations such as

where

where

whose alternative expression in the form of modified energy density (9) is

3 Structure scalars

where

where

-

explains how the homogeneous energy density affects the fluid distribution. -

determines the inhomogeneity in the density. - the local anisotropy is controlled by the factor

. -

plays the role of both and .

that becomes after some necessary calculations as

It is crucial to emphasize that the system with null complexity is not solely characterized by an isotropic and homogeneous configuration. In fact, Eq. (30) also explains such a structure (

4 Physical conditions for compact models

this context have been suggested and adhered to by various researchers [79,80]. Some of these conditions are outlined below.

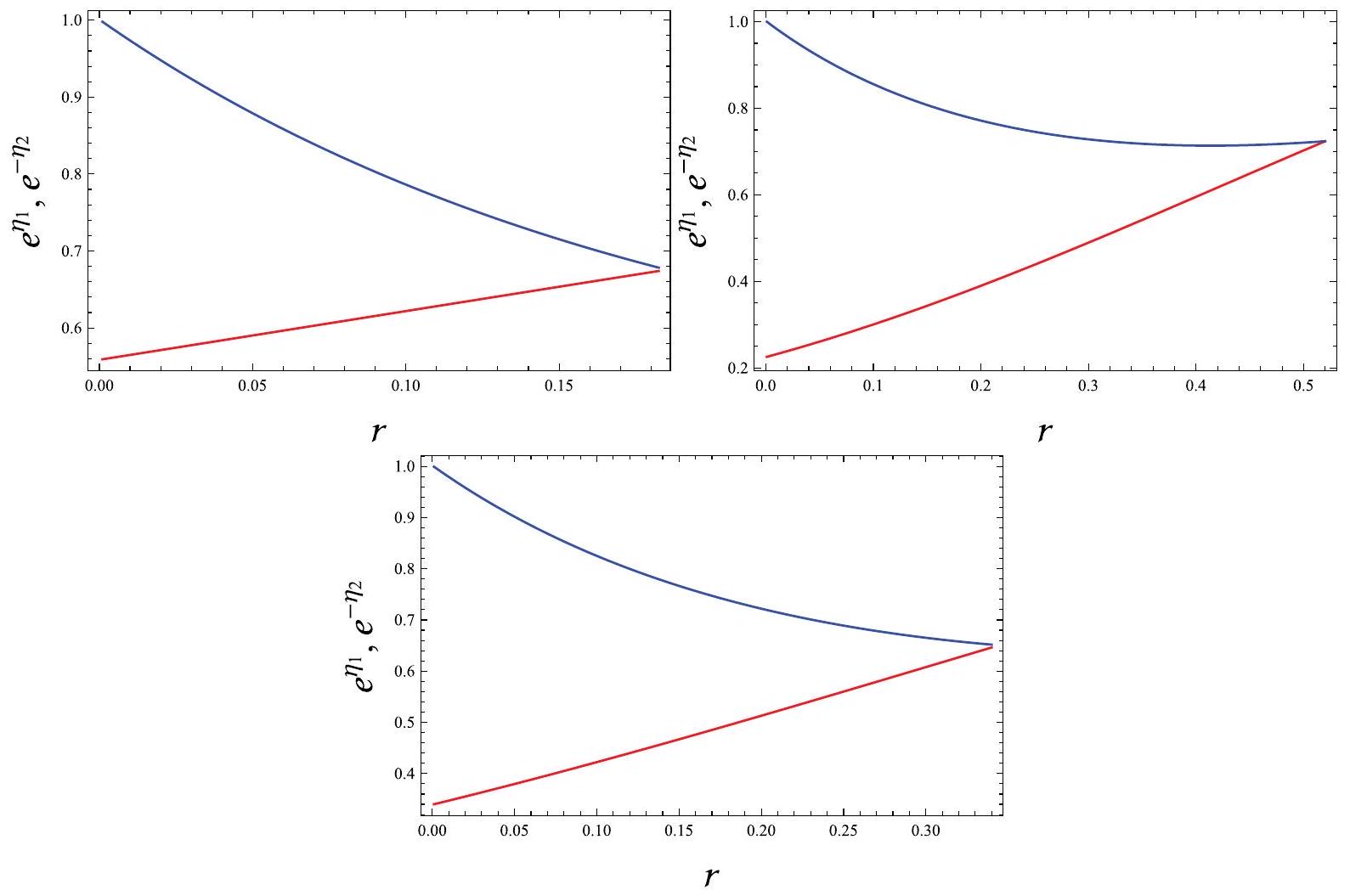

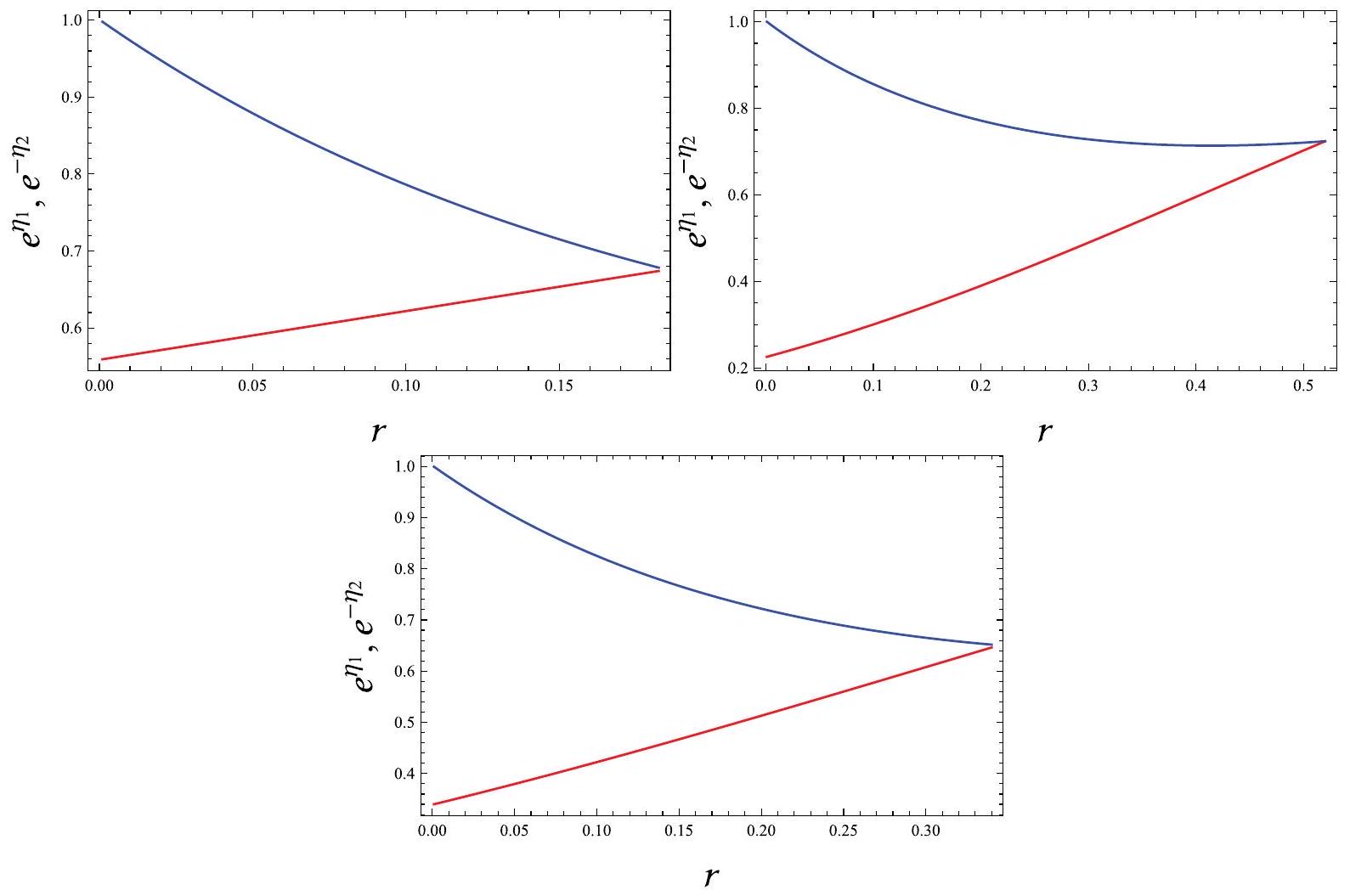

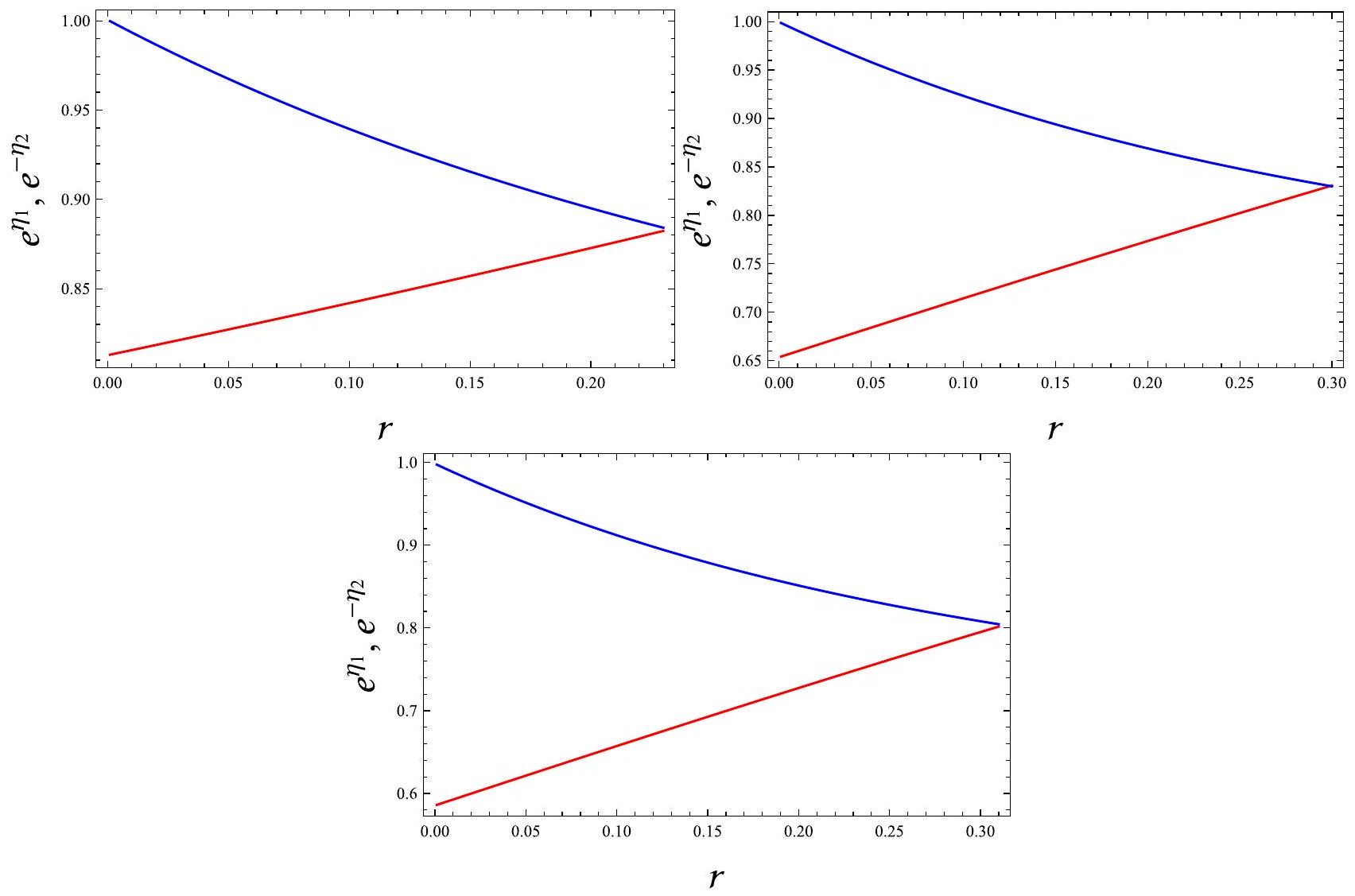

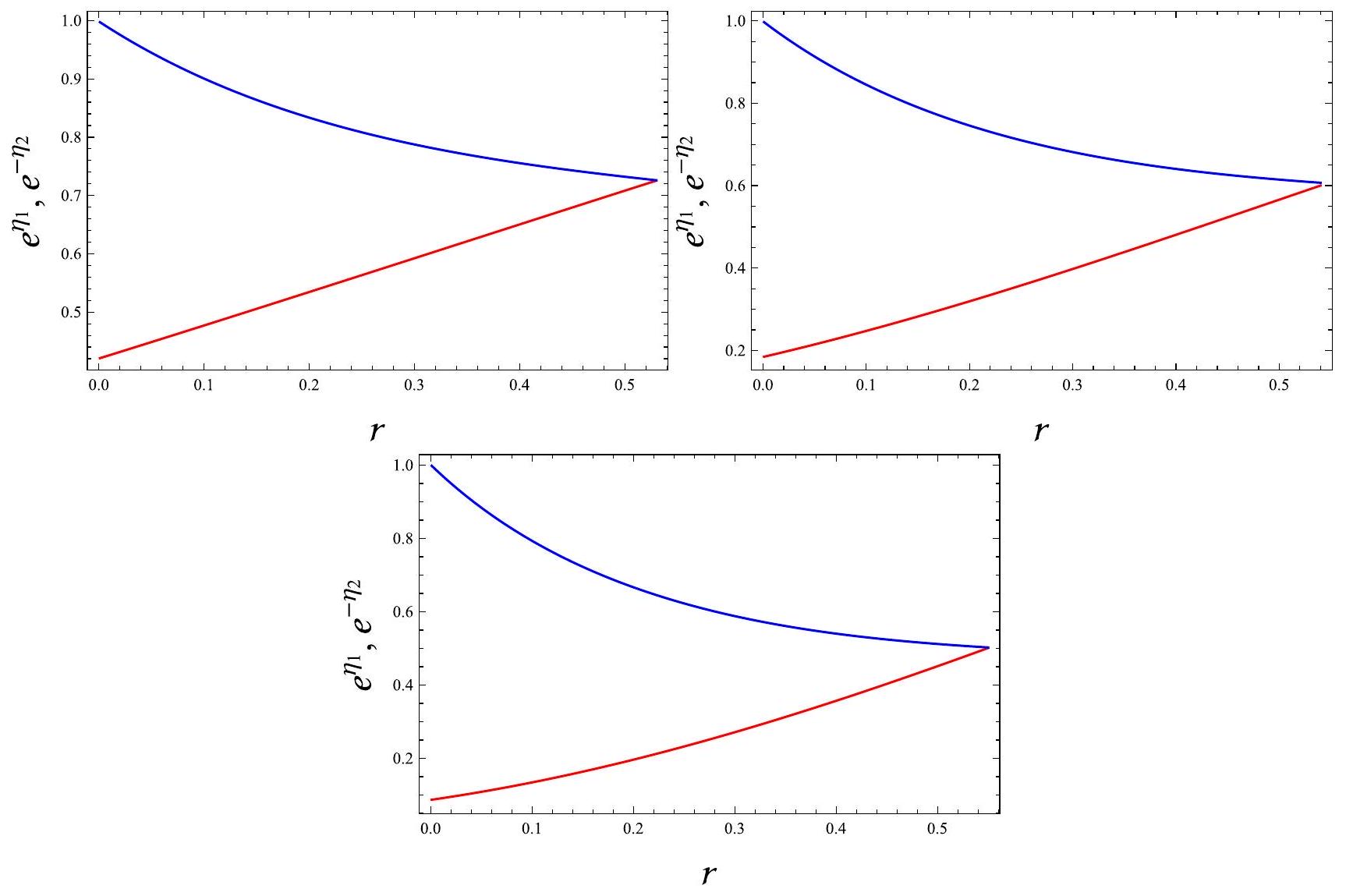

- The radial/temporal metric functions should exhibit finiteness, free of singularities and remain positive everywhere in a self-gravitating fluid interior.

