DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-076460

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38346815

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-12

دليل العملية للدراسات الاستنتاجية باستخدام بيانات الرعاية الصحية من الممارسة السريرية الروتينية لتقييم التأثيرات السببية للأدوية (PRINCIPLED): اعتبارات من مركز الابتكار في FDA Sentinel

المواد الإضافية تُنشر عبر الإنترنت فقط. لعرضها، يرجى زيارة المجلة على الإنترنت.

استشهد بهذا كـ: BMJ2024;384:e076460

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/

bmj-2023-076460

تم القبول: 11 ديسمبر 2023

الملخص

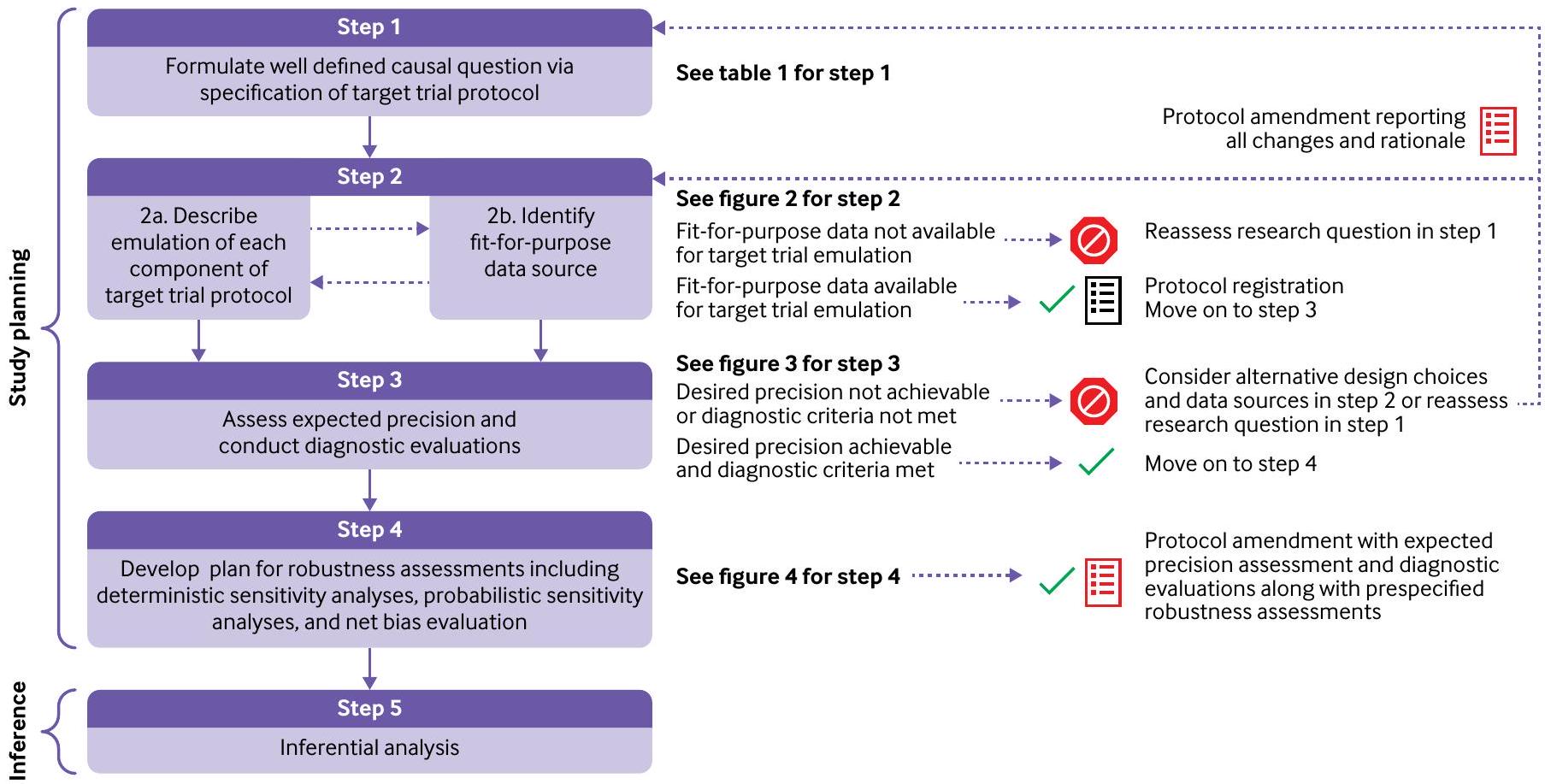

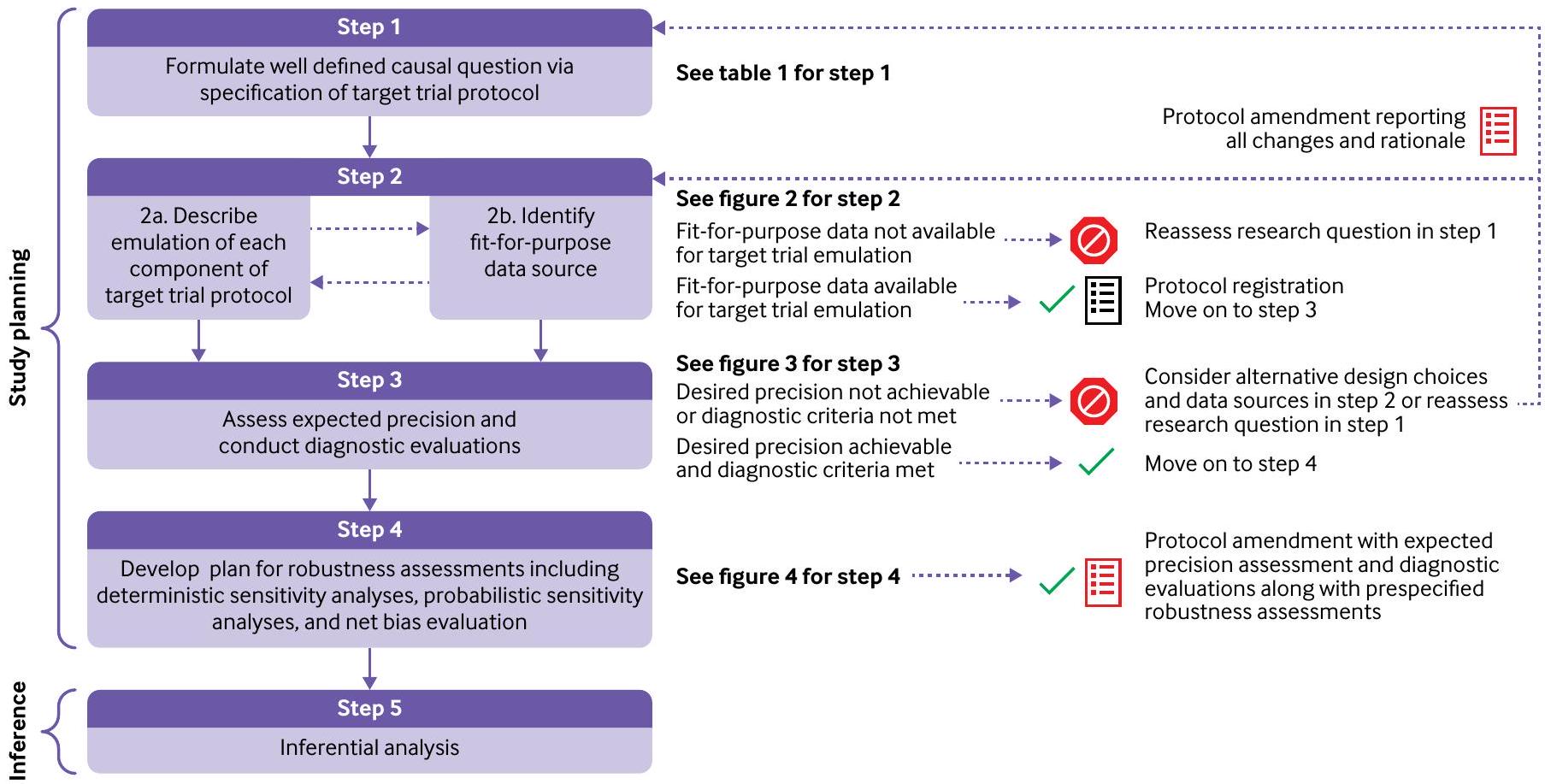

يقترح هذا التقرير عملية خطوة بخطوة تغطي مجموعة من الاعتبارات للنظر بشكل منهجي في الخيارات الرئيسية لتصميم الدراسة وتحليل البيانات للدراسات غير التدخلية مع الهدف المركزي المتمثل في تعزيز توليد أدلة موثوقة وقابلة للتكرار. تشمل هذه الخطوات (1) صياغة سؤال سببي محدد جيدًا من خلال تحديد بروتوكول التجربة المستهدفة؛ (2) وصف محاكاة كل مكون من مكونات بروتوكول التجربة المستهدفة وتحديد البيانات المناسبة؛ (3) تقييم الدقة المتوقعة وإجراء تقييمات تشخيصية؛ (4) تطوير خطة لتقييمات القوة بما في ذلك تحليلات الحساسية الحتمية، وتحليلات التحيز الكمي، وتقييم التحيز الصافي؛ و(5) التحليلات الاستنتاجية.

نقاط الملخص

PRINCIPLED (دليل العملية للدراسات الاستنتاجية باستخدام بيانات الرعاية الصحية من الممارسة السريرية الروتينية لتقييم التأثيرات السببية للأدوية) هو عملية خطوة بخطوة مقترحة للنظر بشكل منهجي في الخيارات الرئيسية لتصميم الدراسة وتحليل البيانات للدراسات غير التدخلية.

يمكن أن تُفيد العملية الموضحة هنا في توجيه إجراء الدراسات غير التدخلية، وتسهيل الاتصالات الشفافة بين مختلف الأطراف المعنية، وقد تحفز اعتبارات مماثلة لمجتمع البحث السريري.

نظام المراقبة النشطة الوطني لما بعد التسويق لمنتجات الأدوية

نظرة عامة على دليل العملية المقترح

الانحراف عن هذه الخطوات. حتى في الحالات التي لا يمكن فيها تنفيذ العملية بالكامل، يمكن إجراء دراسة معقولة، ولكن قد تحتاج بعض التنازلات إلى أن تُجرى.

