DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14030047

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38534908

تاريخ النشر: 2024-03-17

دراسة قبول الطلاب واستخدامهم لـ ChatGPT في التعليم العالي السعودي

تمت المراجعة: 10 مارس 2024

تم القبول: 15 مارس 2024

نُشر: 17 مارس 2024

الملخص

تدرس هذه الدراسة قبول الطلاب واستخدامهم لـ ChatGPT في التعليم العالي في المملكة العربية السعودية، حيث يزداد الاهتمام باستخدام هذه الأداة منذ إطلاقها في عام 2022. تم جمع بيانات البحث الكمي، من خلال استبيان ذاتي يعتمد على “النظرية الموحدة لقبول واستخدام التكنولوجيا” (UTAUT2)، من 520 طالبًا في إحدى الجامعات العامة في السعودية في بداية الفصل الدراسي الأول من العام الدراسي 2023-2024. دعمت نتائج نمذجة المعادلات الهيكلية جزئيًا UTAUT والبحوث السابقة فيما يتعلق بالتأثير المباشر الكبير لتوقع الأداء (PE) والتأثير الاجتماعي (SI) وتوقع الجهد (EE) على النية السلوكية (BI) لاستخدام ChatGPT، والتأثير المباشر الكبير لـ PE وSI وBI على الاستخدام الفعلي لـ ChatGPT. ومع ذلك، لم تدعم النتائج الأبحاث السابقة فيما يتعلق بالعلاقة المباشرة بين الظروف الميسرة (FCs) وكلا من BI والاستخدام الفعلي لـ ChatGPT، والتي وُجد أنها سلبية في العلاقة الأولى وغير ذات دلالة في الثانية. كانت هذه النتائج بسبب غياب الموارد والدعم والمساعدة من المصادر الخارجية فيما يتعلق باستخدام ChatGPT. أظهرت النتائج وجود وساطة جزئية لـ BI في الرابط بين PE وSI وFC والاستخدام الفعلي لـ ChatGPT في التعليم، ووساطة كاملة في الرابط بين BI وEE والاستخدام الفعلي لـ ChatGPT في التعليم. تقدم النتائج العديد من الدلالات للباحثين ومؤسسات التعليم العالي في السعودية، والتي تهم أيضًا مؤسسات أخرى في سياقات مشابهة.

1. المقدمة

من المتوقع أن يتأثر سلبًا. لذلك، تم الإشارة إلى أنه يجب على المؤسسات الأكاديمية اتخاذ الحذر لمنع الاعتماد المفرط من قبل الطلاب على استخدام ChatGPT لأغراض أكاديمية [1].

2. مراجعة الأدبيات

2.1. قبول الطلاب لـ ChatGPT ونواياهم السلوكية

أو تعقيد استخدام التكنولوجيا [13،22]. تلعب دورًا رئيسيًا في تشكيل استعداد الناس ونواياهم للتفاعل مع نموذج اللغة [12]. جادل مينون وشيلبا [15] بأن تصور الطلاب لـ ChatGPT كأداة سهلة الاستخدام، وسهلة الفهم، ومتكاملة بسلاسة في الأنشطة اليومية يؤثر بشكل إيجابي على نواياهم السلوكية. علاوة على ذلك، تشير الدراسات الحديثة، مثل المراجع.

H2: للتعليم تأثير إيجابي كبير على نية استخدام ChatGPT في التعليم.

H3: لدى SI تأثير إيجابي كبير على BI لاستخدام ChatGPT في التعليم.

H4: FC له تأثير إيجابي كبير على BI لاستخدام ChatGPT في التعليم.

2.2. قبول الطلاب والاستخدام الفعلي لـ ChatGPT

H6: للتعليم الإلكتروني تأثير إيجابي كبير على استخدام ChatGPT.

H7: لدى SI تأثير إيجابي كبير على استخدام ChatGPT.

H8: لدى مراكز الاتصال تأثير إيجابي كبير على استخدام ChatGPT.

2.3. الذكاء التجاري واستخدام ChatGPT

2.4. دور ذكاء الأعمال في العلاقة بين قبول الطلاب واستخدام ChatGPT

H11: تلعب أنظمة المعلومات التجارية دور الوسيط بين الانخراط في العمل واستخدام ChatGPT.

H12: الوسائط التجارية تربط بين الذكاء الاصطناعي واستخدام ChatGPT.

H13: تلعب أنظمة المعلومات التجارية دور الوسيط بين التواصل الفعال واستخدام ChatGPT.