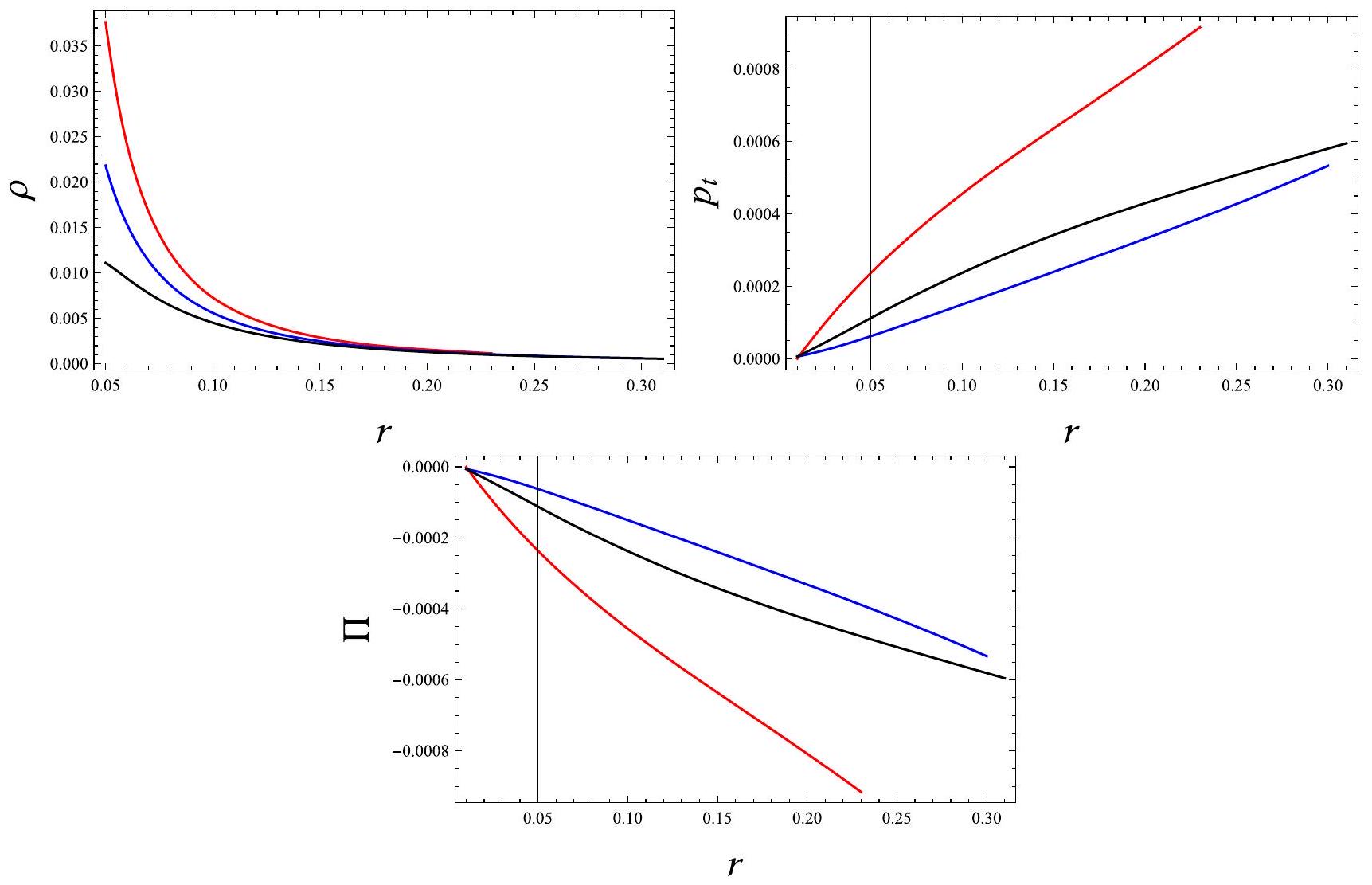

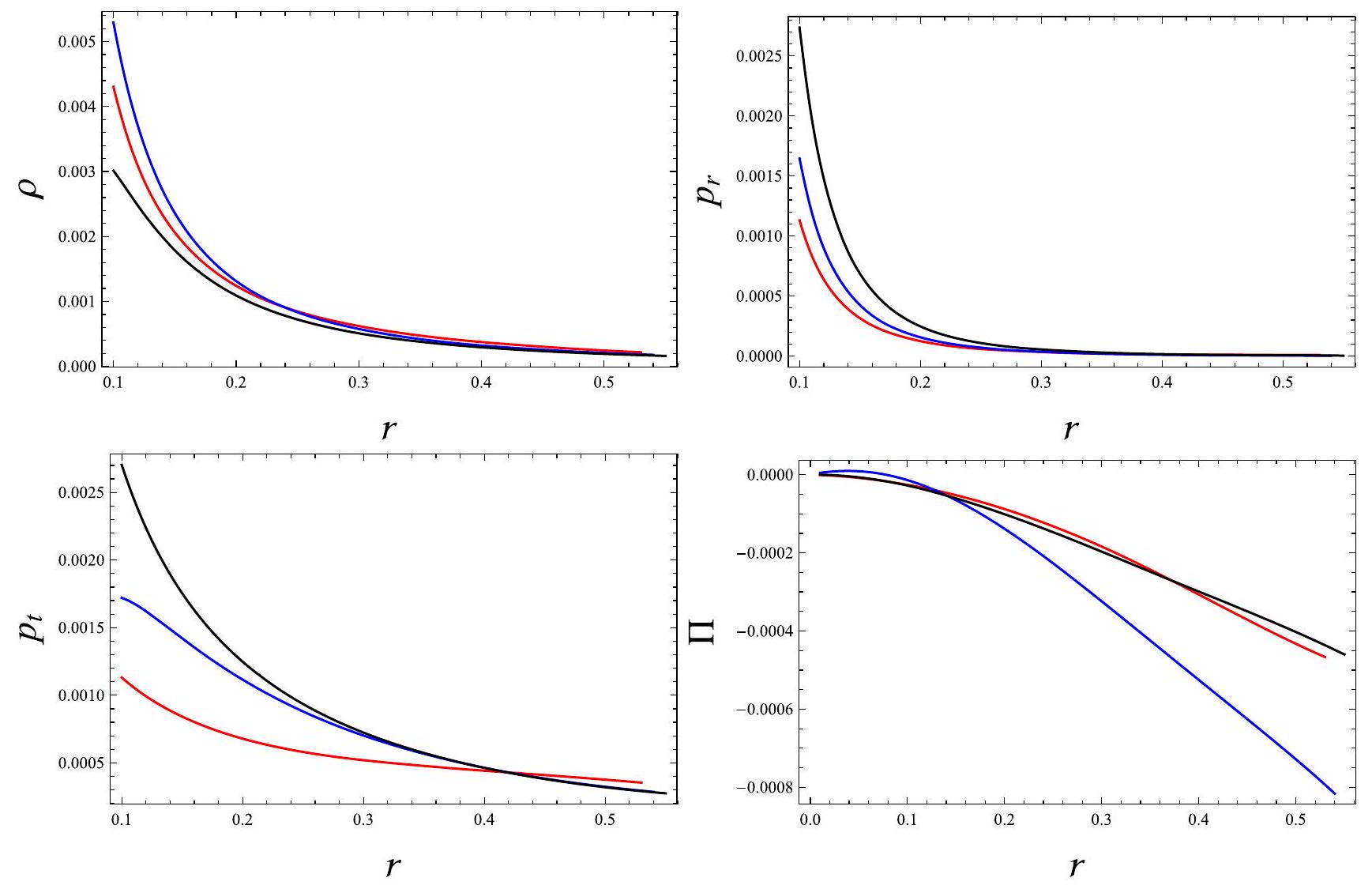

- The matter variables, including energy density and pressure, must reach their maximum at the center (

), exhibiting positively finite trend across the entire domain. Additionally, their first-order derivatives needed to be null at and follows negative profile towards the boundary. - In a compact body, the particles are arranged in a certain manner. This arrangement tells how much these particles are closed to each other, ultimately defining the compactness of that system. One can also define it as the mass to radius ratio which necessarily be lower than the proposed limit for spherical fluid distribution given by [81,82]