الخطوة 1: صياغة سؤال سببي من خلال تحديد بروتوكول التجربة المستهدفة

الخطوة 2: وصف محاكاة كل مكون من بروتوكول التجربة المستهدفة وتحديد مصدر بيانات مناسب

| عنصر | التحديد | المحاكاة باستخدام مصادر بيانات العالم الحقيقي | ||

| معايير الأهلية | المرضى الذين يعانون من داء السكري من النوع 2؛ أعمارهم

|

نفس بروتوكول التجربة المستهدفة | ||

| استراتيجيات العلاج |

|

نفس بروتوكول التجربة المستهدفة | ||

| تخصيص العلاج | عشوائي، غير مُعمى | غير مُعمى ويفترض أنه عشوائي ضمن مستويات العوامل المربكة المقاسة* | ||

| بداية المتابعة (الوقت 0) | عند التخصيص | نفس بروتوكول التجربة المستهدفة | ||

| نهاية المتابعة | الأول من نهاية المتابعة الإدارية (اليوم 365)، فقدان المتابعة، الوفاة، أو حدوث النتيجة | نفس بروتوكول التجربة المستهدفة | ||

| النتيجة الأساسية | العدوى التناسلية | نفس بروتوكول التجربة المستهدفة | ||

| التباين السببي | تأثير النية للعلاج (تأثير التخصيص للعلاج) | نظير الملاحظة لتأثير النية للعلاج |

*تشمل العوامل المربكة المقاسة الخصائص الديموغرافية (العمر، الجنس، العرق، علامات الحالة الاجتماعية والاقتصادية)، متغيرات شدة السكري بما في ذلك المضاعفات الدقيقة والكبيرة، مقاييس تتعلق بالتحكم في السكري مثل

حول اختيار العوامل المربكة عندما تكون المعرفة المحتوى كافية.

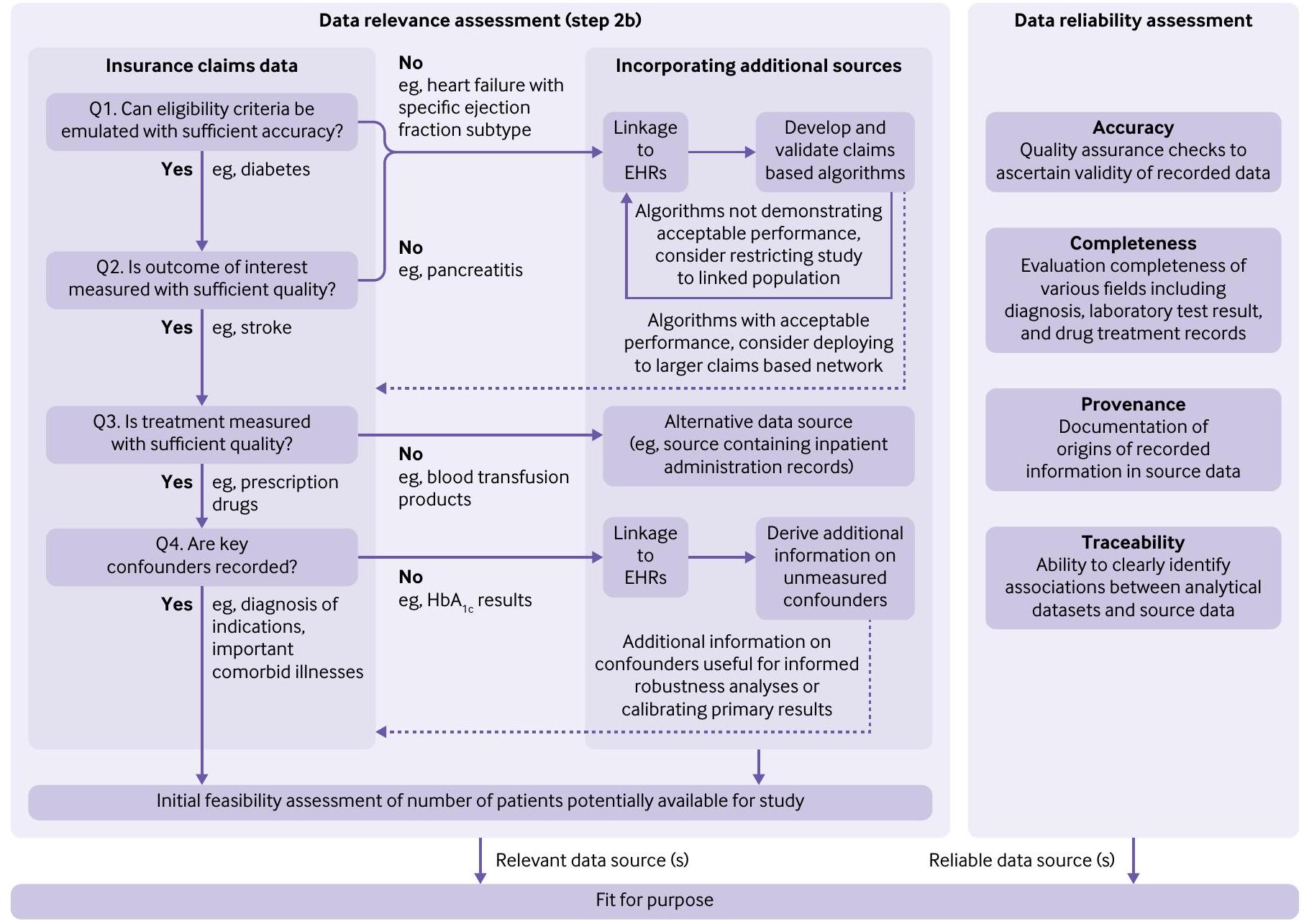

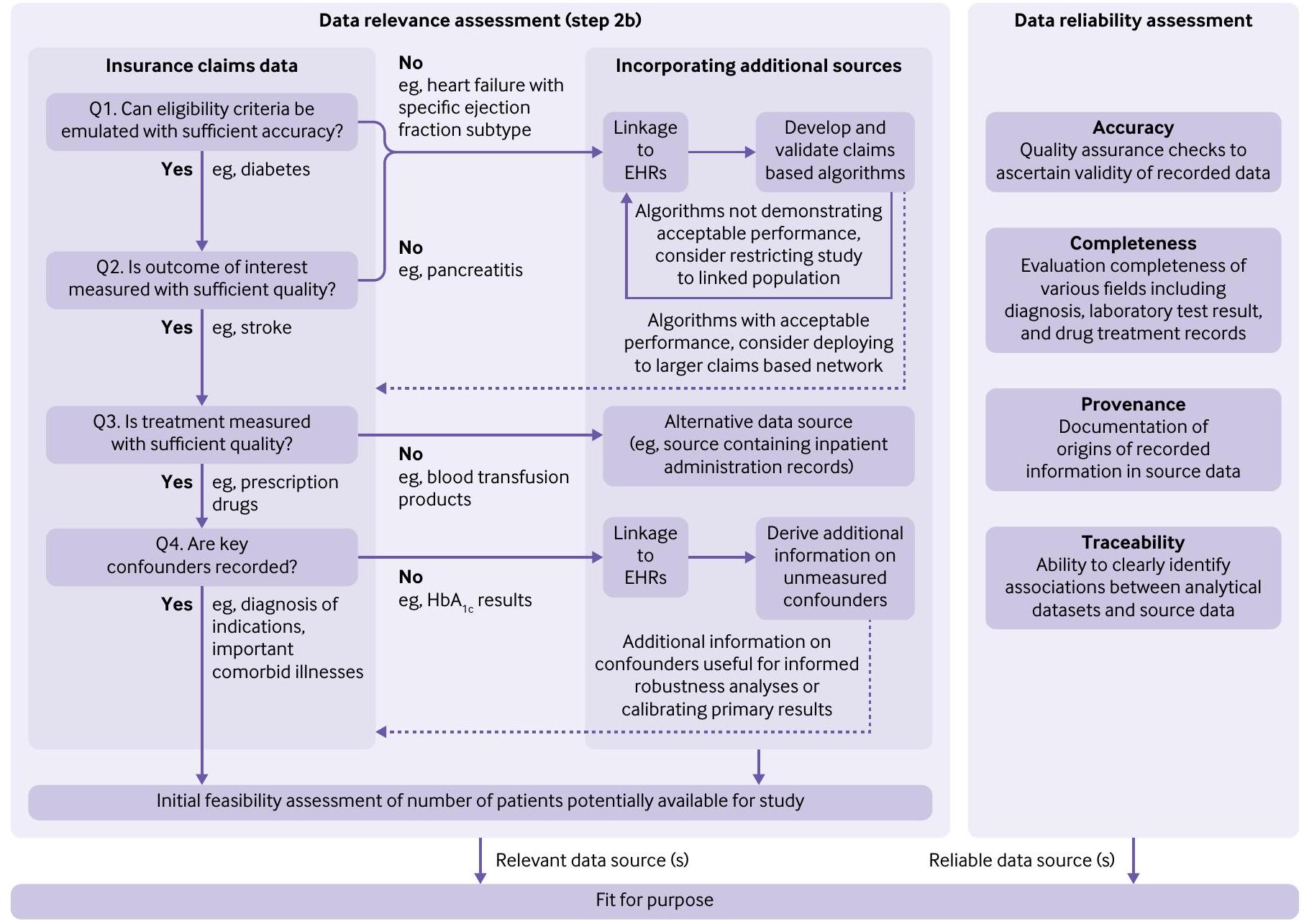

فرصًا للتعزيز. في هذه الحالة، يعتمد تحديد الملاءمة على سلسلة من الأسئلة التي تركز على خصائص القياس لأربعة أنواع من المتغيرات المركزية في سؤال البحث المعني في بيانات مطالبات التأمين: معايير الأهلية، النتيجة، العلاج، والعوامل المربكة الرئيسية. إذا تم اعتبار قياس أي من هذه المتغيرات غير كافٍ، فسيكون من الضروري تعزيز مطالبات التأمين بمصادر بديلة مثل السجلات الصحية الإلكترونية المرتبطة. نصف أدناه الفروق الدقيقة المحددة عند النظر في هذه الأسئلة الأربعة الرئيسية.

- السؤال 1: هل يمكن محاكاة معايير الأهلية بدقة كافية؟

قد لا تكون بعض معايير الأهلية المحددة في بروتوكول التجربة المستهدفة (مثل بعض الحالات الطبية) قابلة للتحديد بشكل صريح في مطالبات التأمين وقد لا تكون خوارزمية تصنيف تم التحقق منها متاحة. في هذه الظروف، سيكون من الضروري الربط بالسجلات الصحية الإلكترونية لتطوير والتحقق من خوارزميات التصنيف التي تحدد الحالات الصحية المعنية باستخدام معلومات بديلة مستندة إلى المطالبات.

على سبيل المثال، لا يمكن تحديد الأنواع الفرعية لفشل القلب المحفوظ والمخفض بشكل مباشر في مطالبات التأمين بسبب نقص قياسات الكسر القذفي. تم تطوير خوارزمية تصنيف احتمالية بناءً على مطالبات Medicare لتحديد الأنواع الفرعية للكسر القذفي لفشل القلب باستخدام مطالبات Medicare المرتبطة بالسجلات الصحية الإلكترونية من نظام الرعاية الصحية Mass General Brigham. أظهرت دقة عامة تبلغفي التمييز بين الأنواع الفرعية المحفوظة والمخفضة للكسر القذفي. سهل هذا النموذج نشر هذه الخوارزمية في بيانات مطالبات Medicare الوطنية لدراسة نتائج علاج الأدوية لهذه الفئات السكانية المحددة من الاهتمام. في الظروف التي تظهر فيها الخوارزمية المطورة أداءً دون المستوى، قد يكون من الضروري تقييد

- السؤال 2: هل تم قياس النتيجة المعنية بجودة كافية؟

تعتمد جودة قياس النتيجة على القيمة المتوقعة الإيجابية للنتائج الثنائية، والنسبة المفقودة للنتائج المستمرة، والبداية الدقيقة للنتائج المتعلقة بالوقت. عادةً، قد يتم تسجيل الحالات الطبية الخطيرة (مثل السكتة الدماغية) بشكل كافٍ في مطالبات التأمين; لكن النتائج الأخرى ليست كذلك، بما في ذلك تلك التي تتطلب نتائج اختبارات مختبرية تأكيدية (مثل، التهاب البنكرياس الحاد ) أو معلومات سياقية من ملاحظات نصية حرة (مثل، الأفكار الانتحارية ). بالنسبة لمثل هذه النتائج، يتطلب الأمر تعزيز البيانات من خلال ربط مطالبات التأمين بالسجلات الصحية الإلكترونية.