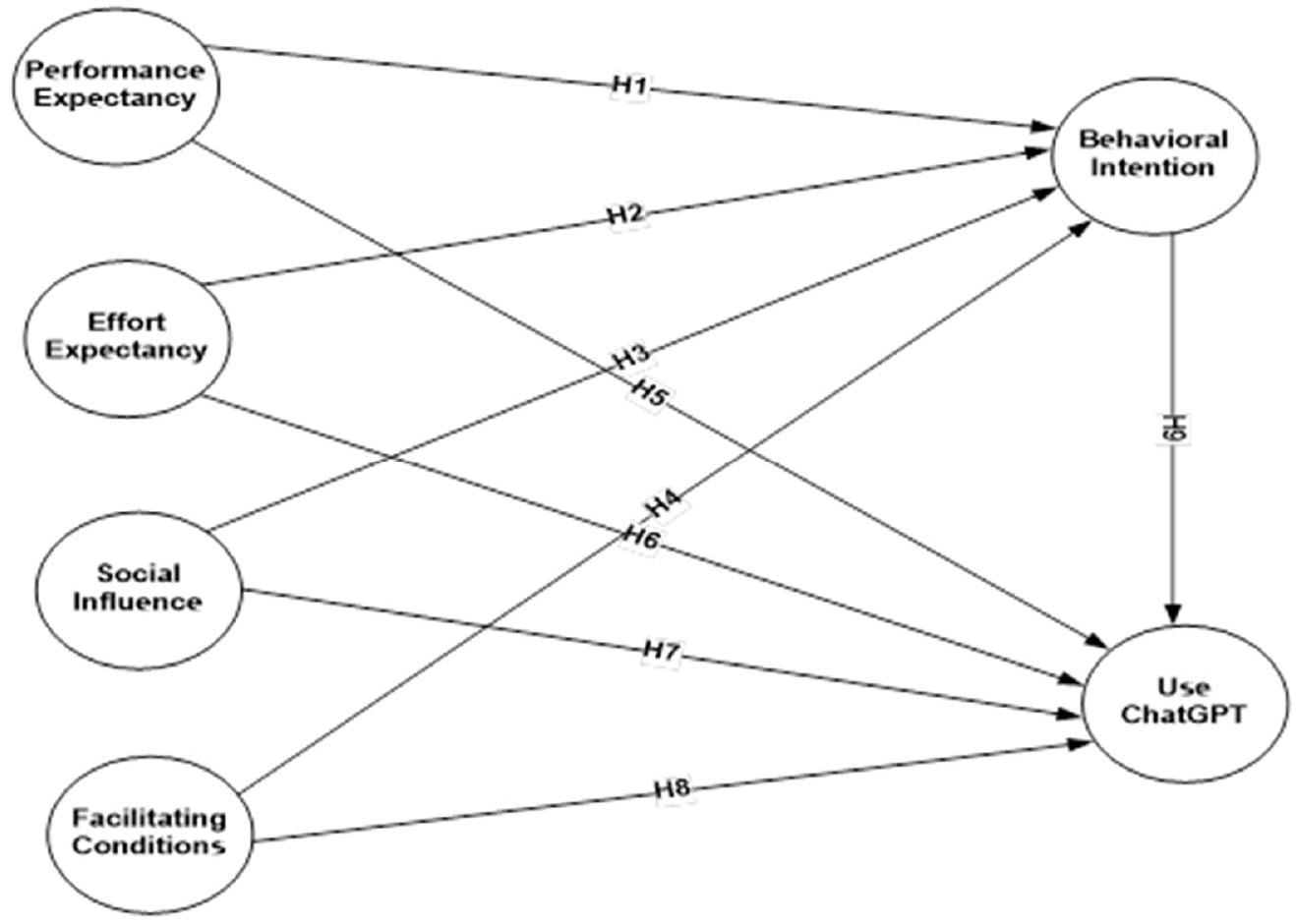

يتم تقديم ملخص لجميع العلاقات في الإطار المفاهيمي للبحث أدناه (الشكل 1).

3. الطرق

3.1. قياس وتطوير المقياس

3.2. عينة البحث وطريقة جمع البيانات

3.3. تحليل البيانات

| ملف شخصي | التردد | % | |

| جنس | ذكر | ٢٨٥ | ٥٤.٨ |

| أنثى | 235 | ٤٥.٢ | |

| أقل من 20 عامًا | 241 | ٤٦.٣ | |

| عمر | من 20 إلى 25 سنة | 267 | ٥١.٣ |

| من 26 إلى 30 عامًا | 12 | ٢.٤ | |

| سنة أولى | ١١٦ | ٢٢.٢ | |

| السنة الثانية | 123 | ٢٣.٧ | |

| مستوى الدراسة | السنة الثالثة | 147 | ٢٨.٣ |

| السنة الرابعة | ١٣٤ | ٢٥.٨ | |

| لا | 113 | 21.7 |

4. نتائج الدراسة

تتجاوز القيم 0.9، مما يثير القلق بشأن صلاحية التمييز. ومع ذلك، كما هو موضح في الجدول 3، تظل جميع النسب أقل من القيمة المحددة 0.9، مما يؤكد صلاحية التمييز.

| متغيرات ومكونات المقياس | التحميلات | VIF | |

| PE: (

|

|||

| PE1 | تشات جي بي تي أداة قيمة لمشاريعي الأكاديمية | 0.861 | 1.613 |

| PE2 | استخدام ChatGPT يزيد من احتمال تحقيق الأهداف المهمة في مساعيك الأكاديمية | 0.791 | 1.710 |

| PE3 | “تشات جي بي تي يعزز الإنتاجية في الدراسات الأكاديمية من خلال تسريع إنجاز المهام والمشاريع” | 0.789 | 1.523 |

| PE4 | استخدام ChatGPT يمكن أن يرفع من أدائي الأكاديمي | 0.734 | 1.613 |

| EE: (

|

|||

| EE1 | أجد أنه من السهل تعلم كيفية استخدام ChatGPT | 0.910 | ٤.٠٣٣ |

| EE2 | التواصل مع ChatGPT شفاف وسهل الفهم | 0.952 | ٤.٨٣٢ |

| EE3 | “تشات جي بي تي سهل الاستخدام وبديهي” | 0.924 | ٤.٢٥٦ |

| EE4 | أجد أنه من السهل اكتساب الخبرة في استخدام ChatGPT | 0.913 | 3.679 |

| SI: (

|

|||

| SI1 | “الأشخاص الذين يلعبون دورًا حاسمًا في حياتي يرون أنه يجب علي استخدام ChatGPT” | 0.898 | 1.806 |

| SI2 | “الأشخاص الذين يشكلون سلوكي يوصون باستخدام ChatGPT” | 0.830 | ٢.٢٨٧ |

| SI3 | “أولئك الذين أكن لهم تقديراً عالياً يقترحون أن أستفيد من ChatGPT” | 0.885 | 2.835 |

| FC:

