DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04451-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39994238

تاريخ النشر: 2025-02-24

بيانات علمية

مفتوح

تعليق

تطبيق مبادئ FAIR على سير العمل الحاسوبي

ملخص

تظهر الاتجاهات الحديثة في العلوم الحاسوبية وعلوم البيانات اعترافًا متزايدًا واعتمادًا على سير العمل الحاسوبية كأدوات للإنتاجية وإمكانية التكرار التي تعمل أيضًا على ديمقراطية الوصول إلى المنصات ومعرفة المعالجة. كأشياء رقمية يجب مشاركتها واكتشافها وإعادة استخدامها، تستفيد سير العمل الحاسوبية من مبادئ FAIR، التي تعني قابلة للاكتشاف، وقابلة للوصول، وقابلة للتشغيل المتبادل، وقابلة لإعادة الاستخدام. لقد تناولت مجموعة العمل لمبادئ FAIR في سير العمل (WCI-FW)، وهي مجتمع عالمي ومفتوح من الباحثين والمطورين الذين يعملون مع سير العمل الحاسوبية عبر التخصصات والمجالات، بشكل منهجي تطبيق كل من بيانات FAIR ومبادئ البرمجيات على سير العمل الحاسوبية. نقدم توصيات مع تعليق يعكس مناقشاتنا ويبرر خياراتنا وتعديلاتنا. هذه موجهة لمستخدمي سير العمل ومؤلفيها، ومطوري أنظمة إدارة سير العمل، ومقدمي خدمات سير العمل كإرشادات للتبني وموضوع للنقاش. ستعظم توصيات FAIR لسير العمل التي نقترحها في هذه الورقة قيمتها كأصول بحثية وتسهيل اعتمادها من قبل المجتمع الأوسع.

سير العمل الحاسوبية ولماذا تهم FAIR

تم تطبيق مبادئ FAIR على سير العمل الحاسوبية

- هل نحتاج إلى تخصيص مبادئ البرمجيات لتناسب الخصائص المحددة لسير العمل؟ نظرًا لأن سير العمل هي برامج تنفيذية، يجب أن تنطبق مبادئ البرمجيات. ومع ذلك، أدت خصائص المكونات غير المتجانسة التي تشكل سير العمل وسلوك المستخدم المتوقع لإعادة الاستخدام والتعديل والنقل إلى بعض التخصيص للمبادئ. هناك حاجة إلى معلومات تقنية تفصل مدخلات كل خطوة، والمخرجات، والاعتمادات، والمتطلبات الحاسوبية بالإضافة إلى ملفات التكوين، وقوائم الاعتمادات البرمجية، ومعلومات أخرى حول السياق التشغيلي. يعد السياق المفقود أحد الصعوبات الرئيسية التي تواجه عند النقل عبر منصات الحوسبة؛ يتطلب تطبيق FAIR على سير العمل وصفًا كاملاً للسياق اللازم لتنفيذ سير العمل كبرمجيات.

- إلى أي مدى تنطبق مبادئ البيانات على سير العمل ككائنات بيانات رقمية؟ غالبًا ما يتم تمثيل سير العمل ومكوناتها كمجموعات من الملفات، تمامًا مثل مجموعات البيانات الأخرى، وتُفسر هذه الملفات كأنواع مختلفة من الكائنات مثل كود المصدر، والبيانات الخام، ونماذج الذكاء الاصطناعي. تعزز سير العمل FAIR هذه الفكرة من خلال تشجيع “مجموعات بيانات” سير العمل الشاملة على تضمين بيانات وصفية مفصلة ووثائق لوصف هياكلها، وأغراضها، ومتطلباتها التقنية. طبقنا مبادئ FAIR للبيانات على مجموعة الملفات التي تمثل سير العمل. على سبيل المثال، يجب أن تتضمن هذه الملفات بيانات وصفية وصفية مثل العنوان، والمؤلفين، وتاريخ الإنشاء، والإصدار، بالإضافة إلى تواريخ الإصدار عند الإمكان. تحتاج سير العمل إلى معرفات دائمة تمامًا مثلما تحتاجها مجموعات البيانات الأخرى، ويجب أن تكون قابلة للوصول كبيانات يمكن استرجاعها عبر بروتوكولات مفتوحة. تحتاج سير العمل أيضًا إلى تراخيص توضح بوضوح الشروط التي يُسمح للآخرين بموجبها باستخدام وتعديل أجزاء أو الكل.

- نظرًا لأن FAIR يتعلق بشكل أساسي بالمعرفات الدائمة والبيانات الوصفية، ما الذي يجب تحديده لعملية العمل، وما هي البيانات الوصفية اللازمة؟ تعتبر عمليات العمل كائنات مركبة، حيث يحتاج الكائن بالكامل (مع معرف دائم وبيانات وصفية) وكذلك مكوناته (أيضًا مع معرفات دائمة وبيانات وصفية) إلى أن تكون جميعها FAIR. يمكن أن تكون المكونات القابلة للتنفيذ مستقلة عن عملية العمل (مثل استدعاءات الأدوات، على سبيل المثال)، أو مدمجة (برامج نصية داخلية)، أو عمليات عمل نفسها (حتى يتم تطبيق مبادئ FAIR بشكل متكرر). يمكن تفسير مكونات البيانات على أنها بيانات وأيضًا كبيانات وصفية. توفر عمليات العمل آليات للتنفيذ في عملية واحدة لمكونات مستقلة قد تكون FAIR بشكل مستقل، ولكن يجب أن تكون تجميعها في عملية عمل أيضًا FAIR.