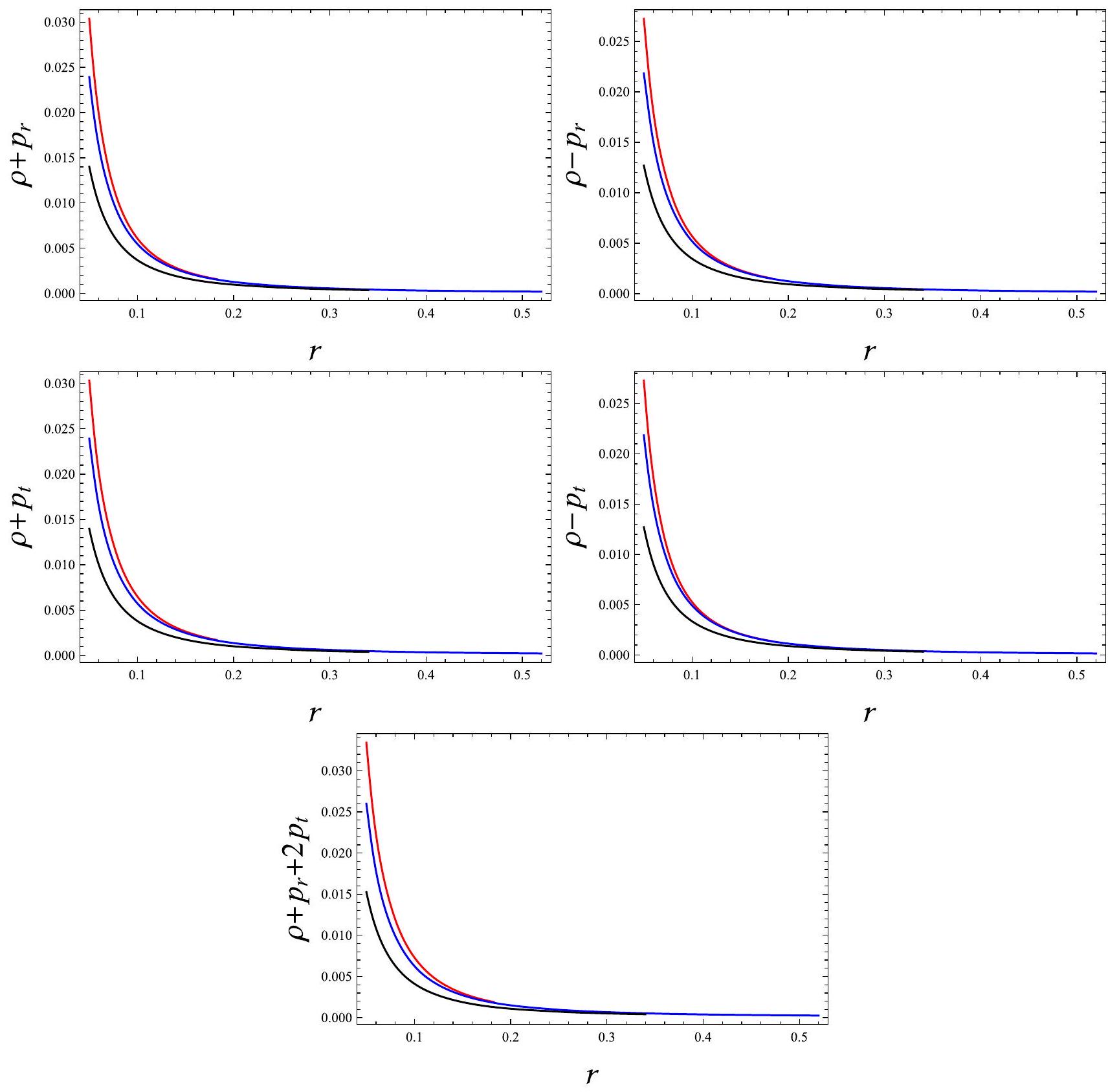

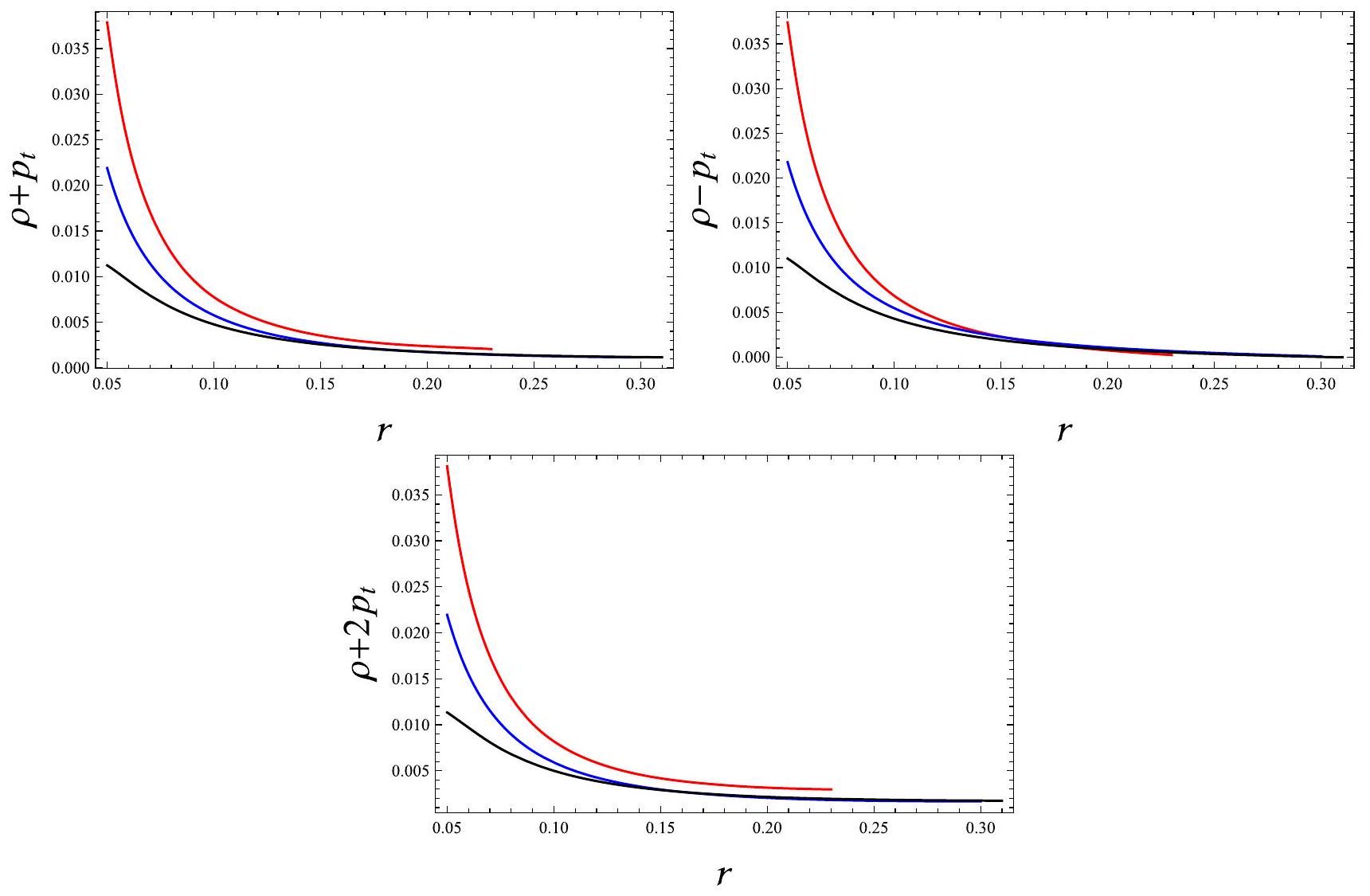

- Bearing an ordinary matter by the interior of a celestial body can be guaranteed through the satisfaction of some constraints. They are referred to the energy conditions which are in fact linear combinations of fluid parameters in the

. In the fluid setup under consideration, these constraints take the following form

- The gravitational redshift can be defined in the interior fluid configuration as

. Given that this factor depends solely on metric potential, it is imperative for it to decrease outwards. Additionally, its value must not exceed 5.211 at for the model to be considered acceptable [81]. - To assess the system’s stability just deviated from the hydrostatic equilibrium has garnered significant attention in modern research. Herrera et al. [83,84] introduced the concept of cracking, occurring within the fluid when the total force in the radial direction switches its sign at a specific point due to some external disturbances. The avoidance of cracking relies on the satisfaction of the

following inequality

5 Formation of different models

5.1 Vanishing complexity condition with null radial pressure

$left.left.+r eta_{1}^{prime 2}+4 eta_{1}^{prime}right}^{2}right]left[pi alpha r^{-1} e^{-eta_{2}}left{2 rleft(eta_{1}^{prime prime}-2 e^{eta_{2}}+2right)right.right.$

$left.-eta_{2}^{prime}left(r eta_{1}^{prime}+4right)+r eta_{1}^{prime 2}+4 eta_{1}^{prime}right}$

$+2 pi]^{-1}-frac{3 r}{pi}left[2 eta_{1}^{prime 2}left{16 alpha+6 alpha r^{2} eta_{2}^{prime prime}right.right.$

$-2 alpha r^{2}left(2 e^{eta_{2}}+1right) eta_{1}^{prime prime}-8 alpha r^{2} e^{eta_{2}}+4 alpha r^{2} e^{2 eta_{2}}$

$left.+4 alpha r^{2}-r^{2} e^{2 eta_{2}}-8 alpha e^{eta_{2}}right}$