|

|||

| FC1 | أنا مجهز بشكل كافٍ بالموارد اللازمة لاستخدام ChatGPT | 0.864 | 3.984 |

| FC2 | أنا متمكن في استخدام ChatGPT بفضل المعرفة المكتسبة | 0.855 | ٤.٠٣٥ |

| FC3 | “تشات جي بي تي مناسب للتقنيات التي أستخدمها” | 0.957 | ٤.١٥٧ |

| FC4 | عند مواجهة صعوبات مع ChatGPT، من الممكن الحصول على الدعم والمساعدة من مصادر خارجية | 0.953 | ٣.٩٨٤ |

|

|

|||

| بي 1 | لقد قررت الاستمرار في استخدام ChatGPT في الأوقات القادمة | 0.900 | ٢.٣٦٦ |

| بي 2 | أنا ملتزم باستخدام ChatGPT كأداة لدراستي | 0.906 | ٢.٣٤٣ |

| بي 3 | أهدف إلى الاستمرار في استخدام ChatGPT بشكل متكرر | 0.783 | 1.572 |

| الاستخدام الفعلي (AU) (

|

|||

| AU1 | أعتزم استخدام المعرفة والمهارات التي اكتسبتها من ChatGPT في أنشطتي التعليمية | 0.785 | 1.578 |

| AU2 | المعرفة والمهارات التي اكتسبتها من ChatGPT ستكون مفيدة لي في الصف | 0.947 | ٤.١٣٤ |

| AU3 | استخدام ChatGPT ساعد في تحسين أدائي الأكاديمي | 0.894 | ٤.١٠٩ |

| ذكاء الأعمال | EE | نادي كرة القدم | التربية البدنية | نعم | الاستخدام | |

| ذكاء الأعمال | 0.864 | |||||

| EE | 0.058 [0.73] | 0.925 | ||||

| نادي كرة القدم | -0.171 [0.154] | 0.450 [0.523] | 0.908 | |||

| التربية البدنية | 0.297 [0.354] | 0.166 [0.188] | -0.027 [0.066] | 0.795 | ||

| نعم | 0.319 [0.361] | -0.136 [0.159] | -0.046 [0.045] | -0.293 [0.354] | 0.872 | |

| الاستخدام | 0.801 [0.195] | 0.017 [0.044] | -0.160 [0.141] | 0.348 [0.417] | 0.286 [0.312] | 0.878 |

| طرق | معامل المسار |

|

|

النتائج |

| PE -> BI [H1]. | 0.398 | 6.346 | 0.000 | مقبول |

| EE -> BI [H2]. | 0.144 | ٢.٥٩٦ | 0.009 | مقبول |

| SI -> BI [H3]. | 0.445 | ٧.٠٩٥ | 0.000 | مقبول |

| FC -> BI [H4]. | -0.204 | ٤.٦٣٥ | 0.000 | مرفوض |

| استخدام ChatGPT [H5]. | 0.141 | ٤.٤٨٩ | 0.000 | مقبول |

| EE -> استخدام ChatGPT [H6]. | -0.042 | 1.610 | 0.107 | مرفوض |

| استخدام ChatGPT [H7]. | 0.070 | ٢.٦٠٣ | 0.009 | مقبول |

| FC -> استخدام ChatGPT [H8]. | 0.001 | 0.026 | 0.979 | مرفوض |

| استخدام BI -> ChatGPT [H9]. | 0.789 | ٢٧.٣٦٦ | 0.000 | مقبول |

| مسارات غير مباشرة محددة | ||||

| PE -> BI -> استخدام ChatGPT [H10]. | 0.314 | 6.076 | 0.000 | مقبول |

| EE -> BI -> استخدام ChatGPT [H11]. | 0.114 | ٢.٥٧٥ | 0.010 | مقبول |

| استخدام SI -> BI -> ChatGPT [H12]. | 0.352 | 6.708 | 0.000 | مقبول |

| FC -> BI -> استخدام ChatGPT [H13]. | -0.161 | ٤.٥٤٠ | 0.000 | مقبول |

5. المناقشة والآثار

بين FC والاستخدام الفعلي لـ ChatGPT في التعليم. مرة أخرى، أدى نقص الموارد المتاحة والدعم المقدم للطلاب إلى تطويرهم لمشاعر سلبية تجاه BI وكان له تأثير غير ملحوظ على استخدامهم لـ ChatGPT في التعليم.

6. القيود واتجاهات البحث المستقبلية

7. الاستنتاجات

on تعلم الطلاب للحفاظ على نتائج تعلم مستدامة. وبالتالي، يجب عليهم تشجيع الاستخدام المسؤول والأخلاقي لـ ChatGPT لأغراض أكاديمية.

مساهمات المؤلفين: التصور، A.E.E.S.، I.A.E. و A.M.H.; المنهجية، I.A.E.، A.E.E.S. و A.M.H.; البرمجيات، I.A.E.; التحقق، A.E.E.S. و I.A.E.; التحليل الرسمي، I.A.E. و A.E.E.S.; التحقيق A.E.E.S.، A.M.H. و I.A.E.; الموارد، A.E.E.S.; تنسيق البيانات، A.E.E.S. و I.A.E.; الكتابة – إعداد المسودة الأصلية، I.A.E.، A.E.E.S. و A.M.H.; الكتابة – المراجعة والتحرير، A.E.E.S. و I.A.E.; التصور، A.M.H. و I.A.E.; الإشراف، I.A.E.; إدارة المشروع، A.E.E.S.، I.A.E. و A.M.H.; الحصول على التمويل، A.E.E.S. جميع المؤلفين قرأوا ووافقوا على النسخة المنشورة من المخطوطة.

بيان توفر البيانات: البيانات متاحة عند الطلب من الباحثين الذين يستوفون معايير الأهلية. يرجى الاتصال بالمؤلف الأول بشكل خاص عبر البريد الإلكتروني.