| إرشادات | استنادًا إلى

|

| F1. يتم تعيين معرف فريد عالميًا ودائم لعملية العمل. | دي-إف1 و إس-إف1 |

| F1.1. يتم تعيين معرفات مميزة لمكونات سير العمل التي تمثل مستويات الدقة. | S-F1.1 |

| F1.2. يتم تعيين معرفات مميزة لإصدارات مختلفة من سير العمل. | S-F1.2 |

| F2. يتم وصف سير العمل ومكوناته ببيانات وصفية غنية. | دي-إف2 و إس-إف2 |

| F3. يجب أن تتضمن البيانات الوصفية بوضوح وبدقة معرف سير العمل وإصدارات سير العمل التي تصفها. | D-F3 و S-F3 |

| F4. يتم تسجيل أو فهرسة البيانات الوصفية وسير العمل في مورد FAIR قابل للبحث. | D-F4 و S-F4 |

| يمكن استرجاع سير العمل ومكوناته بواسطة معرّفاتها باستخدام بروتوكول اتصالات موحد. | دي-أيه 1 و إس-أيه 1 |

| أ1.1. البروتوكول مفتوح ومجاني وقابل للتنفيذ عالميًا. | D-A1.1 و S-A1.1 |

| A1.2. البروتوكول يسمح بإجراء مصادقة وتفويض، عند الضرورة. | D-A1.2 و S-A1.2 |

| أ2. البيانات الوصفية متاحة، حتى عندما لم يعد سير العمل متاحًا. | دي-أيه 2 و إس-أيه 2 |

| 1. تستخدم سير العمل وبياناته الوصفية (بما في ذلك أصل تشغيل سير العمل) لغة رسمية، يمكن الوصول إليها، مشتركة، شفافة، وقابلة للتطبيق على نطاق واسع لتمثيل المعرفة. | D-I1 و S-R1.2 |

| المعطيات الوصفية وسير العمل تستخدم مفردات تتبع مبادئ FAIR. | دي-آي2 |

| يتم تحديد سير العمل بطريقة تسمح لمكوناته بقراءة البيانات وكتابتها وتبادلها (بما في ذلك البيانات الوسيطة) بطريقة تتوافق مع المعايير ذات الصلة بالمجال. | D-R3 و S-I1 |

| يتضمن سير العمل وبياناته الوصفية (بما في ذلك أصل تشغيل سير العمل) مراجع مؤهلة لأشياء أخرى ومكونات سير العمل. | D-I3، S-I2، و S-R1.2 |

| R1. يتم وصف سير العمل بمجموعة من السمات الدقيقة والملائمة. | دي-آر1 وإس-آر1 |

| R1.1. تم إصدار سير العمل بترخيص واضح وسهل الوصول. | D-R1.1 و S-R1.1 |

| R1.2. يتم منح مكونات سير العمل التي تمثل مستويات الدقة تراخيص واضحة وسهلة الوصول. | D-R1.1 و S-R1.1 |

| يرتبط سير العمل R1.3 بأصل مفصل لسير العمل ومنتجات سير العمل. | D-R1.2 و S-R1.2 |

| R2. تتضمن سير العمل مراجع مؤهلة إلى سير عمل أخرى. | دي-آي3 و إس-آر2 |

| R3. يتوافق سير العمل مع معايير المجتمع ذات الصلة بالمجال. | D-R1.3 و S-R3 |

المبادئ R1.2 حيث يتم ربط البيانات (في هذه الحالة منتجات سير العمل) بأصل مفصل يجب أن يكون نظام سير العمل قادرًا على توفيره. إحدى فوائد استخدام أنظمة سير العمل المتكاملة هي التقاط الأصل (البيانات الوصفية) القابلة للتفسير بواسطة الكمبيوتر لتتبع تاريخ وأصل خطوات معالجة البيانات. تتوقع R1 و R3 أن تكون مجموعات البيانات المدخلة والمخرجة موصوفة بدقة مع بيانات مدخلة نموذجية وبيانات مخرجة متوقعة لكل خطوة تتوافق مع معايير هيكل البيانات وتنسيق الملفات.

أمثلة

العدالة تتجاوز مبادئ FAIR

الخاتمة

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 24 فبراير 2025

References

- Schintke, F. et al. Validity constraints for data analysis workflows. Future Generation Computer Systems 157, 82-97, https://doi. org/10.1016/j.future.2024.03.037 (2024).

- Di Tommaso, P. et al. Nextflow enables reproducible computational workflows. Nature Biotechnology 35, 316-319, https://doi. org/10.1038/nbt. 3820 (2017).

- Abueg, L. A. L. et al. The galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible, and collaborative data analyses: 2024 update. Nucleic Acids Research 52, W83-W94, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae410 (2024).

- Mölder, F. et al. Sustainable data analysis with snakemake. F1000Research 10, 33, https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.29032.2 (2021).