وشدة الحدث الضار. معرفة خصائص القياس من خلال التحقق في السجلات الصحية الإلكترونية المرتبطة، حتى عندما تكون دون المستوى الأمثل، سيمكن من تحليل التحيز الكمي.

- السؤال 3: هل تم قياس العلاج بجودة كافية؟

تشير جودة القياس لعلاج معين إلى دقة التسجيل في بيانات مطالبات التأمين فيما يتعلق بالتوقيت والكمال. بالنسبة للعديد من المنتجات مثل علاجات الأدوية الموصوفة للمرضى الخارجيين، تكون مطالبات التأمين عمومًا كافية لالتقاط العلاج من خلال سجلات صرف الأدوية الخارجية. ومع ذلك، فإن مثال العلاج الذي غالبًا ما يتم تسجيله بشكل غير كافٍ في المطالبات هو منتجات نقل الدم.في مثل هذه الظروف، هناك حاجة إلى مصادر بيانات بديلة تحتوي على معلومات حول الإدارات الداخلية للإجابة على سؤال البحث. إذا كانت استراتيجيات العلاج الديناميكية تتم مقارنتها، يجب أن تكون العوامل السريرية المتغيرة مع الزمن المستخدمة لتعريف الاستراتيجيات متاحة أيضًا. - السؤال 4: هل تم تسجيل العوامل المربكة الرئيسية؟

البيانات الخام من المصادر المساهمة إلى نموذج البيانات المشترك لـ Sentinel – والذي يُستخدم بعد ذلك لجميع التحليلات اللاحقة.

إذا لم يكن من الممكن محاكاة كل مكون من بروتوكول التجربة المستهدفة باستخدام مصدر البيانات الذي يتم النظر فيه، يمكن للباحثين إعادة تقييم السؤال في الخطوة 1 من خلال تحديد بروتوكول تجربة مستهدفة معدلة تتطلب مجموعة مختلفة من عناصر البيانات مع الاستمرار في طرح سؤال سببي ذي أهمية. يُشجع الباحثون على تسجيل جميع تقييمات ملاءمة البيانات وموثوقية البيانات لتتبع القرارات التصميمية الرئيسية التي تؤدي إلى اختيار بيانات ملائمة للغرض يمكن أن تدعم محاكاة التجربة المقابلة.

إذا كانت محاكاة كل مكون من بروتوكول التجربة المستهدفة ممكنة باستخدام مصدر البيانات الذي يتم النظر فيه، يجب على الباحثين النظر في تسجيل بروتوكول الدراسة في هذه المرحلة قبل المضي قدمًا في تقييم الدقة المتوقعة والتقييمات التشخيصية (الخطوة 3). بديل تسجيل البروتوكول هو نشر بروتوكول التجربة المستهدفة مع الشيفرة الحاسوبية المشروحة مع جعل البيانات متاحة للباحثين المهتمين كلما كان ذلك ممكنًا. يمكن أن يكون التسجيل المسبق للبروتوكولات واتفاقيات مشاركة البيانات رادعًا لتعدين البيانات، وهو مصدر قلق شائع مع تحليلات بيانات الرعاية الصحية.

بالنسبة لدراسة الحالة المثال، تم اعتبار الديموغرافيات (العمر، الجنس، العرق، علامات الحالة الاجتماعية والاقتصادية)؛ المتغيرات المتعلقة بشدة مرض السكري بما في ذلك المضاعفات الدقيقة والكبيرة؛ التدابير المتعلقة بالتحكم في مرض السكري مثل

تجيب الشكل 1 من الملحق على الأسئلة 1-4 لتوفير وضوح حول البيانات المحتملة الملائمة للغرض لدراسة الحالة لدينا. باختصار، يتم التقاط النتيجة والعلاج بشكل جيد في مطالبات Medicare؛ ومع ذلك، قد يكون الربط بالسجلات الصحية الإلكترونية مهمًا لتحديد العوامل السريرية التي تُستخدم كمعايير أهلية

أو عوامل مربكة. في هذه الحالة المثال، استخدمنا بيانات مطالبات Medicare Fee For Service من الأجزاء A و B،