References

- Hasanein, A.M.; Sobaih, A.E.E. Drivers and Consequences of ChatGPT Use in Higher Education: Key Stakeholder Perspectives. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 2599-2614. [CrossRef]

- Benuyenah, V. Commentary: ChatGPT use in higher education assessment: Prospects and epistemic threats. J. Res. Innov. Teach. Learn. 2023, 16, 134-135. [CrossRef]

- Rasul, T.; Nair, S.; Kalendra, D.; Robin, M.; Santini, F.d.O.; Ladeira, W.J.; Sun, M.; Day, I.; Rather, R.A.; Heathcote, L. The role of ChatGPT in higher education: Benefits, challenges, and future research directions. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2023, 6, 41-56.

- Strzelecki, A. To use or not to use ChatGPT in higher education? A study of students’ acceptance and use of technology. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Obaid, O.I.; Ali, A.H.; Yaseen, M.G. Impact of Chat GPT on Scientific Research: Opportunities, Risks, Limitations, and Ethical Issues. Iraqi J. Comput. Sci. Math. 2023, 4, 13-17. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Watanobe, Y. ChatGPT for education and research: Opportunities, threats, and strategies. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5783. [CrossRef]

- King, M.R. ChatGPT. A conversation on artificial intelligence, chatbots, and plagiarism in higher education. Cell Mol. Bioeng. 2023, 16, 1-2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, B.D.; Wang, T.; Mannuru, N.R.; Nie, B.; Shimray, S.; Wang, Z. ChatGPT and a new academic reality: Artificial Intelligencewritten research papers and the ethics of the large language models in scholarly publishing. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2023, 74, 570-581. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M.; Rauschenberger, M.; Schön, E.M. “We Need to Talk About ChatGPT”: The Future of AI and Higher Education. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACM 5th International Workshop on Software Engineering Education for the Next Generation (SEENG), Melbourne, Australia, 16 May 2023.

- Alotaibi, N.S.; Alshehri, A.H. Prospers and obstacles in using artificial intelligence in Saudi Arabia higher education institutions-The potential of AI-based learning outcomes. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10723. [CrossRef]

- Magsamen-Conrad, K.; Upadhyaya, S.; Joa, C.Y.; Dowd, J. Bridging the divide: Using UTAUT to predict multigenerational tablet adoption practices. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 186-196. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, V. Adoption and use of AI tools: A research agenda grounded in UTAUT. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 308, 641-652. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425-478. [CrossRef]

- Shahsavar, Y.; Choudhury, A. User Intentions to Use ChatGPT for Self-Diagnosis and Health-Related Purposes: Cross-sectional Survey Study. JMIR Hum. Factors 2023, 10, e47564. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, D.; Shilpa, K. “Chatting with ChatGPT”: Analyzing the factors influencing users’ intention to Use the Open AI’s ChatGPT using the UTAUT model. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20962. [CrossRef]

- Fagan, M.; Kilmon, C.; Pandey, V. Exploring the adoption of a virtual reality simulation: The role of perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness and personal innovativeness. Campus-Wide Inf. Syst. 2012, 29, 117-127. [CrossRef]

- Kasilingam, D.L. Understanding the attitude and intention to use smartphone chatbots for shopping. Technol. Soc. 2020, 62, 101280. [CrossRef]

- Brachten, F.; Kissmer, T.; Stieglitz, S. The acceptance of chatbots in an enterprise context—A survey study. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 60, 102375. [CrossRef]

- Mogaji, E.; Balakrishnan, J.; Nwoba, A.C.; Nguyen, N.P. Emerging-market consumers’ interactions with banking chatbots. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 65, 101711. [CrossRef]

- Bin-Nashwan, S.A.; Sadallah, M.; Bouteraa, M. Use of ChatGPT in academia: Academic integrity hangs in the balance. Technol. Soc. 2023, 75, 102370. [CrossRef]

- Al-Emran, M.; AlQudah, A.A.; Abbasi, G.A.; Al-Sharafi, M.A.; Iranmanesh, M. Determinants of using AI-based chatbots for knowledge sharing: Evidence from PLS-SEM and fuzzy sets (fsQCA). IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 71, 4985-4999. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157-178. [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, B.; Senali, M.G.; Iranmanesh, M.; Khanfar, A.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Annamalai, N.; Naghmeh-Abbaspour, B. Determinants of Intention to Use ChatGPT for Educational Purposes: Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. Int. J. Human-Computer Interact. 2023, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Shaengchart, Y.; Bhumpenpein, N.; Kongnakorn, K.; Khwannu, P.; Tiwtakul, A.; Detmee, S. Factors influencing the acceptance of ChatGPT usage among higher education students in Bangkok, Thailand. Adv. Knowl. Exec. 2023, 2, 1-14.

- Tiwari, C.K.; Bhat, M.A.; Khan, S.T.; Subramaniam, R.; Khan, M.A.I. What drives students toward ChatGPT? An investigation of the factors influencing adoption and usage of ChatGPT. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 2023, ahead-of-print.

- Jo, H. Understanding AI tool engagement: A study of ChatGPT usage and word-of-mouth among university students and office workers. Telemat. Inform. 2023, 85, 102067. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Huo, Y. Are users willing to embrace ChatGPT? Exploring the factors on the acceptance of chatbots from the perspective of AIDUA framework. Technol. Soc. 2023, 75, 102362. [CrossRef]

- Oye, N.D.; A.Iahad, N.; Ab.Rahim, N. The history of UTAUT model and its impact on ICT acceptance and usage by academicians. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2014, 19, 251-270. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S.; Soliman, M. Game of algorithms: ChatGPT implications for the future of tourism education and research. J. Tour. Futur. 2023, 9, 214-221. [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K.Y.; Zhou, W. Deconstructing Student Perceptions of Generative AI (GenAI) through an Expectancy Value Theory (EVT)-based Instrument. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.01186.