- Babuji, Y. et al. Parsl: Pervasive parallel programming in python, HPDC’19 https://doi.org/10.1145/3307681.3325400 (ACM, 2019).

- Kanwal, S., Khan, F. Z., Lonie, A. & Sinnott, R. O. Investigating reproducibility and tracking provenance -a genomic workflow case study. BMC Bioinformatics 18, 337, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-017-1747-0 (2017).

- Ferreira da Silva, R. et al. Workflows community summit 2022: A roadmap revolution https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 7750670 (2023).

- Garijo, D. et al. Workflow reuse in practice: A study of neuroimaging pipeline users 1, 239-246, https://doi.org/10.1109/ eScience.2014.33 (2014).

- Wilkinson, M. D. et al. The FAIR guiding principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 3, 160018, https://doi. org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18 (2016).

- Barker, M. et al. Introducing the FAIR principles for research software. Sci. Data 9, 622, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01710-x (2022).

- van Vlijmen, H. et al. The need of industry to go fair. Data Intelligence 2, 276-284, https://doi.org/10.1162/dint_a_00050 (2020).

- Harrow, I., Balakrishnan, R., Küçük McGinty, H., Plasterer, T. & Romacker, M. Maximizing data value for biopharma through fair and quality implementation: Fair plus q. Drug Discovery Today 27, 1441-1447, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2022.01.006 (2022).

- de Visser, C. et al. Ten quick tips for building FAIR workflows. PLoS Comput. Biol. 19, e1011369, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pcbi. 1011369 (2023).

- Goble, C. et al. FAIR computational workflows. Data Intell. 2, 108-121, https://doi.org/10.1162/dint_a_00033 (2020).

- Wolf, M. et al. Reusability first: Toward fair workflows, 444-455 https://doi.org/10.1109/Cluster48925.2021.00053 (2021).

- Wilkinson, S. R. et al. F*** workflows: when parts of FAIR are missing,

://doi.org/10.1109/eScience55777.2022.00090 (IEEE, 2022). - Niehues, A. et al. A multi-omics data analysis workflow packaged as a fair digital object. GigaScience 13, giad115, https://doi. org/10.1093/gigascience/giad115 (2024).

- Zulfiqar, M. et al. Implementation of fair practices in computational metabolomics workflows-a case study. Metabolites 14, 118, https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo14020118 (2024).

- Leo, S. et al. Recording provenance of workflow runs with ro-crate. PLOS ONE 19, e0309210, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone. 0309210 (2024).

- Crusoe, M. R. et al. Methods included: standardizing computational reuse and portability with the common workflow language. Communications of the ACM 65, 54-63, https://doi.org/10.1145/3486897 (2022).

- Voss, K., Auwera, G. V. D. & Gentry, J. Full-stack genomics pipelining with gatk4 + wdl + cromwell https://doi.org/10.7490/ f1000research. 1114634.1 (2017).

- Goble, C. et al. Implementing fair digital objects in the eosc-life workflow collaboratory https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 4605654 (2021).

- Yuen, D. et al. The dockstore: enhancing a community platform for sharing reproducible and accessible computational protocols. Nucleic Acids Research 49, W624-W632, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab346 (2021).

- Zhao, J. et al. Why workflows break – understanding and combating decay in taverna workflows https://doi.org/10.1109/ eScience.2012.6404482 (IEEE, 2012).

- Richardson, L. et al. MGnify: the microbiome sequence data analysis resource in 2023. Nucleic Acids Research 51, D753-D759, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac1080 (2022).

- Nicolae, B. et al. Building the

(interoperability) of fair for performance reproducibility of large-scale composable workflows in recup, 1-7 https://doi.org/10.1109/e-Science58273.2023.10254808 (2023). - Lamprecht, A.-L. et al. Perspectives on automated composition of workflows in the life sciences. F1000Research 10, 897, https://doi. org/10.12688/f1000research.54159.1 (2021).

- Cohen-Boulakia, S. et al. Scientific workflows for computational reproducibility in the life sciences: Status, challenges and opportunities. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 75, 284-298, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2017.01.012 (2017).

- Soiland-Reyes, S. et al. Making canonical workflow building blocks interoperable across workflow languages. Data Intelligence 4, 342-357, https://doi.org/10.1162/dint_a_00135 (2022).

- Ison, J. et al. EDAM: an ontology of bioinformatics operations, types of data and identifiers, topics and formats. Bioinformatics 29, 1325-1332, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt113 (2013).

- Leo, S. Run of digital pathology tissue/tumor prediction workflow https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 7774351 (2023).

- Khan, F. Z. et al. Sharing interoperable workflow provenance: A review of best practices and their practical application in cwlprov. GigaScience 8, giz095, https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giz095 (2019).

- Sefton, P. et al. Ro-crate metadata specification 1.1.3 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 7867028 (2023).

- Goode, A., Gilbert, B., Harkes, J., Jukic, D. & Satyanarayanan, M. Openslide: A vendor-neutral software foundation for digital pathology. Journal of Pathology Informatics 4, 27, https://doi.org/10.4103/2153-3539.119005 (2013).

- Hoyt, C. T. & Gyori, B. M. The o3 guidelines: open data, open code, and open infrastructure for sustainable curated scientific resources. Scientific Data 11, 547, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03406-w (2024).