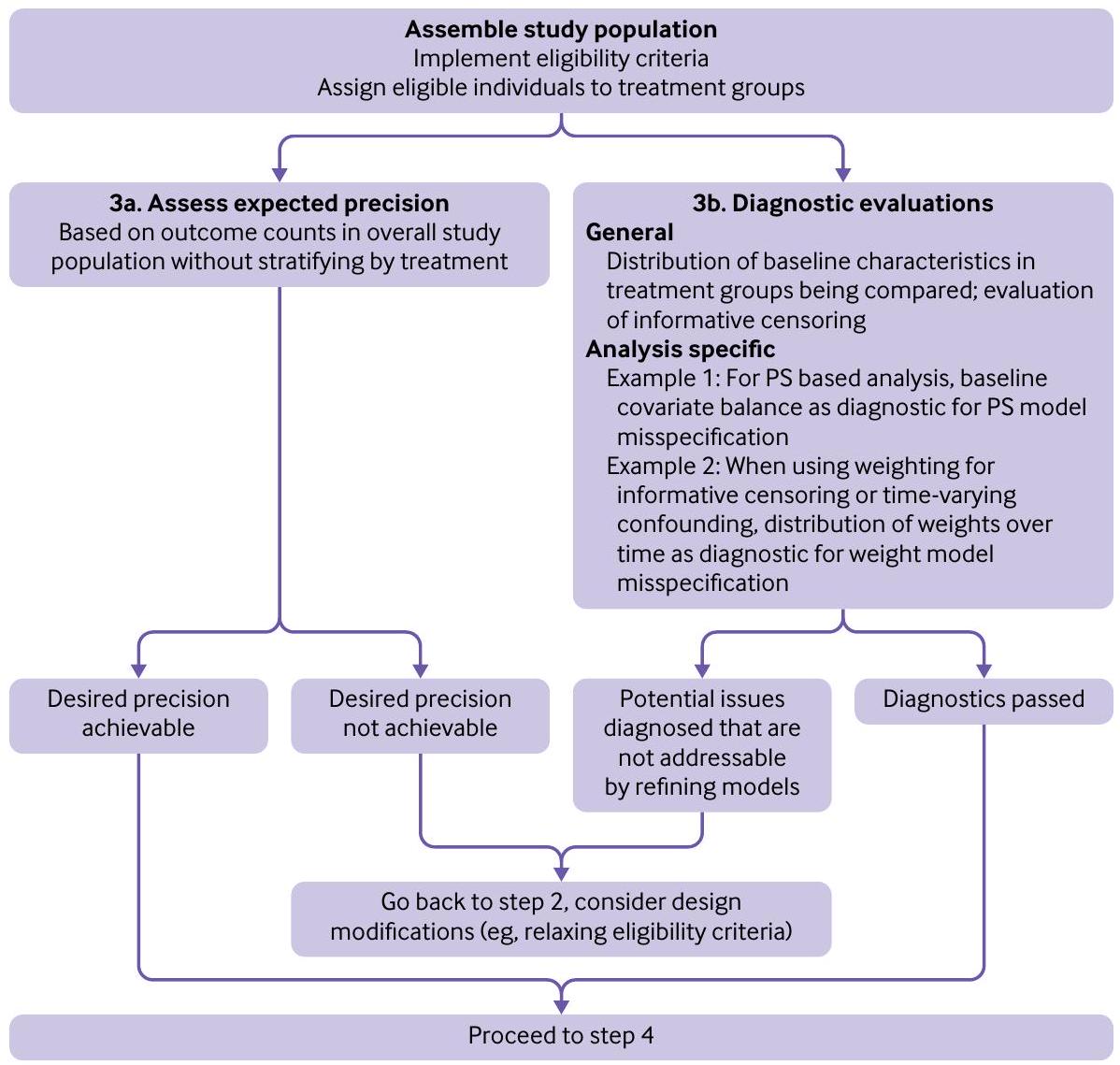

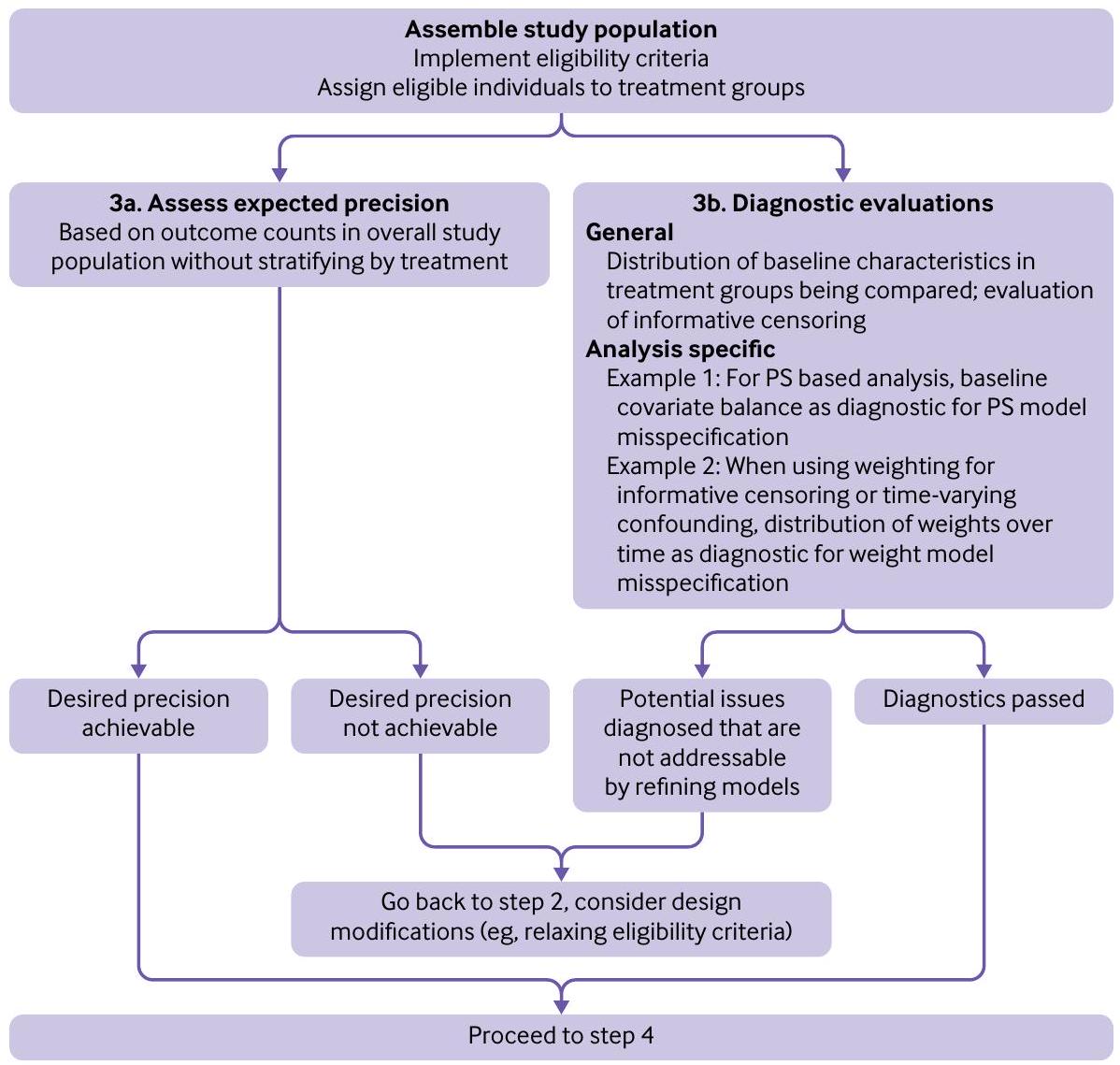

الخطوة 3: تقييم الدقة المتوقعة وإجراء التقييمات التشخيصية

- الخطوة 3أ: تقييم الدقة المتوقعة

- الخطوة 3ب: التقييمات التشخيصية

قمنا بتقييم تداخل التوزيع (الشكل الملحق 3)، توزيع الوزن (الشكل الملحق 4)، وتوازن المتغيرات باستخدام الفروق المعيارية بعد الوزن (الجداول الملحقة 2 و3).

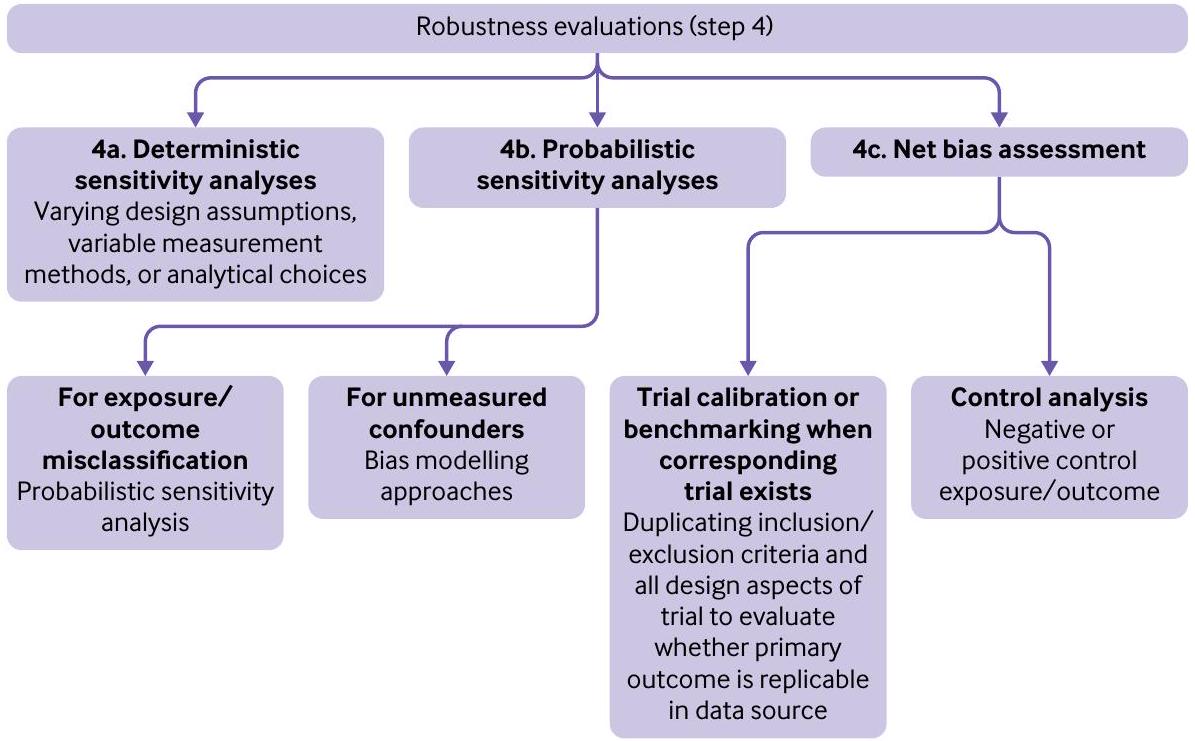

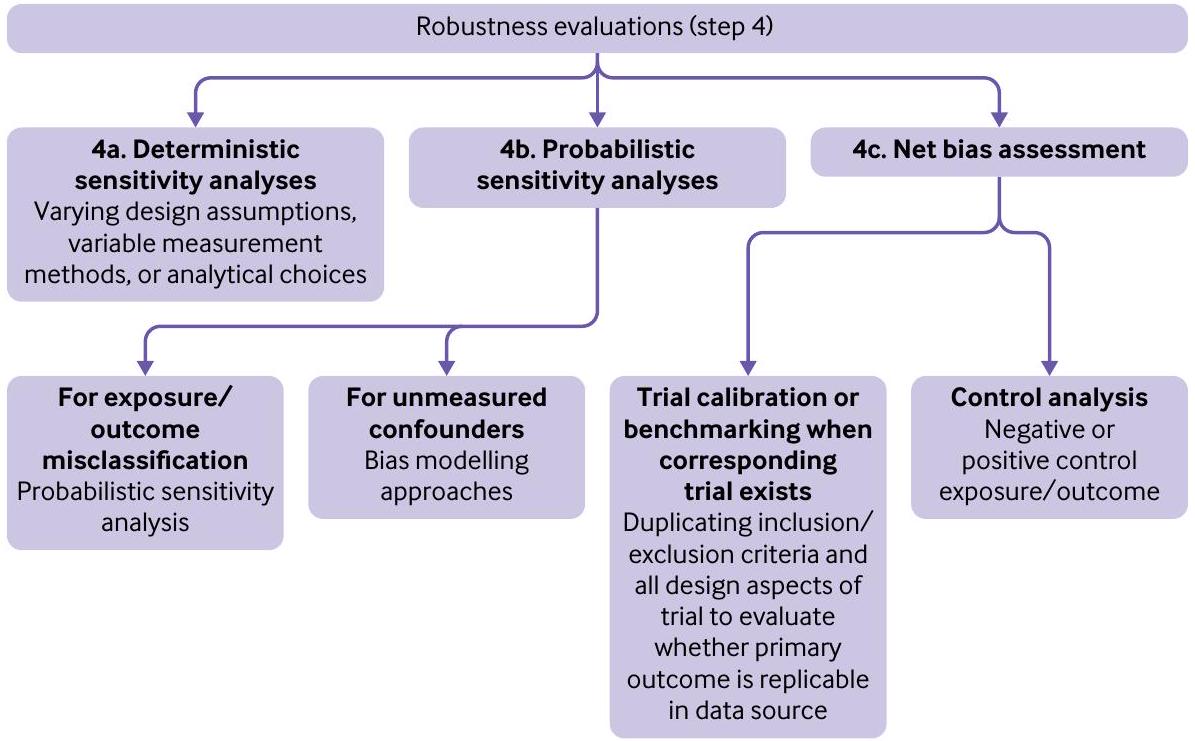

الخطوة 4: تطوير خطة لتقييمات القوة بما في ذلك تحليلات الحساسية الحتمية، وتحليلات الحساسية الاحتمالية، وتقييم الانحياز الصافي

- الخطوة 4أ: تحليلات الحساسية الحتمية

- الخطوة 4ب: تحليلات الحساسية الاحتمالية

- الخطوة 4ج: تقييم الانحياز الصافي

أولاً، حيثما كان ذلك ممكنًا، يجب على المحققين تحديد النتائج الضابطة أو التعرضات الضابطة المعروفة بعدم وجود ارتباطات (ضوابط سلبية) أو ارتباطات مثبتة جيدًا (ضوابط إيجابية) مع التعرض أو النتيجة المعنية. من الناحية المثالية، يجب أن تحتوي هذه المتغيرات الضابطة على هيكل تداخلي أو آلية لخطأ القياس مشابهة للتأثير المستهدف للدراسة.

ثانيًا، عندما يوجد تجربة عشوائية جيدة التنفيذ للمقارنة قيد التحقيق مع نقطة نهاية أولية مختلفة أو أجريت ضمن مجموعة سكانية أكثر تقييدًا، قد يتم السعي إلى المعايرة أو ضبط التجربة.

بالإضافة إلى تقييمات القوة المحددة مسبقًا كإضافات للبروتوكول المسجل قبل الانتقال إلى الخطوة 5. إذا أدى تقييم الدقة المتوقعة والتقييمات التشخيصية، التي لا تسمح صراحة بأي تحليلات استنتاجية، إلى أي تعديلات ذات مغزى في التصميم أو القياس، يجب توثيق جميع هذه التغييرات أيضًا كإضافات للبروتوكول المسجل قبل بدء التحليلات الاستنتاجية.

في مثالنا، حددنا تحليل حساسية حتمي (الخطوة 4أ) لتقييم تأثير تصنيف النتائج بشكل خاطئ. عرفنا النتيجة بعد استبعاد الرموز غير المحددة للبيلانيتس والبيلانوبوستيتس في المرضى الذكور والفاجينيتس والفولفوفاجينيتس في المرضى الإناث والتركيز فقط على الكانديدا في المواقع التناسلية.

كما حددنا تحليل تحيز كمي (الخطوة 4ب). لاستكشاف تأثير افتراضنا أن

أخيرًا، حددنا تحليل التحيز الصافي (الخطوة 4ج)، من خلال تقييم دخول المستشفى بسبب فشل القلب كنتيجة ضابطة إيجابية. لقد ثبت أن مثبطات SGLT-2 لها ارتباط مثبت مع انخفاض خطر دخول المستشفى بسبب فشل القلب. لقد لوحظ هذا الارتباط باستمرار عبر التجارب العشوائية المحكمة بما في ذلك CANVAS وCREDENCE وDAPA-HF وDECLARE-TIMI-58 وEMPAREG OUTCOME وEMPERORREDUCED وVERTIS-CV.

| متغير | الأحداث/سنوات الشخص | |||||

| مثبطات SGLT-2 DPP-4 | نسبة المخاطر (95% CI) | نسبة المخاطر (95% CI) | ||||

| التحليل الأساسي | ||||||

| المجموعة الكاملة | 123/1553 | 170/5785 | – | 2.68 (1.86 إلى 3.86) | ||

| الجنس الذكري | 41/912 | 54/2781 | – | 2.32 (1.21 إلى 4.46) | ||

| الجنس الأنثوي | 82/620 | 134/3055 | – | 3.00 (2.08 إلى 4.32) | ||

| العمر <75 سنة | 77/1026 | 77/2755 | – | 2.69 (1.84 إلى 3.93) | ||

| العمر

|

44/500 | 81/3068 | – | 3.32 (2.04 إلى 5.41) | ||

| مع تاريخ من عوامل خطر العدوى | 67/655 | 80/2821 | – | – | 3.60 (2.48 إلى 5.23) | |

| بدون تاريخ من عوامل خطر العدوى | 56/886 | 90/2910 | – | 2.04 (1.07 إلى 3.91) | ||

| تقييمات القوة | ||||||

| تحليل الحساسية: تعريف أكثر تحديدًا للنتيجة | 47/1596 | 68/5826 | – | 2.51 (1.54 إلى 4.11) | ||

| QBA: تصحيح للمتغير غير المقاس

|

– | – | – | – | 2.63 (1.82 إلى 3.78) | |

| نتيجة الضبط الإيجابي: دخول المستشفى بسبب فشل القلب | 23/1612 | 149/5785 |

|

0.55 (0.34 إلى 0.91) | ||

| 0.5 | 1 | 4 | 8 | |||

الخطوة 5: التحليل الاستنتاجي

لمطالبات التأمين التجاري الأمريكية أبلغ عن زيادة خطر العدوى التناسلية بمقدار ثلاثة أضعاف مع مثبطات SGLT-2 مقابل مثبطات DPP-4.