- Duong, C.D.; Vu, T.N.; Ngo, T.V.N. Applying a modified technology acceptance model to explain higher education students’ usage of ChatGPT: A serial multiple mediation model with knowledge sharing as a moderator. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2023, 21, 100883. [CrossRef]

- Terblanche, N.; Kidd, M. Adoption factors and moderating effects of age and gender that influence the intention to use a non-directive reflective coaching chatbot. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221096136. [CrossRef]

- Anayat, S.; Rasool, G.; Pathania, A. Examining the context-specific reasons and adoption of artificial intelligence-based voice assistants: A behavioural reasoning theory approach. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 1885-1910. [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Wu, Y. An Empirical Study of Adoption of ChatGPT for Bug Fixing among Professional Developers. Innov. Technol. Adv. 2023, 1, 21-29. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Lin, Y.; Yu, Z. Factors Influencing Learner Attitudes Towards ChatGPT-Assisted Language Learning in Higher Education. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2023, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitudes and normative beliefs as factors influencing behavioral intentions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1972, 21, 1. [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill Series in Psychology; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994.

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated Guidelines on Which Method to Use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107. [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing. In Advances in International Marketing; Sinkovics, R.R., Ghauri, P.N., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277-319, ISBN 978-1-84855-468-9.

- Do Valle, P.O.; Assaker, G. Using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling in Tourism Research: A Review of Past Research and Recommendations for Future Applications. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 695-708. [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Mitchell, R.; Gudergan, S.P. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling in HRM Research. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 1617-1643. [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382-388. [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A.E.E.; Algezawy, M.; Elshaer, I.A. Adopting an Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour to Examine Buying Intention and Behaviour of Nutrition-Labelled Menu for Healthy Food Choices in Quick Service Restaurants: Does the Culture of Consumers Really Matter? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4498. [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A.E. Ethical concerns for using artificial intelligence chatbots in research and publication: Evidences from Saudi Arabia. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2024, 7, 1-11. [CrossRef]

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14030047

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38534908

Publication Date: 2024-03-17

Examining Students’ Acceptance and Use of ChatGPT in Saudi Arabian Higher Education