- From a chat with @soilandreyes, the idea of “inner fair”, in the spirit of “inner source”. https://web.archive.org/web/20221224155747/ https://twitter.com/biocrusoe/status/976827491460493312. (2018).

- Turilli, M., Balasubramanian, V., Merzky, A., Paraskevakos, I. & Jha, S. Middleware building blocks for workflow systems. Computing in Science & Engineering 21, 62-75, https://doi.org/10.1109/MCSE.2019.2920048 (2019).

- Brack, P. et al. Ten simple rules for making a software tool workflow-ready. PLOS Computational Biology 18, e1009823, https://doi. org/10.1371/journal.pcbi. 1009823 (2022).

- Soiland-Reyes, S. et al. Packaging research artefacts with ro-crate. Data Science 5, 97-138, https://doi.org/10.3233/DS-210053 (2022).

- Antypas, K. B. et al. Enabling discovery data science through cross-facility workflows https://doi.org/10.1109/BigData52589.2021.9671421 (IEEE, 2021).

الشكر والتقدير

من قبل حلول التكنولوجيا والهندسة الوطنية في سانديا، LLC (NTESS)، وهي شركة مملوكة بالكامل لشركة هانيويل الدولية، لصالح إدارة الأمن النووي الوطنية التابعة لوزارة الطاقة الأمريكية (DOE/NNSA) بموجب العقد DE-NA0003525 (LP)؛ برنامج الاتحاد الأوروبي هورايزون أوروبا بموجب اتفاقيات المنح HORIZON-INFRA-2021-EOSC-01 101057388 (EuroScienceGateway)، HORIZON-INFRA-2023-EOSC-01-02 101129744 (EVERSE؛ SS)، HORIZON-INFRA-2021-EOSC-01-05 101057344 ومن قبل أبحاث المملكة المتحدة والابتكار (UKRI) بموجب منح ضمان تمويل هورايزون أوروبا من الحكومة البريطانية 10038963 (EuroScienceGateway؛ CG، S-SR)، 10038992 (FAIR-IMPACT؛ NJ)؛ الأسترالية BioCommons، التي تم تمكينها بواسطة NCRIS عبر تمويل Bioplatforms Australia (JG)؛ مؤسسة الأبحاث الألمانية (DFG، مؤسسة الأبحاث الألمانية) كجزء من GHGA – أرشيف الجينوم-الظاهرة البشري الألماني (www.ghga.de, رقم المنحة 441914366 (NFDI 1/1))؛ الوكالة الوطنية للبحث بموجب برنامج فرنسا 2030، مع الإشارة إلى ANR-22-PESN0007 (KB). تم تأليف هذه المخطوطة بواسطة UT-Battelle، LLC، بموجب العقد DE-AC0500OR22725 مع وزارة الطاقة الأمريكية (DOE). هذا العمل المكتوب مؤلف من قبل موظف في NTESS. الموظف، وليس NTESS، يمتلك الحق والملكية والمصلحة في العمل المكتوب وهو مسؤول عن محتوياته. أي آراء أو وجهات نظر ذات طابع شخصي قد يتم التعبير عنها في العمل المكتوب لا تمثل بالضرورة وجهات نظر الحكومة الأمريكية. تحتفظ الحكومة الأمريكية ويدرك الناشر، بقبول المقال للنشر، أن الحكومة الأمريكية تحتفظ بترخيص غير حصري، مدفوع، غير قابل للإلغاء، عالمي لنشر أو إعادة إنتاج الشكل المنشور لهذه المخطوطة، أو السماح للآخرين بذلك، لأغراض الحكومة الأمريكية. ستوفر وزارة الطاقة الوصول العام إلى نتائج هذه الأبحاث المدعومة من الحكومة الفيدرالية وفقًا لخطة الوصول العام لوزارة الطاقة (https://www.energy.gov/doe-public-access-plan).

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على www.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر تظل Springer Nature محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

© UT-Battelle، LLC والمؤلفون 2025

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04451-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39994238

Publication Date: 2025-02-24

scientific data

OPEN

COMMENT

Applying the FAIR Principles to computational workflows

Abstract

Recent trends within computational and data sciences show an increasing recognition and adoption of computational workflows as tools for productivity and reproducibility that also democratize access to platforms and processing know-how. As digital objects to be shared, discovered, and reused, computational workflows benefit from the FAIR principles, which stand for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. The Workflows Community Initiative’s FAIR Workflows Working Group (WCI-FW), a global and open community of researchers and developers working with computational workflows across disciplines and domains, has systematically addressed the application of both FAIR data and software principles to computational workflows. We present recommendations with commentary that reflects our discussions and justifies our choices and adaptations. These are offered to workflow users and authors, workflow management system developers, and providers of workflow services as guidelines for adoption and fodder for discussion. The FAIR recommendations for workflows that we propose in this paper will maximize their value as research assets and facilitate their adoption by the wider community.