الاستنتاج

الانتماءات المؤلفين

المساهمون: RJD و SVW و ST و JCN و SS و SD و RB و GDP لديهم أدوار قيادية في مبادرة Sentinel التابعة لإدارة الغذاء والدواء، وهي النظام الوطني للمراقبة النشطة بعد التسويق للمنتجات الطبية في الولايات المتحدة. جميع المؤلفين الآخرين هم خبراء مدعوون من الأوساط الأكاديمية أو إدارة الغذاء والدواء ولديهم سنوات عديدة من الخبرة المشتركة في تطوير الأساليب التي تُعلم إجراء الدراسات غير التدخلية. المؤلفون المشاركون من

التمويل: تم دعم هذا المشروع من خلال الاتفاقية الرئيسية 75F40119D10037 من إدارة الغذاء والدواء الأمريكية (FDA). وافقت إدارة الغذاء والدواء على بروتوكول الدراسة المستخدم في المثال التوضيحي الموضح في الملحق الإلكتروني 2، بما في ذلك خطة التحليل الإحصائي، وراجعت ووافقت على هذه المخطوطة. لم يكن لإدارة الغذاء والدواء أي دور في جمع البيانات أو إدارتها أو تحليلها. الآراء المعبر عنها هي آراء المؤلفين وليست بالضرورة آراء إدارة الغذاء والدواء.

المصالح المت competing: جميع المؤلفين قد أكملوا نموذج الإفصاح الموحد ICMJE فيwww.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ويعلن: دعم من إدارة الغذاء والدواء للعمل المقدم. يذكر RJD أنه يعمل كمدير رئيسي للمشاريع البحثية الممولة من مستشفى بريغهام والنساء من نوفارتس وفيرتيكس وباير في مشاريع غير ذات صلة. SS هو مدير مشارك لمشروع بحثي ممول من مستشفى بريغهام والنساء من بوهرينجر إنجلهايم غير مرتبط بموضوع هذه الدراسة، وهو مستشار لشركة Aetion، وهي شركة تصنيع برمجيات يمتلك أسهمًا فيها؛ وقد تم إعلان اهتماماته ومراجعتها والموافقة عليها من قبل مستشفى بريغهام والنساء ونظام ماس جنرال بريغهام للرعاية الصحية وفقًا لسياسات الامتثال المؤسسية الخاصة بهم. RB هو مؤلف في براءة اختراع أمريكية رقم 9075796 (في استخراج النصوص من مجموعات البيانات الطبية الكبيرة وتصنيف النصوص الطبية المقابلة باستخدام اختيار الميزات المفيدة)، والتي في الوقت الحالي ليست مرخصة ولا تولد إيرادات. يذكر JCN تمويلًا بحثيًا من موديرنا مقابل خدمته في لجنة مراقبة السلامة الخاصة بهم.

الأصل ومراجعة الأقران: لم يتم تكليفه؛ تمت مراجعته من قبل أقران خارجيين.

إدارة الغذاء والدواء. أفضل الممارسات لإجراء وتقرير دراسات السلامة الدوائية باستخدام مجموعات بيانات الرعاية الصحية الإلكترونية. 2013.https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/best-practices-conducting-and-reporting-pharmacoepidemiologic-safety-studies-using-electronic.

3 الشبكة الأوروبية لمراكز علم الأوبئة الدوائية واليقظة الدوائية. دليل ENCePP للمعايير المنهجية في علم الأوبئة الدوائية. 2022https://www.encepp.eu/standards_ و_الإرشادات/الدليل_المنهجي.shtml.

4 نجوم نعم، هيرنان MA، ريفز BC، وآخرون. ROBINS-I: أداة لتقييم خطر التحيز في الدراسات غير العشوائية للتدخلات. BMJ 2016؛ 355: i4919. doi:10.1136/bmj.i4919

5 دريير ن.أ، براينت أ، فيلنتغاس ب. قائمة فحص GRACE: أداة تقييم موثوقة لدراسات الملاحظة عالية الجودة حول الفعالية المقارنة. مجلة إدارة الرعاية والصيدلة المتخصصة 2016؛ 22: 1107-13. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.10.1107

6 لانغان إس إم، شميت إس إيه، وينغ ك، وآخرون. بيان تقارير الدراسات التي أجريت باستخدام بيانات الصحة المجمعة بشكل روتيني لأغراض علم الأوبئة الدوائية (RECORD-PE). BMJ 2018؛ 363: k3532. doi:10.1136/bmj.k3532

7 وانغ إس في، بينهيرو إس، هوا و، وآخرون. STaRT-RWE: قالب منظم للتخطيط والإبلاغ عن تنفيذ دراسات الأدلة الواقعية. BMJ 2021;372:m4856. doi:10.1136/bmj.m4856

8 وانغ إس في، بوتيغارد أ، كراون و، وآخرون. نموذج بروتوكول موحد لتعزيز قابلية إعادة إنتاج الدراسات التي تقيم فرضيات الأدلة الواقعية حول آثار العلاج: تقرير ممارسات جيدة من مجموعة عمل مشتركة بين ISPE/ISPOR. قيمة الصحة 2022؛ 25: 1663-72. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2022.09.001

9 برجر ML، سوكس H، ويلكي RJ، وآخرون. ممارسات جيدة لدراسات البيانات الواقعية حول العلاج و/أو الفعالية المقارنة: توصيات من فريق العمل الخاص المشترك ISPOR-ISPE حول الأدلة الواقعية في اتخاذ قرارات الرعاية الصحية. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2017؛ 26: 1033-9. doi:10.1002/pds.4297

10 أورسيني إل إس، بيرجر م، كراون و، وآخرون. تحسين الشفافية لبناء الثقة في دراسات البيانات الثانوية الواقعية لاختبار الفرضيات – لماذا، ماذا، وكيف: توصيات وخارطة طريق من مبادرة شفافية الأدلة الواقعية. قيمة الصحة 2020؛ 23: 1128-36. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2020.04.002

12 دانغ إل إي، غروبر إس، لي إتش، وآخرون. خارطة طريق سببية لتوليد أدلة عالية الجودة من العالم الحقيقي. مجلة العلوم السريرية والترجمة 2023؛7:e212. doi:10.1017/cts.2023.635

13 Ball R، Robb M، Anderson SA، Dal Pan G. مبادرة السنتينل التابعة لإدارة الغذاء والدواء – نهج شامل لمراقبة المنتجات الطبية. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2016;99:265-8. doi:10.1002/cpt.320

14 إدارة الغذاء والدواء. تحذر إدارة الغذاء والدواء من حدوث حالات نادرة لعدوى خطيرة في منطقة الأعضاء التناسلية مع مثبطات SGLT2 لمرض السكري. 2018.https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-warns-about-rare-occurrences-serious-infection-genital-area-sglt2-inhibitors-diabetes.

15 هيرنان م. الكلمة C: التلاعب العلمي لا يحسن الاستدلال السببي من البيانات الملاحظة. مجلة الصحة العامة الأمريكية 2018؛ 108: 616-9. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304337

16 E9(R1) المبادئ الإحصائية للتجارب السريرية. ملحق: التقديرات وتحليل الحساسية في التجارب السريرية. 2022.https://www.fda.gov/معلومات-تنظيمية/بحث-وثائق-إرشادية-إدارة-الغذاء-والدواء/e9r1-المبادئ-الإحصائية-التجارب-السريرية-ملحق-التقديرات-وتحليل-الحساسية-السريرية

17 هيرنان MA، روبينز JM. استخدام البيانات الكبيرة لمحاكاة تجربة مستهدفة عندما لا تكون تجربة عشوائية متاحة. أم أ Epidemiol 2016؛ 183: 75864. doi:10.1093/aje/kwv254

19 هيرنان MA، هيرنانديز-دياز S، ويرلر MM، ميتشل AA. المعرفة السببية كشرط مسبق لتقييم التداخل: تطبيق على وبائيات عيوب الولادة. أم / وبائيات 2002؛ 155: 176-84. doi:10.1093/aje/155.2.176

20 تينانت PWG، موري EJ، أرنولد KF، وآخرون. استخدام الرسوم البيانية الموجهة غير الدائرية (DAGs) لتحديد العوامل المربكة في أبحاث الصحة التطبيقية: مراجعة وتوصيات. المجلة الدولية لعلم الأوبئة 2021؛50:620-32. doi:10.1093/ije/dyaa213

21 فاندرويل تي جي. مبادئ اختيار العوامل المربكة. المجلة الأوروبية لعلم الأوبئة 2019;34:211-9. doi:10.1007/s10654-019-00494-6

22 شنيوايس س، راسين JA، براون JS، وآخرون. التصوير البياني لتصاميم الدراسات الطولية في قواعد بيانات الرعاية الصحية. آن إنترن ميد 2019؛ 170: 398-406. doi:10.7326/M18-3079

إدارة الغذاء والدواء. مبادرة سينتينل. 2022.https://www. sentinelinitiative.org/about/key-database-statistics

24 ديساي RJ، ماثيني ME، جونسون K، وآخرون. توسيع نطاق نظام FDA Sentinel: خارطة طريق لدمج بيانات السجلات الصحية الإلكترونية في إطار تحليل سببي. NPJ Digit Med 2021؛ 4:170. doi:10.1038/s41746-021-00542-0

25 إدارة الغذاء والدواء. البيانات الواقعية: تقييم السجلات الصحية الإلكترونية وبيانات المطالبات الطبية لدعم اتخاذ القرارات التنظيمية للمنتجات الدوائية والبيولوجية. إرشادات للصناعة. 2021.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/real-world-data-assessing-electronic-health-records-and-medical-claims-data-support-regulatory.