$-alpha eta_{2}^{prime 2}left{4left(4left(3 r^{2}+e^{eta_{2}}-2right)+11 r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime prime}right)+left(2 e^{eta_{2}}+15right)right.$

$left.times r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime 2}+12 rleft(e^{eta_{2}}+6right) eta_{1}^{prime}right}$

$+2 eta_{2}^{prime}left{eta_{1}^{prime}left(4 alpha r^{2}left(e^{eta_{2}}+6right) eta_{1}^{prime prime}right.right.$

$-32 alpha-14 alpha r^{2} eta_{2}^{prime prime}+4 alpha r^{2}$

$left.+8 alpha r^{2} e^{eta_{2}}-4 alpha r^{2} e^{2 eta_{2}}+r^{2} e^{2 eta_{2}}+16 alpha e^{eta_{2}}right)$

$+alpha r^{2}left(2 e^{eta_{2}}+1right) eta_{1}^{prime 3}+2 rleft(8 alpha-28 alpha eta_{2}^{prime prime}right.$

$+2 alphaleft(3 e^{eta_{2}}+14right) eta_{1}^{prime prime}+12 alpha e^{eta_{2}}-4 alpha e^{2 eta_{2}}$

$left.left.+12 alpha r eta_{1}^{(3)}+e^{2 eta_{2}}right)+4 alpha rleft(3 e^{eta_{2}}+2right) eta_{1}^{prime 2}right}$

$-alpha r^{2}left(2 e^{eta_{2}}-1right) eta_{1}^{prime 4}+12 alpha r eta_{2}^{prime 3}left(r eta_{1}^{prime}+4right)$

$+4 rleft{4 alphaleft(2 eta_{2}^{(3)}+rleft(left(e^{eta_{2}}-1right)^{2}-eta_{1}^{(4)}right)right.right.$

$left.-4 eta_{1}^{(3)}right)+8 alpha r eta_{2}^{prime prime}left(eta_{1}^{prime prime}+1right)-alpha rleft(2 e^{eta_{2}}+3right) eta_{1}^{prime prime 2}$

$+rleft(4 alpha-8 alpha e^{eta_{2}}+(4 alpha-1) e^{2 eta_{2}}right)$

$left.times eta_{1}^{prime prime}right}+4 r eta_{1}^{prime}left{8 alpha+2 alpha r eta_{2}^{(3)}+16 alpha eta_{2}^{prime prime}right.$

$-2 alphaleft(3 e^{eta_{2}}+4right) eta_{1}^{prime prime}-6 alpha r eta_{1}^{(3)}-12 alpha e^{eta_{2}}$

$left.left.-e^{2 eta_{2}}+4 alpha e^{2 eta_{2}}right}-4 alpha rleft(3 e^{eta_{2}}-2right) eta_{1}^{prime 3}right]$