Computational workflows and why FAIR matters

FAIR Principles applied to computational workflows

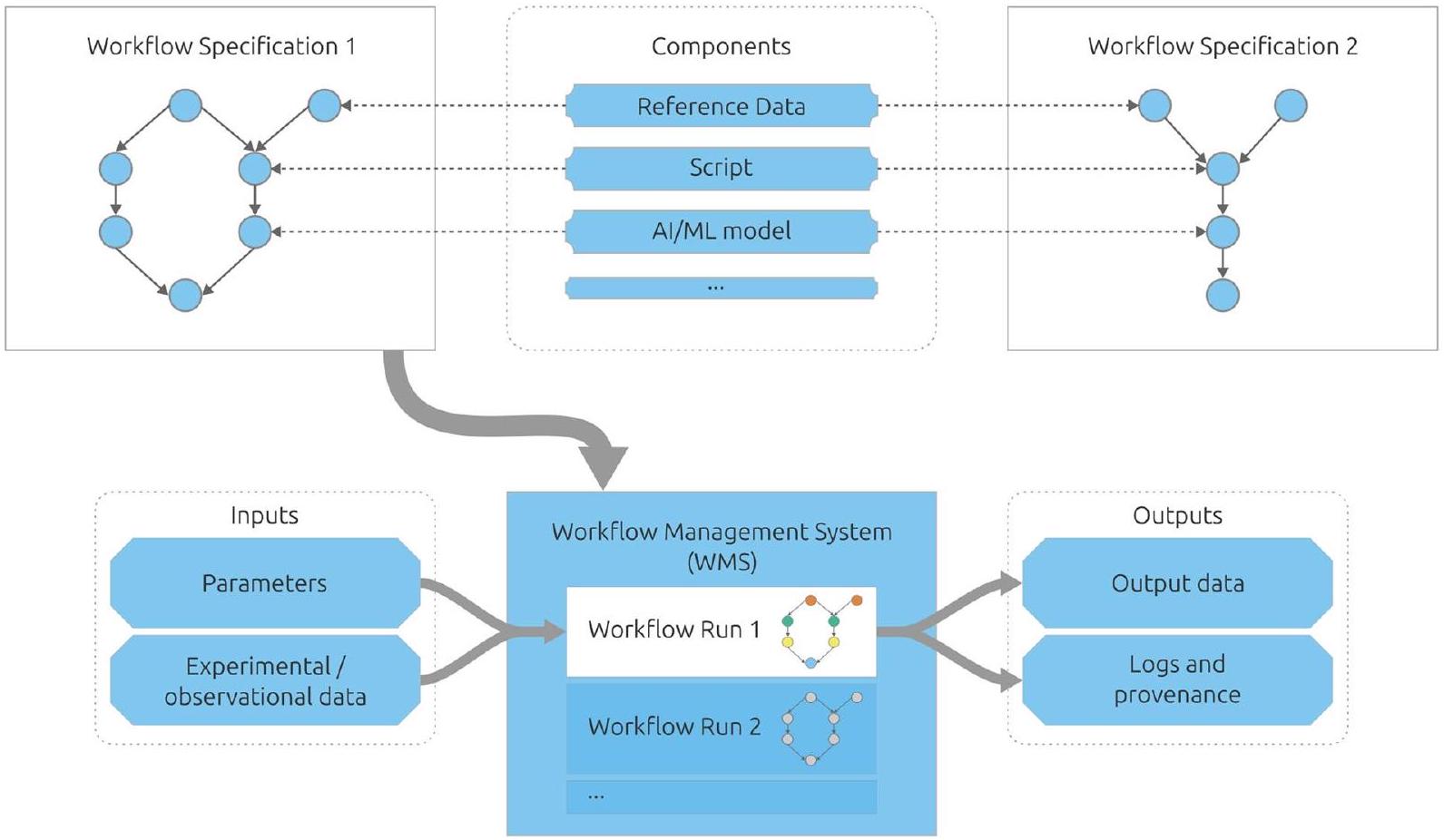

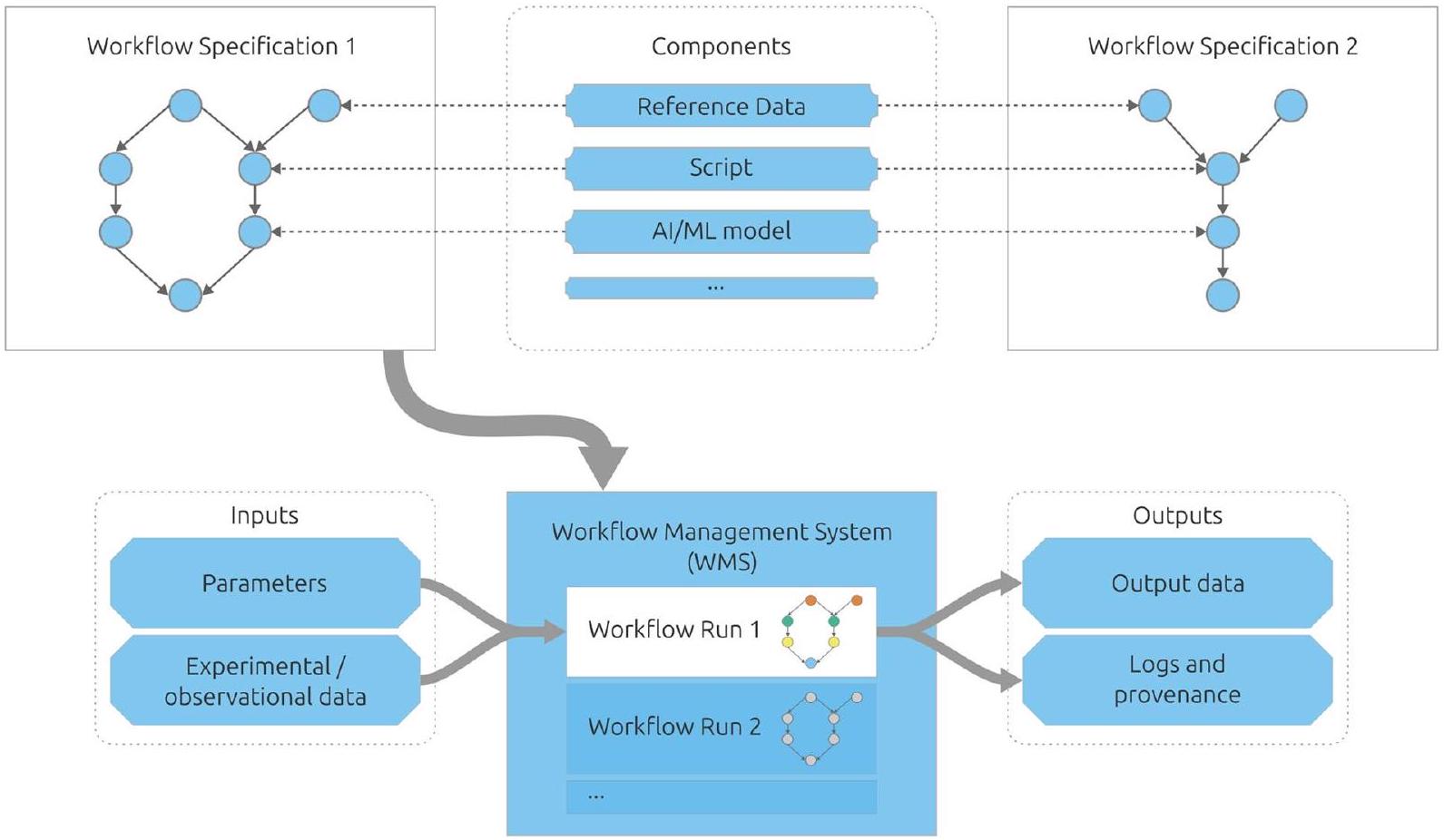

- Do we need to tailor software principles to the specific characteristics of workflows? As workflows are executables, the principles of software should apply. Nevertheless, the characteristics of the heterogeneous components that make up workflows and the expected user behavior of variant reuse, modification, and portability led us to some customization of the principles. Technical information is needed that details each step’s inputs, outputs, dependencies, and computational requirements as well as configuration files, lists of software dependencies, and other information about the operational context. Missing context is one of the main difficulties faced when porting across computing platforms; applying FAIR to workflows requires fully describing the context necessary for executing the workflows as software.

- How far do the data principles apply to workflows as digital data objects? Workflows and their components are frequently represented as collections of files, just like other datasets, and these files are interpreted as different kinds of objects like source code, raw data, and AI models. FAIR workflows augment this idea by encouraging comprehensive workflow “datasets” to include detailed metadata and documentation to describe their structures, purposes, and technical requirements. We applied the FAIR principles for data to the collection of files that represent the workflow. For example, these files should include descriptive metadata such as title, authors, creation date, and version, as well as version histories when possible. Workflows need persistent identifiers just like other datasets do, and they need to be accessible as data that can be retrieved over open protocols. Workflows also need licenses that explain clearly the conditions under which others are permitted to use and modify parts or the whole.