26 ديساي RJ، لين KJ، باتورنو E، وآخرون. تطوير والتحقق الأولي من نموذج قائم على مطالبات ميديكير للتنبؤ بفئة كسر قذف البطين الأيسر لدى المرضى الذين يعانون من فشل القلب. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2018;11:e004700. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.004700

27 بهات AS، فادوجاناتان M، زهو M، فو EL، سولومون SD، ديساي RJ. خطر الإصابة بالفشل الكلوي الحاد بين كبار السن الذين يعانون من فشل القلب مع انخفاض الكسر القذفي المعالج بمثبطات أنجيوتنسين-نيبريلازين مقابل مثبطات نظام الرينين-أنجيوتنسين في الرعاية السريرية الروتينية. J Card Fail 2023؛ 29: 138-46. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2022.09.004

28 ديساي RJ، سولومون SD، فادوجاناتان M. معدلات بدء استخدام سبيرونولاكتون وعمليات الاستشفاء اللاحقة بسبب فرط بوتاسيوم الدم لدى المرضى الذين يعانون من فشل القلب مع الحفاظ على كسر القذف بعد تجربة TOPCAT: دراسة جماعية لمستفيدي ميديكير. J Card Fail 2022;28:1035-9. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2022.01.012

29 Wahl PM، Rodgers K، Schneeweiss S، وآخرون. التحقق من صحة رموز التشخيص والإجراءات المستندة إلى المطالبات للأحداث السلبية الخطيرة المتعلقة بالقلب والجهاز الهضمي في سكان مؤمن عليهم تجارياً. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2010؛ 19:596-603. doi:10.1002/pds.1924

30 فلويد جي إس، بان MA، فيلشر AH، وآخرون. التحقق من صحة التهاب البنكرياس الحاد بين البالغين في نظام رعاية صحية متكامل. علم الأوبئة 2023؛34:33-37. doi:10.1097/EDE.0000000000001541

31 فيرنانديز إيه سي، دوتا آر، فيلوبيللاي إس، سانيل جي، ستيوارت آر، تشاندرا إن. تحديد أفكار الانتحار ومحاولات الانتحار في قاعدة بيانات البحث السريري النفسي باستخدام معالجة اللغة الطبيعية. ساي ريب 2018؛8:7426. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-25773-2

32 لاش تي إل، فوكس إم بي، ماكلوهوز آر إف، مالدونادو جي، مككاندلس إل سي، غرينلاند إس. ممارسات جيدة لتحليل التحيز الكمي. المجلة الدولية لعلم الأوبئة 2014؛43:1969-85. doi:10.1093/ije/dyu149

34 كين لي، روبينز جي إم، لانو إي، لوغان آر، كوستاجليولا دي، هيرنان إم إيه. متى نبدأ العلاج؟ نهج منهجي لمقارنة الأنظمة الديناميكية باستخدام البيانات الملاحظة. المجلة الدولية للإحصاء الحيوي 2010؛6:18. doi:10.2202/1557-4679.1212

35 شني وايس س. تحليل الحساسية والتعديل الخارجي للعوامل المربكة غير المقاسة في دراسات قواعد البيانات الوبائية للعلاج. سلامة الأدوية وعلم الأوبئة 2006؛ 15: 291-303. doi:10.1002/pds.1200

36 ستورمر تي، شنيوايس إس، أفورن جي، غلين آر جي. تعديل تقديرات التأثير للخلط غير المقاس باستخدام بيانات التحقق من صحة باستخدام معايرة درجة الميل. مجلة علم الأوبئة الأمريكية 2005؛162:279-89. doi:10.1093/aje/kwi192

37 مركز عمليات الحارس. ممارسات ضمان جودة بيانات الحارس. 2017.https://www.sentinelinitiative.org/sites/default/files/data/distributed-database/Sentinel_DataQAPractices_Memo.pdf

38 سميث جي دي، إبراهيم س. استخراج البيانات، التحيز، أو التداخل، يمكن أن تؤدي جميعها إلى نشر مقالك في BMJ والصحف يوم الجمعة. BMJ 2002؛ 325: 14378. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7378.1437

41 باتورنو إي، هويبرختس ك.ف، باتيمان ب.ت، وآخرون. استخدام الليثيوم أثناء الحمل وخطر التشوهات القلبية. نيو إنجلند جورنال أوف ميديسن 2017؛ 376: 2245-54. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1612222

42 سميث LH، غارسيا-ألبينيز X، تشان JM، وآخرون. محاكاة تجربة مستهدفة مع استراتيجيات علاج مستدامة: تطبيق على سرطان البروستاتا باستخدام كل من وزن الاحتمالات العكسية وصيغة g. يوروب) إبييديميو 2022؛37:1205-13. doi:10.1007/s10654-022-00929-7

43 هيرنان م. أ. تحليلات سببية لقاعدة البيانات الموجودة: لا حاجة لحسابات القوة. / علم الأوبئة السريرية 2022;144:203-5. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.08.028

44 روثمان ك.ج، غرينلاند س. تخطيط حجم الدراسة بناءً على الدقة بدلاً من القوة. علم الأوبئة 2018؛29:599-603. doi:10.1097/EDE.0000000000000876

45 زو ي، هوبارد ر. أ، تشوباك ج، روي ج، ميترا ن. المفاهيم الأساسية في علم الأوبئة الدوائية: انتهاكات فرضية الإيجابية في التحليل السببي للبيانات الملاحظة: العواقب والأساليب الإحصائية. علم الأوبئة الدوائية وسلامة الأدوية 2021؛30:1471-85. doi:10.1002/pds.5338

46 ويستبر-كلارك م، ستورمر ت، وانغ ت، وآخرون. استخدام درجات الميل لتقدير آثار قرارات بدء العلاج: حالة العلم. ستات ميد 2021؛ 40: 1718-35. doi:10.1002/sim.8866

47 ويس آر، إليس إيه آر، بروكهارت م أ، وآخرون. دور نمذجة التنبؤ في تقدير درجة الميل: تقييم الانحدار اللوجستي، bCART، ودرجة الميل المتوازنة للمتغيرات. أم / وبائيات 2014؛180:645-55. doi:10.1093/aje/kwu181

48 كول SR، هيرنان MA. بناء أوزان الاحتمالات العكسية لنماذج الهيكل الهامشي. مجلة علم الأوبئة الأمريكية 2008؛168:656-64. doi:10.1093/aje/kwn164

49 شولتز ك. ف، ألتمن د. ج، موهر د. بيان CONSORT 2010: إرشادات محدثة للإبلاغ عن التجارب العشوائية ذات المجموعات المتوازية. مجلة علم الأدوية والعلاج 2010؛1:100-7. doi:10.4103/0976-500X.72352

51 ديساي ر. ماكرو SAS لتصنيف الدرجات الاحتمالية الدقيقة. doi:10.7910/DVN/U8JLCW. الطبعة الخامسة: Harvard Dataverse، 2020.

52 فوكس إم بي، لاش تي إل، غرينلاند إس. طريقة لأتمتة التحليلات الحساسية الاحتمالية للمتغيرات الثنائية المصنفة بشكل خاطئ. المجلة الدولية لعلم الأوبئة 2005؛34:1370-6. doi:10.1093/ije/dyi184

53 لاش تي إل، فوكس إم بي، كوني دي، لو واي، فورشي آر إيه. تحليل التحيز الكمي في الإعدادات التنظيمية. مجلة الصحة العامة الأمريكية 2016؛ 106: 122730. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303199

55 Lipsitch M، Tchetgen Tchetgen E، Cohen T. الضوابط السلبية: أداة للكشف عن التداخل والتحيز في الدراسات الرصدية. علم الأوبئة 2010؛21:383-8. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181d61eeb

56 خسرو-خاور ف، كيم إس سي، لي إتش، لي إس بي، ديساي آر جي. توفاسيتينيب ومخاطر النتائج القلبية الوعائية: نتائج من دراسة سلامة توفاسيتينيب في مرضى الروماتويد في الرعاية الروتينية (STAR-RA). آن رومات ديس 2022؛81:798-804. doi:10.1136/ annrheumdis-2021-221915

57 ماثيوز AA، داهابره IJ، فروبيرت O، وآخرون. تقييم التحليلات الملاحظة قبل استخدامها للإجابة على الأسئلة التي لا تجيب عليها التجارب: تطبيق على سحب الجلطة التاجية. أم I إيبيديميول 2022؛ 191: 1652-65. doi:10.1093/aje/kwac098

58 فانديرز WD، خوري MJ. التقييم غير المباشر للتشويش: الوصف الرسومي والحدود على تأثير التعديل للمتغيرات المشتركة. علم الأوبئة 1990؛1:239-46. doi:10.1097/00001648-199005000-00010

59 مور أ، ديكرز أوم، نيلسن ج.س، بيك-نيلسن هـ، سورنسن هـ.ت، طومسن ر.و. تأثير التحكم في نسبة السكر في الدم على خطر العدوى لدى مرضى السكري من النوع 2: دراسة قائمة على السكان. أم أي إيبيديميول 2017؛186:227-36. doi:10.1093/aje/kwx049

60 زيلنيكر TA، ويفيوت SD، راز I، وآخرون. مثبطات SGLT2 للوقاية الأولية والثانوية من النتائج القلبية الوعائية والكلوية في داء السكري من النوع 2: مراجعة منهجية وتحليل تلوي لتجارب النتائج القلبية الوعائية. لانسيت 2019؛393:31-9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32590-X

61 فادوجاناتان M، دوشرتي KF، كلاغيت BL، وآخرون. مثبطات SGLT-2 في المرضى الذين يعانون من فشل القلب: تحليل تلوي شامل لخمس تجارب عشوائية محكومة. لانسيت 2022؛400:757-67. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01429-5

62 تشيو M، دينغ L-L، زانغ M، زو HR. سلامة أربعة مثبطات SGLT2 في ثلاث أمراض مزمنة: تحليل تلوي لتجارب عشوائية كبيرة لمثبطات SGLT2. داء السكري وأبحاث الأمراض الوعائية 2021؛18:14791641211011016. doi:10.1177/14791641211011016

63 ديف CV، شنيوايس S، باتورنو E. المخاطر المقارنة للعدوى التناسلية المرتبطة بمثبطات ناقل الصوديوم والجلوكوز 2. داء السكري والسمنة والتمثيل الغذائي 2019؛21:434-8. doi:10.1111/dom.13531

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-076460

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38346815

Publication Date: 2024-02-12

Process guide for inferential studies using healthcare data from routine clinical practice to evaluate causal effects of drugs (PRINCIPLED): considerations from the FDA Sentinel Innovation Center

Additional material is published online only. To view please visit the journal online.

Citethis as:BMJ2024;384:e076460

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/

bmj-2023-076460

Accepted: 11 December 2023

Abstract

This report proposes a stepwise process covering the range of considerations to systematically consider key choices for study design and data analysis for noninterventional studies with the central objective of fostering generation of reliable and reproducible evidence. These steps include (1) formulating a well defined causal question via specification of the target trial protocol; (2) describing the emulation of each component of the target trial protocol and identifying fit-for-purpose data; (3) assessing expected precision and conducting diagnostic evaluations; (4) developing a plan for robustness assessments including deterministic sensitivity analyses, quantitative bias analyses, and net bias evaluation; and (5) inferential analyses.