$-4 e^{eta_{2}} rleft[4 alpha r eta_{1}^{prime 2}left(2 r^{2} e^{eta_{2}}-2 r^{2} eta_{2}^{prime prime}-r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime prime}right.right.$

$left.-2 r^{2}+4 e^{eta_{2}}-12right)-alpha r^{3} eta_{1}^{prime 4}-12 alpha r^{2} eta_{2}^{prime 3}left(r eta_{1}^{prime}+4right)$

$+alpha r eta_{2}^{prime 2}left(44 r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime prime}+11 r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime 2}right.$

$left.+48 r^{2}+48 r eta_{1}^{prime}-64right)-4 rleft{4left(8 alpha-2 alpha r^{2} e^{eta_{2}}right.right.$

$+alpha r^{2} e^{2 eta_{2}}-alpha r^{2} eta_{1}^{(4)}+alpha r^{2}-12 alpha e^{eta_{2}}$

$+2 alpha r eta_{2}^{(3)}+4 alpha e^{2 eta_{2}}-4 alpha r eta_{1}^{(3)}+2 e^{eta_{2}}$

$left.-e^{2 eta_{2}}right)+8 alpha r^{2} eta_{2}^{prime prime}left(eta_{1}^{prime prime}+1right)-4 alphaleft(left(r^{2}+2right) e^{eta_{2}}right.$

$left.left.-r^{2}-4right) eta_{1}^{prime prime}-3 alpha r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime prime 2}right}-8 alpha r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime 3}$

$+8 alpha eta_{1}^{prime}left(2 r^{3} eta_{1}^{(3)}-6 r^{2} eta_{2}^{prime prime}+4 r^{2} e^{eta_{2}}-r^{3} eta_{2}^{(3)}right.$

$left.+2 r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime prime}-4 r^{2}+8 e^{eta_{2}}-16right)-2 eta_{2}^{prime}left{alphaleft(-r^{3}right) eta_{1}^{prime 3}right.$

$+2 alpha r eta_{1}^{prime}left(9 r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime prime}-2 r^{2}-7 r^{2} eta_{2}^{prime prime}right.$

$left.+2 r^{2} e^{eta_{2}}+4 e^{eta_{2}}-28right)-4 alpha r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime 2}$

$+4left(-16 alpha+6 alpha r^{3} eta_{1}^{(3)}-14 alpha r^{2} eta_{2}^{prime prime}+8 alpha r^{2} e^{eta_{2}}right.$

$left.left.left.+12 alpha r^{2} eta_{1}^{prime prime}-r^{2} e^{eta_{2}}+8 alpha e^{eta_{2}}right)right}right]$

$timesleft[2 rleft{2 alpha+(1-2 alpha) e^{eta_{2}}+alpha eta_{1}^{prime prime}right}-alpha eta_{2}^{prime}left(r eta_{1}^{prime}+4right)right.$

$left.+alpha r eta_{1}^{prime 2}+4 alpha eta_{1}^{prime}right]^{-1}=0$.

- For

, we obtain and the compactness becomes

- For

, we obtain and the compactness becomes

- For

, we obtain and the compactness becomes

5.2 Polytrope admitting vanishing complexity

-

symbolizes the polytropic constant, -

indicates the polytropic index, -

is the polytropic exponent.

- For

, we obtain and the compactness becomes

- For

, we obtain and the compactness becomes

- For

, we obtain and the compactness becomes

when

5.3 Vanishing complexity condition with a non-local equation of state

- For

, we obtain and the compactness becomes

- For

, we obtain and the compactness becomes

- For

, we obtain and the compactness becomes

6 Conclusions

factor. Furthermore, we have orthogonally split the curvature tensor, leading to the derivation of four distinct scalars accompanying various physical quantities. It was observed that a factor denoted as

Data Availability Statement This manuscript has no associated data or the data will not be deposited. [Authors’ comment: This is a theoretical study and no experimental data has been listed.]

Funded by SCOAP

References

- A.G. Riess et al., Astron. J. 116, 1009 (1998)

- S. Perlmutter et al., Astrophys. J. 517, 565 (1999)

- M. Tegmark et al., Phys. Rev. D 69, 103501 (2004)

- C.L. Bennett et al., Astrophys. J. 583, 1 (2003)

- D.N. Spergel et al., Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 148, 175 (2003)

- R.R. Caldwell, Phys. Lett. B 545, 23 (2002)

- S. Nojiri, S.D. Odintsov, Phys. Lett. B 565, 1 (2003)

- A. Sen, J. High Energy Phys. 04, 048 (2002)

- V. Gorini, A. Kamenshchik, U. Moschella, Phys. Rev. D 67, 063509 (2003)

- S. Nojiri, S.D. Odintsov, Phys. Rev. D 74, 086005 (2006)

- S. Capozziello, P. Martin-Moruno, C. Rubano, Phys. Lett. B 664, 12 (2008)

- S. Nojiri, S.D. Odintsov, TSPU Bulletin N8(110), 7 (2011)

- A.D. Felice, S. Tsujikawa, Living Rev. Relativ. 13, 3 (2010)

- J.L. Said, K.Z. Adami, Phys. Rev. D 83, 043008 (2011)

- S.K. Tripathy, B. Mishra, Eur. Phys. J. Plus 131, 273 (2016)

- A.S. Agrawal, S.K. Tripathy, B. Mishra, Chin. J. Phys. 71, 333 (2021)

- A.V. Astashenok, S. Capozziello, S.D. Odintsov, Phys. Lett. B 742, 160 (2015)

- G. Mustafa, I. Hussain, M.F. Shamir, Universe 6, 48 (2020)

- M.F. Shamir, A. Malik, G. Mustafa, Chin. J. Phys. 73, 634 (2021)

- L. Herrera, N.O. Santos, Phys. Rep. 286, 53 (1997)

- J. Ovalle, Phys. Rev. D 95, 104019 (2017)

- J. Ovalle, R. Casadio, R. da Rocha, A. Sotomayor, Eur. Phys. J. C 78, 122 (2018)

- L. Herrera, Phys. Rev. D 101, 104024 (2020)

- L. Herrera, J. Ospino, A. Di Prisco, Phys. Rev. D 77, 027502 (2008)