- Given that FAIR is primarily about persistent identifiers and metadata, what should be identified for a workflow, and what is the necessary metadata? Workflows are composite objects, where the entire object (with a persistent identifier and metadata) as well as its components (also with persistent identifiers and metadata), all in turn need to be FAIR. Executable components can be independent of the workflow (call-outs to tools, for example), embedded (internal scripts), or workflows themselves (so that FAIR principles are applied recursively). Data components may be interpreted as data and as metadata. Workflows provide mechanisms to execute in one run independent components that may be independently FAIR, but their aggregation into a workflow also needs to be FAIR.

| Guideline | Based on

|

| F1. A workflow is assigned a globally unique and persistent identifier. | D-F1 and S-F1 |

| F1.1. Components of the workflow representing levels of granularity are assigned distinct identifiers. | S-F1.1 |

| F1.2. Different versions of the workflow are assigned distinct identifiers. | S-F1.2 |

| F2. A workflow and its components are described with rich metadata. | D-F2 and S-F2 |

| F3. Metadata clearly and explicitly include the identifier of the workflow, and workflow versions, that they describe. | D-F3 and S-F3 |

| F4. Metadata and workflow are registered or indexed in a searchable FAIR resource. | D-F4 and S-F4 |

| A1. Workflow and its components are retrievable by their identifiers using a standardized communications protocol. | D-A1 and S-A1 |

| A1.1. The protocol is open, free, and universally implementable. | D-A1.1 and S-A1.1 |

| A1.2. The protocol allows for an authentication and authorization procedure, when necessary. | D-A1.2 and S-A1.2 |