Revised: 10 March 2024

Accepted: 15 March 2024

Published: 17 March 2024

Abstract

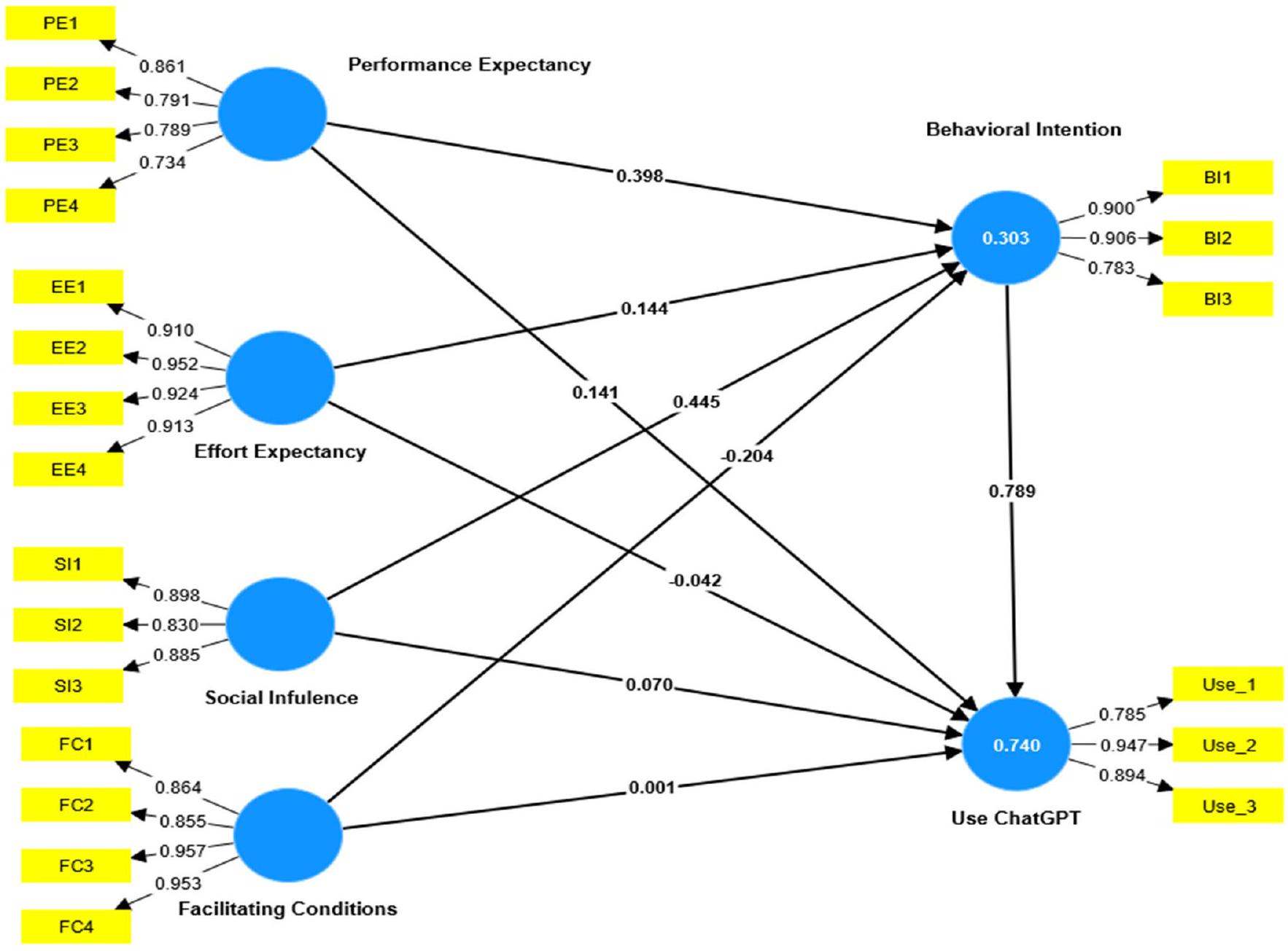

This study examines students’ acceptance and use of ChatGPT in Saudi Arabian (SA) higher education, where there is growing interest in the use of this tool since its inauguration in 2022. Quantitative research data, through a self-reporting survey drawing on the “Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology” (UTAUT2), were collected from 520 students in one of the public universities in SA at the start of the first semester of the study year 2023-2024. The findings of structural equation modeling partially supported the UTAUT and previous research in relation to the significant direct effect of performance expectancy (PE), social influence (SI), and effort expectancy (EE) on behavioral intention (BI) on the use of ChatGPT and the significant direct effect of PE, SI, and BI on actual use of ChatGPT. Nonetheless, the results did not support earlier research in relation to the direct relationship between facilitating conditions (FCs) and both BI and actual use of ChatGPT, which was found to be negative in the first relationship and insignificant in the second one. These findings were because of the absence of resources, support, and aid from external sources in relation to the use of ChatGPT. The results showed partial mediation of BI in the link between PE, SI, and FC and actual use of ChatGPT in education and a full mediation in the link of BI between EE and actual use of ChatGPT in education. The findings provide numerous implications for scholars and higher education institutions in SA, which are also of interest to other institutions in similar contexts.

1. Introduction

expected to be negatively affected. Therefore, it has been argued that caution should be taken by academic institutions to prevent over-dependence by students on using ChatGPT for academic purposes [1].

2. Literature Review

2.1. Students’ Acceptance of ChatGPT and Behavioral Intentions

or complexity of using the technology [13,22]. It plays a key part in shaping people’s willingness and intention to engage with the language model [12]. Menon and Shilpa [15] argued that students’ perception of ChatGPT as user-friendly, easily understandable, and seamlessly integrated into daily activities positively influences their BIs. Moreover, recent studies, e.g., refs. [

H2: EE has a significant positive effect on BI to use ChatGPT in education.

H3: SI has a significant positive effect on BI to use ChatGPT in education.

H4: FC has a significant positive effect on BI to use ChatGPT in education.

2.2. Students’ Acceptance and Actual Use of ChatGPT

H6: EE has a significant positive effect on Use of ChatGPT.

H7: SI has a significant positive effect on Use of ChatGPT.

H8: FCs have a significant positive effect on Use of ChatGPT.

2.3. BI and Use of ChatGPT

2.4. The Role of BI in the Link between Students’ Acceptance and Usage of ChatGPT

H11: BIs mediate the link between EE and Use of ChatGPT.

H12: BIs mediate the link between SI and Use of ChatGPT.

H13: BIs mediate the link between FC and Use of ChatGPT.

A summary of all the relationships in the research conceptual framework is presented below (Figure 1).

3. Methods

3.1. Measures and Scale Development

3.2. Research Sample and Data Collection Method

3.3. Data Analysis

| Profile | Freq. | % | |

| Gender | Male | 285 | 54.8 |

| Female | 235 | 45.2 | |

| Less than 20 years | 241 | 46.3 | |

| Age | 20 to 25 years | 267 | 51.3 |

| 26 to 30 years | 12 | 2.4 | |

| Freshman (year one) | 116 | 22.2 | |

| Sophomore (year two) | 123 | 23.7 | |

| Study level | Junior (year three) | 147 | 28.3 |

| Senior (year four) | 134 | 25.8 | |

| No | 113 | 21.7 |

4. Results of the Study

values exceed 0.9, concerns about discriminant validity arise. However, as shown in Table 3, all ratios remain below the specified value of 0.9 , confirming discriminant validity.

| Scale Variables and Items | Loadings | VIF | |

| PE: (

|

|||

| PE1 | “ChatGPT is a valuable tool for my academic pursuits” | 0.861 | 1.613 |

| PE2 | “Utilizing ChatGPT improves the probability of attaining important objectives in your academic pursuits” | 0.791 | 1.710 |

| PE3 | “ChatGPT enhances productivity in academic studies by expediting the completion of tasks and projects” | 0.789 | 1.523 |

| PE4 | “Using ChatGPT can elevate my academic performance” | 0.734 | 1.613 |

| EE: (

|

|||

| EE1 | “I find it easy to learn how to use ChatGPT” | 0.910 | 4.033 |

| EE2 | “Communication with ChatGPT is transparent and easy to comprehend” | 0.952 | 4.832 |

| EE3 | “ChatGPT is user-friendly and intuitive” | 0.924 | 4.256 |

| EE4 | “I find it effortless to acquire expertise in using ChatGPT” | 0.913 | 3.679 |

| SI: (

|

|||

| SI1 | “People who play a crucial role in my life are of the opinion that I should utilize ChatGPT” | 0.898 | 1.806 |

| SI2 | “People who shape my behavior recommend the utilization of ChatGPT” | 0.830 | 2.287 |

| SI3 | “Those whose opinions I hold in high esteem suggest that I make use of ChatGPT” | 0.885 | 2.835 |

| FC:

|

|||

| FC1 | “I am adequately equipped with the necessary resources to make use of ChatGPT” | 0.864 | 3.984 |

| FC2 | “I am proficient in utilizing ChatGPT due to acquired knowledge” | 0.855 | 4.035 |

| FC3 | “ChatGPT is suitable for the technologies I utilize” | 0.957 | 4.157 |

| FC4 | “When facing difficulties with ChatGPT, it is possible to receive support and aid from external sources” | 0.953 | 3.984 |