SUMMARY POINTS

PRINCIPLED (process guide for inferential studies using healthcare data from routine clinical practice to evaluate causal effects of drugs) is a stepwise process proposed to systematically consider key choices for study design and data analysis for non-interventional studies

The process outlined here can inform the conduct of non-interventional studies, facilitate transparent communications between various stakeholders, and could motivate similar considerations for the clinical research community

national, postmarketing active surveillance system for drug products

Overview of the proposed process guide

deviation from these steps. Even in situations where the process cannot be fully implemented, a reasonable study could still be conducted, but certain trade-offs might need to be made.

Step 1: Formulate a causal question via specification of the target trial protocol

Step 2: Describe the emulation of each component of the target trial protocol and identify a fit-for-purpose data source

| Element | Specification | Emulation using real world data sources | ||

| Eligibility criteria | Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus; aged

|

Same as target trial | ||

| Treatment strategies |

|

Same as target trial | ||

| Treatment assignment | Randomized, non-blinded | Non-blinded and assumed to be randomized within levels of measured confounders* | ||

| Follow-up start (time 0) | At assignment | Same as target trial | ||

| Follow-up end | First of administrative end of follow-up (day 365), loss to follow-up, death, or outcome occurrence | Same as target trial | ||

| Primary outcome | Genital infections | Same as target trial | ||

| Causal contrast | Intention-to-treat effect (effect of being assigned to the treatment) | Observational analogue of intention-to-treat effect |

*Measured confounders include demographics (age, sex, race, socioeconomic status markers), diabetes severity related variables including microvascular and macrovascular complications, measures related to diabetes control such as

about confounder selection when sufficient content knowledge is available.

opportunities for augmentation. In this case, relevance determination depends on a series of questions focused on measurement characteristics of four variable types central to the research question of interest in insurance claims data: eligibility criteria, outcome, treatment, and key confounders. If measurement of any of these variables is deemed to be insufficient, augmentation of insurance claims with alternate sources such as linked electronic health records would be needed. We describe below the specific nuances when considering these four key questions.

- Question 1: Can the eligibility criteria be emulated with sufficient accuracy?

Certain eligibility criteria specified in the target trial protocol (eg, some medical conditions) might not be explicitly identifiable in insurance claims and a previously validated phenotyping algorithm might not be available. In these circumstances, linkage to electronic health records will be needed for development and validation of phenotyping algorithms identifying the health conditions of interest using claims based proxy information.

For instance, heart failure subtypes of preserved and reduced ejection fraction are not directly identifiable in insurance claims owing to lack of ejection fraction measurements. A probabilistic phenotyping algorithm based on Medicare claims for identifying ejection fraction subtypes for heart failure was developed using Medicare claims linked to electronic health records from the Mass General Brigham healthcare system. It demonstrated overall accuracy ofin differentiating between preserved and reduced ejection fraction subtypes. This model facilitated deployment of this algorithm in national Medicare claims data to study drug treatment outcomes for these specific populations of interest. In circumstances where a developed algorithm demonstrates suboptimal performance, limiting

- Question 2: Is the outcome of interest measured with sufficient quality?

The quality of outcome measurement depends on positive predicted value for binary outcomes, proportion missing for continuous outcomes, and accurate onset for time-to-event outcomes. Typically, serious medical conditions (eg, stroke) might be adequately recorded in insurance claims; but other outcomes are not, including those that require confirmatory laboratory test results (eg, acute pancreatitis ) or contextual information from free text notes (eg, suicidal ideation ). For such outcomes, data augmentation through linkage of insurance claims with electronic health records is required.

and the severity of the adverse event. Knowing the measurement characteristics through validation in linked electronic health records, even when they are suboptimal, will enable quantitative bias analysis.

- Question 3: Is the treatment measured with sufficient quality?

Quality of measurement for a particular treatment refers to the accuracy of recording in insurance claims data with respect to the timing and completeness. For many products such as outpatient prescription drug treatments, insurance claims are generally sufficient to capture treatment through outpatient pharmacy dispensing records. However, an example treatment that is often insufficiently recorded in claims is blood transfusion products.In such circumstances, alternate data sources that have information on inpatient administrations are needed to answer the research question. If dynamic treatment strategies are being compared, the time-varying clinical factors used to define the strategies over time should also be available. - Question 4: Are key confounders recorded?

raw data from contributing sources to the Sentinel common data model-which is then used for all subsequent analyses.

If emulation of each component of the target trial protocol is not feasible with the data source being considered, investigators can reassess the question in step 1 by specifying a modified target trial protocol that requires a different set of data elements while still asking a causal question of interest. Investigators are encouraged to record all assessments of data relevance and data reliability to trace key design decisions leading to selection of fit-for-purpose data that can support the corresponding trial emulation.

If emulation of each component of the target trial protocol is feasible with the data source being considered, investigators should consider registration of the study protocol at this stage before proceeding with assessment of expected precision and diagnostic evaluations (step 3). An alternative to protocol registration is publication of the target trial protocol along with the annotated computer code while making the data available to interested investigators whenever feasible. Pre-registration of protocols and data sharing agreements can serve as deterrent to data dredging, which is a common concern with analyses of healthcare data.

For the case example study, demographics (age, sex, race, socioeconomic status markers); variables related to diabetes severity including microvascular and macrovascular complications; measures related to diabetes control such as

Appendix figure 1 answers questions 1-4 to provide clarity on likely fit-for-purpose data for our case example. Briefly, outcome and treatment are well captured in Medicare claims; however, linkage to electronic health records could be important to ascertain clinical factors that are used as eligibility

criteria or confounders. In this case example, we used US Medicare Fee For Service claims data from parts A, B,

Step 3: Assess expected precision and conduct diagnostic evaluations

- Step 3a: Assess expected precision

- Step 3b: Diagnostic evaluations

we evaluated distributional overlap (appendix fig 3), weight distribution (appendix fig 4), and covariate balance using standardized differences post-weighting (appendix tables 2 and 3).

Step 4: Develop a plan for robustness assessments including deterministic sensitivity analyses, probabilistic sensitivity analyses, and net bias evaluation

- Step 4a: Deterministic sensitivity analyses

- Step 4b: Probabilistic sensitivity analyses

- Step 4c: Net bias assessment

Firstly, where possible, investigators should a priori identify and include control outcomes or control exposures that are known to have no associations (negative controls) or well established associations (positive controls) with either the exposure or outcome of interest. Ideally, these control variables will have confounding structure or mechanism of measurement error similar to the effect targeted for study.

Secondly, when a well conducted randomized trial exists for the comparison under investigation with a different primary endpoint or conducted within a more restrictive population, benchmarking or trial calibration might be pursued.

along with prespecified robustness assessments as amendments to the registered protocol before moving on to step 5. If assessment of expected precision and diagnostic evaluations, which explicitly do not allow any inferential analyses, lead to any meaningful adaptations in the design or measurement, all such changes should also be documented as amendments to the registered protocol before starting the inferential analyses.

For our case example, we specified a deterministic sensitivity analysis (step 4a) to evaluate the impact of outcome misclassification. We defined the outcome after excluding non-specific codes of balanitis and balanoposthitis in male patients and vaginitis and vulvovaginitis in female patients and focusing solely on candida of urogenital sites.

We also specified a quantitative bias analysis (step 4b). To explore the impact of our assumption that

Finally, we specified a net bias analysis (step 4c), by assessing hospital admission for heart failure as a positive control outcome. SGLT-2 inhibitors have an established association with a reduced risk of hospital admission for heart failure. This association has been observed consistently across randomized controlled trials including CANVAS, CREDENCE, DAPA-HF, DECLARE-TIMI-58, EMPAREG OUTCOME, EMPERORREDUCED, and VERTIS-CV.

| Variable | Events/person years | |||||

| SGLT-2 DPP-4 inhibitors inhibitors | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | ||||

| Primary analysis | ||||||

| Full cohort | 123/1553 | 170/5785 | – | 2.68 (1.86 to 3.86) | ||

| Male sex | 41/912 | 54/2781 | – | 2.32 (1.21 to 4.46) | ||

| Female sex | 82/620 | 134/3055 | – | 3.00 (2.08 to 4.32) | ||

| Age <75 years | 77/1026 | 77/2755 | – | 2.69 (1.84 to 3.93) | ||

| Age

|

44/500 | 81/3068 | – | 3.32 (2.04 to 5.41) | ||

| With history of infection risk factors | 67/655 | 80/2821 | – | – | 3.60 (2.48 to 5.23) | |

| Without history of infection risk factors | 56/886 | 90/2910 | – | 2.04 (1.07 to 3.91) | ||

| Robustness evaluations | ||||||

| Sensitivity analysis: more specific outcome definition | 47/1596 | 68/5826 | – | 2.51 (1.54 to 4.11) | ||

| QBA: correcting for unmeasured

|

– | – | – | – | 2.63 (1.82 to 3.78) | |

| Positive control outcome: heart failure hospital admission | 23/1612 | 149/5785 |

|

0.55 (0.34 to 0.91) | ||

| 0.5 | 1 | 4 | 8 | |||

Step 5: Inferential analysis

of US commercial insurance claims reported about a threefold increased risk of genital infections with SGLT-2 inhibitors versus DPP-4 inhibitors.

Conclusion

AUTHOR AFFILIATIONS

Contributors: RJD, SVW, ST, JCN, SS, SD, RB, and GDP have leadership roles in the FDA’s Sentinel initiative, which is the national active postmarketing surveillance system for medical products in the US. All other authors are invited experts from academia or FDA with many years of combined experience in development of methods informing conduct of non-interventional studies. Coauthors from the

Funding: This project was supported by Master Agreement 75F40119D10037 from the FDA. The FDA approved the study protocol used in the illustrative example shown in web appendix 2, including statistical analysis plan and reviewed and approved this manuscript. The FDA had no role in data collection, management, or analysis. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the FDA.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare: support from the FDA for the submitted work. RJD reports serving as principal investigator on investigator initiated grants to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Novartis, Vertex, and Bayer on unrelated projects. SS is co-principal investigator of an investigator initiated grant to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Boehringer Ingelheim unrelated to the topic of this study, and is a consultant to Aetion, a software manufacturer of which he owns equity; his interests were declared, reviewed, and approved by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Mass General Brigham HealthCare System in accordance with their institutional compliance policies. RB is an author on US Patent 9075796 (on text mining for large medical text datasets and corresponding medical text classification using informative feature selection), which at present is not licensed and does not generate royalties. JCN reports research funding from Moderna for service on their safety monitoring committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

2 Food and Drug Administration. Best Practices for Conducting and Reporting Pharmacoepidemiologic Safety Studies Using Electronic Healthcare Data Sets. 2013. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/best-practices-conducting-and-reporting-pharmacoepidemiologic-safety-studies-using-electronic.

3 European Network of Centres for Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance. ENCePP Guide on Methodological Standards in Pharmacoepidemiology. 2022 https://www.encepp.eu/standards_ and_guidances/methodologicalGuide.shtml.