| A2. Metadata are accessible, even when the workflow is no longer available. | D-A2 and S-A2 |

| I1. Workflow and its metadata (including workflow run provenance) use a formal, accessible, shared, transparent, and broadly applicable language for knowledge representation. | D-I1 and S-R1.2 |

| I2. Metadata and workflow use vocabularies that follow FAIR principles. | D-I2 |

| I3. Workflow is specified in a way that allows its components to read, write, and exchange data (including intermediate data), in a way that meets domain-relevant standards. | D-R3 and S-I1 |

| I4. Workflow and its metadata (including workflow run provenance) include qualified references to other objects and the workflow’s components. | D-I3, S-I2, and S-R1.2 |

| R1. Workflow is described with a plurality of accurate and relevant attributes. | D-R1 and S-R1 |

| R1.1. Workflow is released with a clear and accessible license. | D-R1.1 and S-R1.1 |

| R1.2. Components of the workflow representing levels of granularity are given clear and accessible licenses. | D-R1.1 and S-R1.1 |

| R1.3 Workflow is associated with detailed provenance of the workflow and of the products of the workflow. | D-R1.2 and S-R1.2 |

| R2. Workflow includes qualified references to other workflows. | D-I3 and S-R2 |

| R3. Workflow meets domain-relevant community standards. | D-R1.3 and S-R3 |

principles R1.2 where data (in this case the products of the workflow) are associated with detailed provenance that a workflow system should be able to provide. A benefit of using fully fledged workflow systems is the capture of computer-interpretable provenance (meta)data to track the history and origin of data processing steps. R1 and R3 expect that input and output datasets are thoroughly described with example input and expected output data for each step that adhere to data structure and file format standards

Examples

FAIRness beyond the FAIR Principles

Conclusion

Published online: 24 February 2025

References

- Schintke, F. et al. Validity constraints for data analysis workflows. Future Generation Computer Systems 157, 82-97, https://doi. org/10.1016/j.future.2024.03.037 (2024).

- Di Tommaso, P. et al. Nextflow enables reproducible computational workflows. Nature Biotechnology 35, 316-319, https://doi. org/10.1038/nbt. 3820 (2017).

- Abueg, L. A. L. et al. The galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible, and collaborative data analyses: 2024 update. Nucleic Acids Research 52, W83-W94, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae410 (2024).

- Mölder, F. et al. Sustainable data analysis with snakemake. F1000Research 10, 33, https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.29032.2 (2021).

- Babuji, Y. et al. Parsl: Pervasive parallel programming in python, HPDC’19 https://doi.org/10.1145/3307681.3325400 (ACM, 2019).

- Kanwal, S., Khan, F. Z., Lonie, A. & Sinnott, R. O. Investigating reproducibility and tracking provenance -a genomic workflow case study. BMC Bioinformatics 18, 337, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-017-1747-0 (2017).

- Ferreira da Silva, R. et al. Workflows community summit 2022: A roadmap revolution https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 7750670 (2023).

- Garijo, D. et al. Workflow reuse in practice: A study of neuroimaging pipeline users 1, 239-246, https://doi.org/10.1109/ eScience.2014.33 (2014).

- Wilkinson, M. D. et al. The FAIR guiding principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 3, 160018, https://doi. org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18 (2016).

- Barker, M. et al. Introducing the FAIR principles for research software. Sci. Data 9, 622, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01710-x (2022).

- van Vlijmen, H. et al. The need of industry to go fair. Data Intelligence 2, 276-284, https://doi.org/10.1162/dint_a_00050 (2020).

- Harrow, I., Balakrishnan, R., Küçük McGinty, H., Plasterer, T. & Romacker, M. Maximizing data value for biopharma through fair and quality implementation: Fair plus q. Drug Discovery Today 27, 1441-1447, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2022.01.006 (2022).

- de Visser, C. et al. Ten quick tips for building FAIR workflows. PLoS Comput. Biol. 19, e1011369, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pcbi. 1011369 (2023).

- Goble, C. et al. FAIR computational workflows. Data Intell. 2, 108-121, https://doi.org/10.1162/dint_a_00033 (2020).

- Wolf, M. et al. Reusability first: Toward fair workflows, 444-455 https://doi.org/10.1109/Cluster48925.2021.00053 (2021).

- Wilkinson, S. R. et al. F*** workflows: when parts of FAIR are missing,

://doi.org/10.1109/eScience55777.2022.00090 (IEEE, 2022). - Niehues, A. et al. A multi-omics data analysis workflow packaged as a fair digital object. GigaScience 13, giad115, https://doi. org/10.1093/gigascience/giad115 (2024).

- Zulfiqar, M. et al. Implementation of fair practices in computational metabolomics workflows-a case study. Metabolites 14, 118, https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo14020118 (2024).

- Leo, S. et al. Recording provenance of workflow runs with ro-crate. PLOS ONE 19, e0309210, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone. 0309210 (2024).

- Crusoe, M. R. et al. Methods included: standardizing computational reuse and portability with the common workflow language. Communications of the ACM 65, 54-63, https://doi.org/10.1145/3486897 (2022).