|

|

|||

| BI1 | “I have decided to continue using ChatGPT in the times ahead” | 0.900 | 2.366 |

| BI2 | “I am dedicated to utilizing ChatGPT as a tool for my studies” | 0.906 | 2.343 |

| BI3 | “I aim to continue using ChatGPT on a frequent basis” | 0.783 | 1.572 |

| Actual Use (AU) (

|

|||

| AU1 | “I intend to use the knowledge and skills I acquired from the ChatGPT in my educational activities” | 0.785 | 1.578 |

| AU2 | “The knowledge and skills I acquired from the ChatGPT will be useful to me in class” | 0.947 | 4.134 |

| AU3 | “Using ChatGPT has helped to improve my academic performance” | 0.894 | 4.109 |

| BI | EE | FC | PE | SI | Usage | |

| BI | 0.864 | |||||

| EE | 0.058 [0.73] | 0.925 | ||||

| FC | -0.171 [0.154] | 0.450 [0.523] | 0.908 | |||

| PE | 0.297 [0.354] | 0.166 [0.188] | -0.027 [0.066] | 0.795 | ||

| SI | 0.319 [0.361] | -0.136 [0.159] | -0.046 [0.045] | -0.293 [0.354] | 0.872 | |

| Usage | 0.801 [0.195] | 0.017 [0.044] | -0.160 [0.141] | 0.348 [0.417] | 0.286 [0.312] | 0.878 |

| Paths | Path Coefficient |

|

|

Results |

| PE -> BI [H1]. | 0.398 | 6.346 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| EE -> BI [H2]. | 0.144 | 2.596 | 0.009 | Accepted |

| SI -> BI [H3]. | 0.445 | 7.095 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| FC -> BI [H4]. | -0.204 | 4.635 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| PE -> ChatGPT usage [H5]. | 0.141 | 4.489 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| EE -> ChatGPT usage [H6]. | -0.042 | 1.610 | 0.107 | Rejected |

| SI -> ChatGPT usage [H7]. | 0.070 | 2.603 | 0.009 | Accepted |

| FC -> ChatGPT usage [H8]. | 0.001 | 0.026 | 0.979 | Rejected |

| BI -> ChatGPT usage [H9]. | 0.789 | 27.366 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| Specific indirect paths | ||||

| PE -> BI -> ChatGPT usage [H10]. | 0.314 | 6.076 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| EE -> BI -> ChatGPT usage [H11]. | 0.114 | 2.575 | 0.010 | Accepted |

| SI -> BI -> ChatGPT usage [H12]. | 0.352 | 6.708 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| FC -> BI -> ChatGPT usage [H13]. | -0.161 | 4.540 | 0.000 | Accepted |

5. Discussion and Implications

between FC and actual use of ChatGPT in education. Again, lack of available resources and support given to students made them develop negative BI and had an insignificant effect on their ChatGPT usage in education.

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

7. Conclusions

on students’ learning to maintain sustainable learning outcomes. Hence, they should encourage responsible and ethical use of ChatGPT for academic purposes.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, A.E.E.S., I.A.E. and A.M.H.; methodology, I.A.E., A.E.E.S. and A.M.H.; software, I.A.E.; validation, A.E.E.S. and I.A.E.; formal analysis, I.A.E. and A.E.E.S.; investigation A.E.E.S., A.M.H. and I.A.E.; resources, A.E.E.S.; data curation, A.E.E.S. and I.A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, I.A.E., A.E.E.S. and A.M.H.; writing—review and editing, A.E.E.S. and I.A.E.; visualization, A.M.H. and I.A.E.; supervision, I.A.E.; project administration, A.E.E.S., I.A.E. and A.M.H.; funding acquisition, A.E.E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement: Data are available upon request from researchers who meet the eligibility criteria. Kindly contact the first author privately through e-mail.

References

- Hasanein, A.M.; Sobaih, A.E.E. Drivers and Consequences of ChatGPT Use in Higher Education: Key Stakeholder Perspectives. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 2599-2614. [CrossRef]

- Benuyenah, V. Commentary: ChatGPT use in higher education assessment: Prospects and epistemic threats. J. Res. Innov. Teach. Learn. 2023, 16, 134-135. [CrossRef]

- Rasul, T.; Nair, S.; Kalendra, D.; Robin, M.; Santini, F.d.O.; Ladeira, W.J.; Sun, M.; Day, I.; Rather, R.A.; Heathcote, L. The role of ChatGPT in higher education: Benefits, challenges, and future research directions. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2023, 6, 41-56.

- Strzelecki, A. To use or not to use ChatGPT in higher education? A study of students’ acceptance and use of technology. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Obaid, O.I.; Ali, A.H.; Yaseen, M.G. Impact of Chat GPT on Scientific Research: Opportunities, Risks, Limitations, and Ethical Issues. Iraqi J. Comput. Sci. Math. 2023, 4, 13-17. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Watanobe, Y. ChatGPT for education and research: Opportunities, threats, and strategies. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5783. [CrossRef]

- King, M.R. ChatGPT. A conversation on artificial intelligence, chatbots, and plagiarism in higher education. Cell Mol. Bioeng. 2023, 16, 1-2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, B.D.; Wang, T.; Mannuru, N.R.; Nie, B.; Shimray, S.; Wang, Z. ChatGPT and a new academic reality: Artificial Intelligencewritten research papers and the ethics of the large language models in scholarly publishing. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2023, 74, 570-581. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M.; Rauschenberger, M.; Schön, E.M. “We Need to Talk About ChatGPT”: The Future of AI and Higher Education. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACM 5th International Workshop on Software Engineering Education for the Next Generation (SEENG), Melbourne, Australia, 16 May 2023.