- G. Abellán, P. Bargueño, E. Contreras, E. Fuenmayor, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 29, 2050082 (2020)

- S. Chandrasekhar, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 93, 390 (1933)

- F.K. Liu, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 281, 197 (1996)

- G. Abellán, E. Fuenmayor, L. Herrera, Phys. Dark Universe 28, 100549 (2020)

- R.F. Tooper, Astrophys. J. 140, 434 (1964)

- S.A. Bludman, Astrophys. J. 183, 637 (1973)

- L. Herrera, W. Barreto, Phys. Rev. D 88, 084022 (2013)

- L. Herrera, A. Di Prisco, W. Barreto, J. Ospino, Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 46, 1827 (2014)

- G. Abellán, E. Fuenmayor, E. Contreras, L. Herrera, Phys. Dark Universe 30, 100632 (2020)

- K.R. Karmarkar, Proc. Indian Acad. Sci. Sect. A 27, 56 (1948)

- K.N. Singh, S.K. Maurya, F. Rahaman, F. Tello-Ortiz, Eur. Phys. J. C 79, 381 (2019)

- J. Ospino, L.A. Núñez, Eur. Phys. J. C 80, 166 (2020)

- G. Mustafa et al., Phys. Dark Universe 31, 100747 (2021)

- A. Ramos, C. Arias, E. Fuenmayor, E. Contreras, Eur. Phys. J. C 81, 203 (2021)

- M. Sharif, T. Naseer, Phys. Scr. 97, 055004 (2022)

- M. Sharif, T. Naseer, Phys. Scr. 97, 125016 (2022)

- L. Herrera, A. Di Prisco, J. Ospino, E. Fuenmayor, J. Math. Phys. 42, 2129 (2001)

- T. Naseer, M. Sharif, A. Fatima, S. Manzoor, Chin. J. Phys. 86, 350 (2023)

- R. López-Ruiz, H.L. Mancini, X. Calbet, Phys. Lett. A 209, 321 (1995)

- X. Calbet, R. López-Ruiz, Phys. Rev. E 63, 066116 (2001)

- C.P. Panos, N.S. Nikolaidis, K.C. Chatzisavvas, C.C. Tsouros, Phys. Lett. A 373, 2343 (2009)

- L. Herrera, Phys. Rev. D 97, 044010 (2018)

- L. Bel, Ann. Inst. Henri Poincaré 17, 37 (1961)

- L. Herrera, J. Ospino, A. Di Prisco, E. Fuenmayor, O. Troconis, Phys. Rev. D 79, 064025 (2009)

- L. Herrera, A. Di Prisco, J. Ospino, Phys. Rev. D 98, 104059 (2018)

- L. Herrera, A. Di Prisco, J. Ospino, Phys. Rev. D 99, 044049 (2019)

- M. Sharif, T. Naseer, Eur. Phys. J. Plus 137, 1304 (2022)

- M. Sharif, T. Naseer, Class. Quantum Gravity 40, 035009 (2023)

- M. Sharif, T. Naseer, Phys. Dark Universe 42, 101324 (2023)

- M. Sharif, T. Naseer, Ann. Phys. 453, 169311 (2023)

- M. Sharif, T. Naseer, Chin. J. Phys. 86, 596 (2023)

- M. Sharif, T. Naseer, Ann. Phys. 459, 169527 (2023)

- G. Abbas, H. Nazar, Eur. Phys. J. C 78, 510 (2018)

- G. Abbas, H. Nazar, Eur. Phys. J. C 78, 957 (2018)

- R. Manzoor, W. Shahid, Phys. Dark Universe 33, 100844 (2021)

- M. Sharif, T. Naseer, Chin. J. Phys. 77, 2655 (2022)

- M. Sharif, T. Naseer, Eur. Phys. J. Plus 137, 947 (2022)

- Z. Yousaf et al., Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 495, 4334 (2020)

- Z. Yousaf, M.Z. Bhatti, T. Naseer, Ann. Phys. 420, 168267 (2020)

- Z. Yousaf, M.Z. Bhatti, T. Naseer, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 29, 2050061 (2020)

- Z. Yousaf et al., Phys. Dark Universe 29, 100581 (2020)

- Z. Yousaf, M.Z. Bhatti, T. Naseer, Phys. Dark Universe 28, 100535 (2020)

- Z. Yousaf, M.Z. Bhatti, T. Naseer, Eur. Phys. J. Plus 135, 353 (2020)

- C. Arias, E. Contreras, E. Fuenmayor, A. Ramos, Ann. Phys. 436, 168671 (2022)

- T. Koivisto, Class. Quantum Gravity 23, 4289 (2006)

- K. Kainulainen, J. Piilonen, V. Reijonen, D. Sunhede, Phys. Rev. D 76, 024020 (2007)

- A.A. Starobinsky, Phys. Lett. B 91, 99 (1980)

- D. Kazanas, Astrophys. J. 241, L59 (1980)

- A.H. Guth, Phys. Rev. D 23, 347 (1981)

- A.A. Starobinsky, J. Exp. Theor. Phys. Lett. 30, 682 (1979)

- A.A. Starobinsky, Sov. Astron. Lett. 9, 302 (1983)

- M. Zubair, G. Abbas, Astrophys. Space Sci. 361, 342 (2016)

- R.C. Tolman, Phys. Rev. 35, 875 (1930)

- H. Hernández, L.A. Núñez, Can. J. Phys. 82, 29 (2004)

- M.S.R. Delgaty, K. Lake, Comput. Phys. Commun. 115, 395 (1998)

- B.V. Ivanov, Eur. Phys. J. C 77, 738 (2017)

- H.A. Buchdahl, Phys. Rev. 116, 1027 (1959)

- A. Alho, J. Natário, P. Pani, G. Raposo, Phys. Rev. D 106, L041502 (2022)

- L. Herrera, Phys. Lett. A 165, 206 (1992)

- H. Abreu, H. Hernández, L.A. Núñez, Class. Quantum Gravity 24, 4631 (2007)

- P.S. Florides, Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 337, 529 (1974)

e-mails: tayyabnaseer48@yahoo.com; tayyab.naseer@math.uol.edu.pk

e-mail: msharif.math@pu.edu.pk (corresponding author)