- Voss, K., Auwera, G. V. D. & Gentry, J. Full-stack genomics pipelining with gatk4 + wdl + cromwell https://doi.org/10.7490/ f1000research. 1114634.1 (2017).

- Goble, C. et al. Implementing fair digital objects in the eosc-life workflow collaboratory https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 4605654 (2021).

- Yuen, D. et al. The dockstore: enhancing a community platform for sharing reproducible and accessible computational protocols. Nucleic Acids Research 49, W624-W632, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab346 (2021).

- Zhao, J. et al. Why workflows break – understanding and combating decay in taverna workflows https://doi.org/10.1109/ eScience.2012.6404482 (IEEE, 2012).

- Richardson, L. et al. MGnify: the microbiome sequence data analysis resource in 2023. Nucleic Acids Research 51, D753-D759, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac1080 (2022).

- Nicolae, B. et al. Building the

(interoperability) of fair for performance reproducibility of large-scale composable workflows in recup, 1-7 https://doi.org/10.1109/e-Science58273.2023.10254808 (2023). - Lamprecht, A.-L. et al. Perspectives on automated composition of workflows in the life sciences. F1000Research 10, 897, https://doi. org/10.12688/f1000research.54159.1 (2021).

- Cohen-Boulakia, S. et al. Scientific workflows for computational reproducibility in the life sciences: Status, challenges and opportunities. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 75, 284-298, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2017.01.012 (2017).

- Soiland-Reyes, S. et al. Making canonical workflow building blocks interoperable across workflow languages. Data Intelligence 4, 342-357, https://doi.org/10.1162/dint_a_00135 (2022).

- Ison, J. et al. EDAM: an ontology of bioinformatics operations, types of data and identifiers, topics and formats. Bioinformatics 29, 1325-1332, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt113 (2013).

- Leo, S. Run of digital pathology tissue/tumor prediction workflow https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 7774351 (2023).

- Khan, F. Z. et al. Sharing interoperable workflow provenance: A review of best practices and their practical application in cwlprov. GigaScience 8, giz095, https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giz095 (2019).

- Sefton, P. et al. Ro-crate metadata specification 1.1.3 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 7867028 (2023).

- Goode, A., Gilbert, B., Harkes, J., Jukic, D. & Satyanarayanan, M. Openslide: A vendor-neutral software foundation for digital pathology. Journal of Pathology Informatics 4, 27, https://doi.org/10.4103/2153-3539.119005 (2013).

- Hoyt, C. T. & Gyori, B. M. The o3 guidelines: open data, open code, and open infrastructure for sustainable curated scientific resources. Scientific Data 11, 547, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03406-w (2024).

- From a chat with @soilandreyes, the idea of “inner fair”, in the spirit of “inner source”. https://web.archive.org/web/20221224155747/ https://twitter.com/biocrusoe/status/976827491460493312. (2018).

- Turilli, M., Balasubramanian, V., Merzky, A., Paraskevakos, I. & Jha, S. Middleware building blocks for workflow systems. Computing in Science & Engineering 21, 62-75, https://doi.org/10.1109/MCSE.2019.2920048 (2019).

- Brack, P. et al. Ten simple rules for making a software tool workflow-ready. PLOS Computational Biology 18, e1009823, https://doi. org/10.1371/journal.pcbi. 1009823 (2022).

- Soiland-Reyes, S. et al. Packaging research artefacts with ro-crate. Data Science 5, 97-138, https://doi.org/10.3233/DS-210053 (2022).

- Antypas, K. B. et al. Enabling discovery data science through cross-facility workflows https://doi.org/10.1109/BigData52589.2021.9671421 (IEEE, 2021).

Acknowledgements

by National Technology & Engineering Solutions of Sandia, LLC (NTESS), a wholly owned subsidiary of Honeywell International Inc., for the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration (DOE/NNSA) under contract DE-NA0003525 (LP); the European Union programme Horizon Europe under grant agreements HORIZON-INFRA-2021-EOSC-01 101057388 (EuroScienceGateway), HORIZON-INFRA-2023-EOSC-01-02 101129744 (EVERSE; SS), HORIZON-INFRA-2021-EOSC-01-05 101057344 and by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) under the UK government’s Horizon Europe funding guarantee grants 10038963 (EuroScienceGateway; CG, S-SR), 10038992 (FAIR-IMPACT; NJ); Australian BioCommons, which is enabled by NCRIS via Bioplatforms Australia funding (JG); Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) as part of GHGA – The German Human Genome-Phenome Archive (www.ghga.de, Grant Number 441914366 (NFDI 1/1)); the National Research Agency under the France 2030 program, with reference to ANR-22-PESN0007 (KB). This manuscript has been authored by UT-Battelle, LLC, under contract DE-AC0500OR22725 with the US Department of Energy (DOE). This written work is authored by an employee of NTESS. The employee, not NTESS, owns the right, title and interest in and to the written work and is responsible for its contents. Any subjective views or opinions that might be expressed in the written work do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Government. The US government retains and the publisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges that the US government retains a nonexclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, worldwide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this manuscript, or allow others to do so, for US government purposes. DOE will provide public access to these results of federally sponsored research in accordance with the DOE Public Access Plan (https://www.energy.gov/doe-public-access-plan).

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

© UT-Battelle, LLC and the Authors 2025