- Alotaibi, N.S.; Alshehri, A.H. Prospers and obstacles in using artificial intelligence in Saudi Arabia higher education institutions-The potential of AI-based learning outcomes. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10723. [CrossRef]

- Magsamen-Conrad, K.; Upadhyaya, S.; Joa, C.Y.; Dowd, J. Bridging the divide: Using UTAUT to predict multigenerational tablet adoption practices. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 186-196. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, V. Adoption and use of AI tools: A research agenda grounded in UTAUT. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 308, 641-652. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425-478. [CrossRef]

- Shahsavar, Y.; Choudhury, A. User Intentions to Use ChatGPT for Self-Diagnosis and Health-Related Purposes: Cross-sectional Survey Study. JMIR Hum. Factors 2023, 10, e47564. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, D.; Shilpa, K. “Chatting with ChatGPT”: Analyzing the factors influencing users’ intention to Use the Open AI’s ChatGPT using the UTAUT model. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20962. [CrossRef]

- Fagan, M.; Kilmon, C.; Pandey, V. Exploring the adoption of a virtual reality simulation: The role of perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness and personal innovativeness. Campus-Wide Inf. Syst. 2012, 29, 117-127. [CrossRef]

- Kasilingam, D.L. Understanding the attitude and intention to use smartphone chatbots for shopping. Technol. Soc. 2020, 62, 101280. [CrossRef]

- Brachten, F.; Kissmer, T.; Stieglitz, S. The acceptance of chatbots in an enterprise context—A survey study. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 60, 102375. [CrossRef]

- Mogaji, E.; Balakrishnan, J.; Nwoba, A.C.; Nguyen, N.P. Emerging-market consumers’ interactions with banking chatbots. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 65, 101711. [CrossRef]

- Bin-Nashwan, S.A.; Sadallah, M.; Bouteraa, M. Use of ChatGPT in academia: Academic integrity hangs in the balance. Technol. Soc. 2023, 75, 102370. [CrossRef]

- Al-Emran, M.; AlQudah, A.A.; Abbasi, G.A.; Al-Sharafi, M.A.; Iranmanesh, M. Determinants of using AI-based chatbots for knowledge sharing: Evidence from PLS-SEM and fuzzy sets (fsQCA). IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 71, 4985-4999. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157-178. [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, B.; Senali, M.G.; Iranmanesh, M.; Khanfar, A.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Annamalai, N.; Naghmeh-Abbaspour, B. Determinants of Intention to Use ChatGPT for Educational Purposes: Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. Int. J. Human-Computer Interact. 2023, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Shaengchart, Y.; Bhumpenpein, N.; Kongnakorn, K.; Khwannu, P.; Tiwtakul, A.; Detmee, S. Factors influencing the acceptance of ChatGPT usage among higher education students in Bangkok, Thailand. Adv. Knowl. Exec. 2023, 2, 1-14.

- Tiwari, C.K.; Bhat, M.A.; Khan, S.T.; Subramaniam, R.; Khan, M.A.I. What drives students toward ChatGPT? An investigation of the factors influencing adoption and usage of ChatGPT. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 2023, ahead-of-print.

- Jo, H. Understanding AI tool engagement: A study of ChatGPT usage and word-of-mouth among university students and office workers. Telemat. Inform. 2023, 85, 102067. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Huo, Y. Are users willing to embrace ChatGPT? Exploring the factors on the acceptance of chatbots from the perspective of AIDUA framework. Technol. Soc. 2023, 75, 102362. [CrossRef]

- Oye, N.D.; A.Iahad, N.; Ab.Rahim, N. The history of UTAUT model and its impact on ICT acceptance and usage by academicians. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2014, 19, 251-270. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S.; Soliman, M. Game of algorithms: ChatGPT implications for the future of tourism education and research. J. Tour. Futur. 2023, 9, 214-221. [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K.Y.; Zhou, W. Deconstructing Student Perceptions of Generative AI (GenAI) through an Expectancy Value Theory (EVT)-based Instrument. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.01186.

- Duong, C.D.; Vu, T.N.; Ngo, T.V.N. Applying a modified technology acceptance model to explain higher education students’ usage of ChatGPT: A serial multiple mediation model with knowledge sharing as a moderator. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2023, 21, 100883. [CrossRef]

- Terblanche, N.; Kidd, M. Adoption factors and moderating effects of age and gender that influence the intention to use a non-directive reflective coaching chatbot. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221096136. [CrossRef]

- Anayat, S.; Rasool, G.; Pathania, A. Examining the context-specific reasons and adoption of artificial intelligence-based voice assistants: A behavioural reasoning theory approach. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 1885-1910. [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Wu, Y. An Empirical Study of Adoption of ChatGPT for Bug Fixing among Professional Developers. Innov. Technol. Adv. 2023, 1, 21-29. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Lin, Y.; Yu, Z. Factors Influencing Learner Attitudes Towards ChatGPT-Assisted Language Learning in Higher Education. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2023, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitudes and normative beliefs as factors influencing behavioral intentions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1972, 21, 1. [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill Series in Psychology; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994.

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated Guidelines on Which Method to Use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107. [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing. In Advances in International Marketing; Sinkovics, R.R., Ghauri, P.N., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277-319, ISBN 978-1-84855-468-9.

- Do Valle, P.O.; Assaker, G. Using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling in Tourism Research: A Review of Past Research and Recommendations for Future Applications. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 695-708. [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Mitchell, R.; Gudergan, S.P. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling in HRM Research. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 1617-1643. [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382-388. [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A.E.E.; Algezawy, M.; Elshaer, I.A. Adopting an Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour to Examine Buying Intention and Behaviour of Nutrition-Labelled Menu for Healthy Food Choices in Quick Service Restaurants: Does the Culture of Consumers Really Matter? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4498. [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A.E. Ethical concerns for using artificial intelligence chatbots in research and publication: Evidences from Saudi Arabia. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2024, 7, 1-11. [CrossRef]