4 Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016;355:i4919. doi:10.1136/bmj.i4919

5 Dreyer NA, Bryant A, Velentgas P. The GRACE checklist: a validated assessment tool for high quality observational studies of comparative effectiveness. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2016;22:1107-13. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.10.1107

6 Langan SM, Schmidt SA, Wing K, et al. The reporting of studies conducted using observational routinely collected health data statement for pharmacoepidemiology (RECORD-PE). BMJ 2018;363:k3532. doi:10.1136/bmj.k3532

7 Wang SV, Pinheiro S, Hua W, et al. STaRT-RWE: structured template for planning and reporting on the implementation of real world evidence studies. BMJ 2021;372:m4856. doi:10.1136/bmj.m4856

8 Wang SV, Pottegård A, Crown W, et al. HARmonized Protocol Template to Enhance Reproducibility of hypothesis evaluating real-world evidence studies on treatment effects: A good practices report of a joint ISPE/ISPOR task force. Value Health 2022;25:1663-72. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2022.09.001

9 Berger ML, Sox H, Willke RJ, et al. Good practices for real-world data studies of treatment and/or comparative effectiveness: Recommendations from the joint ISPOR-ISPE Special Task Force on real-world evidence in health care decision making. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2017;26:1033-9. doi:10.1002/ pds. 4297

10 Orsini LS, Berger M, Crown W, et al. Improving Transparency to Build Trust in Real-World Secondary Data Studies for Hypothesis Testing-Why, What, and How: Recommendations and a Road Map from the Real-World Evidence Transparency Initiative. Value Health 2020;23:1128-36. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2020.04.002

12 Dang LE, Gruber S, Lee H, et al. A causal roadmap for generating high-quality real-world evidence. J Clin Transl Sci 2023;7:e212. doi:10.1017/cts.2023.635

13 Ball R, Robb M, Anderson SA, Dal Pan G. The FDA’s sentinel initiative–A comprehensive approach to medical product surveillance. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2016;99:265-8. doi:10.1002/cpt. 320

14 Food and Drug Administration. FDA warns about rare occurrences of a serious infection of the genital area with SGLT2 inhibitors for diabetes. 2018. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-warns-about-rare-occurrences-serious-infection-genital-area-sglt2-inhibitors-diabetes.

15 Hernán MA. The C-word: scientific euphemisms do not improve causal inference from observational data. Am J Public Health 2018;108:616-9. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304337

16 E9(R1) Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials. Addendum: Estimands and Sensitivity Analysis in Clinical Trials. 2022. https://www.fda. gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/ e9r1-statistical-principles-clinical-trials-addendum-estimands-and-sensitivity-analysis-clinical

17 Hernán MA, Robins JM. Using Big Data to Emulate a Target Trial When a Randomized Trial Is Not Available. Am I Epidemiol 2016;183:75864. doi:10.1093/aje/kwv254

19 Hernán MA, Hernández-Díaz S, Werler MM, Mitchell AA. Causal knowledge as a prerequisite for confounding evaluation: an application to birth defects epidemiology. Am / Epidemiol 2002;155:176-84. doi:10.1093/aje/155.2.176

20 Tennant PWG, Murray EJ, Arnold KF, et al. Use of directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) to identify confounders in applied health research: review and recommendations. Int J Epidemiol 2021;50:620-32. doi:10.1093/ije/dyaa213

21 VanderWeele TJ. Principles of confounder selection. Eur J Epidemiol 2019;34:211-9. doi:10.1007/s10654-019-00494-6

22 Schneeweiss S, Rassen JA, Brown JS, et al. Graphical depiction of longitudinal study designs in health care databases. Ann Intern Med 2019;170:398-406. doi:10.7326/M18-3079

23 Food and Drug Administration. Sentinel Initiative. 2022. https://www. sentinelinitiative.org/about/key-database-statistics

24 Desai RJ, Matheny ME, Johnson K, et al. Broadening the reach of the FDA Sentinel system: A roadmap for integrating electronic health record data in a causal analysis framework. NPJ Digit Med 2021;4:170. doi:10.1038/s41746-021-00542-0

25 Food and Drug Administration. Real-World Data: Assessing Electronic Health Records and Medical Claims Data To Support Regulatory Decision-Making for Drug and Biological Products Guidance for Industry. 2021. fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/real-world-data-assessing-electronic-health-records-and-medical-claims-data-support-regulatory.

26 Desai RJ, Lin KJ, Patorno E, et al. Development and preliminary validation of a Medicare claims-based model to predict left ventricular ejection fraction class in patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2018;11:e004700. doi:10.1161/ CIRCOUTCOMES.118.004700

27 Bhatt AS, Vaduganathan M, Zhuo M, Fu EL, Solomon SD, Desai RJ. Risk of Acute Kidney Injury Among Older Adults With Heart Failure and With Reduced Ejection Fraction Treated With AngiotensinNeprilysin Inhibitor vs Renin-Angiotensin System Inhibitor in Routine Clinical Care. J Card Fail 2023;29:138-46. doi:10.1016/j. cardfail.2022.09.004

28 Desai RJ, Solomon SD, Vaduganathan M. Rates of Spironolactone Initiation and Subsequent Hyperkalemia Hospitalizations in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction Following the TOPCAT trial: A Cohort Study of Medicare Beneficiaries. J Card Fail 2022;28:1035-9. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2022.01.012

29 Wahl PM, Rodgers K, Schneeweiss S, et al. Validation of claimsbased diagnostic and procedure codes for cardiovascular and gastrointestinal serious adverse events in a commercially-insured population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2010;19:596-603. doi:10.1002/pds. 1924

30 Floyd JS, Bann MA, Felcher AH, et al. Validation of acute pancreatitis among adults in an integrated healthcare system. Epidemiology 2023;34:33-7. doi:10.1097/EDE. 0000000000001541

31 Fernandes AC, Dutta R, Velupillai S, Sanyal J, Stewart R, Chandran D. Identifying suicide ideation and suicidal attempts in a psychiatric clinical research database using natural language processing. Sci Rep 2018;8:7426. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-25773-2

32 Lash TL, Fox MP, MacLehose RF, Maldonado G, McCandless LC, Greenland S. Good practices for quantitative bias analysis. Int/ Epidemiol 2014;43:1969-85. doi:10.1093/ije/dyu149

34 Cain LE, Robins JM, Lanoy E, Logan R, Costagliola D, Hernán MA. When to start treatment? A systematic approach to the comparison of dynamic regimes using observational data. Int I Biostat 2010;6:18. doi:10.2202/1557-4679.1212

35 Schneeweiss S. Sensitivity analysis and external adjustment for unmeasured confounders in epidemiologic database studies of therapeutics. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2006;15:291-303. doi:10.1002/pds. 1200

36 Stürmer T, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, Glynn RJ. Adjusting effect estimates for unmeasured confounding with validation data using propensity score calibration. Am J Epidemiol 2005;162:279-89. doi:10.1093/aje/kwi192

37 Sentinel Operations Center. Sentinel Data Quality Assurance Practices. 2017. https://www.sentinelinitiative.org/sites/default/files/data/ distributed-database/Sentinel_DataQAPractices_Memo.pdf

38 Smith GD, Ebrahim S. Data dredging, bias, or confounding, They can all get you into the BMJ and the Friday papers. BMJ 2002;325:14378. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7378.1437

41 Patorno E, Huybrechts KF, Bateman BT, et al. Lithium use in pregnancy and the risk of cardiac malformations. NEngl) Med 2017;376:2245-54. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1612222

42 Smith LH, García-Albéniz X, Chan JM, et al. Emulation of a target trial with sustained treatment strategies: an application to prostate cancer using both inverse probability weighting and the g-formula. Eur) Epidemiol 2022;37:1205-13. doi:10.1007/s10654-022-00929-7

43 Hernán MA. Causal analyses of existing databases: no power calculations required. / Clin Epidemiol 2022;144:203-5. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.08.028

44 Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Planning study size based on precision rather than power. Epidemiology 2018;29:599-603. doi:10.1097/ EDE. 0000000000000876

45 Zhu Y, Hubbard RA, Chubak J, Roy J, Mitra N. Core concepts in pharmacoepidemiology: Violations of the positivity assumption in the causal analysis of observational data: Consequences and statistical approaches. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2021;30:1471-85. doi:10.1002/pds. 5338

46 Webster-Clark M, Stürmer T, Wang T, et al. Using propensity scores to estimate effects of treatment initiation decisions: State of the science. Stat Med 2021;40:1718-35. doi:10.1002/sim. 8866

47 Wyss R, Ellis AR, Brookhart MA, et al. The role of prediction modeling in propensity score estimation: an evaluation of logistic regression, bCART, and the covariate-balancing propensity score. Am / Epidemiol 2014;180:645-55. doi:10.1093/aje/kwu181

48 Cole SR, Hernán MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol 2008;168:656-64. doi:10.1093/aje/kwn164

49 Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2010;1:100-7. doi:10.4103/0976-500X.72352

51 Desai R. Propensity score fine stratification SAS macro. doi:10.7910/ DVN/U8JLCW. V5 ed: Harvard Dataverse, 2020.

52 Fox MP, Lash TL, Greenland S. A method to automate probabilistic sensitivity analyses of misclassified binary variables. Int / Epidemiol 2005;34:1370-6. doi:10.1093/ije/dyi184

53 Lash TL, Fox MP, Cooney D, Lu Y, Forshee RA. Quantitative bias analysis in regulatory settings. Am J Public Health 2016;106:122730. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303199

55 Lipsitch M, Tchetgen Tchetgen E, Cohen T. Negative controls: a tool for detecting confounding and bias in observational studies. Epidemiology 2010;21:383-8. doi:10.1097/ EDE.0b013e3181d61eeb

56 Khosrow-Khavar F, Kim SC, Lee H, Lee SB, Desai RJ. Tofacitinib and risk of cardiovascular outcomes: results from the Safety of TofAcitinib in Routine care patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (STAR-RA) study. Ann Rheum Dis 2022;81:798-804. doi:10.1136/ annrheumdis-2021-221915

57 Matthews AA, Dahabreh IJ, Fröbert O, et al. Benchmarking observational analyses before using them to address questions trials do not answer: an application to coronary thrombus aspiration. Am I Epidemiol 2022;191:1652-65. doi:10.1093/aje/kwac098

58 Flanders WD, Khoury MJ. Indirect assessment of confounding: graphic description and limits on effect of adjusting for covariates. Epidemiology 1990;1:239-46. doi:10.1097/00001648-199005000-00010

59 Mor A, Dekkers OM, Nielsen JS, Beck-Nielsen H, Sørensen HT, Thomsen RW. Impact of glycemic control on risk of infections in patients with type 2 diabetes: a population-based cohort study. Am I Epidemiol 2017;186:227-36. doi:10.1093/aje/kwx049

60 Zelniker TA, Wiviott SD, Raz I, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet 2019;393:31-9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32590-X

61 Vaduganathan M, Docherty KF, Claggett BL, et al. SGLT-2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure: a comprehensive meta-analysis of five randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2022;400:757-67. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01429-5

62 Qiu M, Ding L-L, Zhang M, Zhou HR. Safety of four SGLT2 inhibitors in three chronic diseases: A metaanalysis of large randomized trials of SGLT2 inhibitors. Diab Vasc Dis Res 2021;18:14791641211011016. doi:10.1177/14791641211011016

63 Dave CV, Schneeweiss S, Patorno E. Comparative risk of genital infections associated with sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors. Diabetes Obes Metab 2019;21:434-8. doi:10.1111/ dom. 13531